The Project Gutenberg EBook of Fragments of Two Centuries, by Alfred Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Fragments of Two Centuries

Glimpses of Country Life when George III. was King

Author: Alfred Kingston

Release Date: May 8, 2007 [EBook #21352]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRAGMENTS OF TWO CENTURIES ***

Produced by Al Haines

Though the town of Royston is frequently mentioned in the following pages, it was no part of my task to deal with the general historical associations of the place, with its interesting background of Court life under James I. These belong strictly to local history, and the references to the town and neighbourhood of Royston simply arise from the accidental association with the district of the materials which have come most readily to my hand in glancing back at the life of rural England in the time of the Georges. Indeed, it may be claimed, I think, that although, by reason of being drawn chiefly from local sources, these "Fragments" have received a local habitation and a name, yet they refer to a state of things which was common to all the neighbouring counties, and for the most part, may be taken to stand for the whole of rural England at the time. For the rest, these glimpses of our old country life are now submitted to the indulgent consideration of the reader, who will, I hope, take a lenient view of any shortcomings in the manner of presenting them.

There remains for me only the pleasing duty of acknowledging many instances of courteous assistance received, without which it would have been impossible to have carried out my task. To the proprietors of the Cambridge Chronicle and the Hertsfordshire Mercury for access to the files of those old established papers; to the authorities of the Cambridge University Library; to the Rev. J. G. Hale, rector of Therfield, and the Rev. F. L. Fisher, vicar of Barkway, for access to their interesting old parish papers; to Mr. H. J. Thurnall for access to interesting MS. reminiscences by the late Mr. Henry Thurnall; to the Rev. J. Harrison, vicar of Royston; to Mr. Thos. Shell and Mr. James Smith, for access to Royston parish papers—to all of these and to others my warmest thanks are due. All the many persons who have kindly furnished me with personal recollections it would be impossible here to name, but mention must be made of Mr. Henry Fordham, Mr. Hale Wortham, Mr. Frederick N. Fordham, and especially of the late Mr. James Richardson and Mr. James Jacklin, whose interesting chats over bygone times are now very pleasant recollections.

A.K.

| PAGE | |

|

CHAPTER I.

Introduction.--"The Good Old Times" |

1 |

|

CHAPTER II. Getting on Wheels.--Old Coaches, Roads and Highwaymen.--The Romance of the Road |

6 |

|

CHAPTER III. Social and Public Life.--Wrestling and Cock-Fighting.--An Eighteenth Century Debating Club |

19 |

|

CHAPTER IV. The Parochial Parliament and the Old Poor-Law |

32 |

|

CHAPTER V. Dogberry "On Duty" |

47 |

|

CHAPTER VI. The Dark Night of the Eighteenth Century.--The Shadow of Napoleon |

56 |

|

CHAPTER VII. Domestic Life and the Tax-Gatherer.--The Doctor and the Body-Snatcher |

73 |

|

CHAPTER VIII. Old Pains and Penalties.--From the Stocks to the Gallows |

83 |

|

CHAPTER IX. Old Manners and Customs.--Soldiers, Elections and Voters.--"Statties," Magic and Spells |

92 |

|

CHAPTER X. Trade, Agriculture and Market Ordinaries |

103 |

|

CHAPTER XI. Royston in 1800-25.--Its Surroundings, its Streets, and its People |

110 |

|

CHAPTER XII. Public Worship and Education.--Morals and Music |

117 |

|

CHAPTER XIII. Sports and Pastimes.--Cricket, Hunting, Racing, and Prize-Fighting.--The Butcher and the Baronet, and other Champions |

130 |

|

CHAPTER XIV. Old Coaching Days.--Stage Wagons and Stage Coaches |

142 |

|

CHAPTER XV. New Wine and Old Bottles.--A Parochial Revolution.--The Old Poor-House and the New "Bastille" |

155 |

|

CHAPTER XVI. When the Policeman Came.--When the Railway Came.--Curious and Memorable Events |

174 |

|

CHAPTER XVII. Then and Now.--Conclusion |

191 |

ERRATA—Page 16, lines 9 and 29, for Dr. Monsey, read Dr. Mowse.

[Transcriber's note: These changes have been incorporated into this e-book.]

The Jubilee Monarch, King George III., and his last name-sake, had succeeded so much that was unsettled in the previous hundred years, that the last half of the 18th Century was a period almost of comparative quiet in home affairs. Abroad were stirring events in abundance in which England played its part, for the century gives, at a rough calculation, 56 years of war to 44 years of peace, while the reign of George III. had 37 years of war and 23 years of peace—the longest period of peace being 10 years, and of war 24 years (1793-1816). But in all these stirring events, there was, in the greater part of the reign, at least, and notwithstanding some murmurings, the appearance of a solidity in the Constitution which has somehow settled down into the tradition of "the good old times." A cynic might have described the Constitution as resting upon empty bottles and blunder-busses, for was it not the great "three-bottle period" of the British aristocracy? and as for the masses, the only national sentiment in common was that of military glory earned by British heroes in foreign wars. In more domestic affairs, it was a long hum-drum grind in settled grooves—deep ruts in fact—from which there seemed no escape. Yet it was a period in which great forces had their birth—forces which were destined to exercise the widest influence upon our national, social, and even domestic affairs. Adam Smith's great work on the causes of the wealth of nations planted a life-germ of progressive thought which was to direct men's minds into what, strange as it may seem, was almost a new field of research, viz., the relation of cause and effect, and was commercially almost as much a new birth and the opening of a flood gate of activity, as was that of the printing press at the close of the Middle Ages; and, this once set in motion, a good many other things seemed destined to follow.

What a host of things which now seem a necessary part of our daily lives were then in a chrysalis state! But the bandages were visibly cracking in all directions. Literature was beginning those {2} desperate efforts to emerge from the miseries of Grub Street, to go in future direct to the public for its patrons and its market, and to bring into quiet old country towns like Royston at least a newspaper occasionally. In the political world Burke was writing his "Thoughts on the present Discontents," and Francis, or somebody else, the "Letters of Junius." Things were, in fact, showing signs of commencing to move, though slowly, in the direction of that track along which affairs have sometimes in these latter days moved with an ill-considered haste which savours almost as much of what is called political expediency as of the public good.

Have nations, like individuals, an intuitive sense or presentiment of something to come? If they have, then there has been perhaps no period in our history when that faculty was more keenly alive than towards the close of the last century. From the beginning of the French Revolution to the advent of the Victorian Era constitutes what may be called the great transition period in our domestic, social, and economic life and customs. Indeed, so far as the great mass of the people were concerned, it was really the dawn of social life in England; and, as the darkest hour is often just before the dawn, so were the earlier years of the above period to the people of these Realms. Before the people of England at the end of the 18th century, on the horizon which shut out the future, lay a great black bank of cloud, and our great grandfathers who gazed upon it, almost despairing whether it would ever lift, were really in the long shadows of great coming events.

Through the veil which was hiding the new order of things, occasionally, a sensitive far-seeing eye, here and there caught glimpses from the region beyond. The French, driven just then well-nigh to despair, caught the least glimmer of light and the whole nation was soon on fire! A few of the most highly strung minds caught the inspiration of an ideal dream of the regeneration of the world by some patent process of redistribution! All the ancient bundle of precedents, and the swaddling bands of restraints and customs in which men had been content to remain confined for thousands of years, were henceforth to be dissolved in that grandiose dream of a society in which each individual, left to follow his unrestrained will, was to be trusted to contribute to the happiness of all without that security from wrong which, often rude in its operation, had been the fundamental basis of social order for ages! The ideal was no doubt pure and noble, but unfortunately it only raised once more the old unsolved problem of the forum whether that which is theoretically right can ever be practically wrong. The French Revolution did not, as a matter of fact, rest with a mere revulsion of moral forces, but as the infection descended from moral heights into the grosser elements of the national life, men soon {3} began to fight for the new life with the old weapons, until France found, and others looking on saw, the beautiful dream of liberty tightening down into that hideous nightmare, and saddest of all tyrannies, the tyranny of the multitude! Into the great bank of cloud which had gathered across the horizon of Europe, towards the close of the 18th century, some of the boldest spirits of France madly rushed with the energy of despair, seeking to carve their way through to the coming light, and fought in the names of "liberty, equality and fraternity," with apparent giants and demons in the mist who turned out to be their brother men!

It would be a total misapprehension of the great throbbing thought of better days to come which stirred the sluggish life of the expiring century, to assume, as we often do, that that cry of "liberty, equality, and fraternity," was merely the cry of the French, driven to desperation by the gulf between the nobility and the people. In truth, almost the whole Western world was eagerly looking on at the unfolding of a great drama, and the infection of it penetrated almost into every corner of England. No glimpses even of our local life at this period would be satisfactory which did not give a passing notice to an event which literally turned the heads of many of the most gifted young men in England.

Upon no individual mind in these realms had that aspiration for a universal brotherhood a more potent spell than upon a youthful genius then at Cambridge, with whom some notable Royston men were afterwards to come in contact. That glorious dream, in which the French Revolution had its birth, had burnt itself into the very soul of young Wordsworth who found indeed that—

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven! Oh! times

In which the meagre, stale forbidding ways

Of custom, law and statute, took at once

The attraction of a country in romance!

In the Autumn of 1789, young Wordsworth, and a fellow student left Cambridge and crossed the Channel to witness that

Glorious opening, the unlooked for dawn,

That promised everlasting joy to France!

The gifted singer caught the blissful intoxication and has told us—

Meanwhile prophetic harps,

In every grove were ringing, war shall cease.

******

Henceforth whate'er is wanting in yourselves

In others ye shall promptly find—and all

Be rich by mutual and reflected wealth!

{4} So the poet went out to stand by the cradle of liberty, only to come back disenchanted, came back to find his republican dreams gradually giving way to a settled conservatism, and the fruit of that disappointed first-love of liberty received with unmeasured opposition from the old school in literary criticism represented by Jeffrey and the Edinburgh Review, with the result that those in high places for long refused to listen to one who had the magical power of unlocking the sweet ministries of Nature as no other poet of the century had.

Other ardent spirits had their dreams too, and for a short time at least there was a sympathy with the French, among many of the English, which left its traces in local centres like Royston—quite an intellectual centre in those days—and was in striking contrast with that hatred of the French which was so soon to settle over England under the Napoleonic régime. But, if many of the English people, weary of the increasing burdens which fell upon them, had their dreams of a good time coming, they, instead of following the mere glimmer of the will-o'-the-wisp, across the darkness of their lot, responded rather to signs of coming activities. Through the darkness they saw perhaps nothing very striking, but they felt occasionally the thrill of coming activities which were struggling for birth in that pregnant mother-night which seemed to be shrouding the sunset of the century—and they were saved from the immediate horrors of a revolution. Feudalism and the Pope had left our fathers obedience, en masse, and Luther had planted hope through the reformation of the individual. So the great wave of aspiration after a patent scheme of universal brotherhood passed over the people of these realms with only a wetting of the spray. Here and there was a weak reflection of the drama, in the calling of hard names, and the taunt of "Jacobin," thrown in the teeth of those who might have sympathised with the French in the earlier stages of the Revolution, was sometimes heard in the streets of Royston for many years after the circumstances which called it forth had passed away.

I have referred thus fully to what may seem a general rather than a local question, because the town of Royston, then full of aspirations after reform, was looked upon almost as a hot-bed of what were called "dangerous principles" by those attached to the old order of things, and because it may help us to understand something of the excitement occasioned by the free expression of opinions in the public debates which took place in Royston to be referred to hereafter.

But though the "era of hope," in the particular example of its application in France, failed miserably and deservedly of realising the great romantic dream-world of human happiness without parchments and formularies, it had at least this distinction, that it was in a sense the birth-hour of the individual with regard to civil life, just as Luther's bursting the bonds of Monasticism had been the birth-hour of the {5} individual in religious life. The birth, however, was a feeble one, and in this respect, and for the social and domestic drawbacks of a trying time, it is interesting to look back and see how our fathers carried what to them were often felt to be heavy burdens, and how bravely and even blithely they travelled along what to us now seems like a weary pilgrimage towards the light we now enjoy. Carrying the tools of the pioneer which have ever become the hands of Englishmen so well, they worked, with such means as they had, for results rather than sentiment, and, cherishing that life-germ planted by Adam Smith, earned, not from the lips of Napoleon as is commonly supposed, but from one of the Revolutionary party—Bertrand Barrère in the National Assembly in 1794, when the tide of feeling had been turned by events the well-known taunt—"let Pitt then boast of his victory to a nation of shop-keepers." The instinct for persistent methodical plodding work which extracted this taunt, afterwards vanquished Napoleon at Waterloo, and enabled the English to pass what, when you come to gauge it by our present standard, was one of the darkest and most trying crises in our modern history. We who are on the light side of that great cloud which brooded over the death and birth of two centuries may possibly learn something by looking back along the pathway which our forefathers travelled, and by the condition of things and the actions of men in those trying times—learn something of the comparative advantages we now enjoy in our public, social, and domestic life, and the corresponding extent of our responsibilities.

In the following sketches it is proposed to give, not a chapter of local history, as history is generally understood, but what may perhaps best be described by the title adopted—glimpses of the condition of things which prevailed in Royston and its neighbourhood, in regard to the life, institutions, and character of its people, during the interesting period which is indicated at the head of this sketch—with some fragments illustrative of the general surroundings of public affairs, where the local materials may be insufficient to complete the picture. Imperfect these "glimpses" must necessarily be, but with the advantage of kindly help from those whose memories carry their minds back to earlier times, and his own researches amongst such materials, both local and general, as seemed to promise useful information, the writer is not without hope that they may be of interest. The interest of the sketches will necessarily vary according to the taste of the reader

From grave to gay,

From lively to severe.

The familiar words "When George III. was King," would, if strictly interpreted, limit the survey to the period from 1760 to 1820, but it may be necessary to extend these "glimpses" up to the {6} commencement of the Victorian Era, and thus cover just that period which may be considered of too recent date to have hitherto found a place in local history, and yet too far away for many persons living to remember. Nor will the sketches be confined to Royston. In many respects it is hoped they may be made of equal interest to the district for many miles round. The first thing that strikes one in searching for materials for attempting such a survey, is the enormous gulf which in a few short years—almost bounded by the lifetime of the oldest individual—has been left between the old order and the new. There has been no other such transition period in all our history, and in some respects perhaps never may be again.

It is worthy of notice how locomotion in all ages seems to have classified itself into what we now know as passenger and goods train, saloon and steerage. Away back in the 18th century when men were only dreaming of the wonders of the good time coming, when carriages were actually to "travel without horses," the goods train was simply a long line or cavalcade of Pack-horses. This was before the age of "fly waggons," distinguished for carrying goods, and sometimes passengers as well, at the giddy rate of two miles an hour under favourable circumstances! Fine strapping broad-chested Lincolnshire animals were these Pack-horses, bearing on either side their bursting packs of merchandise to the weight of half-a-ton. Twelve or fourteen in a line, they would thus travel the North Road, through Royston, from the North to the Metropolis, to return with other wares of a smarter kind from the London Market for the country people. The arrival of such caravans was the principal event which varied the life of Roystonians in the last century, for was not the Talbot a very caravansarai for Pack-horses! This old inn, kept at the time of which I am writing by Widow Dixon, as the Royston parish books show, then extended along the West side of the High Street, from Mrs. Beale's corner shop to Mr. Abbott's. The Talbot formed a rendez-vous for the Pack-horses known throughout the land, and in its stables at the back of the new Post Office, with an entrance from Melbourn Street, known as the Talbot Back-yard, there was accommodation for about a score of these Pack-horses.

{7}Occasionally a rare sign-board at a way-side public-house bearing a picture of the Pack-horse may be seen, but it is only in this way, or in some old print, that a glimpse can now be obtained of a means of locomotion which has completely passed away from our midst. But besides the Pack-horses being a public institution, this was really the chief means of burden-bearing, whether in the conveyance of goods to market or of conveying friends on visits from place to place. As to the conveyance of goods, we find that as late as 1789, even the farmers were only gradually getting on wheels. A few carts were in use, no wagons, and the bulk of the transit in many districts was by means of Pack-horses; in the colliery districts, coals were carried by horses from the mines; and even manure was carried on to the land in some places on the backs of horses! trusses of hay were also occasionally met with loaded upon horses' backs, and in towns, builders' horses might be seen bending under a heavy load of brick, stone, and lime! Members of Parliament travelled from their constituents to London on horseback, with long over-alls, or wide riding breeches, into which their coat tails were tucked, so as to get rid of traces of mud on reaching the Metropolis! Commercial travellers, then called "riders," travelled with their packs of samples on each side of their horses. Farmers rode from the surrounding villages to the Royston Market on horseback, with the good wife on a pillion behind them with the butter and eggs, &c., and a similar mode of going to Church or Chapel, if any distance, was used on a Sunday. Among the latest in this district must have been the one referred to in a note by Mr. Henry Fordham, who says: "I remember seeing an old pillion in my father's house which was used by my mother, as I have been told, in her early married days." [Mr. Henry Fordham's mother was a daughter of Mr. William Nash, a country lawyer of some note.]

Some months ago the writer was startled by hearing, casually dropped by an old man visiting a shop in Royston, the strange remark—"My grandfather was chairman to the Marquis of Rockingham." The remark seemed like the first glimpse of a rare old fossil when visiting an old quarry. Of the truth of it further inquiry seemed to leave little doubt, and the meaning of it was simply this: The Marquis of Rockingham, Prime Minister in the early years of George III., would, like the rest of the beau monde, be carried about town in his Sedan chair, by smart velvet-coated livery men ["I have a piece of his livery of green silk velvet by me now," said my informant, when further questioned about his grandfather] preceded at night by the "link boy," or someone carrying a torch to light the way through the dark streets! I have been unable to find any trace of the use of the Sedan Chair by any of the residents of Royston, albeit that gifted but ill-fated youth, John Smith, alias Charles Stuart, alias King Charles I., did, with the {8} Duke of Buckingham, alias Thomas Smith, come back to his royal father, King James I., at Royston, from that romantic Spanish wooing expedition and bring with him a couple of Sedan Chairs, instead of a Spanish bride!

The old stage wagons succeeding to the pack-horses, which carried goods and occasionally passengers stowed away, were a curiosity. A long-bodied wagon, with loose canvas tilt, wheels of great breadth, so as to be independent of ruts, except the very broadest; with a series of four or five iron tires or hoops round the feloes, and the whole drawn by eight or ten horses, two abreast with a driver riding on a pony with a long whip, which gave him command of the whole team! Average pace about 1 1/2 to 2 miles an hour, including stoppages, as taken from old time tallies, for their journeys! These ponderous wagons, with their teams of eight horses and broad wheels, were actually associated with the idea of "flying," for I find an announcement in the year 1772, that the Stamford, Grantham, Newark and Gainsboro' wagons began "flying" on Tuesday, March 24th, &c. Twenty and thirty horses have been known to be required to extricate these lumbering wagons when they became embedded in deep ruts, in which not infrequently, the wagon had to remain all night. Many a struggling, despairing scene of this kind has been witnessed at the bottom of our hills, such as that at the bottom of Reed Hill, before the road was raised out of the hollow; the London Road, before the cutting was made through the hill; and along the Baldock Road by the Heath, on to which wagons not infrequently turned and began those deep ruts which are still visible, and the example, which every one must regret, of driving along the Heath at the present day, with no such excuse as the "fly wagons" had.

Bad as were the conditions of travel, however, it should be understood that for some time before regular mail coaches were introduced in 1784 (by a Mr. Palmer) there had been some coaching through Royston. Evidence of this is perhaps afforded by the old sign of the "Coach and Horses," in Kneesworth Street, Royston. This old public-house is mentioned in the rate-books for Royston, Cambs., as far back as the beginning of the reign of George III., or about the middle of last century, and as its old sign, probably a picture of a coach and four, hanging over the street, was a reflection of previous custom, we may take it that public coaches passed up and down our High Street, occasionally, in the first half of the last century, but the palmy days of coaching were to come nearly a century after this. It is interesting to note that Royston itself had a much larger share in contributing to the coaching of the last century, than it had during the present, and its interest in the traffic was not confined to the fact of its situation on two great thoroughfares. The most interesting of all the local coaching announcements for last century, is one which refers to the existence of a Royston coach at a much earlier date. In 1796 the following announcement was made, which I copy verbatim:

Will set out on Monday, 2nd May, and will continue to set out during the summer, every Monday and Friday morning at four o'clock; every Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Saturday at six o'clock, from the Old Crown Inn, Royston; arrives at the Four Swans Inn, Bishopsgate Street, London, at ten and twelve o'clock. Returns every day (Sunday excepted) from the said Inn, precisely at two o'clock, and arrives at Royston at eight o'clock at night.

The proprietors of this undertaking, being persons who have rose by their own merit, and being desirous of accommodating the public from Royston and its environs, they request the favour of all gentlemen travellers for their support, who wish to encourage the hand of industry, when their favours will be gratefully acknowledged by their servants with thanks.

John Sporle, Royston.

Thomas Folkes, London, and Co.

Fare as under:—

From Royston to London, inside, L0 12s. 0d.

" Buntingford ditto, L0 10s. 0d.

" Puckeridge ditto, L0 9s. 0d.

Ware and other places the same as other coaches.

Outsiders, and children in lap, half-price.

N.B.—No parcels accounted for above five pounds, unless paid for and entered as such.

A much earlier announcement was that in 1763, of the St. Ives and Royston Coach, which was announced to run with able horses from the Bell and Crown, Holborn, at five o'clock in the morning, every Monday and Friday to the Crown, St. Ives, returning on Tuesday and Saturday. Fare from London to Royston 8s., St. Ives 13s. This was performed by John Lomax, of London, and James Gatward, of Royston, and in the following year the same proprietors extended the route to Chatteris, March and Wisbech. This James Gatward was probably a brother of the unfortunate Gatward (son of Mrs. Gatward, for many years landlady of the Red Lion Inn, at Royston), whose strange career and tragic end will be referred to presently.

In 1772 I find a prospectus of the Royston, Buntingford, Puckeridge and Ware "Machine" which set out from the Hull Hotel, Royston, "every Monday and Friday at half after five o'clock, and returns from the Vine Inn every Tuesday and Thursday at half after eight o'clock, and dines at Ware on the return. To begin on 20th of this instant, April, 1772. Performed by their most humble servant, A. Windus (Ware)."

In 1776 occurs this announcement "The Royston, Buntingford, Puckeridge and Ware Machine run from Royston (Bull Inn) to London, by Joshua Ellis and Co." In the same year was announced the Cambridge and London Diligence in 8 hours—through Ware and Royston to Cambridge, performed by J. Roberts, of London, Thomas Watson, Royston, and Jacob Brittain, of Cambridge.

In October, 1786, at two o'clock in the morning, the first coach carrying the mails came through Royston, and in the same month of the same year the Royston Coach was "removed from the Old Crown to the Red Lyon."

In 1788 we learn that "The Royston Post Coach, constructed on a most approved principle for speed and pleasure in travelling goes from Royston to London in six hours, admits of only four persons inside, and sets out every morning from Mr. Watson's the Red Lion."

In 1793, W. Moul and Co. began with their Royston Coach.

Some of the old announcements of Coach routes indicate a spirit of improvement which had set in even thus early, such as "The Cambridge and Yarmouth Machine upon steel springs, with four able horses." It was a common name to apply to public coaches during the last century to call them "Machines," and when an improved Machine is announced with steel springs one can imagine the former state of things! It was a frequent practice, notwithstanding the apparent difficulty of maintaining one's perch for a long weary journey and sleeping by the road, for these old coaches to be overloaded at the top, and coachmen fined for it. In his "Travels in England in 1782," Moritz, the old German pastor, in his delightful pages, says on this point: {11} "Persons to whom it is not convenient to pay a full price, instead of the inside, sit on the top of the coach, without any seats or even a rail. By what means passengers thus fasten themselves securely on the roof of these vehicles, I know not."

Reference has been made to the condition of the roads, and the terrible straits to which the old coaches and wagons of the last century were sometimes put on this account. The system of "farming" the highways was responsible for a great deal of this. An amusing instance occurred in October, 1789. A part of one of the high roads out of London was left in a totally neglected condition by the last lessee, excepting that some men tried to let out the water from the ruts, and when they could not do this, "these labourers employed themselves in scooping out the batter," and the plea for its neglect was that it was taken, but not yet entered upon by the person who had taken it to repair, it being some weeks before his time of entrance commenced! What was its state in November may be imagined. "When the ruts were so deep that the fore wheels of the wagons would not turn round, they placed in them fagots twelve or fourteen feet long, which were renewed as they were worn away by the traffic" (Gunning's "Reminiscences of Cambridge," 1798).

Some of the ruts were described as being four feet deep. In Young's Tours through England (1768) the Essex roads are spoken of as having ruts of inconceivable depth, and the roads so overgrown with trees as to be impervious to the sun. Some of the turnpikes were spoken of as being rocky lanes, with stones "as big as a horse, and abominable holes!" He adds that "it is a prostitution of language to call them turnpikes—ponds of liquid dirt and a scattering of loose flints, with the addition of cutting vile grips across the road under the pretence of letting water off, but without the effect, altogether render these turnpike roads as infamous a turnpike as ever were made!"

If the early coaches on the main roads were in such a sorry plight, what was to be expected of traffic on the parish roads? In some villages in this district lying two or three miles off the Great North Road, it was not unusual for carts laden with corn for Royston market to start over night to the high road so as to be ready for a fair start in the morning, in which case one man would ride on the "for'oss" (fore horse) carrying a lantern to light the way; and a sorry struggle it was! Years later when a carriage was kept here and there, it was not uncommon for a dinner party to get stuck in similar difficulties, and to have to call up the horses from a neighbouring farm to pull them through!

The difficulties for the older coaches and wagons were peculiarly trying in this district on account of the hills and hollows, but one of the most dreadful pieces of road at that time and for long afterwards, was {12} that between Chipping and Buntingford, the foundations of which were often little else but fagots thrown into a quagmire!

But besides bad vehicles and worse roads, there was a weird and a horrid fascination about coaching in the eighteenth century, arising from the vision of armed and well-mounted highwaymen, or of a malefactor, after execution, hanging in chains on the gibbet by the highway near the scene of his exploits!

Let us take one well authenticated case—the best authenticated perhaps now known in England—in which a member of a respectable family in Royston turned highwayman—an amateur highwayman one would fain hope and believe—and paid the full penalty of the law, and was made to illustrate the horrible custom of those times by hanging in chains on the public highway! For this we must take the liberty of going a few years back before George III. came to the throne. For some years before and after that time, the noted old Posting House of the Red Lion, in the High Street, Royston, was kept by a Mrs. Gatward. This good lady, who managed the inn with credit to herself and satisfaction to her patrons, unfortunately had a son, who, while attending apparently to the posting branch of the business, could not resist the fascination of the life of the highwaymen, who no doubt visited his mother's inn under the guise of well-spoken gentlemen. Probably it was in dealing with them for horses that young Gatward caught the infection of their roving life, but what were the precise circumstances of his fall we can hardly know; suffice it to say that his crime was one of robbing His Majesty's mails, that he was evidently tried at the Cambridgeshire Assizes, sentenced to death and afterwards to hang in chains on a gibbet, and according to the custom of the times, somewhere near the scene of his crime. The rest of his story is so well told by Cole, the Cambridgeshire antiquary, in his MSS. in the British Museum, that the reader will prefer to have it in his own words:—

"About 1753-4, the son of Mrs. Gatward, who kept the Red Lion, at Royston, being convicted of robbing the mail, was hanged in chains on the Great Road. I saw him hanging in a scarlet coat; after he had hung about two or three months, it is supposed that the screw was filed which supported him, and that he fell in the first high wind after. Mr. Lord, of Trinity, passed by as he laid on the ground, and trying to open his breast to see what state his body was in, not being offensive, but quite dry, a button of brass came off, which he preserves to this day, as he told me at the Vice-Chancellor's, Thursday, June 30, 1779. I sold this Mr. Gatward, just as I left college in 1752, a pair of coach horses, which was the only time I saw him. It was a great grief to his mother, who bore a good character, and kept the inn for many years after."

{13}There is a tradition, at least, that Mrs. Gatward afterwards obtained her son's body and had it buried in the cellar of her house in the High Street. The story is in the highest degree creditable to human nature, but there is no proof beyond the tradition. As to the spot where the gibbeting took place, the only clue we have is given in Cole's words: "Hanged in chains on the Great Road." There seems no road that would so well answer this description as the North Road or Great North Road, and, as the spot must have been somewhere within a riding distance of Cambridge, the incident has naturally been associated with Caxton gibbet, a half-a-mile to the north of the village of Caxton, where a finger-post like structure, standing on a mound by the side of the North Road, still marks the spot where the original gibbet stood.

It seems almost incredible that we have travelled so far within so short a time! That almost within the limits of two men's lives a state of things prevailed which permitted a corpse to be lying about by the side of the public highway, subject now to the insults, now to the pity, of the passer-by! Yet many persons living remember the fire-side stories of the dreadful penalties awaiting any person who dared to interfere with the course of the law, and remove the malefactor from the gibbet!

Towards the end of the century the horrors of gibbeting, as illustrated in Gatward's case, were tempered somewhat by a method of public execution near the spot where the crime was committed, but, apparently of sparing the victim and his friends the exposure of the body for months afterwards till a convenient "high wind" blew it down. The latest instance I have found of an execution of this kind by the highway occurred in Hertfordshire, and to a Hertfordshire man. This was James Snook, who had formerly been a contractor in the formation of the Grand Junction Canal, but turning his attention to the "romance of the road" was tried at the Hertfordshire Assizes in 1802 for robbing the Tring mail. He was capitally convicted and ordered to be executed near the place where the robbery was committed. He was executed there a few days afterwards. The spot was, I am informed, on the Boxmoor Common, and his grave, at the same spot, is still, or was until recent years, marked by a head stone standing, solitary and alone to tell the sorry tale!

Situate on the York Road, one of the greatest coach roads in England, with open Heath on all sides, it would have been strange indeed if Royston and the neighbourhood had not got mixed up with traditions of Dick Turpin, and that famous ride to York in which we get a flying vision as the horseman passes the boundaries of the two counties. The stories of Dick Turpin, regarded as an historical figure, would not quite fall within the limits assigned to these sketches, but as {14} the traditions in this district which have become associated with the name of Turpin, are a real reflection of a state of things which did undoubtedly prevail in this locality during the latter half of the last century, a passing reference to them will scarcely be out of place in this concluding sketch of the old locomotion and its dangers. The stories have unquestionably been handed down orally from father to son in this neighbourhood, without, I believe, having appeared in cold type hitherto. There is, for instance, the tradition of a young person connected with one of the well-known families still represented in the town, being accosted by a smart individual in a cocked hat, who insisted upon kissing her, but gave her this consolation that she would be able to say that she had been "kissed by Dick Turpin."

Among other stories associated with Dick Turpin, which have gained a local habitation in Royston and its neighbourhood, the best known is that which clings around the old well (now closed) in the "Hoops" Yard in the High Street and Back Street, though other wells have been coupled with the scene. As the story goes, Turpin on one occasion played something of the part of Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde, with his horses. Having a sort of duplicate of Black Bess, he used this animal for his minor adventures in this neighbourhood, reserving Black Bess for real emergencies. He had been out on one of these errands, probably across the Heath, leaving Black Bess in the stables in the Hoops Yard in the Back Street. As luck would have it he was so hotly pursued by the officers of the law, that the pattering of their horses was pretty close upon him down the street. Finding himself almost at bay, with the perspiring horse to testify against him, he conceived and promptly carried out the bold expedient of backing the tell-tale horse into the well in the inn yard! He had only just accomplished this desperate feat and rushed into the house and jumped into bed, when his pursuers rode up and demanded their man. With the utmost coolness the highwayman denied having been out, and advised them to examine his mare, which they would find in the stall, and they would see that she had never been out at all that night. The party proceeded to the stables where they found, as Turpin had told them, that Black Bess was indeed without a wet hair upon her and could not have been ridden! They were obliged to accept this evidence as establishing Turpin's innocence, and he escaped the clutches of the law by the sacrifice of one of his steeds!

Another story, reflecting the hero's manner of tempering the demands of his profession with generosity, is that on one occasion a Therfield labouring man was returning home across the wilds of Royston Heath, with his week's wages in his pocket, when he met with Dick Turpin. In answer to the demand for his money the man pleaded that it was all he had to support his wife and children. The {15} highwayman's code, however, was inexorable, and the money had to be handed over, but with a promise from the highwayman that if he would meet him at a certain spot another night it should be returned to him. The man made the best of what seemed a hard bargain, but on going to the trysting place, his money was returned to him with substantial interest! Upon this one may very well add the sentiment of the boy who, on finding the place in his hand for a tip suddenly occupied by one of Turpin's guineas, is made to remark:—"And so that be Dick Turpin folks talk so much about! Well, he's as civil speaking a chap as need be; blow my boots if he ain't!"

Of course these are only legends, but the desire to be impartial, is, I hope, perfectly consistent with a tender regard for the legendary background of history. To subject a legend or tradition to the logical process of reasoning and analysis, is like crushing a butterfly or breaking a scent bottle, and expecting still to keep the beauty of the one and the fragrance of the other. I do not, therefore, push the inquiry further than to remark that legend and tradition are generally the reflection of a certain amount of truth, and the truth in this case is that highwaymen and their practices were closely identified with this district. The case of Gatward is the strongest possible proof that travelling along the great cross roads meeting at Royston, was very frequently interrupted by the exploits of highwaymen possessing some at least of the accomplishments indicated by one of the characters in Ainsworth's story, that it was "as necessary for a man to be a gentleman before he can turn highwayman, as for a doctor to have his diploma or an attorney his certificate." I am able to add, on the authority of the Cambridge Chronicle for the year 1765, the files of which are preserved in the Cambridge University Library, that Royston Heath and the road across it—for the Heath was then on both sides of the Baldock Road—and especially that part of the road along what was then known as Odsey Heath, near the present Ashwell Railway Station, was at that time (and also later) infested by highwaymen, whom the old Chronicle describes as "wearing oil-skin hoods over their faces, and well-mounted and well-spoken."

Intimately connected with the old locomotion, and with the exploits of highwaymen, were the landmarks, such as old mile-stones and old hostelries, the one to tell the pace of the traveller, and the other to invite a welcome halt by the way!

Those who have travelled much along the old turnpike road from Barkway by the Flint House to Cambridge, must have noticed the monumental character of the mile-stones with their bold Roman figures, denoting the distances. These mile-stones, an old writer says, were the first set up in England. I do not know whether this be true or not, but as the writer at the same time commented upon the system adopted {16} of marking the stones with Roman figures, and as the mile-stones still remaining along that road bear dates, in Roman figures, between thirty and forty years before the time the above was written, they must be the identical stones he is referring to.

The following particulars of these old milestones (contributed by Mr. W. M. Palmer, of Charing Cross Hospital, London) are taken from the MS. collections for a History of Trinity Hall, Cambridge. [Add. MSS., 5859, Brit. Mus.]

Dr. William Mowse, Master of Trinity Hall (1586), and Mr. Robert Hare (1599), left 1,600 pounds in trust to Trinity Hall, the interest of which was to mend the highways "in et circa villam nostram Cantabrigiae praecipue versus Barkway."

On October 20th, 1725, Dr. Wm. Warren, Master of Trinity Hall, had the first five mile-stones set up, starting from Great St. Mary's Church.

On June 25th, 1726, another five stones were set up. And on June 15th, 1727, five more were set up. The sixteenth mile was measured and ended at the sign of the Angel, at Barkway, but no stone was then set up.

Of these stones, the fifth, tenth, and fifteenth, were large stones, each about six feet high, and having the Trinity Hall arms cut on them, viz., sable, a crescent in Fess ermine, with a bordure engrailed of the 2nd. The others were small, having simply the number of miles cut on them. Between the years 1728 and 1732, Dr. Warren caused all these small mile-stones to be replaced by larger ones, each bearing the college arms. The sixteenth mile-stone was set up on May 29th, 1728.

In addition to the Trinity College arms there were placed upon the first stone the arms of Dr. Mowse, and on the Barkway stone those of Mr. Hare. The crescent of the Trinity Hall arms may still be easily recognised on the Barkway stone, and on others along the road to Cambridge.

Bright spots in the older locomotion were the road-side inns, and if the testimony of old travellers is to be credited, the way-farer met with a degree of hospitality which made some amends for the difficulties and dangers of the road, and of course figured in the bill to a degree which gave the older Boniface a comfortable subsistence such as his successors to-day would never dream of. But the most characteristic thing about these old inns was the outward sign of their presence, ever seeming to say "know ye all men by these presents," &c. At the entrance to every village the eye of the traveller would fall upon an erection having a mixed resemblance to a gibbet, a gallows, and a triumphal arch, extended across the village street, and in many villages {18} he would have to pass beneath more than one of these erections, upon which were suspended the signs of the road-side inns——

Where village Statesmen tallied with looks profound,

And news, much older than their ale, went round.

These picturesque features of our rural country life have now disappeared almost as entirely as the parish stocks. Perhaps the most perfect specimen in existence, and one which could have hardly been rivalled for picturesqueness even in the old days, is that which still points the modern wayfarer to the "Fox and Hounds," in the village of Barley, near Royston, where the visitor may see Reynard making his way across the beam overhead, from one side of the street to the other, into the "cover" of a sort of kennel in the thatch roof, with hounds and huntsmen in full cry behind him! This old picturesque scene was painted some time ago by Mr. H. J. Thurnall, and the picture exhibited in one of the Scottish Exhibitions, and as the canvas may out-live the structure, the artist will have preserved what was an extremely interesting feature of rural life in the last century.

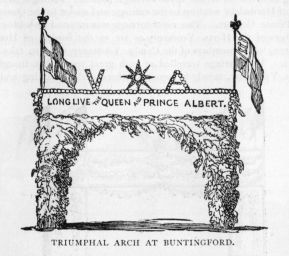

The illustration on the preceding page gives a good idea of this characteristic old sign, and of those of the period under review, and also of the point of view from which Mr. Thurnall's picture is taken, viz., from the position of a person looking down the hill towards Royston.

Upon this question of old signs it may not be out of place to add that when George III. was King local tradesmen in Royston had their signs, and especially the watchmakers, of which the following are specimens:—In 1767 we find an announcement of William Warren, watch and clock-maker at the "Dial and Crown," in the High Street, Royston, near the Red Lion; and again that:—

"William Valentine, clock and watch-maker at the 'Dial and Sun,' in Royston, begs leave to inform his friends that he has taken the business of the late Mr. Kefford" [where he had been previously employed].

These glimpses of our forefathers "getting on wheels," of the highways, their passengers, their dangers, and their welcome signs of halting places by the way, may perhaps be allowed to conclude with the following curious inscription to be seen upon an old sign on a chandler's shop in a village over the borders in Suffolk, in 1776:—

Har lifs won woo Cuers a Goose,

Gud Bare. Bako. sole Hare.

The modern rendering of which would be—

Here lives one who cures Agues,

Good Beer, Tobacco sold here.

It may be well here to take a nearer view of local life between the years 1760 and 1800. In doing so we shall probably see two extremes of social and political life, with rather a dead level of morality and public spirit between them—at the one extreme an unreasoning attachment to, and a free and easy acquiescence in, the state of things which actually existed, with too little regard for the possibility of improving it; and at the other extreme an unreasonable ardour in debating broad principles of universal philanthropy, with too little regard for their particular application to some improvable things nearer home. Between these two extremes was comfortably located the good old notion which looked for moral reforms to proclamations and the Parish Beadle! As approximate types of this state of things there was the Old Royston Club at the one extreme, and the Royston Book Club, at least in the debating period of its existence, at the other, and between these extremes there were some instructive measures of local government bearing upon public morals, of which the reader will be afforded some curious illustrations in the course of this chapter.

The Old Royston Club must have been established before 1698, for at that time there was a list of members, but what was the common bond of fellowship, which enabled the Club to figure so notably among the leading people of the neighbouring counties, we are left to infer from one or two of its rules, and the emblems by which the members were surrounded, rather than from any documentary proof. It flourished in an age of Clubs, of which the Fat Men's Club (five to a ton), the Skeleton Club, the Hum-drum Club, and the Ugly Club, are given by Addison as types in the Spectator. The usual form of this institution in the Provinces was the County Club. The Royston Club itself has been considered by some to have been the Herts. County Club, but the County Clubs usually met in the county towns. Mr. Hale Wortham has in his possession some silver labels, bearing the words "County Club," said to have been handed down as part of the Royston Club property; but on the other hand there is the direct evidence of the contemporary account of the Club given in the Gentleman's Magazine, for 1783, describing it as the Royston Club, by which title it has always been known.

{20}It may not have been strictly speaking a political institution, and yet, according to the custom of the times, could never have assembled without a toast list pledging the institutions of the country, and the prominent men of the day.

But push round the claret,

Come, stewards, don't spare it,

With rapture you'll drink to the toast that I give!

Indeed, among some old papers placed at the writer's disposal, is this candid expression of opinion by an old Roystonian:—"Probably the members were strong partisans of the Stuarts; but, whatever may have been their loyalty to the King, there is no doubt of their devotion to Bacchus." If so, they reflected the custom of the times rather than the weakness of their institution which could scarcely have existed for a century, and included such a distinguished membership, without promoting much good feeling and adding to the importance of the town in this respect. The Club held its meetings at the Red Lion—then the chief posting inn in the town—in two large rooms erected at the back of the inn at the expense of the members. In the first of these two rooms, or ante-chamber, were half-length portraits of James I. and Charles I.; whole lengths of Charles II. and James II., and of William and Mary, and Anne; a head of the facetious Dr. Savage, of Clothall, "the Aristippus of the age," who was one of its most famous members, and its first Chaplain. In the larger room were portraits of many notable men in full wigs, and yellow, blue and pink coats of the period.

One of the rules of the Club was that the steward for the day had to furnish the wine, or five guineas in lieu of it; and as politics went up the wine went down, and vice versa, for, in 1760, after a Hertfordshire election had gone wrong, and damped the ardour of the Club, now in its old age, the attendance of members appears to have fallen off, and the wine in the cellar had accumulated so much that no steward was chosen for three months. By September, 1783, there remained of claret, Madeira, port, and Lisbon, about three pipes. There is also a reference to "venison fees," from which it appears that the gatherings were as hospitable as the list of membership was notable for distinguished names—Sir Edward Turner, Knight, and Speaker of the House of Commons; Sir John Hynde Cotton, Sir Thomas Middleton, Sir Peter Soame, Sir Charles Barrington, the Earl of Suffolk, Sir Thomas Salisbury, of Offley, and many other men of title, besides local and county family names not a few. Such an institution must have given to the old town a prestige out of all proportion to what it has ever known since. A fuller account of the Royston Club belongs, however, to a history of Royston, rather than to these sketches.

{21}It is more to the purpose here to note that the head-quarters of the Old Club remained for many years after the Club itself had disappeared, a rallying point for social and festive gatherings of a brilliant kind, in which political distinctions were less prominent. For anything I know, this over-ripe institution, with its old age and cellar full of wine, may have been responsible for the following dainty morceau; at any-rate it is in perfect harmony with the Club's traditions:—

"April, 1764. On Monday last at the Red Lion, at Royston, there was a very brilliant and polite Assembly of Ladies and Gentlemen, which was elegantly conducted. The company did not break up till six the next morning, and would have continued longer had not a Northern Star suddenly disappeared."

The poetical conclusion of the paragraph just quoted implies, I suspect, a very elegant personal compliment to one of the belles of the ball, and who should the "Northern Star" be if not my lady Hardwicke, the first lady of that name, in whose newly acquired title the Royston people took a pride—or at least it must have been a lady from the Mansion on the North Road!

What a picture the Old Assembly Room at the Red Lion must have presented! Ladies with gorgeous and triumphant achievements in the matter of head dresses, hair dressing, and hair powder, and frillings, such as young ladies of to-day never dream of; and gentlemen in their wigs, gold lace, silken hose, buckles, and elegant but economical pantaloons! A dazzling array of candles, artistic decorations, and Kings and Queens looking down from the walls! "A brilliant and polite assembly elegantly conducted." These brilliant assemblies were a common and not unfrequent feature in our old town and district life {22} all through the reign of George III., and more especially towards the close of the eighteenth century. Verily, "the world went very well then," or seems to have done, at least, so far as one half of it was concerned. Of the other half we may get some other glimpses hereafter.

What were known during the present century as the Royston Races were a continuation, with more or less interruption, of the old Odsey Races established as far back as James I., and probably before that time. The original course for these races was along the level land by the side of the Baldock Road, near Odsey, and as time went on the course was brought nearer the town of Royston. Until the later years of last century the course was just beyond King James' Stables, afterwards, from the association with the course, called the Jockey House. The running of the "Royston" Races over a course on the west end of the present Heath will be referred to under the head of "Sports and Pastimes."

In September, 1764, when the Odsey Races were run, the principal event was the 100 guineas subscription purse, besides minor events of 50 guineas. That large numbers of persons attended them is evident from what is related for that year when we learn that James Butler, a servant of Mr. Beldam, of Royston, was, while engaged in keeping the horses without the ropes of the course, unfortunately thrown down, and {23} run over by several horses, by which he was so miserably bruised that he expired next day; and on Friday the stand, which was erected for the nobility, ladies and gentry, being overcrowded with spectators, suddenly broke down, but luckily none of the company received any damage. An old woman, however, who got underneath the stand to avoid the crowd, was so much hurt that she died.

In September, 1766, at these races we read that "never was finer sport seen," and that there was, as now, a good deal of betting connected with race meetings, seems evident from the hint that the result of the race was such that "the knowing ones were pretty deeply taken in."

The old Odsey Races only came once a year, in September, and other sports were required to meet the popular taste. Cricket had hardly taken practical shape, but representative contests did take place in the favourite pastime of cock-fighting—or "cocking" as it was always called in the last century—in which contests the Hertfordshire side of the town brought its birds into the pit against those of the Cambridgeshire side. Of this the following is a specimen under date 1767:—

"On Monday next at the Old Crown, and on Tuesday at the Talbot Inns, in Royston, will be fought a main of cocks between gentlemen of Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire; fourteen cocks on each side for two guineas a battle, and ten the odd. Ten byes for each guinea."

The Red Lion also had its "assemblies and cookings as usual," on the day of Odsey Races, from which it appears that the patrons of the races finished up with cock fights at the inns in the town. Indeed it would be impossible to understand the social life of the period without taking into account the universal popularity of cock-fighting. Often the stakes took the form of a fat hog or a fat ox, and the technicalities of the sport read something like this:—"No one cock to exceed the weight of 4 pounds, 10 ounces, when fairly brought to scale; to fight in fair repute, silver weapons, and fair main hackles." On one occasion in the year 1800 a main of cocks was fought at Newmarket for 1,000 guineas a side, and 40 guineas for each battle, when there was "a great deal of betting."

Another form of sport was that of throwing at cocks on Shrove Tuesday. Badger-baiting continued in Royston occasionally till the first decade of the present century, and was sometimes a popular sport at the smaller public-houses on the Market Hill.

Wrestling was emphatically the most generally practised recreation, and the charming sketches in the Spectator of young men wrestling on the village green was no mere picture from the realms of fancy. Such scenes have been frequently witnessed on Royston Heath where the active swain threw his opponent for a bever hat, or coloured {24} waistcoat offered by the Squire, and for the smiles of his lady-love. Wrestling matches were very common events between the villages of Bassingbourn (a good wrestling centre), the Mordens, Whaddon, Melbourn and Meldreth, but when these events came off there was generally something else looked for besides the prize-winning. Sports in 1780 to 1800 were not so refined and civil as those of to-day, and it was pretty well understood that every match would end in a general fight between the two contending villages; indeed, without this the spectators would have come home greatly disappointed, and feeling that they had been "sold."

A favourite spot for such meetings was in a Bassingbourn field known as the Red Marsh, on the left of the Old North Road beyond Kneesworth, nearly opposite the footpath to Whaddon, where the Bassingbourn men—who, when a bonâ fide contest did come off, could furnish some of the most expert wrestlers in the district—frequently met those of the Mordens and other villages, and many a stubborn set-to has been witnessed there by hundreds of spectators from the surrounding districts.

During the whole of the last half of the 18th century, bowling greens did for the past what lawn tennis does for the present, always excepting that the ladies were not thought of as they are now in regard to physical recreation. There was an excellent bowling green at the "Green Man," smooth and level as a billiard table. Earlier in the century another bowling green was situate in Royston, Cambs., for which Daniel Docwra was rated. The gentry had private bowling greens on their lawns.

As to other kinds of out-door sport of a more individual kind, shooting parties were not quite so select as at the present day, and the farmers had good reason to complain of the young sportsmen from Cambridge. Foulmire Mere, as it was sometimes called during the last century, was a favourite spot for this kind of thing.

It seems that about this time the undergraduates were in the habit of freely indulging in sport to the prejudice of the farmers, for in 1787 a petition, almost ironical in its simplicity, was advertised in the Cambridge Chronicle of that date, commencing—

"We poor farmers do most humbly beg the favour of the Cambridge gunners, coursers and poachers (whether gentleman barbers or gyps of colleges), to let us get home our crops, &c." In those days, and for many years after, during the present century, there appears to have been very little of what we now know as "shooting rights," over any given lands, and the man or boy who could get behind an old flint-lock with a shooting certificate went wherever he felt inclined in pursuit of game.

{25}The foregoing were some of the ways in which the people of Royston and the neighbourhood took the pleasures of life, how they sought to amuse themselves, and under what conditions. If the glimpses afforded seem to suggest that they allowed themselves a good deal of latitude it must not be supposed that our great grandfathers had no care whatever for public decency, or no means of defining what was allowable in public morals. In place of modern educating influences they could only trust for moral restraints to proclamations and the parish beadle. Perhaps one of the best instances of this kind of machinery for raising public morals is afforded by the Royston parish books, and I cannot do better than let the old chronicler speak for himself. The entries refer to the proceedings of a joint Committee which practically governed the town of Royston, and was elected by the parishes of Royston Herts. and Cambs., which, as we shall see hereafter, were united for many years for the purposes of local government.

"An Extraordinary Meeting of the Committee was held on 31st October, 1787, for the purpose of taking into consideration the Proclamation for preventing and punishing profaneness, vice, and immorality, by order of the Rev. Mr. Weston, present:—Daniel Lewer, Wm. Stamford, Jos. Beldam, Wm. Nash, Wm. Seaby, Thomas Watson, Michael Phillips, Wm. Butler, and Robt. Bunyan (chief constable).

"Words of the Act—No drover, horse courier, waggoner, butcher, higlar, or their servants shall travel on a Sunday.

"Ordered that the above be prevented so far as relates to Carriages—Punishments 21s., and for default stocks 2 hours.

"No fruit, herbs or goods of any kind shall be cried or exposed to sale on a Sunday. N.B.—Goods forfeited.

"No shoemaker shall expose to sale upon a Sunday any boots, shoes or slippers—3s, 4d. per pair and the value forfeited.

"Any persons offending against these Laws are to be prosecuted, except butchers, who may sell meat till nine o'clock in the morning, at which time all barbers' shops are to be shut up and no business to be done after that time.

"No person without a reasonable excuse shall be absent from some place of Divine Worship on a Sunday—1s. to the poor.

"The Constables to go about the town, and particularly the Cross, to see that this is complied with, and if they find any number of people assembled together, to take down their names and return them to the Committee that they may be prosecuted.

"No inn-keeper or alehouse-keeper shall suffer anyone to continue drinking or tippling in his house—Forfeit 10s. and disabled for 3 years.

"Ordered that the Constables go to the public-houses to see that no tippling or drinking is done during Divine Service—and to prevent drunkenness, &c., any time of the day.

{26}"Persons who sell by fake weights and measures in market towns, 6s. 8d. first offence; 13s. 4d. second offence; 20s. third, and pillory.

"Order'd that the Constables see that the weights and measures are good and lawful."

A few years after the above bye-laws were adopted the Cambridge Mayor and Corporation were considering the same question, and issued notices warning persons against exposing to sale any article whatever or keeping open their shops after 10 o'clock in the morning on Sunday.

Secular life was not so low but that it had its bright spots. Bands of music were not so well organized or so numerous as they are to-day, but there was much more of what may be styled chamber music in those days than is imagined. Fiddles, bass viols, clarinets, bassoons, &c., were used on all public occasions, and in 1786 we find that the Royston "Musick Club" altered its night of meeting to Wednesday. That is all there is recorded of it, but it is sufficient to show us a working institution with its regular meetings.

The effect of the French Revolution even in remote districts in England has been referred to, and it may be added that a good deal of the "dangerous" sentiment of the times was associated with the name of Paine, the "Arch-traitor" as he was called, and as an instance of how these sentiments were sometimes received even in rural districts we learn that in the year 1793 Paine's effigy was "drawn through the village of Hinxton, attended by nearly all the inhabitants of the place singing 'God Save the Queen,' 'Rule Britannia,' &c., accompanied with a band of music. He was then hung on a gallows, shot at, and blown to pieces with gunpowder, and burnt to ashes, and the company afterwards spent the evening with every demonstration of loyalty." At such a time it was easy for even some of our local men of a reforming spirit to be misunderstood, and the name of "Jacobin" was attached to very worthy persons in Royston who happened to entertain a little freedom of opinion.

With the waning of the old Royston Club, another institution had sprung up which at this time reflected the life of the place in a manner which, while it was highly creditable to the intellectual life of the townspeople, was, on the other hand, open to the suspicion of representing what were called "dangerous principles" in the estimation of those belonging to the old order. This was the Royston Dissenting Book Club, which played an important part as a centre of mental activity during the last quarter of the 18th and the first quarter of the 19th centuries. The Club was an institution, the influence and usefulness of which were felt and recognised far beyond the place of its birth, and brought some notable men within the pale of its activity. It was founded on the 14th December, 1761, the first meetings being held at the Green Man, then and for many years afterwards one of the foremost {27} inns in the town. Among the earliest members of the Club occur the names of the Rev. Robert Wells, Joseph Porter, John Fordham, Edward Fordham, George Fordham, Valentine Beldam, James Beldam, John Wylde, Thomas Bailey, John Butler, Wm. Coxall, and Edward Rutt. While the circulation of books amongst its members was one of the primary objects of the Club—for which purpose its existence has continued down to the present time—it was chiefly as an intellectual forum or debating club that it is of interest here to notice. From this point of view it fairly reflects the influential position of the dissenting body in Royston towards the end of the last century, and that growing tendency to the discussion of abstract principles in national affairs which prevailed more or less from the French Revolution to the Reform Bill, but especially during the last few years of the last century.

In Henry Crabb Robinson's Diary, for the year 1796, there occurs this reference to the great debates at the Club's half-yearly meetings:—

"There had been established at Royston a Book Club, and twice a year the members of it were invited to a tea party at the largest room the little town supplied, and a regular debate was held. In former times this debate had been honoured by no less a man than Robert Hall. * * To one of these meetings my brother was invited, and I as a sort of satellite to him. There was a company of forty-four gentlemen and forty-two ladies. The question discussed was—'Is private affection inconsistent with universal benevolence?'" This question, it seemed, was meant to involve the merits of Godwin's Political Justice, which was making a stir just then, and among those who took part besides the writer of this diary were Benjamin Flower, editor and proprietor of the Cambridge Intelligencer, and also four or five ministers of the best reputation in the place. "Yet," adds the writer, then a young man but fluent speaker, "I obtained credit, and the solid benefit of the good opinion of Mr. Nash." Among other names was that of George Dyer, author of a History of Cambridge, and a biography of Mr. Robinson, successor to Robert Hall, at Cambridge, a biography which Wordsworth pronounced to be the best in the language.

At least on two occasions the celebrated Robert Hall, then a Baptist minister at Cambridge, attended the Club and took a leading part in the debates. From one of the old minute books of the Club [for a perusual of this book I am indebted to Miss Pickering, whose father's shop in John Street was the depôt of the Club till recent years] for the years 1786-90, I find that on two occasions the question for debate stands in the name of Mr. Hall, and the subjects were, on the first occasion—"Does extensive knowledge of the world tend to increase or diminish our virtue?" and on the second occasion the subject was—"Whether mankind are at present in a state of moral improvement."

{28} At the monthly debates it was the practice of the Club, having debated some stated subject, to vote upon it, and enter the result in the margin of the minute book, and many of these entries are curious and instructive. Against the second question standing in the name of the famous preacher, there is no such entry, but against the first, the opinion of the forum seems to have been that an extensive knowledge of the world tends to diminish our virtue, but it was only by a "majority of 1" that this opinion was arrived at.

This old minute book throws some interesting light upon the intellectual attitude of a large number of thoughtful men upon various public questions and social problems. The majority of the entries in the book are in the handwriting of the venerable Edward King Fordham, the Royston banker, whose long life covered more than the whole period selected for these sketches. The following resolution shows the modus operandi of the institution known as the forum, which was a very general institution both in the Metropolis and in many centres in the country—"It was unanimously agreed that a question or subject shall be proposed for discussion or debate, every club night, as soon after eight o'clock, as the book business is finished. The question to be proposed on a preceding meeting, and balloted for (if required by any member) before admitted in the list for discussion."

Then follow, through page after page of the old book, questions put down for discussion, and in most cases the opinion arrived at. Among the names in which questions stand are E. K. Fordham, Joseph Beldam, senr., Wm. Nash, Elias Fordham, James Phillips, Samuel Bull, Valentine Beldam, John Fordham (Kelshall), John Walbey, Wm. Wedd, Robert Hall, Mr. Crabb, Mr. Tate, Richard Flower, Mr. Carver, Mr. Jameson, Mr. Barfield. These were some of the men who figured in the intellectual tournaments of the time. Let us glance at a few of the questions debated and the result, and we shall get some idea of the subjects which engaged men's attention, and what they thought upon them. The subjects cover a great variety of matters, and frequently were as wide apart as the poles in their nature. Here are the first two questions debated:—

"Whether a General Enclosure will be beneficial or prejudicial to the Nation?"

"Whether Hope or Fear be the most powerful incentive to Action?"

I venture to transcribe a few more questions at random, with the decision of the forum upon them.

"Whether it be right for the Legislature to make Laws to punish prophane swearing?—James Phillips.—Determined." [That is, determined that it was right.]

{29}"Whether free Inquiry is not upon the whole beneficial to Society though it may be attended with some ill effects to Individuals?—E. K. Fordham.—Determined unanimously for full inquiry."

"Whether a Candidate for Parliament ought to engage to support any particular measures in Parliament previous to his election?—He ought."

"Whether it would be better to maintain the Poor of this Kingdom by Charity or Rate?—By Charity."

"Whether Publick or Private Punishments are to be preferred in a Free Country?—Publick Punishment preferred, August 27th, 1787."

"Whether a Man can or cannot be a real Christian, and at the same time a gentleman in the World's esteem?—Joseph Beldam, senr.—Can 13, Cannot 11."

"Whether the Art of expressing our thoughts by written characters is not superior to any other art whatever?—John Walby."

To the above question is given the very curious answer—15 for Writing, 9 for Agriculture. Evidently there were some farmers of the old school in the forum!

The character of the schools of the period is reflected in the following:—

"Whether a Public or a Private Education for youth is to be preferred?—Unan. for a private one, in favour of virtue."

"Whether the use of well-composed forms, or extempore prayer in dissenting congregations be most agreeable to the Dignity of Religious worship, and the general Edification?—2 for Forms, 16 for Extempore."

"Which is the greater Evil, to Educate Children above or beneath their probable station or Circumstances?—5 above Circumstances, 9 below."

Here we get a hundred years' old opinion that in effect it is better to educate children above their probable station and let them take their chance in the competition of life than to educate them below it. This was evidently a vigorous reforming opinion for those days, considering that Board Schools were yet nearly a hundred years off!

Fifty years even before the Reform Bill it was possible to get such an opinion as the following upon the suffrage:—

"If we could get a Reform in Parliament would it be expedient or just to exclude any Order of subjects from giving their vote for a Representative in the House of Commons?—John Fordham (Kelshall).—Yeas 2, Noes 7." That is seven out of nine were in favour of universal suffrage!

Here is an instance of the logical and discriminating faculties which these forums called forth in such a high degree:—

"Is good sense or good nature most productive of Happiness—taking both the Individual and Society into the Account?—Good Nature to Individuals 13, Good Sense to ditto 8; Good Sense to Society 19, Good Nature to ditto 1."

{30}The foregoing answer is a very nice discrimination and involved a "reasoning out" which is in striking contrast with most modern debates in which the facts can be read up from various almanacks. The meaning of it is of course that good nature between man and man and good sense in general society are most productive of happiness.

The following is quoted of a different type:—

"Which of the three learned Professions—Law, Physic, or Divinity—has been most useful to Society?—Law 7, Physic 1, Divinity 9."

This was rather hard upon the doctors, it must be confessed, but, then, society had no reason to be very grateful to a class of men who in those days dealt so largely in bleeding, blistering and purging! It would be interesting to know what sort of a vote would be given on such a question now. Probably it would be found that the doctors had pulled up a bit during the last hundred years.

Here is another on the State and individual opinion:—

"Has the State a Right to take Cognizance of any Opinions whatever, either civil, political, or religious?—A, 6; N, 12."

The following shows the financial insecurity of the times:—

"Ought country Banks to be encouraged in Great Britain"—A majority of more than two to one were of opinion that they ought not! This was in 1791.