| Main Index | Next Part |

INTRODUCTION

STORY THE FIRST — THE REVERSE OF THE MEDAL.

The first story tells of how one found means to enjoy the wife of his

neighbour, whose husband he had sent away in order that he might have

her the more easily, and how the husband returning from his journey,

found his friend bathing with his wife. And not knowing who she was, he

wished to see her, but was permitted only to see her back—, and then

thought that she resembled his wife, but dared not believe it. And

thereupon left and found his wife at home, she having escaped by a

postern door, and related to her his suspicions.

STORY THE SECOND — THE MONK-DOCTOR.

The second story, related by Duke Philip, is of a young girl who had

piles, who put out the only eye he had of a Cordelier monk who was

healing her, and of the lawsuit that followed thereon.

STORY THE THIRD — THE SEARCH FOR THE RING.

Of the deceit practised by a knight on a miller's wife whom he made

believe that her front was loose, and fastened it many times. And the

miller informed of this, searched for a diamond that the knight's lady

had lost, and found it in her body, as the knight knew afterwards: so he

called the miller "fisherman", and the miller called him "fastener".

STORY THE FOURTH — THE ARMED CUCKOLD.

The fourth tale is of a Scotch archer who was in love with a fair

and gentle dame, the wife of a mercer, who, by her husband's orders

appointed a day for the said Scot to visit her, who came and treated her

as he wished, the said mercer being hid by the side of the bed, where he

could see and hear all.

STORY THE FIFTH — The Duel with the Buckle-Strap.

The fifth story relates two judgments of Lord Talbot. How a Frenchman

was taken prisoner (though provided with a safe-conduct) by an

Englishman, who said that buckle-straps were implements of war, and who

was made to arm himself with buckle-straps and nothing else, and meet

the Frenchman, who struck him with a sword in the presence of Talbot.

The other, story is about a man who robbed a church, and who was made to

swear that he would never enter a church again.

STORY THE SIXTH —THE DRUNKARD IN PARADISE.

The sixth story is of a drunkard, who would confess to the Prior of the

Augustines at the Hague, and after his confession said that he was then

in a holy state and would die; and believed that his head was cut off

and that he was dead, and was carried away by his companions who said

they were going to bury him.

STORY THE SEVENTH — THE WAGGONER IN THE BEAR.

Of a goldsmith of Paris who made a waggoner sleep with him and his

wife, and how the waggoner dallied with her from behind, which the

goldsmith perceived and discovered, and of the words which he spake to

the waggoner.

STORY THE EIGHTH — TIT FOR TAT.

Of a youth of Picardy who lived at Brussels, and made his master's

daughter pregnant, and for that cause left and came back to Picardy to

be married. And soon after his departure the girl's mother perceived the

condition of her daughter, and the girl confessed in what state she was;

so her mother sent her to the Picardian to tell him that he must undo

that which he had done. And how his new bride refused then to sleep with

him, and of the story she told him, whereupon he immediately left her

and returned to his first love, and married her.

STORY THE NINTH — THE HUSBAND PANDAR TO HIS OWN WIFE.

Of a knight of Burgundy, who was marvellously amorous of one of his

wife's waiting women, and thinking to sleep with her, slept with his

wife who was in the bed of the said tire-woman. And how he caused, by

his order, another knight, his neighbour to sleep with the said woman,

believing that it was really the tirewoman—and afterwards he was not

well pleased, albeit that the lady knew nothing, and was not aware, I

believe, that she had had to do with aught other than her own husband.

STORY THE TENTH — THE EEL PASTIES.

Of a knight of England, who, after he was married, wished his mignon to

procuré him some pretty girls, as he did before; which the mignon would

not do, saying that one wife sufficed; but the said knight brought him

back to obedience by causing eel pasties to be always served to him,

both at dinner and at supper.

STORY THE ELEVENTH — A SACRIFICE TO THE DEVIL.

Of a jealous rogue, who after many offerings made to divers saints to

curé him of his jealousy, offered a candle to the devil who is usually

painted under the feet of St. Michael; and of the dream that he had and

what happened to him when he awoke.

STORY THE TWELFTH — THE CALF.

Of a Dutchman, who at all hours of the day and night ceased not to

dally with his wife in love sports; and how it chanced that he laid her

down, as they went through a wood, under a great tree in which was a

labourer who had lost his calf. And as he was enumerating the charms of

his wife, and naming all the pretty things he could see, the labourer

asked him if he could not see the calf he sought, to which the Dutchman

replied that he thought he could see a tail.

STORY THE THIRTEENTH — THE CASTRATED CLERK.

How a lawyer's clerk in England deceived his master making him believe

that he had no testicles, by which reason he had charge over his

mistress both in the country and in the town, and enjoyed his pleasure.

STORY THE FOURTEENTH — THE POPE-MAKER, OR THE HOLY MAN.

Of a hermit who deceived the daughter of a poor woman, making her

believe that her daughter should have a son by him who should become

Pope; and how, when she brought forth it was a girl, and thus was the

trickery of the hermit discovered, and for that cause he had to flee

from that countery.

STORY THE FIFTEENTH — THE CLEVER NUN.

Of a nun whom a monk wished to deceive, and how he offered to shoo her

his weapon that she might feel it, but brought with him a companion whom

he put forward in his place, and of the answer she gave him.

STORY THE SIXTEENTH — ON THE BLIND SIDE.

Of a knight of Picardy who went to Prussia, and, meanwhile his lady

took a lover, and was in bed with him when her husband returned; and how

by a cunning trick she got her lover out of the room without the knight

being aware of it.

STORY THE SEVENTEENTH — THE LAWYER AND THE BOLTING-MILL.

Of a President of Parliament, who fell in love with his chamber-maid,

and would have forced her whilst she was sifting flour, but by fair

speaking she dissuaded him, and made him shake the sieve whilst she

went unto her mistress, who came and found her husband thus, as you will

afterwards hear.

STORY THE EIGHTEENTH — FROM BELLY TO BACK.

Of a gentleman of Burgundy who paid a chambermaid ten crowns to sleep

with her, but before he left her room, had his ten crowns back, and

made her carry him on her shoulders through the host's chamber. And in

passing by the said chamber he let wind so loudly that all was known, as

you will hear in the story which follows.

STORY THE NINETEENTH — THE CHILD OF THE SNOW.

Of an English merchant whose wife had a child in his absence, and told

him that it was his; and how he cleverly got rid of the child—for his

wife having asserted that it was born of the snow, he declared it had

been melted by the sun.

STORY THE TWENTIETH — THE HUSBAND AS DOCTOR.

Of a young squire of Champagne who, when he married, had never mounted

a Christian creature,—much to his wife's regret. And of the method her

mother found to instruct him, and how the said squire suddenly wept at

a great feast that was made shortly after he had learned how to perform

the carnal act—as you will hear more plainly hereafter.

The highest living authority on French Literature—Professor George Saintsbury—has said:

"The Cent Nouvelles is undoubtedly the first work of literary prose in French, and the first, moreover, of a long and most remarkable series of literary works in which French writers may challenge all comers with the certainty of victory. The short prose tale of a comic character is the one French literary product the pre-eminence and perfection of which it is impossible to dispute, and the prose tale first appears to advantage in the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles. The subjects are by no means new. They are simply the old themes of the fabliaux treated in the old way. The novelty is in the application of prose to such a purpose, and in the crispness, the fluency, and the elegance, of the prose used."

Besides the literary merits which the eminent critic has pointed out, the stories give us curious glimpses of life in the 15th Century. We get a genuine view of the social condition of the nobility and the middle classes, and are pleasantly surprised to learn from the mouths of the nobles themselves that the peasant was not the down-trodden serf that we should have expected to find him a century after the Jacquerie, and 350 years before the Revolution.

In fact there is an atmosphere of tolerance, not to say bonhommie about these stories which is very remarkable when we consider under what circumstances they were told, and by whom, and to whom.

This seems to have struck M. Lenient, a French critic, who says:

"Generally the incidents and personages belong to the bourgeoisée; there is nothing chivalric, nothing wonderful; no dreamy lovers, romantic dames, fairies, or enchanters. Noble dames, bourgeois, nuns, knights, merchants, monks, and peasants mutually dupe each other. The lord deceives the miller's wife by imposing on her simplicity, and the miller retaliates in much the same manner. The shepherd marries the knight's sister, and the nobleman is not over scandalized.

"The vices of the monks are depicted in half a score tales, and the seducers are punished with a severity not always in proportion to the offence."

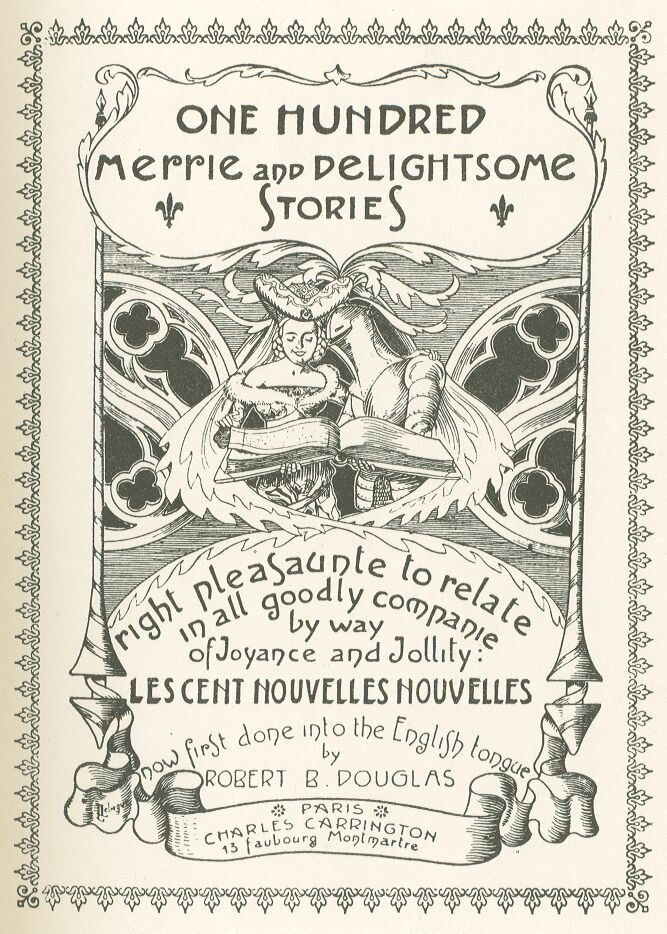

It seems curious that this valuable and interesting work has never before been translated into English during the four and a half centuries the book has been in existence. This is the more remarkable as the work was edited in French by an English scholar—the late Thomas Wright. It can hardly be the coarseness of some of the stories which has prevented the Nouvelles from being presented to English readers when there are half a dozen versions of the Heptameron, which is quite as coarse as the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles, does not possess the same historical interest, and is not to be compared to the present work as regards either the stories or the style.

In addition to this, there is the history of the book itself, and its connection with one of the most important personages in French history—Louis XI. Indeed, in many French and English works of reference, the authorship of the Nouvelles has been attributed to him, and though in recent years, the writer is now believed—and no doubt correctly—to have been Antoine de la Salle, it is tolerably certain that Prince Louis heard all the stories related, and very possibly contributed several of them. The circumstances under which these stories came to be narrated requires a few words of explanation.

At a very early age, Louis showed those qualities by which he was later distinguished. When he was only fourteen, he caused his father, Charles VII, much grief, both by his unfilial conduct and his behaviour to the beautiful Agnes Sorel, the King's mistress, towards whom he felt an implacable hatred. He is said to have slapped her face, because he thought she did not treat him with proper respect. This blow was, it is asserted, the primary cause of his revolt against his father's authority (1440). The rebellion was put down, and the Prince was pardoned, but relations between father and son were still strained, and in 1446, Louis had to betake himself to his appanage of Dauphiné, where he remained for ten years, always plotting and scheming, and braving his father's authority.

At length the Prince's Court at Grenoble became the seat of so many conspiracies that Charles VII was obliged to take forcible measures. It was small wonder that the King's patience was exhausted. Louis, not content with the rule of his province, had made attempts to win over many of the nobility, and to bribe the archers of the Scotch Guard. Though not liberal as a rule, he had also expended large sums to different secret agents for some specific purpose, which was in all probability to secure his father's death, for he was not the sort of man to stick at parricide even, if it would secure his ends.

The plot was revealed to Charles by Antoine de Chabannes, Comte de Dampmartin. Louis, when taxed with his misconduct, impudently denied that he had been mixed up with the conspiracy, but denounced all his accomplices, and allowed them to suffer for his misdeeds. He did not, however, forget to revenge them, so far as lay in his power. The fair Agnès Sorel, whom he had always regarded as his bitterest enemy, died shortly afterwards at Jumièges, and it has always been believed, and with great show of reason, that she was poisoned by his orders. He was not able to take vengeance on Antoine de Chabannes until after he became King.

Finding that his plots were of no avail, he essayed to get together an army large enough to combat his father, but before he completed his plans, Charles VII, tired of his endless treason and trickery, sent an army, under the faithful de Chabannes, into the Dauphiné, with orders to arrest the Dauphin.

The forces which Louis had at his disposal were numerically so much weaker, that he did not dare to risk a battle.

"If God or fortune," he cried, "had been kind enough to give me but half the men-at-arms which now belong to the King, my father, and will be mine some day, by Our Lady, my mistress, I would have spared him the trouble of coming so far to seek me, but would have met him and fought him at Lyon."

Not having sufficient forces, and feeling that he could not hope for fresh pardon, he resolved to fly from France, and take refuge at the Court of the Duke of Burgundy.

One day in June, 1456, he pretended to go hunting, and then, attended by only half a dozen friends, rode as fast as he could into Burgundian territory, and arrived at Saint Claude.

From there he wrote to his father, excusing his flight, and announcing his intention of joining an expedition which Philippe le Bon, the reigning Duke of Burgundy was about to undertake against the Turks. The Duke was at that moment besieging Utrecht, but as soon as he heard the Dauphin had arrived in his dominions, he sent orders that he was to be conducted to Brussels with all the honours befitting his rank and station.

Shortly afterwards the Duke returned, and listened with real or pretended sympathy to all the complaints that Louis made against his father, but put a damper on any hopes that the Prince may have entertained of getting the Burgundian forces to support his cause, by saying;

"Monseigneur, you are welcome to my domains. I am happy to see you here. I will provide you with men and money for any purpose you may require, except to be employed against the King, your father, whom I would on no account displease."

Duke Philippe even tried to bring about a reconciliation between Charles and his son; but as Louis was not very anxious to return to France, nor Charles to have him there, and a good many of the nobles were far from desiring that the Prince should come back, the negotiations came to nothing.

Louis could make himself agreeable when he pleased, and during his stay in the Duke's domains, he was on good terms with Philippe le Bon, who granted him 3000 gold florins a month, and the castle of Genappe as a residence. This castle was situated on the Dyle, midway between Brussels and Louvain, and about eight miles from either city. The river, or a deep moat, surrounded the castle on every side. There was a drawbridge which was drawn up at night, so Louis felt himself quite safe from any attack.

Here he remained five years (1456-1461) until the death of his father placed him on the throne of France.

It was during these five years that these stories were told to amuse his leisure. Probably there were many more than a hundred narrated—perhaps several hundreds—but the literary man who afterwards "edited" the stories only selected those which he deemed best, or, perhaps, those he heard recounted. The narrators were the nobles who formed the Dauphin's Court. Much ink has been spilled over the question whether Louis himself had any share in the production. In nearly every case the author's name is given, and ten of them (Nos. 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 29, 33, 69, 70 and 71) are described in the original edition as being by "Monseigneur." Publishers of subsequent editions brought out at the close of the 15th, or the beginning of the 16th, Century, jumped to the conclusion that "Monseigneur" was really the Dauphin, who not only contributed largely to the book, but after he became King personally supervised the publication of the collected stories.

For four centuries Louis XI was credited with the authorship of the tales mentioned. The first person—so far as I am aware—to throw any doubt on his claim was the late Mr. Thomas Wright, who edited an edition of the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles, published by Jannet, Paris, 1858. He maintained, with some show of reason, that as the stories were told in Burgundy, by Burgundians, and the collected tales were "edited" by a subject of the Duke (Antoine de la Salle, of whom I shall have occasion to speak shortly) it was more probable that "Monseigneur" would mean the Duke than the Dauphin, and he therefore ascribed the stories to Philippe le Bel. Modern French scholars, however, appear to be of opinion that "Monseigneur" was the Comte de Charolais, who afterwards became famous as Charles le Téméraire, the last Duke of Burgundy.

The two great enemies were at that time close friends, and Charles was a very frequent visitor to Genappe. It was not very likely, they say, that Duke Philippe who was an old man would have bothered himself to tell his guest indecent stories. On the other hand, Charles, being then only Comte de Charolais, had no right to the title of "Monseigneur," but they parry that difficulty by supposing that as he became Duke before the tales were printed, the title was given him in the first printed edition.

The matter is one which will, perhaps, never be satisfactorily settled. My own opinion—though I claim for it no weight or value—is that Louis appears to have the greatest right to the stories, though in support of that theory I can only adduce some arguments, which if separately weak may have some weight when taken collectively. Vérard, who published the first edition, says in the Dedication; "Et notez que par toutes les Nouvelles où il est dit par Monseigneur il est entendu par Monseigneur le Dauphin, lequel depuis a succédé à la couronne et est le roy Loys unsieme; car il estoit lors es pays du duc de Bourgoingne."

The critics may have good reason for throwing doubt on Vérard's statement, but unless he printed his edition from a M.S. made after 1467, and the copyist had altered the name of the Comte de Charolais to "Monseigneur" it is not easy to see how the error arose, whilst on the other hand, as Vérard had every facility for knowing the truth, and some of the copies must have been purchased by persons who were present when the stories were told, the mistake would have been rectified in the subsequent editions that Vérard brought out in the course of the next few years, when Louis had been long dead and there was no necessity to flatter his vanity.

On examining the stories related by "Monseigneur," it seems to me that there is some slight internal evidence that they were told by Louis.

Brantôme says of him that, "he loved to hear tales of loose women, and had but a poor opinion of woman and did not believe they were all chaste. (This sounds well coming from Brantôme) Anyone who could relate such tales was gladly welcomed by the Prince, who would have given all Homer and Virgil too for a funny story." The Prince must have heard many such stories, and would be likely to repeat them, and we find the first half dozen stories are decidedly "broad," (No XI was afterwards appropriated by Rabelais, as "Hans Carvel's Ring") and we may suspect that Louis tried to show the different narrators by personal example what he considered a really "good tale."

We know also Louis was subject to fits of religious melancholy, and evinced a superstitious veneration for holy things, and even wore little, leaden images of the saints round his hat. In many of the stories we find monks punished for their immorality, or laughed at for their ignorance, and nowhere do we see any particular veneration displayed for the Church. The only exception is No LXX, "The Devil's Horn," in which a knight by sheer faith in the mystery of baptism vanquishes the Devil, whereas one of the knight's retainers, armed with a battle-axe but not possessing his master's robust faith in the efficacy of holy water, is carried off bodily, and never heard of again. It seems to me that this story bears the stamp of the character of Louis, who though suspicious towards men, was childishly credulous in religious matters, but I leave the question for critics more capable than I to decide.

Of the thirty-two noblemen or squires who contributed the other stories, mention will be made in the notes. Of the stories, I may here mention that 14 or 15 were taken from Boccaccio, and as many more from Poggio or other Italian writers, or French fabliaux, but about 70 of them appear to be original.

The knights and squires who told the stories had probably no great skill as raconteurs, and perhaps did not read or write very fluently. The tales were written down afterwards by a literary man, and they owe "the crispness, fluency, and elegance," which, as Prof. Saintsbury remarks, they possess in such a striking degree, to the genius of Antoine de la Sale. He was born in 1398 in Burgundy or Touraine. He had travelled much in Italy, and lived for some years at the Court of the Comte d' Anjou. He returned to Burgundy later, and was, apparently, given some sort of literary employment by Duke Philippe le Bel. At any rate he was appointed by Philippe or Louis to record the stories that enlivened the evenings at the Castle of Genappe, and the choice could not have fallen on a better man. He was already known as the author of two or three books, one of which—Les Quinze Joyes de Mariage—relates the woes of married life, and displays a knowledge of character, and a quaint, satirical humour that are truly remarkable, and remind the reader alternately of Thackeray and Douglas Jerrold,—indeed some of the Fifteen Joys are "Curtain Lectures" with a mediaeval environment, and the word pictures of Woman's foibles, follies, and failings are as bright to-day as when they were penned exactly 450 years ago. They show that the "Eternal Feminine" has not altered in five centuries—perhaps not in five thousand!

The practised and facile pen of Antoine de la Sale clothed the dry bones of these stories with flesh and blood, and made them live, and move. Considering his undoubted gifts as a humourist, and a delineator of character it is strange that the name of Antoine de la Sale is not held in higher veneration by his countrymen, for he was the earliest exponent of a form of literary art in which the French have always excelled.

In making a translation of these stories I at first determined to adhere as closely as possible to the text, but found that the versions differed greatly. I have followed the two best modern editions, and have made as few changes and omissions as possible.

Three or four of the stories are extremely coarse, and I hesitated whether to omit them, insert them in the original French, or translate them, but decided that as the book would only be read by persons of education, respectability, and mature age, it was better to translate them fully,—as has been done in the case of the far coarser passages of Rabelais and other writers. This course appeared to me less hypocritical than that adopted in a recent expensive edition of Boccaccio in which the story of Rusticus and Alibech was given in French—with a highly suggestive full-page illustration facing the text for the benefit of those who could not read the French language.

Paris, 21st October 1899.

Good friends, my readers, who peruse this book,

Be not offended, whilst on it you look:

Denude yourselves of all deprav'd affection,

For it contains no badness nor infection:

'T is true that it brings forth to you no birth

Of any value, but in point of mirth;

Thinking therefore how sorrow might your mind

Consume, I could no apter subject find;

One inch of joy surmounts of grief a span;

Because to laugh is proper to the man.

(RABELAIS: To the Readers).

The first story tells of how one found means to enjoy the wife of his neighbour, whose husband he had sent away in order that he might have her the more easily, and how the husband returning from his journey, found his friend bathing with his wife. And not knowing who she was, he wished to see her, but was permitted only to see her back—, and then thought that she resembled his wife, but dared not believe it. And thereupon left and found his wife at home, she having escaped by a postern door, and related to her his suspicions.

In the town of Valenciennes there lived formerly a notable citizen, who had been receiver of Hainault, who was renowned amongst all others for his prudence and discretion, and amongst his praiseworthy virtues, liberality was not the least, and thus it came to pass that he enjoyed the grace of princes, lords, and other persons of good estate. And this happy condition, Fortune granted and preserved to him to the end of his days.

Both before and after death unloosed him from the chains of matrimony, the good citizen mentioned in this Story, was not so badly lodged in the said town but that many a great lord would have been content and honoured to have such a lodging. His house faced several streets, in one of which was a little postern door, opposite to which lived a good comrade of his, who had a pretty wife, still young and charming.

And, as is customary, her eyes, the archers of the heart, shot so many arrows into the said citizen, that unless he found some present remedy, he felt his case was no less than mortal.

To more surely prevent such a fate, he found many and subtle manners of making the good comrade, the husband of the said quean, his private and familiar friend, so, that few of the dinners, suppers, banquets, baths, and other such amusements took place, either in the hotel or elsewhere, without his company. And of such favours his comrade was very proud, and also happy.

When our citizen, who was more cunning than a fox, had gained the good-will of his friend, little was needed to win the love of his wife, and in a few days he had worked so much and so well that the gallant lady was fain to hear his case, and to provide a suitable remedy thereto. It remained but to provide time and place; and for this she promised him that, whenever her husband lay abroad for a night, she would advise him thereof.

The wished-for day arrived when the husband told his wife that he was going to a chateau some three leagues distant from Valenciennes, and charged her to look after the house and keep within doors, because his business would not permit him to return that night.

It need not be asked if she was joyful, though she showed it not either in word, or deed, or otherwise. Her husband had not journeyed a league before the citizen knew that the opportunity had come.

He caused the baths to be brought forth, and the stoves to be heated, and pasties, tarts, and hippocras, and all the rest of God's good gifts, to be prepared largely and magnificently.

When evening came, the postern door was unlocked, and she who was expected entered thereby, and God knows if she was not kindly received. I pass over all this.

Then they ascended into a chamber, and washed in a bath, by the side of which a good supper was quickly laid and served. And God knows if they drank often and deeply. To speak of the wines and viands would be a waste of time, and, to cut the story short, there was plenty of everything. In this most happy condition passed the great part of this sweet but short night; kisses often given and often returned, until they desired nothing but to go to bed.

Whilst they were thus making good cheer, the husband returned from his journey, and knowing nothing of this adventure, knocked loudly at the door of the house. And the company that was in the ante-chamber refused him entrance until he should name his surety.

Then he gave his name loud and clear, and so his good wife and the citizen heard him and knew him. She was so amazed to hear the voice of her husband that her loyal heart almost failed her; and she would have fainted, had not the good citizen and his servants comforted her.

The good citizen being calm and well advised how to act, made haste to put her to bed, and lay close by her; and charged her well that she should lie close to him and hide her face, so that no one could see it. And that being done as quickly as may be, yet without too much haste, he ordered that the door should be opened. Then his good comrade sprang into the room, thinking to himself that there must be some mystery, else they had not kept him out of the room. And when he saw the table laid with wines and goodly viands, also the bath finely prepared, and the citizen in a handsome bed, well curtained, with a second person by his side, God knows he spoke loudly, and praised the good cheer of his neighbour. He called him rascal, and whore-monger, and drunkard, and many other names, which made those who were in the chamber laugh long and loud; but his wife could not join in the mirth, her face being pressed to the side of her new friend.

"Ha!" said the husband, "Master whore-monger, you have well hidden from me this good cheer; but, by my faith, though I was not at the feast, you must show me the bride."

And with that, holding a candle in his hand, he drew near the bed, and would have withdrawn the coverlet, under which, in fear and silence, lay his most good and perfect wife, when the citizen and his servants prevented him; but he was not content, and would by force, in spite of them all, have laid his hand upon the bed.

But he was not master there, and could not have his will, and for good cause, and was fain to be content with a most gracious proposal which was made to him, and which was this, that he should be shown the backside of his wife, and her haunches, and thighs—which were big and white, and moreover fair and comely—without uncovering and beholding her face.

The good comrade, still holding a candle in his hand, gazed for long without saying a word; and when he did speak, it was to praise highly the great beauty of that dame, and he swore by a great oath that he had never seen anything that so much resembled the back parts of his own wife, and that were he not well sure that she was at home at that time, he would have said it was she.

She had by this somewhat recovered, and he drew back much disconcerted, but God knows that they all told him, first one and then the other, that he had judged wrongly, and spoken against the honour of his wife, and that this was some other woman, as he would afterwards see for himself.

To restore him to good humour, after they had thus abused his eyes, the citizen ordered that they should make him sit at the table, where he drowned his suspicions by eating and drinking of what was left of the supper, whilst they in the bed were robbing him of his honour.

The time came to leave, and he said good night to the citizen and his companions, and begged they would let him leave by the postern door, that he might the sooner return home. But the citizen replied that he knew not then where to find the key; he thought also that the lock was so rusted that they could not open the door, which they rarely if ever used. He was content therefore to leave by the front gate, and make a long detour to reach his house, and whilst the servants of the citizen led him to the door, the good wife was quickly on her feet, and in a short time, clad in a simple sark, with her corset on her arm, and come to the postern. She made but one bound to her house, where she awaited her husband (who came by a longer way) well-prepared as to the manner in which she should receive him.

Soon came our man, and seeing still a light in the house, knocked at the door loudly; and this good wife, who was pretending to clean the house, and had a besom in her hands, asked — what she knew well; "Who is there?"

And he replied; "It is your husband."

"My husband!" said she. "My husband is not here! He is not in the town!"

With that he knocked again, and cried, "Open the door! I am your husband."

"I know my husband well," quoth she, "and it is not his custom to return home so late at night, when he is in the town. Go away, and do not knock here at this hour."

But he knocked all the more, and called her by name once or twice. Yet she pretended not to know him, and asked why he came at that hour, but for all reply he said nothing but, "Open! Open!"

"Open!" said she. "What! are you still there you rascally whore-monger? By St. Mary, I would rather see you drown than come in here! Go! and sleep as badly as you please in the place where you came from."

Then her good husband grew angry, and thundered against the door as though he would knock the house down, and threatened to beat his wife, such was his rage,—of which she had not great fear; but at length, because of the noise he made, and that she might the better speak her mind to him, she opened the door, and when he entered, God knows whether he did not see an angry face, and have a warm greeting. For when her tongue found words from a heart overcharged with anger and indignation, her language was as sharp as well-ground Guingant razors.

And, amongst other things, she reproached him that he had wickedly pretended a journey in order that he might try her, and that he was a coward and a recreant, unworthy to have such a wife as she was.

Our good comrade, though he had been angry, saw how wrong he had been, and restrained his wrath, and the indignation that in his heart he had conceived when he was standing outside the door was turned aside. So he said, to excuse himself, and to satisfy his wife, that he had returned from his journey because he had forgotten a letter concerning the object of his going.

Pretending not to believe him, she invented more stories, and charged him with having frequented taverns and bagnios, and other improper and dissolute resorts, and that he behaved as no respectable man should, and she cursed the hour in which she had made his acquaintance, and doubly cursed the day she became his wife.

The poor man, much grieved, seeing his wife more troubled than he liked, knew not what to say. And his suspicions being removed, he drew near her, weeping and falling upon his knees and made the following fine speech.

"My most dear companion, and most loyal wife, I beg and pray of you to remove from your heart the wrath you have conceived against me, and pardon me for all that I have done against you. I own my fault, I see my error. I have come now from a place where they made good cheer, and where, I am ashamed to say, I fancied I recognised you, at which I was much displeased. And so I wrongfully and causelessly suspected you to be other than a good woman, of which I now repent bitterly, and pray of you to forgive me, and pardon my folly."

The good woman, seeing her husband so contrite, showed no great anger.

"What?" said she, "You have come from filthy houses of ill-fame, and you dare to think that your honest wife would be seen in such places?"

"No, no, my dear, I know you would not. For God's sake, say no more about it." said the good man, and repeated his aforesaid request.

She, seeing his contrition, ceased her reproaches, and little by little regained her composure, and with much ado pardoned him, after he had made a hundred thousand oaths and promises to her who had so wronged him. And from that time forth she often, without fear or regret, passed the said postern, nor were her escapades discovered by him who was most concerned. And that suffices for the first story.

The second story, related by Duke Philip, is of a young girl who had piles, who put out the only eye he had of a Cordelier monk who was healing her, and of the lawsuit that followed thereon.

In the chief town of England, called London, which is much resorted to by many folks, there lived, not long ago, a rich and powerful man who was a merchant and citizen, who beside his great wealth and treasures, was enriched by the possession of a fair daughter, whom God had given him over and above his substance, and who for goodness, prettiness, and gentleness, surpassed all others of her time, and who when she was fifteen was renowned for her virtue and beauty.

God knows that many folk of good position desired and sought for her good grace by all the divers manners used by lovers,—which was no small pleasure to her father and mother, and increased their ardent and paternal affection for their beloved daughter.

But it happened that, either by the permission of God, or that Fortune willed and ordered it so, being envious and discontented at the prosperity of this beautiful girl, or of her parents, or all of them,—or may be from some secret and natural cause that I leave to doctors and philosophers to determine, that she was afflicted with an unpleasant and dangerous disease which is commonly called piles.

The worthy family was greatly troubled when they found the fawn they so dearly loved, set on by the sleuth-hounds and beagles of this unpleasant disease, which had, moreover, attacked its prey in a dangerous place. The poor girl—utterly cast down by this great misfortune,—could do naught else than weep and sigh. Her grief-stricken mother was much troubled; and her father, greatly vexed, wrung his hands, and tore his hair in his rage at this fresh misfortune.

Need I say that all the pride of that household was suddenly cast down to the ground, and in one moment converted into bitter and great grief.

The relations, friends, and neighbours of the much-enduring family came to visit and comfort the damsel; but little or nothing might they profit her, for the poor girl was more and more attacked and oppressed by that disease.

Then came a matron who had much studied that disease, and she turned and re-turned the suffering patient, this way, and that way, to her great pain and grief, God knows, and made a medicine of a hundred thousand sorts of herbs, but it was no good; the disease continued to get worse, so there was no help but to send for all the doctors of the city and round about, and for the poor girl to discover unto them her most piteous case.

There came Master Peter, Master John, Master This, Master That—as many doctors as you would, who all wished to see the patient together, and uncover that portion of her body where this cursed disease, the piles had, alas, long time concealed itself.

The poor girl, as much cast down and grieved as though she were condemned to die, would in no wise agree or permit that her affliction should be known; and would rather have died than shown such a secret place to the eyes of any man.

This obstinacy though endured not long, for her father and her mother came unto her, and remonstrated with her many times,—saying that she might be the cause of her own death, which was no small sin; and many other matters too long to relate here.

Finally, rather to obey her father and mother than from fear of death, the poor girl allowed herself to be bound and laid on a couch, head downwards, and her body so uncovered that the physicians might see clearly the seat of the disease which troubled her.

They gave orders what was to be done, and sent apothecaries with clysters, powders, ointments, and whatsoever else seemed good unto them; and she took all that they sent, in order that she might recover her health.

But all was of no avail, for no remedy that the said physicians could apply helped to heal the distressing malady from which she suffered, nor could they find aught in their books, until at last the poor girl, what with grief and pain was more dead than alive, and this grief and great weakness lasted many days.

And whilst the father and mother, relations, and neighbours sought for aught that might alleviate their daughter's sufferings, they met with an old Cordelier monk, who was blind of one eye, and who in his time had seen many things, and had dabbled much in medicine, therefore his presence was agreeable to the relations of the patient, and he having gazed at the diseased part at his leisure, boasted much that he could cure her.

You may fancy that he was most willingly heard, and that all the grief-stricken assembly, from whose hearts all joy had been banished, hoped that the result would prove as he had promised.

Then he left, and promised that he would return the next day, provided and furnished with a drug of such virtue, that it would at once remove the great pain and martyrdom which tortured and annoyed the poor patient.

The night seemed over-long, whilst waiting for the wished-for morrow; nevertheless, the long hours passed, and our worthy Cordelier kept his promise, and came to the patient at the hour appointed. You may guess that he was well and joyously received; and when the time came when he was to heal the patient, they placed her as before on a couch, with her backside covered with a fair white cloth of embroidered damask, having, where her malady was, a hole pierced in it through which the Cordelier might arrive at the said place.

He gazed at the seat of the disease, first from one side, then from the other: and anon he would touch it gently with his finger, or inspect the tube by which he meant to blow in the powder which was to heal her, or anon would step back and inspect the diseased parts, and it seemed as though he could never gaze enough.

At last he took the powder in his left hand, poured upon a small flat dish, and in the other hand the tube, which he filled with the said powder, and as he gazed most attentively and closely through the opening at the seat of the painful malady of the poor girl, she could not contain herself, seeing the strange manner in which the Cordelier gazed at her with his one eye, but a desire to burst out laughing came upon her, though she restrained herself as long as she could.

But it came to pass, alas! that the laugh thus held back was converted into a f—t, the wind of which caught the powder, so that the greater part of it was blown into the face and into the eye of the good Cordelier, who, feeling the pain, dropped quickly both plate and tube, and almost fell backwards, so much was he frightened. And when he came to himself, he quickly put his hand to his eye, complaining loudly, and saying that he was undone, and in danger to lose the only good eye he had.

Nor did he lie, for in a few days, the powder which was of a corrosive nature, destroyed and ate away his eye, so that he became, and remained, blind.

Then he caused himself to be led one day to the house where he had met with this sad mischance, and spoke to the master of the house, to whom he related his pitiful case, demanding, as was his right, that there should be granted to him such amends as his condition deserved, in order that he might live honourably.

The merchant replied that though the misadventure greatly vexed him, he was in nowise the cause of it, nor could he in any way be charged with it, but that he would, out of pity and charity, give him some money, and though the Cordelier had undertaken to cure his daughter and had not so done, would give him as much as he would if she had been restored to health, though not forced to do so.

The Cordelier was not content with this offer, but required that he should be kept for the rest of his life, seeing that the merchant's daughter had blinded him, and that in the presence of many people, and thereby he was deprived from ever again performing Mass or any of the services of the Holy Church, or studying what learned men had written concerning the Holy Scriptures, and thus could no longer serve as a preacher; which would be his destruction, for he would be a beggar and without means, save alms, and these he could no longer obtain.

But all that he could say was of no avail, and he could get no other answer than that given. So he cited the merchant before the Parliament of the said city of London, which called upon the aforesaid merchant to appear. When the day came, the Cordelier's case was stated by a lawyer well-advised as to what he should say, and God knows that many came to the Court to hear this strange trial, which much pleased the lords of the said Parliament, as much for the strangeness of the case as for the allegations and arguments of the parties debating therein, which were not only curious but amusing.

To many folk was this strange and amusing case known, and was often adjourned and left undecided by the judges, as is their custom. And so she, who before this was renowned for her beauty, goodness, and gentleness, became notorious through this cursed disease of piles, but was in the end cured, as I have been since told.

Of the deceit practised by a knight on a miller's wife whom he made believe that her front was loose, and fastened it many times. And the miller informed of this, searched for a diamond that the knight's lady had lost, and found it in her body, as the knight knew afterwards: so he called the miller "fisherman", and the miller called him "fastener".

In the Duchy of Burgundy lived formerly a noble knight, whose name is not mentioned in the present story, who was married to a fair and gentle lady. And near the castle of the said knight lived a miller, also married to a fair young wife.

It chanced once, that the knight, to pass the time and enjoy himself, was strolling around his castle, and by the banks of the river on which stood the house and mill of the said miller, who at that time was not at home, but at Dijon or Beaune,—he saw and remarked the wife of the said miller carrying two jars and returning from the river, whither she had been to draw water.

He advanced towards her and saluted her politely, and she, being well-mannered, made him the salutation which belonged to his rank. The knight, finding that the miller's wife was very fair but had not much sense, drew near to her and said.

"Of a truth, my friend, I see well that you are in ill case, and therefore in great peril."

At these words the miller's wife replied.

"Alas, monseigneur, and what shall I do?"

"Truly, my dear, if you walk thus, your 'front piece' is in danger of falling off, and if I am not mistaken, you will not keep it much longer."

The foolish woman, on hearing these words was astonished and vexed;—astonished to think how the knight could know, without seeing, of this unlucky accident, and vexed to think of the loss of the best part of her body, and one that she used well, and her husband also.

She replied; "Alas! sir, what is this you tell me, and how do you know that my 'front piece' is in danger of falling off? It seems to keep its place well."

"There, there! my dear," replied the knight. "Let it suffice that I have told you the truth. You would not be the first to whom such a thing had happened."

"Alas, sir," said she. "I shall be an undone, dishonoured and lost woman; and what will my husband say when he hears of the mischance? He will have no more to do with me."

"Be not discomforted to that degree, my friend; it has not happened yet; besides there is a sure remedy."

When the young woman heard that there was a remedy for her complaint, her blood began to flow again, and she begged the knight for God's sake that he would teach her what she must do to keep this poor front-piece from falling off. The knight, who was always most courteous and gracious, especially towards the ladies, replied;

"My friend, as you are a good and pretty girl, and I like your husband, I will teach you how to keep your front-piece."

"Alas, sir, I thank you; and certainly you will do a most meritorious work: for it would be better to die than to live without my front-piece. And what ought I to do sir?

"My dear," he said, "to prevent your front-piece from falling off, you must have it fastened quickly and often."

"Fastened, sir? And who will do that? Whom shall I ask to do this for me?"

"I will tell you, my dear," replied the knight. "And because I warned you of this mischance being so near, and told you of the remedy necessary to obviate the inconveniences which would arise, and which I am sure would not please you,—I am content, in order to further increase the love between us, to fasten your front-piece, and put it in such a good condition that you may safely carry it anywhere, without any fear or doubt that it will ever fall off; for in this matter I am very skilful."

It need not be asked whether the miller's wife was joyful. She employed all the little sense she had to thank the knight. So they walked together, she and the knight, back to the mill, where they were no sooner arrived than the knight kindly began his task, and with a tool that he had, shortly fastened, three or four times, the front-piece of the miller's wife, who was most pleased and joyous; and after having appointed a day when he might again work at this front-piece, the knight left, and returned quickly to his castle.

On the day named, he went again to the mill, and did his best, in the way above mentioned, to fasten this front-piece; and so well did he work as time went on, that this front-piece was most safely fastened, and held firmly and well in its place.

Whilst our knight thus fastened the front-piece of the miller's wife, the miller one day returned from his business, and made good cheer, as also did his wife. And as they were talking over their affairs, this most wise wife said to her husband.

"On my word, we are much indebted to the lord of this town."

"Tell me how, and in what manner," replied the miller.

"It is quite right that I should tell you, that you may thank him, as indeed you must. The truth is that, whilst you were away, my lord passed by our house one day that I was carrying two pitchers from the river. He saluted me and I did the same to him; and as I walked away, he saw, I know not how, that my front-piece was not held properly, and was in danger of falling off. He kindly told me so, at which I was as astonished and vexed as though the end of the world had come. The good lord who saw me thus lament, took pity on me, and showed me a good remedy for this cursed disaster. And he did still more, which he would not have done for every one, for the remedy of which he told me,—which was to fasten and hold back my front-piece in order to prevent it from dropping off,—he himself applied, which was great trouble to him, and he did it many times because that my case required frequent attention.

"What more shall I say? He, has so well performed his work that we can never repay him. By my faith, he has in one day of this week fastened it three times; another day, four times; another day, twice; another day, three times; and he never left me till I was quite cured, and brought to such a condition that my front-piece now holds as well and firmly as that of any woman in our town."

The miller, on hearing this adventure, gave no outward sign of what was passing in his mind, but, as though he had been joyful, said to his wife:

"I am very glad, my dear, that my lord hath done us this service, and, God willing, when it shall be possible, I will do as much for him. But at any rate, as it is not proper it should be known, take care that you say no word of this to anyone; and also, now that you are cured, you need not trouble my lord any further in this matter."

"You have warned me," replied his wife, "not to say a word about it and that is also what my lord bade me."

Our miller, who was a good fellow, often thought over the kindness that my lord had done him, and conducted himself so wisely and carefully that the said lord never suspected that he knew how he had been deceived, and imagined that he knew nothing. But alas, his heart and all his thoughts were bent on revenge and how he could repay in like manner the deceit practised on his wife. And at length he bethought himself of a way by which he could, he imagined, repay my lord in butter for his eggs.

At last, owing to other circumstances, the knight was obliged to mount his horse and say farewell to his wife for a month; at which our miller was in no small degree pleased.

One day, the lady had a desire to bathe, and caused the bath to be brought forth and the stoves to be heated in her private apartments; of which our miller knew soon, because he learned all that went on in the house; so he took a fine pike, that he kept in the ditch near his house, and went to the castle to present it to the lady.

None of the waiting-women would he let take the fish, but said that he must present it himself to the lady, or else he would take it back home. At last, because he was well-known to the household, and a good fellow, the lady allowed him to enter whilst she was in her bath.

The miller gave his present, for which the lady thanked him, and caused it to be taken to the kitchen and cooked for supper.

Whilst he was talking, the miller perceived on the edge of the bath, a fine large diamond which she had taken from her finger, fearing lest the water should spoil it. He took it so quietly that no one saw him, and having gained his point, said good night to the lady and her women, and returned to the mill to think over his business.

The lady, who was making good cheer with her attendants, seeing that it was now very late, and supper-time, left the bath and retired to her bed. And as she was looking at her arms and hands, she saw not the diamond, and she called her women, and asked them where was the diamond, and to whom she had given it. Each said, "It was not to me;"—"Nor to me,"—"Nor to me either."

They searched inside and outside the bath, and everywhere, but it was no good, they could not find it. The search for this diamond lasted a long time, without their finding any trace of it, which caused the lady much vexation, because it had been unfortunately lost in her chamber, and also because my lord had given it to her the day of their betrothal, and she held it very precious. They did not know whom to suspect nor whom to ask, and much sorrow prevailed in the household.

Then one of the women bethought herself, and said.

"No one entered the room but ourselves and the miller; it seems right that he should be sent for."

He was sent for, and came. The lady who was much vexed, asked the miller if he had not seen her diamond. He, being as ready to lie as another is to tell the truth, answered boldly, and asked if the lady took him for a thief? To which she replied gently;

"Certainly not, miller; it would be no theft if you had for a joke taken away my diamond."

"Madame," said the miller, "I give you my word that I know nothing about your diamond."

Then were they all much vexed, and my lady especially, so that she could not refrain from weeping tears in great abundance at the loss of this trinket. They all sorrowfully considered what was to be done. One said that it must be in the chamber, and another said that they had searched everywhere, and that it was impossible it should be there or they would have found it, as it was easily seen.

The miller asked the lady if she had it when she entered the bath; and she replied, yes.

"If it be so, certainly, madam, considering the diligence you have made in searching for it, and without finding it, the affair is very strange. Nevertheless, it seems to me that if there is any man who could give advice how it should be found, I am he, and because I would not that my secret should be discovered and known to many people, it would be expedient that I should speak to you alone."

"That is easily managed," said the lady. So her attendants left, but, as they were leaving, Dames Jehanne, Isabeau, and Katherine said,

"Ah, miller, you will be a clever man if you bring back this diamond."

"I don't say that I am over-clever," replied the miller, "but I venture to declare that if it is possible to find it I am the man to do so."

When he saw that he was alone with the lady, he told her that he believed seriously, that as she had the diamond when she entered the bath, that it must have fallen from her finger and entered her body, seeing that there was no one who could have stolen it.

And that he might hasten to find it, he made the lady-get upon her bed, which she would have willingly refused if she could have done otherwise.

After he had uncovered her, he pretended to look here and there, and said,

"Certainly, madam, the diamond has entered your body."

"Do you say, miller, that you have seen it?"

"Truly, yes."

"Alas!" said she, "and how can it be got out?"

"Very easily, madam. I doubt not to succeed if it please you."

"May God help you! There is nothing that I would not do to get it again," said the lady, "or to advance you, good miller."

The miller placed the lady on the bed, much in the same position as the lord had placed his wife when he fastened her front-piece, and with a like tool was the search for the diamond made.

Whilst resting after the first and second search that the miller made for the diamond, the lady asked him if he had not felt it, and he said, yes, at which she was very joyful, and begged that he would seek until he had found it.

To cut matters short, the good miller did so well that he restored to the lady her beautiful diamond, which caused great joy throughout the house, and never did miller receive so much honour and advancement as the lady and her maids bestowed upon him.

The good miller, who was high in the good graces of the lady after the much-desired conclusion of his great enterprise, left the house and went home, without boasting to his wife of his recent adventure, though he was more joyful over it than though he had gained the whole world.

A short time after, thank God, the knight returned to his castle, and was kindly received and humbly welcomed by the lady, who whilst they were enjoying themselves in bed, told him of the most wonderful adventure of the diamond, and how it was fished out of her body by the miller; and, to cut matters short, related the process, fashion, and manner employed by the said miller in his search for the diamond, which hardly gave her husband much joy, but he reflected that the miller had paid him back in his own coin.

The first time he met the good miller, he saluted him coldly, and said,

"God save you! God save you, good diamond-searcher!"

To which the good miller replied,

"God save you! God save you, fastener of front-pieces!"

"By our Lady, you speak truly," said the knight. "Say nothing about me, and I will say nothing about you."

The miller was satisfied, and never spoke of it again; nor did the knight either, so far as I know.

The fourth tale is of a Scotch archer who was in love with a fair and gentle dame, the wife of a mercer, who, by her husband's orders appointed a day for the said Scot to visit her, who came and treated her as he wished, the said mercer being hid by the side of the bed, where he could see and hear all.

When the king was lately in the city of Tours, a Scottish gentleman, an archer of his bodyguard, was greatly enamoured of a beautiful and gentle damsel married to a mercer; and when he could find time and place, related to her his sad case, but received no favourable reply,—at which he was neither content nor joyous. Nevertheless, as he was much in love, he relaxed not the pursuit, but besought her so eagerly, that the damsel, wishing to drive him away for good and all, told him that she would inform her husband of the dishonourable and damnable proposals made to her,—which at length she did.

The husband,—a good and wise man, honourable and valiant, as you will see presently,—was very angry to think that the Scot would dishonour him and his fair wife. And that he might avenge himself without trouble, he commanded his wife that if the Scot should accost her again, she should appoint a meeting on a certain day, and, if he were so foolish as to come, he would buy his pleasure dearly.

The good wife, to obey her husband's will, did as she was told. The poor amorous Scot, who spent his time in passing the house, soon saw the fair mercer, and when he had humbly saluted her, he besought her love so earnestly, and desired that she would listen to his final piteous prayer, and if she would, never should woman be more loyally served and obeyed if she would but grant his most humble and reasonable request.

The fair mercer, remembering the lesson that her husband had given her, finding the opportunity propitious, after many subterfuges and excuses, told the Scot that he could come to her chamber on the following evening, where he could talk to her more secretly, and she would give him what he desired.

You may guess that she was greatly thanked, and her words listened to with pleasure and obeyed by her lover, who left his lady feeling more joyous than ever he had in his life.

When the husband returned home, he was told of all the words and deeds of the Scot, and how he was to come on the morrow to the lady's chamber.

"Let him come," said the husband. "Should he undertake such a mad business I will make him, before he leaves, see and confess the evil he has done, as an example to other daring and mad fools like him."

The evening of the next day drew near,—much to the joy of the amorous Scot, who wished to see and enjoy the person of his lady;—and much also to the joy of the good mercer who was desiring a great vengeance to be taken on the person of the Scot who wished to replace him in the marriage bed; but not much to the taste of his fair wife, who expected that her obedience to her husband would lead to a serious fight.

All prepared themselves; the mercer put on a big, old, heavy suit of armour, donned his helmet and gauntlets, and armed himself with a battle-axe. Like a true champion, he took up his post early, and as he had no tent in which to await his enemy, placed himself behind a curtain by the side of the bed, where he was so well-hidden that he could not be perceived.

The lover, sick with desire, knowing the longed-for hour was now at hand, set out for the house of the mercer, but he did not forget to take his big, good, strong two-handed sword; and when he was within the house, the lady went up to her chamber without showing any fear, and he followed her quietly. And when he came within the room, he asked the lady if she were alone? To which she replied casually, and with some confusion, that she was.

"Tell me the truth," said the Scot. "Is not your husband here?"

"No," said she.

"Well! let him come! By Saint Aignan, if he should come, I would split his skull to the teeth. By God! if there were three of them I should not fear them. I should soon master them!"

After these wicked words, he drew his big, good sword, and brandished it three or four times; then laid it on the bed by his side.

With that he kissed and cuddled her, and did much more at his leisure and convenience, without the poor coward by the side of the bed, who was greatly afraid he should be killed, daring to show himself.

Our Scot, after this adventure, took leave of the lady for a while, and thanked her as he ought for her great courtesy and kindness, and went his way.

As soon as the valiant man of arms knew that the Scot was out of the house, he came out of his hiding place, so frightened that he could scarcely speak, and commenced to upbraid his wife for having let the archer do his pleasure on her. To which she replied that it was his fault, as he had made her appoint a meeting.

"I did not command you," he said, "to let him do his will and pleasure."

"How could I refuse him," she replied, "seeing that he had his big sword, with which he could have killed me?"

At that moment the Scot returned, and came up the stairs to the chamber, and ran in and called out, "What is it?" Whereupon the good man, to save himself, hid under the bed for greater safety, being more frightened than ever.

The Scot served the lady as he had done before, but kept his sword always near him. After many long love-games between the Scot and the lady, the hour came when he must leave, so he said good-night and went away.

The poor martyr who was under the bed would scarcely come out, so much did he fear the return of his adversary,—or rather, I should say, his companion. At last he took courage, and by the help of his wife was, thank God, set on his feet, and if he had scolded his wife before he was this time harder upon her than ever, for she had consented, in spite of his forbidding her, to dishonour him and herself.

"Alas," said she, "and where is the woman bold enough to oppose a man so hasty and violent as he was, when you yourself, armed and accoutred and so valiant,—and to whom he did more wrong than he did to me—did not dare to attack him, and defend me?"

"That is no answer," he replied. "Unless you had liked, he would never have attained his purpose. You are a bad and disloyal woman."

"And you," said she, "are a cowardly, wicked, and most blamable man; for I am dishonoured since, through obeying you, I gave a rendezvous to the Scot. Yet you have not the courage to undertake the defence of the wife who is the guardian of your honour. For know that I would rather have died than consent to this dishonour, and God knows what grief I feel, and shall always feel as long as I live, whilst he to whom I looked for help suffered me to be dishonoured in his presence."

He believed that she would not have allowed the Scot to tumble her if she had not taken pleasure in it, but she maintained that she was forced and could not resist, but left the resistance to him and he did not fulfil his charge. Thus they both wrangled and quarrelled, with many arguments on both sides. But at any rate, the husband was cuckolded and deceived by the Scot in the manner you have heard.

The fifth story relates two judgments of Lord Talbot. How a Frenchman was taken prisoner (though provided with a safe-conduct) by an Englishman, who said that buckle-straps were implements of war, and who was made to arm himself with buckle-straps and nothing else, and meet the Frenchman, who struck him with a sword in the presence of Talbot. The other, story is about a man who robbed a church, and who was made to swear that he would never enter a church again.

Lord Talbot (whom may God pardon) who was, as every one knows, so victorious as leader of the English, gave in his life two judgments which were worthy of being related and held in perpetual remembrance, and in order that the said judgments should be known, I will relate them briefly in this my first story, though it is the fifth amongst the others. I will tell it thus.

During the time that the cursed and pestilent war prevailed between France and England, and which has not yet finished, (*) it happened, as was often the case, that a French soldier was taken prisoner by an Englishman, and, a ransom having been fixed, he was sent under a safe-conduct, signed by Lord Talbot, to his captain, that he might procure his ransom and bring it back to his captor.

As he was on his road, he was met by another Englishman, who, seeing he was a Frenchman, asked him whence he came and whither he was going? The other told him the truth.

"Where is your safe-conduct?" asked the Englishman.

"It is not far off," replied the Frenchman. With that he took the safe-conduct, which was in a little box hung at his belt, and handed it to the Englishman, who read it from one end to the other. And, as is customary, there was written on the safe-conduct, "Forbidden to carry any implements of warfare."

The Englishman noted this, and saw that there were esguillettes on the Frenchman's doublet. (**) He imagined that these straps were real implements of war, so he said,

"I make you my prisoner, because you have broken your safe-conduct."

"By my faith, I have not," replied the Frenchman, "saving your grace. You see in what condition I am."

"No! no!" said the Englishman. "By Saint John you have broken your safe-conduct. Surrender, or I will kill you."

The poor Frenchman, who had only his page with him, and was quite unprovided with weapons, whilst the other was accompanied by three or four archers, did the best thing he could, and surrendered. The Englishman led him to a place near there, and put him in prison.

(*) It had virtually finished, and the English only retained

the town of Calais when this tale was written (about 1465)

but they had not relinquished their claim to the French

Crown, and hostilities were expected to recommence.

(**) Esguillettes were small straps or laces, used to

fasten the cuirass to the doublet.

The Frenchman, finding himself thus ill-treated, sent in great haste to his captain, who when he heard his man's case, was greatly and marvellously astonished. Thereupon he wrote a letter to Lord Talbot, and sent it by a herald, to ask how it was that one of his men had been arrested by one of Lord Talbot's men whilst under that general's safe-conduct.

The said herald, being well instructed as to what he was to say and do, left his master, and presented the letters to Lord Talbot. He read them, and caused them to be read also by one of his secretaries before many knights and squires and others of his followers.

Thereupon he flew into a great rage, for he was hot-tempered and irritable, and brooked not to be disobeyed, and especially in matters of war; and to question his safe-conduct made him very angry.

To shorten the story, he caused to be brought before him both the Frenchman and the Englishman, and told the Frenchman to tell his tale.

He told how he had been taken prisoner by one of Lord Talbot's people, and put to ransom;

"And under your safe-conduct, my lord, I was on my way to my friends to procure my ransom. I met this gentleman here, who is also one of your followers, who asked me whither I was going, and if I had a safe-conduct? I told him, yes, and showed it to him. And when he had read it he told me that I had broken it, and I replied that I had not, and that he could not prove it. But he would not listen to me, and I was forced, if I would not be killed on the spot, to surrender. I know of no cause why he should have detained me, and I ask justice of you."

Lord Talbot, when he had heard the Frenchman, was not well content, nevertheless when the latter had finished, my Lord turned to the Englishman and asked,

"What have you to reply to this?"

"My lord," said he, "it is quite true, as he has said, that I met him and would see his safe-conduct, which when I had read from end to end, I soon perceived that he had broken and violated; otherwise I should never have arrested him."

"How had he broken it?" asked Lord Talbot. "Tell me quickly!"

"My Lord, because in his safe-conduct he is forbidden all implements of war, and he had, and has still, real implements of war; that is to say he has on his doublet, buckle-straps, which are real implements of war, for without them a man cannot be armed."

"Ah!" said Lord Talbot, "and so buckle-straps are implements of war are they? Do you know of any other way in which he had broken his safe-conduct?"

"Truly, my lord, I do not," replied the Englishman.

"What, you villain!" said Lord Talbot. "Have you stopped a gentleman under my safe-conduct for his buckle-straps? By St. George, I will show you whether they are implements of war."

Then, hot with anger and indignation, he went up to the Frenchman, and tore from his doublet the two straps, and gave them to the Englishman; then he put a sword in the Frenchman's hand, and drawing his own good sword out of the sheath, said to the Englishman,

"Defend yourself with that implement of war, as you call it, if you know how!"

Then he said to the Frenchman,

"Strike that villain who arrested you without cause or reason, and we shall see how he can defend himself with this implement of war. If you spare him, by St. George I will strike you."

Thus the Frenchman, whether he would or not, was obliged to strike at the Englishman with the sword, and the poor Englishman protected himself as best he could, and ran about the room, with Talbot after him, who made the Frenchman keep striking the other, and cried out;

"Defend yourself, villain, with your implement of war!" In truth, the Englishman was so well beaten that he was nearly dead, and cried for mercy to Talbot and the Frenchman. The latter was released from his ransom by Lord Talbot, and his horse, harness, and all his baggage, were given back to him.

Such was the first judgment of Lord Talbot; there remains to be given an account of the other, which was thus.

He learned that one of his soldiers had robbed a church of the pyx in which is placed the Corpus Domini, and sold it for ready money—I know not for how much, but the pyx was big and fine, and beautifully enamelled.

Lord Talbot, who though he was very brutal and wicked in war, had always great reverence for the Church, and would never allow a monastery or church to be set on fire or robbed, heard of this, and he was very severe on those who broke his regulations.

So he caused to be brought before him the man who had stolen the pyx from the church; and when he came, God knows what a greeting he had. Talbot would have killed him, if those around had not begged that his life might be saved. Nevertheless, as he would punish him, he said.

"Rascal traitor! why have you dared to rob a church in spite of my orders?"

"Ah, my lord," said the poor thief, "for God's sake have mercy upon me; I will never do it again."

"Come here, villain," said Talbot; and the other came up about as willingly as though he were going to the gallows. And the said Lord Talbot rushed at him, and with his fist, which was both large and heavy, struck him on the head, and cried.

"Ha! you thief! have you robbed a church?"

And the other cried,

"Mercy my lord! I will never do it again."

"Will you do it again?"

"No, my lord!"

"Swear then that you will never again enter a church of any kind. Swear, villain!"

"Very good, my lord," said the other.

Then Talbot made the thief swear that he would never set foot in a church again, which made all who were present and who heard it, laugh, though they pitied the thief because Lord Talbot had forbidden him the church for ever, and made him swear never to enter it. Yet we may believe that he did it with a good motive and intention. Thus you have heard the two judgments of Lord Talbot, which were such as I have related to you.

The sixth story is of a drunkard, who would confess to the Prior of the Augustines at the Hague, and after his confession said that he was then in a holy state and would die; and believed that his head was cut off and that he was dead, and was carried away by his companions who said they were going to bury him.

In the city of The Hague in Holland, as the prior of the Augustine Monastery was one day saying his prayers on the lawn near the chapel of St. Antony, he was accosted by a great, big Dutchman who was exceedingly drunk, and who lived in a village called Schevingen, about two leagues from there.

The prior, who saw him coming from afar, guessed his condition by his heavy and uncertain step, and when they met, the drunkard saluted the prior, who returned the salute, and passed on reading his prayers, proposing neither to stop nor question him.

The drunkard, being half beside himself, turned and pursued the prior, and demanded to be confessed.

"Confession!" said the prior. "Go away! Go away! You have confessed already."

"Alas, sir," replied the drunkard, "for God's sake confess me. At present, I remember all my sins, and am most contrite."

The prior, displeased to be interrupted by a drunkard, replied.

"Go your ways; you have no need of confession, for you are in a very comfortable case as it is."

"Oh, no," said the drunkard, "as sure as death you shall confess me, master Curé, for I am most devout," and he seized him by the sleeve, and would have stopped him.

The priest would not listen to him, and made wonderful efforts to escape, but it was no good, for the other was obstinate in his desire to confess, which the priest would not hear.

The devotion of the drunkard increased more and more, and when he saw that the priest still refused to hear his sins, he put his hand on his big knife and drew it from its sheath, and told the priest he would kill him, if he did not listen to his confession.

The priest, being afraid of a knife in such dangerous hands, did not know what to do, so he asked the other,

"What is is you want?"

"I wish to confess," said he.

"Very well; I will hear you," said the priest. "Come here."

Our drunkard,—being more tipsy than a thrush in a vineyard,—began, so please you, his devout confession,—over which I pass, for the priest never revealed it, but you may guess it was both novel and curious.

The priest cut short the wearisome utterances of the drunkard, and gave him absolution, and, to get rid of him, said;

"Go away now; you have made a good confession."

"Say you so, sir?" he replied.

"Yes, truly," said the priest, "it was a very good confession. Go, and sin no more!"

"Then, since I have well confessed and received absolution, if I were to die now, should I go to paradise?" asked the drunkard.