| Note: |

Images of the original pages are available through the Florida

Board of Education, Division of Colleges and Universities,

PALMM Project, 2001. (Preservation and Access for American and

British Children's Literature, 1850-1869.) See http://purl.fcla.edu/fcla/dl/UF00001875.jpg or http://purl.fcla.edu/fcla/dl/UF00001875.pdf |

This little work, with its companion, Jonas On A Farm In Summer, is intended as the continuation of a series, the first two volumes of which, Jonas's Stories and Jonas A Judge, have already been published. They are all designed, not merely to interest and amuse the juvenile reader, but to give him instruction, by exemplifying the principles of honest integrity, and plain practical good sense, in their application to the ordinary circumstances of childhood.

CHAPTER II.

COMMANDING AND OBEYING

CHAPTER VIII.

THE CARDING-MILL

CHAPTER XI.

THE SNOW FORT, OR GOOD FOR EVIL

MORNING

Early one winter morning, while Jonas was living upon the farm, in the employment of Oliver's father, he came groping down, just before daylight, into the great room.

The great room was, as its name indicated, quite large, occupying a considerable portion of the lower floor of the farmer's house. There was a very spacious fireplace in one side, with a settle, which was a long seat, with a very high back, near it. The room was used both for kitchen and parlor, and there was a great variety of furniture in different parts of it. There were chairs and tables, a bookcase with a desk below, a loom in one corner by a window, and a spinning-wheel near it. Then, there were a great many doors. One led out into the back yard, one up stairs, one into a back room,—which was used for coarse work, and which was generally called the kitchen,—and one into a large store closet adjoining the great room.

Jonas groped his way down stairs; but as soon as he opened the great room door, he found the room filled with a flickering light, which came from the fireplace. There was a log there, which had been buried in the ashes the night before. It had burned slowly, through the night, and the fire had broken out at one end, which now glowed like a furnace, and illuminated the whole room with a faint red light.

Jonas went up towards the fire. The hearth was very large, and formed of great, flat stones. On one side of it was a large heap of wood, which Jonas had prepared the night before, to be ready for his fire. On the other side was a black cat asleep, with her chin upon her paws. When the cat heard Jonas coming, she rose up, stretched out her fore paws, and then began to purr, rubbing her cheeks against the bottom of the settle.

"Good morning, Darco," said Jonas. "It is time to get up."

The cat's name was Darco.

Jonas took a pair of heavy iron tongs, which stood by the side of the fire, and pulled forward the log. He found that it had burned through, and by three or four strokes with the tongs, he broke it up into large fragments of coal, of a dark-reddish color. The air being thus admitted, they soon began to brighten and crackle, until, in a few minutes, there was before him a large heap of glowing and burning coals. He put a log on behind, then placed the andirons up to the log, and a great forestick upon the andirons. He placed the forestick so far out as to leave a considerable space between it and the backlog, and then he put the coals up into this space,—having first put in a slender stick, resting upon the andirons, to keep the coals from falling through. He then placed on a great deal more wood, and he soon had a roaring fire, which crackled loud, and blazed up into the chimney.

"Now for my lantern," said Jonas.

So saying, he took down a lantern, which hung by the side of the fire. The lantern was made of tin, with holes punched through it on all sides, so as to allow the light to shine through; and yet the holes were not large enough to admit the wind, to blow out the light.

Jonas opened the lantern, and took out a short candle from the socket within. Just as he was lighting it, the door opened, and Amos came in.

"Ah, Jonas," said he, "you are before me, as usual."

"Why, the youngest hand makes the fire, of course," said Jonas.

"Then it ought to be Oliver," said Amos,—"or else Josey."

"There! I promised to wake Oliver up," said Jonas.

"O, he's awake; and he and Josey are coming down. They have found out that there is snow on the ground."

"Is there much snow?" asked Jonas.

"I don't know," said Amos; "the ground seems pretty well covered. If there is enough to make sledding, you are going after wood to-day."

"And what are you going to do?" said Jonas.

"I am going up among the pines to get out the barn frame, I believe."

Here a door opened, and Oliver came in, followed by Josey shivering with the cold, and in great haste to get to the fire.

"Didn't your father say," said Amos to Oliver, "that he was going with me to-day, to get out the timber for the barn frame?"

"Yes," said Oliver, "he is going to build a great barn next summer. But I'm going up into the woods with Jonas, to haul wood. There's plenty of snow."

"I'd go too," said Josey, "if it wasn't so cold."

"It won't be cold in the woods," said Jonas. "There's no wind in the woods."

While they had been talking thus, Jonas had got his lantern ready, and had gone to the door, and stood there a minute, ready to go out.

"Jonas," said Josey, "are you going out into the barn?"

"Yes," said Jonas.

"Wait a minute, then, for me, just till I put on my other boot."

Jonas waited a minute, according to Josey's request, and then they all went out together.

They found the snow pretty deep, all over the yard, but they waded through it to the barn. They had to go through a gate, which led them into the barn-yard. From the barn-yard they entered the barn itself, by a small door near one corner.

There were two great doors in the middle of the barn, made so large that, when they were opened, there was space enough for a large load of hay to go in. Opposite these doors there was a space floored over with plank, pretty wide, and extending through the barn to the back side. This was called the barn floor. On one side was a place divided off for stables for the horses, and on the other side was the tie-up, a place for the oxen and cows. There was also the bay, and the lofts for hay and grain; and at the end of the tie-up there was a door leading into a calf-pen, and thence, by a passage behind the calf-pen, to a work-shop and shed. The small door where the boys came in, led to a long and narrow passage, between the tie-up and the bay.

They walked along, Jonas going before with his lantern in his hand. The cattle which had lain down, began to get up, and the horses neighed in their stalls; for the shining of the lantern in the barn was the well-known signal which called them to breakfast.

Jonas clambered up by a long ladder to the hay-loft, to pitch down some hay, and Josey and Oliver followed him; while Amos remained below to "feed out" the hay, as he called it, as fast as they pitched it down. It was pretty dark upon the loft, although the lantern shed a feeble light upon the rafters above.

"Boys," said Jonas, "it is dangerous for you to be up here; I'd rather you'd go down."

"Well," said Oliver, and he began to descend.

"Why?" said Josey; "I don't think there's any danger."

"Yes," said Jonas, "a pitchfork wound is worse than almost any other. It is what they call a punctured wound."

"What kind of a wound is that?" said Josey.

"I'll tell you some other time," said Jonas. "But don't stay up here. You don't obey so well as Oliver. Go down and give the old General some hay."

The old General was the name of a large white horse, quite old and steady, but of great strength. When he was younger, he belonged to a general, who used to ride him upon the parade, and this was the origin of his name.

Josey, at this proposal, made haste down the ladder, and began to put some hay over into the old General's crib. He then went round into the General's stall, and, patting him upon the neck, he asked him if his breakfast was good.

In the mean time, Oliver opened the great barn doors, and, taking a shovel, he began to clear away the snow from before them. The sky in the east was by this time beginning to be quite bright; and a considerable degree of light from the sky, and from the new-fallen snow, came into the barn. Josey got a shovel, and went out to help Oliver. After they had shoveled away the snow from the great barn doors, they went to the house, and began to clear the steps before the doors, and to make paths in the yards. They worked in this way for half an hour, and then, just as the sun began first to show its bright, glittering rays above the horizon, they went into the house. They found that the great fire which Jonas had built, was burnt half down; the breakfast-table was set, and the breakfast itself was nearly ready.

The boys came to the fireplace, to see what they were going to have for breakfast.

"Boys," said the farmer's wife, while she was turning her cakes, "go and call Amos in to family prayers,—and Jonas."

"You go, Oliver," said Josey.

Oliver said nothing, but obeyed his mother's direction. He went into the barn-yard, and he found Amos and Jonas at work in a shed beyond, getting down a sled which had been stowed away there during the summer. It was a large and heavy sled, and had a tongue extending forward to draw it by.

"What are you getting out that sled for?" said Oliver.

"To haul wood on," said Jonas. "We're going to haul wood after breakfast, and I want to get all ready."

There was another smaller and lighter sled, which had been upon the top of the heavy one, before Amos and Jonas had taken it off. This smaller sled had two shafts to draw it by, instead of a tongue. Jonas knew by this, that it was intended to be drawn by a horse, while the one with a tongue was meant for oxen.

"Oliver," said Jonas, "I think it would be a good plan for you and Josey to take this sled and the old General, and go with me to haul wood."

"Well," said Oliver, "I should like it very much."

"We can all go up together. You and Josey can be loading the horse-sled, while I load the ox-sled, and then we can drive them down, and so get two loads down, instead of one."

"Well," said Oliver, "I mean to ask my father."

"Or perhaps," continued Jonas, "you can be teamster for the oxen, and Josey can drive the horse, and so I remain up in the woods, cutting and splitting."

"No," said Oliver, "because we can't unload alone."

"No," said Jonas; "I had forgotten that."

"But I mean to ask my father," said Oliver, "to let me have the old General, and haul a load down when you come."

So saying, the boys walked along towards the house. The sun was now shining beautifully upon the fresh snow, making it sparkle in every direction, all around. They walked in by the path which Oliver and Josey had shoveled.

"Why didn't you make your path wider?" said Amos. "This isn't wide enough for a cow-path."

"O, yes, Amos," said Jonas, "it will do very well. I can widen it a little when I come out after breakfast."

When they got to the door, Jonas stopped a moment to look around. The fields were white in every direction, and the branches of the trees near the house were loaded with the snow. The air was keen and frosty, and the breaths of the boys were visible by the vapor which was condensed by the cold. The pond was one great level field of dazzling white. All was silent—nothing was seen of life or motion, except that Darco, who came out when the door was opened, looked around astonished, took a few cautious steps along the path, and then, finding the snow too deep and cold, went back again to take her place once more by the fire.

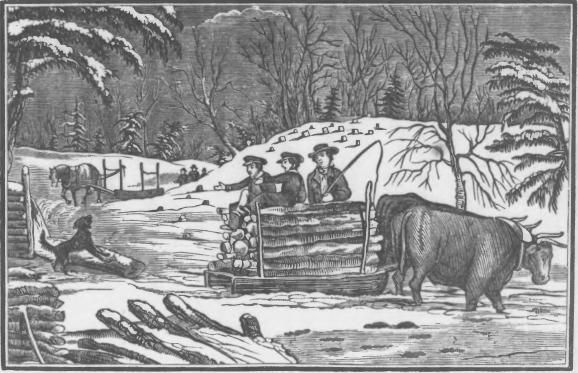

COMMANDING AND OBEYING

About an hour after breakfast, Jonas with the oxen, and Oliver and Josey with the horse, were slowly moving along up the road which led back from the pond towards the wood lot. The wood lot was a portion of the forest, which had been reserved, to furnish a supply of wood for the winter fires. The road followed for some distance the bank of the brook, which emptied into the pond at the place where Jonas and Oliver had cleared land, when Jonas first came to live on this farm.

It was a very pleasant road. The brook was visible here and there through the bushes and trees on one side of it. These bushes and trees were of course bare of leaves, excepting the evergreens, and they were loaded down with the snow. Some were bent over so that the tops nearly touched the ground.

The brook itself, too, was almost buried and concealed in the snow. In the still places, it had frozen over; and so the snow had been supported by the ice, and thus it concealed both ice and water. At the little cascades and waterfalls, however, which occurred here and there, the water had not frozen. Water does not freeze easily where it runs with great velocity. At these places, therefore, the boys could see the water, and hear it bubbling and gurgling as it fell, and disappeared under the ice which had formed below.

At last, they came to the wood lot. The wood which they were going to haul had been cut before, and it had been piled up in long piles, extending here and there under the trees which had been left. These piles were now, however, partly covered with the snow, which lay light and unsullied all over the surface of the ground.

The sticks of wood in these piles were of different sizes, though they were all of the same length. Some had been cut from the tops of the trees, or from the branches, and were, consequently, small in diameter; others were from the trunks, which would, of course, make large logs. These logs had, however, been split into quarters by a beetle and wedges, when the wood had been prepared, so that there were very few sticks or logs so large, but that Jonas could pretty easily get them on to the sled.

Jonas drove his team up near to one end of the pile, while Josey and Oliver went to the other, where the wood was generally small. While Jonas was loading, he heard a conversation something like this between the other boys:—

"Let's put some good large logs on our sled," said Josey.

"Well," said Oliver, "as large as we can; only we'd better put this small wood on first."

"I wish you'd go around to the other side, Oliver," said Josey again; "you're in my way."

"No," said Oliver, "I can't work on that side very well."

"Then I mean to move the old General round a little."

"No," said Oliver, "the sled stands just right now; only you get up on the top of the pile, and I'll stay here." "No," said Josey, "I'd rather stand here myself."

So the boys continued at work a few minutes longer, each being in the other's way.

At length, Josey said again,—

"O, here is a large log, and I mean to get it out, and put it upon our sled."

The log was covered with smaller wood, so that Josey could only get hold of the end of it. He clasped his hands together under this end, and began to lift it up, endeavoring to get it free from the other wood. He succeeded in raising it a little, but it soon got wedged in again, worse than before.

"Come, Oliver," said Josey, "help me get out this log. It is rock maple."

"No," said Oliver, "I'm busy."

"Jonas," said Josey, calling out aloud, "Jonas, here's a stick of wood, which I can't get out. I wish you'd come and help me."

In answer to this request, Jonas only called both the boys to come to him.

They accordingly left the old General standing in the snow, with his sled partly loaded, and came to the end of the pile, where Jonas was at work.

"I see you don't get along very well," said Jonas.

"Why, you see," said Josey, "that Oliver wouldn't help me put on a great log."

"The difficulty is," said Jonas, "that you both want to be master. Whereas, when two people are working together, one must be master, and the other servant."

"I don't want to be servant," said Josey.

"It's better to be servant on some accounts," said Jonas; "then you have no responsibility."

"Responsibility?" repeated Josey.

"Yes," said Jonas. "Power and responsibility always go together;—or at least they ought to. But come, boys, be helping me load, while we are settling this difficulty, so as not to lose our time."

So the boys began to put wood upon Jonas's sled, while the conversation continued as follows:—

"Can't two persons work together, unless one is master, and the other servant?" asked Josey.

"At least," replied Jonas, "one must take the lead, and the other follow, in order to work to advantage. There must be subordination. For you see that, in all sorts of work, there are a great many little questions coming up, which are of no great consequence, only they ought to be decided, one way or the other, quick, or else the work won't go on. You act, in your work, like Jack and Jerry, when they ran against the horse-block."

"Why, how was that?" said Josey.

"They were drawing the wagon along to harness the horse in, and the horse-block was in the way; so they both got hold of the shafts, and Jack wanted to pull it around towards the right, while Jerry said it would be better to have it go to the left. So they pulled, one one way, and the other the other, and thus they got it up chock against the horse-block, one shaft on each side. Here they stood pulling in opposition for some time, and all the while their father was waiting for them to turn the wagon, and harness the horse."

"What did he say to them," said Oliver, "when he found it out?"

"He made Jack bring it round Jerry's way, and then made Jerry draw it back again, and bring it along Jack's way.

"When men are at work," continued Jonas, "one acts as director, and the rest follows on, as he guides. Then all the unimportant questions are decided promptly."

"Well," said Josey, "let us do so, Oliver. I'll be director."

"How do they decide who shall be director?" said Oliver.

"The oldest and most experienced directs, generally; or, if one is the employer, and the others are employed by him, then the employer directs the others. If a man wants a stone bridge built, and hires three men to do it, there is always an understanding, at the beginning, who shall have the direction of the work, and all the others obey.

"So," continued Jonas, "if a carpenter were to send two of his men into the woods to cut down a tree for timber, without saying which of them should have the direction,—then the oldest or most experienced, or the one who had been the longest in the carpenter's employ, would take the direction. He would say, 'Let us go out this way,' and the other would assent; or, 'I think we had better take this tree,' and the other would say, perhaps, 'Here's one over here which looks rather straighter; won't you come and look at this?' But they would not dispute about it. One would leave it to the other to decide."

"Suppose," said Josey, "one was just as old and experienced as the other."

"Why, if there was no reason, whatever, why one should take the lead, rather than the other, then they would not either of them be tenacious of their opinion. If one proposed to do a thing, the other would comply without making any objection, unless he had a very decided objection indeed. So they would get along peaceably.

"Now," continued Jonas, "boys are very apt to have different opinions, and to be very tenacious of them, and so get into disputes and difficulties when they are working together. Therefore, when boys are set to work, it is generally best to appoint one to take charge; for they haven't, generally, good sense enough to find out, themselves, which it is most proper should be in charge.

"For instance, now," continued Jonas, "which of you, do you think, on the whole, is the proper one to take the direction of the work, when you are set to work together?"

"I," said Josey, with great promptness.

Oliver did not answer a tall.

"There's one reason why you ought not to be the one," said Jonas.

"What is it?" said Josey.

"Why, you don't obey very well. No person is well qualified to command, until he has learned to obey."

"I obey," said Josey, "I'm sure."

"Not always," said Jonas. "This morning, when you were upon the haymow, and I told you both to go down, Oliver went down immediately; but you remained up, and made excuses instead of obeying."

Josey was silent. He perceived that Jonas's charge against him was just.

"Besides," continued Jonas, "there are some other reasons why Oliver should command, rather than you. First he understands more of farmer's work, being more accustomed to it; secondly, he is older."

"No," interrupted Josey, "he isn't older. I'm the oldest."

"Are you?" said Jonas.

"Yes," replied Josey. "I'm two months older than he is."

Oliver had so much more prudence and discretion, and being, besides, a little larger than Josey, made Jonas think that he was older.

"Well," said Jonas, "at any rate, he has more judgement and experience, and he certainly obeys better. So you may go back to your work, and let Oliver take the command, and then, after a little while, if Oliver says that you have obeyed him well, I'll try the experiment of letting you, Josey, command."

The boys accordingly went back, and finished loading up the old General. Oliver took the direction, and Josey obeyed very well. Now and then he would forget for a moment, and begin to argue; but Josey would submit pretty readily, for he was very desirous that Jonas would let him command next time; and he thought that he would not allow him to command until he had learned to obey.

They had the two sleds loaded nearly at the same time, and then went down. When they were going back after the second load, they all got on to Jonas's sled, which was forward, to ride, leaving the old General to follow with his sled. He was so well trained that he walked along very steadily. Oliver fastened the reins to one of the stakes, so that they should not get down under the horse's feet. The boys all got together upon the forward sled, in order that they might talk with one another as they were going back to the woods.

"Now, Josey," said Jonas, "we will let you have the command for the next trip, and, while we are going back, I will give you both some instructions."

"About obeying?" said Josey.

"Yes, and about commanding too," said Jonas. "It requires rather more skill to know how to command, than how to obey; to know how to direct work, than to know how to execute it. A good director, in the first place, takes care to plan wisely, and he feels a responsibility about the work, and a desire to have it go on to good advantage. If some men build a way, and, after it is finished, it tumbles down, the man who had charge of the work would feel more concerned about it than any of the others, because the chief responsibility comes upon him. So with your work,—if you have the command, and you and Oliver idle away the time, and when my sled is loaded, yours has but little wood in it, you would be more to blame than Oliver."

"What, if I didn't play any more than Oliver?"

"Yes," said Jonas, "because you are responsible. It is your duty to be industrious, and it is also your duty to see that Oliver is industrious, if you are the director,—so that you neglect two duties.

"It is a good plan, too," said Jonas, "for a director to give his directions in a mild and gentle tone. Some boys are very domineering and authoritative in their manner."

"How do you mean?" said Josey.

"Why, they would say, for example, 'Get out of the way, John, quick.' Whereas, it would be better to say, 'John, you are in the way, where we want to come along.' Some men give their directions with great noise and vociferation, and others give them quietly and gently."

"I shouldn't think they'd mind 'em," said Josey.

"Yes," said Jonas. "Directions ought to be given very distinctly, so as to be plainly understood; but they are not obeyed any better for violence and noise in giving them. "

A commander ought to have a regard for those under him," continued Jonas, "and deal justly by them. If a number of boys were going to ride a wagon, and their father put one of them in charge, he ought not to keep the best seat in the wagon for himself."

While talking thus, the oxen continued slowly advancing along the road. Their previous trip had broken out the road, but the pathway was filled with loose snow of a pure and spotless white, through which the great sled runners, following the oxen, ploughed their way. On each side of the track which they had made, the surface was smooth and unbroken, excepting under some of the trees, where masses of snow had fallen down from above. They saw, at length, as they were passing along by the brook, a little track, like a double dotting, running along, in a winding way, under the trees,—then crossing the road, and disappearing under the trees upon the other side.

"What's that?" asked Josey.

"That's a rabbit track," replied Oliver.

"Let's go and catch him," said Josey.

"No," said Jonas, "we must go on with our work."

At a little distance farther on, they saw another track. It was larger than the first, and not so regular.

"What sort of a track is that?" said Josey.

"I don't know," said Oliver; "it looks like a dog's track; but I shouldn't think there would be a dog out here in the woods."

They found that this track followed the road along for some distance. The animal which made it, seemed sometimes to have gone in the middle of the road, and sometimes out at the side; and Jonas said that he had passed there since they went down with the first load of wood.

"How do you know?" said Oliver.

"Because," said Jonas, "his track is made upon the broken snow, in the middle of the road."

They watched the track for some time, and then they lost sight of it. Presently, however, they saw it again.

"I wonder which way he went," said Oliver.

"I'll jump off, and look at the track," said Jonas.

So saying, he jumped off the sled, and examined the track.

"He went up," said Jonas, "the same way that we are going. It may be a dog which has lost his master. Perhaps we shall find him up by our wood piles."

Jonas was right, for, when the boys arrived at the wood piles, they found there, waiting for them, a large black dog. He stood near one end of a wood pile, with his fore feet upon a log, by which his head and shoulders were raised, so that he could see better who was coming. He was of handsome form, and he had an intelligent and good-natured expression of countenance. He was looking very intently at the party coming up, to see whether his master was among them.

"Whose dog is that?" said Josey.

"I don't know," said Oliver; "I never saw him before."

"I wonder what his name is," said Josey. "Here! Towzer, Towzer, Towzer," said he.

"Here! Caesar, Caesar, Caesar," said Oliver.

"Pompey, Pompey, Pompey," said Jonas.

The dog remained motionless in his position, until, just as the boys had finished their calls, and as the foremost sled was drawn pretty near him, he suddenly wheeled around with a leap, and bounded away through the snow, for half the length of the first wood pile, and then stopped, and again looked round.

"I wish we had something for him to eat," said Jonas.

"I've got a piece of bread and butter," said Josey. "I went in and got it when you and Oliver were unloading."

So Josey took his bread and butter out of his pocket. There were two small slices put together, and folded up in a piece of paper. Jonas took a piece, and walked slowly towards the dog.

"Here! Franco, Franco," said Jonas.

"He's coming," said Josey, who remained with Oliver at the sled.

The dog was slowly and timidly approaching the bread which Jonas held out towards him.

"He's coming," said Josey. "His name is Franco. I wonder how Jonas knew."

"Franco, Franco," said Jonas again. "Come here, Franco. Good Franco!"

The dog came timidly up to Jonas, and took the bread and butter from Josey's hand, and devoured it eagerly. While he was doing it, Jonas patted him on the head.

"He's very hungry," said Jonas; "bring the rest of your bread and butter, Josey."

So Josey brought the rest of his luncheon, and the dog ate it all.

After this, he seemed to be quite at ease with his new friends. He staid about there with the boys until the sleds were loaded, and then he went down home with them. There they fed him again with a large bone. Jonas said that he was undoubtedly a dog that had lost his master, and had been wandering about to find him, until he became very hungry. So he said they would leave him in the yard to gnaw his bone, and that then he would probably go away. Josey wanted to shut him up and keep him, but Jonas said it would be wrong.

So the boys left the dog gnawing his bone, and went up after another load; but before they had half loaded their sleds, Oliver saw Franco coming, bounding up the road, towards them. He came up to Jonas, and stood before him, looking up into his face and wagging his tail.

FRANCO

Franco followed the boys all that forenoon, as they went back and forth for their wood. At dinner, they did not say any thing about him to the farmer, because they supposed that he would go away, when they came in and left him, and that they should see no more of him in the afternoon. But when Jonas went out, after dinner, to get the old General, to harness him for work again, he found Franco lying snugly in the General's stall, under the crib.

At night, therefore, he told the farmer about him. The farmer said that he was some dog that had strayed away from his master; and he told Jonas to go out after supper and drive him away. Josey begged his uncle to keep him, but his aunt said she would not have a dog about the house. She said it would cost as much to keep him as to keep a sheep, and that, instead of bringing them a good fleece, a dog was good for nothing, but to track your floors in wet weather, and keep you awake all night with his howling.

So the farmer told Jonas to go out after supper, and drive the dog away.

"Let us give him some supper first, father," said Oliver.

"No," said his father; "the more you give him, the more he won't go away. I expect now, you've fooled with him so much, that it will be hard to get him off, at any rate."

"Jonas has not fooled with him any," said Oliver.

"Nor I," said Josey.

After supper, Jonas went out, according to orders, to drive Franco away. It was a raw, windy night, but not very cold. Franco was in a little shed where there was a well, near the back door. He was lying down, but he got up and came to Jonas when he saw him appear at the door.

"Come, Franco," said Jonas, "come with me."

Franco wagged his tail, and followed Jonas.

Jonas walked out into the road, Franco after him. He walked along until he had got to some distance from the house, Franco keeping up with him all the way, sometimes on one side of the road, and sometimes on the other. At length, when Jonas thought that he had gone far enough, he stopped. Franco stopped too, and looked up at Jonas.

"Now, Franco, I've got to send you away. It's a hard case, Franco, but you and I must both submit to orders. So go off, Franco, as fast as you can."

So saying, Jonas pointed along the road, in the direction away from the house, and said, "St---- boy! St---- boy!"

Franco darted along the road a few steps, barked once, and then turned round, and looked eagerly at Jonas, as if he did not know what he wanted him to do.

"Get home!" said Jonas, in a stern and severe tone; "get home!" and he stamped with his foot upon the ground, and looked at Franco with a countenance of displeasure.

Franco bounded forward a few steps over the smooth and icy road, and then he turned round, and stood in the middle of the road, facing Jonas, and looking very much astonished.

"Get home, Franco!" said Jonas again; and, stooping down, he took a piece of hardened snow or ice from the road, and threw it towards him. The ice fell, before it reached Franco, and rolled along towards his feet, which made him scamper along a little farther; and then he stopped, and turned around, and looked at Jonas, as before.

Jonas began slowly to turn backwards, keeping his eye on Franco.

"It's a hard case, Franco, I acknowledge. If I had a barn of my own, I'd let you sleep in a corner of it; but I must obey orders. You must go and find your master."

So saying, Jonas turned round and walked slowly home. Just before he turned to go into the house, he looked back, to see what had become of the dog. He was standing motionless in the place where Jonas had left him.

"I wish the farmer would let me give him a bone," said he to himself; and then he turned away, and walked slowly around to the barn, to fodder the cattle.

That night, just before bed-time, he went to the front door, and looked out into the road, and all around, to see if he could see any thing of Franco. It was rather dark and windy,—though he could see the moon shining dimly throught the broken clouds, which were driving across the sky. The roads looked black, as they do about the commencement of a thaw. Presently the moon shone out full through the interstices of the clouds. Jonas took advantage of the opportunity to look all up and down the road; but Franco was nowhere to be seen.

The next morning, however, when he went out into the stable to give the cattle some hay, he found Franco in his old place, under the General's crib.

"Why, Franco," said Jonas, "how came you here?"

Franco said nothing, but stood looking up into Jonas's face, and wagging his tail.

"Franco," said Jonas, "how could you get in here?"

Franco remained in the same position; the light of the lantern shining in his face, and his tail wagging a very little. He could not tell certainly whether Jonas was scolding him or not.

Franco remained about the barn until breadfast-time, and then Jonas, at the table, told the farmer that he tried to drive the dog away the night before, but that in the morning he found him in the barn.

"I don't believe you really tried," said the farmer's wife. "I can drive him away, I know,—as I'll show you after breakfast."

Accordingly, after breakfast, putting on hastily an old straw bonnet, she went out into the yard and took a small stick from the wood pile, to use for a club, and then called to Franco.

"Franco," said she, "come here."

Franco looked first at her, and then at Jonas, who was standing in the door-way, as if at a loss to know what to do.

"Go, Franco," said Jonas.

The farmer's wife walked out in front of the house into the wind, calling Franco to follow. She then attempted to drive him along the road, much as Jonas had done. She brandished her stick at him, and, when she had succeeded in getting him as far from her as she could, by stern and threatening language, in order to drive him farther, she threw the stick at him with all her force.

Franco jumped out of its way. The stick rolled along the road before him. He sprang forward to it, seized it in his mouth, and came trotting back to the farmer's wife, and laid it down at her feet; and then, standing back a few steps, he looked up into her face, with a very earnest expression of countenance, which seemed to say,—

"What do you want me to do next?"

This very act of Franco's embarrassed the woman considerably. She could not bear to take up the very stick, which Franco had himself brought to her, and throw it at him again; and, on the other hand, she could not bear to give up, and let Franco remain. She, however, picked up the stick, and brandished it again towards Franco, and, stamping with her foot at him, she said,—

"Away with you, dog; get home!"

What the result of this contest would have been, it is very difficult to say, had it not been that it was soon decided by the occurrence of a singular incident; for, as the farmer's wife nodded her head, and stamped at the dog, the jar or the motion seemed to give the wind a momentary advantage over her bonnet, which, in her haste, she had not tied on very securely. A strong gust carried it clear from her head, and blew it away over Franco, upon the snow by the side of the road beyond. Franco, who was all ready for a spring, bounded after it, and pursued it at full speed. The snow was nearly level with the top of the stone walls, and the wind carrying it diagonally from the road, it rolled over the little ridge of stones which remained above the drifts, and then swept across the field, down a long descent, like a feather before the gale.

Franco pursued it with flying leaps over the snow, which had become sufficiently consolidated to support his steps. He gained upon it rapidly, and at length overtook and seized it; and then, turning round, he trotted swiftly back, leaped over the top of the wall, and brought the bonnet, and laid it down at its owner's feet, with an air of great satisfaction.

The good woman took up her bonnet, and threw her stick away, and, turning around, walked back to the house. The farmer, who had been looking out at the window, was laughing heartily. She herself smiled as she returned to her work, saying,—

"The dog has something in him, I acknowledge; go and see if you can't find him a bone, Jonas." "Yes, Jonas," said the farmer, "you may have him for your dog till the owner comes and claims him."

And this is the way that Jonas first got his dog Franco. He told Oliver that morning, as he was patting his head under the old General's crib, that the dog had taught them one good lesson.

"What is it?" asked Oliver.

"Why, that the Christian duty of returning good for evil, is good policy as well as good morals."

DOG LOST

About the middle of the winter, the farmer went to market with his produce. The vehicle on which he carried it was a kind of box upon runners, with a pole in front, to which two horses were fastened. He was gone three days.

When he came back, he said that he had bargained for another load of his produce, at the market town, and that he was going to send Jonas with it. Jonas was very glad when he heard this. He liked to take journeys.

"What day shall I go, sir?" said Jonas.

"Day after to-morrow," said the farmer, "as early as possible. We'll let the horses rest one day."

About the middle of the afternoon, on the day following the one on which this conversation had taken place, Jonas and the farmer began to load up the box sleigh, in order to have it ready for the morning. He had about forty miles to go, and he wanted to get to market, deliver his load, and return five or ten miles that same evening.

It was quite cold that afternoon, and it seemed to be growing colder and colder. Jonas got the box sleigh ready under a shed, first shoveling in some snow under the runners, in order that the horses might draw the sled out easily, when it was loaded. He put in the various articles of produce, which were contained in bags, and firkins, and boxes. Over these he spread blankets and buffalo-skins, and put in a bag of oats for his horses, and a box of bread and cheese for himself. He did not know whether Franco was to go with him, or not; but he arranged the bags in such a way, that he could easily make a warm nest for him in one corner, if the farmer should allow him to go.

The farmer helped him about all the arrangements, and, when they were completed, he told Jonas to go in and get his supper, and go to bed, so as to get up and set off early in the morning.

"It will be a fine starlight night," said he, "and you'd better be ten miles on your way by sunrise."

When Amos got up the next morning, and went out with his lantern, to go to the barn, as he passed by the shed on his way, he saw that the sleigh was gone. He proceeded to the barn, and, as he opened the door, he was startled at something which suddenly darted past him and rushed out.

"What's that?" said Oliver, who was behind him. "It is Franco," said he. "Where is he going?"

Franco ran off to the shed where Jonas had harnesses his horses, and began smelling around upon the ground. He followed the scent along the yard, up to a post by the side of the house, where Jonas had stopped a moment ago to go in and get his great-coat, when all was ready; and then, after pausing here a moment, he darted off towards the road.

"Here! Franco, Franco," said Amos, "come back here."

"Franco, Franco," repeated Oliver, "here—here—here—here."

Franco paid no attention to these calls, but ran off along the road at full speed.

In the mean time, Jonas had traveled rapidly onward, by the light of the stars, over the glittering and frosty road.

The keen air made his ears tingle a little, but he rubbed them, and they soon became warm. His feet were comfortably stowed away down in his box, among the bags and buffalo-skins, so that they were warm and comfortable.

The horses trotted along at good speed, and soon brought Jonas and his load to the village at the mill. The street was vacant, and the houses dark, excepting that a faint light shone behind a curtain in one chamber window. Jonas supposed that somebody was sick there. Even the mill was silent, and the gate shut down; and, instead of the ordinary roar of the water under the wheel, only a hissing sound was heard, where the imprisoned water spouted through the crevices of the flume. Vast stalactites of ice extended continuously along the whole face of the dam, like a frozen waterfall, behind which the water percolated curiously down into the foaming abyss, at the bottom of the fall. Jonas thought that all this, seen by starlight, looked very cold. The horses trotted across the bridge with a loud sound, which reverberated far and wide in the still night. He ascended the hill beyond, and drove on. His woollen comforter, tied about his neck, became frosted over from his breath; and the breasts, and mane, and sides, of the horses were gradually sprinkled with white, in the same way. They were both black horses,—the General having been left at home. They trotted down the hills and along the level portions of the road, and wheeled around the curves, with great speed. Jonas found that he had no occasion for his whip, and so he put it away behind him, under the buffaloes.

He went on in this way, without any special adventure, for a couple of hours, and then began to see a gray light appearing in the eastern sky. About the same time, the windows of the farm-houses, which he passed on the road, began to be illuminated by the fires, which they were kindling within. Now and then, he could see a man hurrying out to a barn, to feed the cattle. Jonas thought that they ought to be up earlier. The sun rose soon after, and the fields on every side sparkled by the reflection of his rays, from the crystalline surface of the snow. Tall columns of dense white smoke ascended from the chimneys, some erect, others leaning a little, some one way, some another. In a word, it was a cold, still, winter morning.

At length, as Jonas was walking his horses up a long hill, he heard light footsteps behind him. He turned round to see what was coming, and, to his utter astonishment, he saw Franco, coming up, upon the full run, and close behind the sleigh. He came to the side of it, and looked up, with every appearance of exultation and joy.

"Why, Franco," said Jonas, "how came you here?"

He stopped his horses, and Franco leaped up before him. His ears, and the glossy black hair which curled under his neck and upon his sides, were tipped with frost. Jonas patted him upon his head, saying,—

"Why, Franco, how did you get out of the barn? and how did you find out which way I came?"

Franco wagged his tail, and curled down around Jonas's feet, but he made no reply.

Jonas was very much surprised, for, as he had no permission to take Franco, he had concluded that it was his duty not to take him; and when he found that he was inclined to come with him, at the time that he was harnessing the horses, he conducted him back into the barn, and, to make it secure, he fastened up the place where he had got in, the first night that he lodged there. He knew that the barn would be opened when Amos came out in the morning, to take care of the old General and the oxen, but said he to himself, "I shall by that time be ten miles off, and it will be too late for him to follow or find me." Jonas was therefore very much surprised, when he found that Franco had contrived to make his escape, and to track his master so many miles.

Jonas drove on very prosperously, until it was about time for him to stop and give his horses some breakfast. As for himself, he ate his breakfast from his box, when they were coming up a long hill. He accordingly stopped at a tavern, and took his horses out of their harness, and rubbed them down well, and gave them a good drink of water, and plenty of oats, which he bought of the tavern-keeper. He kept the oats in his bag to use in the town. By the time that he stopped, he was comfortably warm, for he had taken some exercise walking up the hills. Franco always got out when Jonas did, at the bottom of the hills, and then got in again at the top. He remained in the sleigh, however, at the tavern, keeping guard, while Jonas went into the house; and he would growl a little if any body came near the sleigh, and thus warn them not to touch any thing that was in it.

While the horses were eating, Jonas went into the tavern, and sat down by the kitchen fire. The fire was very large, and many persons were busy getting breakfast. Jonas wished that he was going to have a cup of the coffee that they were making; but he thought it better that he should content himself with what the farmer had provided for him. There was a young woman in the back part of the room, at a window, sewing. She asked Jonas how far he had come that morning, and he told her. Then she said that he must have set out very early; and she said that he had a pair of very handsome black horses. She had seen them as Jonas passed the window.

There was a small girl sitting near her, with a slate, ciphering. She seemed very busy for a few minutes, and then she looked up to the young woman, and said,—

"My sum does not come right, aunt Lucia."

"Doesn't it? I'm sorry, but I can't help you now, very well," replied aunt Lucia. "I am very busy with my sewing."

The little girl then got up, and came towards the fire, with her slate hanging by a string from her finger, and her Arithmetic under her arm.

"Where are you ciphering?" asked Jonas.

"In fractions," said the girl.

"If you will let me look at your sum, perhaps I can tell you how to do it," replied Jonas.

The girl handed her book to him, and showed him the sum in it. She also let him see the work upon her slate. Jonas looked it over very carefully, and then said,—

"You have done very well indeed, with such a hard sum. There is only one mistake."

And Jonas pointed out the mistake to her, and she corrected it, and then the answer was right. She then went and put away her slate and book, with an appearance of great satisfaction. As she passed by the window, aunt Lucia whispered to her, to say,—

"I think you had better thank that young man, and give him a mug of coffee."

"Well," said the little girl, "I will." So she went to a cupboard at the side of the room, and took down a tin mug. She poured out some coffee from a coffee-pot, and put in some milk and sugar, and then brought it to Jonas, and asked him if he wouldn't like a little coffee. Jonas thanked her, and took the coffee; and he liked it very much.

After this, Jonas harnessed his horses again, and went on. He traveled until nearly noon, and then he arrived at the town where he was to leave his load. He had a letter to a merchant, who had bought the produce of the farmer, and, in a very short time, his load was taken out, and the other articles put in, which he was to carry back in exchange. He had some money given him by the merchant, in part payment for his load of produce. It was in bank-notes, and he put it into his waistcoat pocket, and pinned it in.

Then he set out on his return. His load was light, the road was smooth, and his horses, though they had traveled fast, had been driven carefully, and they carried him rapidly over the ground. It was the middle of the afternoon, however, before he set out, and the days were then so short, that the sun soon began to go down. He had to ride quite into the evening, before he reached the place where he was to stop for the night.

He put up his horses, and then went into the house. He called for some supper, for his own provisions had long since been exhausted. After supper, he carried out something for Franco, whom he had left in the sleigh in the barn, lying upon a good warm buffalo, to watch the property.

"Franco," said he, "here is your supper."

Franco jumped up when he heard Jonas's voice, and leaped out of the sleigh. He took his supper, and Jonas, after once more feeding his horses, went out, and shut the door, leaving Franco to finish his bone by himself.

Jonas went back into the tavern, and took his seat by the fire. There was a table before the fire, with a lamp upon it; and there were one or two books and an old newspaper lying upon another table, in the back part of the room. Jonas looked at the books, but they were not interesting to read. One was a dictionary. He read the newspaper for some time, and then he took the lamp up, and began to look at some pictures of the prodigal son, which were hung up upon the wall over the mantel-piece.

Beyond the pictures were some advertisements. One was for a farm for sale. Jonas read the description, and he wished that he was old enough to buy a farm, and then he would go and look at that.

The next advertisement was about some machinery, which a man had invented; and the next was headed, in large letters, Dog Lost. This caught Jonas's attention immediately. It was in writing, and he could not read it very easily, it was so high. So he got a chair, and stood up in it, and read as follows:—

"'DOG LOST.

"'Strayed or stolen from the subscriber, a valuable dog, of large size and black color.'

"I wonder if it isn't Franco," said Jonas, interrupting himself in his reading.

"'He had on a brass collar marked with the owner's name.'

"No," said Jonas, "there was no collar. But then the man that stole him might have taken it off.

"'Answers to the name of Ney.'

"Ney, Ney," said Jonas,—"I never called him Ney. I wonder if he would answer, if I should call him Ney.

"'Is kind and docile, and quite intelligent.'

"Yes," said Jonas, "I verily believe it is Franco.

"'Any person who will return said dog to the subscriber, at his residence at Walton Plain, shall be suitably rewarded.

"'JAMES EDWARDS.'

"I verily believe it is Franco," said Jonas, as he slowly got down from the chair,—"Walton Plain."

He stood a moment, looking thoughtfully into the fire.

"Yes," he repeated, "I verily believe it is Franco. I wonder where Walton Plain is."

Jonas had learned from Mr. Holiday, that it was never wise to communicate important information relating to private business, unless necessary. So he said nothing about Franco to any of the people at the tavern, but quietly went to bed; and, after thinking some time what to do, he went to sleep, and slept finely until morning.

About daylight, he arose, and, as he had paid his bill the night before, he went to the barn, harnessed his horses, and set off. At the first village that he came to after sunrise, he stopped at a store, and inquired whether there was any such town as Walton Plain, in that neighborhood.

"Yes," said the boy, who stood with a broom in his hand, with which he was sweeping out the store,—"yes, it is about five miles from here, right on the way you are going."

Jonas thanked the boy, got into his sleigh, and rode on.

"Poor Franco," said he, "I am afraid I must lose you."

He had hoped that Walton Plain would have proved to be off of his road, so that he could have had a good reason for not doing any thing about restoring the dog, until after he had gone home, and reported the facts to the farmer. But now, as he found that it was on his way, and as he would very probably go directly by Mr. Edwards's door, he concluded that he ought, at any rate, to call and let him look at Franco, and see whether it was his dog or not.

When he reached Walton Plain, he inquired whether Mr. James Edwards lived in the village. They told him that he lived about half a mile out of the village. They said it was a handsome white house, under the trees, back from the road, with a portico over the door.

Jonas rode on, observing all the houses as he passed; and he at once recognized the one which had been described to him. He stopped before the great gate, and fastened his horses to a post. He then walked along a road-way, which led in by the end of the house, and presently came to a door, where he stopped and knocked. A girl came and opened the door.

"Is Mr. Edwards at home?"

"Yes," said the girl.

"Will you ask him to come to the door a minute?"

"You'd better walk in, and I'll speak to him."

Jonas stepped into an entry, which was carpeted, and which had a large map, hanging against the wall. The girl opened a door into a little room, which looked somewhat like Mr. Holiday's study. There was a great deal of handsome furniture in it, and book-shelves around the walls. A large table was in the middle of the room, covered with books and papers.

The girl handed Jonas a seat.

"Who shall I say has called?" said she to Jonas, as she was about to go out of the room.

"Why—I—my name is Jonas," he replied; "but I don't suppose Mr. Edwards knows me. I came to see him about his dog."

At this remark, the girl looked around towards the fire, and Jonas involuntarily turned his eyes in the same direction. He saw there a large dog, very much like Franco in form and size, lying upon the carpet. He was as handsome as Franco. Jonas was surprised to see him. The girl, too, looked surprised. She, however, said nothing, but went out, and shut the door.

In a few minutes, the door opened, and an elderly gentleman, with grayish hair, and a mild and pleasant expression of countenance, came in. He nodded to Jonas as he entered, and Jonas rose to receive him. The gentleman then took a seat by the fire, and asked Jonas to sit down again.

"I came to see you, sir, about your dog," said Jonas.

"Well, my boy," replied the man, "and what about my dog?" and, as he said this, he looked down at the dog, which was lying upon the floor.

"I don't know but that I have got him."

"You have got him?" repeated Mr. Edwards.

"Yes, sir; a dog like that one came to me in the woods one day this winter."

"O," said Mr. Edwards, "you mean the dog that I lost.—Yes,—I had forgotten that, it is so long ago. When did you find him?"

Jonas then told the whole story of the dog's coming to them, and of their attempt to drive him away; and also of his seeing the advertisement in the tavern. Mr. Edwards asked him a great many questions, such as what his name was, where he lived, and how long he had lived there, and how he happened to be journeying now. At last he said,—

"I think it very probable that it is my dog. I lost one of that description six or eight months ago, and advertised him; but I couldn't hear any thing of him, and so I got another as much like him as I could. It is probable yours is the same dog; but I don't know that there is any particular proof of it. You haven't called him Ney, have you?"

"No, sir," said Jonas; "we call him Franco."

"If he should come at the call of Ney, that would be proof. Where is he now?"

"He is with me, sir; he is out in my sleigh."

"O, well, then," said the man, "we can tell in a moment. I'll step to the door and call him."

So Mr. Edwards put on his hat, and stepped to the door. The dog was standing up in the sleigh, and looking wildly around. When he saw Mr. Edwards, he seemed more excited still.

"Here, Ney," said Mr. Edwards.

The dog leaped down from the sled, and came bounding up the road. He leaped first about Mr. Edwards, and then about Jonas, as if at a loss which was his master.

"Why, Ney," said Mr. Edwards,—"poor Ney,—have you got back at last? Come, walk in, Ney."

Ney slipped in through the door, and turned immediately into the little room, as if he was perfectly familiar with the localities. Jonas and Mr. Edwards followed. They shut the door, and took their seats again. Ney ran around the room, and examined every thing. He looked at the strange dog lying so comfortably in his old place upon the warm carpet, and then came and gazed up eagerly into his old master's face a moment. He came to Jonas, and wagged his tail, and then he went to the door and whined, as if he wanted to go out.

"Won't you let him out?" said Mr. Edwards. "We will see what he will do."

Jonas opened the door, and the dog ran out into the entry, and then made the same signs to have the outer door opened. Jonas opened it, and let him out. Jonas stepped out himself a moment, to see what he would do, and presently returned again to the room where he had left Mr. Edwards.

"Where did he go?" said Mr. Edwards.

"He has run to the sleigh," said Jonas, "and jumped up into it, and is lying down on the buffalo."

"The dog seems to have become attached to you, Jonas," said Mr. Edwards, "and I presume that you have become somewhat attached to him."

"Yes, sir, very much indeed," replied Jonas.

Mr. Edwards was silent a few minutes, appearing lost in thought.

"I hardly know what to say about this dog," he continued, at length. "You did very right to come and let me know about him. I am afraid that some boys would have kept him, without saying any thing about it. I am glad that you were honest. I valued the dog very much, and would have given a large sum to have recovered him, when he was first lost. But I have got another now, and don't really need two. Should you be disposed to buy him?"

"Yes, sir," said Jonas, "if I could. But I haven't got but a dollar at my command, and I suppose he is worth more than that."

Jonas had a dollar of his own. Mr. Holiday had given it to him when he left his house, thinking it probable that he would want to buy something for himself. Jonas had taken this money with him when he left the farmer's, intending to expend a part of it in the market town; but he did not see any thing that he really wanted, and so the money was in his pocket now.

"Why, yes," said Mr. Edwards, "I gave a great deal more for him than that. Haven't you any more money with you?"

"Not of my own," said Jonas.

"I suppose you got some for your produce."

"Yes, sir," said Jonas; "but it belongs to the farmer that I work with."

"And don't you think that he would be willing to have you pay a part of it for the dog?"

"I don't know, sir," said Jonas. "I know he likes the dog very much, but I have no authority to buy him with his money."

If Jonas had been willing to have used his employer's money without authority, Mr. Edwards would not have taken it. He made the inquiry to see whether Jonas was trustworthy.

After a few minutes' pause, Mr. Edwards resumed the conversation, as follows:—

"Well, Jonas," said he, "I have been thinking of this a little, and have concluded to let you keep the dog for me a little while,—that is, if he is willing to go with you. But remember he is my property still, and I shall have a right to call for him, whenever I choose, and you must give him up to me."

"Yes, sir," said Jonas, "I will. And I wish that you would not agree to sell him to any body else, without letting me know."

"Well," replied Mr. Edwards, "I will not. So you may take him, and keep him till I send for him,—that is, provided he will go with you of his own accord. I can't drive him away from his old home."

Jonas thanked Mr. Edwards, and rose to go. Mr. Edwards took his hat, and followed him to the door, to see whether the dog would go willingly. When he was upon the step, he called him.

"Ney," said he, "Ney."

Ney looked up, and, in a moment afterwards, jumped out of the sleigh, and came running up to the door.

"Now," continued Mr. Edwards, "if you can call him back, while I am standing here, it is pretty good proof that you have been kind to him, and that he would like to go with you."

So Jonas walked down towards the gate, looking back, and calling,—

"Franco, Franco, Franco!"

The dog ran down towards him a little way, and then stopped, looked back, and, after a moment's pause, he returned a few steps towards his former master. He seemed a little at a loss to know which to choose.

Jonas got into his sleigh.

"Franco!" said he.

Franco looked at him, then at Mr. Edwards, then at Jonas; and finally he went back to the door, and began to lick his old master's hand.

Jonas turned his horses' heads a little towards the road, and moved them on a step.

"Come, Franco," said he; "Franco, come."

Franco, hearing these words, and seeing that Jonas was actually going, seemed to come to a final decision. He leaped off the steps, and bounded down the road, through the gate, and jumped up into Jonas's sleigh. Mr. Edwards continued to call him, but he paid no attention to it. He curled down before Jonas a moment, then he raised himself up a little, so as to look back towards the house; but he showed no disposition to get out again. Jonas put his hand upon his head, and patted it gently as he drove away; and, when he found that Franco was really going with him, he turned his head back, and said, with a look of great satisfaction,—

"Good-by, sir. I'm very much obliged to you."

"Good-by, Jonas. Take good care of Ney."

"Yes, sir," said he, "I certainly will."

"You're a good dog, Franco," he continued, patting his head, "to come with me,—very good dog, Franco, to choose the coarse hay for a bed under the old General's crib, rather than that good warm carpet, for the sake of coming with me. I'll make you a little house, Franco,—I certainly will, and I'll put a carpet on the floor. I'll make it as soon as I get home."

And Jonas did, the next evening after he got home, make Franco a house, just big enough for him; and he found an old piece of carpet to put upon the floor. He put Franco in; but the next morning he found him in his old place under the General's crib. Franco liked that place better. The truth was, it was rather warmer; and then, besides, he liked the old General's company.

SIGNS OF A STORM

One evening early in February, the farmer told Jonas that his work, the next day, would be to get out four or five bushels of corn and grain, and go to mill. Accordingly, after he had got through with his morning's work of taking care of the stock, he took a half-bushel measure, and several bags, and went into the granary. The granary was a small, square building, with narrow boards and wide cracks between them on the south side. The building itself was mounted on posts at the four corners, with flat stones upon the top of the posts, for the corners to rest upon.

The open work upon the side was to let the air in, to dry the corn; and the high posts and the flat stones were to keep the mice from getting in and eating it up.

Jonas put a short board across the top of the half-bushel, and sat upon it. Then he began taking the corn and shelling it off from the cob, by rubbing it against the edge of the board. As he sat thus at work, he occasionally looked up, and he could see out of the open door of the granary, into the farm-yards.

It was a very pleasant morning. The sun shone beautifully; and now and then a drop fell from the roof on the south side of the barn. The cattle were standing, basking in the sun, in the barn-yard, and in the sheds, where the sun could shine in upon them. The whole area of the barn-yard was trodden smooth and hard by the footsteps of the cattle; and broad and smooth paths had been worn in every direction, about the house. Behind the barn was a large sheep-yard, also well worn with the footsteps of the sheep. A great many sheep were there,—now and then eating hay from a long rack, which extended across the yard.

When Jonas had shelled out the corn, he carried the bags, and put them into the sleigh, which was generally used in going to mill. Then he locked the granary, and put the key away, and afterwards went to the barn, and opened the great doors, which led in to the barn floor. He climbed up a tall ladder to a loft under the roof of the barn, and threw down some sheaves of wheat,—as many as he thought would be necessary to produce the quantity of grain which the farmer had ordered. He then descended the ladder, and got a flail, and began to thresh them out.

Standing, now, in a new position, he had a different prospect before him. Beyond the barn-yard he could see another larger yard nearer the house, in which the snow had also been beaten down by the going and coming of teams, sleds, and all sorts of travel, for two or three weeks, during which there had been no new falls of snow. Upon one side of this yard was an enormous heap of wood, which Jonas and Oliver had been hauling nearly all the winter. On the other side was a quantity of timber, of all sizes and lengths, which the farmer and Amos had been getting out for the new barn. Some of it was hewed, and some not; and several large pieces were laid out upon the level surface of the yard, and the farmer and Amos were sitting upon them, working upon the frame. Amos was boring holes with an auger, and the farmer was cutting the holes thus made into a square form with a chisel. Josey was there, too, and Amelia. They were building a house of the blocks which had been sawed off from the ends of the timbers.

When, however, they heard the sound of Jonas's flail, they left their play, and came along to the barn to see him. Josey came into the barn; Amelia remained at the door.

"What are you doing, Jonas?" said Josey.

"Threshing some wheat," replied Jonas; "but stand back, or I shall hit you with the flail."

"Are you going to mill?" said Josey.

"Yes, I or somebody else. I am getting a grist ready."

"Here comes uncle," said Josey; "I mean to ask him to let me go."

The farmer came in, and told Jonas that he expected that they were going to have a snow-storm, and, therefore, as soon as his grist was ready, he might harness a horse into the sleigh, and drive directly to mill.

"Then," said he, "you may come directly back, and not wait to have it ground; for I want you to go up to the woods this afternoon, and bring down a load of small spruces, which I cut for rafters. I want them down before the road gets blocked up with snow."

The farmer had reflected that, about this time in the winter, they were generally exposed to long and driving snow-storms, by which the roads were often blocked up. He usually endeavored to get all out of the woods which he had to get, early in the season, while the snow was not deep. He had now got down all his wood, and all his timber, except one or two loads of rafters; and he wished, therefore, to get those down, so that, in case of a severe storm, he would not have to break out the road again.

Jonas accordingly despatched his preparations for going to mill, as rapidly as possible, and soon was ready. In driving out, he stopped opposite the place where the farmer was at work upon his frame.

"All ready, I believe, sir," said Jonas.

"Very well," said the farmer. "The pond road is a little the nearest, isn't it?"

"Yes, sir," said Jonas.

"And Josey wants to go with you; have you any objection to take him?"

"No, sir," said Jonas; "I should like very much to have him go."

"Well, Josey, get your great-coat, and come."

"O, no, sir," said Josey; "I don't need any great-coat; it isn't cold."

"Very well, then; jump in."

Josey got in upon the top of the bags, and Jonas drove on. After riding a short distance, they turned down by a road which led to the pond, which was now covered with so thick and solid a sheet of ice, that it was safe travelling upon it, and it was accordingly intersected with roads in every direction. They rode down at a rapid trot to the ice, followed by Franco, who was always glad to go upon an expedition.

The road led them over, very nearly, the same part of the pond that Jonas had navigated in his boat, when he fitted a sail to it,—though now the appearances were so different all around, that one would hardly have supposed the scene to have been the same. There was the same level surface, but it was now a solid field, white with snow, instead of the undulating expanse of water, of the deep-blue color reflected from the sky. There were the same islands, and promontories, and beaches; but the verdure was gone, and the naked whiteness of the beach seemed to have spread over the whole landscape. It was a very pleasant ride, however. The road was level, though very winding, as it passed around capes and headlands, and now and then took a wide circuit to avoid a breathing-hole. The sun shone pleasantly, too.

"I don't see what signs there are of a snow-storm," said Josey.

"Such a calm and pleasant day in February portends a storm," said Jonas. "Besides, the wind, what there is, is north-east; and don't you see that snow-bank off south?"

Josey looked in the direction in which they were going, which was towards the south-west, and he saw a long, white bank of cloud, extending over that quarter of the heavens.

"Is that a snow-bank?" asked Josey.

"It is a bank of snow-clouds, I suppose," said Jonas. "They call it a snow-bank."

By the time that the boys reached the mill, a hazy appearance had overspread the whole sky. They took out the grist, and left it to be ground, and then immediately got into the sleigh again, and commenced their return. Before they had gone far, the sky became entirely overcast, and the distant hills to the south-east were enveloped in what appeared to be a kind of mist, but which was really falling snow.

"How windy it is!" said Josey.

"No," said Jonas, "it is not much more windy than it was when we came; but then we were riding with it, and now we are going against it. You feel cold, don't you?"

"Why, yes, a little," said Josey, "now the sun has gone, and the wind has come."

"Well, then," said Jonas, "get down in the bottom of the sleigh, and I'll cover you up with buffaloes."

So Josey crept down into the bottom of the sleigh, and Jonas covered him up; and he found his place very warm and comfortable.

"How do you like your place?" said Jonas.

"Very well," said Josey, "only I can't see where we are going."

"Trust yourself to me," said Jonas. "I'll drive you safely."

"I know it," said Josey, "and I wish you'd tell me, now and then, what you see."

"Well," replied Jonas, "I see a load of hay coming along on the pond before us."

"A large load?" said Josey.

"Yes," replied Jonas; "and now we're going pretty near the round island. There, the load of hay is turning off by another road. O, there is a sleigh behind it; it was hid before. The sleigh is coming this way."

"I don't hear any bells," said Josey.

"We are too far off yet; you'll hear them presently."

Very soon Josey did hear the bells. They came nearer and nearer, and at last jingled by close to his ears. As soon as the sound had gone by, he threw up the buffalo with his arms, and looked out, saying to Jonas,—

"I guess they wondered what you had got here, covered up with the buffalo, Jonas."

Jonas smiled, and Josey covered himself up again. Not long after this, it began to snow, and Jonas said that he could hardly see the shore in some places.

"Suppose it should snow so fast," said Josey, "that you could not see the land at all; then, if you should come to two roads, how could you tell which one to take?"

"Why, one way, replied Jonas, "would be to let Franco trot on before us; and he'd know the way."

"Is Franco coming along with us?" said Josey.

"Yes," said Jonas, "he is close behind."

"Why don't you call him Ney?" asked Josey; "that is his real name."

"I was uncertain which to call him for some time," said Jonas; "but finally I concluded to let him keep both names, and so now he is Franco Ney."

"Well," said Josey, "I think that is a good plan."

A short time after this, Jonas turned up off from the pond, and soon reached home.

THE RESCUE

Jonas found, when he reached home, that it was about dinner-time. The farmer said that the storm was coming on sooner than he had expected, and he believed that they should have to leave the rafters where they were. But Jonas said that he thought he could get them without any difficulty, if the farmer would let him take the oxen and sled.

The farmer, finding that Jonas was very willing to go, notwithstanding the storm, said that he should be very glad to have him try. And Josey, he said, might accompany him or not, just as he pleased.

"I wouldn't go, Jonas," said Josey, "if I were you. It is going to be a great storm."

He, however, walked along with Jonas to the barn, to see him yoke the oxen. The yard was covered with a thin coating of light snow, which made the appearance of it very different from what it had been when they had left it. The cows and oxen stood out still exposed, their backs whitened a little with the fine flakes which had fallen upon them. Jonas went to the shed, and brought out the yoke.

"Jonas," said Josey, "I wouldn't go."

"No, I think it very likely that you wouldn't. You are not a very efficient boy."

"What is an efficient boy?" asked Josey.

"One that has energy and resolution enough to go on and accomplish his object, even if there are difficulties in the way."

"Is that what you mean by being efficient?" said Josey.

"Yes;—a boy that hasn't some efficiency, isn't good for much."

As he said this, Jonas had got one of the oxen yoked. He then went to bring up the other.

When the other ox was up in his place, Jonas raised the end of the yoke, and put it over his neck.

"You see," continued he, "your uncle wants all those rafters got down. It will be a little harder getting them, in the storm; but I care nothing for that. It will be a great satisfaction to him to have them all safe down here before it drifts. He doesn't require me to go; but if I go voluntarily and bring them down, don't you think that, to-morrow morning, when he finds two feet of snow on the ground, he'll be glad to think that all his rafters are safe in the yard?"

"Why, yes," said Josey. "I've a great mind to go with you."

"Do just as you please," said Jonas.

"Well, do you want me to go?"

"Yes, I should like your company very well; and, besides, perhaps you can help me."

"Well," said Josey, "I'll go."

He accordingly followed Jonas as he drove the oxen along to the sled. Jonas held up the tongue, while Josey backed the oxen, so that he could enter the end of the tongue into the ring attached to the lower side of the yoke. He then put the iron pin in, and all was ready.

Jonas drove the oxen along, till he came to the great gate in the back yard, and then he stopped to go and get some chains. The chains he fastened to the stakes, which were in the sides of the sled. Then he opened the great gate, and the oxen went through; after which he seated himself upon the sled by the side of Josey, and so they rode along up into the woods.

The storm increased, though very slowly. The road into the woods, which had become well worn, was now beginning to be covered, here and there, with little white patches, wherever new snow, driven along by the wind, found places where it could lodge. At length, however, they came to the woods; and there they were sheltered from the wind, and the snow fell more equally. Josey had found it quite cold riding in the open ground, for the wind was against them; but under the shelter of the trees he found it quite warm and comfortable.

The forest appeared very silent and solitary. It is true they could hear the moaning of the wind upon the tops of the trees, but there was no sound of life, and no motion but that of the fine flakes descending through the air in a gentle shower. The whole surface of the ground, and every thing lying upon it, was covered with the snow; for the branches, and the stumps, and the stems trimmed up for timber, and the places where the old snow had been trampled down by the oxen and by the woodcutters, were now all whitened over again and concealed.

"Who would think," said Jonas, "that there could be any thing alive here?"

"Is there any thing?" said Josey.

"Yes, thousands of animals, all covered up in the snow,—mice in the ground, and squirrels in the hollow logs, and millions of insects, frozen up in the bark of the dead trees."

"And they'll be covered up deeper before morning," said Josey.

"Yes," said Jonas, "and so would our rafters, if we didn't get them out. We could not have found half of them, if we had left them till after this storm."

The rafters were lying around upon the old snow, wherever small trees, from which they had been formed, had fallen. They could be distinguished very plainly now, although covered with an inch of snow.

Jonas and Josey immediately went to work, getting them together, and placing them upon the sled. When they had been at work in this way for some time, Jonas said,—

"We shall not get half of them, at this load."

"Then what shall you do?" said Josey.

"O, come up again, and get the rest."

"But then it will be dark before you get home."

"That will be no matter," said Jonas.

"Only you'll get lost, and buried up in the snow."

"No," said Jonas; "there might be some danger to-morrow evening, after it shall have been snowing four and twenty hours; but not to-night. The snow will not be more than a foot deep at midnight."