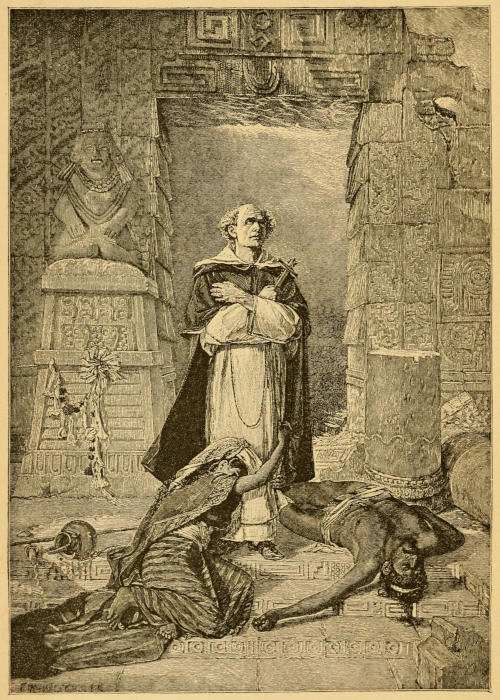

LAS CASAS PROTECTING THE AZTECS.

By Felix Parra.

Title: Old Mexico and her lost provinces

A journey in Mexico, southern California, and Arizona by way of Cuba

Author: William Henry Bishop

Release date: February 7, 2026 [eBook #77881]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Harper & brothers, 1883

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[i]

LAS CASAS PROTECTING THE AZTECS.

By Felix Parra.

[ii]

[iii]

A JOURNEY IN

MEXICO, SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, AND ARIZONA

BY WAY OF CUBA

By WILLIAM HENRY BISHOP

AUTHOR OF “DETMOLD” “THE HOUSE OF A MERCHANT PRINCE” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE

1883

[iv]

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All rights reserved.

[v]

| PAGE | ||

| Part I.—OLD MEXICO. | ||

| I. | By Way of Cuba and the Spanish Main | 1 |

| II. | Vera Cruz | 16 |

| III. | Up the Long Mountain Slope | 24 |

| IV. | The Capital | 37 |

| V. | The Projectors | 54 |

| VI. | The Ferro-carriles | 70 |

| VII. | The Railways at Work | 80 |

| VIII. | The Question of Money, and Shopping | 96 |

| IX. | Social Life, and some Notable Institutions | 107 |

| X. | The Fine Arts and Literature | 120 |

| XI. | Some Traits of Peculiar History, and the Mexican “Warwick” | 134 |

| XII. | Cuatitlan, and Around Lakes Xochimilco and Chalco | 149 |

| XIII. | To Old Texcoco | 162 |

| XIV. | Popocatepetl Ascended | 175 |

| XV. | A Banquet, and a Tragedy, at Cuautla-Morelos | 185 |

| XVI. | San Juan, Orizaba, and Cordoba Revisited | 192 |

| XVII. | Puebla, Cholula, Tlaxcala | 210 |

| XVIII. | Mines and Mining Traits, at Pachuco and Regla | 227 |

| XIX. | A Week at a Mexican Country-house | 245 |

| XX. | On Horseback and Muleback to Acapulco | 263 |

| XXI. | Conversations by the Way with a Colonel | 275[vi] |

| Part II.—THE LOST PROVINCES. | ||

| XXII. | San Francisco | 295 |

| XXIII. | San Francisco (Continued) | 324 |

| XXIV. | The Villas of the Bonanza Kings | 343 |

| XXV. | The Vintage Season, and Monterey | 359 |

| XXVI. | A Wondrous Valley, and a Desert that Blossoms like the Rose | 380 |

| XXVII. | Visalia, Bakersfield, and Life on a Spacious Ranch | 399 |

| XXVIII. | Los Angeles | 421 |

| XXIX. | To San Diego, and the Mexican Frontier | 448 |

| XXX. | Across Arizona | 469 |

| XXXI. | Tombstone | 482 |

| XXXII. | Camp Lowell, Tucson, and San Xavier del Bac | 496 |

[vii]

| PAGE | |

| LAS CASAS PROTECTING THE AZTECS. By Felix Parra | Frontispiece |

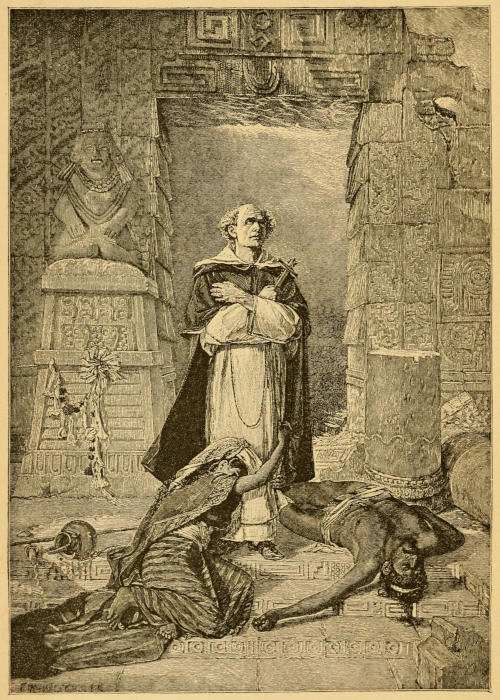

| MEXICO, SHOWING PRESENT AND OLD FRONTIER | 5 |

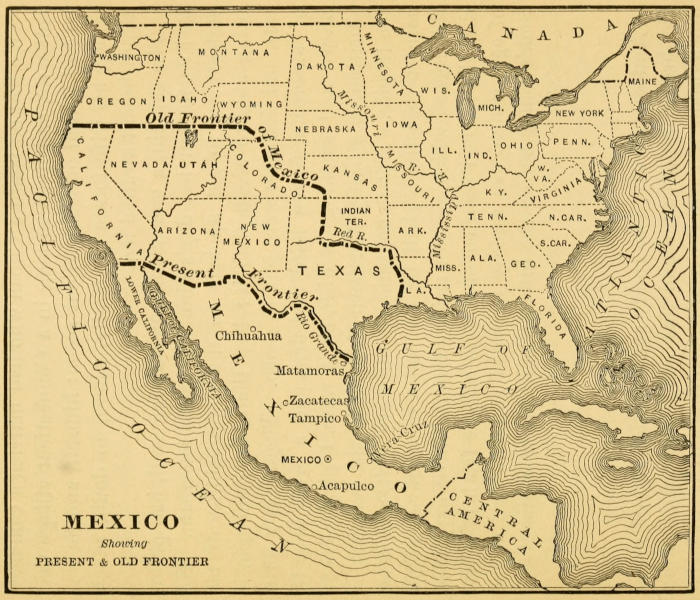

| CATHEDRAL OF MEXICO | 9 |

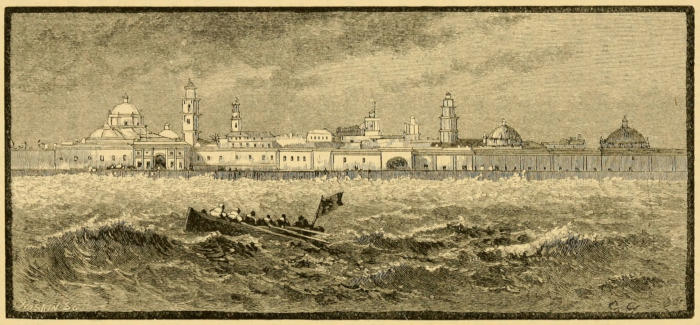

| DOMES OF VERA CRUZ | 17 |

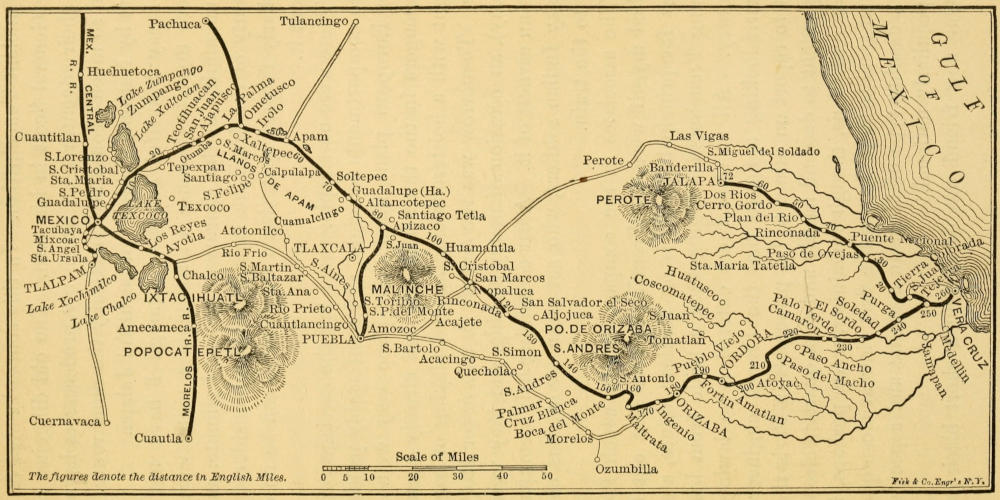

| MAP OF ENGLISH RAILROAD FROM VERA CRUZ TO MEXICO | 25 |

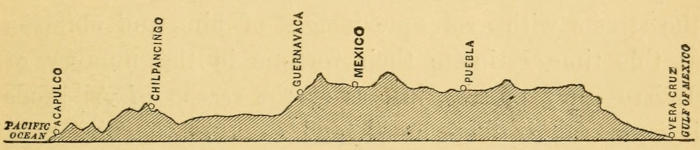

| TRANSCONTINENTAL PROFILE OF MEXICO | 31 |

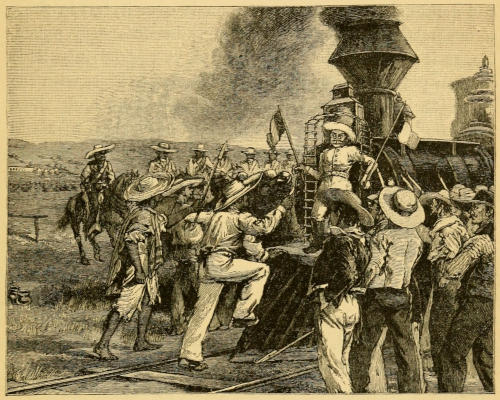

| A RAILWAY JUDAS | 33 |

| A FLOWER-SHOW IN THE ZOCALO | 43 |

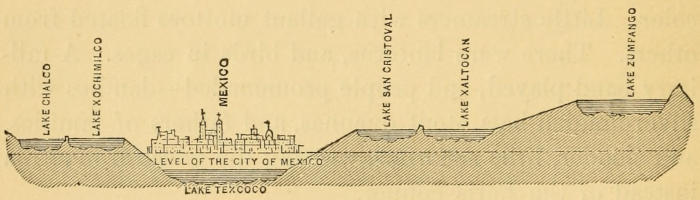

| COMPARATIVE LEVELS OF LAKES | 46 |

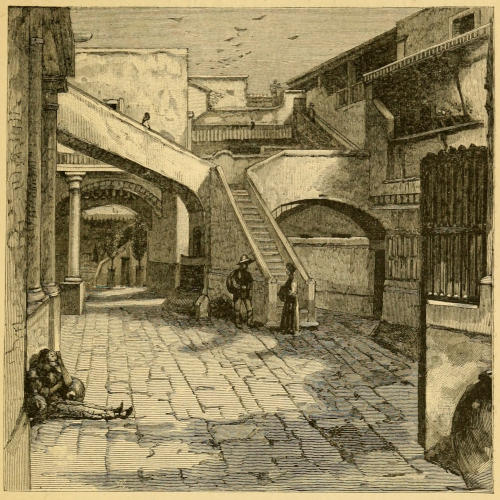

| THE HOMES OF THE POOR | 49 |

| ENTRANCE TO A TENEMENT-HOUSE | 51 |

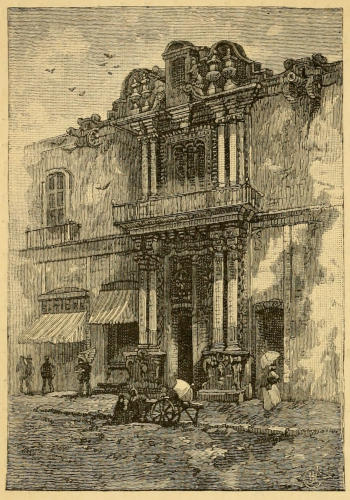

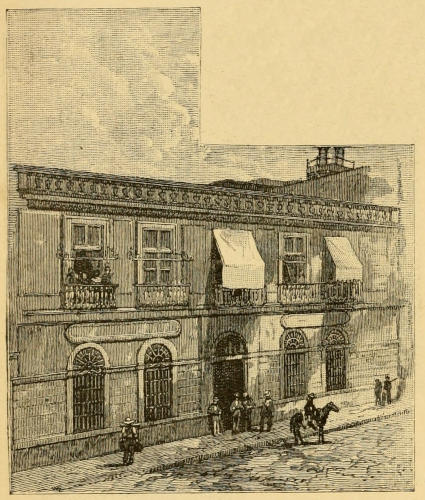

| OLD SPANISH PALACE IN THE CALLE DE JESUS | 56 |

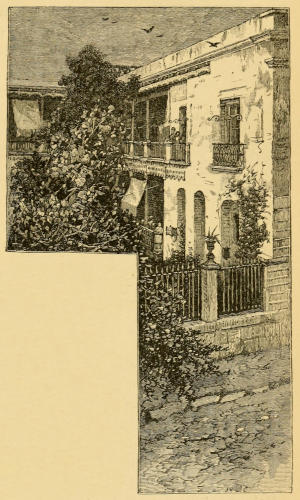

| SEMI-VILLA ON THE PASEO OF BUCARELLI | 57 |

| THE MODERN STYLE | 58 |

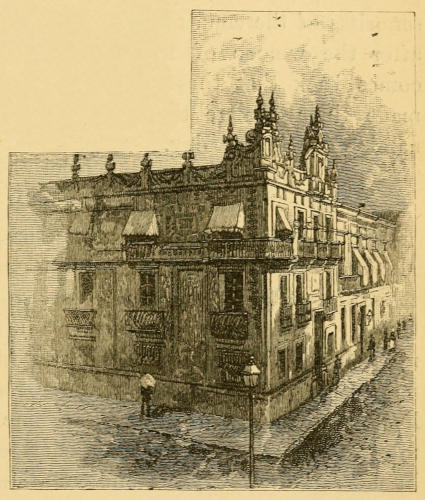

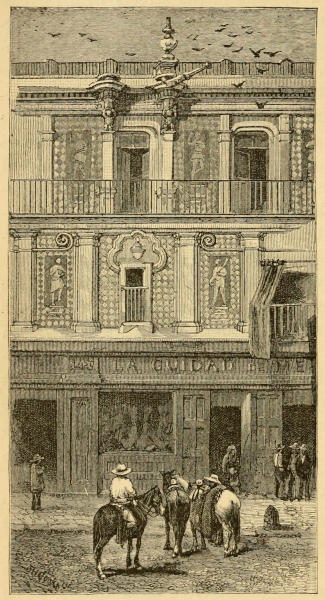

| PORCELAIN HOUSE IN SAN FRANCISCO STREET | 59 |

| THE DRIVE TO CHAPULTEPEC | 63 |

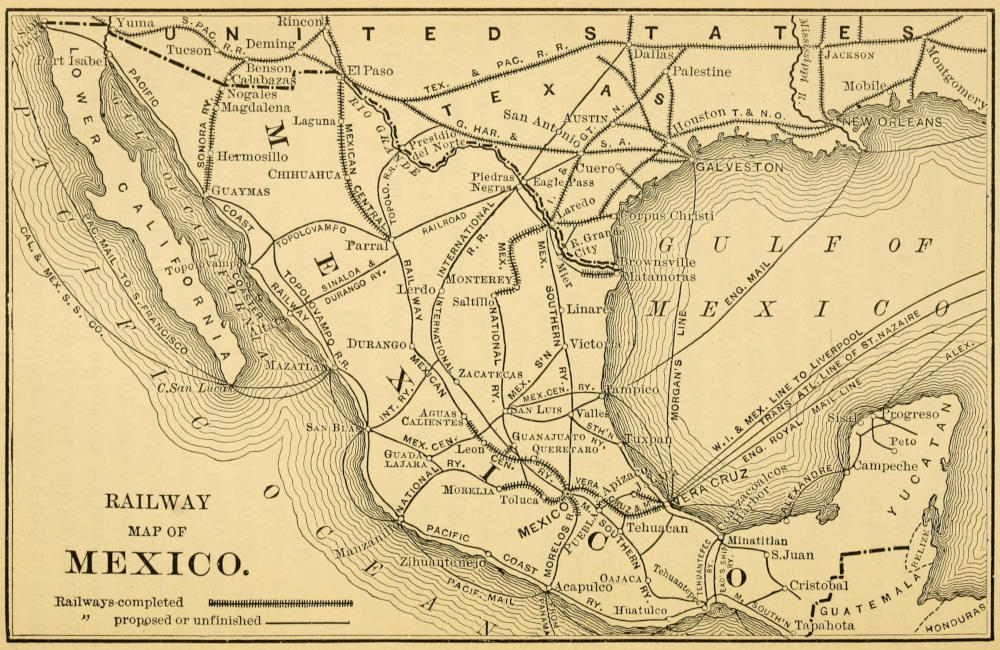

| GENERAL RAILWAY SYSTEM OF MEXICO | 75 |

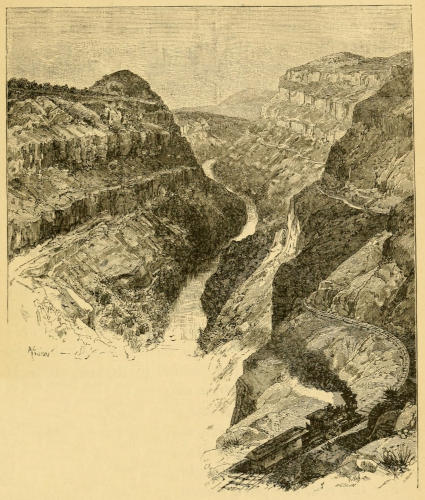

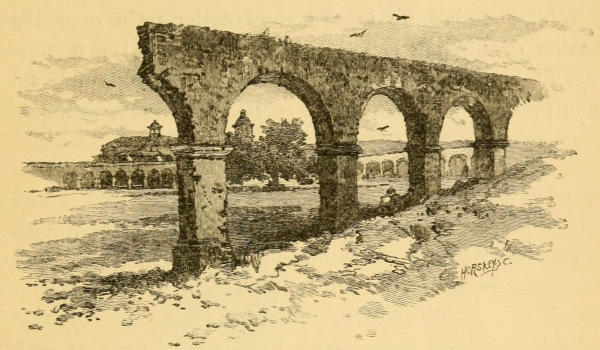

| THE GREAT SPANISH DRAINAGE CUT | 85 |

| PAY CARAVAN ON THE MEXICAN NATIONAL ROAD | 91 |

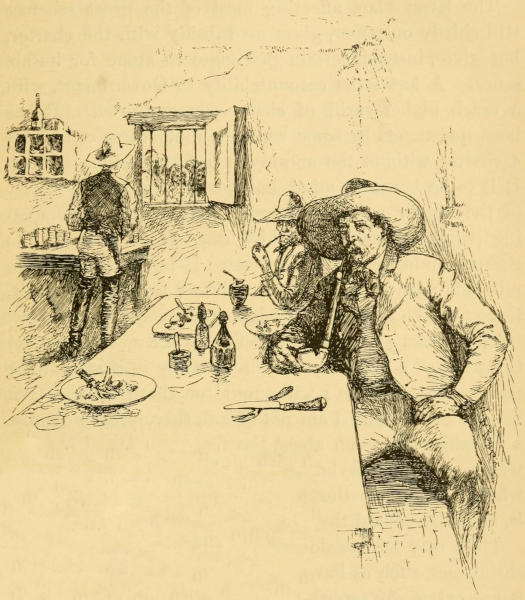

| “NOT HERE FOR THEIR HEALTH” | 93 |

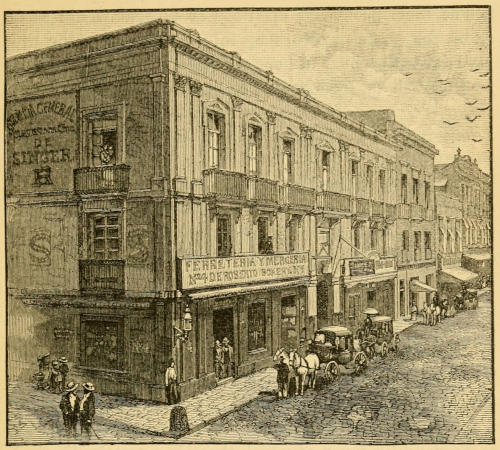

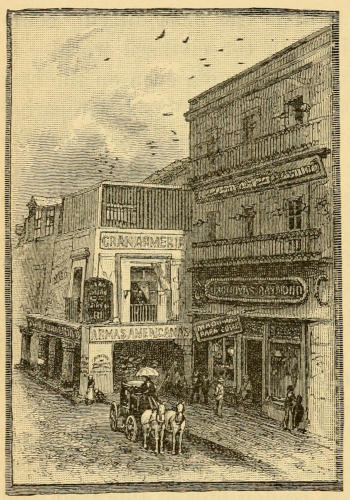

| MODERN SHOP-FRONTS AT MEXICO | 99 |

| THE “PORTALES” AT MEXICO | 102 |

| A “MERCERIA” AT PUEBLA | 106 |

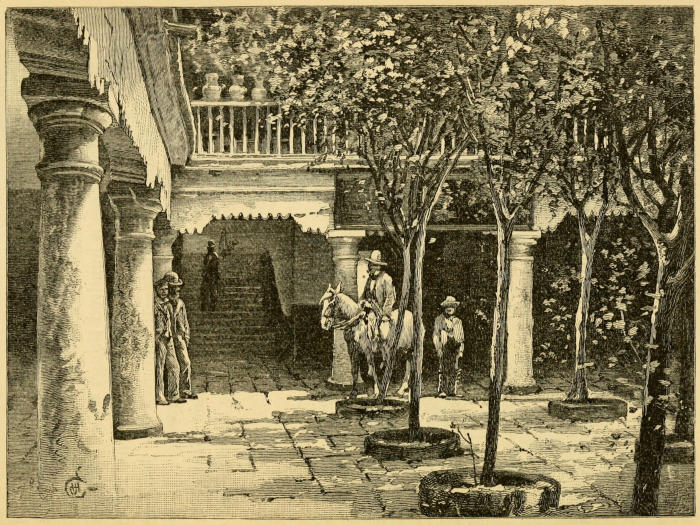

| INTERIOR COURT-YARD OF MEXICAN RESIDENCE | 111 |

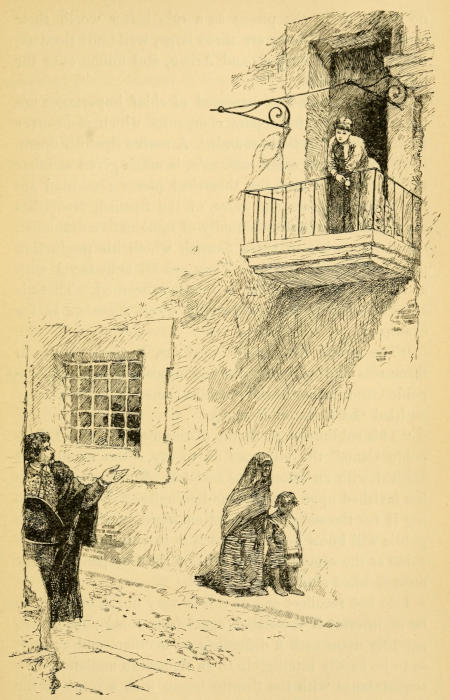

| MEXICAN COURTSHIP | 113 |

| THE DEATH OF ATALA. By Luis Monroy | 123[viii] |

| GENERAL PORFIRIO DIAZ, EX-PRESIDENT OF MEXICO | 139 |

| GENERAL MANUEL GONZALES, PRESIDENT OF MEXICO | 143 |

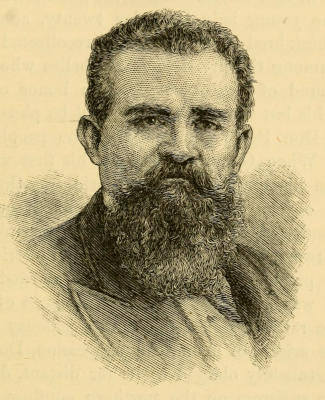

| ENVIRONS OF MEXICO | 150 |

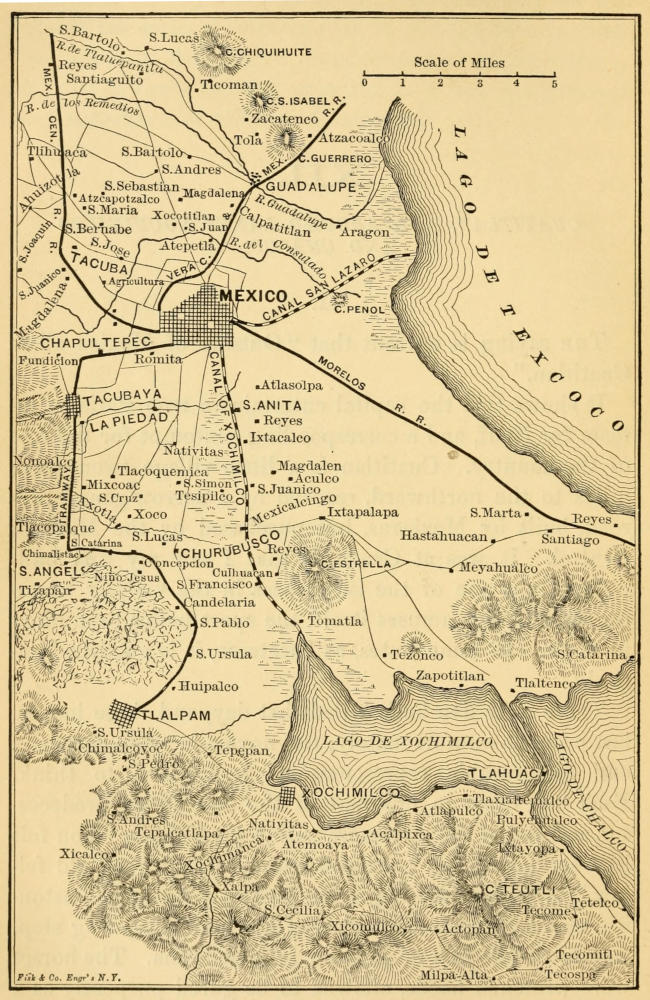

| SUNDAY DIVERSIONS AT SANTA ANITA | 153 |

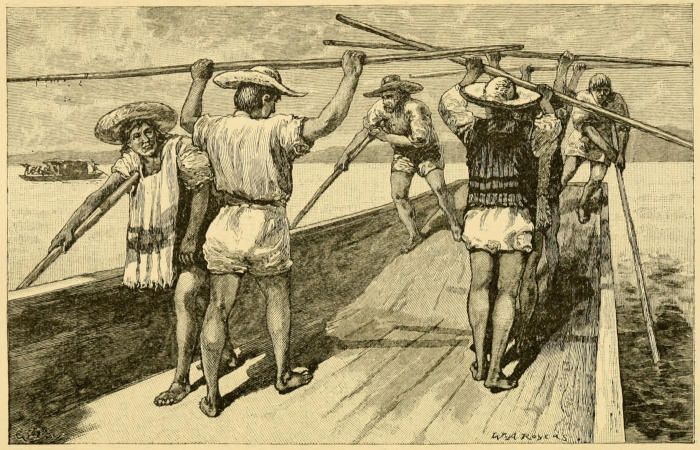

| CREW OF “LA NINFA ENCANTADORA” | 165 |

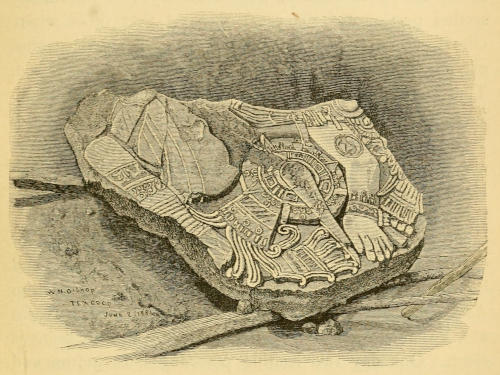

| THE “FIND” | 169 |

| IN TIERRA CALIENTE | 186 |

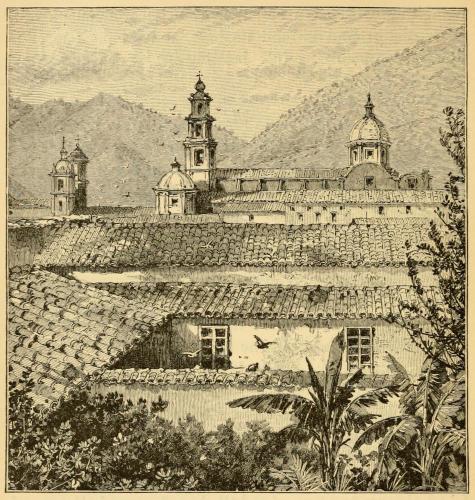

| THE HILL OF EL BORREGO, AT ORIZABA | 196 |

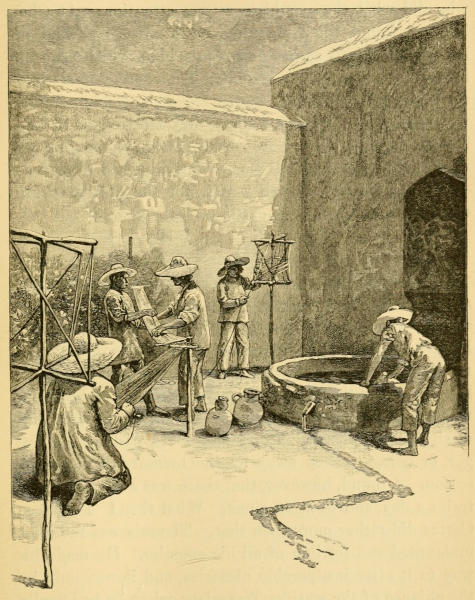

| PRISONERS WEAVING SASHES AT CHOLULA | 217 |

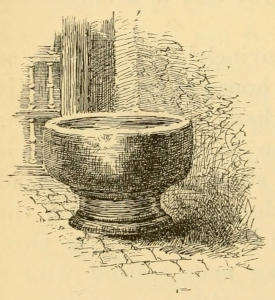

| OLD FONT AT TLAXCALA | 222 |

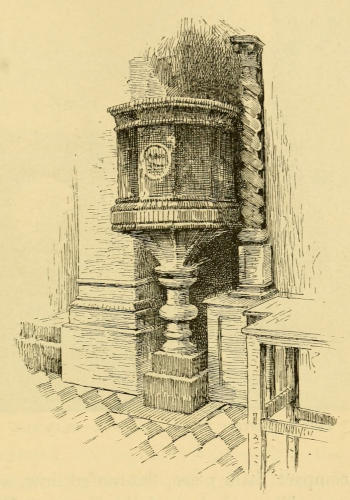

| THE FIRST CHRISTIAN PULPIT IN AMERICA. TLAXCALA | 223 |

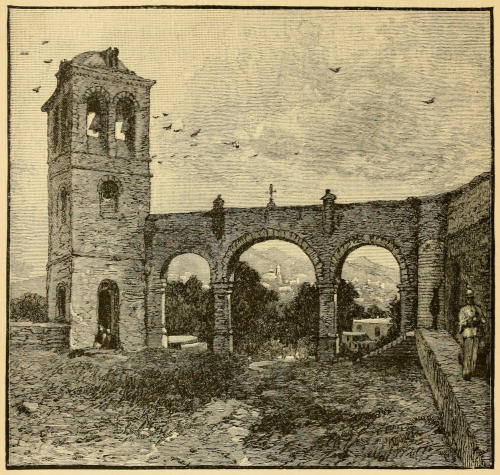

| PART OF CONVENT OF SAN FRANCISCO. TLAXCALA | 224 |

| SUPERINTENDENT’S HOUSE AT REGLA | 241 |

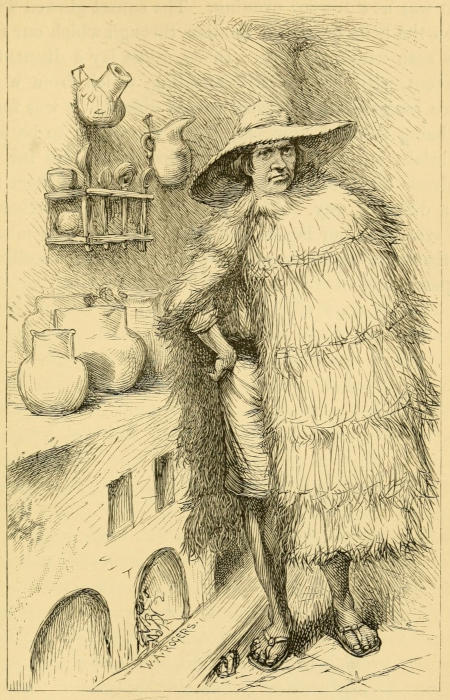

| PLOUGHMAN IN GRASS CLOAK | 243 |

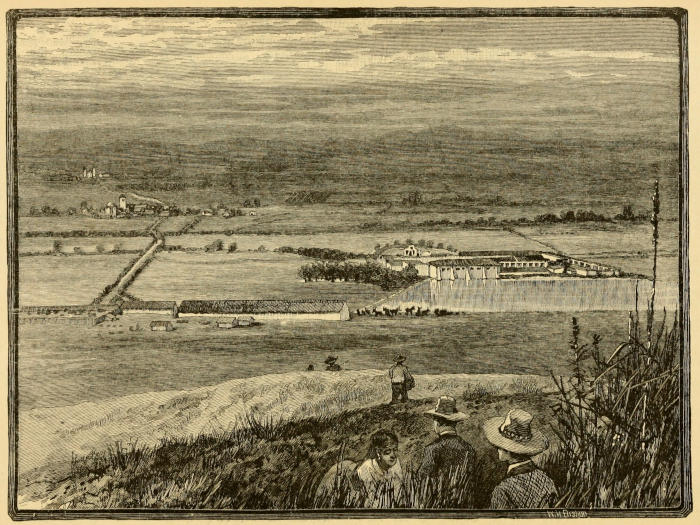

| THE HACIENDA OF TEPENACASCO | 246 |

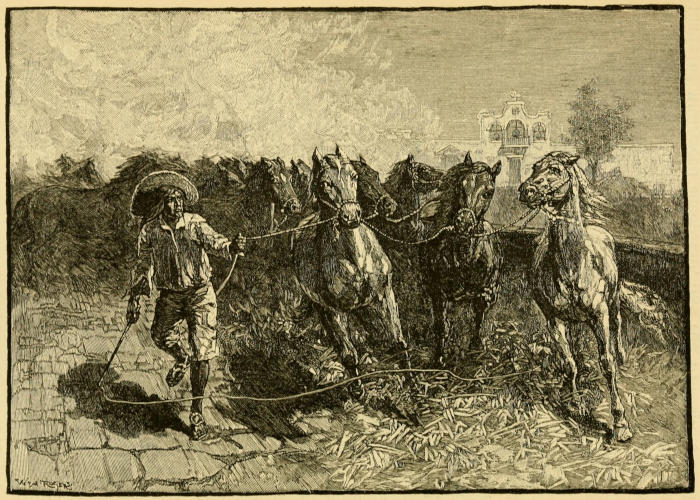

| THE THRESHING-FLOOR | 249 |

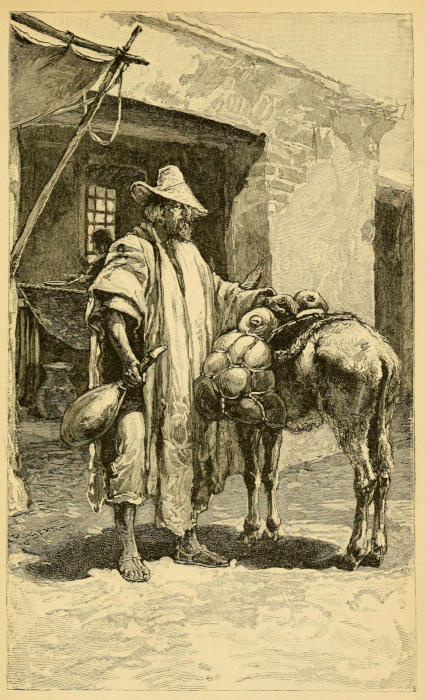

| THE TLACHIQUERO | 251 |

| NURSE AND CHILDREN AT THE HACIENDA | 261 |

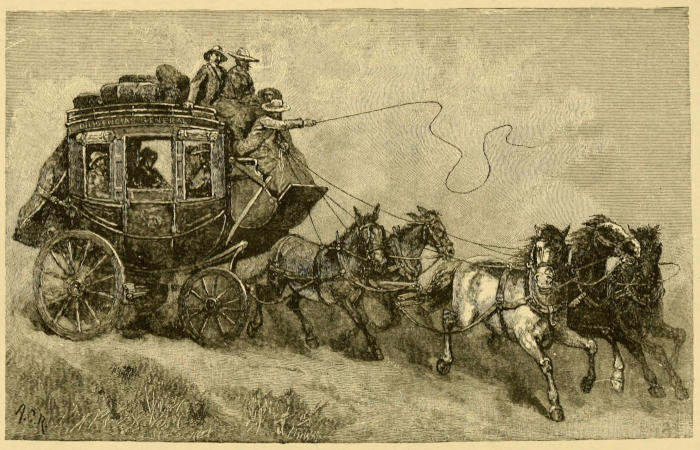

| THE “DILIGENCIA” | 267 |

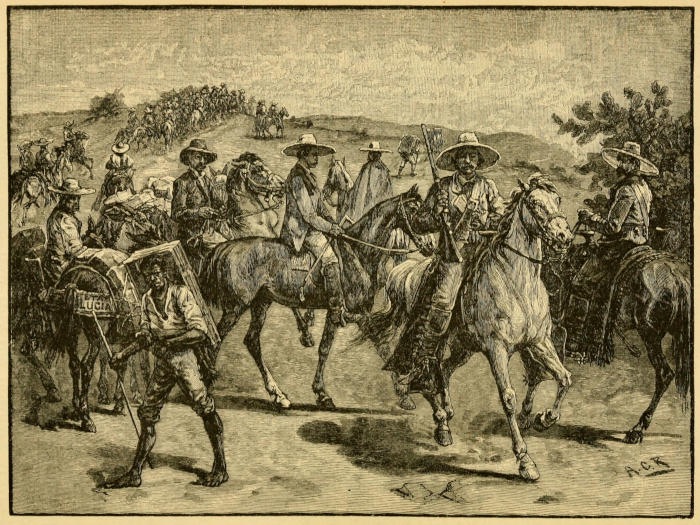

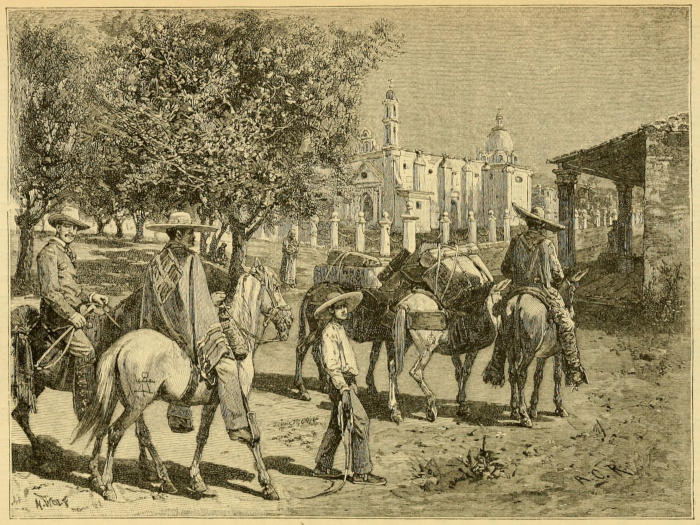

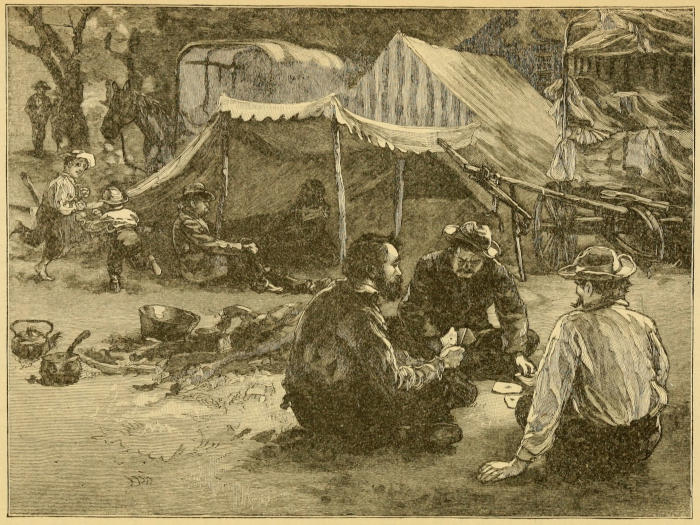

| OUR CAVALCADE AT IGUALA | 281 |

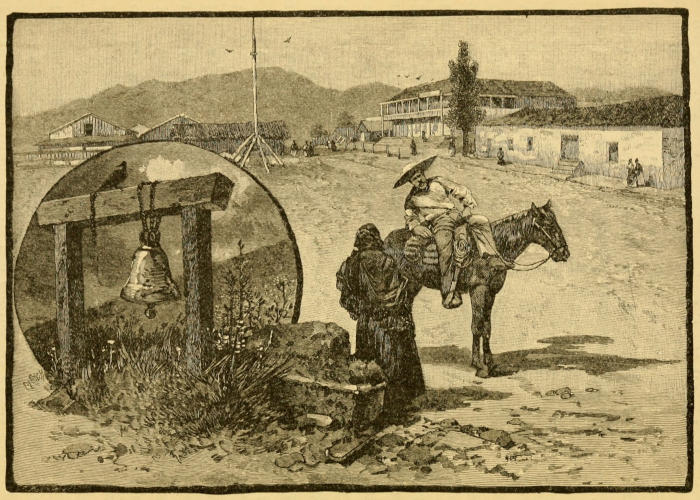

| THE BELLS OF SAN BLAS | 290 |

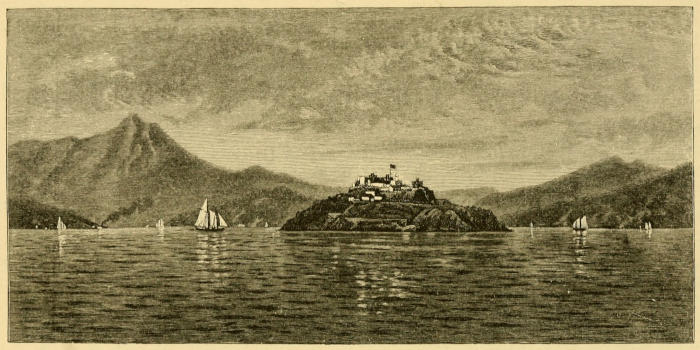

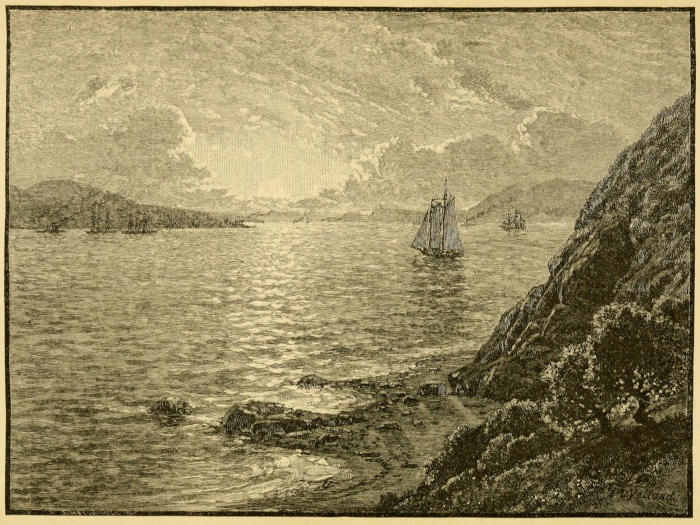

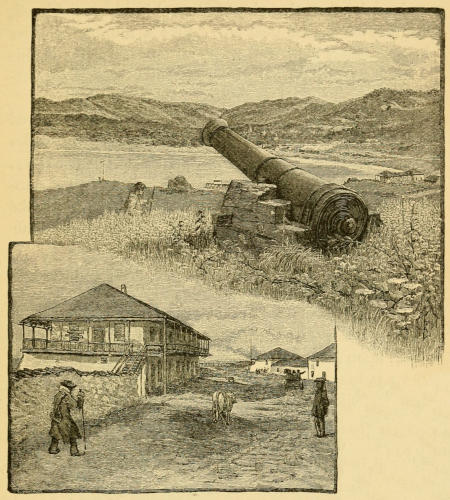

| ALCATRAZ ISLAND | 297 |

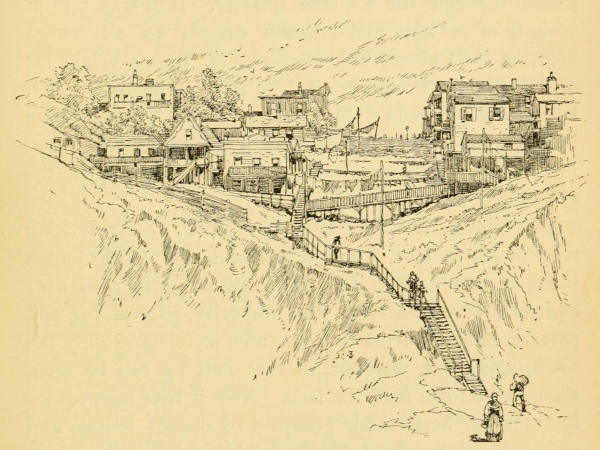

| “NOB” HILL, FROM THE BAY | 299 |

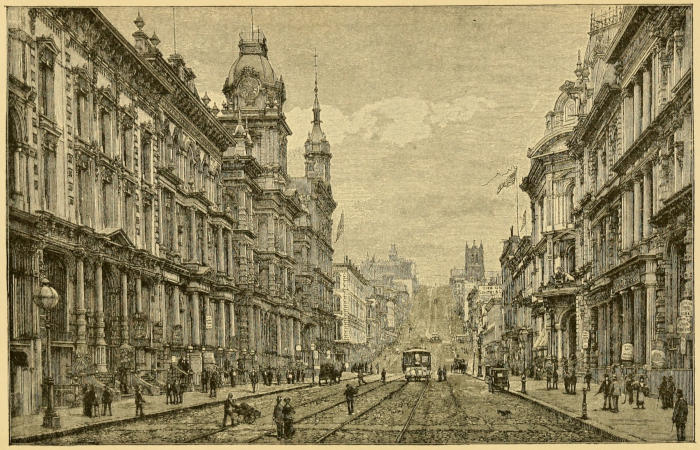

| CALIFORNIA STREET, SAN FRANCISCO | 305 |

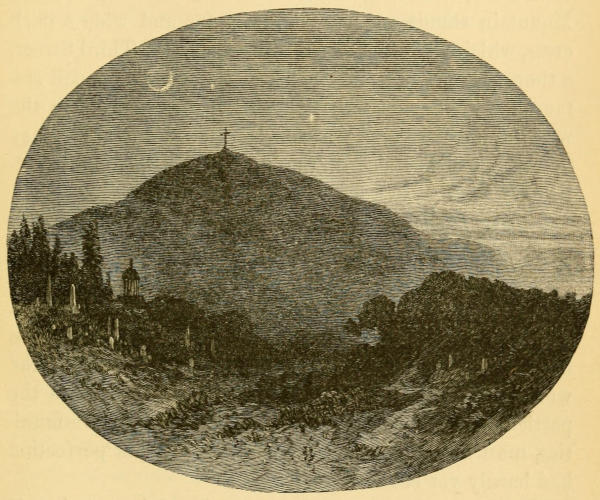

| LONE MOUNTAIN | 309 |

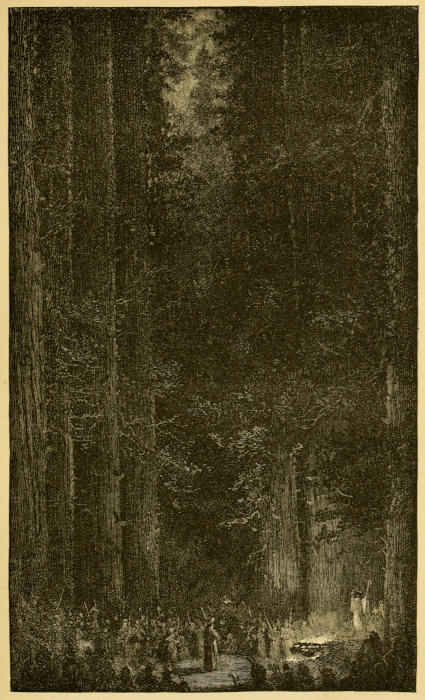

| “HIGH JINKS” OF THE BOHEMIAN CLUB AMONG THE BIG TREES | 313 |

| GOLDEN GATE, FROM GOAT ISLAND | 317 |

| HIGH-GRADE RESIDENCES | 327 |

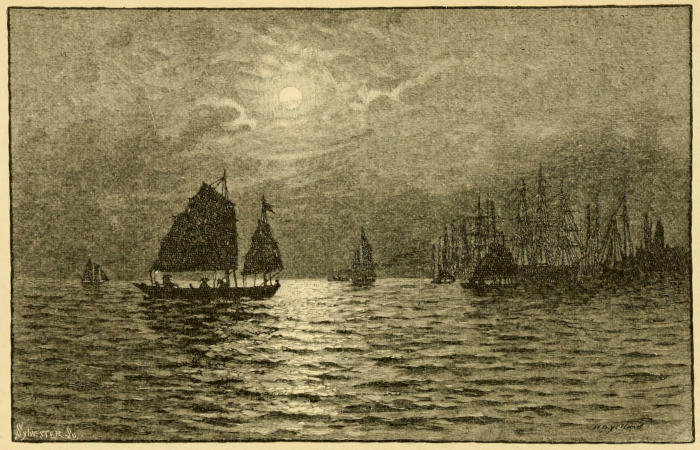

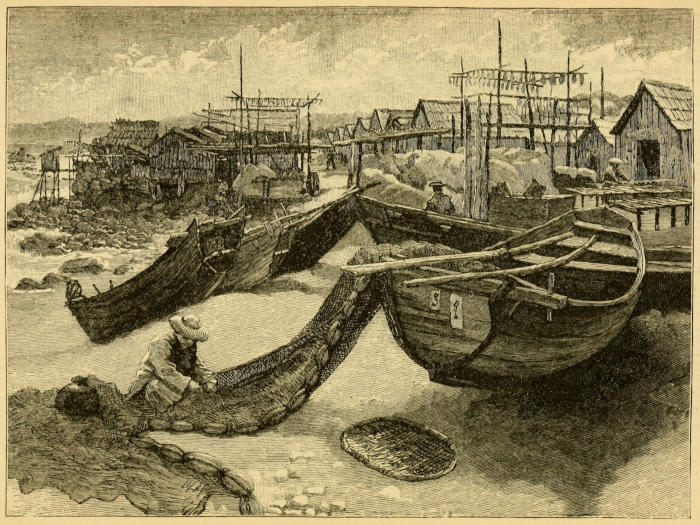

| CHINESE FISHING-BOATS IN THE BAY | 331 |

| CHINESE QUARTER, SAN FRANCISCO | 335 |

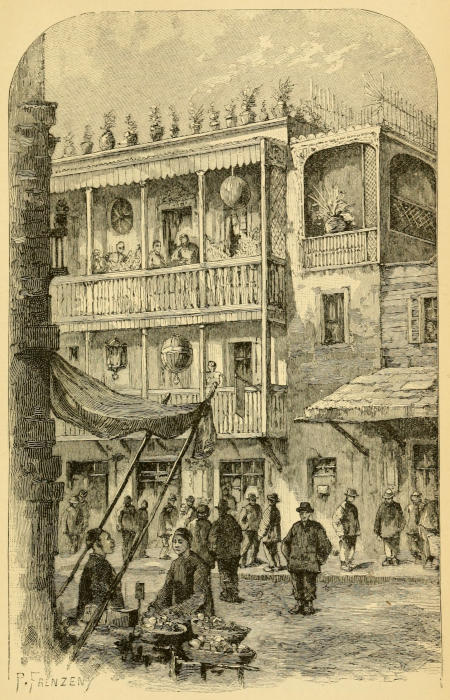

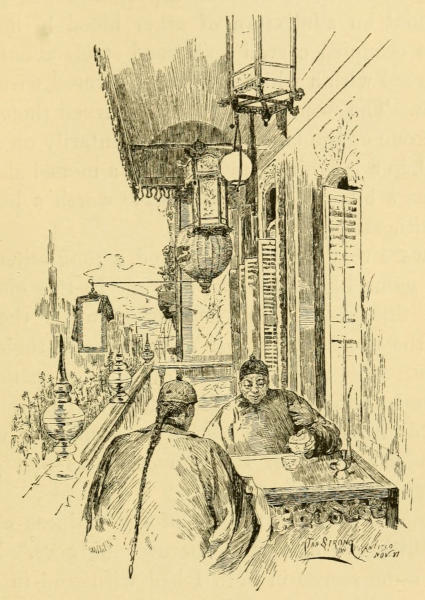

| A BALCONY IN THE CHINESE QUARTER | 337 |

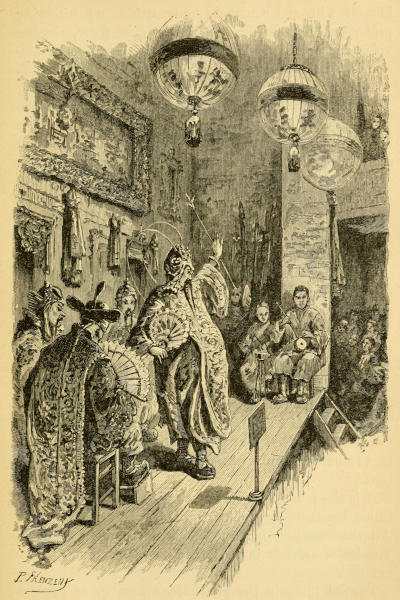

| IN A CHINESE THEATRE | 339 |

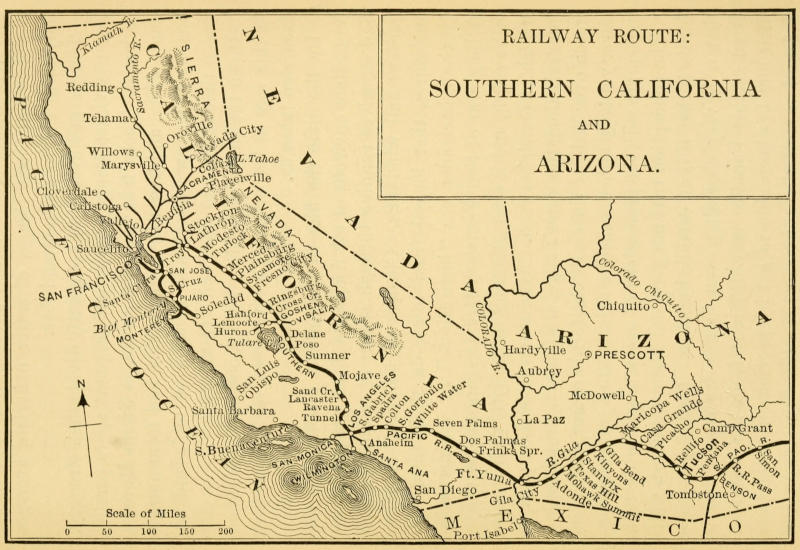

| RAILWAY ROUTE: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA AND ARIZONA | 345 |

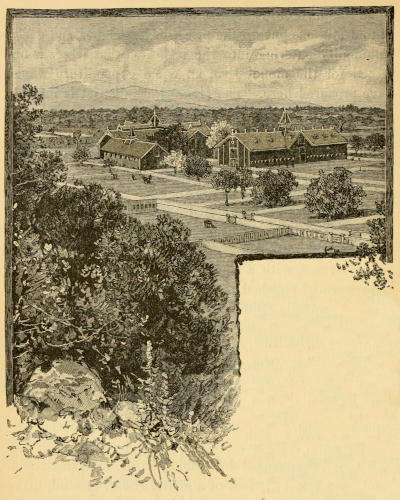

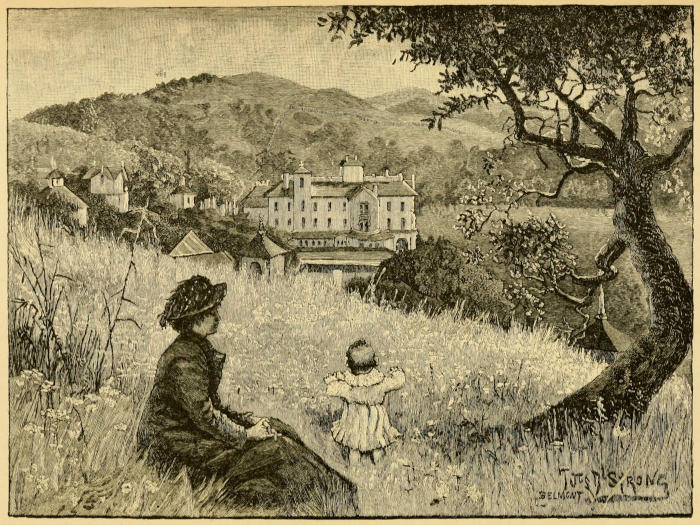

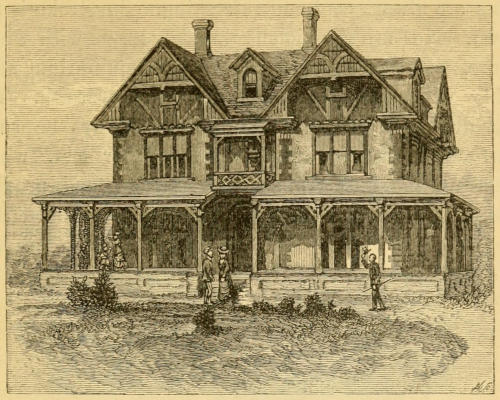

| PALO ALTO | 354 |

| RALSTON’S COUNTRY HOUSE | 357 |

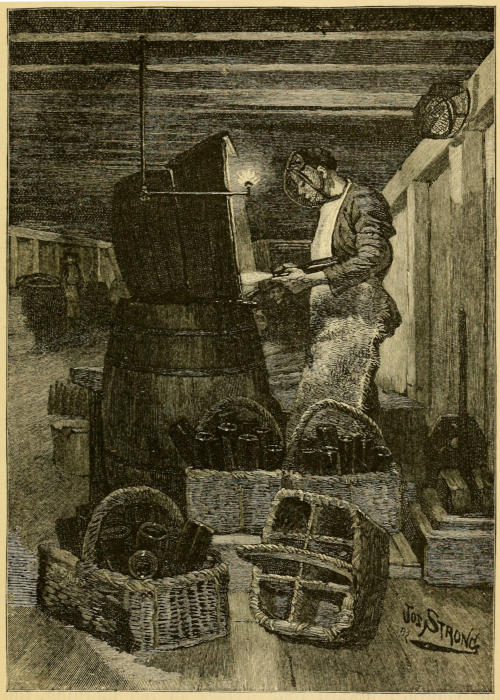

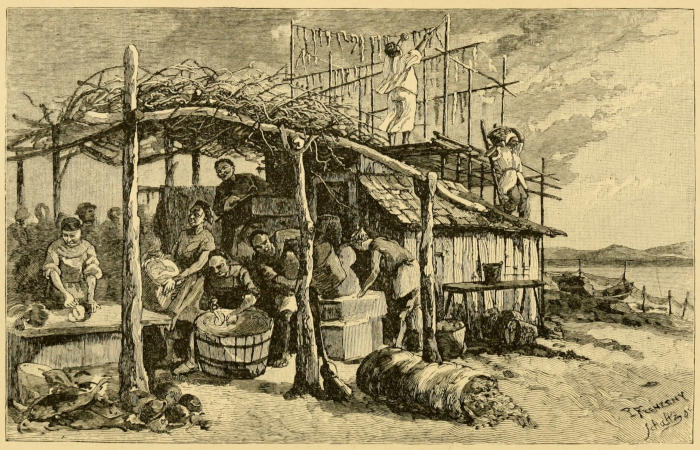

| BOTTLING CHAMPAGNE AT SAN FRANCISCO | 361 |

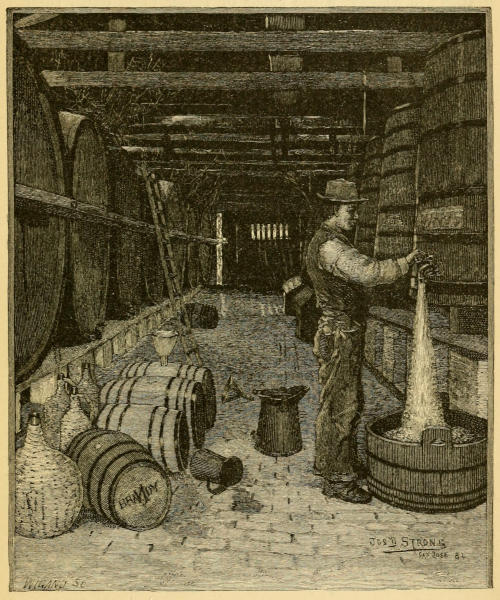

| A BRANDY CELLAR, SAN JOSÉ | 363[ix] |

| A BIT OF OLD MONTEREY | 365 |

| LOOKOUT STATION | 367 |

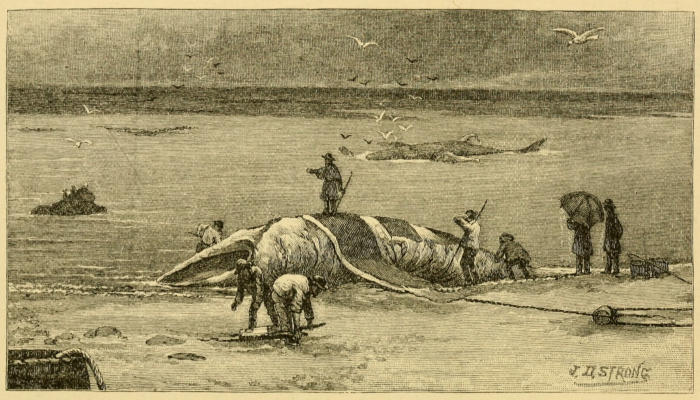

| CUTTING UP THE WHALE | 369 |

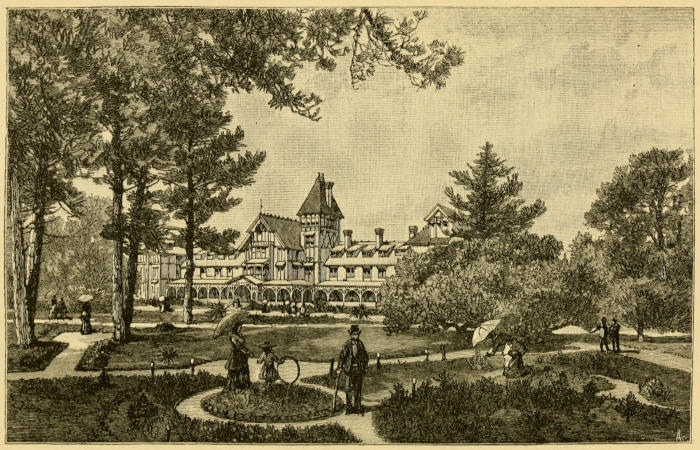

| THE HOTEL DEL MONTE, MONTEREY | 371 |

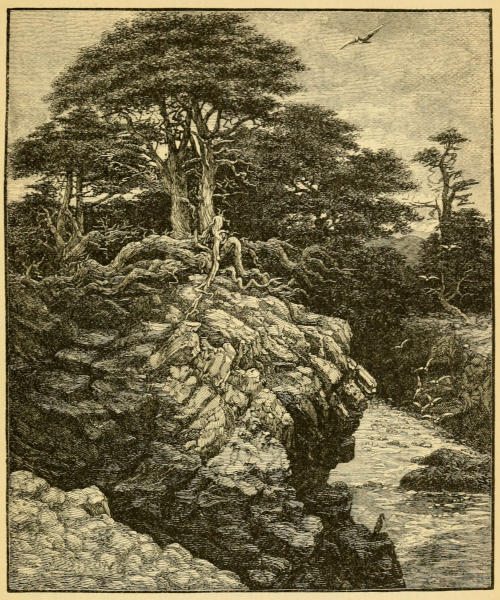

| CLIFFS AND FOREST AT MONTEREY | 373 |

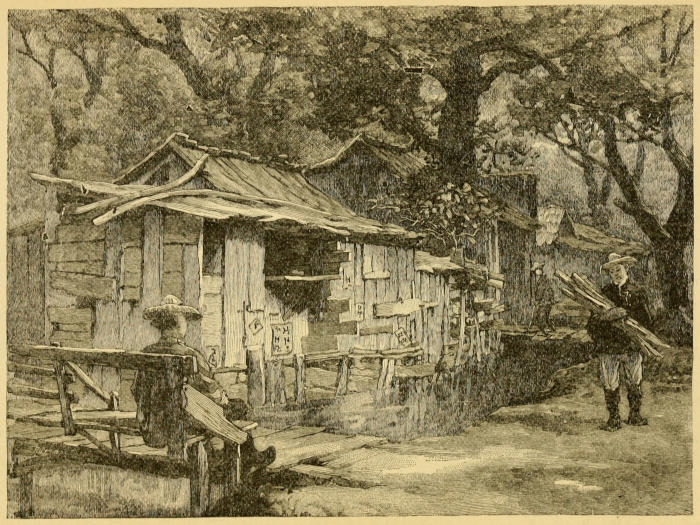

| CHINESE FISHING VILLAGE | 375 |

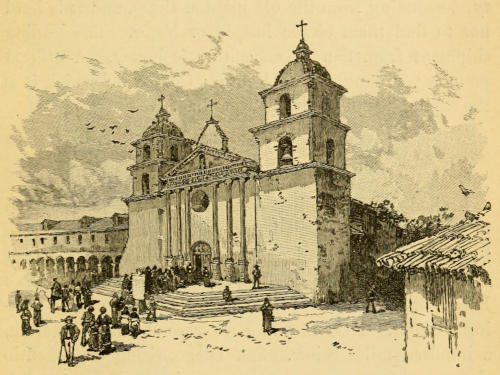

| SAN CARLOS’S-DAY AT THE OLD MISSION | 376 |

| DRYING FISH AT CHINESE VILLAGE | 377 |

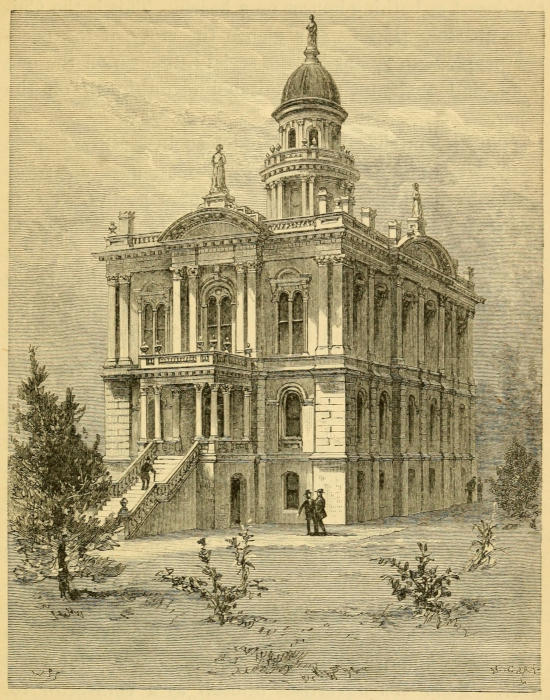

| COURT-HOUSE AT FRESNO | 387 |

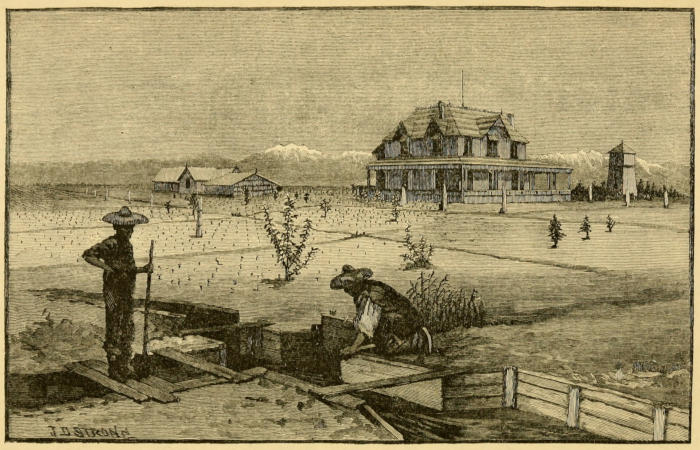

| PRIVATE RESIDENCE AT FRESNO | 393 |

| FIRST BUILDING IN VISALIA | 400 |

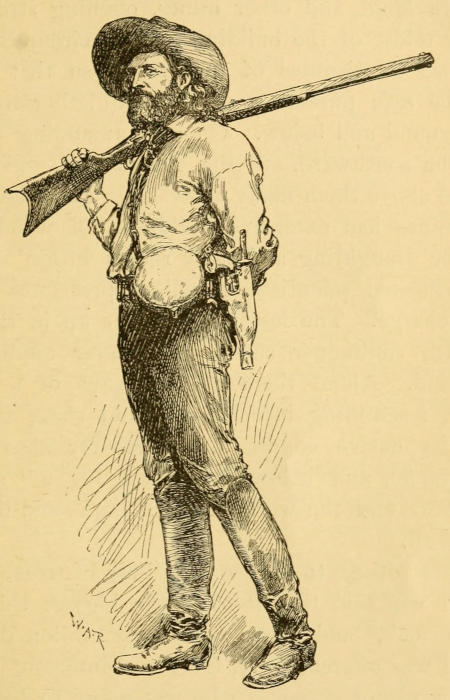

| AN OLD-TIMER | 401 |

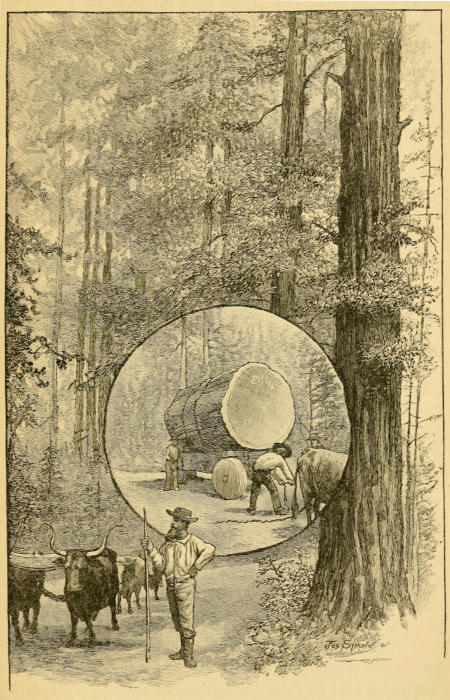

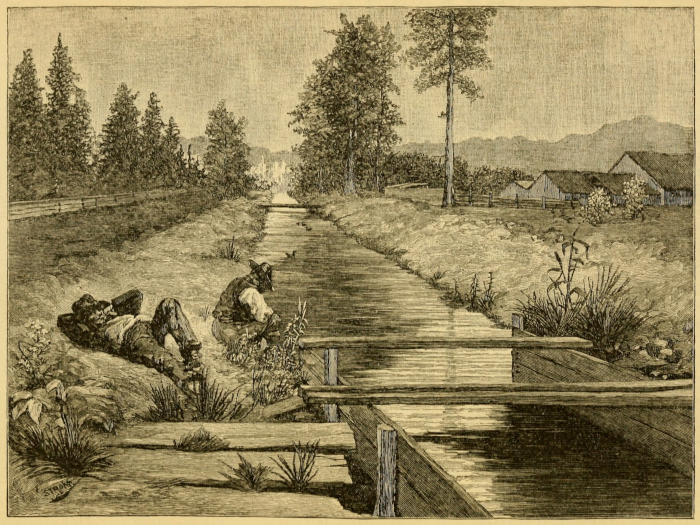

| LOGGING, BACK OF VISALIA | 403 |

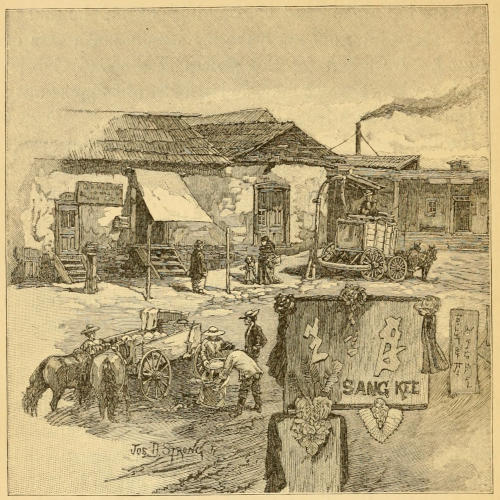

| CHINATOWN, BAKERSFIELD | 409 |

| GYPSY CAMP AT BAKERSFIELD | 411 |

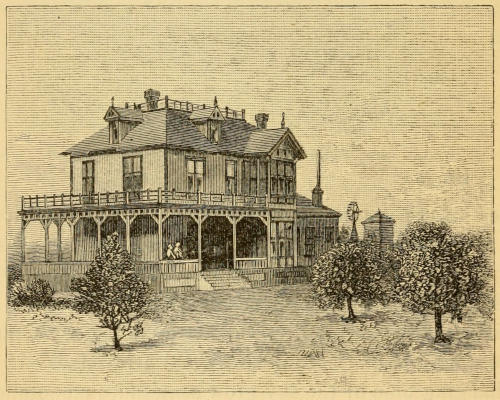

| A TYPICAL RANCH-HOUSE | 414 |

| SAN LUIS OBISPO | 416 |

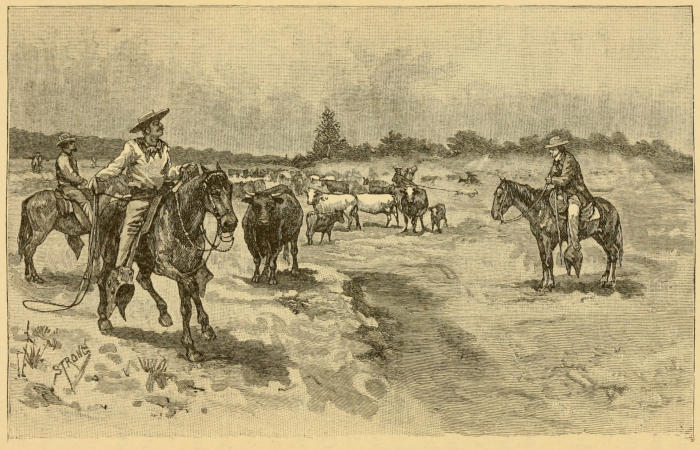

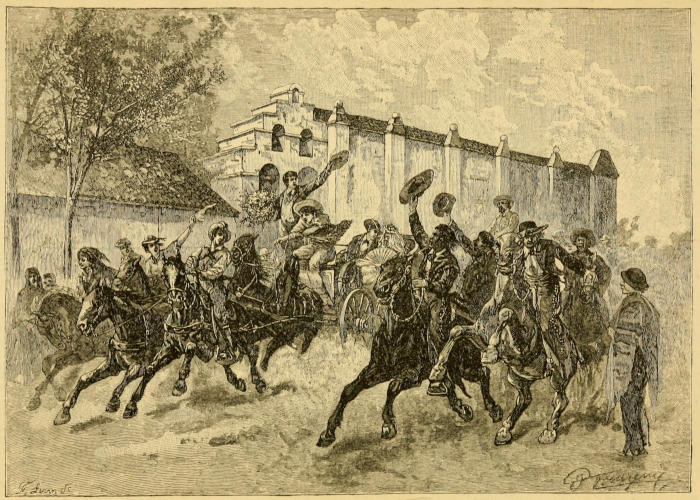

| A RODEO | 418 |

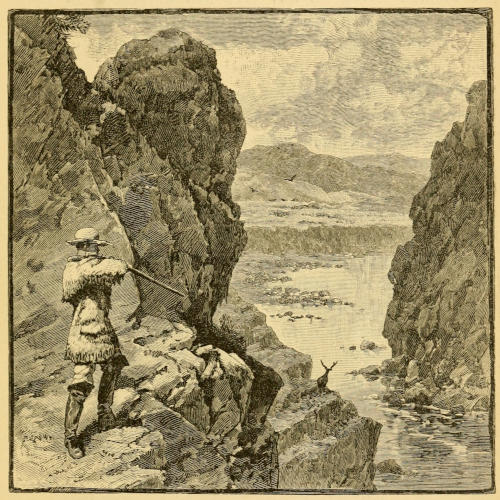

| THE KERN RIVER CAÑON | 419 |

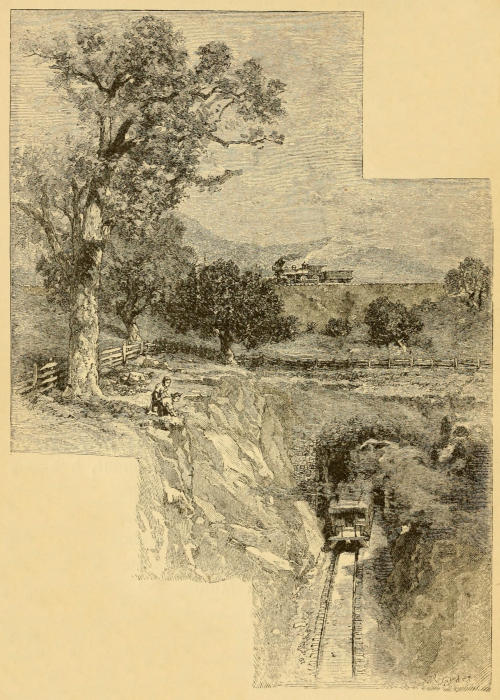

| TEHACHAPI PASS | 422 |

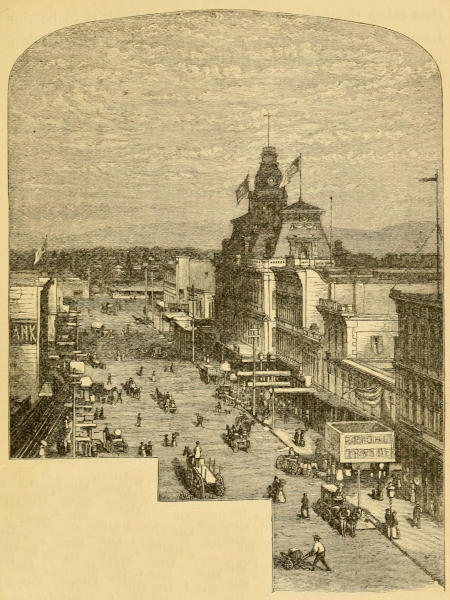

| MAIN STREET, LOS ANGELES | 425 |

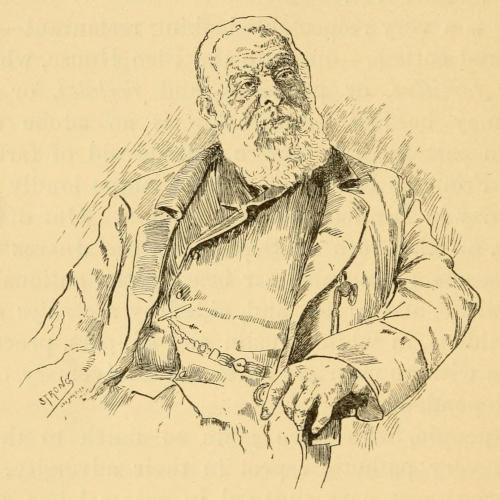

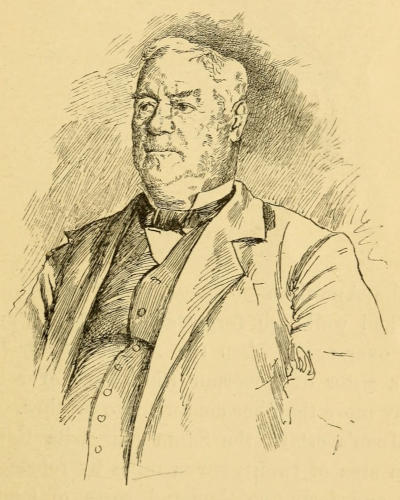

| DON PIO PICO | 428 |

| MONGOLIAN AND MEXICAN | 430 |

| PARADISE | 437 |

| A MEXICAN WEDDING AT SAN GABRIEL | 441 |

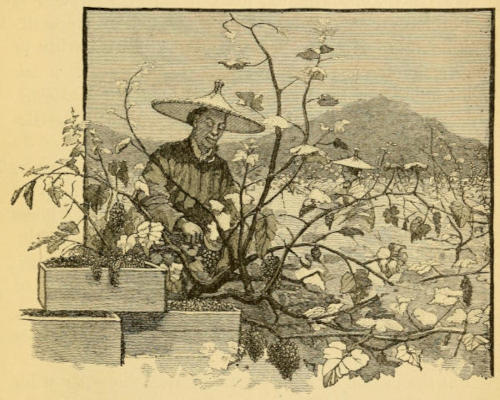

| THE VINTAGE, SAN GABRIEL | 443 |

| IRRIGATING AN ORANGE-ORCHARD | 445 |

| A SYLVAN GLIMPSE AT RIVERSIDE | 449 |

| ADOBE RESIDENCE AT RIVERSIDE | 451 |

| ADOBE RESIDENCE AT RIVERSIDE | 452 |

| OLD MISSION AT SANTA BARBARA | 455 |

| PLAZA OF SAN DIEGO, OLD TOWN | 457 |

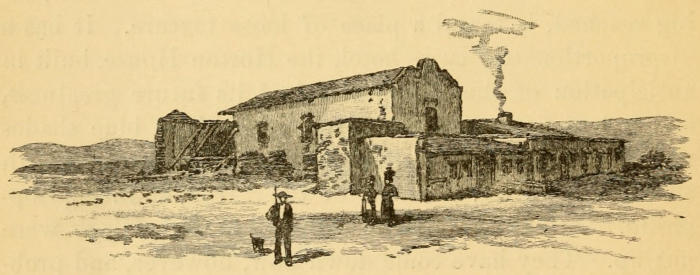

| OLD MISSION AT SAN DIEGO | 460 |

| DON JUAN FORSTER | 461 |

| SEÑORA FORSTER | 462 |

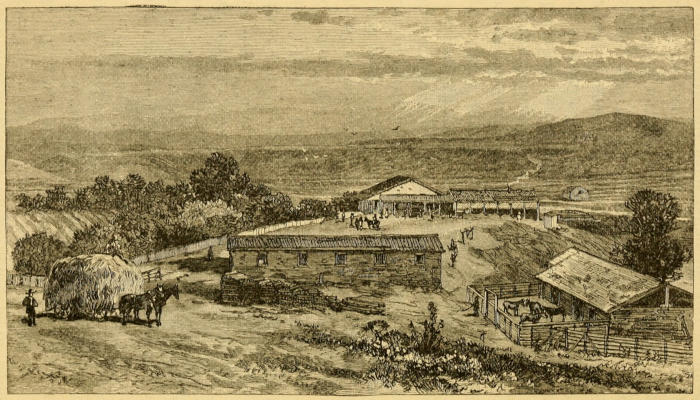

| FORSTER’S RANCH | 463 |

| SAN LUIS REY | 465[x] |

| A TICHBORNE CLAIMANT | 466 |

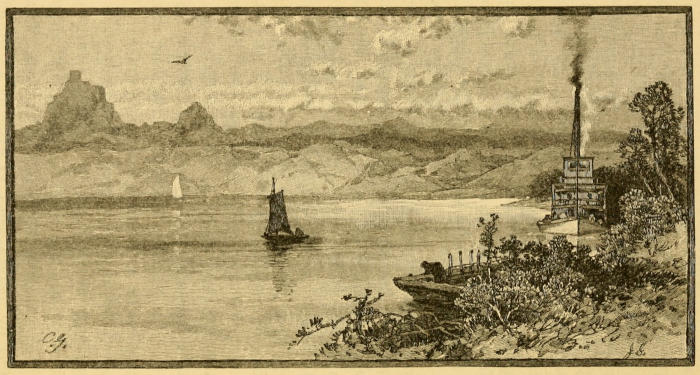

| THE COLORADO RIVER AT YUMA | 473 |

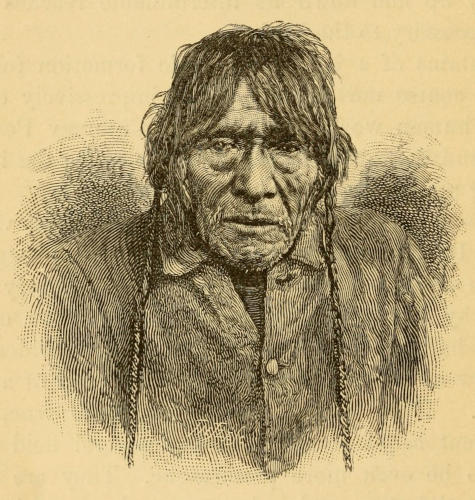

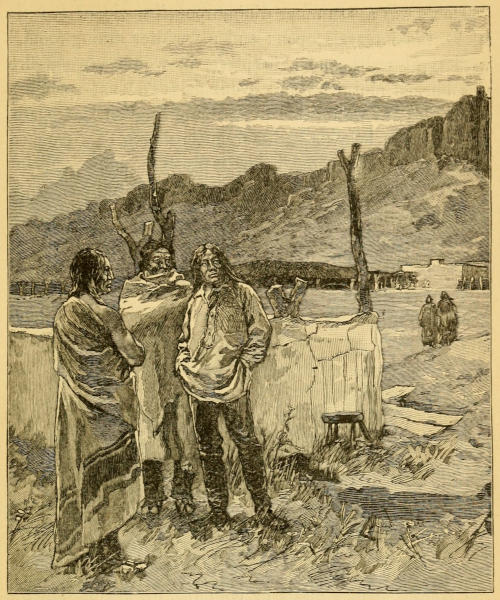

| PASQUAL, CHIEF OF THE YUMAS | 476 |

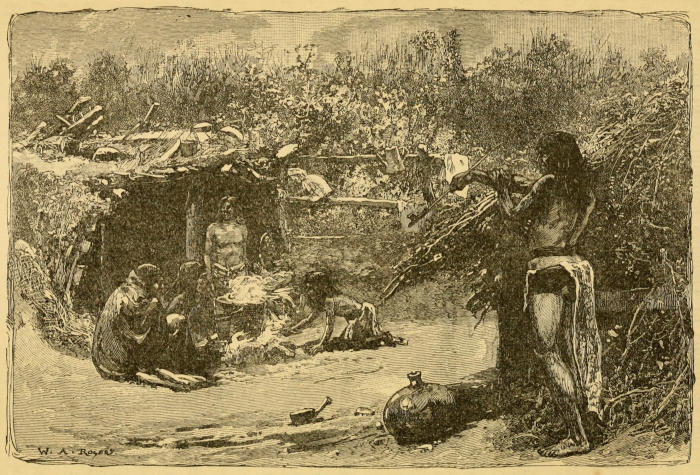

| YUMA INDIANS AT HOME | 477 |

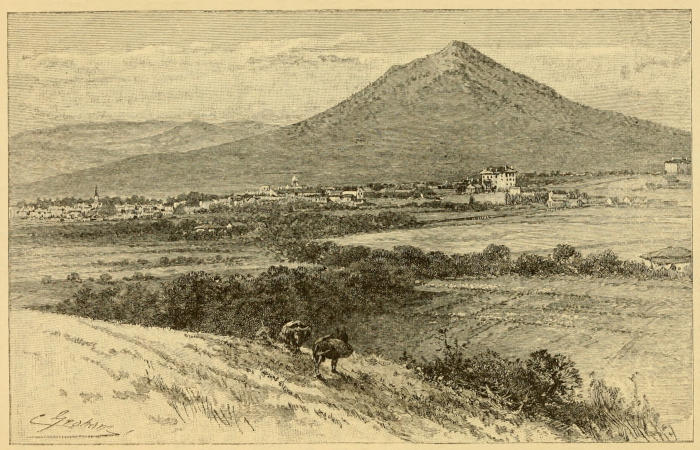

| DISTANT VIEW OF TOMBSTONE | 484 |

| “ED” SCHIEFFELIN | 487 |

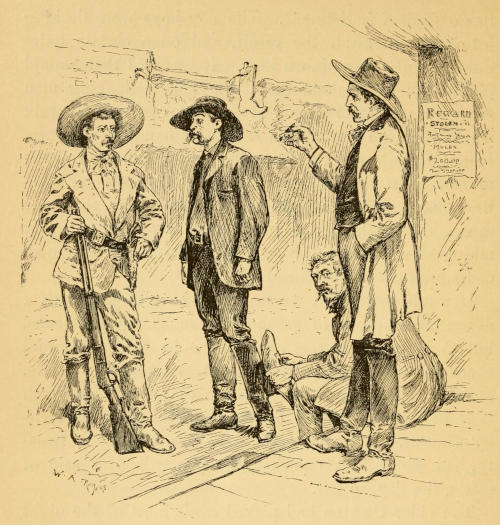

| A TOMBSTONE SHERIFF AND CONSTITUENTS | 494 |

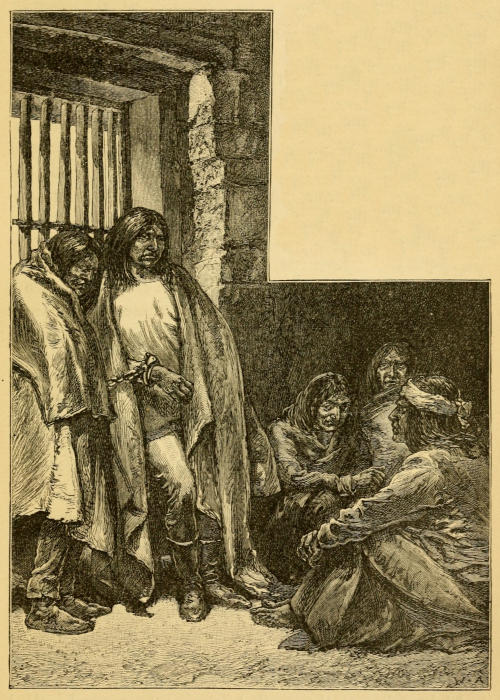

| APACHE PRISONERS AT CAMP LOWELL | 497 |

| AN ARIZONA WATERING-PLACE | 499 |

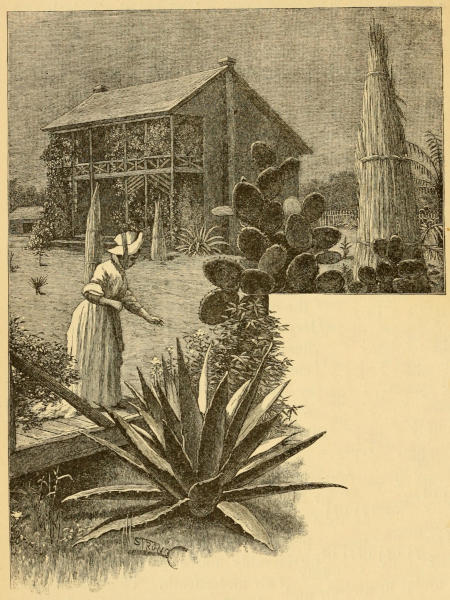

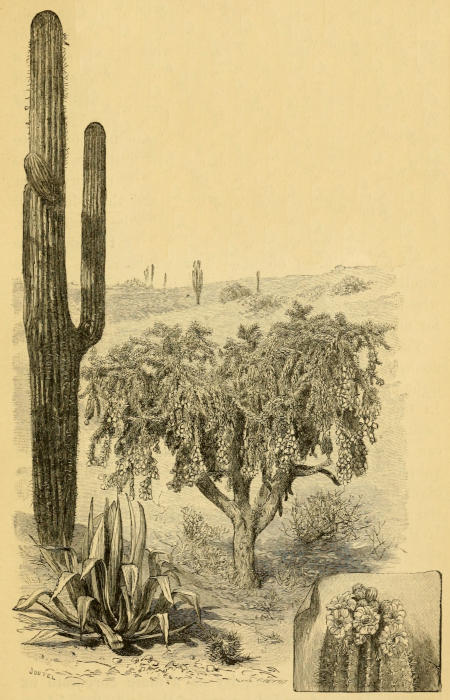

| CACTUS GROWTHS OF THE DESERT | 501 |

| STREET VIEW IN TUCSON | 503 |

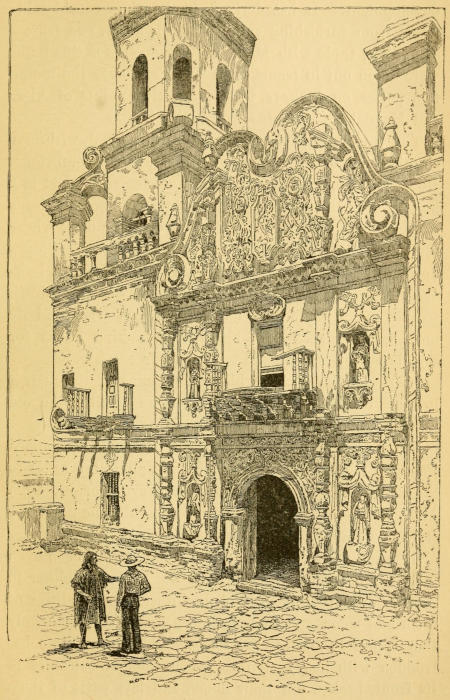

| EXTERIOR OF MISSION CHURCH OF SAN XAVIER DEL BAC | 505 |

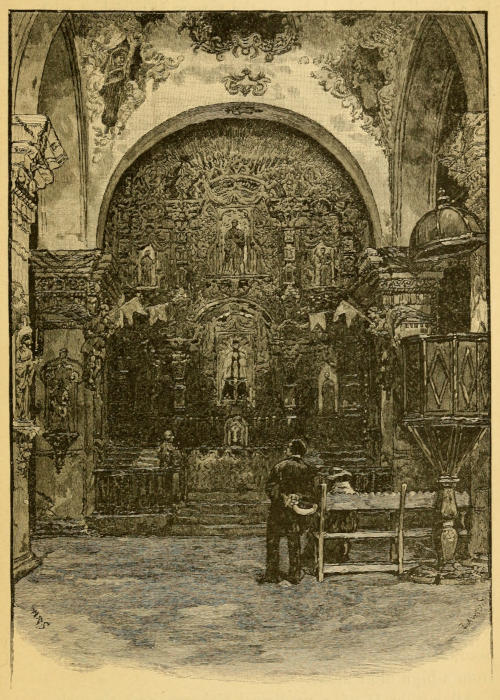

| INTERIOR OF CHURCH OF SAN XAVIER DEL BAC | 507 |

[1]

Boom! Two ruddy old castles domineering a narrow harbor entrance; on the other side a city, gray, warm-colored, and time-stained, and the bells of the Church of the Angels chiming for very early morning service! It was Havana!

I began this journey to Old Mexico and her Lost Provinces by sailing away from the foot of Wall Street, East River, on the 31st day of March, 1881. Some would have begun it, no doubt, by taking the railroad to our Southern confines, and sailing by the steamers, of medium size, which ply from New Orleans, Galveston, and Morgan City—all places feeling very much the new stimulus lately given to Mexican trade. Others—and very likely they could not do better—would have taken direct the excellent Alexandre Line, which carries the mail from New York, calling at Havana, Progreso, Campeachy, Frontera, and Vera Cruz.

Others, perchance, more adventurous, and fond of mixing as much hardship as possible in their pleasure, might have crossed the frontier at Texas, and, the new railroads [2]being yet unfinished, been bumped and thumped a thousand miles to the capital in the wretched diligencias (stage-coaches) of the country.

I did none of these. I shall not be guilty of the egotism of insisting that I did any better; but I had formed a little plan of infusing variety into the trip without making it too onerous. I stood boldly upon the deck of the luxurious steamer Newport, bound for Cuba only. From there I was to take the French packet making regular trips from the ports of St. Nazaire and Santander to Vera Cruz, and bringing much of the French and Spanish migration; or a British steamer from Southampton, or a Spanish one from Cadiz, might be taken in the same way. The fare by any and all of the direct sea routes is about the same, and may be set down roughly at $85.00. The time consumed, where all connections are expeditiously made, should be about eleven days.

There was no uncontrollable excitement on that raw 31st of March when we took our departure. People in the great financial mart, hurrying about their stocks and bonds, even blockaded us in an unthinking way as we came down to the steamer. It might have been simply a case of going to Europe, or anything else quite usual and of little import. It was, instead, a case of going to a land remote far beyond its distance in miles; shrouded in an atmosphere of mystery and danger; little travelled or sought for; the very antipodes of our own, though adjoining it; venerable with age, though a part of a new world; and said to have been suddenly awakened from slumber by the first touches of a phenomenal new development.

[3]

There are those of us whose conception of Mexico has been composed principally of the cuts in our early school geography, and the brief telegrams in the morning papers announcing new revolutions. We rest satisfied with this kind of concept about many another part of the globe as well till the necessity arrives for going there or otherwise clearing it up. I saw, I think, a snow volcano, and a string of donkeys, conducted by a broad-brim hatted peasant across a cactus-covered plain. I heard dimly isolated pistol-shots fired by brigands, and high-sounding pronunciamentos and cruel fusillades accompanying the overthrow from the Presidency of General this by General that, who would be served in the same way by General somebody else to-morrow. To this should be added some reminiscence of actions in the Mexican War, and notably the portraits of General Scott and bluff old Zachary Taylor.

To this, again, I would add fancies of buried cities in Central America, and of Aztec antiquity, and the valor and astuteness of Hernando Cortez and his cavaliers, remaining from Prescott’s history of the Conquest. One of the most captivating of volumes, this had seemed almost mythical in its remoteness; and as to the idea of actually verifying its scenes in person, it was beyond the wildest imagination.

But now all at once this uncertain territory had become real. The railroad had penetrated it, and made it accessible to the average private citizen. Not that it could yet be reached by railway, for the first international line is still incomplete, though its termination is near at hand; but a multitude of lines, undertaken by American capital and enterprise, and aided by a Government of liberal ideas, were traced over every part of the land, [4]and some of them in progress. The locomotive screamed along-side the troops of laden donkeys and in sight of the snow volcanoes. Even the brigands were said to have been dislodged from their fastnesses, the revolutions had ceased, and a reign of peace and security begun.

Momentous rumors from these new enterprises were frequent in the newspapers, and predictions indulged in of the great increase of trade and population to result to Mexico by them. General Grant, to whose personal influence much of the turning of public attention in this unwonted direction, after his first visit, should certainly be ascribed, had taken the presidency of one of them. Their stocks and bonds were being prepared in bank-parlors, but as yet there was no “boom,” little that was overt.

I did not quite know, when standing on the deck of the departing steamer, that I was to return to this dense New York, with its tall towers and mansards and fairy-like bridge, from the other side of the world. This journey lengthened out into a long, desultory ramble, beginning with Cuba, and, after Mexico, concluding with the most remote, novel, and characteristic of our own possessions on the Pacific slope. There is unity of subject, and even a certain pathos, in the recollection that this latter was once Mexican territory also. Its most obvious basis of life is still Spanish, and it may be sentimentally considered a kind of Alsace-Lorraine—a part of the sister republic when it was well-nigh as large and powerful as ourselves.

MEXICO SHOWING PRESENT & OLD FRONTIER

It was naturally cold on the 31st day of March, and blustering weather followed us down the coast as far as it dared. Then I awoke one morning early, at the [5]warm gleam of summer in the yellow lattices of my cabin window, and, looking out, saw that we were voyaging, on an even keel, on the placid blue sea of the tropics. Fragrant odors were wafted over to us from Florida, though we did not see the land. The Pan of Matanzas came in sight, and we studied the long, bold outline of the island of Cuba. It was the Spanish Main. It was the perfection of weather for piracy. If the “long, low, suspicious-looking [6]craft, with raking masts,” which used to steal out from sheltered covers to plunder rich galleons, had many such days for their occupation, it was, so far at least, an enviable one.

We had on board a Cuban who had married a Connecticut wife, and lived so long in a Connecticut village that he had a kind of Connecticut accent himself, and he was taking his wife to see his family, where, no doubt, much astonishment awaited her.

The captain, a merry and entertaining soul, had promised us, for our last day’s dinner, a baked ice-cream. He endeavored to get up bets on the improbability of his being able to accomplish it; but there, sure enough, it was, and doubters were put to scorn. There was a form of ice-cream, frozen hard and firm, and a crust over it, brown and smoking—a dish, as it were, typical of our situation, as a hardy Northern element in the embrace of the tropics. Not to continue the mystery of it, and as an earnest that there shall be no “tales of a traveller” in this record which are not strictly true, let it be explained that the ice had been covered with a light froth of white of egg, which was rapidly browned and scorched at the cook’s galley before the interior had time to be dissolved.

And so, as I say, two ruddy stone castles, full of green old bronze guns (we found that out afterward), looking down upon a narrow harbor-entrance; and it was Havana!

It was the morning of the 5th of April on which we entered it. We steamed up the strait to where it widens out into a basin, made fast to a buoy, and had our first glimpse of cocoa-palms, growing, unfortunately, around [7]a cluster of coaling-sheds. Some harbor boats took us ashore. We landed at broad stone steps pervaded by smells, passed into the Custom-house (which had been an old convent), and out of it into paved lanes full of donkeys, negroes, soldiers, sellers of fruits and lottery-tickets, engaged in transactions in a debased fractional currency. The money of the debt-ridden island is that of our “shin-plaster” war period, of unhappy memory. A couple of boiled eggs in a common restaurant cost forty cents; a ride in a horse-car, thirty-five. The wages of a minor clerk at the same time were but $30 or $40 a month. How does he make ends meet and provide for his future? He buys regularly a certain amount of hope in the Government lottery. “A demoralizing system indeed!” I said, as I frowned over the wares of a dealer who had lost a leg in the insurrection. I think it was No. 11,014 I bought, however, in a grand extra drawing, the first prize of which was to be a million, in paper. I trust the gentle reader will feel that I repented when I heard the result, some months after, in Mexico, and that I should have tried just as hard to repent had I won.

The Havanese were exercised just then over the discovery of great frauds in their Marine Department. Forty million dollars had been stolen, by collusion between contractors and the commissariat, since the outbreak of the rebellion in 1868. The Morro Castle was full of prisoners of distinction—officers, marquises, and counts, of the sugar aristocracy of the island, and Old Spain—awaiting their trial by court-martial. The principal operator, one Antonio Gassol, had already been sentenced to two years’ confinement and the restitution of a million of his ill-gotten gains.

The talk of not a few intelligent persons was, that the [8]ten years’ insurrection had been purposely kept alive by rings of contractors for purposes of spoliation, and by ambition for military advancement. Dulce, they said—going through the list of Captains-General—had married a Cuban wife, and was secretly a traitor; De Rodas, when asked for re-enforcements at a certain place, withdrew a portion of the troops already there; Pieltan was occupied in intriguing for the republican cause in Spain, and the easy-going Concha for the cause of King Alfonso. Finally, Martinez Campos and Jovellar were sent out, and, yielding to the demand of the universal weariness, by a little display of vigor, the one in the cabinet, the other in the field, made an end of the languishing struggle.

This may have been, however, merely the story of the discontented, which should be taken with a grain of salt. It is true, on the one hand, that the area of the island is not great, and the despatch of forces from Spain easy; the insurgents never held a town, and received no aid worth mentioning from without. But, on the other hand, there were no railroads of consequence, the ordinary roads were wretched, and there was the wild manigua, as it is called, half forest, half swamp, with which a good part of the island has abounded from the date of Christopher Columbus down. It was in the manigua that the insurgents found refuge from pursuit.

It so happened that the Ville de Brest was delayed in her coming, and I had six or seven days of leisure in the island. I employed part of it in a run down to Matanzas, the second city. I saw on the way the manigua, which is sentimentally pretty, from a distance, with[9] masses of laurel, cypress, and graceful palms; but within it is a thicket of intertwisted cactus, thorns, and creepers, through which a way must be opened with the machete, a formidable half knife, half cleaver, carried by the peasants for general uses on the plantations, and which served also as their weapon in the strife.

[10]

CATHEDRAL OF MEXICO.

[11]

There was an International Exhibition in progress at Matanzas, easily rivalled by almost any American county fair. The railway ride of three hours and a half by a ram-shackle train, run by a Chinese engineer, was hot and dusty, but how well repaid by the first deep draughts of satisfaction in understanding at last the heart of a tropical country! There was the thatched cabin, shaded by the broad-leafed banana. It was like “Paul and Virginia.” Where was the faithful negro Domingo? The hedges were of cactus and dwarf pine-apple. There were groves of cocoa-nuts like apple-orchards with us, and unknown fruits too numerous to mention. It was as if each peasant proprietor had cultivated a gigantic conservatory, and were indulging himself in the luxuries of life in consideration of foregoing its necessities.

Matanzas was dull, even with its Exposition, a pretty plaza, and the memory of a locally immortal poet, Milanes, of whom a tablet in a wall testified that he was born and died in a certain house. I looked into his works at a book-stall. He wrote on “Tears,” “The Sea,” “Spring and Love,” “The Fall of the Leaves,” “To Lola,” and “A Coquette.” “Your mother little thought, when she held you an infant in her arms,” he says, in substance, to the coquette, “of what wiles and perfidies you would be capable. Your beauteous aspect will in time fade away, and what remorseful memories will you not then have to look back upon!”

With this dip into the poetic inspiration of the heart [12]of the island of Cuba let me take the train back to town, having made a beginning of the discovery that a glib rhyming talent—and facility in speech-making as well—is common among the Spanish-Americans.

I visited a sugar plantation, where the negro slaves, swarming out of a great stone barracks—the men in ragged coffee-sacks, the women in bright calicoes—were as wild and uncouth as if just from the Congo. Next I went to the bathing suburb of Chorrera, where there is a battered old fort that has done service against the pirates, and where the American game of base-ball has been acclimated.

Havana was gay with parks, opera-houses, clubs, and military music. Awnings were stretched completely across the two narrow streets of principal shops. Bright tinting of the modern walls contrasted with a gray old rococo architecture. An interior court of my hotel was colored of so pure an azure that it was puzzling at the first glance to say where the sky began and the wall ended. The more important mansions were of a size and stateliness within which is probably nowhere surpassed, but neither in them nor the shabby little attempt at a gallery were there any pictures worthy of the name.

“You will find all that—the treasures of art—in Mexico,” the Havanese say. “Yes indeed! that is the place for them.”

They speak with great respect of Mexico, with which, perhaps, they have no very intimate personal acquaintance. Up to the independence of the latter, in 1821, it was the richest and greatest of all the Spanish possessions; and Cuba, made more important in its turn by this independence, was but a stopping-place on the way to it.

[13]

It is worth while to have seen Havana and Cuba as a preliminary to Mexico. The Spanish tradition pervading both is the same, with local modifications. It was here, too, that Hernando Cortez prepared his immortal expedition of discovery and conquest. Since I am preparing my own, to follow over exactly the same course, why should I repine that the Ville de Brest is a day or two longer in coming?

He was a wild young fellow in the island in early days, this Cortez, his chroniclers say, and gave little promise of the great qualities he developed in the enterprise which steadied him. The shilly-shally Velasquez would have stopped the sailing of his expedition and thrown him into prison, but he dropped down the harbor before his preparations were half completed and finished them elsewhere. He put to sea at last, with five hundred and fifty men, in nine small vessels, to undertake the conquest of an empire teeming with millions. The largest of his vessels was of a hundred tons, and some were mere open boats. In these he conveyed, too, sixteen horses, which cost him, it is said of them, “inexpressibly dear.”

We make a boast of our hardihood sometimes, yet grumble at sea-sickness, delays, the ordinary mischances of the traveller. But think of it! To set out in such a fashion, without steam, without charts, subject to every bodily ill for which modern science has found a remedy, and carrying your horses, worth well-nigh their weight in gold, to proceed against an unknown empire! Why, we do not know the first principles of boldness!

At last, on the 11th of April, the Ville de Brest came in, and went out again on the same day. She was a [14]steady-going, bourgeois-looking craft, as compared with the elegant American steamer, and showed traces of hard knocks in her long, plodding journey of twenty days to this point. She treated us well enough, however, and presented the novelty of surroundings for which I had come aboard. There was a little, gold-laced captain, and the crew wore white canvas hats and suits of two shades of blue cotton, as if equipped for some charming nautical opera. I believe I was the only English-speaking passenger; and as it has never been known to occur to a foreigner to practise his English, it was an excellent opportunity for practising the languages likely to be needed in the new country.

There was a young Frenchman who had been back to his own country to marry a wife, and brought her with him. There was a French engineer coming to report for principals in Paris on Mexican mines; an agent of a scheme for the establishment of a national bank. A young Italian of Novara, who had “Student” printed on his visiting-card, had secured an engagement as clerk in the capital for three years. An elderly Spaniard was coming over to look into the subject of forgotten heritages; another had obtained a position in the mines at Guanajuato. There were commercial men, and a well-to-do Mexican family, returning from their travels, with a son who had studied law at a Spanish university.

It has been proposed to call this body of water—made up of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico—the Columbian Sea, in compliment to sadly-neglected Columbus; and it seems a good idea, but it will hardly now be carried out. My predecessors have seen many an interesting sight on this tropical old Spanish Main, the source, too, of that greatest of natural mysteries, the Gulf Stream. But these must have been in times long gone by. In the [15]day of steam, with the swift prow always in motion, the ocean is vacant. There is no catching of sharks and dolphins, hardly even a covey of flying-fish. Those things were for the long, lazy periods of calm, when the denizens of the deep gathered curiously around the craft half quiescent among them.

One of my predecessors in 1839—Madame Calderon de la Barca, whose book on Mexico remains full of interest still—was twenty-five days making the voyage from Havana to Vera Cruz. She saw, too, as she approached, the snow-clad peaks of Orizaba and the Cofre of Perote, thirty leagues inland. We saw nothing of these. The sky was of an opaque gray above low sand-hills, on which a white surf was tumbling. We made our transit in three days, including some stoppage by a “norther.” The norther is of peculiar moment to the Mexican harbors of the eastern coast; they are little more than open roadsteads, and when it blows they cannot be entered.

[16]

The sea of the subsiding “norther” was still running heavily toward Vera Cruz, as if it would overwhelm it. It was a little Venice that we saw when we came to it. A half-mile or so of buildings, compact and solid, with blackened old rococo domes and steeples; yellow for the most part, scarlet, pink, green, and blue, in patches; a stone landing-quay, and a long, light iron pier projecting from it. At the end of the pier from a crane hung an iron hook, and to this the imagination instantly hooked on. It was the termination of the English railway to the capital. By that road, with all possible expedition, we should be borne up out of the miasmatic lands of the coast—the over-luxuriant Tierra Caliente—to the wonders of the interior.

To the left a reddish castellated fort. No suburbs—not a sign of them—only long, dreary stretches of sand. Very far down on the sand, with the sea breaking white over her, was the English steamer Chrysolite, dragged from her moorings by the gale and wrecked. We came in at evening, and joined ourselves to a little cluster of steamers and sailing-vessels made fast to buoys under the lee of a coral reef, on which stands the disreputable old castle of San Juan d’Ulloa. It is whitewashed in part, and partly as blackened by time and powder as the reef itself. A revolving lantern moved round on its summit. It was told to the confiding that the Government kept prisoners there to turn it; and they were instructed to look for their dark, flitting forms and hear their lugubrious cries. We heard all night, at any rate, the creaking of the pumps of an American bark along-side, which had come disabled into port, with a freight of logs from Alvarado, and could barely keep afloat.

[17]

DOMES OF VERA CRUZ.

[18]

It so happened that it was the anniversary of the arrival of Cortez, in the year 1519. He had arrived on the evening of Thursday of Holy Week, and so had I. It was on the morning of Good Friday that I went ashore. We were taken off in small boats, and our ship unloaded by lighters, for there is not one of these Mexican harbors where a ship can lie up to a wharf in safety.

More than the usual embarrassments await the ordinary traveller on the quay at Vera Cruz, by so much as he is apt to know less of Spanish than of French—in which most of the dearly-bought early foreign experience is acquired—and nobody will tell him the truth. Let it be fixed in mind that but one train a day starts for the capital, and this at eleven at night. The designing bystanders make you take your baggage to a hotel, pretending that no other course is possible. Take it, instead, to the depot at once and get rid of it, and then see the town.

For the town is by all means to be seen. One had not expected much of a place the reputed home of pestilence, and I shall not advise a lengthened stay; but, from the point of view of the picturesque, it has some pleasant surprises.

Founded by the Count de Monterey in the early part of the seventeenth century—for it is not quite the site of the original Vera Cruz of Cortez, which was above—it has now attained a population of about seventeen thousand. [19]The principal shops had a large, well-furnished aspect, especially those in groceries and heavy hardware. The Custom-house square was piled to repletion with bales of cotton, railroad iron, and miscellaneous goods awaiting transit.

I walked, the very first thing, into a large, cool public library, which had once been a convent. It was not much of a public library, the books being few, and to a certain extent bound in vellum, as if they too had belonged to the convent; but it was public, and what one did not expect.

The churches were of a well-proportioned, solid, grandiose, rococo architecture, and had charming bells. The principal one, in a little shaded plaza, had its dome encrusted with colored china tiles, which shone in the sun—a feature waiting in plenty farther on. They were draped in black, and crowded with worshippers to-day, and abounded in strange figures of bleeding Christs, with other evidences of a florid form of devotion.

Grass grew in joints of the pavement in the minor streets, as I had seen it, for instance, in some such place as Mantua. Long water-spouts project from the tops of the flat-roofed white and yellow houses, and upon these sit the solemn zopilotes. All the world knows that the street-cleaning of Vera Cruz is conducted by the ravens, or buzzards; but all the world does not know with what a dignity these large zopilotes, of a glossy blackness, often pose themselves immovably on the eaves against the deep blue sky. They might be carved there for ornament. Many a street-cleaning department is at least less sculpturesque, and perhaps less efficient.

The principal thoroughfare, called of the Independence, leads to a short, concrete-covered promenade, bordered with benches and a double row of cocoanut-palms, [20]and this to the open country. It is an early discovery that the Mexican is patriotic. He is fond of naming his streets and squares after his military achievements, and particularly the Cinco de Mayo (the Fifth of May). We shall hear plenty more of it, this Cinco de Mayo. It was won at Puebla over the French, in 1862. He attaches also to cities the names of his heroes. Thus Vera Cruz itself is Vera Cruz of Llave, a general and governor; Oaxaca, Oaxaca of Juarez, the sagacious President; and Puebla, Puebla of Zaragoza, its commandant on the 5th of May above-named.

There were notices of a bull-fight posted on the dead walls. Nearly all typical notes are struck at once—plaza, Renaissance churches, patriotism, bull-fight, and tropical vegetation. I took a tram-car of a peculiar, wide, open pattern (made, however, in New York) out to the open fields, and saw a dancing-place, a ball-ground, and the dark, heavily walled-in cemetery.

The road to this latter should not be grass-grown, if half the tales of dread told abroad be true. And yet there are apologists even for the yellow-fever, or rather those who say that its ravages are greatly magnified.

I fell in with the Yankee captain of the disabled bark which had lain by us during the night. He was sitting on a low stone post at a street corner, and was half disconsolate, half desperate, by turns. He could find no dry-dock in which to lie up for repairs; and he could get no steam-pump, by the aid of which he might have kept on his way. He was condemned to see his venture sold for a song, for want of means to save it.

If little, as I say, was expected from the land at this place, a good deal, on the other hand, was expected from the water, at an ancient port, the New York of Mexico, receiving nine-tenths of the commerce of a nation of ten [21]million people. But not a year passes without a number of disasters, which has led the underwriters to make their risks to Vera Cruz about five times higher than to most other ports. The aggregate of these losses for a brief time would pay the cost of works needed to make the inhospitable roadstead a harbor.

A few rudimentary preparations are absolutely necessary before Mexico can enter upon the expected period of prosperity, and the creation of harbors in some degree commensurate with the new transportation facilities is one of them. A breakwater plan will, no doubt, have to be adopted like that so much in use on our great lakes and the Channel ports of Europe. It was of interest to hear, during my stay in the country, that this need had impressed itself upon the authorities at Vera Cruz and Tampico, and that they had taken the step of counselling on what was best to be done with the American engineer, Captain Eads, who was engaged in his unique scheme of a ship railway across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

I had the pleasure of spending the evening, pending the departure of the train, in a large, cool, roomy house, with the American consul. He had been a resident for twelve years, and had brought up a family of daughters here. It did not seem, at first sight, an attractive place in which to bring up a family; but they saw a good deal of company from the ships in port, took an occasional run to the capital, or a vacation at Jalapa or Cordova, above the danger-line, and seemed well content.

The consul was himself a physician, and had much to say on the subject of the yellow-fever. He insisted that it was epidemic, but not contagious. The local authorities [22]put afflicted patients in their hospitals along-side others suffering from ordinary sickness, and these latter do not take it.

“Great damage,” he said, “is done to the commercial interests of both countries by the annoying restrictions of quarantine arising from this cause. There is no more need of quarantine against yellow-fever than against common fever and ague, since it cannot be transmitted.”

He quoted eminent medical authority at New Orleans as sharing his views. From which it would seem that the subject is worth careful looking into from official sources, in order that, if there be a mere popular delusion, it may be dispelled. As I write the Mexican Government has just granted authority to the steamer line which carries the mail into New Orleans to reduce the number of its trips to one each month during the quarantine, increase its freight and passenger rates fifty per cent., and, if the traffic does not pay even under the increase, to abandon it entirely.

The consul, in conclusion, had known but one countryman of ours to die of it during his stay, and only a few to be attacked. I may say, however, that the consul succeeding this one—who has since gone away—arrived fresh from Minnesota, and died at his post within a week.

Another interesting subject of talk with the consul was the tariff laws and the usages of the port of entry, naturally of leading importance here. The tariff system, based on an original law of 1872, has been greatly tampered with since, and is in a confused state; so that, with the best intentions, importers are apt to be visited with double duties, fines, detentions of goods, and law-suits. There are some three hundred and seventy-eight articles in the specified list. New articles are charged for after the manner of those which they resemble. Thus, when [23]the article of celluloid was first introduced there was doubt whether it ought to be taxed twenty-nine cents a kilogram as bone, or $2.20 a kilogram as ivory, and the decision was finally in favor of the latter.

The merchant must use the names employed in the country. Thus, our “muslin” should be merely “shirting” or “calico;” while what is understood here by muslin is really lawn, taxed twice as much. The least variation in a label or form of package is visited with penalties. Storage in the warehouses, too, is estimated, not by the space occupied, but by the package, which is a hardship. A case is told of where ordinary argenté hooks-and-eyes, which should pay nineteen cents a kilogram, were charged for as “plated silver,” which pays $1.15, and then a double duty imposed for “false declaration,” making the total $2.30 a kilogram. As a rule, a “venture” is not a success. The laws, framed with excessive severity against contrabandists, whom they often fail to reach, afflict well-meaning persons. They make the consignee of goods subject to all the penalties; and many of these latter are afraid to touch, without the most ample guarantees, consignments of goods which they have not specifically ordered. The Germans succeed best in this traffic, through their painstaking attention to the local requirements.

“I will tell you a story,” said the consul, “of an unlucky fellow who came here from England with a small venture of fancy goods, part free of duty. The whole cost him originally $1200; and he had consulted the Mexican consul at Liverpool, and thought he knew what he was about. When he got through the Custom-house his total charges and fines had amounted to $2850. He sold his stock for $2000, and borrowed money to pay the difference and get out of the country.”

[24]

There is but one train a day, each way, on the English railway, and the journey occupies twenty hours. The road is a great piece of engineering, and has been described more than anything else in Mexico. Photographs—almost the only good ones to be had in the country—are plentiful, displaying its notable points. It climbs seven thousand six hundred feet to the table-land in a distance of about two hundred miles, the whole way to the capital being about two hundred and sixty. It has the transporting of the greater amount of construction material brought into the country for the new roads, and has lately been quite profitable. A first-class fare is $16; a second-class, $12.50; and baggage is charged for, as on the Continent of Europe.

Behold us at last at the station, at eleven o’clock at night, ready to climb to the capital—but how unlike our great predecessor, Cortez—by railway. No, indeed; poor hero! he had to linger at the coast for months before beginning his long and painful march, with a battle at every step. Nor was it by the same route. He went in by Tlaxcala, Cholula, Puebla, and so over between the great snow-peaks of Popocatepetl and Ixtacihuatl (the White Woman), down to the gleaming lakes and palaces of ancient Tenochtitlan. In this course he was followed by General Scott in his turn. The old diligence road—of their adventures on which my predecessors have written so much—continued practically the same route, going first by National Bridge and beautiful Jalapa.

[25]

MAP OF ENGLISH RAILROAD FROM VERA CRUZ TO MEXICO.

[26]

I say beautiful Jalapa—although I have not been there myself—because all testimonies point with such a unanimity to the charms of soil and climate, and the beauty of the feminine type, in what is considered a peculiarly favored spot, that I think there can be no doubt about it.

There were no sleeping-cars; but the carriages, divided into compartments for eight, and comfortably padded (on the European plan), filled their place very well. The passengers in the third-class cars had already begun the night with a boisterous singing and playing of harmonicas. To-morrow was the Sabado de Gloria (or Holy Saturday), an occasion of merry-making, and they were taking an earnest of it. A car containing half a company of dusky Indian soldiers, who act as an escort, was coupled on to the train.

The associates in the compartment in which I established myself were the French engineer sent out to report for principals in Paris on Mexican mines, and the young Frenchman bringing back a bride from his own country. All at once there entered it so lawless and bizarre-looking a figure that the French engineer sent out to report on mines to his principals in Paris thought it prudent to descend hastily and seek quarters elsewhere. The rest of us, though remaining, were, perhaps, in no small trepidation. It was the first view at close quarters of a dashing type of Mexican costume and aspect which is peculiarly national.

Our new friend was dressed in a short black jacket, [27]under which showed a navy revolver, in a sash; tight pantaloons, adorned up and down with rows of silver coins; a great felt sombrero, bordered and encircled with silver braid; and a red handkerchief knotted around his neck. A person in such a hat seemed capable of anything. And I had forgotten to mention silver spurs, weighing a pound or two each, upon boots with exaggerated high and narrow heels. This last, by-the-way, is a peculiarity of all boots and shoes in the market, which aim thus, it would seem, to continue the old Castilian tradition of a high instep.

Would it be his plan to overawe us with his huge revolver, alone?

Or would he, at a preconcerted signal, be joined by confederates from the third-class car or a way-station, who would assist him to slaughter us?

The traveller is rare who arrives in Mexico for the first time without a head full of stories of violence. The numerous revolutions, the confused intelligence which reaches us from the country, give a color to anything of the kind; and the stories retain their hold for a time even in the most frequented precincts.

We got under way. The new arrival, instead of devouring us, proved the most amiable of persons, and we were soon upon excellent terms with him. He was a wealthy young hacendado, or planter, returning to estates of his, on which he said six hundred hands were employed. He offered cigars, gave us details in answer to our eager curiosity about his novel dress; and we had shortly even tried on—bride and all—the formidable sombrero, and learned that the price of such an one in the market is from $20 to $30. The silver-bound sombrero, and ornaments of coins, are a favorite kind of Mexican extravagance even among the lower classes, [28]which is perhaps accounted for by the lack of proper places of deposit for savings in other forms.

It was moonlight. Sleep on such a night was out of the question. Not a foot of the scenery ought to be lost. But the padded coach was comfortable; the fatigues of the day had been severe. The lively conversation became fitful, then lapsed into long silences. The events of that first night, half dozing, half waking, sometimes even alighting at the little stations, seem wholly like a dream—the waking part, if possible, stranger than the other.

Palms and bananas and dense coffee shrubbery, with hamlets of thatched cottages sleeping peacefully among them; a glimpse of a cataract; an Indian mother singing to her baby; perfumes coming in at the window; statuesque, silent men in blankets, and Moorish-looking women, offering fruits; stations from the outer doors of which, when reached, no town was visible, but only an immense darkness; persons taking coffee in lighted interiors; the dusky soldiers laughing loud in their compartment; a few startling words of English, sometimes with a Southern or even Hibernian accent, spoken by imported employés of the line meeting to exchange a comment, generally unfavorable, on their situation—these are the impressions that stamp themselves upon the memory.

As soon as the first gray of daylight appears it seems incumbent on us to begin to admire the country. We are not far past Cordoba, the centre of its most important coffee-growing interest.

“Pouf!” says our friend, the hacendado, with an air of disdain.

[29]

He will not take the trouble to look out of the window. He expects things very much better. We have, in fact, passed remarkable scenes in the night, but the best is still before us, and presently begins.

At a little station called Fortin we commence to wind along the side of one of the vast sudden gorges which impede travel in the country, the barranca of Metlac. There are horseshoe curves which almost permit the traditional feat in which the brakeman of the rear car is said to light his pipe at the locomotive. We pass tunnels and trestle bridges, see our route above and below us on the hills in such varied ways that it is hardly possible to understand that these are not so many different roads instead of the same. There is a point above Maltrata, distant but two and a half miles in a direct line, which must be reached by twenty miles of zigzag.

The history of this road, from the political point of view, presents hardly fewer obstacles and vicissitudes than those opposed by nature to its engineers. It has passed, in its time, under the rule of forty different presidencies, and lost and recovered its charter in the revolutions. Though of so moderate length it required over thirty years and $30,000,000 to build it.

The passengers ran out at the small stations for flowers, with which we adorned ourselves. So, too, wreaths were hung about the neck of Cortez’s horse in his progress, and a chaplet of roses upon his helmet. We gave the new bride heliotrope, roses, jasmine, and the splendid large scarlet flower—the tulipan—which may pass for the type of tropical beauty.

The sun came up and lighted Orizaba, rising 17,375 feet beside us to the right, making it first rosy-red, then golden. The peak is a perfect sugar-loaf in form, with [30]nothing splintered and savage about it, as in Switzerland. It seems almost too tame at first—a sort of drawing-master’s mountain—and, above the tropical landscape, is like snow in sherbet. The city of Orizaba is an important small place, the scene of a dashing surprise of the Mexicans by the French, at the hill of El Borrego. It has charming torrents, which furnish water-power for cotton and paper mills. One of these torrents, conveyed in an arched aqueduct, turns the machinery of the ingenio, or sugar plantation, of Jalapilla, once a country residence of Maximilian.

A delegation of relatives had come down the night before to await our young couple here. What embracing and chattering! A Mexican embrace has a character of its own. The parties fall upon each other’s necks, as we are accustomed to see done on the stage. It is given, too, between mere acquaintances, almost as commonly as shaking hands.

A vivacious sister-in-law aimed to give the new-comer an idea of what was before her in her future home. “Such flowers as I have in the court-yard!” she said, raising her eyes, with an expressive gesture; “such oranges, camellias, azaleas! Ah yes, indeed, I believe it well.”

“And Jack?” inquired the husband, addressed as Prosper; “how always goes poor Jack?”

“Ah! he is dead,” replied the vivacious sister-in-law. “I regret to tell you, but so it is.”

It appeared that Jack was a favorite monkey, and for a moment his untimely fate cast a certain gloom over the company.

From the heights where we were little villages, with squares of cultivated fields around them, were seen at vast [31]distances below, with the effect of those miniature topographical preparations in relief displayed at international exhibitions.

It greatly simplifies Mexico to remember that, in profile, it is a long, continuous mountain-slope, rising from the Atlantic to a central table-land, and falling, though more gradually, on the other side to the Pacific. Along the ascents, as well as at the top, are some benches, or level breathing-places. These table-lands are the chief seats of population, and they are utilized as much as possible for the lines of the north and south railways.

TRANSCONTINENTAL PROFILE OF MEXICO.

This steep formation accounts for absence of navigable streams and for the existence of climates verging from tropical to temperate, nearly side by side. The sharpness of contrasts in climate is scarcely to be appreciated by the hasty voyager. The really tropical vegetation is succeeded by a kind which to the eye of the American of the North is quite as exotic. Banana and cocoa-nut are followed by a hardy kind of fan-palm; by nopal, or prickly-pear, as large as the apple-tree with us; by the tall, straight organ-cactus, in use for hedges; and the remarkable maguey, or century-plant.

What would not some of our American conservatories or a certain well-known New York club give for some of these splendid specimens! The spiky maguey, like a sheaf of sword-blades, grows eight and ten feet high. It is the typical production of the central table-land. Its [32]sap furnishes in extraordinary quantities the beverage called pulque—the wine of the country. From it, in addition, are made thatch, fuel, rope, paper, and even stuffs for wearing apparel.

Our third-class passengers celebrated their Sabado de Gloria with great spirit, by shouting, and firing pistols and Chinese crackers from the car windows. Teams of mules, with their load, whatever it might be, gayly adorned, showed that it was being equally observed in the country. It is a day devoted by custom to the particular abasement of Judas, who is treated as a kind of Guy Fawkes and dishonored in effigy. Venders parade the streets with grotesque images of him, and children at this time estimate their fortune in the number of Judases they possess, just as at the season of All-Souls it is in cakes, gingerbread, and even more substantial viands, fashioned into death’s-heads, cross-bones, and coffins.

At Apizaco, the junction of a branch-road to Puebla, we met a merry excursion, decorated with rosettes and streamers. It had two mammoth Judases, stuffed with fire-works, one on the locomotive, the other on a baggage-car. The former was blown up, as a kind of compliment to us by way of exchange of ceremonies with our own train, amid hilarious uproar.

We had now entered upon the central table-land of Mexico. Long, dotted, perspective lines of maize and maguey stretched to distant volcanic-looking hills. A few laborers in white cotton were ploughing with wooden ploughs, after the pattern of the ancient Egyptians. At the stations squads of a mounted rural police, in buff leather uniforms and crimson sashes, which give them a certain resemblance to Cromwell’s troopers, salute the train.

[33]

The sparse towns consist of a nucleus of excellently built old churches amid an environment of mud-colored habitations. They are in crying need of whitewash. Will they ever get it?

A RAILWAY JUDAS.

The face of the country was not the verdant paradise that may have been expected, but parched and brown. We had come at the end of the rainy season. Small columns of dust, whirling like water-spouts, were a constant feature of the landscape. A stage-coach going along a distant road was marked by its own dust, as a locomotive by its smoke.

Isolated houses there were none, with the exception of (at long intervals) some gloomy, square, fort-like hacienda, with straw-stacks and flocks and herds near it. [34]Indian peasants offered for sale, all along the way, cakes spiced with green and red peppers. The village of Apam is the centre of the Bordelais of the pulque industry. The new-comer here usually makes his first trial of that beverage, milk-like in aspect, but somewhat viscid and sour to the taste, with heady properties. It does not commend itself to favor on a first acquaintance. Wry and contemptuous grimaces are made over it, but in time, as occurred in my own case, it may become very palatable, as it is said to be healthful. It is poured into little earthen pitchers from bags of whole sheep-skins, with the wool-side in, like the wine-skins of the East and “Don Quixote.” These bags, resembling dressed pigs, lie about on the ground or the freight-car, with their legs dumbly kicking up in the air, in many a grotesque attitude.

But one glimpse of real Aztec antiquity along the way, and that at San Juan Teotihuacan, thirty miles from the capital. The deceptive shapes of the hills, which assume symmetrical forms, had frequently produced a throb of half self-delusion, but here are two genuine pagan teocallis, pyramids dedicated to the sun and moon, and a great area covered with broken fragments and vestiges of tombs. It is thought to have been old and ruined even in the time of the Aztecs. Children offer at the train caritas, as they call them (“little faces”), and other fragments of earthen-ware, together with occasional pots and idols of large size, which they represent as having been dug up out of the soil. They have certainly been buried in the soil; but later, finding that the manufacture of spurious antiquities is a thriving industry, one takes leave to question for what length of time.

And yet, what can it matter? These ancient-seeming jars, with their symbols and images of the war-god and what not upon them, are at least unique and historically [35]correct. One does well to bring home what he can get, for default of better, and not ask too many questions.

San Juan is a place that one mentally makes a note of as to be returned to; and I spent some pleasant days there later, poking among the potsherds of the past, and picking up ordinary caritas and bits of flint weapons, for myself.

But no dallying now. The shades of evening draw on. We are weary and travel-stained with the twenty hours’ journey and the many excitements of the day; but the great moment is at hand. Gleams of distant water, thickets of maguey and cacti, with a peasant stealing mysteriously among them, behind a troop of donkeys! The geography picture is realized to the life. The water comes nearer; we skirt its borders. Can it be that these lonesome, shallow expanses, without vestige of sail or even skiff, their muddy shores white with a deposit of salt and alkali—can it be that these are the great lakes of Tenochtitlan, on which Cortez launched his brigantines? And the famous floating gardens, where are they? All in good time! We shall see. The sacred hill of the Virgin of Guadalupe, with a cluster of interesting-looking churches upon it, is passed. Remains of ruined haciendas and fortifications, and dilapidated adobe hovels, appear. We run out upon a long, low causeway, skirted by the arches of an aqueduct, over marshes. Other similar causeways are seen converging from a distance. One had not expected to find everything so unrelievedly flat. It is like climbing the mountain to find the Louisiana lowlands. A chain of yet higher mountains surrounds it, it is true; the snowy summits of Popocatepetl and its mate, the White Woman, always shine upon it from a [36]distance, but Mexico itself is a basin. It has been under water, and would be yet, but for artificial works by which the lakes have been made to recede and left behind them these alkali-whitened margins.

It is a disillusionment very like that of approaching Venice at low tide.

[37]

There was a custom-house at the Buena Vista station. Part of its profits are national, part municipal. The capital is in a Federal District, ruled by a governor, not unlike the District of Columbia. There is little inter-state comity as yet among the different parts of the republic. Each state still collects dues at its own frontiers, and the towns take tolls (the alcabalas) on merchandise and food entering their gates.

Mexico is not a cheap city of abode. Its hackney-coaches, as in European countries as well, are an exception to the general rule; but even these, with the various commissionaires, who zealously aid you in putting your baggage upon them, after getting it through the custom-house, are dear for the first time. Travelling is like so many other things in the world: you pay a bonus, or initiation fee, in the beginning, after which the charges are in a declining series. The particular hackney-coach which conveyed us, a travelling companion and myself, may have been a trifle dearer on account of a driver who aspired to a few words of English. Not that we greatly wanted it. The injury to one’s feelings in these cases of the indifferent reception by the native of your first overtures in his own language (as if his own language were not good enough for him, forsooth), is sufficient, without [38]a pecuniary burden added. But he charged for it, as I say.

“Well, good-night,” he said, saluting us as patrons. “Wass you wants?” And, after having passed the long, shady strip of park called the Alameda, he even ventured upon a certain facetiousness, as, “Wills you to want a wiskey?”

He had learned this proud acquirement in the military service on the frontiers of Texas.

A long, dark ride conveyed us to the principal hotel. As it was once the palace of the Emperor Iturbide, after whom it is named, it should have something stately about it, and so it has. There is a high, sculptured door-way, of an Aztec touch in the design, though not in the details, and long, grotesque water-spouts project into the street. Within is a large, dark, arcaded court, from which open café and billiard-room, the leading resort of the golden youth of the town.

The office is a dark little box of a place, with two serious functionaries, who seem to receive the visitor only with suspicion. The gorgeous and affable hotel clerk of northern latitudes is unknown. In the rear are more courts, not arcaded; and around all of these the rooms are ranged in several stories.

It is not so late on the evening of his arrival but that the traveller may, after dinner, still take a stroll. He will be apt to fancy at first, from the quietude, that his hotel is not on a principal street; but it is in the most central part of the city—on the street which, with three others running parallel for say half a mile, and the included cross-streets, contain the principal retail traffic.

It is an early discovery that Mexico is a grave and not a gay city. There are no crowds on the sidewalks, no eating of ices in public, no cafés chantants, nothing [39]Parisian. By nine or ten o’clock the people seem to have retired, perhaps to be up betimes in the morning for the work of the day. A military band plays three evenings in the week, but even these concerts, except on Sundays, are so sparsely attended that the men seem discoursing the music for their own amusement.

Policemen are stationed at short intervals apart in the quiet streets, with their lanterns set in the middle of the roadway. They are obliged, by regulation, to signal their whereabouts every quarter of an hour. The sound of their whistles, which have a shrill, doleful note, like that of a November wind, is heard repeated from one to another all the night through.

As Mexico has not, until lately, at any rate, expected tourists, there are almost none of the usual appurtenances for their pleasure and information to be met with. While this may have its annoyances, if an ardent curiosity be baffled too long, on the other hand freedom from the sense of responsibility to exacting Baedekers and Murrays has advantages of its own. The visitor with an eye for the picturesque dips into a delicious feast of novelties, makes discoveries on every hand, and has the pleasure of testing the value of his own unaided conclusions. By daylight, with all its bright colors upon it, and its normal stir of life going on, the famous capital is a very different place from what it was at night. By little and little misapprehensions are shaken off. After the first moments of disappointment we like it always more instead of less, and in the end it takes a powerful hold.

Here at length is the great central plaza, in which events of such moment have been transacted. To actually [40]sit down upon a bench in the midst of it, and gaze comfortably about—can it be possible?

The imposing cathedral makes a new pyramid on the spot where once stood the pyramid of the Aztec war-god. These stones should be ankle-deep with all the blood of various sorts that has been spilled upon them. For a moment one renews the pagan superstition. I would gladly see set up again, for a brief instant, old Hutzilopotchli, the war-god, aloft on his ancient terrace, hear the beat of the lugubrious war-drum, and see the mournful procession of captives winding up to the sacrifice, in charge of the sinister priests with their black locks flowing down upon their shoulders.

But not one instant too long. What! hideous priests, you will indeed lay them down on the sacrificial stone, and raise the knives of flint above their bared breasts for the monstrous slaughter? Not one hair of their heads shall be harmed. San Jago and Spain! When was Castilian ever known to turn his back upon a foe? Up the pyramid we go, leaping from step to step, though with no better weapon than a sun-umbrella in hand, to their deliverance. Ay, howl if you will, baffled miscreants, and rattle your spears and arrows like hail upon us! Down with your old Hutzilopotchli till he crashes in fragments below there. Your carven sacrificial stone shall be set up in the court-yard of the Academy of Fine Arts of San Carlos for this, and your great calendar-stone, a show-piece, against the side of the cathedral.

It is a good day’s work. I estimate that there were in that train of captives not less than a hundred souls!

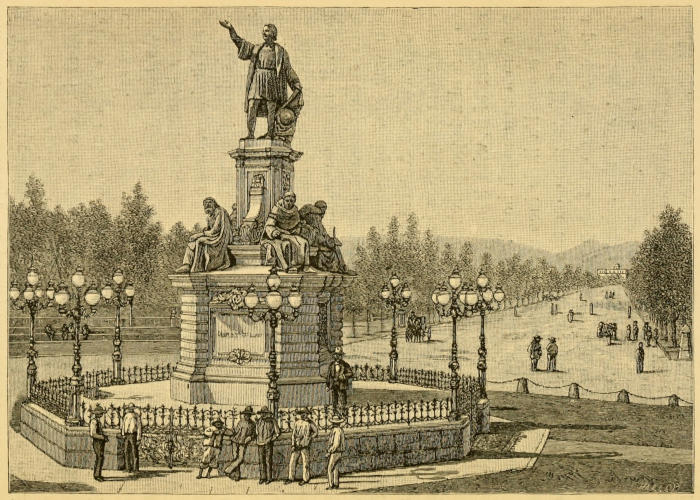

But it is hard to conjure up images of desperate conflicts, though there have been so many, in this bright sunshine, with the multitude of pretty, novel sights. On one side of the square a beneficent institution, the National [41]Loan Establishment, occupies what was once the site of the palace of Cortez; on another, the long, white, monotonous National Palace, the site of that of Montezuma. In the centre is a charming little garden, with benches, the Zocalo.

The cathedral, like most of the earlier architecture, is in the Renaissance style, far gone to the vagaries of rococo. It is saved from finicality, however, by its great size and massiveness, except in respect to the terminations of its towers, which are in the shape of immense bells. Adjoining, and forming a part of it, is a parish church, in a rich, dark-red volcanic stone, with carving that recalls the fantastic façades of Portuguese Belem. What a painting it would make, on one of the perfect moonlight nights, which bring out every line of the sculpture softly, and show the whole like a lovely vision!

There are little book-stalls in front, and gay booths devoted to the sale of refreshing drinks—aguas nevadas—from large, simple jars and pitchers of most noble and pleasing shapes. The drinks are dispensed by dusky Juanas and Josefas of Indian blood, with straight black braids of hair down their backs. With a characteristic taste the fronts of their booths are often wholly studded and banked up with flowers, and furnished with inscriptions formed in letters of carnation pinks and blue cornflowers.

Figures go by in blankets which one hankers to take from them for portières or rugs. The men of the poorer sort wear or carry, universally, the serape—a blanket with a slit in the centre for the insertion of the head. Apart from its artistic patterns, it is a useful garment in many emergencies. It is not the most improbable thing in the world that, in the course of the Mexican revival, we may yet see it introduced in the States, and running a course [42]of popularity like the ulster. The corresponding garment of the women is the rebozo, a shawl or scarf, generally of blue cotton, which, crossed over the head and lower part of the face, gives a Moorish appearance. The background of life here seems more like opera than sober existence. Two other sides of the square are occupied by long arcades, among the merchants of which, protected from the sun and rain, one may wander by the hour, watching the shrewd devices of trade, and picking up those knick-knacks, trifling in the country of their origin, which are certain to be curiosities elsewhere. From time to time pass across the view, dark and Egyptian-like, in a peculiar dress of bluish woollen, trudging under heavy burdens, Indians who have yet preserved the tradition of their race. Followed to their homes, they are found to dwell, among the ruined walls of the outskirts, in adobe huts which can have changed little since the time of the Conquest.

These genuine Aztecs have peculiarly soft, pleasant voices, in contrast with the Spanish voice, which is apt to be harsh. They are shiftless and squalid, but their manners are above their surroundings. It is a favorite way with the Mexican to say, “This is your house;” and I have had said to me on being introduced, “Well, now, remember! number so-and-so, such a street, is your house.”

Having looked into one of these Indian abodes, and asked an elderly woman, by way of making talk, if it were hers, she replied, “Yes, Señor, and yours also.”

Neither in the Zocalo nor the Alameda (a park, which holds somewhat the position of the Common, in Boston), are there trees with the hoary antiquity one might expect in such time-honored places. But it appears that the setting out of the trees, and the formation of the Zocalo[43] entirely, is of modern date, the work of Maximilian, a monarch who, in his short, ill-fated reign, had many excellent projects.

[44]

A FLOWER-SHOW IN THE ZOCALO.

[45]

The Zocalo is occasionally allowed to be enclosed, and an admission-fee charged, for select festivities. The orations were delivered there, for instance, on the national festival of the 5th of May. When I first arrived a flower-show was in progress. I have never seen anything more charming of the sort. Our florists might get a score of new ideas for the arrangement of bouquets. Strawberries were introduced into some for effects of color. Little streamers with gallant mottoes floated from others. There were lanterns, and birds in cages. A military band played, and people promenaded—dandies with silver-braided hats, stout duennas, and fathers of families, and slender, lithe señoritas, wearing the graceful mantilla instead of the Paris bonnet.

In front of the Zocalo a permanent flower market is held every morning, which is almost as pleasing.

Tramway cars run out of the plaza in numerous directions. The city early utilized this invention, and boasts of having one of the most complete systems existing. The inscriptions on them have an attractive look. One would like to take all the different routes at once. Patience! it is all accomplished in time. Shall we go to Guadalupe Hidalgo, with its treasures and its miraculous Virgin; to Tacubaya and San Angel, with their villas; Dolores, with its pensive cemetery, full of sculptures; La Viga, with its picturesque canal, giving access to the chinampas of flowers and vegetables; the gates of Belem and Niño Perdido, familiar in the story of the American conquest; Chapultepec? Yes, that shall be the very first—Chapultepec, theatre of exploits of American valor and of moving events in every historic epoch.

[46]

Mexico is extraordinarily flat, and laid out as regularly at right angles as our own symmetrical towns. At the ends of all the streets the view is closed by mountains. Its flatness, together with its position in reference to the adjoining lakes, are circumstances which have occasioned great solicitude in the past, and still call for almost as much, on a different ground. Formerly it was danger of inundation; now it is defective drainage. Bad odors offend the nostrils, and stagnant gutters and heaps of garbage the sight, of the wayfarer about the interesting streets.

COMPARATIVE LEVELS OF LAKES.

The drainage problem, divested of the mystery with which it has been surrounded in learned treatises, is simply this. When the vast slope from the sea has been surmounted, and the Valley of Mexico—as high as the Swiss pass of St. Gothard—is reached, it is found to be a shallow depression, containing six lakes. These are of many different levels—Texcoco the largest and lowest. On the edge of Texcoco, or in the midst of it, like another Venice, with canals for streets, was built ancient Mexico. This principal lake received the overflow of the others, and the city was subject to frequent inundations. It is even now, after a large shrinkage in the lakes, but a little more than six feet, at its central portion, above Texcoco. The waters of the three upper lakes—San Cristoval, Xaltocan, and Zumpango—were turned back as [47]has been done with the Chicago River of late. A great Spanish drain in the early seventeenth century, the Tajo of Nochistongo, was cut through the mountains, and got rid of it in the direction of the Atlantic.

But Texcoco itself has no outlet, and, as experience has proved, even with only Chalco and Xochimilco to be taken care of, is still liable to overflow. With relief from this peril is inseparably bound up the drainage problem. The fall is so slight at best, that though Lake Texcoco be preserved at a normal level, and kept from backing up into the sewers, there is no destination for the sewage received by it, which lies festering in the stagnant water. With the rest is complicated also the irrigation of the valley. No end of plans have been offered to resolve these difficulties. Their history would make an interesting chapter by itself. Some have proposed to pump out the lake by steam; others, to intercept the waters running into it, and allow it to dry up naturally; another, to exhaust it by means of a great siphon of stone and cement. But the judgment of most is in favor of establishing a current, through a canal, to some point lower than the lake; and the mountains in the neighborhood have been searched for the most favorable point of exit for such a canal.

The plan was officially adopted, in fact, and a considerable beginning made, under the direction of an able engineer of foreign education, Don Francisco Garay. But the works were allowed to languish. Neither government nor community seemed more than half-hearted in the effort to get rid of evils to which they had so long been used. The problem still remains one of the most pressing of those to be resolved, and one of the most interesting to foreigners intending to make Mexico their home.

[48]

Choosing any street at random where all are so attractive, and proceeding to its termination, in this direction or that, you arrive now at a mere cul-de-sac, now at a city gate, now at vestiges of adobe fortifications, with a moat. Few vehicles, apart from the hackney-coaches, are to be seen, but plenty of troops of laden donkeys, and everywhere the cotton-clad natives themselves bearing loads under which the regular beasts of burden might stagger. There is a story that when wheelbarrows were first introduced to their notice on the railroad works, the natives filled them in the usual way, and then carried them on their backs.

Each separate kind of business has its distinctive emblem. The butcher—elsewhere not a person noted for great taste in ornament—displays a crimson banner, and has his brass scales decked with rosettes. His supplies are brought him by a mule, trotting along with quarters of beef or carcasses of mutton on each side hung from hooks. But it is especially the pulque shops (corresponding to our corner liquor stores) which devote themselves to decoration in its most florid form. Not one so poor as to be without its great colored tumblers, and ambitious fresco of a battle scene, or subject from mythology or romance. They delight in such titles as “The Ancient Glories of Mexico,” “The Famous St. Lorenzo,” “The Sun For All,” “The Terrestrial Paradise,” and even “The Delirium,” which often enough expresses the condition of customers who imbibe too freely.

[49]

THE HOMES OF THE POOR.

[50]

On the tramways pass not only passenger-cars, but others for freight. They move the household goods of a family, for instance. There are also impressive catafalques and mourning-cars, running smoothly along, with funeral processions. You may graduate from a hearse with six horses, driver, lackey, and four pall-bearers, all in livery, for $120, to one drawn by a single mule for $3; and there are cars for the mourners in the grand style at $12 and plain for $4.

Both these ideas, it would seem, might be advantageously adopted by suburban lines of our own.

Presently comes by a more economical funeral—a couple of peons (as the Indian laborers are called), at a jog-trot, bearing a pine coffin on their shoulders.

Battered old churches and convents on a great scale, and of a grand architecture, now for the most part devoted to other purposes, are extraordinarily frequent. Before the sequestration of Church property—in the war called of the Reform, under Juarez, in 1859—Mexico was well-nigh one great ecclesiastical estate. Without going into the religious question, and supposing only the operation of ordinary causes, it is easy to see how the Church corporations—repositories of the gifts of the faithful, moved by no feverish haste in speculation, and with no reckless heirs to spend their gains—must in course of time have become possessed of an enormous share of worldly goods.

There is no lack of sculptured old rococo palaces, of the conquerors and their successors, either. Many of these are of a peculiar, rich red stone, with carved escutcheons above their door-ways. There is one of which I was fond, in the Calle de Jesus, with immense water-spouts to its cornice, in the shape of field-pieces. Wheels and all project in high relief.

Only infinitesimal quantities of vacant land exist within the compass of the city. All is compactly built. The Continental system of portes cochères and interior court-yards [51]prevails. How many glimpses, both pleasing and curious, into these interiors! What a pity that the severity of our winters prevents building in a style which would be so admirably adapted to our summers! Over the entrances of some tenement-houses are placed pious dedicatory signs, as “Casa de la Santisima,” “Casa de la Divina Providencia.”

ENTRANCE TO A TENEMENT-HOUSE.

One day, as I made a hasty sketch of one of these, with a water-carrier lying asleep in the archway, the custodian came out and offered strenuous objections. “You are mapping the house” (mappando la casa), he said, “and I do not see how it can be for other than evil purposes.”

[52]

One of the most charming of all the mansions I saw stood nearly opposite our hotel, and was faced up entirely with china tiles, chiefly blue and white, and set with old bronze balconies, as dainty and quaint as a dwelling in fairy-land. I examined the interior of this house also, and found it faced within as well with the same simple, Moorish-looking, tiles, in staircase walls, ceilings, and even the high, banked-up furnace, or range, in the kitchen. An affable major-domo occupied his leisure with painting, in a large library on the ground-floor. He was just now engaged in copying and enlarging, very poorly, the photograph of a lady, over which he held up his brush for criticism. A maroon carpet was laid up the centre of a grand staircase, and the same uniform color prevailed in the carpets throughout. The rooms were large and high, the principal ones opening both on the street, and, by means of light glass doors draped with lace, on the balconies running around the courts. These balconies are edged in the general practice with climbing vines and rows of handsome plants. In one of the rear courts could be heard and seen the family carriage-horses, together with others for the saddle, stabled according to custom under the common roof.

There was a large saloon, with divans, and old-fashioned mirrors, sloped forward from the walls, instead of pier-glasses; and a little boudoir, with furniture entirely in gilded wood and cane. There was a pretty family chapel, with two prie-dieux for the master and mistress, and a couple of benches for the use of the servants. In the bedrooms of such houses are usually religious pictures, copies of Murillo and the like; and there are also found quaint effigies of sacred things, as a representation of the Nativity; a Christ, with purple mantle and crown of thorns; a life-size Virgin, in raiment of tissue of silver, [53]standing upon the globe and a serpent’s head. The men of the country are very widely imbued with the sceptical spirit of the age, but the women, whose property these objects are, are still devoutly Catholic.

These rooms, in such interiors, though less lofty and impressively finished perhaps than those at Havana, have not the complexity of objects with which we, in an ill-understood passion for decoration, overload our own in the United States. They are large, and contain a few simple articles, with plenty of space around, and have an unmistakable dignity of effect. When we can make up our minds to do that, instead of depending upon a complication of costly rarities in little space, we shall begin to be palatial, and not merely bon bourgeois.

We do not know how republican we are, after all our travelling abroad and reverence for things European, till we come to where the stately old Continental traditions are actually in force.