The Project Gutenberg EBook of At the Point of the Sword, by Herbert Hayens This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: At the Point of the Sword Author: Herbert Hayens Release Date: September 14, 2007 [EBook #22595] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AT THE POINT OF THE SWORD *** Produced by Al Haines

[Transcriber's note: frontispiece missing from book.]

| I. | A BIRTHDAY EVE |

| II. | AN EXCITING VOYAGE |

| III. | THE END OF THE "AGUILA" |

| IV. | THE SILVER KEY |

| V. | IN THE HIDDEN VALLEY |

| VI. | WE LEAVE THE HIDDEN VALLEY |

| VII. | WHOM THE GODS LOVE DIE YOUNG |

| VIII. | A FRIENDLY OPPONENT |

| IX. | A GLEAM OF HOPE |

| X. | A STORMY INTERVIEW |

| XI. | A NARROW ESCAPE |

| XII. | A STERN PURSUIT |

| XIII. | HOME AGAIN |

| XIV. | FRIEND OR FOE? |

| XV. | WE CATCH A TARTAR |

| XVI. | GLORIOUS NEWS |

| XVII. | DUTY FIRST |

| XVIII. | DARK DAYS |

| XIX. | FALSE PLAY, OR NOT? |

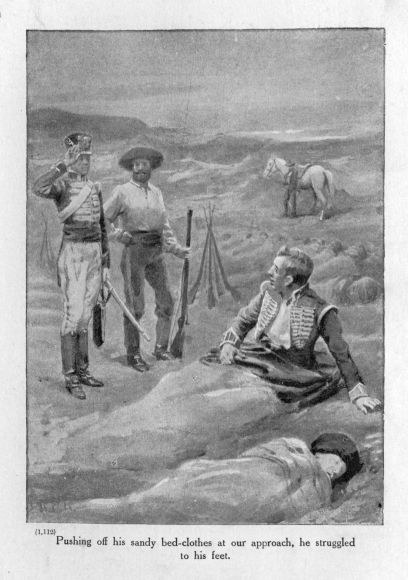

| XX. | "SAVE HIM, JUAN, SAVE HIM!" |

| XXI. | ROUGH JUSTICE |

| XXII. | THE "SILVER KEY" AGAIN |

| XXIII. | AN OPEN-AIR PRISON |

| XXIV. | A DANGEROUS JOURNEY |

| XXV. | BACK TO DUTY |

| XXVI. | THE HUSSARS OF JUNIN |

| XXVII. | A DISASTROUS RETREAT |

| XXVIII. | THE BATTLE OF THE GENERALS |

| XXIX. | HOME AGAIN |

In spite of my English name—Jack Crawford—and my English blood, I have never set foot on that famous little island in the North Sea, and now it is quite unlikely that I ever shall do so.

I was born in Peru, on the outskirts of beautiful Lima, where, until the year 1819, on the very eve of my fourteenth birthday, the days of my childhood were passed.

I expect you know that in ancient days Peru was called the "Land of the Sun," because the sun was worshipped by the natives. Their great city was Cuzco, built, it is said, in 1043 A.D., by Manco Capac, the first of the Incas, or Emperors of Peru.

The natives believed Manco to be a child of the sun; but I have heard an old story that his father was a shipwrecked Englishman, who married the daughter of a Peruvian chief. I do not think this tale correct, but it is full of interest.

Most of the Incas ruled very wisely, and the remains of palaces, temples, and aqueducts show that the people were highly civilized; but in 1534 the Spaniards, under Pizarro, invaded the country, and swept away the glorious empire of the Incas.

After that Peru became a part of Spanish America, and Pizarro founded the city of Lima, which he made the capital.

My father, who settled in the country when quite a young man, married a Peruvian lady of wealthy and influential family. The estate near Lima formed part of her marriage portion, and a beautiful place it was, with a fine park, and a lake which served me both for boating and bathing. I had several friends, chiefly Spaniards, but two English boys, whose fathers were merchants in Callao, often visited me, and many a pleasant game we had together.

At this time Peru was a Spanish colony, but some people, among whom was my father, wanted to make it an independent country, having its own ruler. Being still a boy, I did not hear much of these things, though, from certain talk, I understood that the country was in a most unsettled state, and that the Spanish governor had thrown many good men into prison for urging the people to free themselves.

One evening, in March 1819, I was busy in my workshop painting a small boat. My father had been absent for nearly a week, but he had promised to return for my birthday, and every moment I expected to see him crossing the courtyard.

Presently, hearing old Antonio unfasten the wicket-gate, I put down my brush, wiped my hands, and ran out joyously.

The happy welcome died on my lips. It was not my father who had entered, but Rosa Montilla, the young daughter of a famous Spanish officer. She was nearly a year younger than myself, and a frequent visitor at our house. Often we had gone together for a row on the lake, or for a gallop on our ponies round the park.

She was very pretty, with deep blue eyes and fair hair, quite unlike most Spanish girls, and generally full of fun and good spirits. Now, however, she was very pale and looked frightened. I noticed, too, that she had no covering on her head or shoulders, and that she had not changed the thin slippers worn in the house.

These things made me curious and uneasy. I feared some evil had befallen her father, and knew not how to act. On seeing me she made a little run forward, and, bursting into tears, cried, "O Juan, Juan!" using, as also did my mother, the Spanish form of my name.

Now, being only a boy, and being brought up for the most part among boys, I was but a clumsy comforter, though I would have done anything to lessen her grief.

"What is it, Rosa?" I asked; "what has happened?" But for answer she could only wring her hands and cry, "O Juan, Juan!"

"Do not cry, Rosa!" I said, and then doing what I should have done in the first place, led her toward the drawing-room, where my mother was. "Mother will comfort you. Tell her all about it," I said confidently, for it was to my mother I always turned when things went wrong.

On this her tears fell faster, but she came with me, and together we entered the room.

"Juan!" cried my mother.—"Rosa! what is the matter? Why are you crying? But come to me, darling;" and in another moment she was pressing the girl to her bosom.

At a sign from her I left the room, but did not go far away. Rosa's action was so odd that I waited with impatience to hear the reason. She must have left her home hurriedly and unobserved, since it was an unheard-of thing that the daughter of Don Felipe Montilla should be out on foot and unattended. I was sure that should her father discover it he would be greatly annoyed. The whole affair was so mysterious that I could make nothing of it. The girl's sobs were more under control now, and she began to speak. As she might not wish me to hear her story, I walked away, meaning to chat with Antonio at the gate, and to await my father's return.

He might not come for hours yet, as it was still early evening, but I hoped he would, and the more so now on Rosa's account. She might need help which I was not old enough to give; while, as it chanced, Joseph Craig, my father's trusty English servant, had gone that afternoon into Callao. However, he also might be back at any moment now, and would not, in any case, be late.

Half an hour had perhaps passed, and I was turning from the gate, when two horsemen dashed up at full speed. One was Joseph Craig, or José as the Spaniards called him, and my feeling of uneasiness returned as I noticed that his face, too, wore a strange and startled look.

José, as I have said, was my father's servant; but we all regarded him more as a friend, and treated him as one of ourselves. He was a well-built man of medium height, with good features and keen gray eyes. He spoke English and Spanish fluently, and could make himself understood in several Indian dialects. He kept the accounts of the estate, and might easily have obtained a more lucrative situation in any counting-house in Callao. He excelled, too, in outdoor sports, and had taught me to fence, to shoot, and to ride straight.

The second man I did not know. He seemed to be an Indian of the mountains, and was of gigantic stature. His dress was altogether different from that of the Spaniards, and in his cap he wore a plume of feathers. His face was scarred by more than one sword-cut, his brows were lowering, and his massive jaw told of great animal strength. José's horse had galloped fast, but the one ridden by the stranger was flaked with foam.

Antonio would have opened the big gate without question: but I, thinking of Rosa, forbade him, saying to José in English, "Does he mean harm to the girl?"

You see, my head was full of the one idea, and I could think of nothing else. I imagined that Rosa had run away from some peril, and that this man with the savage face and cruel eyes had tracked her to our gate. So I put the question to José, who looked at me wonderingly.

"The girl?" he repeated slowly; "what girl?"

"Rosa Montilla," I answered.

We spoke in English; but at the mention of Rosa's name the mountaineer scowled savagely, and leaned forward as if to take part in the conversation.

"The man has come from the mountains with a message for your mother," said José; "I met him at the entrance to the park. But if Rosa Montilla is here, the news is known already."

His face was very pale, and he spoke haltingly, as if his words were burdensome, and there was a look in his eyes which I had never seen before.

I motioned to Antonio, and the two passed through. What message did they bring? What news could link dainty little Rosa with this wild outlaw of the hills?

José jumped to the ground and walked with me, laying a hand on my shoulder. Until then I had no thought of the truth, but the touch of his fingers sent a shiver of fear through me, and I looked at his face in alarm.

"What is it, José?" I asked; "what has happened? Why did Rosa steal here alone and sob in my mother's arms as if her heart would break?"

"The little maid has heard bad news," he answered quietly, "though how I do not know."

"And as she had no mother, she came to mine for comfort," I said. "It was a happy thought: mother will make her forget her trouble."

José stopped, and looked searchingly in my face.

"Poor boy!" he said. "You have no idea of the truth, and how can I tell you? The little maid did not weep for her own sorrow, but for yours and your mother's."

At that I understood without further words, though I was to learn more soon. The reason of it I guessed, though not the matter; but I knew that somewhere my dear father lay dead—killed by order of the Spanish viceroy.

José saw from my face that I knew, and there was sympathy in the very touch of his hand.

"It is true," he whispered. "The Spaniards trapped him in the mountains, whither he had gone to meet the Indians. They wished to rise against the government; but he knew it was madness just now, and thought to keep them quiet till his own plans were ready."

"And the Spaniards slew him?"

"Yes," replied José simply. "Here," pointing to the mountaineer, "is our witness."

"But how did Rosa hear of it? she was not in the mountains. Ah, I forgot! Her father stands high in the viceroy's favour. And so my father is dead!"

The thought unnerved me, and I could have cried aloud in my sorrow.

"Hold up your head, boy!" exclaimed the harsh voice of the mountaineer. "Tears are for women and girls. Years ago my father's head was cut off, but I did not cry. I took my gun and went to the mountains," and he finished with a bitter laugh.

"But my mother!" I said. "The news will break her heart."

"The world will not know it," he answered, and he spoke truly.

"I am glad the little maid has told her," remarked José, giving his horse and that of the stranger to a serving-man. "Jack, do you go in and prepare her for our coming."

A single glance showed that Rosa had indeed told her story. She sat on a lounge, looking very miserable. My mother rose and came toward me. Taking my hands, she clasped them in her own. She was a very beautiful woman, famous for her beauty even among the ladies of Lima. She was tall and slightly built, with black hair and glorious dark eyes that shone like stars. I have heard that at one time she was called the "Lady of the Stars," and I am not surprised. They shone now, but all gentleness had gone from them, and was replaced by a hard, fierce glitter which half frightened me. Her cheeks were white, and her lips bloodless; but as far as could be seen, she had not shed a tear.

Still holding my hands, and looking into my face, she said, "You have heard the news, Juan? You know that your father lies dead on the mountains, slain while carrying a message of peace to the fierce men who live there?"

I bowed my head, but could utter no sound save the anguished cry of "Mother, mother!"

"Hush!" she exclaimed; "it is no time for tears now. I shall weep later in my own room, but not before the world, Juan. Our grief is our own, my son, not the country's. And there is little Rosa, brave little Rosa, who came to bring me the news; she must go back. Let Miguel bring round the carriage, and see that half a dozen of the men ride in attendance. Don Felipe's daughter must have an escort befitting her father's rank."

I began to speak of the strange visitor outside; but Rosa was her first care, and she would see no one until Rosa had been attended to. So I hurried Miguel, the coachman, and the men who were to ride on either side of the carriage, returning to the room only when all was ready.

Mother had wrapped Rosa up warmly, and now, kissing her, she said, "Good-bye, my child. You were very good to think of me, and I shall not forget. Tell your father the truth; he will not mind now."

Rosa kissed my mother in reply, and walked unsteadily to the coach. She was still sobbing, and the sight of her white face added to my misery.

"Don't cry, Rosa," said I, as I helped her into the carriage and wished her good-bye, neither of us having any idea of the strange events which would happen before we met again.

As soon as the carriage had gone, my mother directed that the stranger should be admitted, and he came in accompanied by José. I would have left the room, but my mother stopped me, saying,—

"No, Juan; your place is here. An hour ago you were but a thoughtless boy; now you must learn to be a man.—Señor, you have brought news? You have come to announce the death of my husband; is it not so?"

The mountaineer bowed almost to the ground.

"It is a sad story, señora, but it will not take long to tell. The Spaniards pretended he was stirring up our people to revolt; they waited for him in the passes, and shot him down like a dog."

"Did you see him fall?"

The fellow's eyes flashed with savage rage. "Had I been there," he cried, "not a soldier of them all would have returned to his quarters! But they shall yet pay for it, señora. My people are mad to rise. Only say the word, and send the son of the dead man to ride at their head, and Lima shall be in flames to-morrow."

My mother made a gesture of dissent.

"Don Eduardo liked not cruelty," she exclaimed; "and it would be but a poor revenge to slay the innocent. But Juan shall take his father's place, and work for his country's freedom. When the time comes to strike he shall be ready."

"Before the time comes he will have disappeared," cried the mountaineer, with a harsh laugh. "Do you think Don Eduardo's son will be allowed to live? Accidents, señora, are common in Peru!"

"It is true," remarked José; "Juan will never be out of danger."

"But the country is not ready for revolt, and only harm can come from a rising now. Should the Indians leave their mountain homes, the trained soldiers will annihilate them."

"But Juan must be saved!"

"Yes," assented my mother; "we must save Juan to take his father's place."

After this there was silence for a time. Then José spoke, "There is one way," said he slowly. "He can find a refuge in Chili till San Martin is ready; but he must go at once."

A spasm of fresh pain shot across my mother's face, but it disappeared instantly; even with this added grief she would not let people know how she suffered. Only as her hand rested on mine I felt it tremble.

"Let it be so, José," she said simply. "I leave it to you."

Then she thanked the mountaineer who had ridden so far to break the terrible news to her, and the two men went away, leaving us two together.

"Mother," I said, "must I really leave you?"

For answer she clasped me in her arms and kissed my face passionately.

"But you will come back, my boy!" she cried; "you will come back. Now that your father is no more, you are my only hope, the only joy of my life. O Juan, Juan! it is hard to let you go; but José is right—there is no other way. I will be brave, dear, and wait patiently for your return. Follow in your father's footsteps. Do the right, and fear not whatever may happen; be brave and gentle, and filled with love for your country, even as he was. Keep his memory green in your heart, and you cannot stray from the path of honour."

"I will try, mother."

"And if—if we never meet again, my boy, I will try to be brave too."

She wiped away the tears which veiled like a mist the brilliance of her starry eyes, and we sat quietly in the darkening room, while outside José was making preparations for our immediate departure.

At last he knocked at the door, and without a tremor in her voice she bade him enter.

"The horses are saddled, señora."

"Yes; and your plan, what is it?" she asked.

"It is very simple, señora. Juan and I will ride straight to Mr. Warren at Callao. He may have a vessel bound for Valparaiso; if not, he will find us one for my master's sake. Once at sea, we shall be out of danger. General San Martin will give us welcome, and there are many Peruvians in his army."

Once my mother's wonderful nerve nearly failed her. "You will take care of him, José," she said brokenly.

"I will guard him with my life, señora!"

"I know it, I am sure of it; and some day yon will bring him back to me. God will reward you, José.—Good-bye, Juan, my boy. Oh how reluctant I am to let you go!"

I will not dwell on the sadness of that parting. The horses were waiting in the courtyard, and after the last fond embrace I mounted.

"Good-bye, mother!"

"Farewell, my boy. God keep you!" and as we moved away I saw her white handkerchief fluttering through the gloom.

At the gate the Indian waited for us, and he followed a few paces in the rear.

I thought this strange, and asked José about it.

"It may be well to have a friend to guard our backs," he replied.

So in the gathering darkness I stole away from my home, with my heart sore for my father's death and my mother's suffering. And it was the eve of my birthday—the eve of the day to which I had looked forward with such delight!

Being so young, I did not really understand the peril that surrounded me; but my faith in José was strong, and I felt confident that in taking me away he was acting for the best.

Our path through the park led us near the lake, and I glanced sorrowfully at its calm waters and fern-fringed border. I would have liked to linger a moment at its margin, dwelling on past joys; but José hurried me on, remarking there was no time to waste.

Only, as the great gates swung open, he let me stop, so that I might bid a silent adieu to the beautiful home where my happy days of childhood had been passed.

"Keep a brave heart," said he kindly; "we shall be back some day. And now for a word of advice. Ride carefully and keep your eyes open. I don't want to frighten you, but the sooner we're clear of Lima the better I shall be pleased."

With that he put spurs to his horse, and with the clanging of the gate in our ears we rode off on the road to Callao, while the gigantic Indian followed about twenty paces behind.

It may be that José's fears on my account had exaggerated the danger, as we reached Callao without interruption, and dismounted outside Mr. Warren's villa. Here the Indian took leave of us, but before going he unfastened a silver key from the chain round his neck, and pressed it into my hand.

"It may happen," said he, "that at some time or other you will need help. That key and the name of Raymon Sorillo will obtain it for you from every patriot in the mountains of Peru. For the present, farewell. When you return from Chili we shall meet again."

Without waiting for my thanks he bade adieu to José and then, spurring his horse into a gallop, he disappeared.

From the man who opened the gate in answer to our summons we learned that my father's friend was at home, and leaving our horses, we went immediately into the house. This English merchant had often been our guest, and it was soon abundantly evident that we had done right in trusting him. He was a short, round-faced man, with a florid complexion, twinkling eyes, and sandy hair. He was very restless and irritable, and had a queer habit of twiddling his thumbs backward and forward whenever his hands were unoccupied.

"How do, Joseph?" exclaimed he, jumping up. "Come to take that berth I offered you? No? Well, well, what a fool a man can be if he tries! Why, bless me, this is young Jack Crawford! Eight miles from home, and at this time of night too! Anything the matter? Get it out, Joseph, and don't waste time."

While Joseph was explaining the circumstances, the choleric little man danced about the room, exclaiming at intervals, "Ted Crawford gone? Dear, dear! Not a better fellow in South America! I'd shoot 'em all or string 'em up! The country's going to the dogs, and a man isn't safe in his own house! Eh? What? Hurt the boy? What's the boy to do with it? They can't punish him if his father had been fifty times a rebel!"

"That is so, sir," remarked José; "but he might meet with an unfortunate accident, or vanish mysteriously, or something of that kind. What's the use of making believe? Those who have got rid of the father won't spare the son, should he happen to stand in their way."

"Which he will," interrupted Mr. Warren. "My poor friend was hand in glove with the Indians, and they'll rally round the boy."

"There are other things, too, which need not be gone into now, however," said José; "but the long and the short of it is that Jack must be got out of the way at present."

"And his mother?"

"She has sent him to you."

"But he can't be hidden here. The rascally Dons will have him in the casemates before one can say 'Jack Robinson!'"

"We don't mean to stay here, sir," replied José. "Our idea is to go to Valparaiso, and we thought if you had a ship—"

"The very thing, Joseph," and the thumbs went backward and forward taster than ever. "Maxwell has a schooner leaving in the morning. You can go on board to-night if you choose, but you had better have some supper first."

As it happened, both José and I had been some time without food, so we were glad to have something to eat; after which Mr. Warren took us to the quay, where the schooner Aguila lay moored.

"There she is," he remarked; "let us go aboard. Most likely we shall find Maxwell there.—Hi, you fellows, show a light!—Lazy dogs, aren't they? Mind your foot there, and don't tumble into the harbour; you won't get to Valparaiso that way.—That you, Maxwell? I have brought a couple of friends who are so charmed with your boat that they want to make a trip in her. Where do you keep your cabin? Let's go down there; we can't talk on deck."

Mr. Maxwell was another English merchant at Callao, and as soon as he heard what had happened, he readily agreed to give us a passage in the Aguila. We must be prepared to rough it, he said. The schooner had no accommodation for passengers, but she was a sound boat, and the Chilian skipper was a trustworthy sailor. Then he sent to his warehouse for some extra provisions, and afterwards introduced us to the captain, whose name was Montevo.

As the schooner was to sail at daylight, our friends remained with us, and, sitting in the dingy cabin, chatted with José about the state of the country. By listening to the talk I learned that General San Martin was a great soldier from Buenos Ayres, who, having overthrown the Spanish power in Chili, was collecting an army with which to drive the Spanish rulers from Peru. At the same time another leader, General Bolivar, was freeing the northern provinces, and it was thought that the two generals, joining their forces, would sweep Peru from north to south.

"And a good thing, too!" exclaimed Mr. Warren. "Perhaps we shall have a little peace then!"

"Pooh! stuff!" said his friend; "things will be worse than ever! These people can't rule themselves. They're like disorderly schoolboys, and need a firm master who knows how to use the birch. I am all for a stern master."

"So am I," agreed José, "if he's just, which the Spaniards aren't."

"That is so," cried Mr. Warren. "What would our property be worth if it wasn't for the British frigate lying in the harbour? Tell me that, Maxwell; tell me that, sir! They'd confiscate the whole lot, and clap us into prison for being paupers," and the thumbs revolved like the sails of a windmill.

So the talk continued until daybreak, when the skipper, knocking at the cabin door, informed us that the schooner was ready to sail; so we all went on deck, where the kindly merchants bade us good-bye, and hoped we should have a pleasant voyage.

"Keep the youngster out of mischief, Joseph. There's plenty of food for powder without using him," were Mr. Warren's last words as he stepped ashore, followed by his friend.

It was the first time I had been on board a ship, and I knew absolutely nothing of what the sailors were doing; but presently the boat began to move, the merchants, waving their hands, shouted a last good-bye, and very quickly we passed to the outer harbour.

I have been in many dangers and suffered numerous hardships since then, some of which are narrated in this book, but I have never felt quite so wretched and miserable as on the morning of our departure from Callao.

Wishing to divert my thoughts, José pointed out the beauties of the bay and the shore; but my gaze went far inland—to the lonely home where my mother sat with her grief, to the mighty cordillera where my father lay dead. Time softened the pain, and brought back the pleasures of life, but just then it seemed as if I should never laugh or sing or be merry again.

The first day or two on the Aguila did not tend to make me more cheerful, though the skipper did what he could to make us comfortable. We slept in a dirty little box, which was really the mate's cabin, and had our meals, or at least José had, at the captain's table.

By degrees, however, my sickness wore off, and on the fourth morning I began to take an interest in things. By this time the land was out of sight; for miles and miles the blue water lay around us—an interminable stretch. There was not a sail to be seen, and the utter loneliness impressed me with a feeling of awe.

José was as ignorant of seafaring matters as myself; but the captain said we were making a good voyage, and with that we were content. A stiff breeze blew the schooner along merrily, the blue sky was flecked only by the softest white clouds, and the swish, swish of the water against the vessel's sides sounded pleasantly in our ears. I began to think there were worse ways of earning a living than by going to sea.

That same evening I turned in early, leaving José on deck, but I was still awake when he entered the cabin.

"There's an ugly storm brewing," said he, kicking off his boots, "and I don't think the skipper much likes the prospect of it. He has all hands at work taking in the sails and getting things ready generally. Rather a lucky thing for us that the Aguila is a stout boat. Listen! That's the first blast!" as the schooner staggered and reeled.

Above us we heard the captain shouting orders, the answering cries of the sailors, and the groaning of the timbers, as if the ship were a living being stretched on a rack. Slipping out of my bunk and dressing quickly, I held on to a bar to steady myself.

"Let us go on deck before they batten down the hatches," said José, putting on his boots again. "I've no mind to stay in this hole. If the ship sinks, we shall be drowned like rats in a trap."

He climbed the steps, and I followed, shuddering at the picture his words had conjured up. The scene was grand, but wild and awful in the extreme. I hardly dared to watch the great waves thundering along as if seeking to devour our tiny craft. Now the schooner hung poised for a moment on the edge of a mountainous wave; the next instant it seemed to be dashing headlong into a fathomless, black abyss. The wind tore on with a fierce shriek, and we scudded before it under bare poles, flying for life.

Two men were at the wheel; the captain, lashed aft, was yelling out orders which no one could understand, or, understanding, obey. The night, as yet, was not particularly dark, and I shivered at sight of the white, scared faces of the crew. They could do nothing more; in the face of such a gale they were helpless as babies; those at the wheel kept the ship's head straight by great effort, but beyond that, everything was unavailing. Our fate was in the hands of God; He alone could determine whether it should be life or death.

Once, above the fury of the storm, the howling of the wind, the straining of the timber, there rose an awful shriek; and though the tragedy was hidden from my sight, I knew it to be the cry of an unhappy sailor in his death-agony. A huge wave, leaping like some ravenous animal to the deck, had caught him and was gone; while the spirit of the wind laughed in demoniacal glee as he was tossed from crest to crest, the sport of the cruel billows.

The captain had seen, but was powerless to help. The schooner was but the plaything of the waves, while to launch a boat—ah, how the storm-fiends would have laughed at the attempt! So leaving the hapless sailor to his fate, we drove on through a blinding wall of rain into the dark night, waiting for the end. No sky was visible, nor the light of any star, but the great cloud walls stood up thick on every side, and it seemed as if the boat were plunging through a dark and dreary tunnel.

Close to me, where a lantern not yet douted [Transcriber's note: doused?] cast its fitful light, a man lay grovelling on the deck. He was praying aloud in an agony of fear, but no sound could be heard from his moving lips. Suddenly there came a crash as of a falling body, the light went out, and I saw the man no more. How long the night lasted I cannot tell; to me it seemed an age, and no second of it was free from fear. Whether we were driving north, south, east, or west no one knew, while the fury of the storm would have drowned the thunder of waves on a surf-beaten shore. But the Aguila was an English boat, built by honest English workmen, and her planks held firmly together despite the raging storm.

For long hours, as I have said, we were swallowed up in darkness, feeling ourselves in the presence of death; but the light broke through at last, a cold gray light, and cheerless withal, which exactly suited our unhappy condition. The wind, too, as though satisfied with its night's work, sank to rest, while by degrees the tossing of the angry billows subsided into a peaceful ripple.

We looked at each other and at the schooner. One man had been washed overboard; another, struck by a falling spar, still lay insensible; the rest were weary and exhausted. Thanks to the skipper's foresight, the Aguila had suffered less than we had expected, and he exclaimed cheerfully that the damage could soon be repaired. But though our good ship remained sound, the storm had wrought a fearful calamity, which dazed the bravest, and blanched every face among us.

The skipper brought the news when he joined us at breakfast, and his lips could scarcely frame the words.

"The water-casks are stove in," he exclaimed, "and we have hardly a gallon of fresh water aboard!"

"Then we must run for the nearest port," said José, trying to speak cheerily.

The captain spread out his hands dramatically.

"There is no port," he replied, in something of a hopeless tone, "and there is no wind. The schooner lies like a log on the water."

We went on deck, forgetting past dangers in the more terrifying one before us. The captain had spoken truly: not a breath of air stirred, and the sea lay beneath us like a sheet of glass. The dark clouds had rolled away, and though the sun was not visible, the thin haze between us and the sky was tinged blood-red. It was such a sight as no man on board had seen, and the sailors gazed at it in awestruck silence.

Hour after hour through the livelong day the Aguila lay motionless, as if held by some invisible cable. No ripple broke the glassy surface, no breath of wind fanned the idle sails, and the air we breathed was hot and stifling, as if proceeding from a furnace.

The men lounged about listlessly, unable to forget their distress even in sleep. The captain scanned the horizon eagerly, looking in vain for the tiniest cloud that might promise a break-up of the hideous weather. José and I lay under an awning, though this was no protection from the stifling atmosphere.

Every one hoped that evening would bring relief, that a breeze might spring up, or that we might have a downpour of rain. Evening came, but the situation was unchanged, and a great fear entered our hearts. How long could we live like this—how long before death would release us from our misery? for misery it was now in downright, cruel earnest.

Once José rose and walked to the vessel's side, but, returning shortly, lay face downward on the deck.

"I must shut out the sight of the sea," he said, "or I shall go mad. What an awful thing to perish of thirst with water everywhere around us!"

This was our second night of horror, but very different in its nature from the first. Then, for long hours, we went in fear of the storm; now, we would have welcomed the most terrible tempest that ever blew, if only it brought us rain.

Very slowly the night crept by, and again we were confronted by the gray haze, with its curious blood-red tint. We could not escape from the vessel, as our boats had been smashed in the hurricane; we could only wait for what might happen in this sea of the dead.

"Rain or death, it is one or the other!" remarked José, as, rising to our feet, we staggered across to the skipper.

Rain or death! Which would come first, I wondered.

The captain could do nothing, though I must say he played his part like a man—encouraging the crew, foretelling a storm which should rise later in the day, and asserting that we were right in the track of ships. We had only to hold on patiently, he said, and all would come right.

José also spoke to the me cheerfully, trying to keep alive a glimmer of hope; but as the morning hours dragged wearily along, they were fain to give way to utter despair. No ships could reach us, they said, while the calm lasted, and not the slightest sign of change could be seen. Our throats were parched, our lips cracked, our eyes bloodshot and staring. One of the crew, a plump, chubby, round-faced man, began talking aloud in a rambling manner, and presently, with a scream of excitement, he sprang into the rigging.

"Sail ho!" he cried, "sail ho!" and forgetting our weakness, we all jumped up to peer eagerly through the gauzy mist.

"Where away?" exclaimed the captain.

The sailor laughed in glee. "Oho! Here she comes!" cried he; "here she comes!" and, tearing off his shirt, waved it frantically.

The action was so natural, the man seemed so much in earnest, that we hung over the schooner's side, anxiously scanning the horizon for our rescuer. Again the fellow shouted, "Here she comes!" and then, with a frenzied laugh, flung himself into the glassy sea.

A groan of despair burst from the crew, and for several seconds no one moved. Then José, crying, "Throw me a rope!" jumped overboard, and swam to the spot where the man had gone down.

"Come back!" cried the skipper hoarsely; "you will be drowned! The poor fellow has lost his senses." But José, unheeding the warning, clutched the man as he came to the surface a second time.

We heard the demented laugh of the drowning sailor, and then the two disappeared—down, down into the depths together.

"He has thrown his life away for a madman!" said the captain, and his words brought me to my senses.

With a prayer in my heart I leaped into the sea, hoping that I might yet save the brave fellow.

A cry from the schooner told me that he had reappeared, and soon I saw him alone, and well-nigh exhausted. A dozen strokes took me to his side, and then, half supporting him, I turned toward the vessel. The men flung us a rope, and willing hands hauled first José and then me aboard.

"A brave act," said the skipper gruffly, "but foolhardy!"

José smiled, and, still leaning on me, went below to the cabin, where, removing our wet things, we had a good rub down.

"Thanks, my boy!" said José, "but for your help I doubt if I could have got back. The poor beggar nearly throttled me, down under!" and I noticed on his throat the marks of fingers that must have pressed him like a vice.

"Do you feel it now?" I asked.

"Only here," touching his throat; "but for that, I should be all the better for the dip. Let us go on deck again; I am stifling here. And keep up your spirits, Jack. Don't give way the least bit, or it will be all over with you. We are in a fearful plight, but help may yet come." And I promised him solemnly that I would do my best.

The drowning of the crazy sailor had a bad effect on the rest of the crew, and it became evident that they had abandoned all hope. They hung about so listlessly that even the captain could not rouse them, and indeed there was nothing they could do.

This utter inability to help ourselves was the worst evil of the case. Even I, though only a boy, wanted to do something, no matter what, if it would help in the struggle for life; but I, like the rest, could only wait—wait with throat like a furnace, peeling lips, smarting eyes, and aching head, till death or rain put an end to the misery.

I tried not to think of it, tried to shut out the horrible end so close at hand; but in vain. José sat beside me, endeavouring to rouse me. It must rain, he said, or the wind would spring up, and we should meet with a ship; but in his heart I think he had no hope.

The day crawled on, afternoon came, and I fell into a troubled sleep. The pain of my throat directed my wandering thoughts perhaps, and conjured up horrible visions. I was lashed to the wheel of the Aguila, and the schooner went drifting, drifting far away into an unknown sea. All was still around me, though I was not alone. Sailors walked the deck or huddled in the forecastle—sailors with skin of wrinkled parchment, with deep-set, burning yet unseeing eyes, with moving lips from which no sound came; and as we sailed away ever further and further into the darkness, the horror of it maddened me. I struggled desperately to free myself, calling aloud to José to save me. Then a hand was laid softly on my forehead, and a kind, familiar voice whispered,—

"Jack! Jack! Wake up. You are dreaming!" Opening my eyes I saw José bending over me, his face stricken with fear. My head burned, but my face and limbs were wet as if I had just come from the sea. "Get up," said José sharply, "and walk about with me. You must not dream again."

It seems that in my sleep I had screamed aloud; but the sailors took no notice of me either then or afterwards. They had troubles enough of their own, and were totally indifferent to those of others.

The red tinge had now gone from the haze, leaving it cold and gray; the sea was dull and lifeless, no ripple breaking the stillness of its surface.

"Is there any hope, José?" I asked in a whisper, and from his face, though not from his speech, learned there was none.

The captain had stored two bottles of liquor in the cabin for his own use. These he shared amongst us; but it was fiery stuff, and even at the first increased rather than allayed our thirst. Most of the crew were lying down now; but one had climbed to the roof of the forecastle, and stood there singing in a weak, quavering voice. José spoke to him soothingly; but he only laughed, and continued his weird song. His face haunted me; even when darkness closed like a pall around us I could still see it. He sang on and on in the gloom, and it appeared to me that he was wailing our death-chant. Presently there was silence, followed by a slight shuffling sound as the man moved to another part of the deck; then the song began again, and was followed by a burst of uncanny laughter. Suddenly it seemed as if the poor fellow realized his position, as he broke into a sob and called on God to save him.

Making our way to the other side of the vessel, we found him sitting disconsolately on a coil of rope, and did our best to cheer him. The skipper joined us, but no other man stirred hand or foot. Apparently their terrible suffering had overpowered all feeling of sympathy.

"Don't give way," said José brightly, laying a hand on his shoulder; "bear up, there's a good fellow. Rain may fall at any moment now, and then we shall be saved."

"Ah, señor," cried the poor fellow huskily, "my throat is parched, parched; my head is like a burning coal! but I will be quiet now and brave—if I can."

"This is terrible," exclaimed the captain piteously, as after a time we turned away.

"Hope must be our sheet-anchor," said José. "Once cut ourselves adrift from that, and we shall go to ruin headlong."

He spoke bravely, but his words came from the lips only, and this we all knew. Sitting down on a coil of rope, we waited for the night to pass, longing for yet dreading the appearance of another dawn. It was dreadfully silent, except when some poor fellow broke the stillness with his groans and cries of anguish.

It was, as nearly as I could judge, about one o'clock in the morning, when José suddenly sprang to his feet with a cry of joy.

"What is it?" I asked; and he, clapping his hands, exclaimed,—

"Lightning! See, there is another flash.—Get up, my hearties; the wind's rising. There's a beautiful clap of thunder. We shall have a fine storm presently!"

One by one the men staggered to their feet. They heard the crash of the thunder, and a broad sheet of lightning showed them banks of cloud gathering thick and black overhead. Directed by the captain and helped by José, they spread every sail and awning that could be used, collected buckets and a spare cask, and awaited the rain eagerly and expectantly. Would it come? Fiery snakes played about the tops of the masts or leaped from sky to sea; the thunder pealed and pealed again through the air; the wind rose, the sails filled, the schooner moved through the water, but no rain fell.

I cannot tell you a tithe of the hopes and fears which passed through our hearts during the next half-hour. Now we exulted in the certainty of relief; again we were thrown into the abyss of despair. We stood looking at the darkness, hoping, praying that the life-giving rain might fall speedily upon our upturned faces.

Another terrific crash, and then—ah, how earnestly we gave thanks to God for His mercy—the raindrops came pattering to the deck, lightly at first, lightly and softly, like scouts sent forward to spy out the land, and afterwards the main body in a crowd beating fiercely, heavily upon us. How we laughed as, making cups of our hands, we lapped the welcome water greedily! What cries of delight ascended heavenward as we filled our spare cask and every vessel that would hold water! The rain came down in a steady torrent, soaking us through; but we felt no discomfort, for it fed us with new life.

Presently the captain got some of the men to work, while the others ate the food which had lain all day untasted, and then, doubly refreshed, they relieved their comrades. José and I, too, ate sparingly of some food; but even this little, with the water, made new beings of us.

As yet the wind was no more than a fair breeze, but by degrees it became boisterous, and the crew, still weak and now short of three men, could barely manage the schooner. José and I knew nothing of seamanship, but we bore a hand here and there, straining at this rope or that as we were bidden, and encouraging the crew to the best of our ability.

As yet we gave little thought to the new danger that menaced us, being full of thanks for our escape from a horrible death; but the fury of the storm increased, the wind battered against the schooner in howling gusts, and presently the topgallant mast fell with a crash to the deck. Fortunately no one was hurt, and we quickly cut the wreckage clear; but misfortune followed misfortune, and at length, with white, scared face, the carpenter announced that water was fast rising in the hold.

Here, at least, José and I were of service. Taking our places at the pumps, we toiled with might and main to keep the water down. Thus the remainder of the night passed with every one working at the pumps or assisting the captain to manage the vessel.

Morning brought no abatement of the storm, but the light enabled us to realize more clearly how near we were, a second time, to death. The rain still poured down in torrents, the wind leaped at us with hurricane fury, the schooner tossed, a helpless wreck, in the midst of a mountainous sea. The carpenter reported that, in spite of all our labours, the water was fast gaining on us. The sailors now lost heart, and one of them left his post, saying sullenly they might as well drown first as last. It was a dangerous example, but the skipper checked the mischief. Running forward with loaded pistol, he shouted,—

"Go back to the pumps, you coward, or I will shoot you down like a dog! Call yourself a man? Why, that youngster there is worth fifty of you!"

The fellow returned to his work; but as the hours passed we became more and more certain that no amount of pumping would save the ship. Even now she was but a floating wreck, and soon she would be engulfed by the raging sea.

While José and I were taking a rest, the captain told us that, even should the storm cease, the Aguila must go down in less than twenty-four hours, and that he knew not whether we were close to the shore or a hundred leagues from it. José received the news coolly. He came of a race that does not believe in whimpering, and his only care was on my account.

"I am sorry for your mother, Jack," said he, "and for you too. We're in a fair hole, and I don't see any way of getting out; but for all that we will keep our heads cool. Never go under without a fight for it—that's as good a motto as any other. You heard the skipper say the schooner is bound to go down, and you know we have no boats—they wouldn't be any good if we had, while this storm lasts; but if the sea calms, a plank will keep you afloat a long time, and maybe a ship will come along handy. Anyhow, make a fight for it, my boy. Now we'll have a snack of something to eat, and then for another spell at the pumps."

By this time a feeling of despair had seized the crew, and but for fear of the captain's pistol they would have stopped work in a body. However, he kept them at it, and towards noon the tempest ceased almost as suddenly as it had begun. The gale dropped to a steady breeze, and the surface of the ocean became comparatively calm.

The change cheered us; we looked on it as a good omen, and toiled at the pumps even harder than before. We could not lessen the quantity of water, but for a time we kept it from gaining, and a germ of hope crept back into our hearts. Every hour now was likely to be in our favour, as the captain judged the wind was blowing us to some part of the coast, where we might either fall in with a vessel or effect a landing. Thus, between hope and fear, the afternoon passed, and then we saw that the captain's judgment was correct.

Straight before us, though far off as yet, appeared the dark line of coast with a barrier of mountains in the background, and in front a broad band of snow-white foam.

Would the schooner cover the distance? If so, would she escape being dashed to pieces in the thundering surf? These were the questions which agitated our minds as, impelled by the breeze, she drove through the water. We of ourselves could do nothing save work at the pumps and wait for what might happen.

Afternoon merged into evening, and evening into night. A few stars peeped forth in the sky, but were soon veiled by grayish clouds. The broad white band along the shore was startlingly distinct, and still the issue was undecided.

The end came with such unexpected suddenness that the men hardly had time to cry out. José and I were resting at the moment, when the schooner lurched heavily, tried to right herself and failed, filled with water, and sank like a stone.

I often think of that shipwreck as a horrible dream. Down, down I went, holding my breath till it seemed impossible to stay longer without opening my mouth and swallowing the salt water. By an effort I restrained myself till my head shot above the surface and once more I was free to breathe.

The ship had disappeared entirely, and it was too dark to see such a small object as a man's head. By great good fortune I managed to seize a floating spar, and, resting on it, called aloud for José. The only answer was the anguished cry of a drowning man across the waste of waters. Twice again it came, and then all was silent, though in imagination I still could hear that anguished cry. The sea rolled in long surges, carrying me forward without effort and at a great rate toward the clear white line. Live or die, I could not help myself now, but was entirely at the mercy of the waves. I thought of José's advice to make a fight for it, but there was nothing to be done. Clinging to my spar, I was tossed from crest to depth like a ball bandied about by boys.

And now my ears were filled with a great roaring as I approached nearer to the crested foam; then feeling that the end was very near, I prayed silently yet fervently that God would comfort my mother in this her new trial, and prepared myself to die.

From the top of a high wave I went down into the depths, rose again to the crest of a second huge roller, and then was flung with the velocity of lightning into the midst of the great sea-horses with their snowy manes.

Of this part of the adventure I remember but little, only that for a moment I lay bruised and battered at the foot of a high rock.

Once more José's advice sounded in my ear, and loosing my spar, I clambered, dizzy and half blind, to the top. The ramping white horses raced after as if to drag me back, but finding that impossible, retired sullenly to spring yet once again. Shrieking and hissing, the great white monsters tore along, dashing in fury and breaking in impotence against the immovable rocks. The wild, weird scene, too, frightened me; for I was but a boy, remember, who up to this had never met with a more stirring adventure, perhaps, than a tussle with a high-spirited pony. I was worn out, too, by hard toil, faint from loss of blood, saddened by the loss of my faithful José, and by the awful calamity that had overtaken the crew of the schooner. Yet, in spite of all, so strong was the instinct to live, that, almost without thought, I clambered along the rocky ridge which jutted out from the mainland, while the baffled waves raced hungrily on either side of me, as if even now loath to abandon their expected prey.

At length the line of white foam was at my back. I found myself on a boulder-strewn beach, and for the time safe! Although half dead with privation and exposure, I wandered some way along the beach, calling aloud on José and the sailors, forgetful that the roar of the surf drowned my voice.

Presently I could go no further, the beach in that direction being walled in by a rocky cliff, steep and high, and but for a narrow fissure upon which I happily came, insurmountable.

I say happily, for at the summit of the cliff I fancied I saw the flash of a lantern. A lantern meant human beings, who on hearing my story would search the shore, and find, perhaps, that others besides myself had escaped from the wreck. With this idea in my head, I began to climb, going very steadily; for, as I have said, the track was little more than a fissure in the rock, and my head was far from clear. I toiled on, cutting my hands and legs with the jagged rocks, but making some progress, till at length I had covered the greater part of the distance; then I could do no more. A tiny crevice gave me foothold, and I was able to rest my arms on a wide ledge, but had no strength to draw myself up to it. Twice I tried and failed; then fearful lest my strength should give way, I strove no more, but, raising my voice, shouted loudly for help. Very mournful the cry sounded in the silent night, as I hung there utterly helpless on the face of the cliff.

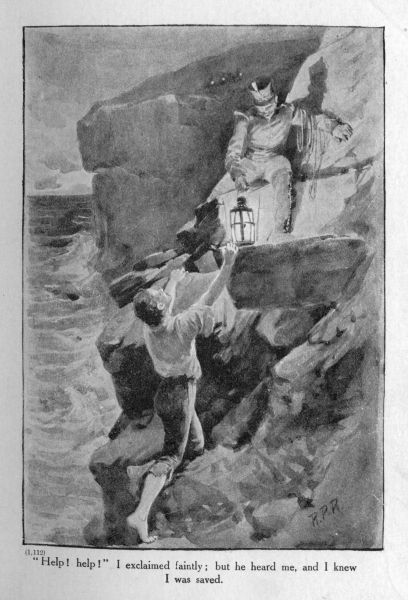

Again and again I shouted with all my might, to be answered at first only by the roar of the surf below. Presently, on the summit of the cliff, not far above me, a lantern flashed, then another, and another, and a voice hailed me through the darkness.

"Help!" I cried, "help!" and my voice was full of despair, for my strength was fast ebbing. I must soon lose my hold, and be dashed to pieces at the foot of the cliff.

The lanterns flashed to and fro above me. Would they never come nearer? What was that? A big stone bounding and bouncing from rock to rock whizzed past my head, and disappeared in the gloom below. Collecting all my strength, I shouted again, fearing that it must be for the last time.

But now—oh, how sincerely I gave thanks to God!—a light had come over the edge of the cliff, and though moving slowly, it certainly advanced in my direction. Yes, I saw a man's outline. In one hand he carried a lantern, in the other a noosed rope, and he felt his way carefully.

"Help! help!" I exclaimed, faintly enough now; but he heard me, and I knew I was saved. Putting the lantern on the ledge and grasping the collar of my coat, he got the noose round my body under the arms, and those above drew me up.

The lanterns showed a group of men in uniform, who crowded around me as I reached the top; but being uncertain how long my strength would last, I cried,—

"A wreck! Search the beach. There may have been others washed ashore."

Upon this there was much talking, and then two men carried me away, leaving their companions, as I hoped, to search for any chance survivors.

It would be hard for me to tell just what happened during the next day or two. I did not lose consciousness altogether, but my nerves were so shattered that I mixed up fact and fancy, and could hardly separate my dreams from events which actually took place.

On the third or fourth day my senses became clearer I lay on a bed in a small cell-like apartment. In the opposite corner was a mattress, with a blanket and rug rolled neatly at the head; above it, on the wall, hung a sword and various military articles, as if the room belonged to a soldier.

Presently, as I lay trying to recall things, the door was pushed open, and a man entered. He was young; his face was frank and open, and he had fine dark eyes. He was in undress uniform, and I judged, rightly as it turned out, that he was a Spanish officer. Seeing me looking at him, he crossed to the bed, and exclaimed in the Spanish tongue, "Are you better this morning?"

I nodded and smiled, but could not speak—my throat hurt me so.

"All right!" he cried gaily. "Don't worry; I understand," and at that he went out, coming back presently with the military doctor.

Now I had no cause, then or afterwards, to love the Spaniards; but I hold it fair to give even an enemy his due, and it is only just to say that this young officer, Captain Santiago Mariano, treated me royally. In a sense I owed my life to him, and I have never forgotten his kindness.

As my strength returned he often sat with me, talking of the wreck, from which I was apparently the only one rescued. Three men, he said, had been washed ashore, but they were all dead. Two were ordinary sailors, and from his description I easily recognized the third as Montevo, the skipper.

There was a rumour, the young officer continued, that a man had been picked up by some Indians further along the coast; but no one really knew anything about it, and for his part he looked on it as an idle tale.

There was small comfort in tills; yet, against my better judgment, I began to hope that José had somehow escaped from the sea. He was a strong man and a stout swimmer, while for dogged courage I have rarely met his equal.

One morning Santiago came into my room—or rather his—with a troubled expression on his face. I was able to walk by this time, and stood by the little window, watching the soldiers at exercise in the courtyard.

"Crawford," said he abruptly, "have you any reason to be afraid of General Barejo?"

Now, until that moment I had not given a thought to the fact that in escaping one danger I had tumbled headlong into another; but this question made me uneasy. As far as safety went, I might as well have stayed at my mother's side in Lima as have blundered into a far-off fortress garrisoned by Spanish soldiers.

"I ought not to speak of this," continued Santiago, "but the warning may help you. Did you hear the guns last night?"

"Yes," said I, wondering.

"It was the salute to the general, who is inspecting the forts along the coast."

"I have heard my father speak of General Barejo."

"Well, after dinner last evening the commandant happened to speak of your shipwreck, and the general was greatly interested. 'A boy named Crawford?' said he thoughtfully; 'is he in the fort now?' and on hearing you were, told the commandant he would see you in the morning. This is he crossing the courtyard. He is coming here, I believe."

I had only time to thank Santiago for his kindness when the general entered the room. He was a short, spare man, with closely-cropped gray hair and a grizzled beard. His face was tanned and wrinkled, but he held himself erect as a youth; and his profession was most pronounced.

The young captain saluted, and, at a sign from the general, left the room.

Barejo eyed me critically, and with a grim smile exclaimed, "By St. Philip, there's no need to ask. You're the son of the Englishman Crawford, right enough."

"Who was murdered by Spanish soldiers," said I, for his cool and somewhat contemptuous tone roused me to anger.

He smiled at this outburst, and spread out his hands as if to say, "The boy's crazy;" but when he spoke, it was to ask why I had left Lima.

"Because I had no wish to meet with my father's fate," I answered brusquely; and he laughed again.

"Faith," he muttered, "the young cockerel ruffles his feathers early!" and then, again addressing me, he asked, "And where were you going?"

"On a sea voyage, for the benefit of my health—and to be out of the way."

To this he made no reply, but his brows puckered up as if he were in deep thought. I stood by the window watching him, and wondering what would be the outcome of this visit.

After a short time he said, slowly and deliberately, so that I might lose nothing of his speech, "Listen to me, young sir. Though you are young, there are some things you can understand. Your father tried, and tried hard, to wrest this country from its proper ruler, our honoured master, the King of Spain. He failed; but others have taken his place, and though you are only a boy, they will endeavour to make use of you. We shall crush the rebellion, and the leaders will lose their lives. I am going to save you from their fate."

I thought this display of kindness rather strange, but made no remark.

"In this fortress," he continued, "you will be out of mischief, and here I intend you shall stay till the troubles are at an end."

"That sounds very much as if you mean to keep me a prisoner!" I exclaimed hotly.

"Exactly," said he; then turning on his heel he walked out.

From the window I watched him cross the courtyard and enter the commandant's quarters. Ten minutes afterwards Santiago appeared with a file of soldiers.

"Very sorry, my boy," said the young captain, coming into the room, "but a soldier must obey orders. You are my prisoner."

"I couldn't wish for a better jailer," said I, laughing.

"I'm glad you take it like that, but unfortunately you won't be under my care. Have you all your things? This way, then."

We marched very solemnly side by side along the corridor, the soldiers a few paces in the rear. At the end stood a half-dressed Indian, holding open the door of a cell.

"Oh, come," said I, looking in, "it's not so bad."

The cell was, indeed, almost a counterpart of Santiago's room, only the window was high up and heavily barred. The furniture consisted of bedstead and rugs, a chair, small table, and one or two other articles. The floor was of earth, but quite dry; and altogether I was fairly satisfied with my new home.

"You'll have decent food and sufficient exercise," said the captain, who had entered with me; "but"—and here he lowered his voice to a whisper—"don't be foolish and try to escape. Barejo's orders are strict, and though it may not appear so, you will be closely guarded."

"Thanks for the hint," said I as he turned away.

The Indian shut the door, the bolts were shot, the footsteps of the soldiers grew fainter, and I was alone.

I shall not dwell long on my prison life. I had ample food, and twice a day was allowed to wander unmolested about the courtyard. The general had gone, and most of the officers, including Santiago, showed me many acts of kindness, which, though trifling in themselves, did much towards keeping me cheerful.

Several weeks passed without incident, and I began to get very tired of doing nothing. There seemed to be little chance of escape, however. Every outlet was guarded by an armed sentry, and I was carefully watched. One day I dragged my bedstead under the window, and making a ladder of the table and chair, climbed to the bars. A single glance showed the folly of trying to escape that way without the aid of wings. That part of the fort stood on the brink of a frightful precipice which fell sheer away for hundreds of feet to the rocky coast.

Of course I had no weapon of any kind, but the Spaniards had allowed me to keep the silver key, which hung around my neck by a thin, stout cord.

I had almost forgotten the mountaineer's strange words, when a trifling incident brought them vividly to my mind. One morning the Indian, as usual, brought in my breakfast, and was turning to go, when he suddenly stopped and stared at me with a look of intense surprise. He was a short, stout, beardless man, with a bright brown complexion and rather intelligent features.

"Well," I exclaimed, "what is it? Have I altered much since yesterday?"

The man bent one knee, and bowing low, exclaimed in great excitement, "It is the key!"

Then I discovered that, my shirt collar being unfastened, the silver key had slipped outside, where it hung in full view.

"Yes," said I, "it is the key right enough. What of it?"

His eyes were flashing now, and the glow in them lit up his whole face.

"What is the master's name?" he whispered eagerly.

Now this was an awkward question for me to answer. In the first place, the man might or might not be trustworthy; and in the second, the only name I knew was that of the bandit chief. However, I concluded the venture was worth making, and said, "Men call the owner of the key Raymon Sorillo."

"Ah!" exclaimed the Indian, with a sigh of satisfaction, "he is a great chief. Hide the key, señor, and wait. A dog's kennel is no place for the friend of our chief."

With that he went out, and the door clanged after him, while I stood lost in astonishment. What did he mean? Was it possible that he intended to help me? Thrusting the mysterious key out of sight, I sat down to breakfast with what appetite I could muster. All that day I was in a state of great excitement, though at exercise I took care to appear calm. I waited with impatience for the evening meal, which, to my disgust, was brought by a strange soldier.

"Hullo!" I exclaimed, "a change of jailers? What has become of the other fellow?"

"The dog of an Indian is ill," answered the man, who was evidently in a very bad temper, "and I have his work to do."

Placing the things on the table, he went out, slamming the door behind him, and shooting the bolts viciously. The next morning he came again, and indeed for four days in succession performed the sick man's duties.

Now you may be sure I felt greatly interested in this sudden illness. It filled me with curiosity, and to a certain extent strengthened my hope that the Indian intended to help me to escape from the fort. What his plans were, of course I could not conjecture.

On the fifth night I undressed and lay down as usual. It was quite dark in the cell, and the only sound that reached me was the periodical "All's well!" of the sentry stationed at the end of the corridor. For a long time I lay puzzling over the strange situation, but at length dropped into a light sleep.

Suddenly I was awakened by a queer sensation, and sat up in bed. It was too dark to see anything, but I felt that some one was creeping stealthily across the floor. Presently I heard a faint sound, and knew that the object, whatever it might be, was approaching nearer. At the side of the bed it stopped, and a muffled voice whispered, "Señor, are you awake?"

"Yes," said I. "Who's there?"

"A friend of the silver key. Dress quickly and come with me; the way is open."

"Where is the sentry?" I asked.

"Gagged and insensible," replied the voice. "Quick, while there is yet time."

Perhaps it was rather venturesome thus to trust myself in the hands of an unknown man, but I slipped on my clothes, and keeping touch of his arm, accompanied him into the dimly-lighted corridor.

Turning to the left, we glided along close to the wall. At the end of this passage the body of the sentry lay on the ground, while near at hand crouched an Indian, keeping watch.

This man joined us, and my guide immediately led the way into an empty room, the door of which was open. As soon as we were inside he closed it softly.

"Keep close to me," he whispered, and then said something to an unseen person in a patois I did not understand.

Presently he stopped, and I could just distinguish the figure of a third man, who, grasping my hand, whispered, "The silver key has unlocked the door, señor."

Before I could recover from my astonishment—for the man who spoke was the sick jailer—my guide let himself down through a trap-door, and called to me to follow. I found myself on a flight of steep steps in a kind of shaft, very narrow, and so foul that breathing was difficult. At the bottom was a fair-sized chamber, with a lofty roof—at least I judged it so by the greater purity of the air—and here the guide stopped until his companion caught up with us. The jailer, to my surprise, had remained in the fort, but there was no time for explanation.

The exit from the chamber was by means of an aperture so low that we had to lie flat on the ground, and so narrow that even I found it hard work to wriggle through.

Of all my adventures, this one impressed itself most strongly on my mind. People are apt to smile when I speak of what one man called "crawling along a passage;" yet had the terrors of the journey been known beforehand, I think I could hardly have summoned the courage to face them.

We went in Indian file, I being second, and my shoulders brushed the sides of what was apparently a stonework tube. There was not a glimmer of light, and the foul air threatened suffocation at every yard. I could breathe only with great difficulty, my throat seemed choked, I was bathed in perspiration, while loathsome creatures crawled or scampered over every part of me.

Before half the distance was covered—and I make the confession without shame—I was truly and horribly afraid. However, there was no turning back—indeed there was no turning at all—so I crawled on, hoping and praying for light and air.

Presently I caught sight of a dull red glow like that from a burning torch, my breath came more easily, and at the end of another hundred yards the guide, rising to his feet, stood upright: we had arrived at the exit from the tunnel. Clambering up, I once more found myself in the open air, and was instantly followed by the second Indian. Two other men waited for us, and the four, with some difficulty, rearranged a huge boulder which effectually blocked the aperture.

Then the light from the torch was quenched, and I was hurried off in the darkness. For an hour perhaps we travelled, but in what direction I had no idea. At first we had the roar of the thundering sea in our ears, but presently that grew faint, until the sound was completely lost. The route was rocky, and I should say dangerous; for the guide clutched my arm tightly, and from time to time whispered a warning.

At last he stopped and whistled softly. The signal was heard and answered, and very soon I became aware of several dusky figures, including both men and horses. No time was wasted in talk; a man brought me a horse, and a loose cloak with a hood in which to muffle my head. I mounted, the others sprang to their cumbrous saddles, and at a word from the guide we set off.

The route now lay over a desert of loose sand, in which the animals sank almost to their fetlocks; every puff of wind blew it around us in clouds, and but for the hood I think I must have been both blinded and choked.

I have not the faintest idea how the leader found his way, unless it was by the direction of the wind, as there were no stars, and it was impossible to see beyond a few yards.

Hour after hour passed; dawn broke cold and gray. The choking sand was left behind, and we approached a narrow valley shut in by two gigantic ranges of hills. Here a voice hailed us from the rocks, the guide answered the challenge, and the whole party passed through the defile to the valley beyond.

It was now light enough to observe a number of Indian huts dotted about on both slopes; and the horsemen who had formed my escort quickly dispersed, leaving me with the guide.

"We are home," said he, "and the dogs have lost their prey."

Dismounting and leading the horses, we approached a hut set somewhat apart from the rest. An Indian boy standing at the entrance took our animals away while we entered the hut.

"Will you eat, señor, or sleep?" asked my rescuer.

"Sleep," said I, "as soon as you have answered a question or two."

I cannot repeat exactly what the man told me, as his Spanish was none of the best, and he mixed it up with a patois which I only half understood. However, the outline of the story was plain enough, and will take but little telling.

My late jailer belonged to the Order of the Silver Key, a powerful Indian society, acting under the leadership of Raymon Sorillo. He had been placed in the fort both as a spy on the garrison and to assist comrades if at any time they endeavoured to capture the stronghold by way of the secret passage. Only the commandant and his chief officer were supposed to know of its existence, but a strange accident had revealed it to the Indians some years previously.

The jailer, of course, could have set me free, but in that case he must have joined in my flight. The plan he adopted was to communicate with his friends, and then, by feigning illness, to divert suspicion from himself. As soon as we descended the steps, he replaced the trap-door, removed all signs of disturbance, and crept cautiously back to his room.

When the Indian had finished his explanation, I asked him to what place he had brought me.

"The Hidden Valley," he replied, "where no Spaniard has ever set foot. Here you are quite safe, for all the armies of Peru could not tear you from this spot."

"Does Sorillo ever come here?" I asked.

"Rarely; but his messengers come and go at their pleasure."

"That is good news," I remarked, thinking of my mother. "I shall be able to get a message through to Lima. And now, if you please, I will go to sleep."

He spread a rug on the earth floor, covered me with another, and in a few minutes I was fast asleep, forgetful even of the dismal tunnel and its horrible associations.

Perhaps my Indian host overstated the case, but he could not have been far wrong in saying that no stranger had ever succeeded in finding the Hidden Valley.

Let me describe the coast of Peru, and then you may be able to form some idea of the district between the Spanish fortress and my new home. The coast is a sandy desert studded with hills, and having in the background stupendous ranges of towering mountains. From north to south the desert is cut at intervals by streams, which in the rainy season are converted into roaring rivers. Little villages dot the banks of these streams, and here and there are patches of cultivated land.

From one river to another the country is for the most part a dreary desert of sand, where rain never falls nor vegetation grows—a dead land, where the song of a bird is a thing unknown. Sometimes after a sandstorm a cluster of dry bones may be seen—the sole remains of lost travellers and their animals. At times even the most experienced guides lose the track, and then they are seen no more. Over such a desert I had ridden from the fort, and the Indians assured me that, even in broad daylight, I could not go back safely without a guide.

As for the valley itself, it was comparatively nothing but a slit in the mass of mountains. A river ran through it, and the water was used by the Indians to irrigate the surrounding land. Their live stock consisted chiefly of oxen and horses, and the principal vegetables cultivated were maize and coca. You may not know that this coca is a plant something like the vine, and it grows to a height of six or eight feet. The leaves are very carefully gathered one by one. They are bitter to the taste, however, and as a rule strangers do not take kindly to coca. The Indian is never without it. It is the first thing he puts into his mouth in the morning, and the last thing that he takes out at night. He carries a supply in a leathern pouch hung round his neck, and with this and a handful of roasted maize he will go a long day's journey. I had never chewed coca before, but soon got into the habit of doing so, much to the delight of my new friends.

My stay in the Hidden Valley, although lasting nearly two years, had little of interest in it. The Indians treated me with every respect. I was lodged in the best house, and was given the best fare the valley produced. Within the valley I was master, but I was not allowed to join any of their expeditions, and without their help it was impossible, as I have explained, to get away.

Their advice to stay quietly in my hiding-place was indeed the best they could give. I was quite safe, the Spanish soldiers in the fort being unable to follow me, and indeed, as we gathered from the spy, quite at a loss to account for my escape. Away from the valley, too, I should be utterly helpless. I could not return to Lima, and without money there was little chance of making my way into Chili.

The two things that troubled me most were José's fate and my mother's unhappiness. At first I had ventured to hope that my friend still lived; but as the weeks and months passed without any tidings, I began to look upon him as dead. The Indians thought it certain I should never see him again.

As to my mother, she would be in no particular uneasiness until the time came for the return of the Aguila; but I dreaded what would happen when Mr. Maxwell had to confess the schooner was overdue, and that nothing had been heard of her. Many miserable hours I spent wandering about the valley, and thinking how my mother would watch and wait, hoping against hope for some tidings of the missing ship.

One night—it was in the December of 1819—I had gone to bed early, when an unusual commotion in the valley caused me to get up. My Indian host had already gone out, so, putting on my things, I followed.

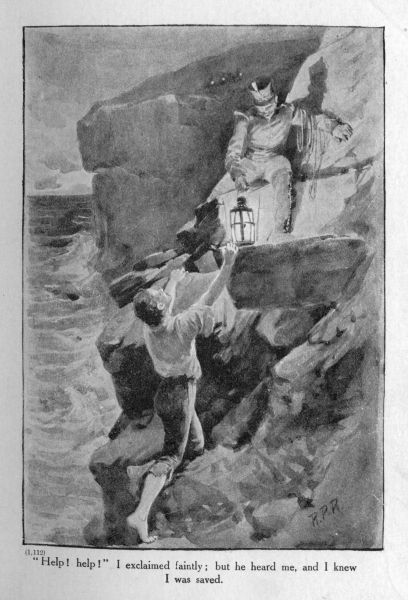

Naturally my first thought was of the Spaniards; but the natives, though flocking towards the entrance to the valley, did not appear alarmed. Several of them carried torches, and a strange picture was revealed by the lurid flames.

On the ground lay a horse so weak and exhausted that it could barely struggle for breath. Close by, supported in the arms of two Indians, was the rider, a short, rather stout man of brown complexion. His eyes were glazed as if in death. Blood gushed from his ears and nostrils, his head hung limply down: it was hard to believe that he lived.

The natives gabbled to each other, and I heard the words frequently repeated, "Sorillo's messenger!" Then an old, old woman—the mother of the village—tottered feebly down the path. In one hand she carried a small pitcher, and in the other a funnel, whose slender stem they inserted between the man's teeth. In this way a little liquid was forced into his mouth, and presently his bared breast heaved slightly—so slightly that the motion was almost imperceptible.

However, the old woman appeared satisfied, and at a sign from her the stricken man was carried slowly up the path. One native attended to the horse, and the rest returned to their huts, talking excitedly of what had happened.

"Is that a messenger from Raymon Sorillo, Quilca?" I asked my host.

"Yes," said he, "and he has had a very narrow escape. He has been caught in a sandstorm. Perhaps he lost the track. Perhaps the soldiers gave chase, and he went further round to baffle them. Who knows? But we shall hear to-morrow."

"Then he is likely to recover?"

"Yes; the medicine saved him. Didn't you see his chest move?"

"Yes," I replied, thinking that but a small thing to go on.

"That showed the medicine was in time," returned Quilca. "It has begun its work, and all will be well."

Quilca spoke so confidently that, had I been the patient, I should have started on the road to recovery at once.

"Will he stay here long?" I asked.

"Who knows?" replied Quilca. "The chief gives orders; the servants obey."

"But he will return at some time?"

"It is likely."

"And will he take a message to my mother, do you think?"

"Oh yes," said the Indian; "I had forgotten. Besides"—and he touched the cord supporting the silver key—"he is your servant, as I am."