Project Gutenberg's Olive, by Dinah Maria Craik, (AKA Dinah Maria Mulock)

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Olive

A Novel

Author: Dinah Maria Craik, (AKA Dinah Maria Mulock)

Illustrator: G. Bowers

Release Date: July 23, 2007 [EBook #22121]

Last Updated: March 6, 2018

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OLIVE ***

Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

Illustrations

Page 45, Olive, Little Noticed, Sat on the Hearthrug

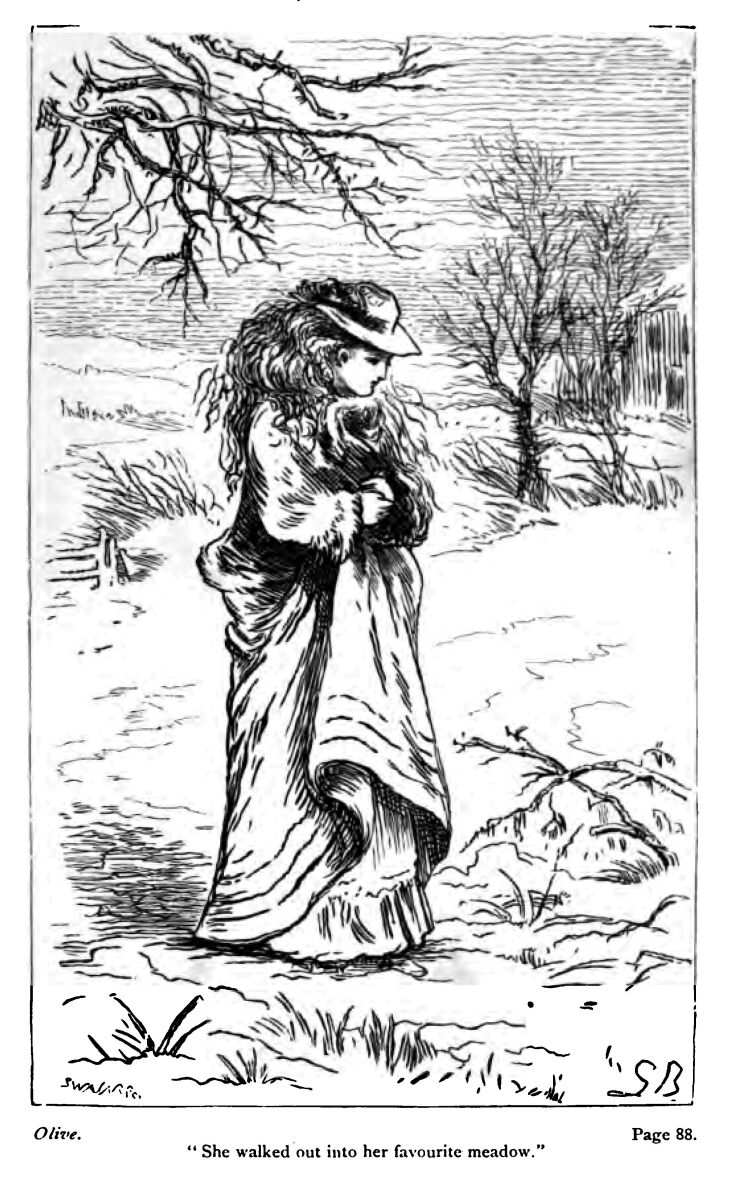

Page 88, She Walked out Into Her Favourite Meadow

Page 205 his Anger Had Vanished

“Puir wee lassie, ye hae a waesome welcome to a waesome warld!”

Such was the first greeting ever received by my heroine, Olive Rothesay. However, she would be then entitled neither a heroine nor even “Olive Rothesay,” being a small nameless concretion of humanity, in colour and consistency strongly resembling the “red earth,” whence was taken the father of all nations. No foreshadowing of the coming life brightened her purple, pinched-up, withered face, which, as in all new-born children, bore such a ridiculous likeness to extreme old age. No tone of the all-expressive human voice thrilled through the unconscious wail that was her first utterance, and in her wide-open meaningless eyes had never dawned the beautiful human soul. There she lay, as you and I, reader, with all our compeers, lay once-a helpless lump of breathing flesh, faintly stirred by animal life, and scarce at all by that inner life which we call spirit. And, if we thus look back, half in compassion, half in humiliation, at our infantile likeness-may it not be that in the world to come some who in this world bore an outward image poor, mean, and degraded, will cast a glance of equal pity on their well-remembered olden selves, now transfigured into beautiful immortality?

I seem to be wandering from my Olive Rothesay; but time will show the contrary. Poor little spirit! newly come to earth, who knows whether that “waesome welcome” may not be a prophecy? The old nurse seemed almost to dread this, even while she uttered it, for with superstition from which not an “auld wife” in Scotland is altogether free, she changed the dolorous croon into a “Gude guide us!” and, pressing the babe to her aged breast, bestowed a hearty blessing upon her nursling of the second generation—the child of him who was at once her master and her foster-son.

“An' wae's me that he's sae far awa', and canna do't himsel. My bonnie bairn! Ye're come into the warld without a father's blessing.”

Perhaps the good soul's clasp was the tenderer, and her warm heart throbbed the warmer to the new-born child, for a passing remembrance of her own two fatherless babes, who now slept—as close together, as when, “twin-laddies,” they had nestled in one mother's bosom—slept beneath the wide Atlantic which marks the sea-boy's grave.

Nevertheless, the memory was now grown so dim with years, that it vanished the moment the infant waked, and began to cry. Rocking to and fro, the nurse tuned her cracked voice to a long-forgotten lullaby—something about a “boatie.” It was stopped by a hand on her shoulder, followed by the approximation of a face which, in its bland gravity, bore “M.D.” on every line.

“Well, my good—— excuse me, but I forget your name.”

“Elspeth, or mair commonly, Elspie Murray. And no an ill name, doctor. The Murrays o' Perth were”——

“No doubt—no doubt, Mrs. Elsappy.”

“Elspie, sir. How daur ye ca' me out o' my name, wi' your unceevil English tongue!”

“Well, then, Elspie, or what the deuce you like,” said the doctor, vexed out of his proprieties. But his rosy face became rosier when he met the horrified and sternly reproachful stare of Elspie's keen blue eyes as she turned round—a whole volume of sermons expressed in her “Eh, sir?” Then she added, quietly,

“I'll thank ye no to speak ill words in the ears o' this puir innocent new-born wean. It's no canny.”

“Humph!—I suppose I must beg pardon again. I shall never get out what I wanted to say—which is, that you must be quiet, my good dame, and you must keep Mrs. Rothesay quiet. She is a delicate young creature, you know, and must have every possible comfort that she needs.”

The doctor glanced round the room as though there was scarce enough comfort for his notions of worldly necessity. Yet though not luxurious, the antechamber and the room half-revealed beyond it seemed to furnish all that could be needed by an individual of moderate fortune and desires. And an eye more romantic and poetic than that of the worthy medico might have found ample atonement for the want of rich furniture within, in the magnificent view without. The windows looked down on a lovely champaign, through which the many-winding Forth span its silver network, until, vanishing in the distance, a white sparkle here and there only showed whither the river wandered. In the distance, the blue mountains rose like clouds, marking the horizon. The foreground of this landscape was formed by the hill, castle-crowned—than which there is none in the world more beautiful or more renowned.

In short, Olive Rothesay shared with many a king and hero the honour of her place of nativity. She was born at Stirling.

Perhaps this circumstance of birth has more influence over character than many matter-of-fact people would imagine. It is pleasant, in after life, to think that we first opened our eyes in a spot famous in the world's story, or remarkable for natural beauty. It is sweet to say, “Those are my mountains,” or “This is my fair valley;” and there is a delight almost like that of a child who glories in his noble or beautiful parents, in the grand historical pride which links us to the place where we were born. So this little morsel of humanity, yet unnamed, whom by an allowable prescience we have called Olive, may perhaps be somewhat influenced in after life by the fact that her cradle was rocked under the shadow of the hill of Stirling, and that the first breezes which fanned her baby brow came from the Highland mountains.

But the excellent presiding genius at this interesting advent “cared for none of these things.” Dr. Jacob Johnson stood at the window with his hands in his pockets—to him the wide beautiful world was merely a field for the exercise of the medical profession—a place where old women died, and children were born. He watched the shadows darkening over Ben-Ledi—calculating how much longer he ought in propriety to stay with his present patient, and whether he should have time to run home and take a cosy dinner and a bottle of port before he was again required.

“Our sweet young patient is doing well, I think, nurse,” said he, at last, in his most benevolent tones.

“Ye may say that, doctor—ye suld ken.”

“I might almost venture to leave her, except that she seems so lonely, without friend or nurse, save yourself.”

“And wha's the best nurse for Captain Angus Rothesay's wife and bairn, but the woman that nursed himsel?” said Elspie, lifting up her tall gaunt frame, and for the second time frowning the little doctor into confused silence. “An' as for friends, ye suld just be unco glad o' the chance that garr'd the leddy bide here, and no amang her ain folk. Else there wadna hae been sic a sad welcome for her bonnie bairn. Maybe a waur, though,” added the woman to herself, with a sigh, as she once more half-buried her little nursling in her capacious embrace.

“I have not the slightest doubt of Captain Rothesay's respectability,” answered Dr. Johnson. Respectability! applied to the scions of a family which had had the honour of being nearly extirpated at Flodden-field, and again at Pinkie. Had the trusty follower of the Rothesays heard the term, she certainly would have been inclined to annihilate the presumptuous Englishman. But she was fortunately engaged in stilling the cries of the poor infant, who, in return for the pains she took in addressing it, began to give full evidence that the weakness of its lungs was not at all proportionate to the smallness of its size.

“Crying will do it good. A fine child—a very fine child,” observed the doctor, as he made ready for his departure, while the nurse proceeded in her task, and the heap of white drapery was gradually removed, until from beneath it appeared a very—very tiny specimen of babyhood.

“Ye needna trouble yoursel to say what's no' true,” was the answer; “it's just a bit bairnie—unco sma' An' that's nae wonder, considering the puir mither's trouble.”

“And the father is gone abroad?”

“Just twa months sin' syne. But eh! doctor, look ye here,” suddenly cried Elspie, as with her great, brown, but tender hand she was rubbing down the delicate spine of the now quieted babe.

“Well—what's the matter now?” said Dr. Johnson rather sulkily, as he laid down his hat and gloves, “The child is quite perfect, rather small perhaps, but as nice a little girl as ever was seen. It's all right.”

“It's no a' richt,” cried the nurse, in a tone trembling between anger and apprehension. “Doctor, see!”

She pointed with her finger to a slight curve at the upper part of the spine, between the shoulder and neck. The doctor's professional anxiety was aroused—he came near and examined the little creature, with a countenance that grew graver each instant.

“Aweel?” said Elspie, inquiringly.

“I wish I had noticed this before; but it would have been of no use,” he answered, his bland tones made earnest by real feeling.

“Eh, what?” said the nurse.

“I am sorry to say that the child is deformed—slightly so—very slightly I hope—but most certainly deformed. Hump-backed.”

At this terrible sentence Elspie sank back in her chair. Then she started up, clasping the child convulsively, and faced the doctor.

“Ye lee, ye ugly creeping Englisher! How daur ye speak so of ane o' the Rothesays,—frae the blude o' whilk cam the tallest men an' the bonniest leddies—ne'er a cripple amang them a —— How daur ye say that my master's bairn will be a———. Wae's me! I canna speak the word.”

“My poor woman!” mildly said the doctor, “I am really concerned.”

“Haud your tongue, ye fule!” muttered Elspie, while she again laid the child on her lap, and examined it earnestly for herself. The result confirmed all. She wrung her hands, and rocked to and fro, moaning aloud.

“Ochone, the wearie day! O my dear master, my bairn, that I nursed on my knee! how will ye come back an' see your first-born, the last o' the Rothesays, a puir bit crippled lassie!”

A faint call from the inner room startled both doctor and nurse.

“Good heavens!” exclaimed the former. “We must think of the mother. Stay—I'll go. She does not, and she must not, know of this. What a blessing that I have already told her the child was a fine and perfect child. Poor thing, poor thing!” he added passionately, as he hurried to his patient leaving Elspie hushed into silence, still mournfully gazing on her charge.

It would have been curious to mark the changes in the nurse's face during that brief interval. At first it wore a look almost of repugnance as she regarded the unconscious child, and then that very unconsciousness seemed to awaken her womanly compassion. “Puir hapless wean, ye little ken what ye're coming to! Lack o' kinsman's love, and lack o' siller, and lack o' beauty. God forgie me—but why did He send ye into the waefu' warld at a'?”

It was a question, the nature of which has perplexed theologians, philosophers, and metaphysicians, in every age, and will perplex them all to the end of time. No wonder, therefore, that it could not be solved by the poor simple Scotswoman. But as she stood hushing the child to her breast, and looking vacantly out of the window at the far mountains which grew golden in the sunset, she was unconsciously soothed by the scene, and settled the matter in a way which wiser heads might often do with advantage.

“Aweel! He kens best. He made the warld and a' that's in't; and maybe He will gie unto this puir wee thing a meek spirit to bear ill-luck. Ane must wark, anither suffer. As the minister says, It'll a' come richt at last.”

Still the babe slept on, the sun sank, and night fell upon the earth. And so the morning and evening made the first day of the new existence, which was about to be developed, through all the various phases which compose that strange and touching mystery—a woman's life.

There is not a more hackneyed subject for poetic enthusiasm than that sight—perhaps the loveliest in nature—a young mother with her first-born child. And perhaps because it is so lovely, and is ever renewed in its beauty, the world never tires of dwelling thereupon.

Any poet, painter, or sculptor, would certainly have raved about Mrs. Rothesay, had he seen her in the days of convalescence, sitting at the window with her baby on her knee. She furnished that rare sight—and one that is becoming rarer as the world grows older—an exquisitely beautiful woman. Would there were more of such!—that the idea of physical beauty might pass into the heart through the eyes, and bring with it the ideal of the soul's perfection, which our senses can only thus receive. So great is this influence—so unconsciously do we associate the type of spiritual with material beauty, that perhaps the world might have been purer and better if its onward progress in what it calls civilisation had not so nearly destroyed the fair mould of symmetry and loveliness which tradition celebrates.

It would have done any one's heart good only to look at Sybilla Rothesay. She was a creature to watch from a distance, and then to go away and dream of, wondering whether she were a woman or a spirit. As for describing her, it is almost impossible—but let us try.

She was very small in stature and proportions—quite a little fairy. Her cheek had the soft peachy hue of girlhood; nay, of very childhood. You would never have thought her a mother. She lay back, half-buried in the great armchair; and then, suddenly springing up from amidst the cloud of white muslins and laces that enveloped her, she showed her young, blithe face.

“I will not have that cap, Elspie; I am not an invalid now, and I don't choose to be an old matron yet,” she said, in a pretty, wilful way, as she threw off the ugly ponderous production of her nurse's active fingers, and exhibited her beautiful head.

It was, indeed, a beautiful head! exquisite in shape, with masses of light-brown hair folded round it. The little rosy ear peeped out, forming the commencement of that rare and dainty curve of chin and throat, so pleasant to an artist's eye. A beauty to be lingered over among all other beauties. Then the delicately outlined mouth, the lips folded over in a lovely gravity, that seemed ready each moment to melt away into smiles. Her nose—but who would destroy the romance of a beautiful woman by such an allusion? Of course, Mrs. Rothesay had a nose; but it was so entirely in harmony with the rest of her face, that you never thought whether it were Roman, Grecian, or aquiline. Her eyes—

“She has two eyes, so soft and brown—

She gives a side-glance and looks down.”

But was there a soul in this exquisite form? You never asked—you hardly cared! You took the thing for granted; and whether it were so or not, you felt that the world, and yourself especially, ought to be thankful for having looked at so lovely an image, if only to prove that earth still possessed such a thing as ideal beauty; and you forgave all the men, in every age, that have run mad for the same. Sometimes, perchance, you would pause a moment, to ask if this magic were real, and remember the calm holy airs that breathed from the presence of some woman, beautiful only in her soul. But then you never would have looked upon Sybilla Rothesay as a woman at all—only a flesh-and-blood fairy—a Venus de Medici transmuted from the stone.

Perhaps this was the way in which Captain Angus Rothesay contrived to fall in love with Sybilla Hyde; until he woke from the dream to find his seraph of beauty—a baby-bride, pouting like a vexed child, because, in their sudden elopement, she had neither wedding-bonnet nor Brussels veil!

And now she was a baby-mother; playing with her infant as, not so very long since, she had played with her doll; twisting its tiny fingers, and making them close tightly round her own, which were quite as elfin-like, comparatively. For Mrs. Rothesay's surpassing beauty included beautiful hands and feet; a blessing which Nature—often niggardly in her gifts—does not always extend to pretty women, but bestows it on those who have infinitely more reason to be thankful for the boon.

“See, nurse Elspie,” said Mrs. Rothesay, laughing in her childish way; “see how fast the little creature holds my finger! Really, I think a baby is a very pretty thing; and it will be so nice to play with until Angus comes home.”

Elspie turned round from the corner where she sat sewing, and looked with a half-suppressed sigh at her master's wife, whose delicate English beauty, and quick, ringing English voice, formed such a strong contrast to herself, and were so opposed to her own peculiar prejudices. But she had learned to love the young creature, nevertheless; and for the thousandth time she smothered the half-unconscious thought that Captain Angus might have chosen better.

“Children are a blessing frae the Lord, as maybe ye'll see, ane o' these days, Mrs. Rothesay,” said Elspie, gravely; “ye maun tak' them as they're sent, and mak' the best o' them.”

Mrs. Rothesay laughed merrily. “Thank you, Elspie, for giving me such a solemn speech, just like one of my husband's. To put me in mind of him, I suppose. As if there were any need for that! Dear Angus! I wonder what he will say to his little daughter when he sees her; the new Miss Rothesay, who has come in opposition to the old Miss Rothesay,—ha! ha!”

“The auld Miss Rothesay! She's your husband's aunt,” observed Elspie, feeling it necessary to stand up for the honour of the family. “Miss Flora was a comely leddy ance, as a' the Rothesays were.”

“And this Miss Rothesay will be too, I hope, though she is such a little brown thing now. But people say that the brownest babies grow the fairest in time, eh, nurse?”

“They do say that,” replied Elspie, with another and a heavier sigh; as she bent closer over her work.

Mrs. Rothesay went on in her blithe chatter. “I half wished for a boy, as Captain Rothesay thought it would please his uncle; but that's of no consequence. He will be quite satisfied with a girl, and so am I. Of course she will be a beauty, my dear little baby!” And with a deeper mother-love piercing through her childish pleasure, she bent over the infant; then took it up, awkwardly and comically enough, as though it were a toy she was afraid of breaking, and rocked it to and fro on her breast.

Elspie started up. “Tak' tent, tak' tent! ye'll hurt it, maybe, the puir wee——Oh, what was I gaun to say!”

“Don't trouble yourself,” said the young mother, with a charming assumption of matronly dignity; “I shall hold the baby safe. I know all about it.”

And she really did succeed in lulling the child to sleep; which was no sooner accomplished than she recommenced her pleasant musical chatter, partly addressed to her nurse, but chiefly the unconscious overflow of a simple nature, which could not conceal a single thought.

“I wonder what I shall call her—the darling! We must not wait until her papa comes home. She can't be 'baby' for three years. I shall have to decide on her name myself. Oh, what a pity! I, who never could decide anything. Poor dear Angus! he does all—he had even to fix the wedding-day!” And her musical laugh—another rare charm that she possessed—caused Elspie to look round with mingled pity and affection.

“Come, nurse, you can help me, I know. I am puzzling my poor head for a name to give this young lady here. It must be a very pretty one. I wonder what Angus would like? A family name, perhaps, after one of those old Rothesays that you and he make so much of.”

“Oh, Mrs. Rothesay! And are ye no proud o' your husband's family?”

“Yes, very proud; especially as I have none of my own. He took me—an orphan, without a single tie in the wide world—he took me into his warm loving arms”—here herm voice faltered, and a sweet womanly tenderness softened her eyes. “God bless my noble husband! I am proud of him, and of his people, and of all his race. So come,” she added, her childish manner reviving, “tell me of the remarkable women in the Rothesay family for the last five hundred years—you know all about them, Elspie. Surely we'll find one to be a namesake for my baby.”

Elspie—pleased and important—began eagerly to relate long traditions about the Lady Christina Rothesay, who was a witch, and a great friend of “Maister Michael Scott,” and how, with spells, she caused her seven step-sons to pine away and die; also the lady Isobel, who let her lover down from her bower-window with the long strings of her golden hair, and how her brother found and slew him;—whence she laid a curse on all the line who had golden hair, and such never prospered, but died unmarried and young.

“I hope the curse has passed away now,” gaily said the young mother, “and that the latest scion will not be a golden-tressed damsel. Yet look here”—and she touched the soft down beneath her infant's cap, which might, by a considerable exercise of imagination, be called hair—“it is yellow, you see, Elspie! But I'll not believe your tradition. My child shall be both beautiful and beloved.”

Smitten with a sudden pang, poor Elspie cried, “Oh, my leddy, dinna think o' the future. Dinna!”—— and she stopped, confused.

“Really, how strange you are. But go on. We'll have no more Christinas nor Isobels.”

Hurriedly, Elspie continued to relate the histories: of noble Jean Rothesay, who died by an arrow aimed at her husband's heart; and Alison, her sister, the beauty of James the Fifth's reckless court, who was “no gude;” and Mistress Katharine Rothesay, who hid two of the “Prince's” soldiers after Culloden, and stood with a pair of pistols before their bolted door.

“Nay, I'll have none of these—they frighten me,” said Sybilla, “I wonder I ever had courage to marry the descendant of such awful women. No! my sweet innocent! you shall not be christened after them,” she continued, stroking the baby cheek with her soft finger. “You shall not be like them at all, except in their beauty. And they were all handsome—were they, Elspie?”

“Ne'er a ane o' the Rothesay line, man or woman, that wasna fair to see.”

“Then so will my baby be!—like her father, I hope—or just a little like her mother, who is not so very ugly, either; at least, Angus says not.” And Mrs. Rothesay drew up her tiny figure, patted one dainty hand—the wedded one—with its fairy fellow; then—touched perhaps with a passing melancholy that he who most prized her beauty, and for whose sake she most prized it herself, was far away—she leaned back and sighed.

However, in a few minutes, she cried out, her words showing how light and wandering was the reverie, “Elspie, I have a thought! The baby shall be christened Olive!”

“It's a strange, heathen name, Mrs. Rothesay.”

“Not at all. Listen how I chanced to think of it. This very morning, just before you came to waken me, I had such a queer, delicious dream.”

“Dream! Are ye sure it was i' the morning-tide?” cried Elspie, aroused into interest.

“Yes; and so it certainly means something, you will say, Elspie? Well, it was about my baby. She was then lying fast asleep in my bosom, and her warm, soft breathing soon sent me to sleep too. I dreamt that somehow I had gradually let her go from me, so that I felt her in my arms no more, and I was very sad, and cried out how cruel it was for any one to steal my child, until I found I had let her go of my own accord. Then I looked up, after awhile, and saw standing at the foot of the bed a little angel—a child-angel—with a green olive-branch in its hand. It told me to follow; so I rose up, and followed it over a wide desert country, and across rivers and among wild beasts; but at every peril the child held out the olive-branch, and we passed on safely. And when I felt weary, and my feet were bleeding with the rough journey, the little angel touched them with the olive, and I was strong again. At last we reached a beautiful valley, and the child, said, 'You are quite safe now.' I answered, 'And who is my beautiful comforting angel?' Then the white wings fell off, and I only saw a sweet child's face, which bore something of Angus's likeness and something of my own, and the little one stretched out her hands and said, 'Mother!'”

While Mrs. Rothesay spoke, her thoughtless manner had once more softened into deep feeling. Elspie watched her with wondering eagerness.

“It was nae dream; it was a vision. God send it true!” said the old woman, solemnly.

“I know not. Angus always laughed at my dreams, but I have a strange feeling whenever I think of this. Oh, Elspie, you can't tell how sweet it was! And so I should like to call my baby Olive, for the sake of the beautiful angel. It may be foolish—but 'tis a fancy of mine. Olive Rothesay! It sounds well, and Olive Rothesay she shall be.”

“Amen; and may she be an angel to ye a' her days. And ye'll mind o' the blessed dream, and love her evermair. Oh, my sweet leddy, promise me that ye will!” cried the nurse, approaching her mistress's chair, while two great tears stole down her hard cheeks.

“Of course I shall love her dearly! What made you doubt it? Because I am so young? Nay, I have a mother's heart, though I am only eighteen. Come, Elspie, do let us be merry; send these drops away;” and she patted the old withered face with her little hand. “Was it not you who told me the saying, 'It's ill greeting ower a new-born wean'? There! don't I succeed charmingly in your northern tongue?”

What a winning little creature she was, this young wife of Angus Rothesay! A pity he had not seen her—the old Highland uncle, Miss Flora's brother, who had disinherited his nephew and promised heir for bringing him a Sassenach niece.

“A charming scene of maternal felicity! I am quite sorry to intrude upon it,” said a bland voice at the door, as Dr. Johnson put in his shining bald head.

Mrs. Rothesay welcomed him in her graceful, cordial way. She was so ready to cling to every one who showed her kindness—and he had been very kind; so kind that, with her usual quick impulses, she had determined to stay and live at Stirling until her husband's return from Jamaica. She told Dr. Johnson so now; and, moreover, as an earnest of the friendship which she, accustomed to be loved by every one, expected from him, she requested him to stand godfather to her little babe.

“She shall be christened after our English fashion, doctor, and her name shall be Olive. What do you think of her now? Is she growing prettier?”

The doctor bowed a smiling assent, and walked to the window. Thither Elspie followed him.

“Ye maun tell her the truth—I daurna. Ye will!” and she clutched his arm with eager anxiety. “An' oh! for Gudesake, say it safyly, kindly.”

He shook her off with an uneasy look. He had never felt in a more disagreeable position.

Mrs. Rothesay called him back again. “I think, doctor, her features are improving. She will certainly be a beauty. I should break my heart if she were not. And what would Angus say? Come—what are you and Elspie talking about so mysteriously?”

“My dear madam—hem!” began Dr. Johnson. “I do hope—indeed, I am sure—your child will be a good child, and a great comfort to both her parents;”——

“Certainly—but how grave you are about it.”

“I have a painful duty—a very painful duty,” he replied. But Elspie pushed him aside.

“Ye're just a fule, man!—ye'll kill her. Say your say at ance!”

The young mother turned deadly pale. “Say what Elspie? What is he going to tell me? Angus”——

“No, no, my darlin' leddy! your husband's safe;” and Elspie flung herself on her knees beside the chair. “But, the lassie—(dinna fear, for it's the will o' God, and a' for gude, nae doubt)—your sweet wee dochter is”——

“Is, I grieve to say it, deformed,” added Dr. Johnson.

The poor mother gazed incredulously on him, on the nurse, and lastly on the sleeping child. Then, without a word, she fell back, and fainted in Espie's arms.

It was many days before Mrs. Rothesay recovered from the shock occasioned by the tidings—to her almost more fearful than her child's death—that it was doomed for life to suffer the curse of hopeless deformity. For a curse, a bitter curse, this seemed to the young and beautiful creature, who had learned since her birth to consider beauty as the greatest good. She was, so to speak, in love with loveliness; not merely in herself, but in every human creature. This feeling sprang more from enthusiasm than from personal vanity, the borders of which meanness she had just touched, but never crossed. Perhaps, also, she was too conscious of her own loveliness, and admired herself too ardently to care for attracting the petty admiration of others. She took it quite as a matter of course; and was no more surprised at being worshipped than if she had been the Goddess of Beauty herself.

But if Sybilla Rothesay gloried in her own perfections, she no less gloried in those of all she loved, and chiefly in her noble-looking husband. And they were so young, so quickly wed, and so soon parted, that this emotion had no time to deepen into that soul-united affection which is independent of outward things, or, rather, becomes so divine, that instead of beauty creating love, love has power to create beauty.

No marvel, then, that not having attained to a higher experience, Sybilla considered beauty as all in all. And this child—her child and Angus's,—would be a deformity, a shame to its parents, a dishonour to its race. How should she ever bear to look upon it? Still more, how should she ever dare to show the poor cripple to its father, and say, “This is our child—our firstborn.” Would he not turn away in disgust, and answer that it had better died?

Such exaggerated fancies as these haunted the miserable mother, when she passed from her long swoon into a sort of fever; which, though scarce endangering her life, was yet for days a source of great anxiety to the devoted Elspie. To the unhappy infant this madness—for it was temporary madness—almost caused death. Mrs. Rothesay positively refused to see or notice her child, scorning alike the tearful entreaties and the stern reproaches of the nurse. At last Elspie ceased to combat this passionate resolve, springing half from anger and half from delirium——

“God forgie ye, and save the innocent bairn—the dochter He gave, and that ye're gaun to murder—unthankfu' woman as ye are,” muttered Elspie, under her breath, as she quitted the room and went to succour the almost dying babe. Over it her heart yearned as it had never yearned before.

“Your mither casts ye aff, ye puir wee thing. Maybe ye're no lang for this warld, but while ye're in it ye sall be my ain lassie, an' I'll be your ain mammie, evermair.”

So, like Naomi of old, Elspie Murray “laid the child in her bosom and became nurse unto it.” But for her, the life of our Olive Rothesay—with all its influences, good or evil, small or great, as yet unknown—would have expired like a faint-flickering taper.

Perhaps, in her madness, the unhappy mother might almost have desired such an ending. As it was, the disappointed hope, which had at first resembled positive dislike, subsided into the most complete indifference. She endured her child's presence, but she took no notice of it; she seemed to have forgotten its very existence. Her shattered health supplied sufficient excuse for the utter abandonment of all a mother's duties, and the poor feeble spark of life was left to Elspie's cherishing. By night and by day the child knew no other resting-place than the old nurse's arms, the mother's seeming to be for ever closed to its helpless innocence. True, Sybilla kissed it once a day, when Elspie brought the little creature to her, and exacted, as a duty, the recognition which Mrs. Rothesay, girlish and yielding as she was, dared not refuse. Her husband's faithful retainer had over her an influence which could never be gainsaid.

Elspie seemed to be the sole regent of the babe's destiny. It was she who took it to its baptism;—not the festal ceremony which had pleased Sybilla's childish fancy with visions of christening robes and cakes, but the beautiful and simple “naming” of Elspie's own church. She stood before the minister, holding the desolate babe in her protecting arms; and there her heart sealed the promise of her lips, to bring it up in the knowledge and fear of God. And with an earnest credulity, which contained the germ of purest faith, she, remembering the mother's dream, called her nursling by the name of Olive.

She carried the babe home and laid it on Mrs. Rothesay's lap. The young creature, who had so strangely renounced that dearest blessing of mother-love, would fain have put the child aside; but Elspie's stern eye controlled her.

“Ye maun kiss and bless your dochter. Nae tongue but her mither's suld ca' her by her new-christened name.”

“What name?”

“The name ye gied her yer ain sel.”

“No, no. Surely you have not called her so. Take her away; she is not my sweet angel-baby—the darling in my dream.” And Sybilla hid her face; not in anger, or disgust, but in bitter weeping.

“She's yer ain dochter—Olive Rothesay,” answered Elspie, less harshly. “She may be an angel to ye yet.”

While she spoke, it so chanced that there flitted over the infant-face one of those smiles that we see sometimes in young children—strange, causeless smiles, which seem the reflection of some invisible influence.

And so, while the babe smiled, there came to its face such an angel-brightness, that it shone into the mother's careless heart. For the first time since that mournful day which had so changed her nature, Sybilla Rothesay sat down and kissed the child of her own accord. Elspie heard no maternal blessing—the name of “Olive” was never breathed; but the nurse was satisfied when she saw that the babe's second baptism was its mother's repentant tears.

There was in Sybilla no hardness nor cruelty, only the disappointment and vexation of a child deprived of an expected toy. She might have grown weary of her little daughter almost as soon, even if her pride and hope had not been crushed by the knowledge of Olive's deformity. Love to her seemed a treasure to be paid in requital, not a free gift bestowed without thought of return. That self-forgetting maternal devotion, lavished first on unconscious infancy, and then on unregarding youth, was a mystery to her utterly incomprehensible. At least it seemed so now, when, with the years and the character of a child, she was called to the highest duty of woman's life. This duty comes to some girlish mothers as an instinct, but it was not so with Mrs. Rothesay. An orphan, and heiress to a competence, if not to wealth, she had been brought up like a plant in a hot-bed, with all natural impulses either warped and suppressed, or forced into undue luxuriance. And yet it was a sweet plant withal; one that might have grown, ay, and might yet grow, into perfect strength and beauty.

Mrs. Rothesay's education—that education of heart, and mind, and temper, which is essential to a woman's happiness, had to begin when it ought to have been completed—at her marriage. Most unfortunate it was for her, that ere the first twelvemonth of their wedded life had passed, Captain Rothesay was forced to depart for Jamaica, whence was derived his wife's little fortune; their whole fortune now, for he had quitted the army on his marriage. Thus Sybilla was deprived of that wholesome influence which man has ever over a woman who loves him, and by which he may, if he so will, counteract many a fault and weakness in her disposition.

Time passed on, and Mrs. Rothesay, a wife and mother, was at twenty-one years old just the same as she had been at seventeen—as girlish, as thoughtless, eager for any amusement, and often treading on the very verge of folly. She still lived at Stirling, enforced thereunto by the entreaties, almost the commands, of Elspie Murray, against whom she bitterly murmured sometimes, for shutting her up in such a dull Scotch town. When Elspie urged her unprotected situation, the necessity of living in retirement, for the “honour of the family,” while Captain Angus was away, Mrs. Rothesay sometimes frowned, but more often put the matter off with a merry jest. Meanwhile she consoled herself by going as much into society as the limited circle of Dr. and Mrs. Johnson allowed; and therein, as usual, the lovely, gay, winning young creature was spoiled to her heart's content.

So she still lived the life of a wayward, petted child, whose natural instinct for all things good and beautiful kept her from ever doing what was positively wrong, though she did a great deal that was foolish enough in its way. She was, as she jestingly said, “a widow bewitched;” but she rarely coquetted, and then only in that innocent way which comes natural to some women, from a universal desire to please. And she never ceased talking and thinking of her noble Angus.

When his letters came, she always made a point of kissing them half-a-dozen times, and putting them under her pillow at night, just like a child! And she wrote to him regularly once a month—pretty, playful, loving letters. But there was in them one peculiarity—they were utterly free from that delicious maternal egotism which chronicles all the little incidents of babyhood. She said, in answer to her husband's questions, that “Olive was well;” “Olive could just walk;” “Olive had learned to say 'Papa and Elspie.'” Nothing more.

The fatal secret she had not dared to tell him.

Her first letters—full of joy about “the loveliest baby that ever was seen”—had brought his in return echoing the rapture with truly paternal pride. They reached her in her misery, to which they added tenfold. Every sentence smote her with bitter regret, even with shame, as though it were her fault in having given to the world the wretched child. Captain Rothesay expressed his joy that his little daughter was not only healthy, but pretty; for, he said, “He should be quite unhappy if she did not grow up as beautiful as her mother.” The words pierced Sybilla's heart; she could not—dared not tell him the truth; not yet, at least. And whenever Elspie's rough honesty urged her to do so, she fell into such agonies of grief and anger, that the nurse was obliged to desist.

Sometimes, when letter after letter came from the father, full of inquiries about his precious first-born,—Sybilla, whose fault was more in weakness than deceit, resolved that she would nerve herself for the terrible task. But it was vain—she had not strength to do it.

The three years extended into four, and still Captain Rothesay sent gift after gift, and message after message, to his daughter. Still he wrote to the conscience-stricken mother how many times he had kissed the “little lock of golden hue,” severed from the baby-head; picturing the sweet face and lithe, active form which he had never seen. And all the while there was stealing about the old house at Stirling a pale, deformed child: small and attenuated in frame—quiet beyond its years, delicate, spiritless, with scarce one charm that would prove its lineage from the young beautiful mother, out of whose sight it instinctively crept.

Thus the years fled with Olive Rothesay and her parents; each month, each day, sowing seeds that would assuredly spring up, for good or for evil, in the destinies of all three.

The fourth year of Captain Rothesay's absence passed,—not without anxiety, for it was war-time, and his letters were frequently interrupted. At first, whenever this happened, his wife fretted extremely—fretted is the right word, for it was more a fitful chafing than a positive grief. Sybilla knew not the sense of deep sorrow. Her nature resembled one of those sunny climes where even the rains are dews. So, after a few disappointments, she composed herself to the certainty that nothing would happen amiss to her Angus; and she determined never to expect a letter until she received it, and not to look for him at all until he wrote her word that he was coming. He was sure to do what was right, and to return to his dearly-loved wife as soon as ever he could. And, though scarce acknowledging the fact to herself, her husband's return involved such a humiliating explanation of truth concealed, if not of positive falsehood, that Sybilla dared not even think of it. Whenever the long-parted wife mused on the joy of meeting—of looking once more into the beloved face, and being lifted up like a child to cling round his neck with her fairy arms, for Angus was a very giant to her—then there seemed to rise between them the phantom of the pale, deformed child.

To drown these fancies, Sybilla rushed into every amusement which her secluded life afforded. At last, she resolved on an exploit at which Elspie looked aghast, and which made the quiet Mrs. Johnson shake her head—an evening party—nay, even a dance, at her own home.

“It will never do for the people here; they're 'unco gude,'” said the doctor's English wife, who had imbibed a few Scottish prejudices by a residence of thirty years. “Nobody ever dances in Stirling.”

“Then I'll teach them,” cried the lively Mrs. Rothesay: “I long to show them a quadrille—even that new dance that all the world is shocked at Oh! I should dearly like a waltz.”

Mrs. Jacob Johnson was scandalised at first, but there was something in Sybilla to which she could not say nay,—nobody ever could. The matter was decided by Mrs. Rothesay's having her own way, except with regard to the waltz, which her friend staunchly resisted. Elspie, too, interfered as long as she could; but her heart was just now full of anxiety about her nursling, who seemed to grow more delicate every year. Day after day the faithful nurse might have been seen trudging across the country, carrying little Olive in her arms, to strengthen the child with the healing springs of Bridge of Allan, and invigorate her weak frame with the fresh mountain air—the heather breath of beautiful Ben-Ledi. Among these influences did Olive's childhood dawn, so that in after-life they never faded from her.

Elspie scarcely thought again about the gay party, until when she came in one evening, and was undressing the sleepy little girl in the dusk, a vision appeared at the nursery door. It quite startled the old Scotswoman at first, it looked so like a fairy apparition, all in white, with a green coronet. She hardly could believe that it was her young mistress.

“Eh! Mrs. Rothesay, ye're no goin' to show yoursel in sic a dress,” she cried, regarding with horror the gleaming bare arms, the lovely neck, and the tiny white-sandaled feet, which the short and airy robe exhibited in all their perfection.

“Indeed, but I am! and 'tis quite a treat to wear a ball-dress. I, that have been smothered up in all sorts of ugly costume for nearly five years. And see my jewels! Why, Elspie, this pearl-set has only beheld the light once since I was married—so beautiful as it is—and Angus's gift too.”

“Dinna say that name,” cried Elspie, driven to a burst of not very respectful reproach. “I marvel ye daur speak of Captain Angus—and ye wi' your havers and your jigs, while yer husband's far awa', and your bairn sick! It's for nae gude I tell ye, Mrs. Rothesay.”

Sybilla had looked a little subdued at the allusion to her husband, but the moment Elspie mentioned the little Olive, her manner changed. “You are always blaming me about the child, and I will not bear it. She is quite well. Are you not, baby?”—the mother never would call her Olive.

A feeble, trembling voice answered from the little bed, “Yes, please, mamma!”

“There, you hear, Elspie! Now don't torment me any more about her. But I must go down stairs.”

She danced across the room in a graceful waltzing step, held out her hand towards the child, and touched one so tiny, cold, and damp, that she felt half inclined to take and warm it in her own. But Elspie's hawk-eyes were watching her, and she was ashamed. So she only said, “Goodnight, baby!” and danced back again, out through the open door.

For hours Elspie sat in the dark room beside the bed of the little child, who lay murmuring, sometimes moaning, in her sleep. She never did moan but in her sleep, poor innocent! The sound of music and dancing rose up from below, and then Mrs. Rothesay's singing.

“Ye'd better be hushin' your puir wee bairnie here, ye heartless woman!” muttered Elspie, who grew daily more jealous over the forsaken child, now the very darling of her old age. She knew not that her love for Olive, and its open tokens shown by reproaches to Olive's mother, were sure to suppress any dawning tenderness that might be awakened in Mrs. Rothesay's bosom.

It had not done so yet, for many a time during the dance and song did the touch of that little cold hand haunt the young mother, rousing a feeling akin to remorse. But she threw it off again and again, and entered with the gaiety of her nature into all the evening's pleasure. Her enjoyment was at its height, when an old acquaintance, just discovered—an English officer, quartered at the castle—proposed a waltz. Before she had time to say “Yes” or “No,” the music struck up one of those enchanting waltz-measures which to all true lovers of dancing, are as irresistible as Maurice Connor's “Wonderful Tune.” Sybilla felt again the same blithe young creature of sixteen, who had led the revels at her first ball, dancing into the heart of one old colonel, six ensigns, a doctor, a lawyer, and of Angus Rothesay. There was no resisting the impulse: in a moment she was whirling away.

In the midst of the dizzy round the door opened, and, like some evil spectre, in stalked Elspie Murray.

Never was there such an uncouth apparition seen in a ball-room. Her grey petticoat exhibited her bare feet; her short upper gown, that graceful and picturesque attire of the Scottish peasantry, was thrown carelessly over her shoulders; her mutch was put on awry, and from under its immense border her face appeared, as white almost as the cap itself. She walked right into the centre of the floor, laid her heavy hand on Sybilla's shoulder, and said,

“Mrs. Rothesay, your husband's come!”

The young wife stood one moment transfixed; she turned pale, afterwards crimson, and then, uttering a cry of joy, sprang to the door—sprang into her husband's arms.

Dazzled with the light, the traveller resisted not, while Elspie half-led, half dragged him—still clasping his wife—into a little room close by, when she shut the door and left them. Then she burst in once more among the astonished guests.

“Ye may gang your gate, ye heathens! Awa wi' ye, for Captain Rothesay's come hame!”

Sybilla and her husband stood face to face in the little gloomy room, lighted only by a solitary candle. At first she clung about him so closely that he could not see her face, though he felt her tears falling, and her little heart beating against his own. He knew it was all for joy. But he was strangely bewildered by the scene which had flashed for a minute before his eyes, while standing at the door of the room.

After a while he drew his wife to the light, and held her out at arm's length to look at her. Then, for the first time, she remembered all. Trembling—blushing scarlet, over face and neck—she perceived her husband's eyes rest on her glittering dress. He regarded her fixedly, from head to foot. She felt his expression change from joy to uneasy wonder, from love to sternness, and then he wore a strange, cold look, such a one as she had never beheld in him before.

“So, the young lady I saw whirling madly in some man's arms—was you, Sybilla—was my wife.”

As Captain Rothesay spoke, Sybilla distinguished in his voice a new tone, echoing the strange coldness in his eyes. She sprang to his neck, weeping now for grief and alarm, as she had before wept for joy; she prayed him to forgive her, told him, with a sincerity that none could doubt, how rejoiced she was at his coming, and how dearly she loved him—now and ever. He kissed her, at her passionate entreaty; said he had nothing to blame; suffered her caresses patiently; but the impression was given, the deed was done.

While he lived, Captain Rothesay never forgot that night. Nor did Sybilla; for then she had first seen that cold, stern look, and heard that altered tone. How many times was it to haunt her afterwards!

Next morning Captain Rothesay and his wife sat together by the fireside, where she had so often sat alone. Sybilla seemed in high spirits—her love was ever exuberant in expression—and the moment her husband seemed serious she sprang on his knee and looked playfully in his face.

“Just as much a child as ever, I see,” said Angus Rothesay, with a rather wintry smile.

And then, looking in his face by daylight, Sybilla had opportunity to see how changed he was. He had become a grave, middle-aged man. She could not understand it. He had never told her of any cares, and he was little more than thirty. She felt almost vexed at him for growing so old; nay, she even said so, and began to pull out a few grey hairs that defaced the beauty of his black curls.

“You shall lecture me presently, my dear,” said Captain Rothesay. “You forget that I had two welcomes to receive, and that I have not yet seen my little girl.”

He had not indeed. His eager inquiries after Olive overnight had been answered by a pretty pout, and several trembling, anxious speeches about “a wife being dearer than a child.” “Baby was asleep, and it was so very late—he might, surely, wait till morning.” To which, though rather surprised, he assented. A few more caresses, a few more excuses, had still further delayed the terrible moment; until at last the father's impatience would no longer be restrained.

“Come, Sybilla, let us go and see our little Olive.”

“O Angus!” and the mother turned deadly white.

Captain Rothesay seemed alarmed. “Don't trifle with me, Sybilla—there is nothing the matter? The child is not ill?”

“No; quite well.”

“Then, why cannot Elspie bring her?” and he pulled the bell violently. The nurse appeared. “My good Elspie, you have kept me waiting quite long enough; do let me see my little girl.”

Elspie gave one glance at the mother, who stood mute and motionless, clinging to the chair for support. In that glance was less compassion than a sort of triumphant exultation. When she quitted the room Sybilla flung herself at her husband's feet. “Angus, Angus, only say you forgive me before”——

The door opened and Elspie led in a little girl. By her stature she might have been two years old, but her face was like that of a child of ten or twelve—so thoughtful, so grave. Her limbs were small and wasted, but exquisitely delicate. The same might be said of her features; which, though thin, and wearing a look of premature age, together with that quiet, earnest, melancholy cast peculiar to deformity, were yet regular, almost pretty. Her head was well-shaped, and from it fell a quantity of amber-coloured hair—pale “lint-white locks,” which, with the almost colourless transparency of her complexion, gave a spectral air to her whole appearance. She looked less like a child than a woman dwarfed into childhood; the sort of being renowned in elfin legends, as springing up on a lonely moor, or appearing by a cradle-side; supernatural, yet fraught with a nameless beauty. She was dressed with the utmost care, in white, with blue ribands; and her lovely hair was arranged so as to hide, as much as possible, the defect, which, alas! was even then only too perceptible. It was not a hump-back, nor yet a twisted spine; it was an elevation of the shoulders, shortening the neck, and giving the appearance of a perpetual stoop. There was nothing disgusting or painful in it, but still it was an imperfection, causing an instinctive compassion—an involuntary “Poor little creature, what a pity!”

Such was the child—the last daughter of the ever-beautiful Rothesay line—which Elspie led to claim the paternal embrace. Olive looked up at her father with her wistful, pensive eyes, in which was no childish shyness—only wonder. He met them with a gaze of frenzied unbelief. Then his fingers clutched his wife's arm with the grasp of an iron vice.

“Tell me! Is that—that miserable creature—our daughter, Olive Rothesay?”

She answered, “Yes.” He shook her off angrily, looked once more at the child, and then turned away, putting his hand before his eyes, as if to shut out the sight.

Olive saw the gesture. Young as she was, it went deep to her child's soul. Elspie saw it too, and without bestowing a second glance on her master or his wife, she snatched up the child and hurried from the room.

The father and mother were left alone—to meet that crisis most fatal to wedded happiness, the discovery of the first deceit Captain Rothesay sat silent, with averted face; Sybilla was weeping—not that repentant shower which rains softness into a man's heart, but those fretful tears which chafe him beyond endurance.

“Sybilla, come to me!” The words were a fond husband's words: the tone was that of a master who took on himself his prerogative. Never had Angus spoken so before, and the wilful spirit of his wife rebelled.

“I cannot come. I dare not even look at you. You are so angry.”

His only answer was the reiterated command, “Sybilla, come!” She crept from the far end of the room, where she was sobbing in a fear-stricken, childish way, and stood before him. For the first time she recognised her husband, whom she must “obey.” Now, with all the power of his roused nature, he was teaching her the meaning of the word. “Sybilla,” he said, looking sternly in her face, “tell me why, all these years, you have put upon me this cheat—this lie!”

“Cheat!—lie! Oh, Angus! What cruel, wicked words!”

“I am sorry I used them, then. I will choose a lighter term—deceit. Why did you so deceive your husband?”

“I did not mean it,” sobbed the young wife. “And this is very unkind of you, Angus! As if Heaven had not punished me enough in giving me that miserable child!”

“Silence! I am not speaking of the child, but of you; my wife, in whom I trusted; who for five long years has wilfully deceived me. Why did you so?”

“Because I was afraid—ashamed. But those feelings are past now,” said Sybilla, resolutely. “If Heaven made me mother, it made you father to this unhappy child. You have no right to reproach me.”

“God forbid! No, it is not the misfortune—it is the falsehood which stings me.”

And his grave, mournful tone, rose into one of bitter anger. He paced the room, tossed by a passion such as his wife had never before seen.

“Sybilla!” he suddenly cried, pausing before her; “you do not know what you have done. You little think what my love has been, nor against how much it has struggled these five years. I have been true to you—ay, to the depth of my heart And you to me have been—not wholly true.”

Here he was answered by a burst of violent hysterical weeping. He longed to call for feminine assistance to this truly feminine ebullition, which he did not understand. But his pride forbade. So he tried to soothe his wife a little with softer words, though even these seemed somewhat foreign to his lips, after so many long-parted years.

“I did not mean to pain you thus deeply, Sybilla. I do not say that you have ceased to love me!”

Would that Sybilla had done as her first impulse taught her; have clung about him, crying “Never! never!” murmuring penitent words, as a tender wife may well do, and in such humility be the more exalted! But she had still the wayward spirit of a petted child. Fancying she saw her husband once more at her feet, she determined to keep him there. She wept on, refusing to be pacified.

At last Angus rose from her side, dignified and cold, his new, not his old self; the lover no more, but the quiet, half-indifferent husband. “I see we had better not talk of these things until you are more composed—perhaps, indeed, not at all. What is past—is past, and cannot be recalled.”

“Angus!” She looked up, frightened at his manner. She determined to conciliate him a little. “What do you want me to do? To say I am sorry? That I will—but,” with an air of coquettish command, “you must say so too.”

The jest was ill-timed; he was in too bitter a mood. “Excuse me—you exact too much, Mrs. Rothesay.”

“Mrs. Rothesay! Oh, call me Sybilla, or my heart will break!” cried the young creature, throwing herself into his arms. He did not repulse her; he even looked down upon her with a melting, half-reproachful tendernes.

“How happy we might have been! How different had been this coming home if you had only trusted me, and told me all from the beginning.”

“Have you told me? Is there nothing you have kept back from me these five years?”

He started a little, and then said resolutely, “Nothing, Sybilla! I declare to Heaven—nothing! save, perhaps, some trifles that I would at any time tell you; now, if you will.”

“Oh no! some other time, I am too much exhausted now,” murmured Sybilla, with an air of languor, half real, half feigned, lest perchance she should lose what she had gained. In the sweetness of this reconciled “lovers' quarrel,” she had almost forgotten its hapless cause. But Angus, after a pause of deep and evidently conflicting thoughts, referred to the child.

“She is ours still. I must not forget that. Shall I send for her again?” he said, as if he wished to soothe the mother's wounded feelings.

Alas! in Sybilla's breast the fountain of mother's feeling was as yet all sealed. “Send for Olive!” she said, “oh no! Do not, I implore you. The very sight of her is a pain to me. Let us two be happy together, and let the child be left to Elspie.”

Thus she said, thinking not only to save herself, but him, from what must be a constant pang. Little she knew him, or guessed the after-effect of her words.

Angus Rothesay looked at his wife, first with amazement, then with cold displeasure. “My dear, you scarcely speak like a mother. You forget likewise that you are speaking to a father. A father who, whatever affection may be wanting, will never forsake his duty. Come, let us go and see our child.”

“I cannot—I cannot!” and Sybilla hung back, weeping anew.

Angus Rothesay looked at his wife—the pretty wayward idol of his bridegroom-memory—looked at her with the eyes of a world-tried, world-hardened man. She regarded him too, and noted the change which years had brought in her boyish lover of yore. His eye wore a fretful reproach—his brow, a proud sorrow.

He walked up to her and clasped her hand. “Sybilla, take care! All these years I have been dreaming of the wife and mother I should find here at home; let not the dream prove sweeter than the reality.”

Sybilla was annoyed—she, the spoilt darling of every one, who knew not the meaning of a harsh word. She answered, “Don't let us talk so foolishly.”

“You think it foolish? Well, then! we will not speak in this confidential way any more. I promise, and you know I always keep my promises.”

“I am glad of it,” answered Sybilla. But she lived to rue the day when her husband made this one promise.

At present, she only felt that the bitter secret was disclosed, and Angus' anger overpast. She gladly let him quit the room, only pausing to ask him to kiss her, in token that all was right between them. He did so, kindly, though with a certain pride and gravity—and departed. She dared not ask him whether it was to see again their hapless child.

What passed between the father and mother whilst they remained shut up together there, Elspie thought not-cared not. She spent the time in passionate caresses of her darling, in half-muttered ejaculations, some of pity some of wrath. All she desired was to obliterate the impression which she saw had gone deeply to the child's heart. Olive wept not—she rarely did; it seemed as though in her little spirit was a pensive repose, above either infant sorrow or infant fear. She sat on her nurse's knee, scarcely speaking, but continually falling into those reveries which we see in quiet children even at that early age, and never without a mysterious wonder, approaching to awe. Of what can these infant musings be?

“Nurse,” said the child, suddenly fixing on Elspie's face her large eyes, “was that my papa I saw?”

“It was just himsel, my sweet wee pet,” cried Elspie, trying to stop her with kisses; but Olive went on.

“He is not like mamma—he is great and tall, like you. But he did not take up and kiss me, as you said he would.”

Elspie had no answer for these words—spoken in a tone of quiet pain—so unlike a child. It is only after many years that we learn to suffer and be silent.

Was it that nature, ever merciful, had implanted in this poor girl, as an instinct, that meek endurance which usually comes as the painful experience of after-life?

A similar thought passed through Elspie's mind, while she sat with little Olive at the window, where, a few years ago, she had stood rocking the new-born babe in her arms, and pondering drearily on its future. That future seemed still as dark in all outward circumstances—but there was one ray of hope, which centred in the little one herself. There was something in Olive which passed Elspie's comprehension. At times she looked almost with an uneasy awe on the gentle, silent child who rarely played, who wanted no amusing, but would sit for hours watching the sky from the window, or the grass and waving trees in the fields; who never was heard to laugh, but now and then smiled in her own peculiar way—a smile almost “uncanny,” as Elspie expressed it. At times the old Scotswoman—who, coming from the debateable ground between Highlands and Lowlands, had united to the rigid piety of the latter much wild Gaelic superstition—was half inclined to believe that the little girl was possessed by some spirit. But she was certain it was a good spirit; such a darling as Olive was—so patient, and gentle, and good—more like an angel than a child.

If her misguided parents did but know this! Yet Elspie, in her secret heart, was almost glad they did not. Her passionate and selfish love could not have borne that any tie on earth, not even that of father or mother, should stand between her and the child of her adoption.

While she pondered, there came a light knock to the door, and Captain Rothesay's voice was heard without—his own voice, soothed down to its soft, gentleman-like tone; it was a rare emotion, indeed, could deprive it of that peculiarity.

“Nurse, I wish to see Miss Olive Rothesay.”

It was the first time that formal appellation had ever been given to the little girl. Still it was a recognition. Elspie heard it with joy. She answered the summons, and Captain Rothesay walked in.

We have never described Olivet father—there could not be a better opportunity than now. His tall, active form—now subsiding into the muscular fulness of middle age—was that of a Hercules of the mountains. The face combined Scottish beauties and Scottish defects, which, perhaps, cease to be defects when they become national peculiarities. There was the eagle-eye: the large, but well-chiselled features— especially the mouth; and also there was the high cheek-bone, the rugged squareness of the chin, which, while taking away beauty, gave character.

When he came nearer, one could easily see that the features of the father were strangely reflected in those of the child. Altered the likeness was—from strength into feebleness—from manly beauty into almost puny delicacy; but it did exist, and, faint as it was, Elspie perceived it.

Olive was looking up at the clouds, her thin cheek resting against the embrasure of the window, gazing so intently that she never seemed to hear her father's voice or step. Elspie motioned him to walk softly, and they came behind the child.

“Do ye no see, Captain Angus,” she whispered, “'tis your ain bonnie face—ay, and your Mither's. Ye mind her yet?”

Captain Rothesay did not answer, but looked earnestly at his little daughter. She, turning round, met his eyes. There was something in their expression which touched her, for a rosy colour suffused her face; she smiled, stretched out her little hands, and said “Papa!”

How Elspie then prided herself for the continual tutoring which had made the image of the absent father an image of love!

Captain Rothesay started from his reverie at the sound of the child's voice. The tone, and especially the word, broke the spell. He felt once more that he was the father, not of the blooming little angel that he had pictured, but of this poor deformed girl. However, he was a man in whom a stern sense of right stood in the place of many softer virtues. He had resolved on his duty—he had come to fulfil it—and fulfil it he would. So he took the two little cold hands, and said—

“Papa is glad to see you, my dear.”

There was a silence, during which Elspie placed a chair for Captain Rothesay, and Olive, sliding quietly down from hers, came and stood beside him. He did not offer to take the two baby-hands again, but did not repulse them, when the little girl laid them on his knee, looking inquiringly, first at him, and then at Elspie.

“What does she mean?” said Captain Rothesay.

“Puir bairn! I tauld her, when her father was come hame, he wad tak' her in his arms and kiss her.”

Rothesay looked angrily round, but recollected himself. “Your nurse was right, my dear.” Then pausing for a moment, as though arming himself for a duty—repugnant, indeed, but necessary—he took his daughter on his knee, and kissed her cheek—once, and no more. But she, remembering Elspie's instructions, and prompted by her loving nature, clung about him, and requited the kiss with many another. They melted him visibly. There is nothing sweeter in this world than a child's unasked voluntary kiss!

He began to talk to her—uneasily and awkwardly—but still he did it. “There, that will do, little one! What is your name, my dear?” he said absently.

She answered, “Olive Rothesay.” “Ay—I had forgotten! The name at least, she told me true.” The next moment, he set down the child—softly but as though it were a relief.

“Is papa going?” said Olive, with a troubled look.

“Yes; but he will come back to-morrow. Once a day will do,” he added to himself. Yet, when his little daughter lifted her mouth for another kiss, he could not help giving it.

“Be a good child, my dear, and say your prayers every night, and love nurse Elspie.”

“And papa too, may I?”

He seemed to struggle violently against some inward feeling, and then answered with a strong effort, “Yes.”

The door closed after him abruptly. Very soon Elspie saw him walking with hasty strides along the beautiful walk that winds round the foot of the castle rock. The nurse sat still for a long time thinking, and then ended her ponderings with her favourite phrase,

“God guide us! it's a' come richt at last.”

Poor, honest, humble soul!

The return of the husband and father produced a considerable change in the little family at Stirling. A household, long composed entirely of women, always feels to its very foundations the incursion of one of the “nobler sex.” From the first morning when there resounded the multiplied ringing of bells, and the creaking of boots on the staircase, the glory of the feminine dynasty was departed. Its easy laisser-aller, its lax rule, and its indifference to regular forms were at an end. Mrs. Rothesay could no longer indulge her laziness—no breakfasting in bed, and coming down in curl-papers. The long gossiping visits of her thousand-and-one acquaintances subsided into frigid morning calls, at which the grim phantom of the husband frowned from a corner and suppressed all idle chatter. Sybilla's favourite system of killing time by half-hours in various idle ways, at home and abroad, was terminated at once. She had now to learn how to be a duteous wife, always ready at the beck and call of her husband, and attentive to his innumerable wants.

She was quite horrified by these at first. The captain actually expected to dine well and punctually, every day, without being troubled beforehand with “What he would like for dinner?” He listened once or twice, patiently too, to her histories of various small domestic grievances, and then requested politely that she would confine such details to the kitchen in future; at which poor Mrs. Rothesay retired in tears. He liked her to stay at home in the evening, make his tea, and then read to him, or listen while he read to her. This was the more arduous task of the two, for dearly as she loved to hear the sound of his voice.

Sybilla never could feel interested in the prosy books he read, and often fell half asleep; then he always stopped suddenly, sometimes looked cross, sometimes sad; and in a few minutes he invariably lighted her candle, with the gentle hint that it was time to retire. But often she woke, hours after, and heard him still walking up and down below, or stirring the fire perpetually, as a man does who is obliged to make the fire his sole companion.

And then Sybilla's foolish, but yet loving heart, would feel itself growing sad and heavy; her husband's image, once painted there in such glittering colours, began to fade. The real Angus was not the Angus of her fancy. Joyful as was his coming home, it had not been quite what she expected. Else, why was it that at times, amidst all her gladness, she thought of their olden past with regret, and of their future with doubt, almost fear.

But it was something new for Sybilla to think at all. It did her good in spite of herself.

While these restless elements of future pain were smouldering in the parents, the little neglected, unsightly blossom, which had sprung up at their feet, lived the same unregarded, monotonous life as heretofore. Olive Rothesay had attained to five years, growing much like a primrose in the field, how, none knew or cared, save Heaven. And that Heaven did both know and care, was evident from the daily sweetness that was stealing into this poor wayside flower, so that it would surely one day be discovered through the invisible perfume which it shed.

Captain Rothesay kept to his firm resolve of seeing his little daughter in her nursery, once a day at least. After a while, the visit of a few minutes lengthened to an hour. He listened with interest to Elspie's delighted eulogiums on her beloved charge, which sometimes went so far as to point out the beauty of the child's wan face, with the assurance that Olive, in features at least, was a true Rothesay. But the father always stopped her with a dignified, cold look.

“We will quit that subject, if you please.”

Nevertheless, guided by his rigid sense of a parent's duty, he showed all kindness to the child, and his omnipotent way over his wife exacted the same consideration from the hitherto indifferent Sybilla. It might be, also, that in her wayward nature, the chill which had unconsciously fallen on the heart of the wife, caused the mother's heart to awaken And then the mother would be almost startled to see the response which this new, though scarcely defined tenderness, created in her child.

For some months after Captain Rothesay's return, the little family lived in the retired old-fashioned dwelling on the hill of Stirling. Their quiet round of uniformity was only broken by the occasional brief absence of the head of the household, as he said, “on business.” Business was a word conveying such distaste, if not horror, to Sybilla's ears, that she asked no questions, and her husband volunteered no information. In fact, he rarely was in the habit of doing so—whether interrogated or not.

At last, one day when he was sitting after dinner with his wife and child—he always punctiliously commanded that “Miss Rothesay” might be brought in with the dessert—Angus made the startling remark:

“My dear Sybilla, I wish to consult with you on a subject of some importance.”

She looked up with a pretty, childish surprise.

“Consult with me! O Angus! pray don't tease me with any of your hard business matters; I never could understand them.”

“And I never for a moment imagined you could. In fact, you told me so, and therefore I have never troubled you with them, my dear,” was the reply, with just the slightest shade of satire. But its bitterness passed away the moment Sybilla jumped up and came to sit down on the hearth at his feet, in an attitude of comical attention. Thereupon he patted her on the head, gently and smilingly, for he was a fond husband still, and she was such a sweet plaything for an idle hour.

A plaything! Would that all women considered the full meaning of the term—a thing sighed for, snatched, caressed, wearied of, neglected, scorned! And would also, that every wife knew that her fate depends less on what her husband makes of her, than what she makes herself to him!

“Now, Angus, begin—I am all attention.”

He looked one moment doubtfully at Olive, who sat in her little chair at the farther end of the room, quiet, silent, and demure. She had beside her some purple plums, which she did not attempt to eat, but was playing with them, arranging them with green leaves in a thousand graceful ways, and smiling to herself when the afternoon sunlight, creeping through the dim window, rested upon them and made their rich colour richer still.

“Shall we send Olive away?” said the mother.

“No, let her stay—she is of no importance.”

The parents both looked at the child's pale, spiritual face, felt the reproach it gave, and sighed. Perhaps both father and mother would have loved her, but for a sense of shame in the latter, and the painful memory of deceit in the former.

“Sybilla,” suddenly resumed Captain Rothesay, “what I have to say is merely, how soon you can arrange to leave Stirling?”

“Leave Stirling?”

“Yes; I have taken a house.”

“Indeed! and you never told me anything about it,” said Sybilla, with a vexed look.

“Now, my little wife, do not be foolish; you never wish to hear about business, and I have taken you at your word; you cannot object to that?”

But she could, and she had a thousand half-pouting, half-jesting complaints to urge. She put them forth rather incoherently; in fact, she talked for five minutes without giving her husband opportunity for a single word. Yet she loved him dearly, and had in her heart no objection to being saved the trouble of thinking beforehand; only she thought it right to stand up a little for her conjugal prerogative.

He listened in perfect silence. When she had done, he merely said, “Very well, Sybilla; and we will leave Stirling this day month. I have decided to live in England. Oldchurch is a very convenient town, and I have no doubt you will find Merivale Hall an agreeable residence.”

“Merivale Hall. Are we really going to live in a Hall?” cried Sybilla, clapping her hands with childish glee. But immediately her face changed. “You must be jesting with me, Angus. I don't know much about money, but I know we are not rich enough to keep up a Hall.”

“We were not, but we are now, I am happy to say,” answered Captain Rothesay, with some triumph.

“Rich! very rich! and you never told me?” Sybilla's hands fell on her knee, and it was doubtful which expression was dominant in her countenance—womanly pain, or womanly indignation.

Angus looked annoyed. “My dear Sybilla, listen to me quietly—yes, quietly,” he added, seeing how her colour came and went, and her lips seemed ready to burst out into petulant reproach. “When I left England, I was taunted with having run away with an heiress. That I did not do, since you were far poorer than the world thought—and I loved little Sybilla Hyde for herself and not for her fortune. But the taunt stung me, and, when I left you, I resolved never to return until I could return a rich man on my own account. I am such now. Are you not glad, Sybilla?”

“Glad—glad to have been kept in the dark like a baby—a fool! It was not proper treatment towards your wife, Angus,” was the petulant answer, as Sybilla drew herself from his arm, which came as a mute peacemaker to encircle her waist.

“Now you are a child indeed. I did it from love—believe me or not, it was so—that you might not be pained with the knowledge of my struggles, toils, and cares. And was not the reward, the wealth, all for you?”

“No; it wasn't.”

“Pray, hear reason, Sybilla!” her husband continued, in those quiet, unconcerned tones, which, to a woman of quick feelings and equally quick resentments, were sure to add fuel to fire.

“I will not hear reason. When you have these four years been rolling in wealth, and your wife and child were—O Angus!” and she began to weep.

Captain Rothesay tried at first, by explanations and by soothings, to stop the small torrent of fretful tears and half-broken accusations. All his words were misconstrued or misapplied. Sybilla would not believe but that he had slighted, ill-used, deceived her.

At the term the husband rose up sternly.

“Mrs. Rothesay, who was it that deceived me?”

He pointed to the child, and the glance of both rested on little Olive.

She sat, her graceful playthings fallen from her hands, her large soft eyes dilated with such a terrified wonder, that both father and mother shrank before them. That fixed gaze of the unconscious child seemed like the reproachful look of some angel of innocence sent from a purer world.

There was a dead silence. In the midst of it the little one crept from her corner, and stood between her parents, her little hands stretched out, and her eyes full of tears.

“Olive has done nothing wrong? Papa and mamma, you are not angry with poor little Olive?”

For the first time, as she looked into the poor child's face, there flashed across the mother's memory the likeness of the angel in her dream. She pressed the thought back, almost angrily, but it came again. Then Sybilla stooped down, and, for the only time since her babyhood, Olive found herself lifted to her mother's embrace.