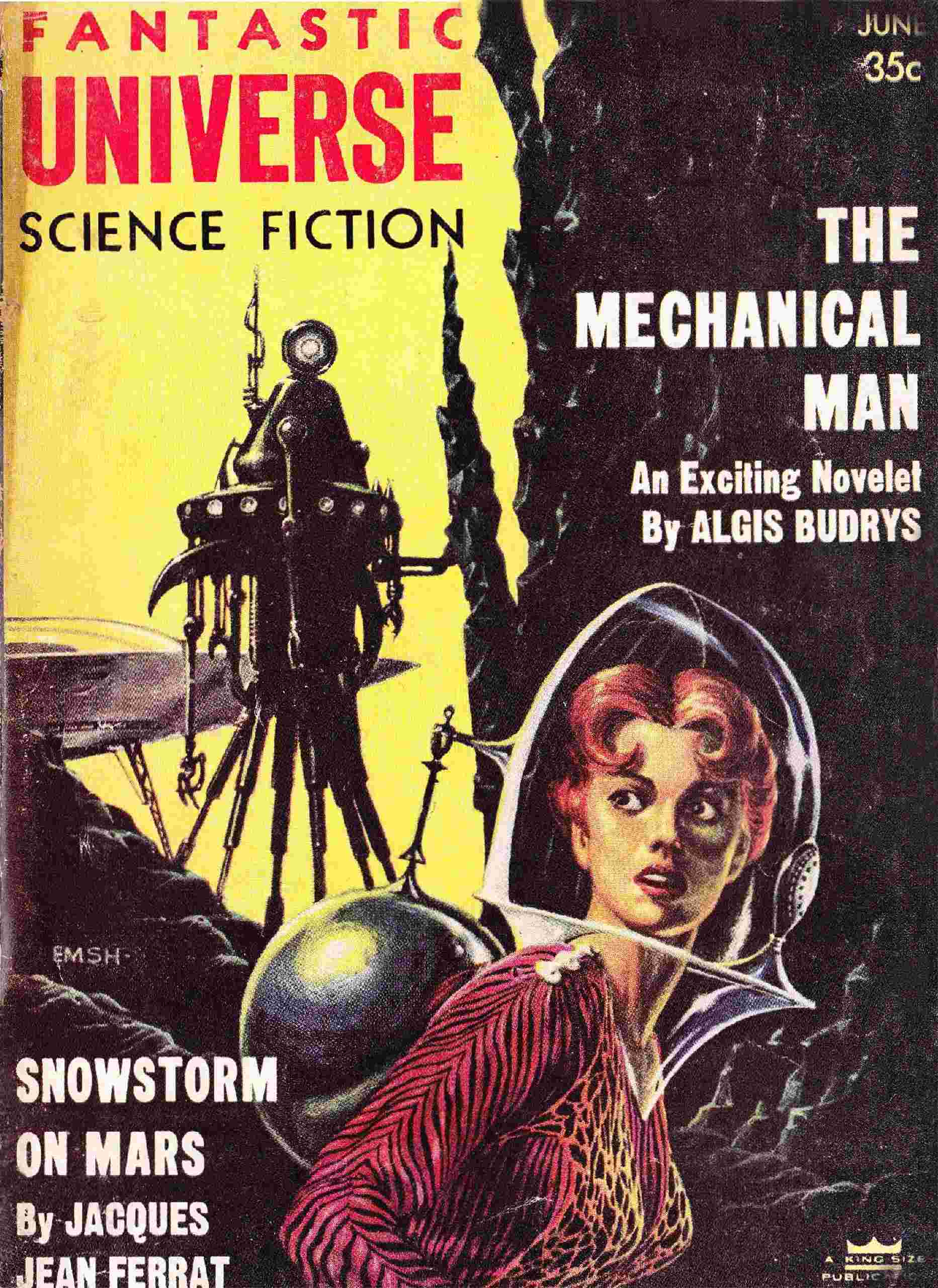

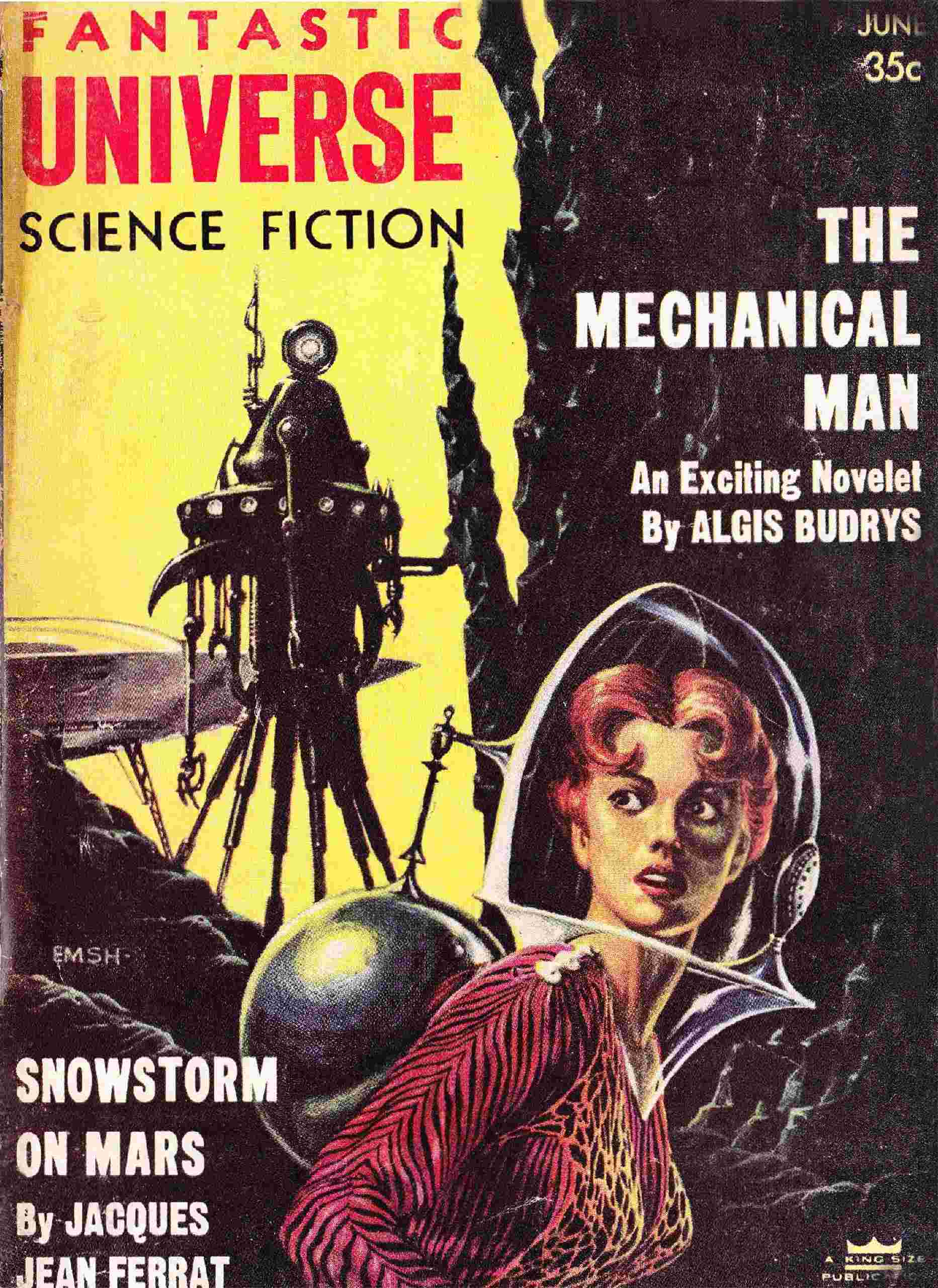

Title: The laugh

Author: Robert Abernathy

Illustrator: Ed Emshwiller

Release date: February 15, 2026 [eBook #77941]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: King-Size Publications, Inc, 1956

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77941

Credits: Tom Trussel (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

by Robert Abernathy

If a lad of eight should get an urge to go tramping into a cosmic shoestore in search of a giant’s boots his egotism might become a frightening thing. Robert Abernathy probably hopes it won’t happen. But he here plants such grave doubts in our mind that we wonder if it’s safe to spoil children.

To Dicky grownups were absurdly like ants. They worked hard for no good purpose. But some day a big, big change would be coming!

Dicky lay comfortably on his stomach in the high backyard weeds, watching the ants. His eyes darted back and forth, trying to see what all of them were doing at the same time—all around their hill on the sun-warmed bare slope by the weed patch.

But there were too many of them and they ran too fast in too many different directions. They skirmished, climbed, and slid. They pushed, lifted, and tugged at bits of straw, at seeds, and even the leg of a beetle. They labored mightily and inefficiently to transport these treasures to their nest. Dicky gazed at them in rapt absorption obscurely awed by their incomprehensible fervor of dedication.

They reminded him— He searched the teeming storehouse of a five-year-old’s memories, and thought that the ants reminded him of the lawn-tender which, every evening when it wasn’t raining, crept out of its little kennel behind the house to see if the grass needed cutting or watering. If it did, the dutiful machine went clicking and buzzing up and down on its fat wheels, pivoting precisely at the edge of the yard. It never came down here, where the ground sloped toward the brook thirty yards away, and the weeds grew rank—where Dicky the courageous wasn’t supposed to go either.

He glanced up the slope, suddenly conscious of the naked sun blazing down on him through the thin cover of foliage and of the nearness of the house beyond its clipped green rectangle of lawn. The cooling intake on the house roof turned slowly, flaring to snare an unreliable faint breeze. The windows had half-shuttered themselves against the July afternoon brilliance, and they now resembled squinting eyes. The eyes were dark with indoor shadow and you couldn’t tell whether they were looking at you or not.

But if Mother did look out, she couldn’t possibly see him here. She would think he was sitting in the sun by the wall of the house, playing as he was supposed to do with his toy cars or his toy helicopter. The cars would run just to the edge of the yard, and the helicopter would fly only as high as the house. So naturally Dicky had grown bored with them.

He wriggled closer to the busy ants, to the very edge of the weed forest. The ants went on behaving as if Dicky wasn’t there. Softly, Dicky said, “Boo! Woo? You!” But the ants didn’t notice.

Judicially, he decided that he would never be an ant, even if the opportunity should be offered him. Ants were like grownups. They worked hard for no good reason which Dicky could understand and they paid no attention to more important things.

But it would be fun to be very small, and live here among weeds like giant trees. It would be fun to hide under the leaves when people came looking for him. He scanned the ground minutely, picturing himself walking here and there among the wonders of the little world—climbing on a straw that was a fallen log, and looking up to see an insect go whirring past with iridescent wings. Then the slope would be a mountain, and the brook at its foot would become a vast shining ocean.

Not an ant, though. He would rather be a frog.

Vividly, for life, Dicky would remember the day when he’d first seen the frog. It had been back when there’d been a hole in the fence, hidden by weeds. It had been a hole which only he knew about, and several times he’d crawled through and visited the forbidden shores beyond. The brook flowed there dark, deep, and quiet between cement banks, severely walled like almost all the world. But under the footbridge a little way below the house lived the frog.

Dicky had known he was there, had heard him at twilight—krraak! krraak! But for a long time he hadn’t known who made the sound. And then, one rain-washed afternoon, he’d crept stealthily along the wet grass of the bank and peered into the shadows beneath the bridge.

The frog was sitting on the slimed rubble close to the water—fat, green, self-important. He was squatting there with his tiny forefeet accurately tucked up under him. He had lazy jewel eyes, and was ballooning his mottled throat to send out his krraak. Smugly happy he seemed, in his confidence that the world had only been waiting to hear his frog noise.

The revelation had been too much for Dicky, and he had burst out laughing. Then he had looked quickly around, alarmed, to see if anyone had heard him. But nobody had except the frog, who promptly went gchonk! into the water.

Now the fence had been repaired and there was no way through. If Dicky so much as went near it—forbidden as he was to go that far—his father’s voice came to his ears, just as if his father were not away at work. It said: “Dicky, go home!”

But Dicky didn’t grieve unduly. Having found the way blocked, he dismissed it from his thoughts. After all, he had seen the frog, and he could remember it any time he wanted to.

Remembering now, he rose to a crouching position among the weeds, and said, “Krraak, krraak!” He said it softly under his breath, and smiled to himself.

A sudden commotion on the sunlit ground recalled his attention to the ants. Two of them had seized hold of a tiny leaf, one on each side, but they seemed unable to agree on which way it should go. They tugged in opposite directions. First one of them found firm footing in a half-buried pebble and dragged the other one, its feet scrabbling madly in loose sand. Then the second ant got a purchase on the pebble and in turn triumphantly wrestled the leaf, and its struggling rival for a fraction of an inch in its chosen direction. Both ants kept skidding.

Dicky bent close to watch them, a well of pure, delighted amusement bubbling up inside him. Suddenly it all seemed irresistibly funny—that grim Lilliputian determination see-sawing across a pebble just when he’d been thinking of the frog and how he’d laughed at the funny frog—

Dicky felt the spasm starting in his stomach, and ascending sneezelike into his throat, making his nose twitch and his eyes half-close. He felt the laughter coming and couldn’t stop it, and suddenly he was laughing uncontrollably, loudly, gleefully....

“Dicky!”

He heard his mother’s shocked voice and scrambled to his feet, the laughter dying into indrawn sobs. The shining afternoon whirled about him into cataclysm.

“What are you doing down there?” she demanded. She stood on the edge of the lawn above him, her voice quivering with anger. “Dicky, answer me!”

“Looking at ants,” he gulped. “I was just—” He crumbled under her reproachful eyes. “I couldn’t help it, Mommie,” he pleaded. “I couldn’t—”

“Come here,” she said in the same strained tone. “What if the neighbors heard you! Do you want them to think crazy people live here? Do you?” She broke off with an effort, and took a deep breath.

“Come straight in the house now. And just you wait until your father comes home!”

The next day Dicky’s father didn’t go to work at the yeast plant. Instead, all three of them went for a ride. They went in a coptercab, which meant downtown, instead of in the car which would have meant a picnic in the country.

The night before there had been a consultation which Dicky had overheard only in snatches: “Laughing at ants! I caught him at it.”

“...At people next, I suppose!”

“But what can we have done wrong?”

Since then, happily, Dicky’s fall from grace hadn’t been mentioned, and in the excitement of a ’copter trip he forgot it altogether.

The automatic pilot set them down on the roof of a building that loomed large even in a neighborhood of huge buildings. Below were long halls with slick tiles and rubber runners. There were also many doors, and a great many people, dressed entirely in white, and all hurrying.

Without knowing quite how it happened, Dicky became separated from his parents in a big room with two men and a lady in white, and a lot of gleaming and mysterious apparatus. He’d been told not to be scared, and he wasn’t—quite.

“Sit right here, Dicky. Just hold still, now....”

They tapped his knees with little mallets, tickled the soles of his bare feet, and shone dazzling lights into his eyes.

“Say ‘black bugs’ blood,’ Dicky.”

“Black bugs’ blood,” stammered Dicky, and looked around anxiously to see what, if anything, the strange incantation might have summoned up.

“That’s a good boy,” said the lady in white soothingly.

“Somatically okay,” said the biggest man in white at last. He nodded to the other two, and they went out.

The big man sat down opposite Dicky and regarded him gravely, but not sternly. He reminded Dicky of his own father in one of his good moods.

“Now, that didn’t hurt, did it?” inquired the big man.

“N-no,” said Dicky.

“We had to give you some tests to make sure you were all right. You are all right. But your parents seem to be a little upset about you. Hmm. Why’s that?” The question was gently authoritative.

“I—I—” Dicky stumbled painfully over the truth. “I guess I laughed.”

The man nodded soberly, and Dicky was aware, with a sudden rush of confidence, that he wasn’t surprised or shocked. It was plain that he wouldn’t be, even if Dicky were to laugh right in his face. Not that Dicky felt like doing that.

“Why did you laugh? Tell me, Dicky.”

“At some ants.” Dicky’s face felt hot, but the big man’s manner was unchanged.

“Do you feel like telling me about the ants?” the big man asked. And Dicky realized that he did.

Dicky’s mother demanded shakily, “But, Doctor, what did we do wrong?”

“We’ve tried to bring the boy up with every scientific advantage,” his father muttered uncertainly.

The man in white sighed imperceptibly. Here were two normally intelligent and well-intentioned people. But obviously the explanations he had just given them in terms of reality had not conveyed a great deal to them. Public education, even in this day and age, left much to be desired.

He said patiently, “So far as I can tell you haven’t done anything seriously wrong. You’ve provided the child with approved play materials, and you’ve proceeded quite properly in supplying him with safely limited opportunities for aggression against authority. Perhaps you’ve left him alone a little too much. What has happened is that in the absence of adult guidance an unhealthy fantasy element has crept into his play.

“When you come back tomorrow, we’ll go over the home environment in detail and I may suggest a few changes. Then, with the prescription I’ve given you, and with Dicky coming to see me once a week, I think we’ll have him entirely straightened out by the time school starts.”

“Oh, I hope so!” exclaimed the mother prayerfully.

The psychologist cast an approving glance at her, and said reassuringly, “You shouldn’t be unduly alarmed. It’s important to remember that at Dicky’s age an occasional emotional explosion—laughter, tears, rage, or the like—isn’t necessarily a sign of dangerous emotional instability. After all,” he smiled faintly, “a hundred years ago your Dicky’s behavior would have been considered quite normal.”

“Normal?” said the father with corrugated brow.

“Ideas of normality differ in different eras. Our ancestors considered laughter—even violent laughter in public—quite permissible ... though they would have frowned on various other types of emotional exhibition. At sundry times and places there have been societies which condoned or even encouraged orgies of grief and guilt—megalomaniac outbursts, religious ecstasies, public sexual excesses.

“Our own forebears continued to laugh right into the twentieth century, at a time when psychiatry had already taken its first great steps forward—steps hampered, naturally, by the cultural bias.... The popular psychology of the period even worked out a theory of the alleged value of ‘emotional outlets,’ disregarding, of course, the fact that energy going into such outlets was wasted. The steam that blows the whistle doesn’t turn the wheels.”

The parents nodded with an understanding that pleased the psychologist. Maybe there was still hope for public education.

“No doubt,” he went on, “some of those immature societies I referred to—when population was sparse and resources under-developed—could afford their eccentricities. But modern civilization requires that all the individual’s inborn aggressive energy be channeled into effective action, directed by the reality principle.

“Before we could accomplish that, we had to get rid of our forefathers’ sterile idea of ‘happiness,’ ideas which the early psychiatrists actually regarded as a therapeutic goal. They tried to alleviate human misery without realizing that it was only one face of the coin, and that to succeed they must also study the causes and cure of happiness!

“So—” The psychologist caught himself with a glance at his watch, which had begun to buzz quietly but insistently to remind him of an appointment. “Don’t worry. You see, a century ago Dicky would have gone without treatment. Upon reaching the age of puberty, he might have fallen in love, or developed other psychosomatic ills—”

The parents exchanged horrified glances.

“But nowadays we know just what to do. You haven’t a thing to worry about.”

He ushered them to the door beyond which Dicky waited with the nurse.

Fall was coming, a first chill in the air. Dicky stood at the edge of the green lawn, looking down the bare slope toward the fence and the brook beyond.

The backyard slope was no longer forbidden to him—hadn’t been since the day the lawn-tender had clicked and buzzed its way along it, mowing the weeds. But he no longer felt any particular urge to explore.

Once, a long time ago in the summer, there had been something very special about the brook and the footbridge over it. But now he couldn’t remember what had seemed so important. He remembered, of course, that he had walked along the brook, and had seen a frog. But he’d been much younger then.

Now summer was over, and in a few days Dicky would be starting to school.

He scuffed his new shoes down the weedless slope aimlessly—as far as the fence and back again. Suddenly he stopped, noticing that the ants were still there. They seemed fewer than they had been, and not so active as they straggled in thinning lines across a patch of ground completely denuded of forage.

The ants reminded him of the big man in white, who was so good at explaining things so that Dicky could understand. One thing he’d explained on request was why ants couldn’t see you, even when you stood right over them.

They couldn’t see you because you were too big. That seemed a strange idea, but the big man, in his patient way, had made it all sound perfectly reasonable. If ants could see you, they’d be scared, but only because you were so much bigger that they couldn’t do anything to help themselves. So it was better for them not even to know you were there.

Dimly, as an echo, he remembered too how he’d watched the ants on a sunny afternoon, and wished he could be as small as they were. That was a silly thought, fit only for little kids that laughed and cried and wet their pants.

But it would be fun to be a very big giant, so big that all the people and cars in all the streets would look like little ants running around. So big they couldn’t even see you, because if they could it wouldn’t do them any good.

“Black bugs’ blood!” said Dicky abruptly to himself.

The hard sharp heel of his new shoe ground into the anthill, obliterating the entrance, burying the frantic workers under tumbled dust. He stamped the anthill flat with careful thoroughness.

Then he turned without another glance, not laughing or crying any more, and walked sedately up the slope to the house.

This etext was produced from Fantastic Universe, June 1956 (Vol. 5, No. 5.). Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Obvious errors in punctuation have been silently corrected in this version.