The Project Gutenberg EBook of Walter and the Wireless, by Sara Ware Bassett This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Walter and the Wireless Author: Sara Ware Bassett Illustrator: William F. Stecher Release Date: December 4, 2007 [EBook #23728] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WALTER AND THE WIRELESS *** Produced by Sigal Alon, David T. Jones, La Monte H.P. Yarroll and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Chapter | Page | |

| I | His Highness | 1 |

| II | The New Job | 17 |

| III | What Worried Mrs. King | 36 |

| IV | Walter Makes His Bow To His Employer | 50 |

| V | The Conquest of Achilles | 64 |

| VI | His Highness in a New Role | 75 |

| VII | The Pursuit of Lola | 92 |

| VIII | A Blunder and What Came of It | 104 |

| IX | More Clues | 116 |

| X | Bob | 127 |

| XI | The Decision | 138 |

| XII | Lessons | 147 |

| XIII | Information from a New Source | 162 |

| XIV | Bob As Pedagogue | 169 |

| XV | Tidings | 183 |

| XVI | Miracles | 197 |

| XVII | The Laws of the Air | 210 |

| XVIII | The Net Tightens | 228 |

| XIX | Walter Steps into the Breach | 238 |

| XX | The Return of the Wanderers | 248 |

His Highness came by the nickname honestly enough and yet those who heard it for the first time had difficulty in repressing a smile at the incongruity of the title. In fact perhaps no term could have been found that would have been less appropriate. For Walter King possessed neither dignity of rank nor of stature. On the contrary he was a short, snub-nosed boy of fifteen, the epitome of good humor and democracy.

His hair was red and towsled, his face spangled with great golden freckles which sea winds and sunshine had multiplied until there was scarce room for another on his beaming countenance. Hands and arms were freckled too, for when one lives in a bathing suit six months of the year and is either in the water or on it most of the time the skin fails to retain its pristine whiteness of hue. But His Highness did not care a fig for that. He was far too busy baiting eel and lobster traps, mending fish nets, untangling lines, and painting boats to give a thought to his personal beauty.

Indeed his mother often bewailed the fact that he was not more interested in his appearance and there were times when it seemed as if she were right. Certainly when her son ambled home at dusk with every rebellious hair standing upended upon his head and a string of flounders dripping salt from the tips of their slimy tails she was justified to a degree in wishing he had more regard for the niceties of life.

"Look at the mess you're making!" she would pipe indignantly. "I've just mopped this floor, Walter."

"You have? Now isn't that the dickens! Well, no matter, Ma; I'll swab the place down again when I've finished cleaning these fish. They're beauties, aren't they? A batch of them fried won't go bad for supper to-night. I'm hungry as a bear. Shouldn't think I'd eaten anything in ten years. Say, Ma, what do you s'pose? Dave Corbett was out in the Nancy three hours and never got a bite. What do you think of that? The wind died down, his engine got stalled, and he and Hosey Talbot had to row home from the Bell Reef Shoals. Haw, haw! Maybe I didn't roar when I saw them come pulling in against the tide, mad as two man-eating sharks. Fit to harpoon the first person they met, they were. I sung out and asked them were they practicing for the Harvard and Yale boat race and Dave was that peeved he shied an oarlock after me. Haw, haw, haw!"

"You ought not to provoke Dave, Walter."

"Provoke him? But he was provoked already, Ma. There's no harm putting an extra stick on the fire when it's burning, anyhow. Besides, Dave is never in earnest when he bawls me out. He just likes to hear himself scold."

"He has a terrible temper."

"Oh, I know half the town is scart to death of him. But he always will take a jolly from me. We understand each other, Dave and I. Say, Ma, these rubber boots leak. Did you know that? Yes, siree! They leak like sieves. I might as well be without 'em."

Mrs. King sighed.

"I don't see," murmured she, "how you manage to go through everything you have so quickly, Walter. Nothing you wear lasts you more than a week."

"Oh, I say, make it a month. Do, now!"

He saw his mother smile faintly.

"Well, a month then."

"You couldn't stretch it to two?"

"Not possibly. Four weeks seems to be your limit."

The sharpness of her tone, however, had weakened.

"Four weeks, eh? I did think I'd had these rubber boots longer than that. It is amazing how attached you can get to things even in a little while."

Holding aloft the knife with which he was preparing to behead the unlucky flounders, His Highness gazed reflectively down at his feet.

"It's awful that I have to keep having so many things, isn't it? I hate to be costing you money all the time. Now if you'd only let me ship for the Grand Banks when the Katie B. goes out——"

"Walter! What is the use of digging up that old bone again? I never shall let you ship for the Grand Banks or any other Banks so long as I live. We've had this out hundreds of times before. You know you and Bob are all I've got in the world. Do you suppose I want you lost in a fog and never heard from again?"

"Oh, Great Scott, Ma! They don't lose fishing boats now as they used to. They carry wireless, and the fleet keeps in touch every minute."

"The dories have no wireless aboard them," observed Mrs. King grimly.

"I suppose not, no, probably they don't," His Highness admitted reluctantly.

"Anyway, wireless or no wireless, you are not going on a fishing cruise to the Grand Banks."

"I hear you, Ma," grinned the boy.

"There is plenty of work right here on the land if you're looking for it. Why must you always be wanting to go to sea to earn money?"

"Faith, Mother, I don't know," laughed Walter. "I expect it's because I see chores to do when I'm afloat that I can't see ashore. It is the way I was born."

"A poor way."

"Maybe it is. At any rate I can't help it."

"I'm afraid you do not try to help it very hard."

The lad shrugged his shoulders.

"There's that chance you have to hire out at the Crowninshields' for the summer."

"Those snobs."

"Beggars cannot be choosers. Besides, they may not be snobs at all. What makes you think they are?"

"Oh, I don't mind the lugs they put on," protested Walter, evading the issue. "I suppose all New York swells do that. It's what they want me for that gets my goat." Again the knife he held was tragically upraised. "How would you like to be nursemaid to six or eight brainless little pups no bigger than rats? Not but what I like dogs. I'd like nothing better than to own a fine dog of some spirit. But those imitations! Why, before a week was out, I'd have their necks wrung."

"Mr. Crowninshield promised to pay you well."

"What's money if all the kids in town are going to josh you?"

"Money is a good deal when you need it." His mother shook her head gravely. "Have you ever considered how badly we are in want of money, Walter?"

"What do you mean, Ma?" The boy wheeled about, startled.

"I haven't said anything about it, dear, because I could not bear to have you boys bothered," was the quiet answer. "But lately things have not been going well and I have been pretty much worried. The money your Uncle Henry invested for us isn't paying any dividends; there seems to be something the matter with the company's affairs. As for your Uncle Mark Miller, I've heard nothing from him in months. His ship was to put in at Shanghai for cargo and I ought to have had a letter by now; but none has come and I am afraid something must be the trouble. He is a good brother and never fails to send me money. I can ill afford to be without help now when the mortgage is coming due and I have so many bills to meet. It takes a deal of money to live nowadays. You boys do not realize that."

"Why, I had no idea you were fussed, Mother, and I'm sure Bob hadn't either," declared Walter soberly.

"Then I have done better than I thought I had," returned his mother, with the shadow of a smile. "I wanted to keep it secret if I could."

"But you shouldn't have tried to keep it a secret, Mater dear," Walter replied. "I'm sure we'd rather know—at least I would."

"But what use is it?"

"Use? Why, all the use in the world, Ma. I shall go ahead and take Mr. Crowninshield's job for one thing."

"But you said——"

"Shucks! I was only fooling about the dogs, Mother. I shan't really mind exercising and taking care of them at all. Of course, I won't deny I'd rather they were Great Danes or police dogs; I'd even prefer Airedales or Cockers. Still I suppose these little mopsey Pekingese must have some brains or the Lord would not have made them. No doubt I shall get used to them in time."

"It is only for the summer vacation anyway, you know," ventured his mother. "The Crowninshields go back to New York in October."

"I certainly ought to be able to bear up a few months," laughed Walter, with a ludicrously wry twist of his mouth. "I hate to think you've been bothered and have been keeping it all to yourself."

"Misery does like company," Mrs. King returned with an unsteady laugh. "I believe I feel better already for having told you. But you must not worry, dear. We shall pull through all right, I guess. How I came to speak of it I don't know. It was only that it seemed such a pity to toss the Crowninshield offer aside without even considering it. Nobody knows where it might end. The village people say Mr. Crowninshield is a very generous man, especially if he takes a fancy to anybody."

"But he may not take a fancy to me."

"He must have done so already to be asking you to help with the dogs."

"Nonsense, Ma! Did you think Mr. Crowninshield picked me out himself? Why, he's never laid eyes on me. That great privilege is still in store for him. No, he simply told Jerry Thomas, the caretaker, to find somebody for the job before the family arrived. He doesn't care a darn who it is so long as he has a person who can be trusted with his priceless pups. Why, I heard the other day that a dealer from New York had offered five thousand dollars for the smallest one."

"Walter!"

"Straight goods!"

"Five thousand dollars for a dog!" gasped Mrs. King.

Her son chuckled at her incredulity.

"Sure!"

"But it's a fortune," murmured she. "I had no idea there was a dog on earth worth that much."

"All of them are not."

"But five thousand dollars!" she repeated. "Why, Walter, I wouldn't have you responsible for a creature like that for anything in the world. You might as well attempt to be custodian of a lot of gold bonds. I shouldn't have a happy moment or sleep a wink thinking of it. Suppose some of the little wretches were to run away and get lost? Or suppose they were to be stolen? Or they might get sick and die on your hands."

"That is why they want a responsible person to keep an eye on them."

His Highness squared his shoulders and threw out his chest.

"But you are not a responsible person," burst out Mrs. King with unflattering candor.

"Mother!"

"Well—are you?" she insisted.

The boy's figure shriveled.

"No," he confessed frankly, "I'm afraid I'm not."

"Of course you're not," continued his mother with the same brutal truthfulness. "It isn't that you do not mean to be, sonny," added she kindly. "But your mind wanders off on all sorts of things instead of the thing you're doing. That is why you do not get on better in school. All your teachers say you are bright enough if you only had some concentration to back it up. What you can be thinking of all the time I cannot imagine; but certainly it isn't your lessons."

"I know," nodded Walter without resentment. "My mind does flop about like a kite. I think of everything but what I ought to. It's a rotten habit."

"Well, all I can say is you'd be an almighty poor one to look after a lot of valuable dogs," sniffed his mother.

"I'll bet I could do it if I set out to."

"But would you set out to—that is the question? Would you really put your entire attention on those dogs so that other people could drop them from their minds? That is what taking care means."

"I couldn't promise. I could only try."

"I should never dare to have you undertake it."

"That settles it, Ma," announced His Highness. "I've evidently got to prove to you that you are wrong. I'm going up to Crowninshields' this minute to tell Jerry he can count on me from July until October."

"You're crazy."

"Wait and see."

"I know what I'll see," was the sharp retort. "I shall see all those puppies kicking up their heels and racing off to Provincetown, and Mr. Crowninshield insisting that you either find them and bring them back or pay him what they cost him."

"Don't you believe it."

"That is what will happen," was the solemn prophecy.

"But you were keen for me to take the job."

"That was before I knew what the little rats were worth."

"You just thought it was a cheap sort of a position and that I was to race round and make it pleasant for a lot of ordinary curs, didn't you?" interrogated the lad with mock indignation.

In spite of herself his mother smiled.

"Well, you see you were wrong," went on Walter. "It is not that sort of thing at all. It is a job for a trustworthy man, Jerry Thomas said, and will bring in good wages."

"It ought to," replied his mother sarcastically, "if a person must spend every day for three months sitting with his eyes glued on those mites watching every breath they draw."

"It isn't just days, Mother; I'd have to be there nights as well."

"What!"

"That's what Jerry told me. I'd have to sleep on the place. Mr. Crowninshield wants some one there all the time."

"But Walter——!" Mrs. King broke off in dismay.

"I know that would mean leaving you alone now that Bob has a regular position at the Seaver Bay Wireless station. Still, why should you mind? I have always been gone all day, anyhow; and at night I sleep so soundly that you yourself have often said burglars might carry away the bed from under me and I not know it."

"You are not much protection, that's a fact," confessed Mrs. King. "Fortunately, though, I am not a timid person. It is not that I am afraid to stay here alone. My chief objection is that it seems foolish to run a great house like this simply for myself."

"Couldn't you get some one to come and keep you company?"

"Who, I should like to know?"

"Why—why—well, I haven't thought about it. Of course there's Aunt Marcia King."

"Mercy on us!" exclaimed his mother, instantly flaring up. "I'd rather see the evil one himself put in an appearance than your Aunt Marcia. Of all the fault-finding, critical, sharp-tongued creatures in the world she is the worst. Why, I'd let burglars carry away every stick and stone I possess and myself thrown in before I would ask her here to board."

"My, Mother! I'd no idea you had such a temper. You're as bad as Dave Corbett," asserted Walter teasingly.

His mother tossed her head but he saw her flush uncomfortably.

"I suppose you wouldn't want a regular boarder," suggested the boy in order to turn the conversation.

"A boarder!" There was less disapproval than surprise in the ejaculation, however.

"Lots of people in the town do take summer boarders," added he.

"The thought never entered my head before," reflected his mother aloud. "There certainly is plenty of room in the house, and we have a royal view of the water. Besides, there's the garden. Strangers are always coming here in vacation time and asking if they may look at it or sketch it. It never seemed anything very remarkable to me for most of the flowers have sown themselves and grow like weeds, but of course there's no denying the hollyhocks, poppies, and larkspur are pretty. But visitors always call it wonderful."

"Most likely you could get a big price if you were to rent rooms."

"I'm sure I could," replied Mrs. King thoughtfully. "It would help toward the mortgage and the other bills, too. I've half a mind to try it, Walter."

"It would mean extra work for you."

"Pooh! What do I care for that? Not a fig! In fact, with both of you boys away I'd rather be busy than not," was the quick retort.

"Do you suppose Bob would mind?"

"Bob? Why, he's seldom at home nowadays. Why should he care?"

"Aunt Marcia might think——" began the boy mischievously. But the comment was cut short.

"Oh, I know what your Aunt Marcia would say," broke in Mrs. King. "She'd hold up her hands in horror and announce that it was beneath the dignity of the family to take boarders."

They both laughed.

"I believe the very notion of scandalizing her will be what will decide me," concluded his mother with finality. "I'll put an advertisement in the Boston paper to-morrow and see what luck I have. If the right people do not turn up, why I don't have to take them."

"Sure you don't."

"It's a good plan, a splendid plan, Walter. Boarders will give me company and money too. I wonder it never occurred to me to do it before." Then she patted the lad's shoulder, adding playfully, "I guess if you have brains in one direction you must have them in another. Still, as I said before, I do not fancy your being responsible for those dogs."

"Pooh! You quit worrying, Ma, or I shall be sorry I told you they were blue ribbon pups."

"I should have heard of it, never fear. You hear of everything in this town. You can't help it. Like as not everybody in the place will know by to-morrow morning that I am going to take boarders. Luckily I don't care—that's one good thing. And as to the dogs, if you are resolved to accept that position all I can say is that you must keep a head on your shoulders. You cannot hire out for a job unless you are prepared to give a full return for the money paid you. It is not honest. So think carefully what you mean to do before you embark. And remember, if you get into some careless scrape you cannot come back on me for money for I haven't any to hand over."

"I shall shoulder my own blame," responded Walter, drawing in his chin.

"Well and good then. If you are ready to do that, it is your affair and I have nothing more to say," announced Mrs. King, preparing to leave the room.

But Walter stayed her on the threshold.

"I don't see," he began, "why you always seem to expect I'm going to get into a scrape. You are never looking for trouble with Bob."

"Bob! Bless your heart I never have to! You know that as well as I do. Any one could trust Bob until the Day of Judgment. He never forgets a word you tell him. Ask him to do an errand and it is as good as done. You can drop it from your mind. From a little child he was dependable like that. His teachers couldn't say enough about him. Wasn't he always at the head of his class? The way he's turned out is no surprise. Think of his picking up wireless enough outside school hours to get a radio job during the war, and afterward that fine position at Seaver Bay! Few lads his age could have done it. And think of the messages he's entrusted with—government work, and sinking ships, and goodness knows what not!"

The proud mother ceased for lack of breath.

"I wish I was like Bob," sighed Walter gloomily.

"Nonsense!" was the instant exclamation. "You're yourself, and scatter-brain as you are, I'd want you no different. You're but a lad yet. When you are Bob's age you may be like him. Who knows?"

"I'm afraid not," came dismally from Walter. "I haven't started out as Bob did."

"What if you haven't? There's time enough to catch up if you hurry. And anyway, I do not want my children all alike. Variety is the spice of life. I wouldn't have you patterned after Bob if I could speak the word."

"You wouldn't?" the boy brightened.

"Indeed I wouldn't! Who would I be patching torn trousers or darning ripped sweaters for if you were like Bob, I'd like to know? Who'd be pestering me to hunt up his cap and mittens? And who would I be frying clams for?"

"Bob never could abide clam fritters, could he?" put in the younger brother.

"Bob never had any frivolities," mused Mrs. King, shaking her head. "Sometimes I've almost wished he had if only to keep the rest of us in countenance. Many's the time I've feared lest he was going to die he was that near perfect."

"Well, Ma, you haven't had to lie awake worrying because I was too good for this world, have you?" chuckled His Highness, breaking into a grin.

His mother regarded him affectionately.

"Oh, you'll make your way too, sonny, some day. It won't be as Bob has done it; but you'll make it nevertheless. Folks are going to do things for you simply because they cannot help it."

The boy studied her with a puzzled expression.

"What do you mean, Mater?"

As if coming out of a reverie Mrs. King started, the mistiness that had softened her eyes vanishing.

"There! Look at the way you've splashed up my nice clean sink!" complained she tartly. "Did any one ever see such a child—always messing up everything! Come, clear out of here and take your fish with you. It does seem as if you needed four nursemaids and a valet at your heels to pick up after you. Be off this minute."

With a cloth in one hand and a bar of soap in the other, she elbowed him away from the dishpan.

"You'll fry these flounders for supper, won't you, Ma?" called the lad as he disappeared into the shed.

"Fry 'em? I reckon I'll have to. It's wicked to catch fish and not use 'em."

But he saw his mother's eyes twinkle and her grumbling assent did not trouble him.

May at Lovell's Harbor was one of the most beautiful seasons of the year. In fact the inhabitants of the town often remarked that they put up with the winters the small isolated village offered for the sake of its springs and summers. Certain it was that when easterly storms swept the marshes and lashed the harbor into foam; when every boat that struggled out of the channel returned whitened to the gunwale with ice, there was little to induce anybody to take up residence in the hamlet. How cold and blue the water looked! How the surf boomed up on the lonely beach and the winds howled and whined around the eaves of the low cottages!

One buttoned himself tightly into a greatcoat then, twisted a muffler many times about his neck, pulled his cap over his ears, and rushed for school with a velocity that almost equaled the scudding schooners whose sails billowed large against the horizon. At least that was what His Highness, Walter King, invariably did.

But from the instant the breath of spring stole into the air,—ah, then Lovell's Harbor became a different place altogether. The stems of the willows fringing the small fresh-water ponds mellowed to bronze before one's very eyes; the dull reaches of salt grass turned emerald; the steely tint of the sea softened to azure and glinted golden in the sun. How shrill sounded the cries of the redwings in the marsh! How jolly the frogs' twilight chorus!

The miracle went on with amazing rapidity. Soon you were scouring the hollows in the woods for arbutus or splashing bare-legged into the bogs for cowslips. You even ventured knee-deep into the sea which although still chill was no longer frigid. And then, before you knew it, you were hauling out your fishing tackle and looking over your flies; inspecting the old dory and calking her seams with a coat of fresh paint. Then came the raking of the leaves, the uncovering of the hollyhocks, and the burning of brush; and through the mists of smoke that rose high in air you could hear the resonant chee-ee of the blackbirds swinging on the reeds along the margin of the creek.

And afterward, when summer had really made its appearance, what days of blue and gold followed! Was ever sky so cloudless, grass so vividly green, or ocean so sparkling? Ah, a boy never lacked amusement now! He wriggled into his bathing suit directly after breakfast and was off to the shore to swim, fish, or sail, or do any of the thousand-and-one alluring things that turned up. And things always did turn up in that small horseshoe where the boats made in. It was the club of Lovell's Harbor.

Here all the men of the village congregated daily to smoke, swap jokes, and heckle those who worked.

"That's no way to mend a net, Eph," one of the spectators would protest. "Where was you fetched up, man? Tote the durn thing over here and I'll show you how they do it off the Horn."

Or another member of the audience would call:

"Was you reckonin' you'd have enough paint in that keg to finish your yawl, Eddie? Never in the world! What are you so scrimpin' of it for? Slither it on good and thick and let it trickle down into the cracks. 'Twill keep 'em tight."

Oh, one learned to curb his temper and bend to the higher criticism if he carried his work down to the beach. He got an abundance of advice whether he asked for it or not and for the most part the counsel was sound and helpful. There you heard also tales of tempests, wrecks, strange ports, and sea serpents,—weird tales that chilled your blood; and sometimes the piping note of an old chanty was raised by one whose sailing days were now only a memory.

What marvel that to be a boy at Lovell's Harbor was a boon to be coveted even if along with the distinction went a throng of homely tasks such as shucking clams, cleaning cod, baiting lobster pots, and running errands? No cake is all frosting and no chowder all broth. You had to take the bad along with the good if you lived at Lovell's Harbor. And while you were sandwiching in work and fun what an education you got! Why, it was better than a dozen schools. Not only did you learn to swim like a spaniel, pull a strong oar, hoist a sail, and gain an understanding of winds and tides, but also you came to handle tools with an ease no manual training school could teach you. You made a wooden pin do if you had no nail; and a bit of rope serve if the whittled pin were lacking. Instead of hurrying to a shop to purchase new you patched up the old, and the triumph of doing it afforded a satisfaction very pleasant to experience.

Moreover, as a result, you had more pennies in your pocket and more brains in your head. Both Bob and Walter King, as well as most of the other village lads, outranked the town-bred boy in all-round practical skill. They may not have cut such a fine figure at golf or dancing; perhaps they did not excel at Latin or French; but they had at the tips of their tongues numberless useful facts which they had tried out and proven workable and which no city dweller could possibly have gleaned.

His Highness might be freckled and towsled and, as his mother affirmed, forgetful and careless, but like a sponge his active young mind had soaked up a deal no books could have given him. You would best beware how you jollied Walter King or put him down for a "Rube." More than likely you would later regret your snap judgment.

No doubt it was this realization that had stimulated Jerry Thomas to ask him to come to Surfside, the Crowninshields' big summer estate, and look after the dogs. Jerry was an old resident of Lovell's Harbor, and having watched the boy grow up, he unquestionably knew what he was about. That there were plenty of other boys at the Harbor to choose from was certain. If the honor descended to His Highness rest assured it was not without reason.

Hence Jerry was not only pleased but immensely gratified when on the morning following Walter rounded the corner of the great barn and appeared in the doorway.

"I've come to say Yes to that job you offered me the other day," announced he, without wasting words on preliminaries.

"Good, youngster!"

"When shall you want me?"

"When can you come?" grinned Jerry.

He was a lank, sharp-featured man with china blue eyes that narrowed to a mere slit when he smiled, and from the corners of which crowsfeet, like fan-shaped streaks of light from the rising sun, radiated across his temples. His skin was tanned to the hue of old hickory and deep down in its furrows were lines of white. He had a big nose that was always sunburned, powerful hands with a reddish fuzz on their backs, and gnarled fingers that bore the scars of innumerable nautical disasters. But the chief glory he possessed was a neatly tattooed schooner that sailed under full canvas upon his forearm and bore beneath it the inscription:

The Mollie D. The finest ship afloat.

The words had been intended as a tribute rather than a challenge for Jerry was a peaceful soul, but unfortunately they had proved provocative of many a brawl, and had the truth been known a certain odd slant of Jerry's chin could have been traced back to this apparently harmless assertion. Possibly had this mate of the Mollie D. foreseen into what straits his boast was to lead him he might not have expressed it so baldly in all the naked glory of blue ink; but with the sentiment once immortalized what choice had he but to defend it? Therefore, being no coward but a sturdy seaman with a swinging undercut, he had in times past delivered many a blow in order to uphold the Mollie D.'s nautical reputation, after which encounters his challengers were wont to emerge with a more profound respect not only for the bark but for Jerry Thomas as well.

All that, however, was long ago. Since the great storm of 1890 when so many ships had perished and the Mollie D., bound from Norfolk to Fairhaven, had gone down with the rest, Jerry had abandoned the sea. It was not the perils of the deep, nevertheless, that had driven him landward, or the fear of future disasters; it was only that since his first love was lost he could not bring himself to ship on any other vessel.

Accordingly he took to the shore and for a time a very strange misfit he was there. How he fumed and fidgeted and roamed from one place to another, searching for some spot in which his restless spirit would find peace! And then one day he had wandered into Lovell's Harbor and there he had stayed ever since. For several seasons he had taken out sailing parties of summer boarders or piloted amateur fishermen out to the Ledges; but the timidity and lack of sophistication of these city patrons at length so rasped his nerves that he gave up the task and was about to betake himself to pastures new when he fell beneath the eye of Mr. Glenmore Archibald Crowninshield, a New York banker, who had bought the strip of land forming one arm of the bay and was on the point of erecting there a diminutive summer palace.

From that instant Jerry's fortune was made. Mr. Crowninshield was a keen student of human nature and was immediately attracted to the sailor with his ambling gait and twinkling blue eyes. Moreover, the New Yorker happened to be in search of just such a man to look out for his interests when he was not at Lovell's Harbor. Hence Jerry was elevated to the post of caretaker and delegated to keep guard over the edifice that was about to be erected.

In view of the fact that up to the moment Jerry had been the most care-free mortal alive and had never from day to day been able to remember the whereabouts of his sou'wester or his rubber boots, his ensuing transformation was nothing short of a miracle. Promptly settling down with doglike fidelity he began mildly to urge on the lagging carpenters; but presently, magnificent in his wrath, he rose above them, whiplash in hand, and drove them forward. His watery blue eyes followed every stick of timber, every foot of piping, every nail that was placed. There was no escaping his watchfulness. If corners were not true or moldings did not meet he saw and called attention to it. Many a time a slipshod workman was ready to throw him over the cliff into the sea and perhaps might have done so had he not been conscious of the justice of the criticism.

In consequence the Crowninshield house was built on honor; and when the bills began to come in and showed a marked falling off in magnitude the owner of the mansion could not but express gratitude. Jerry, however, did not covet thanks. Instead he tagged along at his employer's heels, proudly calling notice first to one skillful bit of work and then to another. The house and all that concerned it became his hobby. It was to him what the Mollie D. had been, the primary interest of his life. He knew every inch of plumbing; where every shut-off, valve, ventilator, and stopcock was located. Moreover, he could have told, had not his jaws been clamped together tightly as a scallop shell, exactly how much every article in the mansion cost.

Later he superintended the grading of the lawns, the laying out of tennis courts, and the building of garages, boathouses, and bathhouses. By this time Mr. Crowninshield would willingly have trusted him with every farthing he possessed so complete was his confidence in his man Friday.

Jerry, however, was modest. He declared he had only done his duty and insisted that it go at that. But having set this high standard of fidelity for himself it followed that he demanded a like faithfulness in others; and if he were not merciful to those who came under his dictatorship at least no one of them could deny that he was just. Hence Walter King did not shrink from the prospect of working with him, stern though he was reputed to be. One can only do one's best and that the boy was determined to do. Therefore he smiled up into Jerry's misty blue eyes and answered:

"I could begin work when school closes toward the end of June."

"Humph! I wish you could make it earlier. Well, we must put up with that since it is the best you can do. Goodness knows I'd be the last one to discourage learning in the young. I got all too little of it when I was a shaver. Not a day goes by that I don't wish I'd had my chance. I shipped to sea when I was only twelve—would go—nothing would stop me—and I've been knocking round ever since, picking up here and there what scraps of knowledge I could get. Don't let anything tempt you to sea till you're full-grown, sonny, for you'll live to regret it, sure as my name is Jerry Taylor."

Walter flushed guiltily, wondering as he did so whether Jerry's little blue eyes had bored their way into his skull and read there his aspirations.

"Nope!" went on the sailor. "Take it from me, seafaring is a man's job. You much better stay ashore and——" he stopped as if at a loss and then smiling broadly added, "play governess to a pack of dogs."

"I figure that is about what I'm going to do," replied His Highness with a comic air of resignation.

"Well, what's the matter with that?" inquired Jerry sharply. "You'll be getting paid for it, won't you—well paid? And you'll have cozy quarters all to yourself, and three good meals a day. Land alive! Some folks want the earth! Why, when I was your age, I was swung up in a hammock between decks with not an inch of space that I could call my own. If I wanted to stow away anything I hadn't a place to put it where it wasn't common property. As for meals I took what I could get and was thankful that I didn't starve. And here you come along and tilt up your freckled pug nose at a room and board and ten a week. Bah! What's come over this generation anyway?"

"I wasn't turning up my nose," Walter ventured to protest. "It turns up anyhow."

"Then you need to be careful how you make it go higher," grinned Jerry.

"And—and—I had no idea you meant to pay me that much."

"What do you think we are up here?" bristled Jerry. "A sweatshop? No siree! We stand for the square deal every time, we do. Only you've got to understand, young one, that it's to be square on both sides. You're to do no shirking; if you do you'll get fired so quick you'll wonder what hit you. But if you do your part you need have no worries. Now think good and plenty before you embark on the cruise."

"I have thought."

"All right then. We'll haul up anchor and be off the latter part of June."

"You'll have to tell me exactly what you want me to do."

"Oh, I'll tell you right 'nough," drawled Jerry, with a humorous twist of his lips. "You'll get a chart to sail by. Still, it won't wholly cover your duties. The thing for you to do is to keep your eyes peeled and look alive. Watch out and see where there's a hole an' be in that hole so it won't be empty. That's the best recipe I know for being useful."

"I'll try."

"If you honestly do that I reckon there'll be no cause for you to worry," observed the caretaker kindly. "Towards the end of June, then, I'll be on the lookout for you. Your quarters will be all ready, shipshape and trim as a liner's cabin."

"Where will they be?" inquired Walter.

"Want to see 'em?"

"I'd like to, yes."

"I s'pose you would," nodded Jerry. "You can as well as not; only they ain't fixed up as they'll be later. Look kinder dismal."

"Oh, I shan't mind."

The big man smiled at the eagerness of the boy's tone.

"Likely you ain't never been away from home before, son," said he, as he took a key out of a glass case on the wall of the barn and slipped it into his pocket.

"No—that is, not to stay."

"Quite some adventure, eh?"

The lad shot a bright glance toward him.

"Yes."

"Well, well! Count yourself lucky, youngster, that you've had a good home and a good mother up to now; and bless your stars, too, that since you are going to start branching out you're coming to a place like Surfside rather'n somewhere else."

His voice was gentle and his misty eyes mistier than ever.

Striding ahead he crossed the lawn, unlocked a low building, and mounting the stairs, stopped before a door in the hall above. With a turn of the key it swung open, disclosing a small sheathed room containing a white iron bed, bureau, table, chairs, and bookshelves.

"Think this will suit your Highness?" grinned he.

"It's—it's corking!" stammered Walter, almost too delighted to reply.

"'Tain't bad," admitted Jerry, strolling over to one of the windows that faced the sea and looking out. "Mr. Crowninshield makes it a rule never to stow away other folks where he wouldn't be stowed himself. It isn't a bad principle, either. You'll have a couple of the chauffeurs for company." With his thumb he motioned to other rooms flanking the narrow hall. "They may josh you some at first. That's part of starting out in the world. Keep a civil tongue in your head and if you don't mind 'em they'll soon quit. If they don't it's up to you to find the way to get on with 'em. Half of life is learning to shy round the corners of the folks about you. And old Tim, who used to be gardener for Mr. Crowninshield's father and has been in the family 'most half a century, bides here, too. A rare soul, Tim. You'll like him. Everybody does. Simple as a child, he is, and so gentle that it well-nigh breaks his heart to kill a potato bug. You can count on Tim standing your friend no matter what the rest may do, so cheer up."

"And the dogs?"

"Oh, the kennels, you mean? They're close by where you'll get the full benefit of the pups' barking in the early morning," said Jerry, with a twinkle. "'Twill give you a pleasant feeling to be certain your charges are alive. Most often, though, they do no yammering until about six, and goodness knows all Christians ought to be up at that hour. You'll find the dogs fitted out comfortable as the rest of us. They've a fine enclosure to stay in when they want to be out of doors; a big airy room if it's better to have 'em under cover; steam heat when it's cold; and blankets and brushes without end. Sometimes Lola, the pet of 'em all, sleeps up at the big house; but mostly she's here with the rest. There's too big a caravan of 'em to have the lot live with the family. Besides, the folks like to sleep late in the morning and not be disturbed by the noise of a pack of puppies. Then there's guests here off and on. So take it all in all, the dogs are best by themselves."

"But I don't know anything about taking care of dogs," faltered Walter.

"I thought you'd had a dog yourself."

"So I had once. But he wasn't like any of these. He was just a dog. All you had to do was to chuck him a bone."

"Well, you'll have a darn sight more to do for these critters than that," announced Jerry.

"But how'll I know——" began the boy, alarmed by the prospect before him.

"Oh, you'll get your instructions from the Madam, most likely—get 'em all written down in black and white along with the history of every dog. She'll tell you just what every one of 'em is to eat, and how much; and where they're all to sleep. And if she don't Miss Nancy or Mr. Dick will. You'll get yards and yards of directions before you're through," chuckled Jerry. "You want to listen well to every word you hear too, son, for these dogs ain't like your Towser—or whatever his name was; a crumb of food too much might kill 'em. Or a blast of air."

"Scott!"

"Oh, there's no use getting panicky at the outset," declared Jerry comfortably. "Follow orders and use your brains; and remember that if you get addled you can always consult Tim. Tim has a world of common sense and a heap of knowledge of odd sorts. And more than that, he's never swept off his feet by the cost of things. Having been brought up in the company of Rolls-Royce cars, and diamond rings, and thousand-dollar dogs they don't move him an inch. He just treats 'em same's he would anything else and often it's the best plan. Instead of losing his head, and standing wringing his hands 'cause the prize roses have got bugs on 'em he sets to work and kills the bugs; sprays the plants same's he would ordinary bushes, and they go to growing again like any other civilized flowers. An orchid ain't no more to him than a buttercup. He's too used to 'em. He's used to dogs as well, and with the shifting fashions he's seen during his fifty years with the family he's had experience with most every kind of dog that ever was. For there's fashions in dogs, you know, as well as in coats and hats. So turn to Tim when you're in a tight place. He'll help you, never fear."

"I hope he will," sighed His Highness ruefully. "I shall need him."

"Nonsense! Why, Mr. Dick has often cared for the pups when there was no one else; and certainly you ought to have as many brains as he."

"Tell me about him."

"Richard? You've seen him round town lots of times—you must have. At the village and other places."

"Oh, of course I've seen him," agreed Walter quickly. "In the summer he drives past our house almost every day in his car. But I don't know him any."

"You will now," asserted Jerry. "He's a great chap, Mr. Dick is! About your age, too, I guess. Quite a mechanic and always tinkering with tools and machinery. If there's anything wrong with the motor boat he can usually fix her up all right. As for mending a car, he beats all the chauffeurs out. They know it and have to say so. Likely you've seen him fluking through the main street in his racer. She's a trim little thing and could go like the wind if his Pa hadn't forbidden letting out the engine. I reckon Mr. Crowninshield is afraid he'll either kill himself or somebody else, and I will own the thing ain't no proper toy for a lad his age. Still, city folks ain't content with what would please you or me. They must have the biggest, the fastest, the most expensive article there is or 'tain't good for nothin'. The mere knowin' it's the biggest, fastest, and cost the most seems to make 'em happy somehow. Funny, ain't it?"

His Highness did not reply. He was thinking.

"And Miss Nancy?" interrogated he presently.

"Ha! There's a girl for you!" ejaculated Jerry with enthusiasm. "She'll be either seventeen or eighteen come June. Swims like a fish. In fact, I ain't sure she couldn't outdistance some of 'em. And such an oar as she pulls! It's strong and steady as any man's. Besides that, she can beat the crowd at tennis, golf, and those other fool games such folks play. Has a runabout of her own, too, and drives it neat as a pin."

"She's better at sports than Mr. Dick, then."

"Oh, she can wipe the ground up with him," sniffed Jerry. "She can swim overhand to the raft and get back almost before her brother has started. By Guy! I never saw a woman swim as she does! Dick gets kinder peeved with her sometimes when she jollies him. But let her car play a prank and he has her, for she's no more idea what to do with an engine than the man in the moon. She treats brother Richard with proper respect then, I can tell you."

Walter smiled.

"And Mrs. Crowninshield?"

"She? She's all right! You'll like her and she'll like you—that is, if you get on with the pups. Dogs are her hobby. What she don't know about raisin' 'em ain't worth knowin'. But I just warn you not to think that because she's so pleasant she's easy goin', 'cause she ain't. Slip up on your job and she'll be down on you like a thousand of brick. She's a fair-weather sailin' craft—that's what she is; floats along nice as anything until something goes wrong and then—my soul—but she kicks up a sea. Yet with all that you'll like her. We all do. Almost everybody on the place would get down and let her walk on 'em. She has a kind of way with her that makes you itch to please her. Tim would let her cut his head clean off if she wanted to and I ain't sure I wouldn't. Have a smart sore throat once and see the things she'll do for you. And she'll do 'em herself, too—not set other people on the job. I believe that woman has the biggest heart in the world."

"And—and—Mr. Crowninshield?" ventured Walter.

"The boss?" Jerry cleared his throat and for the first time hesitated. "You've got to understand the boss, my son," said he earnestly. "He ain't like other men. And in order that you may, I better give you a pointer or two for it will most probably save you trouble. The boss is something like a big dog that barks fit to murder you and don't mean a thing by it. You've seen the kind. To hear him go on when he's roused you'd believe he was going to have your blood. My, how he does orate!" Jerry smiled and shook his head indulgently. "I've seen the men stand up before him with their knees shaking until you'd expect 'em to give way every second. And the master would rage and rage because they'd done something he didn't want done. And then, like a hurricane that's blown itself out, he'll calm down and the next you know he's given you a smile that's made you forget all the rest of it. That's him all over. Learn not to be afraid of him, that's the only thing to do. He wouldn't hurt a fly really. He just gets to blusterin' and tearin' round from force of habit. It don't mean nothin'—not a thing in the world. And with all his money he ain't a mite cocky. To see him you'd scarce dream he had a copper in his pocket. Yet he could paper the house with thousand-dollar bills was he so minded. There's no end to his money, seems to me. Just the same, you don't want to go wastin' it for him on that account. Remember you ain't got the right to, not havin' earned it. If he chooses to splash it round that's his hunt. He made it. But it ain't yours or mine to slosh away. Jot that down in your log. It may help you later."

Jerry paused.

"You deal square and honorable with the boss, standing up to what you've done like you was a trooper at your gun, and he'll deal square and honorable with you. But go to hoodwinking and imposing on him and instead of a lamb you'll find you've got a rattlesnake at your heels. Now you have an idea, I guess, what you're going to be up against here," concluded the caretaker, taking out his pipe and cramming it with tobacco. "If there's anything else you want to know now's your chance, for after to-day I am never going to open my lips again about any of the Crowninshield family. You'll be one of the employees and your job will be to hold your tongue on them and their affairs, and be loyal to 'em. Their bread will be feeding you and 'twill be only decent. After you once have got your place the keeping of it will rest with you. That's fair, ain't it?"

Walter nodded.

Yet he turned slowly toward home, depressed by a throng of misgivings. Suppose he was not able to hold the job at Surfside once it was his? What then?

By the middle of May Lovell's Harbor had fully awakened from its winter's sleep. Freshly painted dories were slipped into the water; newly rigged yawls and knockabouts were anchored in the bay; the float was equipped with renovated bumpers, and a general air of anticipation pervaded the community.

Yes, hot weather was really on the way. Already the summer cottages were being opened, aired, and put in order, and even some of the houses had gayly figured hangings at the windows and a film of smoke could be seen issuing from the chimneys.

At Surfside workmen bustled about, hurrying across the lawn with boards, paint pots, and hammers. Tim Cavenough and his little host of helpers scurried to uncover the flower beds, and from morning to night trudged back and forth from the greenhouses bearing shallow boxes of seedlings which they transplanted to the gardens. Shutters were removed and stored away, piazza chairs brought out, awnings put up, and lawns and tennis courts rolled and cut.

As far as one could see a spangled expanse of ocean dazzled the eye and the tiny salt creeks that meandered across the meadows were like winding ribbons of blue. Certainly it was no weather to be shut up in school and boys and girls went hither with reluctant feet, checking off the days on their fingers and even counting the hours that must drag by before they would be free to roam at will amid this panorama of beauty.

To Walter King it seemed as if the closing period of his captivity would never be at an end. He studied rebelliously, and with only a half—nay, rather a quarter—of his mind on his lessons. All his thought was centered around Surfside and the novel experiences that beckoned him there. So impatient was he to begin his new duties that he found it impossible to settle down to anything.

"You'll be failing in your last examinations, Walter, if you don't watch what you're doing," cautioned his mother. "And should you do that, little profit would it be that you are hired out to Mr. Crowninshield for the summer. In the fall you'd have to stay behind your class, and think of the disgrace of that! Why, I'd be ready to hide my head with shame! Money or no money, you must buck up and put the Crowninshields and their doings out of your head. To lose a year now would mean just that much longer before you could graduate and take a regular job. I almost wish Jerry Thomas had never asked you to come up there, I do indeed."

"Oh, don't go getting all fussed up, Ma," returned His Highness, irritated because he recognized the truth of his mother's words. "I'm going to buckle down until the term is over, honest I am. It is hard, though, with the weather so fine. It seems as if I must be out. It's like being on a leash."

"You're thinking of those dogs again!"

The lad flushed sheepishly.

"No, I wasn't."

"But you were—whether you realized it or not. It is all you talk of nowadays—dogs! What it will be after they get here and you're up at Surfside living with them I don't know. Whatever else you do, though, you must not fail in your lessons and at the last moment spoil your whole year's record. School is your first duty now and you have no moral right to put anything else in its place."

"I know it, Ma," Walter agreed.

"Of course you know it," was the tart response. "Just see that you do not forget it, that's all."

With this final admonition Mrs. King whisked about and taking up her cake of Sapolio and pail of steaming water ascended the stairs. Like the rest of Lovell's Harbor she was busy as a bee in clovertime. She had rented all her rooms and had so many things to do in preparation for her expected guests that she had not a second to waste.

After she had gone Walter loitered in the kitchen, whistling absently and at the same time winding a piece of string aimlessly over his fingers. His mother's words had stirred a vague, uncomfortable possibility in his mind. What if he were to fail in those final exams? It would be terrible. Such a disaster did not seem real. It couldn't happen—actually happen—to him. It would be too awful. Nevertheless, try as he would to banish them, visions of Surfside with its myriad fascinations would dance in his head.

He had never been away from home for more than a night before and to take up residence elsewhere for an entire season was in itself a novelty. Then there were the tennis courts, the golf links, the automobiles, motor boats, and the yacht! Why, it would be like fairyland! The next instant, however, his spirits drooped. It was absurd to imagine for a moment that he was to have any part in those magic amusements. He was not going to Surfside for recreation but for work. Notwithstanding that fact, though, it was beyond his power to forget that all these many activities would be going on about him and there was the chance, the bare chance, that an occasion might arise when he would be invited to participate in some of them.

Fancy spinning over the sandy roads of the Cape in that wonderful racing car! Or sailing the blue waters of the harbor in one of those snowy motor boats! As for the yacht, with its trimmings of glistening brass and spotless decks, had he not dreamed of going aboard it ever since the day it had first steamed into the bay two summers ago? People said there was every imaginable contrivance aboard: ice-making machines, electric lights, and electric piano, goodness only knew what! Simply to see such things would be wonderful. And if it ever should come about (of course it never would and it was absurd to picture it—ridiculous) but if it ever did that he should go sailing out of the bay on that mystic craft what a miracle that would be!

With such visions floating through his mind what marvel that it was well-nigh out of the question for Walter King to focus his attention on algebra, Latin, history, and physics. X + Y seemed of very little consequence, and as for the Punic Wars they were so far away as to be hazy beyond any reality at all.

Possibly, although she was quite unconscious of it, some of the fault was his mother's for she kept the topic of his departure to the Crowninshields' ever before him.

"I have your new shirts almost finished, son," she would assert with satisfaction, "and they're as neat and well made as any New York tailor could make them, if I do say it; and you've three pairs of khaki trousers besides your old woolen ones and corduroys. With your Sunday suit of blue serge and those fresh ties and cap you'll have nothing to be ashamed of. Then you've those denim overalls, and your slicker, and Bob's outgrown pea-coat. I can't see but what you have everything you can possibly need. Do be watchful of your shoes and use them carefully, won't you, for they cost a mint of money? And remember whenever you can to work in your old duds and save your others. You can just as well as not if you only think of it. Your washing you'll bring home and don't forget that I want you to keep neat and clean. Rich folks notice those things a lot. So scrub your hands and neck and clean your nails, even if I'm not there to tell you to. Just because you are going to traipse round with the dogs is no excuse for looking like 'em," concluded she.

"I'll remember, Ma," returned His Highness patiently.

"And if you eat with the chauffeurs and a pack of men, don't go stuffing yourself with food until you're sick. There's a time to stop, you know. Don't wait until you've got past it and are so crammed that you can't swallow another mouthful."

"I won't, Ma," was the meek response.

"Brush your teeth faithfully, too. I've spent too much money on them to have them go to waste now."

"Yes," came wearily from Walter.

"Of course there's no call for me to talk to a person your age about smoking," continued his mother. "When you've got your full growth and can earn money enough to pay for such foolishness you've a right to indulge in it if you see fit; but until then don't start a habit that will do you no good and may make a pigmy of you for life."

"I promise you right now, Ma, that I——"

"No, don't promise. A promise is a sacred thing and one that it is a sacrilege to break. Never make a promise lightly. But just remember, laddie, that I'd far rather you didn't smoke for a few years yet. But should you feel you must why come and tell me, that's all."

"I will, Ma," answered the boy soberly. Somehow going away from home suddenly seemed a very solemn business.

"I guess that's the end of my cautions," smiled Mrs. King, "the end, except to say that I hope you won't like Surfside so well that you'll forget to come home now and then and tell me how you are making out. Of course I'll have my boarders and work same's you; still, there'll be times when we won't be busy and can see each other," her voice trembled a little. "Nobody will be more anxious to hear of your doings than I—remember that. I shall miss you, sonny. It's the first time you've been away from me and I can't but feel it's a sort of milestone. You'll be getting grown up and leaving home for good now before I know it, same as Bob has."

Her eyes glistened and for an instant she turned her head aside.

"Oh, I shan't be branching out to make my fortune yet, Mother," protested Walter gayly. "I don't know enough. I'm not clever like Bob—you said so yourself only the other day."

"You're clever as is good for you," was the ambiguous retort. "I'm glad you're no different."

"Think of the money I'd be handing in if I could only earn as much as Bob."

"The money? Aye, there's no denying it would be a help. However, with what you and Bob and I are going to earn this summer we should make out very well, even if your Uncle Mark Miller has left us in the lurch and your Uncle Henry King's investments have gone bad on us. I'll be turning a tidy penny with my boarders, thanks to you. And for a lad your age ten dollars a week is not to be sneezed at. Why, we'll have quite a little fortune between us!"

He saw her face brighten.

"Now if Bob could only be near at hand like you I believe I should be entirely happy," she sighed. "I hate to think of him way out there on that spit of sand with the sea booming all around him and nothing for company but the other fellow, who's asleep whenever he's awake, and that clicking wireless instrument. Imagine the loneliness of it! The solitude would drive me crazy inside a week—I know it would."

"Bob doesn't mind."

"He's not the lad to say so if he did," replied the mother grimly. "Nobody'd be any the wiser for what Bob thinks. Often at night I fall to wondering what he'd do was he to be taken sick."

"Oh, he'd be all right, Mother," answered His Highness cheerfully. "O'Connel is there, you know."

"And what kind of a nurse would he be, do you think, with his ear to that switchboard from daylight until dark?"

"Not quite that. Mother."

"Well, almost that, anyhow. It is all well enough for you to say so jauntily that Bob doesn't mind being off there with the wind howling round him and nothing to do but listen to it."

"Nothing to do!" repeated Walter. "Why, Ma, he's busy all the time."

"Tinkering with those wires, you mean?" was the indignant question. "Yes, I grant he has plenty of that, especially in bad weather. But I mean pleasures——"

"Moving pictures, church sociables, strawberry festivals," interrupted the lad mischievously.

"Yes, I do," maintained Mrs. King stoutly. "Folks must have something to brighten up their lives. Bob doesn't have a thing."

"He often has days that are lively enough, according to his stories."

"When there's wrecks, you mean?" She shook her head gravely. "It isn't those that I'm talking about. It's sitting day after day and listening to the meaningless taps and buzzings that come whining through that instrument."

"They're not meaningless to him."

"No-o, I suppose not," sighed the woman. For a moment she paused only to resume her complaints. "Then there's the responsibility of it. I never did like to think of that. Should he tap once too much or too little when sending one of those dot and dash messages, think what it might mean! And suppose he heard a dot too much and didn't get the thing the other fellow was trying to tell him straight?"

"But he has been trained so he does not make mistakes."

"All human clay makes mistakes," was the tragic answer, "although I will say Bob makes fewer than most. And then the thunder storms—I'm always worried about those."

"Yes, I'll confess there is some danger from lightning," owned Walter unwillingly. "And of course there is danger from the current at all times if one is not careful. Even then accidents sometimes happen. However, Bob explained once that accidental shocks seldom result fatally unless the person is left too long without help. The man in charge of the radio outfit would almost never get the full force of the current, because part of it would be carried off through the wires and ground. Such accidents are mainly due to the temporary and faulty contact of the conductors."

"I can't help what they're due to," sniffed Mrs. King. "The point is that Bob might get knocked out and die."

"Nonsense, Mother. You would not worry if you understood more about it. Besides, should a man get a shock, if you go promptly to work over him and keep at it long enough, you can almost always bring him back to consciousness. They do just about the same things to restore him that they do for a person that's been drowned. The aim is to make him breathe. If you can get him to, he will probably live. Of course, though, you have to break the circuit first."

"The circuit?"

"Stop the current that is going through his body," explained Walter.

"But how can you?"

"Bob told me how. He saw a chap knocked out once and helped fix him up. You had to be awfully careful about moving him away from the apparatus, Bob said, or you might get a shock yourself. They took a dry stick because it was a nonconductor of electricity, you know, and rolled the man over to one side, so he was out of reach of the wires. Had you covered your hands with dry cloth you could have moved him, too; rubber gloves are best but Bob did not happen to have any handy at the minute. So they poked the fellow out of the way with the stick, turned him over on his back, loosened his collar and clothing, and went to work on him. You know how they always roll up a coat or something and stuff it under drowned persons' shoulders to throw their head backward? Well, they did that; and afterward they began to move his arms up and down to make him breathe. The idea is to depress and expand the chest. We learned it in our 'first aid' class. Of course there are lots of things you have to do besides, and if you can get a doctor he will know of others that are better still. But Bob said the chief point was not to get discouraged and give up. Sometimes people die just because the folks fussing over them do not keep at it long enough. They get tired and when they see no results they decide it is no use and stop trying. You ought to work an hour anyhow, repeating the exercises at the rate of sixteen times a minute, Bob said. Then, if the poor chap does not come to, you can at least feel you have done all you can."

"Ugh! It makes me shiver to think of it!"

"You didn't shiver when Minnie Carlton fell off the float and almost got drowned," remarked Walter significantly.

"I had too much to think of," was Mrs. King's laconic reply.

"It was the fussing you did over her that saved her life."

"They said so."

"You know it was."

"Mebbe it was," admitted his mother modestly. "But it wasn't any credit to me. I've always lived near the water and I feel at home with drowned people."

"These electric accidents are much the same—easier, if anything, because the lungs are not filled with water."

"I hadn't thought of that."

"This is just a straight case of making a man breathe. You did that for Minnie."

"I contrived to, yes."

"Well, this stunt is the same. Bob said if you once got that through your head and kept in mind what you were driving at instead of flying off the handle you would get on all right."

"Perhaps he's right. He generally is," sighed Mrs. King. "Still it is a worrisome business having him tinkering with those wires all the time. I am thankful you are not doing it. I'd rather you tended dogs."

"But you've forgotten what they're worth," put in His Highness.

"So I had. Oh, dear! I don't see but what I've got to worry about both of you."

"Pooh, Ma! Don't be foolish. Think of the money we'll have by fall, the three of us. Why, we'll be rich!"

"Not rich, with that last payment on the mortgage looming ahead."

"But it is the last—think of that! We won't ever have another to make."

A radiant smile flitted over Mrs. King's face but a moment later it was eclipsed by a cloud.

"There'll be other things to pay; there always are," fretted she.

"Oh, shucks, Ma! Why borrow trouble? It's always hanging round wanting to be borrowed. Why gratify it?"

"I know. It is a foolish habit, isn't it? Still, it was always my way to be prepared for the worst. I've done it all my life."

"Then why not whiffle round now and just for a change be prepared for the best?"

In spite of herself his mother laughed.

"I expect that if I was as young as you and as happy-go-lucky I'd never worry," she answered not unkindly. "But since I'm made with a worrying disposition and bound to worry anyhow, at least I've got something perfectly legitimate to worry about this summer, and you can't deny it. With one son liable to be electrocuted by wireless and the other likely to be run into jail for losing a million-dollar dog I shall have plenty to occupy my mind, not to mention all those boarders that are coming."

"Now, Ma, you know you are actually looking forward to the boarders," Walter declared. "Already you are simply itching to see them and find out what they are like."

"And if I am, what then?" admitted his mother flushing that she should have been read so accurately. "Seeing them isn't all there is to it by a good sight. There is feeding them, and to keep them filled up in this bracing climate is no small matter."

"Did you ever know any one to go hungry in this house?"

"Well, no; I can't say I ever did."

"Do you imagine boarders will eat more than Bob or I?"

"Mercy on us! I hope not."

"Well, you always gave us enough to eat. I guess if you contrived to do that you needn't worry about your boarders," chuckled His Highness.

The last day of June dawned dismal and foggy. A grim gray veil enshrouded Lovell's Harbor, rendering it cold and dreary. Had one been visiting it for the first time he would probably have turned his back on its forlornity and never have come again. The sea was wrapped in a mist so dense that its vast reach of waves was as complete a secret as if they had been actually curtained off from the land. On every leaf trembled beads of moisture and from the eaves of the sodden houses the water dripped with a melancholy trickle.

It was wretched weather for the Crowninshields to be coming to Surfside and yet that they were already on the way the jangling telephone attested.

"I wouldn't have had 'em put in an appearance a day like this for the world!" fretted Jerry Taylor, who for some unaccountable reason seemed to hold himself responsible for the general dampness and discomfort. "Fog ain't nothin' to us folks who are used to it. We've lived by the ocean long enough to love it no matter how it behaves. But for it to go actin' up this way for strangers is a pity. It gives 'em a bad impression same's a ill-behaved child does."

"But you can't help it," ventured Walter, who had just come into sight.

"N-o. Still, somehow, I'm always that anxious for the place to look it's prettiest that I feel to blame when it doesn't."

The boy nodded sympathetically. Deep down within him lay an inarticulate affection for the hamlet in which he had been born and the great throbbing sea that lapped its shores. He therefore understood Jerry's attitude and shared in it far more than he would, perhaps, have been willing to admit. Nevertheless he merely knocked the drops from his rubber hat, muttered that it was a rotten day, and loitered awkwardly about, wondering just what to do.

At last school was at an end. He had squeaked through the examinations with safety if not with glory, and having wheeled his small trunk up to Surfside on a wheelbarrow and deposited it in his room he speculated as to what to do next. There was plenty he might have done. There was no question about that. He might at the very moment have been unpacking his possessions, hanging his clothes in the closet, and stowing away his undergarments in the chest of drawers provided for the purpose. Moreover, there were books to tuck into place on his bookshelves and other minor duties relative to the settling of his new quarters.

Oh, there were a score of things he might have done. His Highness, however, was in much too agitated a frame of mind to turn his attention to such humdrum tasks. Furthermore, since he had pledged himself to bear a hand wherever it was needed, he felt he should be on the spot and within call. And if beneath this worthy motive lurked a certain desire to see whatever there was to be seen, who can say his curiosity was not pardonable? One does not set forth every day to make his fortune. The adventure was very alluring to him who had never tried it.

Possibly Jerry Taylor had enough of the boy in him to understand this. However that might be, he did not hurry the lad indoors to unpack even though he sensed full well that precious time was being wasted; instead, as he started across the lawn he called back over his shoulder:

"If you've nothing better to do, sonny, than to stand shivering in the barn, come along up to the house with me and help bring up some wood; I'm going to start fires burning in the rooms to cheer the folks up and dry 'em off when they get here. To my mind there ain't nothin' like an open fire to right you if you're out of sorts. And likely they will be out of sorts. Mr. Crowninshield will, that's sure. Now I myself don't mind a gray day off and on. It's sorter restful and calming. But these city people can't see it that way. My eye, no! They begin to groan so you can hear 'em a mile away the minute the sun is clouded over; and by the second day of a good northeaster they are done for. You'd think to listen to 'em that the end of the world had come. No motoring! No golf! No tennis! Why, they might as well be dead. They begin to wonder why they ever came here anyway and talk of nothing but how nice it is in New York. Why, you would split your sides laughing to hear Mr. Crowninshield moan for Wall Street and Fifth Avenue. Three days of fog is his limit. After that ropes couldn't tie him here. He tumbles his traps into a suitcase and off he goes to the city."

"Great Scott!" Walter ejaculated.

"Oh, 'tain't a bad thing to have him go, take it by and large. He ain't much addition here when he's fidgeting round, poking into everything and suggesting it better be done some other way. He's much better off somewhere else—he's happier and so are we. By and by he comes back again cheerful as if nothing had happened. Mebbe it's as well you should be told what's in store for you in foggy weather," concluded Jerry, with a touch of humor, "for you'll come in for your share together with the rest of us. Everybody gets it. Most likely you'll hear that an egg-beater is a much better thing to smooth down a dog's hair with than a brush; that all the world knows that and only an idiot uses anything else. Don't smile or venture a yip in reply. Just say you'll be glad to use the egg-beater if he prefers it. Remark that, in fact, you quite hanker to try the egg-beater. To agree with him always takes the wind out of his sails quicker'n anything else. He'll calm down soon as he sees you aren't ruffled and go off and hunt up somebody else to reform. And when the fog blows out to sea his temper will go with it and he will forget he ever suggested an egg-beater. Oh, we understand the boss. He's all right! If you only know how to take him you'll never have a mite of trouble with him."

By this time they had reached the house and having removed rubbers and dripping coats they entered the basement door and proceeded to the cellar. It was not the sort of cellar with which His Highness was familiar although his mother's cellar was clean, as cellars go. This one was immaculate. Indeed it seemed, on glancing about, that one might have done far worse than live in the Crowninshields' cellar. Every inch of the interior was light, dry, and spotless with whitewash, paint, and tiling. Even the coal that filled the bins had taken on a borrowed glory and shone as if polished.

"This is my kingdom!" announced Jerry proudly. "You could eat off the floor were you so minded."

"I should say you could!"

"When once you've set out it's no more work to keep things shipshape than to let 'em go helter-skelter. Now here's a basket. Load into it as many of those birch logs as you can carry and bring 'em upstairs. I've kindlings there already."

While Walter was obeying these instructions Jerry himself was piling up on his lank arm a pyramid of wood, and together the two ascended the stairway and tiptoed through the kitchen. As they went the boy caught a glimpse of gleaming porcelain walls; ebon-hued stoves resplendent with nickel trimmings; a blue and white tiled floor; and smart little window hangings that matched it.

"They don't cook here!" he gasped.

"Everything in the house is electric," explained Jerry, as if he were conducting a sight-seeing party through the Louvre. "All the baking, washing, ironing, bread-making, and cleaning is done by electricity. There's even an electric sewing-machine to sew with, and an electric breeze to keep you cool while you're doing it. If I hadn't seen the thing with my own eyes I'd never have believed it."

He paused to watch the effect of his words.

"'Tain't much like the way you and me are used to," he grinned.

"No."

"I suppose in time you get so nothing knocks the breath out of you. I'm just coming to looking round here without feeling all of a flutter. The place did used to turn me endwise at first, it was so white and awesome. I actually hated to set foot within its walls. Seems 's if my fingers was always all thumbs every time I come inside the room. Still, I had to come in though; there were things I had to do here. So I schooled myself to forget the whiteness, and the blueness, and all the silvery glisten and call it just a kitchen. Besides, I found that grand as it is, it ain't a patch on some of the other things in the house. My eye! It's like the Arabian Nights!"

The Cape Codder stopped quite speechless from retailing these marvels.

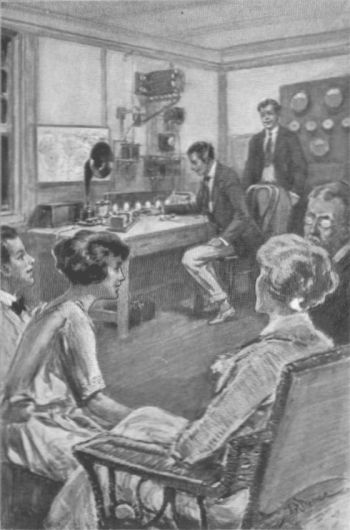

"Yes," he went on presently, "they've got almost everything the electric market has to offer. Last year, though, Mr. Dick got a hankerin' for a wireless set. It appears that you can buy an outfit that will make you hear concerts, sermons, speeches, and about everything that's going on; at least that's what Mr. Crowninshield undertook to tell me, though whether he was fooling or not I couldn't quite make out. Still, it may be true. After what I've seen in this house I'm ready to believe about anything. Was he to say you could put your eye to a hole in the wall and see the Chinese eating rice in Hongkong it wouldn't astonish me."

Walter laughed.

"You can hear music and such things. My brother, who is a wireless operator, told me so. They broadcast all sorts of entertainments—songs, band-playing, sermons, and stories so that those who have amateur apparatus can listen in."

"Broadcast? Listen in?" repeated Jerry vaguely.

"Broadcasting means sending out stuff of a specified wave length from a central station so that amateurs with a range of from two hundred to three hundred meters can pick it up."

Jerry halted midway in the passage.

"Do you mean to say," inquired he, "that a person can sling a song off the top of a wire into the air and tell it to stop when it's gone two hundred meters?"

"Something like that," chuckled Walter, amused.

"I don't believe it!" declared Jerry bluntly.

"But it can be done; really it can."

"No doubt you think you are speaking the truth, youngster," returned the skeptic mildly. "Somebody's stuffed you, though. Such a thing couldn't be, any way in the world."

As if that were the end of the matter Jerry opened a door confronting him and stepped into the great hall, the splendor of which instantly blotted every other thought from Walter King's mind.

Not only was the interior spacious and imposing but it was bewilderingly beautiful and contained marvel after marvel that the lad longed to examine. The large tiger-skin rugs that covered the floor piqued his interest, so did the chiming clock, and a fountain that welled up and splashed into a marble pool filled with goldfish. Why, he could have entertained himself for an hour with this latter wonder alone!

There was, however, no leisure for loitering for on hearing the cadence of the chimes Jerry ejaculated in consternation:

"Eleven o'clock already! Land alive! We'll have to get the fires blazing lively. Why, the folks may be here any minute now. Here, hand me one of those long sticks you've got, sonny; or rather—wait! You know how to lay a fire, don't you?"

"I reckon I've done such a thing once or twice in my lifetime," was the dry response.

"Then go ahead. You build this fire while I go upstairs and start the others," said Jerry. "After you've got this one going you can make one in the library, that red room through those curtains."

"All right."

"Step lively! Don't take all day about it."