Fig. I.

Title: Technique of modern tactics

Author: P. S. Bond

M. J. McDonough

Release date: February 4, 2026 [eBook #77863]

Language: English

Original publication: Menashs: George Banta Publishing Co, 1919

Credits: Brian Coe and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

A STUDY OF TROOP LEADING

METHODS IN THE OPERATIONS

OF DETACHMENTS OF ALL ARMS

BY

P. S. BOND

Major, Corps of Engineers, U. S. Army,

AND

M. J. McDONOUGH

Major, Corps of Engineers, U. S. Army.

THIRD EDITION, REVISED AND ENLARGED

Adopted by the War Department as a preparation for the War College; Bulletin 4, War Department, 1915.

Adopted by the War Department as a text for garrison schools and in the examination of officers for promotion. For issue to organizations of the Army and the Militia; Bulletin 3, War Department, 1914.

Adopted by the War Department as one of the books recommended by the Division of Militia Affairs for the use of the Organized Militia. Circular No. 3, Division Militia Affairs, War Department, 1914.

Adopted as a text for the garrison course for all officers of the Marine Corps—Orders No. 18, 1914, U. S. Marine Corps.

Adopted as a text for use in the Marine Officers’ School, Norfolk, Virginia.

Adopted as a text for use in the Coast Artillery School, Fort Monroe, Virginia.

Recommended for study and reference in the National Guard Division of New York; G. O. 4, 1914, Headquarters Division, N. G. N. Y.

Used as a reference at the Army Service Schools, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

For sale by Book Department, Army Service Schools, Ft. Leavenworth, Kan., by the U. S. Cavalry Association, Ft. Leavenworth, and by the publishers.

The Collegiate Press

George Banta Publishing Company

Menasha, Wisconsin

Copyright 1916

by

P. S. BOND

The cordial reception that has been accorded this volume by the Army, the Marine Corps, the National Guard, Military Schools, Training Camps, etc., has made necessary a second and third editions. The present edition embodies the essential modifications contained in the 1914 F. S. R., and the act of June 3, 1916.

The chief reason leading to the publication of the volume in the first instance was the authors’ belief that the excellent instruction given at the Leavenworth Schools should be disseminated to the widest extent practicable among all those in the United States who are charged with preparation for the active physical defense of the nation. To assist in such an extension of military education, there seemed a need for a volume which would collect and make available within a small compass, the fruits of the study, observation, and experience of those officers who have unceasingly devoted themselves to the improvement of American tactical training.

It is well that the traditional indifference of the American people toward military preparedness is in this day being rudely disturbed. Fate has hitherto been lenient to the growing American nation. It has not demanded the full or the logical forfeit proportionate to the laxity displayed by us in meeting former crises. In the Revolution, fate was indeed kind to the Colonists. In the War of 1812 it awarded us greatly more than our efforts merited, and seemed to overlook the pitiful inefficiency of our land forces. At sea the brilliant series of naval exploits was made possible only by the unfaltering determination of the naval chieftains serving under a supine administration that desired to lock up the navy in home ports. In the Mexican War, in permitting us to conduct two campaigns without the loss of a single battle, and in spite of a woeful deficiency in men, in equipment, and in administrative support, fate was more than indulgent.

In the Civil War fate did not assess the full retribution of disruption of the Union, which it might logically have done, but it did exact for our neglect of preparation an immense payment in blood and treasure. This indulgence of fate may be not wholly a kindness. To the extent that it violates justice, it merely postpones the final reckoning and tends to lull its recipient into a false sense of national security, resulting from unearned success. The nation has not yet experienced the chastening discipline of defeat. In the future, therefore, we must not be surprised when full compensation is exacted if, as an adult people, we continue to misread the true import of history and persist in our traditional negligence.

A people may not logically assume great responsibilities without making timely provision for the discharge of those responsibilities. Sooner or later an exact accounting will be had. History shows many examples of nations which have paid the price of their neglect. Despite the hopes of Utopians history shows that human nature undergoes no progressive change, and it shows to the present day no substantial diminution in the frequency of wars.

That our people are beginning to manifest an intelligent interest in the condition of the National defense cannot fail to be gratifying to those whose lives are consecrated to such defense. Such interest is a vital support and an inspiration to the defenders. It is hoped that this volume may be of assistance in guiding to some extent the awakening interest.

In the first edition the subjects of air craft and motor vehicles were not treated, because although it was recognized from the outset that these machines would exert a very great influence upon the conduct of war, their tactics was at the time largely speculative. Such is not the case today.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | 5 | |

| Organization of the U. S. Army. | ||

| Road distances and camp areas | 10 | |

| I | The preparation and solution of tactical problems. | |

| Bibliography | 19 | |

| II | Field orders | 37 |

| III | Patrolling | 45 |

| IV | Advance guards | 56 |

| V | Rear guards. Flank guards | 70 |

| VI | Marches, Change of direction of march, | |

| Camps and bivouacs | 83 | |

| VII | Convoys | 95 |

| VIII | Artillery tactics | 109 |

| IX | Cavalry tactics | 144 |

| X | Outposts | 170 |

| XI | Combat. Attack and defense | 204 |

| XII | Organization of a defensive position | 248 |

| XIII | Combat-Attack and defense of a river line, Withdrawal | |

| from action, Rencontre or meeting engagement, | ||

| Delaying action, Pursuit, Night attacks, | ||

| Machine guns | 277 | |

| XIV | A position in readiness | 308 |

| XV | Sanitary tactics | 318 |

| XVI | The rifle in War | 324 |

| XVII | Division tactics and supply | 337 |

| XVIII | Air craft and Motor vehicles in War | 381 |

| Glossary | 393 | |

| Index | 405 |

LIST OF PLATES

| Figure | Facing Page | |

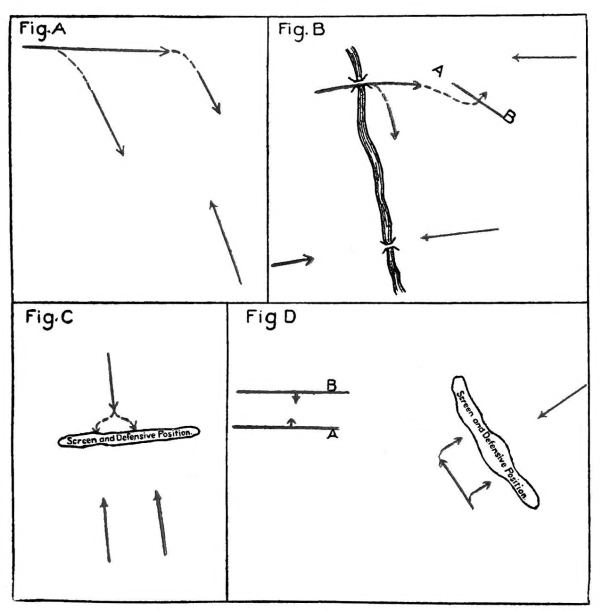

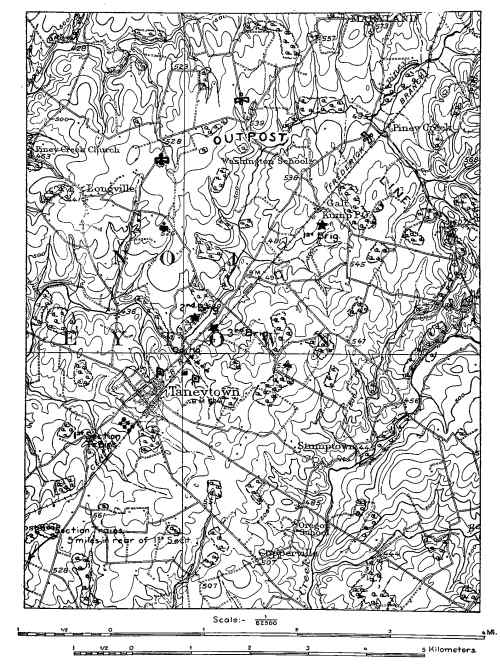

| I | Diagrammatic analysis of tactical problems | 31 |

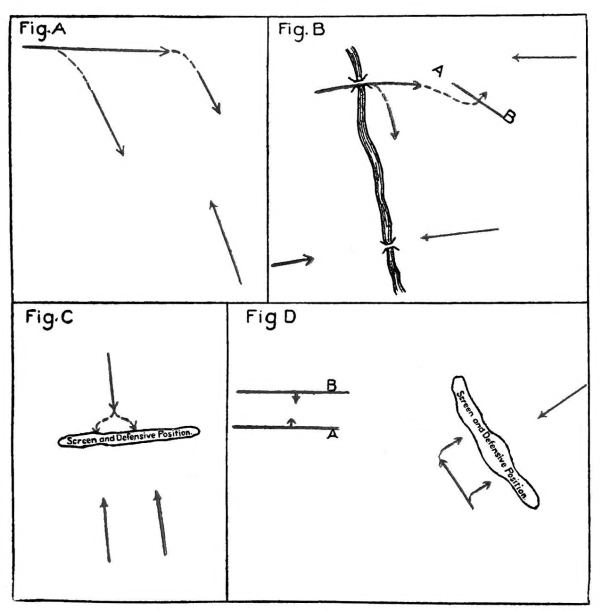

| II | Typical arrangements of a convoy on the march | 104 |

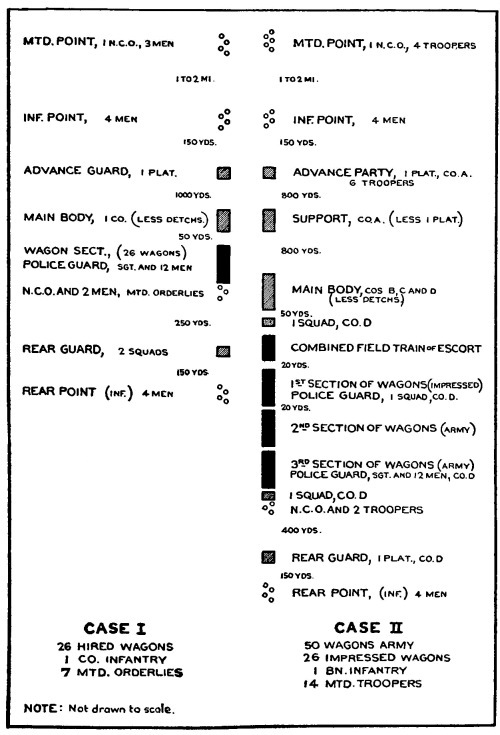

| III | Typical arrangements of a convoy on the march | 107 |

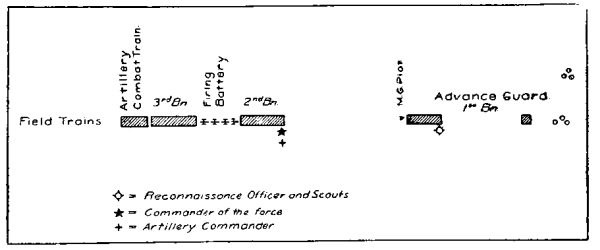

| IV | Battery of artillery on the march | 126 |

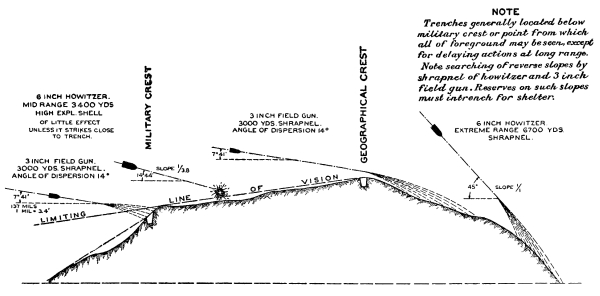

| V | Trajectories and cones of dispersion of shell | |

| and shrapnel | 134 | |

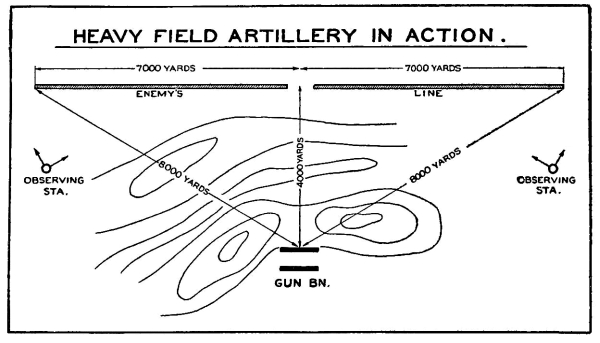

| VI | Heavy field artillery in action | 135 |

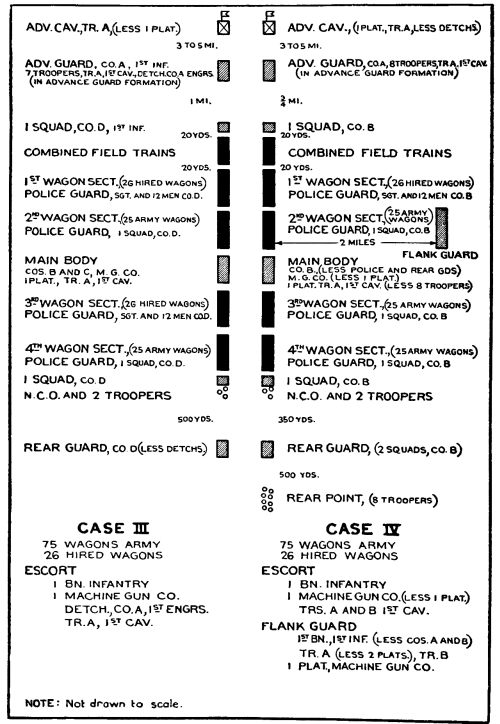

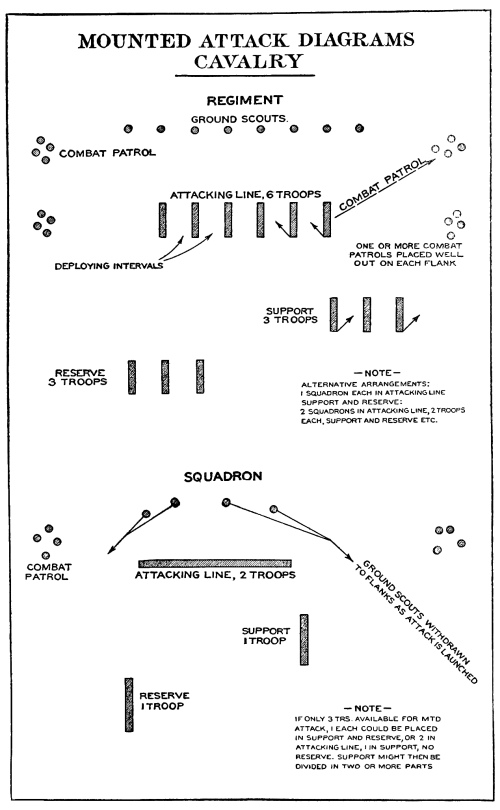

| VII | Cavalry mounted attack diagrams | 163 |

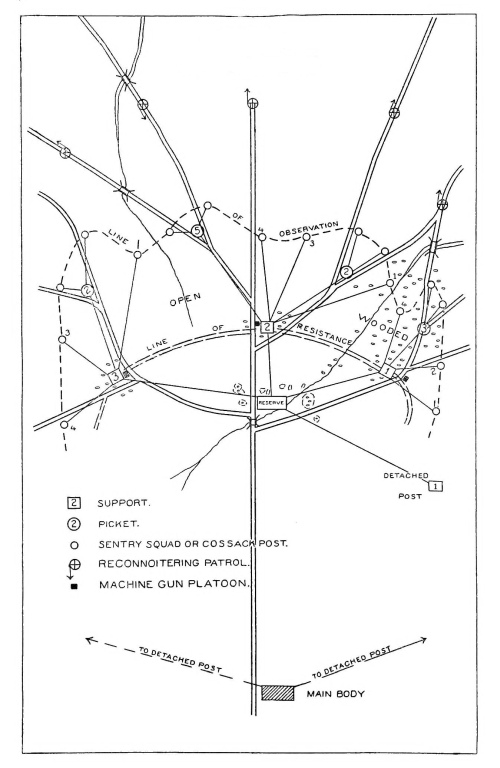

| VIII | Diagram of an outpost | 195 |

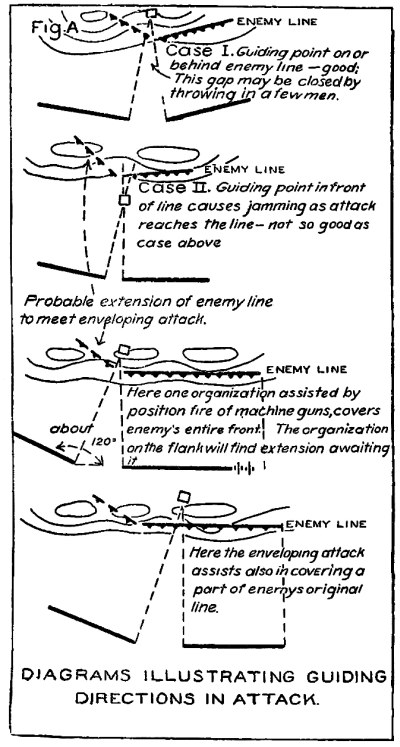

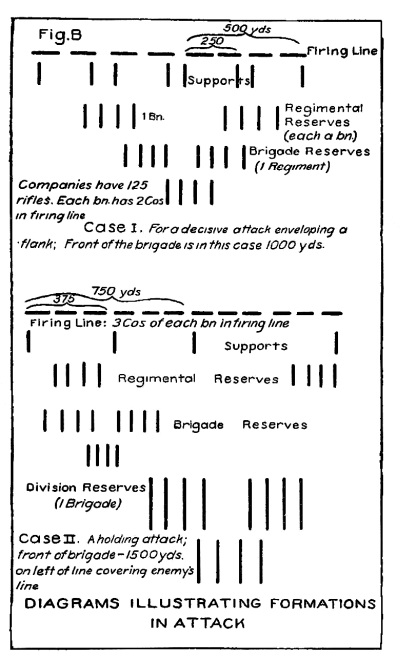

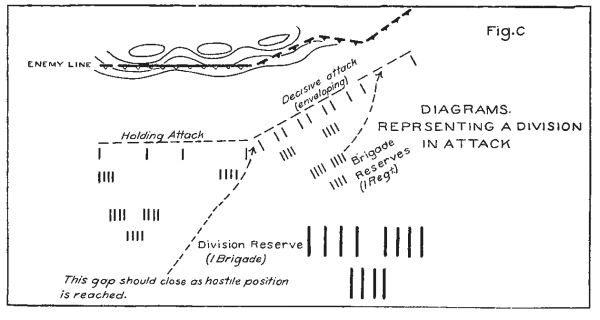

| IX | Infantry attack diagrams | 219 |

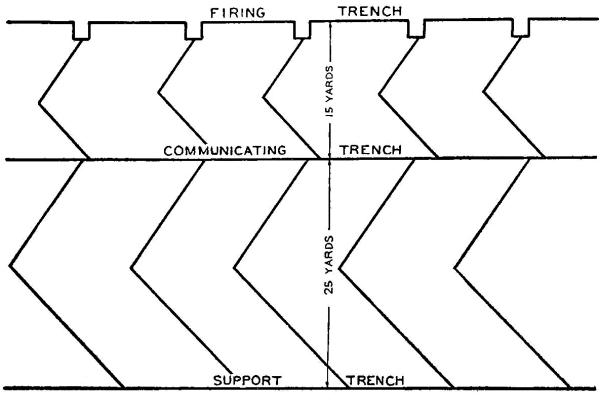

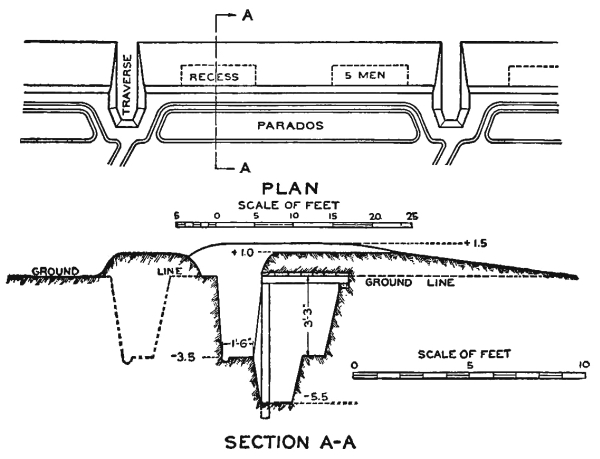

| X | Standard field trenches | 265 |

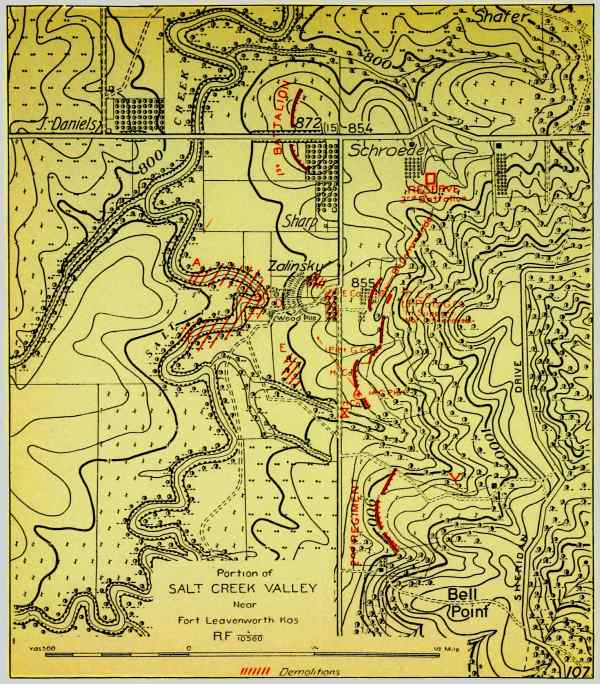

| XI | Illustrating Problem No. 1, Field Fortification | 274 |

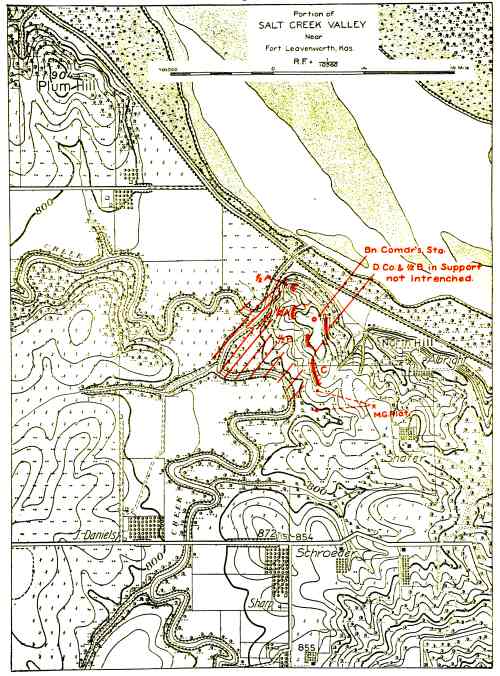

| XII | Illustrating Problem No. 2, Field Fortification | 276 |

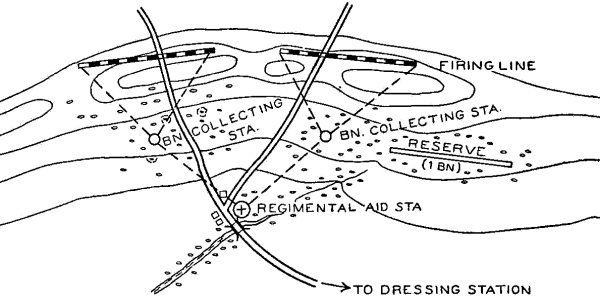

| XIII | Regimental sanitary troops in battle | 320 |

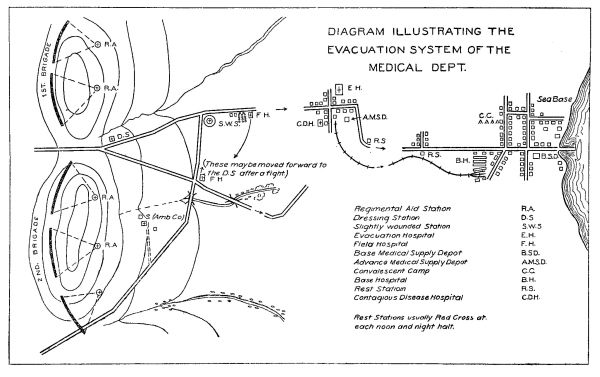

| XIV | Diagram illustrating the evacuation system of | |

| the medical department | 322 | |

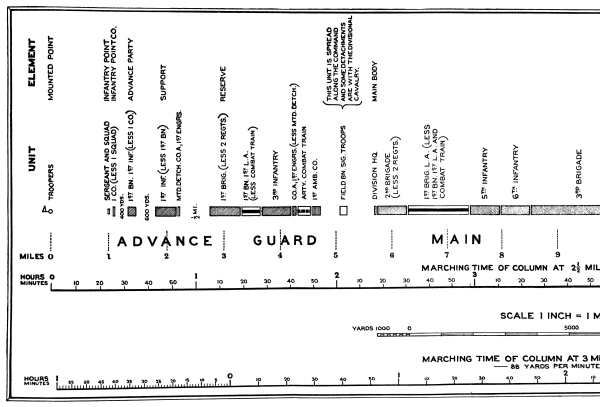

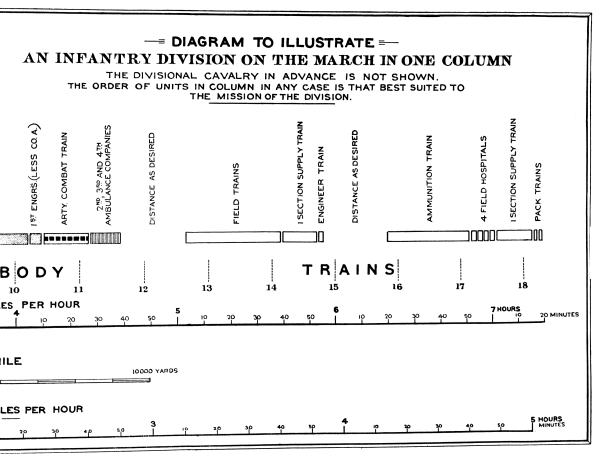

| XV | A division on the march | 342 |

| XVI | Camp of a division | 358 |

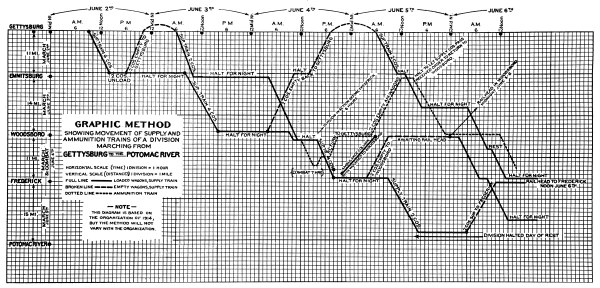

| XVII | Diagram showing movements of the supply and | |

| ammunition trains of a division during a march | 368 | |

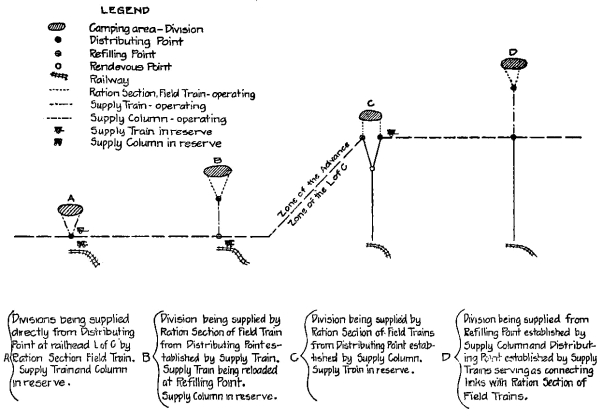

| XVIII | Outline of the system for supplying an army | |

| in the field | 375 | |

| Page | |

| INTRODUCTION | 5-9 |

| ORGANIZATION OF THE U. S. ARMY. |

|

| ROAD DISTANCES. CAMP AREAS | 10-17 |

| CHAPTER I |

|

| THE PREPARATION AND SOLUTION OF | |

| TACTICAL PROBLEMS | 18-36 |

| PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THE SOLUTION OF | |

| TACTICAL PROBLEMS (table) | 18 |

| THE APPLICATORY SYSTEM OF MILITARY INSTRUCTION | 19 |

| Kinds of problems. Map problems, terrain exercises, war games, | |

| tactical walks and rides, field maneuvers | 19-20 |

| Problems of decision | 19 |

| Troop leading problems | 19 |

| Limitations of terrain exercises | 19 |

| General form and details of tactical problems | 20-21 |

| General and special situation | 20 |

| Estimate of the situation | 21-22 |

| The mission | 21-22 |

| General and special assumptions | 22-23 |

| Use of maps | 23 |

| Visibility problems | 24 |

| Principles of the Art of War | 24 |

| Military responsibility and the peace training of officer | 24-25 |

| Mental processes and methods in the solution | |

| of tactical problems | 25-28 |

| Independent solutions. Personality of the author | 26-27 |

| Simplicity of plan | 27 |

| Advantages of the initiative | 27 |

| Reviews of solutions | 27-28 |

| Apparatus required | 28 |

| DIAGRAMMATIC ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS | 29-31 |

| SUGGESTIONS FOR THE PREPARATION OF PROBLEMS | 31-33 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 33-36 |

| CHAPTER II |

|

| FIELD ORDERS | 37-44 |

| Forms for orders. Verbiage of orders, how acquired | 37-38 |

| Administrative and routine matters | 38 |

| What to include in orders | 38-39 |

| Detailed instructions usually inadvisable | 38 |

| KINDS OF ORDERS—verbal, written, dictated, | |

| individual, combined | 39 |

| STRUCTURE OF ORDERS | 39-40 |

| The 5 paragraph form. Contents of numbered paragraphs | 39-40 |

| Marginal distribution of troops | 40 |

| Map references. Signature | 40 |

| Transmission of orders. Receipts for orders | 40 |

| Simple English. Short sentences. Arguments and | |

| discussions. Ambiguity | 40 |

| Abbreviations. Description of localities | 41 |

| Amount of information contained in an order | 41-42 |

| Plan of the commander. Good and bad news | 41 |

| Trespassing upon the province of a subordinate | 42 |

| Division of responsibility with a subordinate | 42 |

| Equivocal language | 42 |

| Discussion of contingencies | 42 |

| Advantages of combined orders | 42 |

| Copies of dictated orders | 42 |

| Proper time for the issue of orders | 42-43 |

| PRELIMINARY OR PREPARATORY ORDERS. Assembly orders | 43 |

| Time required for preparation and circulation of orders | 43-44 |

| Motor cars and motorcycles | 44 |

| Consonance of orders and plans. Minor details | 44 |

| Duty of staff officers in the preparation of orders | 44 |

| CHAPTER III |

|

| PATROLLING | 45-55 |

| CLASSIFICATION OF PATROLS | 45 |

| COMPOSITION AND STRENGTH. Commander | 45 |

| Mounted and dismounted patrols. Auto patrols | 45-47 |

| Functions of mounted orderlies | 46 |

| Cavalry and aeronautical services | 47 |

| Motor cars for patrolling | 47 |

| INSTRUCTIONS GIVEN PATROL LEADER | |

| BEFORE THE START | 47-48 |

| ACTION TAKEN BY THE LEADER BEFORE THE START | 48-49 |

| Preliminary arrangements, equipment, inspection of patrol, etc. | 48-49 |

| CONDUCT OF PATROL | 49-55 |

| Formations. Gaits | 49-50 |

| Routes. Reconnoitering | 50 |

| Advance by “successive bounds” | 50 |

| Woods and defiles | 50 |

| Detachments from the patrol | 50 |

| Houses, villages and inclosures. Rendezvous | 50 |

| Corrections to maps | 50 |

| Watering the horses | 50 |

| Civilians preceding patrol | 50 |

| Combats—when justifiable | 51 |

| Prisoners | 51 |

| Lookout points. Halts. March outposts | 51 |

| Hostile patrols. Conduct in case of attack, etc. | 51 |

| Exchange of information with friendly patrols | 51 |

| Signs of the enemy | 52 |

| Accomplishment of the mission | 52 |

| Main and secondary roads | 52 |

| Interviewing inhabitants. Bivouac of patrol | 53 |

| Hearsay evidence | 53 |

| MESSAGES. How transmitted. Relay posts | 53-54 |

| Form and contents of messages | 54 |

| WHAT TO REPORT | 54-55 |

| Prompt transmission of information | 54 |

| First certain information of enemy | 54 |

| Final reports | 55 |

| Negative messages | 55 |

| Use of telegraph and telephone | 55 |

| CHAPTER IV |

|

| ADVANCE GUARDS | 56-69 |

| STRENGTH AND COMPOSITION | 56-58 |

| Advance guards of various organizations | 56 |

| Machine guns | 56 |

| Mounted men. Advance guard cavalry. Duties | 56 |

| Engineers. Signal and sanitary troops | 56-58 |

| Artillery. Field trains | 57-58 |

| Splitting organizations to form advance guard | 57 |

| Leading troops | 57 |

| Removal of obstacles to the march | 58 |

| THE START—DETAILS OF. Initial point | 58 |

| Route of advance guard | 58 |

| Outpost troops and cavalry | 58 |

| Assembly of field trains | 58 |

| Assembly in column of route. Elongation | 59 |

| ASSEMBLY ORDER | 59 |

| Calculations of times of starting for various organizations | 59 |

| Interference of routes | 59 |

| Subdivisions of advance guard | 60 |

| DISTANCES. How regulated | 60 |

| Cavalry advance guards | 60-63 |

| RECONNAISSANCE | 60-62 |

| Duty of cavalry. Independent and advance cavalry | 60-62 |

| Parallel roads | 61 |

| Flank guards | 61 |

| Mounted point | 61 |

| Method of “offset patrolling,” by infantry | 61 |

| Connecting files | 61 |

| Operations of advance cavalry | 61-62 |

| Communication with neighboring troops | 62 |

| Important features of the terrain | 62 |

| Places of advance guard and supreme commanders | 62 |

| March outposts | 62 |

| Control of means of communication | 62 |

| Civilians not to precede advance guard | 63 |

| Conduct of advance guard on meeting the enemy | 63 |

| Passage of bridges and defiles | 63 |

| OUTLINE OF SOLUTION OF SMALL ADVANCE | |

| GUARD PROBLEMS | 64 |

| EXAMPLES OF ADVANCE GUARD ORDERS | 65-69 |

| CHAPTER V |

|

| REAR GUARDS. FLANK GUARDS | 70-82 |

| STRENGTH AND COMPOSITION OF REAR GUARDS | |

| IN RETREAT | 70-72 |

| Rear guard on a forward march and in retreat | 70 |

| Delaying actions | 70 |

| Reinforcements of rear guard | 70 |

| Outpost troops | 70 |

| Infantry. Cavalry. Artillery | 70-71 |

| Use of motor cars in retreat and pursuit | 71 |

| Engineers—duties in retreat | 71 |

| Machine guns. Signal and sanitary troops | 71 |

| Field trains | 71 |

| Subdivisions of rear guard | 71 |

| Tactical employment of cavalry | 72 |

| DISTANCES—HOW REGULATED. Progress of main body | 72 |

| CONDUCT OF REAR GUARD | 72-75 |

| Contact with enemy. Observation of routes adjacent to line | |

| of march or retreat | 72 |

| Covering the main body | 72-73 |

| Delaying actions of a rear guard | 73 |

| Reinforcement of rear guard | 73 |

| Requirements of a delaying position | 73-74 |

| Use of cavalry, artillery and machine guns in delaying the enemy | 73-74 |

| Withdrawal of outpost | 73 |

| Masking the fire of the delaying position | 73 |

| Use of flank positions for delaying the enemy | 73 |

| Security of line of retreat from delaying position | 73 |

| Advantages of a single determined stand | 74 |

| Keeping rear guard in hand. Simplicity of movements | 74 |

| Latitude allowed rear guard commander | 74 |

| Special patrols from main body | 74 |

| Flank detachments | 74-75 |

| Retreating upon the front of a defensive position | 75 |

| Offensive tactics by rear guards | 75 |

| Supreme commander with rear guard | 75 |

| EXAMPLE OF RETREAT ORDER | 75-77 |

| STRENGTH AND COMPOSITION OF FLANK GUARDS | 78-79 |

| Movements in two columns | 78-79 |

| Cavalry, artillery, machine guns, signal and sanitary troops | |

| and field trains with a flank guard | 78 |

| Wagon trains, routes and escorts. Double column | 78-79 |

| FLANK GUARDS-WHEN REQUIRED | 79-80 |

| Considerations influencing the decision as to use of a flank guard | 79 |

| Examples of use of flank guards | 80 |

| Flank guards with large and small forces | 80-81 |

| Distance between flank guard and main body, obstacles and | |

| communicating routes | 80-82 |

| Convoys, armored autos, auto transport for escort | 80 |

| Cavalry flank guards | 81 |

| CONDUCT OF FLANK GUARDS | 81-82 |

| Formation | 81 |

| Reconnaissance on exposed flank. Contact with enemy | 81 |

| Duty of cavalry with a flank guard | 81 |

| Bringing on a decisive engagement | 81 |

| Communication with other troops. | |

| Relation of flank guard to rear guard | 81-82 |

| Reinforcement of flank guard | 82 |

| Latitude allowed flank guard commander | 82 |

| CHAPTER VI |

|

| MARCHES. CHANGE OF DIRECTION | |

| OF MARCH. CAMPS AND BIVOUACS | 83-94 |

| ARRANGEMENT OF TROOPS ON THE MARCH | 83-84 |

| Marches in peace time | 83 |

| Intermingling of foot and mounted troops | 83 |

| Auto truck trains | 83 |

| Artillery and trains. Protection of long columns of wagons | 83 |

| Handling of trains on the march | 83-84 |

| Separation of trains and troops | 84 |

| Passage of defiles | 85 |

| Alternation of organizations in column on successive days | 85 |

| Advance guards, rear guards and leading troops | 85 |

| Distribution of troops in camp. Camping in column | 85 |

| Independent mission for cavalry. Prospects of combat, | |

| and tactical use of cavalry | 85 |

| Place of the supreme commander | 85-86 |

| Distances between elements in a flank march | 86 |

| TIMES OF STARTING FOR FOOT AND MOUNTED | |

| TROOPS AND TRAINS | 86-87 |

| Early starting | 86 |

| Late arrivals in camp | 87 |

| Night marches | 87-89 |

| Movements by rail | 87 |

| Movements by motor car | 87 |

| TABLE OF TIMES OF SUNRISE AND SUNSET | 88 |

| MANNER OF STARTING THE MARCH | 88-89 |

| Initial point | 88 |

| Regulation of march. End of a day’s march | 89 |

| LENGTH AND SPEED OF MARCHES | 89-90 |

| Forced marches. Marches by green troops. | |

| Progressive increase in length of marches. | |

| Marches by large and small bodies | 89 |

| Halts | 89 |

| Days of rest | 89 |

| Speed of infantry, mixed troops, artillery and trains | 90 |

| TABLE OF RATES OF MARCH OF DIFFERENT ARMS | 90 |

| Elongation | 90 |

| Limiting depths of fords | 90 |

| Selection of route | 90 |

| Effects of temperature on marching troops | 91 |

| Artillery and trains in double column | 91 |

| CHANGE IN DIRECTION OF MARCH | 91-92 |

| Reasons for change of direction. | |

| “Marching to the sound of the guns” | 91 |

| “Containing” a hostile force | 91 |

| Manner of changing direction. Use of a flank guard | 91-92 |

| Safety of trains in changing direction | 92 |

| EXAMPLE OF ORDER FOR CHANGE OF DIRECTION | |

| OF MARCH | 92-93 |

| CAMPS AND BIVOUACS | 93-94 |

| When to bivouac | 93 |

| Time of issue of halt order. | |

| Arrangements for distribution of troops in camp | 93 |

| Requirements of a camp site | 93-94 |

| Assignment with reference to convenience of arrival | |

| and departure. Camping in column | 94 |

| Use of buildings for shelter. Billeting | 94 |

| CHAPTER VII |

|

| CONVOYS | 95-108 |

| Definition of convoy | 95 |

| Vulnerability of a convoy. Limit of size. Straggling | 95 |

| Flank marches by convoys. Moving trains on separate road | 95 |

| General rule for position of covering troops | 95 |

| Subdivisions and dispositions of escort | 95-96 |

| Motor convoys | 96 |

| ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE MARCH | 96-97 |

| Division of wagon train into sections | 96 |

| Classification of wagons-army, hired, impressed | 96 |

| Teamsters and wagonmasters | 96 |

| Order of march | 96 |

| Field train of escort | 96 |

| Police guards, infantry and cavalry | 96-97 |

| Duties of quartermaster in charge of wagons | 96-97 |

| THE ESCORT | 97-100 |

| Commander. Duty of escort | 97-98 |

| Strength and composition of escort | 98-100 |

| Infantry, cavalry, artillery, machine guns, engineers | 98 |

| Motor transport for escort. Armored cars. | |

| Motor cars in pursuit of a convoy | 98 |

| DISTRIBUTION AND DUTIES OF TROOPS | 98 |

| Subdivisions and relative strengths | 98-99 |

| Reconnaissance. Dispersion of fighting force | 99 |

| Position of main body of escort | 99 |

| Infantry in middle of a long column of wagons | 99 |

| Police guards | 99 |

| Advance cavalry and scouting parties | 99 |

| Mounted and dismounted point | 99 |

| Establishing contact with friendly troops in direction of march | 99 |

| Selection of defensive positions and camp sites | 99 |

| Engineers | 99 |

| Flank guards | 99-100 |

| Method of employing the cavalry of the escort | 100 |

| Rear guards. Strength, position, duties | 100 |

| Routes available for the march. Considerations governing the | |

| selection of route. Topography | 100-101 |

| Rate of progress and halts | 101 |

| Position and movements of the enemy | 101 |

| Defensive measures to be adopted. Lines of retreat. | |

| Alternative routes | 101 |

| Localities favorable for the attack of a convoy | 101 |

| Change of direction of march. Precautions | 101-102 |

| Parking the convoy for the night. Measures for the | |

| security of the camp | 102 |

| Change of route in moving back and forth | 102 |

| CONDUCT ON ENCOUNTERING THE ENEMY | 102-103 |

| Halting or parking the convoy prematurely | 102 |

| Localities favorable for defense | 102 |

| Details of defensive operations. Messages to | |

| adjacent friendly troops | 102-103 |

| ATTACK OF A CONVOY | 103 |

| Cavalry, armored cars | 103 |

| Obstacles. Ambuscades | 103 |

| Usual method of attack | 103 |

| Damaging the convoy by long range fire | 103 |

| CONVOYS OF PRISONERS. Strength of escort. Conduct | 104 |

| EXAMPLE OF ORDER FOR THE MARCH OF A CONVOY | 107-108 |

| CHAPTER VIII |

|

| ARTILLERY TACTICS | 109-148 |

| MATERIEL OF LIGHT FIELD ARTILLERY, U. S. ARMY | 109-110 |

| Subdivisions of a battery | 109 |

| Signal equipment. Ammunition | 109 |

| Description of carriage and sights. Weights behind the teams | 109-110 |

| Front covered by fire of a battery | 110 |

| DISPOSITIONS OF ARTILLERY ON THE MARCH. | |

| Combat trains. Field trains. Protection of long columns | 110 |

| Usual dispositions of battery and combat trains in action | 110 |

| Concealment from hostile observation | 110-111 |

| DUTIES OF ARTILLERY PERSONNEL. Artillery commander. | |

| Regimental commander. Battalion commander. | |

| Battery commander. Lieutenants. Reconnaissance officer. | |

| Sergeants and corporals. Scouts, signalers, agents | |

| and route markers | 111-113 |

| Artillery officers with supreme commander and with advance guard | 113 |

| KINDS OF FIRE. Masked and unmasked fire. Defilade. Fire for | |

| adjustment, demolition, registration and effect. Direct | |

| and indirect laying. Salvo fire, continuous fire, volley | |

| fire and fire at will. Time fire and percussion fire. | |

| Area of burst of shrapnel. Fire at single and at successive | |

| ranges, sweeping fire | 113-116 |

| Individual and collective distribution. Adjustment | 116 |

| Firing data. Aiming point | 116 |

| OBSERVATION AND CONTROL OF FIRE | 117-118 |

| Post of officer conducting the fire | 117 |

| Battery commander’s station and auxiliary observing | |

| stations. Location | 117 |

| Aiming points. Location | 117-118 |

| TACTICAL EMPLOYMENT OF FIELD ARTILLERY | 118-128 |

| Covering the front of a defensive position | 118 |

| Considerations governing the dispositions of artillery in attack | 118-120 |

| Position in interval between frontal and enveloping attack. | |

| Position on the flank | 120 |

| Ranges in attack and defense | 120 |

| Mission of the artillery | 120-121 |

| Operations of attacker’s artillery during the combat | 120-121 |

| Dispositions and employment of artillery in defense. | |

| Dagger batteries | 121-122 |

| Advantages enjoyed by defense | 121-122 |

| Firing over heads of friendly troops | 122 |

| Movements to position | 122 |

| Supports for the artillery. Machine guns | 122 |

| Positions and duties of artillery. By whom prescribed | 122 |

| Positions “for immediate action,” “in observation,” and | |

| “in readiness.” Subdivision for action | 122-124 |

| Positions of field and combat trains. Communication | 123 |

| Subdivision of battalions and batteries | 123 |

| Grouping of artillery. Fire control | 124-125 |

| Artillery “reserves.” Number of guns to place in action | 123-124 |

| Positions of ammunition trains | 124 |

| Special tasks and duties of artillery. Counter batteries, | |

| infantry batteries, etc. | 124 |

| “Prepare for action.” “March Order” | 125 |

| Changes of position during action. Why, how and when made. | |

| Economy of ammunition | 125-126 |

| Co-operation of artillery and other arms | 126 |

| Dummy emplacements | 126 |

| Horse artillery | 126 |

| Ranges, targets, ammunition employed, etc. | 126 |

| Oblique, enfilade and frontal fire | 127 |

| Moving across country to position | 127 |

| Supports for the artillery | 127 |

| Ranging and bracketing | 127 |

| ARTILLERY WITH ADVANCE GUARDS, | |

| REAR GUARDS AND OUTPOSTS | 127-128 |

| PROBLEM INVOLVING A BATTERY IN POSITION. | |

| (Duties of personnel. B. C. and auxiliary observing | |

| stations. Limbers and combat trains. Field trains. | |

| Communication. Moving to position, etc., etc.) | 128-130 |

| BATTALION OR LARGER UNIT IN ACTION | 130-132 |

| EMPLOYMENT OF HEAVY FIELD ARTILLERY | 132-136 |

| Heavy field ordnance of U. S. Army. Description, ranges, etc. | 132-133 |

| Organization and methods of fire | 133-135 |

| Tactical employment. Heavy artillery on the march | 133-136 |

| Motor transport | 136 |

| EMPLOYMENT OF MOUNTAIN ARTILLERY | 136-138 |

| Description of materiel. Tactical employment | 136-138 |

| ANTI-AIRCRAFT ARTILLERY | 138-139 |

| Types of guns | 138 |

| Effective ranges | 138 |

| Observation and fire control | 139 |

| Function of anti-aircraft artillery | 139 |

| REMARKS CONCERNING THE TACTICAL EMPLOYMENT | |

| OF LIGHT FIELD ARTILLERY | 139-143 |

| Subdivision of battalions | 140 |

| Positions for artillery and combat trains | 140 |

| Concealment and covered approach to position | 140-141 |

| Positions between frontal and enveloping attacks | 140 |

| Positions for direct fire | 140 |

| Flash defilade | 140 |

| Ranges | 141 |

| Movements of artillery daring an action | 141 |

| Elimination of “dead space” | 141 |

| Reconnaissance | 141 |

| Battery commander’s station | 141 |

| Use of shrapnel and shell. Ranging | 141 |

| The artillery duel. Firing over heads of infantry | 141 |

| Proper targets for artillery. Co-operation with other arms | 141 |

| Place of artillery commander | 142 |

| General positions for artillery in attack and defense | 142 |

| Orders and instructions to artillery. | |

| What to include and what to omit | 142-143 |

| CHAPTER IX |

|

| CAVALRY TACTICS | 144-169 |

| USES OF CAVALRY IN CAMPAIGN SUMMARIZED | 144 |

| Improper uses of cavalry. Division of the cavalry forces | 144 |

| Conservation of energies of men and horses. Night work | 144 |

| Wagons and pack trains with cavalry | 144-145 |

| Artillery, signal troops and mounted engineers with cavalry | 145 |

| Discretionary powers of the cavalry commander and nature | |

| of the instructions to be given him | 145-146 |

| Cavalry in masses seeks hostile cavalry | 146 |

| ARMY AND DIVISIONAL CAVALRY. Duties | 146 |

| Cavalry with advance, rear and flank guards, | |

| outposts and detachments | 147 |

| Cavalry in delaying actions | 147 |

| Independent cavalry. When employed | 147-148 |

| Principal duties of the independent cavalry. | |

| Range of its operations. | |

| Return to main camp at night | 148 |

| Contact with the enemy. Reports | 148 |

| Functions of cavalry and aeronautical services | 149 |

| Overthrow of hostile cavalry. How accomplished | 149 |

| Cavalry screen | 149 |

| Contact squadrons and strategic patrols | 149-150 |

| Means of transmitting information. Relay and collecting stations, | |

| etc. Field wireless equipment, automobiles, motorcycles, etc. | 150 |

| CAVALRY IN COMBAT | 150-160 |

| Methods of offensive action. Mounted charge, | |

| mounted and dismounted fire action | 150-151 |

| Dismounted fire action, when employed | 151 |

| Advantages of remaining mounted. Mounted reserve | 151-152 |

| Mounted reconnaissance | 152 |

| Horse holders. Mobility and immobility of horses. Coupling | 152 |

| Time required to dismount and to mount | 152 |

| Horse artillery, machine guns and mounted engineers | |

| with cavalry. Functions | 152-153 |

| Training of cavalry for pioneer work | 153 |

| CAVALRY vs. INFANTRY | 153-155 |

| Mounted attack on infantry, when practicable | 153 |

| The element of surprise | 153 |

| Dismounted action | 153 |

| Turning movements by cavalry. Delaying actions. Successive | |

| positions. Harrassing the flanks of a pursuing enemy | 153 |

| Mounted reserves and combat patrols | 154 |

| Security of led horses | 154 |

| Requirements of a delaying position | 154 |

| Time to withdraw. How close enemy may be allowed to | |

| approach. Provisions for withdrawal | 154-155 |

| CAVALRY vs. CAVALRY | 155-160 |

| Mounted action and element of surprise | 155 |

| Recall of detachments | 155 |

| Preparations for the charge | 156 |

| Ground scouts and combat patrols | 156 |

| Protection of the flanks | 156 |

| Dismounted fire action in support of mounted action. | |

| Machine guns and artillery fire | 156-157 |

| Division of troops for mounted action. Formations and gaits | 157-158 |

| Approach to position | 157-158 |

| Formation for and delivery of charge. The rally | 158 |

| Duties of support, reserve and dismounted troops | 158-159 |

| Distance at which charge should be launched | 159 |

| Wheeled vehicles and pack trains during combat | 159 |

| Carriage of extra ammunition and rations | 159 |

| Most favorable times for attacking cavalry, mounted | 159-160 |

| SOLUTION OF PROBLEMS IN CAVALRY COMBAT, FOR | |

| SMALL FORCES. Procedure and orders | 160-164 |

| THE CAVALRY SCREEN | 164-165 |

| Position and duties of cavalry screen | 164-165 |

| Offensive and defensive screens | 165 |

| Front covered by screen | 165 |

| Daily marching rates of cavalry and patrols | 165 |

| CAVALRY PATROLS | 165-166 |

| Classification and functions | 165-166 |

| Reconnoitering and screening patrols. | |

| Tactical and strategical patrols | 165-166 |

| Nature of information gathered. Distances from supporting | |

| troops, radii of action | 165-166 |

| Combat by patrols | 166 |

| Strength of patrols | 166 |

| LESSONS IN CAVALRY TACTICS FROM | |

| THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR | 166-169 |

| CHAPTER X |

|

| OUTPOSTS | 170-203 |

| DUTIES OF THE OUTPOST | 170 |

| Outpost in advance and retreat, how detailed | 170 |

| STRENGTH AND COMPOSITION | 170-174 |

| General rule for strength of outpost | 170 |

| Considerations influencing the decision as to the strength | |

| of an outpost | 170-171 |

| Front covered by a battalion as a support | 171 |

| Outposts in close and in open country. Influence of roads | 171 |

| Cavalry and other mounted troops on outpost. | |

| Effect on strength of infantry outpost | 171-172 |

| Proportions of cavalry and infantry on outpost | 172 |

| Apportioning the burden of outpost duty | 172 |

| Duties and assignments of mounted troops on outpost | 172 |

| Artillery, machine guns, engineers, signal and sanitary troops | |

| on outpost | 172-173 |

| Distribution of the elements of a large command in camp | 173 |

| Outposts of small commands | 174 |

| Use of cavalry for the security of a stationary command | 174 |

| Organization of a cavalry outpost | 174 |

| INTEGRITY OF TACTICAL UNITS, how preserved | 175 |

| Strength of supports, pickets, sentry squads and cossack posts | 175 |

| Assignment of patrols | 175 |

| LOCATION OF OUTPOST | 176-177 |

| Selection of camp site and outpost line | 176 |

| Distance at which enemy must be held | 176 |

| Line of resistance. Obstacles in front of position. | |

| Security of the flanks | 176 |

| Outpost on the line of a river | 176 |

| Influence of roads on disposition of outpost. | |

| Rule for general guidance | 176-177 |

| Contact with enemy | 177 |

| Special mounted patrols | 177 |

| Regimental sectors of an outpost line | 177 |

| LIMITS OF FRONT OF AN OUTPOST | 177-178 |

| Line of resistance | 178 |

| Security of the flanks. Detached posts | 178 |

| Interior guards | 178 |

| DISTANCES AND INTERVALS IN AN OUTPOST | 179-180 |

| Relative positions of reserve, supports and outguards | 179 |

| Position of outpost or advance cavalry | 179 |

| Depth of the outpost | 179 |

| Intervals between adjacent groups | 179-180 |

| Bivouac in line of battle | 180 |

| Guarding the line of a stream. Bridge heads | 179-180 |

| THE RESERVE. Post. Camping arrangements. | |

| Cavalry and mounted men. Artillery. Field trains | 180-181 |

| Field trains of the supports | 181-182 |

| THE SUPPORTS. Strength and composition | 181 |

| Patrolling. Assignment of the cavalry of an outpost | 181-182 |

| Stations of supports. Influence of roads | 182 |

| Support sectors | 182 |

| Selection and preparation of defensive positions | 182-183 |

| Machine guns. Company wagons of supports | 182 |

| Fires, tent pitching, meals, etc. | 183 |

| Number of supports from one reserve | 183 |

| Numerical designation of supports | 183 |

| OUTGUARDS AND SENTINELS | 183-184 |

| Disposition of outguards. Influence of roads | 183 |

| Classification of outguards. Numerical designation | 183 |

| Strength of outguards | 183 |

| Intrenching, meals, concealment | 184 |

| Reliefs for sentinels and patrols | 184 |

| Examining posts | 184 |

| Communications within the outpost. Clearing and marking routes | 184 |

| OUTPOST PATROLS | 184-187 |

| The cordon and patrol systems of outpost | 184 |

| Reconnoitering patrols. Strength and composition. | |

| Radius of action. Functions | 185 |

| Special information patrols | 185 |

| Visiting patrols. Strength. Radius of action | 185-186 |

| Reliefs for patrols | 186 |

| Patrolling during the day | 186 |

| Patrols from the reserve | 186 |

| Patrolling by supports. Mounted men | 186-187 |

| Patrolling by pickets | 187 |

| Night signals | 187 |

| DAY AND NIGHT POSITIONS AND DUTIES OF | |

| ELEMENTS OF AN OUTPOST | 187-189 |

| Posting of reserve, supports, outguards and sentinels. | |

| Patrolling by day and by night | 187-188 |

| Preparation of defensive positions. Reconnaissance | 187 |

| Times for assuming day and night positions | 187 |

| Time of relief of outpost | 188 |

| Position and duties of advance cavalry by day and by night | 188-189 |

| Independent cavalry | 189 |

| Standing patrols | 189 |

| Cavalry patrolling on the flanks of an outpost | 189 |

| CAVALRY OUTPOSTS. Organization. Patrolling. | |

| Disposition of horses | 189-190 |

| MARCH OUTPOSTS. Duties of cavalry | 190-191 |

| OUTPOST ORDERS | 191-192 |

| Issue of halt order | 191-192 |

| Orders of advance guard and outpost commanders | 191 |

| ESTABLISHING THE OUTPOST | 191-193 |

| Selection of camp site | 191 |

| Use of maps | 192 |

| Inspection of terrain by advance guard and outpost commanders | 192 |

| Inspection of outpost dispositions | 193 |

| Demolitions, obstacles, etc. | 193 |

| OUTPOST SKETCHES AND TABLES | 193-196 |

| OUTLINES OF HALT AND OUTPOST ORDERS | 196-199 |

| VERBAL OUTPOST ORDER FOR A SMALL COMMAND | 199-200 |

| ADVANCE GUARD COMMANDER’S HALT | |

| AND OUTPOST ORDER | 200-202 |

| OUTPOST COMMANDER’S FIRST ORDER | 202-203 |

| CHAPTER XI |

|

| COMBAT. ATTACK AND DEFENSE | 204-247 |

| GENERAL OBSERVATIONS | 204-205 |

| Offensive and defensive tactics | 204 |

| Raw troops, how utilized | 204 |

| Passive defense—when to be adopted | 204 |

| Fire superiority keynote of success | 204 |

| Dispersion, complicated movements, half-hearted measures | 204 |

| Uncovering the line of retreat and main body | 204-205 |

| Concentration of forces. Detachments—when permissible | 205 |

| Containing and covering forces | 205 |

| Night attacks. Night movements—when advisable | 205 |

| Examination of terrain preliminary to attack. Use of maps | 205 |

| Attacks offering no chance of success | 205 |

| Reconnaissance during an action | 205 |

| Integrity of tactical units | 205 |

| FORMS OF ATTACK | 205-209 |

| Advantages and disadvantages of frontal and of | |

| enveloping attacks | 206 |

| Considerations influencing the decision as to form | |

| and direction of attack | 206-207 |

| Considerations influencing selection of | |

| flank to be enveloped | 207 |

| Best dispositions for attacking infantry the | |

| primary consideration | 207 |

| Envelopment of both hostile flanks | 207 |

| Combined frontal and enveloping attacks | 208 |

| Relative strengths of frontal and enveloping attacks | 208 |

| Density of firing line in attack | 208 |

| Strength of supports | 208 |

| Envelopment to be provided for in first deployment | 208 |

| Convergence of fire. Separation of frontal and enveloping attacks | 209 |

| ADVANCING TO THE ATTACK. | |

| Formation in approaching the position | 209 |

| Establishment of fire superiority | 209 |

| Conjunction of movement | 209 |

| Cover for advancing troops. Contact during advance | 209 |

| ASSIGNMENT OF FRONTS | 210-211 |

| Covering the defender’s line | 210 |

| Landmarks and guiding points. Routes | 210 |

| Extension of defender’s line to meet enveloping attack | 210 |

| Orders to the attacking columns | 210-211 |

| RESERVES | 211-212 |

| Need for reserves. The influence of their judicious use | |

| on the course of the action | 211 |

| Concentration of force at critical point | 211 |

| Relative strength of reserves in attack and in defense | 211 |

| Battalion supports. Regimental and brigade reserves | 211 |

| Employment of local reserves | 211 |

| Supports and reserves in defense. Position of the reserves. | |

| Division of reserves | 211 |

| Distances of supports and reserves from firing line | 212 |

| PROTECTION OF THE FLANKS | 212-214 |

| Necessity for protecting the flanks. Means employed | 212 |

| Obstacles and field of fire | 212 |

| Cavalry and mounted men on the flanks | 212 |

| Infantry flank combat patrols. Strength and duties | 212-213 |

| Duty of flank organization in providing protection | 213 |

| Supreme commander’s orders for flank protection | 213 |

| Reconnaissance to the front | 213 |

| Strength of flank combat patrols | 213-214 |

| Ammunition in combat trains. When and by whom issued. | |

| Time required for issue. Disposition of empty wagons | |

| of combat trains | 214 |

| Ammunition trains | 214 |

| Amount of ammunition available. How carried on the march | 214 |

| Expenditure of ammunition in attack and defense. | |

| Long range fire in attack and in defense | 214-215 |

| Economy of ammunition | 215 |

| INTRENCHMENTS, OBSTACLES, ETC. | 215-217 |

| Intrenchments in attack and in defense. | |

| Time required for construction. | |

| Objects of intrenchments in defense | 215-216 |

| Location and construction of firing and of support trenches. | |

| Communicating trenches | 216 |

| Duties of engineers in intrenching, removal of obstacles, etc. | 216 |

| Obstacles, nature and effect. Artificial obstacles | 216-217 |

| Location of obstacles | 217 |

| Obstacles to be covered by fire of defense | 217 |

| Measuring and marking ranges | 217 |

| FRONTAGES IN ATTACK AND IN DEFENSE | 217-219 |

| Density of the firing line. Strength of supports and reserves | 219 |

| THE ATTACK OF A POSITION BY A SMALL | |

| INFANTRY FORCE | 219-225 |

| Disposal of trains | 220 |

| Examination of terrain | 220 |

| Orders to subordinates | 220 |

| ATTACK ORDER FOR A SMALL FORCE | 220-223 |

| Routes to position | 223 |

| Issues of ammunition | 223 |

| Description of localities | 223-224 |

| Hostile artillery fire | 224 |

| Hostile reinforcements | 224 |

| Designation of enemy’s line | 224 |

| Engineers, signal and sanitary troops in attack | 224 |

| Dressing stations and slightly wounded stations | 224-225 |

| REMARKS CONCERNING AN ATTACK BY A | |

| REINFORCED BRIGADE | 225-228 |

| Reconnaissance and preliminary orders of the commander | 225 |

| Locating the enemy’s flanks | 226 |

| Considerations prior to attack | 226 |

| Assignment of regiments | 226-227 |

| Conjunction of holding and enveloping attacks | 227 |

| Provisions for the protection of the flanks | 227 |

| Duties of cavalry prior to and during the action | 227 |

| Dispositions of attacking artillery | 227-228 |

| Reserve, station and functions | 228 |

| Engineers, signal and sanitary troops and trains during the | |

| attack. Dressing stations. Empty ammunition wagons | 228 |

| Station of the supreme commander during the action | 228 |

| REMARKS CONCERNING ADVANCE GUARD ACTION | 228-230 |

| Occasions for committing the advance guard to action | 228-229 |

| Considerations influencing the decision as to action to be taken | |

| on meeting the enemy. Mission of the command as a whole | 229 |

| Advantages of frontal attack by advance guard | 229 |

| Pursuit of a defeated enemy | 229-230 |

| Supreme commander with advance guard | 230 |

| THE OCCUPATION OF A DEFENSIVE POSITION | 230-236 |

| Considerations prior to the occupation of a defensive position. | |

| Requirements of a position | 230-231 |

| Position in readiness, when to be assumed | 231 |

| Positions farther to front or rear. Rencontre engagements | 231 |

| Time that small forces can maintain themselves against larger | 231-232 |

| Effect of improvements in weapons on power of defense | 232 |

| Delaying and decisive actions | 232 |

| Posts of artillery in defense | 232 |

| Obstacles in front of position. Passages for counter attack | 232 |

| Probable direction of hostile attack. Posting the reserve | 232 |

| Division of defensive line into sections and assignment of troops | 232-233 |

| Use of machine guns in defense | 232-233 |

| Openings in the line | 233 |

| Detailed organization of sectors or sections | 233 |

| Density of firing line. Influence of terrain | 233 |

| Employment of large reserves in defense | 233 |

| Long range fire in defense | 233 |

| Delaying actions. Cavalry in delaying actions | 233 |

| Marking ranges and clearing field of fire | 233-234 |

| Preparation of position for defense | 234 |

| Disposal of empty wagons of combat trains | 234 |

| Direct fire by artillery in defense | 234 |

| Duties of the cavalry | 234 |

| Security to the front during the preparation and occupation | |

| of the position | 234 |

| Machine guns. “Dagger” batteries | 234-235 |

| Flank combat patrols. General and special measures for the | |

| security of the flanks | 235 |

| Security of the lines of retreat | 235 |

| Employment of reserves and engineers in the preparation | |

| of the position | 235 |

| Dressing station | 235 |

| Strong reserves characteristic of active defense | 235 |

| Advanced posts and advanced positions | 235 |

| THE COUNTER ATTACK | 236-238 |

| Eventual assumption of offensive | 236 |

| Employment of the general reserve | 236 |

| Concealment of troops for counter attack | 236 |

| Time and manner of delivering the counter attack | 236-237 |

| Supporting points in rear of line | 237 |

| Artillery of defense | 237 |

| Selection of terrain to favor counter attack | 237 |

| Suggestions as to the conduct of an active defense | 237-238 |

| Aggressive employment of large reserves by defense | 237 |

| Most favorable opportunity for a counter-stroke | 238 |

| ORDER FOR A FRONTAL ATTACK BY AN | |

| ADVANCE GUARD | 238-242 |

| ORDER FOR AN ENVELOPING ATTACK BY | |

| A REINFORCED BRIGADE | 243-244 |

| ORDER FOR THE OCCUPATION OF A | |

| DEFENSIVE POSITION | 244-247 |

| CHAPTER XII |

|

| THE ORGANIZATION OF A DEFENSIVE POSITION | 248-276 |

| Field and permanent fortification | 248 |

| Defensive principles applicable to portions of an extended line | 248 |

| Small forces in intrenched positions | 248 |

| PRINCIPAL REQUIREMENTS OF A DEFENSIVE POSITION | 248-249 |

| The rôle of field fortifications | 248-249 |

| Selection of the general line from a map | 249 |

| Study of details on the terrain | 249 |

| Reconnaissance by supreme and subordinate commanders | 249 |

| Necessity for an examination of the position from | |

| the enemy’s point of view | 249-250 |

| Matters to be considered in the organization of a defensive position | 250 |

| Field of fire for the infantry | 250 |

| Utilization of natural advantages of the terrain | 250-251 |

| Thin defensive lines. Dummy trenches | 251 |

| Location and disposition of the fire trenches | 251 |

| Offsets, re-entrants and salients | 251 |

| SUPPORTING POINTS. Location with reference to the terrain | 251-252 |

| Closed works and rifle trenches in field fortification | 252 |

| Development of frontal and cross fire | 252 |

| Covering the foreground with fire. Expedients by which this | |

| may be accomplished | 252-253 |

| Cross fire of adjacent supporting points. | |

| Distribution of trenches. Removal of obstructions to | |

| fire. Construction of obstacles to enemy’s advance | 252-253 |

| Traverses. Head cover. Grenade nets. Concealment of trenches | 253 |

| Intervals in the defensive line. Discontinuity of trenches | 253-254 |

| Defensive lines in close country | 254 |

| Division of front into sections or sectors | 254 |

| Relative strength of firing line, supports and reserves | 254 |

| Purpose of field fortifications. Misuse thereof | 254-255 |

| Supporting points by whom organized | 255 |

| Portable and park tools | 255 |

| DETAILS IN THE ORGANIZATION OF A | |

| REGIMENTAL SECTOR | 255 |

| DETAILS IN THE ORGANIZATION OF A BATTALION | |

| SUPPORTING POINT | 255-256 |

| Relative importance of different tasks | 256-257 |

| Relative importance of near and distant fields of fire | |

| under various conditions | 257 |

| Distance of battalion supports behind the firing line | 257 |

| Natural cover. Support and communicating trenches | 257 |

| Utilization of natural features | 257 |

| Posts and duties of and cover for reserves | 257 |

| Division of reserves | 257 |

| Position fire by supports and local reserves | 257-258 |

| Study of ground in location of trenches. Avoidance of | |

| unnecessary labor | 258 |

| Removal of trees from field of fire. Filling ravines and hollows | 258 |

| Blending the works with the terrain for concealment | 258 |

| Employment of engineers. Demolitions, obstacles, communications, | |

| measuring ranges, head and overhead cover, observing stations, | |

| splinter-proofs, works in the second line of defense, etc. | 258 |

| Division and assignment of engineer troops. Tasks of engineers, | |

| by whom indicated | 258-259 |

| Provisions for security to front and flanks during the organization | |

| of the position | 259 |

| Location of artificial obstacles. Distance in front of firing line | 259 |

| ORGANIZATION OF THE FLANKS | 259-260 |

| Protection of the flanks, natural obstacles, fortifications and reserves | 259 |

| Flanks “in the air” | 259 |

| Refusing the line to provide security for a flank | 260 |

| Echeloning trenches to the rear on a flank | 260 |

| Concealment of works. Utilization of natural features of the terrain | 260 |

| TABLE OF PERSONNEL, TIME AND TOOLS REQUIRED FOR VARIOUS | |

| TASKS IN CONNECTION WITH FIELD FORTIFICATION | 261 |

| Character of soils | 261 |

| Simple standing and completed standing trenches | 261 |

| Size of individual tasks. Reliefs for workers | 261-262 |

| BRITISH EXPERIENCES IN TRENCH WARFARE | 262-266 |

| Concealment of trenches from hostile artillery | 262 |

| Limited field of fire better than loss of concealment | 262 |

| Concealment of obstacle | 262 |

| Accuracy of modern artillery fire | 262 |

| Narrow and deep trenches | 262 |

| Position of support trenches | 262 |

| Communicating trenches | 262-263 |

| Parados. Dummy parapets | 263 |

| Recesses under parapet. Ceiling | 263 |

| Head and overhead cover. Loopholes | 263 |

| Night attacks | 263 |

| Frontal and cross fire. Straight trenches | 263 |

| Dressing stations. Latrines. Drainage | 263-265 |

| Machine guns | 265 |

| Cover and concealment for reserves | 265 |

| Barbed wire entanglements. Concealment | 265 |

| Repair of obstacles. Supports for wire | 265 |

| Illumination | 265 |

| Echeloned trenches on the flanks | 265 |

| Conspicuous features of field fortifications as seen by aeronauts | 265-266 |

| Resemblance of modern trench warfare to siege operations | 266 |

| Power of defense of modern weapons | 266 |

| Need for artillery support | 266 |

| The guiding principles of field fortification | 266-267 |

| PRACTICAL PROBLEMS IN FIELD FORTIFICATION, | |

| WITH SOLUTIONS | 267-276 |

| CHAPTER XIII |

|

| COMBAT-ATTACK AND DEFENSE OF A RIVER LINE, WITHDRAWAL FROM ACTION, RENCONTRE, DELAYING ACTION, PURSUIT, NIGHT ATTACKS, MACHINE GUNS |

277-307 |

| Mountain ranges, deserts and rivers as obstacles | 277 |

| ATTACK AND DEFENSE OF A RIVER LINE | 277-288 |

| Use of existing bridges and fords, hasty bridges and ferries | 277-278 |

| METHODS OF ATTACK OF A RIVER LINE. Turning movement. | |

| Turning movement combined with holding attack. | |

| Frontal attacks at one or more points | 278-279 |

| Object of feint attack | 279 |

| Conditions to be fulfilled by feint | 279-280 |

| Conditions to be fulfilled by main attack | 280-281 |

| Necessity of deceiving the defender | 281 |

| Counter attack by the defender | 281 |

| CONDUCT OF THE ATTACK | 281-283 |

| Reconnaissance. Seizure of bridges | 281 |

| Outpost troops, cavalry and artillery | 281-282 |

| Time for attack. Night movements | 281 |

| Camping prior to attack | 281 |

| Artillery positions in attack of a river line | 281-282 |

| Machine guns. Position fire by infantry | 282 |

| Duties of the outpost | 282 |

| Launching the feint and main attack | 282 |

| Demonstrations on flank by cavalry. Pursuit | 282 |

| Position of reserve | 283 |

| Engineer reconnaissance. Construction of crossings | 283 |

| DEFENSE OF A RIVER LINE | 284 |

| General dispositions for and essential elements of a river line defense | 284 |

| Alternative plans for defense. Counter attacks | 284 |

| Prompt detection of enemy’s intentions | 284 |

| Need of mobile reserves | 284 |

| Aerial reconnaissance | 284 |

| ORDERS FOR ATTACK OF A RIVER LINE | 285-288 |

| WITHDRAWAL FROM ACTION | 288-295 |

| Occasions for withdrawal | 288 |

| Difficulty of withdrawing troops committed to an action | 288-289 |

| Sacrifice of a portion of the command to save the remainder | 289 |

| Withdrawal under cover of darkness | 289 |

| Intrenching the advanced position in attack | 289 |

| Removal of trains, ambulance company and wounded | 289 |

| Requirements of supporting position to be occupied by the reserves | 289-290 |

| Masking fire of supporting position | 290 |

| Flank positions | 290 |

| Long range fire. Cover. Getaway | 290 |

| Distance to rear of supporting position | 290 |

| Artillery fire during withdrawal. Withdrawal of artillery. | |

| Ammunition trains | 291 |

| General rule for withdrawal | 291 |

| Order of withdrawal of troops and conditions influencing same | 291 |

| Rendezvous positions for retiring troops | 292 |

| Stream crossings | 292 |

| Utilization of several lines of retreat | 292 |

| Successive supporting positions to cover withdrawal | 292 |

| Formation of and troops for rear guard | 292 |

| Cavalry and signal troops | 292-293 |

| Transmission of orders | 293 |

| EXAMPLES OF VERBAL ORDERS FOR A WITHDRAWAL | |

| FROM ACTION | 293-295 |

| RENCONTRE OR MEETING ENGAGEMENT | 295-297 |

| Advantages of prompt action. Seizing the initiative | 295 |

| Reconnaissance prior to attack | 295 |

| Greatest possible force to be launched at enemy | 296 |

| Direction of deployment and of attack. Machine guns and artillery | 296 |

| General duties of an advance guard. Proper strength and | |

| distance from main body | 296-297 |

| Maneuvering zone for main body | 296 |

| Place of the supreme commander on the march | 297 |

| DELAYING ACTION | 297-300 |

| Offensive and defensive tactics in delaying actions | 297 |

| Use of long thin lines and weak supports | 297 |

| Necessity for a secure line of retreat | 297 |

| Delay of enemy, how accomplished | 297 |

| Necessity for good field of fire at mid and long ranges | 297-298 |

| Occupation of the geographical crest | 298 |

| Relative difficulty of withdrawing infantry and cavalry | 298 |

| Deceiving the enemy as to the strength of the position. | |

| Risk involved | 298 |

| Assumption of the offensive. Obstacles | 298-299 |

| Number of successive positions to be occupied | 299 |

| Advantages of a determined stand | 299 |

| Danger of decisive engagement | 299 |

| Selection and preparation of delaying positions | 299 |

| Tendency of troops to break straight to rear | 299 |

| Flank positions. Distance between positions. | |

| Step by step defensive. Rallying | 299 |

| Demolitions. Ambuscades | 299 |

| Line of an unfordable stream as a delaying position | 300 |

| Seizure of a position well to the front. Orderly occupation | |

| of the position | 300 |

| Artillery and machine guns in delaying actions | 300 |

| Issue of ammunition for delaying actions | 300 |

| PURSUIT | 300-302 |

| Energetic pursuit necessary to reap fruits of victory | 300 |

| Fresh troops necessary for pursuit | 301 |

| Prompt initiation of pursuit | 301 |

| Cavalry, horse artillery and motor cars | 301 |

| Continuous contact with enemy | 301 |

| Gaining the flanks and rear | 301 |

| Seizure of bridges and defiles | 301 |

| Pursuit on a broad front | 301 |

| ORDER FOR A PURSUIT | 301-302 |

| NIGHT ATTACKS | 302-304 |

| Essential features of night attacks | 302-303 |

| Simplicity of plan | 303 |

| Importance of preliminary reconnaissance | 303 |

| Infantry, cavalry and artillery in night attacks | 303 |

| Badges and watchwords | 303 |

| Depth of attacking formations. Formed reserves | 303 |

| Night attacks by large and by small forces | 303 |

| Assembly for attack | 303 |

| Precautions to insure surprise of the enemy | 303-304 |

| Point of attack. False attacks and demonstrations | 304 |

| Rendezvous for assembly after the attack | 304 |

| Collection of scattered forces in case of failure | 304 |

| Time for delivery of attack | 304 |

| Night attack of a bridge head | 304 |

| Protection against night attacks. Field of fire | 304 |

| Artificial illumination. Alarm signals. Obstacles. Close ranges for fire | 304 |

| Use of the bayonet. Machine guns | 304 |

| MACHINE GUNS. | 304-307 |

| Extensive use in modern warfare | 304 |

| Effective ranges and rates of fire. Need for skilled operators | 304-305 |

| Pack and motor transport | 305 |

| Chief purpose of machine guns | 305 |

| Ammunition supply. Most favorable targets | 305 |

| Artillery vs. machine guns | 305-306 |

| Offensive and defensive use. Mobility | 305-306 |

| Immobilization of machine guns | 305 |

| Dispersion of guns | 306 |

| Supports for machine guns | 306 |

| SPECIAL CASES IN WHICH MACHINE GUNS MAY BE | |

| EFFECTIVELY EMPLOYED | 306-307 |

| CHAPTER XIV |

|

| A POSITION IN READINESS | 308-317 |

| When to assume a position in readiness. Examples | 308 |

| CONSIDERATIONS PRIOR TO THE OCCUPATION OF A | |

| POSITION IN READINESS | 308-309 |

| Cross roads. Cover. Lines of retreat | 309 |

| Reconnaissance of enemy and his possible lines of approach | 309 |

| Intrenching. “Framework” of position | 309-310 |

| Influence of ill-advised intrenchments | 309-310 |

| Posts of the artillery and combat trains. Firing data | 310 |

| Concentration of the forces. Advanced posts | 310 |

| Obstacles in front of the position | 310 |

| Duties of the cavalry | 311 |

| Security provided by the other arms | 311 |

| Issue of ammunition. Field trains and sanitary troops | 311-312 |

| Security of lines of retreat | 312 |

| Short movements to a position in readiness | 312 |

| ORDER FOR A POSITION IN READINESS WHILE | |

| ON THE MARCH | 312-314 |

| FIRST ORDER FOR A RETREAT, DELAYING THE ENEMY | 314-317 |

| CHAPTER XV |

|

| SANITARY TACTICS | 318-323 |

| SANITARY PERSONNEL AND MATERIEL WITH | |

| COMBATANT TROOPS | 318 |

| GENERAL DUTY OF THE SANITARY UNITS | 318 |

| Capacities of ambulance companies and field hospitals | 319 |

| SANITARY STATIONS DURING COMBAT. | |

| Battalion collecting stations. | |

| Regimental aid stations. Dressing stations. | |

| Slightly wounded stations. Location, duties, etc. | 319-320 |

| POLICE OF THE BATTLEFIELD. Transportation of wounded | 321-322 |

| CHAPTER XVI |

|

| THE RIFLE IN WAR | 324-336 |

| Location of firing line with respect to geographical and military crests | 324 |

| The skyline | 324 |

| Grazing effect and plunging fire | 324 |

| Firing line in retreat or in delaying actions | 324 |

| Location of supports with respect to firing line | 324 |

| Defilade on reverse slopes. Formations of supports | 324-325 |

| Position fire in attack and in defense | 325 |

| RELATIVE VULNERABILITIES OF DIFFERENT FORMATIONS | |

| UNDER AIMED AND UNDER SWEEPING FIRE | |

| OF SMALL ARMS | 325-326 |

| Effects of oblique and enfilade fire | 326 |

| Squad and platoon columns. Successive thin lines | 326-327 |

| Formations in approaching combat position. Proper time for deployment | 326 |

| Effect of slopes on vulnerability | 326-327 |

| Deployment of squad and platoon columns | 326-327 |

| ADVANCE UNDER SHRAPNEL FIRE | 327-329 |

| Area covered by burst of shrapnel | 327 |

| Vulnerability of lines of skirmishers and of squad columns | 327-328 |

| Effect of oblique and enfilade fire, errors in range, direction and burst | 327-328 |

| Squad columns, when employed | 328 |

| Vulnerability of lines of platoon columns | 328 |

| Use of successive thin lines, advantages and disadvantages | 328-329 |

| Slow, controlled fire. Rapid fire. Volley fire | 329 |

| Maximum and minimum rates of fire | 329 |

| Tendency of troops to fire rapidly | 329 |

| Ranges at which fire is opened in attack and in defense. | |

| Firing on cavalry and artillery | 329-330 |

| Number of rounds to fire. Density of firing line | 330 |

| Effect of visibility of target and prominent landmarks on | |

| dispersion and distribution | 330 |

| Methods of designating and identifying indistinct targets | 330-331 |

| Use of combined sights. Battle sights | 331 |

| Targets for attacker and for defender | 331 |

| Concentration of fire on critical points. How accomplished | 331 |

| Assignment of fronts. Covering the enemy’s line with fire | 331-332 |

| Overlapping and switching fire. Platoon sectors | 331-332 |

| Too great refinement to be avoided | 332 |

| DUTIES OF PERSONNEL IN A FIRE FIGHT. Major. Captain. | |

| Chief of Platoon. Platoon Guide. Squad leader | 332-334 |

| Orders of the Captain | 334 |

| A CATECHISM OF THE RIFLE IN WAR | 334-336 |

| CHAPTER XVII |

|

| DIVISION TACTICS AND SUPPLY | 337-380 |

| MARCHES | 337-344 |

| Length of a day’s march. Marching rate. Rest days | 337 |

| Strength of advance guard. Splitting tactical units | 337 |

| Different arms and auxiliary troops with an advance guard | 337 |

| Position of division commander | 337 |

| Initial point of march and time of departure, in march orders | 337 |

| Rotation of units in position in column during a march | 337-338 |

| Division cavalry on the march. Time of starting. Duty | 338 |

| Distribution of artillery on the march. Artillery with advance guard. | |

| Heavy field artillery. Combat trains of the artillery | 338-339 |

| Artillery with flank guards or in two column formation | 339 |

| Artillery in rencontre engagements. Right of way for firing batteries | 339-340 |

| Engineer troops and bridge trains on the march | 340 |

| Road space and capacities of light and heavy bridge equipage | 340 |

| Distribution and duties of signal troops on the march. | |

| Telegraph and telephone lines | 340-341 |

| Time of starting the march. Details of the start. Assembly of trains. | |

| Escort for trains. March outposts | 341 |

| ORDER FOR THE FORWARD MARCH OF A DIVISION | 342-344 |

| COMBAT | 344-353 |

| Time required for deployment of a division | 344 |

| FRONTAL AND ENVELOPING ATTACKS | 344-345 |

| Separation of attacks. Coordination. Launching the attack. | |

| Obstacles of terrain | 344-345 |

| TURNING MOVEMENTS. Advantages and disadvantages | 345 |

| Plan of attack based on best dispositions of the infantry | 345 |

| Development and attack orders | 346 |

| FRONTAGES FOR DEPLOYMENT OF LARGER UNITS | 346 |

| Timing the advance. Signals | 346 |

| Distance from hostile line at which brigades deploy | 346 |

| Position of reserves | 346-347 |

| Depth of deployment. Distribution in depth | 347-349 |

| CONSIDERATIONS INFLUENCING DEPTH OF DEPLOYMENT | 348 |

| Dispositions of artillery | 349 |

| Release of trains on entering combat | 349 |

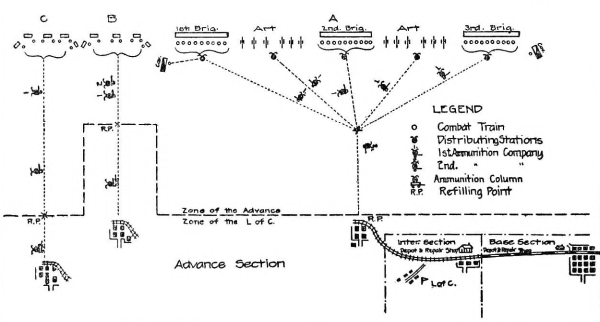

| Posts of artillery and small arms ammunition | 349 |

| Sanitary and engineer trains | 349 |

| Ambulance companies and field hospitals. Stations and duties | 349-350 |

| Messages during combat | 350 |

| DUTIES SUBSEQUENT TO COMBAT. Evacuation of wounded. | |

| Police of battlefield. Replenishment of ammunition and rations. | |

| Prisoners. Trains. Instructions to commander of line | |

| of communications | 350-351 |

| ORDER FOR A DIVISION ATTACK | 351-353 |

| CAMPING | 353-360 |

| TACTICAL AND SANITARY REQUIREMENTS OF A CAMP SITE | 353-354 |

| EXAMPLE OF A DIVISION CAMP ILLUSTRATED AND DISCUSSED | 354-356 |

| Routine orders in connection with camp. | |

| Issues, disposal of empty wagons, etc. | 356 |

| ORDER FOR CAMPING AND OUTPOSTING OF A DIVISION | 357-360 |

| SUPPLY | 360-380 |

| AUTHORIZED TRAINS OF A DIVISION | 360-361 |

| Bakery train. Engineer train | 361 |

| SOURCES OF SUPPLY FOR ARMIES IN THE FIELD | 361 |

| Purchase and requisition. Methods | 361-362 |

| Authority of field Commander | 362 |

| Living off the country | 362 |

| Base depot. Advance supply depot. Means of transportation | 362-367 |

| Zone of the advance | 364 |

| Multiple lines of communication | 364 |

| The supply unit | 364 |

| Classes of trains. Ammunition, supply and field trains. | |

| General supply trains. Combat trains | 365-368 |

| Access to trains by troops. Excessive size of trains | 365 |

| Methods of replenishing trains | 366-367 |

| Rations carried by individual soldiers and in trains | 366-367 |

| General supply column. Flying depots and refilling points | 367 |

| Personnel of field transport service | 368 |

| EXAMPLE OF THE SUPPLY OF A DIVISION ON THE MARCH, | |

| WITH DISCUSSION | 368-370 |

| Problem of the supply of an advancing division mathematically illustrated | 370-372 |

| Refilling points. Location | 372 |

| Maintenance of advance supply depot well to the front | |

| Railroads and steamboats | 372 |

| Field bakery on line of communications | 372 |

| GENERAL RULES FOR GUIDANCE OF SUPPLY OFFICERS | 372-373 |

| Supply of Sherman’s army in the Atlanta campaign, | |

| and of Grant’s army in the campaign of '64 | 373 |

| Protection of supply depot | 373 |

| Camping place of division trains. Issues of rations and ammunition | 373-375 |

| Access to trains by troops | 375 |

| Supplies for the cavalry | 375 |

| Arrangement of division trains on the march according to probable needs | 376 |

| Stations of trains during combat | 376 |

| Rates of march of wagon trains | 376-377 |

| Supplies obtained locally | 377-378 |

| Miscellaneous data on supply and transportation | 378-380 |

| Table of rations, kinds, weights, number of rations to an army wagon, | |

| a railroad car, ship’s ton, etc. | 379 |

| CHAPTER XVIII |

|

| AIR CRAFT AND MOTOR VEHICLES IN WAR | 381-390 |

| History of development | 381 |

| Precursors of air craft of today | 381 |

| Aeroplanes and airships | 381 |

| Development of scope in military operations | 381 |

| Tendency to exaggerate importance and minimize limitations | 381 |

| CHARACTERISTICS | 381-383 |

| Aeroplanes, flying radius, speed, carrying capacity, starting and landing, | |

| susceptibility to hostile fire | 381-382 |

| Dependability for immediate service | 381 |

| Machine and engine fragile | 382 |

| Care and repair of aeroplanes. Need of highly trained personnel | 382 |

| Development. Types of craft, destroyers, battleplanes, | |

| artillery spotters, scouts | 382 |

| Equipment. Organization. Motor trucks as tenders | 382 |

| Airships, flying radius, speed, ability to hover over spot, carrying | |

| capacity, effect of rain and darkness | 382-383 |

| Reconnaissance, wireless equipment | 383 |

| Target afforded | 383 |

| Large crews required | 383 |

| Bases of operation | 383 |

| Balloons. Hydroaeroplanes | 383 |

| Armor and armament of aircraft | 383 |

| DUTIES OF AIRCRAFT. Strategic and tactical reconnaissance | 383-384 |

| Verification by actual contact | 384 |

| Prevention of hostile reconnaissance | 384 |

| Direction of artillery fire. Air raids | 384 |

| Messenger and staff duty | 384 |

| PRACTICABLE HEIGHTS FOR OBSERVATION | 384-385 |

| Altitude and speed demanded by reconnaissance | 385 |

| Fire of small arms and anti-aircraft artillery | 385 |

| Use of field glasses | 385 |

| Relative vulnerabilities of airships and aeroplanes | 385 |

| DEFENSIVE MEASURES | 385-386 |

| Command of the air. Tactics of aircraft | 385 |

| Anti-aircraft artillery. Methods of fire | 385-386 |

| POWERS AND LIMITATIONS OF AIR CRAFT | 386 |

| THE MOTOR CAR IN WAR | 387-390 |

| Tactical movements of troops by auto | 387 |

| Facility of loading, dispatch and unloading | 387 |

| Difficulty of interrupting motor transport | 387 |

| Concentration of reserves at critical points | 387 |

| Motor cars in retreat and pursuit | 387 |

| Motor transport for artillery | 387 |

| Armored cars | 387 |

| Overseas operations | 388 |

| Motor cars for staff transportation | 388 |

| Motor trucks for supply. Advantages over animal transport | 388 |

| Motor kitchens | 388 |

| Effect of motor transport on distance of an army from its base | 388 |

| Economic size of motor trucks for supply | 388-389 |

| Use of motor trucks on railroads | 389 |

| Motor ambulances | 389 |

| Service of information. Motor patrols | 389 |

| Motors as adjunct to aero service | 389 |

| Necessity for motor cars in modern war | 389 |

| Employment of motor cars in groups of the same type | 389-390 |

| Animal transport for field and combat trains | 390 |

[Pg 5]

The almost studied indifference of the American people toward reasonable preparation for the contingency of war makes more urgent the duty of all officers or those who hope to become officers, to do all in their power in advance to prepare themselves and those committed to their care for the immense responsibilities that will rest upon them when the storm bursts upon the nation.

The modern theory of war as exemplified in the practice of the so-called military nations, is that all the resources of the state—moral, physical and intellectual—should be at the disposal of the government for use in case of war. War is the most critical condition of the modern state with its highly developed and peculiarly sensitive and vulnerable industrial and commercial systems. For the successful prosecution of a conflict on which the very fate of the nation may depend, every ounce of its strength should be available. The aim is to strike immediately with all the force at the nation’s command. That state is best prepared which can most rapidly bring to bear its resources in men and materials. In this modern theory is involved the principle that every able-bodied male citizen owes to the state the obligation of service. This principle is not incompatible with democratic ideals and is recognized in theory by our own constitution. Personal service to be truly effective must be universal, compulsory and regular. It constitutes the true and only solution of the problem of adequate defense. All other solutions are makeshifts resulting from the attempt to get something without paying the cost. All have been tried again and again by the United States and other countries, and all have invariably been found wanting.

War today is one of the most highly developed of the arts—the field of the expert and the professional. This being the case there is more than ever before a need for adequate preparation in advance of the outbreak of war. The unprepared people or government who now-a-days find themselves on the brink of hostilities with a nation that is trained for the struggle, must expect inevitably to pay a severe national penalty.

The preparation of a nation for war is of two kinds; one of material things, the construction of forts, arsenals, fabrication of weapons, munitions, etc., the other the training of its people. While both are [Pg 6] essential, the latter is the more important, as well as the more difficult to provide. The American people, in fancied security, have steadfastly refused to pass laws or vote funds for adequate military preparation, either in materiel or personnel. It is evident that we regard the risk as insufficient to warrant the insurance, and we prefer to court war and pay its cost in blood and pensions, not to mention the risk of huge indemnities and the loss of valuable territory, national prestige and honor. We insure our own insignificant lives and pitiful possessions but refuse to insure the life of the nation.

The systematic and intelligent progress that has marked our industrial growth has been conspicuously lacking in our military affairs. “Whether we may be willing to admit it or not,” says General Upton, “in the conduct of war we have rejected the practice of European nations and, with little variation, have thus far pursued the policy of China.”

As to the amount of the risk involved in our policy of national defense or, as some would say, our lack of policy, it has increased by leaps and bounds with the constantly augmented military strength of the other great nations of the earth. This strength is hundreds of times as great as in the days of our thirteen colonies. The seas, which we have hitherto regarded as barriers for our protection, are today favorable avenues for the transport of troops and materials. As to the imminence of the risk we may gain an insight from contemplation of the present situation in Europe, and consideration of the effect of our vast undefended territory and wealth upon the envy and cupidity of other powerful states less fortunately situated than ourselves.

Preparedness for national defense, says Hudson Maxim, is simply a quarantine against the pestilence of war.

The best training for war is, of course, the actual experience of warfare; but for practical purposes this school is too limited to be of much assistance to the actors in person. If a reasonable period of peace intervenes between wars the actors of one war are to a very limited extent only, those having experience of the previous conflict. Even the general lessons of war are too quickly set aside. How little military knowledge has the present generation of Americans to show for the priceless expenditure of the Nation in the unsurpassed school of the Civil War. Wars are fought by the very young men of the country, and this is true not only of the rank and file but also of the majority [Pg 7] of the commanders. The hope of the nation lies therefore, in its youth, and how shall this youth be trained?

The duty devolves upon the older officers. There is no higher mission for older officers in time of peace than the systematic development of the talents of the younger officers entrusted to their care. These young officers will be the leaders in the next great war and the fate of the nation may indeed depend upon them. The nation, therefore, has every right to demand of the superiors that nothing will be left undone that may prepare these youths for the trial. Thus will the superiors be exerting their powerful influence upon the course of the coming war. The methods available are the study of history, working of map problems, and terrain exercises, tactical rides or walks, the war game—all in connection with field maneuvers with troops.