TABLE OF CONTENTS:

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES:

❧

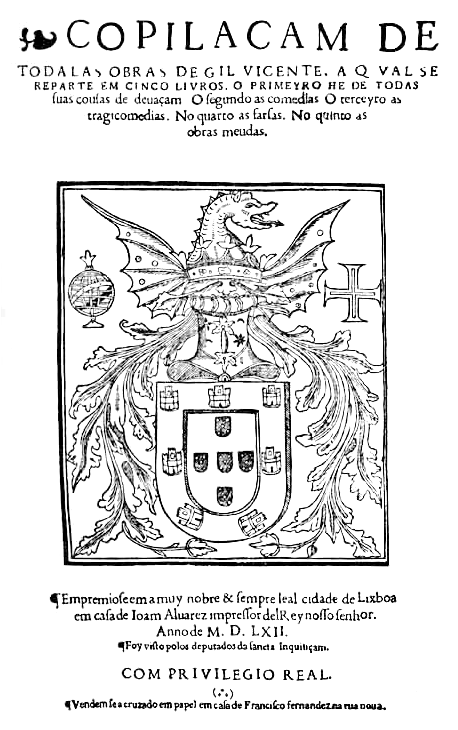

COPILACAM DE

TODALAS OBRAS DE GIL VICENTE, A QVAL SE

REPARTE EM CINCO LIVROS O PRIMEYRO HE DE TODAS

suas cousas de deuaçam. O segundo as comedias. O terceyro as

tragicomedias. No quarto as farsas. No quinto as

obras meudas.

¶ Empremiose em a muy nobre & sempre leal cidade de Lixboa em casa de Ioam Aluarez impressor del Rey nosso senhor Anno de M D LXII

¶ Foy visto polos deputados da Sancta Inquisiçam.

COM PRIVILEGIO REAL.

(⁂)

¶ Vendem se a cruzado em papel em casa de Francisco fernandez na rua noua.

TITLE-PAGE OF THE FIRST (1562) EDITION OF GIL VICENTE'S WORKS

Edited from the editio princeps (1562),

with

Translation and Notes, by

AUBREY F. G. BELL

Θαρρει̂ν χρὴ τὸν καὶ σμικρόν τι δυνάμεηοη εἰς τὸ πρόσθεν ἀεὶ προϊέναι.

Plato, Sophistes.

CAMBRIDGE

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

1920

KRAUS REPRINT CO.

New York

1969

TO ALL THOSE WHO HAVE LABOURED IN

THE VICENTIAN VINEYARD

LC 24-15201

First Published 1920

Reprinted by permission of the Cambridge University Press

KRAUS REPRINT CO.

A U. S. Division of Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited

Printed in U. S. A.

Gil Vicente, that sovereign genius[1], is too popular and indigenous for translation and this may account for the fact that he has not been presented to English readers. It is hoped, however, that a fairly accurate version, with the text in view[2], may give some idea of his genius. The religious, the patriotic-imperial, the satirical and the pastoral sides of his drama are represented respectively by the Auto da Alma, the Exhortação, the Almocreves and the Serra da Estrella, while his lyrical vein is seen in the Auto da Alma and in two delightful songs: the serranilha of the Almocreves and the cossante of the Serra da Estrella. Many of his plays, including some of the most charming of his lyrics, were written in Spanish and this limited the choice from the point of view of Portuguese literature, but there are others of the Portuguese plays fully as well worth reading as the four here given.

The text is that of the exceedingly rare first edition (1562). Apart from accents and punctuation, it is reproduced without alteration, unless a passage is marked by an asterisk, when the text of the editio princeps will be found in the foot-notes, in which variants of other editions are also given.

In these notes A represents the editio princeps (1562): Copilaçam de todalas obras de Gil Vicente, a qual se reparte em cinco livros. O primeyro he de todas suas cousas de deuaçam. O segundo as comedias. O terceyro as tragicomedias. No quarto as farsas. No quinto as obras meudas. Empremiose em a muy nobre & sempre leal cidade de Lixboa em casa de Ioam Aluarez impressor del Rey nosso senhor. Anno de MDLXII. The second (1586) edition (B) is the Copilaçam de todalas obras de Gil Vicente... Lixboa, por Andres Lobato, Anno de MDLXXXVJ. A third edition in three volumes appeared in 1834 (C): Obras de Gil Vicente, correctas e emendadas pelo cuidado e diligencia de J. V. Barreto Feio e J. G. Monteiro. Hamburgo, 1834. This was based, although not always with scrupulous accuracy, on the editio princeps, and subsequent editions have faithfully adhered to that of 1834: Obras, 3 vol. Lisboa, 1852 (D), and Obras, ed. Mendes dos Remedios, 3 vol. Coimbra,[Pg vi] 1907, 12, 14 [Subsidios, vol. 11, 15, 17][3] (E). Although there has been a tendency of late to multiply editions of Gil Vicente, no attempt has been made to produce a critical edition. It is generally felt that that must be left to the master hand of Dona Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcellos[4]. Since the plays of Vicente number over forty the present volume is only a tentative step in this direction, but it may serve to show the need of referring to, and occasionally emending, the editio princeps in any future edition of the most national poet of Portugal[5].

AUBREY F. G. BELL.

8 April 1920.

[1] Este soberano ingenio. Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, Antologia, tom. 7, p. clxiii.

[2] Although the text has been given without alteration it has not been thought necessary to provide a precise rendering of the coarser passages.

[3] The Paris 1843 edition is the Hamburg 1834 edition with a different title-page. The Auto da Alma was published separately at Lisbon in 1902 and again (in part) in Autos de Gil Vicente. Compilação e prefacio de Affonso Lopes Vieira, Porto, 1916; while extracts appeared in Portugal. An Anthology, edited with English versions, by George Young. Oxford, 1916. The present text and translation are reprinted, by permission of the Editor, from The Modern Language Review.

[4] I understand that the eminent philologist Dr José Leite de Vasconcellos is also preparing an edition.

[5] Facsimiles of the title-pages of the two early editions of Vicente's works are reproduced here through the courtesy of Senhor Anselmo Braamcamp Freire.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | v |

| INTRODUCTION | ix |

| AUTO DA ALMA (The Soul's Journey) | 1 |

| EXHORTAÇAO DA GUERRA (Exhortation to War) | 23 |

| FARSA DOS ALMOCREVES (The Carriers) | 37 |

| TRAGICOMEDIA PASTORIL DA SERRA DA ESTRELLA | 55 |

| NOTES | 73 |

| LIST OF PROVERBS IN GIL VICENTE'S WORKS | 84 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY OF GIL VICENTE | 86 |

| CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE OF GIL VICENTE'S LIFE AND WORKS | 89 |

| INDEX OF PERSONS AND PLACES | 95 |

|

|

|

| FACSIMILE OF TITLE-PAGE OF THE FIRST EDITION (1562) OF GIL VICENTE'S WORKS |

Frontispiece |

| FACSIMILE OF TITLE-PAGE OF THE SECOND EDITION (1586) | page lii |

Those who read the voluminous song-book edited by jolly Garcia de Resende in 1516 are astonished at its narrowness and aridity. There is scarcely a breath of poetry or of Nature in these Court verses. In the pages of Gil Vicente[6], who had begun to write fourteen years before the Cancioneiro Geral was published, the Court is still present, yet the atmosphere is totally different. There are many passages in his plays which correspond to the conventional love-poems of the courtiers and he maintains the personal satire to be found both in the [Pg x]Cancioneiro da Vaticana and the Cancioneiro de Resende. But he is also a child of Nature, with a marvellous lyrical gift and the insight to revive and renew the genuine poetry which had existed in Galicia and the north of Portugal before the advent of the Provençal love-poetry, had sprung into a splendid harvest in rivalry with that poetry and died down under the Spanish influence of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. He was moreover a national and imperial poet, embracing the whole of Portuguese life and the whole rapidly growing Portuguese empire. We can only account for the difference by saying that Gil Vicente was a genius, the only great genius of that day in Portugal, and the most gifted poet of his time. It is therefore all the more tantalizing that we should know so little about him. A few documents recently unearthed, one or two scanty references by contemporary or later authors, are all the information we have apart from that which may be gleaned from the rubrics and colophons of his plays and from the plays themselves. The labours of Dona Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcellos, Dr José Leite de Vasconcellos[7] and Snr Anselmo Braamcamp Freire are likely to provide us before long with the first critical edition of his plays. The ingenious suppositions of Dr Theophilo Braga[8] have, as usual, led to much discussion and research. He is the Mofina Mendes of critics, putting forward a hypothesis, translating it a few pages further on into a certainty and building rapidly on these foundations till an argument adduced or a document discovered by another critic brings the whole edifice toppling to the ground. The documents brought to light by General Brito Rebello[9] and Senhor Anselmo Braamcamp Freire[10] enable us to construct a sketch of Gil Vicente's life, while D. Carolina Michaëlis has shed a flood of light upon certain points[11]. The chronological table at the end of this volume is founded mainly, as to the order of the plays, on the documents and arguments recently set forth by one of the most distinguished of modern historical critics, Senhor Anselmo Braamcamp Freire. The plays, read in this order, throw a certain amount of new light on Gil Vicente's life and give it a new cohesion. Whether we consider it from the point of view of his own country or of the world, or of literature, art and science, his life coincides with one of the most wonderful periods in the world's history. At his birth Portugal was a sturdy mediaeval country, proud of her traditions and heroic past. Her heroes were so national as scarcely to be known beyond her own borders. Nun' Alvarez (1360-1431), one of the greatest men of all time, is even now unknown to Europe. And Portugal herself as yet hardly[Pg xi] appraised at its true worth the life and work of Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460), at whose incentive she was still groping persistently along the western coast of Africa. His nephew Afonso V, the amiable grandson of Nun' Alvarez' friend, the Master of Avis, and the English princess Philippa of Lancaster, daughter of John of Gaunt, was on the throne, to be succeeded by his stern and resolute son João II in 1481. In his boyhood, spent in the country, somewhere in the green hills of Minho or the rugged grandeur and bare, flowered steeps of the Serra da Estrella, all ossos e burel[12], Gil Vicente might hear dramatic stories of the doings at the capital and Court, of the beginning of the new reign, of the beheadal of the Duke of Braganza in the Rocio of Evora, of the stabbing by the King's own hand of his cousin and brother-in-law, the young Duke of Viseu, of the baptism and death at Lisbon of a native prince from Guinea.

The place of his birth is not certain. Biographers have hesitated between Lisbon, Guimarães and Barcellos: perhaps he was not born in any of these towns but in some small village of the north of Portugal. We can at least say that he was not brought up at Lisbon. The proof is his knowledge and love of Nature and his intimate acquaintance with the ways of villagers, their character, customs, amusements, dances, songs and language. It is legitimate to draw certain inferences—provided we do not attach too great importance to them—from his plays, especially since we know that he himself staged them and acted in them[13]. His earliest compositions are especially personal and we may be quite sure that the parts of the herdsman in the Visitaçam (1502) and of the mystically inclined shepherd, Gil Terron, in the Auto Pastoril Castelhano (1502) and the rustico pastor in the Auto dos Reis Magos (1503) were played by Vicente himself. It is therefore well to note the passage in which Silvestre and Bras express surprise at Gil's learning:

S. Mudando vas la pelleja,

Sabes de achaque de igreja!

G. Ahora lo deprendi....

B. Quien te viese no dirá

Que naciste en serranía.

G. Dios hace estas maravillas.

It is possible that Gil Vicente, like Gil Terron, had been born en serranía. Dr Leite de Vasconcellos was the first to call attention to his special knowledge of the province of Beira, and the reference to the[Pg xii] Serra da Estrella dragged into the Comedia do Viuvo is of even more significance than the conventional beirão talk of his peasants. Nor is the learning in his plays such as to give a moment's support to the theory that he had, like Enzina, received a university education, or, as some, relying on an unreliable nobiliario, have held, was tutor (mestre de rhetorica) to Prince, afterwards King, Manuel. The King, according to Damião de Goes, 'knew enough Latin to judge of its style.' Probably he did not know much more of it than Gil Vicente himself. His first productions are without the least pretension to learning: they are close imitations of Enzina's eclogues. Later his outlook widened; he read voraciously[14] and seems to have pounced on any new publication that came to the palace, among them the works of two slightly later Spanish playwrights, Lucas Fernández and Bartolomé de Torres Naharro. With the quickness of genius and spurred forward by the malicious criticism of his audience, their love of new things and the growing opposition of the introducers of the new style from Italy, he picked up a little French and Italian, while Church Latin and law Latin early began to creep into his plays. The parade of erudition (which is also a satire on pedants) at the beginning of the Auto da Mofina Mendes is, however, that of a comparatively uneducated man in a library, of rustic Gil Vicente in the palace. Rather we would believe that he spent his early life in peasant surroundings, perhaps actually keeping goats in the scented hills like his Prince of Wales, Dom Duardos: De mozo guardé ganado, and then becoming an apprentice in the goldsmith's art, perhaps to his father or uncle, Martim Vicente, at Guimarães. It is extremely probable that he was drawn to the Court, then at Evora, for the first time in 1490 by the unprecedented festivities in honour of the wedding of the Crown Prince and Isabel, daughter of the Catholic Kings, and was one of the many goldsmiths who came thither on that occasion[15]. If that was so, his work may have at once attracted the attention of King João II, who, as Garcia de Resende tells us, keenly encouraged the talents of the young men in his service, and the protection of his wife, Queen Lianor. He may have been about 25 years old at the time. The date of his birth has become a fascinating problem, [Pg xiii]over which many critics have argued and disagreed. As to the exact year it is best frankly to confess our ignorance. The information is so flimsy and conflicting as to make the acutest critics waver. While a perfectly unwarranted importance has been given to a passage in Vicente's last comedia, the Floresta de Enganos (1536), in which a judge declares that he is 66 (therefore Gil Vicente was born in 1470), sufficient stress has perhaps not been laid on the lines in the play from the Conde de Sabugosa's library, the Auto da Festa, in which Gil Vicente is declared to be 'very stout and over 60.' This cannot be dismissed like the former passage, for it is evidently a personal reference to Gil Vicente. It was the comedian's ambition to raise a laugh in his audience and this might be effected by saying the exact opposite of what the audience knew to be true: e.g. to speak of Gil Vicente as very stout and over 60 if he was very young and spectre-thin. But Vicente was certainly not very young when this play was written and we may doubt whether the victim of calentura and hater of heat (he treats summer scurvily in his Auto dos Quatro Tempos) was thin. We have to accept the fact that he was over 60 when the Auto da Festa was written. But when was it written? Its editor, the Conde de Sabugosa, to whom all Vicente lovers owe so deep a debt of gratitude[16], assigned it to 1535, while Senhor Braamcamp Freire, who uses Vicente's age as a double-edged weapon[17], places it twenty years earlier, in 1515. This was indeed necessary if the year 1452 was to be maintained as the date of his birth. The theory of the exact date 1452 was due to another passage of the plays: the old man in O Velho da Horta, formerly assigned to 1512, is 60 (III. 75). Yet there is something slightly comical in stout old Gil Vicente beginning his actor's career at the age of 50 and keeping it up till he was 86. Other facts that may throw light on his age are as follows: in 1502 he almost certainly acted the boisterous part of vaqueiro in the Visitaçam[18]. In 1512 he is over 40 and married (inference from his appointment as one of the 24 representatives of Lisbon guilds in that year). In 1512 a 'son of Gil Vicente' is in India. His son Belchior is a small boy in 1518. In 1515 he received a sum of money to enable his sister Felipa Borges to marry. In 1531 he declares himself to be 'near death'[19], although evidently not ill at the time. He died very probably at the end of 1536 or beginning of 1537[20]. Accepting the fact that the Auto da Festa was written before the Templo de Apolo (1526) I would place it as late as possible, i.e. in the year 1525, and subtracting 60 believe that the date c. 1465 for Gil Vicente's [Pg xiv]birth will be found to agree best with the various facts given above.

The wedding of the Crown Prince of Portugal and the Infanta Isabel was celebrated most gorgeously at Evora. The Court gleamed with plate and jewellery[21]. There were banquets and tournaments, ricos momos and singulares antremeses, pantomimes or interludes produced with great splendour—e.g. a sailing ship moved on the stage over what appeared to be waves of the sea, a band of twenty pilgrims advanced with gilt staffs, etc., etc.—all the luxurious show which had made the entremeses of Portugal famous and from which Vicente must have taken many an idea for the staging of his plays. Next year the tragic death of the young prince, still in his teens, owing to a fall from his horse at Santarem, turned all the joy to ashes. Gil Vicente was certainly not less impressed than Luis Anriquez, who laments the death of Prince Afonso in the Cancioneiro Geral, or Juan del Enzina, who made it the subject of his version or paraphrase of Virgil's 5th eclogue. Vicente's acquaintance with Enzina's works may date from this period, although we need not press Enzina's words yo vi too literally to mean that he was actually present at the Portuguese Court. Vicente may have accompanied the King and Queen to Lisbon in October of this year, but for the next ten years we know as much of his life as for the preceding twenty, that is to say, we know nothing at all. The only reference to his sojourn at the Court of King João II occurs in the mouth of Gil Terron (I, 9):

¿Conociste a Juan domado

Que era pastor de pastores?

Yo lo vi entre estas flores

Con gran hato de ganado

Con su cayado real.

A note in the editio princeps declares the reference to be to King João II. If we read domado it can only be applied to the indomitable João II in the sense of having yielded to the will of Queen Lianor in acknowledging as heir her brother Manuel in preference to his illegitimate son Jorge. Perhaps however it is best to read damado, which recurs in the same play. Perhaps we may even see in the passage an allusion merely to an incident occurring in the time of João II and[Pg xv] not to the King himself[22]. We may surmise that about this time, perhaps as early as 1490, Vicente became goldsmith to Queen Lianor. The events of this wonderful decade must have moved him profoundly, events sufficient to stir even a dullard's imagination as new world after new world swept into his ken: the conquest of Granada from the Moors in 1492, the arrival of Columbus at Lisbon from America in 1493, the similar return of Vasco da Gama six years later from India, the discovery of Brazil in 1500. Two years later Vicente emerges into the light of day. King Manuel had succeeded to the throne on the death of King João (25 Oct. 1495) and had married the princess Maria, daughter of the Catholic Kings. Their eldest son, João, who was to rule Portugal as King João III from 1521 to 1557, was born on June 6, 1502, on which day a great storm swept over Lisbon. On the following evening[23] or on the evening of June 8 Gil Vicente, dressed as a herdsman, broke into the Queen's chamber in the presence of the Queen, King Manuel, his mother Dona Beatriz, his sister Queen Lianor, who was one of the prince's godmothers, and others, and recited in Spanish a brief monologue of 114 lines. Having expressed rustic wonder at the splendour of the palace and the universal joy at the birth of an heir to the throne he calls in some thirty companions to offer their humble gifts of eggs, milk, curds, cheese and honey. Queen Lianor was so pleased with this 'new thing'—for hitherto there had been no literary entertainments to vary either the profane serãos de dansas e bailos or the religious solemnities of the court—that she wished Vicente to repeat the performance at Christmas. He preferred, however, to compose a new auto more suitable to the occasion and duly produced the Auto Pastoril Castelhano. King Manuel had just returned to Lisbon from a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in thanksgiving for the discovery of the sea-route to India. He found the Queen in the palace of Santos o Velho and was received com muita alegria. But no allusion to great contemporary events troubles the rustic peace of this auto, which is some four times as long as the Visitaçam, and which introduces several simple shepherds to whom the Angel announces the birth of the Redeemer. Queen Lianor was delighted (muito satisfeita) and a few days later, on the Day of Kings (6 Jan. 1503), a third pastoral play, the Auto dos Reis Magos, was acted, the introduction of a knight and a hermit giving it a greater variety. The Auto da Sibila Cassandra has been assigned to the same year[Pg xvi], and the Auto dos Quatro Tempos and Quem tem farelos? to 1505, but there are good reasons for giving them a later date. The only play that can be confidently asserted to have been produced by Vicente between January 1503 and the end of 1508 is the brief dialogue between the beggar and St Martin: the Auto de S. Martinho, in ten Spanish verses de rima cuadrada, recited before Queen Lianor in the Caldas church during the Corpus Christi procession of 1504. The reasons for this silence are not far to seek. In September 1503, Dom Vasco da Gama returned from his second voyage to India with the first tribute of gold: 'The lords and nobles who were then at Court went to visit him on his ship and accompanied him to the palace. A page went before him bearing in a bason the 2000 miticaes of gold of the tribute of the King of Quiloa and the agreement made with him and the Kings of Cananor and Cochin. Of this gold King Manuel ordered a monstrance to be wrought for the service of the altar, adorned with precious stones, and commanded that it should be presented to the Convent of Bethlehem[24].' At this monstrance, still the pride of Portuguese art, Gil Vicente worked during three years (1503-6). He was perhaps already living in the Lisbon house in the Rua de Jerusalem assigned to him by his patroness, Queen Lianor[25]. There were other reasons for his silence. The death of Queen Isabella of Spain in 1504 and again the death of King Manuel's mother, Dona Beatriz, in 1506, threw the Portuguese Court into mourning. Plague and famine raged at Lisbon from 1505 to 1507, while, after the awful massacre of Jews at Easter 1506, during which some thousands were stabbed or burnt to death, the city of Lisbon was placed under an interdict which was not raised till 1508.

Let us take advantage of Vicente's long silence to explain why it can be asserted so confidently that he was now at work on the Belem custodia. The burden of producing some definite document to show that Gil Vicente the poet and Gil Vicente the goldsmith were two different persons rests on the opponents of identity. The late Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, whose death in 1912 was a great blow to Portuguese as well as to Spanish literature, would certainly have changed his view if he had lived. In his brilliant study of Gil Vicente, a 'sovereign genius,' 'the most national[Pg xvii] playwright before Lope de Vega[26],' 'the greatest figure of our primitive theatre[27],' he remarked that if Vicente had been a goldsmith and one of such skill he must infallibly have left some trace of it in his dramatic works and that the contemporaries who mention him would not have preserved a profound silence as to his artistic talent[28]; yet Menéndez y Pelayo himself speaks of Vicente's alma de artista[29] and of the plastic character which the most fantastic allegorical figures receive at his hands[30]. If we were assured that the dreamy Bernardim Ribeiro had fashioned the Belem monstrance we might well remain sceptical, but Vicente stands out from among the vaguer poets of Portugal in having, like Garcia de Resende, an extremely definite style, and his imagination, as in his dream of fair women in the Templo de Apolo, coins concrete figures, not intellectual abstractions. Resende, we know, was a skilled draughtsman as well as poet, chronicler and musician, and it is curious that the very phrase applied by Vicente to Resende, de tudo entende (II, 406), is used of Vicente himself in an anecdote quoted by Senhor Braamcamp Freire. As to his own silence and that of his contemporaries, their silence[31] concerning the presence of two Gil Vicentes at Court would be quite as astonishing, especially as they distinguish between other homonyms of the time[Pg xviii], and the silent satellite dogged the poet Vicente's steps with the strangest persistence. According to the discoveries or inventions of the Visconde Sanches de Baena[32] he was the poet's uncle; according to Dr Theophilo Braga they were cousins[33]. The poet, as many passages in his plays show, was interested in the goldsmith's art[34]; the goldsmith wrote verses[35]. The poet made his first appearance in 1502, the artist in 1503. Splendid as was the Portuguese Court and although its members had almost doubled in number in less than a century[36], the King did not keep men there merely on the chance of their producing 'a new thing.' The sovereign of a great and growing empire had something better to do than to indulge in forecasts as to the potential talents of his subjects. When Gil Vicente in 1502 produced a new thing in Portugal his presence in the palace can only be explained by his having an employment there, and since we know that Queen Lianor had a goldsmith called Gil Vicente who wrote verses and since the poet wrote all his earlier plays for Queen Lianor[37], it is rational to suppose that this employment was that of goldsmith to the Queen-Dowager. His presence at Court was certainly not by right of birth: Vicente was not a 'gentleman of good family,' as Ticknor and others have supposed, but the noble art of the goldsmith (its practice was forbidden in the following century to slaves and negroes) would enable him to associate familiarly with the courtiers. In 1509 or later[38] the poet joined, at the request of Queen Lianor, in a poetical contest concerning a gold chain, in which another poet, addressing Vicente, refers especially to necklaces and jewels. In the same year Gil Vicente is appointed overseer of works of gold and silver at the Convent of the Order of Christ, Thomar, the Hospital of All Saints, Lisbon, and the Convent of Belem. At the Hospital of All Saints the poet staged one of his plays. To Thomar and its fevers he refers more than once and presented the Farsa de Ines Pereira there in 1523. In 1513 he is appointed Mestre da Balança, in 1517 he resigns and in 1521 the poet alludes to the goldsmith's former colleagues: os da Moeda, while his production as playwright increases after the resignation and his complaints of poverty become more frequent[39]. In 1520 Gil Vicente the goldsmith is entrusted by King Manuel with the preparations for the royal entry into Lisbon, an auto figuring in the programme. If there was nothing new in a gol[Pg xix]dsmith writing verses the drama of Vicente was an innovation and João de Barros would quite naturally refer (as André de Resende before him) to the poet-goldsmith as Gil Vicente comico. On the other hand there is an almost brutal egoism in the silence concerning his unfortunate uncle (or cousin) maintained by Gil Vicente, who refers to himself as poet more than once, with evident pride in his autos. Recently General Brito Rebello (1830-1920), whose researches helped to give shape and substance to Gil Vicente's life, discovered a document of 1535 in which the poet's signature differs notably from that of the goldsmith in 1515[40]. It is, however, possible to maintain that the former signature is not that of Gil Vicente at all and that the words of the document per seu filho Belchior Vicente mean that Belchior signed in his father's name; or, alternatively, we can only say that Gil Vicente's handwriting had changed, a change especially frequent in artists. To those who examine all the evidence impartially there can remain very little doubt that Gil Vicente was first known at Court for his skill as goldsmith, and that he began writing verses and plays at the suggestion of his patroness, Queen Lianor.

On March 3, 1506, Vicente momentarily resumed his literary character and composed for Queen Lianor a long lay sermon, spoken before the King on the occasion of the birth of the Infante Luis (1506-55), who was himself a poet and the friend and patron of men of letters. The envious feared that Vicente was playing too many parts and contended that this was no time for a sermon by a layman, but Vicente excused himself with the saying, commonly attributed to Garci Sanchez de Badajoz, that if they would permit him to play the fool this once he would leave it to them for the rest of their lives, and launched into the exposition of his text: Non volo, volo et deficior. His next play Quem tem farelos? is assigned by Senhor Braamcamp Freire to December 1508 or January 1509[41]. The reference to the embate in Africa in all probability alludes to the siege of Arzila in 1508. King Manuel had made preparations to set sail for an African campaign in 1501 and 1503, but the word embate implies something more definite. The later date (it was formerly assigned to 1505) is more suitable to the finished art of this first farce and to the fact that its success—so great that the people gave it the name by which it is[Pg xx] still known, i.e. the first three words of the play—would be likely to cause its author to produce another farce without delay. Its successor, the Auto da India, acted before Queen Lianor at Almada in 1509, has not the same unity and its action begins in 1506 and ends in 1509. It displays a broader outlook and the influence of the discovery of India on the home-life of Portugal. In 1509 the fleet sailed from Lisbon under Marshal Coutinho on March 12 and Maio (III. 28) might be a misprint for Março; the partida alluded to, however, is that of Tristão da Cunha and Afonso de Albuquerque in 1506. It is just possible that Quem tem farelos? was begun in 1505 (the date of its rubric) and the Auto da India in 1506. Early in this year 1509 (Feb. 15) Vicente received the appointment of Vedor and at Christmas of the following year he produced a play at Almeirim, a favourite residence of King Manuel, who spent a part of most winters there in the pleasures of the chase[42]. This Auto da Fé is but a simple conversation between Faith and two peasants, who marvel at the richness of the Royal Chapel. In 1511, perhaps at Carnival[43], the Auto das Fadas further shows the expansion, perhaps we may say the warping, of his natural genius, for although we may rejoice in the presentation of the witch Genebra Pereira, the play soon turns aside to satirical allusions to courtiers, while the Devil gabbles in picardese. Peasants' beirão with a few scraps of biblical Latin had hitherto been Vicente's only theatrical resource as regards language. The Farsa dos Fisicos is now[44] assigned to 1512, early in the year. It is leap year (III. 317) and Senhor Braamcamp Freire sees in the lines (III. 323):

Voyme a la huerta de amores

Y traeré una ensalada

Por Gil Vicente guisada

Y diz que otra de mas flores

Para Pascoa tien sembrada

a reference to O Velho da Horta, acted before King Manuel in 1512. In August of the following year James, Duke of Braganza, set sail from Lisbon with a fleet of 450 ships to conquer Azamor:

Foi hũa das cousas mais para notar

Que vimos nem vio a gente passada[45].

Gil Vicente was in the most successful period of his life. In December 1512 he was chosen by the Guild of Goldsmiths to be one of[Pg xxi] the twenty-four Lisbon guild representatives and some months later he was selected by the twenty-four to be one of their four proctors, with a seat in the Lisbon Town Council. On February 4, 1513, he had become Master of the Lisbon Mint. For the departure of the fleet against Azamor he comes forward as the poet laureate of the nation and vehemently inveighs against sloth and luxury while he sings a hymn to the glories of Portugal. The play alludes to the gifts sent to the Pope in the following year and this probably led to the date of the rubric (1514), but it also refers to the royal marriages of 1521, 1525 and 1530, and we may thus assume that it was written in 1513 and touched up for a later production or for the collection of Vicente's plays. Perhaps at Christmas of this year was acted before Queen Lianor in the Convent of Enxobregas at Lisbon the Auto da Sibila Cassandra, hitherto placed ten years earlier. Senhor Braamcamp Freire points out that the Convent was only founded in 1509[46]. A scarcely less cogent argument for the later date is the finish of the verse and the exquisiteness of the lyrics, although the action is simple and the reminiscences of Enzina are many[47] (a fact which does not necessarily imply an early date: Enzina's echo verses are imitated in the Comedia de Rubena, 1521). We may note that the story of Troy is running in Vicente's head as in the Exhortação of 1513 (he had probably just read the Cronica Troyana). The last lyric, A la guerra, caballeros, is out of keeping with the rest of the play, but fighting in Africa was so frequent that it cannot help to determine the play's date. It is in this period (1512-14) that it is customary to place the death of Vicente's first wife Branca Bezerra, leaving him two sons, Gaspar and Belchior. She was buried at Evora with the epitaph:

Aqui jaz a mui prudente

Senhora Branca Becerra

Mulher de Gil Vicente

Feita terra.

This gives the Comedia do Viuvo, acted in 1514, a personal note, which is emphasized by the names of the widower's daughters, Paula, the name of Gil Vicente's eldest daughter, and Melicia, the name of his second wife. In the following year private grief was merged in the growing renown of Portugal in the Auto da Fama, which the rubric attributes to 1510, although it alludes to the siege of Goa (1510), the capture of Malaca (1511), the victorious expedition against Azamor[Pg xxii] (1513), and the attack on Aden (1513). It was acted first before Queen Lianor and then before King Manuel at Lisbon, and we may surmise that it was written or begun when the first news of Albuquerque's successes reached Lisbon and recast in 1515. The year 1516 has also been suggested, but the death of King Ferdinand the Catholic in January of that year and the death of Albuquerque in December 1515 render this date unsuitable. Even if the play was acted at Christmas 1515, there is the ironical circumstance that, at the moment when the Court was ringing with praises of the Portuguese deeds in India, the great Governor was lying dead at Goa. The date of the Auto dos Quatro Tempos is equally problematic. It was acted before King Manuel at the command of Queen Lianor in the S. Miguel Chapel of the Alcaçova palace on a Christmas morning. The name of the palace indicates the year 1505 or an earlier date[48], and it has been assigned to the year 1503 or 1504; but the superior development of the play's structure and even of its thought (e.g. I. 78), its resemblance to the Triunfo do Inverno (1529), the introduction of a French song, of the gods of Greece and of a psalm similar to that in the Auto da Mofina Mendes (1534)[49] and the perfection of the metre all indicate a fairly late date, while imitations of Enzina[50] are not conclusive. On the whole the intrinsic evidence counterbalances the statement of the rubric as to the Alcaçova palace and we may boldly assign this delightful piece to Christmas 1516[51], while admitting that in a rougher form it may have been presented to Queen Lianor[52] at a much earlier date.

The approximate date of the next play, the Auto da Barca do Inferno, is certain. This first part of Vicente's remarkable trilogy of Barcas was acted 'in the Queen's chamber for the consolation of the very catholic and holy Queen Dona Maria in the illness of which she died in 1517.' If we manipulate the commas so as to make the date refer to the play as well as to the Queen's death, the remedy proved fatal, for she died on March 7, but it is possible that it was acted earlier, towards t[Pg xxiii]he end of 1516. The subject was a gloomy one but its treatment was intended to raise many a laugh and it ends with the famous brief invocation of the Angel to the knights who had died fighting in Africa. On August 6, 1517, Vicente resigned the post of Master of the Mint in favour of Diogo Rodriguez and probably about this time he married his second wife, Melicia Rodriguez. The second and third parts of the Barcas trilogy were given in 1518 and 1519, but between the first and third parts Senhor Braamcamp Freire now places the Auto da Alma, and his scholarly suggestion[53] is amply borne out by the maturity and perfection of this beautiful play[54] and by the likelihood that Vicente when he wrote it was acquainted with Lucas Fernández' Auto de la Pasion (1514). The Auto da Barca do Purgatorio was acted before Queen Lianor on Christmas morning, 1518, at the Hospital de Todolos Santos (Lisbon). King Manuel had been at Lisbon in July of this year, going thence to Sintra, Collares, Torres Vedras and Almeirim, whence at the end of November he proceeded to Crato to welcome his new Queen, Dona Lianor. They returned together to Almeirim and the next months were spent there 'in great bullfights, jousts, balls and other entertainments till the beginning of Spring [May] when the King went to Evora[55].' The Auto da Barca da Gloria was played before his Majesty in Holy Week, 1519, and the fact that it is in Spanish and treats not of 'low figures,' but of nobles and prelates, reveals the taste of the Court and the wish to please the young Queen. In the following year (Nov. 29, 1520) Vicente was sent from Evora to Lisbon to prepare for the entry of the King and Queen into their capital (January 1521). He seems to have worked hard in arranging and directing the festivities, and in the same year (1521) he staged both the Comedia de Rubena and the Cortes de Jupiter. The latter is the only Vicente play of which we have a contemporary description. It was acted on the departure of the King's daughter, Beatriz, at the age of sixteen to espouse the Duke of Savoy. Her dowry, including precious stones, pearls and necklaces, was magnificent, and after brilliant rejoicings at Lisbon she embarked on a ship of a thousand tons in a fleet commanded by the Conde de Villa Nova. She was accompanied by the Archbishop of Lisbon and many nobles. On the evening of August 4, in the Ribeira palace 'in a large hall all adorned with rich tapestry of gold, well carpeted, with canopy, chairs and cushions of rich brocade, began a great ball in which the King our lord danced with the lady Infanta Duchess his dau[Pg xxiv]ghter and the Queen our lady with the Infanta D. Isabel, and the Prince our lord and the Infante D. Luis with ladies they chose; and so all the courtiers danced who were going to Savoy and many other gentlemen and courtiers for a long space. And the dancing over, began an excellent and well devised comedy with many most natural and well adorned figures, written and acted for the marriage and departure of the Infanta; and with this very skilful and suitable play the evening ended[56].'

Twenty weeks after these splendid scenes and the alegrias d'aquelas naves tam belas[57] the King was dead. He died (13 Dec. 1521) in the full tide of apparent prosperity. As he watched the slow funeral procession passing in the night from the palace to Belem amid 600 burning torches[58] Gil Vicente must have thought of his own altered position. King Manuel had treated his sister's goldsmith generously[59] and had personally attended the acting of many of his plays. The diversion of elephant and rhinoceros had been only a momentary backsliding, and he had sat through the whole of the Barca da Gloria, in which a King and an Emperor fared so lamentably at the hands of the modern Silenus. But he does not appear to have done anything to secure the poet's well-being. King Manuel's sister, Vicente's faithful patroness, was, however, still alive, and he had much to hope from the new king who had grown up along with the Vicentian drama. Vicente's first literary production had celebrated his birth, at the age of nine the prince had been given a special verse in the Auto das Fadas (III. 111), at the age of twelve he had actually intervened in the acting of the Comedia do Viuvo (II. 99), although his part was confined to a single sentence. Finally, in the very year of his accession, he had been represented as a second Alexander in the Cortes de Jupiter, and the Comedia de Rubena had been acted especially for him[60]. But King João III had not the careless temperament or graceful magnificence of his father, and while he evidently trusted Vicente and showed him constant goodwill—we have the proof in the pensions received by Vicente during this reign—the favourite of one king rarely finds the same atmosphere in the entourage of his successor, however friendly the king himself. Thus while João III brooded over affairs of Church and State the detractores had more opportunity to attack the Court dramatist. On December 19 the new king was proclaimed at Lisbon and Vicente, placed too far away to hear what was said at the ceremony, invented verses which he placed on the lips of the various courtiers as they kissed hands (III. 358-64). It was not only the king but the times that had changed, and King Manuel died not a moment too soon if he wished not to see the reverse side of the brightly coloured tapestry of his reign. Vicente ends his verses with the significant words:

Diria o povo em geral:

Bonança nos seja dada,

Que a tormenta passada

Foi tanta e tam desigual.

In the following year he wrote a burlesque lamentation and testament, entitled Pranto de Maria Parda, 'because she saw so few branches in the streets of Lisbon and wine so dear, and she could not live without it[61].' In the late summer of 1523 in the celebrated convent of Thomar he presented one of his most famous farces before the King: Farsa de Ines Pereira. The critics were already gaining ground and 'certain men of good learning' doubted whether he was the author of his plays or stole them from others, a doubt suggested perhaps by the somewhat close resemblance of the Barca da Gloria to the Spanish Danza de la Muerte.

Vicente vindicated his originality by taking as his theme the proverb 'Better an ass that carries me than a horse that throws me,' and developing it into this elaborate comedy. At Christmas of the same year at Evora, in the introductory speech of the Auto Pastoril Portugues, placed in the mouth of a beirão peasant, the audience is informed that poor Gil who writes plays for the King is without a farthing and cannot be expected to produce them as splendidly as when he had the means (I. 129). He was probably disappointed that the 6 milreis which he had received that year (May 1523) was not a regular pension. His complaint fell on listening ears and in 1524 (the year of Camões' birth) he was granted two pensions, of 12 and of 8 milreis, while in January 1525 he received a yet further pension of three bushels of wheat. Thus, although his possession of an estate near Torres Vedras, not far from Lisbon, has been proved to be a myth and we know that the entire fortune of his widow consisted in 1566 of ten milreis and that of his son [Pg xxvi]Luis of thirty[62], and while we must remember his expenses in travelling and in the production of his plays, his financial position compares very favourably with that of Luis de Camões half a century later.

The Fragoa de Amor, wrongly assigned to 1525, belongs to the year 1524, the occasion being the betrothal of King João III to Catharina, sister of the Emperor Charles V[63]. The year 1525 is the most discussed date in the Vicentian chronology. Two plays are doubtfully assigned to it and we may perhaps add a third, the Auto da Festa, as well as the trovas addressed to the Conde de Vimioso. Senhor Braamcamp Freire[64] plausibly places in this year the Farsa das Ciganas, although the date of the rubric is 1521, the year perhaps in which the idea of this slight piece took shape in the poet's brain. There is a more definite reason for assigning Dom Duardos to this year. It is a play based on the romance of chivalry commonly known as Primaleon, of which a new edition appeared at Seville in October 1524[65], and we know from Gil Vicente's dedication that Queen Lianor († 17 Dec. 1525) was still alive[66]. Yet we are still in the region of hypothesis, for the adventures of Dom Duardos were in print since 1512 (Salamanca)[67], and we may perhaps doubt whether this 'delicious idyl[68],' the longest of Vicente's works, was ready a year after the publication of the Seville edition, although as Senhor Braamcamp Freire points out[69], the betrothal of the Emperor Charles V to the King's sister was a suitable occasion for the production of the play[70]. The only play assigned with some certainty to 1525 is that in which the husband of Ines Pereira reappears as a rustic judge à la Sancho Panza: O Juiz da Beira, acted before the King at Almeirim.

It was a year of famine and plague at Lisbon. The fact that the verses addressed by Vicente to the Conde de Vimioso inform us that Vicente's household was down with the plague and his own life in danger (III. 38) bind these verses to no particular date, the plague being then all too common a visitation. Indeed General Brito Rebello and Senhor Braamcamp Freire both attribute this poem to 1518. His complaints of poverty woul[Pg xxvii]d thus have begun immediately after his resignation of the lucrative post of Master of the Mint and before he had received his pensions. 'He who does not beg receives nothing,' he says, and later on in the same poem 'If hard work and merit spelt success I would have enough to live on and give and leave in my will' (III. 382-3). The general tone of these verses is more in accordance with that of his later plays[71], and the occasion was more probably that in which he composed the Templo de Apolo, written when he was enfermo de grandes febres (II. 371), and acted in January 1526[72]. In his verses he tells the Conde de Vimioso that 'I have now in hand a fine farce. I call it A Caça dos Segredos. It will make you very gay.' 'I call it'; but the name given by the author was more than once ousted by a popular title. This implied popularity of Gil Vicente's plays, acted before the Court and not published in a collected edition till a quarter of a century after his death, might seem unaccountable were it not for the fact that some of his pieces, printed separately, were eagerly read, and that the people might be present in fairly large numbers when his plays were represented in church or convent. We know too that plays were acted in private houses. The publication of Antonio Ribeiro Chiado's Auto da Natural Invençam (c. 1550) by the Conde de Sabugosa throws much light on this subject. This auto, acted a few years after Vicente's death, contains the description of the presentation of a play in a private house at Lisbon. The play was to begin at 10 or 11 p.m., the actors having to play first at two other private houses. So great is the interest that not only is the house crowded and its door besieged but the throng in the street outside is so thick that the players have much difficulty in forcing their way through it. The owner of the house had given 10 cruzados for the play[73]. Vicente's Auto da Festa was similarly acted in a private house. The most interesting of all the facts recorded by Chiado is the eagerness of the people. Uninvited persons from the crowd outside kept pressing in at the door. Thus we can easily understand how the people could give their own name to a play, fastening on words or incident that especially struck them. The Farce of the Poor Squire became Quem tem farelos?[74], the author's name for the Auto da Mofina Mendes was Os Mysterios da Virgem (I. 103), the Clerigo da Beira was also known as the Auto de Pedreanes[75]. Therefore when we come upon a new title of a Vicente play unknown to us we need not[Pg xxviii] conclude that it is a new play.

Of the seven Vicente plays[76] placed on the Portuguese Index of 1551 four are known to us. The Auto da Vida do Paço may be identified with some probability with the Romagem de Aggravados[77]. If we may not identify the Jubileu de Amores with the Auto da Feira its disappearance must be accounted for by the wrath of the Church of Rome, which fell upon it when produced at Brussels in 1531[78]. The remaining play O Auto da Aderencia do Paço can scarcely be identified with the Auto da Festa on the ground that the vilão says (1906 ed., p. 123):

Quem quiser ter que comer

Trabalhe por aderencia:

Haverá quanto quiser.

Vosoutros que andais no paço....

especially as there was scarcely anything for the Censorship to condemn: merely the mention of the Priol's two sons (p. 111) and the ease with which the old woman obtains a Bull from the Nuncio (pp. 120, 124). There is far more reason, 'in my simple conjectures,' for believing that A Caça dos Segredos altered its name before or after it was produced and became A farsa chamada Auto da Lusitania. In the burlesque passage concerning Gil Vicente in this play (III. 275-6) we learn that he was instructed for seven years and a day in the Sibyl's cave and informed by the Sibyl of the secrets which she knew about the past:

E ali foi ensinado

Sete anos e mais um dia

E da Sibila informado

Dos segredos que sabia

Do antigo tempo passado.

If the Trovas ao Conde de Vimioso were written in 1525, the seven years du[Pg xxix]ring which Vicente hunted for secrets bring us to 1532, the date of the Auto da Lusitania. The necessary allusions to the birth of the Prince were inserted, but the play had been ready long before[79].

The Auto da Festa was probably acted in a private house at Evora. It contains scarcely an indication as to its date[80], but it has passages similar to others in the Farsa de Ines Pereira (1523), the Fragoa de Amor[81] (1524) and the Farsa das Ciganas (1525?)[82]. That the play was prior to the Templo de Apolo seems evident, and the author would be unlikely to copy from what he calls an obra doliente (II. 373) with Portuguese passages introduced to prop up a play originally written wholly in Spanish (ibid.). Nor need the anti-Spanish passages tell against the year of the betrothal of Charles V and the Infanta Isabel, for they are placed in the mouth of a vilão and the play was performed in private. In the Templo de Apolo the anti-Spanish atmosphere has not quite vanished, but the vilão contents himself with saying that Deos não é castelhano, and even so Apollo feels bound to present his excuses:

Villano ser descortés

No es mucho de espantar.

Quem não parece esquece, says Vicente in his trovas to Vimioso. Les absents ont tort. After a quarter of a century he could no longer describe his autos as a new thing and he was now confronted by the formidable novelty of the hendecasyllabic metre introduced by Sá de Miranda from Italy. He felt that he had his back against the wall[83]. He made a prodigious effort to vary the themes of his plays and to produce them with increasing frequency. The year 1527 is his annus mirabilis. The Sumario da Historia de Deos and the Dialogo sobre a Ressurreiçam are assigned, if not to this year, to the period 1526-8[84]. The Nao de Amores celebrated the entry of Queen Catharina into Lisbon in 1527, and before the autumn[85] three plays, the Divisa da Cidade de Coimbra, the Farsa dos Almocreves and the Tragicomedia da Serra da Estrella, h[Pg xxx]ad been presented before the Court at the charming old town of Coimbra which ten years later definitively became the University town of Portugal. His great efforts were not unrewarded, for in the following year he received a yet further pension of 12 milreis. On his way back from Coimbra to Santarem he fell among some Spanish carriers who took advantage of the new Queen's favour to fleece the poet, and he wrote some verses of comic complaint to the King (II. 383-4). The rubric assigns to the same year the famous Auto da Feira (Lisbon: Christmas 1527) but Snr Braamcamp Freire[86] points out that King João did not spend Christmas of this year at Lisbon and assigns it to 1528, the year in which the celebrated Dialogues of Alfonso and Juan de Valdés saw the light. In April 1529 the Triunfo do Inverno celebrated the birth of the Infanta Isabel. The author introduced the play in a long lament in verse over the forgotten jollity of earlier times and then, to show that his own hand had lost none of its cunning, he gave his audience a feast of lyrical passages in the Triumphs of Winter and Spring.

In 1527 Vicente seems clearly to have aimed his allusions to the sons of priests at Francisco de Sá de Miranda, whose father was a priest and who was born at Coimbra. And now in O Clerigo da Beira[87] we have a priest addressing his son Francisco and telling him that a priest's son will never come to any good. On his part the grave Sá de Miranda had protested against the introduction of scenes from the Bible into the farsas: the allusion to Vicente was clear although his treatment of such scenes was usually reverent. Vicente still had the ear of the Court and Sá de Miranda could only lament that the new style had at first so little vogue in Portugal. That the King, when he had leisure, consulted Vicente on weightier matters than the production of Court plays is proved by a passage[88] in the letter addressed to him by the poet from Santarem. A terrible earthquake shock on Jan. 26, 1531, followed by other severe shocks, kept the people in a panic for fifty days. Terruerant satis haec pavidam praesagia plebem, and to make matters worse the monks of Santarem, with an eye on the new Christians, spoke of the wrath of God and announced another earthquake as calmly as if they were giving out the hour of evensong. Vicente, who in his letter to the King[89] says, like Newman's Gerontius, 'I am near to death,' assembled the monks and preached them an eloquent sermon. The prestige of the Court poet restrained their zeal and probably avoided another massacre such as he had seen at Lisbon a quarter of a century before. It was in December of this year that the Jubileu de Amores was acted in the house of the Portuguese Ambassador at Brussels, to the[Pg xxxi] horror of Cardinal Aleandro, who almost persuaded himself that he was witnessing the sack of Rome four years earlier. It was perhaps before this that King João commanded Vicente to publish his works, but he could not be greatly perturbed that a play by Vicente had given offence to the Holy See, with which he was himself often in unpleasant relations at this time. At all events Vicente continued to produce his plays. In 1532 the birth of the long desired heir to the throne was celebrated at Lisbon, and Vicente presented the Auto da Lusitania, while two long plays, the Romagem de Aggravados and Amadis de Gaula, belong to the following year. The former was acted at Evora in honour of the birth of the Infante Felipe (May 1533). Amadis de Gaula perhaps shows some signs of weariness, and if he played the part of Amadis he would apply to himself the lines

Que ya veis que soy pasado

A la vida de los muertos (II. 282).

The Auto da Cananea was written at the request of the Abbess of Oudivellas and acted at that convent near Lisbon in 1534. It contains perhaps a reference to the earthquake of 1531 (I. 373). The Auto da Mofina Mendes may have been written some years before it was acted in the presence of the King at Evora on Christmas morning 1534: it alludes to the capture of Francis I at Pavia (1525) and to the sack of Rome (1527). Vicente had returned to Evora at least as early as August 1535, and in 1536 he produced there before the King his last play, the Floresta de Enganos, which may well have been a collection of farcical scenes written at various periods of his career[90]. We know that he was dead on April 16, 1540. He did not follow the Court to Lisbon in August 1537 and his death may be assigned with some plausibility to the end of 1536 at Evora[91]. The children of his second marriage were almost[Pg xxxii] certainly with him, Paula and Luis, who edited his works in 1562 and were now still in their teens, and the even younger Valeria. Paula seems to have inherited her father's versatility and his musical, dramatic and literary tastes. Tradition connects her closely with him and would even assign her a part in the composition of his plays. Another and a more reliable tradition says that he was buried in the Church of S. Francisco at Evora. His life had been full and strenuous and we leave him in this quiet little town depois da vida cansada descansando[92].

If we were limited to the information about Gil Vicente furnished by his contemporaries, we should but know that he had introduced into Portugal representações of eloquent style and novel invention imitating Enzina's eclogues with great skill and wit[93], and that the mordant comic poet Gil Vicente, who hid a serious aim beneath his gaiety and was skilled in veiling his satire in light-hearted jests, might have excelled Menander, Plautus and Terence if he had written in Latin instead of in the vulgar tongue[94]. That is, we should have known nothing that we could not learn from his plays and it is to his plays that we must go if we would be more closely acquainted with his character and his attitude towards the problems of his day. King Manuel, says Damião de Goes, always kept at his Court Spanish buffoons as a corrective of the manners and habits of the courtiers[95]. The King may have had something of the sort in his mind in encouraging Gil Vicente, and probably he especially favoured his allusions to the courtiers; but we cannot for a moment consider that Vicente, friend and adviser of King João III, the grave town-councillor whose influence could check the fanaticism of the monks at Santarem—can we imagine them bowing before a mere mountebank, a strolling player?—was looked upon simply as a Court jester. The impression left by his plays is, rather, that of the worthy thoughtful face of Velazquez as painted in his Las Meninas picture, a figure closely familiar with the Court yet still somewhat aloof, apartado. like Gil Terron. Vicente regards himself as a rustico peregrino (III. 390), an ignorante sabedor (I. 373) as opposed to the ignorant-malicious or ignorant-presumptuous of the Court. But Vicente was no ascetic, his was a genial, generous nature, he liked to have enough to spend and give and leave in his will. Kindly and chivalrous, he was a champion of the down-trodden but had first-hand knowledge of the malice and intrigu[Pg xxxiii]es of the peasants and of the poor in the towns. Above all he was thoroughly Portuguese. He might place his scene in Crete but in that very scene he would refer to things so Portuguese as the janeiras and lampas de S. João. Portugal is

Pequeno e muy grandioso,

Pouca gente e muito feito,

Forte e mui victorioso,

Mui ousado e furioso

Em tudo o que toma a peito,

and he appears to have shared the popular prejudice against Spain. Did he also share the people's hostility towards the priests and the Jews? It cannot be said that the priests presented in his plays are patterns of morality. As to the Jews he knows of their corrupt practices and describes them in a late play as a mais falsa ralé[96]. It was during the last ten years of Vicente's life that the question of the new Christians came especially to the front (from 1525). In earlier plays Vicente seems more sympathetic towards them and the pleasant sketch of the Jewish family in Lisbon is as late as 1532[97]. In 1506, the very year of the massacre of Jews at Lisbon, he had gone to the root of the question when he declared in his lay sermon that:

Es por demás pedir al judío

Que sea cristiano en el corazón ...

Que es por demás al que es mal cristiano

Doctrina de Cristo por fuerza ni ruego[98].

And twenty-five years later he said to the monks at Santarem: 'If there are some here who are still strangers to our faith it is perhaps for the greater glory of God[99].' That is to say: if you force the Jews to become Christians you will only make them hypocrites; far better to treat them frankly as Jews and not expect figs from thistles. That Vicente himself was a devout Christian and Catholic and a deeply religious man such plays as the Auto da Alma, the Barcas, the Sumario, the Auto da Cananea are sufficient proof. He had much of the Erasmian spirit but nothing in common with the Reformation. His irreverence is wholly external, it was abuses not doctrine that he attacked, the ministers of the Church and not the Church itself. He may have been in the secret of King João's somewhat stormy negotiations with the Holy See and he took the national and regalist view: in the Auto da Feira Mercury addresses Rome as follows:

Nam culpes aos reis da terra,

Que tudo te vem de cima (I. 166).[Pg xxxiv]

He wished to reform the Church from within. All are perversely asleep, a sleep of death[100]. Many prayers do not suffice without almas limpas e puras[101]. Men must be judged by their works[102]. In the Auto da Fé (1510) we have a simple declaration of faith:

Fé he amar a Deos só por elle

Quanto se pode amar,

Por ser elle singular,

Nam por interesse delle;

E se mais quereis saber,

Crer na Madre Igreja Santa

E cantar o que ella canta

E querer o que ella quer[103].

But four years earlier and ten before Luther's formal protest against the papal indulgences we find Vicente in his lay sermon referring to the question 'whether the Pope may grant so many pardons' and laughing at the hair-splitting of preachers: was the fruit that Eve ate an apple, a pear or a melon[104]? His own religion certainly had a mystical and pantheistic tendency[105]. It was as deep as was his love of Nature. He would have the hearts of men dance with jocund May[106]:

Hei de cantar e folgar

E bailar c'os corações,

and he had an eye for the humblest flower that blows—chicory and camomile, hedge flowerets, honeysuckle and wild roses:

Almeirones y magarzas,

Florecitas por las zarzas,

Madresilvas y rosillas (I. 95. Cf. II. 29).

And he sympathized closely with what was nearest to Nature: peasants and children. Of the people of the towns he was probably less enamoured and he speaks of a desvairada opinião do vulgo and of the folly of pandering to it[107]. At Court he certainly had many friends. A friendly rivalry in art and letters bound him to Garcia de Resende for probably over forty years and he was no doubt on excellent terms with the dadivoso Conde de Penella (II. 511), the muito jucundo Conde de Tentugal (III. 360) and the Conde de Vimioso. High rank was no certain shelter from the shafts of Vicente's wit, but when it was a case of princes he[Pg xxxv] was more careful:

Agora cumpre atentar

Como poemos as mãos,

as he ingenuously remarks[108]. King João II had seen to it that no class or individual should dispute the power of the throne, and now the King reigned supreme. Kings, says Vicente, are the image of God[109]. That was in 1533, when it might seem to him that the authority of the throne was more than ever necessary to cope with the confusion of the times. The King's power stood for the nation, that of a noble might mean mere private ambition or power in the hands of one unworthy, and Gil Vicente asks nobly:

Quem não é senhor de si

Porqué o será de ninguem?

(Who himself cannot control

Why should he o'er others rule?)

He had witnessed many changes, and looking back as an old man his memory might well be overwhelmed by a period so crowded[110]. He had seen the provinces and capital of Portugal transformed by the overseas discoveries. We may be sure that he had watched with more interest than the ordinary lisboeta the extension of the Portuguese empire and the deeds of the unfortunate Dom Francisco de Almeida ('Tomou Quiloa e Mombaça, Parece cousa de graça Ver de que morte acabou') and the redoubtable Afonso de Albuquerque, who snatched victories from defeat in the teeth of all manner of obstruction and indifference and placed Portugal's glory on a pinnacle scarcely dreamed of even in the intoxicating moment of Gama's first return to Belem in 1499:

Outro mundo encuberto

Vimos então descubrir

Que se tinha por incerto:

Pasma homem de ouvir.

Meanwhile Vicente never lost sight of the fact that the nation's strength lay not in rich imports, however fabulous and envied, but in[Pg xxxvi] the good use of its own soil and capacities and in the vigour, energy and discipline of its inhabitants, and a note of warning sounded again and again in his plays as he saw the old simplicity sink and disappear before wave on wave of luxury, ambition and hollow display. He had felt the good old times, content with rustic dance and song, vanishing since 1510:

De vinte annos a ca

Não ha hi gaita nem gaiteiro[111].

Now no one is content: ninguem se contenta da maneira que sohia[112]. Tudo bem se vai ao fundo[113]. He especially deplored the new confusion between the classes[114]. Shepherd, page and priest all wish to serve the King, that is, to become an official and to idle for a fixed wage while the land remained unploughed. The peasants do not know what they want and murmuram sem entender[115]. There is slackness everywhere (todos somos negligentes)[116]. Portugal was suffering from a crisis similar to that of four centuries later and men were inclined to leave their professions in order to theorize or in the hope of growing rich by a short cut or by chance instead of by hard, steady work; and the result was a period of upheaval and disquiet. Vicente suffered like the rest. He had embodied in his plays the simple pastimes of the Portuguese people, their delight in the processions, services and dramatic displays of the Church, in the mimicry of the early arremedillos, in the rich fancy-dress momos which were an essential element at great festivities. But his drama was not classical, often it was not drama. Technically he is less dramatic than Lucas Fernández or Torres Naharro. He defied every rule of Aristotle and mingled together the grave and gay, coarse and courtly in a way faithful to life rather than to any accepted theories of the stage. While he continued to produce these natural and delightful plays all kinds of new conditions arose. It was the irony of circumstance that when the old Portuguese poetry held the field the taste of the Court for personal satire and magnificent show could scarcely appreciate at its[Pg xxxvii] true value the lyrical gift of Vicente; and later, after King Manuel's death, Vicente found himself confronted by a new school in which classicism carried the day, the long Italian metres superseded the merry native redondilha of eight syllables, and the latinisers began to transform the language and shuddered like femmes savantes at Vicente's barbarisms and uncouth voquibles. His attitude towards his critics was one of humility and good humour. It is at least good to know that Vicente with his redondilhas continued to triumph personally in his old age and it was only the hand of death that drove him from the scene. Nor did he cease to point out abuses: the increase of a falsa mentira, the corruption of justice[117], the greed for money[118] and the growth of luxury[119]. He pillories the ignorance of pilots[120] by which so many ships were lost now and later, and he seems to doubt the wisdom of keeping women shut up like nuns both before[121] and after[122] marriage. If in many respects Vicente belonged to the Middle Ages, in his curiosity and many-sidedness he was a true child of the Renaissance. He dabbled in astrology and witchcraft, loved music (he wrote tunes for some of his lyrics), poetry, reading, acting and the goldsmith's art, and maintained his zest in old age: Mofina Mendes was probably written when he was over sixty. Attempts to represent him as a Lutheran reformer, a deep philosopher or an authority in questions philological fall to the ground. He was a jovial poet and a keen observer who loved his country, and when he saw its inhabitants all at sixes and sevens he would willingly have brought them back to what he called a boa diligencia.

In Vicente's notes and sketches of the Portugal of his day we may see the master hand of the goldsmith accustomed to set jewels. His miniatures are so distinct and the types described are so various that had we no other record of the first third of the sixteenth century in Portugal we might form a very fair and singularly vivid estimate from his plays. With a comic poet we have, of course, to be on our guard. When Vicente introduces the lavrador who steals his neighbour's land, is he drawing from life or from Berceo's mal labrador or from the Danza de la Muerte (fasiendo furto en la tierra agena) or from the Bible: 'Cursed be he that removeth his neighbour's landmark'? When he presents the[Pg xxxviii] poverty-stricken nobleman, the dissipated priest, rustics from Beira, or negro slaves, for how much does the conventional satire of the day stand in these portraits and how much is drawn from Nature? Are they merely literary types? It is obvious that these themes were a great resource for the satirists of that time but their value to the satirist lay in their truth. The sad existence of the poor gentleman and the splendour maintained by penniless nobles are all too well attested. As to the priests, when we find King Manuel joining with King Ferdinand of Spain in a protest to the Pope to the effect that the whole of Christendom was scandalized by the dissolute life of the clergy and by the traffic in Bulls[123], and grave ecclesiastics in Spain and friends of grave ecclesiastics, like Franco Sacchetti[124] earlier in Italy, using language even more violent than that of Vicente, we need not doubt the truth of his sketches. He was perhaps more vivid than the other critics and his satire penetrated deeply for the very reason that he was a realist. There was no doubt some professional exaggeration in the language of his beirão rustics, but his sympathy with the peasants and his wide knowledge of the province of Beira prove that his object was not merely mockery: zombar da gente da Beira[125]. Many of his types are foreshadowed in the Cancioneiro Geral, and especially in the Arrenegos of Gregorio Afonso, of the household of the Bishop of Evora: the 'priest who lives like a layman,' 'the gentleman who has not enough to eat,' 'the man of great estate and small income,' the preciosos, the borrachas, the fantasticos, the alcouviteira, 'the peasants placed in a position of importance.' In developing these figures Vicente was always careful to keep close to Nature. Each speaks in his own language, 'the negro as a negro, the old man as an old man.' This is carried to such a length that the Spanish Queen in the lament on the death of King Manuel is made to speak her few lines in Spanish, the rest of the poem being in Portuguese[126].

Vicente is not an easy writer because his styles are so many and his allusions so local. But we must be infinitely grateful to him for the way in which he portrays a type in a few lines and for the fact that although they are types they are evidently taken from individuals whom he had observed and who continue to live for us in his pages. His gallery of priests is for all time. Frei Paço comes, with his velvet cap and gilt sword, 'mincing like a very sweet courtier'; Frei Narciso starves and studies, tinging his complexion to an artificial yellow in the hope t[Pg xxxix]hat his hypocritical asceticism may win him a bishopric; the worldly courtier monk fences and sings and woos; the Lisbon priest, like his confessor one of Love's train, fares well on rabbits and sausages and good red wine, even as the portly pleasure-loving Lisbon canons; the country priest resembles a kite pouncing on chickens; the ambitious chaplain accepts the most menial tasks, compared with whom the sporting priest of Beira is at least pleasantly independent; and there are the luxurious hermit, the dissipated village priest who never prayed the hours, the inconstant monk who had been carrier and carpenter and now wishes to be unfrocked in order to join more freely in dance and pilgrimage, the mad friar Frei Martinho persecuted by dogs and Lisbon gamins, the ambitious preacher who glosses over men's sins. If the priests fared well in this life the satirists were determined that they should not be equally fortunate after their death. Vicente's proud Bishop is to be boiled and roasted, the grasping Archbishop is left perpetually aboiling, the ambitious Cardinal is to be devoured by dogs and dragons in a den of lions, while the sensual and simoniacal Pope is to have his flesh torn with red-hot iron. And we have—although here Vicente discreetly went to the Danza de la Muerte for his satire—the vainglorious and tyrannical Emperor, the Duke who had adored himself and the King who had allowed himself to be adored. There are the careless hedonistic Count more given to love than to charity or churchgoing, the fidalgo de raça, the haughty fidalgo de solar with a page to carry his chair, the judge who through his wife accepts bribes from the Jews, the rhetorical goldsmith, the usurer (onzeneiro) with his heart in his cassette (arca)[127]. There too the pert servant-girl, the gossiping maidservant, the witch busy at night over a hanged man at the cross-roads, the faithless wife of the India-bound lisboeta, the Lisbon old woman copious in malediction, her genteel daughter Isabel, the wife who in her husband's absence only leaves her house to go to church or pilgrimage, the mal maridada imprisoned by her husband, the peasant bride singing and dancing in skirt of scarlet, the woman superstitiously devout, the beata alcouviteira who would not have escaped the Inquisition had she been printed like Aulegrafia in the seventeenth century, lisping gypsies, the alcouviteiras Anna and Branca and Brigida, the curandera with her quack remedies, the poor farmer's daughter brought to be a Court lady and still stained from the winepress, the old woman desirous of a young husband, the slattern Catherina Meigengra, the market-woman who plays the pandero in the market-place, the peasant girls with pretentio[Pg xl]us names coming down to market basket on head from the hills, the shrew Branca and the timid wife Marta, the two irrepressible Lisbon fishwives, the voluble saloia who sells milk well watered and charges cruel prices for her eggs and other wares, the country priest's greedy 'wife' who eats the baptism cake and is continually roasting chestnuts, the mystical ingenuous little shepherdess Margarida who sees visions on the hills, the superior daughter of the peasant judge who had once spoken to the King, the small Beira girl keeping ducks, Lediça the affectedly ingenuous daughter of the Jewish tailor, Cezilia of Beira possessed by a familiar spirit.

Or, again, we have the ceremonious Lisbon lover Lemos, the high-flown Castilian of fearful presence and a lion's heart, however threadbare his capa[128], the starving gentleman who makes a tostão (= 5d.) last a month and dines off a turnip and a crust of bread, another—a sixteenth century Porthos—who imagines himself a grand seigneur and has not a sixpence to his name but hires a showy suit of clothes to go to the palace, another who is an intimate at Court (o mesmo paço) but who to satisfy a passing passion has to sell boots and viola and pawn his saddle, the poor gentleman's servant (moço) who sleeps on a chest, or is rudely awakened at midnight to light the lamp and hold the inkpot while his master writes down his latest inspiration in his song-book, the incompetent Lisbon doctors with their stereotyped formulas, the frivolous persons who are bored by three prayers at church but spend nights and days listening to novellas, the parvo, predecessor of the Spanish gracioso, the Lisbon courtier descended from Aeneas, the astronomer, unpractical in daily life as he gazes on the stars, the old man amorous, rose in buttonhole, playing on a viola, the Jewish marriage-brokers, the country bumpkin, the lazy peasant lying by the fire, the poor but happy gardener and his wife, the quarrelsome blacksmith with his wife the bakeress, the carriers jingling along the road and amply acquainted with the wayside inns, the aspiring vilão, the peasant who complains bitterly of the ways of God, the lavrador with his plough who did not forget his prayers and was charitable to tramps but skimped his tithes, the illiterate but not unmalicious beirão shepherd who had led a hard life and whose chief offence was to have stolen grapes from time to time, the devout bootmaker who had industriously robbed the people during thirty years, the card-player blasphemous as the taful of King Alfonso's Cantigas de Santa Maria, the delinquent from Lisbon's prison (the Limoeiro) whom his confessor had deceived before his hanging with promises of Paradise, the peasant[Pg xli] O Moreno who knows the dances of Beira, the negro chattering in his pigeon-Portuguese 'like a red mullet in a fig-tree,' the deceitful negro expressing the strangest philosophy in Portuguese equally strange, the rustic clown Gonçalo with his baskets of fruit and capons, who when his hare is stolen turns it like a canny peasant to a kind of posthumous account: leve-a por amor de Deos pola alma de meus finados, the Jew Alonso Lopez who had formerly been prosperous in Spain but is now a poor new Christian cobbler at Lisbon, the Jewish tailor who in the streets gives himself fidalgo airs and is overjoyed at the regard shown him by officials and who at home sings songs of battle as he sits at his work[129].