Project Gutenberg's Furnishing the Home of Good Taste, by Lucy Abbot Throop

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Furnishing the Home of Good Taste

A Brief Sketch of the Period Styles in Interior Decoration with

Suggestions as to Their Employment in the Homes of Today

Author: Lucy Abbot Throop

Release Date: January 28, 2005 [EBook #14824]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FURNISHING THE HOME OF GOOD TASTE ***

Produced by Charles Aldarondo, Susan Skinner and the PG Online

Distributed Proofreading Team.

Trowbridge & Livingston, architects. A principle which can be applied to both large and small houses is shown in the beauty of the panel spacing and the adequate support of the cornice by the pilasters

| A modern dining-room | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Italian Renaissance fireplace and overmantel, modern | 8 |

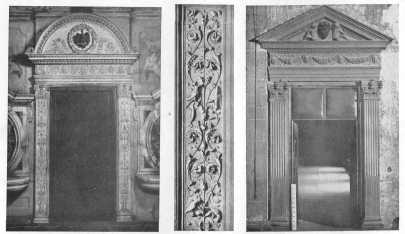

| Doorways and pilaster details, Italian Renaissance | 9 |

| Two Louis XIII chairs | 22 |

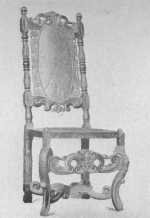

| A Gothic chair of the fifteenth century | 23 |

| A Louis XIV chair | 32 |

| Louis XIV inlaid desk-table | 33 |

| Louis XIV chair with underbracing | 33 |

| A modern French drawing-room | 40 |

| A drawing-room, old French furniture and tapestry | 41 |

| Early Louis XIV chair | 44 |

| Louis XV bergère | 44 |

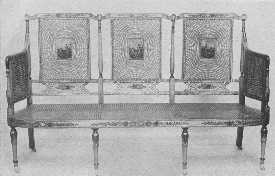

| Louis XVI bench | 45 |

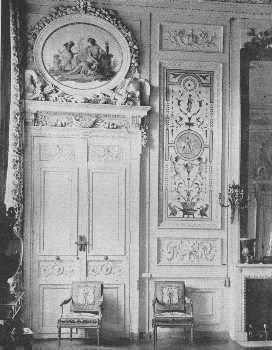

| Louis XVI from Fontainebleau | 50 |

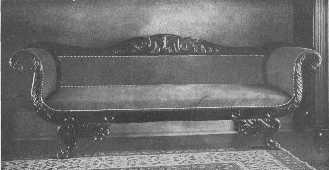

| American Empire bed | 51 |

| An Apostles bed of the Tudor period | 60 |

| Adaptation of the style of William and Mary to dressing table | 61 |

| Reproduction of Charles II chair | 61 |

| Living-room with reproductions of different periods | 64 |

| Original Jacobean sofa | 65 |

| Reproductions of Charles II chairs | 65 |

| Reproductions of Queen Anne period | 72 |

| Reproduction of James II chair | 73 |

| Reproduction of William and Mary chair | 73 |

| Gothic and Ribbonback types of Chippendale chairs | 78 |

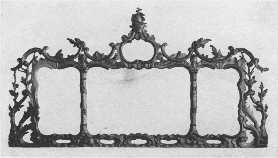

| Chippendale mantel mirror showing French influence | 79 |

| Chippendale fretwork tea-table | 79 |

| Chippendale china cupboard | 82 |

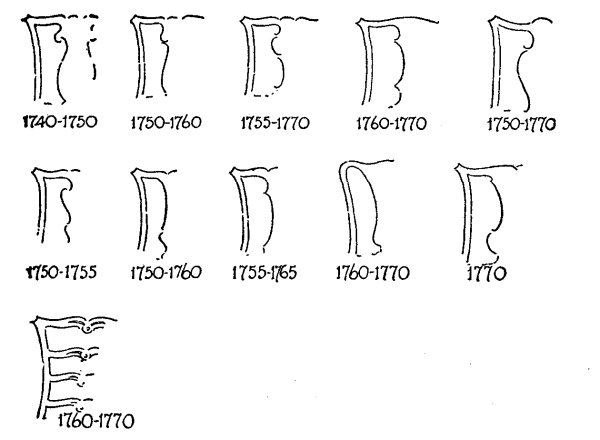

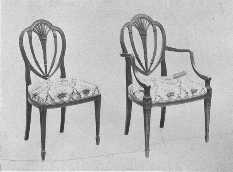

| Typical chairs of the eighteenth century | 83 |

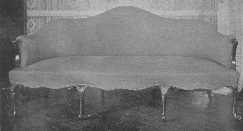

| Chippendale and Hepplewhite sofas | 86 |

| Adam mirror, block-front chest of drawers, and Hepplewhite chair | 87 |

| Two Adam mantels | 92 |

| A group of old mirrors | 93 |

| Dining-room furnished with Hepplewhite furniture | 96 |

| Old Hepplewhite sideboard | 97 |

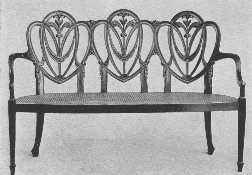

| Reproduction of Hepplewhite settee | 97 |

| Sheraton chest of drawers | 104 |

| Sheraton desk and sewing-table | 105 |

| Dining-room in simple country house | 112 |

| Dining-room furnished with fine old furniture | 113 |

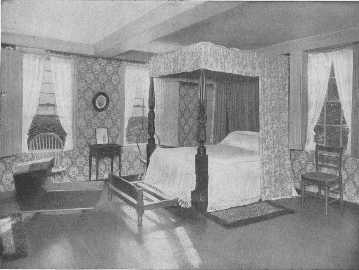

| Dorothy Quincy's bed-room | 124 |

| Two valuable old desks | 125 |

| Pembroke inlaid table | 144 |

| Sheraton sideboard | 144 |

| Four post bed | 145 |

| Doorway detail, Compiègne | 152 |

| Reproduction of a bed owned by Marie Antoinette | 153 |

| Reproduction of Louis XVI bed | 153 |

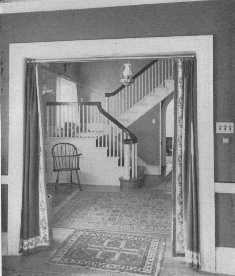

| A Georgian hallway | 162 |

| Rare block-front chest of drawers | 163 |

| A modern living-room | 178 |

| Curtain treatment for a summer home | 179 |

| Hallway showing rugs | 188 |

| Hallway showing rugs | 189 |

| Colonial bed-room | 189 |

| Dining-room with paneled walls | 196 |

| Four post bed owned by Lafayette | 197 |

| Modern dining-room | 204 |

| Four post bed | 205 |

| Reproductions of Adam painted furniture | 222 |

| Three-chair Sheraton settee | 223 |

| Reproduction of a Sheraton wing-chair | 223 |

| Slat-backed chair | 223 |

| Group of chairs and pie-crust table | 232 |

| Groups of chairs | 233 |

| Reproduction of Jacobean buffet | 236 |

| Group of mirrors | 237 |

| Reproduction of William and Mary settee | 240 |

| Adaptation of Georgian ideas to William and Mary dressing table | 240 |

| Two Adam chairs | 241 |

| Jacobean day-bed | 241 |

| Reproductions of Chippendale table and Hepplewhite desk | 244 |

| Reproduction of Sheraton chest of drawers | 245 |

| Reproduction of William and Mary chest of drawers | 245 |

| A modern sun-room | 246 |

| Sheraton sofa | 247 |

| Hepplewhite chair and nest of tables | 247 |

| Chippendale wing-chair | 247 |

| Modern paneled living-room | 248 |

| Empire bed | 248 |

| Hancock desk, and fine old highboy | 249 |

To try to write a history of furniture in a fairly short space is almost as hard as the square peg and round hole problem. No matter how one tries, it will not fit. One has to leave out so much of importance, so much of historic and artistic interest, so much of the life of the people that helps to make the subject vivid, and has to take so much for granted, that the task seems almost impossible. In spite of this I shall try to give in the following pages a general but necessarily short review of the field, hoping that it may help those wishing to furnish their homes in some special period style. The average person cannot study all the subject thoroughly, but it certainly adds interest to the problems of one's own home to know something of how the great periods of decoration grew one from another, how the influence of art in one country made itself felt in the next, molding and changing taste and educating the people to a higher sense of beauty.

It is the lack of general knowledge which makes it possible for furniture built on amazingly bad lines to be sold masquerading under the name of some great period. The customer soon becomes bewildered, and, unless he has a decided taste of his own, is apt to get something which will prove a white elephant on his hands. One must have some standard of comparison, and the best and simplest way is to study the great work of the past. To study its rise and climax rather than the decline; to know the laws of its perfection so that one can recognize the exaggeration which leads to degeneracy. This ebb and flow is most interesting: the feeling the way at the beginning, ever growing surer and surer until the high level of perfection is reached; and then the desire to "gild the lily" leading to over-ornamentation, and so to decline. However, the germ of good taste and the sense of truth and beauty is never dead, and asserts itself slowly in a transition period, and then once more one of the great periods of decoration is born.

There are several ways to study the subject, one of the pleasantest naturally being travel, as the great museums, palaces, and private collections of Europe offer the widest field. In this country, also, the museums and many private collections are rich in treasures, and there are many proud possessors of beautiful isolated pieces of furniture. If one cannot see originals the libraries will come to the rescue with many books showing research and a thorough knowledge and appreciation of the beauty and importance of the subject in all its branches.

I have tried to give an outline, (which I hope the reader will care to enlarge for himself), not from a collector's standpoint, but from the standpoint of the modern home-maker, to help him furnish his house consistently,—to try to spread the good word that period furnishing does not necessitate great wealth, and that it is as easy and far more interesting to furnish a house after good models, as to have it banal and commonplace.

The first part of this little book is devoted to a short review of the great periods, and the second part is an effort to help adapt them to modern needs, with a few chapters added of general interest to the home-maker.

A short bibliography is also added, both to express my thanks and indebtedness to many learned and delightful writers on this subject of house furnishing in all its branches, and also as a help to others who may wish to go more deeply into its different divisions than is possible within the covers of a book.

I wish to thank the Editors of House and Garden and The Woman's Home Companion for kindly allowing me to reprint articles and portions of articles which have appeared in their magazines.

I wish also to thank the owners of the different houses illustrated, and Messrs. Trowbridge and Livingston, architects, for their kindness in allowing me to use photographs.

Thanks are also due Messrs. Bergen & Orsenigo, Nahon & Company, Tiffany Studios, Joseph Wild & Co. and the John Somma Co. for the use of photographs to illustrate the reproduction of period furniture and rugs of different types.

The early history of art in all countries is naturally connected more closely with architecture than with decoration, for architecture had to be developed before the demand for decoration could come. But the two have much in common. Noble architecture calls for noble decoration. Decoration is one of the natural instincts of man, and from the earliest records of his existence we find him striving to give expression to it, we see it in the scratched pieces of bone and stone of the cave dwellers, in the designs of savage tribes, and in Druidical and Celtic remains, and in the great ruins of Yucatan. The meaning of these monuments may be lost to us, but we understand the spirit of trying to express the sense of beauty in the highest way possible, for it is the spirit which is still moving the world, and is the foundation of all worthy achievement.

Egypt and Assyria stand out against the almost impenetrable curtain of pre-historic days in all the majesty of their so-called civilization. Huge, massive, aloof from the world, their temples and tombs and ruins remain. Research has given us the key to their religion, so we understand much of the meaning of their wall-paintings and the buildings themselves. The belief of the Egyptian that life was a short passage and his house a mere stopping-place on the way to the tomb, which was to be his permanent dwelling-place, explains the great care and labor spent on the pyramids, chapels, and rock sepulchers. They embalmed the dead for all eternity and put statues and images in the tombs to keep the mummy company. Colossal figures of their gods and goddesses guarded the tombs and temples, and still remain looking out over the desert with their strange, inscrutable Egyptian eyes. The people had technical skill which has never been surpassed, but the great size of the pyramids and temples and sphinxes gives one the feeling of despotism rather than civilization; of mass and permanency and the wonder of man's achievement rather than beauty, but they personify the mystery and power of ancient Egypt.

The columns of the temples were massive, those of Karnak being seventy feet high, with capitals of lotus flowers and buds strictly conventionalized. The walls were covered with hieroglyphics and paintings. Perspective was never used, and figures were painted side view except for the eye and shoulder. In the tombs have been found many household belongings, beautiful gold and silver work, beside the offerings put there to appease the gods. Chairs have been found, which, humorous as it may sound, are certainly the ancestors of Empire chairs made thousands of years later. This is explained by the influence of Napoleon's Egyptian campaign, but there is something in common between the two times so far apart, of ambition and pride, of grandeur and colossal enterprise.

Greece may well be called the Mother of Beauty, for with the Greeks came the dawn of a higher civilization, a striving for harmony of line and proportion, an ideal clear, high and persistent. When the Dorians from the northern part of Greece built their simple, beautiful temples to their gods and goddesses they gave the impetus to the movement which brought forth the highest art the world has known. Traces of Egyptian influence are to be found in the earliest temples, but the Greeks soon rose to their own great heights. The Doric column was thick, about six diameters in height, fluted, growing smaller toward the top, with a simple capital, and supported the entablature. The horizontal lines of the architrave and cornice were more marked than the vertical lines of the columns. The portico with its row of columns supported the pediment. The Parthenon is the most perfect example of the Doric order, and shattered as it is by time and man it is still one of the most beautiful buildings in the world. It was built in the time of Pericles, from about 460 to 435 B.C., and the work was superintended by Phidias, who did much of the work himself and left the mark of his genius on the whole.

The Ionic order of architecture was a development of the Doric, but was lighter and more graceful. The columns were more slender and had a greater number of flutes and the capitals formed of scrolls or volutes were more ornamental.

The Corinthian order was more elaborate than the Ionic as the capitals were foliated (the acanthus being used), the columns higher, and the entablature more richly decorated. This order was copied by the Romans more than the other two as it suited their more florid taste. All the orders have the horizontal feeling in common (as Gothic architecture has the vertical), and the simple plan with its perfect harmony of proportion leaves no sense of lack of variety.

The perfection attained in architecture was also attained in sculpture, and we see the same aspiration toward the ideal, the same wonderful achievement. This purity of taste of the Greeks has formed a standard to which the world has returned again and again and whose influence will continue to be felt as long as the world lasts.

The minor arts were carried to the same state of perfection as their greater sisters, for the artists and artisans had the same noble ideal of beauty and the same unerring taste. We have carved gems and coins, and wonderful gold ornaments, painted and silver vases, and terra-cotta figurines, to show what a high point the household arts reached. No work of the great Grecian painters remains; Apelles, Zeuxis, are only names to us, but from the wall paintings at Pompeii where late Greek influence was strongly felt we can imagine how charming the decorations must have been. Egypt and Greece were the torch bearers of civilization.

The Gothic period has been treated in later chapters on France and England, as it is its development in these countries which most affects us, but the Renaissance in Italy stands alone. So great was its strength that it could supply both inspiration and leaders to other countries, and still remain preëminent.

It was in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that this great classical revival in Italy came, this re-birth of a true sense of beauty which is called the Renaissance. It was an age of wonders, of great artistic creations, and was one of the great epochs of the world, one of the turning points of human existence. It covered so large a field and was so many-sided that only careful study can give a full realization of the giants of intellect and power who made its greatness, and who left behind them work that shows the very quintessence of genius.

Italy, stirring slightly in the fourteenth century, woke and rose to her greatest heights in the fifteenth and sixteenth. The whole people responded to the new joy of life, the love of learning, the expression of beauty in all its forms. All notes were struck,—gay, graceful, beautiful, grave, cruel, dignified, reverential, magnificent, but all with an exuberance of life and power that gave to Italian art its great place in human culture. The great names of the period speak for themselves,—Michelangelo, Raphael, Botticelli, Titian, Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea del Sarto, Machiavelli, Benvenuto Cellini, and a host of others.

An exquisite and true Renaissance feeling is shown in the pilasters.

The inspiration of the Renaissance came largely from the later Greek schools of art and literature, Alexandria and Rhodes and the colonies in Sicily and Italy, rather than ancient Greece. It was also the influence which came to ancient Rome at its most luxurious period. The importance of the taking of Alexandria and Constantinople in 1453 must not be underestimated, as it drove scholars from the great libraries of the East carrying their manuscripts to the nobles and priests and merchant princes of Italy who thus became enthusiastic patrons of learning and art. This later type of Greek art lacked the austerity of the ancient type, and to the models full of joy and beauty and suffering, the Italians of the Renaissance added the touch of their own temperament and made them theirs in the glowing, rich and astounding way which has never been equaled and probably never will be. Perfection of line and beauty was not sufficient, the soul with its capacity for joy and suffering, "the soul with all its maladies" as Pater says, had become a factor. The impression made upon Michelangelo by seeing the Laocoön disinterred is vividly described by Longfellow—

The Italian Renaissance is still inspiring the world. In the two doorways the use of pilasters and frieze, and the pedimented and round over-door motifs are typical of the period.

"It was an age productive in personalities, many-sided, centralized, complete. Artists and philosophers and those whom the action of the world had elevated and made keen, breathed a common air and caught light and heat from each other's thoughts. It is this unity of spirit which gives unity to all the various products of the Renaissance, and it is to this intimate alliance with mind, this participation in the best thoughts which that age produced, that the art of Italy in the fifteenth century owes much of its grave dignity and influence."[A]

[A]Walter Pater: "Studies in the Renaissance."

It is to this unity of the arts we owe the fact that the art of beautifying the home took its proper place. During the Middle Ages the Church had absorbed the greater part of the best man had to give, and home life was rather a hit or miss affair, the house was a fortress, the family possessions so few that they could be packed into chests and easily moved. During the Renaissance the home ideal grew, and, although the Church still claimed the best, home life began to have comforts and beauties never dreamed of before. The walls glowed with color, tapestries and velvets added their beauties, and the noble proportions of the marble halls made a rich background for the elaborately carved furniture.

The doors of Italian palaces were usually inlaid with woods of light shade, and the soft, golden tone given by the process was in beautiful, but not too strong, contrast with the marble architrave of the doorway, which in the fifteenth century was carved in low relief combined with disks of colored marble, sliced, by the way, from Roman temple pillars. Later as the classic taste became stronger the carving gave place to a plain architrave and the over-door took the form of a pediment.

Mantels were of marble, large, beautifully carved, with the fireplace sunk into the thickness of the wall. The overmantel usually had a carved panel, but later, during the sixteenth century, this was sometimes replaced by a picture. The windows of the Renaissance were a part of the decoration of the room, and curtains were not used in our modern manner, but served only to keep out the draughts. In those days the better the house the simpler the curtains. There were many kinds of ceilings used, marble, carved wood, stucco, and painting. They were elaborate and beautiful, and always gave the impression of being perfectly supported on the well-proportioned cornice and walls. The floors were usually of marble. Many of the houses kept to the plan of mediæval exteriors, great expanses of plain walls with few openings on the outsides, but as they were built around open courts, the interiors with their colonnades and open spaces showed the change the Renaissance had brought. The Riccardi Palace in Florence and the Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome, are examples of this early type. The second phase was represented by the great Bramante, whose theory of restraining decoration and emphasizing the structure of the building has had such important influence. One of his successors was Andrea Palladio, whose work made such a deep impression on Inigo Jones. The Library of St. Mark's at Venice is a beautiful example of this part. The third phase was entirely dominated by Michelangelo.

The furniture, to be in keeping with buildings of this kind, was large and richly carved. Chairs, seats, chests, cabinets, tables, and beds, were the chief pieces used, but they were not plentiful at all in our sense of the word. The chairs and benches had cushions to soften the hard wooden seats. The stuffs of the time were most beautiful Genoese velvet, cloth of gold, tapestries, and wonderful embroideries, all lending their color to the gorgeous picture. The carved marriage chest, or cassone, is one of the pieces of Renaissance furniture which has most often descended to our own day, for such chests formed a very important part of the furnishing in every household, and being large and heavy, were not so easily broken as chairs and tables. Beds were huge, and were architectural in form, a base and roof supported on four columns. The classical orders were used, touched with the spirit of the time, and the fluted columns rose from acanthus leaves set in an urn supported on lion's feet. The tester and cornice gave scope for carving and the panels of the tester usually had the lovely scrolls so characteristic of the period. The headboard was often carved with a coat-of-arms and the curtains hung from inside the cornice.

Grotesques were largely used in ornament. The name is derived from grottoes, as the Roman tombs being excavated at the time were called, and were in imitation of the paintings found on their walls, and while they were fantastic, the word then had no unkindly humorous meaning as now. Scrolls, dolphins, birds, beasts, the human figure, flowers, everything was called into use for carving and painting by genius of the artisans of the Renaissance. They loved their work and felt the beauty and meaning of every line they made, and so it came about that when, in the course of years, they traveled to neighboring countries, they spread the influence of this great period, and it is most interesting to see how on the Italian foundation each country built her own distinctive style.

Like all great movements the Renaissance had its beginning, its splendid climax, and its decline.

When Caesar came to Gaul he did more than see and conquer; he absorbed so thoroughly that we have almost no knowledge of how the Gauls lived, so far as household effects were concerned. The character which descended from this Gallo-Roman race to the later French nation was optimistic and beauty-loving, with a strength which has carried it through many dark days. It might be said to be responsible for the French sense of proportion and their freedom of judgment which has enabled them to hold their important place in the history of art and decoration. They have always assimilated ideas freely but have worked them over until they bore the stamp of their own individuality, often gaining greatly in the process.

One of the first authentic pieces of furniture is a bahut or chest dating from sometime in the twelfth century and belonging to the Church of Obazine. It shows how furniture followed the lines of architecture, and also shows that there was no carving used on it. Large spaces were probably covered with painted canvas, glued on. Later, when panels became smaller and the furniture designs were modified, moldings, etc., began to be used. These bahuts or huches, from which the term huchiers came (meaning the Corporation of Carpenters), were nothing more than chests standing on four feet. From all sources of information on the subject it has been decided that they were probably the chief pieces of furniture the people had. They served as a seat by day and, with cushions spread upon them, as a bed by night. They were also used as tables with large pieces of silver dressé or arranged upon them in the daytime. From this comes our word "dresser" for the kitchen shelves. In those days of brigands and wars and sudden death, the household belongings were as few as possible so that the trouble of speedy transportation would be small, and everything was packed into the chests. As the idea of comfort grew a little stronger, the number of chests grew, and when a traveling party arrived at a stopping-place, out came the tapestries and hangings and cushions and silver dishes, which were arranged to make the rooms seem as cheerful as possible. The germ of the home ideal was there, at least, but it was hard work for the arras and the "ciel" to keep out the cold and cover the bare walls. When life became a little more secure and people learned something of the beauty of proportion, the rooms showed more harmony in regard to the relation of open spaces and walls, and became a decoration in themselves, with the tapestries and hangings enhancing their beauty of line. It was not until some time in the fifteenth century that the habit of traveling with all one's belongings ceased.

The year 1000 was looked forward to with abject terror, for it was firmly believed by all that the world was then coming to an end. It cast a gloom over all the people and paralyzed all ambition. When, however, the fatal year was safely passed, there was a great religious thanksgiving and everyone joined in the praise of a merciful God. The semi-circular arch of the Romanesque style gave way to the pointed arch of the Gothic, and wonderful cathedrals slowly lifted their beautiful spires to the sky. The ideal was to build for the glory of God and not only for the eyes of man, so that exquisite carving was lavished upon all parts of the work. This deeply reverent feeling lasted through the best period of Gothic architecture, and while household furniture was at a standstill church furniture became more and more beautiful, for in the midst of the religious fervor nothing seemed too much to do for the Church. Slowly it died out, and a secular attitude crept into decoration. One finds grotesque carvings appearing on the choir stalls and other parts of churches and cathedrals and the standard of excellence was lowered.

The chest, table, wooden arm-chair, bed, and bench, were as far as the imagination had gone in domestic furniture, and although we read of wonderful tapestries and leather hangings and clothes embroidered in gold and jewels, there was no comfort in our sense of the word, and those brave knights and fair ladies had need to be strong to stand the hardships of life. Glitter and show was the ideal and it was many more years before the standard of comfort and refinement gained a firm foothold.

Gothic architecture and decoration declined from the perfection of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to the over-decorated, flamboyant Gothic of the fifteenth century, and it was in the latter period that the transition began between the Gothic and the Renaissance epochs.

The Renaissance was at its height in Italy in the fifteenth century, and its influence began to make itself felt a little in France at that time.

When the French under Louis XII seized Milan, the magnificence of the court of Ludovico Sforza, the great duke of Milan, made such an impression on them that they could not rest content with the old order, and took home many beautiful things. Italian artisans were also imported, and as France was ready for the change, their lessons were learned and the French Renaissance came slowly into existence. This transition is well shown by the Chateau de Gaillon, built by Cardinal d'Amboise. Gothic and Renaissance decoration were placed side by side in panels and furniture, and we also find some pure Gothic decoration as late as the early part of the sixteenth century, but they were in parts of France where tradition changed slowly. Styles overlap in every transition period, so it is often difficult to place the exact date on a piece of furniture; but the old dies out at last and gives way to the new.

With the accession of Frances I in 1515 the Renaissance came into its own in France. He was a great patron of art and letters, and under his fostering care the people knew new luxuries, new beauties, and new comforts. He invited Andrea del Sarto and Leonardo da Vinci to come to France. The word Renaissance means simply revival and it is not correctly used when we mean a distinct style led or inspired by one person. It was a great epoch, with individuality as its leading spirit, led by the inspiration of the Italian artists brought from Italy and molded by the genius of France. This renewal of classic feeling came at the psychological moment, for the true spirit of the great Gothic period had died. The Renaissance movements in Italy, France, England and Germany all drew their inspiration from the same source, but in each case the national characteristics entered into the treatment. The Italians and Germans both used the grotesque a great deal, but the Germans used it in a coarser and heavier way than the Italians, who used it esthetically. The French used more especially conventional and beautiful floral forms, and the inborn French sense of the fitness of things gave the treatment a wonderful charm and beauty. If one studies the French chateaux one will feel the true beauty and spirit of the times—Blois with its history of many centuries, and then some of the purely Renaissance chateaux, like Chambord. Although great numbers of Italian artists came to France, one must not think they did all the beautiful work of the time. The French learned quickly and adapted what they learned to their own needs, so that the delicate and graceful decorations brought from Italy became more and more individualized until in the reign of Henry II the Renaissance reached its high-water mark.

The furniture of the time did not show much change or become more varied or comfortable. It was large and solid and the chairs had the satisfactory effect of good proportion, while the general squareness of outline added to the feeling of solidity. Oak was used, and later walnut. The chair legs were straight, and often elaborately turned, and usually had strainers or under framing. Cushions were simply tied on at first, but the knowledge of upholstering was gaining ground, and by the time of Louis XIII was well understood. Cabinets had an architectural effect in their design. The style of the decorative motive changed, but it is chiefly in architecture and the decorative treatment of it that one sees the true spirit of the Renaissance. Two men who had great influence on the style of furniture of the time were Androuet du Cerceau and Hugues Sambin. They published books of plates that were eagerly copied in all parts of France. Sambin's influence can be traced in the later style of Louis XIV.

|

|

| Louis XIII chair now in the Cluny Museum showing the Flemish influence. | A typical Louis XIII chair, many of which were covered with velvet or tapestry. |

By courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This Gothic chair of the 16th century shows the beautiful linen-fold design in the carving on the lower panels, and also the keyhole which made the chest safe when traveling.

The marriage of Henry II and Catherine de Medici naturally continued the strong Italian influence. The portion of the Renaissance called after Henry II lasted about seventy-five years, and corresponds with the Elizabethan period in England.

During the regency of Marie de Medici, Flemish influence became very strong, as she invited Rubens to Paris to decorate the Luxembourg. There were also many Italians called to do the work, and as Rubens had studied in Italy, Italian influence was not lacking.

Degeneracy began during the reign of Henry IV, as ornament became meaningless and consistency of decoration was lost in a maze of superfluous design.

It was in the reign of Louis XIII that furniture for the first time became really comfortable, and if one examines the engravings of Abraham Bosse one will see that the rooms have an air of homelikeness as well as richness. The characteristic chair of the period was short in the back and square in shape—it was usually covered with leather or tapestry, fastened to the chair with large brass nails, and the back and seat often had a fringe. A set of chairs usually consisted of arm-chairs, plain chairs, folding stools and a lit-de-repos. Many of the arm-chairs were entirely covered with velvet or tapestry, or, if the woodwork showed, it was stained to harmonize with the covering on the seat and back.

The twisted columns used in chairs, bedposts, etc., were borrowed from Italy and were very popular. Another shape often used for chair legs was the X that shows Flemish influence. The lit-de-repos, or chaise-longue, was a seat about six feet long, sometimes with arms and sometimes not, and with a mattress and bolster. The beds were very elaborate and very important in the scheme of decoration, as the ladies of the time held receptions in their bedrooms and the king and nobles gave audiences to their subjects while in bed. These latter were therefore necessarily furnished with splendor. The woodwork was usually covered with the same material as the curtains, or stained to harmonize. The canopy never reached to the ceiling but was, from floor to top, about 7 ft. 3 in. high, and the bed was 6-1/2 ft. square. The curtains were arranged on rods and pulleys, and when closed this "lit en housse" looked like a huge square box. The counterpane, or "coverture de parade," was of the curtain material. The four corners of the canopy were decorated with bunches of plumes or panache, or with a carved wooden ornament called pomme, or with a "bouquet" of silk. The beds were covered with rich stuffs, like tapestry, silk, satin, velvet, cloth-of-gold and silver, etc., all of which were embroidered or trimmed with gold or silver lace. One of the features of a Louis XIII room was the tapestry and hangings. A certain look of dignity was given to the rooms by the general square and heavy outlines of the furniture and the huge chimney-pieces.

The taste for cabinets kept up and the cabinets and presses were large, sometimes divided into two parts, sometimes with doors, sometimes with open frame underneath. The tables were richly carved and gilded, often ornamented with bronze and copper. The cartouche was used a great deal in decoration, with a curved surface. This rounded form appears in the posts used in various kinds of furniture. When rectangles were used they were always broader than high. The garlands of fruit were heavy, the cornucopias were slender, with an astonishing amount of fruit pouring from them, and the work was done in rather low relief. Carved and gilded mirrors were introduced by the Italians as were also sconces and glass chandeliers. It was a time of great magnificence, and shadowed forth the coming glory of Louis XIV. It seems a style well suited to large dining-rooms and libraries in modern houses of importance.

It is often a really difficult matter to decide the exact boundary lines between one period and another, for the new style shows its beginnings before the old one is passed, and the old style still appears during the early years of the new one. It is an overlapping process and the years of transition are ones of great interest. As one period follows another it usually shows a reaction from the previous one; a somber period is followed by a gay one; the excess of ornament in one is followed by restraint in the next. It is the same law that makes us want cake when we have had too much bread and butter.

The world has changed so much since the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that it seems almost impossible that we should ever again have great periods of decoration like those of Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI. Then the monarch was supreme. "L'état c'est moi," said Louis XIV, and it was true. He established the great Gobelin works on a basis that made France the authority of the world and firmly imposed his taste and his will on the country. Now that this absolute power of one man is a thing of the past, we have the influence of many men forming and molding something that may turn into a beautiful epoch of decoration, one that will have in it some of the feeling that brought the French Renaissance to its height, though not like it, for we have the same respect for individuality working within the laws of beauty that they had.

The style that takes its name from Louis XIV was one of great magnificence and beauty with dignity and a certain solidity in its splendor. It was really the foundation of the styles that followed, and a great many people look upon the periods of Louis XIV, the Regency, Louis XV and Louis XVI as one great period with variations, or ups and downs—the complete swing and return of the pendulum.

Louis XIV was a man with a will of iron and made it absolute law during his long reign of seventy-two years. His ideal was splendor, and he encouraged great men in the intellectual and artistic world to do their work, and shed their glory on the time. Condé, Turenne, Colbert, Molière, Corneille, La Fontaine, Racine, Fénélon, Boulle, Le Brun, are a few among the long and wonderful list. He was indeed Louis the Magnificent, the Sun King.

One of the great elements toward achieving the stupendous results of this reign was the establishment of the "Manufacture des Meubles de la Couronne," or, as it is usually called, "Manufacture des Gobelins." Artists of all kinds were gathered together and given apartments in the Louvre and the wonderfully gifted and versatile Le Brun was put at the head. Tapestry, goldsmiths' work, furniture, jewelry, etc., were made, and with the royal protection and interest France rose to the position of world-wide supremacy in the arts. Le Brun had the same taste and love of magnificence as Louis, and had also extraordinary executive ability and an almost unlimited capacity for work, combined with the power of gathering about him the most eminent artists of the time. André Charles Boulle was one, and his beautiful cabinets, commodes, tables, clocks, etc., are now almost priceless. He carried the inlay of metals, tortoise-shell, ivory and beautiful woods to its highest expression, and the mingling of colors with the exquisite workmanship gave most wonderful effects. Sheets of white metal or brass were glued together and the pattern was then cut out. When taken apart the brass scrolls could be fitted exactly into the shell background, and the shell scrolls into the brass background, thus making two decorations. The shell background was the more highly prized. The designs usually had a Renaissance feeling. The metal was softened in outline by engraving, and then ormolu mounts were added. Ormolu or gilt bronze mounts, formed one of the great decorations of furniture. The most exquisite workmanship was lavished on them, and after they had been cast they were cut and carved and polished until they became worthy ornaments for beautiful inlaid tables and cabinets. The taste for elaborately carved and gilded frames to chairs, tables, mirrors, etc., developed rapidly. Mirrors were made by the Gobelins works and were much less expensive than the Venetian ones of the previous reign. Walls were painted and covered with gold with a lavish hand. Tapestries were truly magnificent with gold and silver threads adding richness to their beauty of color, and were used purely as a decoration as well as in the old utilitarian way of keeping out the cold. The Gobelins works made at this time some of the most beautiful tapestries the world has known. The massive chimney-pieces were superseded by the "petite-cheminée" and had great mirrors over them or elaborate over-mantels. The whole air of furnishing and decoration changed to one of greater lightness and brilliancy. The ideal was that everything, no matter how small, must be beautiful, and we find the most exquisite workmanship lavished on window-locks and door-knobs.

One of a set of three rare Louis XIV chairs, beautifully carved and gilded, and said to have belonged to the great Louis himself.

In the early style of Louis XIV, we find many trophies of war and mythological subjects used in the decorative schemes. The second style of this period was a softening and refining of the earlier one, becoming more and more delicate until it merged into the time of the Regency. It was during the reign of Louis XIV that the craze for Chinese decoration first appeared. La Chinoiserie it was called, and it has daintiness and a curious fascination about it, but many inappropriate things were done in its name. The furniture of the time was firmly placed upon the ground, the arm-chairs had strong straining-rails, square or curved backs, scroll arms carved and partly upholstered and stuffed seats and backs. The legs of chairs were usually tapering in form and ornamented with gilding, or marquetry, or richly carved, and later the feet ended in a carved leaf design. Some of the straining-rails were in the shape of the letter X, with an ornament at the intersection, and often there was a wooden molding below the seat in place of fringe. Many carved and gilded chairs had gold fringe and braid and were covered with velvet, tapestry or damask.

|

|

| By courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Inlaid desk with beautifully chiselled ormolu mounts. |

Rare Louis XIV chair, showing the characteristic underbracing. |

There were many new and elaborate styles of beds that came into fashion at this time. There was the lit d'ange, which had a canopy that did not extend over the entire bed, and had no pillars at the foot, the curtains were drawn back at the head and the counterpane went over the foot of the bed. There was the lit d'alcove, the lit de bout, lit clos, lit de glace, with a mirror framed in the ceiling, and many others. A lit de parade was like the great bed of Louis XIV at Versailles.

Both the tall and bracket clocks showed this same love of ornament and they were carved and gilded and enriched with chased brass and wonderful inlay by Boulle. The dials also were beautifully designed. Consoles, tables, cabinets, etc., were all treated in this elaborate way. Many of the ceilings were painted by great artists, and those at Versailles, painted by Le Brun and others, are good examples. There was always a combination of the straight line and the curve, a strong feeling of balance, and a profusion of ornament in the way of scrolls, garlands, shells, the acanthus, anthemion, etc. The moldings were wide and sometimes a torus of laurel leaves was used, but in spite of the great amount of ornament lavished on everything, there is the feeling of balance and symmetry and strength that gives dignity and beauty.

Louis was indeed fortunate in having the great Colbert for one of his ministers. He was a man of gigantic intellect, capable of originating and executing vast schemes. It was to his policy of state patronage, wisely directed, and energetically and lavishly carried out, that we owe the magnificent achievements of this period.

Everywhere the impression is given of brilliancy and splendor—gold on the walls, gold on the furniture, rich velvets and damasks and tapestries, marbles and marquetry and painting, furniture worth a king's ransom. It all formed a beautiful and fitting background for the proud king, who could do no wrong, and the dazzling, care-free people who played their brilliant, selfish parts in the midst of its splendor. They never gave a thought to the great mass of the common people who were over-burdened with taxation; they never heard the first faint mutterings of discontent which were to grow, ever louder and louder, until the blood and horror of the Revolution paid the debt.

When Louis XIV died in 1715, his great-grandson, Louis XV, was but five years old, so Philippe, Duc d'Orleans, became Regent. During the last years of Louis XIV's life the court had resented more or less the gloom cast over it by the influence of Madame de Maintenon, and turned with avidity to the new ruler. He was a vain and selfish man, feeling none of the responsibilities of his position, and living chiefly for pleasure. The change in decoration had been foreshadowed in the closing years of the previous reign, and it is often hard to say whether a piece of furniture is late Louis XIV or Regency.

The new gained rapidly over the old, and the magnificent and stately extravagance of Louis XIV turned into the daintier but no less extravagant and rich decoration of the Regency and Louis XV. One of the noticeable changes was that rooms were smaller, and the reign of the boudoir began. It has been truly said that after the death of Louis XIV "came the substitution of the finery of coquetry for the worship of the great in style." There was greater variety in the designs of furniture and a greater use of carved metal ornament and gilt bronze, beautifully chased. The ornaments took many shapes, such as shells, shaped foliage, roses, seaweed, strings of pearls, etc., and at its best there was great beauty in the treatment.

It was during the Regency that the great artist and sculptor in metal, Charles Cressant, flourished. He was made ébeniste of the Regent, and his influence was always to keep up the traditions when the reaction against the severe might easily have led to degeneration. There are beautiful examples of his work in many of the great collections of furniture, notably the wonderful commode in the Wallace collection. The dragon mounts of ormolu on it show the strong influence the Orient had at the time. He often used the figures of women with great delicacy on the corners of his furniture, and he also used tortoise-shell and many colored woods in marquetry, but his most wonderful work was done in brass and gilded bronze.

In 1723, when Louis was thirteen years old, he was declared of age and became king. The influence of the Regent was, naturally, still strong, and unfortunately did much to form the character of the young king. Selfishness, pleasure, and low ideals, were the order of court life, and paved the way for the debased taste for rococo ornament which was one marked phase of the style of Louis XV.

The great influence of the Orient at this time is very noticeable. There had been a beginning of it in the previous reign, but during the Regency and the reign of Louis XV it became very marked. "Singerie" and "Chinoiserie" were the rage, and gay little monkeys clambered and climbed over walls and furniture with a careless abandon that had a certain fascination and charm in spite of their being monkeys. The "Salon des Singes" in the Chateau de Chantilly gives one a good idea of this. The style was easily overdone and did not last a great while.

During this time of Oriental influence lacquer was much used and beautiful lacquer panels became one of the great features of French furniture. Pieces of furniture were sent to China and Japan to be lacquered and this, combined with the expense of importing it, led many men in France to try to find out the Oriental secret. Le Sieur Dagly was supposed to have imported the secret and was established at the Gobelins works where he made what was called "vernis de Gobelins."

The Martin family evolved a most characteristically French style of decoration from the Chinese and Japanese lacquers. The varnish they made, called "vernis Martin," gave its name to the furniture decorated by them, which was well suited to the dainty boudoirs of the day. All kinds of furniture were decorated in this way—sedan chairs and even snuff-boxes, until at last the supply became so great that the fashion died. There are many charming examples of it to be seen in museums and private collections, but the modern garish copies of it in many shops give no idea of the charm of the original. Watteau's delightful decorations also give the true spirit of the time, with their gayety and frivolity showing the Arcadian affectations—the fad of the moment.

As the time passed decoration grew more and more ornate, and the followers of Cressant exaggerated his traits. One of these was Jules Aurèle Meissonier, an Italian by birth, who brought with him to France the decadent Italian taste. He had a most marvelous power of invention and lavished ornament on everything, carrying the rocaille style to its utmost limit. He broke up all straight lines, put curves and convolutions everywhere, and rarely had two sides alike, for symmetry had no charms for him. The curved endive decoration was used in architraves, in the panels of overdoors and panel moldings, everywhere it possibly could be used, in fact. His work was in great demand by the king and nobility. He designed furniture of all kinds, altars, sledges, candelabra and a great amount of silversmith's work, and also published a book of designs. Unfortunately it is this rococo style which is meant by many people when they speak of the style of Louis XV.

Louis XV furniture and decoration at its best period is extremely beautiful, and the foremost architects of the day were undisturbed by the demand for rococo, knowing it was a vulgarism of taste which would pass. In France, bad as it was, it never went to such lengths as it did in Italy and Spain.

The mantel with its great glass reaching to the cornice, the wall panels, paintings over the doors, and beautiful furniture, all show the spirit of the best Louis XV period. The fur rug is an anachronism and detracts from the effect of the room.

The rare console tables and chairs and the Gobelin tapestry, "Games of Children," show to great advantage in this beautifully proportioned room of soft dull gold. The side-and centre-lights, reflected in the mirror, light the room correctly.

The easy generalization of the girl who said the difference between the styles of Louis XV and Louis XVI was like the difference in hair, one was curly and one was straight, has more than a grain of truth in it. The curved line was used persistently until the last years of Louis XV's time, but it was a beautiful, gracious curve, elaborate, and in furniture, richly carved, which was used during the best period. The decline came when good taste was lost in the craze for rococo.

Chairs were carved and gilded, or painted, or lacquered, and also beautiful natural woods were used. The sofas and chairs had a general square appearance, but the framework was much curved and carved and gilded. They were upholstered in silks, brocades, velvets, damasks in flowered designs, edged with braid. Gobelin, Aubusson and Beauvais tapestry, with Watteau designs, were also used. Nothing more dainty or charming could be found than the tapestry seats and chair backs and screens which were woven especially to fit certain pieces of furniture. The tapestry weavers now used thousands of colors in place of the nineteen used in the early days, and this enabled them to copy with great exactness the charming pictures of Watteau and Boucher. The idea of sitting on beautiful ladies and gentlemen airily playing at country life, does not appeal to our modern taste, but it seems to be in accord with those days.

Desks were much used and were conveniently arranged with drawers, pigeon-holes and shelves, and roll-top desks were made at this time. Commodes were painted, or richly ornamented with lacquer panels, or panels of rosewood or violet wood, and all were embellished with wonderful bronze or ormolu. Many pieces of furniture were inlaid with lovely Sèvres plaques, a manner which is not always pleasing in effect. There were many different and elaborate kinds of beds, taking their names from their form and draping. "Lit d'anglaise" had a back, head-board and foot-board, and could be used as a sofa. "Lit a Romaine" had a canopy and four festooned curtains, and so on.

The most common form of salon was rectangular, with proportions of 4 to 3, or 2 to 1. There were also many square, round, octagonal and oval salons, these last being among the most beautiful. They all were decorated with great richness, the walls being paneled with carved and gilded—or partially gilded—wood. Tapestry and brocade and painted panels were used. Large mirrors with elaborate frames were placed over the mantels, with panels above reaching to the cornice or cove of the ceiling, and large mirrors were also used over console tables and as panels. The paneled overdoors reached to the cornice, and windows were also treated in this way. Windows and doors were not looked upon merely as openings to admit air and light and human beings, but formed a part of the scheme of decoration of the room. There were beautiful brackets and candelabra of ormolu to light the rooms, and the boudoirs and salons, with their white and gold and beautifully decorated walls and gilded furniture, gave an air of gayety and richness, extravagance and beauty.

An apartment in the time of Louis XV usually had a vestibule, rather severely decorated with columns or pilasters and often statues in niches. The first ante-room was a waiting-room for servants and was plainly treated, the woodwork being the chief decoration. The second ante-room had mirrors, console tables, carved and gilded woodwork, and sometimes tapestry was used above a wainscot. Dining-rooms were elaborate, often having fountains and plants in the niches near the buffet. Bedrooms usually had an alcove, and the room, not counting the alcove, was an exact square. The bed faced the windows and a large mirror over a console table was just opposite it. The chimney faced the principal entrance.

A "chambre en niche" was a room where the bed space was not so large as an alcove. The designs for sides of rooms by Meissonier, Blondel, Briseux Cuilles and others give a good idea of the arrangement and proportions of the different rooms. The cabinets or studies, and the garde robes, were entered usually from doors near the alcove. The ceilings were painted by Boucher and others in soft and charming colors, with cupids playing in the clouds, and other subjects of the kind. Great attention was given to clocks and they formed an important and beautiful part of the decoration.

The natural consequence of the period of excessive rococo with its superabundance of curves and ornament, was that, during the last years of Louis's reign, the reaction slowly began to make itself felt. There was no sudden change to the use of the straight line, but people were tired of so much lavishness and motion in their decoration. There were other influences also at work, for Robert Adam had, in England, established the classic taste, and the excavations at Pompeii were causing widespread interest and admiration. The fact is proved that what we call Louis XVI decoration was well known before the death of Louis XV, by his furnishing Luciennes for Madam Du Barri in almost pure Louis XVI style.

There is a special charm about this old Louis XVI bench with its Gobelin tapestry cover

Louis XVI came to the throne in 1774, and reigned for nineteen years, until that fatal year of '93. He was kind, benign, and simple, and had no sympathy with the life of the court during the preceding reign. Marie Antoinette disliked the great pomp of court functions and liked to play at the simple life, so shepherdesses, shepherd's crooks, hats, wreaths of roses, watering-pots and many other rustic symbols became the fashion.

Marie Antoinette was but fifteen years old when in 1770 she came to France as a bride, and it is hardly reasonable to think that the taste of a young girl would have originated a great period of decoration, although the idea is firmly fixed in many minds. It is known that the transition period was well advanced before she became queen, but there is no doubt that her simpler taste and that of Louis led them to accept with joy the classical ideas of beauty which were slowly gaining ground. As dauphin and dauphiness they naturally had a great following, and as king and queen their taste was paramount, and the style became established.

Architecture became more simple and interior decoration followed suit. The restfulness and beauty of the straight line appeared again, and ornament took its proper place as a decoration of the construction, and was subordinate to its design. During the period of Louis XVI the rooms had rectangular panels formed by simpler moldings than in the previous reign, with pilasters of delicate design between the panels. The overdoors and mantels were carried to the cornice and the paneling was usually of oak, painted in soft colors or white and gilded. Walls were also covered with tapestry and brocade. Some of the most characteristic marks of the style are the straight tapering legs of the furniture, usually fluted, with some carving. Fluted columns and pilasters often had metal quills filling them for a part of the distance at top and bottom, leaving a plain channel between. The laurel leaf was used in wreath form, and bell flowers were used on the legs of furniture. Oval medallions, surmounted by a wreath of flowers and a bow-knot, appear very often, and in about 1780 round medallions were used. Furniture was covered with brocade or tapestry, with shepherds and shepherdesses or pastoral scenes for the design. The gayest kinds of designs were used in the silks and brocades; ribbons and bow-knots and interlacing stripes with flowers and rustic symbols scattered over them. Curtains were less festooned and cut with great exactness. The canopies of beds became smaller, until often only a ring or crown held the draperies, and it became the fashion to place the bed sideways, "vu de face."

There was a great deal of beautiful ornament in gilded bronze and ormolu on the furniture, and many colored woods were used in marquetry. The fashion of using Sèvres plaques in inlay was continued. There was a great deal of white and colored marble used and very fine ironwork was made. Riesener, Roentgen, Gouthiére, Fragonard and Boucher are some of the names that stand out most distinctly as authors of the beautiful decorations of the time. Marie Antoinette's boudoir at Fontainebleau is a perfect example of the style and many of the other rooms both there and at the Petit Trianon show its great beauty, gayety and dignity combined with its richness and magnificence.

The influence of Pompeii must not be overlooked in studying the style of Louis XVI, for it appeared in much of the decoration of the time. The beautiful little boudoir of the Marquise de Sérilly is a charming example of its adaptation. The problem of bad proportion is also most interestingly overcome. The room was too high for its size, so it was divided into four arched openings separated by carved pilasters, and the walls covered with paintings. The ceiling was darker than the walls, which made it seem lower, and the whole color scheme was so arranged that the feeling of extreme height was lessened. The mantel is a beautiful example of the period. This room was furnished about 1780-82.

Compared to the lavish curves of the style of Louis XV, the fine outlines and the beautiful ornament of Louis XVI appear to some people cold, but if they look carefully at the matter, they will find them not really so. The warmth of the Gallic temperament still shows through the new garb, giving life and beauty to the dainty but strong furniture.

If one studies the examples of the styles of Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI that one finds in the great palaces, collections, museums and books of prints and photographs, one will see that the wonderful foundation laid by Louis XIV was still there in the other two reigns. During the time of Louis XVI the pose of rustic simplicity was a very sophisticated pose indeed, but the reaction from the rocaille style of Louis XV led to one of the most beautiful styles of decoration that the world has seen. It had dignity, true beauty and the joy of life expressed in it.

Rare Louis XVI chair—an original from Fontainebleau.

The American Empire sofa, when not too elaborate, is a very beautiful article of furniture.

The French Revolution made a tremendous change in the production of beautiful furniture, as royalty and the nobility could no longer encourage it. Many of the great artists died in poverty and many of them went to other countries where life was more secure.

After the Revolution there was wholesale destruction of the wonderful works of art which had cost such vast sums to collect. Nothing was to remain that would remind the people of departed kings and queens, and a committee on art was appointed to make selections of what was to be saved and what was to be destroyed. That committee of "tragic comedians" set up a new standard of art criticism; it was not the artistic merits of a piece of tapestry, for instance, that interested them, but whether a king or queen dared show their heads upon it. If so, into the flames it went. Thousands of priceless things were destroyed before they finished their dreadful work.

When Napoleon came into power he turned to ancient Rome for inspiration. The Imperial Cæsars became his ideal and gave him a wide field in which to display his love for splendor, uncontrolled by any true artistic sense. It gave decoration a blow from which it was hard to recover. Massive furniture without real beauty of line, loaded with ormolu, took the place of the old. The furniture was simple in construction with little carving, until later when all kinds of animal heads and claws, and animals never seen by man, and horns of plenty, were used to support tables and chairs and sofas. Everywhere one turned the feeling of martial grandeur was in the air. Ormolu mounts of bay wreaths, torches, eagles, military emblems and trophies, winged figures, the sphinx, the bee, and the initial N, were used on furniture; and these same motives were used in wall decoration. The furniture was left the natural color of the wood, and mahogany, rosewood, and ebony, were used. Veneer was also extensively used. The front legs of chairs were usually straight, and the back legs slightly curved. Beds were massive, with head and foot-board of even height, and the tops rolled over into a scroll. Swans were used on the arms of chairs and sofas and the sides of beds. Tables were often round, with tripod legs; in fact, the tripod was a great favorite. There was a great deal of inlay of the favorite emblems but little carving. Plain columns with Doric caps and metal ornaments were used. The change in the use of color was very marked, for deep brown, blue and other dark colors were used instead of the light and gay ones of the previous period. The materials used were usually of solid colors with a design in golden yellow, a wreath, or a torch, or the bee, or one of the other favorite emblems being used in a spot design, or powdered on. Some of the color combinations in the rooms we read of sound quite alarming.

Since the time of the Empire, France has done as the rest of the world has, gone without any special style.

The early history of furniture in all countries is very much the same—there is not any. We know about kings and queens, and war and sudden death, and fortresses and pyramids, but of that which the people used for furniture we know very little. Research has revealed the mention in old manuscripts once in a while of benches and chests, and the Bayeux tapestry and old seals show us that William the Conquerer and Richard Coeur de Lion sat on chairs, even if they were not very promising ones, but at best it is all very vague. It is natural to suppose that the early Saxons had furniture of some kind, for, as the remains of Saxon metalwork show great skill, it is probable they had skill also in woodworking.

In England, as in France, the first pieces of furniture that we can be sure of are chests and benches. They served all purposes apparently, for the family slept on them by night and used them for seats and tables by day. The bedding was kept in the chests, and when traveling had to be done all the family possessions were packed in them. There is an old chest at Stoke d'Abernon church, dating from the thirteenth century, that has a little carving on it, and another at Brampton church of the twelfth or thirteenth century that has iron decorations. Some chests show great freedom in the carving, St. George and the Dragon and other stories being carved in high relief.

An Apostles bed of the Tudor period, so-called from the carved panels of the back. The over elaboration of the late Tudor work corresponded in time with France's deterioration in the reign of Henry IV.

Nearly all the existing specimens of Gothic furniture are ecclesiastical, but there are a few that were evidently for household use. These show distinctly the architectural treatment of design in the furniture. Chairs were not commonly used until the sixteenth century. Our distinguished ancestors decided that one chair in a house was enough, and that was for the master, while his family and friends sat on benches and chests. It is a long step in comfort and manners from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. Later the guest of honor was given the chair, and from that may come the saying that a speaker "takes the chair." Gothic tables were probably supported by trestles, and beds were probably very much like the early sixteenth century beds in general shape. There were cupboards and armoires also, but examples are very rare. From an old historical document we learn that Henry III, in 1233, ordered the sheriff to attend to the painting of the wainscoted chamber in Winchester Castle and to see that "the pictures and histories were the same as before." Another order is for having the wall of the king's chamber at Westminster "painted a good green color in imitation of a curtain." These painted walls and stained glass that we know they had, and the tapestry, must have given a cheerful color scheme to the houses of the wealthy class even if there was not much comfort.

|

|

| In this walnut dressing-table the period of William and Mary has been adapted to modern needs. | This reproduction of a Charles II chair shows cherubs supporting crowns. |

The history of the great houses of England, and also the smaller manor-houses, is full of interest in connection with the study of furniture. There are many manor-houses that show all the characteristics of the Gothic, Renaissance, Tudor and Jacobean periods, and from them we can learn much of the life of the times. The early ones show absolute simplicity in the arrangement, one large hall for everything, and later a small room or two added. The fire was on the floor and the smoke wandered around until it found its way out at the opening, or louvre, in the roof. Then a chimney was built at the dais end of the hall, and the mantelpiece became an important part of the decoration. The hall was divided by "screens" into smaller rooms, leaving the remainder for retainers, and causing the clergy to inveigh against the new custom of the lord of the manor "eating in secret places." The staircase developed from the early winding stair about a newel or post to the beautiful broad stairs of the Tudor period. These were usually six or seven feet broad, with about six wide easy steps and then a landing, and the carving on the balusters was often very elaborate and sometimes very beautiful—a ladder raised to the nth power.

Slowly the Gothic period died in England and slowly the Renaissance took its place. There was never the gayety of decorative treatment that we find in France, but the English workmen, while keeping their own individuality, learned a tremendous amount from the Italians who came to the country. Their influence is shown in the Henry VIIth Chapel in Westminster Abbey, and in the old part of Hampton Court Palace, built by Cardinal Wolsey.

The religious troubles between Henry VIII and the Pope and the change of religion helped to drive the Italians from the country, so the Renaissance did not get such a firm foothold in England as it did in France. The mingling of Gothic and Renaissance forms what we call the Tudor period. During the time of Elizabeth all trace of Gothic disappeared, and the influence of the Germans and Flemings who came to the country in great numbers, helped to shorten the influence of the Renaissance. The over-elaboration of the late Tudor time corresponded with the deterioration shown in France in the time of Henry IV. The Hall of Gray's Inn, the Halls of Oxford, the Charterhouse and the Hall of the Middle Temple are all fine examples of the Tudor period.

We find very few names of furniture makers of those days; in fact, there are very few names known in connection with the buildings themselves. The word architect was little used until after the Renaissance. The owner and the "surveyor" were the people responsible, and the plans, directions and details given to the workmen were astonishingly meager.

The great charm that we all feel in the Tudor and Jacobean periods is largely due to the beautiful paneled walls. Their woodwork has a color that only age can give and that no stain can copy. The first panels were longer than the later ones. Wide use was made of the beautiful "linen-fold" design in the wainscoting, and there was also much elaborate carving and strapwork. Scenes like the temptation of Adam and Eve were represented, heads in circular medallions, and simply decorative designs were used. In the days of Elizabeth it became the fashion to have the carving at the top of the paneling with plain panels below. Tudor and Jacobean mantelpieces were most elaborate and were of wood, stone, or marble richly carved, to say nothing of the beautiful plaster ones, and there are many fine examples in existence. They were fond of figure decoration, and many subjects were taken from the Bible. The overmantels were decorated with coats-of-arms and other carving, and the entablature over the fireplace often had Latin mottoes. The earliest firebacks date from the fifteenth century. Coats-of-arms and many curious designs were used upon them.

The furniture of the Tudor period was much carved, and was made chiefly of oak. Cornices of beds and cabinets often had the egg-and-dart molding used on them, and the S-curve is often seen opposed on the backs of settees and chairs. It has a suggestion of a dolphin and is reminiscent of the dolphins of the Renaissance. The beds were very large, the "great bed of Ware" being twelve feet square. The cornice, the bed-head, the pedestals and pillars supporting the cornice were all richly carved. Frequently the pillars at the foot of the bed were not connected with it, but supported the cornice which was longer than the bed. The "Courtney bedstead," dated 1593, showing many of the characteristics of the ornament of the time, is 103-1/2 inches high, 94 inches long, 68 inches wide. The majority of the beds were smaller and lower, however, and the pillars usually rose out of drum-like members, huge acorn-like bulbs that were often so large as to be ugly. They appeared also on other articles of furniture. When in good proportion, with pillars tapering from them, they were very effective, and gradually they grew smaller. Some of the beds had the four apostles, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, carved on the posts. They were probably the origin of the nursery rhyme:

In this living-room, Italian, Jacobean, and modern stuffed furniture, give a satisfactory effect because each piece is good of its kind and is in a certain relationship to each other. The huge clock with chimes and the animal casts are out of keeping.

Bed hanging were of silk, velvet, damask, wool damask, tapestry, etc., and there were fine linen sheets and blankets and counterpanes of wool work. The chairs were high-backed of solid oak with cushions. There were also jointed stools, folding screens, chests, cabinets, tables with carpets (table covers) tapestry hangings, curtains, cushions, silver sconces, etc.

Original Jacobean settle with tapestry covering. These pieces of furniture range in price between $900 and $1,400.

Fine reproductions of Jacobean chairs of the time of Charles II. The carved front rail balances the carving on the back perfectly.

The Jacobean period began with James I, and lasted until the time of William and Mary, or from 1603 to about 1689. In the early part there was still a strong Tudor feeling, and toward the end foreign influence made itself felt until the Dutch under William became paramount. Inigo Jones did his great work at this time in the Palladian style of architecture. His simpler taste did much to reduce the exaggeration of the late Tudor days.

Chests of various kinds still remained of importance. Their growth is interesting: first the plain ones of very early days, then panels appeared, then the pointed arch with its architectural effect, then the low-pointed arch of Tudor and early Jacobian times, and the geometrical ornament. Then came a change in the general shape, a drawer being added at the bottom, and at last it turned into a complete chest of drawers.

Cabinets or cupboards were also used a great deal, and the most interesting are the court-and livery-cupboards. The derivation of the names is a bit obscure, but the court cupboard probably comes from the French court, short. The first ones were high and unwieldy and the later ones were lower with some enclosed shelves. They were used for a display of plate, much as the modern sideboard is used. The number of shelves was limited by rank; the wife of a baronet could have two, a countess three, a princess four, a queen five. They were beautifully carved, very often, the doors to the enclosed portions having heads, Tudor roses, arches, spindle ornaments and many other designs common to the Tudor and Jacobean periods. They had a silk "carpet" put on the shelves with the fringe hanging over the ends, but not the front, and on this was placed the silver.

The livery-cupboard was used for food, and the word probably comes from the French livrer, to deliver. It had several shelves enclosed by rails, not panels, so the air could circulate, and some of them had open shelves and a drawer for linen. They were used much as we use a serving-table, or as the kitchen dresser was used in old New England days. In them were kept food and drink for people to take to their bedrooms to keep starvation at bay until breakfast.

Drawing-tables were very popular during Jacobean times. They were described as having two ends that were drawn out and supported by sliders, while the center, previously held by them, fell into place by its own weight. Another characteristic table was the gate-legged or thousand-legged table, that was used so much in our own Colonial times. There were also round, oval and square tables which had flaps supported by legs that were drawn out. Tables were almost invariably covered with a table cloth.

Some of the chairs of the time of James I were much like those of Louis XIII, having the short back covered with leather, damask, or tapestry, put on with brass or silver nails and fringe around the edge of the seat. The chief characteristic of the chairs of this time was solidity, with the ornament chiefly on the upper parts, which were molded oftener than carved, with the backs usually high. A plain leather chair called the "Cromwell chair," was imported from Holland. The solid oak back gave way at last to the half solid back, then came the open back with rails, and then the Charles II chair, with its carved or turned uprights, its high back of cane, and an ornamental stretcher like the top of the chair back, between the front legs. This is a very attractive feature, as it serves to give balance of decoration and also partly hides the plain stretcher from sight. A typical detail of Charles II furniture is the crown supported by cherubs or opposed S-curves. James II used a crown and palm leaves.

Grinling Gibbons did his wonderful work in carving at this time, using chiefly pear and lime wood. The greater part of his work was wall decoration, but he made tables, mirrors and other furniture as well. The carving was often in lighter wood than the background, and was in such high relief that portions of it had often to be "pinned" together, for it seemed almost in the round. Evelyn discovered Gibbons in a little shop working away at such a wonderful piece of carving that he could not rest until he had taken him to Sir Christopher Wrenn. From this introduction came the great amount of work they did together. The influence of his work was still seen in the early eighteenth century.

The room at Knole House that was furnished for James I is of great interest, as it is the same to-day as when first furnished. The bed is said to have cost £8,000. As it is one of the show places of England one should not miss a chance of seeing it.

Until the time of the Restoration the furniture of England could not compare in sumptuousness with that of the Continental countries. England, besides having a simpler point of view, was in a perpetual state of unrest. The honest and hard-working English joiners and carpenters adapted in a plain and often clumsy way the styles of the different foreigners who came to the country. Through it all, however, they kept the touch of national character that makes the furniture so interesting, and they often did work of great beauty and worth. When Charles II came to the throne he brought with him the ideas of France, where he had spent so many years, and the change became very marked. The natural Stuart extravagance also helped to form his taste, and soon we hear of much more elaborate decoration throughout the land.

Many of the country towns were far behind London in the style of furniture, and this explains why some furniture that is dated 1670, for instance, seems to belong to an earlier time. The famous silver furniture of Knole House, Seven-oaks, belongs to this time. Evelyn mentions in his diary that the rooms of the Duchess of Portsmouth were full of "Japan cabinets and screens, pendule clocks, greate vases of wrought plate, tables, stands, chimney furniture, sconces, branches, baseras, etc., all of massive silver," and later he mentions again her "massy pieces of plate, whole tables and stands of incredible value."

In the reign of William and Mary, Dutch influence was naturally very pronounced, as William disliked everything English. The English, being now well grounded in the knowledge of construction, took the Dutch ideas as a foundation and developed them along their own lines, until we have the late Queen Anne type made by Chippendale.