Transcriber’s Note:

This etext was produced from Astounding Science Fiction, August, 1950.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the copyright on this

publication was renewed.

Along the U-shaped table, the subdued clatter of dinnerware and the buzz of conversation was dying out; the soft music that drifted down from the overhead sound outlets seemed louder as the competing noises diminished. The feast was drawing to a close, and Dallona of Hadron fidgeted nervously with the stem of her wineglass as last-moment doubts assailed her.

The old man at whose right she sat noticed, and reached out to lay his hand on hers.

“My dear, you’re worried,” he said softly. “You, of all people, shouldn’t be, you know.”

“The theory isn’t complete,” she replied. “And I could wish for more positive verification. I’d hate to think I’d got you into this—”

Garnon of Roxor laughed. “No, no!” he assured her. “I’d decided upon this long before you announced the results of your experiments. Ask Girzon; he’ll bear me out.”

“That’s true,” the young man who sat at Garnon’s left said, leaning forward. “Father has meant to take this step for a long time. He was waiting until after the election, and then he decided to do it now, to give you an opportunity to make experimental use of it.”

The man on Dallona’s right added his voice. Like the others at the table, he was of medium stature, brown-skinned and dark-eyed, with a wide mouth, prominent cheekbones and a short, square jaw. Unlike the others, he was armed, with a knife and pistol on his belt, and on the breast of his black tunic he wore a scarlet oval patch on which a pair of black wings, with a tapering silver object between them had been superimposed.

“Yes, Lady Dallona; the Lord Garnon and I discussed this, oh, two years ago at the least. Really, I’m surprised that you seem to shrink from it, now. Of course, you’re Venus-born, and customs there may be different, but with your scientific knowledge—”

“That may be the trouble, Dirzed,” Dallona told him. “A scientist gets in the way of doubting, and one doubts one’s own theories most of all.”

“That’s the scientific attitude, I’m told,” Dirzed replied, smiling. “But somehow, I cannot think of you as a scientist.” His eyes traveled over her in a way that would have made most women, scientists or otherwise, blush. It gave Dallona of Hadron a feeling of pleasure. Men often looked at her that way, especially here at Darsh. Novelty had something to do with it—her skin was considerably lighter than usual, and there was a pleasing oddness about the structure of her face. Her alleged Venusian origin was probably accepted as the explanation of that, as of so many other things.

As she was about to reply, a man in dark gray, one of the upper-servants who were accepted as social equals by the Akor-Neb nobles, approached the table. He nodded respectfully to Garnon of Roxor.

“I hate to seem to hurry things, sir, but the boy’s ready. He’s in a trance-state now,” he reported, pointing to the pair of visiplates at the end of the room.

Both of the ten-foot-square plates were activated. One was a solid luminous white; on the other was the image of a boy of twelve or fourteen, seated at a big writing machine. Even allowing for the fact that the boy was in a hypnotic trance, there was an expression of idiocy on his loose-lipped, slack-jawed face, a pervading dullness.

“One of our best sensitives,” a man with a beard, several places down the table on Dallona’s right, said. “You remember him, Dallona; he produced that communication from the discarnate Assassin, Sirzim. Normally, he’s a low-grade imbecile, but in trance-state he’s wonderful. And there can be no argument that the communications he produces originates in his own mind; he doesn’t have mind enough, of his own, to operate that machine.”

Garnon of Roxor rose to his feet, the others rising with him. He unfastened a jewel from the front of his tunic and handed it to Dallona.

“Here, my dear Lady Dallona; I want you to have this,” he said. “It’s been in the family of Roxor for six generations, but I know that you will appreciate and cherish it.” He twisted a heavy ring from his left hand and gave it to his son. He unstrapped his wrist watch and passed it across the table to the gray-clad upper-servant. He gave a pocket case, containing writing tools, slide rule and magnifier, to the bearded man on the other side of Dallona. “Something you can use, Dr. Harnosh,” he said. Then he took a belt, with a knife and holstered pistol, from a servant who had brought it to him, and gave it to the man with the red badge. “And something for you, Dirzed. The pistol’s by Farnor of Yand, and the knife was forged and tempered on Luna.”

The man with the winged-bullet badge took the weapons, exclaiming in appreciation. Then he removed his own belt and buckled on the gift.

“The pistol’s fully loaded,” Garnon told him.

Dirzed drew it and checked—a man of his craft took no statement about weapons without verification—then slipped it back into the holster.

“Shall I use it?” he asked.

“By all means; I’d had that in mind when I selected it for you.”

Another man, to the left of Girzon, received a cigarette case and lighter. He and Garnon hooked fingers and clapped shoulders.

“Our views haven’t been the same, Garnon,” he said, “but I’ve always valued your friendship. I’m sorry you’re doing this, now; I believe you’ll be disappointed.”

Garnon chuckled. “Would you care to make a small wager on that, Nirzav?” he asked. “You know what I’m putting up. If I’m proven right, will you accept the Volitionalist theory as verified?”

Nirzav chewed his mustache for a moment. “Yes, Garnon, I will.” He pointed toward the blankly white screen. “If we get anything conclusive on that, I’ll have no other choice.”

“All right, friends,” Garnon said to those around him. “Will you walk with me to the end of the room?”

Servants removed a section from the table in front of him, to allow him and a few others to pass through; the rest of the guests remained standing at the table, facing toward the inside of the room. Garnon’s son, Girzon, and the gray-mustached Nirzav of Shonna, walked on his left; Dallona of Hadron and Dr. Harnosh of Hosh on his right. The gray-clad upper-servant, and two or three ladies, and a nobleman with a small chin beard, and several others, joined them; of those who had sat close to Garnon, only the man in the black tunic with the scarlet badge hung back. He stood still, by the break in the table, watching Garnon of Roxor walk away from him. Then Dirzed the Assassin drew the pistol he had lately received as a gift, hefted it in his hand, thumbed off the safety, and aimed at the back of Garnon’s head.

They had nearly reached the end of the room when the pistol cracked. Dallona of Hadron started, almost as though the bullet had crashed into her own body, then caught herself and kept on walking. She closed her eyes and laid a hand on Dr. Harnosh’s arm for guidance, concentrating her mind upon a single question. The others went on as though Garnon of Roxor were still walking among them.

“Look!” Harnosh of Hosh cried, pointing to the image in the visiplate ahead. “He’s under control!”

They all stopped short, and Dirzed, holstering his pistol, hurried forward to join them. Behind, a couple of servants had approached with a stretcher and were gathering up the crumpled figure that had, a moment ago, been Garnon.

A change had come over the boy at the writing machine. His eyes were still glazed with the stupor of the hypnotic trance, but the slack jaw had stiffened, and the loose mouth was compressed in a purposeful line. As they watched, his hands went out to the keyboard in front of him and began to move over it, and as they did, letters appeared on the white screen on the left.

Garnon of Roxor, discarnate, communicating, they read. The machine stopped for a moment, then began again. To Dallona of Hadron: The question you asked, after I discarnated, was: What was the last book I read, before the feast? While waiting for my valet to prepare my bath, I read the first ten verses of the fourth Canto of “Splendor of Space,” by Larnov of Horka, in my bedroom. When the bath was ready, I marked the page with a strip of message tape, containing a message from the bailiff of my estate on the Shevva River, concerning a breakdown at the power plant, and laid the book on the ivory-inlaid table beside the big red chair.

Harnosh of Hosh looked at Dallona inquiringly; she nodded.

“I rejected the question I had in my mind, and substituted that one, after the shot,” she said.

He turned quickly to the upper-servant. “Check on that, right away, Kirzon,” he directed.

As the upper-servant hurried out, the writing machine started again.

And to my son, Girzon: I will not use your son, Garnon, as a reincarnation-vehicle; I will remain discarnate until he is grown and has a son of his own; if he has no male child, I will reincarnate in the first available male child of the family of Roxor, or of some family allied to us by marriage. In any case, I will communicate before reincarnating.

To Nirzav of Shonna: Ten days ago, when I dined at your home, I took a small knife and cut three notches, two close together and one a little apart from the others, on the under side of the table. As I remember, I sat two places down on the left. If you find them, you will know that I have won that wager that I spoke of a few minutes ago.

“I’ll have my butler check on that, right away,” Nirzav said. His eyes were wide with amazement, and he had begun to sweat; a man does not casually watch the beliefs of a lifetime invalidated in a few moments.

To Dirzed the Assassin: the machine continued. You have served me faithfully, in the last ten years, never more so than with the last shot you fired in my service. After you fired, the thought was in your mind that you would like to take service with the Lady Dallona of Hadron, whom you believe will need the protection of a member of the Society of Assassins. I advise you to do so, and I advise her to accept your offer. Her work, since she has come to Darsh, has not made her popular in some quarters. No doubt Nirzav of Shonna can bear me out on that.

“I won’t betray things told me in confidence, or said at the Councils of the Statisticalists, but he’s right,” Nirzav said. “You need a good Assassin, and there are few better than Dirzed.”

I see that this sensitive is growing weary, the letters on the screen spelled out. His body is not strong enough for prolonged communication. I bid you all farewell, for the time; I will communicate again. Good evening, my friends, and I thank you for your presence at the feast.

The boy, on the other screen, slumped back in his chair, his face relaxing into its customary expression of vacancy.

“Will you accept my offer of service, Lady Dallona?” Dirzed asked. “It’s as Garnon said; you’ve made enemies.”

Dallona smiled at him. “I’ve not been too deep in my work to know that. I’m glad to accept your offer, Dirzed.”

Nirzav of Shonna had already turned away from the group and was hurrying from the room, to call his home for confirmation on the notches made on the underside of his dining table. As he went out the door, he almost collided with the upper-servant, who was rushing in with a book in his hand.

“Here it is,” the latter exclaimed, holding up the book. “Larnov’s ‘Splendor of Space,’ just where he said it would be. I had a couple of servants with me as witnesses; I can call them in now, if you wish.” He handed the book to Harnosh of Hosh. “See, a strip of message tape in it, at the tenth verse of the Fourth Canto.”

Nirzav of Shonna re-entered the room; he was chewing his mustache and muttering to himself. As he rejoined the group in front of the now dark visiplates, he raised his voice, addressing them all generally.

“My butler found the notches, just as the communication described,” he said. “This settles it! Garnon, if you’re where you can hear me, you’ve won. I can’t believe in the Statisticalist doctrines after this, or in the political program based upon them. I’ll announce my change of attitude at the next meeting of the Executive Council, and resign my seat. I was elected by Statisticalist votes, and I cannot hold office as a Volitionalist.”

“You’ll need a couple of Assassins, too,” the nobleman with the chin beard told him. “Your former colleagues and fellow-party-members are regrettably given to the forcible discarnation of those who differ with them.”

“I’ve never employed personal Assassins before,” Nirzav replied, “but I think you’re right. As soon as I get home, I’ll call Assassins’ Hall and make the necessary arrangements.”

“Better do it now,” Girzon of Roxor told him, lowering his voice. “There are over a hundred guests here, and I can’t vouch for all of them. The Statisticalists would be sure to have a spy planted among them. My father was one of their most dangerous opponents, when he was on the Council; they’ve always been afraid he’d come out of retirement and stand for re-election. They’d want to make sure he was really discarnate. And if that’s the case, you can be sure your change of attitude is known to old Mirzark of Bashad by this time. He won’t dare allow you to make a public renunciation of Statisticalism.” He turned to the other nobleman. “Prince Jirzyn, why don’t you call the Volitionist headquarters and have a couple of our Assassins sent here to escort Lord Nirzav home?”

“I’ll do that immediately,” Jirzyn of Starpha said. “It’s as Lord Girzon says; we can be pretty sure there was a spy among the guests, and now that you’ve come over to our way of thinking, we’re responsible for your safety.”

He left the room to make the necessary visiphone call. Dallona, accompanied by Dirzed, returned to her place at the table, where she was joined by Harnosh of Hosh and some of the others.

“There’s no question about the results,” Harnosh was exulting. “I’ll grant that the boy might have picked up some of that stuff telepathically from the carnate minds present here; even from the mind of Garnon, before he was discarnated. But he could not have picked up enough data, in that way, to make a connected and coherent communication. It takes a sensitive with a powerful mind of his own to practice telesthesia, and that boy’s almost an idiot.” He turned to Dallona. “You asked a question, mentally, after Garnon was discarnate, and got an answer that could have been contained only in Garnon’s mind. I think it’s conclusive proof that the discarnate Garnon was fully conscious and communicating.”

“Dirzed also asked a question, mentally, after the discarnation, and got an answer. Dr. Harnosh, we can state positively that the surviving individuality is fully conscious in the discarnate state, is telepathically sensitive, and is capable of telepathic communication with other minds,” Dallona agreed. “And in view of our earlier work with memory-recalls, we’re justified in stating positively that the individual is capable of exercising choice in reincarnation vehicles.”

“My father had been considering voluntary discarnation for a long time,” Girzon of Roxor said. “Ever since the discarnation of my mother. He deferred that step because he was unwilling to deprive the Volitionalist Party of his support. Now it would seem that he has done more to combat Statisticalism by discarnating than he ever did in his carnate existence.”

“I don’t know, Girzon,” Jirzyn of Starpha said, as he joined the group. “The Statisticalists will denounce the whole thing as a prearranged fraud. And if they can discarnate the Lady Dallona before she can record her testimony under truth hypnosis or on a lie detector, we’re no better off than we were before. Dirzed, you have a great responsibility in guarding the Lady Dallona; some extraordinary security precautions will be needed.”

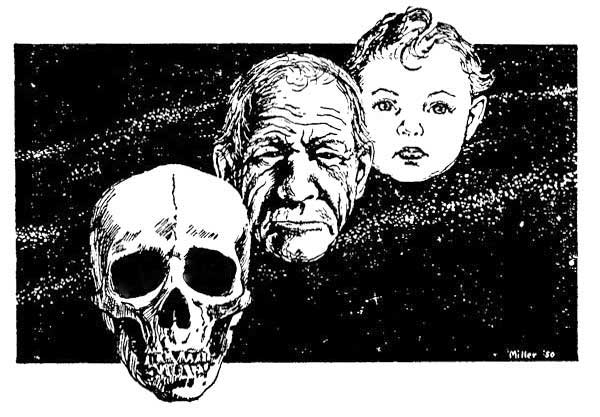

In his office, in the First Level city of Dhergabar, Tortha Karf, Chief of Paratime Police, leaned forward in his chair to hold his lighter for his special assistant, Verkan Vall, then lit his own cigarette. He was a man of middle age—his three hundredth birthday was only a decade or so off—and he had begun to acquire a double chin and a bulge at his waistline. His hair, once black, had turned a uniform iron-gray and was beginning to thin in front.

“What do you know about the Second Level Akor-Neb Sector, Vall?” he inquired. “Ever work in that paratime-area?”

Verkan Vall’s handsome features became even more immobile than usual as he mentally pronounced the verbal trigger symbols which should bring hypnotically acquired knowledge into his conscious mind. Then he shook his head.

“Must be a singularly well-behaved sector, sir,” he said. “Or else we’ve been lucky, so far. I never was on an Akor-Neb operation; don’t even have a hypno-mech for that sector. All I know is from general reading.

“Like all the Second Level, its time-lines descend from the probability of one or more shiploads of colonists having come to Terra from Mars about seventy-five to a hundred thousand years ago, and then having been cut off from the home planet and forced to develop a civilization of their own here. The Akor-Neb civilization is of a fairly high culture-order, even for Second Level. An atomic-power, interplanetary culture; gravity-counteraction, direct conversion of nuclear energy to electrical power, that sort of thing. We buy fine synthetic plastics and fabrics from them.” He fingered the material of his smartly-cut green police uniform. “I think this cloth is Akor-Neb. We sell a lot of Venusian zerfa-leaf; they smoke it, straight and mixed with tobacco. They have a single System-wide government, a single race, and a universal language. They’re a dark-brown race, which evolved in its present form about fifty thousand years ago; the present civilization is about ten thousand years old, developed out of the wreckage of several earlier civilizations which decayed or fell through wars, exhaustion of resources, et cetera. They have legends, maybe historical records, of their extraterrestrial origin.”

Tortha Karf nodded. “Pretty good, for consciously acquired knowledge,” he commented. “Well, our luck’s run out, on that sector; we have troubles there, now. I want you to go iron them out. I know, you’ve been going pretty hard, lately—that night-hound business, on the Fourth Level Europo-American Sector, wasn’t any picnic. But the fact is that a lot of my ordinary and deputy assistants have a little too much regard for the alleged sanctity of human life, and this is something that may need some pretty drastic action.”

“Some of our people getting out of line?” Verkan Vall asked.

“Well, the data isn’t too complete, but one of our people has run into trouble on that sector, and needs rescuing—a psychic-science researcher, a young lady named Hadron Dalla. I believe you know her, don’t you?” Tortha Karf asked innocently.

“Slightly,” Verkan Vall deadpanned. “I enjoyed a brief but rather hectic companionate-marriage with her, about twenty years ago. What sort of a jam’s little Dalla got herself into, now?”

“Well, frankly, we don’t know. I hope she’s still alive, but I’m not unduly optimistic. It seems that about a year ago, Dr. Hadron transposed to the Second Level, to study alleged proof of reincarnation which the Akor-Neb people were reported to possess. She went to Gindrabar, on Venus, and transposed to the Second Paratime Level, to a station maintained by Outtime Import & Export Trading Corporation—a zerfa plantation just east of the High Ridge country. There she assumed an identity as the daughter of a planter, and took the name of Dallona of Hadron. Parenthetically, all Akor-Neb family-names are prepositional; family-names were originally place names. I believe that ancient Akor-Neb marital relations were too complicated to permit exact establishment of paternity. And all Akor-Neb men’s personal names have -irz- or -arn- inserted in the middle, and women’s names end in -itra- or -ona. You could call yourself Virzal of Verkan, for instance.

“Anyhow, she made the Second Level Venus-Terra trip on a regular passenger liner, and landed at the Akor-Neb city of Ghamma, on the upper Nile. There she established contact with the Outtime Trading Corporation representative, Zortan Brend, locally known as Brarnend of Zorda. He couldn’t call himself Brarnend of Zortan—in the Akor-Neb language, zortan is a particularly nasty dirty-word. Hadron Dalla spent a few weeks at his residence, briefing herself on local conditions. Then she went to the capital city, Darsh, in eastern Europe, and enrolled as a student at something called the Independent Institute for Reincarnation Research, having secured a letter of introduction to its director, a Dr. Harnosh of Hosh.

“Almost at once, she began sending in reports to her home organization, the Rhogom Memorial Foundation of Psychic Science, here at Dhergabar, through Zortan Brend. The people there were wildly enthusiastic. I don’t have more than the average intelligent—I hope—layman’s knowledge of psychics, but Dr. Volzar Darv, the director of Rhogom Foundation, tells me that even in the present incomplete form, her reports have opened whole new horizons in the science. It seems that these Akor-Neb people have actually demonstrated, as a scientific fact, that the human individuality reincarnates after physical death—that your personality, and mine, have existed, as such, for ages, and will exist for ages to come. More, they have means of recovering, from almost anybody, memories of past reincarnations.

“Well, after about a month, the people at this Reincarnation Institute realized that this Dallona of Hadron wasn’t any ordinary student. She probably had trouble keeping down to the local level of psychic knowledge. So, as soon as she’d learned their techniques, she was allowed to undertake experimental work of her own. I imagine she let herself out on that; as soon as she’d mastered the standard Akor-Neb methods of recovering memories of past reincarnations, she began refining and developing them more than the local yokels had been able to do in the past thousand years. I can’t tell you just what she did, because I don’t know the subject, but she must have lit things up properly. She got quite a lot of local publicity; not only scientific journals, but general newscasts.

“Then, four days ago, she disappeared, and her disappearance seems to have been coincident with an unsuccessful attempt on her life. We don’t know as much about this as we should; all we have is Zortan Brend’s account.

“It seems that on the evening of her disappearance, she had been attending the voluntary discarnation feast—suicide party—of a prominent nobleman named Garnon of Roxor. Evidently when the Akor-Neb people get tired of their current reincarnation they invite in their friends, throw a big party, and then do themselves in in an atmosphere of general conviviality. Frequently they take poison or inhale lethal gas; this fellow had his personal trigger man shoot him through the head. Dalla was one of the guests of honor, along with this Harnosh of Hosh. They’d made rather elaborate preparations, and after the shooting they got a detailed and apparently authentic spirit-communication from the late Garnon. The voluntary discarnation was just a routine social event, it seems, but the communication caused quite an uproar, and rated top place on the System-wide newscasts, and started a storm of controversy.

“After the shooting and the communication, Dalla took the officiating gun artist, one Dirzed, into her own service. This Dirzed was spoken of as a generally respected member of something called the Society of Assassins, and that’ll give you an idea of what things are like on that sector, and why I don’t want to send anybody who might develop trigger-finger cramp at the wrong moment. She and Dirzed left the home of the gentleman who had just had himself discarnated, presumably for Dalla’s apartment, about a hundred miles away. That’s the last that’s been heard of either of them.

“This attempt on Dalla’s life occurred while the pre-mortem revels were still going on. She lived in a six-room apartment, with three servants, on one of the upper floors of a three-thousand-foot tower—Akor-Neb cities are built vertically, with considerable interval between units—and while she was at this feast, a package was delivered at the apartment, ostensibly from the Reincarnation Institute and made up to look as though it contained record tapes. One of the servants accepted it from a service employee of the apartments. The next morning, a little before noon, Dr. Harnosh of Hosh called her on the visiphone and got no answer; he then called the apartment manager, who entered the apartment. He found all three of the servants dead, from a lethal-gas bomb which had exploded when one of them had opened this package. However, Hadron Dalla had never returned to the apartment, the night before.”

Verkan Vall was sitting motionless, his face expressionless as he ran Tortha Karf’s narrative through the intricate semantic and psychological processes of the First Level mentality. The fact that Hadron Dalla had been a former wife of his had been relegated to one corner of his consciousness and contained there; it was not a fact that would, at the moment, contribute to the problem or to his treatment of it.

“The package was delivered while she was at this suicide party,” he considered. “It must, therefore, have been sent by somebody who either did not know she would be out of the apartment, or who did not expect it to function until after her return. On the other hand, if her disappearance was due to hostile action, it was the work of somebody who knew she was at the feast and did not want her to reach her apartment again. This would seem to exclude the sender of the package bomb.”

Tortha Karf nodded. He had reached that conclusion, himself.

“Thus,” Verkan Vall continued, “if her disappearance was the work of an enemy, she must have two enemies, each working in ignorance of the other’s plans.”

“What do you think she did to provoke such enmity?”

“Well, of course, it just might be that Dalla’s normally complicated love-life had got a little more complicated than usual and short-circuited on her,” Verkan Vall said, out of the fullness of personal knowledge, “but I doubt that, at the moment. I would think that this affair has political implications.”

“So?” Tortha Karf had not thought of politics as an explanation. He waited for Verkan Vall to elaborate.

“Don’t you see, chief?” the special assistant asked. “We find a belief in reincarnation on many time-lines, as a religious doctrine, but these people accept it as a scientific fact. Such acceptance would carry much more conviction; it would influence a people’s entire thinking. We see it reflected in their disregard for death—suicide as a social function, this Society of Assassins, and the like. It would naturally color their political thinking, because politics is nothing but common action to secure more favorable living conditions, and to these people, the term ‘living conditions’ includes not only the present life, but also an indefinite number of future lives as well. I find this title, ‘Independent’ Institute, suggestive. Independent of what? Possibly of partisan affiliation.”

“But wouldn’t these people be grateful to her for her new discoveries, which would enable them to plan their future reincarnations more intelligently?” Tortha Karf asked.

“Oh, chief!” Verkan Vall reproached. “You know better than that! How many times have our people got in trouble on other time-lines because they divulged some useful scientific fact that conflicted with the locally revered nonsense? You show me ten men who cherish some religious doctrine or political ideology, and I’ll show you nine men whose minds are utterly impervious to any factual evidence which contradicts their beliefs, and who regard the producer of such evidence as a criminal who ought to be suppressed. For instance, on the Fourth Level Europo-American Sector, where I was just working, there is a political sect, the Communists, who, in the territory under their control, forbid the teaching of certain well-established facts of genetics and heredity, because those facts do not fit the world-picture demanded by their political doctrines. And on the same sector, a religious sect recently tried, in some sections successfully, to outlaw the teaching of evolution by natural selection.”

Tortha Karf nodded. “I remember some stories my grandfather told me, about his narrow escapes from an organization called the Holy Inquisition, when he was a paratime trader on the Fourth Level, about four hundred years ago. I believe that thing’s still operating, on the Europo-American Sector, under the name of the NKVD. So you think Dalla may have proven something that conflicted with local reincarnation theories, and somebody who had a vested interest in maintaining those theories is trying to stop her?”

“You spoke of a controversy over the communication alleged to have originated with this voluntarily discarnated nobleman. That would suggest a difference of opinion on the manner of nature of reincarnation or the discarnate state. This difference may mark the dividing line between the different political parties. Now, to get to this Darsh place, do I have to go to Venus, as Dalla did?”

“No. The Outtime Trading Corporation has transposition facilities at Ravvanan, on the Nile, which is spatially co-existent with the city of Ghamma on the Akor-Neb Sector, where Zortan Brend is. You transpose through there, and Zortan Brend will furnish you transportation to Darsh. It’ll take you about two days, here, getting your hypno-mech indoctrinations and having your skin pigmented, and your hair turned black. I’ll notify Zortan Brend at once that you’re coming through. Is there anything special you’ll want?”

“Why, I’ll want an abstract of the reports Dalla sent back to Rhogom Foundation. It’s likely that there is some clue among them as to whom her discoveries may have antagonized. I’m going to be a Venusian zerfa-planter, a friend of her father’s; I’ll want full hypno-mech indoctrination to enable me to play that part. And I’ll want to familiarize myself with Akor-Neb weapons and combat techniques. I think that will be all, chief.”

The last of the tall city units of Ghamma were sliding out of sight as the ship passed over them—shaft-like buildings that rose two or three thousand feet above the ground in clumps of three or four or six, one at each corner of the landing stages set in series between them. Each of these units stood in the middle of a wooded park some five miles square; no unit was much more or less than twenty miles from its nearest neighbor, and the land between was the uniform golden-brown of ripening grain, crisscrossed with the threads of irrigation canals and dotted here and there with sturdy farm-village buildings and tall, stack-like granaries. There were a few other ships in the air at the fifty-thousand-foot level, and below, swarms of small airboats darted back and forth on different levels, depending upon speed and direction. Far ahead, to the northeast, was the shimmer of the Red Sea and the hazy bulk of Asia Minor beyond.

Verkan Vall—the Lord Virzal of Verkan, temporarily—stood at the glass front of the observation deck, looking down. He was a different Verkan Vall from the man who had talked with Tortha Karf in the latter’s office, two days before. The First Level cosmeticists had worked miracles upon him with their art. His skin was a soft chocolate-brown, now; his hair was jet-black, and so were his eyes. And in his subconscious mind, instantly available to consciousness, was a vast body of knowledge about conditions on the Akor-Neb sector, as well as a complete command of the local language, all hypnotically acquired.

He knew that he was looking down upon one of the minor provincial cities of a very respectably advanced civilization. A civilization which built its cities vertically, since it had learned to counteract gravitation. A civilization which still depended upon natural cereals for food, but one which had learned to make the most efficient use of its soil. The network of dams and irrigation canals which he saw was as good as anything on his own paratime level. The wide dispersal of buildings, he knew, was a heritage of a series of disastrous atomic wars of several thousand years before; the Akor-Neb people had come to love the wide inter-vistas of open country and forest, and had continued to scatter their buildings, even after the necessity had passed. But the slim, towering buildings could only have been reared by a people who had banished nationalism and, with it, the threat of total war. He contrasted them with the ground-hugging dome cities of the Khiftan civilization, only a few thousand para-years distant.

Three men came out of the lounge behind him and joined him. One was, like himself, a disguised paratimer from the First Level—the Outtime Export and Import man, Zortan Brend, here known as Brarnend of Zorda. The other two were Akor-Neb people, and both wore the black tunics and the winged-bullet badges of the Society of Assassins. Unlike Verkan Vall and Zortan Brend, who wore shoulder holsters under their short tunics, the Assassins openly displayed pistols and knives on their belts.

“We heard that you were coming two days ago, Lord Virzal,” Zortan Brend said. “We delayed the take-off of this ship, so that you could travel to Darsh as inconspicuously as possible. I also booked a suite for you at the Solar Hotel, at Darsh. And these are your Assassins—Olirzon, and Marnik.”

Verkan Vall hooked fingers and clapped shoulders with them.

“Virzal of Verkan,” he identified himself. “I am satisfied to intrust myself to you.”

“We’ll do our best for you, Lord Virzal,” the older of the pair, Olirzon, said. He hesitated for a moment, then continued: “Understand, Lord Virzal, I only ask for information useful in serving and protecting you. But is this of the Lady Dallona a political matter?”

“Not from our side,” Verkan Vall told him. “The Lady Dallona is a scientist, entirely nonpolitical. The Honorable Brarnend is a business man; he doesn’t meddle with politics as long as the politicians leave him alone. And I’m a planter on Venus; I have enough troubles, with the natives, and the weather, and blue-rot in the zerfa plants, and poison roaches, and javelin bugs, without getting into politics. But psychic science is inextricably mixed with politics, and the Lady Dallona’s work had evidently tended to discredit the theory of Statistical Reincarnation.”

“Do you often make understatements like that, Lord Virzal?” Olirzon grinned. “In the last six months, she’s knocked Statistical Reincarnation to splinters.”

“Well, I’m not a psychic scientist, and as I said, I don’t know much about Terran politics,” Verkan Vall replied. “I know that the Statisticalists favor complete socialization and political control of the whole economy, because they want everybody to have the same opportunities in every reincarnation. And the Volitionalists believe that everybody reincarnates as he pleases, and so they favor continuance of the present system of private ownership of wealth and private profit under a system of free competition. And that’s about all I do know. Naturally, as a land-owner and the holder of a title of nobility, I’m a Volitionalist in politics, but the socialization issue isn’t important on Venus. There is still too much unseated land there, and too many personal opportunities, to make socialism attractive to anybody.”

“Well, that’s about it,” Zortan Brend told him. “I’m not enough of a psychicist to know what the Lady Dallona’s been doing, but she’s knocked the theoretical basis from under Statistical Reincarnation, and that’s the basis, in turn, of Statistical Socialism. I think we’ll find that the Statisticalist Party is responsible for whatever happened to her.”

Marnik, the younger of the two Assassins, hesitated for a moment, then addressed Verkan Vall:

“Lord Virzal, I know none of the personalities involved in this matter, and I speak without wishing to give offense, but is it not possible that the Lady Dallona and the Assassin Dirzed may have gone somewhere together voluntarily? I have met Dirzed, and he has many qualities which women find attractive, and he is by no means indifferent to the opposite sex. You understand, Lord Virzal—”

“I understand all too perfectly, Marnik,” Verkan Vall replied, out of the fullness of experience. “The Lady Dallona has had affairs with a number of men, myself among them. But under the circumstances, I find that explanation unthinkable.”

Marnik looked at him in open skepticism. Evidently, in his book, where an attractive man and a beautiful woman were concerned, that explanation was never unthinkable.

“The Lady Dallona is a scientist,” Verkan Vall elaborated. “She is not above diverting herself with love affairs, but that’s all they are—a not too important form of diversion. And, if you recall, she had just participated in a most significant experiment: you can be sure that she had other things on her mind at the time than pleasure jaunts with good-looking Assassins.”

The ship was passing around the Caucasus Mountains, with the Caspian Sea in sight ahead, when several of the crew appeared on the observation deck and began preparing the shielding to protect the deck from gunfire. Zortan Brend inquired of the petty officer in charge of the work as to the necessity.

“We’ve been getting reports of trouble at Darsh, sir,” the man said. “Newscast bulletins every couple of minutes: rioting in different parts of the city. Started yesterday afternoon, when a couple of Statisticalist members of the Executive Council resigned and went over to the Volitionalists. Lord Nirzav of Shonna, the only nobleman of any importance in the Statisticalist Party, was one of them; he was shot immediately afterward, while leaving the Council Chambers, along with a couple of Assassins who were with him. Some people in an airboat sprayed them with a machine rifle as they came out onto the landing stage.”

The two Assassins exclaimed in horrified anger over this.

“That wasn’t the work of members of the Society of Assassins!” Olirzon declared. “Even after he’d resigned, the Lord Nirzav was still immune till he left the Government Building. There’s too blasted much illegal assassination going on!”

“What happened next?” Verkan Vall wanted to know.

“About what you’d expect, sir. The Volitionalists weren’t going to take that quietly. In the past eighteen hours, four prominent Statisticalists were forcibly discarnated, and there was even a fight in Mirzark of Bashad’s house, when Volitionalist Assassins broke in; three of them and four of Mirzark’s Assassins were discarnated.”

“You know, something is going to have to be done about that, too,” Olirzon said to Marnik. “It’s getting to a point where these political faction fights are being carried on entirely between members of the Society. In Ghamma alone, last year, thirty or forty of our members were discarnated that way.”

“Plug in a newscast visiplate, Karnil,” Zortan Brend told the petty officer. “Let’s see what’s going on in Darsh now.”

In Darsh, it seemed, an uneasy peace was being established. Verkan Vall watched heavily-armed airboats and light combat ships patrolling among the high towers of the city. He saw a couple of minor riots being broken up by the blue-uniformed Constabulary, with considerable shooting and a ruthless disregard for who might get shot. It wasn’t exactly the sort of policing that would have been tolerated in the First Level Civil Order Section, but it seemed to suit Akor-Neb conditions. And he listened to a series of angry recriminations and contradictory statements by different politicians, all of whom blamed the disorders on their opponents. The Volitionalists spoke of the Statisticalists as “insane criminals” and “underminers of social stability,” and the Statisticalists called the Volitionalists “reactionary criminals” and “enemies of social progress.” Politicians, he had observed, differed little in their vocabularies from one time-line to another.

This kept up all the while the ship was passing over the Caspian Sea; as they were turning up the Volga valley, one of the ship’s officers came down from the control deck, above.

“We’re coming into Darsh, now,” he said, and as Verkan Vall turned from the visiplate to the forward windows, he could see the white and pastel-tinted towers of the city rising above the hardwood forests that covered the whole Volga basin on this sector. “Your luggage has been put into the airboat, Lord Virzal and Honorable Assassins, and it’s ready for launching whenever you are.” The officer glanced at his watch. “We dock at Commercial Center in twenty minutes; we’ll be passing the Solar Hotel in ten.”

They all rose, and Verkan Vall hooked fingers and clapped shoulders with Zortan Brend.

“Good luck, Lord Virzal,” the latter said. “I hope you find the Lady Dallona safe and carnate. If you need help, I’ll be at Mercantile House for the next day or so; if you get back to Ghamma before I do, you know who to ask for there.”

A number of assassins loitered in the hallways and offices of the Independent Institute of Reincarnation Research when Verkan Vall, accompanied by Marnik, called there that afternoon. Some of them carried submachine-guns or sleep-gas projectors, and they were stopping people and questioning them. Marnik needed only to give them a quick gesture and the words, “Assassins’ Truce,” and he and his client were allowed to pass. They entered a lifter tube and floated up to the office of Dr. Harnosh of Hosh, with whom Verkan Vall had made an appointment.

“I’m sorry, Lord Virzal,” the director of the Institute told him, “but I have no idea what has befallen the Lady Dallona, or even if she is still carnate. I am quite worried; I admired her extremely, both as an individual and as a scientist. I do hope she hasn’t been discarnated; that would be a serious blow to science. It is fortunate that she accomplished as much as she did, while she was with us.”

“You think she is no longer carnate, then?”

“I’m afraid so. The political effects of her discoveries—” Harnosh of Hosh shrugged sadly. “She was devoted, to a rare degree, to her work. I am sure that nothing but her discarnation could have taken her away from us, at this time, with so many important experiments still uncompleted.”

Marnik nodded to Verkan Vall, as much as to say: “You were right.”

“Well, I intend acting upon the assumption that she is still carnate and in need of help, until I am positive to the contrary,” Verkan Vall said. “And in the latter case, I intend finding out who discarnated her, and send him to apologize for it in person. People don’t forcibly discarnate my friends with impunity.”

“Sound attitude,” Dr. Harnosh commented. “There’s certainly no positive evidence that she isn’t still carnate. I’ll gladly give you all the assistance I can, if you’ll only tell me what you want.”

“Well, in the first place,” Verkan Vall began, “just what sort of work was she doing?” He already knew the answer to that, from the reports she had sent back to the First Level, but he wanted to hear Dr. Harnosh’s version. “And what, exactly, are the political effects you mentioned? Understand, Dr. Harnosh, I am really quite ignorant of any scientific subject unrelated to zerfa culture, and equally so of Terran politics. Politics, on Venus, is mainly a question of who gets how much graft out of what.”

Dr. Harnosh smiled; evidently he had heard about Venusian politics. “Ah, yes, of course. But you are familiar with the main differences between Statistical and Volitional reincarnation theories?”

“In a general way. The Volitionalists hold that the discarnate individuality is fully conscious, and is capable of something analogous to sense-perception, and is also capable of exercising choice in the matter of reincarnation vehicles, and can reincarnate or remain in the discarnate state as it chooses. They also believe that discarnate individualities can communicate with one another, and with at least some carnate individualities, by telepathy,” he said. “The Statisticalists deny all this; their opinion is that the discarnate individuality is in a more or less somnambulistic state, that it is drawn by a process akin to tropism to the nearest available reincarnation vehicle, and that it must reincarnate in and only in that vehicle. They are labeled Statisticalists because they believe that the process of reincarnation is purely at random, or governed by unknown and uncontrollable causes, and is unpredictable except as to aggregates.”

“That’s a fairly good generalized summary,” Dr. Harnosh of Hosh grudged, unwilling to give a mere layman too much credit. He dipped a spoon into a tobacco humidor, dusted the tobacco lightly with dried zerfa, and rammed it into his pipe. “You must understand that our modern Statisticalists are the intellectual heirs of those ancient materialistic thinkers who denied the possibility of any discarnate existence, or of any extraphysical mind, or even of extrasensory perception. Since all these things have been demonstrated to be facts, the materialistic dogma has been broadened to include them, but always strictly within the frame of materialism.

“We have proven, for instance, that the human individuality can exist in a discarnate state, and that it reincarnates into the body of an infant, shortly after birth. But the Statisticalists cannot accept the idea of discarnate consciousness, since they conceive of consciousness purely as a function of the physical brain. So they postulate an unconscious discarnate personality, or, as you put it, one in a somnambulistic state. They have to concede memory to this discarnate personality, since it was by recovery of memories of previous reincarnations that discarnate existence and reincarnation were proven to be facts. So they picture the discarnate individuality as a material object, or physical event, of negligible but actual mass, in which an indefinite number of memories can be stored as electronic charges. And they picture it as being drawn irresistibly to the body of the nearest non-incarnated infant. Curiously enough, the reincarnation vehicle chosen is almost always of the same sex as the vehicle of the previous reincarnation, the exceptions being cases of persons who had a previous history of psychological sex-inversion.”

Dr. Harnosh remembered the unlighted pipe in his hand, thrust it into his mouth, and lit it. For a moment, he sat with it jutting out of his black beard, until it was drawing to his satisfaction. “This belief in immediate reincarnation leads the Statisticalists, when they fight duels or perform voluntary discarnation, to do so in the neighborhood of maternity hospitals,” he added. “I know, personally, of one reincarnation memory-recall, in which the subject, a Statisticalist, voluntarily discarnated by lethal-gas inhaler in a private room at one of our local maternity hospitals, and reincarnated twenty years later in the city of Jeddul, three thousand miles away.” The square black beard jiggled as the scientist laughed.

“Now, as to the political implications of these contradictory theories: Since the Statisticalists believe that they will reincarnate entirely at random, their aim is to create an utterly classless social and economic order, in which, theoretically, each individuality will reincarnate into a condition of equality with everybody else. Their political program, therefore, is one of complete socialization of all means of production and distribution, abolition of hereditary titles and inherited wealth—eventually, all private wealth—and total government control of all economic, social and cultural activities. Of course,” Dr. Harnosh apologized, “politics isn’t my subject; I wouldn’t presume to judge how that would function in practice.”

“I would,” Verkan Vall said shortly, thinking of all the different time-lines on which he had seen systems like that in operation. “You wouldn’t like it, doctor. And the Volitionalists?”

“Well, since they believe that they are able to choose the circumstances of their next reincarnations for themselves, they are the party of the status quo. Naturally, almost all the nobles, almost all the wealthy trading and manufacturing families, and almost all professional people, are Volitionalists; most of the workers and peasants are Statisticalists. Or, at least, they were, for the most part, before we began announcing the results of the Lady Dallona’s experimental work.”

“Ah; now we come to it,” Verkan Vall said as the story clarified.

“Yes. In somewhat oversimplified form, the situation is rather like this,” Dr. Harnosh of Hosh said. “The Lady Dallona introduced a number of refinements and some outright innovations into our technique of recovering memories of past reincarnations. Previously, it was necessary to keep the subject in an hypnotic trance, during which he or she would narrate what was remembered of past reincarnations, and this would be recorded. On emerging from the trance, the subject would remember nothing; the tape-recording would be all that would be left. But the Lady Dallona devised a technique by which these memories would remain in what might be called the fore part of the subject’s subconscious mind, so that they could be brought to the level of consciousness at will. More, she was able to recover memories of past discarnate existences, something we had never been able to do heretofore.” Dr. Harnosh shook his head. “And to think, when I first met her, I thought that she was just another sensation-seeking young lady of wealth, and was almost about to refuse her enrollment!”

He wasn’t the only one whom little Dalla had surprised, Verkan Vall thought. At least, he had been pleasantly surprised.

“You see, this entirely disproves the Statistical Theory of Reincarnation. For example, we got a fine set of memory-recalls from one subject, for four previous reincarnations and four inter-carnations. In the first of these, the subject had been a peasant on the estate of a wealthy noble. Unlike most of his fellows, who reincarnated into other peasant families almost immediately after discarnation, this man waited for fifty years in the discarnate state for an opportunity to reincarnate as the son of an over-servant. In his next reincarnation, he was the son of a technician, and received a technical education; he became a physics researcher. For his next reincarnation, he chose the son of a nobleman by a concubine as his vehicle; in his present reincarnation, he is a member of a wealthy manufacturing family, and married into a family of the nobility. In five reincarnations, he has climbed from the lowest to the next-to-highest rung of the social ladder. Few individuals of the class from whence he began this ascent possess so much persistence or determination. Then, of course, there was the case of Lord Garnon of Roxor.”

He went on to describe the last experiment in which Hadron Dalla had participated.

“Well, that all sounds pretty conclusive,” Verkan Vall commented. “I take it the leaders of the Volitionalist Party here are pleased with the result of the Lady Dallona’s work?”

“Pleased? My dear Lord Virzal, they’re fairly bursting with glee over it!” Harnosh of Hosh declared. “As I pointed out, the Statisticalist program of socialization is based entirely on the proposition that no one can choose the circumstances of his next reincarnation, and that’s been demonstrated to be utter nonsense. Until the Lady Dallona’s discoveries were announced, they were the dominant party, controlling a majority of the seats in Parliament and on the Executive Council. Only the Constitution kept them from enacting their entire socialization program long ago, and they were about to legislate constitutional changes which would remove that barrier. They had expected to be able to do so after the forthcoming general elections. But now, social inequality has become desirable: it gives people something to look forward to in the next reincarnation. Instead of wanting to abolish wealth and privilege and nobility, the proletariat want to reincarnate into them.” Harnosh of Hosh laughed happily. “So you can see how furious the Statisticalist Party organization is!”

“There’s a catch to this, somewhere,” Marnik the Assassin, speaking for the first time, declared. “They can’t all reincarnate as princes, there aren’t enough vacancies to go ’round. And no noble is going to reincarnate as a tractor driver to make room for a tractor driver who wants to reincarnate as a noble.”

“That’s correct,” Dr. Harnosh replied. “There is a catch to it; a catch most people would never admit, even to themselves. Very few individuals possess the will power, the intelligence or the capacity for mental effort displayed by the subject of the case I just quoted. The average man’s interests are almost entirely on the physical side; he actually finds mental effort painful, and makes as little of it as possible. And that is the only sort of effort a discarnate individuality can exert. So, unable to endure the fifty or so years needed to make a really good reincarnation, he reincarnates in a year or so, out of pure boredom, into the first vehicle he can find, usually one nobody else wants.” Dr. Harnosh dug out the heel of his pipe and blew through the stem. “But nobody will admit his own mental inferiority, even to himself. Now, every machine operator and field hand on the planet thinks he can reincarnate as a prince or a millionaire. Politics isn’t my subject, but I’m willing to bet that since Statistical Reincarnation is an exploded psychic theory, Statisticalist Socialism has been caught in the blast area and destroyed along with it.”

Olirzon was in the drawing room of the hotel suite when they returned, sitting on the middle of his spinal column in a reclining chair, smoking a pipe, dressing the edge of his knife with a pocket-hone, and gazing lecherously at a young woman in the visiplate. She was an extremely well-designed young woman, in a rather fragmentary costume, and she was heaving her bosom at the invisible audience in anger, sorrow, scorn, entreaty, and numerous other emotions.

“... this revolting crime,” she was declaiming, in a husky contralto, as Verkan Vall and Marnik entered, “foul even for the criminal beasts who conceived and perpetrated it!” She pointed an accusing finger. “This murder of the beautiful Lady Dallona of Hadron!”

Verkan Vall stopped short, considering the possibility of something having been discovered lately of which he was ignorant. Olirzon must have guessed his thought; he grinned reassuringly.

“Think nothing of it, Lord Virzal,” he said, waving his knife at the visiplate. “Just political propaganda; strictly for the sparrows. Nice propagandist, though.”

“And now,” the woman with the magnificent natural resources lowered her voice reverently, “we bring you the last image of the Lady Dallona, and of Dirzed, her faithful Assassin, taken just before they vanished, never to be seen again.”

The plate darkened, and there were strains of slow, dirgelike music; then it lighted again, presenting a view of a broad hallway, thronged with men and women in bright varicolored costumes. In the foreground, wearing a tight skirt of deep blue and a short red jacket, was Hadron Dalla, just as she had looked in the solidographs taken in Dhergabar after her alteration by the First Level cosmeticians to conform to the appearance of the Malayoid Akor-Neb people. She was holding the arm of a man who wore the black tunic and red badge of an Assassin, a handsome specimen of the Akor-Neb race. Trust little Dalla for that, Verkan Vall thought. The figures were moving with exaggerated slowness, as though a very fleeting picture were being stretched out as far as possible. Having already memorized his former wife’s changed appearance, Verkan Vall concentrated on the man beside her until the picture faded.

“All right, Olirzon; what did you get?” he asked.

“Well, first of all, at Assassins’ Hall,” Olirzon said, rolling up his left sleeve, holding his bare forearm to the light, and shaving a few fine hairs from it to test the edge of his knife. “Of course, they never tell one Assassin anything about the client of another Assassin; that’s standard practice. But I was in the Lodge Secretary’s office, where nobody but Assassins are ever admitted. They have a big panel in there, with the names of all the Lodge members on it in light-letters; that’s standard in all Lodges. If an Assassin is unattached and free to accept a client, his name’s in white light. If he has a client, the light’s changed to blue, and the name of the client goes up under his. If his whereabouts are unknown, the light’s changed to amber. If he is discarnated, his name’s removed entirely, unless the circumstances of his discarnation are such as to constitute an injury to the Society. In that case, the name’s in red light until he’s been properly avenged, or, as we say, till his blood’s been mopped up. Well, the name of Dirzed is up in blue light, with the name of Dallona of Hadron under it. I found out that the light had been amber for two days after the disappearance, and then had been changed back to blue. Get it, Lord Virzal?”

Verkan Vall nodded. “I think so. I’d been considering that as a possibility from the first. Then what?”

“Then I was about and around for a couple of hours, buying drinks for people—unattached Assassins, Constabulary detectives, political workers, newscast people. You owe me fifteen System Monetary Units for that, Lord Virzal. What I got, when it’s all sorted out—I taped it in detail, as soon as I got back—reduces to this: The Volitionalists are moving mountains to find out who was the spy at Garnon of Roxor’s discarnation feast, but are doing nothing but nothing at all to find the Lady Dallona or Dirzed. The Statisticalists are making all sorts of secret efforts to find out what happened to her. The Constabulary blame the Statistos for the package bomb: they’re interested in that because of the discarnation of the three servants by an illegal weapon of indiscriminate effect. They claim that the disappearance of Dirzed and the Lady Dallona was a publicity hoax. The Volitionalists are preparing a line of publicity to deny this.”

Verkan Vall nodded. “That ties in with what you learned at Assassins’ Hall,” he said. “They’re hiding out somewhere. Is there any chance of reaching Dirzed through the Society of Assassins?”

Olirzon shook his head. “If you’re right—and that’s the way it looks to me, too—he’s probably just called in and notified the Society that he’s still carnate and so is the Lady Dallona, and called off any search the Society might be making for him.”

“And I’ve got to find the Lady Dallona as soon as I can. Well, if I can’t reach her, maybe I can get her to send word to me,” Verkan Vall said. “That’s going to take some doing, too.”

“What did you find out, Lord Virzal?” Olirzon asked. He had a piece of soft leather, now, and was polishing his blade lovingly.

“The Reincarnation Research people don’t know anything,” Verkan Vall replied. “Dr. Harnosh of Hosh thinks she’s discarnate. I did find out that the experimental work she’s done, so far, has absolutely disproved the theory of Statistical Reincarnation. The Volitionalists’ theory is solidly established.”

“Yes, what do you think, Olirzon?” Marnik added. “They have a case on record of a man who worked up from field hand to millionaire in five reincarnations. Deliberately, that is.” He went on to repeat what Harnosh of Hosh had said; he must have possessed an almost eidetic memory, for he gave the bearded psychicist’s words verbatim, and threw in the gestures and voice-inflections.

Olirzon grinned. “You know, there’s a chance for the easy-money boys,” he considered. “‘You, too, can Reincarnate as a millionaire! Let Dr. Nirzutz of Futzbutz Help You! Only 49.98 System Monetary Units for the Secret, Infallible, Autosuggestive Formula.’ And would it sell!” He put away the hone and the bit of leather and slipped his knife back into its sheath. “If I weren’t a respectable Assassin, I’d give it a try, myself.”

Verkan Vall looked at his watch. “We’d better get something to eat,” he said. “We’ll go down to the main dining room; the Martian Room, I think they call it. I’ve got to think of some way to let the Lady Dallona know I’m looking for her.”

The Martian Room, fifteen stories down, was a big place, occupying almost half of the floor space of one corner tower. It had been fitted to resemble one of the ruined buildings of the ancient and vanished race of Mars who were the ancestors of Terran humanity. One whole side of the room was a gigantic cine-solidograph screen, on which the gullied desolation of a Martian landscape was projected; in the course of about two hours, the scene changed from sunrise through daylight and night to sunrise again.

It was high noon when they entered and found a table; by the time they had finished their dinner, the night was ending and the first glow of dawn was tinting the distant hills. They sat for a while, watching the light grow stronger, then got up and left the table.

There were five men at a table near them; they had come in before the stars had grown dim, and the waiters were just bringing their first dishes. Two were Assassins, and the other three were of a breed Verkan Vall had learned to recognize on any time-line—the arrogant, cocksure, ambitious, leftist politician, who knows what is best for everybody better than anybody else does, and who is convinced that he is inescapably right and that whoever differs with him is not only an ignoramus but a venal scoundrel as well. One was a beefy man in a gold-laced cream-colored dress tunic; he had thick lips and a too-ready laugh. Another was a rather monkish-looking young man who spoke earnestly and rolled his eyes upward, as though at some celestial vision. The third had the faint powdering of gray in his black hair which was, among the Akor-Neb people, almost the only indication of advanced age.

“Of course it is; the whole thing is a fraud,” the monkish young man was saying angrily. “But we can’t prove it.”

“Oh, Sirzob, here, can prove anything, if you give him time,” the beefy one laughed. “The trouble is, there isn’t too much time. We know that that communication was a fake, prearranged by the Volitionalists, with Dr. Harnosh and this Dallona of Hadron as their tools. They fed the whole thing to that idiot boy hypnotically, in advance, and then, on a signal, he began typing out this spurious communication. And then, of course, Dallona and this Assassin of hers ran off somewhere together, so that we’d be blamed with discarnating or abducting them, and so that they wouldn’t be made to testify about the communication on a lie detector.”

A sudden happy smile touched Verkan Vall’s eyes. He caught each of his Assassins by an arm.

“Marnik, cover my back,” he ordered. “Olirzon, cover everybody at the table. Come on!”

Then he stepped forward, halting between the chairs of the young man and the man with the gray hair and facing the beefy man in the light tunic.

“You!” he barked. “I mean YOU.”

The beefy man stopped laughing and stared at him; then sprang to his feet. His hand, streaking toward his left armpit, stopped and dropped to his side as Olirzon aimed a pistol at him. The others sat motionless.

“You,” Verkan Vall continued, “are a complete, deliberate, malicious, and unmitigated liar. The Lady Dallona of Hadron is a scientist of integrity, incapable of falsifying her experimental work. What’s more, her father is one of my best friends; in his name, and in hers, I demand a full retraction of the slanderous statements you have just made.”

“Do you know who I am?” the beefy one shouted.

“I know what you are,” Verkan Vall shouted back. Like most ancient languages, the Akor-Neb speech included an elaborate, delicately-shaded, and utterly vile vocabulary of abuse; Verkan Vall culled from it judiciously and at length. “And if I don’t make myself understood verbally, we’ll go down to the object level,” he added, snatching a bowl of soup from in front of the monkish-looking young man and throwing it across the table.

The soup was a dark brown, almost black. It contained bits of meat, and mushrooms, and slices of hard-boiled egg, and yellow Martian rock lichen. It produced, on the light tunic, a most spectacular effect.

For a moment, Verkan Vall was afraid the fellow would have an apoplectic stroke, or an epileptic fit. Mastering himself, however, he bowed jerkily.

“Marnark of Bashad,” he identified himself. “When and where can my friends consult yours?”

“Lord Virzal of Verkan,” the paratimer bowed back. “Your friends can negotiate with mine here and now. I am represented by these Gentlemen-Assassins.”

“I won’t submit my friends to the indignity of negotiating with them,” Marnark retorted. “I insist that you be represented by persons of your own quality and mine.”

“Oh, you do?” Olirzon broke in. “Well, is your objection personal to me, or to Assassins as a class? In the first case, I’ll remember to make a private project of you, as soon as I’m through with my present employment; if it’s the latter, I’ll report your attitude to the Society. I’ll see what Klarnood, our President-General, thinks of your views.”

A crowd had begun to accumulate around the table. Some of them were persons in evening dress, some were Assassins on the hotel payroll, and some were unattached Assassins.

“Well, you won’t have far to look for him,” one of the latter said, pushing through the crowd to the table.

He was a man of middle age, inclined to stoutness; he made Verkan Vall think of a chocolate figure of Tortha Karf. The red badge on his breast was surrounded with gold lace, and, instead of black wings and a silver bullet, it bore silver wings and a golden dagger. He bowed contemptuously at Marnark of Bashad.

“Klarnood, President-General of the Society of Assassins,” he announced. “Marnark of Bashad, did I hear you say that you considered members of the Society as unworthy to negotiate an affair of honor with your friends, on behalf of this nobleman who has been courteous enough to accept your challenge?” he demanded.

Marnark of Bashad’s arrogance suffered considerable evaporation-loss. His tone became almost servile.

“Not at all, Honorable Assassin-President,” he protested. “But as I was going to ask these gentlemen to represent me, I thought it would be more fitting for the other gentleman to be represented by personal friends, also. In that way—”

“Sorry, Marnark,” the gray-haired man at the table said. “I can’t second you; I have a quarrel with the Lord Virzal, too.” He rose and bowed. “Sirzob of Abo. Inasmuch as the Honorable Marnark is a guest at my table, an affront to him is an affront to me. In my quality as his host, I must demand satisfaction from you, Lord Virzal.”

“Why, gladly, Honorable Sirzob,” Verkan Vall replied. This was getting better and better every moment. “Of course, your friend, the Honorable Marnark, enjoys priority of challenge; I’ll take care of you as soon as I have, shall we say, satisfied, him.”

The earnest and rather consecrated-looking young man rose also, bowing to Verkan Vall.

“Yirzol of Narva. I, too, have a quarrel with you, Lord Virzal; I cannot submit to the indignity of having my food snatched from in front of me, as you just did. I also demand satisfaction.”

“And quite rightly, Honorable Yirzol,” Verkan Vall approved. “It looks like such good soup, too,” he sorrowed, inspecting the front of Marnark’s tunic. “My seconds will negotiate with yours immediately; your satisfaction, of course, must come after that of Honorable Sirzob.”

“If I may intrude,” Klarnood put in smoothly, “may I suggest that as the Lord Virzal is represented by his Assassins, yours can represent all three of you at the same time. I will gladly offer my own good offices as impartial supervisor.”

Verkan Vall turned and bowed as to royalty. “An honor, Assassin-President: I am sure no one could act in that capacity more satisfactorily.”

“Well, when would it be most convenient to arrange the details?” Klarnood inquired. “I am completely at your disposal, gentlemen.”

“Why, here and now, while we’re all together,” Verkan Vall replied.

“I object to that!” Marnark of Bashad vociferated. “We can’t make arrangements here; why, all these hotel people, from the manager down, are nothing but tipsters for the newscast services!”

“Well, what’s wrong with that?” Verkan Vall demanded. “You knew that when you slandered the Lady Dallona in their hearing.”

“The Lord Virzal of Verkan is correct,” Klarnood ruled. “And the offenses for which you have challenged him were also committed in public. By all means, let’s discuss the arrangements now.” He turned to Verkan Vall. “As the challenged party, you have the choice of weapons; your opponents, then, have the right to name the conditions under which they are to be used.”

Marnark of Bashad raised another outcry over that. The assault upon him by the Lord Virzal of Verkan was deliberately provocative, and therefore tantamount to a challenge; he, himself, had the right to name the weapons. Klarnood upheld him.

“Do the other gentlemen make the same claim?” Verkan Vall wanted to know.

“If they do, I won’t allow it,” Klarnood replied. “You deliberately provoked Honorable Marnark, but the offenses of provoking him at Honorable Sirzob’s table, and of throwing Honorable Yirzol’s soup at him, were not given with intent to provoke. These gentlemen have a right to challenge, but not to consider themselves provoked.”

“Well, I choose knives, then,” Marnark hastened to say.

Verkan Vall smiled thinly. He had learned knife-play among the greatest masters of that art in all paratime, the Third Level Khanga pirates of the Caribbean Islands.

“And we fight barefoot, stripped to the waist, and without any parrying weapon in the left hand,” Verkan Vall stipulated.

The beefy Marnark fairly licked his chops in anticipation. He outweighed Verkan Vall by forty pounds; he saw an easy victory ahead. Verkan Vall’s own confidence increased at these signs of his opponent’s assurance.

“And as for Honorable Sirzob and Honorable Yirzol, I chose pistols,” he added.

Sirzob and Yirzol held a hasty whispered conference.

“Speaking both for Honorable Yirzol and for myself,” Sirzob announced, “we stipulate that the distance shall be twenty meters, that the pistols shall be fully loaded, and that fire shall be at will after the command.”

“Twenty rounds, fire at will, at twenty meters!” Olirzon hooted. “You must think our principal’s as bad a shot as you are!”

The four Assassins stepped aside and held a long discussion about something, with considerable argument and gesticulation. Klarnood, observing Verkan Vall’s impatience, leaned close to him and whispered:

“This is highly irregular; we must pretend ignorance and be patient. They’re laying bets on the outcome. You must do your best, Lord Virzal; you don’t want your supporters to lose money.”

He said it quite seriously, as though the outcome were otherwise a matter of indifference to Verkan Vall.

Marnark wanted to discuss time and place, and proposed that all three duels be fought at dawn, on the fourth landing stage of Darsh Central Hospital; that was closest to the maternity wards, and statistics showed that most births occurred just before that hour.

“Certainly not,” Verkan Vall vetoed. “We’ll fight here and now; I don’t propose going a couple of hundred miles to meet you at any such unholy hour. We’ll fight in the nearest hallway that provides twenty meters’ shooting distance.”

Marnark, Sirzob and Yirzol all clamored in protest. Verkan Vall shouted them down, drawing on his hypnotically acquired knowledge of Akor-Neb duelling customs. “The code explicitly states that satisfaction shall be rendered as promptly as possible, and I insist on a literal interpretation. I’m not going to inconvenience myself and Assassin-President Klarnood and these four Gentlemen-Assassins just to humor Statisticalist superstitions.”

The manager of the hotel, drawn to the Martian Room by the uproar, offered a hallway connecting the kitchens with the refrigerator rooms; it was fifty meters long by five in width, was well-lighted and soundproof, and had a bay in which the seconds and other could stand during the firing.

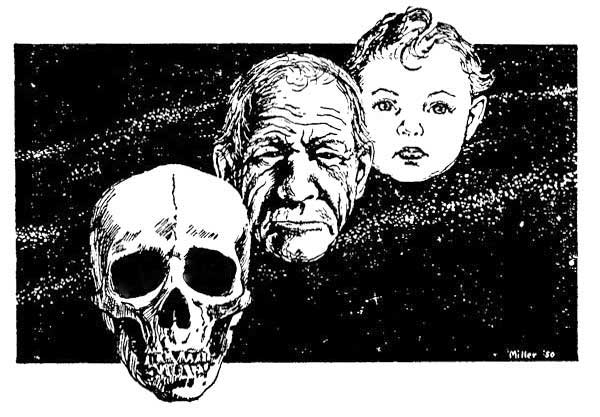

They repaired thither in a body, Klarnood gathering up several hotel servants on the way through the kitchen. Verkan Vall stripped to the waist, pulled off his ankle boots, and examined Olirzon’s knife. Its tapering eight-inch blade was double-edged at the point, and its handle was covered with black velvet to afford a good grip, and wound with gold wire. He nodded approvingly, gripped it with his index finger crooked around the cross-guard, and advanced to meet Marnark of Bashad.

As he had expected, the burly politician was depending upon his greater brawn to overpower his antagonist. He advanced with a sidling, spread-legged gait, his knife hand against his right hip and his left hand extended in front. Verkan Vall nodded with pleased satisfaction; a wrist-grabber. Then he blinked. Why, the fellow was actually holding his knife reversed, his little finger to the guard and his thumb on the pommel!

Verkan Vall went briskly to meet him, made a feint at his knife hand with his own left, and then side-stepped quickly to the right. As Marnark’s left hand grabbed at his right wrist, his left hand brushed against it and closed into a fist, with Marnark’s left thumb inside of it, He gave a quick downward twist with his wrist, pulling Marnark off balance.

Caught by surprise, Marnark stumbled, his knife flailing wildly away from Verkan Vall. As he stumbled forward, Verkan Vall pivoted on his left heel and drove the point of his knife into the back of Marnark’s neck, twisting it as he jerked it free. At the same time, he released Marnark’s thumb. The politician continued his stumble and fell forward on his face, blood spurting from his neck. He gave a twitch or so, and was still.

Verkan Vall stooped and wiped the knife on the dead man’s clothes—another Khanga pirate gesture—and then returned it to Olirzon.

“Nice weapon, Olirzon,” he said. “It fitted my hand as though I’d been born holding it.”

“You used it as though you had, Lord Virzal,” the Assassin replied. “Only eight seconds from the time you closed with him.”

The function of the hotel servants whom Klarnood had gathered up now became apparent; they advanced, took the body of Marnark by the heels, and dragged it out of the way. The others watched this removal with mixed emotions. The two remaining principals were impassive and frozen-faced. Their two Assassins, who had probably bet heavily on Marnark, were chagrined. And Klarnood was looking at Verkan Vall with a considerable accretion of respect. Verkan Vall pulled on his boots and resumed his clothing.

There followed some argument about the pistols; it was finally decided that each combatant should use his own shoulder-holster weapon. All three were nearly enough alike—small weapons, rather heavier than they looked, firing a tiny ten-grain bullet at ten thousand foot-seconds. On impact, such a bullet would almost disintegrate; a man hit anywhere in the body with one would be killed instantly, his nervous system paralyzed and his heart stopped by internal pressure. Each of the pistols carried twenty rounds in the magazine.

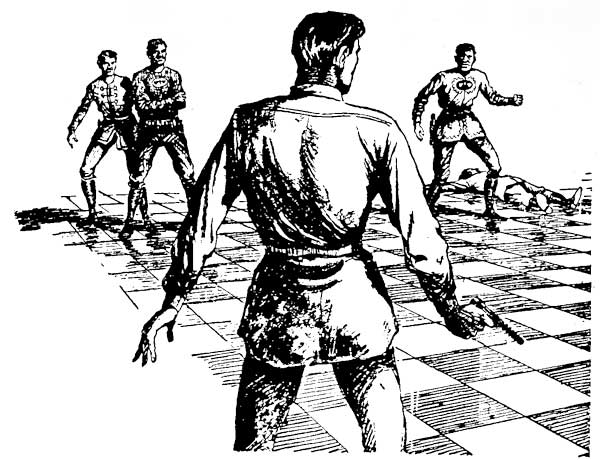

Verkan Vall and Sirzob of Abo took their places, their pistols lowered at their sides, facing each other across a measured twenty meters.

“Are you ready, gentlemen?” Klarnood asked. “You will not raise your pistols until the command to fire; you may fire at will after it. Ready. Fire!”

Both pistols swung up to level. Verkan Vall found Sirzob’s head in his sights and squeezed; the pistol kicked back in his hand, and he saw a lance of blue flame jump from the muzzle of Sirzob’s. Both weapons barked together, and with the double report came the whip-cracking sound of Sirzob’s bullet passing Verkan Vall’s head. Then Sirzob’s face altered its appearance unpleasantly, and he pitched forward. Verkan Vall thumbed on his safety and stood motionless, while the servants advanced, took Sirzob’s body by the heels, and dragged it over beside Marnark’s.

“All right; Honorable Yirzol, you’re next,” Verkan Vall called out.

“The Lord Virzal has fired one shot,” one of the opposing seconds objected, “and Honorable Yirzol has a full magazine. The Lord Virzal should put in another magazine.”

“I grant him the advantage; let’s get on with it,” Verkan Vall said.

Yirzol of Narva advanced to the firing point. He was not afraid of death—none of the Akor-Neb people were; their language contained no word to express the concept of total and final extinction—and discarnation by gunshot was almost entirely painless. But he was beginning to suspect that he had made a fool of himself by getting into this affair, he had work in his present reincarnation which he wanted to finish, and his political party would suffer loss, both of his services and of prestige.

“Are you ready, gentlemen?” Klarnood intoned ritualistically. “You will not raise your pistols until the command to fire; you may fire at will after it. Ready, Fire!”

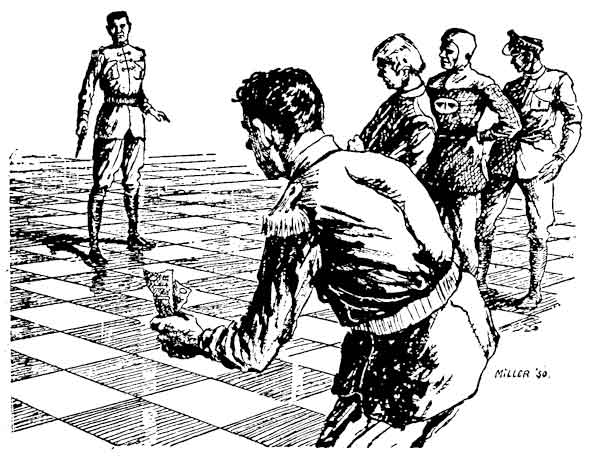

Verkan Vall shot Yirzol of Narva through the head before the latter had his pistol half raised. Yirzol fell forward on the splash of blood Sirzob had made, and the servants came forward and dragged his body over with the others. It reminded Verkan Vail of some sort of industrial assembly-line operation. He replaced the two expended rounds in his magazine with fresh ones and slid the pistol back into its holster. The two Assassins whose principals had been so expeditiously massacred were beginning to count up their losses and pay off the winners.

Klarnood, the President-General of the Society of Assassins, came over, hooking fingers and clapping shoulders with Verkan Vall.

“Lord Virzal, I’ve seen quite a few duels, but nothing quite like that,” he said. “You should have been an Assassin!”

That was a considerable compliment. Verkan Vall thanked him modestly.

“I’d like to talk to you privately,” the Assassin-President continued. “I think it’ll be worth your while if we have a few words together.”