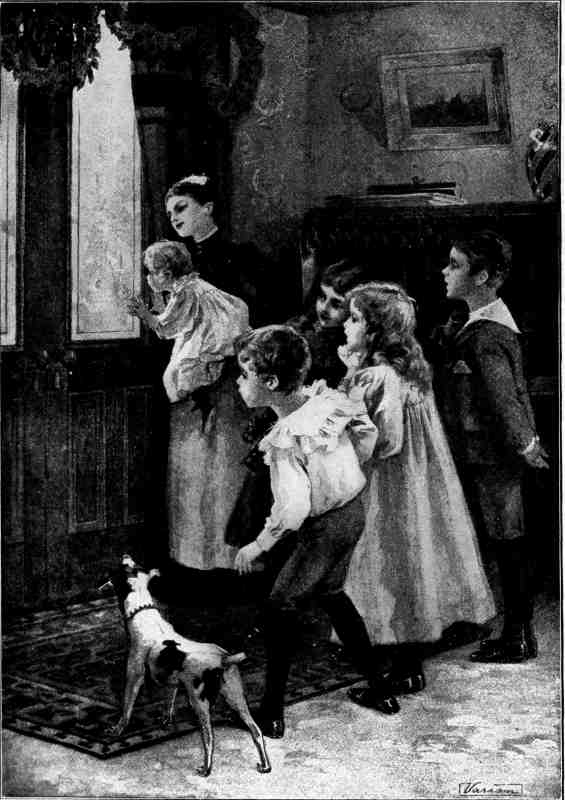

HO, FOR THE CHRISTMAS TREE!

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Our Holidays, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Our Holidays

Their Meaning and Spirit; retold from St. Nicholas

Author: Various

Release Date: January 29, 2005 [EBook #14829]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OUR HOLIDAYS ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Jennifer Zickerman and the PG Online

Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net).

Each about 200 pages. Full cloth, 12mo.

THE CENTURY CO.

To most young people, holidays mean simply freedom from lessons and a good time. All this they should mean—and something more.

It is well to remember, for example, that we owe the pleasure of Thanksgiving to those grateful Pilgrims who gave a feast of thanks for the long-delayed rain that saved their withering crops—a feast of wild turkeys and pumpkin pies, which has been celebrated now for nearly three centuries.

It is most fitting that the same honor paid to Washington's Birthday is now given to that of Lincoln, who is as closely associated with the Civil War as our first President is with the Revolution.

Although the birthdays of the three American poets, Whittier, Lowell, and Longfellow, are not holidays, stories relating to these days are included in this collection as signalizing days to be remembered.

In this book are contained stories bearing on our holidays and annual celebrations, from Hallowe'en to the Fourth of July.

BY HENRY JOHNSTONE

|

Oh, Friday night's the queen of nights, because it ushers in The Feast of good St. Saturday, when studying is a sin, When studying is a sin, boys, and we may go to play Not only in the afternoon, but all the livelong day. St. Saturday—so legends say—lived in the ages when The use of leisure still was known and current among men; Full seldom and full slow he toiled, and even as he wrought He'd sit him down and rest awhile, immersed in pious thought. He loved to fold his good old arms, to cross his good old knees, And in a famous elbow-chair for hours he'd take his ease; He had a word for old and young, and when the village boys Came out to play, he'd smile on them and never mind the noise. So when his time came, honest man, the neighbors all declared That one of keener intellect could better have been spared; By young and old his loss was mourned in cottage and in hall, For if he'd done them little good, he'd done no harm at all. In time they made a saint of him, and issued a decree— Since he had loved his ease so well, and been so glad to see The children frolic round him and to smile upon their play— That school boys for his sake should have a weekly holiday. They gave his name unto the day, that as the years roll by His memory might still be green; and that's the reason why We speak his name with gratitude, and oftener by far Than that of any other saint in all the calendar. Then, lads and lassies, great and small, give ear to what I say— Refrain from work on Saturdays as strictly as you may; So shall the saint your patron be and prosper all you do— And when examinations come he'll see you safely through. |

October 31

The Eve of All Saints' Day

This night is known in some places as Nutcrack Night, or Snapapple Night. Supernatural influences are pretended to prevail and hence all kinds of superstitions were formerly connected with it. It is now usually celebrated by children's parties, when certain special games are played.

BY DAVID BROWN

As the world grows old and wise, it ceases to believe in many of its superstitions. But, although they are no longer believed in, the customs connected with them do not always die out; they often linger on through centuries, and, from having once been serious religious rites, or something real in the life of the people, they become at last mere children's plays or empty usages, often most zealously enjoyed by those who do not understand their meaning.

All-hallow Eve is now, in our country towns, a time of careless frolic, and of great bonfires, which, I hear, are still kindled on the hill-tops in some places. We also find these fires in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and from their history we learn the meaning of our celebration. Some of you may know that the early inhabitants of Great Britain, Ireland, and parts of France were known as Celts, and that their religion was directed by strange priests called Druids. Three times in the year, on the first of May, for the sowing; at the solstice, June 21st, for the ripening and turn of the year; and on the eve of November 1st, for the harvesting, those mysterious priests of the Celts, the Druids, built fires on the hill-tops in France, Britain, and Ireland, in honor of the sun. At this last festival the Druids of all the region gathered in their white robes around the stone altar or cairn on the hill-top. Here stood an emblem of the sun, and on the cairn was a sacred fire, which had been kept burning through the year. The Druids formed about the fire, and, at a signal, quenched it, while deep silence rested on the mountains and valleys. Then the new fire gleamed on the cairn, the people in the valley raised a joyous shout, and from hill-top to hill-top other fires answered the sacred flame. On this night, all hearth-fires in the region had been put out, and they were kindled with brands from the sacred fire, which was believed to guard the households through the year.

But the Druids disappeared from their sacred places, the cairns on the hill-tops became the monuments of a dead religion, and Christianity spread to the barbarous inhabitants of France and the British Islands. Yet the people still clung to their old customs, and felt much of the old awe for them. Still they built their fires on the first of May,—at the solstice in June,—and on the eve of November 1st. The church found that it could not all at once separate the people from their old ways, so it gradually turned these ways to its own use, and the harvest festival of the Druids became in the Catholic Calendar the Eve of All Saints, for that is the meaning of the name "All-hallow Eve." In the seventh century, the Pantheon, the ancient Roman temple of all the gods, was consecrated anew to the worship of the Virgin and of all holy martyrs.

By its separation from the solemn character of the Druid festival, All-hallow Eve lost much of its ancient dignity, and became the carnival-night of the year for wild, grotesque rites. As century after century passed by, it came to be spoken of as the time when the magic powers, with which the peasantry, all the world over, filled the wastes and ruins, were supposed to swarm abroad to help or injure men. It was the time when those first dwellers in every land, the fairies, were said to come out from their grots and lurking-places; and in the darkness of the forests and the shadows of old ruins, witches and goblins gathered. In course of time, the hallowing fire came to be considered a protection against these malicious powers. It was a custom in the seventeenth century for the master of a family to carry a lighted torch of straw around his fields, to protect them from evil influence through the year, and as he went he chanted an invocation to the fire. The chief thing which we seek to impress upon your minds in connection with All-hallow Eve is that its curious customs show how no generation of men is altogether separated from earlier generations. Far as we think we are from our uncivilized ancestors, much of what they did and thought has come into our doing and thinking,—with many changes perhaps, under different religious forms, and sometimes in jest where they were in earnest. Still, these customs and observances (of which All-hallow Eve is only one) may be called the piers, upon which rests a bridge that spans the wide past between us and the generations that have gone before.

The first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

This day is now a holiday so that every man may have an opportunity to cast his vote. Unlike most other holidays, it does not commemorate an event, but it is a day which has a tremendous meaning if rightly looked upon and rightly used. Its true spirit and significance are well set forth in the following pages. By act of Congress the date for the choosing of Presidential electors is set for the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November in the years when Presidents are elected, and the different States have now nearly all chosen the same day for the election of State officers.

BY S.E. FORMAN

Read the bill of rights in the constitution of your State and you will find there, set down in plain black and white, the rights which you are to enjoy as an American citizen. This constitution tells you that you have the right to your life, to your liberty, and to the property that you may honestly acquire; that your body, your health and your reputation shall be protected from injury; that you may move freely from place to place unmolested; that you shall not be imprisoned or otherwise punished without a fair trial by an impartial jury; that you may worship God according to the promptings of your own conscience; that you may freely write and speak on any subject providing you do not abuse the privilege; that you may peaceably assemble and petition government for the redress of grievances. These are civil rights. They, together with many others equally dear, are guaranteed by the State and national constitutions, and they belong to all American citizens.

These civil rights, like the air and the sunshine, come to us in these days as a matter of course, but they did not come to our ancestors as a matter of course. To our ancestors rights came as the result of hard-fought battles. The reading of the bill of rights would cause your heart to throb with gratitude did you but know the suffering and sacrifice each right has cost.

Now just as our rights have not been gained without a struggle, so they will not be maintained without a struggle. We may not have to fight with cannon and sword as did our forefathers in the Revolution, but we may be sure that if our liberty is to be preserved there will be fighting of some kind to do. Such precious things as human rights cannot be had for nothing.

One of the hardest battles will be to fulfil the duties which accompany our rights, for every right is accompanied by a duty. If I can hold a man to his contract I ought (I owe it) to pay my debts; if I may worship as I please, I ought to refrain from persecuting another on account of his religion; if my property is held sacred, I ought to regard the property of another man as sacred; if the government deals fairly with me and does not oppress me, I ought to deal fairly With it and refuse to cheat it; if I am allowed freedom of speech, I ought not to abuse the privilege; if I have a right to a trial by jury, I ought to respond when I am summoned to serve as a juror; if I have a right to my good name and reputation, I ought not to slander my neighbor; if government shields me from injury, I ought to be ready to take up arms in its defense.

Foremost among the rights of American citizenship is that of going to the polls and casting a ballot. This right of voting is not a civil right; it is a political right which grew out of man's long struggle for his civil rights. While battling with kings and nobles for liberty the people learned to distrust a privileged ruling class. They saw that if their civil rights were to be respected, government must pass into their own hands or into the hands of their chosen agents. Hence they demanded political rights, the right of holding office and of voting at elections.

The suffrage, or the right of voting, is sometimes regarded as a natural right, one that belongs to a person simply because he is a person.

People will say that a man has as much right to vote as he has to acquire property or to defend himself from attack. But this is not a correct view. The right to vote is a franchise or privilege which the law gives to such citizens as are thought worthy of possessing it. It is easy to see that everybody cannot be permitted to vote. There must be certain qualifications, certain marks of fitness, required of a citizen before he can be entrusted with the right of suffrage. These qualifications differ in the different States. In most States every male citizen over twenty-one years of age may vote. In four States, women as well as men exercise the right of suffrage.

But the right of voting, like every other right, has its corresponding duty. No day brings more responsibilities than Election Day. The American voter should regard himself as an officer of government. He is one of the members of the electorate, that vast governing body which consists of all the voters and which possesses supreme political power, controlling all the governments, federal and State and local. This electorate has in its keeping the welfare and the happiness of the American people. When, therefore, the voter takes his place in this governing body, that is, when he enters the polling-booth and presumes to participate in the business of government, he assumes serious responsibilities. In the polling-booth he is a public officer charged with certain duties, and if he fails to discharge these duties properly he may work great injury. What are the duties of a voter in a self-governing country? If an intelligent man will ask himself the question and refer it to his conscience as well as deliberate upon it in his mind, he will conclude that he ought to do the following things:

| 1. To vote whenever it is his privilege. |

| 2. To try to understand the questions upon which he votes. |

| 3. To learn something about the character and fitness of the men for whom he votes. |

| 4. To vote only for honest men for office. |

| 5. To support only honest measures. |

| 6. To give no bribe, direct or indirect, and to receive no bribe, direct or indirect. |

| 7. To place country above party. |

| 8. To recognize the result of the election as the will of the people and therefore as the law. |

| 9. To continue to vote for a righteous although defeated cause as long as there is a reasonable hope of victory. |

|

"The proudest now is but my peer, The highest not more high; To-day of all the weary year, A king of men am I. "To-day alike are great and small, The nameless and the known; My palace is the people's hall, The ballot-box my throne!" WHITTIER. |

Appointed by the President—usually the last Thursday in November.

Now observed as a holiday in all the States, but not a legal holiday in all. The President's proclamation recommends that it be set apart as a day of prayer and rejoicing. The day is of New England origin, the first one being set by Governor Bradford of the Massachusetts colony on December, 1621. Washington issued a thanksgiving proclamation for Thursday, December 18, 1777, and again at Valley Forge for May 7, 1778. The Thanksgiving of the present incorporates many of the genial features of Christmas. The feast with the Thanksgiving turkey and pumpkin-pie crowns the day. Even the poorhouse has its turkey. The story of "An Old-Time Thanksgiving," in "Indian Stories" of this series, well brings out the original spirit of the day.

BY H. BUTTERWORTH

"Honk!"

I spun around like a top, looking nervously in every direction. I was familiar with that sound; I had heard it before, during two summer vacations, at the old farm-house on the Cape.

It had been a terror to me. I always put a door, a fence, or a stone wall between me and that sound as speedily as possible.

I had just come down from the city to the Cape for my third summer vacation. I had left the cars with my arms full of bundles, and hurried toward Aunt Targood's.

The cottage stood in from the road. There was a long meadow in front of it. In the meadow were two great oaks and some clusters of lilacs. An old, mossy stone wall protected the grounds from the road, and a long walk ran from the old wooden gate to the door.

It was a sunny day, and my heart was light. The orioles were flaming in the old orchards; the bobolinks were tossing themselves about in the long meadows of timothy, daisies, and patches of clover. There was a scent of new-mown hay in the air.

In the distance lay the bay, calm and resplendent, with white sails and specks of boats. Beyond it rose Martha's Vineyard, green and cool and bowery, and at its wharf lay a steamer.

I was, as I said, light-hearted. I was thinking of rides over the sandy roads at the close of the long, bright days; of excursions on the bay; of clam-bakes and picnics.

I was hungry; and before me rose visions of Aunt Targood's fish dinners, roast chickens, berry pies. I was thirsty; but ahead was the old well-sweep, and, behind the cool lattice of the dairy window, were pans of milk in abundance.

I tripped on toward the door with light feet, lugging my bundles and beaded with perspiration, but unmindful of all discomforts in the thought of the bright days and good things in store for me.

"Honk! honk!"

My heart gave a bound!

Where did that sound come from?

Out of a cool cluster of innocent-looking lilac bushes, I saw a dark object cautiously moving. It seemed to have no head. I knew, however, that it had a head. I had seen it; it had seized me once on the previous summer, and I had been in terror of it during all the rest of the season.

I looked down into the irregular grass, and saw the head and a very long neck running along on the ground, propelled by the dark body, like a snake running away from a ball. It was coming toward me, and faster and faster as it approached.

I dropped all my bundles.

In a few flying leaps I returned to the road again, and armed myself with a stick from a pile of cord-wood.

"Honk! honk! honk!"

It was a call of triumph. The head was high in the air now. My enemy moved grandly forward, as became the monarch of the great meadow farm-yard.

I stood with beating heart, after my retreat.

It was Aunt Targood's gander.

How he enjoyed his triumph, and how small and cowardly he made me feel!

"Honk! honk! honk!"

The geese came out of the lilac bushes, bowing their heads to him in admiration. Then came the goslings—a long procession of awkward, half-feathered things: they appeared equally delighted.

The gander seemed to be telling his admiring audience all about it: how a strange girl with many bundles had attempted to cross the yard; how he had driven her back, and had captured her bundles, and now was monarch of the field. He clapped his wings when he had finished his heroic story, and sent forth such a "honk!" as might have startled a major-general.

Then he, with an air of great dignity and coolness, began to examine my baggage.

Among my effects were several pounds of chocolate caramels, done up in brown paper. Aunt Targood liked caramels, and I had brought her a large supply.

He tore off the wrappers quickly. Bit one. It was good. He began to distribute the bon-bons among the geese, and they, with much liberality and good-will, among the goslings.

This was too much. I ventured through the gate swinging my cord-wood stick.

"Shoo!"

He dropped his head on the ground, and drove it down the walk in a lively waddle toward me.

"Shoo!"

It was Aunt Targood's voice at the door.

He stopped immediately.

His head was in the air again.

"Shoo!"

Out came Aunt Targood with her broom.

She always corrected the gander with her broom. If I were to be whipped I should choose a broom—not the stick.

As soon as he beheld the broom he retired, although with much offended pride and dignity, to the lilac bushes; and the geese and goslings followed him.

"Hester, you dear child, come here. I was expecting you, and had been looking out for you, but missed sight of you. I had forgotten all about the gander."

We gathered up the bundles and the caramels. I was light-hearted again.

How cool was the sitting-room, with the woodbine falling about the open windows! Aunt brought me a pitcher of milk and some strawberries; some bread and honey; and a fan.

While I was resting and taking my lunch, I could hear the gander discussing the affairs of the farm-yard with the geese. I did not greatly enjoy the discussion. His tone of voice was very proud, and he did not seem to be speaking well of me. I was suspicious that he did not think me a very brave girl. A young person likes to be spoken well of, even by the gander.

Aunt Targood's gander had been the terror of many well-meaning people, and of some evildoers, for many years. I have seen tramps and pack-peddlers enter the gate, and start on toward the door, when there would sound that ringing warning like a war-blast. "Honk, honk!" and in a few minutes these unwelcome people would be gone. Farm-house boarders from the city would sometimes enter the yard, thinking to draw water by the old well-sweep: in a few minutes it was customary to hear shrieks, and to see women and children flying over the walls, followed by air-rending "honks!" and jubilant cackles from the victorious gander and his admiring family.

"Aunt, what makes you keep that gander, year after year?" said I, one evening, as we were sitting on the lawn before the door. "Is it because he is a kind of a watch-dog, and keeps troublesome people away?"

"No, child, no; I do not wish to keep most people away, not well-behaved people, nor to distress nor annoy any one. The fact is, there is a story about that gander that I do not like to speak of to every one—something that makes me feel tender toward him; so that if he needs a whipping, I would rather do it. He knows something that no one else knows. I could not have him killed or sent away. You have heard me speak of Nathaniel, my oldest boy?"

"Yes."

"That is his picture in my room, you know. He was a good boy to me. He loved his mother. I loved Nathaniel—you cannot think how much I loved Nathaniel. It was on my account that he went away.

"The farm did not produce enough for us all: Nathaniel, John, and I. We worked hard and had a hard time. One year—that was ten years ago—we were sued for our taxes.

"'Nathaniel,' said I, 'I will go to taking boarders.'

"Then he looked up to me and said (oh, how noble and handsome he appeared to me!):

"'Mother, I will go to sea.'

"'Where?' asked I, in surprise.

"'In a coaster.'

"I turned white. How I felt!

"'You and John can manage the place,' he continued. 'One of the vessels sails next week—Uncle Aaron's; he offers to take me.'

"It seemed best, and he made preparations to go.

"The spring before, Skipper Ben—you have met Skipper Ben—had given me some goose eggs; he had brought them from Canada, and said that they were wild-goose eggs.

"I set them under hens. In four weeks I had three goslings. I took them into the house at first, but afterward made a pen for them out in the yard. I brought them up myself, and one of those goslings is that gander.

"Skipper Ben came over to see me, the day before Nathaniel was to sail. Aaron came with him.

"I said to Aaron:

"'What can I give to Nathaniel to carry to sea with him to make him think of home? Cake, preserves, apples? I haven't got much; I have done all I can for him, poor boy.'

"Brother looked at me curiously, and said:

"'Give him one of those wild geese, and we will fatten it on shipboard and will have it for our Thanksgiving dinner.'

"What brother Aaron said pleased me. The young gander was a noble bird, the handsomest of the lot; and I resolved to keep the geese to kill for my own use and to give him to Nathaniel.

"The next morning—it was late in September—I took leave of Nathaniel. I tried to be calm and cheerful and hopeful. I watched him as he went down the walk with the gander struggling under his arms. A stranger would have laughed, but I did not feel like laughing; it was true that the boys who went coasting were usually gone but a few months and came home hardy and happy. But when poverty compels a mother and son to part, after they have been true to each other, and shared their feelings in common, it seems hard, it seems hard—though I do not like to murmur or complain at anything allotted to me.

"I saw him go over the hill. On the top he stopped and held up the gander. He disappeared; yes, my own Nathaniel disappeared. I think of him now as one who disappeared.

"November came—it was a terrible month on the coast that year. Storm followed storm; the sea-faring people talked constantly of wrecks and losses. I could not sleep on the nights of those high winds. I used to lie awake thinking over all the happy hours I had lived with Nathaniel.

"Thanksgiving week came.

"It was full of an Indian-summer brightness after the long storms. The nights were frosty, bright, and calm.

"I could sleep on those calm nights.

"One morning, I thought I heard a strange sound in the woodland pasture. It was like a wild goose. I listened; it was repeated. I was lying in bed. I started up—I thought I had been dreaming.

"On the night before Thanksgiving I went to bed early, being very tired. The moon was full; the air was calm and still. I was thinking of Nathaniel, and I wondered if he would indeed have the gander for his Thanksgiving dinner: if it would be cooked as well as I would have cooked it, and if he would think of me that day.

"I was just going to sleep, when suddenly I heard a sound that made me start up and hold my breath.

"'Honk!'

"I thought it was a dream followed by a nervous shock.

"'Honk! honk!'

"There it was again, in the yard. I was surely awake and in my senses.

"I heard the geese cackle.

"'Honk! honk! honk!'

"I got out of bed and lifted the curtain. It was almost as light as day. Instead of two geese there were three. Had one of the neighbors' geese stolen away?

"I should have thought so, and should not have felt disturbed, but for the reason that none of the neighbors' geese had that peculiar call—that hornlike tone that I had noticed in mine.

"I went out of the door.

"The third goose looked like the very gander I had given Nathaniel. Could it be?

"I did not sleep. I rose early and went to the crib for some corn.

"It was a gander—a 'wild' gander—that had come in the night. He seemed to know me.

"I trembled all over as though I had seen a ghost. I was so faint that I sat down on the meal-chest.

"As I was in that place, a bill pecked against the door. The door opened. The strange gander came hobbling over the crib-stone and went to the corn-bin. He stopped there, looked at me, and gave a sort of glad "honk," as though he knew me and was glad to see me.

"I was certain that he was the gander I had raised, and that Nathaniel had lifted into the air when he gave me his last recognition from the top of the hill.

"It overcame me. It was Thanksgiving. The church bell would soon be ringing as on Sunday. And here was Nathaniel's Thanksgiving dinner; and brother Aaron's—had it flown away? Where was the vessel?

"Years have passed—ten. You know I waited and waited for my boy to come back. December grew dark with its rainy seas; the snows fell; May lighted up the hills, but the vessel never came back. Nathaniel—my Nathaniel—never returned.

"That gander knows something he could tell me if he could talk. Birds have memories. He remembered the corn-crib—he remembered something else. I wish he could talk, poor bird! I wish he could talk. I will never sell him, nor kill him, nor have him abused. He knows!"

JOHN GREENLEAF WHITTIER

Born December 17, 1807 Died September 7, 1892

Whittier is known not only as a poet, but as a reformer and author. He was a member of the Society of Friends. He attended a New England academy; worked on a farm; taught school in order to afford further education, and at the age of twenty-two edited a paper at Boston. He was a leading opponent of slavery and was several times attacked by mobs on account of his opinions.

BY WILLIAM H. RIDEING

The life of Whittier may be read in his poems, and, by putting a note here and a date there, a full autobiography might be compiled from them. His boyhood and youth are depicted in them with such detail that little need be added to make the story complete, and that little, reverently done as it may be, must seem poor in comparison with the poetic beauty of his own revelations.

What more can we do to show his early home than to quote from his own beautiful poem, "Snow-bound"? There the house is pictured for us, inside and out, with all its furnishings; and those who gather around its hearth, inmates and visitors, are set before us so clearly that long after the book has been put away they remain as distinct in the memory as portraits that are visible day after day on the walls of our own homes. He reproduces in his verse the landscapes he saw, the legends of witches and Indians he listened to, the schoolfellows he played with, the voices of the woods and fields, and the round of toil and pleasure in a country boy's life; and in other poems his later life, with its impassioned devotion to freedom and lofty faith, is reflected as lucidly as his youth is in "Snow-bound" and "The Barefoot Boy."

He himself was "The Barefoot Boy," and what Robert Burns said of himself Whittier might repeat: "The poetic genius of my country found me, as the prophetic bard Elijah did Elisha, at the plow, and threw her inspiring mantle over me." He was a farmer's son, born at a time when farm-life in New England was more frugal than it is now, and with no other heritage than the good name and example of parents and kinsmen, in whom simple virtues—thrift, industry, and piety—abounded.

His birthplace still stands near Haverhill, Mass.,—a house in one of the hollows of the surrounding hills, little altered from what it was in 1807, the year he was born, when it was already at least a century and a half old.

He had no such opportunities for culture as Holmes and Lowell had in their youth. His parents were intelligent and upright people of limited means, who lived in all the simplicity of the Quaker faith, and there was nothing in his early surroundings to encourage and develop a literary taste. Books were scarce, and the twenty volumes on his father's shelves were, with one exception, about Quaker doctrines and Quaker heroes. The exception was a novel, and that was hidden away from the children, for fiction was forbidden fruit. No library or scholarly companionship was within reach; and if his gift had been less than genius, it could never have triumphed over the many disadvantages with which it had to contend. Instead of a poet he would have been a farmer like his forefathers. But literature was a spontaneous impulse with him, as natural as the song of a bird; and he was not wholly dependent on training and opportunity, as he would have been had he possessed mere talent.

Frugal from necessity, the life of the Whittiers was not sordid nor cheerless to him, moreover; and he looks back to it as tenderly as if it had been full of luxuries. It was sweetened by strong affections, simple tastes, and an unflinching sense of duty; and in all the members of the household the love of nature was so genuine that meadow, wood, and river yielded them all the pleasure they needed, and they scarcely missed the refinements of art.

Surely there could not be a pleasanter or more homelike picture than that which the poet has given us of the family on the night of the great storm when the old house was snowbound:

|

"Shut in from all the world without, We sat the clean-winged hearth about, Content to let the north wind roar In baffled rage at pane and door, While the red logs before us beat The frost-line back with tropic heat. And ever when a louder blast Shook beam and rafter as it passed, The merrier up its roaring draught The great throat of the chimney laughed. The house-dog on his paws outspread, Laid to the fire his drowsy head; The cat's dark silhouette on the wall A couchant tiger's seemed to fall, And for the winter fireside meet Between the andiron's straddling feet The mug of cider simmered slow, The apples sputtered in a row, And close at hand the basket stood With nuts from brown October's wood." |

For a picture of the poet himself we must turn to the verses in "The Barefoot Boy," in which he says:

|

"O for boyhood's time of June, Crowding years in one brief moon, When all things I heard or saw, Me, their master, waited for. I was rich in flowers and trees, Humming-birds and honey-bees; For my sport the squirrel played, Plied the snouted mole his spade; For my taste the blackberry cone Purpled over hedge and stone; Laughed the brook for my delight Through the day and through the night, Whispering at the garden-wall, Talked with me from fall to fall; Mine the sand-rimmed pickerel pond, Mine the walnut slopes beyond, Mine on bending orchard trees, Apples of Hesperides! Still as my horizon grew, Larger grew my riches, too; All the world I saw or knew Seemed a complex Chinese toy, Fashioned for a barefoot boy!"[1] |

I doubt if any boy ever rose to intellectual eminence who had fewer opportunities for education than Whittier. He had no such pasturage to browse on as is open to every reader who, by simply reaching them out, can lay his hands on the treasures of English literature. He had to borrow books wherever they could be found among the neighbors who were willing to lend, and he thought nothing of walking several miles for one volume. The only instruction he received was at the district school, which was open a few weeks in midwinter, and at the Haverhill Academy, which he attended two terms of six months each, paying tuition by work in spare hours, and by keeping a small school himself. A feeble spirit would have languished under such disadvantages. But Whittier scarcely refers to them, and instead of begging for pity, he takes them as part of the common lot, and seems to remember only what was beautiful and good in his early life.

Occasionally a stranger knocked at the door of the old homestead in the valley; sometimes it was a distinguished Quaker from abroad, but oftener it was a peddler or some vagabond begging for food, which was seldom refused. Once a foreigner came and asked for lodgings for the night—a dark, repulsive man, whose appearance was so much against him that Mrs. Whittier was afraid to admit him. No sooner had she sent him away, however, than she repented. "What if a son of mine was in a strange land?" she thought. The young poet (who was not yet recognized as such) offered to go out in search of him, and presently returned with him, having found him standing in the roadway just as he had been turned away from another house.

"He took his seat with us at the supper-table," says Whittier in one of his prose sketches, "and when we were all gathered around the hearth that cold autumnal evening, he told us, partly by words and partly by gestures, the story of his life and misfortunes, amused us with descriptions of the grape-gatherings and festivals of his sunny clime, edified my mother with a recipe for making bread of chestnuts, and in the morning, when, after breakfast, his dark sallow face lighted up, and his fierce eyes moistened with grateful emotion as in his own silvery Tuscan accent he poured out his thanks, we marveled at the fears which had so nearly closed our doors against him, and as he departed we all felt that he had left with us the blessing of the poor."

Another guest came to the house one day. It was a vagrant old Scotchman, who, when he had been treated to bread and cheese and cider, sang some of the songs of Robert Burns, which Whittier then heard for the first time, and which he never forgot. Coming to him thus as songs reached the people before printing was invented, through gleemen and minstrels, their sweetness lingered in his ears, and he soon found himself singing in the same strain. Some of his earliest inspirations were drawn from Burns, and he tells us of his joy when one day, after the visit of the old Scotchman, his schoolmaster loaned him a copy of that poet's works. "I began to make rhymes myself, and to imagine stories and adventures," he says in his simple way.

Indeed, he began to rhyme very early and kept his gift a secret from all, except his oldest sister, fearing that his father, who was a prosaic man, would think that he was wasting time. He wrote under the fence, in the attic, in the barn—wherever he could escape observation; and as pen and ink were not always available, he sometimes used chalk, and even charcoal. Great was the surprise of the family when some of his verses were unearthed, literally unearthed, from under a heap of rubbish in a garret; but his father frowned upon these evidences of the bent of his mind, not out of unkindness, but because he doubted the sufficiency of the boy's education for a literary life, and did not wish to inspire him with hopes which might never be fulfilled.

His sister had faith in him, nevertheless, and, without his knowledge, she sent one of his poems to the editor of The Free Press, a newspaper published in Newburyport. Whittier was helping his father to repair a stone wall by the roadside when the carrier flung a copy of the paper to him, and, unconscious that anything of his was in it, he opened it and glanced up and down the columns. His eyes fell on some verses called "The Exile's Departure."

|

"Fond scenes, which delighted my youthful existence, With feelings of sorrow I bid ye adieu— A lasting adieu; for now, dim in the distance, The shores of Hibernia recede from my view. Farewell to the cliffs, tempest-beaten and gray, Which guard the loved shores of my own native land; Farewell to the village and sail-shadowed bay, The forest-crowned hill and the water-washed strand." |

His eyes swam; it was his own poem, the first he ever had in print.

"What is the matter with thee?" his father demanded, seeing how dazed he was; but, though he resumed his work on the wall, he could not speak, and he had to steal a glance at the paper again and again, before he could convince himself that he was not dreaming. Sure enough, the poem was there with his initial at the foot of it,—"W., Haverhill, June 1st, 1826,"—and, better still, this editorial notice: "If 'W.,' at Haverhill, will continue to favor us with pieces beautiful as the one inserted in our poetical department of to-day, we shall esteem it a favor."

Fame never passes true genius by, and when it came it brought with it the love and reverence of thousands, who recognize in Whittier a nature abounding in patience, unselfishness, and all the sweetness of Christian charity.

[1] The selections from Mr. Whittier's poems contained in this article are included by kind permission of Messrs. Houghton, Mifflin & Co.

December 25

A festival held every year in memory of the birth of Christ. Christmas is essentially a day of rejoicing and thanksgiving and of good will toward others. Many customs older than Christianity mark the festivities. In our country the observance of the day was discouraged in colonial times, and in England in 1643 Parliament abolished the day. Now its celebration is world-wide and by all classes and creeds.

BY CLIFFORD HOWARD

Of course Uncle Sam is best acquainted with the good old-fashioned Christmas—the kind we have known all about since we were little bits of children. There are the Christmas trees with their pretty decorations and candles, and the mistletoe and holly and all sorts of evergreens to make the house look bright, while outside the trees are bare, the ground is white with snow, and Jack Frost is prowling around, freezing up the ponds and pinching people's noses. And then there is dear old Santa Claus with his reindeer, galloping about on the night before Christmas, and scrambling down chimneys to fill the stockings that hang in a row by the fireplace.

It is the time of good cheer and happiness and presents for everybody; the time of chiming bells and joyful carols; of turkey and candy and plum-pudding and all the other good things that go to make up a truly merry Christmas. And here and there throughout the country, some of the quaint old customs of our forefathers are still observed at this time, as, for instance, the pretty custom of "Christmas waits"—boys and girls who go about from house to house on Christmas eve, or early Christmas morning, singing carols.

But, aside from the Christmas customs we all know so well, Uncle Sam has many strange and special ways of observing Christmas; for in this big country of his there are many different kinds of people, and they all do not celebrate Christmas in the same way, as you shall see.

Siss! Bang! Boom! Sky-rockets hissing, crackers snapping, cannons roaring, horns tooting, bells ringing, and youngsters shouting with wild delight. That is the way Christmas begins down South.

It starts at midnight, or even before; and all day long fire-crackers are going off in the streets of every city, town, and village of the South, from Virginia to Louisiana. A Northern boy, waking up suddenly in New Orleans or Mobile or Atlanta, would think he was in the midst of a rousing Fourth-of-July celebration. In some of the towns the brass bands come out and add to the jollity of the day by marching around and playing "My Maryland" and "Dixie"; while the soldier companies parade up and down the streets to the strains of joyous music and fire salutes with cannons and rifles.

To the girls and boys of the South, Christmas is the noisiest and jolliest day of the year. The Fourth of July doesn't compare with it. And as for the darkies, they look upon Christmas as a holiday that was invented for their especial happiness. They take it for granted that all the "white folks" they know will give them presents; and with grinning faces they are up bright and early, asking for "Christmus gif', mistah; Christmus gif, missus." No one thinks of refusing them, and at the end of the day they are richer and happier than at any other time during the whole year.

Except for the jingle of sleigh-bells and the presence of Jack Frost, a Christmas in the South is in other ways very much like that in the North. The houses are decorated with greens, mistletoe hangs above the doorways, Santa Claus comes down the chimneys and fills the waiting stockings, while Christmas dinner is not complete without the familiar turkey and cranberry sauce, plum puddings and pies.

For a great many years there was no Christmas in New England. The Pilgrims and the Puritans did not believe in such celebrations. In fact, they often made it a special point to do their hardest work on Christmas day, just to show their contempt for what they considered a pagan festival.

During colonial times there was a law in Massachusetts forbidding any one to celebrate Christmas; and if anybody was so rash in those days as to go about tooting a horn and shouting a "Merry Christmas!" he was promptly brought to his senses by being arrested and punished.

Of course things are very different in New England now, but in many country towns the people still make more of Thanksgiving than they do of Christmas; and there are hundreds of New England men and women still living who knew nothing of Christmas as children—who never hung up their stockings; who never waited for Santa Claus; who never had a tree; who never even had a Christmas present!

Nowadays, however, Christmas in New England is like Christmas anywhere else; but here and there, even now, the effects of the early Puritan ideas may still be seen. In some of the smaller and out-of-the-way towns and villages you will find Christmas trees and evergreens in only a very few of the houses, and in some places—particularly in New Hampshire—one big Christmas tree does for the whole town. This tree is set up in the town hall, and there the children go to get their gifts, which have been hung on the branches by the parents. Sometimes the tree has no decorations—no candles, no popcorn strings, no shiny balls. After the presents are taken off and given to the children, the tree remains perfectly bare. There is usually a short entertainment of recitations and songs, and a speech or two perhaps, and then the little folks, carrying their presents with them, go back to their homes.

In certain parts of New Mexico, among the old Spanish settlements, the celebration of Christmas begins more than a week before the day. In the evenings, a party of men and women go together to the house of some friend—a different house being visited each evening. When they arrive, they knock on the door and begin to sing, and when those in the house ask, "Who is there?" they reply, "The Virgin Mary and St. Joseph seek lodgings in your house." At first the inmates of the house refuse to let them in. This is done to carry out the Bible story of Joseph and Mary being unable to find lodgings in Bethlehem. But in a little while the door is opened and the visitors are heartily welcomed. As soon as they enter, they kneel and repeat a short prayer; and when the devotional exercises are concluded, the rest of the evening is spent in merrymaking.

On Christmas eve the people of the village gather together in some large room or hall and give a solemn little play, commemorating the birthday of the Saviour. One end of the room is used as a stage, and this is fitted up to represent the stable and the manger; and the characters in the sacred story of Bethlehem—Mary and Joseph, the shepherds, the wise men, and the angels—are represented in the tableaux, and with a genuine, reverential spirit. Even the poorer people of the town take part in these Christmas plays.

The Shakers observe Christmas by a dinner at which the men and women both sit down at the same table. This custom of theirs is the thing that serves to make Christmas different from any other day among the Shakers. During all the rest of the year the men and women eat their meals at separate tables.

At sunset on Christmas day, after a service in the church, they march to the community-house, where the dinner is waiting. The men sit on one side of the table and the women on the other. At the head sits an old man called the elder, who begins the meal by saying grace, after which each one in turn gets up and, lifting the right hand, says in a solemn voice, "God is love." The dinner is eaten in perfect silence. Not a voice is heard until the meal comes to an end. Then the men and women rise and sing, standing in their places at the table. As the singing proceeds they mark time with their hands and feet. Then their bodies begin to sway from side to side in the peculiar manner that has given this sect its name of Shakers.

When the singing comes to an end, the elder chants a prayer, after which the men and women silently file out and leave the building.

"You'd better look out, or Pelznickel will catch you!" This is the dire threat held over naughty boys and girls at Christmas-time in some of the country settlements of the Pennsylvania Germans, or Pennsylvania Dutch, as they are often called.

Pelznickel is another name for Santa Claus. But he is not altogether the same old Santa that we welcome so gladly. On Christmas eve some one in the neighborhood impersonates Pelznickel by dressing up as an old man with a long white beard. Arming himself with a switch and carrying a bag of toys over his shoulder, he goes from house to house, where the children are expecting him.

He asks the parents how the little ones have behaved themselves during the year. To each of those who have been good he gives a present from his bag. But—woe betide the naughty ones! These are not only supposed to get no presents, but Pelznickel catches them by the collar and playfully taps them with his switch.

The Porto Rican boys and girls would be frightened out of their wits if Santa Claus should come to them in a sleigh drawn by reindeer and should try to enter the houses and fill their stockings. Down there, Santa Claus does not need reindeer or any other kind of steeds, for the children say that he just comes flying through the air like a bird. Neither does he bother himself looking for stockings, for such things are not so plentiful in Porto Rico as they are in cooler climates. Instead of stockings, the children use little boxes, which they make themselves. These they place on the roofs and in the courtyards, and old Santa Claus drops the gifts into them as he flies around at night with his bag on his back.

He is more generous in Porto Rico than he is anywhere else. He does not come on Christmas eve only, but is likely to call around every night or two during the week. Each morning, therefore, the little folks run out eagerly to see whether anything more has been left in their boxes during the night.

Christmas in Porto Rico is a church festival of much importance, and the celebration of it is made up chiefly of religious ceremonies intended to commemorate the principal events in the life of the Saviour. Beginning with the celebration of his birth, at Christmas-time, the feast-days follow one another in rapid succession. Indeed, it may justly be said that they do not really come to an end until Easter.

One of the most popular of these festival-days is that known as Bethlehem day. This is celebrated on the 12th of January, in memory of the coming of the Magi. The celebration consists of a procession of children through the streets of the town. The foremost three, dressed in flowing robes to represent the wise men of the East, come riding along on ponies, holding in their hands the gifts for the Infant King; following them come angels and shepherds and flute-players, all represented by children dressed in pretty costumes and carrying garlands of flowers. These processions are among the most picturesque of all Christmas celebrations.

For many days before Christmas the Moravian housewives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, are busy in their kitchens making good things for the holidays—mint-cakes, pepper-nuts, Kümmelbrod, sugar-cake, mince-pies, and, most important of all, large quantities of "Christmas cakes." These Christmas cakes are a kind of ginger cooky, crisp and spicy, and are made according to a recipe known only to the Moravians. They are made in all sorts of curious shapes—birds, horses, bears, lions, fishes, turtles, stars, leaves, and funny little men and women; so that they are not only good to eat, but are ornamental as well, and are often used by the good fathers and mothers as decorations for the "Putz."

Every Moravian family has its Putz at Christmas-time. This consists of a Christmas tree surrounded at its base by a miniature landscape made up of moss and greens and make-believe rocks, and adorned with toy houses and tiny fences and trees and all sorts of little animals and toy people.

On Christmas eve a love-feast is held in the church. The greater part of the service is devoted to music, for which the Moravians have always been noted. While the choir is singing, cake and coffee are brought in and served to all the members of the congregation, each one receiving a good-sized bun and a large cup of coffee. Shortly before the end of the meeting lighted wax candles carried on large trays are brought into the church, by men on one side and women on the other, and passed around to the little folks—one for each boy and girl. This is meant to represent the coming of the Light into the world, and is but one of the many beautiful customs observed by the Moravians.

"Going around with the star" is a popular Christmas custom among some of the natives of Alaska who belong to the Greek Church. A large figure of a star, covered with brightly colored paper, is carried about at night by a procession of men and women and children. They call at the homes of the well-to-do families of the village, marching about from house to house, headed by the star-bearer and two men or boys carrying lanterns on long poles. They are warmly welcomed at each place, and are invited to come in and have some refreshments. After enjoying the cakes and other good things, and singing one or two carols, they take up the star and move on to the next house.

These processions take place each night during Christmas week; but after the second night the star-bearers are followed by men and boys dressed in fantastic clothes, who try to catch the star-men and destroy their stars. This part of the game is supposed to be an imitation of the soldiers of Herod trying to destroy the children of Bethlehem; but these happy folks of Alaska evidently don't think much about its meaning, for they make a great frolic of it. Everybody is full of fun, and the frosty air of the dark winter nights is filled with laughter as men and boys and romping girls chase one another here and there in merry excitement.

The natives of Hawaii say that Santa Claus comes over to the islands in a boat. Perhaps he does; it would be a tedious journey for his reindeer to make without stopping from San Francisco to Honolulu. At all events, he gets there by some means or other, for he would not neglect the little folks of those islands away out in the Pacific.

They look for him as eagerly as do the boys and girls in the lands of snow and ice, and although it must almost melt him to get around in that warm climate with his furs on, he never misses a Christmas.

Before the missionaries and the American settlers went to Hawaii, the natives knew nothing about Christmas, but now they all celebrate the day, and do it, of course, in the same way as the Americans who live there. The main difference between Christmas in Honolulu and Christmas in New York is that in Honolulu in December the weather is like June in New York. Birds are warbling in the leafy trees; gardens are overflowing with roses and carnations; fields and mountain slopes are ablaze with color; and a sunny sky smiles dreamily upon the glories of a summer day. In the morning people go to church, and during the day there are sports and games and merry-making of all sorts. The Christmas dinner is eaten out of doors in the shade of the veranda, and everybody is happy and contented.

"BUENAS PASQUAS!" This is the hearty greeting that comes to the dweller in the Philippines on Christmas morning, and with it, perhaps, an offering of flowers.

The Filipino, like the Porto Rican and all others who have lived under Spanish rule, look upon Christmas as a great religious festival, and one that requires very special attention. On Christmas eve the churches are open, and the coming of the great day is celebrated by a mass at midnight; and during all of Christmas day mass is held every hour, so that every one may have an opportunity to attend. Even the popular Christmas customs among the people are nearly all of a religious character, for most of them consist of little plays or dramas founded upon the life of the Saviour.

These plays are called pastures, and are performed by bands of young men and women, and sometimes mere boys and girls, who go about from village to village and present their simple little plays to expectant audiences at every stopping-place. The visit of the wise men, the flight into Egypt—these and many other incidents as related in the Scriptures are acted in these pastores.

January 1

The custom of celebrating the first day of the year is a very ancient one. The exchange of gifts, the paying of calls, the making of good resolutions for the new year and feasting often characterize the day. The custom of ringing the church bells is of the widest extent.

The old-world custom of sitting up on New Year's eve to see the old year out is still very common.

The Century Magazine, July 1885

BY EDWARD EGGLESTON

New Year's Day was celebrated among the New York Dutch by the calls of the gentlemen on their lady friends; it is perhaps the only distinctly Dutch custom that afterward came into widespread use in the United States. New Year's Day, and the church festivals kept alike by the Dutch and English, brought an intermission of labor to the New York slaves, who gathered in throngs to devote themselves to wild frolics. The Brooklyn fields were crowded with them on New Year's Day, at Easter, at Whitsuntide, or "Prixter," as the Dutch called it, and on "San Claus Day"—the feast of St. Nicholas.

BY H.H.

The Chinese in California have a week of holiday at their New Year's in February, just as we do between the twenty-fifth of December and the first of January.

In the cities they make a fine display of fire-works. They use barrels full of fire-crackers, and the Chinese boys do not fire them off, as the American boys do, a cracker at a time; they bring out a large box full, or a barrel full, and fire them off package after package, as fast as they can.

In Santa Barbara, where I was during the Chinese New Year's of 1882, we heard the crackers long before we reached Chinatown. After these stopped we went into the houses. Every Chinese family keeps open house on New Year's day all day long. They set up a picture or an image of their god in some prominent place, and on a table in front of this they put a little feast of good things to eat. Some are for an offering to the god and some are for their friends who call. Everyone is expected to take something.

There was no family so poor that it did not have something set out, and some sort of a shrine made for its idol; in some houses it was only a coarse wooden box turned up on one end like a cupboard, with two or three little teacups full of rice or tea, and one poor candle burning before a paper picture of the god pasted or tacked at the back of the box.

It was amusing to watch the American boys darting about from shop to shop and house to house, coming out with their hands full of queer Chinese things to eat, showing them to each other and comparing notes.

"Oh, let me taste that!" one boy would exclaim on seeing some new thing; and "Where did you get it? Which house gives that?" Then the whole party would race off to make a descent on that house and get some more. I thought it wonderfully hospitable on the part of the Chinese people to let all these American boys run in and out of their houses in that way, and help themselves from the New Year's feast.

Some of the boys were very rude and ill-mannered—little better than street beggars; but the Chinese were polite and generous to them all. The joss-house, where they held their religious services, was a chamber opening out upon an upper balcony. This balcony was hung with lanterns and decorated. The door at the foot of the stairs which led to this chamber stood open all day, and any one who wished could go up and say his prayers in the Chinese fashion, which is a curious fashion indeed. They have slender reeds with tight rolls of brown paper fastened at one end. In front of the image or picture of their god they set a box or vase of ashes, on which a little sandalwood is kept burning. When they wish to make a prayer they stick one of the reeds down in these ashes and set the paper on fire. They think the smoke of the burning paper will carry the prayer up to heaven.

I asked a Chinese man who could speak a little English why they put teacups of wine and tea and rice before their god; if they believed that the god would eat and drink.

"Oh, no," he said, "that not what for. What you like self, you give god. He see. He like see."

February 12

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

Born February 12, 1809 Died April 15, 1865

Lincoln was the sixteenth President of the United States. He was descended from a Quaker family of English origin. He followed various occupations, including those of a farm laborer, a salesman, a merchant, and a surveyor; was admitted to the bar in 1836 and began the practice of law in this year. He was twice elected President, the second time receiving 212 out of 233 electoral votes. He was shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford's Theater, Washington, April 14, 1865, and died the following day.

BY HELEN NICOLAY

Abraham Lincoln was not an ordinary man. He was, in truth, in the language of the poet Lowell, a "new birth of our new soil." His greatness did not consist in growing up on the frontier. An ordinary man would have found on the frontier exactly what he would have found elsewhere—a commonplace life, varying only with the changing ideas and customs of time and place. But for the man with extraordinary powers of mind and body, for one gifted by Nature as Abraham Lincoln was gifted, the pioneer life, with its severe training in self-denial, patience, and industry, developed his character, and fitted him for the great duties of his after life as no other training could have done.

His advancement in the astonishing career that carried him from obscurity to world-wide fame—from postmaster of New Salem village to President of the United States, from captain of a backwoods volunteer company to Commander-in-chief of the army and navy—was neither sudden nor accidental nor easy. He was both ambitious and successful, but his ambition was moderate, and his success was slow. And, because his success was slow, it never outgrew either his judgment or his powers. Between the day when he left his father's cabin and launched his canoe on the head waters of the Sangamon River to begin life on his own account, and the day of his first inauguration, lay full thirty years of toil, self-denial, patience; often of effort baffled, of hope deferred; sometimes of bitter disappointment. Even with the natural gift of great genius, it required an average lifetime and faithful, unrelaxing effort to transform the raw country stripling into a fit ruler for this great nation.

Almost every success was balanced—sometimes overbalanced—by a seeming failure. He went into the Black Hawk war a captain, and through no fault of his own came out a private. He rode to the hostile frontier on horseback, and trudged home on foot. His store "winked out." His surveyor's compass and chain, with which he was earning a scanty living, were sold for debt. He was defeated in his first attempts to be nominated for the legislature and for Congress; defeated in his application to be appointed Commissioner of the General Land Office; defeated for the Senate, when he had forty-five votes to begin with, by a man who had only five votes to begin with; defeated again after his joint debates with Douglas; defeated in the nomination for Vice-President, when a favorable nod from half a dozen politicians would have brought him success.

Failures? Not so. Every seeming defeat was a slow success. His was the growth of the oak, and not of Jonah's gourd. He could not become a master workman until he had served a tedious apprenticeship. It was the quarter of a century of reading, thinking, speech-making, and law-making which fitted him to be the chosen champion in the great Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. It was the great moral victory won in those debates (although the senatorship went to Douglas), added to the title "Honest Old Abe," won by truth and manhood among his neighbors during a whole lifetime, that led the people of the United States to trust him with the duties and powers of President.

And when, at last, after thirty years of endeavor, success had beaten down defeat, when Lincoln had been nominated, elected, and inaugurated, came the crowning trial of his faith and constancy. When the people, by free and lawful choice, had placed honor and power in his hands, when his name could convene Congress, approve laws, cause ships to sail and armies to move, there suddenly came upon the government and the nation a fatal paralysis. Honor seemed to dwindle and power to vanish. Was he then, after all, not to be President? Was patriotism dead? Was the Constitution only a bit of waste paper? Was the Union gone?

The outlook was indeed grave. There was treason in Congress, treason in the Supreme Court, treason in the army and navy. Confusion and discord were everywhere. To use Mr. Lincoln's forcible figure of speech, sinners were calling the righteous to repentance. Finally the flag, insulted and fired upon, trailed in surrender at Sumter; and then came the humiliation of the riot at Baltimore, and the President for a few days practically a prisoner in the capital of the nation.

But his apprenticeship had been served, and there was to be no more failure. With faith and justice and generosity he conducted for four long years a war whose frontiers stretched from the Potomac to the Rio Grande; whose soldiers numbered a million men on each side. The labor, the thought, the responsibility, the strain of mind and anguish of soul that he gave to his great task, who can measure? "Here was place for no holiday magistrate, no fair-weather sailor," as Emerson justly said of him. "The new pilot was hurried to the helm in a tornado. In four years—four years of battle days—his endurance, his fertility of resources, his magnanimity, were sorely tried and never found wanting." "By his courage, his justice, his even temper, ... his humanity, he stood a heroic figure in a heroic epoch."

What but a lifetime's schooling in disappointment; what but the pioneer's self-reliance and freedom from prejudice; what but the clear mind quick to see natural right and unswerving in its purpose to follow it; what but the steady self-control, the unwarped sympathy, the unbounded charity of this man with spirit so humble and soul so great, could have carried him through the labors he wrought to the victory he attained?

With truth it could be written, "His heart was as great as the world, but there was no room in it to hold the memory of a wrong." So, "with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gave him to see the right," he lived and died. We, who have never seen him, yet feel daily the influence of his kindly life, and cherish among our most precious possessions the heritage of his example.

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

The above address was delivered by Abraham Lincoln, November 19, 1863, at the dedication of the Gettysburg battle-field as a national cemetery for Union soldiers.

|

O captain. My captain. Our fearful trip is done; The ship has weathered every rack, the prize we sought is won; The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting, While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring: But O heart! Heart! Heart! Leave you not the little spot, Where on the deck my captain lies, Fallen cold and dead. O captain. My captain. Rise up and hear the bells; Rise up—for you the flag is flung—for you the bugle trills; For you bouquets and ribbon'd wreaths—for you the shores a-crowding; For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning; O captain. Dear father. This arm I push beneath you; It is some dream that on the deck, You've fallen cold and dead. My captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still; My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will; But the ship, the ship is anchor'd safe, its voyage closed and done; From fearful trip, the victor ship, comes in with object won: Exult O shores, and ring, O bells. But I with silent tread, Walk the spot the captain lies, Fallen cold and dead. |

February 14

Custom decrees that on this day the young shall exchange missives in which the love of the sender is told in verses, pictures, and sentiments. No reason beyond a guess can be given to connect St. Valentine with these customs. He was a Christian martyr, about 270 A.D., while the practice of sending valentines had its origin in the heathen worship of Juno. It is Cupid's day, and no boy or girl needs any encouragement to make the most of it.

BY OLIVE THORNE

There's one thing we know positively, that St. Valentine didn't begin this fourteenth of February excitement; but who did is a question not so easy to answer. I don't think any one would have begun it if he could have known what the simple customs of his day would have grown into, or could even have imagined the frightful valentines that disgrace our shops to-day.

It began, for us, with our English ancestors, who used to assemble on the eve of St. Valentine's day, put the names of all the young maidens promiscuously in a box, and let each bachelor draw one out. The damsel whose name fell to his lot became his valentine for the year. He wore her name in his bosom or on his sleeve, and it was his duty to attend her and protect her. As late as the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries this custom was very popular, even among the upper classes.

But the wiseacres have traced the custom farther back. Some of them think it was begun by the ancient Romans, who had on the fourteenth or fifteenth of February a festival in honor of Lupercus, "the destroyer of wolves"—a wolf-destroyer being quite worthy of honor in those wild days, let me tell you. At this festival it was the custom, among other curious things, to pair off the young men and maidens in the same chance way, and with the same result of a year's attentions.

Even this is not wholly satisfactory. Who began it among the Romans? becomes the next interesting question. One old writer says it was brought to Rome from Arcadia sixty years before the Trojan war (which Homer wrote about, you know). I'm sure that's far enough back to satisfy anybody. The same writer also says that the Pope tried to abolish it in the fifth century, but he succeeded only in sending it down to us in the name of St. Valentine instead of Lupercus.

Our own ancestry in England and Scotland have observed some very funny customs within the last three centuries. At one time valentines were fashionable among the nobility, and, while still selected by lot, it became the duty of a gentleman to give to the lady who fell to his lot a handsome present. Pieces of jewelry costing thousands of dollars were not unusual, though smaller things, as gloves, were more common.

There was a tradition among the country people that every bird chose its mate on Valentine's day; and at one time it was the custom for young folks to go out before daylight on that morning and try to catch an owl and two sparrows in a net. If they succeeded, it was a good omen, and entitled them to gifts from the villagers. Another fashion among them was to write the valentine, tie it to an apple or orange, and steal up to the house of the chosen one in the evening, open the door quietly, and throw it in.

Those were the days of charms, and of course the rural maidens had a sure and infallible charm foretelling the future husband. On the eve of St. Valentine's day, the anxious damsel prepared for sleep by pinning to her pillow five bay leaves, one at each corner and one in the middle (which must have been delightful to sleep on, by the way). If she dreamed of her sweetheart, she was sure to marry him before the end of the year.

But to make it a sure thing, the candidate for matrimony must boil an egg hard, take out the yolk, and fill its place with salt. Just before going to bed, she must eat egg, salt, shell and all, and neither speak nor drink after it. If that wouldn't insure her a vivid dream, there surely could be no virtue in charms.

Modern valentines, aside from the valuable presents often contained in them, are very pretty things, and they are growing prettier every year, since large business houses spare neither skill nor money in getting them up. The most interesting thing about them, to "grown-ups," is the way they are made; and perhaps even you youngsters, who watch eagerly for the postman, "sinking beneath the load of delicate embarrassments not his own," would like to know how satin and lace and flowers and other dainty things grew into a valentine.

It was no fairy's handiwork. It went through the hands of grimy-looking workmen before it reached your hands.

To be sure, a dreamy artist may have designed it, but a lithographer, with inky fingers, printed the picture part of it; a die-cutter, with sleeves rolled up, made a pattern in steel of the lace-work on the edge; and a dingy-looking pressman, with a paper hat on, stamped the pattern around the picture. Another hard-handed workman rubbed the back of the stamped lace with sand-paper till it came in holes and looked like lace, and not merely like stamped paper; and a row of girls at a common long table put on the colors with stencils, gummed on the hearts and darts and cupids and flowers, and otherwise finished the thing exactly like the pattern before them.

You see, the sentiment about a valentine doesn't begin until Tom, Dick, or Harry takes it from the stationer, and writes your name on it.

February 22

GEORGE WASHINGTON

Born February 22, 1732 Died December 14, 1799

Washington was the first President of the United States, and the son of a Virginia planter. He attended school until about sixteen years of age, was engaged in surveying, 1748-51, became an officer in the Continental army, and President in 1789. He was re-elected in 1793. He was preëminent for his sound judgment and perfect self-control. It is said that no act of his public life can be traced to personal caprice, ambition, or resentment.

BY HORACE E. SCUDDER

It was near the shore of the Potomac River, between Pope's Creek and Bridge's Creek, that Augustine Washington lived when his son George was born. The land had been in the family ever since Augustine's grandfather, John Washington, had bought it, when he came over from England in 1657. John Washington was a soldier and a public-spirited man, and so the parish in which he lived—for Virginia was divided into parishes as some other colonies into townships—was named Washington. It is a quiet neighborhood; not a sign remains of the old house, and the only mark of the place is a stone slab, broken and overgrown with weeds and brambles, which lies on a bed of bricks taken from the remnants of the old chimney of the house. It bears the inscription:

Here

The 11th of February, 1732 (old style)

George Washington

was born

The English had lately agreed to use the calendar of Pope Gregory, which added eleven days to the reckoning, but people still used the old style as well as the new. By the new style, the birthday was February 22, and that is the day which is now observed. The family into which the child was born consisted of the father and mother, Augustine and Mary Washington, and two boys, Lawrence and Augustine. These were sons of Augustine Washington and a former wife who had died four years before. George Washington was the eldest of the children of Augustine and Mary Washington; he had afterward three brothers and two sisters, but one of the sisters died in infancy.

It was not long after George Washington's birth that the house in which he was born was burned, and as his father was at the time especially interested in some iron-works at a distance, it was determined not to rebuild upon the lonely place. Accordingly Augustine Washington removed his family to a place which he owned in Stafford County, on the banks of the Rappahannock River opposite Fredericksburg. The house is not now standing, but a picture was made of it before it was destroyed. It was, like many Virginia houses of the day, divided into four rooms on a floor, and had great outside chimneys at either end.

Here George Washington spent his childhood. He learned to read, write, and cipher at a small school kept by Hobby, the sexton of the parish church. Among his playmates was Richard Henry Lee, who was afterward a famous Virginian. When the boys grew up, they wrote to each other of grave matters of war and state, but here is the beginning of their correspondence, written when they were nine years old.

It looks very much as if Richard Henry sent his letter off just as it was written. I suspect that his correspondent's letter was looked over, corrected, and copied before it was sent. Very possibly Augustine Washington was absent at the time on one of his journeys; but at any rate the boy owed most of his training to his mother, for only two years after this, his father died, and he was left to his mother's care.

She was a woman born to command, and since she was left alone with a family and an estate to care for, she took the reins into her own hands, and never gave them up to any one else. She used to drive about in an old-fashioned open chaise, visiting the various parts of her farm, just as a planter would do on horseback. The story is told that she had given an agent directions how to do a piece of work, and he had seen fit to do it differently, because he thought his way a better one. He showed her the improvement.

"And pray," said the lady, "who gave you any exercise of judgment in the matter? I command you, sir; there is nothing left for you but to obey."