This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Story of John G. Paton

Or Thirty Years Among South Sea Cannibals

Author: James Paton

Release Date: February 8, 2009 [eBook #28025]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF JOHN G. PATON***

EVER since the story of my brother's life first appeared (January 1889) it has been constantly pressed upon me that a YOUNG FOLKS' EDITION would be highly prized. The Autobiography has therefore been re-cast and illustrated, in the hope and prayer that the Lord will use it to inspire the Boys and Girls of Christendom with a wholehearted enthusiasm for the Conversion of the Heathen World to Jesus Christ.

A few fresh incidents have been introduced; the whole contents have been rearranged to suit a new class of readers; and the service of a gifted Artist has been employed, to make the book every way attractive to the young. For full details as to the Missionary's work and life, the COMPLETE EDITION must still of course be referred to.

JAMES PATON.

GLASGOW, Sept, 1892.

MY early days were all spent in the beautiful county of Dumfries, which Scotch folks call the Queen of the South. There, in a small cottage, on the farm of Braehead, in the parish of Kirkmahoe, I was born on the 24th May, 1824. My father, James Paton, was a stocking manufacturer in a small way; and he and his young wife, Janet Jardine Rogerson, lived on terms of warm personal friendship with the "gentleman farmer," so they gave me his son's name, John Gibson; and the curly-haired child of the cottage was soon able to toddle across to the mansion, and became a great pet of the lady there. On my visit to Scotland in 1884 I drove out to Braehead; but we found no cottage, nor trace of a cottage, and amused ourselves by supposing that we could discover by the rising of the grassy mound, the outline where the foundations once had been!

While yet a mere child, five years or so of age, my parents took me to a new home in the ancient village of Torthorwald, about four and a quarter miles from Dumfries, on the road to Lockerbie. At that time, say 1830, Torthorwald was a busy and thriving village, and comparatively populous, with its cottars and crofters, large farmers and small farmers, weavers and shoemakers, doggers and coopers, blacksmiths and tailors. Fifty-five years later, when I visited the scenes of my youth, the village proper was extinct, except for five thatched cottages where the lingering patriarchs were permitted to die slowly away,—soon they too would be swept into the large farms, and their garden plots plowed over, like sixty or seventy others that had been blotted out!

From the Bank Hill, close above our village, and accessible in a walk of fifteen minutes, a view opens to the eye which, despite several easily understood prejudices of mine that may discount any opinion that I offer, still appears to me well worth seeing amongst all the beauties of Scotland. At your feet lay a thriving village, every cottage sitting in its own plot of garden, and sending up its blue cloud of "peat reek," which never somehow seemed to pollute the blessed air; and after all has been said or sung, a beautifully situated village of healthy and happy homes for God's children is surely the finest feature in every landscape! Looking from the Bank Hill on a summer day, Dumfries with its spires shone so conspicuous that you could have believed it not more than two miles away; the splendid sweeping vale through which Nith rolls to Solway, lay all before the naked eye, beautiful with village spires, mansion houses, and white shining farms; the Galloway hills, gloomy and far-tumbling, bounded the forward view, while to the left rose Criffel, cloud-capped and majestic; then the white sands of Solway, with tides swifter than horsemen; and finally the eye rested joyfully upon the hills of Cumberland, and noticed with glee the blue curling smoke from its villages on the southern Solway shores.

There, amid this wholesome and breezy village life, our dear parents found their home for the long period of forty years. There too were born to them eight additional children, making in all a family of five sons and six daughters. Theirs was the first of the thatched cottages on the left, past the "miller's house," going up the "village gate," with a small garden in front of it, and a large garden across the road; and it is one of the few still lingering to show to a new generation what the homes of their fathers were. The architect who planned that cottage had no ideas of art, but a fine eye for durability! It consists at present of three, but originally of four, pairs of "oak couples" (Scottice kipples) planted like solid trees in the ground at equal intervals, and gently sloped inwards till they meet or are "coupled" at the ridge, this coupling being managed not by rusty iron, but by great solid pins of oak. A roof of oaken wattles was laid across these, till within eleven or twelve feet of the ground, and from the ground upwards a stone wall was raised, as perpendicular as was found practicable, towards these overhang-wattles, this wall being roughly "pointed" with sand and clay and lime. Now into and upon the roof was woven and intertwisted a covering of thatch, that defied all winds and weathers, and that made the cottage marvelously cozy,—being renewed year by year, and never allowed to remain in disrepair at any season. But the beauty of the construction was and is its durability, or rather the permanence of its oaken ribs! There they stand, after probably not less than four centuries, japanned with "peat reek" till they are literally shining, so hard that no ordinary nail can be driven into them, and perfectly capable of service for four centuries more on the same conditions. The walls are quite modern, having all been rebuilt in my father's time, except only the few great foundation boulders, piled around the oaken couples; and parts of the roofing also may plead guilty to having found its way thither only in recent days; but the architect's one idea survives, baffling time and change—the ribs and rafters of oak.

Our home consisted of a "but" and a "ben" and a "mid room," or chamber, called the "closet." The one end was my mother's domain, and served all the purposes of dining-room and kitchen and parlor, besides containing two large wooden erections, called by our Scotch peasantry "box beds"; not holes in the wall, as in cities, but grand, big, airy beds, adorned with many-colored counterpanes, and hung with natty curtains, showing the skill of the mistress of the house. The other end was my father's workshop, filled with five or six "stocking-frames," whirring with the constant action of five or six pairs of busy hands and feet, and producing right genuine hosiery for the merchants at Hawick and Dumfries. The "closet" was a very small apartment betwixt the other two, having room only for a bed, a little table and a chair, with a diminutive window shedding diminutive light on the scene. This was the Sanctuary of that cottage home. Thither daily, and oftentimes a day, generally after each meal, we saw our father retire, and "shut to the door"; and we children got to understand by a sort of spiritual instinct (for the thing was too sacred to be talked about) that prayers were being poured out there for us, as of old by the High Priest within the veil in the Most Holy Place. We occasionally heard the pathetic echoes of a trembling voice pleading as if for life, and we learned to slip out and in past that door on tiptoe, not to disturb the holy colloquy. The outside world might not know, but we knew, whence came that happy light as of a new-born smile that always was dawning on my father's face: it was a reflection from the Divine Presence, in the consciousness of which he lived. Never, in temple or cathedral, on mountain or in glen, can I hope to feel that the Lord God is more near, more visibly walking and talking with men, than under that humble cottage roof of thatch and oaken wattles. Though everything else in religion were by some unthinkable catastrophe to be swept out of memory, or blotted from my understanding, my soul would wander back to those early scenes, and shut itself up once again in that Sanctuary Closet, and, hearing still the echoes of those cries to God, would hurl back all doubt with the victorious appeal, "He walked with God, why may not I?"

A FEW notes had better here be given as to our "Forebears," the kind of stock from which my father and mother sprang. My father's mother, Janet Murray, claimed to be descended from a Galloway family that fought and suffered for Christ's Crown and Covenant in Scotland's "killing time," and was herself a woman of a pronouncedly religious development. Her husband, our grandfather, William Paton, had passed through a roving and romantic career, before he settled down to be a douce deacon of the weavers of Dumfries, like his father before him.

Forced by a press-gang to serve on board a British man-of-war, he was taken prisoner by the French, and thereafter placed under Paul Jones, the pirate of the seas, and bore to his dying day the mark of a slash from the captain's sword across his shoulder for some slight disrespect or offense. Determining with two others to escape, the three were hotly pursued by Paul Jones's men. One, who could swim but little, was shot, and had to be cut adrift by the other two, who in the darkness swam into a cave and managed to evade for two nights and a day the rage of their pursuers. My grandfather, being young and gentle and yellow-haired, persuaded some kind heart to rig him out in female attire, and in this costume escaped the attentions of the press-gang more than once; till, after many hardships, he bargained with the captain of a coal sloop to stow him away amongst his black diamonds; and thus, in due time, he found his way home to Dumfries, where he tackled bravely and wisely the duties of husband, father, and citizen for the remainder of his days. The smack of the sea about the stories of his youth gave zest to the talks round their quiet fireside, and that, again, was seasoned by the warm Evangelical spirit of his Covenanting wife, her lips "dropping grace."

On the other side, my mother, Janet Rogerson, had for parents a father and mother of the Annandale stock. William Rogerson, her father, was one of many brothers, all men of uncommon strength and great force of character, quite worthy of the Border Rievers of an earlier day. Indeed, it was in some such way that he secured his wife, though the dear old lady in after days was chary about telling the story. She was a girl of good position, the ward of two unscrupulous uncles who had charge of her small estate, near Langholm; and while attending some boarding school she fell devotedly in love with the tall, fair-haired, gallant young blacksmith, William Rogerson. Her guardians, doubtless very properly, objected to the "connection"; but our young Lochinvar, with his six or seven stalwart brothers and other trusty "lads," all mounted, and with some ready tools in case of need, went boldly and claimed his bride, and she, willingly mounting at his side, was borne off in the light of open day, joyously married, and took possession of her "but and ben," as the mistress of the blacksmith's castle.

Janet Jardine bowed her neck to the self-chosen yoke, with the light of a supreme affection in her heart, and showed in her gentler ways, her love of books, her fine accomplishments with the needle, and her general air of ladyhood, that her lot had once been cast in easier, but not necessarily happier, ways. Her blacksmith lover proved not unworthy of his lady bride, and in old age found for her a quiet and modest home, the fruit of years of toil and hopeful thrift, their own little property, in which they rested and waited a happy end. Amongst those who at last wept by her grave stood, amidst many sons and daughters, her son the Rev. James J. Rogerson, clergyman of the Church of England, who, for many years thereafter, and till quite recently, was spared to occupy a distinguished position at ancient Shrewsbury and has left behind him there an honored and beloved name.

From such a home came our mother, Janet Jardine Rogerson, a bright-hearted, high-spirited, patient-toiling, and altogether heroic little woman; who, for about forty-three years, made and kept such a wholesome, independent, God-fearing, and self-reliant life for her family of five sons and six daughters, as constrains me, when I look back on it now, in the light of all I have since seen and known of others far differently situated, almost to worship her memory. She had gone with her high spirits and breezy disposition to gladden as their companion, the quiet abode of some grand or great-grand-uncle and aunt, familiarly named in all that Dalswinton neighborhood, "Old Adam and Eve." Their house was on the outskirts of the moor, and life for the young girl there had not probably too much excitement. But one thing had arrested her attention. She had noticed that a young stocking-maker from the "Brig End," James Paton, the son of William and Janet there, was in the habit of stealing alone into the quiet wood, book in hand, day after day, at certain hours, as if for private study and meditation. It was a very excusable curiosity that led the young bright heart of the girl to watch him devoutly reading and hear him reverently reciting (though she knew not then, it was Ralph Erskine's Gospel Sonnets, which he could say by heart sixty years afterwards, as he lay on his bed of death); and finally that curiosity awed itself into a holy respect, when she saw him lay aside his broad Scotch bonnet, kneel down under the sheltering wings of some tree, and pour out all his soul in daily prayers to God. As yet they had never spoken. What spirit moved her, let lovers tell—was it all devotion, or was it a touch of unconscious love kindling in her towards the yellow-haired and thoughtful youth? Or was there a stroke of mischief, of that teasing, which so often opens up the door to the most serious step in all our lives? Anyhow, one day she slipped in quietly, stole away his bonnet, and hung it on a branch near by, while his trance of devotion made him oblivious of all around; then, from a safe retreat, she watched and enjoyed his perplexity in seeking for and finding it! A second day this was repeated; but his manifest disturbance of mind, and his long pondering with the bonnet in hand, as if almost alarmed, seemed to touch another chord in her heart—that chord of pity which is so often the prelude of love, that finer pity that grieves to wound anything nobler or tenderer than ourselves. Next day, when he came to his accustomed place of prayer, a little card was pinned against the tree just where he knelt, and on it these words: "She who stole away your bonnet is ashamed of what she did; she has a great respect for you, and asks you to pray for her, that she may become as good a Christian as you."

Staring long at that writing, he forgot Ralph Erskine for one day! Taking down the card, and wondering who the writer could be, he was abusing himself for his stupidity in not suspecting that some one had discovered his retreat and removed his bonnet, instead of wondering whether angels had been there during his prayer,—when, suddenly raising his eyes, he saw in front of old Adam's cottage, though a lane amongst the trees, the passing of another kind of angel, swinging a milk-pail in her hand and merrily singing some snatch of old Scottish song. He knew, in that moment, by a Divine instinct, as infallible as any voice that ever came to seer of old, that she was the angel visitor that had stolen in upon his retreat—that bright-faced, clever-witted niece of old Adam and Eve, to whom he had never yet spoken, but whose praises he had often heard said and sung—"Wee Jen." I am afraid he did pray "for her," in more senses than one, that afternoon; at any rate, more than a Scotch bonnet was very effectually stolen; a good heart and true was there virtually bestowed, and the trust was never regretted on either side, and never betrayed.

Often and often, in the genial and beautiful hours of the autumntide of their long life, have I heard my dear father tease "Jen" about her maidenly intentions in the stealing of that bonnet; and often have heard her quick mother-wit in the happy retort, that had his motives for coming to that retreat been altogether and exclusively pious, he would probably have found his way to the other side of the wood, but that men who prowled about the Garden of Eden ran the risk of meeting some day with a daughter of Eve!

SOMEWHERE in or about his seventeenth year, my father passed through a crisis of religious experience; and from that day he openly and very decidedly followed the Lord Jesus. His parents had belonged to one of the older branches of what is now called the United Presbyterian Church; but my father, having made an independent study of the Scotch Worthies, the Cloud of Witnesses, the Testimonies, and the Confession of Faith, resolved to cast in his lot with the oldest of all the Scotch Churches, the Reformed Presbyterian, as most nearly representing the Covenanters and the attainments of both the first and second Reformations in Scotland. This choice he deliberately made, and sincerely and intelligently adhered to; and was able at all times to give strong and clear reasons from Bible and from history for the principles he upheld.

Besides this, there was one other mark and fruit of his early religious decision, which looks even fairer through all these years. Family Worship had heretofore been held only on Sabbath Day in his father's house; but the young Christian, entering into conference with his sympathizing mother, managed to get the household persuaded that there ought to be daily morning and evening prayer and reading of the Bible and holy singing. This the more readily, as he himself agreed to take part regularly in the same, and so relieve the old warrior of what might have proved for him too arduous spiritual toils! And so began in his seventeenth year that blessed custom of Family Prayer, morning and evening, which my father practised probably without one single avoidable omission till he lay on his deathbed, seventy-seven years of age; when ever to the last day of his life, a portion of Scripture was read, and his voice was heard softly joining in the Psalm, and his lips breathed the morning and evening Prayer,—falling in sweet benediction on the heads of all his children, far away many of them over all the earth, but all meeting him there at the Throne of Grace.

Our place of worship was the Reformed Presbyterian Church at Dumfries, under the ministry, during most of these days, of Rev. John McDermid—a genuine, solemn, lovable Covenanter, who cherished towards my father a warm respect, that deepened into apostolic affection when the yellow hair turned snow-white and both of them grew patriarchal in their years. The Minister, indeed, was translated to a Glasgow charge; but that rather exalted than suspended their mutual love. Dumfries was four miles fully from our Torthorwald home; but the tradition is that during all these forty years my father was only thrice prevented from attending the worship of God—once by snow, so deep that he was baffled and had to return; once by ice on the road, so dangerous that he was forced to crawl back up the Roucan Brae on his hands and knees, after having descended it so far with many falls; and once by the terrible outbreak of cholera at Dumfries.

Each of us, from very early days, considered it no penalty, but a great joy, to go with our father to the church; the four miles were a treat to our young spirits, the company by the way was a fresh incitement, and occasionally some of the wonders of city-life rewarded our eager eyes. A few other pious men and women, of the best Evangelical type, went from the same parish to one or other favorite Minister at Dumfries; and when these God-fearing peasants "forgathered" in the way to or from the House of God, we youngsters had sometimes rare glimpses of what Christian talk may be and ought to be.

We had, too, special Bible Readings on the Lord's Day evening,—mother and children and visitors reading in turns, with fresh and interesting question, answer, and exposition, all tending to impress us with the infinite grace of a God of love and mercy in the great gift of His dear Son Jesus, our Saviour. The Shorter Catechism was gone through regularly, each answering the question asked, till the whole had been explained, and its foundation in Scripture shown by the proof-texts adduced. It has been an amazing thing to me, occasionally to meet with men who blamed this "catechizing" for giving them a distaste to religion; every one in all our circle thinks and feels exactly the opposite. It laid the solid rock-foundations of our religious life. After-years have given to these questions and their answers a deeper or a modified meaning, but none of us has ever once even dreamed of wishing that we had been otherwise trained. Of course, if the parents are not devout, sincere, and affectionate,—if the whole affair on both sides is taskwork, or worse, hypocritical and false,—results must be very different indeed!

Oh, I can remember those happy Sabbath evenings; no blinds down, and shutters up, to keep out the sun from us, as some scandalously affirm; but a holy, happy, entirely human day, for a Christian father, mother and children to spend. Others must write and say what they will, and as they feel; but so must I. There were eleven of us brought up in a home like that; and never one of the eleven, boy or girl, man or woman, has been heard, or ever will be heard, saying that Sabbath was dull and wearisome for us, or suggesting that we have heard of or seen any way more likely than that for making the Day of the Lord bright and blessed alike for parents and for children. But God help the homes where these things are done by force and not by love!

As I must, however, leave the story of my father's life—much more worthy, in many ways, of being written than my own—I may here mention that his long and upright life made him a great favorite in all religious circles far and near within the neighborhood, that at sick-beds and at funerals he was constantly sent for and much appreciated, and that this appreciation greatly increased, instead of diminishing, when years whitened his long, flowing locks, and gave him an apostolic beauty; till finally, for the last twelve years or so of his life, he became by appointment a sort of Rural Missionary for the four nearest parishes, and spent his autumn in literally sowing the good seed of the Kingdom as a Colporteur of the Tract and Book Society of Scotland. His success in this work, for a rural locality, was beyond all belief. Within a radius of five miles he was known in every home, welcomed by the children, respected by the servants, longed for eagerly by the sick and aged. He gloried in showing off the beautiful Bibles and other precious books, which he sold in amazing numbers. He sang sweet Psalms beside the sick, and prayed like the voice of God at their dying beds. He went cheerily from farm to farm, from cot to cot; and when he wearied on the moorland roads, he refreshed his soul by reciting aloud one of Ralph Erskine's "Sonnets," or crooning to the birds one of David's Psalms. His happy partner, our beloved mother, died in 1865, and he himself in 1868, having reached his seventy-seventh year, an altogether beautiful and noble episode of human existence having been enacted, amid the humblest surroundings of a Scottish peasant's home, through the influence of their united love by the grace of God; and in this world, or in any world, all their children will rise up at mention of their names and call them blessed!

IN my boyhood, Torthorwald had one of the grand old typical Parish Schools of Scotland; where the rich and the poor met together in perfect equality; where Bible and Catechism were taught as zealously as grammar and geography; and where capable lads from the humblest of cottages were prepared in Latin and Mathematics and Greek to go straight from their Village class to the University bench. Besides, at that time, an accomplished pedagogue of the name of Smith, a learned man of more than local fame, had added a Boarding House to the ordinary School, and had attracted some of the better class gentlemen and farmers' sons from the surrounding country; so that Torthorwald, under his régime, reached the zenith of its educational fame. In this School I was initiated into the mystery of letters, and all my brothers and sisters after me, though some of them under other masters than mine. My teacher punished severely—rather, I should say, savagely—especially for lessons badly prepared. Yet, that he was in some respects kindly and tender-hearted, I had the best of reasons to know.

When still under twelve years of age, I started to learn my father's trade, in which I made surprising progress. We wrought from six in the morning till ten at night, with an hour at dinner-time and half an hour at breakfast and again at supper. These spare moments every day I devoutly spent on my books, chiefly in the rudiments of Latin and Greek; for I had given my soul to God, and was resolved to aim at being a Missionary of the Cross, or a Minister of the Gospel. Yet I gladly testify that what I learned of the stocking frame was not thrown away; the facility of using tools, and of watching and keeping the machinery in order, came to be of great value to me in the Foreign Mission field.

One incident of this time I must record here, because of the lasting impression made upon my religious life. Our family, like all others of peasant rank in the land, were plunged into deep distress, and felt the pinch severely, through the failure of the potato, the badness of other crops, and the ransom-price of food. Our father had gone off with work to Hawick, and would return next evening with money and supplies; but meantime the meal barrel ran low, and our dear mother, too proud and too sensitive to let any one know, or to ask aid from any quarter, coaxed us all to rest, assuring us that she had told God everything, and that He would send us plenty in the morning. Next day, with the carrier from Lockerbie came a present from her father, who, knowing nothing of her circumstances or of this special trial, had been moved of God to send at that particular nick of time a love-offering to his daughter, such as they still send to each other in those kindly Scottish shires—a bag of new potatoes, a stone of the first ground meal or flour, or the earliest homemade cheese of the season—which largely supplied all our need. My mother, seeing our surprise at such an answer to her prayers, took us around her knees, thanked God for His goodness, and said to us:

"O my children, love your Heavenly Father, tell Him in faith and prayer all your needs, and He will supply your wants so far as it shall be for your good and His glory."

Perhaps, amidst all their struggles in rearing a family of eleven, this was the hardest time they ever had, and the only time they ever felt the actual pinch of hunger; for the little that they had was marvelously blessed of God, and was not less marvelously utilized by that noble mother of ours, whose high spirit, side by side with her humble and gracious piety, made us, under God, what we are to-day.

I saved as much at my trade as enabled me to go for six weeks to Dumfries Academy; this awoke in me again the hunger for learning, and I resolved to give up that trade and turn to something that might be made helpful to the prosecution of my education. An engagement was secured with the Sappers and Miners, who were mapping and measuring the county of Dumfries in connection with the Ordnance Survey of Scotland. The office hours were from 9 A. M. till 4 P. M.; and though my walk from home was above four miles every morning, and the same by return in the evening, I found much spare time for private study, both on the way to and from my work and also after hours. Instead of spending the mid-day hour with the rest, at football and other games, I stole away to a quiet spot on the banks of the Nith, and there pored over my book, all alone. Our lieutenant, unknown to me, had observed this from his house on the other side of the stream, and after a time called me into his office and inquired what I was studying. I told him the whole truth as to my position and my desires. After conferring with some of the other officials there, he summoned me again, and in their presence promised me promotion in the service, and special training in Woolwich at the Government's expense, on condition that I would sign an engagement for seven years. Thanking him most gratefully for his kind offer, I agreed to bind myself for three years or four, but not for seven.

Excitedly he said, "Why? Will you refuse an offer that many gentlemen's sons would be proud of?"

I said, "My life is given to another Master, so I cannot engage for seven years." He asked sharply, "To whom?" I replied, "To the Lord Jesus; and I want to prepare as soon as possible for His service in the proclaiming of the Gospel."

In great anger he sprang across the room, called the paymaster and exclaimed, "Accept my offer, or you are dismissed on the spot!"

I answered, "I am extremely sorry if you do so, but to bind myself for seven years would probably frustrate the purpose of my life; and though I am greatly obliged to you, I cannot make such an engagement."

His anger made him unwilling or unable to comprehend my difficulty; the drawing instruments were delivered up, I received my pay, and departed, without further parley. Hearing how I had been treated, and why, Mr. Maxwell, the Rector of Dumfries Academy, offered to let me attend all classes there, free of charge so long as I cared to remain; but that, in lack of means of support, was for the time impossible, as I would not and could not be a burden on my dear father, but was determined rather to help him in educating the rest. I went therefore to what was known as the Lamb Fair at Lockerbie, and for the first time in my life took a "fee" for the harvest. On arriving at the field when shearing and mowing began, the farmer asked me to bind a sheaf; when I had done so, he seized it by the band, and it fell to pieces! Instead of disheartening me, however, he gave me a careful lesson how to bind; and the second that I bound did not collapse when shaken, and the third he pitched across the field, and on finding that it still remained firm, he cried to me cheerily:

"Right now, my lad; go ahead!"

It was hard work for me at first, and my hands got very sore; but, being willing and determined, I soon got into the way of it, and kept up with the best of them. The male harvesters were told off to sleep in a large hayloft, the beds being arranged all along the side, like barracks. Many of the fellows were rough and boisterous; and I suppose my look showed that I hesitated in mingling with them, for the quick eye and kind heart of the farmer's wife prompted her to suggest that I, being so much younger than the rest, might sleep with her son George in the house—an offer, oh, how gratefully accepted! A beautiful new steading had recently been built for them; and during certain days, or portions of days, while waiting for the grain to ripen or to dry, I planned and laid out an ornamental garden in front of it, which gave great satisfaction—a taste inherited from my mother, with her joy in flowers and garden plots. They gave me, on leaving, a handsome present, as well as my fee, for I had got on very pleasantly with them all. This experience, too, came to be valuable to me, when, in long-after days, and far other lands, Mission buildings had to be erected, and garden and field cropped and cultivated without the aid of a single European hand.

BEFORE going to my first harvesting, I had applied for a situation in Glasgow, apparently exactly suited for my case; but I had little or no hope of ever hearing of it further. An offer of £50 per annum was made by the West Campbell Street Reformed Presbyterian Congregation, then under the good and noble Dr. Bates, for a young man to act as district visitor and tract distributor, especially amongst the absentees from the Sabbath School; with the privilege of receiving one year's training at the Free Church Normal Seminary, that he might qualify himself for teaching, and thereby push forward to the Holy Ministry. The candidates, along with their application and certificates, were to send an essay on some subject, of their own composition, and in their own handwriting. I sent in two long poems on the Covenanters, which must have exceedingly amused them, as I had not learned to write even decent prose. But, much to my surprise, immediately on the close of the harvesting experience, a letter arrived, intimating that I, along with another young man, had been put upon the short leet, and that both were requested to appear in Glasgow on a given day and compete for the appointment.

Two days thereafter I started out from my quiet country home on the road to Glasgow. Literally "on the road," for from Torthorwald to Kilmarnock—about forty miles—had to be done on foot, and thence to Glasgow by rail. Railways in those days were as yet few, and coach-travelling was far beyond my purse. A small bundle contained my Bible and all my personal belongings. Thus was I launched upon the ocean of life. I thought on One who says, "I know thy poverty, but thou art rich."

My dear father walked with me the first six miles of the way. His counsels and tears and heavenly conversation on that parting journey are fresh in my heart as if it had been but yesterday; and tears are on my cheeks as freely now as then, whenever memory steals me away to the scene. For the last half mile or so we walked on together in almost unbroken silence,—my father, as was often his custom, carrying hat in hand, while his long, flowing yellow hair (then yellow, but in later years white as snow) streamed like a girl's down his shoulders. His lips kept moving in silent prayers for me; and his tears fell fast when our eyes met each other in looks of which all speech was vain! We halted on reaching the appointed parting-place; he grasped my hand firmly for a minute in silence, and then solemnly and affectionately said:

"God bless you, my son! Your father's God prosper you, and keep you from all evil!"

Unable to say more, his lips kept moving in silent prayer; in tears we embraced, and parted. I ran off as fast as I could; and, when about to turn a corner in the road where he would lose sight of me, I looked back and saw him still standing with head uncovered where I had left him—gazing after me. Waving my hat in adieu, I was round the corner and out of sight in an instant. But my heart was too full and sore to carry me farther, so I darted into the side of the road and wept for a time. Then, rising up cautiously, I climbed the dyke to see if he yet stood where I had left him; and just at that moment I caught a glimpse of him climbing the dyke and looking out for me! He did not see me, and after he had gazed eagerly in my direction for a while he got down, set his face towards home, and began to return—his head still uncovered, and his heart, I felt sure, still rising in prayers for me. I watched through blinding tears, till his form faded from my gaze; and then, hastening on my way, vowed deeply and oft, by the help of God, to live and act so as never to grieve or dishonor such a father and mother as He had given me. The appearance of my father, when we parted,—his advice, prayers, and tears—the road, the dyke, the climbing up on it and then walking away, head uncovered—have often, often, all through life, risen vividly before my mind, and do so now while I am writing, as if it had been but an hour ago. In my earlier years particularly, when exposed to many temptations, his parting form rose before me as that of a guardian angel.

I REACHED Glasgow on the third day, having slept one night at Thornhill, and another at New Cumnock; and having needed, owing to the kindness of acquaintances upon whom I called by the way, to spend only three halfpence of my modest funds. Safely arrived, but weary, I secured a humble room for my lodging, for which I had to pay one shilling and sixpence per week. Buoyant and full of hope and looking up to God for guidance, I appeared at the appointed hour before the examiners, as did also the other candidate; and they having carefully gone through their work, asked us to retire. When recalled, they informed us that they had great difficulty in choosing, and suggested that the one of us might withdraw in favor of the other, or that both might submit to a more testing examination. Neither seemed inclined to give it up, both were willing for a second examination; but the patrons made another suggestion. They had only £50 per annum to give; but if we would agree to divide it betwixt us, and go into one lodging, we might both be able to struggle through, they would pay our entrance fees at the Free Normal Seminary, and provide us with the books required; and perhaps they might be able to add a little to the sum promised to each of us. By dividing the mission work appointed, and each taking only the half, more time also might be secured for our studies. Though the two candidates had never seen each other before, we at once accepted this proposal, and got on famously together, never having had a dispute on anything of common interest throughout our whole career.

As our fellow-students at the Normal were all far advanced beyond us in their education, we found it killing work, and had to grind away incessantly, late and early. Both of us, before the year closed, broke down in health; partly by hard study, but principally, perhaps, for lack of nourishing diet. A severe cough seized upon me; I began spitting blood, and a doctor ordered me at once home to the country and forbade all attempts at study. My heart sank; it was a dreadful disappointment, and to me a bitter trial. Soon after, my companion, though apparently much stronger than I, was similarly seized. He, however, never entirely recovered, though for some years he taught in a humble school; and long ago he fell asleep in Jesus, a devoted and honored Christian man.

I, on the other hand, after a short rest, nourished by the hill air of Torthorwald and by the new milk of our family cow, was ere long at work again. Renting a house, I began to teach a small school at Girvan, and gradually but completely recovered my health.

Having saved £10 by my teaching, I returned to Glasgow, and was enrolled as a student at the College; but before the session was finished my money was exhausted—I had lent some to a poor student, who failed to repay me—and only nine shillings remained in my purse. There was no one from whom to borrow, had I been willing; I had been disappointed in attempting to secure private tuition; and no course seemed open for me, except to pay what little I owed, give up my College career, and seek for teaching or other work in the country. I wrote a letter to my father and mother, informing them of my circumstances; that I was leaving Glasgow in quest of work, and that they would, not hear from me again till I had found a suitable situation. I told them that if otherwise unsuccessful, I should fall back on my own trade, though I shrank from that as not tending to advance my education; but that they might rest assured I would do nothing to dishonor them or my own Christian profession. Having read that letter over again through many tears, I said,—I cannot send that, for it will grieve my darling parents; and therefore, leaving it on the table, I locked my room door and ran out to find a place where I might sell my precious books, and hold on a few weeks longer. But, as I stood on the opposite side and wondered whether these folks in a shop with the three golden balls would care to have a poor student's books, and as I hesitated, knowing how much I needed them for my studies, conscience smote me as if for doing a guilty thing; I imagined that the people were watching me like one about to commit a theft; and I made off from the scene at full speed, with a feeling of intense shame at having dreamed of such a thing! Passing through one short street into another, I marched on mechanically; but the Lord God of my father was guiding my steps, all unknown to me.

A certain notice in a window, into which I had probably never in my life looked before, here caught my eye, to this effect—"Teacher wanted, Maryhill Free Church school; apply at the Manse." A coach or bus was just passing, when I turned round; I leapt into it, saw the Minister, arranged to undertake the School, returned to Glasgow, paid my landlady's lodging score, tore up that letter to my parents and wrote another full of cheer and hope; and early next morning entered the School and began a tough and trying job. The Minister warned me that the School was a wreck, and had been broken up chiefly by coarse and bad characters from mills and coal-pits, who attended the evening classes. They had abused several masters in succession; and, laying a thick and heavy cane on the desk, he said:

"Use that freely, or you will never keep order here!"

I put it aside into the drawer of my desk, saying, "That will be my last resource."

There were very few scholars for the first week—about eighteen in the Day School and twenty in the Night School. The clerk of the mill, a good young fellow, came to the evening classes, avowedly to learn book-keeping, but privately he said he had come to save me from personal injury.

The following week, a young man and a young woman began to attend the Night School, who showed from the first moment that they were bent on mischief. On my repeated appeals for quiet and order, they became the more boisterous, and gave great merriment to a few of the scholars present. I finally urged the young man, a tall, powerful fellow, to be quiet or at once to leave, declaring that at all hazards I must and would have perfect order; but he only mocked at me, and assumed a fighting attitude. Quietly locking the door and putting the key in my pocket, I turned to my desk, armed myself with the cane, and dared any one at his peril to interfere betwixt us. It was a rough struggle—he smashing at me clumsily with his fists, I with quick movements evading and dealing him blow after blow with the heavy cane for several rounds—till at length he crouched down at his desk, exhausted and beaten, and I ordered him to turn to his book, which he did in sulky silence. Going to my desk, I addressed them and asked them to inform all who wished to come to the School,—That if they came for education, everything would be heartily done that it was in my power to do; but that any who wished for mischief had better stay away, as I was determined to conquer, not to be conquered, and to secure order and silence, whatever it might cost. Further, I assured them that that cane would not again be lifted by me, if kindness and forbearance on my part could possibly gain the day, as I wished to rule by love and not by terror. But this young man knew he was in the wrong, and it was that which had made him weak against me, though every way stronger far than I. Yet I would be his friend and helper, if he was willing to be friendly with me, the same as if this night had never been. At these words a dead silence fell on the School: every one buried face diligently in book; and the evening closed in uncommon quiet and order.

The attendance grew, till the School became crowded, both during the day and at night. During the mid-day hour even, I had a large class of young women who came to improve themselves in writing and arithmetic. By and by the cane became a forgotten implement; the sorrow and pain which I showed as to badly-done lessons, or anything blameworthy, proved the far more effectual penalty.

The School Committee had promised me at least ten shillings per week, and guaranteed to make up any deficit if the fees fell short of that sum; but if the income from fees exceeded that sum, all was to be mine. Affairs went on prosperously for a season; indeed, too much so for my selfish interest. The Committee took advantage of the large attendance and better repute of the School, to secure the services of a master of the highest grade. The parents of many of the children offered to take and seat a hall, if I would remain, but I knew too well that I had neither education nor experience to compete with an accomplished teacher. Their children, however, got up a testimonial and subscription, which was presented to me on the day before I left and this I valued chiefly because the presentation was made by the young fellows who at first behaved so badly, but were now my devoted friends.

Once more I committed my future to the Lord God of my father, assured that in my very heart I was willing and anxious to serve Him and to follow the blessed Saviour, yet feeling keenly that intense darkness had again enclosed my path.

BEFORE undertaking the Maryhill School, I had applied to be taken on as an agent in the Glasgow City Mission; and the night before I had to leave Maryhill, I received a letter from Rev. Thomas Caie, the superintendent of the said Mission, saying that the directors had kept their eyes on me ever since my application, and requesting, as they understood I was leaving the School, that I would appear before them the next morning, and have my qualifications for becoming a Missionary examined into. Praising God, I went off at once, passed the examination successfully, and was appointed to spend two hours that afternoon and the following Monday in visitation with two of the directors, calling at every house in a low district of the town, and conversing with all the characters encountered there as to their eternal welfare. I had also to preach a "trial" discourse in a Mission meeting, where a deputation of directors would be present, the following evening being Sunday; and on Wednesday evening they met again to hear their report and to accept or reject me.

All this had come upon me so unexpectedly, that I almost anticipated failure; but looking up for help I went through with it, and on the fifth day after leaving the School they called me before a meeting of directors, and informed me that I had passed my trials most successfully, and that the reports were so favorable that they had unanimously resolved to receive me at once as one of their City Missionaries. Deeply solemnized with the responsibilities of my new office, I left that meeting praising God for all His undeserved mercies, and seeing most clearly His gracious hand in all the way by which He had led me, and the trials by which He had prepared me for this sphere of service. Man proposes—God disposes.

I found the district a very degraded one. Many families said they had never been visited by any Minister; and many were lapsed professors of religion who had attended no church for ten, sixteen, or twenty years, and said they had never been called upon by any Christian visitor. In it were congregated many avowed infidels, Romanists, and drunkards,—living together, and associated for evil, but apparently without any effective counteracting influence. In many of its closes and courts sin and vice walked about openly—naked and not ashamed.

After nearly a year's hard work, I had only six or seven non-church-goers, who had been led to attend regularly there, besides about the same number who met on a week evening in the ground-floor of a house kindly granted for the purpose by a poor and industrious but ill-used Irishwoman. She supported her family by keeping a little shop, and selling coals. Her husband was a powerful man—a good worker, but a hard drinker; and, like too many others addicted to intemperance, he abused and beat her, and pawned and drank everything he could get hold of. She, amid many prayers and tears, bore everything patiently, and strove to bring up her only daughter in the fear of God. We exerted, by God's blessing, a good influence upon him through our meetings. He became a Total Abstainer, gave up his evil ways, and attended Church regularly with his wife. As his interest increased, he tried to bring others also to the meetings, and urged them to become Abstainers. His wife became a center of help and of good influence in all the district, as she kindly invited all and welcomed them to the meeting in her house, and my work grew every day more hopeful.

By and by Meetings and Classes were both too large for any house that was available for us in the whole of our district. We instituted a Bible Class, a Singing Class, a Communicants' Class, and a Total Abstinence Society; and, in addition to the usual meetings, we opened two prayer-meetings specially for the Calton division of the Glasgow Police—one at a suitable hour for the men on day duty, and another for those on night duty. The men got up a Mutual Improvement Society and Singing Class also amongst themselves, weekly, on another evening. My work now occupied every evening in the week; and I had two meetings every Sabbath. By God's blessing they all prospered, and gave evidence of such fruits as showed that the Lord was working there for good by our humble instrumentality.

The kind cowfeeder had to inform us—and he did it with much genuine sorrow—that at a given date he would require the hay-loft, which was our place of meeting; and as no other suitable house or hall could be got, the poor people and I feared the extinction of our work. At that very time however, a commodious block of buildings, that had been Church, Schools, Manse, etc., came into the market. My great-hearted friend, the late Thomas Binnie, persuaded Dr. Symingrton's congregation, Great Hamilton Street, in connection with which my Mission was carried on, to purchase the whole property. Its situation at the foot of Green Street gave it a control of the district where my work lay; and so the Church was given to me in which to conduct all my meetings, while the other Halls were adapted as Schools for poor girls and boys, where they were educated by a proper master, and were largely supplied with books, clothing, and sometimes even food, by the ladies of the congregation.

Availing myself of the increased facilities, my work was all reorganized. On Sabbath morning, at seven o'clock, I had one of the most deeply interesting and fruitful of all my Classes for the study of the Bible. It was attended by from seventy to a hundred of the very poorest young women and grown-up lads of the whole district. They had nothing to put on except their ordinary work-day clothes,—all without bonnets, some without shoes. Beautiful was it to mark how the poorest began to improve in personal appearance immediately after they came to our Class; how they gradually got shoes and one bit of clothing after another, to enable them to attend our other Meetings, and then to go to Church; and, above all, how eagerly they sought to bring others with them, taking a deep personal interest in all the work of the Mission. Long after they themselves could appear in excellent dress, many of them still continued to attend in their working clothes, and to bring other and poorer girls with them to that Morning Class, and thereby helped to improve and elevate their companions. My delight in that Bible Class was among the purest joys in all my life, and the results were amongst the most certain and precious of all my Ministry.

I had also a very large Bible Class—a sort of Bible-Reading—on Monday night, attended by all, of both sexes and of any age, who cared to come or had any interest in the Mission. Wednesday evening, again, was devoted to a prayer-meeting for all; and the attendance often more than half-filled the Church. There I usually took up some book of Holy Scripture and read and lectured right through, practically expounding and applying it. On Thursday I held a Communicants' Class, intended for the more careful instruction of all who wished to become full members of the Church. Our constant text-book was Paterson on the Shorter Catechism (Nelson and Sons), than which I have never seen a better compendium of the doctrines of Holy Scripture. Each being thus trained for a season, received from me, if found worthy, a letter to the Minister of any Protestant Church which he or she felt inclined to join. In this way great numbers became active and useful communicants in the surrounding congregations; and eight young lads of humble circumstances educated themselves for the Ministry of the Church—most of them getting their first lessons in Latin and Greek from my very poor stock of the same! Friday evening was occupied with a Singing Class, teaching Church music, and practising for our Sabbath meetings. On Saturday evening we held our Total Abstinence meeting, at which the members themselves took a principal part, in readings, addresses, recitations, singing hymns, etc.

Great good resulted from this Total Abstinence work. Many adults took and kept the pledge, thereby greatly increasing the comfort and happiness of their homes. Many were led to attend the Church on the Lord's Day, who had formerly spent it in rioting and drinking. But, above all, it trained the young to fear the very name of intoxicating drink, and to hate and keep far away from everything that led to intemperance.

I would add my testimony also against the use of tobacco, which injures and leads many astray, especially lads and young men, and which never can be required by any person in ordinary health. But I would not be understood to regard the evils that flow from it as deserving to be mentioned in comparison with the unutterable woes and miseries of intemperance.

To be protected, however, from suspicion and from evil, all the followers of our Lord Jesus should in self-denial (how small!) and in consecration to His service, be pledged Abstainers from both of these selfish indulgences, which are certainly injurious to many, which are no ornament to any character, and which can be no help in well-doing. Praise God for the many who are now so pledged!

ON one occasion, it becoming known that we had arranged for a special Saturday afternoon Temperance demonstration, a deputation of Publicans complained beforehand to the Captain of the Police—that our meetings were interfering with their legitimate trade. The Captain, a pious Wesleyan, who was in full sympathy with us and our work, informed me of the complaints made, and intimated that his men would be present; but I was just to conduct the meeting as usual, and he would guarantee that strict justice would be done. The Publicans having announced amongst their sympathizers that the Police were to break up and prevent our meeting and take the conductors in charge, a very large crowd assembled, both friendly and unfriendly, for the Publicans and their hangers-on were there "to see the fun," and to help in "baiting" the Missionary. Punctually, I ascended the stone stair, accompanied by another Missionary who was also to deliver an address, and announced our opening hymn. As we sang, a company of Police appeared, and were quietly located here and there among the crowd, the sergeant himself taking his post close by the platform, whence the whole assembly could be scanned. Our enemies were jubilant, and signals were passed betwixt them and their friends, as if the time had come to provoke a row. Before the hymn was finished, Captain Baker himself, to the infinite surprise of friend and foe alike, joined us on the platform, devoutly listened to all that was said, and waited till the close. The Publicans could not for very shame leave, while he was there at their suggestion and request, though they had wit enough to perceive that his presence had frustrated all their sinister plans. They had to hear our addresses and prayers and hymns; they had to listen to the intimation of our future meetings. When all had quietly dispersed, the Captain warmly congratulated us on our large and well-conducted congregation, and hoped that great good would result from our efforts. This opposition also the Lord overruled to increase our influence, and to give point and publicity to our assaults upon the kingdom of Satan.

Though Intemperance was the main cause of poverty, suffering, misery, and vice in that district of Glasgow, I had also considerable opposition from Romanists and Infidels, many of whom met in clubs, where they drank together, and gloried in their wickedness and in leading other young men astray.

An Infidel, whose wife was a Roman Catholic, became unwell, and gradually sank under great suffering and agony. His blasphemies against God were known and shuddered at by all the neighbors. His wife pled with me to visit him. She refused, at my suggestion, to call her own priest, so I accompanied her at last. The man refused to hear one word about spiritual things, and foamed with rage. He even spat at me, I mentioned the name of Jesus. "The natural receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God; for they are foolishness unto him!" There is a "wisdom" which is at best earthly, and at worst "sensual and devilish." I visited the poor man daily, but his enmity to God and his sufferings together seemed to drive him mad. Towards the end I pleaded with him even then to look to the Lord Jesus, and asked if I might pray with him? With all his remaining strength he shouted at me, "Pray for me to the devil!"

Reminding him how he had always denied that there was any devil, I suggested that he must surely believe in one now, else he would scarcely make such a request, even in mockery. In great rage he cried, "Tes, I believe there is a devil, and a God, and a just God too; but I have hated Him in life, and I hate Him in death!" With these awful words he wriggled into Eternity; but his shocking death produced a very serious impression for good, especially amongst young men, in the district where his character was known.

How different was the case of that Doctor who also had been an unbeliever as well as a drunkard! Highly educated, skilful, and gifted above most in his profession, he was taken into consultation for specially dangerous cases, whenever they could find him tolerably sober. After one of his excessive "bouts" he had a dreadful attack of delirium tremens. At one time wife and watchers had a fierce struggle to dash from his lips a draught of prussic acid; at another, they detected the silver-hafted lancet concealed in the band of his shirt, as he lay down, to bleed himself to death. His aunt came and pleaded with me to visit him. My heart bled for his poor young wife and two beautiful little children. Visiting him twice daily, and sometimes even more frequently, I found the way somehow into his heart, and he would do almost anything for me and longed for my visits. When again the fit of self-destruction seized him, they sent for me; he held out his hand eagerly, and grasping mine said, "Put all these people out of the room, remain you with me; I will be quiet, I will do everything you ask!"

I got them all to leave, but whispered to one in passing to "keep near the door."

Alone I sat beside him, my hand in his, and kept up a quiet conversation for several hours. After we had talked of everything that I could think of, and it was now far into the morning, I said, "If you had a Bible here, we might read a chapter, verse about."

He said dreamily, "There was once a Bible above yon press; if you can get up to it, you might find it there yet."

Getting it, dusting it, and laying it on a small table which I drew near to the sofa on which we sat, we read there and then a chapter together. After this I said; "Now, shall we pray?"

He replied heartily, "Yes."

I having removed the little table, we kneeled down together at the sofa; and after a solemn pause I whispered, "You pray first."

He replied, "I curse, I cannot pray; would you have me curse God to His face?"

I answered, "You promised to do all that I asked; you must pray, or try to pray, and let me hear that you cannot."

He said, "I cannot curse God on my knees; let me stand, and I will curse Him; I cannot pray."

I gently held him on his knees, saying, "Just try to pray, and let me hear you cannot."

Instantly he cried out, "O Lord, Thou knowest I cannot pray," and was going to say something dreadful as he strove to rise up. But I took up gently the words he had uttered as if they had been my own and continued the prayer, pleading for him and his dear ones as we knelt there together, till he showed that he was completely subdued and lying low at the feet of God. On rising from our knees he was manifestly greatly impressed, and I said, "Now, as I must be at College by daybreak and must return to my lodging for my books and an hour's rest, will do you one thing more for me before I go?"

"Yes," was his reply.

"Then," said I, "it is long since you had a refreshing sleep: now, will you lie down, and I will sit by you till you fall asleep?"

He lay down, and was soon fast asleep. After commending him to the care and blessing of the Lord, I quietly slipped out, and his wife returned to watch by his side. When I came back later in the day, after my Classes were over, he, on hearing my foot and voice, came to meet me, and clasping me in his arms, cried, "Thank God, I can pray now! I rose this morning refreshed from sleep, and prayed with my wife and children for the first time in my life; and now I shall do so every day, and serve God while I live, who hath dealt in so great mercy with me!"

After delightful conversation, he promised to go with me to Dr. Symington's church on Sabbath Day; there he took sittings beside me; at next half-yearly Communion he and his wife were received into membership, and their children were baptized; and from that day till his death he led a devoted and most useful Christian life. He now sleeps in Jesus; and I do believe I shall meet him in Glory as a trophy of redeeming grace and love!

In my Mission district I was the witness of many joyful departures to be with Jesus,—I do not like to name them "deaths" at all. They left us rejoicing in the bright assurance that nothing present or to come "could ever separate them or us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord." Many examples might be given; but I can find room for only one. John Sim, a dear little boy, was carried away by consumption. His child-heart seemed to be filled with joy about seeing Jesus. His simple prattle, mingled with deep questionings, arrested not only his young companions, but pierced the hearts of some careless sinners who heard him, and greatly refreshed the faith of God's dear people. It was the very pathos of song incarnated to hear the weak quaver of his dying voice sing out—

"I lay my sins on Jesus,

The spotless Lamb of God."

Shortly before his decease he said to his parents, "I am going soon to be with Jesus; but I sometimes fear that I may not see you there."

"Why so, my child?" said his weeping mother.

"Because," he answered, "if you were set upon going to Heaven and seeing Jesus there, you would pray about it, and sing about it; you would talk about Jesus to others, and tell them of that happy meeting with Him in Glory. All this my dear Sabbath School teacher taught me, and she will meet me there. Now why did not you, my father and mother, tell me all these things about Jesus, if you are going to meet Him too?" Their tears fell fast over their dying child; and he little knew, in his unthinking eighth year, what a message from God had pierced their souls through his innocent words.

One day an aunt from the country visited his mother, and their talk had run in channels for which the child no longer felt any interest. On my sitting down beside him, he said, "Sit you down and talk with me about Jesus; I am tired hearing so much talk about everything else but Jesus; I am going soon to be with Him. Oh, do tell me everything you know or have ever heard about Jesus, the spotless Lamb of God!"

At last the child literally longed to be away, not for rest, or freedom from pain—for of that he had very little—but, as he himself always put it, "to see Jesus." And, after all, that was the wisdom of the heart, however he learned it. Eternal life, here or hereafter, is just the vision of Jesus.

HAPPY in my work as I felt through these ten years, and successful by the blessing of God, yet I continually heard, and chiefly during my last years in the Divinity Hall, the wail of the perishing Heathen in the South Seas; and I saw that few were caring for them, while I well knew that many would be ready to take up my work in Calton, and carry it forward perhaps with more efficiency than myself. Without revealing the state of my mind to any person, this was the supreme subject of my daily meditation and prayer; and this also led me to enter upon those medical studies, in which I purposed taking the full course; but at the close of my third year, an incident occurred, which led me at once to offer myself for the Foreign Mission field.

The Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland, in which I had been brought up, had been advertising for another Missionary to join the Rev. John Inglis in his grand work on the New Hebrides. Dr. Bates, the excellent convener of the Heathen Missions Committee, was deeply grieved, because for two years their appeal had failed. At length, the Synod, after much prayer and consultation, felt the claims of the Heathen so gently pressed upon them by the Lord's repeated calls, that they resolved to cast lots, to discover whether God would thus select any Minister to be relieved from his home-charge, and designated as a Missionary to the South Seas. Each member of Synod, as I was informed, agreed to hand in, after solemn appeal to God, the names of the three best qualified in his esteem for such a work, and he who had the clear majority was to be loosed from his congregation, and to proceed to the Mission field—or the first and second highest, if two could be secured. Hearing this debate, and feeling an intense interest in these most unusual proceedings, I remember yet the hushed solemnity of the prayer before the names were handed in. I remember the strained silence that held the Assembly while the scrutineers retired to examine the papers; and I remember how tears blinded my eyes when they returned to announce that the result was so indecisive, that it was clear that the Lord had not in that way provided a Missionary. The cause was once again solemnly laid before God in prayer, and a cloud of sadness appeared to fall over all the Synod.

The Lord kept saying within me, "Since none better qualified can be got, rise and offer yourself!" Almost overpowering was the impulse to answer aloud, "Here am I, send me." But I was dreadfully afraid of mistaking my mere human emotions for the will of God. So I resolved to make it a subject of close deliberation and prayer for a few days longer, and to look at the proposal from every possible aspect. Besides, I was keenly solicitous about the effect upon the hundreds of young people and others, now attached to all my Classes and Meetings; and yet I felt a growing assurance that this was the call of God to His servant, and that He who was willing to employ me in the work abroad, was both able and willing to provide for the on-carrying of my work at home. My medical studies, as well as my literary and divinity training, had specially qualified me in some ways for the Foreign field, and from every aspect at which I could look the whole facts in the face, the voice within me sounded like a voice from God.

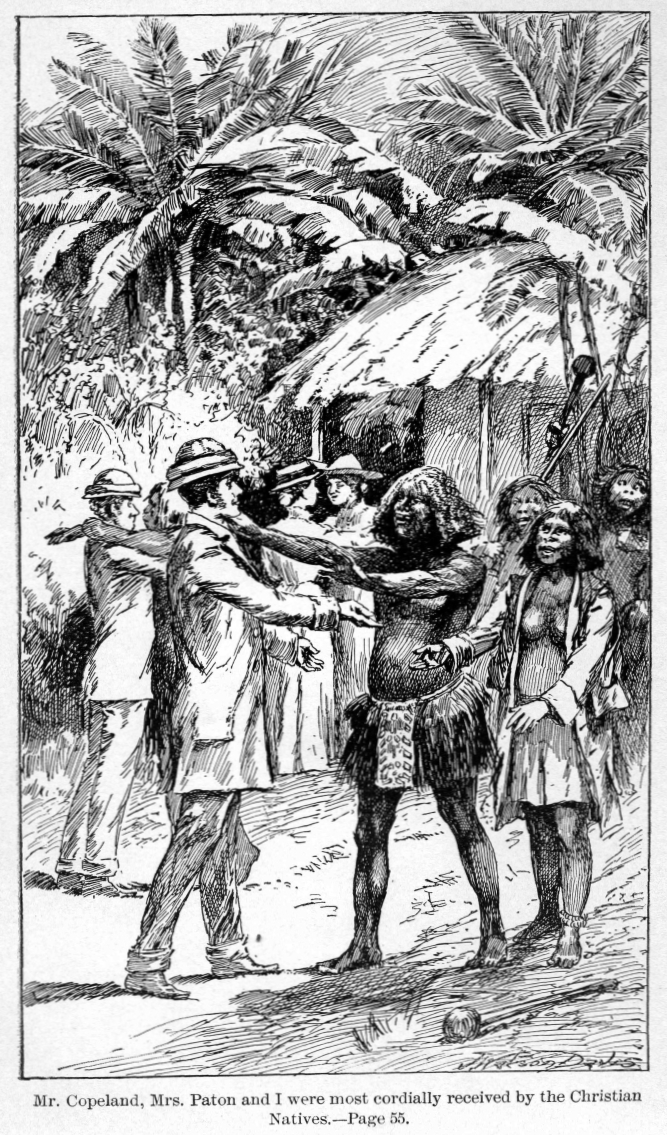

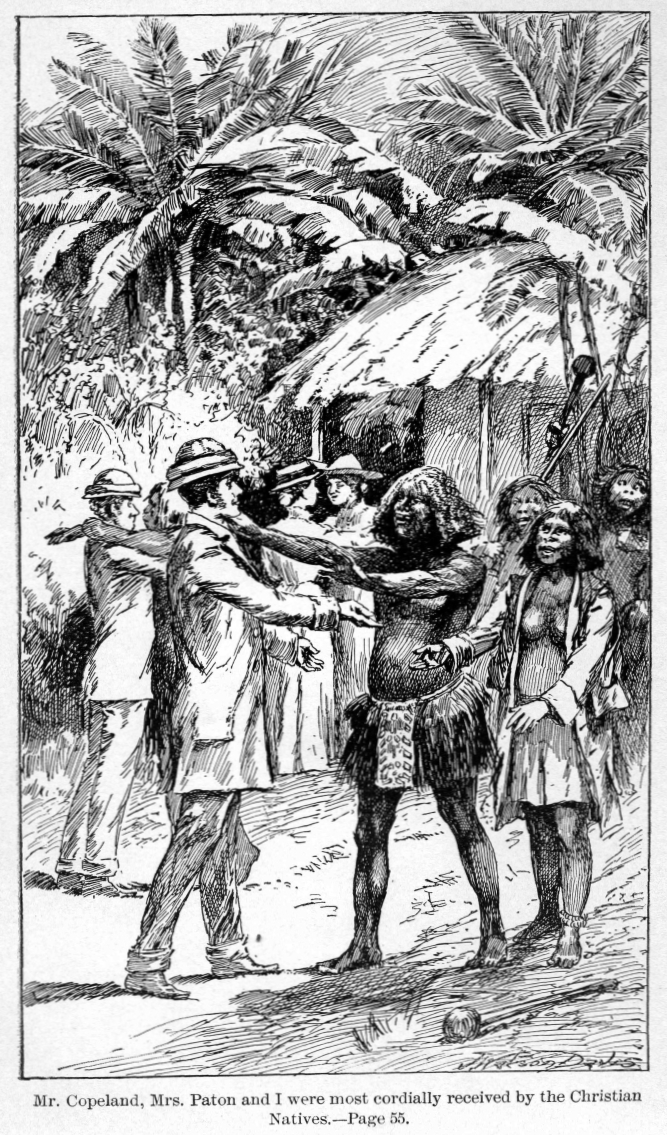

It was under good Dr. Bates of West Campbell Street that I had begun my career in Glasgow—receiving £25 per annum for district visitation in connection with his Congregation, along with instruction under Mr. Hislop and his staff in the Free Church Normal Seminary—and oh, how Dr. Bates did rejoice, and even weep for joy, when I called on him, and offered myself for the New Hebrides Mission! I returned to my lodging with a lighter heart than I had for sometime enjoyed, feeling that nothing so clears the vision, and lifts up the life, as a decision to move forward in what you know to be entirely the will of the Lord. I said to my fellow-student, Joseph Copeland, who had chummed with me all through our course at college, "I have been away signing my banishment" (a rather trifling way of talk for such an occasion). "I have offered myself as a Missionary for the New Hebrides."

After a long and silent meditation, in which he seemed lost in far-wandering thoughts, his answer was, "If they will accept of me, I am also resolved to go!"

I said, "Will you write the Convener to that effect, or let me do so?"

He replied, "You may."

A few minutes later his letter of offer was in the post-office. Next morning Dr. Bates called upon us, early, and after a long conversation, commended us and our future work to the Lord God in fervent prayer. At a meeting of the Foreign Missions Committee, held immediately thereafter, both were, after due deliberation, formally accepted, on condition that we passed successfully the usual examinations required of candidates for the Ministry. And for the next twelve months we were placed under a special committee for advice as to medical experience, acquaintance with the rudiments of trades, and anything else which might be thought useful to us in the Foreign field.

When it became known that I was preparing to go abroad as Missionary, nearly all were dead against the proposal, except Dr. Bates and my fellows-student. My dear father and mother, however, when I consulted them, characteristically replied, "that they had long since given me away to the Lord, and in this matter also would leave me to God's disposal." From other quarters we were besieged with the strongest opposition on all sides. Even Dr. Symington, one of my professors in divinity, and the beloved Minister in connection with whose congregation I had wrought so long as a City Missionary, and in whose Kirk Session I had for years sat as an Elder, repeatedly urged me to remain at home.

To his arguments I replied, "that my mind was finally resolved; that, though I loved my work and my people, yet I felt that I could leave them to the care of Jesus, who would soon provide them a better pastor than I; and that, with regard to my life amongst the Cannibals, as I had only once to die, I was content to leave the time and place and means in the hand of God who had already marvelously preserved me when visiting cholera patients and the fever-stricken poor; on that score I had positively no further concern, having left it all absolutely to the Lord, whom I sought to serve and honor, whether in life or by death."

The house connected with my Green Street Church was now offered to me for a Manse, and any reasonable salary that I cared to ask (as against the promised £120 per annum for the far-off and dangerous New Hebrides), on condition that I would remain at home. I cannot honestly say that such offers or opposing influences proved a heavy trial to me; they rather tended to confirm my determination that the path of duty was to go abroad.

Amongst many who sought to deter me, was one dear old Christian gentleman, whose crowning argument always was, "The cannibals! you will be eaten by cannibals!" At last I replied, "Mr. Dickson, you are advanced in years now, and your own prospect is soon to be laid in the grave, there to be eaten by worms, I confess to you, that if I can but live and die serving and honoring the Lord Jesus, it will make no difference to me whether I am eaten by cannibals or by worms; and in the Great Day my resurrection body will arise as fair as yours in the likeness of our risen Redeemer."

The old gentleman, raising his hands in a deprecating attitude, left the room exclaiming, "After that I have nothing more to say!"

My dear Green Street people grieved excessively at the thought of my leaving them, and daily pleaded with me to remain. Indeed, the opposition was so strong from nearly all, and many of them warm Christian friends, that I was sorely tempted to question whether I was carrying out the Divine will, or only some headstrong wish of my own. But conscience said louder and clearer every day, "Leave all these results with Jesus your Lord, who said, 'Go ye into all the world, preach the Gospel to every creature, and lo! I am with you alway.'" These words kept ringing in my ears; these were our marching orders.

Some retorted upon me, "There are Heathen at home; let us seek and save, first of all, the lost ones perishing at our doors." This I felt to be most true, and an appalling fact; but I unfailingly observed that those who made this retort neglected these Home Heathen themselves; and so the objection, as from them, lost all its power.

On meeting, however, with so many obstructing influences, I again laid the whole matter before my dear parents, and their reply was to this effect:—"Heretofore we feared to bias you, but now we must tell you why we praise God for the decision to which you have been led. Your father's heart was set upon being a Minister, but other claims forced him to give it up! When you were given to them, your father and mother laid you upon the altar, their first-born, to be consecrated, if God saw fit, as a Missionary of the Cross; and it has been their constant prayer that you might be prepared, qualified, and led to this very decision; and we pray with all our heart that the Lord may accept your offering, long spare you, and give you many souls from the Heathen World for your hire." From that moment, every doubt as to my path of duty forever vanished. I saw the hand of God very visibly, not only preparing me for, but now leading me to, the Foreign Mission field.

Well did I know that the sympathy and prayers of my dear parents were warmly with me in all my studies and in all my Mission work; but for my education they could of course, give me no money help. All through, on the contrary, it was my pride and joy to help them, being the eldest in a family of eleven; though I here most gladly and gratefully record that all my brothers and sisters, as they grew up and began to earn a living, took their full share in this same blessed privilege. For we stuck to each other and to the old folks like burs, and had all things "in common," as a family in Christ—and I knew that never again, howsoever long they might be spared through the peaceful autumn of life, would the dear old father and mother lack any joy or comfort that the willing hands and loving hearts of all their children could singly or unitedly provide. For all this I did praise the Lord! It consoled me beyond description, in parting from them, probably forever, in this world at least.

ON the first of December 1857—being then in my thirty-third year—the other Missionary-designate and I were "licensed" as preachers of the Gospel. Thereafter we spent four months in visiting and addressing nearly every Congregation and Sabbath School in the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland, that the people might see us and know us, and thereby take a personal interest in our work. On the 23d March 1858, in Dr. Symington's church, Glasgow, in presence of a mighty crowd, and after a magnificent sermon on "Come over and help us," we were solemnly ordained as Ministers of the Gospel, and set apart as Missionaries to the New Hebrides. On the 16th April of the same year, we left the Tail of the Bank at Greenock, and set sail in the Clutha for the Foreign Mission field.

Our voyage to Melbourne was rather tedious, but ended prosperously, under Captain Broadfoot, a kindly, brave-hearted Scot, who did everything that was possible for our comfort. He himself led the singing on board at Worship, which was always charming to me, and was always regularly conducted—on deck when the weather was fair, below when it was rough. I was also permitted to conduct Bible Classes amongst both the crew and the passengers, at times and places approved of by the Captain—in which there was great joy.

Arriving at Melbourne, we were welcomed by Rev. Mr. Moor, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Wilson, and Mr. Wright, all Reformed Presbyterians from Geelong. Mr. Wilson's two children, Jessie and Donald, had been under our care during the voyage; and my young wife and I went with them for a few days on a visit to Geelong, while Mr. Copeland remained on board the Clutha to look after our boxes and to watch for any opportunity of reaching our destination on the Islands. He heard that an American ship, the Frances P. Sage, was sailing from Melbourne to Penang; and the Captain agreed to land us on Aneityum, New Hebrides, with our two boats and fifty boxes, for £100. We got on board on the 12th August, but such a gale blew that we did not sail till the 17th. On the Clutha all was quiet, and good order prevailed; in the F. P. Sage all was noise and profanity. The Captain said he kept his second mate for the purpose of swearing at the men and knocking them about. The voyage was most disagreeable to all of us, but fortunately it lasted only twelve days. On the 29th we were close up to Aneityum; but the Captain refused to land us, even in his boats; some of us suspecting that his men were so badly used that had they got on shore they would never have returned to him! In any case he had beforehand secured his £100.

He lay off the island till a trader's boat pulled across to see what we wanted, and by it we sent a note to Dr. Geddie, one of the Missionaries there. Early next horning, Monday, he arrived in his boat, accompanied by Mr. Mathieson, a newly arrived Missionary from Nova Scotia; bringing also Captain Andersen in the small Mission schooner, the John Knox, and a large Mission boat called the Columbia, well manned with crews of able and willing Natives. Our fifty boxes were soon on board the John Knox, the Columbia, and our own boats—all being heavily loaded and built up, except those that had to be used in pulling the others ashore. Dr. Geddie, Mr. Mathieson, Mrs. Paton, and I were perched among the boxes on the John Knox, and had to hold on as best we could. On sheering off from the F. P. Sage, one of her davits caught and broke the mainmast of the little John Knox by the deck; and I saved my wife from being crushed to death by its fall, through managing to swing her instantaneously aside in an apparently impossible manner. It did graze Mr. Mathieson, but he was not hurt. The John Knox, already overloaded, was thus quite disabled; we were about ten miles at sea, and in imminent danger; but the captain of the F. P. Sage heartlessly sailed away, and left us to struggle with our fate.