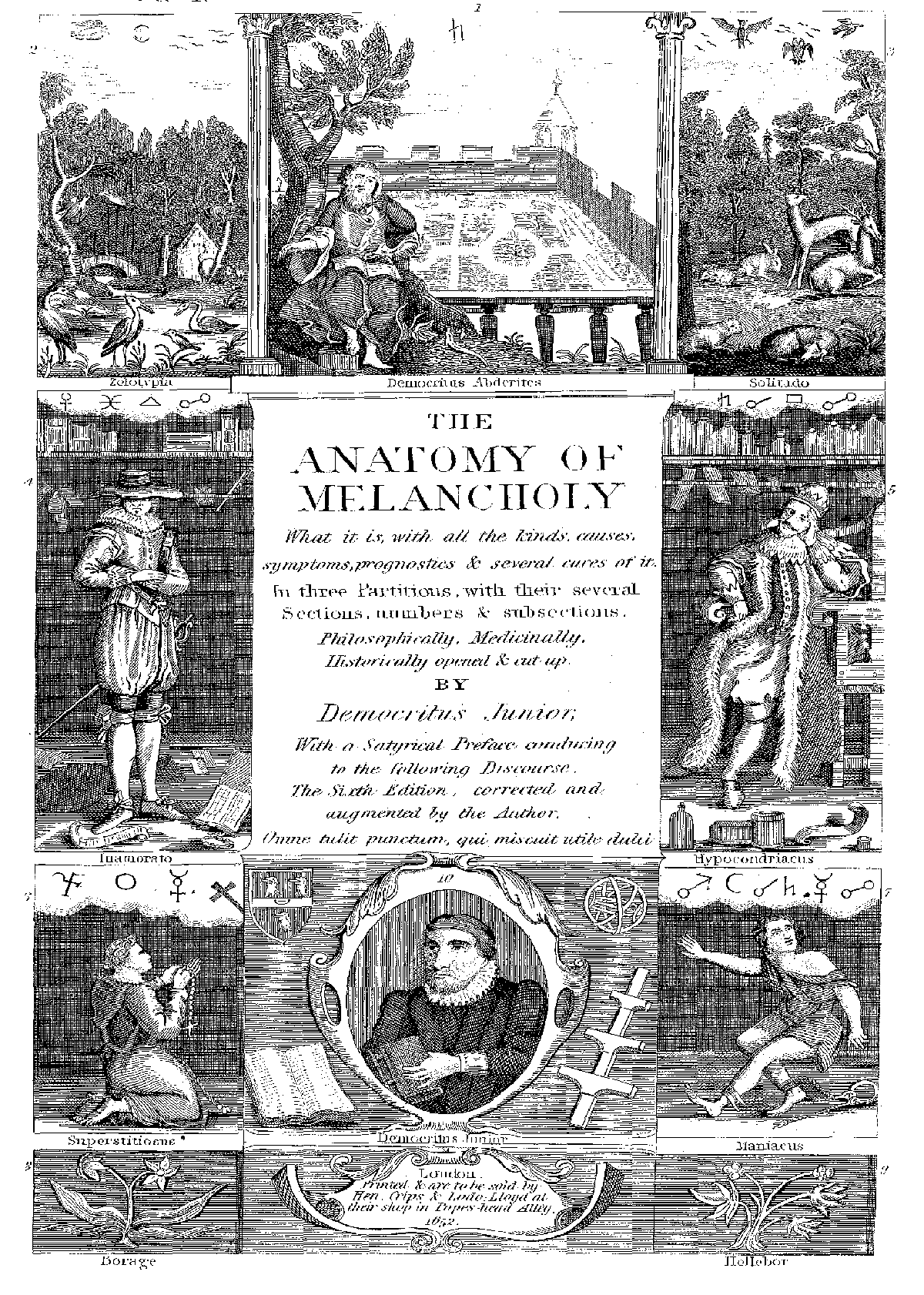

DEMOCRITUS JUNIOR TO THE READER.

Gentle reader, I presume thou wilt be very inquisitive to know what antic

or personate actor this is, that so insolently intrudes upon this common

theatre, to the world's view, arrogating another man's name; whence he is,

why he doth it, and what he hath to say; although, as [7]he said, Primum

si noluero, non respondebo, quis coacturus est? I am a free man born, and

may choose whether I will tell; who can compel me? If I be urged, I will as

readily reply as that Egyptian in [8]Plutarch, when a curious fellow would

needs know what he had in his basket, Quum vides velatam, quid inquiris in

rem absconditam? It was therefore covered, because he should not know what

was in it. Seek not after that which is hid; if the contents please thee,

[9]“and be for thy use, suppose the Man in the Moon, or whom thou wilt to

be the author;” I would not willingly be known. Yet in some sort to give

thee satisfaction, which is more than I need, I will show a reason, both of

this usurped name, title, and subject. And first of the name of Democritus;

lest any man, by reason of it, should be deceived, expecting a pasquil, a

satire, some ridiculous treatise (as I myself should have done), some

prodigious tenet, or paradox of the earth's motion, of infinite worlds, in

infinito vacuo, ex fortuita atomorum collisione, in an infinite waste, so

caused by an accidental collision of motes in the sun, all which Democritus

held, Epicurus and their master Lucippus of old maintained, and are lately

revived by Copernicus, Brunus, and some others. Besides, it hath been

always an ordinary custom, as [10]Gellius observes, “for later writers and

impostors, to broach many absurd and insolent fictions, under the name of

so noble a philosopher as Democritus, to get themselves credit, and by that

means the more to be respected,” as artificers usually do, Novo qui

marmori ascribunt Praxatilem suo. 'Tis not so with me.

[11]Non hic Centaurus, non Gorgonas, Harpyasque

Invenies, hominem pagina nostra sapit.

No Centaurs here, or Gorgons look to find,

My subject is of man and human kind.

Thou thyself art the subject of my discourse.

[12]Quicquid agunt homines, votum, timor, ira, voluptas,

Gaudia, discursus, nostri farrago libelli.

Whate'er men do, vows, fears, in ire, in sport,

Joys, wand'rings, are the sum of my report.

My intent is no otherwise to use his name, than Mercurius Gallobelgicus,

Mercurius Britannicus, use the name of Mercury, [13]Democritus

Christianus, &c.; although there be some other circumstances for which I

have masked myself under this vizard, and some peculiar respect which I

cannot so well express, until I have set down a brief character of this our

Democritus, what he was, with an epitome of his life.

Democritus, as he is described by [14]Hippocrates and [15]Laertius, was a

little wearish old man, very melancholy by nature, averse from company in

his latter days, [16]and much given to solitariness, a famous philosopher

in his age, [17]coaevus with Socrates, wholly addicted to his studies at

the last, and to a private life: wrote many excellent works, a great

divine, according to the divinity of those times, an expert physician, a

politician, an excellent mathematician, as [18]Diacosmus and the rest of

his works do witness. He was much delighted with the studies of husbandry,

saith [19]Columella, and often I find him cited by [20]Constantinus and

others treating of that subject. He knew the natures, differences of all

beasts, plants, fishes, birds; and, as some say, could [21]understand the

tunes and voices of them. In a word, he was omnifariam doctus, a general

scholar, a great student; and to the intent he might better contemplate,

[22]I find it related by some, that he put out his eyes, and was in his

old age voluntarily blind, yet saw more than all Greece besides, and [23]

writ of every subject, Nihil in toto opificio naturae, de quo non

scripsit. [24]A man of an excellent wit, profound conceit; and to attain

knowledge the better in his younger years, he travelled to Egypt and [25]

Athens, to confer with learned men, [26]“admired of some, despised of

others.” After a wandering life, he settled at Abdera, a town in Thrace,

and was sent for thither to be their lawmaker, recorder, or town-clerk, as

some will; or as others, he was there bred and born. Howsoever it was,

there he lived at last in a garden in the suburbs, wholly betaking himself

to his studies and a private life, [27]“saving that sometimes he would

walk down to the haven,” [28]“and laugh heartily at such variety of

ridiculous objects, which there he saw.” Such a one was Democritus.

But in the mean time, how doth this concern me, or upon what reference do I

usurp his habit? I confess, indeed, that to compare myself unto him for

aught I have yet said, were both impudency and arrogancy. I do not presume

to make any parallel, Antistat mihi millibus trecentis, [29]parvus sum,

nullus sum, altum nec spiro, nec spero. Yet thus much I will say of

myself, and that I hope without all suspicion of pride, or self-conceit, I

have lived a silent, sedentary, solitary, private life, mihi et musis in

the University, as long almost as Xenocrates in Athens, ad senectam fere

to learn wisdom as he did, penned up most part in my study. For I have been

brought up a student in the most flourishing college of Europe, [30]

augustissimo collegio, and can brag with [31]Jovius, almost, in ea luce

domicilii Vacicani, totius orbis celeberrimi, per 37 annos multa

opportunaque didici; for thirty years I have continued (having the use of

as good [32]libraries as ever he had) a scholar, and would be therefore

loath, either by living as a drone, to be an unprofitable or unworthy member

of so learned and noble a society, or to write that which should be any way

dishonourable to such a royal and ample foundation. Something I have done,

though by my profession a divine, yet turbine raptus ingenii, as [33]he

said, out of a running wit, an unconstant, unsettled mind, I had a great

desire (not able to attain to a superficial skill in any) to have some

smattering in all, to be aliquis in omnibus, nullus in singulis, [34]

which [35]Plato commends, out of him [36]Lipsius approves and furthers,

“as fit to be imprinted in all curious wits, not to be a slave of one

science, or dwell altogether in one subject, as most do, but to rove

abroad, centum puer artium, to have an oar in every man's boat, to [37]

taste of every dish, and sip of every cup,” which, saith [38]Montaigne,

was well performed by Aristotle, and his learned countryman Adrian

Turnebus. This roving humour (though not with like success) I have ever

had, and like a ranging spaniel, that barks at every bird he sees, leaving

his game, I have followed all, saving that which I should, and may justly

complain, and truly, qui ubique est, nusquam est, [39]which [40]Gesner

did in modesty, that I have read many books, but to little purpose, for

want of good method; I have confusedly tumbled over divers authors in our

libraries, with small profit, for want of art, order, memory, judgment. I

never travelled but in map or card, in which mine unconfined thoughts have

freely expatiated, as having ever been especially delighted with the study

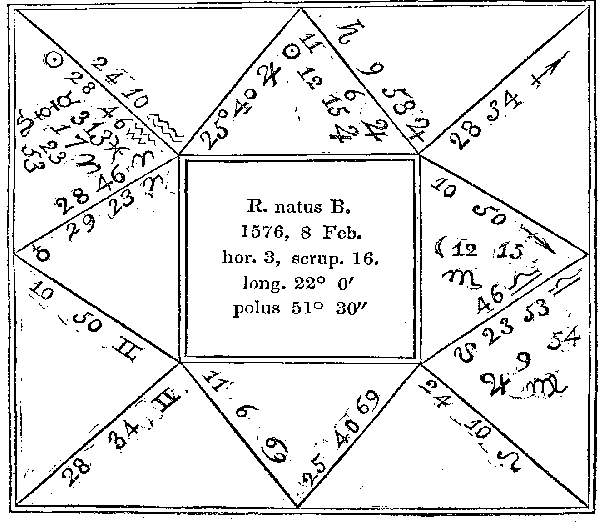

of Cosmography. [41]Saturn was lord of my geniture, culminating, &c., and

Mars principal significator of manners, in partile conjunction with my

ascendant; both fortunate in their houses, &c. I am not poor, I am not

rich; nihil est, nihil deest, I have little, I want nothing: all my

treasure is in Minerva's tower. Greater preferment as I could never get, so

am I not in debt for it, I have a competence (laus Deo) from my noble and

munificent patrons, though I live still a collegiate student, as Democritus

in his garden, and lead a monastic life, ipse mihi theatrum, sequestered

from those tumults and troubles of the world, Et tanquam in specula

positus, ([42]as he said) in some high place above you all, like Stoicus

Sapiens, omnia saecula, praeterita presentiaque videns, uno velut

intuitu, I hear and see what is done abroad, how others [43]run, ride,

turmoil, and macerate themselves in court and country, far from those

wrangling lawsuits, aulia vanitatem, fori ambitionem, ridere mecum soleo:

I laugh at all, [44]only secure, lest my suit go amiss, my ships perish,

corn and cattle miscarry, trade decay, I have no wife nor children good or

bad to provide for. A mere spectator of other men's fortunes and

adventures, and how they act their parts, which methinks are diversely

presented unto me, as from a common theatre or scene. I hear new news every

day, and those ordinary rumours of war, plagues, fires, inundations,

thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, comets, spectrums, prodigies,

apparitions, of towns taken, cities besieged in France, Germany, Turkey,

Persia, Poland, &c., daily musters and preparations, and such like, which

these tempestuous times afford, battles fought, so many men slain,

monomachies, shipwrecks, piracies and sea-fights; peace, leagues,

stratagems, and fresh alarms. A vast confusion of vows, wishes, actions,

edicts, petitions, lawsuits, pleas, laws, proclamations, complaints,

grievances are daily brought to our ears. New books every day, pamphlets,

corantoes, stories, whole catalogues of volumes of all sorts, new

paradoxes, opinions, schisms, heresies, controversies in philosophy,

religion, &c. Now come tidings of weddings, maskings, mummeries,

entertainments, jubilees, embassies, tilts and tournaments, trophies,

triumphs, revels, sports, plays: then again, as in a new shifted scene,

treasons, cheating tricks, robberies, enormous villainies in all kinds,

funerals, burials, deaths of princes, new discoveries, expeditions, now

comical, then tragical matters. Today we hear of new lords and officers

created, tomorrow of some great men deposed, and then again of fresh

honours conferred; one is let loose, another imprisoned; one purchaseth,

another breaketh: he thrives, his neighbour turns bankrupt; now plenty,

then again dearth and famine; one runs, another rides, wrangles, laughs,

weeps, &c. This I daily hear, and such like, both private and public news,

amidst the gallantry and misery of the world; jollity, pride, perplexities

and cares, simplicity and villainy; subtlety, knavery, candour and

integrity, mutually mixed and offering themselves; I rub on privus

privatus; as I have still lived, so I now continue, statu quo prius,

left to a solitary life, and mine own domestic discontents: saving that

sometimes, ne quid mentiar, as Diogenes went into the city, and

Democritus to the haven to see fashions, I did for my recreation now and

then walk abroad, look into the world, and could not choose but make some

little observation, non tam sagax observator ac simplex recitator, [45]

not as they did, to scoff or laugh at all, but with a mixed passion.

[46]Bilem saepe, jocum vestri movere tumultus.

Ye wretched mimics, whose fond heats have been,

How oft! the objects of my mirth and spleen.

I did sometime laugh and scoff with Lucian, and satirically tax with

Menippus, lament with Heraclitus, sometimes again I was

[47]petulanti

splene chachinno, and then again,

[48]urere bilis jecur, I was much

moved to see that abuse which I could not mend. In which passion howsoever

I may sympathise with him or them, 'tis for no such respect I shroud myself

under his name; but either in an unknown habit to assume a little more

liberty and freedom of speech, or if you will needs know, for that reason

and only respect which Hippocrates relates at large in his Epistle to

Damegetus, wherein he doth express, how coming to visit him one day, he

found Democritus in his garden at Abdera, in the suburbs,

[49]under a

shady bower,

[50]with a book on his knees, busy at his study, sometimes

writing, sometimes walking. The subject of his book was melancholy and

madness; about him lay the carcases of many several beasts, newly by him

cut up and anatomised; not that he did contemn God's creatures, as he told

Hippocrates, but to find out the seat of this

atra bilis, or melancholy,

whence it proceeds, and how it was engendered in men's bodies, to the

intent he might better cure it in himself, and by his writings and

observation

[51]teach others how to prevent and avoid it. Which good

intent of his, Hippocrates highly commended: Democritus Junior is therefore

bold to imitate, and because he left it imperfect, and it is now lost,

quasi succenturiator Democriti, to revive again, prosecute, and finish in

this treatise.

You have had a reason of the name. If the title and inscription offend your

gravity, were it a sufficient justification to accuse others, I could

produce many sober treatises, even sermons themselves, which in their

fronts carry more fantastical names. Howsoever, it is a kind of policy in

these days, to prefix a fantastical title to a book which is to be sold;

for, as larks come down to a day-net, many vain readers will tarry and

stand gazing like silly passengers at an antic picture in a painter's shop,

that will not look at a judicious piece. And, indeed, as [52]Scaliger

observes, “nothing more invites a reader than an argument unlooked for,

unthought of, and sells better than a scurrile pamphlet,” tum maxime cum

novitas excitat [53]palatum. “Many men,” saith Gellius, “are very

conceited in their inscriptions,” “and able” (as [54]Pliny quotes out of

Seneca) “to make him loiter by the way that went in haste to fetch a midwife

for his daughter, now ready to lie down.” For my part, I have honourable

[55]precedents for this which I have done: I will cite one for all,

Anthony Zara, Pap. Epis., his Anatomy of Wit, in four sections, members,

subsections, &c., to be read in our libraries.

If any man except against the matter or manner of treating of this my

subject, and will demand a reason of it, I can allege more than one; I

write of melancholy, by being busy to avoid melancholy. There is no greater

cause of melancholy than idleness, “no better cure than business,” as [56]

Rhasis holds: and howbeit, stultus labor est ineptiarum, to be busy in

toys is to small purpose, yet hear that divine Seneca, aliud agere quam

nihil, better do to no end, than nothing. I wrote therefore, and busied

myself in this playing labour, oliosaque diligentia ut vitarem torporum

feriandi with Vectius in Macrobius, atque otium in utile verterem

negatium.

[57]Simul et jucunda et idonea dicere vita,

Lectorem delectando simul atque monendo.

Poets would profit or delight mankind,

And with the pleasing have th' instructive joined.

Profit and pleasure, then, to mix with art,

T' inform the judgment, nor offend the heart,

Shall gain all votes.

To this end I write, like them, saith Lucian, that “recite to trees, and

declaim to pillars for want of auditors:” as [58]Paulus Aegineta

ingenuously confesseth, “not that anything was unknown or omitted, but to

exercise myself,” which course if some took, I think it would be good for

their bodies, and much better for their souls; or peradventure as others

do, for fame, to show myself (Scire tuum nihil est, nisi te scire hoc

sciat alter). I might be of Thucydides' opinion, [59]“to know a thing and

not to express it, is all one as if he knew it not.” When I first took this

task in hand, et quod ait [60]ille, impellents genio negotium suscepi,

this I aimed at; [61]vel ut lenirem animum scribendo, to ease my mind by

writing; for I had gravidum cor, foetum caput, a kind of imposthume in my

head, which I was very desirous to be unladen of, and could imagine no

fitter evacuation than this. Besides, I might not well refrain, for ubi

dolor, ibi digitus, one must needs scratch where it itches. I was not a

little offended with this malady, shall I say my mistress Melancholy, my

Aegeria, or my malus genius? and for that cause, as he that is stung with

a scorpion, I would expel clavum clavo, [62]comfort one sorrow with

another, idleness with idleness, ut ex vipera Theriacum, make an antidote

out of that which was the prime cause of my disease. Or as he did, of whom

[63]Felix Plater speaks, that thought he had some of Aristophanes' frogs

in his belly, still crying Breec, okex, coax, coax, oop, oop, and for

that cause studied physic seven years, and travelled over most part of

Europe to ease himself. To do myself good I turned over such physicians as

our libraries would afford, or my [64]private friends impart, and have

taken this pains. And why not? Cardan professeth he wrote his book, De

Consolatione after his son's death, to comfort himself; so did Tully write

of the same subject with like intent after his daughter's departure, if it

be his at least, or some impostor's put out in his name, which Lipsius

probably suspects. Concerning myself, I can peradventure affirm with Marius

in Sallust, [65]“that which others hear or read of, I felt and practised

myself; they get their knowledge by books, I mine by melancholising.”

Experto crede Roberto. Something I can speak out of experience,

aerumnabilis experientia me docuit; and with her in the poet, [66]Haud

ignara mali miseris succurrere disco; I would help others out of a

fellow-feeling; and, as that virtuous lady did of old, [67]“being a leper

herself, bestow all her portion to build an hospital for lepers,” I will

spend my time and knowledge, which are my greatest fortunes, for the common

good of all.

Yea, but you will infer that this is [68]actum agere, an unnecessary

work, cramben bis coctam apponnere, the same again and again in other

words. To what purpose? [69]“Nothing is omitted that may well be said,” so

thought Lucian in the like theme. How many excellent physicians have

written just volumes and elaborate tracts of this subject? No news here;

that which I have is stolen, from others, [70]Dicitque mihi mea pagina

fur es. If that severe doom of [71]Synesius be true, “it is a greater

offence to steal dead men's labours, than their clothes,” what shall become

of most writers? I hold up my hand at the bar among others, and am guilty

of felony in this kind, habes confitentem reum, I am content to be

pressed with the rest. 'Tis most true, tenet insanabile multos scribendi

cacoethes, and [72]“there is no end of writing of books,” as the wiseman

found of old, in this [73]scribbling age, especially wherein [74]“the

number of books is without number,” (as a worthy man saith,) “presses be

oppressed,” and out of an itching humour that every man hath to show

himself, [75]desirous of fame and honour (scribimus indocti

doctique——) he will write no matter what, and scrape together it boots

not whence. [76]“Bewitched with this desire of fame,” etiam mediis in

morbis, to the disparagement of their health, and scarce able to hold a

pen, they must say something, [77]“and get themselves a name,” saith

Scaliger, “though it be to the downfall and ruin of many others.” To be

counted writers, scriptores ut salutentur, to be thought and held

polymaths and polyhistors, apud imperitum vulgus ob ventosae nomen artis,

to get a paper-kingdom: nulla spe quaestus sed ampla famae, in this

precipitate, ambitious age, nunc ut est saeculum, inter immaturam

eruditionem, ambitiosum et praeceps ('tis [78]Scaliger's censure); and

they that are scarce auditors, vix auditores, must be masters and

teachers, before they be capable and fit hearers. They will rush into all

learning, togatam armatam, divine, human authors, rake over all indexes

and pamphlets for notes, as our merchants do strange havens for traffic,

write great tomes, Cum non sint re vera doctiores, sed loquaciores,

whereas they are not thereby better scholars, but greater praters. They

commonly pretend public good, but as [79]Gesner observes, 'tis pride and

vanity that eggs them on; no news or aught worthy of note, but the same in

other terms. Ne feriarentur fortasse typographi vel ideo scribendum est

aliquid ut se vixisse testentur. As apothecaries we make new mixtures

everyday, pour out of one vessel into another; and as those old Romans

robbed all the cities of the world, to set out their bad-sited Rome, we

skim off the cream of other men's wits, pick the choice flowers of their

tilled gardens to set out our own sterile plots. Castrant alios ut libros

suos per se graciles alieno adipe suffarciant (so [80]Jovius inveighs.)

They lard their lean books with the fat of others' works. Ineruditi

fures, &c. A fault that every writer finds, as I do now, and yet faulty

themselves, [81]Trium literarum homines, all thieves; they pilfer out of

old writers to stuff up their new comments, scrape Ennius' dunghills, and

out of [82]Democritus' pit, as I have done. By which means it comes to

pass, [83]“that not only libraries and shops are full of our putrid

papers, but every close-stool and jakes,” Scribunt carmina quae legunt

cacantes; they serve to put under pies, to [84]lap spice in, and keep

roast meat from burning. “With us in France,” saith [85]Scaliger, “every

man hath liberty to write, but few ability.” [86]“Heretofore learning was

graced by judicious scholars, but now noble sciences are vilified by base

and illiterate scribblers,” that either write for vainglory, need, to get

money, or as Parasites to flatter and collogue with some great men, they

put cut [87]burras, quisquiliasque ineptiasque. [88]Amongst so many

thousand authors you shall scarce find one, by reading of whom you shall be

any whit better, but rather much worse, quibus inficitur potius, quam

perficitur, by which he is rather infected than any way perfected.

Quid didicit tandem, quid scit nisi somnia, nugas?

So that oftentimes it falls out (which Callimachus taxed of old) a great

book is a great mischief.

[90]Cardan finds fault with Frenchmen and

Germans, for their scribbling to no purpose,

non inquit ab edendo

deterreo, modo novum aliquid inveniant, he doth not bar them to write, so

that it be some new invention of their own; but we weave the same web

still, twist the same rope again and again; or if it be a new invention,

'tis but some bauble or toy which idle fellows write, for as idle fellows

to read, and who so cannot invent?

[91]“He must have a barren wit, that in

this scribbling age can forge nothing.

[92]Princes show their armies, rich

men vaunt their buildings, soldiers their manhood, and scholars vent their

toys;” they must read, they must hear whether they will or no.

[93]Et quodcunque semel chartis illeverit, omnes

Gestiet a furno redeuntes scire lacuque,

Et pueros et anus———

What once is said and writ, all men must know,

Old wives and children as they come and go.

“What a company of poets hath this year brought out,” as Pliny complains to

Sossius Sinesius.

[94]“This April every day some or other have recited.”

What a catalogue of new books all this year, all this age (I say), have our

Frankfort Marts, our domestic Marts brought out? Twice a year,

[95]

Proferunt se nova ingenia et ostentant, we stretch our wits out, and set

them to sale,

magno conatu nihil agimus. So that which

[96]Gesner much

desires, if a speedy reformation be not had, by some prince's edicts and

grave supervisors, to restrain this liberty, it will run on

in infinitum.

Quis tam avidus librorum helluo, who can read them? As already, we shall

have a vast chaos and confusion of books, we are

[97]oppressed with them,

[98]our eyes ache with reading, our fingers with turning. For my part I am

one of the number,

nos numerus sumus, (we are mere ciphers): I do not

deny it, I have only this of Macrobius to say for myself,

Omne meum, nihil

meum, 'tis all mine, and none mine. As a good housewife out of divers

fleeces weaves one piece of cloth, a bee gathers wax and honey out of many

flowers, and makes a new bundle of all,

Floriferis ut apes in saltibus omnia libant,

I have laboriously

[99]collected this cento out of divers

writers, and that

sine injuria, I have wronged no authors, but given

every man his own; which

[100]Hierom so much commends in Nepotian; he

stole not whole verses, pages, tracts, as some do nowadays, concealing

their authors' names, but still said this was Cyprian's, that Lactantius,

that Hilarius, so said Minutius Felix, so Victorinus, thus far Arnobius: I

cite and quote mine authors (which, howsoever some illiterate scribblers

account pedantical, as a cloak of ignorance, and opposite to their affected

fine style, I must and will use)

sumpsi, non suripui; and what Varro,

lib. 6. de re rust. speaks of bees,

minime maleficae nullius opus

vellicantes faciunt delerius, I can say of myself, Whom have I injured?

The matter is theirs most part, and yet mine,

apparet unde sumptum sit

(which Seneca approves),

aliud tamen quam unde sumptum sit apparet, which

nature doth with the aliment of our bodies incorporate, digest, assimilate,

I do

concoquere quod hausi, dispose of what I take. I make them pay

tribute, to set out this my Maceronicon, the method only is mine own, I

must usurp that of

[101]Wecker

e Ter. nihil dictum quod non dictum prius,

methodus sola artificem ostendit, we can say nothing but what hath been

said, the composition and method is ours only, and shows a scholar.

Oribasius, Aesius, Avicenna, have all out of Galen, but to their own method,

diverso stilo, non diversa fide. Our poets steal from Homer; he spews,

saith Aelian, they lick it up. Divines use Austin's words verbatim still,

and our story-dressers do as much; he that comes last is commonly best,

———donec quid grandius aetas

Postera sorsque ferat melior.———

[102]

Though there were many giants of old in physic and philosophy, yet I say

with

[103]Didacus Stella, “A dwarf standing on the shoulders of a giant

may see farther than a giant himself;” I may likely add, alter, and see

farther than my predecessors; and it is no greater prejudice for me to

indite after others, than for Aelianus Montaltus, that famous physician, to

write

de morbis capitis after Jason Pratensis, Heurnius, Hildesheim, &c.,

many horses to run in a race, one logician, one rhetorician, after another.

Oppose then what thou wilt,

Allatres licet usque nos et usque

Et gannitibus improbis lacessas.

I solve it thus. And for those other faults of barbarism,

[104]Doric

dialect, extemporanean style, tautologies, apish imitation, a rhapsody of

rags gathered together from several dunghills, excrements of authors, toys

and fopperies confusedly tumbled out, without art, invention, judgment,

wit, learning, harsh, raw, rude, fantastical, absurd, insolent, indiscreet,

ill-composed, indigested, vain, scurrile, idle, dull, and dry; I confess

all ('tis partly affected), thou canst not think worse of me than I do of

myself. 'Tis not worth the reading, I yield it, I desire thee not to lose

time in perusing so vain a subject, I should be peradventure loath myself to

read him or thee so writing; 'tis not

operae, pretium. All I say is this,

that I have

[105]precedents for it, which Isocrates calls

perfugium iis

qui peccant, others as absurd, vain, idle, illiterate, &c.

Nonnulli alii

idem fecerunt; others have done as much, it may be more, and perhaps thou

thyself,

Novimus et qui te, &c. We have all our faults;

scimus, et hanc,

veniaim, &c.;

[106]thou censurest me, so have I done others, and may do

thee,

Cedimus inque vicem, &c., 'tis

lex talionis, quid pro quo. Go

now, censure, criticise, scoff, and rail.

[107]Nasutus cis usque licet, sis denique nasus:

Non potes in nugas dicere plura meas,

Ipse ego quam dixi, &c.

Wert thou all scoffs and flouts, a very Momus,

Than we ourselves, thou canst not say worse of us.

Thus, as when women scold, have I cried whore first, and in some men's

censures I am afraid I have overshot myself, Laudare se vani, vituperare

stulti, as I do not arrogate, I will not derogate. Primus vestrum non

sum, nec imus, I am none of the best, I am none of the meanest of you. As

I am an inch, or so many feet, so many parasangs, after him or him, I may

be peradventure an ace before thee. Be it therefore as it is, well or ill,

I have essayed, put myself upon the stage; I must abide the censure, I may

not escape it. It is most true, stylus virum arguit, our style bewrays

us, and as [108]hunters find their game by the trace, so is a man's genius

descried by his works, Multo melius ex sermone quam lineamentis, de

moribus hominum judicamus; it was old Cato's rule. I have laid myself open

(I know it) in this treatise, turned mine inside outward: I shall be

censured, I doubt not; for, to say truth with Erasmus, nihil morosius

hominum judiciis, there is nought so peevish as men's judgments; yet this

is some comfort, ut palata, sic judicia, our censures are as various as

our palates.

[109]Tres mihi convivae prope dissentire videntur,

Poscentes vario multum diversa palato, &c.

Three guests I have, dissenting at my feast,

Requiring each to gratify his taste

With different food.

Our writings are as so many dishes, our readers guests, our books like

beauty, that which one admires another rejects; so are we approved as men's

fancies are inclined.

Pro captu lectoris habent sua fata libelli..

That which is most pleasing to one is amaracum sui, most harsh to another.

Quot homines, tot sententiae, so many men, so many minds: that which thou

condemnest he commends.

[110]Quod petis, id sane est invisum acidumque

duobus. He respects matter, thou art wholly for words; he loves a loose

and free style, thou art all for neat composition, strong lines,

hyperboles, allegories; he desires a fine frontispiece, enticing pictures,

such as [111]Hieron. Natali the Jesuit hath cut to the Dominicals, to draw

on the reader's attention, which thou rejectest; that which one admires,

another explodes as most absurd and ridiculous. If it be not point blank to

his humour, his method, his conceit, [112]si quid, forsan omissum, quod

is animo conceperit, si quae dictio, &c. If aught be omitted, or added,

which he likes, or dislikes, thou art mancipium paucae lectionis, an

idiot, an ass, nullus es, or plagiarius, a trifler, a trivant, thou art

an idle fellow; or else it is a thing of mere industry, a collection

without wit or invention, a very toy. [113]Facilia sic putant omnes quae

jam facta, nec de salebris cogitant, ubi via strata; so men are valued,

their labours vilified by fellows of no worth themselves, as things of

nought, who could not have done as much. Unusquisque abundat sensu suo,

every man abounds in his own sense; and whilst each particular party is so

affected, how should one please all?

[114]Quid dem? quid non dem? Renuis tu quod jubet ille.

———What courses must I choose?

What not? What both would order you refuse.

How shall I hope to express myself to each man's humour and

[115]conceit,

or to give satisfaction to all? Some understand too little, some too much,

qui similiter in legendos libros, atque in salutandos homines irruunt, non

cogitantes quales, sed quibus vestibus induti sint, as

[116]Austin

observes, not regarding what, but who write,

[117]orexin habet auctores

celebritas, not valuing the metal, but stamp that is upon it,

Cantharum

aspiciunt, non quid in eo. If he be not rich, in great place, polite and

brave, a great doctor, or full fraught with grand titles, though never so

well qualified, he is a dunce; but, as

[118]Baronius hath it of Cardinal

Caraffa's works, he is a mere hog that rejects any man for his poverty.

Some are too partial, as friends to overween, others come with a prejudice

to carp, vilify, detract, and scoff; (

qui de me forsan, quicquid est, omni

contemptu contemptius judicant) some as bees for honey, some as spiders to

gather poison. What shall I do in this case? As a Dutch host, if you come

to an inn in. Germany, and dislike your fare, diet, lodging, &c., replies

in a surly tone,

[119]aliud tibi quaeras diversorium, if you like not

this, get you to another inn: I resolve, if you like not my writing, go

read something else. I do not much esteem thy censure, take thy course, it

is not as thou wilt, nor as I will, but when we have both done, that of

[120]Plinius Secundus to Trajan will prove true, “Every man's witty labour

takes not, except the matter, subject, occasion, and some commending

favourite happen to it.” If I be taxed, exploded by thee and some such, I

shall haply be approved and commended by others, and so have been

(

Expertus loquor), and may truly say with

[121]Jovius in like case,

(absit verbo jactantia) heroum quorundam, pontificum, et virorum

nobilium familiaritatem et amicitiam, gratasque gratias, et multorum [122]

bene laudatorum laudes sum inde promeritus, as I have been honoured by

some worthy men, so have I been vilified by others, and shall be. At the

first publishing of this book, (which

[123]Probus of Persius satires),

editum librum continuo mirari homines, atque avide deripere caeperunt, I

may in some sort apply to this my work. The first, second, and third

edition were suddenly gone, eagerly read, and, as I have said, not so much

approved by some, as scornfully rejected by others. But it was Democritus

his fortune,

Idem admirationi et [124]irrisioni habitus. 'Twas Seneca's

fate, that superintendent of wit, learning, judgment,

[125]ad stuporem

doctus, the best of Greek and Latin writers, in Plutarch's opinion; that

“renowned corrector of vice,” as,

[126]Fabius terms him, “and painful

omniscious philosopher, that writ so excellently and admirably well,” could

not please all parties, or escape censure. How is he vilified by

[127]

Caligula, Agellius, Fabius, and Lipsius himself, his chief propugner?

In

eo pleraque pernitiosa, saith the same Fabius, many childish tracts and

sentences he hath,

sermo illaboratus, too negligent often and remiss, as

Agellius observes,

oratio vulgaris et protrita, dicaces et ineptae,

sententiae, eruditio plebeia, an homely shallow writer as he is.

In

partibus spinas et fastidia habet, saith

[128]Lipsius; and, as in all his

other works, so especially in his epistles,

aliae in argutiis et ineptiis

occupantur, intricatus alicubi, et parum compositus, sine copia rerum hoc

fecit, he jumbles up many things together immethodically, after the

Stoics' fashion,

parum ordinavit, multa accumulavit, &c. If Seneca be

thus lashed, and many famous men that I could name, what shall I expect?

How shall I that am

vix umbra tanti philosophi hope to please? “No man so

absolute” (

[129]Erasmus holds) “to satisfy all, except antiquity,

prescription, &c., set a bar.” But as I have proved in Seneca, this will

not always take place, how shall I evade? 'Tis the common doom of all

writers, I must (I say) abide it; I seek not applause;

[130]Non ego

ventosa venor suffragia plebis; again,

non sum adeo informis, I would

not be

[131]vilified:

Non fastiditus si tibi, lector, ero.

I fear good men's censures, and to their favourable acceptance I submit my

labours,

[133]———et linguas mancipiorum

Contemno.———

As the barking of a dog, I securely contemn those malicious and scurrile

obloquies, flouts, calumnies of railers and detractors; I scorn the rest.

What therefore I have said,

pro tenuitate mea, I have said.

One or two things yet I was desirous to have amended if I could, concerning

the manner of handling this my subject, for which I must apologise,

deprecari, and upon better advice give the friendly reader notice: it was

not mine intent to prostitute my muse in English, or to divulge secreta

Minervae, but to have exposed this more contract in Latin, if I could have

got it printed. Any scurrile pamphlet is welcome to our mercenary

stationers in English; they print all

———cuduntque libellos

In quorum foliis vix simia nuda cacaret;

But in Latin they will not deal; which is one of the reasons

[134]Nicholas

Car, in his oration of the paucity of English writers, gives, that so many

flourishing wits are smothered in oblivion, lie dead and buried in this our

nation. Another main fault is, that I have not revised the copy, and

amended the style, which now flows remissly, as it was first conceived; but

my leisure would not permit;

Feci nec quod potui, nec quod volui, I

confess it is neither as I would, nor as it should be.

[135]Cum relego scripsisse pudet, quia plurima cerno

Me quoque quae fuerant judice digna lini.

When I peruse this tract which I have writ,

I am abash'd, and much I hold unfit.

Et quod gravissimum, in the matter itself, many things I disallow at this

present, which when I writ,

[136]Non eadem est aetas, non mens; I would

willingly retract much, &c., but 'tis too late, I can only crave pardon now

for what is amiss.

I might indeed, (had I wisely done) observed that precept of the poet,

———nonumque prematur in annum,

and have taken more care: or, as

Alexander the physician would have done by lapis lazuli, fifty times washed

before it be used, I should have revised, corrected and amended this tract;

but I had not (as I said) that happy leisure, no amanuenses or assistants.

Pancrates in [137]Lucian, wanting a servant as he went from Memphis to

Coptus in Egypt, took a door bar, and after some superstitious words

pronounced (Eucrates the relator was then present) made it stand up like a

serving-man, fetch him water, turn the spit, serve in supper, and what work

he would besides; and when he had done that service he desired, turned his

man to a stick again. I have no such skill to make new men at my pleasure,

or means to hire them; no whistle to call like the master of a ship, and

bid them run, &c. I have no such authority, no such benefactors, as that

noble [138]Ambrosius was to Origen, allowing him six or seven amanuenses

to write out his dictates; I must for that cause do my business myself, and

was therefore enforced, as a bear doth her whelps, to bring forth this

confused lump; I had not time to lick it into form, as she doth her young

ones, but even so to publish it, as it was first written quicquid in

buccam venit, in an extemporean style, as [139]I do commonly all other

exercises, effudi quicquid dictavit genius meus, out of a confused

company of notes, and writ with as small deliberation as I do ordinarily

speak, without all affectation of big words, fustian phrases, jingling

terms, tropes, strong lines, that like [140]Acesta's arrows caught fire as

they flew, strains of wit, brave heats, elegies, hyperbolical exornations,

elegancies, &c., which many so much affect. I am [141]aquae potor, drink

no wine at all, which so much improves our modern wits, a loose, plain,

rude writer, ficum, voco ficum et ligonem ligonem and as free, as loose,

idem calamo quod in mente, [142]I call a spade a spade, animis haec

scribo, non auribus, I respect matter not words; remembering that of

Cardan, verba propter res, non res propter verba: and seeking with

Seneca, quid scribam, non quemadmodum, rather what than how to write:

for as Philo thinks, [143]“He that is conversant about matter, neglects

words, and those that excel in this art of speaking, have no profound

learning,”

[144]Verba nitent phaleris, at nullus verba medullas

Intus habent———

Besides, it was the observation of that wise Seneca,

[145]“when you see a

fellow careful about his words, and neat in his speech, know this for a

certainty, that man's mind is busied about toys, there's no solidity in

him.”

Non est ornamentum virile concinnitas: as he said of a nightingale,

———

vox es, praeterea nihil, &c.

I am therefore in this point a professed

disciple of

[146]Apollonius a scholar of Socrates, I neglect phrases, and

labour wholly to inform my reader's understanding, not to please his ear;

'tis not my study or intent to compose neatly, which an orator requires,

but to express myself readily and plainly as it happens. So that as a river

runs sometimes precipitate and swift, then dull and slow; now direct, then

per ambages, now deep, then shallow; now muddy, then clear; now broad,

then narrow; doth my style flow: now serious, then light; now comical, then

satirical; now more elaborate, then remiss, as the present subject

required, or as at that time I was affected. And if thou vouchsafe to read

this treatise, it shall seem no otherwise to thee, than the way to an

ordinary traveller, sometimes fair, sometimes foul; here champaign, there

enclosed; barren, in one place, better soil in another: by woods, groves,

hills, dales, plains, &c. I shall lead thee

per ardua montium, et lubrica

valllum, et roscida cespitum, et [147]glebosa camporum, through variety of

objects, that which thou shalt like and surely dislike.

For the matter itself or method, if it be faulty, consider I pray you that

of Columella, Nihil perfectum, aut a singulari consummatum industria, no

man can observe all, much is defective no doubt, may be justly taxed,

altered, and avoided in Galen, Aristotle, those great masters. Boni

venatoris ([148]one holds) plures feras capere, non omnes; he is a good

huntsman can catch some, not all: I have done my endeavour. Besides, I

dwell not in this study, Non hic sulcos ducimus, non hoc pulvere

desudamus, I am but a smatterer, I confess, a stranger, [149]here and

there I pull a flower; I do easily grant, if a rigid censurer should

criticise on this which I have writ, he should not find three sole faults,

as Scaliger in Terence, but three hundred. So many as he hath done in

Cardan's subtleties, as many notable errors as [150]Gul Laurembergius, a

late professor of Rostock, discovers in that anatomy of Laurentius, or

Barocius the Venetian in Sacro boscus. And although this be a sixth

edition, in which I should have been more accurate, corrected all those

former escapes, yet it was magni laboris opus, so difficult and tedious,

that as carpenters do find out of experience, 'tis much better build a new

sometimes, than repair an old house; I could as soon write as much more, as

alter that which is written. If aught therefore be amiss (as I grant there

is), I require a friendly admonition, no bitter invective, [151]Sint

musis socii Charites, Furia omnis abesto, otherwise, as in ordinary

controversies, funem contentionis nectamus, sed cui bono? We may contend,

and likely misuse each other, but to what purpose? We are both scholars,

say,

Et Cantare pares, et respondere parati.

Both young Arcadians, both alike inspir'd

To sing and answer as the song requir'd.

If we do wrangle, what shall we get by it? Trouble and wrong ourselves,

make sport to others. If I be convict of an error, I will yield, I will

amend.

Si quid bonis moribus, si quid veritati dissentaneum, in sacris vel

humanis literis a me dictum sit, id nec dictum esto. In the mean time I

require a favourable censure of all faults omitted, harsh compositions,

pleonasms of words, tautological repetitions (though Seneca bear me out,

nunquam nimis dicitur, quod nunquam satis dicitur) perturbations of

tenses, numbers, printers' faults, &c. My translations are sometimes rather

paraphrases than interpretations,

non ad verbum, but as an author, I use

more liberty, and that's only taken which was to my purpose. Quotations are

often inserted in the text, which makes the style more harsh, or in the

margin, as it happened. Greek authors, Plato, Plutarch, Athenaeus, &c., I

have cited out of their interpreters, because the original was not so

ready. I have mingled

sacra prophanis, but I hope not profaned, and in

repetition of authors' names, ranked them

per accidens, not according to

chronology; sometimes neoterics before ancients, as my memory suggested.

Some things are here altered, expunged in this sixth edition, others

amended, much added, because many good

[153]authors in all kinds are come

to my hands since, and 'tis no prejudice, no such indecorum, or

oversight.

[154]Nunquam ita quicquam bene subducta ratione ad vitam fuit,

Quin res, aetas, usus, semper aliquid apportent novi,

Aliquid moneant, ut illa quae scire te credas, nescias,

Et quae tibi putaris prima, in exercendo ut repudias.

Ne'er was ought yet at first contriv'd so fit,

But use, age, or something would alter it;

Advise thee better, and, upon peruse,

Make thee not say, and what thou tak'st refuse.

But I am now resolved never to put this treatise out again,

Ne quid

nimis, I will not hereafter add, alter, or retract; I have done. The last

and greatest exception is, that I, being a divine, have meddled with

physic,

[155]Tantumne est ab re tua otii tibi,

Aliena ut cures, eaque nihil quae ad te attinent.

Which Menedemus objected to Chremes; have I so much leisure, or little

business of mine own, as to look after other men's matters which concern me

not? What have I to do with physic?

Quod medicorum est promittant medici.

The

[156]Lacedaemonians were once in counsel about state matters, a

debauched fellow spake excellent well, and to the purpose, his speech was

generally approved: a grave senator steps up, and by all means would have

it repealed, though good, because

dehonestabatur pessimo auctore, it had

no better an author; let some good man relate the same, and then it should

pass. This counsel was embraced,

factum est, and it was registered

forthwith,

Et sic bona sententia mansit, malus auctor mutatus est. Thou

sayest as much of me, stomachosus as thou art, and grantest, peradventure,

this which I have written in physic, not to be amiss, had another done it,

a professed physician, or so, but why should I meddle with this tract? Hear

me speak. There be many other subjects, I do easily grant, both in humanity

and divinity, fit to be treated of, of which had I written

ad

ostentationem only, to show myself, I should have rather chosen, and in

which I have been more conversant, I could have more willingly luxuriated,

and better satisfied myself and others; but that at this time I was fatally

driven upon this rock of melancholy, and carried away by this by-stream,

which, as a rillet, is deducted from the main channel of my studies, in

which I have pleased and busied myself at idle hours, as a subject most

necessary and commodious. Not that I prefer it before divinity, which I do

acknowledge to be the queen of professions, and to which all the rest are

as handmaids, but that in divinity I saw no such great need. For had I

written positively, there be so many books in that kind, so many

commentators, treatises, pamphlets, expositions, sermons, that whole teams

of oxen cannot draw them; and had I been as forward and ambitious as some

others, I might have haply printed a sermon at Paul's Cross, a sermon in

St. Marie's Oxon, a sermon in Christ Church, or a sermon before the right

honourable, right reverend, a sermon before the right worshipful, a sermon

in Latin, in English, a sermon with a name, a sermon without, a sermon, a

sermon, &c. But I have been ever as desirous to suppress my labours in this

kind, as others have been to press and publish theirs. To have written in

controversy had been to cut off an hydra's head,

[157]Lis litem

generat, one begets another, so many duplications, triplications, and

swarms of questions.

In sacro bello hoc quod stili mucrone agitur, that

having once begun, I should never make an end. One had much better, as

[158]Alexander, the sixth pope, long since observed, provoke a great

prince than a begging friar, a Jesuit, or a seminary priest, I will add,

for

inexpugnabile genus hoc hominum, they are an irrefragable society,

they must and will have the last word; and that with such eagerness,

impudence, abominable lying, falsifying, and bitterness in their questions

they proceed, that as he

[159]said,

furorne caecus, an rapit vis acrior,

an culpa, responsum date? Blind fury, or error, or rashness, or what it is

that eggs them, I know not, I am sure many times, which

[160]Austin

perceived long since,

tempestate contentionis, serenitas charitatis

obnubilatur, with this tempest of contention, the serenity of charity is

overclouded, and there be too many spirits conjured up already in this kind

in all sciences, and more than we can tell how to lay, which do so

furiously rage, and keep such a racket, that as

[161]Fabius said, “It had

been much better for some of them to have been born dumb, and altogether

illiterate, than so far to dote to their own destruction.”

At melius fuerat non scribere, namque tacere

Tutum semper erit,———

[162]

'Tis a general fault, so Severinus the Dane complains

[163]in physic,

“unhappy men as we are, we spend our days in unprofitable questions and

disputations,” intricate subtleties,

de lana caprina about moonshine in

the water, “leaving in the mean time those chiefest treasures of nature

untouched, wherein the best medicines for all manner of diseases are to be

found, and do not only neglect them ourselves, but hinder, condemn, forbid,

and scoff at others, that are willing to inquire after them.” These motives

at this present have induced me to make choice of this medicinal subject.

If any physician in the mean time shall infer, Ne sutor ultra crepidam,

and find himself grieved that I have intruded into his profession, I will

tell him in brief, I do not otherwise by them, than they do by us. If it be

for their advantage, I know many of their sect which have taken orders, in

hope of a benefice, 'tis a common transition, and why may not a melancholy

divine, that can get nothing but by simony, profess physic? Drusianus an

Italian (Crusianus, but corruptly, Trithemius calls him) [164]“because he

was not fortunate in his practice, forsook his profession, and writ

afterwards in divinity.” Marcilius Ficinus was semel et simul; a priest

and a physician at once, and [165]T. Linacer in his old age took orders.

The Jesuits profess both at this time, divers of them permissu

superiorum, chirurgeons, panders, bawds, and midwives, &c. Many poor

country-vicars, for want of other means, are driven to their shifts; to

turn mountebanks, quacksalvers, empirics, and if our greedy patrons hold us

to such hard conditions, as commonly they do, they will make most of us

work at some trade, as Paul did, at last turn taskers, maltsters,

costermongers, graziers, sell ale as some have done, or worse. Howsoever in

undertaking this task, I hope I shall commit no great error or indecorum,

if all be considered aright, I can vindicate myself with Georgius Braunus,

and Hieronymus Hemingius, those two learned divines; who (to borrow a line

or two of mine [166]elder brother) drawn by a “natural love, the one of

pictures and maps, prospectives and chorographical delights, writ that ample

theatre of cities; the other to the study of genealogies, penned theatrum

genealogicum.” Or else I can excuse my studies with [167]Lessius the

Jesuit in like case. It is a disease of the soul on which I am to treat,

and as much appertaining to a divine as to a physician, and who knows not

what an agreement there is betwixt these two professions? A good divine

either is or ought to be a good physician, a spiritual physician at least,

as our Saviour calls himself, and was indeed, Mat. iv. 23; Luke, v. 18;

Luke, vii. 8. They differ but in object, the one of the body, the other of

the soul, and use divers medicines to cure; one amends animam per corpus,

the other corpus per animam as [168]our Regius Professor of physic well

informed us in a learned lecture of his not long since. One helps the vices

and passions of the soul, anger, lust, desperation, pride, presumption, &c.

by applying that spiritual physic; as the other uses proper remedies in

bodily diseases. Now this being a common infirmity of body and soul, and

such a one that hath as much need of spiritual as a corporal cure, I could

not find a fitter task to busy myself about, a more apposite theme, so

necessary, so commodious, and generally concerning all sorts of men, that

should so equally participate of both, and require a whole physician. A

divine in this compound mixed malady can do little alone, a physician in

some kinds of melancholy much less, both make an absolute cure.

[169]Alterius sic altera poscit opem.

———when in friendship joined

A mutual succour in each other find.

And 'tis proper to them both, and I hope not unbeseeming me, who am by my

profession a divine, and by mine inclination a physician. I had Jupiter in

my sixth house; I say with

[170]Beroaldus,

non sum medicus, nec medicinae

prorsus expers, in the theory of physic I have taken some pains, not with

an intent to practice, but to satisfy myself, which was a cause likewise of

the first undertaking of this subject.

If these reasons do not satisfy thee, good reader, as Alexander Munificus

that bountiful prelate, sometimes bishop of Lincoln, when he had built six

castles, ad invidiam operis eluendam, saith [171]Mr. Camden, to take

away the envy of his work (which very words Nubrigensis hath of Roger the

rich bishop of Salisbury, who in king Stephen's time built Shirburn castle,

and that of Devises), to divert the scandal or imputation, which might be

thence inferred, built so many religious houses. If this my discourse be

over-medicinal, or savour too much of humanity, I promise thee that I will

hereafter make thee amends in some treatise of divinity. But this I hope

shall suffice, when you have more fully considered of the matter of this my

subject, rem substratam, melancholy, madness, and of the reasons

following, which were my chief motives: the generality of the disease, the

necessity of the cure, and the commodity or common good that will arise to

all men by the knowledge of it, as shall at large appear in the ensuing

preface. And I doubt not but that in the end you will say with me, that to

anatomise this humour aright, through all the members of this our

Microcosmus, is as great a task, as to reconcile those chronological errors

in the Assyrian monarchy, find out the quadrature of a circle, the creeks

and sounds of the north-east, or north-west passages, and all out as good a

discovery as that hungry [172]Spaniard's of Terra Australis Incognita, as

great trouble as to perfect the motion of Mars and Mercury, which so

crucifies our astronomers, or to rectify the Gregorian Calendar. I am so

affected for my part, and hope as [173]Theophrastus did by his characters,

“That our posterity, O friend Policles, shall be the better for this which

we have written, by correcting and rectifying what is amiss in themselves

by our examples, and applying our precepts and cautions to their own use.”

And as that great captain Zisca would have a drum made of his skin when he

was dead, because he thought the very noise of it would put his enemies to

flight, I doubt not but that these following lines, when they shall be

recited, or hereafter read, will drive away melancholy (though I be gone)

as much as Zisca's drum could terrify his foes. Yet one caution let me give

by the way to my present, or my future reader, who is actually melancholy,

that he read not the [174]symptoms or prognostics in this following tract,

lest by applying that which he reads to himself, aggravating, appropriating

things generally spoken, to his own person (as melancholy men for the most

part do) he trouble or hurt himself, and get in conclusion more harm than

good. I advise them therefore warily to peruse that tract, Lapides

loquitur (so said [175]Agrippa de occ. Phil.) et caveant lectores ne

cerebrum iis excutiat. The rest I doubt not they may securely read, and to

their benefit. But I am over-tedious, I proceed.

Of the necessity and generality of this which I have said, if any man

doubt, I shall desire him to make a brief survey of the world, as [176]

Cyprian adviseth Donat, “supposing himself to be transported to the top of

some high mountain, and thence to behold the tumults and chances of this

wavering world, he cannot choose but either laugh at, or pity it.” S. Hierom

out of a strong imagination, being in the wilderness, conceived with

himself, that he then saw them dancing in Rome; and if thou shalt either

conceive, or climb to see, thou shalt soon perceive that all the world is

mad, that it is melancholy, dotes; that it is (which Epichthonius

Cosmopolites expressed not many years since in a map) made like a fool's

head (with that motto, Caput helleboro dignum) a crazed head, cavea

stultorum, a fool's paradise, or as Apollonius, a common prison of gulls,

cheaters, flatterers, &c. and needs to be reformed. Strabo in the ninth

book of his geography, compares Greece to the picture of a man, which

comparison of his, Nic. Gerbelius in his exposition of Sophianus' map,

approves; the breast lies open from those Acroceraunian hills in Epirus, to

the Sunian promontory in Attica; Pagae and Magaera are the two shoulders;

that Isthmus of Corinth the neck; and Peloponnesus the head. If this

allusion hold, 'tis sure a mad head; Morea may be Moria; and to speak what

I think, the inhabitants of modern Greece swerve as much from reason and

true religion at this day, as that Morea doth from the picture of a man.

Examine the rest in like sort, and you shall find that kingdoms and

provinces are melancholy, cities and families, all creatures, vegetal,

sensible, and rational, that all sorts, sects, ages, conditions, are out of

tune, as in Cebes' table, omnes errorem bibunt, before they come into the

world, they are intoxicated by error's cup, from the highest to the lowest

have need of physic, and those particular actions in [177]Seneca, where

father and son prove one another mad, may be general; Porcius Latro shall

plead against us all. For indeed who is not a fool, melancholy, mad?—[178]

Qui nil molitur inepte, who is not brain-sick? Folly, melancholy,

madness, are but one disease, Delirium is a common name to all. Alexander,

Gordonius, Jason Pratensis, Savanarola, Guianerius, Montaltus, confound

them as differing secundum magis et minus; so doth David, Psal. xxxvii. 5. “I said unto the fools, deal not so madly,” and 'twas an old Stoical

paradox, omnes stultos insanire, [179]all fools are mad, though some

madder than others. And who is not a fool, who is free from melancholy? Who

is not touched more or less in habit or disposition? If in disposition,

“ill dispositions beget habits, if they persevere,” saith [180]Plutarch,

habits either are, or turn to diseases. 'Tis the same which Tully maintains

in the second of his Tusculans, omnium insipientum animi in morbo sunt, et

perturbatorum, fools are sick, and all that are troubled in mind: for what

is sickness, but as [181]Gregory Tholosanus defines it, “A dissolution or

perturbation of the bodily league, which health combines:” and who is not

sick, or ill-disposed? in whom doth not passion, anger, envy, discontent,

fear and sorrow reign? Who labours not of this disease? Give me but a

little leave, and you shall see by what testimonies, confessions,

arguments, I will evince it, that most men are mad, that they had as much

need to go a pilgrimage to the Anticyrae (as in [182]Strabo's time they

did) as in our days they run to Compostella, our Lady of Sichem, or

Lauretta, to seek for help; that it is like to be as prosperous a voyage as

that of Guiana, and that there is much more need of hellebore than of

tobacco.

That men are so misaffected, melancholy, mad, giddy-headed, hear the

testimony of Solomon, Eccl. ii. 12. “And I turned to behold wisdom, madness

and folly,” &c. And ver. 23: “All his days are sorrow, his travel grief,

and his heart taketh no rest in the night.” So that take melancholy in what

sense you will, properly or improperly, in disposition or habit, for

pleasure or for pain, dotage, discontent, fear, sorrow, madness, for part,

or all, truly, or metaphorically, 'tis all one. Laughter itself is madness

according to Solomon, and as St. Paul hath it, “Worldly sorrow brings

death.” “The hearts of the sons of men are evil, and madness is in their

hearts while they live,” Eccl. ix. 3. “Wise men themselves are no better.”

Eccl. i. 18. “In the multitude of wisdom is much grief, and he that

increaseth wisdom, increaseth sorrow,” chap. ii. 17. He hated life itself,

nothing pleased him: he hated his labour, all, as [183]he concludes, is

“sorrow, grief, vanity, vexation of spirit.” And though he were the wisest

man in the world, sanctuarium sapientiae, and had wisdom in abundance, he

will not vindicate himself, or justify his own actions. “Surely I am more

foolish than any man, and have not the understanding of a man in me,” Prov.

xxx. 2. Be they Solomon's words, or the words of Agur, the son of Jakeh,

they are canonical. David, a man after God's own heart, confesseth as much

of himself, Psal. xxxvii. 21, 22. “So foolish was I and ignorant, I was

even as a beast before thee.” And condemns all for fools, Psal. xciii.;

xxxii. 9; xlix. 20. He compares them to “beasts, horses, and mules, in

which there is no understanding.” The apostle Paul accuseth himself in like

sort, 2 Cor. ix. 21. “I would you would suffer a little my foolishness, I

speak foolishly.” “The whole head is sick,” saith Esay, “and the heart is

heavy,” cap. i. 5. And makes lighter of them than of oxen and asses, “the

ox knows his owner,” &c.: read Deut. xxxii. 6; Jer. iv.; Amos, iii. 1;

Ephes. v. 6. “Be not mad, be not deceived, foolish Galatians, who hath

bewitched you?” How often are they branded with this epithet of madness and

folly? No word so frequent amongst the fathers of the Church and divines;

you may see what an opinion they had of the world, and how they valued

men's actions.

I know that we think far otherwise, and hold them most part wise men that

are in authority, princes, magistrates, [184]rich men, they are wise men

born, all politicians and statesmen must needs be so, for who dare speak

against them? And on the other, so corrupt is our judgment, we esteem wise

and honest men fools. Which Democritus well signified in an epistle of his

to Hippocrates: [185]the “Abderites account virtue madness,” and so do

most men living. Shall I tell you the reason of it? [186]Fortune and

Virtue, Wisdom and Folly, their seconds, upon a time contended in the

Olympics; every man thought that Fortune and Folly would have the worst,

and pitied their cases; but it fell out otherwise. Fortune was blind and

cared not where she stroke, nor whom, without laws, Audabatarum instar,

&c. Folly, rash and inconsiderate, esteemed as little what she said or did.

Virtue and Wisdom gave [187]place, were hissed out, and exploded by the

common people; Folly and Fortune admired, and so are all their followers

ever since: knaves and fools commonly fare and deserve best in worldlings'

eyes and opinions. Many good men have no better fate in their ages: Achish,

1 Sam. xxi. 14, held David for a madman. [188]Elisha and the rest were no

otherwise esteemed. David was derided of the common people, Ps. ix. 7, “I

am become a monster to many.” And generally we are accounted fools for

Christ, 1 Cor. xiv. “We fools thought his life madness, and his end without

honour,” Wisd. v. 4. Christ and his Apostles were censured in like sort,

John x.; Mark iii.; Acts xxvi. And so were all Christians in [189]Pliny's

time, fuerunt et alii, similis dementiae, &c. And called not long after,

[190]Vesaniae sectatores, eversores hominum, polluti novatores, fanatici,

canes, malefici, venefici, Galilaei homunciones, &c. 'Tis an ordinary thing

with us, to account honest, devout, orthodox, divine, religious,

plain-dealing men, idiots, asses, that cannot, or will not lie and

dissemble, shift, flatter, accommodare se ad eum locum ubi nati sunt,

make good bargains, supplant, thrive, patronis inservire; solennes

ascendendi modos apprehendere, leges, mores, consuetudines recte observare,

candide laudare, fortiter defendere, sententias amplecti, dubitare de

nullus, credere omnia, accipere omnia, nihil reprehendere, caeteraque quae

promotionem ferunt et securitatem, quae sine ambage felicem, reddunt

hominem, et vere sapientem apud nos; that cannot temporise as other men

do, [191]hand and take bribes, &c. but fear God, and make a conscience of

their doings. But the Holy Ghost that knows better how to judge, he calls

them fools. “The fool hath said in his heart,” Psal. liii. 1. “And their

ways utter their folly,” Psal. xlix. 14. [192]“For what can be more mad,

than for a little worldly pleasure to procure unto themselves eternal

punishment?” As Gregory and others inculcate unto us.

Yea even all those great philosophers the world hath ever had in

admiration, whose works we do so much esteem, that gave precepts of wisdom

to others, inventors of Arts and Sciences, Socrates the wisest man of his

time by the Oracle of Apollo, whom his two scholars, [193]Plato and [194]

Xenophon, so much extol and magnify with those honourable titles, “best and

wisest of all mortal men, the happiest, and most just;” and as [195]

Alcibiades incomparably commends him; Achilles was a worthy man, but

Bracides and others were as worthy as himself; Antenor and Nestor were as

good as Pericles, and so of the rest; but none present, before, or after

Socrates, nemo veterum neque eorum qui nunc sunt, were ever such, will

match, or come near him. Those seven wise men of Greece, those Britain

Druids, Indian Brachmanni, Ethiopian Gymnosophist, Magi of the Persians,

Apollonius, of whom Philostratus, Non doctus, sed natus sapiens, wise

from his cradle, Eoicuras so much admired by his scholar Lucretius:

Qui genus humanum ingenio superavit, et omnes

Perstrinxit stellas exortus ut aetherius sol.

Whose wit excell'd the wits of men as far,

As the sun rising doth obscure a star,

Or that so much renowned Empedocles,

[196]Ut vix humana videatur stirpe creatus.

All those of whom we read such [197]hyperbolical eulogiums, as of

Aristotle, that he was wisdom itself in the abstract, [198]a miracle of

nature, breathing libraries, as Eunapius of Longinus, lights of nature,

giants for wit, quintessence of wit, divine spirits, eagles in the clouds,

fallen from heaven, gods, spirits, lamps of the world, dictators, Nulla

ferant talem saecla futura virum: monarchs, miracles, superintendents of

wit and learning, oceanus, phoenix, atlas, monstrum, portentum hominis,

orbis universi musaeum, ultimus humana naturae donatus, naturae maritus,

———merito cui doctior orbis

Submissis defert fascibus imperium.

As Aelian writ of Protagoras and Gorgias, we may say of them all,

tantum a

sapientibus abfuerunt, quantum a viris pueri, they were children in

respect, infants, not eagles, but kites; novices, illiterate,

Eunuchi

sapientiae. And although they were the wisest, and most admired in their

age, as he censured Alexander, I do them, there were 10,000 in his army as

worthy captains (had they been in place of command) as valiant as himself;

there were myriads of men wiser in those days, and yet all short of what

they ought to be.

[199]Lactantius, in his book of wisdom, proves them to

be dizzards, fools, asses, madmen, so full of absurd and ridiculous tenets,

and brain-sick positions, that to his thinking never any old woman or sick

person doted worse.

[200]Democritus took all from Leucippus, and left,

saith he, “the inheritance of his folly to Epicurus,”

[201]insanienti dum

sapientiae, &c. The like he holds of Plato, Aristippus, and the rest,

making no difference

[202]“betwixt them and beasts, saving that they could

speak.”

[203]Theodoret in his tract,

De cur. grec. affect. manifestly

evinces as much of Socrates, whom though that Oracle of Apollo confirmed to

be the wisest man then living, and saved him from plague, whom 2000 years

have admired, of whom some will as soon speak evil as of Christ, yet

re

vera, he was an illiterate idiot, as

[204]Aristophanes calls him,

irriscor et ambitiosus, as his master Aristotle terms him,

scurra

Atticus, as Zeno, an

[205]enemy to all arts and sciences, as Athaeneus, to

philosophers and travellers, an opiniative ass, a caviller, a kind of

pedant; for his manners, as Theod. Cyrensis describes him, a

[206]

sodomite, an atheist, (so convict by Anytus)

iracundus et ebrius, dicax,

&c. a pot-companion, by

[207]Plato's own confession, a sturdy drinker; and

that of all others he was most sottish, a very madman in his actions and

opinions. Pythagoras was part philosopher, part magician, or part witch. If

you desire to hear more of Apollonius, a great wise man, sometime

paralleled by Julian the apostate to Christ, I refer you to that learned

tract of Eusebius against Hierocles, and for them all to Lucian's

Piscator, Icaromenippus, Necyomantia: their actions, opinions in general

were so prodigious, absurd, ridiculous, which they broached and maintained,

their books and elaborate treatises were full of dotage, which Tully

ad

Atticum long since observed,

delirant plerumque scriptores in libris

suis, their lives being opposite to their words, they commended poverty to

others, and were most covetous themselves, extolled love and peace, and yet

persecuted one another with virulent hate and malice. They could give

precepts for verse and prose, but not a man of them (as

[208]Seneca tells

them home) could moderate his affections. Their music did show us

flebiles

modos, &c. how to rise and fall, but they could not so contain themselves

as in adversity not to make a lamentable tone. They will measure ground by

geometry, set down limits, divide and subdivide, but cannot yet prescribe

quantum homini satis, or keep within compass of reason and discretion.

They can square circles, but understand not the state of their own souls,

describe right lines and crooked, &c. but know not what is right in this

life,

quid in vita rectum sit, ignorant; so that as he said,

Nescio an Anticyram ratio illis destinet omnem.

I think all the Anticyrae will not

restore them to their wits,

[209]if these men now, that held

[210]

Xenodotus' heart, Crates' liver, Epictetus' lantern, were so sottish, and had

no more brains than so many beetles, what shall we think of the commonalty?

what of the rest?

Yea, but you will infer, that is true of heathens, if they be conferred

with Christians, 1 Cor. iii. 19. “The wisdom of this world is foolishness

with God, earthly and devilish,” as James calls it, iii. 15. “They were

vain in their imaginations, and their foolish heart was full of darkness,”

Rom. i. 21, 22. “When they professed themselves wise, became fools.” Their

witty works are admired here on earth, whilst their souls are tormented in

hell fire. In some sense, Christiani Crassiani, Christians are Crassians,

and if compared to that wisdom, no better than fools. Quis est sapiens?

Solus Deus, [211]Pythagoras replies, “God is only wise,” Rom. xvi. Paul

determines “only good,” as Austin well contends, “and no man living can be

justified in his sight.” “God looked down from heaven upon the children of

men, to see if any did understand,” Psalm liii. 2, 3, but all are corrupt,

err. Rom. iii. 12, “None doeth good, no, not one.” Job aggravates this, iv.

18, “Behold he found no steadfastness in his servants, and laid folly upon

his angels;” 19. “How much more on them that dwell in houses of clay?” In

this sense we are all fools, and the [212]Scripture alone is arx

Minervae, we and our writings are shallow and imperfect. But I do not so

mean; even in our ordinary dealings we are no better than fools. “All our

actions,” as [213]Pliny told Trajan, “upbraid us of folly,” our whole

course of life is but matter of laughter: we are not soberly wise; and the

world itself, which ought at least to be wise by reason of his antiquity,

as [214]Hugo de Prato Florido will have it, “semper stultizat, is every

day more foolish than other; the more it is whipped, the worse it is, and

as a child will still be crowned with roses and flowers.” We are apish in

it, asini bipedes, and every place is full inversorum Apuleiorum of

metamorphosed and two-legged asses, inversorum Silenorum, childish,

pueri instar bimuli, tremula patris dormientis in ulna. Jovianus

Pontanus, Antonio Dial, brings in some laughing at an old man, that by

reason of his age was a little fond, but as he admonisheth there, Ne

mireris mi hospes de hoc sene, marvel not at him only, for tota haec

civitas delirium, all our town dotes in like sort, [215]we are a company

of fools. Ask not with him in the poet, [216]Larvae hunc intemperiae

insaniaeque agitant senem? What madness ghosts this old man, but what

madness ghosts us all? For we are ad unum omnes, all mad, semel

insanivimus omnes not once, but alway so, et semel, et simul, et semper,

ever and altogether as bad as he; and not senex bis puer, delira anus,

but say it of us all, semper pueri, young and old, all dote, as

Lactantius proves out of Seneca; and no difference betwixt us and children,

saving that, majora ludimus, et grandioribus pupis, they play with babies

of clouts and such toys, we sport with greater baubles. We cannot accuse or

condemn one another, being faulty ourselves, deliramenta loqueris, you

talk idly, or as [217]Mitio upbraided Demea, insanis, auferte, for we

are as mad our own selves, and it is hard to say which is the worst. Nay,

'tis universally so, [218]Vitam regit fortuna, non sapientia.

When [219]Socrates had taken great pains to find out a wise man, and to

that purpose had consulted with philosophers, poets, artificers, he

concludes all men were fools; and though it procured him both anger and