THE NEXT MOMENT THE MIDWAY JUNCTION GHOST STEPPED

GRIMLY FROM HIS BOX.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Young Railroaders

Tales of Adventure and Ingenuity

Author: Francis Lovell Coombs

Release Date: June 21, 2008 [eBook #25868]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE YOUNG RAILROADERS***

THE

YOUNG RAILROADERS

THE

YOUNG RAILROADERS

TALES OF ADVENTURE

AND INGENUITY

BY

F. LOVELL COOMBS

With Illustrations

by F. B. MASTERS

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1910

Copyright, 1909, 1910, by

The Century Co.

Published September, 1910

Electrotyped and Printed by

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston

To

B. R. C. AND K. L. C.

A REMEMBRANCE

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | One Kind Of Wireless | 3 |

| II. | An Original Emergency Battery | 24 |

| III. | A Tinker Who Made Good | 38 |

| IV. | The Other Tinker Also Makes Good | 54 |

| V. | An Electrical Detective | 68 |

| VI. | Jack Has His Adventure | 86 |

| VII. | A Race Through The Flames | 102 |

| VIII. | The Secret Telegram | 117 |

| IX. | Jack Plays Reporter, With Unexpected Results | 132 |

| X. | A Runaway Train | 146 |

| XI. | The Haunted Station | 163 |

| XII. | In A Bad Fix, And Out | 180 |

| XIII. | Professor Click, Mind Reader | 198 |

| XIV. | The Last Of The Freight Thieves | 225 |

| XV. | The Dude Operator | 246 |

| XVI. | A Dramatic Flagging | 262 |

| XVII. | Wilson Again Distinguishes Himself | 279 |

| XVIII. | With The Construction Train | 295 |

| XIX. | The Enemy’s Hand Again, And A Capture | 310 |

| XX. | A Prisoner | 325 |

| XXI. | Turning The Tables | 337 |

| XXII. | The Defense Of The Viaduct | 357 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

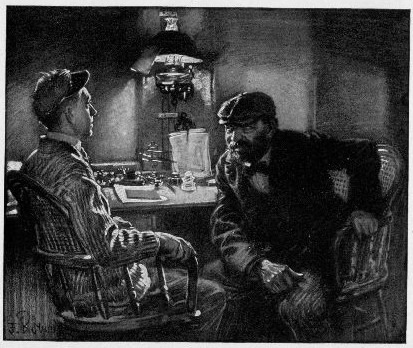

| The next moment the Midway Junction ghost stepped grimly from his box. | Frontispiece |

| “Now I am going to cut your cords,” Alex went on softly. | 8 |

| Held it over the bull’s-eye, alternately covering and uncovering the stream of light. | 14 |

| Threw himself at the front door, pounding upon it with his fists. | 28 |

| In the middle of the floor, the center of all eyes, hurriedly working with chisel and hammer. | 34 |

| He was gazing into the barrel of a revolver. | 58 |

| But the response click did not come. | 64 |

| The clerk was colorless, but only faltered an instant. | 78 |

| “There!” said Jack, pointing in triumph. | 84 |

| Looped it over the topmost strand, near one of the posts. | 94 |

| There, in the corner of the big barn, Jack sent as he had never sent before. | 100 |

| With a rush they dashed into the wall of smoke. | 108 |

| Closer came the roaring monster. | 114 |

| “Come on! Come on!” exclaimed the man in the doorway. | 124 |

| “How did you do it, Smarty?” snapped the shorter man. | 130 |

| They whirled by, and the rest was lost. | 154 |

| The engineer stepped down from his cab to grasp Alex’s hand. | 158 |

| The wait was not long. | 162 |

| Jack made out a thin, clean-shaven face bending over a dark-lantern. | 176 |

| The stranger drew the chair immediately before him, and seating himself, leaned forward secretively. | 182 |

| “And it’s awfully like the light, jumpy sending of a girl!” | 196 |

| The next instant Jack felt himself hurled out into the darkness. | 234 |

| He saw the detective led by, his arms bound behind him. | 242 |

| Jack rose to his knees, and began working his way forward from tie to tie. | 272 |

| With the sharp words he again grasped the key. | 276 |

| With the boys’ prisoner securely bound to the saddle of the wandering horse, the Indian was off across the plain. |

372 |

| The Indian pulled up in a cloud of dust. | 376 |

THE YOUNG RAILROADERS

THE YOUNG RAILROADERS

When, after school that afternoon, Alex Ward waved a good-by to his father, the Bixton station agent for the Middle Western, and set off up the track on the spring’s first fishing, he had little thought of exciting experiences ahead of him. Likewise, when two hours later a sudden heavy shower found him in the woods three miles from home, and with but three small fish, it was only with feelings of disappointment that he wound up his line and ran for the shelter of an old log-cabin a hundred yards back from the stream.

Scarcely had Alex reached the doorway of the deserted house when he was startled by a chorus of excited voices from the rear. He turned quickly to a window, and with a cry sprang back out of sight. Emerging from the woods, excitedly talking and gesticulating, was a party of foreigners who had been working on the track near Bixton, and in their midst, 4 his hands bound behind him, was Hennessy, their foreman.

For a moment Alex stood rooted to the spot. What did it mean? Suddenly realizing his own possible danger, he caught up his rod and fish, and sprang for the door.

On the threshold he sharply halted. In the open he would be seen at once, and pursued! He turned and cast a quick glance round the room. The ladder to the loft! He darted for it, scrambled up, and drew himself through the opening just as the excited foreigners poured in through the door below. For some moments afraid to move, Alex lay on his back, listening to the hubbub beneath him, and wondering in terror what the trackmen intended doing with their prisoner. Then, gathering courage at their continued ignorance of his presence, he cautiously moved back to the opening and peered down.

The men were gathered in the center of the room, all talking at once. But he could not see the foreman. As he leaned farther forward heavy footfalls sounded about the end of the house, and Big Tony, a huge Italian who had recently been discharged from the gang, appeared in the doorway.

“We puta him in da barn,” he announced in broken English; for the rest of the gang were Poles. “Tomaso, he watcha him.”

“An’ now listen,” continued the big trackman fiercely, as the rest gathered about him. “I didn’t tell everyt’ing. Besides disa man Hennessy he say 5 cuta da wage, an’ send for odders take your job, he tella da biga boss you no worka good, so da biga boss he no pay you for all da last mont’!”

The ignorantly credulous Poles uttered a shout of rage. Several cried: “Keel him! Keel him!” Alex, in the loft, drew back in terror.

“No! Dere bettera way dan dat,” said Tony. “Da men to taka your job come to-night on da Nomber Twent’. I hava da plan.

“You alla know da old track dat turn off alonga da riv’ to da old brick-yard? Well, hunerd yard from da main line da old track she washed away. We will turn da old switch, Nomber Twent’ she run on da old track—an’ swoosh! Into da riv’!”

Run No. 20 into the river! Alex almost cried aloud. And he knew the plan would succeed—that, as Big Tony said, a hundred yards from the main-line track the old brick-yard siding embankment was washed out so that the rails almost hung in the air.

“Dena we all say,” went on Big Tony, “we alla say, Hennessy, he do it. We say we caughta him. See?”

Again Alex glanced down, and with hope he saw that some of the Poles were hesitating. But Tony quickly added: “An’ no one else be kill buta da strike-break’. No odder peoples on da Nomber Twent’ disa day at night. An’ da trainmen dey alla have plent’ time to jomp.

“Only da men wat steala your job,” he repeated craftily. And with a sinking heart Alex saw that 6 the rest of the easily excitable foreigners had been won.

Again he moved back out of sight. Something must be done! If he could only reach the barn and free the foreman!

But of course the first thing to do was to make his own escape from the house. He rose on his elbow and glanced about.

At the far end of the loft a glimmer of light through a crack seemed to indicate a door. Cautiously Alex rose to his knees, and began creeping forward to investigate. When half way a loud creak of the boards brought him to a halt with his heart in his mouth. But the loud conversation below continued, and heartily thanking the drumming rain on the roof overhead, Alex moved on, and finally reached his goal.

As he had hoped, it was a small door. Feeling cautiously about, he found it to be secured by a hook. When he sought to raise the catch, however, it resisted. Evidently it had not been lifted for many years, and had rusted to the staple. Carefully Alex threw his weight upward against it. It still refused to move. He pushed harder, and suddenly it gave with a piercing screech.

Instantly the talking below ceased, and Alex stood rigid, scarcely breathing. Then a voice exclaimed, “Up de stair!” quick footsteps crossed the floor towards the ladder, and in a panic of fear Alex threw himself bodily against the door, in a mad endeavor to force it. But it still held, and with a thrill of despair he dropped flat to the floor, and saw the foreigner’s head come above the opening.

There, however, the man paused, and turned to gaze about, listening. For a brief space, while only the rain on the roof broke the silence, the foreigner apparently looked directly at the boy on the floor, and Alex’s heart seemed literally to stand still. But at last, after what appeared an interminable time, the man again turned, and withdrew, and with a sigh of relief Alex heard him say to those below, “Only de wind, dat’s all.”

Waiting until the buzz of conversation had been fully resumed, Alex rose once more to his knees, and began a cautious examination of the door. The cause of its refusal to open was soon apparent. The old hinges had given, allowing it to sag and catch against a raised nail-head in the sill.

Promptly Alex stood upright, grasped one of the cross-pieces, carefully lifted, and in another moment the door swung silently outward.

With a glance Alex saw that the way was clear, and quickly lowering himself by his hands, dropped. Here the rain once more helped him. On the wet, soggy ground he alighted with scarcely a sound. Momentarily, however, though he now breathed easily for the first time since he had entered the house, he stood, listening. The excited talking inside went on uninterruptedly, and moving to the corner, he peered about in the direction of the barn.

Leaning in the doorway, smoking, and most fortunately, 10 with his back towards the house, was the Italian, Tomaso. Beyond doubt the foreman was inside!

At the rear of the barn, and some hundred feet from where Alex stood, was a small cow-stable. Alex determined to make an effort to reach it, and see if from there he could not get, unseen, into the barn itself.

The Italian continued to smoke peacefully, and with his eyes constantly on him Alex stepped forth, and set off across the clearing on tiptoe. The guard puffed on, and he neared the stable. Then suddenly the man moved, and made as though to turn. But with a bound Alex shot forward on the run, made the remaining distance, and was out of view.

The rear door of the stable was open. On tiptoe Alex made his way inside. The door leading into the barn also was ajar. With bated breath, pausing after each step, Alex went forward, reached it, and peered within.

Yes, the foreman was there, a dim figure sitting on the floor a few feet from him. But the outer doorway, in which stood the man on guard, also was only a few feet away, and at once Alex saw that the problem of reaching the foreman without being discovered was to be a difficult one. Trusting to the now gathering gloom of the twilight, however, Alex determined to make a try. Opening his knife and holding it in his teeth, he sank to the floor, and began slowly worming his way forward, flat on his stomach. It was a nerve-trying 11 ordeal. A dozen times he was sure the crackling straw had betrayed him. But pluckily he kept on, inch by inch, and finally was almost within touch of the unsuspecting prisoner.

Then very softly he hissed. Sharply, as he had feared, the foreman twisted about. But at the moment, by great good luck, the foreigner at the door turned to knock his pipe against the door-post, and hurriedly Alex whispered, “Don’t move, Mr. Hennessy! It’s Alex Ward! I was in the old house, and saw them bring you up.

“And, Mr. Hennessy, they plan to run Twenty into the river to-night. Tony told them there were strike-breakers aboard her to take their places.”

In spite of himself the foreman uttered a low exclamation. At once the man in the door turned. But with quick presence of mind the prisoner changed the exclamation to a loud cough, and after a moment, while Alex lay holding his breath, the Italian turned his attention again to his pipe.

“Now I am going to cut your cords,” Alex went on softly. “Be careful not to let your arms seem to be free.”

The foreman nodded.

“There,” announced Alex as the twine dropped from the prisoner’s wrists.

“Now, what shall we do? There is a door behind you into the cow-stable—the one I came in by. Suppose you work back towards it as far as you dare, then make a dash for it?” 12

“Good,” whispered the foreman over his shoulder. “But you get out first.”

“All right,” responded Alex, and immediately began moving backwards, feet first, as he had come.

Their escape was to be made more easy, however. At the moment from the house came a call. The man in the doorway stepped out to reply, and in an instant seeing the opportunity both Alex and the foreman were on their feet, and had darted out into the stable.

“Now for a sprint!” said the foreman.

“Or, say, suppose I hide here in the stable,” suggested Alex. “They don’t know of my being here. Then as soon as the way is clear I can get off in the opposite direction, and one of us would be sure to get away.”

“Good idea,” agreed the foreman. “All right, you—”

There came a loud cry from the barn, and instantly he was off, and Alex, darting back, crept low under a stall-box. As he did so the Italian dashed by and out, and uttered a second cry as he discovered the fleeing foreman. From the house came an answer, then a chorus of shouts that told the rest of the gang had joined in the chase.

Alex lay still until the last sound of pursuit had died away, then slipped forth, glanced sharply about, and dashed off for the woods in the direction of the river and the railroad bridge.

The adventure was not yet over, however. Alex had almost reached the shelter of the trees, and was already congratulating himself on his safety, when suddenly from the opposite side of the clearing rose a shout of “De boy! De boy!” Glancing back in alarm he saw several of the Poles cutting across in an endeavor to head him off.

Onward he dashed with redoubled speed. With a final rush he reached the trees ahead of them, and plunging into the friendly gloom, darted on recklessly, diving between trunks, and over logs and bushes like a young hare.

A quarter of a mile Alex ran desperately, then halted, panting, to listen. Not a sound save his own breathing broke the stillness. Surely, thought Alex, I haven’t shaken them off that easily, unless they were already winded from their chase after—

Off to the right rose a shrill whistle. From immediately to the left came an answer. Then he understood. They were heading him off from the railroad and the river spur.

Alex’s heart sank, and momentarily he stood, in despair. Then suddenly he thought of the old brick-yard. It lay less than a mile north, and was full of good hiding-places! If he could reach it ahead of them, what with the daylight now rapidly failing, he would almost certainly be safe. At once he turned, and was off with renewed vigor.

And finally, utterly exhausted, but cheered through not having heard a sound from his pursuers for the last quarter mile, Alex stumbled into the clearing of the abandoned brick-works, ran low for a distance 16 under cover of a long drying-frame, and scrambling through the low doorway of an old tile oven, threw himself upon the floor, done out, but confident that at last he was safe.

As he lay panting and listening, Alex turned his thoughts again to the train. Had the foreman made his escape? With so many promptly after him, it seemed scarcely probable. Then the saving of Twenty was still upon his own shoulders!

And there was little time in which to do anything, for she was due at 7:50, and it must be after 7 already!

Could he not reach the switch itself, and throw it back just before the train was due? That would be surest. And in the rapidly growing darkness there should be at least a fair chance of getting by any of the foreigners who might be on the watch.

Determinedly Alex gathered himself together, and crawled back to the entrance. Near the doorway he stumbled over something. “Oh, our old switch lantern!” he exclaimed, holding it to the light, and momentarily paused to examine it. For it had been placed under cover there the previous fall by himself and some other boys, after being used in a game of “hold-up” on the brick-yard siding.

“Just as we left it,” said Alex to himself, and was about to put it aside, when he paused with a start, studied it sharply a moment, then uttered a cry, shook it to see that it still contained oil, and scrambled hurriedly forth, taking it with him.

A moment he paused to listen, then set off on the 17 run for the old yard semaphore, dimly discernible a hundred yards distant. Reaching it, he caught the lantern in his teeth, and ran up the ladder hand over hand, clambered onto the little platform, and turned toward the town.

Yes! Through the trees the station lamps were plainly visible! With a cry of delight Alex at once set about carrying out his inspiration. Quickly trimming the lantern wick, he lit it, with his handkerchief tied it to the semaphore arm, and turned it so that the bull’s-eye pointed toward the station.

Then, catching off his cap, he held it over the bull’s-eye, and alternately covering and uncovering the stream of light, began flashing across the darkness signals that corresponded with the telegraphic call of the Bixton station.

“BX,” he flashed. “BX, BX, BX!

“BX, BX—AW (his private sign)! BX, BX, AW!”

The station lights streamed on.

“Qk! Qk! BX, BX!” called Alex.

His right hand tired, and he changed to the left. “Surely they should be on the lookout for me, and see it,” he told himself. “For when I go fishing I am always home at—”

One of the station lights disappeared. Breathlessly Alex repeated his call, and waited. Was it merely some one pulling down a blind, or—

The light appeared again, then disappeared, several times in quick succession, and Alex uttered a joyful 18 “Hurrah!” and turning his whole attention to the lamp, that the signals might be perfect, began flashing across the night his thrilling message of warning:

“THE FOREIGN TRACK HANDS—”

From a short distance down the spur came a shout. Startled, Alex hesitated. Again came a cry, then the sound of swiftly running feet.

He had been discovered! In a panic Alex turned and began to scramble down the ladder. But sharply he pulled up. No! That would be playing the coward! He must complete the message! And bravely choking down his terror, he climbed back onto the platform, and while the running feet and threatening cries came nearer every moment, continued his message:

“HANDS ARE—”

“Stop dat! Queek! I shoot! I shoot!” cried the voice of Big Tony, immediately below him. Again for a moment Alex quailed, then again went bravely on, while the old semaphore rocked and swayed as the enraged Italian threw himself at it and scrambled up toward him.

“GOING TO RUN—”

With a plunge the big trackman reached up and caught him by the ankle, wrenched him back from the lantern, and clambered up beside him. Catching the light off the semaphore arm, he thrust it into the boy’s face. “O ho!” he exclaimed. “So it you, da station-man boy, eh? An’ you da one whata help Hennessy get away, eh? 19

“An’ whata now you do wid dis?” he demanded fiercely, indicating the lantern.

“If you can’t guess, I’m not going to tell you,” declared Alex stoutly, though his heart was in his throat.

“O ho! You wonta, eh? Alla right,” said Tony softly through his teeth, and in a grim silence more terrifying than the threat of his words, he blew the lantern out, tossed it to the ground, and proceeding to clamber down, grasped Alex by the leg and dragged him down after.

But help was at hand. As they reached the ground a second tall figure loomed up suddenly out of the darkness. “Who dat?” demanded Big Tony. The answer was a rush, and a blow, and with a throttled cry of terror the big track worker went to the ground in a heap, the foreman on top of him.

Alex uttered a cry of joy, then with quick wit, while the two men engaged in a terrific struggle, he darted in search of the lantern, found it, fortunately unbroken, and in a trice was again running up the semaphore ladder.

As he once more reached his post on the platform the big Italian succeeded in breaking from the foreman, scrambled to his feet, and dashed off across the brick-yard. “Come down, Alex. It’s all over,” called Hennessy, gathering himself up. “And now we’ve got to hike right off, a mile a minute, for the main-line if we are to stop that train. They ran me so far I only just got back. Unless Twenty’s late we—” 20

“I am trying to stop her from up here,” interrupted Alex, relighting the lantern.

“Up there? What do you mean?” exclaimed the foreman.

“Signalling father at the station, with the telegraph code,” said Alex as he replaced the lantern on the semaphore arm. “Come on up.”

“Al,” said the incredulous foreman as he reached the platform, “can you really do it?”

“I had it going when that Italian stopped me. Watch.”

But Alex was doomed again to interruption. Scarcely had he begun once more flashing forth the telegraph call of the station when from the direction of the woods came a shout, several answers, then a rush of feet.

“Some of the Poles!” exclaimed the foreman. “But you go ahead, Al, and I’ll see that they don’t get up to interfere,” he added, determinedly.

The running figures came dimly into view below. “If any of you idiots come up here I’ll crack your heads!” shouted Hennessy, warningly.

“I’ve got the station again,” announced Alex. “Now it will take only a few minutes.”

One of the men below reached the ladder, and, looking up, shouted threateningly: “Stop dat! Stop dat, or I shoot!”

“Go ahead, Al,” said the foreman, looking down. “He hasn’t a gun.” But even as he spoke there was a flash and a report, and a thud just over Alex’s head. 21

“Yes, stop! Stop!” cried the foreman. “Stop. They’ve got us. No use being foolhardy.”

Leaning over, he addressed the men below. “Look here,” he said, persuasively, “can’t you fellows see that Big Tony is only using you to make trouble for me, because I fired him for being drunk? As I told you at first, everything he has said is untrue. Why won’t you believe it?”

The men were silent a moment, then one of them addressed Alex. “Boy, is dat true?”

“Every word of it,” said Alex, earnestly. “And I would have heard all about it at the station if they had intended cutting your wages, or bringing others here to take your places.”

“Den I believe it,” said the Pole.

The man with the pistol returned it to his pocket. “I am sorry I shoot,” he said.

“And now, what about the train?” inquired the foreman, quickly. “Did you touch the switch?”

In the look of guilt the foreigners turned on one another he saw the alarming answer. Whipping out his watch, he held it to the light.

“Alex,” he said, sharply, “you have just ten minutes to catch that train at the Junction! If you don’t get her she’s gone! There’s not time now to get down to the main line from here to flag her!”

Before he had ceased speaking Alex had his cap over the light and was once more flashing an urgent “BX! BX! BX!” while below the foreigners looked 22 on, now with an anxiety equal to that of the two on the tower.

“BX! Qk! Qk!” flashed the lantern.

The station light disappeared. “Got ’em!” cried Alex.

“Just tell them first to stop Twenty at the Junction,” said the foreman.

“Right,” responded Alex, and while the rest watched in profound silence, he signaled:

“STOP NUMBER 20 AT JUNCTION. SPUR SWITCH IS THROWN. GOT IT?”

As Alex read off the promptly flashed “OK,” the foreman sprang to his feet and gave vent to a joyful hurrah of relief that echoed again in the clearing and woods. Then, as Alex recovered the lantern, he caught him under one arm, carried him down the ladder, and there, despite his objections, hoisted him to the shoulders of two of the now enthusiastic Poles, and all set off jubilantly down the spur for the switch, and home.

And an hour later Alex’s father and mother, anxiously awaiting him at the station, discovered his approach carried at the head of a sort of triumphal procession of the entire gang of trackmen.

When Alex’s father the following morning reported the occurrence to the chief despatcher, that official called Alex to the wire to congratulate him personally.

“That was a fine bit of work, my boy,” he clicked. 23 “I see you are cut out for the right kind of railroader. If fourteen wasn’t a bit too young I would give you a job on the spot. But we will give you a start just as soon as we can, you may be sure.”

One afternoon two weeks later Alex returned from school to find his father and mother hurriedly packing his suit-case.

“Why, what’s up, Dad?” he exclaimed.

“You are off for Watson Siding in twenty minutes, to take charge of the station there nights,” said his father. “The regular man is ill, the despatcher had no one else to send, and asked for you, and of course I told him you’d be delighted.”

“Delighted? Well, rather!” cried Alex, gleefully, and throwing his school-books into a corner, he dashed up-stairs to change his clothes, hastily ate a lunch his mother had prepared, and fifteen minutes later was hurrying for the depot.

Needless to say Alex was a proud boy when shortly after seven o’clock he reached Watson Siding, and at once took over the station for the night. For it is not often a lad of fourteen is given such responsibility, even though brought up on the railroad.

Alex was soon to learn that the responsibility was a very real one. The first night passed pleasantly enough, but early the succeeding night, following a day of rain, a heavy spring fog set in, and shortly before 25 ten o’clock Alex found, to his alarm, that he could not make himself heard on the wire by the despatcher. Evidently there was a heavy escape of current between them, because of the dampness.

Again the despatcher called, again Alex sought to interrupt him, failed, and gave it up. “Now I am in for trouble,” he said in dismay. “If anything should—”

From apparently just without came a low, ominous rumble, then a crash. Alex started to his feet and ran to the window. He could see nothing but fog, and hastily securing a lantern, went out onto the station platform.

As he closed the door there was a second terrific crash, from the darkness immediately opposite, and a rain of stones rattling against iron.

“The bank above the siding!” cried Alex, and springing to the tracks, he dashed across, and with an exclamation brought up before a mound of earth six feet high over the siding rails.

As he gazed Alex felt his heart tighten. The westbound Sunset Express was due to take the siding in less than half an hour, to await the Eastern Mail, and at once he saw that if the engineer misjudged the distance in the fog, and ran onto the siding at full speed, there would be a terrible calamity.

And suppose the cars were thrown onto the main line track, and the Mail crashed into them! And, apparently, he could not reach the despatcher, to give warning of her danger! 26

What could he do to stop them? Helplessly Alex looked at the lantern in his hand. Its light was smothered by the fog within ten feet of him.

Running back to the operating room he seized the key and once more sought to attract the attention of the despatcher. It was useless. The despatcher did not hear him. He sank back in his chair, sick with dread.

But he must attempt something! Determinedly he sprang to his feet. A lantern was useless. Then why not a fire? A big fire on the track? Hurrah! That was it! But—he gazed at the coal box, and thought of the rain soaked wood outside, and his heart sank. Then came remembrance of the big woodshed at the farm-house where he boarded, three hundred yards away, and in a moment he had recovered the lantern, and was out, and off through the darkness, running desperately.

On arriving at the house Alex found all in silence, and the family retired, but without a moment’s hesitation he threw himself at the front door, pounding upon it with his fists.

It seemed an age before a window was raised. “Mr. Moore,” he cried, “there has been a landslide in the cut at the station, and there is danger of the Sunset running into it. May I have wood from the shed to make a fire on the track to stop her?”

“Gracious! Certainly, certainly!” exclaimed the voice from the window. “And the boys and I will be down in a minute to help you. You run around and be pulling out some kindling.”

Alex darted about to the woodshed, there the farmer and his two sons soon joined him, and each catching up an armful of wood, they were quickly off for the railroad, Alex leading with the lantern.

Reaching the tracks, they hurried east, and a quarter mile distant halted, and began hastily building a huge bonfire between the rails.

“There,” said Alex, as the flames leaped up, “that ought to stop her.”

“And now, Mr. Moore, suppose we leave Dick here to tend the fire, and you and Billy and I hurry back to the station, and tackle the earth on the track. We may get enough off to let the train plow through.”

“All right, certainly,” agreed the farmer; and retracing their steps, the three secured shovels and more lanterns at the depot, and soon were hard at work on the obstructed siding.

They had been digging some ten minutes when suddenly Billy paused. “Listen,” he said. “There’s a horse coming, on the run.” His father and Alex also ceased shoveling, and a moment later the quick pounding of horse’s hoofs was plainly discernible.

“It must be something urgent to make a man drive like that in the dark,” said Mr. Moore.

The racing hoofs drew nearer, and placing his hands to his mouth he cried: “Hello! What’s up?”

There was a sound of scrambling and plunging, and out of the darkness came a man’s excited voice: “How near am I to the station?”

“Thank God! Run quick and tell the operator there has been a landslip in the big cutting just beyond the river! My son discovered it when coming home by the track from a party! I thought I could get here quicker than do anything else!”

For a moment Alex stood speechless at this further calamity, then once more dashed for the station. To reach Zeisler, two miles west of the cut, was the only hope for the Mail.

Rushing in to the instruments, he in feverish haste began calling “Z. Z, Z,” he whirled. “Qk! Z, Z, WS!”

There was no answer. Z heard him no more than did the despatcher.

A feeling of despair settled upon the boy. But again returned the old spirit of determination and contriving, and spinning about in his chair, he cast his eyes around the room for some suggestion. They halted at the big stoneware water-cooler. With a cry he was on his feet, thinking rapidly.

Only a few hours before, during an idle moment, the similarity of the big jar to a gravity cell had occurred to him, and the speculation as to whether it could not be turned into a battery if need be.

Could he really make a battery of it? If he could, undoubtedly it would be strong enough to so increase the current in the wire that both Zeisler and the despatcher could hear him.

He ran to a little storage closet at the rear of the room. Yes; there was enough bluestone! But no copper, or zinc! What could he do for that? 31

As though directed by Providence, his gaze fell on the floor-board of the office stove. It was covered with a sheet of zinc! And even as he uttered a glad “Good!” there came the remembrance that at the house that afternoon he had seen a fine new wash-boiler—with a thick copper bottom.

“That’s it,” cried Alex, again catching up the lantern and darting for the door.

A short distance from the depot Alex was halted by a long, muffled whistle from the east. “The Express,” he exclaimed, and in keen anxiety awaited the next whistle. Would it be for the crossing this side of the bonfire, or—

It came, a series of quick, sharp toots. Yes; they had seen the fire!

“Thank Heaven! She’s safe at any rate,” said Alex, at once running on.

A few minutes later he burst into Mrs. Moore’s kitchen. The farmer’s wife was at the stove, preparing coffee for them.

“Mrs. Moore, where is your new copper-bottomed boiler? I must have it, quick,” said Alex.

“What! My new wash-boiler?”

“Yes; the copper-bottomed one. It’s a matter of life and death!”

The astonished woman hesitated, then, wonderingly, pointed toward the outer kitchen. Alex ran thither, and quickly reappeared with the fine new boiler on his shoulder.

“And I must have that kettle of boiling water,” he 32 added, on a thought. “I’ll explain later.” And catching it from the stove, he rushed away.

As he ran Alex further thought out his plans, and once more at the station, he placed the kettle on the office stove, emptied the bluestone into it, and poked up the fire.

Then, with a hammer and chisel, he attacked the copper bottom of the boiler.

He was still pounding and cutting when presently there was the sound of hurried footsteps without, the door flew open, and a voice exclaimed: “In Heaven’s name, young man, what are you doing? Why are you not at your wire, trying to stop the other train?”

It was none other than the division superintendent of the road, who had been aboard the Sunset.

Only pausing a moment in his work, Alex replied: “I can’t reach anybody, sir, the wire is so weak. I am making a battery of that water-cooler, to strengthen it. It’s the only hope, sir.”

The superintendent uttered a horrified exclamation, then quickly added: “Here, can’t I help you?”

“Yes, sir,” replied Alex, promptly. “Lift up the stove and slide out the floor-board. I must have the sheet of zinc off it.”

And a few minutes later a group of passengers from the stalled train, seeking the cause of delay, paused in the doorway to gaze in blank astonishment at the spectacle of the division superintendent of the Middle Western, his coat off, energetically working under the direction of his youngest operator.

“There you are, my lad,” said the superintendent. “What next?”

“Get a stick, sir, and stir the bluestone in the kettle. We must have it dissolved if the battery is to work the moment we connect it to the wire.”

The copper bottom of the boiler was at last cut through, and hastily doubling it over several times, in order that it would lie flat in the crock, Alex turned his attention to the zinc on the stove-board.

The scene in the little station had now become dramatic—the crowd of passengers, increased until it half filled the room, looking on in strained silence, or talking in whispers; the tall figure of the superintendent at the stove, busily stirring the kettle, and in the middle of the floor, the center of all eyes, the fourteen-year-old boy hurriedly working with chisel and hammer, seemingly only conscious of the task before him and the necessity of making the most of every minute.

The zinc was cut, and hurriedly folding it as he had the copper, Alex sprang to his feet, and running to the cupboard, dragged out a bundle of wire, and began sorting out a number of short ends.

“How much longer?” said the superintendent in a tense voice. “The train should be at Zeisler now.”

“Just a minute. But she’s sure to be a little late, from the fog,” said Alex, hopefully, never pausing. “Has the bluestone dissolved, sir?”

“All but a few lumps.”

“Then that’ll do. Now please lift down the water-cooler, sir, and place it by the table.” 36

As the superintendent complied all conversation ceased, and the crowd, moving hurriedly out of the way, looked on breathlessly, then turned to Alex, on his knees, fastening two pieces of wire to the squares of copper and zinc.

This done, Alex dropped the square of copper to the bottom of the big jar, hung the zinc from the top, connected one wire end to the ground connection at the switchboard, and the other to the side of the key. And the task was complete.

“Now the kettle, sir,” he said, dropping into his chair. The superintendent seized the kettle, and emptied its blue-green liquid into the cooler. The moment the water had covered the zinc Alex opened his key.

It worked strongly and sharply.

“Thank God! Thank God!” said the superintendent, fervently. “Now, hurry, boy!”

Already Alex was whirring off a string of letters. “Z, Z, Z, WS!” he called. “Qk! Qk! Z, Z—”

The line opened, and at the quick sharp dots that came Alex could not restrain a cry of triumph. “It works! I’ve got him,” he exclaimed. Then rapidly he sent:

“Has Number 12 passed?”

The line again opened, and over the boy leaned a circle of white, anxious faces. Had the train passed? Had it gone on to destruction? Or—

The instruments clicked. “No! No! He says, no!” cried Alex.

And then, while the crowd about him relieved its 37 pent-up feelings in wild shouts and hurrahs, Alex quickly sent the order to stop the train.

“And now three good cheers for the little operator,” said one of the passengers as Alex closed his key. In confusion Alex drew back in his chair, then suddenly recollecting the others who had taken part in the night’s work, he told the superintendent of the part played by Mr. Moore and his sons, and of the sacrifice of Mrs. Moore’s new wash-boiler.

“And then there was the man on the horse, who told us of the slide in the cut across the river. He was the real one to save the Mail,” said Alex, modestly.

“I see you are as fair as you are ingenious,” said the superintendent, smiling. “We’ll look after them all, you may be sure. By the first express Mrs. Moore shall have two, instead of one, of the finest boilers money can buy. And as for you, my boy, I’ll see that you are given a permanent station within a year, if you wish to take it. We need resourceful operators like you.”

Most telegraph operators, young operators especially, have a number of over-the-wire friends. Alex Ward’s particular telegraph chum was Jack Orr, or “OR,” as he knew him on the wire, a lad of just his own age, son of the proprietor of the drug-store in which the town, or commercial, office was located at Haddowville, a small place at the end of the line. The two boys had become warm friends through “sending” for one another’s improvement in “reading,” in the evenings when the wire was idle; but also because of the similarities of taste they had discovered. Both were fond of experimenting, and learning the “why and wherefore” of things electrical.

And not infrequently they got themselves into trouble, as young investigators will.

One evening that summer, the instruments being silent, Jack, at Haddowville, bethought himself of taking the relay, the main receiving instrument, to pieces, to discover exactly how the wire connections in the base were arranged. To think with Jack was to act. Half an hour later his father, entering with an important message, found Jack with the instrument in a dozen pieces. 39

Mr. Orr viewed the muss with consternation. Then he spoke sharply. “Jack, if that relay is not together again, and working, in five minutes, I’ll take you out to the woodshed!” Needless to say, Jack threw himself into the restoring of the instrument with ardor, while his father stood grimly by. And fortunately the relay was in its place again, and clicking, within the prescribed time.

“But don’t let me ever catch you tinkering with the instruments again,” said Jack’s father warningly, as he gave Jack the message to send. “Another time it’ll be the woodshed whether you get them together or no. Remember!”

Shortly after midnight the night following Jack suddenly found himself sitting up in bed, wondering what had awakened him. From the street below came the sound of running feet, simultaneously the window lighted with a yellow glare, and with a bound and an exclamation of “Fire!” Jack was across the room and peering out.

“Jones’ coal sheds! Or the station!” he ejaculated, and in a moment was back at the bedside, dressing as only a boy can dress for a fire. Running to his parents’ bedroom he told them of his going, and was down the stairs and out into the street in a trice.

Dim figures of men and other boys were hurrying by in the direction of the town fire-hall, a block distant, and on the run Jack also headed thither. For to help pull the fire-engine or hose-cart to a fire was the ardent hobby of every lad in town. 40

A half dozen members of the volunteer fire company and as many boys were at the doors when Jack arrived, and the fire chief, already equipped with helmet and speaking-trumpet, was fumbling at the lock.

“Where is it, Billy?” inquired Jack of a boy acquaintance.

“They say it’s the station and freight shed, and Johnson’s lumber yard, and the coal sheds—the whole shooting match,” said Billy, hopefully.

“Bully!” responded Jack; who, never having seen his own home in flames, likewise regarded fires as the most thrilling sort of entertainment.

“Out of the way!” cried the chief. The big doors swung open, and with a rush the little crowd divided and went at the old-fashioned hand-engine and the hose-cart. Billy and Jack secured the particular prize, the head of the engine drag-rope, and like a pair of young colts pranced out with it to its full length. Others seized it, and with the cry of “Let ’er go!” they went rumbling forth, and swung up the street.

The hose-cart, with its automatic gong, clanged out immediately after, and the race that always occurred was on. The engine of course had the start, but the hose-cart, a huge two-wheeled reel, about which the hose was wound, was much lighter, and speedily was clanging abreast of them. Here, however, Big Ed. Hicks, the blacksmith, and Nick White, a colored giant, rushed up, dodged beneath the rope, and took their accustomed places at the tongue, and with a burst of speed the engine began to draw ahead. Other 41 firemen appeared from side streets and banging doorways, and took their places on the rope, and a shout from the juvenile contingent presently announced that the reel was falling to the rear.

Meanwhile the glare in the sky had brightened and spread; and when at last the rumbling engine swung into the station road the whole sky was ablaze. Overhead, before a stiff wind, large embers and sparks were beginning to fly.

With a dash the panting company swept into the station square. Before them the station and adjoining freight-shed were enveloped in flames from end to end. It was apparent at once that there was no possibility of saving either. But with a final rush the engine-squad made for the fire-well at the corner of the square, brought up all-standing, and in a jiffy the intake pipe was unstrapped and dropped into the water. The reel clanged up, two of its crew sprang for the engine with the hose-end and couplers, and the cart sped on, peeling the hose out behind it.

The speed with which they could get into action was a matter of pride with the Haddowville firemen. Almost before the coupling had been made at the engine the men and boys at the long pumping-bars were working them gently; within the minute a shout from the cart announced that the hose was being broken, the pumpers threw themselves into the work with zest, and the next moment from the distant nozzle shot a sputtering stream.

With the other boys, Jack, though now considerably 42 winded, was throwing himself energetically up and down against one of the long handles. Before many minutes, however, the remainder of the regular enginemen appeared, and took their places, and presently Jack also was ousted.

At once he set off for a closer view of the fire. Half way he was halted by a call.

“Hi, Jack! Come and help push the freight cars!”

The shout came from a group of boys running for the rear of the burning freight-shed, and responding with alacrity, Jack joined them, and soon, just beyond the burning building, was pushing against the corner of a slowly moving box-car with all his might.

One car was rolled safely out of the danger zone, and Jack’s party hastened back for another. The innermost of the remaining cars, and on a separate siding, was but a short distance from the flaming shed, and already was blazing on the roof. Jack and several other adventurous spirits determined to tackle this one on their own account. After much straining they got it in motion.

Suddenly a wildly excited figure appeared rushing through the smoke, and shouted at the top of his voice, “Get back! Get back! There’s blasting powder in that car!”

In a twinkle there was a wild stampede. And but just in time. With a blinding flash and a roar like a thunderbolt, the car shot into the air in a million pieces. Many persons in the vicinity were thrown violently to the ground, including Jack. As he scrambled, 43 thoroughly frightened, to his feet, someone shouted, “Look out overhead!” and glancing up, Jack saw a shower of burning fragments high in the air.

Then rose the cry, “The wind is taking them right over the town!” In alarm many people began leaving the square for their homes.

Jack’s own home and the drug-store block were well on the other side of the town, however, and with no thought of anxiety Jack remained to watch the burning station, now a solid mass of flame from ground to roof.

Presently, glancing toward the opposite corner of the square, Jack noted a general, hurried movement of the crowd there into the street. He set out to investigate. As he neared the fire-engine, still clanking vigorously, a bareheaded man rushed up and asked excitedly for the fire chief. “The telephone building and a house on Essex Street, and one on the next street back, are burning!” he cried. “Quick, and do something, or the whole town will be afire!”

Looking in the direction indicated, Jack saw a wavering glare, and with a new thrill of excitement was immediately off on the run. The telephone exchange was one of the largest buildings in town.

As he came within sight of the new conflagration the flames already were leaping from the roof and roaring from the upper windows. Despite the heat, the crowd before the building was clustered close about the door of the telephone office, and Jack hastened to join them, to learn the cause. Making his way through the throng, he reached the front as a blanketed figure 44 staggered, smoking, from the doorway. Someone sprang forward and caught the blanket from the stumbling man, at the same time crying, “Did you get them?”

“No,” gasped the telephone operator, for Jack saw it was he; “the whole office is in flames. I couldn’t get inside the door.”

Mayor Davis, the first speaker, turned quickly about. “Then we’ll run down to Orr’s and telegraph.”

At once Jack understood. The mayor wished to send for help from other towns. He sprang forward. “I’m here, Mr. Davis—Jack Orr. I’ll take a message!”

“Good!” said the mayor. “Run like the wind, my boy, and send a telegram to the mayors of Zeisler and Hammerton for help. As many steam engines as they can spare. And have the railroad people supply a special at once. Write the message yourself, and sign my name. Tell them four more fires have broken out, and that the whole town may be in danger.”

Jack broke through the crowd, and was off like a deer.

Farther down the street he passed another building, a small dwelling, burning, with its frightened occupants and their neighbors hurrying furniture out, and fighting the flames with buckets.

Down the next cross-street he saw flames bursting from a second house. 45

Then it was that the real gravity of the situation began to come home to Jack. Till now it had all been only a thrilling drama—even the bearing of the mayor’s urgent message had appeared rather a dramatically prominent stage-part he had had thrust upon him.

On he sped with redoubled speed, and turned into the main street. Then his alarm became genuine. Lurid flames were licking over the tree-tops directly ahead of him—in the direction of the store! A moment later a cry of horror broke from him. It was indeed the store block!

But his own personal alarm was quickly lost in a greater. Suppose the telegraph office also should be in flames, and he unable to reach it? He ran on madly.

He neared the store, and with hope saw that so far the flames were only in the second story. Men were hurrying in and out, and from the hardware-store adjoining. But as he rushed to the drug-store door a cloud of heavy smoke rolled forth, driving a group of men before it.

Among them he recognized his father.

“Dad,” he cried, “can’t I reach the instruments? I’ve a message for help to Hammerton and Zeisler from the mayor! The ’phone office and the station are burned. There is no other way of getting word out.”

Mr. Orr had halted in consternation. “No; you couldn’t get to them. The telegraph room is a furnace. 46 The fire came in through the office windows from the outhouse, and I closed the door from the store.”

Through the haze of smoke within burst a lurid fork of flame.

“There! The fire is out through the telegraph-room door,” said the druggist. “You couldn’t get near the table. And anyway, Jack, the instruments would be useless by this time.”

It was this remark that aroused Jack. “If I could rip them from the table in any kind of shape, perhaps I could fix them up quickly so I could use them,” he thought.

To his father he said with sudden determination, “Dad, I’m going to make a try for the key and relay.”

“No. I won’t permit it,” declared Mr. Orr decisively.

“But father, if we don’t get word out the whole town may be burned,” cried Jack.

“I’ll make a try myself,” said Mr. Orr, and without further word lowered his head and dashed back into the smoke.

While Jack stood anxiously awaiting his father’s reappearance the owner of the adjacent hardware-store stumbled from his doorway under a bundle of horse-blankets. With an immediate idea Jack ran toward him. “Mr. Wells, let me have some of those blankets,” he said hurriedly. “We want to try and reach the telegraph instruments. They are the only 47 hope for getting word out of town for help. Father is in after them, but I don’t think he can reach them with nothing over him.”

The merchant promptly threw the whole bundle to the ground. “Help yourself,” he directed.

At the door again, he called back. “Can you use anything else?”

“No—Say, yes! A pair of leather gauntlets.” The merchant disappeared, reappeared, and threw toward Jack a bundle of leather gloves. “Many as you want,” he shouted.

Catching them up and two of the blankets, Jack sprang back for their own store as his father reappeared.

“They can’t be reached,” coughed Mr. Orr. “Couldn’t even get to the door.”

“I’ll try with these blankets, then,” said Jack decisively. “Throw them over my head, please.”

His father hesitated. “But my boy—”

“There’s little danger, Dad. The blankets are thick. And I know just where the instruments are. And see, I’ll wear these gauntlets,” he added, pulling a pair over his hands.

Somewhat reluctantly Mr. Orr took the blankets and threw them over Jack’s head, and on the run Jack plunged into the wall of smoke.

With one gloved hand outstretched he found the telegraph-room door, and the knob. He pressed against it, and with a crash and then a roar the door collapsed before him. But without a moment’s hesitation 48 he darted on within, groped his way to the table, found the relay, and with a desperate wrench tore it from its place. The next moment he dashed blindly into his father’s arms at the outer door, and threw the smoking blankets and sizzling, burning relay to the sidewalk.

“Water on it quick,” gasped Jack, pointing to the instrument. Catching it up in a corner of one of the blankets Mr. Orr ran with it to a horse-trough in front, and plunged it into the water.

As he returned Jack was drawing on a second pair of gauntlets.

“Jack, you’re not going back!” said his father sharply.

“I want the key, Dad.”

“Look there.” Glancing within Jack saw that the whole rear of the store was now enveloped in flames.

“And it would be of no use in any case. Look at this,” said Mr. Orr, holding up the smoking relay.

The instrument did indeed look a hopeless wreck as Jack took it. The base was cracked and charred, the rubber jacket about the magnet-coils was frizzled and warped, the fine wire connections beneath were gone, and the armature spring was missing.

But Jack was not one to give up while a single hope remained. “I could improvise a key,” he said, and with decision hastily sought the hardware merchant.

“Mr. Wells, did you save any screw-drivers?” he asked.

“In a box down there. Help yourself.” 49

Running thither Jack found the tool, and immediately began taking the relay apart.

An exclamation of disappointment greeted the discovery that the fine copper wire within one of the coil-jackets had been melted into a solid mass. On ripping open the sizzled jacket of the other, however, Jack found the silk covering the wire to be only scorched, and determined to do the best he could with the one magnet.

Removing the relay entirely from the burned base, he secured a thin piece of board from one of the boxes near him, from the miscellaneous tools in another box found a gimlet, and made the necessary perforations. And soon he had the brass coil-frame mounted.

Meantime Mr. Orr, not for a moment thinking Jack could do anything with the charred instrument, had joined the crowd of men and women watching the burning building from across the street.

“Father! Here, please!” called Jack.

In some wonder Mr. Orr responded, and with him the hardware merchant.

“Have you a rubber band in your pocket?” asked Jack. “I want it for the armature spring.”

“Why you are really not doing anything with it, Jack!” exclaimed his father.

“Yes, sir. I think I can make it go,” responded Jack with a little touch of elation. “And with only one magnet. But have you the rubber?”

“Here,” said Mr. Wells, snapping a rubber band from his pocketbook. “This do?” 50

“Just the thing. Thanks.” And while the two men looked on, Jack secured one end of the elastic to the little hook on the armature, and knotted the other about the tension thumb-screw.

That done, Jack caught up a hammer and smashed the useless coil to pieces, from the wreck, secured several intact ends of the fine wire, and with them quickly restored the burnt connections between the magnet and the binding-posts. And with a cry, half of jubilation and half of nervous excitement, he caught up the now roughly-restored instrument and ran toward an iron gas street-lamp. In the roadway a short distance from the lamp-post lay the burned-off end of the telegraph wire. Placing the instrument on the sidewalk, Jack ran for the wire, and dragged it also to the post.

Then, as the crowd, following his father and the hardware merchant, gathered about him, they saw him secure a piece of wire about the iron lamp-post, then to the instrument; and, dropping to a sitting position, place the instrument on his knees, catch up the telegraph line, and hold it to the other side of the relay.

Jack’s low cry of disappointment was echoed by his father. “No use. I was afraid of it, my boy,” said Mr. Orr resignedly.

There was a disturbance on the outskirts of the crowd, and the mayor appeared pushing his way through. “Didn’t you get that message off, Jack?” he cried excitedly. 51

“The fire was too quick for us,” said Mr. Orr. “Jack risked his life getting out one of the instruments. But it has proved useless.”

“Oh say! Now I know what’s the matter!” With the cry Jack sprang to his feet, broke through the circle about him, and sped back toward the store. The flames were now bursting from the front, but with head down he ran to the iron door covering the street entrance to the cellar, and lifted it. A thin stream of smoke arose, then disappeared as a draft toward the rear set in. With a thankful “Good!” Jack leaped into the opening.

His father, the mayor, and several others who had rushed after in consternation reached the sidewalk as Jack’s head reappeared, followed by a green battery jar. Placing the jar on the ledge, he stooped, and raised another.

“What do you think you are doing?” cried his father.

“I’ll explain in a minute. Take them over to the post, please.” And Jack had again disappeared.

The mayor promptly caught up the two cells, but Mr. Orr as promptly dropped through the opening and followed Jack.

“What are you trying to do?” he demanded as he groped his way to the battery-shelf. “You can’t do anything with the battery if you have no instrument.”

“The instrument is all right, Father. The line has been ‘grounded’ south, that’s all. If we put battery 52 on here, we can reach some office between here and wherever the ‘ground’ is on.”

“May it be so,” said Mr. Orr fervently, but not hopefully, as they hurried with four more jars to the entrance.

When they had carried out a dozen jars Jack declared the number to be sufficient, and scrambling forth, they hastened back to the lamp-post.

Without delay Jack connected the cells in proper series, and removing the wire between the instrument and the iron post, substituted the battery—zinc to the post, and copper to the instrument.

Then once more he caught up the severed end of the main-line wire, and touched the opposite side of the instrument.

A cry of triumph, then a mighty shout, greeted the responding click.

“But what about a key, son?” said Mr. Orr.

“This, for the moment,” replied Jack, and simply resting his elbow on his knee, and tapping with the end of the wire against the brass binding-post, he began urgently calling.

“HN, HN, HN!” he clicked. “HN, HN, HV! Rush! Qk! HN, HN!”

“Perhaps the wire is grounded between here and Hammerton,” suggested his father breathlessly.

“Anybody answer! Qk!” sent Jack. “Does anybody hear this?”

“What’s the matter? This is Z.”

“Got Zeisler!” shouted Jack. 53

The mayor stepped forward. “Send them the message,” he directed, “and have them ’phone it to Hammerton.”

Jack did so. And fifteen minutes later the cheering news ran quickly about the threatened town that two steam fire-engines were starting by special train from Hammerton immediately, would pick up another at Zeisler, and would be on the scene within half an hour. All of which report proved true, the engines arriving on the dot—and by daylight the last of the several different fires were under control, and the safety of the town was assured.

Needless to say, Jack’s name played an important part in the dramatic newspaper accounts of the conflagration—nor to add that he was the envied hero of every other lad in town for weeks to come.

The final and particular result of the affair, however, was the offer to Jack of a good position in the large commercial telegraph office at Hammerton, which he at last induced his parents to permit him to accept.

One evening shortly after the beginning of the summer holidays Alex was chatting over the wire with Jack, who was now a full-fledged operator at Hammerton, when the despatching office abruptly broke in and called Bixton.

“I, I, BX,” answered Alex.

“Is young Ward there?” clicked the instruments.

“This is ‘young Ward.’”

“Say, youngster, would you care to do a couple of weeks’ vacation relief at Hadley Corners, beginning next Monday? The man there wants to get off badly, and we have no one here we can send.”

“Most certainly I would,” replied Alex, promptly.

“OK then. We’ll count on you. I’ll send a pass down to-night,” said the despatcher.

Thus it came about that the following Monday morning Alex alighted at the little crossing depot known as Hadley Corners, and for the second time found himself, if but temporarily, in full charge of a station.

Entering the little telegraph room, he announced his arrival to the despatcher at “X.”

“Good,” clicked the sounder. “And now, look 55 here, Ward. Don’t do any tinkering with the instruments while you are there. We don’t want a repetition of the mix-up you got the wire into at BX through your joking a month or so ago.”

The joke referred to was a hoax Alex had played on his father the previous First of April. Through an arrangement of wires beneath the office table, by which with his foot, unseen, he could make the instruments above click as though worked from another office, he had called his father to the wire, and posing as the despatcher, had severely reprimanded him for some imaginary mistake in a train order. It had been “all kinds of a lark,” until, unfortunately, the connections became disarranged, tying up the entire eastern end of the line for half an hour.

At the recollection of the escapade Alex laughed heartily. Nevertheless he promptly replied, “OK, sir. I won’t touch a thing.” And the despatcher saying nothing more, he began calling Bixton.

“I’m here, Dad,” he announced when his father answered; “and it’s a fine little place. The woods come almost up to the back of the station, and the nearest house is a mile away. That’s where I am to board. The other operator arranged it. It’s going to be a regular little picnic.”

“That’s nice,” ticked the sounder. “I thought you would like it.” And then Alex again laughed as his father added, “And now, no tinkering with things, my boy! Remember!”

“OK, Dad. I won’t touch a thing. Good-by.” 56

It was the following Monday that the “all agents” message was sent over the wire announcing an unusually heavy shipment of gold from the Black Hill Mines, and warning station agents and operators to look out for and report any suspicious persons about their stations. But these messages, usually following hold-ups on other roads, had been intermittently sent for years, and nothing had happened on the Middle Western; and in his turn Alex gave his “OK,” and thought nothing more about it.

A half hour later he sat at the open window of the telegraph room, deeply interested in the July St. Nicholas—so interested, indeed, that he did not hear soft footfalls on the station platform without. The man came quietly nearer—reached the window. Then suddenly Alex glanced up, the magazine fell to the floor, and with a loud cry he sprang to his feet.

He was gazing into the barrel of a revolver, and behind it was a black-masked face!

Hold-up men! The gold train!

Wildly Alex turned toward the telegraph-key. But the man leaned quickly forward, seized him by the shoulder, and threw him heavily back into the chair. “You move again and I’ll shoot!” he said sharply, and Alex sank back helpless.

Yes; hold-up men. And he had betrayed his trust. Betrayed his trust! That thought stood out even above his terror. Oh, if he had only kept a lookout!

The man, who had said nothing further, presently withdrew the revolver and took a comfortable seat on the window-ledge. As the silence continued, Alex began somewhat to recover himself, and fell to wondering what the other bandits were doing while this man was watching him.

A few moments later the answer came in a single upward click from the instruments.

“There—wires cut, ain’t they?” said his captor.

“Yes, I suppose,” said Alex, bitterly.

“They sure are,” said the voice from behind the mask. “And when we get through, them wires’ll be cut so you won’t be able to fix ’em up in a hurry.”

Fifteen minutes later a second masked and heavily armed figure appeared. “Every wire cut five poles back on either side of the station,” he announced briefly. “It’ll take a lineman half a day to fix ’em up again, and we’ll be twenty miles away by that time. Now we’ll put the hobbles on the youngster, and git.”

Often Alex had longed for just such an adventure as this. The final disenchantment was anything but glorious. Roughly seizing him, the two men forced him stiffly upright in the chair, drew his arms about the back of it, and there secured them, wrist to wrist, drawing the knot until Alex almost cried out in pain. Then, as tightly, they bound his ankles to the lower rungs, one on either side.

“Now one of us is going to watch from the woods for a spell—we’ll leave the back door open, so we can see right in—and if you make a move, you get 60 this quick! See?” said one of the desperadoes, tapping his pistol significantly.

Therewith they passed out, leaving the rear door wide open, and in utter misery of mind Alex watched them stride toward the trees.

Before the two bandits had crossed the open space, however, Alex’s mind had cleared. For plainly they were hurrying! Then their promise to watch him must have been only a threat, to keep him quiet! Good! At once he began straining at his wrists, paused as the two men reached the edge of the clearing and momentarily turned, and as they disappeared amid the trees, began struggling with grim determination.

It seemed a hopeless task at first, and the rawhide thongs cut cruelly into Alex’s wrists and ankles. But bravely he struggled on, wriggled and twisted, paused for breath, and struggled again. And finally one hand came suddenly free.

It required but a few seconds to get into his pocket, reach his knife, and open it with his teeth. A moment later Alex was on his feet, and staggered out onto the platform.

Yes, the wires were cut, five poles in either direction! Alex clenched his hands. After all, what could he do? To restore the line was entirely out of the question. Had there been but one break he could not have climbed the pole and carried aloft that heavy stretch of wire.

And there was less than twenty minutes in which 61 to work, to catch the Overland at Broken Gap. For undoubtedly it was beyond that point that the bandits planned holding her up—probably on one of the steep grades of the Little Timber hills.

Suddenly Alex uttered a gasp of hope. A moment he debated, with nervously clasped hands, then, exhaustion forgotten, dashed back into the little telegraph room, found a screw-driver, and in a few minutes had loosened from the table the telegraph-key and the receiving instrument. Catching them up, with some short ends of wire, he darted out and up the track to the west.

Two hundred yards distant the intact end of the telegraph line drooped into the drainage ditch. Alex caught it up and dragged it to the rails. Placing the key and relay on the end of a tie, he connected them on one side to the rail, and on the other side to the end of the line wire.

But the responding click did not come. Alex groaned in disappointment. He had counted on the rails giving a “ground” connection. Then the line would have closed, and he could have worked it to the west. But apparently the hot weather had entirely dried out the sand beneath the rails, and thus insulated them.

But he was not yet beaten. There was a ground wire at the station. Why could he not use the rails that far, if they were insulated? With a hurrah he seized the end of the line wire, and in a few moments had connected it to one of the rail joints. Then, catching 62 up the instruments, he dashed back for the station.

Placing the instruments again on the table, he found a piece of loose wire that would reach from the instruments, out through the window, to the rails; ran out and quickly connected it to a rail joint, and, darting back, connected the other end to the instruments. Instantly there was a sharp downward click. The line was closed!

Alex could not suppress a quick “Thank Heaven!” and, trembling with excitement, he seized the key and began swiftly calling the despatcher. “X, X, X, HC,” he called. “X, X—”

He felt the line open, and closed his own key. Then, in surprise, he read: “So you have been monkeying with the wires there after all, have you? Now look here—”

Quickly Alex interrupted, and shot back: “Train robbers are after the Overland. They held me up, and cut the wires both sides of the station. I got free, and have made a connection through the rails—HC.”

For a moment the line remained silent, while at his end of the wire the despatcher sat bolt upright in his chair, eyes and mouth wide open. But in another moment the despatcher had recovered himself, and, springing back to the key, began madly calling Broken Gap.

“B, B, B, X!” he called. “B, B, X! Qk! Qk!”

Alex shot a glance at the clock, and leaned forward over the instruments, scarcely breathing. There was yet three minutes before the Overland was due at Broken Gap. But she did not stop there, and frequently passed ahead of time. If “B” did not answer the call immediately—

The whir of “B’s” was interrupted, and slowly and deliberately came an “I, I, B.” Alex leaped in his chair, and again strained forward tensely.

“Has 68 passed?” hurled the despatcher.

“Just coming.”

“Stop her! Flag her! Qk! Qk!”

The line opened, as though “B” was about to make a reply, then smartly closed again.

“Stop her! Stop her!” repeated “X.”

There was a leaden, breathless silence, while Alex nervously clenched and unclenched his hands. At last the line again clicked open, and with a characteristic deliberation that caused the nerve-strung boy a moment’s hysterical laugh, “B” announced: “Just got her. She’s slowing in now. What’s up?”

The despatcher at “X” had regained his equilibrium, and in his usual crisp manner he replied: “Take this for Conductor Bedford:

“Bedford: Hold-up apparently planned between Broken Gap and Hadley Corners. Probably on one of the grades of the Little Timbers. Gather a posse quickly, and make sure of capturing them. Report at HC.

“(Signed) Jordan, X.”

As “B” gave his “OK” with the stumbling hesitation of blank astonishment, the line again opened. And at the first word the intense strain broke, and Alex sank forward over the table with a convulsive sob.

“Grand, my boy! Grand!” clicked the sounder. It was his father, at Bixton. He had overheard it all.

“Grand! That’s the word,” came the despatcher. “There’s not another operator on the division who would have known enough to do what he did to-day. I guess we won’t bother him any more about his ‘tinkering,’ will we?”

Only half an hour late, the mighty mogul pulling the Overland Limited drew panting to a stop before the little station, and in a moment Alex was surrounded by a crowd of congratulating trainmen and passengers. And when he reappeared after sending the message which notified the despatcher of the train’s safe arrival and of the capture of the two bandits, he was surprised and speechlessly confused by having pressed upon him by the enthusiastic passengers an impromptu purse of seventy-five dollars.

Later in the afternoon Alex was called to the wire by Jack, at Hammerton. “Say, what is all this you’ve gone and done, Al?” clicked Jack enthusiastically. “The afternoon papers here have a whole column story! ‘Please attach statement at once!’”

“Oh, it looks much bigger than it really was,” responded Alex modestly. “And anyway, it came about 67 through my own carelessness. I ought to have been reprimanded, instead of patted on the back.”

“Nonsense! Those hold-up men would have got you, anyway. If you had seen them coming, they would simply have approached in a friendly way, then got the drop on you. You had no gun.

“But, say,” added Jack mock-seriously, “how is it these real high class adventures always come your way? I’m getting jealous.”

“I can assure you you needn’t be. It’s lots more fun reading about them. Wait and see,” said Alex.

Jack was soon to have his opportunity of “seeing,” though a more disagreeable experience was first to come.

“Orr, Mr. Black wants you.”

Jack, who was passing through the business department of the Hammerton office, toward the stair which led to the operating room, promptly turned aside and entered the manager’s private room.

“Good morning, Jack. Sit down.

“My boy,” began the manager, “can you keep a secret?”

“Why yes, sir,” responded Jack, wondering.

“Very well. But I must explain first. I suppose you did not know it—we kept it quiet—but the real reason Hansen, the janitor, was discharged a month ago was that he was found taking money from the safe here, which he had in some way learned to open. After he left I changed the safe combination, and thought the trouble was at an end.

“Last Tuesday morning the cash was again a little short. At the time I simply thought an error had been made in counting the night before. This morning a second ten-dollar bill is missing, and the cash-box shows unmistakable signs of having been tampered with.

“Now Johnson, the counter clerk, to whom I had 69 confided the new combination (for it is customary, you know, that two shall be able to open a safe, as a precaution against the combination being forgotten)—Johnson is entirely above suspicion. Still, to make doubly sure, I am going to alter the combination once more, and share it with someone outside of the business department. And as you have impressed me very favorably, I have chosen you.

“That is, of course,” concluded the manager, “if you have no objection.”

“Certainly not. I am sure I appreciate the confidence, sir,” said Jack quickly.

“Very well, then. The combination is ‘Right twenty, twice; back nine; right ten.’ Can you remember that? For you must not write it down, you know.”

Jack repeated the number several times; and again thanking the manager for the compliment, continued up-stairs to the telegraph-room.

Two mornings later Jack was again called into Mr. Black’s office. For a moment, while Jack wondered, the manager eyed him strangely, then asked, “What was that combination, Jack?”

“Right ninety—no, right thirty—Why, I believe I have forgotten it, sir,” declared Jack in confusion.

“Perhaps you have forgotten this too, then?” As he spoke the manager took from his desk a small notebook. “I found it on the floor in front of the safe this morning.”

“It is mine, sir. I must have dropped it last night. 70 I worked extra until after midnight, sir,” explained Jack, “and on the way out I chased a mouse in here from the stairway, and when it ran under the safe I dropped to my knees to find it. The book must have fallen from my pocket.

“But what is wrong, sir?”

“The cash-box is not in the safe this morning.”

Jack started back, the color fading from his cheeks as the significance of it all came to him.

“And now you pretend to have the combination entirely wrong,” went on the manager.

Jack found his voice. “Mr. Black, you are mistaken! You are mistaken! I never could do such a thing! Never!”

“I would prefer proof,” Mr. Black said coldly.

Jack caught at the idea. “Would you let me try to prove it, sir? Will you give me a week in which to try and clear myself?”

“Well, I did not mean it that way. But, all right—a week. And if things do not look different by that time, and you still claim ignorance, you will have to go. That is all there is to it.”

“Thank you, sir.”

At the door Jack turned back. “Mr. Black, you are positive you returned the box to the safe?”

“Positive. It is the last thing I do before going home.”

During spare moments on his wire that morning Jack debated the mystery from every side. Finally he had boiled it down to two conflicting facts: 71

“First: That the box was placed in the safe the night before, and in the morning was gone; and that, besides the manager, he was the only one who could have opened the safe and taken it. And,

“Second: That, of course, he knew his own innocence.”

The only alternative, then, was that Mr. Black had been mistaken in thinking he had returned the box to the safe.

Grasping at this possibility, Jack argued on. How could the manager have been mistaken? Overlooked the box, say because of its being covered by something?

“Why it may be there yet!” exclaimed Jack hopefully. And a few minutes later, relieved from his wire for lunch, he hurriedly descended again to the manager’s office.

“Mr. Black, may I look around here a bit?” he requested.

“Look around? What for?”

“To see if I cannot find something to help solve this mystery,” responded Jack, not wishing directly to suggest that the manager had overlooked the box.

“So you keep to it that you know nothing, eh? Well, go ahead,” said the manager shortly, turning back to his desk.

Jack’s hopes were quickly shattered. Neither on the desk, nor a table beside the safe, was there anything which could have concealed the missing box. 72

Stooping, he glanced under the table. Something white, a newspaper, leaning against the wall, caught his eye. With a flutter of hope he reached beneath and threw it aside. There was nothing behind it.

Disappointedly he caught the newspaper up and tossed it into the waste-basket. Suddenly, on a thought, he recovered the paper, and opened it. On discovering it was the “Bulletin,” a paper he knew Mr. Black seldom read, the idea took definite shape. And, yes, it was of yesterday’s date!

“Mr. Black,” exclaimed Jack, “this is not your paper, is it?”

Somewhat impatiently the manager glanced up. “The ‘Bulletin’? No.”

“Were you reading it yesterday, sir?”