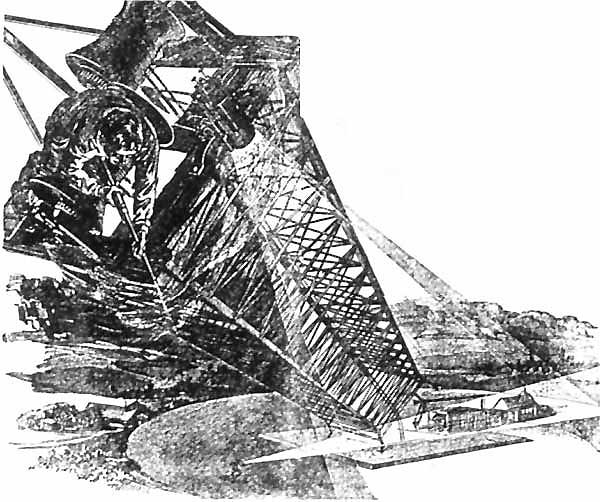

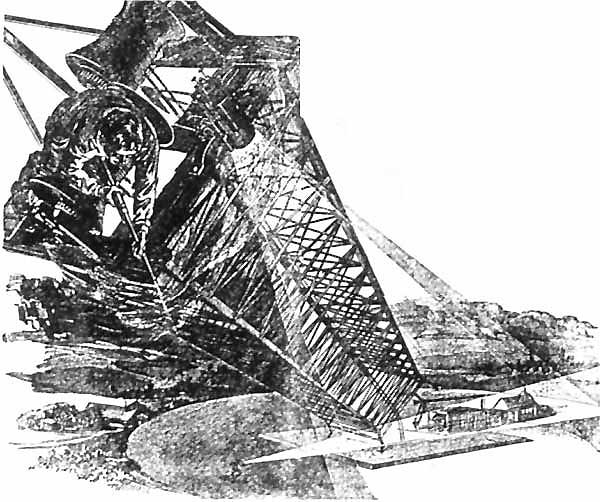

The derrick was falling as he fired again.

The derrick was falling as he fired again.

Project Gutenberg's Two Thousand Miles Below, by Charles Willard Diffin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Two Thousand Miles Below Author: Charles Willard Diffin Release Date: September 12, 2009 [EBook #29965] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TWO THOUSAND MILES BELOW *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Astounding Stories June, September, November 1932, January 1933. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

The Table of Contents is not part of the original magazines.

The derrick was falling as he fired again.

The derrick was falling as he fired again.

n the gray darkness the curved fangs of a saber-toothed tiger gleamed white and ghostly. The man-figure that stood half crouched in the mouth of the cave involuntarily shivered.

"Gwanga!" he said. "He goes, too!"

But the man did not move more than to shift a club to his right hand. Heavy, that club, and knotted and with a head of stone tied and wrapped with leather thongs; but Gor of the tribe of Zoran swung it easily with one of his long arms. He paid only casual attention as the great cat passed on into the night.

One leathery hand was raised to shield his slitted eyes; the wind from the north struck toward the mouth of the cave, and it brought with it cold driving rain and whirling flurries of frozen pellets that bit and stung.

Snow! Gor had traveled far, but never had he seen a storm like this with white cold in the air. Again a shiver that was part fear rippled through his muscles and gripped with invisible fingers at his knotted arms.

"The Beast of the North is angry!" he told himself.

Through the dark and storm, animals drifted past before the blasts of cold. They were fleeing; they were full of fear—fear of something that the dull mind of Gor could not picture. But in that mind was the same wordless panic.

Gor, the man-animal of that pre-glacial day, stared wondering, stupidly, into the storm with eyes like those of the wild pig. His arms were long, almost to his knees; his hair, coarse and matted, hung in greasy locks about his savage face. Behind his low, retreating forehead was place for little of thought or reason. Yet Gor was a man, and he met the threat of disaster by something better than blind, terrified, animal flight.

A scant hundred in the tribe—men and women and little pot-bellied brown children—Gor gathered them together in the cave far back from the mouth.

"For many moons," he told them by words and signs, "the fear has been upon us. There have been signs for us to see and for all the Four-feet—for Hathor, the great, and for little Wahti in his hole in the sand-hill. Hathor has swung his long snout above his curved tusks and has cried his fear, and the Eaters of the Dead have circled above him and cried their cry.

"And now the Sun-god does not warm us. He has gone to hide behind the clouds. He is afraid—afraid of the cold monster that blows white stinging things in his breath.

"The Sun-god is gone—now, when he should be making hot summer! The Four-feet are going. Even Gwanga, the long-toothed, puts his tail between his legs and runs from the cold."

he naked bodies shivered in the chill that struck in from the storm-wrapped world; they drew closer their coverings of fur and hides. The light of their flickering fires played strange tricks with their savage faces to make them still uglier and to show the dull terror that gripped them.

"Run—we must run—run away—the breath of the beast is on us—he follows close—run...." Through the mutterings and growls a sick child whimpered once, then was still. Gor was speaking again:

"Run! Run away!" he mocked them. "And where shall the tribe of Zoran go? With Gwanga, to make food for his cat belly or to be hammered to death with the stones of the great tribes of the south?"

There was none to reply—only a despairing moan from ugly lips. Gor waited, then answered his own question.

"No!" he shouted, and beat upon his hairy chest that was round as the trunk of a tree. "Gor will save you—Gor, the wanderer! You named me well: my feet have traveled far. Beyond the red-topped mountains of the north I have gone; I have seen the tribes of the south, and I brought you a head for proof. I have followed the sun, and I have gone where it rises."

In the half light, coarse strands of hair waved as hideous heads were nodded in confirmation of the boast, though many still drooped despairingly.

"If Gor leads, where will he go?" a voice demanded.

Another growled: "Gor's feet have gone far: where have they gone where the Beast cannot follow our scent?"

"Down!" said Gor with unconscious dramatic effect, and he pointed at the rocky floor of the cave. "I have gone where even the Beast of the North cannot go. The caves back of this you have seen, but only Gor has seen the hole—the hole where a strong man can climb down; a hole too small for the great beast to get through. Gor has gone down to find more caves below and more caves below them.

"Far down is a place where it is always warm. There is water in lakes and streams. Gor has caught fish in that water, and they were good. There are growing things like the round earth-plants that come in the night, and they, too, were good.

"Will you follow Gor?" he demanded. "And when the Beast is gone and the Sun-god comes back we will return—"

he blast that found its way inside the cave furnished its own answer; the echoing, "We follow! We follow!" spoken through chattering teeth was not needed. The women of the tribe shivered more from the cold than from fear as they gathered together their belongings, their furs and hides and crude stone implements; and the shambling man-shape, called Gor, led them to the hole down which a strong man might climb, led them down and still down....

But, as to the rest—Gor's promise of safe return to the light of day and that outer world where the Sun-god shone—how was Gor to know that a mighty glacier would lock the whole land in ice for endless years, and, retreating, leave their upper caves filled and buried under a valley heaped with granite rocks?

Even had the way been open to the land above, Gor himself could never have known when that ice-sheet left. For when that day came and once more the Sun-god drew steamy spirals from the drenched and thawing ground, Gor, deep down in the earth, had been dead for countless years. Only the remote descendants of that earlier tribe now lived in their subterranean home, though even with them there were some who spoke at times of those legends of another world which their ancestors had left.

And through the long centuries, while evolution worked its slow changes, they knew nothing of the vanishing ice, of the sun and the gushing waters, the grass and forests that came to cover the earth. Nor did their descendants, exploring interminable caves, learning to tame the internal fires, always evolving, always growing, have any remote conception of a people who sailed strange seas to find new lands and live and multiply and build up a country of sky-reaching cities and peaceful farmlands, of sunlit valleys and hills.

But always there were adventurous souls who made their way deeper and deeper into the earth; and among them in every generation was one named Gor who was taught the tribal legends and who led the adventurers on. But legends have a trick of changing, and instead of searching upward, it was through the deeper strata that they made their slow way in their search for a mystic god and the land of their fathers' fathers....

eat! Heat of a white-hot sun only two hours old. Heat of blazing sands where shimmering, gassy waves made the sparse sagebrush seem about to burst into flames. Heat of a wind that might have come out of the fire-box of a Mogul on an upgrade pull.

A highway twisted among black masses of outcropping lava rock or tightened into a straightaway for miles across the desert that swept up to the mountain's base. The asphalt surface of the pavement was almost liquid; it clung stickily to the tires of a big car, letting go with a continuous, ripping sound.

Behind the wheel of the weatherbeaten, sunburned car, Dean Rawson squinted his eyes against the glare. His lean, tanned face was almost as brown as his hair. The sun had done its work there; it had set crinkly lines about the man's eyes of darker brown. But the deeper lines in that young face had been etched by responsibility; they made the man seem older than his twenty-three years, until the steady eyes, flashing into quick amusement, gave them the lie.

And now Rawson's lips twisted into a little grin at his own discomfort—but he knew the desert driver's trick.

"A hundred plus in the shade," he reasoned silently. "That's hot any way you take it. But taking it in the face at forty-five an hour is too much like looking into a Bessemer converter!"

He closed the windows of his old coupe to within an inch of the top, then opened the windshield a scant half inch. The blast that had been drawing the moisture from his body became a gently circulating current of hot air.

He had gone only another ten miles after these preparations for fast driving, when he eased the big weatherbeaten car to a stop.

n his right, reaching up to the cool heights under a cloudless blue sky, the gray peaks of the Sierras gave promise of relief from the furnace breath of the desert floor. There were even valleys of snow glistening whitely where the mountains held them high. A watcher, had there been one to observe in the empty land, might have understood another traveler's pausing to admire the serene majesty of those heights—but he would have wondered could he have seen Rawson's eyes turned in longing away from the mountains while he stared across the forbidding sands.

There were other mountains, lavender and gray, in the distance. And nearer by, a matter of twenty or thirty elusive miles through the dancing waves of hot air, were other barren slopes. Across the rolling sand-hills wheel marks, faint and wind-blown, led straight from the highway toward the parched peaks.

"Tonah Basin!" Rawson was thinking. "It's there inside these hills. It's hotter than this is by twenty degrees right this minute—but I wish I could see it. I'd like to have one more look before I face that hard-boiled bunch in the city!"

He looked at his watch and shook his head. "Not a chance," he admitted. "I'm due up in Erickson's office in five hours. I wonder if I've got a chance with them...."

ive hours of driving, and Rawson walked into the office of Erickson, Incorporated, with a steady step. Another hour, and his tanned face had gone a trifle pale; his lips were set grimly in a straight line that would not relax under the verdict he felt certain he was about to hear.

For an hour he had faced the steely-eyed man across the long table in the Directors Room—faced him and replied to questions from this man and the half-dozen others seated there. Skeptical questions, tricky questions; and now the man was speaking:

"Rawson, six months ago you laid your Tonah Basin plans before us—plans to get power from the center of the Earth, to utilize that energy, and to control the power situation in this whole Southwest. It looked like a wild gamble then, but we investigated. It still looks like a gamble."

"Yes," said Rawson, "it is a gamble. Did I ever call it anything else?"

"The Ehrmann oscillator," the man continued imperturbably, "invented in 1940, two years ago, solves the wireless transmission problem, but the success of your plan depends upon your own invention—upon your straight-line drills that you say will not wander off at a tangent when they get down a few miles. And more than that, it depends upon you.

"Even that does not damn the scheme; but, Rawson, there's only one factor we gamble on. No wild plans, no matter how many hundreds of millions they promise: no machines, no matter what they are designed to do, get a dollar of our backing. It's men we back with our money!"

Rawson's face was set to show no emotion, but within his mind were insistent, clamoring thoughts:

"Why can't he say it and get it over with? I've lost—what a hard-boiled bunch they are!—but he doesn't need to drag out the agony." But—but what was the man saying?

"Men, Rawson!" the emotionless voice continued. "And we've checked up on you from the time you took your nourishment out of a bottle; it's you we're backing. That's why we have organized the little company of Thermal Explorations, Limited. That's why we've put a million of hard coin into it. That's why we've put you in charge of operations."

He was extending a hand that Dean Rawson had to reach for blindly.

"I'd drill through to hell," Dean said and fought to keep his voice steady, "with backing like that!"

He allowed his emotion to express itself in a shaky laugh. "Perhaps I will at that," he added: "I'll certainly be heading in the right direction."

nder another day's sun the hot asphalt was again taking the print of the tires of Rawson's old car. But this time, when he came to the almost obliterated marks that led through the sand toward distant mountains, he stopped, partially deflated the tires to give them a grip on the sand, and swung off.

"A fool, kid trick," he admitted to himself, "but I want to see the place. I'll see plenty of it before I'm through, but right now I've got to have a look; then I'll buckle down to work.

"Thermal Explorations, Limited!" The name rang triumphantly in his mind. "A million things to do—men, crews for the drills, derricks.... We'll have to truck in over this road; I'll lay a plank road over the sand. And water—we'll have to haul that, too, until we can sink a well. We'll find water under there somewhere. I've got to see the place...."

The black sides of the mountains were nearer: every outcropping rock was plainly volcanic, and great sweeping slopes were beds of ash and pumice; the wheel marks, where they showed at all, wound off and into a canyon hidden in the tremendous hills that thrust themselves abruptly from the desert floor.

The mountains themselves towered hugely at closer range, but the road that Rawson followed climbed through them without traversing the highest slopes. It was scarcely more than a trail, barely wide enough for the car at times, but boulder-filled gullies showed where the hands of men had worked to build it.

e came at last into the open where a shoulder of rock bent the road outward above a sea of sand far below. And now the mountains showed their circular arrangement—a great ring, twenty miles across. At one side were three conical peaks, unmistakable craters, whose scarred sides were smothered under ash and sand that had rained down from their shattered tops in ages past. Yet, so hot they were, so clear-cut the irregularly rimmed cups at their tops, that they seemed to have pushed themselves up through the earth in that very instant. At their bases were signs of human habitation—broken walls, scattered stone buildings whose empty windows gaped blackly. This was all that remained of New Rhyolite.

Rawson looked at the "ghost town" which had never failed to interest him, but he gave no thought now to the hardy prospectors who had built it or to the vein of gold that had failed them. His searching eyes came back to the fiery pit, the Tonah Basin, a vast cauldron of sand and ash—great sweeps of yellow and gray and darker brown into which the sun was pouring its rays with burning-glass fierceness.

But to Rawson, there was more than the eye could see. He was picturing a great powerhouse, steel derricks, capped pipes that led off to whirring turbines, generators, strings of cables stretching out on steel supports into the distance, a wireless transmitter—and all of this the result of his own vision, of the stream he would bring from deep in the earth!

Then, abruptly, the pictures faded. Far below him on the yellow, sun-blasted floor, a fleck of shadow had moved. It appeared suddenly from the sand, moved erratically, staggeringly, for a hundred feet, then vanished as if something had blotted it out—and Dean Rawson knew that it was the shadow of a man.

he road widened beyond the turn. He had intended to swing around; he had wanted only to take a clear picture of the place with him. But now the big car's gears wailed as he took the downgrade in second, and the brakes, jammed on at the sharp curves, added their voice to the chorus of haste.

"Confounded desert rats!" Rawson was saying under his breath. "They'll chance anything—but imagine crossing country like that! And he hasn't a burro—he's got only the water he can carry in a canteen!"

But even the canteen was empty, he found, when he stopped the car in a whirl of loose sand beside a prone figure whose khaki clothes were almost indistinguishable against the desert soil.

Before Rawson could get his own lanky six feet of wiry length from the car, the man had struggled to his feet. Again the little blot of shadow began its wavering, uncertain, forward movement.

He was a little shorter than Rawson, a little heavier of build, and younger by a year or two, although his flushed face and a two days' stubble of black beard might have been misleading. Rawson caught the staggering man and half carried him to the shadow of the car, the only shelter in that whole vast cauldron of the sun.

From a mouth where a swollen tongue protruded thickly came an agonized sound that was a cry for, "Water—water!" Rawson gave it to him as rapidly as he dared, until he allowed the man to drink from the desert bag at the last. And his keen eyes were taking in all the significant details as he worked.

The khaki clothes earned a nod of silent approval. The compact roll that had been slung from the younger man's shoulders, even the broad shoulders themselves, and the square jaw, unshaved and grimy, got Rawson's inaudible, "O. K.!" But the face was more burned than tanned.

e introduced himself when the stranger was able to stand. "I'm Rawson, Dean Rawson, mining engineer when I'm working at it," he explained. "I'm bound north. I'll take you out of this. You can travel with me as far as you please."

The dark-haired youngster was plainly youthful now, as he stood erect. His voice was recovering what must have been its usual hearty ring.

"I'm not trying to say 'thank you,'" he said, as he took Rawson's hand. "I was sure sunk—going down for the last time—taps—all that sort of thing! You pulled me out—the good old helping hand. Can't thank a fellow for that—just return the favor or pass it on to someone else. And, by the way—you won't believe it—but my name is Smith."

Rawson smiled good-naturedly. "No," he agreed, "I don't believe it. But it's a good, handy name. All right, Smithy, jump in! Here, let me give you a lift; you're still woozy."

Rawson found his passenger uncommunicative. Not but what Smithy talked freely of everything but himself, but it was of himself that Rawson wanted to know.

"Drop me at the first town," said Smithy. "You're going north: I'm south-bound—looking for a job down in Los. I won't take any more short cuts; I was two days on this last one. I'll stick to the road."

They were through the mountains that ringed in the fiery pit of Tonah Basin. Smooth sand lay ahead; only the shallow marks that his own tires had ploughed needed to be followed. Dean Rawson turned and looked with fair appraisal at the man he had saved.

"Drifter?" he asked himself silently. "Road bum? He doesn't look the part; there's something about him...."

Aloud he inquired: "What's your line? What do you know?"

And the young man answered frankly: "Not a thing!"

ean sensed failure, inefficiency. He resented it in this youngster who had fought so gamely with death. His voice was harsh with a curious sense of his own disappointment as he asked:

"Found the going too hard for you up north, did you? Well, it won't be any easier—" But Smithy had interrupted with a weak movement of his hand.

"Not too hard," he said laconically; "too damn soft! I don't know what I'm looking for—pretty dumb: got a lot to learn!—but it'll be a job that needs to take a good licking!"

"'Too damn soft!'" Dean was thinking. "And he tackled the desert alone!" There was a lot here he did not understand. But the look in the eyes of Smithy that met his own searching gaze and returned it squarely if a bit whimsically—that was something he could understand. Dean Rawson was a judge of men. The sudden impulse that moved him was founded upon certainty.

"You've found that job," he said. "The desert almost got you a little while ago—now it's due to take that licking you were talking about. I'm going to teach it to lie down and roll over and jump through hoops. Fact is, my job is to get it into harness and put it to work. I'll be working right out there in the Basin where I found you. It will be only about two degrees cooler than hell. If that sounds good to you, Smithy, stick around."

He warmed oddly to the look in the younger man's deep-set, dark eyes, as Smithy replied:

"Try to put me out, Rawson—just try to put me out!"

rom the black, night-wrapped valley, far below, the singer's voice went silent with the slamming of a door in one of the bunkhouses. The song was popular; some rimester in the Tonah Basin camp had written the parody for the tormenting of the drill crews. And, high on the mountainside, Dean Rawson hummed a few bars of the lilting air after the singer's voice had ceased.

"Ten miles down!" he said at last to his assistant, sprawled out on the stone beside him. "That's about right, Smithy. And maybe the rest of the doggerel isn't so far off either. 'Pokin' through the crust of hell'—well, there was hell popping around here once, and I am gambling that the furnaces aren't all out."

They were on the outthrust shoulder of rock where the mountain road hung high above the valley floor. Below, where, months before, Rawson had rescued a man from desert death, was blackness punctured by points of light—bunkhouse windows, the drilling-floor lights at the foot of a big derrick, a single warning light at the derrick's top. But the buildings and the towering steelwork of the derrick that handled the rotary drills were dim and ghostly in the light of the stars.

"We've gone through some places I'd call plenty warm," said Smithy, "but you—you craves it hot! Think we're about due?" he asked.

Rawson answered indirectly.

"One great big old he-crater!" he said. His outstretched arm swept the whole circle of starlit mountains that enclosed the Basin. "That's what this was once. Twenty miles across—and when it blew its head off it must have sprayed this whole Southwest.

"Now, those craters"—he pointed contemptuously toward the three conical peaks off to the right—"those were just blow-holes on the side of this big one."

n the ragged ring of mountains, the throat of some volcanic monster of an earlier age, the three cones towered hugely. Their tops were plainly cupped; their ashy sloping sides swept down to the desert floor. At their base, the gray walls of stone in the ghost town of Little Rhyolite gleamed palely, like skeleton remains.

"I've seen steam, live steam," Rawson went on, "coming out of a fissure in the rocks. I know there's heat and plenty of it down below. We're about due to hit it. The boys are pulling the drill now; they cut through into a whale of a cave down below there—"

He broke off abruptly to fix his attention on the dark valley below, where lights were moving. One white slash of brilliance cut across the dark ground; another, then a cluster of flood lights blazed out. They picked the skeleton framework of the giant derrick in black relief against the white glare of the sand. From far below; through the quiet air, came sounds of excited shouting; the voices of men were raised in sudden clamor.

"They've pulled the drill," said Rawson. "But why all the excitement?"

He had already turned toward their car when the crackle of six quick shots came from below. His abrupt command was not needed; Smithy was in the car while still the echoes were rolling off among the hills. Their own lights flashed on to show the mountain grade waiting for their quick descent.

he sandy floor of this part of the Tonah Basin was littered with the orderly disorder of a big construction job—mountains of casing, tubular drill rod, a foot in diameter; segmental bearings to clamp around the rod every hundred feet and give it smooth play. Dean drove his car swiftly along the surfaced road that was known as "Main Street" to the entire camp.

There were men running toward the derrick—men of the day shift who had been aroused from their sleep. Others were clustered about the wide concrete floor where the derrick stood. Clad only in trousers and shoes, their bodies, tanned by the desert sun, were almost black in the glare of the big floods. They milled wildly about the derrick; and, through all their clamor and shouting, one word was repeated again and again:

"Gold! Gold! Gold!"

The big drill head was suspended above the floor. Dean Rawson, with Smithy close at hand, pushed through the crowd. He was prepared to see traces of gold in the sludge that was bailed out through the hollow shaft—quartz, perhaps, whose richness had set the men wild before they realized how impossible it would be to develop such a mine. But Rawson stopped almost aghast at the glaring splendor of the golden drill hanging naked in the blinding light.

iley, foreman of the night shift, was standing beside it, a pistol in his hand. "L'ave it be," he was commanding. "Not a hand do ye lay on it till the boss gets here." At sight of Rawson he stepped forward.

"I shot in the air," he explained. "I knew ye were up in the hills for a breath of coolness. I wanted to get ye here quick."

"Right," said Rawson tersely. "But, man, what have you done with the drill? It's smeared over with gold!"

"Fair clogged wid it, sir," Riley's voice betrayed his own excitement. "You remimber we couldn't pull it at first—the drill was jammed-like after it bruk through at the ten-mile livil. Then it come free—and luk at it! Luk at the damn thing! Sent down for honest work, it was, and it comes back all dressed up in jewelry like a squaw Indian whin there's oil struck on the reservation! Or is it gold ye were after all the time?" he demanded.

"Gold! Gold!" a hundred voices were shouting. Dean hardly heard the voice of the foreman, made suddenly garrulous with excitement. He stared at the big drill head, heaped high with the precious metal. It was jammed into the diamond-studded face of the drill; it filled every crack and crevice, a smooth, solid mass on top of the head and against the stem. A workman had brought a singlejack and chisel; he was prying at a ribbon of the yellow stuff. Riley went for him, gun in hand.

"L'ave it be!" he shouted.

"But, confound it all, Dean," Smithy's voice was saying in a tone of disgust, "I thought we were working on a power plant. Not that a gold mine is so bad; but we can't work it—we can't go down after it at ten miles."

"Gold mine!" Rawson echoed. "I'll say it's a gold mine—but not because of the gold. Do you notice anything peculiar about that, Smithy?"

His assistant replied with a quick exclamation:

"You're right, Dean! I knew there was something haywire with that. Solid chunk—been cast around that stem—melted on. And that means—"

"Heat," said Rawson. "It means we've found what we're after. Give the gold to the men; tell them we'll divide it evenly among them. There's more down there, but there's something better: there's energy, power!"

He snapped out quick orders. "Get the temperature. Drop a recording pyrometer. Let me know at once. There'll be plenty doing now!"

rill rods and cables, all were made of the newest aluminum alloy. The long tube that held the pyrometer was formed of the same metal. Smithy sent it down to get a recording of the temperatures of that subterranean cave into which their tools had plunged.

He adjusted the recording mechanism himself and stood beside the twenty-inch casing that held back the loose sand from the big bore. Then he watched ten sections of cable, each a mile in length, each heavier than the last, as they went hissing into the earth.

From the cable control shed the voice of Riley was calling the depth.

"Fifty-two thousand." Then by hundreds until he cried: "Fifty-two-seven. We're into the big cave! Now another hundred feet."

The cable was moving slowly. In the middle of Riley's call of "Fifty-two-eight," a jangling bell told that the bottom of the pyrometer carrier had touched.

"Up with it," Smithy ordered. "Make it snappy. We'll see if we've got another cargo of gold."

There was an undeniable thrill in this reaching to a tremendous distance underground, this groping about in a deep-hidden cave, where molten gold was to be found. What had they tapped?—he asked himself. He saw visions of some vast pool of hot, liquid gold. Perhaps Dean would have to change his plans. They could rig up some kind of a bailer; they could bring out thousands of dollars at a time.

He was watching for the first sight of the metal carrier, far more interested in what might be clinging to it than in the record of the pyrometer it held. He saw it emerge—then he stared in disbelief at the stubby mass at the cable's end, where all that remained of the long tube he had sent down was a dangling two feet of discolored metal, warped and distorted. The lower part, a full twenty feet in length, had been fused cleanly off.

Dean Rawson was there to watch the next attempt. Again Riley's roaring bass rolled out the count, but this time the call stopped at fifty-two-seven. The jangling bell told that the carrier had touched.

"Divil a bit do I understand this," Riley was calling. "We're right at the point where we dropped through into the clear. Right at the roof of the big cave—fifty-two-seven, it says—and no lower do we go. The bottom of the hole is plugged!"

awson made no reply. He was scowling while he stared speculatively at the mouth of the twenty-inch bore—a vertical tunnel that led from the drilling floor down, down to some inner vault. "Molten gold," he was thinking. "It melted a cylinder of the new Krieger alloy—melted it when its melting point is way higher than that of any rock that we've hit. And now the bore is closed...."

He was trying vainly to project his mental vision through those miles of hard rock to see what manner of mystery this was into which he had probed. He shook his head slowly in baffled speculation, then spoke sharply.

"Drill it out!" he ordered. "We're into a hot spot sure enough, though I can't just figure out the how of it. But we'll tame it, Smithy. Send down the drill. Clean it out. Then we'll poke around down there and get the answer to all this."

Five days were needed to send down the big drill with a new drill-head replacing the other too fouled with gold for any use. The tubular sections, a hundred feet in length, were hooked together and lowered one by one. Each joint meant the coupling of the air-pipe as well. Air, mixed with water from the outer jacket, must come foaming up through the central core to bring the powdered rock to the surface.

Five days, then one hour of boring, and another five days to pull out the drill before Rawson could hope for his answer. But he found it in the severed shaft of the great drill where the head had been melted completely off. The big stem that would have resisted all but electric furnace heat, and been cut through like a tallow candle in the blast of an oxy-acetylene flame.

he flat-roofed shack of yellow boards that was Dean Rawson's "office" had a second canopy roof built above it and extending out on all sides like a wooden umbrella. Thick pitch fried almost audibly from the fir boards when the sun drove straight from overhead, but beneath their shelter the heat was more bearable.

By an open window, where a hot breeze stirred sluggishly, Rawson sat in silent contemplation of the camp. His face was as copper-colored as an Apache's and as motionless. His eyes were fixed unwaveringly upon a distant derrick and the blasted stub of a big drill that hung unmoving above the concrete floor.

But the man's eyes did not consciously record the details of that scene. He saw nothing of the derrick or of the heat waves that made the steel seem writhingly alive; he was looking at something far more distant, something many miles away, something vague and mysterious, hidden miles beneath the surface of the earth.

"Heat," he said at last, as if talking in a dream. "Heat, terrific temperatures—but I can't make it out; I can't see it!"

The younger, broad-shouldered man, whose khaki shirt, thrown open at the neck showed a chest tanned to the black-brown of his face, stopped his restless pacing back and forth in the hot room.

"Yes?" he asked with a touch of irritation in his tone. "There's plenty of heat there—heat enough to melt off the shaft of that high-temp alloy! What the devil's the use of wondering about the heat, Dean? What gets me is this: the shaft has been plugged again. Now, what kind of...."

ean Rawson's face had not moved a muscle during the other's outburst. His eyes were still fixed on that place that was so far away, yet which he tried to bring close in his mind, close enough to see, to comprehend the mystery that should be so plain.

"Lava wouldn't do it!" he said softly. "No melted stone would melt the Krieger alloy, unless it was under pressure, which this was not. There was no blast coming out of our shaft. Yet we dipped into that gold; we stuck the drill right down into it. But what did we go into the next time? What did we dip into?"

He swung quickly, violently, toward Smithy who was facing him from the middle of the room. He aimed one finger at him as if it were a pistol, and his words cracked out as sharply as if they came from a gun:

"That tube you sent down—that piece of casing! How was it burned? Were there straggling ends, frozen gobs of metal? Did it look like an old-fashioned molasses candy bar that's been melted? Did it?"

"Why, no," said Smithy. "It hadn't dripped any; it was cut off nice and clean."

"Cut!" Rawson almost shouted the word. "You said it, Smithy. So was the shaft of the drill. And if you ever saw a piece of this alloy being melted you know that it's as gummy as a pot of old paint. It was cut, Smithy! Dipping into that melted gold threw us off the track; we were thinking of ramming the drill down into a mess of lava. But we didn't. It was cut off by a blast of flame so much hotter than lava that melted rock would seem cold!"

"And that helps us a lot, doesn't it," asked Smithy, scornfully, "when the flame melts the end of the shaft shut as fast as we open it?"

Dean Rawson's lean, muscular hands took Smithy's broad shoulders and spun the younger man around. "Cheer up," Dean told him. "We've got it licked. Why it doesn't blow out of that shaft like hell out for noon is more than I can see; but the heat's there! We've won!"

"But—" Smithy began. Rawson sent him spinning toward the door in a good-natured showing of strength that his assistant had not yet guessed.

"Soup!" he ordered. "Break out the nitroglycerine, Smithy. Get that Swede, Hanson, on the job; he's a shooter. He knows his stuff. We'll blow open the bottom end of our shaft so it'll never go shut!"

anson knew his stuff and did it. But he met Rawson's inquiring eyes with a puzzled shake of his head when the open mouth of the twenty-inch bore gave faint echo of the deep explosion and followed after a time with only a feeble puff of air.

"Like a cannon, she should have gone," Hanson stated. "And she yoost go phht!"

"It's open down below," said Rawson briefly. "This is a different kind of a well from the kind you've been shooting."

To the waiting Riley he said: "Hook a bailer onto that cable and send it down. See what you can tell about the hole."

Again ten miles of cable hissed smoothly down the gaping throat. Then it slowed.

"Fifty-two-seven," said Riley, "and she's open. Seven twenty-five! Seven fifty, and we're on bottom!"

"Up," Rawson ordered, "if there's anything left of the bailer. It's probably melted into scrap."

But strangely it was not. It hung from the dangling cable spinning lazily until Riley stepped in to check its motion.

There was a check valve in the bottom—a door that opened inwardly, to take in water and fragments of rock when need arose. Riley, disregarding the possible heat of the twirling bailer, reached for it with bare hands. He drew them back, then held them before him—and a hundred watching eyes saw what had been unseen before: the slow dropping of red liquid from the bailer's end. The same drops were falling from Riley's hands that had touched that end.

"Blood!" The word came from the foreman's throat in one horrified gasp. It ran in a whispering echo from one to another of the watching crew. From far across the hot sands came the rattle of a truck that brought the first of many loads of cement and steel for Rawson's buildings. Its driver was singing lustily:

But Rawson, looking dazedly into Smithy's eyes, said only: "It's cold—the bailer's cold. There's no heat there."

f course it wasn't blood!" said Smithy explosively. "But try to tell the men that. See how far you get. 'Devils!' That's been their talk since yesterday when Riley got smeared up—and now that the bailer's gone we can't prove a thing."

Again he was pacing restlessly back and forth in the little board shack that was Rawson's field head-quarters. Rawson, seated by the window, was looking at tables of comparative melting points. He glanced up sharply.

"You haven't found it yet?" he questioned. "A forty-foot bailer! Now that's a nice easy little thing to mislay."

Riley had followed the excited Smithy into the room; he stood silently by the door until he caught Rawson's questioning glance.

"Forty feet or forty inches," he said, "'tis gone! 'Twas there by the derrick last night, and this marnin'—"

"That's fine," Rawson interrupted with heavy sarcasm. "I haven't enough down below ground to keep my mind occupied—I need a few mysteries up top. Now do you really expect me to believe that a thing like that bailer has been carried off?"

This time it was Smithy who interrupted. "You can just practise believing on that, Dean," he said. "When you get so you can believe a forty-foot bailer can vanish into thin air, then you'll be ready for what I've got. This is what I came in to tell you: that one truckload of steel grillage beams for the turbine footings—they were put out where we surveyed for the first power house—dumped on the sand...."

"Well?" questioned Rawson, as Smithy paused. His look was daring Smithy to say what he knew was coming.

"Five tons of steel beams," said Smithy softly, "gone—just like that! Just a hollow in the sand!"

he big figure of the Irish foreman was still beside the door. Rawson saw one clumsy hand make the sign of the Cross; then Riley held that hand before him and stared at it in horror. "Divils' blood," he whispered. "And I dipped my hands in it. Saints protect us all!"

"That will be all of that!" Dean Rawson's usually quiet voice was as full of crackling emphasis as if it had been charged with electrical energy. "If anyone thinks that I have gone this far, just to be scared out by some dirty sabotage....

"I see it all. I don't know how they did it, but it's all come since the gold was found. Someone else wants it. They think they can scare off the men, maybe take a pot-shot at me, come back here and clean up later on, pull up gold by the pailful, I suppose—"

Riley leaped forward and banged his big fist down on the table. "Right ye are!" he shouted, until loitering men in the open "street" outside stared curiously. "Divils they are, but they're the kind of divils we know how to handle. And now I'll tell ye somethin' else, sir: I know where they are hidin'.

"There was no work for anyone last night, but I'm used to bein' up. I couldn't sleep. I was wanderin' around, thinkin' of nothin' at all out of the way, and I thought I saw some shadows, like it might be men, way off on the sand. Then later over to the old ghost town, d'ye mind! I saw a light, a queer, green sort of light. Sure, a fool I was callin' meself at the time, but now I believe it."

ean Rawson had crossed the room while the man was still speaking. He dragged a wooden case from beneath his cot and smashed at the lid with a wrecking bar. Then he reached inside and drew forth a blue-black .45.

He tossed the pistol to Riley. "Know how to use one of these?" he asked. The manner in which the big Irishman snapped open the side ejection was sufficient answer. Dean handed another gun to Smithy, then pulled out more and laid them on his cot together with a little pile of cartridge boxes.

"You're all right, Riley," he said. "Just keep your head. Don't let your damned superstitions run away with you, and I wouldn't ask for a better man to stand alongside of in a scrap."

The foreman beamed with pleasure: Rawson went on in crisp sentences:

"Take these guns. Take plenty of ammunition. Pick five or six men you know you can depend on. Mount guard around this camp to-night. I'll post an order saying you're in charge—and I'm telling you now to use those guns on anything you see.

"Smithy," he said to the other man who had been quietly listening, "you and I are going to start for town. Only Riley will know that we're gone for the night. We'll have a little listening post of our own up here in the hills."

But Rawson postponed their going. More material was arriving; one casting in particular needed all the men and Rawson's supervision to place it on the sand where an erection crew could swing it into place at some later date. And then, when he and Smithy had driven away from camp with the distant city as their announced destination, Rawson still did not go directly to the mountain grade. He swung off instead where rolling sand-hills blocked all view from the camp, and he headed the car into a gusty wind that brought whirling clouds of dust; they almost obscured the crumbling walls at the volcano's base.

The ghost towns that are found here and there in the forsaken wilderness of the West are depressing to one who walks their empty streets. Little Rhyolite was no exception. In gray, ghostly walls, empty windows stared steadily, disconcertingly like sockets of dead eyes in tattered, weatherbeaten skulls.

ean and Smithy walked among the roofless ruins. Lizards, the color of the cold, gray walls, slipped from sight on silent, clinging feet. Once a sidewinder, almost invisible against the sand, looped away from the intruders with smooth deliberation.

"No marks here," said Rawson at last. "Even an Indian can't read sign in this ashy sand when the wind has dusted it off."

He turned his head from a whirl of fine ash where the wind, sweeping around a wall of stone, was scouring at a sand dune's sloping side.

"Dean," said Smithy, "old Riley may have been looking for banshees when he saw these lights. Superstitious old cuss, Riley! Maybe there wasn't anything here. But, Dean, there's some confoundedly funny things happening around here."

"Are you telling me?" Rawson asked grimly. "But we want to remember one thing," he added: "We've punched a hole in the ground, and we've got into a place that is hot enough to melt Krieger alloy one minute and is stone cold the next. That's disturbing enough, but we don't want to get that mixed up with what's happening up top. There's dirty work going on—"

He stopped. His eyes, that had never ceased to search for some mark of special meaning, had come to rest upon an object half hidden in the sand. He stooped and picked it up.

"Now what the devil is this?" Smithy began. But Rawson was staring at the smooth lava block that was in his hand. It was tapered; it was pierced through with a straight, smooth hole, and its base was round and ringed as if it had been held in a clamp.

"That," he said at last, "was brought in from outside. Outside, Smithy—get that."

ean Rawson's face was wreathed in a sudden smile of pure pleasure. "No, I don't know what the darn thing is," he admitted. "And I don't care. But I know that someone, or some bunch of someones—outsiders—are trying to horn in. I might even go so far as to say that I suspect the power monopoly gentlemen. I think they have started in on us, plan to run off our men, interfere in every way and drive me out of the field with the boring a failure. Smithy, I begin to think I'm going to enjoy this job!"

Again the hot wind, only beginning to cool with the setting of the sun, swept around the building where they stood and tore at the hill of sand. "Come on," said Rawson. "It's getting dark. We'll get up to our lookout—"

"Hold on!" called Smithy sharply.

Rawson turned. Smithy was rubbing his eyes when the whirl of wind-borne sand had passed; he was staring at the sand dunes.

"I'm seeing things, I guess," he said. "I thought for a minute there was a hole there, and the sand was slipping. I'm getting as bad as Riley."

The two went back through the gathering shadows to their waiting car. And Smithy's involuntary shiver told Rawson that he was not the only one to feel a sense of relief at the sound of the exhaust as their car took them away from the dead bones of a dead city in a barren, trackless waste.

he shoulder of rock, where the mountain road swung out, gave a comprehensive view of camp and desert and the encircling mountains. Above in a vault of black was the dazzling array of stars as the desert lands know them; so low they were, the ragged, broken tops of the three ancient craters seemed touching the warm velvet of the sky on which the stars were hung. Beyond their smooth slopes a spreading glow gave promise of the rising moon.

Rawson headed the car downgrade in readiness for a quick return; he ran it close to the inner wall of rock out of which the road had been carved, then seated himself on the outer rim without thought of the thousand-foot sheer drop beneath his dangling legs. With a glass he was sweeping the foreground where the scattered lights of the camp were like vagrant reflections of the stars thrown back to them from the dead sea of sand.

"Riley's on the job," he told Smithy when he passed over the glass later on. "And I've got my pocket portable." He took the little radio receiver from his pocket as he spoke. "Riley will signal me from my office if he sees anything."

The moon had cleared the mountains; its flood of light poured across their rugged heights and filled the bowl of Tonah Basin as some master of a great theatrical switchboard might have flooded a dark stage with magic illumination, half concealing, transforming whatever things it touched.

All the hard brilliance of sunlit sands was gone. The rolling dunes were softly mellow; the more distant mountains were dream-peaks. Half real, they seemed, and half imagined in a veil of haze. Even the buildings, the scattered piles of material, the gaunt skeleton of the derrick—their stark blackness of outline and clear-cut shadow were gone; the whole land was drenched in the mystery and magic of a desert moon.

awson and the man beside him were silent. Even a mind perplexed by unanswerable problems must pause before the witchery of nature's softer moods.

"If Riley were here," said Smithy softly at last, "he wouldn't be seeing any devils. Fairies, pixies, the 'little people'—he'd be seeing them dancing."

Rawson shot his companion a sidelong, appraising glance. He had never penetrated before to this sub-stratum of Smithy's nature. He had never, in fact, felt that he knew much about Smithy, whose past was still the one topic that was never mentioned. He saw his thick mop of black hair and the profile of his face as Smithy stared fixedly down toward the sleeping camp. It was a matter of a minute or so before he knew that the head was outlined against an aura of red light.

Smithy was seated at his right. Off beyond him the three extinct craters made a dark background where the moonlight had not yet reached to their inner slopes. Smithy's head was directly in line with the largest crater's irregularly broken top; and about it was the faintest tinge of red.

For a moment the light flamed close; it seemed to be hovering about the head of the silent, seated man. Then Rawson moved, looked past, and found a true perspective for the phenomenon. One rugged cleft in the rim of the crater's cup made a peephole for seeing within. It was plainly red—the light came from inside the age-old throat.

t's alive!" Rawson whispered in quick consternation. Almost he expected to see billowing clouds of smoke, the fearful pyrotechnics of volcanic eruption.

He sensed more than saw that Smithy had not turned his head. "Look!" he was shouting by now. "Wake up, Smithy! Good Lord!"

He stopped, open-mouthed. The red glow had meant volcanic fires; to have it change abruptly to a green radiance was disconcerting.

Green—pale green. Only through the gap, like a space where a tooth was missing in the giant jaw, could Dean Rawson see the changed light. Only from this one point could the view be had—there would be nothing visible from the camp below. And as quickly as it had come all thought of volcanic fires left him; he knew with quick certainty that this was something that concerned him, that threatened, and that was linked up with the other threatening, mysterious happenings of the recent nights and days.

Still Smithy had not turned. Rawson felt one quick flash of annoyance at his helper's dullness—or indifference; then he knew that Smithy's dark-haired head was reached forward, that he was bending at a precarious angle to stare below him into the valley. Then:

"They're there!" said Smithy in a hushed voice, as if someone or something on that desert floor far below might hear and take alarm. "Look, Dean. Where's your glass? What are they?"

is cautious whispering was unnecessary. Below them a thin line of light pierced the darkness; another; then three more in quick succession before the sharp crack of pistol fire came to the men a thousand feet above. Rawson had snatched up his binoculars.

"To the left," Smithy was directing. "Off there, by the big casting. Great Scott! what's that light?"

Rawson got it in the glass—a single flash of green that cut the blackness with an almost audible hiss. It was gone in an instant while a man's voice screamed once in fear and agony, one scream that broke like brittle steel in the same instant that it began.

Dean found the big casting in the circle of his glass. There were black figures moving near it; they were indistinct. He changed the focus—they were gone before he could get their images sharp.

But the casting! Plainly he saw its great bulk that many men had worked to ease down to the sand. It was outlined clearly now until its edge became a blur, until the sand rolled in upon it, and its black mass became a circle that shrank and shrank and vanished utterly at the last.

"It's gone!" Rawson shouted. "It sank into the sand! I saw it...."

He was running for the car. A clamor of voices was coming from below; the sound died under the thunder of the car's exhaust as Rawson gave it the gun and sent the big machine leaping toward the waiting curves.

very light of the camp was on as Rawson and his assistant approached. A shallow depression in the sand marked the place where the big casting had been. Beyond it a hundred feet was a black swarm of men that parted as the car drew near. They had been gathered about a figure upon the sand.

Dean sensed something peculiar about that figure as the big car ploughed to a stop. He leaped out and ran forward.

He knew it was Riley there on the ground, knew it while still he was a score of feet away. Only when he was close, however, did he realize that the body ended in two stubs of legs; only when he leaned above him did he know that the Irish foreman's big frame had been cut in two as if by a knife.

The severed legs lay a short distance beyond the body; they had fallen side by side in horrible awkwardness, their stumps of flesh protruding from charred clothing—and suddenly, shockingly, Rawson knew that the flesh of body and legs had been seared. The knife had been hot—its blade had been forged of flame!

He heard Smithy cursing softly, unconsciously, at his side.

"The green light," Smithy was saying in horrified understanding. "But who did it? How did they do it? Where did they go?"

"Quiet!" ordered Rawson sharply. He dropped to his knees beside the mutilated body. Riley's eyes had opened in a sudden movement of consciousness.

he voice that came from his lips was a ghastly whisper at first, but in that stricken thing that had been the body of Riley, foreman of the night drilling crew, some reservoir of strength must still have remained untapped.

He drew upon it now. His voice roared again as it had done so many times before through the Tonah Basin camp. It reached to every listening ear where crowding men stood hushed and motionless; and the overtone of terror that altered its customary timber was apparent to all.

"Devils!" said Riley. "Devils, straight out o' hell!... I saw 'em—I saw 'em plain!... I shot—as if hot lead could harm the imps of Satan....

"Oh, sir,"—his eyes had found those of Dean Rawson who was leaning above—"for the love of hivin, Mister Rawson, do ye be quittin' drillin'. The place is damned. L'ave it, sir; go away...."

His eyes closed. But he started up once more; he raised his head from the sand with one final convulsive movement, and his voice was high and shrill.

"The fire! The fire of hell! He's turnin' it on me! God help...."

But Riley, before his failing mind could recall again that torturing jet of flame, must have slipped away into a darkness as softly enveloping as the velvet shadow world behind the low-hung stars. Rawson's hand that felt for a moment above the heart, confirmed the message of the closed eyes and the head that fell inertly back.

He came slowly to his feet.

"Keep the floods on!" he ordered. "Take command of the armed guard, Smithy; keep the whole camp patrolled."

Then to the men:

"Boys, Riley was wrong. He believed what he said, all right, but Smith and I know better. Don't worry about devils. These're just some dirty, skulking dogs who got away with murder this time but who won't do it again. We know where they're hiding. I'm checking up on them right now. After that you'll all get a chance to square accounts for poor old Riley!"

ut the casting!" Smithy protested when he and Rawson were alone. "You can't explain that disappearance so easy, Dean."

"No, I can't explain that," Rawson's words came slowly. "They've got something that we don't understand as yet—but I'm going to know the answer, and I'm going to find out to-night!"

He was seated behind the wheel of his old car.

"I'm as good a desert man as there is in this crowd," he told Smith. "And it's my fight, you know. I'm going alone. But there'll be no fighting this trip; I'll just be scouting around."

He leaned from the car to grip Smithy's shoulder with a hand firm and steady.

"You didn't see the crater when the show was on. You think that I'm crazy to believe it, but up in that crater is where I'll find the answer to a lot of questions. Lord knows what that answer will be. I've quit trying to guess. I'm just going up there to find out."

He was gone, the rear wheels of the car throwing a spray of sand as he started heedless of Smithy's protests against the plan. Rawson was in no mood to argue. He must climb the mountain while it was night; under the sun he would never reach the top alive. He would go alone and unseen.

He swung wide of the deserted town at the mountain's base. The spectral walls of Little Rhyolite still showed their empty windows that stared like dead eyes, and the man guided his car without lights along a hidden stretch of hard, salt-crusted desert. He felt certain that other eyes were watching.

e began his climb at a point five miles away. The slopes that seemed smooth and hard from a distance became, at closer range, a place of wind-heaped, sandy ash, carved and scoured into fantastic forms. But its very roughness offered protection, and Rawson fought the dragging sand, and the gray, choking ash that dried his throat and cut it like emery, without fear of being observed.

He fought against time, too. Above Little Rhyolite, whatever mysterious men were making the ascent would find the going easy. There were windswept areas, long fields of pumice; a man could make good time there. Rawson had none of these to aid him. He cast anxious glances toward the eastern sky as he struggled on, till he saw gray light change to rose and gold—but he stood in the titanic cleft in the crater's rim as the first straight rays of the sun struck across.

The volcano's top had been stripped clean by the winds of countless years. Rocks, black, brown, even blood-red, were naked to the pitiless glare of the sun. Their colors were mingled in a weird fantasy of twisted lines that told of the inferno of heat in which they had been formed.

They towered high above the head of Dean Rawson as he stood, panting and trembling with exhaustion. The cleft before him had become enormous: it was a canyon, half filled with pumice and coarse ash.

awson stood for long minutes in quiet listening. At the canyon's end would lie the crater, and in that crater he would find.... But there was no slightest picture in his mind of what he might see. He knew only that he himself must remain unseen. He went forward cautiously.

Rocky walls; a floor of sand where his feet left no mark. He was watching ahead and above him. His gun was ready in his hand; he did not propose to be ambushed. He moved with never a sound.

The silence persisted; no living thing other than himself lent any flicker of motion to the scene. Not even a lizard could hope for existence amid these dead and barren heights. He was alone—the certainty of it had driven deeply into his mind before the canyon end was reached. And, desert man though he was and accustomed to traveling the waste places of the earth, Rawson learned a new meaning and depth of solitude.

Here was no voiceless companionship of trees or brush or cactus; no little living things scuttled across the rocks—he was alone, the only speck of life in a place where life seemed forbidden.

So sure of this was he that he stepped boldly from the canyon's end. He knew before he looked that he would see only more of the same desolation. And his mind was filled equally with anger and disappointment.

omething was opposing him! Something had come into their camp—had killed old Riley. And he, Rawson, had been so sure he would find traces here that would allow him to give that opposing force a name....

He stared out from the rocky cleft into a sun-blasted pit. Already the rising sun was pouring its energy ever the jagged rim of bleak rocks and down into the vast throat, choked and filled with ash.

It sloped gently from all sides, the gray-brown powder that had been coughed from within the earth. It made a floor where Rawson could have walked with safety. But he did not go on.

"Damn it!" he said with sudden savagery. "What a fool I was to think of finding anyone here. Who would ever pick out a spot like this for a base of operations?"

He stared angrily at the floor of ash, at the black, outcropping masses of tufa. He was angry with himself, angry and baffled and tired from his climb. Far down in the vast, shallow pit blazing sunlight glinted from massive blocks whose sides were mirror-smooth. A whirl of wind eddied there for a moment and lifted the dust into a vertical gray column—the only sign of motion in the whole desolate scene. Rawson turned and tramped back toward the long hot descent to the floor of the Basin.

e tried to maintain an air of confidence before the men. He kept them busy placing and stacking materials; to all appearances the work would go on despite the mysterious happenings of the night.

Dean even prepared to resume drilling operations. He sent down another bailer on the end of the ten-mile cable, but he left it there; he did not care to raise it and risk more inexplicable results with the consequent destruction of the men's morale.

"Too late to do any more," he said to Smithy that afternoon. "We'll drop all work—let the men get a good night's sleep. I'll take guard duty to-night, and you can run the job to-morrow."

There were men of the drilling crew standing near, though Rawson was handling the hoisting drums himself. A ratchet release lever hooked its end under a ring on Rawson's hand and pinched the flesh. Dean made this an excuse for waiting a moment while the drillers walked away.

"Ought not to wear it, I suppose," he said, and dabbed at a spot of blood under the gold band. "But it's an old cameo—it belonged to my Dad."

He was showing the ring to Smithy as the men passed from hearing.

"Don't want to be seen talking," he explained tersely. "Mustn't let the men know we are on edge—they're about ready to bolt. But you be ready for a call. Have your men armed. I am looking for more trouble to-night."

The two were laughing loudly as they followed the men toward the building where the cook was banging on an iron tire that served as a bell.

ome three hours later Rawson was not smiling as he climbed the steel ladder of the great derrick; he was grimly intent upon the job at hand.

All thought of his drilling operations had gone from him. He was not anxious about the project. This was merely an interruption; the work would go on later. But right now there was an enemy to be met and a mystery to be solved.

A rifle slung from his shoulder bumped against him satisfyingly as he climbed. A man was on duty at a master switch—he would flood the camp with light at the rifle's first crack.

Dean seated himself at the top of the derrick. The cylinder of a huge floodlight was beside him. Beyond was the massive sheave block; the cables ran dizzily down to the concrete drilling floor so far below. And on every side the quiet camp spread out dark and silent in the night. Dean surveyed it all with satisfaction. Nothing would get by him now.

But his further reflections were not so satisfying.

"Who did it? How? Where did they go?" He was echoing Smithy's questions and finding no ready answers. And that flame-thrower that had cut down old Riley—how was that worked? Its one green flash had been almost instantaneous.

He was puzzling over such futile questioning when he saw the first sign of attack.

t the foot of the derrick was the hoisting shed. Except for that, there was clear sand for a radius of fifty feet around the derrick's base. Dean was staring suspiciously at that open space almost directly underneath.

Moving sand! He hardly knew what he had seen at first. Then the sand at one point bulged upward unmistakably.

For one instant Dean's thoughts shot off at a tangent. It was like the work of a huge gopher—he had seen the little animals break through like that. Then the sand parted, and something, indistinct, blurred, dark against the yellow background, broke from cover.

Rawson swung the rifle's muzzle over and down. Below him the vague shadow had moved. Dean caught the blurred mass beyond his sights, then swung the weapon aside. Who was it? He would have a look first.

The thin crack of his rifle ripped the silence of the sleeping camp. Dean had aimed to one side and he regretted it in the instant of firing. For, in the same second, there had come from the moving shadow the gleam of starlight reflected upward from polished metal.

ean swung the rifle back. He fired quickly a second time. Beside him the big light hissed into action and the whole camp sprang to sudden, blazing light. And through the quick brilliance, more dazzling even than the white glare itself, was one blinding line of green flame.

Dean saw it as it began. It came from the dim shadow that had sprung suddenly into sharp outline as the big lights came on. He saw the figure. He sensed that it was a man, though he knew vaguely that the figure was grotesque and hideous in some manner he had no time to discern.

The thin line of green flame ripped straight out, swinging in a quick, sweeping trajectory, slashing through the steelwork of the great derrick itself!

Dean knew he was lost in the blinding instant while that fiery jet was sweeping in a fan-shaped sector of vivid green. A knife of flame! It had destroyed a man: it was now cutting down a framework of steel as well!

The derrick was falling as he fired again. There came a crushing jar downward as the metal melted and failed, and the wild outward swing in the beginning of the toppling fall. In the mind of Dean Rawson was but one thought: the sights—and a something blurred beyond—a trigger to be pressed.

He was still firing when the shriek of torn steel went to thundering silence, and even the lights of Tonah Basin Camp were swallowed up in the whirling night....

mithy's agonized face was above him when he came back to life. "God!" Smithy was breathing. "I thought you were gone, Dean! I thought you were dead!"

As it had been with Riley, there was one thought uppermost in Rawson's bewildered mind: "The fire!" he choked. "He's swinging it...."

Then, after a time: "The derrick—it's falling! I went down with it!... I hit—"

"I'll say you did," said the relieved Smithy. "The derrick smashed across the bunkhouse, snapped you off, sent you skidding down the side of a sand dune. It darned near scoured the clothes off you at that."

Slowly Rawson began to feel the return flow of life through his body; the shock had jarred every nerve to insensibility. Slowly he remembered and comprehended what had happened.

He was in his little office; he recognized his surroundings now. The windows were open. Outside the sun was shining. He realized at last the utter silence of that outer world.

He tried to raise himself from the cot, but fell back as his surroundings began to spin. "The camp!" he gasped weakly. "The men—I don't hear them."

"Gone!" Smith told him, while his eyes narrowed at some recollection and his hand came up unconsciously to a bruise of his cheek. "They beat it—went last night after the derrick fell. I tried to stop them. The fools were crazy with fear—devils, hell, all that kind of stuff. It all wound up in a fight—I couldn't hold 'em.

"You've got to get better kind of fast," he told Rawson. "We've got to get out of here ourselves—that flame-throwing stuff is too strong for me to take."

Rawson suddenly remembered the vague figure that had directed that flame. "Did I get him?" he demanded eagerly.

"You got him, yes, but then a whole swarm of things boiled up out of nowhere and carried him off! We weren't any of us close enough to see. The men said they were devils; I'm not sure they were wrong, either. Dean, old man, we're up against something rotten. We've got to get fixed for a fight; we can't handle this by ourselves."

awson was silent. He spoke slowly at last:

"You mean we've got to quit—quit without knowing what we're up against. Can you imagine what they'll say to me back in town? Scared out, licked by something I've never even seen!"

"Scared?" Smithy inquired. "You couldn't find a better word for it if you hunted through the whole dictionary. Scared? Why, say, I'm so damn scared I'm shaking yet, and the only thing that will cure me of it is to look at those devils along the top of a machine gun! We'll go catch us some equipment and a few service men—"

"You're a good guy, Smithy," Rawson reached out and gripped one brown hand. "And we'll do as you say; but first I've got to get a line on things. I'm becoming as irrational as the men. I'm imagining all sort of crazy things."

"You don't have to imagine them." Smithy's voice was strained; it showed the tension under which he was laboring. "Men or beasts—God knows what they are!—but when they come up from nowhere—"

"Out of the sand," Rawson explained.

Smithy stared at him. "Out of the sand," he repeated. "Then, when they cut a man in two, melt steel as if it were butter, pull a few tons of metal down out of sight as easy as we would sink it in the ocean, flash their lights over in the ghost town, up on top of a volcano—"

"Stop!" shouted Rawson unexpectedly. Some sudden gleam of understanding had flashed through his mind. He dragged himself to his feet and staggered to the doorway where he clung until the nausea of a whirling world had passed. "The dust! The dust!" he gasped.

Smithy put a hand on his shoulder. Plainly he thought Rawson out of his mind. "Easy, old-timer," he cautioned. "We'll get out of here. I hate to make you walk in the shape you're in, but the dirty cowards ran off with the trucks. They even took your car; there isn't a thing here on wheels."

But Rawson did not hear. He was staring off across the sand, and he was muttering bitter words.

"Fool! Oh, you utter fool!" he said. "The dust—the dust." Then he let the roughly tender hands of Smithy guide him back to the cot where he fell into a troubled sleep.

he comparative coolness of dusk was tempering the feverish midday heat when Rawson awoke. And, strangely, his troubles and all his conflicting plans had been simplified by the magic of sleep. His course was entirely plain. He was going to the crater again.

"What's there?" Smithy demanded. "What do you think that you'll find?"

"I don't know," was the reply.

"Then why—what the devil's the idea?"

"It's my job. They put it up to me, Erickson and his crowd. I've got to go."

And nothing Smithy could say seemed able to reach Rawson and swerve him from his single idea.

"You'll be safe on the road," Rawson told him, while he filled a canteen with water in preparation for his own trip. "You can get to the highway by morning."

Smithy did not trouble to reply. Was Rawson out of his mind? He could not be sure. Certainly he had got an awful bump, but there were no bones broken. However, it might be that he was still dazed—a crack on the head might have done it.

But there was no use in further argument, he admitted to himself. Dean was going to the crater again—there was no stopping him—but he was not going alone; Smithy could see to that.

gain Rawson took the more difficult ascent. They went first to the ghost town: the slope above Little Rhyolite would save weary miles. But, once there, they knew that the route was not a place where they would care to be in the night. The realization came when Smithy, walking where they had been the day before, passing the sand dune where the wind had been scouring, seized Rawson's arm.

"I thought so," he said softly. "I thought I saw something there the other day, but the sand fell in and hid it. I didn't know the old-timers went in for subways in Little Rhyolite."

And Rawson looked as did Smithy, in wondering amazement, at the roughly round opening in the sand, a tunnel mouth, driven through the shifting sands—a tunnel, if Rawson was any judge, lined with brown glistening glass.

Understanding came quickly.

"The jet of flame!" he exclaimed half under his breath. "They melted their way through; the sand turned to glass; they held it some way for an instant while it hardened." He walked cautiously toward the dark entrance and peered inside.

Darkness but for the nearer glinting reflections from walls that had once been molten and dripping. The tunnel dipped down at a slight angle, then straightened off horizontally. Rawson could have stood upright in it with easily another two feet of headroom to spare.

"And that," said Smithy, "is how the dirty rats got over to the camp. Like moles in their runway. No wonder they could pop up from nowhere. But, Dean, old man, I'm thinkin' we're up against something we haven't dared speak of to each other. Don't tell me that it's just men we've got to meet—"

"Wait," Rawson begged in a hushed whisper. "Wait till we know. That's why I didn't dare go out without something definite to report. We'll go up—but not here. We'll get a line on this up top."

e led the way from the crumbling walls and skirted the mountain's base to the place where he had climbed before. And, with the help of a supporting arm at times, he found himself again in the great cleft in the rocks.

Darkness now made the passageway a place of somber shadows. The broad cupped crater lay beyond in silent waiting; the vast sand-filled pit seemed, under the starlight, to have been only that instant cooled. The twisted rocks that formed the rim had been caught in the very instant of their tortures and frozen to deep silence and eternal death: the black masses of tufa, protruding from the packed ashy sand might have been buried by the smothering mass but a moment before. It was a place of death, a place where nothing moved—until again the breeze that whirled gustily over the saw-tooth crags snatched at the sand in that lowest pit and drew it up in a spiral of dust.

The word was on Rawson's lips. "Dust—dust in the crater. Fool! I said I could read sign; I thought I was a desert man."

"Dust? And why shouldn't there be dust? How do you usually have your volcanoes arranged, old man?"

"Fine dust!" Rawson interrupted in the same whisper. He was glancing sharply about him as if in fear of being overheard. "See, the wind is blowing it. Coarse sand and pumice—that's to be expected; but light dust in a place that the winds have been sweeping for the last million years! I don't have them arranged that way, Smithy—not unless the sand has been recently disturbed!"

e moved soundlessly across the sand. There was no chance for concealment; the surface was too smooth for that. Yet he wished, as he moved onward down the long, gentle slope, that he had been able to keep under cover. In all the wide bowl of the great crater top was nothing but dead ashes of fires gone long centuries before, coarse, igneous rock—nothing to set the little nerves of one's spine to tingling. Rawson tried to tell himself he was alone. Even the gun in his hand seemed an absurd precaution. Yet he knew, with a certainty that went beyond mere seeing, that invisible eyes were upon him.

The blocks were massive when he drew near to them. They were buried in the sand, their sides like mirrors, their edges true and straight. "Crystals," Rawson tried to tell himself, but he knew they were not.

Gun in hand, he moved among the great rocks. Open sand lay beyond, running off at a steeper pitch to make a throat—a smaller pit in the great pit of the crater itself. Rawson noted it, then forgot it as he stooped for something that lay half hidden, its protruding end shining under the light of the stars, as he had seen it gleam before at the derrick's base.

He snatched up the metal tube, noting the lava tip, and that it was like the one Smithy had found in the ghost town. The tube, clearly, was part of some other mechanism, and Rawson realized with startling suddenness that he was holding in his hand the jet of a flame-thrower—the same one, perhaps, that had almost sent him to his death.

The thought, while he was still thinking it, was blotted from his mind. He was thrown suddenly to the sandy earth; the sand was slipping swiftly from beneath his feet; he was scrambling on all fours, clawing wildly for some anchorage that would keep him from being swept away.

e touched a corner of shining stone, drew himself to it, reached its slanting side, then scrambled frenziedly to the top and threw himself about to face the place of slipping sands. But where the sand had been, his wildly glaring eyes found only a black hole—a vertical bore, like the ancient throat of the volcano; and this, like the tunnel in the sand, was lined with smooth and glistening glass.

It was black at first, a yawning, ominous maw, till the polished sides caught a reflection from below and blazed red with the glare of hidden fires.

No time was needed for Dean's quick searching eyes to grasp the meaning of the change. Whatever had menaced the camp had set this trap. He swung sharply to leap from the block, but stopped at the sight of Smith's chunky figure coming slowly across the sand.

"Back!" he shouted. His voice was almost a scream, shrill and crackling with excitement. "Get back, Smithy! I'm coming!"

e would have leaped. Below the block the sand bulged upward as a yellow animal-thing came clawing up into the night. Dimly he saw it—saw this one and the others that must have been hidden in the sand. They were between him and Smithy! A blaze of red came from behind him—there must be others there! He snatched his gun from its holster as he turned.

Flames were hissing into the darkness, five or six of them in lines of hot crimson fire. They changed to green as he watched, and the livid light spread out in ghastly illumination over the creatures that directed them.

He saw them now—saw them in one age-long instant while he stood in horror on the black shining rock. He saw their heads, red-skinned, pointed, their staring eyes as large as saucers—owl-eyes. They were naked, and their bodies, that would have been almost crimson in the light of day, were blotched and ghastly in the green light. And each one held in long clawlike hands a thing of shining metal—a lava tip like the one he had found projected and ended in the hissing line of green.