The Project Gutenberg EBook of L'Aiglon, by Edmond Rostand This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: L'Aiglon Author: Edmond Rostand Translator: Louis N. Parker Release Date: September 17, 2009 [EBook #30012] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK L'AIGLON *** Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.)

A PLAY IN SIX ACTS

BY

TRANSLATED BY

LOUIS N. PARKER

Copyright 1900

By Robert Howard Russell

The First Act

The Second Act

The Third Act

The Fourth Act

The Fifth Act

The Sixth Act

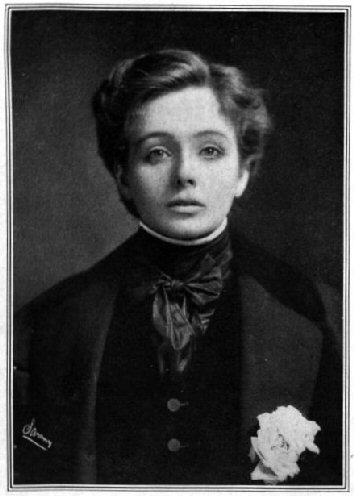

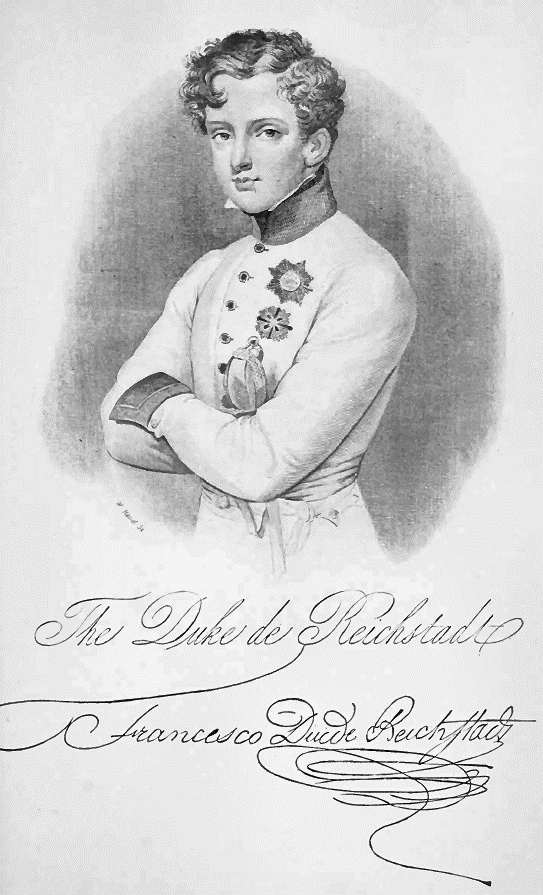

| The Duke of Reichstadt, son of Napoleon I. and the Archduchess Maria Louisa of Austria | Maude Adams | |

| Flambeau, a veteran | J. H. Gilmour | |

| Prince Metternich, Chancellor of Austria | Edwin Arden | |

| Count Prokesch | Percy Lyndall | |

| Baron Friedrich von Gentz | Eugene Jepson | |

| The Attaché of the French Embassy at the Austrian Court | Oswald York | |

| The Tailor, a conspirator | William Lewers | |

| Count Maurice Dietrichstein | Edward Lester | |

| Baron von Obenaus | R. Peyton Carter | |

| The Emperor Francis of Austria | Jos. Francœur | |

| Marshal Marmont, Duke of Ragusa | J. H. Benrimo | |

| Count Sedlinzky, Prefect of the Austrian Police | William Crosby | |

| The Marquis of Bombelles, betrothed to Maria Louisa | Clayton Legge | |

| Tiburtius de Loget | William Irving | |

| Lord Cowley, English Ambassador at the Austrian Court | Rienzi de Cordova | |

| Count Sandor | Edward Jacobs | |

| Doctor Malfatti | H. D. James | |

| General Hartmann | Herbert Carr | |

| Captain Foresti | John S. Robertson | |

| An Austrian Sergeant | Lloyd Carleton | |

| A Country Doctor | Frederick Spencer | |

| His Son | Byron Ongley | |

| Thalberg | B. B. Belcher | |

| Montenegro | Morton H. Weldon | |

| The Chamberlain | Charles Martin | |

| An Officer of the Noble Guard, the Emperor of Austria's Bodyguard | Henry P. Davis | |

| The Marquis of Otranto, son of Fouche | Charles Henderson | |

| Goubeaux | Don C. Merrifield | |

| Pionnet | {Bonapartist} | Henry Clarke |

| Morchain | {conspirators} | Thomas H. Elwood |

| Guibert | George Klein | |

| Borowski | Frank Goodman | |

| First Police Officer | Ralph Yoerg | |

| First Archduke, a child | Walter Butterworth | |

| Second Archduke, a child | John Leeman | |

| Maria Louisa, second wife of Napoleon I., widow of Count Neipperg | Ida Waterman | |

| The Archduchess Sophia of Austria | Sarah Converse | |

| Theresa de Loget, sister of Tiburtius de Loget | Ellie Collmer | |

| The Countess Napoleone Camerata, daughter of Napoleon's sister, Elisa Baciocchi | Sarah Perry | |

| Fanny Elssler | Margaret Gordon | |

| Scarampi, Mistress of the Robes | Francis Comstock | |

| Mina, a maid-of-honor | Edith Scott | |

| An Archduchess, a child | Beatrice Morrison | |

Princes, Princesses, Archdukes, Archduchesses, Maids-of-Honor, Officers, Noble Guard, Masks (Male and Female), Crotian Peasants, Hungarian Peasant, Austrian Soldiers, Police Officers.

The period covered by the play is from 1830 to 1832.

THE DUKE OF REICHSTADT

FROM THE PAINTING BY SIR THOMAS LAWRENCE

At Baden, near Vienna, in 1830.

The drawing-room of the villa occupied by Maria Louisa. The walls are painted al fresco in bright colors. The frieze is decorated with a design of sphinxes.

At the back, between two other windows, a window reaching to the ground and forming the entrance from the garden. Beyond, the balustrade of the terrace leading into the garden; a glimpse of lindens and pine-trees. A magnificent day in the beginning of September. Empire furniture of lemonwood decorated with bronze. A large china stove in the centre of the wall on the left. In front of it a door. On the right, two doors. The first leads to the apartments of Maria Louisa. In front of the window on the left at the back an Erard piano of the period, and a harp. A big table on the right, and against the right wall a small table with shelves filled with books. On the left, facing the audience, a Récamier couch, and a large stand for candlesticks. A great many flowers in vases. Framed engravings on the walls representing the members of the Imperial Family of Austria. A portrait of the Emperor Francis.

At the rise of the curtain a group of elegant ladies is discovered at the further end of the room. Two of them are seated at the piano, with their backs to the audience, playing a duet. Another is at the harp. They are playing at sight, amid much laughter and many interruptions. A lackey ushers in a modestly dressed young girl who is accompanied by an officer of the Austrian Cavalry. Seeing that no one notices their entrance, these two remain standing a moment in a corner. The Count de Bombelles comes in from the door on the right and goes toward the piano. He sees the young girl, and stops, with a smile.

The Ladies.

[Surrounding the piano, laughing, and all talking at

the same time.]

She misses all the flats!—It's scandalous!—

I'll take the bass!—Loud pedal!—One! Two!—Harp!

Bombelles.

[To Theresa.]

What! You!

Theresa.

Good-day, my Lord Bombelles!

A Lady.

[At the piano.]

Mi, sol.

Theresa.

I enter on my readership—

Another Lady.

[At the piano.]

The flats!

Theresa.

It's thanks to you.

Bombelles.

My dear Theresa! Nothing!

You are my relative, and you are French.

Theresa.

[Presenting the officer.]

Tiburtius—

Bombelles.

Ah, your brother!

[He gives him his hand and pushes forward a

chair for Theresa.]

Take a seat.

Theresa.

I'm very nervous.

Bombelles.

[With a smile.]

Heavens! What about?

Theresa.

To venture near the persons of the two

The Emperor left!

Bombelles.

Oh, is that all, my child?

Tiburtius.

Our people hated Bonaparte of old—

Theresa.

Yes—but to see—

Bombelles.

His widow?

Theresa.

And perhaps

His son?

Bombelles.

Assuredly.

Theresa.

Why, it would mean

I'd never thought or read, and was not French,

Nor born in recent years, if I could stand

Unmoved so near them. Is she lovely?

Bombelles.

Who?

Theresa.

Her Majesty of Parma?

Bombelles.

Why—

Theresa.

She's sad

And that itself is beauty.

Bombelles.

But I'm puzzled.

Surely you've seen her?

Theresa.

No.

Tiburtius.

We've just come in.

Bombelles.

Yes, but—

Tiburtius.

We feared we might disturb these ladies

Whose laughter sings new gamuts to the piano.

Theresa.

Here in my corner I await her notice.

Bombelles.

What? Why, it's she who's playing bass this moment!

Theresa.

The Emp—?

Bombelles.

I'll go and tell her.

[He goes to the piano and whispers to one of the

ladies who are playing.]

Maria Louisa.

[Turning.]

Ah! this child—

Quite a pathetic story—yes—you told me:

A brother—

Bombelles.

Father exiled. Son an exile.

Tiburtius.

The Austrian uniform is to my taste;

And then there's fox-hunting, which I adore.

Maria Louisa.

[To Theresa.]

So that's the rascal whose extravagance

Eats up your little fortune?

Theresa.

Oh!—my brother—

Maria Louisa.

The wretch has ruined you, but you forgive him!

Theresa de Loget, I think you're charming!

[She takes Theresa by both hands and makes her

sit beside her on the couch.]

[Bombelles and Tiburtius retire to the back.]

Now you're among my ladies. I may boast

I'm not unpleasant; rather sad at times

Since—

Theresa.

I am grieved beyond the power of words.

Maria Louisa.

Yes, to be sure. It was a grievous loss.

That lovely soul was little known!

Theresa.

Oh, surely!

Maria Louisa.

[Turning to Bombelles.]

I've just been writing; they're to keep his horse—

[To Theresa.]

Since the dear General's death—

Theresa.

The—General's?

Maria Louisa.

He'd kept that title.

Theresa.

Ah, I understand!

Maria Louisa.

I weep.

Theresa.

That title was his greatest glory.

Maria Louisa.

One cannot know at first all one has lost;

And I lost all when General Neipperg died.

Theresa.

Neipperg?

Maria Louisa.

I came to Baden for distraction.

It's nice. So near Vienna.—Ah, my dear,

My nerves are troublesome; they say I'm thinner—

And growing very like Madame de Berry.

'Twas Vitrolles said so. Now I do my hair

Like her. Why did not Heaven take me too?

This villa's small, of course; but 'tisn't bad;

Metternich is our guest in passing.

[She points to the door on the left.]

There.

He leaves to-night. The life at Baden's gay.

We have the Sandors and the pianist Thalberg,

And Montenegro sings to us in Spanish.

Fontana howls an air from Figaro.

The wife of the Ambassador of England

And the Archduchess come; we go for drives—

But nothing soothes my grief!—Ah, could the General—!

Of course you're coming to the ball to-night?

Theresa.

Why—

Maria Louisa.

At the Meyendorffs'. Strauss will be there.

She must be present, mustn't she, Bombelles?

Theresa.

May I solicit of your Majesty

News of the Duke of Reichstadt?

Maria Louisa.

In good health.

He coughs a little; but the air of Baden

Is good for him. He's quite a man. He's reached

The critical hour of entrance in the world!

Oh dear! when I consider he's already

Lieutenant-Colonel! Think how grieved I am

Never to have seen him in his uniform!

[Enter the Doctor and his son, bringing a box.

Maria Louisa.

Ah! These must be for him!

The Doctor.

Yes; the collections.

Maria Louisa.

Please put them down.

Bombelles.

What are they?

The Doctor.

Butterflies.

Theresa.

Butterflies?

Maria Louisa.

Yes; when I was visiting

This amiable old man, the local doctor,

I saw his boy arranging these collections.

I sighed aloud, Alas! would but my son,

Whom nothing moves, take interest in these!

The Doctor.

So then I answered, Well, your Majesty,

One never knows. Why not? We can but try;

I'll bring my butterflies!

Theresa.

His butterflies!

Maria Louisa.

Could he but leave his solitary musings

To occupy his mind with—

The Doctor.

Lepidoptera.

Maria Louisa.

Leave them; come back; he's out at present.

[To Theresa.] You

Come, I'll present you to Scarampi. She's

The Mistress of the Robes.

[She sees Metternich, who enters L.]

Ah, Metternich!

Dear Prince, we leave you the saloon.

Metternich.

Indeed,

I had to come here to receive the Envoy—

Maria Louisa.

I know—

Metternich.

Of General Belliard, French Ambassador;

And Councillor Gentz, and several Estafets.

With your permission—

[To a lackey.] First, Baron von Gentz.

Maria Louisa.

The room is yours.

[She goes out with Theresa. Tiburtius and

Bombelles follow her. Gentz enters.]

Metternich.

Good-morning, Gentz. You know

The Emperor recalls me to Vienna?

I'm going back to-day.

Gentz.

Ah?

Metternich.

Yes; it's tiresome—

The town in summer!

Gentz.

Empty as my pocket.

Metternich.

Oh, come now! No offence, you know, but—eh?

Surely the Russian Government has—

Gentz.

Me!

Metternich.

Be frank. Who's bought you? Eh?

Gentz.

[Munching sweetmeats.]

The highest bidder.

Metternich.

Where does the money go?

Gentz.

[Smelling at a scent-bottle he has taken out of his

pocket.]

In riotous living.

Metternich.

Good Heavens! And you're considered my right hand!

Gentz.

Let not your left know what your right receives.

Metternich.

Sweetmeats and perfumes! Oh!

Gentz.

Why, yes, of course.

I've money; I love sweets and perfumes. Yes,

I'm a depraved old baby.

Metternich.

Affectation!

Mere pose of self-contempt.

[Suddenly.] And Fanny?

Gentz.

Elssler? Won't love me. I'm ridiculous

From every point of view. She loves the Duke.

I'm but a screen; but I'm content to suffer

When I remember how it serves the state

If he's amused. And so I play the fool,

And dance attendance on the little dancer.

She bade me bring her here this very night,

Just to surprise the Duke.

Metternich.

You scandalize me.

Gentz.

His mother's going out. There's dancing.

[He hands Metternich a letter which he has

taken out of a pocket-book.]

Read—

From Fouché's son.

Metternich.

[Reading the letter.] August the twentieth,

Eighteen hundred and thirty—

Gentz.

He'd transform—

Metternich.

Good Viscount of Otranto!

Gentz.

Our Duke of Reichstadt to Napoleon Two.

Metternich.

[Handing back the letter.]

A list of partisans?

Gentz.

Yes.

Metternich.

Make a note.

Gentz.

Do we refuse?

Metternich.

Without destroying hope.

Ah, but my little Colonel serves me well

To keep these Frenchmen straight. When they forget

Their Metternich, and lean too much to the left,

I let him show his nose out of his box, and—crack!—

When they come right, I pop him in again!

Gentz.

When can one see the springs work?

Metternich.

Now.

[Enter the French Attaché.

Metternich.

The Envoy

Of General Belliard. Welcome, sir.

[Hands him papers.] The papers.

We accept in principle King Louis Philip;

But don't let's have too much of '99,

Or we might crack a little egg-shell!

The Attaché.

Sir,

Are you alluding to Prince Francis Charles?

Metternich.

The Duke of Reichstadt? Oh, sir, as for me,

I don't admit his father reigned.

The Attaché.

[Generously.]

I do.

Metternich.

So I'll do nothing for the Duke. Yet—

The Attaché.

Yet?

Metternich.

Yet, should you give too loose a reign to freedom,

Permit yourself the slightest propaganda,

Let Monsieur Royer-Collard come too often

And bare his bosom to your king; in short,

If your new kingdom's too republican,

We might—our temper's not angelical—

We might remember Francis is our grandson.

The Attaché.

Our lilies never shall turn red.

Metternich.

And while

They keep their whiteness bees shall not approach them.

The Attaché.

'Tis feared in spite of you the Duke may hope.

Metternich.

No.

The Attaché.

Things are happening.

Metternich.

But we filter them.

The Attaché.

Doesn't he know that France has changed her king?

Metternich.

Yes; but the detail he does not yet know

Is that his father's flag, the tricolor,

Is re-established. 'Twill be time enough—

The Attaché.

He would be drunk with hope!

Metternich.

We'll keep him sober.

The Attaché.

He's not so strictly guarded here at Baden.

Metternich.

Oh, here there's nought to fear. He's with his mother.

The Attaché.

Well, sir?

Metternich.

What spy could have such interest

In watching him? For any plot would trouble

Her lovely calm.

The Attaché.

Is not that calmness feigned?

She cannot have a thought but for her eaglet!

Maria Louisa.

[Entering hurriedly.

My parrot!

The Attaché.

[Starting.]

Eh?

Maria Louisa.

[To Metternich.]

Margharitina's flown!

Metternich.

Oh!

Maria Louisa.

My parrot, Margharitina!

Metternich.

[To the Attaché.]

There, sir!

The Attaché.

[To Maria Louisa.]

May I not seek it, Highness?

Maria Louisa.

[Curtly.]

No. [She goes out.

The Attaché.

[To Metternich.]

What's wrong?

Metternich.

We say, Your Majesty; you called her Highness.

The Attaché.

But if we don't allow the Emperor reigned

She cannot be addressed as Majesty

Except as Parma's Duchess—

Metternich.

That's her title.

The Attaché.

Then that was why she looked such daggers at me!

Metternich.

Question of protocols and of precedence.

The Attaché.

[Preparing to take his leave.]

May the French Embassy from this day forward

Display the tricolor cockade?

Metternich.

[With a sigh.] Of course,

Since we're agreed—

[Seeing the Attaché silently throw away the

white cockade which was on his hat and replace

it with a tricolor which he takes out of his

pocket.]

Come, come! You lose no time!

[Noise of harness-bells without.]

Metternich.

What is it now?

Gentz.

[Who is on the terrace.]

The guests of the Archduke.

The Meyendorffs, Lord Cowley, Thalberg—

Bombelles.

[Who has quickly come in R. at the sound of the

bells, followed by Tiburtius.]

Meet them!

The Archduchess.

[Appearing on the threshold surrounded by a

crowd of lords and ladies in elegant summer

costumes. (Light dresses and parasols; large

hats.) Two little boys and a little girl dressed in the

latest fashion.]

'Tis but a villa; not a palace.

[The room is crowded. She turns to a young

man.]

Quick!

Thalberg, my Tarantelle!

[Thalberg sits at the piano and plays.]

[To Metternich.] Where is her Majesty,

My lovely sister?

A Lady.

We looked in to fetch her.

Another Lady.

We're rushing through the valley on a coach.

Sandor is driving.

A Man's Voice.

We must thrust the lava

Back in its crater!

The Archduchess.

Oh! do hold your tongues

They will insist on talking of volcanoes.

Bombelles.

What's this volcano?

A Lady.

[To another.]

Astrachan this winter.

Sandor.

[To Bombelles.]

Why, liberal opinions.

Bombelles.

Ah!

Lord Cowley.

Or, rather, France!

Metternich.

[To the Attaché.]

You hear him?

A Lady.

[To a young man.]

Montenegro, sing to me

Under your breath, for me alone.

Montenegro.

[Whom Thalberg accompanies, sings very softly.]

Corazon—

[He continues, pianissimo.]

Another Lady.

[To Gentz.]

Ah, Gentz!

[She dips into her reticule.]

Some bon-bons, Gentz?

[She gives him some.]

Gentz.

You are an angel.

Another Lady.

[Similar business.]

Perfume from Paris?

[She takes out a little bottle of scent and gives it to him.]

Metternich.

[Hurriedly to Gentz.]

Tear the label off!

"The Reichstadt scent"!

Gentz.

[Smelling perfume.]

It smells of violets.

Metternich.

[Snatches the bottle out of his hand and scrapes

the label off with a pair of scissors he takes from

the table.]

If the Duke came he'd see that still at Paris—

A Voice.

[Among the group at the back of the stage.]

The Hydra lifts its head—

A Lady.

Our husbands talk

Of Hydras!

Lord Cowley.

And it must be stifled.

A Lady.

Yes;

Volcanoes first, then hydras.

A Maid of Honor of Maria Louisa.

[Followed by a servant bringing a tray with large

glasses of iced coffee.]

Eis-Kaffee?

The Archduchess.

[Seated; to a young lady.]

Recite some verses, Olga.

Gentz.

May we have

Something of Heine's?

Several Voices.

Yes!

Olga.

[Rising.]

The Grenadiers?

Metternich.

[Quickly.]

Oh! No!

Scarampi.

[Coming out of Maria Louisa's apartment.]

Her Majesty is on her way!

All.

Scarampi!

Sandor.

We'll drive out to Krainerhütten,

The ladies there can rest upon the green.

Metternich.

[To Gentz.]

What are you reading yonder?

Gentz.

The "Debats."

Lord Cowley.

The politics?

Gentz.

The Theatres.

The Archduchess.

How futile!

Gentz.

Guess what they're playing at the Vaudeville.

Metternich.

Well?

Gentz.

"Bonaparte."

Metternich.

[With indifference.]

Oh?

Gentz.

The Nouveautés?

Metternich.

Well?

Gentz.

"Bonaparte." And the Variétés?

"Napoleon." The Luxembourg announces

"Fourteen years of his life." At the Gymnase

They are reviving the "Return from Russia."

What is the Gaiety to play this season?

"Napoleon's Coachman" and "La Malmaison."

An unknown author's done "Saint Helena."

The Porte-Saint-Martin's going to produce

"Napoleon."

Lord Cowley.

It's the fashion.

Tiburtius.

It's the rage.

Gentz.

The Ambigu "Murat;" the Cirque "The Emperor."

Sandor.

A fashion.

Bombelles.

Yes, a fashion.

Gentz.

Yes, a fashion

Which will recur from time to time in France.

A Lady.

[Reading the paper over Gentz's shoulder through

a long-handled eye-glass.]

They want to bring his ashes home.

Metternich.

The Phœnix

May rise again, but not the eagle.

Tiburtius.

What

An unknown quantity is France!

Metternich.

Oh, no;

I've gauged it.

A Lady.

Well, then, mighty prophet, speak!

The Archduchess.

His words are graven in bronze.

Gentz.

Or, maybe, zinc.

Lord Cowley.

Who will be France's Saviour?

Metternich.

Henry the Fifth.

The others—Fashion.

Theresa.

That's a useful name

For calling glory by at times.

Metternich.

So long

As all the shouting's only done in theatres,

I think there's no—

Cries.

[Without.]

Long live Napoleon!

All.

What?—Here, at Baden!—Here!

Metternich.

Ridiculous!

Pray, have no fear!

Lord Cowley.

We must not lose our heads

Because a name is shouted.

Gentz.

He is dead.

Tiburtius.

[On the terrace.]

It's nothing.

Metternich.

Yes, but what?

Tiburtius.

An Austrian soldier.

Metternich.

Austrian?

Tiburtius.

Two of them. I saw them.

Metternich.

Vexing!

Maria Louisa.

[Entering hurriedly and pale with fear from her room.]

Did you not hear the shout? Oh, horrible!

It brought to mind—One day the people surged

About my coach in Parma with that cry!

It's done to vex me!

Metternich.

What could it have meant?

Tiburtius.

Two of the Duke of Reichstadt's regiment

Caught sight of him as he was riding homeward.

You know the deep ditch bordering the road?

His Highness wished to leap it, but his horse

Shied, swerved, and backed. The Duke sat firm,

And brought him to it again, and—over! Then

The men, to applaud him, shouted. And that's all.

Metternich.

[To a lackey.]

Fetch one of them at once!

Maria Louisa.

They seek my death!

[An Austrian sergeant is brought in.]

Metternich.

A sergeant! Now, my man, speak up. What meant

That shouting?

The Sergeant.

I don't know.

Metternich.

What! You don't know?

The Sergeant.

No; nor downstairs the corporal don't know neither.

He shouted with me. It was good to see

The Prince so young and slender on his horse.

And then we're proud of having for our Colonel

The son of—

Metternich.

That'll do.

The Sergeant.

He took the ditch

So cool and calm! As pretty as a picture!

So then a sort of lump came in our throats,

Pride and affection—I don't know—we shouted

"Long live—!

Metternich.

Enough, enough! It's just as easy

To shout "Long live the Duke of Reichstadt," idiot!

The Sergeant.

Well—

Metternich.

What?

The Sergeant.

"Long live the Duke of Reichstadt"

Isn't so easy as "Long live—"

Metternich.

Be off.

Don't shout at all!

Tiburtius.

[To the Sergeant as he passes him to go out.]

You fool!

Maria Louisa.

[To the ladies who surround her.]

I'm better, thank you.

Theresa.

The Empress!

Maria Louisa.

[To Dietrichstein, pointing to Theresa.]

Baron Dietrichstein, this is

My new companion-reader.

[To Theresa, presenting Dietrichstein.]

My son's tutor.

And, by the way, I've never thought of asking—

Do you read well?

Tiburtius.

Oh, very!

Theresa.

I don't know.

Maria Louisa.

Take one of Franz's books from yonder table,

Open it anywhere.

Theresa.

[Taking a book and reading the title.]

"Andromache"—

[She reads.]

"What is this fear, my lord, which strikes the heart?

Has any Trojan hero slipped his chains?

Their hate of Hector is not yet appeased:

They dread his son! fit object of their dread!

A hapless child, who is not yet aware

His master's Pyrrhus and his father Hector."

[General embarrassment.]

I—

Gentz.

Charming voice.

Maria Louisa.

Select another passage.

Theresa.

"Alas the day, when, prompted by his valor,

To seek Achilles and to meet his doom,

He called his son and wrapped him to his heart:

'Dear wife,' quoth he, and brushed away a tear,

'I know not what the fates may have in store.

I leave my son to thee—'"

[General embarrassment.]

H'm—yes—

Maria Louisa.

Let's try

Some other volume. Take—

Theresa.

The "Meditations"?

Maria Louisa.

I know the author! 'Twill not be so dull.

He dined with us. [To Scarampi.] The Diplomat,

you know.

Theresa.

[Reads.]

"Never had hymns more strenuous and high

From seraph lips rung through the listening sky:

Courage! Oh, fallen child of godlike race—"

The Duke.

[Who has entered unnoticed.]

Forgive the interruption, Lamartine!

Maria Louisa.

Well, Franz? A pleasant ride?

The Duke.

Delightful, mother.

But, Mademoiselle, where did my entrance stop you?

Theresa.

[Looking at him with emotion.]

"Courage! Oh, fallen child of godlike race,

The glory of your birth is in your face!

All men who look on you—"

Maria Louisa.

That's quite sufficient.

The Archduchess.

[To the children.]

Go, bid good morrow to your cousin.

[The children run up to the Duke, who is seated,

and surround him.]

Scarampi.

[To Theresa.]

Fie!

Theresa.

Why, what?

A Lady.

[Looking at the Duke.]

How pale he is!

Another Lady.

He looks half dead!

Scarampi.

[To Theresa.]

You chose such awkward passages.

Theresa.

The book

Fell open by itself. I did not choose.

Gentz.

[Who has overheard.]

Books always open where most often read.

Theresa.

[Looking at the Duke.]

Archdukes upon his knees!

The Archduchess.

[Leaning over the back of the Duke's chair.]

I am delighted

To see you, Franz. I am your friend.

[She holds out her hand to him.]

The Duke.

[Kissing her hand.]

I know it.

Gentz.

[To Theresa.]

What do you think of him? I say he's like

A cherub who had secretly read "Werther."

The Little Girl.

[To the Duke.]

How nice your collar is!

The Duke.

Your Highness flatters.

Theresa.

His collars!

The Little Boy.

No one has such sticks!

The Duke.

No. No one.

Theresa.

His sticks!

The Other Little Boy.

Oh! and your gloves!

The Duke.

Superb, my dear.

The Little Girl.

What is your waistcoat made of?

The Duke.

That's cashmere.

Theresa.

Oh!

The Archduchess.

And you wear your nosegay—?

The Duke.

Latest fashion:

In the third buttonhole. So glad you noticed.

[At this moment Theresa bursts into sobs.]

The Ladies.

Eh? What's the matter?

Theresa.

Nothing. I don't know.

Forgive me. I'm alone here—far from friends.

Oh, it was silly!—suddenly—

Maria Louisa.

Poor dear!

Theresa.

I held my heart in—

Maria Louisa.

Tears will do you good.

The Duke.

What's this I trod on? Why, a white cockade!

Metternich.

H'm!

The Duke.

[To the Attaché.]

Yours, no doubt, sir. Favor me: your hat.

[The Attaché gives him his hat unwillingly.

The Duke sees the tricolor cockade.]

Ah!

[To Metternich.]

I was not aware—but then—the flag?

Metternich.

Highness—

The Duke.

Is that changed, too?

Metternich.

A trivial detail.

The Duke.

Nothing.

Metternich.

Question of color—

The Duke.

Of a shade.

See for yourself. Looked at in certain lights,

I really think this is the more effective. [He moves

a few steps.]

[His mother takes him by the arm and leads him

to the butterfly-cases, which the Doctor, who

has come back, has spread out.]

The Duke.

Butterflies?

Maria Louisa.

You admire the black one?

The Duke.

Charming.

The Doctor.

The plants it loves are umbelliferous.

The Duke.

It seems to see me with its wings.

The Doctor.

Those eyes?

We call them lunulæ.

The Duke.

Indeed? I'm glad.

The Doctor.

Are you examining the spotted grey?

The Duke.

No, sir.

The Doctor.

What then, my lord?

The Duke.

The pin that killed it.

The Doctor.

[To Maria Louisa.]

No use.

Maria Louisa.

[To Scarampi.]

We'll wait. I count on the effect—

Scarampi.

Ah, yes!—Of our surprise.

Gentz.

[Who has approached the Duke.]

A sweetmeat?

The Duke.

[Taking one and tasting it.]

Perfect.

A flavor of verbena and of pear,

And something else—wait—yes—

Gentz.

It's not worth while—

The Duke.

What's not worth while?

Gentz.

To feign an interest.

I'm not so blind as Metternich.

[He offers him another sweetmeat.]

A chocolate?

The Duke.

What do you see?

Gentz.

I see a youth who suffers,

Rather than live a favored prince's life.

Your soul is still alive, but here at court

They'll lull it fast asleep with love and music.

I had a soul once, like the rest of the world;

But—! And I wither, decently obscene—

Till some day, in the cause of liberty,

One of those rash young fools of the University

Amid my sweetmeats, perfumes, and dishonor

Slays me as Kotzebue was slain by Sand.

Yes, I'm afraid—do try a sugared raisin—

That I shall perish at his hand.

The Duke.

You will.

Gentz.

What?—How?

The Duke.

A youth will slay you.

Gentz.

But—

The Duke.

A youth of your acquaintance.

Gentz.

Sir—?

The Duke.

His name

Is Frederick. 'Tis the youth you were yourself.

For now he's risen again in you; and since

He whispers in your ear like dull remorse,

All's over with you: he will show no mercy.

Gentz.

'Tis true, my youth cuts like a knife within me.

Ah, well I knew that gaze had not deceived me!

'Tis that of one who ponders upon Empire.

The Duke.

I do not understand, sir, what you mean.

[He moves away.]

Metternich.

[To Gentz.]

You've had a chat with—?

Gentz.

Yes.

Metternich.

Delightful?

Gentz.

Very.

Metternich.

He's in the hollow of my hand.

Gentz.

Entirely.

The Duke.

[Stopping before Theresa.]

Why did you weep?

Theresa.

Because, my Lord—

The Duke.

Ah, no!

I know. But do not weep.

Metternich.

[Bowing to the Duke.]

I take my leave.

[He goes out with the Attaché.]

The Duke.

[To Maria Louisa and Dietrichstein, who are turning

over some papers on his table.]

Examining my work?

Dietrichstein.

It's excellent.

But why on purpose make mistakes in German?

Pure mischief!

Maria Louisa.

Oh! and at your age, mischief!

The Duke.

How can I help it? I am not an eagle.

Dietrichstein.

You still make France a noun of feminine gender.

The Duke.

I never know what's der or die or das.

Dietrichstein.

In this case neuter is correct.

The Duke.

But mean.

I don't much care about a neuter France.

Maria Louisa.

[To Thalberg, who is playing softly on the piano.]

My son detests all music.

The Duke.

I detest it.

Lord Cowley.

[Coming toward the Duke.]

Highness—

Dietrichstein.

[Aside to the Duke.]

A pleasant word.

The Duke.

Eh?

Dietrichstein.

The English

Ambassador.

Lord Cowley.

Where had you been just now

When you came galloping and out of breath?

The Duke.

I? To Saint Helena.

Lord Cowley.

I beg your pardon?

The Duke.

A wholesome, leafy nook. So gay!—At evening

Delightful. I should like to see you there.

Gentz.

[Hastily to the Ambassador, while the Duke moves

away.]

They call the village in the Helenenthal

Saint Helena. A fashionable stroll.

Lord Cowley.

Ah, really? I was almost wondering

Whether he meant it as a hit—?

[He turns away.]

Gentz.

[Lifting his hands in amazement at Lord Cowley's

dulness.]

These English!

Voices.

We're off!

The Archduchess.

[To Maria Louisa.]

Louisa?

Maria Louisa.

No, I stay at home.

Voices.

The carriages.

The Archduchess.

[To the Duke.]

And you, Franz?

Maria Louisa.

He hates nature.

He even gallops through Saint Helena.

The Duke.

Yes! I gallop!

[General leave-taking and gradual departure.

Maria Louisa.

So devoid of fancy!

Montenegro.

[Going.]

I know a place for supper where the cider—

Cries.

[Without.]

Good-bye! Good-bye!

Gentz.

[On the terrace.]

Don't talk about the hydra!

Theresa.

[To Tiburtius.]

Brother, good-bye!

Tiburtius.

Good-by.

[He goes out with Bombelles.]

Maria Louisa.

[To the Maids of Honor, indicating Theresa.]

Show her her rooms.

[Theresa goes out accompanied by the Maids of

Honor. Maria Louisa calls the Duke, who was

going toward the garden.]

Maria Louisa.

Franz!

[He turns.]

Now I'm going to amuse you.

The Duke.

Really?

[Scarampi carefully closes all the doors.]

Maria Louisa.

Hush!—I've conspired!

The Duke.

Mother! You!—Conspired!

Maria Louisa.

Hush! They've forbidden whatever comes from France—

But I have ordered secretly from Paris,

From the best houses—Oh! my fop shall smile!—

For you, a tailor,

[Pointing to Scarampi.]

and for us, a fitter.

I really think the notion—

The Duke.

Exquisite!

Scarampi.

[Opening the door of Maria Louisa's apartment.]

Come in!

[Enter a young lady, dressed with the elegance of

a milliner's dummy, and carrying two great

card-board dress-boxes, and a young man

dressed like a fashion plate, who also carries

two big boxes.]

The Tailor.

[Coming down to the Duke, while the young lady unpacks

the dresses on a sofa at the back.]

If you will favor me, my Lord—

I've here some charming novelties. My clients

Are good enough to trust my taste: I guide them.

The neck-cloths first. A languid violet;

A serious brown. Bandannas are much worn.

I note with pleasure that your Highness knows

The delicate art of building up a stock.

Here's a check pattern makes an elegant knot.

How does this waistcoat strike your Lordship's fancy,

Down which meander wreaths of blossoms?

The Duke.

Hideous!

The Tailor.

Will these, I wonder, leave your Highness cold?

Here's doeskin. Here a genuine Scottish tweed.

Bottle-green riding-coat with narrow cuffs;

Extremely gentlemanly. Here's a waistcoat:

Six-buttoned. Three left open. Very tasty.

Now, what about this blue frock-coat? We've rubbed

The newness off artistically. Worn

With salt and pepper trousers, what a picture!

We'll throw aside this heavy yellow stuff—

Can Hamlet wear the clumsy clouts of Falstaff?—

We'll pass to mantles, Prince. A splendid plaid,

Demi-collar with simili-sleeves behind.

Eccentric? Granted.—This, called the Roulière:

Sober, a large, Hidalgo-like effect;

The very thing to woo a Doña Sol in.

Excellent workmanship; a silver chain; the collar

Of finest sable; made in our own workshops;

Simple, but what a cut! The cut is everything.

Maria Louisa.

The Duke is weary of your chatter.

The Duke.

No.

He sets me dreaming. I'm not used to it.

For when my tailor from Vienna comes

I never hear these bright, descriptive words;

And so this wealth of curious adjectives

And all that seems to you mere vulgar chatter,

Has moved me—stirred me. Let him be, dear mother.

Maria Louisa.

[Going to the fitter.]

We'll look at ours. Shoulder of mutton sleeves?

The Fitter.

Always.

The Tailor.

[Displaying a pattern.]

This cloth is called Marengo.

The Duke.

What?

Marengo?

The Tailor.

Yes; it wears uncommon well.

The Duke.

So I should think. Marengo lasts forever.

The Tailor.

Your Highness orders—?

The Duke.

I have need of nothing.

The Tailor.

One always needs a perfect-fitting coat.

The Duke.

I might invent—

The Tailor..

To suit your personal taste?

O client, soar to fancy's wildest heights!

Speak! We will follow! That's our special line;

Why, we are Monsieur Théophile Gautier's tailors.

The Duke.

Let's see—

The Fitter.

A Panama with muslin trimmings—

That's not the sort of hat for everybody.

The Duke.

Could you make—

The Tailor.

Anything.

The Duke.

A—

The Tailor.

What you choose!

The Duke.

A coat?

The Tailor.

Assuredly.

The Duke.

Of broadcloth. Yes

But now the texture? Simple?

The Tailor.

Certainly.

The Duke.

And then the color. What do you say to green?

The Tailor.

Green's capital.

The Duke.

A little coat of green.

With glimpses of the waistcoat?

The Tailor.

Coat wide open!

The Duke.

Then, to give color when the wearer moves,

The skirts are lined with scarlet.

The Tailor.

Scarlet!

Oh, ravishing.

The Duke.

Well, but about the waistcoat.

How do you see the waistcoat?

The Tailor.

Shall we say—?

The Duke.

The waistcoat's white.

The Tailor.

What taste!

The Duke.

And then I think

Knee breeches.

The Tailor.

Ah!

The Duke.

Yes.

The Tailor.

Any color?

The Duke.

No.

I rather think I see them white cashmere.

The Tailor.

Well, after all, white is the more becoming.

The Duke.

The buttons are engraved.

The Tailor.

That's not good style.

The Duke.

Yes; something—nothing—merely little eagles.

The Tailor.

Eagles!

The Duke.

Well? What are you afraid of, sir?

And wherefore does your hand shake, master tailor?

What is there strange about the suit of clothes?

Do you no longer boast your skill to make it?

The Fitter.

Coalscuttle bonnet neatly trimmed with poppies.

The Duke.

Take home your latest fashions and your patterns;

That little suit's the only one I want.

The Tailor.

But I—

The Duke.

'Tis well. Begone, and be discreet.

The Tailor.

Yet—

The Duke.

'Twould not fit me.

The Tailor.

It would fit you.

The Duke.

What!

The Tailor.

It would fit you well.

The Duke.

You're very bold, sir!

The Tailor.

And I'm empowered to take your order for it.

The Duke.

Ah!

The Tailor.

Yes!

The Fitter.

A flowing cloak of China crape;

Embroidered lining with enormous sleeves.

The Duke.

Indeed?

The Tailor.

Yes, Highness.

The Duke.

A conspirator?

Now I no longer wonder you cite Shakespeare!

The Tailor.

The little coat of green holds in its thrall

Deputies, schools, a Peer, and a Field Marshal.

The Fitter.

Spencer of figured muslin. Satin skirt.

The Tailor.

We can arrange your flight.

The Duke.

Should I agree

I must beforehand—ay, and there's the rub—

Consult my friend Prince Metternich.

The Tailor.

You'll trust us

When you are told our leader is your cousin

The Countess Camerata.

The Duke.

Ah, I know!

The daughter of Elisa Baciocchi.

The Tailor.

The strange, unarmored amazon, who bears

Her father's likeness proudly in her face,

Seeks dangers, rides unbroken horses, fences—

The Fitter.

A little sleeveless gown of lightest muslin.

The Tailor.

And when you know it's this Penthesilea—

The Fitter.

The collar's only pinned, the shoulders basted—

The Tailor.

Who heads the plot I spoke of—

The Duke.

Give me proof!

The Tailor.

Turn round, your Highness; glance at the young person

Who on her knees unpacks the clothes.

The Duke.

'Tis she!

Not long ago I met her in Vienna,

Wrapped in a cloak. She swiftly kissed my hand

And fled, exclaiming, Haven't I the right

To greet the Emperor's son who is my master?

She is a Bonaparte! We are alike!—

Ay, but her hair is dark; not fair like mine.

Maria Louisa.

We'll try them on in there. Come, follow me.

Only Parisians, Franz, know how to fit us.

The Duke.

Yes, mother.

Maria Louisa.

Don't you love Parisian taste?

The Duke.

It's very true they dress you well in Paris.

[Maria Louisa, Scarampi, and the Fitter go

into Maria Louisa's apartment with the things

they are to try on.]

The Duke.

Now! Who are you, sir?

The Tailor.

I? A nameless atom.

Weary of life in mean and paltry times,

Of smoking pipes and dreaming of ideals.

Who am I? How do I know? That's my trouble.

Am I at all?—It's very hard to "be."

I study Victor Hugo; spout his odes—

I tell you this, because this sort of thing

Is all contemporary youth. I spend

Extravagant fortunes in acquiring boredom.

I am an artist, Highness, and Young France.

Also I'm carbonaro at your service.

And as I'm always bored I wear red waistcoats,

And that amuses me. At tying neck-cloths

I once was very good indeed. That's why

They sent me here to-day to play the tailor.

I'll add, to make the picture quite complete,

That I'm a liberal and a king-devourer.

My life and dagger are at your command.

The Duke.

I like you, sir, although your talk is crazy.

The Young Man.

You must not judge me by my whirling words;

The itch of notoriety consumes me,

But the disease beneath is very real,

And makes me seek forgetfulness in danger.

The Duke.

Disease?

The Young Man.

A shuddering disgust.

The Duke.

Your soul

Heavy with foiled ambitions?

The Young Man.

Dull disquiet—

The Duke.

Morbid enjoyment of our sufferings,

And pride in showing off our pallid brows?

The Young Man.

My Lord!

The Duke.

Contempt for those who live content?

The Young Man.

My Lord!

The Duke.

And doubt?

The Young Man.

In what mysterious volume

Has one so young learnt all the human heart?

For that is what I feel.

The Duke.

Give me your hand!

For, as a sapling, friend, which is transplanted,

Feels all the forest in its ignorant veins,

And suffers when its distant mates are hurt,

So I, who knew you not, here, all alone,

Felt the distemper stirring in my blood

Which at this moment blights the youth of France.

The Young Man.

Rather I think our malady is yours,

For whence upon you falls this giant robe?

Child, whom beforehand they have robbed of glory,

Pale Prince, so pale against your sable suit,

Why are you pale, my Prince?

The Duke.

I am his son.

The Young Man.

Well! Feeble, feverish, dreaming of the past,

Like you rebellious, what is left to do?—

We're all, to some extent, your father's sons.

The Duke.

You are his soldiers' sons: that's just as glorious.

And 'tis no less redoubtable a burden;

But it emboldens me, for I can say

They're but the sons of heroes of the empire:

They'll be content to take the Emperor's son!

The Countess Camerata.

[Coming out of Maria Louisa's apartments.]

The scarf!—Oh, hush! I'm doing such a trade!

The Duke.

Thank you!

The Countess.

I only wish 'twere selling swords!

That silly baby-talk will be my death.

The Duke.

Warlike, I know.

A Voice.

[Within.]

The scarf!

The Countess.

I'm looking for it!

The Duke.

It seems this little hand can tame—

The Countess.

I love

A fiery horse.

The Duke.

You're mistress of the foils?

The Countess.

And of the sword!

The Duke.

Ready for anything?

The Countess.

[Speaking toward the room.]

Indeed, I'm looking for it everywhere.

[To the Duke.]

Ready for anything for your Imperial Highness.

The Duke.

You're lion-hearted, Cousin!

The Countess.

And my name

Is glorious.

The Duke.

Which name?

The Countess.

Napoleone!

Scarampi's Voice.

[Within.]

Well? Can't you find it?

The Countess.

No.

A Voice.

Look on the piano.

The Countess.

I must be off. Discuss our great design.

[With a cry, as if she had found what she was

looking for.]

Ah! here it is!

The Voice.

You've found it?

The Countess.

On the harp.

You understand, it's gathered up in folds—

[She goes into Maria Louisa's room.]

The Young Man.

Well? You accept?

The Duke.

I don't quite understand

Zealous Imperialism from a liberal—

The Young Man.

True: a republican—

The Duke.

You come to me

Rather a long way round—

The Young Man.

All roads to-day

Lead to the King of Rome. My scarlet badge

I thought unfading—

The Duke.

Faded in the sun?

The Young Man.

Of Austerlitz! Yes! History makes us drunk.

The battles which no more are fought, are told.

The blood is vanished, but the glory gleams.

So that to-day there is no he but HE!

He never won such victories as now:

His soldiers perished, but his poets live.

The Duke.

In short—

The Young Man.

In short the huckstering times; the god

They exiled; you, your touching fate, our weariness,

And everything—I said—

The Duke.

You said as artist

'Twould be effective to be Bonapartist!

The Young Man.

So you accept?

The Duke.

No.

The Young Man.

What?

The Duke.

I listened well.

And you were charming as you spoke, but nothing.

No quiver of your voice, told me of France;

You voiced a craze, a form of literature.

The Young Man.

I've carried out my mission clumsily;

Could but the Countess yonder speak!

The Duke.

No use.

I love the bravery glowing in her eyes,

But that's not France: that is my Family!

When next you seek me, later, by and by,

Let the call come through some untutored voice,

Wherein rough accents of the people throb;

Your Byronism is much too like myself.

You could not have persuaded me to-night—

I feel myself unready for the crown.

The Countess.

[Coming out of Maria Louisa's apartment.]

Unready? You?

[She turns toward the room.]

Don't trouble; I'm just going.

And for the ball the white one, not the mauve.

[Coming hastily toward the Duke.]

Unready? What do you want?

The Duke.

A year of dreams,

Of study.

The Countess.

Come and reign.

The Duke.

My brain's not ripe.

The Countess.

The crown's enough to ripen any brain.

The Duke.

The crown of light, shed by the midnight lamp.

The Young Man.

It's such a chance!

The Duke.

I beg your pardon? "Chance"?

Is this the tailor reappearing?

The Countess.

Yet—

The Duke.

I will be honest in default of genius.

I only ask three hundred wakeful nights.

The Young Man.

But this refusal will confirm the rumors.

The Countess.

They say you've never really been of us.

The Young Man.

You are Young France: you're called Old Austria.

The Countess.

They say your mind is being weakened.

The Young Man.

Yes!

They say you're cheated, even in your studies.

The Countess.

They say you do not know your father's history.

The Duke.

Do they say that?

The Young Man.

What shall we answer them?

The Duke.

Answer them thus—

[Enter Dietrichstein.]

Dear Count!

Dietrichstein.

'Tis Obenaus.

The Duke.

Ah! for my history lesson! Let him come.

[Dietrichstein goes out. The Duke points to

the clothes scattered about.]

Spend as much time as possible in packing,

And try to get forgotten in your corner.

[Seeing Dietrichstein come in with Baron von

Obenaus.]

Good-day, dear Baron.

[Carelessly to the Young Man and the Countess,

pointing to the screen.]

Finish over there.

[To Obenaus.]

My tailor.

Obenaus.

Ah?

The Duke.

My mother's fitter.

Obenaus.

Yes?

The Duke.

Will they disturb you?

Obenaus.

[Who has seated himself behind the table with Dietrichstein.]

Not at all, my Lord.

The Duke.

[Who sits facing them, sharpening a pencil.]

I'm all attention. Let me sharpen this

To note a date, or jot down an idea.

Obenaus.

We'll take our work up where we last left off.

Eighteen hundred and five, I think?

The Duke.

[Busy with his pencil.] Exactly.

Obenaus.

In eighteen hundred and six—

The Duke.

Did no event

Make that year memorable?

Obenaus.

Which, my Lord?

The Duke.

[Blowing the dust off the pencil.]

Why, eighteen hundred and five.

Obenaus.

I beg your pardon,

I thought you meant—h'm—Destiny

Was cruel to the righteous cause. We'll cast

Only a fleeting glance at hapless hours.

When the philosopher with pensive gaze—

The Duke.

And so in eighteen five, sir, nothing happened?

Obenaus.

A great event, my Lord! I had forgotten.

The restoration of the Calendar.

A little later, having challenged England,

Spain—

The Duke.

[Demurely.]

And the Emperor?

Obenaus.

Which Emp—?

The Duke.

My father.

Obenaus.

He—he—

The Duke.

Had he not left Boulogne?

Obenaus.

Oh, yes.

The Duke.

Where was he, then?

Obenaus.

Well, as it happened, here.

The Duke.

[With mock amazement.]

Indeed?

Dietrichstein.

[Hastily.]

He took great interest in Bavaria!

Obenaus.

Your father's wishes in the Pressburg Treaty,

As far as that went, chimed with those of Austria.

The Duke.

What was the Pressburg Treaty?

Obenaus.

The agreement

Which closed an era.

The Duke.

There! I've smashed my point!

Obenaus.

In eighteen hundred and seven—

The Duke.

So soon? How quick!

Strange epoch! Nothing happened in it!

Obenaus.

Yes.

For instance, take the House of the Braganzas:

The King—

The Duke.

The Emperor, sir?

Obenaus.

Which Emp—?

The Duke.

Of France.

Obenaus.

Nothing of any consequence till eighteen-eight.

Yet let us note the Treaty of Tilsit.

The Duke.

Was nothing done but making treaties?

Obenaus.

Europe—

The Duke.

I see. A general survey?

Obenaus.

I'll come to details

When we've—

The Duke.

Did nothing happen?

Obenaus.

Well—

The Duke.

Well, what?

Obenaus.

I—

The Duke.

What? What happened? Won't you tell me?

Obenaus.

Well—

I hardly know—you're in a merry humor—

The Duke.

You hardly know? Then, gentlemen, I'll tell you!

The sixth October, eighteen-five—

Obenaus and Dietrichstein.

[Leaping to their feet.]

Eh? What?

The Duke.

When he was least expected, when Vienna,

Watching the Eagle hover ere he swooped,

Sighed with relief, The blow is aimed at London!

Having left Strassburg, crossed the Rhine at Kehl,

The Emperor—

Obenaus.

Emperor!

The Duke.

Yes! and you know which!

Marches through Würtemberg, marches through Baden—

Dietrichstein.

Great Heavens!

The Duke.

Gives Austria a morning song,

With drums by Soult, and trumpets by Murat!

At Wertingen and Augsburg leaves his Marshals

With here and there a victory to play with—

Obenaus.

My Lord!

The Duke.

Pursues with wonderful manœuvres.

Arrives at Ulm before he's changed his boots.

Bids Ney take Elchingen, sits down and writes

A joyous, terrible, and calm despatch.

Prepares the assault:—the seventeenth October

Sees seven thousand Austrians disarmed,

And eighteen generals at the hero's feet;

And then he starts again!

Dietrichstein.

My Lord!

The Duke.

November

Finds him at Schönbrunn, sleeping in my bedroom.

Obenaus.

But—!

The Duke.

He pursues! his foes are in his hand!

One night he says "To-morrow!" and to-morrow

Says, galloping along the bannered front—

A spot of grey among his brilliant staff—

"Soldiers, we'll finish with a thunderbolt!"

The army is an ocean. He awaits

The rising sun, and places with a smile

This risen sun athwart his history!

Obenaus.

Oh, Dietrichstein!

The Duke.

So there!

Dietrichstein.

Oh, Obenaus!

The Duke.

Terror and death! Two Emperors beaten by one!

And twenty thousand prisoners!

Obenaus.

I beseech you!

People might hear!

The Duke.

When the campaign was over—

The corpses floating on the freezing lake—

My Grandsire seeks my Father in his camp!

Obenaus.

My Lord!

The Duke.

His camp!

Obenaus.

Will nothing keep you quiet?

The Duke.

And so my Father grants my Grandsire peace!

Dietrichstein.

If any heard you!

The Duke.

And the conquered banners

Distributed! Eight to the town of Paris—

[The Countess and the Young Man have gradually

come out, pale and excited, from behind the

screen. They listen to the Duke with increasing

emotion, and suddenly the boxes they are

carrying slip from their hands.]

Obenaus.

[Turning and seeing them.]

Oh!

The Duke.

The Senate fifty!

Obenaus.

Look! The man and woman!

Dietrichstein.

Be off with you!

The Duke.

Fifty to Notre Dame!

Obenaus.

Oh, Lord! Oh, Lord!

The Duke.

And banners!

Dietrichstein.

Take your things!

[He pushes them out.]

Be off! Be off!

The Duke.

And banners! And still banners!

[The Countess and The Young Man go.]

Dietrichstein.

They heard it all!

The Duke.

And banners!

Dietrichstein.

What a business!

My Lord!

The Duke.

I'm dumb!

Dietrichstein.

A little late, my Lord!

What will Prince Metternich—? These people here!

The Duke.

Moreover, that's as far as I have got.

My dear professor—

[He coughs.]

Dietrichstein.

Oh, you're coughing! Water!

The Duke.

I've made good progress with my history?

Dietrichstein.

And yet no books come near you! That I'm sure of!

Obenaus.

When Metternich discovers—

The Duke.

You won't tell him!

The blame would fall on you.

Dietrichstein.

We'd best keep still,

And ask his mother to expostulate.

[He knocks at Maria Louisa's door.]

The Duchess—?

Scarampi.

[Appearing.]

She is ready. You may come.

[Dietrichstein goes in.]

The Duke.

[Mockingly to Obenaus.]

Your course, Ad usum, sir, Delphini, sir,

Is finished, sir!

Obenaus.

I can't think how you learnt—!

[Maria Louisa comes in in great agitation, in a

superb ball-dress, and with her cloak on. Obenaus

and Dietrichstein go out quietly.]

Maria Louisa.

Oh Heavens! what is't again? What must I hear?

Perhaps you will explain—

The Duke.

[Showing her the open window.]

My mother, look,

The day is hushed, but for belated birds.

Oh, with what tenderness the gloaming fades!

The trees—

Maria Louisa.

What, you! Can you feel nature's beauty?

The Duke.

Perhaps.

Maria Louisa.

Perhaps you will explain—

The Duke.

Oh, mother,

Inhale the perfume. All the forest floats

Into the chamber on its breath!

Maria Louisa.

Explain!

The Duke.

With every gust a branch is wafted in!

A fairer miracle than that which scared

Macbeth; the forest is not walking only,

Not like a mad thing walking; lo! on wings

The scented evening sets the forest flying!

Maria Louisa.

What! You can be poetical!

The Duke.

At times.

[Distant music is heard.]

Listen! A waltz. An ordinary waltz;

Yet distance gives it dignity. Who knows?

Journeying through the woods the master haunted.

Under the cyclamen, among the bracken,

It may have chanced upon Beethoven's soul!

Maria Louisa.

What! Musical as well!

The Duke.

Yes; when I choose.

I do not choose! I hate the mystery

Of sounds! And in a lovely sunset, feel

With dread some fair thing growing soft within me!

Maria Louisa.

That fair thing in your heart, my son, is I!

The Duke.

You said it.

Maria Louisa.

Do you hate it?

The Duke.

I love you.

Maria Louisa.

Then think a little ere you do me harm.

My father and Prince Metternich are so good!

When the decree, for instance, made you Count,

I said, Not Count; Duke at the least; for Duke

Is something. And you're Duke of Reichstadt.

The Duke.

Lord of Gross-Bohen, Buchtiehrad, Tirnowan,

Schwaden, Kron-Porsitschan—

Maria Louisa.

And then, the tact!

Your father's name was never mentioned once!

The Duke.

Why not have called me "Son of unknown Father"?

Maria Louisa.

With your estates and revenues you can be

The pleasantest and richest Prince of Austria.

The Duke.

The richest Prince?

Maria Louisa.

And pleasantest—

The Duke.

Of—Austria!

Maria Louisa.

Enjoy your happiness.

The Duke.

I drain its lees.

Maria Louisa.

First in precedence after the Archdukes,

Some day you'll marry with a fair Princess,

Or an Archduchess, or perhaps a—

The Duke.

Ever

I see what once my childish eyes caught sight of:

His little throne, whose back was like a drum,

And, made of gold, more splendid since Saint Helena.

Upon that back the simple little N,

The letter which cries No to time!

Maria Louisa.

But—

The Duke.

Yes!

The N with which he branded Kings!

Maria Louisa.

The Kings

Whose blood runs through your mother's veins and yours!

The Duke.

I do not need their blood! What use to me?

Maria Louisa.

A glorious heritage!

The Duke.

Oh, paltry!

Maria Louisa.

What!

Not proud to bear the blood of Charles the Fifth?

The Duke.

No! for it courses in the veins of others!

But when I tell myself I bear in mine

A Corsican Lieutenant's blood, I weep

To see the thin blue trickle at my wrist.

Maria Louisa.

Franz!

The Duke.

And the old blood can but harm the new.

If I bear blood of Kings, let me be bled.

Maria Louisa.

Silence!

The Duke.

What am I saying, after all?

If ever I had yours long since I've lost it.

His blood and yours have fought in me, and yours

Was put to flight, as usual, by the other.

Maria Louisa.

Peace, Duke of Reichstadt!

The Duke.

Metternich, the fool,

Thought to scrawl "Duke of Reichstadt" o'er my name.

But hold the paper up before the sun:

You'll see "Napoleon" in the watermark!

Maria Louisa.

My son!

The Duke.

You called me Duke of Reichstadt? No!

But would you have my veritable name?

'Tis what the people call me in the Prater

As they make way: The Little Bonaparte!

I am his son! and no one's son but his!

Maria Louisa.

You hurt me.

The Duke.

Ah, forgive me, mother, mother.

Go to the ball, forget my frenzied words.

You need not even trouble to repeat them

To Metternich, my mother.

Maria Louisa.

Do you think so?

The Duke.

Softly the waltz floats through the evening air;

No, tell him nothing; that will save you trouble.

Forget it all: you, who forget so quickly!

Maria Louisa.

Yet—

The Duke.

Think of Parma, of the Sala palace,

And of your happy life. Is this a brow

To bear the shadow of an eagle's wing?

Ah! but I love you more than you can think!

And take no heed of aught—not even—O gods!—

Of being faithful: I'll be that for both.

Come, let me thrust you gently toward the ball;

Good-night, The mosses must not wet your feet.

Your headdress is perfection.

Maria Louisa.

Do you think so?

The Duke.

The carriage waits. It's fine. The night is clear.

Good-night, Mamma; enjoy yourself.

[Maria Louisa goes out. The Duke sinks in a

chair before his table.]

Alas,

Poor mother!

[His manner changes, and he draws books and

papers toward him.]

Now! to work!

[The wheels of a departing carriage are heard.

The door at the back opens gently and Gentz

is seen introducing a woman wrapped in a

cloak.]

Gentz.

She's gone.

[He calls the Prince.]

Prince!

The Duke.

[Turning and seeing him.]

Fanny?

Fanny Elssler.

Franz!

Gentz.

[Aside.]

Farewell to dreams of Empire!

Fanny.

[In the Duke's arms.]

Franz!

Gentz.

[Going out.]

Capital!

Fanny.

[Lovingly.]

My Franz!

[The door closes on Gentz. Fanny quickly

leaves the Duke and speaks respectfully after

making a profound curtsey.]

My Lord!

The Duke.

[After looking round to assure himself Gentz is gone.]

To work!

Fanny.

[Swinging herself on to the table.]

I've learnt whole chapters for to-day!

The Duke.

Go on.

Fanny.

So, then, while Marshal Ney marched through the night,

The Generals Gazan—

The Duke.

[Learning the names by heart.]

Gazan—

Fanny.

Suchet—

The Duke.

Suchet—

Fanny.

Kept up a lively cannonade;

And at the earliest dawn the Imperial Guard—

Curtain.

The Duke's cabinet at Schönbrunn. It is the famous Lacquered Chamber. At the back is a window opening on a balcony. In the distance, at the end of a beautiful avenue, the "Gloriette," a Corinthian Portico. There are two doors on the left, and two on the right. Between these doors stand two large Louis XV. consoles. There is a large writing-table and other furniture in the styles of Louis XIV. and Louis XV. In the right-hand corner in front stands a large swinging mirror, with its back to the audience.

At the rise of the curtain Sedlinzky (the Prefect of the Police), the Usher, and a number of Lackeys are discovered.

Sedlinzky.

That's all?

First Lackey.

That's all.

Sedlinzky.

Nothing abnormal?

Second Lackey.

Nothing.

Third Lackey.

Eats little.

Fourth Lackey.

Reads a lot.

Fifth Lackey.

Sleeps very badly.

Sedlinzky.

[To the Usher.]

And can you trust his personal attendants?

The Usher.

Why, they are all professional policemen,

As you, the Prefect of Police, must know.

Sedlinzky.

Thank you. I fear the Duke may find me here.

First Lackey.

No, sir; he's out.

Second Lackey.

As usual at this hour.

Third Lackey.

In uniform.

Fourth Lackey.

And with his Aides-de-Camp.

The Usher.

There are manœuvres.

Sedlinzky.

Well, be keen and tactful.

Let him not know he's watched.

The Usher.

I'm very cunning.

Sedlinzky.

Not too much zeal! I dread a zealous man.

Don't listen at his keyhole in a crowd.

The Usher.

I've given that duty to a special man.

Sedlinzky.

To whom?

The Usher.

The Piedmontese.

Sedlinzky.

Ah yes; he's clever.

The Usher.

I place him every evening in this chamber

Immediately his Highness seeks his room

Sedlinzky.

Is he here now?

The Usher.

No. As he wakes all night

He sleeps by daytime, while the Duke is out.

He'll be here when the Duke is.

Sedlinzky.

Let him watch.

The Usher.

Trust me.

Sedlinzky.

[Glancing at the table.]

The papers—?

The Usher.

[With a smile.]

Searched.

Sedlinzky.

[Stooping under the table.]

The basket, too?

[Seeing scraps of paper under the table, he hastily

kneels to examine them.]

These scraps?

[He tries to read.]

Perhaps a letter?

[Urged by professional curiosity he creeps under

the table.]

But from whom?

[The Duke enters in the uniform of an Austrian

officer, followed by his Staff. The Lackeys

hurriedly range themselves.]

The Duke.

[Seeing Sedlinzky's legs protruding from under the

table; very simply.]

Why, how are you, Sedlinzky?

Sedlinzky.

[Emerging amazed on all fours.]

Highness!

The Duke.

An accident. Excuse me. Just come in.

Sedlinzky.

[Standing.]

You knew me? Yet I was—

The Duke.

Flat on your stomach?

Oh yes, I knew you.

[He sees the Archduchess, who enters hurriedly

carrying a large album.]

Ah, I feared as much!

They've frightened you.

The Archduchess.

They told me—

The Duke.

It was nothing.

The Archduchess.

But yet—

The Duke.

[Seeing Doctor Malfatti enter.]

The doctor! But I am not ill!

[To the Archduchess.]

Nothing. A choking. So I left parade.

I had been shouting.

[To the Doctor, who is feeling his pulse.]

Doctor, you're a nuisance!

[To Sedlinzky, who is sidling toward the door.]

'Twas very kind of you to sort my papers.

You're spoiling me. Indeed you are. You've chosen

Even my lackeys from among your friends.

Sedlinzky.

Your Highness does not think—!

The Duke.

I shouldn't mind

If only they performed their duties better.

But I am villainously groomed. My stock

Rides up. In short, since this is your department,

I wish you'd black my boots a little better.

[A Lackey brings a tray with refreshments, which

the Doctor takes.]

The Archduchess.

[Anxious to help the Duke from the tray.]

Franz—

The Duke.

[To Sedlinzky, who is again making for the door.]

You take nothing—?

Sedlinzky.

I have taken—

The Archduchess.

A Tartar!

The Duke.

Orders, Foresti!

Foresti.

Colonel!

The Duke.

We'll manœuvre

At early dawn the day after to-morrow;

Assemble at Grosshofen.

Foresti.

Good, my Colonel!

The Duke.

[To the Officers.]

I'll not detain you, gentlemen. Good-day.

[Foresti and the Officers go out.]

The Duke.

[To Sedlinzky, taking a letter out of his pocket, and

tossing it toward him.]

Dear Count, here is another you've not read.

[Sedlinzky and the Doctor go out.]

Dietrichstein.

[Who came in a moment ago.]

I think you treat him rather harshly, Highness.

The Archduchess.

Is not the Duke at perfect liberty?

Dietrichstein.

Of course the Duke is not a prisoner, but—

The Duke.

I like that "but," I hope you feel its value!

Good Lord, I'm not a prisoner, "but"—that's all!

"But"—not a prisoner, "but"—that is the word,

The formula! A prisoner? Oh, not a moment!

"But" there are always people at my heels.

A prisoner? Not I! You know I'm not;

"But" if I risk a stroll across the park

A hidden eye blossoms behind each leaf.

Of course not prisoner, "but" let anyone

Seek private speech with me, beneath each hedge

Up springs the mushroom ear. I'm truly not

A prisoner, "but" when I ride, I feel

The delicate attention of an escort.

I'm not the least bit in the world a prisoner,

"But" I'm the second to unseal my letters.

Not at all prisoner, "but" at night they post

A lackey at my door—look! there he goes.

I, Duke of Reichstadt, prisoner? Never! never!

I, prisoner? No! I'm not a prisoner—"but"—!

Dietrichstein.

I love to see this mirth—so rare—

The Duke.

Yes, devilish!

Dietrichstein.

[Taking his leave.]

Your Highness—

The Duke.

Serenissimus!

Dietrichstein.

Eh!

The Duke.

—issimus!

That is my title. My particular title

Kindly remember it another time!

Dietrichstein.

[Bowing.]

I leave you—

[He goes.]

The Duke.

[To the Archduchess.]

Serenissimus! how glorious!

[Pointing to the album.]

What's that?

The Archduchess.

The Emperor's herbarium.

The Duke.

Lord!

Grandpapa's botany!

The Archduchess.

He lent it me

This morning, Franz.

The Duke.

[Examining it.]

It's pretty.

The Archduchess.

You know Latin,

What is this withered black thing?

The Duke.

That's a rose.

The Archduchess.

Franz, there's been something wrong with you of late.

The Duke.

[Reading.]

Bengalensis.

The Archduchess.

Of Bengal?

The Duke.

That's right.

The Archduchess.

I find you nervous. What's the matter?

The Duke.

Nothing.

The Archduchess.

Yes, but I know, your bosom-friend Prokesch,

The confidant of hopes they think too vast,

They've sent him far away.

The Duke.

But in exchange

They give me Marshal Marmont as a friend.

Despised in France, he crawls to Austria

To gather praise for treason to my Father.

The Archduchess.

Hush!

The Duke.

And a man like that is here to set

The son against the Father!—Oh!—

[Reading.]

Volubilis.

The Archduchess.

Franz, when you promise do you keep your word?

The Duke.

You've been so good to me, I could not break it.

The Archduchess.

Besides, you liked my birthday present, Franz.

The Duke.

Ah, yes! These relics from the archducal trophy!

[He takes the things he mentions, which are on a

console between the doors on the right.]

A tinder box—a busby of the Guard—

An ancient musket—No! it isn't loaded!

And above all—

The Archduchess.

Oh, hush!

The Duke.

That other thing—

I've hidden it.

The Archduchess.

Where, you bandit?

The Duke.

In my den.

The Archduchess.

Well, promise then—your grandfather—you know

His kindness—

The Duke.

[Picking up a paper which has fallen from the herbarium.]

What is this? A sheet of paper?

[He reads.]

"And if the students still persist in shouting.

Let them be crimped and sent on active service—".

[To the Archduchess.]

You said—his kindness—

The Archduchess.

Yes; the Emperor loves you.

His goodness—

The Duke.

[Picking up another paper fallen from the herbarium.]

Here's another.

[He reads.]

"As the mob

Resist you, cut them down."

[To the Archduchess.]

His goodness—

The Archduchess.

He hates the ferment of the modern mind,

But he's an excellent old man.

The Duke.

Two-sided.

Flowers from whose leaves death-sentences are shed,

Good Emperor Franz is like these specimens.

[He closes the herbarium.]

However, he's beloved, he's popular,

I love him well.

The Archduchess.

How he could help your cause!

The Duke.

Ah! if he would!

The Archduchess.

Promise you'll never fly

Until you've tried your utmost with him.

The Duke.

Yes,

I promise that.

The Archduchess.

And I'll reward you now.

The Duke.

You?

The Archduchess.

Oh, one has one's little influence!

The astounding Prokesch they deprived you of—

I said and did so much—in short, he's here.

[She strikes the ground with her parasol. The

door opens and Prokesch enters. The Duke

rushes to him. The Archduchess goes out

quickly.]

The Duke.

At last!

Prokesch.

They may be listening.

The Duke.

Oh, they are!

They never tell, though.

Prokesch.

What?

The Duke.

I've tested them.

Uttered the most seditious sentiments;

They've never been repeated. Never.

Prokesch.

Strange!

The Duke.

I think the listener, paid by the police,

Pockets the cash and stops his friendly ears.

Prokesch.

The Countess Camerata? Any news?

The Duke.

Nothing.

Prokesch.

Oh!

The Duke.