The Project Gutenberg EBook of Heath's Modern Language Series: Mariucha, by Benito Pérez Galdós This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Heath's Modern Language Series: Mariucha Author: Benito Pérez Galdós Release Date: March 25, 2008 [EBook #24917] Language: Spanish Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HEATH'S MOD. LANG. SER.: MARIUCHA *** Produced by Stan Goodman, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

POR

EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION, NOTES, AND VOCABULARY

BY

S. GRISWOLD MORLEY, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Spanish in the University of California

| D. C. HEATH & CO., PUBLISHERS | ||

| BOSTON | NEW YORK | CHICAGO |

Copyright, 1921,

BY D. C. Heath & Co.

Some one will naturally ask: "Why did not the editor select Galdós' best play, El abuelo, for publication?" I should like to reply to this question in advance. El abuelo, with all its beauties, has certain features which make it slightly undesirable for use by classes of American students in High Schools and the elementary years of College. First, one of its beauties is itself a drawback for this particular purpose; namely, the rather vague and abstract moral it conveys. Then, the main-spring of the plot, like that of Electra, lies in a dubious obscurity to which it is not necessary to direct the attention of young people. Mariucha, on the other hand, presents clean-cut, open problems of daily life, and they are also problems which any American can readily understand, not local Spanish anachronisms. I chose Mariucha believing it to be the best fitted for general class use among all the dramas of Galdós; and I hope that Spanish teachers may not find me wrong.

The Introduction is confined to a discussion of Galdós as a dramatic author, since a study of his entire work or of his influence on his generation would be quite out of place.

To my friend and colleague Professor Erasmo Buceta I am deeply grateful for generous and suggestive help; and I am indebted to Doña María Pérez-Galdós de Verde for information which gives the Bibliography an accuracy it could not otherwise have had.

S.G.M.

October, 1920.

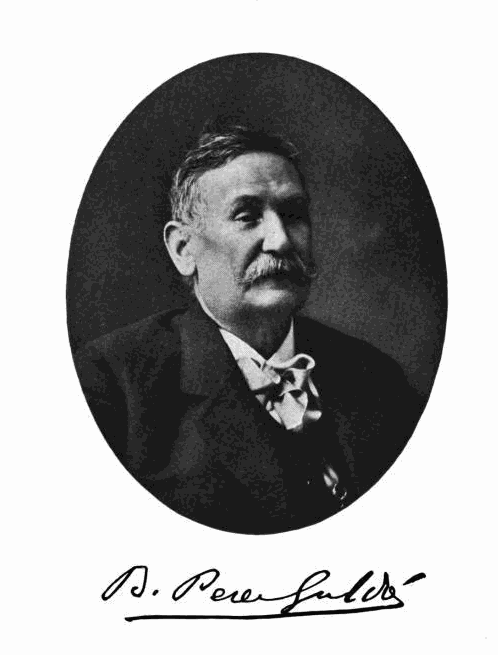

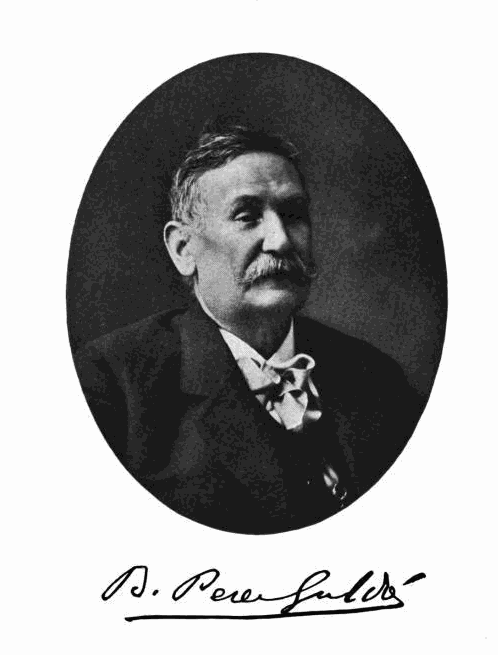

A. THE LIFE OF D. BENITO PÉREZ GALDÓS

Benito Pérez Galdós was born May 10, 1843, in Las Palmas, Grand Canary Island. The first school he attended was kept by English people; hence perhaps his great admiration for the English. He showed an early and lasting talent for music and drawing. In 1864 or 1865 he went alone to Madrid to study law, which he disliked. He made slow progress, but completed the course in 1869. Latin was his favorite study, and he never practised law.

His first writing was done for Madrid newspapers; he reported sessions of the Cortes, and wrote all sorts of general articles. During this period he wrote two poetic dramas, never performed. His failure to gain the stage turned him to the novel, and he did not again attempt drama till 1892. Dickens and Balzac most influenced his conception of the novel. His first book, La fontana de oro, was published in 1870; the first of the Episodios nacionales, Trafalgar, in 1873. Since then the Episodios reached the number of forty-six; the Novelas de la primera época (those based on history rather than on observation), seven; the Novelas españolas contemporáneas (based on observation), twenty-four; dramas and comedies, twenty-one; opera, one.

Galdós was never entirely dependent on his pen for his living; he always had a slight income from family property. He never married. He traveled all over Europe at different times, and made a special study of Spain, journeying third class, in carriage and on horse, throughout the country, always by day, and usually in the company of a servant. Fondness for children was a distinctive trait. In 1897 he became a member of the Spanish Academy. He was a liberal deputy for Porto Rico from 1886 to 1890. In 1907 he was elected deputy from Madrid by the Republican party, and retained the post for some years, but without any liking for politics. In 1912 he became completely blind.

For many years he published his own works from the famous office at Hortaleza 132; but handling no other books and cheated by an unscrupulous partner, he finally had to transfer the business to a regular firm. Galdós' novels have enjoyed an enormous sale, but at the low price of two or three pesetas a volume, instead of the customary four or five. In 1914 Galdós was represented as in poverty, for reasons never made clear, and a public subscription opened for his benefit; an episode sadder for the sponsors than for him. He died on Jan. 4, 1920.

B. BENITO PÉREZ GALDÓS AS A DRAMATIC WRITER

I. The Background.—The closing decades of the nineteenth century saw a curious state of affairs in the drama of Spain. They were years when dogmatic naturalism, with its systematically crude presentation of life, was at its height in France, and France, during the nineteenth century, had more often than not set the fashion for Spain in literary matters. The baldness of Zola and the pessimism of de Maupassant were quickly taken up on the French stage, and Henri Becque and the Théâtre libre served slices of raw life to audiences fascinated by a tickling horror. The same naturalism had, indeed, crossed the Pyrenees and found a few half-hearted disciples among Spanish novelists, but, on the whole, Spanish writers resolutely refused to follow this particular French current.

During the years from 1874 to 1892, when Europe was permeated with the new doctrine, the stage of Spain was dominated by one man, who gave no sign that he had ever heard the name of Zola. José Echegaray held the audiences of Madrid for twenty years with his hectic and rhetorical plays. The great dramatic talent of this mathematician and politician drew upon the cheap tricks of Scribe and the appalling situations of Sardou, and combined them with a few dashes of Ibsenian thesis and the historical pundonor, to form a dose which would harrow the vitals of the most hardened playgoer. Only a gift of sonorous, rather hollow lyrism and a sincere intention to emphasize psychology saved the work of this belated Romanticist from being the cheapest melodrama.

Romanticism is never wholly out of season in Spain, and that is doubtless why the art of Echegaray held its own so long, for it was neither novel nor especially perfect. In spite of the solitary and unrewarded efforts of Enrique Gaspar, a Spanish John the Baptist of realism in the drama, the reaction was slow in coming, and the year 1892 may be said to mark its arrival. That was the date of Realidad, Pérez Galdós' first drama. Two years later Jacinto Benavente made his début with El nido ajeno. In 1897 the brothers Quintero produced their first characteristic work. It will be seen that although the contemporary era of literature in Spain is generally considered to date from the Spanish-American war, the remarkable efflorescence of her drama was well under way before that event. The new school, of which Pérez Galdós is admitted to be the father, is a school of literary and social progress, vitally interested in a new Spain, where the conditions of life may be more just.

II. Galdós Turns from Novel to Drama.—When Realidad was performed, Galdós was the most popular novelist in Spain, the peer of any in his own generation, and the master of the younger men of letters. He was known as a radical, an anti-clerical, who exercised a powerful influence upon the thought of his nation, but, above all, as a marvelous creator of fictional characters. He had revealed Spain to herself in nineteen novels of manners, and evoked her recent past in twenty historical novels. He had proved, in short, that in his own sphere he was one of the great vital forces of modern times.

What persuaded this giant of the novel to depart from the field of his mastery and attempt the drama, in which he was a novice? Was it because he desired a more direct method of influencing public opinion in Spain?[1] Was it, as Sra. Pardo Bazán suggests, with the hope of infusing new life into the Spanish national drama, which had been too long in a rut? Both these motives may have been present, but I do not doubt that the chief was the pure creative urge, the eagerness of an explorer to conquer an unknown region. The example of certain French novelists, his contemporaries, was not such as to encourage him. Zola, Daudet, de Maupassant, the de Goncourts, had all tried the drama with indifferent success or failure. But Galdós held the theory[2] that novel and drama are not essentially different arts, that the rules of one are not notably divergent from the rules of the other. Few or no dramatic critics will subscribe to this opinion, which explains most of the weaknesses of Galdós' plays.

Again, Galdós had been working toward a dramatic form in his novels, by the increasing use of pure dialog and the exclusion of narrative and description. This tendency culminated in the novelas dialogadas, El abuelo and Realidad, and, later, in Casandra and La razón de la sinrazón. The inner reason for the gradual shift toward dialog was increasing interest in human motives and character, and a corresponding distaste for colorful description. Galdós had never, like Pereda, taken great delight in word pictures per se, though his early novels contain some admirable ones, and as he grew older his genius was more and more absorbed in the study of man.

His transition to the drama was not, then, so abrupt as might appear. But two things were against his success. First, few writers have approached the stage with so poor a practical equipment. His friends assure us that, cut off as Galdós was from social diversions by his continuous writing, he had hardly attended the theater once from his university days till the performance of Realidad, although it is true that his lack of practical experience was compensated at first by the personal advice of a trained impresario, don Emilio Mario. Second, the drama is above all the genre of condensation, and Galdós, even as a novelist, never condensed. His art was not that of the lapidary, nor even that of the short story writer. He has few novelas cortas to his credit, and he required pages and pages to develop a situation or a character.

III. His Dramatic Technique.—His Success.—It is not to be wondered at, then, that Galdós found himself hampered by the time limit of the play. He uttered now and then rather querulous protests against the conventions (artificial, as he regarded them) which prevented him from developing his ideas with the richness of detail to which he was accustomed.[3] Such complaints are only confessions of weakness on the part of an author. One has only to study the first five pages of any comedy of the brothers Quintero to see how a genuine theatrical talent can make each character define itself perfectly with its first few speeches. To such an art as this Galdós brought a fertile imagination, the habit of the broad canvas, a love of multiplying secondary figures, and of studying the minutiae of their psychology. Only by sheer genius and power of ideas could he have succeeded in becoming, as he did, a truly great dramatist. Naturally enough, he never attained the technical skill of infinitely lesser playwrights. His usual defects are, as one would suppose, clumsy exposition, superfluous minor characters and scenes, mistakes in counting upon a dramatic effect where the audience found none, and tedious dilution of a situation. Bad motivation and unsustained characters are rarer. The unity of time is observed in Pedro Minio and Alceste; the unity of place, in Voluntad and El tacaño Salomón.

Galdós was not an imitator of specific foreign models. His first play, Realidad, was a pure expression of his own genius. But it placed him at once in the modern school which aims to discard the factitious devices of the "well-made" play, and to present upon the stage a picture of life approximately as it is. If he frequently deviated from this ideal (the farthest in La de San Quintín), it was due more to his innate romanticism, of which we shall speak later, than to a straining for effect. Never, except in the play just named, did he restore to the stock coincidences of Scribe and Pinero.

In the modern drama the conduct of the plot is of secondary importance, and character, ideas and dialog become the primary elements. In the first two Galdós needed no lessons. In naturalness and intensity of dialog he never reached the skill which distinguishes the pure dramatic talents of contemporary Spain: Benavente, the Quintero brothers, Linares Rivas. Galdós' dialog varies considerably in vitality, and it may happen that it is spirited and nervous in some plays otherwise weak (Electra, Celia en los infiernos), while in others, intrinsically more important (Amor y ciencia, Mariucha), it inclines toward rhetoric. Realidad and El abuelo, however, are strong plays strongly written. Galdós never succeeded in forging an instrument perfectly adapted to his needs, like the Quinteros' imitation of the speech of real life, or Benavente's conventional literary language. It took him long to get rid of the old-fashioned soliloquy and aside. In his very last works, however, in Sor Simona and Santa Juana de Castilla, as in the novels El caballero encantado and La razón de la sinrazón, Galdós, through severe self-discipline, attained a fluidity and chastity of style which place him among the most distinguished masters of pure Castilian.

But at the same time signs of flagging constructive energy began to appear. Pedro Minio and the plays after it reveal a certain slothfulness of working out. The writer shrinks from the labor required to extract their full value from certain situations and characters, and he is prone to find the solution of the plot in a deus ex machina. Fortunately, the last drama, Santa Juana de Castilla, does not suffer from such weaknesses, and is, in its way, as perfect a structure as El abuelo.

Galdós experienced almost every variety of reception from audiences. It is not recorded that any play of his was ever hissed off the stage, but Gerona ended in absolute silence, and was not given after the first night. Los condenados was nearly as unsuccessful. His greatest triumph was at the first performance of Electra, when the author was carried home on the shoulders of his admirers. La de San Quintín and El abuelo were not far behind. But neither success nor failure made the dramatist swerve a hair's breadth in his methods. Firmly serene in his consciousness of artistic right, he kept on his way with characteristic stubbornness and impassivity. Only on two occasions did he allow the criticisms of the press to goad him into a reply. In the prefaces to Los condenados and Alma y vida he defended those plays and explained his aims and methods with entire self-control and urbanity.[4] But he never deigned to cater to applause. The attack upon Los condenados did not deter him from employing a similar symbolism and similar motifs again; and, after the tremendous hit of Electra, he deliberately chose, for Alma y vida, his next effort, a subject and style which should discourage popular applause.[5] Such was the modesty, unconsciousness and intellectual probity of this man.

IV. The Development of Galdós.—M. E. Martinenche, writing in 1906, classified the dramatic work of Galdós into three periods, and as his classification has sometimes been quoted, it may be worth while to repeat it. In the first period, according to him, which extends from Realidad to Los condenados, Galdós presented broad moral theses, and accustomed his countrymen to witness on the stage the clash of ideas instead of that of swords. Then (Voluntad to Alma y vida) he narrowed his subjects so as to present matters of purely national interest. In the succeeding works (Mariucha to Amor y ciencia), he strove to unite Spanish color with philosophic breadth, and to lay aside even the appearance of polemic. Such a classification is ingenious, but, we feel, untenable. Aside from the fact that M. Martinenche was not acquainted with Galdós' third play, Gerona, which does not fit into his scheme, it seems apparent that there is no essential difference in localization between La de San Quintín of the first period and Mariucha of the third; and that the former has no more general thesis than Voluntad, of the second. And later plays, such as Casandra of 1910, so closely allied to Electra, have come to disturb the arrangement.

The only division by time which it is safe to attempt must be very general. No one will dispute that in his last years Galdós rose to a less particular, a more broad and poetic vision, to describe which we cannot do better than to quote some words of Gómez de Baquero.[6] "The last works of Galdós, which belong to his allegorical manner, offer a sharp contrast to the intense realism, so plastic and so picturesque," of earlier writings. First he mastered inner motivation and minute description of external detail, and from that mastery he passed to "the art, rather vague and diffuse, though lofty and noble, of allegories, of personifications of ideas, of symbols." This tendency appeared even as early as Miau (1888), then in Electra, and more strongly in Alma y vida, in Bárbara, and in most of the later plays. "Tired of imitating the concrete figures of life, Galdós rose to the region of ideas. His spirit passed from the contemplation of the external to the representation of the inward life of individuals, and took delight in wandering in that serene circle where particular accidents are only shadows projected by the inner light of each person and of each theme. His style became poetic, a Pythagorean harmony, a distant music of ideas." These words apply especially to Alma y vida, Bárbara, Sor Simona, and Santa Juana de Castilla, but they indicate in general Galdós' growing simplicity of manner and his increasing interest in purely moral qualities.

V. The Subject-matter of His Plays.—Rather than by time, it is better to classify Galdós' plays by their subject-matter, although the different threads are often tangled. Galdós had three central interests in all his work, novels and dramas alike: the study of characters for their own sake; the national problems of Spain; the philosophy of life.

1. Character Study.—"Del misterio de las conciencias se alimentan las almas superiores," said Victoria in La loca de la casa (IV, 7), and that phrase may serve as a guide to all his writings that are not purely historical. The study of the human conscience, not propaganda, was the central interest of the early novel, Doña Perfecta, just as it was in Electra, and to a far greater degree in works of broader scope.

Yet the statement, often made, that Galdós was a realist, as if he were primarily an observer, a transcriber of life, requires to be modified where the dramas are concerned. Pure realism is present in his dramatic work, but it does not occupy anything like the predominant place which some suppose. A "keen, minute, subtle study of the manners of humble folk" (Azorín) formed, indeed, the backbone of certain novels, but in the later period, to which the plays belong, it was already overshadowed by other interests. In the dramas, realism is usually abandoned to the secondary characters and the minor scenes. For genre studies of a purely observed type one may turn to the picture of a dry-goods store in Voluntad, to the parasites and the children in El abuelo, to the peasants in Doña Perfecta and Santa Juana de Castilla, and to other details, but hardly to any crucial scene or front-rank personage. So too, Galdós' humor, the almost unfailing accompaniment of his realism, is reserved for the background. Only in Pedro Minio, the sole true comedy, is the chief figure a comic type. Not a single play of Galdós, not even Realidad, can be called a genuine realistic drama.

To demonstrate was Galdós' aim, not to entertain or to reproduce life. Hence, in the studies of unusual or mystical types, in which he grew steadily more interested, one always feels the presence of a cerebral element; that is, one feels that these persons are not so much plastic, living beings as creations of a superior imagination. In this respect also Galdós resembles Balzac. The plays having the largest proportion of realism are the most convincing. That is why Realidad, with its immortal three, La loca de la casa, with the splendidly-conceived Pepet, Bárbara, which contains extraordinarily successful studies of complex characters, and especially El abuelo, with the lion of Albrit and the fine group of cleanly visualized secondary characters, are the ones which seem destined to live upon the stage.

We should like to emphasize the cerebral or intellectual quality of Galdós' work, because it has been often overlooked. It contrasts sharply with the naturalness of Palacio Valdés, the most human of Spain's recent novelists. Nothing shows this characteristic of Galdós more clearly than his weakness in rendering the passion of love. The Quinteros, in their slightest comedy, will give you a love-scene warm, living, straight from the heart. But the Galdós of middle age seemed to have lost the freshness of his youthful passions, and Doña Perfecta, precisely because its story dated from his youth, is the only play which contains a really affecting love interest. Read the passional scenes of Mariucha, as of La fiera, Voluntad, or of any other, and you will see that the intellectual interest is always to the fore. Examine the scene in Voluntad (II, 9) where Isidora, who has been living with a lover and who has plucked up strength to break away from him, is sought out by him and urged to return. The motif is precisely the same as that used by the Quinteros in the third act of Las flores (Gabriel and Rosa María), but a comparison of the handling will show that all the emotional advantage is in favor of the Quinteros. Galdós depicts a purely intellectual battle between two wills; while the creations of the Andalusian brothers vibrate with the intense passion of the human heart. For the same reason, Galdós, in remodeling Euripides' Alceste, was unable to clothe the queen with the tenderness of the original, and substituted a rational motive, the desire to preserve Admetus for the good of his kingdom, in the place of personal affection. The neglect of the sex problem in the dramas is indeed striking: in Amor y ciencia, Voluntad and Bárbara it enters as a secondary interest, but Realidad is the only play based upon it.

This may be the place to advert to Galdós' romantic tendencies, which French critics have duly noted. In his plays Galdós, when imaginative, was incurably romantic, almost as romantic as Echegaray, and proof of it lies on every side. Sra. Pardo Bazán coined his formula exactly when she christened his dramatic genre "el realismo romántico-filosófico" (Obras, VI, 233). Many of the leading characters are pure romantic types: the poor hero of unknown parentage, Víctor of La de San Quintín; the outlaw beloved of a noble lady, José León, of Los condenados; the redeemed courtesan, Paulina, of Amor y ciencia. In his fondness for the reapparition of departed spirits (Realidad, Electra, Casandra, novela), a device decidedly out of place in the modern drama,[7] the same tendency crops out. Some of the speeches in Gerona (II, 12) might have been written in 1835; and the plot of La fiera dates from the same era.

All this shows that Galdós was not, in the direction of pure realism, an original creator. The Quintero brothers and Benavente excel him in presenting a clear-cut profile of life, informed by a vivifying human spirit.

2. National Problems.—Galdós is not the most skilled technician among the Spaniards who discuss, through the drama, the burning problems of the day. Linares Rivas excels him in this rather ephemeral branch of dramaturgy. But Galdós has the great advantage of breadth. He is never didactic in the narrow sense. He sometimes hints at a moral in the last words of a play, but he is never so lacking in artistic feeling as to expound his thesis in set terms, like Echegaray and Brieux. The intention speaks from the action.

Galdós has said that the three great evils which afflict Spain to-day are the power of the Church, caciquismo or political bossism, and la frescura nacional or brazen indifference to need of improvement. All three he tried to combat. In spite of the common belief, however, his plays—thesis plays as they nearly all are in one way or another—seldom attack these evils directly. Caciquismo is an issue only in Mariucha and Alma y vida, and in them occupies no more than a niche in the background. Sloth and degeneracy are a more frequent butt, and Voluntad, Mariucha, La de San Quintín, and, in less degree, La loca de la casa, hold up to scorn the indolent members of the bourgeoisie or aristocracy, and spur them into action. From this motive, perhaps, Galdós devoted so much space to domestic finance. The often made comparison with Balzac holds good also in the fluency with which he handled complicated money transactions on paper, and in the business embarrassment which overtook him in real life. He had a lurking affection for a spendthrift: witness Pedro Minio and El tacaño Salomón.

Against the organization of the Catholic Church Galdós harbored intense feeling, yet he never displayed the bitterness which clericals are wont to impute to him. In view of his flaming zeal to remedy the backwardness of Spain, a zeal so great as to force him into politics, which he detested, Galdós' moderation is noteworthy. The dramas in which the clerical question appears are Electra, and Casandra. Doña Perfecta attacks, not the Church, but religious fanaticism, just as La fiera and Sor Simona attack political fanaticism; and the dramatist is so far from showing bias that he allows each side to appear in its own favorable light. Thus, in Casandra, Doña Juana, the bigot, is a more attractive figure personally than the greedy heirs. Doña Perfecta gives the impression of an inevitable tragic conflict between two stages of culture, rather than of a murder instigated by the malice of any one person. One can even detect a growing feeling of kindliness toward the clergy themselves: there was a time when Galdós would not have chosen a priest to be the good angel of his lovers, as he did in Mariucha.

For Galdós was not only by nature impartial, but he was fundamentally religious. It may be necessary to stress this fact, but only for those who are not well acquainted with his work. If the direct testimony of his friend Clarín be needed, it is there (Obras completas, I, 34); but careful attention to his writings could leave no doubt of it. Máximo in Electra repeats, "I trust in God"; Los condenados and Sor Simona are full of Christian spirit, and the last play, Santa Juana de Castilla, is practically a confession of faith.

The problems which concern Galdós the dramatist are, then, not so often the purely local ones of the Peninsula as broader social questions. The political tolerance which it is the aim of La fiera to induce, is not needed by Spain alone, though perhaps there more urgent; the comity of social classes eulogized in La de San Quintín, the courage and energy of Voluntad, the charity of Celia en los infiernos, the thrift of El tacaño Salomón, and the divine love of Sor Simona, would profit any nation. The loftier moral studies which we shall approach in the next section are, of course, still more universal.

One point should be made clear at once, however, and that is that Galdós, with regard to social questions, was neither a radical nor an original thinker. When one considers the sort of ideas which had been bandied about Europe under the impulse of Ibsen, Tolstoy and others,—the Nietzschean doctrine of self-expression at any cost, the right of woman to live her own life regardless of convention, the new theories of governmental organization or lack of organization—one cannot regard Galdós as other than a social conservative, who could be considered a radical nowhere outside of Spain. In how many plays does a conventional marriage furnish the facile cure for all varieties of social affliction (Voluntad, La de San Quintín, La fiera, Mariucha, etc.)! The only socialist whom he brings upon the stage—Víctor of La de San Quintín—has received an expensive education from his father, and, though compelled to do manual labor, it is apparent that he is not concerned with any far-reaching rational reorganization of society, but only with the betterment of his own position. In Celia en los infiernos, a mere broadcasting of coin by the wealthy will relieve all suffering; in El tacaño Salomón, the death of a rich relative lifts the spendthrift out of straits before he has reformed. It is clear that in this order of ideas Galdós is strictly conventional.

Various possible attitudes may be adopted by one who sees political and social evils, and desires to abolish them. The natural conservative dreams of a benevolent despotism as the surest path to improvement. This attitude Galdós never held, for he was born an optimist, and believed in the regenerative power of human nature. The natural liberal believes in a reform obtainable through radical propaganda in writing and at the polls. Such a man was the Galdós of the early novels and of some of the dramas,—the Galdós of La de San Quintín, of Voluntad, of Mariucha, full of exhortations to labor and change as the hope of redemption. Then, there is a third attitude, likely to be that of older persons, whom sad experience has led to despair of political action, and to believe that society can be improved only through a conversion of the race to loyalty and brotherly love; in short, through practical application of the Christian virtues. This change in Galdós' point of view was foreshadowed in Alma y vida, where one tyranny (absolutism) is replaced by another (parliamentarism); without soul, "wickedness, corruption, injustice continue to reign among men." In his old age the reformer appeared to renounce his faith in vote or revolution, and to place himself by the side of Tolstoy. The note which rings with increasing clearness is that of charity, of the healing power of love. There is something pathetic in the spectacle of this powerful genius who, as the shadow of death drew near him, became more and more absorbed in spiritual problems, and less in practical ones. Amor y ciencia, Celia en los infiernos, Sor Simona, Santa Juana de Castilla, reiterate that love is the only force which can relieve the suffering and injustice of the world. And, in harmony with the gentle theme of the last plays, their form becomes simple and even naïve, while the characters are enveloped in a vaporous softness which suffuses them with a halo of humane divinity.

3. Galdós' Philosophy.—Before passing to a consideration of Galdós' ideas, we should examine for a moment his manner of conveying them. He was able to express himself in forceful, direct language when he chose, but he came to prefer the indirect suggestion of symbolism.

Symbolism, of course, is nothing but a device by which a person or idea is made to do double duty; it possesses, besides its obvious, external meaning, another meaning parallel to that, but hidden, and which must be supplied by the intelligence of the reader or spectator.

The interpretation of a symbol may be more or less obvious, and the esoteric meaning may be conveyed in a variety of ways. Galdós has expressed his opinion about the legitimate uses of symbolism in his prefaces to Los condenados and Alma y vida, in passages capital for the understanding of his methods. In the earlier work he said, "To my mind, the only symbolism admissible in the drama is that which consists in representing an idea with material forms and acts." This he did himself in the famous kneading scene of La de San Quintín, in the fusion of metal in the third act of Electra, etc. "That the figures of a dramatic work should be personifications of abstract ideas, has never pleased me." Personified abstractions Galdós never did, we believe, employ in his plays, though critics have sometimes credited him with such a use.[8] Nevertheless we should remember that precisely this kind of symbolism was very popular in Spain in the seventeenth century, and gave rise to the splendid literary art of the autos sacramentales. Galdós then goes on to refute the allegation of certain critics that he was influenced by Ibsen.

"I admire and enjoy," he says, "those of Ibsen's dramas which are sane and clear, but those generally termed symbolic have been unintelligible to me, and I have never found the pleasure in them which those may who can disentangle their intricate meaning." What a curious statement, in the light of the other preface, written eight years later! "Symbolism," he there wrote, "would not be beautiful if it were clear, with a solution which can be arrived at mechanically, like a charade. Leave it its dream-vagueness, and do not look for a logical explanation, or a moral like that of a child's tale. If the figures and acts were arranged to fit a key, those who observe them would be deprived of the joy of a personal interpretation.... Clearness is not a condition of art." Did Galdós change his mind in the interval between writing these two prefaces? I think not. The change merely illustrates the difference in viewpoint between an author and a reader. For very, very many persons in his audiences have regarded the symbolism of Los condenados (if it be there), of Electra, of Casandra, of Pedro Minio, of Santa Juana de Castilla, and especially of Alma y vida and Bárbara, with the same feeling of hopeless bewilderment which Galdós experienced when he read The Wild Duck, The Master-builder and The Lady from the Sea. To the creator his creation is clear and lovely.

Leaving aside the question of influence, it cannot be denied that the symbolism of Galdós has much in common with that of Ibsen. Both have the delightful vagueness which permits of diverse interpretations,—in Alma y vida the author was obliged to come to the rescue with his own version; in neither is the identification of person and idea carried so far that the character loses its definite human contour; and both are employed to convey a profound philosophy.

What is Galdós' philosophy? First and foremost, he believed that nothing in life is too insignificant or too wicked to be entirely despised. Sympathy with everything human stands out even above his keen indignation against those who oppress the unfortunate. A search through his works will reveal few figures wholly bad, too wicked to receive some touch of pity. César of La de San Quintín and Monegro of Alma y vida are probably the closest to stage villains, and this precisely because they are a part of the melodramatic elements of those plays, not of the central thought.

A corollary of his universal sympathy is the doctrine, not very profound or novel, that opposite qualities complement one another, and must be joined in order to give life a happy completeness. This thread runs through many plays, sometimes unobtrusively, as in La fiera, Amor y ciencia, La de San Quintín, sometimes erected into the dogma of primary concern, as in Alma y vida (the union of spirit and physical vigor), La loca de la casa (evil and good, selfishness and sacrifice), and Voluntad (practical sense and dreamy imagination).

This is one manifestation of that splendid impartiality, that impassiveness which enabled Galdós to retain his balance and serenity in the trials of a stormy and disastrous era. Another evidence of his desire to present both sides of each question is found in those dramas which appear to contradict one another. Pedro Minio supports literally, in a way to dishearten earnest toilers, the Biblical injunction to take no thought for the morrow, and to give away all that one has; but El tacaño Salomón teaches thrift. Most of Galdós' writing advocates change, advancement, rebellion against old forms; but Bárbara drives home the strange burden that all things must return to their primitive state. I do not add El abuelo, with its anti-determinist lesson, because Galdós never was a determinist; he never believed, as did Zola, that the secrets of heredity can be laid bare by a set of rules worked out by the human mind.

These citations prove, at least, that Galdós was careful not to be caught enslaved by any dogma, and they show, too, that he set no store by the letter of the law, and prized only the spirit. That is the secret of his fondness for the dangerous situation of the beneficent lie, or justifiable false oath, which brought him severe criticism when he first used it in Los condenados (II, 16), and which nevertheless he repeated in an equally conspicuous climax in Sor Simona (II, 10). Galdós defended the lie through which good may come, in the preface to Los condenados, with reasoning like that of a trained casuist; and such a lie appears hypocritical upon the lips of Pantoja (Electra, IV, 8), though it is not so intended. As a dramatic theme the idea is not entirely novel, for Ibsen, in the Wild Duck, had said that happiness may be based upon a lie. As usual, Galdós provided his own antidote, for, with what appeared a strange inconsistency, and was really a desire for balance, the lesson of the very drama, Los condenados, is that "man lives surrounded by lies, and can find salvation only by embracing the truth, and accepting expiation." This idea also can be paralleled in Ibsen and Tolstoy, but it was overbold to exhibit both sides of the shield in the same play.

There still remain the major threads in the broad and varied fabric of Galdós' ideology. Stoicism, that characteristic Spanish attitude of mind, allured him often, and he succeeded in giving dramatic interest to the least emotional of philosophies. In Realidad and Mariucha is found the most explicit setting forth of that theory of life which enables an oppressed spirit to rise above its conditioning circumstances.[9] At times Galdós appeared to dally with Buddhism: at least some critics have so explained the reincarnation of doña Juana in Casandra, novela. Another tenet of Buddhism, or, as some would have it, of Krausism, was often in Galdós' thought, and is emphasized particularly in Los condenados and Bárbara. Every sin of man must be at some time expiated; and not alone sins actually committed against the statutes, but sins of thought, sins against ideal justice, which is far more exacting than any human laws.[10]

All these phases of thought spring from one mother-idea, the perfectioning of the human soul. For Galdós, in spite of the unfortunate times in which his life fell, in spite of the clearness with which he observed the character of those times, was an unconquerable optimist. He believed that Spain could be remade, or he would not have worked to that end. He believed that humanity is capable of better impulses than it ordinarily exhibits, and his life was devoted to calling forth generous and charitable sentiments in men. Whether through stoicism, which is the beautifying of the individual soul, or through divine and all-embracing love, which is the primal social virtue, Galdós worked in a spirit of the purest self-sacrifice for the betterment of his nation and of humanity. He had grasped a truth which Goethe knew, but which Ibsen and his followers overlooked—that the price of advance, either in the individual or in society, is self-control.

VI. The Position of Galdós as a Dramatist.—The enemies of Pérez Galdós have often declared that he had no dramatic gifts, and should never have gone outside his sphere as a novelist. Other distinguished writers, among them Benavente, consider him one of the greatest dramatists of modern times. The truth lies close to the second estimate, surely. Galdós will always be thought of first as a novelist, since as a novelist he labored during his most fertile years, and the novel best suited his luxuriant genius. But he possessed a very definite theatrical sense, and it would be possible to show, if space permitted, how it enabled him to achieve success in the writing of difficult situations, and how he never avoided the difficult. Had Galdós entered the dramatic field earlier in life, he might have been a more skilled technician, but as it is, El abuelo and Bárbara are there to prove him a creative dramatist of the first order.

From what has been said in the preceding sections, it will be evident that Pérez Galdós does not fit exactly into any single one of the convenient classifications which dramatic criticism has formulated. His genius was too exuberant, too varied. Of the three stages which mark the progress of the modern drama, romanticism, naturalism, and symbolism, the second, in its strict dogmatic form, affected Galdós not at all. Realism, in the good old sense of the Spanish costumbristas, furnishes a background for his plays, but only a background. A picture of Spanish society does emerge from the dramas, indeed. It is a society in which there are great extremes of wealth and poverty, in which the old titled families are generally degenerate and slothful, and the middle classes display admirable spiritual qualities, but are too often unthrifty and inefficient. Of the laboring classes, Galdós has little to say. Bitter religious and political intolerance creates an atmosphere of hatred which a few exceptional characters strive to dissipate. Galdós, however, was seldom willing to face these conditions frankly and tell us what he saw and what must result from such conditions. In the later period of his life, to which the plays belong, the sincere study of reality was swept away by a combination of romanticism and symbolism which lifted the author into the realm of pure speculation, giving his work a universal philosophic value as it lost in the representation of life. From the spectacle of his unfortunate land he fled willingly to the contemplation of general truth. El abuelo, because it unites a faithful picture of local society and well-observed figures with a sublime thought, is beyond doubt Galdós' greatest drama.

Menéndez y Pelayo pointed out that Galdós lacks the lyric flame which touches with poignant emotion the common things of life. He did not entirely escape the rhetoric of his race. And he was curiously little interested in the passions of sex—too little to be altogether human, perhaps. But his work appears extraordinarily vast and many-sided when one compares it with that of his French contemporaries of the naturalistic drama, who observed little except sex. He was not an exquisite artist; he was, judged by the standards of the day, naïve, unsophisticated, old-fashioned. But he was a creative giant, a lofty soul throbbing with sympathy for humanity, and with yearning for the infinite.

Galdós wrote but five tragedies: Realidad, Los condenados, Doña Perfecta, Alma y vida, Santa Juana de Castilla. Of them, Doña Perfecta creates the deepest, most realistic tragic emotion, the tragic emotion of a thwarted prime of life; and after it, Santa Juana de Castilla, the tragedy of lonely old age. El abuelo and Bárbara, also, in some way intimate the mysterious and crushing power of natural conditions,—the conception which is at the heart of modern tragedy. Galdós attained that serene vision of the inevitableness of sorrow too seldom to be ranked with the foremost of genuine realists. Instead, he reaches a very eminent position as an imaginative philosopher.

Galdós is said to have written two verse dramas before he was twenty-five, neither of which was ever staged. One, La expulsión de los moriscos, has disappeared. The other, El hombre fuerte, was published in part by Eduardo de Lustonó in 1902. (See Bibliography.) It appears from the extracts to be a character play with strong romantic elements. It is written in redondillas.

Some of Galdós' novels have been dramatized by others: El equipaje del rey José, by Catarineu and Castro, in 1903; La familia de León Roch, by José Jerique, in 1904; Marianela, by the Quinteros, in 1916; El Audaz, by Benavente, in 1919.

1. Realidad, drama en cinco actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Comedia, March 15, 1892. Condensed from the "novela en cinco jornadas" of the same name (1889). Ran twenty-two nights, but did not rouse popular enthusiasm.

Realidad presents the eternal triangle, but in a novel way. Viera, the seducer, is driven by remorse to suicide, and Orozco, the deceived husband, who aspires to stoic perfection of soul, is ready to forgive his wife if she will open her heart to him. She is unable to rise to his level, and, though continuing to live together, their souls are permanently separated.

Realidad has superfluous scenes and figures, and a scattered viewpoint. Nevertheless, it remains one of the most original and profound of Galdós' creations, a penetrating study of unusual characters. There are two parallel dramatic actions, the first, more obvious and theatrical, the fate of Viera; the second, of loftier moral, the relations of Orozco and Augusta, which are decided in a quiet scene, pregnant with spiritual values. Running counter to the traditional Spanish conception of honor, this drama was fortunate to be as well received as it was.

To understand the title one must know that Realidad, the novela dialogada, is only another version of the epistolary novel, La incógnita, written the year previous. The earlier work gave, as Galdós says (La incógnita, pp. 291-93), the external appearance of a certain sequence of events; Realidad shows its inner reality. Browning employed a somewhat similar procedure in The Ring and the Book.

2. La loca de la casa, comedia en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Comedia, Jan. 16, 1893. This play, a success, is printed in two forms, one as originally written, the other as cut down for performance. In a foreword to the former version, the author protests against the brevity demanded by modern audiences. It was doubtless to the long version that Galdós referred when he included La loca de la casa in the list of titles of his Novelas españolas contemporáneas.

This is a drama of two conflicting personalities, united by chance in marriage: Pepet Cruz, a teamster's boy, grown rich after a hard struggle in America, and Victoria, the daughter of a Barcelona capitalist who has met with reverses.

Its merit lies in the study of these characters, especially in the very human figure of Pepet, homely, rough, and unscrupulous, who resembles in many ways Jean Giraud of Dumas' La Question d'argent. The theme, the conquest of a rude man by a Christian and mystic girl, is also the theme of Galdós' novel Ángel Guerra. The first two acts are the best; the third borders on melodrama, and the last, though containing some excellent comedy, is flat. The real flaw lies in the extensive use of financial transactions to express a psychological contest; Victoria's victory over Cruz is ill symbolized in terms of money.

The title is based on a pun: "la loca de la casa" is a common expression for "imagination."[11]

3. Gerona, drama en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, Feb. 3, 1893. Never published by the author, but appeared in El cuento semanal, nos. 70, 71, May 1 and 8, 1908.—Galdós' worst failure on the stage; it was withdrawn after the first night, and critics treated it more severely than the audience.[12]

Gerona is a dramatization of the Episodio nacional (1874) of the same name, which describes the siege of the city of Gerona and its final surrender to the French (May 6—Dec. 12, 1809). There are many minor changes from the novel; among them, a nebulous love story is added as a secondary interest.

To a reader the play does not appear so bad as the event indicated. The first act is conceded to be a model; and, in spite of confused interests and some wildly romantic speeches, the whole presents a vivid picture of siege horrors, without melodrama or exaggeration. Possibly the failure was due to the fact that doctor Nomdedeu, the chief character, places his daughter's health ahead of patriotism, and to the final tableau, in which the defeated Spaniards lay down their arms before the French marshal.

4. La de San Quintín, comedia en tres actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Comedia, Jan. 27, 1894.—Aroused great enthusiasm, and received fifty consecutive performances in Madrid. Was given in Paris, in Spanish, in 1900 (?).

This "furiously romantic" drama, Galdós' most meretricious play, is intended to symbolize the union of the worn-out aristocracy and the vigorous plebs to form a new and thriving stock. The duchess of San Quintín, left poor and a widow, weds Víctor, a socialist workman of doubtful parentage. The last act is weak and superfluous, the devices of the action cheap, and the motivation often faulty. Víctor's socialism is more heard of than seen, and it appears that he will be satisfied when he becomes rich. He is not a laboring man in any real sense, since his supposed father gave him an expensive education. He is no true symbol of the masses.

However, the duchess Rosario is a charming figure, and the secondary figures are well done. There is excellent high comedy in the famous "kneading scene" of the second act, in which the duchess kneads dough for "rosquillas" while her lover looks on. The kneading is symbolic of the amalgamation of the upper and lower classes. Without doubt, the popularity of this play in Spain is in part due to its propaganda.

Again, a punning title. "La de San Quintín" means "a hard-fought battle" (from a Spanish victory outside the French city of Saint-Quentin, in 1557).

5. Los condenados, drama en tres actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Comedia, Dec. 11, 1894. (The Prólogo is important as a piece of self-criticism and an exposition of the author's aims.)—A failure, given three nights only, and severely criticized in the press.

Los condenados is an ambitious and fascinating excursion into symbolic ethics. Salomé, the inexperienced daughter of a rich Aragonese farmer, elopes with a wild character, José León, who does not repent till his sweetheart loses her mind as a result of his perversity. No play of Galdós contains more glaring weaknesses of construction or greater flaws in logic, many of them admitted by the author in his preface. To make two saintly characters take oath to a lie (II, 16) in an attempt to save a man's soul (spirit above letter) was, in Spain at least, a deliberate courting of failure. And why introduce a bold example of a justified lie into an indictment of false living? The purest romanticism reigns in the play, as Martinenche has pointed out; José León and Salomé are not other than less poetic versions of Hernani and Doña Sol. Paternoy, the spirit of eternal justice, resembles Orozco of Realidad, and still more, Horacio of Bárbara.

The lesson conveyed is that we all live in the midst of lies, and that salvation is attained only by sincerity and by confession of one's own free will, not under compulsion. This is an idea familiar to Ibsen and Tolstoy; the added element, that conditions fit for complete repentance can be found only after death, is perhaps original. Martinenche thinks the failure of Los condenados was due to the fact that the Spanish public was not accustomed to the spiritual drama. But one should remember that Calderón's autos are both spiritual and symbolic. The failure was more probably due to faults of form than to any inherent weakness of theme.

6. Voluntad, comedia en tres actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, Dec. 20, 1895. Coldly received. Ran six nights.

Voluntad, which contains some good genre scenes in a Madrid petty store, is meant to show how energy, in the person of a wayward daughter, can repair the faults of sloth and laxness. But Isidora, who saves her father's business, can hardly conquer the will of a dreamy idler whom she loves.

Yet there is no real conflict of wills, only of events, and the lover's conversion to a useful life by means of poverty is cheap, and the ending commonplace. On the whole, the stimulating exhortation to will and work is run into a mold not worthy of it.

Galdós has, in fact, mingled here, with resulting confusion, two themes which have no necessary connection,—the doctrine of salvation by work, and the doctrine of the necessary union of complementary qualities. (Cf. page xxiv.) The latter theory is the central one in Voluntad, and a failure to discern this fact has led critics to some unwarranted conclusions.

7. Doña Perfecta, drama en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Comedia, Jan. 28, 1896. Adapted from the well-known novel (1876). Successful.

The novel Doña Perfecta, one of the best Galdós ever wrote, both as an artistic story and as a symbol of the chronic particularism of Spain, has been somewhat weakened in dramatization. The third act is almost unnecessary, the dénoûment hurried. One misses especially the first two chapters of the novel, which furnish such a colorful background for the story. Yet, as a whole, the play gives a more favorable impression of Galdós' purely theatrical talent than almost any other of his dramas. The second act, with its distant bugle calls at the end, is one of the best he ever wrote, and the first is not far behind. It is to be noted that the motivation, especially in the part of Perfecta, is made much clearer here than in the novel; the play serves as a commentary and exegesis to the earlier tale. The gain in clarity is offset, however, by the loss of the mysterious grandeur which clothes Perfecta in the novel. There, her reticences speak for her.

8. La fiera, drama en tres actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Comedia, Dec. 23, 1896. Coldly received.

La fiera is allied in subject to the Episodios nacionales, although it is not taken from any of them. The year is 1822, the scene, the city of Urgell, in the Pyrenees, attacked at that moment by the liberals under Espoz y Mina, and defended by the absolutists. A young liberal spy is loved by an absolutist baroness, and after numberless intrigues during which the hero's life is in danger from friends and enemies, he kills first the leader of the liberals, then the commander of the fortress, "the two heads of the beast," and the lovers flee toward regions of peace. As an appeal for tolerance, La fiera is unexceptionable, and Galdós, the radical, has painted the excesses of both sides with perfect impartiality. But as a drama, it is an example of wildly improbable romanticism, and might have been written in the thirties, except that in that case the comedy element would not be so insipid as it is, but would have tasted of the pungent realism which was the virtue of the best romantics. The characters are unconvincing, the love-story a poor parallel to Romeo and Juliet.

9. Electra, drama en cinco actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, Jan. 30, 1901. A wild success. A French adaptation made a hit in Paris in 1905.

This "strictly contemporary" drama depicts a contest for the hand and soul of Electra, an eighteen-year-old girl whose mother was a woman of dubious life. She loves the young scientist Máximo, but Pantoja, the religious adviser of the family with whom she stays, believing himself her father, desires her to enter a convent. Since he cannot otherwise dissuade her from marriage, he tells her falsely that she is Máximo's half sister. She cannot be convinced that this is a lie until the spirit of her mother reassures her.

Concerning Electra and the battle which it excited between radicals and clericals, one can consult contemporary periodicals, and Olmet y Carraffa, cap. XIV. Its estreno happened to coincide with a popular protest against the forced retirement to a convent of a Señorita de Ubao, and the Spanish public saw in the protagonist a symbol of Spain, torn between reaction and progress. Consequently, no play of Galdós has been so unduly praised or so bitterly attacked. Two facts appear to stand out from the confusion: (1) Galdós did not deliberately trade upon popular passions, since this play was written before the exciting juncture of events arose; (2) The enormous vogue of Electra, its wide sale and performance in many European countries, were not justified by its intrinsic value.

Electra appears now as a drama of secondary importance, with some cheap effectism, excellent third and fourth acts, and a weakly romantic ending. The ghost of Eleuteria is less in place than the corresponding spirits of Realidad and Casandra, both because it is unnecessary for the solution of the plot, and because it is an anachronism in a play devoted to the eulogy of the modern and the practical. On the other side, it is clear to an impartial reader that Galdós did not intend an attack on the clergy, much less an attack on religion. Máximo is careful to affirm his belief in God. And Pantoja is not the scheming hypocrite that some have seen in him; he is a man of firm convictions and courage, sincere in his religious mysticism. Galdós was interested in studying such a character and in showing that his religion is not of the best type.

A punning title. Beside the Greek allusion, Máximo's laboratory is a "taller de electrotecnia."

10. Alma y vida, drama en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, April 9, 1902. (Published with an important preface.) Succès d'estime.

This play is Galdós' vital contribution to the sentiment aroused in Spain by the Spanish-American war. The heroine, Laura, an invalid duchess of the late eighteenth century, is ruled by a tyrannical administrator, until freed by the love of a vigorous young hidalgo. But the effort of will involved exhausts the delicate girl, and she dies just as the triumph of her partisans is announced. She was the divine beauty of the soul; without her there is left only a tyranny of one sort or another, and evil, injustice, corruption, are perpetuated.

Alma y vida is Galdós' most ambitious attempt to write a literary symbolic drama on a grand scale. In it he resumes, with Aragonese stubbornness (to use his own words), the attempt made unsuccessfully in Los condenados, only this time the symbolism is not abstract, but has a definite application to Spain. The extreme care which Galdós took with the costumes of the pastoral interlude in the second act, going to Paris for advice on their historical accuracy, the spectacular and costly settings, the length of time, four hours, consumed in the performance, the passages of verse,[13] all demonstrate that Galdós put his full will into the elaboration of this drama. The result was disappointing. Audiences were bored, despite their desire to approve. They knew some symbolism was involved, but could not decide upon its character until the author solved the problem in his Prólogo. He there defended the vagueness of his play, as more suggestive than clearness, and explained that Alma y vida symbolizes the decline of Spain, the dying away of its heraldic glories, and the melancholy which pervades the soul of Spain; the common people, though possessing reservoirs of strength, are plunged in vacillation and doubt. The sad ending is the most appropriate to the national psychology of the time. Warned by Electra, he says, he deliberately avoided popular applause, and sought to gain the approval of cultured persons.

Although the pathetic figure of Laura is most affecting, the author did not fully reach the goal he had set for himself, yet "no mediocre mind or ordinary imagination could have conceived such vast thoughts."

11. Mariucha, comedia en cinco actos. Barcelona, Teatro Eldorado, July 16, 1903. Given for the first time in Madrid on Nov. 10, 1903. A fair success, especially in the provinces. The aristocratic portion of the Madrid public did not like it.

Mariucha carries a moral aimed directly at the Spanish people. Like Voluntad, it preaches firm will and the gospel of labor; like La de San Quintín, it points out a new path which the decayed aristocracy may follow in order to found a renovated Spain. In the exaltation of stoicism (V, 4) it resembles Realidad. Clericalism does not enter into the discussion. Instead it is caciquism which Galdós attacks in passing. The play overflows with daring and optimism; it is like a trumpet call summoning the Spanish youth to throw off the shackles of tradition and political tyranny, and to walk freely, confiding in its own strength. One's best impulses must be followed, no matter what ties may be broken or what feelings hurt in the process. We recognize here a favorite doctrine of Ibsen.

Mariucha is not quite so good a drama as its theme deserves. The two chief characters suffer from the weight of the message they bear, and are, in fact, rather symbols than characters or even types. The play possesses, however, many interesting features. One is the fact that the "good angel" of the play is a priest. His figure proves that Galdós grew in sympathy for the representatives of religion, if not for bigots, as he grew older. Another is the protest against thoughtless charity, which fosters shiftlessness. Galdós gave expression to a different point of view in Celia en los infiernos.

12. El abuelo, drama en cinco actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, Feb. 14, 1904. Adapted from the "novela en cinco jornadas" of the same title (1897). Galdós' greatest public success, next to Electra.

In this drama Galdós considers a general problem of inheritance of character. The aged, poor and nearly blind count of Albrit knows that of his two granddaughters one is not his son's child. Which? His efforts to read the characters of the children are vain, and when at last he learns the truth, it is to realize that the girl of his own race is fickle and vain while the bastard is generous and devoted. Then his pride knows that good may come out of evil, that honor lies not in blood, but in virtue and love.

El abuelo is beyond question Galdós' best play, practically considered. The plot is simple, the handling of it direct and skilful, there is no propaganda to interfere with the characters, who are few, interesting, and admirably drawn. The contrast between the lion of Albrit (so often compared to King Lear) and the playful children is a master-stroke. Free from effectism, dealing only with inner values of the heart and morals, El abuelo can properly rank as one of the masterpieces of modern drama. Its theme is diametrically opposed to the traditional Spanish conception of family honor (cf. Realidad), and so its popularity at home is a sign that Galdós was able to educate his public to some extent.

In condensing the dialoged novel to a drama, Galdós made a number of alterations in character and action, and all, in our opinion, for the better. Nevertheless, Manuel Bueno says: "Prefiero, sin embargo, la novela. Me llena más."

13. Bárbara, tragicomedia en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, March 28, 1905. Coolly received.

The overshadowing figure of this drama is Horacio, governor of Syracuse in 1815, who "entertains the idle moments of his tyranny modeling out of human wickedness the ideal statue of justice." He forces the countess Barbara, who stabbed her brutal husband, to marry the latter's brother, instead of a chivalrous and mystical Spaniard whom she loves, and who is blamed for the murder. How does such an outcome represent ideal justice? It seems to teach that unhappiness, caused by oppression, must not provoke any effort for freedom on the part of the victims. Revolt must be punished and expiated. Letter is placed above spirit, and the theme is repeated often: "There is no change, no reform possible in the world. All things must return to their first state." How to reconcile such doctrine with the body of Galdós' work?

These considerations nonplussed contemporary audiences and critics, and caused Martinenche to regard the play as an "ironique divertissement," intended to demonstrate that "Galdós' art was supple and objective enough to set forth an idea apparently at variance with the general inspiration of his theater." Such an explanation would be in harmony with Galdós' favorite custom of balancing one argument against another, but perhaps Bárbara may be interpreted in the light of Los condenados, where also penance for both lovers was insisted upon. In the ideal justice, it makes no difference whether the crime committed is against oppression or against liberty. In the latter case, punishment assumes the form of a liberal revolt; in the former, it appears reactionary. This is why Galdós, holding the balance even, with the impartiality which is the root of his character, seems in Bárbara to advocate a static philosophy, whereas in most of his work he is the liberal whom Spain, a backward nation, needed.

In any case, Bárbara is a fascinating, enigmatic play, too elevated ever to be popular, but one which, on account of its closely studied characters, delicate motivation and suggestive ideas ought always to be a favorite among the thoughtful. No other play arouses greater respect for Galdós as an original creator.

14. Amor y ciencia, comedia en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Comedia, Nov. 7, 1905. Coldly received.

The redemption of an erring woman is a frequent dramatic theme, from the Romantic era to the present. Malvaloca, of the brothers Quintero, presents it, as does Palacio Valdés' novel Tristán, with a plot and spirit not unlike that of Amor y ciencia. Here, love and science are forces which together heal and redeem the soul of Paulina, the repentant wife of a famous physician. Once more, as in Realidad, and as in Tristán, we are shown a husband who pardons. But here the treatment of the theme lacks vitality, and the abstract idea is not beautified by the veil of poetry which gives charm to Los condenados, Alma y vida, and Sor Simona.

16. Pedro Minio, comedia en dos actos. Madrid, Teatro Lara, Dec. 15, 1908. A fair success.

Galdós' only real comedy is distinctly a minor play, with a languid second act. The scene is laid in a wonderfully perfect Old Folks' Home. The hero is an inmate, once a jolly liver and spendthrift, who still enjoys every moment, while as a foil to him is placed a wealthy money-grubber, who at forty is ridden with a dozen plagues. There is much quiet humor, and some obvious symbolism,—perhaps also some not so obvious. That reformed profligates wish to restrict the pleasures of others, while the blameless allow them harmless freedom; that the money-seeker meets with torment, while the generous spender lives happily; that "peace, fraternity and innocent love of life are all God has given humanity, to make its passage through the world less painful"; these are the plain morals. It is thus united in spirit with Galdós' latest work. But the form in which this lesson is conveyed is not calculated to encourage a life of productive toil.

16. Zaragoza," "drama lírico en cuatro actos; música del maestro D. Arturo Lapuerta. Saragossa, Teatro Principal, June 4, 1908.

This opera, only the libretto of which has ever been published, was given four nights during the centennial celebration of the siege of Saragossa, and was never performed elsewhere. The book is a mere scenario of the well-known Episodio nacional, and contains practically no spoken lines. It cannot be judged without the music. The chorus of citizens is the protagonist.

17. Casandra, drama en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, Feb. 28, 1910. Adapted from the "novela en cinco jornadas" of the same name, 1905. The occasion of hot political demonstrations.

Casandra is frankly anti-clerical, but with an Olympian irony, not bitterness. The central figure is an aged, childless widow, whose enormous wealth is eagerly awaited by a host of distant relatives. She changes her mind, and starts to give away her property to the Church, with natural disappointment to the heirs. Casandra, not an heir, but the mistress of an illegitimate son of Doña Juana's husband, is a woman without money-interest, but Doña Juana's desire to deprive her of her children and lover stirs her to stab the aged bigot. The novel is admirably genial, full of convincing characters and pregnant thoughts; the play much changed, and inferior to it. It teaches that Dogmatism is sterile and only Love is fertile. Only Love is powerful enough to drive away the specter that oppresses Spain. Unconscious well-doing alone aids humanity, not ostentatious aristocratic charity. It is doubtful if the elaborate allegory suggested by R. D. Perés (see above, p. xxii, note 1 [Footnote #8]) was intended by Galdós.

18. Celia en los infiernos, comedia en cuatro actos. Madrid, Teatro Español, Dec. 9, 1913. Successful.

The story of a beautiful, good-hearted marchioness who, being an orphan, comes at the age of twenty-three into the free management of her enormous property. She soon becomes disgusted with society life, and, accompanied by an elderly confidant, disguises herself as a peasant girl, and visits the infernal regions of the slums, partly to learn how the other half lives, and partly to learn the fate of some former servants. After interviewing don Pedro Infinito, a half-demented astrologer and employment agent, who furnishes the best scene and the most interesting character in the play, they inspect a rag-picking factory. Celia buys it and promises to establish profit-sharing and old-age pensions, if all the workers will live decently. The project is hailed with delight, and the benefactress returns to her heaven. The rag factory is a symbol of Nature: "Nothing dies, nothing is lost; what we abandon as useless is reborn and again has a part in our existence." Only silk rags, the refuse of elegant things, are of no further use.

The plot of Celia en los infiernos is romantically commonplace. In dramatic interest each act is weaker than the one before. The slums shown here would never appal an unaccustomed visitor. Moreover, Galdós abets in Celia the vice of ill-considered charity which he condemned in Mariucha. Decidedly, the author's heart got the better of his intelligence in this play.

19. Alceste, tragicomedia en tres actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Princesa, April 21, 1914. Succès d'estime.

The sacrifice of Queen Alceste, who dies in place of her husband, Admetus, was used for a drama by Euripides, and from his have been drawn many later plays, as well as a famous opera by Gluck. In his Preface Galdós details the changes which he introduced into the story, so many that his plot and characters may almost be considered original. Galdós has abandoned the surpassing lyric quality of the Greek, so far removed from his own genius, and set the theme down into a key of everyday humanity, at times half humorous. The figure of the queen has lost at his hands its poignant tenderness, but Admetus has gained in dignity, and the dramatic movement is much heightened. The realistic visualization of Pherés and Erectea, Admetus' selfish parents, the excision of the buffoonery in the rôle of Hercules, who restores the queen to life, are excellent adaptations to modern taste. Galdós' Alceste, mingling comedy and pathos with singular charm, power, and discretion, must henceforth take its place among superior modern interpretations of the story, beside Alfieri's severely dignified Alceste seconda (1798). Balaustrion's Adventure (1871) by Robert Browning is hardly more than a rude paraphrase of Euripides.

20. Sor Simona, drama en tres actos y cuatro cuadros. Madrid, Teatro Infanta Isabel, Dec. 1, 1915. Received with applause, but soon withdrawn.

The action takes place during the last Carlist war (1875) in Aragonese villages. Sister Simona is a runaway nun, thought slightly demented, who devotes herself to nursing the wounded of the war. She attempts to save the life of a young Alfonsist spy by declaring him her own son. This serves only to destroy her reputation for saintliness, and the situation is suddenly saved by an offer to exchange prisoners.

It will be seen that there is, properly speaking, no plot, and the ending is full of improbabilities. Once more Galdós, with characteristic persistence, has used the justifiable lie, which failed so signally in Los condenados. The work is saved by its poetic atmosphere and by the spiritual central figure. Charity is not to be imprisoned in convents; it is as free as the divine breath that moves the planets. God is reached by good works; the only fatherland worth fighting for is humanity; the only king, mankind. These are the teachings of Sor Simona. Her name is to be connected with Simon Peter, the cornerstone of the Church of Christ.

21. El tacaño Salomón, comedia en dos actos. Madrid, Teatro Lara, Feb. 2, 1916. (Sub-title, Sperate miseri.)

The scene is the modest home of a Madrid engraver who earns good wages, but is victimized by all who appeal to him for help. Stingy Salomón is sent him by a wealthy brother in Buenos Aires to assist his want if he will reform and acquire thrift. The engraver proves incorrigible, but, through his brother's death, receives the money nevertheless.

The play is of the same type as Celia en los infiernos, but is less interesting and even more improbable. In a way it is a complement to Pedro Minio, which taught the beauties of an open and generous life, while El tacaño Salomón appears to preach thrift. But the author has hard work to become enthusiastic over that virtue, and at the close quite lets it slip away from him. Both Celia and the present play are the work of a man who has despaired of accomplishing any good in society by logical and practical means, and resorts to the illusions of a child dreaming of a fairy godmother.

22. Santa Juana de Castilla, tragicomedia en tres actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Princesa, May 8, 1918.

A picture of the old age and death of Juana la Loca, the daughter of the Catholic Kings, and widow of Philip the Handsome. The Queen's mad passion for Philip is barely mentioned, her figure is idealized, and she is made a symbol of humility, self-effacement, and love for the humble. Closely guarded by a harsh agent of her son Charles V, she escapes for a day to a country village, where she talks in a friendly way with the peasants, discussing their problems with a simplicity which conceals much wisdom. To those who wish to use her name as a standard to restore the power of the common people, she insists that she desires nothing but darkness and silence in which to end her days. She had been suspected of heresy, because she read Erasmus, but the Jesuit Francisco de Borja, a man of saintly life, is with her at her death, and bears witness that her faith is untainted and that she will receive in the bosom of God the reward for her many sufferings.

As far back as 1907 Galdós was deeply interested in the life of this wretched Queen: "No hay drama más intenso que el lento agonizar de aquella infeliz viuda, cuya psicología es un profundo y tentador enigma. ¿Quién lo descifrará?"[14] In his interpretation of her last moments, Galdós has made the figure of the Queen vaguely symbolic of present-day Spain, like Laura of Alma y vida. But she embodies still more the soul of the aged author, blind, feeble, living in silence and obscurity, absorbed in contemplation of approaching death.

The construction of the play is flawless, of diaphanous simplicity, the dialog is pure and brief, the characters are delicately outlined in a few sure touches. "A mournful, somber triptych," says Luis Brun of its three acts, "the central panel of which is lit by a ray of light." An atmosphere of serene melancholy broods over this admirable drama, fitting close to the career of a well-poised spirit.

No definitive critical study has yet been made of any side of Galdós' work. The following list, by no means complete, does not include general histories of Spanish literature, encyclopedia articles or reviews in contemporary periodicals of first performances. The best of the last-named are those by Gómez de Baquero in España moderna. Criticisms dealing only with the novels of Galdós are not cited here.

1. BIOGRAPHY

Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), "Galdós" in Obras completas, tomo I, Madrid, 1912.

L. Antón del Olmet and A. García Carraffa, Galdós, Madrid, 1912. [Contains the most information.]

"El Bachiller Corchuelo" (González Fiol), "Benito Pérez Galdós," in Por esos mundos, vol. 20 (1910, I), 791-807; and vol. 21 (1910, II), 27-56. [Important.]

William Henry Bishop, in Warner's Library of the World's Best Literature, vol. XI, pp. 6153-63.

"El Caballero Audaz" (José María Carretero), Lo que sé por mí, 1ª serie, Madrid, 1915, pp. 1-11.

E. Díez-Canedo, "La Vida del Maestro," in El Sol, Jan. 4, 1920.

Archer M. Huntington, "Pérez Galdós in the Spanish Academy," in The Bookman, V (1897), pp. 220-22.

Rafael de Mesa, Don Benito Pérez Galdós, Madrid, 1920.

Emilia Pardo Bazán, "El Estudio de Galdós en Madrid," in Nuevo teatro crítico, agosto de 1891, pp. 65-74. (Obras completas, vol. 44.)

B. Pérez Galdós, "Memorias de un desmemoriado," in La esfera, vol. III, 1916 (especially the first two instalments).

B. Pérez Galdós, Prólogo to J. M. Salaverría, Vieja España, Madrid, 1907.

Camille Pitollet, "Comment vit le patriarche des lettres espagnoles," in Revue de l'enseignement des langues vivantes, Feb. 1918 (vol. XXXV).

Camille Pitollet, "Le monument Pérez Galdós à Madrid," in Revue de l'enseignement des langues vivantes, Feb. 1919 (vol. XXXVI).

Luis Ruiz Contreras, Memorias de un desmemoriado, Madrid, 1916, pp. 10, 65-72.

2. CRITICISM

J. M. Aicardo, De literatura contemporánea, Madrid, 1905, pp. 316-50. [A Catholic point of view.]

Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), Galdós, Madrid, 1912. [Already a classic.]

Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), Palique, Madrid, 1893.

Rafael Altamira, De historia y arte (estudios críticos), Madrid, 1898, pp. 275-314.

Rafael Altamira, Psicología y literatura, Madrid, 1905, pp. 155-56 and 192-98.

Andrenio (Gómez de Baquero), Novelas y novelistas, Madrid, 1918, pp. 11-112.

Anonymous, "Benito Pérez Galdós," in The Drama, May, 1911, pp. 1-11 (vol. I).

Azorín, "Don Benito Pérez Galdós," in Blanco y negro, no. 1260 (July 11, 1915).

Azorín, Lecturas españolas, Madrid, 1912, pp. 171-76.

R. E. Bassett, in Modern Language Notes, XIX (1904), pp. 15-17.

Luis Bello, Ensayos e imaginaciones sobre Madrid, Madrid, 1919, pp. 95-129.

Christian Brinton, "Galdós in English," in The Critic, vol. 45 (1904), pp. 449-50.

Manuel Bueno, Teatro español contemporáneo, Madrid, 1909, pp. 77-107.

Barrett H. Clark, The Continental Drama of To-day, New York, 1915, pp. 228-32.

Barrett H. Clark, in Preface to Masterpieces of Modern Spanish Drama, New York, 1917.

José Díaz, Electra, Barcelona, 1901.

Havelock Ellis, "Electra and the progressive movement in Spain," in The Critic, vol. 39 (1901), pp. 213-217.

Havelock Ellis, "The Spirit of Present-day Spain," in The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 98 (1906), pp. 757-65.