The Project Gutenberg EBook of Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery

in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves, by Work Projects Administration

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves

Mississippi Narratives

Author: Work Projects Administration

Release Date: April 15, 2004 [EBook #12055]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLAVE NARRATIVES ***

Produced by Andrea Ball and PG Distributed Proofreaders. Produced

from images provided by the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

[TR: ***] = Transcriber Note

[HW: ***] = Handwritten Note

[FN: ***] = Footnote

Illustrated with Photographs

WASHINGTON 1941

[TR: Footnotes have been moved to appear within the text.]

[TR: Informant names and locations that appear in brackets have been drawn

from interviews.]

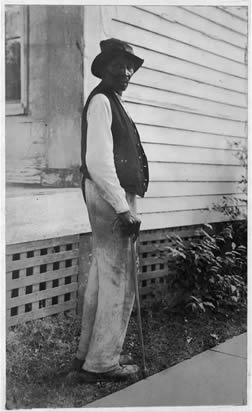

Jim Allen, West Point, age 87, lives in a shack furnished by the city. With him lives his second wife, a much older woman. Both he and his wife have a reputation for being "queer" and do not welcome outside visitors. However, he readily gave an interview and seemed most willing to relate the story of his life.

"Yas, ma'm, I 'members lots about slav'ry time, 'cause I was old 'nough.

"I was born in Russell County, Alabamy, an' can tell you 'bout my own mammy an' pappy an' sisters an' brudders.

"Mammy's name was Darkis an' her Marster was John Bussey, a reg'lar old drunkard, an' my pappy's name was John Robertson an' b'longed to Dr. Robertson, a big farmer on Tombigbee river, five miles east of Columbus. De doctor hisself lived in Columbus.

"My sister Harriett and brudder John was fine fiel' hands an' Marster kep' 'em in de fiel' most of de time, tryin' to dodge other white folks.

"Den dere was Sister Vice an' brudder George. Befo' I could 'member much, I 'members Lee King had a saloon close to Bob Allen's store in Russell County, Alabama, and Marse John Bussey drunk my mammy up. I means by dat, Lee King tuk her an' my brudder George fer a whiskey debt. Yes, old Marster drinked dem up. Den dey was car'ied to Florida by Sam Oneal, an' George was jes a baby. You know, de white folks wouldn't often sep'rate de mammy an' baby. I ain't seen' em since.

"Did I work? Yes ma'm, me an' a girl worked in de fiel', carryin' one row; you know, it tuk two chullun to mek one han'.

"Did we have good eatins? Yes ma'm, old Marster fed me so good, fer I was his pet. He never 'lowed no one to pester me neither. Now dis Marster was Bob Allen who had tuk me for a whiskey debt, too. Marse Bussey couldn't pay, an' so Marse Allen tuk me, a little boy, out'n de yard whar I was playin' marbles. De law 'lowed de fust thing de man saw, he could take.

"I served Marse Bob Allen 'til Gen'al Grant come 'long and had me an' some others to follow him to Miss'sippi. We was in de woods hidin' de mules an' a fine mare. Dis was after Emanc'pation, an' Gen'al Grant was comin' to Miss'sippi to tell de niggers dey was free.

"As I done tol' you, I was Marse Allen's pet nigger boy. I was called a stray. I slep' on de flo' by old Miss an' Marse Bob. I could'a slep' on de trun'le bed, but it was so easy jes to roll over an' blow dem ashes an' mek dat fire burn.

"Ole Miss was so good, I'd do anything fer her. She was so good an' weighed' round 200 poun's. She was Marse Bob's secon' wife. Nobody 'posed on me, No, Sir! I car'ied water to Marse Bob's sto' close by an' he would allus give me candy by de double han'full, an' as many juice harps as I wanted. De bes' thing I ever did eat was dat candy. Marster was good to his only stray nigger.

"Slave niggers didn't fare wid no gardens 'cept de big garden up at de Big House, when fiel' han's was called to wuk out hers (old Miss). All de niggers had a sight of good things to eat from dat garden an' smoke house.

"I kin see old Lady Sally now, cookin' for us niggers, an' Ruth cooked in de white folk's kitchen. Ruth an' old Man Pleas' an' old Lady Susan was give to Marse Bob when he mar'ied an' come to Sandford, Alabamy.

"No, dere wa'nt no jails, but a guard house. When niggers did wrong, dey was oft'n sent dere, but mos' allus dey was jes whupped when too lazy to wuk, an' when dey would steal.

"Our clo'es was all wove and made on de plan'ation. Our ever'day ones, we called 'hick'ry strips.' We had a' plen'y er good uns. We was fitted out an' out each season, an' had two pairs of shoes, an' all de snuff an' 'bacco we wanted every month.

"No, not any weddin's. It was kinder dis way. Dere was a good nigger man an' a good nigger woman, an' the Marster would say, 'I knows you both good niggers an' I wants you to be man an' wife dis year an' raise little niggers; den I won't have to buy' em.'

"Marse Bob lived in a big white house wid six rooms. He had a cou't house an' a block whar he hired out niggers, jes like mules an' cows.

"How many slaves did us have? Les' see. Dere was old Lady Sally an' her six chullun an' old Jake, her husban', de ox driver, fer de boss. Den dere was old Starlin', Rose, his wife an' fo' chullun. Some of dem was mixed blood by de oberseer. I sees 'em right now. I knowed de oberseer was nothin' but po' white trash, jes a tramp. Den dere was me an' Katherin. Old Lady Sally cooked for de oberseers, seven miles 'way frum de Big House.

"Ever'body was woke up at fo' o'clock by a bugle blowed mos'ly by a nigger, an' was at dey work by sun-up. Den dey quits at sunset. I sho' seed bad niggers whupped as many times as dere is leaves on dat groun'. Not Marse Bob's niggers, but our neighbors. We was called 'free,' 'cause Marse Bob treated us so good. The whuppin' was done by de oberseer or driver, who would say as he put de whup to de back, 'Pray sir, pray sir!'

"I seed slaves sol' oft'ener dan you got fingers an' toes. You know I tol' you dere was a sellin' block close to our sto'. Den plen'y niggers had to be chained to a tree or post 'cause he would run 'way an' wouldn' wuk.

"Dey would track de runways wid dogs an' sometimes a white scal'wag or slacker wud be kotched dodgin' duty. I seed as many deserters as I see corn stalks ober in dat fiel'. Dey would hide out in day time an' steal at night.

"No'm I didn' learn to read an' write but my folks teached me to be honest an' min' Old Miss an' Granny. Dey didn' want us to learn how to go to de free country.

"We had a neighborhood chu'ch an bofe black an' white went to it. Dere was a white preacher an' sometimes a nigger preacher would sit in de pulpit wid him. De slaves set on one side of de aisle an' white folks on de other. I allus liked preacher Williams Odem, an' his brudder Daniel, de 'Slidin' Elder'.[FN: back slider] Dey come frum Ohio. Marse Bob Allen was head steward. I' members lots of my fav'rite songs. Some of dem was, Am I born to Die, Alas and Did my Savior Bleed, an' Must I to de Judgment be Brought. The preacher would say 'Pull down de line and let de spirit be a witnes, workin' fer faith in de future frum on high.'

"I seed de patyrollers every week. If de niggers didn' get a pass in han' right frum one plan'ation to 'nother, dem patyrollers would git you. Dey would be six an' twelve in a drove, an' day would git you if you didn' have dat piece of paper. No sun could go down on a pass. Dere was no trouble twixt niggers den.

"We lay down an' res' at night in de week time. Niggers in slav'ry time riz up in de Quarters, you could hear 'em for miles. Den da cornshucking tuk place. Den we would have singin'. When one foun' a red ear of corn, dey would take a drink of whiskey frum de jug an' cup. We'd get through' bout ten o'clock. De men did'n care if dey worked all night, fer we had the 'Heav'nly Banners'[FN: women and whiskey] by us[HW:?].

"Sometimes we worked on Sat'day a'ternoon, owin' to de crops; but women all knocked off on Sat'day a'ternoon. On Sat'day night, we mos'ly had fun, playin' an drinking whiskey an' beer—no time to fool 'roun' in de week time.

"Some went to chu'ch an' some went fishin' on Sunday. On Chris'mas we had a time—all kinds eatin'—wimmen got new dresses—men tobacco—had stuff to las' 'til Summer. Niggers had good times in mos' ways in slav'ry time. July 4th, we would wash up an' have a good time. We hallowed dat day wid de white folks. Dere was a barbecue; big table set down in bottoms. Dere was niggers strollin' 'roun' like ants. We was havin' a time now. White folks too. When a slave died, dere was a to-do over dat, hollerin' an' singin'. More fuss dan a little—'Well, sich a one has passed out an we gwine to de grave to 'tend de fun'ral; we will talk about Sister Sallie.' De niggers would be jumpin' as high as a cow er mule.

"A song we used to sing was"

[HW: Sang]

'Come on Chariot an' Take Her Home, Take Her Home, Here Come Chariot, les' ride, Come on les' ride, Come on les' ride.'

"Yessum we believed ha'nts would be at de grave yard. I didn' pay no' tention to dem tho', for I know de evil spirit is dere. Iffen you don't believe it, let one of 'em slap you. I ain't seed one, but I'se heard 'em. I seed someone, dey said was a ghos', but it got 'way quick.

"When we got sick de doctor come at once, and Mistiss was right dere to see we was cared fer. A doctor lived on our place. If you grunt he was right dere. We had castor oil an' pills an' turpentine an' quinine when needful, an' herbs was used. I can fin' dat stuff now what we used when I was a boy.

[HW: Superstition]

"Some of us wore brass rings on our fingers to keep off croup. Really good—good now. See mine?

"Yessum I knows all 'bout when Yankees come. Dey got us out'er de swamp. I was layin' down by a white oak tree 'sleep, an' when I woke up an' looked up an' saw nothin' but blue, blue, I said, 'Yonder is my Boss's fine male hoss, Alfred. He 'tended dat horse hisself.' He took it to heart, an' he didn' live long afte' de Blue Coats took Alfred.

"Peace was declared to us fust in January in Alabamy, but not in Miss'sippi 'til Grant come back, May 8th.

"I ain't seen my boss since dem Yankees took me 'way. I was seven miles down in de swamp when I was tuk. I wouldn' of tol' him goodbye. I jes wouldn' of lef' him. No sir, I couldn' have lef' my good boss. He tol' me dem Yankees was comin' to take me off. I never wanted to see him 'cause I would have went back 'cause he pertected me an' loved me.

"Like dis week, I lef' de crowd. One day, Cap'in Bob McDaniel came by, an' asked me if I wanted to mek fires an' wuk 'round de house. I said, 'I'd like to see de town whar you want me to go, an' den I come to West Point. It wa'nt nothin' but cotton rows—lot of old shabby shanties, with jes one brick sto', an' it b'longed to Ben Robertson, an' I hope[FN: helped] build all de sto'es in West Point since den.

"I seed de KuKlux. We would be workin'. Dem people would be in de fiel', an' must get home 'fo dark an' shet de door. Dey wo' three cornered white hats with de eyes way up high. Dey skeered de breeches off'n me. First ones I got tangled up wid was right down here by de cemetery. Dey just wanted to scare you. Night riders was de same thing. I was one of de fellers what broke 'em up.

"Old man Toleson was de head leader of de Negroes. Tryin' to get Negroes to go 'gainst our white people. I spec' he was a two faced Yankee or carpetbagger.

"We had clubs all 'round West Point. Cap'in Shattuck out about Palo Alto said to us niggers one day, 'Stop your foolishness—go live among your white folks an' behave. Have sense an' be good citizens.' His advice was good an' we soon broke up our clubs.

"I ain't been to no school 'cept Sunday School since Surrender. A good white man I worked with taught me 'nough to spell 'comprestibility' and 'compastibility.' I had good 'membrance an' I could have learned what white folks taught me, an' dey sees dey manners in me.

"I mar'ied when I was turnin' 19, an' my wife, 15. I mar'ied at big Methodist Chu'ch in Needmore. Same old chu'ch is dere now. I hope build it in 1865. Aunt Emaline Robertson an' Vincent Petty an' Van McCanley started a school in de northeast part of town two years afte' de War.

"Emaline was Mr. Ben Robertson's cook, an' her darter, Callie, was his housekeeper, an' George an' Walter was mechanics. George became a school teacher.

"Abraham Lincoln worked by 'pinions of de Bible. He got his meanin's from de Bible. 'Every man should live under his own vine and fig tree.' Dis was Abraham's commandments. Dis is where Lincoln started, 'no one should work for another.'

"Jefferson Davis wanted po' man to work for rich man. He was wrong in one 'pinion, an' right in t'other. He tried to take care of his Nation. In one instance, Lincoln was destroying us.

"I j'ined the church to do better an' to be with Christians an' serve Christ. Dis I learned by 'sociation an' harmonious livin' with black an' white, old an' young, an' to give justice to all.

"Be fust work I did after de War was for Mr. Bob McDaniel who lived near Waverly on de Tombigbee River. Yes ma'am, I knowed de Lees, an' de Joiners, but on de river den an' long afte', an' worked for 'em lots in Clay County."

Anna Baker, 80-year old ex-slave, is tall and well built. She is what the Negroes term a "high brown." Her high forehead and prominent cheek bones indicate that there is a strain of other than the pure African in her blood. She is in fair health.

"Lemme see how old I is. Well, I tells you jus' lak I tol' dat Home Loan man what was here las' week. I 'members a pow'ful lot 'bout slavery times an' 'bout 'fore surrender. I know I was a right smart size den, so's 'cording to dat I mus' be 'roun' 'bout eighty year old. I aint sho' 'bout dat an' I don't want to tell no untruth. I know I was right smart size 'fore de surrender, as I was a-sayin', 'cause I 'members Marster comin' down de road past de house. When I'd see 'im 'way off I'd run to de gate an' start singin' dis song to 'im:

'Here come de marster, root toot too! Here come Marster, comin' my way! Howdy, Marster, howdy do! What you gwine a-bring from town today?'

Dat would mos' nigh tickle him to death an' he'd say, 'Loosahna (dat was his pet name for me) what you want today? I'd say, 'Bring me some goobers, or a doll, or some stick candy, or anything. An' you can bet yo' bottom doller he'd always bring me somp'n'.

"One reason Marse Morgan thought so much o' me, dey say I was a right peart young'n' an' caught on to anything pretty quick. Marster would tell me, 'Loosanna, if you keep yo' ears open an' tell me what de darkies talk 'bout, dey'll be somp'n' good in it for you.' (He meant for me to listen when dey'd talk 'bout runnin' off an' such.) I'd stay 'roun' de old folks an' make lak I was a-playin'. All de time I'd be a-listenin'. Den I'd go an' tell Marster what I hear'd. But all de time I mus' a-had a right smart mind, 'cause I'd play 'roun' de white folks an' hear what dey'd say an' den go tell de Niggers.—Don't guess de marster ever thought 'bout me doin' dat.

"I was born an' bred 'bout seven miles from Tuscaloosa, Alabama. I was de baby of de fam'ly. De house was on de right han' side o' de road to town. I had four sisters an' one brother dat I knows of. Dey was named Classie, Jennie, Florence, Allie, an' George. My name was Joanna, but dey done drap de Jo part a long time ago.

"I don't recollec' what my ma's mammy an' pappy was named, but I know dat her pappy was a full blooded Injun. (I guess dat is where I gits my brown color.) Her mammy was a full blooded African though, a great big woman.

"I recollec' a tale ray mammy tol' me 'bout my gran'pa. When he took up wid my gran'mammy de white man what owned her say, 'If you want to stay wid her I'll give you a home if you'll work for me lak de Niggers do.' He 'greed, 'cause he thought a heap o' his Black Woman. (Dat's what he called her.) Ever'thing was all right 'til one o' dem uppity overseers tried to act smart. He say he gwine a-beat him. My gran'pappy went home dat night an' barred de door. When de overseer an' some o' his frien's come after him, he say he aint gwine a-open dat door. Dey say if he don't dey gwine a-break it in. He tell' em to go 'head.

"Whilst dey was a-breakin' in he filled a shovel full o' red hot coals an' when dey come in he th'owed it at 'em. Den whilst dey was a-hollerin' he run away. He aint never been seen again to dis good day. I'se hear'd since den dat white folks learnt dat if dey started to whip a Injun dey'd better kill him right den or else he might git dem.

"My mammy's name was Harriet Clemens. When I was too little to know anything 'bout it she run off an' lef' us. I don't 'member much 'bout her 'fore she run off, I reckon I was mos' too little.

"She tol' me when she come after us, after de war was over, all 'bout why she had to run away: It was on 'count of de Nigger overseers. (Dey had Niggers over de hoers an' white mens over de plow han's.) Dey kep' a-tryin' to mess 'roun' wid her an' she wouldn' have nothin' to do wid 'em. One time while she was in de fiel' de overseer asked her to go over to de woods wid him an' she said, 'All right, I'll go find a nice place an' wait.' She jus' kep'a-goin. She swum de river an' run away. She slipped back onct or twict at night to see us, but dat was all. She hired out to some folks dat warnt rich' nough to have no' slaves o' dey own. Dey was good to her, too. (She never lacked for work to do.)

"When my ma went off a old woman called Aunt Emmaline kep' me. (She kep' all de orphunt chillun an' dem who's mammas had been sent off to de breedin' quarters. When dem women had chillun dey brung 'em an' let somebody lak Aunt Emmaline raise em.) She was sho' mean to me. I think it was 'cause de marster laked me an' was always a-pettin' me. She was jealous.

"She was always a-tryin' to whip me for somethin' or nother. One time she hit me wid a iron miggin. (You uses it in churnin'.) It made a bad place on my head. She done it 'cause I let some meal dat she was parchin' burn up. After she done it she got sort a scared an' doctored me up. She put soot on de cut to make it stop bleedin'. Nex' day she made me promise to tell de marster dat I hurt my head when I fell out o' de door dat night he whip Uncle Sim for stealin' a hog. Now I was asleep dat night, but when he asked me I said, 'Aunt Emmaline say tell you I hurt my head fallin' out de door de night you whip Uncle Sim.' Den he say, 'Is dat de truf?' I say, 'Naw sir.' He took Aunt Emmaline down to de gear house an' wore her out. He wouldn' tell off on me. He jus' tol' her dat she had no bus'ness a-lettin' me stay up so late dat I seen him do de whippin'.

"My pa was named George Clemens. Us was all owned by Marster Morgan Clemens. Master Hardy, his daddy, had give us to him when he 'vided out wid de res' o' his chillun. (Marster Morgan was a settled man. He went 'roun' by hisse'f mos' o' de time. He never did marry.)

"My pa went to de war wid Marster Morgan an' he never come back. I don't 'member much 'bout 'em goin', but after dey lef' I 'member de Blue Coats a-comin'. Dey tore de smoke house down an' made a big fire an' cooked all de meat dey could hol'. All us Niggers had a good time, 'cause, dey give us all us wanted. One of 'em put me up on his knee an' asked me if I'd ever seen Marster wid any little bright 'roun' shiny things. (He held his hand up wid his fingers in de shape of a dollar.) I, lak a crazy little Nigger said, 'Sho', Marster draps 'em 'hind de mantelpiece.' Den, if dey didn' tear dat mantel down an' git his money, I's a son-of-a-gun!

"After de war was over my ma got some papers from de progo[FN: provost] marshal. She come to de place an 'tol' de marster she want her chillun. He say she can have all 'cept me. She say she want me, too, dat I was her'n an' she was gwine a-git me. She went back an 'got some more papers an' showed 'em to Marster Morgan. Den he lemme go.

"She come out to de house to git us. At firs' I was scared o' her, 'cause I didn' know who she was. She put me in her lap an' she mos' nigh cried when she seen de back o' my head. Dey was awful sores where de lice had been an' I had scratched 'em. (She sho' jumped Aunt Emmaline 'bout dat.) Us lef' dat day an' went right on to Tuscaloosa. My ma had married again an' she an' him took turns 'bout carrying me when I got tired. Us had to walk de whole seven miles.

"I went to school after dat an' learnt to read an' write. Us had white Yankee teachers. I learnt to read de Bible well' nough an' den I quit.

"I was buried in de water lak de Savior. I's a real Baptis'. De Holy Sperrit sho' come into my heart.

"I b'lieves in de Sperrit. I b'lieves all o' us when us dies is sperrits. Us jus' hovers 'roun' in de sky a-ridin' on de clouds. Course, some folks is born wid a cloud over dey faces. Dey can see things dat us can't. I reckon dey sees de sperrits. I know' bout dem Kloo Kluxes. I had to go to court one time to testify 'bout' em. One night after us had moved to Tuscaloosa dey come after my step-daddy. Whilst my ma an' de res' went an' hid I went to de door. I warnt scared. I says, 'Marster Will, aint dat you?' He say, 'Sho', it's me. Whar's yo' daddy?' I tol' 'im dat he'd gone to town. Den dey head out for 'im. In de meantime my ma she had started out, too. She warned him to hide, so dey didn' git 'im.

"Soon after dat de Yankees hel' a trial in Tuscaloosa. Dey carried me. A man hel' me up an' made me p'int out who it was dat come to our house. I say, 'Dat's de man, aint it Marster Will?' He couldn' say "No", 'cause he'd tol' me twas him dat night. Dey put 'em in jail for six months an' give 'em a big fine.

"Us moved from Tuscaloosa while I was still a young girl an' went to Pickensville, Alabama. Us stayed dar on de river for awhile an' den moved to Columbus, Mississippi. I lived dar 'til I was old 'nough to git out to myse'f.

"Den I come to Aberdeen an' married Sam Baker. Me an' Sam done well. He made good money an' us bought dis very house I lives in now. Us never had no chillun, but I was lef' one by a cousin o' mine what died. I raised her lak she was my own. I sont her to school an' ever'thing. She lives in Chicago now an' wants me to come live wid her. But shucks! What would a old woman lak me do in a place lak dat?

"I aint got nothin' lef now 'cept a roof over my head. I wouldn' have dat 'cept for de President o' de United States. Dey had loaned me some money to fix up de house to keep it from fallin' down on me. Dey said I'd have fifteen year to pay it back in. Now course, I knowed I'd be dead in dat time, so I signed up wid' em.

"Las' year de men dat collec' nearly worrit me to death a-tryin' to git some money from me. I didn' have none, so dey say dey gwine a-take my home.

"Now I hear tell o' dat barefoot Nigger down at Columbus callin' de president an' him bein' so good to 'im. So I 'cided to write an' tell 'im what a plight dis Nigger was in. I didn' say nothin noxious[FN: obnoxious], but I jus' tol' him plain facts. He writ me right back an' pretty soon he sont a man down to see me. He say I needn' bother no more, dat dey won't take my house 'way from me. An' please de Lawd! Dey aint nobody else been here a-pesterin' me since.

"Dat man tol' me soon as de old age pension went th'ough I'd git thirty dollars a mont' stid[FN: instead] o' de four I's a-gittin' now. Now won't dat be gran'? I could live lak de white folks on dat much.

"I'se had 'ligion all my born days. (I never learnt to read de Bible an' 'terpet de Word 'til I was right smart size, but I mus' o' b'lieved in de Lawd since 'way back.) I'se gwine a-go right 'long an' keep a-trustin' de good Lawd an' I knows ever'thing gwine a-come out all right.

"'Twixt de Lawd an' de good white folks I know I's gwine always have somethin' t'eat. President Roosevelt done 'tended to de roof over my head."

John Cameron, ex-slave, lives in Jackson. He was born in 1842 and was owned by Howell Magee. He is five feet six inches tall, and weighs about 150 pounds. His general coloring is blackish-brown with white kinky hair. He is in fairly good health.

"I'se always lived right here in Hinds County. I's seen Jackson grow from de groun' up.

"My old Marster was de bes' man in de worl'. I jus' wish I could tell, an' make it plain, jus' how good him an' old Mistis was. Marster was a rich man. He owned 'bout a thousand an' five hund'ed acres o' lan' an' roun' a hund'ed slaves. Marster's big two-story white house wid lightning rods standin' all 'bout on de roof set on top of a hill.

"De slave cabins, 'cross a valley from de Big House, was built in rows. Us was 'lowed to sing, play de fiddles, an' have a good time. Us had plenty t' eat and warm clo'es an' shoes in de winter time. De cabins was kep' in good shape. Us aint never min' workin' for old Marster, cause us got good returns. Dat meant good livin' an' bein' took care of right. Marster always fed his slaves in de Big House.

"De slaves would go early to de fiel's an work in de cotton an' corn. Dey had different jobs.

"De overseers was made to un'erstan' to be 'siderate of us. Work went on all de week lak dat. Dey got off from de fiel's early on Satu'd'y evenin's, washed up an' done what dey wanted to. Some went huntin' or fishin', some fiddled an' danced an' sung, while de others jus' lazed roun' de cabins. Marse had two of de slaves jus' to be fiddlers. Dey played for us an' kep' things perked up. How us could swing, an' step-'bout by dat old fiddle music always a-goin' on. Den old Marster come 'roun' wid his kin'ly smile an' jov'al sp'rits. When things went wrong he always knowed a way. He knowed how to comfort you in trouble.

"Now, I was a gardner or yard boy. Dat was my part as a slave. I he'ped keep de yard pretty an' clean, de grass cut, an' de flowers' tended to an' cut. I taken dat work' cause I lak's pretty flowers. I laks to buil' frames for 'em to run on an' to train 'em to win' 'roun'. I could monkey wid 'em all de time.

"When folks started a-comin' through talkin' 'bout a-freein' us an' a-givin' us lan' an' stuff, it didn' take wid Marster's slaves. Us didn' want nothin' to come 'long to take us away from him. Dem a tellin' de Niggers dey'd git lan' an' cattle an' de lak of dat was all foolis'ness, nohow. Us was a-livin' in plenty an' peace.

"De war broke out spite o' how Marster's Niggers felt. When I seen my white folks leave for war, I cried myself sick, an' all de res' did too. Den de Yankees come through a-takin' de country. Old Marster refugeed us to Virginny. I can't say if de lan' was his'n, but he had a place for us to stay at. I know us raised 'nough food stuff for all de slaves. Marster took care o' us dere 'til de war ended.

"Den he come to camp late one evenin' an tol' us dat us was free as he was; dat us could stay in Virginny an work or us could come to Mississippi wid him. Might nigh de whole passel bun'led up an' come back, an' glad to do it, too. Dar us all stayed 'til de family all died. De las' one died a few years ago an' lef' us few old darkies to grieve over 'em.

"I don' know much 'bout de Klu Klux Klan an' all dat. Dey rode 'bout at night an' wore long white ghos'-lak robes. Dey whup folks an' had meetin's way off in de woods at midnight. Dey done all kinds o' curious things. None never did bother 'bout Marster's place, so I don' know much 'bout 'em.

"After de War it took a mighty long time to git things a-goin' smooth. Folks an' de Gov'ment, too, seem lak dey was all up-set an' threatened lak. For a long time it look lak things gwine bus' loose ag'in. Mos' ever'thing was tore up an' burned down to de groun'. It took a long time to build back dout no money. Den twant de gran' old place it was de firs' time.

"I married when I was a young man. I was lucky 'nough to git de nex' bes' woman in de worl'. (Old Mis' was de bes'.) Dat gal was so good 'til I had to court 'er mos' two years 'fore she'd say she'd have me.

"Us had six chillun. Three of 'em's still livin'. I can't say much for my chillun. I don' lak to feel hard, but I tried to raise my chillun de bes' I could. I educated 'em; even bought 'em a piano an' give em' music. One of 'em is in Memphis, 'nother'n in Detroit, an' de other'n in Chicago. I writes to 'em to he'p me, but don' never hear from 'em. I's old an' dey is forgot me, I guess.

"Dat seems to be de way of de worl' now. Ever'thing an' ever'body is too fas' an' too frivoless[FN: frivilous] dese here times. I tell you, folks ought to be more lak old Marster was.

"I's a Christian an' loves de Lawd. I expects to go to him 'fore long. Den I know I's gwine see my old Marstar an' Mistis ag'in."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

John Cameron: Jackson, Mississippi.

Uncle Gus Clark and his aged wife live in a poverty-stricken deserted village about an eighth of a mile east of Howison.

Their old mill cabin, a relic of a forgotten lumber industry, is tumbling down. They received direct relief from the ERA until May, 1934, when the ERA changed the dole to work relief. Uncle Gus, determined to have a work card, worked on the road with the others until he broke down a few days later and was forced to accept direct relief. Now, neither Gus nor Liza is able to work, and the only help available for them is the meager State Old Age Assistance. Gus still manages to tend their tiny garden.

He gives his story:

"I'se gwine on 'bout eighty-five. 'At's my age now. I was born at Richmond, Virginny, but lef' dare right afte' de War. Dey had done surrendered den, an' my old marster doan have no mo' power over us. We was all free an' Boss turned us loose.

"My mammy's name was Judy, an' my pappy was Bob. Clark was de Boss's name. I doan 'member my mammy, but pappy was workin' on de railroad afte' freedom an' got killed.

"A man come to Richmond an' carried me an' pappy an' a lot of other niggers ter Loos'anna ter work in de sugar cane. I was little but he said I could be a water boy. It sho' was a rough place. Dem niggers quar'l an' fight an' kills one 'nother. Big Boss, he rich, an' doan 'low no sheriff ter come on his place. He hol' cou't an' settle all 'sputes hisself. He done bury de dead niggers an' put de one what killed him back to work.

"A heap of big rattlesnakes lay in dem canebrakes, an' dem niggers shoot dey heads off an' eat 'em. It didn' kill de niggers. Dem snakes was fat an' tender, an' fried jes lak chicken.

"Dere in Loos'anna we doan get no pay 'til de work is laid by. Den we'se paid big money, no nickels. Mos' of de cullud mens go back to where dey was raised.

"Dat was afte' freedom, but my daddy say dat de niggers earn money on Old Boss' place even durin' slav'ry. He give 'em every other Sat'dy fer deyse'ves. Dey cut cordwood fer Boss, wimmens an' all. Mos' of de mens cut two cords a day an' de wimmens one. Boss paid 'em a dollar a cord. Dey save dat money, fer dey doan have to pay it out fer nothin'. Big Boss didn' fail to feed us good an' give us our work clo'es. An' he paid de doctor bills. Some cullud men saved enough to buy deyse'ves frum Boss, as free as I is now.

"Slav'ry was better in some ways 'an things is now. We allus got plen'y ter eat, which we doan now. We can't make but fo' bits a day workin' out now, an' 'at doan buy nothin' at de sto'. Co'se Boss only give us work clo'es. When I was a kid I got two os'berg[FN: Osnaberg: the cheapest grade of cotton cloth] shirts a year. I never wo' no shoes. I didn' know whut a shoe was made fer, 'til I'se twelve or thirteen. We'd go rabbit huntin' barefoot in de snow.

"Didn' wear no Sunday clo'es. Dey wa'nt made fer me, 'cause I had nowhere ter go. You better not let Boss ketch you off'n de place, less'n he give you a pass to go. My Boss didn' 'low us to go to church, er to pray er sing. Iffen he ketched us prayin' er singin' he whupped us. He better not ketch you with a book in yo' han'. Didn' 'low it. I doan know whut de reason was. Jess meanness, I reckin. I doan b'lieve my marster ever went to church in his life, but he wa'nt mean to his niggers, 'cept fer doin' things he doan 'low us to. He didn' care fer nothin' 'cept farmin'.

"Dere wa'nt no schools fer cullud people den. We didn' know whut a school was. I never did learn to read.

"We didn' have no mattresses on our beds like we has now. De chullun slep' under de big high beds, on sacks. We was put under dem beds 'bout eight o'clock, an' we'd jes better not say nothin' er make no noise afte' den. All de cullud folks slep' on croker sacks full of hay er straw.

"Did I ever see any niggers punished? Yessum, I sho' has. Whupped an' chained too. Day was whupped 'til de blood come, 'til dey back split all to pieces. Den it was washed off wid salt, an' de nigger was put right back in de fiel'. Dey was whupped fer runnin' away. Sometimes dey run afte' 'em fer days an nights with dem big old blood houn's. Heap o' people doan b'lieve dis. But I does, 'cause I seed it myse'f.

"I'se lived here forty-five years, an' chipped turpentine mos' all my life since I was free.

"I'se had three wives. I didn' have no weddin's, but I mar'ied 'em 'cordin to law. I woan stay with one no other way. My fust two wives is dead. Liza an' me has been mar'ied 'bout 'leven years. I never had but one chile, an' 'at by my fust wife, an' he's dead. But my other two wives had been mar'ied befo', an' had chullun. 'Simon here,' pointing to a big buck of fifty-five sitting on the front porch, 'is Liza's oldest boy.'"

James Cornelius lives in Magnolia in the northwestern part of the town, in the Negro settlement. He draws a Confederate pension of four dollars per month. He relates events of his life readily.

"I does not know de year I was borned but dey said I was 15 years old when de War broke out an' dey tell me I'se past 90 now. Dey call me James Cornelius an' all de white folks says I'se a good 'spectable darkey.

"I was borned in Franklin, Loos'anna. My mammy was named Chlo an' dey said my pappy was named Henry. Dey b'longed to Mr. Alex Johnson an' whil'st I was a baby my mammy, my brudder Henry, an' me was sol' to Marse Sam Murry Sandell an' we has brung to Magnolia to live an' I niver remember seein' my pappy ag'in.

"Marse Murry didn' have many slaves. His place was right whar young Mister Lampton Reid is buildin' his fine house jes east of de town. My mammy had to work in da house an' in de fiel' wid all de other niggers an' I played in de yard wid de little chulluns, bofe white an' black. Sometimes we played 'tossin' de ball' an' sometimes we played 'rap-jacket' an' sometimes 'ketcher.' An' when it rained we had to go in de house an' Old Mistess made us behave.

"I was taught how to work 'round de house, how to sweep an' draw water frum de well an' how to kin'le fires an' keep de wood box filled wid wood, but I was crazy to larn how to plow an' when I could I would slip off an' get a old black man to let me walk by his side an' hold de lines an' I thought I was big 'nouf to plow.

"Marse Murry didn' have no overseer. He made de slaves work, an' he was good an' kind to 'em, but when dey didn' do right he would whip 'em, but he didn' beat 'em. He niver stripped 'em to whip 'em. Yes ma'm, he whipped me but I needed it. One day I tol' him I was not goin' to do whut he tol' me to do—feed de mule—but when he got through wid me I wanted to feed dat mule.

"I come to live wid Marse Murry 'fo dar was a town here. Dar was only fo' houses in dis place when I was a boy. I seed de fust train dat come to dis here town an' it made so much noise dat I run frum it. Dat smoke puffed out'n de top an' de bell was ringin' an' all de racket it did make made me skeered.

"I heered dem talkin' 'bout de war but I didn' know whut dey meant an' one day Marse Murry said he had jined de Quitman Guards an' was goin' to de war an' I had to go wid him. Old Missus cried an' my mammy cried but I thought it would be fun. He tuk me 'long an' I waited on him. I kept his boots shinin' so yer could see yer face in 'em. I brung him water an' fed an' cur'ied his hoss an' put his saddle on de hoss fer him. Old Missus tol' me to be good to him an' I was.

"One day I was standin' by de hoss an' a ball kilt[FN: killed] de hoss an' he fell over dead an' den I cried like it mout[FN: might] be my brudder. I went way up in Tennessee an' den I was at Port Hudson. I seed men fall dawn an' die; dey was kilt like pigs. Marse Murry was shot an' I stayed wid him 'til dey could git him home. Dey lef' me behin' an' Col. Stockdale an' Mr. Sam Matthews brung me home.

"Marse Murry died an' Old Missus run de place. She was good an' kind to us all an' den she mar'ied afte' while to Mr. Gatlin. Dat was afte' de war was over.

"Whil'st I was in de war I seed Mr. Jeff Davis. He was ridin' a big hoss an' he looked mighty fine. I niver seed him 'ceptin he was on de hoss.

"Dey said old man Abe Lincoln was de nigger's friend, but frum de way old Marse an' de sojers talk 'bout him I thought he was a mighty mean man.

"I doan recollec' when dey tol' us we was freed but I do know Mr. Gatlin would promise to pay us fer our work an' when de time would come fer to pay he said he didn' have it an' kep' puttin us off, an' we would work some more an' git nothin' fer it. Old Missus would cry an' she was good to us but dey had no money.

"'Fo de war Marse Murry would wake all de niggers by blowin' a big 'konk' an' den when dinner time would come Old Missus would blow de 'konk' an' call dem to dinner. I got so I could blow dat 'konk' fer Old Missus but oh! it tuk my wind.

"Marse Murry would 'low me to drive his team when he would go to market. I could haul de cotton to Covin'ton an' bring back whut was to eat, an' all de oxen could pull was put on dat wagon. We allus had good eatin afte' we had been to market.

"Every Chris'mus would come I got a apple an' some candy an' mammy would cook cake an' pies fer Old Missus an' stack dem on de shelf in de big kitchen an' we had every thing good to eat. Dem people sho' was good an' kind to all niggers.

"Afte de war de times was hard an' de white an' black people was fightin' over who was to git de big office, an' den dere was mighty leetle to eat. Dar was plen'y whiskey, but I'se kep' 'way frum all dat. I was raised right. Old Missus taught me ter 'spect white folks an' some of dem promised me land but I niver got it. All de land I'se ever got I work mighty hard fer it an' I'se got it yit.

"One day afte' Mr. Gatlin said he couldn' pay me I run 'way an' went to New Orleans an' got a job haulin' cotton, an' made my 50 cents an' dinner every day. I sho' had me plen'y money den. I stayed dere mighty close on to fo' years an' den I went to Tylertown an' hauled cotton to de railroad fer Mr. Ben Lampton. Mr. Lampton said I was de bes' driver of his team he ever had caze I kep' his team fat.

"Afte I come back to Miss'ssippi I mar'ied a woman named Maggie Ransom. We stayed together 51 years. I niver hit her but one time. When we was gittin' mar'ied I stopped de preacher right in de ceremony an' said to her, 'Maggie, iffen you niver call me a liar I will niver call you one' an' she said, 'Jim, I won't call you a liar.' I said, 'That's a bargain' an' den de preacher went on wid de weddin'. Well, one day afte' we had been mar'ied' bout fo' years, she ast[FN: asked] me how come I was so late comin' to supper, an' I said I found some work to do fer a white lady, an' she said, that's a lie,' an' right den I raised my han' an' let her have it right by de side of de head, an' she niver called me a liar ag'in. No ma'm, dat is somethin' I won't stand fer.

"My old lady had seven chulluns dat lived to git grown. Two of 'em lived here in Magnolia an' de others gone North. Maggie is daid an' I live wid my boy Walter an' his wife Lena. Dey is mighty good to me. I owns dis here house an' fo' acres but day live wid me an' I gits a Confed'rate pension of fo' dollars a month. Dat gives me my coffee an' 'bacco. I'se proud I'se a old sojer, I seed de men fall when dey was shot but I was not skeered. We et bread when we could git it an' if we couldn' git it we done widout.

"Afte' I lef' Mr. Lampton I'se come here an' went to work fer Mr. Enoch at Fernwood when his mill was jes a old rattletrap of a mill. I work fer him 45 years. At fust I hauled timber out'n de woods an' afte' whil'st I hauled lumber to town to build houses. I sometimes collec' fer de lumber but I niver lost one nickle, an' dem white folks says I sho' was a honest nigger.

"I lived here on dis spot an' rode a wheel to Fernwood every day, an' fed de teams an' hitched 'em to de wagons an' I was niver late an' niver stopped fer anything, an' my wheel niver was in de shop. I niver 'lowed anybody to prank wid it, an' dat wheel was broke up by my gran'chulluns.

"Afte I quit work at de mill I'se come home an' plow gardens fer de white folks an' make some more money. I sho' could plow.

"I jined de New Zion Baptist Church here in Magnolia an' was baptized in de Tanghipoa River one Sunday evenin'. I was so happy dat I shouted, me an' my wife bofe. I'se still a member of dat church but I do not preach an' I'm not no deacon; I'se jes a bench member an' a mighty po' one at dat. My wife was buried frum dat church.

"Doan know why I was not called Jim Sandell, but mammy said my pappy was named Henry Cornelius an' I reckin I was give my pappy's name.

"When I was a young man de white folks' Baptist Church was called Salem an' it was on de hill whar de graveyard now is. It burnt down an' den dey brung it to town, an' as I was goin' to tell yer I went possum huntin' in dat graveyard one night. I tuk my ax an' dog 'long wid me an' de dog, he treed a possum right in de graveyard. I cut down dat tree an' started home, when all to once somethin' run by me an' went down dat big road lak light'ning an' my dog was afte' it. Den de dog come back an' lay down at my feet an' rolled on his back an' howled an' howled, an' right den I knowed it was a sperit an' I throwed down my 'possum an' ax an' beat de dog home. I tell you dat was a sperit—I'se seed plen'y of 'em. Dat ain't de only sperit I ever seed. I'se seen 'em a heap of times. Well, dat taught me niver to hunt in a grave yard ag'in.

"No ma'm, I niver seed a ghost but I tell yer I know dere is sperits. Let me tell yer, anudder time I was goin' by de graveyard an' I seed a man's head. He had no feet, but he kep' lookin' afte' me an' every way I turned he wouldn' take his eye offen me, an' I walked fast an' he got faster an' den I run an' den he run, an' when I got home I jes fell on de bed an' hollered an' hollered an' tol' my old lady, an' she said I was jes' skeered, but I'se sho' seed dat sperit an' I ain't goin' by de grave yard at night by myse'f ag'in.

An' let me tell yer dis. Right in front of dis house—yer see dat white house?—Well, last Febr'ary a good old cullud lady died in dat house, an' afte' she was buried de rest of de fambly moved away, an' every night I kin look over to dat house an' see a light in de window. Dat light comes an' goes, an' nobody lives dar. Doan I know dat is de sperit of dat woman comin' back here to tell some of her fambly a message? Yes ma'm, dat is her sperit an' dat house is hanted an' nobody will live dar ag'in.

"No ma'm, I can't read nor write."

"I was named Charlie Davenport an' encordin'[FN: according] to de way I figgers I ought to be nearly a hund'ed years old. Nobody knows my birthday, 'cause all my white folks is gone.

"I was born one night an' de very nex' mornin' my po' little mammy died. Her name was Lucindy. My pa was William Davenport.

"When I was a little mite dey turnt me over to de granny nurse on de plantation. She was de one dat 'tended to de little pickaninnies. She got a woman to nurse me what had a young baby, so I didn' know no dif'ence. Any woman what had a baby 'bout my age would wet nurse me, so I growed up in de quarters an' was as well an' as happy as any other chil'.

"When I could tote taters[FN: sweet potatoes] dey'd let me pick' em up in de fiel'. Us always hid a pile away where us could git' em an' roast' em at night.

"Old mammy nearly always made a heap o' dewberry an' 'simmon[FN: persimmon]. wine.

"Us little tykes would gather black walnuts in de woods an' store 'em under de cabins to dry.

"At night when de work was all done an' de can'les was out us'd set 'roun' de fire an' eat cracked nuts an' taters. Us picked out de nuts wid horse-shoe nails an' baked de taters in ashes. Den Mammy would pour herse'f an' her old man a cup o' wine. Us never got none o' dat less'n[FN: unless] us be's sick. Den she'd mess it up wid wild cherry bark. It was bad den, but us gulped it down, anyhow.

"Old Granny used to sing a song to us what went lak dis:

'Kinky head, whar-fore you skeered? Old snake crawled off, 'cause he's afeared. Pappy will smite 'im on de back Wid a great big club—ker whack! Ker whack!'

"Aventine, where I was born an' bred, was acrost Secon' Creek. It was a big plantation wid 'bout a hund'ed head o' folks a-livin' on it. It was only one o' de marster's places, 'cause he was one o' de riches' an' highes' quality gent'men in de whole country. I's tellin' you de trufe, us didn' b'long to no white trash. De marster was de Honorable Mister Gabriel Shields hisse'f. Ever'body knowed 'bout him. He married a Surget.

"Dem Surgets was pretty devilish; for all dey was de riches' fam'ly in de lan'. Dey was de out-fightin'es', out-cussin'es', fastes' ridin', hardes' drinkin', out-spendin'es' folks I ever seen. But Lawd! Lawd! Dey was gent'men even in dey cups. De ladies was beautiful wid big black eyes an' sof' white han's, but dey was high strung, too.

"De marster had a town mansion what's pictured in a lot o' books. It was called 'Montebella.' De big columns still stan' at de end o' Shields Lane. It burnt 'bout thirty years ago (1937).

"I's part Injun. I aint got no Nigger nose an' my hair is so long I has to keep it wropped[FN: wrapped]. I'se often heard my mammy was redish-lookin' wid long, straight, black hair. Her pa was a full blooded Choctaw an' mighty nigh as young as she was. I'se been tol' dat nobody dast[FN: dared] meddle wid her. She didn' do much talkin', but she sho' was a good worker. My pappy had Injun blood, too, but his hair was kinky.

"De Choctaws lived all 'roun' Secon' Creek. Some of 'em had cabins lak settled folks. I can 'member dey las' chief. He was a tall pow'ful built man named 'Big Sam.' What he said was de law, 'cause he was de boss o' de whole tribe. One rainy night he was kilt in a saloon down in 'Natchez Under de Hill.' De Injuns went wild wid rage an' grief. Dey sung an' wailed an' done a heap o' low mutterin'. De sheriff kep' a steady watch on' em, 'cause he was afeared dey would do somethin' rash. After a long time he kinda let up in his vig'lance. Den one night some o' de Choctaw mens slipped in town an' stobbed[FN: stabbed] de man dey b'lieved had kilt Big Sam. I 'members dat well.

"As I said b'fore, I growed up in de quarters. De houses was clean an' snug. Us was better fed den dan I is now, an' warmer, too. Us had blankets an' quilts filled wid home raised wool an' I jus' loved layin' in de big fat feather bed a-hearin' de rain patter on de roof.

"All de little darkeys he'ped bring in wood. Den us swept de yards wid brush brooms. Den sometimes us played together in de street what run de length o' de quarters. Us th'owed horse-shoes, jumped poles, walked on stilts, an' played marbles. Sometimes us made bows an' arrows. Us could shoot 'em, too, jus lak de little Injuns.

"A heap of times old Granny would brush us hide wid a peach tree limb, but us need it. Us stole aigs[FN: eggs] an' roasted 'em. She sho' wouldn' stan' for no stealin' if she knowed it.

"Us wore lowell-cloth shirts. It was a coarse tow-sackin'. In winter us had linsey-woolsey pants an' heavy cow-hide shoes. Dey was made in three sizes—big, little, an' mejum[FN: medium]. Twant no right or lef'. Dey was sorta club-shaped so us could wear 'em on either foot.

"I was a teasin', mis-che-vious chil' an' de overseer's little gal got it in for me. He was a big, hard fisted Dutchman bent on gittin' riches. He trained his pasty-faced gal to tattle on us Niggers. She got a heap o' folks whipped. I knowed it, but I was hasty: One day she hit me wid a stick an' I th'owed it back at her. 'Bout dat time up walked her pa. He seen what I done, but he didn' see what she done to me. But it wouldn' a-made no dif'ence, if he had.

"He snatched me in de air an' toted me to a stump an' laid me 'crost it. I didn' have but one thickness 'twixt me an' daylight. Gent'men! He laid it on me wid dat stick. I thought I'd die. All de time his mean little gal was a-gloatin' in my misery. I yelled an' prayed to de Lawd 'til he quit.

"Den he say to me,

'From now on you works in de fiel'. I aint gwine a-have no vicious boy lak you 'roun de lady folks.' I was too little for fiel' work, but de nex' mornin' I went to choppin' cotton. After dat I made a reg'lar fiel' han'. When I growed up I was a ploughman. I could sho' lay off a pretty cotton row, too.

"Us slaves was fed good plain grub. 'Fore us went to de fiel' us had a big breakfas' o' hot bread, 'lasses, fried salt meat dipped in corn meal, an' fried taters[FN: sweet potatoes]. Sometimes us had fish an' rabbit meat. When us was in de fiel', two women 'ud come at dinner-time wid baskets filled wid hot pone, baked taters, corn roasted in de shucks, onion, fried squash, an' b'iled pork. Sometimes dey brought buckets o' cold buttermilk. It sho' was good to a hongry man. At supper-time us had hoecake an' cold vi'tals. Sometimes dey was sweetmilk an' collards.

"Mos' ever' slave had his own little garden patch an' was 'lowed to cook out of it.

"Mos' ever plantation kep' a man busy huntin' an' fishin' all de time. (If dey shot a big buck, us had deer meat roasted on a spit.)

"On Sundays us always had meat pie or fish or fresh game an' roasted taters an' coffee. On Chris'mus de marster 'ud give us chicken an' barrels o' apples an' oranges. 'Course, ever' marster warnt as free handed as our'n was. (He was sho' 'nough quality.) I'se hear'd dat a heap o' cullud people never had nothin' good t'eat.

"I warnt learnt nothin' in no book. Don't think I'd a-took to it, nowhow. Dey learnt de house servants to read. Us fiel' han's never knowed nothin' 'cept weather an' dirt an' to weigh cotton. Us was learnt to figger a little, but dat's all.

"I reckon I was 'bout fifteen when hones' Abe Lincoln what called hisse'f a rail-splitter come here to talk wid us. He went all th'ough de country jus' a-rantin' an' a-preachin' 'bout us bein' his black brothers. De marster didn' know nothin' 'bout it, 'cause it was sorta secret-lak. It sho' riled de Niggers up an' lots of 'em run away. I sho' hear'd him, but I didn' pay 'im no min'.

"When de war broke out dat old Yankee Dutch overseer o' our'n went back up North, where he b'longed. Us was pow'ful glad an' hoped he'd git his neck broke.

"After dat de Yankees come a-swoopin' down on us. My own pappy took off wid 'em. He j'ined a comp'ny what fit[FN: fought] at Vicksburg. I was plenty big 'nough to fight, but I didn' hanker to tote no gun. I stayed on de plantation an' put in a crop.

"It was pow'ful on easy times after dat. But what I care 'bout freedom? Folks what was free was in misery firs' one way an' den de other.

"I was on de plantation closer to town, den. It was called 'Fish Pond Plantation.' De white folks come an' tol' us we mus' burn all de cotton so de enemy couldn' git it.

"Us piled it high in de fiel's lak great mountains. It made my innards hurt to see fire 'tached to somethin' dat had cost us Niggers so much labor an' hones' sweat. If I could a-hid some o' it in de barn I'd a-done it, but de boss searched ever'where.

"De little Niggers thought it was fun. Dey laughed an' brung out big armfuls from de cotton house. One little black gal clapped her han's an' jumped in a big heap. She sunk down an' down' til she was buried deep. Den de wind picked up de flame an' spread it lak lightenin'. It spread so fas' dat 'fore us could bat de eye, she was in a mountain of fiah. She struggled up all covered wid flames, a-screamin',' Lawdy, he'p me!' Us snatched her out an' rolled her on de groun', but twant no use. She died in a few minutes.

"De marster's sons went to war. De one what us loved bes' never come back no more. Us mourned him a-plenty, 'cause he was so jolly an' happy-lak, an' free wid his change. Us all felt cheered when he come 'roun'.

"Us Niggers didn' know nothin' 'bout what was gwine on in de outside worl'. All us knowed was dat a war was bein' fit. Pussonally, I b'lieve in what Marse Jefferson Davis done. He done de only thing a gent'man could a-done. He tol' Marse Abe Lincoln to 'tend to his own bus'ness an' he'd 'tend to his'n. But Marse Lincoln was a fightin' man an' he come down here an' tried to run other folks' plantations. Dat made Marse Davis so all fired mad dat he spit hard 'twixt his teeth an' say, 'I'll whip de socks off dem dam Yankees.'

"Dat's how it all come 'bout.

"My white folks los' money, cattle, slaves, an' cotton in de war, but dey was still better off dan mos' folks.

"Lak all de fool Niggers o' dat time I was right smart bit by de freedom bug for awhile. It sounded pow'ful nice to be tol':

'You don't have to chop cotton no more. You can th'ow dat hoe down an' go fishin' whensoever de notion strikes you. An' you can roam' roun' at night an' court gals jus' as late as you please. Aint no marster gwine a-say to you, "Charlie, you's got to be back when de clock strikes nine."'

"I was fool 'nough to b'lieve all dat kin' o' stuff. But to tell de hones' truf, mos' o' us didn' know ourse'fs no better off. Freedom meant us could leave where us'd been born an' bred, but it meant, too, dat us had to scratch for us ownse'fs. Dem what lef' de old plantation seemed so all fired glad to git back dat I made up my min' to stay put. I stayed right wid my white folks as long as I could.

"My white folks talked plain to me. Dey say real sad-lak, 'Charlie, you's been a dependence, but now you can go if you is so desirous. But if you wants to stay wid us you can share-crop. Dey's a house for you an' wood to keep you warm an' a mule to work. We aint got much cash, but dey's de lan' an' you can count on havin' plenty o' vit'als. Do jus' as you please.' When I looked at my marster an' knowed he needed me, I pleased to stay. My marster never forced me to do nary thing' bout it. Didn' nobody make me work after de war, but dem Yankees sho' made my daddy work. Dey put a pick in his han' stid[FN: instead] o' a gun. Dey made' im dig a big ditch in front o' Vicksburg. He worked a heap harder for his Uncle Sam dan he'd ever done for de marster.

"I hear'd tell 'bout some Nigger sojers a-plunderin' some houses: Out at Pine Ridge dey kilt a white man named Rogillio. But de head Yankee sojers in Natchez tried 'em for somethin' or nother an' hung 'em on a tree out near de Charity Horspital. Dey strung up de ones dat went to Mr. Sargent's door one night an' shot him down, too. All dat hangin' seemed to squelch a heap o' lousy goin's-on.

"Lawd! Lawd! I knows 'bout de Kloo Kluxes. I knows a-plenty. Dey was sho' 'nough devils a-walkin' de earth a-seekin' what dey could devour. Dey larruped de hide of'n de uppity Niggers an' driv[FN: drove] de white trash back where dey b'longed.

"Us Niggers didn' have no secret meetin's. All us had was church meetin's in arbors out in de woods. De preachers 'ud exhort us dat us was de chillun o' Israel in de wilderness an' de Lawd done sont us to take dis lan' o' milk an' honey. But how us gwine a-take lan' what's already been took?

"I sho' aint never hear'd' bout no plantations bein' 'vided up, neither. I hear'd a lot o' yaller Niggers spoutin' off how dey was gwine a-take over de white folks' lan' for back wages. Dem bucks jus' took all dey wages out in talk. 'Cause I aint never seen no lan' 'vided up yet.

"In dem days nobody but Niggers an' shawl-strop[FN: carpet baggers] folks voted. Quality folks didn' have nothin' to do wid such truck. If dey had a-wanted to de Yankees wouldn' a-let 'em. My old marster didn' vote an' if anybody knowed what was what he did. Sense didn' count in dem days. It was pow'ful ticklish times an' I let votin' alone.

"De shawl-strop folks what come in to take over de country tol' us dat us had a right to go to all de balls, church meetin's, an' 'tainments de white folks give. But one night a bunch o' uppity Niggers went to a 'tainment in Memorial Hall. Dey dressed deysef's fit to kill an' walked down de aisle an' took seats in de very front. But jus' 'bout time dey got good set down, de curtain drapped[FN: dropped] an' de white folks riz[FN: arose] up widout a-sayin' airy word. Dey marched out de buildin' wid dey chins up an' lef' dem Niggers a-settin' in a empty hall.

"Dat's de way it happen ever' time a Nigger tried to git too uppity. Dat night after de breakin' up o' dat' tainment, de Kloo Kluxes rid[FN: rode] th'ough de lan'. I hear'd dey grabbed ever' Nigger what walked down dat aisle, but I aint hear'd yet what dey done wid 'em.

"Dat same thing happened ever' time a Nigger tried to act lak he was white.

"A heap o' Niggers voted for a little while. Dey was a black man what had office. He was named Lynch. He cut a big figger up in Washington. Us had a sheriff named Winston. He was a ginger cake Nigger an' pow'ful mean when he got riled. Sheriff Winston was a slave an', if my mem'ry aint failed me, so was Lynch.

"My granny tol' me 'bout a slave uprisin' what took place when I was a little boy. None o' de marster's Niggers' ud have nothin' to do wid it. A Nigger tried to git 'em to kill dey white folks an' take dey lan'. But what us want to kill old Marster an' take de lan' when dey was de bes' frien's us had? Dey caught de Nigger an' hung 'im to a limb.

"Plenty folks b'lieved in charms, but I didn' take no stock in such truck. But I don't lak for de moon to shine on me when I's a-sleepin'.

"De young Niggers is headed straight for hell. All dey think' bout is drinkin' hard likker, goin' to dance halls, an' a-ridin' in a old rattle trap car. It beats all how dey brags an' wastes things. Dey aint one whit happier dan folks was in my day. I was as proud to git a apple as dey is to git a pint o' likker. Course, schools he'p some, but looks lak all mos' o' de young'n's is studyin' 'bout is how to git out o' hones' labor.

"I'se seen a heap o' fools what thinks 'cause they is wise in books, they is wise in all things.

"Mos' all my white folks is gone, now. Marse Randolph Shields is a doctor 'way off in China. I wish I could git word to' im, 'cause I know he'd look after me if he knowed I was on charity. I prays de Lawd to see 'em all when I die."

Gabe Emanuel is the blackest of Negroes. He is stooped and wobbly from his eighty-five years and weighs about one hundred and thirty-five pounds. His speech is somewhat hindered by an unbelievable amount of tobacco rolled to one side of his mouth. He lives in the Negro quarters of Port Gibson. Like most ex-slaves he has the courtesy and the gentleness of a southern gentleman.

"Lawsy! Dem slav'ry days done been s'long ago I jus' 'member a few things dat happen den. But I's sho' mighty pleased to relate dat what I recollec'.

"I was de house boy on old judge Stamps' plantation. He lived 'bout nine miles east o' Port Gibson an' he was a mighty well-to-do gent'man in dem days. He owned 'bout 500 or 600 Niggers. He made plenty o' money out o' his fiel's. Dem Niggers worked for dey keep. I 'clare, dey sho' did.

"Us 'ud dike out in spick an' span clean clothes come Sund'ys. Ever'body wore homespun clo'es den. De mistis an' de res' o' de ladies in de Big House made mos' of 'em. De cullud wimmins wore some kin' o' dress wid white aprons an' de mens wore overalls an' homespun pants an' shirts. Course, all de time us gits han'-me-downs from de folks in de Big House. Us what was a-servin' in de Big House wore de marster's old dress suits. Now, dat was somep'n'! Mos' o' de time dey didn' fit—maybe de pants hung a little loose an' de tails o' de coat hung a little long. Me bein' de house boy, I used to look mighty sprucy when I put on my frock tail.

"De mistis used to teach us de Bible on Sund'ys an' us always had Sund'y school. Us what lived in de Big House an' even some o' de fiel' han's was taught to read an' write by de white folks.

"De fiel' han's sho' had a time wid dat man, Duncan. He was de overseer man out at de plantation. Why, he'd have dem poor Niggers so dey didn' know if dey was gwine in circles or what.

"One day I was out in de quarters when he brung back old man Joe from runnin' away. Old Joe was always a-runnin' away an' dat man Duncan put his houn' dogs on 'im an' brung 'im back. Dis time I's speakin' 'bout Marster Duncan put his han' on old Joe's shoulder an' look him in de eye sorrowful-lak. 'Joe', he say, 'I's sho' pow'ful tired o' huntin' you. I'spect I's gwina have to git de marster to sell you some'r's else. Another marster gwina whup you in de groun' if he ketch you runnin' 'way lak dis. I's sho sad for you if you gits sol' away. Us gwina miss you 'roun' dis plantation.' After dat old Joe stayed close in an' dey warnt no more trouble out o' him.

"Dat big white man called Duncan, he seen dat de Niggers b'have deyse'ves right. Dey called him de 'Boss Man.' He always carried a big whup an' when dem Niggers got sassy, dey got de whup 'crost dey hides.

"Lawsy! I's recallin' de time when de big old houn' dog what fin' de run-away Niggers done die wid fits. Dat man Duncan, he say us gwina hol' fun'al rites over dat dog. He say us Niggers might better be's pow'ful sad when us come to dat fun'al. An' dem Niggers was sad over de death o' dat poor old dog what had chased 'em all over de country. Dey all stan' 'roun' a-weepin' an' a-mournin'. Ever' now an' den dey'd put water on dey eyes an' play lak dey was a-weepin' bitter, bitter tears. 'Poor old dog, she done died down dead an' can't kotch us no more. Poor old dog. Amen! De Lawd have mercy!'

"De Judge was a great han' for 'tainment[FN: entertainment]. He always had a house full o' folks an' he sho' give 'em de bes' o' food an' likker. Dey was a big room he kep' all polished up lak glass. Ever' now an' den he'd th'ow a big party an' 'vite mos' ever'body in Mississippi to come. Dey was fo' Niggers in de quarters what could sing to beat de ban', an' de Judge would git 'em to sing for his party.

"I 'member how 'cited I'd git when one o' dem shindigs 'ud come off. I sho' would strut den. De mistis 'ud dress me up an' I'd carry de likker an' drinks' roun' 'mongst de peoples. 'Would you prefer dis here mint julip, Marster? Or maybe you'd relish dis here special wine o' de Judge's. 'Dem white folks sho' could lap up dem drinks, too. De Judge had de bes' o' ever'thing.

"Dey was always a heap o' fresh meat in de meat house. De pantry fairly bu'sted wid all kin' o' preserves an' sweetnin's. Lawdy! I mean to tell you dem was de good days.

"I 'member I used to hate ever' Wednesday. Dat was de day I had to polish de silver. Lawsy! It took me mos' all day. When I'd think I was 'bout th'ough de mistis was sho' to fin' some o' 'dat silver dat had to be did over.

"Den de war broke out. De marster went 'way wid de sojers an' gradual' de hardness come to de plantation.

"Us never knowed when dem Yankee sojers would come spen' a few weeks at de Big House. Dey'd eat up all de marster's vit'als an' drink up all his good likker.

"I 'member one time de Yankees camped right in de front yard. Dey took all de meat out'n de curin' house. Well sir! I done 'cide by myse'f dat no Yankee gwina eat all us meat. So dat night I slips in dey camp; I stole back dat meat from dem thievin' sojers an' hid it, good. Ho! Ho! Ho! But dey never did fin' dat meat.

"One time us sot fire to a bridge de Yankees had to cross to git to de plantation. Dey had to camp on de other side, 'cause dey was too lazy to put out de fire. Dat's jus' lak I figgered it.

"When de war was over my mammy an' pappy an' us five chillun travelled here to Port Gibson to live. My mammy hired out for washin'. I don't know zackly what my pappy done.

"Lincoln was de man dat sot us free. I don't recollec' much 'bout 'im 'ceptin' what I hear'd in de Big House 'bout Lincoln doin' dis an' Lincoln doin' dat.

"Lawdy! I sho' was happy when I was a slave.

"De Niggers today is de same as dey always was, 'ceptin' dey's gittin' more money to spen'. Dey aint got nobody to make' em' 'have deyse'ves an' keep 'em out o' trouble, now.

"I lives here in Port Gibson an' does mos' ever' kin' o' work. I tries to live right by ever'body, but I 'spect I won't be here much longer.

"I'se been married three times.

"When de time comes to go I hopes to be ready. De Lawd God Almighty takes good care o' his chillun if dey be's good an' holy."

Dora Franks, ex-slave, lives at Aberdeen, Monroe County. She is about five feet tall and weighs 100 pounds. Her hair is inclined to be curly rather than kinky. She is very active and does most of her own work.

"I was born in Choctaw County, but I never knowed zackly how old I was, 'cause none o' my folks could read an' write. I reckon I be's 'bout a hund'ed, 'cause I was a big girl long time fo' Surrender. I was old 'nough to marry two years after dat.

"My mammy come from Virginny. Her name was Harriet Brewer. My daddy was my young Marster. His name was Marster George Brewer an' my mammy always tol' me dat I was his'n. I knew dat dere was some dif'ence 'tween me an' de res' o' her chillun, 'cause dey was all coal black, an' I was even lighter dan I is now. Lawd, it's bean to my sorrow many a time, 'cause de chillun used to chase me 'round an' holler at me, 'Old yallow Nigger.' Dey didn' treat me good, neither.

"I stayed in de house mos' o' de time wid Miss Emmaline. Miss Emmaline's hair was dat white, den. I loved her' cause she was so good to me. She taught me how to weave an' spin. 'Fore I was bigger'n a minute I could do things dat lots o' de old han's couldn' come nigh doin'. She an' Marse Bill had 'bout eight chillun, but mos' of 'em was grown when I come 'long. Dey was all mighty good to me an' wouldn' 'low nobody to hurt me.

"I 'members one time when dey all went off an' lef' me wid a old black woman call Aunt Ca'line what done de cookin' 'round de place some o' de time. When dey lef' de house I went in de kitchen an' asked her for a piece o' white bread lak de white folks eat. She haul off an' slap me down an' call me all kin' o' names dat I didn' know what dey meant. My nose bled an' ruint de nice clean dress I had on. When de Mistis come back Marse George was wid 'er. She asked me what on earth happen to me an' I tol' 'er. Dey call Ca'line in de room an' asked her if what I say was de truf. She tell 'em it was, an' dey sent 'er away. I hear tell dat dey whup her so hard dat she couldn' walk no mo'.

"Us never had no big fun'als or weddin's on de place. Didn' have no marryin' o' any kin'. Folks in dem days jus' sorter hitched up together an' call deyse'ves man an' wife. All de cullud folks was buried on what dey called Platnum Hill. Dey didn' have no markers nor nothin' at de graves. Dey was jus' sunk in places. My brother Frank showed me once where my mammy was buried. Us didn' have no preachin', or singin', or nothin', neither. Us didn' even git to have meetin's on Sund'y less us slip off an' go to some other plantation. Course, I got to go wid de white folks sometime an' set in de back, or on de steps. Dat was whan I was little.

"Lots o' Niggers would slip off from one plantation to de other to see some other Niggers. Dey would always manage to git back' fore daybreak. De wors' thing I ever heard 'bout dat was once when my Uncle Alf run off to 'jump de broom.' Dat was what dey called goin' to see a woman. He didn' come back by daylight, so dey put de Nigger hounds after him. Dey smelled his trail down in de swamp an' foun' where he was hidin'.

"Now, he was one of da biggest Niggers on de place an' a powerful fas' worker. But dey took an' give him 100 lashes wid de cat o' ninety-nine tails. His back was somethin' awful, but dey put him in de fiel' to work while de blood was still a-runnin'. He work right hard 'til dey lef'. Den, when he got up to de end o' de row nex' to de swamp, he lit out ag'in.

"Dey never foun' 'im dat time. Dey say he foun' a cave an' fix him up a room whar he could live. At nights he would come out on de place an' steal enough t'eat an' cook it in his little dugout. When de war was over an' de slaves was freed, he come out. When I saw him, he look lak a hairy ape, 'thout no clothes on an' hair growin' all over his body.

"Dem was pretty good days back in slav'ry times. My Marstar had a whole passal o' Niggers on his place. When any of 'em would git sick dey would go to de woods an' git herbs an roots an' make tea for 'em to drink. Hogweed an' May apples was de bes' things I knowed of. Sometimes old Mistis doctored 'em herse'f. One time a bunch o' us chillun was playin' in de woods an foun' some o' dem May apples. Us et a lot of 'em an' got awful sick. Dey dosed us up on grease an' Samson snake root to clean us out. An' it sho' done a good job. I'se been a-usin' dat snake root ever since.

"De firs' thing dat I 'member hearin' 'bout de war was one day when Marse George come in de house an' tell Miss Emmaline dat dey's gwine have a bloody war. He say he feared all de slaves 'ud be took away. She say if dat was true she feel lak jumpin' in de well. I hate to hear her say dat, but from dat minute I started prayin' for freedom. All de res' o' de women done de same.

"De war started pretty soon after dat an' all de men folks went off an' lef' de plantation for de women an' de Niggers to run. Us seen de sojers pass by mos' ever' day. Once de Yankees come an' stole a lot o' de horses an' somp'in' t'eat. Dey even took de trunk full o' 'Federate money dat was hid in de swamp. How dey foun' dat us never knowed.

"Marse George come home' bout two years after de war started an' married Miss Martha Ann. Dey had always been sweethearts. Dey was promised 'fore he lef'.

"Marse Lincoln an' Marse Jeff Davis is two I 'members 'bout. But, Lawzee! Dat was a long time back. Us liked Marse Jeff Davis de bes' on de place. Us even made up a song 'bout him, but, I 'clare 'fore goodness, I can't even 'member de firs' line o' dat song. You see, when I got 'ligion, I asked de Lawd to take all de other songs out o' my head an' make room for his word.

"Since den it's de hardes' thing in de worl' for me to 'member de songs us used to dance by. I do' member a few lak 'Shoo, Fly', 'Old Dan Tucker', an' 'Run, Nigger, Run, de Pateroller Catch You.' I don' 'member much o' de words. I does 'member a little o' 'Old Dan Tucker.' It went dis way:

'Old Don Tucker was a mighty mean man, He beat his wife wid a fryin' pan. She hollered an' she cried, "I's gwineter go, Dey's plenty o' men, won't beat me so." 'Git out o' de way, Old Dan Tucker, You come too late to git yo' supper. 'Old Dan Tucker, he got drunk, Fell in de fire, kicked up a chunk, Red hot coal got down his shoe Oh, Great Lawd, how de ashes flew. 'Git out o' de way, Old Dan Tucker, You come too late to git yo' supper.'

"When de war was over, my brother Frank slipped in de house where I was still a-stayin'. He tol' me us was free an' for me to come out wid de res'. 'Fore sundown dere warnt one Nigger lef' on de place. I hear tell later dat de Mistis an' de gals had to git out an' work in de fiel's to he'p gather in de crop.

"Frank foun' us a place to work an' put us all in de fiel'. I never had worked in de fiel' before. I'd faint away mos' ever'day 'bout eleven o'clock. It was de heat. Some of 'em would have to tote me to de house. I'd soon come to. Den I had to go back to de fiel'. Us was on Marse Davis Cox's place den.

"Two years later I met Pet Franks an' us married. De Cox's was good folks an' give us a big weddin'. All de white folks an' de Niggers for miles a-round come to see us git married. De Niggers had a big supper an' had a peck t'eat. Us had eight chillun, but aint but three of 'em livin'. Me an' Pet aint been a-livin' together for de las' twenty-three years. Us jus' couldn' git 'long together, so us quit. He lives out at Acker's Fishing Lodge now an' does de cookin' for 'em.

"I never will forgit de Klu Klux Klan. Never will [TR: "I" deleted] forgit de way dat horn soun' at night when dey was a-goin' after some mean Nigger. Us'd all run an' hide. Us was livin' on de Troup place den, near old Hamilton, in one o' de brick houses back o' de house whar dey used to keep de slaves. Marse Alec Troup was one o' de Klu Klux's an' so was Marse Thad Willis dat lived close by. Dey'd make plans together sometime an' I'd hear 'em. One time dey caught me lis'nin', but dey didn' do nothin' to me, 'cause dey knowed I warnt gwine tell. Us was all good Niggers on his place.

"Lawd, Miss, dese here young folks today is gwine straight to de Devil. All dey do all day an' all night is run 'round an' drink corn likker an' ride in automobiles. I'se got a grand-daughter here, an' she's dat wil'. I worries a right smart 'bout her, but it don't do no good, 'cause her mammy let her do jus' lak she please anyhow.

"Den I tells you, de one thing I worries 'bout mos'. Dat is de white folks what lives here 'mongst de Niggers. You know what kinda folks dey is, an' it sho' is bad influence on 'em. You knows Niggers aint s'posed to always know de right from de wrong. Dey aint got Marsters to teach 'em now. For de white folks to come down here an' do lak dey do, I tells you, it aint right. De quality white folks ought-a do somethin' bout it.

"I's had a right hard life, but I puts my faith in de Lawd an' I know ever'thing gwine come out all right. I's lived a long life an' will soon be a hund'ed, I guess. I's glad dat slav'ry is over, 'cause de Bible don't say nothin' 'bout it bein right. I's a good Christian. I gits sort-a res'less mos' o' de time an' has to keep busy to keep from thinkin' too much."

Uncle Pet, 92 year old ex-slave, is the favorite of Ackers' Fishing Lodge which is situated 14 miles north of Aberdeen, Monroe County. He is low and stockily built. His ancestry is pure African. Scarcely topping five feet one inch, he weighs about 150 pounds. Though he walks with the slightest limp, he is still very active and thinks nothing of cooking for the large groups who frequent the lodge. He has his own little garden and chickens which he tends with great care.

"I knows all 'bout slav'ry an' de war. I was right dere on de spot when it all happened. I wish to goodness I was back dere now, not in de war, but in de slav'ry times. Niggers where I lived didn' have nothin' to worry 'bout in dem days. Dey aint got no sense now-a-days. All dey b'lieves in now is drinkin' an' carousin'. Dey aint got no use for nothin' but a little corn likker an' a fight. I dont b'lieve in no such gwine-on, no sir-ree. Dat's de reason I stays out here by myse'f all de time. I don't want to have nothin' to do wid 'em. I goes to town 'bout once a mont' to git s'pplies, but I don' never fool 'roun' wid dem Niggers den. I gits 'long wid my white folks, too. All da mens an' wimmens what comes out to de club is pow'ful good to me.

"I was born up near Bartley's Ferry right on de river. De way I cal'clates my age makes me 'bout 92 years old. My firs' Marster was name Mr. Harry Allen. He died when I was a boy an' I don't 'member much 'bout him. De Mistis, dat was his wife, married ag'in an' dat husband's name was Marse Jimmy Tatum. Dey was sho' good white folks. My mammy an' pappy was name Martha an' Martin Franks. Marse Harry brung 'em down from Virginny, I thinks. Or else he bought 'em from Marse Tom Franks in West Point. Anyways dey come from Virginny an' I don't know which one of 'em brought 'em down here. Dey did b'long to Marse Tom. I knows dat.

"Bartley's used to be some place. My folks had a big hotel down on de river bank. Dey was a heap of stores right on de bank, too. De river done wash' em all 'way now. Dey aint nothin' lef'. But Lawdy! When I was a kid de boats used to come a-sailin' up de river 'bout once a week an' I used to know de names o' all de big ones. Dey would stop an' pick up a load o' cotton to carry to Mobile. When dey come back dey would be loaded wid all kin' o' gran' things.

"Us chillun had a big time playin' roun' de dock. Us played 'Hide de Switch' an' 'Goose and Gander' in de day time. Den at nighttime when de moon was shinin' big an' yaller, us'd play 'Ole Molly Bright.' Dat was what us call de moon. Us'd make up stories 'bout her. Dat was de bes' time o' all. Sometimes de old folks would join in an' tell tales too. Been so long I forgits de tales, but I know dey was good'ns.

"When I got big 'nough to work I he'ped 'roun' de lot mostly. Fac' is I'se worked right 'roun' white folks mos' all my days. I did work in de fiel' some, but us had a good overseer. His name was Marse Frank Beeks an' he was good as any white man dat ever lived. I don't never 'member him whippin' one o' de slaves, leastways not real whippin's. I do 'member hearin' 'bout slaves on other places gittin' whipped sometimes. I guess Niggers lak dat wished dey was free, but I didn' want to leave my white folks, ever.

"Us had preachin' an' singin'. Dey was some mighty good meetin's on de place. Old Daddy Young was 'bout de bes' preacher us ever had. Dey was plenty o' Niggers dere, 'cause it was a powerful big place. Old Daddy could sho' make 'em shout an' roll. Us have to hol' some of 'em dey'd git so happy. I knowed I had 'ligion when I got baptized. Dey took me out in de river an' it took two of 'em to put me under. When I come up I tol' 'em, 'turn me loose, I b'lieve I can walk right on top o' de water.' Dey don' have no 'ligion lak dat now-a-days.

"All de Niggers on de Tatum place had dey own patches where dey could plant what ever day wanted to. Dey'd work 'em on Satu'd'ys. When dey sol' anything from dey patch Mistis 'ud let 'em keep de money. When de boats went down to Mobile us could sen' down for anything us want to buy. One time I had $10.00 saved up an' I bought lots o' pretties wid it. Us always had plenty t'eat, too. All de greens, eggs, wheat, corn, meat, an' chitlins dat anybody'd want. When hog killin' time come us always have some meat lef' over from de year befo'. Us made soap out of dat.