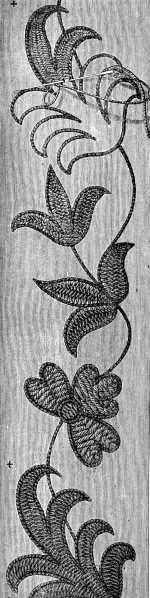

Stripe of gold embroidery in gold thread, purl, and flattened gold wire.

Stripe of gold embroidery in gold thread, purl, and flattened gold wire.

Stripe of gold embroidery in gold thread, purl, and flattened gold wire.

Stripe of gold embroidery in gold thread, purl, and flattened gold wire.

The terms, flat stitch and gold embroidery, suggest as a rule, needle-work upon rich materials, such as velvet, brocade, plush and the like.

Nevertheless, a great deal of beautiful embroidery is to be met with, in silk and gold thread upon quite common stuffs; Persian and Moorish embroidery for instance, both remarkable for their delicacy and minuteness, and executed upon ordinary linen, or cotton fabrics.

As a fact, the material is quite a secondary matter; almost any will do equally well as a foundation, for the stitches described in these pages. Flat stitch, and some of the other stitches used in gold embroidery, can be worked with any kind of thread, but best of all with the D.M.C cottons.

Flat stitch embroidery.—Decorative designs, and conventional flowers, are the most suitable for flat stitch embroidery; a faithful representation of natural flowers should not be attempted, unless it be so well executed, as to produce the effect of a painting and thus possess real artistic merit.

Encroaching flat stitch (fig. 221).—Small delicate flowers, leaves, and arabesques, should in preference, be worked either in straight flat stitch (figs. 189 and 190) or in encroaching flat stitch. The stitches should all be of equal length, the length to be determined by the quality of the thread; a fine thread necessitating short, and a coarse one, long stitches. The stitches should run, one into the other, as shown in the illustration. They are worked in rows, those of the second row encroaching on those of the first, and fitting into one another.

Work your flowers and leaves from the point, never from the calyx or stalk. If they are to be shaded, begin by choosing the right shade for the outside edge, varying the depth according to the light in which the object is supposed to be placed. The stitches should always follow the direction of the drawing.

Oriental stitch (figs. 222, 223, 224).—The three following stitches, which we have grouped under one heading, are known also, under the name of Renaissance or Arabic stitches. We have used the term Oriental, because they are to be met with in almost all Oriental needlework and probably derive their origin from Asia, whose inhabitants have, at all times, been renowned for the beauty of their embroideries.

These kind of stitches are only suitable for large, bold designs. Draw in the vertical threads first; in working with a soft, silky material, to economise thread, and prevent the embroidery from becoming too heavy, you can begin your second stitch close to where the first ended.

But if the thread be one that is liable to twist, take it back underneath the stuff and begin your next stitch in a line with the first, so that all the stitches of the first layer, which form the grounding, are carried from the top to the bottom. The same directions apply to figs. 223, 224 and 226.

When you have laid your vertical threads, stretch threads horizontally across, and fasten them down with isolated stitches, set six vertical threads apart. The position of these fastening stitches on the transverse threads must alternate in each row, as indicated in fig. 222.

For fig. 223, make a similar grounding to the one above described, laying the horizontal threads a little closer together, and making the fastening stitches over two threads.

In fig. 224, the second threads are carried diagonally across the foundation-threads, and the fastening stitches are given a similar direction.

For these stitches, use either one material only, a fleecy thread like Coton à repriser D.M.C for instance, or else two, such as Coton à repriser D.M.C for the grounding, and a material with a strong twist like Cordonnet 6 fils D.M.C or Fil à pointer D.M.C for the stem stitch.

Plaited stitch (fig. 225).—When the vertical stitches are laid, a kind of plait is formed in the following way. Pass the thread three times, alternately under and over three foundation threads. To do this very accurately, you must take the thread back, underneath, to its starting-point; and consequently, always make your stitch from right to left.

If you have chosen a washing material, and D.M.C cottons to work with, use one colour of cotton for the foundation, and Chiné d'or D.M.C No. 30, for the plaited stitch.

Mosaic stitch (fig. 226).—In old embroideries we often find this stitch, employed as a substitute for plush or other costly stuffs, appliquéd on to the foundation. It is executed in the same manner as the four preceding stitches, but can only be done in thick twist, such as Cordonnet 6 fils D.M.C or Ganse turque D.M.C.

Each stitch should be made separately, and must pass underneath the foundation, so that the threads which form the pattern are not flat, as they are in the preceding examples, but slightly rounded.

Border in Persian stitch (fig. 227).—This stitch, of Persian origin, resembles the one represented in fig. 175. Instead of bringing the needle out, however, as indicated in fig. 176, take it back as you see in the illustration, to the space between the outlines of the drawing, and behind the thread that forms the next stitch. Before filling in the pattern, outline it with short stem stitches, or a fine cord, laid on, and secured with invisible stitches.

Fig. 227. Border in persian stitch.

Fig. 227. Border in persian stitch.This graceful design which can be utilised in various ways is formed of leaves of 7 lobes, worked alternately in dark and light green; of flowers of 3 petals, worked in red and the centres in yellow, and of small leaves in violet. The setting, throughout, is worked either in black or in dark brown.

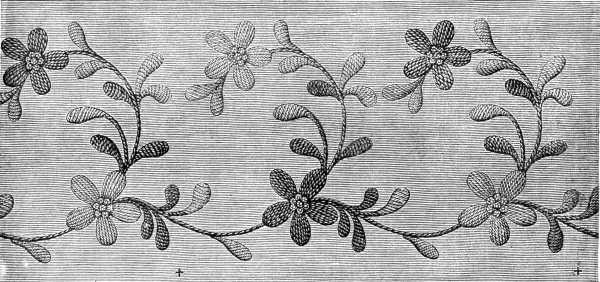

Stripe worked in flat stitch (fig. 228).—This pattern, simple as it is, will be found both useful and effective for the trimming of all kinds of articles of dress. The bottom edge should be finished off with rounded scallops or toothed vandykes worked in button-hole stitch. The flowers in flat stitch, are worked alternately, in Rouge-Géranium 351 and 352, and the leaves alternately, in Vert-de-gris 474 and 475; the centres of the flowers are worked in knot stitch, in Jaune-Rouille 308.

Fig. 228. Stripe worked in flat stitch.

Fig. 228. Stripe worked in flat stitch.Bouquet in straight and encroaching flat stitch (fig. 229). As we have already observed, it is by no means easy to arrange the colours in an embroidery of this kind, so as to obtain a really artistic effect. Whether the design be a conventional one or not, the great point is to put in the lights and shadows at the right place. If you want to make a faithful copy of a natural flower, take the flower itself, or a coloured botanical drawing of it, and if possible, a good black and white drawing of the same, match the colours in 6 or 7 shades, by the flower itself, keeping them all rather paler in tone, and take the black and white drawing as a guide for the lights and shadows. The colours for the leaves and petals, which should always be worked from the outside, should be chosen with a view to their blending well together. The stamens and the centres of the flowers should be left to the last, but the veins and ribs of the leaves, should always be put in before the grounding.

Fig. 229. Bouquet in straight and encroaching flat stitch.

Fig. 229. Bouquet in straight and encroaching flat stitch.For embroideries of this kind, suitable materials must be selected; the more delicate and minute the design, and the more varied the colouring, the softer and finer should be the quality of the material employed. Specially to be recommended, as adapted to every form of stitch and as being each of them capable of being subdivided, are Filoselle, Marseille, open Chinese silk and Coton à repriser D.M.C.[A]

Flowers embroidered in the Chinese manner (fig. 230).—All Chinese embroidery displays undoubted originality and wonderful skill and judgment in the choice of material and colour. It excels particularly, in the representation of figures, flowers, and animals, but differs from European work in this, that instead of using flat stitch and making the colours blend together as we do, the Chinese put them, side by side, without intermediate tones, or they sometimes work the whole pattern in knot stitch. The little knots, formed by this stitch are generally set in gold thread.

Often too, instead of combining a number of colours, as we do, the Chinese fill in the whole leaf with long stitches and upon this foundation, draw the veins in a different stitch and colour. Even the flowers, they embroider in the same way, in very fine thread, filling in the whole ground first, with stitches set very closely together and marking in the seed vessels afterwards, by very diminutive knots, wide apart.

Chinese encroaching flat stitch (fig. 231).—Another easy kind of embroidery, common in China, is done in encroaching flat stitch. The branch represented in our drawing, taken from a large design, is executed in three shades of yellow, resembling those of the Jaune-Rouille series on the D.M.C colour card.[A]

Fig. 231. Chinese encroaching flat stitch.

Fig. 231. Chinese encroaching flat stitch.The stitches of the different rows encroach upon one another, as the working detail shows, and the three shades alternate in regular succession. Flowers, butterflies and birds are represented in Chinese embroidery, executed in this manner. It is a style, that is adapted to stuffs of all kinds, washing materials as well as others, and can be worked in the hand and with any of the D.M.C threads and cottons.[A]

Raised embroidery (figs. 232 and 233).—Raised embroidery worked in colours, must be stuffed or padded first, like the white embroidery in fig. 191. If you outline your design with a cord, secure it on the right side with invisible stitches, untwisting the cord slightly as you insert your needle and thread, that the stitch may be hidden between the strands. Use Coton à repriser D.M.C No. 25, for the padding. These cottons are to be had in all the colours, indicated in the D.M.C colour card, and are the most suitable for the kind of work.

Use Coton à broder D.M.C for the transverse stitches and over the smooth surface which is thus formed, work close lines of satin stitch in silk or cotton; the effect produced, will bear more resemblance to appliqué work than to embroidery. The centres of the flowers are filled in with knot stitches, which are either set directly on the stuff or on an embroidered ground.

Embroidery in the Turkish style (figs. 234 and 235).—This again is a style of embroidery different from any we are accustomed to. The solid raised parts are first padded with common coarse cotton and then worked over with gold, silver, or silk thread.

Contrary to what is noticeable in the real Turkish embroidery, the preparatory work here is very carefully done, with several threads of Coton à repriser D.M.C used as one. A rope of five threads is laid down, and carried from right to left and from left to right, across the width of the pattern. After laying it across to the right, as explained in fig. 234, bring the needle out a little beyond the space occupied by the threads, insert it behind them and passing it under the stuff, draw it out at the spot indicated by the arrow. The stitch that secures the threads, should be sufficiently long to give them a little play, so that they may lie perfectly parallel, side by side, over the whole width of the pattern.

This kind of work can be done on wollen or cotton materials, and generally speaking, with D.M.C cottons, and gold thread shot with colour (Chiné d'or D.M.C.)

Very pretty effects can be obtained, by a combination of three shades of Rouge-Cardinal 347, 346 and 304, with Chiné d'or gold and dark blue or with Chiné d'or, gold and light blue.[A]

This kind of embroidery may be regarded as the transition from satin stitch to gold embroidery.

Gold embroidery.—Up to the present time, dating from the end of the eighteenth century, gold embroidery has been almost exclusively confined to those who made it a profession; amateurs have seldom attempted what, it was commonly supposed, required an apprenticeship of nine years to attain any proficiency in.

But now, when it is the fashion to decorate every kind of fancy article, whether of leather, plush, or velvet, with monograms and ingenious devices of all descriptions, the art of gold embroidery has revived and is being taken up and practised with success, even by those to whom needlework is nothing more than an agreeable recreation.

We trust that the following directions and illustrations will enable our readers to dispense with the five years training, which even now, experts in the art consider necessary.

Implements and materials.—The first and needful requisites for gold embroidery, are a strong frame, a spindle, two pressers, one flat and the other convex, a curved knife, a pricker or stiletto, and a tray, to contain the materials.

Embroidery frame (fig. 236).—The frame, represented here, is only suitable for small pieces of embroidery, for larger ones, which have to be done piece by piece, round bars on which to roll up the stuff, are desirable, as sharp wooden edges are so apt to mark the stuff.

Every gold embroidery, on whatever material it may be executed, requires a stout foundation, which has to be sewn into the frame, in doing which, hold the webbing loosely, almost in folds, and stretch the stuff very tightly. Sew on a stout cord to the edges of the foundation, which are nearest the stretchers, setting the stitches, 3 or 4 c/m. apart. Then put the frame together and stretch the material laterally to its fullest extent, by passing a piece of twine, in and out through the cord at the edge and over the stretchers. Draw up the bracing until the foundation is strained evenly and tightly. Upon this firm foundation lay the stuff which you are going to embroider, and hem or herring-bone it down, taking care to keep it perfectly even with the thread of the foundation and, if possible, more tightly stretched to prevent it from being wrinkled or puckered when you come to take it off the backing. For directions how to transfer the pattern to your stuff, and prepare the paste with which the embroidery has to be stiffened before it is taken out of the frame, see the concluding chapter in the book.

The spindle (fig. 237).—The spindle to wind the gold thread upon, should be 20 c/m. long and made of hard wood. Cover the round stalk and part of the prongs with a double thread of Coton à broder D.M.C No. 16, or pale yellow Cordonnet D.M.C No. 25, and terminate this covering with a loop, to which you fasten the gold thread that you wind round the stalk.

The pressers (figs. 238 and 239).—These, so called 'pressers', are small rectangular boards with a handle in the middle. The convex one, fig. 238, should be 15 c/m. long by 9 broad; the other, fig. 239, which is quite flat, should be 32 c/m. by 20.

Fig. 238.

Convex presser, for pressing

the stuff on the wrong side.

Fig. 238.

Convex presser, for pressing

the stuff on the wrong side.

Fig. 239.

Flat presser for laying on the pattern.

Fig. 239.

Flat presser for laying on the pattern.

Having cut out your pattern in cartridge paper, lay it down, on the wrong side, upon a board thinly spread with embroidery paste. Let it get thoroughly impregnated with the paste and then transfer it carefully to its proper place on the stuff; press it closely down with the large presser, and with the little convex one rub the stuff firmly, from beneath, to make it adhere closely to the pasted pattern; small, pointed leaves and flowers will be found to need sewing down besides, as you will observe in fig. 242, where each point is secured by stitches. The embroidery should not be begun until the paste is perfectly dry, and the pattern adheres firmly to the stuff.

The knife (fig. 240).—Most gold embroideries require a foundation of stout cartridge paper, and, in the case of very delicate designs, the paper should further be covered with kid, pasted upon it.

Transfer the design on to the paper or kid, in the manner described in the concluding chapter, and cut it out with the knife. You can only make very short incisions with this tool, which should be kept extremely sharp and held, in cutting, with the point outwards, and the rounded part towards you, as shown in the drawing.

Tray to contain the materials (fig. 241).—Cut out as many divisions in a thin board, or sheet of stout cardboard, as you will require materials for your embroidery; these include not only gold thread of all kinds, but likewise beads and spangles of all sorts and sizes as well as bright and dead gold and silver purl, or bullion, as it is also called. For the pieces of purl alone, which should be cut ready to hand, you should have several divisions, in order that the different lengths may be kept separate.

Use of the spindle (fig. 242).—Gold embroidery thread should be wound double upon the spindle. It is laid backwards and forwards and secured with two stitches at each turn, as described in fig. 234. Small holes where the stitches are to come, have first to be pierced in the material with the pricker, from the right side, for the needle to pass through. In soft stuffs, this is unnecessary, but in brocaded materials, and in plush and leather, where every prick shows and would often spoil the whole effect, it is indispensable.

Gold thread which is stiff and difficult to work with, can be rendered soft and pliable by putting it into the oven, or any other warm place, for a short time.

Embroidery with gold purl (fig. 243).—Embroidery is the easiest kind of gold embroidery; you have only to thread the little pieces of purl, cut into the required lengths beforehand, like beads on your needle, and fasten them down upon the foundation like the beads in bead-work. Smooth and crimped gold purl, or silver and gold purl used together, look exceedingly well, particularly where the pattern requires effects of light and shade to be reproduced.

Embroidery in diamond stitch (fig. 244).—The diamond stitch is a charming novelty in gold embroidery. Short lengths of purl, not more than 1-1/2 m/m. long, are threaded on the needle, and the needle is put in and drawn out at the same hole. These stitches which resemble knot stitches, form so many little glittering knots, turned alternately to the right and left, and look like seed-diamonds in appearance, more especially, when they are made in silver purl. The shorter the pieces are, and the more closely you set the knots together, the handsomer and richer the effect will be.

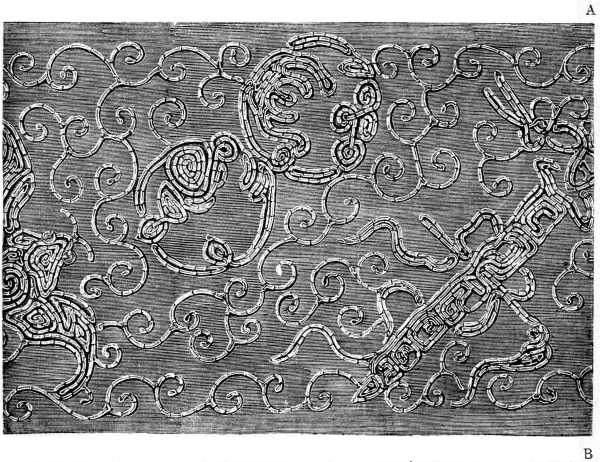

Chinese gold embroidery (figs. 245 and 246).—We recommend the imitation of Chinese gold embroidery to our readers as an easy and grateful recreation. It consists simply in laying down a gold thread, on a delicately outlined pattern and securing it by stitches. It can be done on any material, washing or other, the costliest as well as the most ordinary.

For a washing material use, Or fin D.M.C pour la broderie, No. 20, 30 or 40,[A] which, as it washes perfectly, is well adapted for the embroidery of wearing apparel, and household linen. Plain gold thread and gold thread with a thread of coloured silk twisted round it, are very effective used together.

Fig. 245. Second part

Fig. 245. Second part

Thus in fig. 245, the trees, foliage and flowers, are worked in plain gold, the grasses, in gold shot with green, the butterflies in gold with red, the two birds in gold with dark blue, and gold with light blue.

Two threads of gold should be laid down side by side and secured by small catching stitches, set at regular intervals from one another, and worked in Fil d'Alsace D.M.C No. 200,[A] of the same colour. Where the design requires it, you may separate the gold threads, and work with one alone.

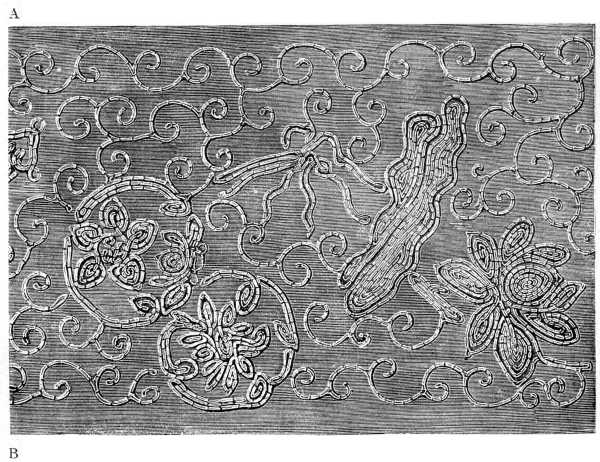

The second specimen of Chinese embroidery, fig. 246, resembles the first, as far as materials and execution are concerned, but the design is different. The grotesque animals, flowers and shells it represents, can be worked separately, or connected together so as to form a running pattern.

Fig. 246. Second part.

Fig. 246. Second part.

Stripe worked in various stitches (fig. 247).—All the designs described thus far, are worked in the same way, but the stripe now presented to our readers introduces them to several kinds of gold thread, and a variety of stitches. The small, turned-back petals of the flowers are worked in plain gold thread, and outlined with crimped; the rest of the petals are worked in darning stitch, with plain gold thread. The latticed leaves are edged with picots, worked with bright purl. The other parts of the design are all worked with a double gold thread, the stalks in dead gold, the leaves in crimped. The gold thread is secured by overcasting stitches in gold-coloured thread, Jaune d'or 667, but it looks very well if you use black or red thread for fastening the crimped gold and dark or light green for the leaves and tendrils.

Gold embroidery on a foundation of cords (fig. 248).—In the old ecclesiastical embroideries, especially those representing the figures of saints, we often find thick whip cords used as a foundation, instead of cardboard, for the good reason that the stiff cardboard does not give such soft and rounded contours as a cord foundation, which will readily take every bend and turn that you give to it. In the following illustrations, we have adhered strictly to the originals, as far as the manner of working the surface is concerned, but have substituted for the cord, which in their case has been used for the foundation, Cordonnet 6 fils D.M.C No. 1, which is better for padding than the grey whip cord, as it can be had in white or yellow, according to whether it is intended to serve as a foundation to silver or gold work.

Lay down as many cords as are necessary to give the design the requisite thickness, in many cases up to 8 or 10 m/m. in height, taking care to lay them closely and solidly in the centre, and graduate them down at the sides and ends. When you have finished the foundation, edge it with a thick gold cord, such as Cordonnet d'or D.M.C No. 6 and then only begin the actual embroidery, all the directions just given, applying merely to the preparatory work.

Only four of the many stitches that are already in use and might be devised are described here. For the pattern, represented in fig. 248, flattened gold or silver wire is necessary, which should be cut into pieces, long enough to be turned in at the ends so as to form a little loop through which the thread that fastens them down is passed. Over each length of gold or silver wire small lengths of purl are laid at regular intervals, close enough just to leave room for the next stitch, the pieces of one row, alternating in position with those of the preceding one.

Plaited stitch in gold purl on a cord foundation (fig. 249). —Distribute the stitches as in the previous figure, substituting purl, for the flattened gold wire, and covering the purl with short lengths of gold thread of the same kind. All these stitches may be worked in gold and silver thread, mixed or in the one, or the other alone.

Scale stitch worked in gold thread and purl on a cord foundation (fig. 250).—Begin by covering the whole padded surface with gold or silver thread, then sew on short lengths of purl, long enough to cover six or eight threads, 2 or 3 m/m. apart, as shown in the engraving. These stitches in dead gold purl are then surrounded by shining or crimped purl.

You bring out the working thread to the left of the purl stitch, which you take on your needle, put the needle in on the other side, draw it out above the little stroke, and secure the crimped purl with an invisible stitch.

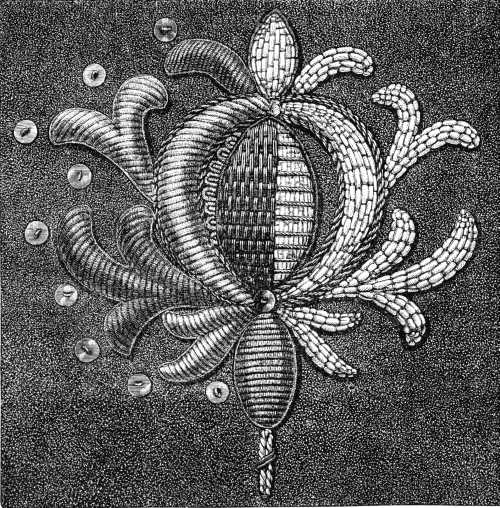

Conventional flower worked on a cord foundation (fig. 251).—The half finished flower, represented here, was copied from a handsome piece of ecclesiastical embroidery enriched with ornament of this kind. The three foregoing stitches and a fourth, are employed in its composition. The finished portions on the left hand side, are executed in silver and gold purl, whilst the egg-shaped heart of the flower is formed of transverse threads, carried over the first padding, and secured by a stitch between the two cords. In the subsequent row, the catching stitch is set between the cords, over which the first gold threads were carried.

Fig. 251. Conventional flower worked on a cord foundation.

Fig. 251. Conventional flower worked on a cord foundation.The heavier the design is, the thicker your padding should be, and cords a good deal thicker than those which are represented in the drawing should be used, as the more light and shade you can introduce into embroidery of this kind, the greater will be its beauty and value.