The Author and Daughter Mary

Title: Screen acting

Author: Mae Marsh

Release date: February 1, 2026 [eBook #77829]

Language: English

Original publication: Los Angeles: Photo-Star Publishing Co, 1921

Credits: Tim Miller, Paul Fatula and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

SCREEN ACTING

Copyright, 1921

PHOTO-STAR PUBLISHING CO.

Los Angeles, California

The Author and Daughter Mary

BY

MAE MARSH

OF

“THE BIRTH OF A NATION,” “INTOLERANCE,” “POLLY OF THE

CIRCUS,” “THE CINDERELLA MAN,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA

PHOTO-STAR PUBLISHING CO.

CHAMBER OF COMMERCE BUILDING

All Rights Reserved

[Pg ix]

In her travels and through her amazing—to put it mildly—correspondence, the motion picture star finds that there is everywhere a great curiosity about screen acting.

What does it require? What, if any, are its mysteries? What system of detail is there that permits fifty-two hundred feet of celluloid ribbon to spin smoothly past the eye to make an interesting story?

I look upon this book as an answer to the thousands of letters I have received in the past several years asking as many thousands of questions. A motion picture star’s most intimate audience, after all, is her correspondence.

There comes to her sometimes the vague realization that in a dozen different countries little children, their sisters, their brothers and their parents may be, at one moment, viewing her image upon the screen in a dozen different plays. It is all too stupendous; too impersonal. But though she cannot be a breathing part of these audiences she learns often what is in the hearts of many. This message comes through the mails; that is her broad point of contact with her international public.

[Pg x]

Five years ago these letters were largely to request photographs and the star could tell something of her popularity by the number of pictures mailed out. But, as the screen has grown in importance and merit, the star’s correspondence has indicated a lively curiosity in the art of camera-acting. So much ambition; so many questions!

I have often thought that to make a satisfactory reply to the thousands of questions I have been asked would be to write a book, and—well, I wrote it. I have tried to outline the important steps in the building of a screen career. In doing this I have evaded technical phraseology. It is not indispensable to a knowledge of screen technic and might tend to confuse.

I believe that anyone desiring a career in motion pictures can profit by that which I have written out of my experience; that others can learn from it something of the work-a-day life of the screen actress.

In conclusion I would take this opportunity to thank the tremendous number of children and grown-ups who have at one time or another written me. They serve always to remind me that those of us upon the screen have an influence and responsibility that go beyond a mere make-believe.

Mae Marsh.

[Pg xi]

[Pg xiii]

| Page | |

| The Author and Mary | Frontispiece |

| Lillian Gish and the late Robert Harron | 27 |

| Charles Ray | 37 |

| Mary Miles Minter | 47 |

| Mary Pickford | 55 |

| Madame Nazimova | 65 |

| Blanche Sweet and Wallace Reid | 77 |

| Norma Talmadge | 85 |

| The Author and Some Beginners | 95 |

| Gloria Swanson and Thomas Meighan | 105 |

| Mr. Griffith | 113 |

| The Author at Home | 125 |

[Pg xiv]

I

II

[Pg 15]

The dilemma of a casting director—A flood of letters

and their four objectives—What every-

one wants to know.

When Mr. Adolph Klauber, former dramatic critic of the New York Times, was casting director for a big picture corporation I chanced to meet him one day in the Fort Lee Studios.

“Read this,” he said, tendering me a letter.

It was from a young girl in Columbus, Ohio, as I remember, who wanted to know how she could get into motion pictures. It was not so much the letter as a small snap-shot photograph of herself which she had pinned to her missive that took my attention.

The picture showed a girl in a sitting position, who was plump to the verge of fatness. She had thick legs and ankles, straight hair, probably brown, and dark eyes. So far as a front view divulged her features were fairly regular. It was not in any way a remarkable picture. Nor did it promise any particular animation in its subject.

[Pg 16]

She had written to ascertain “what chance she would have in motion pictures.”

“What are you going to answer?” I asked of Mr. Klauber.

“That’s a poser,” he replied. “I was about to write her that she didn’t have any chance; that she probably would be happier if she remained home; certainly so until she obtained her parents’ consent for plans of a career. Looking at the picture I should say she had one chance in a million.”

“That is probably true,” I said.

“But do you know,” continued Mr. Klauber, “that the more I think of it the less I believe that I am endowed with authority to tell anyone that he or she has no chance in motion pictures. How can I know? We see about us every day celebrated stars who, perhaps, began their career with apparently no more chance than this little Columbus girl.”

Mr. Klauber paused.

“For that reason I have not sent the discouraging letter which it was on the tip of my pen to write,” he continued. “Instead I am going to send her a letter telling her that her chance of screen success is altogether problematical; that everything depends upon circumstance, hard work and the native talent that is developed before the camera.”

“I should like to see a copy of that letter,” I said.

[Pg 17]

I never happened to see Mr. Klauber’s reply to the girl in Columbus. But I am sure it was interesting.

In the past eight years I have received hundreds of thousands of letters from motion picture fans in every part of the world. In answer now to a question I have often heard asked, “Does a motion picture star immediately read all her mail?” I can say for myself, “Bless you, no.”

A single mail has brought as many as a thousand letters and I shall leave it to the reader to determine how one could possibly read one thousand letters and arrive at the studio at 8:30 o’clock. Personally, my secretaries are instructed to attend to such fan letters as request a reply—which practically all of them do—and then preserve the letters that I may read them in leisure moments.

In that way I have managed I think to peruse at one time or another the majority of the letters that come to me. I find the reading of them a great pleasure.

It is nice to receive pleasant compliments on one’s hard and honest effort to do something worth while. I have on many occasions found helpful criticism in my mail. Almost anyone can dismiss a picture with a “I liked it” or “I didn’t like it.” There is the exceptional one in a thousand who will tell you he didn’t like it and why, placing his finger upon a real defect. Often that is a help.

[Pg 18]

To get back to my point: The letters I receive seem to be written with one, and sometimes all of the following objectives—

1. To request a photograph.

2. To request an autographed photograph.

3. To ask for “old clothes.”

4. To find out how “I can learn to act for motion pictures.”

As for Numbers 1 and 2, the many of you who are making a “collection” know that a picture, autographed if requested, is sent you in due time. Up to very recently the star has considered it a matter of good advertising to remember those friends who are kind enough to ask for photographs. But the demand for pictures has become so tremendous that some of the stars are now making a flat charge of twenty-five cents for their photographs. This barely covers the cost of production and postage.

It was Miss Billie Burke, I believe, who was first to establish a cost charge on her photographs. She did this during the war and donated the receipts to charity.

The most of us have feared to risk offending those picture fans who have been at the pains of writing us by asking them for a photographic fee. We have spent from $10,000 to $25,000 a year out of our own pockets—unless by our contracts our producers agreed to bear this expense—and have trusted that it was money well expended. In the amount of pleasure [Pg 19]brought to the little ones I, for one, am sure it has been.

But, as the demand for pictures grows greater and letters pour in from all parts of the world, the cost of materials has been steadily climbing. In 1915 I could send out three photographs for what it now costs to send one. That means something when thousands of photo-mailers each month are being sent to a dozen different countries.

Recently a well known star, a particular friend of mine, declared that it was but a matter of months before all the more popular stars would institute a photographic fee.

As to Number 3, regarding old clothes, I am sure that while the requests emanate from worthy sources no star could possibly satisfy these many supplications.

To begin with if the story calls for clothes that are actually old—old enough to be considered “costumes”—they are usually supplied by the producer and belong to him after production. In the case of modern clothes—meaning new ones—most stars are very pleased to wear them themselves when they have finished before the camera.

Such is mine own case. Whenever there is any danger of my reaching a point of clothes saturation I have several growing sisters who, so far, have been able to handle the situation. After that our clothes go through certain pre-arranged channels of charity.

[Pg 20]

I make this point in the hope that many young ladies who have written me for my “old clothes” will understand that I have few or none, as much as I should like to accommodate each one of them.

Which brings me to Number 4.

“How can I learn to act for motion pictures?” Six years ago in “The Birth of a Nation” days my mail brought me many such inquiries. Since then, with the motion picture steadily gaining in favor, I have been swamped with this universal request.

“Do brown eyes photograph better than blue?” “Is it necessary to have stage training to act before a camera?” “Can a girl with a big nose succeed in the movies?” “What is the accepted height for a motion picture star?” “Are the morals of motion pictures safe for the average girl?” “If I came to Hollywood and got work as an extra how long would it be before I am featured?” “Do you know any director who will star a small girl, of blond type, who has played parts in high school comedies?” “Are the star salaries we hear of the real thing?” “Does Charlie Chaplin make $1,000,000 a year?”

I have picked at random these few questions. I think I could go on and on, farther than Mr. Tennyson’s charming brook, with others of the same kind. Sometimes I am given to the thought that every young girl in the United States wants to go into motion pictures.

[Pg 21]

Possibly I am right. You know as well as I. Receiving so many of these letters I have begun to feel as Mr. Klauber felt. I don’t know exactly what to say.

But since there are undoubtedly many thousands of boys and girls not only in the United States but in foreign countries—the Japanese boy, for instance, is particularly keen on knowing the how of motion picture acting—who would like to get into motion pictures, I feel that such information as I have acquired through a wide experience will interest many and perhaps prove of value to those others who are destined to be our cinema stars of tomorrow.

As for my qualifications I was about to say that I am one of the motion picture pioneers. Yet when I say pioneer I think of Daniel Boone. And Mr. Boone, had he lived, would have been an old, old man.

The myth of the “overnight” star—An instance of

success after long sustained effort—

What the beginner faces.

To become an artistic success one must assuredly be in love with the art he has elected to follow. In business or finance a so-called lucky stroke may make of a man or a woman a success without there being those qualities of esteem and enthusiasm for the thing itself that are so essential to artistic endeavor.

Such lucky strokes are rare in pictures. Appearances to the contrary, notwithstanding, motion picture stars are not made over-night. Every now and then some actor or actress begins to assert his or her right to cinema stardom. But if one will take the trouble to examine the records in such cases he will usually find that the privilege of stardom has come only after a slow climb.

There have been cases where producers have tried to “manufacture” stars. But, in the main, it hasn’t worked.

[Pg 24]

To recall one example: One of the shrewdest of our producers not long ago signed a young, beautiful and talented vaudeville actress to a long time motion picture contract. Screen tests proved that she photographed beautifully. She had the grace of carriage to be expected of the professional dancer. Her face was expressive. That a capable director would find in her all the qualities necessary for stardom the producer never doubted.

Thousands of dollars were spent in an ocean of advertising ink announcing the debut of this star. Her name was flashed from one end of the country to the other, indeed, around the world, in electric lights and on bill boards. Her photograph was published in the metropolitan dailies and small town papers. So far as the campaign was concerned it was an unqualified success. By the time the little star’s first picture was ready for release there had been built up about her a tremendous curiosity.

I own I was as curious as the next. I think the majority of us, who had attained stardom only after years of rigorous training, self denial and hard work, were interested, even anxious, to know if motion picture stars could be developed after the formula of this producer. It meant something to us.

If the magnitude of the motion picture actress was to be in proportion to the size of an introductory advertising campaign then our own position was none too secure.

[Pg 25]

As a star this little actress failed. Thanks to some natural talent her failure was not so disastrous as it might have been. But as a star, she was soon withdrawn. The fortune spent in exploiting her was gone, but not forgotten. As a proof of the impossibility of “manufacturing” stars under the most favorable of circumstances it probably served a purpose.

Why did she fail? Why would a baby, who had never walked, fail if she were told to run a foot race? She simply didn’t know how.

All the little important things that one can learn by nothing save experience, things which mean everything to successful screen acting, were missing in her work. She was like one trying to paint without knowing color, to compose without a knowledge of counter-point, to write without having learned grammar school English. Contrary to a tradition which exists in some localities the best swimmers are not developed by throwing the child into the water and telling him to sink or float.

There is another interesting point in the case which I have cited. When the plans to make this young lady an over-night star failed she became a featured player in a group. Surrounded by experienced, capable screen actors and relieved of the responsibility that stardom entails she has developed splendidly and is, in point of fact, a better actress today than she was when she was advertised as a star.

[Pg 26]

It has been simply a matter of training. If sometime in the future she is again starred she will be prepared to make a better job of it.

I have brought up this case because it has been my observation that there exists a feeling that in motion pictures anybody can be a star anytime. There is talk of influence, managerial favoritism, luck and, goodness knows, what not? There may be truth to some of these assertions.

But the year in and year out stars—Mary Pickford, Dorothy and Lillian Gish, William Hart, Mme. Nazimova, Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Ray, etc.—are those who stand solidly on the ground of genuine merit.

And the solidity of their stance is usually determined by the amount of their natural talent, plus the excellence and length of their training.

I believe many people have the habit of falling in love with an idea. The idea of becoming a motion picture star is appealing. But like many other general conceptions the idea of the star’s life—as gathered from a smoothly displayed picture drama or a magazine article portraying the artist’s home, her automobile and her pets—is misleading.

Robert Louis Stevenson wept in despair over the composition of many of his stories. A great many of us have had occasion to weep over our own more modest efforts. We have found, indeed, that the most beautiful roses are very often those with the cruelest thorns.

[Pg 27]

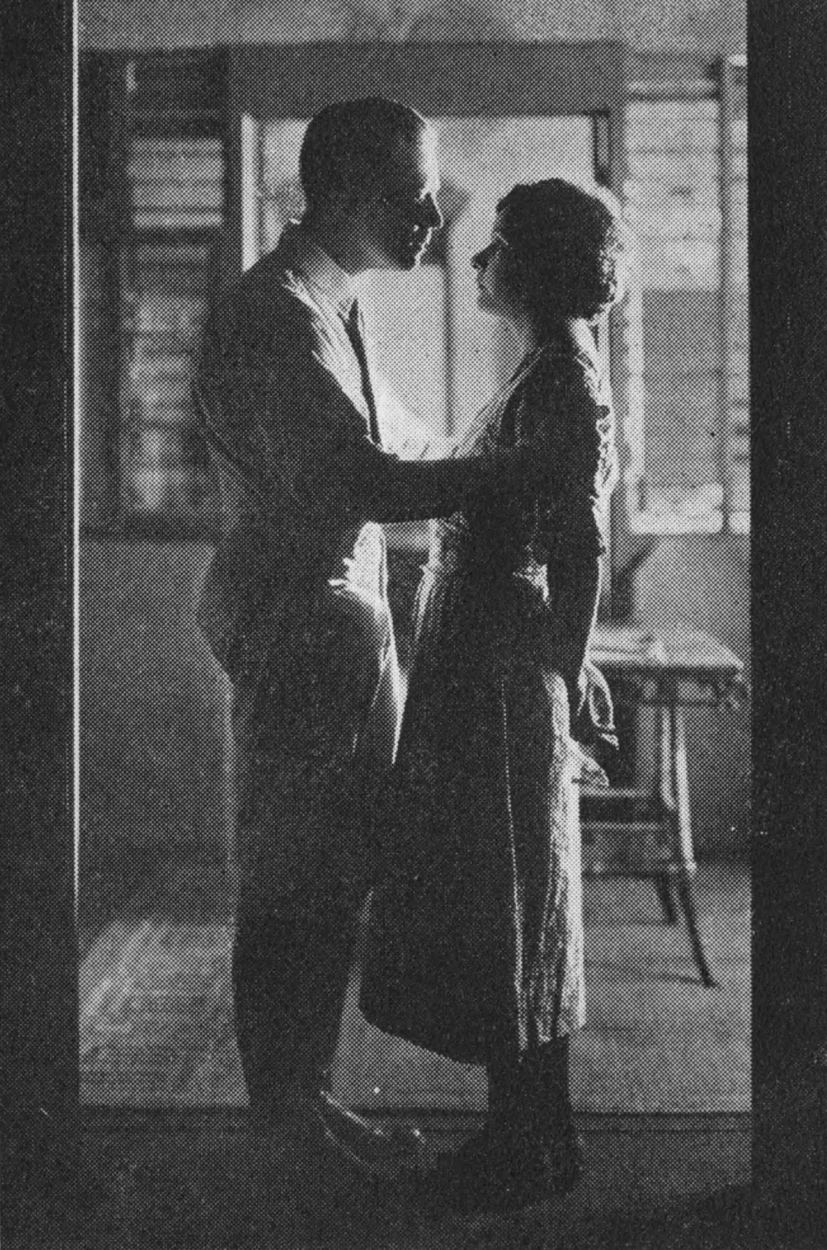

Lillian Gish and the late Robert Harron in a love scene from “The Greatest Question.”

[Pg 29]

It has been proved that motion picture stars cannot be made over-night. It is equally true that many promising actresses do not become stars—in the accepted professional sense of the word—even after long years of work.

I suppose if I said that nobody can succeed in motion pictures and that the star is the exception to the rule I should be accused of being a pessimist. Yet that is more nearly the truth than may appear on the surface.

Consider, for instance, the thousands of actors and actresses who have appeared before a camera in the past decade. After you have done that count the number of genuine stars now before the public. You can name the majority of them on the fingers and thumbs of four hands.

Yet in the heart of each of the thousands, who have stepped before the batteries of motion picture cameras, there was undoubtedly the hope that natural ability, circumstance or hard work would bring success.

It is well to take this into consideration when one looks toward the screen for a career.

But sometimes this law of average is defeated by that exceptional person whose faith is undiminished, whose confidence in one’s self is boundless and whose capacity for work never flags.

Let me cite you the case of one of the best known young actresses on the screen who, as [Pg 30]this is written, has never enjoyed the full privileges of stardom though she has shared most of its disadvantages.

She began her screen career more than a half dozen years ago. She was frail, and slow to absorb the lessons of the screen. Even her dearest friends never imputed to her a great natural acting talent.

But this young lady was dauntless. She kept everlastingly at it. By systematically exercising she gradually built up strength and endurance. When she was given a part she read everything she had access to which would help her in the development of her character portrayal.

She over-came any tendency toward self-consciousness while before the camera. She became adept in the matter of thinking up business. The fact that she did not attain stardom, in its generally accepted sense, never deterred her. Year after year she gave to the screen and to her parts the best that was in her.

Her courageousness has been rewarded. It is my opinion that in the past two years she has contributed to the photographic drama two of its most distinguished characterizations. She is a motion picture star in the true sense of the word. Her name is Lillian Gish.

If I seem to be gazing on the darker side of a screen career I assure you that it is not because such is my habit. Quite the contrary. [Pg 31]But it appears to me that since there seems to be such a universal impulse to gain fame through the medium of the moving picture drama that it is as well to consider some of its difficulties.

Trained actors and actresses from the spoken stage to their sorrow have found these difficulties. The established star finds sometimes that success has seemed merely to double her troubles.

The beginner will discover, therefore, that when he or she sets his or her face toward a screen career there will come moments when it will seem much easier to give up than go on. Those who give up will be those who should never have started. They will have wasted time that could have been otherwise more profitably spent.

Those who go on—well, there is always hope for such.

I am always interested in and can sympathize with the young girl who yearns for a career. It seems but yesterday that I was in short skirts and Miss Marjorie Rambeau was the most talented and beautiful actress that was ever permitted upon the face of the earth. After a matinee at the old Burbank theater in Los Angeles a young girl friend and I often followed Miss Rambeau discreetly and at what might be called a worshipful distance.

[Pg 32]

Then there was Mr. Richard Bennett. What a masterful, handsome man was he! My goodness! he was one to occupy one’s dreams; to make one wonder if somehow it might not be possible to grow up and become his leading lady. I am sure that the very paragon of modern-day leading men could not come up to my childhood estimate of Mr. Richard Bennett.

[Pg 33]

Seven qualities that indicate fitness for a screen career

—Why they are important—An illus-

tration of vitality.

As I have said, I have been asked by thousands of correspondents for the formula for screen success. I have never felt able to answer. I don’t believe there is any such formula.

Putting the proposition another way:

If I were requested to choose from among ten beginners the one who would go the farthest in motion pictures I should unhesitatingly lay my finger upon the one who possessed the following qualifications:

(1) Natural talent.

(2) Ambition.

(3) Personality.

(4) Sincerity.

(5) Agreeable appearance.

(6) Vitality and strength.

(7) Ability to learn quickly.

[Pg 34]

I am sure that I should not go far wrong if I were to place my trust in one endowed with these qualities.

A natural talent for acting implies more than a mere desire to act. It is the art, usually discovered during childhood, of mimicry, and the joy in that art.

How many of us have been convulsed in our earlier years at some school girl friend’s take-off of our teacher? How many of us, indeed, have played the mimics? I seem to remember that in my grammar school days I was called upon more or less to take-off one of our teachers.

If not called upon I volunteered. None of my school chums got more enjoyment out of my “imitation of Miss Blank” than I did. I never dreamed at that time—or, if I did, they were vague dreams—that I was to become an actress. Since then I have come to the conclusion that I was actually taking my first steps toward what I chose as a career.

Natural talent, as I have called it, is no more than a tendency toward, or an aptitude for, some form of endeavor. In youth my first artistic loves were for mimicry and painting—the latter of which took the form of sculpturing—and both of these loves have been enduring.

For that reason unless my candidate for screen success had previously shown some love for acting or mimicry I should come to the conclusion [Pg 35]that he or she was intoxicated merely with the glamour of the profession, with no especial love for the fundamental thing itself.

This is an important point. If its significance were duly impressed upon the thousands of girls and boys, who would like to choose the screen for a career, perhaps, some of them would abandon their dreams and turn to things for which they have displayed some natural aptitude.

Ambition must, of course, go hand in hand with natural talent. In any form of vocational training it is assumed that the student has a feverish desire to succeed in the particular line that he has elected to follow. It is the same on the screen.

Possibly I might have written down enthusiasm in the place of ambition. After one has attained stardom and thus, perhaps, achieved his or her ambition the ability to sustain enthusiasm in one’s work becomes more important than ambition. But ambition and enthusiasm are closely correlated.

They mean that one has an ambition to gain the top, and that to reach that position one has the enthusiasm to practise all the forms of self-denial, discipline and study that are important to artistic success in any line.

Personality is important for the reason that the camera has a way of registering it unerringly. It is keen in detecting the weak or vapid.

[Pg 36]

In my eight years before a motion picture camera I have never met a person of inferior fibre whose inferiority was not accentuated by the camera. For that reason to sustain success on the screen I believe there is nothing more important than clean thoughts and clean living. They do register.

It is precisely the same with sincerity. In any line there is probably little hope for those who lack this salient quality. But a motion picture camera seems especially to delight in exposing insincerity.

I think considerable of the success of Mary Pickford and Charles Ray—to name but two stars—is due to their absolute and abundant sincerity. The camera, finding so much that is clean and real, has joyously reproduced it. It is the love that Miss Pickford radiates from the screen and the obvious manliness of Mr. Ray that are among their biggest assets. This is sincere love and sincere manliness, or it would never be so emphasized by the camera.

My candidate for screen honors, therefore, must have the God-given quality of sincerity. Only that kind can feel deeply, think cleanly and develop the sterling traits without which neither a camera or a public can be very long deceived.

I now come to the matter of personal appearance. This is a topic in which every man under 65, and every woman under 100 years seem interested. I sometimes wonder if it is not the desire to see how they would look on the screen, rather than how they might act, that fills so many boys and girls and men and women with an ambition for a screen career.

[Pg 37]

Charles Ray, plus his abundant sincerity, as reflected in “The Old Swimmin’ Hole.”

[Pg 39]

I have found the subject of such universal interest that I believe it deserves a chapter to itself. Therefore I shall dismiss this matter until the next. I may say, however, that in my candidate I should rank agreeable appearance and an expressive face as superior to mere beauty.

To paraphrase, nothing succeeds like good health. Of itself it is the most valuable thing that we should own. Good health can be translated into terms of capacity for work. Therefore since a screen career means both hard and trying work I should insist that my candidate possess or develop the qualities of strength and vitality.

I am aware that in many forms of art such artists as Chopin, Stevenson and Milton, have become famous in spite of great physical handicaps. I do not believe the same can be done in pictures.

It seems to me that healthy persons like to see and be among well people. Motion picture audiences being invariably in first-class physical shape themselves, desire that those who appear before them on the screen be likewise fortunate. It is my belief that an audience is usually bored to tears by a convalescing hero or heroine. If I were in charge of all the [Pg 40]scenarios played I should cut such episodes very short. They beget more impatience than sympathy.

But it is not only because good health radiates from the screen that it is important. In point of nervous and muscular strain, and the often long studio hours that are necessary when production has begun, good health is essential.

To illustrate: While we were filming “Polly of the Circus” in Fort Lee one morning I reported at the studio at nine o’clock. We were working on some interior scenes that were vital to the success of the story. My director at that time was Mr. Charles Horan. Mr. Vernon Steele was playing the male lead.

That day we became so engrossed in playing some rather delicate scenes that before we knew it—or at least before I could realize it—it was six o’clock, and we weren’t half done.

“What do you say to continuing?” asked Mr. Horan.

“Good; we’re right in the spirit of it,” I replied.

We had a bite to eat and worked on until midnight. In spite of our hard and earnest efforts there were several scenes with which we were dissatisfied.

“Well,” said Mr. Horan ruefully. “Tomorrow will be another day.”

As he spoke it dawned upon me how one of [Pg 41]the scenes on which we felt we had failed could be done with probable success.

“Why tomorrow?” I replied. “Let’s make a night of it if necessary. We simply have to get that scene.”

Mr. Horan grinned. That had been his wish. But he had feared breaking the camel’s back.

We worked until four o’clock that morning. Things went swimmingly. It was broad daylight when I ferried across the Hudson but if I was very tired I was equally happy.

Several times during “Polly of the Circus” we had experiences which, in the number of hours put in, were similar to that which I have related. But in the end it was worth while. We had a picture.

At that time I was feeling in the best of health but, even so, the long hours had been a severe drain upon my none too great vitality. For anyone lacking strength and vitality such hours would have been impossible.

It is not my intention to write a booklet on health. But all of us should be very careful of our most precious possession. I know of so many young girls in motion pictures who have let their health get away from them. And some of the cases are so pitiful....

My candidate, then, will have strength and vitality and, equally important, he or she will cling to both, whatever social sacrifices may have to be made to preserve them.

[Pg 42]

The ability to learn quickly will save anyone going into screen work so much trouble and possible humiliation that it may well be listed as an essential qualification.

The screen is no place for the mental laggard. The beginner, particularly, must be alive to learn the new lessons that each day will bring, and learning them he must remember.

During the course of production in a studio things are at high tension. Time is money. Each of us constitutes a more or less important cog in a great machine. Those cogs that inexcusably forget to function are eliminated.

[Pg 43]

Beauty and the measure of looks upon the screen—

Expression most important—Tragedies of

doll-faces—Photographic “angles.”

What follows happened during the National Convention of Motion Picture Producers in 1917 at Chicago. The convention was held at the Coliseum. There were jazz bands, gay and costly decorations, and motion picture celebrities from both Coasts. The carnival spirit ran high and thousands of motion picture fans squeezed into that huge old building.

The opening was called “Mae Marsh Day.” I shall not soon forget it. That night as our party entered the Coliseum through the manager’s private office I espied in the center of the building a newly erected platform draped with bunting and decorated with flowers.

“You will make a little speech,” the manager said.

I gasped. I think I almost fainted. I had never made a formal speech. The idea of it [Pg 44]was as foreign to me as becoming Queen of the South Sea Islands.

“All right,” I gurgled weakly.

My voice has never been strong. As I walked to the platform the Coliseum was a bedlam of sound. I was introduced with difficulty. With sinking knees I stepped forward.

“Ladies and gentlemen I am sure I am pleased to—”

A jazz band, which seemed to be located somewhere immediately beneath my feet, began to loudly play. I didn’t know whether to dance or sing. It was a medley in which “The Star-Spangled Banner” was predominant. I blessed the band. I doubly blessed our national anthem. Looking about me I saw a small American flag. I grasped it and stood waving it to the strains of our national air. The convention was duly opened.

Afterward, when I stood upon a small table giving away carnations until my wrist ached—smiling like a chorus girl meantime—a woman informed my mother that she wished to see me on an important matter. In the press of those thousands of children and grown-ups I was virtually trapped.

“Tell her,” I suggested, “to call at the Blackstone Hotel tomorrow morning.”

She came. She was a plain woman with an honest eye. She brought along two small [Pg 45]daughters aged, respectively, ten and twelve, I afterward ascertained.

“Miss Marsh,” she declared, leaning forward expectantly in her chair, “I think my two daughters should succeed in motion pictures. One of them is very beautiful, and the other looks like you.”

I told this honest lady, with as straight a face as I could command, that while her daughters were still too young to think of playing in motion pictures that some day, perhaps, I could do something for them, particularly the one that looked like me.

In approaching the matter of screen faces I am strongly reminded of that Chicago lady. I believe her logic was essentially sound. There is no measure of looks for the motion picture screen. If there is a yardstick it applies to expression, or animation, and not looks.

No one admires a beautiful face upon the screen more than I. If it so happens that this beauty is allied with ability then I am often given to the thought that they are not a congenial combination. For beauty, ever a queenly quality, is diverting and manages in this way and that to steal some of the thunder that rightfully belongs to ability.

If, as sometimes happens, I see mere beauty being exploited on the screen with no semblance of acting talent, I am ready to give up my seat to the next one along about the third reel. Nothing palls upon one more quickly.

[Pg 46]

Therefore, I am at odds with those who believe that beauty is necessary for the screen beginner. Say for beauty that it has the merit of more quickly attracting attention to the one who possesses it and you have done it full justice. But even then, if it is unaccompanied by ability, it is just another tragedy of a doll-face.

Acting is primarily the ability to express something. If the face that conveys that feeling is not disagreeable then it becomes a matter of not how much beauty is in the face but how much expression. That was certainly the case with Mme. Sarah Bernhardt. All of us know plain appearing persons whose faces, when they have something to say, become interesting and expressive.

They impress us as individuals whose beauty is inside or spiritual. That is a lovely quality for the screen. On the other hand we know, all of us, persons who are generally considered beautiful whose faces, under any circumstances, have no more animation than a mask. These people strike us as spiritually barren, lacking in humor, or something.

If my candidate for screen honors has simply an agreeable appearance and good eyes—which I consider most important of all facial features—I shall be satisfied provided his or her face, and particularly the eyes, are expressive.

[Pg 47]

A beautiful young star and her director, Mary Miles Minter and Chester Franklin.

[Pg 49]

It has been my observation that while beauty or good looks is largely a matter of opinion—which has furnished many lively debates—the quality of expression or animation is seldom denied those who possess it. For that reason my candidate, if he or she has an expressive face, will have a more valuable and certain stock-in-trade than mere good looks.

In spite of this logic most of us stars go on wishing to be thought beautiful, or to have it thought that we could be beautiful if we wanted to be. I recollect that it took time and courage for some of us to brave our publics in other than our pet make-ups.

There are, for instance, two stars who had always regarded their curls as indispensable. After many years of stardom one of them decided to take what she thought was a desperate chance. She skinned her hair back and played the part of a little English slavey. The result was that she turned out one of the most successful pictures in her career.

Another, a dear friend of mine, we used to call “The Primper.” She never appeared upon the set without her curls just so. I think at that time she thought they were the most important part of her career.

She has reformed. As her art developed she became less particular about her hair dress. One night in a little theater in Jamaica, Long Island, I dropped in to see one of her photoplays. It was an excellent picture. Her hair was drawn back tightly over her head into a knot. That night I wired her congratulations.

[Pg 50]

No; curls, Grecian noses, up-tilted chins and rose-tinted cheeks are not the measure of success upon the screen. It is something that goes deeper than that.

It is something that goes deep enough to over-ride facial defects. There is one excellent little star, for example, who, because of a nose unfortunately large, must always work full face when near the camera. I think she is charming. Another, for an odd reason, permits only a one-way profile to be taken. There are many such cases.

Indeed, the majority of us have our “angles.” By “angles” I mean the full, three-quarters, one-quarter or profile views in which we think we appear at our best. Each star has studied that point out for his or herself. And, since we are taking largely our own opinion for it, it is possible we are mistaken. But our vanity upholds us.

In my own case I was hauled into motion pictures while sitting rather forlornly on a soapbox waiting for my sister Marguerite. Since at that time I was without curls, having never had any before or since, and looked as I look, so to speak, it has never been necessary for me to expend any great amount of time in make-up. That has been satisfactory to me.

[Pg 51]

The story, make-up and costuming—Rouge riots and

their disadvantages—The blond

and the “back spot.”

In any art or profession the ability to seize opportunity when it presents itself is important. This is especially true in motion pictures. Things move very fast there. It is like a game where the knack of doing the right thing at the right time determines one’s value.

After the beginner has done his extra work, or small bits, if he is of the right stuff, he will some day be given a part. He may be unaware of it, but that will be the biggest moment of his screen career.

When doing extra work or small bits the critics, the public, and the profession have paid little attention to the beginner. But once the beginner secures a part he comes instantly into the eye of everyone interested in the screen. We are all diverted by new faces.

Thus the impression that the beginner will make in his first part is one that will for a long time endure. It comes very near making or [Pg 52]breaking him. This may seem hard. Often it is unjust—a beginner may have a part forced upon him for which he is unfitted. But it is true. And we have to deal with conditions on the screen as we find them.

For that reason when the big moment comes, and the part is secured, the beginner must do everything within his or her power to be as well prepared as possible.

There are in this respect three important mechanical details that must be looked after. I should list them as follows:

(1) Studying the story.

(2) Studying make-up.

(3) Studying costuming.

The beginner will be given the story—or script—typewritten in continuity form. Continuity means the scene by scene action through which the story is told. Ordinarily there will be some three hundred scenes or “shots” to the average photoplay.

The beginner will first look to the plot and theme of the story. We want to know what the author is telling and how he is trying to tell it. We find the big situations and the action that precedes them. More important, we locate the why of it.

When I have established the idea of the play I immediately go over the script again with an eye alert for business. By business I mean the tricks, mannerisms, and the apparent unexpected [Pg 53]or involuntary moves that help to sustain action.

The value of good business cannot be over-rated. It goes a long way toward making up for the lack of voice. Without clever business any photoplay would drag. The two-reel comedy, which I have observed is popular with audiences of all ages, is usually but a sequence of business.

If the business that is planned upon seems natural to the character—the wiggling of a foot when excited, the inability to control the hands, the apparent unconscious raising of an eyebrow, etc.—I am sure there can be no real objection to it. The audience, who are the final critics, love it.

Just the other night I saw Mr. Douglas Fairbanks in a play the final scene of which depicted him in the act of making love to his intended. That there might be some privacy to the undertaking they were screening themselves from the view of the guests—and the audience!—with a large silken handkerchief.

The girl might have stood still. If she had there could have no criticism. Neither would there have been much of anything else, as her face was hidden from view. She laid her hands over a balustrade and wiggled her fingers. The audience roared.

These are the things which keep a photoplay from dragging. They give the action a piquancy and charm.

[Pg 54]

Now while the audience may believe that these things are done on the spur of the moment the facts are very contrary. These bits of business must be planned in advance and it is only an evidence that they have been well planned when they appear to be done unconsciously.

While it is true that we have all discovered very telling bits of business during the actual photographing of a scene, we can count this as nothing but good fortune. To leave the matter of business until the director called “Camera!” would be fatal.

Thus in going over a script I look for business. I think of all the business I can, knowing that much of it will prove impracticable and will have to be discarded. Nor is that all. When the scenic sets upon which we are to work are erected at the studio or on location, I look them over very carefully in the hope that some article of furniture, etc., will suggest some attractive piece of business. An odd fan, a pillow, a door, in fact, anything may prove valuable.

I should suggest to my candidate that he or she be just as alert for good business as the star is. The good director is always open to suggestion. Business may make all the difference between a colorless and a vivid portrayal of a part. Thus for the beginner who, in obtaining a part, has reached the most vital moment of his career, the value of keeping an eye open to the possibilities of business is apparent.

[Pg 55]

Mary Pickford’s love radiates from the screen. A scene from “Pollyanna.”

[Pg 57]

Make-up, like much of everything else on the screen, is a personal matter. There are, however, some general rules that can be followed to advantage.

I should instruct my candidate not to make up too much. It seems to me that I have observed a tendency in this direction recently.

Some actresses have laid on lip rouge so thickly that their lips seem to run liquid. Rouge photographs black. The result has been that this riot of lip paint has given them the appearance of having no teeth. Others have used too much and too dark make-up about the eyes. Nothing more quickly ruins expression. Such eyes have the look of holes burned in a blanket and for dramatic purposes are only slightly more useful.

Since my candidate will have youth, good health and vitality he or she will not have to resort to tricks of make-up. There are many such. I recall the case of one actress who is considered a beauty on the spoken stage. On the screen she discovered that the motion picture camera is not very kind to some people. The lines and flabbiness which were in her face were accurately reproduced. She thought, of course, they were exaggerated.

She was in despair until she found that by laying heavy strips of adhesive tape over her ears and behind her neck—she wore a wig—these lines and flabbiness were overcome. The [Pg 58]tape pulled her face into shape! But, I am sure it must have been painful.

Another actress, it is an open secret, undergoes periodic operations for the removal of the flabby flesh underneath her chin. Others afflicted with the hated “double chin” rouge the guilty member heavily with more or less success. Still others wear collars and necklaces to thwart flabbiness.

None of us need laugh; that is if we are in motion pictures. If we stay there long enough we may be driven to similar measures.

In make-up, to begin at the top, is to consider the hair. Let me say, first of all, that this should always be kept very clean. The camera has a way of treating us unpleasantly if it isn’t.

Some actresses have set styles of hair dress which they seldom vary. I think of Madge Kennedy’s “band of hair,” Dorothy Gish’s black wig and the Pickford Curls.

Dorothy Gish had tried many styles of hair dress and found none of them to her liking. She experimented with a black wig and was delighted with the result. It contributed something to her expression—brought it out, as it were—which she felt had been lacking. Since “Hearts of the World” she has never stepped before a camera without her trusty B. W.

But while most of us have a favorite style of wearing our hair most of us are forced often to lay aside that style to suit the character we [Pg 59]are playing. Playing a child we let our hair hang. The length or abundance doesn’t seem to particularly matter.

If enacting the daughter of a well-to-do business man then we may have our hair plain or marceled to suit our fancy. Plain hair seems to suggest sweetness. If playing a saucy character we must contrive some dress that will convey the desired effect.

Blonds, in motion pictures, are traditionally fluffy-haired. There is a very good reason for this, by the way. Some years ago Mr. Griffith—who usually does everything first—discovered that by leveling a back spotlight on Blanche Sweet’s fluffy, blond hair it gave the appearance of sunlight showing through.

On the screen it was beautiful. Since that time the “back spot” has been worked to death. In spite of the fact that it is an old trick it is one that is still very much respected by the actress—or us blond actresses, as it were.

The back light shining through the hair has a tendency to take away all the hard lines of the face. It leaves it smooth and free from worry. How often in a motion picture have I heard the involuntary expression, “How beautiful!” when such a shot—usually a close-up—is shown.

Many of you may have wondered why a blond seems to have dark hair in many interior scenes and blond hair out of doors. Here is one fault, at least, that we can shift to other [Pg 60]shoulders. If a blond’s hair is dark indoors it is because the cameraman has failed in his lighting arrangement.

But even with the most expert manipulation of lights there is no rival in motion pictures for the sun. For blonds and brunettes alike he is Allah.

And now since this matter of make-up requires more space and this chapter is growing long we shall skip to the next.

[Pg 61]

More about noses and chins—Costumes as important

to the star as a story to the director—

Rags and riches.

In the matter of face and make-up we seldom think of the forehead. Yet I personally admire a pretty forehead very much and think it is as important as a good mouth or nose, if secondary to the eyes. Comprising as it does—or should—one-third of the face it is nothing if not conspicuous.

If to be deep and learned is to have an extremely high forehead then to be deep and learned on the screen is to labor under one definite handicap. For the girl with a too high forehead cannot skin her hair back without appearing ugly.

Those of us with medium foreheads are more fortunate. Whatever may be said for our mental capacity we can, at any rate, skin our hair back and thereby add very much to our expression.

The girl with the high forehead compromises by trying to keep some of it covered but [Pg 62]it never gives quite the effect of hair drawn tightly back.

I should particularly admonish my screen beginner against too much make-up about the eyes. For blue or gray eyes, a light gray make-up is used; for brown or black eyes, a light brown make-up.

We frequently hear it said that brown eyes photograph best for the screen, but I have never heard anyone whom I would accept as an authority say that. I believe that all colors are equally good. It is far more important that a screen actress’s eyes be expressive than it is that they be either brown or blue.

Thus if we have expressive eyes and evade the error of making them up so heavily as to create the “burnt hole” aspect we shall have nothing to worry about. Generally speaking the more prominent the eyes and eyebrows the less of make-up should be used. There are exceptions.

A nose is something we can do nothing about. We either have or haven’t a good nose. If the nose is so badly out of symmetry with the face as to be unsightly its possessor will probably have to confine himself, or herself, to character parts. There are some who have attained stardom, even with ill-shaped noses, but I think of very few. These by devious practices conceal the defect as well as possible.

Make-up for the nose is usually for character and not star parts. A spot of rouge at the [Pg 63]tip of the nose will give it a turned up or pug appearance. When playing a mulatto in “The Birth of a Nation” Miss Mary Alden inserted within her nostrils two plugs that permitted her to breathe and yet had the effect of greatly widening her nostrils. The late and beloved “Bobby” Harron broadened his nose with putty in the same play in one of the scenes in which he doubled as a negro. The screen lost one of its sweetest and most lovable characters when “Bobby” Harron died.

But these cases were characterizations. For star purposes a nose is a nose. The pity is that sometimes even well-shaped noses seem to lose something or gain too much when they are reproduced on the screen.

The lips and chin require a light make-up for the very good reason, again, that to overdo in this respect is to stifle expression. It is my opinion that those who are becoming addicted to an extremely heavy make-up of lips are making a mistake. It is unreal. It is not art. Such thick, sensuous, liquid lips as I have beheld on the screen during the past year have never been seen on land or sea.

The chin is a good deal like the nose. Very little can be done about it. If it protrudes too much, or is abruptly receding, its possessor will probably find himself chosen for character parts. Here what are otherwise considered facial defects will be no handicap at all. On the contrary they may be a decided help.

[Pg 64]

As in the case of the ill-shaped nose there are stars who have succeeded in spite of an absence, or too great presence, of chin. They have learned the photographic angles at which they appear to the best advantage. In one way or another, when working close to the camera, they keep always within these angles. Thus they prove that there can be an exception to any rule.

If in the matter of make-up I can convince my candidate that he or she will be better off by using as little as possible of it, I shall be willing to pass on to the next topic.

Hands, too, must be kept clean and are usually made up with white chalk.

I often think that costumes are to the star as important as the story is to the director.

Whatever may be the case in everyday life clothes do make the man, or the woman, in motion pictures. They establish character even more swiftly than action or expression. No where so much as in motion pictures does the general public accept people at their clothes value. There are the over-dress of vulgarity, the shoddiness of poverty, the conservatism of decency and so on, each of them speaking as plainly as words of the person so attired.

Now if mere over-dress, shoddiness, conservatism, and so on, were all that were necessary the process would be quite simple. But the art of costuming is more subtle than that.

[Pg 65]

Madame Nazimova, one of the few dramatic stars who quickly mastered the art of the screen.

[Pg 67]

In each costume there must be something original and personal. In other words, something that is peculiarly suited to the precise character that is being portrayed. There must be also a color contrast or harmony that will be favorable to good motion picture photography.

In addition, the costume in a broader sense should harmonize with the scenic setting. The costume, more than anything else, will establish the fiction of age. To appear very young or middle-aged is to dress young or middle-aged.

In addition to its value in suggesting character the costume has attained a new importance in that the screen has become a sort of fashion magazine. The thousands of young ladies who live outside of New York, London or Paris have come to look more and more to the screen for the latest fashions, and are accordingly influenced.

With this phase of costuming my candidate need not particularly interest herself beyond remembering that women love to see pretty clothes and that those who give them the opportunity occupy an especial niche in their affections.

The beginner who learns the knack of dressing for the screen in a manner that is sharply expressive of the character being played, and, in a way to bring out what the actress herself has come to regard as her strong point, will find her pains rewarded.

[Pg 68]

Mr. Griffith has always been extremely painstaking about screen clothes. Even in the early days of the old Biograph two-reelers we had screen tests for costumes. It was no unusual thing to hear him say, after one of us had been at much pains to select a costume which we thought did justice to both our part and ourselves, “No, that won’t do!” Possibly we were trying to do too much justice to ourselves.

Anyhow we often had as many as four costumes made before Mr. Griffith was suited. Then he invariably suggested a ribbon, a fan, a bit of old lace, etc., the effect of which upon the screen was always pleasing.

I have been told that one of the sweetest and, at the same time, most pathetic scenes done in motion pictures occurred in “The Birth of a Nation” where I, as Flora Cameron, the little sister of the Confederate soldier, trimmed my cheap, home-made dress in preparing to welcome home my big brother.

It was Mr. Henry Walthall, himself a southerner by birth, who suggested this bit of business.

You will remember the situation. The Camerons, an old and distinguished Southern family, had been impoverished by the war. They were preparing for the return of the big brother—played capitally by Mr. Walthall—with the mixture of emotion to be expected under the circumstances. I, as the youngest [Pg 69]member of the family, was least affected by our cruel poverty. The joy of being about to see my big brother again overcame any other feeling.

I begin to dress. The sadness of my stricken family cannot affect my holiday spirit. I have but one dress. It is of sack cloth. I find that its pitiful plainness is not in keeping with my happiness or the importance of the event. Looking about for something with which to trim that dress I find some strips of cotton—“southern ermine,” as it was called. With these I trim that homely old dress, spotting the “ermine” with soot from the fireplace, in a manner that I think will be pleasing to my big brother.

Mr. Walthall suggested the “southern ermine” and it was Mr. Griffith, always kindly in the matter of accepting a suggestion, who built the drama about it. I have had many women, from the North as well as the South, tell me that to them this scene is the most affecting they ever have seen in the picture drama. I know I have played few, if any, in which I have felt more deeply the spirit of the action.

In “The Birth of a Nation,” by the way, all of us were forced to do a great deal of research work upon our costumes. This is a good thing. It gets one quickly into the spirit of the drama that is to be played.

[Pg 70]

As I say, I have always appreciated the advantages of modish dress upon the screen even though I have had in my eight years of acting only one “clothes” part. By clothes part I mean one in which the star dresses in modern garments in every scene. I began my career as a screen waif with the result that the literary men who have to do with the stories picked for me, have kept me at this style of part.

There is never a story written in which a poor, little heroine conquers against great odds—usually after much suffering and not a few beatings—but that many friends rush to tell me that so and so is “a regular Mae Marsh part.” Such is the power of association.

Yet I very much enjoyed my one dressed-up part. That was “The Cinderella Man.” I understand that there was great doubt expressed by the scenario department that I should be able to play such a role for, since the heroine was the daughter of a wealthy man, there was no occasion for her appearing in rags.

Miss Margaret Mayo, the well-known dramatist, who wrote “Polly of the Circus,” “Baby Mine,” etc., was here my stanch advocate. Both she and Mr. George Loane Tucker, one of our greatest directors, insisted that I could do the part. It was decided to make the trial.

“Go to Lucille,” suggested Miss Mayo, “explain the story to the designer and let her show you the kind of costumes she would suggest.”

[Pg 71]

Expense was to be no object. Mr. Tucker and I met one afternoon on Fifty-seventh street and, entering Lucille’s, we went into a clothes conference with a designer. The result was a mild orgy of beautiful gowns.

It was decided that Lucille should make two dresses of a particular design, one green and one gray, as the gown which I was to wear in a great many of the scenes.

Showing that cost does not indicate fitness I remember that the gray dress—which was $100 cheaper than the green—was the one which we decided to use. My costume bill for “The Cinderella Man” exceeded $2,000. There are many actresses who spend far more than that for clothes on every picture. But compared with the amount that I had been spending in my “poor girl” roles that $2,000 was as a mountain to a sand dune.

“The Cinderella Man” was a great success and we were happy; particularly Miss Mayo and Mr. Tucker, who had never doubted that I could do a dressed-up part.

The matter of costumes, then, is one of the important things that the beginner must consider. On the screen clothes may be said to talk; even to act. The male artists, I am sure, also realize this. But the actress, particularly, must always dress in a manner to get the maximum of benefit from her clothes whether they be cheap or expensive.

[Pg 72]

In “The Birth of a Nation” during the famous cliff scene I experimented with a half dozen dresses until I hit upon one whose plainness was a guarantee that it would not divert from my expression in that which was a very vital moment.

[Pg 73]

Camera-consciousness and a way to cure it—Why it is

fatal to imitate—Some scenes

in “Intolerance.”

The several qualities most likely to succeed upon the screen having been discussed, and the importance of knowing the story, make-up and costuming having been established, my candidate is now ready to go before the camera.

All that has been done before is but to build up to this vital moment. The camera tells at once and usually in no uncertain terms whether one is possessed of star possibilities.

It is a sort of court from which there is no appeal. For that reason every expression, every movement, every feeling and, I verily believe, every thought are important once the camera has begun to turn.

Now the actress or actor is standing entirely upon her or his own feet. Previously they have had the benefit of all the advice and help that the many departments of a studio could proffer. In a word they have been able to [Pg 74]lean upon someone else and to correct mistakes at leisure.

It is different before the camera. The beginner will at once feel very much alone and terribly conspicuous. This tends toward self-consciousness, or camera-consciousness, which must be immediately overcome or success is impossible. Camera-consciousness is the bane of the beginner. I think most of us have suffered more or less from it. I have known actresses who possessed it to such a degree that, finding they could not rid themselves of it, they left the screen. By extreme good fortune this never happened to be one of my troubles.

Self-consciousness on the screen is much the same thing as stage fright in the spoken drama and proceeds, I suppose, from the same source, which is the inability to forget one’s self.

When a dear friend of mine first began playing small parts she found that she suffered from it. She also saw that it would certainly be fatal if she didn’t cure it.

“For that reason,” she said to herself, “the best thing to do is to think so hard about the part that I am playing that I won’t have time to think of anything else.”

She gave herself good advice. Anyhow it worked and I am sure it will be successful in the case of the average beginner. If so, then camera-consciousness will really be a blessing in disguise, for it will have taught the actress [Pg 75]concentration upon her part and concentration, in every fiber of one’s being, I believe, is the big secret of screen success.

I remember the case of one young actress who came to me in tears saying that when she rehearsed her part in the privacy of her own home, or dressing room, she felt every inch of it, but once under the gaze of the director, the assistant director, the cameraman, possibly the author and perhaps a number of privileged persons about the studio, she seemed to wilt.

“Look at it this way,” I advised. “When you are acting the director has his work to do and is doing it. So has the assistant director. Likewise the cameraman and the assistant cameraman have their work to do and are doing it. So are the other actors. As for the lookers-on, request that they leave. Then imagine you are in a big schoolroom where everyone is busy at his or her lessons. You have your lesson to get which is concentrating upon your part. Go ahead with it.”

It helped the girl in question. She has become a very excellent and charming star and while she still prefers to work upon a secluded stage she does not find it positively necessary, as do some actresses. In any event there is no trace of camera-consciousness in her acting.

Camera-consciousness having been eliminated the beginner can now throw himself or herself entirely into the part being played. By throwing one’s self into the part I do not mean [Pg 76]forcing it. Nothing is quite so bad as that. I mean feeling it. If you do not feel the particular action being played then the result will certainly be a lack of sincerity. We have already decided that that is fatal.

Let me illustrate:

While we were playing “Intolerance,” one cycle of which is still being released as “The Mother and the Law,” I had to do a scene where, in the big city’s slums, my father dies.

The night before I did this scene I went to the theater—something, by the way, I seldom do when working—to see Marjorie Rambeau in “Kindling.”

To my surprise and gratification she had to do a scene in this play that was somewhat similar to the one that I was scheduled to play in “Intolerance.” It made a deep impression upon me.

As a consequence, the next day before the camera in the scene depicting my sorrow and misery at the death of my father, I began to cry with the memory of Marjorie Rambeau’s part uppermost in my mind. I thought, however, that it had been done quite well and was anxious to see it on the screen.

I was in for very much of a surprise. A few of us gathered in the projection room and the camera began humming. I saw myself enter with a fair semblance of misery. But there was something about it that was not convincing.

[Pg 77]

Back to the old Mutual days with Blanche Sweet and Wallace Reid.

[Pg 79]

Mr. Griffith, who was closely studying the action, finally turned in his seat and said:

“I don’t know what you were thinking about when you did that, but it is evident that it was not about the death of your father.”

“That is true,” I said. I did not admit what I was thinking about.

We began immediately upon the scene again. This time I thought of the death of my own father and the big tragedy to our little home, then in Texas. I could recall the deep sorrow of my mother, my sisters, my brother and myself.

This scene is said to be one of the most effective in “The Mother and the Law.”

The beginner may learn from that that it never pays to imitate anyone else’s interpretation of any emotion. Each of us when we are pleased, injured, or affected in any way have our own way of showing our feelings. This is one thing that is our very own.

When before the camera, therefore, we must remember that when we feel great sorrow the audience wants to see our own sorrow and not an imitation of Miss Blanche Sweet’s or Mme. Nazimova’s. We must feel our own part and take heed of my favorite screen maxim, which is that thoughts do register.

It is true that we have good and bad days before the camera. There are times when to feel and to act are the easiest things imaginable and other occasions when it seems impossible [Pg 80]to catch the spirit that we know is necessary. In this we are more fortunate than our brothers upon the spoken stage, for we can do it over again.

It is also very often true that even when we are entirely in the spirit of our part, and believe we have done a good day’s work, that there will be some mechanical defect in the scenes taken which makes it necessary to do them over, possibly when we feel least like so doing.

In this event it is a good thing to remember that it doesn’t pay to cry over spilt milk. We must learn to take the bitter with the sweet. Fortunately the mechanics of picture taking are constantly improving.

The hardest dramatic work I ever did was in the courtroom scenes in “Intolerance.” We retook these scenes on four different occasions. Each time I gave to the limit of my vitality and ability. I put everything into my portrayal that was in me. It certainly paid. Parts of each of the four takes—some of them done at two weeks’ intervals—were assembled to make up those scenes which you, as the audience, finally beheld upon the screen.

Therefore, when first going before a camera it is well to resolve to put as much into one’s performance as possible. We cannot too greatly concentrate upon our parts. If we do not feel them we can be very sure they will not convince our audiences.

[Pg 81]

Over-acting and a horrible example—the value of

repression and emphasis—How we

act with the body.

Good screen acting consists of the ability to accurately portray a state of mind.

That sounds simple, yet how often upon the screen have you seen an important part played in a manner that made you, yourself, feel that you were passing through the experiences being unfolded in the plot. I imagine not often.

If a part is under-played or, worse, over-played—for there is nothing so depressing as a screen actress run amuck in a flood of sundry emotions—it exerts a definite influence upon you, the audience.

You begin to lose sympathy with the character itself. You are interested or irritated by the mannerisms—often hardly less than gymnastics—of the actor or actress. You never identify such an actor or actress with the part they are playing for the very good reason that they are not playing the part. They are playing their idea of acting at a part.

[Pg 82]

In any event your interest in the story crumbles. What the author intended as a subtle character development flattens out. An ingenious plot is ruined by its treatment. You index that particular evening as among those wasted. I know. I have done the same.

For those who would like to take up the screen as a career, however, such an evening may prove very profitable. For it is the learning what not to do that is important. There never was a character portrayal done upon the screen that could not have been spoiled without this knowledge.

I have in mind a photodrama of 1920 that because of the excellence of its plot gained quite a success. But for me it was ruined by the ridiculous overacting of the heroine.

She had beautiful dark eyes and seemed to think—it was a melodrama—that the proper way to display screen talent was to dilate and roll those eyes as though she were constantly in terror.

She had added to that trick one of dropping her jaw which I understood to be her idea of the way to register astonishment. I cannot begin to describe the effect upon me of those horrified eyes and open mouth. At the end of six reels I felt like screaming. There was no time when I should have been surprised had she wiggled her ears.

Either she was unfortunate in her choice of a director or he, poor fellow, was powerless to [Pg 83]stop her once she had decided upon her program of mouth and eyes.

One of the first things that a screen actress must learn is the value of emphasis. In the case that I have cited above the actress threw herself emotionally (?) so far beyond the mark in little moments that when a big situation in the development of the plot occurred she had nothing left. The impression consequently was one of a strained sameness. Than that there is no quicker way to wear out one’s audience. It is like shouting at one who has sat down for a quiet chat. The shout should be used at no distance less than a city block.

No screen actress makes a shrewder use of emphasis than Norma Talmadge. She seems invariably to hold much in reserve with the result that when she does let go in a big emotional scene the effect is brought home to the audience with telling force. There are other actresses who play with reserve. But it is important that with Miss Talmadge her repression seems ever illuminated by the fires of potential emotion.

The student of the screen will do well to study these matters of emphasis and repression. They are all important. Our manner of life itself is an accepted repression, outlined by laws for the streets and conventions for the drawing room. From the screen viewpoint repression is a vital thing, if for no other reason than the fact that it gives the audience a [Pg 84]breathing spell. After a breathing spell it is the better disposed to appreciate emphasis.

Whenever I study a scenario or story it is with an eye for the contrast of moods and the situations that call for emotional emphasis. I plan in advance of the actual camera work the pace at which I will play various stages in the development of the story. By shutting my eyes I can almost see how the part will look upon the screen. If there is a sufficient contrast of moods and opportunity for emphasis I feel that I shall, at least, be able to do all within my power to make the story a success.

The physical strain before a camera is a peculiar thing. At no time is the motion picture actress or actor called upon for a sustained performance such as is true on the spoken stage. For that reason we should theoretically be in condition to put forth our very best efforts on each of the short scenes or “shots”—averaging not over two minutes in photographing—that we are called upon to do. The ordinary director is well satisfied if he averages twenty “shots” a day during production.

But here, I should say, appearances are deceiving. Genius has been described as the ability to resume a mood. In the case of motion pictures it is necessary that a mood be resumed not once or twice, but possibly twenty times during a day.

[Pg 85]

Norma Talmadge whose acting is notable for its admirable repression.

[Pg 87]

This is no less important than it is at first difficult. There may be an hour or two hours’ interval between scenes—often longer than that—and picking up the thread of the story where it was dropped, the actress must resume the mood of her characterization.

I can suggest no better aid to this undertaking than retiring to one’s dressing room and remaining quiet. Absolute quiet is an excellent thing for the actress during the working day. It gives her a rest from the turmoil of the studio set. It provides her a chance to do a little mental bookkeeping on the part she is playing. I have found it a great help.

This ability to resume a mood, however, soon becomes something that is subconsciously accomplished and for that reason need not be too much worried over by the beginner.

There is one quality on the screen that the audience always likes. That is vivacity, and by vivacity I mean both of the face and the body.

Vivacity in this respect is a lively and likable sort of animation which goes a long way toward establishing that mercurial quality which is known as “screen personality.”

I have never heard anyone give a very good definition of “screen personality.” The most that can be said is that some seem to have it and some don’t. Certain it is that it is valuable quality, for it will not stay hidden.

In the news weeklies that are so popular on the screen I can, in a group of men or women, [Pg 88]almost instantly pick those persons who have screen personality. It makes them stand out sharply in contrast to their companions. Ex-President Wilson, for instance, has screen personality while President Harding, I am certain, will make a better President than he would an actor.

The movement of the body contributes to this sought after animation. The body is almost the equal of the face in expression and the way to talk and use the hands and feet are things that must be sedulously studied.

Many stage directors have advised famous actresses to “learn how to walk” and before a camera one not only has to learn how to walk but how to walk in many different ways.

We would not, for example, expect a little girl on New York’s East Side to employ the same body carriage as a society girl walking down Fifth avenue. There seem to be so many schools of walking!

Thus in going over a part it is of the utmost importance that we decide upon the way our heroine is going to carry herself and then throw our body, as well as our thoughts and expression, into our role. I have often used this matter of walking—I was about to say art of walking—to very good effect. I should advise the beginner to observe the many different [Pg 89]ways in which various persons accomplish expression through the movement of the body.

It was in the early days. It was in Yonkers. We were making “The Escape.” It was a street scene and we were working with a concealed camera. Mr. Donald Crisp was playing the brutal husband. He drew back his fist to strike me. I was the forlorn wife.

“If yu’ touch that lady I’ll knock yer block off,” said a threatening voice.

It was a young Yonkers bravo. Absorbed in the scene he had forgotten that it was acting, particularly with the camera concealed.

I often think of that incident when at a picture play I hear someone say: “People don’t act like that in real life.”

[Pg 90]

If I were a director there is nothing I should rank as more important than rehearsals. I do not mean merely running over the scene before it is filmed. All directors do that. The ideal rehearsal is one which calls together the leading parts perhaps a week before production and meticulously works out every vital scene in the story.

No director of the spoken stage would think of producing a play without doing this. Yet in motion pictures a production that may cost twenty times as much as the average spoken drama is often put on with twenty times less of care in rehearsal. It is illogical and costly.

Working with the director of the type who leaves everything until the last minute the actor or actress feels a strain that takes away from the performance rendered. On the other hand where painstaking rehearsal is practiced the actor acquires a poise and deftness of touch that justify the preliminary preparation, say nothing of the labor spared in editing.

[Pg 91]

Long shots, intermediates and close-ups—“Hogging

the camera” and ingenious leading men—

Keeping one’s poise under fire.

While the actress will exert herself in every “shot” or “take”—as the separate exposures of a scene are called—she comes to know that the result of her acting upon the screen is greatly influenced by the distance from the camera that she has worked.

There are, for our present purposes, three different distances which we work from the camera. There is the long shot, the intermediate and the close-up or insert. With the gradations of these we need not now concern ourselves.

The long shot is usually taken to establish the atmosphere and setting of a scene. In this the actress finds herself ordinarily so far from the camera that her facial expression registers indifferently. For that reason the body movement, with which she is playing a character, substitutes for facial expression. She is known [Pg 92]to the audience by her costume and carriage and makes her appeal largely through these.

Most of the dramatic action is now played at three-quarters length; that is from the face to the knees. As we weave in and out of a scene, very often the entire body is shown and the feet have their opportunity for expression—they assuredly act!—but the majority of the intermediate shots through which the dramatic action is conducted cut off the lower part of the body.