The Wilton Family.—Story of Frederic Hamilton

The Wiltons.—Dora Leslie.—Charles Dorning.—The Mediterranean.—Corsica.—Candia.—Rhodes.—Malta.—Valetta.—The Caledonia.—A Story by Krummacher.—Adriatic Sea.—Venice.—Turkish Rowers.—Elgin Marbles.—Isle of Wight.—Thunder Storm.—Jersey.—Romaine's Journal.—Slave Ship.—Horrible Cruelty.—Slave Trade.—Wreck of the Royal George.—Eddystone Lighthouse

The Wiltons.—A great Naval Victory.—Monster Fish.—The Downs.—St. Augustine.—Yarmouth.—Brock the Swimmer and Yarmouth Boatman.—The North Sea.—The Bell Rock.—Mr. Barraud.—Jock of Jedburgh.—Wreck of the Forfarshire.—Remarkable Providence.—Denmark.—The Baltic.—Journey to the Gulf of Finland.—Reindeer and Sledge.—Reval.—Superstitions.—Strange Fashions.—Ungern Sternberg.—Gulf of Bothnia.—Islands of the Baltic.—Lapland.—Aurora Borealis.—Russia.—Odessa.—Reflections

Stanzas by Mrs. Howitt.—Caspian Sea.—Astracan.—Droll Legend.—Yellow Sea.—The Japanese.—Monsoons.—Trade Winds.—Description of a Monsoon.—Asia.—The Red Sea.—Isthmus of Suez.—An Interesting Locality.—The Arabs.—Sea of Aral.—Chinese Islands.—Fishing for Mice.—The Typhon.—Fishing Birds.—Cinnamon Forests.—Eating Birds' Nests.—Bible Lands.—The Sea of Galilee.—The Dead Sea.—The Slave Merchant.—A Japan Puzzle

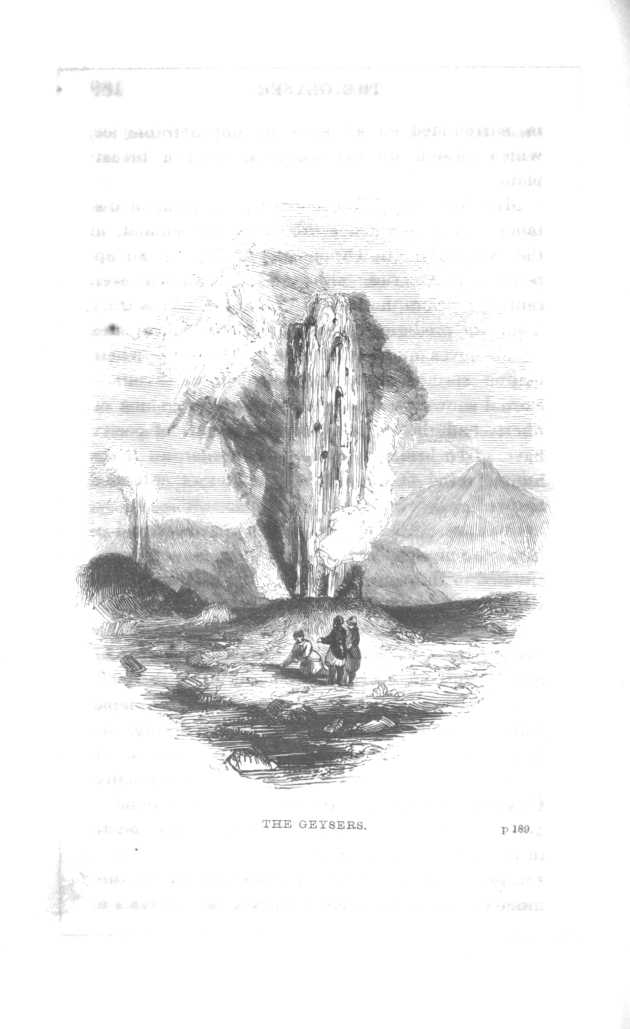

Story of Era.—Assistance of Goodwill.—Madeira.—Man-of-War.—Dinner on Ship-board.—Computing Latitude.—Pipe to Dinner.—The Azores.—Newfoundland.—Newfoundland Dogs.—Greenland.—Whale Fishing.—Flying Fish.—A Ship In the Polar Regions.—An Awful Sight.—The Geysers.—Icelanders.—Spitzbergen.—The Ferroe Islands.—Maelstrom.—The Norwegian Mouse.—Hudson's Bay.—Hudson's Straits.—Nova Scotia.—Henry May.—The Ancient Mariner.—Cuba.—Jamaica.—Beauty of Jamaica.—A Hurricane.—Devastation.—Ruins of Yucatan.—Indians of Mexico.—The American Lakes.—Niagara.—The Caribbean Sea.—Panama.—Gala Days.—Diving for Pearls.—The Sea-Boy's Grave.—The Funeral.—Gulf of Trieste.—Guiana.—Brazil.—Rio de Janeiro.—Montevideo.—Patagonia.—Cape Horn.—Depth of the Atlantic

The Separation.—Deception Isle.—The Gulf of Penas.—Island of Chiloe.—Juan Fernandez.—Alexander Selkirk.—The Ladies of Lima.—The Peruvians.—Columbia.—Catching Wild Fowl.—The Two Oceans.—A Singular Funeral.—Magellan.—Guatemala.—Ladies Smoking.—Christian Indians.—California.—San Francisco.—Nootka Sound.—Story of Boone and the Bear.—Cleaveland and the Infant.—United States' Navy.—Cannibals.—Kamschatka.—Polynesia.—The Sandwich Islands.—Captain Cook.—Contest.—Adventure of Kapiolani.—A Delightful Anecdote.—Spanish Missionaries.—Philippine Islands.—The Pelew Islands.—Birds of Paradise.—The Friendly Islands.—Otaheite.—The Society Islanders.—Pitcairn's Islands.—Shocking Barbarity.—Nobb's Letter.—Marquesas.—The Low Islands.—New Caledonia.—New Zealand.—The Bay of Islands.—Captain Cook's Story.—A Curious Idea.—Aranghie.—Cannibalism.—New Holland.—Story of Mr. Meredith.—Australian Barbarism.—Australian Lakes.—Van Diemen's Land.—Coral Reefs.—Story of Kemba

Packing up.—Letter from Mr. Stanley.—Mr. Stanley.—Celebes.—Dress of the Alfoors.—Curious Hospitality.—Java.—Whimsical Superstition.—Productions of Java.—Sumatra.—Water Spouts.—Burman Despotism.—The White Elephant.—Sir James Brooke.—Borneo.—Isle of Bourbon.—Isle of France.—Madagascar.—The Four Spirits.—The Missionaries.—Horrible Custom.—The Pirates' Retreat.—Malagassy Fable.—Kerguelen's Land.—Isle of Desolation.—Story of a Sailor.—Morocco.—A Moorish Beauty.—Algiers.—Egypt.—Abyssinia.—Abyssinian Customs.—Religion.—African Coast.—Seychelle Isles.—Mozambique.—Smoking the Hubble-Bubble.—Caffraria.—Story of the Little Caffre.—Algoa Bay.—Graham's Town.—Cape of Good Hope.—Cape Town.—Constantia.—The Boschmen.—A Transformation.—Dressing in Skins.—The Slave Trade.—Fish Bay.—St. Helena.—Kabenda.—Black Jews.—Ferdinand Po.—The Ape and the Oven.—The Slave-Coast.—Dahomey.—Ashantee.—King Opocco.—A Singular Belief.—The Ashantee Wife.—Liberia.—A Bowchee Mother.—Sierra Leone.—The Lakes of Africa.—Bornou.—The Sultan of Bornou.—African Wedding.—The Deluge.—The Telescope.—The End

It is not my purpose to detain you with a long preface, because I am aware that long prefaces are seldom read; but I wish to inform you that I have written this book, in the humble hope of being useful to those in whom I am so anxiously interested. I am myself happy in acknowledging the endearing appellation of "Mother," and I love all children, and regard them as priceless treasures, entrusted to the care and guidance of parents and teachers; with whom it rests in a great measure to render them blessings to their fellow-creatures, and happy themselves, or contrariwise.

Should the perusal of this little volume imbue you with a taste for the beautiful and ennobling science of Geography, my object will be gained; and that such may be the result of these humble endeavors is the sincere wish of

Your affectionate Friend,

FANNY OSBORNE.

LONDON.

Oh ye seas and floods,

Bless ye the Lord:

Praise him, and magnify him forever.

"Oh! what beautiful weather," exclaimed George Wilton, as he drew his chair nearer the fire. "This sort of evenings is so suitable for story-telling, that I regret more than ever the disagreeable necessity which has taken Mr. Stanley to foreign countries, and broken up our delightful parties. But yet, there are enough of us remaining at home to form a society; we might manage without him. Do not you remember, papa, you said, when Julia Manvers was with us last summer, we were to examine into the particulars respecting the seas and oceans of the world; and not once was the subject mentioned while we were at Herne Bay, although the sea was continually before us to remind us of it. Are we ever to have any more of those conversations? I liked them amazingly, and I am sure I learned a great deal more geography by them than I ever did out of Goldsmith, or any other dry lesson-book, which compels one to learn by rule. I wish, dear papa, you would settle to have these meetings again; we would write down all the particulars, and enclose them in a letter to Mr. Stanley: I am sure he would be quite pleased."

"I think he would, George," replied Mr. Wilton, "and I also think that we have been rather careless in this matter; but, at the same time, you must remember that the fault does not rest solely with us, for when we appointed certain times during our sojourn at Herne Bay for these same geographical discussions, on every occasion something occurred to prevent the meeting, and all our arrangements fell to the ground. Since then, the illness of your sister,—which, thank God, has terminated so happily,—the departure of Mr. Stanley, and the removal to our present abode; all these circumstances conspired to render ineffectual any attempt at regularity, and precluded the possibility of an occasional quiet chat on this really important subject. The past, present, and future, in the history of man, are so connected with the positions of the great seas of the globe, and the navigation of them, that I do regard the study of geography as one of the most important branches of a Christian education; and, now that all impediments are removed, I think we may venture to propose the re-establishment of our little society; and as we are deprived of the valuable services of Mr. Stanley, we must endeavor to supply his place by procuring the aid of another learned friend, who will not consider it derogatory to assist in our edifying amusement. And, in order to render these meetings more extensively beneficial and interesting, I further propose that we increase our number by admitting two new members, to be selected by you, my dear children, from amongst your juvenile acquaintances; but we must not admit any except on the original terms, which were, 'that each member add his or her mite of information to the general fund.' What says mamma about it? Suppose we put it to the vote?"

"Oh! dear papa," exclaimed Emma, "I am quite sure that will be unnecessary. Grandy has often talked of the meetings held last year, and regretted that there seemed no disposition to renew them; therefore, we are sure of her vote. Mamma was so useful with her descriptions, that she is not likely to object. Then you know, dear papa, how very much I enjoyed these conversations; and, as far as any one else is concerned, I am convinced that my candidate will be glad to prepare a portion of the subject as her admission fee, and will be as much interested in the welfare of the society as we old members are, who have already felt the advantages arising from it. May we decide now, papa?"

All hands were raised in reply, and the resolution carried unanimously.

"I have a question to ask," said George. "May we have the meetings twice during the month, instead of once, as before? It will induce us to be more industrious, as we shall be obliged to work to get up the information. I can share the labor with Emma now, because I can write easily, and quickly; besides, it will be such pleasant employment for the half-holidays."

"Very well, my dear," said Mr. Wilton; "then once a fortnight it shall be; and take care, as the time will be short, that you are thoroughly prepared: do not reckon on me, for I cannot assist you as Mr. Stanley did, so you must be, in a great measure, dependent upon your own resources. My library is at your disposal, and I hope you will have sufficient perseverance to investigate each point carefully, before you come to a decision. Should you require assistance in the preparation of any particular part of the subject, of course, I shall have no objections to render it; but remember, I do not promise to be an active member, as I wish you to exert yourselves, and be in some degree independent. It will thus be more advantageous to you: it will not only impress all you learn effectually on your mind, but improve your reasoning faculties, and enable you to understand much that the most careful explanation might fail to render intelligible."

"And when shall we begin, papa?" asked Emma.

MR. WILTON. "My engagements until the 7th of February are so numerous as to preclude the possibility of my presence at a meeting before that time; but after the 7th inst. I shall be more at liberty, and we will, if you please, commence our voyage, and (wind and weather permitting) travel on regularly and perseveringly until we have circumnavigated the globe."

"Agreed! agreed!" merrily shouted the children.

"I know which of my friends I shall ask," said George; "and I fancy I can guess who will be Emma's new member."

"I fancy you cannot," returned Emma: "I do not intend to tell any one, either, until I hear whether or not she can come; therefore check your inquisitiveness, Master George, and wait patiently, for you will not know before the 7th, when I will introduce my friend."

"Now," said Grandy, "having settled the most important part of the business, I have a few words to say. You must all be aware, that in the accounts of seas and oceans, there cannot possibly be so much time disposed of in descriptive facts as there was in our former conversations concerning the rivers of the world, which are so numerous, and require so many minute particulars in tracing their courses, that they positively (although occupying a smaller portion of the globe,) take more time to sail over in our ship 'The Research,' than the boundless ocean, which occupies two thirds of our world; it will, under these circumstances, be advisable to illustrate our subject largely, and to lose no opportunity of extending it for our benefit. We need not fear to exhaust the topic; for do not the vast waters encompass the globe; and can we contemplate these great works of our Creator, without having our hearts filled with wonder and admiration? This, my children, will lead us to the right source; to the Author of all the wonders contained in 'heaven and earth, and in the waters under the earth;' and, if we possess any gratitude, our hearts will be raised in thankfulness to Him who 'hath done all things well;' and we shall bless him for giving us powers of discernment and reasoning faculties, which not only enable us to see and appreciate the goodness of God, but also, by his grace assisting us, to turn our knowledge to advantage for our temporal and eternal good."

"We may now," said Mr. Wilton, "leave these resolutions to be acted upon at a proper time; and, as we have two hours' leisure before supper, if you, dear mother, will tell us one of your sweet stories of real life, it will be both a pleasant and profitable way of passing the evening. We have all employment for our fingers, and can work while we listen; George and I with our pencils, and you ladies with your sewing and knitting."

GRANDY. "Well, what must it be? Something nautical, I suppose; for as we are about to set sail in a few days, it will be appropriate, will it not?"

GEORGE. "Oh yes! dear Grandy, a nautical story, if you please."

"The first time I saw Frederic Hamilton was on board the 'Neptune,' outward bound for Jamaica: he was then a lad of twelve or fourteen years: I cannot be sure which; but I remember he was tall for his age, and extremely good looking.

"There were so many circumstances during the voyage, which brought me in contact with this boy, and so many occasions to arouse my sympathies in his behalf, (for he was evidently in delicate health, and unfit for laborious work.) that in a short time I became deeply interested concerning him, and I determined as soon as I had recovered from sea-sickness, to watch for an opportunity of inquiring into the particulars of his earlier history.

"I must first tell you, before proceeding with the story of my hero, that the captain of the 'Neptune' was a very harsh, cruel man, and made every one on board his vessel as uncomfortable as he could by his violent temper, and ungentlemanly conduct. I was the only lady-passenger; and had it not been for the kindness of my fellow-travellers, I scarcely think I could have survived all the terrors of that dreadful voyage. The sailors, without one dissentient voice, declared they had never sailed with such a master, and wished they had known a trifle of the rough side of his character before they engaged with him, and then he would have had to seek long enough to make up a crew, for not one of them would have shipped with him.' They even went so far as to say, that if at any time they could escape from the vessel, they would not hesitate a moment, but would get away, and leave the captain to work the ship by himself. I could not take part with the captain, because I saw too much of his tyranny to entertain a particle of respect for him, and I confess I was not in the least surprised at the language of the ill-used sailors. He had no good feature in his character that I could discover; for he was mean, vulgar, discontented, and brutal. He never encouraged the men in the performance of their duty, by kind expressions; on the contrary, he never addressed them on the most simple matter without oaths and imprecations, and oftentimes enforced his commands with a rope's end or his fist.

"We had yet other causes of discomfort besides these continual uproars. Contrary winds, constant gales, and violent storms, made our hearts fail from fear. We knew the captain could not expect His blessing, whose laws he openly set at defiance; indeed, by his life and conversation, he proved that he 'cared for none of these things.'

"I believe he was a clever seaman: he had certainly had much experience, having been upwards of fifty times across the Atlantic: so that we felt at ease with regard to the management of the ship. But we did not put our trust in the skill of the captain alone; for of what avail would that be if the Lord withheld his hand, and left us to perish? No! my dears, we saw that the captain never prayed, and we felt there was a greater necessity for us to be diligent in the duty; and daily, nay hourly, we entreated the forbearance and assistance of Almighty God to conduct us in safety to land.

"After a time, the men became very unmanageable; for they hated the captain: he treated them like slaves, and imposed upon them on every occasion; so that at length, goaded to desperation by his cruelty, they positively refused to handle a rope until he agreed to the terms they intended to propose.

"The captain, fierce as he was, felt it would be useless to contend with twenty angry men, and he knew the passengers would not befriend him: he therefore deemed it expedient to endeavor to conciliate them by promises he never intended to perform, and, after a few hours' confusion, all was again comparatively quiet.

"I could tell you much more about the quarrels and disturbances of which we unfortunate passengers had to be the passive witnesses, and which, accustomed as we were to them in the day-time, filled me with greater horror than I can describe, breaking upon the stillness of the night, when all was quiet but the troubled ocean, whose murmurs, instead of arousing, served to lull us into a deeper repose. Yes, often, when no other sound but the low splashing of the waves against the side of the ship was to be heard, and we were all either sleeping quietly, or thinking deeply of home and friends, loud cries and shouts would reach us, and, in an instant, we would all be gathered together to inquire into the cause of the disturbance. It was always the captain and some of the men fighting; and on one occasion, the battle was so close to us, actually in the cabin, between the captain and the steward, that I screamed aloud, and do not remember ever to have been so much alarmed.

"But as my principal object is to make you acquainted with Frederic Hamilton, and not with my adventures, I will say no more about Captain Simmons, and his ship, than is necessary in the course of my tale.

"I was just getting over the unpleasant sensations of sea-sickness, when, one morning as I was dressing in my berth, a noise of scuffling on the quarter-deck, over my head, interrupted my operations. I laid my brush on the table, and listened. At first I could distinguish nothing, and, thinking it was the captain and a sailor disputing, I continued my toilet; when, suddenly, a piercing cry reached me, and I knew the voice to be Frederic's. At the same time the sound of heavy blows fell on my ear, and again I recognized his voice: he called out so loudly, that I heard him distinctly say, 'Oh, sir! have mercy. Pray, pray do not kill me! Oh, sir! think of my mother, and have pity upon me. I will try to please you, sir; indeed, indeed, I will. Oh, mercy! mercy!' His cries became fainter and fainter, while the blows continued, accompanied occasionally by the gruff voice of the captain, until, my soul shrinking with horror, I could endure it no longer. I rushed out of my cabin, and there on the poop beheld a sight I can never forget. Poor Frederic was lashed to the shrouds with his hands above his head, which was then drooping on his shoulder; his back bare and bleeding. The brutal captain was standing by with a thick rope in his grasp, which, by the crimson stains upon it, sufficiently proved the vile purpose for which its services had just been required.

"I called out hastily and angrily to the captain to cease beating the boy, and declared I would fetch out the gentlemen to interfere if he did not stop his unmanly behavior. He glared on me with the fiercest expression imaginable (for he was in a towering rage,) and told me I had better not meddle with him in the performance of his duty, for he would do as he liked; he was master of the ship and nobody else, and he would like to see anybody else try to be. Then he made use of such fearful language, that I dreaded to approach him; but my fear lest he should again attack the boy, overcame my fear for him in his anger; and I ascended the ladder. He desired, nay commanded, me to retire to my cabin; but I said, 'No, captain, I will not stir hence until you release Frederic, and if you strike him again I will be a witness of your cowardly behavior towards a poor boy whose only fault is want of strength to do the work assigned him. I am quite sure, whatever you may say on board-ship, you will not be able to justify your conduct on shore.'

"He did not again address me; but, muttering curses loud and deep, he untied the fainting boy, and, giving him a savage push, laid him prostrate on the deck: he then walked forward, and began to shout aloud his orders to the men on the main-deck.

"The man at the helm, pitying the poor boy, called to the boatswain, who was standing on the forecastle, and begged him to send some water to throw over the lad, and some dressing for his wounded back. I stayed by him for a short time, and when he was somewhat recovered, I went below.

"I fancied, when I met the captain at the dinner-table, that he looked rather ashamed; for I had related the whole affair to the other passengers, and he could perceive, by their indifference towards him, that they despised him for his cowardice. He tried to be jocular, but could not succeed in exciting our risibility: we did not even encourage his jokes by the shadow of a smile, and he seemed uneasy during the remainder of the time we sat at table.

"I now felt more than ever interested in the fate of Frederic Hamilton and was not sorry I had said so much in the morning. Prudence might have dictated milder language certainly; but my indignation was aroused; and when I found that my remonstrance had the desired effect, I did not repent of my impetuosity.

"About a week after this unhappy occurrence, as I was leaning over the rail on the quarter-deck, watching the shoals of porpoises (for we were then in a warm latitude) playing in the bright blue sea at the vessel's side, the boatswain, who was a fine specimen of a sea-faring man, came up and, seating himself on a fowl-coop near me, commenced sorting rope-yarns for the men to spin. Presently Frederic walked up the ladder with a bucket of water to pour into the troughs for the thirsty poultry, who were stretching their necks through the bars and opening their bills, longing for the refreshing draught: the heat was overpowering, and the poor things were closely packed in their miserable coops.

"I remarked to Williams how pale the boy looked, and how thin, and said, I feared he was not only badly treated, but had not proper nourishment.

"'Why, ma'am,' said he, 'to say the truth, the lad's not been used to this kind of living, and it was the worst thing as ever happened to him to be brought on board the "Neptune," with our skipper for a master. You see, madam,' he continued, 'his father was a parson; but he is dead, and the mother tried hard to persuade the lad (for, poor thing, he is her only boy,) to turn parson too, when his father died. But no. The boy had set his mind on going to sea; and as he had no friends who could help him to go to school or college, and his godfather, Captain Hartly, offered to pay the apprenticeship fees if his mother would let him learn navigation, she at last, though much against her will, consented that he should be bound apprentice to our skipper here. But it pretty nigh broke her heart to part with the child; and she begged the captain to use him gently and bear with him a little, for he was not so hardy as many boys of his age; and, moreover, had been accustomed to kindness and delicate treatment. The lad is a fine noble-hearted lad, but he is not strong; and it is my opinion that the master wants to get rid of him to have the fee for nothing, and he's trying what hard living, hard work, and hard usage will do towards making him go the faster. But he had better mind what he is about. There's many a man on board that can speak a good word for Frederic when he gets ashore; and, if all comes out, it will go hard with the master. The poor lad cries himself to sleep every night, and when he is asleep he has no rest, for in his dreams he talks of his mother and sister, and often sobs loud enough to wake the men whose hammocks swing near him. I am very sorry to see all this, for he is a fine boy, as I said before, and we are all fond of him; but he's not fit for this kind of work, leastwise not yet. I am glad you have taken notice of him, madam; for, though you cannot do any good while we're at sea, may be when you come ashore you won't forget poor Frederic Hamilton.'

"When the boatswain left me, I walked up and down the deck pondering on these things, and contriving all sorts of schemes for the relief of my young friend, and wondering how I could manage to have some conversation with him on the subject; when a circumstance occurred, which at once enabled me not only to learn all I was anxious to know, but also in a great measure to improve his condition on board the 'Neptune.'

"I knew that Frederic must have been trained up in the fear of the Lord, for his daily conduct testified that he not only knew what was right, but tried to perform it also; and notwithstanding the severe trials he had to undergo, while with us on the voyage to Jamaica, yet I never heard a harsh or disrespectful expression fall from his lips; but he would attribute all the captain's unkind treatment of him to something wrong in himself, and he every day tried beyond his strength to obtain a look of approbation from his stern master. But, alas! he knew not to whom he looked; although he was cuffed and kicked about whenever he tried to be brisk in the task allotted to him, he was always the same patient, melancholy little fellow, throughout the voyage.

"Sometimes during the night watch, I have caught the musical tones of his voice, as he walked the quarter-deck; when, the captain being in his berth fast asleep, the boy was comparatively happy; and as the ship sailed quietly along in the pale moonlight, his thoughts would wander back to the home of his beloved mother and sister, and, the buoyancy of youthful spirits gaining the ascendency over more melancholy musings, he would for a while forget his present sorrows, and almost involuntarily break out in singing some of the sweet hymns in which he had been accustomed to join when the little family assembled for devotional exercises.

"It was then I used to open my cabin window, and breathlessly listen to the clear voice of my gentle protégé; and not unfrequently could even distinguish the words he sang; now loud—now soft, as he approached or retreated. One hymn in particular seemed to be a special favorite, and was so applicable to his situation, that I have remembered several of the verses.

"'Jesus, I my cross have taken,

All to leave and follow thee:

Destitute, despised, forsaken,

Thou from hence my all shall be.

Perish every fond ambition,

All I've sought, and hoped, and known;

Yet how rich is my condition,—

God and heaven are still my own!

"'Man may trouble and distress me;

'Twill but drive me to thy breast.

Life with trials hard may press me;

Heaven will bring me sweeter rest.

Oh! 'tis not in grief to harm me,

While thy love is left to me!

Oh! 'twere not in joy to charm me,

Were that joy unmixed with Thee.

"'Take, my soul, thy full salvation;

Rise o'er sin, and fear, and care;

Joy to find in every station

Something still to do or bear!

Think what Spirit dwells within thee;

What a Father's smile is thine;

What thy Saviour did to win thee,—

Child of Heav'n, should'st thou repine?

"'Haste then on from grace to glory,

Armed by faith, and winged by prayer;

Heaven's eternal day's before thee;

Heaven's own hand shall guide thee there.

Soon shall close thy earthly mission;

Swift shall pass thy pilgrim days;

Hope soon change to glad fruition,

Faith to sight, and prayer to praise.'"

EMMA. "What a beautiful hymn, grandmamma. I should like to learn those words. But I want to hear how you got Frederic away from that horrid man, and what became of him afterwards, because I cannot understand why you are telling us this story. I know you never tell us anything for amusement only."

GRANDY. "No, my dear child; this story is not solely for your amusement. This morning I observed a strangeness in George's behavior, when he was requested to put up his microscope, and assist in laying the cloth, because John was out, and he was aware that Hannah had sprained her foot, and could not walk up and down stairs. He said such extraordinary things about being ill-used, and worked hard, and never having an hour to amuse himself, that I am desirous of convincing him that it is quite possible (with God's assistance) not only to bear all this, without thinking it a shame, as George termed it, but even to praise God for the troubles and trials which may fall to your lot; and I also wish to inform him, that there are some boys more patient and grateful than himself. But I see, by the color mounting to his cheeks, that my boy is sorry for his past behavior; nevertheless, I will continue my story. And now for the incident, as I presume you will call it, Emma.

"We were about a week's voyage from Jamaica. The wind was favorable, but light, the sky clear, the sun directly overhead;—we were all beginning to feel the effects of a warm climate; the sailors were loosely clad in canvass trousers, striped shirts, and straw hats, and went lazily about their work;—the ship moved as lazily through the rippling waves;—the man at the helm drew his hat over his eyes, to shade them from the glare of the sun, and lounged listlessly upon the wheel;—the captain was below taking a nap, to the great relief of men and boys;—some of the passengers were sitting on the poop, under an awning, drowsily perusing a book or old newspaper; some leaning on the taffrail, watching the many-colored dolphin, and those beautiful, but spiteful, little creatures, the Portuguese men-of-war, which look so splendid as they sail gently on the smooth surface of the blue ocean, every little ripple causing a change of color in their transparent sails. I was admiring these curious navigators, as I stood with two or three friends, who, like myself, felt idle, and cared only to dispose of the time in the most agreeable manner attainable in such a ship, with such a commander; and I said, rather thoughtlessly, considering Frederic was at my side, 'How I should like to possess one of those little creatures; I suppose they can be caught?'

"Frederic moved from me, and an instant after he was on the forecastle; presently, I heard a splash in the water, and, leaning over the rail, I saw him swimming after a fine specimen, which shone in all the bright and varied colors of the rainbow, as it floated proudly by. He had no sooner reached the treasure, and made a grasp at it, than he gave a loud scream, for the creature had encircled the poor boy's body with its long fibrous legs, or, as they are properly called, 'tentacula'. He struggled violently, for he was in great agony; at length he escaped, and was helped on deck by one of the men, who said, he wished, 'he had known what the youngster had in his head, and he would have prevented him attempting to catch such a thing,' for he was aware of the extraordinary peculiarities of these singular little creatures. When he came on deck, he looked exactly as if he had been rolled in a bed of nettles, and the steward had to rub him with oil, and give him medicine to reduce the fever caused by the pain of the sting.

"You may be sure, that directly the captain heard of this affair, he was more disposed to chastise, than to pity, our friend Frederic; but I interfered, and begged he would leave him to me, as I had been the cause of the disaster, and must now make amends by attending him, until he was well enough to return to his duty. The captain was very much displeased, and I regretted extremely that a foolish wish of mine should have caused so much annoyance, and felt it my duty to endeavor to alleviate the boy's sufferings as much as possible. Poor Frederic! he was laid up three or four days, and had experienced enough to caution him against ever again attempting to capture a 'Portuguese man-of-war.'[1]

"I used to sit by his hammock for hours talking and reading to him; when one day, as I closed my book to leave him, he said with a sigh, while tears filled his eyes, 'I am very grateful to you, madam, for your kindness to me: you have been a friend when I most needed one; how my dear mother would love you if she knew what you had done for her boy. But I do not deserve that any one should love me; I have been wilful and disobedient, and my sorrows are not half so great as, in justice for my wickedness, they ought to be; but every day proves to me that God is long-suffering and merciful, and doeth us good continually. I have thanked him often and often for making you love me, and I feel so happy that in the midst of my trials, God has raised me up a friend to cheer me in the path of duty; to teach me how to correct my faults; and to sympathize with me in my daily sorrows. God will bless you for it, madam,' he continued: 'he will bless you for befriending the orphan in his loneliness; and my mother will bless you, and pray God to shower his mercies thick and plenteous on you all the days of your life.' He paused, and, burying his face in the scanty covering of his bed, he wept unrestrainedly. I was hastening away, for my heart was full, and the effort to check my tears almost choked me; when he raised his head, and, stretching his hand towards me, said, 'I want to tell you something more, madam, if you will not think me bold; but my heart reproaches me every time I see your kind face; I feel as if I were imposing upon you, and fancy that, did you know more about me, you would deem me unworthy of your interest and attention. May I relate to you all I can remember of myself before I came here? It will be such a comfort to have some person near me, who will allow me to talk of those I love, without ridiculing me, and calling me "home-sick."'

"This was the very point at which I had been for some time aiming, as I did not wish to ask him for the particulars, not knowing whether the question might wound his feelings; but now that he offered to tell me, I was delighted, and readily answered his appeal, assuring him nothing would give me greater pleasure than to hear an account of himself from his own lips: 'But,' I added, 'I cannot wait now, for they are striking "eight bells:" I must go in to dinner: after dinner I will come to you again, and listen to all you have to say; so farewell for the present, my dear boy, in an hour's time I will be with you.'

"As soon as dinner was over, I returned to Frederic: he looked so pleased, I shall never forget the glow that overspread his fair face, as I entered the berth, for he was really handsome; his eyes were bright hazel, his hair auburn, and waving over his head in the most graceful curls, while his complexion was the clearest and most beautiful I had ever seen. I found a seat on a chest near his hammock, and, telling him I was ready to attend to his narrative, he began:—

"'The first impression I have of home was when I was about five years old, and was surrounded by a little troop of brothers and sisters, for I can remember when there was seven healthy, happy children in my "boyhood's home." We lived at Feltham, Middlesex, in the pretty parsonage-house. It was situated at the end of a long avenue of elm-trees whose arching boughs, meeting over our heads, sheltered us from the mid-day glare. Here in the winter we used to trundle our hoops; and in the summer stroll about to gather bright berries from the hedges to make chains for the adornment of our bowers. But death came to our happy home, and made sad the hearts of our good parents: the whooping-cough was very prevalent in the village, and a child of one of the villagers, who occasionally came to my father for relief, brought the contagion amongst us, and in a short time we were all seized with it. Two sisters died in one day, and the morning they were laid in the grave, sweet baby breathed his last. Then my mother fell sick, and she was very ill indeed; my brother and I were placed in a cot by her bedside, and when pain has prevented me sleeping, I have been comforted by hearing this dear, kind mother beseeching God to spare her boys. She seemed regardless of her own sufferings, and only repined when she thought how useful she might have been to us, had she too not been laid on a bed of sickness. But fever and delirium came on, and we were removed from her chamber. The next day poor Frank died, and was buried by the side of Clara and Lucy. The funeral service was read by my dear father, who was enabled to stand under all these trials of his faith, for God sustained him; and, having trained us up in the fear and admonition of the Lord, he did not grieve as one without hope, when his darlings were taken from him, for he knew they were gone to a better world, and were happy in the bosom of their heavenly Father. His greatest trial was the illness of my mother; but before we were all quite well, she was able to leave her chamber, and once again kneel with us at our family altar, to return thanks to God for his many mercies. There were only three of her seven children left to her, and when my father blessed God that they were not rendered childless, my mother's feelings overpowered her, and she was borne fainting from the room.

"'But I fear I am tiring you with these melancholy accounts, madam. You know not how deeply I enjoy the recollection of those days, for through this wilderness of sorrow there was a narrow stream of happiness placidly gliding, to which we could turn amidst the troubles of the world, and refresh our fainting souls; and, though we grieved at the remembrance of the loved ones now gone from us, yet we would not have recalled them to these scenes of woe, to share future troubles with us. Oh no! my dear father was a faithful follower of Christ; he used to show us so many causes for thankfulness in our late afflictions, which he said were "blessings in disguise," that happiness and tranquillity were soon restored to our home.

"'Two or three years glided by, and when I was eleven years old, my father, one day, called me into his study, and, looking seriously at me, said, "Frederic, my child, God has been very good to you; he has spared your life through many dangers; you, of all my sons, only remain to me, and may your days be many and prosperous! Now, what can you render unto the Lord for all his mercies towards you; ought not the life God has so graciously spared be in gratitude consecrated to his service? Tell me what you think in this matter. I speak thus early, my dear Frederic, because I wish you to consider well, before you are sent from home, what are to be your future plans; for as life is uncertain, and none of us know the day nor the hour in which the summons may arrive, I should feel more happy, were I assured that you would tread in my footsteps when I am gone; that you, my only boy," and he clasped me in his arms as he spoke, "that you would be a comfort to your mother and sisters, when my labors are ended, and would carry on the work which I have begun in this portion of the Lord's vineyard, and His blessing and the blessing of a fond father will ever attend your steps."

"'I raised my eyes to my father's face, and, for the first time, noticed how pale and haggard he looked; all the bright and joyous expression of his countenance when in health had given place to a mild and melancholy shade of sadness, which affected me painfully; for the thought struck me that my father was soon to be called away.

"'I evaded answering his question, and when he found I did not reply, he said, "My son, let us ask the direction of Almighty God in this great work." I knelt with him, and was lost in admiration. I could not remove my eyes from his face during the prayer; his whole soul seemed absorbed in communion with God, and as I gazed, I wondered what the glorious angels must be like, when the face of my beloved father, while here on earth, looked so exquisitely lovely, glowing in the beauty of holiness.

"'For several days, the conversation in the study was continually in my mind; I could think of nothing else. I did not like the profession well enough to have chosen it myself, for I disliked retirement; but after an inward struggle, betwixt my inclination and my duty, I resolved, that, to please my father, I would study for the church. One day, my godfather, Captain Hartly, came to see us, and he took great notice of me. He asked me if I should like to go to sea? Then he told me such fine things about life in the navy, and on board ship, that my wavering mind fired at his descriptions, and I determined to be a sailor, for such a life would be more congenial to my feelings than the quiet life of a country clergyman. I did not mention this to my father, for he was ill, and I feared to grieve him; nevertheless, had he asked me, I should certainly have opened my heart to him without dissimulation. I often fretted when I thought how sorry he would be to hear that I did not care to be engaged in the service of his Master; when one morning, as I was lying in bed, a servant came into my room, and desired me to hasten to my father's chamber, to receive his blessing, for he was dying.

"'I did hasten. I know not how I got there. I rushed into his arms, I threw myself on his neck, and felt as if I too must die. He was too much exhausted to speak; but he placed his hand on my head, and, slightly moving his lips, the expression of his features told, in plain language, that his heart was engaged in prayer. He was praying, and for me,—me, his unworthy son, and when I considered that I could not comply with his wishes without being a hypocrite, I thought my heart would burst. For several minutes, was my dear father thus occupied; then, turning to my weeping mother, who was kneeling by the bedside, he softly uttered her name. Alas! it was with his parting breath, for gently, as an infant falls asleep on the bosom of its nurse, did my revered parent fall asleep in the arms of that Saviour who had been his guide and comforter through life, and who accompanied him through the dark valley, and by his presence made bright the narrow path which leads to the abode of the redeemed.

"'The only earthly friend we had to look to, in our bereavement, was Captain Hartly; and he could only promise to assist me if I would enter the navy, or go on board a merchant-ship. My poor mother objected to this, and I remained at home another twelvemonth, and again mourned the loss of a dear relative. My sister Bertha fell a victim to consumption, exactly nine months after the death of my lamented father. It was cruel to leave my mother under such circumstances, particularly as she remonstrated with me so earnestly on my project of going to sea, and offered to make any sacrifice, if I would consent to go to college, and follow out my father's plans. But my heart was fixed; and every visit from my godfather tended to inflame me still more with a longing for a sea-faring life; and, at length, I told him I was willing to be bound apprentice to a captain of a merchant-ship, rather than lose the chance of going to sea. He eagerly embraced the offer, and in a few weeks the affair was settled satisfactorily for all parties but my dear mother and sister. Marian wept bitterly when the letter came which concluded the arrangements, and informed me what day to be on board. My mother went to see the captain, and entreated him to be kind to me. But she knew not the disposition of the man to whose care I was entrusted, or I am sure nothing would have induced her to consent to my plans. I dare say it is all for the best. I shall, perhaps, learn my duty better with Captain Simmons than I should have done with a kinder master. It is well my mother knows nothing of this; for, even believing I should be treated with the utmost kindness, the separation was almost more than she had fortitude to bear, and she bade me farewell nearly heart-broken. I have never ceased to regret that I preferred my own will to the authority of my parents; I deserve all I suffer, and much more, for my rebellion against them. This, madam, is all I have to tell you. I hope you will not cast me off, because I have been so self-willed; for here I have no friend to aid me, and I still feel the same desire for my present mode of life. I am quite sure I am not suited for a clergyman; but I do not think I could live long with this captain. If I could get shipped in another vessel, with a master not quite so severe, in a little time I should be able to work for money, and assist my dear mother; and if she saw me occasionally, and knew I was well and happy, she would be content and thankful.'

"Such was Frederic's simple account of himself. In five days we came in sight of Port Royal, and anchored off there during the night: the next day we went ashore, and my brother Herbert, who was a merchant in Kingston, was ready to receive me, and welcome me to his house.

"I took the earliest opportunity of speaking to him concerning Frederic: he promised to make some arrangement for the boy's advantage, and he fulfilled his promise. He got him transferred to the 'Albatross,' Captain Hill, a kind, gentlemanly man. There Frederic remained for several years, and gained such approbation by his exemplary conduct, that, at length, he became first mate, and afterwards (on the death of Captain Hill) master.

"A few years back, Captain Hartly died; leaving him considerable property. He made it his first business to settle his mother comfortably, and she is now residing with Marian (who married a surgeon,) in St. John's Wood. He next purchased a ship, and has already made six voyages in her to the West Indies; so that you see all things have prospered with Frederic Hamilton, because 'he feared the Lord always.' I hear from him after every voyage, and have seen him several times since he became a great man and a ship-owner; but he is not altered in one respect, for he is still the same grateful, affectionate creature as when I first met him on board the 'Neptune.' His story proves the truth of the text, 'I have never seen the righteous forsaken, nor his children begging their bread.'"

Mr. and Mrs. Wilton were as much pleased as the children with this little story of Grandy's reminiscences. "And now, George," said Mr. Wilton, "carry my drawings into the study, for I hear John coming up-stairs with the supper."

George collected his papa's pencils and paper. Emma folded up the cotton frock she had been making for one of her young pupils in the Sunday-school, locked her work-box, cleared the table of all signs of their recent occupation, and took her seat by the side of her brother.

The children were not allowed except on particular occasions to sit up after ten o'clock; but as it was Mr. Wilton's wish that they should be present night and morning at family prayers he always had supper about nine o'clock, to give them time for their devotions before retiring to rest.

Supper over, the domestics were summoned, and, having humbly petitioned for pardon and grace, they besought the protection of Almighty God during the night season; then, with hearts filled with love to God, and good-will towards all men, they retired to their several apartments, and silence reigned throughout the house.

Beautiful, sublime and glorious;

Mild, majestic, foaming, free;—

Over time itself victorious,

Image of eternity.

Every day throughout the following week the young folks were busily engaged. It is needless to specify the nature of their occupations, or the reason of their untiring industry: it will be sufficient for their credit to mention that they did not work with the foolish desire of ostentatiously displaying a larger portion of information than the rest of the party, but really because they were fond of study; and as they advanced in knowledge, they became more sensible of their own comparative ignorance, and more anxious to learn. They made no parade of their own abilities; were equally gratified at the meetings, whether they were required to speak, or be silent; and no evil passions disturbed their repose, when they heard other members more praised than themselves. To prove this, the young lady to whom Emma had decidedly given the preference amongst her companions, was three years her senior, had nearly completed her education, and was a clever intelligent girl; consequently, it was very probable that she would far surpass her in knowledge, and be in fact more serviceable to the society than Emma ever had been, or could hope to be, for some time to come. But Emma's heart was a stranger to the wicked feeling of jealousy; it was overflowing with kindness; and she was delighted that she knew a person so agreeable, and so efficient to introduce, and thought how admirably they would travel "o'er the glad waters of the bright blue sea," if all the new members were as well qualified as Dora Leslie.

Day after day passed, and every day added to their stores, for they devoted at least two hours of their recreation to the pleasant and profitable occupation of making discoveries in the great oceans and smaller seas; and when they closed their books, it was with a sigh, that they were obliged to leave this interesting study to attend to other business of equal importance.

On the evening of the 7th instant the large round table in the front drawing-room presented a formidably learned appearance, covered with maps, papers, and books, and surrounded with chairs placed at convenient distances for the accommodation of the members of the Geographical Society.

They were to take tea in another apartment that evening, to give them an opportunity of arranging the requisite documents before the party assembled, and thereby prevent much trouble and confusion.

George's blue eyes sparkled with joy, as he carefully folded his large paper of notes, and placed it in an Atlas; and then, for the first time, he confessed that he felt very curious to see the "new members."

They had scarcely concluded their arrangements, when there was a knocking at the hall-door, and, seizing his sister's hand, George hurried down stairs.

The arrivals were shortly announced; for strange to say, the two young friends arrived at the same instant. John opened the parlor door, and ushered in "Miss Dora Leslie,"—"Master Charles Dorning."

These young people never having previously met at Mr. Wilton's house, as members of his Geographical Society, it seemed necessary that there should be a formal introduction,—at least, so thought George; and as he proposed it, they required him to perform the ceremony, which he did in a most facetious way, affixing the initials M.G.S. after every name.

They were all seated around the cheerful fire, laughing heartily, when again John threw open the door, and announced "Mr. Barraud." Immediately their mirth was checked, for to the younger folks this gentleman was a total stranger. Mr. Wilton advanced to greet his friend, and Mrs. Wilton and Grandy both appeared delighted to see him: they conversed together some time, until tea was ready, when the conversation became more general, and our little friends were occasionally required to give an opinion.

Before I proceed any farther, I should like to make you acquainted with Charles Dorning and Dora Leslie. Perhaps if I give you a slight sketch of their personal appearance, you could contrive to form a tolerably correct estimate of their characters from the conversations in which they both figured to such advantage at the evening meetings held in the drawing-room of Mr. Wilton's hospitable mansion.

Charles Dorning—No! We ought to describe the lady first. Dora Leslie was fourteen years of age; a gentle, quiet girl, with a meek yet intelligent countenance, which spoke of sorrow far beyond her years; and a decided expression of placidity, which none but the people of God wear, was stamped upon her delicate features and glowing in her mild blue eye. She had been in early childhood encompassed by the heavy clouds of worldly sorrow: she had wept over the tomb of both her parents; but now that she could think calmly of her afflictions, she could kiss the rod which chastened her, and praise God for thus testifying his exceeding love towards a sinful child. Her trials had indeed been sanctified to her; they had changed, but not saddened, her heart; for she was at the time of her visit to the Wiltons a cheerful, happy girl, delighting in the innocent amusements suitable to her age, though ever ready to turn all events to the advantage of her fellow-creatures, and the glory of her God. But I am telling you more than I intended. I was only to describe her person, and here I am giving a full, true, and particular account of the beauties of her mind also. Well, I trust you will excuse me; for the mind and the body are so nearly connected, that it is impossible to give a just idea of the graces of one without in some degree touching upon the merits of the other. I will now turn to Charles Dorning, as I think I have said enough of Dora Leslie to induce you to regard her with friendliness.

Charles Dorning was a fine romping boy of eleven years; he had no bright flaxen curls like our friend George, but straight dark hair, which, however, was so glossy and neat that no person thought it unbecoming. His eyes were the blackest I ever saw, and so sparkling when animated with merriment, that it was impossible to resist their influence, and maintain a serious deportment if he were inclined to excite your risibility. Charles was a merry boy, but so innocent in his mirth, that Mr. Wilton was always pleased to have him for his son's companion, knowing by observation that his mirth was devoid of mischief, and that he possessed a most inquiring mind, which urged George on to the attainment of much solid knowledge that would be greatly serviceable to him in after years.

I flatter myself you will, from this slight sketch, be able to form some idea of the "new members," and regard them as old acquaintances, as you already do Emma and George.

While they were drinking tea, there was an animated conversation, which still continued when the meal was over, until the tray had disappeared, and John had brushed the crumbs from the table; when Mrs. Wilton said, "Suppose we adjourn into the next room, and commence business"

There was a general move, and in a few moments the table was surrounded, and each person preparing to enjoy the evening's occupation. Miss Leslie seated George next to her, because she could assist him considerably in finding places on the maps; and Charles Dorning was gallant enough to offer to point out the localities for Emma. Thus they were arranged. Grandy only was away from the table: she was in her customary seat by the fire, with the pussy at her feet, and her fingers nimbly engaged on a par à tête, which she was knitting with extraordinary facility considering her age and impaired vision.

"Who is to commence?" inquired Mr. Wilton. "Emma, what have you prepared?"

EMMA. "Dora is to begin, papa, and my paper will be required presently."

MR. WILTON. "Very well. We are all ready, Dora, and most attentive. I think, as we have hitherto commenced with our own quarter of the world, it would be more systematic to do so now. Are you prepared for the seas of Europe?"

DORA. "I will readily impart all I have prepared, sir, and be thankful to listen to the rest.

"Europe is bounded on the north by the frozen ocean, south by the Mediterranean sea, east by Asia, and west by the Atlantic ocean. Seas being smaller collections of water than oceans, I have selected them for our first consideration, and, thinking the Mediterranean the most important of Europe, I have placed it at the head of my list. This sea separates Europe from Africa, and is the largest inland sea in the world. It contains some beautiful islands, and washes the shores of many countries planted with the myrtle, the palm, and the olive, and famous both in history and geography as scenes of remarkable adventures, warfares, and discoveries. Numerous rivers from Italy, Turkey, Spain, and France empty their waters into this great sea. Africa sends a contribution from the mighty Nile, that valuable river which is of such inestimable benefit to the Egyptians.

"The principal islands in the Mediterranean are Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Candia, Cyprus, Rhodes, Majorca, Minorca, and Iviza. There are scores of smaller isles, such as Malta, Zante, Cephalonia (the two latter are included in the Ionian isles); but it would be endless work to particularize each spot of earth fertile or otherwise, inhabited or uninhabited in every sea, unless there be something positively interesting connected with them, or something important to be known concerning them. I believe Mrs. Wilton undertakes to supply the particulars of which we are in need with respect to the various islands already specified. Therefore I close my paper for the present"

MRS. WILTON. "Sicily, formerly called Trinacria, from its triangular shape, is separated from Italy by the Straits of Messina, which are seven miles across. In these straits were the ancient Scylla and Charybdis, long regarded as objects of terror; but now, owing to the improved state of navigation, they are of little consequence, and have ceased to excite fears in the hearts of the poor mariners. The chief towns of Sicily are Messina, Palermo, and Syracuse. In the middle of this island stands the famous burning mountain Etna.

"Of Sardinia, the chief town is Cagliari.

"Corsica is a beautifully wooded country: its capital is Bastia. The great Napoleon Bonaparte was borne at Ajaccio, a sea port in this island."

MR. BARRAUD. "There are two interesting associations with Napoleon to be seen in the Mediterranean off Toulon. One is an old dismantled frigate, which is moored just within the watergates of the basin, and carefully roofed over and painted. She is the 'Muiron,' with an inscription in large characters on the stern, as follows:—'Cette frégate prise à Venise est celle qui ramena Napoleon d'Egypte.' Every boat which passes from the men of war to the town must go immediately under the stern of the Muiron. The hold of the Muiron is at present used as a dungeon for the forçats or galley-slaves who misbehave.

"The next association with the Emperor is a stately frigate in deep mourning, painted entirely black, which claims the distinction of having brought the remains of Napoleon to France. 'La belle Poule' is the pride of French frigates."[2]

MRS. WILTON. "Candia is the ancient Crete: it is a fine fertile island, about 160 miles Jong, and 30 broad. The famous mount Ida of heathen mythology (now only a broken rock) stands here, with many other remains of antiquity; and through nearly the whole length of this island runs the chain of White Mountains, so called on account of their snow coverings. The island abounds with cattle, sheep, swine, poultry, and game, all excellent; and the wine made there is balmy and delicious. The people of Candia were formerly celebrated for their want of veracity; St. Paul alludes to their evil habits in the first chapter of his epistle to Titus, where he says, 'The Cretians are always liars.' There are some remarkably ugly dogs in Candia, which seem to be a race between the wolf and the fox.

"Cyprus contains the renowned Paphos: it is not quite so long an island as Candia, but it is ten miles broader.

"Rhodes is fifty miles long, and twenty-five broad. At the north of the harbor stood the celebrated colossus of brass, once reckoned one of the wonders of the world. It was placed with a foot on either side of the harbor, so that ships in full sail passed between its legs. This enormous statue was 130 feet high; it was thrown down by an earthquake, and afterwards destroyed, and taken to pieces in the year A.D. 653.

"Of Majorca I have little to say: its chief town is Majorca.

"Port Mahon is the capital of Minorca; and Iviza is the principal town in the island of that name.

"Malta—"

GEORGE. "Excuse me for interrupting you, dear mamma; but I wish Grandy to tell me if Malta is the same island as the Melita mentioned in the 28th chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, where St. Paul was shipwrecked?"

GRANDY. "Yes, my dear; it is commonly supposed to be the same. It is a very rocky island, inhabited by a people whom most modern travellers describe as very selfish, very insincere, and very superstitious. The population amounts to upwards of 63,000. In the days of St. Paul, the inhabitants were, without doubt, an uncivilized race, for he calls them a barbarous people! 'And the barbarous people showed us no little kindness: for they kindled a fire, and received us every one, because of the present rain, and because of the cold.' Here it was that from the circumstance of St. Paul experiencing no evil effects from the viper clinging to his hand, that the people concluded him to be a god; here too he was allowed to perform many mighty works, such as healing the sick, &c., which caused him to be 'honored with many honors;' and 'when they departed, they were laden with the bounty of the people.' Can any one of you young folks tell me the name of the chief town in this little island?"

"Yes, madam," replied Charles, "I know it; it is Valetta, so named from the noble Provençal Valette, who, after vainly endeavoring to defend the holy sepulchre from the defilements of the infidels, was by them driven with his faithful Christian army from island to island, until he ultimately planted the standard of the cross on this sea-girt rock, and bravely and successfully withstood the attacks of his enemies. Malta was given to the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in 1530 by the Emperor Charles V., when the Turks drove them out of Rhodes. They have since been called 'Knights of Malta.' The island is in possession of the English."

DORA. "And so are the Ionian Islands, which include Zante, Cephalonia, and St. Maura: they are all pretty spots near the coast of Greece."

MR. WILTON. "In the Mediterranean Sea lays the largest ship in the world, the 'Mahmoud:' it is floating off Beyrout."

"I can tell you, papa," said George, "the size of the largest ship in the time of Henry VIII.; it was called the 'Henri Grace à Dieu,' and was of 1000 tons burthen; it required 349 soldiers, 301 sailors, and 50 gunners to man her."

MR. WILTON. "That was the first double-decked ship built in England; it cost £14,000, and was completed in 1509. Before this, twenty-four gun-ships were the largest in our navy; and these had no port-holes, the guns being on the upper decks only. Port-holes were invented by Descharges, a French builder at Brest, in the year 1500."

CHARLES. "That was a useful and simple invention enough: it must have been very inconvenient to have all the guns on the upper decks; besides, there could not be space for so many as the vessels of war carry now. Pray what is the size of a first-rate man-of-war, and how many guns does she carry?"

MR. BARRAUD. "The 'Caledonia,' built at Plymouth in 1808, is 2616 tons burthen, carries 120 guns, and requires 875 men without officers. You can imagine the size of a vessel that could contain so many men. But all are not so large: that is a first-rate: there are some sixth-rate, which only carry twenty guns, are not more than 400 tons burthen, and their complement of men is only 155. The intermediate ships, 2d, 3d, 4th, and 5th rate, vary in every respect according to their size, and are classed according to their force and burthen. Only first and second-rate men-of-war have three decks. Ships of the line include all vessels up to the highest rate, and not lower than the frigate."

GEORGE. "How I should like to have a fleet of ships. Will you buy me more, dear papa, when I have rigged the 'Stanley?' I am getting on very fast with her; Emma has stitched all the sails, and only three little men remain to be dressed; while I have cut the blocks, and set the ropes in order. It will look very handsome when it is quite finished; but a miniature fleet would be beautiful to launch on the lake at Horbury next summer. If I rig this vessel properly, may I have some others of different sizes, with port-holes to put cannon in? The 'Stanley,' you know, is a merchantman; but now I want some men-of-war."

MR. WILTON. "My dear, when your friend sent you the 'Stanley,' do you remember how delighted you were, and the remark you made at the time? I have not forgotten your exclamation—'Now I am a ship-owner! I should be quite satisfied if I were a man to possess one vessel to cross the great ocean, and bring all sorts of curiosities from foreign lands. I should not care to have half a dozen, because they would be a great deal of trouble to me, and would make me anxious and unhappy.' How quickly you have changed your opinion. I fear that if you had a little fleet, your desires would not be checked, for you would, after a while, be wishing for large ships, and real men, and, instead of being a contented ship-owner, would not be satisfied with any station short of the Lord High Admiral. I do not think it would be wise in me to gratify your desires in this matter, for then I should be like the foolish father of whom Krummacher relates a story."

"Oh! what is it, papa," inquired George: "will you tell us?"

MR. WILTON. "A father returned from the sea-coast to his own home, and brought with him, for his son, some beautiful shells, which he had picked up on the shore. The delight of the boy was great. He took them, and sorted them, and counted them over. He called all his playfellows, to show them his treasures; and they could talk of nothing but the beautiful shells. He daily found new beauties, and gave each of them a name. But in a few months, the boy's father said to himself, 'I will now give him a still higher pleasure; I will take him to the coast of the sea itself; there he will see thousands more of beautiful shells, and may choose for himself.' When they came to the beach, the boy was amazed at the multitude of shells that lay around, and he went to and fro and picked them up. But one seemed still more beautiful than another, and he kept always changing those he had gathered for fresh shells. In this manner he went about changing, vexed, and out of humor with himself. At length, tired of stooping and comparing, and selecting, he threw away all he had picked up, and, returning home weary of shells, he gave away all those which had afforded him so much pleasure. Then his father was sorry, and said, 'I have acted unwisely; the boy was happy in his small pleasures, and I have robbed him of his simplicity, and both of us of a gratification.' Now, my boy, does not this advise you to be content with such things as you have? King Solomon says, 'Better is a little with the fear of the Lord, than great treasure and trouble therewith;' and surely your trouble would be largely increased were you to have a whole fleet of ships to rig and fit up against next summer; and I rather think Emma would be bringing forward various objections, as her time would be required to prepare the sails and dress the sailors."

"Indeed, dear papa," said Emma, "I have had quite enough trouble with his 'merchantman,' for George is so very particular. I am sure I could not dress the marines for a man-of-war: they require an immense deal of care in fitting their clothes: loose trousers and check shirts are easy to make, but tight jackets and trousers, with all the other et ceteras required to dress a marine, would be more than I should like to undertake, as I feel convinced I could not do it to the admiral's satisfaction."

CHARLES. "George, shall I give you the dictionary definition of an admiral?"

GEORGE. "I know what an admiral is. He is an officer of the first rank; but I do not know what the dictionary says."

CHARLES. "Then I will tell you how to distinguish him: according to Falconer, an admiral may be distinguished by a flag displayed at his main-top-gallant-mast-head."

This caused a burst of merriment, when Emma exclaimed, "That sounds very droll, Charles, but I understand it: it refers to the admiral's ship, does it not, papa?"

MR. WILTON. "Yes, my dear. The Sicilians were the first by whom the title was adopted in 1244: they took it from the Eastern nations, who often visited them. Well, George, do not you think you had better be content with your merchant-ship, because, then, you can reckon on Emma's services?"

GEORGE. "I will try, papa, to exercise my patience on the 'Stanley,' and be satisfied to read of the men-of-war. Now, dear papa, I want to know if the Mediterranean has ever been frozen over like the Thames?"

MR. WILTON. "Not exactly like the Thames, but it has been frozen. In the year 1823, the Mediterranean was one sheet of ice; the people of the south never experienced so severe a winter, or, if they did, there is no mention made of it in history."

EMMA. "Ought not Venice, being nearly or totally surrounded by water, to be included in the islands of the Mediterranean?"

MRS. WILTON. "It is not in the Mediterranean, my dear, but situated to the north of the Adriatic Sea, which sea is undoubtedly connected with the Mediterranean, as are many other seas and gulfs; for instance, we may include the Archipelago or Egean Sea, the Sea of Marmora, the Gulf of Tarento, and the first-mentioned, the Adriatic Sea, or Gulf of Venice, the mouth of which is also called the Ionian Sea; and I cannot tell you how many smaller gulfs, or, more properly speaking, bays, beside; for in the Archipelago alone there are no fewer than eleven. However, while we are so near, it may be of some advantage to take a peep at Venice, 'the dream-like city of a hundred isles:' that expression is a poetical exaggeration, for Venice is built upon seventy-two small islands. Over the several canals, are laid nearly five hundred bridges, most of them built of stone. The Rialto was once considered the largest single-arched bridge in the world, and is well known to English readers from the work of our greatest dramatist, Shakspeare,—the 'Merchant of Venice,' and from 'Venice Preserved,' written by the unhappy poet Otway, who died of starvation. Although no longer the brilliant and prosperous city, from whose stories Shakspeare selected such abundant subjects for his pen, there is yet much to admire and wonder at. On the great canal, which has a winding course between the two principal parts of the city, are situated the most magnificent of the great houses, or palaces as they are termed; some of them of a beautiful style of architecture, with fronts of Istrian marble, and containing valuable collections of pictures. The canals penetrate to every part of the town, so that almost every house has a communication by a landing-stair, leading directly into the house by one way, and on to the water by another. The place of coaches is supplied by gondolas, which are light skiffs with cabins, in which four or five persons can sit, covered and furnished with a door and glass windows like a carriage. They are propelled by one man standing near the stern, with a single oar, which he pushes, moving the boat in the same direction as he looks. Those persons who are not rich enough to possess a gondola of their own, hire them, as we do cabs, when they require to go abroad. The Venetian territories are as fruitful as any in Italy, abounding with vineyards, and mulberry plantations. Its chief towns are Venice (which I have described), Padua, Verona, Milan, Cremona, Lodi, and Mantua. Venice was once at the head of the European naval powers; 'her merchants were princes, and her traffickers the honorable of the earth,' but now—

"'Her pageants on the sunny waves are gone,

Her glory lives in memory's page alone.'

"In a beautiful poem written by the lamented Miss Landon, there are some very appropriate lines:—

"'But her glory is departed,

And her pleasure is no more,

Like a pale queen broken-hearted,

Left lonely on the shore.

No more thy waves are cumbered

With her galleys bold and free;

For her days of pride are numbered,

And she rules no more the sea.

Her sword has left her keeping,

Her prows forget the tide,

And the Adriatic, weeping,

Wails round his mourning bride.'

"'In those straits is desolation,

And darkness and dismay—

Venice, no more a nation,

Has owned the stranger's sway.'"

CHARLES. "I have some scraps belonging to the 'tideless sea,' which will come in here very well. The first is the account of the Bosphorus, now called the Canal of Constantinople, situated between the Euxine and the Sea of Marmora. The whole length of it is about seventeen miles, and most delightful excursions are made on it in pretty vessels called 'Caiques.' They rest so lightly on the water, that you are never certain of being 'safely stowed.' The rowers are splendid-looking fellows from two to four in number, each man with two light sculls, and they sit lightly on thwarts on the same level with the gunwale of the caique. Their costume is beautiful; the head covered with the crimson tarbouche, and the long silk tassel dangling over the shoulders; a loose vest of striped silk and cotton, fine as gauze, with wide open collar, and loose flowing sleeves; a brilliant-colored shawl envelops the waist, and huge folds of Turkish trousers extend to the knee; the leg is bare, and a yellow slipper finishes the fanciful costume. In the aft part of this caique is the space allotted for the 'fare,' a crimson-cushioned little divan[3] in the bottom of the boat, in which two persons can lounge comfortably. The finish of the caique is often extraordinary—finest fret-work and moulding, carved and modelled as for Cleopatra. The caiques of the Sultan are the richest boats in the world, and probably the most rapid and easy. They are manned by twenty or thirty oarsmen, and the embellishment, and conceits of ornament are superb. Nothing can exceed the delightful sensation of the motion; and the skill of the rowers in swiftly turning, and avoiding contact with the myriads of caiques is astonishing. My next scrap is about the Hellespont,[4] situated between the Sea of Marmora and the Archipelago: it is broader at the mouth than at any other part; about half-way up, the width is not more than a mile, and the effect is more like a superb river than a strait; its length of forty-three miles should also give it a better claim to the title of a river. In the year 1810, on the 10th of May, Lord Byron accompanied by a friend, a lieutenant on board the 'Salsette,' swam across the Hellespont, from Abydos to Sestos, a distance of four miles; but this was more than the breadth of the stream, and caused principally by the rapidity of the current, which continually carried them out of the way, the stream at this particular place being only a mile in width. It was here also that Leander is reported to have swam every night in the depth of winter, to meet his beloved Hero; and, alas! for both, swam once too often."

MR. WILTON. "Before we sail out of the Mediterranean, I wish to mention the singular loss of the 'Mentor,' a vessel belonging to Lord Elgin, the collector of the Athenian marbles, now called by his name, and to be seen in the British Museum. The vessel was cast away off Cerigo, with no other cargo on board but the sculptures: they were, however, too valuable to be given up for lost, because they had gone to the bottom of the sea. A plan was adopted for recovering them, and it occupied a number of divers three years, before the operations were completed, for the Mentor was sunk in ten fathoms water, and the cases of marble were so heavy as to require amazing skill and good management to be ultimately successful. The cases were all finally recovered, and none of the contents in the least damaged, when they were forwarded to England. The whole cost of these marbles, all expenses included, in the collecting, weighing up, and conveying, is estimated at the enormous sum of 36,000l."

CHARLES. "When was this valuable collection made, sir?"

MR. WILTON. "It was many years in hand. I believe about the year 1799 investigations commenced; but the 'Mentor' was lost in 1802, and the marbles did not all arrive in England until the end of the year 1812; since then an immense number of valuable medals have been added to the collection."

DORA. "May we now sail through the straits of Gibraltar into the Atlantic?"

MR. WILTON. "We must necessarily pass through the straits of Gibraltar to get out of the Mediterranean; but as we proposed to examine into the different situations of the lesser divisions of water, first, we will merely sail through a portion of the Atlantic, and have a little information concerning the Bay of Biscay."

DORA. "The Bay of Biscay washes the shores of France and Spain; but the sea is so very rough there, that I think, were our voyage real instead of imaginary, we should all be anxious to leave this Bay as quickly as possible: and the next name on the list is the British Channel."

EMMA. "I have that. The British Channel is the southern boundary of Great Britain, and extends to the coast of France. The islands in this channel are the Isle of Wight—capital Newport,—Guernsey, Jersey, Alderney and Sark."

MRS. WILTON. "The Isle of Wight has, from time immemorial, been eulogized for its beautiful scenery. It is about twenty-three miles from east to west, and twelve from north to south. You have all heard of the Needles, which obtained their name from a lofty pointed rock on the western coast, bearing a resemblance to that little implement; and which, with other pieces of rock, had been disjointed from the mainland by the force of the waves. This rock was 120 feet high. About seventy years ago, it fell, and totally disappeared in the sea. The height of the cliffs now standing, is in some places 600 feet, and, when viewed from a distance, they are magnificent in the extreme. In this island her majesty Queen Victoria has a delightful residence.

"Guernsey is the most westerly of the Channel Islands: it is eight miles one way, and six miles the other, very fertile, with a mild and healthy climate. A striking object presents itself on approaching Guernsey, called Castle Cornet, situated on a rock somewhat less than half a mile from the shore, entirely surrounded by water, supposed to have been built by the Romans, and formerly the residence of the governors."

MR. BARRAUD. "I have read a curious description of a most remarkable thunder storm, which visited this place in December, 1672. It is as follows:—