| Volume II. | Volume III. | Volume IV. | Volume V. |

CONTENTS

Explanation of the Initials appended to the Notes.

MARGARET OF ANGOULÊME, QUEEN OF NAVARRE.

Peter Boaistuau, surnamed Launay, To the Reader

List of Illustrations

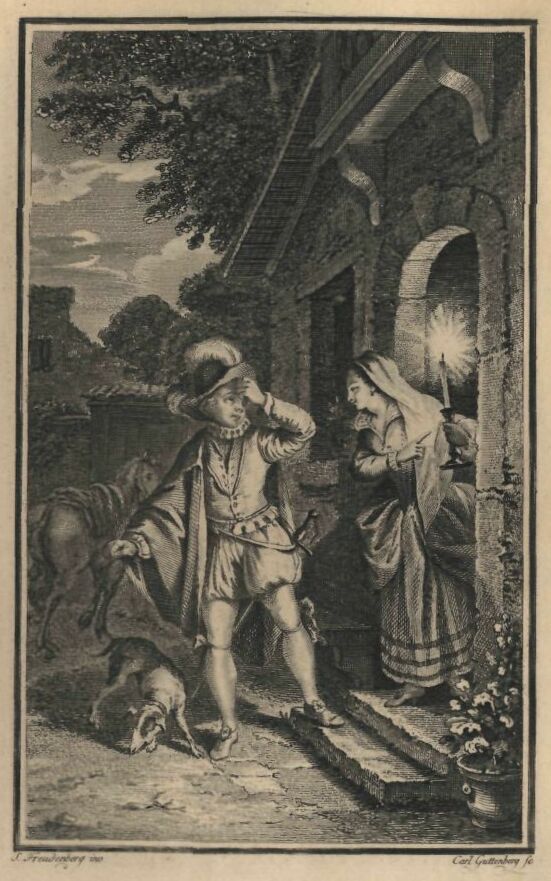

039a.jpg Du Mesnil Learns his Mistress’s Infidelity from Her Maid

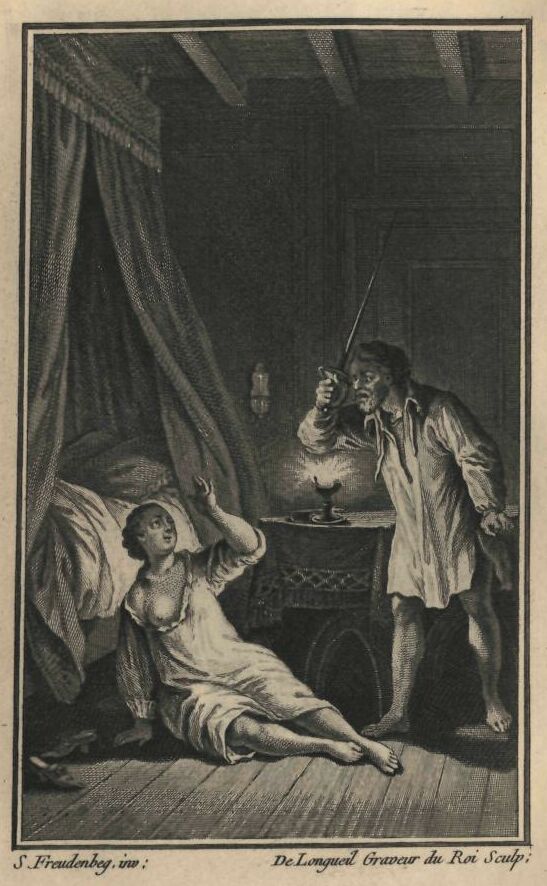

057a.jpg the Muleteer’s Servant Attacking his Mistress

079a.jpg Hurrying to Her Mistress’s Assistance

095a.jpg the Boatwoman of Coulon Outwitting The Friars

103a.jpg the Wife’s Ruse to Secure The Escape of Her Lover

109.jpg the Merchant Transferring his Caresses from The Daughter to the Mother

|

FIRST DAY. Tale I. The pitiful history of a Proctor of Alençon, named St. Aignan, and of his wife, who caused her husband to assassinate her lover, the son of the Lieutenant-General Tale II. The fate of the wife of a muleteer of Amboise, who suffered herself to be killed by her servant rather than sacrifice her chastity Tale III. The revenge taken by the Queen of Naples, wife to King Alfonso, for her husband’s infidelity with a gentleman’s wife Tale IV. The ill success of a Flemish gentleman who was unable to obtain, either by persuasion or force, the love of a great Princess Tale V. How a boatwoman of Coulon, near Nyort, contrived to escape from the vicious designs of two Grey Friars Tale VI. How the wife of an old valet of the Duke of Alençon’s succeeded in saving her lover from her husband, who was blind of one eye Tale VII. The craft of a Parisian merchant, who saved the reputation of the daughter by offering violence to the mother |

The first printed version of the famous Tales of Margaret of Navarre, issued in Paris in the year 1558, under the title of “Histoires des Amans Fortunez,” was extremely faulty and imperfect. It comprised but sixty-seven of the seventy-two tales written by the royal author, and the editor, Pierre Boaistuau, not merely changed the order of those narratives which he did print, but suppressed numerous passages in them, besides modifying much of Margaret’s phraseology. A somewhat similar course was adopted by Claude Gruget, who, a year later, produced what claimed to be a complete version of the stories, to which he gave the general title of the Heptameron, a name they have ever since retained. Although he reinstated the majority of the tales in their proper sequence, he still suppressed several of them, and inserted others in their place, and also modified the Queen’s language after the fashion set by Boaistuau. Despite its imperfections, however, Gruget’s version was frequently reprinted down to the beginning of the eighteenth century, when it served as the basis of the numerous editions of the Heptameron in beau langage, as the French phrased it, which then began to make their appearance. It served, moreover, in the one or the other form, for the English and other translations of the work, and down to our own times was accepted as the standard version of the Queen of Navarre’s celebrated tales. Although it was known that various contemporary MSS. were preserved at the French National Library in Paris, no attempt was made to compare Gruget’s faulty version with the originals until the Société des Bibliophiles Français entrusted this delicate task to M. Le Roux de Lincy, whose labours led to some most valuable discoveries, enabling him to produce a really authentic version of Margaret’s admired masterpiece, with the suppressed tales restored, the omitted passages reinstated, and the Queen’s real language given for the first time in all its simple gracefulness.

It is from the authentic text furnished by M. Le Roux de Lincy that the present translation has been made, without the slightest suppression or abridgment. The work moreover contains all the more valuable notes to be found in the best French editions of the Heptameron, as well as numerous others from original sources, and includes a résumé of the various suggestions made by MM. Félix Frank, Le Roux de Lincy, Paul Lacroix, and A. de Montaiglon, towards the identification of the narrators of the stories, and the principal actors in them, with well-known personages of the time. An Essay on the Heptameron from the pen of Mr. George Saintsbury, M.A., and a Life of Queen Margaret, are also given, as well as the quaint Prefaces of the earlier French versions; and a complete bibliographical summary of the various editions which have issued from the press.

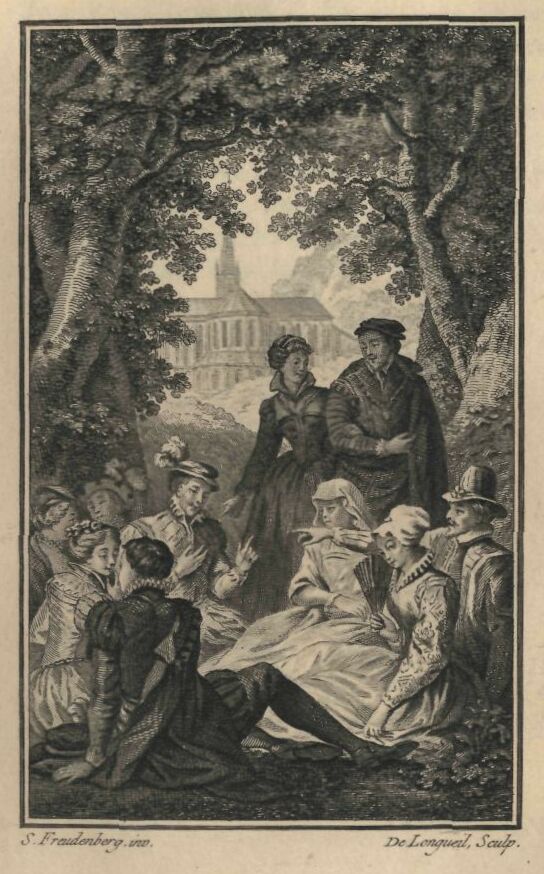

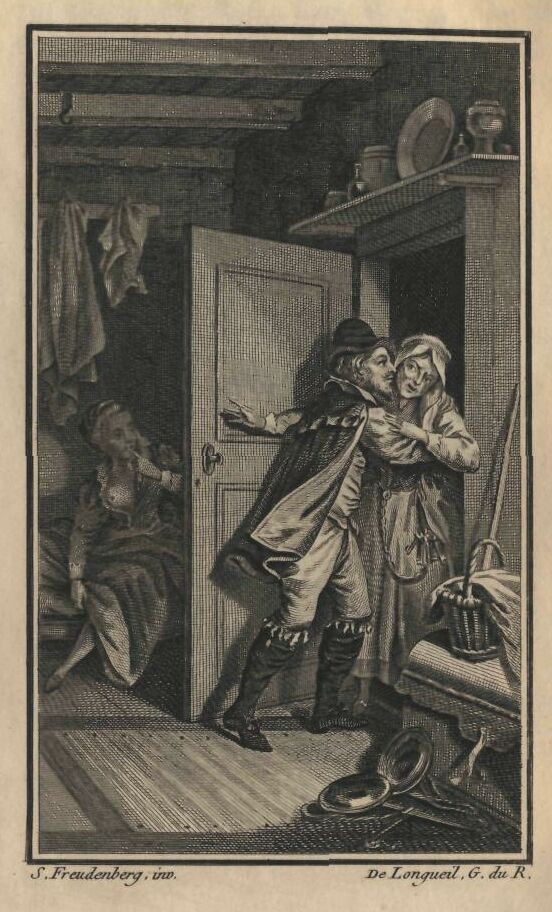

It may be supposed that numerous illustrated editions have been published of a work so celebrated as the Heptameron, which, besides furnishing scholars with a favourite subject for research and speculation, has, owing to its perennial freshness, delighted so many generations of readers. Such, however, is not the case. Only two fully illustrated editions claim the attention of connoisseurs. The first of these was published at Amsterdam in 1698, with designs by the Dutch artist, Roman de Hooge, whose talent has been much overrated. To-day this edition is only valuable on account of its comparative rarity. Very different was the famous edition illustrated by Freudenberg, a Swiss artist—the friend of Boucher and of Greuze—which was published in parts at Berne in 1778-81, and which among amateurs has long commanded an almost prohibitive price.

The Full-page Illustrations to the present translation are printed from the actual copperplates engraved for the Berne edition by Lon-geuil, Halbou, and other eminent French artists of the eighteenth century, after the designs of S. Freudenberg. There are also the one hundred and fifty elaborate head and tail pieces executed for the Berne edition by Dunker, well known to connoisseurs as one of the principal engravers of the Cabinet of the Duke de Choiseul.

The Portrait of Queen Margaret placed as frontispiece to the present volume is from a crayon drawing by Clouet, preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Ernest A. Vizetelly.

London,

|

B.J...Bibliophile Jacob, i.e. Paul Lacroix. D.....F. Dillaye. F.....Félix Frank. L.....Le Roux de Lincy. M.....Anatole de Montaiglon. Ed....E. A. Vizetelly. |

Louise of Savoy; her marriage with the Count of Angouleme—

Birth of her children Margaret and Francis—Their father’s

early death—Louise and her children at Amboise—Margaret’s

studies and her brother’s pastimes—Marriage of Margaret

with the Duke of Alençon—Her estrangement from her husband—

Accession of Francis I.—The Duke of Alençon at Marignano—

Margaret’s Court at Alençon—Her personal appearance—Her

interest in the Reformation and her connection with Clement

Marot—Lawsuit between Louise of Savoy and the Constable de

Bourbon.

In dealing with the life and work of Margaret of Angouleme (1) it is necessary at the outset to refer to the mother whose influence and companionship served so greatly to mould her daughter’s career.

1 This Life of Margaret is based upon the memoir by M, Le

Roux de Lincy prefixed to the edition of the Heptameron

issued by the Société des Bibliophiles Français, but various

errors have been rectified, and advantage has been taken of

the researches of later biographers.

Louise of Savoy, daughter of Count Philip of Bresse, subsequently Duke of Savoy, was born at Le Pont d’Ain in 1477, and upon the death of her mother, Margaret de Bourbon, she married Charles d’Orléans, Count of Angoulême, to whom she brought the slender dowry of thirty-five thousand livres. (1) She was then but twelve years old, her husband being some twenty years her senior. He had been banished from the French Court for his participation in the insurrection of Brittany, and was living in straitened circumstances. Still, on either side the alliance was an honourable one. Louise belonged to a sovereign house, while the Count of Angoulême was a prince of the blood royal of France by virtue of his descent from King Charles V., his grandfather having been that monarch’s second son, the notorious Duke Louis of Orleans, (2) who was murdered in Paris in 1417 at the instigation of John the Bold of Burgundy.

1 The value of the Paris livre at this date was twenty

sols, so that the amount would be equivalent to about L1400.

2 This was the prince described by Brantôme as a “great

débaucher of the ladies of the Court, and invariably of the

greatest among them.”—Vies des Dames galantes (Disc. i.).

Louise, who, although barely nubile, impatiently longed to become a mother, gave birth to her first child after four years of wedded life. “My daughter Margaret,” she writes in the journal recording the principal events of her career, “was born in the year 1492, the eleventh day of April, at two o’clock in the morning; that is to say, the tenth day, fourteen hours and ten minutes, counting after the manner of the astronomers.” This auspicious event took place at the Château of Angoulême, then a formidable and stately pile, of which nowadays there only remains a couple of towers, built in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Soon afterwards Cognac became the Count of Angoulême’s favourite place of residence, and it was there that Louise gave birth, on September 12th, 1494, to her second child, a son, who was christened Francis.

Louise’s desires were now satisfied, but her happiness did not long remain complete. On January 1st, 1496, when she was but eighteen years old, she lost her amiable and accomplished husband, and forthwith retiring to her Château of Romorantin, she resolved to devote herself entirely to the education of her children. The Duke of Orleans, who, on the death of Charles VIII. in 1498, succeeded to the throne as Louis XII., was appointed their guardian, and in 1499 he invited them and their mother to the royal Château of Amboise, where they remained for several years.

The education of Francis, who had become heir-presumptive to the throne, was conducted at Amboise by the Marshal de Gié, one of the King’s favourites, whilst Margaret was intrusted to the care of a venerable lady, whom her panegyrist does not mention by name, but in whom he states all virtues were assembled. (1) This lady took care to regulate not only the acts but also the language of the young princess, who was provided with a tutor in the person of Robert Hurault, Baron of Auzay, great archdeacon and abbot of St. Martin of Autun. (2) This divine instructed her in Latin and French literature, and also taught her Spanish and Italian, in which languages Brantôme asserts that she became proficient. “But albeit she knew how to speak good Spanish and good Italian,” he says, “she always made use of her mother tongue for matters of moment; though when it was necessary to join in jesting and gallant conversation she showed that she was acquainted with more than her daily bread.” (3)

1 Sainte-Marthe’s Oraison funèbre de la Royne de Navarre,

p. 22. Margaret’s modern biographers state that this lady was

Madame de Chastillon, but it is doubtful which Madame

de Chastillon it was. The Rev. James Anderson assumes it was

Louise de Montmorency, the mother of the Colignys, whilst

Miss Freer asserts it was Anne de Chabannes de Damniartin,

wife of James de Chastillon, killed in Italy in 1572. M.

Franck has shown, in his edition of the Heptameron, that

Anne de Chabannes died about 1505, and that James de

Chastillon then married Blanche de Tournon. Possibly his

first wife may have been Margaret’s governess, but what is

quite certain is that the second wife became her lady of

honour, and that it is she who is alluded to in the

Heptameron.

2 Odolant Desnos’s Mémoires historiques sur Alençon,

vol. ii.

3 Brantôme’s Rodomontades espagnoles, 18mo, 1740, vol.

xii. p. 117.

Such was Margaret’s craving for knowledge that she even wished to obtain instruction in Hebrew, and Paul Paradis, surnamed Le Canosse, a professor at the Royal College, gave her some lessons in it. Moreover, a rather obscure passage in the funeral oration which Sainte-Marthe devoted to her after her death, seemingly implies that she acquired from some of the most eminent men then flourishing the precepts of the philosophy of the ancients.

The journal kept by Louise of Savoy does not impart much information as to the style of life which she and her children led in their new abode, the palatial Château of Amboise, originally built by the Counts of Anjou, and fortified by Charles VII. with the most formidable towers in France. (1)

1 The Château of Amboise, now the private property of the

Count de Paris, is said to occupy the site of a Roman

fortress destroyed by the Normans and rebuilt by Foulques

the Red of Anjou. When Francis I. ascended the French throne

he presented the barony of Amboise with its hundred and

forty-six fiefs to his mother, Louise of Savoy.

Numerous authorities state, however, that Margaret spent most of her time in study with her preceptors and in the devotional exercises which then had so large a place in the training of princesses. Still she was by no means indifferent to the pastimes in which her brother and his companions engaged. Gaston de Foix, the nephew of the King, William Gouffier, who became Admiral de Bonnivet, Philip Brion, Sieur de Chabot, Fleurange, “the young adventurer,” Charles de Bourbon, Count of Montpensier, and Anne de Montmorency—two future Constables of France—surrounded the heir to the throne, with whom they practised tennis, archery, and jousting, or played at soldiers pending the time when they were to wage war in earnest. (1)

Margaret was a frequent spectator of these pastimes, and took a keen interest in her brother’s efforts whenever he was assailing or defending some miniature fortress or tilting at the ring. It would appear also that she was wont to play at chess with him; for we have it on high authority that it is she and her brother who are represented, thus engaged, in a curious miniature preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. (2) In this design—executed by an unknown artist—only the back of Francis is to be seen, but a full view of Margaret is supplied; the personage standing behind her being Artus Gouffier, her own and her brother’s governor.

1 Fleurange’s Histoire des Choses mémorables advenues du

Reigne de Louis XII. et François I.

2 Paulin Paris’s Manuscrits françois de la Bibliothèque du

Roi, &c., Paris, 1836, vol. i. pp. 279-281. The miniature

in question is contained in MS. No. 6808: Commentaire sur

le Livre des Échecs amoureux et Archiloge Sophie.

Whatever time Margaret may have devoted to diversion, she was certainly a very studious child, for at fifteen years of age she already had the reputation of being highly accomplished. Shortly after her sixteenth birthday a great change took place in her life. On August 3rd, 1508, Louise of Savoy records in her journal that Francis “this day quitted Amboise to become a courtier, and left me all alone.” Margaret accompanied her brother upon his entry into the world, the young couple repairing to Blois, where Louis XII. had fixed his residence. There had previously been some unsuccessful negotiations in view of marrying Margaret to Prince Henry of England (Henry VIII.), and at this period another husband was suggested in the person of Charles of Austria, Count of Flanders, and subsequently Emperor Charles V. Louis XII., however, had other views as regards the daughter of the Count of Angoulême, for he knew that if he himself died without male issue the throne would pass to Margaret’s brother. Hence he decided to marry her to a prince of the royal house, Charles, Duke of Alençon.

This prince, born at Alençon on September 2nd, 1489, had been brought up at the Château of Mauves, in Le Perche, by his mother, the pious and charitable Margaret of Lorraine, who on losing her husband had resolved, like Louise of Savoy, to devote herself to the education of her children. (1)

1 Hilarion de Coste’s Vies et Éloges des Dames illustres,

vol. ii. p. 260.

It had originally been intended that her son Charles should marry Susan, daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Bourbon—the celebrated Peter and Anne de Beaujeu—but this match fell through owing to the death of Peter and the opposition of Anne, who preferred the young Count of Montpensier (afterwards Constable de Bourbon) as a son-in-law. A yet higher alliance then presented itself for Charles: it was proposed that he should marry Anne of Brittany, the widow of King Charles VIII., but she was many years his senior, and, moreover, to prevent the separation of Brittany from France, it had been stipulated that she should marry either her first husband’s successor (Louis XII.) or the heir-presumptive to the throne. Either course seemed impracticable, as the heir, Francis of Angoulême, was but a child, while the new King was already married to Jane, a daughter of Louis XI. Brittany seemed lost to France, when Louis XII., by promising the duchy of Valentinois to Cæsar Borgia, prevailed upon Pope Alexander VI. to divorce him from his wife. He then married Anne of Brittany, while Charles of Alençon proceeded to perfect his knightly education, pending other matrimonial arrangements.

In 1507, when in his eighteenth year, he accompanied the army which the King led against the Genoese, and conducted himself bravely; displaying such courage, indeed, at the battle of Agnadel, gained over the Venetians—who were assailed after the submission of Genoa—that Louis XII. bestowed upon him the Order of St. Michael. It was during this Italian expedition that his mother negotiated his marriage with Margaret of Angoulême. The alliance was openly countenanced by Louis XII., and the young Duke of Valois—as Francis of Angoulême was now called—readily acceded to it. Margaret brought with her a dowry of sixty thousand livres, payable in four instalments, and Charles, who was on the point of attaining his twenty-first year, was declared a major and placed in possession of his estates. (1) The marriage was solemnised at Blois in October 1509.

1 Odolant Desnos’s Mémoires historiques sur Alençon,

vol. ii. p. 231

Margaret did not find in her husband a mind comparable to her own. Differences of taste and temper brought about a certain amount of coolness, which did not, however, hinder the Duchess from fulfilling the duties of a faithful, submissive wife. In fact, although but little sympathy would appear to have existed between the Duke and Duchess of Alençon, their domestic differences have at least been singularly exaggerated.

During the first five years of her married life Margaret lived in somewhat retired style in her duchy of Alençon, while her husband took part in various expeditions, and was invested with important functions. In 1513 he fought in Picardy against the English and Imperialists, commanded by Henry VIII., being present at the famous “Battle of Spurs;” and early in 1514 he was appointed Lieutenant-General and Governor of Brittany. Margaret at this period was not only often separated from her husband, but she also saw little of her mother, who had retired to her duchy of Angoulême. Louise of Savoy, as mother of the heir-presumptive, was the object of the homage of all adroit and politic courtiers, but she had to behave with circumspection on account of the jealousy of the Queen, Anne of Brittany, whose daughters, Claude and Renée, were debarred by the Salic Law from inheriting the crown. Louis XII. wished to marry Claude to Francis of Angoulême, but Anne refusing her consent, it was only after her death, in 1514, that the marriage was solemnised.

It now seemed certain that Francis would in due course ascend the throne; but Louis XII. abruptly contracted a third alliance, marrying Mary of England, the sister of Henry VIII. Louise of Savoy soon deemed it prudent to keep a watch on the conduct of this gay young Queen, and took up her residence at the Court in November 1514. Shortly afterwards Louis XII. died of exhaustion, as many had foreseen, and the hopes of the Duchess of Angoulême were realised. She knew the full extent of her empire over her son, now Francis I., and felt both able and ready to exercise a like authority over the affairs of his kingdom.

The accession of Francis gave a more important position to Margaret and her husband. The latter was already one of the leading personages of the state, and new favours increased his power. He did not address the King as “Your Majesty,” says Odolant Desnos, but styled him “Monseigneur” or “My Lord,” and all the acts which he issued respecting his duchy of Alençon began with the preamble, “Charles, by the grace of God.” Francis had scarcely become King than he turned his eyes upon Italy, and appointing his mother as Regent, he set out with a large army, a portion of which was commanded by the Duke of Alençon. At the battle of Marignano the troops of the latter formed the rearguard, and, on perceiving that the Swiss were preparing to surround the bulk of the French army, Charles marched against them, overthrew them, and by his skilful manouvres decided the issue of the second day’s fight. (1) The conquest of the duchy of Milan was the result of this victory, and peace supervening, the Duke of Alençon returned to France.

1 Odolant Desnos’s Mémoires historiques sur Alençon, vol.

ii. p. 238.

It was at this period that Margaret began to keep a Court, which, according to Odolant Desnos, rivalled that of her brother. We know that in 1517 she and her husband entertained the King with a series of magnificent fêtes at their Château of Alençon, which then combined both a palace and a fortress. But little of the château now remains, as, after the damage done to it during the religious wars between 1561 and 1572, it was partially demolished by Henry IV. when he and Biron captured it in 1590. Still the lofty keep built by Henry I. of England subsisted intact till in 1715 it was damaged by fire, and finally in 1787 razed to the ground.

The old pile was yet in all its splendour in 1517, when Francis I. was entertained there with jousts and tournaments. At these gay gatherings Margaret appeared apparelled in keeping with her brother’s love of display; for, like all princesses, she clothed herself on important occasions in sumptuous garments. But in every-day life she was very simple, despising the vulgar plan of impressing the crowd by magnificence and splendour. In a portrait executed about this period, her dark-coloured dress is surmounted by a wimple with a double collar and her head covered with a cap in the Bearnese style. This portrait (1) tends, like those of a later date, to the belief that Margaret’s beauty, so celebrated by the poets of her time, consisted mainly in the nobility of her bearing and the sweetness and liveliness spread over her features. Her eyes, nose, and mouth were very large, but although she had been violently attacked with small-pox while still young, she had been spared the traces which this cruel illness so often left in those days, and she even preserved the freshness of her complexion until late in life. (2)

1 It is preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris,

where it will be found in the Recueil de Portraits au

crayon par Clouett Dumonstier, &c, fol. xi.

2 Referring to this subject, she says in one of her letters:

“You can tell it to the Count and Countess of Vertus, whom

you will go and visit on my behalf; and say to the Countess

that I am sorely vexed that she has this loathsome illness.

However, I had it as severely as ever was known. And if it

be that she has caught it as I have been told, I should like

to be near her to preserve her complexion, and do for her

what Ï did for myself.”—Génin’s lettres de Marguerite

d’Angoulême, Paris, 1841, p. 374.

Like her brother, whom she greatly resembled, she was very tall. Her gait was solemn, but the dignified air of her person was tempered by extreme affability and a lively humour, which never left her. (1)

1 Sainte-Marthe says on this subject: “For in her face, in

her gestures, in her walk, in her words, in all that she did

and said, a royal gravity made itself so manifest and

apparent, that one saw I know not what of majesty which

compelled every one to revere and dread her. In seeing her

kindly receive every one, refuse no one, and patiently

listen to all, you would have promised yourself easy and

facile access to her; but if she cast eyes upon you, there

was in her face I know not what of gravity, which made you

so astounded that you no longer had power, I do not say to

walk a step, but even to stir a foot to approach her.”—

Oraison-funèbre, &c, p. 53.

Francis I. did not allow the magnificent reception accorded to him at Alençon to pass unrewarded. He presented his sister with the duchy of Berry, where she henceforward exercised temporal control, though she does not appear to have ever resided there for any length of time. In 1521, when her husband started to the relief of Chevalier Bayard, attacked in Mézières by the Imperial troops, she repaired to Meaux with her mother so as to be near to the Duke. Whilst sojourning there she improved her acquaintance with the Bishop, William Briçonnet, who had gathered around him Gerard Roussel, Michael d’Arande, Lefèvre d’Etaples, and other celebrated disciples of the Reformation. The effect of Luther’s preaching had scarcely reached France before Margaret had begun to manifest great interest in the movement, and had engaged in a long correspondence with Briçonnet, which is still extant. Historians are at variance as to whether Margaret ever really contemplated a change of religion, or whether the protection she extended to the Reformers was simply dictated by a natural feeling of compassion and a horror of persecution. It has been contended that she really meditated a change of faith, and even attempted to convert her mother and brother; and this view is borne out by some passages in the letters which she wrote to Bishop Briçonnet after spending the winter of 1521 at Meaux.

Whilst she was sojourning there, her husband, having contributed to the relief of Mézières, joined the King, who was then encamped at Fervacques on the Somme, and preparing to invade Hainault. It was at this juncture that Clement Marot, the poet, who, after being attached to the person of Anne of Brittany, had become a hanger-on at the Court of Francis I., applied to Margaret to take him into her service. (1)

1 Epistle ii.: Le Despourveu à Madame la Duchesse

d’Alençon, in the OEuvres de Clément Marot, 1700, vol. i.

p. 99.

Shortly afterwards we find him furnishing her with information respecting the royal army, which had entered Hainault and was fighting there. (1)

1 Epistle iii.: Du Camp d’ Attigny à ma dite Dame d’

Alençon, ibid., vol. i. p. 104.

Lenglet-Dufresnoy, in his edition of Marot’s works, originated the theory that the numerous poems composed by Marot in honour of Margaret supply proofs of an amorous intrigue between the pair. Other authorities have endorsed this view; but M. Le Roux de Lincy asserts that in the pieces referred to, and others in which Marot incidentally speaks of Margaret, he can find no trace either of the fancy ascribed to her for the poet or of the passion which the latter may have felt for her. Like all those who surrounded the Duchess of Alençon, Marot, he remarks, exalted her beauty, art, and talent to the clouds; but whenever it is to her that his verses are directly addressed, he does not depart from the respect he owes to her. To give some likelihood to his conjectures, Lenglet-Dufresnoy had to suppose that Marot addressed Margaret in certain verses which were not intended for her. In the epistles previously mentioned, and in several short pieces, rondeaux, epigrams, new years’ addresses, and epitaphs really written to or for the sister of Francis I., one only finds respectful praise, such as the humble courtier may fittingly offer to his patroness. There is nothing whatever, adds M. Le Roux de Lincy, to promote the suspicion that a passion, either unfortunate or favoured, inspired a single one of these compositions.

The campaign in which Francis I. was engaged at the time when Marot’s connection with Margaret began, and concerning which the poet supplied her with information, was destined to influence the whole reign, since it furnished the occasion of the first open quarrel between Francis I. and the companion of his childhood, Charles de Bourbon, Count of Montpensier, and Constable of France. Yielding too readily on this occasion to the persuasions of his mother, Francis intrusted to Margaret’s husband the command of the vanguard, a post which the Constable considered his own by virtue of his office. He felt mortally offended at the preference given to the Duke of Alençon, and from that day forward he and Francis were enemies for ever.

Whilst the King was secretly jealous of Bourbon, who was one of the handsomest, richest, and bravest men in the kingdom, Louise of Savoy, although forty-four years of age, was in love with him. The Constable, then thirty-two, had lost his wife, Susan de Bourbon, from whom he had inherited vast possessions. To these Louise of Savoy, finding her passion disregarded, laid claim, as being a nearer relative of the deceased. A marriage, as Chancellor Duprat suggested, would have served to reconcile the parties, but the Constable having rejected the proposed alliance—with disdain, so it is said—the suit was brought before the Parliament and decided in favour of Louise. Such satisfaction as she may have felt was not, however, of long duration, for Charles de Bourbon left France, entered the service of Charles V., and in the following year (1524) helped to drive the French under Bonnivet out of Italy.

The Regency of Louise of Savoy—Margaret and the royal

children—The defeat of Pavia and the death of the Duke of

Alençon—The Royal Trinity—“All is lost save honour”—

Margaret’s journey to Spain and her negotiations with

Charles V.—Her departure from Madrid—The scheme to arrest

her, and her flight on horseback—Liberation of Francis I.—

Clever escape of Henry of Navarre from prison—Margaret’s

secret fancy for him—Her personal appearance at this

period—Marriage of Henry and Margaret at St. Germain.

The most memorable events of Margaret’s public life date from this period. Francis, who was determined to reconquer the Milanese, at once made preparations for a new campaign. Louise of Savoy was again appointed Regent of the kingdom, and as Francis’s wife, Claude, was dying of consumption, the royal children were confided to the care of Margaret, whose husband accompanied the army. Louise of Savoy at first repaired to Lyons with her children, in order to be nearer to Italy, but she and Margaret soon returned to Blois, where the Queen was dying. Before the royal army had reached Milan Claude expired, and soon afterwards Louise was incapacitated by a violent attack of gout, while the children of Francis also fell ill. The little ones, of whom Margaret had charge, consisted of three boys and three girls, the former being Francis, the Dauphin, who died in 1536, Charles, Duke of Orleans, who died in 1545, and Henry, Count of Angoulême, who succeeded his father on the throne. The girls comprised Madeleine, afterwards the wife of James V. of Scotland, Margaret, subsequently Duchess of Savoy, and the Princess Charlotte. The latter was particularly beloved by her aunt Margaret, who subsequently dedicated to her memory her poem Le Miroir de l’Ame Pécheresse. While the other children recovered from their illness, little Charlotte, as Margaret records in her letters to Bishop Briçonnet, was seized “with so grievous a malady of fever and flux,” that after a month’s suffering she expired, to the deep grief of her aunt, who throughout her illness had scarcely left her side.

This affliction was but the beginning of Margaret’s troubles. Soon afterwards the Constable de Bourbon, in conjunction with Pescara and Lannoy, avenged his grievances under the walls of Pavia. On this occasion, as at Marignano, the Duke of Alençon commanded the French reserves, and had charge of the fortified camp from which Francis, listening to Bonnivet, sallied forth, despite the advice of his best officers. The King bore himself bravely, but he was badly wounded and forced to surrender, after La Palisse, Lescun, Bonnivet, La Trémoïlle, and Bussy d’Amboise had been slain before his eyes. Charles of Alençon was then unable to resist the advice given him to retreat, and thus save the few Frenchmen who had escaped the arms of the Imperialists. With four hundred lances he abandoned the camp, crossed the Ticino, and reaching France by way of Piedmont, proceeded to Lyons, where he found Louise of Savoy and Margaret.

It has been alleged that they received him with harsh reproaches, and that, unable to bear the shame he felt for his conduct, he died only a few days after the battle. (1)

1 See Garnier’s Histoire de France, vol. xxiv.; Gaillard’s

Histoire de France, &c. Odolant Desnos, usually well

informed, falls into the same error, and asserts that when

the Duke, upon his arrival, asked Margaret to kiss him, she

replied, “Fly, coward! you have feared death. You might find

it in my arms, as I do not answer for myself.”—Mémoires

historiques, vol. ii. p. 253.

There are several errors in these assertions, which a contemporary document enables us to rectify. The battle of Pavia was fought on February 14th, 1525, and Charles of Alençon did not die till April 11th, more than a month after his arrival at Lyons. He was carried off in five days by pleurisy, and some hours before his death was still able to rise and partake of the communion. Margaret bestowed the most tender care upon him, and the Regent herself came to visit him, the Duke finding strength enough to say to her, “Madam, I beg of you to let the King know that since the day he was made a prisoner I have been expecting nothing but death, since I was not sufficiently favoured by Heaven to share his lot or to be slain in serving him who is my king, father, brother, and good master.” After kissing the Regent’s hand he added, “I commend to you her who has been my wife for fifteen years, and who has been as good as she is virtuous towards me.” Then, as Louise of Savoy wished to take Margaret away, Charles turned towards the latter and said to her, “Do not leave me.”

The Duchess refused to follow her mother, and embracing her dying husband, showed him the crucifix placed before his eyes. The Duke, having summoned one of his gentlemen, M. de Chan-deniers, instructed him to bid farewell on his part to all his servants, and to thank them for their services, telling them that he had no longer strength to see them. He asked God aloud to forgive his sins, received the extreme unction from the Bishop of Lisieux, and raising his eyes to heaven, said “Jesus,” and expired. (1)

Whilst tending her dying husband, Margaret was also deeply concerned as to the fate of her captive brother, for whom she always evinced the warmest affection. Indeed, so close were the ties uniting Louise of Savoy and her two children that they were habitually called the “Trinity,” as Clement Marot and Margaret have recorded in their poems. (2)

1 From a MS. poem in the Bibliothèque Nationale entitled

Les Prisons, probably written by William Philander or

Filandrier, a canon of Rodez.

2 See OEuvres de Clément Marot, 1731, vol. v. p. 274; and

A. Champoîlion-Figeac’s Poésies de François Ier, &c.,

Paris, 1847, p. 80.

In this Trinity Francis occupied the highest place; his mother called him “her Cæsar and triumphant hero,” while his sister absolutely reverenced him, and was ever ready to do his bidding. Thus the intelligence that he was wounded and a prisoner threw them into consternation, and they were yet undecided how to act when they received that famous epistle in which Francis wrote—not the legendary words, “All is lost save honour,” but—“Of all things there have remained to me but honour and life, which is safe.” After begging his mother and sister to face the extremity by employing their customary prudence, the King commended his children to their care, and expressed the hope that God would not abandon him. (1) This missive revived the courage of the Regent and Margaret, for shortly afterwards we find the latter writing to Francis: “Your letter has had such effect upon the health of Madame [Louise], and of all those who love you, that it has been to us as a Holy Ghost after the agony of the Passion.... Madame has felt so great a renewal of strength, that whilst day and evening last not a moment is lost over your business, so that you need have no grief or care about your kingdom and children.” (2)

1 See extract from the Registers of the Parliament of Paris

(Nov. 10, 1525) in Dulaure’s Histoire de Paris, Paris,

1837, vol. iii. p. 209; and Lalanne’s Journal d’un

Bourgeois de Paris, Paris, 1854, p. 234. The original of

the letter no longer exists, but the authenticity of the

text cannot be disputed, as all the more essential portions

are quoted in the collective reply of Margaret and Louise of

Savoy, which is still extant. See Champollion-Figeac’s

Captivité de François Ier, pp. 129, 130.

2 Génin’s Nouvelles Lettres de la Peine de Navarre,

Paris, 1842, p. 27.

Louise of Savoy was indeed now displaying courage and ability. News shortly arrived that the King had been transferred to Madrid, and that Charles demanded most onerous conditions for the release of his prisoner. At this juncture Francis wrote to his mother that he was very ill, and begged of her to come to him. Louise, however, felt that she ought not to accede to this request, for it would be jeopardising the monarchy to place the Regent as well as the King of France in the Emperor’s hands; accordingly she resolved that Margaret should go instead of herself.

The Baron of St. Blancard, general of the King’s galleys, who had previously offered to rescue Francis while the latter was on his way to Spain, received orders to make the necessary preparations for Margaret’s voyage, of which she defrayed the expense, as is shown by a letter she wrote to John Brinon, Chancellor of Alençon. In this missive she states that the Baron of St. Blancard has made numerous disbursements on account of her journey which are to be refunded to him, “so that he may know that I am not ungrateful for the good service he has done me, for he hath acquitted himself thereof in such a way that I have occasion to be gratified.” (1)

1 Génin’s Lettres de Marguerite, &c., p. 193.—Génin’s

Notice, ibid., p. 19.

Despite adverse winds, Margaret embarked on August 27th, 1525, at Aigues-Mortes, with the President de Selves, the Archbishop of Embrun, the Bishop of Tarbes, and a fairly numerous suite of ladies. The Emperor had granted her a safe-conduct for six months, and upon landing in Spain she hurried to Madrid, where she found her brother very sick both in mind and body. She eagerly caressed and tended him, and with a good result, as she knew his nature and constitution much better than the doctors. To raise his depressed spirits she had recourse to religious ceremonies, giving orders for an altar to be erected in the room where he was lying. She then requested the Archbishop of Embrun to celebrate mass, and received the communion in company of all the French retainers about the prisoner. It is stated that the King, who for some hours had given no sign of life, opened his eyes at the moment of the consecration of the elements, and asked for the communion, saying, “God will cure me, soul and body.” From this time forward he began to recover his health, though he remained fretful on account of his captivity.

It was a difficult task to obtain his release. The Court and the Emperor were extremely polite, but Margaret soon recognised the emptiness of their protestations of good-will. “They all tell me that they love the King,” she wrote, “but I have little proof of it. If I had to do with honest folks, who understand what honour is, I should not care, but it is the contrary.” (1)

1 Lettres de Marguerite, &c., p. 21.

She was not the woman to turn back at the first obstacle, however; she began by endeavouring to gain over several high personages, and on perceiving that the men avoided speaking with her on serious business, she addressed herself to their mothers, wives, or daughters. In a letter to Marshal de Montmorency, then with the King, she thus refers to the Duke del Infantado, who had received her at his castle of Guadalaxara. “You will tell the King that the Duke has been warned from the Court that if he wishes to please the Emperor neither he nor his son is to speak to me; but the ladies are not forbidden me, and to them I will speak twofold.” (1)

Throughout the negotiations for her brother’s release Margaret always maintained the dignity and reserve fitting to her sex and situation. Writing to Francis on this subject she says: “The Viceroy (Lannoy) has sent me word that he is of opinion I should go and see the Emperor, but I have told him through M. de Senlis that I have not yet stirred from my lodging without being asked, and that whenever it pleases the Emperor to see me I shall be found there.” (2)

1 Lettres de Marguerite, &c., p. 197.

2 Captivité de François Ier, p. 358.

Margaret was repeatedly admitted to the Imperial council to discuss the conditions of her brother’s ransom. She showed as much ability as loftiness of mind on these occasions, and several times won Charles V. himself and the sternest of his Ministers to her opinion. (1)

1 Brantôme states that the Emperor was greatly impressed and

astonished by her plain speaking. She reproached him for

treating Francis so harshly, declaring that this course

would not enable him to attain his ends. “For although he

(the King) might die from the effects of this rigorous

treatment, his death would not remain unpunished, as he had

children who would some day become men and wreak signal

vengeance.” “These words,” adds Brantôme, “spoken so bravely

and in such hot anger, gave the Emperor occasion for

thought, insomuch that he moderated himself and visited the

King and made him many fine promises, which he did not keep,

however.” With the Ministers Margaret was even more

outspoken; but we are told that she turned her oratorical

powers “to such good purpose that she rendered herself

agreeable rather than odious or unpleasant; the more readily

as she was also good-looking, a widow, and in the flower of

her age.”—OEuvres de Brantôme, 8vo, vol. v. (Les Dames

illustres).

She highly favoured the proposed marriage between Francis and his rival’s sister, Eleanor of Austria, detecting in this alliance the most certain means of a speedy release. Eleanor, born at Louvain in 1498, had in 1519 married Emanuel, King of Portugal, who died two years afterwards. Since then she had been promised to the Constable de Bourbon, but the Emperor did not hesitate to sacrifice the latter to his own interests.

He himself, being fascinated by Margaret’s grace and wit, thought of marrying her, and had a letter sent to Louise of Savoy, plainly setting forth the proposal. In this missive, referring to the Constable de Bourbon, Charles remarked that “there were good matches in France in plenty for him; for instance, Madame Renée, (1) with whom he might very well content himself.” (2) These words have led to the belief that there had been some question of a marriage between Margaret and the Constable; however, there is no mention of any such alliance in the diplomatic documents exchanged between France and Spain on the subject of the King’s release. These documents comprise an undertaking to restore the Constable his estates, and even to arrange a match for him in France, (3) but Margaret is never mentioned. She herself, in the numerous letters handed down to us, does not once refer to the famous exile, and the intrigue described by certain historians and romancers evidently rests upon no solid foundation. (4)

1 Renée, the younger daughter of Louis XII. and Anne of

Brittany, subsequently celebrated as Renée of Ferrara.

2 This letter is preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale,

Béthune MSS., No. 8496, fol. xiii.

3 Captivité de Francois Ier, &c., pp. 167-207.

4 Varillas is the principal historian who has mentioned

this supposed intrigue, which also furnished the subject of

a romance entitled Histoire de Marguerite, Reine de

Navarre, &c., 1696.

After three months of negotiations, continually broken off and renewed, Margaret and her brother, feeling convinced of Charles V.‘s evil intentions, resolved to take steps to ensure the independence of France. By the King’s orders Robertet, his secretary, drew up letters-patent, dated November 1525 by which it was decreed that the young Dauphin should be crowned at once, and that the regency should continue in the hands of Louise of Savoy, but that in the event of her death the same power should be exercised by Francis’s “very dear and well-beloved only sister, Margaret of France, Duchess of Alençon and Berry.” (1) However, all these provisions were to be deemed null and void in the event of Francis obtaining his release.

It has been erroneously alleged that Margaret on leaving Spain took this deed of abdication with her, and that the Emperor, informed of the circumstance, gave orders for her to be arrested as soon as her safe-conduct should expire. (2) However, it was the Marshal de Montmorency who carried the deed to France, and Charles V. in ordering the arrest of Margaret had no other aim than that of securing an additional hostage in case his treaty with Francis should not be fulfilled.

1 Captivité de François 1er, &c., p. 85.

2 Génin’s Notice in the Lettres de Marguerite, &c., p.

25.

Margaret, pressed by her brother, at last asked for authorisation to leave Spain. By the manner in which the permission was granted she perceived that the Emperor wished to delay rather than hasten her journey. During November she wrote Francis a letter in which this conviction was plainly expressed, and about the 19th of the month she left Madrid upon her journey overland to France.

At first she travelled very leisurely, but eventually she received a message from her brother, advising her to hasten her speed, as the Emperor, hoping that she would still be in Spain in January, when her safe-conduct would expire, had given orders for her arrest. Accordingly, on reaching Medina-Celi she quitted her litter and mounted on horseback, accomplishing the remainder of her journey in the saddle. Nine or ten days before the safe-conduct expired she passed Perpignan and reached Salces, where some French nobles were awaiting her.

Soon after her return to France she again took charge of the royal children, who once more fell ill, this time with the measles, as Margaret related in the following characteristic letter addressed to her brother, still a prisoner in Spain:—

“My Lord,—The fear that I have gone through about your children, without saying anything of it to Madame (Louise of Savoy), who was also very ill, obliges me to tell you in detail the pleasure I feel at their recovery. M. d’Angoulême caught the measles, with a long and severe fever; afterwards the Duke of Orleans took them with a little fever; and then Madame Madeleine without fever or pain; and by way of company the Dauphin without suffering or fever. And now they all are quite cured and very well; and the Dauphin does marvels in the way of studying, mingling with his schooling a hundred thousand other occupations. And there is no more question of passions, but rather of all the virtues; M. d’Orléans is nailed to his book, and says that he wants to be good; but M. d’Angoulême does more than the others, and says things that are to be esteemed rather as prophecies than childish utterances, which you, my lord, would be amazed to hear. Little Margot resembles myself; she will not be ill; but I am assured here that she has very graceful ways, and is getting prettier than ever Mademoiselle d’Angoulême (1) was.”

1 Génin’s Lettres de Marguerite, &c, p. 70. The

Mademoiselle d’Angoulême alluded to at the end of the letter

is Margaret herself.

Francis having consented to the onerous conditions imposed by Charles V., was at last liberated. On March 17th, 1526, he was exchanged for his two elder sons, who were to serve as hostages for his good faith, and set foot upon the territory of Bearn. He owed Margaret a deep debt of gratitude for her efforts to hasten his release, and one of his first cares upon leaving Spain was to wed her again in a fitting manner. He appears to have opened matrimonial negotiations with Henry VIII. of England, (1) but, fortunately for Margaret, without result. She, it seems, had already made her choice. There was then at the French Court a young King, without a kingdom, it is true, but endowed with numerous personal qualities. This was Henry d’Albret, Count of Bearn, and legitimate sovereign of Navarre, then held by Charles V. in defiance of treaty rights. Henry had been taken prisoner with Francis at Pavia and confined in the fortress there, from which, however, he had managed to escape in the following manner.

Having procured a rope ladder in view of descending from the castle, he ordered Francis de Rochefort, his page, to get into his bed and feign sleep. Then he descended by the rope, the Baron of Arros and a valet following him. In the morning, when the captain on duty came to see Henry, as was his usual custom, he was asked by a page to let the King sleep on, as he had been very ill during the night. Thus the trick was only discovered when the greater part of the day had gone by, and the fugitives were already beyond pursuit. (2)

1 Lettres de Marguerite, &c, p. 31.

2 Olhagaray’s Histoire de Faix, Béarn, Navarre, &c,

Paris, 1609. p. 487.

As the young King of Navarre had spent a part of his youth at the French Court, he was well known to Margaret, who apparently had a secret fancy for him. He was in his twenty-fourth year, prepossessing, and extremely brave. (1) There was certainly a great disproportion of age between him and Margaret, but this must have served to increase rather than attenuate her passion. She herself was already thirty-five, and judging by a portrait executed about this period, (2) in which she is represented in mourning for the Duke of Alençon, with a long veil falling from her cap, her personal appearance was scarcely prepossessing.

The proposed alliance met with the approval of Francis, who behaved generously to his sister. He granted her for life the enjoyment of the duchies of Alençon and Berry, with the counties of Armagnac and Le Perche and several other lordships. Finally, the marriage was celebrated on January 24th, 1527, at St. Germain-en-Laye, where, as Sauvai records, “there were jousts, tourneying, and great triumph for the space of eight days or thereabouts.” (3)

1 He was born at Sanguesa, April 1503, and became King of

Navarre in 1517.

2 This portrait is at the Bibliothèque Nationale in the

Recueil de Portraits au crayon by Clouet, Dumonstier, &c.

(fol. 88).

3 Antiquités de Paris, vol. ii. p. 688.

The retirement of King Henry to Bearn—Margaret’s intercourse with her brother—The inscription at Chambord—Margaret’s adventure with Bonnivet—Margaret’s relations with her husband—Her opinions upon love and conjugal fidelity—Her confinements and her children—The Court in Bearn and the refugee Reformers—Margaret’s first poems—Her devices, pastorals, and mysteries—The embellishment of Pau—Margaret at table and in her study—Reforms and improvements in Bearn—Works of defence at Navarreinx—Scheme of refortifying Sauveterre.

Some historians have stated that in wedding his sister to Henry d’Albret, Francis pledged himself to compel Charles V. to surrender his brother-in-law’s kingdom of Navarre. This, however, was but a political project, of which no deed guaranteed the execution. Francis no doubt promised Margaret to make every effort to further the restitution, and she constantly reminded him of his promise, as is shown by several of her letters. However, political exigencies prevented Francis from carrying out his plans, and in a diplomatic document concerning the release of the children whom Charles held as hostages the following clause occurs: “Item, the said Lord King promises not to help or favour the King of Navarre (although he has married his only and dear beloved sister) in reconquering his kingdom.” (1)

The indifference shown by Francis for the political fortunes of his brother-in-law, despite the numerous and signal services the latter had rendered him, justly discontented Henry, who at last resolved to withdraw from the Court, where Montmorency, Brion, and several other personages, his declared enemies, were in favour. Margaret apparently had to follow her husband in his retirement, for Sainte-Marthe remarks: “When the King of Navarre, disgusted with the Court, and seeing none of the promises that his brother-in-law had made him realised, resolved to withdraw to Bearn, Margaret, although the keen air of the mountains was hurtful to her health, and her doctors had threatened her with a premature death if she persevered in braving the rigours of the climate, preferred to put her life in peril rather than to fail in her duty by not accompanying her husband.” (2)

1 Bibliothèque Nationale, MS. No. 8546 (Béthune), fol. 107.

2 Oraison funèbre, &c, p. 70.

Various biographers express the opinion that this retirement took place in 1529, shortly after the Peace of Cambray, and others give 1530 as the probable date. Margaret, we find, paid a flying visit to Bearn with her husband in 1527; on January 7th, 1528, she was confined of her first child, Jane, at Fontainebleau, and the following year she is found with her little daughter at Longray, near Alençon. In 1530 she is confined at Blois of a second child, John, Prince of Viana, who died at Alençon on Christmas Day in the same year, when but five and a half months old. Then in 1531 her letters show her with her mother at Fontainebleau; and Louise of Savoy being stricken with the plague, then raging in France, Margaret closes her eyes at Gretz, a little village between Fontainebleau and Nemours, on September 22nd in that year.

It was after this event that the King and Queen of Navarre determined to proceed to Bearn, but so far as Margaret herself is concerned, it is certain that retirement was never of long duration whilst her brother lived. She is constantly to be found at Alençon, Fontainebleau, and Paris, being frequently with the King, who did not like to remain separated from her for any length of time. He was wont to initiate her into his political intrigues in view of availing himself of her keen and subtle mind. Brantôme, referring to this subject, remarks that her wisdom was such that the ambassadors who “spoke to her were greatly charmed by it, and made great report of it to those of their nation on their return; in this respect she relieved the King her brother, for they (the ambassadors) always sought her after delivering the chief business of their embassy, and often when there was important business the King handed it over to her, relying upon her for its definite resolution. She understood very well how to entertain and satisfy the ambassadors with fine speeches, of which she was very lavish, and also very clever at worming their secrets out of them, for which reason the King often said that she helped him right well and relieved him of a great deal.” (1)

1 OEuvres de Brantôme, 8vo, vol. v. p. 222.

Margaret’s own letters supply proof of this. She is constantly to be found intervening in state affairs and exercising her influence. She receives the deputies from Basle, Berne, and Strasburg who came to Paris in 1537 to ask Francis I. for the release of the imprisoned Protestants. She joins the King at Valence when he is making preparations for a fresh war against Charles V.; then she visits Montmorency at the camp of Avignon, which she praises to her brother; next, hastening to Picardy, when the Flemish troops are invading it, she writes from Amiens and speaks of Thérouenne and Boulogne, which she has found well fortified.

Francis, however, did not value her society and counsel solely for political reasons; he was also fond of conversing with her on literature, and at times they composed amatory verses together. According to an oft-repeated tradition, one day at the Château of Chambord, whilst Margaret was boasting to her brother of the superiority of womankind in matters of love, the King took a diamond ring from his finger and wrote on one of the window panes this couplet:—

“Souvent femme varie, Bien fol est qui s’y fie.” (1)

Brantôme, who declares that he saw the inscription, adds, however, that it consisted merely of three words, “Toute femme varie” (all women are fickle), inscribed in large letters at the side of the window. (2) He says nothing of any pane of glass (all window panes were then extremely small) or of a diamond having been used; (3) and in all probability Francis simply traced these words with a piece of chalk or charcoal on the side of one of the deep embrasures, which are still to be seen in the windows of the château.

1 “Woman is often fickle,

Crazy indeed is he who trusts her.”

2 Vies des Dames galantes, Disc. iv.

3 The practice of cutting glass with diamonds does not seem

to have been resorted to until the close of the sixteenth

century. See Les Subtiles et Plaisantes Inventions de J.

Prévost, Lyons, 1584, part i. pp. 30, 31.

Margaret carried her complaisance for her brother so far as to excuse his illicit amours, and she was usually on the best of terms with his favourites. (1) It has been asserted that improper relations existed between the brother and sister, but this charge rests solely upon an undated letter from her to Francis, which may be interpreted in a variety of ways. Count de la Ferrière, in his introduction to Margaret’s record of her expenditure, (2) expresses the opinion that it was penned in 1525, prior to her hasty departure from Spain; while M. Le Roux de Lincy assigns it to a later date, remarking that it was probably written during one of the frequent quarrels which arose between Margaret’s brother and her husband. However, they are both of opinion that the letter does not bear the interpretation which other writers have placed upon it. (3)

1 E. Fournier’s L’Esprit dans l’Histoire, Paris,

1860, p. 132 et seq.

2 Livre de Dépenses de Marguerite d’Angoulême, &c.

(Introduction).

3 See Lettres de Marguerite, &c., p. 246.

The only really well-authenticated love intrigue in which Margaret was concerned—and in that she played a remarkably virtuous part—was her adventure with the Admiral de Bonnivet, upon which the fourth story of the Heptameron is based. (1) She was certainly unfortunate in both her marriages. Her life with the Duke of Alençon has already been spoken of; and as regards her second union, although contracted under apparently favourable auspices, it failed to yield Margaret the happiness she had hoped for. But four years after its celebration she wrote to the Marshal de Montmorency: “Since you are with the King of Navarre, I have no fear but that all will go well, provided you can keep him from falling in love with the Spanish ladies.” (2) And again: “My nephew, I have received the letters you wrote to me, by which I have learnt that you are a much better relation than the King of Navarre is a good husband, for you alone have given me news of the King (Francis) and of him, without his being willing to give pleasure to a poor wife, big with child, by writing a single word to her.” (3)

1 Particulars concerning this adventure will be found in

the notes to Tale iv., and also in the Appendix to the

present volume (C).

2 Lettres de Marguerite, &c., p. 246.

3 Ibid., p. 248.

In another letter written to the Marshal at the same period she says: “If you listen to the King of Navarre, he will make you commit so many disorders that he will ruin you.” (1) Perhaps these words should not be taken literally; still they furnish cause for reflection when it is remembered that they were written by a woman just turned forty concerning her husband who was not yet thirty years old.

Margaret’s views upon love and the affinity of souls were somewhat singular, but they indicate an elevated and generous nature. In several passages of the Heptameron she has expressed her opinion on these matters, ardently defending the honour of her sex and condemning those wives who show themselves indulgent as regards their husbands’ infidelities. (2) She blames those who sow dissension between husbands and wives, leading them on to blows; (3) and when some one asked her what she understood perfect love to be, she made answer, “I call perfect lovers those who seek some perfection in the object of their love, be it beauty, kindness, or good grace, tending to virtue, and who have such high and honest hearts that they will not even for fear of death do base things that honour and conscience blame.”

1 Lettres de Marguerite, &c, p. 251.

2 Epilogue of Tale xxxvii.

3 Epilogue of Tale xlvi.

In reference to this subject of conjugal fidelity a curious story is told of Margaret. One day at Mont-de-Marsan, upon seeing a young man convicted of having murdered his father being led to execution, she remarked to those about her that it was very wrong to put to death a young fellow who had not committed the crime imputed to him. It was pointed out to her that the judges had only condemned him upon conclusive proofs and the acknowledgments that he himself had made. Margaret, however, persisted in her remark, whereupon some of her intimates begged of her to justify it, for it seemed to them at least singular. “I do not doubt,” she replied, “that this poor wretch killed his mother’s husband, but he certainly did not kill his own father.” (1)

Besides being unfortunate as regards her husbands, Margaret was also denied a mother’s privileges. She experienced great suffering at her confinements, (2) and on two occasions she was delivered of still-born infants of the female sex.

1 Gabriel de Minut’s De la Beauté, Discours divers, &c.,

Lyons, 1587. p. 74.

2 Nouvelles Lettres de Marguerite, pp. 84 and 93.

She had centred many hopes upon her little boy, John, of whom she was confined without accident, but he died, as already stated, in infancy, and this misfortune was a great shock to her, though she tried to conceal it by having the Te Deum sung at the funeral in lieu of the ordinary service, and by setting up in the streets of Alençon the inscription, “God gave him, God has taken him away.” However, from that time forward she never laid aside her black dress, though later on she wore it trimmed with marten’s fur. Her best known portrait (1) represents her attired in this style with the quaint Bearnese cap, which she had also adopted, set upon her head.

1 Bibliothèque Nationale, Recueil de Portraits au crayon,

&c., fol. 46.

Not only did Margaret lose her son by death, but she was prevented from enjoying the companionship of her daughter Jane. Francis, who never once lost sight of his own interests, deemed it advisable to possess himself of this child, who was the heiress to the throne of Navarre. Accordingly when Jane was but two years old she was sent by the King to the Château of Plessis-lès-Tours, where she was carefully brought up in strict seclusion.

To the fact that Margaret was never really happy with either of her husbands, and that she was precluded from discharging a mother’s duties, one may ascribe, in part, her fondness for gathering round her a Court in which divines, scholars, and wits prominently figured. The great interest which she took in religious matters, as is shown by so many of her letters, (1) led her to shelter many of the persecuted Reformers in Bearn; others she saved from the stake, and frequently in writing to the King and Marshal de Montmorency she begs for the release of some imprisoned heretic.

1 One of these letters, written by her either to Philiberta

of Savoy, Duchess of Nemours, or to Charlotte d’Orléans,

Duchess of Nemours, both of whom were her aunts, may be thus

rendered in English: “My aunt, on leaving Paris to escort

the King, Monsieur de Meaux (Bishop Briçonnet), sent me the

Gospels in French, translated by Fabry, word for word, which

he says we should read with as much reverence and as much

preparation to receive the Spirit of God, such as He has

left it us in His Holy Scriptures, as when we go to receive

it in the form of Sacrament. And inasmuch as Monsieur de

Villeroy has promised to deliver them to you, I have

requested him to do so, for these words (the Gospels) must

not fall into evil hands. I beg, my aunt, that if by their

means God grants you some grace, you will not forget her who

is above all else your good niece and sister, Margaret.”

Fabry’s translation of the Gospels was made in 1523-24.

Margaret’s religious views frequently caused dissension between her and her husband, in whose presence she abstained from giving expression to them. Hilarion de Coste mentions that “King Henry having one day been informed that a form of prayer and instruction contrary to that of his fathers was held in the chamber of the Queen, his wife, entered it intending to chastise the minister, and finding that he had been hurried away, the remains of his anger fell upon his wife, who received a blow from him, he remarking, ‘Madam, you want to know too much about it,’ and he at once sent word of the matter to King Francis.”

It was at Nérac that most of the divines protected by Margaret found a refuge from the persecutions of the Sorbonne. Here she kept court in a castle of which there now only remains a vaulted fifteenth-century gallery formerly belonging to the northern wing. Nérac has, however, retained intact a couple of quaint mediaeval bridges, which Margaret must have ofttimes crossed in her many journeyings. Moreover, the townsfolk still point out the so-called Palace of Marianne, said to have been built by Margaret’s husband for one of his mistresses, and also the old royal baths, which the Queen no doubt frequented.

It was at the castle of Nérac that Margaret’s favourite protégé, the venerable Lefèvre d’Étaples, died at the age of one hundred and one, in the presence of his patroness, to whom before expiring he declared that he had never known a woman carnally in his life. However, he regretfully added that in his estimation he had been guilty of a greater sin, for he had neglected to lay down his life for his faith. Another partisan of the Reform, Gerard Roussel, whom Margaret had almost snatched from the stake and appointed Bishop of Oloron, had no occasion to express any such regret. His own flock speedily espoused the doctrines of the Reformation, but when he proceeded to Mauléon and tried to preach there, the Basques refused to listen to him, and hacked the pulpit to pieces, the Bishop being precipitated upon the flagstones, and so grievously injured that he died.

Beside the divines who sought an asylum at Nérac, there were various noted men of letters, foremost among whom we may class the Queen’s two secretaries, Clement Marot, the poet, and Peter Le Maçon, the translator of Boccaccio’s Decameron. This translation was undertaken at the Queen’s request, as Le Maçon states in his dedication to her, and it has always been considered one of the most able literary works of the period. With Marot and Le Maçon, but in the more humble capacity of valet, at the yearly wages of one hundred and ten livres, there came the gay Bonaventure Despériers, the author of Les Joyeux Devis; (1) other writers, such as John Frotté, John de la Haye and Gabriel Chapuis, were also among Margaret’s retainers.

1 Livre de Dépenses de Marguerite d’Angoulême.

She herself had long practised the writing of verses. It was in 1531, and at Alençon, that she issued her first volume of poems, the Miroir de l’Ame Pécheresse, (1) which created a great stir at the time, for when it was re-issued in Paris by Augereau in 1533 (2) the Sorbonne denounced it as unorthodox, and Margaret would have been branded as a heretic if Francis had not intervened and ordered the Rector of the Sorbonne to withdraw the decree censuring his sister’s work. Nor did that content the King, for he caused Noël Béda, the syndic of the Faculty of Theology, to be arrested and confined in a dungeon at Mont St. Michel, where he perished miserably.

1 Brunet’s Manual, 4th ed., vol. iii. p. 275.

2 A second edition also appeared at Alençon in the same

year.

Margaret thus gained the day, but the annoyance she had been subjected to doubtless taught her to be prudent, for although she steadily went on writing, sixteen years elapsed before any more of her poems were published. In the meantime various manuscript copies, some of which are still in existence, were made of them, notably one of the poem called “Débat d’Amour” by Margaret, and re-christened “La Coche” by her secretary, John de la Haye, when he subsequently published it in the Marguerites de la Marguerite. This manuscript is enriched with eleven curious miniatures, the last of which represents the Queen handing the volume bound in white velvet (1) to the Duchess of Etampes, her brother’s mistress, whose qualities the poem extols. The Queen of Navarre was on the best of terms with this favourite, to whom in one of her letters she recommends certain servants.

Margaret was not only given to versifying, but was fond of’ framing devices, which she inscribed upon her books and furniture. At one time she adopted as her device a marigold turning towards the sun’s rays, with the motto, “Non inferiora secutus,” implying that she turned “all her acts, thoughts, will, and affections towards the great Sun of Justice, God Almighty.” (2)

1 From the Queen’s Livre de Dépenses, published by M. de

la Ferrière, we learn that this MS., with the miniatures and

binding, cost Margaret fifty golden crowns. It was formerly

in the possession of M. Jérôme Pichon, and was afterwards

acquired by M. Didot, at the sale of whose library it

realised £804. The MS. was recently in the possession of M.

de La Roche-la-Carelle.

2 Claude Paradin’s Dévises héroïques, Lyons, 1557, p. 41.

In her Miroir de l’Ame Pécheresse, previously referred to, there figures another device composed merely of the three words “Ung pour tout;” and in the manuscript of “La Coche” presented to the Duchess of Etampes, the motto “Plus vous que moys” is inscribed beneath each of the miniatures. Margaret also composed a series of devices for some jewels which her brother presented to his favourite, Madame de Châteaubriant. Respecting these Brantôme tells the following curious anecdote:—

“I have heard say, and hold on good authority, that when King Francis I. had left Madame de Châteaubriant, his favourite mistress, to take Madame d’Etampes, as one nail drives out another, Madame d’Etampes begged the King to take back from the said Madame de Châteaubriant all the finest jewels that he had given her, not on account of their cost and value, for pearls and precious stones were not then so fashionable as they have been since, but for the love of the fine devices that were engraved and impressed upon them; which devices the Queen of Navarre, his sister, had made and composed, for she was a mistress in such matters.

“King Francis granted the request, and promised that he would do it. Having with this intent sent a gentleman to Madame de Châteaubriant to ask for the jewels, she at once feigned illness, and put the gentleman off for three days, when he was to have what he asked for. However, out of spite, she sent for a goldsmith, and made him melt down all these jewels without exception, and without having any respect for the handsome devices engraved upon them. And afterwards, when the said gentleman returned, she gave him all the jewels converted into gold ingots.

“‘Go,’ said she, ‘and take these to the King, and tell him that since he has been pleased to take back from me that which he had given me so freely, I restore it and send it back in golden ingots. As for the devices, I have impressed them so firmly on my mind and hold them so dear in it, that I could not let any one have and enjoy them save myself.’

“When the King had received all this, the ingots and the lady’s remark, he only said, ‘Take her back all. What I did was not for the value, for I would have restored her that twofold, but for the love of the devices, and since she has thus destroyed them, I do not want the gold, and send it back. She has shown in this matter more courage and generosity than it would have been thought could come from a woman.’” (1)

Besides writing verses and framing devices, Margaret, as Brantôme tells us, “often composed comedies and moralities, which were in those days styled pastorals, and which she had played by the young ladies of her Court.” (2)

1 OEuvres de Brantôme, 8vo, vol. vii. p. 567.

2 Ibid., 8vo, vol. v. p. 219.

Hilarion de Coste states, moreover, that “she composed a tragi-comic translation of almost the whole of the New Testament, which she caused to be played before the King, her husband, having assembled with this object some of the best actors of Italy; and as these buffoons are only born to give pleasure and make time pass away, in order to amuse the company they invariably introduced rondeaux and virelais against the ecclesiastics, especially the monks and village priests.” (1)

1 M. Le Roux de Lincy points out that this statement is

exaggerated, for Margaret, instead of turning the whole of

the New Testament into verse, merely wrote four Mysteries

which mainly dealt with the childhood of Christ.

These performances took place at the Château of Pau, which Margaret and her husband seem to have preferred to that of Nérac, though political reasons often compelled them to fix their abode at the latter. Pau, however, possessed the advantage of a mild climate, necessary for Margaret’s health, besides being delightfully situated on the Bearnese Gave, the view from the château extending over a fertile valley limited by the snow-capped Pyrenees. There had been a château at Pau as early as the tenth century, but the oldest portions of the structure now subsisting date from the time of Edward III., when Pau was the capital of the celebrated Gaston-Phoebus. The château was considerably enlarged and embellished in the fifteenth century, but it was not until after Margaret’s marriage with Henry d’Albret that the more remarkable decorative work was executed. Upon leaving Nérac to reside at Pau, Margaret summoned a number of Italian artists and confided the embellishment of the château to them.(1)

It was not, however, merely the château which Margaret beautified at Pau. Already at Alençon she had laid out a charming park, which a contemporary poet called a terrestrial paradise,(2) and upon coming to reside at Pau she transformed the surrounding woods into delightful gardens, pronounced to be the finest then existing in Europe.(3)

1 Some of the doors and windows of the château are

elaborately ornamented in the best style of the Renaissance,

whilst the grand staircase, although dating from Margaret’s

time, has vaulted arches, sometimes in the Romanesque and at

others in the Gothic style. Entwined on the friezes are the

initials H and M (Henry and Margaret), occasionally

accompanied by the letter R, implying Rex or Regina. On

the first floor of the chateau is the bedroom occupied by

Margaret’s husband, remarkable for its Renaissance chimney-

piece, and also a grand reception hall, now adorned with

tapestry made for Francis I. in Flanders. It was in this

latter room that the Count of Montgomery—the same who had

thrust out the eye of Henry II. at a tournament, and thereby

caused that monarch’s death—acting at the instigation of

Margaret’s daughter Jane, assembled the Catholic noblemen of

Bearn on August 24, 1569, and, after entertaining them with a

banquet, had them treacherously massacred. Bascle de

Lagrèze’s Château de Pau, Paris, 1854.

2 Le Recueil de l’Antique pré-excellence de Gaule, &c., by

G. Le Roville, Paris, 1551 (fol. 74).

3 Hilarion de Coste’s Vies et Éloges des Dames illustres,

&c., vol. ii. p. 272.

Some idea of their appearance may be gained from a couple of the miniatures adorning a curious manuscript catechism composed for Margaret and now in the Arsenal Library at Paris.(1)

1 Manuscrits théologiques français, No. 60, Initiatoire

Instruction en la Religion chrétienne, &c. In one of these

miniatures the Saviour is represented carrying the cross,

followed by Henry of Navarre, his brother Charles d’Albret,

Margaret, and other personages, all of whom bear crosses,

whilst in the background are some pleasure-grounds with a

castle, a little waterfall, and a lake. Another miniature in

the same manuscript shows King Henry of Navarre with a

flower in his hand, which he seems to be offering to the

Queen, who stands in the background among a party of

courtiers. The King wears a surtout of cloth of gold, edged

with ermine, over a blue jerkin, and a red cap with a white

feather. Margaret is also arrayed in cloth of gold, but with

a black cap and wimple. She is standing in a garden enclosed

by a railing, and adorned with a fountain in the form of a

temple which rises among groves and arbours. Beyond a white

crenellated wall is a castle which has been identified with

that of Pau. On fol. 1 of the same MS. the artist has

depicted Queen Margaret’s escutcheon, by which we find that

she quartered the arms of France with those of Navarre,

Aragon, Castile, Leon, Bearn, Bigorre, Evreux, and Albret.