The Project Gutenberg EBook of The International Monthly, Volume 5, No. 3, March, 1852, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The International Monthly, Volume 5, No. 3, March, 1852 Author: Various Release Date: February 3, 2010 [EBook #31162] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INTERNATIONAL MONTHLY, MARCH 1852 *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections.)

Transcriber's Note: Minor typos have been corrected and footnotes moved to the end of the article. Table of contents has been created for the HTML version.

THE AZTECS AT THE SOCIETY LIBRARY.

A DAY AT CHATSWORTH.

MEN AND WOMEN OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY.

A MODEL TRAVELLER.

A MYSTERIOUS HISTORY.

EDWARD EVERETT AND DANIEL WEBSTER.

ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING.

THE HAPPINESS OF OYSTERS.

THE RECLAIMING OF THE ANGEL.

THE ENEMY OF VIRGINIA.

A WORD ABOUT THE ARMY-PRIVATE.

TO SUNDRY CRITICS.

THE "RED FEATHER."

THRENODIA.

MR. ASHBURNER IN NEW-YORK.

LEONORA TO TASSO.

HUNGARIAN POPULAR SONGS.

A SONG FOR THIS DAY AND GENERATION.

FEATHERTOP: A MORALIZED LEGEND.

A CHAPTER ON GAMBLING.

AN ELECTION ROW IN NEW-YORK.

THE JEWISH HEROINE: A STORY OF TANGIER.

LAMAS AND LAMAISM.

STORY OF GASPAR MENDEZ.

JOHN ROBINSON, THE PASTOR OF THE PILGRIMS.

A CHAPTER ON CATS.

THE HEIRS OF RANDOLPH ABBEY.

NEW DISCOVERIES IN GHOSTS.

THE WOLF-GATHERING.

MY NOVEL

THE WHITE LAMB.

AUTHORS AND BOOKS.

HISTORICAL REVIEW OF THE MONTH.

THE FINE ARTS.

SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIES AND PROCEEDINGS OF LEARNED SOCIETIES.

RECENT DEATHS.

LADIES' FASHIONS FOR MARCH.

For several weeks the attention of the curious has been more and more attracted to a remarkable ethnological exhibition at the Society Library. Two persons, scarcely larger than the fabled gentlemen of Lilliput, (though one is twelve or thirteen and the other eighteen years of age), of just and even elegant proportions, and physiognomies striking and peculiar, but not deficient in intellect or refinement, have been visited by throngs of idlers in quest of amusement, wonder-seekers, and the profoundest inquirers into human history. Until very recently, Mexico was properly described as Terra Incognita. The remains of nations are there shrouded in oblivion, and cities, in their time surpassing Tadmor and Thebes, untrodden except by the jaguar and the ocelot. A few persons, indeed, attracted by uncertain rumors of ancient grandeur in Palenque, have visited her temples and tombs—

but no one has been found to read the hieroglyphics of Tolteca, to disclose the history of the dwellers in Anahuac, to make known the annals of the rise and fall of Tlascala, Otumba, Copan, or Papantla. In the great work of Lord Kingsborough are collected many important remains of Mexican and Aztec art and learning; Mr. Prescott has combined with a masterly hand the traditions of the country; and Mr. Stevens and Mr. Squier have done much in the last few years to render us familiar with the more accessible and probably most significant ruins which illustrate the civilization of the race subdued by the Spaniards; but still Central America is unexplored. In the second volume of the work of Mr. Stevens, he mentions that a Roman Catholic priest of Santa Cruz del Quiche told him marvellous stories of a "large city, with turrets white and glittering in the sun," beyond the Cordilleras, where a people still existed in the condition of the subjects of Montezuma. He proceeds:

"The interest awakened in us, was the most thrilling I ever experienced. One look at that city, was worth ten years of an every-day life. If he is right, a place is left where Indians and a city exist, as Cortez and Alvarado found them; there are living men who can solve the mystery that hangs over the ruined cities of America; who can, perhaps, go to Copan and read the inscription on its monuments. No subject more exciting and attractive presents itself to any mind, and the deep impression in my mind will never be effaced. Can it be true? Being now in [Pg 290]my sober senses, I do verily believe there is much ground to suppose that what the Padre told us is authentic. That the region referred to does not acknowledge the government of Gautamala, and has never been explored, and that no white man has ever pretended to have entered it; I am satisfied. From other sources we heard that a large ruined city was visible; and we were told of another person who had climbed to the top of the sierra, but on account of the dense clouds rising upon it, he had not been able to see any thing. At all events, the belief at the village of Chajul is general, and a curiosity is aroused that burns to be satisfied. We had a craving desire to reach the mysterious city. No man if so willing to peril his life, could undertake the enterprise, with any hope of success, without hovering for one or two years on the borders of the country, studying the language and character of the adjoining Indians, and making acquaintance with some of the natives. Five hundred men could probably march directly to the city, and the invasion would be more justifiable than any made by Spaniards; but the government is too much occupied with its own wars, and the knowledge could not be procured except at the price of blood. Two young men of good constitution, and who could afford to spend five years, might succeed. If the object of search prove a phantom, in the wild scenes of a new and unexplored country, there are other objects of interest; but, if real, besides the glorious excitement of such a novelty, they will have something to look back upon through life. As to the dangers, they are always magnified, and, in general, peril is discovered soon enough for escape. But, in all probability, if any discovery is made, it will be made by the Padres. As for ourselves, to attempt it alone, ignorant of the language, and with the mozos who were a constant annoyance to us, was out of the question. The most we thought of, was to climb to the top of the sierra, thence to look down upon the mysterious city; but we had difficulties enough in the road before us; it would add ten days to a journey already almost appalling in the perspective; for days the sierra might be covered with clouds; in attempting too much, we might lose all; Palenque was our great point, and we determined not to be diverted from the course we had marked out."—Vol. ii., p. 193-196.

Mr. Stevens appears to have had some confidence in the Padre's statement, and expresses a belief that the race of the aboriginal inhabitants of Central America is not extinct, but that, scattered perhaps and retired, like our own Indians, into wildernesses which have never been penetrated by white men—erecting buildings of "lime and stone," "with ornaments of sculpture, and plastered," "large courts," and "lofty towers, with high ranges of steps," and carving on tablets of stone mysterious hieroglyphs, there are still in secluded cities "unconquered, unvisited, and unsought aborigines." It is stated in a pamphlet before us, that such a city was discovered in 1849 by three adventurous travellers, and that one of them succeeded in bringing to New York two specimens of its diminutive and peculiar inhabitants—the persons now being exhibited in Broadway. Of the credibility of this account we express no opinion, but the "Aztec Children" have the phrenological and general appearance of the ancient Mexican sculptures, and may well be regarded for their probable origin, their physical structure, or their mere appearance, as among the "most wonderful specimens of humanity." We assent to the following paragraph by Mr. Horace Greeley, whose testimony agrees with the common impressions they have produced:

"I hate monstrosities, however remarkable, and am rather repelled than attracted by the idea of their truthfulness. Assuming that there is a propensity in human nature—an 'organ,' as the phrenologists would phrase it—that finds gratification in the inspection and scrutiny of Joice Heths, Woolly Horses, and six-legged Swine, I would rather have it gratified by fabricated and factitious than by natural and veritable productions, and would rather not share in the process from which that gratification is extracted. There is a superabundance of ugliness and deformity which one is obliged to see, without running after and nosing any out. It was, therefore, with some reluctance that I obeyed a polite invitation to visit the Aztec children, and ratify or dispute the commendations hitherto bestowed on them, in these columns and elsewhere. I did not expect to find ogres nor any thing hideous, but, among all similar exhibitions, remembering with pleasure only Tom Thumb, I could not hope to find gratification in the sight of two dwarf Indians. But I was disappointed. These children are simply abridgements or pocket editions of Humanity—bright-eyed, delicate-featured, olive-complexioned little elves, with dark, straight, glossy hair, well-proportioned heads, and animated, pleasing countenances. That their ages are honestly given, and that the boy weighs just about as many pounds as he is years old (twenty), while the girl is about half his age and three pounds lighter, I see no reason at all for doubting. That they are human beings, though of a low grade morally and intellectually, as well as diminutive physically, there can be no doubt; and they are not freaks of Nature, but specimens of a dwindled, minnikin race, who almost realize in bodily form our ideas of the 'brownies,' 'bogles,' and other fanciful creations of a more superstitious age. Their heads, unlike those of dwarfs, are small and not ill-looking, but with very low foreheads and a general conformation strongly confirmatory of certain fundamental assertions of Phrenology. Idiotic they are not; but their intellect and language are those of children of three or four years, to whom their gait also assimilates them; but they have none of childhood's reserve or shyness, are inquisitive and restless, and articulate with manifest efforts and difficulty. To children of three to six or eight years, their incessant pranks and gambols must be a source of intense and unfailing delight. The story that they were procured from an unknown, scarcely approachable Aboriginal City of Central America called Iximaya, situated high among the mountains and rarely visited by civilized man, may be true or false; but that they are natives of that part of the world, I cannot doubt. To the moralist, the student, the physiologist, they are subjects deserving of careful scrutiny and thoughtful observation; while to those whose highest motive is the gratification of curiosity, but especially to children, they must be objects of vivid interest."

THE ENTRANCE GATES.

THE ENTRANCE GATES.

Among the most magnificent of the palatial homes of England—indeed one of the most rich and splendid residences occupied in all the world by an uncrowned master—is Chatsworth, in Derbyshire, the most beautiful district in the British islands. With some abridgment we transfer to the International an account of a recent visit to Chatsworth, by Mrs. S. C. Hall, with the illustrations by Mr. Finhalt, from the January number of the London Art-Journal. Our agreeable authoress, after some general observations respecting the attractions of the neighborhood, proceeds:

"We are so little proud of the beauties of England, that the foreigner only hears of Derbyshire as the casket which contains the rich jewel of Chatsworth. The setting is worthy of the gem. It ranks foremost among proudly beautiful English mansions; and merits its familiar title of the Palace of the Peak. It was the object of our pilgrimage; and we recalled the history of the nobles of its House. The family of Cavendish is one of our oldest descents; it may be traced lineally from Robert de Gernon, who entered England with the Conqueror, and whose descendant, Roger Gernon, of Grimston, in Suffolk, marrying the daughter and sole heiress of Lord Cavendish in that county, in the reign of Edward II., gave the name of that estate as a surname to his children, which they ever after bore. The study of the law seems to have been for a long period the means of according position and celebrity to the family, Sir William Cavendish, in whose person all the estates conjoined, was Privy Councillor to Henry VIII., Edward VI., and Mary; he had been Gentleman-Usher to Wolsey; and after the fall of the great Cardinal, was retained in the service of Henry VIII. He accumulated much wealth, but chiefly by his third marriage, with Elizabeth, the wealthy widow of Robert Barley, at whose instigation he sold his estates in other parts of England, to purchase lands in Derbyshire, where her great property lay. Hardwick Hall was her paternal residence, but Sir William began to build another at Chatsworth, which he did not live to finish. Ultimately, Elizabeth became the wife of George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury; she was one of the most remarkable women of her time, and the foundress of the two houses of Devonshire and Newcastle. Her second son, William, by the death of his elder brother in 1616, after being created Baron Cavendish, of Hardwick, was in 1618 created Earl of Devonshire. It was happily said of him, 'his learning operated on his conduct, but was seldom shown in his discourse.' His son, the third Earl, was a zealous loyalist; like his father, remarkable for his cultivated taste and learning, perfected under the superintendence of the famous Hobbes of Malmesbury. His eldest son, William, was the first Duke of Devonshire; the friend of Lord Russell, and one of the few who fearlessly testified to his honor on his memorable trial. Wearied of courts, he retired to Chatsworth, which at that time was a quadrangular building, with turrets in the Elizabethan taste; and then, 'as if his mind rose upon the depression of his fortune,' says Kennett, 'he first projected the now glorious pile of Chatsworth;' he pulled down the south side of 'that good old seat,' and rebuilt it on a plan 'so fair an august, that it looked like a model only of what might be done in after ages.' After seven years, he added the other sides, 'yet the building was his least charge, if regard be had to his gardens, water-works, statues, pictures, and other the finest pieces of Art and Nature that could be obtained abroad or at home.' He was highly honored with the favor and confidence of William III. and his successor Anne. Dying in 1707, his son William, who was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, spent the latter part of his life at Chatsworth, dying there in 1755. It is now the favorite country residence of his great grandson, the sixth Duke and ninth Earl of Devonshire.

"The Duke's tastes, as evinced at Chatsworth, are of the purest and happiest order;—and are to be found in the adornments of his rooms, the shelves of his library, the riches of his galleries of art, and the rare and beautiful exotic marvels of his gardens and conservatories. Charles Cotton, in his poem, the Wonders of the Peak, wrote, two centuries ago, of the then Earl of Devonshire—and[Pg 292] no language can apply with greater truth to the Duke who is now master of Chatsworth:

THE EMPEROR FOUNTAIN.

THE EMPEROR FOUNTAIN.

"Although carriages are permitted to drive from the railway terminus at Rowsley, to the pretty and pleasant inn at Edenson, by a road which passes directly under the house, the stranger should receive his first impressions of Chatsworth from one of the surrounding heights. It is impossible to convey a just idea of its breadth and dignity; the platform upon which it stands is a fitting base for such a structure; the trees, that at intervals relieve and enliven the vast space, are of every rich variety, the terraces nearly twelve hundred feet in extent—'the emperor fountain' throwing its jet two hundred and seventy feet into the air, far overtopping the avenue of majestic trees, of which it forms the centre. The dancing fountain, the great cascade, even the smaller fountains (wonderful objects any where, except here, where there are so many more wonderful) sparkle through the foliage; while all is backed by magnificent hanging woods, and the high lands of Derbyshire, extending from the hills of Matlock to Stony Middleton. And the foreground of the picture is, in its way, equally beautiful; the expansive view, the meadows now broken into green hills and mimic valleys, the groups of fallow deer, and herds of cattle, reposing beneath the shade of wide-spreading chestnuts, or the stately beech—all is harmony to perfection; nothing is wanting to complete the fascination of the whole. The enlarged and cultivated minds which conceived these vast yet minute arrangements, did not consider minor details as unimportant; every tree, and brake, and bush; every ornament, every path, is exactly in its right place, and seems to have ever been there. Nothing, however great, or however small, has escaped consideration; there are no bewildering effects, such as are frequently seen in large domains, and which render it difficult to recall what at the time may have been much admired; all is arranged with the dignity of order; all, however graceful, is substantial; the ornaments sometimes elaborate, never descend into prettiness; the character[Pg 293] of the scenery has been borne in mind, and its beauty never outraged by extravagance. All is in harmony with the character which nature in her most generous mood gave to the hills and valleys; God has been gracious to the land, and man has followed in the pathway He has made.

THE TEMPLE CASCADE.

THE TEMPLE CASCADE.

THE WELLINGTON ROCK AND CASCADE.

THE WELLINGTON ROCK AND CASCADE.

"A month at Chatsworth would hardly suffice to count its beauties; but much may be done in a day, when eyes and ears are open, and the heart beats in sympathy with the beauties of Nature and of Art. It is, perhaps, best to visit the gardens of Chatsworth first; they are little more than half a mile to the north of the park; and there Sir Joseph Paxton is building his new dwelling, or rather adding considerably to the beauty and convenience of the old. In the Kitchen-Gardens, containing twelve acres, there are houses for every species of plant, but the grand attraction is the house which contains the Royal Lily (Victoria Regia), and other lilies and water-plants from various countries. It will be readily believed that the flower-gardens are among the most exquisitely[Pg 294] beautiful in Europe; they have been arranged by one of the master minds of the age, and bear evidence of matured knowledge, skill, and taste; the nicest judgment seems to have been exercised over even the smallest matter of detail, while the whole is as perfect a combination as can be conceived of grandeur and loveliness. The walks, lawns, and parterres are lavishly, but unobtrusively, decorated with vases and statues; terraces occur here and there, from which are to be obtained the best views of the adjacent country; 'Patrician trees' at intervals form umbrageous alleys; water is made contributory from a hundred mountain streams and rivulets, to form jets, cascades, and fountains, which, infinitely varied in their 'play,' ramble among lilies, or—it is scarcely an exaggeration to say—fling their spray into the clouds, and descend to refresh the topmost leaves of trees that were in their prime three centuries ago. The most striking and original of the walks is that which leads through mimic Alpine scenery to the great conservatory; here Art has been most triumphant; the rocks, which, have been all brought hither, are so skilfully combined, so richly clad in mosses, so luxuriantly covered with heather, so judiciously based with ferns and water-plants, that you move among or beside them in rare delight at the sudden change which transports you from trim parterres to the utmost wildness of natural beauty. From these again you pass into a garden, in the centre of which is the conservatory, always renowned, but now more than ever, as the prototype of the famous Palace of Glass, which, in this Annus Mirabilis, received under its roof six millions of the people of all nations, tongues, and creeds. In extent, the conservatory at Chatsworth is but a pigmy compared with that which glorifies Hyde Park: but it is filled with the rarest Exotics from all parts of the globe—from 'farthest Ind,' from China, from the Himalayas, from Mexico; here you see the rich banana, Eschol's grape hanging in ripe profusion beneath the shadow of immense paper-like leaves; the feathery cocoa-palm, with its head peering almost to the lofty arched roof; the far-famed silk cotton-tree, supplying a sheet of cream-colored blossoms, at a season when all outward vegetable gayety is on the wane: the singular milk-tree of the Caraccas—the fragrant cinnamon and cassia—with thousands of other rare and little-known species of both flowers and fruits. The Italian Garden—opposite the library windows, with its richly colored parterres, and its clustered foliage wreathed around the pillars which support the statues and busts scattered among them, and hanging from one to the other with a luxurious verdure which seems to belong to the south—is a relief to the eye sated with the splendors of the palatial edifice.

THE ROCK-WORK.

THE ROCK-WORK.

"The water-works, which were constructed under the direction of M. Grillet, a French artist, were begun in 1690, when a pipe for what was then called 'the great fountain' was laid down; the height of twenty feet to which it threw water being, at that time, considered sufficiently wonderful to justify the hyperbolical language of Cotton:

It was afterward elevated to fifty feet, and then to ninety-four feet; but it is now celebrated as the most remarkable fountain in the world; it rises to the height of two hundred and sixty-seven feet, and has been named the Emperor Fountain, in honor of the visit of the Emperor of Russia to Chatsworth in 1844. Such is the velocity with which the water is ejected, that it is shown to escape at the rate of one hundred miles per minute; for the purpose of supplying it, a reservoir, or immense artificial lake, has been constructed on the hills, above Chatsworth, which is fed by the streams around and the springs on the moors drains being cut for this purpose, commencing at Humberly Brook, on the Chesterfield Road, two miles and a half from the reservoir, which covers eight acres; a pipe winds down the hill side, through which the water passes; and such is its waste, that a diminution of a foot may be perceived when the water-works have been played for three hours. Nothing can exceed the stupendous effect of this column, which may be seen for many miles around, shooting upwards to the sky in varied and graceful evolutions. From this upper lake the waterfalls are also supplied, which are constructed with so natural an effect on the hill side, behind the water-temple, which reminds the spectator of the glories of St. Cloud. From the dome of this temple bursts forth a gush of water[Pg 295] that covers its surface, pours through the urns at its sides, and springs up in fountains underneath, thence descending in a long series of step-like falls, until it sinks beneath the rocks at the base, and—after rising again to play as 'the dancing fountain' is conveyed by drains under the garden and park,—being emptied into the Derwent.[1] But we may not forget that our space is limited: to describe the gardens and conservatories of Chatsworth would occupy more pages than we can give to the whole theme; suffice it that the taste and liberality of the Duke of Devonshire, and the skill and judgment of Sir Joseph Paxton, have so combined Nature and Art in this delicious region, as to supply all the enjoyment that may be desired or is attainable, from trees, shrubs, and flowers seen under the happiest arrangement of countries, classes, and colors.

THE GREAT CONSERVATORY.

THE GREAT CONSERVATORY.

THE ITALIAN GARDEN.

THE ITALIAN GARDEN.

"The erection of the present house is narrated by Lysons, who says, the south front was begun to be rebuilt on the 12th of April, 1687, and the great hall and staircase covered in about the middle of April, 1690; the east front was begun in 1693, and finished in 1700; the south gallery was pulled down and rebuilt in 1703; in 1704, the north front was pulled down; the west front was finished in 1706; and the whole of the building not long afterwards completed, being about twenty years from the time of its commencement. The architect was Mr. William Talman, but in[Pg 296] May, 1692, the works were surveyed by Sir Christopher Wren.

"On entering—the Lower Hall or Western Lodge contains some very fine antique statuary, and fragments which deserve the especial attention of the connoisseur. Among them are several which were the treasured relics of Canova and Sir Henry Englefield, and others found in Herculaneum, and presented by the King of Naples to 'the beautiful' Duchess of Devonshire. A corridor leads thence to the Great Hall, which is decorated with paintings by the hand of a famous artist in his day—Verrio—celebrated by Pope for his proficiency in ceiling-painting. The effect of the hall is singularly good, with its grand stair and triple arches opening to the principal rooms. The sub-hall, behind, is embellished by a graceful fountain, with the story of Diana and Actæon, and the abundance of water at Chatsworth is sufficient for it to be constantly playing, producing an effect seldom attempted within doors. A long gallery leads to the various rooms inhabited by the Duke, the walls being decorated with a large number of fine pictures by the older masters of the Flemish and Italian schools. In the billiard-room are Landseer's famed picture of Bolton Abbey in the Olden Time, with charming specimens of Collins, and other British painters.

THE ENTRANCE HALL

THE ENTRANCE HALL

"The chapel is richly decorated with foliage in carved woodwork, which has been erroneously attributed to Grinling Gibbons. It was executed by Thomas Young, who was engaged as the principal carver in wood in 1689, and by a pupil of his, Samuel Watson, a native of Heanor, in Derbyshire, whose claim to the principal ornamental woodcarving at Chatsworth is set forth in verses on his tomb in Heanor Church.

"Over the Colonnade on the north side of the quadrangle, is a gallery nearly one hundred feet long in which have been hung a numerous and valuable collection of drawings by the old masters, arranged according to the schools of art of which they are examples. There is no school unrepresented, and as the eye wanders over the thickly-covered wall, it is arrested by sketches from the hands of Raffaelle, Da Vinci, Claude Poussin, Paul Veronese, Salvator Rosa, and the other great men who have made Art immortal. To describe these works would occupy a volume;[Pg 297] to study them a life; it is a glorious collection fitly displayed.

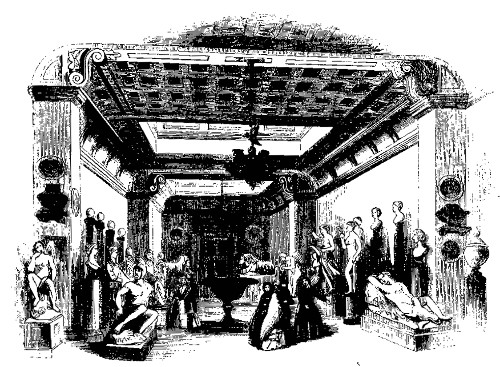

THE SCULPTURE GALLERY.

THE SCULPTURE GALLERY.

"The old state-rooms, which form the upper floors of the south front, occupy the same position as those which were appropriated to the unfortunate Mary Queen of Scots during her long residence here. There is, however, but little to see of her period; if we except some needlework at the back of a canopy representing hunting scenes, worked by the hand of the famous Countess of Shrewsbury, popularly known as 'Bess of Hardwick.'

"The gallery, ninety feet by twenty-two, originally constructed for dancing, has been fitted up by the present Duke as a library. Among the books which formed the original library at Chatsworth, are several which belonged to the celebrated Hobbes, who was many years a resident at the old hall. The library of Henry Cavendish, and the extensive and valuable collection at Devonshire House have aided to swell its stores. Thin quartos of the rarest order, unique volumes of old poetry, scarce and curious pamphlets by the early printers, first editions of Shakspeare, early pageants, and the rarest dramatic and other popular literature of the Elizabethan era, may be found in this well-ordered room—not to speak of its great treasure, the Liber Veritalus of Claude.

QUEEN MARY'S BOWER.

QUEEN MARY'S BOWER.

"The statue gallery, a noble room erected by the present Duke, contains a judiciously-selected series of sculptures. The gem of the collection is the famous seated statue of Madame Bonaparte, mother of Napoleon, by Canova. The same style characterizes that of Pauline Borghese, by Campbell. Other works of Canova are here—his statue of Hebe, and Endymion sleeping; a bust of Petrarch's[Pg 298] Laura, and the famous Lions, copied by Benaglia from the colossal originals on the monument of Clement XIV., at Rome. Thorwaldsen is abundantly represented by his Night and Morning, and his bas-reliefs of Priam Petitioning for the Body of Hector, and Briseis, taken from Achilles by the Heralds. Schadow's Filatrice, or Spinning Girl, and his classic bas-reliefs are worthy of all admiration. The English school of sculpture appears to advantage in Gibson's fine group, Mars and Cupid, and his bas-relief of Hero and Leander—Chantry's busts of George IV. and Canning—Westmacott's Cymbal Plaery—Wyatt's Musidora, and many others.

"Our visit to the mansion may conclude with a brief notice of one of its most interesting relics. Queen Mary's Bower is a sad memorial of the unhappy Queen's fourteen years' imprisonment here. It has been quaintly described as 'an island plat, on the top of a square tower, built in a large pool.' It is reached by a bridge, and in this lonely island-garden did Mary pass many days of a captivity, rendered doubly painful by the jealous bickerings of the Countess of Shrewsbury, who openly complained to Elizabeth of the Queen's intimacy with her husband; an unfounded aspersion, which Mary's urgent solicitations to Elizabeth obliged the Countess to retract, but which led to Mary's removal from the Earl's custody to that of Sir Amias Pawlet.

THE HUNTING TOWER.

THE HUNTING TOWER.

"To the Hunting-Tower on the hill above the house, the ascent is by a road winding gracefully among venerable trees, planted 'when Elizabeth was Queen,' and occasionally passing beside a fall of water, which dashes among rocks from the moors above. The tower stands on the edge of the steep and thickly-wooded hill; it is built on a platform of stone, reached by a few steps; it is one of the relics of old Chatsworth, and is a characteristic and curious feature of the scene. Such towers were frequently placed near lordly residences in the olden time, for the purpose 'of giving the ladies of those days an opportunity of enjoying the sport of hunting,' which, from the heights above, they saw in the vales beneath. The view from the tower is one of the finest in England. The house and grounds below, embosomed in foliage, peep through the umbrage far beneath your feet; the rapid Derwent courses along through the level valley. The wood opposite crowns the rising ground, above Edensor—the picturesque and beautiful village within whose humble church many members of the noble family are buried. The village itself may be considered as a model of taste; it resembles a group of Italian and Gothic villas, the utmost variety and the most picturesque styles of architecture being adopted for their construction, while the little flower-gardens before them are as carefully tended as those at Chatsworth itself. Upon the hills above are traces of Roman encampments, and from the summit you look down upon the beautiful[Pg 299] village of Bakewell, and far-famed Haddon Hall—the antique residence of the dukes of Rutland, an unspoiled relic of the sixteenth century. Looking toward the north, the eye traverses the fertile and beautiful valley of the Derwent, with the quiet little villages of Pilsley, Hassop, and Baslow, consisting of groups of cottages and quiet homesteads, speaking of pastoral life in its most favorable aspect. The eye, following the direction of the stream, is carried over the village of Calver, beyond which the rocks of Stony Middleton converge and shut in the prospect, with their gates of stone; amid distant trees, the village of Eyam, celebrated for its mournful story of the plague, and the heroism of its pastor, is embosomed. The ridge of rock stretches around the plain to the right, and upon the moors are traces of the early Britons in circles of stones and tumuli, with various other singular and deeply-interesting relics of 'the far off past.' Turning to the south, the prospect is bounded by the hills of Matlock; the villages of Darley-le-Dale, and Rowsley, reposing in mid-distance; the entire prospect comprising a series of picturesque mountains, fertile plains, wood, water, and rock, which cannot be surpassed in the world for variety and beauty. The noble domain in the foreground forming the grand centre of the whole:

"It was evening when we ascended this charming hill, and stood beneath the shadow of its famous Hunting Tower. The sun had just set, leaving a landscape of immense extent sleeping beneath rose-colored clouds; the air was balmy and fragrant with the peculiar odor of the pine-trees which topped the summit of the promontory on which we stood. We were told of Taddington Hill—of Beeley Edge—of Brampton Moor—of Robin Hood's bar—of Froggat Edge—until our eyes ached from the desire to distinguish the one from the other. There was Tor this, and Dale that, and such a hall and such a hamlet; but the stillness by which we were surrounded had become so delicious that we longed to enjoy it in solitude.

THE BRIDGE ACROSS THE DERWENT.

THE BRIDGE ACROSS THE DERWENT.

"What pen can tell of the beams of light that played on the highlands, when, after the fading of that gorgeous sunset, the valley became steeped in a soft blue-gray color, so tender, and clear and pure, that it conveyed the idea of 'atmosphere' to perfection. Then, as the shadows, the soothing shadows of evening, increased around us, the woods seemed to melt into the mountains; the rivers veiled their course by their misty incense to the heavens—wreath after wreath of vapor creeping upwards; and as the distances faded into indistinctness, the bold headlands seemed to grow and prop the clouds; the heavens let down the pall of mystery and darkness with a tender, not terrific, power; earth and sky blended together, softly and gently; the coolness of the air refreshed us, and yet the stillness on that high point was so intense as to become almost painful. As we looked into the valley, lights sprung up in cottage dwellings; and then, softly on a wandering breeze, came at intervals the tolling of a deep bell from the venerable church at Edensor, a token that some one had been summoned to another home—perhaps in one of those pale stars that at first singly, but then in troops, were beaming on us from the pale blue sky.

"While slowly descending from our eyrie, amid the varied shadows of a most lustrous moonlight, our eyes fell upon the distant wood which surrounded Haddon Hall; its massive walls, its mouldering tapestries, its stately terrace, its quaint rooms and closets, its protected though decayed records of the olden time, its minstrel gallery—were again present to our minds; and it was a natural and most pleasing contrast—that of the deserted and half-ruined house, with the mansion happily inhabited,[Pg 300] filled with so many art-treasures, and presided over by one of the best gentlemen a monarch ever ennobled and a people ever loved."

THE MOORISH SUMMER HOUSE.

THE MOORISH SUMMER HOUSE.

[1] A quaint whim of the olden time is constructed near one of the walks; it is the model of a willow-tree in copper, which has all the appearance of a living one, situated on a raised mound of earth. From each branch, however, water suddenly bursts, and also small jets from the grassy borders around. It was considered a good jest some years ago to delude novices to examine this tree, and wet them thoroughly by suddenly turning on the water above and around them. This tree was originally made by a London plumber in 1693; but it has been recently repaired by a plumber in the neighborhood of Chesterfield, under the direction of Sir Joseph Paxton.

We have Louis Quinze chairs in our parlors, Louis Quinze carving and gilding about our mirrors, our ladies (in a double sense, of grace and utility), sweep past us in the streets or rustle in the ball-room in Louis Quinze brocades, with the boddice, if not the train, of pattern identical with that of Madame de Pompadour, as depicted in the excellent portrait before us in Mr. Redfield's elegant volumes, and we are, if scandal does not lie more than usual, making very practical acquaintance with Louis Quinze morals. It may be as well, therefore, to become more familiar with a period we find it so convenient to imitate. The great events of French history since 1789, their rapid sequence and ever varying character, have thrown into the shade the previous annals of the kingdom. Especially has this been the case with the period immediately preceding the days of terror. This period has been dispatched in a few sentences, in the opening chapters of works on the French Revolution—in some vague generalities on its profligacy and chaotic infamy. We have had glimpses, through the Œil de Bœuf, at groups of exquisite gentlemen and gay ladies; abbés who wrote every thing but sermons, and were free from the censure of not practising what they preached since they did not preach at all; generals who fought a campaign as deliberately and ceremoniously as they danced a minuet; statesmen whose diplomacy was more of the seraglio than the council; painters who improved on nature, applying the same tricks of art to the landscape as with powders to their curls; and simpering lips of the Marquise, and poets whose highest flights were a sonnet to Pompadour, or a pastoral to a sheep-tending Phillis. Our casual observations of all these people, however, have been vague and slight, for few have probably had patience to follow these worthies to their retirement, and look over their shoulders at the memoirs which every mother's son and daughter of the set, from the prime minister to the cook, found—it is impossible to tell how—time to scribble down for the edification of posterity. In the volumes of Arsene Houssaye before us, these gay but unsubstantial shadows take flesh and blood, and become the Men and Women—the living realities of the Eighteenth Century. We have here the most piquant adventures of the Memoirs and the choicest mots of the Anas, culled from the hundreds of volumes which weigh down the shelves of the French public libraries. Not only indeed have we the run of the petites soupers of Versailles, but we may wander at will in the coulisses of the Grand Opera, picking up the latest[Pg 301] gossip of Camargo or Sophie Arnold, enter the foyer of the classic Theatre Française, or adjourn to the Café Procope to hear the last joke of Piron, or the latest news from Fernay. And better than all these, we may mount, au cinquième, au sexième, to the lofty yet humble garret of the author or the artist, and there find, in an age of sickening heartlessness, refreshing scenes of household sincerity, patient endurance of hardship, showing that even that depraved age was not utterly devoid of the heroic and the pure. M. Houssaye is no rigid moralist, he employs no historic pillory, and often displays the painful flippancy of the modern French school on religious points, but he does honor to these better traits of humanity when he meets them. And we are not sure but that the morality of the work is the more impressive for the absence of the didactic. Here is little danger of our falling in love with vice, seductive as she appears in the annals of Louis XV., for we see the rotten canvas as well as the brilliant scene. We remember with the gaudy blossoms of 1740-60, the ashen fruit of 1789-'95. It is as hard to select extracts from M. Houssaye's volumes on account of the embarras des richesses, as it would be to choose a gem or two for our drawing-room from a gallery of Watteau and Greuze, or a row of Laucret's passets. Much as the reader, we doubt not, will enjoy those we have picked for him, he will still find equal or greater pleasure in those we have left untouched.

Here are the first steps in the ascent of Madame de Pompadour to that "bad eminence" she attained of virtual though virtueless Queen of France. The entire sketch is the best life of this celebrated woman with which we are acquainted:

"Madame de Pompadour was born in Paris, in 1720. She always said it was 1722. It is affirmed, that Poisson, her father, at least the husband of her mother, was a sutler in the army; some historians state that he was the butcher of the Hospital of the Invalides, and was condemned to be hung; according to Voltaire, she was the daughter of a farmer of Ferté-sous-Jouarre. What matters it, since he who was truly a father to her was the farmer-general, Lenormant de Tourneheim. This gentleman, thinking her worthy of his fortune, took her to his home, and brought her up, as if she had been his own daughter. He gave her the name of Jeanne-Antoinette. She bore till she was sixteen years of age this sweet name of Jeanne. From her infancy, she exhibited a passion for music and drawing. All the first masters of the day were summoned to the hotel of Lenormant de Tourneheim. Her masters did not disgust Jeanne with the fine arts of which she was so fond. Her talent was soon widely known. Fontenelle, Duclos, and Crébillon, who were received at the hotel as men of wit, went about every where, talking of her beauty, her grace, and talent.

"Madame de Pompadour was an example of a woman that was both handsome and pretty; the lines of her face possessed all the harmony and elevation of a creation of Raphael's; but instead of the elevated sentiment with which that great master animated his faces, there was the smiling expression of a Parisian woman. She possessed in the highest degree all that gives to the face brilliancy, charm, and sportive gayety. No lady at court had then so noble and coquettish a bearing, such delicate and attractive features, so elegant and graceful a figure. Her mother used always to say, 'A king alone is worthy of my daughter.' Jeanne had an early presentiment of a throne! at first, from the ambitious longings of her mother; afterward, because she believed that she was in love with the king. 'She confessed to me,' says Voltaire, in his memoirs, 'that she had a secret presentiment that the king would fall in love with her, and that she had a violent inclination for him.' There is a time in life when destiny reveals itself. All those who have succeeded in climbing the rugged mountain of human vanity relate that, from their earliest youth, dazzling visions revealed to them their future glory.

"Well, how was the throne of France to be reached, the very idea of which made her head turn? In the mean time, full of genius, always admired, and always listened to, she familiarized herself with the life of a beautiful queen; she saw at her feet all the worshippers of the fortune of her father; she gathered about her poets, artists, and philosophers, over whom she already threw a royal protection.

"The farmer-general had a nephew, Lenormant d'Etioles. He was an amiable young man, and had the character and manners of a gentleman; he was heir to the immense fortune of the farmer-general, at least, according to law. Jeanne, on her side, had some claim to a share of this fortune. It was a very simple way of making all agreed, by marrying the young people. Jeanne, as we have seen, was already in love with the king; she married D'Etioles without shifting her point in view: Versailles, Versailles, that was her only horizon. Her young husband became desperately enamored of her; but this passion of his, which amounted almost to madness, she never felt in the least. She received it with resignation, as a misfortune that could not last long.

"The hotel of the newly-married couple, Rue-Croix-des-Petits-Champs, was established on a lordly footing; the best company in Paris left the fashionable salons for that of Madame D'Etioles until that time, there had never been such a gorgeous display of luxury in France. The young bride hoped by this means to make something of a noise at court, and thus excite the curiosity of the king. Day after day passed away in feasts and brilliant entertainments. Celebrated actors, poets, artists, and foreigners, all made their rendezvous at this hotel, the mistress of which was its life and ornament; all the world went there, in one word, except the king."

The painters are among the pleasantest personages of Mr. Houssaye's book, as they generally are in whatever society or whatever time we find them, all the world over. Watteau is familiar to us all, if not from his works, at second-hand in engravings, or those dainty little china shepherdesses and shepherds which we have seen on our grandmothers' mantel-pieces, and which are again[Pg 302] emerging from the glass corner cupboard to the rosewood and mirrored étagère. The following passages descriptive of his early life, are full of animation:

"He was born in 1684, at the time the king of France was bombarding Luxembourg. His family was poor, as a matter of course. He was put to school just long enough not to learn any thing. He was never able to read and write without great difficulty, but it was not in that his strength lay. He learned early to discover genius in a picture, to copy with a happy touch the gay face of Nature. There had been painters in his family, among others, a great uncle, who had died at Antwerp, without leaving any property. The father of Watteau had little leaning toward painting; but he was one of those who let men and things here below take their course. Watteau, therefore, was permitted to take his. Now Watteau was born a painter. God had given him the fire of genius, if not genius. His first master was chance, the greatest of all masters after God. His father lived in the upper story of a house with its gable-end to the street. Watteau had his nose out of the window oftener than over a book; he loved to amuse himself with the varied spectacle of the street. Sometimes it was the fresh-looking Flemish peasant-girl, driving her donkey through the market-place, sometimes the little girls of the neighborhood, playing at shuttlecock during the fine evenings. Peasant-maid and little child were traced in original lines in the memory of the scholar; he already admired the indolent naïveté of the one, the prattling grace of the other. He had his eye also on some smiling female neighbor, such as are to be found every where; but the most attractive spectacle to him was that of some strolling troop of dancers or country-players. On fête-days sellers of elixirs, fortune-tellers, keepers of bears and rattlesnakes, halted under his window. They were sure of a spectator. Watteau suddenly fell into a profound revery at the sight of Gilles and Margot upon the stage; nothing could divert his attention from this amusement, not even the smile of his female neighbor: he smiled at the grotesque coquetries of Margot; he laughed till out of breath at the quips of Gilles. He was frequently seen seated in the window, his legs out, his head bent, holding on with difficulty, but not losing a word or a gesture. What would he not have given to have been the companion of Margot, to kiss the rusty spangles of her robe, to live with her the happy life of careless adventure? Alas! this happiness was not for him. Margot descended from the boards, Gilles became a man as before, the theatre was taken down, Watteau still on the watch; but by degrees he became sad; his friends were departing, departing without him, with their gauze dresses, their scarfs fringed with gold, their silver lace, their silk breeches, and their jokes.—"Those people are truly happy," said he, "they are going to wander gayly about the world, to play comedy wherever they may be, without cares and without tears!"—Watteau, with his twelve-year-old eyes, saw only the fair side of life. He did not guess, be it understood, that beneath every smile of Margot there was a stifled tear. Watteau seems to have always seen with the same eyes; his glance, diverted by the expression and the color, did not descend as far down as the soul. It was somewhat the fault of his times. What had he to do while painting queens of comedy, or dryads of the opera, with the heart, tears, or divine sentiment?

"After the strollers had departed, he sketched on the margins of the 'Lives of the Saints,' the profile of Gilles, a gaping clown, or some grotesque scene from the booth. As he often shut himself up in his room with this book, his father, having frequently surprised him in a dreamy and melancholy mood, imagined that he was becoming religious. He, however, soon discovered that Watteau's attachment to the folio was on account of the margin, and not of the text. He carried the book to a painter in the city. This painter, bad as he was, was struck with the original grace of certain of Watteau's figures, and solicited the honor of being his master. In the studio of this worthy man, Watteau did not unlearn all that he had acquired, although he painted for pedlers, male and female saints by the dozen. From this studio he passed to another, which was more profane and more to his taste. Mythology was the great book of the place. Instead of St. Peter, with his eternal keys, or the Magdalen, with her infinite tears, he found a dance of fauns and naiads, Venus, issuing from the waves, or from the net of Vulcan. Watteau bowed amorously before the gods and demigods of Olympus; he had found the gate to his Eden. He progressed daily, thanks to the profane gods, in the religion of art. He was already seen to grow pale under that love of beauty and of glory which swallows up all other loves. On his return from a journey to Antwerp, his friends were astonished at the enthusiasm with which he spoke of the wonders of art. He had beheld the masterpieces of Rubens and Vandyke, the ineffable grace of Murillo's Virgins, the ingenuously-grotesque pieces of Teniers and Van Ostade, the beautiful landscapes of Ruysdael. He returned with head bent and eyes fatigued, and his mind filled with lasting recollections.

"He was not twenty when he set out for Paris with his master. The opera, in its best days, enlisted the aid of all painters of gracefulness. At the opera, Watteau threw the lightning flashes of his pencil right and left: mountains, lakes, cascades, forests, nothing dismayed him, not even the Camargos, whom he had for models. He ended by taming himself down to this cage of gayly-singing and fluttering birds. A dancing-girl, who had not much to do, deigned to grant the little Flemish dauber, the favor of sitting for her portrait. Fleming as he was, Watteau made the progress of the portrait last longer than the scornfulness of Mademoiselle la Montagne. This was not all: the portrait was considered so graceful in the dancing-world, that sitters came to him every day, on the same terms.

"He left the opera with his master, as soon as the new decorations were finished. Besides Gillot, the great designer of fauns and naiads had returned there more flourishing than ever. The master returned to Valenciennes, Watteau remained at Paris, desiring to depend upon his fortune, good or bad. He passed from the opera into the studio of a painter of devotional subjects, who manufactured St. Nicholases for Paris and the provinces, to suit to the price. So Watteau manufactured[Pg 303] St. Nicholases, 'My pencil,' he said, 'did penance.' The opera always attracted him; there he could give free scope to all the extravagance of his fancy, to all the charming caprices of his pencil; but at the opera, his master and himself had given way to Gillot; and the latter was not disposed to give way to any body."

An allegro morceau from the life of Grétry:

"Other adventures also occurred, to convince Remacle that his fellow-travellers were worthy of him. Ever in dread of the before-mentioned officers, the old smuggler forced them to make a detour of some leagues, to see, as he said with a disinterested air, a superb monastery, where alms were bestowed once a week on all the poor of the country. On entering the great hall, in the midst of a noisy crowd, Grétry saw a fat monk, mounted on a platform, who was angrily superintending this Christian charity. He looked as if he would like rather to exterminate his fellow-creatures than aid them to live; he was just bullying a poor French vagabond who implored his aid. When he suddenly saw the noble face of Grétry he approached the young musician.—'It is curiosity which brings you here,' he remarked with vexation.—'It is true,' said Grétry, bowing; 'the beauty of your monastery, the sublimity of the scenery, and the desire of contemplating the asylum where the unfortunate traveller is received with so much humanity, have drawn us from our route. In beholding you, I have seen the angel of mercy. All the victims of sorrow should bless your edifying gentleness. Tell me, father, do you make as many happy every day as I have just witnessed?'

"The monk, irritated by this bantering, begged Grétry to return whence he came.—'Father,' retorted Grétry, 'have the evangelists taught you this mode of bestowing alms, giving with one hand and striking with the other?'—A low murmur was heard through the hall; the monk not knowing what to say, complained of the toothache; the cunning student lost no time, but running up to him with an air of touching compassion, 'I am a surgeon,' he said, as he forced him down on the bench. The monk tried to push him off, but he held on well. 'It is Heaven which has directed me to you, father.' Willing or not, the monk had to open his mouth. 'Courage, father, the great saints were all martyrs! the Saviour was crucified; and you may at least let me pull out a tooth.' The monk struggled: 'Never, never!' he exclaimed. The student turned with great coolness toward the bystanders, who were all laughing in their sleeves. 'My friends,' (he addressed crippled travellers, mountain-brigands, and poor people of every class,) 'my friends, for the love of God, who suffered, come and hold this good father: I do not want him to suffer any longer!'

"The beggars understood the joke; four of them separated from the group, and came to the surgeon's aid. The monk struggled furiously, but it was no use to kick and scream; he had to submit, Grétry was not the last to come to his friend's aid; the malicious student seized the first tooth he got hold of, and wrenched the head of the monk by a turn of his elbow, to the great joy of the beggars, who saw themselves revenged in a most opportune manner. 'Well, father, what do you think of it?' asked Grétry, after the operation; 'I am sure you do not now suffer at all!'—The monk shook with rage; the other monks attracted by his cries, soon arrived, but it was too late."

The following is among the most touching of narratives. It is exquisitely delivered:

"Grétry was therefore happy. Happy in his wife and children, in his old mother, who had come to sanctify his house, with her sweet and venerable face. Happy in fortune, happy in reputation. The years passed quickly away! He was one day very much astonished to learn that his daughter Jenny was fifteen. Alas! a year afterward the poor child was no longer in the family, neither was happiness. But for this sad history we must return to the past. Grétry, during his sojourn at Rome, in the spring-time of his life, was fond of seeking religious inspiration in the garden of an almost deserted convent. He observed one day, in the summer-house, an old monk of venerable form, who was separating seeds with a meditative air, and at the same time observing them with a microscope. The absent-minded musician approached him in silence. 'Do you like flowers?' the monk asked him. 'Very much,' 'At your age, however, we only cultivate the flowers of life; the culture of the flowers of earth is pleasing only to the man who has fulfilled his task. It is then almost like cultivating his recollection. The flowers recall the birth, the natal land, the garden of the family, and what more? You know better than I who have thrown to forgetfulness all worldly enjoyments!' 'I do not see, father,' replied Grétry, 'why you separate these seeds which seem to me to be all alike. 'Look through this microscope, and see this black speck on those which I place aside; but I wish to carry the horticultural lesson still further.' He took a flower-pot, made six holes in the earth, and planted three of the good seeds, and three of the spotted ones. 'Recollect that the bad ones are on the side of the crack, and when you come and take a walk, do not forget to watch the stalks as they grow.'

"Grétry found a melancholy charm in returning frequently to the garden of the convent. As he passed, he each time cast a glance on the old flower-pot. The six stems at first shot up, each equally verdant. The spotted seeds soon grew the longest, to his great surprise. He was about to accuse the old monk of having lost his wits; but what was afterwards his sorrow, when he saw his three plants gradually fading away in their spring-time! With each setting sun a leaf fell and dried up, while the leaves of the other stems thrived more and more with every breeze, every ray of the sun, every drop of dew. He went to dream every day before his dear plants, with exceeding sadness. He soon saw them wither away, even to the last leaf. On the same day the others were in flower.

"This accident of nature was a cruel horoscope. Thirty years afterward poor Grétry saw three other flowers alike fated, fade and fall under the wintry wind of death. He had forgotten the name of the flowers of the Roman convent, but in dying he still repeated the names of the others. They were his three daughters, Jenny, Lucile, and Antoinette. 'Ah!' exclaimed the poor musician, in relating the death of his three daughters, 'I[Pg 304] have violated the laws of nature to obtain genius. I have watered with my blood the most frivolous of my operas, I have nourished my old mother, I have seized on reputation by exhausting my heart and my soul; Nature has avenged herself on my children! My poor children, I foredoomed them to death!'

"Grétry's daughters all died at the age of sixteen. There is something strange in their life and in their death, which strikes the dreamer and the poet. This sport of destiny, this freak of death, this vengeance of Nature, appears here invested with all the charms of romance. You will see.

"Jenny had the pale, sweet countenance of a virgin. On seeing her, Greuze said one day, 'If I ever paint Purity, I shall paint Jenny.' 'Make haste!' murmured Grétry, already a prey to sad presentiments. 'Then she is going to be married?' said Greuze. Grétry did not answer. Soon, however, seeking to blind himself, he continued: 'She will be the staff of my old age; like Antigone, she will lead her father into the sun at the decline of life.'

"The next day Grétry came unexpectedly upon Jenny, looking more pale and depressed than ever. She was playing on the harpischord, but sweetly and slowly. As she was playing an air from Richard Cœur-de-Lion, in a melancholy strain, the poor father fancied that he was listening to the music of angels. One of her friends entered. 'Well, Jenny, you are going to-night to the ball?' 'Yes, yes, to the ball,' answered poor Jenny, looking toward heaven; and suddenly resuming, 'No, I shall not go, my dance is ended.' Grétry pressed his daughter to his heart, 'Jenny, are you suffering?' 'It is over!' said she.

"She bent her head and died instantly, without a struggle! Poor Grétry asked if she was asleep. She slept with the angels.

"Lucile was a contrast to Jenny; she was a beautiful girl, gay, enthusiastic, and frolicksome, with all the caprices of such a disposition. She was almost a portrait of her father, and possessed, besides, the same heart and the same mind. 'Who knows,' said poor Grétry, 'but that her gayety may save her.' She was unfortunately one of those precocious geniuses who devour their youth. At thirteen she had composed an opera which was played every where, Le Marriage d'Antonio. A journalist, a friend of Grétry, who one day found himself in Lucile's apartment, without her being aware of it, so much was she engrossed with her harp, has related the rage and madness which transported her during her contests with inspiration, that was often rebellious. 'She wept, she sang, she struck the harp with incredible energy. She either did not see me, or took no notice of me; for my own part, I wept with joy, in beholding this little girl transported with so glorious a zeal, and so noble an enthusiasm for music.'

"Lucile had learned to read music before she knew her alphabet. She had been so long lulled to sleep with Grétry's airs, that at the age when so many other young girls think only of hoops and dolls, she had found sufficient music in her soul for the whole of a charming opera. She was a prodigy. Had it not been for death, who came to seize her at sixteen like her sister, the greatest musician of the eighteenth century would, perhaps, have been a woman. But the twig, scarcely green, snapped at the moment when the poor bird commenced her song. Grétry had Lucile married at the solicitation of his friends. 'Marry her, marry her,' they incessantly repeated; 'if Love has the start of Death, Lucile is safe.' Lucile suffered herself to be married with the resignation of an angel, foreseeing that the marriage would not be of long duration. She suffered herself to be married to one of those artists of the worst order, who have neither the religion of art nor the fire of genius, and who have still less heart, for the heart is the home of genius. The poor Lucile saw at a glance the desert to which her family had exiled her. She consoled herself with a harp and a harpsichord; but her husband, who had been brought up like a slave, cruelly took delight, with a coward's vengeance, in making her feel all the chains of Hymen. She would have died, like Jenny, on her father's bosom, amidst her loving family, after having sung her farewell song; but thanks to this barbarous fellow, she died in his presence, that is to say, alone. At the hour of her death, 'Bring me my harp!' said she, raising herself a little. 'The doctor has forbidden it,' said this savage. She cast a bitter, yet a suppliant look upon him. 'But as I am dying!' said she. 'You will die very well without that.' She fell back on her pillow. 'My poor father,' murmured she, 'I wished to bid you adieu on my harp; but here I am not free except to die!' Lucile, it is the nurse who related the scene, suddenly extended her arms, called Jenny with a broken voice, and fell asleep like her for ever.

"Antoinette was sixteen. She was fair and smiling like the morn, but she was fated to die like the others. Grétry prayed and wept, as he saw her growing pale; but death was not stopped so easily. Cruel that he is, he stops his ears, there is no use to pray to him! Grétry, however, still hoped. 'God,' said he, 'will be touched by my thrice bitter tears.' He almost abandoned music, in order to have more time to consecrate to his dear Antoinette. He anticipated all her fancies, dresses, and ornaments, books and excursions,—in a word, she enjoyed to her heart's desire every pleasure the world could afford. At each new toy she smiled with that divine smile which seems formed for heaven. Grétry succeeded in deceiving himself; but she one day revealed to him all her ill-fortune in these words, which accidentally escaped from her: 'My godmother died on the scaffold: she was a godmother of bad augury, Jenny died at sixteen, Lucile died at sixteen, and I am now sixteen myself.' The godmother of Antoinette was the queen Maria Antoinette.

"Another day, Antoinette was meditating over a pink at the window. On seeing her with this flower in her hand, Grétry imagined that the poor girl was suffering herself to be carried away by a dream of love. It was the dream of death! He soon heard Antoinette murmur; 'I shall die this spring, this summer, this autumn, this winter!' She was at the last leaf. 'So much the worse,' she said; 'I should like the autumn better.' 'What do you say, my dear angel?' said Grétry, pressing her to his heart. 'Nothing, nothing! I was playing with death; why do you not let the children play?'

"Grétry thought that a southern journey would be a beneficial change; he took his daughter to Lyons, where she had friends. For a short time[Pg 305] she returned to her gay and careless manner. Grétry went to work again, and finished Guillaume Tell. He went every morning, in search of inspiration, to the chamber of his daughter, who said to him one day, on awaking: 'Your music has always the odor of a poem; this will have that of wild thyme.'

"Towards autumn, she again lost her natural gayety. Grétry took his wife aside—'You see your daughter,' said he to her. At this single word, an icy shudder seized both. They shed a torrent of tears. The same day they thought of returning to Paris. 'So we are to go back to Paris', said Antoinette; 'it is well. I shall rejoin there those whom I love.' She spoke of her sisters. After reaching Paris, the poor, fated girl concealed all the ravages of death with care; her heart was sad, but her lips were smiling. She wished to conceal the truth from her father to the end. One day, while she was weeping and hiding her tears, she said to him with an air of gayety: 'You know that I am going to the ball to-morrow, and I want to appear well-dressed there. I want a pearl necklace, and shall look for it when I wake up to-morrow morning.'

"She went to the ball. As she set out with her mother, Rouget Delisle, a musician more celebrated at that time than Grétry, said rapturously: 'Ah, Grétry, you are a happy man! What a charming girl! what sweetness and grace!' 'Yes,' said Grétry, in a whisper, 'she is beautiful and still more amiable; she is going to the ball, but in a few weeks we shall follow her together to the cemetery!' 'What a horrible idea! You are losing your senses!' 'Would I were not losing my heart! I had three daughters; she is the only left to me, but already I must weep for her!'

"A few days after this ball, she took to her bed, and fell into a sad but beautiful delirium. She had found her sisters again in this world; she walked with them hand in hand; she waltzed in the same saloon; she danced in the same quadrille; she took them to the play: all the while recounting to them her imaginary loves. What a picture for Grétry! 'She had,' he says in his Memoirs, some serene moments before death.—She took my hand, and that of her mother, and with a sweet smile, 'I see well,' she murmured, 'that we must bear our destiny; I do not fear death; but what is to become of you two?' She was propped up by her pillow while she spoke with us for the last time. She was laid back, then closed her beautiful eyes, and went to join her sisters!

"Grétry is very eloquent in his grief. There Is in this part of his Memoirs a cry which came from his heart, and wrings our own. 'Oh, my friends,' he exclaims, throwing down the pen, 'a tear, a tear upon the beloved tomb of my three lovely flowers, predestined to die, like those of the good Italian monk.'"

One of the most readable of living travellers is certainly our own Bayard Taylor, who is now somewhere in the interior of the African continent, and whose letters in the Tribune are every where perused with the greatest satisfaction. Worthy to be named along with him is the German, Frederick Gerstäcker, whose adventures form one of the most interesting features in that cyclopediac journal, the Augsburg Allgemeine Zeitung. It is now some two years since Gerstäcker set out upon his present explorations. The backwoods of the United States furnished a broad field for his love of a wild and changeful life, and gave full play to his passion for the study of human character in all its out of the way phases. His accounts of these regions were touched with the most vivid colors; not Cooper nor Irving has more truly reproduced the grand and savage features of American scenery, or the reckless generous daring of the rude backwoodsman, than Gerstäcker, writing, from some chance hut, his nocturnal landing place on the shore of some mighty river in Nebraska or Arkansas. Next we hear of him in South America, and then in California, passing a winter among the miners of the remotest districts, digging gold, hunting, trafficking, fighting in case of need like the rest, and every where sending home the most lively daguerreotypes of the country, the people, and his own adventures among them. Finally, having seen all that was in California, he takes passage for the Sandwich Islands, where he remains long enough to exhaust all the romance remaining, and to gather every sort of useful information. From there he set out upon an indefinite voyage on board of a whaler going to the Southern seas in search of oil. Chance, however, brings him up at Australia: and he at once sets about travelling through the settled portions of the Continent, taking the luck of the day every where with exhaustless good humour, and never getting low spirited, no matter how untoward the mishaps encountered. Less elegant and poetic than Taylor, he dashes ahead with a more perfect indifference to consequences, and a more utter reliance on coming out all right in the end. In his last letter, he gives an account of a voyage in a canoe from Albury, on the upper waters of Hume River, down to Melbourne, at its mouth. He had got out of funds, and was thus obliged to set out on this route contrary to the advice of the settlers at Albury, who represented to him that the danger of being killed and eaten by the natives along shore, who had never come in contact with whites, was inevitable, and that they would be sure to destroy him before he reached his destination. This was, however, only an additional inducement to the trip. While making preparations for it, he fell in with a young fellow-countryman in the settlement, who desired to make the same journey, and who was willing to encounter the risks of the river rather than pay the heavy expenses of the trip by land. They accordingly proceeded to dig a canoe out of a caoutchouc tree, furnished themselves with paddles, a frying-pan, blankets, some crackers, sugar, salt, tea, and powder, and embarked. The river was shallow, and full of windings and sandbanks, sunken caoutchouc trees had planted the[Pg 306] stream with frequent snags, and often heavy masses of fallen timber, still adhering to the earth at its roots, and thus preserving its vitality, and flourishing with all the luxuriance of a primitive tropical forest, covered the only part of the channel where the water was deep enough to admit of the passage of their canoe. Thus they toiled on day by day, often getting out into the water to help their vessel over shallows, or to pick up the ducks that Gerstäcker shot, which furnished the only meat for their daily meals. Cloudy or fair, cold or warm, rain or sunshine, found Gerstäcker still in the same flow of spirits, and the notes of his daily experiences show him bearing ill-luck almost as gaily as good. After they had gone some 400 miles, however, their journey by the river came to a sudden end by the oversetting of their canoe, and the loss of almost all their equipments. Gerstäcker saved his rifle and the ammunition that was upon his person; but the remaining powder was spoiled, and the provisions and part of the blankets and clothing were carried away by the current. The canoe sunk, but by holding upon the rope as they jumped out upon the overhanging trunks of trees, the voyagers succeeded in dragging it up again, and freeing it from water. Then one of them dived to the bottom, and managed to bring up the frying-pan and tea-canister. They also recovered part of their blankets, and then, with the frying-pan for their sole paddle, renewed their voyage till they found a good camping-place, where they built a roaring fire to dry themselves, and finally discovered that in the operations of the day each had utterly ruined his shoes, so that they were afterwards forced to go barefoot. In this way they continued for some days, paddling with their frying-pan, and going ashore to get a duck occasionally shot by Gerstäcker. This was often exceedingly painful, from the stubble of the grass along the banks, burnt over by fires accidentally set by the natives. Luckily, through the whole they did not come in contact with the savages at all. At last they reached a settlement, where they swapped their canoe for a couple pair of shoes, and started on foot for the rest of the way. Gerstäcker had for some time desired to get rid of his companion, who was wilful, and by no means a helper in their difficulties. They now came to Woolshed, a place 180 miles distant from Melbourne, whence there were two roads to their destination; the one was perfectly free from the savages, the other was dangerous. Here Gerstäcker separated from his companion, giving him the safe road, and, with his rifle on his arm and his knapsack slung upon his shoulders, struck off alone into the forest-path light-hearted as a boy, and sure, whatever might happen, of enjoying a fresher and healthier excitement in that journey through the woods of Australia than the dwellers in crowded cities enjoy in all their lives.

Paris, says the Independence Belge, the leading journal of Brussels, is now occupied not with politics so much as with ghost stories. At the theatres, the Vampyre and the Imagier de Harlaem, feed this appetite for supernatural horrors. Among other incidents of that kind, says the Independance, the following narrative was told to the company in the salon of an aristocratic Polish lady by the Comte de R——. He had promised to tell a recent adventure with an inhabitant of the other world, and when the clock struck midnight he began, while his auditors gathered around him in breathless attention. His story we translate for the International:—

At the beginning of last December, one of his friends, the Marquis de N., came to see him. "You know, Count," said the Marquis, "what an invincible repugnance I feel against returning to my chateau in Normandy, where I had last summer the misfortune to lose my wife. But I left there in a writing desk some important papers, which now happen to be indispensable in a matter of family business. Here is the key; do me the kindness to go and get the papers, for so delicate a mission I can only intrust to you." M. de R. agreed to the request of his friend, and set out the following day. He stopped at a station on the Rouen railroad, whence a drive of two hours brought him to his friend's house. He stopped before it, and a gardener came out and spoke with him through the latticed iron gate, which he did not open. The Count was surprised at this distrust, which even a card of admission from the proprietor of the chateau did not overcome. Finally, after a brief absence, which seemed to have been employed in seeking the advice of some one within, the gardener came back and opened the gate. When the Count entered the court-yard he saw that the blinds on the hundred windows of the chateau were all closed, with one exception, where the blind had fallen off and lay upon the ground. As he afterwards discovered, this window was exactly in the middle of the chamber where his commission was to be executed.

The Count's attention had been excited by his singular reception, and he carefully observed every thing. He noticed a small stove-pipe leading into a chimney. "Is the house inhabited?" he inquired. "No," replied the gardener, gruffly, as he opened a door upon a side stairway, which he mounted before the Count, opening at each story the little apertures for light in the queer old fashioned front of the chateau.

In the third story, the gardener stopped, and pointing to a door, said, "There." And without adding a word he turned about and went down stairs. The Count opened the door and found himself in a dark ante-chamber. The light from the stairway was sufficient, however, for him to distinguish a[Pg 307] second door, which he opened, and through which he went into the apartment lighted from the window whence the blind had fallen. The appearance of the room was cold, bare, and deserted. On the floor stood a vacant bird-cage. The writing-desk indicated to the Count by his friend, stood directly opposite the window. Without further delay, the Count went directly up to the desk and opened it.

As he turned the key, the lock creaked very loudly, but at the same moment he was aware of another and a different sound—that of a door opening. The Count turns, and in the centre of an obscure side-room, whose door was open, he sees a white figure, with its arms stretched toward him.

"Count!" exclaims a low but most expressive voice, "you come to rob me of Theodore's letters? Why?"

(Theodore is not the name of the proprietor of the chateau, at whose request the Count had come.)

"Madame!" exclaims M. de R., "who are you?"

"Do you not know me, much as I must be altered?"

"The Marchioness!" exclaims the Count, astounded and even terrified.

"Yes, it is me. We were friends once, and now you come to add terribly to my sufferings! Who sends you? My husband? What does he yet desire? In mercy leave me the letters!"

While she said this, the figure made signs to the Count to come nearer. He obeyed, forcing from his mind every suggestion that the apparition was supernatural, and finally convinced that the Marchioness stood before him living, under some strange mystery. He followed her into the second room.

She was dressed in a robe, or more properly, a shroud of a gray color. Her beautiful hair, which had for years been the envy of all other women, fell in disorder upon her shoulders. The vague light, which came in from the adjoining room, was just enough for the Count to remark the extraordinary thinness and deathly pallor of the Marchioness.

Hardly had he come near her, when she said to him, quickly, almost with vehemence:

"I suffer from incredible pains in my head. The cause is in my hair,—for eight months it has not been combed. Count, do me this service—comb it!"