The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volumes I-VI.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volumes I-VI.

The Songs of Scotland of the Past Half Century

Author: Various

Release Date: September 5, 2007 [eBook #22515]

[Most recently updated: July 12, 2023]

Language: English

Produced by: Susan Skinner, Ted Garvin and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MODERN SCOTTISH MINSTREL ***

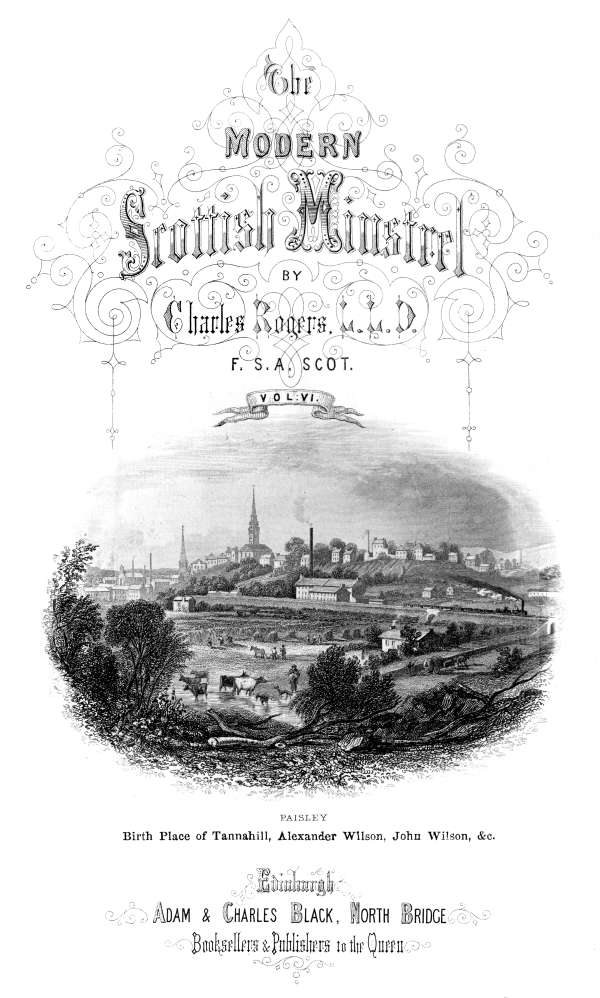

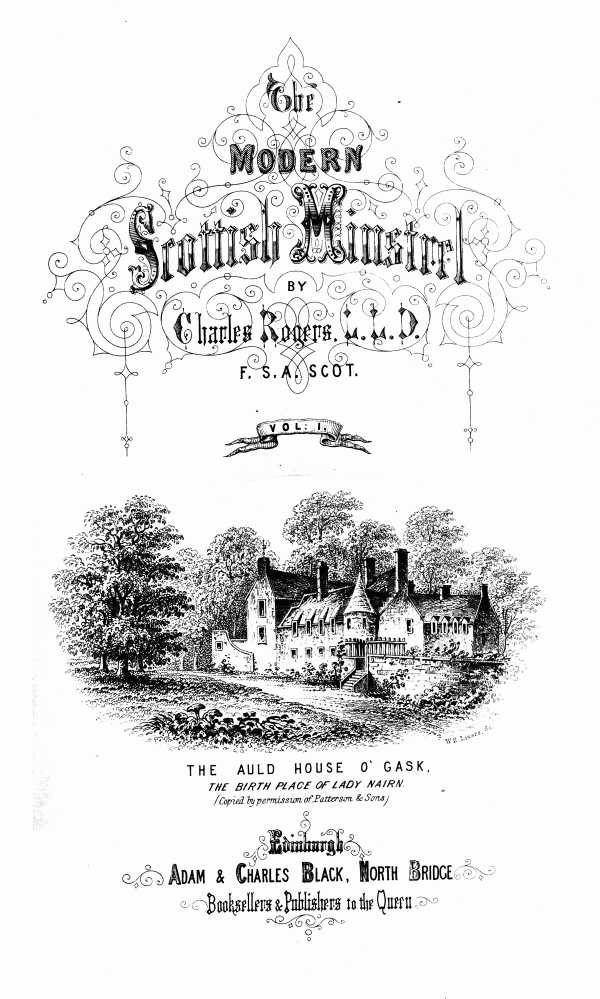

THE

MODERN SCOTTISH MINSTREL;

OR,

THE SONGS OF SCOTLAND OF THE

PAST HALF CENTURY.

WITH

Memoirs of the Poets,

AND

SKETCHES AND SPECIMENS

IN ENGLISH VERSE OF THE MOST CELEBRATED

MODERN GAELIC BARDS.

BY

CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D.

F.S.A. SCOT.

IN SIX VOLUMES;

VOLS. I.-VI.

EDINBURGH:

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK, NORTH BRIDGE,

BOOKSELLERS AND PUBLISHERS TO HER MAJESTY.

M.DCCC.LV.

CONTENTS.

Contents of Volume I.

Contents of Volume II.

Contents of Volume III.

Contents of Volume IV.

Contents of Volume V.

Contents of Volume VI.

Index of First Lines

Index of Authors

Volume I.

CONTENTS.

- JOHN SKINNER, 1

-

- WILLIAM CAMERON, 35

-

- MRS JOHN HUNTER, 39

-

- ALEXANDER, DUKE OF GORDON, 46

-

- MRS GRANT OF CARRON, 50

-

- ROBERT COUPER, M.D., 53

-

- LADY ANNE BARNARD, 58

-

- JOHN TAIT, 70

-

- HECTOR MACNEILL, 73

- Mary of Castlecary, 82

- My boy, Tammy, 83

- Oh, tell me how for to woo, 85

- Lassie wi' the gowden hair, 87

- Come under my plaidie, 89

- I lo'ed ne'er a laddie but ane, 90

- Donald and Flora, 92

- My luve's in Germany, 95

- Dinna think, bonnie lassie, 96

-

- MRS GRANT OF LAGGAN, 99

-

- JOHN MAYNE, 107

-

- JOHN HAMILTON, 117

- The rantin' Highlandman, 118

- Up in the mornin' early, 119

- Go to Berwick, Johnnie, 121

- Miss Forbes' farewell to Banff, 121

- Tell me, Jessie, tell me why? 122

- The hawthorn, 123

- Oh, blaw, ye westlin' winds! 124

-

- JOANNA BAILLIE, 126

- The maid of Llanwellyn, 132

- Good night, good night! 133

- Though richer swains thy love pursue, 134

- Poverty parts good companie, 134

- Fy, let us a' to the wedding, 136

- Hooly and fairly, 139

- The weary pund o' tow, 141

- The wee pickle tow, 142

- The gowan glitters on the sward, 143

- Saw ye Johnnie comin'? 145

- It fell on a morning, 146

- Woo'd, and married, and a', 148

-

- WILLIAM DUDGEON, 151

-

- WILLIAM REID, 153

-

- ALEXANDER CAMPBELL, 161

-

- MRS DUGALD STEWART, 167

-

- ALEXANDER WILSON, 172

-

- CAROLINA, BARONESS NAIRN, 184

- The ploughman, 194

- Caller herrin', 195

- The land o' the leal, 196

- The Laird o' Cockpen, 198

- Her home she is leaving, 200

- The bonniest lass in a' the warld, 201

- My ain kind dearie, O! 202

- He 's lifeless amang the rude billows, 202

- Joy of my earliest days, 203

- Oh, weel's me on my ain man, 204

- Kind Robin lo'es me 205

- Kitty Reid's house, 205

- The robin's nest, 206

- Saw ye nae my Peggy? 208

- Gude nicht, and joy be wi' ye a'! 209

- Cauld kail in Aberdeen, 210

- He 's ower the hills that I lo'e weel, 211

- The lass o' Gowrie, 213

- There grows a bonnie brier bush, 215

- John Tod, 216

- Will ye no come back again? 218

- Jamie the laird, 219

- Songs of my native land, 220

- Castell Gloom, 221

- Bonnie Gascon Ha', 223

- The auld house, 224

- The hundred pipers, 226

- The women are a' gane wud, 227

- Jeanie Deans, 228

- The heiress, 230

- The mitherless lammie, 231

- The attainted Scottish nobles, 232

- True love is watered aye wi' tears, 233

- Ah, little did my mother think, 234

- Would you be young again? 235

- Rest is not here, 236

- Here's to them that are gane, 237

- Farewell, O farewell! 238

- The dead who have died in the Lord, 239

-

- JAMES NICOL, 240

-

- JAMES MONTGOMERY, 247

-

- ANDREW SCOTT, 260

-

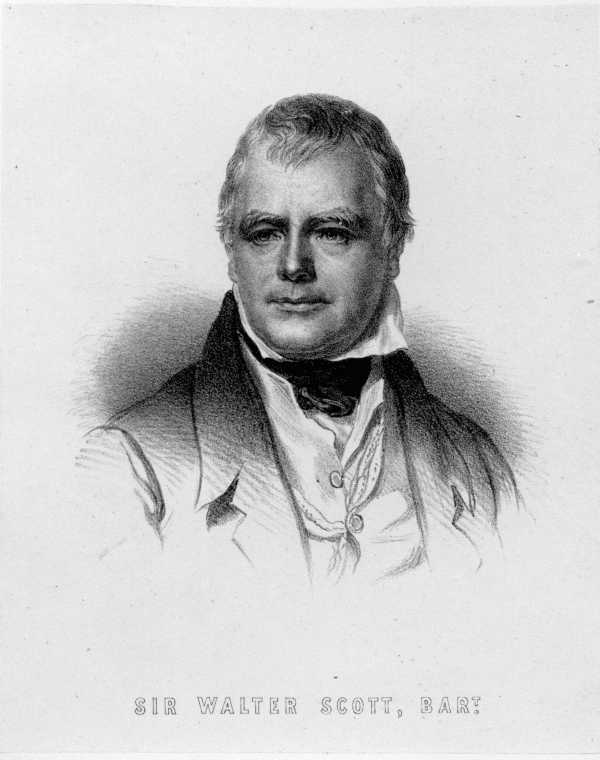

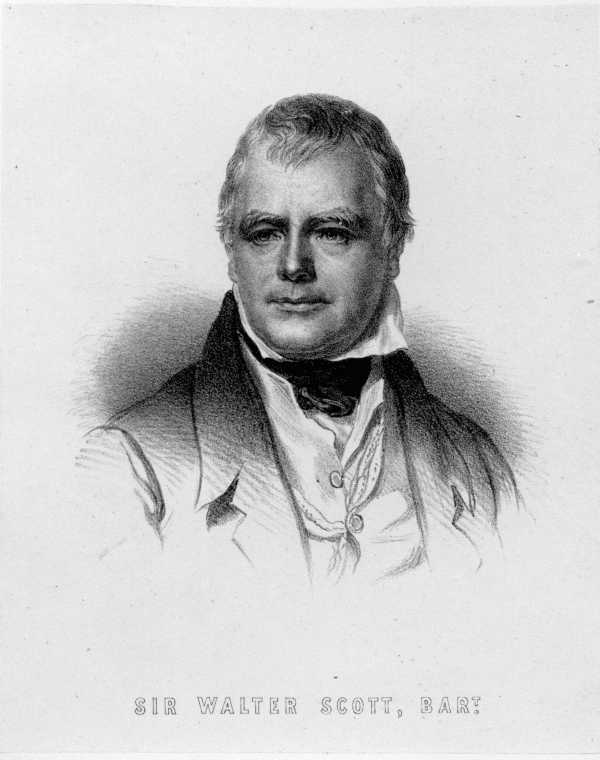

- SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART., 275

- It was an English ladye bright, 289

- Lochinvar, 290

- Where shall the lover rest, 292

- Soldier, rest! thy warfare o'er, 294

- Hail to the chief who in triumph advances, 295

- The heath this night must be my bed, 297

- The imprisoned huntsman, 298

- He is gone on the mountain, 299

- A weary lot is thine, fair maid, 300

- Allen-a-Dale, 300

- The cypress wreath, 302

- The cavalier, 303

- Hunting song, 304

- Oh, say not, my love, with that mortified air, 305

METRICAL TRANSLATIONS FROM THE MODERN

GAELIC MINSTRELSY.

Volume II.

CONTENTS.

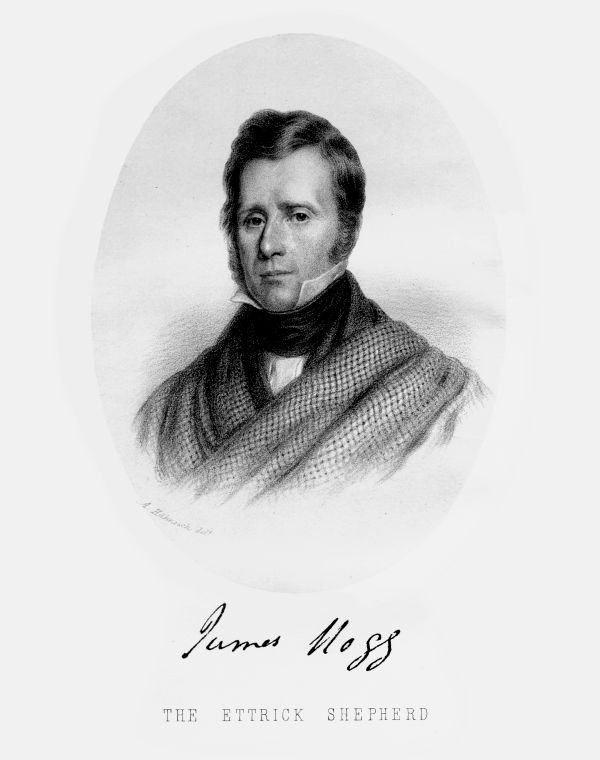

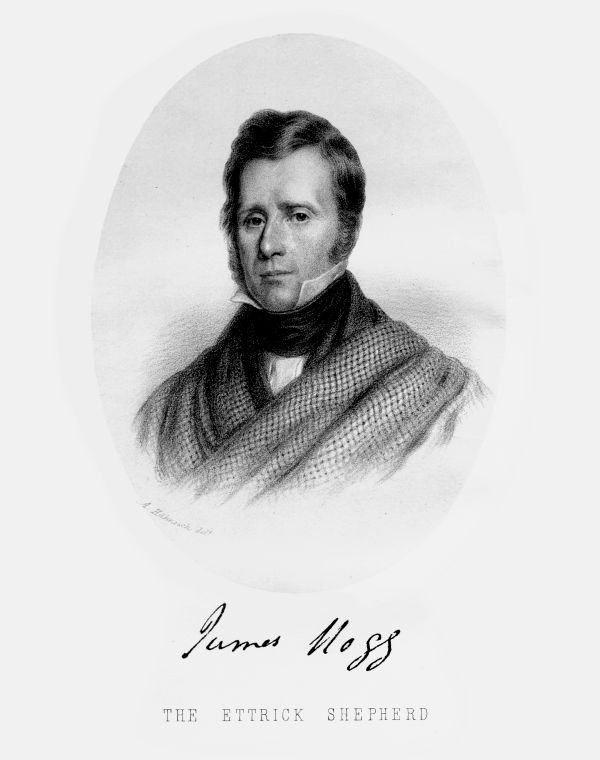

- JAMES HOGG, 1

- Donald Macdonald, 48

- Flora Macdonald's farewell, 50

- Bonnie Prince Charlie, 51

- The skylark, 52

- Caledonia, 53

- O Jeanie, there 's naething to fear ye, 54

- When the kye comes hame, 55

- The women folk, 58

- M'Lean's welcome, 59

- Charlie is my darling, 61

- Love is like a dizziness, 62

- O weel befa' the maiden gay, 64

- The flowers of Scotland, 66

- Lass, an' ye lo'e me, tell me now, 67

- Pull away, jolly boys, 69

- O, saw ye this sweet bonnie lassie o' mine? 70

- The auld Highlandman, 71

- Ah, Peggy, since thou 'rt gane away, 72

- Gang to the brakens wi' me, 74

- Lock the door, Lariston, 75

- I hae naebody now, 77

- The moon was a-waning, 78

- Good night, and joy, 79

-

- JAMES MUIRHEAD, D.D., 81

-

- MRS AGNES LYON, 84

-

- ROBERT LOCHORE, 91

-

- JOHN ROBERTSON, 98

-

- ALEXANDER BALFOUR, 101

-

- GEORGE MACINDOE, 106

-

- ALEXANDER DOUGLAS, 110

-

- WILLIAM M'LAREN, 114

-

- HAMILTON PAUL, 120

-

- ROBERT TANNAHILL, 131

- Jessie, the flower o' Dumblane, 136

- Loudon's bonnie woods and braes, 137

- The lass of Arranteenie, 139

- Yon burn side, 140

- The braes o' Gleniffer, 141

- Through Crockston Castle's lanely wa's, 142

- The braes o' Balquhither, 143

- Gloomy winter 's now awa', 145

- O! are ye sleeping, Maggie? 146

- Now winter, wi' his cloudy brow, 147

- The dear Highland laddie, O, 148

- The midges dance aboon the burn, 149

- Barrochan Jean, 150

- O, row thee in my Highland plaid, 151

- Bonnie wood of Craigie lea, 153

- Good night, and joy, 154

-

- HENRY DUNCAN, D.D., 156

-

- ROBERT ALLAN, 169

- Blink over the burn, my sweet Betty, 171

- Come awa, hie awa, 171

- On thee, Eliza, dwell my thoughts, 173

- To a linnet, 174

- The primrose is bonnie in spring, 174

- The bonnie lass o' Woodhouselee, 175

- The sun is setting on sweet Glengarry, 176

- Her hair was like the Cromla mist, 177

- O leeze me on the bonnie lass, 178

- Queen Mary's escape from Lochleven Castle, 179

- When Charlie to the Highlands came, 180

- Lord Ronald came to his lady's bower, 181

- The lovely maid of Ormadale, 183

- A lassie cam' to our gate, 184

- The thistle and the rose, 186

- The Covenanter's lament, 187

- Bonnie lassie, 188

-

- ANDREW MERCER, 189

-

- JOHN LEYDEN, M.D., 191

-

- JAMES SCADLOCK, 199

-

- SIR ALEXANDER BOSWELL, BART., 204

-

- WILLIAM GILLESPIE, 218

-

- THOMAS MOUNSEY CUNNINGHAM, 223

-

- JOHN STRUTHERS, 235

-

- RICHARD GALL, 241

- How sweet is the scene, 243

- Captain O'Kain, 243

- My only jo and dearie, O, 244

- The bonnie blink o' Mary's e'e, 245

- The braes o' Drumlee, 246

- I winna gang back to my mammy again, 248

- The bard, 249

- Louisa in Lochaber, 249

- The hazlewood witch, 250

- Farewell to Ayrshire, 251

-

- GEORGE SCOTT, 253

-

- THOMAS CAMPBELL, 255

-

- MRS G. G. RICHARDSON, 269

-

- THOMAS BROWN, M.D., 278

-

- WILLIAM CHALMERS, 285

-

- JOSEPH TRAIN, 288

-

- ROBERT JAMIESON, 297

-

- WALTER WATSON, 302

-

- WILLIAM LAIDLAW, 310

METRICAL TRANSLATIONS FROM THE MODERN GAELIC MINSTRELSY.

Volume III.

CONTENTS.

- ALLAN CUNNINGHAM, 1

- She 's gane to dwall in heaven, 9

- The lovely lass of Preston mill, 10

- Gane were but the winter cauld, 12

- It's hame, and it's hame, 13

- The lovely lass of Inverness, 14

- A wet sheet and a flowing sea, 15

- The bonnie bark, 16

- Thou hast sworn by thy God, my Jeanie, 17

- Young Eliza, 19

- Lovely woman, 20

-

- EBENEZER PICKEN, 22

-

- STUART LEWIS, 27

-

- DAVID DRUMMOND, 34

-

- JAMES AFFLECK, 38

-

- JAMES STIRRAT, 40

-

- JOHN GRIEVE, 43

-

- CHARLES GRAY, 50

-

- JOHN FINLAY, 57

-

- WILLIAM NICHOLSON, 63

-

- ALEXANDER RODGER, 71

-

- JOHN WILSON, 81

-

- DAVID WEBSTER, 91

-

- WILLIAM PARK, 97

-

- THOMAS PRINGLE, 102

-

- WILLIAM KNOX, 112

-

- WILLIAM THOM, 118

-

- WILLIAM GLEN, 126

- Waes me for Prince Charlie! 128

- Mary of sweet Aberfoyle, 129

- The battle-song, 131

- The maid of Oronsey, 134

- Jess M'Lean, 136

- How eerily, how drearily, 137

- The battle of Vittoria, 139

- Blink over the burn, sweet Betty, 140

- Fareweel to Aberfoyle, 141

-

- DAVID VEDDER, 143

-

- JOHN M'DIARMID, 155

-

- PETER BUCHAN, 162

-

- WILLIAM FINLAY, 166

-

- JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART, 171

-

- THOMAS MATHERS, 184

-

- JAMES BROWN, 186

-

- DANIEL WEIR, 194

-

- ROBERT DAVIDSON, 206

-

- PETER ROGER, 212

-

- JOHN MALCOLM, 215

-

- ERSKINE CONOLLY, 220

-

- GEORGE MENZIES, 223

-

- JOHN SIM, 226

-

- WILLIAM MOTHERWELL, 230

-

- DAVID MACBETH MOIR, 242

-

- ROBERT FRASER, 252

-

- JAMES HISLOP, 254

-

- ROBERT GILFILLAN, 261

METRICAL TRANSLATIONS FROM THE MODERN GAELIC MINSTRELSY.

Volume IV.

CONTENTS.

- HENRY SCOTT RIDDELL,

1

- The wild glen sae green,

49

- Scotia's thistle,

50

- The land of gallant hearts,

51

- The yellow locks o' Charlie,

52

- We 'll meet yet again,

53

- Our ain native land,

54

- The Grecian war-song,

56

- Flora's lament,

57

- When the glen all is still,

58

- Scotland yet,

58

- The minstrel's grave,

60

- My own land and loved one,

61

- The bower of the wild,

62

- The crook and plaid,

63

- The minstrel's bower,

65

- When the star of the morning,

66

- Though all fair was that bosom,

67

- Would that I were where wild-woods

wave, 68

- O tell me what sound,

69

- Our Mary,

70

-

- MRS MARGARET M. INGLIS,

73

-

- JAMES KING,

83

-

- ISOBEL PAGAN,

88

-

- JOHN MITCHELL,

90

-

- ALEXANDER JAMIESON,

95

-

- JOHN GOLDIE,

98

-

- ROBERT POLLOK,

103

-

- J. C. DENOVAN,

106

-

- JOHN IMLAH,

108

- Kathleen,

109

- Hielan' heather,

110

- Farewell to Scotland,

111

- The rose of Seaton Vale,

112

- Katherine and Donald,

113

- Guid nicht, and joy be wi' you a',

114

- The gathering,

115

- Mary,

116

- Oh! gin I were where Gadie rins,

117

-

- JOHN TWEEDIE,

120

-

- THOMAS ATKINSON,

122

-

- WILLIAM GARDINER,

126

-

- ROBERT HOGG,

129

-

- JOHN WRIGHT,

137

-

- JOSEPH GRANT,

143

-

- DUGALD MOORE,

147

-

- REV. T. G. TORRY ANDERSON,

158

-

- GEORGE ALLAN,

163

-

- THOMAS BRYDSON,

172

-

- CHARLES DOYNE SILLERY,

174

-

- ROBERT MILLER,

179

-

- ALEXANDER HUME,

182

-

- THOMAS SMIBERT,

195

-

- JOHN BETHUNE,

203

-

- ALLAN STEWART,

211

-

- ROBERT L. MALONE,

216

-

- PETER STILL,

220

-

- ROBERT NICOLL,

225

-

- ARCHIBALD STIRLING IRVING,

235

-

- ALEXANDER A. RITCHIE,

237

-

- ALEXANDER LAING,

241

-

- ALEXANDER CARLILE,

252

-

- JOHN NEVAY,

257

-

- THOMAS LYLE,

261

-

- JAMES HOME,

267

-

- JAMES TELFER,

273

METRICAL TRANSLATIONS FROM THE MODERN GAELIC MINSTRELSY.

Volume V.

CONTENTS.

- FRANCIS BENNOCH,

1

- Truth and honour,

7

- Our ship,

8

- Auld Peter Macgowan,

10

- The flower of Keir,

11

- Constancy,

12

- My bonnie wee wifie,

13

- The bonnie bird,

14

- Come when the dawn,

15

- Good-morrow,

16

- Oh, wae's my life,

17

- Hey, my bonnie wee lassie,

18

- Bessie,

20

- Courtship,

21

- Together,

22

- Florence Nightingale,

23

- JAMES BALLANTINE,

198

- Naebody's bairn,

200

- Castles in the air,

201

- Ilka blade o' grass keps its ain

drap o' dew, 202

- Wifie, come hame,

203

- The birdie sure to sing is

aye the gorbel o' the nest, 204

- Creep afore ye gang,

205

- Ae guid turn deserves anither,

205

- The nameless lassie,

206

- Bonnie Bonaly,

207

- Saft is the blink o' thine e'e, lassie,

208

- The mair that ye work, aye the

mair will ye win, 209

- The widow,

209

METRICAL TRANSLATIONS FROM THE MODERN GAELIC MINSTRELSY.

Volume VI.

CONTENTS.

- CHARLES MACKAY, LL.D.,

1

- Love aweary of the world,

8

- The lover's second thoughts on

world weariness, 9

- A candid wooing,

11

- Procrastinations,

12

- Remembrances of nature,

13

- Believe, if you can,

15

- Oh, the happy time departed,

17

- Come back! come back!

17

- Tears,

18

- Cheer, boys, cheer,

20

- Mourn for the mighty dead,

21

- A plain man's philosophy,

22

- The secrets of the hawthorn,

24

- A cry from the deep waters,

25

- The return home,

26

- The men of the North,

28

- The lover's dream of the wind,

29

METRICAL TRANSLATIONS FROM THE MODERN GAELIC MINSTRELSY.

INDEX

TO THE

FIRST LINES OF THE SONGS.

- A bonnie rose bloom'd wild and fair, vol. iv., 112.

- Adieu—a long and last adieu, vol. iii., 207.

- Adieu, lovely summer, I see thee declining, vol. i., 273.

- Adieu, romantic banks of Clyde, vol. iii., 30.

- Adieu, ye streams that smoothly glide, vol. i., 42.

- Adieu, ye wither'd flow'rets, vol. iv., 207.

- Admiring nature's simple charms, vol. ii., 239.

- Ah! do not bid me wake the lute, vol. ii., 283.

- Adown the burnie's flowery bank, vol. ii., 227.

- Ae morn, last ouk, as I gaed out, vol. i., 118.

- Ae morn of May, when fields were gay, vol. iii., 31.

- Ah! faded is that lovely bloom, vol. ii., 276.

- Afar from the home where his youthful prime, vol. vi., 165.

- Afore the Lammas tide, vol. iv., 197.

- Afore the muircock begin to craw, vol. ii., 67.

- Again the laverock seeks the sky, vol. v., 82.

- Ages, ages have departed, vol. i., 258.

- A health to Caberfae, vol. i., 357.

- Alake for the lassie! she's no right at a', vol. ii., 317.

- A lassie cam' to our gate yestreen, vol. ii., 184.

- Alas! how true the boding voice, vol. v., 87.

- Allen-a-Dale has no faggot for burning, vol. i., 300.

- Ah! little did my mother think, vol. i., 234.

- A lively young lass had a wee pickle tow, vol. i., 142.

- All lovely and bright, 'mid the desert of time, vol. iv., 173.

- All night, by the pathway that crosses the muir, vol. iv., 141.

- Alone to the banks of the dark rolling Danube, vol. ii., 264.

- Along by Levern stream so clear, vol. ii., 201.

- Although the lays o' ither lands, vol. vi., 96.

- Amang the birks sae blithe an' gay, vol. ii., 227.

- Amang the breezy heights and howes, vol. vi., 49.

- Ah! Mary, sweetest maid, farewell, vol. ii., 211.

- And can thy bosom bear the thought, vol. iv., 100.

- And dost thou speak sincere, my love, vol. ii., 116.

- And hast thou sought thy heavenly home, vol. iii., 245.

- Ah no! I cannot say farewell, vol. iii., 79.

- Ah, Peggie, since thou 'rt gane away, vol. ii., 72.

- A pretty young maiden sat on the grass, vol. iii., 251.

- Argyle is my name, and you may think it strange, vol. ii., 216.

- As clear is Luther's wave, I ween, vol. iii., 224.

- As I sat by the grave, at the brink of its cave, vol. i., 326.

- As lockfasted in slumber's arms, vol. i., 330.

- As o'er the Highland hills I hied, vol. i., 37.

- A song, a song, brave hearts, a song, vol. v., 8.

- As sunshine to the flowers in May, vol. v., 99.

- At hame or afield, I 'm cheerless and lone, vol. iii., 124.

- Ah! the wound of my breast sinks my heart to the dust, vol. ii., 343.

- At waking so early, vol. i., 311.

- At Willie's weddin' on the green, vol. ii., 210.

- Auld Peter MacGowan cam' down the craft, vol. v., 10.

- Awake, thou first of creatures, indignant in their frown, vol. iii., 123.

- Away, away, like a child at play, vol. vi., 68.

- Away, away, my gallant bark, vol. vi., 84.

- Away on the breast of the ocean, vol. vi., 211.

- Away on the wings of the wind she flies, vol. iv., 160.

- Away to the Highlands, where Lomond is flowing, vol. v., 254.

- A weary lot is thine, fair maid, vol. i., 300.

- A wee bird cam' to our ha' door, vol. iii., 128.

- A wee bird sits upon a spray, vol. iv., 190.

- A wee bit laddie sits wi' a bowl upon his knees, vol. vi., 145.

- A wet sheet and a flowing sea, vol. iii., 15.

- A young gudewife is in my house, vol. i., 141.

- Bare was our burn brae, vol. v., 65.

- Beautiful moon, wilt thou tell me where, vol. vi., 44.

- Be eident, be eident, fleet time rushes on, vol. v., 209.

- Behave yoursel' before folk, vol. iii., 74.

- Believe me or doubt me, I dinna care whilk, vol. ii., 108.

- Ben Cruachan is king of the mountains, vol. vi., 115.

- Beneath a hill, 'mang birken bushes, vol. iv., 294.

- Bird of the wilderness, vol. i., 52.

- Blaw saftly, ye breezes, ye streams, smoothly murmur, vol. i., 243.

- Blest be the hour of night, vol. vi., 48.

- Blink over the burn, my sweet Betty, vol. ii., 171.

- Blink over the burn, sweet Betty, vol. iii., 140.

- Blithe be the mind of the ploughman, vol. v., 176.

- Blithe was the time when he fee'd wi' my father, O, vol. ii., 148.

- Blithe young Bess to Jean did say, vol. ii., 82.

- Blue are the hills above the Spey, vol. v., 212.

- Bonnie Bessie Lee had a face fu' o' smiles, vol. iv., 233.

- Bonnie Bonaly's wee fairy-led stream, vol. v., 207.

- Bonnie Charlie 's now awa, vol. i., 218.

- Bonnie Clouden, as ye wander, vol. ii., 230.

- Bonnie lassie, blithesome lassie, vol. ii., 188.

- Bonnie Mary Hay, I will lo'e thee yet, vol. vi., 33.

- Born where the glorious starlights trace, vol. iv., 150.

- Bring the rod, the line, the reel, vol. v., 221.

- Brither Jamie cam' west wi' a braw burn trout, vol. ii., 109.

- Built on Time's uneven sand, vol. vi., 198.

- By Logan's streams, that rin sae deep, vol. i., 110.

- By Niagara's flood, vol. vi., 81.

- By the lone Mankayana's margin gray, vol. iii., 107.

- By yon hoarse murmurin' stream, 'neath the moon's chilly beam, vol. i., 212.

- Caledonia! thou land of the mountain and rock, vol. ii., 53.

- Calm sleep the village dead, vol. v., 260.

- Cam' ye by Athol, lad wi' the philabeg, vol. ii., 51.

- Can my dearest Henry leave me, vol. iii., 41.

- Can ought be constant as the sun, vol. ii., 249.

- Can ye lo'e, my dear lassie, vol. v., 63.

- Ca' the yowes to the knowes, vol. iv., 89.

- Cauld blaws the wind frae north to south, vol. i., 119.

- Change! change! the mournful story, vol. v., 173.

- Charlie 's comin' o'er the sea, vol. vi., 160.

- Chaunt me no more thy roundelay, vol. ii., 174.

- Cheer, boys, cheer! no more of idle sorrow, vol. vi., 20.

- Clan Lachlan's tuneful mavis, I sing on the branches early, vol. iv., 282.

- Close by the marge of Leman's Lake, vol. vi., 177.

- Come all ye jolly shepherds, vol. ii., 55.

- Come awa', come awa', vol. iii., 109.

- Come awa', hie awa', vol. ii., 171.

- Come back, come back, thou youthful time, vol. vi., 17.

- Come gie us a sang, Montgomery cried, vol. i., 11.

- Come, maid, upon yon mountain brow, vol. iii., 19.

- Come, memory, paint, though far away, vol. vi., 52.

- Come o'er the stream, Charlie, vol. ii., 59.

- Come see my scarlet rose-bush, vol. vi., 37.

- Come sit down, my cronie, an' gie me your crack, vol. ii., 306.

- Come under my plaidie, the night's gaun to fa', vol. i., 89.

- Come when the dawn of the morning is breaking, vol. v., 15.

- Confide ye aye in Providence, for Providence is kind, vol. v., 202.

- Could we but look beyond our sphere, vol. iii., 199.

- Creep awa', my bairnie, creep afore ye gang, vol. v., 205.

- Culloden, on thy swarthy brow, vol. iii., 46.

- Dark lowers the night o'er the wide stormy main, vol. i., 179.

- Dear aunty, I've been lang your care, vol. ii., 95.

- Dear aunty, what think ye o' auld Johnny Graham, vol. v., 107.

- Dearest love believe me, vol. iii., 110.

- Dear to my heart as life's warm stream, vol. i., 44.

- Does grief appeal to you, ye leal, vol. ii., 341.

- Down by a crystal stream, vol. vi., 207.

- Down in the valley lone, vol. v., 181.

- Down whar the burnie rins whimplin' and cheery, vol. v., 25.

- Do you know what the birds are singing? vol. vi., 134.

- Each whirl of the wheel, vol. v., 61.

- Easy is my pillow press'd, vol. ii., 349.

- Eliza fair, the mirth of May, vol. v., 138.

- Eliza was a bonnie lass, and, oh! she lo'ed me weel, vol. iv., 187.

- Ere eild wi' his blatters had warsled me doun, vol. ii., 246.

- Ere foreign fashions crossed the Tweed, vol. iii., 189.

- Exiled far from scenes of pleasure, vol. ii., 165.

- Eye of the brain and heart, vol. v., 133.

- Fain wad I, fain wad I hae the bloody wars to cease, vol. i., 269.

- Fair are the fleecy flocks that feed, vol. ii., 128.

- Fair as a star of light, vol. vi., 179.

- Fair Ellen, here again I stand, vol. v., 141.

- Fair modest flower of matchless worth, vol. i., 157.

- Fair Scotland, dear as life to me, vol. v., 137.

- Fare-thee-weel, for I must leave thee, vol. iii., 263.

- Fare-thee-weel, my bonnie lassie, vol. iii., 225.

- Fareweel, O! fareweel, vol. i., 238.

- Fareweel to ilk hill whar the red heather grows, vol. v., 91.

- Fareweel, ye fields and meadows green, vol. i., 121.

- Farewell, and though my steps depart, vol. iii., 116.

- Farewell, our father's land, vol. iii., 249.

- Farewell ye braes of broad Braemar, vol. vi., 117.

- Farewell, ye streams sae dear to me, vol. ii., 232.

- Far lone amang the Highland hills, vol. ii., 139.

- Far over yon hills of the heather sae green, vol. ii., 50.

- Fierce as its sunlight, the East may be proud, vol. vi., 28.

- Fife, an' a' the land about it, vol. ii., 112.

- Float forth, thou flag of the free, vol. vi., 221.

- Flowers of summer sweetly springing, vol. v., 251.

- Flow saftly thou stream through the wild spangled valley, vol. iii., 243.

- For mony lang year I hae heard frae my granny, vol. ii., 250.

- For success a prayer with a farewell bear, vol. iii., 284.

- For twenty years and more, vol. v., 80.

- From beauty's soft lips, like the balm of its roses, vol. iv., 97.

- From the climes of the sun all war-worn and weary, vol. ii., 220.

- From the deep and troubled waters, vol. vi., 25.

- From the village of Leslie with a heart full of glee, vol. i., 182.

- Fy, let us a' to the wedding, vol. i., 136.

- Gae bring my guid auld harp ance mair, vol. iv., 58.

- Gane were but the winter cauld, vol. iii., 12.

- Gang wi' me to yonder howe, bonnie Peggie, O! vol. iv., 133.

- Give me the hour when bells are rung, vol. vi., 149.

- Give the swains of Italia, vol. vi., 223.

- Glad tidings for the Highlands, vol. ii., 335.

- Gloomy winter's now awa', vol. ii., 145.

- Good morrow, good morrow, warm, rosy, and bright, vol. v., 16.

- Good night, and joy be wi' ye a', vol. ii., 214.

- Good night, the silver stars are clear, vol. v., 246.

- Go to Berwick, Johnnie, vol. i., 121.

- Go to him then if thou canst go, vol. ii., 300.

- Grim winter was howlin' owre muir and owre mountain, vol. iii., 55.

- Guid night and joy be wi' ye a', vol. iv., 114.

- Had I the wings of a dove I would fly, vol. v., 261.

- Hae ye been in the north, bonnie lassie, vol. ii., 308.

- Hail to the chief who in triumph advances, vol. i., 295.

- Hark, hark, the skylark singing, vol. ii., 202.

- Hark, the martial drums resound, vol. ii., 164.

- Haste all ye fairy elves hither to me, vol. iv., 131.

- Heard ye the bagpipe or saw ye the banners, vol. iv., 78.

- Heart, take courage, 'tis not worthy, vol. vi., 9.

- Heaven speed the righteous sword, vol. i., 254.

- Hech, what a change hae we now in this toun, vol. ii., 215.

- Hech, hey, the mirth that was there, vol. i., 205.

- He left his native land, and far away, vol. v., 111.

- He loved her for her merry eyes, vol. v., 244.

- Here 's to them, to them that are gane, vol. i., 237.

- Her eyes were red with weeping, vol. iii., 136.

- Here we go upon the tide, vol. ii., 69.

- Here 's to the year that 's awa', vol. v., 78.

- Her hair was like the Cromla mist, vol. ii., 177.

- Her lip is o' the rose's hue, vol. v., 117.

- Hersell pe auchty years and twa, vol. ii., 71.

- He 's a terrible man, John Tod, John Tod, vol. i., 216.

- He is gone, he is gone, vol. iii., 240.

- He 's gone on the mountain, vol. i., 299.

- He 's lifeless amang the rude billows, vol. i., 202.

- He 's no more on the green hill, he has left the wide forest, vol. i., 272.

- He sorrowfu' sat by the ingle cheek, vol. vi., 138.

- He 's ower the hills that I lo'e weel, vol. i., 211.

- Hey for the Hielan' heather, vol. iv., 110.

- Hey, my bonnie wee lassie, vol. v., 18.

- Home of my fathers, though far from thy grandeur, vol. iii., 136.

- Hope cannot cheat us, vol. vi., 15.

- How blest were the days o' langsyne, when a laddie, vol. iii., 39.

- How blithely the pipe through Glenlyon was sounding, vol. v., 26.

- How brightly beams the bonnie moon, vol. iii., 73.

- How early I woo'd thee, how dearly I lo'ed thee, vol. v., 160.

- How eerily, how drearily, how eerily to pine, vol. iii., 137.

- How happy a life does the parson possess, vol. i., 28.

- How happy lives the peasant by his ain fireside, vol. iii., 78.

- How often death art waking, vol. i., 321.

- How pleasant, how pleasant to wander away, vol. ii., 274.

- How sweet are Leven's silver streams, vol. iii., 36.

- How sweet are the blushes of morn, vol. v., 35.

- How sweet is the scene at the waking of morning, vol. ii., 243.

- How sweet the dewy bell is spread, vol. iii., 259.

- How sweet thy modest light to view, vol. ii., 196.

- Hurra! for the land o' the broom-cover'd brae, vol. vi., 103.

- Hurrah for Scotland's worth and fame, vol. v., 229.

- Hurrah for the Highlands, the brave Scottish Highlands, vol. v., 249.

- Hurrah for the Thistle, the brave Scottish Thistle, vol. v., 232.

- Hurrah, hurrah for the boundless sea, vol. vi., 189.

- Hurrah, hurrah, we 've glory won, vol. v., 89.

- Hush, ye songsters, day is done, vol. iii., 159.

- I ask no lordling's titled name, vol. ii., 166.

- I canna leave my native land, vol. vi., 228.

- I canna sleep a wink, lassie, vol. v., 183.

- I cannot give thee all my heart, vol. vi., 11.

- I dream'd thou wert a fairy harp, vol. vi., 29.

- If Fortune with a smiling face, vol. vi., 12.

- I fleet along, and the empires fall, vol. vi., 167.

- I fly from the fold since my passion's despair, vol. i., 316.

- I form'd a green bower by the rill o' yon glen, vol. iv., 62.

- If there 's a word that whispers love, vol. v., 266.

- If wealth thou art wooing, or title, or fame, vol. v., 7.

- I gaed to spend a week in Fife, vol. vi., 55.

- I hae naebody noo, I hae naebody noo, vol. ii., 77.

- I have wander'd afar, 'neath stranger skies, vol. vi., 88.

- I heard a wee bird singing, vol. v., 32.

- I heard the evening linnet's voice the woodland tufts amang, vol. iii., 61.

- I lately lived in quiet ease, vol. ii., 62.

- I like to spring in the morning bricht, vol. v., 98.

- I 'll no be had for naething, vol. i., 230.

- I 'll no walk by the kirk, mother, vol. vi., 42.

- I 'll sing of yon glen of red heather, vol. ii., 74.

- I 'll tend thy bower, my bonnie May, vol. v., 155.

- I 'll think on thee, Love, when thy bark, vol. vi., 50.

- I 'll think o' thee, my Mary Steel, vol. iv., 268.

- I 'll twine a gowany garland, vol. vi., 105.

- I lo'ed ne'er a laddie but ane, vol. i., 90.

- I love a sweet lassie, mair gentle and true, vol. vi., 144.

- I love the free ridge of the mountain, vol. iii., 108.

- I love the merry moonlight, vol. iv., 135.

- I love the sea, I love the sea, vol. iv., 162.

- I 'm afloat, I 'm afloat on the wild sea waves, vol. vi., 187.

- I mark'd her look of agony, vol. iii., 167.

- I 'm a very little man, vol. vi., 147.

- I 'm away, I 'm away like a thing that is wild, vol. v., 255.

- I 'm naebody noo, though in days that are gane, vol. v., 182.

- I 'm now a guid farmer, I 've acres o' land, vol. i., 263.

- I 'm wand'rin' wide this wintry night, vol. v., 158.

- I 'm wearin' awa', John, vol. i., 196.

- I met four chaps yon birks amang, vol. ii., 208.

- In a dream of the night I was wafted away, vol. iii., 257.

- In a howm, by a burn, where the brown birks grow, vol. vi., 234.

- In all its rich wildness her home she is leaving, vol. i., 200.

- In a saft simmer gloamin', vol. iii., 236.

- In distant years when other arms, vol. v., 123.

- I neither got promise of siller nor land, vol. iii., 147.

- I never thocht to thole the waes, vol. iv., 221.

- In her chamber, vigil keeping, vol. vi., 213.

- In life's gay morn, when hopes beat high, vol. iii., 42.

- In that home was joy and sorrow, vol. vi., 184.

- In the morning of life, when its sunny smile, vol. iii., 200.

- I pray for you of your courtesy, before we further move, vol. v., 144.

- I remember the time, thou roaring sea, vol. vi., 13.

- Isabel Mackay is with the milk kye, vol. i., 318.

- I sat in the vale 'neath the hawthorns so hoary, vol. iv., 60.

- I saw my true love first on the banks of queenly Tay, vol. iii., 121.

- I see, I see the Hirta, the land of my desire, vol. v., 282.

- I see the wretch of high degree, vol. i., 315.

- Is not the earth a burial-place, vol. v., 269.

- I sing of gentle woodcroft gay, for well I love to rove, vol. v., 92.

- Is our Helen very fair, vol. vi., 182.

- Is your war-pipe asleep, and for ever, M'Crimman, vol. iv., 166.

- It fell on a morning when we were thrang, vol. i., 146.

- It has long been my fate to be thought in the wrong, vol. i., 22.

- It 's dowie in the hint o' hairst, vol. v., 62.

- It 's hame, and it 's hame, hame fain wad I be, vol. iii., 13.

- It was an English ladye bright, vol. i., 289.

- I 've listened to the midnight wind, vol. iii., 203.

- I 've a guinea I can spend, vol. vi., 22.

- I 've been upon the moonlit deep, vol. vi., 70.

- I 've loved thee, old Scotia, and love thee I will, vol. ii., 296.

- I 've met wi' mony maidens fair, vol. vi., 91.

- I 've no sheep on the mountain nor boat on the lake, vol. i., 132.

- I 've rocked me on the giddy mast, vol. iii., 20.

- I 've seen the lily of the wold, vol. iii., 48.

- I 've seen the smiling summer flower, vol. iv., 245.

- I 've wander'd east, I 've wander'd west, vol. iii., 233.

- I 've wander'd on the sunny hill, I 've wander'd in the vale, vol. iv., 192.

- I wadna gi'e my ain wife, vol. iv., 246.

- I walk'd by mysel' owre the sweet braes o' Yarrow, vol. iii., 86.

- I wander'd alane at the break o' the mornin', vol. vi., 89.

- I warn you, fair maidens, to wail and to sigh, vol. ii., 197.

- I wiled my lass wi' lovin' words to Kelvin's leafy shade, vol. v., 274.

- I will sing a song of summer, vol. vi., 186.

- I will think of thee yet, though afar I may be, vol. iv., 167.

- I will wake my harp when the shades of even, vol. iv., 170.

- I winna bide in your castle ha's, vol. iv., 229.

- I winna gang back to my minny again, vol. ii., 248.

- I winna love the laddie that ca's the cart and pleugh, vol. iv., 63.

- I wish I were where Helen lies, vol. i., 111.

- Jenny's heart was frank and free, vol. i., 114.

- John Anderson, my jo, John, vol. i., 155.

- Joy of my earliest days, vol. i., 203.

- Keen blaws the wind o'er the braes o' Gleniffer, vol. ii., 141.

- Land of my fathers! night's dark gloom, vol. iii., 167.

- Land of my fathers, I leave thee in sadness, vol. vi., 207.

- Lane on the winding Earn there stands, vol. i., 223.

- Lass, gin ye wad lo'e me, vol. iv., 224.

- Lassie, dear lassie, the dew 's on the gowan, vol. iv., 168.

- Lassie wi' the gowden hair, vol. i., 87.

- Last midsummer's morning, as going to the fair, vol. i., 123.

- Lat me look into thy face, Jeanie, vol. vi., 135.

- Leafless and bare were the shrub and the flower, vol. iv., 76.

- Leave the city's busy throng, vol. vi., 143.

- Let Highland lads, wi' belted plaids, vol. iv., 77.

- Let ither anglers choose their ain, vol. v., 222.

- Let the maids of the Lowlands, vol. iii., 272.

- Let the proud Indian boast of his jessamine bowers, vol. iv., 177.

- Let us go, lassie, go, vol. ii., 143.

- Let us haste to Kelvin grove, bonnie lassie, O, vol. iv., 264.

- Let wrapt musicians strike the lyre, vol. iii., 146.

- Life's pleasure seems sadness and care, vol. vi., 194.

- Liking is a little boy, vol. vi., 120.

- Listen to me, as when ye heard our father, vol. iii., 183.

- Lock the door, Lariston, lion of Liddisdale, vol. ii., 75.

- Look up, old friend, why hang thy head, vol. vi., 199.

- Lord Ronald came to his lady's bower, vol. ii., 181.

- Loudon's bonnie woods and braes, vol. ii., 137.

- Love brought me a bough o' the willow sae green, vol. iii., 188.

- Love flies the haunts of pomp and power, vol. v., 79.

- Love is timid, love is shy, vol. iii., 196.

- Loved land of my kindred, farewell, and for ever, vol. iv., 111.

- Lovely maiden, art thou sleeping, vol. iii., 76.

- Lowland lassie, wilt thou go, vol. ii., 151.

- 'Mang a' the lasses young and braw, vol. iii., 214.

- Meet me on the gowan lea, vol. v., 147.

- Meg muckin' at Geordie's byre, vol. i., 244.

- Men of England, who inherit, vol. ii., 268.

- Mild as the morning, a rose-bud of beauty, vol. v., 37.

- More dark is my soul than the scenes of yon islands, vol. iv., 57.

- Mourn for the mighty dead, vol. vi., 21.

- Mournfully, oh, mournfully, vol. iii., 239.

- Musing, we sat in our garden bower, vol. v., 100.

- My beauty dark, my glossy bright, vol. ii., 347.

- My beauty of the shieling, vol. vi., 250.

- My Bessie, oh, but look upon these bonnie budding flowers, vol. iv., 189.

- My bonnie wee Bell was a mitherless bairn, vol. v., 67.

- My bonnie wee wifie, I 'm waefu' to leave thee, vol. v., 13.

- My brothers are the stately trees, vol. iv., 254.

- My brown dairy, brown dairy, vol. ii., 327.

- My couthie auld wife, aye blithsome to see, vol. vi., 102.

- My darling is the philabeg, vol. v., 290.

- My dearest, wilt thou follow, vol. vi., 252.

- My dear little lassie, why, what 's the matter? vol. i., 246.

- My hawk is tired of perch and hood, vol. i., 298.

- My lassie is lovely, as May-day adorning, vol. iii., 48.

- My love, come let us wander, vol. iii., 197.

- My love 's in Germanie, send him hame, send him hame, vol. i., 95.

- My luve 's a flower in garden fair, vol. v., 189.

- My mother bids me bind my hair, vol. i., 41.

- My mountain hame, my mountain hame, vol. iv., 194.

- My name it is Donald M'Donald, vol. ii., 48.

- My native land, my native land, vol. vi., 206.

- My soul is ever with thee, vol. v., 106.

- My spirit could its vigil hold, vol. iv., 152.

- My tortured bosom long shall feel, vol. iii., 141.

- My wee wife dwells in yonder cot, vol. iv., 187.

- My wife 's a winsome wee thing, vol. ii., 299.

- My young heart's luve! twal' years hae been, vol. iv., 259.

- My young, my fair, my fair-haired Mary, vol. i., 335.

- Nae mair we 'll meet again, my love, by yon burn-side, vol. iii., 227.

- Name the leaves on all the trees, vol. vi., 118.

- Never despair! when the dark cloud is lowering, vol. v., 75.

- Night turns to day, vol. i., 255.

- No homeward scene near me, vol. iv., 290.

- No more by thy margin, dark Carron, vol. vi., 202.

- No one knows what silent secrets, vol. vi., 24.

- No sky shines so bright as the sky that is spread, vol. iv., 61.

- No sound was heard o'er the broom-covered valley, vol. iv., 86.

- Not the swan on the lake, or the foam on the shore, vol. iv., 281.

- Now bank and brae are clad in green, vol. ii., 245.

- Now, Jenny lass, my bonnie bird, vol. ii., 92.

- Now, Mary, now, the struggle 's o'er, vol. iii., 229.

- Now rests the red sun in his caves of the ocean, vol. ii., 254.

- Now simmer decks the field wi' flowers, vol. ii., 304.

- Now smiling summer's balmy breeze, vol. ii., 229.

- Now summer shines with gaudy pride, vol. ii., 116.

- Now the beams of May morn, vol. iii., 149.

- Now there 's peace on the shore, now there 's calm on the sea, vol. iii., 177.

- Now winter wi' his cloudy brow, vol. ii., 147.

- Now winter's wind sweeps o'er the mountains, vol. i., 165.

- Oh! are ye sleeping, Maggie, vol. ii., 156.

- Oh! away to the Tweed, vol. v., 94.

- Oh, beautiful and bright thou art, vol. vi., 197.

- Oh, blaw ye westlin winds, blaw saft, vol. i., 124.

- Oh, blessing on her star-like e'en, vol. v., 102.

- Oh! blessing on thee, land, vol. v., 104.

- Oh, bonnie are the howes, vol. iv., 200.

- Oh, bonnie buds yon birchen-tree, vol. ii., 240.

- Oh, bonnie Nelly Brown, I will sing a song to thee, vol. v., 276.

- Oh, bonnie 's the lily that blooms in the valley, vol. v., 194.

- Oh, brave Caledonians, my brothers, my friends, vol. iii., 114.

- Oh, bright the beaming queen o' night, vol. v., 146.

- Oh, Castell Gloom! thy strength is gone, vol. i., 221.

- Oh, Charlie is my darling, vol. iii., 53.

- Oh, come my bonnie bark, vol. iii., 16.

- Oh, come with me for the queen of night, vol. iii., 59.

- October winds wi' biting breath, vol. ii., 203.

- O dear, dear to me, vol. vi., 92.

- Oh! dear to my heart are my heather-clad mountains, vol. v., 239.

- Oh! dear were the joys that are past, vol. iii., 62.

- Oh, dinna ask me gin I lo'e thee, vol. v., 78.

- Oh, dinna be sae sair cast down, vol. v., 43.

- Oh, dinna cross the burn, Willie, vol. v., 150.

- Oh, dinna look ye pridefu' doon on a' beneath your ken, vol. v., 204.

- Oh, dinna think, bonnie lassie, I 'm gaun to leave thee, vol. i., 96.

- Oh, distant, but dear, is that sweet island wherein, vol. ii., 109.

- O'er mountain and valley, vol. iii., 169.

- O'er the mist-shrouded cliffs of the gray mountain straying, vol. v., 47.

- Of learning long a scantling was the portion of the Gael, vol. v., 295.

- Of Nelson and the north, vol. ii., 265.

- Of streams that down the valley run, vol. ii., 129.

- Oh, gentle sleep wilt thou lay thy head, vol. iii., 90.

- Oh, gin I were where Gadie rins, vol. iv., 117.

- Oh, grand bounds the deer o'er the mountain, vol. i., 55.

- Oh, guess ye wha I met yestreen, vol. vi., 129.

- Oh, hame is aye hamely still, though poor at times it be, vol. iv., 218.

- Oh, hast thou forgotten the birk-tree's shade, vol. iv., 269.

- Oh, haud na' yer noddle sae hie, ma doo! vol. v., 108.

- Oh, heard ye yon pibroch sound sad in the gale, vol. ii., 263.

- O hi', O hu', she 's sad for scolding, vol. v., 288.

- Oh! how can I be cheerie in this hameless ha', vol. iii., 125.

- Oh, how I love the evening hour, vol. v., 265.

- Oh! I have traversed lands afar, vol. v., 12.

- Oh! I lo'ed my lassie weel, vol. iii., 253.

- O June, ye spring the loveliest flowers, vol. v., 44.

- Oh, lady, twine no wreath for me, vol. i., 302.

- Oh, lassie! I lo'e dearest, vol. v., 47.

- Oh, lassie! if thou 'lt gang to yonder glen wi' me, vol. iv., 65.

- Oh, lassie! wilt thou gang wi' me, vol. iii., 65.

- Oh, lassie! wilt thou go? vol. ii., 287.

- Old Scotland, I love thee, thou 'rt dearer to me, vol. v., 250.

- Oh, leave me not! the evening hour, vol. v., 74.

- Oh, leeze me on the bonnie lass, vol. ii., 178.

- Oh, let na gang yon bonnie lassie, vol. v., 58.

- Oh, love the soldier's daughter dear, vol. v., 270.

- Oh, many a true Highlander, many a liegeman, vol. iii., 280.

- Oh! Mary, while thy gentle cheek, vol. v., 122.

- Oh, merrily and gallantly, vol. v., 116.

- Oh, mind ye the ewe-bughts, Marion, vol. i., 56.

- Oh, mony a turn of woe and weal, vol. i., 347.

- Oh, mony a year has come and gane, vol. v., 20.

- Oh, my lassie, our joy to complete again, vol. ii., 54.

- Oh, my love, leave me not, vol. i., 106.

- Oh! my love 's bonnie, bonnie, bonnie, vol. v., 52.

- Oh! my love is very lovely, vol. vi., 8.

- Oh, my love was fair as the siller clud, vol. vi., 173.

- Once more on the broad-bosom'd ocean appearing, vol. iv., 199.

- Once more in the Highlands I wander alone, vol. v., 257.

- Oh, neighbours! what had I to do for to marry? vol. i., 139.

- On, on to the fields where of old, vol. iv., 56.

- On fair Clydeside thair wonnit ane dame, vol. v., 119.

- On thee, Eliza, dwell my thoughts, vol. ii., 173.

- On the greensward lay William in anguish extended, vol. ii., 163.

- On the airy Ben-Nevis the wind is awake, vol. iv., 250.

- On the banks o' the burn, while I pensively wander, vol. ii., 316.

- On the fierce savage cliffs that look down on the flood, vol. iv., 105.

- On this unfrequented plain, vol. ii., 294.

- O our childhood's once delightful hours, vol. iii., 198.

- Or ere we part, my heart leaps hie to sing ae bonnie sang, vol. v., 193.

- Oh, saft is the blink o' thine e'e, lassie, vol. v., 208.

- Oh, sarely may I rue the day, vol. ii., 58.

- Oh, sair I feel the witching power, vol. iii., 192.

- Oh, saw ye my wee thing, saw ye my ain thing, vol. i., 82.

- Oh, saw ye this sweet, bonnie lassie o' mine, vol. ii., 70.

- Oh, saw ye this sweet, bonnie lassie o' mine, vol. iv., 271.

- Oh! say na you maun gang awa, vol. iv., 201.

- Oh! say not life is ever drear, vol. v., 88.

- Oh! say not o' war the young soldier is weary, vol. iv., 214.

- Oh! say not 'tis the March wind, 'tis a fiercer blast that drives, vol. v., 293.

- Oh! say not, my love, with that mortified air, vol. i., 305.

- Oh, softly sighs the westlin' breeze, vol. v., 167.

- Oh, some will tune their mournful strain, vol. i., 232.

- Oh! stopna, bonnie bird, that strain, vol. iii., 134.

- O sweet is the blossom o' the hawthorn-tree, vol. v., 187.

- O sweet is the calm, dewy gloamin', vol. iv., 247.

- Oh, sweet were the hours, vol. iii., 94.

- Oh, swiftly bounds our gallant bark, vol. vi., 154.

- O tell me, bonnie young lassie, vol. i., 85.

- Oh! tell me what sound is the sweetest to hear, vol. iv., 69.

- Oh, that I were the shaw in, vol. ii., 329.

- Oh, the auld house, the auld house! vol. i., 224.

- Oh! the bonnie Hieland hills, vol. iv., 230.

- Oh, the breeze of the mountain is soothing and sweet, vol. ii., 19.

- Oh! the happy days o' youth are fast gaun by, vol. iii., 266.

- Oh! the happy time departed, vol. vi., 17.

- Oh! the sunny peaches glow, vol. iii., 150.

- O these are not my country's hills, vol. iv., 127.

- Oh, to bound o'er the bonnie, blue sea, vol. iv., 133.

- Oh! the land of hills is the land for me, vol. iv., 270.

- Oh! the winning charm of gentleness, so beautiful to me, vol. v., 242.

- Oh, there 's naebody hears Widow Miller complain, vol. v., 237.

- Our ain native land, our ain native land, vol. iv., 54.

- Oh, tuneful voice, I still deplore, vol. i., 44.

- Our Mary liket weel to stray, vol. iv., 70.

- Our minstrels a', frae south to north, vol. iii., 95.

- Our native land, our native vale, vol. iii., 106.

- Ours is the land of gallant hearts, vol. iv., 51.

- Oh, wae be to the orders that march'd my love awa, vol. iii., 238.

- Oh! wae's me on gowd, wi' its glamour and fame, vol. vi., 148.

- Oh, wae 's my life, and sad my heart, vol. v., 17.

- Oh, waft me to the fairy clime, vol. iv., 92.

- Oh! waste not thy woe on the dead, nor bemoan him, vol. vi., 126.

- Oh, we aft hae met at e'en, bonnie Peggie, O! vol. iii., 227.

- Oh, weel's me on my ain man, vol. i., 204.

- Oh, weel befa' the maiden gay, vol. ii., 64.

- Oh, weel I lo'e our auld Scots sangs, vol. v., 85.

- Oh! weep not thus, though the child thou hast loved, vol. iii., 201.

- Oh! we hae been amang the bowers that winter didna bare, vol. vi., 236.

- Oh, wha 's at the window, wha, wha, wha? vol. iv., 253.

- Oh, what are the chains of love made of, vol. iv., 136.

- Oh, what care I where Love was born, vol. v., 11.

- Oh! what is in this flaunting town, vol. vi., 203.

- Oh, when shall I visit the land of my birth, vol. i., 254.

- Oh, where are the pretty men of yore, vol. v., 129.

- Oh, where has the exile his home, vol. iv., 250.

- Oh, where snared ye that bonnie, bonnie bird, vol. v., 14.

- Oh, where, tell me where is your Highland laddie gone, vol. i., 104.

- Oh! why left I my hame, vol. iii., 264.

- O! why should old age so much wound us, vol. i., 20.

- Oh! will ye go to yon burn-side, vol. iii., 68.

- Oh! will ye walk the wood wi' me, vol. iv., 273.

- Oh! would I were throned on yon glossy golden cloud, vol. iv., 139.

- Oh! would that the wind that is sweeping now, vol. iv., 180.

- Oh! years hae come an' years hae gane, vol. iv., 193.

- Oh, yes, there 's a valley as calm and as sweet, vol. iv., 255.

- O ye tears! O ye tears! that have long refused to flow, vol. vi., 18.

- Oh, young Lochinvar is come out of the West, vol. i., 290.

- Peace be upon their banners, vol. v., 224.

- Phœbus, wi' gowden crest, leaves ocean's heaving breast, vol. v., 51.

- Preserve us a' what shall we do, vol. ii., 99.

- Put off, put off, and row with speed, vol. ii., 179.

- Quoth Rab to Kate, My sonsy clear, vol. ii., 94.

- Raise high the battle-song, vol. iii., 131.

- Red gleams the sun on yon hill tap, vol. i., 55.

- Reft the charm of the social shell, vol. iii., 276.

- Removed from vain fashion, vol. iv., 80.

- Returning Spring, with gladsome ray, vol. i., 169.

- Rise, little star, vol. vi., 224.

- Rise, my love! the moon unclouded, vol. iv., 149.

- Rise, rise, Lowland and Highlandman, vol. iv., 115.

- Rise, Romans, rise at last, vol. vi., 216.

- Rising o'er the heaving billow, vol. v., 29.

- Robin is my ain gudeman, vol. i., 205.

- Roy's wife of Aldivalloch, vol. i., 52.

- Saw ye Johnnie comin', quo' she, vol. i., 145.

- Saw ye my Annie, vol. iv., 121.

- Saw ye nae my Peggie, vol. i., 208.

- Say wilt thou, Leila, when alone, vol. vi., 40.

- Scenes of woe and scenes of pleasure, vol. ii., 251.

- Scotia's thistle guards the grave, vol. iv., 50.

- Scotland, thy mountains, thy valleys, and fountains, vol. vi., 33.

- See the moon o'er cloudless Jura, vol. iii., 196.

- See the winter clouds around, vol. ii., 87.

- Send a horse to the water, ye 'll no mak him drink, vol. i., 219.

- Shadows of glory, the twilight is parting, vol. vi., 139.

- Shall I leave thee, thou land to my infancy dear, vol. iii., 99.

- She died, as die the roses, vol. vi., 256.

- She died in beauty, like a rose, vol. iv., 177.

- She 's aff and awa, like the lang simmer day, vol. iv., 124.

- She 's gane to dwall in heaven, my lassie, vol. iii., 9.

- She was mine when the leaves of the forest were green, vol. iii., 116.

- She was Naebody's bairn, she was Naebody's bairn, vol. v., 200.

- Should my numbers essay to enliven a lay, vol. i., 352.

- Sing a' ye bards wi' loud acclaim, vol. iii., 139.

- Sing not to me of sunny shores, vol. vi., 155.

- Sing on, fairy Devon, vol. vi., 104.

- Sing on, thou little bird, vol. ii., 286.

- Sister Jeanie, haste, we 'll go, vol. v., 166.

- Soldier, rest! thy warfare 's o'er, vol. i., 294.

- Songs of my native land, vol. i., 220.

- Star of descending night, vol. iv., 92.

- Stay, proud bird of the shore, vol. iv., 141.

- St Leonard's hill was lightsome land, vol. i., 228.

- Sublime is Scotia's mountain land, vol. vi., 169.

- Summer ocean, vol. vi., 61.

- Surrounded wi' bent and wi' heather, vol. i., 265.

- Sweet bard of Ettrick's glen, vol. iv., 75.

- Sweet 's the gloamin's dusky gloom, vol. vi., 94.

- Sweet 's the dew-deck'd rose in June, vol. iv., 101.

- Sweetly shines the sun on auld Edinbro' toun, vol. iv., 239.

- Sweet summer now is by, vol. iv., 275.

- Sweet the rising mountains, red with heather bells, vol. vi., 254.

- Talk not of temples—there is one, vol. iii., 152.

- Taste life's glad moments, vol. ii., 212.

- Tell me, Jessie, tell me why? vol. i., 122.

- Tell me, dear! in mercy speak, vol. vi., 131.

- The auld meal mill, oh! the auld meal mill, vol. v., 230.

- The bard strikes his harp the wild valleys among, vol. ii., 249.

- The bard strikes his harp the wild woods among, vol. v., 50.

- The beacons blazed, the banners flew, vol. v., 38.

- The best o' joys maun hae an end, vol. i., 209.

- The blackbird's hymn is sweet, vol. iv., 145.

- The bonnie, bonnie bairn, sits pokin' in the ase, vol. v., 201.

- The bonnie rowan bush, vol. iv., 231.

- The bonniest lass in a' the warld, vol. i., 201.

- The breath o' spring is gratefu', vol. v., 143.

- The bride she is winsome and bonnie, vol. i., 148.

- The bucket, the bucket, the bucket for me, vol. iv., 223.

- The cantie spring scarce reared her head, vol. iii., 52.

- The cranreuch's on my head, vol. vi., 107.

- The dark gray o' gloamin', vol. iv., 243.

- The dawn is breaking, but lonesome and eerie, vol. iii., 274.

- The daylight was dying, the twilight was dreary, vol. vi., 72.

- The dreary reign of winter's past, vol. v., 55.

- The e'e o' the dawn, Eliza, vol. iv., 146.

- The fairies are dancing, how nimbly they bound, vol. ii., 273.

- The favouring wind pipes aloft in the shrouds, vol. vi., 26.

- The fields, the streams, the skies, are fair, vol. v., 267.

- The gathering clans 'mong Scotia's glens, vol. iv., 52.

- The gloamin' star was showerin', vol. vi., 106.

- The gloom of dark despondency, vol. vi., 193.

- The gloomy days are gone, vol. v., 218.

- The golden smile of morning, vol. vi., 122.

- The gowan glitters on the sward, vol. i., 143.

- The happy days of yore, vol. vi., 156.

- The harvest morn breaks, vol. iv., 266.

- The hawk whoops on high, and keen, keen from yon cliff, vol. i., 168.

- The heath this night must be my bed, vol. i., 297.

- The Highland hills, there are songs of mirth, vol. vi., 168.

- The ingle cheek is bleezin' bricht, vol. v., 235.

- Their nest was in the leafy bush, vol. i., 206.

- The king is on his throne, wi' his sceptre an' his croon, vol. v., 216.

- The laird o' Cockpen, he 's proud and he 's great, vol. i., 198.

- The lake is at rest, love, vol. iv., 85.

- The land I lo'e, the land I lo'e, vol. iv., 215.

- The lark has left the evening cloud, vol. iii., 10.

- The last gleam o' sunset in ocean was sinkin', vol. iii., 221.

- The lily of the vale is sweet, vol. v., 35.

- The little comer 's coming, the comer o'er the sea, vol. v., 132.

- The loved of early days, vol. iv., 179.

- The love-sick maid, the love-sick maid, vol. iv., 93.

- The maidens are smiling in rocky Glencoe, vol. vi., 130.

- The maid is at the altar kneeling, vol. iv., 160.

- The maid who wove the rosy wreath, vol. iv., 96.

- The midges dance aboon the burn, vol. ii., 149.

- The mitherless lammie ne'er miss'd its ain mammie, vol. i., 231.

- The moon hung o'er the gay greenwood, vol. iv., 140.

- The moon shone in fits, vol. ii., 221.

- The moon was a waning, vol. ii., 78.

- The mother with her blooming child, vol. v., 172.

- The music of the night, vol. iii., 217.

- The music o' the year is hush'd, vol. ii., 161.

- The neighbours a' they wonder how, vol. ii., 293.

- The night winds Eolian breezes, vol. iv., 265.

- The noble otter hill, vol. i., 337.

- The oak is Britain's pride, vol. v., 223.

- The parting kiss, the soft embrace, vol. iii., 90.

- The primrose is bonnie in spring, vol. iii., 174.

- There are moments when my spirit wanders back to other years, vol. vi., 209.

- There grew in bonnie Scotland, vol. ii., 186.

- There grows a bonnie brier-bush in our kail-yard, vol. i., 215.

- There is a bonnie blushing flower, vol. v., 256.

- There is a concert in the trees, vol. iv., 208.

- There is a pang for every heart, vol. iii., 148.

- There is music in the storm, love, vol. vi., 180.

- There lived a lass in Inverness, vol. iii., 14.

- There lives a lassie i' the braes, vol. i., 24.

- There lives a young lassie, vol. iv., 116.

- There 's a thrill of emotion, half painful, half sweet, vol. iii., 222.

- There 's cauld kail in Aberdeen, vol. i., 48.

- There 's cauld kail in Aberdeen, vol. i., 210.

- There 's high and low, there 's rich and poor, vol. i., 194.

- There 's meikle bliss in ae fond kiss, vol. vi., 128.

- There 's mony a flower beside the rose, vol. iv., 188.

- There 's music in the flowing tide, there 's music in the air, vol. ii., 275.

- There 's music in a mother's voice, vol. vi., 51.

- There 's nae covenant noo, lassie, vol. ii., 187.

- There 's nae hame like the hame o' youth, vol. iv., 228.

- There 's nae love like early love, vol. iii., 185.

- There 's nane may ever guess or trow my bonnie lassie's name, vol. v., 206.

- There 's some can be happy and bide whar they are, vol. vi., 163.

- There was a musician wha play'd a good stick, vol. i., 271.

- The rosebud blushing to the morn, vol. ii., 105.

- The Rover o' Lochryan, he 's gane, vol. v., 64.

- The Scotch blue bell, vol. v., 233.

- The season comes when first we met, vol. i., 43.

- The sea, the deep, deep sea, vol. iii., 218.

- The shadows of evening fall silent around, vol. vi., 146.

- The sky in beauty arch'd, vol. iv., 154.

- The skylark sings his matin lay, vol. vi., 63.

- The soldier waves the shining sword, the shepherd-boy his crook; vol. v., 68.

- The spring comes back to woo the earth, vol. v., 156.

- The storm grew faint as daylight tinged, vol. iv., 212.

- The summer comes wi' rosy wreaths, vol. vi., 36.

- The sun blinks sweetly on yon shaw, vol. ii., 175.

- The sun-down had mantled Ben Nevis with night vol. iv., 287.

- The sun hadna peep'd frae behint the dark billow, vol. iii., 129.

- The sun has gane down o'er the lofty Ben Lomond, vol. ii., 136.

- The sun is setting on sweet Glengarry, vol. ii., 176.

- The sun is sunk, the day is done, vol. i., 133.

- The sun sets in night, and the stars shun the day, vol. i., 41.

- The sunny days are come, my love, vol. vi., 172.

- The sweets o' the simmer invite us to wander, vol. ii., 305.

- The tears I shed must ever fall, vol. i., 168.

- The tempest is raging, vol. iii., 151.

- The troops were all embarked on board, vol. i., 115.

- The weary sun 's gane down the west, vol. ii., 154.

- The widow is feckless, the widow 's alane, vol. v., 200.

- The wild rose blooms in Drummond woods, vol. iv., 236.

- The women are a' gane wud, vol. i., 227.

- The year is wearing to an end, vol. ii., 79.

- They 're stepping off, the friends I knew, vol. vi., 45.

- They speak o' wiles in woman's smiles, vol. iii., 122.

- They tell me first and early love, vol. vi., 73.

- They tell me o' a land whar the sky is ever clear, vol. vi., 212.

- Thou bonnie wood o' Craigie Lee, vol. ii., 153.

- Thou cauld gloomy Feberwar, vol. iii., 164.

- Thou dark stream slow wending thy deep rocky way, vol. v., 114.

- Thou gentle and kind one, vol. v., 128.

- Thou hast left me, dear Dermot, to cross the wide sea, vol. iv., 107.

- Thou hast sworn by thy God, my Jeanie, vol. iii., 17.

- Though all fair was that bosom heaving white, vol. iv., 67.

- Though fair blooms the rose in gay Anglia's bowers, vol. iv., 217.

- Though long the wanderer may depart, vol. vi., 225.

- Though richer swains thy love pursue, vol. i., 134.

- Though siller Tweed rin o'er the Lea, vol. ii., 104.

- Though the winter of age wreathes her snow on his head, vol. ii., 117.

- Though this wild brain is aching, vol. iv., 155.

- Thou ken'st, Mary Hay, that I lo'e thee weel, vol. ii., 167.

- Thou morn full of beauty, vol. v., 140.

- Through Crockstoun Castle's lanely wa's, vol. ii., 144.

- Thus sang the minstrel Cormack, his anguish to beguile, vol. iii., 275.

- Thy cheek is o' the rose's hue, vol. ii., 244.

- Thy queenly hand, Victoria, vol. v., 264.

- Thy wily eyes, my darling, vol. iv., 292.

- 'Tis finish'd, they 've died for their forefathers' land, vol. iv., 153.

- 'Tis haena ye heard, man, o' Barrochan Jean, vol. ii., 150.

- 'Tis not the rose upon the cheek, vol. iii., 60.

- 'Tis sair to dream o' them we like, vol. iii., 266.

- 'Tis sweet wi' blithesome heart to stray, vol. v., 186.

- 'Tis the fa' o' the leaf, and the cauld winds are blawing, vol. v., 258.

- 'Tis the first rose o' summer that opes to my view, vol. iii., 264.

- 'Tis Yule! 'tis Yule! all eyes are bright, vol. vi., 65.

- Together, dearest, we have play'd, vol. v., 22.

- To live in cities, and to join, vol. v., 245.

- Touch once more a sober measure, vol. iii., 178.

- To Scotland's ancient realm, vol. v., 272.

- To wander lang in foreign lands, vol. iii., 210.

- True love is water'd aye wi' tears, vol. i., 233.

- Trust not these seas again, vol. vi., 232.

- Tuck, tuck, feer—from the green and growing leaves, vol. vi., 76.

- 'Twas a balmy summer gloamin', vol. vi., 158.

- 'Twas on a Monday morning, vol. ii., 61.

- 'Twas on a simmer afternoon, vol. i., 213.

- 'Twas summer, and softly the breezes were blowing, vol. i., 72.

- 'Twas when December's dark'ning scowl the face of heaven o'ercast, vol. vi., 239.

- 'Twas when the wan leaf frae the birk-tree was fa'in', vol. ii., 314.

- Up with the dawn, ye sons of toil, vol. vi., 142.

- Waken, lords and ladies gay, vol. i., 304.

- Walkin' out ae mornin' early, vol. iii., 24.

- Warlike chieftains now assembled, vol. v., 40.

- Weep away, heart, weep away, vol. vi., 59.

- Weep not over poet's wrong, vol. vi., 69.

- Welcome, pretty little stranger, vol. i., 257.

- We 'll meet beside the dusky glen on yon burn-side, vol. ii., 140.

- We 'll meet yet again, my loved fair one, when o'er us, vol. iv., 53.

- We part, yet wherefore should I weep, vol. v., 105.

- Were I a doughty cavalier, vol. v., 127.

- Were I but able to rehearse, vol. i., 17.

- We were baith neebor bairns, thegither we play'd, vol. vi., 185.

- Wha 'll buy caller herrin', vol. i., 195.

- Whan Jamie first woo'd me he was but a youth, vol. iii., 25.

- Whare hae ye been a' day, vol. i., 83.

- What ails my heart—what dims my e'e? vol. v., 253.

- What ails ye, my lassie, my dawtie, my ain? vol. vi., 78.

- What are the flowers of Scotland, vol. ii., 66.

- What fond, delicious ecstasy does early love impart, vol. vi., 85.

- What makes this hour a day to me? vol. v., 33.

- What though ye hae nor kith nor kin, vol. v., 238.

- What 's this vain world to me, vol. i., 236.

- What wakes the poet's lyre, vol. iv., 91.

- When a' ither bairnies are hush'd to their hame, vol. iii., 123.

- When autumn comes and heather bells, vol. iv., 132.

- When Charlie to the Highlands came, vol. ii., 180.

- When cities of old days, vol. iv., 156.

- When first I cam' to be a man, vol. i., 13.

- When fops and fools together prate, vol. i., 31.

- When friendship, love, and truth abound, vol. i., 253.

- When hope lies dead within the heart, vol. i., 45.

- When I began the world first, vol. i., 33.

- When I look far down on the valley below me, vol. iv., 169.

- When I think on the lads and the land I hae left, vol. v., 66.

- When I think on the sweet smiles o' my lassie, vol. ii., 307.

- When I was a miller in Fife, vol. iii., 92.

- When Katie was scarce out nineteen, vol. i., 157.

- When loud the horn is sounding, vol. vi., 63.

- When merry hearts were gay, vol. i., 92.

- When my flocks upon the heathy hill are lyin' a' at rest, vol. iv., 49.

- When others are boasting 'bout fetes and parades, vol. v., 153.

- When rosy day far in the west has vanish'd frae the scene, vol. v., 151.

- When sets the sun o'er Lomond's height, vol. ii., 183.

- When shall we meet again, vol. iv., 81.

- When the bee has left the blossom, vol. v., 73.

- When the fair one and the dear one, vol. ii., 190.

- When the glen all is still save the stream of the fountain, vol. iv., 58.

- When the lark is in the air, vol. iii., 158.

- When the maid of my heart, with the dark rolling eye, vol. iv., 270.

- When the morning's first ray saw the mighty in arms, vol. iv., 79.

- When the sheep are in the fauld, vol. i., 64.

- When the star of the morning is set, vol. iv., 66.

- When the sun gaes down, vol. v., 109.

- When thy smile was still clouded, vol. ii., 282.

- When we meet again, Lisette, vol. vi., 190.

- When white was my owrelay, vol. i., 134.

- When winter winds forget to blaw, vol. i., 268.

- Where Manor's stream rins blithe an' clear, vol. iii., 262.

- Where shall the lover rest, vol. i., 292.

- Where the faded flower shall freshen, vol. vi., 230.

- Where windin' Tarf, by broomy knowes, vol. iii., 67.

- While beaux and belles parade the street, vol. iv., 213.

- While the dawn on the mountain was misty and gray, vol. i., 303.

- Why does the day whose date is brief, vol. iii., 202.

- Why gaze on that pale face, vol. vi., 161.

- Why is my spirit sad, vol. vi., 41.

- Why tarries my love, vol. i., 68.

- Wi' a hundred pipers an' a', an a', vol. i., 226.

- Wifie, come hame, vol. v., 203.

- Wi' heart sincere I love thee, Bell, vol. iii., 54.

- Will ye gang o'er the lea rig, vol. i., 202.

- Will ye go to the Highlands, my Mary, vol. iii., 66.

- Will you go to the woodlands with me, with me, vol. v., 180.

- Winter's cauld and cheerless blast, vol. v., 196.

- With a breezy burst of singing, vol. v., 285.

- With drooping heart he turn'd away, vol. vi., 218.

- Within the towers of ancient Glammis, vol. ii., 88.

- With laughter swimming in thine eye, vol. iii., 88.

- With lofty song we love to cheer, vol. v., 23.

- Would that I were where wild woods wave, vol. iv., 68.

- Would you be young again? vol. i., 235.

- Ye briery bields, where roses blaw, vol. ii., 231.

- Ye daisied glens and briery braes, vol. iii., 208.

- Ye dark, rugged rocks that recline o'er the deep, vol. i., 179.

- Ye hameless glens and waving woods, vol. vi., 151.

- Ye have cross'd o'er the wave from the glades where I roved, vol. vi., 195.

- Ye ken whaur yon wee burnie, love, vol. v., 148.

- Ye mariners of England, vol. ii., 262.

- Ye mauna be proud, although ye be great, vol. v., 205.

- Ye needna be courtin' at me, auld man, vol. iv., 222.

- Yes, the shades we must leave which my childhood has haunted, vol. ii., 281.

- Yestreen, as I strayed on the banks o' the Clyde, vol. iii., 187.

- Yestreen, on Cample's bonnie flood, vol. v., 21.

- Ye swains wha are touch'd wi' saft sympathy's feelin', vol. ii., 96.

- Ye 've seen the blooming rosy brier, vol. iv., 249.

- Yon old temple pile, where the moon dimly flashes, vol. v., 174.

- Young Donald, dearer loved than life, vol. iv., 113.

- Young Love once woo'd a budding rose, vol. vi., 64

- Young Randal was a bonnie lad when he gaed awa, vol. v., 126.

- Your foes are at hand, and the brand that they wield, vol. v., 84.

- You 've surely heard of famous Neil, vol. ii., 86.

INDEX OF AUTHORS

- Affleck, James, vol. iii., 38.

- Ainslie, Hew, vol. v., 60.

- Aird, Marion Paul, vol. v., 258.

- Aird, Thomas, vol. v., 131.

- Allan, George, vol. iv., 163.

- Allan, Robert, vol. ii., 169.

- Anderson, Rev. J. G. Torry, vol. iv., 158.

- Anderson, William, vol. v., 178.

- Atkinson, Thomas, vol. iv., 122.

- Baillie, Joanna, vol. i., 126.

- Bald, Alexander, vol. v., 34.

- Balfour, Alexander, vol. ii., 101.

- Ballantine, James, vol. v., 198.

- Barnard, Lady Ann, vol. i., 58.

- Bell, Henry Glassford, vol. vi., 39.

- Bennet, William, vol. vi., 47.

- Bennoch, Francis, vol. v., 1.

- Bethune, Alexander, vol. iv., 203.

- Bethune, John, vol. iv., 203.

- Blackie, John Stuart, vol. vi., 109.

- Blair, William, vol. v., 82.

- Bonar, Horatius, D.D., vol. vi., 229.

- Boswell, Sir Alex., Bart., vol. ii., 204.

- Brockie, William, vol. vi., 78.

- Brown, Colin Rae, vol. vi., 159.

- Brown, James, vol. iii., 186.

- Brown, John, vol. iv., 286.

- Brown, Thomas., M.D., vol. ii., 278.

- Brydson, Thomas, vol. iv., 172.

- Buchanan, Alexander, vol. vi., 89.

- Buchanan, Dugald, vol. i., 322.

- Buchan, Peter, vol. iii., 162.

- Burns, James D., vol. vi., 224.

- Burtt, John, vol. v., 46.

- Cadenhead, William, vol. vi., 133.

- Cameron, William, senr., vol. i., 35.

- Cameron, William, junr., vol. v., 146.

- Campbell, Alexander, vol. i., 161.

- Campbell, John, vol. v., 292.

- Campbell, Thomas, vol. ii., 255.

- Carlile, Alexander, vol. iv., 252.

- Cathcart, Robert, vol. vi., 94.

- Chalmers, William, vol. ii., 285.

- Chambers, Robert, vol. v., 124.

- Conolly, Erskine, vol. iii., 220.

- Couper, Robert, M.D., vol. i., 53.

- Craig, Isabella, vol. vi., 182.

- Crawford, Archibald, vol. vi., 31.

- Crawford, John, vol. vi., 98.

- Crawford, Margaret, vol. vi., 205.

- Cunningham, Allan, vol. iii., 1.

- Cunningham, Thomas Mounsey, vol. ii., 223.

- Davidson, Robert, vol. iii., 206.

- Denovan, J. C., vol. iv., 106.

- Dick, Thomas, vol. v., 160.

- Dickson, John Bathurst, vol. vi., 220.

- Dobie, William, vol. v., 54.

- Dodds, James, vol. vi., 238.

- Donald, George, sen., vol. vi., 35.

- Donald, George, jun., vol. vi., 212.

- Douglas, Alexander, vol. ii., 110.

- Drummond, David, vol. iii., 34.

- Dudgeon, William, vol. i., 151.

- Dunbar, William, D.D., vol. v., 28.

- Duncan, Henry, D.D., vol. ii., 156.

- Dunlop, John, vol. v., 77.

- Duthie, Robert, vol. vi., 187.

- Elliott, Thomas, vol. vi., 141.

- Ferguson, William, vol. v., 155.

- Finlay, John, senr., vol. iii., 57.

- Finlay, John, junr., vol. v., 215.

- Finlay, William, vol. iii., 166.

- Finlayson, Charles James, vol. v., 49.

- Fleming, Charles, vol. v., 153.

- Fletcher, Angus, vol. iv., 292.

- Foster, William Air, vol. v., 91.

- Fraser, Robert, vol. iii., 252.

- Gall, Richard, vol. ii., 241.

- Gardiner, William, vol. iv., 126.

- Gibson, Allan, vol. vi., 137.

- Gilfillan, Robert, vol. iii., 261.

- Gillespie, William, vol. ii., 218.

- Glen, William, vol. iii., 126.

- Goldie, John, vol. iv., 98.

- Gordon, Alexander, Duke of, vol. i., 46.

- Grant, Joseph, vol. iv., 143.

- Grant, Mrs, of Carron, vol. i., 50.

- Grant, Mrs, of Laggan, vol. i., 99.

- Gray, Charles, vol. iii., 50.

- Grieve, John, vol. iii., 43.

- Halliday, John, vol. vi., 234.

- Hamilton, John, vol. i., 117.

- Hedderwick, James, vol. vi., 67.

- Henderson, George, vol. vi., 227.

- Henderson, James, vol. vi., 165.

- Hendry, Robert, M.D., vol. v., 57.

- Hetherington, William, D.D., LL.D., vol. v., 185.

- Hislop, James, vol. iii., 254.

- Hogg, James, vol. ii., 1.

- Hogg, Robert, vol. iv., 129.

- Home, James, vol. iv., 267.

- Hume, Alexander, sen., vol. iv., 182.

- Hume, Alexander, jun., vol. v., 276.

- Hunter, Mrs John, vol. i., 39.

- Hunter, John, vol. v., 119.

- Imlah, John, vol. iv., 108.

- Inglis, Henry, vol. vi., 59.

- Inglis, Mrs Margaret M., vol. iv., 73.

- Irving, Archibald Stirling, vol. iv., 235.

- Jamieson, Alexander, vol. iv., 95.

- Jamieson, Robert, vol. ii., 288.

- Jamie, William, vol. vi., 96.

- Jeffrey, John, vol. vi., 215.

- Jerdan, William, vol. v., 30.

- Kennedy, Duncan, vol. v., 284.

- King, James, vol. iv., 83.

- Knox, William, vol. iii., 112.

- Laidlaw, William, vol. ii., 310.

- Laing, Alexander, vol. iv., 241.

- Latto, Thomas C., vol. vi., 127.

- Leighton, Robert, vol. vi., 163.

- Lewis, Stuart, vol. iii., 27.

- Leyden, John, M.D., vol. ii., 191.

- Little, James, vol. vi., 153.

- Lochore, Robert, vol. ii., 91.

- Lockhart, John Gibson, vol. iii., 171.

- Logan, William, vol. vi., 151.

- Lyle, Thomas, vol. iv., 261.

- Lyon, Mrs Agnes, vol. ii., 84.

- Macansh, Alexander, vol. v., 171.

- Macarthur, Mrs Mary, vol. v., 111.

- Mackay, Charles, LL.D., vol. vi., 1.

- M'Coll, Evan, vol. vi., 222.

- M'Diarmid, John, vol. iii., 155.

- Macdonald, Alexander, vol. ii., 321.

- Macdonald, James, vol. v., 192.

- Macdonald, John, sen., vol. v., 281.

- Macdonald, John, jun., vol. vi., 254.

- M'Dougall, Allan, vol. v., 287.

- Macfarlan, Duncan, vol. vi., 249.

- Macfarlan, James, vol. vi., 196.

- Macgregor, James, D.D., vol. v., 294.

- Macgregor, Joseph, vol. v., 25.

- Macindoe, George, vol. ii., 106.

- Macintyre, Duncan, vol. i., 334.

- Mackay, Archibald, vol. v., 85.

- Mackay, Robert, sen., vol. i., 309.

- Mackay, Robert, jun., vol. ii., 349.

- Mackenzie, Kenneth, vol. v., 290.

- M'Lachlan, Alexander, vol. vi., 80.

- M'Lachlan, Evan, vol. iv., 279.

- Maclagan, Alexander, vol. v., 226.

- Maclagan, James, vol. iii., 282.

- Maclardy, James, vol. vi., 171.

- M'Laren, William, vol. ii., 114.

- Macleod, Norman, vol. i., 355.

- Macneill, Hector, vol. i., 73.

- Macodrum, John, vol. i., 351.

- Macvurich, Lachlan, vol. iii., 279.

- Malcolm, John, vol. iii., 215.

- Malone, Robert L., vol. iv., 216.

- Manson, James, vol. vi., 61.

- Marshall, Charles, vol. v., 97.

- Mathers, Thomas, vol. iii., 184.

- Mayne, John, vol. i., 107.

- Menzies, George, vol. iii., 223.

- Mercer, Andrew, vol. ii., 189.

- Miller, Hugh, vol. v., 161.

- Miller, Robert, vol. iv., 179.

- Miller, William, vol. v., 274.

- Mitchell, John, vol. iv., 90.

- Moir, David Macbeth, vol. iii., 24.

- Montgomery, James, vol. i., 247.

- Moore, Dugald, vol. iv., 147.

- Morrison, John, vol. ii., 346.

- Motherwell, William, vol. iii., 230.

- Muirhead, James, D.D., vol. ii., 81.

- Munro, John, vol. vi., 251.

- Nairn, Carolina, Baroness, vol. i., 184.

- Nevay, John, vol. iv., 257.

- Nicholson, William, vol. iii., 63.

- Nicol, James, vol. i., 24.

- Nicoll, Robert, vol. iv., 225.

- Ogilvy, Mrs Eliza H., vol. v., 211.

- Outram, George, vol. vi., 54.

- Pagan, Isobel, vol. iv., 88.

- Park, Andrew, vol. v., 248.

- Part, William, vol. iii., 97.

- Parker, James, vol. v., 116.

- Paul, Hamilton, vol. ii., 120.

- Picken, Ebenezer, vol. iii., 22.

- Polin, Edward, vol. vi., 87.

- Pollok, Robert, vol. iv., 103.

- Pringle, James, vol. v., 176.

- Pringle, Thomas, vol. iii., 102.

- Ramsay, John, vol. v., 114.

- Reid, William, vol. i., 153.

- Richardson, Mrs E. G., vol. ii., 255.

- Riddell, Henry Scott, vol. iv., 7.

- Riddell, William B. C., vol. vi., 201.

- Ritchie, Alexander A., vol. iv., 237.

- Robertson, John, vol. ii., 98.

- Rodger, Alexander, vol. iii., 71.

- Roger, Peter, vol. iii., 212.

- Ross, William, vol. iii., 271.

- Scadlock, James, vol. ii., 199.

- Scott, Andrew, vol. i., 260.

- Scott, George, vol. ii., 253.

- Scott, Patrick, vol. vi., 218.

- Scott, Sir Walter, vol. i., 275.

- Sillery, Charles Doyne, vol. iv., 174.

- Sim, John, vol. iii., 226.

- Simpson, Mrs Jane C, vol. v., 241.

- Sinclair, William, vol. v., 263.

- Skinner, John, vol. i., 1.

- Smart, Alexander, vol. v., 71.

- Smibert, Thomas, vol. iv., 195.

- Stewart, Allan, vol. iv., 211.

- Stewart, Charles, D.D., vol. iv., 289.

- Stewart, Mrs Dugald, vol. i., 167.

- Still, Peter, vol. iv., 220.

- Stirling, William, M.P., vol. vi., 121.

- Stirrat, James, vol. iii., 40.

- Stoddart, Thomas Tod, vol. v., 220.