Ethel Morton, called from the color of her eyes Ethel "Blue" to distinguish her from her cousin, also Ethel Morton, whose brown eyes gave her the nickname of Ethel "Brown," was looking out of the window at the big, damp flakes of snow that whirled down as if in a hurry to cover the dull January earth with a gay white carpet.

"The giants are surely having a pillow fight this afternoon," she laughed.

"In honor of your birthday," returned her cousin.

"The snowflakes are really as large as feathers," added Dorothy Smith, another cousin, who had come over to spend the afternoon.

All three cousins had birthdays in January. The Mortons always celebrated the birthdays of every member of the family, but since there were three in the same month they usually had one large party and noticed the other days with less ceremony. This year Mrs. Emerson, Ethel Brown's grandmother, had invited the whole United Service Club, to which the girls belonged, to go to New York on a day's expedition. They had ascended the Woolworth Tower, gone through the Natural History Museum, seen the historic Jumel Mansion, lunched at a large hotel and gone to the Hippodrome. Everybody called it a perfectly splendid party, and Ethel Blue and Dorothy were quite willing to consider it as a part of their own birthday observances.

Next year it would be Dorothy's turn. This year her party had consisted merely in taking her cousins on an automobile ride. A similar ride had been planned for Ethel Blue's birthday, but the giants had plans of their own and the young people had had to give way to them. Dorothy had come over to spend the afternoon and dine with her cousins, however. She lived just around the corner, so her mother was willing to let her go in spite of the gathering drifts, because Roger, Ethel Brown's older brother, would be able to take her home such a short distance, even if he had to shovel a path all the way.

The snow was so beautiful that they had not wanted to do anything all the afternoon but gaze at it. Dicky, Ethel Brown's little brother, who was the "honorary member" of the U.S.C., had come in wanting to be amused, and they had opened the window for an inch and brought in a few of the huge flakes which grew into ferns and starry crystals under the magnifying glass that Mrs. Morton always kept on the desk.

"Wouldn't it be fun if our eyeth could thee thingth like that!" exclaimed Dicky, and the girls agreed with him that it would add many marvels to our already marvellous world.

"As long as our eyes can't see the wee things I'm glad Aunt Marion taught us to use this glass when we were little," said Ethel Blue who had been brought up with her cousins ever since she was a baby.

"Mother says that when she and Uncle Roger and Uncle Richard," said Dorothy, referring to Ethel Brown's and Ethel Blue's fathers, her uncles—"were all young at home together Grandfather Morton used to make them examine some new thing every day and tell him about it. Sometimes it would be the materials a piece of clothing was made of, or the paper of a magazine or a flower—anything that came along."

"When I grow up," said Ethel Blue, "I'm going to have a large microscope like the one they have in the biology class in the high school. Helen took me to the class with her one day and the teacher let me look through it. It was perfectly wonderful. There was a slice of the stem of a small plant there and it looked just as if it were a house with a lot of rooms. Each room was a cell, Helen said."

"A very suitable name," commented Ethel Brown.

"What are you people talking about?" asked Helen, who came in at that instant.

"I was telling the girls about that time when I looked through the high school microscope," answered Ethel Blue.

"You saw among other things, some cells in the very lowest form of life. A single cell is all there is to the lowest animal or vegetable."

"What do you mean by a single cell?"

"Just a tiny mass of jelly-like stuff that is called protoplasm. The cells grow larger and divide until there are a lot of them. That's the way plants and animals grow."

"If each is as small as those I saw under the microscope there must be billions in me!" and Ethel Blue stretched her arms to their widest extent and threw her head upwards as far as her neck would allow.

"I guess there are, young woman," and Helen went off to hang her snowy coat where it would dry before she put it in the closet.

"There'th a thnow flake that lookth like a plant!" cried Dicky who had slipped open the window wide enough to capture an especially large feather.

"It really does!" exclaimed Ethel Blue, who was nearest to her little cousin and caught a glimpse of the picture through the glass before the snow melted.

"Did it have 'root, stem and leaves'?" asked Dorothy. "That's what I always was taught made a plant—root, stem and leaves. Would Helen call a cell that you couldn't see a plant?"

"Yes," came a faint answer from the hall. "If it's living and isn't an animal it's a vegetable—though way down in the lower forms it's next to impossible to tell one from the other. There isn't any rule that doesn't have an exception."

"I should think the biggest difference would be that animals eat plants and plants eat—what do plants eat?" ended Dorothy lamely.

"That is the biggest difference," assented Helen. "Plants are fed by water and mineral substances that come from the soil directly, while animals get the mineral stuff by way of the plants."

"Father told us once about some plants that caught insects. They eat animals."

"And there are animals that eat both vegetables and animals, you and I, for instance. So you can't draw any sharp lines."

"When a plant gets out of the cell stage and has a 'root, stem and leaves' then you know it's a plant if you don't before," insisted Dorothy, determined to make her knowledge useful.

"Did any of you notice the bean I've been sprouting in my room?" asked Helen.

"I'll get it, I'll get it!" shouted Dicky.

"Trust Dicky not to let anything escape his notice!" laughed his big sister.

|

Dicky returned in a minute or two carrying very carefully a shallow earthenware dish from which some thick yellow-green tips were sprouting.

"I soaked some peas and beans last week," explained Helen, "and when they were tender I planted them. You see they're poking up their heads now."

"They don't look like real leaves," commented Ethel Blue.

"This first pair is really the two halves of the bean. They hold the food for the little plant. They're so fat and pudgy that they never do look like real leaves. In other plants where there isn't so much food they become quite like their later brothers."

"Isn't it queer that whatever makes the plant grow knows enough to send the leaves up and the roots down," said Dorothy thoughtfully.

"That's the way the life principle works," agreed Helen. "This other little plant is a pea and I want you to see if you notice any difference between it and the bean."

She pulled up the wee growth very delicately and they all bent over it as it lay in her hand.

"It hathn't got fat leaveth," cried Dicky.

|

"Good for Dicky," exclaimed Helen. "He has beaten you girls. You see the food in the pea is packed so tight that the pea gets discouraged about trying to send up those first leaves and gives it up as a bad job. They stay underground and do their feeding from there."

"A sort of cold storage arrangement," smiled Ethel Brown.

"After these peas are a little taller you'd find if you pulled them up that the supply of food had all been used up. There will be nothing down there but a husk."

"What happens when this bean plant uses up all its food?"

"There's nothing left but a sort of skin that drops off. You can see how it works with the bean because that is done above the ground."

"Won't it hurt those plants to pull them up this way?"

"It will set them back, but I planted a good many so as to be able to pull them up at different ages and see how they looked."

"You pulled that out so gently I don't believe it will be hurt much."

"Probably it will take a day or two for it to catch up with its neighbors. It will have to settle its roots again, you see."

"What are you doing this planting for?" asked Dorothy.

"For the class at school. We get all the different kinds of seeds we can—the ones that are large enough to examine easily with only a magnifying glass like this one. Some we cut open and examine carefully inside to see how the new leaves are to be fed, and then we plant others and watch them grow."

"I'd like to know why you never told me about that before?" demanded Ethel Brown. "I'm going to get all the grains and fruits I can right off and plant them. Is all that stuff in a horse chestnut leaf-food?"

"The horse chestnut is a hungry one, isn't it?"

"I made some bulbs blossom by putting them in a tall glass in a dark place and bringing them into the light when they had started to sprout," said Ethel Blue, "but I think this is more fun. I'm going to plant some, too."

"Grandmother Emerson always has beautiful bulbs. She has plenty in her garden that she allows to stay there all winter, and they come up and are scrumptious very early in the Spring. Then she takes some of them into the house and keeps them in the dark, and they blossom all through the cold weather."

"Mother likes bulbs, too," said Dorothy, "crocuses and hyacinths and Chinese lilies—but I never cared much about them. Somehow the bulb itself looks too fat. I don't care much for fat things or people."

"Don't think of it as fat; it's the food supply."

"Well, I think they're greedy things, and I'm not going ever to bother with them. I'll leave them to Mother, but I am really going to plant a garden this summer. I think it will be loads of fun."

"We haven't much room for a garden here," said Helen, "but we always have some vegetables and a few flowers."

"Why don't we have a fine one this summer, Helen?" demanded Ethel Brown. "You're learning a lot about the way plants grow, I should think you'd like to grow them."

"I believe I should if you girls would help me. There never has been any member of the family who was interested, and I wasn't wild about it myself, and I just never got started."

"The truth is," confessed Ethel Brown, "if we don't have a good garden Dorothy here will have something that will put ours entirely in the shade."

The girls all laughed. They never had known Dorothy until the previous summer. When she came to live in Rosemont in September they had learned that she was extremely energetic and that she never abandoned any plan that she attempted. The Ethels knew, therefore, that if Dorothy was going to have a garden the next summer they'd better have a garden, too, or else they would see little of her.

"If we both have gardens Dorothy will condescend to come and see ours once in a while and we can exchange ideas and experiences," continued Ethel Brown.

"I'd love to have a garden," said Ethel Blue. "Do you suppose Roger would be willing to dig it up for us?"

"Dig up what?" asked Roger, stamping into the house in time to hear his name.

The girls told him of their new plan.

"I'll help all of you if you'll plant one flower that I like; plant enough of it so that I can pick a lot any time I want to. The trouble with the little garden we've had is that there weren't enough flowers for more than the centrepiece in the dining-room. Whenever I wanted any I always had to go and give a squint at the dining room table and then do some calculation as to whether there could be a stalk or two left after Helen had cut enough for the next day."

"And there generally weren't any!" sympathized Helen.

"What flower is it you're so crazy over?" asked Ethel Blue.

"Sweetpeas, my child. Never in all my life have I had enough sweetpeas."

"I've had more than enough," groaned Ethel Brown. "One summer I stayed a fortnight with Grandmother Emerson and I picked the sweetpeas for her every morning. She was very particular about having them picked because they blossom better if they're picked down every day."

"It must have taken you an awfully long time; she always has rows and rows of them," said Helen.

"I worked a whole hour in the sun every single day! If we have acres of sweetpeas we'll all have to help Roger pick."

"I'm willing to," said Ethel Blue. "I'm like Roger, I think they're darling; just like butterflies or something with wings."

"We'll have to cast our professional eyes into the garden and decide on the best place for the sweetpeas," said Roger. "They have to be planted early, you know. If we plant them just anywhere they'll be sure to be in the way of something that grows shorter so it will be hidden."

"Or grows taller and is a color that fights with them."

"It would be hard to find a color that wasn't matched by one sweetpea or another. They seem to be of every combination under the sun."

"It's queer, some of the combinations would be perfectly hideous in a dress but they look all right in Nature's dress."

"We'll send for some seedsmen's catalogues and order a lot."

"I suppose you don't care what else goes into the garden?" asked Helen.

"Ladies, I'll do all the digging you want, and plant any old thing you ask me to, if you'll just let me have my sweetpeas," repeated Roger.

"A bargain," cried all the girls.

"I'll write for some seed catalogues this afternoon," said Helen. "It's so appropriate, when it's snowing like this!"

"'Take time by the fetlock,' as one of the girls says in 'Little Women,'" laughed Roger. "If you'll cast your orbs out of the window you'll see that it has almost stopped. Come on out and make a snow man."

Every one jumped at the idea, even Helen who laid aside her writing until the evening, and there was a great putting on of heavy coats and overshoes and mittens.

The snow was of just the right dampness to make snowballs, and a snow man, after all, is just a succession of snowballs, properly placed. Roger started the one to go at the base by rolling up a ball beside the house and then letting it roll down the bank toward the gate.

"See it gather moss!" he cried. "It's just the opposite of a rolling stone, isn't it?"

When it stopped it was of goodly size and it was standing in the middle of the little front lawn.

"It couldn't have chosen a better location," commended Helen.

"We need a statue in the front yard," said Ethel Brown.

"This will give a truly artistic air to the whole place," agreed Ethel Blue.

"What's the next move?" asked Dorothy, who had not had much experience in this kind of manufacture.

"We start over here by the fence and roll another one, smaller than this, to serve as the body," explained Roger. "Come on here and help me; this snow is so heavy it needs an extra pusher already."

Dorothy lent her muscles to the task of pushing on the snow man's "torso," as Ethel Blue, who knew something about drawing figures, called it. The Ethels, meanwhile, were making the arms out of small snowballs placed one against the next and slapped hard to make them stick. Helen was rolling a ball for the head and Dicky had disappeared behind the house to hunt for a cane.

"Heigho!" Roger called after him. "I saw an old clay pipe stuck behind a beam in the woodshed the other day. See if it's still there and bring it along."

Dicky nodded and raised a mittened paw to indicate that he understood his instructions.

It required the united efforts of Helen and Roger to set the gentleman's head on his shoulders, and Helen ran in to the cellar to get some bits of coal to make his eyes and mouth.

"He hasn't any expression. Let me try to model a nose for the poor lamb!" begged Ethel Blue. "Stick on this arm, Roger, while I sculpture these marble features."

By dint of patting and punching and adding a long and narrow lump of snow, one side of the head looked enough different from the other to warrant calling it the face. To make the difference more marked Dorothy broke some straws from the covering of one of the rosebushes and created hair with them.

"Now nobody could mistake this being his speaking countenance," decided Helen, sticking two pieces of coal where eyes should be and adding a third for the mouth. Dicky had found the pipe and she thrust it above his lips.

"Merely two-lips, not ruby lips," commented Roger. "This is an original fellow; he's 'not like other girls.'"

"This cane is going to hold up his right arm; I don't feel so certain about the left," remarked Ethel Brown anxiously.

"Let it fall at his side. That's some natural, anyway. He's walking, you see, swinging one arm and with the other on the top of his cane."

"He'll take cold if he doesn't have something on his head. I'm nervous about him," and Dorothy bent a worried look at their creation.

"Hullo," cried a voice from beyond the gate. "He's bully. Just make him a cap out of this bandanna and he'll look like a Venetian gondolier."

James Hancock and his sister, Margaret, the Glen Point members of the United Service Club, came through the gate, congratulated Ethel Blue on her birthday, and paid elaborate compliments to the sculptors of the Gondolier.

"That red hanky on his massive brow gives the touch of color he needed," said Margaret.

"We don't maintain that his features are 'faultily faultless,'" quoted Roger, "but we do insist that they're 'icily regular.'"

"Thanks to the size of the nose Ethel Blue stuck on they're not 'splendidly null.'"

"No, there's no 'nullness' about that nose," agreed James. "That's 'some' nose!"

When they were all in the house and preparing for dinner Ethel Blue unwrapped the gift that Margaret had brought for her birthday. It was a shallow bowl of dull green pottery in which was growing a grove of thick, shiny leaves. The plants were three or four inches tall and seemed to be in the pink of condition.

"This is for the top of your Christmas desk," Margaret explained.

"It's perfectly beautiful," exclaimed not only Ethel Blue but all the other girls, while Roger peered over their shoulders to see what it was.

"I planted it myself," said Margaret with considerable pride. "Each one is a little grapefruit tree."

"Grapefruit? What we have for breakfast? It grows like this?"

"Mother has some in a larger bowl and it is really lovely as a centrepiece on the dining room table."

"Watch me save grapefruit seeds!" and Ethel Brown ran out of the room to leave an immediate request in the kitchen that no grapefruit seeds should be thrown away when the fruit was being prepared for the table.

"When Mr. Morton and I were in Florida last winter," said Mrs. Morton, "they told us that it was not a great number of years ago that grapefruit was planted only because it was a handsome shrub on the lawn. The fruit never was eaten, but was thrown away after it fell from the tree."

"Now nobody can get enough of it," smiled Helen.

"Mother has a receipt for grapefruit marmalade that is better than the English orange marmalade that is made of both sweet and sour oranges," said Dorothy. "Sometimes the sour oranges are hard to find in the market, but grapefruit seems to have both flavors in itself."

"Is it much work?" asked Margaret.

"It isn't much work at any one time but it takes several days to get it done."

"Why?"

"First you have to cut up the fruit, peel and all, into tiny slivers. That's a rather long undertaking and it's hard unless you have a very, very sharp knife."

"I've discovered that in preparing them for breakfast."

"The fruit are of such different sizes that you have to weigh the result of your paring. To every pound of cut-up fruit add a pint of water and let it stand over night. In the morning pour off that water and fill the kettle again and let it boil until the toughest bit of skin is soft, and then let it stand over night more."

"It seems to do an awful lot of resting," remarked Roger.

"A sort of 'weary Willie,'" commented James.

"When you're ready to go at it again, you weigh it once more and add four times as many pounds of sugar as you have fruit."

"You must have to make it in a wash-boiler!"

"Not quite as bad as that, but you'll be surprised to find how much three or four grapefruit will make. You boil this together until it is as thick as you like to have your marmalade."

"I can recommend Aunt Louise's marmalade," said Ethel Brown. "It's the very best I ever tasted. She taught me to make these grapefruit chips," and she handed about a bonbon dish laden with delicate strips of sugared peel.

"Let's have this receipt, too," begged Margaret, as Roger went to answer the telephone.

"You can squeeze out the juice and pulp and add a quart of water to a cup of juice, sweeten it and make grapefruit-ade instead of lemonade for a variety. Then take the skins and cut out all the white inside part as well as you can, leaving just the rind."

"The next step must be to snip the rind into these long, narrow shavings."

"It is, and you put them in cold water and let them come to a boil and boil twenty minutes. Then drain off all the water and add cold water and do it again."

"What's the idea of two boilings?" asked James.

"I suppose it must be to take all the bitterness out of the skin at the same time that it is getting soft."

"Does this have to stand over night?"

"Yes, this sits and meditates all night. Then you put it on to boil again in a syrup made of one cup of water and four cups of sugar, and boil it until the bits are all saturated with the sweetness. If you want to eat them right off you roll them now in powdered sugar or confectioner's sugar, but if you aren't in a hurry you put them into a jar and keep the air out and roll them just before you want to serve them."

"They certainly are bully good," remarked James, taking several more pieces.

"That call was from Tom Watkins," announced Roger, returning from the telephone, and referring to a member of the United Service Club who, with his sister, Della, lived in New York.

"O dear, they can't come!" prophesied Ethel Blue.

"He says he has just been telephoning to the railroad and they say that all the New Jersey trains are delayed and so Mrs. Watkins thought he'd better not try to bring Della out. She sends her love to you, Ethel Blue, and her best wishes for your birthday and says she's got a present for you that is different from any plant you ever saw in a conservatory."

"That's what Margaret's is," laughed Ethel. "Isn't it queer you two girls should give me growing things when we were talking about gardens this afternoon and deciding to have one this summer."

"One!" repeated Dorothy. "Don't forget mine. There'll be two."

"If Aunt Louise should find a lot and start to build there'd be another," suggested Ethel Brown.

"O, let's go into the gardening business," cried Roger. "I've already offered to be the laboring man at the beck and call of these young women all for the small reward of having all the sweetpeas I want to pick."

"What we're afraid of is that he won't want to pick them," laughed Ethel Brown. "We're thinking of binding him to do a certain amount of picking every day."

"Anyway, the Morton-Smith families are going to have gardens and Helen is going to write for seed catalogues this very night before she seeks her downy couch—she has vowed she will."

"Mother has always had a successful garden, she'll be able to give you advice," offered Margaret.

"We'll ask it from every one we know, I rather imagine," and Dorothy beamed at the prospect of doing something that had been one of her great desires all her life.

The little thicket of grapefruit trees served as the centrepiece of Ethel Blue's dinner table, and every one admired all over again its glossy leaves and sturdy stems.

"When spring comes we'll set them out in the garden and see what happens," promised Ethel Blue.

"We have grapefruit salad to-night. You must have sent a wireless over to the kitchen," Ethel Brown declared to Margaret.

It was a delicious salad, the cubes of the grapefruit being mixed with cubes of apple and of celery, garnished with cherries and served on crisp yellow-green lettuce leaves with French dressing.

Ethel Blue always liked to see her Aunt Marion make French dressing at the table, for her white hands moved swiftly and skilfully among the ingredients. Mary brought her a bowl that had been chilled on ice. Into it she poured four tablespoonfuls of olive oil, added a scant half teaspoonful of salt with a dash of red pepper which she stirred until the salt was dissolved. To that combination she added one tablespoonful either of lemon juice or vinegar a drop at a time and stirring constantly so that the oil might take up its sharper neighbor.

Dorothy particularly approved her Aunt Marion's manner of putting her salads together. To-night, for instance, she did not have the plates brought in from the kitchen with the salad already upon them.

"That always reminds me of a church fair," she declared.

She was willing to give herself the trouble of preparing the salad for her family and guests with her own hands. From a bowl of lettuce she selected the choicest leaves for the plate before her; upon these she placed the fruit and celery mixture, dotted the top with a cherry and poured the dressing over all. It was fascinating to watch her, and Margaret wished that her mother served salad that way.

The Club was indeed incomplete without the Watkinses, but the members nevertheless were sufficiently amused by several of the "Does"—things to do—that one or another suggested. First they did shadow drawings. The dining table proved to be the most convenient spot for that. They all sat around under the strong electric light. Each had a block of rather heavy paper with a rough surface, and each was given a camel's hair brush, a bottle of ink, some water and a small saucer. From a vase of flowers and leaves and ferns which Mrs. Morton contributed to the game each selected what he wanted to draw. Then, holding his leaf so that the light threw a sharp shadow upon his pad, he quickly painted the shadow with the ink, thinning it with water upon the saucer so that the finished painting showed several shades of gray.

"The beauty of this stunt is that a fellow who can't draw at all can turn out almost as good a masterpiece as Ethel Blue here, who has the makings of a real artist," and James gazed at his production with every evidence of satisfaction.

As it happened none of them except Ethel Blue could draw at all well, so that the next game had especial difficulties.

"All there is to it is to draw something and let us guess what it is," said Ethel Blue.

"You haven't given all the rules," corrected Roger. "Ethel Blue makes two dots on a piece of paper—or a short line and a curve—anything she feels like making. Then we copy them and draw something that will include those two marks and she sits up and 'ha-has' and guesses what it is."

"I promise not to laugh," said Ethel Blue.

"Don't make any such rash promise," urged Helen. "You might do yourself an injury trying not to when you see mine."

It was fortunate for Ethel Blue that she was released from the promise, for her guesses went wide of the mark. Ethel Brown made something that she guessed to be a hen, Roger called it a book, Dicky maintained firmly that it was a portrait of himself. The rest gave it up, and they all needed a long argument by the artist to believe that she had meant to draw a pair of candlesticks.

"Somebody think of a game where Ethel Brown can do herself justice," cried James, but no one seemed to have any inspiration, so they all went to the fire, where they cracked nuts and told stories.

"If you'll write those orders for the seed catalogues I'll post them to-night," James suggested to Helen.

"Oh, will you? Margaret and I will write them together."

"What's the rush?" demanded Roger. "This is only January."

"I know just how the girls feel," sympathized James. "When I make up my mind to do a thing I want to begin right off, and the first step of this new scheme is to get the catalogues hereinbefore mentioned."

"We can plan out our back yards any time, I should think," said Dorothy.

"Father says that somebody—was it Bacon, Margaret?—says that a man's nature runs always either to herbs or to weeds. Let's start ours running to herbs in the first month of the year and perhaps by the time the herbs appear we'll catch up with them."

"How queer it is that when you're interested in something you keep seeing and hearing things connected with it!" exclaimed Ethel Blue about a week after her birthday, when Della Watkins came out from town to bring her her belated birthday gift.

The present proved to be a slender hillock covered with a silky green growth exquisite in texture and color.

"What is it? What is it?" cried Ethel Blue. "We mentioned plants and gardens on my birthday and that very evening Margaret brought me this grapefruit jungle and now you've brought me this. Do tell me exactly what it is."

"A cone, child. That's all. A Norway spruce cone. When it is dry its scales are open. I filled them with grass seed and put the cone in a small tumbler so that the lower end might be damp all the time. The dampness makes the scales close and starts the seed to sprouting. This has been growing a few days and the cone is almost hidden."

"It's one of the prettiest plants—would you call it a plant or a greenhouse?—I ever saw. Does it have to be a Norway spruce cone?"

"O, no. Only they have very regular scales that hold the seed well. I brought you out two more of them and some grass seed and canary seed so you could try it for yourself."

"You're a perfect duck," and Ethel gave her friend a hug. "Now let me show you what one of the girls at school gave Ethel Brown."

She indicated a strange-looking brown object hanging before the window.

"What in the world is it? It looks—yes, it looks like a sweet potato."

"That's what it is—a sweet potato with one end cut off and a cage of tape to hold it. You see it's sprouting already, and they say that the vines hang down from it and it looks like a little green hanging basket."

"What's the object of cutting off the end?"

"Anna—that's Ethel Brown's friend—said that she scooped hers out just a little bit and put a few drops of water inside so that the sun shouldn't dry it too much."

"I should think it would grow better in a dark place. Don't you know how Irish potatoes send out those white shoots when they're in the cellar?"

"She said she started hers in the cellar and then brought them into the light."

"Just like bulbs."

"Exactly. Aunt Louise is having great luck with her bulbs now. She had them in the cellar and now she is bringing them out a pot at a time, so she has something new coming forward every few days."

"Dorothy doesn't care much for bulbs, but I think it's pretty good fun. You can make them blossom just about when you please by keeping them in the dark or bringing them into the light. I'm going to ask Aunt Louise to give me some of hers when they're finished flowering. She says you can plant them out of doors and next year they'll bloom in the garden."

"Mother has some this winter, too. I'll ask her for them after she's through forcing them."

"I like them in the garden, too—tulips and hyacinths and daffodils and narcissus and, jonquils. They come so early and give you a feeling that spring really has arrived."

"You look as if spring had really arrived in the house here. If there wasn't a little bit of that snow man left in front I shouldn't know it had snowed last week. How in the world did you get all these shrubs to blossom now? They don't seem to realize that it's only January."

"That's another thing that's happened since my birthday. Margaret told us about bringing branches of the spring shrubs into the house and making them come out in water, so we've been trying it. She sent over those yellow bells, the Forsythia, and Roger brought in the pussy willows from the brook on the way to Mr. Emerson's."

"This thorny red affair is the Japan quince, but I don't recognize these others."

"That's because you're a city girl! You'll laugh when I tell you what they are."

"They don't look like flowering shrubs to me."

"They aren't. They're flowering trees; fruit trees!"

"O-o! That really is a peach blossom, then!"

"The deep pink is peach, and the delicate pink is apple and the white is plum."

"They're perfectly dear. Tell me how you coaxed them out. Surely you didn't just keep them in water in this room?"

"We put them in the sunniest window we had, not too near the glass, because it wouldn't do for them to run any chance of getting chilled. They stayed there as long as the sun did, and then we moved them to another warm spot and we were very careful about them at night."

"How often do you change the water?"

"Every two or three days; and once in a while we spray them to keep the upper part fresh—and there you are. It's fun to watch them come out. Don't want to take some switches back to town with you?"

Della did.

"They make me think of a scheme that my Aunt Rose is putting into operation. She went round the world year before last," she said, "and she saw in Japan lots of plants growing in earthenware vases hanging against the wall or in a long bamboo cut so that small water bottles might be slipped in. She has some of the very prettiest wall decorations now—a queer looking greeny-brown pottery vase has two or three sprigs of English ivy. Another with orange tints has nasturtiums and another tradescantia."

"Are they growing in water?"

"The ivy and the tradescantia are, but the nasturtiums and a perfectly darling morning glory have earth. She's growing bulbs in them, too, only she doesn't use plain water or earth, just bulb fibre."

"What's that?"

"Why, bulbs are such fat creatures that they don't need the outside food they would get from earth; all they want is plenty of water. This fibre stuff holds enough water to keep them damp all the time, and it isn't messy in the house like dirt."

"What are you girls talking about?" asked Dorothy, who came in with Ethel Brown at this moment.

Both of them were interested in the addition that Della had made to their knowledge of flowers and gardening.

"Every day I feel myself drawn into more and more gardening," exclaimed Dorothy. "I've set up a notebook already."

"In January!" laughed Della.

"January seems to be the time to do your thinking and planning; that's what the people who know tell me."

"It seems to be the time for some action," retorted Della, waving her hand at the blossoming branches about the room.

"Aren't they wonderful? I always knew you could bring them out quickly in the house after the buds were started out of doors, but these fellows didn't seem to be started at all—and look at them!"

"Mother says they've done so well because we've been careful to keep them evenly warm," said Ethel Brown. "Dorothy's got the finest piece of news to tell you. If she doesn't tell you pretty soon I shall come out with it myself!"

"O, let her tell her own secret!" remonstrated Blue. "What is it?"

You know that sloping piece of ground about a quarter of a mile beyond the Clarks' on the road to Mr. Emerson's?"

"You don't mean the field with the brook where Roger got the pussy willows?"

"This side of it. There's a lovely view across the meadows on the other side of the road, and the land runs back to some rocks and big trees."

"Certainly I know it," assented Ethel Blue. "There's a hillock on it that's the place I've chosen for a house when I grow up and build one."

"Well, you can't have it because I've got there first!"

"What do you mean? Has Aunt Louise—?"

"She has."

"How grand! How grand! You'll be farther away from us than you are now but it's a dear duck of a spot—"

"And it's right on the way to Grandfather Emerson's," added Ethel Brown.

"Mother signed the papers this morning and she's going to begin to build as soon as the weather will allow."

"With peach trees in blossom now that ought not to be far off," laughed Della, waving her hand again at the blossoms that pleased her so much.

"How large a house is she going to build?" asked Ethel Blue.

"Not very big. Large enough for her and me and a guest or two and of course Elisabeth and Miss Merriam," referring to a Belgian baby who had been brought to the United Service Club from war-stricken Belgium, and to her caretaker, a charming young woman from the School of Mothercraft.

"Will it be made of concrete?"

"Yes, and Mother says we may all help a lot in making the plans and in deciding on the decoration and everything."

"Isn't she the darling! It will be the next best thing to building a house yourself!"

"There will be a garage behind the house."

"A garage! Is Aunt Louise going to set up a car?"

"Just a small one that she can drive herself. Back of the garage there's plenty of space for a garden and she says she'll turn that over to me. I can do anything I want with it as long as I'll be sure to have enough vegetables for the table and lots of flowers for the house."

"O, my; O, my; what fun we'll have," ejaculated Della, who knew that Dorothy could have no pleasure that she would not share equally with the rest of the Club.

"I came over now to see if you people didn't want to walk over there and see it."

"This minute?"

"This minute."

"Of course we do—if Della doesn't have to take the train back yet?"

"Not for a long time. I'd take a later one anyway; I couldn't wait until the Saturday Club meeting to see it."

"How did you know I'd suggest a walk there for the Saturday Club meeting?"

"Could you help it?" retorted Della, laughing.

They timed themselves so that they might know just how far away from them Dorothy was going to be and they found that it was just about half way to Grandfather Emerson's. As somebody from the Mortons' went there every day, and as the distance was, in reality, not long, they were reassured as to the Smiths being quite out in the country as the change had seemed to them at first.

"You won't be able to live in the house this summer, will you?" asked Ethel Blue.

"Not until late in the summer or perhaps even later than that. Mother says she isn't in a hurry because she wants the work to be done well."

"Then you won't plant the garden this year?"

"Indeed I shall. I'm going to plant the new garden and the garden where we are now."

"Roger will strike on doing all the digging."

"He'll have to have a helper on the new garden, but I'll plant his sweetpeas for him just the same. At the new place I'm going to have a large garden."

"Up here on the hill?"

The girls were climbing up the ascent that rose sharply from the road.

"The house will perch on top of this little hill. Back of it, you see, on top of the ridge, it's quite flat and the garden will be there. I was talking about it with Mr. Emerson this morning—"

"Oho, you've called Grandfather into consultation already!"

"He's going to be our nearest neighbor on that side. He said that a ridge like this was one of the best places for planting because it has several exposures to the sun and you can find a spot to suit the fancy of about every plant there is."

"Your garden will be cut off from the house by the garage. Shall you have another nearer the road?"

"Next summer there will have to be planting of trees and shrubs and vines around the house but this year I shall attend to the one up here in the field."

"Brrrr! It looks bleak enough now," shivered Ethel Blue.

"Let's go up in those woods and see what's there."

"Has Aunt Louise bought them?"

"No, but she wants to. They don't belong to the same man who owned this piece of land. They belong to the Clarks. She's going to see about it right off, because it looks so attractive and rocky and woodsy."

"You'd have the brook, too."

"I hope she'll be able to get it. Of course just this piece is awfully pretty, and this is the only place for a house, but the meadow with the brook and the rocks and the woods at the back would be too lovely for words. Why, you'd feel as if you had an estate."

The girls laughed at Dorothy's enthusiasm over the small number of acres that were included even in the combined lots of land, but they agreed with her that the additional land offered a variety that was worth working hard to obtain.

They made their way up the slope and among the jumble of rocks that looked as if giants had been tossing them about in sport. Small trees grew from between them as they lay heaped in disorder and taller growths stretched skyward from an occasional open space. The brook began in a spring that bubbled clear and cold, from under a slab of rock. Round about it all was covered with moss, still green, though frozen stiff by the snowstorm's chilly blasts. Shrivelled ferns bending over its mouth promised summer beauties.

"What a lovely spot!" cried Ethel Blue. "This is where fairies and wood nymphs live when that drift melts. Don't you know this must be a great gathering place for birds? Can't you see them now dipping their beaks into the water and cocking their heads up at the sky afterwards!" and she quoted:—

"Dip, birds, dip

Where the ferns lean over,

And their crinkled edges drip,

Haunt and hover."

"Here's the best place yet!" called Dorothy, who had pushed on and was now out of sight.

"Where are you?"

"Here. See if you can find me," came a muffled answer.

"Where do you suppose she went to?" asked Ethel Brown, as they all three straightened themselves, yet saw no sign of Dorothy.

"I hope she hasn't fallen down a precipice and been killed!" said Ethel Blue, whose imagination sometimes ran away with her.

"More likely she has twisted her ankle," practical Ethel Brown.

"She wouldn't sound as gay as that if anything had happened to her," Della reminded them.

The cries that kept reaching them were unquestionably cheerful but where they came from was a problem that they did not seem able to solve. It was only when Dorothy poked out her head from behind a rock almost in front of them that they saw the entrance of what looked like a real cave.

"It's the best imitation of a cave I ever did see!" the explorer exclaimed. "These rocks have tumbled into just the right position to make the very best house! Come in."

Her guests were eager to accept her invitation. There was space enough for all of them and two or three more might easily be accommodated within, while a bit of smooth grass outside the entrance almost added another room, "if you aren't particular about a roof," as Ethel Brown said.

"Do you suppose Roger has never found this!" wondered Dorothy. "See, there's room enough for a fireplace with a chimney. You could cook here. You could sleep here. You could live here!"

The others laughed at her enthusiasm, but they themselves were just as enthusiastic. The possibilities of spending whole days here in the shade and cool of the trees and rocks and of imagining that they were in the highlands of Scotland left them almost gasping.

"Don't you remember when Fitz-James first sees Ellen in the 'Lady of the Lake'?" asked Ethel Blue.

"He was separated from his men and found himself in a rocky glen overlooking a lake. The rocks were bigger than these but we can pretend they were just the same," and she recited a few lines from a poem whose story they all knew and loved.

"But not a setting beam could glow

Within the dark ravines below,

Where twined the path in shadow hid,

Round many a rocky pyramid."

"I remember; he looked at the view a long time and then he blew his horn again to see if he could make any of his men hear him, and Ellen came gliding around a point of land in a skiff. She thought it was her father calling her."

"And the stranger went home to their lodge and fell in love with her—O, it's awfully romantic. I must read it again," and Dorothy gazed at the rocks around her as if she were really in Scotland.

"Has anybody a knife?" asked Della's clear voice, bringing them all sharply back to America and Rosemont. "My aunt—the one who has the hanging flowerpots I was telling you about—isn't a bit well and I thought I'd make her a little fernery that she could look at as she lies in bed."

"But the ferns are all dried up."

"'Greenery' is a better name. Here's a scrap of partridge berry with a red berry still clinging to it, and here's a bit of moss as green as it was in summer, and here—yes, it's alive, it really is!" and she held up in triumph a tiny fern that had been so sheltered under the edge of a boulder that it had kept fresh and happy.

There was nothing more to reward their search, for they all hunted with Della, but she was not discouraged.

"I only want a handful of growing things," she explained. "I put these in a finger bowl, and sprinkle a few seeds of grass or canary seed on the moss and dash some water on it from the tips of my fingers. Another finger bowl upside down makes the cover. The sick person can see what is going on inside right through the glass without having to raise her head."

"How often do you water it?"

"Only once or twice a week, because the moisture collects on the upper glass of the little greenhouse and falls down again on the plants and keeps them, wet."

"We'll keep our eyes open every time we come here," promised Dorothy. "There's no reason why you couldn't add a little root of this or that any time you want to."

|

"I know Aunty will be delighted with it," cried Della, much pleased. "She likes all plants, but especially things that are a little bit different. That's why she spends so much time selecting her wall vases—so that they shall be unlike other people's."

"Fitz-James's woods," as they already called the bit of forest that Dorothy hoped to have possession of, extended back from the road and spread until it joined Grandfather Emerson's woods on one side and what was called by the Rosemonters "the West Woods" on the other. The girls walked home by a path that took them into Rosemont not far from the station where Della was to take the train.

"Until you notice what there really is in the woods in winter you think there isn't anything worth looking at," said Ethel Blue, walking along with her eyes in the tree crowns.

"The shapes of the different trees are as distinct now as they are in summer," declared Ethel Brown. "You'd know that one was an oak, and the one next to it a beech, wouldn't you?"

"I don't know whether I would or not," confessed Dorothy honestly, "but I can almost always tell a tree by its bark."

"I can tell a chestnut by its bark nowadays," asserted Ethel Blue, "because it hasn't any!"

"What on earth do you mean?" inquired city-bred Della.

"Something or other has killed all the chestnuts in this part of the world in the last two or three years. Don't you see all these dead trees standing with bare trunks?"

"Poor old things! Is it going to last?"

"It spread up the Hudson and east and west in New York and Massachusetts, and south into Pennsylvania."

"Roger was telling Grandfather a few days ago that a farmer was telling him that he thought the trouble—the pest or the blight or whatever it was—had been stopped."

"I remember now seeing a lot of dead trees somewhere when one of Father's parishioners took us motoring in the autumn. I didn't know the chestnut crop was threatened."

"Chestnuts weren't any more expensive this year. They must have imported them from far-off states."

There were still pools of water in the wood path, left by the melting snow, and the grass that they touched seemed a trifle greener than that beside the narrow road. Once in a while a bit of vivid green betrayed a plant that had found shelter under an overhanging stone. The leaves were for the most part dry enough again to rustle under their feet. Evergreens stood out sharply dark against the leafless trees.

"What are the trees that still have a few leaves left clinging to them?" asked Della.

"Oaks. Do you know why the leaves stay on?"

"Is it a story?"

"Yes, a pleasant story. Once the Great Evil Spirit threatened to destroy the whole world. The trees heard the threat and the oak tree begged him not to do anything so wicked. He insisted but at last he agreed not to do it until the last leaf had fallen in the autumn. All the trees meant to hold On to their leaves so as to ward off the awful disaster, but one after the other they let them go—all except the oak. The oak never yet has let fall every one of its leaves and so the Evil Spirit never has had a chance to put his threat into execution."

"That's a lesson in success, isn't it? Stick to whatever it is you want to do and you're sure to succeed."

"Watch me make my garden succeed," cried Dorothy. "If 'sticking' will make it a success I'm a stick!"

When Saturday came and the United Service Club tramped over Dorothy's new domain, including the domain that she hoped to have but was not yet sure of, every member agreed that the prospect was one that gave satisfaction to the Club as well as the possibility of pleasure and comfort to Mrs. Smith and Dorothy. The knoll they hailed as the exact spot where a house should go; the ridge behind it as precisely suited to the needs of a garden.

As to the region of the meadow and the brook and the rocks and the trees they all hoped most earnestly that Mrs. Smith would be able to buy it, for they foresaw that it would provide much amusement for all of them during the coming summer and many to follow.

Strangely enough Roger had never found the cave, and he looked on it with yearning.

"Why in the world didn't I know of that three or four years ago!" he exclaimed. "I should have lived out here all summer!"

"That's what we'd like to do," replied the Ethels earnestly. "We'll let you come whenever you want to."

Roger gave a sniff, but the girls knew from his longing gaze that he was quite as eager as they to fit it up for a day camp even if he was nearly eighteen and going to college next autumn.

When the exploring tour was over they gathered in their usual meeting place—Dorothy's attic—and discussed the gardens which had taken so firm a hold on the girls' imaginations.

"There'll be a small garden in our back yard as usual," said Roger in a tone that admitted of no dispute.

"And a small one in Dorothy's present back yard and a LARGE one on Miss Smith's farm," added Tom, who had confirmed with his own eyes the glowing tales that Della had brought home to him.

"I suppose we may all have a chance at all of these institutions?" demanded James.

"Your mother may have something to say about your attentions to your own garden," suggested Helen pointedly.

"I won't slight it, but I've really got to have a finger in this pie if all of you are going to work at it!"

"Well, you shall. Calm yourself," and Roger patted him with a soothing hand. "You may do all the digging I promised the girls I'd do."

A howl of laughter at James's expense made the attic ring.

James appeared quite undisturbed.

"I'm ready to do my share," he insisted placidly. "Why don't we make plans of the gardens now?"

"Methodical old James always has a good idea," commended Tom. "Is there any brown paper around these precincts, Dorothy?"

"Must it be brown?"

"Any color, but big sheets."

"I see. There is plenty," and she spread it on the table where James had done so much pasting when they were making boxes in which to pack their presents for the war orphans.

"Now, then, Roger, the first thing for us to do is to see—"

"With our mind's eye, Horatio?"

"—how these gardens are going to look. Take your pencil in hand and draw us a sketch of your backyard as it is now, old man."

"That's easy," commented Roger. "Here are the kitchen steps; and here is the drying green, and back of that is the vegetable garden and around it flower beds and more over here next the fence."

"It's rather messy looking as it is," commented Ethel Brown. "We never have changed it from the way the previous tenant laid it out."

"The drying green isn't half large enough for the washing for our big family," added Helen appraisingly. "Mary is always lamenting that she can hang out only a few lines-ful at a time."

"Why don't you give her this space behind the green and limit your flower beds to the fence line?" asked Tom, looking over Roger's shoulder as he drew in the present arrangement with some attention to the comparative sizes.

"That would mean cutting out some of the present beds."

"It would, but you'll have a share in Dorothy's new garden in case Mrs. Morton needs more flowers for the house; and the arrangement I suggest makes the yard look much more shipshape."

"If we sod down these beds here what will Roger do for his sweetpeas? They ought to have the sun on both sides; the fence line wouldn't be the best place for them."

"Sweetpeas ought to be planted on chicken wire supported by stakes and running from east to west," said Margaret wisely, "but under the circumstances, I don't see why you couldn't fence in the vegetable garden with sweetpeas. That would give you two east and west lines of them and two north and south."

"And there would be space for all the blossoms that Roger would want to pick on a summer's day," laughed Della.

"I've always wanted to have a garden of all pink flowers," announced Dorothy. "My room in the new house is going to be pink and I'd like to keep pink powers in it all the time."

"I've always wanted to do that, too. Let's try one here," urged Ethel Brown, nodding earnestly at Ethel Blue.

"I don't see why we couldn't have a pink bed and a blue bed and a yellow bed," returned Ethel Blue whose inner eye saw the plants already well grown and blossoming.

"A wild flower bed is what I'd like," contributed Helen.

"We mustn't forget to leave a space for Dicky," suggested Roger.

"I want the garden I had latht year," insisted a decisive voice that preceded the tramp of determined feet over the attic stairs.

"Where was it, son? I've forgotten."

"In a corner of your vegetable garden. Don't you remember my raditheth were ripe before yourth were? Mother gave me a prithe for the firtht vegetableth out of the garden."

"So she did. You beat me to it. Well, you may have the same corner again."

"We ought to have some tall plants, hollyhocks or something like that, to cover the back fence," said Ethel Brown.

"What do you say if we divide the border along the fence into four parts and have a wild garden and pink and yellow and blue beds? Then we can transplant any plants we have now that ought to go in some other color bed, and we can have the tall plants at the back of the right colors to match the bed in front of them?"

"There can be pink hollyhocks at the back of the pink bed and we already have pinks and bleeding heart and a pink peony. We've got a good start at a pink bed already," beamed Ethel Brown.

"We can put golden glow or that tall yellow snapdragon at the back of the yellow bed and tall larkspurs behind the blue flowers."

"The Miss Clarks have a pretty border of dwarf ageratum—that bunchy, fuzzy blue flower. Let's have that for the border of our blue bed."

"I remember it; it's as pretty as pretty. They have a dwarf marigold that we could use for the yellow border."

"Or dwarf yellow nasturtiums."

"Or yellow pansies."

"We had a yellow stock last summer that was pretty and blossomed forever; nothing seemed to stop it but the 'chill blasts of winter.'"

"Even the short stocks are too tall for a really flat border that would match the others. We must have some 'ten week stocks' in the yellow border, though."

"Whatever we plant for the summer yellow border we must have the yellow spring bulbs right behind it—jonquils and daffodils and yellow tulips and crocuses."

"They're all together now. All we'll have to do will be to select the spot for our yellow bed."

"That's settled then. Mark it on this plan."

Roger held it out to Ethel Brown, who found the right place and indicated the probable length of the yellow bed upon it.

"We'll have the wild garden on one side of the yellow bed and the blue on the other and the pink next the blue," decreed Ethel Blue.

"We haven't decided on the pink border," Dorothy reminded them.

"There's a dwarf pink candytuft that couldn't be beaten for the purpose," said James decisively. "Mother and I planted some last year to see what it was like and it proved to be exactly what you want here."

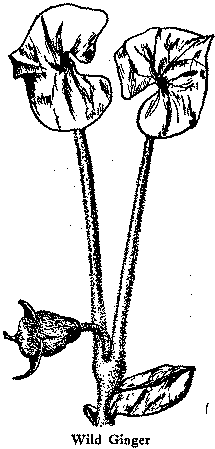

"I know what I'd like to have for the wild border—either wild ginger or hepatica," announced Helen after some thought.

"I don't know either of them," confessed Tom.

"You will after you've tramped the Rosemont woods with the U.S.C. all this spring," promised Ethel Brown. "They have leaves that aren't unlike in shape—"

"The ginger is heart-shaped," interposed Ethel Blue, "and the hepatica is supposed to be liver-shaped."

|

"You have to know some physiology to recognize them," said James gravely. "There's where a doctor's son has the advantage," and he patted his chest.

"Their leaves seem much too juicy to be evergreen, but the hepatica does stay green all winter."

"The ginger would make the better edging," Helen decided, "because the leaves lie closer to the ground."

"What are the blossoms?"

"The ginger has such a wee flower hiding under the leaves that it doesn't count, but the hepatica has a beautiful little blue or purple flower at the top of a hairy scape."

"A hairy what?" laughed Roger.

"A scape is a stem that grows up right from the or root-stock and carries only a flower—not any leaves," defined Helen.

"That's a new one on me. I always thought a stem was a stem, whatever it carried," said Roger.

"And a scape was a 'grace' or a 'goat' according to its activities," concluded Tom.

"The hepatica would make a border that you wouldn't have to renew all the time," contributed Dorothy, who had been thinking so deeply that she had not heard a word of this interchange, and looked up, wondering why every one was laughing.

"Dorothy keeps her eye on the ball," complimented James. "Have we decided on the background flowers for the wild bed?"

"Joe-Pye-Weed is tall enough," offered James. "It's way up over my head."

"It wouldn't cover the fence much; the blossom is handsome but the foliage is scanty."

"There's a feathery meadow-rue that is tall. The leaves are delicate."

"I know it; it has a fine white blossom and it grows in damp places. That will be just right. Aren't you going to have trouble with these wild plants that like different kinds of ground?"

"Perhaps we are," Helen admitted. "Our garden is 'middling' dry, but we can keep the wet lovers moist by watering them more generously than the rest."

"How about the watering systems of all these gardens, anyway? You have town water here and at Dorothy's, but how about the new place?"

"The town water runs out as far as Mr. Emerson's, luckily for us, and Mother says she'll have the connection made as soon as the frost is out of the ground so the builders may have all they want for their work and I can have all I need for the garden there."

"If you get that next field with the brook and you want to plant anything there you'll have to dig some ditches for drainage."

"I think I'll keep up on the ridge that's drained by nature."

"That's settled, then. We can't do much planning about the new garden until we go out in a body and make our decisions on the spot," said Margaret. "We'll have to put in vegetables and flowers where they'd rather grow."

"That's what we're trying to do here, only it's on a small scale," Roger reminded her. "Our whole garden is about a twentieth of the new one."

"I shouldn't wonder if we had to have some expert help with that," guessed James, who had gardened enough at Glen Point not to be ashamed to confess ignorance now and then.

"Mr. Emerson has promised to talk it all over with me," said Dorothy.

"Let's see what there is at Dorothy's present abode, then," said Roger gayly, and he took another sheet of brown paper and began to place on it the position of the house and the existing borders. "Do I understand, madam, that you're going to have a pink border here?"

"I am," replied his cousin firmly, "both here and at the new place."

"Life will take on a rosy hue for these young people if they can make it," commented Della. "Pink flowers, a pink room—is there anything else pink?"

"The name. Mother and I have decided on 'Sweetbrier Lodge.' Don't you think it's pretty?"

"Dandy," approved Roger concisely, as he continued to draw. "Do you want to change any of the beds that were here last summer?" he asked.

"Mother said she liked their positions very well. This long, narrow one in front of the house is to be the pink one. I've got pink tulip bulbs in the ground now and there are some pink flowering shrubs—weigelia and flowering almond—already there against the lattice of the veranda. I'm going to work out a list of plants that will keep a pink bed blossoming all summer and we can use it in three places," and she nodded dreamily to her cousins.

"We'll do that, but I think it would be fun if each one of us tried out a new plant of some kind. Then we can find out which are most suitable for our needs next year. We can report on them to the Club when they come into bloom. It will save a lot of trouble if we tell what we've found out about what some plant likes in the way of soil and position and water and whether it is best to cut it back or to let it bloom all it wants to, and so on."

"That's a good idea. I hope Secretary Ethel Blue is taking notes of all these suggestions," remarked Helen, who was the president of the Club.

Ethel Blue said she was, and Roger complimented her faithfulness in terms of extravagant absurdity.

"Your present lot of land has the best looking fencing in Rosemont, to my way of thinking," approved Tom.

"What is it? I hardly remember myself," said Dorothy thoughtfully.

"Why, across the front there's a privet hedge, clipped low enough for your pink garden to be seen over it; and separating you from the Clarks' is a row of tall, thick hydrangea bushes that are beauties as long as there are any leaves on them; and at the back there is osage orange to shut out that old dump; and on the other side is a row of small blue spruces."

"That's quite a showing of hedges all in one yard." exclaimed Ethel Blue admiringly. "And I never noticed them at all!"

"At the new place Mother wants to try a barberry hedge. It doesn't grow regularly, but each bush is handsome in itself because the branches droop gracefully, and the leaves are a good green and the clusters of red berries are striking."

"The leaves turn red in the autumn and the whole effect is stunning," contributed Della. "I saw one once in New England. They aren't usual about here, and I should think it would be a beauty."

"You can let it grow as tall as you like," said James. "Your house is going to be above it on the knoll and look right over it, so you don't need a low hedge or even a clipped one."

"At the side and anywhere else where she thinks there ought to be a real fence she's going to put honey locust."

They all laughed.

"That spiny affair will be discouraging to visitors!" Helen exclaimed. "Why don't you try hedges of gooseberries and currants and raspberries and blackberries around your garden?"

"That would be killing two birds with one stone, wouldn't it!"

"You'll have a real problem in landscape gardening over there," said Margaret.

"The architect of the house will help on that. That is, he and Mother will decide exactly where the house is to be placed and how the driveway is to run."

"There ought to be some shrubs climbing up the knoll," advised Ethel Brown. "They'll look well below the house and they'll keep the bank from washing. I noticed this afternoon that the rains had been rather hard on it."

"There are a lot of lovely shrubs you can put in just as soon as you're sure the workmen won't tramp them all down," cried Ethel Blue eagerly. "That's one thing I do know about because I went with Aunt Marion last year when she ordered some new bushes for our front yard."

"Recite your lesson, kid," commanded Roger briefly.

"There is the weigelia that Dorothy has in front of this house; and forsythia—we forced its yellow blossoms last week, you know; and the flowering almond—that has whitey-pinky-buttony blossoms."

They laughed at Ethel's description, but they listened attentively while she described the spiky white blossoms of deutzia and the winding white bands of the spiraea—bridal wreath.

"I can see that bank with those white shrubs all in blossom, leaning toward the road and beckoning you in," Ethel ended enthusiastically.

"I seem to see them myself," remarked Tom, "and Dorothy can be sure that they won't beckon in vain."

"You'll all be as welcome as daylight," cried Dorothy.

"I hate to say anything that sounds like putting a damper on this outburst of imagination that Ethel Blue has just treated us to, but I'd like to inquire of Miss Smith whether she has any gardening tools," said Roger, bringing them all to the ground with a bump.

"Miss Smith hasn't one," returned Dorothy, laughing. "You forget that we only moved in here last September and there hasn't been need for any that we couldn't borrow of you."

"You're perfectly welcome to them," answered Roger, "but if we're all going to do the gardening act there'll be a scarcity if we don't add to the number."

"What do we need?"

"A rake and a hoe and a claw and a trowel and a spade and a heavy line with some pegs to do marking with."

"We've found that it's a comfort to your back to have another claw mounted on the end of a handle as long as a hoe," contributed Margaret.

"Two claws," Dorothy amended her list, isn't many."

"And a lot of dibbles."

"Dibbles!"

"Short flat sticks whittled to a point. You use them when you're changing little plants from the to the hot bed or the hot bed to the garden."

"Mother and I ought to have one set of tools here and one set at Sweetbrier Lodge," decided Dorothy.

"We keep ours in the shed. I'm going to whitewash the corner where they belong and make it look as fine as a fiddle before the time comes to use them."

"We have a shed here where we can keep them but at Sweetbrier there isn't anything," and Dorothy's mouth dropped anxiously.

"We can build you a tool house," Tom was offering when James interrupted him.

"If we can get a piano box there's your toolhouse all made," he suggested. "Cover it with tar paper so the rain won't come in, and hang the front on hinges with a hasp and staple and padlock, and what better would you want?"

"Nothing," answered Ethel Brown, seriously. Ethel Blue noted it down in her book and Roger promised to visit the local piano man and see what he could find.

"We haven't finished deciding how we shall plant Dorothy's yard behind this house," Margaret reminded them.

"We shan't attempt a vegetable garden here," Dorothy said. "We'll start one at the other place so that the soil will be in good condition next year. We'll have a man to do the heavy work of the two places, he can bring over every morning whatever vegetables are ready for the day's use."

"You want more flowers in this yard, then?"

"You'll laugh at what I want!"

"Don't you forget what you promithed me," piped up Dicky.

"That's what I was going to tell them now. I've promised Dicky to plant a lot of sunflowers for his hens. He says Roger never has had space to plant enough for him."

"True enough. Give him a big bed of them so he can have all the seeds he wants."

"I'd like to have a wide strip across the back of the whole place, right in front of the osage orange hedge. They'll cover the lower part that's rather scraggly—then everywhere else I want nasturtiums, climbing and dwarf and every color under the sun."

"That's a good choice for your yard because it's awfully stony and nasturtiums don't mind a little thing like that."

"Then I want gourds over the trellis at the back door."

"Gourds!"

"I saw them so much in the South that I want to try them. There's one shape that makes a splendid dipper when it's dried and you cut a hole in it; and there's another kind just the size of a hen's egg that I want for nest eggs for Dickey's hens; and there's the loofa full of fibre that you can use for a bath sponge; and there's a pear-shaped one striped green and yellow that Mother likes for a darning ball; and there's a sweet smelling one that is as fragrant as possible in your handkerchief case. There are some as big as buckets and some like base ball bats, but I don't care for those."

"What a collection," applauded Ethel Brown.

"Beside that my idea of Japanese morning glories and a hop vine for our kitchen regions has no value at all," smiled Helen.

"I'm going to have hops wherever the vines can find a place to climb at Sweetbrier," Dorothy determined. "I love a hop vine, and it grows on forever."

"James and I seem to be in the same condition. If we don't start home we'll go on talking forever," Margaret complained humorously.

"There's to be hot chocolate for us down stairs at half past four," said Dorothy, jumping up and looking at a clock that was ticking industriously on a shelf. "Let's go down and get it, and we'll ask Mother to sing the funny old song of 'The Four Seasons' for us."

"Why is it funny?" asked Ethel Blue.

"It's a very old English song with queer spelling."

"Something like mine?" demanded Della.

Ethel Blue kissed her.

"Never mind; Shakspere spelled his name in several different ways," she said encouragingly, "Anyway, we can't tell how this is spelled when Aunt Louise sings it."

As they sat about the fire in the twilight drinking their chocolate and eating sandwiches made of nuts ground fine, mixed with mayonnaise and put on a crisp lettuce leaf between slices of whole wheat bread, Mrs. Smith sang the old English song to them.

"Springe is ycomen in,

Dappled lark singe;

Snow melteth,

Runnell pelteth,

Smelleth winde of newe buddinge.

"Summer is ycomen in,

Loude singe cucku;

Groweth seede,

Bloweth meade,

And springeth the weede newe.

"Autumne is ycomen in,

Ceres filleth horne;

Reaper swinketh,

Farmer drinketh,

Creaketh waine with newe corn.

"Winter is ycomen in,

With stormy sadde cheere;

In the paddocke,

Whistle ruddock,

Brighte sparke in the dead yeare."

"That's a good stanza to end with," said Ethel Blue, as she bade her aunt "Good-bye." "We've been talking about gardens and plants and flowers all the afternoon, and it would have seemed queer to put on a heavy coat to go home in if you hadn't said 'Winter is ycomen in.'"

In spite of their having made such an early start in talking about gardens the members of the United Service Club did not weary of the idea or cease to plan for what they were going to do. The only drawback that they found in gardening as a Club activity was that the gardens were for themselves and their families and they did not see exactly how there was any "service" in them.

"I'll trust you youngsters to do some good work for somebody in connection with them," asserted Grandfather Emerson one day when Roger had been talking over with him his pet plan for remodelling the old Emerson farmhouse into a place suitable for the summer shelter of poor women and children from the city who needed country air and relief from hunger and anxiety.

"We aren't rushing anything now," Roger had explained, "because we boys are all going to graduate this June and we have our examinations to think about. They must come first with us. But later on we'll be ready for work of some sort and we haven't anything on the carpet except our gardens."

"There are many good works to be done with the help of a garden," replied Mr. Emerson. "Ask your grandmother to tell you how she has sent flowers into New York for the poor for many, many summers. There are people right here in Rosemont who haven't enough ground to raise any vegetables and they are glad to have fresh corn and Brussels sprouts sent to them. If you really do undertake this farmhouse scheme there'll have to be a large vegetable garden planted near the house to supply it, and you can add a few flower beds. The old place will look better flower-dressed than empty, and perhaps some of the women and children will like to work in the garden."

Roger went home comforted, for he was very loyal to the Club and its work and he did not want to become so involved with other matters that he could not give himself to the purpose for which the Club was organized—helping others.

As he passed the Miss Clarks he stopped to give their furnace its nightly shaking, for he was the accredited furnace man for them and his Aunt Louise as well as for his mother. He added the money that he earned to the treasury of the Club so that there might always be enough there to do a kind act whenever there should be a chance.

As he labored with the shaker and the noise of his struggles was sent upward through the registers a voice called to him down the cellar stairs.

"Ro-ger; Roger!"

"Yes, ma'am," replied Roger, wishing the old ladies would let him alone until he had finished his work.

"Come up here, please, when you've done."

"Very well," he agreed, and went on with his racket.

When he went upstairs he found that the cause of his summons was the arrival of a young man who was apparently about the age of Edward Watkins, the doctor brother of Tom and Della.

"My nephew is a law student," said Miss Clark as she introduced the two young people, "and I want him to know all of our neighbors."

"My name is Stanley Clark," said the newcomer, shaking hands cordially. "I'm going to be here for a long time so I hope I'll see you often."

Roger liked him at once and thought his manner particularly pleasant in view of the fact that he was several years older. Roger was so accustomed to the companionship of Edward Watkins, who frequently joined the Club in their festivities and who often came to Rosemont to call on Miss Merriam, that the difference did not seem to him a cause of embarrassment. He was unusually easy for a boy of his age because he had always been accustomed to take his sailor father's place at home in the entertainment of his mother's guests.

Young Clark, on his side, found his new acquaintance a boy worth talking to, and they got on well. He was studying at a law school in the city, it seemed, and commuted every day.

"It's a long ride," he agreed when Roger suggested it, "but when I get home I have the good country air to breathe and I'd rather have that than town amusements just now when I'm working hard."

Roger spoke of Edward Watkins and Stanley was interested in the possibility of meeting him. Evidently his aunts had told him all about the Belgian baby and Miss Merriam, for he said Elisabeth would be the nearest approach to a soldier from a Belgian battlefield that he had seen.

Roger left with the feeling that his new acquaintance would be a desirable addition to the neighborhood group and he was so pleased that he stopped in at his Aunt Louise's not only to shake the furnace but to tell her about Stanley Clark.

During the next month they all came to know him well and they liked his cheerfulness and his interest in what they were doing and planning. On Saturdays he helped Roger build a hot bed in the sunniest spot against the side of the kitchen ell. They found that the frost had not stiffened the ground after they managed to dig down a foot, so that the excavation was not as hard as they had expected. They dug a hole the size of two window sashes and four feet deep, lining the sides with some old bricks that they found in the cellar. At first they filled the entire bed with fresh stable manure and straw. After it had stayed under the glass two days it was quite hot and they beat it down a foot and put on six inches of soil made one-half of compost and one-half of leaf mould that they found in a sheltered corner of the West Woods.

"Grandfather didn't believe we could manage to get good soil at this season even if we did succeed in digging the hole, but when I make up my mind to do a thing I like to succeed," said Roger triumphantly when they had fitted the sashes on to planks that sloped at the sides so that rain would run off the glass, and called the girls out to admire their result.

"What are we going to put in here first?" asked Ethel Brown, who liked to get at the practical side of matters at once.

"I'd like to have some violets," said Ethel Blue. "Could I have a corner for them? I've had some plants promised me from the Glen Point greenhouse man. Margaret is going to bring them over as soon as I'm ready for them."

"I want to see if I can beat Dicky with early vegetables," declared Roger. "I'm going to start early parsley and cabbage and lettuce, cauliflower and egg plants, radishes and peas and corn in shallow boxes—flats Grandfather says they're called—in my room and the kitchen where it's warm and sunny, and when they've sprouted three leaves I'll set them out here and plant some more in the flats."

"Won't transplanting them twice set them back?"

"If you take up enough earth around them they ought not to know that they've taken a journey."

"I've done a lot of transplanting of wild plants from the woods," said Stanley, "and I found that if I was careful to do that they didn't even wilt."

"Why can't we start some of the flower seeds here and have early blossoms?"