Project Gutenberg's The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volume VI, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volume VI

The Songs of Scotland of the Past Half Century

Author: Various

Editor: Charles Rogers

Release Date: August 3, 2007 [EBook #22229]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MODERN SCOTTISH MINSTREL ***

Produced by Susan Skinner, Ted Garvin and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE

MODERN SCOTTISH MINSTREL;

OR,

THE SONGS OF SCOTLAND OF THE

PAST HALF CENTURY.

WITH

Memoirs of the Poets,

AND

SKETCHES AND SPECIMENS

IN ENGLISH VERSE OF THE MOST CELEBRATED

MODERN GAELIC BARDS.

BY

CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D.

F.S.A. SCOT.

IN SIX VOLUMES;

VOL. VI.

EDINBURGH:

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK, NORTH BRIDGE,

BOOKSELLERS AND PUBLISHERS TO HER MAJESTY.

M.DCCC.LVI.

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED BY BALLANTYNE AND COMPANY,

PAUL'S WORK.

TO

CHARLES BAILLIE, ESQ.,

SHERIFF OF STIRLINGSHIRE,

CONVENER OF THE ACTING COMMITTEE FOR REARING

A NATIONAL MONUMENT

TO THE

ILLUSTRIOUS DEFENDER OF SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE,

THIS SIXTH VOLUME

OF

The Modern Scottish Minstrel

IS DEDICATED,

WITH SENTIMENTS OF THE HIGHEST RESPECT AND ESTEEM,

BY

HIS VERY OBEDIENT FAITHFUL SERVANT,

CHARLES ROGERS.

[Pg v]

CONTENTS.

- CHARLES MACKAY, LL.D., 1

- Love aweary of the world, 8

- The lover's second thoughts on world weariness, 9

- A candid wooing, 11

- Procrastinations, 12

- Remembrances of nature, 13

- Believe, if you can, 15

- Oh, the happy time departed, 17

- Come back! come back! 17

- Tears, 18

- Cheer, boys, cheer, 20

- Mourn for the mighty dead, 21

- A plain man's philosophy, 22

- The secrets of the hawthorn, 24

- A cry from the deep waters, 25

- The return home, 26

- The men of the North, 28

- The lover's dream of the wind, 29

METRICAL TRANSLATIONS FROM THE MODERN GAELIC MINSTRELSY.

[Pg xi]

INTRODUCTION.

As if pointing to a condition of primeval happiness, Poetry has been the

first language of nations. The Lyric Muse has especially chosen the land

of natural sublimity, of mountain and of flood; and such scenes she has

only abandoned when the inhabitants have sacrificed their national

liberties. Edward I., who massacred the Minstrels of Wales, might have

spared the butchery, as their strains were likely to fall unheeded on

the ears of their subjugated countrymen. The martial music of Ireland is

a matter of tradition; on the first step of the invader the genius of

chivalric song and melody departed from Erin. Scotland retains her

independence, and those strains which are known in northern Europe as

the most inspiriting and delightful, are recognised as the native

minstrelsy of Caledonia. The origin of Scottish song and melody is as

difficult of settlement as is the era or the genuineness of Ossian.

There probably were songs and music in Scotland in ages long prior to

the period of written history. Preserved and transmitted through many

generations of men, stern and defiant as the mountains amidst which it

was produced, the Minstrelsy of the North has, in the course of

centuries, continued steadily to increase alike in aspiration of

sentiment and harmony of numbers.

The spirit of the national lyre seems to have been[Pg xii] aroused during the

war of independence,[1] and the ardour of the strain has not since

diminished. The metrical chronicler, Wyntoun, has preserved a stanza,

lamenting the calamitous death of Alexander III., an event which proved

the commencement of the national struggle.

"Quhen Alysandyr oure kyng wes dede,

That Scotland led in luve and le,

Away wes sons of ale and brede,

Of wyne and wax, of gamyn and gle:

Oure gold wes changyd into lede.

Cryst, borne in-to virgynyté

Succour Scotland and remede,

That stad is in perplexyté."

The antiquity of these lines has been questioned, and it must be

admitted that the strain is somewhat too dolorous for the times. Stung

as they were by the perfidious dealings of their own nobility, and the

ruthless oppression of a neighbouring monarch, the Minstrels sought

every opportunity of astirring the patriotic feelings of their

countrymen, while they despised the efforts of the enemy, and

anticipated in enraptured pæans their defeat. At the siege of Berwick in

1296, when Edward I. began his first expedition against Scotland, the

Scottish Minstrels ridiculed the attempt of the English monarch to

capture the place in some lines which have been preserved. The ballad of

"Gude Wallace" has been ascribed to this age; and if scarcely bearing

the impress of such antiquity, it may have had its prototype in another

of similar strain. Many songs, according to the elder Scottish

historians, were composed and sung among the common people both in

celebration of Wallace and King Robert Bruce.

The battle of Bannockburn was an event peculiarly[Pg xiii] adapted for the

strains of the native lyre. The following Bardic numbers commemorating

the victory have been preserved by Fabyan, the English chronicler:—

"Maydens of Englande,

Sore may ye morne,

For your lemmans, ye

Haue lost at Bannockysburne.

With heue-a-lowe,

What weneth the king of England,

So soon to have won Scotland?

Wyth rumbylowe."

Rhymes in similar pasquinade against the south were composed on the

occasion of the nuptials of the young Prince, David Bruce, with the

daughter of Edward II., which were entered into as a mean of cementing

the alliance between the two kingdoms.

After the oblivion of a century, the Scottish Muse experienced a revival

on the return, in 1424, of James I. from his English captivity to occupy

the throne. Of strong native genius, and possessed of all the learning

which could be obtained at the period, this chivalric sovereign was

especially distinguished for his skill in music and poetry. By Tassoni,

the Italian writer, he has been designated a composer of sacred music,

and the inventor of a new kind of music of a plaintive character. His

poetical works which are extant—"The King's Quair," and "Peblis to the

Play"—abound not only in traits of lively humour, but in singular

gracefulness. To his pen "Christ's Kirk on the Green" may also be

ascribed. The native minstrelsy was fostered and promoted by many of his

royal successors. James III., a lover of the arts and sciences,

delighted in the society of Roger, a musician; James IV. gave frequent

grants to Henry the Minstrel, cherished the poet Dunbar, and[Pg xiv] himself

wrote verses; James V. composed "The Gaberlunzie Man" and "The Jollie

Beggar," ballads which are still sung; Queen Mary loved music, and wrote

verses in French; and James VI., the last occupant of the Scottish

throne, sought reputation as a writer both of Latin and English poetry.

Under the patronage of the Royal House of Stewart, epic and lyric poetry

flourished in Scotland. The poetical chroniclers Barbour, Henry the

Minstrel, and Wyntoun, are familiar names, as are likewise the poets

Henryson, Dunbar, Gavin Douglas, and Sir David Lyndsay. But the authors

of the songs of the people have been forgotten. In a droll poem entitled

"Cockelby's Sow," ascribed to the reign of James I., is enumerated a

considerable catalogue of contemporary lyrics. In the prologue to Gavin

Douglas' translation of the Æneid of Virgil, written not later than

1513, and in the celebrated "Complaynt of Scotland," published in 1549,

further catalogues of the popular songs have been preserved.

The poetic gift had an influence upon the Reformation both of a

favourable and an unfavourable character. By exposing the vices of the

Popish clergy, Sir David Lyndsay and the Earl of Glencairn essentially

tended to promote the interests of the new faith; while, on the event of

the Reformation being accomplished, the degraded condition of the Muse

was calculated to undo the beneficial results of the ecclesiastical

change. The Church early attempted to remedy the evil by sanctioning the

replacement of profane ditties with words of religious import. Of this

nature the most conspicuous effort was Wedderburne's "Book of Godly and

Spiritual Ballads," a work more calculated to provoke merriment than to

excite any other feeling.

On the union of the Crowns a new era arose in the[Pg xv] history of the

Scottish Muse. The national spirit abated, and the poets rejoiced to

write in the language of their southern neighbours. In the time of

Barbour, the Scottish and English languages were almost the same; they

were now widely dissimilar, and the Scottish poets, by writing English

verse, required to translate their sentiments into a new tongue. Their

poetry thus became more the expression of the head than the utterance of

the heart. The national bards of this period, the Earl of Stirling, Sir

Robert Aytoun, and Drummond of Hawthornden, have, amidst much elegant

versification, left no impression on the popular mind. Other poets of

that and the succeeding age imitated Buchanan, by writing in Latin

verse. Though a considerable portion of our elder popular songs may be

fairly ascribed to the seventeenth century, the names of only a few of

the writers have been preserved. The more conspicuous song writers of

this century are Francis Semple, Lord Yester, Lady Grizzel Baillie, and

Lady Wardlaw.

The taste for national song was much on the wane, when it was restored

by the successful efforts of Allan Ramsay. He revived the elder ballads

in his "Evergreen," and introduced contemporary poets in his "Tea Table

Miscellany." The latter obtained a place on the tea table of every lady

of quality, and soon became eminently popular. Among the more

conspicuous promoters of Scottish song, about the middle of last

century, were Mrs Alison Cockburn, Miss Jane Elliot of Minto, Sir

Gilbert Elliot, Sir John Clerk of Pennycuik, Dr Austin, Dr Alexander

Geddes, Alexander Ross, James Tytler, and the Rev. Dr Blacklock. The

poet Robert Fergusson, though peculiarly fond of music, did not write

songs. Scottish song reached its climax on the appearance of Robert

Burns, whose genius burst[Pg xvi] forth meteor-like amidst circumstances the

most untoward. He so struck the chord of the Scottish lyre, that its

vibrations were felt in every bosom. The songs of Caledonia, under the

influence of his matchless power, became celebrated throughout the

world. He purified the elder minstrelsy, and by a few gentle, but

effective touches, completely renovated its fading aspects. "He could

glide like dew," writes Allan Cunningham, "into the fading bloom of

departing song, and refresh it into beauty and fragrance." Contemporary

with Burns, being only seven years his junior, though upwards of half a

century later in becoming known, Carolina Oliphant, afterwards Baroness

Nairn, proved a noble coadjutor and successor to the rustic bard in

renovating the national minstrelsy. Possessing a fine musical ear, she

adapted her lyrics with singular success to the precise sentiments of

the older airs, and in this happy manner was enabled rapidly to

supersede many ribald and vulgar ditties, which, associated with

stirring and inspiring music, had long maintained a noxious popularity

among the peasantry. Of Burns' immediate contemporaries, the more

conspicuous were, John Skinner, Hector Macneill, John Mayne, and Richard

Gall. Grave as a pastor, Skinner revelled in drollery as a versifier;

Macneill loved sweetness and simplicity; Mayne, with a perception of the

ludicrous, was plaintive and sentimental; Gall was patriotic and

graceful.

Sir Walter Scott, the great poet of the past half century, if his

literary qualifications had not been so varied, had obtained renown as a

writer of Scottish songs; he was thoroughly imbued with the martial

spirit of the old times, and keenly alive to those touches of nature

which give point and force to the productions of the national lyre.

Joanna Baillie sung effectively[Pg xvii] the joys of rustic social life, and

gained admission to the cottage hearth. Lady Anne Barnard aroused the

nation to admiration by one plaintive lay. Allan Cunningham wrote the

Scottish ballad in the peculiar rhythm and with the power of the older

minstrels. Alike in mirth and tenderness, Sir Alexander Boswell was

exquisitely happy. Tannahill gave forth strains of bewitching sweetness;

Hogg, whose ballads abound with supernatural imagery, evinced in song

the utmost pastoral simplicity; Motherwell was a master of the

plaintive; Robert Nicoll rejoiced in rural loves. Among living

song-writers, Charles Mackay holds the first place in general

estimation—his songs glow with patriotic sentiment, and are redolent in

beauties; in pastoral scenes, Henry Scott Riddell is without a

competitor; James Ballantine and Francis Bennoch have wedded to

heart-stirring strains those maxims which conduce to virtue. The

Scottish Harp vibrates to sentiments of chivalric nationality in the

hands of Alexander Maclagan, Andrew Park, Robert White, and William

Sinclair. Eminent lyrical simplicity is depicted in the strains of

Alexander Laing, James Home, Archibald Mackay, John Crawford, and Thomas

C. Latto. The best ballad writers introduced in the present work are

Robert Chambers, John S. Blackie, William Stirling, M.P., Mrs Ogilvy,

and James Dodds.[2] Amply sustained is the national reputation in female

lyric poets, by the compositions of Mrs Simpson, Marion Paul Aird,

Isabella Craig, and Margaret Crawford. The national sports are

celebrated with stirring effect by Thomas T. Stoddart, William A.

Foster, and John Finlay. Sacred poetry is admirably represented by such

lyrical writers as Horatius[Pg xviii] Bonar, D.D., and James D. Burns. Many

thrilling verses, suitable for music, though not strictly claiming the

character of lyrics, have been produced by Thomas Aird, so distinguished

in the higher walks of Poetry, Henry Glassford Bell, James Hedderwick,

Andrew J. Symington, and James Macfarlan.

Of the collections of the elder Scottish Minstrelsy, the best catalogue

is supplied by Mr David Laing in the latest edition of Johnson's Musical

Museum. Of the modern collections we would honourably mention, "The Harp

of Caledonia," edited by John Struthers (3 vols. 12mo); "The Songs of

Scotland, Ancient and Modern" (4 vols. 8vo), edited by Allan Cunningham;

"The Scottish Songs" (2 vols. 12mo), edited by Robert Chambers; and,

"The Book of Scottish Song," edited by Alexander Whitelaw. Most of these

works contain original songs, but the amplest collections of these are

M'Leod's "Original National Melodies," and the several small volumes of

"Whistle Binkie."[3] The more esteemed modern collections with music are

"The Scottish Minstrel," edited by R. A. Smith[4] (6 vols. 8vo); "The

Songs of Scotland, adapted to their appropriate[Pg xix] Melodies arranged with

Pianoforte Accompaniments," edited by G. F. Graham, Edinburgh: 1848 (3

vols. royal 8vo); "The Select Songs of Scotland, with Melodies, &c."

Glasgow: W. Hamilton, 1855 (1 vol. 4to); "The Lyric Gems of Scotland, a

Collection of Scottish Songs, Original and Selected, with Music,"

Glasgow: 1856 (12mo). Of district collections of Minstrelsy, "The Harp

of Renfrewshire," published in 1820, under the editorship of Motherwell,

and "The Contemporaries of Burns," containing interesting biographical

sketches and specimens of the Ayrshire bards, claim special

commendation.

The present collection proceeds on the plan not hitherto attempted in

this country, of presenting memoirs of the song writers in connexion

with their compositions, thus making the reader acquainted with the

condition of every writer, and with the circumstances in which his

minstrelsy was given forth. In this manner, too, many popular songs, of

which the origin was generally unknown, have been permanently connected

with the names of their authors. In the preparation of the work,

especially in procuring materials for the memoirs and biographical

notices, the editor has been much occupied during a period of four

years. The translations from the Gaelic Minstrelsy have been supplied,

with scarcely an exception, by a gentleman, a native of the Highlands,

who is well qualified to excel in various departments of literature.[Pg xx]

OBSERVATIONS ON SCOTTISH SONG:

WITH

REMARKS ON THE GENIUS

OF

LADY NAIRN, THE ETTRICK SHEPHERD, AND ROBERT TANNAHILL.

BY HENRY SCOTT RIDDELL.

Songs are the household literature of the Scottish people; they are

especially so as regards the rural portion of the population. Till of

late years, when collections of song have become numerous, and can be

procured at a limited price, a considerable trade was carried on by

itinerant venders of halfpenny ballads. Children who were distant from

school, learned to read on these; and the aged experienced satisfaction

in listening to words and sentiments familiar to them from boyhood. That

the Scots, a thoughtful and earnest people, should have evinced such a

deep interest in minstrelsy, is explained in the observation of Mr

Carlyle, that "serious nations—all nations that can still listen to the

mandates of Nature—have prized song and music as the highest." Deep

feeling, like powerful thought, seeks and finds relief in expression;

the wisdom of Divine benevolence has so arranged, that what brings

relief to one, generally[Pg xxi] affords peace or pleasure to another. And,

further, where there is a susceptibility, a capacity of enjoyment, there

will be efforts made in order to its gratification. The human heart

loves the things of romance, and in the exercise of its native

privilege, delights to feel. Scottish song has been written in harmony

with nature, scenery, and circumstances; and fledged in its own

melodies, which seem no less the outpouring of native sensibility, has

borne itself onward from generation to generation.

Respecting these airs or melodies, a few remarks may be offered. The

genius of our mountain land, as if prompted alike by thought and

feeling, has in these wrought a spell of matchless power—a fascination,

which, reaching the hearts both of old and young, maintains an

imperishable sway over them. One has said,—

"'Tis not alone the scenes of glen and hill,

And haunts and homes beside the murmuring rill;

Nor all the varied beauties of the year,

That so can Scotland to our hearts endear—

The merry both and melancholy strain,

Their power assert, and o'er the spirit reign;

Indebted more to nature than to art,

They reach the ear to fascinate the heart;

And waken hope that, animating, cheers,

Or bathe our being in the flow of tears."

Native, as well as foreign writers, assert that King James the First was

the inventor of a new kind of music, which they further characterise as

being sweet and plaintive. These terms certainly indicate the leading

features of Scottish music. There is something not only of wild

sweetness, but touches of pathos even in its merriest measures. Though

termed a new kind of music, however, it was not new. The king took up

the key-note[Pg xxii] of the human heart—the primitive scale, or what has been

defined the scale of nature, and produced some of those wild and

plaintive strains which we now call Scottish melodies. His poetry was

descriptive of, and adapted to the feelings, customs, and manners of his

countrymen; and he followed, doubtless, the same course in the music

which he composed. By his skill and education, he rendered his

compositions more regular and palpable, than those songs and their airs

which had been framed and sung by the sad-hearted swain on the hill, or

the love-lorn maiden in the green wood.

Not in music only, but in the words of song, some of the Scottish kings

had such a share as to stamp the art and practice of song-writing with

royal sanction. Thus encouraged, the native minstrelsy was fostered by

the whole community, receiving accessions from succeeding generations. A

people who, along with their heroic leader, possessed sufficient courage

to face, with such appalling odds, the foe at Bannockburn—who, at an

after date, fought at Flodden against both their better wit and will,

rather than gainsay their king—and who, in more recent times, protected

him whom they regarded as their rightful prince, at the risk of life and

fortune, were not likely to fail in advancing what royalty had loved,

especially when it was deemed so essential to their happiness. The

poetic spirit entered in and arose out of the heart of the people. The

song and air produced in the court, represented the sentiment of the

cottage. It is still the same. Rights and privileges have been lost,

manners and customs have changed, but song, the forthgiving of the

heart, does not on the heart quit its claim.

Within the modern period, the harp of Caledonia gives forth similar

utterances in the hands of Lady Nairn, the[Pg xxiii] Ettrick Shepherd, and Robert

Tannahill. Different in station and occupations—even in motives to

composition—these three great lyrists were each deeply influenced by

that peculiar acquaintance with Scottish feeling which, brilliantly

illustrated by their genius, has deeply impressed their names on the

national heart.

Lady Nairn, highly born and educated, delighted to sympathise with the

people. If among these she found the forthgivings of human nature less

sophisticated, the principles upon which she proceeded impelled her to

write for the humbler classes of society, and the result has been that

she has written for all. In every class human nature is essentially the

same; and though hearts may have wandered far from the primitive truths

which belong to the life and character of mankind in common, they may

yet be brought back by that which tells winningly upon them—by that

which awakens native feeling and early associations. There is much of

this kind of efficiency in song, when song is what it ought to be. If,

when the true standard is adhered to by those who exercise their powers

in producing it, and who have been born and bred in circumstances of

life so different, it can establish a unity of sentiment—it must

necessarily effect, in a greater or less degree, the same thing among

those who learn and sing the lays which they produce. And, indeed, it

would seem a truth that, by the congenial influences of song, the hearts

of a nation are more united—more willing to be subdued into

acquiescence and equality, than by any other merely human

instrumentality.

If, in Scotland till of late years, writing for fortune was rather than

otherwise regarded as disreputable, writing for fame was never so

accounted. But even than for fame Lady Nairn had a higher motive. She

knew that the minstrels of ruder times had composed, and, through[Pg xxiv] the

aid of the national melodies, transmitted to posterity strains ill

fitted to promote the interests of sound morality, yet that the love of

these sweet and wild airs made the people tenacious of the words to

which they were wedded. Her principal, if not her sole object, was to

disjoin these, and to supplant the impurer strains. Doubtless that

capacity of genius, which enabled her to write as she has done, might,

as an inherent stimulus, urge her to seek gratification in the exercise

of it; but, even in this case, the virtue of her main motive underwent

no diminution. She was well aware how deeply the Scottish heart imbibed

the sentiments of song, so that these became a portion of its nature, or

of the principles upon which the individuals acted, however

unconsciously, amid the intercourse of life. Lessons could thus be

taught, which could not, perhaps, be communicated with the same effect

by any other means. This pleasing agency of education in the school of

moral refinement Lady Nairn has exercised with genial tact and great

beauty; and, liberally as she bestowed benefactions on her fellow-kind

in many other respects, it may be said no gifts conferred could bear in

their beneficial effects a comparison to the songs which she has

written. Her strains thrilled along the chords of a common nature,

beguiling ruder thought into a more tender and generous tone, and

lifting up the lower towards the loftier feeling. If feeling constitutes

the nursery of much that is desirable in national character, it is no

less true that well assorted and confirmed nationality will always prove

the most trustworthy and lasting safeguard of freedom. It is the

combination of heart—the universal unity of sentiment—which renders a

people powerful in the preservation of right and privilege, home and

hearth; and few things of merely human origin will serve more thoroughly

to promote such unity, than the[Pg xxv] songs of a song-loving people. The

continual tendency of these is to imbue all with the same sentiment, and

to awaken, and keep awake, those sympathies which lead mankind to a

knowledge of themselves individually, and of one another in general,

thus preventing the different grades of society from diverging into

undue extremes of distinction. Nor ought the observation to be omitted,

that if a lady of high standing in society, of genius, refined taste and

feeling, and withal of singular purity of heart, could write songs that

the inhabitants of her native land could so warmly appreciate as by

their singing to render them popular, it would evince no inconsiderable

worth in that people that she could so sympathise and so identify

herself with them.

From the position and circumstances of Lady Nairn, those of the Ettrick

Shepherd were entirely different. Hogg was one of the people. To write

songs calculated to be popular, he needed only to embody forth in poetic

shape what he felt and understood from the actual experiences of life

amid the scenes and circumstances in which he had been born and bred;

his compeers, forming that class of society in which it has been thought

the nature of man wears least disguise, were his first patrons. He

required, therefore, less than Lady Nairn the exercise of that sympathy

by which we place ourselves in the circumstances of others, and know how

in these, others think and feel. His poetic effusions were homely and

graphic, both in their sprightful humour and more tender sentiment. They

were sung by the shepherd on the hill, and the maiden at the hay-field,

or when the kye cam' hame at "the farmer's ingle," and in the bien

cottage of the but and ben, where at eventide the rustics delighted

to meet. As experience gave him increased command over the hill harp,

his ambition to produce strains[Pg xxvi] of greater beauty and refinement also

increased. By and by his minstrel numbers manifested a vigour and

perfection which rendered them the admiration of persons of higher rank,

and more competent powers of judgment.

If, with the very simple and seemingly insignificant weapon of Scottish

song, the Baroness Nairn "stooped," the Shepherd stood up "to conquer."

Both adhered to the dictates of nature, and in both cases the result was

the same; nor could the most marked inconveniences which circumstances

imposed hinder that result. A time comes when false things shew their

futility, and things depending upon truth assert their supremacy. The

difference between the authoress and the author lay in those external

circumstances of station and position which could not long, much less

always, be of avail. Their minds were directed by a power of nature to

do essentially the same thing; the difference only being that each did

it in her and his own way. We may suppose that while Lady Nairn in her

baronial hall wrote—

"Bonnie Charlie 's now awa',

Safely ower the friendly main,

Mony a heart will break in twa

Should he ne'er come back again;"

the Ettrick Shepherd seated on "a moss-gray stane," or a heather-bush,

and substituting his knee for his writing desk, might be furnishing

forth for the world's entertainment the lament, commencing—

"Far over yon hills of the heather sae green,

And down by the corrie that sings to the sea,

The bonnie young Flora sat sighing alane,

Wi' the dew on her plaid and the tear in her e'e."

Or when the lady was producing "The land o' the[Pg xxvii] leal," a lay which has

reached and sunk so deeply into all hearts, the Shepherd might be

singing among the wild mountains the affecting and popular ditty, the

truth of which touched his own heart so powerfully, of "The moon was a'

waning," or saying to the skylark—

"Bird of the wilderness,

Blithesome and cumberless,

Sweet be thy matin o'er moorland and lea;

Emblem of happiness,

Blest is thy dwelling-place,

Oh! to abide in the desert with thee!"

Tannahill has likewise written a number of songs which have been

deservedly admired, loved, and sung. Allan Cunningham used to say, that

if he could only succeed in writing two songs which the inhabitants of

his native land would continue to sing, he would account it sufficient

fame. Tannahill has accomplished this, and much more. In temperament, as

well as circumstances, he differed widely both from Lady Nairn and the

Ettrick Shepherd. Amiable and good in all her ways, Lady Nairn's career

appears to have been lovely and alluring as the serene summer eve; the

Shepherd was rich as autumn, in the enjoyment of life itself, and all

that life could bring; but Tannahill's nature was cloudy, sensitive, and

uncertain as the April day. Lady Nairn, ambitious of doing good and

promoting happiness, dwelt, in heart at least, "among her own people,"

giving and receiving alike those charms of unbroken delight which spring

from the kindness of the kind, and fearing nothing so much as public

notoriety. Hogg loved fame, yet took no pains to secure it. Fame,

nevertheless, reached him; but when found, it was with him a possession

much resembling the child's toy. His heart to the last appeared too

deeply imbued with the[Pg xxviii] unsuspicious simplicity and carelessness of the

boy to have much concern about it. On this point Tannahill was morbidly

sensitive; his was an unfortunate cast of temperament, which, deepening

more and more, surrounded him with imaginary evils, and rendered life

insupportable. Lady Nairn was too modest not to be distrustful of the

extent of her genius, and presumed only to exercise it in composing

words to favourite melodies. The genius of Tannahill was more

circumscribed, and he was consequently more timid and painstaking. Hogg,

ambitious of originality, was bold and reckless. He had the power of

assuming many distinct varieties of style, his mind, taking the tone of

the subject entered upon, as easily as the musician passes from one note

to another. In education, Tannahill had the advantage over the Shepherd,

but in nothing else. The Shepherd's occupation was much more calculated

to inspire him with the feelings, and more fitted in everything to urge

to the cultivation of poetry, than the employment at which Tannahill was

doomed to labour. The beauty and grandeur of nature, solemn and sublime,

surround the path of him who tends the flocks. Though occasionally

called upon to face the blast, and wrestle with the storm, he still

experiences a charm. But when the broad earth is green below, and the

wide bending sky blue above, the voice of nature in the sounding of

streams, the song of birds, and the bleating of sheep differ widely from

what the susceptible and poetic mind is destined to experience amidst

the clanking din of shuttles in the dingy, narrow workshop of the

handloom weaver. Here the breath of the light hill breeze cannot come;

the form is bowed down, and the cheek is pale. Life, however buoyant and

aspiring at first, necessarily ere long becomes saddened and subdued. To

poor Tanna[Pg xxix]hill it became a burden—more than he could bear. Yet it was

among these circumstances that he contrived to compose those chaste and

beautiful songs which have delighted, and still continue to delight, the

hearts of so many. Though not marked with much that can be termed

strikingly original, this, instead of militating against them, may have

told in their favour. Wayward conceits, fanciful thoughts and

expressions in songs, are like the hectic hue on the cheek of the

unhealthy; it may appear to give a surpassing beauty, but it is a beauty

which forebodes decay. "Oh, are ye sleeping, Maggie?" may be regarded as

the most original of Tannahill's songs. It is more ardent in tone, and

in every respect more poetic, than his other lyrics. The imagery is not

only striking, but true to nature, though in maintaining the simple and

tender, it does more than approach the sublime. His style is uniformly

distinguished by a chaste simplicity, and well sustained power.

In these observations, we have pointed to that affinity of mind which

unites in sentiment those possessing it, in spite of worldly

distinctions. And song, too, we have found, is a prevalent and

far-pervading agency, which become the mean of binding together a

nation's population on the ground of that which is true to nature. It,

therefore, does so in a manner more congenial and pleasurable than most

other ties which bind; those of interest and necessity may be stronger,

indeed, but these ties being much more selfish, are also, in most

instances, much less harmonious. Song-writing is the highest attribute

of poetic genius. The epic poet has to do with the exercise of energies,

which produce deeds that are decided, together with the operation of

passions and feelings which are borne into excess. These are more easily

depicted than the gentler sentiments and feelings, to[Pg xxx]gether with the

lights and shades of national character which constitute the materials

of song. Nor will strains which set forth the actions of mankind as

operating in excess, ever be so popular as simple song. Though

communities are liable to periods of excitement, this is not their

natural condition. Songs founded upon such, may be popular while the

excitement lasts, but not much longer. Philosophers and inquiring

individuals may revert to and dwell upon them, but the generality of the

people will renounce them. Those who linger over them, will do so

through a disposition to ascertain the causes which gave them birth, and

how far these were natural in the circumstances. He who sings, feels

that the same ardour cannot be re-awakened; and the sentiments which the

poet has expressed become as things that are false and foolish.

Nearly all the poems of Burns proceed on the same principles upon which

popular song proceeds. He approved himself considerably original and

singularly interesting, by taking up and saying, in the language best

suited for the purpose, what his countrymen had either already, to one

extent or other, thought and felt, or were, at his suggestion, fully

prepared to think and feel. It is thus that song becomes the truest

history of a people; they, properly speaking, have rarely any other

historian than the poet. History, in its stateliness, does not deign to

dwell upon their habits, their customs and manners, and, therefore,

cannot unfold their usual modes of thinking and feeling; it only notices

those more anomalous emergencies when the ebullitions of high passion

and excitement prevail; and such not being the natural condition of any

people, a true representation of their real character is not given. If

song equally tends to strengthen the bonds of nationality, it is also

that from which the true cast of a land's[Pg xxxi] inhabitants can be gathered.

From habits and training, together with the native shades of peculiar

character, there is in human nature great variety; so, consequently, is

there also in song, for perhaps it might be difficult to fix upon one of

these peculiarities, whether of outward manner or inward disposition,

which song has not taken up and illustrated in its own way. Every song,

of course, has an aim or leading sentiment pervading it. It either tells

a tale calculated to interest human nature and revive feeling, or sets

forth a sentiment which human nature entertains, so that it shall be

turned to better account. This involves the field which song has it in

its power to cultivate and improve. But neither the pure moralist, nor

the accomplished critic, must expect a very great deal to be done on

this field at once. The song-writer has difficulties to contend with,

both in regard to those by whom he would have his songs sung, and the

airs to which he writes them. If in the latter case he would willingly

substitute classical and sounding language for monosyllables and

contracted words, the measures which the air require will not allow him;

and should he suddenly lift up and bear high the standard of moral

refinement, those who should attend may fail to appreciate the movement,

and refuse to follow him. If he can contrive, therefore, to interest and

entertain with what is at least harmless, it is much, considering how

wide a field even one popular song occupies, and how many of an

undesirable kind it may meanwhile displace and eventually supersede. The

tide of evil communications cannot be barred back at once, and song

remedy the evil which song in its impurer state has done. Nor is the

critic, who weighs these disadvantages, likely to pronounce a very

decided judgment upon the superiority and inferiority of songs, whether

in general or individually.[Pg xxxii]

Few of the different classes of society may view them in the same light,

and estimate them on the same grounds that he does. If he thinks, the

people feel; and they overturn his decisions by the songs which they

adopt and render popular. It is by no means so much the correct beauty

of the composition, as the suitableness of the sentiment, which insures

their patronage. Few of the songs of Burns are so correctly and

elegantly composed as "The lass of Ballochmyle;" yet few of his songs

have been more rarely sung.[Pg 1]

THE

MODERN SCOTTISH MINSTREL.

CHARLES MACKAY, LL.D.[5]

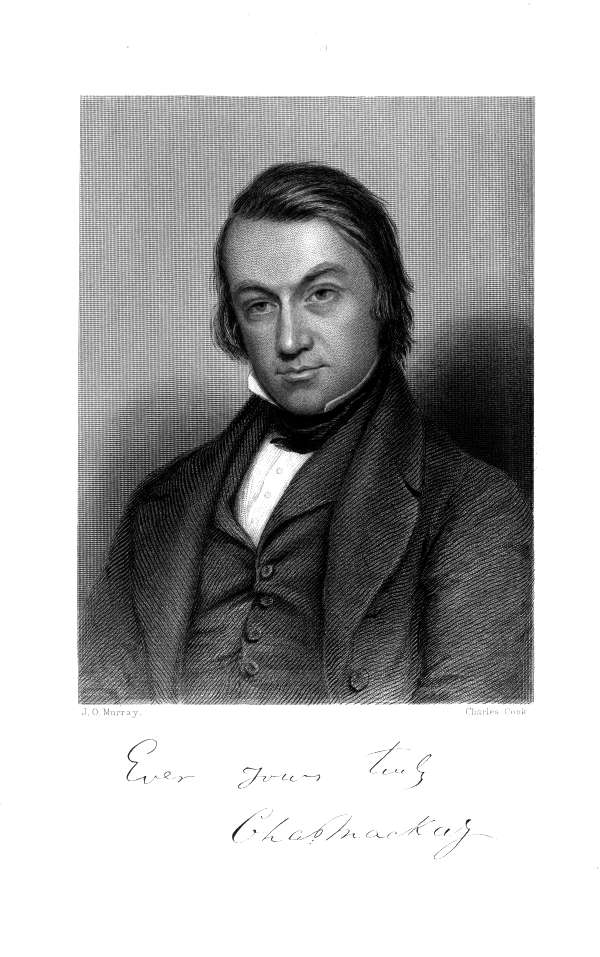

Our first volume contained the portrait of Sir Walter Scott; our sixth

and concluding volume is adorned by the portrait of Charles Mackay. In

these distinguished men there is not only a strong mental similarity,

but also a striking physical resemblance. Those who are curious in such

matters will do well to compare the two portraits. The one was the most

prolific and popular writer at the commencement of the century; the

other is the most prolific and popular song-writer of the present day.

Wherever the English language is heard and patriotic songs are sung,

Charles Mackay will be present in his verse. He rejoices in his English

songs; but Scotland claims him as a son.

Charles Mackay is of ancient and honourable extraction. His paternal

ancestors were the Mackays of Strathnaver, in Sutherlandshire; while, on

the mother's side, he is descended from the Roses of Kilravock, near

Inverness, for many centuries the proprietors of one of the[Pg 2] most

interesting feudal strongholds in the Highlands. The Mrs Rose of

Kilravock, whose name appears in the "Correspondence" of Burns, was

Charles Mackay's maternal grandmother.

He was born at Perth in 1814; but his early years were spent in London,

his parents having removed to the metropolis during his infancy. There

he received the rudiments of an education which was completed in the

schools of Belgium and Germany. His relation, General Mackay, intended

that he should adopt the military profession; but family arrangements

and other circumstances prevented the fulfilment of that intention.

The poetical faculty cannot be acquired; it must be born with a man,

growing with his growth, and strengthening with his strength, until

developed by the first great impulse that agitates his being, and

generally that is love. There are versifiers innumerable who are not

poets, but there are no poets whose hearts remain unstirred by the

exciting passion of irrepressible love, when song becomes the written

testimony of the inner life. Whether it was so with Charles Mackay we

have not ascertained, nor have we cared to inquire. His love-songs,

however, are exquisitely touching, and among the purest compositions in

the language. Certain it is that the poetical power was early

manifested; for we find that, in 1836, he gave his first poems to the

public. The unpretending volume attracted the attention of John Black,

who was then the distinguished editor of the Morning Chronicle. Ever

ready to recognise genius wherever it could be found, and always

prepared to lend a hand to lift into light the unobtrusive author who

laboured in the shade, he offered young Mackay a place on the paper,

which was accepted, and filled with such ability that he was[Pg 3] rapidly

promoted to the responsible position of sub-editor. He soon became one

of the marked men of the time in connexion with the press; and, in 1844,

he undertook the editorship of the Glasgow Argus, a journal devoted to

the advocacy of advanced liberal opinions.

This paper he conducted for three years, and returned to London, where

he received the appointment of editor of the Illustrated London News,

a situation which, considering the peculiar character of the paper, he

fills with consummate tact. Some of the great organs of public opinion

may thunder forth embittered denunciations, others, in the silkiest

tone, will admonish so gently that they half approve the misconduct of

people in power if their birth happens to have been sufficiently

elevated. The distinguishing characteristics of the political articles

written by Charles Mackay are their manly and thoroughly independent

spirit, avoiding alike fulsome adulation and indiscriminate abuse. His

censure and his praise are always governed by strictest impartiality.

Whether he condemns or whether he applauds he secures the respect even

of those from whom he differs the most. It is no small merit to possess

such a power in the conflict and strife of politics. We happen to know a

circumstance which speaks volumes on this subject. The peculiarities of

the press of England were being discussed in the presence of a foreign

nobleman, of high rank and political influence, who expressed himself to

this effect:—"Some of your newspapers are feared, some simply

tolerated, some detested, and some merit our contempt, but the

Illustrated London News is respected. It is admitted everywhere, it is

read everywhere; and, although it is sometimes severe, its very severity

is appreciated, because it is the expression of earnest conviction and

sterling good sense; the result is, that it has,[Pg 4] on the Continent, a

wider influence than any paper published in England."

Mackay's works have been numerous and various. Without presuming to be

perfectly accurate, we shall attempt a list of his several publications.

His first, as we have already stated, was a small volume of "Poems,"

published in 1836. This was followed by the "Hope of the World," a poem,

in heroic verse, published in 1839. Soon afterwards appeared "The Thames

and its Tributaries," a most suggestive, agreeable, and gossiping book.

In 1841 appeared his "Popular Delusions," a work of considerable merit;

and next came, in 1842, his romance of "Longbeard, Lord of London," so

well conceived and cleverly executed, that an archæologist of

considerable pretensions mistook it for a genuine historical record of

the place on which it was written. His next work, and up till that

period his noblest poem, "The Salamandrine, or Love and Immortality,"

appeared in 1843. As there is no hesitation in his thought, there is no

vagueness in his language; it is terse, clear, and direct in every

utterance. An enemy to spasms in every form, he abhors the Spasmodic

School of Poets. If the true poet be the seer—the far seer into

futurity—he should see his way clear before him. He should write

because he has a thought to utter, and ought to utter it in the clearest

and the fittest language, and this is the principle which manifestly

governs the compositions of Charles Mackay. The "Salamandrine" lifted

his works high in the poetic scale, and permanently fixed him, not only

in the ranks, but marked him as a leader of the host of eminent British

poets. His residence in Scotland enabled him to visit many places famous

in Scottish history. The results were his "Legends of the Isles,"

published in[Pg 5] 1845 and his "Voices from the Mountains" in 1846. A few

months before the publication of the last named volume, the University

of Glasgow conferred upon him the degree of LL.D.

When the London Daily News was started, he contributed some stirring

lyrics, under the title of "Voices from the Crowd." They arrested the

attention of the public, and tended greatly to popularise and establish

the reputation of that journal. In 1847 appeared his "Town Lyrics," a

series of ballads which harrowed the soul by laying bare many of the

secret miseries of the town. In 1850 was published his exquisite poem of

"Egeria," probably the most refined and artistic of all his productions;

and in 1856 he gave to the world "The Lump of Gold," and "Under Green

Leaves," two volumes of charming poetry; the first tracing the evils

that flow from unrestrained cupidity; the second the delights of the

country, under every circumstance that can or does occur. Latterly he

has composed some popular airs, set to his own lyrics; thus giving to

the melody he has conceived the immortality of his verse. With the late

Sir Henry Bishop he was associated in re-arranging a hundred of the

choicest old English melodies. The music has been re-arranged; and many

a lovely air, inadmissible to cultivated society from its being

associated with vulgar or debasing words, has been re-admitted to the

social circle, and is fast floating into public favour in union with the

words composed by Mackay.

Here we stop. This is not the time, nor is it the place, to discuss,

with any great elaboration, the merits or peculiarities of Charles

Mackay as an author. We have to do with him as the most successful of

song-writers. Two of his songs, perhaps not among his best, have[Pg 6]

obtained a world-wide popularity. His "Good Time Coming," and his

"Cheer, Boys, Cheer," have been ground to death by barrel-organs, but

only to experience a resurrection to immortality. On the wide sea, amid

the desert, across the prairies, in burning India, in far Australia, and

along the frozen steppes of Russia are floating those imperishable airs

suggested by the "Lyrics" whose names they bear. The soldier and the

sailor, conscious of impending danger, think of beloved ones at home;

unconsciously they hum a melody, and comfort is restored. The emigrant,

forced by various circumstances to leave his native land, where, instead

of inheriting food and raiment, he had experienced hunger, nakedness,

and cold, endeavours to express his feelings, and is discovered crooning

over the tune that correctly interprets his emotions, and thrills his

heart with gladness. The poet's song has become incorporated with the

poor man's nature. You may see that it fills his eyes with tears; but

they are not of sorrow. His cheek is flushed with hope, and a radiant

expectation, founded on experience, which seems to illuminate and gild

his future destiny. Marvellous, indeed, are the influences of a true

song; and while they are rare, they are by fashion rarely appreciated.

In it are embodied the best thoughts in the best language. By it the

best of every class in every clime are swayed. In it they find

expression for sensations, which, but for the poet, might have slumbered

unexpressed till the day of doom.

Whether we think of Charles Mackay as a journalist, as a novelist, as a

poet, or as a musician, he wins our admiration in all. Possessing, as he

does in a high degree, a fine imagination, allied to the kindliest

feelings springing from a sensitive and considerate heart, he is beloved

by his friends, and cares little for the vulgar admiration[Pg 7] of the

crowd. The pomp, and circumstance, and self-exaltation, so current

now-a-days, he utterly despises. But the kindliness, the glowing

sympathies of a few kindred spirits gladden him and make him happy.

Though modest and retiring in his disposition, he has no shamefacedness.

His conversation is like his verse; there is neither tinsel nor glitter,

but genuine, solid stuff. Something that bears examination; something

you can take up and handle; something to brood over and reflect upon;

something that wins its way by its truthfulness, and compels you to

accept it as a principle; something that sticks close, and springs up in

the future a very fountain of pure and unadulterated joy; from all this

it will be inferred that no man can remain long in his company without

feeling that he is not only a wiser, but a better man for the privilege

enjoyed. He is still in the prime of life and the maturity of his

intellect. May we not, in concluding this slight notice of his life and

character, express a hope which we know to be a general one—that he may

yet live to write many more poems and many more songs, as good or better

than those which he has already given to the world?[Pg 8]

LOVE AWEARY OF THE WORLD.

Oh! my love is very lovely,

In her mind all beauties dwell;

She, robed in living splendour,

Grace and modesty attend her,

And I love her more than well.

But I 'm weary, weary, weary,

To despair my soul is hurl'd;

I am weary, weary, weary,

I am weary of the world!

She is kind to all about her,

For her heart is pity's throne;

She has smiles for all men's gladness,

She has tears for every sadness,

She is hard to me alone.

And I 'm weary, weary, weary,

From a love-lit summit hurl'd;

I am weary, weary, weary,

I am weary of the world!

When my words are words of wisdom

All her spirit I can move,

At my wit her eyes will glisten,

But she flies and will not listen

If I dare to speak of love.

Oh! I 'm weary, weary, weary,

By a storm of passions whirl'd;

I am weary, weary, weary,

I am weary of the world!

[Pg 9]

True, that there are others fairer—

Fairer?—No, that cannot be—

Yet some maids of equal beauty,

High in soul and firm in duty,

May have kinder hearts than she.

Why, by heart, so weary, weary,

To and fro by passion whirl'd?—

Why so weary, weary, weary,

Why so weary of the world?

Were my love but passing fancy,

To another I might turn;

But I 'm doom'd to love unduly

One who will not answer truly,

And who freezes when I burn.

And I 'm weary, weary, weary,

To despair my soul is hurl'd;

I am weary, weary, weary,

I am weary of the world!

THE LOVER'S SECOND THOUGHTS ON WORLD WEARINESS.

Heart! take courage! 'tis not worthy

For a woman's scorn to pine,

If her cold indifference wound thee,

There are remedies around thee

For such malady as thine.

Be no longer weary, weary,

From thy love-lit summits hurl'd;

Be no longer weary, weary,

Weary, weary of the world!

[Pg 10]

If thou must be loved by woman,

Seek again—the world is wide;

It is full of loving creatures,

Fair in form, and mind, and features—

Choose among them for thy bride.

Be no longer weary, weary,

To and fro by passion whirl'd;

Be no longer weary, weary,

Weary, weary of the world!

Or if Love should lose thy favour,

Try the paths of honest fame,

Climb Parnassus' summit hoary,

Carve thy way by deeds of glory,

Write on History's page thy name.

Be no longer weary, weary,

To the depth of sorrow hurl'd;

Be no longer weary, weary,

Weary, weary of the world!

Or if these shall fail to move thee,

Be the phantoms unpursued,

Try a charm that will not fail thee

When old age and grief assail thee—

Try the charm of doing good.

Be no longer weak and weary,

By the storms of passion whirl'd;

Be no longer weary, weary,

Weary, weary of the world!

Love is fleeting and uncertain,

And can bate where it adored,

Chase of glory wears the spirit,

Fame not always follows merit,

Goodness is its own reward.

[Pg 11]

Be no longer weary, weary,

From thine happy summit hurl'd;

Be no longer weary, weary,

Weary, weary of the world!

A CANDID WOOING.

I cannot give thee all my heart,

Lady, lady,

My faith and country claim a part,

My sweet lady;

But yet I 'll pledge thee word of mine

That all the rest is truly thine;—

The raving passion of a boy,

Warm though it be, will quickly cloy—

Confide thou rather in the man

Who vows to love thee all he can,

My sweet lady.

Affection, founded on respect,

Lady, lady,

Can never dwindle to neglect,

My sweet lady;

And, while thy gentle virtues live,

Such is the love that I will give.

The torrent leaves its channel dry,

The brook runs on incessantly;

The storm of passion lasts a day,

But deep, true love endures alway,

My sweet lady.

[Pg 12]

Accept then a divided heart,

Lady, lady,

Faith, Friendship, Honour, each have part,

My sweet lady.

While at one altar we adore,

Faith shall but make us love the more;

And Friendship, true to all beside,

Will ne'er be fickle to a bride;

And Honour, based on manly truth,

Shall love in age as well as youth,

My sweet lady.

PROCRASTINATIONS.

If Fortune with a smiling face

Strew roses on our way,

When shall we stoop to pick them up?

To-day, my love, to-day.

But should she frown with face of care,

And talk of coming sorrow,

When shall we grieve—if grieve we must?

To-morrow, love, to-morrow.

If those who 've wrong'd us own their faults

And kindly pity pray,

When shall we listen and forgive?

To-day, my love, to-day.

But if stern Justice urge rebuke,

And warmth from memory borrow,

When shall we chide—if chide we dare?

To-morrow, love, to-morrow.

[Pg 13]

If those to whom we owe a debt

Are harm'd unless we pay,

When shall we struggle to be just?

To-day, my love, to-day.

But if our debtor fail our hope,

And plead his ruin thorough,

When shall we weigh his breach of faith?

To-morrow, love, to-morrow.

If Love, estranged, should once again

His genial smile display,

When shall we kiss his proffer'd lips?

To-day, my love, to-day,

But, if he would indulge regret,

Or dwell with bygone sorrow,

When shall we weep—if weep we must?

To-morrow, love, to-morrow.

For virtuous acts and harmless joys

The minutes will not stay;

We 've always time to welcome them

To-day, my love, to-day.

But care, resentment, angry words,

And unavailing sorrow

Come far too soon, if they appear

To-morrow, love, to-morrow.

REMEMBRANCES OF NATURE.

I remember the time, thou roaring sea,

When thy voice was the voice of Infinity—

A joy, and a dread, and a mystery.

[Pg 14]

I remember the time, ye young May flowers,

When your odours and hues in the fields and bowers

Fell on my soul as on grass the showers.

I remember the time, thou blustering wind,

When thy voice in the woods, to my youthful mind,

Seem'd the sigh of the earth for human kind.

I remember the time, ye suns and stars,

When ye raised my soul from its mortal bars

And bore it through heaven on your golden cars.

And has it then vanish'd, that happy time?

Are the winds, and the seas, and the stars sublime

Deaf to thy soul in its manly prime?

Ah, no! ah, no! amid sorrow and pain,

When the world and its facts oppress my brain,

In the world of spirit I rove—I reign.

I feel a deep and a pure delight

In the luxuries of sound and sight—

In the opening day, in the closing night.

The voices of youth go with me still,

Through the field and the wood, o'er the plain and the hill,

In the roar of the sea, in the laugh of the rill.

Every flower is a lover of mine,

Every star is a friend divine:

For me they blossom, for me they shine.

[Pg 15]

To give me joy the oceans roll,

They breathe their secrets to my soul,

With me they sing, with me condole.

Man cannot harm me if he would,

I have such friends for my every mood

In the overflowing solitude.

Fate cannot touch me: nothing can stir

To put disunion or hate of her

'Twixt Nature and her worshipper.

Sing to me, flowers! preach to me, skies!

Ye landscapes, glitter in mine eyes!

Whisper, ye deeps, your mysteries!

Sigh to me, wind! ye forests, nod!

Speak to me ever, thou flowery sod!

Ye are mine—all mine—in the peace of God.

BELIEVE IF YOU CAN.

Music by the Author.

Hope cannot cheat us,

Or Fancy betray;

Tempests ne'er scatter

The blossoms of May;

The wild winds are constant,

By method and plan;

Oh! believe me, believe me,

Believe if you can!

[Pg 16]

Young Love, who shews us

His midsummer light,

Spreads the same halo

O'er Winter's dark night;

And Fame never dazzles

To lure and trepan;

Oh! believe me, believe me,

Believe if you can!

Friends of the sunshine

Endure in the storm;

Never they promise

And fail to perform.

And the night ever ends

As the morning began;

Oh! believe me, believe me,

Believe if you can!

Words softly spoken

No guile ever bore;

Peaches ne'er harbour

A worm at the core;

And the ground never slipp'd

Under high-reaching man;

Oh! believe me, believe me,

Believe if you can!

Seas undeceitful,

Calm smiling at morn,

Wreck not ere midnight

The sailor forlorn.

And gold makes a bridge

Every evil to span;

Oh! believe me, believe me,

Believe if you can.

[Pg 17]

OH, THE HAPPY TIME DEPARTED!

Air by Sir H. R. Bishop.

Oh, the happy time departed!

In its smile the world was fair;

We believed in all men's goodness;

Joy and hope were gems to wear;

Angel visitants were with us,

There was music in the air.

Oh, the happy time departed!

Change came o'er it all too soon;

In a cold and drear November

Died the leafy wealth of June;

Winter kill'd our summer roses;

Discord marr'd a heavenly tune.

Let them pass—the days departed—

What befell may ne'er befall;

Why should we with vain lamenting

Seek a shadow to recall?

Great the sorrows we have suffer'd—

Hope is greater than them all.

COME BACK! COME BACK!

Come back! come back! thou youthful Time,

When joy and innocence were ours,

When life was in its vernal prime,

And redolent of sweets and flowers.

[Pg 18]

Come back—and let us roam once more,

Free-hearted, through life's pleasant ways,

And gather garlands as of yore—

Come back—come back—ye happy days!

Come back! come back!—'twas pleasant then

To cherish faith in love and truth,

For nothing in dispraise of men

Had sour'd the temper of our youth.

Come back—and let us still believe

The gorgeous dream romance displays,

Nor trust the tale that men deceive—

Come back—come back—ye happy days!

Come back!—oh, freshness of the past,

When every face seem'd fair and kind,

When sunward every eye was cast,

And all the shadows fell behind.

Come back—'twill come; true hearts can turn

Their own Decembers into Mays;

The secret be it ours to learn—

Come back—come back—ye happy days!

TEARS.

Music by Sir H. R. Bishop.

O ye tears! O ye tears! that have long refused to flow,

Ye are welcome to my heart—thawing, thawing, like the snow;

[Pg 19]

I feel the hard clod soften, and the early snowdrops spring,

And the healing fountains gush, and the wildernesses sing.

O ye tears! O ye tears! I am thankful that ye run;

Though ye trickle in the darkness, ye shall glitter in the sun;

The rainbow cannot shine if the rain refuse to fall,

And the eyes that cannot weep are the saddest eyes of all.

O ye tears! O ye tears! till I felt you on my cheek,

I was selfish in my sorrow, I was stubborn, I was weak.

Ye have given me strength to conquer, and I stand erect and free,

And know that I am human by the light of sympathy.

O ye tears! O ye tears! ye relieve me of my pain;

The barren rock of pride has been stricken once again;

Like the rock that Moses smote, amid Horeb's burning sand,

It yields the flowing water to make gladness in the land.

There is light upon my path, there is sunshine in my heart,

And the leaf and fruit of life shall not utterly depart.

Ye restore to me the freshness and the bloom of long ago—

O ye tears! happy tears! I am thankful that ye flow.

[Pg 20]

CHEER, BOYS! CHEER!

Cheer, boys! cheer! no more of idle sorrow;

Courage, true hearts, shall bear us on our way!

Hope points before, and shews the bright to-morrow—

Let us forget the darkness of to-day!

So farewell, England! much as we may love thee,

We 'll dry the tears that we have shed before;

Why should we weep to sail in search of fortune?

So farewell, England! farewell evermore!

Cheer, boys! cheer! for England, mother England!

Cheer, boys! cheer! the willing strong right hand;

Cheer, boys! cheer! there 's work for honest labour,

Cheer, boys! cheer! in the new and happy land!

Cheer, boys! cheer! the steady breeze is blowing,

To float us freely o'er the ocean's breast;

The world shall follow in the track we 're going,

The star of empire glitters in the west.

Here we had toil and little to reward it,

But there shall plenty smile upon our pain;

And ours shall be the mountain and the forest,

And boundless prairies, ripe with golden grain.

Cheer, boys! cheer! for England, mother England!

Cheer, boys! cheer! united heart and hand!

Cheer, boys! cheer! there 's wealth for honest labour,

Cheer, boys! cheer! in the new and happy land!

[Pg 21]

MOURN FOR THE MIGHTY DEAD.

Music by Sir H. R. Bishop.

Mourn for the mighty dead,

Mourn for the spirit fled,

Mourn for the lofty head—

Low in the grave.

Tears such as nations weep

Hallow the hero's sleep;

Calm be his rest, and deep—

Arthur the brave!

Nobly his work was done;

England's most glorious son,

True-hearted Wellington,

Shield of our laws.

Ever in peril's night

Heaven send such arm of might—

Guardian of truth and right—

Raised in their cause!

Dried be the tears that fall;

Love bears the warrior's pall,

Fame shall his deeds recall—

Britain's right hand!

Bright shall his memory be!

Star of supremacy!

Banner of victory!

Pride of our land.

[Pg 22]

A PLAIN MAN'S PHILOSOPHY.

Music by the Author.

I 've a guinea I can spend,

I 've a wife, and I 've a friend,

And a troop of little children at my knee, John Brown;

I 've a cottage of my own,

With the ivy overgrown,

And a garden with a view of the sea, John Brown;

I can sit at my door

By my shady sycamore,

Large of heart, though of very small estate, John Brown;

So come and drain a glass

In my arbour as you pass,

And I 'll tell you what I love and what I hate, John Brown.

I love the song of birds,

And the children's early words,

And a loving woman's voice, low and sweet, John Brown;

And I hate a false pretence,

And the want of common sense,

And arrogance, and fawning, and deceit, John Brown;

I love the meadow flowers,

And the brier in the bowers,

And I love an open face without guile, John Brown;

And I hate a selfish knave,

And a proud, contented slave,

And a lout who 'd rather borrow than he 'd toil, John Brown.

[Pg 23]

I love a simple song

That awakes emotions strong,

And the word of hope that raises him who faints, John Brown;

And I hate the constant whine

Of the foolish who repine,

And turn their good to evil by complaints, John Brown;

But ever when I hate,

If I seek my garden gate,

And survey the world around me, and above, John Brown,

The hatred flies my mind,

And I sigh for human kind,

And excuse the faults of those I cannot love, John Brown.

So, if you like my ways,

And the comfort of my days,

I will tell you how I live so unvex'd, John Brown;

I never scorn my health,

Nor sell my soul for wealth,

Nor destroy one day the pleasures of the next, John Brown;

I 've parted with my pride,

And I take the sunny side,

For I 've found it worse than folly to be sad, John Brown;

I keep a conscience clear,

I 've a hundred pounds a-year,

And I manage to exist and to be glad, John Brown.

[Pg 24]

THE SECRETS OF THE HAWTHORN.

Music by the Author.

No one knows what silent secrets

Quiver from thy tender leaves;

No one knows what thoughts between us

Pass in dewy moonlight eves.

Roving memories and fancies,

Travellers upon Thought's deep sea,

Haunt the gay time of our May-time,

O thou snow-white hawthorn-tree!

Lovely was she, bright as sunlight,

Pure and kind, and good and fair,

When she laugh'd the ringing music

Rippled through the summer air.

"If you love me—shake the blossoms!"

Thus I said, too bold and free;

Down they came in showers of beauty,

Thou beloved hawthorn-tree!

Sitting on the grass, the maiden

Vow'd the vow to love me well;

Vow'd the vow; and oh! how truly,

No one but myself can tell.

Widely spreads the smiling woodland,

Elm and beech are fair to see;

But thy charms they cannot equal,

O thou happy hawthorn-tree!

[Pg 25]

A CRY FROM THE DEEP WATERS.

From the deep and troubled waters

Comes the cry;

Wild are the waves around me—

Dark the sky:

There is no hand to pluck me

From the sad death I die.

To one small plank, that fails me,

Clinging low,

I am dash'd by angry billows

To and fro;

I hear death-anthems ringing

In all the winds that blow.

A cry of suffering gushes

From my lips

As I behold the distant

White-sail'd ships

O'er the white waters gleaming

Where the horizon dips.

They pass; they are too lofty

And remote,

They cannot see the spaces

Where I float.

The last hope dies within me,

With the gasping in my throat.

[Pg 26]

Through dim cloud-vistas looking,

I can see

The new moon's crescent sailing

Pallidly:

And one star coldly shining

Upon my misery.

There are no sounds in nature

But my moan,

The shriek of the wild petrel

All alone,

And roar of waves exulting

To make my flesh their own.

Billow with billow rages,

Tempest trod;

Strength fails me; coldness gathers

On this clod;

From the deep and troubled waters

I cry to Thee, my God!

THE RETURN HOME.

The favouring wind pipes aloft in the shrouds,

And our keel flies as fast as the shadow of clouds;

The land is in sight, on the verge of the sky,

And the ripple of waters flows pleasantly by,—

And faintly stealing,

Booming, pealing,

Chime from the city the echoing bells;

And louder, clearer,

Softer, nearer,

Ringing sweet welcome the melody swells;

[Pg 27]

And it 's home! and it 's home! all our sorrows are past—

We are home in the land of our fathers at last.

How oft with a pleasure akin to a pain,

In fancy we roam'd through thy pathways again,

Through the mead, through the lane, through the grove, through the corn,

And heard the lark singing its hymn to the morn;

And 'mid the wild wood,

Dear to childhood,

Gather'd the berries that grew by the way;

But all our gladness

Died in sadness,

Fading like dreams in the dawning of day;—

But we 're home! we are home! all our sorrows are past—

We are home in the land of our fathers at last.

We loved thee before, but we 'll cherish thee now

With a deeper emotion than words can avow;

Wherever in absence our feet might delay,

We had never a joy like the joy of to-day;

And home returning,

Fondly yearning,

Faces of welcome seem crowding the shore—

England! England!

Beautiful England!

Peace be around thee, and joy evermore!

And it 's home! and it 's home! all our sorrows are past—

We are home in the land of our fathers at last.

[Pg 28]

THE MEN OF THE NORTH.

Fierce as its sunlight, the East may be proud

Of its gay gaudy hues and its sky without cloud;

Mild as its breezes, the beautiful West

May smile like the valleys that dimple its breast;

The South may rejoice in the vine and the palm,

In its groves, where the midnight is sleepy with balm:

Fair though they be,

There 's an isle in the sea,

The home of the brave and the boast of the free!

Hear it, ye lands! let the shout echo forth—

The lords of the world are the Men of the North!

Cold though our seasons, and dull though our skies,

There 's a might in our arms and a fire in our eyes;

Dauntless and patient, to dare and to do—

Our watchword is "Duty," our maxim is "Through!"

Winter and storm only nerve us the more,

And chill not the heart, if they creep through the door:

Strong shall we be

In our isle of the sea,

The home of the brave and the boast of the free!

Firm as the rocks when the storm flashes forth,

We 'll stand in our courage—the Men of the North!

Sunbeams that ripen the olive and vine,

In the face of the slave and the coward may shine;

Roses may blossom where Freedom decays,

And crime be a growth of the Sun's brightest rays.

[Pg 29]

Scant though the harvest we reap from the soil,

Yet Virtue and Health are the children of Toil:

Proud let us be

Of our isle of the sea,

The home of the brave and the boast of the free!

Men with true hearts—let our fame echo forth—

Oh, these are the fruit that we grow in the North!

THE LOVER'S DREAM OF THE WIND.

I dream'd thou wert a fairy harp

Untouch'd by mortal hand,

And I the voiceless, sweet west wind,

A roamer through the land.

I touch'd, I kiss'd thy trembling strings,

And lo! my common air,

Throbb'd with emotion caught from thee,

And turn'd to music rare.

I dream'd thou wert a rose in bloom,

And I the gale of spring,

That sought the odours of thy breath,

And bore them on my wing.

No poorer thou, but richer I—

So rich, that far at sea,

The grateful mariners were glad,

And bless'd both thee and me.

[Pg 30]

I dream'd thou wert the evening star,

And I a lake at rest,

That saw thine image all the night

Reflected on my breast.

Too far!—too far!—come dwell on Earth!

Be Harp and Rose of May;—

I need thy music in my heart,

Thy fragrance on my way.

[Pg 31]

ARCHIBALD CRAWFORD.

Archibald Crawford, a writer of prose and poetry of considerable merit,

was born at Ayr in 1785. In his ninth year, left an orphan, he was

placed under the care of a brother-in-law, a baker in London. With no

greater advantages than the somewhat limited school education then given

to the sons of burgesses of small provincial towns, his ardent love of

literature and powerful memory enabled him to become conversant with the

works of the more distinguished British authors, as well as the best

translations of the classics. At the expiry of eight years he returned

to Ayr, and soon after entered the employment of Charles Hay, Esq., of

Edinburgh, in whose service he continued during a course of years. In

honour of a daughter of this gentleman, who had shewn him much kindness

during a severe attack of fever, he composed his song of "Bonnie Mary

Hay," which, subsequently set to music by R. A. Smith, has become

extremely popular. He was afterwards in the employment of General Hay of

Rannes, with whom he remained several years. At the close of that period

he was offered by his employer an ensigncy in the service of the

Honourable East India Company, which, however, he respectfully declined.

In 1810 he opened a grocery establishment in his native town; but, with

less aptitude for business than literature, he lost the greater part of

the capital he had embarked in trade. He afterwards exchanged this

business for that of auctioneer and general merchant.

The literary inclinations of his youth had been assiduously followed up,

and his employers, sympathising with[Pg 32] his tastes, gave him every

opportunity, by the use of their libraries, of indulging his favourite

studies. With the exception of some fugitive pieces, he did not however

seek distinction as an author till 1819, when a satirical poem, entitled

"St James's in an uproar," appeared anonymously from his pen. This

composition intended to support the extreme political opinions then in

vogue, exposed to ridicule some leading persons in the district, and was

attended with the temporary apprehension and menaced prosecution of the

printer. To the columns of the Ayr and Wigtonshire Courier he now

began to contribute a series of sketches, founded on traditions in the

West of Scotland; and these, in 1824, he collected into a volume, with

the title, "Tales of a Grandmother," which was published by

subscription. In the following year the tales, with some additions, were

published, in two duodecimo volumes, by Constable and Co.; but the