The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol. 99., December 13, 1890, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol. 99., December 13, 1890 Author: Various Release Date: July 14, 2004 [EBook #12905] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

(By WATER DECANT, Author of "Chaplin off his Feet," "All Sorts of Editions for Men," "The Nuns in Dilemma," "The Cream he Tried," "Blue-the-Money Naughty-boy," "The Silver Gutter-Snipe," "All for a Farden Fare," "The Roley Hose," "Caramel of Stickinesse," &c., &c., &c.)

[Of this story the Author writes to us as follows:—"I can honestly recommend it, as calculated to lower the exaggerated cheerfulness which is apt to prevail at Christmas time. I consider it, therefore, to be eminently suited for a Christmas Annual. Families are advised to read it in detachments of four or five at a time. Married men who owe their wives' mothers a grudge should lock them into a bare room, with a guttering candle and this story. Death will be certain and not painless. I've got one or two rods in pickle for the publishers. You wait and see.—W.D."]

GEORGE GINSLING was alone in his College-rooms at Cambridge. His friends had just left him. They were quite the tip-top set in Christ's College, and the ashes of the cigarettes they had been smoking lay about the rich Axminster carpet. They had been talking about many things, as is the wont of young men, and one of them had particularly bothered GEORGE by asking him why he had refused a seat in the University Trial Eights after rowing No. 5 in his College boat. GEORGE had no answer ready, and had replied angrily. Now, he thought of many answers. This made him nervous. He paced quickly up and down the deserted room, sipping his seventh tumbler of brandy, as he walked. It was his invariable custom to drink seven tumblers of neat brandy every night to steady himself, and his College career had, in consequence, been quite unexceptionable up to the present moment. He used playfully to remind his Dean of PORSON's drunken epigram, and the good man always accepted this as an excuse for any false quantities in GEORGE's Greek Iambics. But to-night, as I have said, GEORGE was nervous with a strange nervousness, and he, therefore, went to bed, having previously blown out his candle and placed his Waterbury watch under his pillow, on the top of which sat a Devil wearing a thick jersey worked with large green spots on a yellow ground.

Now this Devil was a Water-Devil of the most pronounced type. His head-quarters were on the Thames at Barking, where there is a sewage outfall, and he had lately established a branch-office on the Cam, where he did a considerable business.

Occasionally, he would run down to Cambridge himself, to consult with his manager, and on these occasions he would indulge his playful humour by going out at night and sitting on the pillows of Undergraduates.

This was one of his nights out, and he had chosen GEORGE GINSLING's pillow as his seat.

GEORGE woke up with a start. What was this feeling in his throat? Had he swallowed his blanket, or his cocoa-nut matting? No, they were still in their respective places. He tore out his tongue and his tonsils, and examined them. They were on fire. This puzzled him. He replaced them. As he did so, a shower of red-hot coppers fell from his mouth on to his feet. The agony was awful. He howled, and danced about the room. Then he dashed at the whiskey, but the bottle ducked as he approached, and he failed to tackle it. Poor GEORGE, you see, was a rowing-man, not a football-player. Then he knew what he wanted. In his keeping-room were six carafes, full of Cambridge water, and a dozen bottles of Hunyádi Janos. He rushed in, and hurled himself upon the bottles with all his weight. The crash was dreadful. The foreign bottles, being poor, frail things, broke at once. He lapped up the liquid like a thirsty dog. The carafes survived. He crammed them with their awful contents, one after another, down his throat. Then he returned to his bed-room, seized his jug, and emptied it at one gulp. His bath was full. He lifted it in one hand, and drained it as dry as a University sermon. The thirst compelled him—drove him—made him—urged him—lashed him—forced him—shoved him—goaded him—to drink, drink, drink water, water, water! At last he was appeased. He had cried bitterly, and drunk up all his tears. He fell back on his bed, and slept for twenty-four hours, and the Devil went out and gave his gyp, STARLING, a complete set of instructions for use in case of flood.

STARLING was a pale, greasy man. He was a devil of a gyp. He went into GEORGE's bed-room and shook his master by the shoulder. GEORGE woke up.

"Bring me the College pump," he said. "I must have it. No, stay," he continued, as STARLING prepared to execute his orders, "a hair of the dog—bring it, quick, quick!"

STARLING gave him three. He always carried them about with him in case of accidents. GEORGE devoured them eagerly, recklessly. Then with a deep sigh of relief, he went stark staring mad, and bit STARLING in the fleshy part of the thigh, after which he fell fast asleep again. On awaking, he took his name off the College books, gave STARLING a cheque for £5000, broke off his engagement, but forgot to post the letter, and consulted a Doctor.

"What you want," said the Doctor, "is to be shut up for a year in the tap-room of a public-house. No water, only spirits. That must cure you."

So GEORGE ordered STARLING to hire a public-house in a populous district. When this was done, he went and lived there. But you scarcely need to be told that STARLING had not carried out his orders. How could he be expected to do that? Only fifty-six pages of my book had been written, and even publishers—the most abandoned people on the face of the earth—know that that amount won't make a Christmas Annual. So STARLING hired a Temperance Hotel. As I have said, he was a devil of a gyp.

The fact was this. One of GEORGE's great-great uncles had held a commission in the Blue Ribbon Army. GEORGE remembered this too late. The offer of a seat in the University Trial Eights must have suggested the blue ribbon which the University Crew wear on their straw hats. Thus the diabolical forces of heredity were roused to fever-heat, and the great-great uncle, with his blue ribbon, whose photograph hung in GEORGE's home over the parlour mantelpiece, became a living force in GEORGE's brain.

GEORGE GINSLING went and lived in a suburban neighbourhood. It was useless. He married a sweet girl with various spiteful relations. In vain. He changed his name to PUMPDRY, and conducted a local newspaper. Profitless striving. STARLING was always at hand, always ready with the patent filter, and as punctual in his appearances as the washing-bill or the East wind. I repeat, he was a devil of a gyp.

They found GEORGE GINSLING feet uppermost in six inches of water in the Daffodil Road reservoir. It was a large reservoir, and had been quite full before GEORGE began upon it. This was his record drink, and it killed him. His last words were, "If I had stuck to whiskey, this would never have happened."

"IT IS THE BOGIE MAN!"—BLACKIE'S Modern Cyclopedia. Nothing to do with the Christy Minstrel Entertainment, but a very useful work of reference, issued from the ancient house of publishers which is now quite BLACKIE with age. We have looked through the "B's" for "Bogie," but "The Bogie Man" is "Not there, not there, my child!" but he is to be found in that other BLACKIE's collection at the St. James's Hall, which Bogie Man is said to be the original of that ilk. Unde derivatur "Bogie"? Perhaps the next edition of BLACKIE's still-more-Modern-than-ever Cyclopedia will explain.

PARS ABOUT PICTURES (by Old Par).—At the Fine Art Society's Gallery I gazed upon the pictures of "Many-sided Nature" with great content, and came to the conclusion that Mr. ALBERT GOODWIN was a many-sided artist. "Now," said I, quoting SHAKSPEARE—Old Par's Improved Edition—"is the GOODWIN of our great content made glorious." O.P., who knows every inch of Abingdon, who has gazed upon Hastings from High Wickham, who is intimate with every brick in Dorchester, who loves every reed and ripple on the Thames, and has a considerable knowledge of the Rigi and Venice, can bear witness to the truth of the painter. There are over seventy pictures—every one worth looking at.

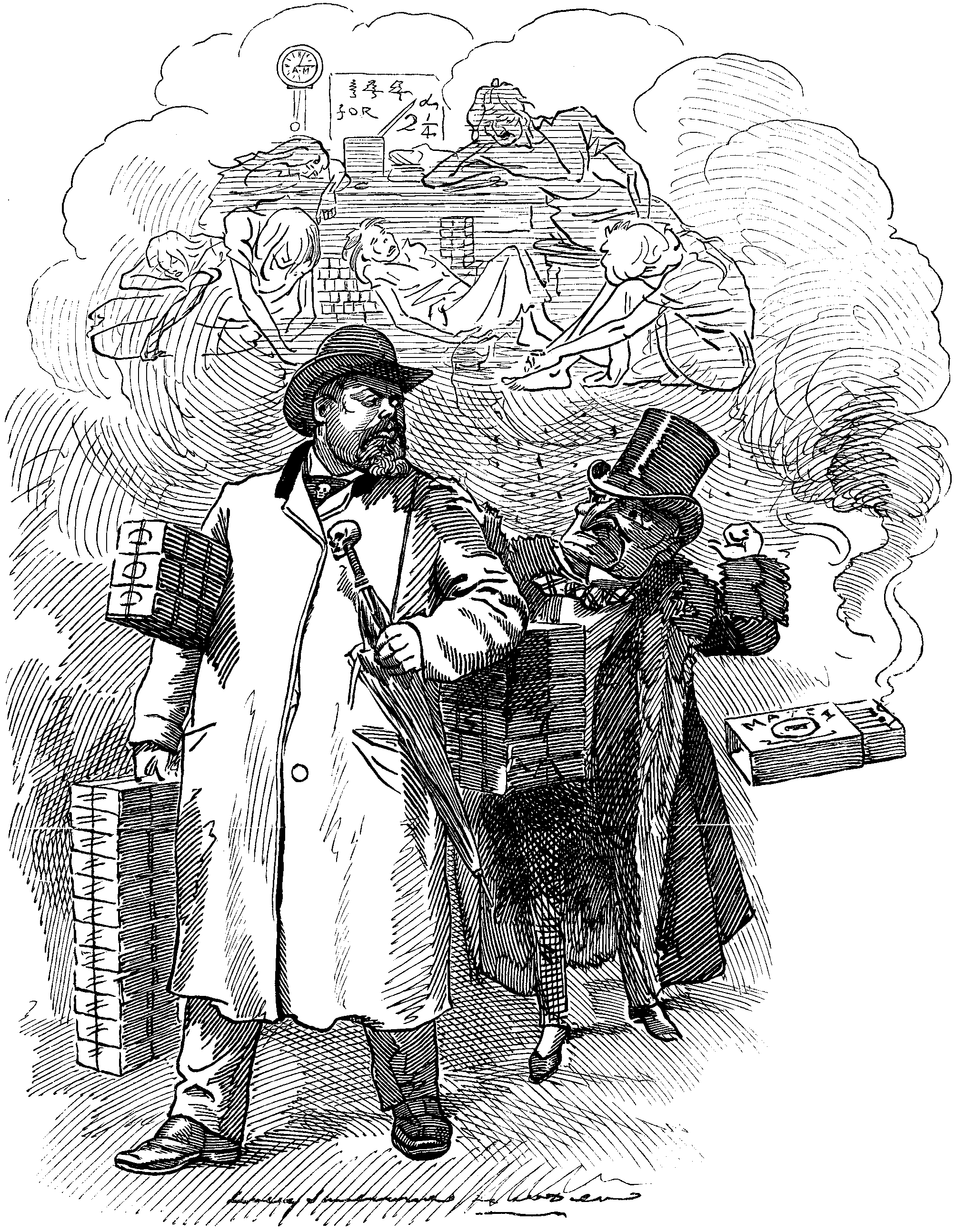

Sweater (to Mr. Punch). "NO USE YOUR INTERFERING. BUSINESS IS BUSINESS!"

Mr. P. "YES, AND UNCOMMONLY BAD BUSINESS, TOO, FOR THEM. COULDN'T THE LARGE FIRMS TAKE A TRIFLE LESS PROFIT, AND PUT A LITTLE PLEASURE INTO THE BUSINESS OF THESE POOR STARVING WORKERS?"

["Business!" cries the Sweater, when remonstrated with for paying the poor Match-box makers twopence-farthing or twopence-half-penny a gross, whilst his own profits reach 22-1/2 to 25 per cent.—Daily News.]

Eh? "Business is business"? Sheer cant, Sir! Pure gammon?

Of all the inhuman, sham Maxims of Mammon,

This one is the worst,

For under its cover lurks cruelty callous,

With murderous meanness that merits the gallows,

And avarice accurst.

Oh, well, I'm aware, Sir, how ruthless rapacity

Loves to take shelter, with cunning mendacity

'Neath an old saw;

[pg 279]But well says the scribe that such "business" is crime, Sir,

And such would be but for gaps half the time, Sir,

'Twixt justice and law.

Bah! Many a man who's sheer rogue in reality,

Hides the harsh knave in the mask of "legality."

When 'tis too gross,

Robbery's rash, but austere orthodoxies

Countenance such things as modern match-boxes

Nine-farthings a gross!

From seven till ten, and sometimes to eleven,

For "six bob" a week. Ah! such life must be heaven;

Whilst as for your "profit,"

That's bound to approach five-and-twenty per cent.,

That Sweaters shall thrive, let their tools be content

With starvation in Tophet.

To starve's bad enough, but to starve and to work

(Mrs. LABOUCHERE hints), the most patient may irk;

And the lady is right—

Business? On brutes who dare mouth such base trash,

Mr. Punch, who loves justice and sense, lays his lash,

With the greatest delight.

He knows the excuses advanced for the Sweater,

But bad is the best, and, until you find better,

'Tis useless to cant

Of freedom of contract, supply and demand,

And all the cold sophistries ever on hand

Sound sense to supplant.

A phrase takes the place of an argument often.

And stomachs go empty, and brains slowly soften,

And sense sick with dizziness,

All in the name of the bosh men embody

In one clap-trap phrase that dupes many a noddy,

That—business is business!

Business? Yes, precious bad business for them, Sir,

Whose joyless enslavement you take with such phlegm, Sir,

Suppose, to enhance

Their small share of ease, such as you, were content, Sir,

To lower a trifle your precious "per cent.," Sir,

And give them a chance!

"BUT I DON'T CALL THIS A FASHIONABLE 'AT!"

"IT WILL SOON BECOME SO, MADAM, IF YOU WEAR IT!"

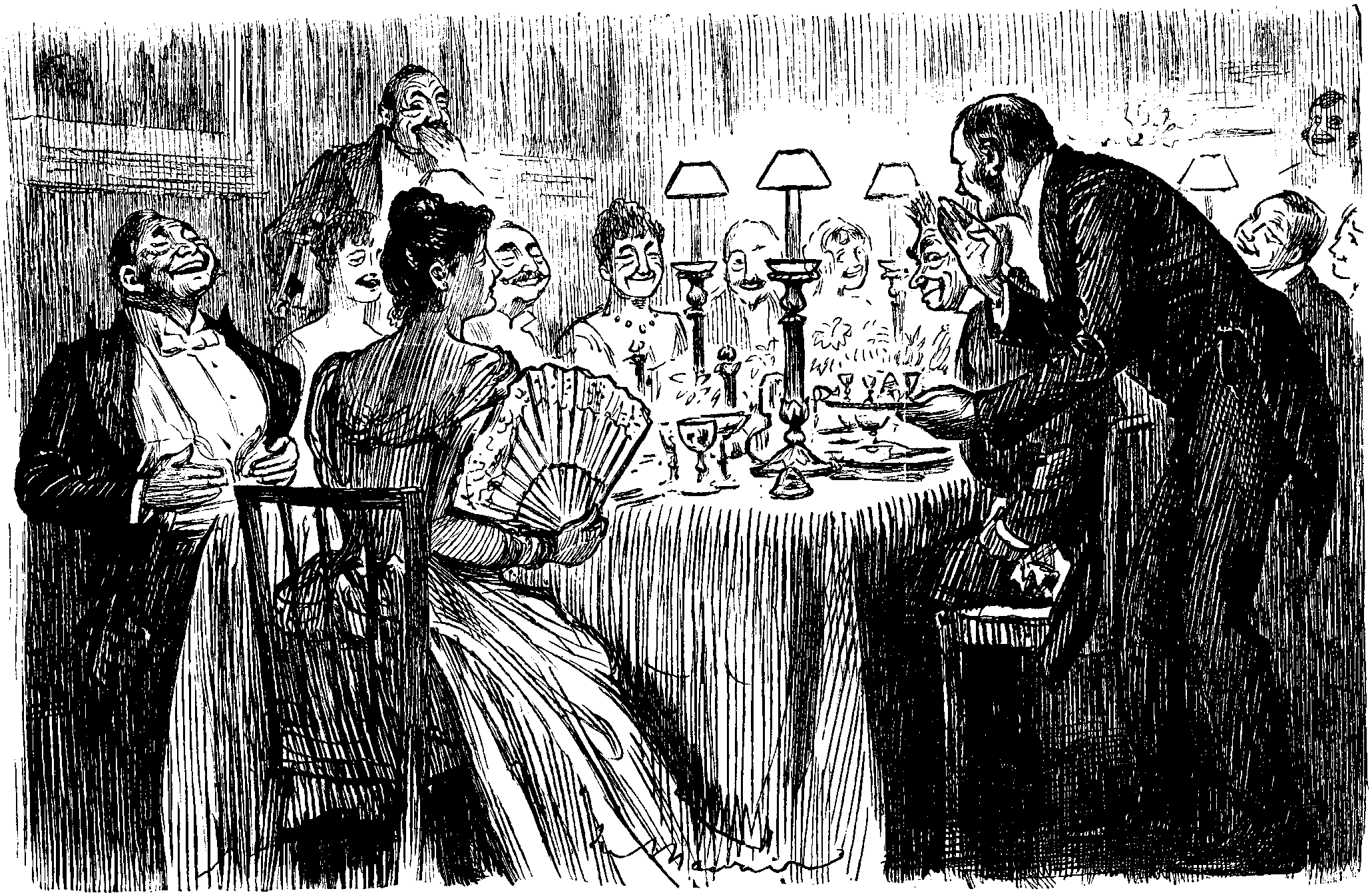

In Camp and Studio, Mr. IRVING MONTAGU, some time on the artistic staff of The Illustrated London News, gives his experiences of the Russo-Turkish Campaign. He concisely sums up the qualifications of a War Correspondent by saying that he should "have an iron constitution, a laconic, incisive style, and sufficient tact to establish a safe and rapid connecting link between the forefront of battle and his own head-quarters in Fleet Street or elsewhere." As Mr. IRVING MONTAGU seems to have lived up to his ideal, it is a little astonishing to find the last chapters of his book devoted to Back in Bohemia, wherein he discourses of going to the Derby, a Hammersmith Desdemona, and of the Postlethwaites and Maudles, "whose peculiarities have been recorded by the facile pen of DU MAURIER." But as the author seems pleased with the reader, it would be indeed sad were the reader to find fault with the author. However, this may be said in his favour—he tells (at least) one good story. On his return from Plevna to Bohemia, a dinner was given in his honour at the Holborn Restaurant. Every detail was perfect—the only omission was forgetfulness on the part of the Committee to invite the guest of the evening! At the last moment the mistake was discovered, and a telegram was hurriedly despatched to Mr. MONTAGU, telling him that he was "wanted." On his arrival he was refused admittance to the dinner by the waiters, because he was not furnished with a ticket! Ultimately he was ushered into the Banqueting Hall, when everything necessarily ended happily.

One might imagine that Birthday Books have had their day, but apparently they still flourish, for HAZELL, WATSON, & VINEY publish yet another, under the title of Names we Love, and Places we Know. The first does not apply to our friends, but to the quotations selected, and places are shown by photos.

Of many Beneficent and Useful Lives, you will hear "in CHAMBERS,"—the reader sitting as judge on the various cases brought before him by Mr. ROBERT COCHRANE.

Unlucky will not be the little girl who reads the book with this name, by CAROLINE AUSTIN.

Everybody's Business, by ISMAY THORN, nobody likes interference, but in this case it proved the friend in need.

Chivalry, by LÉON GAUTIER, translated by HENRY FRITH, is a chronicle of knighthood, its rules, and its deeds. To the scientific student, Discoveries and Inventions of the Nineteenth Century, by ROBERT ROUTLEDGE, B.S., F.C.S., will be interesting, and help him to discover a lot he does not know. Those who have not already read it, A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys, by NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, will have a real treat in the myths related; Tanglewood Tales are included, and these are delightful for all. Rosebud, by Mrs. ADAMS ACTON, a tale for girls, who will love this bright little flower, bringing happiness all around.

Holly Leaves, the Special Number of The Sporting and Dramatic, is quite a seasonable decoration for the drawing-room table during the Christmas holidays.

My faithful "Co." has been reading Jack's Secret, by Mrs. LOVETT CAMERON, which, he says, has greatly pleased him. It has an interesting story, and is full of clever sketches of character. Jack, himself, is rather a weak personage, and scarcely deserves the good fortune which ultimately falls to his lot. After flirting with a born coquette, who treats him with a cruelty which is not altogether unmerited, he settles down with a thoroughly lovable little wife, and a seat in the House of Lords. From this it will be gathered that all ends happily. Jack's Secret will be let out by MUDIE's, and will be kept, for a considerable time—by the subscribers.

Girls will be the richer this year by Fifty-two more Stories for Girls, and boys will be delighted with Fifty-two more Stories for Boys, by many of the best authors: both these books are edited by ALFRED MILES, and published by HUTCHISON & Co. Lion Jack, by P.T. BARNUM, is an account of JACK's perilous adventures in capturing wild animals. If they weren't, of course, all true, Lyin' Jack would have been a better title.

Syd Belton, unlike most story-book boys, would not go to sea, [pg 280] but he was made to go, by the author, Mr. MANVILLE FENN. Once launched, he proved himself a British salt of the first water. Dumps and I, by Mrs. PARR, is a particularly pretty book for girls, and quite on a par with, her other works. METHUEN & CO. publish these.

Pictures and Stories from English History, and Royal Portrait Gallery, are two Royal Prize Books for the historical-minded child; they are published by T. NELSON AND SONS, as likewise "Fritz" of Prussia, Germany's Second Emperor, by LUCY TAYLOR. Dictionary of Idiomatic English Phrases, by JAMES MAIN DIXON, M.A., F.R.S.E., which may prove a useful guide to benighted foreigners in assisting them to solve the usual British vagaries of speech; like the commencement of the Dictionary, it is quite an "A1" book.

"Dear Diary!" as one of Mr. F.C. PHILLIPS's heroines used to address her little book, but DE LA RUE's are not "dear Diaries," nor particularly cheap ones. This publisher is quite the Artful Dodger in devising diaries in all shapes and sizes, from the big pocket-book to the more insidious waistcoat-pocket booklet,—"small by degrees, but beautifully less."

"Here's to you, TOM SMITH!"—it's BROWN in the song, but no matter,—"Here's to you," sings the Baron, "with all my heart!" Your comic gutta-percha-faced Crackers are a novelty; in fact, you've solved a difficulty by introducing into our old Christmas Crackers several new features.

This year the Baron gives the prize for pictorial amusement to LOTHAR MEGGENDORFER (Gods! what a name!), who, assisted by his publishers, GREVEL & CO., has produced an irresistibly funny book of movable figures, entitled Comic Actors. What these coloured actors do is so moving, that the spectators will be in fits of chuckling. Recommended, says THE BARON DE BOOK-WORMS.

ARGUMENT.—EDWIN has taken ANGELINA, his fiancée, to an entertainment by a Mesmerist, and, wishing to set his doubts at rest, has gone upon the platform, and placed himself entirely at the Mesmerist's disposition. On rejoining ANGELINA, she has insisted upon being taken home immediately, and has cried all the way back in the hansom—much to EDWIN's perplexity. They are alone together, in a Morning-room; ANGELINA is still sobbing in an arm-chair, and EDWIN is rubbing his ear as he stands on the hearthrug.

Edwin. I say, ANGELINA, don't go on like this, or we shall have somebody coming in! I wouldn't have gone up if I'd known it would upset you like this; but I only wanted to make quite sure that the whole thing was humbug, and—(complacently)—I rather think I settled that.

Ang. (in choked accents). You settled that?—but how?... Oh, go away—I can't bear to think of it all! [Fresh outburst.

Ed. You're a little nervous, darling, that's all—and you see, I'm all right. I felt a little drowsy once, but I knew perfectly well what I was about all the time.

Ang. (with a bound). You knew?—then you were pretending—and you call that a good joke! Oh!

Ed. Hardly pretending. I just sat still, with my eyes shut, and the fellow stroked my face a bit. I waited to see if anything would come of it—and nothing did, that's all. At least, I'm not aware that I did anything peculiar. In fact, I'm certain I didn't. (Uneasily.) Eh, ANGELINA?

Ang. (indistinctly, owing to her face being buried in cushions). If you d-d-d-on't really know, you'd bub-bub-better-not ask—but I believe you do—quite well!

Ed. Look here, ANGIE, if I behaved at all out of the common, it's just as well that I should know it. I don't recollect it, that's all. Do pull yourself together, and tell me all about it.

Ang. (sitting up). Very well—if you will have it, you must. But you can't really have forgotten how you stood before the footlights, making the most horrible faces, as if you were in front of a looking-glass. All those other creatures were doing it, too; but, oh, EDWIN, yours were far the ugliest—they haunt me still.... I mustn't think of them—I won't! [Buries her face again.

Ed. (reddening painfully). No, I say—did I? not really—without humbug, ANGELINA!

Ang. You know best if it was without humbug! And, after that, he gave you a glass of cuc-cod-liver oil, and—and pup-pup-paraffin, and you dud-drank it up, and asked for more, and said it was the bub-bub-best Scotch whiskey you ever tasted. You oughtn't even to know about Scotch whiskey!

Ed. I can't know much if I did that. Odd I shouldn't remember it, though. Was that all?

Ang. Oh, no. After that you sang—a dreadful song—and pretended to accompany yourself on a broom. EDWIN, you know you did; you can't deny it!

Ed. I—I didn't know I could sing; and—did you say on a broom? It's bad enough for me already, ANGELINA, without howling! Well, I sang—and what then?

Ang. Then he put out a cane with a silver top close to your face, and you squinted at it, and followed it about everywhere with your nose; you must have known how utterly idiotic you looked!

Ed. (dropping into a chair). Not at the time.... Well, go on, ANGELINA; let's have it all. What next?

Ang. Next? Oh, next he told you you were the Champion Acrobat of the World, and you began to strike foolish attitudes, and turn great clumsy somersaults all over the stage, and you always came down on the flat of your back!

Ed. I thought I felt a trifle stiff. Somersaults, eh? Anything else? (With forced calm.)

Ang. I did think I should have died of shame when you danced?

Ed. Oh, I danced, did I? Hum—er—was I alone?

Ang. There were four other wretches dancing too, and you imitated a ballet. You were dressed up in an artificial wreath and a gug-gug-gauze skirt.

Ed. (collapsing). No?? I wasn't!... Heavens! What a bounder I must have looked! But I say, ANGIE, it was all right. I suppose? I mean to say I wasn't exactly vulgar, or that sort of thing, eh?

Ang. Not vulgar? Oh, EDWIN? I can only say I was truly thankful Mamma wasn't there!

Ed. (wincing). Now, don't, ANGELINA it's quite awful enough as it is. What beats me is how on earth I came to do it all.

Ang. You see, EDWIN, I wouldn't have minded so much if I had had the least idea you were like that.

Ed. Like that! Good Heavens. ANGIE, am I in the habit of making hideous grimaces before a looking-glass? Do you suppose I am given to over-indulgence in cod-liver oil and whatever the other beastliness was? Am I acrobatic in my calmer moments? Did you ever know me sing—with or without a broom? I'm a shy man by nature (pathetically), more shy than you think, perhaps,—and in my normal condition, I should be the last person to prance about in a gauze skirt for the amusement of a couple of hundred idiots? I don't believe I did, either!

Ang. (impressed by his evident sincerity). But you said you knew what you were about all the time!

Ed. I thought so, then. Now—well, hang it, I suppose there's more in this infernal Mesmerism than I fancied. There, it's no use talking about it—it's done. You—you won't mind shaking hands before I go, will you? Just for the last time?

Ang. (alarmed). Why—where are you going?

Ed. (desperate). Anywhere—go out and start on a ranche, or something, or join the Colonial Police force. Anything's better than staying on here after the stupendous ass I've made of myself!

Ang. But—but, EDWIN, I daresay nobody noticed it much.

Ed. According to you, I must have been a pretty conspicuous object.

Ang. Yes—only, you see, I—I daresay they'd only think you were a confederate or something—no, I don't mean that—but, after all, indeed you didn't make such very awful faces. I—I liked some of them!

Ed. (incredulously). But you said they haunted you—and then the oil, and the somersaults, and the ballet-dancing. No, it's no use, ANGELINA, I can see you'll never get over this. It's better to part and have done with it!

Ang. (gradually retracting). Oh, but listen. I—I didn't mean quite all I said just now. I mixed things up. It was really whiskey he gave you, only he said it was paraffin, and so you wouldn't drink it, and you did sing, but it was only about some place where an old horse died, and it was somebody else who had the broom! And you didn't dance nearly so much as the others, and—and whatever you did, you were never in the least ridiculous. (Earnestly). You weren't, really, EDWIN!

Ed. (relieved). Well. I thought you must have been exaggerating a little. Why, look here, for all you know, you may have been mistaking somebody else for me all the time—don't you see?

Ang. I—I am almost sure I did, now. Yes, why, of course—how stupid I have been! It was someone very like you—not you at all!

Ed. (resentfully). Well, I must say, ANGELINA, that to give a fellow a fright like this, all for nothing—

Ang. Yes—yes, it was all for nothing, it was so silly of me. Forgive me, EDWIN, please!

Ed. (still aggrieved). I know for a fact that I didn't so much as leave my chair, and to say I danced, ANGELINA!

Ang. (eagerly). But I don't. I remember now, you sat perfectly still the whole time, he—he said he could do nothing with you, don't you recollect? (Aside.) Oh, what stories I'm telling!

Ed. (with recovered dignity). Of course I recollect—perfectly. Well, ANGELINA, I'm not annoyed, of course, darling; but another time, you should really try to observe more closely what is done and who does it—before making all this fuss about nothing.

[pg 281]Ang. But you won't go and be mesmerised again, EDWIN—not after this?

Ed. Well, you see, as I always said, it hasn't the slightest effect on me. But from what I observed, I am perfectly satisfied that the whole thing is a fraud. All those other fellows were obviously accomplices, or they'd never have gone through such absurd antics—would they now?

Ang. (meekly). No, dear, of course not. But don't let's talk any more about it. There are so many things it's no use trying to explain.

SCENE I.—A Horse-Sale. Inexperienced Person, in search of a cheap but sound animal for business purposes, looking on in a nervous and undecided manner, half tempted to bid for the horse at present under the hammer. To him approaches a grave and closely-shaven personage, in black garments, of clerical cut, a dirty-white tie, and a crush felt hat.

Clerical Gent. They are running that flea-bitten grey up pretty well, are they not. Sir?

Inexperienced Person. Ahem! ye-es, I suppose they are. I—er—was half thinking of bidding myself, but it's going a bit beyond me, I fear.

C.G. Ah, plant, Sir—to speak the language of these horsey vulgarians—a regular plant! You are better out of it, believe me.

I.P. In-deed! You don't say so?

C.G. (sighing). Only too true. Sir. Why—(in a gush of confidence)—look at my own case. Being obliged to leave the country, and give up my carriage, I put my horse into this sale, at a very low reserve of twenty pounds. (Entre nous, it's worth at least double that.) Between the Auctioneer, and a couple of rascally horse-dealers—who I found out, by pure accident, wanted my animal particularly for a match pair—the sale of my horse is what they call "bunnicked up." Then they come to me, and offer me money. I spot their game, and am so indignant that I'll have nothing to do with them, at any price. Wouldn't sell dear old Bogey, whom my wife and children are so fond of, to such brutal blackguards, on any consideration. No, Sir, the horse has done me good service—a sounder nag never walked on four hoofs; and I'd rather sell it to a good, kind master, for twenty pounds, aye, or even eighteen, than let these rascals have it, though they have run up as high as thirty q——, ahem! guineas.

I.P. Have they indeed, now? And what have you done with the horse?

C.G. Put it into livery close by, Sir. And, unless I can find a good master for it, by Jove, I'll take it back again, and give it away to a friend. Perhaps, Sir, you'd like to have a look at the animal. The stables are only in the next street, and—as a friend, and with no eye to business—I should be pleased to show poor Bogey to anyone so sympathetic as yourself.

[I.P., after some further chat of a friendly nature, agrees to go and "run his eye over him."

SCENE II.—Greengrocer's yard at side of a seedy house in a shabby street, slimy and straw-bestrewn. Yard is paved with lumpy, irregular cobbles, and some sooty and shaky-looking sheds stand at the bottom thereof. Enter together, Clerical Gent and Inexperienced Person.

C.G. (smiling apologetically). Not exactly palatial premises for an animal used to my stables at Wickham-in-the-Wold! But I know these people, Sir; they are kind as Christians, and as honest as the day. Hoy! TOM! TOM!! TOM!!! Are you there, TOM? [From the shed emerges a very small boy with very short hair, and a very long livery, several sizes too large for him, the tail of the brass-buttoned coat and the bottoms of the baggy trousers alike sweeping the cobbles as he shambles forward]. (C.G. genially.) Ah, there you are, TOM, my lad. Bring out dear old Bogey, and show it to my friend here. [Boy leads out a rusty roan Rosinante, high in bone, and low in flesh, with prominent hocks, and splay hoofs, which stumble gingerly over the cobbles.] (Patting the horse affectionately.) Ah, poor old Bogey, he doesn't like these lumpy stones, does he? Not used to them, Sir. My stable-yard at Wickham-in-the-Wold, is as smoothly paved as—as the Alhambra, Sir. I always consider my animals, Sir. A merciful man is merciful to his beast, as the good book says. But isn't he a Beauty?

I.P. Well—ahem!—ye-es; he looks a kind, gentle, steady sort of a creature. But—ahem!—what's the matter with his knees?

C.G. Oh, nothing, Sir, nothing at all. Only a habit he has got along of kind treatment. Like us when we "stand at ease," you know, a bit baggy, that's all. You should see him after a twenty miles spin along our Wickham roads, when my wife and I are doing a round of visits among the neighbouring gentry. Ah, Bogey, Bogey, old boy—kissing his nose—I don't know what Mrs. G. and the girls will say when they hear I've parted with you—if I do, if I do.

Enter two horsey-looking Men as though in search of something.

First Horsey Man. Ah, here you are. Well, look 'ere, are you going to take Thirty Pounds for that horse o' yourn? Yes or No!

C.G. (turning upon them with dignity). No, Sir; most emphatically No! I've told you before I will not sell him to you at any price. Have the goodness to leave us—at once, I'm engaged with my friend here.

[Horsey Men turn away despondently. Enter hurriedly, a shabby-looking Groom.

Groom. Oh, look here, Mister—er—er—wot's yer name? His Lordship wants to know whether you'll take his offer of Thirty-five Pounds—or Guineas—for that roan. He wouldn't offer as much, only it happens jest to match—

C.G. (with great decisiveness). Inform his Lordship, with my compliments, that I regret to be entirely unable to entertain his proposition.

Groom. Oh, very well. But I wish you'd jest step out and tell his Lordship so yerself. He's jest round the corner at the 'otel entrance, a flicking of his boots, as irritated as a blue-bottle caught in a cowcumber frame.

C.G. Oh, certainly, with pleasure. (To I.P.) If you'll excuse me, Sir, just one moment, I'll step out and speak to his Lordship.

[Exit, followed by Groom.

Horsey Person (making a rush at I.P. as soon as C.G. has disappeared, speaking in a breathless hurry). Now lookye here, guv'nor—sharp's the word! He'll be back in arf a jiff. You buy that 'oss! He won't sell it to us, bust 'im; but you've got 'im in a string, you 'ave. He'll sell it to you for eighteen quid—p'raps sixteen. Buy it, Sir, buy it! We'll be outside, by the pub at the corner, my pal and me, and—(producing notes)—we'll take it off you agen for thirty pounds, and glad o' the charnce. We want it pertikler, we do, and you can 'elp us, and put ten quid in your own pocket too as easy as be blowed. Ah! here he is! Mum's the word! Round the corner by the pub! [Exeunt hurriedly.

Clerical Gent (blandly). Ah! that's settled. His Lordship was angry, but I was firm. Take Bogey back to the stable, TOM—unless, of course—(looking significantly at Inexperienced Person).

Inexperienced Person (hesitating). Well, I'm not sure but what the animal would suit me, and—ahem!—if you care to trust it to me—

Clerical Gent (joyously). Trust it to you, Sir? Why, with pleasure, with every confidence. Dear old Bogey! He'll be happy with such a master—ah, and do him service too. I tell you, Sir, that horse, to a quiet, considerate sort o' gent like yourself, who wants to work his animal, not to wear it out, is worth forty pound, every penny of it—and cheap at the price!

I.P. Thanks! And—ah—what is the figure?

C.G. Why—ah—eighteen—no, dash it!—sixteen to you, and say no more about it.

[Inexperienced Person closes with the offer, hands notes to Clerical Gent (who, under pressure of business, hurries off), takes Bogey from the grinning groom-lad, leads him—with difficulty—out into the street, searches vainly for the two horsey Men, who, like "his Lordship," have utterly and finally disappeared, and finds himself left alone in a bye-thoroughfare with a "horse," which he cannot get along anyhow, and which he is presently glad to part with to a knacker for thirty shillings.

As so many private letters are sold at public sales nowadays, it has become necessary to consider the purport of every epistle regarded, so to speak, from a post-mortem point of view. If a public man expresses a confidential opinion in the fulness of his heart to an intimate friend, or proposes an act of charity to a cherished relative, he may rest assured that, sooner or later, both communications will be published to an unsympathetic and autograph-hunting world. Under these circumstances it may be well to answer the simplest communications in the most guarded manner possible. For instance, a reply to a tender of hospitality might run as follows:—

Private and Confidential. Not negotiable.

Mr. DASH BLANK has much pleasure in accepting Mr. BLANK DASH's invitation to dinner on the 8th inst.

N.B.—This letter is the property of the Writer. Not for publication. All rights reserved.

Or, if the writer feels that his letter, if it gets into the hands of the executors, will be sold, he must adopt another plan. It will be then his object to so mix up abuse of the possible vendors with ordinary matter, that they (the possible vendors) may shrink, after the death of the recipient, from making their own condemnation public. The following may serve as a model for a communication of this character. The words printed in italics in the body of the letter are the antidotal abuse introduced to prevent a posthumous sale by possible executors.

Private and Confidential. Not to be published. Signature a forgery.

DEAR OLD MAN,—I nearly completed my book. Your nephew, TOM LESLEIGH, is an ass. My wife is slowly recovering from influenza. Your Aunt, JANE JENKINS, wears a wig. TOMMY, you will be glad to learn, has come out first of twenty in his new class at school. Your Uncle, BENJAMIN GRAHAM, is a twaddling old bore. I am thinking of spending the Midsummer holidays with the boys and their mother at Broadstairs. Your Cousin, JACK JUGGERLY, is a sweep that doesn't belong to a single respectable Club. Trusting that you will burn this letter, to prevent its sale after we are gone,

I remain, yours affectionately,

BOBBY.

N.B.—The foregoing letter is the property of the Author, and, as it is only intended for private circulation, must not be printed. Solicitors address,—Ely Place.

But perhaps the best plan will be, not to write at all. The telegraph, at the end of the century, costs but a halfpenny a word, and we seem to be within measurable distance of the universal adoption of the telephone. Under these circumstances, it is easy to take heed of the warning contained in that classical puzzle of our childhood, Litera scripta manet.

Mr. Punch. Well, Madam, what can I do for you?

Female (of Uncertain Age, gushingly). A very great favour, my dear Sir; it is a matter of sanitation.

Mr. P. (coldly). I am at your service, Madam, but I would remind you that I have no time to listen to frivolous complaints.

Fem. I would ask you—do you think that a building open to the public should be crowded with double as many persons as it can conveniently hold?

Mr. P. Depends upon circumstances, Madam. It might possibly be excusable in a Church, assuming that the means of egress were sufficient. Of what building do you wish to complain?

Fem. Of the Old Bailey—you know, the Central Criminal Court.

Mr. P. Have you to object to the accommodation afforded you in the Dock?

Fem. I was not in the Dock!

Mr. P. (dryly). That is the only place (when not in the Witness-Box) suitable for women at the Old Bailey. I cannot imagine that they would go to that unhappy spot of their own free will.

Fem. (astonished). Not to see a Murder trial? Then you are evidently unaccustomed to ladies' society.

Mr. P. (severely). I do not meet ladies at the Old Bailey.

Fem. (bridling up). Indeed! But that is nothing to do with the matter of the overcrowding. Fancy, with our boasted civilisation—I was half stifled!

Mr. P. It is a pity, with our boasted civilisation, that you were not stifled—quite! (Severely.) You can go!

[The Female retires, with an expression worthy of her proper place—the Chamber of Horrors!

I have so often been urged by my friends to write my autobiography, that at length I have taken up my pen to comply with their wishes. My memory, although I may occasionally become slightly mixed, is still excellent, and having been born in the first year of the present century I consequently can remember both the Plague and Fire of London. The latter is memorable to me as having been the cause of my introduction to Sir CHRISTOPHER WREN, an architect of some note, and an intimate friend of Sir JOSHUA REYNOLDS, and the late Mr. TURNER, R.A. Sir CHRISTOPHER had but one failing—he was never sober. To the day of his death he was under the impression that St. Paul's was St. Peter's!

One of my earliest recollections is the great physician HARVEY, who, indeed, knew me from my birth. Although an exceedingly able man, he was a confirmed glutton. He would at the most ceremonious of dinner-parties push his way through the guests (treating ladies and gentlemen with the like discourtesy) and plumping himself down in front of the turtle soup, would help himself to the entire contents of the tureen, plus the green fat! During the last years of his life he abandoned medicine to give his attention to cookery, and (so I have been told) ultimately invented a fish sauce!

I knew HOWARD, the so-called philanthropist, very well. He was particularly fond of dress, although extremely economical in his washing bill. It was his delight to visit the various prisons and obtain a hideous pleasure in watching the tortures of the poor wretches therein incarcerated. He was fined and imprisoned for ill-treating a cat, if my memory does not play me false. I have been told that he once stole a pockethandkerchief, but at this distance of time cannot remember where I heard the story.

It is one of my proudest recollections that, in early youth, I had the honour of being presented to her late most gracious Majesty, Queen ANNE, of glorious memory. The drawing-room was held at Buckingham Palace, which in those days was situated on the site now occupied by Marlborough House. I accompanied my mother, who wore, I remember, yellow brocade, and a wreath of red roses, without feathers. Round the throne were grouped—the Duke of MARLBOROUGH (who kept in the background because he had just been defeated at Fontenoy), Lord PALMERSTON, nick-named "Cupid" by Mistress NELL GWYNNE (a well-known Court beauty), Mr. GARRICK, and Signor GRIMALDI, two Actors of repute, and Cardinal WISEMAN, the Papal Nuncio. Her Majesty was most gracious to me, and introduced me to one of her predecessors, Queen ELIZABETH, a reputed daughter of King HENRY THE EIGHTH. Both Ladies laughed heartily at my curls, which in those days were more plentiful than they are now. I was rather alarmed at their lurching forward as I passed them, but was reassured when the Earl of ROCHESTER (the Lord Chamberlain) whispered in my ear that the Royal relatives had been lunching. As I left the presence, I noticed that both their Majesties were fast asleep.

I have just mentioned Lord ROCHESTER, whose acquaintance I had the honour to possess. He was extremely austere, and very much disliked by the fair sex. On one occasion it was my privilege to clean his shoes. He had but one failing—he habitually cheated at cards. I will now tell a few stories of the like character about Bishop WILBERFORCE, THACKERAY, Mrs. FRY, PEABODY, WALTER SCOTT, and Father MATTHEW.

[No you don't, my venerable twaddler!—ED.]

You lie on the oaken mantle-shelf,

A cigar of high degree,

An old cigar, a large cigar,

A cigar that was given to me.

The house-flies bite you day by day—

Bite you, and kick, and sigh—

And I do not know what the insects say,

But they creep away and die.

My friends they take you gently up,

And lay you gently down;

They never saw a weed so big,

Or quite so deadly brown.

They, as a rule, smoke anything

They pick up free of charge;

But they leave you to rest while the bulbuls sing

Through the night, my own, my large!

The dust lies thick on your bloated form,

And the year draws to its close,

And the baccy-jar's been emptied—by

My laundress, I suppose.

Smokeless and hopeless, with reeling brain,

I turn to the oaken shelf,

And take you down, while my hot tears rain,

And smoke you, you brute, myself.

House of Commons, Monday, December 1.—Tithes Bill down for Second Reading. GRAND YOUNG GARDNER places Amendment on the paper, which secures for him opportunity of making a speech. Having availed himself of this, did not move his Amendment; opening thus made for STUART-RENDEL, who had another Amendment on the paper. Would he move it? Only excitement of Debate settled round this point. Under good old Tory Government new things in Parliamentary procedure constantly achieved. Supposing half-a-dozen Members got together, drew up a number of Amendments, then ballot for precedence, they might arrange Debate without interposition of SPEAKER. First man gets off his speech, omits to move Amendment: second would come on, and so on, on to the end of list. But STUART-RENDEL moved Amendment, and on this Debate turned.

Not very lively affair, regarded as reflex of passionate protestation of angry little Wales. OSBORNE AP MORGAN made capital speech, but few remained to listen. Welshmen at outset meant to carry Debate over to next day; couldn't be done; and by half-past eleven, STUART-RENDEL's Amendment negatived by rattling majority.

Fact is, gallant little Wales was swamped by irruptive Ireland. To-day, first meeting of actual Home Rule Parliament held, and everybody watching its course. This historic meeting gathered in Committee-room No. 15; question purely one of Home Rule; decided, after some deliberation, that, in order to have proceedings in due dramatic form, there should be incorporated with the meeting an eviction scene. After prolonged Debate, concluded that, to do the thing thoroughly, they should select PARNELL as subject of eviction.

"No use," TIM HEALY said, "in half-doing the thing. The eyes of the Universe are fixed upon us. Let us give them a show for their money."

PARNELL, at first, demurred; took exception on the ground that, as he had no fixed place of residence, he was not convenient subject for eviction; objection over-ruled; then PARNELL insisted that, if he yielded on this point, he must preside over proceedings. TIM and the rest urged that it was not usual, when a man's conduct is under consideration upon a grave charge, that he should take the Chair. Drawing upon the resources of personal observation, Dr. TANNER remarked that he did not remember any case in which the holder of a tenure, suffering process of eviction, bossed the concern, acting simultaneously, as it were, as the subject of the eviction process, and the resident Magistrate.

Whilst conversation going on, PARNELL had unobserved taken the Chair, and now ruled Dr. TANNER out of order.

House sat at Twelve o'Clock; at One the Speaker (Mr. PARNELL), interrupting SEXTON in passage of passionate eloquence, said he thought this would be convenient opportunity for going out to his chop. So he went off; Debate interrupted for an hour; resumed at One, and continued, with brief intervals for refreshment, up till close upon midnight. Proceedings conducted with closed doors, but along the corridor, from time to time, rolled echoes which seemed to indicate that the first meeting of the Home-Rule Parliament was not lacking inanimation.

"I think they are a little 'eated, Sir," said the policeman on duty outside. "Man and boy I've been in charge of this beat for twenty years; usually a quiet spot; this sudden row rather trying for one getting up in years. Do you think, Sir, that, seeing it's an eviction, the Police can under the Act claim Compensation for Disturbance?"

Promised to put question on subject to JOKIM.

Long dispute on point of order raised by NOLAN. TIM HEALY referring to difficulty of dislodging PARNELL, alluded to him as "Sitting Bull." Clamour from Parnellite section anxious for preservation of decency of debate. Speaker said, question most important. Irish Parliament in its infancy; above all things essential [pg 288] they should well consider precedents. Must reserve decision as to whether the phrase was Parliamentary; would suggest, therefore, that House should adjourn five weeks. On this point Debate proceeded up to midnight.

Business done.—In British Parliament Tithes Bill read a Second Time; in Irish (which sat four hours longer), None.

Tuesday.—Cork Parliament still sitting upstairs in Committee Room No. 15, debating question of adjournment. We hear them occasionally through open doors and down long corridor. Once a tremendous yell shook building.

"What's that?" I asked DICK POWER, who happened to be taking glass of sherry-wine at Bar in Lobby.

"That," said RICHARD, "is the Irish wolves crying for the blood of PARNELL," and DICK, tossing down his sherry-wine, as if he had a personal quarrel with it, hurried back to the shambles.

Quite a changed man! No longer the débonnaire DICK, whose light heart and high spirits made him a favourite everywhere. Politics have suddenly become a serious thing, and DICK POWER is saddened with them.

"I take bitters with my sherry-wine now," DICK mentioned just now in sort of apologetic way at having been discovered, as it were, feasting in the house of mourning. "At the present sad juncture, to drink sherry-wine with all its untamed richness might, I feel, smack of callousness. Therefore I tell the man to dash it with bitters, which, whilst it has a penitential sound, adds a not untoothsome flavour in anticipation of dinner."

Even with this small comfort ten years added to his age; grey hairs gleam among his hyacinthine locks; his back is bent; his shoes are clogged with lead. A sad sight; makes one wish the pitiful business was over, and RICHARD himself again.

All the best of the Irish Members, whether Cavaliers or Cromwellians, are depressed in same way. Came upon SWIFT MacNEILL in retired recess in Library this afternoon; standing up with right hand in trouser-pocket, and left hand extended (his favourite oratorical attitude in happier times) smiling in really violent fashion.

"What are you playing at?" I asked him, noticing with curiosity that whilst his mouth was, so to speak, wreathed in smiles, a tear dewed the fringe of his closed eyelids.

"Ah, TOBY, is that you?" he said, "I didn't see you coming. The fact is I came over here by myself to have me last smile."

"Well, you're making the most of it," I said, wishing to encourage him.

"I generally do, and as this is me last, I'm not stinting measurement. They're sad times we've fallen on. Just when it seemed victory was within our grasp it is snatched away, and we are, as one may say, flung on the dunghill amid the wreck of our country's hopes and aspirations. This is not a time to make merry. Me country's ruined, and SWIFT MacNEILL smiles no more."

With that he shut up his jaws with a snap, and strode off. I'm sorry he should take the matter to heart so seriously. We shall miss that smile.

Business done.—Irish Land Bill in British Parliament. Cork Parliament still sitting.

Thursday.—Cork Parliament still sitting; PARNELL predominant; issues getting a little mixed; understood that Session summoned to decide whether, in view of certain proceedings before Mr. Justice BUTT, PARNELL should be permitted to retain Leadership. Everything been discussed but that. Things got so muddled up, that O'KEEFE, walking about, bowed with anxious thought, not quite certain whether it is TIM HEALY, SEXTON, or JUSTIN McCARTHY, who was involved in recent Divorce suit. Certainly, it couldn't have been PARNELL, who to-day suggests that the opportunity is fitting for putting Mr. G. in a tight place.

"You go to him," says PARNELL, "and demand certain pledges on Home Rule scheme. If he does not consent, he will be in a hole; threatened with loss of Irish Vote. You will be in a dilemma, as you cannot then side with him against me, the real friend of Ireland; whilst I shall be confirmed in my position as the only possible Leader of the Party. If, on the contrary, this unrivalled sophist is drawn into anything like a declaration that will satisfy you in the face of the Irish People, he will be hopelessly embarrassed with his English friends; I shall have paid off an old score, and can afford to retire from the Leadership, certain that in a few months the Irish People will clamour for the return of the man who showed that, if only he could serve them, he was ready to sacrifice his personal position and advantages. Don't, Gentlemen, let us, at a crisis like this, descend to topics of mere personality. In spite of what has passed at this table, I should like to shield my honourable friends, Mr. TIMOTHY HEALY, Mr. SEXTON, and that beau idéal of an Irish Member, Mr. JUSTIN McCARTHY, from references, of a kind peculiarly painful to them, to certain proceedings in a court of law with respect to which I will, before I sit down, say this, that, if all the facts were known, they would be held absolutely free from imputation of irregularity."

General cheering greeted this speech. Members shook hands all round, and nominated Committee to go off and make things hot for Mr. G. Business done.—In British House Prince ARTHUR expounded Scheme for Relief of Irish Distress.

Friday.—A dark shadow falls on House to-day. Mrs. PEEL died this morning, and our SPEAKER sits by a lonely hearth, OLD MORALITY, in his very best style, speaking with the simple language of a kind heart, voices the prevalent feeling. Mr. G., always at his best on these occasions, adds some words, though, as he finely says, any expression of sympathy is but inadequate medicine for so severe a hurt. Members reverently uncover whilst these brief speeches are made. That is a movement shown only when a Royal Message is read; and here is mention of a Message from the greatest and final King. Mrs. PEEL, though the wife of the First Commoner in the land, was not une grande dame. She was a kindly, homely lady, of unaffected manner, with keen sympathies for all that was bright and good. Every Member feels that something is lost to the House of Commons now that she lies still in her chamber at Speaker's Court.

THE DRAMA ON CRUTCHES.—A Mr. GREIN has suggested, according to some Friday notes in the D.T., a scheme for subsidising a theatre and founding a Dramatic School. The latter, apparently, is not to aid the healthy but the decrepit drama, as it is intended "to afford succour to old or disabled actors and actresses." Why then call it a "Dramatic School?" Better style it, a "Dramatic-Second-Infancy-School."

DEATH IN THE FIELD.—If things go on as they have been going lately, the statisticians who compile the "Public Health" averages will have to include, as one important item in their "Death Rates," the ravages of that annual epidemic popularly known as—Football!

"JUSTICE FOR IRELAND!"—The contest on the Chairmanship of the Irish Parliamentary Party may be summed up:—PARNELL—Just out, McCARTHY Just in.

NOTICE—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol.

99., December 13, 1890, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 12905-h.htm or 12905-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/1/2/9/0/12905/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.