| Previous Part | Main Index | Next Part |

|

65.jpg Indiscretion Reproved, But Not Punished. 71.jpg The Considerate Cuckold 72.jpg Necessity is The MoTher of Invention. |

STORY THE SIXTY-FIRST — CUCKOLDED—AND DUPED.

Of a merchant who locked up in a bin his wife's lover, and she secretly

put an ass there which caused her husband to be covered with confusion.

STORY THE SIXTY-SECOND — THE LOST RING.

Of two friends, one of whom left a diamond in the bed of his hostess,

where the other found it, from which there arose a great discussion

between them, which the husband of the said hostess settled in an

effectual manner.

STORY THE SIXTY-THIRD — MONTBLERU; OR THE THIEF.

Of one named Montbleru, who at a fair at Antwerp stole from his

companions their shirts and handkerchiefs, which they had given to the

servant-maid of their hostess to be washed; and how afterwards they

pardoned the thief, and then the said Montbleru told them the whole of

the story.

STORY THE SIXTY-FOURTH — THE OVER-CUNNING CURÉ.

Of a priest who would have played a joke upon a gelder named

Trenche-couille, but, by the connivance of his host, was himself

castrated.

STORY THE SIXTY-FIFTH — INDISCRETION REPROVED, BUT NOT PUNISHED.

Of a woman who heard her husband say that an innkeeper at Mont St.

Michel was excellent at copulating, so went there, hoping to try for

herself, but her husband took means to prevent it, at which she was much

displeased, as you will hear shortly.

STORY THE SIXTY-SIXTH — THE WOMAN AT THE BATH.

Of an inn-keeper at Saint Omer who put to his son a question for which

he was afterwards sorry when he heard the reply, at which his wife was

much ashamed, as you will hear, later.

STORY THE SIXTY-SEVENTH — THE WOMAN WITH THREE HUSBANDS

Of a "fur hat" of Paris, who wished to deceive a cobbler's wife, but

over-reached, himself, for he married her to a barber, and thinking that

he was rid of her, would have wedded another, but she prevented him, as

you will hear more plainly hereafter.

STORY THE SIXTY-EIGHTH — THE JADE DESPOILED.

Of a married man who found his wife with another man, and devised

means to get from her her money, clothes, jewels, and all, down to

her chemise, and then sent her away in that condition, as shall be

afterwards recorded.

STORY THE SIXTY-NINTH — THE VIRTUOUS LADY WITH TWO HUSBANDS.

Of a noble knight of Flanders, who was married to a beautiful and noble

lady. He was for many years a prisoner in Turkey, during which time his

good and loving wife was, by the importunities of her friends, induced

to marry another knight. Soon after she had remarried, she heard that

her husband had returned from Turkey, whereupon she allowed herself to

die of grief, because she had contracted a fresh marriage.

STORY THE SEVENTIETH — THE DEVIL'S HORN.

Of a noble knight of Germany, a great traveller in his time; who after

he had made a certain voyage, took a vow to never make the sign of

the Cross, owing to the firm faith and belief that he had in the holy

sacrament of baptism—in which faith he fought the devil, as you will

hear.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FIRST — THE CONSIDERATE CUCKOLD

Of a knight of Picardy, who lodged at an inn in the town of St. Omer,

and fell in lave with the hostess, with whom he was amusing himself—you

know how—when her husband discovered them; and how he behaved—as you

will shortly hear.

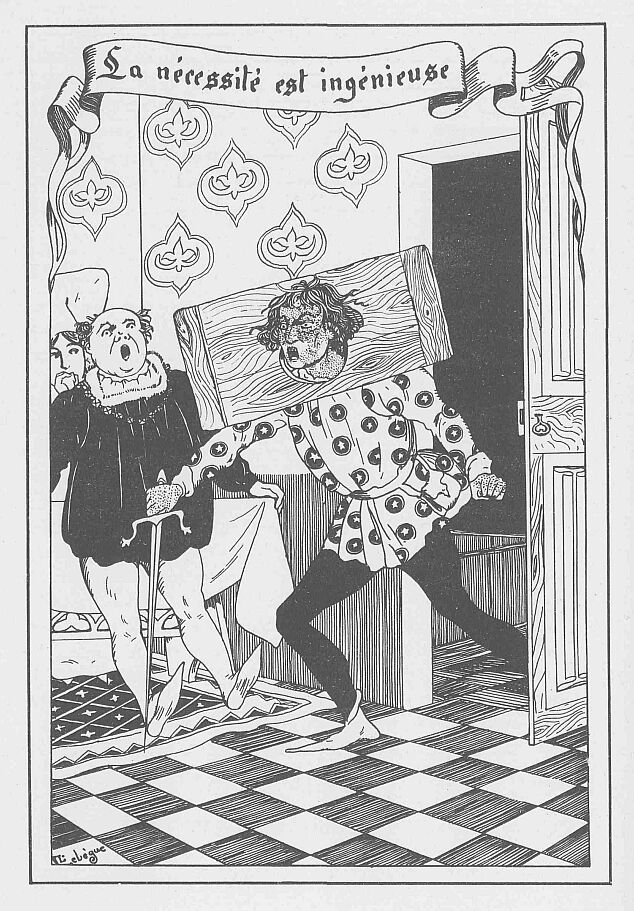

STORY THE SEVENTY-SECOND — NECESSITY IS THE MOTHER OF INVENTION.

Of a gentleman of Picardy who was enamoured of the wife of a knight his

neighbour; and how he obtained the lady's favours and was nearly caught

with her, and with great difficulty made his escape, as you will hear

later.

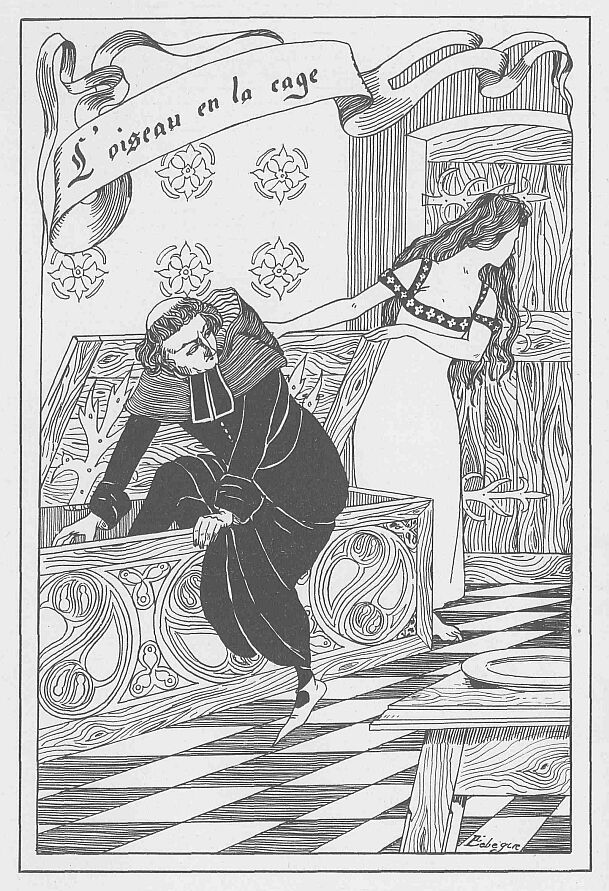

STORY THE SEVENTY-THIRD — THE BIRD IN THE CAGE.

Of a curé who was in love with the wife of one of his parishioners,

with whom the said curé was found by the husband of the woman, the

neighbours having given him warning—and how the curé escaped, as you

will hear.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FOURTH — THE OBSEQUIOUS PRIEST.

Of a priest of Boulogne who twice raised the body of Our Lord whilst

chanting a Mass, because he believed that the Seneschal of Boulogne

had come late to the Mass, and how he refused to take the Pax until the

Seneschal had done so, as you will hear hereafter.

STORY THE SEVENTY-FIFTH — THE BAGPIPE.

Of a hare-brained half-mad fellow who ran a great risk of being put

to death by being hanged on a gibbet in order to injure and annoy the

Bailly, justices, and other notables of the city of Troyes in Champagne

by whom he was mortally hated, as will appear more plainly hereafter.

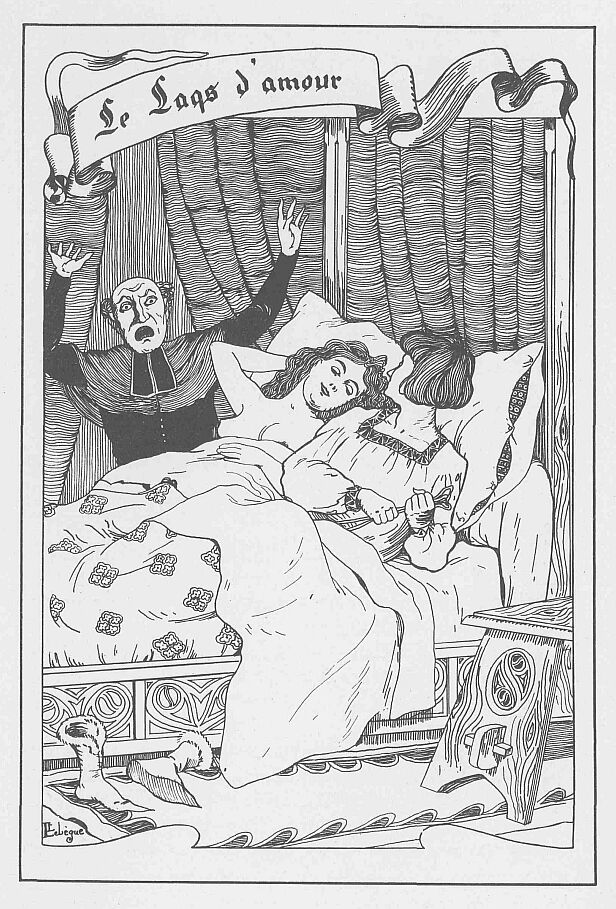

STORY THE SEVENTY-SIXTH — CAUGHT IN THE ACT.

Of the chaplain to a knight of Burgundy who was enamoured of the wench

of the said knight, and of the adventure which happened on account of

his amour, as you will hear below.

STORY THE SEVENTY-SEVENTH — THE SLEEVELESS ROBE.

Of a gentleman of Flanders, who went to reside in France, but whilst he

was there his mother was very ill in Flanders; and how he often went

to visit her believing that she would die, and what he said and how he

behaved, as you will hear later.

STORY THE SEVENTY-EIGHTH — THE HUSBAND TURNED CONFESSOR.

Of a married gentleman who made many long voyages, during which time his

good and virtuous wife made the acquaintance of three good fellows, as

you will hear; and how she confessed her amours to her husband when he

returned from his travels, thinking she was confessing to the curé, and

how she excused herself, as will appear.

STORY THE SEVENTY-NINTH — THE LOST ASS FOUND.

Of a good man of Bourbonnais who went to seek the advice of a wise man

of that place about an ass that he had lost, and how he believed that he

miraculously recovered the said ass, as you will hear hereafter.

STORY THE EIGHTIETH — GOOD MEASURE!

Of a young German girl, aged fifteen or sixteen or thereabouts who was

married to a gentle gallant, and who complained that her husband had too

small an organ for her liking, because she had seen a young ass of only

six months old which had a bigger instrument than her husband, who was

24 or 26 years old.

Of a merchant who locked up in a bin his wife's lover, and she secretly put an ass there which caused her husband to be covered with confusion.

It happened once that in a large town of Hainault there lived a good merchant married to a worthy woman. He travelled much, to buy and sell his merchandise, and this caused his wife to have a lover in his absence, and this continued for a long time.

Nevertheless, the secret was at last discovered by a neighbour, who was a relative of the husband, and lived opposite the merchant's house, and who often saw a gallant enter the merchant's house at night and leave in the morning. Which matter was brought to the knowledge of the person to whose prejudice it was, by this neighbour.

The merchant was much vexed, nevertheless he thanked his relative and neighbour, and said that he would shortly see into the matter, and for that purpose would shut himself up one night in his neighbour's house, that he might see if anyone visited his wife.

Lastly, he pretended to start on a journey, and told his wife and his servants that he did not know when he should return. He started in the early morning, but returned the same evening, and having left his horse at some house, came secretly to his cousin, and peeped through a little lattice, expecting to see that which would hardly have pleased him.

He waited till about nine o'clock, when the gallant, whom the damsel had informed that her husband was away, passed once or twice before his lady-love's house, and looked at the door to see if he might enter, but found it closed. He guessed that it was not yet time, and whilst he strolled about waiting, the good merchant, who thought that this was the man he wanted, came down, and went to his door, and said,

"Friend, the lady heard you, and as she is afraid that the master may come back, she sent me down to let you in, if you please."

The gallant, thinking it was the servant, followed him, the door was opened gently, and he was conducted into a chamber in which there was a large bin, which the merchant unlocked and made the young man enter, that he should not be discovered if the husband returned. "My mistress will come and talk to you and let you out," added the merchant as he turned the key in the lock.

The gallant suffered all this for the sake of what was to follow, and because he believed that the other spoke the truth.

Then the merchant started off at once as quickly as he could, and went to the cousin and his wife, and said to them:

"The rat is caught; but now we must consider what to do."

The cousin, and more particularly his wife—for there was no love lost between the two women—were very glad to hear this, and said that it would be best for him to show the gallant to all his wife's relations in order that they might know how she conducted herself.

This being determined on, the merchant went to the house of his wife's father and mother, and told them that if ever they wished to see their daughter alive they must come at once to his house.

They jumped up at once, and, whilst they were preparing, he also went off to two of her brothers and her sisters, and told them the same thing. Then he took them all to the cousin's house, and related the whole history, and how the rat had been caught.

Now you must know what the gallant did in the bin all the time, until he was luckily released. The damsel, who wondered greatly that her lover did not come, went backwards and forwards to the door, to see if he were coming. The young man, who heard her pass close to him without ever speaking to him, began to thump with his fist on the side of the bin. The damsel heard it, and was greatly frightened; nevertheless she asked who was there, and the gallant replied;

"Alas, my dearest love, I am dying here of heat and doubt, for I am much surprised that I have been shut in here, and that no one has yet come to me."

"Virgin Mary! who can have put you there, my dear?"

"By my oath I know not," he replied; "but your varlet came to me and told me that you had asked him to bring me into the house, and that I was to get into this bin, that the husband might not find me if by chance he should come back to-night."

"Ah!" said she, "by my life that must have been my husband. I am a lost woman; and our secret has been discovered."

"Do you know what is to be done?" he said. "In the first place you must let me out, or I will break everything, for I can no longer endure being shut up."

"By my oath!" said the damsel, "I have not the key; and if you break through, I am undone, for my husband will say that I did it to save you."

Finally, the damsel searched about, and found a lot of old keys, amongst which was one that delivered the poor captive. As soon as he was out, he tumbled the lady, to show her what a grudge he had against her, which she bore patiently. After that her lover would have left her, but the damsel hung round his neck, and told him that if he went away like that, she would be as much dishonoured as though he had broken out of the bin.

"What is to be done then?" said the gallant.

"We must put something there for my husband to find, or he will think that I have let you out."

"And what shall we put there?" asked the lover. "For it is time for me to go."

"We have in the stable," she said, "an ass, that we will put in if you will help me."

"Certainly, I will," he answered.

The ass was driven into the bin, and it was locked again, and then her lover took leave of her with a sweet kiss, and left by a back-door, whilst the damsel quickly got into bed.

Whilst these things were happening, her husband had assembled all his wife's relatives, and brought them to his cousin's house, as has been said, where he informed them of what he had done, and how he had caught the gallant, and had him under lock and key.

"And in order that you shall not say," he added, "that I blame your daughter without cause, you shall both see and touch the scoundrel who has done us this dishonour, and I beg that he may be killed before he can get away."

Every one present declared that it should be so.

"And then," said the merchant, "I will send you back your daughter for such as she is."

With that they all accompanied him, though sorrowing much at the news, and they took with them torches and flambeaux, so as to be better able to search, and that nothing should escape them.

They knocked so loudly that the damsel came before anyone else in the house was awakened, and opened the door, and when they had come in, she abused her husband, her father, her mother, and the others, and declared that she wondered greatly what could have brought them all at that hour of the night. At these words her husband stepped forward, and gave her a good buffet, and said,

"You shall know soon enough, false such and such that you are."

"Ah! take care what you say. Was it for that you brought my father and mother here?"

"Yes," said the mother, "false wench that you are. We will drag forth your paramour directly."

And her sisters said,

"By God, sister you did not learn at home to behave like this."

"Sisters," she replied, "by all the saints of Rome, I have done nothing that a good woman should not do. I should like to see anyone prove the contrary."

"You lie!" said her husband. "I can prove it at once, and the rascal shall be killed in your presence. Up quickly! and open me this bin."

"I?" she replied. "In truth I think you must be dreaming, or out of your senses, for you know well that I have never had the key, but that it hangs at your belt along with the others, ever since the time that you locked up your goods. If you want to open it, open it. But I pray to God that, as truly as I have never kept company with whoever is in that box, that He will deliver me, to my great joy, and that the evil spite that you have against me may be clearly proved and demonstrated—and I have full hope and confidence that it will be so."

"And I hope," said her husband, addressing the crowd, "that you will see her on her knees, weeping and groaning, and squalling like a drenched cat. She would deceive anybody who was fool enough to believe her, but I have suspected her for a long time past. Now I am going to unlock the bin, and I beg you, gentlemen, to lay hands on the scoundrel, that he escape us not, for he is strong and bold."

"Have no fear!" they cried in chorus. "We will give a good account of him."

"With that they drew their swords, and brandished their hammers to knock down the poor lover, and they shouted to him,

"Confess your sins! for you will never have a priest nearer you."

The mother and sisters, not wishing to witness the murder, drew on one side, and then the good man opened the bin, and as soon as the ass saw the light, it began to bray so hideously that the boldest person there was affrighted.

And when they saw that it was an ass, and that they had been befooled, they cursed the merchant, and showered more abuse on him than ever St. Peter had praise, and even the women inveighed against him. In fact, if he had not fled, his wife's brothers would have killed him, in revenge for the blame and dishonour he had wrongly tried to bring on the family.

There was such ado between him and his wife's family that peace had to be made between them by the chief burghers of the town, and this was not effected without much trouble, and many demands on the part of her friends, and many strict promises on his part. But ever after that he was all kindness and consideration, and never did a man conduct himself better to his wife than he did all his life; and thus they passed their days together.

Of two friends, one of whom left a diamond in the bed of his hostess, where the other found it, from which there arose a great discussion between them, which the husband of the said hostess settled in an effectual manner.

About the month of July (*) a great meeting and assembly was held between Calais and Gravelines, and near the castle of Oye, at which were assembled many princes and great lords, both of France and of England, to consider the question of the ransom of the Duke of Orléans, (**) then prisoner to the king of England. Amongst the English representatives was the Cardinal of Winchester, who had come to the said assembly in great and noble state, with many knights, and squires and ecclesiastics.

(*) 1440.

(**) Charles, Duke of Orléans, was taken prisoner at the

battle of Agincourt in 1415, and, as his ransom was not

forthcoming was detained a captive for 25 years, when the

Duke and Duchess of Burgundy intervened to procure his

freedom. Cardinal Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester, accepted a

ransom of 200,000 gold crowns, payment of which was

guaranteed by the Dauphin of France, Duke Philip of

Burgundy, and other princes, with the consent of the King of

France. The agreement was signed 22 Nov. 1440.

And amongst the other noblemen were two named John Stockton, squire, and carver, and Thomas Brampton, cup-bearer to the said Cardinal—which said John and Thomas loved each other like two brothers, for their clothes, harness, and arms were always as nearly alike as possible, and they usually shared the same room and the said bed, and never was there heard any quarrel, dispute, or misunderstanding between them.

When the said Cardinal arrived at the said town of Calais, there was hired for him to lodge the said noblemen, the house of Richard Fery, which is the largest house in the town of Calais, and it is the custom of all great lords passing through the town to lodge there.

The said Richard was married to a Dutchwoman; who was beautiful, courteous, and well accustomed to receive guests.

While the treaty was being discussed, which was for more than two months, John Stockton and Thomas Brampton, who were both of the age of 26 or 28 years, wore bright crimson clothes, (*) and were ready for feats of arms by night or day—during this time, I say, notwithstanding the intimacy and friendship which existed between these two brothers-in-arms, the said John Stockton, unknown to the said Thomas, found means to visit their hostess, and often conversed with her, and paid her many of those attentions customary in love affairs, and finally was emboldened to ask the said hostess if he might be her friend, and she would be his lady-love.

(*) Shakespeare several times in the course of the First

Part of Henry VI mentions "the tawny robes of Winchester."

Which is right?

To which, as though pretending to be astonished at such a request, she replied coldly that she did not hate him, or anyone, nor wish to, but that she loved all the world as far as in honour she could, but if she rightly understood his request, she could not comply with it without great danger of dishonour and scandal, and perhaps risk to her life, and for nothing in the world would she consent thereto.

John replied that she might very well grant his request, for that he would rather perish, and be tormented in the other world, than that she should be dishonoured by any fault of his, and that she was in no wise to suspect that her honour would not be safe in his keeping, and he again begged her to grant him this favour, and always deem him her servant and loving friend.

She pretended to tremble, and replied that truly he made all the blood freeze in her veins, such fear and dread had she of doing that which he asked. Then he approached her and requested a kiss, which the ladies and damsels of the said country of England are ready enough to grant, (*) and kissing her, begged her tenderly not to be afraid, for no person living should ever be made acquainted with what passed between them.

(*) Is this a libel on the English ladies of the 16th

century, or is it true—as Bibliophile Jacob asserts in the

foot-note to this passage—that "English prudery is a

daughter of the Reformation?"

Then she said;

"I see that there is no escape, and that I must do as you wish, and as this must be so, in order to guard my honour, let me tell you that a regulation has been made by all the lords now living in Calais that every householder shall watch one night a week on the town walls. But as my husband has done so much, either himself or by his friends, for the lords and noblemen of the Cardinal, your master, who lodge here, he has only to watch half the night, and he will do so on Thursday next, from the time the bell rings in the evening until midnight; and whilst my husband is away on his watch, if you have anything to say to me, you will find me in my chamber, quite willing to listen to you, and along with my maid;"—who was quite ready to perform whatever her mistress wished.

John Stockton was much pleased with this answer, and thanked his hostess, and told her that it would not be his fault if he did not come at the appointed hour.

This conversation took place on the Monday, after dinner. But it should here be stated that Thomas Brampton had, unknown to his friend John Stockton, made similar requests to their hostess, but she would not grant his desire, but now raised his hopes and then dashed them to the ground, saying that he must have but a poor idea of her virtue, and that, if she did what he wished, she was sure that her husband and his relations and friends would take her life.

To this Thomas replied;

"My beloved mistress and hostess, I am a nobleman, and for no consideration would I bring upon you blame or dishonour, or I should be unworthy of the name of a gentleman. Believe me, that I would guard your honour as I do my own, and would rather die than reveal your secret; and that there is no friend or other person in the world, however dear to me, to whom I would relate our love-affair."

She, therefore, noting the great affection and desire of the said Thomas, told him, on the Wednesday following the day on which she had given John the gracious reply recorded above—that, as he had a great desire to do her any service, she would not be so ungrateful as not to repay him. And then she told him how it was arranged that her husband should watch the morrow night, like the other chief householders of the town, in compliance with the regulation made by the lords then staying in Calais. But as—thank God—her husband had powerful friends to speak to the Cardinal for him, he had only to watch half the night, that is to say from midnight till the morning, and that if Thomas wished to speak to her during that time, she would gladly hear him, but, for God's sake let him come so secretly that no blame could attach to her.

Thomas replied that he desired nothing better, and with that he took leave of her.

On the morrow, which was Thursday, at vespers, after the bell had rung for the watch, John Stockton did not forget to appear at the hour his hostess had appointed. He went to her chamber, and found her there quite alone, and she received him and made him welcome, for the table was laid.

John requested that he might sup with her, that they might the better talk together,—which she would not at first grant, saying that it might cause scandal if he were found with her. But she finally gave way, and the supper—which seemed to John to take a long time—being finished, he embraced his hostess, and they enjoyed themselves together, both naked.

Before he entered the chamber, he had put on one of his fingers, a gold ring set with a large fine diamond, of the value of, perhaps, thirty nobles. And in playing together, the ring slipped from his finger in the bed without his knowing it.

When it was about 11 o'clock, the damsel begged him kindly to dress and leave, that he might not be found by her husband, whom she expected as soon as midnight sounded, and that he would guard her honour as he had promised.

He, supposing that her husband would return soon, rose, dressed, and left the chamber as soon as the clock struck twelve, and without remembering the diamond he had left in the bed.

Not far from the door of the chamber John Stockton met Thomas Brampton, whom he mistook for his host, Richard. Thomas,—who had come at the hour the lady appointed,—made a similar mistake, and took John Stockton for Richard, and waited a few moments to see which way he would go.

Having watched the other disappear, Thomas went to the chamber, found the door ajar, and entered. The lady pretended to be much frightened and alarmed, and asked Thomas, with doubt and fear, whether he had met her husband who had just left to join the watch? He replied that he had met a man, but did not know whether it was her husband or another, and had waited a little in order to see which way he would go.

When she heard this, she kissed him boldly, and told him he was welcome, and Thomas, without more ado, laid her on the bed and tumbled her. When she found what manner of man he was, she made haste to undress, and he also, and they both got into bed, and sacrificed to the god of love, and broke several lances.

But in performing these feats, Thomas met with an adventure, for he suddenly felt under his thigh, the diamond that John Stockton had left there, and without saying anything, or evincing any surprise, he picked it up, and put it on his finger.

They remained together until the morning, when the watch bell was about to ring, when, at the request of the damsel he rose, but before he left they embraced with a long, loving kiss. He had scarcely gone when Richard came off the watch, on which he had been all night, very cold and sleepy, and found his wife just getting up. She made him a fire, and then he went to bed, for he had worked all night,—and so had his wife though not in the same fashion.

It is the custom of the English, after they have heard Mass, to breakfast at a tavern, with the best wine; and about two days after these events, John and Thomas were in a company of other gentlemen and merchants, who were breakfasting together, and Stockton and Brampton were seated opposite each other.

Whilst they were eating, John looked at Thomas, and saw on one of his fingers the diamond. He gazed at it a long time, and came to the conclusion that it was the ring he had lost, he did not know where or when, and he begged Thomas to show him the diamond, who accordingly handed it to him, and when he had it in his hand he saw that it was his own, and told Thomas so, and asked him how he came by it. To this Thomas replied that it belonged to him. Stockton maintained, on the contrary, that he had lost it but a short time before, and that if Thomas had found it in the chamber where they slept, it was not right of him to keep it, considering the affection and fraternity which had always existed between them. High words ensued, and both were angry and indignant with each other.

Thomas wished to get the diamond back, but could not obtain it. When the other gentlemen and merchants heard the dispute, all tried to bring about a reconciliation, but it was no good, for he who had lost the diamond would not let it out of his hands, and he who had found it wanted it back, as a memento of his love-encounter with his mistress, so that it was difficult to settle the dispute.

Finally, one of the merchants, seeing that all attempts to make up the quarrel were useless, said that he had hit upon a plan with which both John and Thomas ought to be satisfied, but he would not say what it was unless both parties promised, under a penalty of ten nobles, to abide by what he said. All the company declared that the merchant had spoken well, and persuaded John and Thomas to abide by this decision, which they at last consented to do.

The merchant ordered the diamond to be placed in his hands, then that all those who had tried to settle the difference should be silent, and that they should leave the house where they were, and the first man they met, whatever his rank or condition should be told the whole matter of the dispute between the said John and Thomas, and, whatever he decided, his verdict should be accepted without demur by both parties.

Thereupon all the company left the house, and the first person they met was Richard, the host of both disputants, to whom the merchant narrated the whole of the dispute.

Richard—after he had heard all, and had asked those, who were present if the account was correct, and the two were unwilling to let this dispute be settled by so many notable persons,—delivered his verdict—namely that the diamond should remain his, and that neither of the parties should have it.

When Thomas saw himself deprived of the diamond he had found, he was much vexed; and most probably so also was John Stockton, who had lost it.

Then Thomas requested all the company, except their host, to return to the house where they had breakfasted, and he would give them a dinner in order that they might hear how the diamond had come into his hands, to which they all agreed. And whilst the dinner was being prepared, he related the conversation he had had with his hostess, how she had appointed him an hour for him to visit her, whilst her husband was out with the watch, and how the diamond was found.

When John Stockton heard this he was astonished, and declared that exactly the same had occurred to him, and on the same night, and that he was convinced that he must have dropped his diamond where Thomas had found it, and that it was far worse for him to lose it than it was for Thomas, for it had cost him dear, whereas Thomas had lost nothing.

To which Thomas replied that he ought not to complain that their host had adjudged it to be his, considering what their hostess had had to suffer, and that he (John) had had first innings, whilst Thomas had had to act as his page or squire, and come after him.

So John Stockton was tolerably reconciled to the loss of his ring, since he could not otherwise help it. And all those who were present laughed loudly at the story of this adventure; and after they had all dined, each returned whithersoever he wished.

Of one named Montbleru, who at a fair at Antwerp stole from his companions their shirts and handkerchiefs, which they had given to the servant-maid of their hostess to be washed; and how afterwards they pardoned the thief, and then the said Montbleru told them the whole of the story.

Montbleru found himself about two years ago at the fair of Antwerp, in the company of Monseigneur d'Estampes, who paid all his expenses—which was much to the liking of Montbleru.

One day amongst others, by chance he met Masters Ymbert de Playne, Roland Pipe, and Jehan Le Tourneur, who were having a merry time; and as he is pleasant and obliging, as everyone knows, they desired his company, and begged him to come and lodge with them, and then they would have a merrier time than ever.

Montbleru at first excused himself, on the ground that he ought not to quit Monseigneur d'Estampes who had brought him there;

"And there is a very good reason," he said, "for he pays all my expenses."

Nevertheless, he was willing to leave Monseigneur d'Estampes if the others would pay his expenses, and they, who desired nothing better than his company, willingly and heartily agreed to this. And now hear how he paid them out.

These three worthy lords, Masters Ymbert, Roland, and Jehan Le Tourneur, stayed at Antwerp longer than they expected when they left Court, and each had brought but one shirt, and these and their handkerchiefs etc. became dirty, which was a great inconvenience to them, for the weather was very hot, it being Pentecost. So they gave them to the servant-maid at their lodgings to wash, one Saturday night when they went to bed, and they were to have them clean the following morning when they rose.

But Montbleru was on the watch. When the morning came, the maid, who had washed the shirts and handkerchiefs, and dried them, and folded them neatly and nicely, was called away by her mistress to go to the butcher to seek provisions for the dinner. She did as her mistress ordered, and left all these clothes in the kitchen, on a stool, expecting to find them on her return, but in this she was disappointed, for Montbleru, when he awoke and saw it was day, got out of bed, and putting on a dressing gown over his shirt, went downstairs.

He went into the kitchen, where there was not a living soul, but only the shirts, handkerchiefs, and other articles, asking to be taken. Montbleru saw his opportunity, and took them, but was much puzzled to know where he could hide them. Once he thought of putting them amongst the big copper pots and pans which were in the kitchen; then of hiding them up his sleeve; but finally he concealed them in the hay in the stable, with a big heap of straw on the top, and that being done, he returned to bed and lay down by the side of Jehan Le Tourneur.

When the servant maid came back from the butcher's, she could not find the shirts, at which she was much vexed, and she asked everybody she met if they had seen them? They all told her they knew nothing about them, and God knows what a time she had. Then came the servants of these worthy lords, who expected the shirts and were afraid to go to their masters without them, and grew angry because the shirts could not be found, and so did the host, and the hostess, and the maid.

When it was about nine o'clock, these good lords called their servants, but none of them answered, for they were afraid to tell their masters about the loss of their shirts; but at last, however, when it was between 11 and 12 o'clock, the host came, and the servants, and told the gentlemen how their shirts had been stolen, at which news two of them—Masters Ymbert and Roland—lost patience, but Jehan Le Tourneur took it easily, and did nothing but laugh, and called Montbleru, who pretended to be asleep, but who heard and knew all, and said to him,

"Montbleru, we are all in a nice mess. They have stolen our shirts."

"Holy Mary! what do you say?" replied Montbleru, pretending to be only just awake. "That is bad news."

When they had discussed the robbery of their shirts for a long time—Montbleru well knew who was the thief—these worthy lords said;

"It is late, and we have not yet heard Mass, and it is Sunday, and we cannot very well go without a shirt. What is to be done?"

"By my oath!" said the host, "I know of nothing better than to lend you each one of my shirts, such as they are. They are not as good as yours, but they are clean, and there is nothing better to be done."

They were obliged to take their host's shirts which were too short and too small, and made of hard, rough linen, and God knows they were a pretty sight in them.

They were soon ready, thank God, but it was so late that they did not know where they could hear Mass. Then said Montbleru, in his familiar way,

"As for hearing Mass, it is too late to-day; but I know a church in this town where at least, we shall not fail to see God."

"That is better than nothing," said the worthy lords. "Come, come! let us get away, for it is very late, and to lose our shirts, and not to hear Mass to-day would be a double misfortune; and it is time we went to church if we want to hear Mass."

Montbleru took them to the principal church in Antwerp, where there is a God on an ass (*).

(*) A picture or bas-relief, representing Christ's entry

into Jerusalem, is probably meant.

When they had each said a paternoster, they said to Montbleru, "Where shall we see God?"

"I will show you," he replied. Then he showed them God mounted on an ass, and added, "You will never fail to find Him here at whatever hour you come."

They began to laugh in spite of the discomfort their shirts caused them. Then they went back to dinner, and were after that I know not how many days at Antwerp, and left without their shirts, for Montbleru had hidden them in a safe place, and afterwards sold them for five gold crowns.

Now God so willed that in the first week of Lent, Montbleru was at dinner with the three worthy gentlemen before named, and in the course of his talk he reminded them of the shirts they had lost at Antwerp, and said,

"Alas, the poor thief who robbed you will be damned for that, unless God and you pardon him. Do you bear him any ill-will?"

"By God!" said Master Ymbert, "my dear sir, I have thought no more about it,—I had forgotten it long since."

"At least," said Montbleru, "you pardon him, do you not?"

"By St. John!" he replied, "I would not have him damned for my sake."

"By my oath, that is well said," answered Montbleru. "And you Master Roland,—do you also pardon him?"

After a good deal of trouble, he agreed to pardon the thief, but as the theft rankled in his mind, he found the word hard to pronounce.

"And will you also pardon him, Master Roland?" said Montbleru. "What will you gain by having a poor thief damned for a wretched shirt and handkerchief?"

"Truly I pardon him," said he. "He is quit as far as I am concerned, since there is nothing else to be done."

"By my oath, you are a good man," said Montbleru.

Then came the turn of Jehan Le Tourneur. Montbleru said to him,

"Now, Jehan, you will not be worse than the others. Everything will be pardoned to this poor stealer of shirts unless you object."

"I don't object," he replied. "I have long since pardoned him, and I will give him absolution into the bargain."

"You could not say more," rejoined Montbleru, "and by my oath I am greatly obliged to you for having pardoned the thief who stole your shirts, as far as I personally am concerned, for I am the thief who stole your shirts at Antwerp. So I profit by your free pardon, and thank you for it, as I ought to do."

When Montbleru confessed this theft, and had been forgiven by all the party as you have heard, it need not be asked if Masters Ymbert, Roland, and Jehan Le Tourneur were astonished, for they had never suspected that it was Montbleru who had played that trick upon them, and they reproached him playfully with the theft. But he, knowing his company, excused himself cleverly for having played such a joke upon them, and told them that it was his custom to take whatever he found unprotected,—especially with people like them.

They only laughed, but asked him how he had managed to effect the theft, and he told them the whole story, and said also that he had made five crowns out of his booty, after which they asked him no more.

Of a priest who would have played a joke upon a gelder named Trenche-couille, but, by the connivance of his host, was himself castrated.

There formerly lived in this country, in a place that I have a good reason for not mentioning (if any should recognise it, let him be silent as I am) a curé who was over-fond of confessing his female parishioners. In fact, there was not one who had not had to do with him, especially the young ones—for the old he did not care.

When he had long carried on this holy life and virtuous exercise, and his fame had spread through all the country round, he was punished in the way that you will hear, by one of his parishioners, to whom, however, he had done nothing concerning his wife.

He was one day at dinner, and enjoying himself, at the inn kept by his parishioner, and as they were in the midst of their dinner, there came a man named Trenchecouille, whose business it was to cut cattle, pull teeth, and other matters, and who had come to the inn for one of these purposes.

The host received him well, and asked him to sit down, and, without being much pressed, he sat down with the curé and the others, to eat.

The curé, who was a great joker, began to talk to this gelder and asked him a hundred thousand questions about his business, and the gelder replied as he best could.

At the end, the curé turned to the host, and whispered in his ear,

"Shall we play a trick upon this gelder?"

"Oh, yes, let us," replied the host. "But how shall we do it?"

"By my oath," said the curé, "we will play him a pretty trick, if you will help me."

"I am quite willing," replied the host.

"I will tell you what we will do," said the curé. "I will pretend to have a pain in the testicle, and bargain with him to cut it out; then I will be bound and laid on the table all ready, and when he comes near to cut me, I will jump up and show him my backside."

"That is well said," replied my host, who at once saw what he had to do. "We shall never hit on anything better. We will all help you with the joke."

"Very well," said the curé.

After this the curé began again to rally the gelder, and at last told him that he had want of a man like him, for that he had a testicle all diseased and rotten, and would like to find a man who would extract it, and he said it so quietly and calmly that the gelder believed him, and replied;

"Monsieur le curé, I would have you know that without either disparaging myself or boasting, there is not a man in this country who can do the job better than I can, and for the sake of the host here, I will do my best to satisfy you."

"Truly, that is well said;" replied the curé.

In short, all was agreed, and when the dinner had been removed, the gelder began to make his preparations, and on the other hand the curé prepared to play the practical joke, (which was to turn out no joke for him) and told the host and the others what they were to do.

Whilst these preparations were being made on both sides, the host went to the gelder, and said,

"Take care, and, whatever the priest may say, cut out both his testicles, clean,—and fail not, if you value your carcass."

"By St. Martin, I will," replied the gelder, "since you wish it. I have ready a knife so sharp that I will present you with his testicles before he has time to say a word."

"We shall see what you can do," said the host, "but if you fail, I will never again have anything to do with you."

All being ready, the table was brought, and the curé, in his doublet, pretended to be in great pain, and promised a bottle of good wine to the gelder.

The host and his servants laid hold of the curé so that he could not get away, and for better security they tied him tightly, and told him that was to make the joke better, and that they would let him go when he wished, and he like a fool believed them. Then came the brave gelder, having a little rasor concealed in his hand, and began to feel the cure's testicles.

"In the devil's name," said the curé, "do it well and with one cut. Touch them first as you can, and afterwards I will tell you which one I want taken out."

"Very well," he replied, and lifting up the shirt, took hold of the testicles, which were big and heavy and without enquiring which was the bad one, cut them both out at a single stroke.

The good curé began to yell, and make more ado than ever man made.

"Hallo, hallo!" said the host; "have patience. What is done, is done. Let us bandage you up."

The gelder did all that was necessary, and then went away, expecting a handsome present from the host.

It need not be said that the curé was much grieved at this deprivation, and he reviled the host, who was the cause of the mischief, but God knows he excused himself well, and said that if the gelder had not disappeared so quickly, he would have served him so that he would never have cut any one again.

"As you imagine," he said, "I am greatly grieved at your misfortune, and still more that it should have happened in my inn."

The news soon spread through the town, and it need not be said that many damsels were vexed to find themselves deprived of the cure's instrument, but on the other hand the long-suffering husbands were so happy that I could neither speak nor write the tenth part of their joy.

Thus, as you have heard, was the curé, who had deceived and duped so many others, punished. Never after that did he dare to show himself amongst men, but soon afterwards ended in grief and seclusion his miserable life.

Of a woman who heard her husband say that an innkeeper at Mont St. Michel was excellent at copulating, so went there, hoping to try for herself, but her husband took means to prevent it, at which she was much displeased, as you will hear shortly.

Often a man says things for which he is sorry afterwards, and so it happened formerly that a good fellow who lived in a village near Mont St. Michel, talked one night at a supper, at which were present his wife, and several strangers and neighbours, of an inn-keeper of Mont St. Michel, and declared, affirmed, and swore on his honour, that this inn-keeper had the finest, biggest, and thickest member in all the country round, and could use it so well that four, five, or six times cost him no more trouble than taking off his hat. All those who were at table listened to this favourable account of the prowess of mine host of Mont St. Michel, and made what remarks they pleased about it, but the person who took the most notice was the lady of the house, the wife of the man who related the story, who had listened attentively, and to whom it seemed that a woman would be most happy and fortunate who had a husband so endowed.

And she also thought in her heart that if she could devise some cunning excuse she would some day go to Mont St. Michel, and put up at the inn kept by the man with the big member, and it would not be her fault if she did not try whether the report were true.

To execute what she had so boldly devised, at the end of six or eight days she took leave of her husband, to go on a pilgrimage to Mont St. Michel; and she invented some clever excuse for her journey, as women well know how to do. Her husband did not refuse her permission to go, though he had his suspicions.

At parting, her husband told her to make an offering to Saint Michael, and that she was to lodge at the house of the said landlord, and he recommended her to him a hundred thousand times.

She promised to accomplish all he ordered, and upon that took leave and went away, much desiring, God knows, to find herself at Mont St. Michel. As soon as she had left, the husband mounted his horse, and went as fast as he could, by another road to that which his wife had taken, to Mont St. Michel, and arrived secretly, before his wife, at the inn kept by the man already mentioned, who most gladly welcomed him. When he was in his chamber, he said to his host,

"My host, you and I have been friends for a long time. I will tell you what has brought me to your town now. About five or six days ago, a lot of good fellows were having supper at my house, and amongst other talk, I related how it was said throughout the country that there was no man better furnished than you"—and then he told him as nearly as possible all that had been said. "And it happened," he continued, "that my wife listened attentively to what I said, and never rested till she obtained permission to come to this town. And by my oath, I verily suspect that her chief intention is to try if she can, if my words were true that I said about your big member. She will soon be here I expect, for she longs to come; so I pray you when she does come you will receive her gladly, and welcome her, and do all that she asks. But at all events do not deceive me; take care that you do not touch her. Appoint a time to come to her when she is in bed, and I will go in your place, and afterwards I will tell you some good news."

"Let me alone," said the host. "I will take care and act my part well."

"At all events," said the other, "be sure and serve me no trick, for I know well enough that she will be ready to."

"By my oath," said the host, "I assure you I will not come near her," and he did not.

Soon after came our wench and her maid, both very tired, God knows; and the good host came forth, and received his guests as he had been enjoined, and as he had promised. He caused mademoiselle to be taken to a fair chamber, and a good fire to be made, and brought the best wine in the house, and sent for some fine fresh cherries, and came to banquet with her whilst supper was getting ready. When he saw his opportunity, he began to make his approaches to her, but in a roundabout way. To cut matters short, an agreement was made between them that he should come secretly at midnight to sleep with her.

This being arranged, he went and told the husband of the dame, who, at the hour named, went in mine host's instead, and did the best he could, and rose before daybreak and returned to his own bed.

When it was day, the wench, quite vexed and melancholy, called her maid, and they rose, and dressed as hastily as they could, and would have paid the host, but he said he would take nothing from her. And with that she left without hearing Mass, or seeing St. Michael, or breakfasting either; and without saying a single word, returned home. But you must know that her husband was there already, and asked her what good news there was at Mont St. Michel. She, feeling as annoyed as she could be, hardly deigned to reply.

"And what sort of welcome," asked her husband, "did mine host give you? By God, he is a good fellow!"

"A good fellow!" she said. "Nothing very wonderful! I will not give him more praise than is his due."

"No, dame?" he replied. "By St. John, I should have thought that for love of me he would have given you a hearty welcome."

"I care not about his welcome," she said. "I do not go on a pilgrimage for the sake of his, or any one else's welcome. I only think of my devotion."

"Devotion, wife!" he answered. "By Our Lady, you had none! I know very well why you are so vexed and sorrowful. You did not find what you expected—that is the exact truth. Ha, ha, madam! I know the cause of your pilgrimage. You wanted to make trial of the physical gifts of our host of St. Michel, but, by St. John, I was on my guard, and always will be if I can help it. And that you may not think that I lied when I told you that he had such a big affair, by God, I said nothing but what is true. But you wanted something more than hearsay evidence, and, if I had not stopped you, you would in your 'devotion' have tried its power for yourself. You see I know all, and to remove any doubts you may have on the subject, I may tell you that I came last night at the appointed hour, and took his place—so be content with what I was able to do, and remain satisfied with what you have. This time I pardon you, but take care that it never occurs again."

The damsel, confused and astonished at being thus caught, as soon as she could speak, begged his pardon, and promised never to do anything of the sort again. And I believe that she never did.

Of an inn-keeper at Saint Omer who put to his son a question for which he was afterwards sorry when he heard the reply, at which his wife was much ashamed, as you will hear, later.

Some time ago I was at Saint Omer with a number of noble companions, some from the neighbourhood and Boulogne, and some from elsewhere, and after a game of tennis, we went to sup at the inn of a tavern-keeper, who is a well-to-do man and a good fellow, and who has a very pretty and buxom wife, by whom he has a fine boy, of the age of six or seven years.

We were all seated at supper, the inn-keeper, his wife, and her son, who stood near her, being with us, and some began to talk, others to sing and make good cheer, and our host did his best to make himself agreeable.

His wife had been that day to the warm baths, and her little son with her. So our host thought, to make the company laugh, to ask his son about the people who were at the baths with his mother, (*) and said;

"Come here, my son, and tell me truly which of all the women at the baths had the finest and the biggest c——?"

(*) The public baths were then much frequented, especially

by the lower classes. Men, women, and children all bathed

together.

The child being questioned before his mother, whom he feared as children usually do, looked at her, and did not speak.

The father, not expecting to find him so quiet, said again;

"Tell me, my son; who had the biggest c—— Speak boldly."

"I don't know, father," replied the child, still glancing at his mother.

"By God, you lie," said his father. "Tell me! I want to know."

"I dare not," said the boy, "my mother would beat me."

"No, she will not," said the father. "You need not mind. I will see she does not hurt you."

Our hostess, the boy's mother, not thinking that her son would tell (as he did) said to him.

"Answer boldly what your father asks you."

"You will beat me," he said.

"No, I will not," she replied.

The father, now that the boy had permission to speak, again asked;

"Well, my son, on your word, did you look at the c——s of all the women who were at the baths?"

"By St. John, yes, father."

"Were there plenty of them? Speak, and don't lie."

"I never saw so many. It seemed a real warren of c——s."

"Well then; tell us now who had the finest and the biggest?"

"Truly," replied the boy, "mother had the finest and biggest—but he had such a large nose."

"Such a large nose?" said the father. "Go along, go along! you are a good boy."

We all began to laugh and to drink, and to talk about the boy who chattered so well. But his mother did not know which way to look, she was so ashamed, because her son had spoken about a nose, and I expect that he was afterwards well beaten for having told tales out of school. Our host was a good fellow, but he afterwards repented having put a question the answer to which made him blush. That is all for the present.

Of a "fur hat" of Paris, who wished to deceive a cobbler's wife, but over-reached, himself, for he married her to a barber, and thinking that he was rid of her, would have wedded another, but she prevented him, as you will hear more plainly hereafter.

About three years ago a noteworthy adventure happened to one of the fur hats of the Parliament of Paris. (*) And that it should not be forgotten, I relate this story, not that I hold all the "fur caps" to be good and upright men; but because there was not a little, but a large measure of duplicity about this particular one, which is a strange and peculiar thing as every one knows.

(*) The councillors of Parliament wore a cap of fur,

bordered with ermine.

To come to my story, this fur hat,—that is to say this councillor of Parliament,—fell in love with the wife of a cobbler of Paris,—a good, and pretty woman, and ready-witted. The fur hat managed, by means of money and other ways, to get an interview with the cobbler's fair wife on the quiet and alone, and if he had been enamoured of her before he enjoyed her, he was still more so afterwards, which she perceived and was on her guard, and resolved to stand off till she obtained her price.

His love for her was at such fever heat, that by commands, prayers, promises, and gifts, he tried to make her come to him, but she would not, in order to aggravate and increase his malady. He sent ambassadors of all sorts to his mistress, but it was no good—she would rather die than come.

Finally—to shorten the story—in order to make her come to him as she used formerly to do, he promised her in the presence of three or four witnesses, that he would take her to wife if her husband died.

As soon as she obtained this promise, she consented to visit him at various times when she could get away, and he continued to be as love-sick as ever. She, knowing her husband to be old, and having the aforesaid promise, already looked upon herself as the Councillor's wife.

But a short time afterwards, the much-desired death of the cobbler was known and published, and his fair widow at once went with a bound to the abode of the fur cap, who received her gladly, and again promised to make her his wife.

These two good people—the fur cap, and his mistress, the cobbler's widow—were now together; But it often happens that what can be got without trouble is not worth the trouble of getting, and so it was in this case, for our fur cap soon began to weary of the cobbler's widow, and his love for her grew cold. She often pressed him to perform the marriage he had promised, but he said;

"By my word, my dear, I can never marry, for I am a churchman, and hold such and such benefices, as you know. The promise I formerly made you is null and void, and was caused by the great love I bear you, to win you to me the more easily."

She, believing that he did belong to the Church, and seeing that she was as much mistress of his house as though she had been his wedded wife, went her accustomed way, and never troubled more about the marriage; but at last was persuaded by the fine words of our fur cap to leave him, and marry a barber, their neighbour, to whom the Councillor gave 300 gold crowns, and God knows that the woman also was well provided with clothes.

Now you must know that our fur cap had a definite object in arranging this marriage, which would never have come off if he had not told his mistress that in future he intended to serve God, and live on his benefices, and give up everything to the Church. But he did just the contrary, as soon as he had got rid of her by marrying her to the barber; for about a year later, he secretly treated for the hand of the daughter of a rich and notable citizen of Paris.

The marriage was agreed to and arranged, and a day fixed for the wedding. He also disposed of his benefices, which were only held by simple tonsure.

These things were known throughout Paris, and came to the knowledge of the cobbler's widow, now the barber's wife, and, as you may guess, she was much surprised.

"Oh, the traitor," she said; "has he deceived me like this? He deserted me under pretence of serving God, and made me over to another man. But, by Our Lady of Clery, the matter shall not rest here."

Nor did it, for she cited our fur cap before the Bishop, and there her advocate stated his case clearly and courteously, saying that the fur cap had promised the cobbler's wife, in the presence of several witnesses, that if her husband died he would make her his wife. When her husband died, the Councillor had kept her for about a year, and then handed her over to a barber.

To shorten the story, the witnesses having been heard, and the case debated, the Bishop annulled the marriage of the cobbler's widow to the barber, and enjoined and commanded the fur cap to take her as his wife, for so she was by right, since he had carnal connection with her after the aforesaid promise.

Thus was our fur cap brought to his senses. He missed marrying the citizen's fair daughter, and lost the 300 crowns, which the barber had for keeping his wife for a year. And if the Councillor was ill-pleased to have his old mistress again, the barber was glad enough to get rid of her.

In the manner that you have heard, was one of the fur caps of the Parliament of Paris once served.

Of a married man who found his wife with another man, and devised means to get from her her money, clothes, jewels, and all, down to her chemise, and then sent her away in that condition, as shall be afterwards recorded.

It is no new and strange thing for wives to make their husbands jealous,—or indeed, by God, cuckolds. And so it happened formerly, in the city of Antwerp, that a married woman, who was not the chastest person in the world, was desired by a good fellow to do—you know what. And she, being kind and courteous, did not like to refuse the request, but gladly consented, and they two continued this life for a long time.

In the end, Fortune, tired of always giving them good luck, willed that the husband should catch them in the act, much to his own surprise. Perhaps though it would be hard to say which was the most surprised—the lover, or his mistress, or the husband. Nevertheless, the lover, with the aid of a good sword he had, made his escape without getting any harm. There remained the husband and wife, and what they said to each other may be guessed. After a few words on both sides, the husband, thinking to himself that as she had commenced to sin it would be difficult to break her of her bad habits, and that if she did sin again it might come to the knowledge of other people, and he might be dishonoured; and considering also that to beat or scold her would be only lost labour, determined to see if he could not drive her out, and never let her disgrace his house again. So he said to his wife;

"Well, I see that you are not such as you ought to be; nevertheless, hoping that you will never again behave as you have behaved, let no more be said. But let us talk of another matter. I have some business on hand which concerns me greatly, and you also. We must put in it all our jewels; and if you have any little hoard of money stored away, bring it forth, for it is required."

"By my oath," said the wench, "I will do so willingly, if you will pardon me the wrong I have done you."

"Don't speak about it," he replied, "and no more will I."

She, believing that she had absolution and remission of her sins, to please her husband, and atone for the scandal she had caused, gave him all the money she had, her gold rings, rich stuffs, certain well-stuffed purses, a number of very fine kerchiefs, many whole furs of great value—in short, all that she had, and that her husband could ask, she gave to do him pleasure.

"The devil!" quoth he; "still I have not enough."

When he had everything, down to the gown and petticoat she wore, he said, "I must have that gown."

"Indeed!" said she. "I have nothing else to wear. Do you want me to go naked?"

"You must," he said, "give it me, and the petticoat also, and be quick about it, for either by good-will or force, I must have them."

She, knowing that force was not on her side, stripped off her gown and petticoat, and stood in her chemise.

"There!" she said; "Have I done what pleases you?"

"Not always," he replied. "If you obey me now, God knows you do so willingly—but let us leave that and talk of another matter. When I married you, you brought scarcely anything with you, and the little that you had you have dissipated or forfeited. There is no need for me to speak of your conduct—you know better than anyone what you are, and being what you are, I hereby renounce you, and say farewell to you for ever! There is the door! go your way; and if you are wise, you will never come into my presence again."

The poor wench, more astounded than ever, did not dare to stay after this terrible reproof, so she left, and went, I believe, to the house of her lover, for the first night, and sent many ambassadors to try and get back her apparel and belongings, but it was no avail. Her husband was headstrong and obstinate, and would never hear her spoken about, and still less take her back, although he was much pressed both by his own friends and those of his wife.

She was obliged to earn other clothes, and instead of her husband live with a friend until her husband's wrath is appeased, but, up to the present, he is still displeased with her, and will on no account see her.

Of a noble knight of Flanders, who was married to a beautiful and noble lady. He was for many years a prisoner in Turkey, during which time his good and loving wife was, by the importunities of her friends, induced to marry another knight. Soon after she had remarried, she heard that her husband had returned from Turkey, whereupon she allowed herself to die of grief, because she had contracted a fresh marriage.

It is not only known to all those of the city of Ghent—where the incident that I am about to relate happened not long ago—but to all those of Flanders, and many others, that at the battle fought between the King of Hungary and Duke Jehan (whom may God absolve) on one side, and the Grand Turk and all his Turks on the other, (*) that many noble knights and esquires—French, Flemish, German, and Picardians—were taken prisoners, of whom some were put to death in the presence of the said Great Turk, others were imprisoned for life, and others condemned to slavery, amongst which last was a noble knight of the said country of Flanders, named Clayz Utenhoven.

(*) The battle of Nicopolis (28th September, 1396) when

Sigismond, King of Hungary, and Jean-sans-Peur, son of the

Duke of Burgundy, who had recruited a large army for the

purpose of raising the siege of Constantinople, were met and

overthrown by the Sultan, Bajazet I.

For many years he endured this slavery, which was no light task but an intolerable martyrdom to him, considering the luxuries upon which he had been nourished, and the condition in which he had lived.

Now you must know that he had formerly married at Ghent a beautiful and virtuous lady, who loved him and held him dear with all her heart, and who daily prayed to God that shortly she might see him again if he were still alive; and that if he were dead, He would of His grace pardon his sins, and include him in the number of those glorious martyrs, who to repel the infidel, and that the holy Catholic faith might be exalted, had given up their mortal lives.

This good lady, who was rich, beautiful, virtuous, and possessed of many noble friends, was continually pressed and assailed by her friends to remarry; they declaring and affirming that her husband was dead, and that if he were alive he would have returned like the others; or if he were a prisoner, she would have received notice to prepare his ransom. But whatever reasons were adduced, this virtuous lady could not be persuaded to marry again, but excused herself as well as she was able.

These excuses served her little or nothing, for her relatives and friends so pressed her that she was obliged to obey. But God knows that it was with no small regret, and after she had been for nine years deprived of the presence of her good and loyal husband, whom she believed to be long since dead, as did most or all who knew him; but God, who guards and preserves his servants and champions, had otherwise ordered it, for he still lived and performed his arduous labours as a slave.

To return to our story. This virtuous lady was married to another knight, and lived with him for half a year, without hearing anything further about her first husband.

By the will of God, however, this good and true knight, Messire Clays, who was still in Turkey, when his wife married again, and there working as a slave, was, by means of some Christian gentlemen and merchants, delivered, and returned in their galley.

As he was on his return, he met and found in passing through various places, many of his acquaintance, who were overjoyed at his delivery, for in truth he was a most valiant man, of great renown and many virtues; and so the most joyful rumour of his much wished-for deliverance spread into France, Artois, and Picardy, where his virtues were not less known than they were in Flanders, of which country he was a native. And from these countries it soon reached Flanders, and came to the ears of his beauteous and virtuous lady and spouse, who was astounded thereat, and her feelings so overcame her as to deprive her of her senses.

"Ah," she said, as soon as she could speak, "my heart was never willing to do that which my relations and friends forced me to do. Alas! what will my most loving lord and husband say? I have not kept faith with him as I should, but—like a frail, frivolous, and weak-minded woman,—have given to another part and portion of that of which he alone should be lord and master! I cannot, and dare not await his coming. I am not worthy that he should look at me, or that I should be seen in his company," and with these words her most chaste, virtuous, and loving heart failed her, and she fell fainting.

She was carried and laid upon a bed, and her senses returned to her, but from that time it was not in the power of man or woman to make her eat or sleep, and thus she continued three days, weeping continually, and in the greatest grief of mind that ever woman was. During which time she confessed and did all that a good Christian should, and implored pardon of all, and most especially of her husband.

Soon afterwards she died, which was a great misfortune; and it need not be told what grief fell upon the said lord, her husband, when he heard the news. His sorrow was such that he was in great danger of dying as his most loving wife had done; but God, who had saved him from many other great perils, preserved him also from this.

Of a noble knight of Germany, a great traveller in his time; who after he had made a certain voyage, took a vow to never make the sign of the Cross, owing to the firm faith and belief that he had in the holy sacrament of baptism—in which faith he fought the devil, as you will hear.

A noble knight of Germany, a great traveller, distinguished in arms, courteous, and largely endowed with all good virtues, had just returned from a long journey, and was in his castle, when he was asked by one of his vassals living in the same town, to be godfather to his child, which had been born on the same day that the knight returned.

To which request the knight willingly acceded, and although he had during his life held many children at the font, he had never before listened to the holy words pronounced by the priest at this holy and excellent sacrament as he did this time, and they seemed to him—as indeed they are-full of high and divine mystery.

The baptism being finished, he being liberal and courteous and willing to oblige his vassals, remained to dine in the town, instead of returning to his castle, and with him dined the curé, his fellow sponsor, and other persons of renown.

The discourse turned on various matters, when the knight began to greatly praise the excellent sacrament of baptism, and said in a loud and clear voice that all might hear;

"If I knew for a truth that at my baptism had been pronounced the great and holy words which I heard to-day at the baptism of my latest god-son, I would not believe that the devil could have any power or authority over me, except to tempt me, and I would refrain from ever making the sign of the Cross, not that—let it be well understood—I do not well know that sign is sufficient to repel the devil, but because I believe that the words pronounced at the baptism of every Christian (if they are such as I have to-day heard) are capable of driving away all the devils of hell, however many they might be."

"Truly then, monseigneur," replied the curé, "I assure you in verbo sacerdotis that the same words which were said to-day at the baptism of your god-son were pronounced at your baptism. I know it well, for I myself baptised you, and I remember it as well as though it were yesterday. God be merciful to monseigneur your father—he asked me the day after your baptism, what I thought of his son; such and such were your sponsors, and such and such were present," and he related all particulars about the baptism, and showed that it was certain that in not a word did it differ from that of his god-son.

"Since it is thus," then said the noble knight, "I vow to God, my creator, that I have such firm faith in the holy sacrament of baptism that never again, for any danger, encounter, or assault that the devil may make against me, will I make the sign of the Cross, but solely by the memory of the sacrament of baptism I will drive him behind me; such a firm belief have I in this divine mystery, that it does not seem possible to me that the devil can hurt a man so shielded, for that rite needs no other aid if accompanied by true faith."

The dinner passed, and I know not how many years after, the good knight was in a large town in Germany, about some business which drew him thither, and was lodged in an inn. As he was one night along with his servants, after supper, talking and jesting with them, he wished to retire, but as his servants were enjoying themselves he would not disturb them, so he took a candle and went alone. As he entered the closet he saw before him a most horrible and terrible monster, having large and long horns, eyes brighter than the flames of a furnace, arms thick and long, sharp and cutting claws,—in fact a most extraordinary monster, and a devil, I should imagine.

And for such the good knight took it, and was at first greatly startled at such a meeting. Nevertheless, he boldly determined to defend himself if he were attacked, and he remembered the vow he had made concerning the holy and divine mystery of baptism. And in this faith he walked up to the monster, whom I have called a devil, and asked him who he was and what he wanted?

The devil, without a word, attacked him, and the good knight defended himself, though he had no other weapons than his hands (for he was in his doublet, being about to go to bed) and the protection of his firm faith in the holy mystery of baptism.

The struggle lasted long, and the good knight was so weary that it was strange he could longer endure such an assault. But he was so well-armed by his faith that the blows of his enemy had but little effect. At last, when the combat had lasted a full hour, the good knight took the devil by the horns, and tore one of them out, and beat him therewith soundly.

Then he went away victorious, leaving the devil writhing on the ground, and went back to his servants, who were still enjoying themselves, as they had been doing when he left. They were much frightened to see their master sweating and out of breath, and with his face all scratched, and his doublet, shirt, and hose disarranged and torn.

"Ah, sir," they cried; "whence come you, and who has thus mauled you?"

"Who?" he replied. "Why it was the devil, with whom I have fought so long that I am out of breath, and in the condition in which you see me; and I swear to you that I truly believe he would have strangled and devoured me, if I had not at that moment remembered my baptism, and the great mystery of that holy sacrament, and the vow that I made I know not how many years ago. And, believe me, I have kept that vow, and though I was in danger, I never made the sign of the Cross, but remembering the aforesaid holy sacrament, boldly defended myself, and have escaped scot free; for which I praise and thank our Lord who with the shield of faith hath preserved me safely. Let all the other devils in hell come; as long as this protection endures, I fear them not. Praise be to our blessed God who is able to endue his knights with such weapons."

The servants of the good knight, when they heard their master relate this story, were very glad to find he had escaped so well, and much astonished at the horn he showed them, and which he had torn out of the devil's head. And they could not discover, neither could any person who afterwards saw it, of what it was formed; if it were bone or horn, as other horns are, or, what it was.

Then one of the knight's servants said that he would go and see if this devil were still where his master had left it, and if he found it he would fight it, and tear out its other horn. His master told him not to go, but he said he would.

"Do not do it," said his master; "the danger is too great."

"I care not," replied the other; "I will go."

"If you take my advice," said his master, "you will not go."

But he would disobey his master and go. He took in one hand a torch, and in the other a great axe, and went to the place where his master had met and fought the devil. What happened no one knows, but his master, who, fearing for his servant, followed him as quickly as he could, found neither man nor devil, nor ever heard what became of the man.

Thus, in the manner that you have heard, did this good knight fight against the devil, and overcome him by the virtue of the holy sacrament of baptism.

Of a knight of Picardy, who lodged at an inn in the town of St. Omer, and fell in love with the hostess, with whom he was amusing himself—you know how—when her husband discovered them; and how he behaved—as you will shortly hear.

At Saint Omer, not long ago, there happened an amusing incident, which is as true as the Gospel, and is known to many notable people worthy of faith and belief. In short, the story is as follows.

A noble knight of Picardy, who was lively and lusty, and a man of great authority and high position, came to an inn where the quartermaster of Duke Philip of Burgundy had appointed him to lodge. (*)

(*) The fourrier—which, for want of a better word, I have

translated as "quartermaster,"—was an officer of the

household of a prince or great lord. One of his duties was

to provide lodgings for all the retinue whenever his master

was travelling.

As soon as he had jumped off his horse, and put foot to the ground, his hostess—as is the custom in that part of the country—came forward smiling most affably, and received him most honourably, and, as he was the most kind and courteous of men, he embraced her and kissed her gently, for she was pretty and nice, healthy-looking and nattily dressed—in fact very tempting to kiss and cuddle—and at first sight each took a strong liking to the other.

The knight wondered by what means he could manage to enjoy the person of his hostess, and confided in one of his servants, who in a very short time so managed the affair that the two were brought together.

When the noble knight saw his hostess ready to listen to whatever he had to say, you may fancy that he was joyful beyond measure; and in his great haste and ardent desire to discuss the question he wanted to argue with her, forgot to shut the door of the room, which his servant, when he departed after bringing the woman in, had left half open.

The knight, without troubling about preludes, began an oration in dumb-show; and the hostess, who was not sorry to hear him, replied to his arguments in such a manner that they soon agreed well together, and never was music sweeter, or instruments in better tune, than it was for those two, by God's mercy.