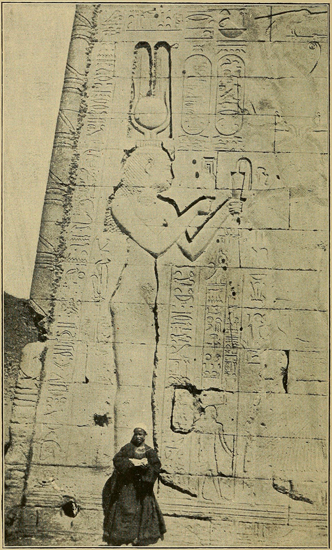

THE FAMOUS RELIEF OF CLEOPATRA AT TEMPLE OF DENDERAH

THE INSTINCT OF STEP-FATHERHOOD. A Novel. 16mo, Cloth, $1.25.

A LITTLE SISTER TO THE WILDERNESS. A Novel. 16mo, Cloth, $1.25.

THE LOVE AFFAIRS OF AN OLD MAID. 16mo, Cloth, $1.25.

THE UNDER SIDE OF THINGS. 16mo, Cloth, $1.25.

FROM A GIRL’S POINT OF VIEW. 16mo, Cloth, $1.25.

TO

THAT MOST INTERESTING SPECK OF HUMANITY, ALL PERPETUAL MOTION AND KINDLING INTELLIGENCE AND SWEETNESS UNSPEAKABLE, MY LITTLE NEPHEW

BILLY

ABSENCE FROM WHOM RACKED MY SPIRIT WITH ITS MOST UNAPPEASABLE PANGS OF HOMESICKNESS, AND WHOSE CONSTANT PRESENCE IN MY STUDY SINCE MY RETURN HAS SPARED THE PUBLIC NO SMALL AMOUNT OF PAIN

The frank conceit of the title to this book will, I hope, not prejudice my friends against it, and will serve not only to excuse my being my own Boswell, but will fasten the blame of all inaccuracies, if such there be, upon the offender—myself. This is not a continuous narrative of a continuous journey, but covers two years of travel over some thirty thousand miles, and presents peoples and things, not as you saw them, perhaps, or as they really are, but only As Seen By Me.

In this day and generation, when everybody goes to Europe, it is difficult to discover the only person who never has been there. But I am that one, and therefore the stir it occasioned in the bosom of my amiable family when I announced that I, too, was about to join the vast majority, is not easy to imagine. But if you think that I at once became a person of importance it only goes to show that you do not know the family. My mother, to be sure, hovered around me the way she does when she thinks I am going into typhoid fever. I never have had typhoid fever, but she is always on the watch for it, and if it ever comes it will not catch her napping. She will meet it half-way. And lest it elude her watchfulness, she minutely questions every pain which assails any one of us, for fear, it may be her dreaded foe. Yet when my sister’s blessed lamb baby had it before he was a year old, and after he had got well and I was not afraid he would be struck dead for my wickedness, I said to her, “Well, mamma, you must have taken solid comfort out of the first real chance you ever had at your pet fever,” she said I ought to be ashamed of myself.

My father began to explain international banking to me as his share in my preparations, but I utterly discouraged him by asking the difference between a check and a note. He said I reminded him of the juryman who asked the difference between plaintiff and defendant. I soothed him by assuring him that I knew I would always find somebody to go to the bank with me.

“Most likely ’twill be Providence, then, as He watches over children and fools,” said my cousin, with what George Eliot calls “the brutal candor of a near relation.”

My brother-in-law lent me ten Baedekers, and offered his hampers and French trunks to me with such reckless generosity that I had to get my sister to stop him so that I wouldn’t hurt his feelings by refusing.

My sister said, “I am perfectly sure, mamma, that if I don’t go with her, she will go about with an ecstatic smile on her face, and let herself get cheated and lost, and she would just as soon as not tell everybody that she had never been abroad before. She has no pride.”

“Then you had better come along and take care of me and see that I don’t disgrace you,” I urged.

“Really, mamma, I do think I had better go,” said my sister. So she actually consented to leave husband and baby in order to go and take care of me. I do assure you, however, that I have bought all the tickets, and carried the common purse, and got her through the custom-houses, and arranged prices thus far. But she does pack my trunks and make out the laundry lists—I will say that for her.

My brother’s contribution to my comfort was in this wise: He said, “You must have a few more lessons on your wheel before you go, and I’ll take you out for a lesson to-morrow if you’ll get up and go at six o’clock in the morning—that is, if you’ll wear gloves. But you mortify me half to death riding without gloves.”

“Nobody sees me but milkmen,” I said, humbly.

“Well, what will the milkmen think?” said my brother.

“Mercy on us, I never thought of that,” I said. “My gloves are all pretty tight when one has to grip one’s handle-bars as fiercely as I do. But I’ll get large ones. What tint do you think milkmen care the most for?”

He sniffed.

“Well, I’ll go and I’ll wear gloves,” I said, “but if I fall off, remember it will be on account of the gloves.”

“You always do fall off,” he said, with patient resignation. “I’ve seen you fall off that wheel in more different directions than it has spokes.”

“I don’t exactly fall,” I explained, carefully. “I feel myself going and then I get off.”

I was ready at six the next morning, and I wore gloves.

“Now, don’t ride into the holes in the street”—one is obliged to give such instructions in Chicago—“and don’t look at anything you see. Don’t be afraid. You’re all right. Now, then! You’re off!”

“Oh, Teddy, don’t ride so close to me,” I quavered.

“I’m forty feet away from you,” he said.

“Then double it,” I said. “You’re choking me by your proximity.”

“Let’s cross the railroad tracks just for practice,” he said, when it was too late for me to expostulate. “Stand up on your pedals and ride fast, and—”

“Hold on, please do,” I shrieked. “I’m falling off. Get out of my way. I seem to be turning—”

He scorched ahead, and I headed straight for the switchman’s hut, rounded it neatly, and leaned myself and my wheel against the side of it, helpless with laughter.

A red Irish face, with a short black pipe in its mouth, thrust itself out of the tiny window just in front of me, and a voice with a rich brogue exclaimed:

“As purty a bit of riding as iver Oi see!”

“Wasn’t it?” I cried. “You couldn’t do it.”

“Oi wouldn’t thry! Oi’d rather tackle a railroad train going at full spheed thin wan av thim runaway critturs.”

“Get down from there,” hissed my brother so close to my ear that it made me bite my tongue.

I obediently scrambled down. Ted’s face was very red.

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself to enter into immediate conversation with a man like that. What do you suppose that man thought of you?”

“Oh, perhaps he saw my gloves and took me for a lady,” I pleaded.

Ted grinned and assisted me to mount.

When I successfully turned the corner by making Ted fall back out of sight, we rode away along the boulevard in silence for a while, for my conversation when I am on a wheel is generally limited to shrieks, ejaculations, and snatches of prayer. I never talk to be amusing.

“I say,” said my brother, hesitatingly, “I wear a No. 8 glove and a No. 10 stocking.”

“I’ve always thought you had large hands and feet,” I said, ignoring the hint.

He giggled.

“No, now, really. I wish you’d write that down somewhere. You can get those things so cheap in Paris.”

“You are supposing the case of my return, or of Christmas intervening, or—a present of some kind, I suppose.”

“Well, no; not exactly. Although you know I am always broke—”

“Don’t I, though?”

“And that I am still in debt—”

“Because papa insists upon your putting some money in the bank every month—”

“Yes, and the result is that I never get my head above water. I owe you twenty now.”

“Which I never expect to recover, because you know I always get silly about Christmas and ‘forgive thee thy debts.’”

“You’re awful good—” he began.

“But I’ll be better if I bring you gloves and silk stockings.”

“I’ll give you the money!” he said, heroically. “Will you borrow it of me or of mamma?” I asked, with a chuckle at the family financiering which always goes on in this manner.

“Now don’t make fun of me! You don’t know what it is to be hard up.”

“Don’t I, though?” I said, indignantly. “Oh—oh! Catch me!”

He seized my handle-bar and righted me before I fell off.

“See what you did by saying I never was hard up,” I said. “I’ll tell you what, Teddy. You needn’t give me the money. I’ll bring you some gloves and stockings!”

“Oh, I say, honest? Oh, but you’re the right kind of a sister! I’ll never forget that as long as I live. You do look so nice on your wheel. You sit so straight and—”

I saw a milkman coming. We three were the only objects in sight, yet I headed for him.

“Get out of my way,” I shrieked at him. “I’m a beginner. Turn off!”

He lashed his horse and cut down a side street.

“What a narrow escape,” I sighed. “How glad I am I happened to think of that.”

I looked up pleasantly at Ted. He was biting his lips and he looked raging.

“You are the most hopeless girl I ever saw!” he burst out. “I wish you didn’t own a wheel.”

“I don’t,” I said. “The wheel owns me.”

“You haven’t the manners of—”

“Stockings,” I said, looking straight ahead. “Silk stockings with polka dots embroidered on them, No. 10.”

Ted looked sheepish.

“I ride so well,” I proceeded. “I sit up so straight and look so nice.”

No answer.

“Gloves,” I went on, still without looking at him. “White and pearl ones for evening, and russet gloves for the street, No. 8.”

“Oh, quit, won’t you? I’m sorry I said that. But if you only knew how you mortify me.”

“Cheer up, Tedcastle. I am going away, you know. And when I come back you will either have got over caring so much or I will be more of a lady.”

“I’m sorry you are going,” said my brother. “But as you are going, perhaps you will let me use your rooms while you are gone. Your bed is the best one I ever slept in, and your study would be bully for the boys when they come to see me.”

I was too stunned to reply. He went on, utterly oblivious of my consternation:

“And I am going to use your wheel while you are gone, if you don’t mind, to take the girls out on. I know some awfully nice girls who can ride, but their wheels are last year’s make, and they won’t ride them. I’d rather like to be able to offer them a new wheel.”

“I am not going to take all my party dresses. Have you any use for them?” I said.

“Why, what’s the matter? Won’t you let me have your rooms?”

“Merciful heavens, child! I should say not!”

“Why, I haven’t asked you for much,” said my small, modest brother. “You offered.”

“Well, just wait till I offer the rest. But I’ll tell you what I will do, Ted. If you will promise not to go into my rooms and rummage once while I am gone, and not to touch my wheel, I’ll buy you a tandem, and then you can take the girls on that.”

“I’d rather have you bring me some things from Europe,” said my shrinking brother.

“All right. I’ll do that, but let me off this thing. I am so tired I can’t move. You’ll have to walk it back and give me five cents to ride home on the car.”

I crawled in to breakfast more dead than alive.

“What’s the matter, dearie? Did you ride too far?” asked mamma.

“I don’t know whether I rode too far or whether it was Ted’s asking if he couldn’t use my rooms while I was gone, but something has made me tired. What’s that? Whom is papa talking to over the telephone?”

Papa came in fuming and fretting.

“Who was it this time?” I questioned, with anticipation. Inquiries over the telephone were sure to be interesting to me just now.

“Somebody who wanted to know what train you were going on, but would not give his name. He was inquiring for a friend, he said, and wouldn’t give his friend’s name either.”

“Didn’t you tell him?” I cried, in distress.

“Certainly not. I told him nobody but an idiot would withhold his name.”

Papa calls such a variety of men idiots.

“Oh, but it was probably only flowers or candy. Why didn’t you tell him? Have you no sentiment?”

“I won’t have you receiving anonymous communications,” he retorted, with the liberty fathers have a little way of taking with their daughters.

“But flowers,” I pleaded. “It is no harm to send flowers without a card. Don’t you see?” Oh, how hard it is to explain a delicate point like that to one’s father—in broad daylight! “I am supposed to know who sent them!”

“But would you know?” asked my practical ancestor.

“Not—not exactly. But it would be almost sure to be one of them.”

Ted shouted. But there was nothing funny in what I said. Boys are so silly.

“Anyway, I am sorry you didn’t tell him,” I said.

“Well, I’m not,” declared papa.

The rest of the day fairly flew. The last night came, and the baby was put to bed. I undressed him, which he regarded as such a joke that he worked himself into a fever of excitement. He loves to scrub like Josie, the cook. I had bought him a little red pail, and I gave it to him that night when he was partly undressed, and he was so enchanted with it that he scampered around hugging it, and saying, “Pile! pile!” like a little Cockney. He gave such squeals of ecstasy that everybody came into the nursery to find him scrubbing his crib with a nail-brush and little red pail.

“Who gave you the pretty pail, Billy?” asked Aunt Lida, who was sitting by the crib.

“Tattah,” said Billy, in a whisper. He always whispers my name.

“Then go and kiss dear auntie. She is going away on the big boat to stay such a long time.”

Billy’s face sobered. Then he dropped his precious pail, and came and licked my face like a little dog, which is his way of kissing.

I squeezed him until he yelled.

“Don’t let him forget me,” I wailed. “Talk to him about me every day. And buy him a toy out of my money often, and tell him Tattah sent it to him. Oh, oh, he’ll be grown up when I come home!”

“Don’t cry, dearie,” said Aunt Lida, handing me her handkerchief. “I’ll see that your grave is kept green.”

My sister appeared at the door. She was all ready to start. She even had her veil on.

“What do you mean by exciting Billy so at this time of night?” she said. “Go out, all of you. We’ll lose the train. Hush, somebody’s at the telephone. Papa’s talking to that same man again.” I jumped up and ran out.

“Let me answer it, papa dear! Yes, yes, yes, certainly. To-night on the Pennsylvania. You’re quite welcome. Not at all.” I hung up the telephone.

I could hear papa in the nursery:

“She actually told him—after all I said this morning! I never heard of anything like it.”

Two or three voices were raised in my defence. Ted slipped out into the hall.

“Bully for you,” he whispered. “You’ll get the flowers all right at the train. Who do you s’pose they’re from? Another box just came for you. Say, couldn’t you leave that smallest box of violets in the silver box? I want to give them to a girl, and you’ve got such loads of others.”

“Don’t ask her for those,” answered my dear sister, “they are the most precious of all!”

“I can’t give you any of mine,” I said, “but I’ll buy you a box for her—a small box,” I added hastily.

“The carriages have come, dears,” quavered grandmamma, coming out of the nursery, followed by the family, one after the other.

“Get her satchels, Teddy. Her hat is upstairs. Her flowers are in the hall. She left her ulster on my bed, and her books are on the window-sill,” said mamma. She wouldn’t look at me. “Remember, dearie, your medicines are all labelled, and I put needles in your work-box all threaded. Don’t sit in draughts and don’t read in a dim light. Have a good time and study hard and come back soon. Good—bye, my girlie. God bless you!”

By this time no handkerchief would have sufficed for my tears. I reached out blindly, and Ted handed me a towel.

“I’ve got a sheet when you’ve sopped that,” he said. Boys are such brutes.

Aunt Lida said, “Good-bye, my dearest. You are my favorite niece. You know I love you the best.”

I giggled, for she tells my sister the same thing always.

“Nobody seems to care much that I am going,” said Bee, mournfully.

“But you are coming back so soon, and she is going to stay so long,” exclaimed grandmamma, patting Bee.

“I’ll bet she doesn’t stay a year,” cried Ted.

“I’ll expect her home by Christmas,” said papa.

“I’ll bet she is here to eat Thanksgiving dinner,” cried my brother-in-law.

“No, she is sure to stay as long as she has said she would,” said mamma.

Mothers are the brace of the universe. The family trailed down to the front door. Everybody was carrying something. There were two carriages, for they were all going to the station with us.

“For all the world like a funeral, with loads of flowers and everybody crying,” said my brother, cheerfully.

I never shall forget that drive to the station; nor the last few moments, when Bee and I stood on the car-steps and talked to those who were on the platform of the station. Can anybody else remember how she felt at going to Europe for the first time and leaving everybody she loved at home? Bee grieved because there were no flowers at the train after all. But the next morning they appeared, a tremendous box, arranged as a surprise.

Telegrams came popping in at all the big stations along the way, enlivening our gloom, and at the steamer there were such loads of things that we might almost have set up as a florist, or fruiterer, or bookseller. Such a lapful of steamer letters and telegrams! I read a few each morning, and some of them I read every morning!

I don’t like ocean travel. They sent grapefruit and confections to my state-room, which I tossed out of the port-hole. You know there are some people who think you don’t know what you want. I travelled horizontally most of the way, and now people roar when I say I wasn’t ill. Well, I wasn’t, you know. We—well, Teddy would not like me to be more explicit. I own to a horrible headache which never left me. I deny everything else. Let them laugh. I was there, and I know.

The steamer I went on allows men to smoke on all the decks, and they all smoked in my face. It did not help me. I must say that I was unspeakably thankful to get my foot on dry ground once more. When we got to the dock a special train of toy cars took us through the greenest of green landscapes, and suddenly, almost before we knew it, we were at Waterloo Station, and knew that London was at our door.

People said to me, “What are you going to London for?” I said, “To get an English point of view.” “Very well,” said one of the knowing ones, who has lived abroad the larger part of his life, “then you must go to ‘The Insular,’ in Piccadilly. That is not only the smartest hotel in London, but it is the most typically British. The rooms are let from season to season to the best country families. There you will find yourself plunged headlong into English life with not an American environment to bless yourself with, and you will soon get your English point of view.”

“Ah-h,” responded the simpleton who goes by my name, “that is what we want. We will go to ‘The Insular.’”

We wrote at once for rooms, and then telegraphed for them from Southampton.

The steamer did not land her passengers until the morning of the ninth day, which shows the vast superiority of going on a fast boat, which gets you in fully as much as fifteen or twenty minutes ahead of the slow ones.

Our luggage would not go on even a four-wheeler, so we took a dear little private bus and proceeded to put our mountainous American trunks on it. We filled the top of this bus as full as it would hold, and put everything else inside. After stowing ourselves in there would not have been room even for another umbrella.

In this fashion we reached “The Insular,” where we were received by four or five gorgeous creatures in livery, the head one of whom said, “Miss Columbia?” I admitted it, and we were ushered in, where we were met by more belonging to this tribe of gorgeousness, another of whom said, “Miss Columbia?”

“Yes,” I said, firmly, privately wondering if they were trying to trip me into admitting that I was somebody else.

“The housekeeper will be here presently,” said this person. “She is expecting you.”

Forth came the housekeeper.

“Miss Columbia?” she said.

Once again I said “Yes,” patiently, standing on my other foot.

“If you will be good enough to come with me I will show you your rooms.”

A door opened outward, disclosing a little square place with two cane-bottomed chairs. A man bounced out so suddenly that I nearly annihilated my sister, who was back of me. I could not imagine what this little cubbyhole was, but as there seemed to be nowhere else to go, I went in. The others followed, then the man who had bounced out. He closed the door and shut us in, where we stood in solemn silence. About a quarter of an hour afterwards I thought I saw something through the glass moving slowly downward, and then an infinitesimal thrill in the soles of my feet led me to suspect the truth.

“Is this thing an elevator?” I whispered to my sister.

“No, they call it a lift over here,” she whispered back.

“I know that,” I murmured, impatiently. “But is this thing it? Are we moving? Are we going anywhere?”

“Why, of course, my dear. They are slower than ours, that’s all.”

I listened to her with some misgivings, for her information is not always to be wholly trusted, but this time it happened that she was right, for after a while we came to the fourth floor, where our rooms were.

I wish you could have seen the size of them. I shall not attempt to describe them, for you would not believe me. I had engaged “two rooms and a bath.” The two rooms were there. “Where is the bath?” I said. The housekeeper lovingly, removed a gigantic crash towel from a hideous tin object, and proudly exposed to my vision that object which is next dearest to his silk hat to an Englishman’s heart—a hip-bath tub. Her manner said, “Beat that if you can.”

My sister prodded me in the back with her umbrella, which in our sign language means, “Don’t make a scene.”

“Very well,” I said, rather meekly. “Have our trunks sent up.”

“Very good, madam.”

She went away, and then we rang the bell and began to order what were to us the barest necessities of life. We were tired and lame and sleepy from a night spent at the pier landing the luggage, and we wanted things with which to make ourselves comfortable.

There was a pocket edition of a fireplace, and they brought us a hatful of the vilest soft coal, which peppered everything in the rooms with soot.

We climbed over our trunks to sit by this imitation of a fire, only to find that there was nothing to sit on but the most uncompromising of straight-backed chairs.

We groaned as we took in the situation. To our poor, racked frames a coal-hod would not have suggested more discomfort. We dragged up our hampers, packed with steamer-rugs and pillows, and my sister sat on hers while I took another turn at the bell. While the maid is answering this bell I shall have plenty of time to tell you what we afterwards discovered the process of bell-ringing in an English hotel to be.

We rang our bell. Presently we heard the most horrible gong, such as we use on our patrol wagons and fire-engines at home. This clanged four times. Then a second bell down the hall answered it. Then feet flew by our door. At this juncture my sister and I prepared to let ourselves down the fire-escape. But we soon discovered that those flying feet belonged to the poor maid, whom that gong had signalled that she was wanted on the fourth floor. She flew to a speaking-tube and asked who on the fourth floor wanted her. She was then given the number of our room, when she rang a bell to signify that our call was answered, by which time she was at liberty, and knocked at our door, saying, in her soft English voice, “Did you ring, miss?”

We told her we wanted rocking-chairs. She said there was not one in the house. Then easy-chairs, we said, or anything cushioned or low or comfortable. She said the housekeeper had no easier chairs.

We sat down on our hampers, and my sister leaned against the corner of the wardrobe with a pillow at her back to keep from being cut in two. I propped my back against the wash-stand, which did very well, except that the wash-stand occasionally slid away from me.

“This,” said my sister, impressively, “is England.”

We had been here only half an hour, but I had already got my point of view.

“Let’s go out and look up a hotel where they take Americans,” I said. “I feel the need of ice-water.”

Our drinking-water at “The Insular” was on the end of the wash-stand nearest the fire.

So, feeling a little timid and nervous, but not in the least homesick, we went downstairs. One of our gorgeous retinue called a cab and we entered it.

“Where shall we go?” asked my sister.

“I feel like saying to the first hotel we see,” I said.

Just then we raised our eyes and they rested simultaneously upon a sign, “The Empire Hotel for Cats and Dogs.” This simple solution of our difficulty put us in such high good humor that we said we wouldn’t look up a hotel just yet—we would take a drive.

Under these circumstances we took our first drive down Piccadilly, and Europe to me dates from that moment. The ship, the landing, the custom-house, the train, the hotel—all these were mere preliminaries to the Europe, which began then. People told me in America how my heart would swell at this, and how I would thrill at that, but it was not so. My first real thrill came to me in Piccadilly. It went all over me in little shivers and came out at the ends of my fingers, and then began once more at the base of my brain and did it all over again.

But what is the use of describing one’s first view of London streets and traffic to the initiated? Can they, who became used to it as children, appreciate it? Can they look back and recall how it struck them? No. When I try to tell Americans over here they look at me curiously and say, “Dear me, how odd!” The way they say it leaves me to draw any one of three conclusions: either they are not impressionable, and are therefore honest in denying the feeling; or they think it vulgar to admit it; or I am the only grown person in America who never has been to Europe before.

But I am indifferent to their opinion. People are right in saying this great tremendous rush of feeling can come but once. It is like being in love for the first time. You like it and yet you don’t like it. You wish it would go away, yet you fear that it will go all too soon. It gets into your head and makes you dizzy, and you want to shut your eyes, but you are afraid if you do that you will miss something. You cannot eat and you cannot sleep, and you feel that you have two consciousnesses: one which belongs to the life you have lived hitherto, and which still is going on, somewhere in the world, unmindful of you, and you unmindful of it; and the other is this new bliss which is beating in your veins and sounding in your ears and shining before your eyes, which no one knows and no one dreams of, but which keeps a smile on your lips—a smile which has in it nothing of humor, nothing from the great without, but which-comes from the secret recesses of your own inner consciousness, where the heart of the matter lies.

I remember nothing definite about that first drive. I, for my part, saw with unseeing eyes. My sister had seen it all before, so she had the power of speech. Occasionally she prodded me and cried, “Look, oh! look quickly.” But I never swerved. “I can’t look. If I do I shall miss something. You attend to your own window and I’ll attend to mine. Coming back I will see your side.”

When we got beyond the shops I said to the cabman:

“Do you know exactly the way you have come?”

“Yes, miss,” he said.

“Then go back precisely the same way.”

“Have you lost something, miss?” he inquired.

“Yes,” I said, “I have lost an impression, and I must look till I find it.”

“Very good, miss,” he said.

If I had said, “I have carelessly let fall my cathedral,” or, “I have lost my orang-outang. Look for him!” an imperturbable British cabby would only touch his cap and say, “Very good, miss!”

So we followed our own trail back to “The Insular.” “In this way,” I said to my sister, “we both get a complete view. To-morrow we will do it all over again.”

But we found that we could not wait for the morrow. We did it all over again that afternoon, and that second time I was able in a measure to detach myself from the hum and buzz and the dizzying effect of foreign faces, and I began to locate impressions. My first distinct recollections are of the great numbers of high hats on the men, the ill-hanging skirts and big feet of the women, the unsteadying effect of all those thousands of cabs, carriages, and carts all going to the left, which kept me constantly wishing to shriek out, “Go to the right or we’ll all be killed,” the absolutely perfect manner in which traffic was managed, and the majestic authority of the London police.

I have seen the Houses of Parliament and the Tower and Westminster Abbey, and the World’s Fair, but the most impressive sight I ever beheld is the upraised hand of a London policeman. I never heard one of them speak except when spoken to. But let one little blue-coated man raise his forefinger and every vehicle on wheels stops, and stops instantly; stops in obedience to law and order; stops without swearing or gesticulating or abuse; stops with no underhanded trying to drive out of line and get by on the other side; just stops, that is the end of it. And why? Because the Queen of England is behind that raised finger. A London policeman has more power than our President.

Even the Queen’s coachmen obey that forefinger. Not long ago she dismissed one who dared to drive even the royal carriage on in defiance of it. Understanding how to obey, that is what makes liberty.

I am the most flamboyant of Americans, the most hopelessly addicted to my own country, but I must admit that I had my first real taste of liberty in England.

I will tell you why. In America nobody obeys anybody. We make our laws, and then most industriously set about studying out a plan by which we may evade them. America is suffering, as all republics must of necessity suffer, from liberty in the hands of the multitude. The multitude are ignorant, and liberty in the hands of the ignorant is always license.

In America, the land of the free, whom do we fear? The President? No, God bless him. There is not a true American in the world who would not stand up as a man or a woman and go into his presence without fear. Are we afraid of our Senators, our chief rulers? No. But we are afraid of our servants, of our street-car conductors. We are afraid of sleeping-car porters, and the drivers of huge trucks. We are afraid they will drive over us in the streets, and if we dare to assert our rights and hold them in check we are afraid of what they will say to us, in the name of liberty, and of the way they will look at us, in the name of liberty.

English servants, I have discovered, have no more respect for Americans than the old-time negro of the Southern aristocracy has for Northerners. I once asked an old black mammy in Georgia why the negroes had so little respect for the white ladies of the North. “Case dey don’ know how to treat black folks, honey.” “Why don’t they?” I persisted. “Are they not kind to you?” “Umph,” she responded (and no one who has never heard a fat old negress say “Umph” knows the eloquence of it). “Umph. Dat’s it. Dey’s too kin’. Dey don’ know how to mek us min’.” And that is just the trouble with Americans here. An English servant takes orders, not requests.

I had such a time to learn that. We could not understand why we were obeyed so well at first, and presently, without any outward disrespect, our wants were simply ignored until all the English people had been attended to.

My sister had told me I was too polite, but one never believes one’s sister, so I questioned our sweet English friends, and they, with much delicacy and many apologies, and the prettiest hesitation in the world—considering the situation—told us the reason.

“But,” I gasped, “if I should speak to our servants in that manner they would leave. They would not stay over night.” Our English friends tried not to smile in a superior way, and they succeeded, only I knew the smile was there, and said, “Oh, no, our servants never leave us. They apologize for having done it wrong.”

On the way home I plucked up courage. “I am going to try it,” I said, firmly. My sister laughed in derision.

“Now I could do it,” she said, complaisantly. And so she could. My sister never plumes herself on a quality she does not possess.

“Are you going to use the tone and everything?” I said, somewhat timidly.

“You wait and see.”

She hesitated some time, I noticed, before she rang the bell, and she looked at herself in the glass and cleared her throat. I knew she was bracing herself.

“I’ll ring the bell if you like,” I said, politely.

She gave one look at me and then rang the bell herself with a firm hand.

“And I’ll get behind you with a poker in One hand and a pitcher of hot water in the other. Speak when you need either.”

“You feel very funny when you don’t have to do it yourself,” she said, witheringly.

“You’ll never put it through. You’ll back down and say ‘please’ before you have finished,” I said, and just then the maid knocked at the door.

I never heard anything like it. My sister was superb. I doubt if Bernhardt at her best ever inspired me with more awe. How that maid flew around. How humble she was. How she apologized. And how, every time my sister said, “Look sharp, now,” the maid said, “Thank you.” I thought I should die. I was so much interested in the dramatic possibilities of my cherished sister that when the door closed behind the maid we simply looked at each other a moment, then simultaneously made a bound for the bed, where we choked with laughter among the pillows. Presently we sat up with flushed faces and rumpled hair. I reached over and shook hands with her.

“How was that?” she asked.

“’Twas grand,” I said. “The Queen couldn’t have done it more to the manner born.”

My sister accepted my compliments complaisantly, as one who should say, “’Tis no more than my deserts.”

“How firm you were,” I said, admiringly.

“Wasn’t I, though?”

“How humble she was.”

“Wasn’t she?”

“You were quite as disagreeable and determined as a real Englishwoman would have been.”

“So I was.”

A pause full of intense admiration on my part. Then she said, “You couldn’t have done it.”

“I know that.”

“You are so deadly civil.”

“Not to everybody, only to servants.” I said this apologetically.

“You never keep a steady hand. You either grovel at their feet or snap their heads off.”

“Quite true,” I admitted, humbly.

“But it was grand, wasn’t it?” she said.

“Unspeakably grand.”

And for Americans it was.

We were still at “The Insular,” when one day I took up a handful of what had once been a tight bodice, and said to my sister:

“See how thin I’ve grown! I believe I am starving to death.”

“No wonder,” she answered, gloomily, “with this awful English cooking! I’m nearly dead from your experiment of getting an English point of view. I want something to eat—something that I like. I want a beefsteak, with mushrooms, and some potatoes au gratin, like those we have in America. I hate the stuff we get here. I wish I could never see another chop as long as I live.”

“‘The Insular’ is considered very good,” I remarked, pensively.

“Considered!” cried she. “Whose consideration counts, I should like to know, when you are always hungry for something you can’t get?”

“I know it; and we are paying such prices, too. Who, except ostriches, could eat their nasty preserves for breakfast when they are having grape-fruit at home? And then their vile aspic jellies and potted meats for luncheon, which look like sausage congealed in cold gravy, and which taste like gum arabic.”

“Let’s move,” said my sister. “Not into another hotel—that wouldn’t be much better. But lot’s take lodgings. I’ve heard that they were lovely. Then we can order what we like. Besides, it will be very much cheaper.”

“I didn’t come over here to economize,” I said.

“Well, I wouldn’t say a word if we were getting anything for our money, but we are not. Besides, when you get to Paris you will wish you hadn’t been so extravagant here.”

“Are the Paris shops more fascinating than those in Regent Street?” I asked.

“Much more.”

“More alluring, than Bond Street?”

“More so than any in the world,” she affirmed, with the religious fervor which always characterizes her tone when she speaks of Paris. The very leather of her purse fairly squeaks with ecstasy when she thinks of Paris.

“Heavens!” I murmured, with awe, for whenever she won’t go to Du Maurier’s grave with me, and when I won’t do the crown jewels in the Tower with her, we always compromise amiably on Bond Street, and come home beaming with joy.

“We might go now just to look,” I said. “I have the addresses of some very good lodgings.”

“We’ll take a cab by the hour,” said she, putting her hat on before the mirror, and turning her head on one side to view her completed handiwork.

“Now take off that watch and that belt and that chatelaine if you don’t want these harpies to think we are ‘rich Americans’ (how I have come to hate that phrase over here!), because they will charge accordingly.”

She looked at me with genuine admiration.

“Do you know, dear, you are really clever at times?”

I colored with pleasure. It is so seldom that she finds anything practical in me to praise.

“Now mind, we are just going to look,” she cautioned, as we rang a bell. “We must not do anything in a hurry.”

We came out half an hour afterwards and got into the cab without looking at each other.

“It was very unbusinesslike,” said she, severely. “You never do anything right.”

“But it was so gloriously impudent of us,” I urged. “First, we wanted lodgings. This was a boarding-house. Second, we wanted two bed-rooms and a drawing-room. They had only one drawing-room in the house; could we have that? Yes, we could. So we took their whole first floor, and made them promise to serve our breakfasts in bed, and our other meals in their best drawing-room, and turned a boarding-house into a lodging-house, all inside of half an hour. It was lovely!”

“It was bad business,” said she. “We could have got it for less, but you are always in such a hurry. If you like a thing, and anybody says you may have it for fifty, you always say, ‘I’ll give you seventy-five,’ You’re so afraid to think a thing over.”

“Second thoughts are never as much fun as first thoughts,” I urged. “Second thoughts are always so sensible and reasonable and approved of.”

“How do you know?” asked my sister, witheringly. “You never waited for any.”

The next day we moved. Everybody said our rooms were charming, and that they were cheap, for I told how much we paid, much to my sister’s disgust. She is such a lady.

“We have cut down our expenses so much,” I said, looking around on the drab walls and the dun-colored carpets, “don’t you think we might have a few flowers?”

“I believe you took this place for the balcony, so that you could put daisies around the edge and in the window-boxes!” she cried.

“No, I didn’t. But the houses in London are so pretty with their flowers. Don’t you think we might have a few?”

“Well, go and get them. I’ve got to write the home letter to-day if it is to catch the Southampton boat.”

I came home with six huge palms, two June roses, some pink heather, a jar of marguerites, and I had ordered the balcony and window-boxes filled. My sister helped me to place them, but when her back was turned I arranged them over again. I can’t tie a veil on the way she can, but I can arrange flowers to look—well, I won’t boast.

Our landladies were two middle-aged, comfortable sisters. We called them “The Tabbies,” meaning no disrespect to cats, either. I thought they took rather too violent an interest in our affairs, but I said nothing until one day after we had been settled nearly a week. I was seated in my own private room trying to write. My sister came in, evidently disturbed by something.

“Do you know,” she said, “that our landlady just asked me how much you paid for those strawberries? And when I told her she said that that made them come to fourpence apiece, and that they were very dear. Now, how did she know that they were strawberries, or how many were in each box, I’d like to know?”

“Probably she opened the package,” I said.

“Exactly what I think. Now I won’t stand that. And then she asked me not to set things on the mahogany tables. It’s just because we are Americans! She never would dare treat English people that way. She has not sufficient respect for us.”

“Then tell her to be more respectful; tell her we are very highly thought of at home.”

“She wouldn’t care for that.”

“Then tell her we have a few rich relations and quite a number of influential friends.”

“Pooh!”

“And if that does not fetch her, there is nothing left to do but to be quite rude to her, and then she will know that we belong to the very highest society. But what do you care what a middle-class landlady thinks, just so she lets you alone?”

My sister meditated, and I added:

“If you would just snub her once, in your most ladylike way, it would settle her. As for me, I am satisfied to think we are paying much less, and we are twice as comfortable as we were at the hotel; and we get such good things to eat that our skeletons are filling out, and once more our clothes fit.”

“That is so,” said she, letting her thoughts wander to the number of hooks in her closet. “We do have more room, and I think our drawing-room with its palms and flowers will look lovely to-morrow.”

“Do you think it was wise,” she added, “to ask all those men to come at once?”

“Oh yes; let them all come together, then we can weed them out afterwards. You never can have too many men.”

“I am glad you have asked in a few women.”

“Why?” I demanded. “Are you insinuating that we are not equal to a handful of Englishmen? Recall the Boston tea-party. We will give them the first strawberries of the season, and plenty of tea. Feed them; that’s the main thing,” I said, firmly, taking up my pen and looking steadily at her.

“I’ll go,” she said, hastily. “Do you have to go to the bank to-day? You know to-morrow we must pay our weekly bill.”

“It won’t be much,” I said, cheerfully; “I am sure I have enough.”

The next day the bill came. Our landlady sent it up on the breakfast-tray. I opened it, then shrieked for my sister. It covered four pages of note-paper.

“For heaven’s sake! what is the matter?” she cried. “Has anything happened to Billy?”

“Billy! This thing is not an American letter. It is the bill for our cheap lodgings. Look at it! Look at the extras—gas, coals, washing bed—linen, washing table—linen, washing towels, kitchen fires, service, oil for three lamps, afternoon tea, and three shillings for sundries on the fourth page! What can sundries include? She hasn’t skipped anything but pew-rent.”

My sister looked at the total, and buried her face in the pillows to smother a groan.

“Ring the bell,” I said; “I want the maid.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to find out what ‘sundries’ are.”

She gave the bell-cord such a pull that she broke the wire, and it fell down on her head.

“That, too, will go in the bill. Wrap your handkerchief around your hand and give the wire a jerk. Give it a good one. I don’t care if it brings the police.”

The maid came.

“Martha, present my compliments to Mrs. Black, and ask her what ‘sundries’ include.”

Martha came back smiling.

“Please, miss, Mrs. Black’s compliments, and ‘sundries’ means that you complained that the coffee was muddy, and after that she cleared it with an egg. ‘Sundries’ means the eggs.”

“Martha,” I said, weakly, “give me those Crown salts. No, no, I forgot; those are Mrs. Black’s salts. Take them out and tell her I only smelled them once.”

“Martha,” said my sister, dragging my purse out from under my pillow, “here is sixpence not to tell Mrs. Black anything.” Then when Martha disappeared she said, “How often have I told you not to jest with servants?”

“I forgot,” I said, humbly. “But Martha has a sense of humor, don’t you think?”

“I never thought anything about it. But what are you going to do about that bill?”

“I’m going to argue about it, and declare I won’t pay it, and then pay it like a true American. Would you have me upset the traditions? But I’ve got to go to the bank first.”

I did just as I said. I argued to no avail. Mrs. Black was quite haughty, and made me feel like a chimney-sweep. I paid her in full, and when I came up I said:

“You are quite right. She has a poor opinion of us. When I asked her how long it would take to drive to a house in West End, she said, ‘Why do you want to know?’ I said I ‘wanted to see the house.’”

“Didn’t you tell her we were invited there?” asked my sister, scandalized.

“No; I said I had heard a good deal about the house, and she said it was open to the public on Fridays. So I said we’d go then.”

“I think you are horrid!” cried Bee. “The insolence of that woman! And you actually think it is funny! You think everything is funny.”

I soothed her by pointing out some of the things which I considered sad, notably English people trying to enjoy themselves. Then the men began to drop in for tea, and that succeeded in making her forget her troubles.

Reggie and the Duke arrived together. My sister at once took charge of the Duke, while Reggie said to me, “I say, what sort of creature is the old girl below?”

“Not a very good sort, I am afraid. Why? What has she done now?”

“Why, she stopped Abingdon and me and asked us to wipe our shoes.”

“She asked the Duke of Abingdon to wipe his shoes?” I gasped, in a whisper.

“Yes; and Freddie, who was just ahead of us, turned back and said, ‘My good woman, was the cab very dirty, do you think?’”

“Oh, don’t tell my sister! She has almost died of Mrs. Black already to-day; this would finish her completely.”

“Well, you must give your woman a talking to—a regular going over, d’ye know? Tell her you’ll be the mistress of the whole blooming house or you’ll tear it to pieces. That’s the way to talk to ’em. I told my landlady in Edinburgh once that I’d chuck her out of the window if she spoke to me until she was spoken to. She came up and rapped on the door one Saturday night at ten o’clock, when I had some fellows there, and told me to send those men home and go to bed.”

“Then she isn’t taking advantage of us because we are Americans, the way the cabmen do?”

“Oh yes, I dare say she is; but you must stand up to her. They’re a set of thieves, the whole of ’em. I say, that’s a pretty picture you’ve got pinned up there.”

“That’s to hide a hole in the lace curtain,” I explained, gratuitously. Then I remembered, and glanced apprehensively at my sister, but fortunately she had not heard me. “That is one of the pictures from Truth, an American magazine. I always save the middle picture when it is pretty, and pin it up on the wall.”

“That is one thing where the States are away ahead of us—in their illustrated magazines.”

“Don’t say ‘the States!’ I’ve told you before. I didn’t know you ever admitted that anything was better in America.”

Reggie only smiled affably. He ignored my offer of battle, and said:

“Abingdon is asking your sister to dine. I’m asked, and Freddie and his wife, and I think you will enjoy it.”

When they were all gone I marched downstairs to Mrs. Black without saying a word to any one. When I came up I found my sister hanging over the banisters.

“What is the matter? What have you done? I knew you were angry by the way you looked.”

“It was lovely!” I said. “I sent for Mrs. Black, and said, ‘Mrs. Black, do you know the name of the gentleman whom you asked to wipe his shoes to-day?’ ‘No,’ said she. ‘It was the Duke of Abingdon,’ I said, sternly, well knowing the unspeakable reverence which the middle-class English have for a title. She turned purple. She fell back against the wall, muttering, ‘The Duke of Abingdon! The Duke of Abingdon!’ I believe she is still leaning up against the wall muttering that holy name. A title to Mrs. Black!”

The next day both the Tabbies were curtsying in the hall when we started out. We were going on a coach to Richmond with Julia and her husband, and another American girl, and then Julia’s husband was going to row us up the Thames to Hampton Court for tea, and they were all going to dine with us at Scott’s when we got home.

It was a lovely day. The trees were a mass of bloom, and everybody ought to have enjoyed himself. We were having a very good time of it among ourselves reading the absurd signs, until we noticed the three girls who sat opposite to us. They had serious faces, and long, consumptive teeth, which they never succeeded in completely hiding. I knew just how they would look when they were dead; I knew that those two long front teeth would still— They listened to all we said without a flicker of the eyelashes. Occasionally they looked down at the size of the American girl’s little feet and then involuntarily drew their own back out of sight.

Presently I espied a sign, “Funerals, for this week only, at half price.” I seized Julia’s hand. “Stop, oh, stop the coach and let’s get a funeral! We may never have an opportunity to get a bargain in funerals again. And the sale lasts only one week. Everybody told me before I came away to get what I wanted at the moment I saw it; not to wait, thinking I would come back. So unless we order one now we may have to pay the full price. And a funeral would be such a good investment; it would keep forever. You’d never feel like using it before you actually needed it. Do let me get one now!”

Of course, Julia, my sister, and Julia’s husband were in gales of laughter; but what finished me off was to see three serious creatures opposite rise as if pulled by one string, look in an anxious way at me and then at the sign, while the teeth began to say to each other: “What did she say? What does she mean? What does she want a funeral for?”

We had a lovely day, but everybody we met on the river looked very unhappy, and nobody seemed to be at all glad that we were there or that we were rising to the occasion. When we got home I was too tired to notice things, but my sister, who sees everything, whispered:

“I verily believe they’ve put down a new stair-carpet to-day.”

The next morning such a sight met our astonished eyes. There was a new carpet on the hall. There were new curtains in our drawing-room. All the covers had been removed from their sacred furniture. Brass andirons replaced the old ones. The piano had a new cover. There was a rocking-chair for each (we had only one before), and while we were still speechless with amazement Mrs. Black came in with our bill.

“I have been thinking this over since yesterday, and I have decided that as long as you did not understand about the extras, it would be no more than right that I should take them off. So I owe you this.”

I took the money, and it dropped from my nerveless fingers. Mrs. Black picked it up and put it on the table—the mahogany table.

“You see I propped your palms for you in your absence, and I repotted four of them. I thought they would grow better. Here are some periodicals I sent to the library for, thinking you might like to look at them, and I put my new calendar over your writing-desk. Now, is there any little delicacy you would like for your luncheon?”

While Bee was getting rid of her I made a few rapid mental calculations.

“Bee,” I said, “we are going to stay over here two years. Let’s buy the Duke and take him with us.”

The reaction has come. I knew it would. It always does. It is a mortification to be obliged to admit it in the face of London, and all that we have had done for us, but the fact is we are homesick—wretchedly, bitterly homesick. I remember how, when other people have been here and written that they were homesick, I have sniffed with contempt and have said to myself, “What poor taste! Just wait until my turn comes to go to Europe! I’ll show them what it is to enjoy every moment of my stay!”

But now—dear me, I can remember that I have made invidious remarks about New York, and have objected to the odors in Chicago, and have hated the Illinois Central turnstiles. But if I could be back in America I would not mind being caught in a turnstile all day. Dear America! Dear Lake Michigan! Dear Chicago!

I have talked the matter over with my sister, and we have decided that it must be the people, for certainly the novelty is not yet worn off of this marvellous London. We like individually nearly every one whom we have met, but as a nation the English are to me an acquired taste—just like olives and German opera.

To explain. My friendly, volatile American feelings are constantly being shocked at the massed and consolidated indifference of English men and women to each other. They care for nobody but themselves. In a certain sense this indifference to other people’s opinions is very satisfactory. It makes you feel that no matter how outrageous you wanted to be you could not cause a ripple of excitement or interest—unless Royalty noticed your action. Then London would tread itself to death in its efforts to see and hear you. But if an Englishman entered a packed theatre on his hands with his feet in the air, and thus proceeded to make the rounds of the house, the audience would only give one glance, just to make sure that it was nothing more abnormal than a man in evening dress, carrying his crush-hat between his feet and walking on his hands, and then they would return to their exciting conversation of where they were “going to show after the play.” Even the maids who usher would not smile, but would stoop and put his programme between his teeth for him, and turn to the next comer.

The English mind their own business, and we Americans are so used to interfering with each other, and minding everybody’s business as well as our own, it makes us very homesick indeed, to find that we can do precisely as we please and be let entirely alone.

The English who have been in America, or those who have a single blessed drop of Irish or Scotch blood in their veins, will quite understand what I mean. Fortunately for us we have found a few of these different sorts, and they have kept us from suicide. They warned us of the differences we would find. One man said to me: “We English do not understand the meaning of the word hospitality compared to you Americans. Now in the States—”

“Stop right there, if you please,” I begged, “and say ‘America.’ It offends me to be called ‘the States’ quite as much as if you called me ‘the Colonies’ or ‘the Provinces!’”

“You speak as if you were America,” he said.

“I am,” I replied.

“Now that is just it. You Americans come over here nationally. We English travel individually.”

I was so startled at this acute analysis from a man whom I had always regarded as an Englishman that I forgot my manners and I said, “Good heavens, you are not all English, are you?”

“My father was Irish,” he said.

“I knew it!” I cried with joy. “Please shake hands with me again. I knew you weren’t entirely English after that speech!”

He laughed.

“I will shake hands with you, of course. But I am a typical Britisher. Please believe that.”

“I shall not. You are not typical. That was really a clever distinction and quite true.”

He looked as if he were going to argue the point with me, so I hurried on. I always get the worst of an argument, so I tried to take his mind off his injury. “Now please go on,” I urged. “It sounded so interesting.”

“Well, I was only going to say that in America you are, as hosts, quite sincere in wishing us to enjoy ourselves and to like America. Here we will only do our duty by you if you bring letters to us, and we don’t care a hang whether you like England or not. We like it, and that’s enough.”

“I see,” I said, with cold chills of aversion for England as a nation creeping over my enthusiasm.

“Now in America,” he proceeded, “your host sends his carriage for you, or calls for you, takes you with him, stays by you, introduces you to the people he thinks you would most care to meet, and tells them who and what you are; sees that you have everything that’s going, and that you see everything that’s going, and then takes you back to your club.”

“Then he asks you if you have had a good time, and if you like America!” I supplemented.

“Oh, Lord, yes! He asks you that all the time, and so does everybody else,” he said, with a groan.

“Now, you were unkind if you didn’t tell him all he wanted you to, for I do assure you it was pure American kindness of heart which made him take all that trouble for you. I know, too, without your telling me, that he introduced you to all the prettiest girls, and gave you a chance to talk to each of them, and only hovered around waiting to take you on to the next one, as soon as he could catch you with ease.”

“He did just that. How did you know?”

“Because he was a typical American host, God bless him, and that is the way we do things over there.”

“Now here,” he went on, “we consider our duty done if we take a man to dine, and then to some reception, where we turn him loose after one or two introductions.”

“What a hateful way of doing!” I said, politely.

“It is. It must seem barbarous to you.”

“It does.”

“Or if you are a woman we send our carriages to let you drive where you like. Or we send you invitations to go to needlework exhibitions where you have to pay five shillings admission.”

I said nothing, and he laughed.

“I know they have done that to you,” he exclaimed. “Haven’t they?”

“I have been delightfully entertained at luncheons and dinners and teas, and I have been introduced to as charming people in London as I ever hope to meet anywhere,” I said, stolidly.

“But you won’t tell about the needlework. Oh, I say, but that’s jolly! Fancy what you said when you began to get those beastly things!” And he laughed again.

“I didn’t say anything,” I said. Then he roared. Yet he claimed to be a “typical Britisher.”

“We mean kindly,” he went on. “You mustn’t lay it up against us.”

“Oh, we don’t. We are having a lovely time.”

There are times when the truth would be brutal.

Then this oasis of a man, this “typical Britisher,” went away, and my sister and I dressed for the theatre. A friend had sent us her box, and assured us that it was perfectly proper for us to go alone. So we went. Up to this time we had not hinted to each other that we were homesick. The play was most amusing, yet we couldn’t help watching the audience. Such a bored-looking set, the women with frizzled hair held down by invisible nets, mingling with their eyebrows, and done hideously in the back. Low-necked gowns, exhibiting the most beautiful shoulders in the world. Gorgeous jewels in their hair and gleaming all over their bodices, but among half a dozen emerald, turquoise, and diamond bracelets there would appear a silver-watch bracelet which cost not over ten dollars, and spoiled the effect of all the others.

English women as a race are the worst-dressed women in the world. I saw thousands of them in Piccadilly and Regent Street, and at Church Parade in the Park, with high, French-heeled slippers over colored stockings. And as to sizes, I should say nines were the average. There are some smaller, but the most are larger.

The Prince of Wales was in the box opposite to ours, and when we were not looking at him we gazed at the impassive faces of the audience. They never smiled. They never laughed. The subtlest points in the play went unnoticed, yet it is one which has had a record run and bids fair to keep the boards for the rest of the season.

Suddenly my sister, although we had not spoken of the homesickness that was weighing us down, touched my arm and said, “Look quick! There’s one!”

“Where? Where?”

“Down there just in front of the pit, talking to that bald-headed idiot with the monocle.”

“Do you think she is American?” I said, dubiously. I couldn’t see her feet. “She might be French. She talks all over.”

“No. She is an American girl. See how thin she is. The French are short and fat.”

“Look at her face,” I said, enviously. “How animated it is. See how it seems to stand out among all the other faces.”

“Yet she is only amusing herself. See how stolid that creature looks that she is wasting all her vitality on.”

“She has told him some joke and she is laughing at it. He has put his monocle in his other eye in his effort to see the point. He will get it by the next boat. Wish she’d come and tell that joke to me. I’d laugh at it.”

My sister eyed me critically.

“You don’t look as if you could laugh,” she said.

“I wonder what would happen if I should fall dead and drop over into the lap of that fat elephant in pink silk with the red neck,” I said, musingly.

“She wouldn’t even wink,” said my sister, laughingly. “But if you struck her just right you would bounce clear up here again and I could catch you.”

“It is just four o’clock in Chicago,” I said.

My sister promptly turned her back on me.

“And Billy has just wakened from his nap, and Katy is giving him his food,” I went on. (Billy is my sister’s baby.) “And then mamma will come into the nursery presently and take him while Katy gets his carriage out, and she will show him my picture and ask him who it is (because she wrote me she always did it at this time), and then he will say, ‘Tattah,’ which is the sweetest baby word for ‘Auntie’ I ever heard from mortal lips, and then he will kiss it of his own accord. Mamma wrote that he had blistered it with his kisses, and it’s one of the big ones, but I don’t care; I’ll order a dozen more if he will blister them all. And then she will say, ‘Where did mamma and Tattah go?’ and he will wave his precious little square hand and say, ‘Big boat,’ and she says he tries to say, ‘Way off’—and, oh, dear, we are ‘way off’—”

“Stop talking, you fiend,” said my sister, from the depths of her handkerchief. “You know I look like a fright when I cry.”

“Boo-hoo,” was my only reply. And once started, I couldn’t stop. That deadly English atmosphere of indifference—and, oh—and everything!

Have you ever been homesick when you couldn’t get home? Have you ever wanted to see your mother so that every bone in your body ached? Have you ever been in the state where to see the baby for five minutes you would give everything on earth you had? That was the way I felt about Billy that grewsome night at this amusing play in an English theatre. I had on my best clothes, but after my handkerchief ceased to avail the tears slopped down on my satin gown, and the blisters will remain as a lasting tribute to the contagion of a company of English people out enjoying themselves.

My sister’s stern sense of decorum caused her to contain herself until she got home, but I am free to confess that after I once loosed my hold over myself and found what a relief it was, I realized the truth of what our old negro cook used to say when I was a child in the South, and asked her why she howled and cried in such an alarming manner when she “got religion.” She used to say, “Lawd, chile, you don’t know how soovin’ it is to jest bust out awn ’casions lake dese!”

Happy negroes! Happy children, who can “bust out” when their feelings get the better of them! Civilization robs us of many of our acutest pleasures.

That night on the way home from the theatre I learned something. Nobody had ever told me that it is the custom to give the cabby an extra sixpence when one takes a cab late at night, so, on alighting in front of our flower-trimmed lodgings, I reached up, deposited my shilling in his hand, and was turning away, when my footsteps were arrested by my cabby’s voice.

Turning, I saw him tossing the despised shilling in his curved palm and saying:

“A shillin’! Twelve o’clock at night! Two ladies in evenin’ dress! You ought to ’a’ gone in a ’bus! A cab’s too expensive for you! I wish you’d ’a’ walked and I wish it had rained!”

With that parting shot he gathered up the lines and drove off, while I leaned up against the door shaking with a laughter which my sister in no wise shared with me. Poor Bee! Things like that jar her so that she can’t get any amusement out of them. To her it was terrifying impudence. To me it was a heart-to-heart talk with a London cabby!

Oh, the sweet viciousness of that “I wish it had rained!” I wonder if that man beats his wife, or if he just converses with her as he does with a recreant fare! Anyway, I loved him.

But if I have discovered nothing else in the brief time since I left my native land, it is worth while to realize the truth of all the poetry and song written on foreign shores about home.

To one accustomed to travel only in America, and to feel at home with all the different varieties of one’s countrymen, such sentiments are no more than vers de société. But now I know what Heimweh is—the home-pain. I can understand that the Swiss really die of it sometimes. The home-pain! Neuralgia, you know, and most other acute pains, attack only one set of nerves. But Heimweh hurts all over. There is not a muscle of the body, nor the most remote fibre of the brain, nor a tissue of the heart that does not ache with it. You can’t eat. You can’t sleep. You can’t read or write or talk. It begins with the protoplasm of your soul—and reaches forward to the end of time, and aches every step of the way along. You want to hide your face in a pillow away from everybody and do nothing but weep, but even that does not cure. It seems to be too private to help materially. The only thing I can recommend is to “bust out.”

Homesickness is an inexplicable thing. I have heard brides relate how it attacked them unmercifully and without cause in the midst of their honeymoon. Girl students, whose sole aim in life has been to come abroad to study, and who, in finally coming, have fondly dreamed that the gates of Paradise had swung open before their delighted eyes, have been among its earliest and most acutely afflicted victims. No success, no realized ambitions ward it off. Like death, it comes to high and low alike. One woman, whose name became famous with her first concert, told me that she spent the first year over here in tears. Nothing that friends can do, no amount of kindness or hospitality avails as a preventive. You can take bromides and cure insomnia. You can take chloroform, and enough of it will prevent seasickness, but nothing avails for Heimweh. And like pride, “let him that thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall.” I have been in the midst of an animated, recital of how homesick I had been the day before, ridiculing myself and my malady with unctuous freedom, when suddenly Billy’s little face would seem to rise out of the flowers on the dinner-table, or the patter of his little flying feet as they used to sound in my ear as he fluttered down the long hall to my study, or the darling way he used to ran towards me when I held out my arms and said, “Come, Billy, let Tattah show you the doves,” with such an expectant face, and that little scarlet mouth opened to kiss me—oh, it is nothing to anybody else, but it is home to me, and I was only recalled to London and my dinner party when a fresh attack was made on America, and I was called once more to battle for my country.

I have “fought, bled, and died” for home and country more times than I can count since I have been here. I ought to come home with honorable scars and the rank of field-marshal, at least. I never knew how many objectionable features America presented to Englishmen until I became their guest and broke bread at their tables. I cannot eat very much at their dinner parties—I am too busy thinking how to parry their attacks on my America, and especially my Chicago, and my West generally. The English adore Americans, but they loathe America, and I, for one, will not accept a divided allegiance. “Love me, love my dog,” is my motto. I go home from their dinners as hungry as a wolf, but covered with Victoria crosses. I am puzzled to know if they really hate Chicago more than any other spot on earth, or if they simply love to hear me fight for it, or if their manners need improving.

I myself may complain of the horrors of our filthy streets, or of the way we tear up whole blocks at once (here in London they only mend a teaspoonful of pavement at a time), or of our beastly winds which tear your soul from your body, but I hope never to sink so low as to permit a lot of foreigners to do it. For even as a Parisian loves his Paris, and as a New Yorker loves his London, so do I love my Chicago.

It was a fortunate thing, after all, that I went to London first, and had my first great astonishment there. It broke Paris to me gently.

For a month I have been in this city of limited republicanism; this extraordinary example of outward beauty and inward uncleanness; this bewildering cosmopolis of cheap luxuries and expensive necessities; this curious city of contradictions, where you might eat your breakfast from the streets—they are so clean—but where you must close your eyes to the spectacles of the curbstones; this beautiful, whited sepulchre, where exists the unwritten law, “Commit any offence you will, provided you submerge it in poetry and flowers”; this exponent of outward observances, where a gentleman will deliberately push you into the street if he wishes to pass you in a crowd, but where his action is condoned by his inexpressible manner of raising his hat to you, and the heartfelt sincerity of his apology; where one man will run a mile to restore a lost franc, but if you ask him to change a gold piece he will steal five; where your eyes are ravished with the beauty, and the greenness, and the smoothness and apparent ease of living of all its inhabitants; where your mind is filled with the pictures, the music, the art, the general atmosphere of culture and wit; where the cooking is so good but so elusive, and where the shops are so bewitching that you have spent your last dollar without thinking, and you are obliged to cable for a new letter of credit from home before you know it—this is Paris.

Paris is very educational. I can imagine its influence broadening some people so much that their own country could never be ample enough to cover them again. I can imagine it narrowing others so that they would return to America more of Puritans than ever. It is amusing, it is fascinating, it is exciting, it is corrupting. The French must be the most curious people on earth. How could even heavenly ingenuity create a more uncommon or bewildering contradiction and combination? Make up your mind that they are as simple as children when you see their innocent picnicking along the boulevards and in the parks with their whole families, yet you dare not trust yourself to hear what they are saying. Believe that they are cynical, and fin de siècle, and skeptical of all women when you hear two men talk, and the next day you hear that one of them has shot himself on the grave of his sweetheart. Believe that politeness is the ruling characteristic of the country because a man kisses your hand when he takes leave of you. But marry him, and no insult as regards other women is too low for him to heap upon you. Believe that the French men are sympathetic because they laugh and cry openly at the theatre. But appeal to their chivalry, and they will rescue you from one discomfort only to offer you a worse. The French have sentimentality, but not sentiment. They have gallantry, but not chivalry. They have vanity, but not pride. They have religion, but not morality. They are a combination of the wildest extravagance and the strictest parsimony. They cultivate the ground so close to the railroad tracks that the trains almost run over their roses, and yet they leave a Place de la Concorde in the heart of the city.

You can buy the wing of a chicken at a butcher’s and take it home to cook it. But your bill at a restaurant will appall you. Water is the most precious and exclusive drink you can order in Paris. Imagine that—you who let the water run to cool it! In Paris they actually pay for water in their houses by the quart.

Artichokes, and truffles, and mushrooms, and silk stockings, and kid gloves are so cheap here that it makes you blink your eyes. But eggs, and cream, and milk are luxuries. Silks and velvets are bewilderingly inexpensive. But cotton stuffs are from America, and are extravagances. They make them up into “costumes,” and trim them with velvet ribbon. Never by any chance could you be supposed to send cotton frocks to be washed every week. The luxury of fresh, starched muslin dresses and plenty of shirt-waists is unknown.

I never shall overcome the ecstasies of laughter which assail me when I see varieties of coal exhibited in tiny shop windows, set forth in high glass dishes, as we exploit chocolates at home. But well they may respect it, for it is really very much cheaper to freeze to death than to buy coal in Paris.

The reason of all this is the city tax on every chicken, every carrot, every egg brought into Paris. Every mouthful of food is taxed. This produces an enormous revenue, and this is why the streets are so clean; it is why the asphalt is as smooth as a ballroom floor; it is why the whole of Paris is as beautiful as a dream.

In fact, the city has ideas of cleanliness which its middle-class inhabitants do not share. On a rainy day in Paris the absurdly hoisted dresses will expose to your view all varieties of trimmed, ruffled, and lace petticoats, which would undeniably be benefited by a bath. All the lingerie has ribbons in it, and sometimes I think they are never intended to be taken out.

When I was at the château of a friend not long ago she overheard her maid apologizing to two sisters of charity, for the presence of a bath-tub in her mistress’s dressing-room: “You must not blame madame la marquise for bathing every day. She is not more untidy than I, and I, God knows, wash myself but twice a year. It is just a habit of hers which she caught from the English.”

My friend called to her sharply, and told her she need not apologize for her bathing, to which the maid replied, in a tone of meek justification, “But if madame la marquise only knew how she was regarded by the people for this habit of hers!”

I like the way the French take their amusements. At the theatre they laugh and applaud the wit of the hero and hiss the villain. They shout their approval of a duel and weep aloud over the death of the aged mother. When they drive in the Bois they smile and have an air of enjoyment quite at variance with the bored expression of English and Americans who have enough money to own carriages. We drove in Hyde Park in London the day before we came to Paris, and nearly wept with sympathy for the unspoken grief in the faces of the unfortunate rich who were at such pains to enjoy themselves.

The second day from that we had a delightful drive in the Bois in Paris.

“How glad everybody seems to be we have come!” I said to my sister. “See how pleased they all look.”

I was enchanted at their gay faces. I felt like bowing right and left to them, the way queens and circus girls do.

I never saw such handsome men as I saw in London. I never saw such beautiful women as I see in Paris.

The Bois has never been so smart as it was the past season, for the horrible fire of the Bazar de la Charité put an end to the Paris season, and left those who were not personally bereaved no solace but the Bois. Consequently, the costumes one saw between five and seven on that one beautiful boulevard were enough to set one wild. I always wished that my neck turned on a pivot and that I had eyes set like a coronet all around my head. My sister and I were in a constant state of ecstasy and of clutching each other’s gowns, trying to see every one who passed. But it was of no use. Although they drove slowly on purpose to be seen, if you tried to focus your glance on each one it seemed as if they drove like lightning, and you got only astigmatism for your pains. I always came home from the Bois with a headache and a stiff neck.

I never dreamed of such clothes even in my dreams of heaven. But the French are an extravagant race. There was hardly a gown worn last season which was not of the most delicate texture, garnished with chiffon and illusion and tulle—the most crushable, airy, inflammable, unserviceable material one can think of. Now, I am a utilitarian. When I see a white gown I always wonder if it will wash. If I see lace on the foot ruffle of a dress I think how it will sound when the wearer steps on it going up-stairs. But anything would be serviceable to wear driving in a victoria in the Bois between five and seven, and as that is where I have seen the most beautiful costumes I have no right to complain, or to thrust at them my American ideas of usefulness. This rage of theirs for beauty is what makes a perpetual honeymoon for the eyes of every inch of France. The way they study color and put greens together in their landscape gardening makes one think with horror of our prairies and sagebrush.

The eye is ravished with beauty all over Paris. The clean streets, the walks between rows of trees for pedestrians, the lanes for bicyclists, the paths through tiny forests, right in Paris, for equestrians, and on each side the loveliest trees—trees everywhere except where there are fountains—but what is the use of trying to describe a beauty which has staggered braver pens than mine, and which, after all, you must see to appreciate?

The Catholic observances one sees everywhere in Paris are most interesting. When a funeral procession passes, every man takes off his hat and stands watching it with the greatest respect.