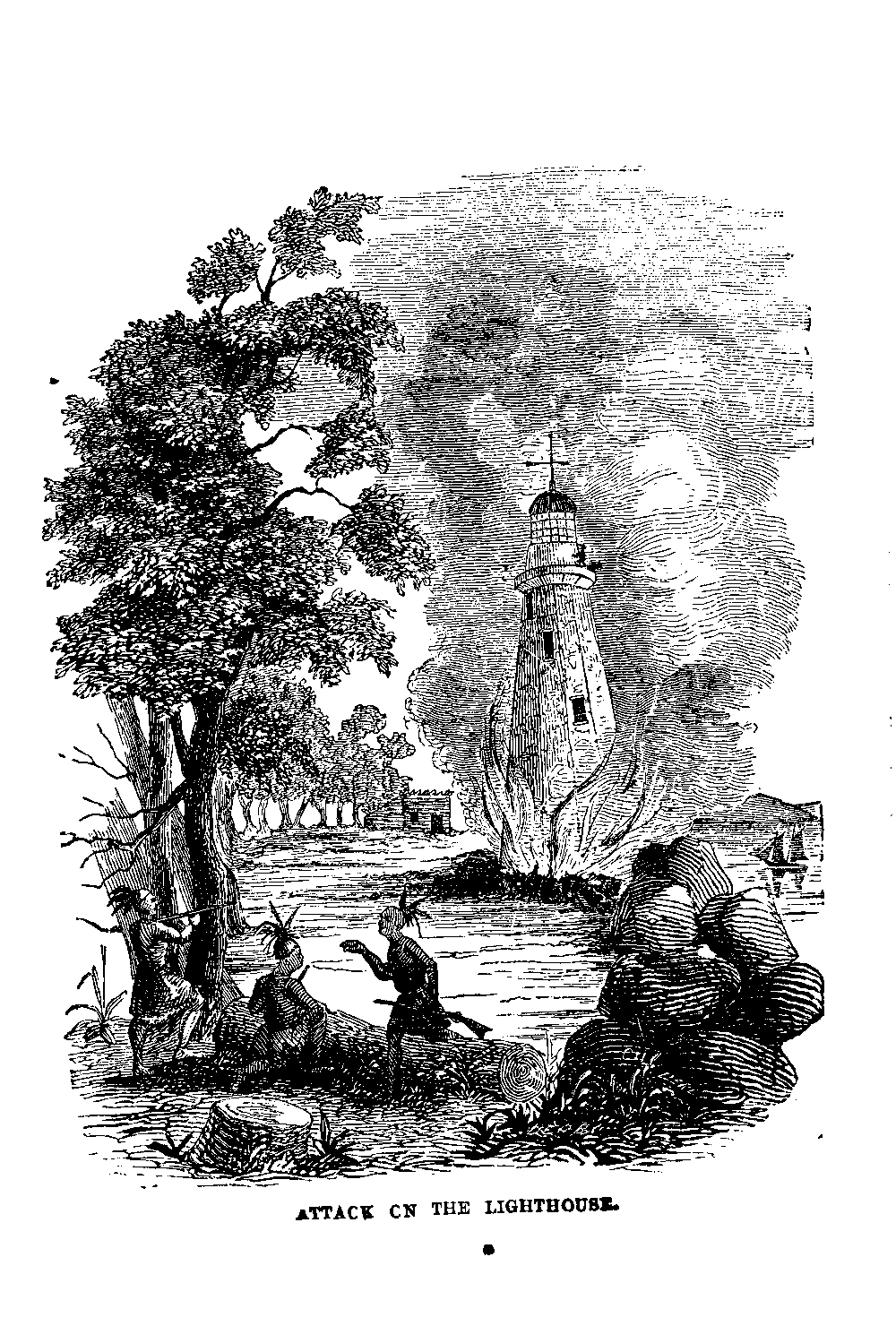

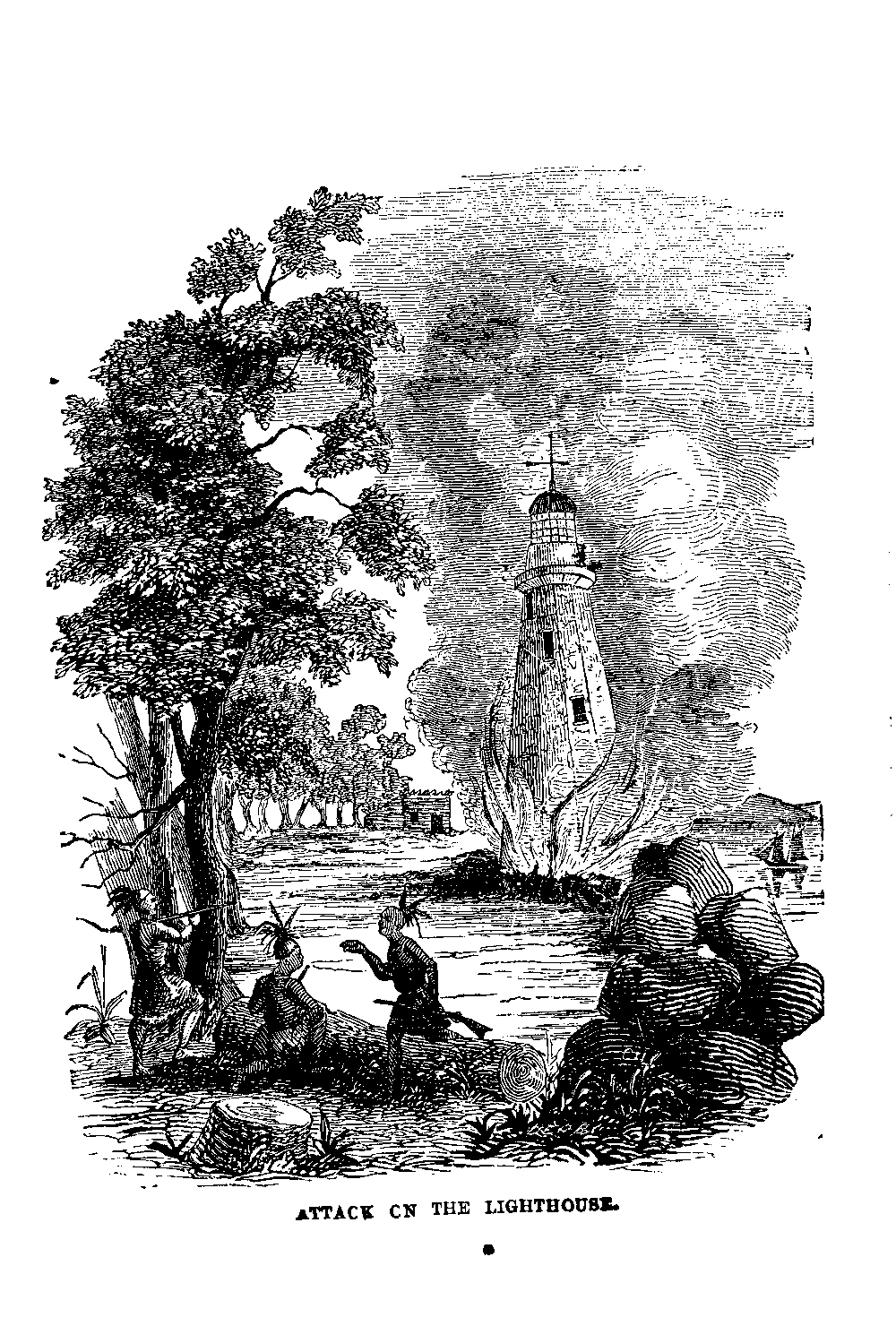

Attack on the Lighthouse.

Project Gutenberg's Thrilling Adventures by Land and Sea, by James O. Brayman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Thrilling Adventures by Land and Sea Author: James O. Brayman Release Date: January 21, 2004 [EBook #10765] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THRILLING ADVENTURES *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Charlie Kirschner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

There is a large class of readers who seek books for the sake of the amusement they afford. Many are not very fastidious as to the character of those they select, and consequently the press of the present day teems with works which are not only valueless, so far as imparting information is concerned, but actually deleterious in their moral tendency, and calculated to vitiate and enervate the mind. Such publications as pander to a prurient taste find a large circulation with a portion of society who read them for the same reason that the inebriate seeks his bowl, or the gambler the instruments of his vocation--for the excitement they produce. The influence of works of this description is all bad--there is not a single redeeming feature to commend them to the favor or toleration of the virtuous or intelligent. It cannot be expected that minds accustomed to such reading can at once be elevated into the higher walks of literature or the more rugged paths of science. An intermediate step, by which they may be lifted into a higher mental position, is required.

There is in the adventures of the daring and heroic, something that interests all. There is a charm about them which, while it partakes of the nature of Romance, does not exercise the same influence upon the mind or heart. When there are noble purposes and noble ends connected with them, they excite in the mind of the reader, noble impulses.

The object of the present compilation is to form a readable and instructive volume--a volume of startling incident and exciting adventure, which shall interest all minds, and by its attractions beget thirst for reading with those who devote their leisure hours to things hurtful to themselves and to community. We have endeavored to be authentic, and to present matter, which, if it sometimes fail to impart knowledge or instruction, or convey a moral lesson, will, at least, be innoxious. But we trust we have succeeded in doing more than this--in placing before the reading public something that is really valuable, and that will produce valuable results.

Sergeant Milton gives the following account of an incident which befel him at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma.

"At Palo Alto," says he, "I took my rank in the troop as second sergeant, and while upon the field my horse was wounded in the jaw by a grape-shot, which disabled him for service. While he was plunging in agony I dismounted, and the quick eye of Captain May observed me as I alighted from my horse. He inquired if I was hurt. I answered no--that my horse was the sufferer. 'I am glad it is not yourself,' replied he; 'there is another,' (pointing at the same time to a steed without a rider, which was standing with dilated eye, gazing at the strife,) 'mount him,' I approached the horse, and he stood still until I put my hand upon the rein and patted his neck, when he rubbed his head alongside of me, as if pleased that some human being was about to become his companion in the affray.

"On the second day, at Resaca de la Palma, our troop stood anxiously waiting for the signal to be given, and never had I looked upon men on whose countenances were more clearly expressed a fixed determination to win. The lips of some were pale with excitement, and their eyes wore that fixed expression which betokens mischief; others, with shut teeth, would quietly laugh, and catch a tighter grip of the rein, or seat themselves with care and firmness in the saddle, while quiet words of confidence and encouragement were passed from each to his neighbor. All at once Captain May rode to the front of his troop--every rein and sabre was tightly grasped. Raising himself and pointing at the battery, he shouted, 'Men, follow!' There was now a clattering of hoofs and a rattling of sabre sheaths--the fire of the enemy's guns was partly drawn by Lieutenant Ridgely, and the next moment we were sweeping like the wind up the ravine. I was in a squad of about nine men, who were separated by a shower of grape from the battery, and we were in advance, May leading. He turned his horse opposite the breastwork, in front of the guns, and with another shout 'to follow,' leaped over them. Several of the horses did follow, but mine, being new and not well trained, refused; two others balked, and their riders started down the ravine to turn the breastwork where the rest of the troop had entered. I made another attempt to clear the guns with my horse, turning him around--feeling all the time secure at thinking the guns discharged--I put his head toward them and gave him spur, but he again balked; so turning his head down the ravine, I too started to ride round the breastwork.

"As I came down, a lancer dashed at me with lance in rest. With my sabre I parried his thrust, only receiving a slight flesh-wound from its point in the arm, which felt at the time like the prick of a pin. The lancer turned and fled; at that moment a ball passed through my horse on the left side and shattered my right side. The shot killed the horse instantly, and he fell upon my left leg, fastening me by his weight to the earth. There I lay, right in the midst of the action, where carnage was riding riot, and every moment the shot, from our own and the Mexican guns, tearing up the earth around me. I tried to raise my horse so as to extricate my leg but I had already grown so weak with my wound that I was unable, and from the mere attempt, I fell back exhausted. To add to my horror, a horse, who was careering about, riderless, within a few yards of me, received a wound, and he commenced struggling and rearing with pain. Two or three times, he came near falling on me, but at length, with a scream of agony and a bound, he fell dead--his body touching my own fallen steed. What I had been in momentary dread of now occurred--my wounded limb, which was lying across the horse, received another ball in the ankle.

"I now felt disposed to give up; and, exhausted through pain and excitement, a film gathered over my eyes, which I thought was the precursor of dissolution. From this hopeless state I was aroused by a wounded Mexican, calling out to me, 'Bueno Americano,' and turning my eyes toward the spot, I saw that he was holding a certificate and calling to me. The tide of action now rolled away from me and hope again sprung up. The Mexican uniforms began to disappear from the chapparal, and squadrons of our troops passed in sight, apparently in pursuit. While I was thus nursing the prospect of escape, I beheld, not far from me, a villainous-looking ranchero, armed with an American sergeant's short sword, dispatching a wounded American soldier, whose body he robbed--the next he came to was a Mexican, whom he served the same way, and thus I looked on while he murderously slew four. I drew an undischarged pistol from my holsters, and laying myself along my horse's neck, watched him, expecting to be the next victim; but something frightened him from his vulture-like business, and he fled in another direction. I need not say that had he visited me I should have taken one more shot at the enemy, and would have died content, had I succeeded in making such an assassin bite the dust. Two hours after, I had the pleasure of shaking some of my comrades by the hand, who were picking up the wounded. They lifted my Mexican friend, too, and I am pleased to say he, as well as myself, live to fight over again the sanguine fray of Resaca de la Palma."

While the plague raged violently at Marseilles, every link of affection was broken, the father turned from the child, the child from the father; cowardice and ingratitude no longer excited indignation. Misery is at its height when it thus destroys every generous feeling, thus dissolves every tie of humanity! the city became a desert, grass grew in the streets; a funeral met you at every step.

The physicians assembled in a body at the Hotel de Ville, to hold a consultation on the fearful disease, for which no remedy had yet been discovered. After a long deliberation, they decided unanimously, that the malady had a peculiar and mysterious character, which opening a corpse alone might develope--an operation it was impossible to attempt, since the operator must infallibly become a victim in a few hours, beyond the power of human art to save him, as the violence of the attack would preclude their administering the customary remedies. A dead pause succeeded this fatal declaration. Suddenly, a surgeon named Guyon, in the prime of life, and of great celebrity in his profession, rose and said firmly, "Be it so: I devote myself for the safety of my country. Before this numerous assembly I swear, in the name of humanity and religion, that to-morrow, at the break of day, I will dissect a corpse, and write down as I proceed, what I observe." He left the assembly instantly. They admired him, lamented his fate, and doubted whether he would persist in his design. The intrepid Guyon, animated by all the sublime energy which patriotism can inspire, acted up to his word. He had never married, he was rich, and he immediately made a will; he confessed, and in the middle of the night received the sacraments. A man had died of the plague in his house within four and twenty hours. Guyon, at daybreak, shut himself up in the same room; he took with him an inkstand, paper, and a little crucifix. Full of enthusiasm, and kneeling before the corpse, he wrote,--"Mouldering remains of an immortal soul, not only can I gaze on thee without horror, but even with joy and gratitude. Thou wilt open to me the gates of a glorious eternity. In discovering to me the secret cause of the terrible disease which destroys my native city, thou wilt enable me to point out some salutary remedy--thou wilt render my sacrifice useful. Oh God! thou wilt bless the action thou hast thyself inspired." He began--he finished the dreadful operation, and recorded in detail his surgical observations. He left the room, threw the papers into a vase of vinegar, and afterward sought the lazaretto, where he died in twelve hours--a death ten thousand times more glorious than the warrior's, who, to save his country, rushes on the enemy's ranks,--since he advances with hope, at least, sustained, admired, and seconded by a whole army.

An incident occurred at the Key Biscayne lighthouse, during the Florida war, which is perhaps worth recording. The lighthouse, was kept by a man named Thompson. His only companion was an old negro man; they both lived in a small hut near the lighthouse. One evening about dark they discovered a party of some fifteen or twenty Indians creeping upon them, upon which they immediately retreated into the lighthouse, carrying with them a keg of gunpowder, with the guns and ammunition. From the windows of the lighthouse Thompson fired upon them several times, but the moment he would show himself at the window, the glasses would be instantly riddled by the rifle balls, and he had no alternative but to lie close. The Indians meanwhile getting out of patience, at not being able to force the door, which Thompson had secured, collected piles of wood, which, being placed against the door and set fire to, in process of time not only burnt through the door, but also set fire to the stair-case conducting to the lantern, into which Thompson and the negro were compelled to retreat. From this, too, they were finally driven by the encroaching flames, and were forced outside on the parapet wall, which was not more than three feet wide.

The flames now began to ascend as from a chimney, some fifteen or twenty feet above the lighthouse. These men had to lie in this situation, some seventy feet above the ground, with a blazing furnace roasting them on one side, and the Indians on the other, embracing every occasion, as soon as any part of the body was exposed to pop at them. The negro incautiously exposing himself, was killed, while Thompson received several balls in his feet, which he had projected beyond the wall.

Nearly roasted to death, and in a fit of desperation, Thompson seized the keg of gunpowder, which he had still preserved from the hands of the enemy, threw it into the blazing lighthouse, hoping to end his own sufferings and destroy the savages. In a few moments it exploded, but the walls were too strong to be shaken, and the explosion took place out of the lighthouse, as though it had been fired from a gun.

The effect of the concussion was to throw down the blazing materials level with the ground, so as to produce a subsidence of the flames, and then Thompson was permitted to remain exempt from their influence. Before day the Indians were off, and Thompson being left alone, was compelled to throw off the body of the negro, while strength was left him, and before it putrefied.

The explosion was heard on board a revenue cutter at some distance, which immediately proceeded to the spot to ascertain what had occurred, when they found the lighthouse burnt, and the keeper above, on top of it. Various expedients were resorted to, to get him down; and finally a kite was made, and raised with strong twine, and so manoeuvered as to bring the line within his reach, to which a rope of good size was next attached, and hauled up by Thompson. Finally, a block, which being fastened to the lighthouse, and having a rope to it, enabled the crew to haul up a couple of men, by whose aid Thompson was safely landed on terra firma.

The Indians had attempted to reach him by means of the lightning rod, to which they had attached thongs of buckskin, but could not succeed in getting more than half way up.

The following thrilling narrative is from a translation in Sharpe's Magazine. A captain in the Mexican insurgent army is giving an account of a meditated night attack upon a hacienda situated in the Cordilleras, and occupied by a large force of Spanish soldiers. After a variety of details, he continues:

"Having arrived at the hacienda unperceived, thanks for the obscurity of a moonless night, we came to a halt under some large trees, at some distance from the building, and I rode forward from my troop, in order to reconnoitre the place. The hacienda, so far as I could see in gliding across, formed a huge, massive parallelogram, strengthened by enormous buttresses of hewn stone. Along this chasm, the walls of the hacienda almost formed the continuation of another perpendicular one, chiselled by nature herself in the rocks, to the bottom of which the eye could not penetrate, for the mists, which incessantly boiled up from below, did not allow it to measure their awful depth. This place was known, in the country, by the name of 'the Voladero.'"

"I had explored all sides of the building except this, when I know not what scruple of military honor incited me to continue my ride along the ravine which protected the rear of the hacienda. Between the walls and the precipice, there was a narrow pathway about six feet wide; by day, the passage would have been dangerous; but, by night, it was a perilous enterprize. The walls of the farm took an extensive sweep, the path crept round their entire basement, and to follow it to the end, in the darkness, only two paces from the edge of a perpendicular chasm, was no very easy task, even for as practiced a horseman as myself. Nevertheless, I did not hesitate, but boldly urged my horse between the walls of the farm-house and the abyss of the Voladero. I had got over half the distance without accident, when, all of a sudden, my horse neighed aloud. This neigh made me shudder. I had just reached a pass where the ground was but just wide enough for the four legs of a horse, and it was impossible to retrace my steps."

"'Hallo!' I exclaimed aloud, at the risk of betraying myself, which was even less dangerous than encountering a horseman in front of me on such a road. 'There is a Christian passing along the ravine! Keep back,'"

"It was too late. At that moment, a man on horseback passed round one of the buttresses which here and there obstructed this accursed pathway He advanced toward me. I trembled in my saddle; my forehead bathed in a cold sweat."

"'For the love of God! can you not return?' I exclaimed, terrified at the fearful situation in which we both were placed."

"'Impossible!' replied the horseman."

"I recommended my soul to God. To turn our horses round for want of room, to back them along the path we had traversed, or even to dismount from them--these were three impossibilities, which placed us both in presence of a fearful doom. Between two horsemen so placed upon this fearful path, had they been father and son, one of them must inevitably have become the prey of the abyss. But a few seconds had passed, and we were already face to face--the unknown and myself. Our horses were head to head, and their nostrils, dilated with terror, mingled together their fiery breathing. Both of us halted in a dead silence. Above was the smooth and lofty wall of the hacienda; on the other side, but three feet distant from the wall, opened the horrible gulf. Was it an enemy I had before my eyes? The love of my country, which boiled, at that period, in my young bosom, led me to hope it was."

"'Are you for Mexico and the Insurgents?' I exclaimed in a moment of excitement, ready to spring upon the unknown horseman, if he answered me in the negative."

"'Mexico e Insurgente--that is my password, replied the cavalier. 'I am the Colonel Garduno.'"

"'I am the Captain Castanos.'"

"Our acquaintance was of long standing; and, but for mutual agitation, we should have had no need to exchange our names. The colonel had left us two days since, at the head of the detachment, which we supposed to be either prisoners, or cut off, for he had not been seen to return to the camp."

"'Well, colonel,' I exclaimed, 'I am sorry you are not a Spaniard; for, you perceive, that one of us must yield the pathway to the other."

"Our horses had the bridle on their necks, and I put my hands to the holsters of my saddle to draw out my pistols."

"'I see it so plainly,' returned the colonel, with alarming coolness, 'that I should already have blown out the brains of your horse, but for the fear lest mine, in a moment of terror, should precipitate me with yourself, to the bottom of the abyss.'"

"I remarked, in fact, that the colonel already held his pistols in his hands. We both maintained almost profound silence. Our horses felt the danger like ourselves, and remained as immovable as if their feet were nailed to the ground. My excitement had entirely subsided. 'What are we going to do?' I demanded of the colonel."

"'Draw lots which of the two shall leap into the ravine.'"

"It was, in truth, the sole means of resolving the difficulty. 'There are, nevertheless, some precautions to take,' said the Colonel."

"'He who shall be condemned by the lot, shall retire backward. It will be but a feeble chance of escape for him, I admit; but, in short, there is a chance, and especially one in favor of the winner,'"

"'You cling not to life, then?' I cried out, terrified at the sang-froid with which this proposition was put to me."

"'I cling to life more than yourself,' sharply replied the colonel, 'for I have a mortal outrage to avenge. But the time is fast slipping away. Are you ready to proceed to draw the last lottery at which one of us will ever exist?"

"How were we to proceed to this drawing by lot? By means of the wet finger, like infants; or by head and tail, like the school boys? Both ways were impracticable. Our hands imprudently stretched out over the heads of our frightened horses, might cause them to give a fatal start. Should we toss up a piece of coin, the night was too dark to enable us to distinguish which side fell upward. The colonel bethought him of an expedient, of which I never should have dreamed."

"'Listen to me, captain,' said the colonel, to whom I had communicated my perplexities. 'I have another way. The terror which our horses feel, makes them draw every moment a burning breath. The first of us two whose horse shall neigh,--"

"'Wins!' I exclaimed, hastily."

"'Not so; shall be looser. I know that you are a countryman, and, as such, you can do whatever you please with your horse. As to myself, who, but last year, wore a gown of a theological student, I fear your equestrian prowess. You may be able to make your horse neigh: to hinder him from doing so, is a very different matter.'"

"We waited in deep and anxious silence until the voice of one of our horses should break forth. The silence lasted for a minute--for an age! It was my horse who neighed the first. The colonel gave no external manifestation of his joy; but, no doubt, he thanked God to the very bottom of his heart."

"'You will allow me a minute to make my peace with heaven?' I said, with falling voice."

"'Will five minutes be sufficient?'"

"'It will,' I replied."

"The colonel pulled out his watch. I addressed toward the heavens, brilliant with stars, which I thought I was looking to for the last time, an intense and burning prayer."

"'It is time,' said the colonel."

"I answered nothing, and, with a firm hand, gathered up the bridle of my horse, and drew it within my fingers, which were agitated by a nervous tremor."

"'Yet one moment more,' I said to the colonel, for I have need of all my coolness to carry into execution the fearful manoeuver which I am about to commence."

"'Granted,' replied Garduno."

"My education, as I have told you, had been in the country. My childhood, and part of my earliest youth, had almost been passed on horseback. I may say, without flattering myself, that if there was any one in the world capable of executing this equestrian feat, it was myself. I rallied myself with an almost supernatural effort, and succeeded in recovering my entire self-possession, in the very face of death. Taking it at the worst, I had already braved it too often to be any longer alarmed at it. From that instant, I dared to hope afresh."

"As soon as my horse felt, for the first time since my rencounter with the colonel, the bit compressing his mouth, I perceived that he trembled beneath me. I strengthened myself firmly on my stirrups, to make the terrified animal understand that his master no longer trembled. I held him up with bridle and the hams, as every good horseman does in a dangerous passage, and, with the bridle, the body, and the spur, together, succeeded in backing him a few paces. His head was already a greater distance from that of the horse of the colonel, who encouraged me all he could with his voice. This done, I let the poor, trembling brute, who obeyed me in spite of his terror, repose for a few moments, and then recommenced the same manoeuver. All on a sudden, I felt his hind legs give way under me. A horrible shudder ran through my whole frame. I closed my eyes, as if about to roll to the bottom of the abyss, and I gave to my body a violent impulse on the side next to the hacienda, the surface of which offered not a single projection, not a tuft of weeds to check my descent. This sudden movement joined to the desperate struggles of my horse, was the salvation of my life. He had sprung up again on his legs, which seemed ready to fall from under him, so desperately did I feel them tremble."

"I had succeeded in reaching between the brink of the precipice and the wall of the building, a spot some few inches broader. A few more would have enabled me to turn him round; but to attempt it here would have been fatal, and I dared not venture. I sought to resume my backward progress, step by step. Twice the horse threw himself on his hind legs, and fell down upon the same spot. It was in vain to urge him anew, either with voice, bridle, or spur; the animal obstinately refused to take a single step in the rear. Nevertheless, I did not feel my courage yet exhausted, for I had no desire to die. One last, solitary chance of safety, suddenly appeared to me, like a flash of light, and I resolved to employ it. Through the fastening of my boot, and in reach of my hand, was placed a sharp and keen knife, which I drew forth from its sheath. With my left hand I began caressing the mane of my horse, all the while letting him hear my voice. The poor animal replied to my caresses by a plaintive neighing; then, not to alarm him abruptly, my hand followed, by little and little, the curve of his nervous neck, and finally rested upon the spot where the last of the vertebrae unites itself with the cranium. The horse trembled; but I calmed him with my voice. When I felt his very life, so to speak, palpitate in his brain beneath my fingers, and leaned over toward the wall, my feet gently slid from the stirrups, and, with one vigorous blow, I buried the pointed blade of my knife in the seat of the vital principle. The animal fell as if thunderstruck, without a single motion; and, for myself, with my knees almost as high as my chin, I found myself a horseback across a corpse! I was saved! I uttered a triumphant cry, which was responded to by the colonel, and which the abyss re-echoed with a hollow sound, as if it felt that its prey had escaped from it. I quitted the saddle, sat down between the wall and the body of my horse, and vigorously pushed with my feet against the carcass of the wretched animal, which rolled down into the abyss. I then arose, and cleared, at a few bounds, the distance which separated the place where I was from the plain; and, under the irresistible reaction of the terror which I had long repressed, I sank into a swoon upon the ground. When I reopened my eyes, the colonel was by my side."

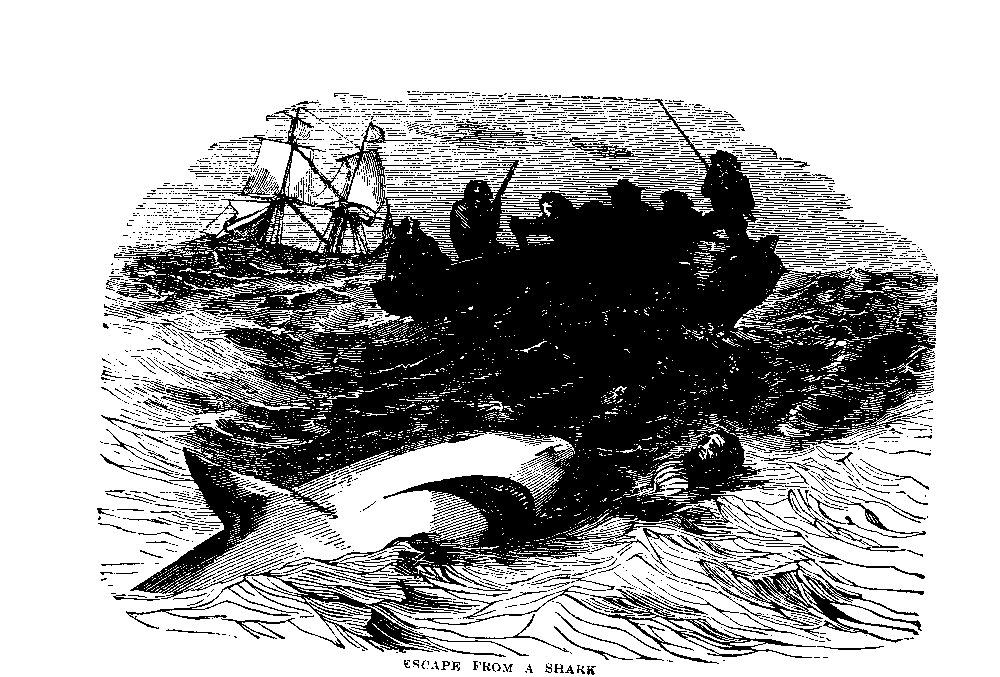

Carthagena lies in the parallel of ten degrees twenty-six minutes north, and seventy-five degrees thirty-eight minutes west longitude; the harbor is good, with an easy entrance; the city is strongly fortified by extensive and commanding fortifications and batteries, and, I should suppose, if well garrisoned and manned, they would be perfectly able to repel any force which might be brought to bear against them. It was well known, at this time, that all the provinces of Spain had shaken off their allegiance to the mother country, and declared themselves independent. Carthagena, the most prominent of the provinces, was a place of considerable commerce; and, about this time, a few men-of-war, and a number of privateers, were fitted out there. The Carthagenian flag now presented a chance of gain to the cupidity of the avaricious and desperate, among whom was our commander, Captain S. As soon, therefore, as we had filled up our water, &c., a proposition was made by him, to the second lieutenant and myself, to cruise under both flags, the American and Carthagenian, and this to be kept a profound secret from the crew, until we had sailed from port. Of course, we rejected the proposition with disdain, and told him the consequence of such a measure, in the event of being taken by a man-of-war of any nation,--that it was piracy, to all intents and purposes, according to the law of nations. We refused to go out in the privateer, if he persisted in this most nefarious act, and we heard no more of it while we lay in port.

In a few days we were ready for sea, and sailed in company with our companion, her force being rather more than ours, but the vessel very inferior, in point of sailing. While together, we captured several small British schooners, the cargoes of which, together with some specie, were divided between two privateers. Into one of the prizes we put all the prisoners, gave them plenty of water and provisions, and let them pursue their course: the remainder of the prizes were burned. We then parted company, and, being short of water, ran in toward the land, in order to ascertain if any could be procured. In approaching the shore, the wind died away to a perfect calm; and, at 4 P.M., a small schooner was seen in-shore of us. As we had not steerage way upon our craft, of course it would be impossible to ascertain her character before dark; it was, therefore, determined by our commander to board her with the boats, under cover of the night. This was a dangerous service; but there was no backing out. Volunteers being called for, I stepped forward; and very soon, a sufficient number of men to man two boats offered their services to back me. Every disposition was made for the attack. The men were strongly armed, oars muffled, and a grappling placed in each boat. The bearings of the strange sail were taken, and night came on perfectly clear and cloudless. I took command of the expedition, the second lieutenant having charge of one boat. The arrangement was to keep close together, until we got sight of the vessel; the second lieutenant was to board on the bow, and I on the quarter. We proceeded in the most profound silence; nothing was heard, save now and then a slight splash of the oars in the water, and, before we obtained sight of the vessel, I had sufficient time to reflect on this most perilous enterprise.

My reflections were not of the most pleasant character, and I found myself inwardly shrinking, when I was aroused by the voice of the bowman saying, "There she is, sir, two points on the starboard bow." There she lay, sure enough, with every sail hoisted, and a light was plainly seen, as we supposed, from her deck, it being too high for her cabin windows. We now held a consultation, and saw no good reason to change the disposition of the attack, except that we agreed to board simultaneously. It may be well to observe here, that any number of men on a vessel's deck, in the night, have double the advantage to repel boarders, because they may secrete themselves in such a position as to fall upon an enemy unawares, and thereby cut them off, with little difficulty. Being fully aware of this, I ordered the men, as soon as we had gained the deck of the schooner, to proceed with great caution, and keep close together, till every hazard of the enterprize was ascertained. The boats now separated, and pulled for their respective stations, observing the most profound silence. When we had reached within a few yards of the schooner, we lay upon our oars for some moments; but could neither hear nor see any thing. We then pulled away cheerily, and the next minute were under her counter, and grappled to her; every man leaped on the deck without opposition. The other boat boarded nearly at the same moment, and we proceeded, in a body, with great caution, to examine the decks. A large fire was in the caboose, and we soon ascertained that her deck was entirely deserted, and that she neither had any boat on deck nor to her stern. We then proceeded to examine the cabin, leaving an armed force on deck. The cabin, like the deck, being deserted, the mystery was easily unraveled. Probably concluding that we should board them under cover of the night, they, no doubt, as soon as it was dark, took to their boats, and deserted the vessel. On the floor of the cabin was a part of an English ensign, and some papers, which showed that she belonged to Jamaica, The little cargo on board consisted of Jamaica rum, sugar, fruit, &c.

The breeze now springing up, and the privateer showing lights, we were enabled to get alongside of her in a couple of hours. A prize-master and crew were put on board, with orders to keep company. During the night, we ran along shore, and, in the morning, took on board the privateer the greater part of the prize's cargo.

Being close in shore in the afternoon, we descried a settlement of huts; and, supposing that water might be obtained there, the two vessels were run in, and anchored about two miles distant from the beach. A proposition was made to me, by Captain S., to get the water-casks on board the prize schooner, and, as she drew a light draught of water, I was to run her in, and anchor her near the beach, taking with me the two boats and twenty men. I observed to Captain S. that this was probably an Indian settlement, and it was well known that all the Indian tribes on the coast of Rio de La Hache were exceedingly ferocious, and said to be cannibals; and it was also well known, that whosoever fell into their hands, never escaped with their lives; so that it was necessary, before any attempt was made to land, that some of the Indians should be decoyed on board, and detained as hostages for our safety. At the conclusion of this statement, a very illiberal allusion was thrown out by Captain S., and some doubts expressed in reference to my courage; he remarking, that if I was afraid to undertake the expedition, he would go himself. This was enough for me; I immediately resolved to proceed, if I sacrificed my life in the attempt. The next morning, twenty water-casks were put on board the prize, together with the two boats and twenty men, well armed with muskets, pistols, and cutlasses, with a supply of ammunition; I repaired on board, got the prize under way, ran in, and anchored about one hundred yards from the beach. The boats were got in readiness, and the men were well armed, and the water casks slung ready to proceed on shore, I had examined my own pistols narrowly, that morning, and had put them in complete order, and, as I believed, had taken every precaution for our future operations, so as to prevent surprise.

There were about a dozen ill-constructed huts, or wigwams; but no spot of grass, or shrub, was visible to the eye, with the exception of, here and there, the trunk of an old tree. One solitary Indian was seen stalking on the beach, and the whole scene presented the most wild and savage appearance, and, to my mind, argued very unfavorably. We pulled in with the casks in tow, seven men being in each boat; when within a short distance of the beach, the boat's heads were put to seaward, when the Indian came abreast of us. Addressing him in Spanish, I inquired if water could be procured, to which he replied in the affirmative. I then displayed to his view some gewgaws and trinkets, at which he appeared perfectly delighted, and, with many signs and gestures, invited me on shore. Thrusting my pistols into my belt, and buckling on my cartridge-box, I gave orders to the boats' crew, that, in case they discovered any thing like treachery or surprise, after I had gotten on shore, to cut the water-casks adrift, and make the best of their way on board the prize. As soon as I had jumped on shore, I inquired if there were any live stock, such as fowls, &c., to be had. Pointing to a hut about thirty yards from the boats, he said that the stock was there, and invited me to go and see it. I hesitated, suspecting some treachery; however, after repeating my order to the boats' crews, I proceeded with the Indian, and when within about half a dozen yards of the hut, at a preconcerted signal, (as I supposed,) as if by magic, at least one hundred Indians rushed out, with the rapidity of thought. I was knocked down, stripped of all my clothing except an inside flannel shirt, tied hand and foot, and then taken and secured to the trunk of a large tree, surrounded by about twenty squaws, as a guard, who, with the exception of two or three, bore a most wild and hideous look in their appearance. The capture of the boat's crews was simultaneous with my own, they being so much surprised and confounded at the stratagem of the Indians, that they had not the power, or presence of mind, to pull off.

After they had secured our men, a number of them jumped into the boats, pulled off, and captured the prize, without meeting with any resistance from those on board, they being only six in number. Her cable was then cut, and she was run on the beach, when they proceeded to dismantle her, by cutting the sails from the bolt-ropes, and taking out what little cargo there was, consisting of Jamaica ram, sugar, &c. This being done, they led ropes on shore, when about one hundred of them hauled her up nearly high and dry.

By this time the privateer had seen our disaster stood boldly in, and anchored within less than gun shot of the beach; they then very foolishly opened a brisk cannonade; but every shot was spent in vain. This exasperated the Indians, and particularly the one who had taken possession of my pistols. Casting my eye round, I saw him creeping toward me with one pistol presented, and when about five yards off, he pulled the trigger. But as Providence had, no doubt, ordered it, the pistol snapped; at the same moment, a shot from the privateer fell a few yards from us, when the Indian rose upon his feet, cocked the pistol, and fired it at the privateer; turning round with a most savage yell, he threw the pistol with great violence, which grazed my head, and then, with a large stick, beat and cut me until I was perfectly senseless. This was about ten o'clock, and I did not recover my consciousness until, as I supposed, about four o'clock in the afternoon. I perceived there were four squaws around me, one of whom, from her appearance,--having on many gewgaws and trinkets,--was the wife of a chief. As soon as she discovered signs of returning consciousness, she presented me with a gourd, the contents of which appeared to be Indian meal mixed with water; she first drank, and then gave it to me, and I can safely aver that I never drank any beverage, before or since, which produced such relief.

Night was now coming on; the privateer had got under weigh, and was standing off-and-on, with a flag of truce flying at her mast-head. The treacherous Indian with whom I had first conversed came, and with a malignant smile, gave me the dreadful intelligence that, at twelve o'clock that night, we were to be roasted and eaten.

Accordingly, at sunset, I was unloosed and conducted, by a band of about half a dozen savages, to the spot, where I found the remainder of our men firmly secured, by having their hands tied behind them, their legs lashed together, and each man fastened to a stake that had been driven into the ground for that purpose. There was no possibility to elude the vigilance of these miscreants. As soon as night shut in, a large quantity of brushwood was piled around us, and nothing now was wanting but the fire to complete this horrible tragedy. Then the same malicious savage approached us once more, and, with the deepest malignity, taunted us with our coming fate. Having some knowledge of the Indian character, I summoned up all the fortitude of which I was capable, and, in terms of defiance, told him, that twenty Indians would be sacrificed for each one of us sacrificed by him. I knew very well that it would not do to exhibit any signs of fear or cowardice; and, having heard much of the cupidity of the Indian character, I offered the savage a large ransom if he would use his influence to procure our release. Here the conversation was abruptly broken off by a most hideous yell from the whole tribe, occasioned by their having taken large draughts of the rum, which now began to operate very sensibly upon them; and, as it will be seen, operated very much to our advantage. This thirst for rum caused them to relax their vigilance, and we were left alone to pursue our reflections, which were not of the most enviable or pleasant character. A thousand melancholy thoughts rushed over my mind. Here I was, and, in all probability, in a few hours I should be in eternity, and my death one of the most horrible description. "Oh!" thought I, "how many were the entreaties and arguments used by my friends to deter me from pursuing an avocation so full of hazard and peril! If I had taken their advice, and acceded to their solicitations, in all probability I should, at this time, have been in the enjoyment of much happiness." I was aroused from this reverie by the most direful screams from the united voices of the whole tribe, they having drunk largely of the rum, and become so much intoxicated that a general fight ensued. Many of them lay stretched on the ground, with tomahawks deeply implanted in their skulls: and many others, as the common phrase is, were "dead drunk." This was an exceedingly fortunate circumstance for us. With their senses benumbed, of course they had forgotten their avowal to roast us, or, it may be, the Indian to whom I proposed ransom had conferred with the others, and they, no doubt, agreed to spare our lives until the morning. It was a night, however, of pain and terror, as well as of the most anxious suspense; and when the morning dawn broke upon my vision, I felt an indescribable emotion of gratitude, as I had fully made up my mind, the night previous, that long before this time I should have been sleeping the sleep of death. It was a pitiable sight, when the morning light appeared, to see twenty human beings stripped naked, with their bodies cut and lacerated, and the blood issuing from their wounds; with their hands and feet tied, and their bodies fastened to stakes, with brushwood piled around them, expecting every moment to be their last. My feelings, on this occasion, can be better imagined than described; suffice it to say, that I had given up all hopes of escape, and gloomily resigned myself to death. When the fumes of the liquor had in some degree worn off from the benumbed senses of the savages, they arose and approached us, and, for the first time, the wily Indian informed me that the tribe had agreed to ransom us. They then cast off the lashings from our bodies and feet, and, with our hands still secure, drove us before them to the beach. Then another difficulty arose; the privateer was out of sight, and the Indians became furious. To satiate their hellish malice, they obliged us to run on the beach, while they let fly their poisoned arrows after us. For my own part, my limbs were so benumbed that I could scarcely walk, and I firmly resolved to stand still and take the worst of it--which was the best plan I could have adopted; for, when they perceived that I exhibited no signs of fear, not a single arrow was discharged at me. Fortunately, before they grew weary of this sport, to my great joy, the privateer hove in sight. She stood boldly in, with the flag of truce flying, and the savages consented to let one man of their own choosing go off in the boat to procure the stipulated ransom. The boat returned loaded with articles of various descriptions, and two of our men were released. The boat kept plying to and from the privateer, bringing such articles as they demanded, until all were released except myself. Here it may be proper to observe, that the mulatto man, who had been selected by the Indians, performed all this duty himself, not one of the privateer's crew daring to hazard their lives with him in the boat. I then was left alone, and for my release they required a double ransom. I began now seriously to think that they intended to detain me altogether. My mulatto friend, however, pledged himself that he would never leave me.

Again, for the last time, he sculled the boat off. She quickly returned, with a larger amount of articles than previously. It was a moment of the deepest anxiety, for there had now arrived from the interior another tribe, apparently superior in point of numbers, and elated with the booty which had been obtained. They demanded a share, and expressed a determination to detain me for a larger ransom. These demands were refused, and a conflict ensued of the most frightful and terrific character. Tomahawks, knives, and arrows, were used indiscriminately, and many an Indian fell in that bloody contest. The tomahawks were thrown with the swiftness of arrows, and were generally buried in the skull or the breast; and whenever two came in contact, with the famous "Indian hug," the strife was soon over with either one or the other, by one plunging the deadly knife up to the hilt in the body of his opponent; nor were the poisoned arrows of less swift execution, for, wherever they struck, the wretched victim was quickly in eternity. I shall never forget the frightful barbarity of that hour; although years have elapsed since its occurrence, still the whole scene in imagination is before me, the savage yell of the warwhoop, and the direful screams of the squaws, still ring afresh in my ears. In the height of this conflict, a tall Indian chief, who, I knew, belonged to the same tribe with the young squaw who gave me the drink, came down to the beach where I was. The boat had been discharged, and was lying with her head off. At a signal given by the squaw to the chief, he caught me up in his arms, with as much ease as if I had been a child, waded to the boat, threw me in, and then, with a most expressive gesture, urged us off. Fortunately, there were two oars in the boat, and, feeble as I was, I threw all the remaining strength I had to the oar. It was the last effort, as life or death hung upon the next fifteen minutes. Disappointed of a share of the booty, the savages were frantic with rage, especially when they saw I had eluded their grasp. Rushing to the beach, about a dozen threw themselves into the other boat, which had been captured, and pulled after us; but, fortunately, in their hurry, they had forgotten the muskets, and being unacquainted with the method of rowing, of course they made but little progress, which enabled us to increase our distance.

The privateer having narrowly watched all these movements, and seeing our imminent danger, stood boldly on toward the beach, and in the next five minutes she lay between us and the Indians, discharging a heavy fire of musketry among them. Such was the high excitement of my feelings, that I scarcely recollected how I gained the privateer's deck. But I was saved, nevertheless, though I was weak with the loss of blood, and savage treatment,--my limbs benumbed, and body scorched with the piercing rays of the sun,--the whole scene rushing through my mind with the celerity of electricity! It unmanned and quite overpowered me; I fainted, and fell senseless on the deck.

The usual restoratives and care were administered, and I soon recovered from the effects of my capture. Some of the others were not so fortunate; two of them, especially, were cut in a shocking manner, and the others were so dreadfully beaten and mangled by clubs, that the greatest care was necessary to save their lives.

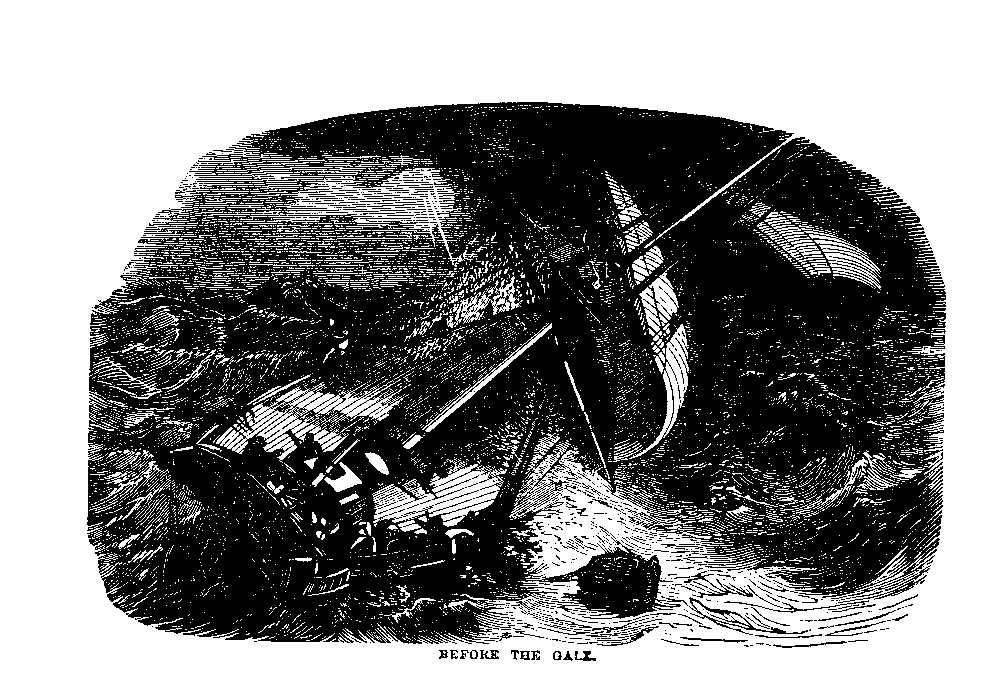

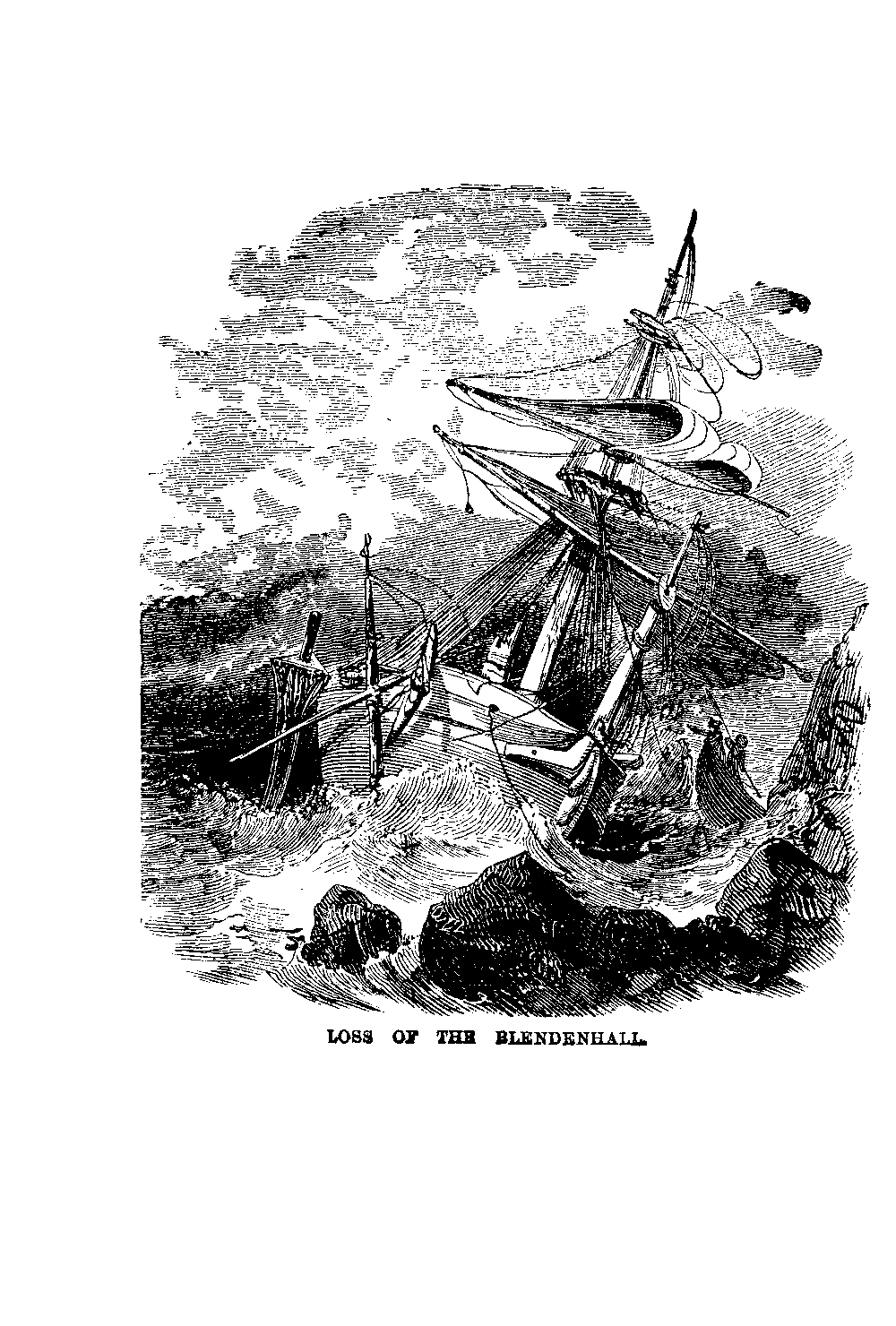

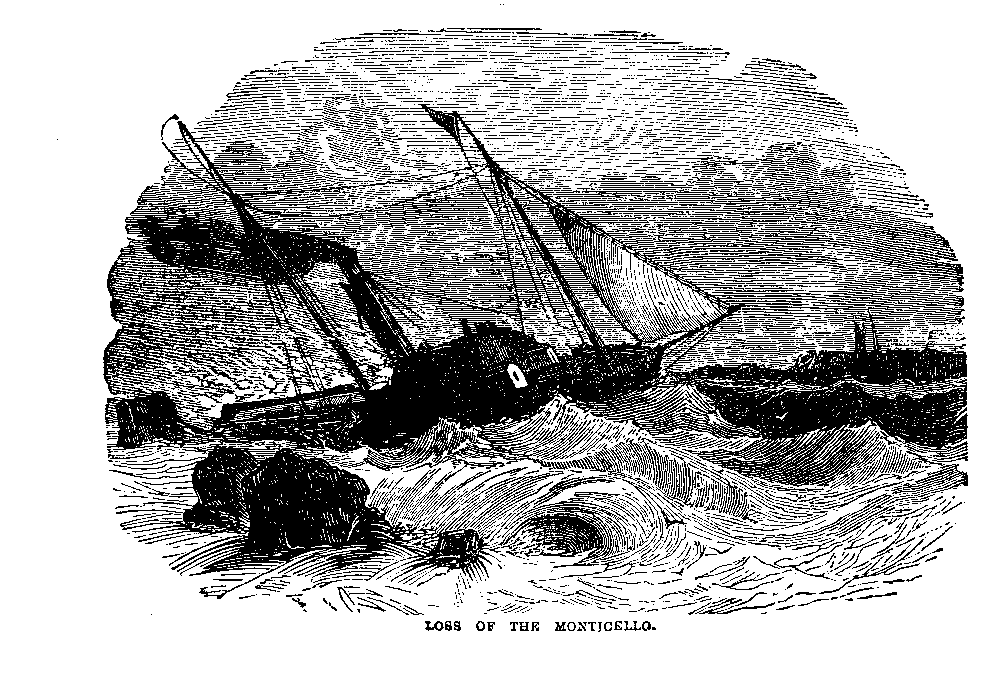

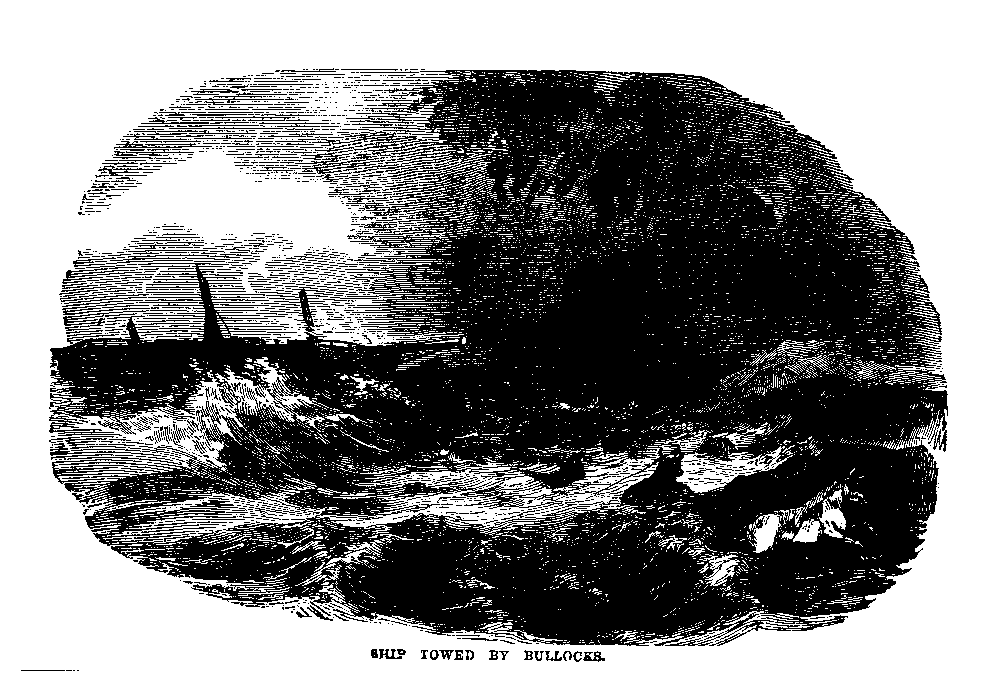

Received orders this day to proceed to London with the ship; and, as the easterly gale abated, and the wind hauled round southward and westward, we got under way, stood out of Falmouth harbor, and proceeded up the British Channel. At sunset, it commenced to rain, and the weather was thick and cloudy. The different lights were seen as far as the Bill of Portland. At midnight, lost sight of the land, and it blew a gale from off the French coast: close reefed the topsails, and steered a course so as to keep in mid-channel. At daybreak, the ship was judged to be off Beachy Head; the weather being so thick, the land could not be seen. The fore and mizzen-topsails were now furled, and the ship hove to. The rain began now to fall in torrents, and the heavy, dense, black clouds rose, with fearful rapidity, from the northward, over the English coast, when suddenly the wind shifted from the south-west to the north, and blew a hurricane. The mist and fog cleared away, and, to our utter astonishment, we found ourselves on a lee shore, on the coast of France, off Boulogne heights. The gale was so violent, that no more sail could be made. The ship was so exceedingly crank, that when she luffed up on a wind, her bulwarks were under water. As she would not stay, the only alternative was, to wear; of course, with this evolution, we lost ground, and, consequently, were driven nearer, every moment, toward the awful strand of rocks. The scene was now terrific; many vessels were in sight, two of which we saw dashed on the rocks; with the tremendous roar of the breakers, and the howling of the tempest, and the heavy sea, which broke as high as the fore-yard, death appeared inevitable. There was only one hope left, and that was, that, should the tide change and take us under our lee-beam, it might possibly set us off on the Nine-fathom bank, which is situated at a distance of twelve miles north-northwest, off Boulogne harbor. On the event of reaching this bank, the safety of the ship and lives of the crew depended,--as it was determined there to try the anchors, for there was no possibility of keeping off shore more than two hours, if the gale continued.

We were now on the larboard tack, and, for the last half hour, it was perceived that the tide had turned, and was setting to the northward; this was our last and only chance, for the rocks were not more than half a mile under our lee, and as it was necessary to get the ship's head round on the starboard tack, which could only be done by wearing, it was certain that much ground would be lost by that evolution. The anchors were got ready, long ranges of cables were hauled on deck, and the ends were clinched to the mainmast below; this being done, the axes were at hand to cut away the masts.

Captain G. was an old, experienced seaman; and I never saw, before or since, more coolness, judgment, and seamanship, than were displayed by him on this trying occasion. In this perilous trial, the most intense anxiety was manifested by the crew, and then was heard the deep-toned voice of Captain G., rising above the bellowing storm, commanding silence. "Take the wheel," said he to me; and then followed the orders, in quick succession: "Lay aft, and man the braces--see every thing clear forward, to wear ship--steady--ease her--shiver away the main-topsail--put your helm up--haul in the weather fore-braces,--gather in the after-yards." The ship was now running before the wind, for a few moments, directly for the rocks; the situation and scene were truly awful, for she was not more than three hundred yards from the breakers. I turned my head aside--being at the helm--to avoid the terrific sight, and silently awaited the crisis. I was roused, at this moment, by Captain G., who shouted, "She luffs, my boys! brace the main-yard sharp up--haul in the larboard fore-braces--down with the fore-tack, lads, and haul aft the sheet;--right the helm! steady, so--haul taut the weather-braces, and belay all." These orders were given and executed in quick succession. The ship was now on the starboard tack, plunging bows under at every pitch. Casting a fitful glance over my shoulder, I saw that we were apparently to leeward of the rocks. Very soon, however, it was quite perceptible that the tide had taken her on the lee beam, and was setting her off shore.

The gloom began now to wear away, although it was doubtful whether we should be able to reach the bank, and, if successful, whether the anchors would hold on. Orders were given to lay aloft and send down the top-gallant-yards, masts, &c. The helm was relieved, and I sprung into the main rigging, the chief mate going up forward. With much difficulty, I reached the main-topmast cross-trees, and, when there, it was almost impossible to work, for the ship lay over at an angle of at least forty-five degrees, and I found myself swinging, not perpendicularly over the ship's deck, but at least thirty feet from it. It was no time, however, for gazing. The yard rope was stoppered out on the quarter of the yard, the sheets, clewlines, and buntlines, cast off, and the shift slackened, and then simultaneously from both mast-heads the cry was heard, "Sway, away!" The parrel cut, the yard was quickly topped and unrigged, and then lowered away on deck. The next duty to be performed, was sending down the top-gallant masts. After much difficulty and hard work, this was also accomplished; and, although I felt some pride in the performance of a dangerous service, yet, on this occasion, I was not a little pleased when I reached the deck in safety.

By this time, we had gained four miles off shore, and it was evident that the soundings indicated our approach to the bank. Tackles were rove and stretched along forward of the windlass, as well as deck-stoppers hooked on to the ringbolts fore and aft. "Loose the fore-topsail!" shouted Captain G., "we must reach this bank before the tide turns, or, by morning, there will not be left a timber head of this ship, nor one of us, to tell the sad tale of our disaster." The topsail was loosed and set, and the ship groaned heavily under the immense pressure of canvass; her lee rail was under water, and every moment it was expected that the topmast or the canvass would yield. The deep-sea-lead was taken forward and hove: when the line reached the after-part of the main channels, the seaman's voice rose high in the air, "By the deep, nine!" It was three o'clock. "Clew up and furl the fore-topsail!" shouted Captain G. The topsail furled of itself, for the moment the weather sheet was started, it blew away from the bolt-rope; the foresail was immediately hauled up and furled. Relieved from the great pressure of canvass, and having now nothing on her except the main-topsail and fore-topmast-staysail, she rode more upright. The main-topsail was clewed up and fortunately saved, the mizzen-staysail was set. "Stand by, to cut away the stoppers of the best bower anchor--to let it go, stock and fluke," said Captain G. "Man the fore-topmast-staysail down-haul; put your helm down! haul down the staysail." This was done, and the ship came up handsomely, head to wind, "See the cable tiers all clear--what water is there?" said Captain G. The leadsman sang out in a clear voice, "And a half-eight!" By this time, the ship had lost her way. "Are you all clear forward there?" "Ay, ay, sir!" was the reply. "Stream the buoy, and let go the anchor!" shouted Captain G. The order was executed as rapidly as it was given; the anchor was on the bottom, and already had fifty fathoms of cable run out, making the windlass smoke; and, although the cable was weather-bitted, and every effort was made with the deck-stoppers and tackles to check her, all was fruitless. Ninety fathoms of cable had run out. "Stand by, to let go the larboard anchor," said Captain G.; "Cheerily, men--let go!" In the same breath he shouted, "Hold on!" for just then there was a lull, and having run out the best bower-cable, nearly to the better end, she brought up. No time was now lost in getting service on the cable, to prevent its chafing. She was now riding to a single anchor of two thousand weight, with one hundred fathoms of a seventeen-inch hemp cable. The sea rolled heavily, and broke in upon the deck fore and aft; the lower yards were got down; the topsail-yards pointed to the wind; and as the tide had now turned, the ship rode without any strain on her cable, because it tended broad on the beam.

The next morning presented a dismal scene, for there were more than fifty sail in-shore of us, some of whom succeeded in reaching the bank, and anchored with loss of sails, topmasts, &c. Many others were dashed upon the rocks, and not a soul was left to tell the tale of their destruction. I shall not forget that, on the second day, a Dutch galliot was driven in to leeward of us; and although, by carrying on a tremendous press of canvass, she succeeded in keeping off shore until five P.M., yet, at sunset she disappeared, and was seen no more. After our arrival in London, we learned that this unfortunate vessel was driven on the rocks, and every soul on board perished.

The gale continued four days, at the expiration of which time, it broke. At midnight, the wind hauled round to the eastward, and the weather became so excessively cold, that, although we commenced heaving in the cable at five A.M., yet we did not get the anchor until nine that night. Close-reefed topsails were set on the ship and we stood over to the English coast, and anchored to the westward of Dungeness. During the whole period of this gale, which lasted four days, Captain G. never for one moment left the deck; and although well advanced in years, yet his iron constitution enabled him to overcome the calls of nature for rest; and, notwithstanding the situation of the ship, was, perhaps more critical than many of those less fortunate vessels which stranded upon the rocks, yet his coolness, and the seaman-like manner with which the ship was handled, no doubt were the means of our being saved.

Thomas Cooper was a fine specimen of the North American trapper. Slightly but powerfully made, with a hardy, weather-beaten, yet handsome face; strong, indefatigable, and a crack shot--he was admirably adapted for a hunter's life. For many years he knew not what it was to have a home, but lived like the beasts he hunted--wandering from one part of the country to another, in pursuit of game. All who knew Tom were much surprised when he came, with a pretty young wife, to settle within three miles of a planter's farm. Many pitied the poor young creature, who would have to lead such a solitary life; while others said, "If she was fool enough to marry him, it was her own look-out." For nearly four months Tom remained at home, and employed his time in making the old hut he had fixed on for their residence more comfortable. He cleared and tilled a small spot of land around it, and Susan began to hope that, for her sake, he would settle down quietly as a squatter. But these visions of happiness were soon dispelled, for, as soon as this work was finished, he recommenced his old erratic mode of life, and was often absent for weeks together, leaving his wife alone, yet not unprotected, for, since his marriage, old Nero, a favorite hound, was always left at home as her guardian. He was a noble dog--a cross between the old Scottish deerhound and the bloodhound, and would hunt an Indian as well as a deer or bear, which, Tom said, "was a proof they Injins was a sort o' warmint, or why should the brute beast take to hunt 'em, nat'ral like--him that took no notice of white men?"

One clear, cold morning, about two years after their marriage, Susan was awakened by a loud crash, immediately succeeded by Nero's deep baying. She recollected that she had shut him in the house, as usual, the night before. Supposing he had winded some solitary wolf or bear prowling around the hut, and effected his escape, she took little notice of the circumstance; but a few moments after came a shrill, wild cry, which made her blood run cold. To spring from her bed, throw on her clothes, and rush from the hut, was the work of a minute. She no longer doubted what the hound was in pursuit of. Fearful thoughts shot through her brain; she called wildly on Nero, and, to her joy, he came dashing through the thick underwood. As the dog drew near, she saw that he galloped heavily, and carried in his mouth some large, dark creature. Her brain reeled; she felt a cold and sickly shudder dart through her limbs. But Susan was a hunter's daughter, and, all her life, had been accustomed to witness scenes of danger and of horror, and in this school had learned to subdue the natural timidity of her character. With a powerful effort, she recovered herself, just as Nero dropped at her feet a little Indian child, apparently between three and four years old. She bent down over him; but there was no sound or motion: she placed her hand on his little, naked chest; the heart within had ceased to beat: he was dead! The deep marks of the dog's fangs were visible on the neck; but the body was untorn. Old Nero stood, with his large, bright eyes fixed on the face of his mistress, fawning on her, as if he expected to be praised for what he had done, and seemed to wonder why she looked so terrified. But Susan spurned him from her; and the fierce animal, who would have pulled down an Indian as he would a deer, crouched humbly at the young woman's feet. Susan carried the little body gently in her arms to the hut, and laid it on her own bed. Her first impulse was to seize the loaded rifle that hung over the fire-place, and shoot the hound; and yet she felt she could not do it, for, in the lone life she led, the faithful animal seemed like a dear and valued friend, who loved and watched over her, as if aware of the precious charge intrusted to him. She thought, also, of what her husband would say, when, on his return, he should find his old companion dead. Susan had never seen Tom roused. To her he had ever shown nothing but kindness; yet she feared as well as loved him, for there was a fire in those dark eyes which told of deep, wild passions hidden in his breast, and she knew that the lives of a whole tribe of Indians would be light in the balance against that of his favorite hound.

Having securely fastened up Nero, Susan, with a heavy heart, proceeded to examine the ground around the hut. In several places she observed the impression of a small moccasined foot; but not a child's. The tracks were deeply marked, unlike the usual light, elastic tread of an Indian. From this circumstance Susan easily inferred that the woman had been carrying her child when attacked by the dog. There was nothing to show why she had come so near the hut: most probably the hopes of some petty plunder had been the inducement. Susan did not dare to wander far from home, fearing a band of Indians might be in the neighborhood. She returned sorrowfully to the hut, and employed herself in blocking up the window, or rather the hole where the window had been, for the powerful hound had, in his leap, dashed out the entire frame, and shattered it to pieces. When this was finished, Susan dug a grave, and in it laid the little Indian boy. She made it close to the hut, for she could not bear that wolves should devour those delicate limbs, and she knew that there it would be safe. The next day Tom returned. He had been very unsuccessful, and intended setting out again, in a few days, in a different direction.

"Susan," he said, when he had heard her sad story, "I wish you'd left the child where the dog killed him. The squaw's high sartain to come back a seekin' for the body, and 'tis a pity the poor crittur should be disappointed. Besides, the Indians will be high sartain to put it down to us; whereas, if so be as they'd found the body 'pon the spot, may be they'd onderstand as 'twas an accident like, for they 're unkimmon cunning warmint, though they an't got sense like Christians."

"Why do you think the poor woman came here?" said Susan. "I never knew an Indian squaw so near the hut before?"

She fancied a dark shadow flitted across her husband's brow. He made no reply; and, on repeating the question, said angrily, "How should I know? 'Tis as well to ask for a bear's reasons as an Injin's."

Tom only staid at home long enough to mend the broken window, and plant a small spot of Indian corn, and then again set out, telling Susan not to expect him home in less than a month. "If that squaw comes this way agin," he said, "as may be she will, just put out any victuals you've a-got for the poor crittur; though may be she wont come, for they Injins be onkimmon skeary." Susan wondered at his taking an interest in the woman, and often thought of that dark look she had noticed, and of Tom's unwillingness to speak on the subject. She never knew that on his last hunting expedition, when hiding some skins which he intended to fetch on his return, he had observed an Indian watching him, and had shot him, with as little mercy as he would have shown to a wolf. On Tom's return to the spot, the body was gone; and in the soft, damp soil was the mark of an Indian squaw's foot; and by its side, a little child's. He was sorry then for the deed he had done; he thought of the grief of the poor widow, and how it would be possible for her to live until she could reach her tribe, who were far, far distant, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains; and now to feel, that, through his means, too, she had lost her child, put thoughts into his mind that had never before found a place there. He thought that one God had formed the red man as well as the white--of the souls of the many Indians hurried into eternity by his unerring rifle; and they, perhaps, were more fitted for their "happy hunting grounds," than he for the white man's heaven. In this state of mind, every word his wife had said to him seemed a reproach, and he was glad again to be alone, in the forest, with his rifle and his hounds.

The afternoon of the third day after Tom's departure, as Susan was sitting at work, she heard something scratching and whining at the door. Nero, who was by her side, evinced no signs of anger, but ran to the door, showing his white teeth, as was his custom when pleased. Susan unbarred it, when, to her astonishment, the two deerhounds her husband had taken with him, walked into the hut, looking weary and soiled. At first she thought Tom might have killed a deer not far from home, and had brought her a fresh supply of venison; but no one was there. She rushed from the hut, and soon, breathless and terrified, reached the squatter's cabin. John Wilton and his three sons were just returned from the clearings, when Susan ran into their comfortable kitchen; her long, black hair, streaming on her shoulders, and her wild and bloodshot eyes, gave her the appearance of a maniac. In a few unconnected words, she explained to them the cause of her terror, and implored them to set off immediately in search of her husband. It was in vain they told her of the uselessness of going at that time--of the impossibility of following a trail in the dark. She said she would go herself: she felt sure of finding him; and, at last, they were obliged to use force to prevent her leaving the house.

The next morning at daybreak, Wilton and his two sons were mounted, and ready to set out, intending to take Nero with them; but nothing could induce him to leave his mistress: he resisted passively for some time, until one of the young men attempted to pass a rope round his neck, to drag him away: then his forbearance vanished, and he sprang upon his tormentor, threw him down, and would have strangled him, if Susan had not been present. Finding it impossible to make Nero accompany them, they left without him, but had not proceeded many miles before he and his mistress were at their side. They begged Susan to return; told her of the inconvenience she would be to them. It was no avail; she had but one answer,--"I am a hunter's daughter, and a hunter's wife." She told them that, knowing how useful Nero would be to them in their search, she had secretly taken a horse and followed them.

The party rode first to Tom Cooper's hut, and there, having dismounted, leading their horses through the forest, followed the trail, as only men long accustomed to savage life can do. At night they lay on the ground, covered with their thick, bear-skin cloaks: for Susan only, they heaped a bed of dried leaves; but she refused to occupy it, saying, it was her duty to bear the same hardships they did. Ever since their departure, she had shown no sign of sorrow. Although slight and delicately formed, she never appeared fatigued: her whole soul was absorbed in one longing desire--to find her husband's body; for, from the first, she had abandoned the hope of ever again seeing him in life. This desire supported her through everything. Early the next morning they were on the trail. About noon, as they were crossing a small brook, the hound suddenly dashed away from them, and was lost in the thicket. At first they fancied they might have crossed the track of a deer or wolf; but a long, mournful howl soon told the sad truth, for, not far from the brook, lay the faithful dog on the dead body of his master, which was pierced to the heart by an Indian arrow.

The murderer had apparently been afraid to approach on account of the dogs, for the body was left as it had fallen--not even the rifle was gone. No sign of Indians could be discovered, save one small footprint, which was instantly pronounced to be that of a squaw. Susan showed no grief at the sight of the body: she maintained the same forced calmness, and seemed comforted that it was found. Old Wilton staid with her to remove all that now remained of her darling husband, and his two sons set out on the trail, which soon led them into the open prairie, where it was easily traced through the tall, thick grass. They continued riding all that afternoon, and the next morning by daybreak were again on the track, which they followed to the banks of a wide but shallow stream. There they saw the remains of a fire. One of the brothers thrust his hand among the ashes, which were still warm. They crossed the river; and, in the soft sand on the opposite bank, saw again the print of small, moccasined footsteps. Here they were at a loss; for the rank prairie-grass had been consumed by one of those fearful fires so common in the prairies, and in its stead grew short, sweet herbage, where even an Indian's eye could observe no trace. They were on the point of abandoning the pursuit, when Richard, the younger of the two, called his brother's attention to Nero, who had, of his own accord, left his mistress to accompany them, an if he now understood what they were about. The hound was trotting to and fro, with his nose to the ground, as if endeavoring to pick out a cold scent Edward laughed at his brother, and pointed to the track of a deer that had come to drink at the river. At last he agreed to follow Nero, who was now cantering slowly across the prairie. The pace gradually increased, until, on a spot where the grass had grown more luxuriantly than elsewhere, Nero threw up his nose, gave a deep bay, and started off at so furious a pace, that, although well mounted, they had great difficulty in keeping up with him. He soon brought them to the borders of another forest, where, finding it impossible to take their horses further, they tethered them to a tree, and set off again on foot. They lost sight of the hound, but still, from time to time, heard his loud baying far away. At last they fancied it sounded nearer instead of becoming less distinct; and of this they were soon convinced. They still went on in the direction whence the sound proceeded, until they saw Nero sitting with his fore-paws against the trunk of a tree, no longer mouthing like a well-trained hound, but yelling like a fury. They looked up in the tree, but could see nothing, until, at last, Edward espied a large hollow about half way up the trunk. "I was right, you see," he said. "After all, it nothing but a bear; but we may as well shoot the brute that has given us so much trouble."

They set to work immediately with their axes to fell the tree. It began to totter, when a dark object, they could not tell what, in the dim twilight, crawled from its place of concealment to the extremity of a branch, and from thence sprung into the next tree. Snatching up their rifles, they both fired together; when, to their astonishment, instead of a bear, a young Indian squaw, with a wild yell, fell to the ground. They ran to the spot where she lay motionless, and carried her to the borders of the wood, where they had that morning dismounted. Richard lifted her on his horse, and springing himself into the saddle, carried the almost lifeless body before him. The poor creature never spoke. Several times they stopped, thinking she was dead: her pulse only told the spirit had not flown from its earthly tenement. When they reached the river which had been crossed by them before, they washed the wounds, and sprinkled water on her face. This appeared to revive her; and when Richard again lifted her in his arms to place her on his horse, he fancied he heard her mutter, in Iroquois, one word,--"revenged!" It was a strange sight, those two powerful men tending so carefully the being they had a few hours before sought to slay, and endeavoring to stanch the blood that flowed from wounds which they had made! Yet so it was. It would have appeared to them a sin to leave the Indian woman to die; yet they felt no remorse at having inflicted the wound, and doubtless would have been better pleased had it been mortal; but they would not have murdered a wounded enemy, even an Indian warrior, still less a squaw. The party continued their journey until midnight, when they stopped, to rest their jaded horses. Having wrapped the squaw in their bear-skins, they lay down themselves, with no covering save the clothes they wore. They were in no want of provisions, as, not knowing when they might return, they had taken a good supply of bread and dried venison, not wishing to loose any precious time in seeking food while on the trail. The brandy still remaining in their flasks, they preserved for the use of their captive. The evening of the following day, they reached the trapper's hut, where they were not a little surprised to find Susan. She told them that, although John Wilton had begged her to live with them, she could not bear to leave the spot where everything reminded her of one to think of whom was now her only consolation; and that, while she had Nero, she feared nothing. They needed not to tell their mournful tale--Susan already understood it but too clearly. She begged them to leave the Indian woman with her. "You have no one," said she, "to tend and watch her as I can do; besides, it is not right that I should lay such a burden on you." Although unwilling to impose on her mind the painful task of nursing her husband's murderess, they could not allow but that she was right; and seeing how earnestly she desired it, at last consented to leave the Indian woman with her.

For many weeks Susan nursed her charge, as tenderly as if it had been her sister. At first she lay almost motionless, and rarely spoke; then she grew delirious, and raved wildly. Susan fortunately could not understand what she said, but often turned shuddering away, when the Indian woman would strive to rise from her bed, and move her arms, as if drawing a bow; or yell wildly, and cower in terror beneath the clothes--reacting in her delirium the fearful scenes through which she had passed. By degrees reason returned; she gradually got better, but seemed restless and unhappy, and could not bear the sight of Nero. The first proof of returning reason she had shown, was a shriek of terror when he once accidentally followed his mistress into the room where she lay. One morning Susan missed her; she searched around the hut, but she was gone, without having taken farewell of her kind benefactress.

A few years after, Susan Cooper,--no longer "pretty Susan," for time and grief had done their work--heard, late one night, a hurried knock, which was repeated several times before she could open the door, each time more loudly than before. She called to ask who it was at that late hour of night. A few hurried words in Iroquois was the reply, and Susan congratulated herself on having spoken before unbarring the door. But, on listening again, she distinctly heard the same voice say, "Quick--quick!" and recognized it as the Indian woman's voice she had nursed. The door was instantly opened, when the squaw rushed into the hut, seized Susan by the arm, and made signs to her to come away. She was too much excited to remember then the few words of English she had picked up when living with the white woman. Expressing her meaning by gestures, with a clearness peculiar to the Indians, she dragged rather than led Susan from the hut. They had just reached the edge of the forest when the wild yells of the Indians sounded in their ears. Having gone with Susan a little way into the forest, her guide left her. For nearly four hours she lay there, half dead with cold and terror, not daring to move from her place of concealment. She saw the flames of the dwelling, where so many lonely hours had been passed, rising above the trees, and heard the shrill "whoops" of the retiring Indians. Nero, who was lying by her side, suddenly rose and gave a low growl. Silently a dark figure came gliding among the trees directly to the spot where she lay. She gave herself up for lost; but it was the Indian woman, who came to her, and dropped at her feet a bag of money, the remains of her late husband's savings. The grateful creature knew where it was kept; and while the Indians were busied examining the rifles and other objects more interesting to them, had carried it off unobserved. Waving her arm around to show that all was now quiet, she pointed in the direction of Wilton's house, and was again lost among the trees.

Day was just breaking when Susan reached the squatter's cabin. Having heard the sad story, Wilton and two of his sons started immediately for the spot. Nothing was to be seen save a heap of ashes. The party had apparently consisted of only three or four Indians; but a powerful tribe being in the neighborhood, they saw it would be too hazardous to follow them. From this time, Susan lived with the Wiltons. She was as a daughter to the old man, and a sister to his sons, who often said, "That, as far as they were concerned, the Indians had never done a kindlier action than in burning down Susan Cooper's hut."

About two years after the Texan revolution, a difficulty occurred between the new government and a portion of the people, which threatened the most serious consequences--even the bloodshed and horrors of civil war. Briefly, the cause was this: The constitution had fixed the city of Austin as the permanent capital, where the public archives were to be kept, with the reservation, however, of a power in the president to order their temporary removal, in case of danger from the inroads of a foreign enemy, or the force of a sudden insurrection.

Conceiving that the exceptional emergency had arrived, as the Camanches frequently committed ravages within sight of the capital itself, Houston, who then resided at Washington, on the Brazos, dispatched an order commanding his subordinate functionaries to send the state records to the latter place, which he declared to be, pro tempore, the seat of government.