Title: Charles O'Malley, The Irish Dragoon, Volume 1

Author: Charles Lever

Release date: February 2, 2007 [eBook #8577]

Most recently updated: February 26, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team. Illustrated

HTML by David Widger

TO THE MOST NOBLE THE MARQUESS OF DOURO, M.P., D.C.L., ETC., ETC. MY DEAR LORD,— The imperfect attempt to picture forth some scenes of the most brilliant period of my country’s history might naturally suggest their dedication to the son of him who gave that era its glory. I feel, however, in the weakness of the effort, the presumption of such a thought, and would simply ask of you to accept these volumes as a souvenir of many delightful hours passed long since in your society, and a testimony of the deep pride with which I regard the honor of your friendship. Believe me, my dear Lord, with every respect and esteem, Yours, most sincerely, THE AUTHOR. BRUSSELS, November, 1841.

KIND PUBLIC,—

Having so lately taken my leave of the stage, in a farewell benefit, it is but fitting that I should explain the circumstances which once more bring me before you,—that I may not appear intrusive, where I have met with but too much indulgence.

A blushing debutante—entre nous, the most impudent Irishman that ever swaggered down Sackville Street—has requested me to present him to your acquaintance. He has every ambition to be a favorite with you; but says—God forgive him—he is too bashful for the foot-lights.

He has remarked—-as, doubtless, many others have done—upon what very slight grounds, and with what slender pretension, my Confessions have met with favor at the hands of the press and the public; and the idea has occurred to him to indite his own. Had his determination ended here, I should have nothing to object to; but unfortunately, he expects me to become his editor, and in some sort responsible for the faults of his production. I have wasted much eloquence and more breath in assuring him that I was no tried favorite of the public, who dared take liberties with them; that the small rag of reputation I enjoyed, was a very scanty covering for my own nakedness; that the plank which swam with one, would most inevitably sink with two; and lastly, that the indulgence so often bestowed upon a first effort is as frequently converted into censure on the older offender. My arguments have, however, totally failed, and he remains obdurate and unmoved. Under these circumstances I have yielded; and as, happily for me, the short and pithy direction to the river Thames, in the Critic, “to keep between its banks,” has been imitated by my friend, I find all that is required of me is to write my name upon the title and go in peace. Such, he informs me, is modern editorship.

In conclusion, I would beg, that if the debt he now incurs at your hands remain unpaid, you would kindly bear in mind that your remedy lies against the drawer of the bill and not against its mere humble indorser,

HARRY LORREQUER

BRUSSELS, March, 1840.

The success of Harry Lorrequer was the reason for writing Charles O’Malley. That I myself was in no wise prepared for the favor the public bestowed on my first attempt is easily enough understood. The ease with which I strung my stories together,—and in reality the Confessions of Harry Lorrequer are little other than a note-book of absurd and laughable incidents,—led me to believe that I could draw on this vein of composition without any limit whatever. I felt, or thought I felt, an inexhaustible store of fun and buoyancy within me, and I began to have a misty, half-confused impression that Englishmen generally labored under a sad-colored temperament, took depressing views of life, and were proportionately grateful to any one who would rally them even passingly out of their despondency, and give them a laugh without much trouble for going in search of it.

When I set to work to write Charles O’Malley I was, as I have ever been, very low with fortune, and the success of a new venture was pretty much as eventful to me as the turn of the right color at rouge-et-noir. At the same time I had then an amount of spring in my temperament, and a power of enjoying life which I can honestly say I never found surpassed. The world had for me all the interest of an admirable comedy, in which the part allotted myself, if not a high or a foreground one, was eminently suited to my taste, and brought me, besides, sufficiently often on the stage to enable me to follow all the fortunes of the piece. Brussels, where I was then living, was adorned at the period by a most agreeable English society. Some leaders of the fashionable world of London had come there to refit and recruit, both in body and estate. There were several pleasant and a great number of pretty people among them; and so far as I could judge, the fashionable dramas of Belgrave Square and its vicinity were being performed in the Rue Royale and the Boulevard de Waterloo with very considerable success. There were dinners, balls, déjeûners, and picnics in the Bois de Cambre, excursions to Waterloo, and select little parties to Bois-fort,—a charming little resort in the forest whose intense cockneyism became perfectly inoffensive as being in a foreign land, and remote from the invasion of home-bred vulgarity. I mention all these things to show the adjuncts by which I was aided, and the rattle of gayety by which I was, as it were, “accompanied,” when I next tried my voice.

The soldier element tinctured strongly our society, and I will say most agreeably. Among those whom I remember best were several old Peninsulars. Lord Combermere was of this number, and another of our set was an officer who accompanied, if indeed he did not command, the first boat party who crossed the Douro. It is needless to say how I cultivated a society so full of all the storied details I was eager to obtain, and how generously disposed were they to give me all the information I needed. On topography especially were they valuable to me, and with such good result that I have been more than once complimented on the accuracy of my descriptions of places which I have never seen and whose features I have derived entirely from the narratives of my friends.

When, therefore, my publishers asked me could I write a story in the Lorrequer vein, in which active service and military adventure could figure more prominently than mere civilian life, and where the achievements of a British army might form the staple of the narrative,—when this question was propounded me, I was ready to reply: Not one, but fifty. Do not mistake me, and suppose that any overweening confidence in my literary powers would have emboldened me to make this reply; my whole strength lay in the fact that I could not recognize anything like literary effort in the matter. If the world would only condescend to read that which I wrote precisely as I was in the habit of talking, nothing could be easier than for me to occupy them. Not alone was it very easy to me, but it was intensely interesting and amusing to myself, to be so engaged.

The success of Harry Lorrequer had been freely wafted across the German ocean, but even in its mildest accents it was very intoxicating incense to me; and I set to work on my second book with a thrill of hope as regards the world’s favor which—and it is no small thing to say it—I can yet recall.

I can recall, too, and I am afraid more vividly still, some of the difficulties of my task when I endeavored to form anything like an accurate or precise idea of some campaigning incident or some passage of arms from the narratives of two distinct and separate “eye-witnesses.” What mistrust I conceived for all eye-witnesses from my own brief experience of their testimonies! What an impulse did it lend me to study the nature and the temperament of narrator, as indicative of the peculiar coloring he might lend his narrative; and how it taught me to know the force of the French epigram that has declared how it was entirely the alternating popularity of Marshal Soult that decided whether he won or lost the battle of Toulouse.

While, however, I was sifting these evidences, and separating, as well as I might, the wheat from the chaff, I was in a measure training myself for what, without my then knowing it, was to become my career in life. This was not therefore altogether without a certain degree of labor, but so light and pleasant withal, so full of picturesque peeps at character and humorous views of human nature, that it would be the very rankest ingratitude of me if I did not own that I gained all my earlier experiences of the world in very pleasant company,—highly enjoyable at the time, and with matter for charming souvenirs long after.

That certain traits of my acquaintances found themselves embodied in some of the characters of this story I do not to deny. The principal of natural selection adapts itself to novels as to Nature, and it would have demanded an effort above my strength to have disabused myself at the desk of all the impressions of the dinner-table, and to have forgotten features which interested or amused me.

One of the personages of my tale I drew, however, with very little aid from fancy. I would go so far as to say that I took him from the life, if my memory did not confront me with the lamentable inferiority of my picture to the great original it was meant to portray.

With the exception of the quality of courage, I never met a man who contained within himself so many of the traits of Falstaff as the individual who furnished me with Major Monsoon. But the major—I must call him so, though that rank was far beneath his own—was a man of unquestionable bravery. His powers as a story-teller were to my thinking unrivalled; the peculiar reflections on life which he would passingly introduce, the wise apothegms, were after a morality essentially of his own invention. Then he would indulge in the unsparing exhibition of himself in situations such as other men would never have confessed to, all blended up with a racy enjoyment of life, dashed occasionally with sorrow that our tenure of it was short of patriarchal. All these, accompanied by a face redolent of intense humor, and a voice whose modulations were managed with the skill of a consummate artist,—all these, I say, were above me to convey; nor indeed as I re-read any of the adventures in which he figures, am I other than ashamed at the weakness of my drawing and the poverty of my coloring.

That I had a better claim to personify him than is always the lot of a novelist; that I possessed, so to say, a vested interest in his life and adventures,—I will relate a little incident in proof; and my accuracy, if necessary, can be attested by another actor in the scene, who yet survives.

I was living a bachelor life at Brussels, my family being at Ostende for the bathing, during the summer of 1840. The city was comparatively empty,—all the so-called society being absent at the various spas or baths of Germany. One member of the British legation, who remained at his post to represent the mission, and myself, making common cause of our desolation and ennui, spent much of our time together, and dined tête-à-tête every day.

It chanced that one evening, as we were hastening through the park on our way to dinner, we espied the major—for as major I must speak of him—lounging along with that half-careless, half-observant air we had both of us remarked as indicating a desire to be somebody’s, anybody’s guest, rather than surrender himself to the homeliness of domestic fare.

“There’s that confounded old Monsoon,” cried my diplomatic friend. “It’s all up if he sees us, and I can’t endure him.”

Now, I must remark that my friend, though very far from insensible to the humoristic side of the major’s character, was not always in the vein to enjoy it; and when so indisposed he could invest the object of his dislike with something little short of antipathy. “Promise me,” said he, as Monsoon came towards us,—“promise me, you’ll not ask him to dinner.” Before I could make any reply, the major was shaking a hand of either of us, and rapturously expatiating over his good luck at meeting us. “Mrs. M.,” said he, “has got a dreary party of old ladies to dine with her, and I have come out here to find some pleasant fellow to join me, and take our mutton-chop together.”

“We’re behind our time, Major,” said my friend, “sorry to leave you so abruptly, but must push on. Eh, Lorrequer,” added he, to evoke corroboration on my part.

“Harry says nothing of the kind,” replied Monsoon, “he says, or he’s going to say, ‘Major, I have a nice bit of dinner waiting for me at home, enough for two, will feed three, or if there be a short-coming, nothing easier than to eke out the deficiency by another bottle of Moulton; come along with us then, Monsoon, and we shall be all the merrier for your company.’”

Repeating his last words, “Come along, Monsoon,” etc., I passed my arm within his, and away we went. For a moment my friend tried to get free and leave me, but I held him fast and carried him along in spite of himself. He was, however, so chagrined and provoked that till the moment we reached my door he never uttered a word, nor paid the slightest attention to Monsoon, who talked away in a vein that occasionally made gravity all but impossible.

Our dinner proceeded drearily enough, the diplomatist’s stiffness never relaxed for a moment, and my own awkwardness damped all my attempts at conversation. Not so, however, Monsoon, he ate heartily, approved of everything, and pronounced my wine to be exquisite. He gave us a perfect discourse on sherry and Spanish wines in general, told us the secret of the Amontillado flavor, and explained that process of browning by boiling down wine which some are so fond of in England. At last, seeing perhaps that the protection had little charm for us, with his accustomed tact, he diverged into anecdote. “I was once fortunate enough,” said he, “to fall upon some of that choice sherry from the St. Lucas Luentas which is always reserved for royalty. It was a pale wine, delicious in the drinking, and leaving no more flavor in the mouth than a faint dryness that seemed to say, another glass. Shall I tell you how I came by it?” And scarcely pausing for reply, he told the story of having robbed his own convoy, and stolen the wine he was in charge of for safe conveyance.

I wish I could give any, even the weakest idea of how he narrated that incident,—the struggle that he portrayed between duty and temptation, and the apologetic tone of his voice in which he explained that the frame of mind that succeeds to any yielding to seductive influences, is often, in the main, more profitable to a man than is the vain-glorious sense of having resisted a temptation. “Meekness is the mother of all the virtues,” said he, “and there is no being meek without frailty.” The story, told as he told it, was too much for the diplomatist’s gravity, he resisted all signs of attention as long as he was able, and at last fairly roared out with laughter.

As soon as I myself recovered from the effects of his drollery, I said, “Major, I have a proposition to make you. Let me tell the story in print, and I’ll give you five naps.”

“Are you serious, Harry?” asked he. “Is this on honor?”

“On honor, assuredly,” I replied.

“Let me have the money down, on the nail, and I’ll give you leave to have me and my whole life, every adventure that ever befell me, ay, and if you like, every moral reflection that my experiences have suggested.”

“Done!” cried I, “I agree.”

“Not so fast,” cried the diplomatist, “we must make a protocol of this; the high contracting parties must know what they give and what they receive, I’ll draw out the treaty.”

He did so at full length on a sheet of that solemn blue-tinted paper, so dedicated to despatch purposes; he duly set fourth the concession and the consideration. We each signed the document; he witnessed and sealed it; and Monsoon pocketed my five napoleons, filling a bumper to any success the bargain might bring me, and of which I have never had reason to express deep disappointment.

This document, along with my university degree, my commission in a militia regiment, and a vast amount of letters very interesting to me, was seized by the Austrian authorities on the way from Como to Florence, in the August of 1847, being deemed part of a treasonable correspondence,—probably purposely allegorical in form,—and never restored to me. I fairly own that I’d give all the rest willingly to repossess myself of the Monsoon treaty, not a little for the sake of that quaint old autograph, faintly shaken by the quiet laugh with which he wrote it.

That I did not entirely fail in giving my major some faint resemblance to the great original from whom I copied him, I may mention that he was speedily recognized in print by the Marquis of Londonderry, the well-known Sir Charles Stuart of the Peninsular campaign. “I know that fellow well,” said he, “he once sent me a challenge, and I had to make him a very humble apology. The occasion was this: I had been out with a single aide-de-camp to make a reconnaissance in front of Victor’s division; and to avoid attracting any notice, we covered over our uniform with two common gray overcoats which reached to the feet, and effectually concealed our rank as officers. Scarcely, however, had we topped a hill which commanded the view of the French, than a shower of shells flew over and around us. Amazed to think how we could have been so quickly noticed, I looked around me, and discovered, quite close in my rear, your friend Monsoon with what he called his staff,—a popinjay set of rascals dressed out in green and gold, and with more plumes and feathers than the general staff ever boasted. Carried away by momentary passion at the failure of my reconnaissance, I burst out with some insolent allusion to the harlequin assembly which had drawn the French fire upon us. Monsoon saluted me respectfully, and retired without a word; but I had scarcely reached my quarters when a ‘friend’ of his waited on me with a message, a very categorical message it was, too, ‘it must be a meeting or an ample apology.’ I made the apology, a most full one, for the major was right, and I had not a fraction of reason to sustain me in my conduct, and we have been the best of friends ever since.”

I myself had heard the incident before this from Monsoon, but told among other adventures whose exact veracity I was rather disposed to question, and did not therefore accord it all the faith that was its due; and I admit that the accidental corroboration of this one event very often served to puzzle me afterwards, when I listened to stories in which the major seemed a second Munchausen, but might, like in this of the duel, have been among the truest and most matter-of-fact of historians. May the reader be not less embarrassed than myself, is my sincere, if not very courteous, prayer.

I have no doubt myself, that often in recounting some strange incident,—a personal experience it always was,—he was himself more amused by the credulity of the hearers, and the amount of interest he could excite in them, than were they by the story. He possessed the true narrative gusto, and there was a marvellous instinct in the way in which he would vary a tale to suit the tastes of an audience; while his moralizings were almost certain to take the tone of a humoristic quiz on the company.

Though fully aware that I was availing myself of the contract that delivered him into my hands, and dining with me two or three days a week, he never lapsed into any allusion to his appearance in print; and the story had been already some weeks published before he asked me to lend him “that last thing—he forgot the name of it—I was writing.”

Of Frank Webber I have said, in a former notice, that he was one of my earliest friends, my chum in college, and in the very chambers where I have located Charles O’Malley, in Old Trinity. He was a man of the highest order of abilities, and with a memory that never forgot, but ruined and run to seed by the idleness that came of a discursive, uncertain temperament. Capable of anything, he spent his youth in follies and eccentricities; every one of which, however, gave indications of a mind inexhaustible in resources, and abounding in devices and contrivances that none other but himself would have thought of. Poor fellow, he died young; and perhaps it is better it should have been so. Had he lived to a later day, he would most probably have been found a foremost leader of Fenianism; and from what I knew of him, I can say he would have been a more dangerous enemy to English rule than any of those dealers in the petty larceny of rebellion we have lately seen among us.

I have said that of Mickey Free I had not one but one thousand types. Indeed, I am not quite sure that in my last visit to Dublin, I did not chance on a living specimen of the “Free” family, much readier in repartée, quicker with an apropos, and droller in illustration than my own Mickey. This fellow was “boots” at a great hotel in Sackville Street; and I owe him more amusement and some heartier laughs than it has been always my fortune to enjoy in a party of wits. His criticisms on my sketches of Irish character were about the shrewdest and the best I ever listened to; and that I am not bribed to this by any flattery, I may remark that they were more often severe than complimentary, and that he hit every blunder of image, every mistake in figure, of my peasant characters, with an acuteness and correctness which made me very grateful to know that his daily occupations were limited to blacking boots, and not polishing off authors.

I believe I have now done with my confessions, except I should like to own that this story was the means of according me a more heartfelt glow of satisfaction, a more gratifying sense of pride, than anything I ever have or ever shall write, and in this wise. My brother, at that time the rector of an Irish parish, once forwarded to me a letter from a lady unknown to him, but who had heard he was the brother of “Harry Lorrequer,” and who addressed him not knowing where a letter might be directed to myself. The letter was the grateful expression of a mother, who said, “I am the widow of a field officer, and with an only son, for whom I obtained a presentation to Woolwich; but seeing in my boy’s nature certain traits of nervousness and timidity which induced me to hesitate on embarking him in the career of a soldier, I became very unhappy and uncertain which course to decide on.

“While in this state of uncertainty, I chanced to make him a birthday present of ‘Charles O’Malley,’ the reading of which seemed to act like a charm on his whole character, inspiring him with a passion for movement and adventure, and spiriting him to an eager desire for a military life. Seeing that this was no passing enthusiasm, but a decided and determined bent, I accepted the cadetship for him; and his career has been not alone distinguished as a student, but one which has marked him out for an almost hare-brained courage, and for a dash and heroism that give high promise for his future.

“Thank your brother for me,” wrote she, “a mother’s thanks for the welfare of an only son; and say how I wish that my best wishes for him and his could recompense him for what I owe him.”

I humbly hope that it may not be imputed to me as unpardonable vanity,—the recording of this incident. It gave me an intense pleasure when I heard it; and now, as I look back on it, it invests this story for myself with an interest which nothing else that I have written can afford me.

I have now but to repeat what I have declared in former editions, my sincere gratitude for the favor the public still continues to bestow on me,—a favor which probably associates the memory of this book with whatever I have since done successfully, and compels me to remember that to the popularity of “Charles O’Malley” I am indebted for a great share of that kindliness in criticism, and that geniality in judgment, which—for more than a quarter of a century—my countrymen have graciously bestowed on their faithful friend and servant,

CHARLES LEVER. TRIESTE, 1872.

DALY’S CLUB-HOUSE.

The rain was dashing in torrents against the window-panes, and the wind sweeping in heavy and fitful gusts along the dreary and deserted streets, as a party of three persons sat over their wine, in that stately old pile which once formed the resort of the Irish Members, in College Green, Dublin, and went by the name of Daly’s Club-House. The clatter of falling tiles and chimney-pots, the jarring of the window-frames, and howling of the storm without seemed little to affect the spirits of those within as they drew closer to a blazing fire before which stood a small table covered with the remains of a dessert, and an abundant supply of bottles, whose characteristic length of neck indicated the rarest wines of France and Germany; while the portly magnum of claret—the wine par excellence of every Irish gentleman of the day—passed rapidly from hand to hand, the conversation did not languish, and many a deep and hearty laugh followed the stories which every now and then were told, as some reminiscence of early days was recalled, or some trait of a former companion remembered.

One of the party, however, was apparently engrossed by other thoughts than those of the mirth and merriment around; for in the midst of all he would turn suddenly from the others, and devote himself to a number of scattered sheets of paper, upon which he had written some lines, but whose crossed and blotted sentences attested how little success had waited upon his literary labors. This individual was a short, plethoric-looking, white-haired man of about fifty, with a deep, round voice, and a chuckling, smothering laugh, which, whenever he indulged not only shook his own ample person, but generally created a petty earthquake on every side of him. For the present, I shall not stop to particularize him more closely; but when I add that the person in question was a well-known member of the Irish House of Commons, whose acute understanding and practical good sense were veiled under an affected and well-dissembled habit of blundering that did far more for his party than the most violent and pointed attacks of his more accurate associates, some of my readers may anticipate me in pronouncing him to be Sir Harry Boyle. Upon his left sat a figure the most unlike him possible. He was a tall, thin, bony man, with a bolt-upright air and a most saturnine expression; his eyes were covered by a deep green shade, which fell far over his face, but failed to conceal a blue scar that crossing his cheek ended in the angle of his mouth, and imparted to that feature, when he spoke, an apparently abortive attempt to extend towards his eyebrow; his upper lip was covered with a grizzly and ill-trimmed mustache, which added much to the ferocity of his look, while a thin and pointed beard on his chin gave an apparent length to the whole face that completed its rueful character. His dress was a single-breasted, tightly buttoned frock, in one button-hole of which a yellow ribbon was fastened, the decoration of a foreign service, which conferred upon its wearer the title of count; and though Billy Considine, as he was familiarly called by his friends, was a thorough Irishman in all his feelings and affections, yet he had no objection to the designation he had gained in the Austrian army. The Count was certainly no beauty, but somehow, very few men of his day had a fancy for telling him so. A deadlier hand and a steadier eye never covered his man in the Phoenix; and though he never had a seat in the House, he was always regarded as one of the government party, who more than once had damped the ardor of an opposition member by the very significant threat of “setting Billy at him.” The third figure of the group was a large, powerfully built, and handsome man, older than either of the others, but not betraying in his voice or carriage any touch of time. He was attired in the green coat and buff vest which formed the livery of the club; and in his tall, ample forehead, clear, well-set eye, and still handsome mouth, bore evidence that no great flattery was necessary at the time which called Godfrey O’Malley the handsomest man in Ireland.

“Upon my conscience,” said Sir Harry, throwing down his pen with an air of ill-temper, “I can make nothing of it! I have got into such an infernal habit of making bulls, that I can’t write sense when I want it!”

“Come, come,” said O’Malley, “try again, my dear fellow. If you can’t succeed, I’m sure Billy and I have no chance.”

“What have you written? Let us see,” said Considine, drawing the paper towards him, and holding it to the light. “Why, what the devil is all this? You have made him ‘drop down dead after dinner of a lingering illness brought on by the debate of yesterday.’”

“Oh, impossible!”

“Well, read it yourself; there it is. And, as if to make the thing less credible, you talk of his ‘Bill for the Better Recovery of Small Debts.’ I’m sure, O’Malley, your last moments were not employed in that manner.”

“Come, now,” said Sir Harry, “I’ll set all to rights with a postscript. ‘Any one who questions the above statement is politely requested to call on Mr. Considine, 16 Kildare Street, who will feel happy to afford him every satisfaction upon Mr. O’Malley’s decease, or upon miscellaneous matters.”

“Worse and worse,” said O’Malley. “Killing another man will never persuade the world that I’m dead.”

“But we’ll wake you, and have a glorious funeral.”

“And if any man doubt the statement, I’ll call him out,” said the Count.

“Or, better still,” said Sir Harry, “O’Malley has his action at law for defamation.”

“I see I’ll never get down to Galway at this rate,” said O’Malley; “and as the new election takes place on Tuesday week, time presses. There are more writs flying after me this instant than for all the government boroughs.”

“And there will be fewer returns, I fear,” said Sir Harry.

“Who is the chief creditor?” asked the Count.

“Old Stapleton, the attorney in Fleet Street, has most of the mortgages.”

“Nothing to be done with him in this way?” said Considine, balancing the corkscrew like a hair trigger.

“No chance of it.”

“May be,” said Sir Harry, “he might come to terms if I were to call and say, ‘You are anxious to close accounts, as your death has just taken place.’ You know what I mean.”

“I fear so should he, were you to say so. No, no, Boyle, just try a plain, straightforward paragraph about my death; we’ll have it in Falkner’s paper to-morrow. On Friday the funeral can take place, and, with the blessing o’ God, I’ll come to life on Saturday at Athlone, in time to canvass the market.”

“I think it wouldn’t be bad if your ghost were to appear to old Timins the tanner, in Naas, on your way down. You know he arrested you once before.”

“I prefer a night’s sleep,” said O’Malley. “But come, finish the squib for the paper.”

“Stay a little,” said Sir Harry, musing; “it just strikes me that if ever the matter gets out I may be in some confounded scrape. Who knows if it is not a breach of privilege to report the death of a member? And to tell you truth, I dread the Sergeant and the Speaker’s warrant with a very lively fear.”

“Why, when did you make his acquaintance?” said the Count.

“Is it possible you never heard of Boyle’s committal?” said O’Malley. “You surely must have been abroad at the time. But it’s not too late to tell it yet.”

“Well, it’s about two years since old Townsend brought in his Enlistment Bill, and the whole country was scoured for all our voters, who were scattered here and there, never anticipating another call of the House, and supposing that the session was just over. Among others, up came our friend Harry, here, and the night he arrived they made him a ‘Monk of the Screw,’ and very soon made him forget his senatorial dignities. On the evening after his reaching town, the bill was brought in, and at two in the morning the division took place,—a vote was of too much consequence not to look after it closely,—and a Castle messenger was in waiting in Exchequer Street, who, when the debate was closing, put Harry, with three others, into a coach, and brought them down to the House. Unfortunately, however, they mistook their friends, voted against the bill, and amidst the loudest cheering of the opposition, the government party were defeated. The rage of the ministers knew no bounds, and looks of defiance and even threats were exchanged between the ministers and the deserters. Amidst all this poor Harry fell fast asleep and dreamed that he was once more in Exchequer Street, presiding among the monks, and mixing another tumbler. At length he awoke and looked about him. The clerk was just at the instant reading out, in his usual routine manner, a clause of the new bill, and the remainder of the House was in dead silence. Harry looked again around on every side, wondering where was the hot water, and what had become of the whiskey bottle, and above all, why the company were so extremely dull and ungenial. At length, with a half-shake, he roused up a little, and giving a look of unequivocal contempt on every side, called out, ‘Upon my soul, you’re pleasant companions; but I’ll give you a chant to enliven you!’ So saying, he cleared his throat with a couple of short coughs, and struck up, with the voice of a Stentor, the following verse of a popular ballad:—

‘And they nibbled away, both night and day, Like mice in a round of Glo’ster; Great rogues they were all, both great and small, From Flood to Leslie Foster. Great rogues all.

Chorus, boys!’ If he was not joined by the voices of his friends in the song, it was probably because such a roar of laughing never was heard since the walls were roofed over. The whole House rose in a mass, and my friend Harry was hurried over the benches by the sergeant-at-arms, and left for three weeks in Newgate to practise his melody.”

“All true,” said Sir Harry; “and worse luck to them for not liking music. But come, now, will this do? ‘It is our melancholy duty to announce the death of Godfrey O’Malley, Esq., late member for the county of Galway, which took place on Friday evening, at Daly’s Club-House. This esteemed gentleman’s family—one of the oldest in Ireland, and among whom it was hereditary not to have any children—‘”

Here a burst of laughter from Considine and O’Malley interrupted the reader, who with the greatest difficulty could be persuaded that he was again bulling it.

“The devil fly away with it,” said he; “I’ll never succeed.”

“Never mind,” said O’Malley, “the first part will do admirably; and let us now turn our attention to other matters.”

A fresh magnum was called for, and over its inspiring contents all the details of the funeral were planned; and as the clock struck four the party separated for the night, well satisfied with the result of their labors.

THE ESCAPE.

When the dissolution of Parliament was announced the following morning in Dublin, its interest in certain circles was manifestly increased by the fact that Godfrey O’Malley was at last open to arrest; for as in olden times certain gifted individuals possessed some happy immunity against death by fire or sword, so the worthy O’Malley seemed to enjoy a no less valuable privilege, and for many a year had passed among the myrmidons of the law as writ-proof. Now, however, the charm seemed to have yielded; and pretty much with the same feeling as a storming party may be supposed to experience on the day that a breach is reported as practicable, did the honest attorneys retained in the various suits against him rally round each other that morning in the Four Courts.

Bonds, mortgages, post-obits, promissory notes—in fact, every imaginable species of invention for raising the O’Malley exchequer for the preceding thirty years—were handed about on all sides, suggesting to the mind of an uninterested observer the notion that had the aforesaid O’Malley been an independent and absolute monarch, instead of merely being the member for Galway, the kingdom over whose destinies he had been called to preside would have suffered not a little from a depreciated currency and an extravagant issue of paper. Be that as it might, one thing was clear,—the whole estates of the family could not possibly pay one fourth of the debt; and the only question was one which occasionally arises at a scanty dinner on a mail-coach road,—who was to be the lucky individual to carve the joint, where so many were sure to go off hungry?

It was now a trial of address between these various and highly gifted gentlemen who should first pounce upon the victim; and when the skill of their caste is taken into consideration, who will doubt that every feasible expedient for securing him was resorted to? While writs were struck against him in Dublin, emissaries were despatched to the various surrounding counties to procure others in the event of his escape. Ne exeats were sworn, and water-bailiffs engaged to follow him on the high seas; and as the great Nassau balloon did not exist in those days, no imaginable mode of escape appeared possible, and bets were offered at long odds that within twenty-four hours the late member would be enjoying his otium cum dignitate in his Majesty’s jail of Newgate.

Expectation was at the highest, confidence hourly increasing, success all but certain, when in the midst of all this high-bounding hope the dreadful rumor spread that O’Malley was no more. One had seen it just five minutes before in the evening edition of Falkner’s paper; another heard it in the courts; a third overheard the Chief-Justice stating it to the Master of the Rolls; and lastly, a breathless witness arrived from College Green with the news that Daly’s Club-House was shut up, and the shutters closed. To describe the consternation the intelligence caused on every side is impossible; nothing in history equals it,—except, perhaps, the entrance of the French army into Moscow, deserted and forsaken by its former inhabitants. While terror and dismay, therefore, spread amidst that wide and respectable body who formed O’Malley’s creditors, the preparations for his funeral were going on with every rapidity. Relays of horses were ordered at every stage of the journey, and it was announced that, in testimony of his worth, a large party of his friends were to accompany his remains to Portumna Abbey,—a test much more indicative of resistance in the event of any attempt to arrest the body, than of anything like reverence for their departed friend.

Such was the state of matters in Dublin when a letter reached me one morning at O’Malley Castle, whose contents will at once explain the writer’s intention, and also serve to introduce my unworthy self to my reader. It ran thus:—

DALY’S, about eight in the evening. Dear Charley,—Your uncle Godfrey, whose debts (God pardon him!) are more numerous than the hairs of his wig, was obliged to die here last night. We did the thing for him completely; and all doubts as to the reality of the event are silenced by the circumstantial detail of the newspaper, “that he was confined six weeks to his bed from a cold he caught, ten days ago, while on guard.” Repeat this; for it is better we had all the same story till he comes to life again, which, may be, will not take place before Tuesday or Wednesday. At the same time, canvass the county for him, and say he’ll be with his friends next week, and up in Woodford and the Scariff barony. Say he died a true Catholic; it will serve him on the hustings. Meet us in Athlone on Saturday, and bring your uncle’s mare with you. He says he’d rather ride home. And tell Father Mac Shane, to have a bit of dinner ready about four o’clock, for the corpse can get nothing after he leaves Mountmellick. No more now, from Yours ever, HARRY BOYLE To CHARLES O’MALLEY, Esq., O’Malley Castle, Galway.

When this not over-clear document reached me I was the sole inhabitant of O’Malley Castle,—a very ruinous pile of incongruous masonry, that stood in a wild and dreary part of the county of Galway, bordering on the Shannon. On every side stretched the property of my uncle, or at least what had once been so; and indeed, so numerous were its present claimants that he would have been a subtle lawyer who could have pronounced upon the rightful owner. The demesne around the castle contained some well-grown and handsome timber, and as the soil was undulating and fertile, presented many features of beauty; beyond it, all was sterile, bleak, and barren. Long tracts of brown heath-clad mountain or not less unprofitable valleys of tall and waving fern were all that the eye could discern, except where the broad Shannon, expanding into a tranquil and glassy lake, lay still and motionless beneath the dark mountains, a few islands, with some ruined churches and a round tower, alone breaking the dreary waste of water.

Here it was that I passed my infancy and my youth; and here I now stood, at the age of seventeen, quite unconscious that the world contained aught fairer and brighter than that gloomy valley with its rugged frame of mountains.

When a mere child, I was left an orphan to the care of my worthy uncle. My father, whose extravagance had well sustained the family reputation, had squandered a large and handsome property in contesting elections for his native county, and in keeping up that system of unlimited hospitality for which Ireland in general, and Galway more especially, was renowned. The result was, as might be expected, ruin and beggary. He died, leaving every one of his estates encumbered with heavy debts, and the only legacy he left to his brother was a boy four years of age, entreating him with his last breath, “Be anything you like to him, Godfrey, but a father, or at least such a one as I have proved.”

Godfrey O’Malley some short time previous had lost his wife, and when this new trust was committed to him he resolved never to remarry, but to rear me up as his own child and the inheritor of his estates. How weighty and onerous an obligation this latter might prove, the reader can form some idea. The intention was, however, a kind one; and to do my uncle justice, he loved me with all the affection of a warm and open heart.

From my earliest years his whole anxiety was to fit me for the part of a country gentleman, as he regarded that character,—namely, I rode boldly with fox-hounds; I was about the best shot within twenty miles of us; I could swim the Shannon at Holy Island; I drove four-in-hand better than the coachman himself; and from finding a hare to hooking a salmon, my equal could not be found from Killaloe to Banagher. These were the staple of my endowments. Besides which, the parish priest had taught me a little Latin, a little French, a little geometry, and a great deal of the life and opinions of Saint Jago, who presided over a holy well in the neighborhood, and was held in very considerable repute.

When I add to this portraiture of my accomplishments that I was nearly six feet high, with more than a common share of activity and strength for my years, and no inconsiderable portion of good looks, I have finished my sketch, and stand before my reader.

It is now time I should return to Sir Harry’s letter, which so completely bewildered me that, but for the assistance of Father Roach, I should have been totally unable to make out the writer’s intentions. By his advice, I immediately set out for Athlone, where, when I arrived, I found my uncle addressing the mob from the top of the hearse, and recounting his miraculous escapes as a new claim upon their gratitude.

“There was nothing else for it, boys; the Dublin people insisted on my being their member, and besieged the club-house. I refused; they threatened. I grew obstinate; they furious. ‘I’ll die first,’ said I. ‘Galway or nothing!’”

“Hurrah!” from the mob. “O’Malley forever!”

“And ye see, I kept my word, boys,—I did die; I died that evening at a quarter past eight. There, read it for yourselves; there’s the paper. Was waked and carried out, and here I am after all, ready to die in earnest for you, but never to desert you.”

The cheers here were deafening, and my uncle was carried through the market down to the mayor’s house, who, being a friend of the opposite party, was complimented with three groans; then up the Mall to the chapel, beside which father Mac Shane resided. He was then suffered to touch the earth once more; when, having shaken hands with all of his constituency within reach, he entered the house, to partake of the kindest welcome and best reception the good priest could afford him.

My uncle’s progress homeward was a triumph. The real secret of his escape had somehow come out, and his popularity rose to a white heat. “An’ it’s little O’Malley cares for the law,—bad luck to it; it’s himself can laugh at judge and jury. Arrest him? Nabocklish! Catch a weasel asleep!” etc. Such were the encomiums that greeted him as he passed on towards home; while shouts of joy and blazing bonfires attested that his success was regarded as a national triumph.

The west has certainly its strong features of identity. Had my uncle possessed the claims of the immortal Howard; had he united in his person all the attributes which confer a lasting and an ennobling fame upon humanity,—he might have passed on unnoticed and unobserved; but for the man that had duped a judge and escaped the sheriff, nothing was sufficiently flattering to mark their approbation. The success of the exploit was twofold; the news spread far and near, and the very story canvassed the county better than Billy Davern himself, the Athlone attorney.

This was the prospect now before us; and however little my readers may sympathize with my taste, I must honestly avow that I looked forward to it with a most delighted feeling. O’Malley Castle was to be the centre of operations, and filled with my uncle’s supporters; while I, a mere stripling, and usually treated as a boy, was to be intrusted with an important mission, and sent off to canvass a distant relation, with whom my uncle was not upon terms, and who might possibly be approachable by a younger branch of the family, with whom he had never any collision.

MR. BLAKE.

Nothing but the exigency of the case could ever have persuaded my uncle to stoop to the humiliation of canvassing the individual to whom I was now about to proceed as envoy-extraordinary, with full powers to make any or every amende, provided only his interest and that of his followers should be thereby secured to the O’Malley cause. The evening before I set out was devoted to giving me all the necessary instructions how I was to proceed, and what difficulties I was to avoid.

“Say your uncle’s in high feather with the government party,” said Sir Harry, “and that he only votes against them as a ruse de guerre, as the French call it.”

“Insist upon it that I am sure of the election without him; but that for family reasons he should not stand aloof from me; that people are talking of it in the country.”

“And drop a hint,” said Considine, “that O’Malley is greatly improved in his shooting.”

“And don’t get drunk too early in the evening, for Phil Blake has beautiful claret,” said another.

“And be sure you don’t make love to the red-headed girls,” added a third; “he has four of them, each more sinfully ugly than the other.”

“You’ll be playing whist, too,” said Boyle; “and never mind losing a few pounds. Mrs. B., long life to her, has a playful way of turning the king.”

“Charley will do it all well,” said my uncle; “leave him alone. And now let us have in the supper.”

It was only on the following morning, as the tandem came round to the door, that I began to feel the importance of my mission, and certain misgivings came over me as to my ability to fulfil it. Mr. Blake and his family, though estranged from my uncle for several years past, had been always most kind and good-natured to me; and although I could not, with propriety, have cultivated any close intimacy with them, I had every reason to suppose that they entertained towards me nothing but sentiments of good-will. The head of the family was a Galway squire of the oldest and most genuine stock, a great sportsman, a negligent farmer, and most careless father; he looked upon a fox as an infinitely more precious part of the creation than a French governess, and thought that riding well with hounds was a far better gift than all the learning of a Parson. His daughters were after his own heart,—the best-tempered, least-educated, most high-spirited, gay, dashing, ugly girls in the county, ready to ride over a four-foot paling without a saddle, and to dance the “Wind that shakes the barley” for four consecutive hours, against all the officers that their hard fate, and the Horse Guards, ever condemned to Galway.

The mamma was only remarkable for her liking for whist, and her invariable good fortune thereat,—a circumstance the world were agreed in ascribing less to the blind goddess than her own natural endowments.

Lastly, the heir of the house was a stripling of about my own age, whose accomplishments were limited to selling spavined and broken-winded horses to the infantry officers, playing a safe game at billiards, and acting as jackal-general to his sisters at balls, providing them with a sufficiency of partners, and making a strong fight for a place at the supper-table for his mother. These fraternal and filial traits, more honored at home than abroad, had made Mr. Matthew Blake a rather well-known individual in the neighborhood where he lived.

Though Mr. Blake’s property was ample, and strange to say for his county, unencumbered, the whole air and appearance of his house and grounds betrayed anything rather than a sufficiency of means. The gate lodge was a miserable mud-hovel with a thatched and falling roof; the gate itself, a wooden contrivance, one half of which was boarded and the other railed; the avenue was covered with weeds, and deep with ruts; and the clumps of young plantation, which had been planted and fenced with care, were now open to the cattle, and either totally uprooted or denuded of their bark and dying. The lawn, a handsome one of some forty acres, had been devoted to an exercise-ground for training horses, and was cut up by their feet beyond all semblance of its original destination; and the house itself, a large and venerable structure of above a century old, displayed every variety of contrivance, as well as the usual one of glass, to exclude the weather. The hall-door hung by a single hinge, and required three persons each morning and evening to open and shut it; the remainder of the day it lay pensively open; the steps which led to it were broken and falling; and the whole aspect of things without was ruinous in the extreme. Within, matters were somewhat better, for though the furniture was old, and none of it clean, yet an appearance of comfort was evident; and the large grate, blazing with its pile of red-hot turf, the deep-cushioned chairs, the old black mahogany dinner-table, and the soft carpet, albeit deep with dust, were not to be despised on a winter’s evening, after a hard day’s run with the “Blazers.” Here it was, however, that Mr. Philip Blake had dispensed his hospitalities for above fifty years, and his father before him; and here, with a retinue of servants as gauches and ill-ordered as all about them, was he accustomed to invite all that the county possessed of rank and wealth, among which the officers quartered in his neighborhood were never neglected, the Miss Blakes having as decided a taste for the army as any young ladies of the west of Ireland; and while the Galway squire, with his cords and tops, was detailing the latest news from Ballinasloe in one corner, the dandy from St. James’s Street might be seen displaying more arts of seductive flattery in another than his most accurate insouciane would permit him to practise in the elegant salons of London or Paris, and the same man who would have “cut his brother,” for a solecism of dress or equipage, in Bond Street, was now to be seen quietly domesticated, eating family dinners, rolling silk for the young ladies, going down the middle in a country dance, and even descending to the indignity of long whist at “tenpenny” points, with only the miserable consolation that the company were not honest.

It was upon a clear frosty morning, when a bright blue sky and a sharp but bracing air seem to exercise upon the feelings a sense no less pleasurable than the balmiest breeze and warmest sun of summer, that I whipped my leader short round, and entered the precincts of “Gurt-na-Morra.” As I proceeded along the avenue, I was struck by the slight traces of repairs here and there evident,—a gate or two that formerly had been parallel to the horizon had been raised to the perpendicular; some ineffectual efforts at paint were also perceptible upon the palings; and, in short, everything seemed to have undergone a kind of attempt at improvement.

When I reached the door, instead of being surrounded, as of old, by a tribe of menials frieze-coated, bare-headed, and bare-legged, my presence was announced by a tremendous ringing of bells from the hands of an old functionary in a very formidable livery, who peeped at me through the hall-window, and whom, with the greatest difficulty, I recognized as my quondam acquaintance, the butler. His wig alone would have graced a king’s counsel; and the high collar of his coat, and the stiff pillory of his cravat denoted an eternal adieu to so humble a vocation as drawing a cork. Before I had time for any conjecture as to the altered circumstances about, the activity of my friend at the bell had surrounded me with “four others worse than himself,” at least they were exactly similarly attired; and probably from the novelty of their costume, and the restraints of so unusual a thing as dress, were as perfectly unable to assist themselves or others as the Court of Aldermen would be were they to rig out in plate armor of the fourteenth century. How much longer I might have gone on conjecturing the reasons for the masquerade around, I cannot say; but my servant, an Irish disciple of my uncle’s, whispered in my ear, “It’s a red-breeches day, Master Charles,—they’ll have the hoith of company in the house.” From the phrase, it needed little explanation to inform me that it was one of those occasions on which Mr. Blake attired all the hangers-on of his house in livery, and that great preparations were in progress for a more than usually splendid reception.

In the next moment I was ushered into the breakfast-room, where a party of above a dozen persons were most gayly enjoying all the good cheer for which the house had a well-deserved repute. After the usual shaking of hands and hearty greetings were over, I was introduced in all form to Sir George Dashwood, a tall and singularly handsome man of about fifty, with an undress military frock and ribbon. His reception of me was somewhat strange; for as they mentioned my relationship to Godfrey O’Malley, he smiled slightly, and whispered something to Mr. Blake, who replied, “Oh, no, no; not the least. A mere boy; and besides—” What he added I lost, for at that moment Nora Blake was presenting me to Miss Dashwood.

If the sweetest blue eyes that ever beamed beneath a forehead of snowy whiteness, over which dark brown and waving hair fell less in curls than masses of locky richness, could only have known what wild work they were making of my poor heart, Miss Dashwood, I trust, would have looked at her teacup or her muffin rather than at me, as she actually did on that fatal morning. If I were to judge from her costume, she had only just arrived, and the morning air had left upon her cheek a bloom that contributed greatly to the effect of her lovely countenance. Although very young, her form had all the roundness of womanhood; while her gay and sprightly manner indicated all the sans gêne which only very young girls possess, and which, when tempered with perfect good taste, and accompanied by beauty and no small share of talent, forms an irresistible power of attraction.

Beside her sat a tall, handsome man of about five-and-thirty or perhaps forty years of age, with a most soldierly air, who as I was presented to him scarcely turned his head, and gave me a half-nod of very unequivocal coldness. There are moments in life in which the heart is, as it were, laid bare to any chance or casual impression with a wondrous sensibility of pleasure or its opposite. This to me was one of those; and as I turned from the lovely girl, who had received me with a marked courtesy, to the cold air and repelling hauteur of the dark-browed captain, the blood rushed throbbing to my forehead; and as I walked to my place at the table, I eagerly sought his eye, to return him a look of defiance and disdain, proud and contemptuous as his own. Captain Hammersley, however, never took further notice of me, but continued to recount, for the amusement of those about him, several excellent stories of his military career, which, I confess, were heard with every test of delight by all save me. One thing galled me particularly,—and how easy is it, when you have begun by disliking a person, to supply food for your antipathy,—all his allusions to his military life were coupled with half-hinted and ill-concealed sneers at civilians of every kind, as though every man not a soldier were absolutely unfit for common intercourse with the world, still more for any favorable reception in ladies’ society.

The young ladies of the family were a well-chosen auditory, for their admiration of the army extended from the Life Guards to the Veteran Battalion, the Sappers and Miners included; and as Miss Dashwood was the daughter of a soldier, she of course coincided in many of, if not all, his opinions. I turned towards my neighbor, a Clare gentleman, and tried to engage him in conversation, but he was breathlessly attending to the captain. On my left sat Matthew Blake, whose eyes were firmly riveted upon the same person, and who heard his marvels with an interest scarcely inferior to that of his sisters. Annoyed and in ill-temper, I ate my breakfast in silence, and resolved that the first moment I could obtain a hearing from Mr. Blake I would open my negotiation, and take my leave at once of Gurt-na-Morra.

We all assembled in a large room, called by courtesy the library, when breakfast was over; and then it was that Mr. Blake, taking me aside, whispered, “Charley, it’s right I should inform you that Sir George Dashwood there is the Commander of the Forces, and is come down here at this moment to—” What for, or how it should concern me, I was not to learn; for at that critical instant my informant’s attention was called off by Captain Hammersley asking if the hounds were to hunt that day.

“My friend Charley here is the best authority upon that matter,” said Mr. Blake, turning towards me.

“They are to try the Priest’s meadows,” said I, with an air of some importance; “but if your guests desire a day’s sport, I’ll send word over to Brackely to bring the dogs over here, and we are sure to find a fox in your cover.”

“Oh, then, by all means,” said the captain, turning towards Mr. Blake, and addressing himself to him,—“by all means; and Miss Dashwood, I’m sure, would like to see the hounds throw off.”

Whatever chagrin the first part of his speech caused me, the latter set my heart a-throbbing; and I hastened from the room to despatch a messenger to the huntsman to come over to Gurt-na-Morra, and also another to O’Malley Castle to bring my best horse and my riding equipments as quickly as possible.

“Matthew, who is this captain?” said I, as young Blake met me in the hall.

“Oh, he is the aide-de-camp of General Dashwood. A nice fellow, isn’t he?”

“I don’t know what you may think,” said I, “but I take him for the most impertinent, impudent, supercilious—”

The rest of my civil speech was cut short by the appearance of the very individual in question, who, with his hands in his pockets and a cigar in his mouth, sauntered forth down the steps, taking no more notice of Matthew Blake and myself than the two fox-terriers that followed at his heels.

However anxious I might be to open negotiations on the subject of my mission, for the present the thing was impossible; for I found that Sir George Dashwood was closeted closely with Mr. Blake, and resolved to wait till evening, when chance might afford me the opportunity I desired.

As the ladies had retired to dress for the hunt, and as I felt no peculiar desire to ally myself with the unsocial captain, I accompanied Matthew to the stable to look after the cattle, and make preparations for the coming sport.

“There’s Captain Hammersley’s mare,” said Matthew, as he pointed out a highly bred but powerful English hunter. “She came last night; for as he expected some sport, he sent his horses from Dublin on purpose. The others will be here to-day.”

“What is his regiment?” said I, with an appearance of carelessness, but in reality feeling curious to know if the captain was a cavalry or infantry officer.

“The —th Light Dragoons,”

“You never saw him ride?” said I.

“Never; but his groom there says he leads the way in his own country.”

“And where may that be?”

“In Leicestershire, no less,” said Matthew.

“Does he know Galway?”

“Never was in it before. It’s only this minute he asked Moses Daly if the ox-fences were high here.”

“Ox-fences! Then he does not know what a wall is?”

“Devil a bit; but we’ll teach him.”

“That we will,” said I, with as bitter a resolution to impart the instruction as ever schoolmaster did to whip Latin grammar into one of the great unbreeched.

“But I had better send the horses down to the Mill,” said Matthew; “we’ll draw that cover first.”

So saying, he turned towards the stable, while I sauntered alone towards the road by which I expected the huntsman. I had not walked half a mile before I heard the yelping of the dogs, and a little farther on I saw old Brackely coming along at a brisk trot, cutting the hounds on each side, and calling after the stragglers.

“Did you see my horse on the road, Brackely?” said I.

“I did, Misther Charles; and troth, I’m sorry to see him. Sure yerself knows better than to take out the Badger, the best steeple-chaser in Ireland, in such a country as this,—nothing but awkward stone-fences, and not a foot of sure ground in the whole of it.”

“I know it well, Brackely; but I have my reasons for it.”

“Well, may be you have; what cover will your honor try first?”

“They talk of the Mill,” said I; “but I’d much rather try Morran-a-Gowl.”

“Morran-a-Gowl! Do you want to break your neck entirely?”

“No, Brackely, not mine.”

“Whose, then, alannah?”

“An English captain’s, the devil fly away with him! He’s come down here to-day, and from all I can see is a most impudent fellow; so, Brackely—”

“I understand. Well, leave it to me; and though I don’t like the only deer-park wall on the hill, we’ll try it this morning with the blessing. I’ll take him down by Woodford, over the Devil’s Mouth,—it’s eighteen foot wide this minute with the late rains,—into the four callows; then over the stone-walls, down to Dangan; then take a short cast up the hill, blow him a bit, and give him the park wall at the top. You must come in then fresh, and give him the whole run home over Sleibhmich. The Badger knows it all, and takes the road always in a fly,—a mighty distressing thing for the horse that follows, more particularly if he does not understand a stony country. Well, if he lives through this, give him the sunk fence and the stone wall at Mr. Blake’s clover-field, for the hounds will run into the fox about there; and though we never ride that leap since Mr. Malone broke his neck at it, last October, yet upon an occasion like this, and for the honor of Galway—”

“To be sure, Brackely; and here’s a guinea for you, and now trot on towards the house. They must not see us together, or they might suspect something. But, Brackely,” said I, calling out after him, “if he rides at all fair, what’s to be done?”

“Troth, then, myself doesn’t know. There is nothing so bad west of Athlone. Have ye a great spite again him?”

“I have,” said I, fiercely.

“Could ye coax a fight out of him?”

“That’s true,” said I; “and now ride on as fast as you can.”

Brackely’s last words imparted a lightness to my heart and my step, and I strode along a very different man from what I had left the house half an hour previously.

THE HUNT.

Although we had not the advantages of a southerly wind and cloudy sky, the day towards noon became strongly over-cast, and promised to afford us good scenting weather; and as we assembled at the meet, mutual congratulations were exchanged upon the improved appearance of the day. Young Blake had provided Miss Dashwood with a quiet and well-trained horse, and his sisters were all mounted as usual upon their own animals, giving to our turnout quite a gay and lively aspect. I myself came to cover upon a hackney, having sent Badger with a groom, and longed ardently for the moment when, casting the skin of my great-coat and overalls, I should appear before the world in my well-appointed “cords and tops.” Captain Hammersley had not as yet made his appearance, and many conjectures were afloat as to whether “he might have missed the road, or changed his mind,” or “forgot all about it,” as Miss Dashwood hinted.

“Who, pray, pitched upon this cover?” said Caroline Blake, as she looked with a practised eye over the country on either side.

“There is no chance of a fox late in the day at the Mill,” said the huntsman, inventing a lie for the occasion.

“Then of course you never intend us to see much of the sport; for after you break cover, you are entirely lost to us.”

“I thought you always followed the hounds,” said Miss Dashwood, timidly.

“Oh, to be sure we do, in any common country, but here it is out of the question; the fences are too large for any one, and if I am not mistaken, these gentlemen will not ride far over this. There, look yonder, where the river is rushing down the hill: that stream, widening as it advances, crosses the cover nearly midway,—well, they must clear that; and then you may see these walls of large loose stones nearly five feet in height. That is the usual course the fox takes, unless he heads towards the hills and goes towards Dangan, and then there’s an end of it; for the deer-park wall is usually a pull up to every one except, perhaps, to our friend Charley yonder, who has tried his fortune against drowning more than once there.”

“Look, here he comes,” said Matthew Blake, “and looking splendidly too,—a little too much in flesh perhaps, if anything.”

“Captain Hammersley!” said the four Miss Blakes, in a breath. “Where is he?”

“No; it’s the Badger I’m speaking of,” said Matthew, laughing, and pointing with his finger towards a corner of the field where my servant was leisurely throwing down a wall about two feet high to let him pass.

“Oh, how handsome! What a charger for a dragoon!” said Miss Dashwood.

Any other mode of praising my steed would have been much more acceptable. The word “dragoon” was a thorn in my tenderest part that rankled and lacerated at every stir. In a moment I was in the saddle, and scarcely seated when at once all the mauvais honte of boyhood left me, and I felt every inch a man. I often look back to that moment of my life, and comparing it with similar ones, cannot help acknowledging how purely is the self-possession which so often wins success the result of some slight and trivial association. My confidence in my horsemanship suggested moral courage of a very different kind; and I felt that Charles O’Malley curvetting upon a thorough-bred, and the same man ambling upon a shelty, were two and very dissimilar individuals.

“No chance of the captain,” said Matthew, who had returned from a reconnaissance upon the road; “and after all it’s a pity, for the day is getting quite favorable.”

While the young ladies formed pickets to look out for the gallant militaire, I seized the opportunity of prosecuting my acquaintance with Miss Dashwood, and even in the few and passing observations that fell from her, learned how very different an order of being she was from all I had hitherto seen of country belles. A mixture of courtesy with naïveté; a wish to please, with a certain feminine gentleness, that always flatters a man, and still more a boy that fain would be one,—gained momentarily more and more upon me, and put me also on my mettle to prove to my fair companion that I was not altogether a mere uncultivated and unthinking creature, like the remainder of those about me.

“Here he is at last,” said Helen Blake, as she cantered across a field waving her handkerchief as a signal to the captain, who was now seen approaching at a brisk trot.

As he came along, a small fence intervened; he pressed his horse a little, and as he kissed hands to the fair Helen, cleared it in a bound, and was in an instant in the midst of us.

“He sits his horse like a man, Misther Charles,” said the old huntsman; “troth, we must give him the worst bit of it.”

Captain Hammersley was, despite all the critical acumen with which I canvassed him, the very beau-ideal of a gentleman rider; indeed, although a very heavy man, his powerful English thorough-bred, showing not less bone than blood, took away all semblance of overweight; his saddle was well fitting and well placed, as also was his large and broad-reined snaffle; his own costume of black coat, leathers, and tops was in perfect keeping, and even to his heavy-handled hunting-whip I could find nothing to cavil at. As he rode up he paid his respects to the ladies in his usual free and easy manner, expressed some surprise, but no regret, at hearing that he was late, and never deigning any notice of Matthew or myself, took his place beside Miss Dashwood, with whom he conversed in a low undertone.

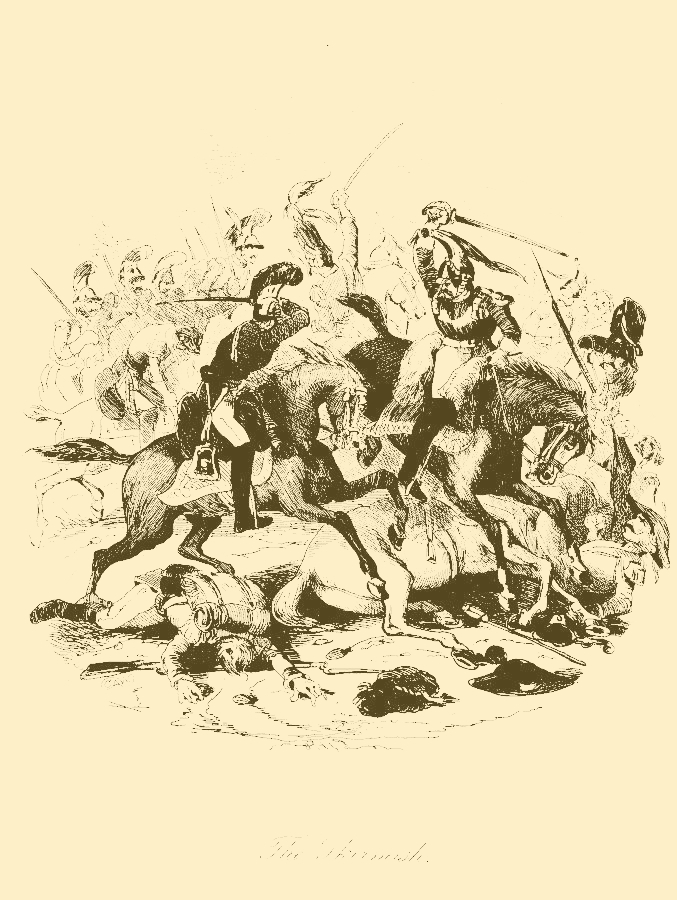

“There they go!” said Matthew, as five or six dogs, with their heads up, ran yelping along a furrow, then stopped, howled again, and once more set off together. In an instant all was commotion in the little valley below us. The huntsman, with his hand to his mouth, was calling off the stragglers, and the whipper-in followed up the leading dogs with the rest of the pack. “They’ve found! They’re away!” said Matthew; and as he spoke a yell burst from the valley, and in an instant the whole pack were off at full speed. Rather more intent that moment upon showing off my horsemanship than anything else, I dashed spurs into Badger’s sides, and turned him towards a rasping ditch before me; over we went, hurling down behind us a rotten bank of clay and small stones, showing how little safety there had been in topping instead of clearing it at a bound. Before I was well-seated again the captain was beside me. “Now for it, then,” said I; and away we went. What might be the nature of his feelings I cannot pretend to state, but my own were a strange mélange of wild, boyish enthusiasm, revenge, and recklessness. For my own neck I cared little,—nothing; and as I led the way by half a length, I muttered to myself, “Let him follow me fairly this day, and I ask no more.”

The dogs had got somewhat the start of us; and as they were in full cry, and going fast, we were a little behind. A thought therefore struck me that, by appearing to take a short cut upon the hounds, I should come down upon the river where its breadth was greatest, and thus, at one coup, might try my friend’s mettle and his horse’s performance at the same time. On we went, our speed increasing, till the roar of the river we were now approaching was plainly audible. I looked half around, and now perceived the captain was standing in his stirrups, as if to obtain a view of what was before him; otherwise his countenance was calm and unmoved, and not a muscle betrayed that he was not cantering on a parade. I fixed myself firmly in my seat, shook my horse a little together, and with a shout whose import every Galway hunter well knows rushed him at the river. I saw the water dashing among the large stones; I heard it splash; I felt a bound like the ricochet of a shot; and we were over, but so narrowly that the bank had yielded beneath his hind legs, and it needed a bold effort of the noble animal to regain his footing. Scarcely was he once more firm, when Hammersley flew by me, taking the lead, and sitting quietly in his saddle, as if racing. I know of little in my after-life like the agony of that moment; for although I was far, very far, from wishing real ill to him, yet I would gladly have broken my leg or my arm if he could not have been able to follow me. And now, there he was, actually a length and a half in advance! and worse than all, Miss Dashwood must have witnessed the whole, and doubtless his leap over the river was better and bolder than mine. One consolation yet remained, and while I whispered it to myself I felt comforted again. “His is an English mare. They understand these leaps; but what can he make of a Galway wall?” The question was soon to be solved. Before us, about three fields, were the hounds still in full cry; a large stone-wall lay between, and to it we both directed our course together. “Ha!” thought I, “he is floored at last,” as I perceived that the captain held his course rather more in hand, and suffered me to lead. “Now, then, for it!” So saying, I rode at the largest part I could find, well knowing that Badger’s powers were here in their element. One spring, one plunge, and away we were, galloping along at the other side. Not so the captain; his horse had refused the fence, and he was now taking a circuit of the field for another trial of it.

“Pounded, by Jove!” said I, as I turned round in my saddle to observe him. Once more she came at it, and once more balked, rearing up, at the same time, almost so as to fall backward.

My triumph was complete; and I again was about to follow the hounds, when, throwing a look back, I saw Hammersley clearing the wall in a most splendid manner, and taking a stretch of at least thirteen feet beyond it. Once more he was on my flanks, and the contest renewed. Whatever might be the sentiments of the riders (mine I confess to), between the horses it now became a tremendous struggle. The English mare, though evidently superior in stride and strength, was slightly overweighted, and had not, besides, that cat-like activity an Irish horse possesses; so that the advantages and disadvantages on either side were about equalized. For about half an hour now the pace was awful. We rode side by side, taking our leaps at exactly the same instant, and not four feet apart. The hounds were still considerably in advance, and were heading towards the Shannon, when suddenly the fox doubled, took the hillside, and made for Dangan. “Now, then, comes the trial of strength,” I said, half aloud, as I threw my eye up a steep and rugged mountain, covered with wild furze and tall heath, around the crest of which ran, in a zigzag direction, a broken and dilapidated wall, once the enclosure of a deer park. This wall, which varied from four to six feet in height, was of solid masonry, and would, in the most favorable ground, have been a bold leap. Here, at the summit of a mountain, with not a yard of footing, it was absolutely desperation.

By the time that we reached the foot of the hill, the fox, followed closely by the hounds, had passed through a breach in the wall; while Matthew Blake, with the huntsmen and whipper-in, was riding along in search of a gap to lead the horses through. Before I put spurs to Badger to face the hill, I turned one look towards Hammersley. There was a slight curl, half-smile, half-sneer, upon his lip that actually maddened me, and had a precipice yawned beneath my feet, I should have dashed at it after that. The ascent was so steep that I was obliged to take the hill in a slanting direction; and even thus, the loose footing rendered it dangerous in the extreme.

At length I reached the crest, where the wall, more than five feet in height, stood frowning above and seeming to defy me. I turned my horse full round, so that his very chest almost touched the stones, and with a bold cut of the whip and a loud halloo, the gallant animal rose, as if rearing, pawed for an instant to regain his balance, and then, with a frightful struggle, fell backwards, and rolled from top to bottom of the hill, carrying me along with him; the last object that crossed my sight, as I lay bruised and motionless, being the captain as he took the wall in a flying leap, and disappeared at the other side. After a few scrambling efforts to rise, Badger regained his legs and stood beside me; but such was the shock and concussion of my fall that all the objects around seemed wavering and floating before me, while showers of bright sparks fell in myriads before my eyes. I tried to rise, but fell back helpless. Cold perspiration broke over my forehead, and I fainted. From that moment I can remember nothing, till I felt myself galloping along at full speed upon a level table-land, with the hounds about three fields in advance, Hammersley riding foremost, and taking all his leaps coolly as ever. As I swayed to either side upon my saddle, from weakness, I was lost to all thought or recollection, save a flickering memory of some plan of vengeance, which still urged me forward. The chase had now lasted above an hour, and both hounds and horses began to feel the pace at which they were going. As for me, I rode mechanically; I neither knew nor cared for the dangers before me. My eye rested on but one object; my whole being was concentrated upon one vague and undefined sense of revenge. At this instant the huntsman came alongside of me.

“Are you hurted, Misther Charles? Did you fall? Your cheek is all blood, and your coat is torn in two; and, Mother o’ God! his boot is ground to powder; he does not hear me! Oh, pull up! pull up, for the love of the Virgin! There’s the clover-field and the sunk fence before you, and you’ll be killed on the spot!”

“Where?” cried I, with the cry of a madman. “Where’s the clover-field; where’s the sunk fence? Ha! I see it; I see it now.”