First serialized ending in circa 1861 in MacMillan's Magazine (mentioned by the author in his preface, and Chapter 28 contains the author's footnote indicating that at least part of this chapter was not written earlier than 1859)

First published in 3 volume book form 1861 by Cambridge, London (British Library)

2nd edition published 1861 by MacMillan & Co., Cambridge & London (British Library)

Published 1861 by Ticknor & Fields, Boston (Library of Congress)

May have been serialized by Ticknor & Fields in 1859 (parts offered on Amazon.com by an antique bookseller)

Published 1863 by Ticknor & Fields, Boston (Library of Congress)

Published 1865 by MacMillan & Co. (British Library)

Published 1870 by Harper Bros., New York (British Library)

Published 1871 by Harper Bros., New York (Library of Congress & British Library)

Published 1879 by unknown, New York (Library of Congress)

Published 1881 by MacMillan & Co., New York (Library of Congress)

French translation published 1881 in Paris with added name Girardin, Jules Marie Alfred who is possibly the translator(?) (British Library)

Published circa 1888-92 by John W. Lovell, New York (Ebook transcriber's scanned copy)

Published 1888 by Porter & Coates, Philadelphia (Ebook transcriber's proofreading copy)

Published 1889 by MacMillan, London & New York (Library of Congress)

Published 1890 by Lovell, Coryell & Co., New York (Library of Congress)

Published 1905 in two volumes with Tom Brown's School Days (British Library)

Published 1914 by T. Nelson & Sons (British Library)

Published 1920 by S.W. Partridge & Co., London (British Library)

Published 2004 as part of a five volume set entitled Victorian Novels of Oxbridge Life, Christopher Stray editor, Thoemmes, Bristol (British Library)

(Transcriber's Notes: Notice the author's name does not appear on the title page or on the cover, and in fact it is only given as T. Hughes at the end of his preface and nowhere else. Sydney Hall, 1842-1922, did portraits, newspaper and magazine illustrations, but oddly enough there are none to be found in the Lovell produced book, though the Porter & Coates edition has one unattributed woodcut)

Printed and Bound by Donohue & Henneberry, Chicago

(Transcriber's Note: Donahue & Henneberry were in business 1871-99 doing book binding and printing for the cheap book trade at various addresses in Chicago's business district known as the Loop, mostly on Dearborn Street.)

A Short Summary, With Some Explanations of Concepts Presented by Hughes, but Not Well Defined by Him, Being Apparently Well Understood in His Day, but With Which Modern Readers May be Unfamiliar.

This is the sequel to Hughes' more successful novel Tom Brown's School Days, which told about Tom at the Rugby School from the age of 11 to 16. Now Tom is at Oxford University for a three year program of study, in which he attends class lectures and does independent reading with a tutor. A student in residence at Oxford is said to be “up” or have “come up”, and one who leaves is said to have gone “down”.

The author weaves a picture of life at Oxford University in the 1840s, where he himself was at that time, at Oriel College, where he excelled in sports rather than academics. The University is made up of a number of separate colleges, and the students form friendships within and develop a loyalty to their own college. Tom's college, St. Ambrose, is fictional. The study programs available to the students are intended to prepare them for the legal, ecclesiastical, medical and educational professions. Students who do poorly might be expected to enter the diplomatic corps or the army or navy, though a son of the aristocracy might be thrust into a minor church role. To enter into business or manufacturing engineering or the research sciences would require an inheritance or family connection.

Latin was still taught because the best literature available to them was still the ancient Greek and Roman poets and philosophers, and the legal and medical professions still used it extensively, though the ecclesiastical and educational fields had largely abandoned it.

Tom finds that there is a social barrier between the wealthy students and the students that are there on the equivalent of a modern academic scholarship, or have to work as a graduate student tutor to earn their stipend. There were no sports scholarships at this time, though the author hints vaguely at one point that someday the idea could be explored.

There were no female students at this time. Tom becomes involved with a local barmaid. The barmaid being of a different social class than Tom, this relationship causes problems for both of them, and it is important for the modern reader to realize that such social distinctions were very real and inflexible in those days. The working class referred to the educated class as their “betters”, meaning better educated and entitled to better respect, regardless of whether it was earned or deserved.

There were no dormitories and self-serve cafeterias as with modern colleges, instead meals were served in a dining hall by scouts, and each student gets what are called “rooms”, consisting of a bedroom and a sitting room for study and entertaining. “Scouts” are a kind of servant attached to one student or a small number of students. They run errands, bring meals from the kitchen, and take care of clothing. A bootblack called the “boots” takes care of footwear. A charwoman called the “char” cleaned the rooms.

If a student wished to study without interruption, he would close the oak door to his rooms, which was called “sporting his oak”, the signal not to disturb.

The term “the eleven” refers to the cricket team, and “prize-men” refers to students who win prizes for scholarship. “Hunting Pinks” are red riding jackets, and “hunters” are horses especially suited to steeplechase or fox hunting type riding.

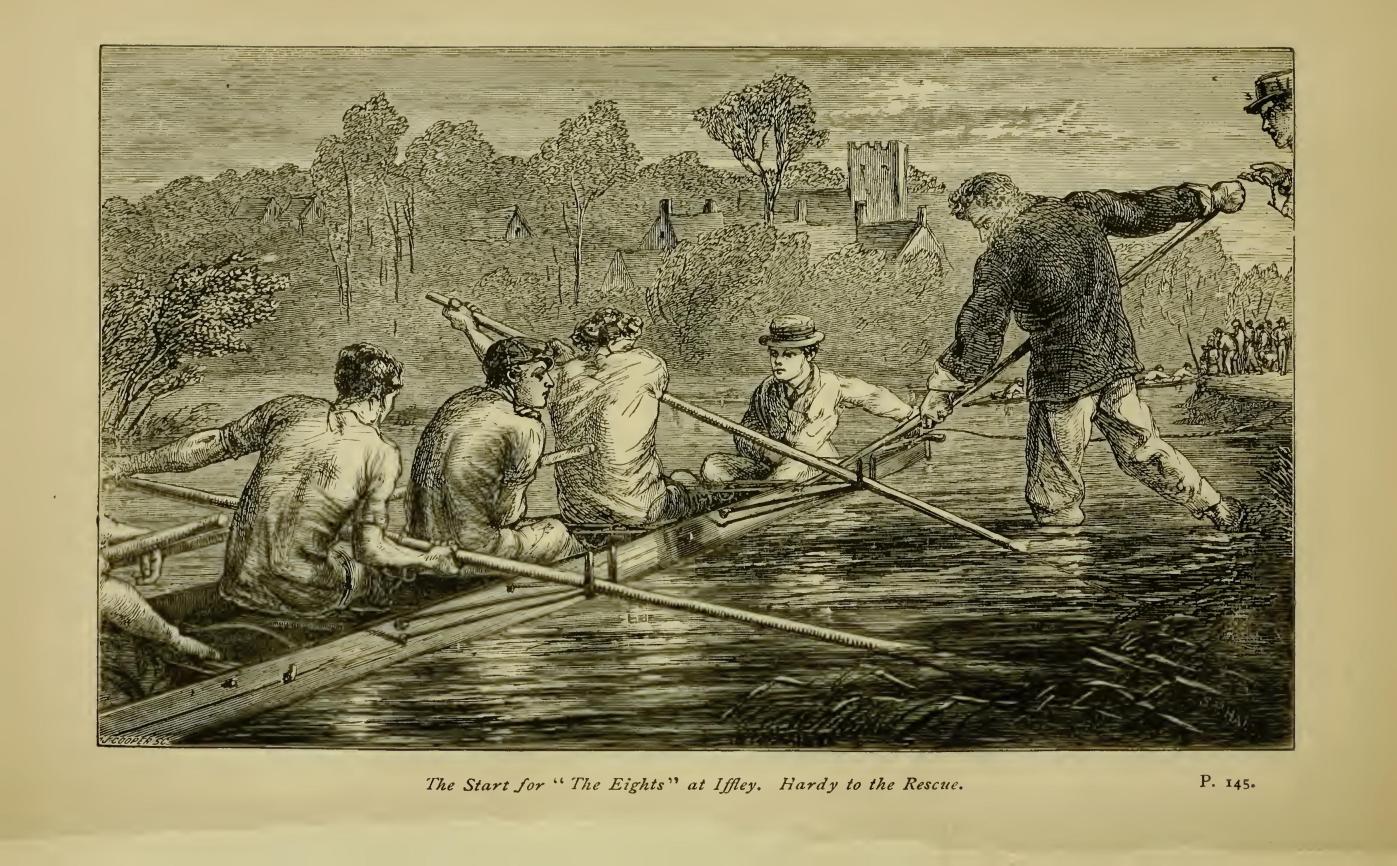

The Boating Club and Boat Racing is the popular sport of crew rowing or sculling, where each college appoints a crew of eight strong scull pullers or oarsmen and one small coxswain or steersman to pilot a long narrow boat called a skiff or shell. The coxswain calls the strokes and is generally the coach and commander of the crew. Unlike in a canoe, the pullers face backwards, and the one nearest the coxswain is called the “stroke oar”, because all the other oars watch him and match his stroke. The racing takes place on the river which runs through Oxford, and since because of the oars the river is too narrow for normal passing as in most other kinds of racing, the race is sometimes with just two boats, one ahead of the other. If the prow of the second boat touches the stern of the first boat, the second boat is considered the winner and advances in ranking. If the first boat rows the length of the course without being bumped, it is considered the winner and maintains its ranking. Sometimes the winning crewmen put their little coxswain in the boat and parade him through the streets of the town. At the end of the season the honor of “Head of the River” belongs to the boat that has not been defeated and is presumably the fastest, whereas the slowest boat, Tail End Charlie, has been defeated by all the other colleges. For another description of boating on the Thames in the nineteenth century, see the humorous travel-log “Three Men in a Boat, to Say Nothing of the Dog” by Jerome K. Jerome, written in 1889, which also mentions the dangers of the lasher at the Sandford Lock.

Students were required to wear the traditional student's gown and mortarboard cap to classes. Professors wore floppy caps and similar gowns with indications of their rank on the sleeves, Doctor, Master or Batchelor. This garb dates from the Middle Ages, but is now only seen at Graduation Day and special university occasions, and the gown has survived in some church choirs. A professor was also called a don, and graduate assistants were called fellows or servitors.

The “tufts” or students from the nobility or titled families were a privileged set, paid double fees and were not required to do much of anything academically. Gentlemen-commoners were from the untitled but wealthy families and also paid double fees. A few students from poorer social classes were accepted if they had good references. “Town and Gown” refers to the animosity between the local permanent residents of the town and the rowdy students, occasionally descending into actual fist fights. To be “gated” was to be confined to college and to be “rusticated” was to be suspended from college.

A “wine” is the nineteenth century equivalent of a student's beer and pizza party, though it seems to have been paid for entirely out of the pocket of the host. It is also a form of student networking, wherein they build relationships useful for their future business, professional or social life. German university students joined a Kadet Korps, which was somewhat like a combination of a modern day fraternity and Officer's Training Corps, but no such equivalent seems to have been at Oxford. Instead there was an academic set called the “reading men” which buckled down to the books, and a set of “fast men” who lived the dissipated high life of drinking, gambling, women and riding fast horses. The fast set, though they were gentleman commoners and not titled nobility, usually were from wealthy families, and often ran up large bills with the local tradesmen, called “going tick”, which could go unpaid for quite a long time.

In Chapter 14 the author mentions Big Ben, but this is not the clock tower bell in London, which at the time of writing had not yet been rung; instead this is Benjamin Caunt, the bare-knuckle boxer who defeated William Thompson in 75 rounds to become Heavyweight Champion of England in 1838. The bell may possibly have been named after him.

It should be remembered that at the time this story was written, the dangers of tobacco smoke were mostly unknown, and cigars, cheroots and pipes were quite commonly used, though the cigarette had not come into use yet. Tobacco, often called weed, was only discouraged during physical training, thus at one point in Chapter 15 Tom recommends smoking to Hardy for an almost therapeutic purpose.

In Chapter 17 the author imagines a flying machine, though at the time of writing only balloons had ever carried men aloft. He imagines it something like a carriage equipped to carry passengers, with the most comfortable carriage type C-springs, steam powered, and faster than the latest trains, which at that time went 40 miles per hour, the fastest speed that anyone had ever achieved.

The author mentions Tractarians and Germanizers. The Tractarians were a group of Oxford dons who, in the 1840s, wrote a series of tracts, aimed at proposing some changes to the theological system of the Anglican Church. Germanizers proposed some changes more along the lines of the Lutheran theology, and these controversies occupied the Anglican theologians of the time. The author did not expand on these subjects, nor even indicate his support or opposition to them, as it was not necessary for the story.

At this time, as in many other times, the evangelical Christians were in the forefront of movements to help poor and downtrodden people, but other elements were attempting to become involved, promoting their own methods and beliefs. Karl Marx was not known in England, and the Russian Revolution was still in the distant future, but a few radical left-wing idealists know as Chartists and Swings were beginning to be heard on campus, and Tom gets briefly involved with them, speaking up for the poor, but realizes their destructive ideas cannot be reconciled with proper Christian behavior, thus voicing some of the author's views on social reforms. The author later in life got involved with a communal living experiment.

Some words and expressions are used differently today than they were used in the nineteenth century. For example, when Tom says “There must always be some blackguards,” he means “Regrettably there will always be blackguards,” not “We ought to have some blackguards”. Katie and Tom discuss “profane” poetry, in the sense of being secular and not sacred or religious. Mary weighs “8 stone”, which is 112 pounds or 50 kilograms, and “famously” is used in the sense of being well done, not in the incorrect modern use of being well known. A “twelve-horse screw” is the propeller of a steam launch. To “give someone a character” is to speak or write about their moral character, either favorably or slanderously.

The book which I scanned using Optical Character Recognition was printed in the 1888-92 period by John W. Lovell of 150 Worth St. New York. Lovell has been described as a book pirate who tried to form a monopoly in the cheap uncopyrighted book trade. The US copyright laws were rather weak in the nineteenth century, and Charles Dickens was particularly hurt by pirates. There was even a book war, with rival publishers of the same book undercutting each other on price. Proof reading was done with another copy of the book published in 1888 by Porter & Coates of Philadelphia, which is in poorer condition with water damage, and would not scan well, but has fewer typesetting errors.

Nineteenth century punctuation made much more use of commas, hyphens and semicolons, and these have been retained as much as possible. British spellings of words such as colour, neighbour, odour, and flavour are retained, though in some cases the American publisher seems to have made his own corrections as he saw fit, and some words such as “connection” have retained the nineteenth century spelling “connexion”, but where a word was obviously spelled wrong by the typesetter, I have corrected it. The author used a few Greek words, which do not scan, and I have entered those manually using Symbol font for the rtf file, but substituted normal characters for the plain txt file and indicated [Greek text] where appropriate. The English pound symbol cannot be expressed in ASCII, so 25 pounds is rendered as 25L. Words printed in italics for emphasis are here rendered with underscores for the ASCII file.

Robert E. Reilly, PE, BSIE, BSME

Chicago, 2008

To the Rev. F. D. Maurice, in memory of fourteen years' fellow work, and in testimony of ever increasing affection and gratitude this volume is dedicated by

The Author.

Prefaces written to explain the objects and meaning of a book, or to make any appeal, ad miseracordiam or other, in its favor, are, in my opinion, nuisances. Any book worth reading will explain its own objects and meaning, and the more it is criticized and turned inside out, the better for it and its author. Of all books, too, it seems to me that novels require prefaces least—at any rate, on their first appearance. Notwithstanding which belief, I must ask readers for three minutes' patience before they make trial of this book.

The natural pleasure which I felt at the unlooked for popularity of the first part of the present story, was much lessened by the pertinacity with which many persons, acquaintance as well as strangers, would insist (both in public and in private) on identifying the hero and the author. On the appearance of the first few numbers of the present continuation in Macmillan's Magazine, the same thing occurred, and, in fact, reached such a pitch, as to lead me to make some changes to the story. Sensitiveness on such a point may seem folly, but if the readers had felt the sort of loathing and disgust which one feels at the notion of painting a favorable likeness of oneself in a work of fiction, they would not wonder at it. So, now that this book is finished and Tom Brown, so far as I am concerned, is done with for ever, I must take this, my first and last chance of saying, that he is not I, either as boy or man—in fact, not to beat about the bush, is a much braver, and nobler, and purer fellow than I ever was.

When I first resolved to write the book, I tried to realize to myself what the commonest type of English boy of the upper middle class was, so far as my experience went; and to that type I have throughout adhered, trying simply to give a good specimen of the genus. I certainly have placed him in the country, and scenes which I know best myself, for the simple reason, that I knew them better than any others, and therefore was less likely to blunder in writing about them.

As to the name, which has been, perhaps, the chief “cause of offense,” in this matter, the simple facts are, that I chose the name “Brown,” because it stood first in the trio of “Brown, Jones, and Robinson,” which had become a sort of synonym for the middle classes of Great Britain. It happens that my own name and that of Brown have no single letter in common. As to the Christian name of “Tom,” having chosen Brown, I could hardly help taking it as the prefix. The two names have gone together in England for two hundred years, and the joint name has not enjoyed much of a reputation for respectability. This suited me exactly. I wanted the commonest name I could get, and did not want any name which had the least heroic, or aristocratic, or even respectable savor about it. Therefore I had a natural leaning to the combination which I found ready to my hand. Moreover, I believed “Tom” to be a more specially English name than John, the only other as to which I felt the least doubt. Whether it be that Thomas a Beckett was for so long the favorite English saint, or from whatever other cause, it certainly seems to be the fact, that the name “Thomas,” is much commoner in England than in any other country. The words, “tom-fool,”

“tom-boy,” etc., though, perhaps not complimentary to the “Tom's” of England, certainly show how large a family they must have been. These reasons decided me to keep the Christian name which had been always associated with “Brown”; and I own that the fact that it happened to be my own, never occurred to me as an objection, till the mischief was done, past recall.

I have only, then, to say, that neither is the hero a portrait of myself, nor is there any other portrait in either of the books, except in the case of Dr. Arnold, where the true name is given. My deep feeling of gratitude to him, and reverence for his memory, emboldened me to risk the attempt at a portrait in his case, so far as the character was necessary for the work. With these remarks, I leave this volume in the hands of readers.

T. Hughes

Lincoln's Inn,

October, 1861

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I—ST. AMBROSE'S COLLEGE

CHAPTER III—A BREAKFAST AT DRYSDALE'S

CHAPTER IV—THE ST. AMBROSE BOAT CLUB: ITS MINISTERY AND THEIR BUDGET.

CHAPTER VI—HOW DRYSDALE AND BLAKE WENT FISHING

CHAPTER XI—MUSCULAR CHRISTIANITY

CHAPTER XII—THE CAPTAIN'S NOTIONS

CHAPTER XIV—A CHANGE IN THE CREW, AND WHAT CAME OF IT

CHAPTER XV—A STORM BREWS AND BREAKS

CHAPTER XVIII—ENGLEBOURNE VILLAGE

CHAPTER XIX—A PROMISE OF FAIRER WEATHER

CHAPTER XXI—CAPTAIN HARDY ENTERTAINED BY ST. AMBROSE.

CHAPTER XXII—DEPARTURES EXPECTED AND UNEXPECTED

CHAPTER XXIII—THE ENGLEBOURN CONSTABLE

CHAPTER XXVI—THE LONG WALK IN CHRISTCHURCH MEADOWS

CHAPTER XXVII—LECTURING A LIONESS

CHAPTER XXVIII—THE END OF THE FRESHMAN'S YEAR

CHAPTER XXIX—THE LONG VACATION LETTER-BAG.

CHAPTER XXX—AMUSEMENTS AT BARTON MANOR

CHAPTER XXXI—BEHIND THE SCENES

CHAPTER XXXIV—[Greek text] MEHDEN AGAN

CHAPTER XXXVII—THE NIGHT WATCH

CHAPTER XXXVIII—MARY IN MAYFAIR

CHAPTER XXXIX—WHAT CAME OF THE NIGHT WATCH

CHAPTER XLI—THE LIEUTENANT'S SENTIMENTS AND PROBLEMS

CHAPTER XLIII—AFTERNOON VISITORS

CHAPTER XLIV—THE INTERCEPTED LETTER-BAG

CHAPTER XLVI—FROM INDIA TO ENGLEBOURN

CHAPTER XLVIII—THE BEGINNING OF THE END

In the Michaelmas term after leaving school, Tom Brown received a summons from the authorities, and went up to matriculate at St. Ambrose's College, Oxford. He presented himself at the college one afternoon, and was examined by one of the tutors, who carried him, and several other youths in like predicament, up to the Senate House the next morning. Here they went through the usual forms of subscribing to the articles, and otherwise testifying their loyalty to the established order of things, without much thought perhaps, but in very good faith nevertheless. Having completed the ceremony, by paying his fees, our hero hurried back home, without making any stay in Oxford. He had often passed through it, so that the city had not the charm of novelty for him, and he was anxious to get home; where, as he had never spent an autumn away from school till now, for the first time in his life he was having his fill of hunting and shooting.

He had left school in June, and did not go up to reside at Oxford till the end of the following January. Seven good months; during a part of which he had indeed read for four hours or so a week with the curate of the parish, but the residue had been exclusively devoted to cricket and field sports. Now, admirable as these institutions are, and beneficial as is their influence on the youth of Britain, it is possible for a youngster to get too much of them. So it had fallen out with our hero. He was a better horseman and shot, but the total relaxation of all the healthy discipline of school, the regular hours and regular work to which he had been used for so many years, had certainly thrown him back in other ways. The whole man had not grown; so that we must not be surprised to find him quite as boyish, now that we fall in with him again, marching down to St. Ambrose's with a porter wheeling his luggage after him on a truck as when we left him at the end of his school career.

Tom was in truth beginning to feel that it was high time for him to be getting to regular work again of some sort. A landing place is a famous thing, but it is only enjoyable for a time by any mortal who deserves one at all. So it was with a feeling of unmixed pleasure that he turned in at the St. Ambrose gates, and inquired of the porter what rooms had been allotted to him within those venerable walls.

While the porter consulted his list, the great college sundial, over the lodge, which had lately been renovated, caught Tom's eye. The motto underneath, “Pereunt et imputantur,” stood out, proud of its new gilding, in the bright afternoon sun of a frosty January day: which motto was raising sundry thoughts in his brain, when the porter came upon the right place in his list, and directed him to the end of his journey: No. 5 staircase, second quadrangle, three pair back. In which new home we shall leave him to install himself, while we endeavor to give the reader some notion of the college itself.

St. Ambrose's College was a moderate-sized one. There might have been some seventy or eighty undergraduates in residence, when our hero appeared there as a freshman. Of these, unfortunately for the college, there were a very large proportion of the gentleman-commoners; enough, in fact, with the other men whom they drew round them, and who lived pretty much as they did, to form the largest and leading set in the college. So the college was decidedly fast.

The chief characteristic of this set was the most reckless extravagance of every kind. London wine merchants furnished them with liqueurs at a guinea a bottle and wine at five guineas a dozen; Oxford and London tailors vied with one another in providing them with unheard-of quantities of the most gorgeous clothing. They drove tandems in all directions, scattering their ample allowances, which they treated as pocket money, about roadside inns and Oxford taverns with open hand, and “going tick” for everything which could by possibility be booked. Their cigars cost two guineas a pound; their furniture was the best that could be bought; pine-apples, forced fruit, and the most rare preserves figured at their wine parties; they hunted, rode steeple-chases by day, played billiards until the gates closed, and then were ready for vingt-et-une, unlimited loo, and hot drink in their own rooms, as long as anyone could be got to sit up and play.

The fast set then swamped, and gave the tone to the college; at which fact no persons were more astonished and horrified than the authorities of St. Ambrose.

That they of all bodies in the world should be fairly run away with by a set of reckless, loose young spendthrifts, was indeed a melancholy and unprecedented fact; for the body of fellows of St. Ambrose was as distinguished for learning, morality and respectability as any in the University. The foundation was not, indeed, actually an open one. Oriel at that time alone enjoyed this distinction; but there were a large number of open fellowships, and the income of the college was large, and the livings belonging to it numerous; so that the best men from other colleges were constantly coming in. Some of these of a former generation had been eminently successful in their management of the college. The St. Ambrose undergraduates at one time had carried off almost all the university prizes, and filled the class lists, while maintaining at the same time the highest character for manliness and gentlemanly conduct. This had lasted long enough to establish the fame of the college, and great lords and statesmen had sent their sons there; head-masters had struggled to get the names of their best pupils on the books; in short, everyone who had a son, ward, or pupil, whom he wanted to push forward in the world—who was meant to cut a figure, and take the lead among men, left no stone unturned to get him into St. Ambrose's; and thought the first, and a very long step gained when he had succeeded.

But the governing bodies of colleges are always on the change, and, in the course of things men of other ideas came to rule at St. Ambrose—shrewd men of the world; men of business, some of them, with good ideas of making the most of their advantages; who said, “Go to; why should we not make the public pay for the great benefits we confer on them? Have we not the very best article in the educational market to supply—almost a monopoly of it—and shall we not get the highest price for it?” So by degrees they altered many things in the college. In the first place, under their auspices, gentlemen-commoners increased and multiplied; in fact, the eldest sons of baronets, even squires, were scarcely admitted on any other footing. As these young gentlemen paid double fees to the college, and had great expectations of all sorts, it could not be expected that they should be subject to quite the same discipline as the common run of men, who would have to make their own way in the world. So the rules as to attendance at chapel and lectures, though nominally the same for them as for commoners, were in practice relaxed in their favour; and, that they might find all things suitable to persons in their position, the kitchen and buttery were worked up to a high state of perfection, and St. Ambrose, from having been one of the most reasonable, had come to be about the most expensive college in the university. These changes worked as their promoters probably desired that they should work, and the college was full of rich men, and commanded in the university the sort of respect which riches bring with them. But the old reputation, though still strong out of doors, was beginning sadly to wane within the university precincts. Fewer and fewer of the St. Ambrose men appeared in the class lists, or amongst the prize-men. They no longer led the debates at the Union; the boat lost place after place on the river; the eleven got beaten in all their matches. The inaugurators of these changes had passed away in their turn, and at last a reaction had commenced. The fellows recently elected, and who were in residence at the time we write of, were for the most part men of great attainments, all of them men who had taken very high honors. The electors naturally enough had chosen them as the most likely persons to restore, as tutors, the golden days of the college; and they had been careful in the selection to confine themselves to very quiet and studious men, such as were likely to remain up at Oxford, passing over men of more popular manners and active spirits, who would be sure to flit soon into the world, and be of little more service to St. Ambrose.

But these were not the men to get any hold on the fast set who were now in the ascendant. It was not in the nature of things that they should understand each other; in fact, they were hopelessly at war, and the college was getting more and more out of gear in consequence.

What they could do, however, they were doing; and under their fostering care were growing up a small set, including most of the scholars, who were likely, as far as they were concerned, to retrieve the college character of the schools. But they were too much like their tutors, men who did little else but read. They neither wished for, nor were likely to gain, the slightest influence on the fast set. The best men amongst them, too, were diligent readers of the Tracts for the Times, and followers of the able leaders of the High-church party, which was then a growing one; and this led them also to form such friendships as they made amongst out-college men of their own way of thinking-with high churchmen, rather than St. Ambrose men. So they lived very much to themselves, and scarcely interfered with the dominant party.

Lastly, there was the boating set, which was beginning to revive in the college, partly from the natural disgust of any body of young Englishmen, at finding themselves distanced in an exercise requiring strength and pluck, and partly from the fact, that the captain for the time being was one of the best oars in the University boat, and also a deservedly popular character. He was now in his third year of residence, had won the pair-oar race, and had pulled seven in the great yearly match with Cambridge, and by constant hard work had managed to carry the St. Ambrose boat up to the fifth place on the river. He will be introduced to you, gentle reader, when the proper time comes; at present, we are only concerned with a bird's-eye view of the college, that you may feel more or less at home in it. The boating set was not so separate or marked as the reading set, melting on one side into, and keeping up more or less connexion with, the fast set, and also commanding a sort of half allegiance from most of the men who belonged to neither of the other sets. The minor divisions, of which of course there were many, need not be particularized, as the above general classification will be enough for the purposes of this history.

Our hero, on leaving school, having bound himself solemnly to write all his doings and thoughts to the friend whom he had left behind him: distance and separation were to make no difference whatever in their friendship. This compact had been made on one of their last evenings at Rugby. They were sitting together in the six-form room, Tom splicing the handle of a favourite cricket bat, and Arthur reading a volume of Raleigh's works. The Doctor had lately been alluding to the “History of the World,” and had excited the curiosity of the active-minded amongst his pupils about the great navigator, statesman, soldier, author, and fine gentleman. So Raleigh's works were seized on by various voracious young readers, and carried out of the school library; and Arthur was now deep in a volume of the “Miscellanies,” curled up on a corner of the sofa. Presently, Tom heard something between a groan and a protest, and, looking up, demanded explanations; in answer to which, Arthur, in a voice half furious and half fearful, read out:—

“And be sure of this, thou shalt never find a friend in thy young years whose conditions and qualities will please thee after thou comest to more discretion and judgment; and then all thou givest is lost, and all wherein thou shalt trust such a one will be discovered.”

“You don't mean that's Raleigh's?”

“Yes—here it is, in his first letter to his son.”

“What a cold-blooded old Philistine,” said Tom.

“But it can't be true, do you think?” said Arthur.

And in short, after some personal reflections on Sir Walter, they then and there resolved that, so far as they were concerned, it was not, could not, and should not be true, that they would remain faithful, the same to each other; and the greatest friends in the world, through I know not what separations, trials, and catastrophes. And for the better insuring this result, a correspondence, regular as the recurring months, was to be maintained. It had already lasted through the long vacation and up to Christmas without sensibly dragging, though Tom's letters had been something of the shortest in November, when he had lots of shooting, and two days a week with the hounds. Now, however, having fairly got to Oxford, he determined to make up for all short-comings. His first letter from college, taken in connexion with the previous sketch of the place, will probably accomplish the work of introduction better than any detailed account by a third party; and it is therefore given here verbatim:—

“St. Ambrose, Oxford,

“February, 184-

“According to promise, I write to tell you how I get on up here, and what sort of a place Oxford is. Of course, I don't know much about it yet, having only been up some weeks, but you shall have my first impressions.

“Well, first and foremost it's an awfully idle place; at any rate for us freshmen. Fancy now. I am in twelve lectures a week of an hour each—Greek Testament, first book of Herodotus, second AEneid, and first book of Euclid! There's a treat! Two hours a day; all over by twelve, or one at latest, and no extra work at all, in the shape of copies of verses, themes, or other exercises.

“I think sometimes I'm back in the lower fifth; for we don't get through more than we used to do there; and if you were to hear the men construe, it would make your hair stand on end. Where on earth can they have come from? Unless they blunder on purpose, as I often think. Of course, I never look at a lecture before I go in, I know it all nearly by heart, so it would be sheer waste of time. I hope I shall take to reading something or other by myself; but you know I never was much of a hand at sapping, and, for the present, the light work suits me well enough, for there's plenty to see and learn about in this place.

“We keep very gentlemanly hours. Chapel every morning at eight, and evening at seven. You must attend once a day, and twice on Sundays—at least, that's the rule of our college—and be in gates by twelve o'clock at night. Besides which, if you're a decently steady fellow, you ought to dine in hall perhaps four days a week. Hall is at five o'clock. And now you have the sum total. All the rest of your time you may just do what you like with.

“So much for our work and hours. Now for the place. Well, it's a grand old place, certainly; and I dare say, if a fellow goes straight in it, and gets creditably through his three years, he may end by loving it as much as we do the old school-house and quadrangle at Rugby. Our college is a fair specimen: a venerable old front of crumbling stone fronting the street, into which two or three other colleges look also. Over the gateway is a large room, where the college examinations go on, when there are any; and, as you enter, you pass the porters lodge, where resides our janitor, a bustling little man, with a pot belly, whose business it is to put down the time at which the men come in at night, and to keep all discommonsed tradesmen, stray dogs, and bad characters generally, out of the college.

“The large quadrangle into which you come first, is bigger than ours at Rugby, and a much more solemn and sleepy sort of a place, with its gables and old mullioned windows. One side is occupied by the hall and chapel; the principal's house takes up half another side; and the rest is divided into staircases, on each of which are six or eight sets of rooms, inhabited by us undergraduates, and here and there a tutor or fellow dropped down amongst us (in the first-floor rooms, of course), not exactly to keep order, but to act as a sort of ballast. This quadrangle is the show part of the college, and is generally respectable and quiet, which is a good deal more than can be said for the inner quadrangle, which you get at through a passage leading out of the other. The rooms ain't half so large or good in the inner quad; and here's where all we freshmen live, besides a lot of the older undergraduates who don't care to change their rooms. Only one tutor has rooms here; and I should think, if he's a reading man, it won't be long before he clears out; for all sorts of high jinks go on on the grass-plot, and the row on the staircases is often as bad, and not half so respectable, as it used to be in the middle passage in the last week of the half-year.

“My rooms are what they call garrets, right up in the roof, with a commanding view of the college tiles and chimney pots, and of houses at the back. No end of cats, both college Toms and strangers, haunt the neighbourhood, and I am rapidly learning cat-talking from them; but I'm not going to stand it—I don't want to know cat-talk. The college Toms are protected by the statutes, I believe; but I'm going to buy an air-gun for the benefit of the strangers. My rooms are pleasant enough, at the top of the kitchen staircase, and separated from all mankind by a great, iron-clamped, outer door, my oak, which I sport when I go out or want to be quiet; sitting room eighteen by twelve, bedroom twelve by eight, and a little cupboard for the scout.

“Ah, Geordie, the scout is an institution! Fancy me waited upon and valeted by a stout party in black of quiet, gentlemanly manners, like the benevolent father in a comedy. He takes the deepest interest in all my possessions and proceedings, and is evidently used to good society, to judge by the amount of crockery and glass, wines, liquors, and grocery, which he thinks indispensable for my due establishment. He has also been good enough to recommend to me many tradesmen who are ready to supply these articles in any quantities; each of whom has been here already a dozen times, cap in hand, and vowing that it is quite immaterial when I pay—which is very kind of them; but, with the highest respect for friend Perkins (my scout) and his obliging friends, I shall make some enquiries before “letting in” with any of them. He waits on me in hall, where we go in full fig of cap and gown at five, and get very good dinners, and cheap enough. It is rather a fine old room, with a good, arched, black oak ceiling and high panelling, hung round with pictures of old swells, bishops and lords chiefly, who have endowed the college in some way, or at least have fed here in times gone by, and for whom, “caeterisque benefactoribus nostris,” we daily give thanks in a long Latin grace, which one of the undergraduates (I think it must be) goes and rattles out at the end of the high table, and then comes down again from the dais to his own place. No one feeds at the high table except the dons and the gentlemen-commoners, who are undergraduates in velvet caps and silk gowns. Why they wear these instead of cloth and serge I haven't yet made out, I believe it is because they pay double fees; but they seem uncommonly wretched up at the high table, and I should think would sooner pay double to come to the other end of the hall.

“The chapel is a quaint little place, about the size of the chancel of Lutterworth Church. It just holds us all comfortably. The attendance is regular enough, but I don't think the men care about it a bit in general. Several I can see bring in Euclids, and other lecture books, and the service is gone through at a great pace. I couldn't think at first why some of the men seemed so uncomfortable and stiff about the legs at morning service, but I find that they are the hunting set, and come in with pea-coats over their pinks, and trousers over their leather breeches and top-boots; which accounts for it. There are a few others who seem very devout, and bow a good deal, and turn towards the altar at different parts of the service. These are of the Oxford High-church school, I believe; but I shall soon find out more about them. On the whole I feel less at home at present, I am sorry to say, in the chapel, than anywhere else.

“I was very near forgetting a great institution of the college, which is the buttery-hatch, just opposite the hall-door. Here abides the fat old butler (all the servants at St. Ambrose's are portly), and serves out limited bread, butter, and cheese, and unlimited beer brewed by himself, for an hour in the morning, at noon, and again at supper-time. Your scout always fetches you a pint or so on each occasion in case you should want it, and if you don't, it falls to him; but I can't say that my fellow gets much, for I am naturally a thirsty soul, and cannot often resist the malt myself, coming up as it does, fresh and cool, in one of the silver tankards, of which we seem to have an endless supply.

“I spent a day or two in the first week, before I got shaken down into my place here, in going round and seeing the other colleges, and finding out what great men had been at each (one got a taste for that sort of work from the Doctor, and I'd nothing else to do). Well, I never was more interested; fancy ferreting out Wycliffe, the Black Prince, our friend Sir Walter Raleigh, Pym, Hampden, Laud, Ireton, Butler, and Addison, in one afternoon. I walked about two inches taller in my trencher cap after it. Perhaps I may be going to make dear friends with some fellow who will change the history of England. Why shouldn't I? There must have been freshmen once who were chums of Wycliffe of Queen's, or Raleigh of Oriel. I mooned up and down the High-street, staring at all the young faces in caps, and wondering which of them would turn out great generals, or statesmen, or poets. Some of them will, of course, for there must be a dozen at least, I should think, in every generation of undergraduates, who will have a good deal to say to the ruling and guiding of the British nation before they die.

“But, after all, the river is the feature of Oxford, to my mind; a glorious stream, not five minutes' walk from the colleges, broad enough in most places for three boats to row abreast. I expect I will take to boating furiously: I have been down the river three or four times already with some other freshmen, and it is glorious exercise; that I can see, though we bungle and cut crabs desperately at present.

“Here's a long yarn I'm spinning for you; and I dare say after all you'll say it tells you nothing, and you'd rather have twenty lines about the men, and what they're thinking about and the meaning, and the inner life of the place, and all that. Patience, patience! I don't know anything about it myself yet, and have had only time to look at the shell, which is a very handsome and stately affair; you shall have the kernel, if I ever get at it, in due time.

“And now write me a long letter directly, and tell me about the Doctor, and who are in the Sixth, and how the house goes on, and what sort of an eleven there'll be, and what you are doing and thinking about. Come up here try for a scholarship; I'll take you in and show you the lions. Remember me to old friends.—Ever your affectionately,

Within a day or two of the penning of this celebrated epistle, which created quite a sensation in the sixth-form room as it went the round after tea, Tom realized one of the objects of his young Oxford ambition, and succeeded in embarking on the river in a skiff by himself, with such results as are now described. He had already been down several times in pair-oar and four-oar boats, with an old oar to pull stroke, and another to steer and coach the young idea, but he was not satisfied with these essays. He could not believe that he was such a bad oar as the old hands' made him out to be, and thought that it must be the fault of the other freshmen who were learning with him that the boat made so little way and rolled so much. He had been such a proficient in all the Rugby games, that he couldn't realize the fact of his unreadiness in a boat. Pulling looked a simple thing enough—much easier than tennis; and he had made a capital start at the latter game, and been highly complimented by the marker after his first hour in the little court. He forgot that cricket and fives are capital training for tennis, but that rowing is a speciality, of the rudiments of which he was wholly ignorant. And so, in full confidence that, if he could only have a turn or two alone, he should not only satisfy himself, but everybody else, that he was a heaven-born oar, he refused all offers of companionship, and started on the afternoon of a fine February day down to the boats for his trial trip. He had watched his regular companions well out of college, and gave them enough start to make sure that they would be off before he himself could arrive at St. Ambrose's dressing room at Hall's, and chuckled, as he came within sight of the river, to see the freshmen's boat in which he generally performed, go plunging away past the University barge, keeping three different times with four oars, and otherwise demeaning itself so as to become an object of mirthful admiration to all beholders.

Tom was punted across to Hall's in a state of great content, which increased when, in answer to his casual inquiry, the managing man informed him that not a man of his college was about the place. So he ordered a skiff with as much dignity and coolness as he could command, and hastened up stairs to dress. He appeared again, carrying his boating coat and cap. They were quite new, so he would not wear them; nothing about him should betray the freshman on this day if he could help it.

“Is my skiff ready?”

“All right, sir; this way, sir;” said the manager, conducting him to a good, safe-looking craft. “Any gentleman going to steer, sir?”

“No” said Tom, superciliously; “You may take out the rudder.”

“Going quite alone, sir? Better take one of our boys—find you a very light one. Here, Bill!”—and he turned to summons a juvenile waterman to take charge of our hero.

“Take out the rudder, do you hear?” interrupted Tom. “I won't have a steerer.”

“Well, sir, as you please,” said the manager, proceeding to remove the degrading appendage. “The river's rather high, please to remember, sir. You must mind the mill stream at Iffley Lock. I suppose you can swim?”

“Yes, of course,” said Tom, settling himself on his cushion. “Now, shove her off.”

The next moment he was well out in the stream, and left to his own resources. He got his sculls out successfully enough, and, though feeling by no means easy on his seat, proceeded to pull very deliberately past the barges, stopping his sculls in the air to feather accurately, in the hopes of deceiving spectators into the belief that he was an old hand just going out for a gentle paddle. The manager watched him for a minute, and turned to his work with an aspiration that he might not come to grief.

But no thought of grief was on Tom's mind as he dropped gently down, impatient for the time when he should pass the mouth of the Cherwell, and so, having no longer critical eyes to fear, might put out his whole strength, and give himself at least if not the world, assurance of a waterman.

The day was a very fine one, a bright sun shining, and a nice fresh breeze blowing across the stream, but not enough to ruffle the water seriously. Some heavy storms up Gloucestershire way had cleared the air, and swollen the stream at the same time; in fact, the river was as full as it could be without overflowing its banks—a state in which, of all others, it is the least safe for boating experiments. Fortunately, in those days there were no outriggers. Even the racing skiffs were comparatively safe craft, and would now be characterized as tubs; while the real tubs (in one of the safest of which the prudent manager had embarked our hero) were of such build that it required considerable ingenuity actually to upset them.

If any ordinary amount of bungling could have done it, Tom's voyage would have terminated within a hundred yards of the Cherwell. While he had been sitting quiet and merely paddling, and almost letting the stream carry him down, the boat had trimmed well enough; but now, taking a long breath, he leaned forward, and dug his sculls into the water, pulling them through with all his strength. The consequence of this feat was that the handles of the sculls came into violent collision in the middle of the boat, the knuckles of his right hand were barked, his left scull unshipped, and the head of his skiff almost blown round by the wind before he could restore order on board.

“Never mind; try again,” thought he, after the first sensation of disgust had passed off, and a glance at the shore showed him that there were no witnesses. “Of course, I forgot one hand must go over the other. It might have happened to anyone. Let me see, which hand shall I keep uppermost; the left, that's the weakest.” And away he went again, keeping his newly-acquired fact painfully in mind, and so avoiding further collision amidships for four or five strokes. But, as in other sciences, the giving of undue prominence to one fact brings others inexorably on the head of the student to avenge his neglect of them, so it happened with Tom in his practical study of the science of rowing that by thinking of his hands he forgot his seat, and the necessity of trimming properly. Whereupon the old tub began to rock fearfully, and the next moment, he missed the water altogether with his right scull, and subsided backwards, not without struggles, into the bottom of the boat; while the half stroke which he had pulled with his left hand sent her head well into the bank.

Tom picked himself up, and settled himself on his bench again, a sadder and wiser man, as the truth began to dawn upon him that pulling, especially sculling, does not, like reading and writing, come by nature. However, he addressed himself manfully to his task; savage indeed, and longing to drive a hole in the bottom of the old tub, but as resolved as ever to get to Sandford and back before hall time, or perish in the attempt.

He shoved himself off the bank, and warned by his last mishap, got out into mid stream, and there, moderating his ardor, and contenting himself with a slow and steady stroke, was progressing satisfactorily, and beginning to recover his temper, when a loud shout startled him; and, looking over his shoulder at the imminent risk of an upset, he beheld the fast sailor the Dart, close hauled on a wind, and almost aboard of him. Utterly ignorant of what was the right thing to do, he held on his course, and passed close under the bows of the miniature cutter, the steersman having jammed his helm hard down, shaking her in the wind, to prevent running over the skiff, and solacing himself with pouring maledictions on Tom and his craft, in which the man who had hold of the sheets, and the third, who was lounging in the bows, heartily joined. Tom was out of ear-shot before he had collected vituperation enough to hurl back at them, and was, moreover, already in the difficult navigation of the Gut, where, notwithstanding all his efforts, he again ran aground; but, with this exception, he arrived without other mishap at Iffley, where he lay on his sculls with much satisfaction, and shouted, “Lock—lock!”

The lock-keeper appeared to the summons, but instead of opening the gates seized a long boat-hook, and rushed towards our hero, calling upon him to mind the mill-stream, and pull his right-hand scull; notwithstanding which warning, Tom was within an ace of drifting past the entrance to the lock, in which case assuredly his boat, if not he, had never returned whole. However, the lock-keeper managed to catch the stern of his skiff with the boat-hook, and drag him back into the proper channel, and then opened the lock-gates for him. Tom congratulated himself as he entered the lock that there were no other boats going through with him; but his evil star was in the ascendant, and all things, animate and inanimate, seemed to be leagued together to humiliate him. As the water began to fall rapidly, he lost his hold of the chain and the tub instantly drifted across the lock, and was in imminent danger of sticking and breaking her back, when the lock-keeper again came to the rescue with his boat-hook and, guessing the state of the case, did not quit him until he had safely shoved him and his boat well out into the pool below, with an exhortation to mind and go outside of the barge which was coming up.

Tom started on the latter half of his outward voyage with the sort of look which Cato must have worn when he elected the losing side, and all the gods went over to the winning one. But his previous struggles had not been thrown away, and he managed to keep the right side of the barge, turn the corner without going around, and zigzag down Kennington reach, slowly indeed, but with much labor, but at any rate safely. Rejoicing in his feat, he stopped at the island, and recreated himself with a glass of beer, looking now hopefully towards Sandford, which lay within easy distance, now upwards again along the reach which he had just overcome, and solacing himself with the remembrance of a dictum, which he had heard from a great authority, that it was always easier to steer up stream than down, from which he argued that the worst part of his trial trip was now over.

Presently he saw a skiff turn the corner at the top of the Kennington reach, and, resolving in his mind to get to Sandford before the new comer, paid for his beer, and betook himself again to his tub. He got pretty well off, and, the island shutting out his unconscious rival from his view, worked away at first under the pleasing delusion that he was holding his own. But he was soon undeceived, for in monstrously short time the pursuing skiff showed around the corner and bore down on him. He never relaxed his efforts, but could not help watching the enemy as he came up with him hand over hand, and envying the perfect ease with which he seemed to be pulling his long steady stroke and the precision with which he steered, scarcely ever casting a look over his shoulder. He was hugging the Berkshire side himself, as the other skiff passed him, and thought he heard the sculler say something about keeping out, and minding the small lasher; but the noise of the waters and his own desperate efforts prevented his heeding, or, indeed, hearing the warning plainly. In another minute, however, he heard plainly enough most energetic shouts behind him and, turning his head over his right shoulder, saw the man who had just passed him backing his skiff rapidly up stream towards him. The next moment he felt the bows of his boat whirl round, the old tub grounded for a moment, and then, turning over on her side, shot him out on to the planking of the steep descent into the small lasher. He grasped at the boards, but they were too slippery to hold, and the rush of water was too strong for him, and rolling him over and over like a piece of driftwood, plunged him into the pool below.

After the first moment of astonishment and fright was over, Tom left himself to the stream, holding his breath hard, and paddling gently with his hands, feeling sure that, if he could only hold on, he should come to the surface sooner or later; which accordingly happened after a somewhat lengthy submersion.

His first impulse on rising to the surface, after catching his breath, was to strike out for the shore, but, in the act of doing so, he caught sight of the other skiff coming stern foremost down the decent after him, and he trod the water and drew in his breath to watch. Down she came, as straight as an arrow, into the tumult below; the sculler sitting upright, and holding his sculls steadily in the water. For a moment she seemed to be going under, but righted herself, and glided swiftly into the still water; and then the sculler cast a hasty and anxious glance around, till his eyes rested on our hero's half-drowned head.

“Oh, there you are!” he said, looking much relieved; “all right, I hope. Not hurt, eh?”

“No, thankee; all right, I believe,” answered Tom. “What shall I do?”

“Swim ashore; I'll look after your boat.” So Tom took the advice, swam ashore, and there stood dripping and watching the other as he righted the old tub which was floating quietly bottom upwards, little the worse for the mishap, and no doubt, if boats can wish, earnestly desiring in her wooden mind to be allowed to go quietly to pieces then and there, sooner to be rescued than be again entrusted to the guidance of freshmen.

The tub having been brought to the bank, the stranger started again, and collected the sculls and bottom boards which were floating about here and there in the pool, and also succeeded in making salvage of Tom's coat, the pockets of which held his watch, purse, and cigar case. These he brought to the bank, and delivering them over, inquired whether there was anything else to look after.

“Thank you, no; nothing but my cap. Never mind it. It's luck enough not to have lost the coat,” said Tom, holding up the dripping garment to let the water run out of the arms and pocket-holes, and then wringing it as well as he could. “At any rate,” thought he, “I needn't be afraid of its looking too new any more.”

The stranger put off again, and made one more round, searching for the cap and anything else which he might have overlooked, but without success. While he was doing so, Tom had time to look him well over, and see what sort of a man had come to his rescue. He hardly knew at the time the full extent of his obligation—at least if this sort of obligation is to be reckoned not so much by the service actually rendered, as by the risk encountered to be able to render it. There were probably not three men in the University who would have dared to shoot the lasher in a skiff in its then state, for it was in those times a really dangerous place; and Tom himself had an extraordinary escape, for, as Miller, the St. Ambrose coxswain, remarked on hearing the story, “No one who wasn't born to be hung could have rolled down it without knocking his head against something hard, and going down like lead when he got to the bottom.”

He was very well satisfied with his inspection. The other man was evidently a year or two older than himself, his figure was more set, and he had stronger whiskers than are generally grown at twenty. He was somewhere about five feet ten in height, very deep-chested, and with long powerful arms and hands. There was no denying, however, that at the first glance he was an ugly man; he was marked with small-pox, had large features, high cheekbones, deeply set eyes, and a very long chin; and had got the trick which many underhung men have of compressing his upper lip. Nevertheless, there was that in his face which hit Tom's fancy, and made him anxious to know his rescuer better. He had an instinct that good was to be gotten out of him. So he was very glad when the search was ended, and the stranger came to the bank, shipped his sculls, and jumped out with the painter of his skiff in his hand, which he proceeded to fasten to an old stump, while he remarked—

“I'm afraid the cap's lost.”

“It doesn't matter the least. Thank you for coming to help me; it was very kind indeed, and more than I expected. Don't they say that one Oxford man will never save another from drowning unless they have been introduced?”

“I don't know,” replied the other; “are you sure you're not hurt?”

“Yes, quite,” said Tom, foiled in what he considered an artful plan to get the stranger to introduce himself.

“Then we're very well out of it,” said the other, looking at the steep descent into the lasher, and the rolling tumbling rush of the water below.

“Indeed we are,” said Tom; “but how in the world did you manage not to upset?”

“I hardly know myself—I had shipped a good deal of water, you see. Perhaps I ought to have jumped out on the bank and come across to you, leaving my skiff in the river, for if I had upset I couldn't have helped you much. However, I followed my instinct, which was to come the quickest way. I thought, too, that if I could manage to get down in the boat I should be of more use. I am very glad I did it,” he added after a moment's pause; “I'm really proud of having come down that place.”

“So ain't I,” said Tom, with a laugh, in which the other joined.

“But now you're getting chilled,” and he turned from the lasher and looked at Tom's chattering jaws.

“Oh, it's nothing. I'm used to being wet.”

“But you may just as well be comfortable if you can. Here's this rough Jersey which I use instead of a coat; pull off that wet cotton affair, and put it on, and then we'll get to work, for we have plenty to do.”

After a little persuasion Tom did as he was bid, and got into the great woolen garment, which was very comforting; and then the two set about getting their skiffs back into the main stream. This was comparatively easy as to the lighter skiff, which was soon baled out and hauled by main force on to the bank, carried across and launched again. The tub gave them much more trouble, for she was quite full of water and very heavy; but after twenty minutes or so of hard work, during which the mutual respect of the labourers for the strength and willingness of each other was much increased, she also lay in the main stream, leaking considerably, but otherwise not much the worse for her adventure.

“Now what do you mean to do?” said the stranger. “I don't think you can pull home in her. One doesn't know how much she may be damaged. She may sink in the lock, or play any prank.”

“But what am I to do with her?”

“Oh, you can leave her at Sandford and walk up, and send one of Hall's boys after her. Or, if you like, I will tow her up behind my skiff.”

“Won't your skiff carry two?”

“Yes; if you like to come I'll take you, but you must sit very quiet.”

“Can't we go down to Sandford first and have a glass of ale? What time is it?—the water has stopped my watch.”

“A quarter past three. I have about twenty minutes to spare.”

“Come along, then,” said Tom; “but will you let me pull your skiff down to Sandford? I resolved to pull to Sandford to-day, and don't like to give it up.”

“By all means, if you like,” said the other, with a smile; “jump in, and I'll walk along the bank.”

“Thank you,” said Tom, hurrying into the skiff, in which he completed the remaining quarter of a mile, while the owner walked by the side, watching him.

They met on the bank at the little inn by Sandford lock, and had a glass of ale, over which Tom confessed that it was the first time he had ever navigated a skiff by himself, and gave a detailed account of his adventures, to the great amusement of his companion. And by the time they rose to go, it was settled, at Tom's earnest request, that he should pull the sound skiff up, while his companion sat in the stern and coached him. The other consented very kindly, merely stipulating that he himself should take the sculls, if it should prove that Tom could not pull them up in time for hall dinner. So they started, and took the tub in tow when they came up to it. Tom got on famously under his new tutor, who taught him to get forward, and open his knees properly, and throw his weight on to the sculls at the beginning of the stroke. He managed even to get into Iffley lock on the way up without fouling the gates, and was then and there complimented on his progress. Whereupon, as they sat, while the lock filled, Tom poured out his thanks to his tutor for his instruction, which had been given so judiciously that, while he was conscious of improving at every stroke, he did not feel that the other was asserting any superiority over him; and so, though more humble than at the most disastrous period of his downward voyage, he was getting into a better temper every minute.

It is a great pity that some of our instructors in more important matters than sculling will not take a leaf out of the same book. Of course, it is more satisfactory to one's own self-love to make everyone who comes to one to learn, feel that he is a fool, and we wise men; but if our object is to teach well and usefully what we know ourselves there cannot be a worse method. No man, however, is likely to adopt it, so long as he is conscious that he has anything himself to learn from his pupils; and as soon as he has arrived at the conviction that they can teach him nothing—that it is henceforth to be all give and no take—the sooner he throws up his office of teacher, the better it will be for himself, his pupils, and his country, whose sons he is misguiding.

On their way up, so intent were they on their own work that it was not until shouts of “Hello, Brown! how did you get there? Why, you said you were not going down today,” greeted them just above the Gut, that they were aware of the presence of the freshmen's four-oar of St. Ambrose College, which had with some trouble succeeded in overtaking them.

“I said I wasn't going down with you,” shouted Tom, grinding away harder than ever, that they might witness and wonder at his prowess.

“Oh, I dare say! Whose skiff are you towing up? I believe you've been upset.”

Tom made no reply, and the four-oar floundered on ahead.

“Are you at St. Ambrose's?” asked his sitter, after a minute.

“Yes; that's my treadmill, that four-oar. I've been down in it almost every day since I came up, and very poor fun it is. So I thought to-day I would go on my own hook, and see if I couldn't make a better hand of it. And I have too, I know, thanks to you.”

The other made no remark, but a little shade came over his face. He had no chance of making out Tom's college, as the new cap which would have betrayed him had disappeared in the lasher. He himself wore a glazed straw hat, which was of no college; so that up to this time neither of them had known to what college the other belonged.

When they landed at Hall's, Tom was at once involved in a wrangle with the manager as to the amount of damage done to the tub; which the latter refused to assess before he knew what had happened to it; while our hero vigorously and with reason maintained, that if he knew his business it could not matter what had happened to the boat. There she was, and he must say whether she was better or worse, or how much worse than when she started. In the middle of which dialogue his new acquaintance, touching his arm, said, “You can leave my jersey with your own things; I shall get it to-morrow,” and then disappeared.

Tom, when he had come to terms with his adversary, ran upstairs, expecting to find the other, and meaning to tell his name, and find out who it was that had played the good Samaritan by him. He was much annoyed when he found the coast clear, and dressed in a grumbling humour. “I wonder why he should have gone off so quick. He might just as well have stayed and walked up with me,” thought he. “Let me see, though; didn't he say I was to leave his Jersey in our room, with my own things? Why, perhaps he is a St. Ambrose man himself. But then he would have told me so, surely. I don't remember to have seen his face in chapel or hall; but then there is such a lot of new faces, and he may not sit near me. However I mean to find him out before long, whoever he may be.” With which resolve Tom crossed in the punt into Christ's Church meadow, and strolled college-wards, feeling that he had had a good hard afternoon's exercise, and was much the better for it. He might have satisfied his curiosity at once by simply asking the manager who it was that had arrived with him; and this occurred to him before he got home, whereat he felt satisfied, but would not go back then, as it was so near hall time. He would be sure to remember it the first thing tomorrow.

As it happened, however, he had not so long to wait for the information which he needed; for scarcely had he sat down in hall and ordered his dinner, when he caught sight of his boating acquaintance, who walked in habited in a gown which Tom took for a scholar's. He took his seat at a little table in the middle of the hall, near the bachelors' table, but quite away from the rest of the undergraduates, at which sat four or five other men in similar gowns. He either did not or would not notice the looks of recognition which Tom kept firing at him until he had taken his seat.

“Who is that man that has just come in, do you know?” said Tom to his next neighbour, a second term man.

“Which?” said the other, looking up.

“That one over at the little table in the middle of the hall, with the dark whiskers. There, he has just turned rather from us, and put his arm on the table.”

“Oh, his name is Hardy.”

“Do you know him?”

“No; I don't think anybody does. They say he is a clever fellow, but a very queer one.”

“Why does he sit at that table!”

“He is one of our servitors; they all sit there together.”

“Oh,” said Tom, not much wiser for the information, but resolved to waylay Hardy as soon as the hall was over, and highly delighted to find that they were after all of the same college; for he had already begun to find out, that however friendly you may be with out-college men, you must live chiefly with those of your own. But now his scout brought his dinner, and he fell to with the appetite of a freshman on his ample commons.

No man in St. Ambrose College gave such breakfasts as Drysdale. Not the great heavy spreads for thirty or forty, which came once or twice a term, when everything was supplied out of the college kitchen, and you had to ask leave of the Dean before you could have it at all. In those ponderous feasts the most hum-drum of the undergraduate kind might rival the most artistic, if he could only pay his battle-bill, or get credit with the cook. But the daily morning meal, when even gentlemen commoners were limited to two hot dishes out of the kitchen, this was Drysdale's forte. Ordinary men left the matter in the hands of scouts, and were content with the ever-recurring buttered toasts and eggs, with a dish of broiled ham, or something of the sort, with a marmalade and bitter ale to finish with; but Drysdale was not an ordinary man, as you felt in a moment when you went to breakfast with him for the first time.

The staircase on which he lived was inhabited, except in the garrets, by men in the fast set, and he and three others, who had an equal aversion to solitary feeding, had established a breakfast-club, in which, thanks to Drysdale's genius, real scientific gastronomy was cultivated. Every morning the boy from the Weirs arrived with freshly caught gudgeon, and now and then an eel or trout, which the scouts on the staircase had learnt to fry delicately in oil. Fresh watercresses came in the same basket, and the college kitchen furnished a spitchedcocked chicken, or grilled turkey's leg. In the season there were plover's eggs; or, at the worst, there was a dainty omelette; and a distant baker, famed for his light rolls and high charges, sent in the bread—the common domestic college loaf being of course out of the question for anyone with the slightest pretension to taste, and fit only for the perquisite of scouts. Then there would be a deep Yorkshire pie, or reservoir of potted game, as a piece, de resistance, and three or four sorts of preserves; and a large cool tankard of cider or ale-cup to finish up with, or soda-water and maraschino for a change. Tea and coffee were there indeed, but merely as a compliment to those respectable beverages, for they were rarely touched by the breakfast eaters of No. 3 staircase. Pleasant young gentlemen they were on No. 3 staircase; I mean the ground and first floor men who formed the breakfast-club, for the garrets were nobodies. Three out of the four were gentlemen-commoners, with allowances of 500L a year at least each; and, as they treated their allowances as pocket-money, and were all in their first year, ready money was plenty and credit good, and they might have had potted hippopotamus for breakfast if they had chosen to order it, which they would most likely have done if they had thought of it.

Two out of the three were the sons of rich men who made their own fortunes, and sent their sons to St. Ambrose's because it was very desirable that the young gentlemen should make good connexions. In fact, the fathers looked upon the University as a good investment, and gloried much in hearing their sons talk familiarly in the vacations of their dear friends Lord Harry This and Sir George That.

Drysdale, the third of the set, was the heir of an old as well of a rich family, and consequently, having his connexion ready made to his hand, cared little enough with whom he associated, provided they were pleasant fellows, and gave him good food and wines. His whole idea at present was to enjoy himself as much as possible; but he had good manly stuff in him at the bottom, and, had he fallen into any but the fast set, would have made a fine fellow, and done credit to himself and his college.

The fourth man at the breakfast-club, the Hon. Piers St. Cloud was in his third year, and was a very well-dressed, well-mannered, well-connected young man. His allowance was small for the set he lived with, but he never wanted for anything. He didn't entertain much, certainly, but when he did, everything was in the best possible style. He was very exclusive, and knew no man in college out of the fast set, and of these he addicted himself chiefly to the society of the rich freshmen, for somehow the men of his own standing seemed a little shy of him. But with the freshmen he was always hand and glove, lived in their rooms, and used their wines, horses, and other movable property as his own. Being a good whist and billiard player, and not a bad jockey, he managed in one way or another to make his young friends pay well for the honour of his acquaintance; as, indeed, why should they not, at least those of them who came to the college to form eligible connexions; for had not his remote lineal ancestor come over in the same ship with William the Conqueror? Were not all his relations about the Court, as lords and ladies in waiting, white sticks or black rods, and in the innermost of all possible circles of the great world; and was there a better coat of arms than he bore in all Burke's Peerage?

Our hero had met Drysdale at a house in the country shortly before the beginning of his first term, and they had rather taken to one another. Drysdale had been amongst his first callers; and, as he came out of chapel one morning shortly after his arrival, Drysdale's scout came up to him with an invitation to breakfast. So he went to his own rooms, ordered his commons to be taken across to No. 3, and followed himself a few minutes afterwards. No one was in the rooms when he arrived, for none of the club had finished their toilettes. Morning chapel was not meant for, or cultivated by gentlemen-commoners; they paid double chapel fees, in consideration of which, probably, they were not expected to attend so often as the rest of the undergraduates; at any rate, they didn't, and no harm came to them in consequence of their absence. As Tom entered, a great splashing in an inner room stopped for a moment, and Drysdale's voice shouted out that he was in his tub, but would be with him in a minute. So Tom gave himself up to contemplation of the rooms in which his fortunate acquaintance dwelt; and very pleasant rooms they were. The large room in which the breakfast-table was laid for five, was lofty and well proportioned, and panelled with old oak, and the furniture was handsome and solid, and in keeping with the room.

There were four deep windows, high up in the wall, with cushioned seats under them, two looking into the large quadrangle, and two into the inner one. Outside these windows, Drysdale had rigged up hanging gardens, which were kept full of flowers by the first nurseryman in Oxford, all the year round; so that even on this February morning, the scent of gardenia and violets pervaded the room, and strove for mastery with the smell of stale tobacco, which hung about the curtains and sofa. There was a large glass in an oak frame over the mantelpiece, which was loaded with choice pipes and cigar cases and quaint receptacles for tobacco; and by the side of the glass hung small carved oak frames, containing lists of meets of the Heyshrop, the Old Berkshire, and Drake's hounds, for the current week. There was a queer assortment of well-framed paintings and engravings on the walls; some of considerable merit, especially some watercolor and sea-pieces and engravings from Landseer's pictures, mingled with which hung Taglioni and Cerito, in short petticoats and impossible attitudes; Phosphurous winning the Derby; the Death of Grimaldi (the famous steeple-chase horse, not poor old Joe); an American Trotting Match, and Jem Belcher and Deaf Burke in attitudes of self-defense. Several tandem and riding whips, mounted in heavy silver, and a double-barrelled gun, and fishing rods, occupied one corner, and a polished copper cask, holding about five gallons of mild ale, stood in another. In short, there was plenty of everything except books—the literature of the world being represented, so far as Tom could make out in his short scrutiny, by a few well-bound but badly used volumes of the classics, with the cribs thereto appertaining, shoved away into a cupboard which stood half open, and contained besides, half-emptied decanters, and large pewters, and dog collars, and packs of cards, and all sorts of miscellaneous articles to serve as an antidote.

Tom had scarcely finished his short survey when the door of the bedroom opened, and Drysdale emerged in a loose jacket lined with silk, his velvet cap on his head, and otherwise gorgeously attired. He was a pleasant-looking fellow of middle size, with dark hair, and a merry brown eye, with a twinkle in it, which spoke well for his sense of humor; otherwise, his large features were rather plain, but he had the look and manners of a thoroughly well-bred gentleman.

His first act, after nodding to Tom, was to seize on a pewter and resort to the cask in the corner, from whence he drew a pint or so of the contents, having, as he said, “'a whoreson longing for that poor creature, small beer.' We were playing Van-John in Blake's rooms till three last night, and he gave us devilled bones and mulled port. A fellow can't enjoy his breakfast after that without something to cool his coppers.”