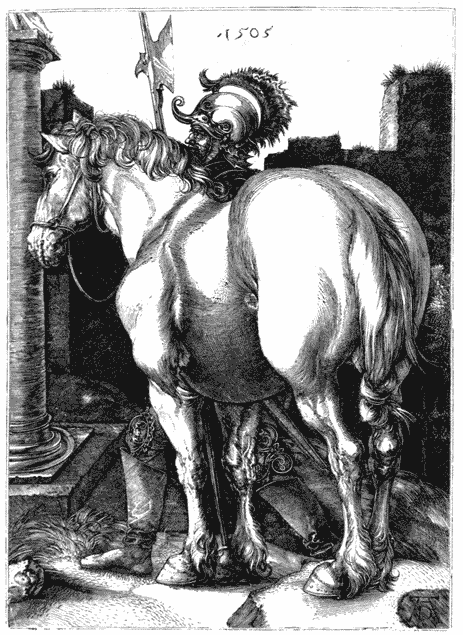

THE GREAT HORSE.

THE GREAT HORSE.From an Allegorical Engraving by Albert Dürer.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rambles of an Archaeologist Among Old Books

and in Old Places, by Frederick William Fairholt

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Rambles of an Archaeologist Among Old Books and in Old Places

Being Papers on Art, in Relation to Archaeology, Painting,

Art-Decoration, and Art-Manufacture

Author: Frederick William Fairholt

Release Date: August 28, 2008 [EBook #26449]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAMBLES OF AN ARCHAEOLOGIST ***

Produced by Julia Miller and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. A list of corrections is found at the end of the text. Inconsistencies in spelling and hyphenation have been maintained. A list of inconsistently spelled and hyphenated words is found at the end of the text.

Text printed in a black-letter typeface in the original has been rendered in bold in this text.

By FREDERICK WILLIAM FAIRHOLT, F.S.A.,

AUTHOR OF “DICTIONARY OF TERMS IN ART,” ETC.

Illustrated with Two Hundred and Fifty-nine Wood Engravings.

LONDON:

VIRTUE AND CO., 26, IVY LANE,

PATERNOSTER ROW.

1871.

The following Papers originally appeared in the Art-Journal, for which they were specially written. They are from the pen of that painstaking and accurate archæologist, the late F. W. Fairholt, F.S.A. The illustrations also were engraved from original sketches by the Author. It has been suggested that the results of so much labour and research should be still further utilised; and that the merit and value of these Essays entitle them to a more lasting form than is afforded by the pages of a magazine. The Editor confidently believes that the popular style in which these articles are written, and the fund of anecdote and curious information they contain, will render them acceptable to a large number of general readers.

A second series of Art-papers, by the same Author, is in the press, and will shortly be published, under the title of “Homes, Haunts, and Works of Rubens, Vandyke, Rembrandt, and Cuyp; and of the Dutch Genre-Painters.”

January, 1871.

RAMBLES OF AN ARCHÆOLOGIST AMONG OLD BOOKS AND IN OLD PLACES.

Ancient art—Mediæval art—The Renaissance—Heraldry—Enamelling—Mosaic—Glass-painting—Gothic metal work—Raffaelle ware—Wood panelling—Decorative furniture—Book illumination—Engraved book ornaments—Metal-workers—Ancient jewellery—Decorative art in the sixteenth century—The Renaissance style—Italian art—The Gothic 1-44

GROTESQUE DESIGN, AS EXHIBITED IN ORNAMENTAL AND INDUSTRIAL ART.

Origin of the term grotesque—Egyptian boxes and spoons—Roman knives and lamps—Mediæval grotesque—Misereres, bosses, and capitals—Domestic utensils—The Ars Memorandi—Decorative plate—The Italian, German, and French goldsmiths—Book illustrations—Grotesque pottery 45-70

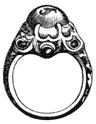

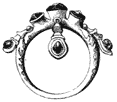

FACTS ABOUT FINGER-RINGS.

Antique rings:—Egyptian rings—Legend concerning the ring of Polycrates—Assyrian, Etruscan, and Greek rings—Roman rings— Inscriptions and devices—Key rings—Gaelic, Celtic, and Saxon rings. Mediæval rings:—Episcopal rings—Thumb rings—Religious rings—Charm rings—The crapaudine, or toad-stone—The “Kings of Cologne”—Mottoes, or “reasons”—“Tower” rings—Martin Luther’s wedding-ring. Modern rings:—Signet rings—Story connected with the ring of the Earl of Essex—Shakespere’s ring—“Gimmal” rings— Wedding-rings and their “poesies”—Poison rings—Modern versions of the Eastern tale of “The Fish and the Ring”—Memorial and relic rings—Death’s-head rings—“Giardinetti” rings—Indian and Moorish rings—“Harlequin-rings”—“Regard-rings”—“Fisherman’s ring” of the Pope 71-157

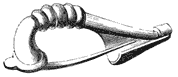

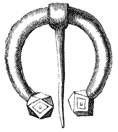

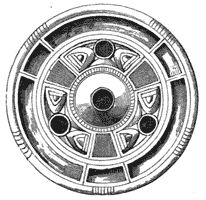

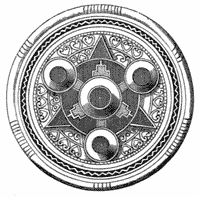

ANCIENT BROOCHES AND DRESS FASTENINGS.

Greek and Roman fibulæ—Roman enamelled brooches—Bow or harp-shaped fibulæ—Bust of the Emperor Constantine Pogonatus—Early grotesque brooches—Circular fibulæ—Anglo-Saxon pins—Irish and Scotch brooches and pins 159-183

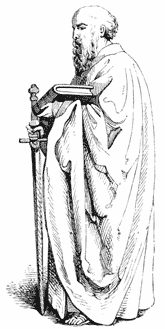

ALBERT DÜRER: HIS WORKS, HIS COMPATRIOTS, AND HIS TIMES.

Nürnberg—Birth of Dürer—His early youth—Michael Wohlgemuth—Dürer’s early works—He settles at Nürnberg—His house—Martin Kötzel—Nürnberg Castle—Dürer’s paintings, woodcuts, and engravings—Melchior Pfintzing—Pirkheimer—Peter Vischer—Shrine of St. Sebald—Adam Krafft—Veit Stoss—Hans Sachs, “the cobbler-bard”—Albert Kügler—Death of Dürer—The Cemetery of St. John, Nürnberg—Grave of Dürer 185-259

Long after the extinction of the practical art-power evolved from the master-minds of Greece and Rome, though rudely shattered by the northern tribes, it failed not to enforce from them an admission of its grandeur. Loving, as all rude nations do, so much of art as goes to the adornment of life, they also felt that there was a still higher aim in the enlarged spirit of classic invention. It is recorded that one of these ancient chieftains gazed thoughtfully in Rome upon the noble statuary of the fallen race, and declared it the work of men superior to any then remaining, and that all the creations of such lost power should be carefully preserved. The quaint imaginings of uncivilised art-workmanship bore the impress of a strong but ruder nature; elaboration took the place of elegance, magnificence that of grandeur. Slowly, as centuries evolved, the art-student came back to the purity of antique taste; but the process was a tardy one, each era preferring the impress of its own ideas: and though the grotesque contortions of mediæval statuary be occasionally modified by the influence of better art on the Gothic[4] mind, it was not till the revival of the study of classic literature, in the fifteenth century, that men began to inquire into the art of the past ages, and endeavoured to obtain somewhat of its sacred fire for the use of their own time. The study was rewarded, and the style popularly known as that of the Renaissance rapidly spread its influence over the world of art, sanctioned by the favour of such master-minds as Raphael, and the great men of his era.

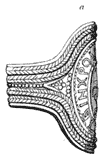

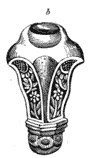

It was not, however, to be expected that any style should be resuscitated in all its purity without the admixture of some peculiarity emanating from the art which adopted it, and which was more completely the mode of the era. The Renaissance is, therefore, a Gothic classicality, engrafting classic form and freedom on the decorative quaintnesses of the middle ages. Fig. 1 is as pertinent a specimen as could be obtained of this characteristic: the Greek volute and the Roman foliage are made to combine with the hideous inventions of monkery, the grotesque heads that[5] are exhibited on the most sacred edifices, and which are simply the stone records of the strife and rivalry that prevailed between monks and friars up to the date of the Reformation, and are therefore of great value to the student of ecclesiology and ecclesiastical history. In this instance they seem to typify death and hell, over whom the Saviour was victorious by his mortal agony: the emblems of which occupy the central shield, and tell with much simple force the story of man’s redemption. Mediæval art has not unfrequently the merit of much condensation of thought, always particularly visible in its choice of types by which to express in a simple form a precise religious idea, at once appealing to the mind of the spectator, and bringing out a train of thought singularly diffuse when its slight origin is considered.

The easy applicability of the revived art to the taste for fanciful display which characterised the fifteenth century, led to its universal adoption in decoration; but the wilder imaginings of the living artist always tampered with the grand features of the design. The panel, Fig. 2, is an instance. The griffins have[6] lost their classic character, and have assumed the Gothic; the foliations are also subjected to the same process. The design is, however, on the whole, an excellent example of the mode in which the style appeared as a decoration in the houses of the nobility, whose love of heraldic display was indulged by the wood carver in panelled rooms rich with similar compartments.

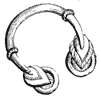

Heraldry, with all its adjuncts, had become so great a passion with the noble, that the invention of the artist and student was taxed for badges and mottoes by noble families. The custom flourished most in Italy, where the impresa of a noble house spoke to the eye at once, whether it was found on a sword-hilt or over a church-door. We give as an instance, in Fig. 3, that adopted by the bold Dukes of Burgundy, sovereigns in their own dominions, and exciting much terror of rivalry in the minds of the kings of France themselves. Their badge, or impresa, was indicative of their rude power; a couple of knotted clubs, saltier-wise, help to support a somewhat conventional figure of the steel used for striking the flint to produce fire; the whole surmounted by the[7] crown, and intended to indicate by analogous reflection the vigour of the ducal house. As a bold defiance, a rival house adopted the rabot, or carpenter’s plane, by which they indicated their determination to smooth by force the formidable knots from the clubs of the proud rulers of Burgundy.

Fig. 4. |

Fig. 5. |

The art of enamelling, which had reached a high degree of perfection in the Roman era, was refined upon in the middle ages, and ultimately its character was so much altered thereby that it ended in rivalling painting, rather than retaining its own particular features, as all arts should do. It may be fairly considered that originally it was used simply to enrich, by vitrified colour, articles of use and ornament. Metal was incised, and the ornamental spaces thus obtained filled with one tint of enamel colour, each compartment having its own. By this means very brilliant effects were often produced, all the more striking from the pure strength of their simplicity. It was not till the twelfth century that an attempt at floating colours together was made, and this led ultimately to a pictorial treatment of enamel which destroyed its truest character. The very old form was, however, practised in the latest days of its use; and our engraving of the very beautiful[8] knife-handle designed by Virgil Solis at the end of the sixteenth century (Figs. 4 and 5), was intended to be filled with a dark blue enamel, in the parts here represented in black, while the interstices of the cross-shaped ornaments above would receive some lighter tint of warmer hue. The birds and foliage would be carefully engraved, the lines of shadow filled with a permanent black, thus assuring a general brilliancy of effect. Such knives were by no means an uncommon decoration of the table at the period when this was designed: it is now a branch of art utilised until all trace of design has gone from it; for we cannot accept[9] the slight scroll work and contour of a modern silver knife-handle as a piece of art-workmanship, when we remember the beautiful objects of the kind produced in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, gorgeous in design and colour, and occasionally enriched by jewels or amber.

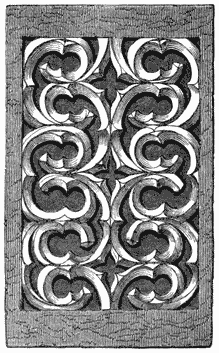

There is one class of ancient manufacturing art which has been revived for the use of the modern world with considerable success. We allude to the Roman works in mosaic, which have furnished designs for our encaustic tile-manufacturers and our floor-cloth painters. Quaint and peculiar in its necessary features, it is singularly well adapted for artisans in both materials. There is also a great variety in the ornamental details of ancient pavements, at home and abroad; the geometric forms being at times very peculiar, as in the specimen we give in the previous page (Fig. 6), which has been selected from one discovered at Aldborough, in Yorkshire (the Isurium Brigantum of the Romans), a lonely spot, containing many traces of its ancient importance, and which has furnished an abundance of relics for the notice of the antiquary from the days of Camden, who describes it with that happy brevity that accompanies full knowledge. The pavement we engrave may be seen in full coloured detail in Mr. Ecroyd Smith’s volume on[10] Isurium; the borders placed on each side are portions of other pavements from the same place, selected as showing the commonest and the most unusual patterns. The variety and beauty of design and colour in encaustic tiles adopted by mediævalists, may be slightly illustrated by the quaint specimen of foliation copied in Fig. 7. The conjunction of four such tiles produces great variety in pattern, and excellent contrasts of colour.

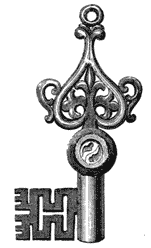

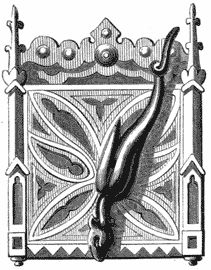

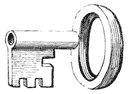

Geometric form, in all its endless variety, was particularly studied in the Middle Ages, and decorative enrichments of all kind subjected to its ruling control. We add two specimens of glass-painting (Figs. 8 and 9), which are in reality the same design slightly varied in the disposition of the tints, and the interlacing[11] of the double or strap-lines of one, while the other has them single only. The striking variety that any given design may elicit, by a mere rearrangement of this interlaced work, or by a different disposition of the coloured compartments, will at once be apparent; it was worked out with singularly good effect by the older artists in decoration of all kinds. The key (Fig. 10) and the latch (Fig. 11) are examples of quaint old Gothic metal works. The latter is copied from the old Hôtel de Ville of Bruges; the dragon is used as a lever to lift the latch, and is one of those grotesque imaginings in which the old art-workmen frequently indulged.

Fig. 10. |

Fig. 11. |

When the Dukes of Urbino, dazzled with the brilliancy of the Moorish potters, had determined to rival their workmanship in[12] manufactories upon their own principality, the so-called Raffaelle-ware soon afterwards fascinated the Italians, by the quaint design and beautiful colour of the dishes and vases there produced. Though popularly named after the great painter, it was unlikely that he had aught to do therewith; but his designs were occasionally adapted to its use by the workmen. The circular plateau (Fig. 12) is a good example of the bold character and vigour of effect occasionally produced in these works.

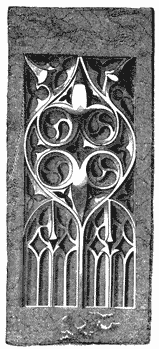

Wood panelling we have already alluded to, and the large amount of decoration it occasionally displayed. Fig. 13 is a beautiful instance of the grace that characterised the style known as the Flamboyant, from the flowing or flame-like curve adopted for the leading lines. In this instance they are happily blended with[13] the earlier Gothic cusps, and the quaint ivy-leaves that spring easily out of the severer lines. The ease with which heraldry may be introduced in the design, gave it a peculiar charm to our ancestors; in this instance the shields bear the sacred monograms—a purpose to which they were very commonly devoted in the church; sometimes being further enriched with religious emblems, as terse and striking as the heraldic ones we have given in a previous page.

Fig. 14. |

Fig. 15. |

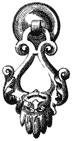

We give two small drawings of cabinet-handles in Figs. 14 and 15, part of the elaborate fittings of a piece of furniture which[14] occupied the place of honour in the state-rooms of the wealthy, and upon which the art of the day was generally lavished with a most liberal hand. Ivory, ebony, and the rarest woods were employed in their construction, occasionally plaques of lapis lazuli, or coloured marbles, were used for the panels; ultimately the whole surface became an encrusted mosaic of figures, birds, and flowers, in coloured wood and stone, occasionally framed in the precious metals. The gorgeous taste of Louis Quatorze excited the fancy of the ébenistes of his court to the most costly invention. Furniture inlaid with engraved metal-work, or embossed with coloured stones, oppressed the sense of utility; and when tables, chairs, and picture-frames were made of silver, chased and overloaded with the scroll-work he so abundantly patronised, common sense seems to have yielded its place to mere display. Despite of the costly character of such works, and their destination as the decoration of a palace, they are positive vulgarisms, and we feel little regret when we read in history of the disastrous wars at the close of the king’s career, which obliged him to melt down the silver furniture of Versailles, and convert it into cash for the payment of his soldiers.

There was more honesty of purpose in the old art-workers, who never swerved from a leading principle. Hence the educated eye can at once detect a piece of genuine old decorative furniture from a Wardour Street made-up bit of pseudo-imitation. It must[15] be borne in mind that specimens of genuine old work are by no means common; the abundance which this street and other localities can supply to order by the cart-load, are ingenious adaptations of fragments of old work pieced and placed together for a general effect; but which are sometimes ludicrous, from the mixture of bits of all ages and style in one cabinet or sideboard. Some twenty years ago the city of Rouen was a mine of wealth to furniture makers. The elaborately carved panels and chimney-pieces in the stately houses of the old Norman capital, were converted into all kinds of articles for domestic display. The progress of “improvement,” as well as the slower process of decay, have cleared that place of many of its fine features of domestic architecture; but its beauties have had an enduring memento in the curious volumes by the artist Langlois, of Pont-de-l’Arche, completed after his death by M. Delaquérrière. In this work every ancient building is carefully noted and described, throughout every street of the city; and the finest or most curious examples engraved with a minute truthfulness for which Langlois was justly celebrated; and which drew forth the plaudits of Dr. Dibdin, in the sumptuous work devoted to his foreign tour in search of rarities.15-*

We propose presently to follow the Doctor in his investigation of old books, and exhibit some few of the enrichments that artist and engraver gave to the written or printed volumes which passed[16] from their hands; at the same time we shall endeavour to take a more general survey of the adaptation of art to works of ordinary use.

The quaint manner in which letters were sometimes braced together may be seen in Fig. 16. Occasionally, a name thus formed in monogram would require much ingenuity to unravel, inasmuch as the entire letters made but one interlaced and closely compacted group, each limb or portion of a letter helping also to form part of another. In the hospital founded at Edinburgh by the famous goldsmith, George Heriot,—the favourite goldsmith and jeweller of James I., a monarch who fully appreciated his art,[17]—the name of “Jingling Geordie,” as his majesty playfully called him, is sculptured in such a group, which appears at first sight an enigma few could unravel; indeed, without knowing what letters to look for, and how to arrange them, it is a chance if they would be arranged correctly. Such a mode of marking would, however, have its advantages, for it would enable those who were in the secret to unravel the mystery of the true proprietorship of any valuable article unfairly abstracted. The shields in Fig. 13 are filled with monograms less elaborate, but bearing a sufficient affinity to those alluded to, to aid in understanding the rest.

We owe the term illumination, as applied to the decoration of old manuscripts, to the mediæval Latin name of the artist himself, alluminor, the root of our English word limner, and of the French word enlumineur, one who colours or paints upon paper or parchment, giving light and ornament to letters and figures. The brilliancy and beauty of much of this ancient art are marvellous to look upon, but the names of few of the patient artists, who devoted their lives to book illustration, have descended to us. There are, however, one or two names well-known to us, a Julio Clovio and a Girolamo da Libri (Jerome Veronese), affording a sufficient warrant of the high-class minds who honoured their art by honouring literature. There can be no greater pleasure than in turning over the matchless pages of these old volumes, and seeing them reveal the passages of the poet or romancist, as understood by the men of the Middle Ages, to whom they were addressed, or giving us pictures of life and manners of which we possess no other record. Their value as adjuncts to books, when simply decorative, is now very generally acknowledged; and the ladies of the present day rival the cloistered recluses in labouring, like them, to enrich a cherished volume. It is, however, the art of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that is now especially imitated, and the reason is to be found in its[19] showy elaboration of design and colour. There is an earlier style that presents strong claims to attention, that of the two preceding centuries, specimens of which are given in Figs. 17-21. In them will be noticed the Orientalism that occasionally prevails, and shows its Byzantine parentage; a trace of the Greek volute and acanthus leaf is visible in Figs. 20 and 21; in the others we seem to look on Turkish design. The applicability of such fragments of ornament is manifold.

Fig. 17. |

Fig. 18. |

Fig. 20. |

Fig. 19. |

Fig. 21. |

When the art of engraving aided the press in producing works [20]of a decorative order, we occasionally turn over pages in which the master-minds of the day taxed their powers of invention. The old wood-engravers were supplied by designers with drawings of the best class, and very quaint and original are the ornaments which embellish the books of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,—particularly such as were published in Germany, or at Lyons, the latter city being then most eminent for the taste and beauty of its illustrated volumes, the former for a bolder but quainter character of art. There are useful hints to be had in the pages of all, for such as would avail themselves of[21] minor book-ornament. To render our meaning more clear, we select a series of scrolls (Figs. 22-25) for inscriptions from German books, of the early part of the sixteenth century, and which might be readily and usefully adapted to modern exigencies, when dates or mottoes are required either by the painter or sculptor. Ornamental frameworks for inscriptions abound in old books, and are not unfrequently of striking design and peculiar elaboration; we give an example in Fig. 26, from a volume dated 1593, as an excellent specimen of this particular branch of design. Such[22] tablets not unfrequently headed the first page of a volume, and received in the centre the title of the book. The wood-engraver is thus the legitimate successor of the older illuminator.

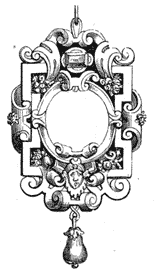

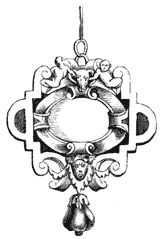

A large demand was made on the imaginative faculties of the designers of that day by the metal-workers, the gold and silversmiths, the jewellers, and all connected with such decorative manufactures as the luxury of wealth and taste calls into exertion. The name of Cellini stands prominently forth as the inventor and fabricator of much that was remarkable; the pages of his singular autobiography detail the peculiar beauty of many of his designs; the Viennese collection still boasts some of the finest of the works so described, particularly the golden salt-cellar he made for Francis I. of France. The high art which he brought to bear on design applied to jewellery was followed by other artist-workmen, such as Stephanus of Paris, and Jamnitzer of Nuremberg. The metal-workers of the latter city, and of Augsburg, had a universal reputation at the close of the sixteenth century for their jewellery and plate, particularly the latter. They kept in employ the best designers of the day, and such men as Hans Holbein, Albert Aldegræf, Virgilius Solis, and a host known as the “little masters,” supplied the demand with apparent abundance, but it could only be satisfied by the multiplication of these designs by means of the engraver’s art. Hence we have at this period, and the early part of the seventeenth century, an abundance of small engravings, comprising a vast variety of designs for all articles of ornament; and from them we have selected, in Figs. 27 and 28, two specimens of those intended to be used in the manufacture of the[23] pendent jewels, then so commonly worn on the breast of rich ladies. These jewels were sometimes elaborately modelled with scriptural and other scenes in their centre, chased in gold, enriched by enamel colours, and resplendent with jewels. The famed “Grüne Gewölbe” at Dresden have many fine examples, in the Louvre are others, and some few of a good kind are to be seen in the Museum at South Kensington. The portraits of the age of Francis I. and our Queen Elizabeth, frequently represent ladies in a superfluity of jewellery, of a most elaborate character. The portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots, in our National Portrait Gallery, is loaded with chains, brooches, and pendants, enough to stock the show-case of a modern manufacturer. This love of elaborate jewellery was a positive mania with many nobles in the olden[24] time. James I. was childishly fond of such trinkets, and most portraits represent the king with hat-bands of jewels, or sprays of jewellery at their sides. His letters to his favourite, Buckingham, are often full of details of the jewels in which his majesty delighted.

Fig. 27. |

Fig. 28. |

Perhaps no article of personal ornament has exhibited a greater variety of design and decorative enrichment than the cross. It has at once been made an embellishment and a badge of faith. We select in Fig. 29 one of singular elaboration and beauty, now the property of Lady Londesborough. It is a work[25] of the early part of the sixteenth century; the ground is of frosted gold, upon which is a foliated ornament in cloissonné enamel of various colours. It is also enriched with pearl and crystal; the lower part of this cross is furnished with a loop, from which a jewel of value might be suspended.

By way of curious contrast, as well as to show the style of various ages in the article of necklaces, we give, in Figs. 30 and 31, two examples of widely different eras. The upper one is that of a Roman lady, whose entire collection of jewellery was accidentally discovered at Lyons, in 1841, by some workmen who were excavating the southern side of the heights of Fourvières, on[26] the opposite side of the Seine. From an inscribed ring and some coins deposited in the jewel-box, the lady appears to have lived in the time of the Emperor Severus, and to have been the wife of one of the wealthy traders, who then, as now, were enriched by the traffic of the Rhone. The necklace we engrave is of gold, set with pearls and emeralds; the cubical beads are cut in lapis lazuli, as are the pendants which hang from others. This love of pendent ornament was common to all antique necklaces, from the days of ancient Greece to the end of the sixteenth century. Our second specimen is an illustration of this: it is copied from the portrait of a lady (bearing date 1593), and composed of a series of enamelled plaques, with jewels inserted, connected with each other by an ornamental chain.

We have already alluded to the constant demand on the inventive faculty of the art-workman for articles of all kinds in the olden times; nothing was thought unworthy his attention. We give a selection of articles of ordinary use which have received a considerable amount of decorative enrichment. The spur-rowels (Figs. 32 and 33), from the collection of M. Sauvageot, of Paris, are remarkable proofs of the faculty of invention possessed by the ancient armourers. So simple a thing as a spur-rowel, in[27] our days of utilitarianism, would seem to be incapable of variety, or at least unworthy to receive much attention. It was not so in past times, when workmen even delighted to adorn their own tools. We engrave an armourer’s hammer (Figs. 34 and 35), from the collection of Lord Londesborough, which has received an amount of enrichment of a very varied character. The animals on one side, and in foliated scrolls, connect the design across the summit of the implement with a totally new composition on the opposite side. We would not insist on any part of the design as remarkable for[28] high character; it is simply given as an instance of the love of decoration so prevalent in the sixteenth century.

The highly-enriched knocker and door-handle (Fig. 36) were sketched from the original, on one of the ancient houses of the quaint city of Nuremberg. The bell-pull beside it (Fig. 37) is also from the same locality. There is probably no town in Germany where more artistic old iron-work is to be seen than in this place,—once the richest of trading communities, when Albert Durer flourished within its walls, and the Emperor Maximilian held royal state in its old castle. To all who would realise the chivalric days of the old German Empire, we would say, “Go to Nuremberg.”

The bellows of carved chestnut-wood (Fig. 39) is in the possession of the Count de Courval. It is of simpler and “severer” design than common,[29] inasmuch as it was usual to enrich these useful domestic implements with an abundance of elaborate designs, and fill their centres with scenes from sacred and profane history.

When ladies delighted in lace-working, and in starching and preparing their produce most carefully, they showed their good housewifery in washing and ironing it with their own hands. It was gallantry on the part of their spouses to make befitting presents of all things requisite for their labours, and worthy their use. The box-iron we engrave in Fig. 39 is one which has thus been given; it bears the monogram of the fair lady who originally owned it, engraved within a “true lover’s knot.” The cupidons of the handle ending in flowers may be an emblem of Love and Hymen, forming an appropriate embellishment.

Applicability is the most useful characteristic of the style popularly known as the Renaissance; it is confined to no one branch of art, but is capable of extension to all, from the most delicate work of the jeweller to the boldest scroll-ornament adopted by the sculptor in wood or stone. The Loggie of the Vatican is the best original example of the style as perfected by Raffaelle and his scholars, and applied to wall-painting. It was a free rendering of the antique fresco ornament then just discovered in the Baths of Petus, where extensive excavations were undertaken in 1506, under the superintendence of the Papal authorities. The classic forms were “severer” than those in use by the artists who resuscitated the style, and were somewhat overlaid with ornament. The details of Raffaelle’s own work will not always bear adverse criticism, inasmuch as there are heterogeneous features introduced occasionally, which are not visible in the purer style of antiquity. As the fashion for this decoration travelled northward, it increased in freedom from classic rule, and more completely deserved the term “grotesque,” which it occasionally received, a term derived from grotte, an underground room of the ancient baths, and which we now use chiefly in the sense of a ludicrous composition. Such compositions were not unfrequent on the walls of Greek and Roman buildings; and the[31] German and Flemish artists, with a nationally characteristic love of whimsical design, occasionally ran riot in invention, having no rule beyond individual caprice. This unfortunate position offering too great a licence to mere whimsicality, was felt in ancient as well as in modern times. Pliny objected, on the grounds of false or incongruous taste, to the arabesques of Pompeii, though they approached nearer to the Greek model; and Vitruvius, with that purity of taste which was his grand characteristic, endorsed the opinion, and enforced it in his teaching. We are often in error when we blindly admire, or unhesitatingly adopt, the works of the ancients as perfection. In Athens and Rome in past time, as in Paris and London at present, we may meet with instances of bad taste; for vulgarity belongs to no age or station, and may be visible in the costly decoration of a rich mansion, whose owner is uneducated in art, and insists on having only what he comprehends.

The decadence of the better-class Renaissance design was a natural consequence of the licence its features might assume, and in the progress of the sixteenth century it became thoroughly vitiated. The troubles which distracted Europe in the later part of that century, and which led to the devastating wars and revolutions of the earlier part of the following one, completed the debasement of art-workmanship. Louis XIV. had the glory, such as it was, of its resuscitation; but his taste was merely that of an over-wealthy display, which not unfrequently lapses into positive vulgarisms. The style known distinctively by the name of this monarch—with all its heterogeneous elements, its scrolls[32] of the most obtrusive form, fixed to ornament having no proper cohesion, and overlaid with festoons of flowers and fruit—is more remarkable for the oppressive ostentation which was the characteristic of the monarch and his age, than for good taste or real elegance. What a very little exaggeration could make of this style may be seen in the productions of the era of his successor, and which the Italians stigmatised by the term rococo.

Fig. 40. |

Fig. 41. |

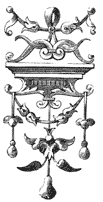

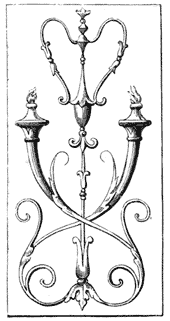

The examples of Renaissance given in our pages exhibit a fair average of its applicability. The pendent ornament (Fig. 40) includes details adopted by jewellers. The shield, with the sacred monogram (Fig. 41), is such as appeared in wood-panelling. The handle (Fig. 42) exhibits as much freedom of design as the style could admit; it is quaint and peculiar, but not without elegance in the mode of bringing the classic dolphin within the scope of the composition.

The distinctive features of the style may be more readily com[33]prehended by contrasting it with a few specimens of the so-called “Gothic style,” a style which possesses the strongest original features, and one which will yield to none in peculiar beauty and applicability. We give two examples—the one German, the other French; they are both wood panel, filled with tracery which bears the distinctive characteristics of the two schools. The German (Fig. 43) is remarkable for the sudden termination of its flowing lines, which occasionally gives to the carving of the epoch an appearance of having been suddenly broken, or chopped off, in parts. At Nuremberg this peculiarity is very observable; our specimen is selected from the church at Rottweil, in the Black Forest, which bears the date of 1340. The French (Fig. 44) is a favourable example of the Flamboyant style, which gave freedom to the mediæval rigidity of the Gothic, and paved the way for the ready adoption of the style of Francis I., which was based on that of the Italians.

Fig. 43. |

Fig. 44. |

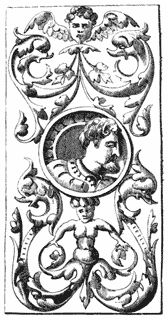

Figs. 45 and 47 display one peculiarity in this northern adaptation—the introduction of busts, in high relief, in central medallions. It is sometimes introduced so unscrupulously in the carved panelling of Elizabethan mansions, that it has almost the effect of a row of wooden dolls peeping through shutters. The latter of the two examples may be received as one of the best of its kind, exhibiting the utmost enrichment of which the style was generally capable, and as few heterogeneous features, though here they are not entirely absent. By way of useful contrast, we give in Fig. 48,[35] a very pure specimen of a panel in Italian workmanship, from a tomb of the sixteenth century, in the church of the Ara Cœli, at Rome. The flow of line here is exceedingly graceful; the whole of the details are characterised by a delicacy unknown to the artists of Germany and Flanders; the torches and volutes point unmistakably to the classic origin of the whole.

Fig. 45. |

Fig. 46. |

Fig. 47. |

Fig. 48. |

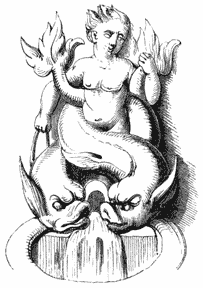

It was not natural to the Roman people ever to forget their great art-works of antiquity; the influence of the “departed spirits” still “ruled them from their urns,” as Byron truthfully expresses it. The artists of Greece and Rome based their compositions on the unvarying truth of nature; and though the barbaric mind might bear sway for awhile, it could not triumph but through ignorance. Rome is now the great art-teacher only because it is the conservator of its ancient relics; and they have had their influence undiminished from the days of Raffaelle and[36] Michael Angelo. There are many pleasing bits of design in the antique city, that show the classic source of inspiration from which their inventors obtained them. The boy and dolphins, forming the pleasing domestic fountain we engrave in Fig. 51, is an evident instance of the influence of antique taste. The abundant supply of water was the grand feature of the Rome of the Cæsars, as it still is of the Rome of the Popes; and the liberality with which every house is served has frequently induced the owners of large mansions to decorate one corner of their external walls with a fountain, at which all wayfarers may be supplied. In a[37] recess of the lowermost story of one of the great palazzi which line the principal street of Rome, “the Corso,” our second specimen (Fig. 52) is placed. It represents a wine-merchant liberally pouring from the bung-hole of his barrel its inexhaustible contents. On great festas in the olden time it was not unusual to make public fountains run with wine for an hour or two, and this may have occurred with the one engraved; it is a work of the latter part of the sixteenth century, when luxury reigned in Rome. As a design it is exceedingly simple and appropriate, reminding, by its quaintness, of German rather than Italian[38] design. The old Teutonic cities present very many striking inventions of the kind: and the promoters and designers of our drinking fountains may obtain good and useful hints from that quarter.

Fig. 51. |

Fig. 52. |

Our street architecture has shown recently a greater freedom of design, and range of study, than was ever exhibited before. We may owe this, in some degree, to the excellent works on the domestic and palatial edifices of the Low Countries, which have issued from the press, and have vindicated the true character of the great mediæval builders. Germany—taking the term for the nation in its widest sense—can show in its antique cities a vast variety of fancy in architecture and its ornamental details. Each[39] city may be made a profitable residence for the study of a young architect; and the superior knowledge of the leading principles of mediæval art, now exhibited in their adaptation of the style to home events, is a clear proof that the fact has been felt and acted on. The “infinite variety” of the old decorator is everywhere apparent, and the play he gave to his invention. We give in Fig. 53, as one instance, the ornamental mouldings of the Chapel of St. Nicholas, in the Cathedral of Aix; in this instance the rigidity of the rule which enforces geometric form to the whole is softened by the introduction of the cable moulding to a portion thereof, with singularly good effect. It is a work executed under the rule of Armand de Hesse, Archbishop of Cologne, and Provost of Aix, probably about 1480.

The Gothic, therefore, of the best era, was by no means the[40] stiff and monotonous style imagined by those who only know its details by the remains of our own ecclesiastical buildings; not that we infer them to be without much freedom and beauty occasionally, as in the Percy shrine at Beverley Minster, or the tomb of Aylmer de Valence, in Westminster Abbey. But we have fewer domestic buildings of a florid Gothic style than are to be found abroad, and the artists who designed for that style delighted in new ideas. It is even visible in the works of their painters and engravers: thus the tracery over the doorway in Durer’s print of[41] “The Crucifixion,” one of his series of the life of the Virgin, while it conforms to the leading principle of architectural design, is composed of branches and leaves which flow with a freedom belonging more to the painter than the architect. Similar instances abound in old pictures.

The foliation of German work was generally crisp and full of convolutions in its minor features, though the leading lines were boldly conceived. We give an example from a panel carved in wood, in the Cathedral of Stuttgard, a work of the middle of the fifteenth century. It is almost a return to the old acanthus leaf, and so completes a cycle of fine art.

Brief as the review has necessarily been of the decorative arts adorning life throughout the centuries which have passed in rapid succession before us, they have taught two great facts—the beauty of art as an adjunct to the most ordinary demands of domesticity, and the value of the study of the varied arts of past ages as an addition to the requirements of our own. “Ever changing, ever new,” may be the lesson derived from the investigation of any epoch. How much then may be obtained from a general review of all! Seroux d’Agincourt deduced a history of art from its monuments;41-* and men of the present day have the advantage of all that the world has produced brought easily, by aid of the burin and the printing-press, to their own firesides. We are evidently less original in idea than our ancestors, from the association of their labours with our thought; but we may yet live in the hope of[42] seeing some new and peculiar feature in the progress of modern decorative art obtained by retrospective glances at the past.

It is to the duty of thus learning from the past, we desire to direct the attention of our readers. Slavishly to copy, or systematically to imitate, are evils scarcely less reprehensible than to neglect them altogether; but frequent study of the great masters in any art is indispensable to those who would excel. It is to the absence of such study that we may trace most of the defects of the British artisan. Unhappily, he seldom either examines, reads, or thinks; generally he is content to work, like a horse in a mill, pursuing the same monotonous round, producing only that which has been produced before, without alteration, and without improvement. Until within the last few years, this defect could hardly have been urged against him as an offence. His employers did not require advancement, seldom encouraged intelligent workmen, and rather preferred the mere machine who was content to do no more than his fathers had done, and who looked upon new inventions as costly whims or expensive absurdities. There were exceptions—glorious exceptions; but the rule was, undoubtedly, as we have stated.

This deplorable disadvantage exists no longer; in nearly every town in the kingdom, of any size, there is some institution where knowledge may be obtained readily and cheaply. The societies in connection with the Department of Science and Art now abound with competent masters and teachers, and all the appliances of instruction.

The South Kensington Museum is alone a mine of wealth.[43] Not only are the artisans enabled to resort to it freely, but every possible inducement is held out to them to do so; the superintendents there almost go into the highways to “compel them to come in.” There is no calling of any sort or kind that may not be educated here; the masters, as well as the workmen, of all trades may here receive the education, “free of charge,” which no sum of money could have procured for them twenty years ago. Ignorance, nowadays, is, therefore, totally without excuse.

No doubt the seed that has been so extensively and abundantly planted is growing rapidly up; in some places it has borne fruit. It is utterly impossible that the existing race of art-workmen, and their successors “rising up,” can be ignorant as were their predecessors. If they use their eyes merely, and permit their minds to remain blanks, they must improve. There is no street in London now that will not teach them something; every shop window contains a lesson; and it requires no very large observation to perceive advancement in every class of British art-manufacture—not, certainly, so marked as to produce content, but exhibiting ample proof that we are progressing in the right direction, and leading to the conclusion that at no very distant period we shall not have to incur the reproach that our artisans are worse educated than those of Germany, Belgium, and France. These remarks result from the brief insight we have given in these pages into the rich volumes which the past has filled for the use of the present. The books to which we have resorted, and the places in which we have sought for rarities, are open to most of those who desire to examine them, and who will find an expendi[44]ture of time and labour to any amount, be it large or small, produce an extent of remuneration of which the searcher will have no idea until he begins to gather in the profit he has made.

We had intended to supply a list of books, to be obtained either at the British Museum or the Museum at South Kensington, to which we desire to direct the attention of our art-producers and art-workmen; but thus to occupy space is needless. The requisite information can be easily procured: any of the superintendents, at either place, will gladly direct the searcher, on receiving information as to his wants. Moreover, it is permitted, under certain restrictions, to take sketches of engravings or drawings, and from objects exhibited; aids to do this readily present themselves.

Books, however, should be regarded only as auxiliaries; they will supply in abundance material for suggestion or adaptation; although, as we have already observed, “slavishly to copy, or systematically to imitate,” are evils to be avoided.

15-* “Biographical, Antiquarian, and Picturesque Tour in France and Germany.” London, 1821. 3 vols.

41-* “Histoire de l’Art par les Monumens, depuis sa Décadence au IVe. Siècle jusqu’à son Renouvellement au XVIe.”

Among the quaint terms in art to which definite meanings are attached, but which do not in themselves convey any such definite construction, we may class the term grotesque. The term grotesque was first applied as a generic appellation in the latter part of the fifteenth century, when the “grottoes,” or baths of ancient Rome, and the lowermost apartments of houses then exhumed, exhibited whimsically designed wall-decorations, which attracted the attention of Raffaelle and other artists, who resuscitated and modified the style; adopting it for the famous Loggie of the Vatican and for garden pavilions or grottoes.

We may safely go back to the earliest era in art for the origin of the style, if, indeed, the grotesque does not so intimately connect itself with the primeval art of all countries as to be almost inseparable. Indeed, it requires a considerable amount of classical education to see seriously the meaning, that ancient artists desired in all gravity to express, in works which now excite a smile by their inherent comicality. Hence the antiquary[48] may be occasionally ruffled by the remarks of some irreverent spectator, on a work which the former gravely contemplates, because he feels the design of its maker, and is familiar with the antique mode of expression. Thus the early Greek figures of Minerva, whether statues or upon coins, have occasionally an irresistibly ludicrous expression: but, as art improved, this expression softened, and ultimately disappeared, the grotesque element taking a more positive form and walk of its own.

In that cradle of art and science, the ancient land of Egypt, we shall find grotesque art flourishing in various forms. Their artists did not scruple to decorate the walls of tombs with pictures of real life, in which comic satire often peeps forth amid the gravest surroundings. Thus we find representations of persons at a social gathering evidently the worse for wine-drinking; or the solemn procession of the funeral boats interrupted by a ludicrous delineation of the “fouling” or upsetting one unlucky boat and its crew, which had drifted in the way; while the most impressive of all scenes, the final judgment of the soul before Osiris, is depicted at Thebes with the grotesque termination of the forced return of a wicked soul to earth, under the form of a pig, in a boat rowed by a couple of monkeys. In the British Museum is a singular papyrus, upon which are drawn figures of animals performing the actions of mankind; and among the large number of antiquities which swell the Egyptian galleries, there are many that exhibit the partiality of this ancient people for the grotesque.

Our first examples consist of a group of wooden boxes and spoons, all of whimsical form, and selected from the[49] great work by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson on the manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians.49-* They were formed to contain cosmetics of divers kinds, and served to deck the dressing-table, or a lady’s boudoir. They are carved in various ways, and loaded with ornamental devices in relief, sometimes representing the favourite lotus-flower, with its buds and stalks, or a goose, gazelle, fox, or other animal. Fig. 55 is a small box, made in the form of a goose; and Fig. 56, also in the shape of the same bird, dressed for the cook. The spoon which[50] succeeds this, Fig. 57, takes the form of the cartouche, or oval, in which royal names were inscribed, and is held forth by a female figure of graceful proportions. Fig. 58 is a still more grotesque combination; a hand holds forth a shell, the arm being elongated and attenuated according to the exigencies of the design, and terminating in the head of a goose. The abundance of quaint fancy that may be lavished on so simple a thing as a spoon cannot be better illustrated than it has been by an American author, who published, in New York, in 1845, an illustrated octavo volume on the history of “The Spoon: Primitive, Egyptian, Roman, Mediæval, and Modern.” Speaking of these antique Egyptian specimens, he says,—“In these forms we have the turns of thought of old artists; nay, casts of the very thoughts themselves. We fancy we can almost see a Theban spoonmaker’s face brighten up as the image of a new pattern crossed his mind; behold him sketch it on papyrus, and watch every movement of his chisel or graver as he gradually embodied the thought, and published it in one of the forms portrayed on these pages—securing an accession of customers and a corresponding reward in an increase of profit. We take it for granted that piratical artisans were not permitted to pounce on every popular invention which the wit of another brought forth. Had there been no checks to unprincipled usurpers of other men’s productions, the energies of inventors would have been paralysed, and the arts could hardly have attained the perfection they did among some of that famous people of old.”

The graceful head and neck of the swan formed for many[51] centuries the favourite termination for the handles of simpula, or ladles. The Greeks and Romans adopted it, as they freely did grotesque art in general; and the walls of Pompeii and Herculaneum exhibit it in untrammelled style; while many articles of ornament and use were constructed in the most whimsical taste. We must restrict ourselves to three specimens of Roman works, as many hundreds might be readily brought together from public museums. Our group consists of two clasp-knives and a lamp. The knife, Fig. 59, was found at Arles, in the south of France; the handle is of bone, and has been rudely fashioned into the human form: the second example, Fig. 60, is of bronze, and represents a[52] canis venati, of the greyhound species, catching a hare; the design is perforated, so that the steel blade shows through it. It was found within the bounds of the Roman station of Reculver, in Kent; another of similar design was found at Hadstock, in Essex: nor are these solitary examples of what appears to have been a popular design in Britain. The superiority of the British hunting dogs has been celebrated by Roman writers, and induced their frequent exportation to the capital of the world. The lamp, with the quaint head of an ivy-wreathed satyr, Fig. 61, was found in the bed of the Thames, while removing the foundations of old London Bridge. The protruding mouth of this very grotesque design holds forth the lighted wick. In nothing more than in lamps did the quaint imaginings of the Roman artists take the wildest license.

When the successful incursions of northern barbarism had quenched the light of classic art, the struggle made by such artists as the Goths had at command to embody the ideas of power or grace they wished to indicate, were often as absurd as the work of a modern child. Hence the grotesque is an inseparable ingredient in their designs, often quite accidental, and frequently in express contradiction to the intention of the designer, who imagined in all seriousness many scenes that now only excite a smile. A strong sense of the ludicrous was, however, felt by mediæval men, and embodied in the art-works they have left for our contemplation. With it was combined a relish for satire of a practical kind. A very good and amusing instance is given in Fig. 62, which is copied from a carved corner-post of an old house[53] in Lower Brook Street, Ipswich. It depicts the old popular legend of the Fox and Geese, the latter attracted toward Reynard by his apparent innocence and sanctity, as he reads a homily from a lectern, and meeting the reward of their foolish trustfulness, in the fattest of their number being carried off by the crafty fox. Both incidents are, as usual with these ancient designers, represented side by side on different angles of the post.

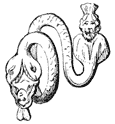

Our next engraving, Fig. 63, is a very striking specimen of grotesque design in ironwork of the fourteenth century. It is a door handle from a church in the High Street of Gloucester, and a more extraordinary admixture of incongruous details could[54] not very readily be imagined. The ring hangs from the neck of a monster with a human head having ass’s ears, the neck is snake-like, bat’s wings are upon the shoulders, the paws are those of a wolf. To the body is conjoined a grotesque head with lolling tongue, the head wrapped in a close hood. Grotesque design, for the reason already stated, frequently appears in the details of church architecture and furniture during the Middle Ages, particularly from the thirteenth to the seventeenth century. The capital of a column was the favourite place for the indulgence of the mason’s taste in caricature; the misereres, or folding scats of the choir, for that of the wood-carver. It is impossible to[55] conceive anything more droll than many of the scenes depicted on these ancient benches. Emblematic pictures of the months, secular games of all kinds, or illustrations of popular legends, frequently appeared; but as frequently satirical and grotesque scenes, often bordering on positive indelicacy; and occasionally satires on the clerical character, which can be only understood when we remember the strength of the odium theologicum, and how completely the well-established regular clergy disliked the wandering barefooted friars, who mixed with the people free of all clerical pretence, and induced unpleasant comparison with the ostentatious pride of the greater dignitaries. The Franciscans were in this way especially obnoxious, and between them and the well-established Benedictines an incessant feud existed. The tone of feeling that pervaded the middle and humbler classes[56] found a mouth-piece in that curious satire, the Vision of Piers Ploughman, than which Luther never spoke plainer.

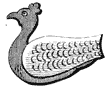

One very prevailing form in early Gothic design was that of the mythic dragon, whose winged body and convoluted tail were easily and happily adapted to mix with the foliage or other decorative enrichments these artists chose to adopt. Hence we find no creature more common in early art than this purely fanciful one, rendered still more fanciful by grotesque combination. The bosses from which spring the vaulted ribs of Wells Cathedral furnish us with the instance engraved in Fig. 64; here two dragons twine round a bunch of foliage, biting each other’s tails.

Domestic utensils were often made to represent living things; the tendency to convert a globular vase or jug into a huge head or a fat figure, has been common to all people in all ages. The[57] highly civilised Greeks indulged the whim, and our own potters continue it. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, vessels for liquids were often constructed of bronze, taking the form of lions, or mounted knights on horseback, of which specimens may be seen in our British Museum. The manufacturers of earthenware imitated these at a cheaper rate, and we engrave (Fig. 65) one example of their skill, the original being rudely coloured with a blue and yellow glaze on the surface of the brown clay which forms the body.

The door-knocker (Fig. 66), whimsically constructed in form of a human leg, the heel hitting against the door, is also a work of the fourteenth century; it is affixed to a house in the Rue des Conseils, at Auxerre, and is very characteristic in execution.

Our selection (Fig. 67) comprises a most rare domestic antiquity, to which a date cannot so readily be assigned, but which cannot be more modern than the sixteenth century, and may be older. It is a toasting-fork in the form of a dog, to whose breast a ring is attached for holding a plate. It is entirely constructed of wrought-iron, the body cut from a flat sheet of metal. It was found in clearing away the foundations of one of the oldest houses in Westminster. The tail of the dog forms a convenient handle; to the front foot a cross bar is appended to preserve its due equilibrium.

Grotesque design was adopted by the artists who decorated books from the very earliest time. The margins of ancient manuscripts are often enriched with whimsical compositions, as well as with flowing designs of much grace and beauty. Occasionally the two styles are very happily combined, and a humorous adjunct gives piquancy to a scholastic composition. The early printed books often adopted a similar style in art, and we give two curious specimens. The letter F, whimsically composed of two figures of minstrels (Fig. 68), one playing the trumpet and the other the tabor, is copied from an alphabet, entirely composed in this manner, and now preserved in the British Museum; it bears no date, but the late Mr. William Young Ottley, keeper of the prints there, was of opinion that it was executed about the middle of the fifteenth century. This quaint alphabet has been repeated by the artists of each succeeding generation, with variations to[59] adapt the letters to the costume or habit of each era; but in this unique series we seem to see the origin of them all.

One of the most singular books ever issued from the press, was published about the same period; it is known as the Ars Memorandi.59-* As its title imports, it was intended to assist the memory in retaining the contents of the Gospels in the New Testament. This is done by making the body of the design of the emblematic figure indicative of each, either the eagle, angel, ox, or lion; in combination with this figure are many small groups,[60] symbolic of the contents of the various chapters. The copy we give (Fig. 69), from the second print devoted to St. Luke’s Gospel, will make the plan of this singular picture-book clearer. The winged bull is spread out as a base to the group of minor emblems, upon its head rests a funeral bier, and in front of it a pot of ointment; the numeral 7 alludes to the chapter, the principal contents being thus called to memory. The bier alludes to the Saviour’s miraculous restoration to life of the widow’s son, whom He met carried out on a bier as He entered the city of Nain; the ointment pot alludes to the anointing of His feet by Mary Magdalene. The bag upon which the figure 8 is placed, indicates the fable of the[61] sower, it is the seed-bag of the husbandman; the boat alludes to the passage of the Lake when the Saviour quelled the storm. The singular group of emblems in the centre of the figure indicates—the power given to the disciples by the key; the Saviour in his transfiguration, by the sun; and the miraculous multiplication of the five loaves; as narrated in the 9th chapter of St. Luke. The following chapter has its chief contents noted by the scroll indicative of the law; the sword which wounded the traveller from Jerusalem whom the good Samaritan aided; and the figure of Mary commended by Jesus. No. 11 is typical of the casting out a devil whose back is depicted broken: and No. 12, of the teaching of that chapter in the Gospel; for here the heart is set upon a treasure-chest, an act we are especially taught to avoid.

These great treasure-chests were important pieces of furniture in ancient houses, and were generally placed at the foot of the master’s bed for the greater safety; in them were packed the chief valuables he possessed, particularly the household plate. At a time when banking was unknown, property was converted into plate, as a most convenient mode of retaining it. Decorative plate increased the public state of its owner, was a portable thing, and could be easily hidden in time of danger, or pledged in time of want. Hence the nobility and gentry of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries gave abundant employment to the goldsmith. Cellini, in his Memoirs, has noted many fine pieces of ornamental plate he was called upon to design and execute; and one of the finest still exists in the Kunst-Kammer, at Vienna—the golden salt-cellar he made for Francis I., of France. The “salt” was an[62] important piece of plate on all tables at this period, and to be placed above or below it, indicated the rank, or honour, done to any seated at the banquet. The large engraving (Fig. 70) delineates a very remarkable salt-cellar, being part of the collection of antique plate formed by the late Lord Londesborough. This curious example of the quaint designs of the old metal-workers, is considered to have been the work of one of the famous Augsburg goldsmiths at the latter part of the sixteenth century. It is a combination of metals, jewels, and rare shells in a singularly grotesque general design. The salt was placed in the large shell of the then rare pecten of the South Seas, which is edged with a silver-gilt rim chased in floriated ornament, and further enriched by garnets; to it is affixed the half-length figure of a lady, whose bosom is formed of the larger orange-coloured pecten, upon which a garnet is affixed to represent a brooch; a crystal forms the caul of the head-dress, another is placed below the waist. The large shell is supported by the tail of the whale on one side, and on the other by the serpent which twists around it; in this reptile’s head a turquoise is set, the eyes are formed of garnet, and the tongue of red onyx. The whole is of silver-gilt, and within the mouth is a small figure of Jonah, whose adventure is thus strangely mixed with the general design. The sea is quaintly indicated by the circular base, chased with figures of sea-monsters disporting in the waves. It would not be easy to select a more characteristic specimen of antique table-plate. The inventories of similar articles once possessed by the French king, Charles V., and his brother, the Duke of Anjou, King of Naples and Provence (preserved in the Royal Library,[63] Paris), give descriptive details of similar quaint pieces of art-manufacture, in which the most grotesque and heterogeneous[64] features are combined, and the work enriched by precious stones and enamels. Jules Labarte observes, “the artists of that period indulged in strange flights of fancy in designing plate for the table, they especially delighted in grotesque subjects: a ewer or a cup may often be seen in the shape of a man, animal, or flower, while a monstrous combination of several human figures serves to form the design of a vase.”

But quaint and fanciful as were the works of the Parisian goldsmiths, they were outdone by the grotesque designs of the German artificers. They invented drinking-cups of the strangest form, the whole animal kingdom, fabulous and real, birds, and sea-monsters, were constructed to hold liquids. A table laid out with an abundance of this strangely-designed plate, must have had a ludicrous effect. Many of their works, though costly in character, refined in execution, and thoroughly artistic in detail, are absolute caricatures. There is one in Lord Londesborough’s collection, and another in that of Baron Rothschild, made in the form of a bagpipe; the bag holds wine, and is supported on human feet; arms emerge from the sides and play on the chanter, which is elongated from the nose of a grotesque face, the hair a mass of foliage. Dozens of similar examples might be cited, of the most extraordinary invention, which the metal-workers of the seventeenth century particularly gave their imaginations licence to construct. Indeed, the German artists of that period seem to have had a spice of lunacy in their compositions, and the works of Breughel were rivalled and outdone by many others whose fancies were of most unearthly type. Salvator Rosa in Italy, and Callot in[65] France, occasionally depicted what their grotesque and mystic imaginings suggested, and Teniers gave the world witch-pictures; but for the wild and wondrous, Germany has always carried the palm from the rest of the world in art as in literature.

Fig. 71. |

Fig. 72. |

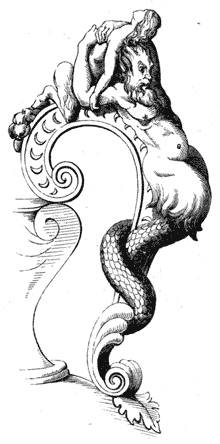

We engrave a fine example of a vase handle (Fig. 71), apparently the work of an Italian goldsmith at the early part of the seventeenth century. The bold freedom of the design is utilised here by the upheaved figure grasped by the monster, and which gives hold and strength to the handle; the flowing character[67] throughout the composition accords well with the general curve of the vase to which it is affixed. There is a prevailing elegance in the Italian grotesque design which is not seen in that of other nations. The knife handle by Francisco Salviati, which we have also selected for engraving (Fig. 72), is a favourable example of this feeling; nothing can be more outré than the figure of the monster which crowns the design; yet for the purpose of utility, as a firm hold to the handle, it is unobjectionable; while the graceful convolutions of the neck, and the flow of line in the figure, combined with this monster, give a certain quaint grace to the design, which is further relieved by enriched foliage.

With one specimen of the later work of the silversmith, we take our leave of grotesque design as applied to art-manufacture; but that work is as whimsical as any we have hitherto seen. It is a pair of silver sugar-tongs (Fig. 73), evidently a work of the conclusion of the seventeenth or beginning of the eighteenth century. It is composed of the figure of Harlequin, who upholds two coiled serpents, forming handles; the body moves on a central pivot, fastened at the girdle, and the right arm and left leg move with the front, as do the others with the back of the body, which is formed by a double plate of silver, the junctures being ingeniously hidden by the chequers of the dress.

We have already had occasion to allude to the adoption of grotesque design in book illustrations, it is often seen in manuscripts, and abounds in early printed works. When wood engraving was extensively applied to the enrichment of the books which issued in abundance from the presses of Germany and France, the[68] head and tail-pieces of chapters gave great scope to the fancies of the artists of Frankfort and Lyons. The latter city became remarkable for the production of elegantly illustrated volumes, which have never been surpassed. Our concluding cuts represent one of these tail-pieces (Fig. 74), in which a fanciful mask combines with scroll-work; and a head-piece (Fig. 75), (one half only being given), where the grotesque element pervades the entire composition to an unusual extent, without an offensive feature. Yet it would not be easy to bring together a greater variety of heterogeneous admixtures than it embraces. Fish, beasts, insects, and foliage, combine with the human form to complete its ensemble. The least natural of the group is the floriated fish, whose general form has evidently been based on that of the dolphin. When Hogarth ridiculed the taste for virtu, which the fashionable people of his own era carried to a childish extent, and displayed its follies[69] in his picture of “Taste in high life,” and in the furniture of his scenes of the “Marriage-à-la-mode,” he exhibited a somewhat similar absurdity in porcelain ornament. In the second scene of the “Marriage” is an amusing example of false combination, in which a fat Chinese is embowered in foliage, above whom floats in air a brace of fish, which emerge from the leaves, and seem to be diving at the lighted candles. Hogarth’s strong sense of the ludicrous was always pertinently displayed in such good-humoured satire.

The pottery manufacturers were always clever at the construction of grotesques. We have noted their past ability, and our readers may note their present talent in many London shops. The French fabricants furnish us with the most remarkable modern works, and very many of the smaller articles for the toilette, or[70] for children’s use, are designed with a strong feeling for the grotesque. Little figures of Chinese, rich in colour, twist about in quaint attitudes, to do duty as tray-holders or match-boxes. Lizards make good paper-weights, and wide-mouthed frogs are converted into small jugs with perfect ease. There is evidently a peculiar charm possessed by the grotesque, which appeals to, and is gladly accepted by, our volatile neighbours. We are ashamed to laugh at a child-like absurdity, and take it to our hearts with the thorough delight which they do not scruple to display. In this we more resemble the Germans, and, like them, we have a sombre element even in our amusements.

This subject, though entering so largely into the decorative designs of all countries and every age, has never been treated with any attention as a branch of fine art. It is by no means intended here to direct study to the reproduction of anything so false as the grotesque; but as it has existed, and does still exist, its presence cannot be ignored, and will be recognised constantly by all who study art.

49-* “History of Ancient Egyptians.”

59-* “Ars Memorandi notabilis per Figuras Evangelistarum,” etc.

Archæology, which was formerly considered by the majority of persons to be a dull and uninteresting study, abounding with dry details of small general interest, which, when not pompously pretentious, were, in the other extreme, of trifling insignificance, has, by a better acquaintance with its true position as the handmaid of history, become so popular that most English counties have societies especially devoted to its district claims, and our large cities have their archæological institutes also. This is due to the good sense which has divested the study of its drier details, or has had the tact to hide them beneath agreeable information. It is not too much to assert that archæology in all its branches may be made pleasurable, abounding as it does in curious and amusing details, sometimes humorously contrasting with our modern manners.

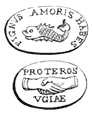

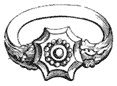

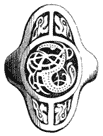

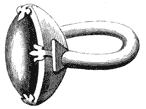

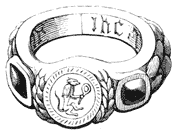

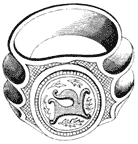

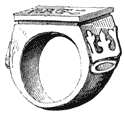

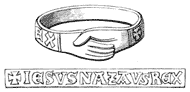

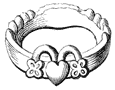

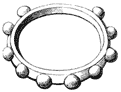

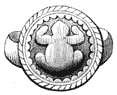

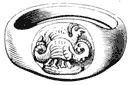

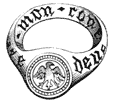

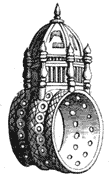

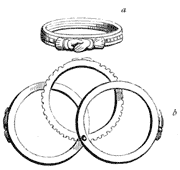

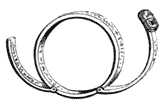

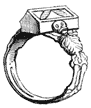

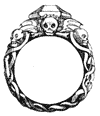

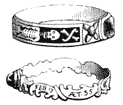

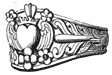

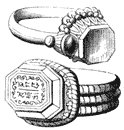

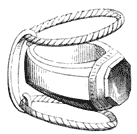

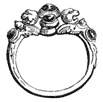

In taking up one of these branches—the history of finger-rings—we shall briefly show the large amount of anecdote and curious collateral information it abounds in. Our illustrations depict the great variety of design and ornamental detail embraced by so[74] simple a thing as a hoop for the finger. It would be easy to multiply the literary and the artistic branch of this subject until a volume of no small bulk resulted from the labour. Volumes have been devoted to the history of rings—Gorlæus among the older, and Edwards,74-* of New York, among the modern authors. The ancients had their Dactyliotheca, or collection of rings; but they were luxurious varieties of rings for wear. The modern collections are historic, illustrative of past tastes and manners. Of these the best have been formed by the late Lord Londesborough (whose collection was remarkable for its beauty and value), and Edmund Waterton, Esq., F.S.A., who still lives to possess the best chronological series of rings ever brought together. We have had the advantage of the fullest access to each collection.

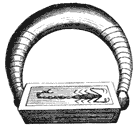

It is in the oldest of histories, the books of Moses, that we find the earliest records of the use of the finger-ring. It originally appears to have been a signet, used as we now use a written autograph; and it is not a little curious that the unchanged habit of Eastern life renders the custom as common now as it was three thousand years ago. When Tamar desired some certain token by which she should again recognise Judah, she made her first request for his signet, and when the time of recognition arrived, it was duly and undoubtingly acknowledged by all.74-† Fig. 76 exhibits the usual form assumed by these signets. It has a somewhat clumsy movable handle, attached to a cross-bar passing through a cube, engraved on each of its facets with symbolical[75] devices. Sir John Gardner Wilkinson75-* speaks of it as one of the largest and most valuable he has seen, containing twenty pounds’ worth of gold. “It consisted of a massive ring, half an inch in its largest diameter, bearing an oblong plinth, on which the devices were engraved, one inch long, six-tenths in its greatest and four-tenths in its smallest breadth. On one face was the name of a king, the successor of Amunoph III., who lived about B.C. 1400; on the other a lion, with the legend ‘lord of strength,’ referring to the monarch: on one side a scorpion, and on the other a crocodile.” Judah’s signet was, of course, formed of less valuable material, and had probably a single device only.

Fig. 76. |

Fig. 77. |

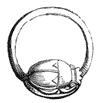

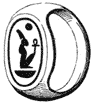

The lighter kind of hooped signet, as generally worn at a somewhat more recent era in Egypt, is shown in Fig. 77. The gold loop passes through a small figure of the sacred beetle, the flat under side being engraved with the device of a crab. It is cut in carnelian, and once formed part of the collection of Egyptian antiquities gathered by our consul at Cairo—Henry Salt, the friend[76] of Burckhardt and Belzoni, who first employed the latter in Egyptian researches, and to whom our national museum owes many of its chief Egyptian treasures.

From a passage in Jeremiah (xxii. 24) it appears to have been customary for the Jewish nation to wear the signet-ring on the right hand. The words of the Lord are uttered against Zedekiah—“though Coniah, the son of Jehoiakim, King of Judah, were the signet on my right hand, yet would I pluck thee thence.”

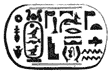

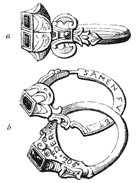

The transition from such signets to the solid finger-ring was natural and easy. The biblical record treats them as contemporaneous even at that early era. Thus the story of Judah and Tamar is immediately followed by that of Joseph, when we are told “Pharaoh took off the ring from his hand and put it upon Joseph’s hand,” when he invested him with authority as a ruler in Egypt. Dr. Abbott, of Cairo, obtained a most curious and valuable ring, inscribed with a royal name. It is now preserved, with his other Egyptian antiquities, at New York, and is thus described in his catalogue:—“This remarkable piece of antiquity is in the highest state of preservation, and was found at Ghizeh, in a tomb near that excavation of Colonel Vyse’s called ‘Campbell’s Tomb.’ It is of fine gold, and weighs nearly three sovereigns. The style of the hieroglyphics is in perfect accordance with those in the tombs about the Great Pyramid; and the hieroglyphics within the oval make the name of that Pharaoh (Cheops) of whom the pyramid was the tomb.” Fig. 78 represents this ring, and beside it (Fig. 79) is placed the hieroglyphic inscription upon the face of the ring, which is cut with the most minute accuracy and beauty.

Fig. 78. |

Fig. 79. |

Fig. 80. |

Fig. 81. |

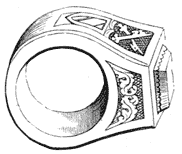

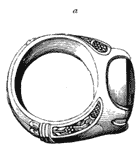

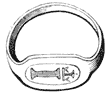

Rings of inferior metal, bearing royal names, were worn, probably, by officials of the king’s household. Henry Salt had one such in his collection, which was afterwards in the remarkable collection of rings formed by the late Lord Londesborough. It is represented in Fig. 80, and is entirely of bronze. The name of Amunoph III. is engraved on the oval face of the ring, exactly as it appears on the tablet of Abydus in the British Museum. Amunoph (who reigned, according to Wilkinson, B.C. 1403-1367) is the same monarch known to the Greeks as Memnon; and the colossal “head of Memnon,” placed in the British Museum through the agency of Mr. Salt, has a similar group of hieroglyphics sculptured on its shoulder. There was another kind of official ring, which we can recognise from the description of Pliny, and of which we give an engraving (Fig. 81) from the original in the[78] author’s possession. It is of bronze, and has engraved upon its face the figure of the scarabæus; such rings were worn by the Egyptian soldiers.

The lower classes, who could not afford rings of precious metals, but, like their modern descendants, coveted the adornment, purchased those made of ivory or porcelain. In the latter material they abounded, and are found in Egyptian sepulchres in large quantities; they are very neatly moulded, and the devices on their faces, whether depicting gods, emblems, or hieroglyphics, are generally well and clearly rendered.

This fondness for loading the fingers with an abundance of rings is well displayed on the crossed hands of a figure of a woman (Fig. 82) upon a mummy case in the British Museum. Here the thumbs as well as the fingers are encircled by them. The left hand is most loaded; upon the thumb is a signet with hieroglyphics on its surface; three rings on the forefinger; two on the second, one formed like a snail-shell; the same number[79] on the next, and one on the little finger. The right hand carries only a thumb-ring, and two upon the third finger. These hands are cut in wood, and the fingers are partially broken.

Wilkinson observes—“The left was considered the hand peculiarly privileged to bear these ornaments; and it is remarkable that its third finger was decorated with a greater number than any other, and was considered by them, as by us, par excellence, the ring-finger; though there is no evidence of its having been so honoured at the marriage ceremony.”