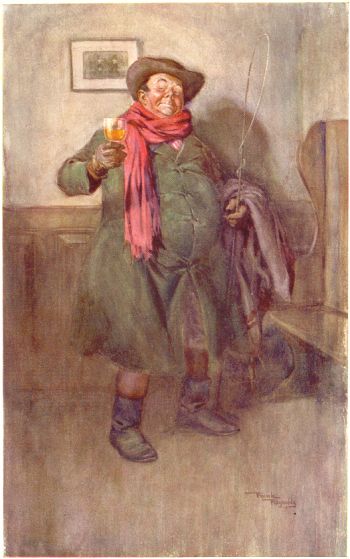

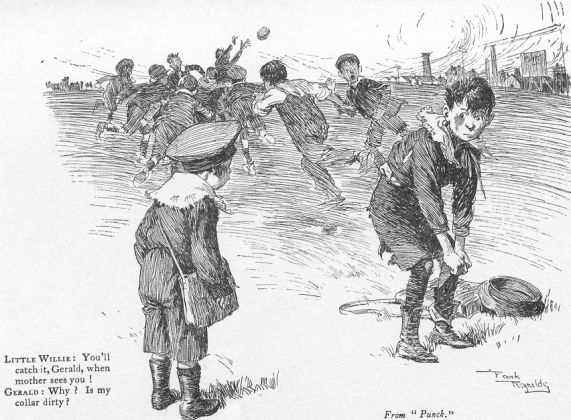

TONY WELLER OF THE BELLE SAUVAGE

BY A. E. JOHNSON

CONTAINING 46 EXAMPLES

OF THE ARTIST'S WORK

IN BRUSH, PEN, AND PENCIL

In presenting under the title of "Brush, Pen, and Pencil" the series of books of which the present volume forms part, the publishers feel that they are meeting a demand which has long existed but has hitherto not been supplied. It is an unfortunate circumstance of the conditions which affect the modern artist who chooses black and white for his principal medium, that as a general rule his work—or, at all events, the reproduction of it—is ephemeral only. In respect of much that appears in the illustrated Press this is small matter for regret; but there is good reason to believe that opportunities of obtaining in permanent form some record of the work of the leading men amongst those artists who work for the Press would be welcomed. It is to afford such opportunities that the present series is issued; and it is hoped that in the volumes composing it the public will have pleasure in finding representative examples of the work with brush, pen, and pencil of the men whose skill and fancy have from time to time delighted them.

For permission to reproduce a very large number of the drawings by Mr. Frank Reynolds which appear in the present volume the publishers wish to acknowledge the courtesy of the proprietors of the Sketch, in the pages of which they first appeared. Their thanks are equally due to Messrs. Bradbury, Agnew & Co. Ltd. for kind permission to reproduce three drawings from the pages of Punch.

IN COLOUR

TONY WELLER OF THE BELLE SAUVAGE

THE INTRODUCTION

FRIVOLITY

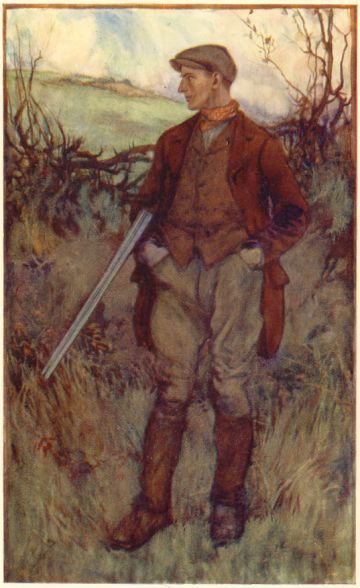

THE WARRENER

IN BLACK AND WHITE

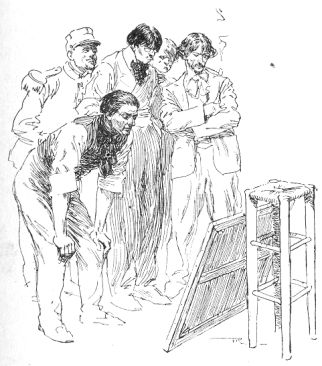

STUDY IN PENCIL

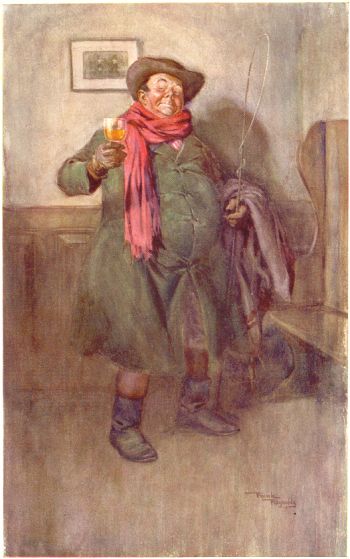

PEN-AND-INK DRAWING FROM "PUNCH"

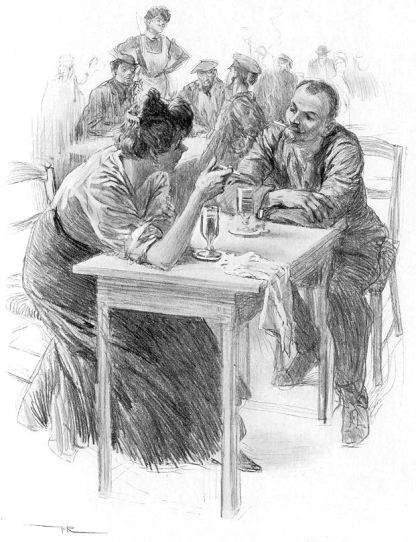

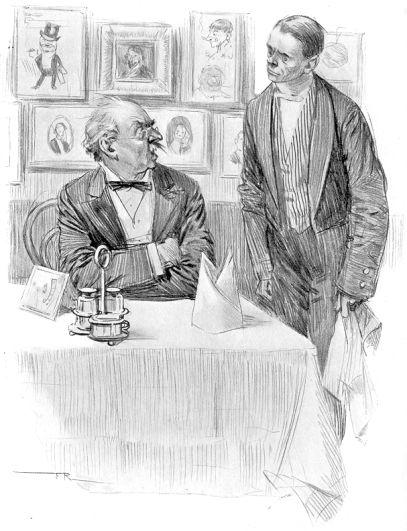

WORKING PARIS AT LUNCHEON

THE DARE-DEVILS

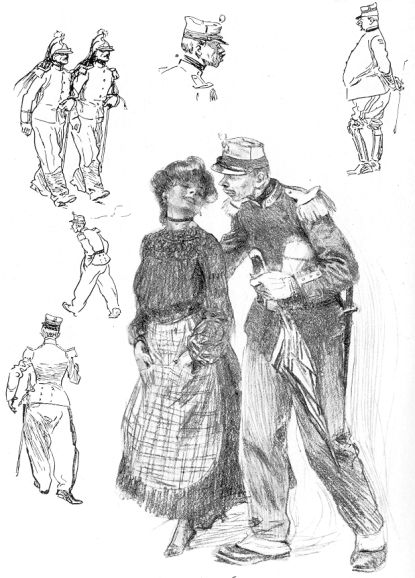

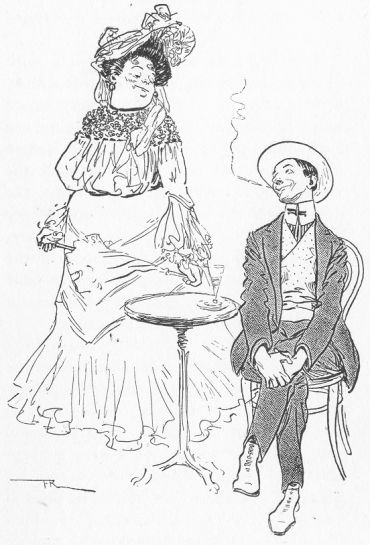

"CHACUN" WITH HIS "CHACUNE"

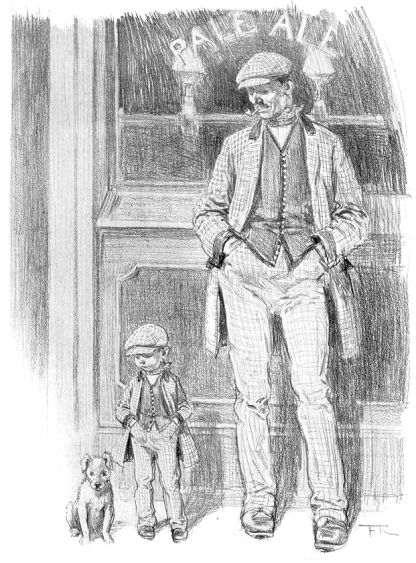

BETHNAL GREEN

THE REAL ARTIST

NOTE FROM A PARIS SKETCH-BOOK

THE SUBURBANITE

FIRST SKETCH FOR THE SUBURBANITE

A GOOD STUDY

PEN-AND-INK DRAWING FROM "PUNCH"

A TRAGEDY IN MINIATURE

OUR CLUB

HAVING THE TIME OF HER LIFE

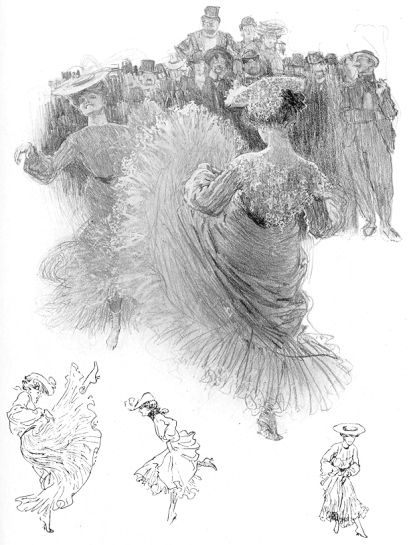

LE 'IGH KICK

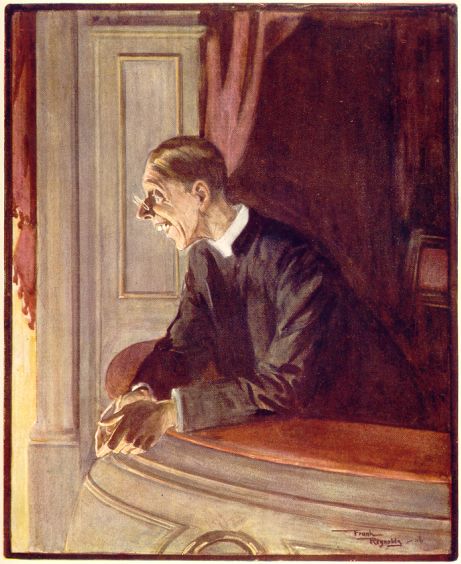

A SPEECH AGAINST THE GOVERNMENT

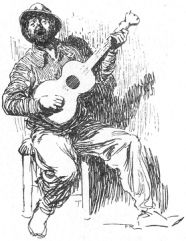

FELIX OF THE "LAPIN AGILE"

VIVE L'ARMÉE

"GAZED ON HAROLD"

FROM A PARIS SKETCH-BOOK

THE DES(S)ERTS OF BOHEMIA

GOING IT!

Also Nineteen smaller illustrations mostly reproduced from sketch-books

It has been said of Tolstoy, anatomising the grim skeleton of human nature,

that his writings are more like life than life itself. Of Frank Reynolds, with

gently satirical pen and pencil depicting the superficial humours of modern

life, it might be said that his drawings, too, are more humanly natural than

real flesh and blood. It is the peculiar faculty of the true observer that his

eye pierces straight to the heart of what he sees, and his mind, disregarding

mere detail, thereby receives and retains a clear perception of the essential,

which those of less clear and direct vision fail to grasp more than

momentarily, though they hail it with instant recognition when in its naked

simplicity it is set before them. The process is unconscious, or at least but

semi-conscious; for your professed observer has never that keen insight which,

being

native, is not to be acquired by even the most assiduous practice,

and alone permits of truthful analysis.

native, is not to be acquired by even the most assiduous practice,

and alone permits of truthful analysis.

In the making of the genuine humorist the faculty of observation is the first necessity. Consider the great pictorial humorists, whether dead or living, whose names are familiar in the mouth as household words. That they gained acknowledgment by masterly handling of the medium in which they chose to work is not to be denied. It is by the peculiar distinction of his technique, indeed, that the work of each, in a general way, is called to mind. But this fame was not achieved solely upon purely artistic merits. Charles Keene, George du Maurier, Phil May, Raven Hill, Bernard Partridge—it is rather for the happy fidelity of their transcripts from life than for the artistic sureness of their hands that they are and will be remembered.

It is the possession of just that subtle power of quiet but comprehensive observation which has obtained for Frank Reynolds the unique position which he occupies amongst the humorous artists of to-day.

For unique his position is. Other men are as funny as he, perhaps funnier. For

when a determined man sets out with a fixed and unshakeable resolve to tickle

your fancy, there is no limit to the means he may adopt to catch you unawares,

and it shall go hard with him but he extorts from you a laugh, however tardy.

Frank Reynolds makes no such desperate efforts. One might say, indeed, that he

makes no effort at all. His simple method is to set down—with the most refined

and delicate

art—just one of those little scenes or incidents which everyone

may every day everywhere witness.

art—just one of those little scenes or incidents which everyone

may every day everywhere witness.

Spectators of such a scene in real life, it is possible—probable, in fact—that we were in no way edified or amused. Not the veriest ghost of a smile, it is likely, flickered across our faces. But reproduced by the subtle humour of the artist, the inherent comedy of the situation stands revealed, and we chuckle. And our enjoyment is the greater for the skill with which the means are concealed by which this magical transformation is effected. We feel that we have discovered the comedy ourselves, not that it has been shown to us. The characters are so perfectly natural, so precisely as we know them and have seen them day after day. The secret lies in the artist's power of restraint. He exaggerates, he caricatures,—he must do so to bring his point home to our dull wits. But he does it with such nicety that the exaggeration and the caricature are unnoticed. Indeed, the terms are misleading. It is better to say that he emphasises.

Frank Reynolds reminds me, if he will forgive my saying so, of a certain profane 'bus-driver whom I have the privilege to number amongst my acquaintance. With this close student of human nature I have had the good fortune to enjoy frequent conversations, and many are the gestures which I recall of the whip-hand towards the pavement, accompanied by the remark (in effect), "Lumme, what funny things a bloke do see!" I confess freely that often I should entirely miss, but for the observant jerk of the whip, the said "funny thing"; and it is just that service which the friendly busman renders to me, as it appears to my mind, that Frank Reynolds performs for the community at large. It is precisely those commonplace "funny things," whether they be persons, scenes, incidents, conversations, or casual remarks, that happen under our very noses, which he excels in depicting; and it is precisely the commonplace familiarity of them that invests them with their peculiar flavour and charm.

Of the fine qualities of Frank Reynolds' technique the reader can judge for

himself from the varied specimens of the artist's work

which are reproduced in the present volume. His pencil drawings

represent, perhaps, his more familiar style, one reason of the

association of his name with this medium in the public mind being

the comparative rarity of its use for the purposes of reproduction.

Certainly it will be conceded that pencil, soft and amenable, with

its opportunities for delicate manipulation, is admirably adapted to

the interpretation of those refined shades of meaning and expression

which constitute the characteristic charm of Reynolds' drawings,

and of his masterly handling of it there can be no two opinions.

which are reproduced in the present volume. His pencil drawings

represent, perhaps, his more familiar style, one reason of the

association of his name with this medium in the public mind being

the comparative rarity of its use for the purposes of reproduction.

Certainly it will be conceded that pencil, soft and amenable, with

its opportunities for delicate manipulation, is admirably adapted to

the interpretation of those refined shades of meaning and expression

which constitute the characteristic charm of Reynolds' drawings,

and of his masterly handling of it there can be no two opinions.

His early drawings for publication were in line, and it was not until his work in the illustrated press had appeared for some time that he began to substitute pencil for pen-and-ink. His first experiments in pencil were made at the Friday evening meetings of the London Sketch Club, and it was at the suggestion of a fellow member of that cheery coterie, his friend John Hassall, that he adopted the softer medium for the purposes of reproduction.

The excellence of his pencil drawings notwithstanding, it is in pen-and-ink that Frank Reynolds appears to me to be at his best. There is a quality about his work in this medium which gives it a peculiar distinction. Always instinct with the most subtle and delicate feeling, there are occasions when his expressive line does more than satisfy. It arrests: revealing in its simple transcription of pose or expression a significance which had previously escaped our shallow observation, but of which the truth is forced upon us. By comparison, one feels that, despite the fine finish of his pencil work, in the latter medium he loses, to a certain extent, the opportunities for that incisive sureness—so suited to his own unerring vision—which pure line affords him. Consider the drawing (on page 32) of the girl singing in a Paris café. There is no dependence on aught extraneous for the achievement of the effect sought. Yet here, if ever, a human soul is laid bare in all its naked tragedy.

For sheer power in the art of drawing, Frank Reynolds has few equals and no betters. As a draughtsman pure and simple, he seems to me well-nigh perfect, whether he has pen, pencil, or stump of charcoal in his hand. It is the great merit of his work, as it appears to me, that it depends for the achievement of its intention solely on its own intrinsic qualities. It has no tricks, no mannerisms, no "fakements" to distract the attention and conceal weaknesses. It is straightforward, direct in its appeal, self-reliant in its challenge.

To quote the words of a critic of discernment, as he passed from

drawing to drawing, "Frank Reynolds is right, right—right

every time." This is praise to which one can hardly add.

To quote the words of a critic of discernment, as he passed from

drawing to drawing, "Frank Reynolds is right, right—right

every time." This is praise to which one can hardly add.

Frank Reynolds is yet another in the long list of artists who have arrived at their true vocation by devious routes. There are certain tendencies of mind which, when a man has them, refuse to be suppressed. The journalistic instinct is one of them. Do what you will with the man in whom it is planted, he can never keep his fingers from the pen. Make him a doctor and you will find him scribbling columns for the press on hygiene in the house and the benefits of breathing through the nose. Send him into the army and he will fill his leisure by writing tales of tiger-shoots and essays on the art of pig-sticking. So with the artist. The man born with the gift to draw finds as irresistible a fascination in pencil or brush as the man with the power of narrative discovers in ink and paper. Whether he serves before the mast as an A.B., or cattle-ranches out west, sooner or later he is certain to drift into his proper sphere of activity. It may take long to get there, but eventually he is bound to arrive.

In the case of Frank Reynolds the period

of bondage was comparatively brief. Entering at first upon a business

career, he had originally no prospect, nor intention, of developing

his artistic impulses. He had scarcely, indeed, a suspicion of his

own powers—certainly no proper knowledge of their latent

possibilities. But commerce had little interest for him, and

circumstances which offered an opportunity of escape combining with

a happy chance which suggested a higher artistic (and monetary)

value for that faculty for drawing which previously he had regarded

in the light of a mere hobby, caused him to throw up his earlier

plans and devote himself entirely to black-and-white illustration.

possibilities. But commerce had little interest for him, and

circumstances which offered an opportunity of escape combining with

a happy chance which suggested a higher artistic (and monetary)

value for that faculty for drawing which previously he had regarded

in the light of a mere hobby, caused him to throw up his earlier

plans and devote himself entirely to black-and-white illustration.

There had been preparation for this, however. The son of an artist,

Frank Reynolds inherited his native talent, and this was developed

in no small measure during boyhood under his father's guidance. It

was the chief delight of Reynolds junior to "mess about" (as he

himself succinctly puts it) with the palette and tools of Reynolds

"CHACUN" WITH HIS "CHACUNE".

From "Paris and some Parisians"

senior, and the licence thus permitted enabled him to discover

for himself much of the rudiments of the craft of the draughtsman

and painter. More was learned from long and absorbed contemplation

of his father at work.

If early inclinations were of more lasting duration than is their

wont, it is likely that Frank Reynolds would now be known to fame

as a painter of martial types and gory battlefields. With him the

fascination which soldiers and all things military have for the

boyish mind took the form of an intense eagerness to reproduce

in colour and line the gay pageant of the march. The skirl of the

fife and the tattoo of the drum inspired him with a desire, not to

shoulder a gun, but to seize a pencil. There was a shop in Piccadilly

where water-colour sketches of military types might frequently be

seen displayed to view, and to Reynolds junior a tramp thither

of several miles from the far west of London was as nothing, could

he but have the

ecstatic joy of gazing, with nose flattened against the window-pane,

upon these transcendent works of art, for an hour or more on end.

where water-colour sketches of military types might frequently be

seen displayed to view, and to Reynolds junior a tramp thither

of several miles from the far west of London was as nothing, could

he but have the

ecstatic joy of gazing, with nose flattened against the window-pane,

upon these transcendent works of art, for an hour or more on end.

This early training, to be regarded as the sure foundation upon which the artist's later education was to rest, owed not a little, perhaps, of its effectiveness to its casual and desultory nature. The natural bent was allowed to reveal itself: development was gradual, and (as it were) automatic. Individuality was neither crushed nor cramped. On the contrary, it was given full play, and that the work of Frank Reynolds is invested with so definite a quality of personality is due in no small degree to the special circumstances of his youthful training.

Heatherley's, in Newman Street, London, was his only school. Here, for some time after his final abandonment of commerce for art as the serious business of his life, Reynolds was a close and persistent student. That conscientious care which presents itself to those who are cognisant of his method of work (and, indeed, to any intelligent critic of his finished drawings) as one of his most salient characteristics was a feature of his days of apprenticeship at Heatherley's. Delight at emancipation from uncongenial occupation was balanced by a sober ambition and a steady purpose. He lived laborious days, laying to heart the lessons of his craft, but he laboured always con amore.

In his student days at Heatherley's Frank Reynolds received much valuable help from Professor John Crompton. On the vital importance of drawing, the latter was especially insistent: this was the dominant note of his teaching, markedly made manifest in the work of his pupil. In the matter of draughtsmanship, few men have so sure a hand, an instinct so unerring.

Leaving Heatherley's, Frank Reynolds set out, armed with a sharp

pencil, and a yet sharper sense of humour, to make a living out of

black-and-white illustration. His work quickly obtained recognition,

and his drawings were soon appearing with regularity in the illustrated

press. It would have been strange if Pick-Me-Up, then in

its sunniest and most audacious days, had not opened its

arms to so keen an observer of life's little comedies, and Frank

Reynolds speedily became one of that clever band which, including

at different times such artists in jest as Raven Hill, S. H. Sime,

Dudley Hardy, J. W. T. Manuel, Eckhardt, and others, succeeded in

making, for a brief but brilliant period, the satirical little

sheet in the blue wrapper the most talked of periodical, perhaps,

of its day. One recalls with relish many of the quaint conceits

that were illustrated in its pages by Reynolds' mirth-provoking

line, and thinks, with regrets for opportunities lost, how admirable

a successor he would have been to Raven Hill and "the man Sime" as

collaborator with Arnold Goldsworthy in those shrewdly flippant

theatrical critiques which the latter contributed over the familiar

signature of "Jingle."

black-and-white illustration. His work quickly obtained recognition,

and his drawings were soon appearing with regularity in the illustrated

press. It would have been strange if Pick-Me-Up, then in

its sunniest and most audacious days, had not opened its

arms to so keen an observer of life's little comedies, and Frank

Reynolds speedily became one of that clever band which, including

at different times such artists in jest as Raven Hill, S. H. Sime,

Dudley Hardy, J. W. T. Manuel, Eckhardt, and others, succeeded in

making, for a brief but brilliant period, the satirical little

sheet in the blue wrapper the most talked of periodical, perhaps,

of its day. One recalls with relish many of the quaint conceits

that were illustrated in its pages by Reynolds' mirth-provoking

line, and thinks, with regrets for opportunities lost, how admirable

a successor he would have been to Raven Hill and "the man Sime" as

collaborator with Arnold Goldsworthy in those shrewdly flippant

theatrical critiques which the latter contributed over the familiar

signature of "Jingle."

It is by his work for the Sketch, however, that Frank Reynolds is best known to the public. Credit is due to that enterprising journal not only for the discrimination which has caused prominence to be given to his drawings in its pages, but for the nice appreciation of the artist's peculiar vein of humour which has given him a free hand to produce those exquisitely subtle studies of character which are his especial province. As examples of what a humorous drawing should be they are well-nigh perfect. To Reynolds it is not enough merely to depict a laughable situation or superficially comic types. The humour of his drawings is inherent, not extraneous; his pictorial jests are self-contained, so to speak, and the printed legend beneath them is incidental only. Frank Reynolds produces a comedy where other men succeed only in perpetrating a farce.

FRANK REYNOLDS. III.

How does one portray a type? What are the rules that govern the

selection of those separate distinctive features which are to form,

A GOOD STUDY.

From "Paris and Some Parisians"

when blended together, one harmoniously characteristic whole? Frank

Reynolds, surely, of all people should be able to answer. But if the

question be asked him, he will reply that he does not know. The

process is unconscious, or almost so. The portrait "comes" of its

own accord. Reflection shows that this must be so. If the artist

were to try deliberately to copy this or that feature from concrete

personalities, the result would fail to carry conviction. The portrait

of a type must be the presentment of an abstract personality—a

print, as it were, from a composite negative comprising the likenesses

of many individuals, so welded together as to reproduce only that

which is common to all: a collective portrait which is like all

but resembles none.

It is related of Charles Dickens that the creation of many of his

famous characters was inspired by a chance remark overheard in the

street. A single telling sentence, uttering some quaint sentiment,

perhaps in quaint idiom, would set up a train of ideas ultimately

resulting, after much meditative elaboration, in a Mrs. Gamp or a

Dick Swiveller. The process is not dissimilar, one imagines, from

that by which the artist evolves a character sketch: with this

difference, that whereas a solitary trait,

accidentally revealed, was to Dickens sufficient foundation upon

which to construct his fanciful portrait, such studies of types

as Frank Reynolds excels in must be the outcome, not of one "thing

seen," but of reiterated observation of the same thing in identical

or closely similar guise. The results in either case vary as the

method employed. Mrs. Gamp, the outcome of a single observation,

is a type certainly, but exaggerated and "founded on fact" rather

than true to life. "The Suburbanite" (see p. 24),

though an equally imaginary portrait, is the real thing—the

absolute personification of a type or class.

as Frank Reynolds excels in must be the outcome, not of one "thing

seen," but of reiterated observation of the same thing in identical

or closely similar guise. The results in either case vary as the

method employed. Mrs. Gamp, the outcome of a single observation,

is a type certainly, but exaggerated and "founded on fact" rather

than true to life. "The Suburbanite" (see p. 24),

though an equally imaginary portrait, is the real thing—the

absolute personification of a type or class.

In the case of Reynolds, his studies of types are the result of an exceptional power of observation coupled with a very retentive memory. His keen eye notes—often unconsciously, as he admits—the small eccentricities by which character is revealed; his sense of humour emphasises them, and his memory retains them. As a result, when he essays to portray a type, there rises before his mental vision, not the figure of this individual or that, but a hazy recollection of all its representatives that he has ever come into contact with. The misty impression materialises as he works, and there grows under his hand a portrait which draws from us an instant smile of recognition, broadening as we perceive the veiled humour and satire that lurk beneath the skilful emphasis which has been laid upon the subject's salient characteristics.

But though his character studies are so largely the result of memory,

it must not be supposed that his drawings are hastily conceived or

carried out. As a discerning critic can guess Frank Reynolds is

slow and careful in his method, and though the central idea of a

drawing is frequently the inspiration of the moment, its elaboration

is a matter which occupies time, and the picture passes through

many stages before attaining in the artist's mind completion. To

lay readers it may be of interest to be initiated into the mystery

of the gradual development from germ to finished drawing. For their

benefit is reproduced (p. 24) the initial

rough sketch made for the portrait of "The Suburbanite," to which

allusion has been made above. It will be seen that all the essentials

are there in a raw state, and a

comparison of this rough sketch with the finished reproduction

of the gradual development from germ to finished drawing. For their

benefit is reproduced (p. 24) the initial

rough sketch made for the portrait of "The Suburbanite," to which

allusion has been made above. It will be seen that all the essentials

are there in a raw state, and a

comparison of this rough sketch with the finished reproduction

will give some hint of the patient labour and careful thought which

has gone to the making of the latter.

will give some hint of the patient labour and careful thought which

has gone to the making of the latter.

To mix as an observer in all ranks of society—especially the lower and more interesting ones—has always been to Frank Reynolds a matter of reflective amusement. The comedy of life affords him never-failing entertainment, for the world can never be dull to the man with the saving grace of humour and a quizzical interest in his fellow men. All is fish that comes to his net, for whether he touches off the foibles of Belgravia or records the broader humours of Bethnal Green he is equally happy. In the well-remembered series of "Dinners with Shakespeare," for instance, he illustrated with genial humour in half a dozen cartoons as many mannerisms of the dinner-table. The drawing which is reproduced opposite to page 56 portrays types that are familiar to all who know the small restaurants of Soho. The historian of the future, I sometimes think, who may wish to describe society in the early part of the twentieth century, will be fortunate if he contrives to illustrate his volume with a collection of contemporary drawings by Frank Reynolds. They will speak more eloquently than any narrative which he may compile from the most diligent searching of written records.

Of Reynolds' exquisite refinement in the art of character drawing, his pictures of life in Paris afford excellent examples. Impressions of Paris through English eyes are familiar enough; but too often they are distortions. The artist is too concerned with the obtaining of an "effect" to be troubled by a strict adherence to truth. No such charge can be levelled against "Pictures of Paris and Some Parisians," as the series of drawings which Frank Reynolds contributed to the Sketch in 1904 was entitled. He viewed Paris through eyes which magnified, perhaps, but never distorted; and his impressions, as set down on paper, carry that instant conviction, even to those who have never crossed the Channel, which is the hallmark of truth.

In some cases these Paris drawings, many of which are reproduced

in the present volume, are literal portraits from life. But for the

most part they are the result of that close and absorbent observation

which has been mentioned as characteristic of the artist's method.

The "Pictures of Paris" were no hurried impressions received during

a flying visit, but the outcome of a long stay in the French capital,

which gave opportunities for a close study of manners, and a sympathetic

insight into men. Accompanied by two brother artists, Reynolds,

commissioned by his editor to depict Paris, betook himself thither,

and established himself for a considerable period in a studio,

whence he could watch and record. Under the guidance of Mr. John N.

Raphael, well known amongst Paris correspondents, who contributed

the clever literary sketches which the drawings by Reynolds nominally

illustrated, explorations were made not only to those familiar

haunts of which the names are known to the veriest tripper, but

into the heart of that Paris which is terra incognita to

the casual stranger.

which has been mentioned as characteristic of the artist's method.

The "Pictures of Paris" were no hurried impressions received during

a flying visit, but the outcome of a long stay in the French capital,

which gave opportunities for a close study of manners, and a sympathetic

insight into men. Accompanied by two brother artists, Reynolds,

commissioned by his editor to depict Paris, betook himself thither,

and established himself for a considerable period in a studio,

whence he could watch and record. Under the guidance of Mr. John N.

Raphael, well known amongst Paris correspondents, who contributed

the clever literary sketches which the drawings by Reynolds nominally

illustrated, explorations were made not only to those familiar

haunts of which the names are known to the veriest tripper, but

into the heart of that Paris which is terra incognita to

the casual stranger.

Thus we have in these drawings a true Paris and the true

Parisian—not the traditional caricature which, though founded

possibly on fundamental facts, has been so elaborated as to bear no

more resemblance to the real thing than the libellous figure with

lantern jaws, protruding front teeth, and side whiskers, generally

beloved of the French artist, bears to the typical Englishman.

Take, for example, the drawing of French workpeople at dinner

(page 8), made from a sketch in a Belleville

café. There is no exaggeration here, but a literal

transcript from life, which reveals, as it were, in one flash,

a whole epitome of town life in working France.

(page 8), made from a sketch in a Belleville

café. There is no exaggeration here, but a literal

transcript from life, which reveals, as it were, in one flash,

a whole epitome of town life in working France.

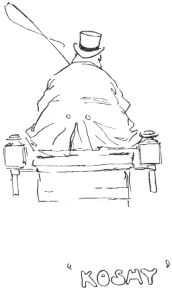

Consider again his drawings of Parisian types. No portrait could more nicely hit off the characteristic slouch of the piou-piou (as Tommy Atkins is called in France), nor catch with more delicate charm the personality of the French grisette of a certain type, than the pencil drawing "Vive l'Armée" (page 49). Not less clever are the pen-and-ink sketches of familiar types which surround the larger figures on this last-named page—like them, the result of humorous observation of many individuals. Reynolds tells quaint stories of his adventures with the sketch-book in the pages of which are to be found the hurried notes—often but a few strokes and scratches intended to serve as a mnemonic—upon which his finished drawings and sketches were based. Frequently he would stalk an imposing Sergent de Ville, or Cuirassier with resplendent helmet and flowing horse-hair plume, for miles along the boulevards, making furtive notes, when opportunities presented themselves and conditions were favourable, of the details of epaulettes, buttons, cuffs, and all the other paraphernalia. In the same way his many sketches of the Paris cocher necessitated frequent drives in an open carriage, during which careful studies could be made of the ample back of the typical French cabman, and of the flowing folds of his usually voluminous neck.

Allusion has already been made to the progressive method by which

Frank Reynolds evolves a finished drawing, step by step, from an

initial idea roughly jotted down with a few strokes of the pencil.

His draughtsmanship depends, as must of course all draughtsmanship,

very largely upon memory. But it is his practice, whenever possible,

to obtain notes on the spot for later use. This was especially the

case with his work in Paris, where a pocket sketch-book was his

inseparable companion. A few pages of the latter are reproduced

here, illustrating the artist's quick perception and the instant

sureness with which, notwithstanding the leisurely pace of his

work under normal

conditions, he conveys the spirit of his subject by means of a

few lines. An excellent example of this faculty is the sketch of

the fat priest (page 53) and his hirsute

companion, admirable in the spontaneity of expression with which

the fleeting impression of a moment has been set down on paper.

Equally vivid is the impression conveyed by the hurried sketch of

an old woman (page 22) made at the stage

door of a theatre. The boulevards of Paris are excellent places

from which to study the comedy of life: and as an example of the

peculiar flavour of Frank Reynolds' humour, it would be hardly

possible to better the irresistible sketch from life, furtively

made whilst sitting amongst the audience at a café

chantant, which, with a nice sense of the absurd, is labelled

in the sketch-book "Having the Time of her Life."

the fat priest (page 53) and his hirsute

companion, admirable in the spontaneity of expression with which

the fleeting impression of a moment has been set down on paper.

Equally vivid is the impression conveyed by the hurried sketch of

an old woman (page 22) made at the stage

door of a theatre. The boulevards of Paris are excellent places

from which to study the comedy of life: and as an example of the

peculiar flavour of Frank Reynolds' humour, it would be hardly

possible to better the irresistible sketch from life, furtively

made whilst sitting amongst the audience at a café

chantant, which, with a nice sense of the absurd, is labelled

in the sketch-book "Having the Time of her Life."

Montmartre, as might be expected, yielded excellent "copy," to employ a journalistic phrase. In the cafés and cabarets artistiques were made some of the portraits from life already referred to. But though portraits of actual individuals, the models from which they were made are in every case so characteristic, so closely in keeping with their surroundings, that they serve nevertheless as types, and the drawings in consequence make as direct an appeal to the stranger as to one who might happen to be familiar with the originals of them. In the famous Cabaret des Quat'-z-Arts was drawn the exquisite pen-and-ink portrait on page 32, previously alluded to, of "Georgette de Bertigny": under which name, for the purposes of the sketch, the identity of a figure at one time very familiar to habitués of the Quat'-z-Arts is concealed. As comment upon the depth of feeling which the drawing reveals, one may read the pen picture which accompanied it:

Then Georgette de Bertigny steps out through the haze, and stands, a tragic little figure, on the platform by the piano. Her hair and eyes are ebon black; her face, thin lipped and pale, is like a mask of ivory. There is no life whatever in it. She stands there like a tragedy in miniature, her hands behind her back, unseeing, motionless. Then, to a low, monotonously modulated melody, she sings a song of utter misery and passion, and, as she sings, her eyes and face light up. The mask of ivory gleams as though there were living light behind it, and the sweet, low voice stirs us as but few singers can. The music ceases. And the light behind the ivory goes out again as Georgette bows her thanks for our enthusiasm.

It is trite to remark that comedy is akin to tragedy, and it is in the natural order of things that an artist of so keen a perception of the comedy of life should be able to strike with such truth and precision the note of pathos or of tragedy.

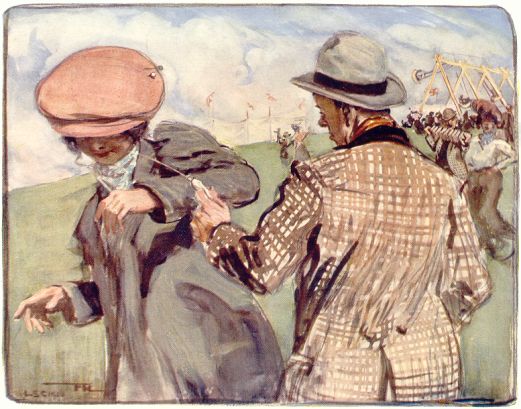

The "Lapin Agile," a strange little café in that "other Montmartre" which the tourist knoweth not, yielded abundance of material to Frank Reynolds' pencil. Needless to say, the curious may search all Paris and find no such sign as that of "The Sprightly Rabbit," but it is not impossible that some may recognise, under his disguise, "Felix," the ruffianly but accomplished host, who was the model for the sketch upon page 43, one of the happiest examples in the present volume of the artist's skill in portraiture, as well as of his rare technique in pen-and-ink. Equally happy is the sketch which depicts "'Chacun' with his 'Chacune'" at the Moulin de la Galette (page 13), in which the pose of the figures and the expression upon their faces exhibit, if one may put it so, the very perfection of naturalness. For a study of expression, again, it would be difficult, or indeed impossible, to better the further of the two figures in the drawing of "Le 'Igh Kick," made one night at the Moulin Rouge. As to pose, could there be anything more exactly right than the attitude of the gentleman "with bright-blue goggle eyes, and a dress-shirt front in accordion pleats," who, on the occasion when his portrait was made, had been to the races and backed a winner, and was delivering "a long and extremely incoherent speech."

Looking through these inimitable sketches of Paris and Parisians, one indulges a fond hope that some day Frank Reynolds will produce a companion set of drawings illustrative of London life. It is answered, perhaps, that Paris affords a unique opportunity such as the artist would hardly find at home; but the supposition is due, of course, only to the familiarity of our immediate surroundings and the difficulty which invariably arises, in consequence, of focussing them to their true proportions. Needless to say, Frank Reynolds has already worked the rich vein of Cockney life to a considerable extent, but his essays in this direction only increase the desire to see an exhaustive pictorial commentary from his pencil and pen upon the men and manners of our own city. Such quaint humour as is contained in his study of "Sunday Clothes at Bethnal Green" (page 17), suggests what possibilities the subject presents.

Incidentally, it may be remarked, apropos of this drawing, that the London coster (whom he knows and loves) has provided some of his most admirable studies from life. To that class belongs the sympathetic study which faces page 1 in the present volume. The broad humours of Whitechapel could scarcely fail to appeal irresistibly to an artist of Reynolds' peculiar temperament, and few men have depicted them with such relish or—thanks to his rare gift of restraint—with such fidelity and truth.

To a certain extent, Frank Reynolds has already recorded contemporary manners in England, and especially in London, in his well-known series of "Social Pests," though it would perhaps be more correct to say that he has pilloried therein the more extravagant of our social freaks. Probably the delighted recognition with which these ruthless analyses of character were hailed was due to the satisfaction which attends the exhibition of a proper object of satire meeting with its just deserts.

No ridicule could be more serene, nor yet more biting, than that with which the artist touches off the desperate efforts to attract attention of the rowdy group of callow youths whom he names, with a flash of inspiration, "The Dare-Devils" (page 10). Of "The Suburbanite," to the writer's mind perhaps the most subtly accurate character-study of all, the artist speaks in terms of apology. It is hardly fair, he contends, to include in a gallery of pests the bulwark of the nation!

A particular aspect of London life which provides a rich fund of material for humorous treatment was dealt with by Frank Reynolds in his series of drawings entitled "The 'Halls' from the Stalls." As every frequenter of the variety theatre is aware, the programme at such places of entertainment is arranged on certain well-defined lines. The music-hall performer may be divided into certain very distinct classes, each with its orthodox methods and mannerisms; and it was on the little peculiarities of these different branches of the profession that the artist seized with characteristic glee.

How little his efforts, unfortunately, were taken in the spirit in

which they were meant, may be gleaned from the annoyance expressed

by one gentleman who considered himself, quite erroneously, to

have been singled out for individual ridicule. A certain drawing

in the series depicts "The Equilibrist"—an individual with

an anxious eye, who is poised upon

a slack wire above the head of an admiring assistant, balancing

sundry cigar-boxes and wine-glasses on one toe, while supporting

on his head a lighted lamp, and discoursing sweet music from a

mandoline. The publication of this skit drew from a wrathful

professional an indignant letter, in which he declared that insomuch

as he was the one and only exponent of the equilibristic art who

could balance a lighted lamp upon his head, the picture which

illustrated this piece of "business" must be intended as a

portrait of himself, though he considered it very badly done, and

a libellous production. From one point of view, it was surprising

that the impression of the "Lion Comique," as seen by Frank Reynolds,

elicited no similar response from the gentlemen of the boards, for

indisputably the picture was a portrait, and a perfect one, of each

individually and of all combined. On second thoughts, however, and

upon consideration of the drawing in question (which many readers

will remember), it is, perhaps, not so very surprising that no

claim to identity with it was forthcoming!

have been singled out for individual ridicule. A certain drawing

in the series depicts "The Equilibrist"—an individual with

an anxious eye, who is poised upon

a slack wire above the head of an admiring assistant, balancing

sundry cigar-boxes and wine-glasses on one toe, while supporting

on his head a lighted lamp, and discoursing sweet music from a

mandoline. The publication of this skit drew from a wrathful

professional an indignant letter, in which he declared that insomuch

as he was the one and only exponent of the equilibristic art who

could balance a lighted lamp upon his head, the picture which

illustrated this piece of "business" must be intended as a

portrait of himself, though he considered it very badly done, and

a libellous production. From one point of view, it was surprising

that the impression of the "Lion Comique," as seen by Frank Reynolds,

elicited no similar response from the gentlemen of the boards, for

indisputably the picture was a portrait, and a perfect one, of each

individually and of all combined. On second thoughts, however, and

upon consideration of the drawing in question (which many readers

will remember), it is, perhaps, not so very surprising that no

claim to identity with it was forthcoming!

Other drawings in the same series, depicting other examples of the strange freaks of humanity by whom the British public delights to be entertained, afford good examples of the innate humour of Frank Reynolds' art. There is often little that is actually comic in the situations depicted, yet each is instinct with humour. It is the triumph of Reynolds' comic art that he can snare, on the wing as it were, humour that is too elusive and nimble for one of slower perception and heavier hand.

"Art and the Man" was a series of drawings in the vein of farce rather than of comedy. The intention was to depict various types of artists rather as fancy might paint them than as they really are. The "Marine Artist," for example, with his canvas slung from davits and the entire furniture of his studio of extremely nautical design, was a purely fanciful conception. The "Pot-Boiler," spending his days in painting one solitary subject over and over again ad infinitum, comes nearer to life, though his portrait again is an exaggerated fancy rather than a study from life. One feels, nevertheless, that if there be indeed such an individual as the pot-boiler in existence, this, and no other, must be his outward guise.

The drawings entitled "Dinners with Shakespeare," to which allusion has already been made, gave scope for a very varied range of character studies. Meal-time is a happy moment at which to catch human nature unawares, and the artist made the most of his opportunities. They add to the debt which the historians of contemporary manners will owe to Reynolds in the future, for as a sidelight on social habits of the present day these pictures of the dinner-table will be instructive. The very triteness of their theme gives them their interest.

Of late years Reynolds' pen-and-ink drawings have been a familiar

feature of the pages of Punch. His gentle satires therein

have been at the expense of all classes of the community. But his

most successful and best remembered jokes have perhaps been those

which depicted the unconscious humours of Cockney low life. His

illustration of "Precedence at Battersea," in which one small

gutter-snipe struggles with another for a cricket bat, indignantly

declaring that "The Treasurer goes in before the bloomin'

Seketery," is by way of becoming a classic. Equally clever is the

study of a small boy, (reproduced on page 27)

whose "pomptiousness" on attaining the dignity of knickers forms the

subject of admiring comment from his mother to a friendly curate:

the mother herself being a wonderful study of low life. In "Going It"

(page 59) the artist harks back to the theme

of "freak-study," if such a term is permissible, the expressions on

the faces of the two figures exhibiting well his acute powers of

observation.

whose "pomptiousness" on attaining the dignity of knickers forms the

subject of admiring comment from his mother to a friendly curate:

the mother herself being a wonderful study of low life. In "Going It"

(page 59) the artist harks back to the theme

of "freak-study," if such a term is permissible, the expressions on

the faces of the two figures exhibiting well his acute powers of

observation.

As an illustrator of stories of a certain type, Frank Reynolds is without an equal. On a tale of mere incident his talent is wasted: but into the spirit of a writer who takes human nature for his text, the artist enters with the keenest sympathy. One is tempted to think that the author who is so fortunate as to have Frank Reynolds for a collaborator, must on occasion be startled at the clear vision with which the artist materialises the private conceptions of his mind. It would hardly be possible to find a more sympathetic series of illustrations than those which Frank Reynolds drew for Keble Howard's idyll of Suburbia, entitled "The Smiths of Surbiton." The author constructed out of the petty doings and humdrum habits of suburban life a charming little story of simple people, and with equal cleverness the artist built up, out of these slight materials, a series of exquisitely natural pictures, which revealed the almost incredible fact that semi-detached villadom is not all dulness.

Illustrators of Charles Dickens are legion, but when one thinks of the opportunities for character-study, without that exaggeration into which previous illustrators have been too prone to indulge, which the works of the great novelist afford, one is inclined to think that until we see that wonderful gallery of fanciful personalities which began with Mr. Pickwick and his companions portrayed by the pencil of Frank Reynolds, we shall have to wait still for the perfect edition of Dickens. One niche in that gallery has already been filled, and a study of the water-colour drawing of "Tony Weller at the Belle Sauvage," which is reproduced in the present volume, only increases our desire, like the immortal Oliver, to ask for more.

Frank Reynolds as a colourist is less

known to the general public than Frank Reynolds the black-and-white

artist. It is only of recent years, indeed, that he has turned his

attention to painting. But his work, as seen at the Royal Institute

of Painters in Water Colours (of which body he was elected a member

in 1903) and elsewhere, proves that his skill with the brush is no

less than with pen or pencil. The present volume includes, besides

the drawing of Tony Weller just referred to, his picture of "The

Warrener," another fine character-study, exhibited at the Royal

Institute in 1907. "The Introduction," an example of a "time sketch"

done at the London Sketch Club, illustrates the quick readiness

with which the artist nimbly catches the spirit of his subject,

and the subtle touch which invests his drawing with the evasive

quality of atmosphere. Another Sketch Club study is that of the

curate at the play, which bears the title "Frivolity." As a study

in expression it is amazingly clever: and it must be a painful

and melancholy respect

for the cloth which can suppress the smile which it summons. Even

an Archbishop will scarce forbear to snigger!

with which the artist nimbly catches the spirit of his subject,

and the subtle touch which invests his drawing with the evasive

quality of atmosphere. Another Sketch Club study is that of the

curate at the play, which bears the title "Frivolity." As a study

in expression it is amazingly clever: and it must be a painful

and melancholy respect

for the cloth which can suppress the smile which it summons. Even

an Archbishop will scarce forbear to snigger!

It is not uncommon to hear modern black-and-white art in this country decried by some persons—mostly of that shallow critical class which can praise nothing in the present, and has encomiums only for that which is past. But while English art can point to such work in black-and-white as Frank Reynolds (to say nothing of others, with whom this volume is not concerned) produces, he must have dull senses who deplores the present and must hark back to the days, let us say, of Charles Keene to find satisfaction for his artistic cravings.

If it be a merit to add to the gaiety of nations, then Frank Reynolds, on that count alone, deserves of his fellow men more than a passing approbation. He is something more than a mere jester, however: his humour but flavours, as it were, a serious study of human nature. Ignoring, for a moment, the skill and charm of his technique, one feels it to be an accident only that his vehicle of expression is pictorial and not literary. He occupies amongst artists the place which the novelist holds amongst men of letters. When to the recognition of this distinction is added a consideration of his artistic ability, per se, his title to the appreciation of men of taste and sensibility must be conceded.

Frank Reynolds is fortunately a young man. Long may we continue to suffer the good-natured pricks with which his gentle shafts of satire, piercing the cracks in our self-complacent armour, stimulate us; long may we continue, secure in our own self-esteem, rapturously to gloat over the spectacle of our dear friends and neighbours held up, by his whimsical humour, to keen but harmless ridicule.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.