A SHORT HISTORY & DESCRIPTION OF ITS FABRIC WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE

DIOCESE AND SEE

HUBERT C. CORLETTE

A.R.I.B.A.

WITH XLV

ILLUSTRATIONS

ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON GEORGE BELL & SONS 1901

All the facts of the following history were supplied to me by many authorities. To a number of these, references are given in the text. But I wish to acknowledge how much I owe to the very careful and original research provided by Professor Willis, in his "Architectural History of the Cathedral"; by Precentor Walcott, in his "Early Statutes" of Chichester; and Dean Stephen, in his "Diocesan History." The footnotes, which refer to the latter work, indicate the pages in the smaller edition. But the volume could never have been completed without the great help given to me on many occassions by Prebendary Bennett. His deep and intimate knowledge of the cathedral structure and its history was always at my disposal. It is to him, as well as to Dr. Codrington and Mr. Gordon P.G. Hills, I am still further indebted for much help in correcting the proofs and for many valuable suggestions.

H.C.C.

Any attempt to write the history of a cathedral requires that the subject shall be approached with two leading ideas in view. One of these has reference to the history of a Church; the other to the story of a building. The two aspects are clearly to be distinguished, but their mutual relation may be better appreciated when we realise how intimately they are bound together.

Ecclesiastical history, or "ecclesiology," and architectural history, or "archaeology," do not exist apart; for the needs of Christian liturgy indicated what arrangement was required in those buildings that were peculiarly dedicated to the use of the Church; hence we have, in the mere building itself, to consider the condition of ecclesiastical and architectural growth displayed by its character during each stage of its development, and this development, this character, is to be discovered as well in the plan and structure of the fabric, with its decorative details, as in the record that documents and traditions have preserved. But we need to remember that one see, one building, represents a link in one long continuing chain, and in doing this we naturally look back as well as forward to observe the relation of either to the past and to the present. Such an attitude as this requires that we refer to that period when the subject of this chapter was not yet part of the native soil of Sussex, and in doing this we find that so early as the eighth century the town of Chichester was even then a known centre of civil, though apparently not ecclesiastical, activity; for it is not until about the middle of the tenth century that some uncertain documentary evidence refers to "Bishop Brethelm and the brethren dwelling at Chichester."1 It may be that Brethelm was a bishop in, though not of, Chichester, who dwelt and worked among the south Saxons living in and about the city, for the history of the diocese and see will show that probably there was no episcopate established under that name until a little more than one hundred years later.

Ceadwalla's foundation of the see at Selsea dated from about the end of the seventh century; but we know nothing about any cathedral church at that place during the following three hundred and fifty years. If, however, there was a bishop in charge of the missionary priests, deacons, and laymen who lived there together, there must necessarily have been a "cathedra" in the church they used.

When Stigand came from Selsea to establish his see in Chichester he found the city already furnished with a minster dedicated to S. Peter. He had effected this transfer because the Council of London had decided in 1075 that all the then village sees should be removed to towns; and as there is no evidence of any attempt to provide a new cathedral until about the year 1088, the existing minster must have been appropriated for the see. It has been supposed that Stigand may have devised some scheme for building a new church, and even that he saw it carried out so far as to provide the foundations on which to execute this idea. But there appears to be no authority which warrants the assumption that he did even so much as this, for history says nothing about such an early beginning of the new operations, tradition asserts no more, and speculation suggests probabilities merely. We are obliged, therefore, to be satisfied with the fact that the work begun about 1088 was consecrated by Bishop Ralph de Luffa, in 1108, and it is possible even now to see the stone which commemorates that ceremony embedded in the walling of the present church. Unfortunately no more than about six years had passed since this, the first, dedication, when a fire occurred which burnt part of the fabric. Ralph was still living, and began at once to repair the damage that had been done; and the king (Henry I.) gave him much help by encouraging his endeavour. What, then, had been accomplished during the twenty years between 1088 and 1108?

In 1075 Stigand transferred the see. About thirteen years later the new cathedral building appears to have been begun under Ralph, and in another twenty years so much had been finished as would allow him to see it dedicated. It is probable that before this ceremony was performed a considerable portion of the eastern section of the work was finished; for in accordance with a general custom with the mediæval church builders, this part would have been that first begun. But how much of it was ready for use? The sanctuary and presbytery, or choir, with its necessary structural appendages, no doubt first appeared. It may be that no more than this was ready when the dedication took place. But it is not possible to say with any authority what actually was finished. Nevertheless, the character of the building itself explains the course in which the structure was developed. After the first fire, in 1114, the work steadily continued, and it is possible that before that mishap occurred, certain other parts had been begun, if not finished. The remains of the original nave still present distinct evidence to show that it was, with the aisles, built in two sections; and these, although they appear at first to be alike, prove upon closer examination that the four bays towards the west are of a later date than those other four eastward. Now it is not essential that we should know exactly how much of the building was finished by a certain year, or what stage towards completion had been reached at any particular time; it is sufficient at present that we should be able to indicate the general trend of the operations,—and this would suggest the conclusion that, having prepared so much as was necessary about the chancel, the builders went on busily, after the dedication, to deal with the transept and the nave. Then followed those four early bays of the nave which are nearest to the east.

It is quite safe to assume upon various grounds that the work had been carried on successfully up to this stage early in the twelfth century; but neither the documentary evidence available, nor the condition of the fabric, enables us to venture more than this surmise concerning its condition at that time.

Between 1114 and the time of the second and serious fire in 1187, the remainder of the whole scheme planned a hundred years before was apparently finished.

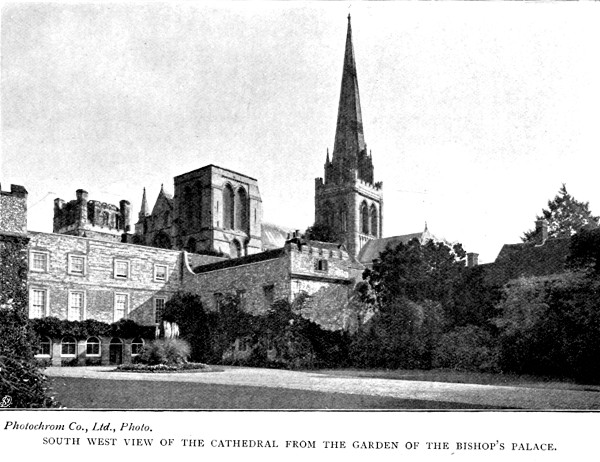

The first fire had excited some public interest in the great enterprise at Chichester, and from this an impetus was derived which helped towards its execution, after the small damage caused by the fire had been quickly repaired, for by about the year 1150 the four western bays of the nave, with its aisles, must have been complete. It should be understood that the fire in 1114 did not lead to any change in the character of the church such as was occasioned by that other fire which shall be considered presently; but the work had quietly continued, so that the aisles of the nave were vaulted by about 1170-1180, the lady-chapel was completed, and in 1184 all was ready for the second ceremony of consecration which then took place. It has been assumed that this act implies that the whole of the original scheme had been executed. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that again there are but few authentic records to show in what manner the work had been carried on, nor are there many indications of the way in which the necessary materials and money were provided to help it forward. But it is interesting to notice that in 1147 William, Earl of Arundel, gave to the see that quarter of the city in which stood the palace of the bishops, the residences of the canons, and the cathedral church. This grant of land confirmed the see in its possession of all that part of the city now within the bounds of the close.

What, then, was the plan of that church which was designed to suit the requirements set down by Bishop Ralph Luffa? The ground-plan at the end of the volume shows the building as it now remains, after many alterations have been made in the original scheme; but the arrangement is still, in its main features, much the same as was at first devised. The usual plan was adopted, and this was the provision of a nave and chancel having a transept between them so as to make the form of a cross. The nave had aisles along its whole length. These were extended on both sides eastward of the transept, and continued as an ambulatory round a semicircular apse. The transept also had a small apsidal chapel on the east side of both its north and south arms. At the point of intersection between the transept and the nave the supports of the central tower rose. Between this and the west end there were eight arches in each of the arcades opening north and south from the nave into the aisles. Beyond the crossing towards the east there were three similar arches in the arcades which connected the apse with the large piers of the central tower. These three bays, together with the apse, enclosed the chancel; and this comprised the sanctuary, which was that part within the apse itself, and also the presbytery, or choir of the priests, which occupied the remaining space between the apse and the arch into the transept beneath the tower. At a later date the accommodation of the choir was increased by making it occupy part of the space farther to the west. Possibly it projected into the nave. At the west end of each of the aisles of the nave a tower was placed, and between these two towers was the chief public entrance to the church. From the subsequent history of the structure it would appear that the two western towers had been built up and finished, so far, at least, as was necessary to allow of the completion of the nave with its aisles and roofs. The same may be concluded of the central tower.

This latter probably rose only just above the ridge of the roofs. To carry it up so far would have been dictated to the builders by structural reasons; for such a height would be required to help the stability of the piers and arches below, since they had to resist a variety of opposed thrusts. But even this tower, low as it no doubt was, like others of the same date, did not survive the dedication more than about twenty-six years. The whole building was covered with a high-pitched wooden roof over the nave, transept, and chancel; and beneath the outer roof there was a flat inner ceiling of wood formed between the tie beams, similar to those now to be seen at Peterborough and S. Albans. The north and south aisles of the nave were protected by roofs which sloped up from their eaves against the wall that rose above the nave arcades. Internally the ceiling to these was a simple groined vault supported by transverse arches.

Immediately above the vault of the aisles was the gallery of the

triforium. This was lighted throughout by small external round-headed

windows, some of which may still be seen embedded in the walls. The

aisles and ambulatory of the chancel were treated by the same methods.

In the triforium gallery, above the transverse arches of the aisles,

were other semicircular arches. These served a double purpose: they

acted as supports to the timber framework of the aisle roofs, and also

as a means of buttressing the upper part of the nave walling in which

the clerestory windows were placed. Such other buttresses as there had

been were broad and flat, with but little projection from the surface

of the wall. The windows throughout the building up to about the end

of the twelfth century were small in comparison with some of those

which were inserted at various times afterwards.

Immediately above the vault of the aisles was the gallery of the

triforium. This was lighted throughout by small external round-headed

windows, some of which may still be seen embedded in the walls. The

aisles and ambulatory of the chancel were treated by the same methods.

In the triforium gallery, above the transverse arches of the aisles,

were other semicircular arches. These served a double purpose: they

acted as supports to the timber framework of the aisle roofs, and also

as a means of buttressing the upper part of the nave walling in which

the clerestory windows were placed. Such other buttresses as there had

been were broad and flat, with but little projection from the surface

of the wall. The windows throughout the building up to about the end

of the twelfth century were small in comparison with some of those

which were inserted at various times afterwards.

It has been remarked that the termination of the early chancel towards the east was an apse, and that round this was carried the north and south choir aisles in the form of a continuous ambulatory. From this enclosing aisle—a semi-circle itself in form—three chapels were projected, each with a semicircular apsidal termination. The central one of the three was the lady-chapel. This consisted then of the three western bays only of the present chapel. The lady-chapel was added about eighty years after the early part of the nave had been built, and has since been much altered.

The presence of this grouping of features is indicative of that influence which Continental architecture had exercised upon English art, and now that Norman government had been established that influence became more directly French. But though so strongly affected by this means, Anglo-Saxon character was always evident in work which was a native expression of the thought and personality of those by whom it was executed.

Thus we see that the plan which Ralph approved for the new church that was to be built for him at Chichester was devised according to accepted traditional arrangement. He adopted no new idea when he decided what general form the cathedral should follow. The disposition of the several parts differed in no wise from that which had been followed during centuries before. The requirements of ritual had decided long since what were those essential features of planning to be insisted upon, for the pattern in germ was shown in the arrangement of the Mosaic Tabernacle. In the earliest plans the same distribution of parts was observed, though at a later date the transept was introduced—an idea which no doubt had its origin in some practical necessity, and was afterwards retained as being representative of an ecclesiastical symbol.

Of the practical and artistic character of the architectural details we shall see more in examining the exterior and the interior of the church. These will lead us, of necessity, to deal more with archaeology in its relation to the history of architecture rather than of this particular church as a building used for ecclesiastical purposes.

After the ceremony of 1184 building operations were continued, but the records available do not tell about anything of much interest for the next two or three years. Then in 1186-1187 a catastrophe occurred—the cathedral was again burnt. But this time the effects of the fire were much more disastrous than had been the case in 1114. So extensive was the destruction that the entire roofing, as well as the internal flat ceiling, was gone; and though we can glean no certain knowledge from documentary evidence, it appears probable that the eastern section of the building suffered more than any other, for whatever other causes may have aided in the wreck of this part—a weakness in the masonry, an insufficiency in the supports or abutments—the fall of such heavy timbers as those which must have formed the outer roof and inner ceiling of the chancel would in itself be sufficient to wreck the remainder.

Whether the change in plan that now followed was really necessary because of the damage that had been done, or whether the fire provided a welcome opportunity by which new features might be introduced, we are not able to discover. It is sufficient that the chance was not lost, for in the eastern ambulatory of the cathedral church at Chichester is to be seen, as a result, one of the most truly beautiful examples of mediæval design that English architecture now possesses.

In the nave some parts of the old limestone walls had been injured by the fall of the roofs; they were also seriously damaged by the beams that had been laid upon them, for these, after their fall, would continue to burn as they rested against those portions of walling which remained standing. It was no doubt by some such cause as this that the early clerestory was disfigured and partly destroyed. In either case, the old clerestory arcade of the twelfth century no longer remained as it was before; and though there were already stone vaults to the aisles of the nave before the fire occurred, yet they also disappeared and made way for newer ones. The outer roof over the triforium evidently shared the fate of the other coverings; and the arched abutment in the triforium, which acted as a support to this roof and the walling below the clerestory, now disappeared. It may be that this arching was not completely destroyed by the fire alone; no doubt some that remained was intentionally removed to prepare the way for the new work.

The same bishop who had witnessed the completion of the earlier operations began with much enterprise to see about the reconstruction, but not the restoration, of what had been destroyed. Some portions were repaired, others rebuilt; but the greater part of the work now undertaken involved an entire change in the character of some of the principal features of the earlier scheme. In fact, this incident in the history of our subject gave "occasion to one of the most curious and interesting examples of the methods employed by the mediæval architects in the repairs of their buildings."2

Having decided that they would, if possible, avoid all future risk of a similar catastrophe, a system of vaulting was adopted as the best solution of the problem,—this involved necessarily a remodelling of the interior; and so, neglecting the Isle of Wight limestone and the Sussex sandstone, which at first had been the material used for the walling, the masons were directed to use stone of finer texture and smaller grain. It has been thought by some that this material was brought from Caen in Normandy. The same stone was used to re-face parts of the nave piers. And in addition Purbeck marble was selected instead of that which was to be found in Sussex.

It is interesting to remember that the new choir of Canterbury had only been finished about three years before the fire occurred at Chichester. This work had been begun by William of Sens and finished by William the Englishman; and though it was so large an undertaking, it appears to have been commenced and completed between the years 1174 and 1184. This would very naturally exert some influence upon the building projects of a neighbouring see. Whether any of the actual craftsmen from Canterbury worked again at Chichester or not we cannot tell, but it is evident that the Kentish experience was of great help to Sussex in the new venture. When it had been decided how they should operate, it was natural that the covering of the building must be the first provision. This involved the repair of the shattered clerestory, and then they were free to proceed in other directions. Further than this we have no means of learning what method was followed in carrying on the new work; but it continued, so that in about twelve years the building was dedicated again.

There is nothing now to indicate that the provision of a vault had been intended by the original builders of these walls. This deficiency was met by the insertion of vaulting shafts and the addition of external buttressing; for as the pressure of the flat wooden roof was exerted for the most part vertically upon its supports, that of the vault would be a strong lateral thrust as well as vertical pressure, and these were to be provided for. We shall see presently that all the real beauties of this most interesting work were the outcome both of the needs of practical structure and the requirements of ritual and a ceremonial expression of the liturgy.

It is not possible for us to discover exactly when the several parts of the work undertaken after the fire of 1186-1187 were begun, nor when they were finished. Of dates we have little knowledge, except that of the dedication in 1199, the fall of two towers in 1210, and the various indications of architectural activity at certain periods given by the several dates mentioned in connection with donations, bequests, and royal sanctions in the episcopal statutes and other documents. These nearly all show that the time of greatest activity was after 1186 and before 1250. If such a feat as has been mentioned was performed at Canterbury between 1174 and 1184, was it not possible also at Chichester? Then it becomes necessary to assume that the structural alterations were continuing during the whole of the period suggested; and this was so. Enough work had been done by 1199 to allow of another dedication of the building. Seffrid II. had been bishop from 1180-1204, and the register of Bishop William Rede, written one hundred and sixty years later, explicitly states that Seffrid "re-edified the Church of Chichester." This is a comprehensive statement, but it might easily include at least the greater part of the vaulting with some form of external roof. Such a change as this involved the alteration of the nave and aisle piers, so that the slight vaulting shafts of finer stone might be inserted in the older masonry. The lower part of each of the piers of the nave arcade on the side towards the centre of the church was re-faced with the same material, and smaller shafts of Purbeck marble were introduced upon the piers, replacing probably the heavy ones of an earlier date. These shafts formed the support to a more delicate moulded member, which was now substituted for the original and very simple outer order of the original arch. A string-course of Purbeck marble was inserted as a line of separation between the nave arcade and the triforium, and also between the triforium and clerestory. The triforium itself remained as it had been before 1186; but the clerestory was dressed again, so that it obtained quite a new character. It was re-faced with the fine-grained stone, and the slight shafts which supported the clerestory arcades were provided with Purbeck capitals and bases. This arcading itself was also changed from its earlier type. The central arch was still made round in form, but those on either side of it were each pointed, and all were more finely moulded than before. Above this point rises the new stone vault, which is carried upon a framework of strong transverse and diagonal ribs. Between these the shell, or filling, which formed the surface of the vault, is of chalk, roughly cut and irregularly laid; above this was placed a thick coat of concrete.

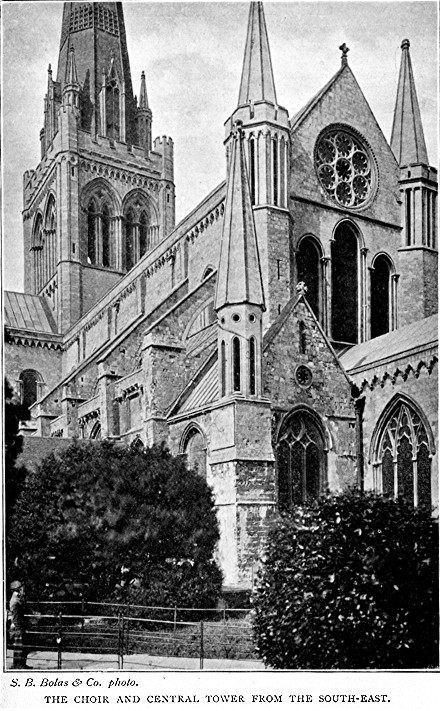

Some flying-buttresses were built now in order to meet the thrust exerted by the new arched vault of the nave. These were constructed in two series, one being concealed under the sloping roof over the triforium and acting in place of the earlier round-arched abutment. Its supports were provided at the points where the transverse and diagonal arches of the nave vault began to spring away from the vertical plane of the walls. The other series was the immediate counter-poise to any direct thrust exerted by the arching of the vault against the upper section of the same walls. There was, in fact, a large buttress added to support these nave walls at that point from which each set of vault-carrying ribs began to rise. This buttress, though apparently sub-divided, was one thing, but of composite structure. It was pierced first by the aisle, next by the triforium, and then again above the roof of the triforium. It will be seen that most of these alterations were the direct result of the introduction of a stone vault. But the almost entire renewal of the eastern part of the cathedral was made possible by the destruction and total removal of the apsidal terminations of the earlier work. It has been suggested that the fire may have so badly damaged this portion as to allow no alternative but rebuilding. What may have been the actual cause of its removal it is impossible for us now to know; but the substitute is quite a perfect piece of work of its kind. This ambulatory, or presbytery, as it is commonly misnamed, was nearly all newly built from the foundations during the first half of the thirteenth century. The continuation of the arcade, the triforium, the clerestory, and the vault, the vaulting of the aisles and the chapels forming their terminations eastwards,—all this, with the new arch at the entrance to the earlier lady-chapel, was work of the same date.

Some new buttressing had been added to the south-west tower when the upper part of the tower itself was rebuilt; but the larger works were the addition of a vaulted sacristy in the corner between the west side of the south end of the transept and the nave. On the opposite side of the same part of the transept a square-ended chapel with a vestry attached was added in place of the original shallow apsidal chapel. The original chapel on the east side of the north end of the transept was also removed to make way for another and much larger one. This is now used as the cathedral library.

The scheme planned after the second fire having been completed by about the middle of the thirteenth century, little further work was undertaken in comparison with that then finished; but before 1250 the wall of the south aisle of the nave was pierced in four bays, and two more chapels were added. Then, on the north of the nave, the outer wall of the aisle was cut through in the second bay, going west from the transept, and a small chapel was built. The other chapels west of this one were added during the latter half of the century. In each case the deeply projecting buttresses which had been introduced against the earlier walls after the second fire were used, where they were available, to form parts of the masonry of these new chapels, and were therefore not disturbed unnecessarily. The old walls having been altered, and the earlier buttresses being changed in their nature, it became necessary to carry the original thrust from the nave still farther out from its source in order to find for it some satisfactory abutment, and in doing this there was that new force, introduced by the vaulting of these added chapels, to be reckoned with in addition. Consequently, to the earlier buttressing more was added. The exact nature and the approximate date of this work are shown by Professor Willis in the sections and plan given in his monograph on the cathedral. The addition to each buttress amounted to an elongation of it as a pierced wing wall which provided lateral support. Upon the end of it a greater mass of masonry was introduced to serve as a weight for steadying the structural device; and this necessary structural idea was the means of introducing another architectural feature—the pinnacle. Between the pinnacles of these buttresses rose the gabled ends of each of the chapels. Professor Willis suggests that a great part of the work done after the fire of 1186-1187 was completed by the time of the dedication ceremony in 1199, and he is no doubt a safe authority to follow. But the nature of many architectural features tends very strongly to confirm the idea that much of the work in the ambulatory eastward of the sanctuary had been delayed. It may have been that the activity which prevailed during the early half of the thirteenth century was caused by the desire to see this portion of the church completed; and the energy with which the plea for new interest and further funds was urged at this time would no doubt be indicative of a supervening lethargy following on the great effort necessary for the completion of so much in these few years. But it should be remembered that these great works of mediæval art were none of them built in a day; they represented the accumulation of even centuries of developing thought and continually improving skill. Therefore must we realise that after this fire had occurred in 1186-1187 not more than eleven or twelve years elapsed before the building was again in use after the consecration in 1199.

Note.—For remarks on Chichester Cathedral, see Archaeologia, xvii., pp. 22-28: "Observations on the Origin of Gothic Architecture." By G. Saunders, 1814.

This process of reconstruction shows that the mediæval builders did not restore in duplication of what had been lost. Where their work was destroyed they built anew and improved upon what had gone.

We need not suppose that this repair, renewal, and addition had all been completed when in 1199 Bishop Seffrid II. and six other bishops again consecrated the church. Doubtless only so much had been done as was necessary to enable the priests to officiate at an altar provided for the purpose and the congregation to assemble within the walls; for the work of building continued with a somewhat persistent manifestation of energy throughout the whole of the thirteenth century. Of this activity and enterprise there are many evidences in proof, both documentary and structural. The documentary evidence indicating the activity which prevailed after this date is sufficient to show at least that much was being done; but it does not often indicate in precise terms what is that particular portion of the building to which it primarily refers. Early in the thirteenth century (1207) the king gave Bishop Simon de Welles (1204-1207) his written permission to bring marble from Purbeck for the repair of his church at Chichester. He attached to this act of favour certain conditions which were to prevent any disposal of the material for other purposes.

John had also two years before given Bakechild Church to the "newly-dedicated" cathedral. Then Bishop Neville, or Ralph II. (1224-1244), at his death in 1244, "Dedit cxxx. marcas ad fabricam Ecclesiae et capellam suam integram cum multis ornamentis." Walcott adds that "his executors, besides releasing a debt of £60 due to him and spent on the bell tower, gave £140 to the fabric of the Church, receiving some benefit in return." This cannot be interpreted as referring to the isolated tower standing apart to the north of the west front; for, as we shall see, this was not erected until at least one hundred and fifty years later. In 1232 "the dean and chapter gave of their substance. During five years they devoted to the glory and beauty of the House of the Lord a twentieth part of the income of every dignity and prebend"; 3 and then, again, ten years after the period covered by this act of the chapter the bishops of some other sees granted indulgences on behalf of the fabric of the church at Chichester. Bishop Richard of Wych (1245-1253) "Dedit ad opus Ecclesiae Circestrensis ecclesias de Stoghton et Alceston, et jus patronatûs ecclesiae de Mundlesham, et pensionem xl. s. in eadem." 4 To this he added a bequest of £40. He had revived in 1249 a statute of his predecessor, Simon de Welles, and extended "the capitular contribution to half the revenues of every prebend, whilst one moiety of a prebend vacant by death went to the fabric and the rest to the use of the canons." Other means were used to provide funds to continue the work.

But apart from these many indications of activity, the fabric as it stands to-day speaks very clearly of the amount of building that went on between 1200 and 1300. But it was not till 1288-1305 that Bishop Gilbert de S. Leophardo had added the two new bays of the lady-chapel eastward.

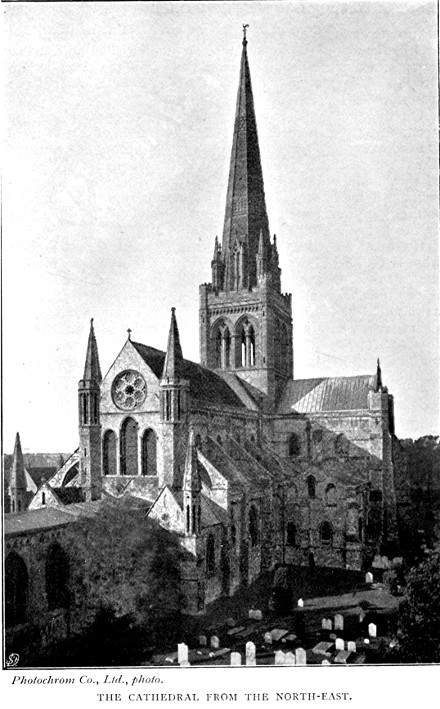

The fire was the direct cause of most of the work that was done. There was another, however; for eleven years after the re-dedication, two of the towers fell. It has been supposed by some that these must have been the early towers of the west front, both of which still preserve indications of having been begun during the twelfth century as part of the original building scheme. It is probable, for reasons that will appear later, that the two towers of the west front did not collapse at the time of the second fire, although it would seem from the Chronicle of Dunstable that their stability may have been impaired in some measure, since the sole cause for this fall of towers is given in the words "impetu venti ceciderunt duae turres Cicestriae." 5 But if these towers had been affected, what of the original central tower? Its risk of receiving serious damage would be far greater. That no more than the upper story of one of these can have fallen is evident from the fact that the south-western tower presents for examination to this day its original base, and the nature of the upper part of this same tower shows that it was rebuilt anew daring the first half of the thirteenth century. It was necessary that the two towers at the west as well as the central tower should be finished up to a certain level, for, placed as they were upon the plan, they became essential parts of the structure, whose absence would diminish the strength of the whole; hence any desire to maintain the fabric satisfactorily would require that those of them which fell should receive the immediate attention of the builders. In the case of the south-west tower we have already seen what was done, and obviously it was one of the two towers that had fallen. But what of the other of these? What suggestions remain to show which it was? It is well known that a central tower had been erected as part of the original plan, and also that a new upper part was being added to this same tower about the middle of the thirteenth century. This new portion eventually rose above the roofs to the level of the top of the square parapet, about the base of the octagonal spire, the spire being a still later addition. Now the heightening of this tower—perhaps with already the idea of a future spire in view—would raise many questions. Experience would already have taught the builders that the early central towers of many other churches were incapable of carrying their own weight. This being so, much less would it do to suppose that it could bear the addition of new weight upon the old piers; for though to all appearance sound, the cores were of rough rubble work, not solidly bedded and not properly bonded with the ashlar casing. So the question arises, did they remove the whole or part of the old central tower and piers, or were they saved this trouble by the structure having shared the fate of many others like itself, which fell, and so made way for new work? Another tower had fallen besides the one to which attention has already been drawn; and as there appears to be nothing to show that this other was the north-west tower, we must see what evidence there is concerning the central tower. That it was added to we already know. But documentary as well as structural evidence comes to our aid. The first is supplied by the records of Bishop Neville's episcopate; the next by the researches of modern archaeology. Professor Willis has shown in his remarks upon the structure of the piers at the time of the collapse of the mediæval tower and spire in 1861, that these had not been rebuilt at a date later than the twelfth century. But Mr. Sharpe6, writing to Professor Willis seven years before the occurrence, indicates his discovery—from a close examination of the structure then existing—that before the upper part of the central tower was rebuilt in the thirteenth century the earlier arches at the crossing which were to support it had been taken down, and probably a large part of the piers carrying them. And that, though the twelfth-century voussoirs were re-used others of a fine grained stone were inserted among them to strengthen the arches, or as a substitute for some of the rougher sandstones that could not be used again. By this means, then, the original form and detail of the twelfth-century arches was preserved, so that the drawings representing the measured studies of the building, which were Sir Gilbert Scott's principal authority upon which to base his restoration of this portion of the tower, were made from work which had already been once rebuilt. But why was this part of the church rebuilt, and by whom? Two alternative suggestions for the reason have been offered.

Evidently, if the upper part of the tower did not fall, it is apparently certain that it was reconstructed, in order to carry the additional weight of the larger tower. But in examining the documentary evidence offered us, we find some further help. The teaching of archaeology shows that the portion of this tower above the main supporting arches and up to the bottom of the parapet was executed between 1225 and 1325—that is, it was finished not very long after the new part of the south-west tower was completed.

The cathedral statutes show that between the years 1244-1247 Bishop Ralph Neville was much concerned about a "stone tower" which he wished to see completed. They tell us, too, that the same bishop had himself expended one hundred and thirty marks upon the fabric,7 and that his executors, besides releasing a debt of £60 due to him and spent on the bell-tower, gave £140 to the fabric of the church. Ralph died in 1244, so it is concluded that the work in which he was so interested was none other than the central or bell-tower of the cathedral, and that the earlier tower, with its supporting arches, must have fallen, else it is not likely that the work would have been rebuilt from below the spring of these arches before the new superstructure could be added; for we are obliged to take the customs of mediæval builders into consideration in any attempt to sift the evidence concerning their work—and they were before all things practical. The claims of structure, the motives of common-sense, rather than abstract and aesthetic ideals of beauty, were the prime causes at work in the evolution of their great art. Here they found themselves faced by a practical need—the rebuilding of a fallen tower. Its reconstruction was necessary to the completeness and stability of the building; so they put it up, applying new and increasing knowledge and skill in the execution of the work. They did their best, and the result was something not only strong and structural, but beautiful. But, as time has shown, it would have been better had they been less respectful of the valueless legacy bequeathed to them in the piers, though in defence of their sagacity it must be admitted that what they deemed sufficient for the purpose then in view was able to carry their own tower for five hundred years in safety, and not only this, but, in addition, a spire, the erection of which they may not have thought of when the restoration was begun.

There is another interesting fact which may be mentioned before quitting this part of our inquiry. Professor Willis found that there still existed in 1861 one of the old wooden trusses of the roof over the west bay of the chancel. It was a specimen of mediæval carpentry six hundred and fifty years old, and it had not, as he showed, been unframed since the fire of 1186-1187. The timbers composing it had been slightly charred by the flames, and some of the lead which covered the burning roof had run in its melted condition into the mortices of the framing.8

In the admirable plan and sections which Professor Willis prepared to illustrate his work upon the history of the fabric it is possible to see at once what work had been done during the different stages of development. The work finished by the end of the thirteenth century changed the earlier church of the eleventh and twelfth centuries in its essential arrangements into the church we see to-day.

We have now briefly to review the changes produced in the plan of the cathedral. There were those effected as an immediate consequence of the fire, and others which were more the result of the continued energy of the thirteenth-century builders. The most remarkable one was that which converted the French chevet, or group of apses, into the more familiar square, and characteristically English, eastern termination. The apsidal chapels on the east side of each arm of the transept had disappeared to make room for others of a different shape and size. The other chapels at the east remained the same in number; but towards the close of the thirteenth century the lady-chapel had been lengthened, and the aisles of the choir, being continued eastward, ended in small chapels to the north and south of the central one. The other changes were those caused by the addition of chapels off the south and north aisles of the nave. The addition of the south and north porches, and the sacristy next to the south arm of the transept, were the only other alterations, if we except the addition of buttresses, which had been made in the original arrangement up to the beginning of the fourteenth century.

Though the quest may not be followed here, it would be interesting to try and trace the cause of this desire to add chapels to mediæval buildings. It had during the thirteenth century already become a clear indication of that gradual movement affecting the arrangement of churches which originated in the introduction of new doctrinal ideas. The particular set of ideas which caused such additions as these had now become a part of the common property of popular thought, imagination, and reverent superstition. The earlier designers and builders had not been taught to consider these features essential to the complete equipment of a church planned in accordance with primitive usages; they were a simple example of the influence which doctrine exercised upon the history of art and the scope of archaeological inquiry.

The course of history that has been followed has led us through the maze of some events which served to produce the cathedral that stands among us now. The later centuries will not require as much attention, since they afford but little material, comparatively, with which we need delay; for the industry expended upon the fabric since this time has produced little change in the general appearance of the building. With the approach of the fourteenth century we meet a period when the peculiarities of the work of the thirteenth century had become merged in transitional forms, and from this application of ever-developing ideas to accepted working principles came the well-known character which English architecture displayed during that time. It was native by parentage and birth; it represented the life which prevailed in the ideas which were then the common currency. By it the ideals of thought and imagination were expressed, until, later, they were represented in other forms of art. At Chichester an early indication of the changed treatment of older methods that was being developed experimentally is shown by the portion which was added to the lady-chapel during the episcopate of Gilbert de Sancto Leophardo. The architects and master-builders devised for him the two new eastern bays complete, together with the larger windows that were inserted in the walls of that part of the chapel already built. Here again, as in the work set in motion by his successor, the designers and builders made no attempt to add these new portions in imitation of earlier ones. Then it was Bishop Langton who, between 1305 and 1337, spent £340 "on a certain wall and windows on the south side, which he constructed from the ground upwards." 9 This work is principally to be seen in the great south window of the transept, under which he provided for himself a "founder's" tomb. In the gable above a rose window was inserted, following the example of that earlier one in the east end of the presbytery. The chapter-house above the treasury, or sacristy, was also added when the new windows were inserted in the lower walls. About the same time the doorway to the nave within the western porch was constructed.

Walcott shows by his study of the early statutes of the cathedral that "in 1359 the first fruits of the prebendal stalls were granted to the fabric; and in 1391, one-twentieth of all their rents was allotted by the dean and chapter to the works, which embraced works round the high altar, for, in 1402, materials 'ad opus summi altaris,' were stored in S. Faith's Chapel. A 'novum opus,' a term applied to some special building, was also in progress." 10 These remarks are of interest, since about the end of the fourteenth century a beautiful wooden reredos was built across the east end of the sanctuary. It was placed just west of the feretory of S. Richard. In many old prints its character is represented, and Dallaway gives some dimensions of it in the long section he shows of the church as it was before the reredos was removed (see page 2). The feretory no doubt had a reredos at this point, but what the type of this earlier arrangement may have been it is impossible exactly to tell. But the work which took its place was evidently beautiful, as the many remains still in existence prove to those who may examine them. Walcott11 gives some interesting details concerning this work. From the representations, descriptions, and remains of it, it may be gathered that the whole was much carved, niched, and canopied, and decorated in colour; and there is a note extant showing that Lambert Bernardi in the sixteenth century repaired "the painted cloth of the crucifix over the high altar." 12 This reredos had a gallery across the top of it, from which the candles on a beam over the altar could be lighted and a watch kept over the precious jewels in S. Richard's shrine. The whole screen was made of oak, and those old sketches and drawings, or prints, of it still preserved, help dimly to show what had been its character. An old letter in the British Museum refers to it as having the finest "glory" above the high altar "we have ever seen." But this so-called "glory" was an eighteenth-century production. Much of the reredos is still hidden away unused in the chamber over the present library of the church, and since its first removal it has travelled as far as London in search of a friendly purchaser. In the chapter on Chichester in Winkles's "Cathedrals" a view in the "presbytery," dated 1836,13 shows the reredos still in its place where it remained till after the fall of the spire. There are in existence two drawings of considerable interest.14 One of these shows the east end and the other the west end of the choir as it was about the beginning of the last century (c. 1818); the other indicates what were the changes made after 1829, when the altar was set back six feet farther eastward. The latter was taken from a water-colour drawing supposed to have been made by Carter, an architect of Winchester.

Other minor works were added during the fourteenth century, but to few of these can any exact dates be assigned. The parapets to the north and south wall of the nave, the choir, and lady-chapel, and the painted oak choir-stalls were some of those additions.

In the fourteenth century we meet many changes in the treatment of the windows. They became larger; they were themselves very treasuries of design, and this not only for the stonework of their tracery, but also for the very beautiful glass with which they had been filled. Their outer arches are more varied in shape, more rich in moulded detail, and the entire character of the curves of the moulded forms had been developed and made more delicate than the stronger and deeper-cut types from which they were derived. Two causes had apparently urged the builders to exert their capacities and apply their increasing technical skill to compass the aims proposed to them.

The small windows, the use of which had so long prevailed, did not admit sufficient light. In the more southern countries there was not the same reason for the change; but where light was less strong, less clear, less penetrating, it might not be spared. So though with their glass they were beautiful in themselves, many of these windows gave place to larger ones. But if the admission of more light was one reason for the change, there was another powerful inducement offered by the larger field that might be provided for the use of decorative colour, and they accepted the opportunity with alacrity—not as a mere chance for display only, but because, rather, they would be enabled to teach by the use of it.

But what was that novum opus, that special building that was already in progress in 1402? What was the reason for granting in 1359 the first-fruits of the prebendal stalls to the fabric? And in 1391 why did the dean and chapter give one-twentieth of all their rents to the works? And these works were not alone about the high altar, for the new work proceeding in 1402 had no doubt some relation to that which was in progress in 1391, and it can have been no mere small undertaking. Can these words be applied to the central tower and the spire that rose above it, or to the detached bell-tower of Ventnor stone northward of the church? It seems they must refer to the former, for to no other work can they be applied, since the angle turrets to the transept, the parapet of the central tower, and the windows inserted during the fifteenth century were not in existence at either of these times. And, further, the action taken in 1359 in order to provide funds for work that was proceeding could have no reference to the detached bell-tower, for its character shows that it was certainly not even begun before quite the end of the fourteenth century, probably not before some time during the first quarter of the fifteenth. So, since there was nothing else proceeding about the structure that could claim such sacrifice, the suggestion occurs that the spire was already in course of construction not long after the middle of the fourteenth century. The late Gordon M. Hills, Esq., in reporting to the chapter in 1892 his opinion concerning the condition of the fabric, said that, "Under Bishop William Rede (1369-1385) was begun a series of works: the completion of the central spire, the conversion of the north end of the north transept into a perpendicular work, the construction of a new library, the construction of the present cloisters, and finally the erection of the great detached belfry, called 'Raymond's, or Redemond's, or Riman's Tower,' was in progress in 1411, 1428, and 1436. All this work was carried on partly by the influence at Chichester of churchmen of the school of William of Wykeham, whose followers were strong at Chichester at this era."15

He also said "that the spire itself was commenced before the death of Bishop Neville. The moulding in the angles cannot, I think, have originated later"; and "that the early work extended to about forty feet above the tower; all the pinnacles and canopies at the base of the spire and the upper part of the spire, were insertions and rebuilding of one hundred years later. At the base the work of the earlier period had had its face cut away to bond in the later work, and the masonry of the two periods did not agree in coursing."

The mere fact that the detached tower was built suggests many questions which are not easily solved. Why was it at all necessary? Perhaps the cathedral bells hung in the south-west tower, and those of the sub-deanery church in the other, or vice-versa. At all events, we know that in the fifteenth century the sub-deanery church was removed from the nave to the north arm of the transept. The great window of the north end of the transept is also early fifteenth century in date, and the detached tower likewise. Angle turrets were placed upon the four angles of the transept during the same century; and if Daniel King's drawing of 1656 is any guide, the tops of the central and western towers had battlemented parapets added during the same period. In any case, it appears that it took much longer to complete the repair of the central tower than that at the south-west. In fact, it is doubtful whether the former was finished until about the end of the thirteenth or the beginning of the fourteenth century, for its fall apparently wrecked much of the vaulting of the transept; and this, from the character of its moulded and carved vaulting ribs in the south arm of the transept, is of the same date as the rose window in the east gable of the presbytery, the rose windows in the east gables of the lady-chapel and the chapels at the east end of the north and south aisles of the choir. This argues that at the end of the thirteenth or the beginning of the fourteenth century, during Bishop Leophardo's episcopate, these works were completed.

About the middle of the fifteenth century a stone rood screen was built up between the western piers of the central tower. It thus separated the choir under the crossing from the nave; but through the middle of this screen there was an open archway with iron gates. On either side, as parts of the screen, to the north and south was a chapel, each with its altar. This new work had been known as the Arundel screen, and its erection is often attributed to the bishop of that name, and at the altar in the south side of it Bishop Arundel founded a chantry for himself. Except that the cloister was added and some details of the building altered during the fifteenth century, no other architectural work of any size appears to have been done for many years.

page 42

page 42The next work of importance was begun by Sherburne. He invited Lambert Bernardi and his sons to decorate the whole of the vaulting of the cathedral. This they did by covering it with beautifully painted designs. But unfortunately, excepting the small remnant now on the vault in the lady-chapel (see page 92), their work was entirely destroyed early in the nineteenth century. Some idea of its original beauty may be formed by an examination of similar work by other hands that may yet be seen in S. Anastasia at Verona, in two churches at Liege, and at S. Albans Abbey. An engraving by T. King, of about 1814, shows some details of the design that was painted on the vault of the choir in the bay next but one to the central tower. The cathedral was at this time an open book, with its walls covered with painted stories. The reredos, the stalls of the canons, as well as the walls, were rich with colour. Now all has gone except a meagre, faded scrap under the arch from the present library into the transept, and one or two other slight remnants. Sherburne also had some large pictures painted by the Bernardis. They represented the kings of England and the bishops of Chichester, and used to hang upon the west and east walls of the south transept.

From Sherburne's death until the seventeenth century little but a tale of destruction is to be recorded; for this period witnessed the dissolution of the monasteries, the beginning of a wholesale system of spoliation urged by self-interest and hypocrisy, and the establishment of "Reformation" methods of procedure in Church and State. By each of these both the fabric and the diocese suffered, even though by some they gained. But especially did vandalism help to destroy, unnecessarily, many things which, legitimately used, might still have been allowed to remain as evidences of the artistic influence of the Church in England. For though some of them were dedicated to uses which the reformation necessarily condemned the wholesale destruction of much beautiful workmanship must be regretted by any who are interested in such treasures. In 1538 it was ordered that all shrines should be abolished. This seriously affected Chichester, as the fate of the feretory of S. Richard was involved by the mandate. Two commissioners were named, whose duty was to see that his shrine was removed. The instructions issued served a double purpose, since in this case, as in others, "reformation" helped to satisfy the claims of avarice. Henry told the commissioners that

"We, wylyng such superstitious abuses and idolatries to be taken away, command you with all convenient diligence to repayre unto the said cathedral church of Chichester and there to take down that shrine and bones of that bishop called S. Richard within the same, with all the sylver, gold, juells, and ornamentes aforesaid, to be safely and surely conveighed and brought unto our Tower of London, there to be bestowed as we shall further determine at your arrival. And also that ye shall see bothe the place where the same shryne standyth to be raysed and defaced even to the very ground, and all such other images of the church as any notable superstition hath been used to be taken and conveyed away."16

Then in 1550

"there were letters sent to every bishop to pluck down the altars, in lieu of them to set up a table in some convenient place of the chancel within every church or chapel to serve for the ministration of the Blessed Communion."

Bishop Daye replied that

"he could not conform his conscience to do what he was by the said letter commanded."

In explanation of his attitude towards this order he wrote that

"he stycked not att the form, situation, or matter [as stone or wood] whereof the altar was made, but I then toke, as I now take, those things to be indifferent.... But the commandment which was given to me to take downe all altars within my diocese, and in lieu of them 'to sett up a table' implying in itselffe [as I take it] a playne abolyshment of the altare [both the name and the things] from the use and ministration of the Holy Communion, I could not with my conscience then execute."

The churches were so ransacked and destroyed in this way that Bishop Harsnett17 said he found the cathedral and the buildings about the close had been criminally neglected for years, so that they were in a decayed and almost ruinous condition. Such was the deliberate opinion which he expressed early in the seventeenth century.

During the first half of the sixteenth century a stone parapet, or screen wall (taken away in 1829), was built up in front of the triforium arcade. It rose to a height of about four feet six inches, and was continued throughout the whole length of the church. It has been supposed that it was intended to render this gallery available as a place from which some of the congregation might observe the great ceremonials. So we see that after the close of the fifteenth century little but decline is to be recorded. Since Sherburne's day no care had been taken of the fabric; and except that an organ was introduced above the Arundel screen, no new schemes were devised, no new building done. It should be remembered, however, that the Reformation did not at once destroy all the beauties of mediæval art that the cathedral contained. Certain things, such as shrines, altars, chantries, and chapels, were removed, dismantled, or totally wrecked. It was with the coming of the Parliamentary army to the city that wholesale pillage and destruction began.

The removal of the altar and other derangements of the building had been effected during the preceding century; but now the vestments, plate, and ornaments were stolen. The decorative and other paintings on the walls, and all parts that could easily be reached, were scratched, scraped, and hacked about until they were mere wretched, disfiguring excrescences; and in this mutilated condition they waited for the whitewash that came later, to cover up these vulgar excesses with a cheap but clean decency. Such criminal procedure culminated in the wilful wreckage of all the beautiful glass. The store of three centuries of labour and consummate skill was destroyed till it lay all strewn in broken fragments, mere rubbish, about the floors. But the decorations on the vaults were saved, because they could not be reached without expensive scaffolding. They were thus preserved to be dealt with by the wisdom and taste of a later century.

Let me quote the remarks of one who lived when these things were done. He says they

"plundered the Cathedral, seized upon the vestments and ornaments of the Church, together with the consecrated plate serving for the altar; they left not so much as a cushion for the pulpit, nor a chalice for the Blessed Sacraments; the common soldiers brake down the organs, and dashing the pipes with their pole-axes, scoffingly said, 'hark how the organs go!' They brake the rail, which was done with that fury that the Table itself escaped not their madness. They forced open all the locks, whether of doors or desks, wherein the singing men laid up their common prayer books, their singing books, their gowns and surplices; they rent the books in pieces, and scattered the torn leaves all over the church even to the covering of the pavement, the gowns and surplices they reserved to secular uses. In the south cross ile the history of the church's foundation, the picture of the Kings of England, and the picture of the bishops of Selsey and Chichester, begun by Robert Sherborn the 37th Bishop of that see, they defaced and mangled with their hands and swords as high as they could reach. On the Tuesday following, after the sermon, possessed and transported by a bacchanalian fury, they ran up and down the church with their swords drawn, defacing the monuments of the dead, hacking and hewing the seats and stalls, and scraping the painted walls. Sir William Waller and the rest of the commanders standby as spectators and approvers of these barbarous impieties."18

This is a history in little of what took place in nearly every cathedral and other church in the kingdom, and this after the Reformation and its best work had been a fact for a century.

The most important disaster to the fabric during the seventeenth century was that which so seriously affected the structure at the west end. It is difficult to decide exactly when and how north-west tower fell or was removed. Professor Willis19 is content to say:

"Mr. Butler informs me that there is evidence to show that the north tower was taken down by the advice of Sir Christopher Wren, on account of its ruinous condition."

But Præcentor Ede, in a paper written about 1684 A.D. and quoted by Præcentor Walcott,20 gives

"an account of Dr. Christopher Wren's opinion concerning the rebuilding of one of the great towers at the west end of the Cathedral Church of Chichester, one third part of which, from top to bottom, fell down above fifty years since, which he gave after he had for about two hours viewed it both without and within, and above and below, and had also observed the great want of repairs, especially in the inside of the other great west tower, and having well surveyed the whole of the west end of the said Church, which was in substance as followeth; that there could be no secure building to the remaining part of the tower now standing; that, if there could and it were so built, there would be little uniformity between that and the other, they never having been alike nor were they both built together or with the Church, and when they were standing the west end could never look very handsome. And therefore considering the vast charge of rebuilding the fallen tower and repairing the other, he thought the best way was to pull down both together, with the west arch of the nave of the church between them; and to lengthen the two northern isles to answer exactly to the two southern; and then to close all with a well designed and fair built west end and porch; which would make the west end of the church look much handsome than ever it did, and would be done with half the charge."21

Such was Dr. Wren's opinion of the west front. It is fortunate that his advice was not followed, for have we not the same west front still in existence? However, Wren spoke of "the remaining part of the tower now standing," and King's print, publishing 1656, shows the portion to which he referred. Fuller22 remarked in 1662 that the church "now is torn, having lately a great part thereof fallen to the ground." He no doubt refers to the same ruin, for it is not to be conjectured that any other part fell then.

Sir Christopher Wren says the towers never were alike in design, nor were they "both built together."

The edition of Dugdale's "Monasticon," published in 1673, gives a view of the north façade of the church. Ede, writing in 1684, said that "above fifty years" before one-third part of the north-west tower had fallen from top to bottom; yet this illustration shows that same tower complete. This affords an opportunity of comparing portions of the two towers. The upper part of each is shown to finish on top with a battlement parapet. It is evidence in itself that during the fifteenth century certain alterations had been effected in them both at this part. But this print must have been made from an original which had been executed quite twenty years earlier—for King's drawing, issued in 1656, shows the north-west tower already partly destroyed; so it is necessary to conclude that the drawing for the "Monasticon" was done before 1656, but after 1610, when Speed's map, or bird's-eye view, of the city was brought out.

Præcentor Walcott has supposed that the two towers in Chichester referred to in the "Annals of Dunstable" as having fallen during the year 1210 were the two at the west end.But taking Sir Christopher Wren's report with the discovery made by Mr. Sharpe in 1853, quoted by Professor Willis, it would seem rather that those two towers were the original central tower and that at the south-west angle of the west front.

Wren in writing of the tower at the north-west, which had fallen about 1630-1640, said that it had not been built at the same date nor in the same manner as the other then remaining to the south of the same front. The upper part of the central tower itself had been built perhaps during the second quarter of the fourteenth century or even earlier. Consequently it seems probable that the two towers which fell in 1210 were the original twelfth-century central tower and that of the same date to the south of the west front. In Speed's map of 1610 both the western towers are represented as having small spires.

Hollar's print in the "Monasticon" shows what appear to be some fifteenth-century buttresses to the north-west tower; but in excavating for the foundations of the new north-west tower, now completed, no traces of any projecting buttresses were discovered, so it may be that it was the original twelfth-century tower which fell about 1630, and the peculiar character of its masonry suggested the remark to Wren when he said it so distinctly differed from its companion.

Towards the close of the seventeenth century the central spire was in an unstable condition, and Elmes, in his "Life," says of Wren that he

"took down and rebuilt the upper part of the spire of the cathedral, and fixed therein a pendulum stage to counteract the effects of the south and the south-westerly gales of wind, which act with some considerable power against it, and had forced it from its perpendicularity."

It is interesting to have this record, for the spire during the following century was still a cause of trouble.

Spershott's memoirs show that about 1725

"a new chamber organ was added to the choir of the cathedral, the tubes of which were at first bright like silver, but are now like old tarnished brass."

Whether this organ contained any parts of that which was destroyed in the previous century is not known; but many old prints and drawings show that the case of the one that was now built on the top of the Arundel screen was quite as beautifully designed as the one in Exeter Cathedral, or King's College Chapel at Cambridge.

About 1749 the Duke of Richmond's vault was "diged and made"23 in the lady-chapel, and ten years later "the kings and bishops in the cathedral" were "new painted." The floor of the lady-chapel was raised to give height to the vault beneath, and a fireplace and chimney built up in front of the east window. Portions of the other windows were plastered up, and so left only partly filled with glass. These served to provide light in what was now to be the library, since, apparently, the originally well-lighted library, above the chamber now used for the purpose, had lost its proper roof and been otherwise made useless.

There is little else to be said concerning the history of the building during eighteenth century; but it is stated by a careful observer,24 writing in 1803, that "in the interior of this cathedral few innovations have been effected." He says that the east window of the lady-chapel is plastered up, and that

"we find that the great window in the west front of the

cathedral has a short time back had its mullions and other

works knocked out, and your common masoned 'muntings'

(mullions) and transoms stuck up in their room, without any

tracery sweeps or turns, of the second and third degrees;

which work may before long be construed by some shallow

dabblers in architectural matters into the classical and

chaste productions of our old workmen. On the north and

south sides of the church are buttresses, with rare and

uncommon octangular-columned terminations; but they have

likewise, to save a trifling expense in reparation, been

deprived of their principal embellishments, and are now

capped with vulgar house-coping....

"It may be well to speak of the west porch as an excellent

performance; and the statue over the double entrance is

remarkably so."

Proceeding, the same writer relates that:

"Against the east and west walls of the said transept are

affixed historic paintings; those on the west side (the

figures as large as life) relate to the founding of the

church and its re-edification in Henry viii.'s time. Among

the various portraits is that of Henry viii. himself. Here

are also in separate circular compartments, the quarter

portraits of our kings, from William the Conqueror to Hen.

viii. (and since his day, in continuation to George i.) On

the east side is the entire collection of the ancient

bishops of the see (quarter lengths, and in circular

compartments). A short time back the faces of the several

portraits were touched upon by some unskilful hand; however

we have before us most curious specimens of the costume of

Henry's day, when the whole of these paintings were done

(excepting those of subsequent dates), in dresses, warlike

habiliments, buildings, etc....

"Looking towards the north, on the outside of the choir, is

the monumental chapel and tomb of St. Richard. The groins

above are embellished with paintings of foliage, arms, etc.,

conveying the eye over the choir; thence into the north

transept, intercepted in the way by the galleries over the

side-aisles, when the general combination of objects is

terminated by the north transept window, which, though

inferior to the southern window, still has its own peculiar

attractions."

At the time these words were written the north porch was in a wrecked condition. Both gables of the transept were in ruins, and the high-pitched roofs of the old library, the lady-chapel, and the south arm of the transept were absent altogether.

But soon the authorities began to take some interest in the condition of the building. James Elmes had been called in to deal with the spire in 1813-1814, and under his direction the "useful piece of machinery" which had been put there by Wren was "taken down and reinstated." In his "Life of Wren" an illustration is given of the device, which he had carefully examined and measured. He describes it thus:

"To the finial is fastened a strong metal ring, and to that is suspended a large piece of yellow fir-timber eighty feet long and thirteen inches square; the masonry at the apex of the spire, being from nine to six inches thick, diminishing as it rises. The pendulum is loaded with iron, adding all its weight to the finial, and has two stout solid oak floors, the lower one smaller by about three, and the upper one by about two and a quarter inches, than the octagonal masonry which surrounds it. The effect in a storm is surprising and satisfactory. While the wind blows high against the vane and spire, the pendulum floor touches on the lee side, and its aperture is double on the windward: at the cessation, it oscillates slightly, and terminates in a perpendicular. The rest of the spire is quite clear of scaffolding. This contrivance is doubtless one of the most ingenious and appropriate of its great inventor's applications."

About 1814 T. King made a plan of the whole building and several drawings of the church as it then appeared. One of these25 shows some carefully copied specimens of the decorations on the vaults. The engraving was published in 1831, and on it is the statement, "Painted 1520. Erased 1817." Another drawing showed the interior of the choir looking west. In this was represented in careful detail the design of the eastern elevation of the organ-case and the "return" stalls against the Arundel screen. It also shows the original iron gates in the archway, which pierced the screen in the centre below the organ, and formed the entrance to the choir. These gates were evidently copied in design from the thirteenth-century iron screen that protected the sanctuary, part of which is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. In the distance the decoration on the nave vaulting is lightly indicated. There is also an original drawing by T. King in the possession of the Chapter, which gives a view looking eastwards. Another drawing26 which was made some time after 1829 shows the choir looking east towards the reredos. It is a careful study, and is of peculiar interest, since it is a record of many features now entirely removed. The early reredos appears still in its place, but the upper portion of it is gone. This was a gallery which was accessible from either triforium, across which boys early in the century used to run races by starting up the staircase in one aisle and down that in the other. The absence of the gallery in the drawing shows that it was made after 1829, the year in which the gallery was removed. The "glory" which was added to the reredos during the eighteenth century appears just above the altar. On the south side of the choir are some spectators in the gallery above the stalls. There were also at this time other galleries on the north and south of the sanctuary, and above the arch on the east side of the north arm of the transept was a gallery too. To this last there was access from the staircase that led to the chamber above the east chapel of the transept close by. These drawings show what the interior of the church was like up to the time when that extraordinary revival of activity in matters ecclesiastical began in the nineteenth century.

Like other churches, that at Chichester felt the sting of controversy in unnecessary vandalism. But it may be admitted that destruction, like a storm, carried at least some virtue in its clouds. In attempting to sweep away the accumulated refuse heaped within the building, some precious things fell before the broom of zealous furnishers, and were lost for ever in the dust raised by this new cleansing dream.

The removal of the gallery above the old fifteenth-century reredos in 1829 was the beginning of a serious attempt to repair, restore, and reanimate the fabric. This revival of faith began to try to do good works—but not always with discretion, not always with knowledge, wisdom, and taste. Here was rash ardour, often without the hesitation of true reverence.It is certain the building was not all it should have been when these works were begun; it is not what it might have been had some of them been deferred. Consequently any illustrations which show its condition before the middle of the nineteenth century are of interest and value to those who would know what changes have been made.

In Winkles's essay on Chichester, in his "Cathedrals of England," published between 1830 and 1840, are many beautiful drawings of the fabric. There is one which shows the Arundel screen still in its original position with the organ above it; and in another the complete design of the back of the reredos appears. These careful studies of the building, which were made before it became so changed by the removal of its best remaining treasures, help to convey some idea of what the place was before it was so radically "restored."

None of the drawings, however, show any of the beautiful decorations of the vaults, for all this had been smeared over with a dirty yellow wash about 1815, which earned for the church the name of "the leather breeches cathedral." And when, later, the plaster on the stone-filling between the ribs was removed, the paintings were utterly obliterated for ever, excepting only the small portion remaining in the lady-chapel bearing the Wykeham motto upon a scroll. But this recital is but a prelude to the changes that were to follow. The energy of revival found expression in many ways, and English architecture suffered sorely at the hands of ardent ignorance. But the very desire to deal well with the fabrics of our churches that were to be repaired taught men to study closely the facts of archaeology. The studies had a practical end, and at Chichester they found their opportunity in the cathedral.