Project Gutenberg's The Cruise of the "Esmeralda", by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Cruise of the "Esmeralda"

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: W.H. Overend

Release Date: June 17, 2008 [EBook #25817]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CRUISE OF THE "ESMERALDA" ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"The Cruise of the Esmeralda"

Chapter One.

The Story of the Buried Treasure.

Those of my readers who happen to be well acquainted with Weymouth, will also be assuredly acquainted with a certain lane, known as Buxton’s Lane, branching off to the right from the high-road at Rodwell, and connecting that suburb with the picturesque little village of Wyke. I make this assertion with the most perfect confidence, because Buxton’s Lane happens to afford one of the most charming walks in that charming neighbourhood; and no one can well be a sojourner for any length of time in Weymouth without discovering this fact for him or herself, either through inquiry or by means of personal exploration.

And of those who have enjoyed a saunter through this lane, some there will doubtless be who can remember a substantial stone-built house, standing back a distance of about a hundred yards or so from the roadway, and environed by a quaint old-fashioned garden, the entire demesne being situate on the crest of the rise just before Wyke is reached, and commanding an unparalleled view of the roadstead of Portland, with the open channel as far as Saint Alban’s Head to the left, while on the right the West Bay (notorious for its shipwrecks) stretches from the Bill of Portland, far away westward, into the misty distance toward Lyme, and Beer, and Seaton; ay, and even beyond that, down to Berry Head, past Torquay, the headland itself having been distinctly seen from Wyke Nap on a clear day, so it is said, though I cannot remember that I ever saw it myself from that standpoint.

The house to which I refer is (or was, for I believe it no longer exists) known as “The Spaniards,” and was built by my ancestor, Hubert Saint Leger, with a portion of the proceeds of the Spanish prize that—having so harried and worried her that she at length became separated from the main body of the Great Armada—he drove into Weymouth Bay, and there, under the eyes of his admiring fellow-townsmen, fought her in his good ship Golden Rose, until she was fain to strike her colours and surrender to a craft of considerably less than half her size.

“The Spaniards” had continued in possession of the Saint Leger family from the time of its building down to the date of my story; and under its roof I was born. And to its roof I had returned from an Australian voyage, a day or two previous to the events about to be related, to find my dear mother in the direst of trouble. My father, like all the rest of the male Saint Legers, for as many generations as we could trace back, had been a seaman, and had died abroad, leaving my mother such a moderate provision as would enable her, with care, to end her days in peace and comfort beneath the old roof-tree. It was a lonely life for her, poor soul! for I was her only child, and—being a Saint Leger—took naturally to the sea as a profession. That I should do so was indeed so completely a foregone conclusion, that I was especially educated for it at Greenwich; upon leaving which, I had been bound apprentice to my father. And under him I had faithfully served my time, and had risen to the position of second mate when death claimed him, and he passed away in my arms, commending my mother to my tenderest care with his last breath.

Since that terrible time I had made several voyages to our eastern possessions, and now, when my story opens, was chief mate of a fine clipper-ship, with some hopes of promotion to the rank of “captain” when a suitable vacancy should occur.

The voyage which I had just concluded had been a singularly fortunate one for me, for on our homeward passage, when a short distance to the eastward of the Cape, we had fallen in with a derelict, homeward-bound from the Moluccas and Philippines, with a cargo of almost fabulous value on board; and, having taken possession of her, I had been placed in command, with a crew of four hands, with instructions to take her into Table Bay, there to raise my crew to the full complement, and, having done so, to afterwards navigate her to her destination. This I had successfully accomplished, arriving home only nine days after my own ship. A claim for salvage had been duly made, and I calculated that when the settling day arrived, my own share would fall very little short of three thousand pounds, if, indeed, it did not fully reach that figure.

I have stated that when, upon the termination of an Australian voyage and the completion of my duties as chief mate, I returned to my ancestral home for the purpose of spending a brief holiday with my mother prior to my departure upon yet another journey to the antipodes, I had found her in dire trouble. This trouble was the natural—and I may say inevitable—result of my father’s mistaken idea that he was as good a man of business as he was a seaman. Acting under this impression, he had relied entirely upon his own unaided judgment in the investment of his savings; and, anxious only to secure as generous a provision as possible for my mother, had been tempted to put his hard-earned money into certain projects that, offering, in their inception, a too alluring promise of continuous prosperity and generous dividends, had failed to withstand the test of time and the altered conditions of trade; with the result that, after paying handsome percentages for a more or less lengthened period, they had suddenly collapsed like a pricked balloon, leaving my poor mother penniless. Of course everything had been done that was possible to save something, though it might be ever so little, from the wreck; but there had been nothing to save; every penny was gone; and when I reached home I found the poor soul literally at her wits’ end to maintain a supply of the ordinary necessaries of life.

My appearance upon the scene of course necessitated the raking up of the whole miserable story once more; but when I had been told everything, I saw at once that nothing more could be done, and that my poor mother would simply have to put up with the loss as best she might.

Then arose the question of what was best to be done under our altered circumstances. The first conclusion at which we arrived was the obvious one that it would be quite impossible for my mother to maintain such an establishment as “The Spaniards” upon my income of ten pounds per month as chief mate; and she therefore suggested that we should let it upon a lease, if a suitable tenant could be found, and that she should retire, with her altered fortunes, into the obscurity of some small cottage. To this, however, I would in no wise consent; and it was while we were discussing the matter in all its bearings, and casting about for an acceptable alternative, that my mother let fall a remark, which, little as we suspected it at the moment, proved to be the key-note of the present story.

“Ah, my son,” she ejaculated, with a hopeless sigh, “if we could but find the lost clue to Richard Saint Leger’s buried treasure, all might yet be well with us!”

“Ah!” I responded, with a still more hopeless sigh, “if only we could! But I suppose there is about as much chance of that as there is of my becoming Lord High Admiral of Great Britain. The clue must be irretrievably lost, or it would have been discovered long ere now. I suppose every Saint Leger, from my great-great-great-grandfather Hugh, downwards, has taken his turn at hunting for that miserable lost clue; and the fact that they all failed to find it is conclusive evidence to me that it is no longer in existence.”

“Well, I really don’t know, my boy; I am not prepared to say so much as that,” answered my mother. “Your dear father took the same view of the matter that you do, and never, to my knowledge, devoted a single hour to the search. And I have heard him say that it was the same with your grandfather. And if they never searched for the lost clue, how can we know or suppose that any one has searched for it since Hugh Saint Leger abandoned the quest? Yet there never appears to have been the slightest shadow of doubt in the minds of any of your ancestors, that when Richard Saint Leger died in the arms of his son Hugh, he held the clue to the secret; indeed, he died in the act of endeavouring to communicate it.”

“So I have always understood,” answered I, with languidly reviving interest. “But it is so long since I last heard the story—not since I was a little shaver in petticoats—that I have practically forgotten the details. I should like to hear it again, if it is not troubling you too much.”

“It is no trouble at all, my dear boy, for it can be told in very few words. Besides, you ought to know it,” answered my mother. “You are aware, of course, that the Saint Legers have been a race of daring and adventurous seamen, as far back as our family records go; and Richard Saint Leger, who was born in 1689, was perhaps the most daring and adventurous of them all. He was a contemporary of the great Captain (afterwards Lord) Anson; and it was upon his return from a voyage to the West Indies that he first became aware of the rumours, which reached England from time to time, of the fabulous value of the galleon which sailed annually from Acapulco to Manilla laden with the treasure of Peru. These rumours, which were no doubt greatly exaggerated, were well calculated to excite the imagination and stimulate the enterprise of the bold and restless spirits of that period; so much so, indeed, that when the English, in 1739, declared war against Spain, the capture of one of these ships became to the English adventurer what the discovery of the fabled El Dorado had been to his predecessor of Elizabethan times. At length—in the year 1742, I think it was—it became whispered about among those restless spirits that a galleon had actually been captured, and that the captors had returned to England literally laden with wealth. Richard Saint Leger was one of the first to hear the news; and it so fired his imagination—and probably his cupidity—that he never rested until he had traced the rumour to its source, and found it to be true. He then sought out the leader of the fortunate expedition, and having pledged himself to the strictest secrecy, obtained the fullest particulars relating to the adventure. This done, his next step was to organise a company of adventurers, with himself as their head and leader, to sail in search of the next year’s galleon. This was in the year 1742. The expedition was a failure, so far as the capture of the galleon was concerned, for she fell into the hands of Commodore Anson. In other respects, however, the voyage proved fairly profitable; for though they missed the great treasure ship, they fell in with and captured another Spanish vessel which had on board sufficient specie to well recompense the captors for the time and trouble devoted to the adventure. And now I come to the part of the story which relates to what has always been spoken of in the family as Richard Saint Leger’s buried treasure. It appears that on board the captured Spanish ship of which I have just spoken, certain English prisoners were found, the survivors of the crew of an English ship that had fought with and been destroyed by the Spanish ship only a few days prior to her own capture. These men were of course at once removed to Richard Saint Leger’s own ship, where they received every care, and their hurts—for it is said that every man of them was more or less severely wounded—treated with such skill as happened to be available, with the result that a few of them recovered. Many, however, were so sorely hurt that they succumbed to their injuries, the English captain being among this number. He survived, however, long enough to tell Richard Saint Leger that he had captured the galleon of the previous year, and had determined upon capturing the next also. With this object in view, and not caring to subject their booty to the manifold risks attendant upon a cruise of an entire year, they had sought out a secluded spot, and had there carefully concealed the treasure by burying it in the earth. Now, however, the poor man was dying, and could never hope to enjoy his share of the spoil, or even insure its possession to his relatives. He therefore made a compact with Richard Saint Leger, confiding to him the secret of the hiding-place, upon the condition that, upon the recovery of the treasure, one half of it was to be handed over in certain proportions to the survivors of the crew who had captured it, or, failing them, to their heirs; Richard Saint Leger to take the other half.

“Now, whether it was that Richard Saint Leger was of a secretive disposition, or whether he had some other motive for keeping the matter a secret, I know not; but certain it is that he never made the slightest reference to the matter—even to his son Hugh, who was sailing with him—until some considerable time afterwards. The occasion which led to his taking Hugh into his confidence was the meeting with another enemy, which they promptly proceeded to engage; and it may have been either as a measure of prudence in view of the impending conflict, or perhaps some premonition of his approaching end that led him to adopt the precaution of imparting the secret to a second person. He had deferred the matter too long, however; and he had only advanced far enough in his narrative to communicate the particulars I have just given, when the two ships became so hotly engaged that the father and son were obliged to separate in the prosecution of their duties, and the conclusion of the story had to be deferred until a more convenient season. That season never arrived, for Richard Saint Leger was struck down, severely wounded, early in the fight, and the command of the ship then devolved upon Hugh. Moreover, not only was there a very great disparity of force in favour of the Spaniards, but, contrary to usual experience, they fought with the utmost valour and determination, so that for some time after the ships had become engaged at close quarters the struggle was simply one for bare life on the part of the English, during which Hugh Saint Leger had no leisure to think of treasure or of anything else, save how to save his comrades and himself from the horrors of capture by their cruel enemies.

“Meanwhile, the consciousness gradually forced itself upon Richard Saint Leger that he was wounded unto death, and that time would soon be for him no more. Realising now, no doubt, the grave mistake he had committed in keeping so important a secret as that of the hiding-place of the treasure locked within his own breast, he despatched a messenger to Hugh, enjoining the latter to hasten to the side of his dying father forthwith, at all risks. The messenger, however, was shot dead ere he could reach Hugh Saint Leger’s side, and the urgent message remained undelivered. At length the stubborn courage of the English prevailed, and, despite their vast superiority in numbers, the Spaniards, who had boarded, were first driven back to their own deck and then below, when, further resistance being useless, they flung down their arms and surrendered.

“Hugh now, after giving a few hasty orders as to the disposal of the prisoners, found time to think of his father, whom he remembered seeing in the act of being borne below, wounded, in the early part of the fight. He accordingly hurried away in search of him, finding him in his own cabin, supported in the arms of one of the seamen, and literally at his last breath. It was with difficulty that Hugh succeeded in rendering his father conscious of his presence; and when this was at length accomplished the sufferer only rallied sufficiently to gasp painfully the words, ‘The treasure—buried—island—full particulars—concealed in my—’ when a torrent of blood gushed from his mouth and nostrils, and, with a last convulsive struggle, Richard Saint Leger sank back upon his pallet, dead.

“He was buried at sea, that same night, along with the others who had fallen in the fight; and some days afterwards, when Hugh Saint Leger had conquered his grief sufficiently to give his attention to other matters, he set himself to the task of seeking for the particulars relating to the buried treasure. But though he patiently examined every document and scrap of paper contained in his father’s desk, and otherwise searched most carefully and industriously in every conceivable hiding-place he could think of, the quest was unavailing, and the particulars have never been found, to this day!”

“It is very curious,” I remarked, when my mother had brought her narrative to a conclusion—“very curious, and very interesting. But what you have related only strengthens my previous conviction, that the document or documents no longer exist. I have very little doubt that, if the truth could only be arrived at, it would be found that Richard Saint Leger kept the papers concealed somewhere about his clothing, and that they were buried with him.”

“No; that was certainly not the case,” rejoined my mother; “for it is distinctly stated that—probably to obviate any such possibility—Hugh Saint Leger carefully preserved every article of clothing which his father wore when he died; and the things exist to this day, carefully preserved, upstairs, together with every other article belonging to Richard Saint Leger which happened to be on board the ship at that time.”

“And have those relics never been examined since my ancestor Hugh abandoned the quest as hopeless?” I inquired.

“They may have been; I cannot say,” answered my mother. “But I do not believe that your dear father—or your grandfather either, for that matter—ever thought it worth while to subject them to a thoroughly exhaustive scrutiny. Your father, I know, always felt convinced, as you do, that the documents had been either irretrievably lost, or destroyed.”

“Then if that be so,” I exclaimed, “they shall have another thorough overhaul from clew to earring before I am a day older. If, as you say, every scrap of property belonging to Richard Saint Leger was carefully collected and removed from the ship when she came home, and still exists, stored away upstairs, why, the papers must be there too; and if they are I will find them, let them be hidden ever so carefully. Whereabouts do you say these things are, mother?”

“In the west attic, where they have always been kept,” answered my mother. “Wait a few minutes, my dear boy, until I have found the keys of the boxes, and we will make the search together.”

Chapter Two.

The Cryptogram.

The west attic was a sort of lumber-room, in which was stored an extensive collection of miscellaneous articles which had survived their era of usefulness, but, either because they happened to be relics of former Saint Legers, or for some other equally sufficient reason, were deemed too valuable to be disposed of. The contents of this chamber could scarcely have proved uninteresting, even to a stranger, for in addition to several handsome pieces of out-of-date furniture—discarded originally in favour of the more modern, substantial mahogany article, and now permitted to remain in seclusion simply because of the bizarre appearance they would present in conjunction with that same ponderous product of the nineteenth-century cabinet-makers’ taste—there were to be found outlandish weapons, and curiosities of all kinds collected from sundry out-of-the-way spots in all quarters of the globe, to say nothing of the frayed and faded flags of silk or bunting that had been taken from the enemy at various times by one or another of the Saint Legers—each one of which represented some especially hard-fought fight or deed of exceptional daring, a complete romance in itself—and the ponderous pistols with inlaid barrels and elaborately carved stocks, the bell-mouthed blunderbusses, and the business-like hangers, notched and dinted of edge, and discoloured to the hilt with dark, sinister stains, that hung here and there upon the walls, relics of dead and gone Saint Legers. To me, the only surviving descendant of that race of sturdy sea-heroes, the room and its contents had of course always proved absorbingly interesting; and never, even in my earliest childhood, had I been so delighted as when, on some fine, warm, summer day, I had succeeded in coaxing my mother up into this room and there extracted from her the legend attached to some flag or weapon. To do her justice she, poor soul, would never of her own free will have opened her lips to me on any such subject; but my father—a Saint Leger to the backbone, despite the fact that his susceptibilities had become refined and sensitive by the more gentle influences of modern teaching—felt none of the scruples that were experienced by his gentle, tender-hearted spouse, and seemed to consider it almost a religious duty that the latest of the Saint Legers should be so trained as to worthily sustain the traditions of his race. Not, it must be understood, that my father preserved the faintest trace of that unscrupulous, buccaneering propensity that was only too probably a strongly marked characteristic of the earlier Saint Legers; far from it; but it had evidently never occurred to him that it was even remotely possible that I should ever adopt any other profession than that of the sea, and, knowing from experience how indispensable to the sailor are the qualities of dauntless courage, patient, unflinching endurance, absolute self-reliance, and unswerving resolution, he had steadily done his utmost to cultivate those qualities in me; and his stories were invariably so narrated as to illustrate the value and desirability of one or another of them.

On the present occasion, however, my thoughts on entering the room were intent upon a subject but remotely connected with the valiant achievements of my ancestors; and I lost no time in collecting together in one corner every article, big or little, that still remained of the possessions of Richard Saint Leger. There were not many of them: his sea-chest, containing a somewhat limited wardrobe, including the clothes in which he died; his writing-desk, a substantial oak-built, brass-bound affair; a roll of charts, still faintly redolent of that peculiar musty odour so characteristic of articles that have been for a long time on shipboard; a few books, equally odoriferous; a brace of pistols; and his sheathed hanger, still attached to its belt.

The writing-desk, as being the most appropriate depository for papers, was, naturally, the object to which I first devoted my attention; and this I completely emptied of its contents, depositing them in a clothes-basket on my right hand, to start with, from which I afterwards removed them, one by one, and after carefully perusing each completely through, tossed them into a similar receptacle on my left. Many of the documents proved to be sufficiently interesting reading, especially those which consisted of notes and memoranda of information relating to the projected or anticipated movements of the enemy’s ships, acquired, in some cases, in the most curious way. Then there were bundles of letters retailing scraps of home news, and signed “Your loving wife, Isabella.” But, though I allowed no single scrap of paper to pass unexamined, not one of them contained the most remote reference to any such matter as buried treasure.

I next subjected the desk itself to a most rigorous examination, half hoping that I might discover some secret receptacle so cunningly contrived as to have escaped the observation of those who had preceded me in the search. But no; the desk was a plain, simple, honest affair, solidly and substantially constructed in such a manner that secret recesses were simply impossible. Having satisfied myself thus far, I carefully restored all the papers to the several receptacles from which I had taken them, locked the desk, and then turned my attention to the sea-chest.

Here I was equally unfortunate; for, though in the bottom of the chest I actually found the identical log-book relating to the cruise during which Richard Saint Leger was supposed to have acquired his knowledge of the hidden treasure, and though I found duly entered therein the usual brief, pithy, log-book entries of both actions with the Spanish ships, not a word was there which even remotely hinted at the existence of the treasure, or any record relating to it. And—not to spin out this portion of my yarn to an unnecessary length—I may as well say, in so many words, that when I had worked my way steadily through every relic left to us of Richard Saint Leger, until nothing remained to be examined but his hanger and belt, I found myself as destitute of any scrap of the information I sought as I had been at the commencement of the search.

It was not in the least likely that any one would select such an unsuitable place as the sheath of a cutlass in which to conceal an important document; still, that I might never in the future have reason to reproach myself with having passed over even the most unlikely hiding-place, I took down the weapon from the peg on which it hung, and with some difficulty drew the blade from its leather sheath.

There was nothing at all extraordinary about the weapon or its mountings; blade and hilt were alike perfectly plain; but what a story that piece of steel could have told, had it been gifted with the power of speech. It was notched and dinted from guard to point, every notch and every dint bearing eloquent evidence of stirring adventure and doughty deeds of valour. But I was not there on that occasion to dream over a notched and rusty cutlass; I therefore laid the weapon aside, and, with the belt across my knees, proceeded to carefully explore the interior of the sheath with the aid of a long wire. And it was while thus engaged that my eye fell upon a portion of the stitching in the belt that had the appearance of being newer than—or perhaps it would be more correct to say of different workmanship from the rest. The belt, I ought to explain, was a leather band nearly four inches wide, the fastening being an ordinary plain, square, brass buckle. The belt was made of two thicknesses of leather stitched together all along the top and bottom edge; and it was a portion of this stitching along the top edge that struck me as differing somewhat in appearance from the rest.

That I might the better inspect the stitching, I moved toward the window with the belt in my hand; and, as I did so, I ran the thick leather through my fingers. Surely the belt felt a shade thicker in that part than anywhere else! And was it only my fancy, or did I detect a faint sound as of the crackling of paper when I bent the belt at that spot in the act of raising it to the light? Was it possible that Richard Saint Leger had actually chosen so unlikely a spot as the interior of his sword-belt in which to hide the important document? And yet, after all, why unlikely? It would be as safe a place of concealment as any; for he doubtless wore the belt, if not the hanger, habitually; and therefore, by sewing the document up inside it, he would be sure of always having it upon his person, with scarcely a possibility of losing it.

Determined to solve the question forthwith, I whipped out my knife and carefully cut through the suspicious-looking stitches, thus separating the two thicknesses of leather along their upper edges for a length of about six inches; then, forcing the two edges apart, I peered into the pocket-like recess; and there, sure enough, was a small, compactly folded paper, which I at once withdrew and carefully unfolded. The result was the disclosure of the following incomprehensible document:—

“11331829 14443401 64519411 74217411 93613918 21541829 154123 49274519 44384914 27163426 41152923 39154319 44214414 44153317 32 24535184 19492442 17321635 24531739 15261943 24381526 29594354 29 43163543 72164627 38537766 79193423 48132915 19412338 18294865 62 93415619 48233516 31233415 43265524 54193743 58274253 87273819 32 43731941 57761738 43581741 19341645 19484368 27435989 28467691 27 43152644 57284327 52193563 74163951 62184227 43699143 68273844 74 58776387 19361641 18424777 19372041 56894566 15452641 19471526 62 91436226 56689115 34425924 42245417 29264163 93284652 831948

“17465383 17322944 17455369 64892351 44742947 16314462 234854 76133526 51235619 31274218 48558817 32294419 43295216 41154619 49 23414354 19431529 24372543 67865983 27385579 23371449 37521342 65 83445515 37497176 92163553 77193323 34164453 72195117 32164418 51 43611635 24375169 25371641 72844458 52741954 26411842 55852439 16 44152623 47193316 45334428 47557716 47537972 91558518 29849842 61 17461545 21321741 15284459 16412642 15451331 53811429 27422743 18 49164419 41436817 41264338 67154528 53164629 47425718 31295743 58 39547697 39645377 16462843 17323867 17472738 57855769 18437485 29 57193329 47349153 97791438 91728386 73564163 53761619 114301848 53711934 26395785 51666378 17382334 45693751 29511829 15392539 35 49153959 92139445 91635467 53355142 51135213 51747294 722371747 19471227 16271847 16471947 12274567 38570277 38671327 26571328 19 48335827 58588814 32163244 72174239 62629224 42112634 46656617 46 31407196 15313161 23417691 36614961 16311941 12311241 41622452 37 62294221 42.”

This I studied for a few minutes, in complete bewilderment, and then carried it downstairs to my mother, who had been called away upon some household matter some time before.

“See here, mother!” I exclaimed. “I have found something; but whether or no it happens to be the long-missing secret of the hidden treasure it is quite impossible for me to determine. If it is, there is every prospect of its remaining a secret, so far as I am concerned, for I can make neither head nor tail of it.”

“Let me look at it, my son. Where did you find it?” she exclaimed, stretching out her hand for the paper.

“It was sewn up in Richard Saint Leger’s sword-belt, from which I have just cut it,” I replied. “So, whether or not it will be the secret of the treasure, I think we may safely take it for granted that it is a document of more than ordinary value, or Dick Saint Leger would never have taken the trouble to conceal it so carefully.”

“Yes,” remarked my mother, “there can be no doubt as to its contents being of very considerable importance. It is a cryptogram, you see, and people do not usually take the trouble to write in cipher unless the matter is of such a nature as to render a written record very highly desirable, whilst it is also equally desirable that it should be preserved a secret from all but the parties who possess the key. It is certainly a most unintelligible-looking affair; but I have no doubt that, with a little study, we shall be able to puzzle out the meaning. As a girl I used to be rather good at solving puzzles.”

“So much the better,” I remarked; “for to me it presents a most utterly hopeless appearance. The only thing I can understand about it is the sketch, which, while it bears the most extraordinary resemblance to the profile of a man’s face, is undoubtedly intended to represent an island. And that, to my mind, is a point in favour of its being the long-sought document. And now,” I continued, “if you feel disposed to take a spell at it and see what you can make of it, I think I will walk into the town and attend to one or two little matters of business. Perhaps you will have the whole thing cut and dried by the time that I return.”

My mother laughed.

“I am afraid you are altogether too sanguine, my dear Jack,” she replied; “this is no ordinary, commonplace cipher, I feel certain. But run along, my dear boy, the walk will do you good; and while you are gone I will sit down quietly and do my best to plumb the secret.”

Dismissing, for the time being, the mysterious document from my mind, I set out along the lane toward Weymouth, giving my thoughts, meanwhile, to the question of what would be the best course for me to pursue under my mother’s altered circumstances. She was now absolutely dependent upon me for food and clothing, for the funds requisite to maintain the household—for everything, in fact, save the roof that covered her; and it needed no very abstruse calculation to convince us that my wages as chief mate were wholly inadequate to the demands that would now be made upon them. If only I could but obtain a command, all would be well; but I had no interest whatever outside the employ in which I was then engaged; and I had already received a distinct assurance from my owners that I should be appointed to the first suitable vacancy. But—as I had taken the trouble to ascertain immediately upon my arrival home—the prospect of any vacancy, suitable or otherwise, was growing more remote and intangible every day; steamers were cutting out the sailing craft in every direction; freights were low and scarce; and ships were being laid up by the hundred, in every port of any consequence, for want of profitable employment. Still, there were exceptions to this rule; and I had met an old shipmate of mine, only a few days before, in London, who, in command of his own ship, was doing exceedingly well. And, as my meeting with him and our subsequent chat recurred to my memory, the thought suggested itself, “Why should not I, too, command my own ship?”

I had a little money—a legacy of a few hundreds left me by an uncle some years previously; and there was my share of the salvage money: it might be possible to obtain a command by purchasing an interest in a ship! Or, better still, I might be able to acquire the sole ownership of a craft large enough for my purpose by executing a mortgage on the ship for the balance of the purchase-money.

The idea was worth thinking over, and talking over also; and, since there is no time like the present, I determined to call upon an old family friend—a retired solicitor, named Richards—forthwith.

I was fortunate enough to find the old gentleman at home when at length I had made my way over the bridge, up through the town, and along the esplanade, to his comfortable villa on the Dorchester road. He was pottering about in his garden when I was announced; and the smart parlour-maid who took my card to him quickly returned with a message requesting that I would join him there. He seemed genuinely glad to see me; and, like most elderly people who have passed their lives in one place, was full of inquiries as to the spots I had last visited, the incidents of my voyage, and so on. Having satisfied his curiosity in this respect, and indulged in a little desultory chat, I unfolded the special object of my call to him, explaining my position, and asking him what he thought of my plan.

“Well,” said he, when I had finished my story, “shipping, and matters connected therewith, are rather out of my line, as you are no doubt aware; but if you can see your way to make the purchase of a ship a paying transaction I should think there ought not to be any very serious difficulty about finding the funds: the money market is said to be tight, just now, it is true; but my experience is that there is always plenty of money to be had when the prospects of a profitable investment are fairly promising. Now, for instance, it is really a most curious coincidence that you should have called upon me just at this time, for it happens that certain mortgages I held have recently been paid off, and I have been casting about for some satisfactory re-investment in which to employ the money. How much do you think it probable you will require?”

I made a rapid calculation, and named the sum which I thought would suffice.

“Coincidence number two!” he exclaimed. “Singularly enough, that happens to be precisely the amount I now have lying idle. Now, Jack, my lad, I have known you from a boy; and, though it is an axiom with us lawyers never to think well of anything or anybody, I would stake my last penny upon your integrity. So far as your honesty is concerned I would not hesitate to advance you any sum you might require that I could spare, upon the mere nominal security of your note of hand. But there are other risks than that of the borrower’s dishonesty to be considered, and they must be guarded against. Take, for example, the possibility of your failing to find remunerative employment for your ship. How is that to be guarded against?”

“You would hold a bottomry bond—in other words, a mortgage—upon the ship for the amount of your debt, which would constitute an ample security for its recovery,” I replied.

“Um—yes; just so,” he commented. “Still, a ship is not a house; the cases are by no means parallel. Then, there is the risk of loss, total or partial. The ship might be stranded, and receive so much damage that it would cost more than she was worth to repair her. Or she might become a total wreck. All such possibilities would have to be provided against by insurance, and, as a business man, I should expect to hold the policy. Would you be willing that I should do that?”

“Certainly,” I replied. “Of course, in the event of your deciding to lend me the money I require, I presume that a proper agreement would be drawn up, specifying the amount, terms, and duration of the loan, the mode of repayment, and so on—an agreement, in short, which would equally protect both our interests; and if that were done there could be no objection whatever to your holding the policy; indeed, I should most probably ask you to do so, apart from any stipulation to that effect, as it would be much safer with you than with me.”

“That is very true,” assented the old gentleman. “The chief question, however, is whether you are practically convinced that you would be acting wisely in entering upon this undertaking. Do you honestly believe that there is a reasonable prospect of your being able to make it pay? I am asking this question on your own behalf, not mine, my dear boy. I shall be quite safe, for, as a business man, I shall take care to make myself so; but failure would be simply disastrous for you. Now, tell me, honestly, have you any doubt at all as to the success of the enterprise?”

“None whatever,” I answered confidently. “There is, doubtless, plenty of hard work and anxiety in store for me, but not failure. I am master of my profession, and I have a certain modicum of business ability, as well as common sense. Never fear for me, my dear sir; I shall come out all right.”

“Upon my word, I believe you will, Jack,” the old gentleman replied. “You are a plucky young fellow, and that is half the battle in these days. However, do not decide upon anything hastily; take a little more time to think the matter over; and if, after doing so, you finally determine upon hazarding the experiment, do not go to a stranger to borrow money; come to me, and you shall be dealt fairly with.”

As I wended my way homeward, on that glorious summer afternoon, I once more turned the whole matter over in my mind, with the result that before I reached “The Spaniards” I had fully come to the determination to take the risk, such as it was, and be my own master. There was no blinking the fact that I should have to do something; and to purchase a ship and sail in my own employ seemed to be not only the best but the only thing I could do, under the circumstances.

On reaching home I found that my mother had spent the entire afternoon in a fruitless effort to decipher the cryptogram, much to her disappointment; so, by way of giving her something else to think about, I told her of the idea that had occurred to me during my walk; of the chat I had had with Mr Richards about it, and of his offer to assist me with a loan, if need were. The dear old mater entered upon the subject with enthusiasm, as she always did upon any plan or scheme upon which I had set my heart; and though at first the idea of trusting all my savings to the mercy of the treacherous sea failed to commend itself to her, she came round to my view at length, and dissipated the only scruples I had had by unreservedly assenting to my proposal.

The matter settled thus far, the next thing to be done was to obtain my master’s certificate; and this I determined to do forthwith, and to look about me for a ship at the same time. I knew exactly what I wanted, but scarcely expected to get it with the amount at my disposal, even with such assistance as Mr Richards might be able to afford me. Still, I was in no hurry for a month or two; I should have a little time to look about me; and if I could not find precisely what I wanted, I should perhaps succeed in obtaining a reasonably near approach to it.

Accordingly, on the following day I made the few preparations that were necessary; called upon Mr Richards again and acquainted him with my decision, and, on the day afterwards, took an early train to London, and not only settled myself in lodgings in the neighbourhood of Tower Hill, but also arranged with a “coach” to give me the “polishing-up” necessary to obtain my certificate, before night closed down upon the great city.

Chapter Three.

The “Esmeralda.”

As I had been sensible enough to make the most of my opportunities at sea, I was both a crack seaman and a first-rate navigator; I needed therefore no very great amount of coaching to enable me to pass my examination; and a month later saw me a full-fledged master, with a certificate in my pocket, which empowered me to take the command of a passenger-ship, if I could obtain it.

Meanwhile, I had been keeping a quiet lookout for such a ship as I had in my mind’s eye, and indeed had looked at several, but had hitherto found nothing to suit me. I had also called two or three times at the office of my late owners, to inquire how the matter of the salvage was progressing, and had been informed on the last occasion that there was every prospect of a speedy settlement. This had been a week previous to the obtaining of my certificate. That last week had been a busy as well as a somewhat anxious one for me; but I was now free; my troubles, so far as the examination was concerned, were over; and on the eventful afternoon, when I received the intimation that I had “passed with flying colours,” I mentally resolved to pay another visit of inquiry after the salvage the first thing the next morning.

When the next morning came, however, my plans for the day suddenly underwent an alteration; for as I sat in my frowsy lodgings at a rather later breakfast than usual, devouring my doubtful eggs, munching my tough toast, and sipping my cold coffee, with an advertisement page of the Shipping Gazette propped up before me on the table, the following advertisement caught my eye.

“For Sale, at Breaking-up Price.—The exceptionally fast and handsome clipper barque Esmeralda, 326 tons B.M., A1 at Lloyd’s. Substantially built of oak throughout; coppered, and copper-fastened. Only 8 years old, and as sound as on the day that she left the stocks. Very light draught (11 feet, fully loaded), having been designed and built especially for the Natal trade. Can be moved without ballast. Has accommodation for twelve saloon and eight steerage passengers. Unusually full inventory, including three suits of sails (one suit never yet bent), 6 boats, fully equipped; very powerful ground-tackle; hawsers, warps; spare topmasts and other spars, booms, etcetera, etcetera, complete. Ready for sea at once. Extraordinary bargain; owners adopting steam. For further particulars apply to, etcetera, etcetera.”

Now, this was exactly the kind of craft I had had in my mind, from the moment when I first thought of purchasing—that is, if the Esmeralda only happened to bear a reasonable resemblance to her description. This, unfortunately, did not always happen—at all events, in the case of vessels for sale; my own experience, hitherto, had been that it was the exception, rather than the rule, for I had found that if indeed the advertisement did not contain some gross mis-statement, it was almost always so cunningly worded as to convey an impression totally at variance with the reality. In this case, however, I was somewhat more hopeful, for these Natal clippers were not wholly strange to me. The ship to which I had lately belonged had loaded her outward cargo in the same dock with one or another of them on more than one occasion, and I had noticed them as being exceptionally smart-looking little craft; and I had frequently heard them spoken of in highly favourable terms, by men who had sailed in them. I knew, moreover, that, until very lately, a strong feeling of rivalry had existed between the owners whose ships were in that particular trade—especially those who made a speciality of passenger-carrying—each owner striving his utmost to earn for his own ships the reputation of being the fastest and most comfortable in the trade. I was therefore in hopes that, if the Esmeralda had indeed been especially built for a Natal liner, she might not prove so hopelessly unlike her description as had been most of the ships I had taken the trouble to inspect; and I therefore determined to have a look at her forthwith, lest so eligible a craft as she seemed to be—on paper—should slip through my fingers.

The place at which it was necessary to apply for further particulars was in Fenchurch Street; and upon making my way thither, I discovered that it was the office of the owners. I stated my business to one of the clerks, and was immediately turned over to a keen-looking elderly man who at once invited me into his private sanctum, and, as a preliminary, showed me a half-model of the vessel. It was a very plainly got up affair, intended merely to exhibit the general shape and mould of the hull; but I had no sooner taken it into my hands and cast a critical glance or two at the lines of the entrance and run, than I decided conclusively that I had never in my life set eyes upon a more handsome craft. The model showed her to be shallow and very beamy of hull; but her lines were as fine as those of a yacht, and indeed the entire shape of the hull was yacht-like in the extreme. Having expressed, in becomingly moderate terms, my satisfaction, so far, I was next given the specification to look through; and a careful perusal of this document convinced me that, if the craft had been built up to it, she was undoubtedly as staunch a ship as wood and metal could make her.

The next question was that of price; and though, when it was named, a disinterested person might perhaps have been disposed to consider the expression “breaking-up price” as somewhat poetic and imaginative, the figure was still a very decidedly moderate one, if the craft only proved to be in somewhat as good condition as she was represented to be. This also meeting with my carefully qualified approval, it was suggested that, as the craft herself was lying in the East India Docks, I should run down and look at her. My new friend and I accordingly took train, and in due time arrived alongside.

It was hard work to restrain the expressions of admiration and delight that sprang to my lips when my eyes first rested upon her, for she was a little beauty indeed. Dirty as she was, and disordered and lumbered-up as were her decks, it was impossible for the professional eye to overlook her many excellencies; and before I had even stepped on board her I had already mentally determined that if her hull were only sound, the little barkie should be mine, and that in her I would seek for Dick Saint Leger’s long-lost treasure. For she not only came up to but far surpassed in appearance the ideal craft upon which I had set my mind. She was as handsome as a picture; with immensely taunt and lofty spars; and though her hold was absolutely empty, her royal yards were across, and the strong breeze that happened to be blowing at the time made scarcely any perceptible impression upon her. She carried a small topgallant forecastle forward, just large enough to comfortably house two pig-pens, which in this position were not likely to prove an annoyance to people aft; and the accommodation below for the crew was both roomy and comfortable. Abaft the foremast, and between it and the main hatch, stood a deck-house, the fore part of which constituted the berthage for the steerage passengers, while the after-part consisted of a commodious galley fitted with a large and very complete cooking-range. The after-part of the deck was raised some two and a half feet, forming a fine roomy half-poop, pierced only by the saloon companion, the saloon skylight, and two small skylights immediately abaft it, which lighted a pair of family cabins situated abaft the main saloon. The wheel was a handsomely carved mahogany affair, elaborately adorned with brasswork; the binnacle also was of brass, with a bronze standard representing three dolphins twisted round each other; and the belaying-pins also were of brass, fore and aft. These, and a few other details that caught my eye, seemed to indicate that no expense had been spared in the fitting-out of the ship.

While we were walking round the decks, making a leisurely inspection of such matters as would repay examination in this part of the ship, a very respectable, seaman-like fellow came on board, and was first accosted by my companion and then introduced to me as “Captain Thomson, our late skipper of the Esmeralda; now looking after the ship until she finds a purchaser. Mr Saint Leger,” my companion continued explanatorily, “has come on board to inspect the ship, with some idea of buying, if he finds her satisfactory.”

“I am very glad to hear it,” answered Thomson, “for she is altogether too good to be laid up idle. As to her being satisfactory—why, that of course depends upon what Mr Saint Leger wants; the ship may be either too large or too small for him; but I’ll defy any man to find a fault in her. She’s a beauty, sir,” he continued, turning to me, “and she’s every bit as good as she looks.”

My unknown friend here pulled out his watch and looked at it anxiously.

“I wonder,” he said, “whether you will consider me very rude if I propose to run away, and leave Captain Thomson to do the honours of the ship in my stead? I should like to remain with you; but the fact is that I have rather an important meeting to attend in the City; and I see that I have no time to lose if I am to be punctual. And Thomson really knows a great deal more about the ship than I do; consequently he will be able to give you more reliable information than I can.”

I of course begged that he would not put himself to the slightest inconvenience on my account, and expressed myself as being perfectly satisfied at being left in the hands of the skipper of the ship; whereupon he turned to Thomson and said—

“Let Mr Saint Leger see everything without reserve, Thomson; and tell him anything he wishes to know, if you please. We have no desire whatever to sell the ship by means of misrepresentation of any sort. Good-bye,” he continued, turning to me, and offering his hand; “I hope we shall see you again, and be able to do business with you.”

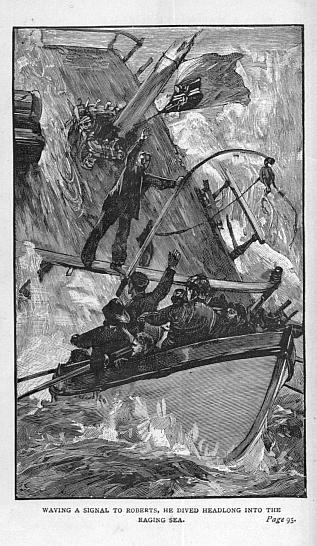

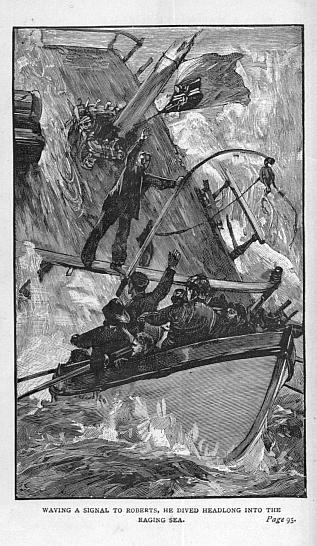

He raised his hat, stepped briskly along the gang-plank, and was soon lost sight of in the crowd.

“Who is that gentleman?” I inquired of Thomson, as the figure vanished.

“That is Mr Musgrave, the junior partner of the firm, and as nice a gentleman as ever stepped,” was the reply.

“Have you been long in the employ?” was my next question.

“For the last eighteen years—in fact, ever since I first took to the sea—and hope to end my days with them. They are now building a steamer for me; and as soon as this craft is sold I am to go and supervise the work upon her.”

“Ah,” I remarked, “an excellent arrangement. And now, captain, tell me, as between man and man, have you ever discovered any faults in the Esmeralda—anything you would like to have had altered in her, had such alteration been possible? You have commanded her for some time, I suppose?”

“Ever since she was launched,” was the reply, “and a sweeter little vessel, in every way, doesn’t float. As to faults, she has none, to my thinking. She is not a great cargo-carrier, it is true; in fact, her lines are so fine that the amount of her register tonnage, in dead weight, just puts her down to Plimsoll’s mark. Some men would no doubt consider this a serious fault; but I do not, for what she wants in carrying capacity she more than makes up in speed; so that when the whole thing comes to be worked out, putting her earnings against her expenses, she carries her tonnage at a less cost than any other ship I happen to be acquainted with.”

“Is she tight?”

I asked.

“Tight as a bottle, sir. Why, she don’t make enough water to keep her sweet! And strong!—just look at her copper—not a wrinkle in it; and yet I tell you, sir, that I have habitually driven this little ship so hard that she has made faster passages than any other ship in the trade. Why, we made the run from these same docks to Natal in fifty-five days, on one trip; and we have never taken longer than seventy days to do it. And a prettier sea-boat you never set eyes on. And weatherly—why, she’ll weather on craft twice her size. As to speed, I have never yet seen anything beat her. The fact is, sir, she is much too good to be a cargo-carrier; she is good enough in every way to be used as a yacht; and a fine, wholesome, comfortable yacht she would make, too.”

This was all exceedingly satisfactory; and so, too, was everything I saw down below. The saloon was beautifully fitted up in white and gold, with a rich carpet on the floor; a handsome mahogany table laid athwartships; revolving chairs; sofa lockers; a beautiful swinging-lamp, aneroid, and tell-tale compass hung in the skylight; pictures were let into the panelling; there was a noble sideboard; and a piano! The berths, too, were lofty and roomy, especially the family cabins abaft, which were lighted not only from above by a skylight, but also by stern-windows. In the hold, too, everything was as I should have wished it; the timbers all perfectly sound; no sign of dry-rot anywhere; in short, and for a wonder, the ship was everything that the advertisement said of her, and more. So thoroughly satisfied was I with her that I did not hesitate to tell the skipper, before I left him, that I should certainly buy her, if the owners and I could come to terms.

“I suppose, sir, you intend to sail her yourself?” he remarked, as I stood on the wharf taking a final look at the little beauty before returning to my lodgings.

I answered that such was my intention.

“Well,” he said, “perhaps you’ll be wanting a mate. If so, I believe my late mate would give you every satisfaction. He is a thorough seaman, a first-rate navigator, a good disciplinarian, and a most sober, steady, reliable man in every way, I should have liked to keep him for myself; but it will be some months before the new steamer will be ready, and Roberts—that is the man’s name—says he can’t afford to remain idle for so long. Shall I write to him, sir, and tell him to call on you?”

I said I should be obliged if he would, and gave him an envelope bearing my temporary address; then, shaking hands with him, and thanking him for the readiness he had exhibited in affording me information and assisting me in my inspection of the ship, I bade him good-bye, and made the best of my way back to my lodgings.

On reaching these I found, as luck would have it, a letter from my late owners conveying the gratifying intelligence that the salvage claim had been settled, and that, upon my calling at the office, my share, amounting to two thousand eight hundred and eighty-six pounds, and some odd shillings, would be paid to me. It was still early in the afternoon; I therefore snatched a hurried lunch; and immediately afterwards chartered a cab and drove into the City; duly received my cheque, with congratulations on my good fortune; and still had time to open an account and safely rid myself of the precious paper before the banks closed for the day. I dined in the City, and afterwards made my way westward to Hyde Park, in the most unfrequented part of which I sauntered to and fro until nearly ten o’clock—my pipe my sole companion—carefully reviewing my plans for the last time, and asking myself whether I had omitted from my calculation any probable element at all likely to disastrously affect them. The result of my self-communing was so far satisfactory as to confirm my resolution to become the owner of the Esmeralda; and, having conclusively arrived at this determination, I sauntered quietly eastward through the summer night to my lodgings, and turned in.

The following morning saw me once more wending my way Cityward, this time to the office of Messrs Musgrave and Company, where the preliminaries of the purchase of the Esmeralda were speedily accomplished, and a cheque for five hundred pounds given to seal the bargain. This done, I spent the remainder of the morning in seeking a freight; and was at length fortunate enough to secure one on advantageous terms for China. My next business was to run down on board my new purchase and take a careful inventory of her stores, with the object of estimating the probable amount of outlay necessary to fit her for the contemplated voyage; and while I was thus engaged a telegram was despatched to Thomson’s friend and late chief mate, Roberts, who, in response, promptly presented himself on board. I liked the appearance of this man from the moment that I first set eyes upon him. He was evidently somewhat more highly educated than the generality of his class; without being in the least dandified, he possessed an ease and polish of manner at that time quite exceptional in the mates of such small craft as the Esmeralda. He was very quiet and unassuming in his behaviour; and altogether he produced so favourable an impression upon me that I unhesitatingly shipped him on the spot, arranging with him to bring his dunnage on board and assume duty on the following day. My overhaul of the stores on board the barque resulted in the satisfactory discovery that the expenditure necessary to complete her for the voyage would be considerably less than I had dared to hope; and, this fact established, I left the ship in Roberts’s charge, and ran down home upon a flying visit to my mother, to fully acquaint her with all that I had done, and to make the arrangements necessary for her comfort and maintenance during my contemplated absence. This involved another visit to my friend, Mr Richards, with whose assistance I made a careful yet generous computation of every expense to which I should be in the least likely to be put before drawing any profit from my adventure; the difference between this sum and the amount of my available assets representing the amount of monetary accommodation which I should require from him. This—thanks to the exceptionally favourable terms upon which I had acquired the ownership of the Esmeralda—was so very small that I undertook the obligation with a light heart; and, having completed this part of my business to my entire satisfaction, I hastened back to town, my mother accompanying me in order that we might have as much as possible of each other’s society during the short interval that was to elapse before the sailing of the ship.

On my return to London, I found that a small portion of our cargo had already come alongside. I therefore lost no time in advertising the ship as “loading for China direct, with excellent accommodation for saloon and steerage passengers;” and then, in a leisurely manner, proceeded to make the necessary purchases of ship’s and cabin stores, filling in the time by taking my mother about to such concerts, picture-galleries, and other places of amusement, as accorded with her quiet and refined tastes.

One morning, about a week after my return to town, being on board the ship and down below, superintending a few trifling alterations that I was having made in my own state-room, the mate, who was taking account of the cargo that was being shipped at the moment, came aft and shouted down the companion to the effect that a lady and gentleman had come on board and were inquiring for me. I accordingly went on deck, and there found a very handsome man, in the prime of life, and a very lovely woman of about three and twenty, standing on the main deck, just by the break of the poop, curiously watching the operation of slinging some heavy cases, and lowering them through the main hatchway.

“Captain Saint Leger?” queried the gentleman, bowing and slightly raising his hat in acknowledgment of my salute as I approached him.

“That is my name,” I replied. “In what way can I be of service to you?”

“I have come down to inspect your passenger accommodation, in the first place,” said he; “and afterwards—in the event of its proving satisfactory—to see whether I can come to an arrangement with you for the whole of it.”

“I am sure I shall be very pleased to do everything I possibly can to meet your views,” said I. “If you will kindly step below, I will show you the cabins; and although we are rather in a litter everywhere just at present, you will perhaps be able to judge whether the accommodation is likely to meet your requirements. Are you a large party?”

“Myself, my wife, my wife’s sister—this young lady—two children, two maids, and a nurse. My wife, I ought to explain, is at present an invalid, and has been ordered a long sea-voyage; but, as her ailment is chiefly of a nervous character, she is greatly averse to the idea of meeting and associating with strangers; hence my desire to secure the whole of your accommodation, should it prove suitable. Ah, a very pretty, airy saloon,” he continued, as I threw open the door and stepped aside to permit my visitors to enter. “The whole width of the ship; sidelights that we can throw open in the tropics, and admit the fresh air. A piano, too, by Erard,” as he opened the instrument and glanced at the name. “You at least would not be likely to find the voyage tedious, Agnes, with an Erard within reach at any moment,” turning to the young lady who accompanied him. “And these, I presume, are the state-rooms,” opening the doors of one or two of the berths and glancing inside.

“These are some of them,” I replied. “In addition to what you now see, there are two family cabins.” And, as I spoke, I opened the door of one of them, and allowed my visitors to pass in.

“Capital, capital!” exclaimed the visitor, as he entered. “Really, these two cabins are far and away more roomy and pleasant than the ordinary berths, even in the big liners. Now, supposing that I make up my mind to take the whole of your accommodation, captain, would you be willing to have a door fitted in that partition? Because, in that case,” he proceeded, again addressing his sister-in-law, “I should propose to have one of the cabins fitted up as a ladies’ boudoir, into which you and Emily could retire when so disposed.”

“Yes, that would be very nice,” assented the lady. “And perhaps Captain Saint Leger would allow the piano to be placed there?”

I replied that I should be happy to do anything and everything in my power to meet their convenience or make them comfortable.

“Very well,” said the gentleman. “Now, Agnes, what do you think of these cabins? Do you think Emily would like them, and find them convenient?”

“I am sure she would,” answered the young lady, confidently. “They are much prettier than anything we have hitherto seen; and the two large cabins, with those great windows looking directly out on to the sea, are simply delightful.”

“So I think,” agreed the gentleman. “And now, captain, as to terms?”

I had already made a little mental calculation as to the amount I ought to ask, and had arrived at a sum which, while it was somewhat less than I should have received had the whole of the cabins been separately taken, would pay me just as well in the long run; and this sum I named.

“There is one little matter I should like to mention,” I said. “My mother is now in town with me, and I had promised her that, if all the cabins were not engaged, she should make the trip home to Weymouth in the ship—”

“An arrangement with which I would not dream of interfering,” interrupted the gentleman. “Even should we determine to take your cabins, captain, we shall certainly not require them all—at the outset of the voyage, at least—and I am quite sure that your mother’s presence, for the few days that she will probably be with us, will be the reverse of disagreeable to my wife. And now I cannot, of course, decide definitely, one way or the other, until I have told my wife what we have seen; but here is my card; and if you will allow me twenty-four hours for consideration, you shall have my definite decision within that time.”

As this was the first inquiry I had had from prospective passengers, I thought the proposal was good enough to justify me in according the grace asked. I therefore undertook to hold the cabins at my visitors’ disposal until noon next day; and they then left, with a cordial hand-shake from each.

I waited till they were fairly out of sight, and then looked at the card. It bore the name of “Sir Edgar Desmond,” with an address in Park Lane, in the corner.

On the following morning, about half-past eleven, the owner of the card again put in an appearance on board, and, greeting me with the utmost cordiality, exclaimed—

“Well, captain, I have hurried down to let you know that the account of our visit to your ship, and the description of her cabins which I was enabled to give my wife last night, proved so thoroughly satisfactory to her that it was definitely determined, in family conclave, that we should secure your cabins upon the terms mentioned by you yesterday. I have accordingly brought you a cheque for half the amount of our passage-money—here it is—in order to properly ratify the arrangement; and now I presume there will be no difficulty about commencing the few alterations in the cabins that I suggested yesterday?”

“None whatever,” I replied; “I will get the carpenters on board to-day, if possible; and in any case the work shall be begun as early as possible, so that the paint may be thoroughly dry and the smell passed off before you come on board.”

“I shall be greatly obliged to you if you will,” said Sir Edgar. “And now there is another little matter upon which I wish to speak to you. My wife being quite an invalid, it will be necessary that she should have many little delicacies that are not included in the ordinary bill of shipboard fare. These I intend to order at once, and will give instructions that they are to be delivered on board here as soon as ready. May I rely upon you to have a careful account taken of them as they come on board, and to see that they are so bestowed that they may be easily got at when required? Among them will be a few cases of wines for Lady Desmond’s personal use; but, so far as the rest of us are concerned, I presume you will be able to supply us with whatever we may require?”

“Certainly,” I replied. “I have not yet ordered my stock of wines, and if you have a partiality for any particular kind or brand, and will let me know, I shall be pleased to select my stock with especial reference to your taste.”

“Oh, thank you. I am sure you are very good,” he laughed; “but we are none of us connoisseurs, nor do I think any of us have a weakness for any one particular kind of wine more than another. If you can undertake to give us a good sound claret every day for dinner, with a bottle of decent champagne now and then, we shall be perfectly content. And now, what is the longest possible time you can allow us in which to get together our outfit for the voyage?”

“We are advertised to sail to-morrow three weeks,” I replied.

“Very well,” he said. “That is rather brief notice for the ladies; but I have no doubt they will be able to manage when once they are given to understand that it must be done. As for me, I shall have no difficulty whatever. I shall be obliged, however, if you will give me a hint or two as to the different climates we shall encounter on the voyage, so that we may prepare accordingly.”

I did so, Sir Edgar jotting down a few memoranda in his note-book meanwhile; and then, with another hearty shake of the hand, my visitor left me.

The succeeding three weeks passed uneventfully away, the cargo, during the first fortnight, coming alongside very slowly; but there was quite a rush at the last, and on the night before the day on which we were advertised to sail, I had the satisfaction of seeing the hatches put on and battened down over a full hold, with the barque down to within an inch of her load-mark.

Meanwhile, private stores in considerable quantities had come on board, bearing Sir Edgar Desmond’s name upon them, and these I had had carefully stowed away by themselves. This had been a busy day for me; for there were the articles to be signed, the ship to clear at the Custom House, bills to pay, and a hundred other little matters to attend to—among them the giving up of my lodgings, and the removal of my mother and myself with our dunnage to the ship—but when I turned in that night, in my own comfortable state-room, it was with the feeling that my business of every kind had been satisfactorily concluded, and that henceforth, until our arrival in Hong Kong, I should only have the ship to look after. Moreover, the whole of my crew, with two exceptions, had faithfully kept their promise to be on board before the dock-gates closed that night, so that I might reasonably hope to go out of dock with a tolerably sober crew in the morning.

We unmoored at seven o’clock next morning, and half an hour later—the two absentees from the forecastle scrambling on board as we passed out through the gates—were clear of the dock and in the river, with the tug ahead and the first of the ebb to help us on our way. We made a pause of half an hour off Gravesend, to pick up Sir Edgar Desmond and his party—who had spent the night at an hotel there—and then, pushing on again, found ourselves, about six o’clock that evening, off the North Foreland, with a light northerly air blowing, which, when we had got the barque under all plain sail, fanned us along at a speed of about five knots.

Chapter Four.

In Blue Water.

As the sun declined toward the west, the light breeze which had prevailed throughout the day became still lighter, dwindling away to such an extent that when, about two bells in the first watch (nine o’clock p.m.), we returned to the deck after partaking of our first sea dinner, the water was like glass for the smoothness of it, while our canvas drooped limp and apparently useless from the yards and stays; a faint rustle aloft now and again, with an accompanying rippling patter of reef-points, betraying rather some subtle heave of the glassy sea than any sign that the breeze still lingered. Yet there must have been a light draught of air aloft, for the vane at our main-royal-masthead occasionally fluttered languidly out along the course we were steering, and our royals exhibited an occasional tendency to fill, albeit they as often collapsed again softly rustling to the masts. Moreover, the barque still retained her steerage-way. I remarked upon this to the mate, who had charge of the deck. He laughed.

“Ay,” said he, “that is one of the Esmeralda’s little tricks. I’ve seen her, before now, sneak up to and right through a large fleet of ships, every one of which, excepting ourselves, was boxing the compass. When this little barkie refuses to steer, you may take your Davy to it, sir, that there ain’t enough wind to be of any use to anybody.”

It was a glorious evening. We were off Deal, slowly drifting past the town on the ebb tide; our progress made apparent only by the quiet, stealthy way in which the masts of the vessels lying at anchor in the roadstead successively approached, covered, and receded from some prominent object on shore, such as a church spire, a lofty building, a tall chimney, and what not. The sun had sunk behind the land, leaving behind him a clear sky of softest primrose tint, against which the outline of the land cut sharply, the town being steeped in rich dusky shadow, out of which the lights were beginning to twinkle here and there. We were close enough in to catch an occasional faint, indefinite sound from the shore, accentuated at intervals by the sharp, clear note of a railway whistle, or the low, intermittent thunder of a moving train; while, nearer at hand, came the occasional splash of oars in the still water, or their thud in the rowlocks; the strains of a concertina played on the forecastle-head of one of the craft lying at anchor; a gruff hail; a laugh; or the hoarse rattle of chain through a hawse-pipe as one of the drifting vessels came to an anchor. Our own lads were very quiet, the watch below having turned in, while those on deck, with the exception of the lookout, had arranged themselves in a group about the windlass, and were conversing in suppressed tones well befitting the exceeding quiet of the night. Lady Desmond, well wrapped up in a fur-lined cloak, occupied a large wicker reclining chair placed close to the after skylight, where it was well out of everybody’s way, and was languidly listening to the conversation which was passing between her sister and my mother, in which she occasionally joined for a moment; while Sir Edgar was down below, chatting and laughing with the two children during their preparation by the nurse for bed. The two maids were also below, busy in their mistress’s cabin.

The ship having been all day—as she still was—in charge of the pilot, I had had leisure to make the first advances toward an acquaintance with my passengers; and, from what I had thus far seen of them, I had every reason to hope that the association would be a particularly pleasant one.

Sir Edgar was a fine, handsome man, of about thirty-five years of age, standing some five feet nine or ten inches in his stockings, well made, with dark brown hair that covered his head in short wavy curls. He had dark blue eyes, with which he looked one frankly and pleasantly in the face; and his manner, while it possessed all the polish of the perfect gentleman, was particularly frank and genial.

Lady Desmond appeared to be some eight or nine years younger than her husband, and was unquestionably an exceedingly handsome woman. She was perhaps three inches less in height than her husband, but, when standing apart from him, gave one the impression of being the taller of the two, probably because she happened to be very thin and fragile-looking when she first joined the Esmeralda. She had evidently only just emerged from a very severe illness, for all her movements were marked by the slowness and languor of one who is still an invalid. She had not a vestige of colour, and her hands, when I saw them ungloved at the dinner table, were attenuated to a degree that was painful to contemplate; but her eyes were magnificent, and her voice, albeit it was weak and low like that of an invalid, was very sweet and sympathetic in tone. I had not been enlightened as to the nature of her illness; but its most marked symptom appeared to be a profound melancholy and depression of spirits which it seemed utterly impossible for her to shake off.

Her sister, Miss Merrivale, was her exact counterpart, except that the latter was the junior by some three or four years, and was, both in form and complexion, the very picture of exuberant health and spirits. She possessed a singularly agreeable and engaging, though high-bred manner; and the patient tenderness with which she studied her invalid sister’s whims quickly won my warmest admiration.

Of the two children, the elder was a fine sturdy boy, about seven years old, named after his father; while the other was a sweet little tot of a girl, about five years old, with the prettiest, most lovable, and confiding ways I had ever beheld in a child. They were both very merry, light-hearted, buoyant-spirited children, but exceedingly well-behaved, very tender and affectionate toward each other; and perfect patterns of obedience while they remembered the parental injunctions laid upon them from time to time; but it must be admitted that their memories in this respect were, like those of most children, a little apt to be short-lived.

And, as to the two maids and the nurse, they impressed me as being very quiet, respectable well-behaved representatives of their class, and not at all likely to give me trouble by encouraging any attempts at flirtation on the part of the men. So that altogether I thought I had every reason to congratulate myself upon my first experience in the command of a passenger-ship.

Then, as to the ship herself. Though it was early yet to form a distinct and definite opinion of her, having had only a few hours’ experience of her under sail, and that, too, in a light breeze and smooth water, still her behaviour under those circumstances had been such as led me to feel assured, from past experience, that she was everything a seaman’s heart could wish. That she was certain to prove extraordinarily fast I was convinced, even before we had spread a single cloth of canvas, by the ease with which the tug had walked away down the river with her. And after the tug had let go our hawser and left us to our own devices, we had overhauled and passed everything in our company with an ease and rapidity that proved her to be a perfect witch in light breezes; while now, when the rest of the fleet were either drifting helplessly with the tide and heading to all points of the compass, or anchoring to avoid falling foul of something else, we were sneaking along at a good two knots through the water, with the ship under perfect command of her helm.

At length the sounds of the children’s happy voices ceased down below: and, a few minutes later, Sir Edgar emerged from the saloon companion. He paused for a moment to address a cheery remark or two to the little party aft, and then joined me near the break of the poop, where I had been standing for some time gazing abstractedly about me in a contented, half-dreamy fashion at our surroundings. He made some conventional remark as to the wonderful calmness and beauty of the evening, and offered me a cigar; upon which, responding to his friendly overtures, I turned, and we proceeded to quietly pace the deck together; the baronet—for such he proved to be—confiding to me, in an easy, chatty manner, the circumstances that had led to the family undertaking the voyage.