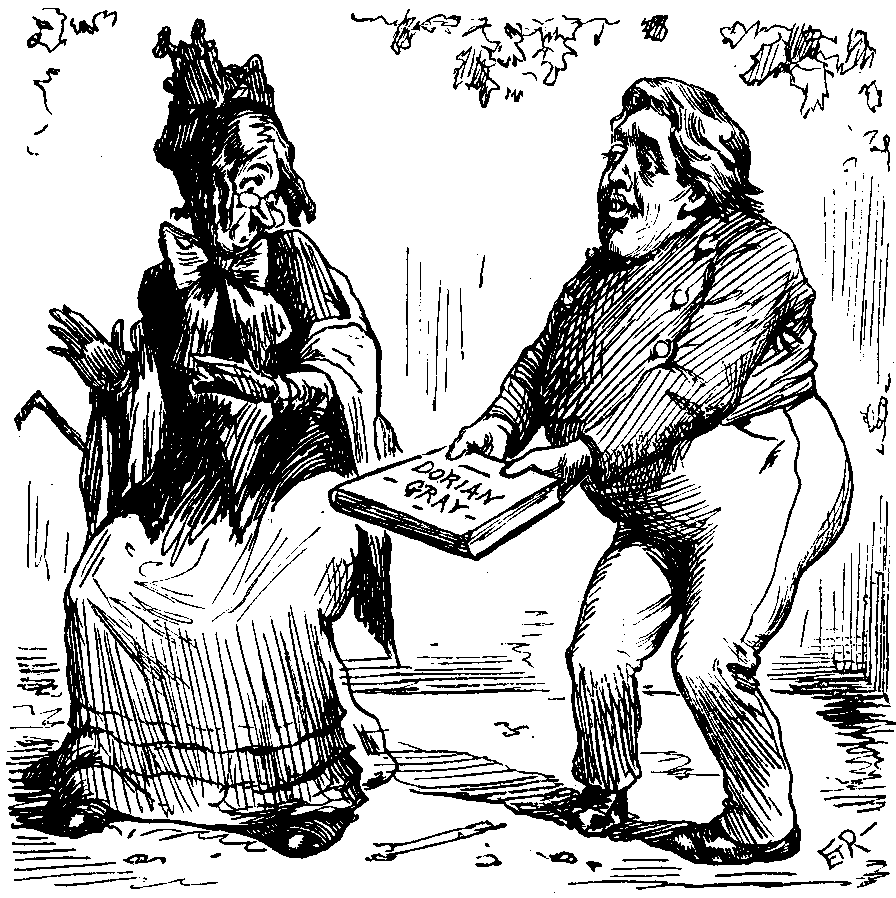

PARALLEL.

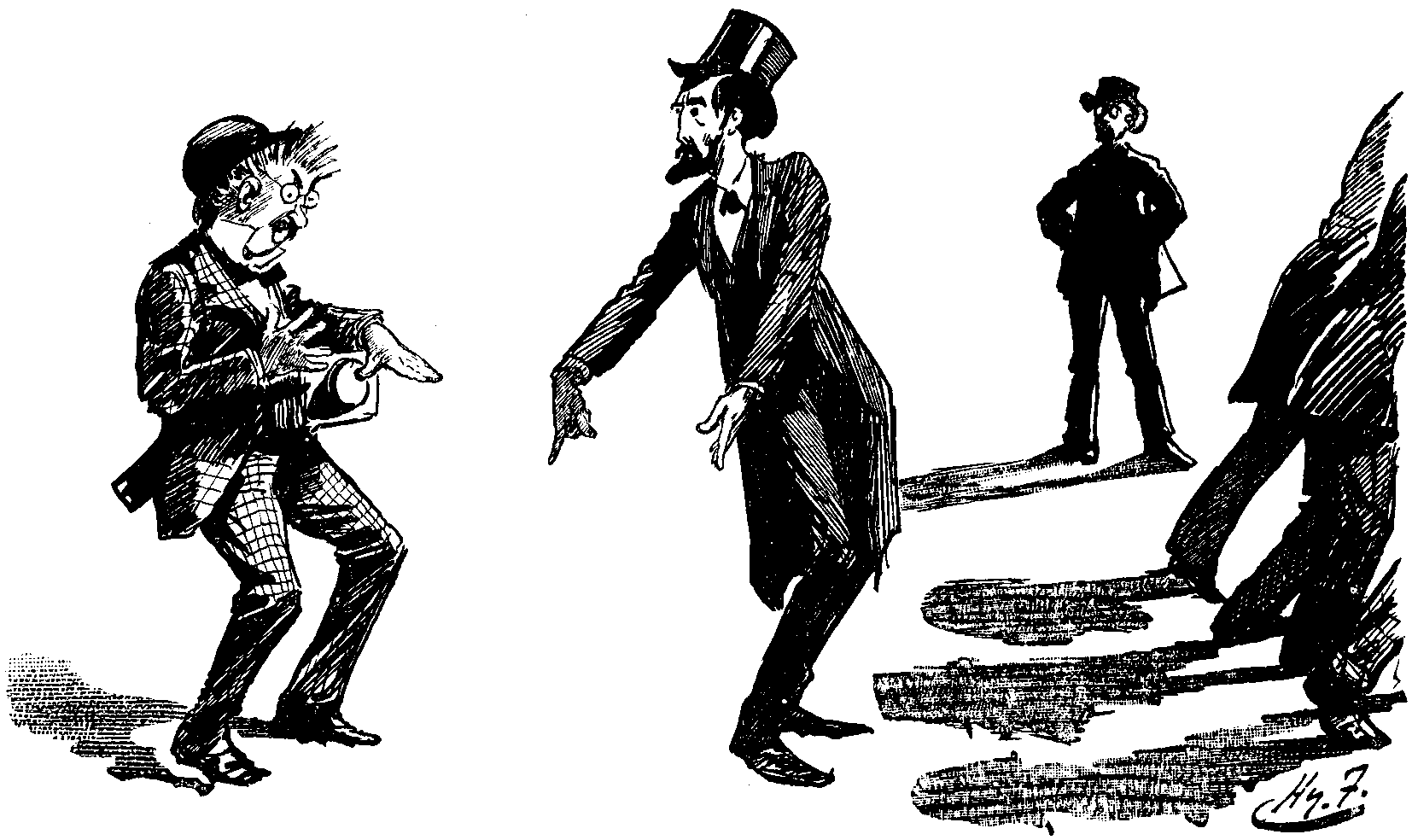

Joe, the Fat Boy in Pickwick, startles the Old Lady; Oscar, the Fad Boy in Lippincott's, startles Mrs. Grundy.Oscar, the Fad Boy. "I want to make your flesh creep!"

The Baron has read OSCAR WILDE'S Wildest and Oscarest work, called Dorian Gray, a weird sensational romance, complete in one number of Lippincott's Magazine. The Baron, recommends anybody who revels in diablerie, to begin it about half-past ten, and to finish it at one sitting up; but those who do not so revel he advises either not to read it at all, or to choose the daytime, and take it in homoeopathic doses. The portrait represents the soul of the beautiful Ganymede-like Dorian Gray, whose youth and beauty last to the end, while his soul, like JOHN BROWN'S, "goes marching on" into the Wilderness of Sin. It becomes at last a devilled soul. And then Dorian sticks a knife into it, as any ordinary mortal might do, and a fork also, and next morning

"Lifeless but 'hideous' he lay,"

while the portrait has recovered the perfect beauty which it possessed when it first left the artist's easel. If OSCAR intended an allegory, the finish is dreadfully wrong. Does he mean that, by sacrificing his earthly life, Dorian Gray atones for his infernal sins, and so purifies his soul by suicide? "Heavens! I am no preacher," says the Baron, "and perhaps OSCAR didn't mean anything at all, except to give us a sensation, to show how like BULWER LYTTON'S old-world style he could make his descriptions and his dialogue, and what an easy thing it is to frighten the respectable Mrs. Grundy with a Bogie." The style is decidedly Lyttonerary. His aphorisms are Wilde, yet forced. Mr. OSCAR WILDE says of his story, "it is poisonous if you like, but you cannot deny that it is also perfect, and perfection is what we artists aim at." Perhaps; but "we artists" do not always hit what we aim at, and, despite his confident claim to unerring artistic marksmanship, one must hazard the opinion, that in this case Mr. WILDE has "shot wide." There is indeed more of "poison" than of "perfection" in Dorian Gray. The central idea is an excellent, if not exactly novel, one; and a finer art, say that of NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, would have made a striking and satisfying story of it. Dorian Gray is striking enough, in a sense, but it is not "satisfying" artistically, any more than it is so ethically. Mr. WILDE has preferred the sensuous and hyperdecorative manner of "Mademoiselle DE MAUPIN," and without GAUTIER'S power, has spoilt a promising conception by clumsy unideal treatment. His "decoration" (upon which he plumes himself) is indeed "laid on with a trowel." The luxuriously elaborate details of his "artistic hedonism" are too suggestive of South Kensington Museum and æsthetic Encyclopædias. A truer art would have avoided both the glittering conceits, which bedeck the body of the story, and the unsavoury suggestiveness which lurks in its spirit. Poisonous! Yes. But the loathly "leperous distilment" taints and spoils, without in any way subserving "perfection," artistic or otherwise. If Mrs. Grundy doesn't read it, the younger Grundies do; that is, the Grundies who belong to Clubs, and who care to shine in certain sets wherein this story will be much discussed. "I have read it, and, except for the ingenious idea, I wish to forget it," says the Baron.

The Baron has seen the new, lively, and eccentric newspaper, entitled The Whirlwind. It has reached the third number. "I am informed," says the Baron, "that, on payment of five guineas down, I can become a life-subscriber to the Whirlwind. But what does life-subscriber mean? Do I subscribe for the term of my life, or for the term of the Whirlwind's life? Suppose the Whirlwind has to be wound up, or whirl-winded up, and suppose I am still going on, can I intervene to stop the proceedings, and insist on my contract to be supplied with a Whirlwind per week for the remainder of my natural or unnatural life being carried out? If the contract is for our lives, then, as a life-subscriber, I should insist on the Whirlwind remaining co-existent with me, so that, up to my latest breath, I might have a Whirlwind. But if the life-subscription of five guineas is only for the term of the Whirlwind's life, then, I fancy the proprietors, editor, and staff, that the Hon. STUART ERSKINE and Mr. HERBERT VIVIAN, who are, I believe, the Proprietors, Editor, and Staff of the Whirlwind, will have by far the better of the bargain. I resist the temptation, and keep my five pounds five shillings in my pocket, and am

"Yours truly, THE BARON DE BOOK-WORMS.

[All applications in answer to be addressed to the office of this journal, accompanied by handsome P.O.O, and lots of shilling stamps, which will in every case be retained, without acknowledgment, as a guarantee of good faith.]

URGENT CASE.—WANTED, by a little Boy, aged 10, of thoroughly disagreeable temper, selfish, greedy, ill-mannered, and thoroughly spoilt at home, a good sound Whipping, weekly, if possible. Great care will be necessary on the part of applicant in fulfilling requirements, parents of youth in question, being firmly convinced that he is a noble little fellow, with a fine manly spirit, just what his dear Papa was at his age (as is very probably the case) and only requiring peculiarly gentle and considerate treatment.—Apply (in first instance, by letter) to Godfather, care of Mr. Punch.

TO PARENTS AND GUARDIANS,—affectionate but practical-minded, and anxious to find economical homes (somewhere else) for young gentlemen who cannot get on without expensive assistance at starting in Mother country, owing to excessive competition in laborious and over-crowded professions. A firm of enterprising Agents offer bracing and profitable occupation (coupled with the use gratis, of two broken spades, an old manure-cart, and an axe without a handle) in a peculiarly romantic and unhealthy district in the backwoods of West-Torrida. Photograph, if desired, of Agent's residence (distant several hundred miles away.) Excellent opening for young men fresh from first-class public school or college-life: who should, of course, be prepared to "rough it" a little before making competence or large fortune, by delightful pursuit of agriculture. No restrictive civilisation. No drains. Excellent supply of water and heavy floods as a rule, during three months of year, bringing on Spring crops without expense of irrigation. Very low death-rate, most of population having recently cleared out. Small village and (horse)-doctor within twenty-five miles' ride. Wild and beautiful country. Every incentive to work. Rare poisonous reptiles, and tarantula spiders, most interesting to young observant naturalist. Capital prospect—great saving offered to careful parents anxious to set up brougham, or increase private expenses. Five boys (reduction on taking a quantity) disposed of for about £250 and outfit, with probably, no further trouble.—Address, Messrs. SHARKEY AND CRIMPIN, Colonial and Emigration Agents. &c.

CONCERTS! CONCERTS!—Amateur Comic Vocalist and impromptu "Vamper" (gentleman born) of several years' experience in best London Society, is anxious to meet with bold and speculative Manager who will offer him a first engagement. Can sing—omitting a few high notes—various popular melodies, comprising, "Aunt Sarah's Back-hair," "The Twopenny Toff of 'Ighgate 'Ill," and "Tommy Robinson's Last Cigar," and also play piano if required, with one finger, but prefers to be accompanied by indefatigable friend, who plays entirely by ear, and if allowed to smoke freely, can "pick up" any tune in a quarter of an hour. Seldom breaks down or forgets words, except before large or unsympathetic audience. Fetching comic "biz," and superlative Music-hall "chic." Would have no objection to black face and appear at evening parties, or in fashionable streets, with banjo (if provided with small police escort.) Testimonials from several highly respectable relatives, now in asylum, or under treatment at seaside.—Address, with terms, the Hon. ALGERNON BRASSLEIGH CHEEKINGTON (or at Chimpanzee Chambers in Piccadilly, W.)

SUGGESTION FOR REFORM IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS' SYSTEM.—"Absence" should be called immediately after dinner, and then each boy, instead of saying, "Here, Sir!" could reply, classically and correctly, "Adsum!" Yours truly, AN OVER-ETON BOY.

The Total Abstainer staggered to his feet. The room seemed to be waltzing round him, and his legs acted independently of each other. One of those legs tried to walk to the right, whilst the other moved to the left! He looked in the mirror and saw a double reflection! He had two noses, a couple of mouths, four eyes, and countless whiskers. This made him merry, and he laughed in very glee. But only for a while! Soon he became utterly depressed. Then his head ached—horribly! He tried to sleep—he could not! "Never too late—to MENDAL!" he gasped out, uttering in his extreme agitation the name of a Physician of Berlin who had made inebriety a special study.

Then his muscles became weak and trembling, his aversion to labour increased, and he had scarcely the energy or power to observe that his complexion (in patches) was ruddier than the cherry.

"Alas!" he sighed, and he succumbed permanently to persistent dyspepsia!

And what was the cause of this unfortunate, this terrible condition? Sad to say, the question was easily answered. The Total Abstainer had taken a drop too much—of Coffee!

Wednesday.—All the Police, having now been replaced by Amateur Special Constables, who are as yet unfamiliar with their duties, the position of the Metropolitan Magistrates becomes impossible, and they resign in a body at five minutes' notice, causing the greatest consternation in signalling their resignation by sending every case on the charge-sheet that morning for trial to a superior Court.

Thursday.—The Judges, overwhelmed by the prospect of an unusual and quite impossible amount of extra work, demand the increase of their salaries to £10,000 per annum. On this being categorically refused by the Treasury, they then and there, on their respective Benches, severally tear off their wigs and robes, and quit their Courts "for good," with threatening gestures.

Friday.—The LORD CHANCELLOR, on being informed of the conduct of the Judges, rips open the Woolsack, scattering its contents over the floor of the House of Lords, and, denouncing the Government, throws up his post on the spot. The legal business of the country, coming thus to a deadlock, is involved in further chaos by a sudden strike of all the Members of both the Senior and Junior Bars, which is further complicated by another of every Solicitor in the three kingdoms.

Saturday.—Gatling guns being posted in the Entrance Hall, and Bow Street having been cleared by a preliminary discharge of artillery, the programme of the Royal Italian Opera for the evening is carried out, as advertised, at Covent Garden. Ladies wearing their diamonds, are conveyed to the theatre in Police Vans, surrounded by detachments of the Household Cavalry, and gentlemen's evening dress is supplemented by a six-chambered revolver, an iron-cased umbrella, a head protector, and a double-edged cut-and-thrusting broad-sword.

Sunday.—The Church having caught the prevailing fever, the entire body of the Clergy, headed by the Bishops, come out on strike, with the result that no morning, afternoon, or evening services are held anywhere. The Medical Profession takes up the idea, and, discovering a grievance, the Royal College of Surgeons issues a manifesto. All the hospitals turn out their patients, and medical men universally drop all their cases. An M.D. who is known, upon urgent pressure, to have made an official visit, is chased up and down Harley Street by a mob of his infuriated brother practitioners, and is finally nearly lynched on a lamp-post in Cavendish Square. The day closes in with a serious riot in Hyde Park, caused by the meeting of the conflicting elements of Society, who have all marched there with their bands and banners to air their respective grievances.

Monday.—The London County Council, School Board, Common Council, Court of Aldermen, and the Royal Academicians after discovering, respectively, some trifling sources of dissatisfaction, wreck their several establishments, and finally march along the Thames Embankment towards Westminster, singing, alternately, the "Marseillaise" and "Ask a Pleece-man."

Tuesday.—The House of Commons, after tossing the SPEAKER in his own gown, declare the Constitution extinct, and, abolishing the House of Lords and giving all the Foreign Ambassadors twelve hours notice to quit the country, announce their own dissolution, and immediately commence their Autumn Holiday.

[pg 27]Wednesday.—Railway Directors, Sweeps, Chairmen of Public Companies, Coal-Heavers, Provincial Mayors, Dentists, Travelling Circus Proprietors, Fish Contractors, Beadles, Cabinet Ministers, Street Scavengers, Dog Fanciers, Archbishops, Gas Fitters, Hereditary Legislators, Prize Fighters, Poor-Law Guardians, Lion Tamers, Green-Grocers, and many other discontented members of the community, having all joined in a universal strike, society, becomes totally disorganised, and the entire country quietly but, effectually collapses, and disappears from the European system.

For shame, be friends, and join for that you jar:

'Tis Union and Strikes, my lads, must do

That you affect; and so must you resolve

That what you cannot severally achieve,

United you may manage as you will.

A speedier course than lingering languishment

Must we pursue, and I have found the path.

My lads, a biggish business is in hand;

Together let brave British Bobbies troop:

The City streets are numerous and wealthy,

And many unfrequented nooks there be,

Fitted by kind for violence and theft;

But take you thence, and many a watchful ruffian

Will soon strike home, by force and not by words:

This way, or not at all, stand you in hope.

Come, come, our comrades, with more sluggish wit,

To vigilance and duty consecrate,

Will we acquaint with all that we intend,

And we will so commit them to our cause

That they cannot stand off or "square" themselves;

But to your wishes' height you'll all advance.

The City's courts have houses of ill-fame,

Town's palaces are full of wanton wealth,

The slums are ruthless, ravenous ripe for crime.

Then speak, and strike, brave boys, and take your turn!

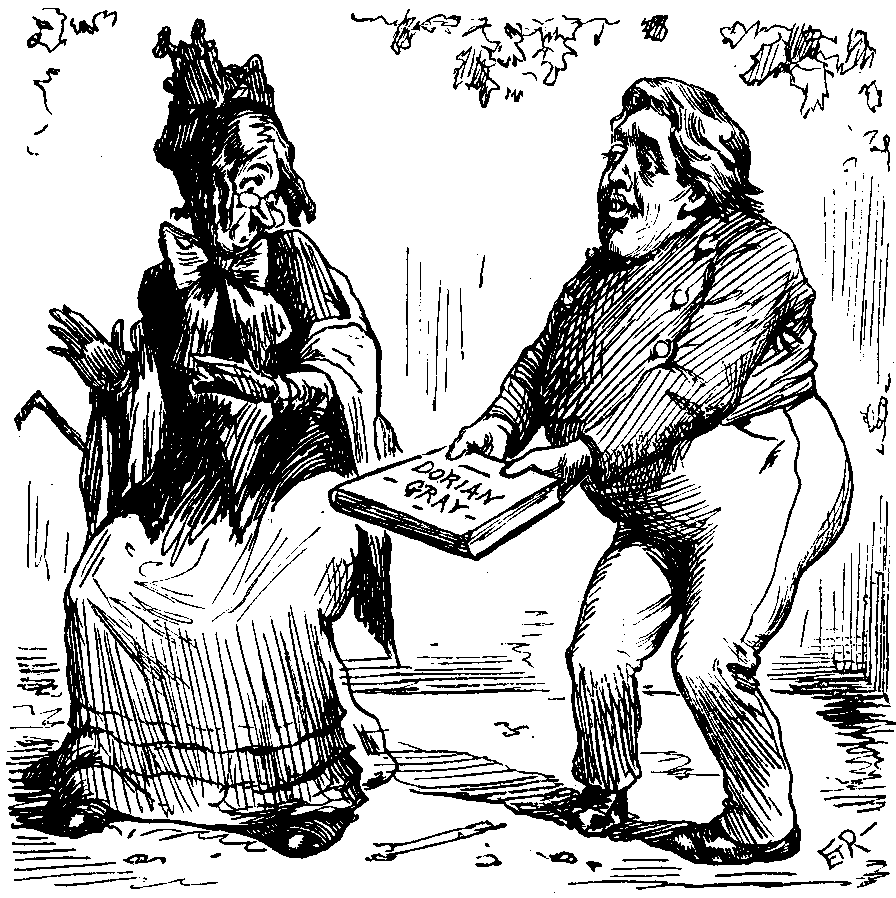

Fair Authoress. "SO SORRY TO BE SO LATE. I'M AFRAID I'M LAST!"

Genial Host. "'LAST—BUT NOT LEAST!'"

When thou art near, the hemisphere

Commissioned to surround me,

(As well as you,) is subject to

Some changes that astound me.

Where'er I look I seem mistook;

All objects—what, I care not—

At once arrange to make a change

To something that they were not!

When thou art near, love,

Strange things occur—

Thickness is clear, love,

Clearness a blur.

Penguins are weasels,

Cheap things are dear,

"Jumps" are but measles

When thou art near!

When thou art close, the doctor's dose

Is quite a decent tonic.

Thy presence, too, makes all things new,

And five-act plays laconic.

And, with thee by, the earth's the sky,

And your "day out" is my day,

While tailors' bills are daffodils,

And Saturday is Friday!

When thou art here, love,

Just where you are,

Far things are near, love,

Near things are far.

Beef-tea is wine, love,

Champagne is beer,

Wet days are fine, love,

When thou art near.

Without you stand quite close at hand,

A broker is a broker;

But stick by me, and then he'll be

A very pleasant joker!

Without thee by, a lie's a lie—

The truth is nought but truthful.

But by me stay, and night is day—

And even you are youthful

When thou art near, love,—

Not, love, unless,—

Thick soup is clear, love,

Football is chess.

IRVINGS are TOOLES, love,

Tadpoles are deer,

Wise men are fools, love,

When thou art near!

When KENNEDY fell out of his boat at Henley, his antagonist, PSOTTA, magnanimously waited for him to get in again. He must be a good Psotta chap.

LOST OPPORTUNITIES.—Last Tuesday week the members of the Incorporated Cain-and-Abel-Authors' Society lost a great treat when Mr. GEORGE AUGUSTUS lost a indignantly refused to take his seat "below the salt," and walked out without making the speech with which his name was associated on the toast-list. But, on the other hand, what a big chance Orator GEORGE AUGUSTUS lost of coming out strong in opposition, and astonishing the Pen-and-Inkorporated ones with a few stirring remarks, in his most genial vein, on the brotherhood of Authors, and their appreciation of distinguished services in the field of Literature. It was an opportunity, too, for suggesting "Re-distribution of Seats."

The merry bells do naught but ring,

The streets are gay with flag and pennant,

The birds more sweetly seem to sing—

A Heart to Let has found a TENNANT!

No more will HENRY MORTON roam,

Nor from your charms away for long go,

But, honeymooning here at home,

Forget he ever saw the Congo!

To Oxford 'twas your husband went—

The stately home of Don and Proctor—

Where, 'mid the deafening cheers that rent

The air, he straight became a Doctor.

As one whose valour none can shake,

We've sung him in a thousand ditties,

And freedoms too we've made him take

Of goodness knows how many cities!

Yet while to honour and to praise

With one another we've been vying,

Has he not told us for the days

Of rest to come he ne'er ceased sighing?

And when, with pomp of high degree,

Your marriage vows and troth you plighted,

Why, everyone was glad to see

Art and Adventure thus united!

"To those about to Marry.—Don't!"

So Mr. Punch did once advise us.

Spread the advice? I'm sure you won't.

A course which hardly need surprise us.

O lovely wife of one we think

Above all others brave and manly,

We clink our glasses as we drink

Long life and health to Mrs. STANLEY!

"I confess I was not at all prepared for the feelings that some South Africans appear to entertain with respect to our conduct in the recent negotiations"—Lord Salisbury to the Deputation of African Merchants respecting the proposed Anglo-German Agreement.

I fancied that this Instrument

Would make a great sensation

And that its music would content

The critics and the nation,

I know it is what vulgar folks

Christen the "Constant-screamer;"

I thought you'd scorn such feeble jokes;

It seems I was a dreamer.

You writhe your lips, you close your ears!

Dear me! Such conduct tries me.

You do not like it, it appears

Well, well,—you do surprise me!

'Tis not, I know, the Jingo drum,

Nor the "Imperial" trumpet.

(The country to their call won't come,

However much you stump it.)

They're out of fashion; 'tis not now

As in the days of "BEAKEY."

People dislike the Drum's tow-row.

And call the Trumpet squeaky.

So I the Concertina try,

As valued friends advise me.

What's that you say? It's all my eye?

Well, well,—you do surprise me!

I fancied you would like it much,

You and the other fellows.

Admire the tone, remark my touch!

And what capacious bellows!

'Tis not as loud as a trombone,

But harmony's not rumpus;

The chords are charming, and you'll own

It has a pretty compass.

I swing like this, I sway like that!

Fate a fine theme supplies me!

The "treatment" you think feeble, flat?

Well, well—you do surprise me!

The "European Concert"? Grand!

(You recollect that term, man!)

This is a Concertina, and

It's make is Anglo-German,

You can't expect the thing to be

English alone, completely;

But really, as 'tis played by me.

Does it not sound most sweetly?

Humph! DONALD CURRIE cocks his nose,

BECKETT disdainfully eyes me,

My Concertina you would—close!

Well, well—you do surprise me!

Scarcely a day passes without bringing us nearer to the end of the year. That is a melancholy reflection, but we are not sure that it exhausts all the possibilities of misery latent in the flight of time. It has been noticed, for instance, that the Duke of X——, whose sporting proclivities are notorious, never fails to celebrate his birthday with a repast at an inferior restaurant, and, as His Grace is powerful, his friends suffer in silence and bewail his increasing ducal age.

Henley Regatta came off as arranged. This is a peculiarity which is very striking in connection with this Royal fixture. We are informed that several certainties were upset, but by whom and why has not been stated. Candidly speaking, such a brutal method as "upsetting" consorts ill with the softer manners of our time. On the Thames, too, it must be extraordinarily disagreeable.

Mrs. WEEDLE, the Hon. Mrs. THREADBARE, and Lady FAWN, have joined the lately established Bureau for the Dissemination of Fashionable Friendships. The Personal Advertising Department is now open, and is daily filled with a distinguished crowd of applicants. Arrangements are in process of completion for supplying the deserving rich with cambric handkerchiefs, and imitation diamonds, at nominal prices.

A well-known Actor has lately been deprived of his customary allowance of fat. His loss of weight (in avoirdupois) has been computed at five-sixteenths of the integral cubit of a patent accumulator's vertical boiling power, divided by the fractional resistance of a plate-glass window to a two-horse-power catapult.

The weather has been variable, with cryptoconchoidal deflections of a solid reverberating isobar previously tested in a solution of zinc and soda-water. This indicates cold weather in December next.

Consols 1/50094th better. Wheat in demand. Jute firm. Bank rate too fast to last.

A Politician, whose name has been frequently mentioned during the late crisis, has stated it as his opinion that a temperance orator's powers of persuasion are to a moral victory as a Prime Minister is to a willow-pattern dinner-plate. The remark caused much excitement in the lobby, where this gentleman's humorous sallies never lack appreciators.

What is this I hear of a certain Noble Duke, well-known in sporting circles, having accepted a three months' engagement to appear in a "comic character sketch of his own composition," at a long-established East End-Music Hall? If there is any truth in the rumour, I should like to ask what the Duchess has been about?

A distinguished Oxford Mathematical Professor has, just after prolonged and patient research, established the undoubted certainty of the following interesting facts beyond any possible question or controversy:—That the quantity of Almond Rock Hard Bake, consumed in the United Kingdom in the year terminating on the 15th of May last, amounted to 17 lbs. 9 oz. for each member of the population, including women and children. That if at all the old and discarded Chimney Pot Hats for a like period were collected in a heap, and packed closely together, they would fill a building twice the height of St. Paul's, and three times the length of the Crystal Palace. That winners of the Derby who have become eventually four-wheeler cab-horses are ninety-six in number, but that there is only one authentic instance of a four-wheeler cab-horse having become a Derby winner.

So great is the craze for the newest idea in locomotion that it is calculated that including Duchesses no less than 1470 grandes dames whose names are well-known in Society, now pass Piccadilly Circus on the outside of the London General Omnibus Company's vehicles, between the hours of 8 A.M. and 10 P.M. daily.

A PASSPORT TO THE BEST SOCIETY, AND A GUARANTEE FOR RESPECTABILITY, is to be a diligent student of Mr. Punch's works, and to have earned the abuse of the Pall-Mall Gazette.

Monday.—Les Huguenots. Great night in consequence of police strike in Bow Street. Rioting, and Life Guards called out late, just as they were retiring for the night. Down they came, in regimentals, in undress, anyhow, to quell the disturbance. At least, such is the report inside the house. But inconvenient to be in two places at once. Henceforth they ought to record this incident by having an extinguisher (typical of going to bed and also of quelling the row) slung on to their breast-plates. Extinguisher clinking against armour would make pretty noise. Their Royal Highnesses the Prince and Princess of WALES, having come to enjoy the Opera, remain undisturbed, and leave in perfect tranquillity. Excellent example to perturbed audience. Excitement within the house. DRURIOLANUS, Earl DE GREY, Mr. HIGGINS, and other members of the Organising Operatic Committee, ready to charge the mob at a moment's notice, to charge up to two guineas a stall, if necessary. Not necessary, however. Calls for the Sheriff-elect. DRURIOLANUS, not having the official costume ready, cannot appear in it, but uses his authority and his persuasive powers in clearing lobbies, saloons, and hall. At any moment he is ready to march out with all the Huguenot soldiers and charge the rioters. Peace restored about midnight, Household troops sent home to bed, and constables decided to strike only on the heads of roughs, rowdies, and burglars. This shows how useful it is to have a Sheriff on the premises. At Her Majesty's last winter they had the nearest approach to it, that is, Sheriff's officers on the premises. But this is not precisely the same thing, as Sheriff's officers wear no uniform, and not being permitted to go out of a house when once it is given into their custody, they, however valiant, are of no use in a crowd.

Tuesday.—Lohengrin. Regardless of rioters, their Royal Highnesses again here. Much cheered outside on driving away. Yet crowd in Strand (so we hear) not particularly good-tempered, and have wrecked a private brougham or two. No effect on Opera, which goes as well as ever. Rumours that the player of the grosse caisse has struck at rehearsal are confirmed, he appears in his place and strikes again, so does the Shakspearian performer "Cymbaline."

Wednesday.—Don Giovanni. ZÉLIE DE LUSSAN as Zerlina, very popular. Still a little too like Carmen in appearance. LASSALLE can't be bettered. Great night everywhere. Mlle. MELBA and Mr. EDOUARD DE RESZKÉ taking a little holiday at a concert in Grosvenor Square, where also are Madame PATEY and another EDWARD yclept LLOYD, whom HERR GANZ accompanies with his "Sons of Tubal Cain"—no political allusion to the recent Barrow Election. Opera comparatively full. Some habitués look in to see how everything's going on, then go on themselves to Reception in Piccadilly, At Homes elsewhere, M.P.Q.'s Smoking Concert, and various other entertainments. Society winding itself up brilliantly. "Rebellion's dead! and now we'll go to supper." And so we do. "Again we come to the Savoy!"

Thursday.—Lucia off-night, but everything and everybody "going on" as usual. H.R.H. again at Opera.

Friday.—La Favorita. Breathing time before the great Operatic event of week to-morrow night.

Saturday.—Esmeralda. Too late at last moment to say anything on this splendid subject, save that the Composer was deservedly greeted with a storm—of applause!

PRIVATE R. VAN WINKLE opened his eyes, and, taking up his rusty rifle, marched towards the new ranges.

"Dear me!" said he, gazing with amazement at his surroundings, "this is not at all like what I saw when I went to sleep."

"No, RIP, it is not," replied Mr. Punch, who happened to be in the neighbourhood. He had been watching his sweetest Princess making a bull's-eye at the opening ceremony.

"Why, it is twice as large as Wimbledon," continued the astounded warrior.

"You are well within the limit," the Sage assented, "and see, there is plenty of space. No fear of damaging any of the tenants of GEORGE RANGER in this part of the country."

"No, indeed!" exclaimed Private VAN WINKLE. "Not that I think His Royal Highness had much cause of complaint. The truth is—"

"Let bygones be bygones," interrupted Mr. Punch. "GEORGE RANGER is no longer your landlord, except, in a certain sense, representing the interests of the Regular Army, and I shall keep my eye upon him in that capacity."

"An entirely satisfactory arrangement. But where are the fancy tents, and the luncheon parties, and all the etceteras that used to be so pleasant at Wimbledon?"

"Disappeared," returned Mr. Punch, firmly. "Bisley is to be more like Shoeburyness (where the Artillery set an excellent example to the Infantry) than the Surrey saturnalia."

"And is it to be all work and no play?"

"That will be the general idea. Of course, in the evening, when nothing better can be done, there will be harmonic meetings round the camp-fires. But while light lasts, the crack of the rifle and the ping of the bullet will be heard in all directions, vice the pop of champagne corks superseded. And if you don't like the prospect, my dear RIP, you had better go to sleep again."

But Private VAN WINKLE remained awake—to his best interests!

Well, we're jest about going it, at the reel "Grand Hotel," we are. We had jest about the werry lovliest wedding here, larst week, as I ewer seed, ewen with my great xperiense. Such a collekshun of brave-looking men and reel handsum women as seldom meets together xcept on these most hintresting occashuns. And as good luck wood have it, jest as we was in the werry wirl and xcitement of it all, who should come in to lunch but the same emminent yung Swell as cum about a munth ago. And he had jest the same helegant but simple lunch as before, with a bottle of the same splendid Champane, as before, and he didn't harf finish it, as before, and not a drop of what he left was wasted, as before; and so, when he paid me his little account, he arsked me if many of the werry bewtifool ladies, as I had told him of when he came larst, had been to the "Grand" lately, so the bold thort seized, me, and I says to him, "Yes, your —— ——, there's jest a nice few of 'em here now, and if you will kindly foller me up to our bewtifool Libery, and will keep your eyes quite wide open as you gos along, you will see jest about a hole room full of 'em."

So I took him parst the grand room in which the Wedding Gests was assembled, and there sure enuff, he seed such a collection of smiling bewty, as ewidently made a great impression on his—— ——'s Art, and one speshally lovely Bridesmade gave him a look, as he passed by, as ewidently went rite thro it. I scarcely xpecs to be bleeved wen I says, as his —— ——'s cheeks quite blusht with hadmirashun, and he turned round to me and says, says he, "Ah, Mr. ROBERT, if there was many such reel lovely angels as that a flying about, I rayther thinks as I shood be perswaded to turn a Bennedictus myself." I didn't at all know what he meant, but I thort as it was werry credittable to him. We got quite a chatting arterwards in the Libery, of course I don't mean to say as I forgot for a moment the strornary difference atween us, but he had werry ewidently been werry much struck by the lovely Bridesmade, for he says, "Mr. ROBERT," says he, "what's about the rite time for a man to marry?"

Of course I was reglar staggered, but I pulls myself together, and I says, without not no hesitashun, "Jest a leetle under 30, your —— ——, for the Gent, and jest a leetle over 20 for the Lady, and then the Gent gits just about 10 years advantage, which I thinks as he's well entitled to." At which he larfs quite hartily, and he says, "Why that wood keep me single for another ten years—but I will think it over;" and, strange to say, jest as we passed again by the room as the Bridal party was in, the same lovely Bridesmade happend to be near the door, so they coud both have a good look at each other, and a hansum cupple they was, if ever I seed one. And when his —— —— wished me good day, which he did, quite in a frendly way, he added, with his most bewtifool smile, "Ten years, MR. ROBERT, seems a long time to wait for such a sweet angel as that!"

Ah, it's a rum world as we all lives in, and in nothink much rummer than in the wunderfool power of a bewtifool face, ah, and as sumbody says, for Wheel or for Wo, jest as it appens, more's the pitty.

I rayther thinks, as I gathers from the tork of the many yung swells as we has dining here, that they are not altogether what I shoud call a marrying race; they seems to think as there's allers plenty of time for that sollem seremony when they're a good deal older.

Ah, of course it isn't for a poor old Hed Waiter to presume to adwise young and hemenent swells, but my xperiense of uman life teaches me, as the werry werry appiest time of a man's life is from 30 to about 40, perwided as he has been lucky enuff to secure for hisself a yung, bewtifool, good-tempered, helegant, and ercomplished Bride, to, as the Poet says, harve his sorrows, and dubble his joys.

ROBERT.

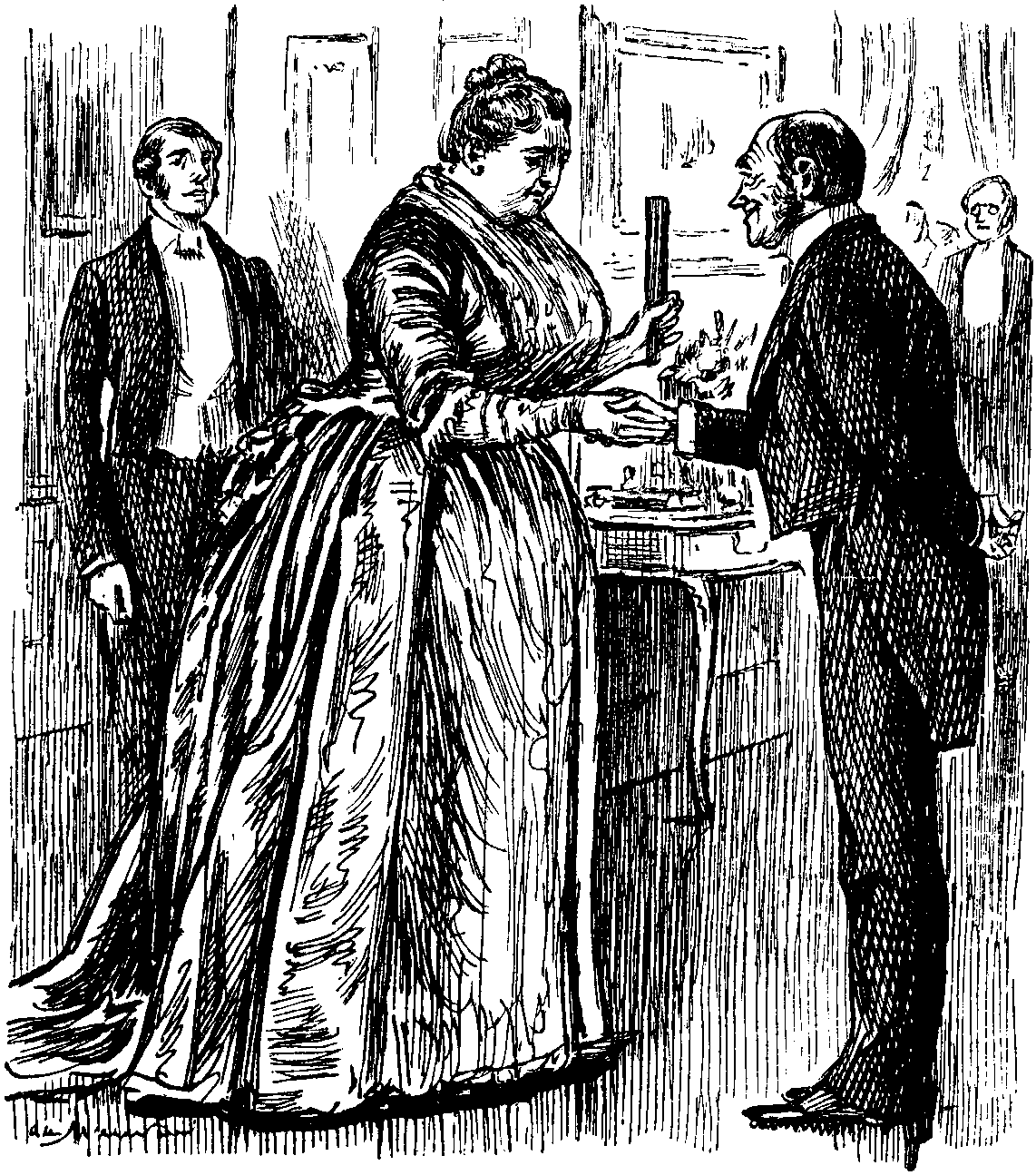

Fair Authoress. "AND, FOR THE FRONTISPIECE, I WANT YOU TO DRAW THE HEROINE STANDING PROUDLY ERECT BY THE SEASHORE, GAZING AT THE STILL IMAGE OF HERSELF IN THE TROUBLED WAVES. THE SUN IS SETTING; IN THE EAST THE NEW MOON IS RISING—A THIN CRESCENT. HER FACE IS THICKLY VEILED; AN UNSHED TEAR IS GLISTENING IN HER BLUE EYE; HER SLENDER, WHITE, JEWELLED HANDS ARE CLENCHED INSIDE HER MUFF. THE CURLEWS ARE CALLING, UNSEEN—"

F.A.'s Husband. "YES; DON'T FORGET THE CURLEWS—THEY COME IN CAPITALLY! I CAN LEND YOU A STUFFED ONE, YOU KNOW—TO DRAW FROM!" &c., &c., &c., &c., &c.

The Lying Spirit! "Doctrine hard!" some mutter,

Dictated by unsympathetic scorn;

A doctrine that on light would draw the shutter,

And close the opening gateways of the morn.

No so; no guiding light would Punch extinguish,

Or chill true champion of the toiling crowd;

But wisdom at its kindliest must distinguish

Between true guides and tricksters false as loud.

The blameless King his headlong knights upbraided

In kindly grief for "following foolish fires,"

False flames that in mere dun marsh-darkness faded,

Leaving lost votaries to its mists and mires;

And here's an ignis fatuus, fired by folly,

And moved by violence as fierce as blind;

The gulf before's a bourne most melancholy,

And what of those fast following behind?

Well-meaning hearts, maybe, all expectation

Of glittering gains upon a perilous road,

Stirred by wild whirling words to keen elation,

Pricked on by poverty's imperious goad;

Hoping,—as who of hope shall be forbidden?—

Striving,—as who hath not the right to strive?—

For flaunted gain through perils shrewdly hidden!

Oh, labourers hard in Industry's huge hive,

What wonder, if, ill-paid and tired, you hasten

To follow the loud bauble and the lure,

Or gird at those who your wild hopes would chasten,

Or guide you on a pathway more secure!

And yet beware! No oriflamme of battle

Is that false radiance round yon impish brow.

The jester's bladder-bauble, with its rattle

Of prisoned peas, is not the tow-row-row

Of Labour's true reveillé. Bonnet Phrygian,

Cap of sham Liberty, the spectre wears;

But he will plunge to depths of darkness Stygian

Whom anti-civic Violence ensnares.

Plain Justice, honest Hope are good to follow,

But Insubordination, fierce and blind,

Mouthing out furious threat or promise hollow.

Is the sworn foe of civilised mankind;

Breaking up ancient bonds of love and duty,

All social links that bear abiding test,

With no sound promise of a better beauty,

A fairer justice, or a truer rest.

No; patient Labour, with its long-borne burden

And guardian Force, with its thrice-noble trust,

Claim from the State the fullest, freest guerdon,

And all wise souls, all spirits fair and just,

Must back the Great Appeal that Time advances,

And Progress justifies in this our time.

But civic Violence, in all circumstances

Now like to hap, is anti-social crime,

Foul in its birth and fatal in its issue.

Tyrannic act, incendiary speech,

Recklessly rend the subtly woven tissue

That binds Society's organs each to each.

Strong Toiler, deft Auxiliar, stalwart Warder,

Your hour has struck, your tyrants face their doom,

But let hot haste unsettle temperate order,

And Hope's bright disc will feel eclipse's gloom.

This is a lying spirit, sly and sinister,

Its promise false, its loud incitements vain.

Not to your true advantage shall it minister,

Mere Goblin Gold its glittering show of Gain:

Spectre of Chaos and the Abyss, it flutters

Before you flaunting high its foolish fire,

But there's a lie in each loud word it utters,

And its true goal is Anarchy's choking mire!

On the 24th of June, 1871, Mr. Punch sang, àpropos of the Germans desiring to purchase Heligoland—

"Though to rule the waves, we may believe they aspire,

If their Navy grow great, we must let it;

But if one British island they think to acquire,

Bless their hearts, don't they wish they may get it?"

And they have got it!

What is this your Punch hears of you? Can't you dissipate his fears?

Did the bugle ring out vainly for the British Grenadiers?

Once the regiment was famous for its deeds of derring-do,

And you followed where the flag went when on alien winds it flew.

Has the soldiers' "oath of duty" been forgotten, that you shirk,

Not the face of foe, we're certain, but this kit-inspecting work?

You have trodden paths of glory (we have seen your banners fly)

Where the murky smoke of battle gathered thickly o'er the sky;

Can you thus besmirch the laurels that in other days you won,

By forgetfulness of duties that by soldiers must be done?

Egad! my gallant lads, your Punch can scarce believe his ears,

When he hears this shocking story of the British Grenadiers!

The Hostess is receiving her Guests at the head of the staircase; a Conscientiously Literal Man presents himself.

Hostess (with a gracious smile, and her eyes directed to the people immediately behind him). So glad you were able to come—how do you do?

The Conscientiously Literal Man. Well, if you had asked me that question this afternoon, I should have said was in for a severe attack of malarial fever—I had all the symptoms—but, about seven o'clock this evening, they suddenly passed off, and—

[Perceives, to his surprise, that his Hostess's attention is wandering, and decides to tell her the rest later in the evening.

Mr. Clumpsole. How do you do, Miss THISTLEDOWN? Can you give me a dance?

Miss Thistledown (who has danced with him before—once). With pleasure—let me see, the third extra after supper? Don't forget.

Miss Brushleigh (to Major Erser). Afraid I can't give you anything just now—but if you see me standing about later on, you can come and ask me again, you know.

Mr. Boldover (glancing eagerly round the room as he enters, and soliloquizing mentally). She ought to be here by this time, if she's coming—can't see her though—she's certainly not dancing. There's her sister over there with the mother. She hasn't come, or she'd be with them. Poor-looking lot of girls here to-night—don't think much of this music—get away as soon as I can, no go about the thing!... Hooray! There she is, after all! Jolly waltz this is they're playing! How pretty she's looking—how pretty all the girls are looking! If I can only get her to give me one dance, and sit out most of it somewhere! I feel as if I could talk to her to-night. By Jove, I'll try it!

[Watches his opportunity, and is cautiously making his way towards his divinity, when he is intercepted.

Mrs. Grappleton. Mr. BOLDOVER, I do believe you were going to cut me! (Mr. B. protests and apologises.) Well, I forgive you. I've been wanting to have another talk with you for ever so long. I've been thinking so much of what you said that evening about BROWNING'S relation to Science and the Supernatural. Suppose you take me downstairs for an ice or something, and we can have it out comfortably together.

[Dismay of Mr. B., who has entirely forgotten any theories he may have advanced on the subject, but has no option but to comply; as he leaves the room with Mrs. GRAPPLETON on his arm, he has a torturing glimpse of Miss ROUNDARM, apparently absorbed in her partner's conversation.

Mr. Senior Roppe (as he waltzes). Oh, you needn't feel convicted of extraordinary ignorance, I assure you, Miss FEATHERHEAD. YOU would be surprised if you knew how many really clever persons have found that simple little problem of nought divided by one too much for them. Would you have supposed, by the way, that there is a reservoir in Pennsylvania containing a sufficient number of gallons to supply all London for eighteen months? You don't quite realise it, I see. "How many gallons is that?" Well, let me calculate roughly—taking the population of London at four millions, and the average daily consumption for each individual at—no, I can't work it out with sufficient accuracy while I am dancing; suppose we sit down, and I'll do it for you on my shirt-cuff—oh, very well; then I'll work it out when I get home, and send you the result to-morrow, if you will allow me.

Mr. Culdersack (who has provided himself beforehand with a set of topics for conversation—to his partner, as they halt for a moment). Er—(consults some hieroglyphics on his cuff stealthily)—have you read STANLEY'S book yet?

Miss Tabula Raiser. No, I haven't. Is it interesting?

Mr. Culdersack. I can't say. I've not seen it myself. Shall we—er—?

[They take another turn.

Mr. C. I suppose you have—er—been to the (hesitates between the Academy and the Military Exhibition—decides on latter topic as fresher) Military Exhibition?

Miss T.R. No—not yet. What do you think of it?

Mr. C. Oh—I haven't been either. Er—do you care to—?

[They take another turn.

Mr. C. (after third halt). Er—do you take any interest in politics?

Miss T.R. Not a bit.

Mr. C. (much relieved). No more do I. (Considers that he has satisfied all mental requirements). Er—let me take you down-stairs for an ice.

[They go.

Mrs. Grappleton (re-entering with Mr. BOLDOVER, after a discussion that has outlasted two ices and a plate of strawberries). Well, I thought you would have explained my difficulties better than that—oh, what a delicious waltz! Doesn't it set you longing to dance?

Mr. B. (who sees Miss ROUNDARM in the distance, disengaged). Yes, I really think I must—

[Preparing to escape.

Mrs. Grappleton. I'm getting such an old thing, that really I oughtn't to—but well, just this once, as my husband isn't here.

[MR. BOLDOVER resigns himself to necessity once more.

First Chaperon (to 2nd ditto). How sweet it is of your eldest girl to dance with that absurd Mr. CLUMPSOLE! It's really too bad of him to make such an exhibition of her—one can't help smiling at them!

Second Ch. Oh, ETHEL never can bear to hurt anyone's feelings—so different from some girls! By the way, I've not seen your daughter dancing to-night—men who dance are so scarce nowadays—I suppose they think they have the right to be a little fastidious.

First Ch. BELLA has been out so much this week, that she doesn't care to dance except with a really first-rate partner. She is not so easily pleased as your ETHEL, I'm afraid.

Second Ch. ETHEL is young, you see, and, when one is pressed so much to dance, one can hardly refuse, can one? When she has had as many Seasons as BELLA, she will be less energetic, I daresay.

[MR. BOLDOVER has at last succeeded in approaching Miss ROUNDARM, and even in inducing her to sit out a dance with him; but, having led her to a convenient alcove, he finds himself totally unable to give any adequate expression to the rapture he feels at being by her side.

Mr. B. (determined to lead up to it somehow). I—I was rather thinking—(he meant to say, "devoutly hoping," but, to his own bitter disgust, it comes out like this)—I should meet you here to-night.

Miss R. Were you? Why?

Mr. B. (with a sudden dread of going too far just yet). Oh, (carelessly), you know how one does wonder who will be at a place, and who won't.

Miss R. No, indeed, I don't.—how does one wonder?

Mr. B. (with a vague notion of implying a complimentary exception in her case). Oh, well, generally—(with the fatal tendency of a shy man to a sweeping statement)—one may be pretty sure of meeting just the people one least wants to see, you know.

Miss R. And so you thought you would probably meet me. I see.

Mr. B. (overwhelmed with confusion, and not in the least knowing what he says). No, no, I didn't think that—I hoped you mightn't—I mean, I was afraid you might—

[Stops short, oppressed by the impossibility of explaining.

Miss R. You are not very complimentary to-night, are you?

Mr. B. I can't pay compliments—to you—I don't know how it is, but I never can talk to you as I can to other people!

Miss R. Are you amusing when you are with other people?

Mr. B. At all events I can find things to say to them.

Enter Another Man.

Another Man (to Miss B.). Our dance, I think?

Miss R. (who had intended to get out of it). I was wondering if you ever meant to come for it. (To Mr. B., as they rise.) Now I shan't feel I am depriving the other people! (Perceives the speechless agony in his expression, and relents.) Well, you can have the next after this if you care about it—only do try to think of something in the meantime! (As she goes off.) You will—won't you?

Mr. B. (to himself). She's given me another chance! If only I can rise to it. Let me see—what shall I begin with? I know—Supper! She hasn't been down yet.

His Hostess. Oh, Mr. BOLDOVER, you're not dancing this—do be good and take someone down to supper—those poor Chaperons are dying for some food.

[Mr. B. takes down a Matron whose repast is protracted through three waltzes and a set of Lancers—he comes up to find Miss ROUNDARM gone, and the Musicians putting up their instruments.

Coachman at door (to Linkman, as Mr. B. goes down the steps). That's the lot, JIM!

[Mr. B. walks home, wishing the Park Gates were not shut, to as to render the Serpentine inaccessible

House of Commons, Monday, July 7.—Cabinet Council on Saturday; House begins to think it's time Ministers made up their minds what they're going to do with business of Session. But OLD MORALITY returns customary answer. Ministry still carefully considering question. Meantime he has nothing to say.

"Except in respect of sex and age, O.M. reminds me." said ALBEBT ROLLIT, "of scene in play recently put on stage by BEERBOHM TREE—A Man's Shadow it was called. Daresay you remember, TOBY; there's a murder witnessed through window by wife and little daughter. They think it's their man that did the deed; but 'twas the other fellow—the Shadow, don't you know. There is police inquiry; mother and daughter cross-examined; believe the murderer is the husband and father; saw him do it with their own eyes; but of course not going to peach; little girl pressed to tell all she knows; makes answer in voice that thrills Gallery, and makes mothers in the Pit weep, 'I have seen nothing, I have heard nothing.' Never see OLD MORALITY come to the table, as he is now accustomed nightly to do, and protest he has no statement to make, than I think of the little TERRY in this Scene, and her wailing, piteous cry, 'I have seen nothing, I have heard nothing.' Quite time he had, though. If Ministers can't make up their minds, what's the House to do? Begin to think if things don't mend soon, I shall have a better record of business done to show at end of Session than the Ministry. Bankruptcy Bill will make three Measures to me this Session."

Irish Constabulary Vote on; Prince ARTHUR lounging on Treasury Bench; prepares to receive Irishry; engagement opens a little flat, with speech from JOHN ELLIS, oration from O'PICTON, and feeble flagellation from FLYNN. Then Prince ARTHUR suddenly, unexpectedly, dashes in. Empty benches fill up; stagnant pool stirred to profoundest depths: ARTHUR professes to be tolerant of Irish Members, but declares himself abhorrent of connivance of Right Hon. Gentleman above Gangway. Talks at Mr. G., who begins visibly to bristle before our very eyes as he sits attentive on Front Bench. ARTHUR in fine fighting trim; Ministerial bark may be labouring in troubled waters; a suddenly gathered storm, coming from all quarters, has surrounded, and threatens to whelm it; MATTHEWS may be sinking under adversity; the Postmen may pull down RAIKES; GOSCHEN is gone; OLD MORALITY'S cheerful nature is being soured; there is talk of Dissolution, and death. But if this is Prince ARTHUR'S last time of defending his rule in Ireland, it shall not be done in half-hearted way. Come storm, come wrack, at least he'll die with harness on his back.

The accused becomes the accuser. Called upon to defend himself, he turns, and makes a slashing attack on his pursuers, carrying the war into their camp. Scorning the Captains and Men-at-arms, he goes straight for Mr. G., and in an instant swords clash across the table, and shields are dinted. Nothing more delightful than to hear Mr. G. complaining, as he rose, and took his coat off, that Prince ARTHUR had "dragged him into the controversy." On the whole, he bore the infliction pretty well, and went for ARTHUR neck and crop. Business done.—Irish Votes in Supply.

Tuesday.—"I have seen nothing; I have heard nothing." Pathetic refrain of OLD MORALITY murmured again to-night: Members wanted to know about various things; but in OLD MORALITY'S mind, fate of the Tithes Bill, intentions of Government touching proposed new Standing Order, and allocation of money originally intended for Publicans, all a blank. "We are still considering," says he.

"A most considerate Government," says WILFRID LAWSON. "Might save time and trouble if they had at table an automatic machine; Members wanting to know how business is to be arranged, what Bills to be dropped, and which gone forward with, could go up to table, drop a penny in the slot, and out would come the answer—'I have seen nothing; I have heard nothing.'"

Seems that HANBURY has exceptional means of obtaining information. OLD MORALITY has privately shown him Military Report with respect to Heligoland. A confidential communication, something of the kind the MARKISS carried on with the population of Heligoland. But HANBURY straightway goes and tells all about it in a letter to one of his Constituents; letter gets into papers. SUMMERS reads it out to House. Eagerly thirsting after knowledge on military matters, SUMMERS wants also to see the text of Report. Why should HANBURY have it all to himself? Quartermaster-General SUMMERS would like opportunity of studying it, and forming opinion as to accuracy of the naval and military men who have drawn up plan. Will OLD MORALITY favour him by placing him on an equality of confidence with HANBURY? No, OLD MORALITY will not. Howl of indignant despair from Radicals. Never heard of this Report before; but that HANBURY should see it, and thereby be enabled to assure his constituents, even by nods and winks, that it was all right about Heligoland, was more than they could put up with. O'PICTON sat morose at the corner seat below the Gangway. Who was HANBURY, that he should have the advantage of studying these military documents when the grand-nephew of PICTON of Waterloo was left out in the cold, his martial instincts unsatisfied, his knowledge of strategical points of the British Empire unsatiated?

Another instance this of the misfortune that pursues the Government. Little did OLD MORALITY think, when in moment of weakness he showed this important document to HANBURY, what a hornet's nest it would bring about his unoffending head.

Business done.—Irish Constabulary Vote passed.

Thursday.—At last OLD MORALITY has heard something and seen something. Heard how things went on to-day in Committee on Procedure. Worse and worse. Prince ARTHUR made curious blunder for one so alert: introduced into draft Report admission of principle that Lords might, an they pleased, refuse to consider in current Session, any Bill coming up to them from Commons. HARCOURT saw his opportunity; used it with irresistible skill and force. Committee adjourned in almost comatose state.

This is what OLD MORALITY has heard from JOKIM, who begins to think that, after all, life is a serious thing. What he sees is, that it is impossible to further delay decision about business. Accordingly announces complete surrender. All, all are gone, the old familiar faces—Land Purchase Bill, Tithe Bill, and even this later project of the new Standing Order. "What, all our pretty chicks?" cry the agonised Ministerialists.

"Yes," said OLD MORALITY, mingling his tears with theirs, "our duty to our QUEEN and Country demands this sacrifice. But," he added, bracing up, significantly eyeing Mr. G., and speaking in dear solemn tones, "we reserve to ourselves absolute freedom of [pg 36] action on a future occasion." Opposition shouted with laughter, whilst OLD MORALITY stood and stared, and wondered what was amusing them now. New Session is, according to present intentions, to open in November. Will the Land Purchase Bill be taken first? Mr. G. wants to know.

"Sir," said OLD MORALITY, "I have indicated the views of the Government as to the Land Purchase Bill, according as those views are held at the present time." (Cheers from the Ministerialists.) Encouraged by this applause, and, happy thought striking him, went on: "But it is impossible for the Government to say what circumstances may occur to qualify those views."

Once more Opposition break into storm of laughter; OLD MORALITY again regards them with dubious questioning gaze.

"Curious thing, TOBY," he said to me afterwards, "those fellows opposite always laugh when I drop in my most diplomatic sentences. It's very well for MACHIAVELLI that he didn't live in these times, and lead House of Commons instead of the Government of the Florentine Republic. He would never have opened his mouth without those Radicals and Irishmen going off into a fit of laughter."

Business done.—Announcement that business won't be done.

Friday.—Still harping on Irish Votes. Want to dock Prince ARTHUR'S salary. SWIFT MACNEILL brought down model of battering-ram used at Falcarragh; holds it up; shows it in working order; Committee much interested; inclined to encourage this sort of thing; pleasant interlude in monotony of denunciation of Prince ARTHUR and all his works; no knowing what developments may not be in store; the other night had magic-lantern performance just off Terrace; that all very well on fine night; but when it's raining must keep indoors and battering-ram suitable for indoor exhibition.

HAVELOCK wanted to borrow it, says he would like to show SCHWANN how it works; but MACNEILL couldn't spare it till Irish Votes through.

New turn given to Debate by plaintive declaration from JOHN DILLON that he has "never been shadowed." "A difficult lot to deal with," says ARTHUR, gazing curiously at the Shadowless Man. "If they are shadowed, they protest; if they're not, they repine."

Business done.—Irish Votes in Committee.

"How well your Picture bears the artificial light!" i.e., "Couldn't look worse than it does by daylight."

"Mustn't keep you on the stairs. Such heaps of your friends asking for you upstairs;" i.e., "Got rid of him, thank goodness!"

"Here you are at last! Been dodging you from room to room!" i.e., "To keep out of your way. Caught at last, worse luck!"

"You look as if you had just stepped out of a picture-frame!" i.e., "Wish you'd step back into one!"

"Not seen Mr. O'Kew's picture? You must see it. Only three rooms from here, and no crowd there now. So go and bring me back word what you think;" i.e., "Now to flee!"

"Yes, I'm so fond of Cricket;" i.e., "How can I find out if Oxford or Cambridge is in?"

"Don't move, pray;" i.e., "If she doesn't, I shall be smothered in lobster-salad!"

"Not the least in my way, thanks;" i.e., "Does she think I can see through her parasol?"

"Pray join us at lunch! Heaps of room in the carriage;" i.e., "Hope she doesn't! It only holds four, and we're six already."

"Don't they call a hit to the left like that, a Drive?" i.e., "Young-rich—good-looking—worth catching—looks as if he liked 'sweet simplicity.'"

"Has at heart the best interests of the Borough;" i.e., Means to subscribe largely to all local clubs and charities.

"The honour of representing you in Parliament;" i.e., "The pleasure of advertising myself."

"I should wish to keep my mind open on that subject;" i.e., "I cannot afford to commit myself just yet."

"I have never heard such an astounding argument;" i.e., "Since I last employed it myself."

"To come to the real question at issue;" i.e., "To introduce my one strong point."

"I do not pledge myself to these figures;" i.e., "The next speaker will very likely show them to be absolutely unreliable."

"Oh, as to all that, I quite agree with you;" i.e., "I wasn't listening."

"I rather understood that you were arguing, &c., &c.;" i.e., "You are now flatly contradicting yourself."

Captain (to Subaltern). Have you proved them?

Subaltern. Sorry, Sir, but the men say they know their places, and it is useless labour.

Capt. Very well—I daresay they are right. You know we have been told to be conciliatory. Open order! March! For inspection—port arms!

Sergeant (stepping forward, and saluting). Beg pardon, Sir, but the men are under the impression that you wish to examine their rifles?

Capt. Certainly. (To Subaltern). Take the rear rank, while I look after the front.

Serg. Beg pardon, Sir, but the men haven't taken open order yet. They say that they are responsible for their rifles when they have to use them before the enemy, and you may rely upon it that they will be all right then.

Capt. Very well—then we will dispense with inspection of arms. Buttons bright, and straps in their proper places?

Serg. (doubtfully). So they say, Sir.

Capt. Well, then, read the orders.

Serg. Beg pardon, Sir, but the men say they know their duty, and don't want to listen to no orders.

Capt. Well, well, I am glad to hear that they are so patriotic. Hope that the Commanding Officer will dispense (under the circumstances) with the formality. Anything more?

Serg. Privates BROWN, JONES, and ROBINSON are told off for duty on guard, Sir.

Capt. March them off, then.

Serg. Please, Sir, they say they want to speak to you.

Capt. Very well—bring them up. (Sergeant obeys.) Now, men, what is it?

Private Brown. Please, Sir, I have got a tooth-ache.

Capt. Very well—fall out, and go to the doctor.

Private B. Please, Sir, I don't want to see no doctor. I can cure myself.

Capt. Very well—cure yourself. (Private salutes, and retires.) And now, JONES and ROBINSON, what do you want?

Private Jones. Please, Sir, me and ROBINSON were told off for guard six months ago, and we think it's too much to expect us to do sentry-go so soon.

Capt. Well, you know your orders.

Private J. Oh, that'll be all right, Sir! We'll explain to the War Office if there's any row about it!

[The Privates salute, and retire.

Capt. Anything else, Sergeant?

Sergt. Well, no, Sir—you see the men won't do anything.

Capt. Under those circumstances, I suppose I have only to give the usual words of command. Company, attention! Right turn—dismiss!

[They dismiss.

Captain.—Now, my men, all you have to do is to keep your heads, and obey orders. Attention! Fix Bayonets!

Subaltern. Sorry to say, Sir, they have paraded without bayonets.

Capt. Well, that's to be regretted; although they are small enough nowadays, in all conscience! Fire a volley! At a thousand yards! Ready!

Sub. Very sorry. Sir, but the men forgot to bring their ammunition.

Capt.—Come, this is getting serious! Here's the Cavalry preparing to charge, and we are useless! Must move 'em off! Right turn!

Sergeant. Please, Sir, the Company's a bit rusty, and don't know their right hands from their left.

Capt. (losing his temper). Confound it! They don't, don't they! Well, hang it all, I suppose they will understand this? (To Company.) Here, you pampered useless idiots—bolt!

[They bolt.

A CUTTING (transplanted from the advertisements in the Belfast News-Letter):—

WANTED, A PARROT: one brought up in a respectable family, and that has not been taught naughty words or bigoted expressions, preferred.—Apply by letter, stating price, &c.

"Preferred!" What sort of a Parrot had they been previously accustomed to at that house?

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.