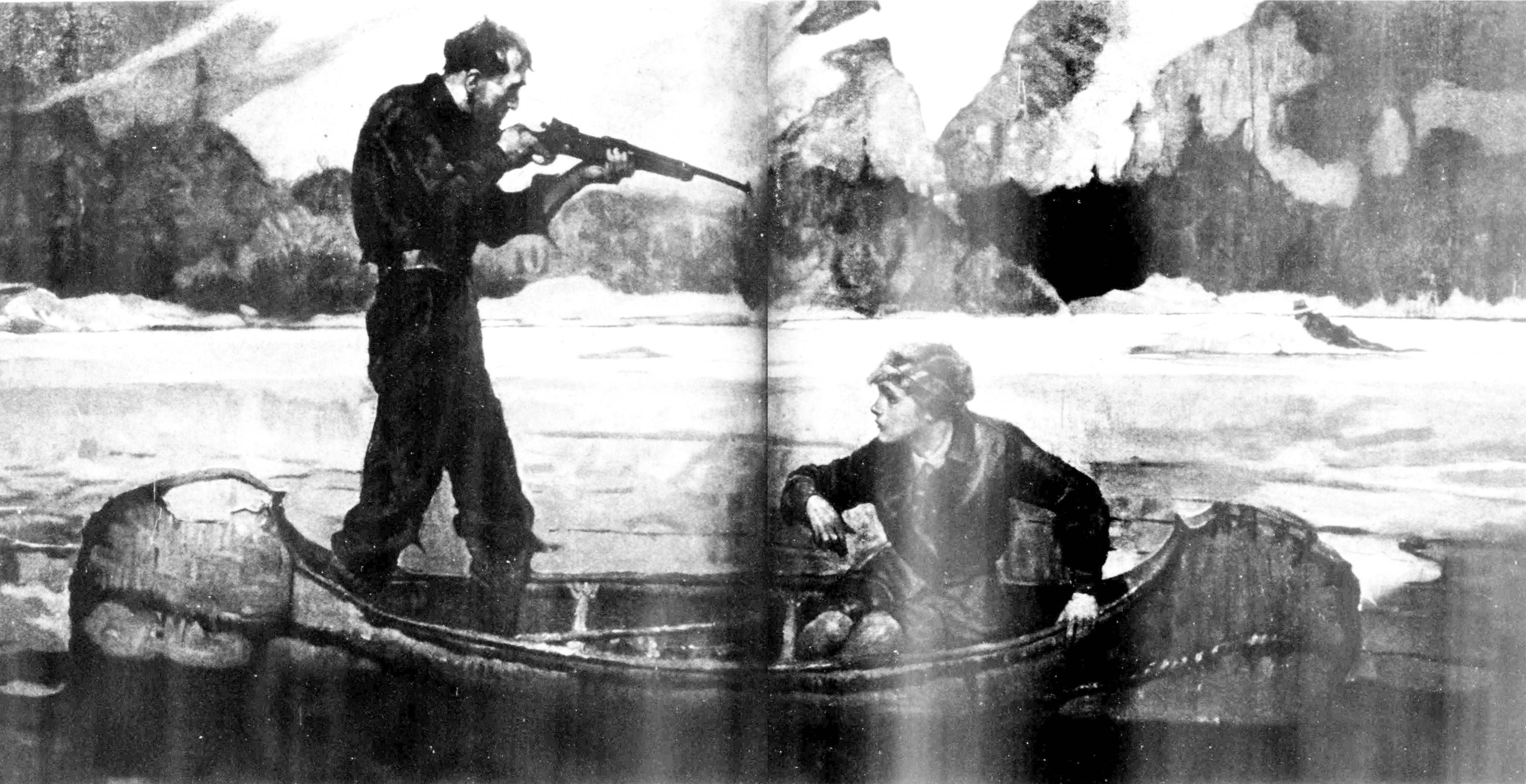

A savage wrench tore the weapon from her grasp. She was in the power of this vicious criminal.

Wolf Pass

A story of the frontier, where a woman is allowed to make but one mistake.

Title: Wolf Pass

Author: William Byron Mowery

Illustrator: Frank E. Schoonover

Release date: February 11, 2026 [eBook #77911]

Language: English

Original publication: Chicago: The McCall Company, 1930

Credits: Prepared by volunteers at BookCove (bookcove.net)

A savage wrench tore the weapon from her grasp. She was in the power of this vicious criminal.

A story of the frontier, where a woman is allowed to make but one mistake.

A lonely portage twenty miles back in the wilderness from the Mounted post at Bighorn, was where it happened to Sylvia. It came all suddenly—this ugly disaster; and exactly as Lorn had prophesied when he ordered her not to go bushloping alone this week.

Carrying her trim little birchbark over the hundred steps from décharge to embarqué, Sylvia walked along a bear trail under the great yellow pines. Around her there were danger signals that should have warned. In the dense mossy woods to her right a moose-bird was chortling angrily at something. A snowshoe rabbit, big-eyed with fright, darted out of the buckbrush there, and leaped across her path. A family of Sitka kinglets were crying their sharp little “snake-call” at some lurking menace of man or beast.

But to Sylvia, a city-born girl not yet wise in the language of this northern Rocky wilderness, these plain signals of “Beware! Beware!” meant nothing; and if she thought at all of her husband’s warning, it was with a spirited defiance of him for ordering her not to leave the post while he was gone.

She wasn’t one of his men, subject to command! What if he was Inspector Hastings—getting married didn’t mean she’d enlisted in the Mounted!

A light breeze, spiked with the delicious tang of pine and cooled with the breath of névés back in the Lodestar ranges, came stirring down the Packhorse Valley. The whisper of fall was in the air, with argosies of yellow poplar leaves drifting down the river with rabbit and ptarmigan bizarre in their mottled autumnal clothes, with those distant snowfields reaching farther every day down the slopes of the Lodestar giants. It was that year-time when creatures of the wood and rock and water sought warmth and security; when uncertainty was a terrible thing. Something of that age-old anxiety, translated into human terms of love and home, Sylvia was feeling this morning, after the quarrel last night with Lorn.

When she stepped out of the heavy timber and set her canoe down at the water-edge, she straightened up, breathing a bit faster from the carrying. Looking on up the wilderness valley, she stood there on the shingle, a slender and girlish figure, lovely in the bright sun that had a way of getting tangled in her golden-reddish hair and deepening the pansy-purple in the depths of her eyes.

The brooding immensity of the huge forest, the mountains, the blue sky above, was borne in upon Sylvia; and for a moment, reveling in the freedom of this huge wilderness, she forgot the trouble between Lorn and her that lay like a heavy weight on her heart. At times this morning she had cried about it, aching for that former one-ness again with him; but now, when she imagined herself idling away this splendid day at Bighorn while he and his men were flung out on their hunt, her aggressive little chin became still more determined and she tossed her head again with a spirited defiance that jarred the sun-spangles in her hair.

Oblivious to the warning of her little friends as she started back the path to bring up her rifle, pack and nested camping set, Sylvia was living over again her clash last night with Lorn.

Once or twice this morning she had actually wondered whether, instead of marrying, she should have gone on with her plans to do social work in Vancouver. She had been trained in criminology; it was the overtowering purpose and ambition of her life. And Lorn wanted her to have a work and purpose. When she met him last spring, dealing sword-strokes at the ugly narcotic demon in Victoria and Vancouver, she had felt that as his wife, helping him in the preventive branch which the Mounted always puts first, she would have a golden chance to carry out her plans.

But gradually she had come to realize that their outlooks were utterly different. To her, Lorn seemed a hunter, a pursuer of men. Sincere—she gave him credit for that—and far more experienced than she; but intolerant of any sympathy for so-called criminals, and flatly hostile to her most cherished beliefs. To work with him was impossible. She could either sink into a useless existence—or break with Lorn.

Their growing estrangement, and especially their clash last night, had shocked and sobered Sylvia. It had taught her that even passionate affection is not all-powerful against different outlooks.

At the décharge, Sylvia gathered up rifle and pack and blanket, and started back the path again.

As she brushed past a tangle of juniper and windfall logs, she felt something catch her rifle, as though it had snagged on a branch. In the next split-second a savage wrench tore the weapon completely from her grasp. She had the sense of something rising up, lunging at her; a hand shot out and seized her wrist; before she even could whirl, she was powerless, weaponless, helpless in that clutch.

A jerk spun her around. Too terrified to struggle, she found herself face to face with a strange unkempt man, who had crept in behind that crisscross of logs and pounced out upon her like an animal.

For several paralyzed seconds Sylvia could only stare at his heavily bearded face, his torn muddied clothes, his shaggy hair, a blood-crusted wound along his temple. Then came memory of the hunt flung out for Slith Behrdal, of the picture she’d seen on hundreds of handbills and posters. Here on the lonely Packhorse, with no one on earth knowing where she’d gone, she was in the power of this hunted man, whom Lorn had emphatically declared was an incorrigible and vicious criminal.

Still holding her wrist, Behrdal set the rifle against a tree, unclasped her saucy cartridge-belt and thrust it into his pocket. Then swiftly he felt of her clothing, her belted jacket, her pockets, for other weapons. Finding none, he looked hard at her a moment, and said:

“Don’t try any yelling. Don’t try pitching off into the bush, either. It wouldn’t be healthy.” He released her wrist, which was reddened by his steely grip, and demanded:

“You got any grub in that pack?”

“Y-yes,” Sylvia managed. “A—a little—”

Picking up her pack, rifle, and blanket, he bade her, “You come along!” and made her walk ahead of him, inland from the path.

They stopped in a little glade where the buckbrush was not dense. Through the forest aisles one could catch a good view of the Packhorse both above and below the portage. By the trampled moss and a rude lean-to of pine branches, Sylvia knew that he had been waiting there for a day or two, watching the river, watching for a chance to ambush some lone traveler.

As he bade her, she sat down against a tree, facing him. She was desperately trying to read what sort of man this Behrdal was, and to read his purpose with her. He looked to be about thirty-eight; he was powerful but gaunt of body; he was plainly of the backwoods, trapper type, but he appeared more intelligent than the average. In spite of his shaggy clothes, long hair, unshaven face, he was not altogether frightening. Though she still trembled from the memory of his lunging out at her, she was no longer panicky; and her first instinctive fears of him were lessening.

She considered: “He’ll take my canoe and rifle and pack, of course; but will he leave me here on this portage or set me off nearer some Indian camp, or—or what?”

Without another word to her, Behrdal tore open the oil-paper packet. As Sylvia watched him seize upon the food, a first sympathy was born in her, in spite of her terrible predicament and her helplessness in his hands. The man was famished, starving! Utterly forgetting her, forgetting to watch the river, he fell to devouring the bread, meat, cake and chocolate-bars as ravenously as any animal. After these months of subsisting only on berries he picked and game he clubbed or snared, he seemed to be especially starved for bread and sweets, for he bolted the chocolate bars in two bites, and picked up the smallest sandwich crumb that fell to the moss.

Sylvia was swiftly thinking of what Lorn had said about Slith Behrdal, and recalling the Mounted record of his history. Years and years ago he had trapped and prospected in these wild Lodestars forty miles on north. Suspected of fur theft, he had escaped to Alaska, had come to light several times in connection with petty crimes from Juneau to Dawson, had been involved in one ugly affair; and then, homing to his old haunts last May, he had gone to a gold-mine of a former prospecting partner, robbed the office of twenty thousand in dust, shot up a guard, got away, and was swallowed up in the oblivion of the Northern bush.

For months not a whisper was heard of him—till just last week an Indian had glimpsed him on a mountain trail west of Bighorn.

As she watched him bolt the last of her food, Sylvia reasoned that Behrdal, goaded by hunger and the relentless hunt, had been ambushing this portage trail to seize a gun and camping things and a canoe—especially a canoe; for in these mountains, foot-slogging through the windfall and over the precipitous goat-paths was next to impossible. And he had caught her, Inspector Hastings’ wife, and had at last secured those desperately needed things!

Behrdal had finished the food; he was watching the river again, breaking a twig in his fingers, thinking. Sylvia studied him keenly, trying to read a hint of his thoughts, his purpose. The details of that ugly affair, as she remembered them, were sinister; but this man somehow did not seem very sinister to her. She did not feel greatly afraid of him. Noticing the long red scratches on his hands and forearms from briar and devil’s-club, the rents in his clothing, patched with thorns, the gaunt famished leanness of his face, she pitied more than feared him; and she was wondering whether Lorn, in his usual stern merciless way, had not made a mistake about this man’s real nature.

“He’s got a rifle, boat and outfit now,” Sylvia reasoned, “and he’ll surely try to whip on north into the Lodestar Mountains. Lorn said he’d try that.”

She thought: “About the quickest and safest way he can get into the Lodestars is by going up the Packhorse. That’s what he’ll do. He’ll go right up this river, through Wolf Pass—”

She stopped there, her heart suddenly pounding. Wolf Pass—with all of Lorn’s men flung out along the Grand Trunk, watching mining camps and timber camps, Lorn had left Bighorn last night secretly, had come up the Packhorse alone, to guard that gateway into the Lodestars. Lorn himself was watching Wolf Pass.

There would be a fight, a rifle-fight, between Lorn, her husband and this armed man desperate for freedom, desperate from months of being hounded!

Behrdal finally spoke to her: “You’re the Inspector’s woman, ain’t you?” And as Sylvia nodded: “I mind seeing your picture in a Prince Rupert paper last spring when you and him got married.”

Sylvia was provoked by a certain condescension in his manner toward her as a girl. “You’re the Inspector’s woman!” It sounded as though she were a piece of property or some kind of lesser creature. But she reasoned: “I shouldn’t blame him for that. I’ve noticed that same attitude in ’breeds and the lower white elements toward their ‘women.’ That lordly male attitude was born and bred in him.”

Behrdal went on: “He wants me bad, don’t he? Been hounding me like I was a dog. Hadn’t been for him, I’d been able to get in south the railroad and work down to the Border. Say, lookee—what’s he doing, where’s he at now?”

“I—I don’t know,” Sylvia stammered.

“The hell you don’t!” Behrdal said roughly, but with an amused laugh at nailing her evasion. “He come past here last night, along after midnight, heading upriver. He’s up there at Wolf Pass, waiting for me. Seen him plain in the moonlight. If I’d had a gun—”

“You—you wouldn’t have shot him?” Sylvia gasped.

Behrdal started to say something, checked himself, and studied her curiously for several moments. A very visible change came into his manner. He had evidently been considering her an enemy, plotting to betray him. A man hounded as he was, must think that the hand of every human was against him. But now he seemed to realize she was inclined to be sympathetic and charitable.

Presently he answered her question. “I wouldn’t have shot him ’less I absolutely had to. You don’t think I’m a murderer, do you? But I’d sure as sin have taken his boat and gun and things. I got to live. A man’ll do most anything to save hisself. You don’t know how hiding around in these mountains takes it out of a fellow—”

As he went on, Sylvia noticed that he wanted to be talking. He seemed as starved for human company as for human food. She reflected: “It’s been months since he’s spoken to a soul. It’s probably been far longer since he’s sat and talked with a white woman.”

The man’s nature was a puzzle to her. She could not quite make him out. Without jumping to any conclusions, she believed more and more that he was at least not the criminal that Lorn considered him. He might even be a very decent sort.

Out on the Packhorse, the cry of a great Northern diver interrupted him. Breaking off, he scrambled to his feet, searched up and down the river, saw nothing suspicious, then turned to her.

“Get up! We got to be moving.”

“We?” Sylvia echoed, startled. Did that mean he was going to take her along with him?

Again he studied her with that curious gaze. It was plain he did not fear her. There was a half-amused glint in his eyes. Was he laughing at her fright?

“Why sure, us both,” he answered. And when a fear spread over her winsome face, he added: “How the devil could you foot-slog back to Bighorn? I was thinking. See here, I got to have your boat, aint I? You come, go along peaceful-like, go on up the Packhorse. Up there, about four miles this way from Wolf Pass, there’s a good trail leading over east to Beaver Valley. Old Thunder Crow and his band live there. Only a couple miles across to Beaver. Old Crow’ll see you get home safe. I wouldn’t let a girl afoot, place like this, would I?”

His words set Sylvia to thinking, to wondering more than ever about this man. His glances at her face, his appraisal of her vigorous young body, did linger longer than she liked. But he hadn’t touched her, hadn’t spoken a wrong word; and now he was actually taking thought for her! Hunted, half-starved in a desperate situation himself, he was taking thought for her.

She thought: “I’m going to get his version of that formidable record. Lorn never gave any ‘criminal’ the benefit of the doubt.”

As Behrdal picked up the rifle and pack, she rose and went with him, unwilling but not frightened, back to the path and along it under the great pines, to her canoe.

Near mid-afternoon, thirty miles on up the Packhorse, they came to a tiny wooded islet in the river. Driving the canoe in to the bank, Behrdal laid aside the paddle, and said:

“Only ten miles to Wolf Pass. We’ll stop here a minute.” He scooped the sweat from his brow with a forefinger. “Pretty hard work dogging a canoe up-current like this. Usta could do it all day ’thout feeling it, but now—”

“I know, I know,” Sylvia agreed in sympathy. “It’s a wonder you lived through these last few months.”

She was facing him, sitting in the prow of the canoe. She knew he had put her there so he could keep a sharp watch on her actions; but to offset that, he’d made her a comfortable seat with the white fluffy H. B. blanket.

Very thoughtful, Sylvia sat with chin cupped in her small hand, bare-headed, with the slant sun tangled in her golden-reddish hair. Behrdal had been staring at her, but now he was looking on up the mountain-cradled Packhorse at the wilderness of ranges which he had trapped in years ago. Freedom was so very near for him now. If only he could get through Wolf Pass—but there Lorn was waiting. Sylvia was in panic at the thought of a rifle fight. Glancing at the high-power weapon there beside Behrdal, she pictured Lorn shot, wounded, dying, and her passion for him welled up. Lorn was her husband, her lover....

But then she reasoned that Behrdal would never try to shoot his way through the Pass. He would surely land this side of it and circle up against the mountain and hit the Packhorse above.

She asked him rather abruptly: “If you don’t mind a personal question, Mr. Behrdal, what was it that started you to—that made you—”

“Made me a bush-sneaker?” he completed. “Well, you see, I stole some furs. A trader, he cheated me four years hand-run. Jickered the auction-sale figgers. So I busted into his storage-shed one night and evened things up. But I had to cut for Alaska.”

“You have several charges against you there,” she suggested, leading him on.

“Them’s damned lies! They knowed I was on the jump, so everything that went wrong, and I was near enough, they hung it onto me. Nothing could happen but what I got blamed for it. I did pull off a couple tricks, when I had to—like with you this morning; but that wasn’t my fault. I’d gone straight if they’d let me.”

Sylvia nodded. In her criminology texts she had studied many cases like his. “Undeserved increment of criminal reputation,” her professor at Berkeley called it.

She pursued: “But that robbery of the Orphan Angel Mine? You were identified—”

“Don’t deny that. But if you knowed the facts.... Look here, I staked that claim myself, years ago. My partner, he euchred me out of it. How? Well, I sent him in to the assay office with the ore to have it tested. He doctored the figgers. Brought back a sheet saying the ore was worthless. After I left, he filed on it hisself. So I tried to even up that old score.”

Sylvia forbore asking him about that more serious offense.

It seemed to her that here was a man who was a living refutation of Lorn’s stern uncompromising attitude, and a living proof of her own beliefs. Society had hounded him, branded him with the stigma of “criminal.” If he could only escape, he would become an honest self-respecting man. Once through Wolf Pass, he would be safe, for he had rifle, boat and pack now. Back in the Lodestars he could never be tracked or found. Sylvia remembered those beautiful Lodestars, for she and Lorn had spent their lune de miel far back in them. Recalling those innumerable cañons and beaten game-trails and dry caves, she knew Behrdal could easily live through the winter there, and then make good his escape.

But what would Lorn say when he found out that Behrdal had secured those desperately needed things because of her disobedience? She visioned her return to Bighorn, visioned Lorn’s silent anger; and she knew that this adventure today was going to be fateful between Lorn and her.

Beginning twilight in the mountain valley—almost within sight of Wolf Pass.... Something was wrong, all wrong. Sylvia was keenly alarmed, and more frightened with every passing moment.

The sun an hour ago had inched down behind the western Lodestars. The twin peaks, lordly, snow-crowned, through which the Packhorse flowed, towered up so high, so close, that she lifted her head to see their summits. But Behrdal hadn’t set her ashore, as he had promised. He didn’t show any signs of intending to set her ashore.

The valley had narrowed to half a mile, with mountains rising steep and huge almost from river edge. A short “squaw-winter” which had passed last week had turned the hardwoods of their lower slopes to brown and golden and flaming red. All day the migrants, flock after flock, had passed overhead, winging south; and Sylvia had the feeling that around her in the mountains animals were laying by their store for the frozen months or seeking out warm caves against the winter to come.

In this last mile she had noticed a marked and alarming change in Behrdal. He was nervous now—with fatal Wolf Pass so near. And he had become surly and heavy-handed with her, snapping her off if she started to say a word. He had reloaded her rifle and dropped a handful of loose cartridges into his pocket. He had said he was going to try to get around Wolf Pass by slipping up along the windfall slope, but now it looked as though he meant to shoot his way through. The suspicion had grown on her that he didn’t mean to put her ashore till he got through the Pass—that he meant to use her as protection against Inspector Hastings’ rifle.

If that was true, then he’d hoodwinked her, he’d been friendly in order that she would “go along peaceful.” It was galling to suspect that this rough boorish man had been playing on her credulity and sympathy—secretly laughing at her all day.

Twilight was deepening in the valley—a soft impalpable purple, though high overhead the clouds were still roseate from the sun. The heavily timbered shores, dark and formidable, awed Sylvia; and the memory of the lonely mountain fastness ahead, where Lorn and she had spent their honeymoon, filled her with prophetic fears.

Unable to bear this terrible uncertainty any longer, she asked tremulously:

“We—we must be close to Wolf Pass; aren’t you going to—aren’t we about to the place where you’ll put me ashore?”

Behrdal glared at her, and his answer was fairly dazing.

“You shut your trap and mind your own business!”

Startled, she shrunk back against the thwart as though he had struck her. He meant to take her on through Wolf Pass! He meant to use her as protection against her husband. How could Lorn battle him—with her in that canoe? This man would kill Lorn—

Silent, panic-stricken, with the canoe carrying her on into Wolf Pass, she sat there helpless, praying that Lorn would not come out at Behrdal. But she knew he would. He’d never let a criminal escape; he’d never let Behrdal take her through Wolf Pass. The prospect of Lorn getting wounded, maybe killed, killed by her own rifle, killed because she’d defied him and gone away alone, frightened Sylvia as nothing in her life before had ever done.

Watching, she saw Behrdal suddenly start, ship the paddle, seize the rifle. From the east shore, from behind the cover of a cypress whose branches swept the water, a canoe had glided out, a canoe with a straight stern figure in it, driving it with powerful strokes, his rifle muzzle sticking up above the gunwale.

It was skirling directly out athwart the current, out into midstream, to block their path.

The last vestige of Slith Behrdal’s pretense dropped away from him.

His eyes were fixed on that canoe. There was fear in them, a craven fear that made him jerky in the manner of a cornered animal. And there was a vengeful light in them, too—a murderous glare at the officer who had hunted him for months and flung out the wilderness dragnet for him, and now blocked his path to safety.

As Behrdal cocked the rifle, Sylvia rose up, wild with fright, nearly tipping over the frail canoe, and pleaded:

“Don’t! Don’t shoot! You mustn’t hurt him. I’ll tell him to keep away—”

Behrdal swung the gun back behind his shoulder, like a heavy club against her, menacing her; and he snarled:

“Get down! Damn you, get down there! You make one move, you just try to help him to take me, you damn’ little softie, and I’ll— I aint aiming to get taken!”

Shrinking back from him in quivering panic, Sylvia helplessly watched him lift the rifle—her rifle—and level it, and draw a bead on that canoe.

In that instant Lorn’s voice, sharp and clear, came ringing across the water, repeating the formula of arrest:

“Halt! In the King’s name, I warn you against resisting!”

Behrdal shot at him. In her terror for Lorn, unmindful of the bullet that screamed past her head, Sylvia turned, looked. Again and again and again, till the magazine was empty, Behrdal shot at her husband. The bullets, kicking up tiny spurts of white, hit all around Lorn. Two of them, striking almost at the wind-water line of Lorn’s canoe, ricocheted and tore through his fragile craft.

She saw Lorn lean forward, stuffing a blanket corner into one of those spouting holes. But he did not shoot. He had recognized her; though a bullet at any moment might kill him, he would never jeopardize her life. Cool and steady, he was driving his canoe on, on out into midstream, to block the path.

She cried out: “Lorn! Lorn! Shoot at him!”

Behrdal swung his reloaded rifle upon her. Had she not been his protection, he would have killed her.

“Shut up!”

He seized the paddle, drove the canoe frantically on with powerful grunting strokes, till less than two hundred yards of water lay between the two crafts. Dropping the paddle, whipping up his rifle, he poured a stream of bullets at Lorn’s canoe.

One, ricocheting, tore a gaping hole through the wind-water line. Another knocked Lorn’s paddle out of his grasp. And then that fatal bullet! In her terrified anguish, she did not clearly see what happened, but Lorn’s canoe suddenly caved in, as though the middle thwart had been splintered, and the craft, collapsing, plunged him into the water, boatless, his rifle gone.

Then that fatal bullet! Lorn’s canoe suddenly caved in and plunged him into the water, his rifle gone.

He reappeared, treaded water, then started swimming strongly—not back to the safety of the shore, which likely he could have reached; but on out into midstream, toward a flat granite rock that reared above the water. With belt-gun in his teeth, he headed for that boulder in a last magnificent effort to make his arrest and save his wife from this man.

Behrdal shot twice at him—at a helpless man swimming. Checking himself, he watched Lorn climb out.

Behrdal shot twice at him—at a helpless man swimming—but his bullets missed. Checking himself, he watched Lorn reach the rock and climb out. His nervous jerky fear slowly ebbed now. As his narrowed eyes studied the boulder, an expression of gloating sureness twisted his mouth. He knew, and Sylvia knew, what chance a man with a belt-gun stood against a long-range rifle. He could edge up closer, could stand off beyond belt-gun range and pour a magazine of bullets into his enemy. Lorn was caught, doomed; he and she too were at Behrdal’s mercy now.

For perhaps half a minute Behrdal held the canoe where it was, stroking a little against the current, studying the rock where Lorn knelt on one knee, waiting.

Beneath his breath he snarled: “That yellow-striped devil won’t hound me any more! Nor he won’t get back home to tell where I faded to, or boss any more hunts after me!”

He dipped paddle to drive the canoe within deadly rifle-range of the rock. Sylvia’s glance went to her little belt-ax loosely tied in the pack within arm’s reach of her. She started to lean forward, to seize it and hurl it with all her strength at that brutal face. Her movement caught Behrdal’s eyes; he whipped back the paddle, swung at her; and the thin blade struck her across the arm she flung up to protect herself.

He grabbed the belt-ax and thrust it safely beneath his leg.

“Didn’t quite, did you? Pretty cocky now, ain’t you? You’ll tame down. You and me—while them men of his are kiting around wondering what happened to him—we’ll be looking up a nice place back in there to den up in.”

In the horror that swept over her, Sylvia had a livid memory of Behrdal bolting her food with an animal’s hunger, of his hunger for human company, of his overbearing, lordly-male attitude, of Lorn’s significant hint that this man had been alone in the bush for many long months.

He taunted her, as he drove the canoe on toward the rock:

“You’re the softest one I ever met up with. Swallowed everything I told you! Come along peaceful-like, you did—no trouble at all. And you thought I was going to set you off, after catching you out here like that, no one knowing what happened to you. You, by God, thought I’d let you go! And you wanted to help me escape!” He laughed throatily. “You sure need a husband—sweet little coonie like you—or need somebody to look after you—letting a fellow string you along like I did!”

He laughed again; and in that horrid laugh Sylvia seemed to be hearing Lorn’s warning, and caught a glimpse of all his long years of hunting men, all his hard-earned knowledge of criminal nature, all his bitterly learned experience and beliefs.

A moment later Behrdal was ignoring her, as a helpless and inferior creature to be noticed or scorned at his fancy. The rock was within good rifle-range; but Lorn had crouched down lower, to offer the smallest possible target to that sharp-speaking gun. Estimating distance, Behrdal shoved the canoe on closer, closer, till at the deadly range of a hundred yards he shipped the paddle and rose up, and lifting his rifle, deliberately took aim.

As she watched that rifle come up, Sylvia grasped the gunwale with both hands, and her body tensed for a swift desperate attempt to save Lorn’s life. A minute ago she had thought to leap forward and struggle with Behrdal and try to wrest the rifle away from him, but she knew he could shoot her before she reached him. There was one other way.

Too swiftly for Behrdal to lower the rifle and shoot at her, she flung herself over the gunwale of the canoe, still gripping the edge of it, dragging the gunwale down by the force of her plunge. She saw Behrdal stagger, lose his footing and topple backwards. As the water closed over her, she felt the canoe suddenly lightened, and knew he had fallen bodily out of it. With a plop that drummed in her ears, the craft overturned, twisting loose her grip on it, plunging her down and down.

For a few moments that seemed endless she struggled in the dark cold depths, fighting upward to the light. When she broke up out, dashing the water from her eyes, tossing the shock of her hair from her forehead, she glimpsed the upturned canoe a dozen yards downstream; and looking again, she saw Behrdal clinging to its prow, clawing frantically for a hold on its keel.

From his frenzied struggles that repeatedly pushed the craft under water, she realized that the man could not swim, and would weaken and sink and drown in this swift icy current. But that sight did not move her; there was no mercy in her heart now.

Turning toward the boulder, she peered through the twilight for sight of Lorn. The rock was bare; he no longer crouched on it. She called to him tremulously; then she saw him, swimming down-current toward her, with long clean strokes.

He bore down upon her, stopped a couple of yards away; and with his eyes on Behrdal’s weakening struggle, he demanded sharply of her:

“Can you get ashore by yourself?”

“Y-yes, but Lorn—but what are you—”

“If you’re certain you can, then get on out!”

“But Lorn! Why don’t you let him drown?” In a flaming pitiless anger against Slith Behrdal, she cried: “He tried to kill you! He was going to take me—me with him! Let him drown!”

Lorn did not even answer, but went on past her. As she started for the west bank, swimming easily at a diagonal down the current, she looked back and saw him overhaul the drifting canoe, and saw the swift finale of it all. Behrdal, a drowning man in a blind crazed frenzy, clutched at Lorn and would have pinioned his arms and dragged him down. But Lorn held him off at arm’s-length, and smashing the butt of his revolver against the man’s temple, knocked him limp. And then, towing him, swimming one-handed, he too headed for the west bank of the Packhorse.

When she reached shoal water and her feet touched, Sylvia stopped and waited, to help Lorn with his burden, to help him retrieve the canoe and paddle. But she dreaded to face him, to speak to him. That steely hardness in his voice—he knew she had disobeyed his orders. And that was not all, not the half of her guilt. Today she had been traitress to him, disloyal to all he stood for—had wanted Behrdal to escape.

Overhead the two o’clock moon, riding through a gossamer mist of clouds, silvered the clear cold waters of the Packhorse and dripped its molten fire from Lorn’s wet paddle-blade. A stiff chilly wind, pouring down the valley, had set the waves lap-lapping against the shores, and was crooning in autumnal tones through the great pines and cedars.

With the current sweeping them along, with Lorn’s rhythmic tireless paddle-strokes hastening them, they had passed the portage where Behrdal that morning had lunged out of the windfall upon Sylvia. A dozen easy downstream miles stretched on to Bighorn.

Bound hand and foot, Slith Behrdal lay in the prow of the canoe, a huddled and spiritless heap, his arms over his face, being carried back to the justice he for years had escaped. He was Lorn’s prisoner; Lorn was taking him in. More than once in the long silent hours since this return began, Sylvia had reflected on that stern unswerving quality in Lorn Hastings which had impelled him to save this man when she herself—she with the humane theories and sympathetic attitude!—had wanted to let him drown. What had Lorn once told her about her theories and wisps of smoke?

For the last half-hour she had been looking up at him, studying his face in the moonlight; but scarcely once had he glanced down at her, and then he had not smiled. In abject silent misery she had inched nearer and nearer him, till her head brushed his knees. He had not noticed her. When she thought of him swimming through the water with a belt-gun in his teeth, she realized that in such a man forgiveness came not lightly.

Across the moon a flock of migrant cranes flapped slowly southward, a weird and macabre procession down the night sky—token of a summer dying and a winter to come. From high above timberline the mournful cry of a wolf floated down, unwordably lonely and sad. As though the sound had its echo in Sylvia’s heart, as though the silence had broken her heart, she stirred and rose a little, and crept nearer and nearer, till that head of golden-reddish hair which had tossed so defiantly at Lorn Hastings, lay now in his lap, beaten, miserable, begging forgiveness.

The rhythmic paddle missed a stroke, a single stroke; then it dipped again, took up its relentless tempo again. The tears came blindingly into Sylvia’s eyes; she was shaken with silent sobbing, but she fought it down.

As though Lorn had felt her sobbing, that relentless tempo slackened; it missed a stroke, two strokes.... As she raised her head, as she started to creep back, it stopped altogether! Dimly through her tears Sylvia saw him looking down at her. He seemed to be bending lower.

“Sylvia!”—a whisper, his whisper, above her. His hand was on her wet cheek, his hand caressing her hair. “You got us into that fix, girl, but you got us out!”

The tears, that came more blindingly than ever, kept her from seeing his face.... It couldn’t be, it couldn’t be that he’d forgiven her.

“If you want to admit you were a bit wrong in our—our arguments, I’ll meet you halfway. I’ll never remind you of today.”

Her heart ceased beating as she saw him bending lower still, and felt him lifting her lips to his for a moment that blotted out all this endless night of unbearable misery.

Then the rhythmic strokes again. Behrdal the criminal a huddled heap in the prow, the sleepy sounds of this mountain wilderness, above her, between her and the star-sprinkled heavens, a beloved face that smiled now with that former one-ness between them—her head still lying upon his lap, on and on and on, homeward under the moonlight.