The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Popular History of France From The

Earliest Times, by Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Popular History of France From The Earliest Times

Volume V. of VI.

Author: Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot

Release Date: April 8, 2004 [EBook #11955]

Last Updated: September 6, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF FRANCE, V5 ***

Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

CHAPTER XXXV. HENRY IV., PROTESTANT KING. (1589-1593.)

CHAPTER XXXVI. HENRY IV., CATHOLIC KING. (1593-1610.)

CHAPTER XXXVII. REGENCY OF MARY DE’ MEDICI. (1610-1617.)

CHAPTER XXXVIII. LOUIS XIII., CARDINAL RICHELIEU, AND THE COURT.

CHAPTER XXXIX. LOUIS XIII., CARDINAL RICHELIEU, AND THE PROVINCES.

CHAPTER XL. LOUIS XIII., RICHELIEU--CATHOLICS AND PROTESTANTS.

CHAPTER XLI. LOUIS XIII., CARDINAL RICHELIEU, AND FOREIGN AFFAIRS.

CHAPTER XII. LOUIS XIII., RICHELIEU, AND LITERATURE.

CHAPTER XLIII. LOUIS XIV., THE FRONDE--CARDINAL MAZARIN.

CHAPTER XLIV. LOUIS XIV., HIS WARS AND HIS CONQUESTS. 1661-1697.

CHAPTER XLV. LOUIS XIV., HIS WARS AND HIS REVERSES. (1697-1713.)

CHAPTER XLVI. LOUIS XIV. AND HOME ADMINISTRATION.

CHAPTER XLVII. LOUIS XIV. AND RELIGION.

CHAPTER XLVIII. LOUIS XIV., LITERATURE AND ART.

ILLUSTRTIONS

“Do Not Lose Sight of My White Plume.”——30

Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma——32

Charles de Lorraine, Duke of Mayenne——35

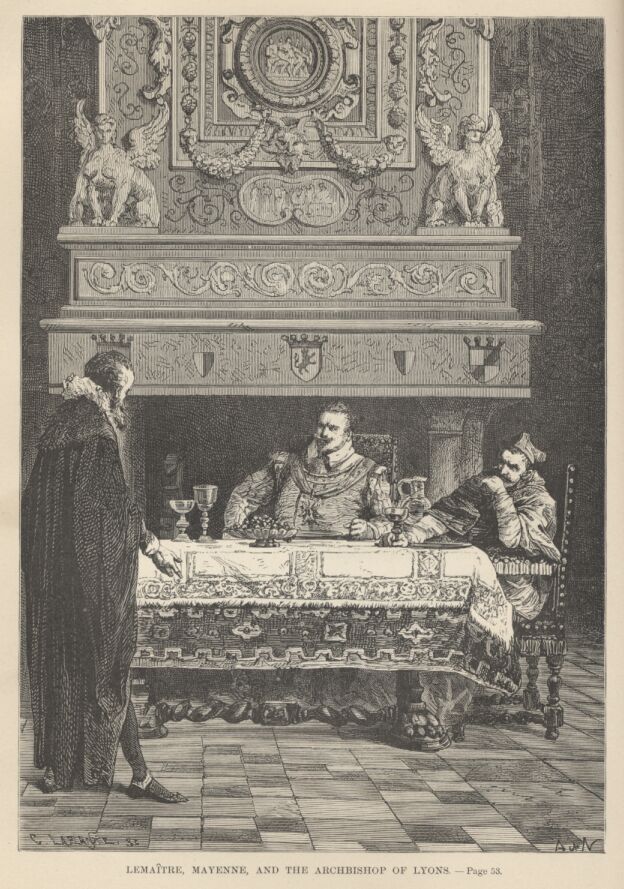

Lemaitre, Mayenne, and the Archbishop of Lyons——53

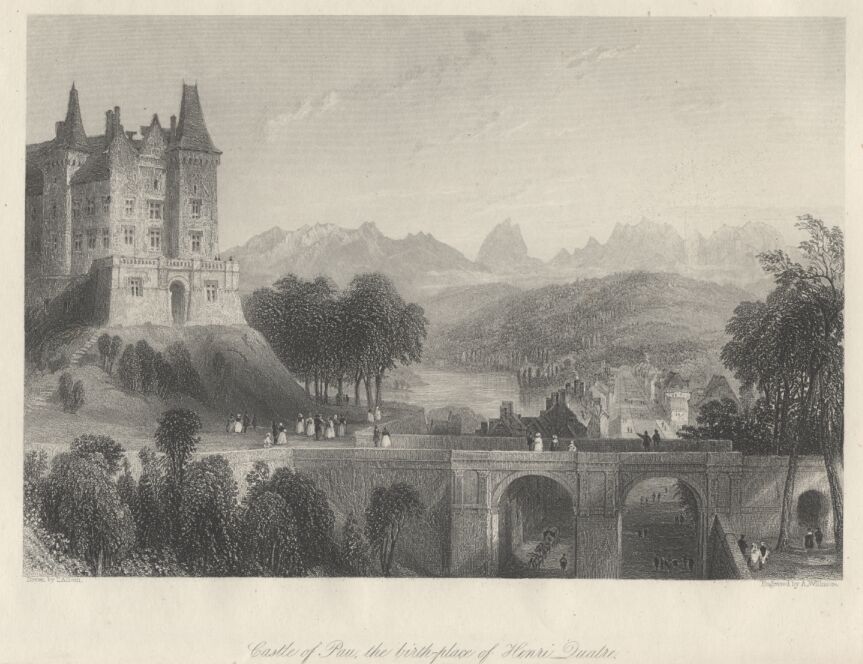

The Castle of St. Germain in the Reign Of Henry IV.—107

The Castle of Fontainbleau——124

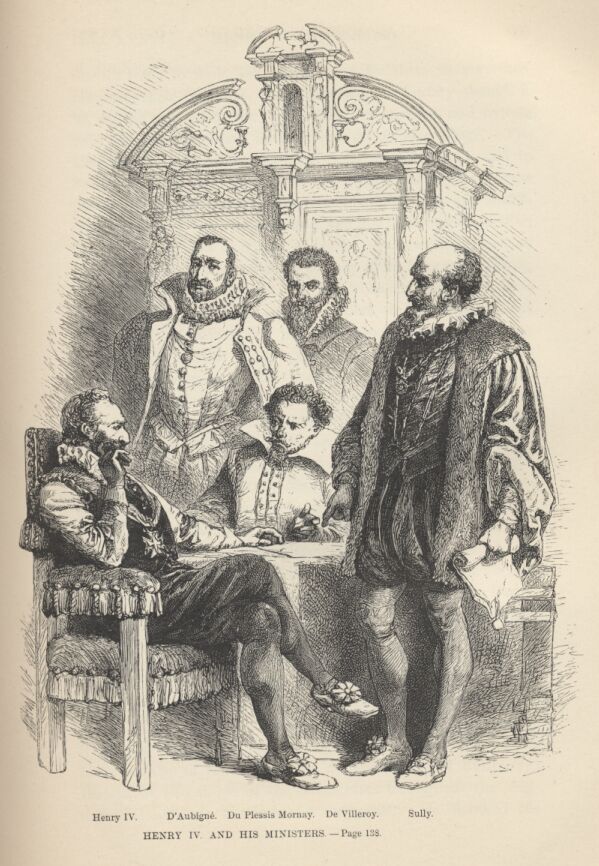

Henry IV. And his Ministers——138

The Arsenal in the Reign of Henry IV.——143

Concini, Leonora Galigai, and Mary De’ Medici——149

Louis XIII. And Albert de Luynes——154

Murder of Marshal D’Ancre——155

“Tapping With his Finger-tips on the Window-pane.”——191

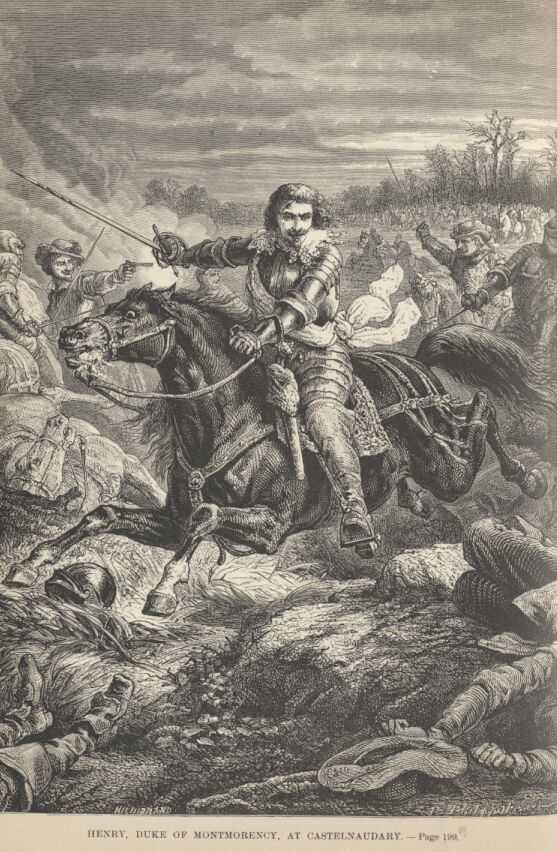

Henry, Duke of Montmorency, at Castelnaudary——199

The King and the Cardinal——204

Cinq-Mars and de Thou Going to Execution——215

The Parliament of Paris Reprimanded——217

Demolishing the Fortifications——244

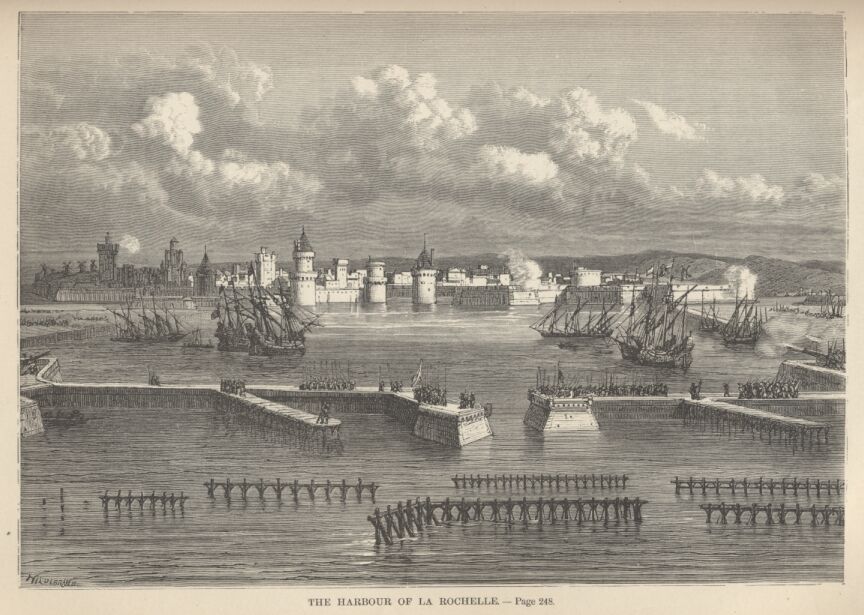

The Harbor of La Rochelle—-248

The King and Richelieu at La Rochelle——250

Richelieu and Father Joseph——280

Death of Gustavus and his Page——290

The Representation of “The Cid.”——335

Corneille at the Hotel Rambouillet—-342

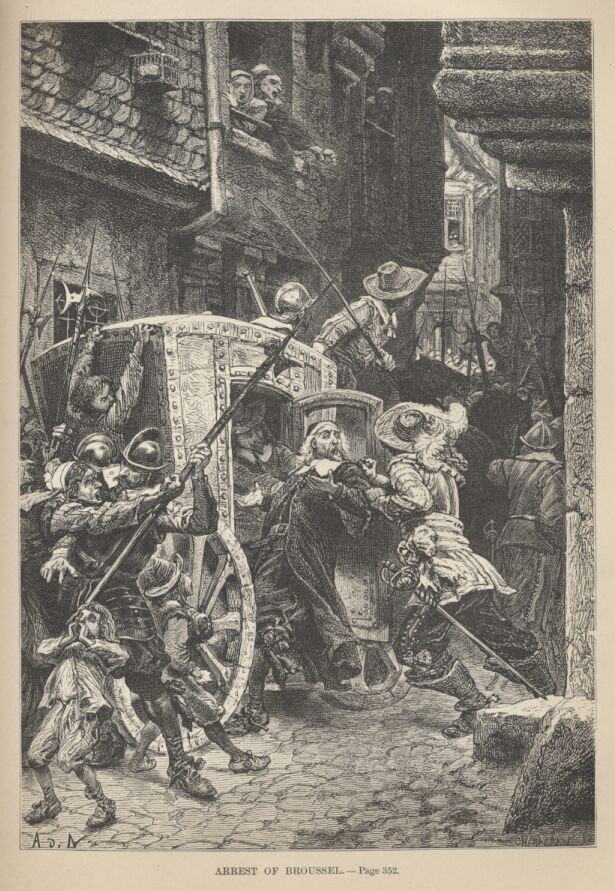

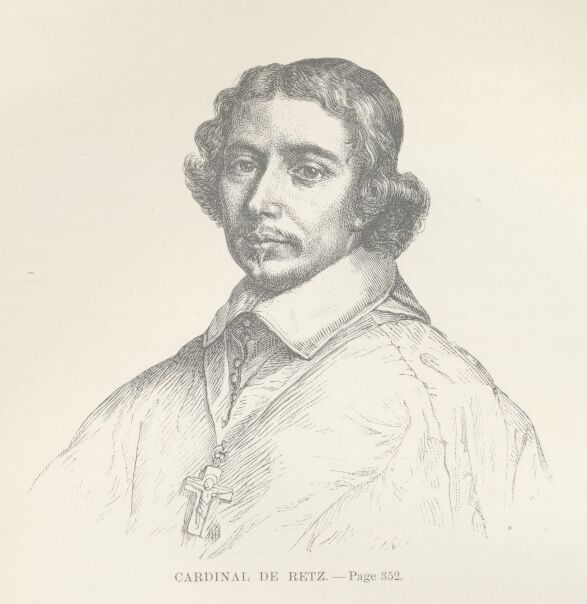

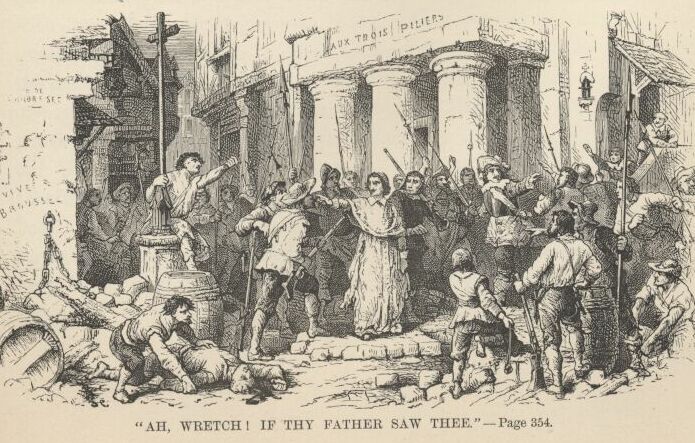

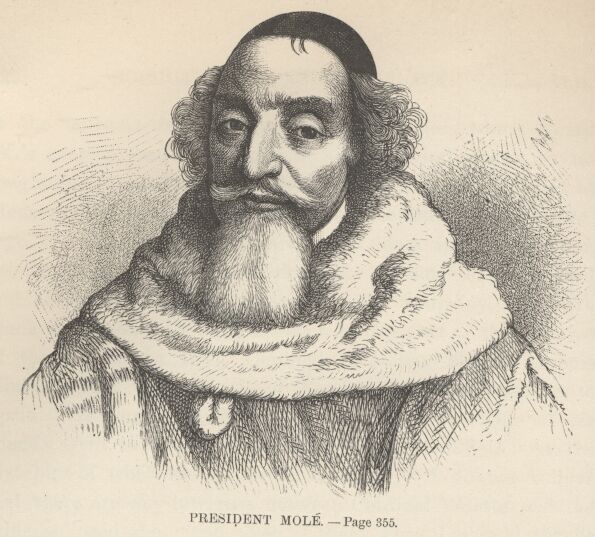

“Ah, Wretch, if Thy Father Saw Thee!”——354

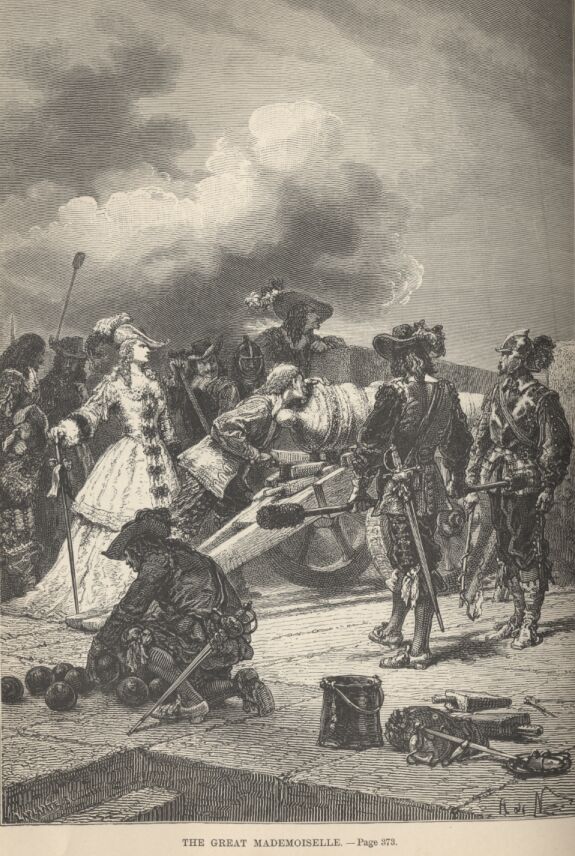

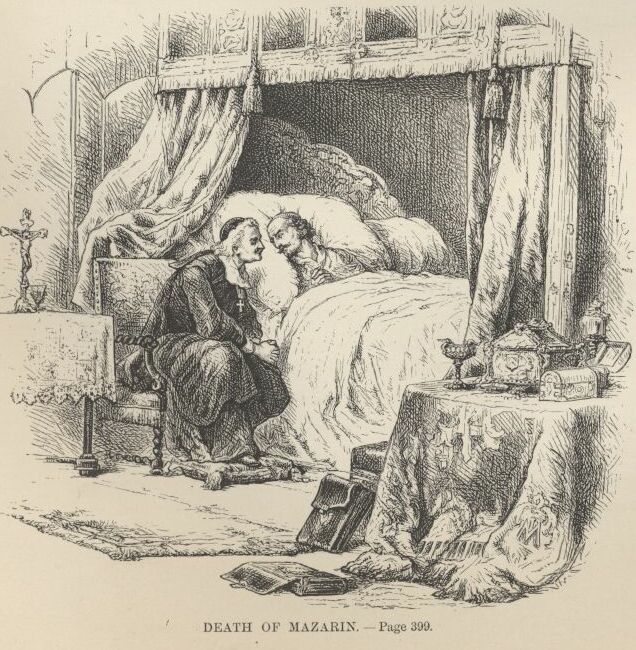

Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin——394

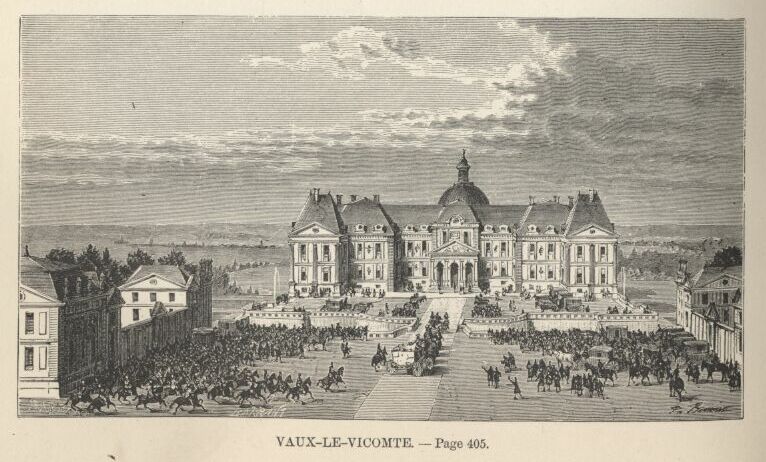

Louis XIV. Dismissing Fouquet——407

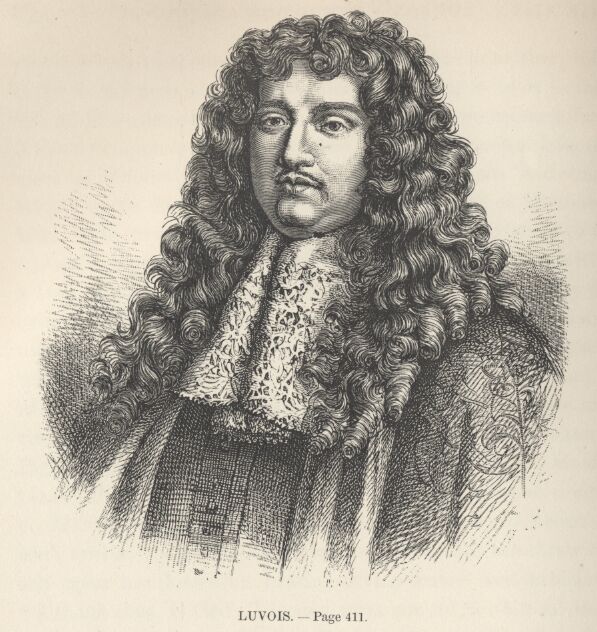

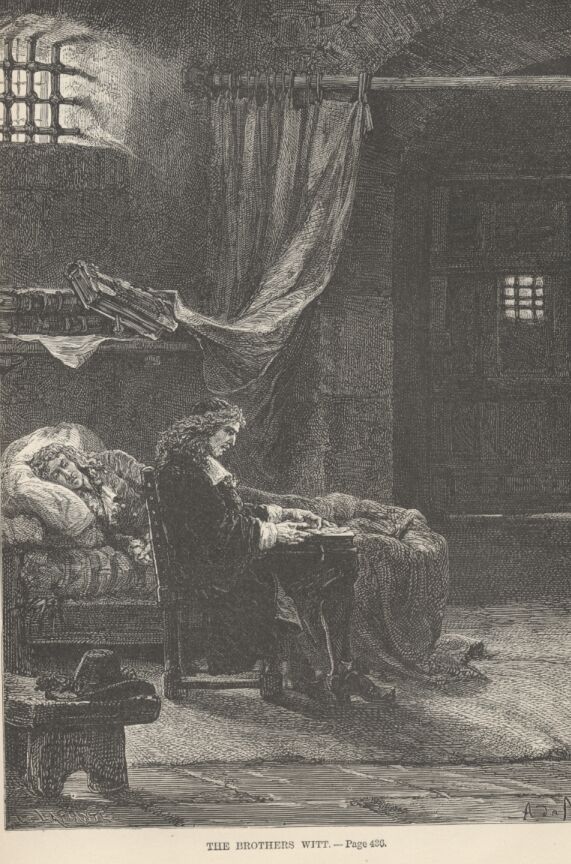

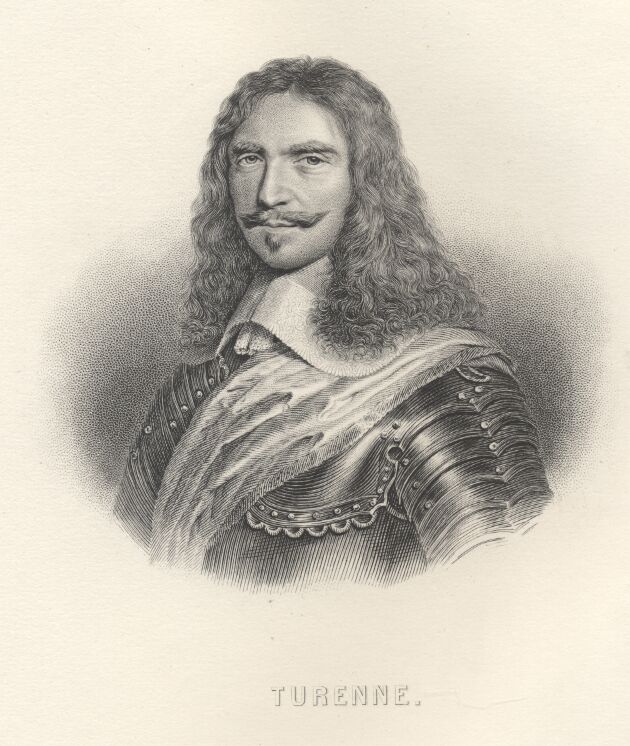

William III., Prince of Orange——434

An Exploit of John Bart’s——446

Duquesne Victorious over Ruyter—446a

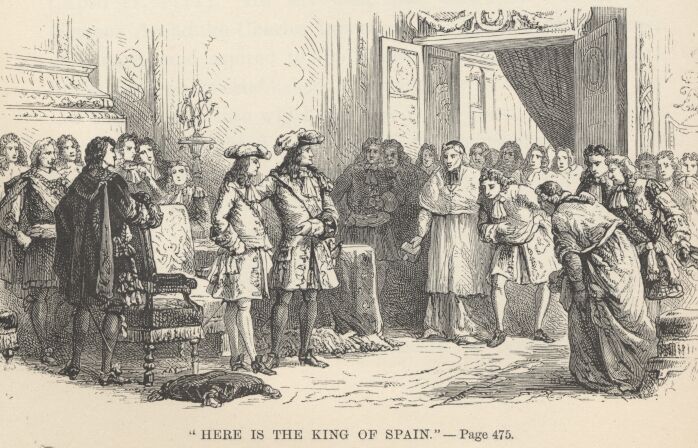

“Here is the King of Spain.”——475

Marshal Villars and Prince Eugene——512

The Torture of the Huguenots—552

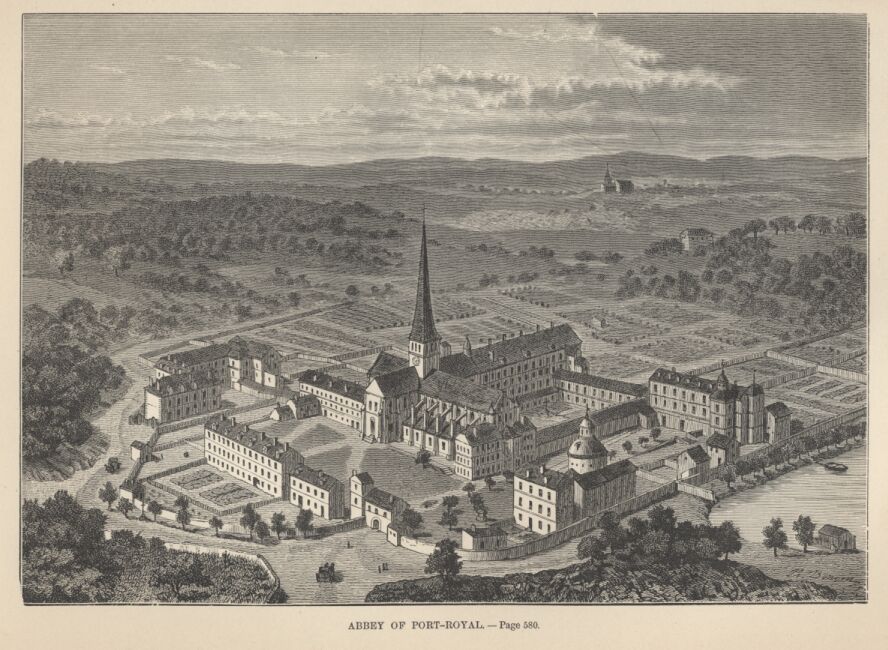

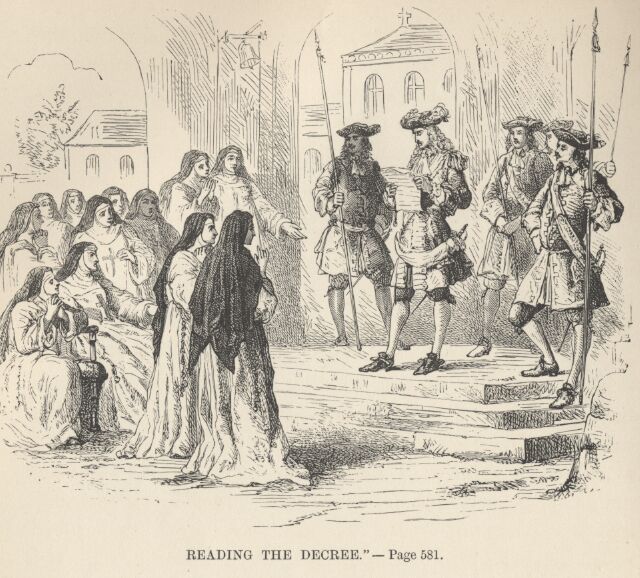

Revocation of the Edict Of Nantes——556

Death of Roland the Camisard——569

Fenelon and the Duke of Burgundy——610

La Rochefoucauld and his Fair Friends——629

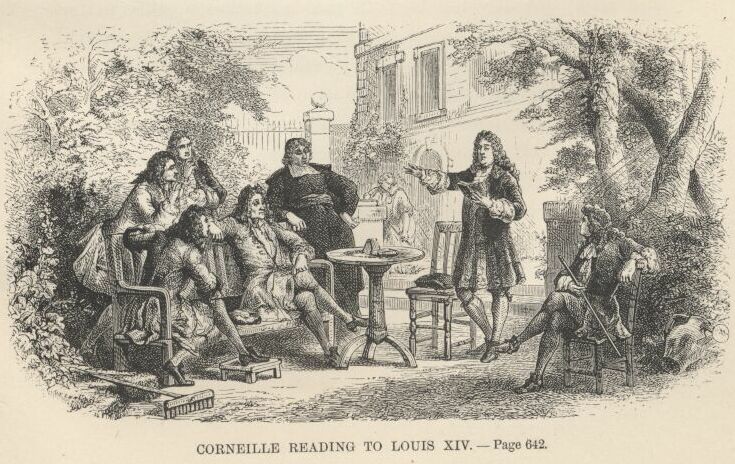

Corneille Reading to Louis XIV.——642

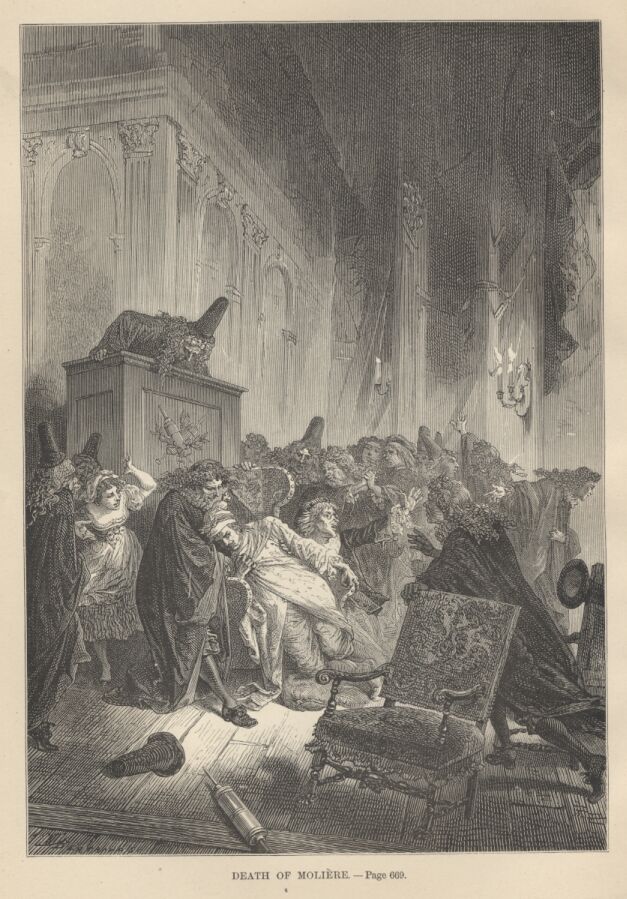

La Fontaine, Boileau, Moliere, and Racine——657

On the 2d of August, 1589, in the morning, upon his arrival in his quarters at Meudon, Henry of Navarre was saluted by the Protestants King of France. They were about five thousand in an army of forty thousand men. When, at ten o’clock, he entered the camp of the Catholics at St. Cloud, three of their principal leaders, Marshal d’Aumont, and Sires d’Humieres and de Givry, immediately acknowledged him unconditionally, as they had done the day before at the death-bed of Henry III., and they at once set to work to conciliate to him the noblesse of Champagne, Picardy, and Ile-de-France. “Sir,” said Givry, “you are the king of the brave; you will be deserted by none but dastards.” But the majority of the Catholic leaders received him with such expressions as, “Better die than endure a Huguenot king!” One of them, Francis d’O, formally declared to him that the time had come for him to choose between the insignificance of a King of Navarre and the grandeur of a King of France; if he pretended to the crown, he must first of all abjure. Henry firmly rejected these threatening entreaties, and left their camp with an urgent recommendation, to them to think of it well before bringing dissension into the royal army and the royal party which were protecting their privileges, their property, and their lives against the League. On returning to his quarters, he noticed the arrival of Marshal de Biron, who pressed him to lay hands without delay upon the crown of France, in order to guard it and save it. But, in the evening of that day and on the morrow, at the numerous meetings of the lords to deliberate upon the situation, the ardent Catholics renewed their demand for the exclusion of Henry from the throne if he did not at once abjure, and for referring the election of a king to the states-general. Biron himself proposed not to declare Henry king, but to recognize him merely as captain-general of the army pending his abjuration. Harlay de Sancy vigorously maintained the cause of the Salic law and the hereditary rights of monarchy. Biron took him aside and said, “I had hitherto thought that you had sense; now I doubt it. If, before securing our own position with the King of Navarre, we completely establish his, he will no longer care for us. The time is come for making our terms; if we let the occasion escape us, we shall never recover it.” “What are your terms?” asked Sancy. “If it please the king to give me the countship of Perigord, I shall be his forever.” Sancy reported this conversation to the king, who promised Biron what he wanted.

Though King of France for but two days past, Henry IV. had already perfectly understood and steadily taken the measure of the situation. He was in a great minority throughout the country as well as the army, and he would have to deal with public passions, worked by his foes for their own ends, and with the personal pretensions of his partisans. He made no mistake about these two facts, and he allowed them great weight; but he did not take for the ruling principle of his policy and for his first rule of conduct the plan of alternate concessions to the different parties and of continually humoring personal interests; he set his thoughts higher, upon the general and natural interests of France as he found her and saw her. They resolved themselves, in his eyes, into the following great points: maintenance of the hereditary rights of monarchy, preponderance of Catholics in the government, peace between Catholics and Protestants, and religious liberty for Protestants. With him these points became the law of his policy and his kingly duty, as well as the nation’s right. He proclaimed them in the first words that he addressed to the lords and principal personages of state assembled around him. “You all know,” said he, “what orders the late king my predecessor gave me, and what he enjoined upon me with his dying breath. It was chiefly to maintain my subjects, Catholic or Protestant, in equal freedom, until a council, canonical, general, or national, had decided this great dispute. I promised him to perform faithfully that which he bade me, and I regard it as one of my first duties to be as good as my word. I have heard that some who are in my army feel scruples about remaining in my service unless I embrace the Catholic religion. No doubt they think me weak enough for them to imagine that they can force me thereby to abjure my religion and break my word. I am very glad to inform them here, in presence of you all, that I would rather this were the last day of my life than take any step which might cause me to be suspected of having dreamt of renouncing the religion that I sucked in with my mother’s milk, before I have been better instructed by a lawful council, to whose authority I bow in advance. Let him who thinks so ill of me get him gone as soon as he pleases; I lay more store by a hundred good Frenchmen than by two hundred who could harbor sentiments so unworthy. Besides, though you should abandon me, I should have enough of friends left to enable me, without you and to your shame, with the sole assistance of their strong arms, to maintain the rights of my authority. But were I doomed to see myself deprived of even that assistance, still the God who has preserved me from my infancy, as if by His own hand, to sit upon the throne, will not abandon me. I nothing doubt that He will uphold me where He has placed me, not for love of me, but for the salvation of so many souls who pray, without ceasing, for His aid, and for whose freedom He has deigned to make use of my arm. You know that I am a Frenchman and the foe of all duplicity. For the seventeen years that I have been King of Navarre, I do not think that I have ever departed from my word. I beg you to address your prayers to the Lord on my behalf, that He may enlighten me in my views, direct my purposes, bless my endeavors. And in case I commit any fault or fail in any one of my duties,—for I acknowledge that I am a man like any other,—pray Him to give me grace that I may correct it, and to assist me in all my goings.”

On the 4th of August, 1589, an official manifesto of Henry IV.‘s confirmed the ideas and words of this address. On the same day, in the camp at St. Cloud, the majority of the princes, dukes, lords, and gentlemen present in the camp expressed their full adhesion to the accession and the manifesto of the king, promising him “service and obedience against rebels and enemies who would usurp the kingdom.” Two notable leaders, the Duke of Epernon amongst the Catholics, and the Duke of La Tremoille amongst the Protestants, refused to join in this adhesion; the former saying that his conscience would not permit him to serve a heretic king, the latter alleging that his conscience forbade him to serve a prince who engaged to protect Catholic idolatry. They withdrew, D’Epernon into Angoumois and Saintonge, taking with him six thousand foot and twelve thousand horse; and La Tremoille into Poitou, with nine battalions of Reformers. They had an idea of attempting, both of them, to set up for themselves independent principalities. Three contemporaries, Sully, La Force, and the bastard of Angouleme, bear witness that Henry IV. was deserted by as many Huguenots as Catholics. The French royal army was reduced, it is said, to one half. As a make-weight, Saucy prevailed upon the Swiss, to the number of twelve thousand, and two thousand German auxiliaries, not only to continue in the service of the new king, but to wait six months for their pay, as he was at the moment unable to pay them. From the 14th to the 20th of August, in Ile-de-France, in Picardy, in Normandy, in Auvergne, in Champagne, in Burgundy, in Anjou, in Poitou, in Languedoc, in Orleanness, and in Touraine, a great number of towns and districts joined in the determination of the royal army. The last instance of such adherence had a special importance. At the time of Henry III.‘s rupture with the League, the Parliament of Paris had been split in two; the royalists had followed the king to Tours, the partisans of the League had remained at Paris. After the accession of Henry IV., the Parliament of Tours, with the president, Achille de Harlay, as its head, increased from day to day, and soon reached two hundred members, whilst the Parliament of Paris, or Brisson Parliament, as it was called from its leader’s name, had only sixty-eight left. Brisson, on undertaking the post, actually thought it right to take the precaution of protesting privately, making a declaration in the presence of notaries “that he so acted by constraint only, and that he shrank from any rebellion against his king and sovereign lord.” It was, indeed, on the ground of the heredity of the monarchy and by virtue of his own proper rights that Henry IV. had ascended the throne; and M. Poirson says quite correctly, in his learned Histoire du Regne d’Henri IV. [t. i. p. 29, second edition, 1862], “The manifesto of Henry IV., as its very name indicates, was not a contract settled between the noblesse in camp at St. Cloud and the claimant; it was a solemn and reciprocal acknowledgment by the noblesse of Henry’s rights to the crown, and by Henry of the nation’s political, civil, and religious rights. The engagements entered into by Henry were only what were necessary to complete the guarantees given for the security of the rights of Catholics. As touching the succession to the throne, the signataries themselves say that all they do is to maintain and continue the law of the land.”

There was, in 1589, an unlawful pretender to the throne of France; and that was Cardinal Charles de Bourbon, younger brother of Anthony de Bourbon, King of Navarre, and consequently uncle of Henry IV., sole representative of the elder branch. Under Henry III., the cardinal had thrown in his lot with the League; and, after the murder of Guise, Henry III. had, by way of precaution, ordered him to be arrested and detained him in confinement at Chinon, where he still was when Henry III. was in his turn murdered. On becoming king, the far-sighted Henry IV. at once bethought him of his uncle and of what he might be able to do against him. The cardinal was at Chinon, in the custody of Sieur de Chavigny, “a man of proved fidelity,” says De Thou, “but by this time old and blind.” Henry IV. wrote to Du Plessis-Mornay, appointed quite recently governor of Saumur, “bidding him, at any price,” says Madame de Mornay, “to get Cardinal de Bourbon away from Chinon, where he was, without sparing anything, even to the whole of his property, because he would incontinently set himself up for king if he could obtain his release.” Henry IV. was right. As early as the 7th of August, the Duke of Mayenne had an announcement made to the Parliament of Paris, and written notice sent to all the provincial governors, “that, in the interval until the states-general could be assembled, he urged them all to unite with him in rendering with one accord to their Catholic king, that is to say, Cardinal de Bourbon, the obedience that was due to him.” The cardinal was, in fact, proclaimed king under the name of Charles X.; and eight months afterwards, on the 5th of March, 1590, the Parliament of Paris issued a decree “recognizing Charles X. as true and lawful king of France.” Du Plessis-Mornay, ill though he was, had understood and executed, without loss of time, the orders of King Henry, going bail himself for the promises that had to be made and for the sums that had to be paid to get the cardinal away from the governor of Chinon. He succeeded, and had the cardinal removed to Fontenay-le-Comte in Poitou, “under the custody of Sieur de la Boulaye, governor of that place, whose valor and fidelity were known to him.” “That,” said Henry IV. on receiving the news, “is one of the greatest services I could have had rendered me; M. du Plessis does business most thoroughly.” On the 9th of May, 1590, not three months after the decree of the Parliament of Paris which had proclaimed him true and lawful King of France, Cardinal de Bourbon, still a prisoner, died at Fontenay, aged sixty-seven. A few weeks before his death he had written to his nephew Henry IV. a letter in which he recognized him as his sovereign.

The League was more than ever dominant in Paris; Henry IV. could not think of entering there. Before recommencing the war in his own name, he made Villeroi, who, after the death of Henry III., had rejoined the Duke of Mayenne, an offer of an interview in the Bois de Boulogne to see if there were no means of treating for peace. Mayenne would not allow Villeroi to accept the offer. “He had no private quarrel,” he said, “with the King of Navarre, whom he highly honored, and who, to his certain knowledge, had not looked with approval upon his brothers’ death; but any appearance of negotiation would cause great distrust amongst their party, and they would not do anything that tended against the rights of King Charles X.” Renouncing all idea of negotiation, Henry IV. set out on the 8th of August from St. Cloud, after having told off his army in three divisions. Two were ordered to go and occupy Picardy and Champagne; and the king kept with him only the third, about six thousand strong. He went and laid the body of Henry III. in the church of St. Corneille at Compiegne, took Meulan and several small towns on the banks of the Seine and Oise, and propounded for discussion with his officers the question of deciding in which direction he should move, towards the Loire or the Seine, on Tours or on Rouen. He determined in favor of Normandy; he must be master of the ports in that province in order to receive there the re-enforcements which had been promised him by Queen Elizabeth of England, and which she did send him in September, 1589, forming a corps of from four to five thousand men, Scots and English, “aboard of thirteen vessels laden with twenty-two thousand pounds sterling in gold and seventy thousand pounds of gunpowder, three thousand cannon-balls, and corn, biscuits, wine, and beer, together with woolens and even shoes.” They arrived very opportunely for the close of the campaign, but too late to share in Henry IV.‘s first victory, that series of fights around the castle of Arques which, in the words of an eye-witness, the Duke of Angouleme, “was the first gate whereby Henry entered upon the road of his glory and good fortune.”

After making a demonstration close to Rouen, Henry IV., learning that the Duke of Mayenne was advancing in pursuit of him with an army of twenty-five thousand foot and eight thousand horse, thought it imprudent to wait for him and run the risk of being jammed between forces so considerable and the hostile population of a large city; so he struck his camp and took the road to Dieppe, in order to be near the coast and the re-enforcements from Queen Elizabeth. Some persons even suggested to him that in case of mishap he might go thence and take refuge in England; but at this prospect Biron answered, “There is no King of France out of France;” and Henry IV. was of Biron’s opinion. At his arrival before Dieppe, he found as governor there Aymar de Chastes, a man of wits and honor, a very moderate Catholic, and very strongly in favor of the party of policists. Under Henry III. he had expressly refused to enter the League, saying to Villars, who pressed him to do so, “I am a Frenchman, and you yourself will find out that the Spaniard is the real head of the League.” He had organized at Dieppe four companies of burgess-guards, consisting of Catholics and Protestants, and he assembled about him, to consider the affairs of the town, a small council, in which Protestants had the majority. As soon as he knew, on the 26th of August, that the king was approaching Dieppe, he went with the principal inhabitants to meet him, and presented to him the keys of the place, saying, “I come to salute my lord and hand over to him the government of this city.” “Ventre-saint-gris!” answered Henry IV., “I know nobody more worthy of it than you are!” The Dieppese overflowed with felicitations. “No fuss, my lads,” said Henry: “all I want is your affections, good bread, good wine, and good hospitable faces.” When he entered the town, “he was received,” says a contemporary chronicler, “with loud cheers by the people; and what was curious, but exhilarating, was to see the king surrounded by close upon six thousand armed men, himself having but a few officers at his left hand.” He received at Dieppe assurance of the fidelity of La Verune, governor of Caen, whither, in 1589, according to Henry III.‘s order, that portion of the Parliament of Normandy which would not submit to the yoke of the League at Rouen, had removed. Caen having set the example, St. Lo, Coutances, and Carentan likewise sent deputies to Dieppe to recognize the authority of Henry IV. But Henry had no idea of shutting himself up inside Dieppe: after having carefully inspected the castle, citadel, harbor, fortifications, and outskirts of the town, he left there five hundred men in garrison, supported by twelve or fifteen hundred well-armed burgesses, and went and established himself personally in the old castle of Arques, standing, since the eleventh century, upon a barren hill; below, in the burgh of Arques, he sent Biron into cantonments with his regiment of Swiss and the companies of French infantry; and he lost no time in having large fosses dug ahead of the burgh, in front of all the approaches, enclosing within an extensive line of circumvallation both burgh and castle. All the king’s soldiers and the peasants that could be picked up in the environs worked night and day. Whilst they were at work, Henry wrote to Countess Corisande de Gramont, his favorite at that time, “My dear heart, it is a wonder I am alive with such work as I have. God have pity upon me and show me mercy, blessing my labors, as He does in spite of a many folks! I am well, and my affairs are going well. I have taken Eu. The enemy, who are double me just now, thought to catch me there; but I drew off towards Dieppe, and I await them in a camp that I am fortifying. Tomorrow will be the day when I shall see them, and I hope, with God’s help, that if they attack me they will find they have made a bad bargain. The bearer of this goes by sea. The wind and my duties make me conclude. This 9th of September, in the trenches at Arques.”

All was finished when the scouts of Mayenne appeared. But Mayenne also was an able soldier: he saw that the position the king had taken and the works he had caused to be thrown up rendered a direct attack very difficult. He found means of bearing down upon Dieppe another way, and of placing himself, says the latest historian of Dieppe, M. Vitet, between the king and the town, “hoping to cut off the king’s communications with the sea, divide his forces, deprive him of his re-enforcements from England, and, finally, surround him and capture him,” as he had promised the Leaguers of Paris, who were already talking of the iron cage in which the Bearnese would be sent to them. “Henry IV.,” continues M. Vitet, “felt some vexation at seeing his forecasts checkmated by Mayenne’s manoeuvre, and at having had so much earth removed to so little profit; but he was a man of resources, confident as the Gascons are, and with very little of pig-headedness. To change all his plans was with him the work of an instant. Instead of awaiting the foe in his intrenchments, he saw that it was for him to go and feel for them on the other side of the valley, and that, on pain of being invested, he must not leave the Leaguers any exit but the very road they had taken to come.” Having changed all his plans on this new system, Henry breathed more freely; but he did not go to sleep for all that: he was incessantly backwards and forwards from Dieppe to Arques, from Arques to Dieppe and to the Faubourg du Pollet. Mayenne, on the contrary, seemed to have fallen into a lethargy; he had not yet been out of his quarters during the nearly eight and forty hours since he had taken them. On the 17th of September, 1589, in the morning, however, a few hundred light-horse were seen putting themselves in motion, scouring the country and coming to fire their pistols close to the fosses of the royal army. The skirmish grew warm by degrees. “My son,” said Marshal de Biron to the young count of Auvergne [natural son of Charles IX. and Mary Touchet], “charge: now is the time.” The young prince, without his hat, and his horsemen charged so vigorously that they put the Leaguers to the rout, killed three hundred of them, and returned quietly within their lines, by Biron’s orders, without being disturbed in their retreat. These partial and irregular encounters began again on the 18th and 19th of September, with the same result. The Duke of Mayenne was nettled and humiliated; he had his prestige to recover. He decided to concentrate all his forces right on the king’s intrenchments, and attack them in front with his whole army. The 20th of September passed without a single skirmish. Henry, having received good information that he would be attacked the next day, did not go to bed. The night was very dark. He thought he saw a long way off in the valley a long line of lighted matches; but there was profound silence; and the king and his officers puzzled themselves to decide if they were men or glow-worms. On the 21st, at five A. M., the king gave orders for every one to be ready and at his post. He himself repaired to the battle-field. Sitting in a big fosse with all his officers, he had his breakfast brought thither, and was eating with good appetite, when a prisoner was brought to him, a gentleman of the League, who had advanced too far whilst making a reconnaissance. “Good day, Belin,” said the king, who recognized him, laughing: “embrace me for your welcome appearance.” Belin embraced him, telling him that he was about to have down upon him thirty thousand foot and ten thousand horse. “Where are your forces?” he asked the king, looking about him. “O! you don’t see them all, M. de Belin,” said Henry: “you don’t reckon the good God and the good right, but they are ever with me.”

The action began about ten o’clock. The fog was still so thick that there was no seeing one another at ten paces. The ardor on both sides was extreme; and, during nearly three hours, victory seemed to twice shift her colors. Henry at one time found himself entangled amongst some squadrons so disorganized that he shouted, “Courage, gentlemen; pray, courage! Can’t we find fifty gentlemen willing to die with their king?” At this moment Chatillon, issuing from Dieppe with five hundred picked men, arrived on the field of battle. The king dismounted to fight at his side in the trenches; and then, for a quarter of an hour, there was a furious combat, man to man. At last, “when things were in this desperate state,” says Sully, “the fog, which had been very thick all the morning, dropped down suddenly, and the cannon of the castle of Arques getting sight of the enemy’s army, a volley of four pieces was fired, which made four beautiful lanes in their squadrons and battalions. That pulled them up quite short; and three or four volleys in succession, which produced marvellous effects, made them waver, and, little by little, retire all of them behind the turn of the valley, out of cannon-shot, and finally to their quarters.” Mayenne had the retreat sounded. Henry, master of the field, gave chase for a while to the fugitives, and then returned to Arques to thank God for his victory. Mayenne struck his camp and took the road towards Amiens, to pick up a Spanish corps which he was expecting from the Low Countries.

For six months, from September, 1589, to March, 1590, the war continued without any striking or important events. Henry IV. tried to stop it after his success at Arques; he sent word to the Duke of Mayenne by his prisoner Belin, whom he had sent away free on parole, “that he desired peace, and so earnestly, that, without regarding his dignity or his victory, he made him these advances, not that he had any fear of him, but because of the pity he felt for his kingdom’s sufferings.” Mayenne, who lay beneath the double yoke of his party’s passions and his own ambitious projects, rejected the king’s overtures, or allowed them to fall through; and on the 21st of October, 1589, Henry, setting out with his army from Dieppe, moved rapidly on Paris, in order to effect a strategic surprise, whilst Mayenne was rejecting at Amiens his pacific inclinations. The king gained three marches on the Leaguers, and carried by assault the five faubourgs situated on the left bank of the Seine. He would perhaps have carried terror-stricken Paris itself, if the imperfect breaking up of the St. Maixent bridge on the Somme had not allowed Mayenne, notwithstanding his tardiness, to arrive at Paris in time to enter with his army, form a junction with the Leaguers amongst the population, and prevail upon the king to carry his arms elsewhither. “The people of Paris,” says De Thou, “were extravagant enough to suppose that this prince could not escape Mayenne. Already a host of idle and credulous women had been at the pains of engaging windows, which they let very dear, and which they had fitted up magnificently, to see the passage of that fanciful triumph for which their mad hopes had caused them to make every preparation—before the victory.” Henry left some of his lieutenants to carry on the war in the environs of Paris, and himself repaired, on the 21st of November, to Tours, where the royalist Parliament, the exchequer-chamber, the court of taxation, and all the magisterial bodies which had not felt inclined to submit to the despotism of the League, lost no time in rendering him homage, as the head and the representative of the national and the lawful cause. He reigned and ruled, to real purpose, in the eight principal provinces of the North and Centre—Ile-de-France, Picardy, Champagne, Normandy, Orleanness, Touraine, Maine, and Anjou; and his authority, although disputed, was making way in nearly all the other parts of the kingdom. He made war not like a conqueror, but like a king who wanted to meet with acceptance in the places which he occupied and which he would soon have to govern. The inhabitants of Le Mans and of Alencon were able to reopen their shops on the very day on which their town fell into his hands, and those of Vendome the day after. He watched to see that respect was paid by his soldiers, even the Huguenots, to Catholic churches and ceremonies. Two soldiers, having made their way into Le Mans, contrary to orders, after the capitulation, and having stolen a chalice, were hanged on the spot, though they were men of acknowledged bravery. He protected carefully the bishops and all the ecclesiastics who kept aloof from political strife. “If minute details are required,” says a contemporary pamphleteer, “out of a hundred or a hundred and twenty archbishops or bishops existing in the realm of France not a tenth part approve of the counsels of the League.” It was not long before Henry reaped the financial fruits of his protective equity; at the close of 1589 he could count upon a regular revenue of more than two millions of crowns, very insufficient, no doubt, for the wants of his government, but much beyond the official resources of his enemies. He had very soon taken his proper rank in Europe: the Protestant powers which had been eager to recognize him—England, Scotland, the Low Countries, the Scandinavian states, and Reformed Germany—had been joined by the republic of Venice, the most judiciously governed state at that time in Europe, but solely on the ground of political interests and views, independently of any religious question. On the accession of Henry IV., his ambassador, Hurault de Maisse, was received and very well treated at Venice; he was merely excluded from religious ceremonies: the Venetian people joined in the policy of their government; the portrait of the new King of France was everywhere displayed and purchased throughout Venice. Some Venetians went so far as to take service in his army against the League. The Holy Inquisition commenced proceedings against them for heresy; the government stopped the proceedings, and even, says Count Daru, had the Inquisitor thrown into prison. The Venetian senate accredited to the court of Henry IV. the same ambassador who had been at Henry III.‘s; and, on returning to Tours, on the 21st of November, 1589, the king received him to an audience in state. A little later on he did more; he sent the republic, as a pledge of his friendship, his sword—the sword, he said in his letter, which he had used at the battle of Ivry. “The good offices were mutual,” adds M. de Daru; “the Venetians lent Henry IV. sums of money which the badness of the times rendered necessary to him; but their ambassador had orders to throw into the fire, in the king’s presence, the securities for the loan.”

As the government of Henry IV. went on growing in strength and extent, two facts, both of them natural, though antagonistic, were being accomplished in France and in Europe. The moderate Catholics were beginning, not as yet to make approaches towards him, but to see a glimmering possibility of treating with him and obtaining from him such concessions as they considered necessary at the same time that they in their turn made to him such as he might consider sufficient for his party and himself. It has already been remarked with what sagacity Pope Sixtus V. had divined the character of Henry IV., at the very moment of condemning Henry III. for making an alliance with him. When Henry IV. had become king, Sixtus V. pronounced strongly against a heretic king, and maintained, in opposition to him, his alliance with Philip II. and the League. “France,” said he, “is a good and noble kingdom, which has infinity of benefices and is specially dear to us; and so we try to save her; but religion sits nearer than France to our heart.” He chose for his legate in France Cardinal Gaetani, whom he knew to be agreeable to Philip II. and gave him instructions in harmony with the Spanish policy. Having started for his post, Gaetani was a long while on the road, halting at Lyons, amongst other places, as if he were in no hurry to enter upon his duties. At the close of 1589, Henry IV., king for the last five months and already victorious at Arques, appointed as his ambassador at Rome Francis de Luxembourg, Duke of Pinei, to try and enter into official relations with the pope. On the 6th of January, 1590, Sixtus V., at his reception of the cardinals, announced to them this news. Badoero, ambassador of Venice at Rome, leaned forward and whispered in his ear, “We must pray God to inspire the King of Navarre. On the day when your Holiness embraces him, and then only, the affairs of France will be adjusted. Humanly speaking, there is no other way of bringing peace to that kingdom.” The pope confined himself to replying that God would do all for the best, and that, for his own part, he would wait. On arriving at Rome, “the Duke of Luxembourg repaired to the Vatican with two and twenty carriages occupied by French gentlemen; but, at the palace, he found the door of the pope’s apartments closed, the sentries doubled, and the officers on duty under orders to intimate to the French, the chief of the embassy excepted, that they must lay aside their swords. At the door of the Holy Father’s closet, the duke and three gentlemen of his train were alone allowed to enter. The indignation felt by the French was mingled with apprehensions of an ambush. Luxembourg himself could not banish a feeling of vague terror; great was his astonishment when, on his introduction to the pontiff, the latter received him with demonstrations of affection, asked him news of his journey, said he would have liked to give him quarters in the palace, made him sit down,—a distinction reserved for the ambassadors of kings, —and, lastly, listened patiently to the French envoy’s long recital. In fact, the receptions intra et, extra muros bore very little resemblance one to the other, but the difference between them corresponded pretty faithfully with the position of Sixtus V., half engaged to the League by Gaetani’s commission and to Philip II. by the steps he had recently taken, and already regretting that he was so far gone in the direction of Spain.” [Sixtus V, by Baron Hubner, late ambassador of Austria at Paris and at Rome, t. ii. pp. 280-282.]

Unhappily Sixtus V. died on the 27th of August, 1590, before having modified, to any real purpose, his bearing towards the King of France and his instructions to his legate. After Pope Urban VIII.‘s apparition of thirteen days’ duration, Gregory XIV. was elected pope on the 5th of December, 1590; and, instead of a head of the church able enough and courageous enough to comprehend and practise a policy European and Italian as well as Catholic in its scope, there was a pope humbly devoted to the Spanish policy, meekly subservient to Philip II.; that is, to the cause of religious persecution and of absolute power, without regard for anything else. The relations of France with the Holy See at once felt the effects of this; Cardinal Gaetani received from Rome all the instructions that the most ardent Leaguers could desire; and he gave his approval to a resolution of the Sorbonne to the effect that Henry de Bourbon, heretic and relapsed, was forever excluded from the crown, whether he became a Catholic or not. Henry IV., had convoked the states-general at Tours for the month of March, and had summoned to that city the archbishops and bishops to form a national council, and to deliberate as to the means of restoring the king to the bosom of the Catholic church. The legate prohibited this council, declaring, beforehand, the excommunication and deposition of any bishops who should be present at it. The Leaguer Parliament of Paris forbade, on pain of death and confiscation, any connection, any correspondence, with Henry de Bourbon and his partisans. A solemn procession of the League took place at Paris, on the 14th of March, and a few days afterwards the union was sworn afresh by all the municipal chiefs of the population. In view of such passionate hostility, Henry IV., a stranger to any sort of illusion at the same time that he was always full of hope, saw that his successes at Arques were insufficient for him, and that, if he were to occupy the throne in peace, he must win more victories. He recommenced the campaign by the siege of Dreux, one of the towns which it was most important for him to possess in order to put pressure on Paris, and cause her to feel, even at a distance, the perils and evils of war.

On Wednesday, the 14th of March, 1590, was fought the battle of Ivry, a village six leagues from Evreux, on the left bank of the Eure. “Starting from Dreux on the 12th of March” [Poirson, Histoire du Regne d’Henri IV., t. i. p. 180], “the royal army had arrived the same day at Nonancourt, marching with the greatest regularity by divisions and always in close order, through fearful weather, frost having succeeding rain; moreover, it traversed a portion of the road during the shades of evening. The soldier was harassed and knocked up. But scarcely had he arrived at his destination for the day, when he found large fires lighted everywhere, and provisions in abundance, served out with intelligent regularity to the various quarters of cavalry and infantry. He soon recovered all his strength and daring.” The king, in concert with the veteran Marshal de Biron, had taken these prudent measures. All the historians, contemporary and posterior, have described in great detail the battle of Ivry, the manoeuvres and alternations of success that distinguished it; by rare good fortune, we have an account of the affair written the very same evening in the camp at Rosny by Henry IV. himself, and at once sent off to some of his principal partisans who were absent, amongst others to M. de la Verune, governor of Caen. We will content ourselves here with the king’s own words, striking in their precision, brevity, and freedom from any self-complacent gasconading on the narrator’s part, respecting either his party or himself.

LETTER OF KING HENRY IV. TOUCHING THE BATTLE OF IVRY.

“It hath pleased God to grant me that which I had the most desired, to have means of giving battle to mine enemies; having firm confidence that, having got so far, God would give me grace to obtain the victory, as it hath happened this very day. You have heretofore heard how that, after the capture of the town of Honfleur, I went and made them raise the siege they were laying to the town of Meulan, and I offered them battle, which it seemed that they ought to accept, having in numbers twice the strength that I could muster. But in the hope of being able to do so with more safety, they made up their minds to put it off until they had been joined by fifteen hundred lances which the Duke of Parma was sending them; which was done a few days ago. And then they spread abroad everywhere that they would force me to fight, wheresoever I might be; they thought to have found a very favorable opportunity in coming to encounter me at the siege I was laying before the town of Dreux; but I did not give them the trouble of coming so far; for, as soon as I was advertised that they had crossed the river of Seine and were heading towards me, I resolved to put off the siege rather than fail to go and meet them. Having learned that they were six leagues from the said Dreux, I set out last Monday, the 12th of this month, and went and took up my quarters at the town of Nonancourt, which was three leagues from them, for to cross the river there. On Tuesday, I went and took the quarters which they meant to have for themselves, and where their quarter-masters had already arrived. I put myself in order of battle, in the morning, on a very fine plain, about a league from the point which they had chosen the day before, and where they immediately appeared with their whole army, but so far from me that I should have given them a great advantage by going so forward to seek them; I contented myself with making them quit a village they had seized close by me; at last, night constrained us both to get into quarters, which I did in the nearest villages.

“To-day, having had their position reconnoitered betimes, and after it had been reported to me that they had shown themselves, but even farther off than they had done yesterday, I resolved to approach so near to them that there must needs be a collision. And so it happened between ten and eleven in the morning; I went to seek them to the very spot where they were posted, and whence they never advanced a step but what they made to the charge; and the battle took place, wherein God was pleased to make known that His protection is always on the side of the right; for in less than an hour, after having spent all their choler in two or three charges which they made and supported, all their cavalry began to take its departure, leaving their infantry, which was in large numbers. Seeing which, their Swiss had recourse to my compassion, and surrendered, colonels, captains, privates, and all their flags. The lanzknechts and French had no time to take this resolution, for they were cut to pieces, twelve hundred of one and as many of the other; the rest prisoners and put to the rout in the woods, at the mercy of the peasants. Of their cavalry there are from nine hundred to a thousand killed, and from four to five hundred dismounted and prisoners; without counting those drowned in crossing the River Eure, which they crossed to Ivry for to put it between them and us, and who are a great number. The rest of the better mounted saved themselves by flight, in very great disorder, having lost all their baggage. I did not let them be until they were close to Mantes. Their white standard is in my hands, and its bearer a prisoner; twelve or fifteen other standards of their cavalry, twice as many more of their infantry, all their artillery; countless lords prisoners, and of dead a great number, even of those in command, whom I have not yet been able to find time to get identified. But I know that amongst others Count Egmont, who was general of all the forces that came from Flanders, was killed. Their prisoners all say that their army was about four thousand horse, and from twelve to thirteen thousand foot, of which I suppose not a quarter has escaped. As for mine, it may have been two thousand horse and eight thousand foot. But of this cavalry, more than six hundred horse joined me after I was in order of battle, on the Tuesday and Wednesday; nay, the last troop of the noblesse from Picardy, brought up by Sire d’Humieres, and numbering three hundred horse, came up when half an hour had already passed since the battle began.

“It is a miraculous work of God’s, who was pleased, first of all, to give me the resolution to attack them, and then the grace to be able so successfully to accomplish it. Wherefore to Him alone is the glory; and so far as any of it may, by His permission, belong to man, it is due to the princes, officers of the crown, lords, captains, and all the noblesse, who with so much ardor rushed forward, and so successfully exerted themselves, that their predecessors did not leave them more beautiful examples than they will leave to their posterity. As I am greatly content and satisfied with them, so I think that they are with me, and that they have seen that I had no mind to make use of them anywhere without I had also shown them the way. I am still following up the victory with my cousins the princes of Conti, Duke of Montpensier, Count of St. Paul, Marshal-duke of Aumont, grand prior of France, La Tremoille, Sieurs de la Guiche and de Givry, and several other lords and captains. My cousin Marshal de Biron remains with the main army awaiting my tidings, which will go on, I hope, still prospering. You shall hear more fully in my next despatch, which shall follow this very closely, the particulars of this victory, whereof I desired to give you these few words of information, so as not to keep you longer out of the pleasure which I know that you will receive therefrom. I pray you to impart it to all my other good servants yonder, and, especially, to have thanks given therefor to God, whom I pray to have you in His holy keeping.

“HENRY.

“From the camp at Rosny, this 14th day of March, 1590.”

History is not bound to be so reserved and so modest as the king was about himself. It was not only as able captain and valiant soldier that Henry IV. distinguished himself at Ivry; there the man was as conspicuous for the strength of his better feelings, as generous and as affectionate as the king was farsighted and bold. When the word was given to march from Dreux, Count Schomberg, colonel of the German auxiliaries called reiters, had asked for the pay of his troops, letting it be understood that they would not fight if their claims were not satisfied. Henry had replied harshly, “People don’t ask for money on the eve of a battle.” At Ivry, just as the battle was on the point of beginning, he went up to Schomberg. “Colonel,” said he, “I hurt your feelings. This may be the last day of my life. I can’t bear to take away the honor of a brave and honest gentleman like you. Pray forgive me and embrace me.” “Sir,” answered Schomberg, “the other day your Majesty wounded me, to-day you kill me.” He gave up the command of the reiters in order to fight in the king’s own squadron, and was killed in action. As he passed along the front of his own squadron, Henry halted; and, “Comrades,” said he, “if you run my risks, I also run yours. I will conquer or die with you. Keep your ranks well, I beg. If the heat of battle disperse you for a while, rally as soon as you can under those three pear trees you see up yonder to my right; and if you lose your standards, do not lose sight of my white plume; you will always find it in the path of honor, and, I hope, of victory too.”

Having galloped along the whole line of his army, he halted again, threw his horse’s reins over his arm, and clasped his hands, exclaiming, “O God, Thou knowest my thoughts, and Thou dost see to the very bottom of my heart; if it be for my people’s good that I keep the crown, favor Thou my cause and uphold my arms. But if Thy holy will have otherwise ordained, at least let me die, O God, in the midst of these brave soldiers who give their lives for me!” When the battle was over and won, he heard that Rosny had been severely wounded in it; and when he was removed to Rosny Castle, the king, going close up to his stretcher, said, “My friend, I am very glad to see you with a much better countenance than I expected; I should feel still greater joy if you assure me that you run no risk of your life or of being disabled forever; the rumor was, that you had two horses killed under you; that you had been borne to earth, rolled over and trampled upon by the horses of several squadrons, bruised and cut up by so many blows that it would be a marvel if you escaped, or if, at the very least, you were not mutilated for life in some limb. I should like to hug you with both arms. I shall never have any good fortune or increase of greatness but you shall share it. Fearing that too much talking may be harmful to your wounds, I am off again to Mantes. Adieu, my friend; fare you well, and be assured that you have a good master.”

Henry IV. had not only a warm but an expansive heart; he could not help expressing and pouring forth his feelings. That was one of his charms, and also one of his sources of power.

The victory of Ivry had a great effect in France and in Europe. But not immediately and as regarded the actual campaign of 1590. The victorious king moved on Paris, and made himself master of the little towns in the neighborhood with a view of investing the capital. When he took possession of St. Denis [on the 9th of July, 1590], he had the relics and all the jewelry of the church shown to him. When he saw the royal crown, from which the principal stones had been detached, he asked what had become of them. He was told that M. de Mayenne had caused them to-be removed. “He has the stones, then,” said the king; “and I have the soil.” He visited the royal tombs, and when he was shown that of Catherine de’ Medici, “Ah!” said he smiling, “how well it suits her!” And, as he stood before Henry III.‘s he said, “Ventre-saint-gris! There is my good brother; I desire that I be laid beside him.” As he thus went on visiting and establishing all his posts around Paris, the investment became more strict; it was kept up for more than three months, from the end of May to the beginning of September, 1590; and the city was reduced to a severe state of famine, which would have been still more severe if Henry IV. had not several times over permitted the entry of some convoys of provisions and the exit of the old men, the women, the children, in fact, the poorest and weakest part of the population. “Paris must not be a cemetery,” he said; “I do not wish to reign over the dead.” “A true king,” says De Thou, “more anxious for the preservation of his kingdom than greedy of conquest, and making no distinction between his own interests and the interests of his people.” Two famous Protestants, Ambrose Pare and Bernard Palissy, preserved, one by his surgical and the other by his artistic genius, from the popular fury, were still living at that time in Paris, both eighty years of age, and both pleading for the liberty of their creed and for peace. “Monseigneur,” said Ambrose Pare one day to the Archbishop of Lyons, whom he met at one end of the bridge of St. Michael, “this poor people that you see here around you is dying of sheer hunger-madness, and demands your compassion. For God’s sake show them some, as you would have God’s shown to you. Think a little on the office to which God hath called you. Give us peace or give us wherewithal to live, for the poor folks can hold out no more.” The Italian Danigarola himself, Bishop of Asti and attache to the embassy of Cardinal Gaetani, having publicly said that peace was necessary, was threatened by the Sixteen with being sewn up in a sack and thrown into the river if he did not alter his tone. Not peace, but a cessation of the investment of Paris, was brought about, on the 23d of August, 1590, by Duke Alexander of Parma, who, in accordance with express orders from Philip II., went from the Low Countries, with his army, to join Mayenne at Meaux and threaten Henry IV. with their united forces if he did not retire from the walls of the capital.

Henry IV. offered the two dukes battle, if they really wished to put a stop to the investment; but “I am not come so far,” answered the Duke of Parma, “to take counsel of my enemy; if my manner of warfare does not please the King of Navarre, let him force me to change it, instead of giving me advice that nobody asks him for.” Henry in vain attempted to make the Duke of Parma accept battle. The able Italian established himself in a strongly intrenched camp, surprised Lagny, and opened to Paris the navigation of the Marne, by which provisions were speedily brought up. Henry decided upon retreating; he dispersed the different divisions of his army into Touraine, Normandy, Picardy, Champagne, Burgundy, and himself took up his quarters at Senlis, at Compiegne, in the towns on the banks of the Oise. The Duke of Mayenne arrived on the 18th of September at Paris; the Duke of Parma entered it himself with a few officers, and left it on the 13th of November with his army on his way back to the Low Countries, being a little harassed in his retreat by the royal cavalry, but easy, for the moment, as to the fate of Paris and the issue of the war, which continued during the first six months of the year 1591, but languidly and disconnectedly, with successes and reverses see-sawing between the two parties and without any important results.

Then began to appear the consequences of the victory of Ivry and the progress made by Henry IV., in spite of the check he received before Paris and at some other points in the kingdom. Not only did many moderate Catholics make advances to him, struck with his sympathetic ability and his valor, and hoping that he would end by becoming a Catholic, but patriotic wrath was kindling in France against Philip II. and the Spaniards, those fomenters of civil war in the mere interest of foreign ambition. We quoted but lately the words used by the governor of Dieppe, Aymar de Chastes, when he said to Villars, governor of Rouen, who pressed him to enter the League, “You will yourself find out that the Spaniard is the real head of this League.” On the 5th of August, 1590, during the investment of Paris, a placard was pasted all over the city. “Poor Parisians,” it said, “I deplore your misery, and I feel even greater pity towards you for being still such simpletons. See you not that this son of perdition of a Spanish ambassador [Bernard de Mendoza], who had our good king murdered, is making game of you, cramming you so with pap that he would fain have had you burst before now in order to lay hands on your goods and on France if he could? He alone prevents peace and the repose of desolated France, as well as the reconciliation of the king and the princes in real amity. Why are ye so tardy to cast him in a sack down stream, that he may return the sooner to Spain?” On the 6th of August, there was found written with charcoal, on the gate of St. Anthony, the following eight lines:—

“Some folks, for Holy League bear more

Than the prodigal son in the Bible bore;

For he, together with his swine,

On bean, and root, and husk would dine;

Whilst they, unable to procure

Such dainty morsels, must endure

Between their skinny lips to pass

Offal and tripe of horse or ass.”

|

“These,” said a Latin inscription on the awnings of the butchers’ shops, “are the rewards of those who expose their lives for Philip” [Haec sunt munera pro iis qui vitam pro Philippo proferunt: Memoires de L’Estoile, t. ii. pp. 73, 74]. In 1591 these public sentiments, reproduced and dilated upon in numerous pamphlets, imported dissension into the heart of the League itself, which split up into two parties, the Spanish League and the French League. The Committee of Sixteen labored incessantly for the formation and triumph of the Spanish League; and its principal leaders wrote, on the 2d of September, 1591, a letter to Philip II., offering him the crown of France, and pledging their allegiance to him as his subjects. “We can positively assure your Majesty,” they said, “that the wishes of all Catholics are to see your Catholic Majesty holding the sceptre of this kingdom and reigning over us, even as we do throw ourselves right willingly into your arms as into those of our father, or at any rate establishing one of your posterity upon the throne.” These ringleaders of the Spanish League had for their army the blindly fanatical and demagogic populace of Paris, and were, further, supported by four thousand Spanish troops whom Philip II. had succeeded in getting almost surreptitiously into Paris. They created a council of ten, the sixteenth century’s committee of public safety; they proscribed the policists; they, on the 15th of November, had the president, Brisson, and two councillors of the Leaguer Parliament arrested, hanged them to a beam and dragged the corpses to the Place de Grove, where they strung them up to a gibbet with inscriptions setting forth that they were heretics, traitors to the city and enemies of the Catholic princes. Whilst the Spanish League was thus reigning at Paris, the Duke of Mayenne was at Laon, preparing to lead his army, consisting partly of Spaniards, to the relief of Rouen, the siege of which Henry IV. was commencing. Being summoned to Paris by messengers who succeeded one another every hour, he arrived there on the 28th of November, 1591, with two thousand French troops; he armed the guard of Burgesses, seized and hanged, in a ground-floor room of the Louvre, four of the chief leaders of the Sixteen, suppressed their committee, re-established the Parliament in full authority, and, finally, restored the security and preponderance of the French League, whilst taking the reins once more into his own hands. But the French League before long found itself, in its turn, placed in a situation quite as embarrassing, if not so provocative of odium, as that in which the Spanish League had lately been; for it had become itself the tool of personal and unlawful ambition. The Lorraine princes, it is true, were less foreign to France than the King of Spain was; they had even rendered her eminent service; but they had no right to the crown. Mayenne had opposed to him the native and lawful heir to the throne, already recognized and invested with the kingly power by a large portion of France, and quite capable of disputing his kingship with the ablest competitors. By himself and with his own party alone, Mayenne was not in a position to maintain such a struggle; in order to have any chance he must have recourse to the prince whose partisans he had just overthrown and chastised.

On the 11th of November, 1591, Henry IV. had laid siege to Rouen with a strong force, and was pushing the operations on vigorously. In order to obtain the troops and money without which he could not relieve this important place, the leader of the French League treated humbly with the patron of the Spanish League. “In the conferences held at La Fere and at Lihom-Saintot, between the 10th and the 18th of January, 1592,” says M. Poirson, “the Duke of Parma, acting for the King of Spain, and Mayenne drew up conventions which only awaited the ratification of Philip II. to be converted into a treaty. Mayenne was to receive four millions of crowns a year and a Spanish army, which together would enable him to oppose Henry IV. He had, besides, a promise of a large establishment for himself, his relatives, and the chiefs of his party. In exchange, he promised, in his own name and that of the princes of his house and the great lords of the League, that Philip II.‘s daughter, the Infanta Isabella (Clara Eugenia), should be recognized as sovereign and proprietress of the throne of France, and that the states-general, convoked for that purpose, should proclaim her right and confer upon her the throne. It is true,” adds M. Poirson, “that Mayenne stipulated that the Infanta should take a husband, within the year, at the suggestion of the councillors and great officers of the crown, that the kingdom should be preserved in its entirety, and that its laws and customs should be maintained. . . . It even appears certain that Mayenne purposed not to keep any of these promises, and to emend his infamy by a breach of faith. . . . But a conviction generally prevailed that he recognized the rights of the Infanta, and that he would labor to place her on the throne. The lords of his own party believed it; the legate reported it everywhere; the royal party regarded it as certain. During the whole course of the year 1592, this opinion gave the most disastrous assistance to the intrigues and ascendency of Philip II., and added immeasurably to the public dangers.” [Poirson, Histoire du Regne d’Henri IV., t. i. pp. 304-306.]

Whilst these two Leagues, one Spanish and the other French, were conspiring thus persistently, sometimes together and sometimes one against the other, to promote personal ambition and interests, at the same time national instinct, respect for traditional rights, weariness of civil war, and the good sense which is born of long experience, were bringing France more and more over to the cause and name of Henry IV. In all the provinces, throughout all ranks of society, the population non-enrolled amongst the factions were turning their eyes towards him as the only means of putting an end to war at home and abroad, the only pledge of national unity, public prosperity, and even freedom of trade, a hazy idea as yet, but even now prevalent in the great ports of France and in Paris. Would Henry turn Catholic? That was the question asked everywhere, amongst Protestants with anxiety, but with keen desire, and not without hope, amongst the mass of the population. The rumor ran that, on this point, negotiations were half opened even in the midst of the League itself, even at the court of Spain, even at Rome, where Pope Clement VIII., a more moderate man than his predecessor, Gregory XIV., “had no desire,” says Sully, “to foment the troubles of France, and still less that the King of Spain should possibly become its undisputed king, rightly judging that this would be laying open to him the road to the monarchy of Christendom, and, consequently, reducing the Roman pontiffs to the position, if it were his good pleasure, of his mere chaplains.” [OEconomies royales, t. ii. p. 106.] Such being the existing state of facts and minds, it was impossible that Henry IV. should not ask himself roundly the same question, and feel that he had no time to lose in answering it.

At the beginning of February, 1593, he sent for Rosny, one evening very late. “And so,” says Rosny, “I found his Majesty in bed, having already wished every one a good night; who, as soon as he saw me come in, ordered a hassock to be brought and me to kneel thereon against his bed, and said to me, ‘My friend, I have sent for you so late for to speak with you about the things that are going on, and to hear your opinions thereon; I confess that I have often found them better than those of many others who make great show of being clever. If you continue to leave me the care of that which concerns you, and yourself to take continual care of my affairs, we shall both of us find it to our welfare. I do not wish to hide any longer that for a long time past I have had my eye upon you in order to employ you personally in my most important affairs, especially in those of my finances, for I hold you to be honest and painstaking. For the present, I wish to speak with you about that large number of persons of all parties, all ranks, and different tempers, who would be delighted to exert themselves for the pacification of the kingdom, especially if I can resolve to make some arrangement as regards religion. I am quite resolved not to hear of any negotiation or treaty, save on these two conditions, that some result may be looked for tending both to the advantage of the people of my kingdom and to the real re-establishment of the kingly authority. I know that it is your custom, whenever I put anything before you, to ask me for time to think well thereon before you are disposed to tell me your opinion; in three or four days I shall send for you to tell me what has occurred to you touching all these fine hopes that many would have me anticipate from their interventions; all of them persons very diverse in temper, purposes, interests, functions, and religion.”

“Whereupon,” says Rosny, “the king having dismissed me with a good evening, he did not fail to send for me again three days afterwards, in order that I should go and see him again in bed, near the which having made me kneel as before, he said, ‘Come, now, tell me this moment, and quite at leisurely length, all your foolish fancies, for so you have always called the best counsels you have ever given me, touching the questions I put to you the other evening. I am ready to listen to you right on to the end, without interrupting you.’”

“Sir,” said Rosny, “I have reflected not only on what your Majesty was pleased to tell me three days ago, but also on what I have been able to learn, as to the same affairs, from divers persons of all qualities and religions, and even women who have talked to me in order to make me talk, and to see if I knew any particulars of your private intentions. . . . As it seems to me, sir, all these goings, comings, writings, letters, journeys, interventions, parleys, and conferences cannot be better compared than to that swarming of attorneys at the courts, who take a thousand turns and walks about the great hall, under pretence of settling cases, and all the while it is they who give them birth, and would be very sorry for a single one to die off. In the next place, not a single one of them troubles himself about right or wrong, provided that the crowns are forthcoming, and that, by dint of lustily shouting, they are reputed eloquent, learned, and well stocked with inventions and subtleties. Consequently, sir, without troubling yourself further with these treaty-mongers and negotiators, who do nothing but lure you, bore you, perplex your mind, and fill with doubts and scruples the minds of your subjects, I opine, in a few words, that you must still for some time exercise great address, patience, and prudence, in order that there may be engendered amongst all this mass of confusion, anarchy, and chimera, that they call the holy catholic union, so many and such opposite desires, jealousies, pretensions, hatreds, longings, and designs, that, at last, all the French there are amongst them must come and throw themselves into your arms, bit by bit, recognize your kingship alone as possible, and look to nothing but it for protection, prop, or stay. Nevertheless, sir, that your Majesty may not regard me as a spirit of contradiction for having found nothing good in all these proposals made to you by these great negotiators, I will add to my suggestions just one thing; if a bit of Catholicism were quite agreeable to you, if it were properly embraced and accepted accordingly, in honorable and suitable form, it would be of great service, might serve as cement between you and all your Catholic subjects; and it would even facilitate your other great and magnificent designs whereof you have sometimes spoken to me. Touching this, I would say more to you about it if I were of such profession as permitted me to do so with a good conscience; I content myself, as it is, with leaving yours to do its work within you on so ticklish and so delicate a subject.”

“I quite understand your opinions,” said the king; “they resolve themselves almost into one single point: I must not allow the establishment of any association or show of government having the least appearance of being able to subsist, by itself or by its members, in any part of my kingdom, or suffer dismemberment in respect of any one of the royal prerogatives, as regards things spiritual as well as temporal. Such is my full determination.”

“I answered the king,” continues Rosny, “that I was rejoiced to see him taking so intelligent a view of his affairs, and that, for the present, I had no advice to give him but to seek repose of body and mind, and to permit me likewise to seek the same for myself, for I was dead sleepy, not having slept for two nights; and so, without a word more, the king gave me good night, and, as for me, I went back to my quarters.”

A few days before this conversation between the king and his friend Rosny, on the 26th of January, 1593, the states-general of the League had met in the great hall of the Louvre, present the Duke of Mayenne, surrounded by all the pomp of royalty, but so nervous that his speech in opening the session was hardly audible, and that he frequently changed color during its delivery. On leaving, his wife told him that she was afraid he was not well, as she had seen him turn pale three or four times. A hundred and twenty-eight deputies had been elected; only fifty were present at this first meeting. They adjourned to the 4th of February. In the interval, on the 28th of January, there had arrived, also, a royalist trumpeter, bringing, “on behalf of the princes, prelates, officers of the crown, and principal lords of the Catholic faith, who were with the King of Navarre, an offer of a conference between the two parties, for to lay down the basis of a peace eagerly desired.” On hearing this message, Cardinal Pelleve, Archbishop of Sens, one of the most fiery prelates of the League, said, “that he was of opinion that the trumpeter should be whipped, to teach him not to undertake such silly errands for the future;” “an opinion,” said somebody, “quite worthy of a thick head like his, wherein there is but little sense.”

The states-general of the League were of a different opinion. After long and lively discussion, the three orders decided, each separately, on the 25th of February, to consent to the conference demanded by the friends of the King of Navarre. On the 4th of February, when they resumed session, Cardinal Philip de Sega, Bishop of Placencia (in Spain) and legate of Pope Clement VIII., had requested to be present at the deliberation of the assembly, but his request was refused; the states confined themselves to receiving his benediction and hearing him deliver an address.

The different fate of these two proposals was a clear indication of the feelings of the assembly; they were very diverse in the three orders which constituted it; almost all the clergy, prelates, and popular preachers were devoted to the Spanish League; the noblesse were not at all numerous at these states. “The most brilliant and most active members of it,” says M. Picot correctly, “had ranged themselves behind Henry IV.; and it covered itself with eternal honor by having been the first to discern where to look for the hopes and the salvation of France.” The third estate was very much divided; it contained the fanatical Leaguers, at the service of Philip II. and the court of Rome, the partisans, much more numerous, of the French League, who desired peace, and were ready to accept Henry IV., provided that he turned Catholic, and a small band of political spirits, more powerful in talent than number.

Regularly as the deputies arrived, Mayenne went to each of them, saying privately, “Gentlemen, you see what the question is; it is the very chiefest of all matters (res maxima rerum agitur). I beg you to give your best attention to it, and to so act that the adversaries steal no march on us and get no advantage over us. Nevertheless, I mean to abide by what I have promised them.” Mayenne was quite right: it was certainly the chiefest of all matters. The head of the Protestants of France, the ally of all the Protestants in Europe—should he become a Catholic and King of France? The temporal head of Catholic Europe, the King of Spain —should he abolish the Salic law in France, by placing upon it his daughter as queen, and dismember France to his own profit and that of the leaders of the League, his hirelings rather than his allies? Or, peradventure, should one of these Leaguer-chiefs be he who should take the crown of France, and found a new dynasty there? And which of these Leaguer-chiefs should attain this good fortune? A half-German or a true Frenchman? A Lorraine prince or a Bourbon? And, if a Lorraine prince, which? The Duke of Mayenne, military head of the League, or his uterine brother, the Duke of Nemours, or his nephew the young Duke of Guise, son of the Balafre? All these questions were mooted, all these pretensions were on the cards, all these combinations had their special intrigue. And in the competition upon which they entered with one another, at the same time that they were incessantly laying traps for one another, they kept up towards one another, because of the uncertainty of their chances, a deceptive course of conduct often amounting to acts of downright treachery committed without scruple, in order to preserve for themselves a place and share in the unknown future towards which they were moving. It was in order to have his opinion upon a position so dark and complicated, and upon the behavior it required, that Henry IV., then at Mantes, sent once more for Rosny, and had a second conversation, a few weeks later, with him.

“Well! my friend,” said the king, “what say you about all these plots that are being projected against my conscience, my life, and my kingdom? Since the death of the Duke of Parma [on the 2d of December, 1592, in the Abbey of St. Waast at Arras, from the consequences of a wound received in the preceding April at the siege of Caudebec], it seems that deeds of arms have given place to intrigues and contests of words. I fancy that such gentry will never leave me at rest, and will at last, perhaps, attempt my liberty and my life. I beg you to tell me your opinion freely, and what remedies, short of cruelty and violence, I might now employ to get rid of all these hinderances and cabals (monopoles) that are going on against the rights which have come to me by the will of God, by birth, and by the laws of the realm.”

“Sir,” said Rosny, “I do not fancy that deferments and temporizations, any more than long speeches, would now be seasonable; there are, it seems to me, but two roads to take to deliver yourself from peril, but not from anxiety, for from anxiety kings and princes, the greater they are, can the less secure themselves if they wish to reign successfully. One of the two roads is to accommodate yourself to the desires and wishes of those of whom you feel distrust; the other, to secure the persons of those who are the most powerful, and of the highest rank, and most suspected by you, and put them in such place as will prevent them from doing you hurt; you know them pretty nearly all; there are some of them very rich; you will be able for a long while to carry, on war. As for advising you to go to mass, it is a thing that you ought not, it seems to me, to expect from me, who am of the religion; but frankly will I tell you that it is the readiest and the easiest means of confounding all these cabals (monopoles), and causing all the most mischievous projects to end in smoke.”

The King: “But tell me freely, I beg of you, what you would do if you were in my place.”

Rosny: “I can assure you honestly, sir, that I have never thought about what I should feel bound to do for to be king, it having always seemed to me that I had not a head able or intended to wear a crown. As to your Majesty it is another affair; in you, sir, that desire is not only laudable, but necessary, as it does not appear now this realm can be restored to its greatness, opulence, and splendor but by the sole means of your eminent worth and downright kingly courage. But whatever right you have to the kingdom, and whatever need it has of your courage and worth for its restoration, you will never arrive at complete possession and peaceable enjoyment of this dominion but by two sole expedients and means. In case of the first, which is force and arms, you will have to employ strong measures, severity, rigor, and violence, processes which are all utterly opposed to your temper and inclination: you will have to pass through an infinity of difficulties, fatigues, pains, annoyances, perils, and labors, with a horse perpetually between your legs, harness [halecret, a species of light cuirass] on back, helmet on head, pistol in fist, and sword in hand. And, what is more, you will have to bid adieu to repose, pleasure, pastime, love, mistress, play, hunting, hawking, and building; for you will not get out of such matters but by multiplicity of town-takings, quantity of fights, signal victories, and great bloodshed. By the other road, which is to accommodate yourself, as regards religion, to the wish of the greatest number of your subjects, you will not encounter so many annoyances, pains, and difficulties in this world, but as to the next, I don’t answer for you; it is for your Majesty to take a fixed resolution for yourself, without adopting it from any one else, and less from me than from any other, as you well know that I am of the religion, and that you keep me by you not as a theologian and councillor of church, but as a man of action and councillor of state, seeing that you have given me that title, and for a long space employed me as such.”

The king burst out laughing, and, sitting up in his bed, said, after scratching his head several times, to Rosny,—

“All you say to me is true; but I see so many thorns on every side that it will go very hard but some of them will prick me full sore. You know well enough that my cousins, the princes of the blood, and ever so many other lords, such as D’Epernon, Longueville, Biron, d’O, and Vitry, are urging me to turn Catholic, or else they will join the League. On the other hand, I know for certain that Messieurs de Turenne, de la Tremoille, and their lot, are laboring daily to have a demand made, if I turn Catholic, on behalf of them of the religion, for an assembly to appoint them a protector and an establishment of councils in the provinces; all things that I could not put up with. But if I had to declare war against them to prevent it, it would be the greatest annoyance and trouble that could ever happen to me: my heart could not bear to do ill to those who have so long run my risks, and have employed their goods and their lives in my defence.”