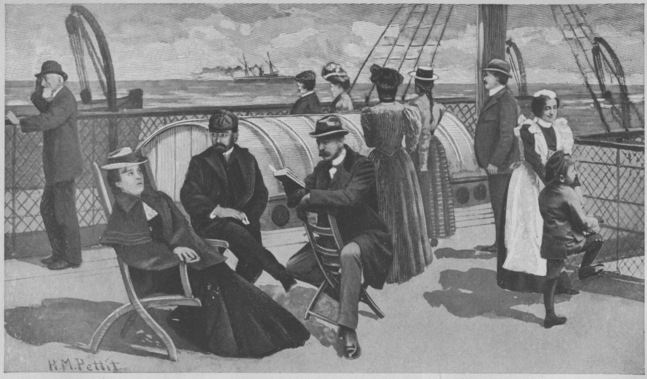

“Oh, Josiah,” sez I, “what a sight!”––Frontispiece. Page 125.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Around the World with Josiah Allen's Wife, by Marietta Holley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Around the World with Josiah Allen's Wife Author: Marietta Holley Illustrator: H. M. Pettit Release Date: October 6, 2009 [EBook #30190] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AROUND THE WORLD *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Note

Archaic and variable spelling, as well as inconsistency in hyphenation, has been preserved as printed in the original book.

“Oh, Josiah,” sez I, “what a sight!”––Frontispiece. Page 125.

AROUND THE WORLD

WITH

JOSIAH ALLEN’S WIFE

BY

MARIETTA HOLLEY

Author of “Samantha at the St. Louis Exposition,” “My Opinion and Betsey Bobbets’,”

“Samantha at Saratoga,” “Samantha at the World’s Fair,” Etc.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

H. M. PETTIT

G. W. DILLINGHAM COMPANY

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1899, 1900 and 1905, by

Marietta Holley.

Entered at Stationers’ Hall,

London, England.

(Issued September, 1905.)

Around the World with

Josiah Allen’s Wife.

J. J. Little & Ives Co.

New York

Our son, Thomas Jefferson, and his wife, Maggie, have been wadin’ through a sea of trouble. He down with inflamatory rumatiz so a move or jar of any kind, a fly walkin’ over the bedclothes, would most drive him crazy; and she with nervious prostration, brought on I spoze by nussin’ her pardner and her youngest boy, Thomas Josiah (called Tommy), through the measles, that had left him that spindlin’ and weak-lunged that the doctor said the only thing that could tone up his system and heal his lungs and save his life would be a long sea voyage. He had got to be got away from the cold fall blasts of Jonesville to once. Oh! how I felt when I heard that ultimatum and realized his danger, for Tommy wuz one of my favorites. Grandparents ort not to have favorites, but I spoze they will as long as the world turns on its old axletrys.

He looks as Thomas J. did when he wuz his age and I married his pa and took the child to my heart, and got his image printed there so it won’t never rub off through time or eternity. Tommy is like his pa and he hain’t like him; he has his pa’s old ways of truthfulness and honesty, and deep––why good land! there hain’t no tellin’ how deep that child is. He has got big gray-blue eyes, with long dark lashes that kinder veil his eyes when he’s thinkin’; his hair 10 is kinder dark, too, about the color his pa’s wuz, and waves and crinkles some, and in the crinkles it seems as if there wuz some gold wove into the brown. He has got a sweet mouth, and one that knows how to stay shet too; he hain’t much of a talker, only to himself; he’ll set and play and talk to himself for hours and hours, and though he’s affectionate, he’s a independent child; if he wants to know anything the worst kind he will set and wonder about it (he calls it wonner). He will say to himself, “I wonner what that means.” And sometimes he will talk to Carabi about it––that is a child of his imagination, a invisible playmate he has always had playin’ with him, talkin’ to him, and I spoze imaginin’ that Carabi replies. I have asked him sometimes, “Who is Carabi, I hearn you talkin’ to out in the yard? Where duz he come from! How duz he look?”

He always acts shy about tellin’, but if pressed hard he will say, “He looks like Carabi, and he comes from right here,” kinder sweepin’ his arms round. But he talks with him by the hour, and I declare it has made me feel fairly pokerish to hear him. But knowin’ what strange avenoos open on every side into the mysterious atmosphere about us, the strange ether world that bounds us on every pint of the compass, and not knowin’ exactly what natives walk them avenoos, I hain’t dasted to poke too much fun at him, and ’tennyrate I spozed if Tommy went a long sea-voyage Carabi would have to go too. But who wuz goin’ with Tommy? Thomas J. had got independent rich, and Maggie has come into a large property; they had means enough, but who wuz to go with him? I felt the mantilly of responsibility fallin’ on me before it fell, and I groaned in sperit––could I, could I agin tempt the weariness and danger of a long trip abroad, and alone at that? For I tackled Josiah on the subject before Thomas J. importuned me, only with his eyes, sad and beseechin’ and eloquent. And Josiah planted himself firm as a rock on his refusal.

Never, never would he stir one step on a long sea-voyage, 11 no indeed! he had had enough of water to last him through his life, he never should set foot on any water deeper than the creek, and that wuzn’t over his pumps. “But I cannot see the child die before my eyes, Josiah, and feel that I might have saved him, and yet am I to part with the pardner of my youth and middle age? Am I to leave you, Josiah?”

“I know not!” sez he wildly, “only I know that I don’t set my foot on any ship, or any furren shore agin. When I sung ‘hum agin from a furren shore’ I meant hum agin for good and all, and here I stay.”

“Oh dear me!” I sithed, “why is it that the apron strings of Duty are so often made of black crape, but yet I must cling to ’em?”

“Well,” sez Josiah, “what clingin’ I do will be to hum; I don’t go dressed up agin for months, and hang round tarvens and deepos, and I couldn’t leave the farm anyway.”

But his mean wuz wild and haggard; that man worships me. But dear little Tommy wuz pinin’ away; he must go, and to nobody but his devoted grandma would they trust him, and I knew that Philury and Ury could move right in and take care of everything, and at last I sez: “I will try to go, Thomas J., I will try to go ’way off alone with Tommy and leave your pa–––.” But here my voice choked up and I hurried out to give vent to some tears and groans that I wouldn’t harrow Thomas J. with. But strange, strange are the workin’s of Providence! wonderful are the ways them apron strings of Duty will be padded and embroidered, strange to the world’s people, but not to them that consider the wonderful material they are made of, and how they float out from that vast atmosphere jest spoke on, that lays all round us full of riches and glory and power, and beautiful surprises for them that cling to ’em whether or no. Right at this time, as if our sharp distress had tapped the universe and it run comfort, two relations of Maggie’s, on their way home from Paris to San Francisco, stopped to see their relations in Jonesville on their own sides.

Dorothy Snow, Maggie’s cousin, wuz a sweet young girl, the only child of Adonirum Snow, who left Jonesville poor as a rat, went to Californy and died independent rich. She wuz jest out of school, had been to Paris for a few months to take special studies in music and languages; a relation on her ma’s side, a kind of gardeen, travelin’ with her. Albina Meechim wuz a maiden lady from choice, so she said and I d’no as I doubted it when I got acquainted with her, for she did seem to have a chronic dislike to man, and havin’ passed danger herself her whole mind wuz sot on preventin’ Dorothy from marryin’.

They come to Maggie’s with a pretty, good natured French maid, not knowin’ of the sickness there, and Maggie wouldn’t let ’em go, as they wuz only goin’ to stay a few days. They wuz hurryin’ home to San Francisco on account of some bizness that demanded Dorothy’s presence there. But they wuz only goin’ to stop there a few days, and then goin’ to start off on another long sea-voyage clear to China, stoppin’ at Hawaii on the way. Warm climate! good for measles! My heart sunk as I hearn ’em tell on’t. Here wuz my opportunity to have company for the long sea-voyage. But could I––could I take it? Thomas Jefferson gently approached the subject ag’in. Sez he, “Mother, mebby Tommy’s life depends on it, and here is good company from your door.” I murmured sunthin’ about the expenses of such a trip.

Sez he, “That last case I had will more than pay all expenses for you and Tommy, and father if he will go, and,” sez he, “if I can save my boy––” and his voice trembled and he stopped.

“But,” I sez, “your father is able to pay for any trip we want to take.” And he says, “He won’t pay a cent for this.” And there it wuz, the way made clear, good company provided from the doorstep. Dorothy slipped her soft little white hand in mine and sez, “Do go, Aunt Samantha. May I call you Auntie?” sez she, as she lifted her sweet 13 voylet eyes to mine. She’s as pretty as a pink––white complected, with wavy, golden hair and sweet, rosy lips and cheeks.

And I sez, “Yes, you dear little creater, you may call me aunt in welcome, and we be related in a way,” sez I.

Sez Miss Meechim, “We shall consider it a great boon if you go with us. And dear little Tommy, it will add greatly to the pleasure of our trip. We only expected to have three in our company.”

“Who is the third?” sez I.

“My nephew, Robert Strong. He has been abroad with us, but had to go directly home to San Francisco to attend to his business before he could go on this long trip; he will join us there. We expect to go to Hawaii and the Philippines, and Japan and China, and perhaps Egypt.”

“And that will be just what you will enjoy, mother,” sez Thomas J.

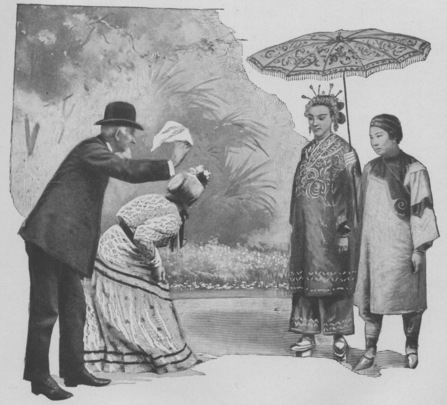

Sez I, in a strange axent, “I never laid plans for going to China, but,” sez I, “I do feel that I would love to see the Empress, Si Ann. There is sunthin’ that the widder Heinfong ort to know.”

Thomas J. asked me what it wuz, but I gently declined to answer, merely sayin’ that it was a matter of duty, and so I told Miss Meechim when she asked about it. She is so big feelin’ that it raised me up considerable to think that I had business with a Empress. But I answered her evasive, and agin I giv vent to a low groan, and sez to myself, “Can I let the Pacific Ocean roll between me and Josiah? Will Duty’s apron string hold up under the strain, or will it break with me? Will it stretch out clear to China? And oh! will my heart strings that are wrapped completely round that man, will they stretch out the enormous length they will have to and still keep hull?” I knew not. I wuz a prey to overwhelmin’ emotions, even as I did up my best night-gowns and sheepshead night-caps and sewed clean lace in the neck and sleeves of my parmetty and gray alpaca and 14 got down my hair trunk, for I knew that I must hang onto that apron string no matter where it carried me to. Waitstill Webb come and made up some things I must have, and as preparations went on my pardner’s face grew haggard and wan from day to day, and he acted as if he knew not what he wuz doin’. Why, the day I got down my trunk I see him start for the barn with the accordeon in a pan. He sot out to get milk for the calf. He was nearly wild.

He hadn’t been so good to me in over four years. Truly, a threatened absence of female pardners is some like a big mustard poultice applied to the manly breast drawin’ out the concealed stores of tenderness and devotion that we know are there all the time, but sometimes kep’ hid for years and years.

He urged me to eat more than wuz good for me––rich stuff that I never did eat––and bought me candy, which I sarahuptishly fed to the pup. And he follered me round with footstools, and het the soap stun hotter than wuz good for my feet, and urged me to keep out of drafts.

And one day he sez to me with a anxious face:

“If you do go, Samanthy, I wouldn’t write about your trip––I am afraid it will be too much for you––I am afraid it will tire your head too much. I know it would mine.”

And then I say to him in a tender axent, for his devotion truly touched me:

“There is a difference in heads, Josiah.”

But he looked so worried that I most promised him I wouldn’t try to write about the trip––oh! how that man loves me, and I him visey versey. And so the days passed, little Tommy pale and pimpin’, Thomas J. lookin’ more cheerful as he thought his ma wuzn’t goin’ to fail him, Maggie tryin’ to keep up and tend to havin’ Tommy’s clothes fixed; she hated to have him go, and wanted him to go. She and Thomas J. wuz clingin’ to that string, black as a coal, and hash feelin’ to our fingers. Miss Meechim and Dorothy wuz as happy as could be. Miss Meechim wuz tall and slim 15 and very genteel, and sandy complected, and she confided her rulin’ passion to me the first time I see her for any length of time.

“I want Dorothy to be a bachelor maid,” sez she. “I am determined that she shall not marry anyone. And you don’t know,” sez she fervently, “what a help my nephew, Robert Strong, has been to me in protectin’ Dorothy from lovers. I am so thankful he is going with us on this long trip. He is good as gold and very rich; but he has wrong ideas about his wealth. He says that he only holds it in trust, and he has built round his big manufactory, just outside of San Francisco, what he calls a City of Justice, where his workmen are as well cared for and happy as he is. That is very wrong, I have told him repeatedly. It is breaking down the Scriptures, which teaches the poor their duty to the rich, and gently admonishes the rich to look down upon and guide the poor. How can the Scriptures be fulfilled if the rich lift up the poor and make them wealthy? I trust that Robert will see his mistake in time, before he makes all his workmen wealthy. But, oh, he is such a help to me in protecting Dorothy from lovers.”

“How duz he protect her?” sez I.

“Oh, he has such tact. He knows just how opposed I am to matrimony in the abstract and concrete, and he has managed gently but firmly to lead Dorothy away from the dangers about her. Now, he don’t care for dancing at all; but there was a young man at home who wuz just winning her heart completely with his dexterity with his heels, as you may say. He was the most graceful dancer and Dorothy dotes on dancing. I told my trouble to Robert, and what should that boy do but make a perfect martyr of himself, and after a few lessons danced so much better that Dorothy wuz turned from her fancy. And one of her suitors had such a melodious voice, he wuz fairly singin’ his way into her heart, and I confided my fears to Robert, and he immediately responded, dear boy. He just practised self-denial 16 again, and commenced singing with her himself, and his sweet, clear tenor voice entirely drowned out the deep basso I had feared. Of course, Robert did it to please me and from principle. I taught him early self-denial and the pleasures of martyrdom. Of course, I never expected he would carry my teachings to such an extent as he has in his business life. I did not mean it to extend to worldly matters; I meant it to be more what the Bible calls ‘the workings of the spirit.’ But he will doubtless feel different as he gets older. And, oh, he is such a help to me with Dorothy. Now, on this trip he knows my fears, and how sedulously I have guarded Dorothy from the tender passion, and it wuz just like him to put his own desires in the background and go with us to help protect her.”

“How did you git such dretful fears of marriage?” sez I. “Men are tryin’ lots of times, and it takes considerable religion to git along with one without jawin’ more or less. But, after all, I d’no what I should do without my pardner––I think the world on him, and have loved to think I could put out my hand any time and be stayed and comforted by his presence. I should feel dretful lost and wobblin’ without him,” sez I, with a deep sithe, “though I well know his sect’s shortcomin’s. But I never felt towards ’em as you do, even in my most maddest times, when Josiah had been the tryinest and most provokinest.”

“Well,” sez she, “my father spent all my mother’s money on horse-racin’, save a few thousand which he had invested for her, and she felt wuz safe, but he took that to run away with a bally girl, and squandered it all on her and died on the town. My eldest sister’s husband beat her with a poker, and throwed her out of a three-story front in San Francisco, and she landin’ on a syringea tree wuz saved to git a divorce from him and also from her second and third husbands for cruelty, after which she gave up matrimony and opened a boarding-house, bitter in spirit, but a good calculator. I lived with her when a young girl, and imbibed 17 her dislike for matrimony, which wuz helped further by sad experiences of my own, which is needless to particularize. (I hearn afterwards that she had three disappointments runnin’, bein’ humbly and poor in purse.)

“And now,” sez she, “I am as well grounded against matrimony as any woman can be, and my whole energies are aimed on teaching Dorothy the same belief I hold.”

“Well,” sez I, “your folks have suffered dretful from men and I don’t wonder you feel as you do. But what I am a goin’ to do to be separated from my husband durin’ this voyage is more than I can tell.” And I groaned a deep holler groan.

“Why, I haven’t told you half,” sez she. “All of my sisters but one had trouble with their husbands. Robert’s step-ma wuz the only one who had a good husband, but he died before they’d been married a year, and she follered him in six months, leaving twins, who died also, and I took Robert, to whom I had got attached, to the boarding-house, and took care on him until he wuz sent away to school and college. His pa left plenty of money,” sez she, “and a big fortune when he came of age, which he has spent in the foolish way I have told you of, or a great part of it.”

Well, at this juncture we wuz interrupted, and didn’t resoom the conversation until some days afterwards, though I wuz dretful interested in the big manufactory of Robert Strong’s, that big co-working scheme. (I had hearn Thomas J. commend it warmly.)

At last the day come for me to start. I waked up feelin’ a strange weight on my heart. I had dremp Philury had sot the soap stun on my chest. But no soap stun wuz ever so hard and heavy as my grief. Josiah and I wuz to be parted! Could it be so? Could I live through it? He wuz out in the wood-house kitchen pretendin’ to file a saw. File a saw before breakfast! He took that gratin’ job to hide his groans; he wuz weepin’; his red eyes betrayed him. Philury got a good breakfast which we couldn’t eat. My trunk wuz 18 packed and in the democrat. The neighborin’ wimmen brung me warm good-byes and bokays offen their house plants, and sister Sypher sent me some woosted flowers, which I left to home, and some caraway seed to nibble on my tower which I took.

She that wuz Arvilly Lanfeare brought me a bottle of bam made out of the bark of the bam of Gilead tree, to use in case I should get bruised or smashed on the train, and also two pig’s bladders blowed up, which she wanted me to wear constant on the water to help me float. She had painted on one of ’em the Jonesville meetin’-house, thinkin’, I spoze, the steeple might bring lofty thoughts to me in hurrycains or cyclones. And on the other one she had painted in big letters the title of the book she is agent for––“The Twin Crimes of America: Intemperance and Greed!” I thought it wuz real cunning in Arvilly to combine so beautifully kindness and business. There is so much in advertising. They looked real well, but I didn’t see how I wuz goin’ to wear ’em over my bask waist. Arvilly said she wanted to go with me the worst kind. Says she:

“I hain’t felt so much like goin’ anywhere sense I deserted.” (Arvilly did enlist in the Cuban army, and deserted, and they couldn’t touch her for it––of which more anon.)

And I sez to her: “I wish you could go, Arvilly; I believe it would do you good after what you have went through.”

Well, the last minute come and Ury took us to the train. Josiah went with me, but he couldn’t have driv no more than a mournin’ weed could.

I parted with the children, and––oh! it wuz a hard wrench on my heart to part with Thomas J.; took pale little Tommy in my arms, like pullin’ out his pa’s heart-strings––and his ma’s, too––and at last the deepo wuz reached.

As we went in we see old Miss Burpy from ’way back of Loontown. She wuz never on the cars before, or see ’em, 19 but she wuz sent for by her oldest boy who lives in the city.

She was settin’ in a big rocken’-chair rocken voyolently, and as I went past her she says:

“Have we got to New York yet?”

“Why,” sez I, “we haint started.”

She sez, “I thought I wuz in the convenience now a-travellin’.”

“Oh, no,” I sez, “the conveyance haint come yet, you will heer it screechin’ along pretty soon.”

Anon we hearn the train thunderin’ towards us. I parted with Tirzah Ann and Whitfield, havin’ shook hands with Ury before; and all others being parted from, I had to, yes, I had to, bid my beloved pardner adoo. And with a almost breakin’ heart clum into the car, Miss Meechim and Dorothy and Aronette having preceeded me before hand. Yes, I left my own Josiah behind me, with his bandanna pressed to his eyes.

Could I leave him? At the last minute I leaned out of the car winder and sez with a choken voice:

“Josiah, if we never meet again on Jonesville sile, remember there is a place where partin’s and steam engines are no more.”

His face wuz covered with his bandanna, from whence issued deep groans, and I felt I must be calm to boy him up, and I sez:

“Be sure, Josiah, to keep your feet dry, take your cough medicine reglar, go to meetin’ stiddy, keep the pumps from freezin’, and may God bless you,” sez I.

And then again I busted into tears. The hard-hearted engine snorted and puffed, and we wuz off.

As the snortin’ and skornful actin’ engine tore my body away from Jonesville, I sot nearly bathed in tears for some time till I wuz aware that little Tommy wuz weepin’ also, frightened I spoze by his grandma’s grief, and then I knew it wuz my duty to compose myself, and I summoned all my fortitude, put my handkerchief in my pocket, and give Tommy a cream cookey, which calmed his worst agony. I then recognized and passed the compliments of the day with Miss Meechim and Dorothy and pretty little Aronette, who wuz puttin’ away our wraps and doin’ all she could for the comfort of the hull of us. Seein’ my agitation, she took Tommy in her arms and told him some stories, good ones, I guess, for they made Tommy stop cryin’ and go to laughin’, specially as she punctuated the stories with some chocolate drops.

Dorothy looked sweet as a rose and wuz as sweet. Miss Meechim come and sot down by me, but she seemed to me like a furiner; I wuz dwellin’ in a fur off realm Miss Meechim had never stepped her foot in, the realm of Wedded Love and Pardner Reminiscences. What did Miss Meechim know of that hallowed clime? What did she know of the grief that wrung my heart? Men wuz to her like shadders; her heart spoke another language.

Thinkin’ that it would mebbe git my mind off a little from my idol, I asked her again about Robert Strong’s City of Justice; sez I, “It has run in my mind considerable since you spoke on’t; I don’t think I ever hearn the name of any place I liked so well, City of Justice! Why the name fairly 21 takes hold of my heart-strings,” sez I; “has he made well by his big manufactory?”

“Why, yes, fairly well,” sez she, “but he has strange ideas. He says he don’t want to coin a big fortune out of other men’s sweat and brains. He wants to march on with the great army of toilers, and not be carried ahead of it on a down bed. He says he wants to feel that he is wronging no man by amassing wealth out of the half-paid labor of their best years, and that he is satisfied with an equal and reasonable share of the labor and capital invested. He has the best of men in his employ and they are all well paid and industrious; all well-to-do, able to live well, educate their children well, and have time for some culture and recreation for themselves and their families. I told him that his ideas were Utopian, but he says they have succeeded even better than he expected they would. But there will come a crash some time, I am sure. There must be rich and there must be poor in this world, or the Scriptures will not be fulfilled.”

Sez I, “There ain’t no need to be such a vast army of poverty marching on to the almshouse and grave, if it wuzn’t for the dram-shop temptin’ poor human nater, and the greed of the world, and the cowardice and indifference of the Church of Christ. Enough money is squandered for stuff that degrades and destroys to feed and clothe all the hungry and naked children of the world.”

“Oh,” sez Miss Meechim, “I don’t believe all this talk and clamor about prohibition. My people all drank genteelly, and though of course it was drink that led to the agony and divorces of three of my sisters, and my father’s first downfall, yet I have always considered that moderate drinking was genteel. Our family physician always drank genteel, and our clergyman always kept it in his wine cellar, and if people would only exert self control and drink genteel, there would be no danger.”

“How duz Robert Strong feel about it?” sez I.

“Oh, he is a fanatic on the subject; he won’t employ 22 a man who drinks at all. He says that the city he is founding is a City of Justice, and it is not just for one member of a family to do anything to endanger the safety and happiness of the rest; so on that ground alone he wouldn’t brook any drinking in his model city. There are no very rich ones there, and absolutely no poor ones; he is completely obliterating the barriers that always have, and I believe always should exist between the rich and the poor. Sez I, ‘Robert, you are sacrilegiously setting aside the Saviour’s words, “the poor ye shall always have with you.”’

“And he said there was another verse that our Lord incorporated in his teachings and the whole of his life-work, that he was trying to carry out: ‘Do unto others as ye would have them to do unto you.’ He said that love and justice was the foundation and cap-stone of our Saviour’s life and work and he was trying in his weak way to carry them out in his own life and work. Robert talked well,” sez she, “and I must confess that to the outward eye his City of Justice is in a happy and flourishing condition, easy hours of work, happy faces of men, women and children as they work or play or study. It looks well, but as I always tell him, there is a weak spot in it somewhere.”

“What duz he say to that?” sez I, dretful interested in the story.

“Why, he says the only weak spot in it is his own incompetence and inability to carry out the Christ idea of love and justice as he wants to.”

“I wish I could see that City of Justice,” sez I dreamily, for my mind’s eye seemed to look up to Robert Strong in reverence and admiration. “Well,” sez she, “I must say that it is a beautiful place; it is founded on a natural terrace that rises up from a broad, beautiful, green plain, flashing rivers run through the valley, and back of it rises the mountains.”

“Like as the mountains are about Jerusalem,” sez I.

“Yes, a beautiful clear stream rushes down the mountain 23 side from the melting snow on top, but warmed by the southern sun, as it flows through the fertile land, it is warm and sweet as it reaches Robert’s place. And Robert says,” continued Miss Meechim, “that that is just how old prejudices and injustices will melt like the cold snow and flow in a healing stream through the world. He talks well, Robert does. And oh, what a help he has been to me with Dorothy!”

“What duz she say about it?” sez I.

“She does not say so, but I believe she thinks as I do about the infeasibility as well as the intrinsic depravity of disproving the Scriptures.”

“Well,” sez I, “Robert was right about the mission of our Lord being to extend justice and mercy, and bring the heart of the world into sweetness, light and love. His whole life was love, self-sacrifice and devotion, and I believe that Robert is in the right on’t.”

“Oh, Robert is undoubtedly following his ideas of right, but they clash with mine,” sez Miss Meechim, shakin’ her head sadly, “and I think he will see his error in time.”

Here Miss Meechim stopped abruptly to look apprehensively at a young man that I knew wuz a Jonesville husband and father of twins. He was lookin’ admirin’ly at Dorothy, and Miss Meechim went and sot down between ’em, and Tommy come and set with me agin.

Tommy leaned up aginst me and looked out of the car window and sez kinder low to himself:

“I wonner what makes the smoke roll and roll up so and feather out the sky, and I wonner what my papa and my mama is doin’ and what my grandpa will do––they will be so lonesome?” Oh, how his innocent words pierced my heart anew, and he begun to kinder whimper agin, and Aronette, good little creeter, come up and gin him an orange out of the lunch-basket she had.

Well, we got to New York that evenin’ and I wuz glad to think that everybody wuz well there, or so as to git about, 24 for they wuz all there at the deepo, excep’ them that wuz in the street, but we got safe through the noise and confusion to a big, high tarven, with prices as high as its ruff and flagpole. Miss Meechim got for her and Dorothy what she called “sweet rooms,” three on ’em in a row, one for each on ’em and a little one for Aronette. But I d’no as they wuz any sweeter than mine, though mine cost less and wuz on the back of the house where it wuzn’t so noisy. Tommy and I occupied one room; he had a little cot-bed made up for him.

Indeed, I groaned out as I sot me down in a big chair, if he wuz here, the pardner of my youth and middle age, no room Miss Meechim ever looked on wuz so sweet as this would be. But alas! he wuz fur away. Jonesville held on to my idol and we wuz parted away from each other. But I went down to supper, which they called dinner, and see that Tommy had things for his comfort and eat sunthin’ myself, for I had to support life, yes, strength had to be got to cling to that black string that I had holt on, and vittles had to supply some of that strength, though religion and principle supplied the biggest heft. Miss Meechim and Aronette wuz in splendid sperits, and after sup––dinner went out to the theatre to see a noted tragedy acted, and they asked me to accompany and go with ’em, for I spoze that my looks wuz melancholy and deprested in extreme, Aronette offerin’ to take care of Tommy if I wanted to go.

But I sez, “No, I have got all the tragedy in my own bosom that I can ’tend to.” And in spite of my cast-iron resolution tears busted out under my eyeleds and trickled down my nose. They didn’t see it, my back wuz turned, and my nose is a big one anyway and could accommodate a good many tears.

But I controlled my agony of mind. I walked round with Tommy for a spell and showed him all the beauties of the place, which wuz many, sot down with him for a spell in the big, richly-furnished parlors, but cold and lonesome 25 lookin’ after all, for the love-light of home wuz lackin’, and looked at the glittering throng passing and repassing; but the wimmen looked fur off to me and the men wuz like shadders, only one man seemed a reality to me, and he wuz small boneded and fur away. And then we went to our room. I read to Tommy for a spell out of a good little book I bought, and then hearn him say his prayers, his innocent voice askin’ for blessin’s from on high for his parents and my own beloved lonely one, and then I tucked him into his little cot and sot down and writ a letter to my dear Josiah, tears dribblin’ down onnoticed while I did so.

For we had promised to write to each other every day of our lives, else I could not, could not have borne the separation, and I also begun a letter to Philury. I laid out to put down things that I wanted her to ’tend to that I thought on from day to day after I got away, and then send it to her bime by. Sez I:

“Philury, be sure and put woolen sheets on Josiah’s bed if it grows colder, and heat the soap stun for him and see that he wears his woolen-backed vest, takin’ it off if it moderates. Tend to his morals, Philury, men are prone to backslide; start him off reg’lar to meetin’, keep clean bandannas in his pocket, let him wear his gingham neckties, he’ll cry a good deal and it haint no use to spile his silk ones. Oh, Philury! you won’t lose nothin’ if you are good to that dear man. Put salt enough on the pork when you kill, and don’t let Josiah eat too much sassage. And so no more to-night, to be continude.”

The next morning I got two letters from my pardner. He had writ a letter right there in the deepo before he went home, and also another on his arrival there. Agony wuz in every word; oh, how wuz we goin’ to bear it!

But I must not make my readers onhappy; no I must harrow them up no more, I must spread the poultice of silence on the deep gaping woond and go on with the sombry history. After breakfast Miss Meechim got a big, handsome 26 carriage, drawed by two prancin’ steeds, held in by a man buttoned up to his chin, and invited me to take Tommy and go with her and Dorothy up to the Park, which I did. They wuz eloquent in praises of that beautiful place; the smooth, broad roads, bordered with tall trees, whose slim branches stood out against the blue sky like pictures. The crowds of elegant equipages, filled with handsome lookin’ folks in galy attire that thronged them roads. The Mall, with its stately beauty, the statutes that lined the way ever and anon. The massive walls of the Museum, the beautiful lake and rivulets, spanned by handsome bridges. It wuz a fair seen, a fair seen––underneath beauty of the rarest kind, and overhead a clear, cloudless sky.

Miss Meechim wuz happy, though she didn’t like the admiring male glances at Dorothy’s fresh, young beauty, and tried to ward ’em off with her lace-trimmed muff, but couldn’t. Tommy wuz in pretty good sperits and didn’t look quite so pale as when we left home, and he wonnered at the white statutes, and kinder talked to himself, or to Carabi about ’em, and I kinder gathered from what he said that he thought they wuz ghosts, and I thought that he wuz kinder reassurin’ Carabi that they wouldn’t hurt him, and he wonnered at the mounted policemen who he took to be soldiers, and at all the beauty with which we wuz surrounded. And I––I kep’ as cheerful a face as I could on the outside, but always between me and Beauty, in whatsoever guise it appeared, wuz a bald head, a small-sized figger. Yes, it weighed but little by the steelyards, but it shaddered lovely Central Park, the most beautiful park in the world, and the hull universe for me. But I kep’ a calm frame outside; I answered Miss Meechim’s remarks mekanically and soothed her nervous apprehensions as well as I could as she glanced fearfully at male admirers by remarkin’ in a casual way to her “that New York and the hull world wuz full of pretty women and girls,” which made her look calmer, and then I fell in to once with her scheme of drivin’ up the long, handsome 27 Boolevard, acrost the long bridge, up to the tomb of Our Hero, General Grant.

Hallowed place! dear and precious to the hull country. The place where the ashes lie that wuz once the casket of that brave heart. Good husband, kind father, true friend, great General, grand Hero, sleeping here by the murmuring waters of the stream he loved, in the city of his choice, sleeping sweetly and calmly while the whole world wakes to do him honor and cherish and revere his memory.

I had big emotions here, I always did, and spoze I always shall. But, alas! true it wuz that even over the memory of that matchless Hero riz up in my heart the remembrance of one who wuz never heroic, onheeded and onthought on by his country, but––oh! how dear to me!

The memory of his words, often terse and short specially before meal-time, echoed high above the memory of him who talked with Kings and Emperors, ruled armies and hushed the seething battle-cry, and the nation’s clamor with “Let us have peace.”

But I will not agin fall into harrow, or drag my readers there, but will simply state that, in all the seens of beauty and grandeur we looked on that day––and Miss Meechim wanted to see all and everything, from magestick meetin’ houses and mansions, bearin’ the stamp of millions of dollars, beautiful arches lifted up to heroes and the national honor, even down to the Brooklyn Bridge and the Goddess of Liberty––over all that memory rained supreme.

The Goddess of Liberty holdin’ aloft her blazin’ torch rousted up the enthusiastick admiration of Dorothy and Miss Meechim. But I thought as I looked on it that she kinder lifted her arm some as I had seen my dear pardner lift his up when he wuz a-fixin’ a stove pipe overhead; and that long span uniting New York and Brooklyn only brought to me thoughts of the length and strength of that apron-string to which I clung and must cling even though death ensued.

Well, after a long time of sight-seeing we returned to 28 our hotel, and, after dinner, which they called luncheon, I laid down a spell with Tommy, for I felt indeed tuckered out with my emotions outside and inside. Tommy dropped off to sleep to once like a lamb, and I bein’ beat out, lost myself, too, and evening wuz almost lettin’ down her mantilly spangled with stars, when I woke, Tommy still sleepin’ peacefully, every minute bringin’ health and strength to him I knew.

Miss Meechim and Dorothy had been to some of the big department stores where you can buy everything under one ruff from a elephant to a toothpick, and have a picture gallery and concert throwed in. They had got a big trunk full of things to wear. I wondered what they wanted of ’em when they wuz goin’ off on another long journey so soon; but considered that it wuzn’t my funeral or my tradin’ so said nothin’.

Anon we went down and had a good supper, which they called dinner, after which they went to the opera. Aronette tended to packin’ their clothes, and offered to help me pack. But as I told her I hadn’t onpacked nothin’ but my nightgown and sheepshead night-cap I could git along with it, specially as sheepshead night-caps packed easier than full crowned ones.

So I took Tommy out for a little walk on the broad beautiful sidewalks, and it diverted him to see the crowds of handsomely dressed men and women all seemin’ to hurry to git to some place right off, and the children who didn’t seem to be in any hurry, and in seein’ the big carriages roll by, some drawed by prancin’ horses, and some by nothin’ at all, so fur as we could see, which rousted up Tommy’s wonder, and it all diverted him a little and mebby it did me too, and then we retired to our room and had a middlin’ good night’s rest, though hanted by Jonesville dreams, and the next morning we left for Chicago.

Dorothy had never seen Niagara Falls or Saratoga, so we went a few milds out of our way that she might see 29 Saratoga’s monster hotels, the biggest in the world; and take a drink of the healin’ waters of the springs that gushes up so different right by the side of each other, showin’ what a rich reservoir the earth is, if we only knew how to tap it, and where.

We didn’t stay at Saratoga only over one train; but drove through the broad handsome streets, and walked through beautiful Congress Park, and then away to Niagara Falls.

It wuz a bright moonlight night when we stood on the bridge not far from the tarven where we had our sup––dinner. And Dorothy and Miss Meechim wuz almost speechless with awe and admiration, they said “Oh, how sublime! Oh! how grand!” as they see the enormous body of water sweepin’ down that immense distance. The hull waters of the hull chain of Lakes, or inland Seas, sweepin’ down in one great avalanche of water.

I wanted dretfully to go and see the place where the cunning and wisdom of man has set a trap to ketch the power of that great liquid Geni, who has ruled it over his mighty watery kingdom sence the creation, and I spoze always calculated to; throwin’ men about, and drawin’ ’em down into its whirlpool jest like forest leaves or blades of grass.

Who would have dremp chainin’ down that resistless, mighty force and make it bile tea-kettles; and light babys to their trundle beds, and turn coffee mills, and light up meetin’ houses, and draw canal boats and propel long trains of cars. How it roared and took on when the subject wuz first broke to it. But it had to yield, as the twentieth century approached and the millennium drew nigh; men not so very big boned either, but knowin’ quite a lot, jest chained that great roarin’ obstropulous Geni, and has made it do good work. After rulin’ the centuries with a high hand nobody dastin’ to go nigh it, it wuz that powerful and awful in its might and magesty, it has been made to serve, jest as the Bible sez:

“He that is mightiest amongst you shall be your servant,” or words to that effect.

But it is a sight, I spoze, to see all the performances they had to go through, the hard labor of years and years, to persuade Niagara to do what they had planned for it to do.

But as I say, this great giant is chained by one foot, as it were, and is doin’ good day’s works, and no knowin’ how much more will be put on it to do when the rest of its strength is buckled down to work. All over the great Empire State, mebby, he will have to light the evenin’ lamps, and cook the mornin’ meals, and bring acrost the continent the food he cooks, and turn the mills that grinds the flour to make the bread he toasts, and sow the wheat that makes the flour, and talk for all the millions of people and play their music for them––I d’no what he won’t be made to do, and Josiah don’t, but I spoze it is a sight to see the monster trap they built to hold this great Force. We wanted to go there, but hadn’t time.

But to resoom backwards a spell. Miss Meechim and Dorothy was perfectly awe-struck to see and hear the Falls, and I didn’t wonder.

But I had seen it before with my beloved pardner by my side, and it seemed to me as if Niagara missed him, and its great voice seemed to roar out: “Where is Josiah? Where is Josiah? Why are you here without him? Swish, swash, roar, roar, Where is Josiah? Where? Roar! Where?”

Oh, the emotions I had as I stood there under the cold light of the moon, cold waters rushin’ down into a cold tomb; cold as a frog the hull thing seemed, and full of a infinite desolation. But I knew that if Love had stood there by my side, personified in a small-sized figger, the hull seen would have bloomed rosy. Yes, as I listened to the awestruck, admirin’ axents of the twain with me, them words of the Poet come back to me: “How the light of the hull life dies when love is gone.”

“Oh,” sez Miss Meechim, as we walked back to the 31 tarven, takin’ in the sooveneer store on the way, “oh, what a immense body of water! how tumultous it sweeps down into the abyss below!” I answered mekanically, for I thought of one who wuz also tumultous at times, but after a good meal subsided down into quiet, some as the waters of Niagara did after a spell.

And Dorothy sez, “How the grand triumphal march of the great Lakes, as they hurry onwards towards the ocean, shakes the very earth in their wild haste.”

I sez mekanically, “Yes, indeed!” but my thoughts wuz of one who had often pranced ’round and tromped, and even kicked in his haste, and shook the wood-house floor. Ah, how, how could I forgit him?

And at the sooveneer stores, oh, how I wuz reminded of him there! how he had cautioned me aginst buyin’ in that very spot; how he had stood by me till he had led me forth empty-handed towards the tarven. Ah well, I tried to shake off my gloom, and Tommy waked up soon after our return (Aronette, good little creeter! had stayed right by him), and we all had a good meal, and then embarked on the sleeping car. I laid Tommy out carefully on the top shelf, and covered him up, and then partially ondressed and stretched my own weary frame on my own shelf and tried to woo the embrace of Morphine, but I could not, so I got up and kinder sot, and took out my pad and writ a little more in my letter to my help.

Sez I, “Philury, if Josiah takes cold, steep some lobely and catnip, half and half; if he won’t take it Ury must hold him and you pour it down. Don’t sell yourself short of eggs, Josiah loves ’em and they cost high out of season. Don’t let the neighbors put upon him because I went off and left him. Give my love to Waitstill Webb and Elder White, give it to ’em simeltaneous and together, tell ’em how much I think on ’em both for the good they’re doin’. Tell Arvilly I often think of her and what she has went through and pity her. Give a hen to the widder Gowdey 32 for Christmas. Let Josiah carry it, or no, I guess Ury had better, I am away and folks might talk. The ketch on the outside suller door had better be fixed so it can’t blow open. Josiah’s thickest socks are in the under draw, and the pieces to mend his overhalls in a calico bag behind the clothespress door. Guard that man like the apples in your eyes, Philury, and you’ll be glad bime by. So no more. To be continude.”

Agin I laid down and tried to sleep; in vain, my thoughts, my heart wuz in Jonesville, so I riz up agin as fur as I could and took my handkerchief pin offen the curtain where I had pinned it and looked at it long and sadly. I hadn’t took any picture of Josiah with me, I hadn’t but one and wuz afraid I should lose it. He hain’t been willin’ to be took sence he wuz bald, and I knew that his picture wuz engraved on my heart in deeper lines than any camera or kodak could do it. But I had a handkerchief pin that looked like him, I bought it to the World’s Fair, it wuz took of Columbus. You know Columbus wuz a changeable lookin’ critter in his pictures, if he looked like all on ’em he must have been fitty, and Miss Columbus must have had a hard time to git along with him. This looked like Josiah, only with more hair, but I held my thumb over the top, and I could almost hear Josiah speak. I might have had a lock of his hair to wep’ over, but my devoted love kep’ me from takin’ it; I knew that he couldn’t afford to spare a hair with winter comin’ on. But I felt that I must compose myself, for my restless moves had waked Tommy up. The sullen roar of the wheels underneath me kep’ kinder hunchin’ me up every little while if I forgot myself for a minute, twittin’ me that my pardner had let me go away from him; I almost thought I heard once or twice the echo, Grass Widder! soundin’ out under the crunchin’ roar and rattle of the wheels, but then I turned right over on my shelf and sez in my agony of sperit: Not that––not grass.

And Tommy called down, “What say, grandma?” And 33 I reached up and took holt of his soft, warm little hand and sez: “Go to sleep, Tommy, grandma is here.”

“You said sunthin’ about grass, grandma.”

And I sez, “How green the grass is in the spring, Tommy, under the orchard trees and in the door-yard. How pretty the sun shines on it and the moonlight, and grandpa is there, Tommy, and Peace and Rest and Happiness, and my heart is there, too, Tommy,” and I most sobbed the last words.

And Tommy sez, “Hain’t your heart here too, grandma? You act as if you wuz ’fraid. You said when I prayed jest now that God would watch over us.”

“And he will, Tommy, he will take care of us and of all them I love.” And leanin’ my weary and mournful sperit on that thought, and leanin’ hard, I finally dropped off into the arms of Morphine.

Well, we reached Chicago with no further coincidence and put up to a big hotel kep’ by Mr. and Miss Parmer. It seems that besides all the money I had been provided with, Thomas J. had gin a lot of money to Miss Meechim to use for me if she see me try to stent myself any, and he had gin particular orders that we should go to the same hotels they did and fare jest as well, so they wanted to go to the tarven kep’ by Mr. Parmerses folks, and we did.

I felt real kinder mortified to think that I didn’t pay no attention to Mr. and Miss Parmer; I didn’t see ’em at all whilst I wuz there. But I spoze she wuz busy helpin’ her hired girls, it must take a sight of work to cook for such a raft of folks, and it took the most of his time to provide.

Well, we all took a long ride round Chicago; Miss Meechim wanted to see the most she could in the shortest time. So we driv through Lincoln Park, so beautiful as to be even worthy of its name, and one or two other beautiful parks and boolevards and Lake Shore drives. And we went at my request to see the Woman’s Temperance Building; I had got considerable tired by that time, and, oh, how a woman’s tired heart longs for the only true rest, the heart rest of love. As we went up the beautiful, open-work alleviator, I felt, oh, that this thing was swinging me off to Jonesville, acrost the waste of sea and land. But immegiately the thought come “Duty’s apron-strings,” and I wuz calm agin.

But all the time I wuz there talkin’ to them noble wimmen, dear to me because they’re tacklin’ the most needed work under the heavens, wagin’ the most holy war, and 35 tacklin’ it without any help as you may say from Uncle Sam, good-natered, shiftless old creeter, well meanin’, I believe, but jest led in blinders up and down the earth by the Whiskey Power that controls State and Church to-day, and they may dispute it if they want to, but it is true as the book of Job, and fuller of biles and all other impurities and tribulations than Job ever wuz, and heaven only knows how it is goin’ to end.

But to resoom backwards. Lofty and inspirin’ wuz the talks I had with the noble ones whose names are on the list of temperance here and the Lamb’s Book of Life. How our hearts burnt within us, and how the “blest tie that binds” seemed to link us clost together; when, alas! in my soarinest moments, as I looked off with my mind’s eye onto a dark world beginnin’ to be belted and lightened by the White Ribbon, my heart fell almost below my belt ribbin’ as I thought of one who had talked light about my W. T. C. U. doin’s, but wuz at heart a believer and a abstainer and a member of the Jonesville Sons of Temperance.

A little later we stood and looked on one of the great grain elevators, histin’ up in its strong grip hull fields of wheat and corn at a time. Ah! among all the wonderin’ and awe-struck admiration of them about me, how my mind soared off on the dear bald head afar, he who had so often sowed the spring and reaped the autumn ears on the hills and dales of Jonesville, sweet land! dear one! when should I see thee again?

And as we walked through one of the enormous stock yards, oh! how the bellerin’ of them cattle confined there put me in mind of the choice of my youth and joy of my middle age. Wuz he too bellerin’ at that moment, shet up as he wuz by environin’ circumstances from her he worshipped.

And so it went on, sad things put me in mind of him and joyful things, all, all speakin’ of him, and how, how wuz I to brook the separation? But I will cease to harrow the 36 reader’s tender bosom. Dry your tears, reader, I will proceed onwards.

The next day we sot off for California, via Salt Lake and Denver.

Jest as we left the tarven at Chicago our mail wuz put in our hands, forwarded by the Jonesville postmaster accordin’ to promise; but not a word from my pardner, roustin’ up my apprehensions afresh. Had his fond heart broken under the too great strain? Had he passed away callin’ on my name?

My tears dribbled down onto my dress waist, though I tried to stanch ’em with my snowy linen handkerchief. Tommy’s tears, too, began to fall, seein’ which I grabbed holt of Duty’s black apron-strings and wuz agin calm on the outside, and handed Tommy a chocolate drop (which healed his woond), although on the inside my heart kep’ on a seethin’ reservoir of agony and forbodin’s.

The next day, as I sot in my comfortable easy chair on the car, knittin’ a little, tryin’ to take my mind offen trouble and Josiah, Tommy wuz settin’ by my side, and Miss Meechim and Dorothy nigh by. Aronette, like a little angel of Help, fixin’ the cushions under our feet, brushin’ the dust offen her mistresses dresses, or pickin’ up my stitches when in my agitation or the jigglin’ of the cars I dropped ’em, and a perfect Arabian Night’s entertainer to Tommy, who worshipped her, when I hearn a exclamation from Tommy, and the car door shet, and I looked round and see a young man and woman advancin’ down the isle. They wuz a bridal couple, that anybody could see. The blessed fact could be seen in their hull personality––dress, demeanor, shinin’ new satchels and everything, but I didn’t recognize ’em till Tommy sez:

“Oh, grandma, there is Phila Henzy and the man she married!”

Could it be? Yes it wuz Phila Ann Henzy, Philemon Henzy’s oldest girl, named for her pa and ma, I knew she 37 wuz married in Loontown the week before. I’d hearn on’t, but had never seen the groom, but knew he wuz a young chap she had met to the Buffalo Exposition, and who had courted her more or less ever sence. They seemed real glad to see me, though their manners and smiles and hull demeanors seemed kinder new, somehow, like their clothes. They had hearn from friends in Jonesville that I wuz on my way to California, and they’d been lookin’ for me. Sez the groom, with a fond look on her:

“I am so glad we found you, for Baby would have been so disappointed if we hadn’t met you.”

Baby! Phila Ann wuz six feet high if she wuz a inch, but good lookin’ in a big sized way. And he wuz barely five feet, and scrawny at that; but a good amiable lookin’ young man. But I didn’t approve of his callin’ her Baby when she could have carried him easy on one arm and not felt it. The Henzys are all big sized, and Ann, her ma, could always clean her upper buttery shelves without gittin’ up in a chair, reach right up from the floor.

But he probable had noble qualities if he wuz spindlin’ lookin’, or she couldn’t adore him as she did. Phila Ann jest worshipped him I could see, and he her, visey versey. Sez she, with a tender look down onto him:

“Yes, I’ve been tellin’ pa how I did hope we should meet you.”

Pa! There wuz sunthin’ else I didn’t approve of; callin’ him pa, when the fact that they wuz on their bridal tower wuz stomped on ’em both jest as plain as I ever stomped a pat of butter with clover leaves. But I didn’t spoze I could do anything to help or hender, for I realized they wuz both in a state of delirium or trance. But I meditated further as I looked on, it wouldn’t probable last no great length of time. The honeymoon would be clouded over anon or before that. The clouds would clear away agin, no doubt, and the sun of Love shine out permanent if their affection for each other wuz cast-iron and sincere. But the light of this 38 magic moon I knew would never shine on ’em agin. The light of that moon makes things look dretful queer and casts strange shadders onto things and folks laugh at it but no other light is so heavenly bright while it lasts. I think so and so duz Josiah.

But to resoom forwards. The groom went somewhere to send a telegram and Phila sot down by me for a spell; their seat wuz further off but she wanted to talk with me. She wuz real happy and confided in me, and remarked “What a lovely state matrimony is.”

And I sez, “Yes indeed! it is, but you hain’t got fur enough along in marriage gography to bound the state on all sides as you will in the future.”

But she smiled blissful and her eyes looked fur off in rapped delight (the light of that moon shin’ full on her) as she said:

“What bliss it is for me to know that I have got sunthin’ to lean on.”

And I thought that it would be sad day for him if she leaned her hull heft, but didn’t say so, not knowin’ how it would be took.

I inquired all about the neighbors in Jonesville and Zoar and Loontown, and sez I, “I spoze Elder White is still doin’ all he can for that meetin’ house of hisen in Loontown, and I inquired particular about him, for Ernest White is a young man I set store by. He come from his home in Boston to visit his uncle, the banker, in East Loontown. He wuz right from the German university and college and preachin’ school, and he wuz so rich he might have sot down and twiddled his thumbs for the rest of his days. But he had a passion for work––a passion of pity for poor tempted humanity. He wanted to reach down and try to lift up the strugglin’ ‘submerged tenth.’ He wuz a student and disciple of Ruskin, and felt that he must carry a message of helpfulness and beauty into starved lives. And, best of all, he wuz a follower of Jesus, who went about doin’ good. 39 When his rich family found that he would be a clergyman they wanted to git him a big city church, and he might have had twenty, for he wuz smart as a whip, handsome, rich, and jest run after in society. But no; he said there wuz plenty to take those rich fat places; he would work amongst the poor, them who needed him.”

East Loontown is a factory village, and the little chapel was standin’ empty for want of funds, but twenty saloons wuz booming, full of the operatives, who spent all of their spare time and most of their money there. So Ernest White stayed right there and preached, at first to empty seats and a few old wimmen, but as they got to know him, the best young men and young wimmen went, and he filled their hearts with aspiration and hope and beauty and determination to help the world. Not being contented with what he wuz doing he spent half his time with the factory hands, who wuz driven to work by Want, and harried by the mighty foe, Intemperance. A saloon on every corner and block, our twin American idols, Intemperance and Greed, taking every cent of money from the poor worshippers, to pour into the greedy pockets of the saloon-keepers, brewers, whiskey men and the Government, and all who fatten on the corpse of manhood.

Well, he jest threw himself into the work of helping those poor souls, and helping them as he did in sickness and health they got to liking him, so that they wuz willing to go and hear him preach, which was one hard blow to the Demon. The next thing he got all the ministers he could to unite in a Church Union to fight the Liquor Power, and undertaking it in the right way, at the ballot-box, they got it pretty well subdued, and as sane minds begun to reign in healthier bodies, better times come.

Elder White not only preached every Sunday, but kep’ his church open every evening of the week, and his boys and girls met there for healthful and innocent amusements. He got a good library, all sorts of good games, music; and had 40 short, interesting lectures and entertainments and his Church of Love rivalled the Idol Temples and drew away its idol worshippers one by one, and besides the ministers, many prominent business men helped him; my son, Thomas J., is forward in helpin’ it along. And they say that besides all the good they’re doing, they have good times too, and enjoy themselves first-rate evenings. They don’t stay out late––that’s another thing Elder White is trying to inculcate into their minds––right living in the way of health as well as morals. Every little while he and somebody else who is fitted for it gives short talks on subjects that will help the boys and girls along in Temperance and all good things. The young folks jest worship him, so they say, and I wuz glad to hear right from him. Phila is a worker in his meetin’ house, and a active member, and so is her pa and ma, and she said that there wuz no tellin’ how much good he had done.

“When he come there,” sez she, “there wuz twenty saloons goin’ full blast in a village of two thousand inhabitants and the mill operatives wuz spendin’ most all they earnt there, leavin’ their families to suffer and half starve; but when Elder White opened his Church of Love week day evenin’s as well as Sunday, you have no idee what a change there is. There isn’t a saloon in the place. He has made his church so pleasant for the young folks that he has drawn away crowds that used to fill the saloons.”

“Yes,” sez I, “Thomas J. is dretful interested in it; he has gin three lectures there.”

“Yes, most all the best citizens have joined the Help Union to fight against the Whiskey Power, though,” sez Phila, “there is one or two ministers who are afraid of contaminating their religion by politics. They had ruther stand up in their pulpits and preach to a few wimmen about the old Jews and the patience of Job than take holt and do a man’s work in a man’s way––the only practical way, grapple 41 with the monster Evil at its lair, where it breeds and fattens––the ballot-box.”

“Yes,” sez I, “a good many ministers think that they can’t descend into the filthy pool of politics. But it hain’t reasonable, for how are you a goin’ to clean out a filthy place if them that want it clean stand on the bank and hold their noses with one hand, and jester with the other, and quote scripter? And them that don’t want it clean are throwin’ slime and dirt into it all the time, heapin’ up the loathsome filth. Somebody has got to take holt and work as well as pray, if these plague spots and misery breeders are ever purified.”

“Well, Elder White is doin’ all he can,” sez Phila. “He went right to the polls ’lection day and worked all day; for the Whiskey Power wuz all riz up and watchin’ and workin’ for its life, as you may say, bound to draw back into its clutches some of the men that Elder White, with the Lord’s help, had saved. They exerted all their influence, liquor run free all day and all the night before, tryin’ to brutalize and craze the men into votin’ as the Liquor Power dictated. But Elder White knew what they wuz about, and he and all the earnest helpers he could muster used all their power and influence, and the election wuz a triumph for the Right. East Loontown went no-license, and not a saloon curses its streets to-day. North Loontown, where the minister felt that he wuz too good to touch the political pole, went license, and five more filthy pools wuz opened there for his flock to fall into, to breed vile influences that will overpower all the good influence he can possibly bring to bear on the souls committed to his care.”

“But,” sez I, “he is writin’ his book, ‘Commentaries on Ancient Sins,’ so he won’t sense it so much. He’s jest carried away with his work.”

Sez Phila, “He had better be actin’ out a commentary on modern sins. What business has he to be rakin’ over the old ashes of Sodom and Gomorrah for bones of antediluvian 42 sinners, and leave his livin’ flock to be burnt and choked by the fire and flames of the present volcano of crime, the Liquor System, that belches forth all the time.”

“Well, he wuz made so,” sez I.

“Well, he had better git down out of the pulpit,” sez Phila, “and let some one git up there who can see a sinner right under his nose, and try to drag him out of danger and ruin, and not have to look over a dozen centuries to find him.”

“Well, I am thankful for Ernest White, and I have felt that he and Waitstill Webb wuz jest made for each other. He thinks his eyes of her I know. When she went and nursed the factory hands when the typhoid fever broke out he said ‘she wuz like a angel of Mercy.’”

“They said he looked like a angel of Wrath ’lection day,” sez Phila. “You know how fair his face is, and how his clear gray eyes seem to look right through you, and through shams and shames of every kind. Well, that day they said his face fairly shone and he did the work of ten men.”

“That is because his heart is pure,” sez I, “like that Mr. Gallyhed I heard Thomas J. read about; you know it sez:

“‘His strength is as the strength of ten

Because his heart is pure.’

“And oh!” sez I agin, “how I would love to see him and Waitstill Webb married, and happy.”

“So would I,” sez Phila. “Oh, it is such a beautiful state, matrimony is.”

“And he needs a wife,” sez I. “You know he wouldn’t stay with his uncle but said he must live with his people who needed him, so he boards there at the Widder Pooler’s.”

“Yes,” sez Phila, “and though she worships him, she had rather any day play the part of Mary than of Martha––she had rather be sittin’ at his feet and learnin’ of him––than 43 cookin’ good nourishin’ food and makin’ a clean, sweet home for him. But he don’t complain.”

“What a companion Waitstill would be for him?” I sez agin.

“Yes,” sez Phila, “but I don’t believe she will ever marry any one, she looks so sad.”

“It seems jest if they wuz made for each other,” sez I, “and I know he worships the ground she walks on. But I don’t know as she will ever marry any one after what she has went through,” and I sithed.

“She would marry,” sez Phila warmly, “if she knew what a lovely, lovely state it wuz.”

How strange it is that some folks are as soft as putty on some subjects and real cute on others. Phila knew enough on any other subject only jest marriage. But I spozed that her brain would harden up on this subject when she got more familiar with it––they generally do. And the light of that moon I spoke on liquefies common sense and a state, putty soft, ensues; but cold weather hardens putty, and I knew that she would git over it. But even as I methought, Phila sez, “I must go to my seat, pa will be lookin’ for me.” I see Miss Meechim smotherin’ a smile on her lace-edged handkerchief, and Dorothy’s eyes kinder laughin’ at the idee of a bride callin’ her husband “pa.”

But the groom returned at jest that minute, and I introduced ’em both to Miss Meechim and Dorothy, and we had quite a good little visit. But anon, the groom mentioned incidentally that they wuz a goin’ to live in Salt Lake City.

“Why!” sez I in horrow, “you hain’t a goin’ to jine the Mormons are you?”

And as I said that I see Miss Meechim kinder git Dorothy behind her, as if to protect her from what might be. But I knew there wuzn’t no danger from the groom’s flirtin’ with any other female or tryin’ to git ’em sealed to him, for quite a spell I knew that he felt himself as much alone with Baby as if them two wuz on a oasis in the middle of the 44 desert of Sarah. I knew that it would be some months before he waked up to the fact of there bein’ another woman in the world. And oh, how Phila scoffed at the idee of pa jinin’ the Mormons. They had bought part of a store of a Gentile and wuz goin’ to be pardners with him and kinder grow up with the country. I felt that hey wuz a likely couple and would do well, but rememberin’ Dorothy’s and Miss Meechim’s smiles I reached up and stiddied myself on that apron-string of Duty, and took Phila out one side and advised her not to call her bridegroom pa. Sez I, “You hain’t but jest married and it don’t look well.”

And she said that “Her ma always called her father pa.”

“Well,” sez I, “if you’ll take the advice of a old Jonesvillian and well-wisher, you’ll wait till you’re a few years older before you call him pa.”

And she sez, lookin’ admirin’ly at him, “I spoze I might call him papa.”

Well, you can’t put sense into a certain bump in anybody’s head if it wuzn’t made there in the first place––there are holler places in heads that you can’t fill up, do your best. But oh! how her devoted love to him put me in mind of myself, and how his small-sized devotion to her––how it reminded me of him who wuz far away––and oh, why did I not hear from him! my heart sunk nearly into my shues as I foreboded about it. It seemed as if everything brung him up before me, the provisions we had on the dining car wuz good and plenty of ’em, and how they made me think of him, who wuz a good provider. The long, long days and nights of travel, the jar and motion of the cars made me think of him who often wuz restless and oneasy. And even the sand of the desert between Cheyenne and Denver, even that sand brought me fond remembrances of one who wuz sandy complected when in his prime. And oh! when did I not think of him? Christmas had gone by, but how could we celebrate it without a home to set up a Christmas tree, or set out a table with good Jonesville vittles. How I 45 thought on him who made a holiday in my heart by his presence, and always helped me put the leaves in the extension table.

Tommy wanted to hang up his little stockin’, and did, hangin’ it out like a little red signal of distress over the side of his top shelf, and we filled it with everything good we could git hold on.

Dorothy put in a little silver watch she had bought on her travels, not bigger than a warnut, and Miss Meechim put in some of the toys she had bought for children of her acquaintance. I got a good little picture book for him in Chicago, and a set of Authors, and Aronette gin him two little linen handkerchiefs, hemstitched by herself, and his name, “Tommy,” worked in the corners. He wuz real tickled with ’em all. I told Miss Meechim that I had hoped to spend Christmas in Salt Lake City. Knowin’ that it wuz a warm climate, I thought I could have a Christmas tree out doors; I thought I could take one of them big pine trees I had read on, and invite Brigham Young’s wives, the hull on ’em, to my party, bein’ out doors I thought there would be room for ’em all, poor creeters!

But Miss Meechim is very cautious, and she said that she wuz afraid that such a party given by folks in my high position might have a tendency to encourage polygamy.

And I said, “I would rather give a dollar bill than do that, and mebbe I had better give it up, for we shan’t git there in time, anyway.”

And so I did, and spent the Christmas holidays on the cars, and tried to keep my heart and mind in a Christmas mood, but don’t spoze I did, so many fond recollections and sad forebodin’s hanted me as the cars swep’ us on, on through the valley of the Platte river on to Denver. Miss Meechim, who is a power on dates, said that Denver wuz five thousand two hundred feet above the sea.

And Tommy wonnered, wonnered who measured it, and if they did it with a yard stick as his ma measured cloth, 46 and then he wonnered if his ma missed her little boy, and then he laid up aginst me and kinder cried a little, evanescent grief soon soothed.

We stayed in Denver two days, sallyin’ out to different points of interest about it, and here I see irrigation carried on, water carried into the channels around the crops and trees some as I’ve dug little holes round my house-plants to hold water; only of course Denver wuz carryin’ it on, on a bigger scale. It is a handsome city with the water of the Platte river brung in and running along in little streams by the curbstones. We rode out to Idaho Springs on a narrer railroad but easy goin’, through Clear Creek Canon. I liked the looks of the Springs first-rate (they made me think of Josiah).

All the way we see Chinamen workin’ hard and patient, as is their wont, and their long frocks they had on made me think of him I mourned for, and their hair hangin’ in long braids down their back. So would his hair look if he had any, and let it grow.

We had to go a little out of our straight way to visit Salt Lake City but felt that it paid.

Salt Lake lays in a rich valley at the foot of a range of snow-capped mountains that tower up ’round it, seemin’ to the saints, I spoze, as if they wuz heavenly ramparts to protect ’em from evil; and lookin’ to them that despise the saints’ ways and customs, as if the very earth itself was liftin’ up its high hands in horrow at their deeds. But to me, hanted as I wuz by a memory, the mountains looked some like old men with white hair; as his would be when he got older if he wuzn’t bald. I knew that I ort not to think on it, but it would come onbid. It is a beautiful city with electric lights, electric railways, broad streets lined with lofty trees, and little rivulets of pure cold snow-water runnin’ along the side of ’em. The houses are clean and comfortable looking, with well-kep’ lawns and gardens about ’em and flowering shrubs. The temple is a magnificent building; it towers up to heaven, as if it wuz jest as sure of bein’ right as our Methodist Episcopal steeple at Jonesville. Though we know that the M. E. steeple, though smaller in size, is pintin’ the right way and will be found out so on that day that tries souls and steeples and everything else.

The old Bee Hive (where the swarm of Mormons first hived and made gall or honey––or mebby both)––is also an interestin’ sight to meditate on. It is shaped a good deal like one of them round straw bee hives you see in old Sabbath School books. The bride and groom went to their own home to live, on whom we called, or Tommy and I did, and left ’em well situated and happy; and I told him, sez I: “If you ’tend strict to the eighth commandment, you’ll git along first rate.”

And he said that he felt he could rise to any height of goodness with Baby’s help. And she scoffed at the idee of pa ever payin’ any attention to any other woman but her, when he worshipped her so.

Well, so other men have felt and got led off, but I won’t forebode. But I left ’em happy in their own cozy home, which I wuz glad to think I could describe to Phileman and Ann if I ever see that blessed haven, Jonesville, agin.

We went out to visit the Mineral Springs. It only took us about ten minutes on the train, and it only took us about half an hour to go to Garfield Beach. It is the only sand beach on Salt Lake, and some say it is the finest beach in the world, and they say that the sunsets viewed from this spot are so heavenly bright in their glowin’ colors that no pen or tongue can describe ’em. The blue-green waves wuz dancin’ as we stood on the shore, and we wuz told that if we fell in, the water would hold us up, but didn’t try it, bein’ in sunthin’ of a hurry.

At Miss Meechim’s strong request we went on a pleasant trip to York City through the valley of the River of Jordan. How good that name sounded to me! How much like scripter! But, alas! it made me think of one who had so often sung with me on the way home from evenin’ meetin’, as the full moon gilded the top of the democrat, and the surroundin’ landscape:

“By Jordan’s stormy banks we stand

And cast a wistful eye

On Canaan’s fair and happy land,

Where my possessions lie.”

Oh, human love and longing, how strong thou art! I knowed that him meant the things of the sperit, but my human heart translated it, and I sithed and felt that the Jordan my soul wuz passin’ through wuz indeed a hard pathway, and I couldn’t help castin’ a wishful eye on Jonesville’s 49 fair and happy land, where my earthly possession, my Josiah, lay.

But to resoom. We had hearn that Polygamy wuz still practised there, and we had hearn that it wuzn’t. But every doubt on that subject wuz laid to rest by an invitation we all had to go and visit a Mormon family livin’ not fur off, and Miss Meechim and I went, she not wantin’ Dorothy to hear a word on the subject. She said with reason, that after all her anxiety and labors to keep her from marryin’ one man, what would be her feelin’s to have her visit a man who had boldly wedded ’leven wives and might want a even dozen!

I could see it to once, so didn’t urge the matter, but left Tommy with her and Aronette. As nigh as I could make out, the Mormons had felt that Miss Meechim and I wuz high in authority in Gentile climes, one on us had that air of nobility and command that is always associated with high authority, and they felt that one on us could do their cause much good if they could impress us favorable with the custom, so they put their best twenty-four feet forward and did their level best to show off their doctrine in flyin’ colors. But they didn’t do any good to “one on us,” nor to Miss Meechim, either; she’s sound in doctrine, though kinder weak and disagreeable in spots.

Well, we found that this family lived in splendid style, and the husband and all his pardners acted happy whether they wuz or not. And I d’no how or why it wuz, but when we all sot down in their large cool parlor, Miss Meechim and I in our luxurious easy chairs, and our host in one opposite with his wife occupyin’ ’leven chairs at his sides, a feelin’ of pity swep’ over me––pity for that man.

Yes, as I looked at that one lonely man, small boneded at that, and then looked at them ’leven portly wimmen that called that man “our husband,” I pitied him like a dog. I had never thought of pityin’ Mormon men before, but had poured out all my pity and sympathy onto the female Mormons. But havin’ a mind like a oxes for strength, I begun 50 to see matters in a new light, and I begun to spozen to myself, even whilst I sot there with my tongue keepin’ up a light dialogue on the weather, the country, etc., with the man and his wife (’leven on ’em). I spozed what if they should all git mad at him at one time how wuz he goin’ to bear their ’leven rages flashin’ from twenty-two eyes, snortin’ from ’leven upturned noses, fallin’ from ’leven angry voices, and the angry jesters from twenty-two scornful hands. Spozein’ they all got to weepin’ on his shoulder at one time how could one shoulder blade stand it under the united weight of ’leven full-sized females, most two ton of ’em, amidst more’n forty-four nervous sobs, for they would naterally gin more’n two apiece. In sickness now, if they wanted to soothe his achin’ brow, and of course they would all want to, and have the right to. But how could twenty-two hands rest on that one small fore-top? Sixty-six rubs at the least figger, for if they stroked his forehead at all they would want to stroke it three times apiece, poor creeter! would not delerium ensue instead of sooth? And spozein’ they all took it into their heads to hang on his arm with both arms fondly whilst out walkin’ by moonlight, how could twenty-two arms be accommodated by two small scrawny elbows?

It couldn’t be done. And as I mused on’t I spoke right out onbeknown to me, and sez I:

“The Lord never meant it to be so; it hain’t reasonable; it’s aginst common sense.”

And the hull twelve sez, “What didn’t the Lord mean? What wuz aginst common sense?”

And bein’ ketched at it, I sez, “The Mormon doctrine;” sez I, “to say nothin’ on moral and spiritual grounds, and state rights, it’s against reason and good sense.”

I felt mortified to think I had spoke out loud, but had to stand my ground after I had said it.

But they all said that the Mormon doctrine wuz the true belief, that it wuz writ in heaven, then it wuz engraved on plates, and dug up by Joe Smith, a Latter Day Saint.

Sez I, “If anybody trys to prove sunthin’ they want to, they can most always dig up sunthin’ to prove it. You say a man dug this plate up; what if some woman should go to diggin’ and find a plate provin’ that one woman ort to have ’leven husbands?”

“Oh, no!” sez the man in deep scorn, “no such plate could be found!”