The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Beggar's Opera, by John Gay

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

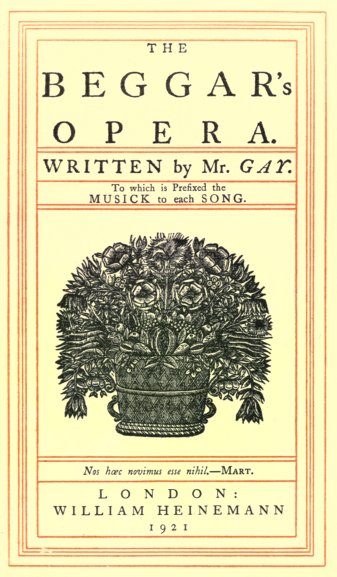

Title: The Beggar's Opera

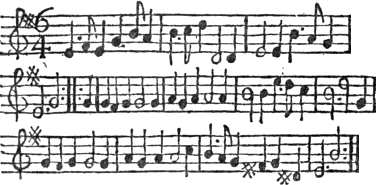

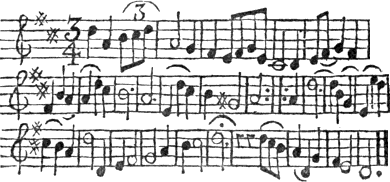

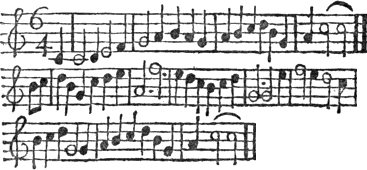

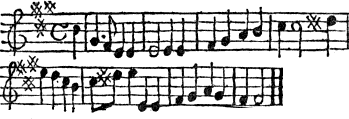

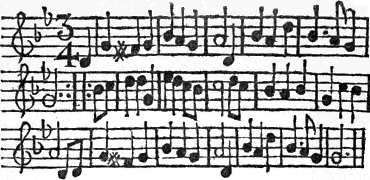

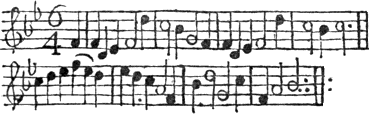

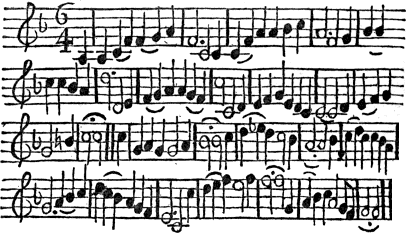

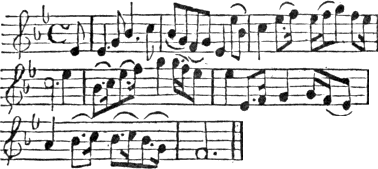

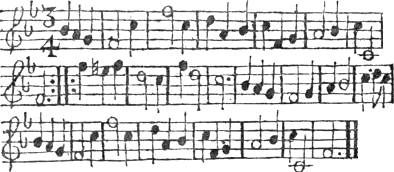

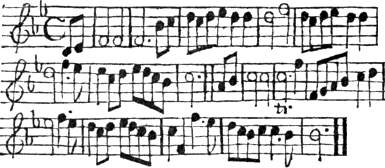

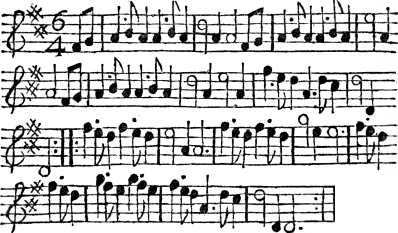

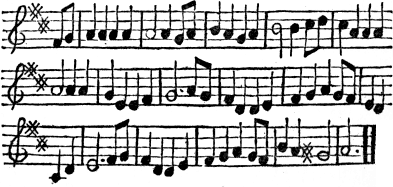

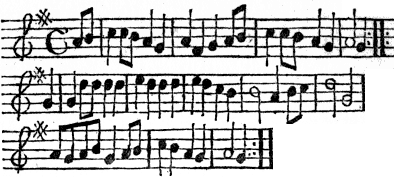

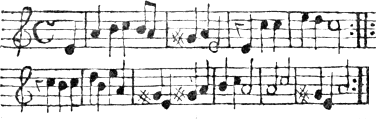

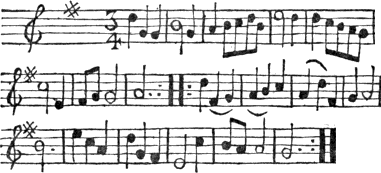

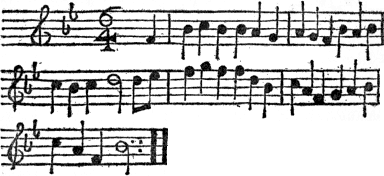

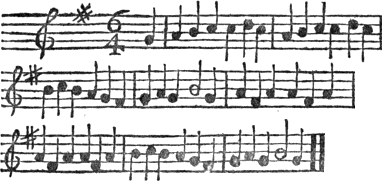

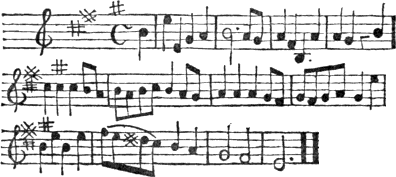

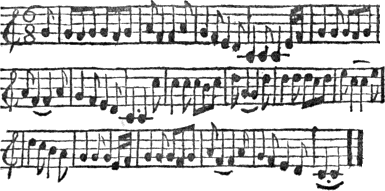

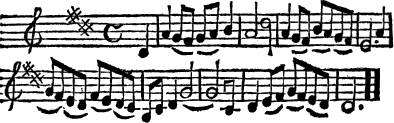

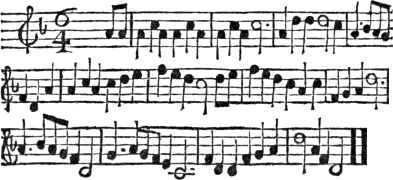

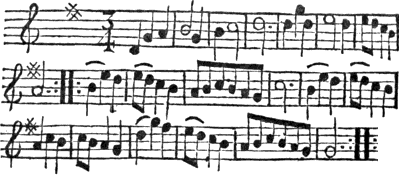

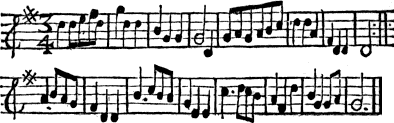

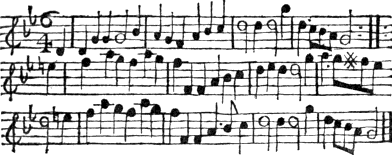

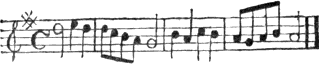

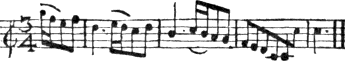

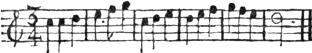

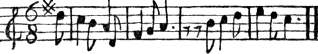

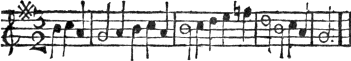

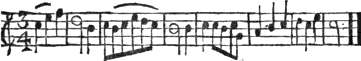

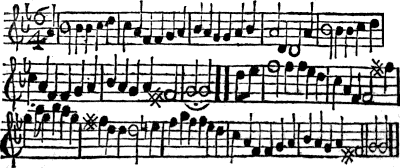

to which is prefixed the Musick to each Song

Author: John Gay

Editor: Claud Lovat Fraser

Release Date: April 13, 2008 [EBook #25063]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BEGGAR'S OPERA ***

Produced by Louise Hope

This text uses utf-8 (unicode) file encoding. If the apostrophes and quotation marks in this paragraph appear as garbage, you may have an incompatible browser or unavailable fonts. First, make sure that the browser’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change your browser’s default font.

The music is shown as printed, except that unused lines at the end of the staff have been deleted. The MIDI and PDF versions include minor corrections; details are given at the end of the e-text. Handling of these files depends on your browser; they may open directly, or they may need to be downloaded and opened through a different application.

The color Plates have been placed between scenes. The List of Plates shows their original locations.

Contents

|

To J. G. and to G. L. F., without whom I should have been powerless, do I dedicate my share in this book. C. L. F.

Note.—The Text here given is taken from the edition of 1765. The scenes have been re-numbered in the modern method denoting actual changes of place or intervals of time.

First published September 1921

New Impression October 1921

v| I. | THE BEGGAR | Frontispiece | |

| II. | MRS. PEACHUM | To face page | 6 |

| III. | POLLY PEACHUM | „ | 18 |

| IV. | SCENE: A TAVERN NEAR NEWGATE | „ | 28 |

| V. | CAPTAIN MACHEATH | „ | 40 |

| VI. | LUCY LOCKIT | „ | 56 |

| VII. | PEACHUM | „ | 70 |

| VIII. | LOCKIT | „ | 82 |

That when I die this word may stand for me—

He had a heart to praise, an eye to see,

And beauty was his king.

Dead at the age of thirty-one after a sudden operation, Claud Lovat Fraser was as surely a victim of the war as though he had fallen in action. He was full of vigour for his work, but shell-shock had left him with a heart that could not stand a strain of this kind, and all his own fine courage could not help the surgeons in a losing fight. We are not sorry for him—we learn that, not to be sorry for the dead. But for ourselves? This terror is always so fresh, so unexampled. I had telephoned to him to ask whether he would help me in a certain theatrical enterprise. I was told by his servant that he was ill, but one hears these things so often that one gave but little thought to it beyond sending a telegram asking for news; and now this. Personal griefs are of no public interest, but here is as sad a public loss as has befallen us, if the world can measure truly, in our generation.

But it is not, I think, of our loss that we should speak now. These desolations, strangely, have a way of bringing their own fortitude. A few hours after hearing, without any warning, of Lovat Fraser’s death, I was walking among the English landscape that he loved so well, and I felt there how poor and inadequate a thing death really was, how little to be feared. This apparent intention to destroy a life and genius so young, so admirable, and so rich in promise, seemed, for all the hurt, in some way wholly to have failed. We all knew that, given health, the next ten years would show a splendid volume of work from the new power and understanding to which he had been coming in these later days. But just as it seems to me not the occasion to lament our own loss, so does it seem idle to speculate with regret upon what art may have lost by this sudden 2 stroke. It is, rather, well to be glad that so few years have borne so abundantly. Not only is the work that Lovat Fraser has left full in volume, it is decisive in character beyond all likelihood in one of his years. Greatly as he would have added to our delight, and wider as his influence would have grown, nothing he might have done could have added to our knowledge of the kind of distinction that was his and that will always mark his fame.

The man himself had a charm of unusual definition. One might go to his studio at five o’clock and find him lumbering with his great frame among a chaos of the rare and curious books that he loved, stacked pell-mell on to the shelves, littered on tables and the floor, his clothes and face and fingers streaked with paint. And then an hour or two later he would come dressed ready for the theatre, an immaculate beau of the ’fifties, his top coat with waist and skirts, his opera hat made to special order by a Bond Street expert on an 1850 last. And then, before setting off, he would talk of some fellow-artist who was a little down and out, and wonder whether some of his drawings might not be bought at a few guineas apiece. Then to book, as it were, such an order gave salt to his evening, and if the evening meant contact with some of his own exquisite work, a word of admiration was taken with that wistful gratitude that it is now almost unbearable to remember.

The theatre is a complex, co-operative affair, and it is idle to inquire who gives more than another to it. But on one side of its effort nobody in these later years has fought for light and beauty more surely and courageously than Claud Lovat Fraser. Like every fine artist, he was sometimes a little puzzled, a little hurt, that the critics could not see the clear motives inspiring his work. But the purpose never faltered. As You Like It, The Beggar’s Opera, If, the exquisite designs for Madame Karsavina’s later ballets—these made it plain enough that a new genius of extraordinary power and fertility was at work on the stage. With a knowledge of tradition that combined the widest learning with profound intuition, Lovat Fraser in his design touched the life of five 3 hundred years with the English spirit of our own time, with a certainty that every one of his colleagues, I know, will be proud to allow was beyond them all. The fertility of which I speak was perhaps his peculiar distinction, and it had no touch of common facility. He could not draw a line that was not hard with thought and rooted in imaginative decision. But he could invent with immense rapidity. It was the old, though rare, story. Alike in his theatre design and his tender landscape, beauty of spirit flowed in everything he did into beauty of execution. He was a man in whose presence everything mean or slipshod withered.

But perhaps it is most fitting at this time that we should think of our dead friend in yet another way. We are governed by two influences, our own character, and example. For each man his own character is for his meditation apart, but of example we may sometimes speak together in the open with profit. Those of us who live always striving towards creative effort believe passionately that the thing towards which we aim makes for all that is most chivalrous and most intelligent in life, that it is indeed the one true honesty in the world. And yet we know how easily that effort is beset by fears and jealousies and failure in generosity, how lightly we who should together give all our energy to the service of our art, waste it in little concerns of spite and self-interest. And it is in just such ways as this that great example may serve us nobly, and there has surely never lived an artist in whom such example more clearly shone. Art, which for him embraced and crystallised all that was brave and adventurous and tender, was the worship of Lovat Fraser’s life, a worship which he kept with an absolute loyalty.

It is my privilege to know most of the best artists, in all kinds, of my age. One has this distinction, another that. But I think that he had the loveliest of them all. I have known nobody who brought to his art a devotion so pure and utterly removed from self-interest. If he could serve the beauty that he loved, he was eager always to do so with perfect indifference to his own reward. Nobody could be with him for ten minutes without 4 feeling that art was a thing far greater than any artist. He had the lovely, humorous humility that is the one sure sign of greatness. One felt always that if he should think that another might do given work better than he, there could be for him nothing but distress if the best was not done, even though it meant the loss of personal opportunity. But it is one of the happy things of genius that this exquisite humility can only live with great creative gifts, so that Lovat Fraser knew from day to day the supreme joy of mastery. The humility, however, is our example, and the thought that seems most worthy to-day is that he stands at this moment, for all he was younger than most of us, as a challenging leader to us all. It will, I think, always be impossible to remember him without feeling that anything mean or grudging in the spirit in which we do our work is a betrayal and an intolerable thing. With all his gaiety, his fun, his simplicities, and his powers, he showed us not only what a fine artist can do but what a fine artist can be. And under his leadership at this moment may we not go back to our work in the world with renewed courage and faith,

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.”

For his fame none of us have any fear. There is in his public achievement and his portfolios a solid body of work that more and more must establish itself. However futile prophecy in these things must be, one is confident that a hundred years hence his name will be highly honoured among the little band who helped to bring back some life and truth to the English theatre of this age. He would wish for nothing better than that. And idle though it is to ask what his death, at little more than youth, may mean in the way of loss to the art that he lived for, his friends know that as dear a life as any of our time has gone suddenly, inexplicably, taking with it the tenderest love of every one who knew him. And he leaves with us an example without any stain.

John Drinkwater.

London,

Midsummer 1921.

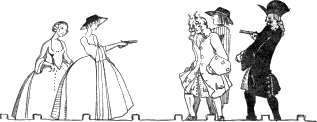

Superficially the task of staging The Beggar’s Opera was one of supreme ease. Indeed, so easy was it that it became a matter of some embarrassment to prune and select the required amount of data. Here was Hogarth and his actual scene of Newgate with Macheath in chains; here was Laroon’s Cries of London falling, in its edition of 1733, pat into the period; here was the National Portrait Gallery and, added to these, here was the benefit of all Mr. Charles E. Pearce’s research.1 After a month or two of work in designing, the ease became so marked and apparent that it engendered in me the beginnings of mistrust. Still, I persevered in scene and costume with historically accurate reproduction and, until three weeks before the actual work was due to be carried out at the costumier’s and in the painting shops, I felt comparatively cheerful. Then I reviewed my forces—the little scale models of the scenes, the characters in painted cardboard—all exact and accurate. Something was wrong and the result was, I confess, appalling. viii I had not made allowances either for my theatre or for my audience. I had forgotten that it required a spacious Georgian theatre, the intimacy of the side-boxes, the great personages sitting on the stage. The Duke of Bolton, Major Pauncefoot and Sir Robert Fagg were not in their places as in Hogarth’s painting; the pit would not be filled with tye-wigs and hoops and there would be a sharper line of division between the actors and the spectators than ever existed in 1728. Something else had to be done. As reproduction was a failure one would try to give an impression of the same thing. Impressionism proved even worse than accuracy. It was neither one thing nor the other. It merged into “making a picture of it”—a crime that is without parallel in the staging of a play. To make a pretty picture at the expense of drama is merely to pander to the voracity of the costumier and scene-painter.

What was then to be done? Added to all these objections was the important fact that I had designed scenes that would have seriously hampered the resources at Hammersmith. The theatre would have required more space for storage than could possibly have been given and, in addition, an army of stage hands would be wanted for whom there was not in this little theatre the accommodation.

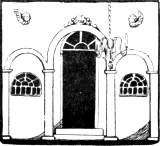

The solution was, of course, to forget one’s past work, to scrap the models, and to start feverishly afresh. The only method left untried was the symbolic. That is to say, to hint at the eighteenth century and to suggest that through the doors on the stage existed the London of 1728. The scene demanded to be simple and one which, with slight modifications in doors and windows, remained before the audience for the whole action of the play. It was, therefore, to be a scene of which people did not easily tire and that remained interesting, unobtrusive ix and formally neat. To find such a scene it is necessary to refer back to days when the Comic and the Tragic scenes were architectural and permanent. This I did and, taking Palladio’s magnificent scene at Vicenza, by a shameless process of reductio ad absurdum, evolved the scene that is now in use at Hammersmith. Palladio and Gay have much to forgive.

So far the scene, but it called for a corresponding treatment in the dresses. In The Beggar’s Opera no one is in the height of fashion. Macheath and certain Ladies of the Town alone “keep Company with Lords and Gentlemen,” and even then there must have been apparent a distinction. Macheath is unaltered. Here it was essential to keep to tradition. Macheath in a blue coat is unthinkable. The rest of the characters are frankly in the neighbourhood of Newgate. The clothes of Peachum and Lockit would be as equally unfashionable and just as possible thirty years before as thirty years after 1728, whilst the footpads are clad in whatever Georgian rags that happened to come their way. With the women I have taken greater licence. I have kept faithfully to the outlines of the age, the close-fitting bodice, the flat hoops, the square-toed shoes, but I have taken considerable liberties in the manner in which I have shorn them of ribbons and laces and—for the sake of dramatic simplicity, be it remembered—I have eliminated yards of trimming.

Just so much explanation is, I consider, due to the public, but whether I have been justified by results or whether, under the sacred mask of Drama, I have erred unpardonably, are points which, so long as this revival draws attention to a forgotten masterpiece, can be of no very great importance.

C. Lovat Fraser.

Chelsea,

February 1921.

1. Polly Peachum and The Beggar’s Opera, by Charles E. Pearce. Messrs. Stanley Paul & Company, 1913.

![]()

| MEN. | |

|---|---|

|

Mr. Peachum Lockit Macheath Filch |

|

|

Jemmy Twitcher Crook-finger’d Jack Wat Dreary Robin of Bagshot Nimming Ned Harry Paddington Mat of the Mint |

|

|

|

|

| Ben Budge | |

|

Beggar Player |

|

|

WOMEN. |

|

|

Mrs. Peachum Polly Peachum Lucy Lockit Diana Trapes |

|

|

Mrs. Coaxer Dolly Trull Mrs. Vixen Betty Doxy Jenny Diver Mrs. Slammekin Suky Tawdry |

|

|

|

|

| Molly Brazen | |

Constables, Drawers, Turnkey, etc.

xiii

If Poverty be a Title to Poetry, I am sure no-body can dispute mine. I own myself of the Company of Beggars; and I make one at their Weekly Festivals at St. Giles’s. I have a small Yearly Salary for my Catches, and am welcome to a Dinner there whenever I please, which is more than most Poets can say.

Player. As we live by the Muses, it is but Gratitude in us to encourage Poetical Merit wherever we find it. The Muses, contrary to all other Ladies, pay no Distinction to Dress, and never partially mistake the Pertness of Embroidery for Wit, nor the Modesty of Want for Dulness. Be the Author who he will, we push his Play as far as it will go. So (though you are in Want) I wish you success heartily.

Beggar. This piece I own was originally writ for the celebrating the Marriage of James Chaunter and Moll Lay, two most excellent Ballad-Singers. I have introduced the Similes that are in all your celebrated Operas: The Swallow, the Moth, the Bee, the Ship, the Flower, &c. xiv Besides, I have a Prison-Scene, which the Ladies always reckon charmingly pathetic. As to the Parts, I have observed such a nice Impartiality to our two Ladies, that it is impossible for either of them to take Offence. I hope I may be forgiven, that I have not made my Opera throughout unnatural, like those in vogue; for I have no Recitative; excepting this, as I have consented to have neither Prologue nor Epilogue, it must be allowed an Opera in all its Forms. The Piece indeed hath been heretofore frequently represented by ourselves in our Great Room at St. Giles’s, so that I cannot too often acknowledge your Charity in bringing it now on the Stage.

Player. But I see it is time for us to withdraw; the Actors are preparing to begin. Play away the Overture.

Exeunt.

Peachum sitting at a Table with a large Book of Accounts before him.

Through all the Employments of Life

Each Neighbour abuses his Brother;

Whore and Rogue they call Husband and Wife:

All Professions be-rogue one another:

The Priest calls the Lawyer a Cheat,

The Lawyer be-knaves the Divine:

And the Statesman, because he’s so great,

Thinks his Trade as honest as mine.

A Lawyer is an honest Employment, so is mine. Like me too he acts in a double Capacity, both against Rogues and for ’em; for ’tis but fitting that we should protect and encourage Cheats, since we live by them.

Enter Filch.

Filch. Sir, Black Moll hath sent word her Trial comes on in the Afternoon, and she hopes you will order Matters so as to bring her off.

Peachum. As the Wench is very active and industrious, you may satisfy her that I’ll soften the Evidence.

Filch. Tom Gagg, Sir, is found guilty.

Peachum. A lazy Dog! When I took him the time before, I told him what he would come to if he did not mend his Hand. This is Death without Reprieve. I may venture to Book him writes. For Tom Gagg, forty Pounds. Let Betty Sly know that I’ll save her from Transportation, for I can get more by her staying in England.

Filch. Betty hath brought more Goods into our Lock to-year than any five of the Gang; and in truth, ’tis a pity to lose so good a Customer.

Peachum. If none of the Gang take her off, she may, in the common course of Business, live a Twelve-month longer. I love to let Women scape. A good Sportsman always lets the Hen Partridges fly, because the Breed of the Game depends upon them. Besides, here the Law allows us no Reward; there is nothing to be got by the Death of Women—except our Wives.

Filch. Without dispute, she is a fine Woman! ’Twas to her I was obliged for my Education, and (to say a bold Word) she hath trained up more young Fellows to the Business than the Gaming table.

3Peachum. Truly, Filch, thy Observation is right. We and the Surgeons are more beholden to Women than all the Professions besides.

Filch.

’Tis Woman that seduces all Mankind,

By her we first were taught the wheedling Arts:

Her very Eyes can cheat; when most she’s kind,

She tricks us of our Money with our Hearts.

For her, like Wolves by Night we roam for Prey,

And practise ev’ry Fraud to bribe her Charms;

For Suits of Love, like Law, are won by Pay,

And Beauty must be fee’d into our Arms.

Peachum. But make haste to Newgate, Boy, and let my Friends know what I intend; for I love to make them easy one way or other.

Filch. When a Gentleman is long kept in suspence, Penitence may break his Spirit ever after. Besides, Certainty gives a Man a good Air upon his Trial, and makes him risk another without Fear or Scruple. But 4 I’ll away, for ’tis a Pleasure to be the Messenger of Comfort to Friends in Affliction.

Exit Filch.

Peachum. But ’tis now high time to look about me for a decent Execution against next Sessions. I hate a lazy Rogue, by whom one can get nothing ’till he is hang’d. A Register of the Gang, Reading. Crook-finger’d Jack. A Year and a half in the Service; Let me see how much the Stock owes to his industry; one, two, three, four, five Gold Watches, and seven Silver ones. A mighty clean-handed Fellow! Sixteen Snuff-boxes, five of them of true Gold. Six Dozen of Handkerchiefs, four silver-hilted Swords, half a Dozen of Shirts, three Tye-Periwigs, and a Piece of Broad-Cloth. Considering these are only the Fruits of his leisure Hours, I don’t know a prettier Fellow, for no Man alive hath a more engaging Presence of Mind upon the Road. Wat Dreary, alias Brown Will, an irregular Dog, who hath an underhand way of disposing of his Goods. I’ll try him only for a Sessions or two longer upon his Good-behaviour. Harry Paddington, a poor petty-larceny Rascal, without the least Genius; that Fellow, though he were to live these six Months, will never come to the Gallows with any Credit. Slippery Sam; he goes off the next Sessions, for the Villain hath the Impudence to have Views of following his Trade as a Tailor, which he calls an honest Employment. Mat of the Mint; listed not above a Month ago, a promising sturdy Fellow, and diligent in his way; somewhat too bold and hasty, and may raise good Contributions on the Public, if he does not cut himself short by Murder. Tom Tipple, a guzzling soaking Sot, who is always too drunk to stand himself, or to make others stand. A Cart is absolutely necessary for him. Robin of Bagshot, alias Gorgon, alias Bluff Bob, alias Carbuncle, alias Bob Booty.

5Enter Mrs. Peachum.

Mrs. Peachum. What of Bob Booty, Husband? I hope nothing bad hath betided him. You know, my Dear, he’s a favourite Customer of mine. ’Twas he made me a present of this Ring.

Peachum. I have set his Name down in the Black List, that’s all, my Dear; he spends his Life among Women, and as soon as his Money is gone, one or other of the Ladies will hang him for the Reward, and there’s forty Pound lost to us for-ever.

Mrs. Peachum. You know, my Dear, I never meddle in matters of Death; I always leave those Affairs to you. Women indeed are bitter bad Judges in these cases, for they are so partial to the Brave that they think every Man handsome who is going to the Camp or the Gallows.

If any Wench Venus’s Girdle wear,

Though she be never so ugly;

Lilies and Roses will quickly appear,

And her Face look wond’rous smugly.

Beneath the left Ear so fit but a Cord,

(A Rope so charming a Zone is!)

The Youth in his Cart hath the Air of a Lord,

And we cry, There dies an Adonis!

But really, Husband, you should not be too hard-hearted, for you never had a finer, braver set of Men than at present. We have not had a Murder among them all, these seven Months. And truly, my Dear, that is a great Blessing.

Peachum. What a dickens is the Woman always a whimpring about Murder for? No Gentleman is ever look’d upon the worse for killing a Man in his own Defence; and if Business cannot be carried on without it, what would you have a Gentleman do?

Mrs. Peachum. If I am in the wrong, my Dear, you must excuse me, for no body can help the Frailty of an over-scrupulous Conscience.

Peachum. Murder is as fashionable a Crime as a Man can be guilty of. How many fine Gentlemen have we in Newgate every Year, purely upon that Article! If they have wherewithal to persuade the Jury to bring it in Manslaughter, what are they the worse for it? So, my Dear, have done upon this Subject. Was Captain Macheath here this Morning, for the Bank-Notes he left with you last Week?

Mrs. Peachum. Yes, my Dear; and though the Bank hath stopt Payment, he was so chearful and so agreeable! Sure there is not a finer Gentleman upon the Road than the Captain! if he comes from Bagshot at any reasonable Hour, he hath promis’d to make one this Evening with Polly and me, and Bob Booty at a Party of Quadrille. Pray, my Dear, is the Captain rich?

Peachum. The Captain keeps too good Company ever to grow rich. Marybone and the Chocolate-houses are his Undoing. The Man that proposes to get Money by play should have the Education of a fine Gentleman, and be train’d up to it from his Youth.

Mrs. Peachum. Really, I am sorry upon Polly’s Account the Captain hath not more Discretion. What Business 7 hath he to keep Company with Lords and Gentlemen? he should leave them to prey upon one another.

Peachum. Upon Polly’s Account! What, a Plague, does the Woman mean?—Upon Polly’s Account!

Mrs. Peachum. Captain Macheath is very fond of the Girl.

Peachum. And what then?

Mrs. Peachum. If I have any Skill in the Ways of Women, I am sure Polly thinks him a very pretty Man.

Peachum. And what then? You would not be so mad to have the Wench marry him! Gamesters and Highwaymen are generally very good to their Whores, but they are very Devils to their Wives.

Mrs. Peachum. But if Polly should be in Love, how should we help her, or how can she help herself? Poor Girl, I am in the utmost Concern about her.

If Love the Virgin’s Heart invade,

How, like a Moth, the simple Maid

Still plays about the Flame!

If soon she be not made a Wife,

Her Honour’s sing’d, and then for Life,

She’s—what I dare not name.

Peachum. Look ye, Wife. A handsome Wench in our way of Business is as profitable as at the Bar of a Temple Coffee-House, who looks upon it as her livelihood to grant every Liberty but one. You see I would indulge the Girl as far as prudently we can. In any thing, but Marriage! After that, my Dear, how shall we be safe? Are we not then in her Husband’s Power? For a Husband hath the absolute Power over all a Wife’s Secrets but her own. If the Girl had the Discretion of a Court-Lady, who can have a Dozen young Fellows at her Ear without complying with one, I should not matter it; but Polly is Tinder, and a Spark will at once set her on a Flame. Married! If the Wench does not know her own Profit, sure she knows her own Pleasure better than to make herself a Property! My Daughter to me should be, like a Court-Lady to a Minister of State, a Key to the whole Gang. Married! If the Affair is not already done, I’ll terrify her from it, by the Example of our Neighbours.

Mrs. Peachum. May-hap, my Dear, you may injure the Girl. She loves to imitate the fine Ladies, and she may only allow the Captain Liberties in the view of Interest.

Peachum. But ’tis your Duty, my Dear, to warn the Girl against her Ruin, and to instruct her how to make the most of her Beauty. I’ll go to her this moment, and sift her. In the meantime, Wife, rip out the Coronets and Marks of these Dozen of Cambric Handkerchiefs, for I can dispose of them this Afternoon to a Chap in the City. Exit Peachum.

Mrs. Peachum. Never was a Man more out of the way in an Argument than my Husband! Why must our Polly, forsooth, differ from her Sex, and love only her Husband? And why must Polly’s Marriage, contrary to all Observations, make her the less followed by other 9 Men? All Men are Thieves in Love, and like a Woman the better for being another’s Property.

A Maid is like the Golden Ore,

Which hath Guineas intrinsical in’t,

Whose Worth is never known before

It is try’d and imprest in the Mint.

A Wife’s like a Guinea in Gold,

Stampt with the Name of her Spouse;

Now here, now there; is bought, or is sold;

And is current in every House.

Enter Filch.

Mrs. Peachum. Come hither, Filch. I am as fond of this Child, as though my Mind misgave me he were my own. He hath as fine a Hand at picking a Pocket as a Woman, and is as nimble-finger’d as a Juggler. If an unlucky Session does not cut the Rope of thy Life, I pronounce, Boy, thou wilt be a great Man in History. Where was your Post last Night, my Boy?

Filch. I ply’d at the Opera, Madam; and considering ’twas neither dark nor rainy, so that there was no great Hurry in getting Chairs and Coaches, made a 10 tolerable Hand on’t. These seven Handkerchiefs, Madam.

Mrs. Peachum. Colour’d ones, I see. They are of sure Sale from our Warehouse at Redriff among the Seamen.

Filch. And this Snuff-box.

Mrs. Peachum. Set in Gold! A pretty Encouragement this to a young Beginner.

Filch. I had a fair Tug at a charming Gold Watch. Pox take the Tailors for making the Fobs so deep and narrow! It stuck by the way, and I was forc’d to make my Escape under a Coach. Really, Madam, I fear I shall be cut off in the Flower of my Youth, so that every now and then (since I was pumpt) I have Thoughts of taking up and going to Sea.

Mrs. Peachum. You should go to Hockley in the Hole, and to Marybone, Child, to learn Valour. These are the Schools that have bred so many brave Men. I thought, Boy, by this time, thou hadst lost Fear as well as Shame. Poor Lad! how little does he know as yet of the Old Baily! For the first Fact I’ll insure thee from being hang’d; and going to Sea, Filch, will come time enough upon a Sentence of Transportation. But now, since you have nothing better to do, ev’n go to your Book, and learn your Catechism; for really a Man makes but an ill Figure in the Ordinary’s Paper, who cannot give a satisfactory Answer to his Questions. But, hark you, my Lad. Don’t tell me a Lye; for you know I hate a Liar. Do you know of anything that hath pass’d between Captain Macheath and our Polly?

Filch. I beg you, Madam, don’t ask me; for I must either tell a Lye to you or to Miss Polly; for I promis’d her I would not tell.

Mrs. Peachum. But when the Honour of our Family is concern’d—

11Filch. I shall lead a sad Life with Miss Polly, if ever she comes to know that I told you. Besides, I would not willingly forfeit my own Honour by betraying any body.

Mrs. Peachum. Yonder comes my Husband and Polly. Come, Filch, you shall go with me into my own Room, and tell me the whole Story. I’ll give thee a Glass of a most delicious Cordial that I keep for my own drinking.

Exeunt.

Enter Peachum, Polly.

Polly. I know as well as any of the fine Ladies how to make the most of myself and of my Man too. A Woman knows how to be mercenary, though she hath never been in a Court or at an Assembly. We have it in our Natures, Papa. If I allow Captain Macheath some trifling Liberties, I have this Watch and other visible Marks of his Favour to shew for it. A Girl who cannot grant some Things, and refuse what is most material, will make but a poor hand of her Beauty, and soon be thrown upon the Common.

Virgins are like the fair Flower in its Lustre,

Which in the Garden enamels the Ground;

Near it the Bees in play flutter and cluster,

And gaudy Butterflies frolick around.

But, when once pluck’d, ’tis no longer alluring,

To Covent-Garden ’tis sent (as yet sweet),

There fades, and shrinks, and grows past all enduring,

Rots, stinks, and dies, and is trod under feet.

Peachum. You know, Polly, I am not against your toying and trifling with a Customer in the way of Business, or to get out a Secret, or so. But if I find out that you have play’d the Fool and are married, you Jade you, I’ll cut your Throat, Hussy. Now you know my Mind.

Enter Mrs. Peachum, in a very great Passion.

Our Polly is a sad Slut! nor heeds what we have taught her.

I wonder any Man alive will ever rear a Daughter!

For she must have both Hoods and Gowns, and Hoops to swell her Pride,

With Scarfs and Stays, and Gloves and Lace; and she will have Men beside;

And when she’s drest with Care and Cost, all tempting, fine and gay,

As Men should serve a Cucumber, she flings herself away.

Our Polly is a sad Slut! &c.

You Baggage! you Hussy! you inconsiderate Jade! had you been hang’d, it would not have vex’d me, for that might have been your Misfortune; but to do such a mad thing by Choice; The Wench is married, Husband.

Peachum. Married! the Captain is a bold Man, and will risk any thing for Money; to be sure he believes her a Fortune. Do you think your Mother and I should have liv’d comfortably so long together, if ever we had been married? Baggage!

Mrs. Peachum. I knew she was always a proud Slut; and now the Wench hath play’d the Fool and Married, because forsooth she would do like the Gentry. Can you support the Expence of a Husband, Hussy, in Gaming, Drinking and Whoring? Have you Money enough to carry on the daily Quarrels of Man and Wife about who shall squander most? There are not many Husbands and Wives, who can bear the Charges of plaguing one another in a handsom way. If you must be married, could you introduce no body into our Family but a Highwayman? Why, thou foolish Jade, thou wilt be as ill-us’d, and as much neglected, as if thou hadst married a Lord!

Peachum. Let not your Anger, my Dear, break through the Rules of Decency, for the Captain looks upon himself in the Military Capacity, as a Gentleman by his Profession. Besides what he hath already, I know he is in a fair way of getting, or of dying; and both these ways, let me tell you, are most excellent Chances for a Wife. Tell me, Hussy, are you ruin’d or no?

Mrs. Peachum. With Polly’s Fortune, she might very well have gone off to a Person of Distinction. Yes, that you might, you pouting Slut!

Peachum. What is the Wench dumb? Speak, or I’ll make you plead by squeezing out an Answer from you. 14 Are you really bound Wife to him, or are you only upon liking? Pinches her.

Polly. Oh! Screaming.

Mrs. Peachum. How the Mother is to be pitied who hath handsom Daughters! Locks, Bolts, Bars, and Lectures of Morality are nothing to them: They break through them all. They have as much Pleasure in cheating a Father and Mother, as in cheating at Cards.

Peachum. Why, Polly, I shall soon know if you are married, by Macheath’s keeping from our House.

Polly.

Can Love be control’d by Advice?

Will Cupid our Mothers obey?

Though my Heart were as frozen as Ice,

At his Flame ’twould have melted away.

When he kist me so closely he prest,

’Twas so sweet that I must have comply’d:

So I thought it both safest and best

To marry, for fear you should chide.

Mrs. Peachum. Then all the Hopes of our Family are gone for ever and ever!

Peachum. And Macheath may hang his Father and Mother-in-law, in hope to get into their Daughter’s Fortune.

15Polly. I did not marry him (as ’tis the Fashion) coolly and deliberately for Honour or Money. But, I love him.

Mrs. Peachum. Love him! worse and worse! I thought the Girl had been better bred. Oh Husband, Husband! her Folly makes me mad! my Head swims! I’m distracted! I can’t support myself—Oh! Faints.

Peachum. See, Wench, to what a Condition you have reduc’d your poor Mother! a Glass of Cordial, this instant. How the poor Woman takes it to heart!

Polly goes out, and returns with it.

Ah, Hussy, now this is the only Comfort your Mother has left!

Polly. Give her another Glass, Sir! my Mama drinks double the Quantity whenever she is out of Order. This, you see, fetches her.

Mrs. Peachum. The Girl shews such a Readiness, and so much Concern, that I could almost find in my Heart to forgive her.

O Polly, you might have toy’d and kist.

By keeping Men off, you keep them on.

Polly.

But he so teaz’d me,

And he so pleas’d me,

What I did, you must have done.

Mrs. Peachum. Not with a Highwayman.—You sorry Slut!

16Peachum. A Word with you, Wife. ’Tis no new thing for a Wench to take Man without Consent of Parents. You know ’tis the Frailty of Women, my Dear.

Mrs. Peachum. Yes, indeed, the Sex is frail. But the first time a Woman is frail, she should be somewhat nice methinks, for then or never is the time to make her Fortune. After that, she hath nothing to do but to guard herself from being found out, and she may do what she pleases.

Peachum. Make yourself a little easy; I have a Thought shall soon set all Matters again to rights. Why so melancholy, Polly? since what is done cannot be undone, we must all endeavour to make the best of it.

Mrs. Peachum. Well, Polly; as far as one Woman can forgive another, I forgive thee.—Your Father is too fond of you, Hussy.

Polly. Then all my Sorrows are at an end.

Mrs. Peachum. A mighty likely Speech in troth, for a Wench who is just married!

Polly.

I, like a Ship in Storms, was tost;

Yet afraid to put in to Land:

17For seiz’d in the Port the Vessel’s lost,

Whose Treasure is contreband.

The Waves are laid,

My Duty’s paid.

O Joy beyond Expression!

Thus, safe a-shore,

I ask no more,

My All is in my Possession.

Peachum. I hear Customers in t’other Room: Go, talk with ’em, Polly; but come to us again, as soon as they are gone.—But, hark ye, Child, if ’tis the Gentleman who was here Yesterday about the Repeating Watch; say, you believe we can’t get Intelligence of it ’till to-morrow. For I lent it to Suky Straddle, to make a figure with it to-night at a Tavern in Drury-Lane. If t’other Gentleman calls for the Silver-hilted Sword; you know Beetle-brow’d Jemmy hath it on, and he doth not come from Tunbridge ’till Tuesday Night; so that it cannot be had ’till then. Exit Polly.

Peachum. Dear Wife, be a little pacified, Don’t let your Passion run away with your Senses. Polly, I grant you, hath done a rash thing.

Mrs. Peachum. If she had only an Intrigue with the Fellow, why the very best Families have excus’d and huddled up a Frailty of that sort. ’Tis Marriage, Husband, that makes it a Blemish.

Peachum. But Money, Wife, is the true Fuller’s Earth for Reputations, there is not a Spot or a Stain but what it can take out. A rich Rogue now-a-days is fit Company for any Gentleman; and the World, my Dear, hath not such a Contempt for Roguery as you imagine. I tell you, Wife, I can make this Match turn to our Advantage.

Mrs. Peachum. I am very sensible, Husband, that 18 Captain Macheath is worth Money, but I am in doubt whether he hath not two or three Wives already, and then if he should die in a Session or two, Polly’s Dower would come into Dispute.

Peachum. That, indeed, is a Point which ought to be consider’d.

A Fox may steal your Hens, Sir,

A Whore your Health and Pence, Sir,

Your Daughter rob your Chest, Sir,

Your Wife may steal your Rest, Sir.

A Thief your Goods and Plate.

But this is all but picking,

With Rest, Pence, Chest and Chicken;

It ever was decreed, Sir,

If Lawyer’s Hand is fee’d, Sir,

He steals your whole Estate.

The Lawyers are bitter Enemies to those in our Way. They don’t care that any body should get a clandestine Livelihood but themselves.

19Enter Polly.

Polly. ’Twas only Nimming Ned. He brought in a Damask Window-Curtain, a Hoop-Petticoat, a pair of Silver Candlesticks, a Periwig, and one Silk Stocking, from the Fire that happen’d last Night.

Peachum. There is not a Fellow that is cleverer in his way, and saves more Goods out of the Fire than Ned. But now, Polly, to your Affair; for Matters must not be left as they are. You are married then, it seems?

Polly. Yes, Sir.

Peachum. And how do you propose to live, Child?

Polly. Like other Women, Sir, upon the Industry of my Husband.

Mrs. Peachum. What, is the Wench turn’d Fool? A Highwayman’s Wife, like a Soldier’s, hath as little of his Pay, as of his Company.

Peachum. And had not you the common Views of a Gentlewoman in your Marriage, Polly?

Polly. I don’t know what you mean, Sir.

Peachum. Of a Jointure, and of being a Widow.

Polly. But I love him, Sir; how then could I have Thoughts of parting with him?

Peachum. Parting with him! Why, this is the whole Scheme and Intention of all Marriage-Articles. The comfortable Estate of Widow-hood, is the only Hope that keeps up a Wife’s Spirits. Where is the Woman who would scruple to be a Wife, if she had it in her Power to be a Widow, whenever she pleas’d? If you have any Views of this sort, Polly, I shall think the Match not so very unreasonable.

Polly. How I dread to hear your Advice! Yet I must beg you to explain yourself.

20Peachum. Secure what he hath got, have him peach’d the next Sessions, and then at once you are made a rich Widow.

Polly. What, murder the Man I love! The Blood runs cold at my Heart with the very thought of it.

Peachum. Fie, Polly! What hath Murder to do in the Affair? Since the thing sooner or later must happen, I dare say, the Captain himself would like that we should get the Reward for his Death sooner than a Stranger. Why, Polly, the Captain knows, that as ’tis his Employment to rob, so ’tis ours to take Robbers; every Man in his Business. So that there is no Malice in the Case.

Mrs. Peachum. Ay, Husband, now you have nick’d the Matter. To have him peach’d is the only thing could ever make me forgive her.

Polly.

O ponder well! be not severe;

So save a wretched Wife!

For on the Rope that hangs my Dear

Depends poor Polly’s Life.

Mrs. Peachum. But your Duty to your Parents, Hussy, obliges you to hang him. What would many a Wife give for such an Opportunity!

Polly. What is a Jointure, what is Widow-hood to me? I know my Heart. I cannot survive him.

21

The Turtle thus with plaintive Crying,

Her Lover dying,

The Turtle thus with plaintive Crying,

Laments her Dove.

Down she drops quite spent with Sighing.

Pair’d in Death, as pair’d in Love.

Thus, Sir, it will happen to your poor Polly.

Mrs. Peachum. What, is the Fool in Love in earnest then? I hate thee for being particular: Why, Wench, thou art a Shame to thy very Sex.

Polly. But hear me, Mother.—If you ever lov’d—

Mrs. Peachum. Those cursed Play-Books she reads have been her Ruin. One Word more, Hussy, and I shall knock your Brains out, if you have any.

Peachum. Keep out of the way, Polly, for fear of Mischief, and consider of what is proposed to you.

Mrs. Peachum. Away, Hussy. Hang your Husband, and be dutiful. Exit Polly.

Re-enter Polly, and listens behind column.

Mrs. Peachum. The Thing, Husband, must and shall be done. For the sake of Intelligence we must take 22 other measures, and have him peached the next Session without her Consent. If she will not know her Duty, we know ours.

Peachum. But really, my Dear, it grieves one’s Heart to take off a great Man. When I consider his Personal Bravery, his fine Stratagem, how much we have already got by him, and how much more we may get, methinks I can’t find in my Heart to have a hand in his Death. I wish you could have made Polly undertake it.

Mrs. Peachum. But in a Case of Necessity—our own Lives are in danger.

Peachum. Then, indeed, we must comply with the Customs of the World, and make Gratitude give way to Interest.—He shall be taken off.

Mrs. Peachum. I’ll undertake to manage Polly.

Peachum. And I’ll prepare Matters for the Old-Baily.

Exeunt severally.

Polly. Now I’m a Wretch, indeed.—Methinks I see him already in the Cart, sweeter and more lovely than the Nosegay in his Hand!—I hear the Crowd extolling his Resolution and Intrepidity!—What Vollies of Sighs are sent from the Windows of Holborn, that so comely a Youth should be brought to Disgrace!—I see him at the Tree! The whole Circle are in Tears!—even Butchers weep!—Jack Ketch himself hesitates to perform his Duty, and would be glad to lose his Fee, by a Reprieve. What then will become of Polly!—As yet I may inform him of their Design, and aid him in his Escape.—It shall be so—But then he flies, absents himself, and I bar myself from his dear dear Conversation! That too will distract me.—If he keep out of the way, my Papa and Mama may in time relent, and we may be happy.—If he stays, he is hang’d, and then he 23 is lost for ever!—He intended to lie conceal’d in my Room, ’till the Dusk of the Evening: If they are abroad I’ll this Instant let him out, lest some Accident should prevent him. Exit, and returns with Macheath.

Macheath.

Pretty Polly, say,

When I was away,

Did your fancy never stray

To some newer Lover?

Polly.

Without Disguise,

Heaving Sighs,

Doting Eyes,

My constant Heart discover.

Fondly let me loll!

Macheath.

O pretty, pretty Poll.

Polly. And are you as fond as ever, my Dear?

Macheath. Suspect my Honour, my Courage, suspect any thing but my Love.—May my Pistols miss Fire, 24 and my Mare slip her Shoulder while I am pursu’d, if I ever forsake thee!

Polly. Nay, my Dear, I have no Reason to doubt you, for I find in the Romance you lent me, none of the great Heroes were ever false in Love.

Macheath.

My Heart was so free,

It rov’d like the Bee,

’Till Polly my Passion requited;

I sipt each Flower,

I chang’d every Hour,

But here every Flower is united.

Polly. Were you sentenc’d to Transportation, sure, my Dear, you could not leave me behind you—could you?

Macheath. Is there any Power, any Force that could tear me from thee? You might sooner tear a Pension out of the Hands of a Courtier, a Fee from a Lawyer, a pretty Woman from a Looking-glass, or any Woman from Quadrille.—But to tear me from thee is impossible!

25

Were I laid on Greenland’s Coast,

And in my Arms embrac’d my Lass;

Warm amidst eternal Frost,

Too soon the Half Year’s Night would pass.

Polly.

Were I sold on Indian Soil,

Soon as the burning Day was clos’d,

I could mock the sultry Toil

When on my Charmer’s Breast repos’d.

Macheath.

And I would love you all the Day,

Polly.

Every Night would kiss and play,

Macheath.

If with me you’d fondly stray

Polly.

Over the Hills and far away.

Polly. Yes, I would go with thee. But oh!—how shall I speak it? I must be torn from thee. We must part.

Macheath. How! Part!

Polly. We must, we must.—My Papa and Mama are set against thy Life. They now, even now are in Search after thee. They are preparing Evidence against thee. Thy Life depends upon a moment.

26

Oh what Pain it is to part!

Can I leave thee, can I leave thee?

O what pain it is to part!

Can thy Polly ever leave thee?

But lest Death my Love should thwart,

And bring thee to the fatal Cart,

Thus I tear thee from my bleeding Heart!

Fly hence, and let me leave thee.

One Kiss and then—one Kiss—be gone—farewel.

Macheath. My Hand, my Heart, my Dear, is so riveted to thine, that I cannot unloose my Hold.

Polly. But my Papa may intercept thee, and then I should lose the very glimmering of Hope. A few Weeks, perhaps, may reconcile us all. Shall thy Polly hear from thee?

Macheath. Must I then go?

Polly. And will not Absence change your Love?

Macheath. If you doubt it, let me stay—and be hang’d.

27Polly. O how I fear! how I tremble!—Go—but when Safety will give you leave, you will be sure to see me again; for ’till then Polly is wretched.

Macheath.

The Miser thus a Shilling sees,

Which he’s oblig’d to pay,

With sighs resigns it by degrees,

And fears ’tis gone for ay.

Parting, and looking back at each other with fondness; he at one Door, she at the other.

Polly.

The Boy, thus, when his Sparrow’s flown,

The Bird in Silence eyes;

But soon as out of Sight ’tis gone,

Whines, whimpers, sobs and cries.

![]()

Jemmy Twitcher, Crook-finger’d Jack, Wat Dreary, Robin of Bagshot, Nimming Ned, Henry Paddington, Matt of the Mint, Ben Budge, and the rest of the Gang, at the Table, with Wine, Brandy and Tobacco.

Ben. But pr’ythee, Matt, what is become of thy Brother Tom? I have not seen him since my Return from Transportation.

Matt. Poor Brother Tom had an Accident this time Twelve-month, and so clever a made fellow he was, that I could not save him from those fleaing Rascals the Surgeons; and now, poor Man, he is among the Otamys at Surgeons Hall.

Ben. So it seems, his Time was come.

Jemmy. But the present Time is ours, and no body alive hath more. Why are the Laws levell’d at us? are we more dishonest than the rest of Mankind? What we win, Gentlemen, is our own by the Law of Arms, and the Right of Conquest.

Crook. Where shall we find such another Set of Practical Philosophers, who to a Man are above the Fear of Death?

Wat. Sound Men, and true!

Robin. Of try’d Courage, and indefatigable Industry!

29Ned. Who is there here that would not die for his Friend?

Harry. Who is there here that would betray him for his Interest?

Matt. Shew me a Gang of Courtiers that can say as much.

Ben. We are for a just Partition of the World, for every Man hath a Right to enjoy Life.

Matt. We retrench the Superfluities of Mankind. The World is avaritious, and I hate Avarice. A covetous fellow, like a Jackdaw, steals what he was never made to enjoy, for the sake of hiding it. These are the Robbers of Mankind, for Money was made for the Free-hearted and Generous, and where is the Injury of taking from another, what he hath not the Heart to make use of?

Jemmy. Our several Stations for the Day are fixt. Good luck attend us all. Fill the Glasses.

Matt.

Fill every Glass, for Wine inspires us,

And fires us

With Courage, Love and Joy.

Women and Wine should life employ.

Is there ought else on Earth desirous?

Chorus.

Fill every Glass, &c.

To them enter Macheath.

Macheath. Gentlemen, well met. My Heart hath been with you this Hour; but an unexpected Affair hath detain’d me. No Ceremony, I beg you.

Matt. We were just breaking up to go upon Duty. Am I to have the Honour of taking the Air with you, Sir, this Evening upon the Heath? I drink a Dram now and then with the Stagecoachmen in the way of Friendship and Intelligence; and I know that about this Time there will be Passengers upon the Western Road, who are worth speaking with.

Macheath. I was to have been of that Party—but—

Matt. But what, Sir?

Macheath. Is there any Man who suspects my Courage?

Matt. We have all been Witnesses of it.

Macheath. My Honour and Truth to the Gang?

Matt. I’ll be answerable for it.

Macheath. In the Division of our Booty, have I ever shewn the least Marks of Avarice or Injustice?

Matt. By these Questions something seems to have ruffled you. Are any of us suspected?

Macheath. I have a fixed Confidence, Gentlemen, in you all, as Men of Honour, and as such I value and respect you. Peachum is a Man that is useful to us.

Matt. Is he about to play us any foul Play? I’ll shoot him through the Head.

Macheath. I beg you, Gentlemen, act with Conduct and Discretion. A Pistol is your last Resort.

Matt. He knows nothing of this Meeting.

Macheath. Business cannot go on without him. He is a Man who knows the World, and is a necessary Agent to us. We have had a slight Difference, and ’till it is 31 accommodated I shall be oblig’d to keep out of his way. Any private Dispute of mine shall be of no ill consequence to my Friends. You must continue to act under his Direction, for the moment we break loose from him, our Gang is ruin’d.

Matt. As a Bawd to a Whore, I grant you, he is to us of great Convenience.

Macheath. Make him believe I have quitted the Gang, which I can never do but with Life. At our private Quarters I will continue to meet you. A Week or so will probably reconcile us.

Matt. Your Instructions shall be observ’d. ’Tis now high time for us to repair to our several Duties; so ’till the Evening at our Quarters in Moor-Fields we bid you farewel.

Macheath. I shall wish myself with you. Success attend you. Sits down melancholy at the Table.

Matt.

Let us take the Road.

Hark! I hear the Sound of Coaches!

The Hour of Attack approaches,

To your Arms, brave Boys, and load.

See the Ball I hold!

32Let the Chymists toil like Asses,

Our Fire their Fire surpasses,

And turns all our Lead to Gold.

The Gang, rang’d in the Front of the Stage, load their Pistols, and stick them under their Girdles; then go off singing the first Part in Chorus.

Macheath. What a Fool is a fond Wench! Polly is most confoundedly bit.—I love the Sex. And a Man who loves Money, might as well be contented with one Guinea, as I with one Woman. The Town perhaps have been as much obliged to me, for recruiting it with free-hearted Ladies, as to any Recruiting Officer in the Army. If it were not for us, and the other Gentlemen of the Sword, Drury-Lane would be uninhabited.

If the Heart of a Man is deprest with Cares,

The Mist is dispell’d when a Woman appears;

Like the Notes of a Fiddle, she sweetly, sweetly

Raises the Spirits, and charms our Ears,

33Roses and Lilies her Cheeks disclose,

But her ripe Lips are more sweet than those.

Press her,

Caress her,

With Blisses,

Her Kisses

Dissolve us in Pleasure, and soft Repose.

I must have Women. There is nothing unbends the Mind like them. Money is not so strong a Cordial for the Time. Drawer— Enter Drawer. Is the Porter gone for all the Ladies according to my Directions?

Drawer. I expect him back every Minute. But you know, Sir, you sent him as far as Hockley in the Hole for three of the Ladies, for one in Vinegar-Yard, and for the rest of them somewhere about Lewkner’s-Lane. Sure some of them are below, for I hear the Bar-Bell. As they come I will shew them up. Coming, Coming.

Enter Mrs. Coaxer, Dolly Trull, Mrs. Vixen, Betty Doxy, Jenny Diver, Mrs. Slammekin, Suky Tawdry, and Molly Brazen.

Macheath. Dear Mrs. Coaxer, you are welcome. You look charmingly to-day. I hope you don’t want the Repairs of Quality, and lay on Paint.—Dolly Trull! kiss me, you Slut; are you as amorous as ever, Hussy? You are always so taken up with stealing Hearts, that you don’t allow yourself Time to steal any thing else.—Ah Dolly, thou wilt ever be a Coquette! Mrs. Vixen, I’m yours, I always lov’d a Woman of Wit and Spirit; they make charming Mistresses, but plaguy Wives—Betty Doxy! Come hither, Hussy. Do you drink as hard as ever? You had better stick to good wholesom Beer; for in troth, Betty, Strong-Waters will in time ruin your Constitution. You should leave those to your Betters.—What! and my pretty Jenny Diver too! As prim and 34 demure as ever! There is not any Prude, though ever so high bred, hath a more sanctify’d Look, with a more mischievous Heart. Ah! thou art a dear artful Hypocrite.—Mrs. Slammekin! as careless and genteel as ever! all you fine Ladies, who know your own Beauty, affect an Undress.—But see, here’s Suky Tawdry come to contradict what I was saying. Every thing she gets one way she lays out upon her Back. Why, Suky, you must keep at least a Dozen Tallymen. Molly Brazen! She kisses him. That’s well done. I love a free-hearted Wench. Thou hast a most agreeable Assurance, Girl, and art as willing as a Turtle.—But hark! I hear Music. The Harper is at the Door. If Music be the Food of Love, play on. Ere you seat yourselves, Ladies, what think you of a Dance? Come in. Enter Harper. Play the French Tune, that Mrs. Slammekin was so fond of.

A Dance a la ronde in the French manner; near the end of it this song and Chorus.

Youth’s the Season made for Joys,

Love is then our Duty,

She alone who that employs,

Well deserves her Beauty.

Let’s be gay,

While we may,

Beauty’s a Flower, despis’d in Decay.

Youth’s the Season, &c.

Let us drink and sport to-day,

Ours is not to-morrow.

Love with Youth flies swift away,

Age is nought but Sorrow.

Dance and sing,

Time’s on the Wing.

Life never knows the Return of Spring.

Chorus.

Let us drink, &c.

Macheath. Now, pray Ladies, take your Places. Here Fellow. Pays the Harper. Bid the Drawer bring us more Wine. Exit Harper. If any of the Ladies choose Ginn, I hope they will be so free to call for it.

Jenny. You look as if you meant me. Wine is strong enough for me. Indeed, Sir, I never drink Strong-Waters, but when I have the Cholic.

Macheath. Just the Excuse of the fine Ladies! Why, a Lady of Quality is never without the Cholic. I hope, Mrs. Coaxer, you have had good Success of late in your Visits among the Mercers.

Mrs. Coaxer. We have so many Interlopers—Yet with Industry, one may still have a little Picking. I carried a silver-flowered Lutestring, and a Piece of black Padesoy to Mr. Peachum’s Lock but last Week.

Mrs. Vixen. There’s Molly Brazen hath the Ogle of a Rattle-Snake. She rivetted a Linen-Draper’s Eye so fast upon her, that he was nick’d of three Pieces of Cambric before he could look off.

Brazen. Oh dear Madam!—But sure nothing can come up to your handling of Laces! And then you have such a sweet deluding Tongue! To cheat a Man is nothing; but the Woman must have fine Parts indeed who cheats a Woman.

Mrs. Vixen. Lace, Madam, lies in a small Compass, 36 and is of easy Conveyance. But you are apt, Madam, to think too well of your Friends.

Mrs. Coaxer. If any woman hath more Art than another, to be sure, ’tis Jenny Diver. Though her Fellow be never so agreeable, she can pick his Pocket as coolly, as if money were her only Pleasure. Now that is a Command of the Passions uncommon in a Woman!

Jenny. I never go to the Tavern with a Man, but in the View of Business. I have other Hours, and other sort of Men for my Pleasure. But had I your Address, Madam—

Macheath. Have done with your Compliments, Ladies; and drink about: You are not so fond of me, Jenny, as you use to be.

Jenny. ’Tis not convenient, Sir, to shew my Fondness among so many Rivals. ’Tis your own Choice, and not the Warmth of my Inclination that will determine you.

Before the Barn-Door crowing,

The Cock by Hens attended,

His Eyes around him throwing,

Stands for a while suspended.

37Then One he singles from the Crew,

And cheers the happy Hen;

With how do you do, and how do you do,

And how do you do again.

Macheath. Ah Jenny! thou art a dear Slut.

Jenny. A Man of Courage should never put any thing to the Risk but his Life. These are the Tools of a Man of Honour. Cards and Dice are only fit for cowardly Cheats, who prey upon their Friends.

She takes up his Pistol. Tawdry takes up the other.

Tawdry. This, Sir, is fitter for your Hand. Besides your Loss of Money, ’tis a Loss to the Ladies. Gaming takes you off from Women. How fond could I be of you! but before Company ’tis ill bred.

Macheath. Wanton Hussies!

Jenny. I must and will have a Kiss to give my Wine a Zest.

They take him about the Neck and make signs to Peachum and Constables, who rush in upon him.

Peachum. I seize you, Sir, as my Prisoner.

Macheath. Was this well done, Jenny?—Women are Decoy Ducks; who can trust them! Beasts, Jades, Jilts, Harpies, Furies, Whores!

Peachum. Your Case, Mr. Macheath, is not particular. The greatest Heroes have been ruin’d by Women. But, to do them Justice, I must own they are a pretty sort of Creatures, if we could trust them. You must now, Sir, take your Leave of the Ladies, and if they have a mind to make you a Visit, they will be sure to find you at home. This Gentleman, Ladies, lodges in Newgate. Constables, wait upon the Captain to his Lodgings.

38

Macheath.

At the Tree I shall suffer with Pleasure,

At the Tree I shall suffer with Pleasure,

Let me go where I will,

In all kinds of Ill,

I shall find no such Furies as these are.

Peachum. Ladies, I’ll take care the Reckoning shall be discharged.

Exit Macheath, guarded with Peachum and Constables.

Mrs. Vixen. Look ye, Mrs. Jenny, though Mr. Peachum may have made a private Bargain with you and Suky Tawdry for betraying the Captain, as we were all assisting, we ought all to share alike.

Mrs. Coaxer. I think Mr. Peachum, after so long an Acquaintance, might have trusted me as well as Jenny Diver.

Mrs. Slammekin. I am sure at least three Men of his hanging, and in a Year’s time too (if he did me Justice) should be set down to my Account.

Trull. Mrs. Slammekin, that is not fair. For you know one of them was taken in Bed with me.

Jenny. As far as a Bowl of Punch or a Treat, I believe Mrs. Suky will join with me.—As for any thing else, Ladies, you cannot in Conscience expect it.

Mrs. Slammekin. Dear Madam—

39Trull. I would not for the World—

Mrs. Slammekin. ’Tis impossible for me—

Trull. As I hope to be sav’d, Madam—

Mrs. Slammekin. Nay, then I must stay here all Night—

Trull. Since you command me.

Exeunt with great Ceremony.

Lockit, Turnkeys, Macheath, Constables.

Lockit. Noble Captain, you are welcome. You have not been a Lodger of mine this Year and half. You know the Custom, Sir. Garnish, Captain, Garnish. Hand me down those Fetters there.

Macheath. Those, Mr. Lockit, seem to be the heaviest of the whole Set. With your Leave, I should like the further Pair better.

Lockit. Look ye, Captain, we know what is fittest for our Prisoners. When a Gentleman uses me with Civility, I always do the best I can to please him.—Hand them down I say.—We have them of all Prices, from one Guinea to ten, and ’tis fitting every Gentleman should please himself.

Macheath. I understand you, Sir. Gives Money. The Fees here are so many, and so exorbitant, that few Fortunes can bear the Expence of getting off handsomly, or of dying like a Gentleman.

Lockit. Those, I see, will fit the Captain better—Take down the further Pair. Do but examine them, Sir.—Never was better work.—How genteely they are made!—They will fit as easy as a Glove, and the nicest Man in England might not be asham’d to wear them. He puts on the Chains. If I had the best Gentleman in the Land in my Custody I could not equip 41 him more handsomly. And so, Sir—I now leave you to your private Meditations.

Exeunt leaving Macheath solus.

Man may escape from Rope and Gun;

Nay, some have out liv’d the Doctor’s Pill;

Who takes a Woman must be undone,

That Basilisk is sure to kill.

The Fly that sips Treacle is lost in the Sweets,

So he that tastes Woman, Woman, Woman,

He that tastes Woman, ruin meets.

To what a woful Plight have I brought myself! Here must I (all Day long, ’till I am hang’d) be confin’d to hear the Reproaches of a Wench who lays her Ruin at my Door—I am in the Custody of her Father, and to be sure, if he knows of the matter, I shall have a fine time on’t betwixt this and my Execution.—But I promis’d the Wench Marriage—What signifies a Promise to a Woman? Does not Man in Marriage itself promise a hundred things that he never means to perform? Do all we can, Women will believe us; for they look upon a Promise as an Excuse for following their own Inclinations.—But here comes Lucy, and I cannot get from her.—Wou’d I were deaf!

42Enter Lucy.

Lucy. You base Man you,—how can you look me in the Face after what hath passed between us?—See here, perfidious Wretch, how I am forc’d to bear about the Load of Infamy you have laid upon me—O Macheath! thou hast robb’d me of my Quiet—to see thee tortur’d would give me Pleasure.

Thus when a good Housewife sees a Rat

In her Trap in the Morning taken,

With Pleasure her Heart goes pit-a-pat,

In Revenge for her Loss of Bacon.

Then she throws him

To the Dog or Cat,

To be worried, crush’d and shaken.

Macheath. Have you no Bowels, no Tenderness, my dear Lucy, to see a Husband in these Circumstances?

Lucy. A Husband!

Macheath. In ev’ry Respect but the Form, and that, my Dear, may be said over us at any time.—Friends should not insist upon Ceremonies. From a Man of Honour, his Word is as good as his Bond.

43Lucy. ’Tis the Pleasure of all you fine Men to insult the Women you have ruin’d.

How cruel are the Traitors,

Who lye and swear in jest,

To cheat unguarded Creatures

Of Virtue, Fame, and Rest!

Whoever steals a Shilling,

Through Shame the Guilt conceals:

In Love the perjur’d Villain

With Boasts the Theft reveals.

Macheath. The very first Opportunity, my Dear, (have but Patience) you shall be my Wife in whatever manner you please.

Lucy. Insinuating Monster! And so you think I know nothing of the Affair of Miss Polly Peachum.—I could tear thy Eyes out!

Macheath. Sure, Lucy, you can’t be such a Fool as to be jealous of Polly!

Lucy. Are you not married to her, you Brute, you.

Macheath. Married! Very good. The Wench gives it out only to vex thee, and to ruin me in thy good 44 Opinion. ’Tis true, I go to the House; I chat with the Girl, I kiss her, I say a thousand things to her (as all Gentlemen do) that mean nothing, to divert myself; and now the silly Jade hath set it about that I am married to her, to let me know what she would be at. Indeed, my dear Lucy, these violent Passions may be of ill consequence to a Woman in your Condition.

Lucy. Come, come, Captain, for all your Assurance, you know that Miss Polly hath put it out of your Power to do me the Justice you promis’d me.

Macheath. A jealous Woman believes every thing her Passion suggests. To convince you of my Sincerity, if we can find the Ordinary, I shall have no Scruples of making you my Wife; and I know the Consequence of having two at a time.

Lucy. That you are only to be hang’d, and so get rid of them both.

Macheath. I am ready, my dear Lucy, to give you Satisfaction—if you think there is any in Marriage.—What can a Man of Honour say more?

Lucy. So then, it seems, you are not married to Miss Polly.

Macheath. You know, Lucy, the Girl is prodigiously conceited. No Man can say a civil thing to her, but (like other fine Ladies) her Vanity makes her think he’s her own for ever and ever.

The first time at the Looking-glass

The Mother sets her Daughter,

The Image strikes the smiling Lass

With Self-love ever after,

Each time she looks, she, fonder grown,

Thinks ev’ry Charm grows stronger.

But alas, vain Maid, all Eyes but your own

Can see you are not younger.

When Women consider their own Beauties, they are all alike unreasonable in their Demands; for they expect their Lovers should like them as long as they like themselves.

Lucy. Yonder is my Father—perhaps this way we may light upon the Ordinary, who shall try if you will be as good as your Word.—For I long to be made an honest Woman. Exeunt.

Enter Peachum and Lockit with an Account-Book.

Lockit. In this last Affair, Brother Peachum, we are agreed. You have consented to go halves in Macheath.

Peachum. We shall never fall out about an Execution—But as to that Article, pray how stands our last Year’s Account?

Lockit. If you will run your Eye over it, you’ll find ’tis fair and clearly stated.

Peachum. This long Arrear of the Government is very hard upon us! Can it be expected that we would hang our Acquaintance for nothing, when our Betters will hardly save theirs without being paid for it. Unless the People in Employment pay better, I promise them for the future, I shall let other Rogues live besides their own.

Lockit. Perhaps, Brother, they are afraid these Matters may be carried too far. We are treated too by them with Contempt, as if our Profession were not reputable.

46Peachum. In one respect indeed our Employment may be reckon’d dishonest, because, like Great Statesmen, we encourage those who betray their Friends.

Lockit. Such Language, Brother, any where else, might turn to your Prejudice. Learn to be more guarded, I beg you.

When you censure the Age,

Be cautious and sage,

Lest the Courtiers offended should be:

If you mention Vice or Bribe,

’Tis so pat to all the Tribe;

Each cries—That was levell’d at me.

Peachum. Here’s poor Ned Clincher’s Name, I see. Sure, Brother Lockit, there was a little unfair Proceeding in Ned’s Case: for he told me in the Condemn’d Hold, that for Value receiv’d, you had promis’d him a Session or two longer without Molestation.

Lockit. Mr. Peachum—this is the first time my Honour was ever call’d in Question.

Peachum. Business is at an end—if once we act dishonourably.

Lockit. Who accuses me?

Peachum. You are warm, Brother.

Lockit. He that attacks my Honour, attacks my 47 Livelihood.—And this Usage—Sir—is not to be borne.

Peachum. Since you provoke me to speak—I must tell you too, that Mrs. Coaxer charges you with defrauding her of her Information-Money, for the apprehending of curl-pated Hugh. Indeed, indeed, Brother, we must punctually pay our Spies, or we shall have no Information.

Lockit. Is this Language to me, Sirrah,—who have sav’d you from the Gallows, Sirrah! Collaring each other.

Peachum. If I am hang’d, it shall be for ridding the World of an arrant Rascal.

Lockit. This Hand shall do the Office of the Halter you deserve, and throttle you—you Dog!—

Peachum. Brother, Brother—We are both in the Wrong—We shall be both Losers in the Dispute—for you know we have it in our Power to hang each other. You should not be so passionate.

Lockit. Nor you so provoking.

Peachum. ’Tis our mutual Interest; ’tis for the Interest of the World we should agree. If I said any thing, Brother, to the Prejudice of your Character, I ask pardon.

Lockit. Brother Peachum—I can forgive as well as resent.—Give me your Hand. Suspicion does not become a Friend.

Peachum. I only meant to give you Occasion to justify yourself: But I must now step home, for I expect the Gentleman about this Snuff-box, that Filch nimm’d two Nights ago in the Park. I appointed him at this Hour. Exit Peachum.

48Enter Lucy.

Lockit. Whence come you, Hussy?

Lucy. My Tears might answer that Question.

Lockit. You have then been whimpering and fondling, like a Spaniel, over the Fellow that hath abus’d you.

Lucy. One can’t help Love; one can’t cure it. ’Tis not in my Power to obey you, and hate him.

Lockit. Learn to bear your Husband’s Death like a reasonable Woman. ’Tis not the fashion, now-a-days, so much as to affect Sorrow upon these Occasions. No Woman would ever marry, if she had not the Chance of Mortality for a Release. Act like a Woman of Spirit, Hussy, and thank your Father for what he is doing.

Lucy.

Is then his Fate decreed, Sir?

Such a Man can I think of quitting?

When first we met, so moves me yet,

O see how my Heart is splitting!

Lockit. Look ye, Lucy—There is no saving him.—So, I think, you must ev’n do like other Widows—buy yourself Weeds, and be chearful.

49

You’ll think ere many Days ensue

This Sentence not severe;

I hang your Husband, Child, ’tis true,

But with him hang your Care.

Twang dang dillo dee.

Like a good Wife, go moan over your dying Husband. That, Child is your Duty—Consider, Girl, you can’t have the Man and the Money too—so make yourself as easy as you can, by getting all you can from him. Exit Lockit.

Enter Macheath.

Lucy. Though the Ordinary was out of the way to-day, I hope, my Dear, you will, upon the first Opportunity, quiet my Scruples—Oh Sir!—my Father’s hard heart is not to be soften’d, and I am in the utmost Despair.

Macheath. But if I could raise a small Sum—Would not twenty Guineas, think you, move him?—Of all the Arguments in the way of Business, the Perquisite is the most prevailing—Your Father’s Perquisites for the Escape of Prisoners must amount to a considerable Sum in the Year. Money well tim’d, and properly apply’d, will do any thing.

50

If you at an Office solicit your Due,

And would not have Matters neglected;

You must quicken the Clerk with the Perquisite too,

To do what his Duty directed.

Or would you the Frowns of a Lady prevent,

She too has this palpable Failing,

The Perquisite softens her into Consent;

That Reason with all is prevailing.

Lucy. What Love or Money can do shall be done: for all my Comfort depends upon your Safety.

Enter Polly.

Polly. Where is my dear Husband?—Was a Rope ever intended for this Neck!—O let me throw my Arms about it, and throttle thee with Love!—Why dost thou turn away from me? ’Tis thy Polly—’Tis thy Wife.

Macheath. Was ever such an unfortunate Rascal as I am!

51Lucy. Was there ever such another Villain!

Polly. O Macheath! was it for this we parted? Taken! Imprisoned! Try’d! Hang’d—cruel Reflection! I’ll stay with thee ’till Death—no Force shall tear thy dear Wife from thee now.—What means my Love?—Not one kind Word! not one kind Look! think what thy Polly suffers to see thee in this Condition.

Thus when the Swallow seeking Prey,

Within the Sash is closely pent,

His Consort, with bemoaning Lay,

Without sits pining for th’ Event.

Her chatt’ring Lovers all around her skim;

She heeds them not (poor Bird!) her Soul’s with him.

Macheath. Aside. I must disown her. Aloud. The Wench is distracted.

Lucy. Am I then bilk’d of my Virtue? Can I have no Reparation? Sure Men were born to lie, and Women to believe them! O Villain! Villain!

Polly. Am I not thy Wife?—Thy Neglect of me, thy Aversion to me too severely proves it.—Look on me.—Tell me, am I not thy Wife?

52Lucy. Perfidious Wretch!

Polly. Barbarous Husband!

Lucy. Hadst thou been hang’d five Months ago, I had been happy.

Polly. And I too—If you had been kind to me ’till Death, it would not have vexed me—And that’s no very unreasonable Request, (though from a Wife) to a Man who hath not above seven or eight Days to live.

Lucy. Art thou then married to another? Hast thou two Wives, Monster?

Macheath. If Women’s Tongues can cease for an Answer—hear me.

Lucy. I won’t.—Flesh and Blood can’t bear my Usage.

Polly. Shall I not claim my own? Justice bids me speak.

Macheath.

How happy could I be with either,

Were t’other dear Charmer away!

But while you thus teaze me together,

To neither a Word will I say;

But tol de rol, &c.

Polly. Sure, my Dear, there ought to be some Preference shewn to a Wife! At least she may claim the Appearance of it. He must be distracted with his Misfortunes, or he could not use me thus.

Lucy. O Villain, Villain! thou hast deceiv’d me.—I could even inform against thee with Pleasure. Not a Prude wishes more heartily to have Facts against her intimate Acquaintance, than I now wish to have Facts against thee. I would have her Satisfaction, and they should all out.

Polly.

I am bubbled.

Lucy.

I am bubbled.I’m bubbled.

Polly.

O how I am troubled!

Lucy.

Bambouzled, and bit!

Polly.

Bambouzled, and bit!My Distresses are doubled.

Lucy.

When you come to the Tree, should the Hangman refuse,

These Fingers, with Pleasure, could fasten the Noose.

Polly.

I’m bubbled, &c.

Macheath. Be pacified, my dear Lucy—This is all a Fetch of Polly’s, to make me desperate with you in case I get off. If I am hang’d, she would fain have the Credit 54 of being thought my Widow—Really, Polly, this is no time for a Dispute of this sort; for whenever you are talking of Marriage, I am thinking of Hanging.

Polly. And hast thou the Heart to persist in disowning me?

Macheath. And hast thou the Heart to persist in persuading me that I am married? Why, Polly, dost thou seek to aggravate my Misfortunes?

Lucy. Really, Miss Peachum, you but expose yourself. Besides, ’tis barbarous in you to worry a Gentleman in his Circumstances.

Polly.

Cease your Funning;

Force or Cunning

Never shall my Heart trapan.

All these Sallies

Are but Malice

To seduce my constant Man.

’Tis most certain,

By their flirting

Women oft’ have Envy shown.

Pleas’d, to ruin

Others wooing;

Never happy in their own.

Polly. Decency, Madam, methinks might teach you to behave yourself with some Reserve with the Husband, while his Wife is present.

Macheath. But seriously, Polly, this is carrying the Joke a little too far.

Lucy. If you are determin’d, Madam, to raise a Disturbance in the Prison, I shall be obliged to send for the Turnkey to shew you the Door. I am sorry, Madam, you force me to be so ill-bred.

Polly. Give me leave to tell you, Madam: These forward Airs don’t become you in the least, Madam. And my Duty, Madam, obliges me to stay with my Husband, Madam.

Lucy.

Why how now, Madam Flirt?

If you thus must chatter;

And are for flinging Dirt,

Let’s try who best can spatter;

Madam Flirt.

Polly.

Why how now, saucy Jade;

Sure the Wench is tipsy!

How can you see me made To him.

The Scoff of such a Gipsy?

Saucy Jade! To her.

Enter Peachum.

Peachum. Where’s my Wench? Ah Hussy! Hussy!—Come you home, you Slut; and when your Fellow is hang’d, hang yourself, to make your Family some Amends.

Polly. Dear, dear Father, do not tear me from him—I must speak; I have more to say to him—Oh! twist thy Fetters about me, that he may not haul me from thee!

Peachum. Sure all Women are alike! If ever they commit the Folly, they are sure to commit another by exposing themselves—Away—Not a Word more—You are my Prisoner, now, Hussy.

Polly.

No Power on Earth can e’er divide

The Knot that sacred Love hath ty’d.

When Parents draw against our Mind,

The True-Love’s Knot they faster bind.

Oh, oh ray, oh Amborah—oh, oh, &c.

Holding Macheath, Peachum pulling her.

![]()

Lucy, Macheath.

Macheath. I am naturally compassionate, Wife; so that I could not use the Wench as she deserv’d; which made you at first suspect there was something in what she said.

Lucy. Indeed, my Dear, I was strangely puzzled.

Macheath. If that had been the Case, her Father would never have brought me into this Circumstance—No, Lucy,—I had rather die than be false to thee.