Title: The story of the universe. Volume 2 (of 4)

The earth : land and sea

Editor: Esther Singleton

Release date: January 26, 2026 [eBook #77792]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: P.F. Collier and Son, 1905

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77792

Credits: John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

Basic fractions are displayed as ½ ⅓ ¼ etc; other fractions were of the form a-b in the original book, for example 1-3000th and 7-100ths, and have been left unchanged.

The text of the heading of Part I of the book (I.—THE EARTH’S CRUST) has been moved to the next page to be directly above the heading of the first Chapter.

Chapter headings have been made consistent, with the title on a single line and the author on the following line.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

Volume I of this set of four volumes can be found in Project Gutenberg at:

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/74571

Told by Great Scientists

and Popular Authors

COLLECTED AND EDITED

By ESTHER SINGLETON

Author of “Turrets, Towers and Temples,” “Wonders of Nature,”

“The World’s Great Events,” “Famous Paintings,” Translator

of Lavignac’s “Music Dramas of Richard Wagner”

FULLY ILLUSTRATED

VOLUME II

THE EARTH:

LAND AND

SEA

P. F. COLLIER AND SON

NEW YORK

Copyright 1905

By P. F. COLLIER & SON

[Pg i]

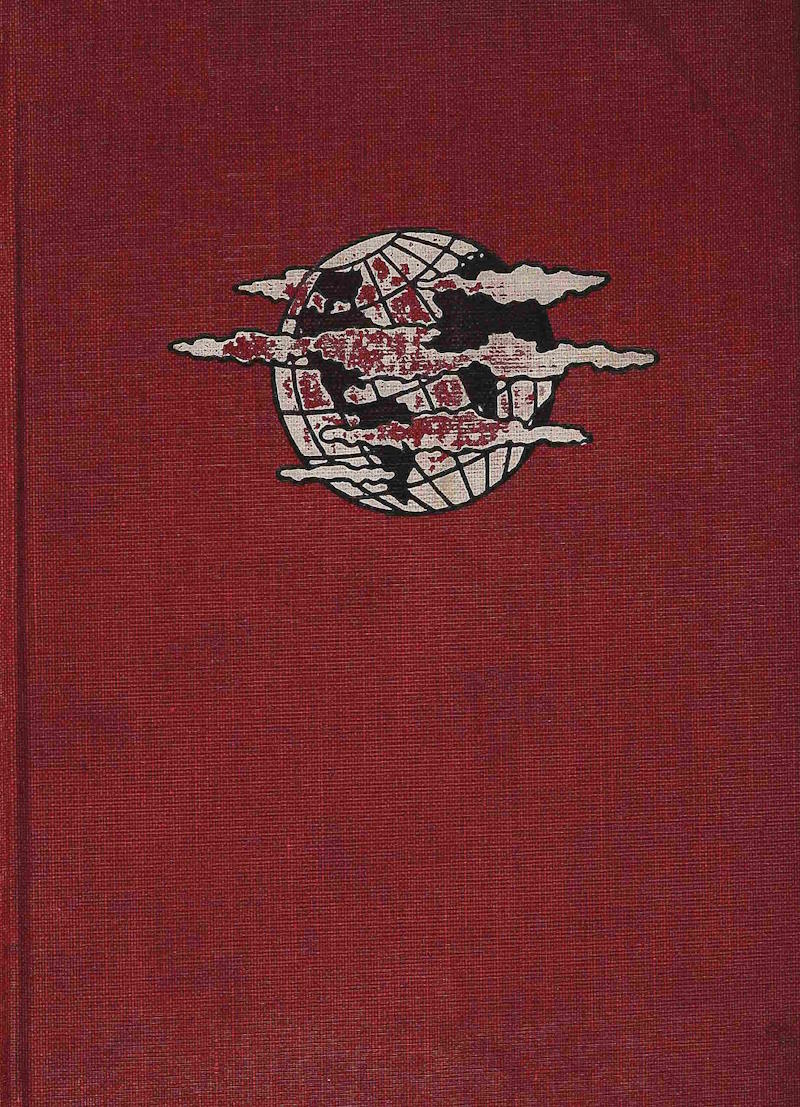

| Hot Springs, Yellowstone Park | Frontispiece | |

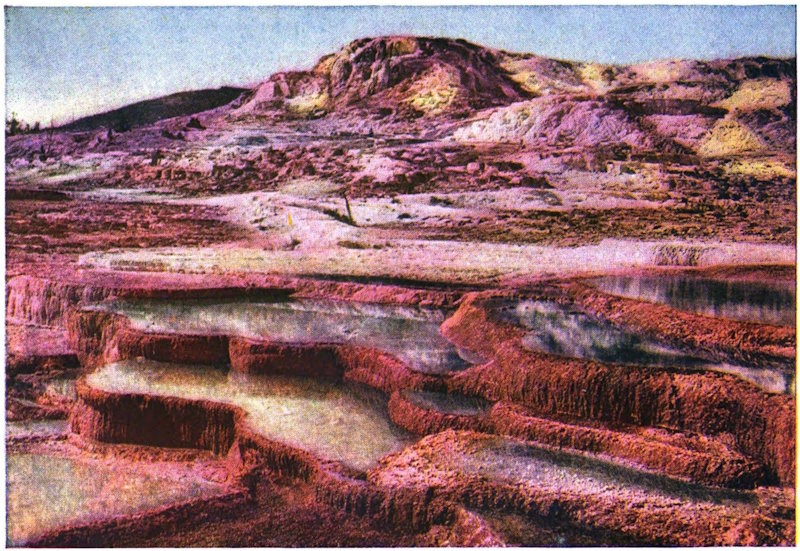

| Fingal’s Cave, Staffa | Opposite | p. 475 |

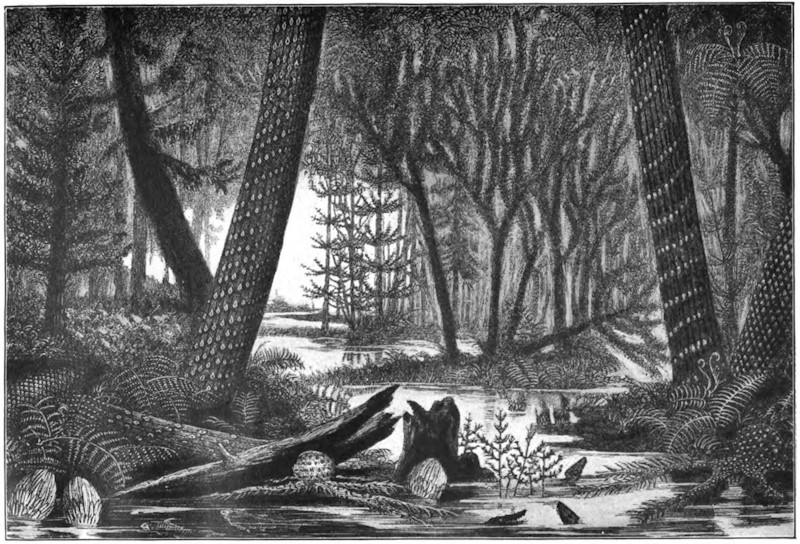

| A Forest of the Carboniferous Period | ” | 523 |

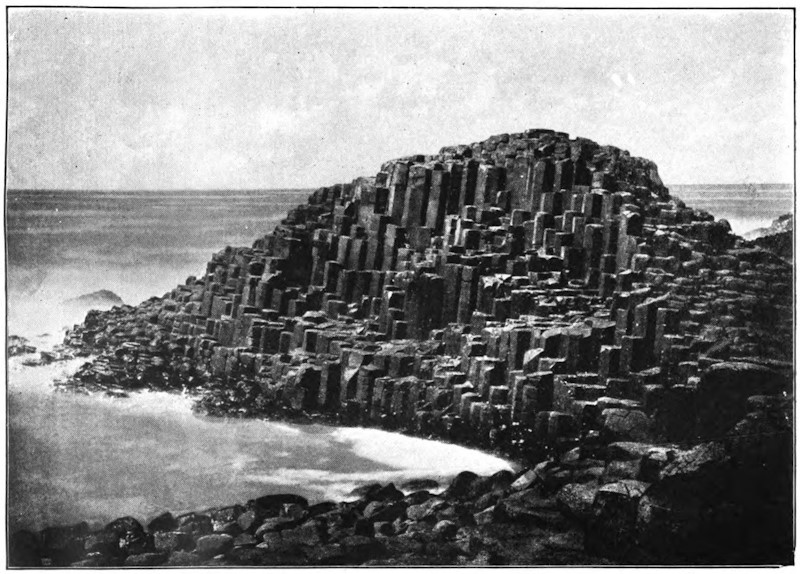

| The Giant’s Causeway, Ireland | ” | 595 |

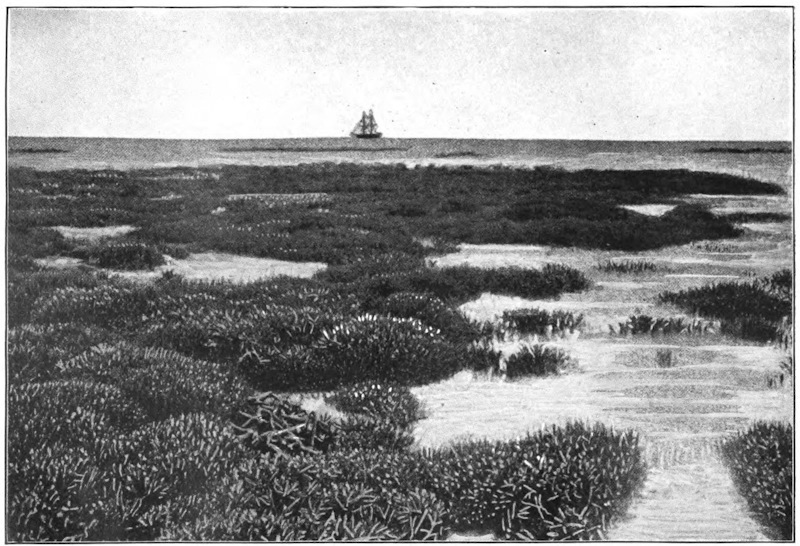

| Stag-Horn Coral Reef, Australia | ” | 643 |

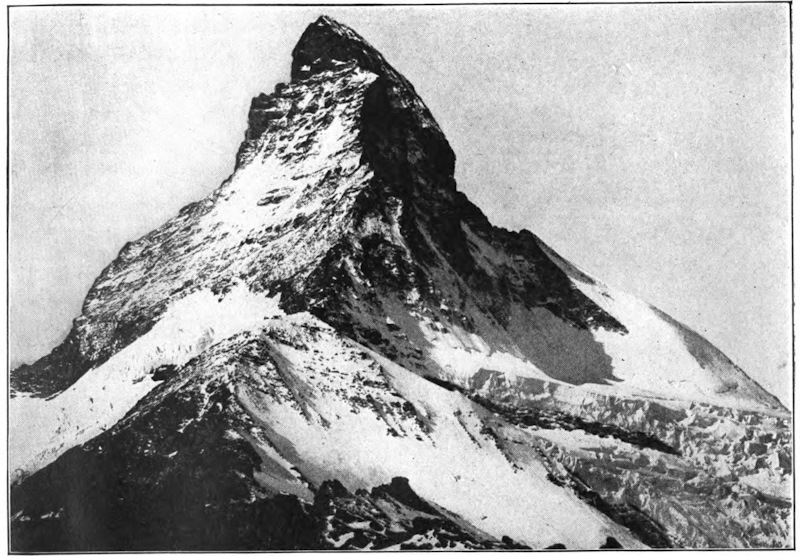

| The Matterhorn | ” | 691 |

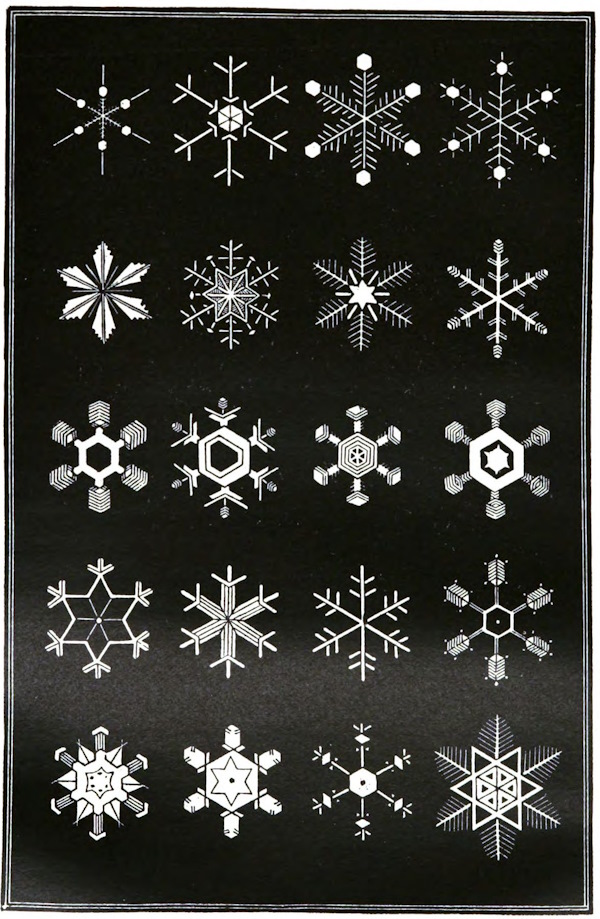

| Forms of Snowflakes | ” | 739 |

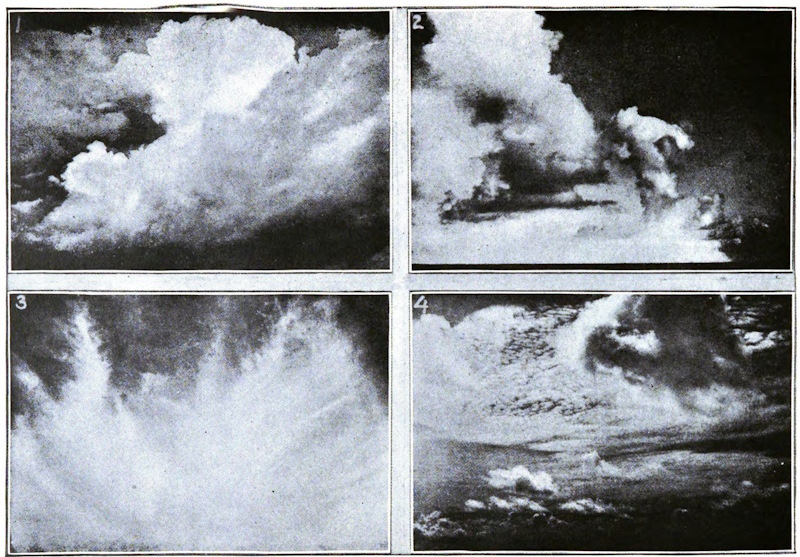

| Forms of Clouds | ” | 787 |

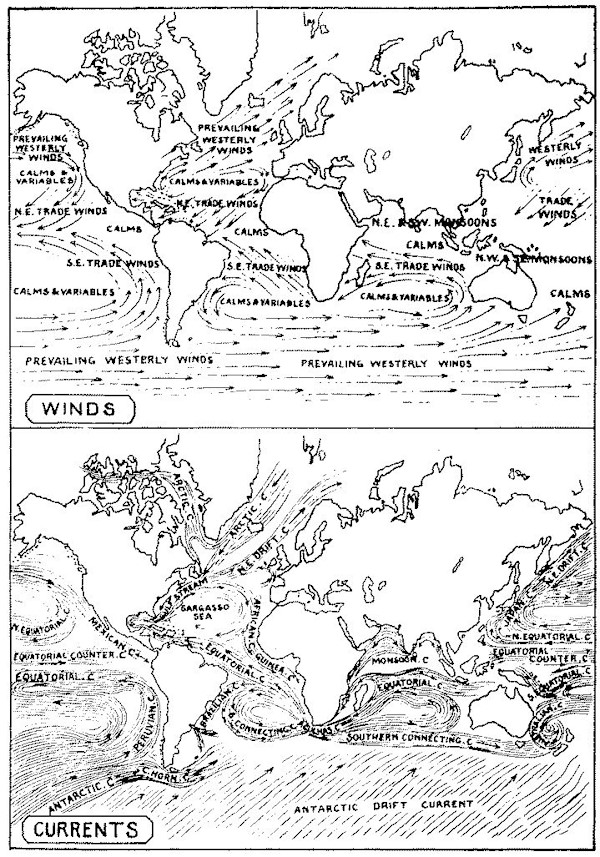

| Chart of Winds and Tides | ” | 835 |

| Formation of the Earth. Élisée Reclus | 433 |

| Classes of Rocks. Sir Charles Lyell | 439 |

| Geological Chronology. Sir J. William Dawson | 450 |

| The Silurian Beach. Louis Agassiz | 456 |

| Carboniferous Period. Louis Figuier | 464 |

| The Palæontological History of Animals. Hugh Miller | 480 |

| European and Asiatic Deluges. Louis Figuier | 493 |

| Glaciers. Louis Agassiz | 502 |

| Volcanic Action. Sir Archibald Geikie | 516 |

| Thoughts About Krakatoa. Sir Robert S. Ball | 527 |

| Volcanoes. Sir Archibald Geikie | 536 |

| Earthquakes. William Hughes | 559 |

| Mountains. A. Keith | 566 |

| Lakes—Fresh, Salt, and Bitter. Sir Archibald Geikie | 573 |

| Underground Water: Springs, Caves, Rivers, and Lakes. Élisée Reclus | 588 |

| Rivers. A. Keith Johnston | 621 |

| Swamps and Marshes. Élisée Reclus | 628 |

| Lowland Plains. William Hughes | 634 |

| The Smell of Earth. G. Clarke Nuttall | 648 |

| Deserts. Élisée Reclus | 654 |

| The Primitive Ocean. G. Hartwig | 666 |

| The Floor of the Ocean. John James Wild | 676 |

| Coral Formations. Charles Darwin | 689 |

| Magnitude and Color of the Sea. G. Hartwig | 707 |

| Tidal Action. Sir Robert S. Ball [iv] | 713 |

| The Gulf Stream. Lord Kelvin | 727 |

| The Phosphorescence of the Sea. G. Hartwig | 750 |

| The Seashore. P. Martin Duncan | 763 |

| The Ocean of Air. Agnes Giberne | 773 |

| Weather. Sir Ralph Abercromby | 784 |

| The Romance of a Raindrop. Arthur H. Bell | 792 |

| The Rainbow. John Tyndall | 799 |

| Snow, Hail, and Dew. Alexander Buchan | 807 |

| The Aurora Borealis. Richard A. Proctor | 813 |

| Clouds. D. Wilson Barker | 819 |

| Winds. William Hughes | 828 |

| Squalls, Whirlwinds, and Tornadoes. Sir Ralph Abercromby | 845 |

THE STORY OF THE UNIVERSE

VOLUME II

THE EARTH: LAND, SEA, AND AIR

[Pg 433]

THE

STORY OF THE UNIVERSE

According to Laplace’s ideas, the whole planetary system formed, in long past ages, a portion of the sun. This luminary, composed solely of gaseous particles much lighter than hydrogen, pervaded with its enormous rotundity the whole of the space in which the planets, including Neptune, are now describing their immense orbits. The diameter of the solar spheroid must then have been 6,500 times greater than it now is, and its bulk must have surpassed its present volume by more than 860,000 millions of times. In the same way, the earth, before it began to get cool and solidify, would have embraced the moon within its limits, and its diameter would have been nearly six times greater than that of the planet Jupiter. But, unsubstantial and aerial as it was, our earth had then nothing but a cosmical life which could hardly be called material; it was not until it became more solid and its outer crust was hardened that it actually commenced its real existence.

This brilliant hypothesis accounts better than any other for the uniform translatory motion of the planets [434]in the direction of west to east; it also apparently agrees in a remarkable way with certain facts in the subsequent history of the earth, as disclosed to us by geology; finally, the marvelous rings which surround the planet Saturn seem to proclaim the truth of the theory devised by Laplace. There have been some experiments on a small scale which appeared to reproduce in miniature the magnificent spectacle presented in the primitive ages by the origin of the planets. M. Plateau, a Belgian savant, managed to make a globe of oil revolve in a mixture of water and spirits of wine which was of exactly the same specific gravity as the oil. When the revolution of the little globe was sufficiently rapid, it was noticed to flatten at the poles and to swell at the equator; after a time it threw off rings which suddenly assumed the shape of globules actuated by a rotatory motion of their own, and turning round the central globe.

Another hypothesis connected with Laplace’s brilliant astronomical theory must be added, in order to describe the formation of the planetary crust. When the gaseous ring became condensed into a globe, it would not cease to contract, owing to the continued radiation of its caloric. The whole mass, having become liquid through the gradual cooling of its molecules, would be changed into a sea of lava whirling round in space; but this state was only one of transition. After an indefinite term of centuries, the loss of heat was sufficient to cause the formation of a light scoria, like a thin sheet of ice over the surface of the fiery sea, perhaps just at one of the poles where nowadays the extreme cold produces icebergs and a frost-bound [435]sea. This first scoria was succeeded by a second, and then by others; next they would unite into continents floating on the surface of the lava, and, finally, would cover the whole circumference of the planet with a continuous layer. A thin but solid crust would then have imprisoned within it an immense burning sea.

This crust was frequently broken through by the lava boiling beneath it, and then, by means of the solidification of the scoriæ, was again united; the cooling process would tend also to slowly thicken it. After a lapse of time, which must have been immensely protracted—since the interval during which the temperature of the terrestrial crust would be lowered from 2,000° to 200° has been estimated, at the very least, at three and a half millions of centuries—the pellicle at last became firm, and the eruptions of the liquid mass within ceased to be a general phenomenon, localizing themselves at those points where the firm crust was the thinnest. The surrounding atmosphere, replete with vapors and various substances maintained by the extreme heat in a gaseous state, would gradually get rid of its burden; all kinds of matter, one after the other, would become disengaged from the luminous and burning aerial mass, and precipitate themselves on the solid crust of the planet. When the temperature was lowered sufficiently to enable them to pass from a gaseous to a liquid state, metals and other substances would fall down in a fiery rain on the terrestrial lava. Next, the steam, confined entirely to higher regions of the gaseous mass, would be condensed into an immense [436]layer of clouds, incessantly furrowed by lightning. Drops of water, the commencement of the atmospheric ocean, would begin to fall down toward the ground, but only to volatilize on their way and again ascend. Finally these little drops reached the surface of the terrestrial scoria, the temperature of the water much exceeding 100°, owing to the enormous pressure exercised by the heavy air of these ages; and the first pool, the rudiment of a great sea, was collected in some fissure of the lava. This pool was constantly increased by fresh falls of water, and ultimately surrounded nearly the whole of the terrestrial crust with a liquid covering; but, at the same time, it brought with it fresh elements for the constitution of future continents. The numerous substances which the water held in solution formed various combinations with the metals and soils of its bed; the currents and tempests which agitated it destroyed its shores only to form new ones; the sediment deposited at the bottom of the water commenced the series of rocks and strata which follow one another above the primitive crust.

Henceforward the igneous planet was externally clothed with a triple covering, solid, liquid, and gaseous; it might therefore become the theatre of life. Vegetables and lowly forms of animals were called into existence in the water, and on the land which had emerged from it; and, finally, when the temperature of the surface of the globe had become less than 50°, allowing albumen to liquefy and blood to flow in the veins, the fauna and the flora would be developed, the remains of which are found in the earliest [437]fossil strata. The era of chaos was succeeded by that of vital harmony; but in the immense series of ages we are dealing with, the life which appeared on the refrigerated planet was little else than the “mouldiness formed in a day.”

According to the theory generally propounded, the solid crust was not very completely formed; it is, indeed, much thinner than the layer of air surrounding the globe; for, following the common estimate, which, however, is purely hypothetical, at 22 to 25, or, at most, 50 miles below the surface of the earth, the terrestrial heat would be sufficient to melt granite. Compared to the diameter of the earth, which is about 250 times greater, this crust is nothing more than a thin skin, a just idea of which may be given by a sheet of thin cardboard surrounding a liquid sphere a yard in diameter. In the case of the earth, this liquid is a sea of lava and molten rocks, having, like the ocean above it, its currents, its tides, and perhaps its storms.

It is, in fact, very probable that a great part of the rocks which form the outer portion of our planet, especially the most ancient formations, existed in former times in a state of fusion like that of volcanic lava. As most geologists are of opinion, granite and other similar rocks, forming the principal building-blocks in the architecture of continents, existed once in a soft or semi-soft state.

Neither must it be forgotten that, under the hypothesis admitted by those who assume the existence of a central fire, our planet is to be considered as actually a liquid mass, as the external crust is in comparison [438]but a thin skin. Under these conditions, it would be difficult to believe that this great ocean of lava is not, like the watery ocean, agitated by the alternating motion of tides, and that it does not move twice every day the raft, as it were, which is floating on its surface. It is difficult to understand how it is that the earth is not much more depressed at the poles than it now is, and has not been transformed into a real disk. This flattening of the poles is not more considerable than the mere superficial inequalities in the equatorial zone between the summits of the Himalayas and the abysses of the Indian Ocean. M. Liais attributes the slight flattening of the two poles to the erosion which the water and ice in those parts, irresistibly drawn as they are toward the equator, incessantly cause, year after year and century after century, by the enormous quantity of débris torn away from the surface of the soil, which they bear with them.

The principal argument of those who look upon the existence of a central fire as a demonstrated fact is that, in the external strata of the earth, so far as they have been explored by miners, the heat keeps on increasing in proportion to the depth of the excavation. In descending the shaft of a mine we invariably pass through zones of increasing temperature; only the rate of increase varies in different parts of the earth, and according to the strata through which the shaft is sunk. The heat increases more rapidly in schist than in granite, and in metallic veins more even than in schist; in lodes of copper more than in those of tin, and in beds of coal more than in metallic [439]veins. M. Cordier, being struck by all the objections which presented themselves to his mind as to the thinness of the terrestrial crust, has admitted that this covering could not be stable without having at least from 75 to 175 miles of thickness.

Of what materials is the earth composed, and in what manner are these materials arranged? These are the first inquiries with which geology is occupied, a science which derives its name from the Greek ge, the earth, and logos, a discourse. Previously to experience we might have imagined that investigations of this kind would relate exclusively to the mineral kingdom, and to the various rocks, soils, and metals which occur upon the surface of the earth, or at various depths beneath it. But, in pursuing such researches, we soon find ourselves led on to consider the successive changes which have taken place in the former state of the earth’s surface and interior, and the causes which have given rise to these changes; and, what is still more singular and unexpected, we soon become engaged in researches into the history of the animate creation, or of the various tribes of animals and plants which have, at different periods of the past, inhabited the globe.

By the “earth’s crust” is meant that small portion of the exterior of our planet which is accessible to human observation. It comprises not merely all of which the structure is laid open in mountain precipices, [440]or in cliffs overhanging a river or the sea, or whatever the miner reveals in artificial excavation; but the whole of that outer covering of the planet on which we are enabled to reason by observations made at or near the surface.

The materials of this crust are not thrown together confusedly; but distinct mineral masses, called rocks, are found to occupy definite spaces, and to exhibit a certain order of arrangement. The term rock is applied indifferently by geologists to all these substances, whether they be soft or strong, for clay and sand are included in the term, and some have even brought peat under this denomination.

The most natural and convenient mode of classifying the various rocks which compose the earth’s crust is to refer, in the first place, to their origin, and in the second to their relative age.

The first two divisions, which will at once be understood as natural, are the aqueous and volcanic, or the products of watery and those of igneous action at or near the surface. The aqueous rocks, sometimes called the sedimentary or fossiliferous, cover a larger part of the earth’s surface than any others. They consist chiefly of mechanical deposits (pebbles, sand, and mud), but are partly of chemical and some of them of organic origin, especially the limestones. These rocks are stratified, or divided into distinct layers or strata. The term stratum means simply a bed, or anything spread out or strewed over a given surface; and we infer that these strata have been generally spread out by the action of water, from what we daily see taking place near the mouths of rivers, [441]or on the land during temporary inundations. For, whenever a running stream, charged with mud or sand, has its velocity checked, as when it enters a lake or sea, or overflows a plain, the sediment, previously held in suspension by the motion of the water, sinks, by its own gravity, to the bottom. In this manner layers of mud and sand are thrown down one upon another.

If we drain a lake which has been fed by a small stream, we frequently find at the bottom a series of deposits, disposed with considerable regularity, one above the other; the uppermost, perhaps, may be a stratum of peat, next below a more dense and solid variety of the same material; still lower a bed of shell-marl, alternating with peat or sand, and then other beds of marl, divided by layers of clay. Now, if a second pit be sunk through the same continuous lacustrine formation at some distance from the first, nearly the same series of beds is commonly met with, yet with slight variations; some, for example, of the layers of sand, clay, or marl may be wanting, one or more of them having thinned out and given place to others, or sometimes one of the masses first examined is observed to increase in thickness to the exclusion of other beds.

The term formation, which I have used in the above explanation, expresses in geology any assemblage of rocks which have some character in common, whether of origin, age, or composition. Thus we speak of stratified and unstratified, fresh-water and marine, aqueous and volcanic, ancient and modern, metalliferous and non-metalliferous formations.

[442]

In the estuaries of large rivers, such as the Ganges and the Mississippi, we may observe, at low water, phenomena analogous to those of the drained lakes above mentioned, but on a grander scale, and extending over areas several hundred miles in length and breadth. When the periodical inundations subside, the river hollows out a channel to the depth of many yards through horizontal beds of clay and sand, the ends of which are seen exposed in perpendicular cliffs. These beds vary in their mineral composition, or color, or in the fineness or coarseness of their particles, and some of them are occasionally characterized by containing driftwood. At the junction of the river and the sea, especially in lagoons nearly separated by sand bars from the ocean, deposits are often formed in which brackish and salt-water shells are included.

In Egypt, where the Nile is always adding to its delta by filling up part of the Mediterranean with mud, the newly deposited sediment is stratified, the thin layer thrown down in one season differing slightly in color from that of a previous year, and being separable from it, as has been observed in Cairo and other places.

When beds of sand, clay, and marl containing shells and vegetable matter are found arranged in a similar manner in the interior of the earth, we ascribe to them a similar origin; and the more we examine their characters in minute detail, the more exact do we find the resemblance. Thus, for example, at various heights and depths in the earth, and often far from seas, lakes, and rivers, we meet with layers of [443]rounded pebbles composed of flint, limestone, granite, or other rocks, resembling the shingles of a sea-beach or the gravel in a torrent’s bed. Such layers of pebbles frequently alternate with others formed of sand or fine sediment, just as we may see in the channel of a river descending from hills bordering a coast, where the current sweeps down at one season coarse sand and gravel, while at another, when the waters are low and less rapid, fine mud and sand alone are carried seaward.

If a stratified arrangement and the rounded form of pebbles are alone sufficient to lead us to the conclusion that certain rocks originated under water, this opinion is further confirmed by the distinct and independent evidences of fossils, so abundantly included in the earth’s crust. By a fossil is meant any body, or the traces of the existence of any body, whether animal or vegetable, which has been buried in the earth by natural causes. Now the remains of animals, especially of aquatic species, are found almost everywhere imbedded in stratified rocks, and sometimes, in the case of limestone, they are in such abundance as to constitute the entire mass of the rock itself. Shells and corals are the most frequent, and with them are often associated the bones and teeth of fishes, fragments of wood, impressions of leaves, and other organic substances. Fossil shells of forms such as now abound in the sea are met with far inland, both near the surface and at great depths below it. They occur at all heights above the level of the ocean, having been observed at elevations of more than 8,000 feet in the Pyrenees, 10,000 in the Alps, [444]13,000 in the Andes, and above 18,000 feet in the Himalayas.

These shells belong mostly to marine testacea, but in some places exclusively to forms characteristic of lakes and rivers. Hence it is concluded that some ancient strata were deposited at the bottom of the sea, and others in lakes and estuaries.

The division of rocks, which we may next consider, are the volcanic, or those which have been produced at or near the surface, whether in ancient or modern times, not by water, but by the action of fire or subterranean heat. These rocks are for the most part unstratified, and are devoid of fossils. They are more partially distributed than aqueous formations, at least in respect to horizontal extension. Among those parts of Europe where they exhibit characters not to be mistaken, I may mention not only Sicily and the country round Naples, but Auvergne, Velay, and Vivarais, now the departments of Puy de Dôme, Haute Loire, and Ardêche, toward the centre and south of France, in which are several hundred conical hills having the forms of modern volcanoes, with craters more or less perfect on many of their summits. These cones are composed, moreover, of lava, sand, and ashes similar to those of active volcanoes. Streams of lava may sometimes be traced from the cones into the adjoining valleys, where they have choked up the ancient channels of rivers with solid rock, in the same manner as some modern flows of lava in Iceland have been known to do, the rivers either flowing beneath or cutting out a narrow passage on one side of the lava. Although none of these [445]French volcanoes has been in activity within the period of history or tradition, their forms are often very perfect. Some, however, have been compared to the mere skeletons of volcanoes, the rains and torrents having washed their sides, and removed all the loose sand and scoriæ, leaving only the harder and more solid materials. By this erosion and by earthquakes their internal structure has occasionally been laid open to view, in fissures and ravines; and we then behold not only many successive beds and masses of porous lava, sand, and scoriæ, but also perpendicular walls, or dikes, as they are called, of volcanic rock, which have burst through the other materials. Such dikes are also observed in the structure of Vesuvius, Etna, and other active volcanoes. They have been formed by the pouring of melted matter, whether from above or below, into open fissures, and they commonly traverse deposits of volcanic tuff, a substance produced by the showering down from the air, or incumbent waters, of sand and cinders, first shot up from the interior of the earth by the explosions of volcanic gases.

Besides the parts of France above alluded to, there are other countries, as the north of Spain, the south of Sicily, the Tuscan territory of Italy, the lower Rhenish provinces, and Hungary, where spent volcanoes may be seen, still preserving in many cases a conical form, and having craters and often lava streams connected with them.

There are also other rocks in England, Scotland, Ireland, and almost every country in Europe, which we infer to be of igneous origin, although they do [446]not form hills with cones and craters. Thus, for example, we feel assured that the rock of Staffa and that of the Giant’s Causeway, called basalt, is volcanic, because it agrees in its columnar structure and mineral composition with streams of lava which we know to have flowed from the craters of volcanoes.

The absence of cones and craters, and long narrow streams of superficial lava in England and many other countries, is principally to be attributed to the eruptions having been submarine, just as a considerable proportion of volcanoes in our own times burst out beneath the sea. The igneous, as well as the aqueous rocks may be classed as a chronological series of monuments, throwing light on a succession of events in the history of the earth.

We have now pointed out the existence of two distinct orders of mineral masses, the aqueous and the volcanic; but if we examine a large portion of a continent, especially if it contain within it a lofty mountain range, we rarely fail to discover two other classes of rocks, very distinct from either of those above alluded to, and which we can neither assimilate to deposits such as are now accumulated in lakes or seas, nor to those generated by ordinary volcanic action. The members of both these divisions of rocks agree in being highly crystalline and destitute of organic remains. The rocks of one division have been called plutonic, comprehending all the granites and certain porphyries, which are nearly allied in some of their characters to volcanic formations. The members of the other class are stratified and often slaty, and have been called by some the crystalline schists, in which [447]group are included gneiss, micaceous-schist (or mica-slate), hornblende-schist, statuary marble, the finer kinds of roofing-slate, and other rocks afterward to be described.

All the various kinds of granites which constitute the plutonic family are supposed to be of igneous or aqueo-igneous origin, and to have been formed under great pressure, at a considerable depth in the earth, or sometimes perhaps under a certain weight of incumbent ocean. Like the lava of volcanoes, they have been melted, and afterward cooled and crystallized, but with extreme slowness, and under conditions very different from those of bodies cooling in the open air. Hence they differ from the volcanic rocks, not only by their more crystalline texture, but also by the absence of tuffs and breccias, which are the products of eruptions at the earth’s surface, or beneath seas of inconsiderable depth. They differ also by the absence of pores or cellular cavities, to which the expansion of the entangled gases gives rise in ordinary lava.

The fourth and last great division of rocks are the crystalline strata and slates, or schists, called gneiss, mica-schist, clay-slate, chlorite-schist, marble, and the like, the origin of which is more doubtful than that of the other three classes. They contain no pebbles, or sand, or scoriæ, or angular pieces of imbedded stone, and no traces of organic bodies, and they are often as crystalline as granite, yet are divided into beds, corresponding in form and arrangement to those of sedimentary formations, and are therefore said to be stratified. The beds sometimes [448]consist of an alternation of substances varying in color, composition, and thickness, precisely as we see in stratified fossiliferous deposits. According to the Huttonian theory, which I adopt as the most probable, the materials of these strata were originally deposited from water in the usual form of sediment, but they were subsequently so altered by subterranean heat as to assume a new texture. It is demonstrable, in some cases at least, that such a complete conversion has actually taken place, fossiliferous strata having exchanged an earthy for a highly crystalline texture for a distance of a quarter of a mile from their contact with granite. In some cases, dark limestones, replete with shells and corals, have been turned into white statuary marble, and hard clays, containing vegetable or other remains, into slates called mica-schist or hornblende-schist, every vestige of the organic bodies having been obliterated.

Although we are in a great degree ignorant of the precise nature of the influence exerted in these cases, yet it evidently bears some analogy to that which volcanic heat and gases are known to produce; and the action may be conveniently called plutonic, because it appears to have been developed in those regions where plutonic rocks are generated, and under similar circumstances of pressure and depth in the earth. Intensely heated water or steam permeating stratified masses under great pressure have no doubt played their part in producing the crystalline texture and other changes, and it is clear that the transforming influence has often pervaded entire mountain masses of strata.

[449]

In accordance with the hypothesis above alluded to, I proposed in the first edition of the Principles of Geology (1833), the term Metamorphic, for the altered strata, a term derived from meta, trans, and morphe, forma.

Hence there are four great classes of rocks considered in reference to their origin—the aqueous, the volcanic, the plutonic, and the metamorphic. Portions of each of these four distinct classes have originated at many successive periods. They have all been produced contemporaneously, and may even now be in the progress of formation on a large scale. It is not true, as was formerly supposed, that all granites, together with the crystalline or metamorphic strata, were first formed, and therefore entitled to be called “primitive,” and that the aqueous and volcanic rocks were afterward superimposed, and should, therefore, rank as secondary in the order of time. This idea was adopted in the infancy of the science, when all formations, whether stratified or unstratified, earthy or crystalline, with or without fossils, were alike regarded as of aqueous origin.

From what has now been said, the reader will understand that each of the four great classes of rocks may be studied under two distinct points of view; first, they may be studied simply as mineral masses deriving their origin from particular causes, and having a certain composition, form, and position in the earth’s crust, or other characters, both positive and negative, such as the presence or absence of organic remains. In the second place, the rocks of each class may be viewed as a grand chronological series of [450]monuments, attesting a succession of events in the former history of the globe and its living inhabitants.

The crust of the earth, as we somewhat modestly term that portion of its outer shell which is open to our observation, consists of many beds of rock superimposed on each other, and which must have been deposited successively, beginning with the lowest. This is proved by the structure of the beds themselves, by the markings on their surfaces, and by the remains of animals and plants which they contain; all these appearances indicating that each successive bed must have been the surface before it was covered by the next.

As these beds of rock were mostly formed under water, and of material derived from the waste of land, they are not universal, but occur in those places where there were extensive areas of water receiving detritus from the land. Further, as the distinction of land and water arises primarily from the shrinkage of the mass of the earth, and from the consequent collapse of the crust in some places and ridging of it up in others, it follows that there have, from the earliest geological periods, been deep ocean-basins, ridges of elevated land, and broad plateaus intervening between the ridges, and which were at some times under water and at other times land, with many intermediate phases. The settlement and crumpling of the crust were not continuous, but took place at [451]intervals; and each such settlement produced not only a ridging up along certain lines, but also an emergence of the plains or plateaus. Thus at all times there have been ridges of folded rock constituting mountain ranges, flat expansions of continental plateau, sometimes dry and sometimes submerged, and deep ocean-basins, never except in some of their shallower portions elevated into land.

By the study of the successive beds, more especially of those deposited in the times of continental submergence, we obtain a table of geological chronology which expresses the several stages of the formation of the earth’s crust, from that early time when a solid shell first formed on our nascent planet to the present day. By collecting the fossil remains imbedded in the several layers and placing these in chronological order, we obtain in like manner histories of animal and plant life parallel to the physical changes indicated by the beds themselves. The facts as to the sequence we obtain from the study of exposures in cliffs, cuttings, quarries, and mines; and by correlating these local sections in a great number of places, we obtain our general table of succession; though it is to be observed that in some single exposures or series of exposures, like those in the great cañons of Colorado, or on the coasts of Great Britain, we can often in one locality see nearly the whole sequence of beds.

The evidence is similar to that obtained by Schliemann on the site of Troy, where, in digging through successive layers of débris, he found the objects deposited by successive occupants of the site, from the [452]time of the Roman Empire back to the earliest tribes, whose flint weapons and the ashes of their fires rest on the original surface of the ground.

Let us now tabulate the whole geological succession with the history of animals and plants associated with it:

| ANIMALS | SYSTEMS OF FORMATIONS | PLANTS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Man and Mammalia | Kainozoic | ||

| Modern | Angiosperms and Palms dominant | ||

| Pleistocene | |||

| Pliocene | |||

| Miocene | |||

| Eocene | |||

| Age of Reptiles | Mesozoic | ||

| Cretaceous | Cycads and Pines dominant | ||

| Jurassic | |||

| Triassic | |||

| Age of Amphibians and Fishes | Palæozoic | ||

| Permian | Acrogens and Gymnosperms dominant | ||

| Carboniferous | |||

| Erian | |||

| Silurian | |||

| Age of Invertebrates | Ordovician | ||

| Cambrian | |||

| Huronian (Upper) | |||

| Age of Protozoa | Eozoic | ||

| Huronian (Lower) | Protogens and Algæ | ||

| Upper Laurentian | |||

| Middle Laurentian | |||

| Lower Laurentian | |||

It will be observed, since only the latest of the systems of formations in this table belongs to the period of human history, that the whole lapse of time embraced in the table must be enormous. If we suppose the modern period to have continued for say ten thousand years, and each of the others to have been equal to it, we shall require two hundred thousand [453]years for the whole. There is, however, reason to believe, from the great thickness of the formations and the slowness of the deposition of many of them in the older systems, that they must have required vastly greater time. Taking these criteria into account, it has been estimated that the time-ratios for the first three great ages may be as one for the Kainozoic to three for the Mesozoic and twelve for the Palæozoic, with as much for the Eozoic as for the Palæozoic. This is Dana’s estimate. Another, by Hull and Houghton, gives the following ratios: Azoic, 34.3 per cent; Palæozoic, 42.5 per cent; Mesozoic and Kainozoic, 23.3 per cent. It is further held that the modern period is much shorter than the other periods of the Kainozoic, so that our geological table may have to be measured by millions of years instead of thousands.

We can not, however, attach any certain and definite value in years to geological time, but must content ourselves with the general statement that it has been vastly long in comparison to that covered by human history.

Bearing in mind this great duration of geological time, and the fact that it probably extends from a period when the earth was intensely heated, its crust thin, and its continents as yet unformed, it will be evident that the conditions of life in the earlier geologic periods may have been very different from those which obtained later. When we further take into account the vicissitudes of land and water which have occurred, we shall see that such changes must have produced very great differences of climate. The [454]warm equatorial waters have in all periods, as superficial oceanic currents, been main agents in the diffusion of heat over the surface of the earth, and their distribution to north and south must have been determined mainly by the extent and direction of land, though it may also have been modified by the changes in the astronomical relations and period of the earth, and the form of its orbit. We know by the evidence of fossil plants that changes of this kind have occurred so great as, on the one hand, to permit the plants of warm temperate regions to exist within the Arctic Circle; and, on the other, to drive these plants into the tropics and to replace them by Arctic forms. It is evident also that in those periods when the continental areas were largely submerged there might be an excessive amount of moisture in the atmosphere, greatly modifying the climate in so far as plants are concerned.

Let us now consider the history of the vegetable kingdom as indicated in the few notes in the right-hand column of the table.

The most general subdivision of plants is into the two great series of Cryptogams, or those which have no manifest flowers, and produce minute spores instead of seeds; and Phænogams, or those which possess flowers and produce seeds containing an embryo of the future plant.

The Cryptogams may be subdivided into the following three groups:

1. Thallogens, cellular plants not distinctly distinguishable into stem and leaf. These are the Fungi, the Lichens, and the Algæ, or sea-weeds.

[455]

2. Anogens, having stem and foliage, but wholly cellular. These are the Mosses and Liverworts.

3. Acrogens, which have long tubular fibres as well as cells in their composition, and thus have the capacity of attaining a more considerable magnitude. These are the Ferns (Filices), the Mare’s-tails (Equisetaceæ), and the Club-mosses (Lycopodiaceæ), and a curious little group of aquatic plants called Rhizocarps (Rhizocarpeæ).

The Phænogams are all vascular, but they differ much in the simplicity or complexity of their flowers or seeds. On this ground they admit of a twofold division:

1. Gymnosperms, or those which bear naked seeds not inclosed in fruits. They are the Pines and their allies, and the Cycads.

2. Angiosperms, which produce true fruits inclosing the seeds. In this group there are two well-marked subdivisions differing in the structure of the seed and stem. They are the Endogens, or inside growers, with seeds having one seed-leaf only, as the grasses and the palms; and the Exogens, having outside-growing woody stems and seeds with two seed-leaves. Most of the ordinary forest trees of temperate climates belong to this group.

On referring to the geological table, it will be seen that there is a certain rough correspondence between the order of rank of plants and the order of their appearance in time. The oldest plants that we certainly know are Algæ, and with these there are plants apparently with the structures of Thallophytes but the habit of trees, and which, for want of a better name, [456]I may call Protogens. Plants akin to the Rhizocarps also appear very early. Next in order we find forests in which gigantic Ferns and Lycopods and Mare’s-tails predominate, and are associated with pines. Succeeding these we have a reign of Gymnosperms, and in the later formations we find the higher Phænogams dominant.

The crust of our earth is a great cemetery where the rocks are tombstones on which the buried dead have written their own epitaphs. They tell us not only who they were and when and where they have lived, but much also of the circumstances under which they lived. We ascertain the prevalence of certain physical conditions at special epochs by the presence of animals and plants whose existence and maintenance requires such a state of things, more than by any positive knowledge respecting it. Where we find the remains of quadrupeds corresponding to our ruminating animals, we infer not only land, but grassy meadows and an extensive vegetation; where we find none but marine animals, we know the ocean must have covered the earth; the remains of large reptiles, representing, though in gigantic size, the half aquatic, half terrestrial reptiles of our own period, indicate to us the existence of spreading marshes still soaked by retreating waters; while the traces of such animals as live now in sand and shoal waters, or in mud, speak to us of shelving sandy [457]beaches and mud flats. The eye of the Trilobite tells us that the sun shone on the old beach where he lived; for there is nothing in nature without a purpose, and when so complicated an organ was made to receive the light there must have been light to enter it. The immense vegetable deposits in the Carboniferous period announce the introduction of an extensive terrestrial vegetation; and the impressions left by the wood and leaves show that these first forests must have grown in a damp soil and a moist atmosphere. In short, all the remains of animals and plants hidden in the rocks have something to tell of the climatic conditions and the general circumstances under which they lived, and the study of fossils is to a naturalist a thermometer by which he reads the variation of temperature in past times, a plummet by which he sounds the depths of the ancient oceans—a register, in fact, of all the important physical changes the earth has undergone.

The Silurian beach was a shelving one, and covered, of course, with shoal waters; but the parallel ridges trending east to west across the State of New York, considered by some geologists as the successive shores of a receding ocean, are believed by others to be the inequalities on the bottom of a shallow sea. Not only, however, does the general character of these successive terraces suggest the idea that they must have been shores, but the ripple marks upon them are as distinct as upon any modern beach. The regular rise and fall of the water is registered there in waving, undulating lines as clearly as on the sand beaches of Newport or Nahant; and we can see on [458]any of those ancient shores the track left by the waves as they rippled back at ebb of the tide thousands of centuries ago. One can often see where some obstacle interrupted the course of the water, causing it to break around it; and such an indentation even retains the soft, muddy, plastic look that we observe on the present beaches, where the resistance made by any pebble or shell to the retreating wave has given it greater force at that point, so that the sand around the spot is soaked and loosened. There is still another sign familiar to those who have watched the action of water on a beach. Where a shore is very shelving and flat, so that the waves do not recede in ripples from it, but in one unbroken sheet, the sand and small pebbles are dragged and form lines which diverge whenever the water meets an obstacle, thus forming sharp angles on the sand. Such marks are as distinct on the oldest Silurian rocks as if they had been made yesterday. Nor are these the only indications of the same fact. There are certain animals living always on sandy or muddy shores which require for their well-being that the beach should be left dry for a part of the day. These animals, moving about in the sand or mud from which the water has retreated, leave their tracks there; and if, at such a time, the wind is blowing dust over the beach and the sun is hot enough to bake it upon the impressions so formed, they are left in a kind of mold. Such trails and furrows made by small shells and crustacea are also found in plenty on the oldest deposits.

Admitting it, then, to be a beach, let us begin with the lowest type of the Animal Kingdom and see [459]what Radiates are to be found there. There are plenty of Corals, but they are not the same kind of Corals as those that build up our reefs and islands now. The modern Coral animals are chiefly Polyps, but the prevailing Corals of the Silurian age were Acalephian Hydroids, animals which indeed resemble Polyps in certain external features, and have been mistaken for them, but which are, nevertheless, Acalephs by their internal structure.

Of the Echinoderms, the class of Radiates represented now by our Star-Fishes and Sea-Urchins, we may gather any quantity, though the old-fashioned forms are very different from the living ones. The Mollusks were also represented then, as now, by their three classes, Acephala, Gasteropoda, and Cephalopoda. The Acephala or Bivalves we find in great numbers, but of a very different pattern from the Oysters, Clams, and Mussels of recent times.

Of the Silurian Univalves or Gasteropods, there is not much to tell, for their spiral shells were so brittle that scarcely any perfect specimens are known, though their broken remains are found in such quantities as to show that this class also was very fully represented in the earliest creation. But the highest class of Mollusks, the Cephalopods or Chambered Shells, or Cuttle-Fishes, as they are called when the animal is unprotected by a shell, are, on the contrary, very well preserved, and they are very numerous.

Of Articulates we find only two classes, Worms and Crustacea. Insects there were none—for, as we have seen, this early world was wholly marine. There is little to be said of the Worms, for their soft [460]bodies, unprotected by any hard covering, could hardly be preserved; but, like the marine Worms of our own times, they were in the habit of constructing envelopes for themselves, built of sand, or sometimes from a secretion of their own bodies, and these cases we find in the earliest deposits, giving us the assurance that the Worms were represented there. I should add, however, that many impressions described as produced by Worms are more likely to have been the tracks of Crustacea. But by far the most characteristic class of Articulates in ancient times were the Crustaceans. The Trilobites stand in the same relation to the modern Crustacea as the Crinoids do to the modern Echinoderms. They were then the sole representatives of their class, and the variety and richness of the type are most extraordinary. They were of nearly equal breadth for the whole length of the body, and rounded at the two ends, so as to form an oval outline.

We have found Radiates, Mollusks, and Articulates in plenty; and now what is to be said of Vertebrates in these old times—of the highest and most important division of the Animal Kingdom, that to which we ourselves belong. They were represented by Fishes alone; and the fish chapter in the history of the early organic world is a curious and, as it seems to me, a very significant one. We shall find no perfect specimens; and he would be a daring, not to say a presumptuous, thinker who would venture to reconstruct a fish of the Silurian age from any remains that are left to us. But still we find enough to indicate clearly the style of those old fishes, [461]and to show, by comparison with the living types, to what group of modern times they belong. We should naturally expect to find the Vertebrates introduced in their simplest form; but this is by no means the case: the common fishes, as Cod, Herring, Mackerel, and the like, were unknown in those days.

I have spoken of the Silurian beach as if there were but one, not only because I wished to limit my sketch and to attempt, at least, to give it the vividness of a special locality, but also because a single such shore will give us as good an idea of the characteristic fauna of the time as if we drew our material from a wider range. There are, however, a great number of parallel ridges belonging to the Silurian and Devonian periods running from east to west, not only through the State of New York, but far beyond, through the States of Michigan and Wisconsin into Minnesota; one may follow nine or ten such successive shores in unbroken lines from the neighborhood of Lake Champlain to the Far West.

Although the early geological periods are more legible in North America, because they are exposed over such extensive tracts of land, yet they have been studied in many parts of the globe. In Norway, in Germany, in France, in Russia, in Siberia, in Kamtchatka, in parts of South America, in short, wherever the civilization of the white race has extended, Silurian deposits have been observed, and everywhere they bear the same testimony to a profuse and varied creation. The earth was teeming then with life as now, and in whatever corner of its surface the geologist finds the old strata, they hold [462]a dead fauna as numerous as that which lives and moves above it. Nor do we find that there was any gradual increase or decrease of any organic forms at the beginning or close of the successive periods.

I think the impression that the faunæ of the early geological periods were more scanty than those of later times arises partly from the fact that the present creation is made a standard of comparison for all preceding creations. Of course, the collection of living types in any museum must be more numerous than those of fossil forms, for the simple reason that almost the whole of the present surface of the earth, with the animals and plants inhabiting it, is known to us, whereas the deposits of the Silurian and Devonian periods are exposed to view only over comparatively limited tracts and in disconnected regions. But let us compare a given extent of Silurian or Devonian seashore with an equal extent of seashore belonging to our own time, and we shall soon be convinced that the one is as populous as the other. On the New England Coast there are about one hundred and fifty different kinds of fishes; in the Gulf of Mexico two hundred and fifty; in the Red Sea about the same. We may allow in present times an average of two hundred or two hundred and fifty different kinds of fishes to an extent of ocean covering about four hundred miles. Now, I have made a special study of the Devonian rocks of Northern Europe, in the Baltic, and along the shore of the German Ocean. I have found in those deposits alone one hundred and ten kinds of fossil fishes. To judge of the total number of species belonging to those early [463]ages by the number known to exist now is about as reasonable as to infer that because Aristotle, familiar only with the waters of Greece, recorded less than three hundred kinds of fishes in his limited fishing-ground, therefore these were all the fishes then living. The fishing-ground of the geologist in the Silurian and Devonian periods is even more circumscribed than his, and belongs, besides, not to a living but to a dead world, far more difficult to decipher.

Extinct animals exist all over the world; heaped together under the snows of Siberia, lying thick beneath the Indian soil, found wherever English settlers till the ground or work the mines in Australia, figured in the old encyclopedias of China, where the Chinese philosophers have drawn them with the accuracy of their nation, built into the most beautiful temples of classic lands—for even the stones of the Parthenon are full of the fragments of these old fossils, and if any chance had directed the attention of Aristotle toward them, the science of Paleontology would not have waited for its founder till Cuvier was born—in short, in every corner of the earth where the investigations of civilized men have penetrated, from the Arctic to Patagonia and the Cape of Good Hope, these relics tell us of successive populations lying far behind our own, and belonging to distinct periods of the world’s history.

[464]

In the history of our globe the Carboniferous period succeeds to the Devonian. It is in the formations of this latter epoch that we find the fossil fuel which has done so much to enrich and civilize the world in our own age. This period divides itself into two great sub-periods: 1. The Coal-measures; and 2. The Carboniferous Limestone. The first, a period which gave rise to the great deposits of coal; the second, to most important marine deposits, most frequently underlying the coal-fields in England, Belgium, France, and America.

The limestone mountains, which form the base of the whole system, attain in places, according to Professor Phillips, a thickness of 2,500 feet. They are of marine origin, as is apparent by the multitude of fossils they contain of Zoophytes, Radiata, Cephalopoda, and Fishes. But the chief characteristic of this epoch is its strictly terrestrial flora—remains of plants now become as common as they were rare in all previous formations, announcing a great increase of dry land.

The monuments of this era of profuse vegetation reveal themselves in the precious Coal-measures of England and Scotland. These give us some idea of the rich verdure which covered the surface of the earth, newly risen from the bosom of its parent waves. It was the paradise of terrestrial vegetation. The grand Sigillaria, the Stigmaria, and other fern-like [465]plants, were especially typical of this age, and formed the woods, which were left to grow undisturbed; for as yet no living Mammals seem to have appeared; everything indicates a uniformly warm, humid temperature, the only climate in which the gigantic ferns of the Coal-measures could have attained their magnitude. Conifers have been found of this period with concentric rings, but these rings are more slightly marked than in existing trees of the same family, from which it is reasonable to assume that the seasonal changes were less marked than they are with us.

Everything announces that the time occupied in the deposition of the Carboniferous Limestone was one of vast duration. Professor Phillips calculates that, at the ordinary rate of progress, it would require 122,400 years to produce only sixty feet of coal. Geologists believe, moreover, that the upper Coal-measures, where bed has been deposited upon bed for ages upon ages, were accumulated under conditions of comparative tranquillity, but that the end of this period was marked by violent convulsions—by ruptures of the terrestrial crust, when the carboniferous rocks were upturned, contorted, dislocated by faults, and subsequently partially denuded, and thus appear now in depressions or basin-shaped concavities; and that upon this deranged and disturbed foundation a fourth geological system, called Permian, was constructed.

Coal, as we shall find, is composed of the mineralized remains of the vegetation which flourished in remote ages of the world. Buried under an enormous [466]thickness of rocks, it has been preserved to our days, after being modified in its inward nature and external aspect. Having lost a portion of its elementary constituents, it has become transformed into a species of carbon, impregnated with those bituminous substances which are the ordinary products of the slow decomposition of vegetable matter.

Thus, coal is the substance of the plants which formed the forests, the vegetation, and the marshes of the ancient world, at a period too distant for human chronology to calculate with anything like precision.

It is a remarkable circumstance that conditions of equable and warm climate, combined with humidity, do not seem to have been limited to any one part of the globe, but the temperature of the whole globe seems to have been nearly the same in very different latitudes. From the equatorial regions up to Melville Island, in the Arctic Ocean, where in our days eternal frost prevails—from Spitzbergen to the centre of Africa, the carboniferous flora is identically the same. When nearly the same plants are found in Greenland and Guinea; when the same species, now extinct, are met with of equal development at the equator as at the pole, we can not but admit that at this epoch the temperature of the globe was nearly alike everywhere. What we now call climate was unknown in these geological times. There seems to have been then only one climate over the whole globe. It was at a subsequent period, that is, in later Tertiary times, that the cold began to make itself felt at the terrestrial poles. Whence, then, proceeded this general superficial [467]warmth, which we now regard with so much surprise? It was a consequence of the greater or nearer influence of the interior heat of the globe. The earth was still so hot in itself that the heat which reached it from the sun may have been inappreciable.

Another hypothesis, which has been advanced with much less certainty than the preceding, relates to the chemical composition of the air during the Carboniferous period. Seeing the enormous mass of vegetation which then covered the globe, and extended from one pole to the other; considering, also, the great proportion of carbon and hydrogen which exists in the bituminous matter of coal, it has been thought, and not without reason, that the atmosphere of the period might be richer in carbonic acid than the atmosphere of the present day. It has even been thought that the small number of (especially air-breathing) animals, which then lived, might be accounted for by the presence of a greater proportion of carbonic acid gas in the atmosphere than is the case in our own times. This, however, is pure assumption, totally deficient in proof. What we can remark, with certainty, as a striking characteristic of the vegetation of the globe during this phase of its history, was the prodigious development which it assumed. The Ferns, which in our days and in our climate are most commonly only small perennial plants, in the Carboniferous age sometimes presented themselves under lofty and even magnificent forms.

Every one knows those marsh-plants with hollow, channeled, and articulated cylindrical stems; whose joints are furnished with a membranous, denticulated [468]sheath, and which bear the vulgar name of “mare’s-tail”; their fructification forming a sort of catkin composed of many rings of scales, carrying on their lower surface sacs full of spores or seeds. These humble Equiseta were represented during the coal-period by herbaceous trees from twenty to thirty feet high and four to six inches in diameter. Their trunks, channeled longitudinally, and divided transversely by lines of articulation, have been preserved to us: they bear the name of Calamites.

The Lycopods of our age are humble plants, scarcely a yard in height, and most commonly creepers; but the Lycopodiaceæ of the ancient world were trees of eighty or ninety feet in height. It was the Lepidodendrons which filled the forests. Their leaves were sometimes twenty inches long, and their trunks a yard in diameter. Such are the dimensions of some specimens of Lepidodendron carinatum which have been found. Another Lycopod of this period, the Lomatophloyos crassicaule, attained dimensions still more colossal. The Sigillarias sometimes exceeded 100 feet in height. Herbaceous Ferns were also exceedingly abundant, and grew beneath the shade of these gigantic trees. It was the combination of these lofty trees with such shrubs (if we may so call them) which formed the forests of the Carboniferous period.

How this vegetation, so imposing, both on account of the dimensions of the individual trees and the immense space which they occupied, so splendid in its aspect, and yet so simple in its organization, must have differed from that which now embellishes the [469]earth and charms our eyes! It certainly possessed the advantage of size and rapid growth; but how poor it was in species—how uniform in appearance! No flowers yet adorned the foliage or varied the tints of the forests. Eternal verdure clothed the branches of the Ferns, the Lycopods, and Equiseta, which composed to a great extent the vegetation of the age. The forests presented an innumerable collection of individuals, but very few species, and all belonging to the lower types of vegetation. No fruit appeared fit for nourishment; none would seem to have been on the branches. Suffice it to say that few terrestrial animals seem to have existed yet; animal life was apparently almost wholly confined to the sea, while the vegetable kingdom occupied the land, which at a later period was more thickly inhabited by air-breathing animals. Probably a few winged insects (some coleoptera, orthoptera, and neuroptera) gave animation to the air while exhibiting their variegated colors; and it was not impossible but that many pulmoniferous mollusca (such as land-snails) lived at the same time.

The vegetation which covered the numerous islands of the Carboniferous sea consisted, then, of Ferns, of Equisetaceæ, of Lycopodiaceæ, and dicotyledonous Gymnosperms. The Annularia and Sigillariæ belong to families of the last-named class, which are now completely extinct.

The Annulariæ were small plants which floated on the surface of fresh-water lakes and ponds; their leaves were verticillate, that is, arranged in a great number of whorls, at each articulation of the stem [470]with the branches. The Sigillariæ were, on the contrary, great trees, consisting of a simple trunk, surmounted with a bunch or panicle of slender drooping leaves, with the bark often channeled, and displaying impressions or scars of the old leaves, which, from their resemblance to a seal, sigillum, gave origin to their name.

The Stigmariæ, according to palæontologists, were roots of Sigillariæ, with a subterranean fructification; all that is known of them is the long roots which carry the reproductive organs, and in some cases are as much as sixteen feet long.

Two other gigantic trees grew in the forests of this period: these were Lepidodendron carinatum and Lomatophloyos crassicaule, both belonging to the family of Lycopodiaceæ, which now includes only very small species. The trunk of the Lomatophloyos threw out numerous branches, which terminated in thick tufts of linear and fleshy leaves. The Ferns composed a great part of the vegetation of the Coal-measure period.

The seas of this epoch included an immense number of Zoophytes, nearly 400 species of Mollusca, and a few Crustaceans and Fishes. Among the Fishes, Psammodus and Coccosteus, whose massive teeth inserted in the palate were suitable for grinding; and the Holoptychius and Megalichthys, are the most important. The Mollusca are chiefly Brachiopods of great size. The Bellerophon, whose convoluted shell in some respects resembles the Nautilus of our present seas, but without its chambered shell, were then represented by many species.

[471]

Crustaceans are rare in the Carboniferous Limestone strata; the genus Phillipsia is the last of the Trilobites, all of which became extinct at the close of this period. As to the Zoophytes, they consist chiefly of Crinoids and Corals. We also have in these rocks many Polyzoa.

Among the corals of the period we may include the genera Lithostrotion and Lonsdalea. Among the Polyzoa are the genera Fenestrella and Polypora. Lastly, to these we may add a group of animals which will play a very important part and become abundantly represented in the beds of later geological periods, but which already abounded in the seas of the Carboniferous period. We speak of the Foraminifera, microscopic animals, which clustered either in one body or divided into segments, and covered with a calcareous, many-chambered shell, as Fusulina cylindrica. These little creatures, which, during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, formed enormous banks and entire masses of rock, began to make their appearance in the period which now engages our attention.

This terrestrial period is characterized, in a remarkable manner, by the abundance and strangeness of the vegetation which then covered the islands and continents of the whole globe. Upon all points of the earth, as we have said, this flora presented a striking uniformity. In comparing it with the vegetation of the present day, the learned French botanist, M. Brongniart, who has given particular attention to the flora of the Coal-measures, has arrived at the conclusion that it presented considerable analogy with [472]that of the islands of the equatorial and torrid zone, in which a maritime climate and elevated temperature exist in the highest degree. It is believed that islands were very numerous at this period; that, in short, the dry land formed a sort of vast archipelago upon the general ocean, of no great depth, the islands being connected together and formed into continents as they gradually emerged from the ocean.

This flora, then, consists of great trees, and also of many smaller plants, which would form a close, thick turf, or sod, when partially buried in marshes of almost unlimited extent. M. Brongniart indicates, as characterizing the period, 500 species of plants which now attain a prodigious development. The ordinary dicotyledons and monocotyledons—that is, plants having seeds with two lobes in germinating and plants having one seed-lobe—are almost entirely absent; the cryptogamic, or flowerless plants, predominate; especially Ferns, Lycopodiaceæ, and Equisetaceæ—but of forms insulated and actually extinct in these same families. A few dicotyledonous gymnosperms, or naked-seed plants forming genera of Conifers, have completely disappeared, not only from the present flora, but since the close of the period under consideration, there being no trace of them in the succeeding Permian flora. Such is a general view of the features most characteristic of the coal-period, and of the Primary epoch in general. It differs, altogether and absolutely, from that of the present day; the climatic condition of these remote ages of the globe, however, enables us to comprehend the characteristics which distinguish its vegetation. [473]A damp atmosphere, of an equable rather than an intense heat like that of the tropics, a soft light veiled by permanent fogs, were favorable to the growth of this peculiar vegetation, of which we search in vain for anything strictly analogous in our own days. The nearest approach to the climate and vegetation proper to the geological period which now occupies our attention would probably be found in certain islands, or on the littoral of the Pacific Ocean—the island of Chloë, for example, where it rains during 300 days in the year, and where the light of the sun is shut out by perpetual fogs; where arborescent Ferns form forests, beneath whose shade grow herbaceous Ferns, which rise three feet and upward above a marshy soil; which gives shelter also to a mass of cryptogamic plants, greatly resembling, in its main features, the flora of the Coal-measures. This flora was, as we have said, uniform and poor in its botanic genera, compared to the abundance and variety of the flora of the present time; but the few families of plants which existed then included many more species than are now produced in the same countries. The fossil Ferns of the coal-series in Europe, for instance, comprehend about 300 species, while all Europe now only produces fifty. The gymnosperms, which now muster only twenty-five species in Europe, then numbered more than 120.

Calamites are among the most abundant fossil plants of the Carboniferous period, and occur also in the Devonian. They are preserved as striated, jointed, cylindrical, or compressed stems, with fluted channels or furrows at their sides, and sometimes [474]surrounded by a bituminous coating, the remains of a cortical integument. They were originally hollow, but the cavity is usually filled up with a substance into which they themselves have been converted.

If, during the coal-period, the vegetable kingdom had reached its maximum, the animal kingdom, on the contrary, was poorly represented. Some remains have been found, both in America and Germany, consisting of portions of the skeleton and the impressions of the footsteps of a Reptile, which has received the name of Archegosaurus. Among the animals of this period we find a few Fishes, analogous to those of the Devonian formation. These are the Holoptychius and Megalichthys, having jawbones armed with enormous teeth. Scales of Pygopterus have been found in the Northumberland Coal-shale at Newsham Colliery, and also in the Staffordshire Coal-shale. Some winged insects would probably join this slender group of living beings. It may then be said with truth that the immense forests and marshy plains, crowded with trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants, which formed on the innumerable isles of the period a thick and tufted sward, were almost destitute of animals.

Coal, as we have said, is only the result of a partial decomposition of the plants which covered the earth during a geological period of immense duration. No one, now, has any doubt that this is its origin. In coal-mines it is not unusual to find fragments of the very plants whose trunks and leaves characterize the Coal-measures, or Carboniferous era. Immense trunks of trees have also been met [475]with in the middle of a seam of coal. In order to explain the presence of coal in the depths of the earth, there are only two possible hypotheses. This vegetable débris may either result from the burying of plants brought from afar and transported by river or maritime currents, forming immense rafts, which may have grounded in different places and been covered subsequently by sedimentary deposits; or the trees may have grown on the spot where they perished, and where they are now found.

Can the coal-beds result from the transport by water, and burial under ground, of immense rafts formed of the trunks of trees? The hypothesis has against it the enormous height which must be conceded to the raft, in order to form coal-seams as thick as some of those which are worked in our collieries. If we take into consideration the specific gravity of wood, and the amount of carbon it contains, we find that the coal-deposits can only be about seven-hundredths of the volume of the original wood and other vegetable materials from which they are formed. If we take into account, besides, the numerous voids necessarily arising from the loose packing of the materials forming the supposed raft, as compared with the compactness of coal, this may fairly be reduced to five-hundredths. A bed of coal, for instance, sixteen feet thick, would have required a raft 310 feet high for its formation. These accumulations of wood could never have arranged themselves with sufficient regularity to form those well-stratified coal-beds, maintaining a uniform thickness [476]over many miles, and that are seen in most coal-fields to lie one above another in succession, separated by beds of sandstone or shale. And even admitting the possibility of a slow and gradual accumulation of vegetable débris, like that which reaches the mouth of a river, would not the plants in that case be buried in great quantities of mud and earth? Now, in most of our coal-beds the proportion of earthy matter does not exceed fifteen per cent of the entire mass. If we bear in mind, finally, the remarkable parallelism existing in the stratification of the coal-formation, and the state of preservation in which the impressions of the most delicate vegetable forms are discovered, it will, we think, be proved to demonstration that those coal-seams have been formed in perfect tranquillity. We are, then, forced to the conclusion that coal results from the mineralization of plants which has taken place on the spot; that is to say, in the very place where the plants lived and died.

It was suggested long ago by Bakewell, from the occurrence of the same peculiar kind of fireclay under each bed of coal, that it was the soil proper for the production of those plants from which coal has been formed.

The clay-beds, “which vary in thickness from a few inches to more than ten feet, are penetrated in all directions by a confused and tangled collection of the roots and leaves, as they may be, of the Stigmaria ficoides, these being frequently traceable to the main stem (Sigillaria), which varies in diameter from about two inches to half a foot. The main stems are noticed as occurring nearer the top than the bottom [477]of the bed, as usually of considerable length, the leaves or roots radiating from them in a tortuous irregular course to considerable distances, and as so mingled with the under-clay that it is not possible to cut out a cubic foot of it which does not contain portions of the plant.”

It is a natural inference to suppose that the present indurated under-clay is only another condition of that soft, silty soil, or of that finely levigated muddy sediment—most likely of still and shallow water—in which the vegetation grew, the remains of which were afterward carbonized and converted into coal.

In order thoroughly to comprehend the phenomena of the transformation into coal of the forests and of the herbaceous plants which filled the marshes and swamps of the ancient world, there is another consideration to be presented. During the coal-period, the terrestrial crust was subjected to alternate movements of elevation and depression of the internal liquid mass, under the impulse of the solar and lunar attractions to which they would be subject, as our seas are now, giving rise to a sort of subterranean tide, operating at intervals, more or less widely apart, upon the weaker parts of the crust, and producing considerable subsidences of the ground. It might, perhaps, happen that, in consequence of a subsidence produced in such a manner, the vegetation of the coal-period would be submerged, and the shrubs and plants which covered the surface of the earth would finally become buried under water. After this submergence new forests sprung up in the same place. Owing to another submergence, the second [478]forests were depressed in their turn, and again covered by water. It is probably by a series of repetitions of this double phenomenon—this submergence of whole regions of forest, and the development upon the same site of new growths of vegetation—that the enormous accumulations of semi-decomposed plants, which constitute the Coal-measures, have been formed in a long series of ages.

But, has coal been produced from the larger plants only—for example, from the great forest-trees of the period, such as the Lepidodendra, Sigillariæ, Calamites, and Sphenophylla? That is scarcely probable, for many coal-deposits contain no vestiges of the great trees of the period, but only of Ferns and other herbaceous plants of small size. It is, therefore, presumable that the larger vegetation has been almost unconnected with the formation of coal, or, at least, that it has played a minor part in its production. In all probability there existed in the coal-period, as at the present time, two distinct kinds of vegetation: one formed of lofty forest-trees, growing on the higher grounds; the other, herbaceous and aquatic plants, growing on marshy plains. It is the latter kind of vegetation, probably, which has mostly furnished the material for the coal; in the same way that marsh-plants have, during historic times and up to the present day, supplied our existing peat, which may be regarded as a sort of contemporaneous incipient coal.

To what modification has the vegetation of the ancient world been subjected to attain that carbonized state which constitutes coal? The submerged plants [479]would, at first, be a light, spongy mass, in all respects resembling the peat-moss of our moors and marshes. While under water, and afterward, when covered with sediment, these vegetable masses underwent a partial decomposition—a moist, putrefactive fermentation, accompanied by the production of much carbureted hydrogen and carbonic acid gas. In this way, the hydrogen escaping in the form of carbureted hydrogen, and the oxygen in the form of carbonic acid gas, the carbon became more concentrated, and coal was ultimately formed. This emission of carbureted hydrogen gas would, probably, continue after the peat-beds were buried beneath the strata which were deposited and accumulated upon them. The mere weight and pressure of the superincumbent mass, continued at an increasing ratio during a long series of ages, have given to the coal its density and compact state.

The heat emanating from the interior of the globe would also exercise a great influence upon the final result. It is to these two causes—that is to say, to pressure and to the central heat—that we may attribute the differences which exist in the mineral characters of various kinds of coal. The inferior beds are drier and more compact than the upper ones; or less bituminous, because their mineralization has been completed under the influence of a higher temperature, and at the same time under a greater pressure.

[480]

However much the faunas of the various geologic periods may have differed from each other, or from the fauna which now exists, in their general aspect and character, they were all, if I may so speak, equally underlaid by the great leading ideas which still constitute the master types of animal life. And these leading ideas are four in number. First, there is the star-like type of life—life embodied in a form that, as in the corals, the sea-anemones, the sea-urchins, and the star-fishes, radiates outward from a centre; second, there is the articulated type of life—life embodied in a form composed, as in the worms, crustaceans, and insects, of a series of rings united by their edges, but more or less movable on each other; third, there is the bilateral or molluscan type of life—life embodied in a form in which there is a duality of corresponding parts, ranged, as in the cuttle-fishes, the clams, and the snails, on the sides of a central axis or plane; and fourth, there is the vertebrate type of life—life embodied in a form in which an internal skeleton is built up into two cavities placed the one over the other; the upper for the reception of the nervous centres, cerebral and spinal—the lower for the lodgment of the respiratory, circulatory, and digestive organs. Such have been the four central ideas of the faunas of every succeeding creation, except, perhaps, the earliest of all, that of the Lower Silurian System, [481]in which, so far as is yet known, only three of the number existed—the radiated, articulated, and molluscan ideas or types.