The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or The London Charivari, Volume 101, October 31, 1891, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or The London Charivari, Volume 101, October 31, 1891 Author: Various Editor: Francis Burnand Release Date: March 23, 2005 [EBook #15442] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

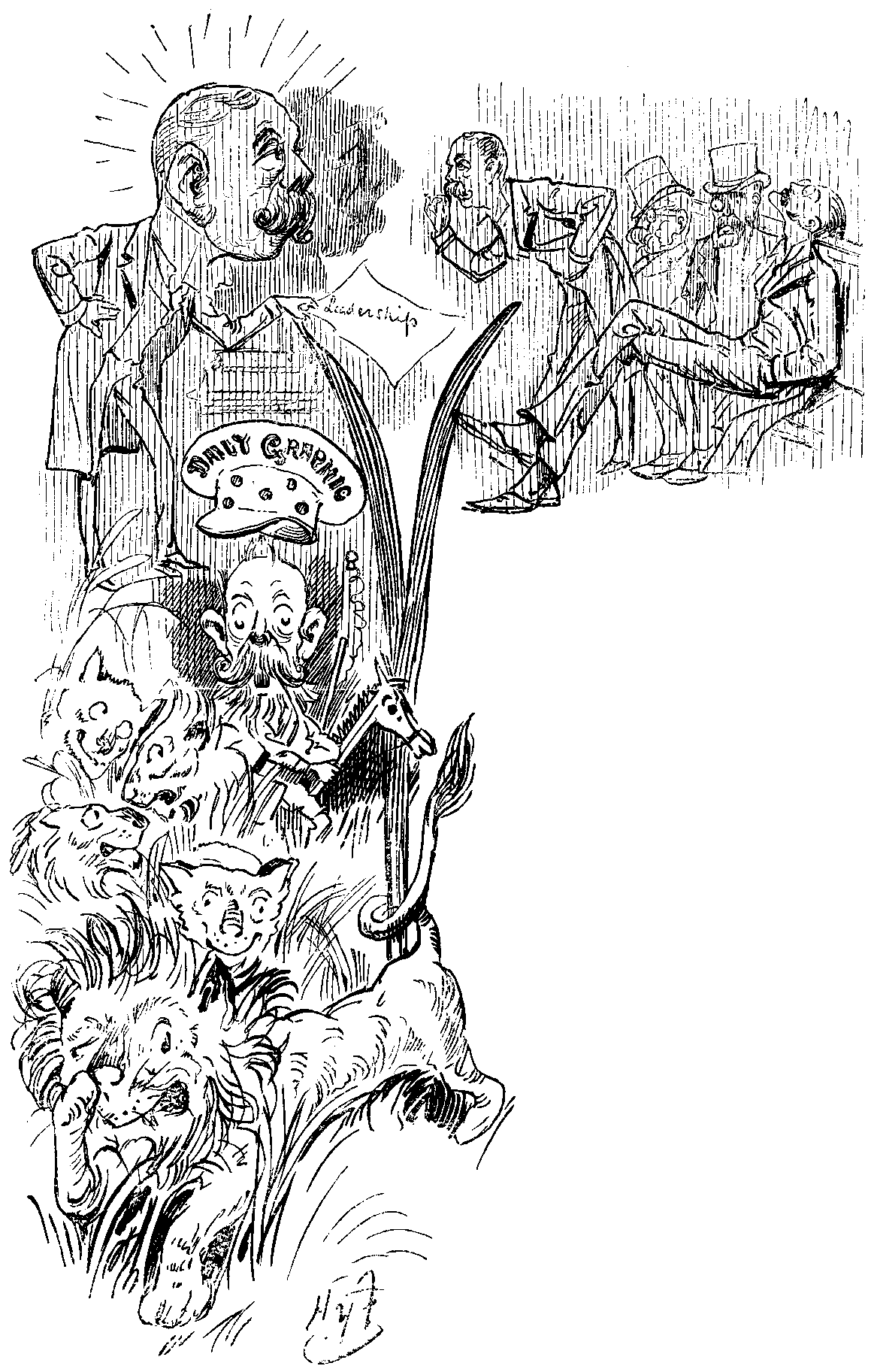

(Afrikander Version of the great Breitmann Ballad, penned, "more in sorrow than in anger," by a "Deutscher" resident in the distant regions where the Correspondent of the "Daily Graphic" is, like der Herr Breitmann himself, "drafellin' apout like eferydings.")

Young GRANDOLPH hat a Barty—

Vhere is dat Barty now?

He fell'd in luf mit der African goldt;

Mit SOLLY he'd hat a row;

He dinks dat his secession

Would make der resht look plue,

But, before he drafel vast and var,

His Barty sphlit in two.

Young GRANDOLPH hat a Barty—

Dere vash B-LF-R, W-LFF, and G-RST,

Dey haf vorgot deir "Leater,"

Und dat ish not deir vorst.

B-LF-R vill "boss" der Commons,

Vhile GRANDOLPH—sore disgraced—

Ish "oop a tree," like der Bumble Bee,

Und W-LFF and G-RST are "placed."

Young GRANDOLPH hat a Barty—

Vhen he dat Barty led,

B-LF-R vash but a "Bummer,"

A loafing lollop-head.

Young Tories schvore by GRANDOLPH,

(Dey schvear at GRANDOLPH now,)

Now at de feet of der "lank æsthete"

Der Times itshelf doth bow!

Young GRANDOLPH hat a Barty,

Dere all vash "Souse und Brouse."1

Now he hets not dat prave gompany

All in der Commons House,

To see him skywgle GL-DST-NE,

Und schlog him on der kop.

Young Tory bloods no longer shout

Till der SCHPEAKER bids dem shtop.

Und, like dat Rhine Mermaiden

"Vot hadn't got nodings on,"

Dey "don't dink mooch of beoplesh

Vat goes mit demselfs alone!"

Young GRANDOLPH hat a Barty—

Where ish dat Barty now?

Where ish dat oder ARTHUR's song

Vot darkened der Champerlain's prow?

Where ish de himmelstrahlende stern,

De shtar of der Tory fight?

All gon'd afay, as on Woodcock's wing,

Afay in de ewigkeit!

Young GRANDOLPH hat a Barty;

He hunt der lions now,

All in der lone Mashonaland,

But he does not "score"—somehow.

One Grand Old Lion he dared to peard,

Und he "potted" Earls and Dukes,

But eight or nine real lions at once,

He thinks are "trop de luxe"

Young GRANDOLPH hat a Barty,

But he scooted 'cross der sea,

Und he tidn't say to dem, "Come, my poys,

Und drafel along mit me!"

Footnote 1: (return)Saus und Braus—Ger., Riot and Bustle.

"CORRECT CARD, GENTS!"—"Wanted a Map of London" was the heading of a letter in the Times last Thursday. No, Sir! that's not what is wanted. There are hundreds of 'em, specially seductive pocket ones, with just the very streets that one wants to discover as short cuts to great centres carefully omitted. What is wanted is a correct map of London, divided into pocketable sections, portable, foldable, durable, on canvas,—but if imperfect, as so many of these small pocket catch-shilling ones are just now, although professedly brought up to date '91, they are worse than useless, and to purchase one is a waste of time, temper and money. We could mention an attractive-looking little map—which, but no— Publishers and public are hereby cautioned! N.B.—Test well your pocket map through a magnifying glass before buying. Experto crede!

[Oysters are very dear, and are likely, as the season advances, to be still higher in price.]

Oh, Oyster mine! Oh, Oyster mine!

You're still as exquisitely nice;

With perfect pearly tints you shine,

But you are such an awful price.

The lemon and the fresh cayenne,

Brown bread and butter and the stout

Are here, and just the same, but then

What if I have to leave you out?

What wonder that my spirits droop,

That life can bring me no delight,

When I must give up oyster soup,

So softly delicately white.

The curry powder stands anear,

The scallop shells, but what care I—

You're so abominably dear,

O Oyster! that I cannot buy.

With sad imaginative flights,

I think upon the days of yore;

Like TICKLER, on Ambrosian nights,

I have consumed them by the score.

And still, whenever you appeared,

My pride it was to use you well;

I let the juice play round your beard,

And always on the hollow shell.

I placed you in the fair lark-pie.

With steak and kidneys too, of course;

Your ancestors were glad to die,

So well I made the oyster sauce.

I had you stewed and featly fried,

And dipped in batter—think of that;

And, as a pleasant change, I've tried

You, skewered in rows, with bacon-fat.

"Where art thou, ALICE?" cried the bard.

"Where art thou, Oyster?" I exclaim.

It really is extremely hard,

To know thee nothing but a name.

For this is surely torment worse

Than DANTE heaped upon his dead;—

To find thee quite beyond my purse,

And so go oysterless to bed.

À PROPOS OF THE SECRETARY FOR WAR'S ROSEATE AFTER—DINNER SPEECH (on the entirely satisfactory state of the Army generally).—(STAN-)"HOPE told a flattering tale."

UNIVERSITY MEM.—The Dean of Christ Church will keep his seat till Christmas, and just a LIDDELL longer.

Secretarial Pangloss sings:—

Late, upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, tired but cheery,

Over many an optimistic record of War Office lore;

Whilst I worked, assorting, mapping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of someone rudely rapping, rapping at my Office-door.

"Some late messenger," I muttered, "tapping at my Office-door—

Only this, but it's a bore."

I remember—being sober—it was in the chill October,

Light from the electric globe or horseshoe lighted wall and floor;

Also that it was the morrow of the Holborn Banquet; sorrow

From the Blue Books croakers borrow—sorrow for the days of yore,

For the days when "Rule Britannia" sounded far o'er sea and shore.

Ah! it must have been a bore!

But on that let's draw the curtain. I am simply cock-sure—certain

That "our splendid little Army" never was so fine before.

It will take a lot of beating! Such remarks I keep repeating;

They come handy—after eating, and are always sure to score—

Dash that rapping chap entreating entrance at my Office-door!

It is an infernal bore!

[pg 207]Presently I grew more placid (Optimists should not be acid.)

"Come in!" I exclaimed—"confound you! Pray stand drumming there no more."

But the donkey still kept tapping. "Dolt!" I muttered, sharply snapping,

"Why the deuce do you come rapping, rapping at my Office-door?

Yet not 'enter' when you're told to?"—here I opened wide the door—

Darkness there, and nothing more.

Open next I flung the shutter, when, with a prodigious flutter,

In there stepped a bumptious Raven, black as any blackamoor.

Not the least obeisance made he, not a moment stopped or stayed he,

But with scornful look, though shady, perched above my Office-door,

Perched upon BRITANNIA's bust that stood above my Office-door—

Perched, and sat, and seemed to snore.

"Well," I said, sardonic smiling, "this is really rather riling;

"It comports not with decorum such as the War Office bore

In old days stiff and clean-shaven. Dub me a Gladstonian craven

If I ever saw a Raven at the W.O. before.

Tell me what your blessed name is. 'Rule Britannia' held of yore,"

Quoth the bird, "'Tis so no more!"

Much I marvelled this sophistic fowl to utter pessimistic

Fustian, which so little meaning—little relevancy bore

To the rule of me and SOLLY; but, although it may sound folly,

This strange fowl a strange resemblance to "Our Only General" wore,

To the W-LS-L-Y whose pretensions to sound military lore

Are becoming quite a bore.

But the Raven, sitting lonely on that much-peeled bust, spake only

Of our Army as a makeshift, small, ill-manned, and precious poor.

Drat the pessimistic bird!—he grumbled of "the hurdy-gurdy

Marching-past side of a soldier's life in peace." "We've fought before,

Winning battles with boy-troops," I cried, "We'll do as we before—"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore!"

"Nonsense!" said I. "After dinner at the Holborn, as a winner

Spake I in the Pangloss spirit to the taxpayers, (Don't snore!)

Told them our recruits—who'll master e'en unmerciful disaster,

Come in fast and come in faster, quite as good as those of yore,"—

"Flattering tales of (Stan) Hope!" cried the bird, whose dismal dirges bore,

One dark burden—"Nevermore!"

"Hang it, Raven, this is riling!" cried I. "Stop your rude reviling!"

Then I wheeled my office-chair in front of bird and bust and door;

And upon its cushion sinking, "I," I said, "will smash like winking

This impeachment you are bringing, O you ominous bird of yore,

O you grim, ungainly, ghastly, grumbling, gruesome feathered bore!"

Croaked the Raven, "You I'll floor."

Then methought the bird looked denser, and his cheek became immenser.

And he twaddled of VON MOLTKE, and his German Army Corps;

"Flattering the tax-payers' vanity," and much similar insanity,

In a style that lacked urbanity, till the thing became a bore.

"Oh, get out of it!" I cried; "our little Army yet will score."

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore!"

"Prophet!" said I, "of all evil, that we're 'going to the devil'

Has been the old croaker's gospel for a century, and more.

Red-gilled Colonels this have chaunted in BRITTANIA's ears undaunted,

By their ghosts you must he haunted. Take a Blue-pill, I implore!

When our Army meets the foe it's bound to lick him as of yore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore!

"Prophet!" said I, "that's uncivil. You may go to—well, the devil!

That Establishments are 'short,' and 'standards' lowered o'er and o'er.

That mere 'weeds,' with chests of maiden, cannot march with knapsack laden;

That the heat of sultry Aden, or the cold of Labrador,

Such can't stand, may be the truth; but keep it dark, bird, I implore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore!"

"Then excuse me, we'll be parting, doleful fowl," I cried, upstarting;

"Get thee back to—the Red River, or the Nile's sand-cumbered shore!

Leave no 'Magazine' as token of the twaddle you have spoken.

What? BRITANNIA stoney-broken? Quit her bust above my door.

Take thy hook from the War Office; take thy beak from off my door!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore!"

And the Raven still is sitting, croaking statements most unfitting,

On BRITANNIA's much-peeled bust that's placed above my Office-door,

And if Pangloss, e'en in seeming, lent an ear to his dark dreaming,

Useless were official scheming, grants of millions by the score,

For my soul were like the shadow that he casts upon the floor,

Dark and dismal evermore!

Aunt Jane. "THAT MAKES THREE WEDDINGS IN OUR FAMILY WITHIN A TWELVEMONTH! IT WILL BE YOUR TURN NEXT, MATILDA!"

Matilda. "OH, NO!"

Aunt Jane. "WELL, THE MOST EXTRAORDINARY THINGS HAPPEN SOMETIMES, YOU KNOW!"

["The range of our inquiry was intended to include the whole migratory range for seals.... Our movements were kept most secret."—Sir George Baden-Powell on the Work of the Behring Sea Commission.]

We came, we saw, we—held our tongues (myself—BADEN-POWELL—and Mr. DAWSON.)

We popped on each seal-island "unbeknownst," and what we discovered we held our jaws on.

We'd five hundred interviews within three months, which I think "cuts the record" in interviewing,

Corresponded with 'Frisco, Japan, and Russia; so I hope you'll allow we've been "up and doing."

(Not up and saying, be't well understood). As TUPPER (the Honourable C.H., Minister

Of Fisheries) said, in the style of his namesake, "The fool imagines all Silence is sinister,

"But the wise man knows that it's often dexterous." Be sure no inquisitive shyness or bounce'll

Make us "too previous" with our Report, which goes first to the QUEEN and the Privy Council.

Some bigwig's motto is, "Say and Seal," but as TUPPER remarked a forefinger laying

To the dexter side of a fine proboscis, "Our motto at present is, Seal without saying!"

LEGAL QUERY.—The oldest of the thirteen Judges on the Scotch Bench is YOUNG. Any chance for a Junior after this?

SCENE—In front of the Hôtel Bodenhaus at Splügen. The Diligence for Bellinzona is having its team attached. An elderly Englishwoman is sitting on her trunk, trying to run through the last hundred pages of a novel from the Hotel Library before her departure. PODBURY is in the Hotel, negotiating for sandwiches. CULCHARD is practising his Italian upon a very dingy gentleman in smoked spectacles, with a shawl round his throat.

The Dingy Italian (suddenly discovering CULCHARD's nationality). Ecco, siete Inglese! Lat us spika Ingelis, I onnerstan' 'im to ze bottom-side. (Laboriously, to CULCHARD, who tries to conceal his chagrin.) 'Ow menni time you employ to go since Coire at here? (C. nods with vague encouragement.) Vich manners of vezzer you vere possess troo your travels—mosh ommerella? (C.'s eyes grow vacant.) Ha, I tink it vood! Zis day ze vicket root sall 'ave plenti 'orse to pull, &c., &c. (Here PODBURY comes up, and puts some rugs the coupé of the diligence.) You sit at ze beginning-end, hey? better, you tink, zan ze mizzle? I too, zen, sall ride at ze front—we vill spika Ingelis, altro!

Podb. (overhearing this, with horror). One minute, CULCHARD. (He draws him aside.) I say, for goodness' sake, don't let's have that old organ-grinding Johnny in the coupé with us!

Culch. Organ-grinder! you are so very insular! For anything you can tell, he may be a decayed nobleman.

Pod. (coarsely). Well, let him decay somewhere else, that's all! Just tell the Conductor to shove him in the intérieur, do, while I nip in the coupé and keep our places.

[CULCHARD, on reflection, adopts this suggestion, and the Italian Gentleman, after fluttering feebly about the coupé door, is unceremoniously bundled by the Conductor into the hinder part of the diligence.

Culch. Glorious view one gets at each fresh turn of the road, PODBURY! Look at Hinter-rhein, far down below there, like a toy village, and that vast desolate valley, with the grey river rushing through it, and the green glacier at the end, and these awful snow-covered peaks all round—look, man!

Podb. I'm looking, old chap. It's all there, right enough!

Culch. (vexed). It doesn't seem to be making any particular impression on you, I must say!

Podb. It's making me deuced peckish, I know that—how about lunch, eh!

Culch. (pained). We are going through scenery like this, and all you think of is—lunch! (PODBURY opens a basket.) You may give me one of those sandwiches. What made you get veal? and the bread's all crust, too! Thanks, I'll take some claret.... (They lunch; the vehicle meanwhile toils up to the head of the Pass.) Dear me, we're at the top already! These rocks shut out the valley altogether—much colder at this height, eh? Don't you find this keen air most exhilarating?

Podb. (shivering). Oh very, do you mind putting your window up? Thanks. You seem uncommon chirpy to-day. Beginning to get over it, eh?

Culch. We shan't get over it for some hours yet.

Podb. I didn't mean the Pass, I meant—(hesitating)—well, your little affair with Miss PRENDERGAST, you know.

Culch. My little affair? Get over? (He suddenly understands.) Oh, ah, to be sure. Yes, thank you, my dear fellow, it is not making me particularly unhappy. [He goes into a fit of silent laughter.

Podb. Glad to hear it. (To himself.) 'Jove, if he only knew what I know! [He chuckles.

Culch. You don't appear to be exactly heartbroken?

Podb. I? why should I be—about what?

Culch. (with an affectation of reserve). Exactly, I was forgetting. (To himself.) It's really rather humorous. (He laughs again.) Ha, we're beginning to go down now. Hey for Italy—la bella Italia! (The diligence takes the first curve.) Good Heavens, what a turn! We're going at rather a sharp pace for downhill, eh? I suppose these Swiss drivers know what they're about, though.

Podb. Oh, yes, generally—when they're not drunk. I can only see this fellow's boots—but they look to me a trifle squiffy.

Culch. (inspecting them, anxiously). He does seem to drive very recklessly. Look at those leaders—heading right for the precipice.... Ah, just saved it! How we do lurch in swinging round!

Podb. Topheavy—I expect, too much luggage on board—have another sandwich?

Culch. Not for me, thanks. I say, I wonder if it's safe, having no parapet, only these stone posts, eh?

Pod. Safe enough—unless the wheel catches one—it was as near as a toucher just then—aren't you going to smoke? No? I am. By the way, what were you so amused about just now, eh?

Culch. Was I amused? (The vehicle gives another tremendous lurch.) Really, this is too horrible!

Podb. (with secret enjoyment). We're right enough, if the horses don't happen to stumble. That off-leader isn't over sure-footed—did you see that? (Culch. shudders.) But what's the joke about Miss PRENDERGAST?

Culch. (irritably). Oh, for Heaven's sake, don't bother about that now. I've something else to think about. My goodness, we were nearly over that time! What are you looking at?

Podb. (who has been leaning forward). Only one of the traces—they've done it up with a penny ball of string, but I daresay it will stand the strain. You aren't half enjoying the view, old fellow.

Culch. Yes, I am. Magnificent!—glorious!—isn't it?

Podb. Find you see it better with your eyes shut? But I say, I wish you'd explain what you were sniggering at.

Culch. Take my advice, and don't press me, my dear fellow; you may regret it if you do!

Podb. I'll risk it. It must be a devilish funny joke to tickle you like that. Come, out with it!

Culch. Well, if you must know, I was laughing.... Oh, he'll never get those horses round in.... I was—er—rather amused by your evident assumption that I must have been rejected by Miss PRENDERGAST.

Podb. Oh, was that it? And you're nothing of the kind, eh? [He chuckles again.

Culch. (with dignity). No doubt you will find it very singular; but, as a matter of fact, she—well, she most certainly did not discourage my pretensions.

Podb. The deuce she didn't! Did she tell you RUSKIN's ideas about courtship being a probation, and ask you if you were ready to be under vow for her, by any chance?

Culch. This is too bad, PODBURY; you must have been there, or you couldn't possibly know!

Podb. Much obliged, I'm sure. I don't listen behind doors, as a general thing. I suppose, now, she set you a trial of some kind, to prove your mettle, eh? [With another chuckle.

Culch. (furiously). Take care—or I may tell you more than you bargain for!

Podb. Go on—never mind me. Bless you, I'm under vow for her, too, my dear boy. Fact!

Culch. That's impossible, and I can prove it. The service she demanded was, that I should leave Constance at once—with you. Do you understand—with you, PODBURY!

Podb. (with a prolonged whistle). My aunt!

Culch. (severely). You may invoke every female relative you possess in the world, but it won't alter the fact, and that alone ought to convince you—

Podb. Hold on a bit. Wait till you've heard my penance. She told me to cart you off, Now, then!

Culch. (faintly). If I thought she'd been trifling with us both like that, I'd never—

Podb. She's no end of a clever girl, you know. And, after all, she may only have wanted time to make up her mind.

Culch. (violently). I tell you what she is—she's a cold-blooded pedantic prig, and a systematic flirt! I loathe and detest a prig, but a flirt I despise—yes, despise, PODBURY!

Podb. (with only apparent irrelevance). The same to you, and many of 'em, old chap! Hullo, we're going to stop at this inn. Let's get out and stretch our legs and have some coffee.

[They do; on returning, they find the Italian Gentleman smiling blandly at them from inside the coupé.

The It. G. Goodaby, dear frens, a riverderla! I success at your chairs. I vish you a pleasure's delay!

Podb. But I say, look here, Sir, we're going on, and you've got our place!

The It. G. Sank you verri moch. I 'ope so. [He blows PODBURY a kiss.

[pg 209]Podb. (with intense disgust). How on earth are we going to get that beggar out? Set the Conductor at him, CULCHARD, do—you can talk the lingo best!

Culch. (who has had enough of PODBURY for the present). Talk to him yourself, my dear fellow, I'm not going to make a row. [He gets in.

Podb. (to Conductor). Hi! sprechen sie Französisch, oder was? il-y-a quelque chose dans mon siège, dites-lui de—what the deuce is the French for "clear out"?

Cond. Montez, Monsieur, nous bartons, montez vîte alors!

[He thrusts PODBURY, protesting vainly, into the intérieur, with two peasants, a priest and the elderly Englishwoman. The diligence starts again.

Tuesday, October 20th.—Opening night. Roméo et Juliette; débuts of Mlle. SIMMONET, of the Opera Comique, and M. COSSIRA, as the lovers. Lady Capulet's Small Dance, quite the smartest of the season, as the Veronese nobility present were evidently remarking, with abundance of easy gesture, to one another, as they led the way to the lemonade. The Juliette of the evening charming, and soon singing herself into the good graces of a large audience; ditto, M. COSSIRA, "than which," as the Prophet NICHOLAS would say, "a more competent Roméo—though perhaps a trifle full in the waist for balcony-scaling by moonlight." If he had really trusted himself to that gossamer ladder in the Fourth Act, he would never have got away to Mantua, especially as Juliette, with the thoughtlessness of her age and sex, omitted to secure it in any way. Fortunately it was not a long drop, and the descent was accomplished without accident, as will be seen from the accompanying sketch.

CHANGE FOR A TENOR.—Mr. SEYMOUR HADEN, the opponent of the Cremation gospel according to THOMPSON (Sir HENRY of that ilk), should come to an arrangement with the English Light Opera tenor, and tack COFFIN on to his name.

It may be interesting at this time of the year to mention the fact that Lord SALISBURY always uses a poker in cracking walnuts. He says it saves the silver. The other day, whilst wielding the poker across the walnuts and the wine, Mr. GLADSTONE chanced to look in. The Premier, with his well-known hospitality, immediately furnished the Right Hon. Gentleman with another poker (brought in from the drawing-room), and ordered up a fresh supply of nuts.

Mr. GLADSTONE, recurring in private conversation to a recent visit paid by him to Lord SALISBURY in Arlington Street, questioned the convenience of a poker as an instrument for shattering the shell of the walnut. For himself, he says, he has always found a pair of tongs more convenient.

The Marquis of HARTINGTON, to whom this remark was reported, observed that as a dissentient Liberal he naturally differed from Mr. GLADSTONE, and was not to the fullest extent able to agree with his noble friend, the Marquis of SALISBURY. For his own part, he found the most convenient way of cracking a walnut was deftly to place the article in the interstice of the dining-room door, and gently close it. He found this plan combined with its original purpose a gentle exercise on the part of the guests highly conducive to digestion.

Two hours later, the Leader of the Opposition was seen walking up Arlington Street, and on reaching Piccadilly, he hailed an omnibus, observing the precaution before entering of requiring the conductor to produce the scale of charges. "No pirate busses for me," the Right Hon. Member remarked, as (omitting the oath) he took his seat.

It is no secret in official circles that before the vacancy in the office of Postmaster-General was filled, it was placed at the disposal of the BARON BE BOOK-WORMS. Upon Sir JAMES FERGUSSON stepping in, the PRIME MINISTER was urgently desirous to have the collaboration of the noble BARON at the Foreign Office. But, somehow, the post of Under-Secretary vacated by Sir JAMES was assigned to Mr. WILLIAM JAMES LOWTHER.

We are authorised to state that His Imperial Majesty the Emperor of GERMANY, feeling the need of a little change, has resolved to stay at home for a fortnight.

We are in a position to state that just prior to the General Election of 1880, Mr. CHAMBERLAIN was observed standing before a cheval glass, alternatively fixing his eyeglass in the right eye and in the left. Asked why he should thus quaintly occupy his leisure moments, he replied: "It is in view of the General Election. If on the platform any person in the crowd poses you with an awkward question, should you be able rapidly to transfer your eyeglass from your right eye to your left, and fix the obtruder with a stony stare, he is so much engaged in wondering whether you can keep the glass in position, that he forgets what he asked you, and you can pass on to less dangerous topics."

When Mr. SCHOMBERG McDONNELL informed his chief that Lord RANDOLPH CHURCHILL had "come upon eight lions," Lord SALISBURY sighed and remained for a moment in deep thought. Then he said, "How different had the eight lions come upon him!"

Mr. GLADSTONE has backed himself to walk a mile, talk a mile, write a mile, review a mile, disestablish a mile, chop a mile and hop a mile in one hour. Sporting circles are much interested in the veteran statesman's undertaking, and little else is talked about at the chief West End resorts. The general opinion of those who ought to know seems to be in favour of the scythe-bearer, but not a few have invested a pound or two on the Mid-Lothian Marvel.

"WHAT, MY DEAR REGINALD! YOU DON'T MEAN TO SAY YOU DON'T ADMIRE BYRON AS A POET?"

"CERTAINLY NOT. INDEED I HAVE A QUITE SPECIAL LOATHING AND CONTEMPT FOR HIM IN THAT PARTICULAR CHARACTAH!"

"DEAR ME! WHY, WHAT PARTICULAR POEMS OF HIS DO YOU OBJECT TO SO STRONGLY?"

"MY DEAH GRANDMOTHAH, I NEVAH READ A LINE OF BYRON IN MY LIFE,—AND I CERTAINLY NEVAH MEAN TO!"

["The natural result of a rapprochement between Russia and Italy, even if avowedly platonic in its character, would be to weaken the prestige and moral force of the Triple Alliance."—The Times.]

Pst! Hang it, quite au mieux! Now what am I to do?

I must draw her attention, if I'm going to have a chance.

She seems so satisfied with those gallants at her side

That just now in my direction she will hardly deign a glance.

Pst! Darling, just a word!

No! Deaf as any post! It is perfectly absurd!

Pst! Heeds me not the least, just as though I were the Beast,

And she the sovereign Beauty that she deems she is, no doubt.

Since she won those burly beaux, it appears to be no go,

But Bruin's an old Masher, and he knows what he's about.

Pst! Darling, look this way!

In your pretty little ear I've a word or two to say!

The coy Gallic girl I've won. It is really awful fun,

For her prejudice was strong as was that of Lady ANNE

To the ugly crookback, DICK. But my wooing there was quick.

Platonic? Oh! of course. That is always Bruin's plan.

A flirtation means no harm,

When you wish not to corrupt or betray, but simply charm.

Fancy Italian girl won by the swagger twirl

Of an Austrian moustache! It is monstrous, nothing less.

What would GARIBALDI say? Well, he doesn't live to-day,

Or he'd tear her from the arm of her ancient foe, I guess.

And that stalwart Teuton too!

Do you really think, my girl, he can really care for you?

Ah! you always were a flirt, Miss ITALIA. You have hurt

France's feelings very much. Why, she stood your faithful friend

When the hated Austrian yoke bowed your neck. Did you invoke

The pompous Prussian then your captivity to end?

Pst! Just a moment, dear.

I've a word or two to say it were worth your while to hear.

Ah! A hasty glance she throws o'er her shoulder. But for those

Big, blonde, burly bullies twain, I could win her, I am sure;

For my manners all girls praise, and I have such winning ways,

And my lips, for kisses made, are for love a lasting lure.

Pst! How those two stride on,

Without a glance at me! Do they think the game is won?

Hrumph! The Bear, although polite, is as pertinacious, quite,

As the tactless Teuton pig. I'll yet spoil their little game.

Triple Alliance? Fudge! If that girl is a good judge,

She will make a third with Me and my latest Gallic "flame."

Pst! Come along with me,

My dark Italian belle! We shall make a lovely Three!

ACCI-DENTAL QUERY.—Let me ask the Patres Conscripti of our Academy Royal, why Dentists are not admitted A.R.A. ex officio. We have all for ever so long, since the memory of the oldest JOE MILLER, which runneth not to the contrary, known that Dentists drew teeth. But they nowadays add to their accomplishments by painting gums. The other day a friend of ours had a gum beautifully painted by a Dentist-artist in a certain Welbeck Street studio. It was a wonderful gathering; our friend in the chair.

To the humorous mind of a cynical cast,

Party change many matters for mirth affords;

But of all the big jokes, we've the biggest at last,

In CHAMBERLAIN's backing the House of Lords!

They toil not, nor spin? That's a very old jeer!

Won't the Lilies take back seats when JOE is a Peer?

[Lord ADDINGTON, speaking recently at a Harvest Festival, said, "If he were a labourer, and saw a rabbit nibbling his cabbages, he would go for that rabbit with the first thing at hand." (Enthusiastic cheers.)—Daily News.]

Lord ADDINGTON, most wonderful

Of people-pleasing peers,

You certainly contrived to raise

"Enthusiastic cheers."

The villagers come flocking in

From all the country through,

To hear Your Lordship speak his mind

And tell them what to do.

You did it well, you told them how

You'd have them understand

A lucky chance has made you own

A quantity of land.

Though very fond of shooting, yet

Your love of shooting stops

At letting rabbits have their way

At decimating crops.

And so, if you a labourer were,

(The which of course you're not),

And saw a rabbit in your ground

A-nibbling—on the spot

You'd go for him with spade or fork,

At which, so it appears,

There rang throughout the crowded room

"Enthusiastic cheers."

A Peer's advice is always good,

So doubtless they will grab it,—

But no one will be happier than

The cabbage-nibbling rabbit!

["At the meeting of the Bermondsey Vestry, the Medical Officer reported that water drawn from the service-pipe of a house in the Jamaica Road, had been submitted to him. The water was clear, but it contained a live horse-leech."—Daily Paper.]

Oh, into our domestic pipes

They crawl and creep by stealth,

The gruesome creatures known unto

An Officer of Health!

Harken to him of Bermondsey,

Think what his murmurings teach,

"The water seemed quite limpid, but—

It did contain a Leech!"

The service-pipe was sound and good

In the Jamaica Road;

The cistern there had harboured ne'er

Microbe, or newt, or toad;

No clearer water softly laved

A coral island beach;

So thought the householder, until—

He found that awful Leech!

Perchance he was a temperance foe

To alcoholic drink,

And from all dalliance with Bung

Did scrupulously shrink.

Yet now to forms of fluid sin

He'll cotton, all and each;

He does not like such liquors, but—

Prefers them to a Leech!

Our pipes will not be pipes of peace

If such things hap, I trow;

And as for Water Trusts, 'tis hard

To trust in water now.

Oh, Co. of Southwark and Vauxhall,

We ratepayers beseech,

Double your filtering charges, but—

Remove the loathly Leech!

There is a judicial review of GEORGE MEREDITH's work in the Quarterly for October—masterly, too, quoth the Baron, as striking a balance between effect and defect, and finding so much to be duly said in high praise of the diffuse and picturesquely-circumnavigating Novelist through whose labyrinthine pages the simple Baron finds it hard to thread his way, and yet keep the clue. When the unskippingly conscientious peruser of GEORGE M.'s novels is most desirous that the author shall go ahead, GEORGE, like an Irish cardriver, will stop to "discoorse us," and at such length, and so diffusely, and with such a wealth of eccentric word-coming and grammar-dodging, that at last the Baron gasps, choked by the rolling billows of sonorously booming or boomingly sonorous words, battles with the waves, ducks, and comes up again breathlessly, wondering where he may be, and what it was all about. "Story! God bless you, I haven't much to tell, Sir!" says the luxuriantly fanciful novel-grinder. And he hasn't much, it must be owned, for essenced it would go into half a volume, or less, and all over and above is pot-fuls of rich colour, spilt about almost at haphazard, permutations and combinations, giving the effect of genius. Which—genius it is; but a little of it goes a great way, in fact, a very great way, wandering and straying until at length the Baron calls for his Richard Feverel, and says, "This is the best that GEORGE MEREDITH has written, as sure as my name is

There was a poor Poet named CLOUGH,

Poet SWINBURNE declares he wrote stuff.

Ah, well, he is dead!

'Tis the living are fed,

By log-rollers, on butter and puff.

A SUGGESTION.—In a new poetical play at the Opera Comique there is a good deal of hide-and-seek. It might have had a second title, and been appropriately called The Queen's Room; or, Secret Passages in the Life of Mary Stuart.

["If we really used the Thames Embankment sensibly and liberally, it would abound with handsome shops and cheerful cafés a and volksgartens, with newspaper kiosks and long lines of bookstalls."—Daily Telegraph, Oct. 21.]

"Water, water everywhere" in the Times recently, except when Messrs. GILBEY wrote their annual, and this time hopeful, account of the Claret vintage, and when subsequently Messrs. "P. and G."—(who on earth are "P. and G."?)—with a few modest lines at the foot of a page, last Wednesday, enlivened our drooping spirits with a brief but satisfactory account of Champagne Prospects. If the vintages of '86 and '87 are good, and those of '90 and '91 poor, why not make a blend? and why not sell it as such? Let "P. and G."—[confound it! who on earth can P. and G. be? "P. and J." would be "Punch and Judy"—and, by the way, in the choice Lingua Tuscana, "P. and G." would stand for "Poncio è Giulia." But, on the other hand, who, unauthorised, would dare to use this signature? No matter—where were we?—ah!—to resume.] Let "P. and G.," whoe'er they be—which is rhyme, though not so intended—(but why this masquerade in initials?)—let them exploit a "Blend of '90-cum-'86 and '91-cum-'87," sell it as such—viz., The "P. and G. Blend," or "The Punchius and Giulia Blend"—at a reasonable figure, and thus the Not-quite-up-to-the-mark vintages will be saved. Have we not seen in City partnerships how a strong house saves a failing one, and then the Blends go on successfully? Let "P. and G." give us a first-rate Champagne, call it, say, The "G.B.," or "Golden Blend," at a reasonable price, and, to drop once again into poetry, No matter what their name may be, We'll ever bless our P. and G.!2

Footnote 2: (return)"P. and G." might stand for "Pay-for-it and Get-it," or "Pour-it and Guzzle-it." A Correspondent has suggested that solution of the initial problem might possibly be found in the names of Pommery and Gre'—No! So common-place a suggestion is evidently, and on the face of it, absurd. Not in this spirit did the Pickwick Club treat the celebrated inscription on the stone that so puzzled the antiquarians.

Cockney Sportsman (eager, but disappointed). "I SAY, MY BOY, SEEN ANY BIRDS THIS WAY?"

'Cute Rustic (likewise anxious to make a bag). "OH, A RARE LOT, GUV'NOR—A RARE LOT—JUST FLEW OVER THIS 'ERE 'EDGE, AND SETTLED IN THAT 'ERE FIELD, CLOSE TO SQUIRE BLANK'S RICKS."

[Grateful Cockney Sportsman tips boy a shilling, and goes hopefully after ... a flock of Starlings!

AUGUSTUS SPARKLER was an exceptionally brilliant man. At school he had done marvellously well, and if he did not distinguish himself at either of the Universities, it was less his fault than his misfortune. When he entered the world, after casting off parental control, he took up Medicine. He was a great success. He rose by leaps and bounds, until at length it was thought highly probable that he would be elected President of the Royal College of Physicians. He was sounded upon the subject, and a question was put to him.

"No," he replied, sorrowfully, and then the courteous Secretary informed him, with tears in his voice, that he feared he was disqualified.

"Well, I will enter the Navy."

He did. He passed through the Britannia, and rose by leaps and bounds, until it was considered desirable to revive the post of Lord High Admiral for his acceptance. But before this was done, he was sounded upon the subject, and asked a question.

"No," he again answered, regretfully.

"I am afraid then, that the scheme must be abandoned," returned the First Civil Lord (he had been chosen as more polite than his sea colleagues), and he was almost moved to tears in his sadness.

"I will enter the Army," cried AUGUSTUS, with determination.

And he did. He rose from the ranks in less than no time to become a Field Marshal. It was then that a certain Illustrious Personage asked him if he would like to become Commander-in-Chief.

"It is not impossible I might resign in your favour," said the I.P. And then he asked him the necessary question.

"No, Sir," returned AUGUSTUS, bowing down his head in shame. Again he found that his career was interrupted.

"I will try the Bar," he shouted.

And he did. He entered at Gray's Inn, and in a very short time became a Q.C., a Judge, and a Lord Justice. Then the entire Ministry begged him, as a personal favour, to accept the post of Lord Chancellor.

"With pleasure," was his modest rejoinder. Then he remembered that he had been asked a certain question on previous occasions, and explained matters.

"I am afraid you won't do," cried the entire Ministry, mournfully.

"Well, then, I will try the Church."

And he tried the Church. He became an eminent divine. Every one spoke well of him; and when, in due course, the Primacy of all England was vacant, he was asked to accept it. Again he explained matters.

"No!" shouted all the Deans and Chapters.

"You can't mean it!" cried the entire body of Archdeacons.

"Well, I never!" exclaimed every other ecclesiastical authority. But it could not be, and the disappointment was too much for poor AUGUSTUS, and he died of grief.

And so they put on the tombstone, that he would have been President of the Royal College of Physicians, Lord High Admiral, Commander-in-Chief, Lord Chancellor, and Archbishop of Canterbury, if—he had only learned Greek!

MY DEAREST DARLING PERSON,

How sweet and amiable of you to allow a humble being like myself to write to you. Dropping your own special style (which, to be perfectly frank with you, I could no more continue through the whole of this letter than I could dine off treacle and butter-scotch), I beg to say that I am heartily glad to have this opportunity of telling you a few things which have been on my mind for a long time. In what corner of the great realm of abstractions do you make your home? I imagine you whiling away the hours on some soft couch of imitation down, with a little army of sweet but irrelevant smiles ready at all times to do your bidding. You are refined, I am sure. You cultivate sympathy as some men cultivate orchids, until it blooms and luxuriates in the strangest and gaudiest shapes. Your real face is known of no other abstraction; indeed, you never see it yourself, so well-fitted and so constant is the mask through which you waft the endearments which have caused you to be avoided everywhere. This, I admit, is imagination; but is it very far from the truth? Perhaps I ask in vain, for truth is the very last thing that may be expected of you and of those who do your bidding upon earth. I will not, therefore, press the question, but proceed at once to business.

About a month ago I met your friend, ALGERNON JESSAMY. What is there about ALGERNON that inspires such distrust? He is very presentable; some people have gone so far as to call him absolutely good-looking. He is tall, his figure is good, his clothes fit him admirably, and are always speckless; his features are regular, his complexion fresh, and his fair hair, carefully parted in the middle, lies like a smooth and shining lid upon his head. I pass over all his remaining advantages, whether of dress or of nature. It is enough to say that, thus equipped, and with the additional merits of wealth and a good position, ALGERNON ought to have found no difficulty in being one of the most popular men in town. Perhaps he would have been if he had not tried with such a persistent energy to make himself "so deuced agreeable." The phrase is not mine, but that of SAMMY MIGGS, who has a contempt for ALGERNON and his methods, which he never attempts to conceal.

"ALGY, my boy," I have heard him say, while the unfortunate JESSAMY smiled uneasily, and shifted on his seat, "ALGY, my boy, I've known you too long to give in to any of your nonsense. All that butter of yours is wasted here, so you'd better keep it for someone who likes it. Try it on QUISBY," he continued, indicating the celebrated actor, who was at that moment frowning furiously over a notice of his latest performance; "he loves it in firkins, and I'll undertake to say you'll never get to the bottom of his swallowing capacity. You'll have to exhaust even your stock, ALGY, my boy; and that's saying a lot."

So thoroughly uncomfortable did the suave and gentle ALGERNON look, that I afterwards ventured to remonstrate mildly with the gadfly MIGGS.

"What?" he said, "made him uncomfortable, did I? And a jolly good job too. Bless you, I know the beggar through and through. I wasn't at Oxford with him for nothing. Wish I had been. He's the sort of chap who loses no end of I.O.U.'s at cards one night, and when he wins piles of ready the next never offers to redeem them. You let me alone about ALGY. I tell you I know him. There's no bigger humbug in Christendom with all his soft sawder and gas about everybody being the dearest and cleverest fellow he's ever met. Bah!"

And therewith SAMMY left me, evidently smarting under some ancient sore inflicted by the apparently angelic ALGERNON.

However, this little incident was not the one I intended to narrate. I met ALGY, as I said, about a month ago. It was in Piccadilly. At first, as I approached, I thought he did not see me, but suddenly he seemed to become aware of my presence. An electric thrill of joy ran through him, a smile of heavenly welcome irradiated his face, he darted towards me with both hands stretched out and almost fell round my neck before all the astonished cabmen.

"My dear, dear fellow," he gasped, apparently struggling hard with an overpowering emotion, "this is almost too much. To think that I should meet the one man of all others whom I have been literally longing to see. Now you simply must walk with me for a bit. I can't afford to let you go without having a good talk with you. It always refreshes me so to hear your opinions of men and things."

Ignoring my assurance that I had an important appointment to keep, he linked his arm closely in mine and dragged me with him in the direction from which I had come. How he pattered and chattered and flattered. He daubed me over with flattery as I have seen bill-stickers brush a hoarding over with paste. Never in my life had I felt so small, so mean and such a perfect fool, for though I own I have no objection to an occasional lollipop of praise, I must say I loathe it in lumps the size of a jelly-fish. Yet such is the fare on which JESSAMY compels me to subsist. And the annoying part of it was that every lump which he crammed down my throat contained an inferential compliment to himself, which I was forced either to accept, or in declining it to appear a churl. I was never more churlish, never less satisfied with myself. Amongst other things we spoke of the affairs of "The Dustheap," a little Club of which we were both members. JESSAMY opined it was going to the dogs. "Just look," he said, "at the men they've got on the Committee; mere nobodies. I've always wondered why you are not on it. Men like you and me wouldn't make the ridiculous mistakes the present lot are constantly making. Fancy their electing MUMPLEY, a regular outsider, without enough manners for a school-boy. I really don't care about being in the same room with him." At this very moment, by one of those curious coincidences which invariably happen, the abused MUMPLEY himself, a wealthy but otherwise inoffensive stockbroker, hove in sight. "There comes the brute himself," said JESSAMY; and in another moment his arms were round MUMPLEY's neck, and he was protesting, with all the fervour of a heartfelt conviction, that MUMPLEY was the one man of all others for whom his heart had been yearning. That being so, I left them together, and departed to my business.

Now does JESSAMY imagine that that kind of thing makes him a favourite? It must be admitted that he is not very artistic in his methods; and I fancy he must sometimes perceive, if I may use a homely phrase, that he doesn't go down. But the poor beggar can't help himself. He is driven by a force which he finds it impossible to resist into the cruel snares that are spread for the over-amiable. You, my dear GUSH, are that force, and to you, therefore, the sugary JESSAMY owes his failure to win the appreciation which he courts so ardently.

And now I think I have relieved my mind of a sufficient load for the time being. If I can remember anything else that might interest you, you may count upon me to address you again. Permit me in the meantime to subscribe myself with all proper curtness,

Sir,—I have not seen Pamela's Prodigy, but I have just read the criticism in the Times, which says of it, "It must be regarded either as a boyish effusion or a sorry joke." The criticism then points out how it lacks "wit, humour, literary skill," and apparently is wanting in everything that goes to make a successful play,—everything that is, except the actors. Mrs. JOHN WOOD was in it: she is a host in herself: not only a host, but the Manageress of the theatre who, with her partner in the business, is responsible for the selection of pieces. Now granting the critic to be right—and, on referring to others, I find a consensus of opinion backing him up—at whose door lies the responsibility of having deliberately selected a failure? Under what compulsion could so clever and experienced an autocrat, sharp as a needle and with the "heye of an 'awk" in theatrical matters, as Mrs. JOHN WOOD, have made so fatal a mistake—that is, if the critics are right, and if it be a mistake? "To err, is human"—and, including even Mrs. JOHN WOOD, and the critics, we are all human,—"To forgive, divine"—the critics not being divine could not forgive; the public apparently, did forgive—and, will, of course, forget. 'Tis all very well to fall foul of the unhappy author—whom we will not name—after the event; but why was the piece ever chosen, and why was not the discovery of its unfitness made during rehearsal? No! "as long as the world goes round" these things will happen in the best regulated theatres, and experience is apparently no sort of guide in such matters.—Yours faithfully,

☞ NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or The London Charivari, Volume

101, October 31, 1891, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 15442-h.htm or 15442-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/1/5/4/4/15442/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.