Project Gutenberg's My Brave and Gallant Gentleman, by Robert Watson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: My Brave and Gallant Gentleman

A Romance of British Columbia

Author: Robert Watson

Release Date: March 21, 2010 [EBook #31728]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MY BRAVE AND GALLANT GENTLEMAN ***

Produced by Al Haines

Lady Rosemary Granton! Strange how pleasant memories arise, how disagreeable nightmares loom up before the mental vision at the sound of a name!

Lady Rosemary Granton! As far back as I could remember, that name had sounded familiar in my ears. As I grew from babyhood to boyhood, from boyhood to youth, it was drummed into me by my father that Lady Rosemary Granton, some day, would wed the future Earl of Brammerton and Hazelmere. This apparently awful calamity did not cause me any mental agony or loss of sleep, for the reason that I was merely The Honourable George, second son of my noble parent.

I was rather happy that morning, as I sat in an easy chair by the library window, perusing a work by my favourite author,—after a glorious twenty-mile gallop along the hedgerows and across country. I was rather happy, I say, as I pondered over the thought that something in the way of a just retribution was at last about to be meted out to my elder, haughty, arrogant and extremely aristocratic rake of a brother, Harry.

My mind flashed back again to the source of my vagrant thoughts. Lady Rosemary Granton! To lose the guiding hand of her mother in her infancy; to spend her childhood in the luxurious lap of New York's pampered three hundred; to live six years more among the ranchers, the cowboys and, no doubt, the cattle thieves of Wyoming, in the care of an old friend of her father, to wit, Colonel Sol Dorry; then to be transferred for refining and general educational purposes for another spell of six years to the strict discipline of a French Convent; to flit from city to city, from country to country, for three years with her father, in the stress of diplomatic service—what a life! what an upbringing for the future Countess of Brammerton! Finally, by way of culmination, to lose her father and to be introduced into London society, with a fortune that made the roués of every capital in Europe gasp and order a complete new wardrobe!

As I thought what the finish might be, I threw up my hands, for it was a most interesting and puzzling speculation.

Lady Rosemary Granton! Who had not heard the stories of her conquests and her daring? They were the talk of the clubs and the gossip of the drawing-rooms. Masculine London was in ecstasies over them and voted Lady Rosemary a trump. The ladies were scandalised, as only jealous minded ladies can be at lavishly endowed and favoured members of their own sex.

Personally, I preferred to sit on the fence. Being a lover of the open air, of the agile body, the strong arm and the quick eye, I could not but admire some of this extraordinary young lady's exploits. But,—the woman who was conceded the face of an angel, the form of a Venus de Milo; who was reported to have dressed as a jockey and ridden a horse to victory in the Grand National Steeplechase; who, for a wager, had flicked a coin from the fingers of a cavalry officer with a revolver at twenty paces; lassooed a cigar from between the teeth of the Duke of Kaslo and argued on the Budget with a Cabinet Minister, all in one week; who could pray with the piety of a fasting monk; weep at will and look bewitching in the process; faint to order with the grace, the elegance and all the stage effect of an early Victorian Duchess: the woman who was styled a golden-haired goddess by those on whom she smiled and dubbed a saucy, red-haired minx by those whom she spurned;—was too, too much of a conglomeration for such a humdrum individual, such an ordinary, country-loving fellow as I,—George Brammerton.

And now, poor old Hazelmere was undergoing a process of renovation such as it had not experienced since the occasion of a Royal visit some twenty years before: not a room in the house where one could feel perfectly safe, save the library: washing, scrubbing, polishing and oiling in anticipation of a rousing week-end House Party in honour of this wonderful, chameleon-like, Lady Rosemary's first visit; when her engagement with Harry would be formally announced to the inquisitive, fashionable world of which she was a spoiled child.

Why all this fuss over a matter which concerned only two individuals, I could not understand. Had I been going to marry the Lady Rosemary,—which, Heaven forbid,—I should have whipped her quietly away to some little, country parsonage, to the registrar of a small country town; or to some village blacksmith, and so got the business over, out of hand. But, of course, I had neither the inclination, nor the intention, let alone the opportunity, of putting to the test what I should do in regard to marrying her, nor were my tastes in any way akin to those of my most elegant, elder brother, Viscount Harry, Captain of the Guards,—egad,—for which two blessings I was indeed truly thankful.

As I was thus ruminating, the library door opened and my noble sire came in, spick and span as he always was, and happier looking than usual.

"'Morning, George," he greeted.

"Good morning, dad."

He rubbed his hands together.

"Gad, youngster! (I was twenty-four) everything is going like clockwork. The house is all in order; supplies on hand to stock an hotel; all London falling over itself in its eagerness to get here. Harry will arrive this afternoon and Lady Rosemary to-morrow."

I raised my eyebrows, nodded disinterestedly and started in again to my reading. Father walked the carpet excitedly, then he stopped and looked down at me.

"You don't seem particularly enthusiastic over it, George. Nothing ever does interest you but boxing bouts, wrestling matches, golf and books. Why don't you brace up and get into the swim? Why don't you take the place that belongs to you among the young fellows of your own station?"

"God forbid!" I answered fervently.

"Not jealous of Harry, are you? Not smitten at the very sound of the lady's name,—like the young bloods, and the old ones, too, in the city?"

"God forbid!" I replied again.

"Hang it all, can't you say anything more than that?" he asked testily.

"Oh, yes! dad,—lots," I answered, closing my book and keeping my finger at the place. "For one thing—I have never met this Lady Rosemary Granton; never even seen her picture—and, to tell you the truth, from what I have heard of her, I have no immediate desire to make the lady's acquaintance."

There was silence for a moment, and from my father's heavy breathing I could gather that his temper was ruffling.

"Look here, you young barbarian, you revolutionary,—what do you mean? What makes you talk in that way of one of the best and sweetest young ladies in the country? I won't have it from you, sir, this Lady Rosemary Granton, this Lady indeed."

"Oh! you know quite well, dad, what I mean," I continued, a little bored. "Harry is no angel, and I doubt not but Lady Rosemary is by far too good for him. But,—you know,—you cannot fail to have heard the stories that are flying over the country of her cantrips;—some of them, well, not exactly pleasant. And, allowing fifty percent for exaggeration, there is still a lot that would be none the worse of considerable discounting to her advantage."

"Tuts, tush and nonsense! Foolish talk most of it! The kind of stuff that is garbled and gossiped about every popular woman. The girl is up-to-date, modern, none of your drawing-room dolls. I admit that she has go in her, vim, animal spirits, youthful exuberance and all that. She may love sport and athletics, but, but,—you, yourself, spend most of your time in pursuit of these same amusements. Why not she?"

"Why! father, these are the points I admire in her,—the only ones, I may say. But, oh! what's the good of going over it all? I know, you know,—everybody knows;—her flirtations, her affairs; every rake in London tries to boast of his acquaintance with her and bandies her name over his brandy and soda, and winks."

"Look here, George," put in my father angrily, "you forget yourself. These stories are lies, every one of them! Lady Rosemary is the daughter of my dearest, my dead friend. Very soon, she will be your sister."

"Yes! I know,—so let us not say any more about it. It is Harry and she for it, and, if they are pleased and an old whim of yours satisfied,—what matters it to an ordinary, easy-going, pipe-loving, cold-blooded fellow like me?"

"Whim, did you say? Whim?" cried my father, flaring up and clenching his hands excitedly. "Do you call the vow of a Brammerton a whim? The pledged word of a Granton a whim? Whim, be damned."

For want of words to express himself, my father dropped into a chair and drummed his agitated fingers on the arms of it.

I rose and went over to him, laying my hand lightly on his shoulder.

Poor old dad! I had not meant to hurt his feelings. After all, he was the dearest of old-fashioned fellows and I loved his haughty, mid-Victorian ways.

"There, there, father,—I did not mean to say anything that would give offence. I take it all back. I am sorry,—indeed I am."

He looked up at me and his face brightened once more.

"'Gad, boy,—I'm glad to hear you say it. I know you did not mean anything by your bruskness. You are an impetuous, headstrong young devil though,—with a touch of your mother in you,—and, 'gad, if I don't like you the more for it.

"But, but," he went on, looking in front of him, "you must remember that although Granton and I were mere boys at the time our vow was made,—he was a Granton and I a Brammerton, whose vows are made to keep. It seems like yesterday, George; it was a few hours after he saved my life in the fighting before Sevastopol. We were sitting by the camp-fire. The chain-shot was still flying around. The cries of the wounded were in our ears. The sentries were challenging continually and drums were rolling in the distance.

"I clasped Fred's hand and I thanked him for what he had done for me that day, right in the teeth of the Russian guns.

"'Freddy, old chap, you're a trump,' I said, 'and, if ever I be blessed with an heir to Brammerton and Hazelmere, I would wish nothing better than that he should marry a Granton.'

"'And nothing would please me so much, Harry, old boy,—as that a maid of Granton should wed a Brammerton,' he answered earnestly.

"'Then it's a go,' said I, full of enthusiasm.

"'It's a go, Harry.'

"And we raised our winecups, such as they were.

"'Your daughter, Fred!'

"'Your heir, Harry!'

"'The future Earl and Countess of Brammerton and Hazelmere,' we chimed together.

"Our winecups clinked and the bond was made;—made for all time, George."

My father's eyes lit up and he seemed to be back in the Crimea. He shook his head sadly.

"And now, poor old Fred is gone. Ah, well! our dream is coming true. In a month, the maid of Granton weds the future Earl of Brammerton.

"'Gad, George, my boy,—Rosemary may be skittish and lively, but were she the most mercurial woman in Christendom, she has never forgotten that she is first of all a Granton, and, as a Granton, she has kept a Granton's pledge."

For a moment I caught the contagion of my father's earnestness. My eyes felt damp as I thought how important, after all, this union was to him. But, even then, I could not resist a little more questioning.

"Does Harry love her, dad?"

"Love her!" He smiled. "Why! my boy, he's madly in love with her."

"Then, why doesn't he mend a bit? give over his mad chasing after,—to put it mildly,—continual excitement; and demonstrate that he is thoroughly in earnest. You know, falling madly in love is a habit of Harry's."

"Don't you worry your serious head about that, George. You talk of Harry as if he were a baby. You talk as if you were his grandfather, instead of his younger brother and a mere boy."

"Does Lady Rosemary love Harry?" I asked, ignoring his admonition.

"Of course, she loves him. Why shouldn't she? He's a good fellow; well bred and well made; he is a soldier; he is in the swim; he has plenty to spend; he is the heir to Brammerton;—why shouldn't she love him? She is going to marry him, isn't she? She may not be of the gushing type, George, but she'll come to it all in good time. She will grow to love him, as every good wife does her husband. So, don't let that foolish head of yours give you any more trouble."

I turned to leave.

"George!"

"Yes, dad!"

"You will be on hand this week-end. I want you at home. I need you to keep things going. No skipping off to sporting gatherings or athletic conventions. I wish you to meet your future sister."

"Well,—I had not thought of that, dad. Big Jim Darrol, Tom Tanner and I have entered for a number of events at the Gartnockan Games on Saturday. I am also on the lists as a competitor for the Northern Counties Golf Championship on Monday."

My father looked up at me in a strange way.

"However," I went on quickly, "much as I dislike the rush, the gush and the clatter of house parties, I shall be on hand."

"Good! I knew you would, my boy," replied my father quietly. "Where away now, lad?"

"Oh! down to the village to tell Jim and Tom not to count on me for their week-end jaunt."

I strolled down the avenue, between the tall trees and on to the broad, sun-baked roadway leading to the sleepy little village of Brammerton, which lay so snugly down in the hollow. Swinging my stout stick and whistling as I went, I felt at peace with the good old world. My head was clear, my arm was strong; rich, fresh blood was dancing in my veins; I was young, single, free;—so what cared I?

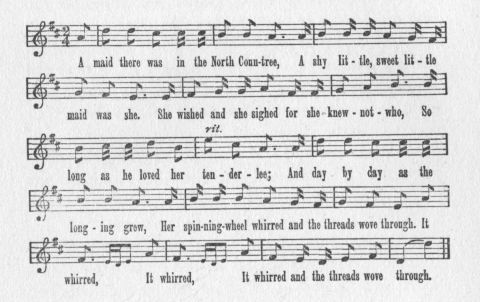

As I walked along, I saw ahead of me a thin line of blue-grey smoke curling up from the roadside. As I drew nearer, I made out the back of a ragged man, leaning over a fire. His voice, lusty and clear as a bell, was ringing out a strange melody. I went over to him.

I was looking over his shoulder, yet he seemed not to have heard me, so intent was he on his song and in his work.

He was toasting the carcass of a poached rabbit, the wet skin of which lay at his side. He was a dirty, ragged rascal, but he seemed happy and his voice was good. The sentiment of his song was not altogether out of harmony with my own feelings.

"A carter swore he'd love always

A skirt, some rouge, a pair of stays.

After his vow, for days and days,

He thought himself the smarter."

The singer bit a piece of flesh from the leg of his rabbit, to test its tenderness, then he resumed his toasting and his song.

"But, underneath the stays and paint

He found the usual male complaint:

A woman's tongue, with Satan's taint;

A squalling, brawling tartar.

"She scratches, bites and blacks his eye.

His head hangs low; he heaves a sigh;

He longs for single days, gone by.

He's doomed to die a martyr."

The peculiar fellow stopped, opened a red-coloured handkerchief, took out a hunk of bread and set it down by his side with slow deliberation. It was quite two minutes ere he started off again.

"Now, friends, beware, take my advice;

When eating sugar, think of spice;

Before you marry, ponder twice:

Remember Ned the carter."

From the words, it seemed to me that he had finished the song, but, judging from the tune, it was never-ending.

"A fine song, my good fellow," I remarked from behind.

The rascal did not turn round.

"Oh!—it's no' so bad. It's got the endurin' quality o' carrying a moral," he answered.

"You seem to be clear in the conscience yourself," said I.

"It'll be clearer when I get outside o' this rabbit," he returned, still not deigning to look at me.

"But you did not seem to be startled when I spoke to you," I remarked in surprise.

"What way should I? I never saw the man yet that I was feart o'. Forby,—I kent you were there."

"But, how could you know? I did not make a noise or display my presence in any way."

"No!—but the wind was blawin' from the back, ye see; and when ye came up behind the smoke curled up a bit further and straighter than it did before; then there was just the ghost o' a shadow."

I laughed. "You are an observant customer."

"Oh, ay! I'm a' that. Come round and let me see ye."

I obeyed, and he seemed satisfied with his inspection.

"Sit doon,—oot o' the smoke," he said.

I did so.

"You are Scotch?" I ventured.

"Ay! From Perth, awa'.

"A Scotch tinker?"

"Just that; a tinker from Perth, and my name's Robertson. I'm a Struan, ye ken. The Struans,—the real Struans,—are a' tinkers or pipers. In oor family, my elder brother fell heir to my father's pipes, so I had just to take to the tinkering. But we're joint heirs to my father's fondness for a dram. Ye havena a wee drop on ye?"

"Not a drop," I remarked.

"That's a disappointment. I was kind o' feart ye wouldna, when I asked ye."

"How so?"

"Oh! ye don't look like a man that wasted your substance. More like a seller o' Bibles, or maybe a horse doctor."

I laughed at the queer comparison, and he looked out at me from under his shaggy, red eyebrows.

"Have a bite o' breakfast wi' me. I like to crack to somebody when I'm eatin'. It helps the digestion."

"No, thank you," I said. "I have breakfasted already."

"It's good meat, man. The rabbit's fresh. I can guarantee it, for it was runnin' half an hour ago. Try a leg."

I refused, but, as he seemed crestfallen, I took the drumstick in my hand and ate the meat slowly from it; and never did rabbit taste so good.

"What makes ye smile?" asked my tattered companion. "Do ye no' like the taste o' it?"

"Oh! the rabbit is all right," I said, "but I was just thinking that had it lived its children might have belonged to a brother of mine some day."

"How's that? Is he a keeper? Od sake!" he went on, scratching his head, as it seemed to dawn on him, "ye don't happen to belong to the big hoose up there?"

"I live there," said I.

He leaned over to me quickly. "Have another leg, man,—have it;—dod! it's your ain, anyway."

"I haven't finished the first yet. Go ahead yourself."

He ate slowly, eying me now and again through the smoke.

"So you're a second son, eh?" he pondered. "Man, ye have my sympathy. I had the same ill-luck. That's how my brother Angus got the pipes and I'm a tinker. Although, I wouldna mind being the second son o' a Laird or a Duke."

"Well, my friend," said I; "that's just where our opinions differ. Now, I'd sooner be the second son of a rag-and-bone man; a—Perthshire piper of the name of Robertson; ay! of the devil himself,—than the second son of an Earl."

"Do ye tell me that now!" he put in, with a cock of his towsled head, picking up another piece of rabbit.

"You see,—you and these other fellows can do as you like; go where you like when you like. An Earl's second son has to serve his House. He has to pave the way and make things smooth for the son and heir. He is supposed to work the limelight that shines on his elder brother. He is tolerated, sometimes spoiled and petted, because,—well, because he has an elder brother who, some day, will be an Earl; but he counts for little or nothing in the world's affairs.

"Be thankful, sir, you are only the second son of a highland piper."

The tramp reflected for a while.

"Ay, ay!" he philosophised at last, "no doot,—maybe,—just that. I can see you have your ain troubles and I'm thinkin', maybe, I'm just as weel the way I am. But it's a queer thing; we aye think the other man is gettin' the best o' what's goin'. It's the way o' the world."

He was quiet a while. He negotiated the rabbit's head and I watched him with interest as he extracted every bit of meat from the maze of bone.

"And you would be the Earl when your father dies, if it wasna for your brother?" he added.

"Yes!" I answered.

"Man, it must be a dreadful temptation."

"What must be?"

"Och! to keep from puttin' something in his whisky; to keep from flinging him ower the window or droppin' a flower pot on his heid, maybe. If my ain father had been an Earl, Angus Robertson would never have lived to blow the pipes. As it was, it was touch and go wi' Angus;—for they were the bonny pipes,—the grand, bonny pipes."

"Do you mean to tell me, you would have murdered your brother for a skirling, screeching bagpipes?" I asked in horror.

"Och! hardly that, man. Murder is no' a bonny name for it. I would just kind o' quietly have done awa' wi' him. It's maybe a pity my conscience was so keen, for he's no' much good, is Angus; he's a through-other customer: no' steady and law-abidin' like mysel'."

"Well, my friend," I said finally——

"Donald! that's my name."

"Well, Donald, I must be on my way."

"What's a' the hurry, man?"

"Business."

"Oh! weel; give me your hand on it. You've a fine face. The face o' a man that, if he had a dram on him, he would give me a drop o' it."

"That I would, Donald."

"It's a pity. But ye don't happen to have the price o' the dram on ye?"

"Maybe I have, Donald."

I handed him a sixpence.

"Thank ye. I'm never wrong in the readin' o' face character."

As I made to go from him, he started off again.

"You don't happen to be a married man, wi' a wife and bairns?" he asked.

"No, Donald. Thank goodness! What made you ask that?"

"Oh! I thought maybe you were and that was the way you liked the words o' my bit song."

I left the tinker finishing his belated breakfast and hurried down the road toward the village.

The sun was getting high in the heavens, birds were singing and the spring workers were busy in the fields. I took the side track down the rough pathway leading to Modley Farm.

My good friend, big, brawny, bluff Tom Tanner,—who was standing under the porch,—hailed me from a distance, with his usual merry shout.

"Where away, George? Feeling fit for our trip?" he asked as I got up to him.

"I am sorry, old boy, but, so far as I am concerned, the trip is off. I just hurried down to tell you and Jim.

"You see, Tom, there is going to be a House Party up there this week-end and my dad's mighty anxious to have me at home; so much so, that I would offend him if I went off. Being merely George Brammerton, I must bow to the paternal commands, although I would rather, a hundred times, be at the games."

Tom's face fell, and I could see he was disappointed. I knew how much he enjoyed those week-end excursions of ours.

"The fact is," I explained, "there is going to be a marriage up there pretty soon, and, naturally, I am wanted to meet the lady."

"Great Scott! George,—you are not trying to break it gently to me? You are not going to get married, are you?" he asked in consternation.

I laughed loudly. "Lord, no! Not for a kingdom. It is my big brother Harry."

Tom seemed relieved. He even sighed.

"I'm glad to hear you say it, George, for there's a lot of fine athletic meetings coming on during the next three or four months and it would be a pity to miss them for, for,—— Oh! hang it all! you know what I mean. You're such a queer, serious, determined sort of customer, that it's hard to say what you will do next."

He looked so solemn over the matter that I laughed again.

His kind-hearted old mother, who had been at work in the kitchen and had overheard our conversation, came to the doorway and placed her arms lovingly around our broad shoulders.

"Lots of time yet to think about getting married. And, let me whisper something into your ears. It's an old woman's advice, and it's good:—when you do think of marrying, be sure you get a wife with a pleasant face and a good figure; a wife that other wives' men will turn round and admire; for, you know, you can never foretell what kind of temper a woman has until you have lived with her. A maid is always on her best behaviour before her lover. And, just think what it would mean if you married a plain, shapeless lass and she proved to have a temper like a termagant! Now, a handsome lass, even if she has a temper, is always—a handsome lass and something to rouse envy of you in other men. And, after all, we measure and treasure what we have in proportion as other people long for it. So, whatever you do, young men, make sure she is handsome!"

"Good, sensible advice, Mrs. Tanner; and I mean to take it," said I. "But I would be even more exacting. In addition to being sweet tempered and fair of face and form, she must have curly, golden hair and golden brown eyes to match."

"And freckles?" put in Mrs. Tanner with a wry face.

"No! freckles are barred," I added.

"But, golden hair and brown eyes are mighty rare to find in one person," said Tom innocently.

"Of course they are; and the combination such as I require is so extremely rare that my quest will be a long one. I am likely therefore to enjoy my bachelorhood for many days to come."

"Good-bye, Mrs. Tanner. Good-bye, Tom; I am going down to the smithy to see Jim."

I strolled away from my happy, contented friends, on to the main road again and down the hill to the village, little dreaming how long it would be ere I should have an opportunity of talking with them again.

The village of Brammerton seemed only half awake. A rumbling cart was slowly wending its way up the hill, three or four old men were standing yarning at the inn corner; now and again, a busy housewife would appear at her door and take a glimpse of what little was going on and disappear inside just as quickly as she had shown herself. The sound of the droning voices of children conning their lessons came through the open window of the old schoolhouse.

These were the only signs and sounds of life that forenoon in Brammerton. Stay!—there was yet another. Breaking in on the general quiet of the place, I could hear distinctly the regular thud of hard steel on soft, followed by the clear double-ring of a small hammer on a mellow-toned anvil.

One man, at any rate, was hard at work,—Jim Darrol,—big, honest, serious giant that he was.

Light of heart and buoyant in body, I turned down toward the smithy. I looked in through the grimy, broken window and admired the brawny giant he looked there in the glare of the furnace, with his broad back to me, his huge arms bared to the shoulders. Little wonder, thought I, Jim Darrol can whirl the hammer and put the shot farther than any man in the Northern Counties.

How the muscles bulged, and wriggled, and crawled under his dark, hairy skin! What a picture of manliness he portrayed! And, best of all,—I knew his heart was as good and clean as his body was sound.

I tiptoed cautiously inside and slapped him between the shoulders. He wheeled about quickly. He always was a solemn-looking owl, but this morning his face was clouded and grim. As he recognised me, a terrible anger seemed to blaze up in his black eyes. I could see the muscles tighten in his arms and his fingers close firmly over the shaft of the hammer he held. I could see a new-born, but fierce hatred burning in every inch of his enormous frame.

"Hello, Jim, old man! Who has been rubbing you the wrong way?" I cried.

His jaws set. He raised his left hand and pointed with his finger to the open doorway.

"Get out!" he growled, in a deep, hoarse voice.

I stood dumbfounded for a brief moment, then I replied roughly and familiarly: "Oh, you go to the devil! Keep your anger for those who have caused it."

"Get out, will you!" he cried again, taking a step nearer to me, his brows lowered, his lips drawn to a thin line.

I had seen these danger signals in Jim before, but never with any ill intent toward me. I was so astounded I could scarcely think aright. What could he mean? What was the matter?

"Jim, Jim," I soothed, "don't talk that way to old friends."

"You're no friend of mine," he shouted. "Will you get out of here?"

In some respects, I was like Jim Darrol: I did not like to be ordered about.

"No! I will not get out," I snapped back at him. "I mean to remain here until you grow sensible."

I went over to his anvil, set my leg across it and looked straight at him.

He raised his hammer high, as if to strike me; and I felt then that if I had taken my eyes from Jim's for the briefest flash of time, my last minute on earth would have arrived.

With an oath,—the first I ever heard him utter,—he cast the hammer from him, sending it clattering into a corner among the old horse shoes.

"Damn you,—I hate you and all your cursed aristocratic breed," he snarled. And, with the spring of a tiger, he had me by the throat, with those great, grabbing hands of his, his fingers closing cruelly on my windpipe as he tried to shake the life out of me.

I had always been able to account for Jim when it came to fisticuffs, but never at close quarters. This time, his attack was violent as it was unexpected. I did not have the ghost of a chance. I staggered back against the furnace wall, still in his devilish clutch. Not a gasp of air entered or left my body from the moment he clutched me.

He shook me as a terrier does a rat.

Soon my strength began to go; my eyes bulged; my head felt as if it were bursting; dancing lights and awful darknesses flashed and loomed alternately before and around me. Then the lights became scarcer and the darknesses longer and more intense. As the last glimmer of consciousness was leaving me, when black gloom had won and there was no more light, I felt a sudden release, painful and almost unwelcome to the oblivion to which I had been hurling. The lights came flashing back to me again and out of the whirling chaos I began to grasp the tangible once more. As I leaned against the side of the furnace, pulling at my throat where those terrible fingers had been,—gasping,—gasping,—for glorious life-giving, life-sustaining air, I gradually began to see as through a haze. Before long, I was almost myself again.

Jim was standing a few paces away, his chest heaving, his shaggy head bent and his great hands clenched against his thighs.

I gazed at him, and as I gazed something wet glistened in his eyes, rolled down his cheeks and splashed on the back of his hand, where it dried up as if it had fallen on a red-hot plate.

I took an unsteady step toward him and held out my hand.

"Jim," I murmured, "my poor old Jim!"

His head remained lowered.

"Strike me," he groaned huskily. "For God's sake strike me, for the coward I am!"

"I want your hand, Jim," I answered. "Tell me what is wrong? What is all this about?"

At last he looked into my eyes. I could see a hundred conflicting emotions working in his expressive face.

"You would be friends after what I have done?" he asked.

"I want your hand, Jim," I said again.

In a moment, both his were clasped over mine, in his vicelike grip.

"George,—George!" he cried. "We've always been friends,—chums. I have always known you were not like the rest of them."

He drew his forearm across his brow. "I am not myself, George. You'll forgive me for what I did, won't you?"

"Man, Jim,—there is nothing done that requires forgiving;—only, you have the devil's own grip. I don't suppose I shall be able to swallow decently for a week.

"But you are in trouble: what is it, Jim? Tell me; maybe I can help."

"Ay,—it's trouble enough,—God forbid. It's Peggy, George,—my dear little sister, Peggy, that has neither mother nor father to guide her;—only me, and I'm a blind fool. Oh!—I can't speak about it. Come over with me and see for yourself."

I followed him slowly and silently out of the smithy, down the lane and across the road to his little, rose-covered cottage. We went round to the back of the house. Jim held up his hand for caution, as he peeped in at the kitchen window. He turned to me again, and beckoned, his big eyes blind with tears.

"Look in there," he gulped. "That's my little sister, my little Peggy; she who never has had a sorrow since mother left us. She's been like that for four hours and she gets worse when I try to comfort her."

I peered in.

Peggy was sitting on the edge of a chair and bending across the table. Her arms were spread out in front of her and her face was buried in them. Her brown, curly hair rippled over her neck and shoulders like a mountain stream. Great sobs seemed to be shaking her supple body. I listened, and my ears caught the sound of a breaking heart. There was a fearful agony in her whole attitude.

I turned away without speaking and followed Jim back to the smithy. When we got there, something pierced me like a knife, although all was not quite clear to my understanding.

"Jim,—Jim," I cried, "surely you never fancied I—I was in any way to blame for this. Why! Jim,—I don't even know yet what it is all about."

He laughed unpleasantly. "No, George, no!—Oh! I can't tell you. Here——"

He went to his coat which hung from a hook in the wall. He pulled a letter from his inside pocket. "Read that," he said.

I unfolded the paper, as he stood watching me keenly.

The note was in handwriting with which I was well familiar.

"My DEAR LITTLE PEGGY,

I am very, very sorry,—but surely you know that what you ask is impossible. I shall try to find time to run out and see you at the usual place, Friday night at nine o'clock. Do not be afraid, little woman; everything will come out all right. You know I shall see that you are well looked after; that you do not want for anything.

Burn this after you read it. Keep our secret, and bear up, like the good little girl you are. Yours affectionately,

H——"

As I read, my blood chilled in my veins, was,—there could be no mistaking it.

"My God! Jim," I cried, "this is terrible. Surely,—surely——"

"Yes! George," he said, in a tensely subdued voice, "your brother did that. Your brother,—with his glib tongue and his masterful way. Oh!—well I know the breed. They are to be found in high and low places; they are generally not much for a man to look at, but they are the kind no woman is safe beside; the kind that gets their soft side whether they be angels or she-devils. Why couldn't he leave her alone? Why couldn't he stay among his own kind?

"And now, he has the gall to think that his accursed money can smooth it over. Damn and curse him for what he is."

I had little or nothing to say. My heart was too full for words and a great anger was surging within me against my own flesh and blood.

"Jim,—does this make any difference between you and me?" I asked, crossing over to him on the spongy floor of hoof parings and steel filings. "Does it, Jim?"

He caught me by the shoulders, in his old, rough way, and looked into my face. Then he smiled sadly and shook his head.

"No, George, no! You're different: you always were different; you are the same straight, honest George Brammerton to me;—still the same."

"Then, Jim, you will let me try to do something here? You will promise me not to get into personal contact with Harry,—at least until I have seen him and spoken with him. Not that he does not deserve a dog's hiding, but I should like to see him and talk with him first."

"Why should I promise that?" he asked sharply.

"For one thing,—because, doubtless, Harry is home now. And again, there is going to be a week-end House Party at our place. Harry's engagement of marriage with Lady Rosemary Granton is to be announced; and Lady Rosemary will be there.

"It would only mean trouble for you, Jim;—and, God knows, this is trouble enough."

"What do I care for trouble?" he cried defiantly. "What trouble can make me more unhappy than I now am?"

"You must avoid further trouble for Peggy's sake," I interposed. "Jim,—let me see Harry first. Do what you like afterwards. Promise me, Jim."

He swallowed his anger.

"God!—it will be a hard promise to keep if ever I come across him. But I do promise, just because I like you, George, as I hate him."

"May I keep this meantime?" I asked, holding up Harry's letter to Peggy.

"No! Give it to me. I might need it."

"But I might find greater use for it, Jim. Won't you let me have it, for a time at least?"

"Oh! all right, all right," he answered, spreading his hands over his leather apron.

I left him there amid the roar of the fire and the odour of sizzling hoofs, and wended my way slowly up the dust-laden hill, back home, having forgotten entirely, in the great sorrow that had fallen, to tell Jim my object in calling on him that day.

On nearing home, I noticed the "Flying Dandy," Harry's favourite horse, standing at the front entrance in charge of a groom.

"Hello, Wally," I shouted in response to the groom's salute and broad grin. "Is Captain Harry home?"

"Yes, sir! Three hours agone, sir. 'E's just agoing for a canter, sir, for the good of 'is 'ealth."

I went inside.

"Hi! William," I cried to the retreating figure of our portly and aristocratic butler. "Where's Harry?"

"Captain Harry, sir, is in the armoury. Any message, sir?"

"No! it is all right, William. I shall go along in and see him."

I went down the corridor, to the most ancient part of Hazelmere House; the old armoury, with its iron-studded oaken doors and its suggestion of spooks and goblins. I pushed in to that sombre-looking place, which held so many grim secrets of feudal times. How many drinking orgies and all-night card parties had been held within its portals, I dared not endeavour to surmise. As to how many plots had been hatched behind its studded doors, how many affairs of honour had been settled for all time under its high-panelled roof,—there was only a meagre record; but those we knew of had been bloody and not a few.

Figures, in suits of armour, stood in every corner; two-edged swords, shields of brass and cowhide, blunderbusses and breech-loading pistols hung from the walls, while the more modern rifles and fowling pieces were ranged in orderly fashion along the far side.

The light was none too good in there, and I failed, at first, to discover the object of my quest.

"How do, farmer Giles?" came that slow, drawling, sarcastic voice which I knew so well.

I turned suddenly, and,—there he was, seated on a brass-studded oak chest almost behind the heavy door, swinging one leg and toying with a seventeenth century rapier. Through his narrow-slitted eyes, he was examining me from top to toe in apparent disgust: tall, thin, perfectly groomed, handsome, cynical, devil-may-care.

I tried to speak calmly, but my anger was greater than I could properly control. Poor little Peggy Darrol was uppermost in my thoughts.

"'Gad, George,—you look like a tramp. Why don't you spruce up a bit? Hobnailed boots, home-spun breeches; ugh! it's enough to make your noble ancestors turn in their coffins and groan.

"Don't you know the Brammerton motto is, 'Clean,—within and without.'"

He bent the blade of his rapier until it formed a half hoop, then he let it fly back with a twang.

"And some of us have degenerated so," I answered, "that we apply the motto only in so far as it affects the outside."

"While some of us, of course, are so busy scrubbing and polishing at our inwards," he put in, "that we have no time to devote to the parts that are seen. But that seems to me deuced like cant; and a cheap variety of it at that.

"So you have taken to preaching, as well as farming. Fine combination, little brother! However, George,—dear boy,—we shall let it go at that. There is something you are anxious to unload. Get it out of your system, man."

"I have just been hearing that you are going to marry Lady Rosemary Granton soon."

"Why, yes! of course. You may congratulate me, for I have that distinguished honour," he drawled.

"And you do consider it an honour?" I asked, pushing my hands deep into my pockets and spreading my legs.

He leaned back and surveyed me tolerantly.

"'Gad!—that's a beastly impertinent question, George. Why shouldn't it be an honour, when every gentleman in London will be biting his finger-tips with envy?"

I nodded and went on.

"You consider also that she will be honoured in marrying a Brammerton?"

"Look here," he answered, a little irritated, "what's all this damned catechising for?"

"I am simply asking questions, Harry; taking liberties seeing I am a Brammerton and your little brother," I retorted calmly.

"And nasty questions they are, too;—but, by Jove! since you ask, and, as I am a Brammerton, and it is I she is going to marry,—why! I consider she is honoured. The honour will be,—ah! on both sides, George. Now,—dear fellow,—don't worry about my feelings. If you have anything more to ask, why! shoot it over, now that I am in the mood for answering," he continued dryly. "I have a hide like a rhino'."

I looked him over coldly.

"Yes, Harry,—Lady Rosemary will come to you as a Granton, fulfilling the pledge made by her father. She will come to you with her honour bright and unsullied."

He bent forward and frowned at me.

"Do you doubt it?" he shot across.

I shook my head. "No!"

He resumed his old position.

"Glad to hear you say so. Now,—what else? Blest if this doesn't make me feel quite a devil, to be lectured and questioned by my young brother,—my own, dear, little, preaching, farmer, kid of a brother."

"You will go to her a Brammerton, fulfilling the vow made by a Brammerton, with a Brammerton's honour, unstained, unblemished,—'Clean,—within and without'?"

He rose slowly from the chest and faced me squarely.

There was nothing of the coward in Harry.

His eye glistened with a cruel light. "Have a care, little brother," he said between his regular, white teeth. "Have a care."

"Why, Harry," I remonstrated in feigned surprise, "what's the matter? What have I said amiss?"

He had always played the big, patronising, bossing brother with me and I had suffered it from him, although, from a physical standpoint, the suffering of late had been one of good-natured tolerance. To-day, there was something in my manner that told him he had reached the end of it.

"Tell me what you mean?" he snarled.

"If you do not know what I mean, brother mine, sit down and I will tell you."

"No!" he answered.

"Oh, well!—I'll tell you anyway."

I went up close to him. "What are you going to do about Peggy Darrol?" I demanded.

The shot hit hard; but he was almost equal to it. He sat down on the chest again and toyed once more with the point of the rapier. Then, without looking up, he answered:

"Peggy Darrol,—eh, George! Peggy Darrol, did you say? Who the devil is she? Oh,—ah,—eh,—oh, yes! the blacksmith's sister,—um,—nice little wench, Peggy:—attractive, fresh, clinging, strawberries and cream and all that sort of thing. Bit of a dreamer, though!"

"Who set her dreaming?" I asked, pushing my anger back.

"Hanged if I know; born in her I suppose. It is part of every woman's make-up. Pretty little thing, though; by Gad! she is."

"Yes! she is pretty; and she was good as she is pretty until she got tangled up with you."

Harry sprang up and menaced me.

"What do you mean, you,—you?—— What are you driving at? What's your game?"

"Oh! give over this rotten hypocrisy," I shouted, pushing him back. "Hit you on the raw, did it?"

He drew himself up.

"No! it didn't. But I have had more than enough of your impertinences. I would box your ears for the unlicked pup you are, if I could do it without soiling my palms."

I smiled.

"Those days are gone, Harry,—and you know it, too. Let us cut this evasion and tom-foolery. You have got that poor girl into a scrape. What are you going to do about getting her out of it?"

"I have got her into trouble? How do you know I have? Her word for it, I suppose? A fine state of affairs it has come to, when any girl who gets into trouble with her clod-hopper sweetheart, has simply to accuse some one in a higher station than she, to have all her troubles ended."

He flicked some dust from his coat-sleeve. "'Gad,—we fellows would never be out of the soup."

"No! not her word," I retorted. "Little Peggy Darrol is not that sort of girl and well you know it. I have your own word for it,—in writing."

His face underwent a change in expression; his cheeks paled slightly.

I drew his letter from my pocket.

"Damn her for a little fool," he growled. He held out his hand for it.

"Oh, no! Harry,—I am keeping this meantime." And I replaced it. "Tell me now,—what are you going to do about Peggy?" I asked relentlessly.

"Oh!" he replied easily, "don't worry. I shall have her properly looked after. She needn't fear. Probably I shall make a settlement on her; although the little idiot hardly deserves that much after giving the show away as she has done."

"Of course, you will tell Lady Rosemary of this before any announcement is made of your marriage, Harry? A Brammerton must, in all things, be honourable, 'Clean,—within and without.'"

He looked at me incredulously, and smiled almost in pity for me and my strange ideas.

"Certainly not! What do you take me for? What do you think Lady Rosemary is that I should trouble her with these petty matters?"

"Petty matters," I cried. "You call this petty? God forgive you, Harry. Petty! and that poor girl crying her heart out; her whole innocent life blasted; her future a disgrace! Petty!—my God!;—and you a Brammerton!

"But I tell you," I blazed, "you shall let Lady Rosemary know."

"And I tell you,—I shall not," he replied.

"Then, by God!—I'll do it myself," I retorted. "I give you two hours to decide which of us it is to be."

I made toward the door. But Harry sprang for his rapier, picked it up and stood with his back against my exit, the point of his weapon to my breast.

There was a wicked gleam in his narrow eyes.

"Damn you! George Brammerton, for a sneaking, prying, tale-bearing lout;—you dare not do it!"

He took a step forward.

"Now, sir,—I will trouble you for that letter."

I looked at him in astonishment. There was a strange something in his eyes I had never seen there before; a mad, irresponsible something that cared not for consequences; a something that makes heroes of some men and murderers of others. I stood motionless.

Slowly he pushed the point of his rapier through my coat-sleeve. It pricked into my arm and I felt a few drops of warm blood trickle. I did not wince.

"Stop this infernal fooling," I cried angrily.

He bent forward, in the attitude of fence with which he was so familiar.

"Fooling, did you say? 'Gad! then, is this fooling?"

He turned the rapier against my breast, ripping my shirt and lancing my flesh to the bone. I staggered back with a gasp.

It was the act of a madman; and I knew in that moment that I was face to face with death by violence for the second time in a few hours. I slowly backed from him, but he followed me, step for step,

As I came up against and sought the wall behind me for support, my hand came in contact with something hard. I closed my fingers over it. It was the handle of an old highland broadsword and the feel of it was not unpleasant. It lent a fresh flow to my blood. I tore the sword from its fastenings, and, in a second, I was standing facing my brother on a more equal, on a more satisfactory footing, determined to defend myself, blow for blow, against his inhuman, insane conduct.

"Ho! ho!" he yelled. "A duel in the twentieth century. 'Gad! wouldn't this set London by the ears? The Corsican Brothers over again!

"Come on, with your battle-axe, farmer Giles, Let's see what stuff you're made of—blood or sawdust."

Twice he thrust at me and twice I barely avoided his dextrous onslaughts. I parried as he thrust, not daring to venture a return. Our strange weapons rang out and re-echoed, time and again, in the dread stillness of the isolated armoury.

My left arm was smarting from the first wound I had received, and a few drops of blood trickled down over the back of my hand, splashing on the floor.

"You bleed!—just like a human being, George. Who would have thought it?" gloated Harry with a taunt.

He came at me again.

My broadsword was heavy and, to me, unwieldy, while Harry's rapier was light and pliable. I could tell that there could be only one ending, if the unequal contest were prolonged,—I would be wounded badly, or killed outright. At that moment, I had no very special desire for either happening.

Harry turned and twisted his weapon with the clever wrist movement for which he was famous in every fencing club in Britain; and every time I wielded my heavy weapon to meet his light one I thought I should never be in time to meet his counter-stroke, his recovery was so very much quicker than mine.

He played with me thus for a time which seemed an eternity. My breath began to come in great gasps. Suddenly he lunged at me with all his strength, throwing the full weight of his body recklessly behind his stroke, so sure was he, evidently, that it would find its mark. I sprang aside just in time, bringing my broadsword down on his rapier and sending six inches of the point of it clattering to the floor.

"Damn the thing!" he blustered, taking a firmer grip of what steel remained in his hand.

"Aren't you satisfied? Won't you stop this madness?" I panted, my voice sounding loud and hollow in the stillness around us.

For answer he grazed my cheek with his jagged steel, letting a little more blood and hurting sufficiently to cause me to wince.

"Got you again, you see," he chuckled, pushing up his sleeves and pulling his tie straight. "George, dear boy, I'll have you in mincemeat before I get at any of your well-covered vitals."

A blind fury seized me. I drove in on him. He turned me aside with a grin and thrust heavily at me in return. I darted to the left, making no endeavour to push aside his weapon with my own but relying only on the agility of my body. With an oath, he floundered forward, and before he could recover I brought the flat of my heavy broadsword crashing down on the top of his head. His arm went up with a nervous jerk and his rapier flew from his hand, shattering against a high window and sending the broken glass rattling on to the cement walk below.

Harry sagged to the floor like a sack of flour and lay motionless on his face, his arms and legs spread out like a spider's.

I was bending down to turn him over, when I heard my father's voice on the other side of the door.

"Stand back! I'll see to this," he cried, evidently addressing the frightened servants.

I turned round. The door swung on its immense hinges and my father stood there, with staring eyes and pallid face, taking in the situation deliberately, looking from me to Harry's inert body beside which I knelt. Slowly he came into the centre of the room.

Full of anxiety, I looked at him. But there was no opening in that stern, old face for any explanations. He did not assail me with a torrent of words nor did he burst into a paroxysm of grief and anger. His every action was calculated, methodical, remorseless.

He turned to the open door.

"Go!" he commanded sternly. "Leave us,—leave Brammerton. I never wish to see you again. You are no son of mine."

His words seared into me. I held out my hands.

"Go!" he repeated quietly, but, if anything, more firmly.

"Good God! father,—won't you hear what I have to say in explanation?" I cried in vexatious desperation.

He did not answer me except with his eyes—those eyes which could say so much.

My anger was still hot within me. My inborn sense of fairness deeply resented this conviction on less than even circumstantial evidence; and, at the back of all that, I,—as well as he, as well as Harry,—was a Brammerton, with a Brammerton's temperament.

"Do you mean this, father?" I asked.

"Go!" he reiterated. "I have nothing more to say to such an unnatural son, such an unnatural brother as you are."

I bowed, pulled my jacket together with a shrug and buttoned it up. After all,—what mattered it? I was in the right and I knew it.

"All right, father! Some day, I know you will be sorry."

I turned on my heel and left the armoury.

The servants were clustering at the end of the corridor, with frightened eyes and pale faces. They opened up and shuffled uneasily as I passed through.

"William," I said to the butler, "you had better go in there. You may be needed."

"Yes, sir! yes, sir!" he answered, and hurried to obey.

Upstairs, in my own room, my knapsack was lying in a corner, ready for my proposed week-end tour. Beside it, stood my golf clubs. These will do, I found myself thinking: a knapsack with a change of linen and a bag of golf clubs,—not a bad outfit to start life with.

I opened my purse:—fifty pounds and a few shillings. Not much, but enough! In fact, nothing would have been plenty.

Suddenly I remembered that, before I went, I had a duty to perform. From my inside pocket, I took the letter which Harry had written to little, forlorn Peggy Darrol. I went to my writing desk and addressed an envelope to Lady Rosemary Granton. I inserted Harry's letter and sealed the envelope. As to the bearer of my message, that was easy. I pushed the button at my bedside and, in a second, sweet little Maisie Brant came to the door.

Maisie always had been my special favourite, and, on account of my having pulled her out of the river when she was only seven years old, I was hers. She had never forgotten. I cried to her in an easy, bantering way in order to reassure her.

"Neat little Maisie, sweet little Maisie;

Only fifteen and as fresh as a Daisy."

She smiled, but behind her smile was a look of concern.

"I am going away, Maisie," I said.

"Going away, sir?" she repeated anxiously, as she came bashfully forward.

"I won't be back again, Maisie. I am going for good."

She looked up at me in dumb disquiet.

"Maisie, Lady Rosemary Granton will be here this week-end."

"Yes, sir!" she answered. "I am to have the honour of looking after her rooms."

I laid my hand gently on her shoulder.

"I want you to do something for me, Maisie. I want you to give her this letter,—see that she gets it when she is alone. It is more important to her than you can ever dream of. She must have it within a few hours of her arrival. No one else must set eyes on it between now and then. Do you understand, Maisie?"

"Oh, yes, sir! You can trust me for that."

"I know I can, Maisie. You are a good girl."

I gave her the letter and she placed it in the safest, the most secret, place she knew,—her bosom. Then her eyes scanned me over.

"Oh! sir," she cried, in sudden alarm, "you are hurt. You are bleeding."

I put my hand to my cheek, but then I remembered I had already wiped away the few drops of blood from there with my handkerchief.

"Your arm, sir," she pointed.

"Oh!—just a scratch, Maisie."

"Won't you let me bind it for you, sir, before you go?" she pleaded.

"It isn't worth the trouble, Maisie."

Tears came to those pretty eyes of hers; so, to please her, I consented.

"All right," I cried, "but hurry, for I have no more business in here now than a thief would have."

She did not understand my meaning, but she left me and was back in a moment with a basin of hot water, a sponge, balsam and bandages.

I slipped off my coat and rolled up my sleeve, then, as Maisie's gentle fingers sponged away the congealed blood and soothed the throb, I began to discover, from the intense relief, how painful had been the hurt, mere superficial thing as it was.

She poured on some balsam and bound up the cut; all gentleness, all tenderness, like a mother over her babe.

"There is a little jag here, Maisie, that aches outrageously now that the other has been lulled to sleep." I pointed to my breast.

She undid my shirt, and, as she surveyed the damage, she cried out in anxiety.

It was a raw, jagged, angry-looking wound, but nothing to occasion concern.

She dealt with it as she had done the other, then she drew the edges of the cut together, binding them in place with strips of sticking plaster. When it was all over, I slipped into my jacket, swung my knapsack across my shoulders, took my golf-bag under my left arm,—and I was ready.

Maisie wiped her eyes with the corner of her apron.

"Never mind, little woman," I sympathised.

"Must you really go away, sir?" she sobbed.

"Yes!—I must. Good-bye, little girl."

I kissed her on the trembling curve of her red, pouting lips, then I went down the stairs, leaving her weeping quietly on the landing.

As I turned at the front door for one last look at the inside of the old home, which I might never see again, I saw the servants carrying Harry from the armoury. I could hear his voice swearing and complaining in almost healthy vigour, so I was pleasantly confirmed in what I already had surmised,—his hurt was as temporary as the flat of a good, trusty, highland broad-sword could make it.

I hurried down the avenue to where it joined the dusty roadway.

I stood for a few moments in indecision. To my left, down in the hollow, the way led through the village. To my right, it stretched far on the level until it narrowed to a grey point piercing a semi-circle of green; but I knew that miles beyond, at the end of that grey line, was the busy town of Grangeborough, with its thronging people, its railways and its steamships. That was the direction for me.

I waved my hand to sleepy little Brammerton and I swung to the right, for Grangeborough and the sea.

Soon the internal tumult, caused by what I had just gone through, began to subside, and my spirits rose attune to the glories of the afternoon.

Little I cared what my lot was destined to be—a prince in a palace or a tramp under a hedge. Although, to say truth, the tramp's existence held for me the greater fascination.

I was young, my lungs were sound and my heart beat well. I was big and endowed with greater strength than is allotted the average man.

Glad to be done with pomp, show and convention, my life was now my very own to plan and make, or to warp and spoil, as fancy, fortune and fate decreed.

I hankered for the undisturbed quiet of some small village by the sea, with work enough,—but no more,—to keep body nourished and covered; with books in plenty and my pipe well filled; with an open door to welcome the sunshine, the scented breeze, the salted spray from the ocean and my congenial fellow-man.

But, if I should be led in the paths of grubbing men, 'mid bustle, strife and quarrel, where the strong and the crafty alone survived, where the weaklings were thrust aside, I was ready and willing to take my place, to take my chance, to pit brawn against brawn, brain against brain, to strike blow for blow, to fail or to succeed, to live or die, as the gods might decree.

As I filled my lungs, I felt as if I had relieved myself of some great burden in cutting myself adrift from Brammerton,—dear old spot as it was. And I whistled and hummed as I trudged along, trying to reach the point of grey at the rim of the semi-circle of green. On, on I went, on my seemingly unending endeavour. But I knew that ultimately the road would end, although merely to open up another and yet another path over which I would have to travel in the long journey of life which lay before me.

As I kept on, I saw the sun go down in a display of blood-red pyrotechnics. I heard the chatter of the birds in the hedgerows as they settled to rest. Now and again, I passed a tired toiler, with bent head and dragging feet,—his drudgery over for the day, but weighted with the knowledge that it must begin all over again on the morrow and on each succeeding morrow till the crash of his doom.

The night breeze came up and darkness gathered round me. A few hours more, and the twinkling lights of Grangeborough came into view. They were welcome lights to me, for the pangs of a healthy hunger were clamouring to be appeased.

As it had been with the country some hours before, so was it now with Grangeborough. The town was settling down for the night. It was late. Most of the shops were closing, or already closed. Business was over for the day. People hurried homeward like shadows.

I looked about me for a place to dine, but failed, at first, in my quest. Down toward the docks there were brighter lights and correspondingly deeper darknesses. I went along a broad thoroughfare, turned down a narrower one until I found myself among lanes and alleys, jostled by drunken sailors and accosted by wanton women, as they staggered, blinking, from the brightly lighted saloons.

My finer sensibilities rose and protested within me, but I had no choice. If I wished to quell my craving for food, there was nothing left for me to do but to brave the foul air and the rough element of one of these sawdust-floored, glass-ornamented whisky palaces, where a snack and a glass of ale, at least, could be purchased.

I looked about me and pushed into what seemed the least disreputable one of its kind. I made through the haze of foul air and tobacco smoke to the counter, and stood idly by until the bar-tender should find it convenient to wait upon me.

The place was crowded with sea-faring men and the human sediment that is found in and around the docks of all shipping cities; it resounded with a babel of coarse, discordant voices.

The greater part of this coterie was gathered round a huge individual, with enormous hands and feet, a stubbly, blue chin,—set, round and aggressive; a nose with a broken bridge spoiled the balance of his podgy face. He had beady eyes and a big, ugly mouth with stained, irregular teeth. From time to time, he laughed boisterously, and his laugh had an echo of hell in it.

He and his followers appeared to be enjoying some good joke. But whenever he spoke every one else became silent. Each coarse jest he mouthed was laughed at long and uproariously. He had a hold on his fellows. Even I was fascinated; but it was by the great similarity of some of the mannerisms of this uncouth man to those I had observed in the lower brute creation.

My attention was withdrawn from him, however, by the sound of the rattling of tin cans in another corner which was partly partitioned from the main bar-room. I followed the new sound.

A tattered individual was seated there, his feet among a cluster of pots and pans all strung together. His head was in his hands and his red-bearded face was a study of dejection and misery.

There was something strangely familiar in the appearance of the man.

Suddenly I remembered, and I laughed.

I went over and sat down opposite him, setting my golf clubs by my side. He ignored my arriving. That same old trick of his!

"Donald,—Donald Robertson!" I exclaimed, laughing again.

Still he did not look across.

Suddenly he spoke, and in a voice that knew neither hope nor gladness.

"Ye laugh,—ye name me by my Christian name,—but ye don't say, 'Donald, will ye taste?'"

I leaned over and pulled his hands away from his head. He flopped forward, then glared at me. His eyes opened wide.

"It's,—it's you,—is it? The second son come to me in my hour o' trial."

"Why! Donald,—what's the trouble?" I asked.

"Trouble,—ye may well say trouble. Have ye mind o' the sixpence ye gied me on the roadside this mornin'."

"Yes!"

"For thirteen long, unlucky hours I saved that six-pence against my time o' need. I tied it in the tail o' my sark for safety. I came in here an hour ago. I ordered a glass o' whisky and a tumbler o' beer. I sat doon here for a while wi' them both before me, enjoying the sight o' them and indulgin' in the heavenly joy o' anteecipation. Then I drank the speerits and was just settlin' doon to the beer,—tryin' to make it spin oot as long as I could; for, ye ken, it's comfortable in here,—when an emissary o' the deevil, wi' hands like shovels and a leer in his e'e, came in and picked up the tumbler frae under my very nose and swallowed the balance o' your six-pence before I could say squeak."

I laughed at Donald's rueful countenance and his more than rueful tale.

"Did the man have a broken nose and a heavy jaw?" I asked.

"Ay, ay!" said Donald, lowering his voice. "Do ye happen to ken him?"

"No!—but he is still out there and he thinks it a fine joke that he played on you."

"So would I," said Donald, "if I had drunk his beer."

"What did you do when he swallowed off your drink?" I asked.

"Do!—what do ye think I did? I remonstrated wi' a' the vehemence that a Struan Robertson in anger is capable o'. But the vehemence o' the Lord himsel' couldna bring the beer back."

"Why didn't you fight, man? Why didn't you knock the bully down?" I asked, pitying his wobegone appearance.

"Mister,—whatever your name is,—I'm a man o' peace; and, forby I'm auld enough to ken it's no' wise to fight on an empty stomach. I havena had a bite since I saw ye last."

"Never mind, Donald,—cheer up. I am going to have some bread and cheese, and a glass of ale, so you can have some with me, at my expense."

His face lit up like a Roman candle.

"Man,—I'm wi' ye. You're a man o' substance, and I'm fonder o' substantial bread and cheese and beer than I am o' the metapheesical drinks I was indulgin' in for ten minutes before ye so providentially came."

I could not help wondering at some of the remarks of this wise, yet good-for-little, old customer; but I did not press him for more enlightenment.

I thumped the hand-bell on the table, and was successful in obtaining more prompt attention from the bar-tender than I had been able to do across the counter.

When the food and drink were placed between us and paid for, Donald stuffed all but one slice of his bread and cheese inside his waistcoat, and he sighed contentedly as he contemplated the sparkling ale.

But, all at once, he startled me by springing to his feet, seizing his tumbler in his hand and emptying the contents down his gullet at two monstrous gulps.

"No, no!—ye thievin' deevil," he shouted, as he regained his breath, "ye canna do that twice wi' Donald Robertson."

I looked toward the opening in the partition. Donald's recent enemy,—the man whom I had been studying at the other end of the bar-room,—was shouldering himself into our company. Behind him, in a semi-circle, a dozen faces grinned in anticipation of some more fun at Donald's expense.

The big bully glared down at me as I sat.

"That there is uncommon good beer, young un," he growled, "and that there is most uncommon good bread and cheese."

I glanced at him with half-shut eyelids, then I broke off another piece of bread.

"Maybe you didn't 'ear me?" he shouted again, "I said that was uncommon good beer."

"I shall be better able to judge of that, my man, after I have tasted it," I replied.

"Not that beer, little boy,—you ain't going to taste that," he thundered, "because I 'appens to want it,—see! I 'appens to 'ave a most aggrawating thirst in my gargler."

A burst of laughter followed this ponderous attempt at humour.

"'And it over, sonny,—I wants it."

I merely raised my head and ran my eyes over him.

He was an ugly brute, and no mistake. A man of tremendous girth.

Although I had no real fear of him,—for, already I had been schooled to the knowledge that fear and its twin brother worry are man's worst opponents.—I was a little uncertain as to what the outcome would be if I got him thoroughly angered. However, I was in no mind to be interfered with.

He thumped his heavy fist on the table.

"'And that over,—quick," he roared.

His great jaws clamped together and his thick, discoloured lips became compressed.

"Why!—certainly, my friend," I remarked easily, rising with slow deliberation. "Which will you have first:—the bread and cheese, or the ale?"

"'Twere the ale I arst and it's th' ale I wants,—and blamed quick about it or I'll know the reason w'y."

"Stupid of me!" I remarked. "I should have known you wanted the ale first. Here you are, my good, genial, handsome fellow."

I picked up the foaming tumbler and offered it to him. When he stretched out his great, grimy paw to take it, I tossed the stuff smack into his face, sending showers of the liquid into the gaping countenances of his supporters.

He staggered back among them, momentarily blinded, and, as he staggered, I sent the tumbler on the same errand as the ale. It smashed in a hundred pieces on the side of his broken nose, opening up an old gash there and sending a stream of blood oozing down over his mouth.

There was no more laughter, nor grinning. The place was as quiet as a church during prayer. I pushed into the open saloon, with the remonstrating Donald at my heels. Then the bull began to roar. He pulled off his coat, while half a dozen of his own kind endeavoured with dirty handkerchiefs and rags to mop the blood from his face.

"Shut the door. Don't let 'im away from 'ere," he shouted. "I'll push his windpipe into his boots, I will. Watch me!"

As I stood with my back against the partition, the bar-tender slipped round the end of the counter.

"Look here, guv'nor," he whispered with good intent, "the back door's open,—run like the devil."

I turned to him in mild surprise.

"Don't be an ijit," he went on. "Git. Why! he's Tommy Flynn, the champion rib cracker and face pusher of Harlford, here on his holidays."

"Tommy Flynn," I answered, "Tommy Rot fits him better."

"You ain't a-going to stand up and get hit, are you?"

"What else is there for me to do?" I asked.

He threw up his arms despairingly.

"Lor' lumme!—then I bids you good-bye and washes my hands clean of you." And he went round behind the counter in disgust, spitting among the sawdust.

By this time, Tommy Flynn, the champion rib cracker and face pusher, was rolling up his sleeves businesslike and thrusting off his numerous seconds in his anxiety to get at me.

"'Ere, Splotch," he cried to a one-eyed bosom friend of his, "'old my watch, while I joggles the puddins out of this kid with a left 'ander. My heye!—'e won't be no blooming golfing swell in another 'alf minute."

He grinned at me a few times in order to hypnotise me with his beauty and to instil in me the necessary amount of frightfulness, before he got to work in earnest. Then, by way of invitation, he thrust forward his jaw almost into my face. I took advantage of his offer somewhat more quickly than he anticipated. I struck him on the chin with my left and drew my right to his body. But his chin was hard as flint and it bruised my knuckles; while his great body was podgy and of an india-rubberlike flexibility.

For my pains, he brushed my ear and drew a little blood, with the grin of an ape on his brutish face.

He threw up his arms to guard, feinted at me, and rushed in.

I parried his blows successfully, much to his surprise, for I could see his eyes widening and a wrinkle in his brow.

"Careful, Tommy!—careful," cautioned Splotch of the one eye. "He's a likely looking young bloke."

"Likely be blowed," said Tommy shortly, as he toyed with me. "Watch this!"

I saw that it would be for my own good, the less I let my antagonist know of my ability at his own game, and I knew also I would have to play caution with my strength all the way, owing to the trying ordeals I had already gone through that day.

Once, my antagonist tried to draw me as he would draw a novice. I ignored the body bait he opened up for me and, instead, I swung in quickly with my right on to his bruised nose, with all the energy I could muster. He staggered and reeled like a drunken man. In fact, had he not been half-besotted by dear-only-knows how many days of debauchery, it might have gone hard with me, but now he positively howled with pain.

I had hit on his most vulnerable part, right at the beginning.

Something inside of me chuckled, for, if there was one special place in any man's anatomy that I always had been able to reach, it was his nose.

Flynn rushed on me again and again. I was lucky indeed in beating back his onslaughts.

Once, a spent blow got me on the cheek; yet, spent as it was, it made me numb and dizzy for the moment. Once, he caught me squarely on the chest right over the wound my brother had given me. The pain of that was like the cut of a red-hot knife, but it passed quickly. I staggered and reeled several times, as flashes of weakness seemed to pass over me. I began to fear that my strength would give out.

I pulled myself together with an effort. Then, once,—twice,—thrice,—in a succession bewildering to myself, I smashed that broken nose of Flynn's, sending him sick and wobbling among his following.

He became maddened with rage. His companions commenced to voice cautions and instructions. He swore back at them in a muddy torrent of abuse.

Already, the fight was over;—I could feel it in my bones;—over, far sooner and more satisfactory to me than I had expected. And, more by good luck than by ability, I was, to all intents and purposes, unscathed.

Tommy Flynn could fight. But he was not the fighter he would have been had he been away from drink and in strict training, as I was. It was my good fortune to meet him when he was out of condition. He spat out a mouthful of blood and returned to the conflict, defending his nose with all the ferocity of a lioness defending her whelps.

"Look out! Take care!" a timely voice whispered on my left.

Something flashed in my opponent's hands in the gaslight. I backed to the partition. We had a terrible mix-up just then. Blow and counterblow rained. He broke down my guard once and drove with fierce force for my face. I ducked, just in time, for he missed me by a mere hair's-breadth. His fist smashed into a metal bolt in the woodwork. Sparks flew and there was a loud ring of metal against metal.

"You cowardly brute!" I shouted, breaking away as it dawned on me that he had attacked me with heavy knuckle-dusters. My blood fairly danced with madness. I sprang in on him in a positive frenzy. He became a child in my hands. Never had I been roused as I was then. I struck and struck again at his hideous face until it sagged away from me.

He was blind with his own blood. I followed up, raining punch upon punch,—pitilessly,—relentlessly. His feet slipped in the slither of bloody sawdust. I struck again and he crashed to the floor, striking his head against the iron pedestal of a round table in the corner.

He lay all limp and senseless, with his mouth wide open and his breath coming roaring and gurgling from his clotted throat.

As his friends endeavoured to raise him, as I stood back against the counter, panting, I heard a battering at the main door of the saloon which had been closed at the commencement of the scuffle.

"Here, sir,—quick!" cried the sympathetic bartender to me. "The cops! Out the back door like hell!"

I had no desire to be mixed up in a police affair, especially in the company of such scum as I was then among. I picked up my golf bag and swung my knapsack on to my back once more. Then I remembered about Donald. I could not leave him. I searched in corners and under the tables. He was nowhere in sight.

"Is it the tinker?" asked the bar-tender excitedly.

"Yes, yes!"

"He's gone. He slunk out with his tin cans, through the back way, as soon as you got started in this scrap."

I did not wait for anything more, for some one was unlocking the front door. I darted out the back exit and into the lane. Down the lane, in the darkness, I tore like a hurricane, then along the waterfront until there was a mile between me and the scene of my late encounter.

I slowed up at a convenient horse-trough, splashed my hands and face in the cooling water and adjusted my clothing as best I could, then I strolled into the shipping shed, where stevedores and dock labourers were busy, by electric light, completing the loading of a smart-looking little cargo boat.

A notion seized me. It was a coaster, so I knew I could not be going very far away.

I walked up the gang-plank, and aboard.

An ordinary seaman, then the second officer of the little steamer passed me on the deck, but both were busy and paid no more attention to my presence than if I had been one of themselves.

I strolled down the narrow companionway, into a cosy, but somewhat cramped, saloon.

After standing for a time in the hope of seeing some signs of life, I pushed open the door of a stateroom on the starboard side. The room had two berths. I tossed my knapsack and clubs into the lower one. As I turned to the door again, I espied a diminutive individual, no more than four and a half feet tall,—or, as I should say, small,—in the full, gold-braided uniform of a ship's chief steward.

He was a queer-looking little customer, grizzled, weather-beaten and, apparently, as hard as nails. He was absolutely self-possessed and, despite his stature, there was "nothing small about him," as an American friend of mine used to put it.

He touched his cap, and smiled. His smile told me at once that he was an Irishman, for only an Irishman could smile as he did. It was a smile with a joke, a drink, a kiss and a touch of the devil himself in it.

"I saw ye come down, sor. Ye'll be makin' for Glasgow?"

Glasgow! I cogitated, yes!—Glasgow as a starting point would suit me as well as anywhere else.

"Correct first guess," I answered. "But, tell me,—how did you know that that was my destination?"

He showed his teeth.

"Och! because it's the only port we're callin' at, sor. Looks like a fine trip north," he went on. "The weather's warm and there's just enough breeze to make it lively. Nothin' like the sea, sor, for keepin' the stomach swate and the mind up to the knocker."