This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Tin Soldier

Author: Temple Bailey

Release Date: March 27, 2006 [eBook #18056]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TIN SOLDIER***

| CHAPTER | |

| I | THE TOY SHOP |

| II | CINDERELLA |

| III | DRUSILLA |

| IV | THE QUESTION |

| V | THE SLACKER |

| VI | THE PROMISE |

| VII | HILDA |

| VIII | THE SHADOWED ROOM |

| IX | ROSE-COLOR! |

| X | A MAN WITH MONEY |

| XI | HILDA WEARS A CROWN |

| XII | WHEN THE MORNING STARS SANG |

| XIII | ARE MEN MADE ONLY FOR THIS? |

| XIV | SHINING SOULS |

| XV | HILDA BREAKS THE RULES |

| XVI | JEAN-JOAN |

| XVII | THE WHITE CAT |

| XVIII | THE BROAD HIGHWAY |

| XIX | HILDA SHAKES A TREE |

| XX | THE VISION OF BRAVE WOMEN |

| XXI | DERBY'S WIFE |

| XXII | JEAN PLAYS PROXY |

| XXIII | THE EMPTY HOUSE |

| XXIV | THE SINGING WOMAN |

| XXV | WHITE VIOLETS |

| XXVI | THE HOPE OF THE WORLD |

| XXVII | MARCHING FEET |

| XXVIII | SIX DAYS |

| XXIX | "HE CAME TO THE WARS!" |

"I cannot bear it," the Tin Soldier said, standing on the shelf, "I

cannot bear it. It is so melancholy here. Let me rather go to the

wars and lose my arms and legs."

HANS ANDERSEN: The Old House.

The lights shining through the rain on the smooth street made of it a golden river.

The shabby old gentleman navigated unsteadily until he came to a corner. A lamp-post offered safe harbor. He steered for it and took his bearings. On each side of the glimmering stream loomed dark houses. A shadowy blot on the triangle he knew to be a church. Beyond the church was the intersecting avenue. Down the avenue were the small exclusive shops which were gradually encroaching on the residence section.

The shabby old gentleman took out his watch. It was a fine old watch, not at all in accord with the rest of him. It was almost six. The darkness of the November afternoon had come at five. The shabby old gentleman swung away from the lamppost and around the corner, then bolted triumphantly into the Toy Shop.

"Here I am," he said, with an attempt at buoyancy, and sat down.

"Oh," said the girl behind the counter, "you are wet."

"Well, I said I'd come, didn't I? Rain or shine? In five minutes I should have been too late—shop closed—" He lurched a little towards her.

She backed away from him. "You—you are—wet—won't you take cold—?"

"Never take cold—glad to get here—" He smiled and shut his eyes, opened them and smiled again, nodded and recovered, nodded and came to rest with his head on the counter.

The girl made a sudden rush for the rear door of the shop. "Look here, Emily. Poor old duck!"

Emily, standing in the doorway, surveyed the sleeping derelict scornfully. "You'd better put him out. It is six o'clock, Jean—"

"He was here yesterday—and he was furious because I wouldn't sell him any soldiers. He said he wanted to make a bonfire of the Prussian ones—and to buy the French and English ones for his son," she laughed.

"Of course you told him they were not for sale."

"Yes. But he insisted. And when he went away he told me he'd come again and bring a lot of money—"

The shabby old gentleman, rousing at the psychological moment, threw on the counter a roll of bills and murmured brokenly:

"'Ten little soldiers fighting on the line,

One was blown to glory, and, then there were nine—!'"

His head fell forward and again he slept.

"Disgusting," said Emily Bridges; "of course we've got to get him out."

Getting him out, however, offered difficulties. He was a very big old gentleman, and they were little women.

"We might call the police—"

"Oh, Emily—"

"Well, if you can suggest anything better. We must close the shop."

"We might put him in a taxi—and send him home."

"He probably hasn't any home."

"Don't be so pessimistic—he certainly has money."

"You don't know where he got it. You can't be too careful, Jean—"

The girl, touching the old man's shoulder, asked, "Where do you live?"

He murmured indistinctly.

"Where?" she bent her ear down to him.

Waking, he sang:

"Two little soldiers, blowing up a Hun—

The darned thing—exploded—

And then there was—One—"

"Oh, Emily, did you ever hear anything so funny?"

Emily couldn't see the funny side of it. It was tragic and it was disconcerting. "I don't know what to do. Perhaps you'd better call a taxi."

"He's shivering, Emily. I believe I'll make him a cup of chocolate."

"Dear child, it will be a lot of trouble—"

"I'd like to do it—really."

"Very well." Emily was not unsympathetic, but she had had a rather wearing life. Her love of toys and of little children had kept her human, otherwise she had a feeling that she might have hardened into chill spinsterhood.

As Jean disappeared through the door, the elder woman moved about the shop, setting it in order for the night. It was a labor of love to put the dolls to bed, to lock the glass doors safely on the puffy rabbits and woolly dogs and round-eyed cats, to close the drawers on the tea-sets and Lilliputian kitchens, to shut into boxes the tin soldiers that their queer old customer had craved.

For more than a decade Emily Bridges had kept the shop. Originally it had been a Thread and Needle Shop, supplying people who did not care to go downtown for such wares.

Then one Christmas she had put in a few things to attract the children. The children had come, and gradually there had been more toys—until at last she had found herself the owner of a Toy Shop, with the thread and needle and other staid articles stuck negligently in the background.

Yet in the last three years it had been hard to keep up the standard which she had set for herself. Toys were made in Germany, and the men who had made them were in the trenches, the women who had helped were in the fields—the days when the bisque babies had smiled on happy working-households were over. There was death and darkness where once the rollicking clowns and dancing dolls had been set to mechanical music.

Jean, coming back with the chocolate, found Emily with a great white plush elephant in her arms. His trappings were of red velvet and there was much gold; he was the last of a line of assorted sizes.

There had always been a white elephant in Miss Emily's window. Painfully she had seen her supply dwindle. For this last of the herd, she had a feeling far in excess of his value, such as a collector might have for a rare coin of a certain minting, or a bit of pottery of a pre-historic period.

She had not had the heart to sell him. "I may never get another. And there are none made like him in America."

"After the war—" Jean had hinted.

Miss Emily had flared, "Do you think I shall buy toys of Germany after this war?"

"Good for you, Emily. I was afraid you might."

But tonight a little pensively Miss Emily wrapped the old mastodon up in a white cloth. "I believe I'll take him home with me. People are always asking to buy him, and it's hard to explain."

"I should say it is. I had an awful time with him," she indicated the old gentleman, "yesterday."

She set the tray down on the counter. There was a slim silver pot on it, and a thin green cup. She poked the sleeping man with a tentative finger. "Won't you please wake up and have some chocolate."

Rousing, he came slowly to the fact of her hospitality. "My dear young lady," he said, with a trace of courtliness, "you shouldn't have troubled—" and reached out a trembling hand for the cup. There was a ring on the hand, a seal ring with a coat of arms. As he drank the chocolate eagerly, he spilled some of it on his shabby old coat.

He was facing the door. Suddenly it opened, and his cup fell with a crash.

A young man came in. He too, was shabby, but not as shabby as the old gentleman. He had on a dilapidated rain-coat, and a soft hat. He took off his hat, showing hair that was of an almost silvery fairness. His eyebrows made a dark pencilled line—his eyes were gray. It was a striking face, given a slightly foreign air by a small mustache.

He walked straight up to the old man, laid his hand on his shoulder, "Hello, Dad." Then, anxiously, to the two women, "I hope he hasn't troubled you. He isn't quite—himself."

Jean nodded. "I am so glad you came. We didn't know what to do."

"I've been looking for him—" He bent to pick up the broken cup. "I'm dreadfully sorry. You must let me pay for it."

"Oh, no."

"Please." He was looking at it. "It was valuable?"

"Yes," Jean admitted, "it was one of Emily's precious pets."

"Please don't think any more about it," Emily begged. "You had better get your father home at once, and put him to bed with a hot water bottle."

Now that the shabby youth was looking at her with troubled eyes, Emily found herself softening towards the old gentleman. Simply as a derelict she had not cared what became of him. But as the father of this son, she cared.

"Thank you, I will. We must be going, Dad."

The old gentleman stood up. "Wait a minute—I came for tin soldiers—Derry—"

"They are not for sale," Miss Emily stated. "They are made in Germany. I can't get any more. I have withdrawn everything of the kind from my selling stock."

The shabby old gentleman murmured, disconsolately.

"Oh, Emily," said the girl behind the counter, "don't you think we might—?"

Derry Drake glanced at her with sudden interest. She had an unusual voice, quick and thrilling. It matched her beauty, which was of a rare quality—white skin, blue eyes, crinkled hair like beaten copper.

"I don't see," he said, smiling for the first time, "what Dad wants of tin soldiers."

"To make 'em fight," said the shabby old man, "we've got to have some fighting blood in the family."

The smile was struck from the young man's face. Out of a dead silence, he said at last, "You were very good to look after him. Come, Dad." His voice was steady, but the flush that had flamed in his cheeks was still there, as he put his arm about the shaky old man and led him to the door.

"Thank you both again," he said from the threshold. Then, with his head high, he steered his unsteady parent out into the rain.

It was late when the two women left the shop. Miss Emily, struggling down the block with her white elephant, found, in a few minutes, harbor in her boarding house. But Jean lived in the more fashionable section beyond Dupont Circle. Her father was a doctor with a practice among the older district people, who, in spite of changing administrations and fluctuating populations, had managed, to preserve their family traditions and social identity.

Dr. McKenzie did not always dine at home. But tonight when Jean came down he was at the head of the table. He was a big, handsome man with crinkled hair like his daughter's, copper-colored and cut close to his rather classic head.

Hilda Merritt was also at the table. She was a trained nurse, who, having begun life as the Doctor's office-girl, had, gradually, after his wife's death, assumed the management of his household. Jean was not fond of her. She had repeatedly begged that her dear Emily might take Miss Merritt's place.

"But Hilda is much younger," her father had contended, "and much more of a companion for you."

"She isn't a companion at all, Daddy. We haven't the same thoughts."

But Hilda had stayed on, and Jean had sought her dear Emily's company in the little shop. Sometimes she waited on customers. Sometimes she worked in the rear room. It was always a great joke to feel that she was really helping. In all her life her father had never let her do a useful thing.

The table was lighted with candles, and there was a silver dish of fruit in the center. The dinner was well-served by a trim maid.

Jean ate very little. Her father noticed her lack of appetite, "Why don't you eat your dinner, dear?"

"I had chocolate at Emily's."

"I don't think she ought to go there so often," Miss Merritt complained.

"Why not?" Jean's voice was like the crack of a whip.

"It is so late when you get home. It isn't safe."

"I can always send the car for you, Jean," her father said. "I don't care to have you out alone."

"Having the car isn't like walking. You know it isn't, Daddy, with the rain against your cheeks and the wind—"

Dr. McKenzie's quick imagination was fired. His eyes were like Jean's, lighted from within.

"I suppose it is all right if she comes straight up Connecticut Avenue, Hilda?"

Miss Merritt had long white hands which lay rather limply on the table. Her arms were bare. She was handsome in a red-cheeked, blond fashion.

"Of course if you think it is all right, Doctor—"

"It is up to Jean. If she isn't afraid, we needn't worry."

"I'm not afraid of anything."

He smiled at her. She was so pretty and slim and feminine in her white gown, with a string of pearls on her white neck. He liked pretty things and he liked her fearlessness. He had never been afraid. It pleased him that his daughter should share his courage.

"Perhaps, if I am not too busy, I will come for you the next time you go to the shop. Would walking with me break the spell of the wind and wet?"

"You know it wouldn't. It would be quite—heavenly—Daddy."

After dinner, Doctor McKenzie read the evening paper. Jean sat on the rug in front of the fire and knitted for the soldiers. She had made sweaters until it seemed sometimes as if she saw life through a haze of olive-drab.

"I am going to knit socks next," she told her father.

He looked up from his paper. "Did you ever stop to think what it means to a man over there when a woman says 'I'm going to knit socks'?"

Jean nodded. That was one of the charms which her father had for her. He saw things. It was tired soldiers at this moment, marching in the cold and needing—socks.

Hilda, having no vision, remarked from the corner where she sat with her book, "There's no sense in all this killing—I wish we'd kept out of it."

"Wasn't there any sense," said little Jean from the hearth rug, "in Bunker Hill and Valley Forge?"

Hilda evaded that. "Anyhow, I'm glad they've stopped playing the 'Star-Spangled Banner' at the movies. I'm tired of standing up."

Jean voiced her scorn. "I'd stand until I dropped, rather than miss a note of it."

Doctor McKenzie interposed:

"'The time has come,' the Walrus said,

'To talk of many things,

Of shoes—and ships—and sealing wax—

Of cabbages—and kings—'"

"Oh, Daddy," Jean reproached him, "I should think you might be serious."

"I am not just twenty—and I have learned to bank my fires. And you mustn't take Hilda too literally. She doesn't mean all that she says, do you, Hilda?"

He patted Miss Merritt on the shoulder as he went out. Jean hated that. And Hilda's blush.

With the Doctor gone, Hilda shut herself up in the office to balance her books.

Jean went on with her knitting, Hilda did not knit. When she was not helping in the office or in the house, her hands lay idle in her lap.

Jean's mind, as she worked, was on those long white hands of Hilda's. Her own hands had short fingers like her father's. Her mother's hands had been slender and transparent. Hilda's hands were not slender, they had breadth as well as length, and the skin was thick. Even the whiteness was like the flesh of a fish, pale and flabby. No, there was no beauty at all in Hilda's hands.

Once Jean had criticised them to her father. "I think they are ugly."

"They are useful hands, and they have often helped me."

"I like Emily's hands much better."

"Oh, you and your Emily," he had teased.

Yet Jean's words came back to the Doctor the next night, as he sat in the Toy Shop waiting to escort his daughter home.

Miss Emily was serving a customer, a small boy in a red coat and baggy trousers. A nurse stood behind the small boy, and played, as it were, Chorus. She wore a blue cape and a long blue bow on the back of her hat.

The small boy was having the mechanical toys wound up for him. He expressed a preference for the clowns, but didn't like the colors.

"I want him boo'," he informed Miss Emily, "he's for a girl, and she yikes boo'."

"Blue," said the nurse austerely, "you know your mother doesn't like baby talk, Teddy."

"Ble-yew—" said the small boy, carefully.

"Blue clowns," Miss Emily stated, sympathetically, "are hard to get. Most of them are red. I have the nicest thing that I haven't shown you. But it costs a lot—"

"It's a birfday present," said the small boy.

"Birthday," from the Chorus.

"Be-yirthday," was the amended version, "and I want it nice."

Miss Emily brought forth from behind the glass doors of a case a small green silk head of lettuce. She set it on the counter, and her fingers found the key, then clickety-click, clickety-click, she wound it up. It played a faint tune, the leaves opened—a rabbit with a wide-frilled collar rose in the center. He turned from side to side, he waggled his ears, and nodded his head, he winked an eye; then he disappeared, the leaves closed, the music stopped.

The small boy was entranced. "It's boo-ful—"

"Beautiful—" from the background.

"Be-yewtiful—. I'll take it, please."

It was while Miss Emily was winding the toy that Dr. McKenzie noticed her bands. They were young hands, quick and delightful hands. They hovered over the toy, caressingly, beat time to the music, rested for a moment on the shoulders of the little boy as he stood finally with upturned face and tied-up parcel.

"I'm coming adain," he told her.

"Again—."

"Ag-yain—," patiently.

"I hope you will." Miss Emily held out her hand. She did not kiss him. He was a boy, and she knew better.

When he had gone, importantly, Emily saw the Doctor's eyes upon her. "I hated to sell it," she said, with a sigh; "goodness knows when I shall get another. But I can't resist the children—"

He laughed. "You are a miser, Emily."

He had known her for many years. She was his wife's distant cousin, and had been her dearest friend. She had taught in a private school before she opened her shop, and Jean had been one of her pupils. Since Mrs. McKenzie's death it had been Emily who had mothered Jean.

The Doctor had always liked her, but without enthusiasm. His admiration of women depended largely on their looks. His wife had meant more to him than that, but it had been her beauty which had first held him.

Emily Bridges had been a slender and diffident girl. She had kept her slenderness, but she had lost her diffidence, and she had gained an air of distinction. She dressed well, her really pretty feet were always carefully shod and her hair carefully waved. Yet she was one of the women who occupy the background rather than the foreground of men's lives—the kind of woman for whom a man must be a Columbus, discovering new worlds for himself.

"Yon are a miser," the Doctor repeated.

"Wouldn't you be, under the same circumstances? If it were, for example, surgical instruments—anaesthetics—? And you knew that when they were gone you wouldn't get any more?"

He did not like logic in a woman. He wanted to laugh and tease. "Jean told me about the white elephant."

"Well, what of it? I have him at home—safe. In a big box—with moth-balls—" Her lips twitched. "Oh, it must seem funny to anyone who doesn't feel as I do."

The door of the rear room opened, and Jean came in, carrying in her arms an assortment of strange creatures which she set in a row on the floor in front of her father.

"There?" she asked, "what do you think of them?"

They were silhouettes of birds and beasts, made of wood, painted and varnished. But such ducks had never quacked, such geese had never waddled, such dogs had never barked—fantastic as a nightmare—too long—too broad—exaggerated out of all reality, they might have marched with Alice from Wonderland or from behind the Looking Glass.

"I made them, Daddy."

"You—."

"Yes, do you like them?"

"Aren't they a bit—uncanny?"

"We've sold dozens; the children adore them."

"And you haven't told me you were doing it. Why?"

"I wanted you to see them first—a surprise. We call them the Lovely Dreams, and we made the ducks green and the pussy cats pink because that's the way the children see them in their own little minds—"

She was radiant. "And I am making money, Daddy. Emily had such a hard time getting toys after the war began, so we thought we'd try. And we worked out these. I get a percentage on all sales."

He frowned. "I am not sure that I like that."

"Why not?"

"Don't I give you money enough?"

"Of course. But this is different."

"How different?"

"It is my own. Don't you see?"

Being a man he did not see, but Miss Emily did. "Any work that is worth doing at all is worth being paid for. You know that, Doctor."

He did know it, but he didn't like to have a woman tell him. "She doesn't need the money."

"I do. I am giving it to the Red Cross. Please don't be stuffy about it, Daddy."

"Am I stuffy?"

"Yes."

He tried to redeem himself by a rather tardy enthusiasm and succeeded. Jean brought out more Lovely Dreams, until a grotesque procession stretched across the room.

"Tomorrow," she announced, triumphantly, "we'll put them in the window, and you'll see the children coming."

As she carried them away, Doctor McKenzie said to Emily, "It seems strange that she should want to do it."

"Not at all. She needs an outlet for her energies."

"Oh, does she?"

"If she weren't your daughter, you'd know it."

On the way home he said, "I am very proud of you, my dear."

Jean had tucked her arm through his. It was not raining, but the sky was full of ragged clouds, and the wind blew strongly. They felt the push of it as they walked against it.

"Oh," she said, with her cheek against his rough coat, "are you proud of me because of my green ducks and my pink pussy cats?"

But she knew it was more than that, although he laughed, and she laughed with him, as if his pride in her was a thing which they took lightly. But they both walked a little faster to keep pace with their quickened blood.

Thus their walk became a sort of triumphant progress. They passed the British Embassy with the Lion and the Unicorn watching over it in the night; they rounded the Circle and came suddenly upon a line of motor cars.

"The Secretary is dining a rather important commission," the Doctor said; "it was in the paper. They are to have a war feast—three courses, no wine, and limited meats and sweets."

They stopped for a moment as the guests descended from their cars and swept across the sidewalk. The lantern which swung low from the arched entrance showed a spot of rosy color—the velvet wrap of a girl whose knot of dark curls shone above the ermine collar. A Spanish comb, encrusted with diamonds, was stuck at right angles to the knot.

Beside the young woman in the rosy wrap walked a young man in a fur coat who topped her by a head. He had gray eyes and a small upturned mustache—Jean uttered an exclamation.

"What's the matter?" her father asked.

"Oh, nothing—" she watched the two ascend the stairs. "I thought for a moment that I knew him."

The great door opened and closed, the rosy wrap and the fur coat were swallowed up.

"Of course it couldn't be," Jean decided as she and her father continued on their wonderful way.

"Couldn't be what, my dear?"

"The same man, Daddy," Jean said, and changed the subject.

The next time that Jean saw Him was at the theater. She and her father went to worship at the shrine of Maude Adams, and He was there.

It was Jean's yearly treat. There were, of course, other plays. But since her very-small-girlhood, there had been always that red-letter night when "The Little Minister" or "Hop-o'-my-Thumb" or "Peter Pan" had transported her straight from the real world to that whimsical, tender, delightful realm where Barrie reigns.

Peter Pan had been the climax!

Do you believe in fairies?

Of course she did. And so did Miss Emily. And so did her father, except in certain backsliding moments. But Hilda didn't.

Tonight it was "A Kiss for Cinderella"—! The very name had been enough to set Jean's cheeks burning and her eyes shining.

"Do you remember, Daddy, that I was six when I first saw her, and she's as young as ever?"

"Younger." It was at such moments that the Doctor was at his best. The youth in him matched the youth in his daughter. They were boy and girl together.

And now the girl on the stage, whose undying youth made her the interpreter of dreams for those who would never grow up, wove her magic spells of tears and laughter.

It was not until the first satisfying act was over that Jean drew a long breath and looked about her.

The house was packed. The old theater with its painted curtain had nothing modern to recommend it. But to Jean's mind it could not have been improved. She wanted not one thing changed. For years and years she had sat in her favorite seat in the seventh row of the parquet and had loved the golden proscenium arch, the painted goddesses, the red velvet hangings—she had thrilled to the voice and gesture of the artists who had played to please her. There had been "Wang" and "The Wizard of Oz"; "Robin Hood"; the tall comedian of "Casey at the Bat"; the short comedian who had danced to fame on his crooked legs; Mrs. Fiske, most incomparable Becky; Mansfield, Sothern—some of them, alas, already gods of yesterday!

At first there had been matinées with her mother—"The Little Princess," over whose sorrows she had wept in the harrowing first act, having to be consoled with chocolates and the promise of brighter things as the play progressed.

Now and then she had come with Hilda. But never when she could help it. "I'd rather stay at home," she had told her father.

"But—why—?"

"Because she laughs in the wrong places."

Her father never laughed in the wrong places, and he squeezed her hand in those breathless moments where words would have been desecration, and wiped his eyes frankly when his feelings were stirred.

"There is no one like you, Daddy," she had told him, "to enjoy things." And so it had come about that he had pushed away his work on certain nights and, sitting beside her, had forgotten the sordid and suffering world which he knew so well, and which she knew not at all.

As her eyes swept the house, they rested at last with a rather puzzled look on a stout old gentleman with a wide shirt-front, who sat in the right-hand box. He had white hair and a red face.

Where had she seen him?

There were women in the box, a sparkling company in white and silver, and black and diamonds, and green and gold. There was a big bald-headed man, and quite in the shadow back of them all, a slender youth.

It was when the slender youth leaned forward to speak to the vision in white and silver that Jean stared and stared again.

She knew now where she had seen the old gentleman with the wide shirt front. He was the shabby old gentleman of the Toy Shop! And the youth was the shabby son!

Yet here they were in state and elegance! As if a fairy godmother had waved a wand—!

The curtain went up on a feverish little slavey with her mind set on going to the ball, on Our Policeman wanting a shave, on the orphans in boxes, on baked potato offered as hospitality by a half-starved hostess, on a waiting Cinderella asleep on a frozen doorstep.

And then the ball—and Mona Lisa, and the Duchess of Devonshire, and The Girl with the Pitcher and the Girl with the Muff—and Cinderella in azure tulle and cloth-of-gold, dancing with the Prince at the end like mad—.

Then the bell boomed—the lights went out—and after a little moment, one saw Cinderella, stripped of her finery, staggering up the stairs.

Jean cried and laughed, and cried again. Yet even in the midst of her emotion, she found her eyes pulled away from that appealing figure on the stage to those faintly illumined figures in the box.

When the curtain went down, her father, most surprisingly, bowed to the old gentleman and received in return a genial nod.

"Oh, do you know him?" she demanded.

"Yes. It is General Drake."

"Who are the others?"

"I am not sure about the women. The boy in the back of the box is his son, DeRhymer Drake."

Derry!

"Oh,"—she had a feeling that she was not being quite candid with her father—"he's rather swank, isn't he, Daddy?"

"Heavens, what slang! I don't see where you get it. He is rich, if that's what you mean, and it's a wonder he isn't spoiled to death. His mother is dead, and the General is his own worst enemy; eats and drinks too much, and thinks he can get away with it."

"Are they very rich—?"

"Millions, with only Derry to leave it to. He's the child of a second wife."

Oh, lovely, lovely, lovely Cinderella, could your godmother do more than this? To endow two rained-on and shabby gentlemen with pomp and circumstance!

Jean tucked her hand into her father's, as if to anchor herself against this amazing tide of revelation. Then, as the auditorium darkened, and the curtain went up, she was swept along on a wave of emotions in which the play world and the real world were inextricably mixed.

And now Our Policeman discovers that he is "romantical." Cinderella finds her Prince, who isn't in the least the Prince of the fairy tale, but much nicer under the circumstance—and the curtain goes down on a glass slipper stuck on the toes of two tiny feet and a cockney Cinderella, quite content.

"Well," Jean drew a long breath. "It was the loveliest ever, Daddy," she said, as he helped her with her cloak.

And it was while she stood there in that cloak of heavenly blue that the young man in the box looked down and saw her.

He batted his eyes.

Of course she wasn't real.

But when he opened them, there she was, smiling up into the face of the man who had helped her into that heavenly garment.

It came to him, quite suddenly, that his father had bowed to the man—the big man with the classic head and the air of being at ease with himself and the world.

He did things to the velvet and ermine wrap that he was holding, which seemed to satisfy its owner, then he gripped his father's arm. "Dad, who is that big man down there—with the red head—the one who bowed to you?"

"Dr. McKenzie, Bruce McKenzie, the nerve specialist—"

Of course it was something to know that, but one didn't get very far.

"Let's go somewhere and eat," said the General, and that was the end of it. Out of the tail of his eye, Derry Drake saw the two figures with the copper-colored heads move down the aisle, to be finally merged into the indistinguishable stream of humanity which surged towards the door.

Jean and her father did not go to supper at the big hotel around the corner as was their custom.

"I've got to get to the hospital before twelve," the Doctor said. "I am sorry, dear—"

"It doesn't make a bit of difference. I don't want to eat," she settled herself comfortably beside him in the car. "Oh, it is snowing, Daddy, how splendid—"

He laughed. "You little bundle of—ecstasy—what am I going to do with you?"

"Love me. And isn't the snow—wonderful?"

"Yes. But everybody doesn't see it that way."

"I am glad that I do. I should hate to see nothing in all this miracle, but—slush tomorrow—"

"Yet a lot of life is just—slush tomorrow—. I wish you need never find that out—."

When Jean went into the house, and her father drove on, she found Hilda waiting up for her.

"Father had to go to the hospital."

"Did you have anything to eat?"

"No."

"I thought I might cook some oysters."

"I am really not hungry." Then feeling that her tone was ungracious, she tried to make amends. "It was nice of you to think of it—"

"Your father may like them. I'll have them hot for him."

Jean lingered uncertainly. She didn't want the food, but she hated to leave the field to Hilda. She unfastened her cloak, and sat down. "How are you going to cook them?"

"Panned—with celery."

"It sounds good—I think I'll stay down, Hilda."

"As you wish."

The Doctor, coming in with his coat powdered with snow, found his daughter in a big chair in front of the library fire.

"I thought you'd be in bed."

"Hilda has some oysters for us."

"Fine—I'm starved."

She looked at him, meditatively, "I don't see how you can be."

"Why not?"

"Oh, on such a night as this, Daddy? Food seems superfluous."

He sat down, smiling. "Don't ever expect to feed any man over forty on star-dust. Hilda knows better, don't you, Hilda?"

Hilda was bringing in the tray. There was a copper chafing-dish and a percolator. She wore her nurse's outfit of white linen. She looked well in it, and she was apt to put it on after dinner, when she was in charge of the office.

"You know better than to feed a man on stardust, don't you?" the Doctor persisted.

Hilda lifted the cover of the chafing-dish and stirred the contents. "Well, yes," she smiled at him, "you see, I have lived longer than Jean. She'll learn."

"I don't want to learn," Jean told her hotly. "I want to believe that—that—" Words failed her.

"That men can live on star-dust?" her father asked gently. "Well, so be it. We won't quarrel with her, will we, Hilda?"

The oysters were very good. Jean ate several with healthy appetite. Her father, twinkling, teased her, "You see—?"

She shrugged, "All the same, I didn't need them."

Hilda, putting things back on the tray, remarked: "There was a message from Mrs. Witherspoon. Her son is on leave for the week end. She wants you for dinner on Saturday night—both of you."

Doctor McKenzie tapped a finger on the table thoughtfully, "Oh, does she? Do you want to go, Jeanie?"

"Yes. Don't you?"

"I am not sure. I should like to build a fence about you, my dear, and never let a man look over. Ralph Witherspoon wants to marry her, Hilda, what do you think of that?"

"Well, why not?" Hilda laid her long hands flat on the table, leaning on them.

Jean felt little prickles of irritability. "Because I don't want to get married, Hilda."

Hilda gave her a sidelong glance, "Of course you do. But you don't know it."

She went out with her tray. Jean turned, white-faced, to her father, "I wish she wouldn't say such things—"

"My dear, I am afraid you don't quite do her justice."

"Oh, well, we won't talk about her. I've got to go to bed, Daddy."

She kissed him wistfully. "Sometimes I think there are two of you, the one that likes me, and the one that likes Hilda."

With his hands on her shoulders, he gave an easy laugh. "Who knows? But you mustn't have it on your mind. It isn't good for you."

"I shall always have you on my mind—."

"But not to worry about, baby. I'm not worth it—."

Hilda came in with the evening paper. "Have you read it, Doctor?"

"No." He glanced at the headlines and his face grew hard. "More frightfulness," he said, stormily. "If I had my way, it should be an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. For every man they have tortured, there should be one of their men—tortured. For every child mutilated, one of theirs—mutilated. For every woman—."

He stopped. Jean had caught hold of his arm. "Don't, Daddy," she said thickly, "it makes me afraid of you." She covered her face with her hands.

He drew her to him and smoothed her hair in silence. Over her head he glanced at Hilda. She was smiling inscrutably into the fire.

The thing that Derry Drake had on his mind the next morning was a tea-cup. There were other things on his mind—things so heavy that he turned with relief to the contemplation of cups.

Stuck all over the great house were cabinets of china—his father had collected and his mother had prized. Derry, himself, had not cared for any of it until this morning, but when Bronson, the old man who served him and had served his father for years, came in with his breakfast, Derry showed him a broken bit which he had brought home with him two nights before. "Have we a cup like this anywhere in the house, Bronson?"

"There's a lot of them, sir, in the blue room, in the wall cupboard."

"I thought so, let me have one of them. If Dad ever asks for it, send him to me. He broke the other, so it's a fair exchange."

He had it carefully wrapped and carried it downtown with him. The morning was clear, and the sun sparkled on the snow. As he passed through Dupont Circle he found that a few children and their nurses had braved the cold. One small boy in a red coat ran to Derry.

"Where are you going, Cousin Derry?"

"Down town."

"To-day is Margaret-Mary's birf-day. I am going to give her a wabbit—."

"Rabbit, Buster. You'd better say it quick. Nurse is on the way."

"Rab-yit. What are you going to give her?"

"Oh, must I give her something?"

"Of course. Mother said you'd forget it. I wanted to telephone, and she wouldn't let me."

"Would a doll do?"

"I shouldn't like a doll. But she is littler. And you mustn't spend much money. Mother said I spent too much for my rab-yit. That I ought to save it for Our Men. And you mustn't eat what you yike—we've got a card in the window, and there wasn't any bacon for bref-fus."

"Breakfast."

"Yes. An' we had puffed rice and prunes—"

Nurse, coming up, was immediately on the job. "You are getting mud on Mr. Derry's spats, Teddy. Stand up like a little gentleman."

"He is always that, Nurse, isn't he? And I should not have on spats at this hour in the morning."

Derry smiled to himself as he left them. He knew that Nurse did not approve of him. He had a way as it were of aiding and abetting Teddy.

But as he went on the smile faded. There were many soldiers on the street, many uniforms, flags of many nations draping doorways where were housed the men from across the sea who were working shoulder to shoulder with America for the winning of the war—. Washington had taken on a new aspect. It had a waked-up look, as if its lazy days were over, and there were real things to do.

The big church at the triangle showed a Red Cross banner. Within women were making bandages, knitting sweaters and socks, sewing up the long seams of shirts and pajamas. A few years ago they had worshipped a Christ among the lilies. They saw him now on the battlefield, crucified again in the cause of humanity.

It seemed to Derry that even the civilians walked with something of a martial stride. Men, who for years had felt their strength sapped by the monotony of Government service, were revived by the winds of patriotism which swept from the four corners of the earth. Women who had lost youth and looks in the treadmill of Departmental life held up their heads as if their eyes beheld a new vision.

Street cars were crowded, things were at sixes and sevens; red tape was loose where it should have been tight and tight where it should have been loose. Little men with the rank of officer sat in swivel chairs and tried to direct big things; big men, without rank, were tied to the trivial. Many, many things were wrong, and many, many things were right, as it is always when war comes upon a people unprepared.

And in the midst of all this clash and crash and movement and achievement, Derry was walking to a toy shop to carry a tea-cup!

He found Miss Emily alone in the big front room.

She did not at once recognize him.

"You remember I was in here the other night—and you wouldn't sell—tin soldiers—."

She flushed a little. "Oh, with your father?"

"Yes. He's a dear old chap—."

It was the best apology he could make, and she loved him for it.

He brought out the cup and set it on the counter. "It is like yours?"

"Yes." But she did not want to take it.

"Please. I brought it on purpose. We have a dozen."

"Of these?"

"Yes."

"But it will break your set."

"We have oodles of sets. Dad collects—you know— There are dishes enough in the house to start a crockery shop."

She glanced at him curiously. It was hard to reconcile this slim young man of fashion with the shabby boy of the other night. But there were the lad's eyes, smiling into hers!

"I should like, too, if you don't mind, to find a toy for a very little girl. It is her birthday, and I had forgotten."

"It is dreadful to forget," Miss Emily told him, "children care so much."

"I have never forgotten before, but I had so much on my mind."

She brought forth the Lovely Dreams—"They have been a great success."

He chose at once a rose-colored cat and a yellow owl. The cat was carved impressionistically in a series of circles. She was altogether celestial and comfortable. The owl might have been lighted by the moon.

"But why?" Derry asked, "a rose-colored cat?"

"Isn't a white cat pink and puffy in the firelight? And a child sees her pink and puffy. If we don't it is because we are blind."

"But why the green ducks and the amethyst cows?"

"The cows are coming tinkling home in the twilight—the green ducks swim under the willows. And they are longer and broader because of the lights and shadows. That's the way you saw them when you were six."

"By Jove," he said, staring, "I believe I did."

"So there's nothing queer about them to the children—you ought to see them listen when Jean tells them."

Jean—!

"She—she tells the children?"

"Yes. Charming stories. I am having them put in a little pamphlet to go with the toys."

"She's Dr. McKenzie's daughter, isn't she? I saw her last night at the play."

"Yes. Such a dear child. She is usually here in the afternoon."

He had hoped until then that Jean might be hidden in that rear room, locked up with the dolls in a drawer, tucked away in a box—he had a blank feeling of the futility of his tea-cup—

Then, suddenly, the gods being in a gay mood, Jean arrived!

At once his errand justified itself. She wore a gray squirrel jacket and a hat to match—and her crinkled copper-colored hair came out from under the hat and over her ears. She carried a little muff. Her eyes—the color of her cheeks! A man might walk to the world's end for less than this—!

He was buying, he told her, pink pussy cats and yellow owls. Had she liked the play last night? He was glad that she adored Maude Adams. He adored—Maude Adams. Did she remember "Peter Pan"? Yes, he had gone to everything—glorified matinées—glorified everything! Wasn't it remarkable that his father knew her father? And she was Jean McKenzie, and he was Derry Drake!

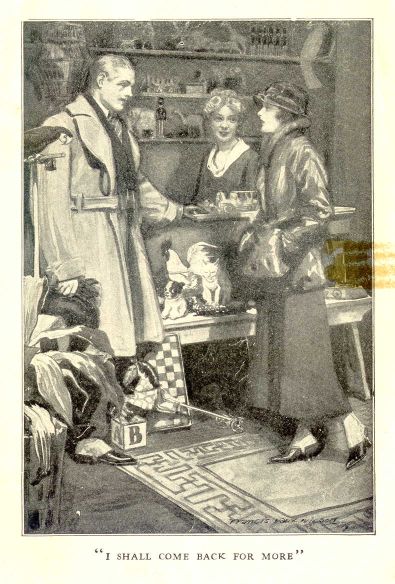

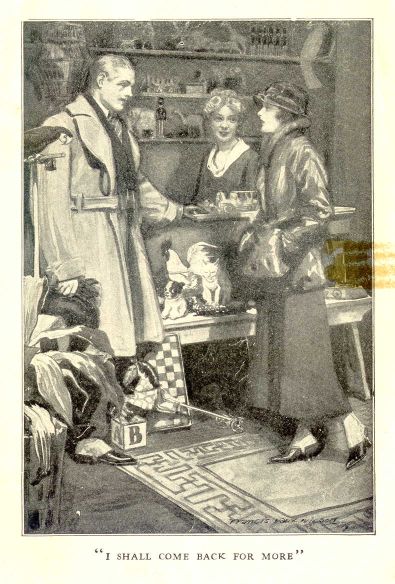

At last there was no excuse for him to linger. "I shall come back for more—Lovely Dreams," he told Miss Emily, and got away.

Alone in the shop the two women looked at each other. Then Emily said, "Jean, darling, how dreadful it must be for him."

"Dreadful—."

"With such a father—."

"Oh, you mean—the other night."

"Yes. He isn't happy, Jean."

"How do you know?"

"He has lonesome eyes."

"Oh, Emily."

"Well, he has, and it must be dreadful."

How dreadful it was neither of them could really know. Derry, having lunched with a rather important committee, went to Drusilla Gray's in the afternoon for a cup of tea. He was called almost at once to the telephone. Bronson was at the other end. "I am sorry, Mr. Derry, but I thought you ought to know—"

Derry, with the sick feeling which always came over him with the knowledge of what was ahead, said steadily, "That's all right, Bronson—which way did he go?"

"He took the Cabin John car, sir. I tried to get on, but he saw me, and sent me back, and I didn't like to make a scene. Shall I follow in a taxi?"

"Yes; I'll get away as soon as I can and call you up out there."

He went back to Drusilla. "Sing for me," he said. Drusilla Gray lived with her Aunt Marion in an apartment winch overlooked Rock Creek. Marion Gray occupied herself with the writing of books. Drusilla had varying occupations. Just now she was interested in interior decoration and in the war.

She was also interested in trying to flirt with Derry Drake. "He won't play the game," she told her aunt, "and that's why I like it—the game, I mean."

"You like him because he hasn't surrendered."

"No. He is a rather perfect thing of his kind, like a bit of jewelled Sèvres or Sang de boeuf. And he doesn't know it. And that's another thing in his favor—his modesty. He makes me think of a little Austrian prince I once met at Palm Beach; who wore a white satin shirt with a high collar of gold embroidery, and white kid boots, and wonderful rings—and his nails long like a Chinaman's. At first we laughed at him—called him effeminate—. But after we knew him we didn't laugh. There was the blood in him of kings and rulers—and presently he had us on our knees. And Derry's like that. When you first meet him you look over his head; then you find yourself looking up—"

Marion smiled. "You've got it bad, Drusilla."

"If you think I am in love with him, I'm not. I'd like to be, but it wouldn't be of any use. He's a Galahad—a pocket-edition Galahad. If he ever falls in love, there'll be more of romance in it than I can give him."

It was to this Drusilla that Derry had come. He liked her immensely. And they had in common a great love of music.

She had tea for him, and some rather strange little spiced cakes on a red lacquer tray. There was much dark blue and vivid red in the room, with white woodwork. Drusilla herself was in unrelieved red. The effect was startling but stimulating.

"I am not sure that I like it," she said, "the red and white and blue, but I wanted to see whether I could do it. And Aunt Marion doesn't care. The red things can all be taken out, and the rest toned down. But I have a feeling that a man couldn't sit in this room and be a slacker."

"No, he couldn't," Derry agreed. "You'd better hang out a recruiting sign, Drusilla."

"I should if they would let me. The best I can do is ask them to tea and sing for them."

It was right here that Bronson's message had broken in, and Derry, coming back from the telephone, had said, "Sing for me."

Drusilla lighted two red candles on the piano in the alcove. She began with a medley of patriotic songs. With her voice never soaring above a repressed note, she managed to give the effect of culminating emotion, so that when she reached a climax in the Marseillaise, Derry rose, thrilled, to his feet.

She whirled around and faced him. "They all do that," she said, with a glowing air Of triumph. "It's when I get them."

"Why did you give the Marseillaise last?"

"It has the tramp in it of marching men—I love it."

"But why not the 'Star Spangled Banner'?"

"That's for sacred moments. I hate to make it common—but I'll sing it—now—"

Still standing, he listened. Drusilla held her voice to that low note, but there was the crash of battle in the music that she made, the hush of dawn, the cry of victory—

"Dear girl, you are a genius."

"No, I am not. But I can feel things—and I can make others feel—"

She rose and went to the window. "There's a new moon," she said, "come and see—"

The curtains were not drawn, and the apartment was high up, so that they looked out beyond the hills to a sky in which the daylight blue had faded to a faint green, and saw the little moon and one star.

"Derry," Drusilla said, softly. "Derry, why aren't you fighting?"

It was the question he had dreaded. He had seen it often in her eyes, but never before had she voiced it.

"I can't tell you, Drusilla, but there's a reason—a good one. God knows I would go if I could."

The passion in his voice convinced her.

"Don't you know I'd be in it if I had my way. But I've got to stay on the shelf like the tin soldier in the fairy tale. Do you remember, Drusilla? And people keep asking me—why?"

"I shouldn't have asked it, Derry?"

"You couldn't know. And you had a right to ask—everybody has a right—and I can't answer."

She laid her hand on his shoulder. "When I was a little girl," she said, softly, "I used to cry—because I was so sorry for the—tin soldier—"

"Are you sorry for me, Drusilla?"

"Dreffly sorry."

They stood in silence among the shadows, with only the red candles burning. Then Derry said, heartily, "You are the best friend that a fellow ever had, Drusilla."

And that was as far as he would play the game!

Whatever else might be said of General Drake, his Bacchanalian adventures were those of a gentleman. Not for him were the sinister streets and the sordid taverns of the town. When his wild moods came upon him, he struck out straight for open country. Up hill and down dale he trudged, a knight of the road, finding shelter and refreshment at wayside inns, or perchance at some friendly farm.

The danger lay in the lawless folk whom he might meet on the way. Unshaven and unshorn he met them, travelling endlessly along the railroad tracks, by highways, through woodland paths. They slept by day and journeyed by night. By reversing this program, the General as a rule avoided them. But not always, and when the little lad Derry had followed his strange quests, he had come now and then upon his father, telling stories to an unsavory circle, lord for the moment of them all.

"Come, Dad," Derry would say, and when the men had growled a threat, he had flung defiance at them. "My mother's motor is up the road with two men in it. If I don't get back in five minutes they will follow me."

The General had always been tractable in the hands of his son. He adored him. It was only of late that he had found anything to criticise.

Derry, driving along the old Conduit road in the crisp darkness, wondered how long that restless spirit would endure in that ageing body. He shuddered as he thought of the two men who were his father—one a polished gentleman ruling his world, by the power of his keen mind and of his money, the other a self-made vagabond—pursuing an aimless course.

The stars were sharp in a sable sky, the river was a thin line of silver, the bills were blotted out.

Bronson was waiting by the big bridge. "He is singing down there," he said, "on the bank. Can you hear him?"

Leaning over the parapet, Derry listened. The quavering voice came up to him.

"_He has sounded forth the—trumpet—that shall never call—retreat—

He is sifting out the—hearts of men—before his judgment—

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer him! Be jubilant, my feet—'_"

Poor old soldier, beating time to the triumphant tune, stumbling over the words—held pathetically to the memory of those days when he had marched in the glory of his youth, strength and spirit given to a mighty cause!

The pity of it wrung Derry's heart. "Couldn't you do anything with him, Bronson?"

"No, sir, I tried, but he sent me home. Told me I was discharged."

They might have laughed over that, but it was not the moment for laughter. In the last twenty years, the General had discharged Bronson more than once, always without the least idea of being taken at his word. To have lost this faithful servant would have broken his heart.

"I see. It won't do for you to show yourself just now. You'd better go home, and have his hot bath ready."

"Are you sure you can bring him, Mr. Derry?"

"Sure, Bronson, thank you."

Bronson walked a few steps and came back. "It is freezing cold, sir, you'd better take the rug from the car."

Laden thus, Derry made his way down. His flashlight revealed the General, a humped-up figure on the bank of a little frozen stream.

"Go home, Derry," he said, as he recognized his son. "I want to sit by myself."

His tone was truculent.

Derry attempted lightness. "You'll be a lump of ice in the morning, Dad. We'd have to chip you off in chunks."

"You go home with Bronson, son, He is up there. Go home—"

He had once commanded a brigade. There were moments when he was hard pushed that he remembered it.

"Go home, Derry."

"Not till you come with me."

"I'm not coming."

Derry spread his rug on the icy ground. "Sit on this and wrap up your legs—you'll freeze out here."

His father did not move. "I am puf-feckly comfa'ble."

The General rarely got his syllables tangled. Things at times happened to his legs, but he usually controlled his tongue.

"I am puf-feckly comfa'ble—go home, Derry."

"I can't leave you, Dad."

"I want to be left."

He had never been quite like this. There had been moods of rebellion, but usually he had yielded himself to his son's guidance.

"Dad, be reasonable."

"I'd rather sit here and freeze—than go home with a—coward."

It was out at last. It struck Derry like a whiplash. He sprang to his feet. "You don't mean that, Dad. You can't mean it."

"I do mean it."

"I am not a coward, and you know it."

"Then why don't you go and fight?"

Silence! The only sound the chuckle of living waters beneath the ice of the little stream.

"Why don't you go and fight like other men?"

The emphasis was insulting. Derry had only one idea—to escape from that taunting voice. "You'll be sorry for this, Dad," he flung out at white heat, and scrambled up the bank.

When he reached the bridge, he paused. He couldn't leave that old man down there to die of the cold—the wind was rising and rattled in the bare trees.

But Derry's blood was boiling. He sat down on the parapet, thick blackness all about him. Whatever had been his father's shortcomings, they had always clung together—and now they were separated by words which had cut like a knife. It was useless to tell himself that his father was not responsible. Out of the heart the mouth had spoken.

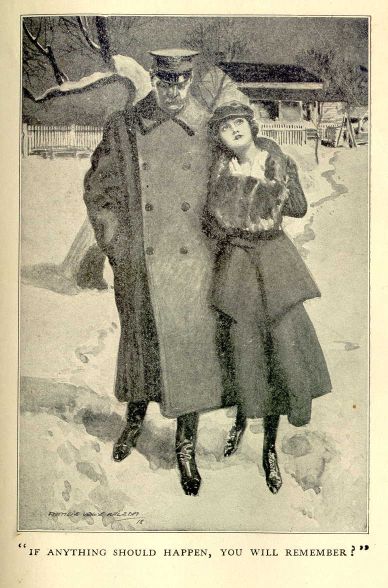

And there were other people who felt as his father did—there had been Drusilla's questions, the questions of others—there had been, too, averted faces. He saw the little figure in the cloak of heavenly blue as she had been the other night,—in her gray furs as she had been this morning—; would her face, too, be turned from him?

Words formed themselves in his mind. He yearned to toss back at his father the taunt that was on his lips. To fling it over the parapet, to shout it to the world—!

He had never before felt the care of his father a sacrifice. There had been humiliating moments, hard moments, but always he had been sustained by a sense of the rightness of the thing that he was doing and of its necessity.

Then, out of the darkness, came a shivering old voice, "Derry, are you there?"

"Yes, Dad."

"Come down—and help me—"

The General, alone in the darkness, had suffered a reaction. He felt chilled and depressed. He wanted warmth and light.

Mounting steadily with his son's arm to sustain him, he argued garrulously for a sojourn at the nearest hostelry, or for a stop at Chevy Chase. He would, he promised, go to bed at the Club, and thus be rid of Bronson. Bronson didn't know his place, he would have to be taught—

Arriving at the top, he was led to Derry's car. He insisted on an understanding. If he got in, they were to stop at the Club.

"No," Derry said, "we won't stop. We are going home."

Derry had never commanded a brigade. But he had in him the blood of one who had. He possessed also strength and determination backed at the moment by righteous indignation. He lifted his father bodily, put him in the car, took his seat beside him, shut the door, and drove off. He felt remarkably cheered as they whirled along at top speed.

The General, yielding gracefully to the inevitable, rolled himself up in the rugs, dropped his head against the padded cushions and, soothed by the warmth, fell asleep.

He waked to find himself being guided up his own stairway by Bronson and the butler.

"Put him into a hot bath, Bronson," Derry directed from the threshold of his father's room, and, the General, quite surprisingly, made no protest. He had his bath, hot drinks to follow, and hot water bags in his bed. When he drifted off finally, into uneasy dreams, he was watched over by Bronson as if he had been a baby.

Derry, looking at his watch, was amazed to find that the evening was yet early. He had lived emotionally through a much longer period than that marked by the clocks.

He had no engagements. He had found himself of late shrinking a little from his kind. The clubs and the hotels were crowded with officers. Private houses, hung with service flags, paid homage to men in uniform. He was aware that he was, perhaps, unduly sensitive, but it was not pleasant to meet the inquiring glance, the guarded question. He was welcomed outwardly as of old. But, then, he had a great deal of money. People did not like to offend his father's son. But if he had not been his father's son? What then?

He dined alone and in state in the great dining room. The portraits of his ancestors looked down on him. There was his mother's grandfather, who had the same fair hair and strongly marked brows. He had been an officer in the English army, and wore the picturesque uniform of the period. There were other men in uniform—ancestors—.

But of what earthly use was an ancestor in uniform to the present situation? It would have been better to have inherited Quaker blood. Derry smiled whimsically as he thought how different he might have felt if there had been benignant men in gray with broad-brimmed hats, staring down.

But to grant a man an inheritance of fighting blood, and then deny him the opportunity to exercise his birthright, was a sort of grim joke which he could not appreciate.

For dessert a great dish of fruit was set before him. He chose a peach!

Peaches in November! The men in the trenches had no peaches, no squabs, no mushrooms, no avacados—for them bully beef and soup cubes, a handful of dates, or by good luck a bit of chocolate.

He left the peach untasted—he had a feeling that he might thus, vicariously, atone for the hardships of those others who fought.

After dinner he walked downtown. Passing Dr. McKenzie's house he was constrained to loiter. There were lights upstairs and down. Was Jean McKenzie's room behind the two golden windows above the balcony? Was she there, or in the room below, where shaded lamps shone softly among the shadows?

He yearned to go in—to speak with her—to learn her thoughts—to read her heart and mind. As yet he knew only the message of her beauty. He fancied her as having exquisite sensibility, sweetness, gentleness, perceptions as vivid as her youth and bloom.

The front door opened, and Jean and her father came out. Derry's heart leaped as he heard her laugh. Then her clear voice, "Isn't it a wonderful night to walk, Daddy?" and her father's response, "Oh, you with your ecstasies!"

They went briskly down the other side of the street. Derry found himself following, found himself straining his ear for that light laugh, found himself wishing that it were he who walked beside her, that her hand was tucked into his arm as it was tucked into her father's.

Their destination was a brilliantly illumined palace on F Street, once a choice little playhouse, now given over to screen productions. The house was packed, and Jean and her father, following the flashlight of the usher, found harbor finally in a box to the left of the stage. Derry settled himself behind them. He was an eavesdropper and he knew it, but he was loath to get out of the range of that lovely laughter.

Yet observing the closeness of their companionship he felt himself lonely—they seemed so satisfied to be together—so sufficient without any other. Once Dr. McKenzie got up and went out. When he came back he brought a box of candy. Derry heard Jean's "Oh, you darling—" and thrilled with a touch of jealousy.

He wondered a little that he should care—his experiences with women had heretofore formed gay incidents in his life rather than serious epochs. He had carried in his heart a vision, and the girl in the Toy Shop had seemed to make that vision suddenly real.

The play which was thrown on the screen had to do with France; with Joan of Arc and the lover who failed her, with the reincarnation of the lover and his opportunity, after long years, to redeem himself from the blot of cowardice.

In the stillness, Derry heard the quick-drawn breath of the girl in front of him. "Daddy, I should hate a man like that."

"But, my dear—"

"I should hate him, Daddy."

The play was over.

The lights went up, and Jean stood revealed. She was pinning on her hat. She saw Derry and smiled at him. "Daddy," she said, "it is Mr. Drake—you know him."

Dr. McKenzie held out his hand. "How do you do? So you young people have met, eh?"

"In Emily's shop, Daddy. He—he came to buy my Lovely Dreams."

The two men laughed. "As if any man could buy your dreams, Jeanie," her father said, "it would take the wealth of the world."

"Or no wealth at all," said Derry quickly.

They walked out together. As they passed the portal of the gilded door, Derry felt that the moment of parting had come.

"Oh, look here, Doctor," he said, desperately, "won't you and your daughter take pity on me—and join me at supper? There's dancing at the Willard and all that—Miss McKenzie might enjoy it, and it would be a life-saver for me."

Light leaped into Jean's eyes. "Oh, Daddy—"

"Would you like it, dear?"

"You know I should. So would you. And you haven't any stupid patients, have you?"

"My patients are always stupid, Drake, when they take me away from her. Otherwise she is sorry for them." He looked at his watch. "When I get to the hotel I'll telephone to Hilda, and she'll know where to find us."

It was the Doctor who talked as they went along—the two young people were quite ecstatically silent. Jean was between her father and Derry. As he kept step with her, it seemed to him that no woman had ever walked so lightly; she laughed a little now and then. There was no need for words.

While her father telephoned, they sat together for a moment in the corridor. She unfastened her coat, and he saw her white dress and pearls. "Am I fine enough for an evening like this?" she asked him; "you see it is just the dress I wear at home."

"It seems to me quite a superlative frock—and I am glad that your hat is lined with blue."

"Why?"

"Your cloak last night was heavenly, and now this—it matches your eyes—"

"Oh." She sat very still.

"Shouldn't I have said that? I didn't think—"

"I am glad you didn't think—"

"Oh, are you?"

"Yes. I hate people who weigh their words—" The color came up finely into her cheeks.

When Dr. McKenzie returned, Derry found a table, and gave his order.

Jean refused to consider anything but an ice. "She doesn't eat at such moments," Doctor McKenzie told his young host. "She lives on star-dust, and she wants me to live on star-dust. It is our only quarrel. She'll think me sordid because I am going to have broiled lobster."

Derry laughed, yet felt that it was after all a serious matter. His appetite, too, was gone. He too wanted only an ice! The Doctor's order was, however, sufficiently substantial to establish a balance.

"May I dance with her?" Derry asked, as the music brought the couples to their feet.

"I don't usually let her. Not in a place like this. But her eyes are begging—and I spoil her, Drake."

Curious glances followed the progress of the young millionaire and his pretty partner. But Derry saw nothing but Jean. She was like thistledown in his arms, she was saying tremendously interesting things to him, in her lovely voice.

"I cried all through the scene where Cinderella sits on the door-step. Yet it really wasn't so very sad—was it?"

"I think it was sad. She was such a little starved thing—starved for love."

"Yes. It must be dreadful to be starved for love."

He glanced down at her. "You have never felt it?"

"No, except after my mother died—I wanted her—"

"My mother is dead, too."

The Doctor sat alone at the head of the table and ate his lobster; he ate war bread and a green salad, and drank a pot of black coffee, and was at peace with the world. Star-dust was all very well for those young things out there. He laughed as they came back to him. "Each to his own joys—the lobster was very good, Drake."

They hardly heard him. Jean had a rosy parfait with a strawberry on top. Derry had another.

They talked of the screen play, and the man who had failed. If he had really loved her he would not have failed, Jean said.

"I think he loved her," was Derry's opinion; "the spirit was willing, but the flesh was weak."

Jean shrugged. "Well, Fate was kind to him—to give him another chance. Oh, Daddy, tell him the story the little French woman told at the meeting of the Medical Association."

"You should have heard her tell it—but I'll do my best. Her eloquence brought us to our feet. It was when she was in Paris—just after the American forces arrived. She stopped at the curb one morning to buy violets of an ancient dame. She found the old flower vendor inattentive and, looking for the cause, she saw across the street a young American trooper loitering at a corner. Suddenly the old woman snatched up a bunch of lilies, ran across the street, thrust them into the hands of the astonished soldier. 'Take them, American,' she said. 'Take the lilies of France and plant them in Berlin.'"

"Isn't that wonderful?" Jean breathed.

"Everything is wonderful to her," the Doctor told Derry, "she lives on the heights."

"But the lilies of France, Daddy—! Can't you see our men and the lilies of France?"

Derry saw them, indeed,—a glorious company—!

"Oh, if I were a man," Jean said, and stopped. She stole a timid glance at him. The question that he had dreaded was in her eyes.

They fell into silence. Jean finished her parfait. Derry's was untouched.

Then the music brought them again to their feet, and they danced. The Doctor smoked alone. Back of him somebody murmured, "It is Derry Drake."

"Confounded slacker," said a masculine voice. Then came a warning "Hush," as Derry and Jean returned.

"It is snowing," Derry told the Doctor. "I have ordered my car."

Late that night when the Doctor rode forth again alone in his own car on an errand of mercy, he thought of the thing which he had heard. Then came the inevitable question: why wasn't Derry Drake fighting?

It was at the Witherspoon dinner that Jean McKenzie first heard the things that were being said about Derry.

"I can't understand," someone had remarked, "why Derry Drake is staying out of it."

"I fancy he'll be getting in," Ralph Witherspoon had said. "Derry's no slacker."

Ralph could afford to be generous. He was in the Naval Flying Corps. He looked extremely well in his Ensign's uniform, and he knew it; he was hoping, in the spring, for active service on the other side.

"I don't see why Derry should fight. I don't see why any man should. I never did believe in getting into other people's fusses."

It was Alma Drew who said that. Nobody took Alma very seriously. She was too pretty with her shining hair and her sea-green eyes, and her way of claiming admiration.

Jean had recognised her when she first came in as the girl she had seen descending from her motor car with Derry Drake on the night of the Secretary's dinner. Alma again wore the diamond-encrusted comb. She was in sea-green, which matched her eyes.

"If I were a man," Alma pursued, "I should run away."

There was a rustle of uneasiness about the table. In the morning papers had been news of Italy—disturbing news; news from Russia—Kerensky had fled to Moscow—there had been pictures of our men in gas masks! It wasn't a thing to joke about. Even Alma might go too far.

Ralph relieved the situation. "Oh, no, you wouldn't run away," he said; "you don't do yourself justice, Alma. Before you know it you will be driving a car over there, and picking me up when I fall from the skies."

"Well, that would be—compensation—." Alma's lashes flashed up and fluttered down.

But she turned her batteries on Ralph in vain. Jean McKenzie was on the other side of him. It would never be quite clear to him why he loved Jean. She was neither very beautiful nor very brilliant. But there was a dearness about her. He hardly dared think of it. It had gone very deep with him.

He turned to her. Her eyes were blazing. "Oh," she said, under her breath, "how can she say things like that? If I knew a man who would run away, I'd never speak to him."

"Of course. That's why I fell in love with you—because you had red blood in your veins."

It was the literal truth. The first time that Ralph had seen Jean McKenzie, he had been riding in Rock Creek Park. She, too, was on horseback. It was in April. War had just been declared, and there was great excitement. Jean, taking the bridle path over the hills, had come upon a band of workers. A long-haired and seditious orator was talking to them. Jean had stopped her horse to listen, and before she knew it she was answering the arguments of the speaker. Rising a little in her stirrups, her riding-crop uplifted to emphasize her burning words, her cheeks on fire, her eyes shining, her hair blowing under her three-cornered hat, she had clearly and crisply challenged the patriotism of the speaker, and she had presented to Ralph's appreciative eyes a picture which he was never to forget.

She had not been in the least embarrassed by his arrival, and his uniform had made him seem at once her ally. "I am sure this gentleman will be glad to talk to you," she had said to her little audience. "I'll leave the field to him," and with a nod and a smile she had ridden off, the applause of the men following her.

Ralph, having put the long-haired one to rout, had asked the men if they knew the young lady who had talked to them. They had, it seemed, seen her riding with Dr. McKenzie. They thought she was his daughter. It had been easy enough after that to find Jean on his mother's visiting list. Mrs. Witherspoon and Mrs. McKenzie had exchanged calls during the life-time of the latter, but they had lived in different circles. Mrs. Witherspoon had aspired to smartness and to the friendship of the new people who brought an air of sophistication to the staid and sedate old capital. Mrs. McKenzie had held to old associations and to old ideals.

Mrs. Witherspoon was a widow and charming. Dr. McKenzie was a widower and an addition to any dinner table. In a few weeks the old acquaintance had been renewed. Ralph had wooed Jean ardently during the short furloughs which had been granted him, and from long distance had written a bit cocksurely. He had sent flowers, candy, books and then, quite daringly; a silver trench ring.

Jean had sent the ring back. "It was dear of you to give it to me, but I can't keep it."

"Why not?" he had asked when he next saw her.

"Because—"

"Because is no reason."

She had blushed, but stood firm. She was very shy—totally unawakened—a little dreaming girl—with all of real life ahead of her—with her innocence a white flower, her patriotism a red one. If only he might wear that white and red above his heart.

As a matter of fact, Jean resented, sub-consciously, his air of possession, the certainty with which he seemed to see the end of his wooing.

"You can't escape me," he had told her.

"As if I were a rabbit," she had complained afterwards to her father. "When I marry a man I don't want to be caught—I want to run to him, with my arms wide open."

"Don't," her father advised; "not many men would be able to stand it. Let them worship you, Jeanie, don't worship."

Jean stuck her nose in the air. "Falling in love doesn't come the way you want it. You have to take it as the good Lord sends it."

"Who told you that?"

"Emily—"

"What does Emily know of love?"

He had laughed and patted her hand. He was cynical generally about romance. He felt that his own perfect love affair with his wife had been the exception. He looked upon Emily as a sentimental spinster who knew practically nothing of men and women.

He did not realize that Emily knew a great deal about dolls that laughed and cried when you pulled a string. And that the world in Emily's Toy Shop was not so very different from his own.

Alma, having turned a cold shoulder to Ralph, was still proclaiming her opinion of Derry Drake to the rest of the table. "He is rich and young and he doesn't want to die—"

"There are plenty of rich young men dying, Alma," said Mrs. Witherspoon, "and it is probably as easy for them as for the poor ones—"

"The poor ones won't mind being muddy and dirty in the trenches," said Alma, "but I can't fancy Derry Drake without two baths a day—"

"I can't quite fancy him a slacker." There was a hint of satisfaction in Mrs. Witherspoon's voice. Her son and Derry Drake had gone to school together and to college. Derry had outdistanced Ralph in every way; but now it was Ralph who was leaving Derry far behind.

Jean wished that they would stop talking. She felt as she might had she seen a soldier stripped of sword and stripes and shamed in the eyes of his fellows.

"Wasn't he in the draft?" she asked Ralph.

"Too old. He doesn't look it, does he? It's a bit hard for the rest of us fellows to understand why he keeps out—"

"Doesn't he ever try to—explain?"

Ralph shook his head. "Not a word. And he's beginning to stay away from things. You see, he knows that people are asking questions, and you hear what they are calling him?"

"Yes," said Jean, "a coward."

"Well, not exactly that—"

"There isn't much difference, is there?"

And now Alma's cool voice summed up the situation. "A man with as much money as that doesn't have to be brave. What does he care about public opinion? After the war everybody will forgive and forget."

Coolly she challenged them to contradict her. "You all know it. How many of you would dare cut the fellow who will inherit his father's millions?"

Mrs. Witherspoon tried to laugh it off; but it was true, and Alma was right. They might talk about Derry Drake behind his back, but they'd never omit sending a card to him.

Jean ate her duckling in flaming silence, ate her salad, ate her ice, drank her coffee, and was glad when the meal ended.

The war from the beginning had been for her a sacred cause. She had yearned to be a man that she might stand in the forefront of battle. She had envied the women of Russia who had formed a Battalion of Death. Her father had laughed at her. "You'd be like a white kitten in a dog fight."

It seemed intolerable that tongues should be busy with this talk of young Drake's cowardice. He had seemed something so much more than that. And he was a man—with a man's right to leadership. What was the matter with him?

The night before she had slept little—Derry's voice—Derry's eyes! She had gone over every word that he had said. She had risen early in the morning to write in her memory book, and she had drawn a most entrancing border about the page, with melting strawberry ice, lilies of France, Cinderella slippers, and red-ink lobsters, rather nightmarishly intermingled!

He had seemed so fine—so—she fell back on her much overworked word wonderful—her heart had run to meet him, and now—it would have to run back again. How silly she had been not to see.

After dinner they danced in the Long Room, which was rather famous from a decorative point of view. It was medieval in effect, with a balcony and tapestries, and some precious bits of armor. There was a lion-skin flung over the great chair where Mrs. Witherspoon was enthroned.

Between dances, Jean and Ralph sat on the balcony steps, and talked of many things which brought the red to Jean's cheeks, and a troubled light into her eyes.

And it was from the balcony-steps that, as the evening waned, she saw Derry Drake standing in the great arched doorway.

There was a black velvet curtain behind him which accentuated his fairness. He did not look nineteen. Jean had a fleeting vision of a certain steel engraving of the "Princes in the Tower" which had hung in her grandmother's house. Derry was not in the least like those lovely imprisoned boys, yet she had an overwhelming sense of his kinship to them.

As young Drake's eyes swept the room, he was aware of Jean on the balcony steps. She was in white and silver, with a touch of that heavenly blue which seemed to belong to her. Her crinkled hair was combed quaintly over her ears and back from her forehead. He smiled at her, but she apparently did not see him.

He made his way to Mrs. Witherspoon. "I was so sorry to get here late. But my other engagements kept me. If I could have dined at two places, you should have had at least a half of me."

"We wanted the whole. You know Dr. McKenzie, Derry?"

The two men shook hands. "May I dance with your daughter?" Derry said, smiling.

"Of course. She is up there on the stairs."

Jean saw him coming. Ever since Derry had stood in the door she had been trying to make up her mind how she would treat him when he came. Somebody ought to show him that his millions didn't count. She hadn't thought of his millions last night. If he had been just the shabby boy of the Toy Shop, she would have liked his eyes just as much, and his voice!

But a slacker was a slacker! A coward was a coward! All the money in the world couldn't take away the stain. A man who wouldn't fight at this moment for the freedom of the world was a renegade! She would have none of him.

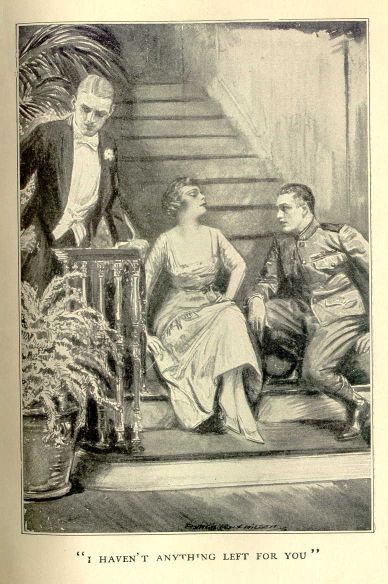

He came on smiling. "Hello, Ralph. Miss McKenzie, your father says you may dance with me—I hope you have something left?"

The blood sang in her ears, her cheeks burned.

"I haven't anything left—for you—" The emphasis was unmistakable.