Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 262, July 7, 1827

Author: Various

Release date: February 1, 2006 [eBook #9882]

Most recently updated: December 27, 2020

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/9882

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram and Project Gutenberg

Distributed Proofreaders

| Vol. 10, No. 262.] | SATURDAY, JULY 7, 1827. | [PRICE 2d. |

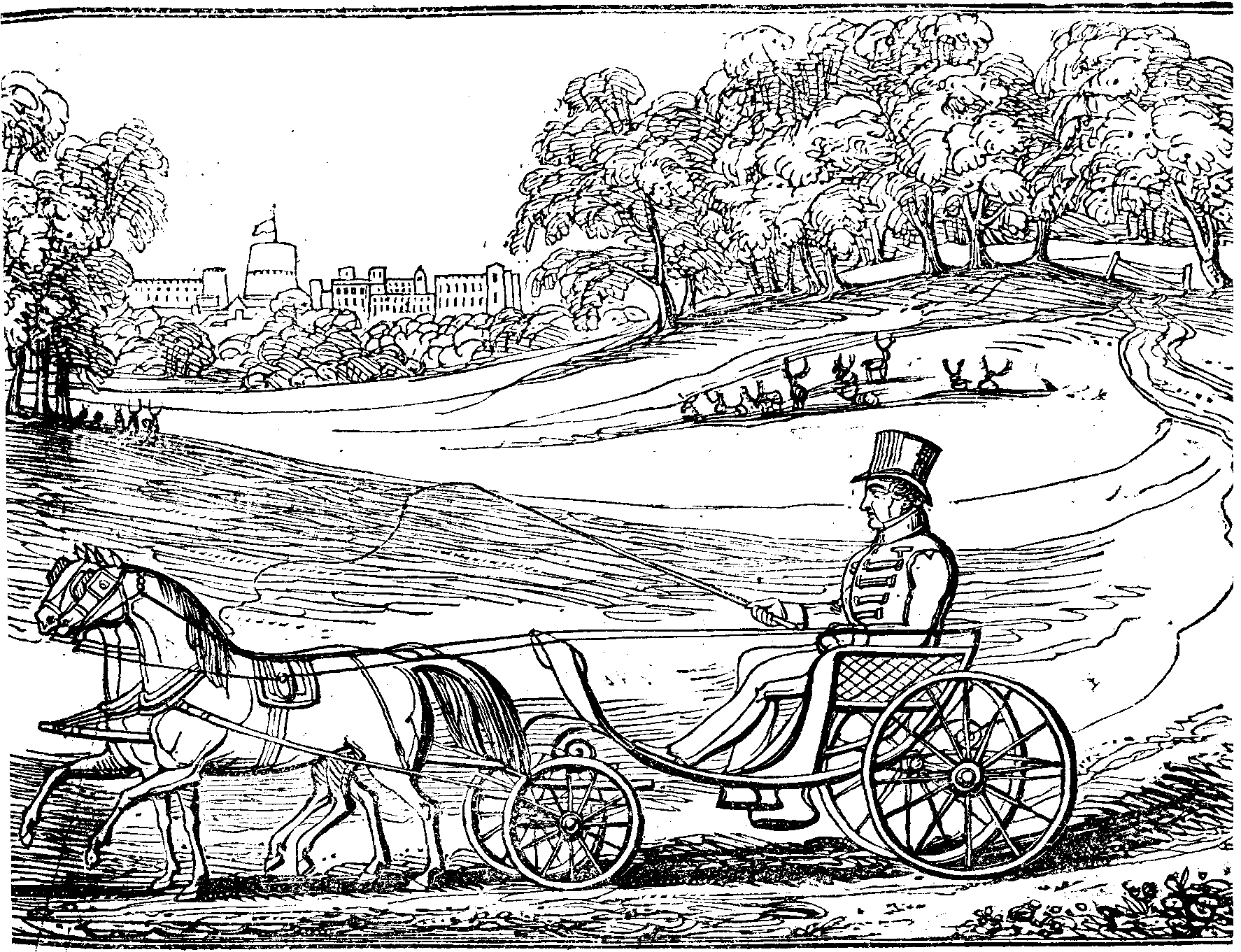

We commence our tenth volume of the MIRROR with an embellishment quite novel in design from the generality of our graphic illustrations, but one which, we flatter ourselves, will excite interest among our friends, especially after so recently, presenting them with a Portrait and Memoir of his Majesty in the Supplement, which last week completed our ninth volume. His Majesty, when residing at his cottage in Windsor Forest, the weather being favourable, seldom allows a day to pass without taking his favourite drive by the Long Walk, and Virginia Water, in his poney phaeton, as represented in the above engraving. Windsor Park being situated on the south side of the town, and 14 miles in circumference, is admirably calculated for the enjoyment of a rural ride. The entrance to the park is by a road called the Long Walk, near three miles in length, through a double plantation of trees on each side, leading to the Ranger's Lodge: on the north east side of the Castle is the Little Park, about four miles in circumference: Queen Elizabeth's Walk herein is much frequented. At the entrance of this park is the Queen's Lodge, a modern erection. This building stands on an easy ascent opposite the upper court, on the south side, and commands a beautiful view of the surrounding country. The gardens are elegant, and have been much enlarged by the addition of the gardens and house of the duke of St. Albans, purchased by his late majesty. The beautiful Cottage Ornée, an engraving of which graces one of our early volumes, is also in the park, and to which place of retirement his present Majesty resorts, and passes much of his time in preference to the bustle and splendour of a royal town life.

Having now given as much description [pg 2] of the engraving as the subject requires, we shall proceed to lay before our readers some further anecdotes connected with the life of his Majesty; for our present purpose, the following interesting article being adapted to our limits, we shall introduce an

Original Letter of his present Majesty, when Prince of Wales, to Alexander Davison, Esq., on the death of Lord Nelson.

I am extremely obliged to you, my dear sir, for your confidential letter, which I received this morning. You may be well assured, that, did it depend upon me, there would not be a wish, a desire of our-ever-to-be-lamented and much-loved friend, as well as adored hero, that I should not consider as a solemn obligation upon his friends and his country to fulfil; it is a duty they owe his memory, and his matchless and unrivalled excellence: such are my sentiments, and I should hope that there is still in this country sufficient honour, virtue, and gratitude to prompt us to ratify and to carry into effect the last dying request of our Nelson, and by that means proving not only to the whole world, but to future ages, that we were worthy of having such a man belonging to us. It must be needless, my dear sir, to discuss over with you in particular the irreparable loss dear Nelson ever must be, not merely to his friends but to his country, especially at the present crisis—and during the present most awful contest, his very name was a host of itself; Nelson and Victory were one and the same to us, and it carried dismay and terror to the hearts of our enemies. But the subject is too painful a one to dwell longer upon; as to myself, all that I can do, either publicly or privately, to testify the reverence, the respect I entertain for his memory as a Hero, and as the greatest public character that ever embellished the page of history, independent of what I can with the greatest truth term, the enthusiastic attachment I felt for him as a friend, I consider it as my duty to fulfil, and therefore, though I may be prevented from taking that ostensible and prominent situation at his funeral which I think my birth and high rank entitled me to claim, still nothing shall prevent me in a private character following his remains to their last resting place; for though the station and the character may be less ostensible, less prominent, yet the feelings of the heart will not therefore be the less poignant, or the less acute.

I am, my dear sir, with the greatest truth,

Ever very sincerely your's,

G. P.1

Brighton, Dec, 18th, 1805.

There is a natural stimulus in man to offer adoration at the shrine of departed genius.—

"There is a tear for all that die."

But, when a transcendant genius is checked in its early age—when its spring-shoots had only began to open—when it had just engaged in a new feature devoted to man, and man to it, we cannot rest

"In silent admiration, mixed with grief."

Too often has splendid genius been suffered to live almost unobserved; and have only been valued as their lives have been lost. Could the divine Milton, or the great Shakspeare, while living, have shared that profound veneration which their after generations have bestowed on their high talents, happier would they have lived, and died more extensively beloved.

True, a Byron has but lately paid a universal debt. His concentrated powers—his breathings for the happiness and liberty of mankind—his splendid intellectual flowers, culled from a mind stored with the choicest exotics, and cultivated with the most refined taste are all still fresh in recollection. As the value of precious stones and metals have become estimated by their scarcity, so will the fame of Byron live.

A mind like Lord Byron's,

"——born, not only to surprise, but cheer

With warmth and lustre all within its sphere,"

was one of Nature's brightest gems, whose splendour (even when uncompared) dazzled and attracted all who passed within its sight.

"So let him stand, through ages yet unborn."

As comparison is a medium through which we are enabled to obtain most accurate judgment, let us use it in the present instance, and compare Lord Byron with the greatest poets that have preceded him, by which means the world of letters will see what they have really lost in Lord Byron. To commence with the great Shakspeare himself, to whom universal admiration continues to be paid. Had Shakspeare been cut off at the same early period as Byron, The Tempest, King Lear, Othello, Macbeth, Julius Caesar, Coriolanus, and several others of an equal character, would never have been written. The high reputation of Dryden would also have been limited—his fame, perhaps, unknown. [pg 3] The Absalom and Achitophel is the earliest of his best productions, which was written about his fiftieth year; his principal production, at the age of Byron, was his Annus Mirabilis; for nearly the whole of his dramatic works were written at the latter part of his life. Pope is the like situated; that which displayed most the power of his mind—which claims for him the greatest praise—his Essay on Man, &c. appeared after his fortieth year. Windsor Forest was published in his twenty-second or twenty-third year, both were the labour of some years; and the immortal Milton, who published some few things before his thirtieth year, sent not his great work, Paradise Lost, to the world until he verged on sixty.

With the poets, and the knowledge of what Byron was, we may ask what he would have been had it pleased the Great Author of all things to suffer the summer of his consummate mental powers to shine upon us? Take the works of any of the abovenamed distinguished individuals previous to their thirty-eighth year, and shall we perceive that flexibility of the English language to the extent that Byron has left behind him? His versatility was, indeed, astonishing and triumphant. His Childe Harold, the Bride of Abydos, the Corsair, and Don Juan, (though somewhat too freely written,) are established proofs of his unequalled energy of mind. His power was unlimited; not only eloquent, but the sublime, grave and gay, were all equally familiar to his muse.

Few words are wanted to show that Byron was not depraved at heart; no man possessed a more ready sympathy, a more generous mind to the distressed, or was a more enthusiastic admirer of noble actions. These feelings all strongly delineated in his character, would never admit, as Sir Walter Scott has observed, "an imperfect moral sense, nor feeling, dead to virtue." Severe as the

"Combined usurpers on the throne of taste"

have been, his character is marked by some of the best principles in many parts of his writings.

"The records there of friendships, held like rocks,

And enmities like sun-touch'd snow resign'd,"

are frequently visible. His glorious attachment to the Grecian cause is a sufficient recompense for previous follies exaggerated and propagated by calumny's poisonous tongue. In a word, "there is scarce a passion or a situation which has escaped his pen; and he might be drawn, like Garrick, between the weeping and the laughing muses."

A. B. C.

O Sink to sleep, my darling boy,

Thy father's dead, thy mother lonely,

Of late thou wert his pride, his joy,

But now thou hast not one to own thee.

The cold wide world before us lies,

But oh! such heartless things live in it,

It makes me weep—then close thine eyes

Tho' it be but for one short minute.

O sink to sleep, my baby dear,

A little while forget thy sorrow,

The wind is cold, the night is drear,

But drearier it will be to-morrow.

For none will help, tho' many see

Our wretchedness—then close thine eyes, love,

Oh, most unbless'd on earth is she

Who on another's aid relies, love.

Thou hear'st me not! thy heart's asleep

Already, and thy lids are closing,

Then lie thee still, and I will weep

Whilst thou, my dearest, art reposing,

And wish that I could slumber free,

And with thee in yon heaven awaken,

O would that it our home might be,

For here we are by all forsaken.

In the twenty-third year of the reign of king Henry III., the salary of the justices of the bench (now called the Common Pleas) was 20l. per annum; in the forty-third year, 40l. In the twenty-seventh year, the chief baron had 40 marks; the other barons, 20 marks; and in the forty, ninth year, 4l. per annum. The justices coram rege (now called the King's Bench) had in the forty-third year of Henry III. 40l. per annum.; the chief of the bench, 100 marks per annum; and next year, another chief of the same court, had 100l.; but the chief of the court coram rege had only 100 marks per annum.

In the reign of Edward I., the salaries of the justices were very uncertain, and, upon the whole, they sunk from what they had been in the reign of Henry III. The chief justice of the bench, in the seventh year of Edward I., had but 40l. per annum, and the other justices there, 40 marks. This continued the proportion in both benches till the twenty-fifth year of Edward III., then the salary of the chief of the King's Bench fell to 50 marks, or 33l. 6s. 8d., while that of the chief of the bench was augmented to 100 marks, which may be considered as an [pg 4] evidence of the increase of business and attendance there. The chief baron had 40l.; the salaries of the other justices and barons were reduced to 20l.

In the reign of Edward II., the number of suitors so increased in the common bench, that whereas there had usually been only three justices there, that prince, at the beginning of his reign, was constrained to increase them to six, who used to sit in two places,—a circumstance not easy to be accounted for. Within three years after they were increased to seven; next year they were reduced to six, at which number they continued.

The salaries of the judges, though they had continued the same from the time of Edward I. to the twenty-fifth year of Edward III., were become very uncertain. In the twenty-eighth year of this king, it appears, that one of the justices of the King's Bench had 80 marks per annum. In the thirty-ninth year of Edward III. the judges had in that court 40l.; the same as the justices of the Common Pleas; but the chief of the King's Bench, 100 marks.

The salaries of the judges in the time of Henry IV. were as follows:—The chief baron, and other barons, had 40 marks per annum; the chief of the King's Bench, and of the Common Pleas, 40l. per annum; the other justices, in either court, 40 marks. But the gains of the practisers were become so great, that they could hardly be tempted to accept a place on the bench with such low salaries; therefore in the eighteenth year of Henry VI. the judges of all the courts at Westminster, together with the king's attorney and sergeants, exhibited a petition to parliament concerning the regular payment of their salaries and perquisites of robes. The king assented to their request, and order was taken for increasing their income, which afterwards became larger, and more fixed; this consisted of a salary and an allowance for robes. In the first year of Edward IV., the chief justice of the King's Bench had 170 marks per annum, 5l. 6s. 6d. for his winter robes, and the same for his Whitsuntide robes. Most of the judges had the honour of knighthood; some of them were knights bannerets; and some had the order of the Bath.

In the first year of Henry VII. the chief justice of the court of King's Bench had the yearly fee of 140 marks granted to him for his better support; he had besides 5l. 6s. 11-1/4 d., and the sixth part of a halfpenny (such is the accuracy of Sir William Dugdale, and the strangeness of the sum,) for his winter robes, and 3l. 6s. 6d. for his robes at Whitsuntide.

In the thirty-seventh year of Henry VIII. a further increase was made to the fees of the judges;—to the chief justice of the King's Bench 30l. per annum; to every other justice of that court 20l. per annum; to every justice of the Common Pleas, 20l. per annum.

There were usually in the court of Common Pleas five judges, sometimes six; and in the reign of Henry VI. there were, it is said, eight judges at one time in that court; but six appear to have been the regular number. In the King's Bench there were sometimes four, sometimes five. They did not sit above three hours a day in court,—from eight in the morning to eleven. The courts were not open in the afternoon; but that time was left unoccupied for suitors to confer with their counsel at home.

F. R. Y.

SIR WALTER SCOTT, the author of Waverley, has become the biographer of Napoleon Bonaparte; and the deepest interest is excited in the literary world to know how the great master of romance and fiction acquits himself in the execution of his task. In the preface to this elaborate history, Sir Walter, with considerable ingenuousness, informs us that "he will be found no enemy to the person of Napoleon. The term of hostility is ended when the battle has been won, and the foe exists no longer." But to our task: we shall attempt an analysis of the volumes before us, and endeavour to gratify our readers with a narrative of incidents that cannot fail interesting every British subject, whose history, in fact, is strongly connected with the important events that belong to the splendid career of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The first and second volumes of Sir Walter's history are taken up with a view of the French Revolution, from whence we shall extract a sketch of the characters of three men of terror, whose names will long remain, we trust, unmatched in history by those of any similar miscreants. These men were the leaders of the revolution, and were called

Danton deserves to be named first, as unrivalled by his colleagues in talent and audacity. He was a man of gigantic size, [pg 5] and possessed a voice of thunder. His countenance was that of an Ogre on the shoulders of a Hercules. He was as fond of the pleasures of vice as of the practice of cruelty; and it was said there were times when he became humanized amidst his debauchery, laughed at the terror which his furious declamations excited, and might be approached with safety, like the Maelstrom at the turn of tide. His profusion was indulged to an extent hazardous to his popularity, for the populace are jealous of a lavish expenditure, as raising their favourites too much above their own degree; and the charge of peculation finds always ready credit with them, when brought against public men.

Robespierre possessed this advantage over Danton, that he did not seem to seek for wealth, either for hoarding or expending, but lived in strict and economical retirement, to justify the name of the Incorruptible, with which he was honoured by his partizans. He appears to have possessed little talent, saving a deep fund of hypocrisy, considerable powers of sophistry, and a cold exaggerated strain of oratory, as foreign to good taste, as the measures he recommended were to ordinary humanity. It seemed wonderful, that even the seething and boiling of the revolutionary cauldron should have sent up from the bottom, and long supported on the surface, a thing so miserably void of claims to public distinction; but Robespierre had to impose on the minds of the vulgar, and he knew how to beguile them, by accommodating his flattery to their passions and scale of understanding, and by acts of cunning and hypocrisy, which weigh more with the multitude than the words of eloquence, or the arguments of wisdom. The people listened as to their Cicero, when he twanged out his apostrophes of Pauvre Peuple, Peuple vertueux! and hastened to execute whatever came recommended by such honied phrases, though devised by the worst of men for the worst and most inhuman of purposes.

Vanity was Robespierre's ruling passion, and though his countenance was the image of his mind, he was vain even of his personal appearance, and never adopted the external habits of a sans culotte. Amongst his fellow Jacobins, he was distinguished by the nicety with which his hair was arranged and powdered; and the neatness of his dress was carefully attended to, so as to counterbalance, if possible, the vulgarity of his person. His apartments, though small, were elegant and vanity had filled them with representations of the occupant. Robespierre's picture at length hung in one place, his miniature in another, his bust occupied a niche, and on the table were disposed a few medallions exhibiting his head in profile. The vanity which all this indicated was of the coldest and most selfish character, being such as considers neglect as insult, and receives homage merely as a tribute; so that, while praise is received without gratitude, it is withheld at the risk of mortal hate. Self-love of this dangerous character is closely allied with envy, and Robespierre was one of the most envious and vindictive men that ever lived. He never was known to pardon any opposition, affront, or even rivalry; and to be marked in his tablets on such an account was a sure, though perhaps not an immediate, sentence of death. Danton was a hero, compared with this cold, calculating, creeping miscreant; for his passions, though exaggerated, had at least some touch of humanity, and his brutal ferocity was supported by brutal courage.—(Continued at page 17.)

The following is described by Alciphron, the hero of the tale, at the termination of a festival, in a tone which strongly reminds us of Rasselas:—

"The sounds of the song and dance had ceased, and I was now left in those luxurious gardens alone. Though so ardent and active a votary of pleasure, I had, by nature, a disposition full of melancholy;—an imagination that presented sad thoughts even in the midst of mirth and happiness, and threw the shadow of the future over the gayest illusions of the present. Melancholy was, indeed, twin-born in my soul with passion; and, not even in the fullest fervour of the latter were they separated. From the first moment that I was conscious of thought and feeling, the same dark thread had run across the web; and images of death and annihilation mingled themselves with the most smiling scenes through which my career of enjoyment led me. My very passion for pleasure but deepened these gloomy fancies. For, shut out, as I was by my creed, from a future life, and having no hope beyond the narrow horizon of this, every minute of delight assumed a mournful preciousness in my eyes, and pleasure, like the flower of the cemetery, grew but more luxuriant from the neighbourhood of death. This very night my triumph, my happiness, had seemed complete. I had been the presiding genius of that voluptuous scene. Both my ambition and my love of pleasure had drunk deep of the cup for which they thirsted. [pg 6] Looked up to by the learned, and loved by the beautiful and the young, I had seen, in every eye that met mine, either the acknowledgment of triumphs already won, or the promise of others, still brighter, that awaited me. Yet, even in the midst of all this, the same dark thoughts had presented themselves; the perishableness of myself and all around me every instant recurred to my mind. Those hands I had prest—those eyes, in which I had seen sparkling a spirit of light and life that should never die—those voices that had talked of eternal love—all, all, I felt, were but a mockery of the moment, and would leave nothing eternal but the silence of their dust!

"Oh, were it not for this sad voice,

Stealing amid our mirth to say,

That all in which we most rejoice,

Ere night may be the earth-worm's prey:

But for this bitter—only this—

Full as the world is brimm'd with bliss,

And capable as feels my soul

Of draining to its depth the whole,

I should turn earth to heaven, and be,

If bliss made gods, a deity!"

I had already seen some of the most celebrated works of nature in different parts of the globe; I had seen Etna and Vesuvius; I had seen the Andes almost at their greatest elevation; Cape Horn, rugged and bleak, buffeted by the southern tempest; and, though last not least, I had seen the long swell of the Pacific; but nothing I had ever beheld or imagined could compare in grandeur with the Falls of Niagara. My first sensation was that of exquisite delight at having before me the greatest wonder of the world. Strange as it may appear, this feeling was immediately succeeded by an irresistible melancholy. Had this not continued, it might perhaps have been attributed to the satiety incident to the complete gratification of "hope long deferred;" but so far from diminishing, the more I gazed, the stronger and deeper the sentiment became. Yet this scene of sadness was strangely mingled with a kind of intoxicating fascination. Whether the phenomenon is peculiar to Niagara I know not, but certain it is, that the spirits are affected and depressed in a singular manner by the magic influence of this stupendous and eternal fall. About five miles above the cataract the river expands to the dimensions of a lake, after which it gradually narrows. The Rapids commence at the upper extremity of Goat Island, which is half a mile in length, and divides the river at the point of precipitation into two unequal parts; the largest is distinguished by the several names of the Horseshoe, Crescent, and British Fall, from its semi-circular form and contiguity to the Canadian shore. The smaller is named the American Fall. A portion of this fall is divided by a rock from Goat Island, and though here insignificant in appearance, would rank high among European cascades....

The current runs about six miles an hour; but supposing it to be only five miles, the quantity which passes the falls in an hour is more than eighty-five millions of tuns avoirdupois; if we suppose it to be six, it will be more than one hundred and two millions; and in a day would exceed two thousand four hundred millions of tuns....

The next morning, with renewed delight, I beheld from my window—I may say, indeed, from my bed—the stupendous vision. The beams of the rising sun shed over it a variety of tints; a cloud of spray was ascending from the crescent; and as I viewed it from above, it appeared like the steam rising from the boiler of some monstrous engine....

This evening I went down with one of our party to view the cataract by moonlight. I took my favourite seat on the projecting rock, at a little distance from the brink of the fall, and gazed till every sense seemed absorbed in contemplation. Although the shades of night increased the sublimity of the prospect and "deepened the murmur of the falling floods," the moon in placid beauty shed her soft influence upon the mind, and mitigated the horrors of the scene. The thunders which bellowed from the abyss, and the loveliness of the falling element, which glittered like molten silver in the moonlight, seemed to complete in absolute perfection the rare union of the beautiful with the sublime.

While reflecting upon the inadequacy of language to express the feelings I experienced, or to describe the wonders which I surveyed, an American gentleman, to my great amusement, tapped me on the shoulder, and "guessed" that it was "pretty droll!" It was difficult to avoid laughing in his face; yet I could not help envying him his vocabulary, which had so eloquently released me from my dilemma....

Though earnestly dissuaded from the undertaking, I had determined to employ the first fine morning in visiting the cavern beneath the fall. The guide recommended my companion and myself to set out as early as six o'clock, that we might have the advantage of the morning sun upon the waters. We came to the guide's [pg 7] house at the appointed hour, and disencumbered ourselves of such garments as we did not wish to have wetted; descending the circular ladder, we followed the course of the path running along the top of the débris of the precipice, which I have already described. Having pursued this track for about eighty yards, in the course of which we were completely drenched, we found ourselves close to the cataract. Although enveloped in a cloud of spray, we could distinguish without difficulty the direction of our path, and the nature of the cavern we were about to enter. Our guide warned us of the difficulty in respiration which we should encounter from the spray, and recommended us to look with exclusive attention to the security of our footing. Thus warned, we pushed forward, blown about and buffeted by the wind, stunned by the noise, and blinded by the spray. Each successive gust penetrated us to the very bones with cold. Determined to proceed, we toiled and struggled on, and having followed the footsteps of the guide as far as was possible consistently with safety, we sat down, and having collected our senses by degrees, the wonders of the cavern slowly developed themselves. It is impossible to describe the strange unnatural light reflected through its crystal wall, the roar of the waters, and the blasts of the hurried hurricane which perpetually rages in its recesses. We endured its fury a sufficient time to form a notion of the shape and dimensions of this dreadful place. The cavern was tolerably light, though the sun was unfortunately enveloped in clouds. His disc was invisible, but we could clearly distinguish his situation through the watery barrier. The fall of the cataract is nearly perpendicular. The bank over which it is precipitated is of concave form, owing to its upper stratum being composed of lime-stone, and its base of soft slate-stone, which has been eaten away by the constant attrition of the recoiling waters. The cavern is about one hundred and twenty feet in height, fifty in breadth, and three hundred in length. The entrance was completely invisible. By screaming in our ears, the guide contrived to explain to us that there was one more point which we might have reached had the wind been in any other direction. Unluckily it blew full upon the sheet of the cataract, and drove it in so as to dash upon the rock over which we must have passed. A few yards beyond this, the precipice becomes perpendicular, and, blending with the water, forms the extremity of the cave. After a stay of nearly ten minutes in this most horrible purgatory, we gladly left it to its loathsome inhabitants the eel and the water-snake, who crawl about its recesses in considerable numbers,—and returned to the inn—De Roos's Travels in the United States, &c.

The first sight, however, which it fell to my lot to witness at Brussels in this second and short visit, was neither gay nor handsome, nor dear in any sense, but the very reverse; it being that of the punishment of the guillotine inflicted on a wretched murderer, named John Baptist Michel. 2 Hearing, at the moment of my arrival, that this tragical scene was on the point of being acted in the great square of the market-place, I determined for once to make a sacrifice of my feelings to the desire of being present at a spectacle, with the nature of which the recollections of revolutionary horrors are so intimately associated. Accordingly, following to the spot a guard of soldiers appointed to assist at the execution, I disengaged myself as soon as possible from the pressure of the immense crowd already assembled, and obtained a seat at the window of a house immediately opposite the Hotel-de-Ville, in front of the principal entrance to which the guillotine had been erected. At the hour of twelve at noon precisely, the malefactor, tall, athletic, and young, having his hands tied behind his back, and being stripped to the waist, was brought to the square in a cart, under an escort of gen-d'armes, attended by an elderly and respectable ecclesiastic; who, having been previously occupied in administering the consolations of religion to the condemned person in prison, now appeared incessantly employed in tranquillizing him on his way to the scaffold. Arrived near the fatal machine, the unhappy [pg 8] man stepped out of the vehicle, knelt at the feet of his confessor, received the priestly benediction, kissed some individuals who accompanied him, and was hurried by the officers of justice up the steps of the cube-form structure of wood, painted of a blood-red, on which stood the dreadful apparatus of death. To reach the top of the platform, to be fast bound to a board, to be placed horizontally under the axe, and deprived of life by its unerring blow, was, in the case of this miserable offender, the work literally of a moment. It was indeed an awfully sudden transit from time to eternity. He could only cry out, "Adieu, mes amis," and he was gone. The severed head, passing through a red-coloured bag fixed under, fell to the ground—the blood spouted forth from the neck like water from a fountain—the body, lifted up without delay, was flung down through a trap-door in the platform. Never did capital punishment more quickly take effect on a human being; and whilst the executioner was coolly taking out the axe from the groove of the machine, and placing it, covered as it was with gore, in a box, the remains of the culprit, deposited in a shell, were hoisted into a wagon, and conveyed to the prison. In twenty minutes all was over, and the Grande Place nearly cleared of its thousands, on whom the dreadful scene seemed to have made, as usual, the slightest possible impression—Stevenson's Tour in France, Switzerland, &c.

Of all the miseries of human life, and God knows they are manifold enough, there are few more utterly heart-sickening and overwhelming than those endured by the unlucky Heir Presumptive; when, after having submitted to the whims and caprices of some rich relation, and endured a state of worse than Egyptian bondage, for a long series of years, he finds himself cut off with a shilling, or a mourning ring; and the El Dorado of his tedious term of probation and expectancy devoted to the endowment of methodist chapels and Sunday schools; or bequeathed to some six months' friend (usually a female housekeeper, or spiritual adviser) who, entering the vineyard at the eleventh hour, (the precise moment at which his patience and humility become exhausted,) carries off the golden prize, and adds another melancholy confirmation, to those already upon record, of the fallacy of all human anticipations. It matters little what may have been the motives of his conduct; whether duty, affection, or that more powerful incentive self-interest; how long or how devotedly he may have humoured the foibles or eccentricities of his relative; or what sacrifices he may have made to enable him to comply with his unreasonable caprices: the result is almost invariably the same. The last year of the Heir Presumptive's purgatory, nay, perhaps even the last month, or the last week, is often the drop to the full cup of his endurance. His patience, however it may have been propped by self-interest, or feelings of a more refined description, usually breaks down before the allotted term has expired; and the whole fabric it has cost him such infinite labour to erect, falls to the ground along with it. It is well if his personal exertions, and the annoyances to which he has subjected himself during the best period of his existence, form the whole of his sacrifices. But, alas! it too often happens that, encouraged by the probability of succeeding in a few years to an independent property, and ambitious, moreover, of making such an appearance in society as will afford the old gentleman or lady no excuse for being ashamed of their connexion with him, he launches into expenses he would never otherwise have dreamed of incurring, and contracts debts without regard to his positive means of liquidating them, on the strength of a contingency which, if he could but be taught to believe it, is of all earthly anticipations the most remote and uncertain. A passion for unnecessary expense is, under different circumstances, frequently repressed by an inability to procure credit; but it is the curse and bane of Mr. Omnium's nephew, and Miss Saveall's niece, that so far from any obstacle being opposed to their prodigality, almost unlimited indulgence is offered, nay, actually pressed upon them, by the trades-people of their wealthy relations; who take especial care that their charges shall be of a nature to repay them for any complaisance or long suffering, as it regards the term of credit, they may be called upon to display. But independently of the additional expense into which the Heir Presumptive is often seduced by the operation of these temptations, and his anxiety to live in a style in some degree accordant with his expectations, what is he not called upon to endure from the caprices, old-fashioned notions, eccentricities, avarice, and obstinacy, of the old tyrant to whom he thus consents to sell himself, and it may be his family, body and soul, for an indefinite number of years.—National Tales.

The sultry noontide of July

Now bids us seek the forest's shade;

Or for the crystal streamlet sigh.

That flows in some sequestered glade.

B. BARTON.

Summer! glowing summer! This is the month of heat and sunshine, of clear, fervid skies, dusty roads, and shrinking streams; when doors and windows are thrown open, a cool gale is the most welcome of all visiters, and every drop of rain "is worth its weight in gold." Such is July commonly—such it was in 1825, and such, in a scarcely less degree, in 1826; yet it is sometimes, on the contrary, a very showery month, putting the hay-maker to the extremity of his patience, and the farmer upon anxious thoughts for his ripening corn; generally speaking, however, it is the heart of our summer. The landscape presents an air of warmth, dryness, and maturity; the eye roams over brown pastures, corn fields "already white to harvest," dark lines of intersecting hedge-rows, and darker trees, lifting their heavy heads above them. The foliage at this period is rich, full, and vigorous; there is a fine haze cast over distant woods and bosky slopes, and every lofty and majestic tree is filled with a soft shadowy twilight, which adds infinitely to its beauty—a circumstance that has never been sufficiently noticed by either poet or painter. Willows are now beautiful objects in the landscape; they are like rich masses of arborescent silver, especially if stirred by the breeze, their light and fluent forms contrasting finely with the still and sombre aspect of the other trees.

Now is the general season of haymaking. Bands of mowers, in their light trousers and broad straw hats, are astir long before the fiery eye of the sun glances above the horizon, that they may toil in the freshness of the morning, and stretch themselves at noon in luxurious ease by trickling waters, and beneath the shade of trees. Till then, with regular strokes and a sweeping sound, the sweet and flowery grass falls before them, revealing at almost every step, nests of young birds, mice in their cozy domes, and the mossy cells of the humble bee streaming with liquid honey; anon, troops of haymakers are abroad, tossing the green swaths wide to the sun. It is one of Nature's festivities, endeared by a thousand pleasant memories and habits of the olden days, and not a soul can resist it.

There is a sound of tinkling teams and of wagons rolling along lanes and fields the whole country over, aye, even at midnight, till at length the fragrant ricks rise in the farmyard, and the pale smooth-shaven fields are left in solitary beauty.

They who know little about it may deem the strong penchant of our poets, and of ourselves, for rural pleasures, mere romance and poetic illusion; but if poetic beauty alone were concerned, we [pg 10] must still admire harvest-time in the country. The whole land is then an Arcadia, full of simple, healthful, and rejoicing spirits. Overgrown towns and manufactories may have changed for the worse, the spirit and feelings of our population; in them, "evil communications may have corrupted good manners;" but in the country at large, there never was a more simple-minded, healthful-hearted, and happy race of people than our present British peasantry. They have cast off, it is true, many of their ancestors' games and merrymakings, but they have in no degree lost their soul of mirth and happiness. This is never more conspicuous than in harvest-time.

With the exception of a casual song of the lark in a fresh morning, of the blackbird and thrush at sunset, or the monotonous wail of the yellow-hammer, the silence of birds is now complete; even the lesser reed-sparrow, which may very properly be called the English mock-bird, and which kept up a perpetual clatter with the notes of the sparrow, the swallow, the white-throat, &c. in every hedge-bottom, day and night, has ceased.

Boys will now be seen in the evening twilight with match, gunpowder, &c., and green boughs for self-defence, busy in storming the paper-built castles of wasps, the larvae of which furnish anglers with store of excellent baits. Spring-flowers have given place to a very different class. Climbing plants mantle and festoon every hedge. The wild hop, the brione, the clematis or traveller's joy, the large white convolvulus, whose bold yet delicate flowers will display themselves to a very late period of the year—vetches, and white and yellow ladies-bed-straw—invest almost every bush with their varied beauty, and breathe on the passer-by their faint summer sweetness. The campanula rotundifolia, the hare-bell of poets, and the blue-bell of botanists, arrests the eye on every dry bank, rock, and wayside, with its beautiful cerulean bells. There too we behold wild scabiouses, mallows, the woody nightshade, wood-betony, and centaury; the red and white-striped convolvulus also throws its flowers under your feet; corn fields glow with whole armies of scarlet poppies, cockle, and the rich azure plumes of viper's-bugloss; even thistles, the curse of Cain, diffuse a glow of beauty over wastes and barren places. Some species, particularly the musk thistles, are really noble plants, wearing their formidable arms, their silken vest, and their gorgeous crimson tufts of fragrant flowers issuing from a coronal of interwoven down and spines, with a grace which casts far into the shade many a favourite of the garden.

But whoever would taste all the sweetness of July, let him go, in pleasant company, if possible, into heaths and woods; it is there, in her uncultured haunts, that summer now holds her court. The stern castle, the lowly convent, the deer and the forester have vanished thence many ages; yet nature still casts round the forest-lodge, the gnarled oak and lovely mere, the same charms as ever. The most hot and sandy tracts, which we might naturally imagine would now be parched up, are in full glory. The erica tetralix, or bell-heath, the most beautiful of our indigenous species, is now in bloom, and has converted the brown bosom of the waste into one wide sea of crimson; the air is charged with its honied odour. The dry, elastic turf glows, not only with its flowers, but with those of the wild thyme, the clear blue milkwort, the yellow asphodel, and that curious plant the sundew, with its drops of inexhaustible liquor sparkling in the fiercest sun like diamonds. There wave the cotton-rush, the tall fox-glove, and the taller golden mullein. There creep the various species of heath-berries, cranberries, bilberries, &c., furnishing the poor with a source of profit, and the rich of luxury. What a pleasure it is to throw ourselves down beneath the verdant screen of the beautiful fern, or the shade of a venerable oak, in such a scene, and listen to the summer sounds of bees, grasshoppers, and ten thousand other insects, mingled with the more remote and solitary cries of the pewit and the curlew! Then, to think of the coach-horse, urged on his sultry stage, or the plough-boy and his teem, plunging in the depths of a burning fallow, or of our ancestors, in times of national famine, plucking up the wild fern-roots for bread, and what an enhancement of our own luxurious ease! 3

But woods, the depths of woods, are the most delicious retreats during the fiery noons of July. The great azure campanulas, or Canterbury bells, are there in bloom, and, in chalk or limestone districts, there are also now to be found those curiosities, the bee and fly orchises. The soul of John Evelyn well might envy us a wood lounge at this period.

Time's Telescope.

The sun is in apogee, or at his greatest distance from the earth on the 2nd, in 10 deg. Cancer; he enters Leo on the 23rd, at 5h. 13m. afternoon; he is in conjunction with the planet Saturn on the 2nd at 11h. 30m. morning, in 9 deg. Cancer, and with Mars on the 12th at 1h. 45m. afternoon, being advanced 10 deg. further in the eliptic.

Venus and Saturn are also in conjunction on the 26th at 3h. afternoon, in 13 deg. Cancer.

Mercury will again be visible for a short time about the middle of the month a little after the sun has set, arriving on the 16th at his greatest eastern elongation, or apparent distance from the centre of the system, as seen from the earth in 20 deg. Leo; and in aphelio, or that point of his orbit most distant from the sun, on the 22nd; he becomes stationary on the 29th.

There is only one visible eclipse of Jupiter's first satellite this month—on the 5th, at 10h. 21m. evening.

The Georgium Sidus, or Herschel, comes to an opposition with the sun on the 19th, at 6h. 15m. evening; he is then nearest the earth, and consequently in the most favourable position for observation; he began retrograding on the 1st of May in 28 deg. 12m. of Capricornus; he rises on the 1st, at 9h. 11m. evening, culminating at 1h. 16m., and setting at 5h. 21m. morning, pursuing the course of the sun on the 17th of January; he moves only 13m. of a deg. in the course of the month, rising 2h. earlier on the 31st.

This planet, called also Uranus, was discovered by Herschel on the 13th of March, 1781. It is the most distant orb in our system yet known. From certain inequalities on the motion of Jupiter and Saturn, the existence of a planet of considerable size beyond the orbit of either had been before suspected; its apparent magnitude, as seen from the earth, is about 3-1/2 sec., or of the size of a star of the sixth magnitude, and as from its distance from the sun, it shines but with a pale light, it cannot often be distinguished with the naked eye. Its diameter is about 4-1/2 times that of the earth, and completes its revolution in something less than 83-1/2 years. The want of light in this planet, on account of its great distance from the sun, is supplied by six moons, which revolve round their primary in different periods. There is a remarkable peculiarity attached to their orbits, which are nearly perpendicular to the plane of the ecliptic, and they revolve in them in a direction contrary to the order of the signs.

"Moore," in an old almanack, speaking on the difference of light and heat enjoyed by the inhabitants of Saturn, and the earth, says,—

"From hence how large, how strong the sun's bright ball,

But seen from thence, how languid and how small,

When the keen north with all its fury blows,

Congeals the floods and forms the fleecy snows:

'Tis heat intense, to what can there be known,

Warmer our poles than in its burning (!) zone;

One moment's cold like their's would pierce the bone,

Freeze the heart's blood, and turn us all to stone."

Were Saturn thus situated, what would the inhabitants of Herschel feel, whose distance is still further?—pursuing this train of reasoning, the heat in the planet Mercury would be seven times greater than on our globe, and were the earth in the same position, all the water on its surface would boil, and soon be turned into vapour, but as the degree of sensible heat in any planet does not depend altogether on its nearness to the sun, the temperature of these planets may be as mild as that of the most genial climate of our globe.

The theory of the sun being a body of fire having been long since exploded, and heat being found to be generated by the union of the sun's rays with the atmosphere of the earth, so the caloric contained in the atmosphere on the surfaces of the planets may be distributed in different quantities, according to the situation they occupy with regard to the sun, and which is put into action by the influence of the solar rays, so as to produce that degree of sensible heat requisite for each respective planet. We have only to suppose that a small quantity of caloric exists in Mercury, and a greater quantity in Herschel, which is fifty times farther from the sun than the other, and there is no reason to believe that those planets nearest the sun suffer under the action of excessive heat, or that the more distant are exposed to the rigours of insufferable cold, which, in either case, might render them unfit for the abodes of intellectual beings.

PASCHE.

My master, at first sight of me, expressed great admiration. He had given his architect of garments orders to make him a blue coat in his best style; in consequence of which I was ushered into the world. The gentleman who introduced me into company was at the time in very high spirits, being engaged in a new literary undertaking, of the success of which he indulged very sanguine hopes. On this occasion we, that is, to use similar language to Cardinal Wolsey, in a well-known instance, I and my master paid a great number of visits to his particular friends, and others whom he thought likely to encourage and promote his project The reception we generally met with was highly satisfactory; smiles and promises of support were bestowed in abundance upon us. I use the plural number, with justice, as it will appear in the sequel, although my master scarcely ever dreamt that I had anything to do with it. As I had, however, the special privilege of being behind his back, I had the advantage which that situation peculiarly confers, of arriving at a knowledge of the truth. He never dreamt that the expressions, "How well you are looking,"—"I am glad to see you," &c. so common in his ears, would scarcely ever have been used had it not been for my influence. To be sure I have overheard him say, as we have been walking along, "There goes an old acquaintance of mine; but, bless me, how altered he is! he looks poor and meanly dressed, but I'm determined I'll speak to him, for fear he should think me so shabby as to shy him." Thus giving an instance in himself, certainly, of respect for the man and not the coat. My short history goes rather to prove that the reverse is almost every day's experience. Matters went on pretty well with us until my master was seized with a severe fit of illness, in consequence of which his literary scheme was completely defeated, and his condition in life materially injured; of course, the glad tones of encouragement which I had been accustomed to hear were changed into expressions of condolence, and sometimes assurances of unabated friendship; but then it must be remembered that I, the handsomest blue coat, was still in good condition, and it will perhaps appear, that if I were not my master's warmest friend, I was, at all events, the only one that stuck to him to the last. Eternal respect to both of us continued much the same for some time longer, but by degrees we both, at the same time, observed, that an alteration began to take place. My master attributed this to his altered fortunes, and I placed it to the score of my decayed appearance—the threadbare cloth and tarnished button came in, I was sure, for their full share of neglect, and he at last fell into the same opinion. To describe all the variety of treatment that we experienced would be a tedious and unpleasant task,—but I was the more convinced that I had at least as much to do with it as my master, from observing that all the gradations in manner, from coolness to shyness, and from shyness to neglect, kept pace, remarkably, with the changes in my appearance. My master was, at length, the only individual who paid any respect or attention to me, after most of his old acquaintances had ceased to notice him. I have heard him exclaim, "Oh, that mankind would treat me with as much constancy as my old true blue! Thou hast faithfully served me throughout the vicissitudes of fortune, and art faithful still, now both of us are left to wither in adversity."

I could make a long story of it, were I to detail all my adventures; they may, however, be easily imagined from what has been stated, and from which it is evident, that in too many instances, the world pays more respect to the coat, than to the man, and therefore that a man would often derive more consequence and benefit if he had the advantage of having for his patron—a tailor instead of a man of rank. J. B.

It was a cold stormy night in December, and the green logs as they blazed and crackled on the Cotter's hearth, were rendered more delightful, more truly comfortable, by the contrast with the icy showers of snow and sleet which swept against the frail casement, making all without cheerless and miserable.

The Cotter was a handsome, intelligent old man, and afforded me much information upon glebes, and flocks, and rural economy; while his spouse, a venerable matron, was humming to herself some long since forgotten ballad; and industriously twisting and twirling about her long knitting needles, that promised soon to produce a pair of formidable winter hose. Their son, a stout, healthy young [pg 13] peasant of three-and-twenty, was sitting in the spacious chimney corner, sharing his frugal supper of bread and cheese with a large, shaggy sheep dog, who sat on his haunches wistfully watching every mouthful, and snap, snap, snapping, and dextrously catching every morsel that was cast to him.

We were all suddenly startled, however, by his loud bark; when, jumping up, he rushed, or rather flew towards the door.

"Whew! whew!" whistled the youth—"Whoy—what the dickens ails thee, Rover?" said he, rising and following him to the door to learn the cause of his alarm. "What! be they gone again, ey?" for the dog was silent. "What do thee sniffle at, boy? On'y look at 'un feyther; how the beast whines and waggles his stump o' tail!—It's some 'un he knows for sartain. I'd lay a wager it wur Bill Miles com'd about the harrow, feyther."

"Did thee hear any knock, lad?" said the father.

"Noa!" replied the youth; "but mayhap Bill peep'd thro' the hoal in the shutter, and is a bit dash'd like at seeing a gentleman here. Bill! is't thee, Master Miles?" continued he, bawling. "Lord! the wind whistles so a' can't hear me. Shall I unlatch the door, feyther?"

"Ay, lad, do, an thou wilt," replied the old man; "Rover's wiser nor we be—a dog 'll scent a friend, when a man would'nt know un."

Rover still continued his low importunate whine, and began to scratch against the door. The lad threw it open—the dog brushed past him in an instant, and his quick, short, continuous yelping, expressed his immoderate joy and recognition.

"Hollo! where be'st thee, Bill?" said the young peasant, stepping over the threshold. "Come, none of thee tricks upon travellers, Master Bill; I zee thee beside the rick yon!" and quitting the door for half a minute, he again hastily entered the cot. The rich colour of robust health had fled from his cheeks—his lips quivered—and he looked like one bereft of his senses, or under the influence of some frightful apparition.

The dame rose up—her work fell from trembling hands—

"What's the matter?" said she.

"What's frighted thee, lad?" asked the old man, rising.

"Oh! feyther!—oh! mother!"—exclaimed he, drawing them hastily on one side and whispering something in a low, and almost inaudible voice.

The old woman raised her hands in supplication and tottered to her chair while the Cotter, bursting out into a paroxysm of violent rage, clutched his son's arm, and exclaimed in a loud voice:

"Make fast the door, boy, an thou'lt not have my curse on thee!—I tell 'ee, she shan't come hither!—No—never—never;—there's poison in her breath—a' will spurn her from me!—A pest on her!—What; wilt not do my bidding?"

"O! feyther, feyther!" cried the young peasant, whose heart seemed overcharged with grief, "It be a cold, raw night—ye wou'dna kick a cur from the door to perish in the storm! Doant 'ee be hot and hasty, feyther, thou art not uncharitable—On me knees!"—

"Psha!" exclaimed the enraged father, only exasperated by his remonstrances. "Whoy talk 'ee to me, son—I am deaf—deaf!—Mine own hand shall bar the door agen her!"—adding with bitterness—"let her die!"—and stepping past his prostrate son, was about to execute his purpose—when, a young girl, whose once gay and flimsy raiment was drenched and stained, and torn by the violence of the storm, appeared at the door. The old man recoiled with a shudder—she was as pale as death—and her trembling limbs seemed scarcely able to support her—a profusion of light brown hair hung dishevelled and in disorder about her neck and shoulders, and added to her forlorn appearance. She stretched forth her arms and pronounced the name of "Father!" but further utterance was prevented by the convulsive sobs that heaved her bosom.

"Mary—woman!" cried the old man, trembling—"Call me not feyther—thou art none of mine—thou hast no feyther now—nor I a daughter—thou art a serpent that hath stung the bosom that cherished thee! Go to the fawning villain—the black-hearted sycophant that dragged thee from our arms—from our happy home to misery and pollution—go, and bless him for breaking thy poor old feyther's heart!"

Overcome by these heart-rending reproaches, the distressed girl fainted; but the strong arm of the young Cotter supported her—for her tender-hearted youth, moved by his fallen sister's sorrows, had ventured again to intercede.

"Hah! touch not her defiled and loathsome body," cried the old man—"thrust her from the door, and let her find a grave where she may. Boy! wilt thou dare disobey me?" and he raised his clenched hand, while anger flashed from his eye.

"Strike! feyther—strike me!" said the poor lad, bursting into tears—"fell me to the 'arth! Kill me, an thou [pg 14] wilt—I care not—I will never turn my heart agen poor Mary!—Bean't she my sister? Did thee not teach me to love her?—Poor lass!—she do want it all now, feyther—for she be downcast and broken-hearted!—Nay, thee art kind and good, feyther—know thee art—I zee thine eyes be full o' tears—and thee—thee woant cast her away from thee, I know thee woant. Mother, speak to 'un; speak to sister Mary too—it be our own Mary! Doant 'ee kill her wi' unkindness!"

The old man, moved by his affectionate entreaties, no longer offered any opposition to his son's wishes, but hiding his face in his hands, he fled from the affecting scene to an adjoining room.

Her venerable mother having recovered from the shock of her lost daughter's sudden appearance, now rose to the assistance of the unfortunate, and by the aid of restoratives brought poor Mary to the full sense of her wretchedness. She was speedily conveyed to the same humble pallet, to which, in the days of her innocence and peace, she had always retired so light-hearted and joyously, but where she now found a lasting sleep—an eternal repose!—Yes, poor Mary died!—and having won the forgiveness and blessing of her offended parents, death was welcome to her.—Absurdities: in Prose and Verse.

"Here waving groves a checkered scene display,

And part admit, and part exclude the day."

POPE.

Of the origin of these enchanting gardens, Mr. Aubrey, in his "Antiquities of Surrey," gives us the following account;—"At Vauxhall, Sir Samuel Morland built a fine room, anno 1667, the inside all of looking-glass, and fountains very pleasant to behold, which is much visited by strangers: it stands in the middle of the garden, covered with Cornish slate, on the point of which he placed a punchinello, very well carved, which held a dial, but the winds have demolished it." And Sir John Hawkins, in his "History of Music," has the following account of it:—"The house seems to have been rebuilt since the time that Sir Samuel Morland dwelt in it. About the year 1730, Mr. Jonathan Tyers became the occupier of it, and, there being a large garden belonging to it, planted with a great number of stately trees, and laid out in shady walks, it obtained the name of Spring Gardens; and the house being converted into a tavern, or place of entertainment, was much frequented by the votaries of pleasure. Mr. Tyers opened it with an advertisement of a Ridotto al Fresco, a term which the people of this country had till that time been strangers to. These entertainments were repeated in the course of the summer, and numbers resorted to partake of them. This encouraged the proprietor to make his garden a place of musical entertainment, for every evening during the summer season. To this end he was at great expense in decorating the gardens with paintings; he engaged a band of excellent musicians; he issued silver tickets at one guinea each for admission, and receiving great encouragement, he set up an organ in the orchestra, and, in a conspicuous part of the garden, erected a fine statue of Mr. Handel." These gardens are said to be the first of the kind in England; but they are not so old as the Mulberry Gardens, (on the spot now called Spring Gardens, near St. James's Park,) where king Charles II. went to regale himself the night after his restoration, and formed an immediate connexion with Mrs. Palmer, afterwards Duchess of Cleveland. The trees, however, are more than a century old, and, according to tradition, were planted for a public garden. This property was formerly held by Jane Fauxe, or Vaux, widow, in 1615; and it is highly probable (says Nichols) that she was the relict of the infamous Guy. In the "Spectator," No. 383, Mr. Addison introduces a voyage from the Temple Stairs to Vauxhall, in which he is accompanied by his friend, Sir Roger de Coverley. In the "Connoisseur," No. 68, we find a very humourous description of the behaviour of an old penurious citizen, who had treated his family here with a handsome supper. The magnificence of these gardens calls to recollection the magic representations in the "Arabian Nights' Entertainments," where

"The blazing glories, with a cheerful ray,

Supply the sun, and counterfeit the day."

Grosely, in his "Tour to London,"4 says, (relating to Ranelagh and Vauxhall,) "These entertainments, which begin in the month of May, are continued every night. They bring together persons of all ranks and conditions; and amongst these, a considerable number of females, whose charms want only that cheerful air, which is the flower and quintessence of beauty. These places [pg 15] serve equally as a rendezvous either for business or intrigue. They form, as it were, private coteries; there you see fathers and mothers, with their children, enjoying domestic happiness in the midst of public diversions. The English assert, that such entertainments as these can never subsist in France, on account of the levity of the people. Certain it is, that those of Vauxhall and Ranelagh, which are guarded only by outward decency, are conducted without tumult and disorder, which often disturb the public diversions of France. I do not know whether the English are gainers thereby; the joy which they seem in search of at those places does not beam through their countenances; they look as grave at Vauxhall and Ranelagh as at the Bank, at church, or a private club. All persons there seem to say, what a young English nobleman said to his governor, Am I as joyous as I should be?"

P. T. W.

A cursory glance at the principal occasion of the amazing success obtained by the Greeks and Romans, in painting and sculpture, during the early ages, may perhaps prove interesting to the lovers of the arts in this country.

The elevation to which the arts in Greece arrived was owing to the concurrence of various circumstances. The imitative arts, we are told, in that classic country formed a part of the administration, and were inseparably connected with the heathen worship. The temples were magnificently erected, and adorned with numerous statues of pagan deities, before which, in reverential awe, the people prostrated themselves. Every man of any substance had an idol in his own habitation, executed by a reputed sculptor. In all public situations the patriotic actions of certain citizens were represented, that beholders might be induced to emulate their virtues. On contemplating these masterpieces of art, which were so truly exquisite that the very coldest spectator was unable to resist their almost magical influence, the vicious were reclaimed, and the ignorant stood abashed. Indeed, it has often been asserted, that the statues by Phidias and Praxiteles were so inimitably executed, that the people of Paros adored them as living gods. Those artists who performed such extraordinary wonders as these were held in an esteemed light, of which we cannot form the least idea. We are certain they were paid most enormous prices for their productions, and consequently could afford to adorn them with every beauty of art, and to bestow more time on them than can ever be expected from any modern artist.

As soon as the arts had arrived at their highest pitch of excellency in Greece, the country was laid waste by the invading power of the Romans. All the Greek cities which contained the greatest treasures were demolished, and all the pictures5 and statues fell into the hands of the victorious general, who had them carefully preserved and conveyed from the land where they had been adored. Of the estimation in which these great works were held by the Romans, we may form some idea by the general assuring a soldier, to whose charge he gave a statue by Praxiteles, that if he broke it, he should get another as well made in its place. War is a very destructive enemy to painting and sculpture; the intestine quarrels which ensued after the Romans had conquered the country, rendered the exercise of the art impracticable.

The arts were neglected in Rome until the introduction of the popish religion. At that eventful era, statues and pictures were eagerly sought for; the admirable Grecian works were appropriated to purposes quite contrary to their pagan origin, for in many cases heathen deities were converted into apostles. The labours of Phidias, Myron, Praxiteles, Lysippus, and Scopas,6 were highly valued by the Romans, who became the correct imitators, and in time the rivals, of those celebrated sculptors.

G.W.N.

She left her own warm home

To tempt the frozen waste,

What time the traveller fear'd to roam,

And hunter shunn'd the blast,

Love pour'd his strength into her soul—

Could peril e'er his power controul!

[pg 16] She left her own warm home.

When stone, and herb, and tree,

And all beneath heaven's lurid dome

By wintry majesty,

In his stern age, were clad with snow,

And human hearts beat chill and slow.

It was a fearful hour

For one so young and fair:

The woods had not one sheltering bower,

The earth was trackless there,

The very boughs in silver slept,

As the sea-foam had o'er them swept.

Snow after snow came down,

The sky look'd fix'd in ice;

She deem'd amid the season's power,

Her love would all suffice

To keep the source of being warm,

And mock the terrors of the storm.

Love was her world of life.

She thought but of her heart,

And knowing that the winter's strife

Could not its hope dispart,

She dream'd not that its home of clay

Might yield before the tempest's sway—

Or judged that passion's power—

Passion so strong and pure.

Might mock the snow-flake's wildering shower,

Proud that it could endure,

As woman oft in times before

Had peril borne as much or more.

She went—dawn past o'er dawn,

None saw her face again,

The eyes she should have gazed upon,

Look'd for her face in vain—

The ear to which her voice was song,

Her voice had sought—how vainly long!

There is in Saco's vale

A gently swelling hill,

Shadows have wrapt it like a veil

From trees that mark it still,

Around, the mountains towering blue

Look on that spot of saddest hue.

'Twas by that little hill,

At the dark noon of night,

Close by a frozen snow-hid rill,

Where branches close unite

Even in winter's leafless time,

The skeletons of summer's prime.

That flash'd the traveller's flame

On tree and precipice,

And show'd a fair unearthly frame

In robes of glittering ice,

With head against a trunk inclined,

Like a dream-spirit of the mind.

'Twas that love-wander'd maid, death-pale,

Her very heart's blood froze,

Love's Niobe, in her own vale,

Now reckless of all woes—

Love's victim fair, and true, find meet,

As she of the famed Paraclete.

The mountains round shall tell

Her tale to travellers long.

The little vale of Saco swell

The western poet's song,

And "Nancy's Hill" in loftier rhymes

Be sung through unborn realms and times.

"I am but a Gatherer and disposer of other men's stuff."—Wotton.

The late Dr. Barclay was a wit and a scholar, as well as a very great physiologist. When a happy illustration, or even a point of pretty broad humour, occurred to his mind, he hesitated not to apply it to the subject in hand; and in this way, he frequently roused and rivetted attention, when more abstract reasoning might have failed of its aim. On one occasion he happened to dine with a large party, composed chiefly of medical men. As the wine cup circulated, the conversation accidentally took a professional turn, and from the excitation of the moment, or some other cause, two of the youngest individuals present were the most forward in delivering their opinions. Sir James McIntosh once told a political opponent, that so far from following his example of using hard words and soft arguments, he would pass, if possible, into the opposite extreme, and use soft words and hard arguments. But our unfledged M.D.'s disregarded the above salutary maxim, and made up in loudness what they wanted in learning. At length, one of them said something so emphatic—we mean as to manner—that a pointer dog started from his lair beneath the table and bow-wow-wowed so fiercely, that he fairly took the lead in the discussion. Dr. Barclay eyed the hairy dialectician, and thinking it high time to close the debate, gave the animal a hearty push with his foot, and exclaimed in broad Scotch—"Lie still, ye brute; for I am sure ye ken just as little about it as ony o'them." We need hardly add, that this sally was followed by a hearty burst of laughter, in which even the disputants good-humouredly joined.

Fair woman was made to bewitch—

A pleasure, a pain, a disturber, a nurse,

A slave, or a tyrant, a blessing, or curse;

Fair woman was made to be—which?

Footnote 2: (return)The circumstances of the case were as follows:—Jean Baptiste Michel, aged 36, a blacksmith, accompanied by a female named Marie Anne Debeyst, aged 22, was proceeding from Brussels to Vilvorde, one day in the month of March, 1824. In the Alléverte, they overtook a servant girl, who was imprudent enough to mention to them that her master had entrusted her with a sum of money. Near Vilvorde, Michel and his paramour, having formed their plan of assassination and robbery, rejoined the poor girl, whom they had momentarily left, and violently demanded the bag containing the gold and silver. The unfortunate young creature resisted their attacks as long as she could, but was soon felled to the ground by Michel, who with a thick stick fractured her skull, whilst Debeyst trod upon the prostrate victim of their horrid crime. These wretches were shortly afterwards arrested and committed to prison. On the 5th of April, 1825, they were condemned to death by the Court of Assize at Brussels, but implored of the royal clemency a commutation of punishment. This was granted to the woman, whose sentence was changed to perpetual imprisonment. Michel's petition was rejected.

Footnote 3: (return)It is a fact not known to every juvenile lover of nature, that a transverse section of a fern-root presents a miniature picture of an oak tree which no painter could rival.

Footnote 5: (return)The pictures alluded to were the works of Apelles, Apollodorus, and Protogenes.

Footnote 7: (return)A few miles below the Notch of the White Mountains in the Valley of Saco, is a little rise of land called "Nancy's Hill." It was formerly thickly covered with trees, a cluster of which remains to mark the spot. In 1773, at Dartmouth, Jefferson co. U.S. lived Nancy——, of respectable connexions. She was engaged to be married. Her lover had set out for Lancaster. She would follow him in the depth of winter, and on foot. There was not a house for thirty miles, and the way through the wild woods a footpath only. She persisted in her design, and wrapping herself in her long cloak, proceeded on her way. Snow and frost took place for several weeks, when some persons passing her route, reached the lull at night. On lighting their fires, an unearthly figure stood before them beneath the bending branches, wrapped in a robe of ice. It was the lifeless form of Nancy.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand (near Somerset House), and sold by all Newsmen and Booksellers.