This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Renée Mauperin

Author: Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt

Release Date: February 13, 2008 [eBook #24604]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RENÉE MAUPERIN***

The

French Classical Romances

Complete in Twenty Crown Octavo Volumes

Editor-in-Chief

EDMUND GOSSE, LL.D.

With Critical Introductions and Interpretative Essays by

HENRY JAMES PROF. RICHARD BURTON HENRY HARLAND

ANDREW LANG PROF. F. C. DE SUMICHRAST

THE EARL OF CREWE HIS EXCELLENCY M. CAMBON

PROF. WM. P. TRENT ARTHUR SYMONS MAURICE HEWLETT

DR. JAMES FITZMAURICE-KELLY RICHARD MANSFIELD

BOOTH TARKINGTON DR. RICHARD GARNETT

PROF. WILLIAM M. SLOANE JOHN OLIVER HOBBES

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH

BY ALYS HALLARD

WITH A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION

BY JAMES FITZMAURICE-KELLY

A FRONTISPIECE AND NUMEROUS

OTHER PORTRAITS WITH

DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY

OCTAVE UZANNE

P. F. COLLIER & SON

NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1902

BY D. APPLETON & COMPANY

The partnership of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt is probably the most curious and perfect example of collaboration recorded in literary history. The brothers worked together for twenty-two years, and the amalgam of their diverse talents was so complete that, were it not for the information given by the survivor, it would be difficult to guess what each brought to the work which bears their names. Even in the light of these confidences, it is no easy matter to attempt to separate or disengage their literary personalities. The two are practically one. Jamais âme pareille n'a été mise en deux corps. This testimony is their own, and their testimony is true. The result is the more perplexing when we remember that these two brothers were, so to say, men of different races. The elder was a German from Lorraine, the younger was an inveterate Latin Parisian: "the most absolute difference of temperaments, tastes, and characters—and absolutely the same ideas, the same personal likes and dislikes, the same intellectual vision." There may be, as there probably always will be, two opinions as to the value of their writings; there can be no difference of view concerning their intense devotion to literature, their unhesitating rejection of all that might distract them from their vocation. They spent a small fortune in collecting materials for works that were not to find two hundred readers; they passed months, and more months, in tedious researches the results of which were condensed into a single page; they resigned most of life's pleasures and all its joys to dedicate themselves totally to the office of their election. So they lived—toiling, endeavouring, undismayed, confident in their integrity and genius, unrewarded by one accepted triumph, uncheered by a single frank success or even by any considerable recognition. The younger Goncourt died of his failure before he was forty; the elder underwent almost the same monotony of defeat during nearly thirty years of life that remained to him. But both continued undaunted, and, if we consider what manner of men they were and how dear fame was to them, the constancy of their ambition becomes all the more admirable.

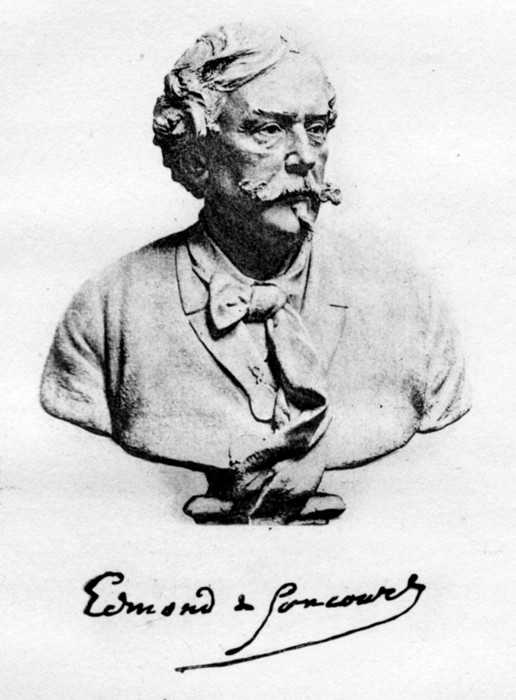

Edmond de Goncourt

Despising, or affecting to despise, the general verdict of their contemporaries, they loved to declare that they wrote for their own personal pleasure, for an audience of a dozen friends, or for the delight of a distant posterity; and, when the absence of all appreciation momentarily weighed them down, they vainly imagined that the acquisition of a new bibelot consoled them. No doubt the passion of the collector was strong in them: so strong that Edmond half forgot his grief for his brother and his terror of the Commune in the pursuit of first editions: so strong that the chances of a Prussian bomb shattering his storehouse of treasures—the Maison d'un artiste—at Auteuil saddened him more than the dismemberment of France. But, even so, the idea that the Goncourts could in any circumstances subordinate literature to any other interest was the merest illusion. Nothing in the world pleased them half so well as the sight of their own words in print. The arrival of a set of proof-sheets on the 1st of January was to them the best possible augury for the new year; the sight of their names on the placards outside the theatres and the booksellers' shops enraptured them; and Edmond, then well on in years, confesses that he thrice stole downstairs, half-clad, in the March dawn, to make sure that the opening chapters of Chérie were really inserted in the Gaulois. These were their few rewards, their only victories. They were fain to be content with such small things—la petite monnaie de la gloire. Still they were persuaded that time was on their side, and, assured as they were of their literary immortality, they chafed at the suggestion that the most splendid renown must grow dim within a hundred thousand years. Was so poor a laurel worth the struggle? This was the whole extent of their misgiving.

Baffled at every point, the Goncourts were unable to account for the unbroken series of disasters which befell them; yet the explanation is not far to seek. For one thing, they attempted so much, so continuously, in so many directions, and in such quick succession, that their very versatility and diligence laid them under suspicion. They were not content to be historians, or philosophers, or novelists, or dramatists, or art critics: they would be all and each of these at once. In every branch of intellectual effort they asserted their claims to be regarded as innovators, and therefore as leaders. Within a month they published Germinie Lacerteux and an elaborate study on Fragonard; and, while they plumed themselves (as they very well might) on their feat, the average intelligent reader joined with the average intelligent critic in concluding that such various accomplishment must needs be superficial. It was not credible that one and the same pair—par nobile fratrum—could be not only close observers of contemporary life, but also authorities on Watteau and Outamaro, on Marie Antoinette and Mlle. Clairon. To admit this would be to emphasize the limitations of all other men of letters. Again, the uncanny element of chance which enters into every enterprise was constantly hostile to the Goncourts. They not only published incessantly: they somehow contrived to publish at inopportune moments—at times when the public interest was turned from letters to politics. Their first novel appeared on the very day of Napoleon III's Coup d'état, and their publisher even refused to advertise the book lest the new authorities should see in the title of En 18—a covert allusion to the 18th Brumaire. It would have been a pleasing stroke of irony had the Ministry of the 16th of May been supported by the country as it was supported by Edmond de Goncourt, for that Ministry intended to prosecute him as the author of La Fille Élisa. La Faustin was issued on the morning of Gambetta's downfall; and the seventh volume of the Journal des Goncourt had barely been published a few hours when the news of Carnot's assassination reached Paris. Lastly, the personal qualities of the brothers—their ostentation of independence, their attitude of supercilious superiority, and, most of all, their fatal gift of irony—raised up innumerable enemies and alienated both actual and possible friends. They gave no quarter and they received none. All this is extremely human and natural; but the Goncourts, being nervous invalids as well as born fighters, suffered acutely from what they regarded as the universal disloyalty of their comrades.

They could not realize that their writings contained much to displease men of all parties, and, living at war with literary society, they sullenly cultivated their morbid sensibility. The simplest trifle stung them into frenzies of inconsistency and hallucination. To-day they denounced the liberty of the press; to-morrow they raged at finding themselves the victims of a Government prosecution. Withal their ferocious wit, there was not a ray of sunshine in their humour, and, instead of smiling at the discomfiture of a dull official, they brooded till their imaginations magnified these petty police-court proceedings into the tragedy of a supreme martyrdom. Years afterward they continually return to the subject, noting with exasperated complacency that the only four men in France who were seriously concerned with letters and art—Baudelaire, Flaubert, and themselves—had been dragged before the courts; and they ended by considering their little lawsuit as one of the historic state trials of the world. Henceforth, in every personal matter—and their art was intensely personal—they lost all sense of proportion, believing that there was a vast Semitic plot to stifle Manette Salomon and that the President had brought pressure on the censor to forbid an adaptation of one of their novels being put upon the boards. Monarchy, Empire, Republic, Right, Centre, Left—no shade of political thought, no public man, no legislative measure, ever chanced to please them. They sought for the causes of their failure in others: it never occurred to them that the fault lay in themselves. Their minds were twin whirlpools of chaotic opinions. Revolutionaries in arts and letters as they claimed to be, they detested novelties in religion, politics, medicine, science, abstract speculation. It never struck them that it was incongruous, not to say absurd, to claim complete liberty for themselves and to denounce ministers for attempting to extend the far more restricted liberty of others. And as with the ordering of their lives, so with their art and all that touched it. Unable to conciliate or to compromise, they were conspicuously successful in stimulating the general prejudice against themselves. They paraded their self-contradictions with a childish pride of paradox. In one breath they deplored the ignorance of a public too uncultivated to appreciate them; in another breath they proclaimed that every government which strives to diminish illiteracy is digging its own grave. Priding themselves on the thoroughness of their own investigations, they belittled the results of learning in others, mocked at the superficial labour of the Benedictines, ridiculed the inartistic surroundings of Sainte-Beuve and Renan, and protested that antiquity was nothing but an inept invention to enable professors to earn their daily bread. Not content with asserting the superiority of Diderot to Voltaire, they pronounced the Abbé Trublet to be the acutest critic who flourished during that eighteenth century which they had come to consider as their exclusive property. Resolute conservatives in theory, piquing themselves on their descent, their personal elegance, their tact and refinement, these worshippers of Marie Antoinette admired the talent shown by Hébert in his infamous Père Duchêne, and then went on to lament the influence of socialism on literature. They were papalini who sympathized with Garibaldi; they looked forward to a repetition of '93, and almost welcomed it as a deliverance from the respectable uniformity of their own time; they trusted to the working men—masons, house-painters, carpenters, navvies—to regenerate an effete civilization and to save society as the barbarians had saved it in earlier centuries. Whatever the value of these views, they can scarcely have found favour among those who rallied to the Second Empire and who imagined that the Goncourts were a pair of firebrands: whereas, in fact, they were petulant, impulsive men of talent, smarting under neglect.

If we were so ingenuous as to take their statements seriously, we might refuse to admit their right to find any place in French literature. For, though it would be easy to quote passages in which they contemn the cosmopolitan spirit, it would be no less easy to set against these their assertions that they are ashamed of being French; that they are no more French than the Abbé Galiani, the Prince de Ligne, or Heine; that they will renounce their nationality, settle in Holland or Belgium, and there found a journal in which they can speak their minds. These are wild, whirling words: the politics of literary men are on a level with the literature of politicians. On their own showing, it does not appear that the Goncourts were in any way fettered. The sum of their achievement, as they saw it, is recorded in a celebrated passage of the preface to Chérie: "La recherche du vrai en littérature, la résurrection de l'art du XVIIIe siècle, la victoire du japonisme." These words are the words of Jules de Goncourt, but Edmond makes them his own. If the brothers were entitled to claim—as they repeatedly claimed—to be held for the leaders of these "three great literary and artistic movements of the second half of the nineteenth century," it is clear that they were justified in thinking that the future must reckon with them. It is equally clear that, if their title proves good, their environment was much less unfavourable than they assumed it to be.

The conclusion is that their sublime egotism disabled them from forming a judicial judgment on any question in which they were personally concerned. They never attempted to reason, to compare, to balance; their minds were filled with the vapour of tumultuous impressions which condensed at different periods into dogmas, and were succeeded by fresh condensations from the same source. But, amid all changes, their self-esteem was constant. They had no hesitation in setting Dunant's Souvenir de Solférino above the Iliad; but when Taine implied that he was somewhat less interested in Madame Gervaisais than in the writings of Santa Teresa, they were startled at his boldness. And, to define their position more precisely, Edmond confidently declares (among many other strange sayings) that the fifth act of La Patrie en Danger contains scenes more dramatically poignant than anything in Shakespeare, and that in La Maison d'un Artiste au XIXe Siècle he takes under his control—though he candidly avows that none but himself suspects it—a capital movement in the history of mankind. These are extremely high pretensions, repeatedly renewed in one form or another—in prefaces, manifestos, articles, letters, conversation, and, above all, in nine invaluable volumes which consist of extracts from a diary covering a period of over forty years. This extraordinary record incidentally embodies the rough sketches of the Goncourts' finished work, but its interest is far wider and more essentially characteristic. Other men have written confessions, memoirs, reminiscences, by the score: mostly books composed long after the events which they relate, recollections revised, reviewed in the light of after events. The Goncourts are perhaps alone in daring to unbosom themselves with an absolute sincerity of their emotions, intentions, aims. If they come forth damaged from such a trial, it is fair to remember that the test is unique, and that no other writers have ever approached them in courage and in what they most valued—truth: la recherche du vrai en littérature.

A most authoritative critic, M. Brunetière, has laid it down that there is more truth, more fidelity to the facts of actual life, in any single romance by Ponson du Terrail or by Gaboriau than in all the works of the Goncourts put together, and so long as we leave truth undefined, this opinion may be as tenable as any other. But it may be well to observe at the outset that the creative work of the Goncourts is not to be condemned or praised en bloc, for the simple reason that it is not a spontaneous, uniform product, but the resultant of diverse forces varying in direction and intensity from time to time. They themselves have recorded that there are three distinct stages in their intellectual evolution. Beginning, under the influence of Heine and Poe, with purely imaginative conceptions, they rebounded to the extremest point of realism before determining on the intermediate method of presenting realistic pictures in a poetic light. Pure imagination in the domain of contemporary fiction seemed to them defective, inasmuch as its processes are austerely logical, while life itself is compact of contradictions; and their first reaction from it was entirely natural, on their own principles. It remains to be seen what sense should be attached to the formula—la recherche du vrai en littérature—in which they summarized their position as regards their predecessors.

Obviously we have to deal with a question of interpretation. The Goncourts did not—could not—pretend that they were the first to introduce truth into literature: they merely professed to have attained it by a different route. The innovation for which they claimed credit is a matter of method, of technique. Their deliberate purpose is to surprise us by the fidelity of their studies, to captivate and convince us by an accumulation of exact minutiæ: in a word, to prove that truth is more interesting than fiction. So history should be written, and so they wrote it. First and last, whatever form they chose, they remained historians. Alleging the example set by Plutarch and Saint-Simon, they make their histories of the eighteenth century a mine of anecdote, a pageant of picturesque situations. State-papers, blue-books, ministerial despatches, are in their view the conventional means used for hoodwinking simpletons and forwarding the interests of a triumphant faction. The most valuable historical material is, as they believed, to be sought in the autograph letter. They held that the secret of the craftiest intriguer will escape him, despite himself, in the expansion of confidential correspondence. The research for such correspondence is to be supplemented by the study of sculpture, paintings, engravings, furniture, broadsides, bills—all of them indispensable for the reconstruction of a past age and for the right understanding of its psychology. But these means are simply complementary. The chief vehicle of authentic truth is the autograph letter, and, though they professed to hold the historical novel in abhorrence, they applied their historical methods to their records of contemporary life. Thus we inevitably arrive at the famous theory of the document humain—a phrase received with much derision when first publicly used in the preface to La Faustin, and a theory conscientiously adopted by many later novelists. And here, again, it is important to realize the restricted extent of the authors' claim.

The Goncourts draw a broad, primary distinction between ancient and modern literature: the first deals mainly with generalities, the second with details. They then proceed to establish an analogous distinction between novels written before and after Balzac's time, the modern novel being based on des documents racontés, ou relevés d'après nature, precisely as formal history is based on des documents écrits. But they make no pretence of having initiated the revolution; their share was limited to continuing Balzac's tradition, to enlarging the field of observation, and especially to multiplying the instruments of research. They declared that Gautier had, so to say, endowed literature with vision; that Fromentin, in describing the silence of the desert, had revealed the literary value of hearing; that with Zola, Loti—and they might surely have added Maupassant—a fresh sense was brought into play: c'est le nez qui entre en scène. Their personal contribution was their nervous sensibility: les premiers nous avons été les écrivains des nerfs. And they were prouder of this morbid quality than of their talent. They were ever on the watch for fragments of talk caught up in drawing-rooms, in restaurants, on omnibuses: ever ready to take notes at death-beds, church, or taverns. Their life was one long pursuit of l'imprévu, le décousu, l'illogique du vrai. These observations they transcribed at night while the impression was still acute, and these they utilized more or less deftly as they advanced towards what they rightly thought to be the goal of art: the perfect adjustment of proportion between the real and the imagined.

It would seem that we are now in a position to judge the Goncourts by their own standard. Le dosage juste de la littérature et de la vie—this formula recurs in one shape or another as a leading principle, and it is supplemented by other still more emphatic indications which should serve to supply a test. Unhappily, with the Goncourts these indications are unsystematic and even contradictory. The elder brother has naturally no hesitation in saying that the highest gift of any writer is his power of creating on paper real beings—comme des êtres créés par Dieu, et comme ayant eu une vraie vie sur la terre—and he is bold enough to add that Shakespeare himself has failed to create more than two or three personages. He protests energetically against the academic virtues, and insists on the importance of forming a personal style which shall reproduce the vivacity, brio, and feverish activity of the best talk. It is, then, all the more disconcerting to learn from another passage in the Journal that the creation of characters and the discovery of an original form of expression are matters of secondary moment. The truth is that if the Goncourts had, as they believed, something new to say, it was inevitable that they should seek to invent a new manner of utterance. Renan was doubtless right in thinking that they were absolutely without ideas on abstract subjects; but they were exquisitely susceptible to every shade and tone of concrete objects, and the endeavour to convey their innumerable impressions taxed the resources of that French vocabulary on whose relative poverty they so often insist. The reproaches brought against them in the matter of verbal audacities by every prominent critic, from Sainte-Beuve in one camp to Pontmartin in the other, are so many testimonies to the fact that they were innovators—apporteurs du neuf—and that their intrepidity cost them dear. Still their boldness in this respect has been generally exaggerated. Setting out as imitators of two such different models as Gautier and Jules Janin, they slowly acquired an individual manner—the manner, say, of Germinie Lacerteux or Manette Salomon—but they never attained the formula which they had conceived as final. It was not given to them to realize their ambition—to write novels which should not contain a single bookish expression, plays which should reveal that hitherto undiscoverable quantity—colloquial speech, raised to the level of consummate art. The famous écriture artiste remained an unfulfilled ideal. The expression, first used in the preface to Les Frères Zemganno, merely foreshadows a possible development of style which shall come into being when realism or naturalism, ceasing to describe the ignoble, shall occupy itself with the attempt to render refinements, reticences, subtleties, and half-tones of a more elusive order. It is an aspiration, a counsel of perfection offered to a younger school by an artist in experiment, who declares the quest to be beyond his powers. It is nothing more.

Leaving on one side these questions of style and manner, it may safely be said that in the novels of the Goncourts the characters are less memorable, less interesting as individuals than as illustrations of an epoch or types of a given social sphere. Charles Demailly, Madame Gervaisais, Manette Salomon, Renée Mauperin, Sœur Philomène, are not so much dramatic creations as figures around which is constituted the life of a special milieu—the world of journalism, of Catholicism seen from two opposite points of view, of artists, of the bourgeoisie, as the case may be. There are in the best work of the Goncourts astonishingly brilliant scenes; there is dialogue vivacious, witty, sparkling, to an extraordinary degree. And this dialogue, as in Charles Demailly, is not only supremely interesting, but intrinsically true to nature. It could not well be otherwise, for the speeches assigned to Masson, Lampérière, Remontville, Boisroger, and Montbaillard are, as often as not, verbatim reports of paradoxes and epigrams thrown off a few hours earlier by Théophile Gautier, Flaubert, Saint-Victor, Banville, and Villemessant. But these flights, true and well worth preserving as they are, fail to impress for the simple reason that they are mere exercises in bravura delivered by men much less concerned with life than with phrases, that they are allotted to subordinate characters, and that they rather serve to diminish than to increase the interest in the central figures. The Goncourts themselves are much less absorbed in life than in writing about it: just as landscapes reminded them of pictures, so did every other manifestation of existence present itself as a possible subject for artistic treatment. They had been called the detectives of history; they became detectives, inquisitors in real life, and, much as they loathed the occupation, they never rested from their task of spying and prying and "documentation." As with Charles Demailly, so with their other books: each character is studied after nature with a grim, revolting persistence. Their aunt, Mlle. de Courmont, is the model of Mlle. de Varandeuil in Germinie Lacerteux; Germinie herself is drawn from their old servant Rose, who had loved them, cheated them, blinded them for half a lifetime; the Victor Chevassier who figures in Quelques créatures de ce temps is sketched from their father's old political ally, Colardez, at Breuvannes; the original of the Abbé Blampoix in Renée Mauperin was the Abbé Caron; the painter Beaulieu and that strange Bohemian Pouthier are both worked into Manette Salomon. And the novel entitled Madame Gervaisais is an almost exact transcription or record of the life of the authors' aunt, Mme. Nephthalie de Courmont: a report so literal that in three hundred pages there are but two trifling departures from the strictest historical truth.

Mommsen himself has not excelled the Goncourts in conscientious "documentation"; and yet, for all their care, their personages do not abide in the memory as living beings. We do not see them as individuals, but as types; and, strangely enough, the authors, despite the remarkable skill with which they materialize many of their impressions, are content to deliver their characters to us as so many illustrations of a species. Thus Marthe Mance in Charles Demailly is un type, l'incarnation d'un âge, de son sexe et d'un rôle de son temps; Langibout is le type pur de l'ancienne école; Madame Gervaisais, too, is un exemple et un type of the intellectual bourgeoise of Louis-Philippe's time; Madame Mauperin is le type of the modern bourgeoise mother; Renée is the type of the modern bourgeoise girl; the Bourjots "represent" wealth; Denoisel is a Parisian—ou plutôt c'était le Parisien. The Goncourts, in their endeavour to be more precise, resort to odd combinations of conflicting elements. Within some twenty pages Renée Mauperin is une mélancolique tintamarresque; the adjectives bourgeoise and diabolique are used to characterize the same thing; the Abbé Blampoix is at once "priest and lawyer, apostle and diplomatist, Fénelon and M. de Foy." And the same types constantly reappear. The physician Monterone in Madame Gervaisais is simply an Italian version of Denoisel in Renée Mauperin; the Abbé Blampoix has his counter-part in Father Giansanti; Honorine is Germinie, before the fall; Nachette and Gautruche might be brothers. The procedure, too, is almost invariable. The antecedents of each personage are given with abundant detail. We have minute information as to the family history of the Mauperins, the Villacourts, Germinie, Couturat, and the rest; and the mention of Father Sibilla involves a brief account of the order of Barefooted Trinitarians from January, 1198, to the spring of 1853! There is a frequent repetition of the same idea with scarcely any verbal change: un dos d'amateur in Renée Mauperin and le dos du cocher in Germinie Lacerteux. And the possibilities of the human back were evidently not exhausted, for at Christmas, 1882, Edmond de Goncourt makes a careful note of the dos de jeune fille du peuple.

It is by no means an accident that the most frequent theme of the brothers is illness: the insanity of Demailly, the tortures of Germinie, the consumption of Madame Gervaisais, the decay of Renée Mauperin, the record of pain in Sœur Philomène, in Les Frères Zemganno, and in other works of the Goncourts. Emotion in less tragic circumstances they rarely convey; and when they attempt it they are prone to stumble into an unimpressive sentimentalism. Their strength lay in pure observation, not in the philosophic or psychological presentment of nature. For their fine powers to have full play, it was necessary that they should deal with things seen: in other words, that feeling should take a concrete shape. Once this condition is fulfilled, they can focus their own impressions and render them with unsurpassable skill. We shall find in them nothing epic, nothing inventive on a grand scale: the transfiguring, ennobling vision of the greatest creators was denied them. But they remain consummate masters in their own restricted province: delicate observers of externals, noting and remembering with unmatched exactitude every detail of gesture, attitude, intonation, and expression. The description of landscape—of the Bois de Vincennes in Germinie Lacerteux, the Forest of Fontainebleau in Manette Salomon, or of the Trastevere quarter in Madame Gervaisais—commonly affords them an occasion for a triumph; but the description of prolonged malady gives them a still greater opportunity. Nor is this due simply to the fact that they, who had never known what it was to enjoy a day of perfect health, spoke from an intimate knowledge of the subject. Each landscape preserves at least its abstract idiosyncrasy; illness is an essentially "typical" state in which individual characteristics diminish till they finally disappear. And it is especially in the portraiture of types, rather than of individuals, that the genius of the Goncourts excels.

In their own opinion, their initiative extended over a vast field and in all directions. They seriously maintained that they were the first to introduce the poor into French fiction, the first to awaken the sentiment of pity for the wretched; they admitted the priority of Dickens, but they apparently forgot that they had likewise been anticipated by George Sand—that George Sand whose merits it took them twenty years to recognise. They forgot, too, that compassion is precisely the quality in which they were most lacking. Gavarni had killed the sentiment of pity in them, and had communicated to them his own mocking, sardonic spirit of inhumanity, his sinister delight in every manifestation of cruelty, baseness, and pain. In their most candid moods they confessed that they were all brain and no heart, that they were without real affections; and their writings naturally suffer from this unsympathetic attitude. But when every deduction is made, it is impossible to deny their importance and significance. For they represent a distinct stage in an organized movement—the reaction against romanticism in the novel and lyrism in the theatre. And there is some basis for their bold assertion that they led the way in every other development of the modern French novel. They believed that they had founded the naturalistic school in Germinie Lacerteux, the psychological in Madame Gervaisais, the symbolic in Les Frères Zemganno, and the satanic in La Faustin. It is unnecessary to recognise all these claims in full: to discuss them at all, even if we deny them, is to admit that the Goncourts were men of striking intellectual force, of singular ambition, of exceptionally rich and diverse gifts amounting, at times, to unquestionable genius. If they were unsuccessful in their attempt to create an entire race of beings as real as any on the planet, their superlative talent produced, in the form of novels, invaluable studies of manners and customs, a brilliant series of monographs on the social history of the nineteenth century. And Daudet and M. Zola, and a dozen others whom it would be invidious to name, may be accounted as in some sort their literary descendants.

It is not unnatural that Edmond de Goncourt should have ended by disliking the form of the novel, which he came to regard as an exhausted convention. His pessimism was universal. Art was dying, literature was perishing daily. The almost universal acceptance of Ibsen and of Tolstoi was in itself a convincing symptom of degeneration, if the vogue of the latter writer were not indeed the result of a cosmopolitan plot against the native realistic school. It was some consolation to reflect that, after all, there was more "philosophy" in Beaumarchais than in Ibsen; that the name of Goncourt was held in honour by Scandinavians and Slavs. Yet it could not be denied that, the world over, aristocracy of every kind was breaking down. To the eyes of the surviving Goncourt all the signs of a last great catastrophe grew visible. Mankind was ill, half-mad, and on the road to become completely insane. There were countless indications of intellectual and physical decadence. Sloping shoulders were disappearing; the physique of the peasant was not what it had been; good food was practically unattainable; in a hundred years a man who had once tasted genuine meat would be pointed out as a curiosity. The probability was, that within half a century there would not be a man of letters in the world; the reporter, the interviewer, would have taken possession. As it was, the younger generation of readers no longer rallied to the Goncourts as it had rallied when Henriette Maréchal was first replayed. The weary old man buried himself in memoirs, biographies, books of travel; then turned to his first loves—to Poe and Heine—and found that "we are all commercial travellers compared to them." But, threatened as he was by blindness, despairing as were his presentiments of what the future concealed, his confidence in the durability of his fame and his brother's fame was undimmed. There would always be the select few interested in two such examples of the littérateur bien né. There would always be the official historians of literature to take account of them as new, perplexing, elemental forces. There would always be the curious who must turn to the Goncourts for positive information. "Our romances," as the brothers had noted forty years earlier, "will supply the greatest number of facts and absolute truths to the moral history of this century." And Edmond de Goncourt clung to the belief, ending, happily and characteristically enough, by conceiving himself and his brother to be "types," and the best of all types: le type de l'honnête homme littéraire, du persévérant dans ses convictions, et du contempteur de l'argent. The praise is deserved. It is a distinction of which greater men might well be proud.

James Fitzmaurice-Kelly.

The Goncourts were the sons of a cavalry officer, commander of a squadron in the Imperial army. Edmond was born at Nancy, on the 26th of May, 1822, and his brother Jules in Paris, on the 17th of December, 1830. They were the grandsons of the deputy of the National Assembly of 1789, Huot de Goncourt. A very close friendship united the brothers from their earliest youth, but it appears to have been in the younger that the irresistible tendency to literature first displayed itself. They were originally drawn almost exclusively to the study of the history of art. They devoted themselves particularly to the close of the eighteenth century, and in their earliest important volumes, "La Révolution dans les Mœurs" (1854), "Histoire de la Société Française pendant la Révolution" (1854), and "Pendant le Directoire" (1855), they invented a new thing, the evolution of the history of an age from the objects and articles of its social existence. They were encouraged to continue these studies further, more definitely concentrating their observations around individuals, and some very curious monographs—made up, as some one said, of the detritus of history—were the result, "Une Voiture de Masques," 1856; "Les Actrices (Armande)," 1856; "Sophie Arnauld," 1857. The most ingenious efforts of the brothers in this direction were, however, concentrated upon "Portraits Intimes du XVIIIe Siècle," 1857-'58, and upon the "Histoire de Marie Antoinette," 1858.

Towards 1860 the Goncourts closed their exclusively historical work, and transferred their minute observation and excessively meticulous treatment of small aspects of life to realistic romance. Their first novel, "Les Hommes de Lettres," 1860 (now known as "Charles Demailly"), showed some lack of ease in using the new medium, but it was followed by "Sœur Philomène," 1861, one of the most finished of their fictions, and this by "Renée Mauperin," 1864; "Germinie Lacerteux," 1864; "Manette Salomon," 1867; and "Madame Gervaisais," 1869. Meanwhile, numerous studies of the art of the bibelot appeared under the name of the two Goncourts, and in particular their great work on "L'Art du XVIIIe Siècle," which began to be published in 1859, although not completed until 1882. All this while, moreover, they were secretly composing their splenetic "Journal." On the 20th of June, 1870, the fair companionship was broken by the death of Jules de Goncourt, and for some years Edmond did no more than complete and publish certain artistic works which had been left unfinished. Of these, the most remarkable were, a monograph on the life and work of Gavarni, 1873; a compilation called "L'Amour au XVIIIe Siècle," 1875; studies of the Du Barry, the Pompadour, and the Duchess of Châteauroux, 1878-'79 (these three afterward united in one volume as "Les Maîtresses de Louis XV"); and notes of a tour in Italy, 1894.

Edmond de Goncourt, however, after several years of silence, returned alone to the composition of prose romance. He published in 1877 "La Fille Élisa," an ultra-realistic tragedy of low life. In 1878, in the very curious story of two mountebanks, "Les Frères Zemganno," he betrayed the secret of his own perennial sorrow. Two more novels, "La Faustin," 1882, and "Chérie," the pathetic portrait of a spoiled child, close the series of his works in fiction. He returned to a close examination of the history of art, and published catalogues raisonnés of the entire work of Watteau (1875) and of Prud'hon (1876). His latest interests were centred around the classical Japanese designers, and he published elaborate monographs on Outamaro (1891) and Hokousaï (1896). In 1885 he collected the Letters of his brother Jules, and issued from 1887 to 1896, in nine volumes, as much as has hitherto been published of the celebrated "Journal des Goncourts."

Edmond de Goncourt died while on a visit to Alphonse Daudet, at Champrosay, the country-house of the latter, on the 16th of July, 1896. He left his considerable fortune, which included valuable collections of bibelots, mainly for the purpose of endowing an Academy of Prose Literature, in opposition to the French Academy. In spite of extreme hostility from the members of his family, and innumerable legal difficulties, this "Académie des Goncourts" was formed, on what seems to be a secure basis, in 1901, and M. Joris Karl Huysmans was elected its first president.

| PAGES | |

| Edmond and Jules de Goncourt | v-xxix |

| James Fitzmaurice-Kelly | |

| Lives of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt | xxxi-xxxiii |

| Edmund Gosse | |

| Renée Mauperin | 1-349 |

| The Portraits of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt | 351-367 |

| Octave Uzanne |

"You don't care about society, then, mademoiselle?"

"You won't tell any one, will you?—but I always feel as though I've swallowed my tongue when I go out. That's the effect society has on me. Perhaps it is that I've had no luck. The young men I have met are all very serious, they are my brother's friends—quotation young men, I call them. As to the girls, one can only talk to them about the last sermon they have heard, the last piece of music they have learned, or their last new dress. Conversation with my contemporaries is somewhat restricted."

"And you live in the country all the year round, do you not?"

"Yes, but we are so near to Paris. Is the piece good they have just been playing at the Opéra Comique? Have you seen it?"

"Yes, it's charming—the music is very fine. All Paris was at the first night—I never go to the theatre except on first nights."

"Just fancy, they never take me to any theatre except the Opéra Comique and the Français, and only to the Français when there is a classical piece on. I think they are terribly dull, classical pieces. Only to think that they won't let me go to the Palais Royal! I read the pieces though. I spent a long time learning 'The Mountebanks' by heart. You are very lucky, for you can go anywhere. The other evening my sister and my brother-in-law had a great discussion about the Opera Ball. Is it true that it is quite impossible to go to it?"

"Impossible? Well——"

"I mean—for instance, if you were married, would you take your wife, just once, to see it?"

"If I were married I would not even take——"

"Your mother-in-law. Is that what you were going to say? Is it so dreadful—really?"

"Well, in the first place, the company is——"

"Variegated? I know what that's like. But then it's the same everywhere. Every one goes to the Marche and the company is mixed enough there. One sees ladies, who are rather queer, drinking champagne in their carriages. Then, too, the Bois de Boulogne! How dull it is to be a young person, don't you think so?"

"What an idea! Why should it be? On the contrary, it seems to me——"

"I should like to see you in my place. You would soon find out what a bore it is to be always proper. We are allowed to dance, but do you imagine that we can talk to our partner? We may say 'Yes,' 'No,' 'No,' 'Yes,' and that's all! We must always keep to monosyllables, as that is considered proper. You see how delightful our existence is. And for everything it is just the same. If we want to be very proper we have to act like simpletons; and for my part I cannot do it. Then we are supposed to stop and prattle to persons of our own sex. And if we go off and leave them and are seen talking to men instead—oh, well, I've had lectures enough from mamma about that! Reading is another thing that is not at all proper. Until two years ago I was not allowed to read the serials in the newspaper, and now I have to skip the crimes in the news of the day, as they are not quite proper.

"Then, too, with the accomplishments we are allowed to learn, we must not go beyond a certain average. We may learn duets and pencil drawing, but if we want anything more, why, it's affectation on our part. I go in for oil-painting, for instance, and that is the despair of my family. I ought only to paint roses and in water-colours. There's quite a current here, though, isn't there? I can scarcely stand."

This was said in an arm of the Seine just between Briche and the Île Saint Denis. The girl and the young man who were conversing were in the water. They had been swimming until they were tired, and now, carried along by the current, they had caught hold of a rope which was fastened to one of the large boats stationed along the banks of the island. The force of the water rocked them both gently at the end of the tight, quivering rope. They kept sinking and then rising again. The water was beating against the young girl's breast; it filled out her woollen bathing-dress right up to the neck, while from behind little waves kept dashing over her which a moment later were nothing but dewdrops hanging from her ears.

She was rather higher up than the young man and had her arms out of the water, her wrists turned round in order to hold the rope more firmly, and her back against the black wood of the boat. Instinctively she kept drawing back as the young man, swayed by the strong current, approached her. Her whole attitude, as she shrank back, suspended from the rope, reminded one of those sea goddesses which sculptors carve upon galleys. A slight tremor, caused partly by the cold and partly by the movement of the river, gave her something of the undulation of the water.

"Ah, now this, for instance," she continued, "cannot be at all proper—to be swimming here with you. If we were at the seaside it would be quite different. We should have just the same bathing costumes as these, and we should come out of a bathing-van just as we have come out of the house. We should have walked across the beach just as we have walked along the river bank, and we should be in the water to the same depth, absolutely like this. The waves would roll us about as this current does, but it would not be the same thing at all; simply because the Seine water is not proper! Oh, dear! I'm getting so hungry—are you?"

"Well, I fancy I shall do justice to dinner."

"Ah! I warn you that I eat."

"Really, mademoiselle?"

"Yes, there is nothing poetical about me at meal-times. If you imagine that I have no appetite you are quite mistaken. You are in the same club as my brother-in-law, are you not?"

"Yes, I am in M. Davarande's club."

"Are there many married men in it?"

"Yes, a great many."

"How odd! I cannot understand why a man marries. If I had been a man it seems to me that I should never have thought of marrying."

"Fortunately you are a woman."

"Ah, yes, that's another of our misfortunes, we women cannot stay unmarried. But will you tell me why a man joins a club when he is married?"

"Oh, one has to be in a club—especially in Paris. Every man of any standing—if only for the sake of going in there for a smoke."

"What! do you mean to say that there are any wives nowadays without smoking-rooms? Why, I would allow—yes, I would allow a halfpenny pipe!"

"Have you any neighbours?"

"Oh, we don't visit much. There are the Bourjots at Sannois, we go there sometimes."

"Ah, the Bourjots! But, here, there cannot be any one to visit."

"Oh, there's the curé. Ha! ha! the first time he dined with us he drank the water in his finger-bowl! Oh, I ought not to tell you that, it's too bad of me—and he's so kind. He's always bringing me flowers."

"You ride, don't you, mademoiselle? That must be a delightful recreation for you."

"Yes, I love riding. It is my one pleasure. It seems to me that I could not do without that. What I like above everything is hunting. I was brought up to that in the part of the world where papa used to live. I'm desperately fond of it. I was seven hours one day in my saddle without dismounting."

"Oh, I know what it is—I go hunting every year in the Perche with M. de Beaulieu's hounds. You've heard of his pack, perhaps; he had them over from England. Last year we had three splendid runs. By-the-bye, you have the Chantilly meets near here."

"Yes, I go with papa, and we never miss one. When we were all together at the last meet there were quite forty horses, and you know how it excites them to be together. We started off at a gallop, and you can imagine how delightful it was. It was the day we had such a magnificent sunset in the pool. Oh, the fresh air, and the wind blowing through my hair, and the dogs and the bugles and the trees flying along before you—it makes you feel quite intoxicated! At such moments I'm so brave, oh, so brave!"

"Only at such moments, mademoiselle?"

"Well—yes—only on horseback. On foot, I own, I am very frightened at night; then, too, I don't like thunder at all—and—well, I'm very delighted that we shall be three persons short for dinner this evening."

"But why, mademoiselle?"

"We should have been thirteen! I should have done the meanest things for the sake of getting a fourteenth—as you would have seen. Ah, here comes my brother with Denoisel; they'll bring us the boat. Do look how beautiful it all is from here, just at this time!"

She glanced round, as she spoke, at the Seine, the river banks on each side, and the sky. Small clouds were sporting and rolling along in the horizon. They were violet, gray, and silvery, just tipped with flashes of white, which looked like the foam of the sea touching the lower part of the sky.

Above them rose the heavens infinite and blue, profound and clear, magnificent and just turning paler as they do at the hour when the stars are beginning to kindle behind the daylight. Higher up than all hung two or three clouds stretching over the landscape, heavy-looking and motionless.

An immense light fell over the water, lying dormant here, flashing there, making the silvery streaks in the shadow of the boats tremble, touching up a mast or a rudder, or resting on the orange-coloured handkerchief or pink jacket of a washerwoman. The country, the outskirts of the town, and the suburbs all met together on both sides of the river. There were rows of poplar trees to be seen between the houses, which were few and far between, as at the extreme limit of a town.

Then there were small, tumble-down cottages, inclosure's planked round, gardens, green shutters, wine-trade signs painted in red letters, acacia trees in front of the doors, old summer arbors giving way on one side, bits of walls dazzlingly white, then some straight rows of manufactories, brick buildings with tile and zinc-covered roofs, and factory bells. Smoke from the various workshops mounted straight upward and the shadow of it fell in the water like the shadows of so many columns.

On one stack was written "Tobacco," and on a plaster façade could be read "Doremus Labiche, Boats for Hire."

Over a canal which was blocked up with barges, a swing-bridge lifted its two black arms in the air. Fishermen were throwing and drawing in their lines. The sound of wheels could be heard, carts were coming and going. Towing-ropes scraped along the road, which was hard, rough, black, and dyed all colours by the unloading of coal, mineral refuse, and chemicals.

From the candle, glucose, and fecula manufactories and sugar-refining works which were scattered along the quay, surrounded by patches of verdure, there was a vague odour of tallow and sugar which was carried away by the emanations from the water and the smell of tar. The noise from the foundries and the whistle of steam engines kept breaking the silence of the river.

It was like Asnières, Saardam, and Puteaux combined, one of those Parisian landscapes on the banks of the Seine such as Hervier paints, foul and yet radiant, wretched yet gay, popular and full of life, where Nature peeps out here and there between the buildings, the work and the commerce, like a blade of grass held between a man's fingers.

"Isn't it beautiful?"

"Well, to tell the truth, I am not in raptures about it. It's beautiful—in a certain degree."

"Oh, yes, it is beautiful. I assure you that it is very beautiful indeed. About two years ago at the Exhibition there was an effect of this kind. I don't remember the picture exactly, but it was just this. There are certain things that I feel——"

"Ah, you have an artistic temperament, mademoiselle."

"Oh!" exclaimed the young girl, with a comic intonation, plunging forthwith into the water. When she appeared again she began to swim towards the boat which was advancing to meet her. Her hair had come down, and was all wet and floating behind her. She shook it, sprinkling the drops of water all round.

Evening was drawing near and rosy streaks were coming gradually into the sky. A breath was stirring over the river, and at the tops of the trees the leaves were quivering. A small windmill, which served for a sign over the door of a tavern, began to turn round.

"Well, Renée, how have you enjoyed the water?" asked one of the rowers as the young girl reached the steps placed at the back of the boat.

"Oh, very much, thanks, Denoisel," she answered.

"You are a nice one," said the other man, "you swim out so far—I began to get uneasy. And what about Reverchon? Ah, yes, here he is."

Charles Louis Mauperin was born in 1787. He was the son of a barrister who was well known and highly respected throughout Lorraine and Barrois, and at the age of sixteen he entered the military school at Fontainebleau. He became sublieutenant in the Thirty-fifth Regiment of infantry, and afterward, as lieutenant in the same corps, he signalized himself in Italy by a courage which was proof against everything. At Pordenone, although wounded, surrounded by a troop of the enemy's cavalry and challenged to lay down arms, he replied to the challenge by giving the command to charge the enemy, by killing with his own hand one of the horsemen who was threatening him and opening a passage with his men, until, overcome by numbers and wounded on the head by two more sword-thrusts, he fell down covered with blood and was left on the field for dead.

After being captain in the Second Regiment of the Mediterranean, he became captain aide-de-camp to General Roussel d'Hurbal, went through the Russian campaign with him, and was shot through the right shoulder the day after the battle of Moscow.

In 1813, at the age of twenty-six, he was an officer of the Legion of Honour and major in the army. He was looked upon as one of the commanding officers with the most brilliant prospects, when the battle of Waterloo broke his sword for him and dashed his hopes to the ground.

He was put on half-pay, and, with Colonel Sauset and Colonel Maziau, he entered into the Bonapartist conspiracy of the Bazar français.

Condemned to death by default, as a member of the managing committee, by the Chamber of Peers, constituted into a court of justice, he was concealed by his friends and shipped off to America.

On the voyage, not knowing how to occupy his active mind, he studied medicine with one of his fellow-passengers who intended taking his degree in America, and on arriving, Mauperin passed the necessary examinations with him. After spending two years in the United States, thanks to the friendship and influence of some of his former comrades, who had been taken again into active service, he obtained pardon and was allowed to return to France.

He went back to the little town of Bourmont, to the old home where his mother was still living. This mother was one of those excellent old ladies so frequently met with in the provincial France of the eighteenth century. She was gay, witty, and fond of her glass of wine. Her son adored her, and on finding her ill and under doctor's orders to avoid all stimulants, he at once gave up wine, liqueurs, and coffee for her sake, thinking that it would be easier for her to abstain if he shared her privations. It was in compliance with her request, and by way of humouring her sick fancies, that he married a cousin for whom he had no especial liking. His mother had selected this wife for her son on account of a joint claim to certain land, fields which touched each other, and all the various considerations which tend to unite families and blend together fortunes in the provinces.

After the death of his mother, the narrow life in the little town, which had no further attraction for him, seemed irksome, and, as he was not allowed to dwell in Paris, M. Mauperin sold his house and land in Bourmont, with the exception of a farm at Villacourt, and went to live with his young wife on a large estate which he bought in the heart of Bassigny, at Morimond. There were the remains of a large abbey, a piece of land worthy of the name which the monks had given it—"Mort-au-monde"—a wild, magnificent bit of Nature with a pool of some hundred acres or more and a forest of venerable oak trees; meadows with canals of freestone where the spring-tide flowed along under bowers of trees, a veritable wilderness where the vegetation had been left to itself since the Revolution; springs babbling along in the shade; wild flowers, cattle-tracks, the remains of a garden and the ruins of buildings. Here and there a few stones had survived. The door was still to be seen, and the benches were there on which the beggars used to sit while taking their soup; here the apse of a roofless chapel and there the seven foundations of walls à la Montreuil. The pavilion at the entrance, built at the beginning of the last century, was all that was still standing; it was complete and almost intact.

M. Mauperin took up his abode in this and lived there until 1830, solitary and entirely absorbed in his studies. He gave himself up to reading, educating himself on all subjects, and reaping knowledge in every direction. He was familiar with all the great historians, philosophers, and politicians, and was thoroughly master of the industrial sciences. He only left his books when he felt the need of fresh air, and then he would rest his brain and tire his body with long walks of some fifteen miles across the fields and through the woods.

Every one was accustomed to see him walk like this, and the country people recognised him in the distance by his step, his long frock-coat, all buttoned up, his officer's gait, his head always slightly bent, and the stick, made from a vine-stalk, which he used as a cane. The only break in his secluded and laborious life was at election time. M. Mauperin then put in an appearance everywhere from one end of the department to the other. He drove about the country in a trap, and his soldierly voice could be heard rousing the electors to enthusiasm at all their meetings; he gave the word of command for the charge on the Government candidates, and to him all this was like war once more.

When the election was over he left Chaumont and returned to his regular routine and to the obscure tranquility of his studies.

Two children had come to him—a boy in 1826 and a girl in 1827. After the Revolution of 1830 he was elected deputy. When he took his seat in the chamber, his American ideas and theories were very much like those of Armand Carrel. His animated speeches—brusque, martial, and full of feeling—made quite a sensation. He became one of the inspirers of the National after being one of its first shareholders, and he suggested articles attacking the budget and the finances.

The Tuileries made advances to him; some of his former comrades, who were now aides-de-camp under the new king, sounded him with the promise of a high military position, a generalship in the army, or some honour for which he was still young enough. He refused everything point-blank. In 1832 he signed the protestation of the deputies of the Opposition against the words "Subjects of the King," which had been pronounced by M. de Montalivet, and he fought against this system until 1835.

That year his wife presented him with a child, a little girl whose arrival stirred him to the depths of his being. His other two children had merely given him a calm joy, a happiness without any gaiety. Something had always seemed wanting—just that something which brightens a father's life and makes the home ring with laughter.

M. Mauperin loved his two children, but he did not adore them. The fond father had hoped to delight in them, and he had been disappointed. Instead of the son he had dreamed of—a regular boy, a mischievous little urchin, one of those handsome little dare-devils with whom an old soldier could live over again his own youth and hear once more, as it were, the sound of gunpowder—M. Mauperin had to do with a most rational sort of a child, a little boy who was always good, "quite a young lady," as he said himself. This had been a great trouble to him, as he felt almost ashamed to have, as his son and heir, this miniature man who did not even break his toys.

With his daughter, M. Mauperin had had the same disappointment. She was one of those little girls who are women when they are born, and who play with their parents merely to amuse them. She scarcely had any childhood, and at the age of five, if a gentleman called to see her father, she always ran away to wash her hands. She would be kissed on certain spots, and she seemed to dread being ruffled or inconvenienced by a father's caresses and love.

Thus repelled, M. Mauperin's affection, so long hoarded up, went out to the cradle of the little newcomer whom he had named Renée after his mother. He spent whole days with his little baby-girl in divine nonsense. He would keep taking off her little cap to look at her silky hair, and he taught her to make grimaces which charmed him. He would lie down beside her on the floor when she was rolling about half naked with all a child's delightful unconsciousness. In the night he would get up to look at her asleep, and would pass hours listening to this first breath of life, so like the respiration of a flower. When she woke up he would be there to have her first smile—that smile of little girl-babies which comes from out of the night as though from Paradise. His happiness kept changing into perfect bliss; it seemed to him that the child he loved so much was a little angel from heaven.

What joy he had with her at Morimond! He would wheel her all round the house in a little carriage, and at every few steps turn round to look at her screaming with laughter, with the sunshine playing on her cheeks, and her little supple, pink foot curled up in her hand. Or he would take her with him when he went for a walk, and would go as far as a village and let the child throw kisses to the people who bowed to him, or he would enter one of the farm-houses and show his daughter's teeth with great pride. On the way, the child would often go to sleep in his arms, as she did with her nurse. At other times he would take her into the forest, and there, under the trees full of robin-redbreasts and nightingales, towards the end of the day when there are voices overhead in the woods, he would experience the most unutterable joy on hearing the child, impressed by the noises around, try to imitate the sounds, and to murmur and prattle as though she were answering the birds and speaking to the singing heavens.

Mme. Mauperin had not given this last daughter so hearty a welcome. She was a good wife and mother, but Mme. Mauperin was eaten up with that pride peculiar to the provinces—namely, the pride of money. She had made all her arrangements for two children, but the third one was not welcome, as it would interfere with the pecuniary affairs of the other two, and, above all, would infringe on her son's share. The division of land which was now one estate, the partition of wealth which had accumulated, and in consequence the lowering of social position in the future and of the importance of the family—all this was what the second little daughter represented to her mother.

M. Mauperin very soon had no more peace. The mother was constantly attacking the politician, and reminding the father that it was his duty to sacrifice himself to the interests of his children. She endeavoured to separate him from his friends and to make him forsake his party and his fidelity to his ideas. She made fun of what she called his tomfoolery, which prevented him from turning his position to account. Every day there were fresh attacks and reproaches until he was fairly haunted by them; it was the terrible battle of all that is most prosaic against the conscience of a Deputy of the Opposition. Finally, M. Mauperin asked his wife for two months' truce for reflection, as he, too, would have liked his beloved Renée to be rich. At the end of the two months he sent his resignation in to the Chamber and opened a sugar-refinery at Briche.

That had been twenty years ago. The children had grown up and the business was thriving. M. Mauperin had done very well with his refinery. His son was a barrister, his elder daughter married, and Renée's dowry was waiting for her.

Every one had gone into the house, and in a corner of the drawing-room, with its chintz hangings gay with bunches of wild flowers, Henri Mauperin, Denoisel, and Reverchon were talking. Near to the chimney-piece, Mme. Mauperin, with great demonstrations of affection, was greeting her son-in-law and daughter, M. and Mme. Davarande, who had just arrived. She felt obliged on this occasion to make a display of family feeling and to exhibit her motherly love.

The greeting between Mme. Mauperin and Mme. Davarande was scarcely over when a little old gentleman entered the drawing-room quietly, wished Mme. Mauperin good-evening with his eyes as he passed, and walked straight across to the group where Denoisel was.

This little gentleman wore a dress-coat and had white whiskers. He was carrying a portfolio under his arm.

"Do you know that?" he asked Denoisel, taking him into a window recess and half opening his folio.

"That? I should just think I do. It's the 'Mysterious Swing,' an engraving after Lavrience's."

The little old gentleman smiled.

"Yes, but look," he said, and he half opened his portfolio again, but in such a way that Denoisel could only just see inside.

"'Before letters.' It's a proof before letters! Can you see?"

"Perfectly."

"And margins!—a gem, isn't it? They didn't give it me, I can tell you, the thieves! It was run up—and by a woman, too!"

"Oh, of course!"

"A cocotte, who asked to see it every time I went any higher. The rascal of an auctioneer kept saying, 'Pass it to the lady.' At last I got it for five pounds eight. Oh, I wouldn't have paid one halfpenny more."

"I should think not! If I had only known—why, there's a proof like that, exactly like it, at Spindler's, the artist's—and with larger margins, too. He does not care about Louis Seize things, Spindler. If I had only asked him!"

"Good heavens!—and before letters, like mine? Are you quite sure?"

"Before letters—before—Oh, yes, it's an earlier one than yours. It's before—" and Denoisel whispered something to the old man which brought a flush of pleasure to his face and a moisture to his lips.

Just at this moment M. Mauperin entered the drawing-room with his daughter. She was leaning on his arm, her head slightly thrown back in an indolent way, rubbing her hair against the sleeve of her father's coat as a child does when it is being carried.

"How are you?" she said as she kissed her sister. She then held her forehead to her mother's lips, shook hands with her brother-in-law, and ran across to the little man with the portfolio.

"Can I see, god-papa?"

"No, little girl, you are not grown-up enough yet," he replied, patting her cheek in an affectionate way.

"Ah, it's always like that with the things you buy!" said Renée, turning her back on the old man, who tied up the ribbon of his portfolio with the special little bow so familiar to the fingers of print collectors.

"Well, what's this I hear?" suddenly exclaimed Mme. Mauperin, turning to her daughter.

Reverchon was sitting next her, so near that her dress touched him every time she moved.

"You were both carried away by the current," she continued. "It was dangerous, I am sure! Oh, that river! I really cannot understand how M. Mauperin allows——"

"Mme. Mauperin," replied her husband, who was by the table looking through an album with his daughter, "I do not allow anything—I tolerate——"

"Coward!" whispered Renée to her father.

"I assure you, mamma, there was no danger," put in Henri Mauperin. "There was no danger at all. They were just slightly carried along by the current, and they preferred holding on to a boat to going half a mile or so lower down the river. That was all! You see——"

"Ah, you comfort me," said Mme. Mauperin, the serenity of her expression gradually returning at her son's words. "I know you are so prudent, but, you see, M. Reverchon, our dear Renée is so foolish that I am always afraid. Oh, dear, there are drops of water on her hair now. Come here and let me brush them off."

"M. Dardouillet!" announced a servant.

"A neighbour of ours," said Mme. Mauperin in a low voice to Reverchon.

"Well, and where are you now?" asked M. Mauperin, as he shook hands with the new arrival.

"Oh, we are getting on—we are getting on—three hundred stakes done to-day."

"Three hundred?"

"Three hundred—I fancy it won't be bad. From the green-house, you see, I am going straight along as far as the water, on account of the view. Fourteen or sixteen inches of slope—not more. If we were on the spot I shouldn't have to explain. On the other side, you know, I shall raise the path about three feet. When all that's done, M. Mauperin, do you know that there won't be an inch of my land that will not have been turned over?"

"But when shall you plant anything, M. Dardouillet?" asked Mlle. Mauperin. "For the last three years you have only had workmen in your garden; sha'n't you have a few trees in some day?"

"Oh, as to trees, mademoiselle, that's nothing. There's plenty of time for all that. The most important thing is the plan of the ground, the hills and slopes, and then afterward trees—if we want them."

Some one had just come in by a door leading from another room. He had bowed as he entered, but no one had seen him, and he was there now without any one noticing him. He had an honest-looking face and a head of hair like a pen-wiper. It was M. Mauperin's cashier, M. Bernard.

"We are all here; has M. Bernard come down? Ah, that's right!" said M. Mauperin on seeing him. "Suppose we have dinner, Mme. Mauperin, these young people must be hungry."

The solemnity of the first few moments when the appetite is keen had worn off, and the buzz of conversation could be heard in place of the silence with which a dinner usually commences, and which is followed by the noise of spoons in the soup plates.

"M. Reverchon," began Mme. Mauperin. She had placed the young man by her, in the seat of honour, and she was amiability itself, as far as he was concerned. She was most attentive to him and most anxious to please. Her smile covered her whole face, and even her voice was not her every-day voice, but a high-pitched one which she assumed on state occasions. She kept glancing from the young man to his plate and from his plate to a servant. It was a case of a mother angling for a son-in-law. "M. Reverchon, we met a lady just recently whom you know—Mme. de Bonnières. She spoke so highly of you—oh, so highly!"

"I had the honour of meeting Mme. de Bonnières in Italy—I was even fortunate enough to be able to render her a little service."

"Did you save her from brigands?" exclaimed Renée.

"No, it was much less romantic than that. Mme. de Bonnières had some difficulty about the bill at her hotel. She was alone and I prevented her from being robbed."

"It was a case of robbers, anyhow, then," said Renée.

"One might write a play on the subject," put in Denoisel, "and it would be quite a new plot—the reduction of a bill leading to a marriage. What a good title, too, 'The Romance of an Awkward Moment, à la Rabelais!'"

"Mme. de Bonnières is a very nice woman," continued Mme. Mauperin. "I like her face. Do you know her, M. Barousse?" she asked, turning to Renée's godfather.

"Yes, she is very pleasant."

"Oh! why, god-papa, she's like a satyr!" exclaimed Renée.

When the word was out some of the guests smiled, and the young girl, turning red, hastened to add: "I only mean she has a face like one."

"That's what I call mending matters!" said Denoisel.

"Did you stay long in Italy, monsieur?" asked M. Mauperin, by way of changing the subject.

"Six months."

"And what did you think of it?"

"It's very interesting, but one has so much discomfort there. I never could get used to drinking coffee out of glasses."

"Italy is the most wretched place to go to; it is the least practical of all places," said Henri Mauperin. "What a state agriculture is in there—and trade, too! One day in Florence at a masked ball I asked the waiter at a restaurant if they would be open all night. 'Oh, no, sir,' he said, 'we should have too many people here.' That's a fact, I heard it myself, and that shows you what the country is. When one thinks of England, of that wonderful initiative power of individuals and of the whole nation, too; when one has seen the business genius of the London citizen and the produce of a Yorkshire farm—Oh, a fine nation that!"

"I agree with Henri," said Mme. Davarande, "there is something so distinguished about England. I like the politeness of the English people, and I approve of their way of always introducing people. Then, too, they wrap your change up in paper—and some of their dress materials have quite a style of their own. My husband bought me a poplin dress at the Exposition—Oh, mamma, I have quite decided about my cloak. I was at Alberic's—it's most amusing. He lets one of the girls put a cloak over your shoulders and then he walks round you and just marks with an ebony ruler the places where it does not fit; he scarcely touches you with it, but just gives little taps—like that—and the girl marks each tap with chalk. Oh, he certainly has a lot of character, that Alberic! And then he's the only one—there isn't another place—he has such good style for cloaks. I recognised two of his yesterday at the races. He is very expensive though."

"Oh, those people get what they like to ask," said Reverchon. "My tailor, Edouard, has just retired—he's made over a hundred thousand pounds."

"Oh, well, quite right," remarked M. Barousse. "I'm always very glad when I see things like that. The workers get the money nowadays—that's just what it is. It's the greatest revolution since the beginning of the world."

"Yes," said Denoisel, "a revolution that makes one think of the words of Chapon, the celebrated thief: 'Robbery, Monsieur le Président, is the principal trade of the world!'"

"Were the races good?" asked Renée.

"Well, there were plenty of people," answered Mme. Davarande.

"Very good, mademoiselle," said Reverchon. "The Diana prize especially was very well run. Plume de coq, that they reckoned at thirty-five, was beaten by Basilicate by two lengths. It was very exciting. The hacks was a very good race, too, although the ground was rather hard."

"Who is the Russian lady who drives four-in-hand, M. Reverchon?" asked Mme. Davarande.

"Mme. de Rissleff. She has some splendid horses, some thoroughbred Orloffs."

"You ought to join the Jockey Club, Jules, for the races," said Mme. Davarande, turning to her husband. "I think it is so common to be with everybody. Really if one has any respect for one's self—a woman I mean—there is no place but the jockey stand."

"Ah, a mushroom patty!" exclaimed M. Barousse. "Your cook is surpassing herself, she really is a veritable cordon-bleu. I shall have to pay her my compliments before leaving."

"I thought you never eat that dish," said Mme. Mauperin.

"I did not eat it in 1848—and I did not eat it up to the second of December. Do you think the police had time then to inspect mushrooms? But now that there is order again."

"Henriette," said Mme. Mauperin to Mme. Davarande, "I must scold your husband. He neglects us. We have not seen you for three weeks, M. Davarande."

"Oh, my dear mother, if you only knew all I have had to do! You know I am on very good terms with Georges. His father has his time taken up at the Chamber and the business falls on Georges as principal. There are hundreds of things that he can only trust to people in whom he has confidence—friends, in fact. There was that big affair—that début at the Opéra. There was no end of interviews and parleyings and journeys backward and forward. It would not have done to have had any strife between the two ministries. Oh, we have been very busy lately. He is so considerate that I could not——"

"So considerate?" put in Denoisel. "He might pay your cab-fares at least. It's more than two years since he promised you a sub-prefectship."

"My dear Denoisel, it's more difficult than you imagine. And then, too, when one does not care about going too far from Paris. Besides, between ourselves, I can tell you that it's almost arranged. In about a month from now I have every reason to believe——"

"What début were you speaking of?" asked Barousse.

"Bradizzi's," answered Davarande.

"Ah, Bradizzi! Isn't she astounding!" said Reverchon. "She has some runs that are wonderfully light. The other day I was in the manager's box on the stage and we couldn't hear her touch the ground when she was dancing."

"We expected to see you yesterday evening, Henri," said Mme. Davarande to her brother.

"Yesterday I was at my lecture," he answered.

"Henri has been appointed reporter," said Mme. Mauperin proudly.

"Ah," put in Denoisel, "the d'Aguesseau lecture? That's still going on then, your speechifying affair? How many are there in it?"

"Two hundred."

"And all statesmen? It's quite alarming. What were you to report on?"

"A law that was proposed with reference to the National Guard."

"You go in for everything," said Denoisel.

"I am sure you do not belong to the National Guard, Denoisel?" observed M. Barousse.

"No, indeed!"

"And yet it is an institution."

"The drums affirm that it is that, M. Barousse."

"And you do not vote either, I would wager?"

"I would not vote under any pretext."

"Denoisel, I am sorry to say so, but you are a bad citizen. You were born as you are, I am not blaming you, but the fact remains——"

"A bad citizen—what do you mean?"

"Well, you are always in opposition to the laws."

"I am?"

"Yes, you are. Without going any farther back, take for instance the money you came into from your Uncle Frédéric. You handed it over to his illegitimate children——"

"What of that?"

"Well, that is what I call an illegal action, most deplorable and blameworthy. What does the law mean? It is quite clear—the law means that children not born in wedlock should not be able to inherit their father's money. You were not ignorant of this, for I told you that it was so; your lawyer told you and the code told you. What did you do? Why, you let the children have the money. You ignored the code, the spirit of the law, everything. To give up your uncle's fortune in that way, Denoisel, was rendering homage to low morals. It was simply encouraging——"

"I know your principles in the matter, M. Barousse. But what was I to do? When I saw those three poor lads I said to myself that I should never enjoy the cigars I smoked with their bread-money. No one is perfect——"

"All that is not law. When there is a law there is some reason for it, is there not? The law is against immorality. Suppose others imitated you——"