Col. John Trumbull.

(Engraved by the Anastatic process)

Title: Life of George Washington, volume 3 of 5

Author: Washington Irving

Release date: January 16, 2026 [eBook #77704]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: G. P. Putnam, 1855

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Emmanuel Ackerman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Col. John Trumbull.

(Engraved by the Anastatic process)

From Houdon’s Bust.

When the Author commenced the publication of this work, he informed his Publishers that he should probably complete it in three volumes. What he gave as a probability, they understood as a certainty, and worded their advertisements accordingly. His theme has unexpectedly expanded under his pen, and he now lays his third volume before the public, with his task yet unaccomplished. He hopes this may not cause unpleasant disappointment. To present a familiar and truthful picture of the Revolution and the personages concerned in it, required much detail and copious citations, that the scenes might be placed in a proper light, and the characters introduced might speak for themselves, and have space in which to play their parts.

The kindness with which the first two volumes have been received, has encouraged the author to pursue the plan he had adopted, and inspires the hope that the public good-will which has cheered him through so long a period of devious authorship, will continue with him to the approaching close of his career.

Sunnyside, June, 1856.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Burke on the State of Affairs in America—New Jersey Roused to Arms—Washington grants Safe Conduct to Hessian Convoys—Encampment at Morristown—Putnam at Princeton—His Stratagem to Conceal the Weakness of his Camp—Exploit of General Dickinson near Somerset Court House—Washington’s Counter Proclamation—Prevalence of the Small-pox—Inoculation of the Army—Contrast of the British and American Commanders and their Camps, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Negotiations for Exchange of Prisoners—Case of Colonel Ethan Allen—Of General Lee—Correspondence of Washington with Sir William Howe about Exchanges of Prisoners—Referees Appointed—Letters of Lee from New York—Case of Colonel Campbell—Washington’s Advice to Congress on the Subject of Retaliation—His Correspondence with Lord Howe about the Treatment of Prisoners—The Horrors of the Jersey Prison-Ship and the Sugar House, | 11 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Exertions to Form a New Army—Calls on the Different States—Insufficiency of the Militia—Washington’s Care for the Yeomanry—Dangers in the Northern Department—Winter Attack on Ticonderoga Apprehended—Exertions to Reinforce Schuyler—Precarious State of Washington’s Army—Conjectures as to the Designs of the Enemy—Expedition of the British against Peekskill, | 24 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Schuyler’s Affairs in the Northern Department—Misunderstandings with Congress—Gives offence by a Reproachful Letter—Office of Adjutant-General offered to Gates—Declined by him—Schuyler Reprimanded by Congress for his Reproachful Letter—Gates Appointed to the Command at Ticonderoga—Schuyler considers himself Virtually Suspended—Takes his Seat as a Delegate to Congress, and Claims a Court of Inquiry—Has Command at Philadelphia, | 31 |

| viii | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Foreign Officers Candidates for Situations in the Army—Difficulties in Adjusting Questions of Rank—Ducoudray—Conway—Kosciuszko—Washington’s Guards—Arnold Omitted in the Army Promotions—Washington takes his part—British Expedition against Danbury—Destruction of American Stores—Connecticut Yeomanry in Arms—Skirmish at Ridgefield—Death of General Wooster—Gallant Services of Arnold—Rewarded by Congress—Exploit of Colonel Meigs at Sag Harbor, | 40 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Schuyler on the Point of Resigning—Committee of Inquiry Report in his Favor—His Memorial to Congress proves Satisfactory—Discussions Regarding the Northern Department—Gates Mistaken as to his Position—He Prompts his Friends in Congress—His Petulant Letter to Washington—Dignified Reply of the Latter—Position of Gates Defined—Schuyler Reinstated in Command of the Department—Gates Appears on the Floor of Congress—His Proceedings there, | 54 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Highland Passes of the Hudson—George Clinton in Command of the Forts—His Measures for Defence—Generals Greene and Knox examine the State of the Forts—Their Report—The General Command of the Hudson offered to Arnold—Declined by Him—Given to Putnam—Appointment of Dr. Craik in the Medical Department—Expedition Planned against Fort Independence—But Relinquished—Washington Shifts his Camp to Middlebrook—State of his Army—General Howe Crosses into the Jerseys—Position of the two Armies at Middlebrook and behind the Raritan—Correspondence between Washington and Colonel Reed, | 64 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Feigned Movements of Sir William Howe—Baffling Caution of Washington—Rumored Inroads from the North—Schuyler applies for Reinforcements—Renewed schemes of Howe to draw Washington from his Stronghold—Skirmish between Cornwallis and Lord Stirling—The Enemy Evacuate the Jerseys—Perplexity as to their next Movement—A Hostile Fleet on Lake Champlain—Burgoyne approaching Ticonderoga—Speculations of Washington—His Purpose of keeping Sir William Howe from ascending the Hudson—Orders George Clinton to call out Militia from Ulster and Orange Counties—Sends Sullivan towards the Highlands—Moves his own Camp back to Morristown—Stir among the Shipping—Their Destination surmised to be Philadelphia—A Dinner at Head-Quarters—Alexander Hamilton—Graydon’s Rueful Description of the Army—His Character of Wayne, | 76 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| ixBritish Invasion from Canada—The Plan—Composition of the Invading Army—Schuyler on the Alert—His Speculations as to the Enemy’s Designs—Burgoyne on Lake Champlain—His War-Speech to his Indian Allies—Signs of his Approach descried from Ticonderoga—Correspondence on the Subject between St. Clair, Major Livingston, and Schuyler—Burgoyne Intrenches near Ticonderoga—His Proclamation—Schuyler’s Exertions at Albany to forward Reinforcements—Hears that Ticonderoga is Evacuated—Mysterious Disappearance of St. Clair and his Troops—Amazement and Concern of Washington—Orders Reinforcements to Schuyler at Fort Edward, and to Putnam at Peekskill—Advances with his Main Army to the Clove—His Hopeful Spirit manifested, | 86 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Particulars of the Evacuation—Indian Scouts in the vicinity of the Fort—Outposts abandoned by St. Clair—Burgoyne secures Mount Hope—Invests the Fortress—Seizes and Occupies Sugar Hill—The Forts overlooked and in Imminent Peril—Determination to Evacuate—Plan of Retreat—Part of the Garrison depart for Skenesborough in the Flotilla—St. Clair crosses with the rest to Fort Independence—A Conflagration Reveals his Retreat—The British Camp aroused—Fraser Pursues St. Clair—Burgoyne with his Squadron makes after the Flotilla—Part of the Fugitives overtaken—Flight of the Remainder to Fort Anne—Skirmish of Colonel Long—Retreat to Fort Edward—St. Clair at Castleton—Attack of his Rear-Guard—Fall of Colonel Francis—Desertion of Colonel Hale—St. Clair reaches Fort Edward—Consternation of the Country—Exultation of the British, | 100 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Capture of General Prescott—Proffered in Exchange for Lee—Reinforcements to Schuyler—Arnold sent to the North—Eastern Militia to repair to Saratoga—Further Reinforcements—Generals Lincoln and Arnold recommended for Particular Services—Washington’s Measures and Suggestions for the Northern Campaign—British Fleet puts to Sea—Conjectures as to its Destination—A Feigned Letter—Appearance and Disappearance of the Fleet—Orders and Counter Orders of Washington—Encamps at Germantown—Anxiety for the Security of the Highlands—George Clinton on Guard—Call on Connecticut, | 112 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Gates on the Alert for a Command—Schuyler Undermined in Congress—Put on his Guard—Courts a Scrutiny, but not before an expected Engagement—Summoned with St. Clair to Head-Quarters—Gates appointed to the Northern Department—Washington’s Speculations on the Successes of Burgoyne—Ill-judged Meddlings of Congress with the Commissariat—Colonel Trumbull Resigns in consequence, | 123 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Washington’s Perplexities about the British Fleet—Putnam and Governor Clinton put on the Alert in the Highlands—Morgan and his Riflemen sent to the North—Washington at Philadelphia—His first Interview with Lafayette—Intelligence about the Fleet—Explanations of its Movements—Review of the Army—Lafayette Mistakes the nature of his Commission—His Alliance with Washington—March of the Army through Philadelphia—Encampment at Wilmington, | 130 |

| x | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Burgoyne at Skenesborough—Prepares to Move towards the Hudson—Major Skene the Royalist—Slow March to Fort Anne—Schuyler at Fort Miller—Painted Warriors—Langdale—St. Luc—Honor of the Tomahawk—Tragical Story of Miss McCrea—Its Results—Burgoyne Advances to Fort Edward—Schuyler at Stillwater—Joined by Lincoln—Burgoyne deserted by his Indian Allies, | 140 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Difficulties of Burgoyne—Plans an Expedition to Bennington—St. Leger before Fort Stanwix—General Herkimer at Oriskany—High Words with his Officers—A Dogged March—An Ambuscade—Battle of Oriskany—Johnson’s Greens—Death of Herkimer—Spirited Sortie of Colonel Willett—Sir John Johnson driven to the River—Flight of the Indians—Sacking of Sir John’s Camp—Colonel Gansevoort maintains his Post—Colonel Willett sent in quest of Aid—Arrives at Schuyler’s Camp, | 148 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Schuyler hears of the Affair of Oriskany—Applies for Reinforcements—His Appeal to the Patriotism of Stark—Schuyler Superseded—His Conduct thereupon—Relief sent to Fort Stanwix—Arnold Volunteers to conduct it—Change of Encampment—Patriotic Determination of Schuyler—Detachment of the Enemy against Bennington—Germans and their Indian Allies—Baum, the Hessian Leader—Stark in the Field—Mustering of the Militia—A Belligerent Parson—Battle of Bennington—Breyman to the Rescue—Routed—Reception of the News in the Rival Camps—Washington urges New England to follow up the Blow, | 158 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Stratagem of Arnold to relieve Fort Stanwix—Yan Yost Cuyler—The Siege Pressed—Indians Intractable—Success of Arnold’s Stratagem—Harassed Retreat of St. Leger—Moral Effect of the two Blows given to the Enemy—Brightening Prospects in the American Camp—Arrival of Gates—Magnanimous Conduct of Schuyler—Poorly requited by Gates—Correspondence between Gates and Burgoyne concerning the Murder of Miss McCrea, | 171 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

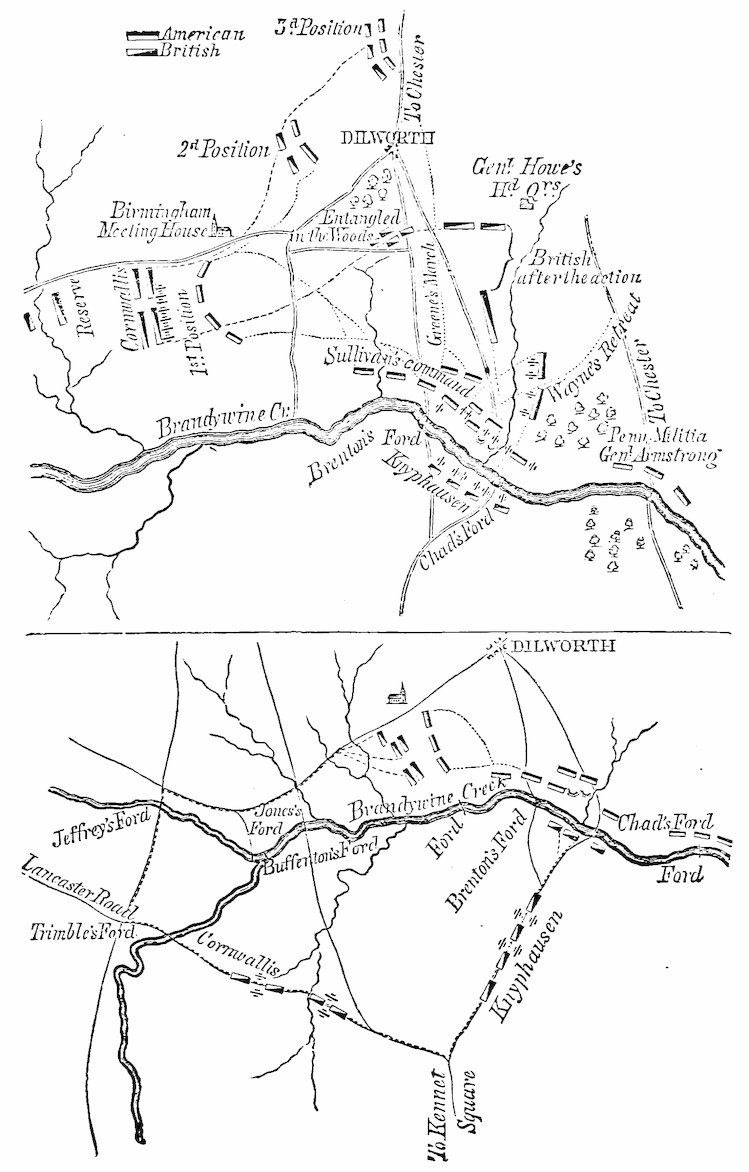

| Landing of Howe’s Army on Elk River—Measures to Check it—Exposed Situation of Washington in Reconnoitring—Alarm of the Country—Proclamation of Howe—Arrival of Sullivan—Foreign Officers in Camp—Deborre—Conway—Fleury—Count Pulaski—First Appearance in the Army of “Light-Horse Harry” of Virginia—Washington’s Appeal to the Army—Movements of the Rival Forces—Battle of the Brandywine—Retreat of the Americans—Halt in Chester—Scenes in Philadelphia during the Battle—Congress Orders out Militia—Clothes Washington with Extraordinary Powers—Removes to Lancaster—Rewards to Foreign Officers, | 179 |

| xi | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| General Howe neglects to pursue his Advantage—Washington Retreats to Germantown—Recrosses the Schuylkill and prepares for another Action—Prevented by Storms of Rain—Retreats to French Creek—Wayne detached to Fall on the Enemy’s Rear—His Pickets Surprised—Massacre of Smallwood’s Men—Manœuvres of Howe on the Schuylkill—Washington sends for Reinforcements—Howe marches into Philadelphia, | 197 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Dubious Position of Burgoyne—Collects his Forces—Ladies of Distinction in his Camp—Lady Harriet Ackland—The Baroness de Riedesel—American Army reinforced—Silent Movements of Burgoyne—Watched from the Summit of the Hills—His March along the Hudson—Position of the two Camps—Battle on the 19th Sept.—Burgoyne Encamps nearer—Fortifies his Camp—Promised Co-operation by Sir Henry Clinton—Determines to await it—Quarrel between Gates and Arnold—Arnold deprived of Command—Burgoyne waits for Co-operation, | 205 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Preparations of Sir Henry Clinton—State of the Highland Defences—Putnam Alarmed—Advance of the Armament up the Hudson—Plan of Sir Henry Clinton—Peekskill Threatened—Putnam Deceived—Secret March of the Enemy through the Mountains—Forts Montgomery and Clinton Overpowered—Narrow Escape of the Commanders—Conflagration and Explosion of the American Frigates—Rallying Efforts of Putnam and Governor Clinton—The Spy and the Silver Bullet—Esopus Burnt—Ravaging Progress of the Enemy up the Hudson, | 221 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Scarcity in the British Camp—Gates bides his Time—Foraging Movement of Burgoyne—Battle of the 7th October—Rout of the British and Hessians—Situation of the Baroness Riedesel and Lady Harriet Ackland during the Battle—Death of Gen. Fraser—His Funeral—Night Retreat of the British—Expedition of Lady Harriet Ackland—Desperate Situation of Burgoyne at Saratoga—Capitulation—Surrender—Conduct of the American Troops—Scenes in the Camp—Gallant Courtesy of Schuyler to the Baroness Riedesel—His Magnanimous Conduct towards Burgoyne—Return of the British Ships down the Hudson, | 234 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Washington Advances to Skippack Creek—The British Fleet in the Delaware—Forts and Obstructions in the River—Washington Meditates an Attack on the British Camp—Battle of Germantown, | 258 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Washington at White Marsh—Measures to cut off the Enemy’s Supplies—The Forts on the Delaware Reinforced—Colonel Greene of Rhode Island at Fort Mercer—Attack and Defence of that Fort—Death of Count Donop, | 269 |

| xii | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| De Kalb Commissioned Major-General—Pretensions of Conway—Thwarted by Washington—Conway Cabal—Gates remiss in Correspondence—Dilatory in Forwarding Troops—Mission of Hamilton to Gates—Wilkinson Bearer of Despatches to Congress—A Tardy Traveller—His Reward—Conway Correspondence Detected—Washington’s Apology for his Army, | 271 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Further Hostilities on the Delaware—Fort Mifflin Attacked—Bravely Defended—Reduced—Mission of Hamilton to Gates—Visits the Camps of Governor Clinton and Putnam on the Hudson—Putnam on his Hobby-Horse—Difficulties in procuring Reinforcements—Intrigues of the Cabal—Letters of Lovell and Mifflin to Gates—The Works at Red Rank Destroyed—The Enemy in Possession of the Delaware, | 284 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Question of an Attack on Philadelphia—General Reed at Head-Quarters—Enemy’s Works Reconnoitred—Opinions in a Council of War—Exploit of Lafayette—Receives Command of a Division—Modification of the Board of War—Gates to Preside—Letter of Lovell—Sally Forth of General Howe—Evolutions and Skirmishes—Conway Inspector-general—Consultation about Winter-Quarters—Dreary March to Valley Forge—Hutting—Washington’s Vindicatory Letters—Retrospect of the Year, | 296 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Gates on the Ascendant—The Conway Letter—Suspicions—Consequent Correspondence between Gates and Washington—Warning Letter from Dr. Craik—Anonymous Letters—Projected Expedition to Canada—Lafayette, Gates, and the Board of War, | 315 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Gates undertakes to explain the Conway Correspondence—Washington’s Searching Analysis of the Explanation—Close of the Correspondence—Spurious Letters Published—Lafayette and the Canada Expedition—His Perplexities—Counsels of Washington, | 326 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| More Trouble about the Conway Letter—Correspondence between Lord Stirling and Wilkinson—Wilkinson’s Honor Wounded—His Passage at Arms with General Gates—His Seat at the Board of War uncomfortable—Determines that Lord Stirling shall Bleed—His Wounded Honor Healed—His Interviews with Washington—Sees the Correspondence of Gates—Denounces Gates and gives up the Secretaryship—Is thrown out of Employ—Closing Remarks on the Conway Cabal, | 337 |

| xiii | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Committee of Arrangement—Reforms in the Army—Scarcity in the Camp—The Enemy revel in Philadelphia—Attempt to Surprise Light-Horse Harry—His Gallant Defence—Praised by Washington—Promoted—Letter from General Lee—Burgoyne returns to England—Mrs. Washington at Valley Forge—Bryan Fairfax visits the Camp—Arrival of the Baron Steuben—His Character—Disciplines the Army—Greene made Quartermaster-general, | 347 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Fortifications of the Hudson—Project to Surprise Sir Henry Clinton—General Howe Forages the Jerseys—Ships and Stores Burnt at Bordentown—Plans for the Next Campaign—Gates and Mifflin under Washington’s Command—Downfall of Conway—Lord North’s Conciliatory Bills—Sent to Washington by Governor Tryon—Resolves of Congress—Letter of Washington to Tryon—Rejoicing at Valley Forge—The Mischianza, | 362 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Lafayette Detached to keep Watch on Philadelphia—His Position at Barren Hill—Plan of Sir Henry to Entrap him—Washington Alarmed for his Safety—Stratagem of the Marquis—Exchange of General Lee and Colonel Ethan Allen—Allen at Valley Forge—Washington’s Opinion of him—Preparations in Philadelphia to Evacuate—Washington’s Measures in consequence—Arrival of Commissioners from England—Their Disappointment—Their Proceedings—Their Failure—Their Manifesto, | 375 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Preparations to Evacuate Philadelphia—Washington calls a Council of War—Lee Opposed to any Attack—Philadelphia Evacuated—Movements in pursuit of Sir Henry Clinton—Another Council of War—Conflict of Opinions—Contradictory Conduct of Lee respecting the Command—The Battle of Monmouth Court House—Subsequent March of the Armies, | 385 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Correspondence between Lee and Washington relative to the Affair of Monmouth—Lee asks a Trial by Court-Martial—The Verdict—Lee’s Subsequent History, | 404 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Arrival of a French Fleet—Correspondence of Washington and the Count D’Estaing—Plans of the Count—Perturbation at New York—Excitement in the French Fleet—Expedition against Rhode Island—Operations by Sea and Land—Failure of the Expedition—Irritation between the Allied Forces—Considerate Letter of Washington to the Count D’Estaing, | 415 |

| xiv | |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Indian Warfare—Desolation of the Valley of Wyoming—Movements in New York—Counter Movements of Washington—Foraging Parties of the Enemy—Baylor’s Dragoons Massacred at Old Tappan—British Expedition against Little Egg Harbor—Massacre of Pulaski’s Infantry—Retaliation on Donop’s Rangers—Arrival of Admiral Byron—Endeavors to Entrap D’Estaing, but is Disappointed—Expedition against St. Lucia—Expedition against Georgia—Capture of Savannah—Georgia Subdued—General Lincoln sent to Command in the South, | 432 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Winter Cantonments of the American Army—Washington at Middlebrook—Plan of Alarm Signals for the Jerseys—Lafayette’s Project for an Invasion of Canada—Favored by Congress—Condemned by Washington—Relinquished—Washington in Philadelphia—The War Spirit Declining—Dissensions in Congress—Sectional Feelings—Patriotic Appeals of Washington—Plans for the Next Campaign—Indian Atrocities to be Repressed—Avenging Expedition set on foot—Discontents of the Jersey Troops—Appeased by the Interference of Washington—Successful Campaign against the Indians, | 445 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Predatory Warfare of the Enemy—Ravages in the Chesapeake—Hostilities on the Hudson—Verplanck’s Point and Stony Point Taken—Capture of New Haven—Fairfield and Norwalk Destroyed—Washington Plans a Counter Stroke—Storming of Stony Point—Generous Letter of Lee, | 458 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| Expedition against Penobscot—Night Surprisal of Paulus Hook—Washington Fortifies West Point—His Style of Living there—Table at Head-Quarters—Sir Henry Clinton Reinforced—Arrival of D’Estaing on the Coast of Georgia—Plans in Consequence—The French Minister at Washington’s Highland Camp—Letter to Lafayette—D’Estaing Co-operates with Lincoln—Repulsed at Savannah—Washington Reinforces Lincoln—Goes into Winter-Quarters—Sir Henry Clinton sends an Expedition to the South, | 471 |

BURKE ON THE STATE OF AFFAIRS IN AMERICA—NEW JERSEY ROUSED TO ARMS—WASHINGTON GRANTS SAFE CONDUCT TO HESSIAN CONVOYS—ENCAMPMENT AT MORRISTOWN—PUTNAM AT PRINCETON—HIS STRATAGEM TO CONCEAL THE WEAKNESS OF HIS CAMP—EXPLOIT OF GENERAL DICKINSON NEAR SOMERSET COURT HOUSE—WASHINGTON’S COUNTER PROCLAMATION—PREVALENCE OF THE SMALL-POX—INOCULATION OF THE ARMY—CONTRAST OF THE BRITISH AND AMERICAN COMMANDERS AND THEIR CAMPS.

The news of Washington’s recrossing the Delaware, and of his subsequent achievements in the Jerseys, had not reached London on the 9th of January. “The affairs of America seem to be drawing to a crisis,” writes Edmund Burke. “The Howes are at this time in possession of, or able to awe the whole middle coast of America, from Delaware to the western boundary of Massachusetts Bay; the naval barrier on the side of Canada is broken. A great tract is open for the supply of the troops; the river Hudson opens a way into the heart of the provinces, and nothing can, in all probability, prevent an early and offensive 2campaign. What the Americans have done is, in their circumstances, truly astonishing; it is indeed infinitely more than I expected from them. But, having done so much for some short time, I began to entertain an opinion that they might do more. It is now, however, evident that they cannot look standing armies in the face. They are inferior in every thing—even in numbers. There seem by the best accounts not to be above ten or twelve thousand men at most in their grand army. The rest are militia, and not wonderfully well composed or disciplined. They decline a general engagement; prudently enough, if their object had been to make the war attend upon a treaty of good terms of subjection; but when they look further, this will not do. An army that is obliged at all times, and in all situations, to decline an engagement, may delay their ruin, but can never defend their country.”[1]

At the time when this was written, the Howes had learnt to their mortification, that “the mere running through a province, is not subduing it.” The British commanders had been outgeneralled, attacked and defeated. They had nearly been driven out of the Jerseys, and were now hemmed in and held in check by Washington and his handful of men castled among the heights of Morristown. So far from holding possession of the territory they had so recently overrun, they were fain to ask safe conduct across it for a convoy to their soldiers captured in battle. It must have been a severe trial to the pride of Cornwallis, when he had to inquire by letter of Washington, whether money and stores could be sent to the Hessians captured at Trenton, and a surgeon and medicines to the wounded at Princeton; and Washington’s reply must have conveyed a reproof still more mortifying: 3No molestation, he assured his lordship, would be offered to the convoy by any part of the regular army under his command; but “he could not answer for the militia, who were resorting to arms in most parts of the State, and were excessively exasperated at the treatment they had met with from both Hessian and British troops.”

In fact, the conduct of the enemy had roused the whole country against them. The proclamations and printed protections of the British commanders, on the faith of which the inhabitants in general had staid at home, and forbore to take up arms, had proved of no avail. The Hessians could not or would not understand them, but plundered friend and foe alike.[2] The British soldiery often followed their example, and the plunderings of both were at times attended by those brutal outrages on the weaker sex, which inflame the dullest spirits to revenge. The whole State was thus roused against its invaders. In Washington’s retreat of more than a hundred miles through the Jerseys, he had never been joined by more than one hundred of its inhabitants; now sufferers of both parties rose as one man to avenge their personal injuries. The late quiet yeomanry armed themselves, and scoured the country in small parties to seize on stragglers, and the militia began to signalize themselves in voluntary skirmishes with regular troops.

In effect, Washington ordered a safe conduct to be given to the Hessian baggage as far as Philadelphia, and to the surgeon and medicines to Princeton, and permitted a Hessian sergeant 4and twelve men, unarmed, to attend the baggage until it was delivered to their countrymen.

Morristown, where the main army was encamped, had not been chosen by Washington as a permanent post, but merely as a halting place, where his troops might repose after their excessive fatigues and their sufferings from the inclement season. Further considerations persuaded him that it was well situated for the system of petty warfare which he meditated, and induced him to remain there. It was protected by forests and rugged heights. All approach from the seaboard was rendered difficult and dangerous to a hostile force by a chain of sharp hills, extending from Pluckamin, by Boundbrook and Springfield, to the vicinity of the Passaic River, while various defiles in the rear afforded safer retreats into a fertile and well peopled region.[3] It was nearly equidistant from Amboy, Newark, and Brunswick, the principal posts of the enemy; so that any movement made from them could be met by a counter movement on his part; while the forays and skirmishes by which he might harass them, would school and season his own troops. He had three faithful generals with him: Greene, his reliance on all occasions; swarthy Sullivan, whose excitable temper and quick sensibilities he had sometimes to keep in check by friendly counsels and rebukes, but who was a good officer, and loyally attached to him; and brave, genial, generous Knox, never so happy as when by his side. He had lately been advanced to the rank of brigadier at his recommendation, and commanded the artillery.

Washington’s military family at this time was composed of his aides-de-camp, Colonels Meade and Tench Tilghman of Philadelphia; gentlemen of gallant spirit, amiable tempers and cultivated 5manners; and his secretary, Colonel Robert H. Harrison of Maryland; the “old secretary,” as he was familiarly called among his associates, and by whom he was described as “one in whom every man had confidence, and by whom no man was deceived.”

Washington’s head-quarters at first were in what was called the Freemason’s Tavern, on the north side of the village green. His troops were encamped about the vicinity of the village, at first in tents, until they could build log huts for shelter against the winter’s cold. The main encampment was near Bottle Hill, in a sheltered valley which was thickly wooded, and had abundant springs. It extended south-easterly from Morristown; and was called the Lowantica Valley, from the Indian name of a beautiful limpid brook which ran through it, and lost itself in a great swamp.[4]

The enemy being now concentrated at New Brunswick and Amboy, General Putnam was ordered by Washington to move from Crosswicks to Princeton, with the troops under his command. He was instructed to draw his forage as much as possible from the neighborhood of Brunswick, about eighteen miles off, thereby contributing to distress the enemy; to have good scouting parties continually on the look-out; to keep nothing with him but what could be moved off at a moment’s warning, and, if compelled to leave Princeton, to retreat towards the mountains, so as to form a junction with the forces at Morristown.

Putnam had with him but a few hundred men. “You will give out your strength to be twice as great as it is,” writes Washington; a common expedient with him in those times of scanty 6means. Putnam acted up to the advice. A British officer, Captain Macpherson, was lying desperately wounded at Princeton, and Putnam, in the kindness of his heart, was induced to send in a flag to Brunswick in quest of a friend and military comrade of the dying man, to attend him in his last moments and make his will. To prevent the weakness of the garrison from being discovered, the visitor was brought in after dark. Lights gleamed in all the college windows, and in the vacant houses about the town; the handful of troops capable of duty were marched hither and thither and backward and forward, and paraded about to such effect, that the visitor on his return to the British camp, reported the force under the old general to be at least five thousand strong.[5]

Cantonments were gradually formed between Princeton and the Highlands of the Hudson, which made the left flank of Washington’s position, and where General Heath had command. General Philemon Dickinson, who commanded the New Jersey militia, was stationed on the west side of Millstone River, near Somerset court house, one of the nearest posts to the enemy’s camp at Brunswick. A British foraging party, of five or six hundred strong, sent out by Cornwallis with forty waggons and upward of a hundred draught horses, mostly of the English breed, having collected sheep and cattle about the country, were sacking a mill on the opposite side of the river, where a large quantity of flour was deposited. While thus employed, Dickinson set upon them with a force equal in number, but composed of raw militia and fifty Philadelphia riflemen. He dashed through the river, waist deep, with his men, and charged the enemy so suddenly and vigorously, that, though supported by three field-pieces, 7they gave way, left their convoy, and retreated so precipitately, that he made only nine prisoners. A number of killed and wounded were carried off by the fugitives on light waggons.[6]

These exploits of the militia were noticed with high encomiums by Washington, while at the same time he was rigid in prohibiting and punishing the excesses into which men are apt to run when suddenly clothed with military power. Such is the spirit of a general order issued at this time. “The general prohibits, in both the militia and Continental troops, the infamous practice of plundering the inhabitants under the specious pretence of their being tories. * * * It is our business to give protection and support to the poor distressed inhabitants, not to multiply and increase their calamities.” After the publication of this order, all excesses of this kind were to be punished in the severest manner.

To counteract the proclamation of the British commissioners, promising amnesty to all in rebellion who should, in a given time, return to their allegiance, Washington now issued a counter proclamation (Jan. 25th), commanding every person who had subscribed a declaration of fidelity to Great Britain, or taken an oath of allegiance, to repair within thirty days to head-quarters, or the quarters of the nearest general officer of the Continental army or of the militia, and there take the oath of allegiance to the United States of America, and give up any protection, certificate, or passport he might have received from the enemy; at the same time granting full liberty to all such as preferred the interest and protection of Great Britain to the freedom and happiness of their country, forthwith to withdraw themselves and families within the enemy’s lines. All who should neglect or 8refuse to comply with this order were to be considered adherents to the crown, and treated as common enemies.

This measure met with objections at the time, some of the timid or over-cautious thinking it inexpedient; others, jealous of the extraordinary powers vested in Washington, questioning whether he had not transcended these powers and exercised a degree of despotism.

The small-pox, which had been fatally prevalent in the preceding year, had again broken out, and Washington feared it might spread through the whole army. He took advantage of the interval of comparative quiet to have his troops inoculated. Houses were set apart in various places as hospitals for inoculation, and a church was appropriated for the use of those who had taken the malady in the natural way. Among these the ravages were frightful. The traditions of the place and neighborhood, give lamentable pictures of the distress caused by this loathsome disease in the camp and in the villages, wherever it had not been parried by inoculation.

“Washington,” we are told, “was not an unmoved spectator of the griefs around him, and might be seen in Hanover and in Lowantica Valley, cheering the faith and inspiring the courage of his suffering men.”[7] It was this paternal care and sympathy which attached his troops personally to him. They saw that he regarded them, not with the eye of a general, but of a patriot, whose heart yearned towards them as countrymen suffering in one common cause.

A striking contrast was offered throughout the winter and spring, between the rival commanders, Howe at New York, and Washington at Morristown. Howe was a soldier by profession. 9War, with him, was a career. The camp was, for the time, country and home. Easy and indolent by nature, of convivial and luxurious habits, and somewhat addicted to gaming, he found himself in good quarters at New York, and was in no hurry to leave them. The tories rallied around him. The British merchants residing there regarded him with profound devotion. His officers, too, many of them young men of rank and fortune, gave a gayety and brilliancy to the place; and the wealthy royalists forgot in a round of dinners, balls and assemblies, the hysterical alarms they had once experienced under the military sway of Lee.

Washington, on the contrary, was a patriot soldier, grave, earnest, thoughtful, self-sacrificing. War, to him, was a painful remedy, hateful in itself, but adopted for a great national good. To the prosecution of it all his pleasures, his comforts, his natural inclinations and private interests were sacrificed; and his chosen officers were earnest and anxious like himself, with their whole thoughts directed to the success of the magnanimous struggle in which they were engaged.

So, too, the armies were contrasted. The British troops, many of them, perchance, slightly metamorphosed from vagabonds into soldiers, all mere men of the sword, were well clad, well housed, and surrounded by all the conveniences of a thoroughly appointed army with a “rebel country” to forage. The American troops for the most part were mere yeomanry, taken from their rural homes; ill sheltered, ill clad, ill fed, and ill paid, with nothing to reconcile them to their hardships but love for the soil they were defending, and the inspiring thought that it was their country. Washington, with paternal care, endeavored to protect them from the depraving influences of the camp. 10“Let vice and immorality of every kind be discouraged as much as possible in your brigade,” writes he in a circular to his brigadier-generals; “and, as a chaplain is allowed to each regiment, see that the men regularly attend divine worship. Gaming of every kind is expressly forbidden, as being the foundation of evil, and the cause of many a brave and gallant officer’s ruin.”

NEGOTIATIONS FOR EXCHANGE OF PRISONERS—CASE OF COLONEL ETHAN ALLEN—OF GENERAL LEE—CORRESPONDENCE OF WASHINGTON WITH SIR WILLIAM HOWE ABOUT EXCHANGES OF PRISONERS—REFEREES APPOINTED—LETTERS OF LEE FROM NEW YORK—CASE OF COLONEL CAMPBELL—WASHINGTON’S ADVICE TO CONGRESS ON THE SUBJECT OF RETALIATION—HIS CORRESPONDENCE WITH LORD HOWE ABOUT THE TREATMENT OF PRISONERS—THE HORRORS OF THE JERSEY PRISON-SHIP AND THE SUGAR HOUSE.

A cartel for the exchange of prisoners had been a subject of negotiation previous to the affair of Trenton, without being adjusted. The British commanders were slow to recognize the claims to equality of those they considered rebels; Washington was tenacious in holding them up as patriots ennobled by their cause.

Among the cases which came up for attention was that of Ethan Allen, the brave, but eccentric captor of Ticonderoga. His daring attempts in the “path of renown” had cost him a world of hardships. Thrown into irons as a felon; threatened with a halter; carried to England to be tried for treason; confined in Pendennis Castle; retransported to Halifax, and now a prisoner in New York. “I have suffered every thing short of death,” writes he to the Assembly of his native State, Connecticut. He had, however, recovered health and suppleness of limb, and with 12them all his swelling spirit and swelling rhetoric. “I am fired,” writes he, “with adequate indignation to revenge both my own and my country’s wrongs. I am experimentally certain I have fortitude sufficient to face the invaders of America in the place of danger, spread with all the horrors of war.” And he concludes with one of his magniloquent, but really sincere expressions of patriotism: “Provided you can hit upon some measure to procure my liberty, I will appropriate my remaining days, and freely hazard my life in the service of the colony, and maintaining the American Empire. I thought to have enrolled my name in the list of illustrious American heroes, but was nipped in the bud!”[8]

Honest Ethan Allen! his name will ever stand enrolled on that list; not illustrious, perhaps, but eminently popular.

His appeal to his native State had produced an appeal to Congress, and Washington had been instructed, considering his long imprisonment, to urge his exchange. This had scarce been urged, when tidings of the capture of General Lee presented a case of still greater importance to be provided for. “I feel much for his misfortune,” writes Washington, “and am sensible that in his captivity our country has lost a warm friend and an able officer.” By direction of Congress, he had sent in a flag to inquire about Lee’s treatment, and to convey him a sum of money. This was just previous to the second crossing of the Delaware.

Lee was now reported to be in rigorous confinement in New York, and treated with harshness and indignity. The British professed to consider him a deserter, he having been a lieutenant-colonel in their service, although he alleged that he had resigned his commission before joining the American army 13Two letters which he addressed to General Howe, were returned to him unopened, enclosed in a cover directed to Lieutenant-colonel Lee.

On the 13th of January, Washington addressed the following letter to Sir William Howe. “I am directed by Congress to propose an exchange of five of the Hessian field-officers taken at Trenton for Major-general Lee; or if this proposal should not be accepted, to demand his liberty upon parole, within certain bounds, as has ever been granted to your officers in our custody. I am informed, upon good authority, that your reason for keeping him hitherto in stricter confinement than usual is, that you do not look upon him in the light of a common prisoner of war, but as a deserter from the British service, as his resignation has never been accepted, and that you intend to try him as such by a court-martial. I will not undertake to determine how far this doctrine may be justifiable among yourselves, but I must give you warning that Major-general Lee is looked upon as an officer belonging to, and under the protection of the United Independent States of America, and that any violence you may commit upon his life and liberty, will be severely retaliated upon the lives or liberties of the British officers, or those of their foreign allies in our hands.”

In this letter he likewise adverted to the treatment of American prisoners in New York; several who had recently been released, having given the most shocking account of the barbarities they had experienced, “which their miserable, emaciated countenances confirmed.”—“I would beg,” added he, “that some certain rule of conduct towards prisoners may be settled; and, if you are determined to make captivity as distressing as possible, let me know it, that we may be upon equal terms, for your conduct shall regulate mine.”

14Sir William, in reply, proposed to send an officer of rank to Washington, to confer upon a mode of exchange and subsistence of prisoners. “This expedient,” observes he, “appearing to me effectual for settling all differences, will, I hope, be the means of preventing a repetition of the improper terms in which your letter is expressed and founded on the grossest misrepresentations. I shall not make any further comment upon it, than to assure you, that your threats of retaliating upon the innocent such punishment as may be decreed in the circumstances of Mr. Lee by the laws of his country, will not divert me from my duty in any respect; at the same time, you may rest satisfied that the proceedings against him will not be precipitated; and I trust that, in this, or in any other event in the course of my command, you will not have just cause to accuse me of inhumanity, prejudice, or passion.”

Sir William, in truth, was greatly perplexed with respect to Lee, and had written to England to Lord George Germaine for instructions in the case. “General Lee,” writes he, “being considered in the light of a deserter, is kept a close prisoner; but I do not bring him to trial, as a doubt has arisen, whether, by a public resignation of his half pay prior to his entry into the rebel army, he was amenable to the military law as a deserter.”

The proposal of Sir William, that all disputed points relative to the exchange and subsistence of prisoners, should be adjusted by referees, led to the appointment of two officers for the purpose; Colonel Walcott by General Howe, and Colonel Harrison, “the old secretary,” by Washington. In the contemplated exchanges was that of one of the Hessian field-officers for Colonel Ethan Allen.

The haughty spirit of Lee had experienced a severe humiliation 15in the late catastrophe; his pungent and caustic humor is at an end. In a letter addressed shortly afterwards to Washington, and enclosing one to Congress which Lord and General Howe had permitted him to send, he writes, “as the contents are of the last importance to me, and perhaps not less so to the community, I most earnestly entreat, my dear general, that you will despatch it immediately, and order the Congress to be as expeditious as possible.”

The letter contained a request that two or three gentlemen might be sent immediately to New York, to whom he would communicate what he conceived to be of the greatest importance. “If my own interests were alone at stake,” writes he, “I flatter myself that the Congress would not hesitate a single instant in acquiescing in my request; but this is far from the case; the interests of the public are equally concerned. * * Lord and General Howe will grant a safe conduct to the gentlemen deputed.”

The letter having been read in Congress, Washington was directed to inform General Lee that they were pursuing and would continue to pursue every means in their power to provide for his personal safety, and to obtain his liberty; but that they considered it improper to send any of their body to communicate with him, and could not perceive how it would tend to his advantage or the interest of the public.

Lee repeated his request, but with no better success. He felt this refusal deeply; as a brief, sad note to Washington indicates.

“It is a most unfortunate circumstance for myself, and I think not less so for the public, that Congress have not thought 16proper to comply with my request. It could not possibly have been attended with any ill consequences, and might with good ones. At least it was an indulgence which I thought my situation entitled me to. But I am unfortunate in every thing, and this stroke is the severest I have yet experienced. God send you a different fate. Adieu, my dear general.

“Yours most truly and affectionately,

How different from the humorous, satirical, self-confident tone of his former letters. Yet Lee’s actual treatment was not so harsh as had been represented. He was in close confinement, it is true; but three rooms had been fitted up for his reception in the Old City Hall of New York, having nothing of the look of a prison excepting that they were secured by bolts and bars.

Congress, in the mean time, had resorted to their threatened measure of retaliation. On the 20th of February, they had resolved that the Board of War be directed immediately to order the five Hessian field-officers and Lieutenant-colonel Campbell into safe and close custody, “it being the unalterable resolution of Congress to retaliate on them the same punishment as may be inflicted on the person of General Lee.”

The Colonel Campbell here mentioned had commanded one of General Fraser’s battalions of Highlanders, and had been captured on board of a transport in Nantasket road, in the preceding summer. He was a member of Parliament, and a gentleman of fortune. Retaliation was carried to excess in regard to him, for he was thrown into the common jail at Concord in Massachusetts.

From his prison he made an appeal to Washington, which at 17once touched his quick sense of justice. He immediately wrote to the council of Massachusetts Bay, quoting the words of the resolution of Congress. “By this you will observe,” adds he, “that exactly the same treatment is to be shown to Colonel Campbell and the Hessian officers, that General Howe shows to General Lee, and as he is only confined to a commodious house with genteel accommodations, we have no right or reason to be more severe on Colonel Campbell, who I would wish should upon the receipt of this be removed from his present situation, and be put into a house where he may live comfortably.”

In a letter to the President of Congress on the following day, he gives his moderating counsels on the whole subject of retaliation. “Though I sincerely commiserate,” writes he, “the misfortunes of General Lee, and feel much for his present unhappy situation, yet with all possible deference to the opinion of Congress, I fear that these resolutions will not have the desired effect, are founded on impolicy, and will, if adhered to, produce consequences of an extensive and melancholy nature.” * * *

“The balance of prisoners is greatly against us, and a general regard to the happiness of the whole should mark our conduct. Can we imagine that our enemies will not mete the same punishments, the same indignities, the same cruelties, to those belonging to us, in their possession, that we impose on theirs in our power? Why should we suppose them to possess more humanity than we have ourselves? Or why should an ineffectual attempt to relieve the distresses of one brave, unfortunate man, involve many more in the same calamities? * * * Suppose,” continues he, “the treatment prescribed for the Hessians should be pursued, will it not establish what the enemy have been aiming to effect by every artifice and the grossest misrepresentations, I mean an opinion of 18our enmity towards them, and of the cruel treatment they experience when they fall into our hands, a prejudice which we on our part have heretofore thought it politic to suppress, and to root out by every act of lenity and of kindness?”

“Many more objections,” added he, “might be subjoined, were they material. I shall only observe, that the present state of the army, if it deserves that name, will not authorize the language of retaliation, or the style of menace. This will be conceded by all who know that the whole of our force is weak and trifling, and composed of militia (very few regular troops excepted) whose service is on the eve of expiring.”

In a letter to Mr. Robert Morris also, he writes: “I wish, with all my heart, that Congress had gratified General Lee in his request. If not too late I wish they would do it still. I can see no possible evil that can result from it; some good, I think, might. The request to see a gentleman or two came from the general, not from the commissioners; there could have been no harm, therefore, in hearing what he had to say on any subject, especially as he had declared that his own personal interest was deeply concerned. The resolve to put in close confinement Lieutenant-colonel Campbell and the Hessian field-officers, in order to retaliate upon them General Lee’s punishment, is, in my opinion, injurious in every point of view, and must have been entered into without due attention to the consequences. * * * * * If the resolve of Congress respecting General Lee strikes you in the same point of view it has done me, I could wish you would signify as much to that body as I really think it fraught with every evil.”

Washington was not always successful in instilling his wise moderation into public councils. Congress adhered to their vindictive 19policy, merely directing that no other hardships should be inflicted on the captive officers, than such confinement as was necessary to carry their resolve into effect. As to their refusal to grant the request of Lee, Robert Morris surmised they were fearful of the injurious effect that might be produced in the court of France, should it be reported that members of Congress visited General Lee by permission of the British commissioners. There were other circumstances beside the treatment of General Lee, to produce this indignant sensibility on the part of Congress. Accounts were rife at this juncture, of the cruelties and indignities almost invariably experienced by American prisoners at New York; and an active correspondence on the subject was going on between Washington and the British commanders, at the same time with that regarding General Lee.

The captive Americans who had been in the naval service were said to be confined, officers and men, in prison-ships, which, from their loathsome condition, and the horrors and sufferings of all kinds experienced on board of them, had acquired the appellation of floating hells. Those who had been in the land service, were crowded into jails and dungeons like the vilest malefactors; and were represented as pining in cold, in filth, in hunger and nakedness.

“Our poor devoted soldiers,” writes an eye-witness, “were scantily supplied with provisions of bad quality, wretchedly clothed, and destitute of sufficient fuel, if indeed they had any. Disease was the inevitable consequence, and their prisons soon became hospitals. A fatal malady was generated, and the mortality, to every heart not steeled by the spirit of party, was truly deplorable.”[8] According to popular account, the prisoners 20confined on shipboard, and on shore, were perishing by hundreds.

A statement made by a Captain Gamble, recently confined on board of a prison-ship, had especially roused the ire of Congress, and by their directions had produced a letter from Washington to Lord Howe. “I am sorry,” writes he, “that I am under the disagreeable necessity of troubling your lordship with a letter, almost wholly on the subject of the cruel treatment which our officers and men in the naval department, who are unhappy enough to fall into your hands, receive on board the prison-ships in the harbor of New York.” After specifying the case of Captain Gamble, and adding a few particulars, he proceeds: “From the opinion I have ever been taught to entertain of your lordship’s humanity, I will not suppose that you are privy to proceedings of so cruel and unjustifiable a nature; and I hope, that, upon making the proper inquiry, you will have the matter so regulated, that the unhappy persons whose lot is captivity, may not in future have the miseries of cold, disease, and famine, added to their other misfortunes. You may call us rebels, and say that we deserve no better treatment; but remember, my lord, that, supposing us rebels, we still have feelings as keen and sensible as loyalists, and will, if forced to it, most assuredly retaliate upon those upon whom we look as the unjust invaders of our rights, liberties and properties. I should not have said thus much, but my injured countrymen have long called upon me to endeavor to obtain a redress of their grievances, and I should think myself as culpable as those who inflict such severities upon them, were I to continue silent,” &c.

Lord Howe, in reply (Jan. 17), expressed himself surprised at the matter and language of Washington’s letter, “so different 21from the liberal vein of sentiment he had been habituated to expect on every occasion of personal intercourse or correspondence with him.” He was surprised, too, that “the idle and unnatural report” of Captain Gamble, respecting the dead and dying, and the neglect of precautions against infection, should meet with any credit. “Attention to preserve the lives of these men,” writes he, “whom we esteem the misled subjects of the king, is a duty as binding on us, where we are able from circumstances to execute it with effect, as any you can plead for the interest you profess in their welfare.”

He denied that prisoners were ill treated in his particular department (the naval). They had been allowed the general liberty of the prison-ship, until a successful attempt of some to escape, had rendered it necessary to restrain the rest within such limits as left the commanding parts of the ship in possession of the guard. They had the same provisions in quality and quantity that were furnished to the seamen of his own ship. The want of cleanliness was the result of their own indolence and neglect. In regard to health, they had the constant attendance of an American surgeon, a fellow-prisoner; who was furnished with medicines from the king’s stores; and the visits of the physician of the fleet.

“As I abhor every imputation of wanton cruelty in multiplying the miseries of the wretched,” observes his lordship, “of treating them with needless severity, I have taken the trouble to state these several facts.”

In regard to the hint at retaliation, he leaves it to Washington to act therein as he should think fit; but adds he grandly, “the innocent at my disposal will not have any severities to apprehend from me on that account.”

22We have quoted this correspondence the more freely, because it is on a subject deeply worn into the American mind; and about which we have heard too many particulars, from childhood upwards, from persons of unquestionable veracity, who suffered in the cause, to permit us to doubt about the fact. The Jersey Prison-ship is proverbial in our revolutionary history; and the bones of the unfortunate patriots who perished on board, form a monument on the Long Island shore. The horrors of the Sugar House converted into a prison, are traditional in New York; and the brutal tyranny of Cunningham, the provost marshal, over men of worth confined in the common jail, for the sin of patriotism, has been handed down from generation to generation.

That Lord Howe and Sir William were ignorant of the extent of these atrocities we really believe, but it was their duty to be well informed. War is, at best, a cruel trade, that habituates those who follow it to regard the sufferings of others with indifference. There is not a doubt, too, that a feeling of contumely deprived the patriot prisoners of all sympathy in the early stages of the Revolution. They were regarded as criminals rather than captives. The stigma of rebels seemed to take from them all the indulgences, scanty and miserable as they are, usually granted to prisoners of war. The British officers looked down with haughty contempt upon the American officers, who had fallen into their hands. The British soldiery treated them with insolent scurrility. It seemed as if the very ties of consanguinity rendered their hostility more intolerant, for it was observed that American prisoners were better treated by the Hessians than by the British. It was not until our countrymen had made themselves formidable by their successes that they were treated, when prisoners, with common decency and humanity.

23The difficulties arising out of the case of General Lee interrupted the operations with regard to the exchange of prisoners; and gallant men, on both sides, suffered prolonged detention in consequence; and among the number the brave, but ill-starred Ethan Allen.

Lee, in the mean time, remained in confinement, until directions with regard to him should be received from government. Events, however, had diminished his importance in the eyes of the enemy; he was no longer considered the American palladium. “As the capture of the Hessians and the manœuvres against the British took place after the surprise of General Lee,” observes a London writer of the day, “we find that he is not the only efficient officer in the American service.”[9]

EXERTIONS TO FORM A NEW ARMY—CALLS ON THE DIFFERENT STATES—INSUFFICIENCY OF THE MILITIA—WASHINGTON’S CARE FOR THE YEOMANRY—DANGERS IN THE NORTHERN DEPARTMENT—WINTER ATTACK ON TICONDEROGA APPREHENDED—EXERTIONS TO REINFORCE SCHUYLER—PRECARIOUS STATE OF WASHINGTON’S ARMY—CONJECTURES AS TO THE DESIGNS OF THE ENEMY—EXPEDITION OF THE BRITISH AGAINST PEEKSKILL.

The early part of the year brought the annual embarrassments caused by short enlistments. The brief terms of service for which the Continental soldiery had enlisted, a few months perhaps, at most a year, were expiring; and the men, glad to be released from camp duty, were hastening to their rustic homes. Militia had to be the dependence until a new army could be raised and organized; and Washington called on the council of safety of Pennsylvania, speedily to furnish temporary reinforcements of the kind.

All his officers that could be spared were ordered away, some to recruit, some to collect the scattered men of the different regiments, who were dispersed, he said, almost over the continent. General Knox was sent off to Massachusetts to expedite the raising of a battalion of artillery. Different States were urged to levy and equip their quotas for the Continental army. “Nothing but the 25united efforts of every State in America,” writes he, “can save us from disgrace, and probably from ruin.”

Rhode Island is reproached with raising troops for home service before furnishing its supply to the general army. “If each State,” writes he, “were to prepare for its own defence independent of each other, they would all be conquered, one by one. Our success must depend on a firm union, and a strict adherence to the general plan.”[10]

He deplores the fluctuating state of the army while depending on militia; full one day, almost disbanded the next. “I am much afraid that the enemy, one day or other, taking advantage of one of these temporary weaknesses, will make themselves masters of our magazines of stores, arms and artillery.”

The militia, too, on being dismissed, were generally suffered by their officers to carry home with them the arms with which they had been furnished, so that the armory was in a manner scattered over all the world, and for ever lost to the public.

Then an earnest word is spoken by him in behalf of the yeomanry, whose welfare always lay near his heart. “You must be fully sensible,” writes he, “of the hardships imposed upon individuals, and how detrimental it must be to the public to have farmers and tradesmen frequently called out of the field, as militia men, whereby a total stop is put to arts and agriculture, without which we cannot long subsist.”

While thus anxiously exerting himself to strengthen his own precarious army, the security of the Northern department was urged upon his attention. Schuyler represented it as in need of reinforcements and supplies of all kinds. He apprehended that 26Carleton might make an attack upon Ticonderoga, as soon as he could cross Lake Champlain on the ice; that important fortress was under the command of a brave officer, Colonel Anthony Wayne, but its garrison had dwindled down to six or seven hundred men, chiefly New England militia. In the present destitute situation of his department as to troops, Schuyler feared that Carleton might not only succeed in an attempt on Ticonderoga, but might push his way to Albany.

He had written in vain, he said, to the Convention of New York, and to the Eastern States, for reinforcements, and he entreated Washington to aid him with his influence. He wished to have his army composed of troops from as many different States as possible; the Southern people having a greater spirit of discipline and subordination, might, he thought, introduce it among the Eastern people.

He wished also for the assistance of a general officer or two in his department. “I am alone,” writes he, “distracted with a variety of cares, and no one to take part of the burden.”[11]

Although Washington considered a winter attack of the kind specified by Schuyler too difficult and dangerous to be very probable, he urged reinforcements from Massachusetts and New Hampshire, whence they could be furnished most speedily. Massachusetts, in fact, had already determined to send four regiments to Schuyler’s aid as soon as possible.

Washington disapproved of a mixture of troops in the present critical juncture, knowing, he said, “the difficulty of maintaining harmony among men from different States, and bringing them to lay aside all attachments and distinctions of a local and provincial 27nature, and consider themselves the same people, engaged in the same noble struggle, and having one general interest to defend.”[12]

The quota of Massachusetts, under the present arrangement of the army, was fifteen regiments: and Washington ordered General Heath, who was in Massachusetts, to forward them to Ticonderoga as fast as they could be raised.[13]

Notwithstanding all Washington’s exertions in behalf of the army under his immediate command, it continued to be deplorably in want of reinforcements, and it was necessary to maintain the utmost vigilance at all his posts to prevent his camp from being surprised. The operations of the enemy might be delayed by the bad condition of the roads, and the want of horses to move their artillery, but he anticipated an attack as soon as the roads were passable, and apprehended a disastrous result unless speedily reinforced.

“The enemy,” writes he, “must be ignorant of our numbers and situation, or they would never suffer us to remain unmolested, and I almost tax myself with imprudence in committing the fact to paper, lest this letter should fall into other hands than those for which it is intended.” And again: “It is not in my power to make Congress fully sensible of the real situation of our affairs, and that it is with difficulty I can keep the life and soul of the army together. In a word, they are at a distance; they think it is but to say presto, begone, and every thing is done; they seem not to have any conception of the difficulty and perplexity of those who have to execute.”

The designs of the enemy being mere matter of conjecture, measures varied accordingly. As the season advanced, Washington 28was led to believe that Philadelphia would be their first object at the opening of the campaign, and that they would bring round all their troops from Canada by water to aid in the enterprise. Under this persuasion he wrote to General Heath, ordering him to send eight of the Massachusetts battalions to Peekskill instead of Ticonderoga, and he explained his reasons for so doing in a letter to Schuyler. At Peekskill, he observed, “they would be well placed to give support to any of the Eastern or Middle States; or to oppose the enemy, should they design to penetrate the country up the Hudson; or to cover New England, should they invade it. Should they move westward, the Eastern and Southern troops could easily form a junction, and this, besides, would oblige the enemy to leave a much stronger garrison at New York. Even should the enemy pursue their first plan of an invasion from Canada, the troops at Peekskill would not be badly placed to reinforce Ticonderoga, and cover the country around Albany.” “I am very sure,” concludes he, “the operations of this army will in a great degree govern the motions of that in Canada. If this is held at bay, curbed and confined, the Northern army will not dare attempt to penetrate.” The last sentence will be found to contain the policy which governed Washington’s personal movements throughout the campaign.

On the 18th of March he despatched General Greene to Philadelphia, to lay before Congress such matters as he could not venture to communicate by letter. “He is an able and good officer,” writes he, “who has my entire confidence, and is intimately acquainted with my ideas.”

Greene had scarce departed when the enemy began to give signs of life. The delay in the arrival of artillery, more than his natural indolence, had kept General Howe from formally 29taking the field; he now made preparations for the next campaign by detaching troops to destroy the American deposits of military stores. One of the chief of these was at Peekskill, the very place whither Washington had directed Heath to send troops from Massachusetts; and which he thought of making a central point of assemblage. Howe terms it “the port of that rough and mountainous tract called the Manor of Courtlandt.” Brigadier-general McDougall had the command of it in the absence of General Heath, but his force did not exceed two hundred and fifty men.

As soon as the Hudson was clear of ice, a squadron of vessels of war and transports, with five hundred troops under Colonel Bird, ascended the river. McDougall had intelligence of the intended attack, and while the ships were making their way across the Tappan Sea and Haverstraw Bay, exerted himself to remove as much as possible of the provisions and stores to Forts Montgomery and Constitution in the Highlands. On the morning of the 23d, the whole squadron came to anchor in Peekskill Bay; and five hundred men landed in Lent’s Cove, on the south side of the bay, whence they pushed forward with four light field-pieces drawn by sailors. On their approach, McDougall set fire to the barracks and principal storehouses, and retreated about two miles to a strong post, commanding the entrance to the Highlands, and the road to Continental Village, the place of the deposits. It was the post which had been noted by Washington in the preceding year, where a small force could make a stand, and hurl down masses of rock on their assailants. Hence McDougall sent an express to Lieutenant-colonel Marinus Willet, who had charge of Fort Constitution, to hasten to his assistance.

The British, finding the wharf in flames where they had 30intended to embark their spoils, completed the conflagration, beside destroying several small craft laden with provisions. They kept possession of the place until the following day, when a scouting party, which had advanced towards the entrance of the Highlands, was encountered by Colonel Marinus Willet with a detachment from Fort Constitution, and driven back to the main body after a sharp skirmish, in which nine of the marauders were killed. Four more were slain on the banks of Canopas Creek as they were setting fire to some boats. The enemy were disappointed in the hope of carrying off a great deal of booty, and finding the country around was getting under arms, they contented themselves with the mischief they had done, and re-embarked in the evening by moonlight, when the whole squadron swept down the Hudson.

SCHUYLER’S AFFAIRS IN THE NORTHERN DEPARTMENT—MISUNDERSTANDINGS WITH CONGRESS—GIVES OFFENCE BY A REPROACHFUL LETTER—OFFICE OF ADJUTANT-GENERAL OFFERED TO GATES—DECLINED BY HIM—SCHUYLER REPRIMANDED BY CONGRESS FOR HIS REPROACHFUL LETTER—GATES APPOINTED TO THE COMMAND AT TICONDEROGA—SCHUYLER CONSIDERS HIMSELF VIRTUALLY SUSPENDED—TAKES HIS SEAT AS A DELEGATE TO CONGRESS, AND CLAIMS A COURT OF INQUIRY—HAS COMMAND AT PHILADELPHIA.

We have now to enter upon a tissue of circumstances connected with the Northern department, which will be found materially to influence the course of affairs in that quarter throughout the current year, and ultimately to be fruitful of annoyance to Washington himself. To make these more clear to the reader, it is necessary to revert to events in the preceding year.

The question of command between Schuyler and Gates, when settled as we have shown by Congress, had caused no interruption to the harmony of intercourse between these generals.

Schuyler directed the affairs of the department with energy and activity from his head-quarters at Albany, where they had been fixed by Congress, while Gates, subordinate to him, commanded the post of Ticonderoga.

The disappointment of an independent command, however, still 32rankled in the mind of the latter, and was kept alive by the officious suggestions of meddling friends. In the course of the autumn, his hopes in this respect revived. Schuyler was again disgusted with the service. In the discharge of his various and harassing duties, he had been annoyed by sectional jealousies and ill will. His motives and measures had been maligned. The failures in Canada had been attributed to him, and he had repeatedly entreated Congress to order an inquiry into the many charges made against him, “that he might not any longer be insulted.”

“I assure you,” writes he to Gates, on the 25th of August, “that I am so sincerely tired of abuse, that I will let my enemies arrive at the completion of their wishes by retiring, as soon as I shall have been tried; and attempt to serve my injured country in some other way, where envy and detraction will have no temptation to follow me.”

On the 14th of September, he actually offered his resignation of his commission as major-general, and of every other office and appointment; still claiming a court of inquiry on his conduct, and expressing his determination to fulfil the duties of a good citizen, and promote the weal of his native country, but in some other capacity. “I trust,” writes he, “that my successor, whoever he may be, will find that matters are as prosperously arranged in this department as the nature of the service will admit. I shall most readily give him any information and assistance in my power.”

He immediately wrote to General Gates, apprising him of his having sent in his resignation. “It is much to be lamented,” writes he, “that calumny is so much cherished in this unhappy country, and that so few of the servants of the public escape the 33malevolence of a set of insidious miscreants. It has driven me to the necessity of resigning.”

As the command of the department, should his resignation be accepted, would of course devolve on Gates, he assures him he will render every assistance in his power to any officer whom Gates might appoint to command in Albany.

All his letters to Gates, while they were thus in relation in the department, had been kind and courteous; beginning with, “My dear General,” and ending with, “adieu” and “every friendly wish.” Schuyler was a warm-hearted man, and his expressions were probably sincere.

The hopes of Gates, inspired by this proffered resignation, were doomed to be again overclouded. Schuyler was informed by President Hancock, “that Congress, during the present state of affairs, could not consent to accept of his resignation; but requested that he would continue in the command he held, and be assured that the aspersions thrown out by his enemies against his character, had no influence upon the minds of the members of that House; and that more effectually to put calumny to silence, they would at an early day appoint a committee to inquire fully into his conduct, which they trusted would establish his reputation in the opinion of all good men.”

Schuyler received the resolve of Congress with grim acquiescence, but showed in his reply that he was but half soothed. “At this very critical juncture,” writes he, October 16, “I shall waive those remarks which, in justice to myself, I must make at a future day. The calumny of my enemies has arisen to its height. Their malice is incapable of heightening the injury. * * * * In the alarming situation of our affairs, I shall continue to act some time longer, but Congress must prepare to put the care of 34this department into other hands. I shall be able to render my country better services in another line: less exposed to a repetition of the injuries I have sustained.”

He had remained at his post, therefore, discharging the various duties of his department with his usual zeal and activity; and Gates, at the end of the campaign, had repaired, as we have shown, to the vicinity of Congress, to attend the fluctuation of events.

Circumstances in the course of the winter had put the worthy Schuyler again on points of punctilio with Congress. Among some letters intercepted by the enemy and retaken by the Americans, was one from Colonel Joseph Trumbull, the commissary-general, insinuating that General Schuyler had secreted or suppressed a commission sent for his brother, Colonel John Trumbull, as deputy adjutant-general.[14] The purport of the letter was reported to Schuyler. He spurned at the insinuation. “If it be true that he has asserted such a thing,” writes he to the president, “I shall expect from Congress that justice which is due to me.”

Three weeks later he enclosed to the president a copy of Trumbull’s letter. “I hope,” writes he, “Congress will not entertain the least idea that I can tamely submit to such injurious treatment. I expect they will immediately do what is incumbent on them on the occasion. Until Mr. Trumbull and I are upon a footing, I cannot do what the laws of honor and a regard to my own reputation render indispensably necessary. Congress can put us on a par by dismissing one or the other from the service.”

Congress failed to comply with the general’s request. They 35added also to his chagrin by dismissing from the service an army physician, in whose appointment he had particularly interested himself.

Schuyler was a proud-spirited man, and, at times, somewhat irascible. In a letter to Congress on the 8th of February, he observed: “As Dr. Stringer had my recommendation to the office he has sustained, perhaps it was a compliment due to me that I should have been advised of the reason of his dismission.”

And again: “I was in hopes some notice would have been taken of the odious suspicion contained in Mr. Commissary Trumbull’s intercepted letter. I really feel myself deeply chagrined on the occasion. I am incapable of the meanness he suspects me of, and I confidently expected that Congress would have done me that justice which it was in their power to give, and which I humbly conceive they ought to have done.”

This letter gave great umbrage to Congress, but no immediate answer was made to it.

About this time the office of adjutant-general, which had remained vacant ever since the resignation of Colonel Reed, to the great detriment of the service, especially now when a new army was to be formed, was offered to General Gates, who had formerly filled it with ability; and President Hancock informed him, by letter, of the earnest desire of Congress that he should resume it, retaining his present rank and pay.

Gates almost resented the proposal. “Unless the commander-in-chief earnestly makes the same request with your Excellency,” replies he, “all my endeavors as adjutant-general would be vain and fruitless. I had, last year, the honor to command in the second post in America; and had the good fortune to prevent the enemy from making their so much wished-for junction with General 36Howe. After this, to be expected to dwindle again to the adjutant-general, requires more philosophy on my part, and something more than words on yours.”[15]

He wrote to Washington to the same effect, but declared that, should it be his Excellency’s wish, he would resume the office with alacrity.

Washington promptly replied that he had often wished it in secret, though he had never even hinted at it; supposing Gates might have scruples on the subject. “You cannot conceive the pleasure I feel,” adds he, “when you tell me that, if it is my desire that you should resume your former office, you will with cheerfulness and alacrity proceed to Morristown.” He thanks him for this mark of attention to his wishes; assures him that he looks upon his resumption of the office as the only means of giving form and regularity to the new army; and will be glad to receive a line from him mentioning the time he would leave Philadelphia.

He received no such line. Gates had a higher object in view. A letter from Schuyler to Congress, had informed that body that he should set out for Philadelphia about the 21st of March, and should immediately on his arrival require the promised inquiry into his conduct. Gates, of course, was acquainted with this circumstance. He knew Schuyler had given offence to Congress; he knew that he had been offended on his own part, and had repeatedly talked of resigning. He had active friends in Congress ready to push his interests. On the 12th of March his letter to President Hancock about the proffered adjutancy was read, and ordered to be taken into consideration on the following day.

37On the 13th, a committee of five was appointed to confer with him upon the general state of affairs.

On the 15th, the letter of General Schuyler of the 3d of February, which had given such offence, was brought before the House, and it was resolved that his suggestion concerning the dismission of Dr. Stringer was highly derogatory to the honor of Congress, and that it was expected his letters in future would be written in a style suitable to the dignity of the representative body of these free and independent States, and to his own character as their officer. His expressions, too, respecting the intercepted letter, that he had expected Congress would have done him all the justice in their power, were pronounced, “to say the least, ill-advised and highly indecent.”[16]

While Schuyler was thus in partial eclipse, the House proceeded to appoint a general officer for the Northern department, of which he had stated it to be in need.

On the 25th of March, Gates received the following note from President Hancock: “I have it in charge to direct that you repair to Ticonderoga immediately, and take command of the army stationed in that department.”